User login

Alzheimer's Association International Conference 2013 (AAIC)

Diagnosing Alzheimer’s: The eyes may have it

You never know what will happen when you look into a mouse’s eyes.

Twelve years ago, Dr. Lee Goldstein was investigating reactive oxygen species’ effect on the brain of a young Alzheimer’s model mouse. Holding the tiny creature in his hand, he carefully inserted a miniscule microdialysis probe through its skull. As he did, he happened to look right into the mouse’s face. And since he was doing some unrelated work on cataracts at the time, something unusual caught his very practiced gaze.

"The mouse had a cataract. I looked at the other eye, and there was a cataract there, too. That’s very unusual – really not ever seen – in a mouse this age."

Then he looked at all the other mice he was using in that experiment, all of which were older. They all had bilateral cataracts. My first thought was, "This can’t be related to Alzheimer’s disease."

But in fact, he said, it appeared to be. He and his lab soon showed that the cataracts contained a large concentration of aggregated beta-amyloid (Abeta) in the same fraction that’s measured in today’s cerebrospinal fluid Alzheimer’s biomarker tests.

That first observation has birthed two investigational noninvasive amyloid eye tests, which Dr. Goldstein envisions could some day be part of everyone’s annual physical exam.

In people destined to develop Alzheimer’s, some research suggests that Abeta proteins may begin to accumulate in the lens long before they build up to dangerous levels in the brain. If this turns out to be a reliable marker of risk, it could be a sign that would trigger early, presymptomatic Alzheimer’s treatment.

That’s in the future, though, because right now, there is no such treatment. But at this time, Dr. Goldstein said, an amyloid eye test could prove invaluable in reaching that goal. One reason that symptomatic patients don’t respond to investigational drugs could be that by the time the patients are treated, irreversible brain damage has already occurred.

"Once you have cognitive symptoms, the horse is not only out of the barn, it’s run out of the state," said Dr. Goldstein, director of the molecular aging and development laboratory at Boston University. "I hate the term ‘mild cognitive impairment,’ because by the time you have that, there’s nothing mild about it."

Researchers now almost universally agree that the best way to get a true picture of any drug’s potential effectiveness in Alzheimer’s will be to implement treatment before symptoms set in. In addition, Dr. Goldstein said, "Research pools are polluted. Control groups contain subjects who would develop Alzheimer’s if they live long enough," which could be skewing study results. Lens amyloid measurements might help stratify groups in drug studies, and even be a way to track very early effect on amyloid.

But that is a future yet to be determined. In the meantime, researchers still need definitive proof that supranuclear amyloid cataracts are inextricably linked to the amyloid brain plaques of Alzheimer’s.

Initial findings

In 2003, Dr. Goldstein, then at Harvard Medical School, published his original proof of concept study. It comprised postmortem eye and brain specimens from nine subjects with Alzheimer’s and eight controls without the disease, and samples of primary aqueous humor from three people without the disorder who were undergoing cataract surgery (Lancet 2003;361:1258-65).

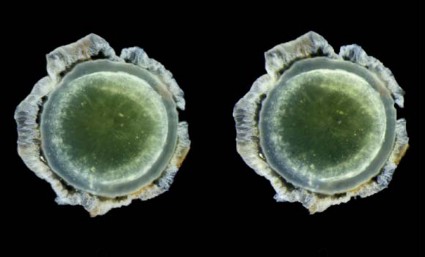

Abeta-40 and Abeta-42 were present in all of the lenses, in amounts similar to those seen in the corresponding brains. But in patients with Alzheimer’s, the protein aggregated into clumps within the lens fiber cells, forming unusual supranuclear cataracts at the equatorial periphery that appeared to be different from common age-related cataracts and that weren’t present in the control subjects.

The cataract location is an important clue to how long the Abeta has been accumulating, Dr. Goldstein said. Lens fiber cells are particularly long lived, remaining alive for as long as a person lives or until the lens is removed during cataract surgery. The lens starts to form in very early fetal life, with more and more lens cells forming in an outward direction, creating a virtual map of a person’s lifetime, "like the rings of a tree," he said.

Dr. Goldstein and his team discovered that these distinctive cataracts develop in some patients with Alzheimer’s. They appear toward the outer edge of the lens and are composed of the same toxic Abeta protein that builds up in the brain. "The history of amyloid in the body is time stamped in the lens," he said.

As lens fiber cells age, they lose most of their organelles and become transparent – just the right state for a device meant to focus light. "They also make tons of Abeta," Dr. Goldstein said, and it appears to have a very specific function in the eye, one Dr. Rudolph Tanzi and his colleagues at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, identified in collaboration with Dr. Goldstein’s team (PLoS ONE 2010;5:e9505).

"It turns out to be a very potent antimicrobial peptide," one of several the eye and brain produce to defend themselves. Amyloid’s sticky nature causes foreign invaders to clump together, so they’re more easily destroyed. This finding also suggests that Abeta could have a similar function in the brain, supporting some theories that Alzheimer’s might be at least partially triggered by a hyperinflammatory response toward an invading pathogen or another immunoreactive incident.

Testing lenses in Down syndrome patients

Interesting as all of that is, it doesn’t prove the theory that the lens amyloid record somehow tracks Alzheimer’s development. But other studies do explore that concept, including one Dr. Goldstein published in 2010. In this study, Dr. Goldstein and his colleagues examined lens amyloid in people with Down syndrome, a group predestined to develop Alzheimer’s (PLoS ONE 2010;5:e10659). The genetic mutation that causes the syndrome also increases production of the amyloid precursor protein (APP), Abeta’s antecedent.

The lenses from subjects with Down syndrome, aged 2-69 years, were compared with lenses from control subjects and people with both familial and late-onset Alzheimer’s. "The 2-year-old with Down syndrome in this study actually had more lens amyloid than the adults with familial Alzheimer’s," Dr. Goldstein said. In unpublished data, he added, the protein has even been observed in Down syndrome fetal lenses.

He expanded on this work in a poster presented at the 2013 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. Dr. Goldstein and his team have developed and validated a laser eye scanning instrument that noninvasively measures how light is reflected from the tiniest particles – in this case clumps of Abeta protein – within the lens of living human subjects.

"We hypothesize that due to the trisomy of chromosome 21 in Down syndrome (and triplication of the APP gene), which results in increased expression of Abeta in the lens, the intensity of scattered light in Down syndrome patients will be higher than [in] age-matched controls," he noted in the poster.

Not everyone agrees with this idea, however. It has stirred controversy since he first introduced the idea, when, he said, "mainstream Alzheimer’s research simply didn’t believe it." In fact, at least two other researchers’ studies have come to quite different conclusions.

Dr. Charles Eberhart, a pathologist at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, published his data in the journal Brain Pathology (2013 June 28 [doi:10.1111/bpa.12070]). The study examined retinas, lenses, and brains from 11 patients with Alzheimer’s, 6 with Parkinson’s, and 6 age-matched controls. Eight eyes (five from Alzheimer’s patients and three from controls) did have cataracts. Dr. Eberhart and his colleagues used immunohistochemistry and Congo red staining to look for amyloid, phosphorylated tau, and alpha-synuclein.

"The short answer is – we didn’t find any amyloid deposits in the lens, or any abnormal tau accumulations," he said in an interview.

The study has two possible interpretations, he said: Either Abeta, tau, and synuclein don’t accumulate in Alzheimer’s eyes as they do in Alzheimer’s brains, or they are there, but simply not detected by his methods. "It certainly might be there. All we can say is that with this method, which is the accepted way of determining amyloid in brain tissue, we didn’t see it in eyes," he said.

The second study, conducted by Dr. Ralph Michael of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and his colleagues, came to a similar conclusion (Exp. Eye Res. 2013;106:5-13). It involved 39 lenses and brains from 21 Alzheimer’s patients, and 15 lenses from age-matched controls. Six of the Alzheimer’s lenses and seven control lenses had cataracts. These investigators used staining methods similar to those in the Hopkins study.

"Beta-amyloid immunohistochemistry was positive in the brain tissues but not in the cornea sample," they wrote. "Lenses from control and AD [Alzheimer’s disease] donors were, without exception, negative after Congo red, thioflavin, and beta-amyloid immunohistochemical staining. ... The absence of staining in AD and control lenses with the techniques employed lead us to conclude that there is no beta-amyloid in lenses from donors with AD or in control cortical cataracts."

Dr. Goldstein said he doesn’t doubt these findings. Congo red staining yields a difficult-to-interpret sign, he said. Amyloid appears red under standard light spectroscopy, but takes on a very characteristic shade, called apple green under polarized light. "This is an old staining method that’s not very sensitive nor is it specific for Abeta – it’s also highly variable."

Technique is critical, he added. "It took us years to perfect our technique for the lens. It’s very difficult to work with lens, harder to work with old lens, and extremely hard to work with old, sick lens."

Instead of relying solely on Congo red or other staining techniques, Dr. Goldstein’s team confirmed their findings using a combination of biochemical analyses, immunogold electron microscopy, and two different types of mass spectrometry – methods he said are irrefutably accurate. "You can’t argue with this unless you are willing to argue with the very concept of mass spectrometry. It’s the gold standard," he said.

Confirmation in transgenic mice and Down syndrome patients strengthens the hypothesis, he said, as do the conclusions of his most recent paper. It looked at data from 1,249 people included in the Framingham Eye Study, and found a genetic link between a specific type of midlife cataracts (consistent with those previously found in Alzheimer’s) and later cognitive and brain structural changes associated with Alzheimer’s (PLoS ONE 2012;7:e43728) .

The culprit appeared to be a mutation of a gene that codes for delta-catenin, which Dr. Goldstein postulated may normally help suppress Abeta production. The altered form, however, appears to affect neuronal structure and is instead associated with an increase in Abeta-42 production in cell culture. The malformed delta-catenin protein was also found throughout the lenses of study subjects with Alzheimer’s, but not in control lenses.

Screening patients in the future?

Dr. Goldstein said he envisions a future in which annual lens exams might guide risk assessment and treatment initiation. But physicians who might someday screen patients certainly won’t have a mass spectrometer in the back room.

He has invented two devices, he said, that will fill that need. The most recent is a laser scanning ophthalmoscope that uses dynamic light scattering to detect the tiniest amyloid particles in the lens – particles less than 30 nm. This is the device he’s using in the ongoing Boston University/Boston Children’s Hospital study of lens amyloid in children with Down syndrome.

The second device combines optical imaging with aftobetin, a fluorescent amyloid ligand. Dr. Goldstein holds a patent on this device, which he invented in partnership with Cognoptix (formerly Neuroptix), a company he cofounded in 2001, although he is no longer operationally affiliated with it.

Cognoptix has developed the SAPPHIRE II system, a combination drug/device that detects amyloid in the lens using aftobetin. The company licensed aftobetin from the University of California, San Diego. It’s formulated into an ophthalmic ointment administered prior to scanning with the SAPPHIRE II system. The procedure uses fluorescent ligand scanning to detect amyloid aggregates in the lens, said Paul Hartung, president and chief executive officer of the Acton, Mass., company.

"We use an eye-safe laser tuned to pick up the fluorescence. It doesn’t require dilation of the pupil, and it has the capability of actually registering itself in the correct location in the eye," he said in an interview.

SAPPHIRE II has had a busy year, including a proof of concept study published in May and reported at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. In this study, the system successfully differentiated five Alzheimer’s patients from five controls (Front. Neurol. 2013 May 27 [doi:10.3389/fneur.2013.00062]).

Cognoptix has begun a second study testing the system against PET amyloid brain imaging in 20 patients with probable Alzheimer’s and 20 controls, Mr. Hartung said.

A third planned study is a pivotal phase III trial that will enroll 400 subjects, all of whom will undergo both the eye exam and PET amyloid imaging. It’s designed to support premarketing approval, Mr. Hartung said. Currently SAPPHIRE II has an investigational device exemption from the Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

"Our end goal is to get this into the general practitioner’s office, where about 40% of Alzheimer’s drug prescriptions are written by general practitioners who really have no data on hand. Right now, based on cognitive assessments, they have only a 50-50 chance of getting the right diagnosis," Mr. Hartung said.

Dr. Goldstein and Mr. Hartung hold financial interests in devices to measure lens amyloid. Dr. Ralph Michael listed no financial disclosures. Dr. Charles Eberhart said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

You never know what will happen when you look into a mouse’s eyes.

Twelve years ago, Dr. Lee Goldstein was investigating reactive oxygen species’ effect on the brain of a young Alzheimer’s model mouse. Holding the tiny creature in his hand, he carefully inserted a miniscule microdialysis probe through its skull. As he did, he happened to look right into the mouse’s face. And since he was doing some unrelated work on cataracts at the time, something unusual caught his very practiced gaze.

"The mouse had a cataract. I looked at the other eye, and there was a cataract there, too. That’s very unusual – really not ever seen – in a mouse this age."

Then he looked at all the other mice he was using in that experiment, all of which were older. They all had bilateral cataracts. My first thought was, "This can’t be related to Alzheimer’s disease."

But in fact, he said, it appeared to be. He and his lab soon showed that the cataracts contained a large concentration of aggregated beta-amyloid (Abeta) in the same fraction that’s measured in today’s cerebrospinal fluid Alzheimer’s biomarker tests.

That first observation has birthed two investigational noninvasive amyloid eye tests, which Dr. Goldstein envisions could some day be part of everyone’s annual physical exam.

In people destined to develop Alzheimer’s, some research suggests that Abeta proteins may begin to accumulate in the lens long before they build up to dangerous levels in the brain. If this turns out to be a reliable marker of risk, it could be a sign that would trigger early, presymptomatic Alzheimer’s treatment.

That’s in the future, though, because right now, there is no such treatment. But at this time, Dr. Goldstein said, an amyloid eye test could prove invaluable in reaching that goal. One reason that symptomatic patients don’t respond to investigational drugs could be that by the time the patients are treated, irreversible brain damage has already occurred.

"Once you have cognitive symptoms, the horse is not only out of the barn, it’s run out of the state," said Dr. Goldstein, director of the molecular aging and development laboratory at Boston University. "I hate the term ‘mild cognitive impairment,’ because by the time you have that, there’s nothing mild about it."

Researchers now almost universally agree that the best way to get a true picture of any drug’s potential effectiveness in Alzheimer’s will be to implement treatment before symptoms set in. In addition, Dr. Goldstein said, "Research pools are polluted. Control groups contain subjects who would develop Alzheimer’s if they live long enough," which could be skewing study results. Lens amyloid measurements might help stratify groups in drug studies, and even be a way to track very early effect on amyloid.

But that is a future yet to be determined. In the meantime, researchers still need definitive proof that supranuclear amyloid cataracts are inextricably linked to the amyloid brain plaques of Alzheimer’s.

Initial findings

In 2003, Dr. Goldstein, then at Harvard Medical School, published his original proof of concept study. It comprised postmortem eye and brain specimens from nine subjects with Alzheimer’s and eight controls without the disease, and samples of primary aqueous humor from three people without the disorder who were undergoing cataract surgery (Lancet 2003;361:1258-65).

Abeta-40 and Abeta-42 were present in all of the lenses, in amounts similar to those seen in the corresponding brains. But in patients with Alzheimer’s, the protein aggregated into clumps within the lens fiber cells, forming unusual supranuclear cataracts at the equatorial periphery that appeared to be different from common age-related cataracts and that weren’t present in the control subjects.

The cataract location is an important clue to how long the Abeta has been accumulating, Dr. Goldstein said. Lens fiber cells are particularly long lived, remaining alive for as long as a person lives or until the lens is removed during cataract surgery. The lens starts to form in very early fetal life, with more and more lens cells forming in an outward direction, creating a virtual map of a person’s lifetime, "like the rings of a tree," he said.

Dr. Goldstein and his team discovered that these distinctive cataracts develop in some patients with Alzheimer’s. They appear toward the outer edge of the lens and are composed of the same toxic Abeta protein that builds up in the brain. "The history of amyloid in the body is time stamped in the lens," he said.

As lens fiber cells age, they lose most of their organelles and become transparent – just the right state for a device meant to focus light. "They also make tons of Abeta," Dr. Goldstein said, and it appears to have a very specific function in the eye, one Dr. Rudolph Tanzi and his colleagues at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, identified in collaboration with Dr. Goldstein’s team (PLoS ONE 2010;5:e9505).

"It turns out to be a very potent antimicrobial peptide," one of several the eye and brain produce to defend themselves. Amyloid’s sticky nature causes foreign invaders to clump together, so they’re more easily destroyed. This finding also suggests that Abeta could have a similar function in the brain, supporting some theories that Alzheimer’s might be at least partially triggered by a hyperinflammatory response toward an invading pathogen or another immunoreactive incident.

Testing lenses in Down syndrome patients

Interesting as all of that is, it doesn’t prove the theory that the lens amyloid record somehow tracks Alzheimer’s development. But other studies do explore that concept, including one Dr. Goldstein published in 2010. In this study, Dr. Goldstein and his colleagues examined lens amyloid in people with Down syndrome, a group predestined to develop Alzheimer’s (PLoS ONE 2010;5:e10659). The genetic mutation that causes the syndrome also increases production of the amyloid precursor protein (APP), Abeta’s antecedent.

The lenses from subjects with Down syndrome, aged 2-69 years, were compared with lenses from control subjects and people with both familial and late-onset Alzheimer’s. "The 2-year-old with Down syndrome in this study actually had more lens amyloid than the adults with familial Alzheimer’s," Dr. Goldstein said. In unpublished data, he added, the protein has even been observed in Down syndrome fetal lenses.

He expanded on this work in a poster presented at the 2013 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. Dr. Goldstein and his team have developed and validated a laser eye scanning instrument that noninvasively measures how light is reflected from the tiniest particles – in this case clumps of Abeta protein – within the lens of living human subjects.

"We hypothesize that due to the trisomy of chromosome 21 in Down syndrome (and triplication of the APP gene), which results in increased expression of Abeta in the lens, the intensity of scattered light in Down syndrome patients will be higher than [in] age-matched controls," he noted in the poster.

Not everyone agrees with this idea, however. It has stirred controversy since he first introduced the idea, when, he said, "mainstream Alzheimer’s research simply didn’t believe it." In fact, at least two other researchers’ studies have come to quite different conclusions.

Dr. Charles Eberhart, a pathologist at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, published his data in the journal Brain Pathology (2013 June 28 [doi:10.1111/bpa.12070]). The study examined retinas, lenses, and brains from 11 patients with Alzheimer’s, 6 with Parkinson’s, and 6 age-matched controls. Eight eyes (five from Alzheimer’s patients and three from controls) did have cataracts. Dr. Eberhart and his colleagues used immunohistochemistry and Congo red staining to look for amyloid, phosphorylated tau, and alpha-synuclein.

"The short answer is – we didn’t find any amyloid deposits in the lens, or any abnormal tau accumulations," he said in an interview.

The study has two possible interpretations, he said: Either Abeta, tau, and synuclein don’t accumulate in Alzheimer’s eyes as they do in Alzheimer’s brains, or they are there, but simply not detected by his methods. "It certainly might be there. All we can say is that with this method, which is the accepted way of determining amyloid in brain tissue, we didn’t see it in eyes," he said.

The second study, conducted by Dr. Ralph Michael of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and his colleagues, came to a similar conclusion (Exp. Eye Res. 2013;106:5-13). It involved 39 lenses and brains from 21 Alzheimer’s patients, and 15 lenses from age-matched controls. Six of the Alzheimer’s lenses and seven control lenses had cataracts. These investigators used staining methods similar to those in the Hopkins study.

"Beta-amyloid immunohistochemistry was positive in the brain tissues but not in the cornea sample," they wrote. "Lenses from control and AD [Alzheimer’s disease] donors were, without exception, negative after Congo red, thioflavin, and beta-amyloid immunohistochemical staining. ... The absence of staining in AD and control lenses with the techniques employed lead us to conclude that there is no beta-amyloid in lenses from donors with AD or in control cortical cataracts."

Dr. Goldstein said he doesn’t doubt these findings. Congo red staining yields a difficult-to-interpret sign, he said. Amyloid appears red under standard light spectroscopy, but takes on a very characteristic shade, called apple green under polarized light. "This is an old staining method that’s not very sensitive nor is it specific for Abeta – it’s also highly variable."

Technique is critical, he added. "It took us years to perfect our technique for the lens. It’s very difficult to work with lens, harder to work with old lens, and extremely hard to work with old, sick lens."

Instead of relying solely on Congo red or other staining techniques, Dr. Goldstein’s team confirmed their findings using a combination of biochemical analyses, immunogold electron microscopy, and two different types of mass spectrometry – methods he said are irrefutably accurate. "You can’t argue with this unless you are willing to argue with the very concept of mass spectrometry. It’s the gold standard," he said.

Confirmation in transgenic mice and Down syndrome patients strengthens the hypothesis, he said, as do the conclusions of his most recent paper. It looked at data from 1,249 people included in the Framingham Eye Study, and found a genetic link between a specific type of midlife cataracts (consistent with those previously found in Alzheimer’s) and later cognitive and brain structural changes associated with Alzheimer’s (PLoS ONE 2012;7:e43728) .

The culprit appeared to be a mutation of a gene that codes for delta-catenin, which Dr. Goldstein postulated may normally help suppress Abeta production. The altered form, however, appears to affect neuronal structure and is instead associated with an increase in Abeta-42 production in cell culture. The malformed delta-catenin protein was also found throughout the lenses of study subjects with Alzheimer’s, but not in control lenses.

Screening patients in the future?

Dr. Goldstein said he envisions a future in which annual lens exams might guide risk assessment and treatment initiation. But physicians who might someday screen patients certainly won’t have a mass spectrometer in the back room.

He has invented two devices, he said, that will fill that need. The most recent is a laser scanning ophthalmoscope that uses dynamic light scattering to detect the tiniest amyloid particles in the lens – particles less than 30 nm. This is the device he’s using in the ongoing Boston University/Boston Children’s Hospital study of lens amyloid in children with Down syndrome.

The second device combines optical imaging with aftobetin, a fluorescent amyloid ligand. Dr. Goldstein holds a patent on this device, which he invented in partnership with Cognoptix (formerly Neuroptix), a company he cofounded in 2001, although he is no longer operationally affiliated with it.

Cognoptix has developed the SAPPHIRE II system, a combination drug/device that detects amyloid in the lens using aftobetin. The company licensed aftobetin from the University of California, San Diego. It’s formulated into an ophthalmic ointment administered prior to scanning with the SAPPHIRE II system. The procedure uses fluorescent ligand scanning to detect amyloid aggregates in the lens, said Paul Hartung, president and chief executive officer of the Acton, Mass., company.

"We use an eye-safe laser tuned to pick up the fluorescence. It doesn’t require dilation of the pupil, and it has the capability of actually registering itself in the correct location in the eye," he said in an interview.

SAPPHIRE II has had a busy year, including a proof of concept study published in May and reported at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. In this study, the system successfully differentiated five Alzheimer’s patients from five controls (Front. Neurol. 2013 May 27 [doi:10.3389/fneur.2013.00062]).

Cognoptix has begun a second study testing the system against PET amyloid brain imaging in 20 patients with probable Alzheimer’s and 20 controls, Mr. Hartung said.

A third planned study is a pivotal phase III trial that will enroll 400 subjects, all of whom will undergo both the eye exam and PET amyloid imaging. It’s designed to support premarketing approval, Mr. Hartung said. Currently SAPPHIRE II has an investigational device exemption from the Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

"Our end goal is to get this into the general practitioner’s office, where about 40% of Alzheimer’s drug prescriptions are written by general practitioners who really have no data on hand. Right now, based on cognitive assessments, they have only a 50-50 chance of getting the right diagnosis," Mr. Hartung said.

Dr. Goldstein and Mr. Hartung hold financial interests in devices to measure lens amyloid. Dr. Ralph Michael listed no financial disclosures. Dr. Charles Eberhart said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

You never know what will happen when you look into a mouse’s eyes.

Twelve years ago, Dr. Lee Goldstein was investigating reactive oxygen species’ effect on the brain of a young Alzheimer’s model mouse. Holding the tiny creature in his hand, he carefully inserted a miniscule microdialysis probe through its skull. As he did, he happened to look right into the mouse’s face. And since he was doing some unrelated work on cataracts at the time, something unusual caught his very practiced gaze.

"The mouse had a cataract. I looked at the other eye, and there was a cataract there, too. That’s very unusual – really not ever seen – in a mouse this age."

Then he looked at all the other mice he was using in that experiment, all of which were older. They all had bilateral cataracts. My first thought was, "This can’t be related to Alzheimer’s disease."

But in fact, he said, it appeared to be. He and his lab soon showed that the cataracts contained a large concentration of aggregated beta-amyloid (Abeta) in the same fraction that’s measured in today’s cerebrospinal fluid Alzheimer’s biomarker tests.

That first observation has birthed two investigational noninvasive amyloid eye tests, which Dr. Goldstein envisions could some day be part of everyone’s annual physical exam.

In people destined to develop Alzheimer’s, some research suggests that Abeta proteins may begin to accumulate in the lens long before they build up to dangerous levels in the brain. If this turns out to be a reliable marker of risk, it could be a sign that would trigger early, presymptomatic Alzheimer’s treatment.

That’s in the future, though, because right now, there is no such treatment. But at this time, Dr. Goldstein said, an amyloid eye test could prove invaluable in reaching that goal. One reason that symptomatic patients don’t respond to investigational drugs could be that by the time the patients are treated, irreversible brain damage has already occurred.

"Once you have cognitive symptoms, the horse is not only out of the barn, it’s run out of the state," said Dr. Goldstein, director of the molecular aging and development laboratory at Boston University. "I hate the term ‘mild cognitive impairment,’ because by the time you have that, there’s nothing mild about it."

Researchers now almost universally agree that the best way to get a true picture of any drug’s potential effectiveness in Alzheimer’s will be to implement treatment before symptoms set in. In addition, Dr. Goldstein said, "Research pools are polluted. Control groups contain subjects who would develop Alzheimer’s if they live long enough," which could be skewing study results. Lens amyloid measurements might help stratify groups in drug studies, and even be a way to track very early effect on amyloid.

But that is a future yet to be determined. In the meantime, researchers still need definitive proof that supranuclear amyloid cataracts are inextricably linked to the amyloid brain plaques of Alzheimer’s.

Initial findings

In 2003, Dr. Goldstein, then at Harvard Medical School, published his original proof of concept study. It comprised postmortem eye and brain specimens from nine subjects with Alzheimer’s and eight controls without the disease, and samples of primary aqueous humor from three people without the disorder who were undergoing cataract surgery (Lancet 2003;361:1258-65).

Abeta-40 and Abeta-42 were present in all of the lenses, in amounts similar to those seen in the corresponding brains. But in patients with Alzheimer’s, the protein aggregated into clumps within the lens fiber cells, forming unusual supranuclear cataracts at the equatorial periphery that appeared to be different from common age-related cataracts and that weren’t present in the control subjects.

The cataract location is an important clue to how long the Abeta has been accumulating, Dr. Goldstein said. Lens fiber cells are particularly long lived, remaining alive for as long as a person lives or until the lens is removed during cataract surgery. The lens starts to form in very early fetal life, with more and more lens cells forming in an outward direction, creating a virtual map of a person’s lifetime, "like the rings of a tree," he said.

Dr. Goldstein and his team discovered that these distinctive cataracts develop in some patients with Alzheimer’s. They appear toward the outer edge of the lens and are composed of the same toxic Abeta protein that builds up in the brain. "The history of amyloid in the body is time stamped in the lens," he said.

As lens fiber cells age, they lose most of their organelles and become transparent – just the right state for a device meant to focus light. "They also make tons of Abeta," Dr. Goldstein said, and it appears to have a very specific function in the eye, one Dr. Rudolph Tanzi and his colleagues at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, identified in collaboration with Dr. Goldstein’s team (PLoS ONE 2010;5:e9505).

"It turns out to be a very potent antimicrobial peptide," one of several the eye and brain produce to defend themselves. Amyloid’s sticky nature causes foreign invaders to clump together, so they’re more easily destroyed. This finding also suggests that Abeta could have a similar function in the brain, supporting some theories that Alzheimer’s might be at least partially triggered by a hyperinflammatory response toward an invading pathogen or another immunoreactive incident.

Testing lenses in Down syndrome patients

Interesting as all of that is, it doesn’t prove the theory that the lens amyloid record somehow tracks Alzheimer’s development. But other studies do explore that concept, including one Dr. Goldstein published in 2010. In this study, Dr. Goldstein and his colleagues examined lens amyloid in people with Down syndrome, a group predestined to develop Alzheimer’s (PLoS ONE 2010;5:e10659). The genetic mutation that causes the syndrome also increases production of the amyloid precursor protein (APP), Abeta’s antecedent.

The lenses from subjects with Down syndrome, aged 2-69 years, were compared with lenses from control subjects and people with both familial and late-onset Alzheimer’s. "The 2-year-old with Down syndrome in this study actually had more lens amyloid than the adults with familial Alzheimer’s," Dr. Goldstein said. In unpublished data, he added, the protein has even been observed in Down syndrome fetal lenses.

He expanded on this work in a poster presented at the 2013 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. Dr. Goldstein and his team have developed and validated a laser eye scanning instrument that noninvasively measures how light is reflected from the tiniest particles – in this case clumps of Abeta protein – within the lens of living human subjects.

"We hypothesize that due to the trisomy of chromosome 21 in Down syndrome (and triplication of the APP gene), which results in increased expression of Abeta in the lens, the intensity of scattered light in Down syndrome patients will be higher than [in] age-matched controls," he noted in the poster.

Not everyone agrees with this idea, however. It has stirred controversy since he first introduced the idea, when, he said, "mainstream Alzheimer’s research simply didn’t believe it." In fact, at least two other researchers’ studies have come to quite different conclusions.

Dr. Charles Eberhart, a pathologist at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, published his data in the journal Brain Pathology (2013 June 28 [doi:10.1111/bpa.12070]). The study examined retinas, lenses, and brains from 11 patients with Alzheimer’s, 6 with Parkinson’s, and 6 age-matched controls. Eight eyes (five from Alzheimer’s patients and three from controls) did have cataracts. Dr. Eberhart and his colleagues used immunohistochemistry and Congo red staining to look for amyloid, phosphorylated tau, and alpha-synuclein.

"The short answer is – we didn’t find any amyloid deposits in the lens, or any abnormal tau accumulations," he said in an interview.

The study has two possible interpretations, he said: Either Abeta, tau, and synuclein don’t accumulate in Alzheimer’s eyes as they do in Alzheimer’s brains, or they are there, but simply not detected by his methods. "It certainly might be there. All we can say is that with this method, which is the accepted way of determining amyloid in brain tissue, we didn’t see it in eyes," he said.

The second study, conducted by Dr. Ralph Michael of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and his colleagues, came to a similar conclusion (Exp. Eye Res. 2013;106:5-13). It involved 39 lenses and brains from 21 Alzheimer’s patients, and 15 lenses from age-matched controls. Six of the Alzheimer’s lenses and seven control lenses had cataracts. These investigators used staining methods similar to those in the Hopkins study.

"Beta-amyloid immunohistochemistry was positive in the brain tissues but not in the cornea sample," they wrote. "Lenses from control and AD [Alzheimer’s disease] donors were, without exception, negative after Congo red, thioflavin, and beta-amyloid immunohistochemical staining. ... The absence of staining in AD and control lenses with the techniques employed lead us to conclude that there is no beta-amyloid in lenses from donors with AD or in control cortical cataracts."

Dr. Goldstein said he doesn’t doubt these findings. Congo red staining yields a difficult-to-interpret sign, he said. Amyloid appears red under standard light spectroscopy, but takes on a very characteristic shade, called apple green under polarized light. "This is an old staining method that’s not very sensitive nor is it specific for Abeta – it’s also highly variable."

Technique is critical, he added. "It took us years to perfect our technique for the lens. It’s very difficult to work with lens, harder to work with old lens, and extremely hard to work with old, sick lens."

Instead of relying solely on Congo red or other staining techniques, Dr. Goldstein’s team confirmed their findings using a combination of biochemical analyses, immunogold electron microscopy, and two different types of mass spectrometry – methods he said are irrefutably accurate. "You can’t argue with this unless you are willing to argue with the very concept of mass spectrometry. It’s the gold standard," he said.

Confirmation in transgenic mice and Down syndrome patients strengthens the hypothesis, he said, as do the conclusions of his most recent paper. It looked at data from 1,249 people included in the Framingham Eye Study, and found a genetic link between a specific type of midlife cataracts (consistent with those previously found in Alzheimer’s) and later cognitive and brain structural changes associated with Alzheimer’s (PLoS ONE 2012;7:e43728) .

The culprit appeared to be a mutation of a gene that codes for delta-catenin, which Dr. Goldstein postulated may normally help suppress Abeta production. The altered form, however, appears to affect neuronal structure and is instead associated with an increase in Abeta-42 production in cell culture. The malformed delta-catenin protein was also found throughout the lenses of study subjects with Alzheimer’s, but not in control lenses.

Screening patients in the future?

Dr. Goldstein said he envisions a future in which annual lens exams might guide risk assessment and treatment initiation. But physicians who might someday screen patients certainly won’t have a mass spectrometer in the back room.

He has invented two devices, he said, that will fill that need. The most recent is a laser scanning ophthalmoscope that uses dynamic light scattering to detect the tiniest amyloid particles in the lens – particles less than 30 nm. This is the device he’s using in the ongoing Boston University/Boston Children’s Hospital study of lens amyloid in children with Down syndrome.

The second device combines optical imaging with aftobetin, a fluorescent amyloid ligand. Dr. Goldstein holds a patent on this device, which he invented in partnership with Cognoptix (formerly Neuroptix), a company he cofounded in 2001, although he is no longer operationally affiliated with it.

Cognoptix has developed the SAPPHIRE II system, a combination drug/device that detects amyloid in the lens using aftobetin. The company licensed aftobetin from the University of California, San Diego. It’s formulated into an ophthalmic ointment administered prior to scanning with the SAPPHIRE II system. The procedure uses fluorescent ligand scanning to detect amyloid aggregates in the lens, said Paul Hartung, president and chief executive officer of the Acton, Mass., company.

"We use an eye-safe laser tuned to pick up the fluorescence. It doesn’t require dilation of the pupil, and it has the capability of actually registering itself in the correct location in the eye," he said in an interview.

SAPPHIRE II has had a busy year, including a proof of concept study published in May and reported at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. In this study, the system successfully differentiated five Alzheimer’s patients from five controls (Front. Neurol. 2013 May 27 [doi:10.3389/fneur.2013.00062]).

Cognoptix has begun a second study testing the system against PET amyloid brain imaging in 20 patients with probable Alzheimer’s and 20 controls, Mr. Hartung said.

A third planned study is a pivotal phase III trial that will enroll 400 subjects, all of whom will undergo both the eye exam and PET amyloid imaging. It’s designed to support premarketing approval, Mr. Hartung said. Currently SAPPHIRE II has an investigational device exemption from the Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

"Our end goal is to get this into the general practitioner’s office, where about 40% of Alzheimer’s drug prescriptions are written by general practitioners who really have no data on hand. Right now, based on cognitive assessments, they have only a 50-50 chance of getting the right diagnosis," Mr. Hartung said.

Dr. Goldstein and Mr. Hartung hold financial interests in devices to measure lens amyloid. Dr. Ralph Michael listed no financial disclosures. Dr. Charles Eberhart said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

Caregiver support program decreases dementia emergency visits

BOSTON – A pilot program that supports the caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients decreased emergency admissions for those patients in San Francisco by more than 40% in 6 months, Elizabeth Edgerly, Ph.D., reported at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

The preliminary analysis also found that caregivers reported significant improvements in 7 out of 10 quality of life and quality of care measures, according to Dr. Edgerly, chief program officer of the Alzheimer’s Association Northern California and Northern Nevada Chapter.

The early results paint an encouraging picture of the future, she said in an interview.

"We are very excited about the emergency utilization data. We’re always confident about our capacity to impact efficacy, but affecting service utilization is a tough nut to crack. The beauty of this is, if we can improve quality of care while reducing utilization costs, it may actually be cost neutral to have this kind of a dementia support program."

The association created its Excellence in Dementia Care program in conjunction with Kaiser Permanente Northern California, the city and county of San Francisco, and the University of California, San Francisco. The Administration on Aging also provided funding.

San Francisco was the perfect city for the pilot project, Dr. Edgerly said. "It’s the only city in the United States with a strategic plan related to dementia. It also has an elderly, diverse population and many of the residents live alone."

The pilot program is part of the city plan’s goal of partnering with other institutions to improve quality of life and quality of care for people with dementia. It was designed to improve dementia care by both enhancing services and educating caregivers.

"Kaiser hired a full-time social worker for just dementia support and who only worked with the caregivers," Dr. Edgerly said. The social worker conducted initial evaluations and assessments and created an individualized dementia care program that was uploaded into the electronic medical record of each patient, making the individualized program available to everyone on the patient’s care team. The social worker also called caregivers proactively to make sure the caregivers’ needs were being met and that they could access community services.

The Alzheimer’s Association provided dementia care support experts manning a 24-hour help line, a MedicAlert + Alzheimer’s Association Safe Return bracelet for the patient, respite grants for day or evening supplemental care to give caregivers a break, and a support group where caregivers could meet to discusses their challenges.

The association also administered the educational portion of the program. The first component provided a primer on Alzheimer’s stage-by-stage effects on thinking, emotions, and behavior, and noted resources that were available for help. Caregivers also were informed about legal and financial planning and ways to keep a positive, safe, and compassionate home environment for as long as the patient could stay at home.

In surveys at baseline and after 6 months, caregivers rated their feelings about their abilities in 10 different areas: handling current patient problems in memory and behavior, handling future patient problems, dealing with their own frustrations, keeping the patient independent, caring for the patient as independently as possible, getting answers to patient problems, finding community organizations that provide answers, finding community organizations that provide services, getting answers to questions about services, independently arranging for services, and paying for services.

Overall, 92 of the 105 patient-caregiver dyads have completed the 6-month assessments, Dr. Edgerly said. The surveys indicated significant improvements on seven of the caregiver measures. Caregivers said they felt better able to handle concerns, to get information, and to obtain and pay for services.

Most importantly, the program led to about a 40% decrease in emergency department visits – a significant change, Dr. Edgerly said. There were also nonsignificant decreases in hospital length of stay, physician visits, and days spent in post–acute or long-term care facilities.

"Even the outcomes that didn’t improve significantly were all going in the right direction," Dr. Edgerly said, adding that she’s hoping for even better results when the data are analyzed in their entirety.

The program’s positive impact on health care resources could be enough to attract the interest of other insurers, she said. "If this intervention reduced expenses associated with hospital or emergency department visits, an insurer might see that as good business sense."

The project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Association of Northern California and Northern Nevada, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, and the National Institute on Aging.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

BOSTON – A pilot program that supports the caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients decreased emergency admissions for those patients in San Francisco by more than 40% in 6 months, Elizabeth Edgerly, Ph.D., reported at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

The preliminary analysis also found that caregivers reported significant improvements in 7 out of 10 quality of life and quality of care measures, according to Dr. Edgerly, chief program officer of the Alzheimer’s Association Northern California and Northern Nevada Chapter.

The early results paint an encouraging picture of the future, she said in an interview.

"We are very excited about the emergency utilization data. We’re always confident about our capacity to impact efficacy, but affecting service utilization is a tough nut to crack. The beauty of this is, if we can improve quality of care while reducing utilization costs, it may actually be cost neutral to have this kind of a dementia support program."

The association created its Excellence in Dementia Care program in conjunction with Kaiser Permanente Northern California, the city and county of San Francisco, and the University of California, San Francisco. The Administration on Aging also provided funding.

San Francisco was the perfect city for the pilot project, Dr. Edgerly said. "It’s the only city in the United States with a strategic plan related to dementia. It also has an elderly, diverse population and many of the residents live alone."

The pilot program is part of the city plan’s goal of partnering with other institutions to improve quality of life and quality of care for people with dementia. It was designed to improve dementia care by both enhancing services and educating caregivers.

"Kaiser hired a full-time social worker for just dementia support and who only worked with the caregivers," Dr. Edgerly said. The social worker conducted initial evaluations and assessments and created an individualized dementia care program that was uploaded into the electronic medical record of each patient, making the individualized program available to everyone on the patient’s care team. The social worker also called caregivers proactively to make sure the caregivers’ needs were being met and that they could access community services.

The Alzheimer’s Association provided dementia care support experts manning a 24-hour help line, a MedicAlert + Alzheimer’s Association Safe Return bracelet for the patient, respite grants for day or evening supplemental care to give caregivers a break, and a support group where caregivers could meet to discusses their challenges.

The association also administered the educational portion of the program. The first component provided a primer on Alzheimer’s stage-by-stage effects on thinking, emotions, and behavior, and noted resources that were available for help. Caregivers also were informed about legal and financial planning and ways to keep a positive, safe, and compassionate home environment for as long as the patient could stay at home.

In surveys at baseline and after 6 months, caregivers rated their feelings about their abilities in 10 different areas: handling current patient problems in memory and behavior, handling future patient problems, dealing with their own frustrations, keeping the patient independent, caring for the patient as independently as possible, getting answers to patient problems, finding community organizations that provide answers, finding community organizations that provide services, getting answers to questions about services, independently arranging for services, and paying for services.

Overall, 92 of the 105 patient-caregiver dyads have completed the 6-month assessments, Dr. Edgerly said. The surveys indicated significant improvements on seven of the caregiver measures. Caregivers said they felt better able to handle concerns, to get information, and to obtain and pay for services.

Most importantly, the program led to about a 40% decrease in emergency department visits – a significant change, Dr. Edgerly said. There were also nonsignificant decreases in hospital length of stay, physician visits, and days spent in post–acute or long-term care facilities.

"Even the outcomes that didn’t improve significantly were all going in the right direction," Dr. Edgerly said, adding that she’s hoping for even better results when the data are analyzed in their entirety.

The program’s positive impact on health care resources could be enough to attract the interest of other insurers, she said. "If this intervention reduced expenses associated with hospital or emergency department visits, an insurer might see that as good business sense."

The project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Association of Northern California and Northern Nevada, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, and the National Institute on Aging.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

BOSTON – A pilot program that supports the caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients decreased emergency admissions for those patients in San Francisco by more than 40% in 6 months, Elizabeth Edgerly, Ph.D., reported at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

The preliminary analysis also found that caregivers reported significant improvements in 7 out of 10 quality of life and quality of care measures, according to Dr. Edgerly, chief program officer of the Alzheimer’s Association Northern California and Northern Nevada Chapter.

The early results paint an encouraging picture of the future, she said in an interview.

"We are very excited about the emergency utilization data. We’re always confident about our capacity to impact efficacy, but affecting service utilization is a tough nut to crack. The beauty of this is, if we can improve quality of care while reducing utilization costs, it may actually be cost neutral to have this kind of a dementia support program."

The association created its Excellence in Dementia Care program in conjunction with Kaiser Permanente Northern California, the city and county of San Francisco, and the University of California, San Francisco. The Administration on Aging also provided funding.

San Francisco was the perfect city for the pilot project, Dr. Edgerly said. "It’s the only city in the United States with a strategic plan related to dementia. It also has an elderly, diverse population and many of the residents live alone."

The pilot program is part of the city plan’s goal of partnering with other institutions to improve quality of life and quality of care for people with dementia. It was designed to improve dementia care by both enhancing services and educating caregivers.

"Kaiser hired a full-time social worker for just dementia support and who only worked with the caregivers," Dr. Edgerly said. The social worker conducted initial evaluations and assessments and created an individualized dementia care program that was uploaded into the electronic medical record of each patient, making the individualized program available to everyone on the patient’s care team. The social worker also called caregivers proactively to make sure the caregivers’ needs were being met and that they could access community services.

The Alzheimer’s Association provided dementia care support experts manning a 24-hour help line, a MedicAlert + Alzheimer’s Association Safe Return bracelet for the patient, respite grants for day or evening supplemental care to give caregivers a break, and a support group where caregivers could meet to discusses their challenges.

The association also administered the educational portion of the program. The first component provided a primer on Alzheimer’s stage-by-stage effects on thinking, emotions, and behavior, and noted resources that were available for help. Caregivers also were informed about legal and financial planning and ways to keep a positive, safe, and compassionate home environment for as long as the patient could stay at home.

In surveys at baseline and after 6 months, caregivers rated their feelings about their abilities in 10 different areas: handling current patient problems in memory and behavior, handling future patient problems, dealing with their own frustrations, keeping the patient independent, caring for the patient as independently as possible, getting answers to patient problems, finding community organizations that provide answers, finding community organizations that provide services, getting answers to questions about services, independently arranging for services, and paying for services.

Overall, 92 of the 105 patient-caregiver dyads have completed the 6-month assessments, Dr. Edgerly said. The surveys indicated significant improvements on seven of the caregiver measures. Caregivers said they felt better able to handle concerns, to get information, and to obtain and pay for services.

Most importantly, the program led to about a 40% decrease in emergency department visits – a significant change, Dr. Edgerly said. There were also nonsignificant decreases in hospital length of stay, physician visits, and days spent in post–acute or long-term care facilities.

"Even the outcomes that didn’t improve significantly were all going in the right direction," Dr. Edgerly said, adding that she’s hoping for even better results when the data are analyzed in their entirety.

The program’s positive impact on health care resources could be enough to attract the interest of other insurers, she said. "If this intervention reduced expenses associated with hospital or emergency department visits, an insurer might see that as good business sense."

The project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Association of Northern California and Northern Nevada, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, and the National Institute on Aging.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

AT AAIC 2013

Major finding: A program designed to support the caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients decreased emergency room visits by 40% over a 6-month period.

Data source: A program that integrated medical and social care and enrolled 105 caregiver-patient pairs.

Disclosures: The project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Association of Northern California and Northern Nevada, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, and the National Institute on Aging.

Studies speak volumes about brain changes and cognition in women

BOSTON – Women who complain about cognitive problems after menopause might have increases rather than decreases in volume of certain brain regions, reported investigators at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

Brain imaging studies of 48 women in the early years of menopause showed that those with subjective cognitive complaints had significantly greater volumes in certain regions of the brain than did noncomplainers, including the right posterior cingulate gyrus (P less than .04), the right transverse temporal cortex (P less than .03), The left caudal middle frontal gyrus, and the right paracentral gyrus (P less than .05 for both), said Lilia Zurkovsky, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow from the Center for Cognitive Medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn.

The findings appear to run counter to those of another study (Neurology 2006;12:67: 834-42) showing that older adults with cognitive complaints had smaller volumes in temporal and frontal areas, compared with healthy age-matched controls, Dr. Zurkovsky acknowledged. She noted, however, that her group studied postmenopausal women in their 50s and 60s, whereas the earlier study included men. In addition, the mean age for each group in that study was above 70 years.

Combined with recent findings pointing to subjective cognitive and/or memory complaints as possible early signs of Alzheimer’s disease, the studies hint at a possible pattern of change as women age.

"If we look at all the data together, it would seem as though in early middle age, 50- to 60-year old individuals with complaints may be having some sort of compensatory mechanism. That’s speculation; all we know is that they have this increase in volume before they have a decrease in volume as shown by other papers," Dr. Zurkovsky said.

She and her colleagues scanned the participants with T1-weight magnetic resonance imaging with a 3 Tesla magnet, and measured cognitive complaints with the Cognitive Complaint Index (CCI) and five surveys with 120 total questions about the individual’s perceptions of cognitive abilities since menopause.

Brain changes in healthy postmenopausal women were the focus of a second, unrelated study also reported at AAIC2013.

Australian investigators followed participants in the Womens Healthy Ageing Project, a longitudinal study of the menopausal transition among cognitively normal women. The investigators looked at MRI brain scans conducted in 2002 and 2012, and brain-amyloid imaging studies with 18-F florbetaben positron emission tomography (FBB-PET). Florbetaben is an investigational amyloid imaging agent, similar to florbetapir (Amyvid).

They found that among the 26 women who had both FBB-PET and the two MRI scans spaced a decade apart, a significant decline was found over time in hippocampal volume, but not in gray matter volume. There was also a nonsignificant trend correlating higher levels of FBB uptake, as measured by a standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) with greater declines in hippocampal volume.

"Those who were in the higher tertile of florbetaben SUVR have had an 18%-19% decrement in hippocampal volume over that 10-year period," said lead author Paul Yates, Ph.D., a neuroscientist and imaging research fellow at Austin Health in Heidelberg, Australia.

Although these findings are preliminary and the changes observed were at the trend level only, they suggest that people with intermediate levels of uptake of an amyloid imaging agent might be at increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease, he said.

Dr. Zurkovsky’s study is supported by funding from the National Institute on Aging, Vanderbilt University, and the University of Vermont, Burlington. Dr. Yates’s study is supported by the National Ageing Research Institute at the University of Melbourne, with additional support from Bayer and Piramal Imaging. Neither Dr. Zurkovsky nor Dr. Yates reported having financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Women who complain about cognitive problems after menopause might have increases rather than decreases in volume of certain brain regions, reported investigators at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

Brain imaging studies of 48 women in the early years of menopause showed that those with subjective cognitive complaints had significantly greater volumes in certain regions of the brain than did noncomplainers, including the right posterior cingulate gyrus (P less than .04), the right transverse temporal cortex (P less than .03), The left caudal middle frontal gyrus, and the right paracentral gyrus (P less than .05 for both), said Lilia Zurkovsky, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow from the Center for Cognitive Medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn.

The findings appear to run counter to those of another study (Neurology 2006;12:67: 834-42) showing that older adults with cognitive complaints had smaller volumes in temporal and frontal areas, compared with healthy age-matched controls, Dr. Zurkovsky acknowledged. She noted, however, that her group studied postmenopausal women in their 50s and 60s, whereas the earlier study included men. In addition, the mean age for each group in that study was above 70 years.

Combined with recent findings pointing to subjective cognitive and/or memory complaints as possible early signs of Alzheimer’s disease, the studies hint at a possible pattern of change as women age.

"If we look at all the data together, it would seem as though in early middle age, 50- to 60-year old individuals with complaints may be having some sort of compensatory mechanism. That’s speculation; all we know is that they have this increase in volume before they have a decrease in volume as shown by other papers," Dr. Zurkovsky said.

She and her colleagues scanned the participants with T1-weight magnetic resonance imaging with a 3 Tesla magnet, and measured cognitive complaints with the Cognitive Complaint Index (CCI) and five surveys with 120 total questions about the individual’s perceptions of cognitive abilities since menopause.

Brain changes in healthy postmenopausal women were the focus of a second, unrelated study also reported at AAIC2013.

Australian investigators followed participants in the Womens Healthy Ageing Project, a longitudinal study of the menopausal transition among cognitively normal women. The investigators looked at MRI brain scans conducted in 2002 and 2012, and brain-amyloid imaging studies with 18-F florbetaben positron emission tomography (FBB-PET). Florbetaben is an investigational amyloid imaging agent, similar to florbetapir (Amyvid).

They found that among the 26 women who had both FBB-PET and the two MRI scans spaced a decade apart, a significant decline was found over time in hippocampal volume, but not in gray matter volume. There was also a nonsignificant trend correlating higher levels of FBB uptake, as measured by a standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) with greater declines in hippocampal volume.

"Those who were in the higher tertile of florbetaben SUVR have had an 18%-19% decrement in hippocampal volume over that 10-year period," said lead author Paul Yates, Ph.D., a neuroscientist and imaging research fellow at Austin Health in Heidelberg, Australia.

Although these findings are preliminary and the changes observed were at the trend level only, they suggest that people with intermediate levels of uptake of an amyloid imaging agent might be at increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease, he said.

Dr. Zurkovsky’s study is supported by funding from the National Institute on Aging, Vanderbilt University, and the University of Vermont, Burlington. Dr. Yates’s study is supported by the National Ageing Research Institute at the University of Melbourne, with additional support from Bayer and Piramal Imaging. Neither Dr. Zurkovsky nor Dr. Yates reported having financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Women who complain about cognitive problems after menopause might have increases rather than decreases in volume of certain brain regions, reported investigators at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

Brain imaging studies of 48 women in the early years of menopause showed that those with subjective cognitive complaints had significantly greater volumes in certain regions of the brain than did noncomplainers, including the right posterior cingulate gyrus (P less than .04), the right transverse temporal cortex (P less than .03), The left caudal middle frontal gyrus, and the right paracentral gyrus (P less than .05 for both), said Lilia Zurkovsky, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow from the Center for Cognitive Medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn.

The findings appear to run counter to those of another study (Neurology 2006;12:67: 834-42) showing that older adults with cognitive complaints had smaller volumes in temporal and frontal areas, compared with healthy age-matched controls, Dr. Zurkovsky acknowledged. She noted, however, that her group studied postmenopausal women in their 50s and 60s, whereas the earlier study included men. In addition, the mean age for each group in that study was above 70 years.

Combined with recent findings pointing to subjective cognitive and/or memory complaints as possible early signs of Alzheimer’s disease, the studies hint at a possible pattern of change as women age.

"If we look at all the data together, it would seem as though in early middle age, 50- to 60-year old individuals with complaints may be having some sort of compensatory mechanism. That’s speculation; all we know is that they have this increase in volume before they have a decrease in volume as shown by other papers," Dr. Zurkovsky said.

She and her colleagues scanned the participants with T1-weight magnetic resonance imaging with a 3 Tesla magnet, and measured cognitive complaints with the Cognitive Complaint Index (CCI) and five surveys with 120 total questions about the individual’s perceptions of cognitive abilities since menopause.

Brain changes in healthy postmenopausal women were the focus of a second, unrelated study also reported at AAIC2013.

Australian investigators followed participants in the Womens Healthy Ageing Project, a longitudinal study of the menopausal transition among cognitively normal women. The investigators looked at MRI brain scans conducted in 2002 and 2012, and brain-amyloid imaging studies with 18-F florbetaben positron emission tomography (FBB-PET). Florbetaben is an investigational amyloid imaging agent, similar to florbetapir (Amyvid).

They found that among the 26 women who had both FBB-PET and the two MRI scans spaced a decade apart, a significant decline was found over time in hippocampal volume, but not in gray matter volume. There was also a nonsignificant trend correlating higher levels of FBB uptake, as measured by a standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) with greater declines in hippocampal volume.

"Those who were in the higher tertile of florbetaben SUVR have had an 18%-19% decrement in hippocampal volume over that 10-year period," said lead author Paul Yates, Ph.D., a neuroscientist and imaging research fellow at Austin Health in Heidelberg, Australia.

Although these findings are preliminary and the changes observed were at the trend level only, they suggest that people with intermediate levels of uptake of an amyloid imaging agent might be at increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease, he said.

Dr. Zurkovsky’s study is supported by funding from the National Institute on Aging, Vanderbilt University, and the University of Vermont, Burlington. Dr. Yates’s study is supported by the National Ageing Research Institute at the University of Melbourne, with additional support from Bayer and Piramal Imaging. Neither Dr. Zurkovsky nor Dr. Yates reported having financial disclosures.

AT AAIC2013

Major finding: Postmenopausal women with subjective cognitive complaints had significantly larger volumes of some brain regions, compared with women without subjective cognitive complaints.

Data source: Prospective study of 48 postmenopausal women in their 50s and 60s; and a prospective, longitudinal study of healthy postmenopausal women, 26 of whom had MRI brain scans a decade apart, and brain amyloid imaging.

Disclosures: Dr. Zurkovsky’s study is supported by funding from the National Institute on Aging, Vanderbilt University, and the University of Vermont, Burlington. Dr. Yates’s study is supported by the National Ageing Research Institute at the University of Melbourne, with additional support from Bayer and Piramal Imaging. Neither Dr. Zurkovsky nor Dr. Yates reported having financial disclosures.

Alzheimer’s biomarkers have limited use in diagnosing frontotemporal dementia

BOSTON – The same biomarkers that successfully discriminate frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer’s disease don’t appear very helpful in differentiating patients with frontotemporal dementia from those with subjective memory problems.

Low cerebrospinal fluid levels of amyloid beta 42 (Abeta42) and high levels of tau are now seen as important diagnostic hallmarks for Alzheimer’s. The median levels of those biomarkers in patients with FTD are significantly different from what is measured in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease, but levels of those markers are too similar between FTD patients and those with subjective memory problems to be useful in differential diagnosis, Dr. Yolande Pijnenburg said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

Even if there were a significant correlation, its clinical specificity might be doubtful at this point, said Dr. Pijnenburg of the VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam. "Frontotemporal dementia is so pathologically heterogeneous that it’s almost unthinkable that we would find one specific biomarker."

The findings of her new study were a bit of a disappointment, failing to confirm her earlier work (Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2011;49:353-66), which suggested that both tau and phosphorylated tau (P-tau) might be diagnostically useful.

She examined biomarker levels in a cohort of 363 patients recruited from the Amsterdam Dementia Cohort and an associated memory clinic. Of these, 121 had Alzheimer’s disease, 121 had FTD, and 121 had subjective memory complaints that were not pathologic.

The FTD group illustrated Dr. Pijnenburg’s comment about diverse pathology: 91 had behavioral variant FTD and 30 met the Gorno-Tempini criteria for semantic dementia (temporal variant FTD), but 30 also met clinical criteria for Alzheimer’s.

All subjects had cerebrospinal fluid drawn for Abeta42, tau, and P-tau levels. The groups were well matched for age (mean, 62 years). The mean disease duration was about 3 years. The mean Mini Mental State Examination score was 24 in the FTD group, 21 in the Alzheimer’s group, and 28 in the controls with memory complaints.

Abeta42 was lowest in the Alzheimer’s patients at a median of 488 pg/mL. This was significantly lower than the level in either the FTD patients (848 pg/mL) or the normal controls (935 pg/mL). But between the FTD and control groups, neither the median levels nor the ranges were significantly different. The diagnostic accuracy was 89% for discriminating FTD from Alzheimer’s and 57% for discriminating FTD from controls.

The picture was similar for total tau. The level was highest in Alzheimer’s patients (median, 662 pg/mL), followed by the FTD group (345 pg/mL) and the control group (245 pg/mL). But again, neither those levels nor their ranges were significantly different from each other. The diagnostic accuracy was 81% for discriminating FTD from Alzheimer’s and 69% for discriminating FTD from controls.

P-tau was similarly elevated in Alzheimer’s patients (median, 86 pg/mL) and nearly identical in both FTD (42 pg/mL) and controls (45 pg/mL). The diagnostic accuracy was 87% for discriminating FTD from Alzheimer’s and 53% for discriminating FTD from controls.

The tau/Abeta42 ratio had a diagnostic accuracy of 91% for discriminating FTD from Alzheimer’s and 72% for discriminating FTD from the controls.

Dr. Pijnenburg expressed some hope for biomarker utility in the future, despite the rather low accuracy levels for the FTD/control discrimination in this study. "There was very little relevance for measuring Abeta42 or P-tau, but total tau and the tau/Abeta42ratio both do have some diagnostic interest," she said.

During discussion, she addressed several questions concerning unexpectedly low tau levels in the FTD cohort. Patients with FTD have a more rapid disease progression and more brain atrophy than do Alzheimer’s patients. Tau is also directly related to neurodegeneration. So why, she was asked, was there not more tau in the cerebrospinal fluid?

"My thought is that it could be related to the focal nature of FTD," she said. "Alzheimer’s is more diffuse."

Dr. Pijnenburg had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

BOSTON – The same biomarkers that successfully discriminate frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer’s disease don’t appear very helpful in differentiating patients with frontotemporal dementia from those with subjective memory problems.

Low cerebrospinal fluid levels of amyloid beta 42 (Abeta42) and high levels of tau are now seen as important diagnostic hallmarks for Alzheimer’s. The median levels of those biomarkers in patients with FTD are significantly different from what is measured in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease, but levels of those markers are too similar between FTD patients and those with subjective memory problems to be useful in differential diagnosis, Dr. Yolande Pijnenburg said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

Even if there were a significant correlation, its clinical specificity might be doubtful at this point, said Dr. Pijnenburg of the VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam. "Frontotemporal dementia is so pathologically heterogeneous that it’s almost unthinkable that we would find one specific biomarker."

The findings of her new study were a bit of a disappointment, failing to confirm her earlier work (Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2011;49:353-66), which suggested that both tau and phosphorylated tau (P-tau) might be diagnostically useful.

She examined biomarker levels in a cohort of 363 patients recruited from the Amsterdam Dementia Cohort and an associated memory clinic. Of these, 121 had Alzheimer’s disease, 121 had FTD, and 121 had subjective memory complaints that were not pathologic.

The FTD group illustrated Dr. Pijnenburg’s comment about diverse pathology: 91 had behavioral variant FTD and 30 met the Gorno-Tempini criteria for semantic dementia (temporal variant FTD), but 30 also met clinical criteria for Alzheimer’s.

All subjects had cerebrospinal fluid drawn for Abeta42, tau, and P-tau levels. The groups were well matched for age (mean, 62 years). The mean disease duration was about 3 years. The mean Mini Mental State Examination score was 24 in the FTD group, 21 in the Alzheimer’s group, and 28 in the controls with memory complaints.

Abeta42 was lowest in the Alzheimer’s patients at a median of 488 pg/mL. This was significantly lower than the level in either the FTD patients (848 pg/mL) or the normal controls (935 pg/mL). But between the FTD and control groups, neither the median levels nor the ranges were significantly different. The diagnostic accuracy was 89% for discriminating FTD from Alzheimer’s and 57% for discriminating FTD from controls.

The picture was similar for total tau. The level was highest in Alzheimer’s patients (median, 662 pg/mL), followed by the FTD group (345 pg/mL) and the control group (245 pg/mL). But again, neither those levels nor their ranges were significantly different from each other. The diagnostic accuracy was 81% for discriminating FTD from Alzheimer’s and 69% for discriminating FTD from controls.

P-tau was similarly elevated in Alzheimer’s patients (median, 86 pg/mL) and nearly identical in both FTD (42 pg/mL) and controls (45 pg/mL). The diagnostic accuracy was 87% for discriminating FTD from Alzheimer’s and 53% for discriminating FTD from controls.

The tau/Abeta42 ratio had a diagnostic accuracy of 91% for discriminating FTD from Alzheimer’s and 72% for discriminating FTD from the controls.

Dr. Pijnenburg expressed some hope for biomarker utility in the future, despite the rather low accuracy levels for the FTD/control discrimination in this study. "There was very little relevance for measuring Abeta42 or P-tau, but total tau and the tau/Abeta42ratio both do have some diagnostic interest," she said.