User login

Office staff cohesiveness remains important

Recently, a lawyer and I were on the phone about a case, and he mentioned how lucky he was to have had the same staff over the course of a 25-year career, and he was afraid they’d retire before he did.

I feel the same way. My medical assistant has been with me since day one 18 years ago, my secretary since 2004. I hope they keep putting up with me until I hang up my reflex hammer.

It’s impossible to put a great team together just by talent alone. The chemistry and ability to work together are as critical as talent, if not more so, and are far more intangible and unpredictable.

I’ve been lucky that way. The three of us are cohesive. We try to keep some degree of fun in our work routine as each day goes on. My secretary’s 2-year-old daughter, who comes with her every day, adds to the family atmosphere that many patients notice. It’s not uncommon to be asked if the group of us are related. (We’re not.)

Back when I started out, it was with a large group that saw its people as replaceable, and treated them as such. As a result there was a high turnover rate of medical assistants and front office and clerical staff. This led to problems with work-flow and patient care, as there was always someone new being trained.

I can’t imagine having a better team than I have now, and will share this advice with anyone starting a practice: When you get the right people, count yourself lucky and do what you have to do to keep them. They’re worth it.

It’s a lot nicer to work with friends than strangers. It makes the drudgery of the job more interesting, the low points better, and the highs fun.

I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Recently, a lawyer and I were on the phone about a case, and he mentioned how lucky he was to have had the same staff over the course of a 25-year career, and he was afraid they’d retire before he did.

I feel the same way. My medical assistant has been with me since day one 18 years ago, my secretary since 2004. I hope they keep putting up with me until I hang up my reflex hammer.

It’s impossible to put a great team together just by talent alone. The chemistry and ability to work together are as critical as talent, if not more so, and are far more intangible and unpredictable.

I’ve been lucky that way. The three of us are cohesive. We try to keep some degree of fun in our work routine as each day goes on. My secretary’s 2-year-old daughter, who comes with her every day, adds to the family atmosphere that many patients notice. It’s not uncommon to be asked if the group of us are related. (We’re not.)

Back when I started out, it was with a large group that saw its people as replaceable, and treated them as such. As a result there was a high turnover rate of medical assistants and front office and clerical staff. This led to problems with work-flow and patient care, as there was always someone new being trained.

I can’t imagine having a better team than I have now, and will share this advice with anyone starting a practice: When you get the right people, count yourself lucky and do what you have to do to keep them. They’re worth it.

It’s a lot nicer to work with friends than strangers. It makes the drudgery of the job more interesting, the low points better, and the highs fun.

I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Recently, a lawyer and I were on the phone about a case, and he mentioned how lucky he was to have had the same staff over the course of a 25-year career, and he was afraid they’d retire before he did.

I feel the same way. My medical assistant has been with me since day one 18 years ago, my secretary since 2004. I hope they keep putting up with me until I hang up my reflex hammer.

It’s impossible to put a great team together just by talent alone. The chemistry and ability to work together are as critical as talent, if not more so, and are far more intangible and unpredictable.

I’ve been lucky that way. The three of us are cohesive. We try to keep some degree of fun in our work routine as each day goes on. My secretary’s 2-year-old daughter, who comes with her every day, adds to the family atmosphere that many patients notice. It’s not uncommon to be asked if the group of us are related. (We’re not.)

Back when I started out, it was with a large group that saw its people as replaceable, and treated them as such. As a result there was a high turnover rate of medical assistants and front office and clerical staff. This led to problems with work-flow and patient care, as there was always someone new being trained.

I can’t imagine having a better team than I have now, and will share this advice with anyone starting a practice: When you get the right people, count yourself lucky and do what you have to do to keep them. They’re worth it.

It’s a lot nicer to work with friends than strangers. It makes the drudgery of the job more interesting, the low points better, and the highs fun.

I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Defensive medicine’s stranglehold on the realities of practice

In the September 2017 issue of JAMA Neurology, Louis R. Caplan, MD, wrote an excellent editorial, “Patient care is all about stories.” He notes that we all hear from patients about a recurrence of their previous stroke deficits, typically caused by infections, medications, or metabolic changes.

His point is that, telling the difference between true vascular events and recrudescence of old deficits can be difficult, but generally can be gleaned by taking a thorough history. He also notes, quite correctly, that the generic, automated features of modern charting systems often make it harder to get the details you need from previous visits.

Obviously, being able to accurately tell the difference between them can save health care costs, too. In a study in the same issue, Mehmet Topcuoglo, MD, and his colleagues discuss methodologies to differentiate between the causes of recrudescence of stroke-related deficits. Currently, the main approach is to admit patients to the hospital, do a knee-jerk repeat work-up with MRI, magnetic resonance angiogram, and echocardiogram (typically ordered before the neurologist has even been told of the consult) and then conclude that nothing has changed neurologically and that it was all caused by a bladder infection.

Surely, if we had an accurate way of telling the difference between them with a careful history, we’d save a lot of time and money on unnecessary hospital admissions. Right?

It sounds good in principle, but, sadly, the answer is “probably not.”

This is where the idealism of medicine meets the reality of its practice.

In the world of the emergency department, time and resources are limited. Emergency medicine physicians don’t have the luxury of taking a detailed neurologic history, nor are they trained (or expected) to be able to do so. Their job is to decide what is (and isn’t) life-threatening and who does (or doesn’t) need to be admitted.

But probably the main reason why Dr. Topcuoglo and his colleagues’ methodologies will never be implemented is defensive medicine. It’s a heck of lot easier and safer for any doctor – emergency medicine, hospitalist, and neurologist – to admit the patient and order more studies than it is to get served for malpractice and have to defend why you didn’t do that.

People can bemoan defensive medicine and its costs all they want. But, if you’ve been sued, you won’t care. You’ll order any test to protect yourself. Claiming that you followed a guideline from a journal, no matter how well researched it was, will likely be worthless the one time a stroke was missed. It’s easy for a plaintiff’s attorney to find someone to say you fell below the standard of care for doing so.

For an example of where this stands, here’s something from personal experience: One of my patients went to the emergency department for recrudescence of an old left hemiparesis, likely caused by a urinary tract infection. This wasn’t the first time it had happened. A head CT was stable while a urine analysis was abnormal. Because of my schedule, I wasn’t in a position to go see him in the ED in an expedient fashion. The ED physician was planning on admitting him and called to notify me. Knowing the history, I suggested sending him home with treatment for the UTI and to follow up with me the next day.

I thought that seemed reasonable, but the ED doctor didn’t. He said, “If you want to do that, then I am going to document that it’s on your instructions, that you are assuming all responsibility for care and outcome if a stroke is missed, and that I entirely disagree with your decision.”

I’m sure another neurologist might have said, “Okay, tell him to come in here tomorrow,” and hung up, but I really don’t have that kind of fortitude or desire for conflict with another physician. So I backed down and let the person on the scene make the decision. I saw the patient later that day as a consult, all his tests (except the urine analysis in the ED) were fine, and he went home the next day. I’m sure the bill was at least $50,000 (what really got paid is another matter), and defensive medicine had, for better or worse, won out over probability and reason.

Dr. Caplan, quite correctly, emphasizes the importance of taking a careful history, and I absolutely agree with him. Unfortunately, the lack of time in the ED setting, and fears driven by legal consequences, often make a good history irrelevant. Even when it’s done, there are other forces that push it to the background in making medical decisions.

I’m not saying that’s a good thing – it isn’t. But that’s the way it is right now in American medicine, and this aspect of the system shows no sign of changing.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

In the September 2017 issue of JAMA Neurology, Louis R. Caplan, MD, wrote an excellent editorial, “Patient care is all about stories.” He notes that we all hear from patients about a recurrence of their previous stroke deficits, typically caused by infections, medications, or metabolic changes.

His point is that, telling the difference between true vascular events and recrudescence of old deficits can be difficult, but generally can be gleaned by taking a thorough history. He also notes, quite correctly, that the generic, automated features of modern charting systems often make it harder to get the details you need from previous visits.

Obviously, being able to accurately tell the difference between them can save health care costs, too. In a study in the same issue, Mehmet Topcuoglo, MD, and his colleagues discuss methodologies to differentiate between the causes of recrudescence of stroke-related deficits. Currently, the main approach is to admit patients to the hospital, do a knee-jerk repeat work-up with MRI, magnetic resonance angiogram, and echocardiogram (typically ordered before the neurologist has even been told of the consult) and then conclude that nothing has changed neurologically and that it was all caused by a bladder infection.

Surely, if we had an accurate way of telling the difference between them with a careful history, we’d save a lot of time and money on unnecessary hospital admissions. Right?

It sounds good in principle, but, sadly, the answer is “probably not.”

This is where the idealism of medicine meets the reality of its practice.

In the world of the emergency department, time and resources are limited. Emergency medicine physicians don’t have the luxury of taking a detailed neurologic history, nor are they trained (or expected) to be able to do so. Their job is to decide what is (and isn’t) life-threatening and who does (or doesn’t) need to be admitted.

But probably the main reason why Dr. Topcuoglo and his colleagues’ methodologies will never be implemented is defensive medicine. It’s a heck of lot easier and safer for any doctor – emergency medicine, hospitalist, and neurologist – to admit the patient and order more studies than it is to get served for malpractice and have to defend why you didn’t do that.

People can bemoan defensive medicine and its costs all they want. But, if you’ve been sued, you won’t care. You’ll order any test to protect yourself. Claiming that you followed a guideline from a journal, no matter how well researched it was, will likely be worthless the one time a stroke was missed. It’s easy for a plaintiff’s attorney to find someone to say you fell below the standard of care for doing so.

For an example of where this stands, here’s something from personal experience: One of my patients went to the emergency department for recrudescence of an old left hemiparesis, likely caused by a urinary tract infection. This wasn’t the first time it had happened. A head CT was stable while a urine analysis was abnormal. Because of my schedule, I wasn’t in a position to go see him in the ED in an expedient fashion. The ED physician was planning on admitting him and called to notify me. Knowing the history, I suggested sending him home with treatment for the UTI and to follow up with me the next day.

I thought that seemed reasonable, but the ED doctor didn’t. He said, “If you want to do that, then I am going to document that it’s on your instructions, that you are assuming all responsibility for care and outcome if a stroke is missed, and that I entirely disagree with your decision.”

I’m sure another neurologist might have said, “Okay, tell him to come in here tomorrow,” and hung up, but I really don’t have that kind of fortitude or desire for conflict with another physician. So I backed down and let the person on the scene make the decision. I saw the patient later that day as a consult, all his tests (except the urine analysis in the ED) were fine, and he went home the next day. I’m sure the bill was at least $50,000 (what really got paid is another matter), and defensive medicine had, for better or worse, won out over probability and reason.

Dr. Caplan, quite correctly, emphasizes the importance of taking a careful history, and I absolutely agree with him. Unfortunately, the lack of time in the ED setting, and fears driven by legal consequences, often make a good history irrelevant. Even when it’s done, there are other forces that push it to the background in making medical decisions.

I’m not saying that’s a good thing – it isn’t. But that’s the way it is right now in American medicine, and this aspect of the system shows no sign of changing.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

In the September 2017 issue of JAMA Neurology, Louis R. Caplan, MD, wrote an excellent editorial, “Patient care is all about stories.” He notes that we all hear from patients about a recurrence of their previous stroke deficits, typically caused by infections, medications, or metabolic changes.

His point is that, telling the difference between true vascular events and recrudescence of old deficits can be difficult, but generally can be gleaned by taking a thorough history. He also notes, quite correctly, that the generic, automated features of modern charting systems often make it harder to get the details you need from previous visits.

Obviously, being able to accurately tell the difference between them can save health care costs, too. In a study in the same issue, Mehmet Topcuoglo, MD, and his colleagues discuss methodologies to differentiate between the causes of recrudescence of stroke-related deficits. Currently, the main approach is to admit patients to the hospital, do a knee-jerk repeat work-up with MRI, magnetic resonance angiogram, and echocardiogram (typically ordered before the neurologist has even been told of the consult) and then conclude that nothing has changed neurologically and that it was all caused by a bladder infection.

Surely, if we had an accurate way of telling the difference between them with a careful history, we’d save a lot of time and money on unnecessary hospital admissions. Right?

It sounds good in principle, but, sadly, the answer is “probably not.”

This is where the idealism of medicine meets the reality of its practice.

In the world of the emergency department, time and resources are limited. Emergency medicine physicians don’t have the luxury of taking a detailed neurologic history, nor are they trained (or expected) to be able to do so. Their job is to decide what is (and isn’t) life-threatening and who does (or doesn’t) need to be admitted.

But probably the main reason why Dr. Topcuoglo and his colleagues’ methodologies will never be implemented is defensive medicine. It’s a heck of lot easier and safer for any doctor – emergency medicine, hospitalist, and neurologist – to admit the patient and order more studies than it is to get served for malpractice and have to defend why you didn’t do that.

People can bemoan defensive medicine and its costs all they want. But, if you’ve been sued, you won’t care. You’ll order any test to protect yourself. Claiming that you followed a guideline from a journal, no matter how well researched it was, will likely be worthless the one time a stroke was missed. It’s easy for a plaintiff’s attorney to find someone to say you fell below the standard of care for doing so.

For an example of where this stands, here’s something from personal experience: One of my patients went to the emergency department for recrudescence of an old left hemiparesis, likely caused by a urinary tract infection. This wasn’t the first time it had happened. A head CT was stable while a urine analysis was abnormal. Because of my schedule, I wasn’t in a position to go see him in the ED in an expedient fashion. The ED physician was planning on admitting him and called to notify me. Knowing the history, I suggested sending him home with treatment for the UTI and to follow up with me the next day.

I thought that seemed reasonable, but the ED doctor didn’t. He said, “If you want to do that, then I am going to document that it’s on your instructions, that you are assuming all responsibility for care and outcome if a stroke is missed, and that I entirely disagree with your decision.”

I’m sure another neurologist might have said, “Okay, tell him to come in here tomorrow,” and hung up, but I really don’t have that kind of fortitude or desire for conflict with another physician. So I backed down and let the person on the scene make the decision. I saw the patient later that day as a consult, all his tests (except the urine analysis in the ED) were fine, and he went home the next day. I’m sure the bill was at least $50,000 (what really got paid is another matter), and defensive medicine had, for better or worse, won out over probability and reason.

Dr. Caplan, quite correctly, emphasizes the importance of taking a careful history, and I absolutely agree with him. Unfortunately, the lack of time in the ED setting, and fears driven by legal consequences, often make a good history irrelevant. Even when it’s done, there are other forces that push it to the background in making medical decisions.

I’m not saying that’s a good thing – it isn’t. But that’s the way it is right now in American medicine, and this aspect of the system shows no sign of changing.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Serotonin syndrome warnings magnify its rare probability

Serotonin syndrome.

What do those words make you think of? A rare neurological condition? The differential diagnosis you got at 2:00 a.m. from an overly enthusiastic resident? Or a fax from a pharmacy that you get a few times a week?

I’ll say the last.

Triptans are not as common, but are still out there in large numbers. To date, they’re the most effective migraine treatment we have.

Inevitably, these roads will cross, especially because SNRIs, and their older cousins the tricylic antidepressants, are commonly used for migraine prevention. And that’s where the fun begins. There’s a suspected incidence of serotonin syndrome when the two are combined, which became widespread knowledge following a 2006 Food and Drug Administration alert. This is a fact drilled into us by multiple call-backs and faxes from pharmacies, terrified patients who use Google, and electronic prescribing systems that flag our attempts to combine them to make sure we know THIS IS DANGEROUS!

But a study published Feb. 26 in JAMA Neurology found that it’s rarer than anyone suspected (JAMA Neurol. 2018 Feb 26. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.5144). Breaking down 14 years’ worth of patient data with more than 19,000 patients on both triptans and serotonergic drugs, there were only two cases (0.01%) that clearly met criteria for serotonin syndrome.

I also understand where the warnings come from. When things go bad, medicine becomes a blame game as each side points at another. The pharmacy wants to say they warned us. The e-prescribing system company wants to say they warned us. The patients want to know why no one warned them when a Google search makes it sound common. And the malpractice lawyers want to blame everyone.

But there are more serious side effects out there. Dilantin has been linked to lymphoma. Sinemet (possibly) to melanoma. But do you remember the last time you had to click or sign off on a pharmacy warning for those? Me neither.

Using any drug is a balance of risks and benefits. We make our judgments, discuss concerns with the patients, and roll the dice every day. Side effects aren’t uncommon. Most serious side effects are rare. But warnings that magnify issues with a rare probability don’t help the situation and can keep patients from receiving the help they need.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Serotonin syndrome.

What do those words make you think of? A rare neurological condition? The differential diagnosis you got at 2:00 a.m. from an overly enthusiastic resident? Or a fax from a pharmacy that you get a few times a week?

I’ll say the last.

Triptans are not as common, but are still out there in large numbers. To date, they’re the most effective migraine treatment we have.

Inevitably, these roads will cross, especially because SNRIs, and their older cousins the tricylic antidepressants, are commonly used for migraine prevention. And that’s where the fun begins. There’s a suspected incidence of serotonin syndrome when the two are combined, which became widespread knowledge following a 2006 Food and Drug Administration alert. This is a fact drilled into us by multiple call-backs and faxes from pharmacies, terrified patients who use Google, and electronic prescribing systems that flag our attempts to combine them to make sure we know THIS IS DANGEROUS!

But a study published Feb. 26 in JAMA Neurology found that it’s rarer than anyone suspected (JAMA Neurol. 2018 Feb 26. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.5144). Breaking down 14 years’ worth of patient data with more than 19,000 patients on both triptans and serotonergic drugs, there were only two cases (0.01%) that clearly met criteria for serotonin syndrome.

I also understand where the warnings come from. When things go bad, medicine becomes a blame game as each side points at another. The pharmacy wants to say they warned us. The e-prescribing system company wants to say they warned us. The patients want to know why no one warned them when a Google search makes it sound common. And the malpractice lawyers want to blame everyone.

But there are more serious side effects out there. Dilantin has been linked to lymphoma. Sinemet (possibly) to melanoma. But do you remember the last time you had to click or sign off on a pharmacy warning for those? Me neither.

Using any drug is a balance of risks and benefits. We make our judgments, discuss concerns with the patients, and roll the dice every day. Side effects aren’t uncommon. Most serious side effects are rare. But warnings that magnify issues with a rare probability don’t help the situation and can keep patients from receiving the help they need.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Serotonin syndrome.

What do those words make you think of? A rare neurological condition? The differential diagnosis you got at 2:00 a.m. from an overly enthusiastic resident? Or a fax from a pharmacy that you get a few times a week?

I’ll say the last.

Triptans are not as common, but are still out there in large numbers. To date, they’re the most effective migraine treatment we have.

Inevitably, these roads will cross, especially because SNRIs, and their older cousins the tricylic antidepressants, are commonly used for migraine prevention. And that’s where the fun begins. There’s a suspected incidence of serotonin syndrome when the two are combined, which became widespread knowledge following a 2006 Food and Drug Administration alert. This is a fact drilled into us by multiple call-backs and faxes from pharmacies, terrified patients who use Google, and electronic prescribing systems that flag our attempts to combine them to make sure we know THIS IS DANGEROUS!

But a study published Feb. 26 in JAMA Neurology found that it’s rarer than anyone suspected (JAMA Neurol. 2018 Feb 26. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.5144). Breaking down 14 years’ worth of patient data with more than 19,000 patients on both triptans and serotonergic drugs, there were only two cases (0.01%) that clearly met criteria for serotonin syndrome.

I also understand where the warnings come from. When things go bad, medicine becomes a blame game as each side points at another. The pharmacy wants to say they warned us. The e-prescribing system company wants to say they warned us. The patients want to know why no one warned them when a Google search makes it sound common. And the malpractice lawyers want to blame everyone.

But there are more serious side effects out there. Dilantin has been linked to lymphoma. Sinemet (possibly) to melanoma. But do you remember the last time you had to click or sign off on a pharmacy warning for those? Me neither.

Using any drug is a balance of risks and benefits. We make our judgments, discuss concerns with the patients, and roll the dice every day. Side effects aren’t uncommon. Most serious side effects are rare. But warnings that magnify issues with a rare probability don’t help the situation and can keep patients from receiving the help they need.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Allscripts’ charges for sending, refilling prescriptions

How much is $9 worth? Not much. Probably less than most people spend on coffee in a given week.

And yet, that $9 is really irritating to me.

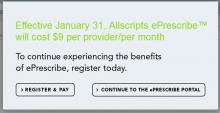

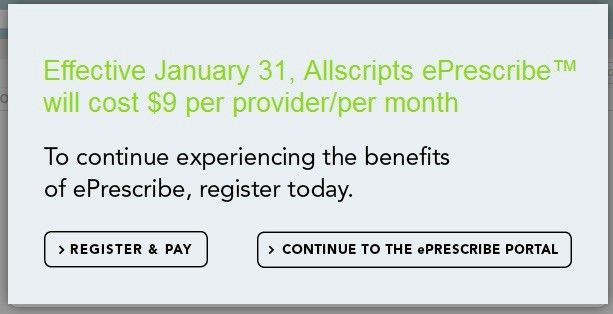

For the last few weeks, when signing into Allscripts to send and refill prescriptions, I’ve encountered this:

I know that $9 a month doesn’t seem like much: It’s $108 a year. But still, it’s irritating.

I understand Allscripts, and every other health care company, is here to make a living. Heck, so am I. Software development isn’t cheap. Neither are the servers hosting it or the security software needed, or the buildings to house them, and a million other things. I get that. None of these things are free.

But, at the same time, it’s part of a general trend of modern health care. Our landlords and vendors can arbitrarily raise prices to keep up with their costs, but we can’t do the same to keep up with ours.

The majority of doctors aren’t in a position to raise our prices to account for these things. We’re stuck with insurance companies and government agencies that tell us to accept a given amount or eat rocks.

There are, of course, concierge practices that can raise their prices, but they’re mostly boutique-level general care with wealthy patients who can afford them. Most small specialists aren’t in that position. We can’t afford to put Keurigs in the lobby.

The few revenue streams most of us have for which we can increase prices, such as legal work and cash patients, are typically not enough of the practice where it would make a difference to overcome it. In fact, the lien company I see patients for recently told me they were lowering their reimbursements to me to compensate for their own higher expenses.

Some people may see the $9 a month as a minor issue and move on. But to a small practice, it’s now another $108 in revenue that I have to bring in each year to cover. And, in a field in which, unlike every other product or service people pay for, I’m not allowed to control my own prices to make up for it.

That doesn’t seem fair, does it?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

How much is $9 worth? Not much. Probably less than most people spend on coffee in a given week.

And yet, that $9 is really irritating to me.

For the last few weeks, when signing into Allscripts to send and refill prescriptions, I’ve encountered this:

I know that $9 a month doesn’t seem like much: It’s $108 a year. But still, it’s irritating.

I understand Allscripts, and every other health care company, is here to make a living. Heck, so am I. Software development isn’t cheap. Neither are the servers hosting it or the security software needed, or the buildings to house them, and a million other things. I get that. None of these things are free.

But, at the same time, it’s part of a general trend of modern health care. Our landlords and vendors can arbitrarily raise prices to keep up with their costs, but we can’t do the same to keep up with ours.

The majority of doctors aren’t in a position to raise our prices to account for these things. We’re stuck with insurance companies and government agencies that tell us to accept a given amount or eat rocks.

There are, of course, concierge practices that can raise their prices, but they’re mostly boutique-level general care with wealthy patients who can afford them. Most small specialists aren’t in that position. We can’t afford to put Keurigs in the lobby.

The few revenue streams most of us have for which we can increase prices, such as legal work and cash patients, are typically not enough of the practice where it would make a difference to overcome it. In fact, the lien company I see patients for recently told me they were lowering their reimbursements to me to compensate for their own higher expenses.

Some people may see the $9 a month as a minor issue and move on. But to a small practice, it’s now another $108 in revenue that I have to bring in each year to cover. And, in a field in which, unlike every other product or service people pay for, I’m not allowed to control my own prices to make up for it.

That doesn’t seem fair, does it?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

How much is $9 worth? Not much. Probably less than most people spend on coffee in a given week.

And yet, that $9 is really irritating to me.

For the last few weeks, when signing into Allscripts to send and refill prescriptions, I’ve encountered this:

I know that $9 a month doesn’t seem like much: It’s $108 a year. But still, it’s irritating.

I understand Allscripts, and every other health care company, is here to make a living. Heck, so am I. Software development isn’t cheap. Neither are the servers hosting it or the security software needed, or the buildings to house them, and a million other things. I get that. None of these things are free.

But, at the same time, it’s part of a general trend of modern health care. Our landlords and vendors can arbitrarily raise prices to keep up with their costs, but we can’t do the same to keep up with ours.

The majority of doctors aren’t in a position to raise our prices to account for these things. We’re stuck with insurance companies and government agencies that tell us to accept a given amount or eat rocks.

There are, of course, concierge practices that can raise their prices, but they’re mostly boutique-level general care with wealthy patients who can afford them. Most small specialists aren’t in that position. We can’t afford to put Keurigs in the lobby.

The few revenue streams most of us have for which we can increase prices, such as legal work and cash patients, are typically not enough of the practice where it would make a difference to overcome it. In fact, the lien company I see patients for recently told me they were lowering their reimbursements to me to compensate for their own higher expenses.

Some people may see the $9 a month as a minor issue and move on. But to a small practice, it’s now another $108 in revenue that I have to bring in each year to cover. And, in a field in which, unlike every other product or service people pay for, I’m not allowed to control my own prices to make up for it.

That doesn’t seem fair, does it?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

No improvement in sight for Alzheimer’s drug development

Another one bites the dust.

Yet another investigational agent joins intepirdine, verubecestat, solanezumab, bapineuzumab, latrepirdine, and many others on the scrap pile of research: The complete release of trial data on idalopirdine found the drug wasn’t of clinically significant benefit in Alzheimer’s disease (JAMA. 2018;319[2]:130-42).

The numbers are bad enough that a handful of companies, including the giant Pfizer, have decided to leave Alzheimer’s drug development entirely to focus on more promising fields. And I get that. All of us – on any exhausting, fruitless, task – will reach the point where it’s time to cut our losses and move on. I don’t blame these companies for mostly leaving the field. (Pfizer is planning to form a neuroscience venture fund to support further research.)

Optimists will argue that you still learn things from a negative trial, which is true, but nothing to date is on the immediate horizon to help. The five agents we’ve had available for the past 15-20 years are all old enough to have lost their patents, and their benefits are modest, at best.

And all this going on as the overall human population, including myself, gradually ages and dementia becomes a medical-cost time bomb on the horizon. This isn’t an American problem. Every country in the world is facing it.

Politicians love to promise hope for these things: creating fast-track programs to get drugs to market faster, finding ways to bring down costs so more people can afford them, and improving methods to treat those in need. But none of those things matter if the medications don’t work.

Many of these trials test similar molecules because the evidence to date suggests they’re targeting the cause of Alzheimer’s. But so far they aren’t working. What if, as the Firesign Theatre and others have said, everything you know is wrong?

Perhaps our greatest quality as a species is resilience. We go on because we have to. The planet keeps moving around the sun as it has for almost 5 billion years, and we face tomorrow. Caregivers wake up for another day of doing their best for a faltering parent. I wake up for another day of doing my best to help them. And the researchers go back for another day hoping to find the real answer and treatment. Without trying, no treatment for anything will ever be found. We owe our patients, and ourselves, a better future than that.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Another one bites the dust.

Yet another investigational agent joins intepirdine, verubecestat, solanezumab, bapineuzumab, latrepirdine, and many others on the scrap pile of research: The complete release of trial data on idalopirdine found the drug wasn’t of clinically significant benefit in Alzheimer’s disease (JAMA. 2018;319[2]:130-42).

The numbers are bad enough that a handful of companies, including the giant Pfizer, have decided to leave Alzheimer’s drug development entirely to focus on more promising fields. And I get that. All of us – on any exhausting, fruitless, task – will reach the point where it’s time to cut our losses and move on. I don’t blame these companies for mostly leaving the field. (Pfizer is planning to form a neuroscience venture fund to support further research.)

Optimists will argue that you still learn things from a negative trial, which is true, but nothing to date is on the immediate horizon to help. The five agents we’ve had available for the past 15-20 years are all old enough to have lost their patents, and their benefits are modest, at best.

And all this going on as the overall human population, including myself, gradually ages and dementia becomes a medical-cost time bomb on the horizon. This isn’t an American problem. Every country in the world is facing it.

Politicians love to promise hope for these things: creating fast-track programs to get drugs to market faster, finding ways to bring down costs so more people can afford them, and improving methods to treat those in need. But none of those things matter if the medications don’t work.

Many of these trials test similar molecules because the evidence to date suggests they’re targeting the cause of Alzheimer’s. But so far they aren’t working. What if, as the Firesign Theatre and others have said, everything you know is wrong?

Perhaps our greatest quality as a species is resilience. We go on because we have to. The planet keeps moving around the sun as it has for almost 5 billion years, and we face tomorrow. Caregivers wake up for another day of doing their best for a faltering parent. I wake up for another day of doing my best to help them. And the researchers go back for another day hoping to find the real answer and treatment. Without trying, no treatment for anything will ever be found. We owe our patients, and ourselves, a better future than that.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Another one bites the dust.

Yet another investigational agent joins intepirdine, verubecestat, solanezumab, bapineuzumab, latrepirdine, and many others on the scrap pile of research: The complete release of trial data on idalopirdine found the drug wasn’t of clinically significant benefit in Alzheimer’s disease (JAMA. 2018;319[2]:130-42).

The numbers are bad enough that a handful of companies, including the giant Pfizer, have decided to leave Alzheimer’s drug development entirely to focus on more promising fields. And I get that. All of us – on any exhausting, fruitless, task – will reach the point where it’s time to cut our losses and move on. I don’t blame these companies for mostly leaving the field. (Pfizer is planning to form a neuroscience venture fund to support further research.)

Optimists will argue that you still learn things from a negative trial, which is true, but nothing to date is on the immediate horizon to help. The five agents we’ve had available for the past 15-20 years are all old enough to have lost their patents, and their benefits are modest, at best.

And all this going on as the overall human population, including myself, gradually ages and dementia becomes a medical-cost time bomb on the horizon. This isn’t an American problem. Every country in the world is facing it.

Politicians love to promise hope for these things: creating fast-track programs to get drugs to market faster, finding ways to bring down costs so more people can afford them, and improving methods to treat those in need. But none of those things matter if the medications don’t work.

Many of these trials test similar molecules because the evidence to date suggests they’re targeting the cause of Alzheimer’s. But so far they aren’t working. What if, as the Firesign Theatre and others have said, everything you know is wrong?

Perhaps our greatest quality as a species is resilience. We go on because we have to. The planet keeps moving around the sun as it has for almost 5 billion years, and we face tomorrow. Caregivers wake up for another day of doing their best for a faltering parent. I wake up for another day of doing my best to help them. And the researchers go back for another day hoping to find the real answer and treatment. Without trying, no treatment for anything will ever be found. We owe our patients, and ourselves, a better future than that.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Withholding elective surgery in smokers, obese patients

No one will argue that obesity and tobacco aren’t serious public health issues, underlying many causes of morbidity and mortality. As a result, they’re driving factors behind a fair amount of health care spending.

In England, the county of Hertfordshire recently adopted a new approach to this: a ban on routine, nonurgent surgeries for both. Those with a body mass index of 30-40 kg/m2 must lose 10% of their weight over 9 months to qualify for a procedure, while those with a BMI above 40 must lose 15%. Smokers have to go 8 weeks without a cigarette and take breath tests to prove it.

The group that formulated the plan noted that resources to help these groups achieve such goals are (and will continue to be) freely available.

Not unexpectedly, the plan is controversial. Robert West, MD, a professor of health psychology and director of tobacco studies at the University College London, told CNN that “rationing treatment on the basis of unhealthy behaviors betrays an extraordinary naivety about what drives those behaviors.”

Of course, this debate is nothing new. In December 2014, I wrote about surgeons in the United States who were refusing to do elective hernia repairs on smokers because of their higher complication rates.

A lot of this is framed in terms of money, since that’s the driving factor. Obese patients and smokers do have higher rates of surgical complications in general, with longer recoveries and, hence, higher costs. This policy tries to put greater responsibility on patients to maintain their own health and well-being. After all, financial resources are a finite, shared commodity.

Like everything in modern health care, there’s no easy answer. Insurers and doctors try to balance better outcomes vs. greater good and cost savings.

Medicine is, and always will be, an ongoing experiment, where some things work, some don’t, and we learn from time and experience.

Unfortunately, patients and their doctors are often caught in the middle, trapped between market and political forces on one side and caring for those who need us on the other. That’s never good, or easy, for those directly involved with individual patients on the front lines of medical care.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

No one will argue that obesity and tobacco aren’t serious public health issues, underlying many causes of morbidity and mortality. As a result, they’re driving factors behind a fair amount of health care spending.

In England, the county of Hertfordshire recently adopted a new approach to this: a ban on routine, nonurgent surgeries for both. Those with a body mass index of 30-40 kg/m2 must lose 10% of their weight over 9 months to qualify for a procedure, while those with a BMI above 40 must lose 15%. Smokers have to go 8 weeks without a cigarette and take breath tests to prove it.

The group that formulated the plan noted that resources to help these groups achieve such goals are (and will continue to be) freely available.

Not unexpectedly, the plan is controversial. Robert West, MD, a professor of health psychology and director of tobacco studies at the University College London, told CNN that “rationing treatment on the basis of unhealthy behaviors betrays an extraordinary naivety about what drives those behaviors.”

Of course, this debate is nothing new. In December 2014, I wrote about surgeons in the United States who were refusing to do elective hernia repairs on smokers because of their higher complication rates.

A lot of this is framed in terms of money, since that’s the driving factor. Obese patients and smokers do have higher rates of surgical complications in general, with longer recoveries and, hence, higher costs. This policy tries to put greater responsibility on patients to maintain their own health and well-being. After all, financial resources are a finite, shared commodity.

Like everything in modern health care, there’s no easy answer. Insurers and doctors try to balance better outcomes vs. greater good and cost savings.

Medicine is, and always will be, an ongoing experiment, where some things work, some don’t, and we learn from time and experience.

Unfortunately, patients and their doctors are often caught in the middle, trapped between market and political forces on one side and caring for those who need us on the other. That’s never good, or easy, for those directly involved with individual patients on the front lines of medical care.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

No one will argue that obesity and tobacco aren’t serious public health issues, underlying many causes of morbidity and mortality. As a result, they’re driving factors behind a fair amount of health care spending.

In England, the county of Hertfordshire recently adopted a new approach to this: a ban on routine, nonurgent surgeries for both. Those with a body mass index of 30-40 kg/m2 must lose 10% of their weight over 9 months to qualify for a procedure, while those with a BMI above 40 must lose 15%. Smokers have to go 8 weeks without a cigarette and take breath tests to prove it.

The group that formulated the plan noted that resources to help these groups achieve such goals are (and will continue to be) freely available.

Not unexpectedly, the plan is controversial. Robert West, MD, a professor of health psychology and director of tobacco studies at the University College London, told CNN that “rationing treatment on the basis of unhealthy behaviors betrays an extraordinary naivety about what drives those behaviors.”

Of course, this debate is nothing new. In December 2014, I wrote about surgeons in the United States who were refusing to do elective hernia repairs on smokers because of their higher complication rates.

A lot of this is framed in terms of money, since that’s the driving factor. Obese patients and smokers do have higher rates of surgical complications in general, with longer recoveries and, hence, higher costs. This policy tries to put greater responsibility on patients to maintain their own health and well-being. After all, financial resources are a finite, shared commodity.

Like everything in modern health care, there’s no easy answer. Insurers and doctors try to balance better outcomes vs. greater good and cost savings.

Medicine is, and always will be, an ongoing experiment, where some things work, some don’t, and we learn from time and experience.

Unfortunately, patients and their doctors are often caught in the middle, trapped between market and political forces on one side and caring for those who need us on the other. That’s never good, or easy, for those directly involved with individual patients on the front lines of medical care.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Private practice’s freedom still outweighs its challenges for me

This past Thanksgiving weekend I left a message on my office machine that we were closed because my staff and I were camping in a tent outside a store to save $3 on socks on Black Friday.

Of course, I had the usual legal disclaimers about calling 911 for emergencies and how to reach the doctor on call, but the message was just silly.

This isn’t anything new for my practice. My patients are used to the occasional humor. Most of them probably expect it by now.

It’s been 17 years since I left a large group and opened up my solo operation, and I’m still here. I have no regrets. My little practice may be eclectic. I wear shorts to work. My secretary’s 2 year old is at work everyday, keeping us laughing. I get to leave goofy messages on office voice mail. But it suits me.

This doesn’t change my focus of trying to practice competent neurology. I don’t claim to be the world’s best doctor, but I hope I know what I’m doing. I may be trying to have some fun here, but that doesn’t mean I take this job any less seriously.

Although things may change, right now I just can’t see myself as part of a large institution. I know my patients. I see each of them myself. I try to understand their concerns and backgrounds so I can treat them appropriately. I don’t try to cram them through in 10 minutes while checking off electronic medical record boxes to document “meaningful use” requirements.

Of course, the flip side is that I don’t make as much money as I could. But as long as I can stay open and support my family, I don’t care. I came here to help in a way that’s meaningful to both my patients and myself, and I’ve found it.

In the November 2017 issue of Medscape Business of Medicine was an article about physicians choosing private practice. Dr. Richard May, a nephrologist in Ohio, said: “We’ve opted to stay with this model because we control our lives. We know the cost of doing that is that we are probably not making as much as we could if we were with a system, but we get up every morning feeling good about how we practice medicine. We’re happy answering to no one but ourselves and not feeling any pressure to meet patient-load quotas and hit monetary goals.”

And all I can say to that is: “Amen, brother.”

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

This past Thanksgiving weekend I left a message on my office machine that we were closed because my staff and I were camping in a tent outside a store to save $3 on socks on Black Friday.

Of course, I had the usual legal disclaimers about calling 911 for emergencies and how to reach the doctor on call, but the message was just silly.

This isn’t anything new for my practice. My patients are used to the occasional humor. Most of them probably expect it by now.

It’s been 17 years since I left a large group and opened up my solo operation, and I’m still here. I have no regrets. My little practice may be eclectic. I wear shorts to work. My secretary’s 2 year old is at work everyday, keeping us laughing. I get to leave goofy messages on office voice mail. But it suits me.

This doesn’t change my focus of trying to practice competent neurology. I don’t claim to be the world’s best doctor, but I hope I know what I’m doing. I may be trying to have some fun here, but that doesn’t mean I take this job any less seriously.

Although things may change, right now I just can’t see myself as part of a large institution. I know my patients. I see each of them myself. I try to understand their concerns and backgrounds so I can treat them appropriately. I don’t try to cram them through in 10 minutes while checking off electronic medical record boxes to document “meaningful use” requirements.

Of course, the flip side is that I don’t make as much money as I could. But as long as I can stay open and support my family, I don’t care. I came here to help in a way that’s meaningful to both my patients and myself, and I’ve found it.

In the November 2017 issue of Medscape Business of Medicine was an article about physicians choosing private practice. Dr. Richard May, a nephrologist in Ohio, said: “We’ve opted to stay with this model because we control our lives. We know the cost of doing that is that we are probably not making as much as we could if we were with a system, but we get up every morning feeling good about how we practice medicine. We’re happy answering to no one but ourselves and not feeling any pressure to meet patient-load quotas and hit monetary goals.”

And all I can say to that is: “Amen, brother.”

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

This past Thanksgiving weekend I left a message on my office machine that we were closed because my staff and I were camping in a tent outside a store to save $3 on socks on Black Friday.

Of course, I had the usual legal disclaimers about calling 911 for emergencies and how to reach the doctor on call, but the message was just silly.

This isn’t anything new for my practice. My patients are used to the occasional humor. Most of them probably expect it by now.

It’s been 17 years since I left a large group and opened up my solo operation, and I’m still here. I have no regrets. My little practice may be eclectic. I wear shorts to work. My secretary’s 2 year old is at work everyday, keeping us laughing. I get to leave goofy messages on office voice mail. But it suits me.

This doesn’t change my focus of trying to practice competent neurology. I don’t claim to be the world’s best doctor, but I hope I know what I’m doing. I may be trying to have some fun here, but that doesn’t mean I take this job any less seriously.

Although things may change, right now I just can’t see myself as part of a large institution. I know my patients. I see each of them myself. I try to understand their concerns and backgrounds so I can treat them appropriately. I don’t try to cram them through in 10 minutes while checking off electronic medical record boxes to document “meaningful use” requirements.

Of course, the flip side is that I don’t make as much money as I could. But as long as I can stay open and support my family, I don’t care. I came here to help in a way that’s meaningful to both my patients and myself, and I’ve found it.

In the November 2017 issue of Medscape Business of Medicine was an article about physicians choosing private practice. Dr. Richard May, a nephrologist in Ohio, said: “We’ve opted to stay with this model because we control our lives. We know the cost of doing that is that we are probably not making as much as we could if we were with a system, but we get up every morning feeling good about how we practice medicine. We’re happy answering to no one but ourselves and not feeling any pressure to meet patient-load quotas and hit monetary goals.”

And all I can say to that is: “Amen, brother.”

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Health care panhandlers: A symptom of our system’s baked-in pressures?

A few nights a week after work I have to stop by the store for this or that.

In the last 1-2 months there’s always been a couple at the parking lot exit, both in wheelchairs, with a big sign asking for money to help one of them beat cancer. They even have the amount listed.

But, by the same token, they could be quite legitimate. The American health care system is full of cracks that seriously ill people can slip through. One recent survey found that about 30% of Americans had trouble paying their medical bills.

It’s easy to look at people like this and think, “I’ll never let that happen to me.” We assume they must be smokers, or irresponsible spenders, or some other reason that makes us feel we won’t stumble into the same pitfalls. That’s reassuring, and sometimes true, but not always. And probably more often than we want to realize.

The world is full of people and families devastated by bad luck. Through no fault of their own, they develop a terrible medical condition or suffer grievous injuries, and suddenly, decent, hard-working, previously healthy people are facing foreclosure and financial ruin. It could, quite literally, be any of us.

Case in point: My family has good insurance and has averaged $10,000 in out-of-pocket medical expenses per year for the last several years. That’s for routine stuff: meeting deductibles, copays on medications, tests, and doctor visits, a few ER trips, etc. The only real “surprise” in there was when my wife broke her leg and needed surgery.

If the panhandlers really did have legitimate medical issues, I might be willing to help out. I give to charity. My grandmother and parents stressed that value to me, and I try to teach it to my kids. But, sadly, we live in a world full of con artists who try to make money by taking advantage of caring peoples’ feelings. Look at all the scams that immediately cropped up following the recent hurricane and wildfire disasters. Without knowing the truth, I’d rather give to an organization like the Salvation Army or Red Cross, hoping they have more experience than I do in sorting out who’s really in need.

As a doctor, I also try to justify it by thinking about how much care I do for “free.” This includes uninsured hospital patients we all see on call, knowing we’ll end up writing their bill off as a loss, and bounced checks for copays and deductible portions that we know we’ll never see.

But, no matter how I try to rationalize it, it still bothers me when I see them sitting there as I leave the store. I don’t know if they’re legitimate. But if they are, they aren’t alone, and there’s something seriously wrong with our health care system.

[polldaddy:9876776]

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

A few nights a week after work I have to stop by the store for this or that.

In the last 1-2 months there’s always been a couple at the parking lot exit, both in wheelchairs, with a big sign asking for money to help one of them beat cancer. They even have the amount listed.

But, by the same token, they could be quite legitimate. The American health care system is full of cracks that seriously ill people can slip through. One recent survey found that about 30% of Americans had trouble paying their medical bills.

It’s easy to look at people like this and think, “I’ll never let that happen to me.” We assume they must be smokers, or irresponsible spenders, or some other reason that makes us feel we won’t stumble into the same pitfalls. That’s reassuring, and sometimes true, but not always. And probably more often than we want to realize.

The world is full of people and families devastated by bad luck. Through no fault of their own, they develop a terrible medical condition or suffer grievous injuries, and suddenly, decent, hard-working, previously healthy people are facing foreclosure and financial ruin. It could, quite literally, be any of us.

Case in point: My family has good insurance and has averaged $10,000 in out-of-pocket medical expenses per year for the last several years. That’s for routine stuff: meeting deductibles, copays on medications, tests, and doctor visits, a few ER trips, etc. The only real “surprise” in there was when my wife broke her leg and needed surgery.

If the panhandlers really did have legitimate medical issues, I might be willing to help out. I give to charity. My grandmother and parents stressed that value to me, and I try to teach it to my kids. But, sadly, we live in a world full of con artists who try to make money by taking advantage of caring peoples’ feelings. Look at all the scams that immediately cropped up following the recent hurricane and wildfire disasters. Without knowing the truth, I’d rather give to an organization like the Salvation Army or Red Cross, hoping they have more experience than I do in sorting out who’s really in need.

As a doctor, I also try to justify it by thinking about how much care I do for “free.” This includes uninsured hospital patients we all see on call, knowing we’ll end up writing their bill off as a loss, and bounced checks for copays and deductible portions that we know we’ll never see.

But, no matter how I try to rationalize it, it still bothers me when I see them sitting there as I leave the store. I don’t know if they’re legitimate. But if they are, they aren’t alone, and there’s something seriously wrong with our health care system.

[polldaddy:9876776]

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

A few nights a week after work I have to stop by the store for this or that.

In the last 1-2 months there’s always been a couple at the parking lot exit, both in wheelchairs, with a big sign asking for money to help one of them beat cancer. They even have the amount listed.

But, by the same token, they could be quite legitimate. The American health care system is full of cracks that seriously ill people can slip through. One recent survey found that about 30% of Americans had trouble paying their medical bills.

It’s easy to look at people like this and think, “I’ll never let that happen to me.” We assume they must be smokers, or irresponsible spenders, or some other reason that makes us feel we won’t stumble into the same pitfalls. That’s reassuring, and sometimes true, but not always. And probably more often than we want to realize.

The world is full of people and families devastated by bad luck. Through no fault of their own, they develop a terrible medical condition or suffer grievous injuries, and suddenly, decent, hard-working, previously healthy people are facing foreclosure and financial ruin. It could, quite literally, be any of us.

Case in point: My family has good insurance and has averaged $10,000 in out-of-pocket medical expenses per year for the last several years. That’s for routine stuff: meeting deductibles, copays on medications, tests, and doctor visits, a few ER trips, etc. The only real “surprise” in there was when my wife broke her leg and needed surgery.

If the panhandlers really did have legitimate medical issues, I might be willing to help out. I give to charity. My grandmother and parents stressed that value to me, and I try to teach it to my kids. But, sadly, we live in a world full of con artists who try to make money by taking advantage of caring peoples’ feelings. Look at all the scams that immediately cropped up following the recent hurricane and wildfire disasters. Without knowing the truth, I’d rather give to an organization like the Salvation Army or Red Cross, hoping they have more experience than I do in sorting out who’s really in need.

As a doctor, I also try to justify it by thinking about how much care I do for “free.” This includes uninsured hospital patients we all see on call, knowing we’ll end up writing their bill off as a loss, and bounced checks for copays and deductible portions that we know we’ll never see.

But, no matter how I try to rationalize it, it still bothers me when I see them sitting there as I leave the store. I don’t know if they’re legitimate. But if they are, they aren’t alone, and there’s something seriously wrong with our health care system.

[polldaddy:9876776]

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Burnout takes its toll on neurology

I’m burned out.

Heck, what doctor isn’t? Politicians say we get paid too much. Lawyers say we make too many mistakes. Insurance companies say we order too many tests and too many expensive treatments. And the patients, while generally good people looking for help, can also on occasion be angry and unreasonable. The bad apples may be in the minority, but it only takes one to ruin a day full of rewarding visits.

That can’t be good.

Some of the study’s listed reasons for burnout are very familiar: complaints about maintenance of certification and about calling insurances to authorize tests and medications, crappy reimbursement for time-consuming visits, having to spend more time at work just to break even, and the constant feeling of never being caught up. I leave work, come home, have dinner with my family, do dictations, go to bed, and do it over again. No matter where I am, I’ve never left the office.

Other common complaints aren’t as much an issue for me. I don’t have, or want, an electronic health record that qualifies for meaningful use; I designed the one I have, and it works fine for me. I don’t have a nonmedical administrator telling me how many patients I’m required to see each day, and my patient population is, overall, appreciative and polite.

There are always trade-offs. When my kids have school breaks, I take that time off from the office to be with them. I enjoy it – I mean, that’s what we’re here for as parents, isn’t it? Of course, the drawback comes a few weeks later when my income drops because I wasn’t working. In solo practice, cash flow is king. I may have more freedom and control than my employed colleagues, but the downside is that I have no guaranteed salary, either. I’m the last one here who gets paid.

I see plenty of columns on how to avoid burnout, none of which seem to be written by someone who’s in a real-world practice. They all recommend taking time off for yourself, maybe seeing a counselor, finding a hobby you enjoy ... Really?

There’s no easy answer, either. We’re stuck with decreasing reimbursements, a gradual whittling away of our profession, a demand to keep putting time we don’t have into our jobs, and many other issues. It’s even worse for those who are coming out of training and are facing these same challenges with six-figure student loans over their heads and, often, the demands of young families. The idealism and energy of youth are all that seem to sustain them, and that can’t last.

I like being a doctor. I enjoy being a neurologist. I love being able to help people and have a sense of service in doing so. But the worsening financial picture for us, and the increasing demands on our often already nonexistent free time, are destroying the field. Like many other docs, I look at my savings here and there and wonder how long until I can retire. That is sad because, as we all gradually leave practice (for whatever reason), new people will need to come in and pick up the mantle. But current conditions are such that I suspect many will find something else to do unless things change.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’m burned out.

Heck, what doctor isn’t? Politicians say we get paid too much. Lawyers say we make too many mistakes. Insurance companies say we order too many tests and too many expensive treatments. And the patients, while generally good people looking for help, can also on occasion be angry and unreasonable. The bad apples may be in the minority, but it only takes one to ruin a day full of rewarding visits.

That can’t be good.

Some of the study’s listed reasons for burnout are very familiar: complaints about maintenance of certification and about calling insurances to authorize tests and medications, crappy reimbursement for time-consuming visits, having to spend more time at work just to break even, and the constant feeling of never being caught up. I leave work, come home, have dinner with my family, do dictations, go to bed, and do it over again. No matter where I am, I’ve never left the office.

Other common complaints aren’t as much an issue for me. I don’t have, or want, an electronic health record that qualifies for meaningful use; I designed the one I have, and it works fine for me. I don’t have a nonmedical administrator telling me how many patients I’m required to see each day, and my patient population is, overall, appreciative and polite.

There are always trade-offs. When my kids have school breaks, I take that time off from the office to be with them. I enjoy it – I mean, that’s what we’re here for as parents, isn’t it? Of course, the drawback comes a few weeks later when my income drops because I wasn’t working. In solo practice, cash flow is king. I may have more freedom and control than my employed colleagues, but the downside is that I have no guaranteed salary, either. I’m the last one here who gets paid.

I see plenty of columns on how to avoid burnout, none of which seem to be written by someone who’s in a real-world practice. They all recommend taking time off for yourself, maybe seeing a counselor, finding a hobby you enjoy ... Really?

There’s no easy answer, either. We’re stuck with decreasing reimbursements, a gradual whittling away of our profession, a demand to keep putting time we don’t have into our jobs, and many other issues. It’s even worse for those who are coming out of training and are facing these same challenges with six-figure student loans over their heads and, often, the demands of young families. The idealism and energy of youth are all that seem to sustain them, and that can’t last.

I like being a doctor. I enjoy being a neurologist. I love being able to help people and have a sense of service in doing so. But the worsening financial picture for us, and the increasing demands on our often already nonexistent free time, are destroying the field. Like many other docs, I look at my savings here and there and wonder how long until I can retire. That is sad because, as we all gradually leave practice (for whatever reason), new people will need to come in and pick up the mantle. But current conditions are such that I suspect many will find something else to do unless things change.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’m burned out.

Heck, what doctor isn’t? Politicians say we get paid too much. Lawyers say we make too many mistakes. Insurance companies say we order too many tests and too many expensive treatments. And the patients, while generally good people looking for help, can also on occasion be angry and unreasonable. The bad apples may be in the minority, but it only takes one to ruin a day full of rewarding visits.

That can’t be good.

Some of the study’s listed reasons for burnout are very familiar: complaints about maintenance of certification and about calling insurances to authorize tests and medications, crappy reimbursement for time-consuming visits, having to spend more time at work just to break even, and the constant feeling of never being caught up. I leave work, come home, have dinner with my family, do dictations, go to bed, and do it over again. No matter where I am, I’ve never left the office.

Other common complaints aren’t as much an issue for me. I don’t have, or want, an electronic health record that qualifies for meaningful use; I designed the one I have, and it works fine for me. I don’t have a nonmedical administrator telling me how many patients I’m required to see each day, and my patient population is, overall, appreciative and polite.

There are always trade-offs. When my kids have school breaks, I take that time off from the office to be with them. I enjoy it – I mean, that’s what we’re here for as parents, isn’t it? Of course, the drawback comes a few weeks later when my income drops because I wasn’t working. In solo practice, cash flow is king. I may have more freedom and control than my employed colleagues, but the downside is that I have no guaranteed salary, either. I’m the last one here who gets paid.

I see plenty of columns on how to avoid burnout, none of which seem to be written by someone who’s in a real-world practice. They all recommend taking time off for yourself, maybe seeing a counselor, finding a hobby you enjoy ... Really?

There’s no easy answer, either. We’re stuck with decreasing reimbursements, a gradual whittling away of our profession, a demand to keep putting time we don’t have into our jobs, and many other issues. It’s even worse for those who are coming out of training and are facing these same challenges with six-figure student loans over their heads and, often, the demands of young families. The idealism and energy of youth are all that seem to sustain them, and that can’t last.

I like being a doctor. I enjoy being a neurologist. I love being able to help people and have a sense of service in doing so. But the worsening financial picture for us, and the increasing demands on our often already nonexistent free time, are destroying the field. Like many other docs, I look at my savings here and there and wonder how long until I can retire. That is sad because, as we all gradually leave practice (for whatever reason), new people will need to come in and pick up the mantle. But current conditions are such that I suspect many will find something else to do unless things change.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Now missing in EHR charts: a good impression

I’ve previously written about “the monster note,” a creation of autofilled blanks with vital signs and test results that tells you very little about what’s really going on.

Recently, while on call, I discovered a new problem: the lack of a decent impression.

I was covering for another doctor, and a cardiologist rounding at a rehab center called to see if he could anticoagulate a recently discharged patient. It was certainly a reasonable question.

Unfortunately, not much was there. Most notes were the usual mishmash of test results, vital signs, and medication lists, with very little about the patient. So I scrolled down to the impressions to find out what the plan was.

Sadly, that area (which to me is the most critical part of a note) was also devoid of anything useful. Hoping for something like “embolic stroke, hoping to anticoagulate in future,” I instead found things like “To SNF or rehab soon” or “case discussed with family” as the entire impression and plan. That tells me nothing. The only note I found that had some sort of assessment and plan was the initial consult, which was done before any test results were in.

This seems to be the current state of things. Notes that actually give you some idea of the thinking and plan have become an endangered species. This helps no one, as most of us rely on other doctors’ notes to coordinate and plan care. While some of this is done through talking or texts, those things aren’t in the chart. So even though the doctors involved may have a good idea of what they’re doing (and I certainly hope they do), an outsider doesn’t.

In my opinion, that does nothing to improve patient care. I suppose it works if the same doctors are involved each day, but that’s not how American hospital medicine is any more. Hospitalists rotate in and out every few days and (as in my case) others cover call on nights, weekends, and holidays.

It’s also a gateway to legal challenges. A malpractice lawyer once told me that notes should be written so that if you have to read it 5 years later, you can get a pretty good idea of what your thinking was. If the details of the plan were carried in your head, or were in conversations with other doctors, those things aren’t going to help you. The written record is everything. If the issues these notes pose to patient care don’t worry you, maybe that thought should.

Back to my patient: It took me about 15-20 minutes of skimming through the note to find the answer I needed. And it wasn’t in any of the doctors’ notes at all.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’ve previously written about “the monster note,” a creation of autofilled blanks with vital signs and test results that tells you very little about what’s really going on.

Recently, while on call, I discovered a new problem: the lack of a decent impression.

I was covering for another doctor, and a cardiologist rounding at a rehab center called to see if he could anticoagulate a recently discharged patient. It was certainly a reasonable question.

Unfortunately, not much was there. Most notes were the usual mishmash of test results, vital signs, and medication lists, with very little about the patient. So I scrolled down to the impressions to find out what the plan was.

Sadly, that area (which to me is the most critical part of a note) was also devoid of anything useful. Hoping for something like “embolic stroke, hoping to anticoagulate in future,” I instead found things like “To SNF or rehab soon” or “case discussed with family” as the entire impression and plan. That tells me nothing. The only note I found that had some sort of assessment and plan was the initial consult, which was done before any test results were in.

This seems to be the current state of things. Notes that actually give you some idea of the thinking and plan have become an endangered species. This helps no one, as most of us rely on other doctors’ notes to coordinate and plan care. While some of this is done through talking or texts, those things aren’t in the chart. So even though the doctors involved may have a good idea of what they’re doing (and I certainly hope they do), an outsider doesn’t.

In my opinion, that does nothing to improve patient care. I suppose it works if the same doctors are involved each day, but that’s not how American hospital medicine is any more. Hospitalists rotate in and out every few days and (as in my case) others cover call on nights, weekends, and holidays.

It’s also a gateway to legal challenges. A malpractice lawyer once told me that notes should be written so that if you have to read it 5 years later, you can get a pretty good idea of what your thinking was. If the details of the plan were carried in your head, or were in conversations with other doctors, those things aren’t going to help you. The written record is everything. If the issues these notes pose to patient care don’t worry you, maybe that thought should.

Back to my patient: It took me about 15-20 minutes of skimming through the note to find the answer I needed. And it wasn’t in any of the doctors’ notes at all.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’ve previously written about “the monster note,” a creation of autofilled blanks with vital signs and test results that tells you very little about what’s really going on.

Recently, while on call, I discovered a new problem: the lack of a decent impression.

I was covering for another doctor, and a cardiologist rounding at a rehab center called to see if he could anticoagulate a recently discharged patient. It was certainly a reasonable question.

Unfortunately, not much was there. Most notes were the usual mishmash of test results, vital signs, and medication lists, with very little about the patient. So I scrolled down to the impressions to find out what the plan was.

Sadly, that area (which to me is the most critical part of a note) was also devoid of anything useful. Hoping for something like “embolic stroke, hoping to anticoagulate in future,” I instead found things like “To SNF or rehab soon” or “case discussed with family” as the entire impression and plan. That tells me nothing. The only note I found that had some sort of assessment and plan was the initial consult, which was done before any test results were in.