User login

Even Small Food Doses Maintain Tolerance in Pediatric Oral Immunotherapy

LOS ANGELES – Food doses as low as 300 mg every other day are enough to retain tolerance in the maintenance phase of pediatric oral immunotherapy for food allergies, according to an investigation involving 62 children over 4 years of age.

The flexibility “to take smaller doses and still maintain desensitization” is why “a lot of our patients continued to do regular dosing of their oral immunotherapy” for up to 6 years, said Dr. Sharon Chinthrajah, a pediatric allergist and immunologist at Stanford (Calif.) University.

The children were originally involved in phase I testing of desensitization for multiple food allergies with omalizumab (Xolair). By reducing the risk of anaphylaxis, the biologic facilitated rapid escalation: 30 children on omalizumab tolerated 2-g food challenges by 9 months. It took about 2 years for 43 children to reach that level without omalizumab.

Subjects had up to five allergies from a list of 15, including egg, milk, and peanut. When tolerance was achieved, they stayed on daily 2-g dosing of each of their food allergens for 4-6 months. They and their parents were then given the option of 2-g daily maintenance dosing or dropping down to as low as 300 mg – about the equivalent of one tree nut – every other day.

The investigators reported follow-up data for 62 subjects at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. Nine children on omalizumab and 22 who did not get omalizumab stuck with 2 g–daily dosing, while 18 omalizumab and 13 no-omalizumab children opted for lower maintenance dosing.

They all remained largely tolerant to 2-g challenges every 6 months for up to 46 months in the omalizumab group and 73 months in the no-omalizumab group, the end of follow-up in each group. There were no differences in immunologic parameters and no differences in tolerance testing between the two groups, and tolerance was maintained regardless of the food allergen. Only about 0.5% of reactions in either group were severe.

“We were excited to find that going down to 300 mg was just as protective” and that long-term maintenance dosing is safe, said Dr. Kari Nadeau, professor of pediatric immunology and allergy at the university. “These are important messages. There’s not a lot of follow-up data on food [oral immunotherapy]. Patient flexibility is key to long-term outcomes,” she added.

“I think people who had milk, egg, and wheat allergies probably didn’t reduce their intake during maintenance, since these are the ones they tend to enjoy,” Dr. Chinthrajah said, but the risk of severe reactions remains, “so we still require patients to carry reaction medication, and review autoinjector use when they come back to our center for testing and food challenges.”

There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators said they have no relevant disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – Food doses as low as 300 mg every other day are enough to retain tolerance in the maintenance phase of pediatric oral immunotherapy for food allergies, according to an investigation involving 62 children over 4 years of age.

The flexibility “to take smaller doses and still maintain desensitization” is why “a lot of our patients continued to do regular dosing of their oral immunotherapy” for up to 6 years, said Dr. Sharon Chinthrajah, a pediatric allergist and immunologist at Stanford (Calif.) University.

The children were originally involved in phase I testing of desensitization for multiple food allergies with omalizumab (Xolair). By reducing the risk of anaphylaxis, the biologic facilitated rapid escalation: 30 children on omalizumab tolerated 2-g food challenges by 9 months. It took about 2 years for 43 children to reach that level without omalizumab.

Subjects had up to five allergies from a list of 15, including egg, milk, and peanut. When tolerance was achieved, they stayed on daily 2-g dosing of each of their food allergens for 4-6 months. They and their parents were then given the option of 2-g daily maintenance dosing or dropping down to as low as 300 mg – about the equivalent of one tree nut – every other day.

The investigators reported follow-up data for 62 subjects at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. Nine children on omalizumab and 22 who did not get omalizumab stuck with 2 g–daily dosing, while 18 omalizumab and 13 no-omalizumab children opted for lower maintenance dosing.

They all remained largely tolerant to 2-g challenges every 6 months for up to 46 months in the omalizumab group and 73 months in the no-omalizumab group, the end of follow-up in each group. There were no differences in immunologic parameters and no differences in tolerance testing between the two groups, and tolerance was maintained regardless of the food allergen. Only about 0.5% of reactions in either group were severe.

“We were excited to find that going down to 300 mg was just as protective” and that long-term maintenance dosing is safe, said Dr. Kari Nadeau, professor of pediatric immunology and allergy at the university. “These are important messages. There’s not a lot of follow-up data on food [oral immunotherapy]. Patient flexibility is key to long-term outcomes,” she added.

“I think people who had milk, egg, and wheat allergies probably didn’t reduce their intake during maintenance, since these are the ones they tend to enjoy,” Dr. Chinthrajah said, but the risk of severe reactions remains, “so we still require patients to carry reaction medication, and review autoinjector use when they come back to our center for testing and food challenges.”

There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators said they have no relevant disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – Food doses as low as 300 mg every other day are enough to retain tolerance in the maintenance phase of pediatric oral immunotherapy for food allergies, according to an investigation involving 62 children over 4 years of age.

The flexibility “to take smaller doses and still maintain desensitization” is why “a lot of our patients continued to do regular dosing of their oral immunotherapy” for up to 6 years, said Dr. Sharon Chinthrajah, a pediatric allergist and immunologist at Stanford (Calif.) University.

The children were originally involved in phase I testing of desensitization for multiple food allergies with omalizumab (Xolair). By reducing the risk of anaphylaxis, the biologic facilitated rapid escalation: 30 children on omalizumab tolerated 2-g food challenges by 9 months. It took about 2 years for 43 children to reach that level without omalizumab.

Subjects had up to five allergies from a list of 15, including egg, milk, and peanut. When tolerance was achieved, they stayed on daily 2-g dosing of each of their food allergens for 4-6 months. They and their parents were then given the option of 2-g daily maintenance dosing or dropping down to as low as 300 mg – about the equivalent of one tree nut – every other day.

The investigators reported follow-up data for 62 subjects at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. Nine children on omalizumab and 22 who did not get omalizumab stuck with 2 g–daily dosing, while 18 omalizumab and 13 no-omalizumab children opted for lower maintenance dosing.

They all remained largely tolerant to 2-g challenges every 6 months for up to 46 months in the omalizumab group and 73 months in the no-omalizumab group, the end of follow-up in each group. There were no differences in immunologic parameters and no differences in tolerance testing between the two groups, and tolerance was maintained regardless of the food allergen. Only about 0.5% of reactions in either group were severe.

“We were excited to find that going down to 300 mg was just as protective” and that long-term maintenance dosing is safe, said Dr. Kari Nadeau, professor of pediatric immunology and allergy at the university. “These are important messages. There’s not a lot of follow-up data on food [oral immunotherapy]. Patient flexibility is key to long-term outcomes,” she added.

“I think people who had milk, egg, and wheat allergies probably didn’t reduce their intake during maintenance, since these are the ones they tend to enjoy,” Dr. Chinthrajah said, but the risk of severe reactions remains, “so we still require patients to carry reaction medication, and review autoinjector use when they come back to our center for testing and food challenges.”

There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators said they have no relevant disclosures.

AT 2016 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Even small food doses maintain tolerance in pediatric oral immunotherapy

LOS ANGELES – Food doses as low as 300 mg every other day are enough to retain tolerance in the maintenance phase of pediatric oral immunotherapy for food allergies, according to an investigation involving 62 children over 4 years of age.

The flexibility “to take smaller doses and still maintain desensitization” is why “a lot of our patients continued to do regular dosing of their oral immunotherapy” for up to 6 years, said Dr. Sharon Chinthrajah, a pediatric allergist and immunologist at Stanford (Calif.) University.

The children were originally involved in phase I testing of desensitization for multiple food allergies with omalizumab (Xolair). By reducing the risk of anaphylaxis, the biologic facilitated rapid escalation: 30 children on omalizumab tolerated 2-g food challenges by 9 months. It took about 2 years for 43 children to reach that level without omalizumab.

Subjects had up to five allergies from a list of 15, including egg, milk, and peanut. When tolerance was achieved, they stayed on daily 2-g dosing of each of their food allergens for 4-6 months. They and their parents were then given the option of 2-g daily maintenance dosing or dropping down to as low as 300 mg – about the equivalent of one tree nut – every other day.

The investigators reported follow-up data for 62 subjects at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. Nine children on omalizumab and 22 who did not get omalizumab stuck with 2 g–daily dosing, while 18 omalizumab and 13 no-omalizumab children opted for lower maintenance dosing.

They all remained largely tolerant to 2-g challenges every 6 months for up to 46 months in the omalizumab group and 73 months in the no-omalizumab group, the end of follow-up in each group. There were no differences in immunologic parameters and no differences in tolerance testing between the two groups, and tolerance was maintained regardless of the food allergen. Only about 0.5% of reactions in either group were severe.

“We were excited to find that going down to 300 mg was just as protective” and that long-term maintenance dosing is safe, said Dr. Kari Nadeau, professor of pediatric immunology and allergy at the university. “These are important messages. There’s not a lot of follow-up data on food [oral immunotherapy]. Patient flexibility is key to long-term outcomes,” she added.

“I think people who had milk, egg, and wheat allergies probably didn’t reduce their intake during maintenance, since these are the ones they tend to enjoy,” Dr. Chinthrajah said, but the risk of severe reactions remains, “so we still require patients to carry reaction medication, and review autoinjector use when they come back to our center for testing and food challenges.”

There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators said they have no relevant disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – Food doses as low as 300 mg every other day are enough to retain tolerance in the maintenance phase of pediatric oral immunotherapy for food allergies, according to an investigation involving 62 children over 4 years of age.

The flexibility “to take smaller doses and still maintain desensitization” is why “a lot of our patients continued to do regular dosing of their oral immunotherapy” for up to 6 years, said Dr. Sharon Chinthrajah, a pediatric allergist and immunologist at Stanford (Calif.) University.

The children were originally involved in phase I testing of desensitization for multiple food allergies with omalizumab (Xolair). By reducing the risk of anaphylaxis, the biologic facilitated rapid escalation: 30 children on omalizumab tolerated 2-g food challenges by 9 months. It took about 2 years for 43 children to reach that level without omalizumab.

Subjects had up to five allergies from a list of 15, including egg, milk, and peanut. When tolerance was achieved, they stayed on daily 2-g dosing of each of their food allergens for 4-6 months. They and their parents were then given the option of 2-g daily maintenance dosing or dropping down to as low as 300 mg – about the equivalent of one tree nut – every other day.

The investigators reported follow-up data for 62 subjects at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. Nine children on omalizumab and 22 who did not get omalizumab stuck with 2 g–daily dosing, while 18 omalizumab and 13 no-omalizumab children opted for lower maintenance dosing.

They all remained largely tolerant to 2-g challenges every 6 months for up to 46 months in the omalizumab group and 73 months in the no-omalizumab group, the end of follow-up in each group. There were no differences in immunologic parameters and no differences in tolerance testing between the two groups, and tolerance was maintained regardless of the food allergen. Only about 0.5% of reactions in either group were severe.

“We were excited to find that going down to 300 mg was just as protective” and that long-term maintenance dosing is safe, said Dr. Kari Nadeau, professor of pediatric immunology and allergy at the university. “These are important messages. There’s not a lot of follow-up data on food [oral immunotherapy]. Patient flexibility is key to long-term outcomes,” she added.

“I think people who had milk, egg, and wheat allergies probably didn’t reduce their intake during maintenance, since these are the ones they tend to enjoy,” Dr. Chinthrajah said, but the risk of severe reactions remains, “so we still require patients to carry reaction medication, and review autoinjector use when they come back to our center for testing and food challenges.”

There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators said they have no relevant disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – Food doses as low as 300 mg every other day are enough to retain tolerance in the maintenance phase of pediatric oral immunotherapy for food allergies, according to an investigation involving 62 children over 4 years of age.

The flexibility “to take smaller doses and still maintain desensitization” is why “a lot of our patients continued to do regular dosing of their oral immunotherapy” for up to 6 years, said Dr. Sharon Chinthrajah, a pediatric allergist and immunologist at Stanford (Calif.) University.

The children were originally involved in phase I testing of desensitization for multiple food allergies with omalizumab (Xolair). By reducing the risk of anaphylaxis, the biologic facilitated rapid escalation: 30 children on omalizumab tolerated 2-g food challenges by 9 months. It took about 2 years for 43 children to reach that level without omalizumab.

Subjects had up to five allergies from a list of 15, including egg, milk, and peanut. When tolerance was achieved, they stayed on daily 2-g dosing of each of their food allergens for 4-6 months. They and their parents were then given the option of 2-g daily maintenance dosing or dropping down to as low as 300 mg – about the equivalent of one tree nut – every other day.

The investigators reported follow-up data for 62 subjects at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. Nine children on omalizumab and 22 who did not get omalizumab stuck with 2 g–daily dosing, while 18 omalizumab and 13 no-omalizumab children opted for lower maintenance dosing.

They all remained largely tolerant to 2-g challenges every 6 months for up to 46 months in the omalizumab group and 73 months in the no-omalizumab group, the end of follow-up in each group. There were no differences in immunologic parameters and no differences in tolerance testing between the two groups, and tolerance was maintained regardless of the food allergen. Only about 0.5% of reactions in either group were severe.

“We were excited to find that going down to 300 mg was just as protective” and that long-term maintenance dosing is safe, said Dr. Kari Nadeau, professor of pediatric immunology and allergy at the university. “These are important messages. There’s not a lot of follow-up data on food [oral immunotherapy]. Patient flexibility is key to long-term outcomes,” she added.

“I think people who had milk, egg, and wheat allergies probably didn’t reduce their intake during maintenance, since these are the ones they tend to enjoy,” Dr. Chinthrajah said, but the risk of severe reactions remains, “so we still require patients to carry reaction medication, and review autoinjector use when they come back to our center for testing and food challenges.”

There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators said they have no relevant disclosures.

AT 2016 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Small food doses work as well as large ones to maintain tolerance after oral immunotherapy induction for pediatric food allergies.

Major finding: After induction, children taking daily 2-g maintenance doses and those taking as little as 300 mg every other day both retained tolerance to 2-g challenges every 6 months for 46-73 months.

Data source: Prospective study of 62 children with multiple food allergies.

Disclosures: There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators said they have no relevant disclosures.

AAAAI: Early Peanut Consumption Brings Lasting Protection From Allergy

LOS ANGELES – A peanut allergy prevention strategy based upon regular consumption of peanut-containing foods from infancy to age 5 continued to provide protection even after peanut intake was halted for a full year from age 5 to 6, according to new results from an extension of the landmark LEAP trial, known as LEAP-On, presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The impetus for LEAP-On was the investigators’ concern that a period of peanut avoidance might cause loss of the protective state. But that didn’t occur.

“I think there is no doubt that we have prevented peanut allergy so far in these high-risk children. Next, the LEAP-Ad Lib study will tell us whether we’ve prevented it by age 10,” said Dr. Gideon Lack of King’s College London, who headed LEAP-On.

A second major randomized trial known as EAT (Enquiring About Tolerance) presented at the meeting provided further support for early dietary introduction of allergenic foods. EAT differed from LEAP (Learning Early About Peanut Allergy) and LEAP-On in that it ambitiously randomized infants to early introduction or avoidance of not one but six allergenic foods: peanut, cooked egg, cow’s milk, fish, sesame, and wheat. Also, while LEAP and LEAP-On involved roughly 600 infants known to be at very high risk for allergy, EAT was conducted in a general population of 1,303 infants who weren’t at increased risk, all of whom were exclusively breast-fed until the intervention beginning at age 3 months.

The presentation of the LEAP-On and EAT results at the AAAAI annual meeting was a major event marked by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases by same-day release of new NIAID-sponsored draft recommendations for the diagnosis and management of food allergies.

In a press conference held at the AAAAI annual meeting to announce the start of a 45-day public comment period for the draft update of the 2010 guidelines, Dr. Daniel Rotrosen, director of NIAID’s division of allergy, immunology and transplantation, said the new guidelines were developed largely in response to the compelling LEAP findings. That trial demonstrated that sustained consumption of peanut starting in infancy resulted in an 81% lower rate of peanut allergy at age 5 years compared to a strategy of peanut avoidance (N Engl J Med. 2015;372:803-13).

The draft guidelines, now available on the NIAID website, represent a sharp departure from the former recommendation that physicians encourage exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life followed by cautious introduction of other foods. Whereas the former orthodoxy was that delayed introduction of allergenic foods protects against development of food allergy, the new evidence-based concept supported by the LEAP and EAT findings is that just the opposite is true: that is, introduction of such foods during the period of immunologic plasticity in infancy induces tolerance.

Thus, the draft guidelines recommend that infants at high risk for peanut allergy because they have severe eczema and/or egg allergy should have introduction of peanut-containing food at 4-6 months of age to reduce their risk of peanut allergy, preceded by evaluation using peanut-specific IgE or skin prick testing to make sure it’s safe. That age window coincides with well-child visits and vaccination schedules, Dr. Rotrosen noted.

These guidelines represent the consensus of 26 organizations that participated in their development. Among them are the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Dermatology, the American College of Gastroenterology, and AAAAI.

“I expect the new guidelines, when finalized, to be endorsed by the leadership of all the participating organizations,” Dr. Rotrosen said.

The new paradigm will require cultural change, said Dr. James R. Baker Jr., CEO and chief medical officer of Food Allergy Research and Education, a nonprofit organization that provided partial funding for LEAP and LEAP-On.

“I think for a long time we’ve vilified these foods. There’s nothing inherently wrong with their intake, and that’s a message we need to get across to parents and physicians so they can start thinking differently,” he said.

“The good news about these studies is that they show there’s no reason not to do this,” Dr. Baker added. “There’s no harm that comes from the early introduction.”

Dr. Lack, who led the EAT trial, noted that the study didn’t meet it’s primary endpoint of a significantly lower prevalence of food allergy to any of the six intervention foods at age 3 years in the intention-to-treat analysis. But adherence to the demanding EAT early-introduction protocol was a problem. Indeed, only 43% of participants adhered to the study protocol. In a per-protocol analysis restricted to the adherent group, however, early introduction was associated with a highly significant 67% reduction in the relative risk of food allergy at 3 years of age compared to controls. And for the two most prevalent food allergies – to peanut and egg – the relative risk reductions in the early-introduction group were 100% and 75%, respectively.

The EAT results suggest that an effective preventive dose of peanut in infants at least 3 months of age is roughly 2 g of peanut protein per week, equivalent to just under 2 tsp of peanut butter, according to Dr. Lack.

Simultaneously with presentation of the LEAP-On and EAT trials in Los Angeles, the studies were published online at NEJM.org (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1514210 for LEAP-ON and 10.1056/NEJMoa1514209 for EAT).

LEAP-On was supported primarily by NIAID. EAT was funded mainly by the UK Foods Standards Agency and the Medical Research Council. Dr. Lack reported receiving grants from those agencies as well as Food Allergy Research and Education.

LOS ANGELES – A peanut allergy prevention strategy based upon regular consumption of peanut-containing foods from infancy to age 5 continued to provide protection even after peanut intake was halted for a full year from age 5 to 6, according to new results from an extension of the landmark LEAP trial, known as LEAP-On, presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The impetus for LEAP-On was the investigators’ concern that a period of peanut avoidance might cause loss of the protective state. But that didn’t occur.

“I think there is no doubt that we have prevented peanut allergy so far in these high-risk children. Next, the LEAP-Ad Lib study will tell us whether we’ve prevented it by age 10,” said Dr. Gideon Lack of King’s College London, who headed LEAP-On.

A second major randomized trial known as EAT (Enquiring About Tolerance) presented at the meeting provided further support for early dietary introduction of allergenic foods. EAT differed from LEAP (Learning Early About Peanut Allergy) and LEAP-On in that it ambitiously randomized infants to early introduction or avoidance of not one but six allergenic foods: peanut, cooked egg, cow’s milk, fish, sesame, and wheat. Also, while LEAP and LEAP-On involved roughly 600 infants known to be at very high risk for allergy, EAT was conducted in a general population of 1,303 infants who weren’t at increased risk, all of whom were exclusively breast-fed until the intervention beginning at age 3 months.

The presentation of the LEAP-On and EAT results at the AAAAI annual meeting was a major event marked by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases by same-day release of new NIAID-sponsored draft recommendations for the diagnosis and management of food allergies.

In a press conference held at the AAAAI annual meeting to announce the start of a 45-day public comment period for the draft update of the 2010 guidelines, Dr. Daniel Rotrosen, director of NIAID’s division of allergy, immunology and transplantation, said the new guidelines were developed largely in response to the compelling LEAP findings. That trial demonstrated that sustained consumption of peanut starting in infancy resulted in an 81% lower rate of peanut allergy at age 5 years compared to a strategy of peanut avoidance (N Engl J Med. 2015;372:803-13).

The draft guidelines, now available on the NIAID website, represent a sharp departure from the former recommendation that physicians encourage exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life followed by cautious introduction of other foods. Whereas the former orthodoxy was that delayed introduction of allergenic foods protects against development of food allergy, the new evidence-based concept supported by the LEAP and EAT findings is that just the opposite is true: that is, introduction of such foods during the period of immunologic plasticity in infancy induces tolerance.

Thus, the draft guidelines recommend that infants at high risk for peanut allergy because they have severe eczema and/or egg allergy should have introduction of peanut-containing food at 4-6 months of age to reduce their risk of peanut allergy, preceded by evaluation using peanut-specific IgE or skin prick testing to make sure it’s safe. That age window coincides with well-child visits and vaccination schedules, Dr. Rotrosen noted.

These guidelines represent the consensus of 26 organizations that participated in their development. Among them are the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Dermatology, the American College of Gastroenterology, and AAAAI.

“I expect the new guidelines, when finalized, to be endorsed by the leadership of all the participating organizations,” Dr. Rotrosen said.

The new paradigm will require cultural change, said Dr. James R. Baker Jr., CEO and chief medical officer of Food Allergy Research and Education, a nonprofit organization that provided partial funding for LEAP and LEAP-On.

“I think for a long time we’ve vilified these foods. There’s nothing inherently wrong with their intake, and that’s a message we need to get across to parents and physicians so they can start thinking differently,” he said.

“The good news about these studies is that they show there’s no reason not to do this,” Dr. Baker added. “There’s no harm that comes from the early introduction.”

Dr. Lack, who led the EAT trial, noted that the study didn’t meet it’s primary endpoint of a significantly lower prevalence of food allergy to any of the six intervention foods at age 3 years in the intention-to-treat analysis. But adherence to the demanding EAT early-introduction protocol was a problem. Indeed, only 43% of participants adhered to the study protocol. In a per-protocol analysis restricted to the adherent group, however, early introduction was associated with a highly significant 67% reduction in the relative risk of food allergy at 3 years of age compared to controls. And for the two most prevalent food allergies – to peanut and egg – the relative risk reductions in the early-introduction group were 100% and 75%, respectively.

The EAT results suggest that an effective preventive dose of peanut in infants at least 3 months of age is roughly 2 g of peanut protein per week, equivalent to just under 2 tsp of peanut butter, according to Dr. Lack.

Simultaneously with presentation of the LEAP-On and EAT trials in Los Angeles, the studies were published online at NEJM.org (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1514210 for LEAP-ON and 10.1056/NEJMoa1514209 for EAT).

LEAP-On was supported primarily by NIAID. EAT was funded mainly by the UK Foods Standards Agency and the Medical Research Council. Dr. Lack reported receiving grants from those agencies as well as Food Allergy Research and Education.

LOS ANGELES – A peanut allergy prevention strategy based upon regular consumption of peanut-containing foods from infancy to age 5 continued to provide protection even after peanut intake was halted for a full year from age 5 to 6, according to new results from an extension of the landmark LEAP trial, known as LEAP-On, presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The impetus for LEAP-On was the investigators’ concern that a period of peanut avoidance might cause loss of the protective state. But that didn’t occur.

“I think there is no doubt that we have prevented peanut allergy so far in these high-risk children. Next, the LEAP-Ad Lib study will tell us whether we’ve prevented it by age 10,” said Dr. Gideon Lack of King’s College London, who headed LEAP-On.

A second major randomized trial known as EAT (Enquiring About Tolerance) presented at the meeting provided further support for early dietary introduction of allergenic foods. EAT differed from LEAP (Learning Early About Peanut Allergy) and LEAP-On in that it ambitiously randomized infants to early introduction or avoidance of not one but six allergenic foods: peanut, cooked egg, cow’s milk, fish, sesame, and wheat. Also, while LEAP and LEAP-On involved roughly 600 infants known to be at very high risk for allergy, EAT was conducted in a general population of 1,303 infants who weren’t at increased risk, all of whom were exclusively breast-fed until the intervention beginning at age 3 months.

The presentation of the LEAP-On and EAT results at the AAAAI annual meeting was a major event marked by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases by same-day release of new NIAID-sponsored draft recommendations for the diagnosis and management of food allergies.

In a press conference held at the AAAAI annual meeting to announce the start of a 45-day public comment period for the draft update of the 2010 guidelines, Dr. Daniel Rotrosen, director of NIAID’s division of allergy, immunology and transplantation, said the new guidelines were developed largely in response to the compelling LEAP findings. That trial demonstrated that sustained consumption of peanut starting in infancy resulted in an 81% lower rate of peanut allergy at age 5 years compared to a strategy of peanut avoidance (N Engl J Med. 2015;372:803-13).

The draft guidelines, now available on the NIAID website, represent a sharp departure from the former recommendation that physicians encourage exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life followed by cautious introduction of other foods. Whereas the former orthodoxy was that delayed introduction of allergenic foods protects against development of food allergy, the new evidence-based concept supported by the LEAP and EAT findings is that just the opposite is true: that is, introduction of such foods during the period of immunologic plasticity in infancy induces tolerance.

Thus, the draft guidelines recommend that infants at high risk for peanut allergy because they have severe eczema and/or egg allergy should have introduction of peanut-containing food at 4-6 months of age to reduce their risk of peanut allergy, preceded by evaluation using peanut-specific IgE or skin prick testing to make sure it’s safe. That age window coincides with well-child visits and vaccination schedules, Dr. Rotrosen noted.

These guidelines represent the consensus of 26 organizations that participated in their development. Among them are the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Dermatology, the American College of Gastroenterology, and AAAAI.

“I expect the new guidelines, when finalized, to be endorsed by the leadership of all the participating organizations,” Dr. Rotrosen said.

The new paradigm will require cultural change, said Dr. James R. Baker Jr., CEO and chief medical officer of Food Allergy Research and Education, a nonprofit organization that provided partial funding for LEAP and LEAP-On.

“I think for a long time we’ve vilified these foods. There’s nothing inherently wrong with their intake, and that’s a message we need to get across to parents and physicians so they can start thinking differently,” he said.

“The good news about these studies is that they show there’s no reason not to do this,” Dr. Baker added. “There’s no harm that comes from the early introduction.”

Dr. Lack, who led the EAT trial, noted that the study didn’t meet it’s primary endpoint of a significantly lower prevalence of food allergy to any of the six intervention foods at age 3 years in the intention-to-treat analysis. But adherence to the demanding EAT early-introduction protocol was a problem. Indeed, only 43% of participants adhered to the study protocol. In a per-protocol analysis restricted to the adherent group, however, early introduction was associated with a highly significant 67% reduction in the relative risk of food allergy at 3 years of age compared to controls. And for the two most prevalent food allergies – to peanut and egg – the relative risk reductions in the early-introduction group were 100% and 75%, respectively.

The EAT results suggest that an effective preventive dose of peanut in infants at least 3 months of age is roughly 2 g of peanut protein per week, equivalent to just under 2 tsp of peanut butter, according to Dr. Lack.

Simultaneously with presentation of the LEAP-On and EAT trials in Los Angeles, the studies were published online at NEJM.org (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1514210 for LEAP-ON and 10.1056/NEJMoa1514209 for EAT).

LEAP-On was supported primarily by NIAID. EAT was funded mainly by the UK Foods Standards Agency and the Medical Research Council. Dr. Lack reported receiving grants from those agencies as well as Food Allergy Research and Education.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE 2016 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

AAAAI: Early peanut consumption brings lasting protection from allergy

LOS ANGELES – A peanut allergy prevention strategy based upon regular consumption of peanut-containing foods from infancy to age 5 continued to provide protection even after peanut intake was halted for a full year from age 5 to 6, according to new results from an extension of the landmark LEAP trial, known as LEAP-On, presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The impetus for LEAP-On was the investigators’ concern that a period of peanut avoidance might cause loss of the protective state. But that didn’t occur.

“I think there is no doubt that we have prevented peanut allergy so far in these high-risk children. Next, the LEAP-Ad Lib study will tell us whether we’ve prevented it by age 10,” said Dr. Gideon Lack of King’s College London, who headed LEAP-On.

A second major randomized trial known as EAT (Enquiring About Tolerance) presented at the meeting provided further support for early dietary introduction of allergenic foods. EAT differed from LEAP (Learning Early About Peanut Allergy) and LEAP-On in that it ambitiously randomized infants to early introduction or avoidance of not one but six allergenic foods: peanut, cooked egg, cow’s milk, fish, sesame, and wheat. Also, while LEAP and LEAP-On involved roughly 600 infants known to be at very high risk for allergy, EAT was conducted in a general population of 1,303 infants who weren’t at increased risk, all of whom were exclusively breast-fed until the intervention beginning at age 3 months.

The presentation of the LEAP-On and EAT results at the AAAAI annual meeting was a major event marked by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases by same-day release of new NIAID-sponsored draft recommendations for the diagnosis and management of food allergies.

In a press conference held at the AAAAI annual meeting to announce the start of a 45-day public comment period for the draft update of the 2010 guidelines, Dr. Daniel Rotrosen, director of NIAID’s division of allergy, immunology and transplantation, said the new guidelines were developed largely in response to the compelling LEAP findings. That trial demonstrated that sustained consumption of peanut starting in infancy resulted in an 81% lower rate of peanut allergy at age 5 years compared to a strategy of peanut avoidance (N Engl J Med. 2015;372:803-13).

The draft guidelines, now available on the NIAID website, represent a sharp departure from the former recommendation that physicians encourage exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life followed by cautious introduction of other foods. Whereas the former orthodoxy was that delayed introduction of allergenic foods protects against development of food allergy, the new evidence-based concept supported by the LEAP and EAT findings is that just the opposite is true: that is, introduction of such foods during the period of immunologic plasticity in infancy induces tolerance.

Thus, the draft guidelines recommend that infants at high risk for peanut allergy because they have severe eczema and/or egg allergy should have introduction of peanut-containing food at 4-6 months of age to reduce their risk of peanut allergy, preceded by evaluation using peanut-specific IgE or skin prick testing to make sure it’s safe. That age window coincides with well-child visits and vaccination schedules, Dr. Rotrosen noted.

These guidelines represent the consensus of 26 organizations that participated in their development. Among them are the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Dermatology, the American College of Gastroenterology, and AAAAI.

“I expect the new guidelines, when finalized, to be endorsed by the leadership of all the participating organizations,” Dr. Rotrosen said.

The new paradigm will require cultural change, said Dr. James R. Baker Jr., CEO and chief medical officer of Food Allergy Research and Education, a nonprofit organization that provided partial funding for LEAP and LEAP-On.

“I think for a long time we’ve vilified these foods. There’s nothing inherently wrong with their intake, and that’s a message we need to get across to parents and physicians so they can start thinking differently,” he said.

“The good news about these studies is that they show there’s no reason not to do this,” Dr. Baker added. “There’s no harm that comes from the early introduction.”

Dr. Lack, who led the EAT trial, noted that the study didn’t meet it’s primary endpoint of a significantly lower prevalence of food allergy to any of the six intervention foods at age 3 years in the intention-to-treat analysis. But adherence to the demanding EAT early-introduction protocol was a problem. Indeed, only 43% of participants adhered to the study protocol. In a per-protocol analysis restricted to the adherent group, however, early introduction was associated with a highly significant 67% reduction in the relative risk of food allergy at 3 years of age compared to controls. And for the two most prevalent food allergies – to peanut and egg – the relative risk reductions in the early-introduction group were 100% and 75%, respectively.

The EAT results suggest that an effective preventive dose of peanut in infants at least 3 months of age is roughly 2 g of peanut protein per week, equivalent to just under 2 tsp of peanut butter, according to Dr. Lack.

Simultaneously with presentation of the LEAP-On and EAT trials in Los Angeles, the studies were published online at NEJM.org (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1514210 for LEAP-ON and 10.1056/NEJMoa1514209 for EAT).

LEAP-On was supported primarily by NIAID. EAT was funded mainly by the UK Foods Standards Agency and the Medical Research Council. Dr. Lack reported receiving grants from those agencies as well as Food Allergy Research and Education.

LOS ANGELES – A peanut allergy prevention strategy based upon regular consumption of peanut-containing foods from infancy to age 5 continued to provide protection even after peanut intake was halted for a full year from age 5 to 6, according to new results from an extension of the landmark LEAP trial, known as LEAP-On, presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The impetus for LEAP-On was the investigators’ concern that a period of peanut avoidance might cause loss of the protective state. But that didn’t occur.

“I think there is no doubt that we have prevented peanut allergy so far in these high-risk children. Next, the LEAP-Ad Lib study will tell us whether we’ve prevented it by age 10,” said Dr. Gideon Lack of King’s College London, who headed LEAP-On.

A second major randomized trial known as EAT (Enquiring About Tolerance) presented at the meeting provided further support for early dietary introduction of allergenic foods. EAT differed from LEAP (Learning Early About Peanut Allergy) and LEAP-On in that it ambitiously randomized infants to early introduction or avoidance of not one but six allergenic foods: peanut, cooked egg, cow’s milk, fish, sesame, and wheat. Also, while LEAP and LEAP-On involved roughly 600 infants known to be at very high risk for allergy, EAT was conducted in a general population of 1,303 infants who weren’t at increased risk, all of whom were exclusively breast-fed until the intervention beginning at age 3 months.

The presentation of the LEAP-On and EAT results at the AAAAI annual meeting was a major event marked by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases by same-day release of new NIAID-sponsored draft recommendations for the diagnosis and management of food allergies.

In a press conference held at the AAAAI annual meeting to announce the start of a 45-day public comment period for the draft update of the 2010 guidelines, Dr. Daniel Rotrosen, director of NIAID’s division of allergy, immunology and transplantation, said the new guidelines were developed largely in response to the compelling LEAP findings. That trial demonstrated that sustained consumption of peanut starting in infancy resulted in an 81% lower rate of peanut allergy at age 5 years compared to a strategy of peanut avoidance (N Engl J Med. 2015;372:803-13).

The draft guidelines, now available on the NIAID website, represent a sharp departure from the former recommendation that physicians encourage exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life followed by cautious introduction of other foods. Whereas the former orthodoxy was that delayed introduction of allergenic foods protects against development of food allergy, the new evidence-based concept supported by the LEAP and EAT findings is that just the opposite is true: that is, introduction of such foods during the period of immunologic plasticity in infancy induces tolerance.

Thus, the draft guidelines recommend that infants at high risk for peanut allergy because they have severe eczema and/or egg allergy should have introduction of peanut-containing food at 4-6 months of age to reduce their risk of peanut allergy, preceded by evaluation using peanut-specific IgE or skin prick testing to make sure it’s safe. That age window coincides with well-child visits and vaccination schedules, Dr. Rotrosen noted.

These guidelines represent the consensus of 26 organizations that participated in their development. Among them are the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Dermatology, the American College of Gastroenterology, and AAAAI.

“I expect the new guidelines, when finalized, to be endorsed by the leadership of all the participating organizations,” Dr. Rotrosen said.

The new paradigm will require cultural change, said Dr. James R. Baker Jr., CEO and chief medical officer of Food Allergy Research and Education, a nonprofit organization that provided partial funding for LEAP and LEAP-On.

“I think for a long time we’ve vilified these foods. There’s nothing inherently wrong with their intake, and that’s a message we need to get across to parents and physicians so they can start thinking differently,” he said.

“The good news about these studies is that they show there’s no reason not to do this,” Dr. Baker added. “There’s no harm that comes from the early introduction.”

Dr. Lack, who led the EAT trial, noted that the study didn’t meet it’s primary endpoint of a significantly lower prevalence of food allergy to any of the six intervention foods at age 3 years in the intention-to-treat analysis. But adherence to the demanding EAT early-introduction protocol was a problem. Indeed, only 43% of participants adhered to the study protocol. In a per-protocol analysis restricted to the adherent group, however, early introduction was associated with a highly significant 67% reduction in the relative risk of food allergy at 3 years of age compared to controls. And for the two most prevalent food allergies – to peanut and egg – the relative risk reductions in the early-introduction group were 100% and 75%, respectively.

The EAT results suggest that an effective preventive dose of peanut in infants at least 3 months of age is roughly 2 g of peanut protein per week, equivalent to just under 2 tsp of peanut butter, according to Dr. Lack.

Simultaneously with presentation of the LEAP-On and EAT trials in Los Angeles, the studies were published online at NEJM.org (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1514210 for LEAP-ON and 10.1056/NEJMoa1514209 for EAT).

LEAP-On was supported primarily by NIAID. EAT was funded mainly by the UK Foods Standards Agency and the Medical Research Council. Dr. Lack reported receiving grants from those agencies as well as Food Allergy Research and Education.

LOS ANGELES – A peanut allergy prevention strategy based upon regular consumption of peanut-containing foods from infancy to age 5 continued to provide protection even after peanut intake was halted for a full year from age 5 to 6, according to new results from an extension of the landmark LEAP trial, known as LEAP-On, presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The impetus for LEAP-On was the investigators’ concern that a period of peanut avoidance might cause loss of the protective state. But that didn’t occur.

“I think there is no doubt that we have prevented peanut allergy so far in these high-risk children. Next, the LEAP-Ad Lib study will tell us whether we’ve prevented it by age 10,” said Dr. Gideon Lack of King’s College London, who headed LEAP-On.

A second major randomized trial known as EAT (Enquiring About Tolerance) presented at the meeting provided further support for early dietary introduction of allergenic foods. EAT differed from LEAP (Learning Early About Peanut Allergy) and LEAP-On in that it ambitiously randomized infants to early introduction or avoidance of not one but six allergenic foods: peanut, cooked egg, cow’s milk, fish, sesame, and wheat. Also, while LEAP and LEAP-On involved roughly 600 infants known to be at very high risk for allergy, EAT was conducted in a general population of 1,303 infants who weren’t at increased risk, all of whom were exclusively breast-fed until the intervention beginning at age 3 months.

The presentation of the LEAP-On and EAT results at the AAAAI annual meeting was a major event marked by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases by same-day release of new NIAID-sponsored draft recommendations for the diagnosis and management of food allergies.

In a press conference held at the AAAAI annual meeting to announce the start of a 45-day public comment period for the draft update of the 2010 guidelines, Dr. Daniel Rotrosen, director of NIAID’s division of allergy, immunology and transplantation, said the new guidelines were developed largely in response to the compelling LEAP findings. That trial demonstrated that sustained consumption of peanut starting in infancy resulted in an 81% lower rate of peanut allergy at age 5 years compared to a strategy of peanut avoidance (N Engl J Med. 2015;372:803-13).

The draft guidelines, now available on the NIAID website, represent a sharp departure from the former recommendation that physicians encourage exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life followed by cautious introduction of other foods. Whereas the former orthodoxy was that delayed introduction of allergenic foods protects against development of food allergy, the new evidence-based concept supported by the LEAP and EAT findings is that just the opposite is true: that is, introduction of such foods during the period of immunologic plasticity in infancy induces tolerance.

Thus, the draft guidelines recommend that infants at high risk for peanut allergy because they have severe eczema and/or egg allergy should have introduction of peanut-containing food at 4-6 months of age to reduce their risk of peanut allergy, preceded by evaluation using peanut-specific IgE or skin prick testing to make sure it’s safe. That age window coincides with well-child visits and vaccination schedules, Dr. Rotrosen noted.

These guidelines represent the consensus of 26 organizations that participated in their development. Among them are the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Dermatology, the American College of Gastroenterology, and AAAAI.

“I expect the new guidelines, when finalized, to be endorsed by the leadership of all the participating organizations,” Dr. Rotrosen said.

The new paradigm will require cultural change, said Dr. James R. Baker Jr., CEO and chief medical officer of Food Allergy Research and Education, a nonprofit organization that provided partial funding for LEAP and LEAP-On.

“I think for a long time we’ve vilified these foods. There’s nothing inherently wrong with their intake, and that’s a message we need to get across to parents and physicians so they can start thinking differently,” he said.

“The good news about these studies is that they show there’s no reason not to do this,” Dr. Baker added. “There’s no harm that comes from the early introduction.”

Dr. Lack, who led the EAT trial, noted that the study didn’t meet it’s primary endpoint of a significantly lower prevalence of food allergy to any of the six intervention foods at age 3 years in the intention-to-treat analysis. But adherence to the demanding EAT early-introduction protocol was a problem. Indeed, only 43% of participants adhered to the study protocol. In a per-protocol analysis restricted to the adherent group, however, early introduction was associated with a highly significant 67% reduction in the relative risk of food allergy at 3 years of age compared to controls. And for the two most prevalent food allergies – to peanut and egg – the relative risk reductions in the early-introduction group were 100% and 75%, respectively.

The EAT results suggest that an effective preventive dose of peanut in infants at least 3 months of age is roughly 2 g of peanut protein per week, equivalent to just under 2 tsp of peanut butter, according to Dr. Lack.

Simultaneously with presentation of the LEAP-On and EAT trials in Los Angeles, the studies were published online at NEJM.org (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1514210 for LEAP-ON and 10.1056/NEJMoa1514209 for EAT).

LEAP-On was supported primarily by NIAID. EAT was funded mainly by the UK Foods Standards Agency and the Medical Research Council. Dr. Lack reported receiving grants from those agencies as well as Food Allergy Research and Education.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE 2016 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

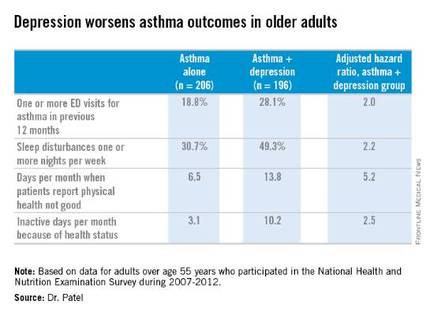

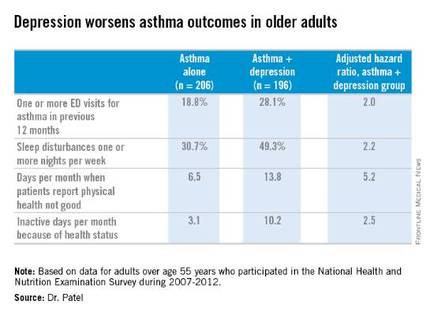

Comorbid depression worsens asthma outcomes in older adults

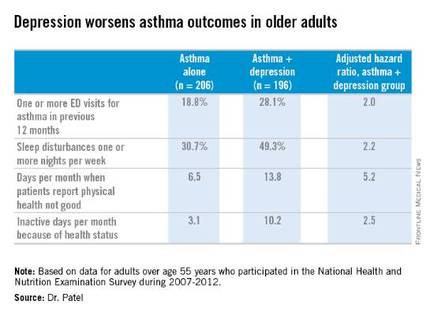

LOS ANGELES – Adults over age 55 with asthma and depression have nearly twice as many emergency department visits for asthma as do asthma patients without depression, based on findings in 402 asthma patients, Dr. Pooja O. Patel reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Comorbid depression also is associated with more asthma-related sleep disturbances and worse health-related quality of life, even though spirometry findings are similar in asthma patients with and without depression, added Dr. Patel of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

She analyzed data on 7,256 adults over age 55 who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey during 2007-2012. The prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma in this nationally representative group of older adults was 5.5%. And 196 of those 402 asthma patients, or fully 49%, had comorbid depression as defined by their scores on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), a validated brief and reliable self-administered measure of depression severity.

One or more emergency department visits for asthma within the last 12 months occurred in 18.8% of the group with asthma alone, compared with 28.1% in those with comorbid depression. In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for the demographic differences, this translated to a twofold increased likelihood of ED visits specifically for asthma in the group with asthma and depression.

These data make a compelling case for routine screening for depression in older adults with asthma. The PHQ-9 is a good, simple tool for this purpose. Future studies will need to be done in order to learn whether early identification and treatment of comorbid depression in older asthmatic adults will result in improved asthma outcomes, but that is a reasonable hope, Dr. Patel added.

Why is asthma control worse in older adults with depression? In an interview, Dr. Patel said she thinks demographic differences may play a role. The older asthma patients with depression had less education and lower socioeconomic status than those without depression. Also, depression could adversely affect adherence to asthma controller medications, as depression is linked to worse medication adherence.

Dr. Patel reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

LOS ANGELES – Adults over age 55 with asthma and depression have nearly twice as many emergency department visits for asthma as do asthma patients without depression, based on findings in 402 asthma patients, Dr. Pooja O. Patel reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Comorbid depression also is associated with more asthma-related sleep disturbances and worse health-related quality of life, even though spirometry findings are similar in asthma patients with and without depression, added Dr. Patel of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

She analyzed data on 7,256 adults over age 55 who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey during 2007-2012. The prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma in this nationally representative group of older adults was 5.5%. And 196 of those 402 asthma patients, or fully 49%, had comorbid depression as defined by their scores on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), a validated brief and reliable self-administered measure of depression severity.

One or more emergency department visits for asthma within the last 12 months occurred in 18.8% of the group with asthma alone, compared with 28.1% in those with comorbid depression. In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for the demographic differences, this translated to a twofold increased likelihood of ED visits specifically for asthma in the group with asthma and depression.

These data make a compelling case for routine screening for depression in older adults with asthma. The PHQ-9 is a good, simple tool for this purpose. Future studies will need to be done in order to learn whether early identification and treatment of comorbid depression in older asthmatic adults will result in improved asthma outcomes, but that is a reasonable hope, Dr. Patel added.

Why is asthma control worse in older adults with depression? In an interview, Dr. Patel said she thinks demographic differences may play a role. The older asthma patients with depression had less education and lower socioeconomic status than those without depression. Also, depression could adversely affect adherence to asthma controller medications, as depression is linked to worse medication adherence.

Dr. Patel reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

LOS ANGELES – Adults over age 55 with asthma and depression have nearly twice as many emergency department visits for asthma as do asthma patients without depression, based on findings in 402 asthma patients, Dr. Pooja O. Patel reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Comorbid depression also is associated with more asthma-related sleep disturbances and worse health-related quality of life, even though spirometry findings are similar in asthma patients with and without depression, added Dr. Patel of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

She analyzed data on 7,256 adults over age 55 who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey during 2007-2012. The prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma in this nationally representative group of older adults was 5.5%. And 196 of those 402 asthma patients, or fully 49%, had comorbid depression as defined by their scores on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), a validated brief and reliable self-administered measure of depression severity.

One or more emergency department visits for asthma within the last 12 months occurred in 18.8% of the group with asthma alone, compared with 28.1% in those with comorbid depression. In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for the demographic differences, this translated to a twofold increased likelihood of ED visits specifically for asthma in the group with asthma and depression.

These data make a compelling case for routine screening for depression in older adults with asthma. The PHQ-9 is a good, simple tool for this purpose. Future studies will need to be done in order to learn whether early identification and treatment of comorbid depression in older asthmatic adults will result in improved asthma outcomes, but that is a reasonable hope, Dr. Patel added.

Why is asthma control worse in older adults with depression? In an interview, Dr. Patel said she thinks demographic differences may play a role. The older asthma patients with depression had less education and lower socioeconomic status than those without depression. Also, depression could adversely affect adherence to asthma controller medications, as depression is linked to worse medication adherence.

Dr. Patel reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

AT 2016 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Screening for depression in older adults with asthma has a high yield, with a 49% prevalence found in a nationally representative population.

Major finding: Older adults with asthma and depression were twice as likely as adults with asthma alone to have one or more emergency department visits for asthma in the past year.

Data source: An analysis of cross-sectional data on a nationally representative sample of 402 adults with physician-diagnosed asthma who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey during 2007-2012.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

AAAAI: EpiPen Jr Needles Too Long for Many Children Under 15 kg

LOS ANGELES – For about half of children under 15 kg, pediatric epinephrine autoinjector needles are too long – they’re likely to hit the femur.

If the drug is deposited at the periosteum, it won’t be absorbed properly. If the needle delivers it to the bone marrow, the results could be disastrous.

“I’ve had three patients where the needle came back bent, so this happens,” said Dr. Harold Kim, an allergist in Kitchener, Ont. “Fortunately, there’s a fairly simple workaround. I ask parents to squeeze the [thigh] muscle before they give the shot, so that the muscle doesn’t compress. If the muscle doesn’t compress, you won’t hit bone, and the kid is going to be fine. Parents are really grateful” to learn this, but “they have to be careful not to inject their fingers.”

The findings come from Dr. Kim’s ultrasound study of thigh tissue thickness in 53 children weighing 7.5-15 kg. He and his colleagues found that with 10 pounds of pressure to simulate autoinjector deployment, the mean skin-to-bone distance was 13.3 mm, plus or minus 2.1 mm (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.1167).

The needle length for EpiPen Jr is 12.7 mm, which was long enough to strike bone in 43% of the subjects.

“Epinephrine autoinjectors should be the mainstay of treatment for anaphylaxis, but our data suggest that the optimal needle length” for patients 7.5-15 kg “should be shorter than the needle length in current, commercially available” products. “There may be some modifications that need to be made in the way they are given. I actually ultrasound all the kids in my clinic to see if there will be problems,” Dr. Kim said at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology annual meeting.

The study was done with an ultrasound probe in a housing that mimicked the footprint of Sanofi’s Auvi-Q, which is no longer on the U.S. and Canadian markets. If anything, the problem would be worse with EpiPen Jr because of its smaller footprint, Dr. Kim said.

On average, the subjects were 20 months old and 11 kg. Just over half were boys, and about 80% were white. The mean height was 79 cm and mean body mass index 19 kg/m2. About 60% of the subjects had injectors because of food allergies. Both transverse and longitudinal images of thigh tissue were used in the study, and distances were read by a blinded ultrasound expert.

Dr. Kim and his colleagues became interested after finding that needles may actually be too short to reach muscle in obese patients. While working on that issue, however, they also discovered “that 30% of kids less than 15 kg were at risk of the needle hitting the bone. We were surprised by those findings,” so looked into them further, he said.

EpiPen Jr is off label for children under 15 kg, but still often prescribed for them.

Sanofi funded the work. Dr. Kim is an advisor for the company, as well as for Pfizer, maker of EpiPen.

LOS ANGELES – For about half of children under 15 kg, pediatric epinephrine autoinjector needles are too long – they’re likely to hit the femur.

If the drug is deposited at the periosteum, it won’t be absorbed properly. If the needle delivers it to the bone marrow, the results could be disastrous.

“I’ve had three patients where the needle came back bent, so this happens,” said Dr. Harold Kim, an allergist in Kitchener, Ont. “Fortunately, there’s a fairly simple workaround. I ask parents to squeeze the [thigh] muscle before they give the shot, so that the muscle doesn’t compress. If the muscle doesn’t compress, you won’t hit bone, and the kid is going to be fine. Parents are really grateful” to learn this, but “they have to be careful not to inject their fingers.”

The findings come from Dr. Kim’s ultrasound study of thigh tissue thickness in 53 children weighing 7.5-15 kg. He and his colleagues found that with 10 pounds of pressure to simulate autoinjector deployment, the mean skin-to-bone distance was 13.3 mm, plus or minus 2.1 mm (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.1167).

The needle length for EpiPen Jr is 12.7 mm, which was long enough to strike bone in 43% of the subjects.

“Epinephrine autoinjectors should be the mainstay of treatment for anaphylaxis, but our data suggest that the optimal needle length” for patients 7.5-15 kg “should be shorter than the needle length in current, commercially available” products. “There may be some modifications that need to be made in the way they are given. I actually ultrasound all the kids in my clinic to see if there will be problems,” Dr. Kim said at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology annual meeting.

The study was done with an ultrasound probe in a housing that mimicked the footprint of Sanofi’s Auvi-Q, which is no longer on the U.S. and Canadian markets. If anything, the problem would be worse with EpiPen Jr because of its smaller footprint, Dr. Kim said.

On average, the subjects were 20 months old and 11 kg. Just over half were boys, and about 80% were white. The mean height was 79 cm and mean body mass index 19 kg/m2. About 60% of the subjects had injectors because of food allergies. Both transverse and longitudinal images of thigh tissue were used in the study, and distances were read by a blinded ultrasound expert.

Dr. Kim and his colleagues became interested after finding that needles may actually be too short to reach muscle in obese patients. While working on that issue, however, they also discovered “that 30% of kids less than 15 kg were at risk of the needle hitting the bone. We were surprised by those findings,” so looked into them further, he said.

EpiPen Jr is off label for children under 15 kg, but still often prescribed for them.

Sanofi funded the work. Dr. Kim is an advisor for the company, as well as for Pfizer, maker of EpiPen.

LOS ANGELES – For about half of children under 15 kg, pediatric epinephrine autoinjector needles are too long – they’re likely to hit the femur.

If the drug is deposited at the periosteum, it won’t be absorbed properly. If the needle delivers it to the bone marrow, the results could be disastrous.

“I’ve had three patients where the needle came back bent, so this happens,” said Dr. Harold Kim, an allergist in Kitchener, Ont. “Fortunately, there’s a fairly simple workaround. I ask parents to squeeze the [thigh] muscle before they give the shot, so that the muscle doesn’t compress. If the muscle doesn’t compress, you won’t hit bone, and the kid is going to be fine. Parents are really grateful” to learn this, but “they have to be careful not to inject their fingers.”

The findings come from Dr. Kim’s ultrasound study of thigh tissue thickness in 53 children weighing 7.5-15 kg. He and his colleagues found that with 10 pounds of pressure to simulate autoinjector deployment, the mean skin-to-bone distance was 13.3 mm, plus or minus 2.1 mm (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.1167).

The needle length for EpiPen Jr is 12.7 mm, which was long enough to strike bone in 43% of the subjects.

“Epinephrine autoinjectors should be the mainstay of treatment for anaphylaxis, but our data suggest that the optimal needle length” for patients 7.5-15 kg “should be shorter than the needle length in current, commercially available” products. “There may be some modifications that need to be made in the way they are given. I actually ultrasound all the kids in my clinic to see if there will be problems,” Dr. Kim said at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology annual meeting.

The study was done with an ultrasound probe in a housing that mimicked the footprint of Sanofi’s Auvi-Q, which is no longer on the U.S. and Canadian markets. If anything, the problem would be worse with EpiPen Jr because of its smaller footprint, Dr. Kim said.

On average, the subjects were 20 months old and 11 kg. Just over half were boys, and about 80% were white. The mean height was 79 cm and mean body mass index 19 kg/m2. About 60% of the subjects had injectors because of food allergies. Both transverse and longitudinal images of thigh tissue were used in the study, and distances were read by a blinded ultrasound expert.

Dr. Kim and his colleagues became interested after finding that needles may actually be too short to reach muscle in obese patients. While working on that issue, however, they also discovered “that 30% of kids less than 15 kg were at risk of the needle hitting the bone. We were surprised by those findings,” so looked into them further, he said.

EpiPen Jr is off label for children under 15 kg, but still often prescribed for them.

Sanofi funded the work. Dr. Kim is an advisor for the company, as well as for Pfizer, maker of EpiPen.

AT 2016 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

AAAAI: EpiPen Jr needles too long for many children under 15 kg

LOS ANGELES – For about half of children under 15 kg, pediatric epinephrine autoinjector needles are too long – they’re likely to hit the femur.

If the drug is deposited at the periosteum, it won’t be absorbed properly. If the needle delivers it to the bone marrow, the results could be disastrous.

“I’ve had three patients where the needle came back bent, so this happens,” said Dr. Harold Kim, an allergist in Kitchener, Ont. “Fortunately, there’s a fairly simple workaround. I ask parents to squeeze the [thigh] muscle before they give the shot, so that the muscle doesn’t compress. If the muscle doesn’t compress, you won’t hit bone, and the kid is going to be fine. Parents are really grateful” to learn this, but “they have to be careful not to inject their fingers.”

The findings come from Dr. Kim’s ultrasound study of thigh tissue thickness in 53 children weighing 7.5-15 kg. He and his colleagues found that with 10 pounds of pressure to simulate autoinjector deployment, the mean skin-to-bone distance was 13.3 mm, plus or minus 2.1 mm (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.1167).

The needle length for EpiPen Jr is 12.7 mm, which was long enough to strike bone in 43% of the subjects.

“Epinephrine autoinjectors should be the mainstay of treatment for anaphylaxis, but our data suggest that the optimal needle length” for patients 7.5-15 kg “should be shorter than the needle length in current, commercially available” products. “There may be some modifications that need to be made in the way they are given. I actually ultrasound all the kids in my clinic to see if there will be problems,” Dr. Kim said at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology annual meeting.

The study was done with an ultrasound probe in a housing that mimicked the footprint of Sanofi’s Auvi-Q, which is no longer on the U.S. and Canadian markets. If anything, the problem would be worse with EpiPen Jr because of its smaller footprint, Dr. Kim said.

On average, the subjects were 20 months old and 11 kg. Just over half were boys, and about 80% were white. The mean height was 79 cm and mean body mass index 19 kg/m2. About 60% of the subjects had injectors because of food allergies. Both transverse and longitudinal images of thigh tissue were used in the study, and distances were read by a blinded ultrasound expert.

Dr. Kim and his colleagues became interested after finding that needles may actually be too short to reach muscle in obese patients. While working on that issue, however, they also discovered “that 30% of kids less than 15 kg were at risk of the needle hitting the bone. We were surprised by those findings,” so looked into them further, he said.

EpiPen Jr is off label for children under 15 kg, but still often prescribed for them.

Sanofi funded the work. Dr. Kim is an advisor for the company, as well as for Pfizer, maker of EpiPen.

LOS ANGELES – For about half of children under 15 kg, pediatric epinephrine autoinjector needles are too long – they’re likely to hit the femur.

If the drug is deposited at the periosteum, it won’t be absorbed properly. If the needle delivers it to the bone marrow, the results could be disastrous.

“I’ve had three patients where the needle came back bent, so this happens,” said Dr. Harold Kim, an allergist in Kitchener, Ont. “Fortunately, there’s a fairly simple workaround. I ask parents to squeeze the [thigh] muscle before they give the shot, so that the muscle doesn’t compress. If the muscle doesn’t compress, you won’t hit bone, and the kid is going to be fine. Parents are really grateful” to learn this, but “they have to be careful not to inject their fingers.”

The findings come from Dr. Kim’s ultrasound study of thigh tissue thickness in 53 children weighing 7.5-15 kg. He and his colleagues found that with 10 pounds of pressure to simulate autoinjector deployment, the mean skin-to-bone distance was 13.3 mm, plus or minus 2.1 mm (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.1167).

The needle length for EpiPen Jr is 12.7 mm, which was long enough to strike bone in 43% of the subjects.

“Epinephrine autoinjectors should be the mainstay of treatment for anaphylaxis, but our data suggest that the optimal needle length” for patients 7.5-15 kg “should be shorter than the needle length in current, commercially available” products. “There may be some modifications that need to be made in the way they are given. I actually ultrasound all the kids in my clinic to see if there will be problems,” Dr. Kim said at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology annual meeting.

The study was done with an ultrasound probe in a housing that mimicked the footprint of Sanofi’s Auvi-Q, which is no longer on the U.S. and Canadian markets. If anything, the problem would be worse with EpiPen Jr because of its smaller footprint, Dr. Kim said.

On average, the subjects were 20 months old and 11 kg. Just over half were boys, and about 80% were white. The mean height was 79 cm and mean body mass index 19 kg/m2. About 60% of the subjects had injectors because of food allergies. Both transverse and longitudinal images of thigh tissue were used in the study, and distances were read by a blinded ultrasound expert.

Dr. Kim and his colleagues became interested after finding that needles may actually be too short to reach muscle in obese patients. While working on that issue, however, they also discovered “that 30% of kids less than 15 kg were at risk of the needle hitting the bone. We were surprised by those findings,” so looked into them further, he said.

EpiPen Jr is off label for children under 15 kg, but still often prescribed for them.

Sanofi funded the work. Dr. Kim is an advisor for the company, as well as for Pfizer, maker of EpiPen.

LOS ANGELES – For about half of children under 15 kg, pediatric epinephrine autoinjector needles are too long – they’re likely to hit the femur.

If the drug is deposited at the periosteum, it won’t be absorbed properly. If the needle delivers it to the bone marrow, the results could be disastrous.

“I’ve had three patients where the needle came back bent, so this happens,” said Dr. Harold Kim, an allergist in Kitchener, Ont. “Fortunately, there’s a fairly simple workaround. I ask parents to squeeze the [thigh] muscle before they give the shot, so that the muscle doesn’t compress. If the muscle doesn’t compress, you won’t hit bone, and the kid is going to be fine. Parents are really grateful” to learn this, but “they have to be careful not to inject their fingers.”

The findings come from Dr. Kim’s ultrasound study of thigh tissue thickness in 53 children weighing 7.5-15 kg. He and his colleagues found that with 10 pounds of pressure to simulate autoinjector deployment, the mean skin-to-bone distance was 13.3 mm, plus or minus 2.1 mm (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.1167).

The needle length for EpiPen Jr is 12.7 mm, which was long enough to strike bone in 43% of the subjects.

“Epinephrine autoinjectors should be the mainstay of treatment for anaphylaxis, but our data suggest that the optimal needle length” for patients 7.5-15 kg “should be shorter than the needle length in current, commercially available” products. “There may be some modifications that need to be made in the way they are given. I actually ultrasound all the kids in my clinic to see if there will be problems,” Dr. Kim said at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology annual meeting.

The study was done with an ultrasound probe in a housing that mimicked the footprint of Sanofi’s Auvi-Q, which is no longer on the U.S. and Canadian markets. If anything, the problem would be worse with EpiPen Jr because of its smaller footprint, Dr. Kim said.

On average, the subjects were 20 months old and 11 kg. Just over half were boys, and about 80% were white. The mean height was 79 cm and mean body mass index 19 kg/m2. About 60% of the subjects had injectors because of food allergies. Both transverse and longitudinal images of thigh tissue were used in the study, and distances were read by a blinded ultrasound expert.

Dr. Kim and his colleagues became interested after finding that needles may actually be too short to reach muscle in obese patients. While working on that issue, however, they also discovered “that 30% of kids less than 15 kg were at risk of the needle hitting the bone. We were surprised by those findings,” so looked into them further, he said.

EpiPen Jr is off label for children under 15 kg, but still often prescribed for them.

Sanofi funded the work. Dr. Kim is an advisor for the company, as well as for Pfizer, maker of EpiPen.

AT 2016 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: EpiPen Jr needles are too long for many children under 15 kg.