User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

SHM Can Help Your Hospital with Opioid Monitoring

Recruitment is under way for 10 hospitals to participate in a one-year mentored-implementation program related to opioid monitoring. SHM will be assigning two mentors to guide them through:

- Needs assessment

- Formal selection of data collection measures

- Data collection

- The implementation of key interventions to enhance safety for patients in the hospital who are prescribed opioid medications

The program will include monthly calls, a site visit with the SHM mentors, and a formal assessment of program implementation. Is your hospital interested in participating? Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/RADEO to learn more and complete the form.

Recruitment is under way for 10 hospitals to participate in a one-year mentored-implementation program related to opioid monitoring. SHM will be assigning two mentors to guide them through:

- Needs assessment

- Formal selection of data collection measures

- Data collection

- The implementation of key interventions to enhance safety for patients in the hospital who are prescribed opioid medications

The program will include monthly calls, a site visit with the SHM mentors, and a formal assessment of program implementation. Is your hospital interested in participating? Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/RADEO to learn more and complete the form.

Recruitment is under way for 10 hospitals to participate in a one-year mentored-implementation program related to opioid monitoring. SHM will be assigning two mentors to guide them through:

- Needs assessment

- Formal selection of data collection measures

- Data collection

- The implementation of key interventions to enhance safety for patients in the hospital who are prescribed opioid medications

The program will include monthly calls, a site visit with the SHM mentors, and a formal assessment of program implementation. Is your hospital interested in participating? Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/RADEO to learn more and complete the form.

Provide Feedback on State of EHRs in Hospital Medicine

According to a report published by AmericanEHR Partners, 61% of respondents in 2010 said they were “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with their electronic health records (EHRs), compared with just 34% in 2014. Additionally, close to half of all respondents reported a negative response to questions related to costs, efficiency, and productivity. SHM’s IT Committee would like to obtain your insight on the EHR within your institution. The findings from the survey will be released in a white paper on how the current state of EHRs affects the quality of patient care and the professional satisfaction of hospitalists.

Please take a few minutes to offer your feedback at www.hospitalmedicine.org/ITEHR.

According to a report published by AmericanEHR Partners, 61% of respondents in 2010 said they were “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with their electronic health records (EHRs), compared with just 34% in 2014. Additionally, close to half of all respondents reported a negative response to questions related to costs, efficiency, and productivity. SHM’s IT Committee would like to obtain your insight on the EHR within your institution. The findings from the survey will be released in a white paper on how the current state of EHRs affects the quality of patient care and the professional satisfaction of hospitalists.

Please take a few minutes to offer your feedback at www.hospitalmedicine.org/ITEHR.

According to a report published by AmericanEHR Partners, 61% of respondents in 2010 said they were “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with their electronic health records (EHRs), compared with just 34% in 2014. Additionally, close to half of all respondents reported a negative response to questions related to costs, efficiency, and productivity. SHM’s IT Committee would like to obtain your insight on the EHR within your institution. The findings from the survey will be released in a white paper on how the current state of EHRs affects the quality of patient care and the professional satisfaction of hospitalists.

Please take a few minutes to offer your feedback at www.hospitalmedicine.org/ITEHR.

Future of Hospital Medicine Program to Tour U.S. Cities

- Chicago: Aug. 27

- St. Louis: September

- Philadelphia: October

- Atlanta: Oct. 13

- Denver: Oct. 18

- San Francisco: Oct. 20

- New York City: Nov. 3

- Chicago: December

Visit www.futureofhospitalmedicine.org/events to learn more and see updated schedule details.

- Chicago: Aug. 27

- St. Louis: September

- Philadelphia: October

- Atlanta: Oct. 13

- Denver: Oct. 18

- San Francisco: Oct. 20

- New York City: Nov. 3

- Chicago: December

Visit www.futureofhospitalmedicine.org/events to learn more and see updated schedule details.

- Chicago: Aug. 27

- St. Louis: September

- Philadelphia: October

- Atlanta: Oct. 13

- Denver: Oct. 18

- San Francisco: Oct. 20

- New York City: Nov. 3

- Chicago: December

Visit www.futureofhospitalmedicine.org/events to learn more and see updated schedule details.

National Program Reduces Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections

Clinical question: Can a program of education, feedback, and proper training reduce catheter-associated urinary tract infections in hospitalized patients?

Bottom line: The Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program, or CUSP, is a national program in the United States that aims to reduce catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) by focusing on proper technical skills, behavioral changes, education, and feedback. Implementation of the CUSP recommendations was effective in reducing catheter use and CAUTIs in patients in nonintensive care units (non-ICUs). The program was likely successful because it included both socioadaptive and technical changes and allowed the individual hospitals to customize interventions based on their own needs.

Reference: Saint S, Greene MT, Krein SL, et al. A program to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infection in acute care. N Engl J Med 2016;374(22):2111-2119.

Design: Case series; LOE: 2b

Setting: Inpatient (any location)

Synopsis: This study reports the results of an 18-month program to reduce CAUTIs that was implemented in 926 inpatient units in 603 acute-care U.S. hospitals (which represents 10% of the acute care hospitals in the country). Overall, 40% of the units were ICUs while the remainder were non-ICUs.

Key recommendations of the program included the following: (1) assessing for the presence and need for a urinary catheter daily, (2) avoiding the use of a urinary catheter while emphasizing alternative urine-collection methods, and (3) promoting proper insertion and maintenance of catheters, when necessary. Hospitals were allowed to decide how best to implement these interventions in their individual units. Furthermore, participating unit teams received education on the prevention of CAUTIs as well as feedback on catheter use and the rate of CAUTIs on their individual units.

Data were collected over a 3-month baseline phase, a 2-month implementation phase, and a 12-month sustainability phase. After adjusting for hospital characteristics, the rate of CAUTIs decreased from 2.40 infections per 1000 catheter-days at the end of the baseline phase to 2.05 infections per 1000 catheter-days at the end of the sustainability phase. The reduction was statistically significant only in non-ICUs where CAUTIs decreased from 2.28 to 1.54 infections per 1000 catheter-days while catheter use decreased from 20.1% to 18.8%. This was not a randomized controlled trial, so confounding variables including secular trends may have affected the findings in this study.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question: Can a program of education, feedback, and proper training reduce catheter-associated urinary tract infections in hospitalized patients?

Bottom line: The Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program, or CUSP, is a national program in the United States that aims to reduce catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) by focusing on proper technical skills, behavioral changes, education, and feedback. Implementation of the CUSP recommendations was effective in reducing catheter use and CAUTIs in patients in nonintensive care units (non-ICUs). The program was likely successful because it included both socioadaptive and technical changes and allowed the individual hospitals to customize interventions based on their own needs.

Reference: Saint S, Greene MT, Krein SL, et al. A program to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infection in acute care. N Engl J Med 2016;374(22):2111-2119.

Design: Case series; LOE: 2b

Setting: Inpatient (any location)

Synopsis: This study reports the results of an 18-month program to reduce CAUTIs that was implemented in 926 inpatient units in 603 acute-care U.S. hospitals (which represents 10% of the acute care hospitals in the country). Overall, 40% of the units were ICUs while the remainder were non-ICUs.

Key recommendations of the program included the following: (1) assessing for the presence and need for a urinary catheter daily, (2) avoiding the use of a urinary catheter while emphasizing alternative urine-collection methods, and (3) promoting proper insertion and maintenance of catheters, when necessary. Hospitals were allowed to decide how best to implement these interventions in their individual units. Furthermore, participating unit teams received education on the prevention of CAUTIs as well as feedback on catheter use and the rate of CAUTIs on their individual units.

Data were collected over a 3-month baseline phase, a 2-month implementation phase, and a 12-month sustainability phase. After adjusting for hospital characteristics, the rate of CAUTIs decreased from 2.40 infections per 1000 catheter-days at the end of the baseline phase to 2.05 infections per 1000 catheter-days at the end of the sustainability phase. The reduction was statistically significant only in non-ICUs where CAUTIs decreased from 2.28 to 1.54 infections per 1000 catheter-days while catheter use decreased from 20.1% to 18.8%. This was not a randomized controlled trial, so confounding variables including secular trends may have affected the findings in this study.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question: Can a program of education, feedback, and proper training reduce catheter-associated urinary tract infections in hospitalized patients?

Bottom line: The Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program, or CUSP, is a national program in the United States that aims to reduce catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) by focusing on proper technical skills, behavioral changes, education, and feedback. Implementation of the CUSP recommendations was effective in reducing catheter use and CAUTIs in patients in nonintensive care units (non-ICUs). The program was likely successful because it included both socioadaptive and technical changes and allowed the individual hospitals to customize interventions based on their own needs.

Reference: Saint S, Greene MT, Krein SL, et al. A program to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infection in acute care. N Engl J Med 2016;374(22):2111-2119.

Design: Case series; LOE: 2b

Setting: Inpatient (any location)

Synopsis: This study reports the results of an 18-month program to reduce CAUTIs that was implemented in 926 inpatient units in 603 acute-care U.S. hospitals (which represents 10% of the acute care hospitals in the country). Overall, 40% of the units were ICUs while the remainder were non-ICUs.

Key recommendations of the program included the following: (1) assessing for the presence and need for a urinary catheter daily, (2) avoiding the use of a urinary catheter while emphasizing alternative urine-collection methods, and (3) promoting proper insertion and maintenance of catheters, when necessary. Hospitals were allowed to decide how best to implement these interventions in their individual units. Furthermore, participating unit teams received education on the prevention of CAUTIs as well as feedback on catheter use and the rate of CAUTIs on their individual units.

Data were collected over a 3-month baseline phase, a 2-month implementation phase, and a 12-month sustainability phase. After adjusting for hospital characteristics, the rate of CAUTIs decreased from 2.40 infections per 1000 catheter-days at the end of the baseline phase to 2.05 infections per 1000 catheter-days at the end of the sustainability phase. The reduction was statistically significant only in non-ICUs where CAUTIs decreased from 2.28 to 1.54 infections per 1000 catheter-days while catheter use decreased from 20.1% to 18.8%. This was not a randomized controlled trial, so confounding variables including secular trends may have affected the findings in this study.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Procalcitonin Guidance Safely Decreases Antibiotic Use in Critically Ill Patients

Clinical question: Can the use of procalcitonin levels to determine when to discontinue antibiotic therapy safely reduce the duration of antibiotic use in critically ill patients?

Bottom line: For patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) who receive antibiotics for presumed or proven bacterial infections, the use of procalcitonin levels to determine when to stop antibiotic therapy results in decreased duration and consumption of antibiotics without increasing mortality.

Reference: De Jong E, Van Oers JA, Beishuizen A, et al. Efficacy and safety of procalcitonin guidance in reducing the duration of antibiotic treatment in critically ill patients: a randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2016;16(7):819-827.

Design: Randomized controlled trial (nonblinded); LOE: 1b

Setting: Inpatient (ICU only)

Synopsis: To test the efficacy and safety of procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy, these investigators recruited patients in the ICU who had received their first doses of antibiotics for a presumed or proven bacterial infection within 24 hours of enrollment. Patients who were severely immunosuppressed and patients requiring prolonged courses of antibiotics (such as those with endocarditis) were excluded.

Using concealed allocation, patients were assigned to procalcitonin-guided treatment (n = 761) or to usual care (n = 785). The usual care group did not have procalcitonin levels drawn. In the procalcitonin group, patients had a procalcitonin level drawn close to the start of antibiotic therapy and daily thereafter until discharge from the ICU or 3 days after stopping antibiotic use. These levels were provided to the attending physician who could then decide whether to stop giving antibiotics.

Although the study protocol recommended that antibiotics be discontinued if the procalcitonin level had decreased by more than 80% of its peak value or reached a level of 0.5 mcg/L, the ultimate decision to do so was at the discretion of the attending physician. Overall, fewer than half the physicians actually discontinued antibiotics within 24 hours of reaching either of these goals. Despite this, the procalcitonin group had decreased number of days of antibiotic treatment (5 days vs 7 days; between group absolute difference = 1.22; 95% CI 0.65-1.78; P < .0001) and decreased consumption of antibiotics (7.5 daily defined doses vs 9.3 daily defined doses; between group absolute difference = 2.69; 1.26-4.12; P < .0001). Additionally, when examining 28-day mortality rates, the procalcitonin group was noninferior to the standard group, and ultimately, had fewer deaths than the standard group (20% vs 25%; between group absolute difference = 5.4%;1.2-9.5; P = .012). This mortality benefit persisted at 1 year.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question: Can the use of procalcitonin levels to determine when to discontinue antibiotic therapy safely reduce the duration of antibiotic use in critically ill patients?

Bottom line: For patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) who receive antibiotics for presumed or proven bacterial infections, the use of procalcitonin levels to determine when to stop antibiotic therapy results in decreased duration and consumption of antibiotics without increasing mortality.

Reference: De Jong E, Van Oers JA, Beishuizen A, et al. Efficacy and safety of procalcitonin guidance in reducing the duration of antibiotic treatment in critically ill patients: a randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2016;16(7):819-827.

Design: Randomized controlled trial (nonblinded); LOE: 1b

Setting: Inpatient (ICU only)

Synopsis: To test the efficacy and safety of procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy, these investigators recruited patients in the ICU who had received their first doses of antibiotics for a presumed or proven bacterial infection within 24 hours of enrollment. Patients who were severely immunosuppressed and patients requiring prolonged courses of antibiotics (such as those with endocarditis) were excluded.

Using concealed allocation, patients were assigned to procalcitonin-guided treatment (n = 761) or to usual care (n = 785). The usual care group did not have procalcitonin levels drawn. In the procalcitonin group, patients had a procalcitonin level drawn close to the start of antibiotic therapy and daily thereafter until discharge from the ICU or 3 days after stopping antibiotic use. These levels were provided to the attending physician who could then decide whether to stop giving antibiotics.

Although the study protocol recommended that antibiotics be discontinued if the procalcitonin level had decreased by more than 80% of its peak value or reached a level of 0.5 mcg/L, the ultimate decision to do so was at the discretion of the attending physician. Overall, fewer than half the physicians actually discontinued antibiotics within 24 hours of reaching either of these goals. Despite this, the procalcitonin group had decreased number of days of antibiotic treatment (5 days vs 7 days; between group absolute difference = 1.22; 95% CI 0.65-1.78; P < .0001) and decreased consumption of antibiotics (7.5 daily defined doses vs 9.3 daily defined doses; between group absolute difference = 2.69; 1.26-4.12; P < .0001). Additionally, when examining 28-day mortality rates, the procalcitonin group was noninferior to the standard group, and ultimately, had fewer deaths than the standard group (20% vs 25%; between group absolute difference = 5.4%;1.2-9.5; P = .012). This mortality benefit persisted at 1 year.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question: Can the use of procalcitonin levels to determine when to discontinue antibiotic therapy safely reduce the duration of antibiotic use in critically ill patients?

Bottom line: For patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) who receive antibiotics for presumed or proven bacterial infections, the use of procalcitonin levels to determine when to stop antibiotic therapy results in decreased duration and consumption of antibiotics without increasing mortality.

Reference: De Jong E, Van Oers JA, Beishuizen A, et al. Efficacy and safety of procalcitonin guidance in reducing the duration of antibiotic treatment in critically ill patients: a randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2016;16(7):819-827.

Design: Randomized controlled trial (nonblinded); LOE: 1b

Setting: Inpatient (ICU only)

Synopsis: To test the efficacy and safety of procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy, these investigators recruited patients in the ICU who had received their first doses of antibiotics for a presumed or proven bacterial infection within 24 hours of enrollment. Patients who were severely immunosuppressed and patients requiring prolonged courses of antibiotics (such as those with endocarditis) were excluded.

Using concealed allocation, patients were assigned to procalcitonin-guided treatment (n = 761) or to usual care (n = 785). The usual care group did not have procalcitonin levels drawn. In the procalcitonin group, patients had a procalcitonin level drawn close to the start of antibiotic therapy and daily thereafter until discharge from the ICU or 3 days after stopping antibiotic use. These levels were provided to the attending physician who could then decide whether to stop giving antibiotics.

Although the study protocol recommended that antibiotics be discontinued if the procalcitonin level had decreased by more than 80% of its peak value or reached a level of 0.5 mcg/L, the ultimate decision to do so was at the discretion of the attending physician. Overall, fewer than half the physicians actually discontinued antibiotics within 24 hours of reaching either of these goals. Despite this, the procalcitonin group had decreased number of days of antibiotic treatment (5 days vs 7 days; between group absolute difference = 1.22; 95% CI 0.65-1.78; P < .0001) and decreased consumption of antibiotics (7.5 daily defined doses vs 9.3 daily defined doses; between group absolute difference = 2.69; 1.26-4.12; P < .0001). Additionally, when examining 28-day mortality rates, the procalcitonin group was noninferior to the standard group, and ultimately, had fewer deaths than the standard group (20% vs 25%; between group absolute difference = 5.4%;1.2-9.5; P = .012). This mortality benefit persisted at 1 year.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

How Should a Hospitalized Patient with Newly Diagnosed Cirrhosis Be Evaluated and Managed?

The Case

A 50-year-old man with no known medical history presents with two months of increasing abdominal distension. Exam is notable for scleral icterus, telangiectasias on the upper chest, abdominal distention with a positive fluid wave, and bilateral pitting lower-extremity edema. An abdominal ultrasound shows large ascites and a nodular liver consistent with cirrhosis. How should this patient with newly diagnosed cirrhosis be evaluated and managed?

Background

Cirrhosis is a leading cause of death among people ages 25–64 and associated with a mortality rate of 11.5 per 100,000 people.1 In 2010, 101,000 people were discharged from the hospital with chronic liver disease and cirrhosis as the first-listed diagnosis.2 Given the myriad etiologies and the asymptomatic nature of many of these conditions, hospitalists frequently encounter patients presenting with advanced disease.

Evaluation

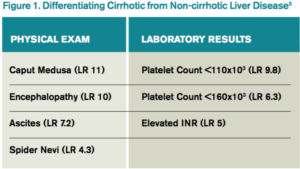

The gold standard for diagnosis is liver biopsy, although this is now usually reserved for atypical cases or where the etiology of cirrhosis is unclear. Alcohol and viral hepatitis (B and C) are the most common causes of chronic liver disease, with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) increasing in prevalence. Other less common etiologies and characteristic test findings are listed in Figure 2.

Recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that adults born between 1945 and 1965 receive one-time testing for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, regardless of other risk factors, given the higher prevalence in this birth cohort and the introduction of newer oral treatments that achieve sustained virologic response.3

Management

The three classic complications of cirrhosis that will typically prompt inpatient admission are volume overload/ascites, gastrointestinal variceal bleeding, and hepatic encephalopathy.

Volume overload/ascites. Ascites is the most common major complication of cirrhosis, with roughly 50% of patients with asymptomatic cirrhosis developing ascites within 10 years.4 Ascites development portends a poor prognosis, with a mortality of 15% within one year and 44% within five years of diagnosis.4 Patients presenting with new-onset ascites should have a diagnostic paracentesis performed to determine the etiology and evaluate for infection.

Ascitic fluid should be sent for an albumin level and a cell count with differential. A serum-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) of greater than or equal to 1.1 g/dL is consistent with portal hypertension and cirrhosis, while values less than 1.1 g/dL suggest a non-cirrhotic cause, such as infection or malignancy. Due to the high prevalence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) in hospitalized patients, fluid should also be immediately inoculated in aerobic and anaerobic culture bottles at the bedside, as this has been shown to improve the yield compared to inoculation of culture bottles in the laboratory. Other testing (such as cytology for the evaluation of malignancy) should only be performed if there is significant concern for a particular disease since the vast majority of cases are secondary to uncomplicated cirrhosis.4

In patients with a large amount of ascites and related symptoms (eg, abdominal pain, shortness of breath), therapeutic paracentesis should be performed. Although there is controversy over the need for routine albumin administration, guidelines currently recommend the infusion of 6–8 g of albumin per liter of ascites removed for paracentesis volumes of greater than 4–5 liters.4

No data support the routine administration of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) or platelets prior to paracentesis. Although significant complications of paracentesis (including bowel perforation and hemorrhage) may occur, these are exceedingly rare. Ultrasonography can be used to decrease risks and identify suitable pockets of fluid to tap, even when fluid is not obvious on physical exam alone.5

For patients with significant edema or ascites that is due to portal hypertension (SAAG >1.1 g/dL), the first-line therapy is sodium restriction to less than 2,000 mg/day. Consulting a nutritionist may be beneficial for patient education.

For patients with significant natriuresis (>78 mmol daily urine sodium excretion), dietary restriction alone can manage fluid retention. Most patients (85%–90%), however, require diuretics to increase sodium output. Single-agent spironolactone is more efficacious than single-agent furosemide, but diuresis is improved when both agents are used.4 A dosing regimen of once-daily 40 mg furosemide and 100 mg spironolactone is the recommended starting regimen to promote diuresis while maintaining normokalemia. Due to the long half-life of spironolactone, the dose can be increased every three to five days if needed for diuresis.4

Gastroesophageal variceal bleeding. Approximately 50% of patients with cirrhosis have gastroesophageal varices as a consequence of portal hypertension, with prevalence increasing in those with more severe disease.6 As many patients with cirrhosis have advanced disease at the time of diagnosis, it is recommended that patients be referred for endoscopic screening when diagnosed.6 Nonselective beta-blockers decrease the risk of bleeding in patients with known varices but should not be initiated empirically in all patients with cirrhosis given significant side effects, including worsening of ascites.

There is increasing evidence that there is a “window” period for beta-blocker use in cirrhosis with the window opening after the diagnosis of varices and the window closing at advanced stages of disease (marked by an episode of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, refractory ascites, or hepatorenal syndrome, for example).7

Hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is another complication of portal hypertension and is seen in 10%–14% of patients at the time of cirrhosis diagnosis.8 Overt HE is estimated to occur in 30%–40% of patients with cirrhosis at some point during their disease course, and more subtle forms (minimal or covert HE) are seen in up to 80%.8 HE can cause numerous neurologic and psychiatric issues including personality changes, poor memory, sleep-wake disturbances, and alterations in consciousness.

In patients with an episode of encephalopathy, precipitating factors should be evaluated. Typical precipitants include infections, bleeding, electrolyte disorders, and constipation. Ammonia levels are frequently drawn as part of the evaluation of hepatic encephalopathy, but elevated levels do not significantly change diagnostic probabilities or add prognostic information.8 A low ammonia level, on the other hand, may be useful in lowering the probability of hepatic encephalopathy in a patient with altered mental status of unknown etiology.8

Routine primary prophylaxis of HE in all patients with cirrhosis is not currently recommended. Treatment is only recommended in patients with overt HE, with secondary prophylaxis administered following an episode due to the high risk for recurrence.

Other Issues

VTE prophylaxis. Although patients with cirrhosis are often presumed to be “auto-anticoagulated” due to an elevated international normalized ratio (INR), they experience thrombotic complications during hospitalization at the same rate or higher than patients with other chronic illnesses.9 Unfortunately, studies examining venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis in hospitalized patients have generally excluded cirrhotics. Therefore, risks/benefits of prophylaxis need to be considered on an individual basis, taking into account the presence of varices (if known), platelet count, and other VTE risk factors.

Drugs to avoid. As detailed above, nonselective beta-blockers should be avoided when outside the “window” period of benefit. Patients with cirrhosis should be counseled to avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) due to an increased risk of bleeding and renal dysfunction. ACE inhibitors (ACE-Is) and angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) can also precipitate renal dysfunction and should generally be avoided unless strongly indicated for another diagnosis.

There is conflicting evidence with regard to whether the use of proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) in cirrhotics increases the risk of SBP.10,11 Nevertheless, it is prudent to reevaluate the need for PPIs in patients with cirrhosis to determine where a true indication exists.

Post-hospitalization care. Patients with a new diagnosis of cirrhosis require screening for esophageal varices and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), with frequency of subsequent testing based on initial results. They should also be immunized against hepatitis A (HAV) and hepatitis B (HBV), if not already immune. Specific treatments are available for many causes of cirrhosis, including new antiviral agents against hepatitis C (HCV), and liver transplantation is an option for select patients. Given the complexity of subsequent diagnostic and treatment options, patients with new cirrhosis should be referred to a gastroenterologist or hepatologist, if possible.

Back to the Case

The patient is hospitalized, and a large-volume paracentesis is performed. Four liters are removed without the administration of albumin. Ascitic fluid analysis reveals a SAAG of greater than 1.1 g/dL and a polymorphonuclear cell count of 50 cell/mm3, suggesting ascites due to portal hypertension and ruling out infection. Nutrition is consulted and educates the patient on a restricted-sodium diet. Furosemide is started at 40 mg daily; spironolactone is started at 100 mg daily. Initial workup and serologies demonstrate active HCV infection (HCV RNA positive), with immunity to HBV due to vaccination. HAV vaccination is administered given lack of seropositivity. The patient is screened for alcohol and found not to drink alcohol. By the time of discharge, the patient is experiencing daily 0.5 kg weight loss due to diuretics and has stable renal function. The patient is referred to outpatient gastroenterology for gastroesophageal variceal screening and consideration of HCV treatment and/or liver transplantation.

Bottom Line

Workup and management of cirrhosis should focus on revealing the underlying etiology, managing complications, and discharging patients with a comprehensive follow-up plan. TH

Dr. Sehgal and Dr. Hanson are hospitalists in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and the South Texas Veterans Health Care System.

References

- Heron M. Deaths: leading causes for 2012. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(10):1-93.

- Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed March 17, 2016.

- Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, Falck-Ytter Y, Holtzman D, Ward JW. Hepatitis C virus testing of persons born during 1945-1965: recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(11):817-822. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-9-201211060-00529.

- Runyon BA, AASLD. Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Practice Guideline management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis 2012. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1651-1653. doi:10.1002/hep.26359.

- Udell JA, Wang CS, Tinmouth J, et al. Does this patient with liver disease have cirrhosis? JAMA. 2012;307(8):832-842. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.186.

- Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W, Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46(3):922-938. doi:10.1002/hep.21907.

- Mandorfer M, Bota S, Schwabl P, et al. Nonselective β blockers increase risk for hepatorenal syndrome and death in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(7):1680-90.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.005.

- Vilstrup H, Amodio P, Bajaj J, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology. 2014;60(2):715-735. doi:10.1002/hep.27210.

- Khoury T, Ayman AR, Cohen J, Daher S, Shmuel C, Mizrahi M. The complex role of anticoagulation in cirrhosis: an updated review of where we are and where we are going. Digestion. 2016;93(2):149-159. doi:10.1159/000442877.

- Terg R, Casciato P, Garbe C, et al. Proton pump inhibitor therapy does not increase the incidence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis: a multicenter prospective study. J Hepatol. 2015;62(5):1056-1060. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2014.11.036.

- Deshpande A, Pasupuleti V, Thota P, et al. Acid-suppressive therapy is associated with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients: a meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(2):235-242. doi:10.1111/jgh.12065.

Key Points

- Cirrhosis has many etiologies, and new diagnoses require further investigation as to the underlying etiology.

- Initial management should focus on evaluation and treatment of complications, including ascites, esophageal varices, and hepatic encephalopathy.

- A diagnostic paracentesis, salt restriction, and a nutrition consult are the initial therapies for ascites although most patients will also require diuretics to increase sodium excretion.

- Once stabilized, the cirrhotic patient will require specialty care for possible liver biopsy (if etiology remains unclear), treatment (eg, HCV antivirals), and/or referral for liver transplantation.

The Case

A 50-year-old man with no known medical history presents with two months of increasing abdominal distension. Exam is notable for scleral icterus, telangiectasias on the upper chest, abdominal distention with a positive fluid wave, and bilateral pitting lower-extremity edema. An abdominal ultrasound shows large ascites and a nodular liver consistent with cirrhosis. How should this patient with newly diagnosed cirrhosis be evaluated and managed?

Background

Cirrhosis is a leading cause of death among people ages 25–64 and associated with a mortality rate of 11.5 per 100,000 people.1 In 2010, 101,000 people were discharged from the hospital with chronic liver disease and cirrhosis as the first-listed diagnosis.2 Given the myriad etiologies and the asymptomatic nature of many of these conditions, hospitalists frequently encounter patients presenting with advanced disease.

Evaluation

The gold standard for diagnosis is liver biopsy, although this is now usually reserved for atypical cases or where the etiology of cirrhosis is unclear. Alcohol and viral hepatitis (B and C) are the most common causes of chronic liver disease, with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) increasing in prevalence. Other less common etiologies and characteristic test findings are listed in Figure 2.

Recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that adults born between 1945 and 1965 receive one-time testing for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, regardless of other risk factors, given the higher prevalence in this birth cohort and the introduction of newer oral treatments that achieve sustained virologic response.3

Management

The three classic complications of cirrhosis that will typically prompt inpatient admission are volume overload/ascites, gastrointestinal variceal bleeding, and hepatic encephalopathy.

Volume overload/ascites. Ascites is the most common major complication of cirrhosis, with roughly 50% of patients with asymptomatic cirrhosis developing ascites within 10 years.4 Ascites development portends a poor prognosis, with a mortality of 15% within one year and 44% within five years of diagnosis.4 Patients presenting with new-onset ascites should have a diagnostic paracentesis performed to determine the etiology and evaluate for infection.

Ascitic fluid should be sent for an albumin level and a cell count with differential. A serum-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) of greater than or equal to 1.1 g/dL is consistent with portal hypertension and cirrhosis, while values less than 1.1 g/dL suggest a non-cirrhotic cause, such as infection or malignancy. Due to the high prevalence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) in hospitalized patients, fluid should also be immediately inoculated in aerobic and anaerobic culture bottles at the bedside, as this has been shown to improve the yield compared to inoculation of culture bottles in the laboratory. Other testing (such as cytology for the evaluation of malignancy) should only be performed if there is significant concern for a particular disease since the vast majority of cases are secondary to uncomplicated cirrhosis.4

In patients with a large amount of ascites and related symptoms (eg, abdominal pain, shortness of breath), therapeutic paracentesis should be performed. Although there is controversy over the need for routine albumin administration, guidelines currently recommend the infusion of 6–8 g of albumin per liter of ascites removed for paracentesis volumes of greater than 4–5 liters.4

No data support the routine administration of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) or platelets prior to paracentesis. Although significant complications of paracentesis (including bowel perforation and hemorrhage) may occur, these are exceedingly rare. Ultrasonography can be used to decrease risks and identify suitable pockets of fluid to tap, even when fluid is not obvious on physical exam alone.5

For patients with significant edema or ascites that is due to portal hypertension (SAAG >1.1 g/dL), the first-line therapy is sodium restriction to less than 2,000 mg/day. Consulting a nutritionist may be beneficial for patient education.

For patients with significant natriuresis (>78 mmol daily urine sodium excretion), dietary restriction alone can manage fluid retention. Most patients (85%–90%), however, require diuretics to increase sodium output. Single-agent spironolactone is more efficacious than single-agent furosemide, but diuresis is improved when both agents are used.4 A dosing regimen of once-daily 40 mg furosemide and 100 mg spironolactone is the recommended starting regimen to promote diuresis while maintaining normokalemia. Due to the long half-life of spironolactone, the dose can be increased every three to five days if needed for diuresis.4

Gastroesophageal variceal bleeding. Approximately 50% of patients with cirrhosis have gastroesophageal varices as a consequence of portal hypertension, with prevalence increasing in those with more severe disease.6 As many patients with cirrhosis have advanced disease at the time of diagnosis, it is recommended that patients be referred for endoscopic screening when diagnosed.6 Nonselective beta-blockers decrease the risk of bleeding in patients with known varices but should not be initiated empirically in all patients with cirrhosis given significant side effects, including worsening of ascites.

There is increasing evidence that there is a “window” period for beta-blocker use in cirrhosis with the window opening after the diagnosis of varices and the window closing at advanced stages of disease (marked by an episode of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, refractory ascites, or hepatorenal syndrome, for example).7

Hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is another complication of portal hypertension and is seen in 10%–14% of patients at the time of cirrhosis diagnosis.8 Overt HE is estimated to occur in 30%–40% of patients with cirrhosis at some point during their disease course, and more subtle forms (minimal or covert HE) are seen in up to 80%.8 HE can cause numerous neurologic and psychiatric issues including personality changes, poor memory, sleep-wake disturbances, and alterations in consciousness.

In patients with an episode of encephalopathy, precipitating factors should be evaluated. Typical precipitants include infections, bleeding, electrolyte disorders, and constipation. Ammonia levels are frequently drawn as part of the evaluation of hepatic encephalopathy, but elevated levels do not significantly change diagnostic probabilities or add prognostic information.8 A low ammonia level, on the other hand, may be useful in lowering the probability of hepatic encephalopathy in a patient with altered mental status of unknown etiology.8

Routine primary prophylaxis of HE in all patients with cirrhosis is not currently recommended. Treatment is only recommended in patients with overt HE, with secondary prophylaxis administered following an episode due to the high risk for recurrence.

Other Issues

VTE prophylaxis. Although patients with cirrhosis are often presumed to be “auto-anticoagulated” due to an elevated international normalized ratio (INR), they experience thrombotic complications during hospitalization at the same rate or higher than patients with other chronic illnesses.9 Unfortunately, studies examining venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis in hospitalized patients have generally excluded cirrhotics. Therefore, risks/benefits of prophylaxis need to be considered on an individual basis, taking into account the presence of varices (if known), platelet count, and other VTE risk factors.

Drugs to avoid. As detailed above, nonselective beta-blockers should be avoided when outside the “window” period of benefit. Patients with cirrhosis should be counseled to avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) due to an increased risk of bleeding and renal dysfunction. ACE inhibitors (ACE-Is) and angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) can also precipitate renal dysfunction and should generally be avoided unless strongly indicated for another diagnosis.

There is conflicting evidence with regard to whether the use of proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) in cirrhotics increases the risk of SBP.10,11 Nevertheless, it is prudent to reevaluate the need for PPIs in patients with cirrhosis to determine where a true indication exists.

Post-hospitalization care. Patients with a new diagnosis of cirrhosis require screening for esophageal varices and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), with frequency of subsequent testing based on initial results. They should also be immunized against hepatitis A (HAV) and hepatitis B (HBV), if not already immune. Specific treatments are available for many causes of cirrhosis, including new antiviral agents against hepatitis C (HCV), and liver transplantation is an option for select patients. Given the complexity of subsequent diagnostic and treatment options, patients with new cirrhosis should be referred to a gastroenterologist or hepatologist, if possible.

Back to the Case

The patient is hospitalized, and a large-volume paracentesis is performed. Four liters are removed without the administration of albumin. Ascitic fluid analysis reveals a SAAG of greater than 1.1 g/dL and a polymorphonuclear cell count of 50 cell/mm3, suggesting ascites due to portal hypertension and ruling out infection. Nutrition is consulted and educates the patient on a restricted-sodium diet. Furosemide is started at 40 mg daily; spironolactone is started at 100 mg daily. Initial workup and serologies demonstrate active HCV infection (HCV RNA positive), with immunity to HBV due to vaccination. HAV vaccination is administered given lack of seropositivity. The patient is screened for alcohol and found not to drink alcohol. By the time of discharge, the patient is experiencing daily 0.5 kg weight loss due to diuretics and has stable renal function. The patient is referred to outpatient gastroenterology for gastroesophageal variceal screening and consideration of HCV treatment and/or liver transplantation.

Bottom Line

Workup and management of cirrhosis should focus on revealing the underlying etiology, managing complications, and discharging patients with a comprehensive follow-up plan. TH

Dr. Sehgal and Dr. Hanson are hospitalists in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and the South Texas Veterans Health Care System.

References

- Heron M. Deaths: leading causes for 2012. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(10):1-93.

- Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed March 17, 2016.

- Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, Falck-Ytter Y, Holtzman D, Ward JW. Hepatitis C virus testing of persons born during 1945-1965: recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(11):817-822. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-9-201211060-00529.

- Runyon BA, AASLD. Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Practice Guideline management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis 2012. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1651-1653. doi:10.1002/hep.26359.

- Udell JA, Wang CS, Tinmouth J, et al. Does this patient with liver disease have cirrhosis? JAMA. 2012;307(8):832-842. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.186.

- Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W, Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46(3):922-938. doi:10.1002/hep.21907.

- Mandorfer M, Bota S, Schwabl P, et al. Nonselective β blockers increase risk for hepatorenal syndrome and death in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(7):1680-90.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.005.

- Vilstrup H, Amodio P, Bajaj J, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology. 2014;60(2):715-735. doi:10.1002/hep.27210.

- Khoury T, Ayman AR, Cohen J, Daher S, Shmuel C, Mizrahi M. The complex role of anticoagulation in cirrhosis: an updated review of where we are and where we are going. Digestion. 2016;93(2):149-159. doi:10.1159/000442877.

- Terg R, Casciato P, Garbe C, et al. Proton pump inhibitor therapy does not increase the incidence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis: a multicenter prospective study. J Hepatol. 2015;62(5):1056-1060. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2014.11.036.

- Deshpande A, Pasupuleti V, Thota P, et al. Acid-suppressive therapy is associated with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients: a meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(2):235-242. doi:10.1111/jgh.12065.

Key Points

- Cirrhosis has many etiologies, and new diagnoses require further investigation as to the underlying etiology.

- Initial management should focus on evaluation and treatment of complications, including ascites, esophageal varices, and hepatic encephalopathy.

- A diagnostic paracentesis, salt restriction, and a nutrition consult are the initial therapies for ascites although most patients will also require diuretics to increase sodium excretion.

- Once stabilized, the cirrhotic patient will require specialty care for possible liver biopsy (if etiology remains unclear), treatment (eg, HCV antivirals), and/or referral for liver transplantation.

The Case

A 50-year-old man with no known medical history presents with two months of increasing abdominal distension. Exam is notable for scleral icterus, telangiectasias on the upper chest, abdominal distention with a positive fluid wave, and bilateral pitting lower-extremity edema. An abdominal ultrasound shows large ascites and a nodular liver consistent with cirrhosis. How should this patient with newly diagnosed cirrhosis be evaluated and managed?

Background

Cirrhosis is a leading cause of death among people ages 25–64 and associated with a mortality rate of 11.5 per 100,000 people.1 In 2010, 101,000 people were discharged from the hospital with chronic liver disease and cirrhosis as the first-listed diagnosis.2 Given the myriad etiologies and the asymptomatic nature of many of these conditions, hospitalists frequently encounter patients presenting with advanced disease.

Evaluation

The gold standard for diagnosis is liver biopsy, although this is now usually reserved for atypical cases or where the etiology of cirrhosis is unclear. Alcohol and viral hepatitis (B and C) are the most common causes of chronic liver disease, with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) increasing in prevalence. Other less common etiologies and characteristic test findings are listed in Figure 2.

Recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that adults born between 1945 and 1965 receive one-time testing for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, regardless of other risk factors, given the higher prevalence in this birth cohort and the introduction of newer oral treatments that achieve sustained virologic response.3

Management

The three classic complications of cirrhosis that will typically prompt inpatient admission are volume overload/ascites, gastrointestinal variceal bleeding, and hepatic encephalopathy.

Volume overload/ascites. Ascites is the most common major complication of cirrhosis, with roughly 50% of patients with asymptomatic cirrhosis developing ascites within 10 years.4 Ascites development portends a poor prognosis, with a mortality of 15% within one year and 44% within five years of diagnosis.4 Patients presenting with new-onset ascites should have a diagnostic paracentesis performed to determine the etiology and evaluate for infection.

Ascitic fluid should be sent for an albumin level and a cell count with differential. A serum-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) of greater than or equal to 1.1 g/dL is consistent with portal hypertension and cirrhosis, while values less than 1.1 g/dL suggest a non-cirrhotic cause, such as infection or malignancy. Due to the high prevalence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) in hospitalized patients, fluid should also be immediately inoculated in aerobic and anaerobic culture bottles at the bedside, as this has been shown to improve the yield compared to inoculation of culture bottles in the laboratory. Other testing (such as cytology for the evaluation of malignancy) should only be performed if there is significant concern for a particular disease since the vast majority of cases are secondary to uncomplicated cirrhosis.4

In patients with a large amount of ascites and related symptoms (eg, abdominal pain, shortness of breath), therapeutic paracentesis should be performed. Although there is controversy over the need for routine albumin administration, guidelines currently recommend the infusion of 6–8 g of albumin per liter of ascites removed for paracentesis volumes of greater than 4–5 liters.4

No data support the routine administration of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) or platelets prior to paracentesis. Although significant complications of paracentesis (including bowel perforation and hemorrhage) may occur, these are exceedingly rare. Ultrasonography can be used to decrease risks and identify suitable pockets of fluid to tap, even when fluid is not obvious on physical exam alone.5

For patients with significant edema or ascites that is due to portal hypertension (SAAG >1.1 g/dL), the first-line therapy is sodium restriction to less than 2,000 mg/day. Consulting a nutritionist may be beneficial for patient education.

For patients with significant natriuresis (>78 mmol daily urine sodium excretion), dietary restriction alone can manage fluid retention. Most patients (85%–90%), however, require diuretics to increase sodium output. Single-agent spironolactone is more efficacious than single-agent furosemide, but diuresis is improved when both agents are used.4 A dosing regimen of once-daily 40 mg furosemide and 100 mg spironolactone is the recommended starting regimen to promote diuresis while maintaining normokalemia. Due to the long half-life of spironolactone, the dose can be increased every three to five days if needed for diuresis.4

Gastroesophageal variceal bleeding. Approximately 50% of patients with cirrhosis have gastroesophageal varices as a consequence of portal hypertension, with prevalence increasing in those with more severe disease.6 As many patients with cirrhosis have advanced disease at the time of diagnosis, it is recommended that patients be referred for endoscopic screening when diagnosed.6 Nonselective beta-blockers decrease the risk of bleeding in patients with known varices but should not be initiated empirically in all patients with cirrhosis given significant side effects, including worsening of ascites.

There is increasing evidence that there is a “window” period for beta-blocker use in cirrhosis with the window opening after the diagnosis of varices and the window closing at advanced stages of disease (marked by an episode of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, refractory ascites, or hepatorenal syndrome, for example).7

Hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is another complication of portal hypertension and is seen in 10%–14% of patients at the time of cirrhosis diagnosis.8 Overt HE is estimated to occur in 30%–40% of patients with cirrhosis at some point during their disease course, and more subtle forms (minimal or covert HE) are seen in up to 80%.8 HE can cause numerous neurologic and psychiatric issues including personality changes, poor memory, sleep-wake disturbances, and alterations in consciousness.

In patients with an episode of encephalopathy, precipitating factors should be evaluated. Typical precipitants include infections, bleeding, electrolyte disorders, and constipation. Ammonia levels are frequently drawn as part of the evaluation of hepatic encephalopathy, but elevated levels do not significantly change diagnostic probabilities or add prognostic information.8 A low ammonia level, on the other hand, may be useful in lowering the probability of hepatic encephalopathy in a patient with altered mental status of unknown etiology.8

Routine primary prophylaxis of HE in all patients with cirrhosis is not currently recommended. Treatment is only recommended in patients with overt HE, with secondary prophylaxis administered following an episode due to the high risk for recurrence.

Other Issues

VTE prophylaxis. Although patients with cirrhosis are often presumed to be “auto-anticoagulated” due to an elevated international normalized ratio (INR), they experience thrombotic complications during hospitalization at the same rate or higher than patients with other chronic illnesses.9 Unfortunately, studies examining venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis in hospitalized patients have generally excluded cirrhotics. Therefore, risks/benefits of prophylaxis need to be considered on an individual basis, taking into account the presence of varices (if known), platelet count, and other VTE risk factors.

Drugs to avoid. As detailed above, nonselective beta-blockers should be avoided when outside the “window” period of benefit. Patients with cirrhosis should be counseled to avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) due to an increased risk of bleeding and renal dysfunction. ACE inhibitors (ACE-Is) and angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) can also precipitate renal dysfunction and should generally be avoided unless strongly indicated for another diagnosis.

There is conflicting evidence with regard to whether the use of proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) in cirrhotics increases the risk of SBP.10,11 Nevertheless, it is prudent to reevaluate the need for PPIs in patients with cirrhosis to determine where a true indication exists.

Post-hospitalization care. Patients with a new diagnosis of cirrhosis require screening for esophageal varices and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), with frequency of subsequent testing based on initial results. They should also be immunized against hepatitis A (HAV) and hepatitis B (HBV), if not already immune. Specific treatments are available for many causes of cirrhosis, including new antiviral agents against hepatitis C (HCV), and liver transplantation is an option for select patients. Given the complexity of subsequent diagnostic and treatment options, patients with new cirrhosis should be referred to a gastroenterologist or hepatologist, if possible.

Back to the Case

The patient is hospitalized, and a large-volume paracentesis is performed. Four liters are removed without the administration of albumin. Ascitic fluid analysis reveals a SAAG of greater than 1.1 g/dL and a polymorphonuclear cell count of 50 cell/mm3, suggesting ascites due to portal hypertension and ruling out infection. Nutrition is consulted and educates the patient on a restricted-sodium diet. Furosemide is started at 40 mg daily; spironolactone is started at 100 mg daily. Initial workup and serologies demonstrate active HCV infection (HCV RNA positive), with immunity to HBV due to vaccination. HAV vaccination is administered given lack of seropositivity. The patient is screened for alcohol and found not to drink alcohol. By the time of discharge, the patient is experiencing daily 0.5 kg weight loss due to diuretics and has stable renal function. The patient is referred to outpatient gastroenterology for gastroesophageal variceal screening and consideration of HCV treatment and/or liver transplantation.

Bottom Line

Workup and management of cirrhosis should focus on revealing the underlying etiology, managing complications, and discharging patients with a comprehensive follow-up plan. TH

Dr. Sehgal and Dr. Hanson are hospitalists in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and the South Texas Veterans Health Care System.

References

- Heron M. Deaths: leading causes for 2012. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(10):1-93.

- Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed March 17, 2016.

- Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, Falck-Ytter Y, Holtzman D, Ward JW. Hepatitis C virus testing of persons born during 1945-1965: recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(11):817-822. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-9-201211060-00529.

- Runyon BA, AASLD. Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Practice Guideline management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis 2012. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1651-1653. doi:10.1002/hep.26359.

- Udell JA, Wang CS, Tinmouth J, et al. Does this patient with liver disease have cirrhosis? JAMA. 2012;307(8):832-842. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.186.

- Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W, Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46(3):922-938. doi:10.1002/hep.21907.

- Mandorfer M, Bota S, Schwabl P, et al. Nonselective β blockers increase risk for hepatorenal syndrome and death in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(7):1680-90.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.005.

- Vilstrup H, Amodio P, Bajaj J, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology. 2014;60(2):715-735. doi:10.1002/hep.27210.

- Khoury T, Ayman AR, Cohen J, Daher S, Shmuel C, Mizrahi M. The complex role of anticoagulation in cirrhosis: an updated review of where we are and where we are going. Digestion. 2016;93(2):149-159. doi:10.1159/000442877.

- Terg R, Casciato P, Garbe C, et al. Proton pump inhibitor therapy does not increase the incidence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis: a multicenter prospective study. J Hepatol. 2015;62(5):1056-1060. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2014.11.036.

- Deshpande A, Pasupuleti V, Thota P, et al. Acid-suppressive therapy is associated with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients: a meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(2):235-242. doi:10.1111/jgh.12065.

Key Points

- Cirrhosis has many etiologies, and new diagnoses require further investigation as to the underlying etiology.

- Initial management should focus on evaluation and treatment of complications, including ascites, esophageal varices, and hepatic encephalopathy.

- A diagnostic paracentesis, salt restriction, and a nutrition consult are the initial therapies for ascites although most patients will also require diuretics to increase sodium excretion.

- Once stabilized, the cirrhotic patient will require specialty care for possible liver biopsy (if etiology remains unclear), treatment (eg, HCV antivirals), and/or referral for liver transplantation.

10 Strategies for Delivering a Great Presentation

It’s noon on Tuesday, and James, a new PGY-2 resident, begins his presentation on COPD. After five minutes, you notice half of the residents playing Words with Friends, the “ortho-bound” medical student talking with a buddy in the back, and the attendings looking on with innate skepticism.

Your talk on atrial fibrillation is next month, and just watching James brings on palpitations of your own. So what do you do?

Introduction

Public speaking is a near certainty for most of us regardless of training stage. A well-executed presentation establishes the clinician as an institutional authority, adroitly educating anyone around you.

So how can you deliver that killer update on atrial fibrillation? Here, we provide you with 10 tips for preparing and delivering a great presentation.

Preparation

1. Consider the audience and what they already know. No matter how interesting we think we are, if we don’t present with the audience’s needs in mind, we might as well be talking to an empty room. Consider what the audience may or may not know about the topic; this allows you to decide whether to give a comprehensive didactic on atrial fibrillation for trainees or an anticoagulation update for cardiologists. Great presenters survey their audience early on with a question such as, “How many of you here know the results of the AFFIRM trial?” This allows you to make small alterations to meet the needs of your audience.

2. Visualize the stage and setting. Understanding the stage helps you anticipate and address barriers to learning. Imagine for a moment the difference in these two scenarios: a discussion of hyponatremia with a group of medical students at 4 p.m. in a dark room versus a discussion on principles of atrial fibrillation management at 11 a.m. in an auditorium. Both require interaction, although an auditorium-based presentation requires testing your audio-visual equipment in advance.

3. Determine your objectives. To determine your objectives, begin with the end in mind. If you were to visualize your audience members at the end of the talk, what would they know (knowledge), be able to do (behavior), or have a new outlook on (attitude)? The objectives will determine the content you deliver and the activities for learning. For a one-hour presentation, identifying three to five objectives is a good rule of thumb.

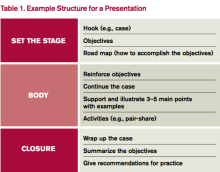

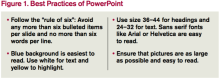

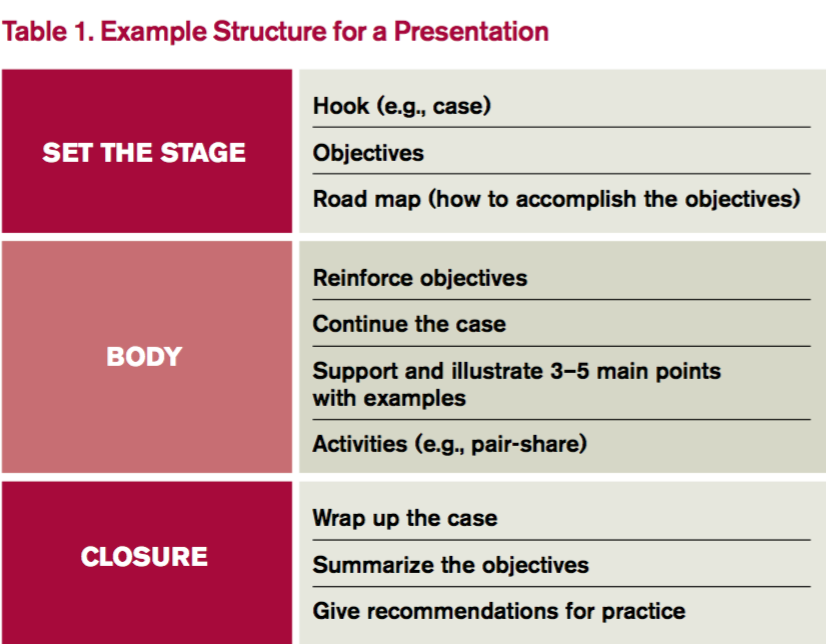

4. Build your presentation. Whether using PowerPoint, Prezi, or a white board, “build” the presentation from the objectives. Table 1 outlines one example format; Figure 1 outlines some best practices of PowerPoint.

Humans evolved to interpret visual imagery, not read text, so try to use pictures instead of bullet points. Consider first building slides with text and then using an internet search engine to convert words to pictures. For example, “atrial rate 200 bpm” is better displayed with an actual ECG.

5. Practice. Practicing helps you become more comfortable with the content itself as well as how to present that content. If you can, practice with a colleague and receive feedback to sharpen your material. No time to spare? Practice the introduction and any major point that you want to get across. Audiences decide within the first five minutes whether your talk is worth listening to before pulling out their cellphones to open up Facebook.

Delivery

1. Confront nervousness. Many of us become nervous when speaking in front of an audience. To address this, it’s perfectly reasonable to rehearse a presentation at home or in a quiet call room ahead of time. If you feel extremely nervous, breathe deeply for five- to 10-second intervals. During the presentation itself, find friendly or familiar faces in the audience and look them in the eyes as you speak. This eases nerves and improves your technique.

2. Hook your audience. The purpose of the hook is to “grab” the attention of the audience. The best presenters intrigue the audience with a story or problem at the outset and use the presentation to address that problem. Consider the differences in these openings:

- “As of 2010, atrial fibrillation has affected 33.5 million Americans each year, with a reported prevalence of stroke of 2.8% to 24.2%.”

- “Sarah is a 67-year-old woman with a history of atrial fibrillation who loved to play the piano until she experienced a stroke, paralysis of her left arm, and the end of her career as a pianist. Today, I’m going to teach you how to reduce the risk of stroke in your patients with atrial fibrillation.”

Then as the presentation proceeds, develop the case to keep the audience thinking about their differential diagnosis or management strategy.

3. Speak clearly. We all use fillers such as “uh” and “um” without noticing. To learn to speak well, practice as much as possible and ask for feedback on your diction. Consider watching TED Talks, short clips of fascinating stories whose presenters are highly coached in public speaking. Use specific statements to key in the audience on important points, such as, “If you remember anything from this talk, I want you to remember …”

Remember, too, that public speaking requires enthusiasm. There’s nothing worse than beginning with, “I know that you all have heard about atrial fibrillation 500 times, so let’s just get through this.” The energy of the audience reflects the energy of the speaker.

4. Facilitate learning. Don’t do all of the talking; in fact, let the audience talk for you. For audience members to learn, they must engage with the material. Use a question/answer forum such as polleverywhere.com, where the audience responds in real time. Alternatively, pose a scenario to discuss using a pair-share technique. For a talk on atrial fibrillation, give direction to “turn to a neighbor and discuss anticoagulation for Mr. Jones, a 66-year-old man with cirrhosis, CVA, and hypertension admitted with atrial fibrillation.” Debrief this activity to solicit thoughts from the audience and then address the scenario.

5. Break the glass. Don’t hide behind the podium! “Breaking the glass” means stepping away from the podium to create an experience more akin to a dialogue. Remember, the audience is interested in hearing what you have to say—otherwise, they would have read about atrial fibrillation from UpToDate. Stepping away from the podium breaks the expected monotony and can help burn nervous energy.

Bottom Line

A fantastic presentation requires preparation and a thoughtful delivery. Spend the time to prepare. After all, that upcoming presentation on atrial fibrillation is only one month away. It will arrive sooner than you think. TH

Dr. Rendon is associate program director and Dr. Roesch is an assistant professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of New Mexico Hospital in Albuquerque. They are co-directors of the medical student clinical reasoning course. Both are members of SHM’s Physicians in Training Committee.

References

- Anderson C. How to give a killer presentation. Harvard Business Review. June 2013.

- Covey C. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. Franklin Covey Co.; 2004.

- Ganz L. Epidemiology of and risk factors for atrial fibrillation. Updated October 15, 2015.

- Sharpe B. How to give a great talk. Presented as part of SHM national conference; 2014; Las Vegas.

- Skeff K, Stratos G. Methods for Teaching Medicine. Philadelphia: ACP Press; 2010.

It’s noon on Tuesday, and James, a new PGY-2 resident, begins his presentation on COPD. After five minutes, you notice half of the residents playing Words with Friends, the “ortho-bound” medical student talking with a buddy in the back, and the attendings looking on with innate skepticism.

Your talk on atrial fibrillation is next month, and just watching James brings on palpitations of your own. So what do you do?

Introduction

Public speaking is a near certainty for most of us regardless of training stage. A well-executed presentation establishes the clinician as an institutional authority, adroitly educating anyone around you.

So how can you deliver that killer update on atrial fibrillation? Here, we provide you with 10 tips for preparing and delivering a great presentation.

Preparation

1. Consider the audience and what they already know. No matter how interesting we think we are, if we don’t present with the audience’s needs in mind, we might as well be talking to an empty room. Consider what the audience may or may not know about the topic; this allows you to decide whether to give a comprehensive didactic on atrial fibrillation for trainees or an anticoagulation update for cardiologists. Great presenters survey their audience early on with a question such as, “How many of you here know the results of the AFFIRM trial?” This allows you to make small alterations to meet the needs of your audience.

2. Visualize the stage and setting. Understanding the stage helps you anticipate and address barriers to learning. Imagine for a moment the difference in these two scenarios: a discussion of hyponatremia with a group of medical students at 4 p.m. in a dark room versus a discussion on principles of atrial fibrillation management at 11 a.m. in an auditorium. Both require interaction, although an auditorium-based presentation requires testing your audio-visual equipment in advance.

3. Determine your objectives. To determine your objectives, begin with the end in mind. If you were to visualize your audience members at the end of the talk, what would they know (knowledge), be able to do (behavior), or have a new outlook on (attitude)? The objectives will determine the content you deliver and the activities for learning. For a one-hour presentation, identifying three to five objectives is a good rule of thumb.

4. Build your presentation. Whether using PowerPoint, Prezi, or a white board, “build” the presentation from the objectives. Table 1 outlines one example format; Figure 1 outlines some best practices of PowerPoint.

Humans evolved to interpret visual imagery, not read text, so try to use pictures instead of bullet points. Consider first building slides with text and then using an internet search engine to convert words to pictures. For example, “atrial rate 200 bpm” is better displayed with an actual ECG.

5. Practice. Practicing helps you become more comfortable with the content itself as well as how to present that content. If you can, practice with a colleague and receive feedback to sharpen your material. No time to spare? Practice the introduction and any major point that you want to get across. Audiences decide within the first five minutes whether your talk is worth listening to before pulling out their cellphones to open up Facebook.

Delivery

1. Confront nervousness. Many of us become nervous when speaking in front of an audience. To address this, it’s perfectly reasonable to rehearse a presentation at home or in a quiet call room ahead of time. If you feel extremely nervous, breathe deeply for five- to 10-second intervals. During the presentation itself, find friendly or familiar faces in the audience and look them in the eyes as you speak. This eases nerves and improves your technique.

2. Hook your audience. The purpose of the hook is to “grab” the attention of the audience. The best presenters intrigue the audience with a story or problem at the outset and use the presentation to address that problem. Consider the differences in these openings:

- “As of 2010, atrial fibrillation has affected 33.5 million Americans each year, with a reported prevalence of stroke of 2.8% to 24.2%.”

- “Sarah is a 67-year-old woman with a history of atrial fibrillation who loved to play the piano until she experienced a stroke, paralysis of her left arm, and the end of her career as a pianist. Today, I’m going to teach you how to reduce the risk of stroke in your patients with atrial fibrillation.”

Then as the presentation proceeds, develop the case to keep the audience thinking about their differential diagnosis or management strategy.

3. Speak clearly. We all use fillers such as “uh” and “um” without noticing. To learn to speak well, practice as much as possible and ask for feedback on your diction. Consider watching TED Talks, short clips of fascinating stories whose presenters are highly coached in public speaking. Use specific statements to key in the audience on important points, such as, “If you remember anything from this talk, I want you to remember …”

Remember, too, that public speaking requires enthusiasm. There’s nothing worse than beginning with, “I know that you all have heard about atrial fibrillation 500 times, so let’s just get through this.” The energy of the audience reflects the energy of the speaker.

4. Facilitate learning. Don’t do all of the talking; in fact, let the audience talk for you. For audience members to learn, they must engage with the material. Use a question/answer forum such as polleverywhere.com, where the audience responds in real time. Alternatively, pose a scenario to discuss using a pair-share technique. For a talk on atrial fibrillation, give direction to “turn to a neighbor and discuss anticoagulation for Mr. Jones, a 66-year-old man with cirrhosis, CVA, and hypertension admitted with atrial fibrillation.” Debrief this activity to solicit thoughts from the audience and then address the scenario.

5. Break the glass. Don’t hide behind the podium! “Breaking the glass” means stepping away from the podium to create an experience more akin to a dialogue. Remember, the audience is interested in hearing what you have to say—otherwise, they would have read about atrial fibrillation from UpToDate. Stepping away from the podium breaks the expected monotony and can help burn nervous energy.

Bottom Line

A fantastic presentation requires preparation and a thoughtful delivery. Spend the time to prepare. After all, that upcoming presentation on atrial fibrillation is only one month away. It will arrive sooner than you think. TH

Dr. Rendon is associate program director and Dr. Roesch is an assistant professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of New Mexico Hospital in Albuquerque. They are co-directors of the medical student clinical reasoning course. Both are members of SHM’s Physicians in Training Committee.

References

- Anderson C. How to give a killer presentation. Harvard Business Review. June 2013.

- Covey C. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. Franklin Covey Co.; 2004.

- Ganz L. Epidemiology of and risk factors for atrial fibrillation. Updated October 15, 2015.

- Sharpe B. How to give a great talk. Presented as part of SHM national conference; 2014; Las Vegas.

- Skeff K, Stratos G. Methods for Teaching Medicine. Philadelphia: ACP Press; 2010.