User login

New Insights Gained Into Biologics' Infection Risk

SNOWMASS, COLO. – A recent, much-ballyhooed, large, observational U.S. study that revised downward the risk of serious infections posed by tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitor therapy may have rendered false comfort to prescribing physicians.

The findings of the U.S. multicenter Safety Assessment of Biologic Therapy study (SABER) were roundly celebrated by many rheumatologists, dermatologists, and gastroenterologists who prescribe biologic agents for autoimmune diseases. But the SABER results are strikingly out of step with those of many large, well-conducted patient registries.

Moreover, at least one SABER organizer is skeptical about the validity of the study’s key conclusion that the serious infection risk in patients who’ve started on anti-TNF therapy isn’t significantly different than the risk in those started on methotrexate or another nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD). He cautioned against taking that conclusion as a lesson from SABER.

"Actually, my belief is that most of our findings in SABER are explained by the fact that anti-TNF agents are prednisone-sparing drugs," Dr. Kevin L. Winthrop said at the symposium, which was sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology. "My belief is that anti-TNF drugs do increase the risk of serious bacterial infections. The fact that they allow people to decrease their prednisone may result in roughly a canceling out of that risk."

SABER was a retrospective cohort study combining data from four large U.S. automated health databases. Investigators were able to compare outcomes in 16,022 patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) who were placed on an anti-TNF biologic vs. an equal number of matched patients who were started on a conventional DMARD.

The rate of serious infections requiring hospitalization during the first year after starting therapy – while impressively high – didn’t differ significantly between the two groups: roughly 8% per year in the RA patients regardless of whether they were on anti-TNF therapy or a conventional DMARD, 5.4% in those with psoriasis or spondyloarthropathies, and 10% in patients with IBD (JAMA 2011;306:2331-9).

But SABER had a major limitation: Data on prednisone use were collected for the year before the new therapy was introduced, but not after, noted Dr. Winthrop, an infectious disease specialist at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

"When you put someone on a biologic, you do a lot of things for that person differently than when you put someone on, say, Plaquenil [hydroxychloroquine]. You screen them for tuberculosis, you may counsel them, you give them vaccines, hopefully you decrease their prednisone, and you may even take off some methotrexate if they have good disease control. All of that probably happens to a much greater extent in the biologic arm than the nonbiologic arm," he explained.

Although infliximab was associated with a 23%-26% higher risk of serious infection compared with adalimumab or etanercept in SABER participants with RA, patients on infliximab were also more likely to concurrently be on methotrexate. "That might have been enough to explain this risk difference," according to Dr. Winthrop.

Unlike the SABER findings, a significantly elevated serious infection risk in association with RA patients receiving anti-TNF agents has been reported from the British Society for Rheumatology registry (Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2368-76), from a Japanese prospective registry (J. Rheumatol. 2011;38:1258-64), from the CORONNA (Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North American) registry (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010;69:380-6), and from the German RABBIT registry (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011;70:1914-20).

These studies generally showed a time-dependent decline in infection risk in patients treated with anti-TNF agents. But physicians shouldn’t assume that this apparent drop off in risk over time is a real phenomenon; rather, it is largely due to what epidemiologists call survivor bias. In other words, people who develop serious infections or other problems early on drop out of treatment, so the case mix in the registries changes, he explained.

Dr. Winthrop was particularly impressed with what he termed the "very elegant" 5,044-patient RABBIT study, which was designed to be able to answer the question SABER couldn’t – namely, what happens to prednisone dosing when patients go on a TNF inhibitor? The answer, as was well documented in RABBIT, is that the use of prednisone drastically decreases.

Moreover, the German investigators, using a multivariate analysis, identified a set of independent risk factors for serious infection. These included treatment with a TNF inhibitor, which was associated with a 1.8-fold increased risk, compared with conventional DMARDS; treatment with glucocorticoids at 7.5-14 mg/day during the study period, which had a 2.1-fold risk; and treatment with steroids at 15 mg/day or more, which conferred a 4.7-fold increased risk of infection. Other studies have also demonstrated that glucocorticoids convey a high and dose-dependent risk of serious infection.

A key lesson of both RABBIT and SABER is that much of the increased serious infection risk stems from comorbid conditions. The RABBIT investigators identified three additional risk factors: chronic lung disease, chronic kidney disease, and age older than 60 years. RA patients who had these three additional risk factors and were on at least 15 mg/day of prednisone had a serious infection rate of 45% per year if they were on an anti-TNF agent and 25% per year when on a conventional DMARD. If they had two additional risk factors rather than three, their serious infection risk dropped to less than 20% per year on anti-TNF therapy, and about half that on a conventional DMARD.

In contrast, patients with all three additional risk factors who were on less than 7.5 mg/day of prednisone or none at all had a serious infection rate below 10% per year if they were on a TNF inhibitor, and 5% if on a nonbiologic DMARD, Dr. Winthrop noted.

Similarly, SABER participants with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at baseline had an absolute two- to threefold greater risk of serious infection on a TNF inhibitor or DMARD, compared with patients without COPD. Baseline diabetes mellitus also magnified the serious infection risk in SABER, although not in RABBIT, he continued.

The RABBIT investigators found that improvement in functional capacity resulting from effective treatment significantly reduced the risk of serious infections. Indeed, functional improvement had a greater impact on infection risk than did improvement in the DAS28 (disease activity score based upon a 28-joint count).

SABER was funded by the Food and Drug Administration, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Department of Health and Human Services.

Dr. Winthrop reported having received consultant fees from Abbott, Amgen, and Pfizer as well as research funding from Pfizer.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – A recent, much-ballyhooed, large, observational U.S. study that revised downward the risk of serious infections posed by tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitor therapy may have rendered false comfort to prescribing physicians.

The findings of the U.S. multicenter Safety Assessment of Biologic Therapy study (SABER) were roundly celebrated by many rheumatologists, dermatologists, and gastroenterologists who prescribe biologic agents for autoimmune diseases. But the SABER results are strikingly out of step with those of many large, well-conducted patient registries.

Moreover, at least one SABER organizer is skeptical about the validity of the study’s key conclusion that the serious infection risk in patients who’ve started on anti-TNF therapy isn’t significantly different than the risk in those started on methotrexate or another nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD). He cautioned against taking that conclusion as a lesson from SABER.

"Actually, my belief is that most of our findings in SABER are explained by the fact that anti-TNF agents are prednisone-sparing drugs," Dr. Kevin L. Winthrop said at the symposium, which was sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology. "My belief is that anti-TNF drugs do increase the risk of serious bacterial infections. The fact that they allow people to decrease their prednisone may result in roughly a canceling out of that risk."

SABER was a retrospective cohort study combining data from four large U.S. automated health databases. Investigators were able to compare outcomes in 16,022 patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) who were placed on an anti-TNF biologic vs. an equal number of matched patients who were started on a conventional DMARD.

The rate of serious infections requiring hospitalization during the first year after starting therapy – while impressively high – didn’t differ significantly between the two groups: roughly 8% per year in the RA patients regardless of whether they were on anti-TNF therapy or a conventional DMARD, 5.4% in those with psoriasis or spondyloarthropathies, and 10% in patients with IBD (JAMA 2011;306:2331-9).

But SABER had a major limitation: Data on prednisone use were collected for the year before the new therapy was introduced, but not after, noted Dr. Winthrop, an infectious disease specialist at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

"When you put someone on a biologic, you do a lot of things for that person differently than when you put someone on, say, Plaquenil [hydroxychloroquine]. You screen them for tuberculosis, you may counsel them, you give them vaccines, hopefully you decrease their prednisone, and you may even take off some methotrexate if they have good disease control. All of that probably happens to a much greater extent in the biologic arm than the nonbiologic arm," he explained.

Although infliximab was associated with a 23%-26% higher risk of serious infection compared with adalimumab or etanercept in SABER participants with RA, patients on infliximab were also more likely to concurrently be on methotrexate. "That might have been enough to explain this risk difference," according to Dr. Winthrop.

Unlike the SABER findings, a significantly elevated serious infection risk in association with RA patients receiving anti-TNF agents has been reported from the British Society for Rheumatology registry (Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2368-76), from a Japanese prospective registry (J. Rheumatol. 2011;38:1258-64), from the CORONNA (Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North American) registry (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010;69:380-6), and from the German RABBIT registry (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011;70:1914-20).

These studies generally showed a time-dependent decline in infection risk in patients treated with anti-TNF agents. But physicians shouldn’t assume that this apparent drop off in risk over time is a real phenomenon; rather, it is largely due to what epidemiologists call survivor bias. In other words, people who develop serious infections or other problems early on drop out of treatment, so the case mix in the registries changes, he explained.

Dr. Winthrop was particularly impressed with what he termed the "very elegant" 5,044-patient RABBIT study, which was designed to be able to answer the question SABER couldn’t – namely, what happens to prednisone dosing when patients go on a TNF inhibitor? The answer, as was well documented in RABBIT, is that the use of prednisone drastically decreases.

Moreover, the German investigators, using a multivariate analysis, identified a set of independent risk factors for serious infection. These included treatment with a TNF inhibitor, which was associated with a 1.8-fold increased risk, compared with conventional DMARDS; treatment with glucocorticoids at 7.5-14 mg/day during the study period, which had a 2.1-fold risk; and treatment with steroids at 15 mg/day or more, which conferred a 4.7-fold increased risk of infection. Other studies have also demonstrated that glucocorticoids convey a high and dose-dependent risk of serious infection.

A key lesson of both RABBIT and SABER is that much of the increased serious infection risk stems from comorbid conditions. The RABBIT investigators identified three additional risk factors: chronic lung disease, chronic kidney disease, and age older than 60 years. RA patients who had these three additional risk factors and were on at least 15 mg/day of prednisone had a serious infection rate of 45% per year if they were on an anti-TNF agent and 25% per year when on a conventional DMARD. If they had two additional risk factors rather than three, their serious infection risk dropped to less than 20% per year on anti-TNF therapy, and about half that on a conventional DMARD.

In contrast, patients with all three additional risk factors who were on less than 7.5 mg/day of prednisone or none at all had a serious infection rate below 10% per year if they were on a TNF inhibitor, and 5% if on a nonbiologic DMARD, Dr. Winthrop noted.

Similarly, SABER participants with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at baseline had an absolute two- to threefold greater risk of serious infection on a TNF inhibitor or DMARD, compared with patients without COPD. Baseline diabetes mellitus also magnified the serious infection risk in SABER, although not in RABBIT, he continued.

The RABBIT investigators found that improvement in functional capacity resulting from effective treatment significantly reduced the risk of serious infections. Indeed, functional improvement had a greater impact on infection risk than did improvement in the DAS28 (disease activity score based upon a 28-joint count).

SABER was funded by the Food and Drug Administration, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Department of Health and Human Services.

Dr. Winthrop reported having received consultant fees from Abbott, Amgen, and Pfizer as well as research funding from Pfizer.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – A recent, much-ballyhooed, large, observational U.S. study that revised downward the risk of serious infections posed by tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitor therapy may have rendered false comfort to prescribing physicians.

The findings of the U.S. multicenter Safety Assessment of Biologic Therapy study (SABER) were roundly celebrated by many rheumatologists, dermatologists, and gastroenterologists who prescribe biologic agents for autoimmune diseases. But the SABER results are strikingly out of step with those of many large, well-conducted patient registries.

Moreover, at least one SABER organizer is skeptical about the validity of the study’s key conclusion that the serious infection risk in patients who’ve started on anti-TNF therapy isn’t significantly different than the risk in those started on methotrexate or another nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD). He cautioned against taking that conclusion as a lesson from SABER.

"Actually, my belief is that most of our findings in SABER are explained by the fact that anti-TNF agents are prednisone-sparing drugs," Dr. Kevin L. Winthrop said at the symposium, which was sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology. "My belief is that anti-TNF drugs do increase the risk of serious bacterial infections. The fact that they allow people to decrease their prednisone may result in roughly a canceling out of that risk."

SABER was a retrospective cohort study combining data from four large U.S. automated health databases. Investigators were able to compare outcomes in 16,022 patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) who were placed on an anti-TNF biologic vs. an equal number of matched patients who were started on a conventional DMARD.

The rate of serious infections requiring hospitalization during the first year after starting therapy – while impressively high – didn’t differ significantly between the two groups: roughly 8% per year in the RA patients regardless of whether they were on anti-TNF therapy or a conventional DMARD, 5.4% in those with psoriasis or spondyloarthropathies, and 10% in patients with IBD (JAMA 2011;306:2331-9).

But SABER had a major limitation: Data on prednisone use were collected for the year before the new therapy was introduced, but not after, noted Dr. Winthrop, an infectious disease specialist at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

"When you put someone on a biologic, you do a lot of things for that person differently than when you put someone on, say, Plaquenil [hydroxychloroquine]. You screen them for tuberculosis, you may counsel them, you give them vaccines, hopefully you decrease their prednisone, and you may even take off some methotrexate if they have good disease control. All of that probably happens to a much greater extent in the biologic arm than the nonbiologic arm," he explained.

Although infliximab was associated with a 23%-26% higher risk of serious infection compared with adalimumab or etanercept in SABER participants with RA, patients on infliximab were also more likely to concurrently be on methotrexate. "That might have been enough to explain this risk difference," according to Dr. Winthrop.

Unlike the SABER findings, a significantly elevated serious infection risk in association with RA patients receiving anti-TNF agents has been reported from the British Society for Rheumatology registry (Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2368-76), from a Japanese prospective registry (J. Rheumatol. 2011;38:1258-64), from the CORONNA (Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North American) registry (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010;69:380-6), and from the German RABBIT registry (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011;70:1914-20).

These studies generally showed a time-dependent decline in infection risk in patients treated with anti-TNF agents. But physicians shouldn’t assume that this apparent drop off in risk over time is a real phenomenon; rather, it is largely due to what epidemiologists call survivor bias. In other words, people who develop serious infections or other problems early on drop out of treatment, so the case mix in the registries changes, he explained.

Dr. Winthrop was particularly impressed with what he termed the "very elegant" 5,044-patient RABBIT study, which was designed to be able to answer the question SABER couldn’t – namely, what happens to prednisone dosing when patients go on a TNF inhibitor? The answer, as was well documented in RABBIT, is that the use of prednisone drastically decreases.

Moreover, the German investigators, using a multivariate analysis, identified a set of independent risk factors for serious infection. These included treatment with a TNF inhibitor, which was associated with a 1.8-fold increased risk, compared with conventional DMARDS; treatment with glucocorticoids at 7.5-14 mg/day during the study period, which had a 2.1-fold risk; and treatment with steroids at 15 mg/day or more, which conferred a 4.7-fold increased risk of infection. Other studies have also demonstrated that glucocorticoids convey a high and dose-dependent risk of serious infection.

A key lesson of both RABBIT and SABER is that much of the increased serious infection risk stems from comorbid conditions. The RABBIT investigators identified three additional risk factors: chronic lung disease, chronic kidney disease, and age older than 60 years. RA patients who had these three additional risk factors and were on at least 15 mg/day of prednisone had a serious infection rate of 45% per year if they were on an anti-TNF agent and 25% per year when on a conventional DMARD. If they had two additional risk factors rather than three, their serious infection risk dropped to less than 20% per year on anti-TNF therapy, and about half that on a conventional DMARD.

In contrast, patients with all three additional risk factors who were on less than 7.5 mg/day of prednisone or none at all had a serious infection rate below 10% per year if they were on a TNF inhibitor, and 5% if on a nonbiologic DMARD, Dr. Winthrop noted.

Similarly, SABER participants with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at baseline had an absolute two- to threefold greater risk of serious infection on a TNF inhibitor or DMARD, compared with patients without COPD. Baseline diabetes mellitus also magnified the serious infection risk in SABER, although not in RABBIT, he continued.

The RABBIT investigators found that improvement in functional capacity resulting from effective treatment significantly reduced the risk of serious infections. Indeed, functional improvement had a greater impact on infection risk than did improvement in the DAS28 (disease activity score based upon a 28-joint count).

SABER was funded by the Food and Drug Administration, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Department of Health and Human Services.

Dr. Winthrop reported having received consultant fees from Abbott, Amgen, and Pfizer as well as research funding from Pfizer.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A SYMPOSIUM SPONSORED BY THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF RHEUMATOLOGY

Pegloticase Safe as Induction Therapy in Tophaceous Gout

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Many rheumatologists may have been scared off from using pegloticase in chronic refractory gout because of the much-publicized risk of infusion reactions – needlessly so, according to Dr. Robert L. Wortmann.

That safety concern has been resolved. Patients on pegloticase who are headed for an infusion reaction can now reliably be identified in advance so that the drug gets stopped before this complication ever occurs, Dr. Wortmann said at the symposium.

Pegloticase (Krystexxa) is a porcinelike pegylated uricase. A uric acid–lowering drug of unprecedented effectiveness, pegloticase converts urate to allantoin. Given intravenously at a dosage of 8 mg every 2 weeks, it quickly drives serum urate to close to 0 and keeps it there.

"Tophi will melt away before your eyes within about 12 weeks," said Dr. Wortmann, professor of medicine at Dartmouth Medical School, Hanover, N.H.

In the major clinical trials, 25%-42% of treated patients had infusion reactions of varied severity. Those statistics have understandably put off a lot of rheumatologists. However, patients experience infusion reactions only when they develop blocking antibodies against the uricase. So as long as the most recent dose they received was effective, they will not have an infusion reaction to the next one.

"When using this agent, get a urate level in the morning, before the patient gets the infusion. If it’s less than 1 mg/dL, it’s okay to proceed," the rheumatologist said.

On the other hand, if the urate level is above about 4 mg/dL, the drug is no longer working. Blocking antibodies have formed, and the patient is at risk for an infusion reaction. It’s time to stop pegloticase for good and move on to other therapy, he continued.

"Pegloticase, to me, is an induction drug. If you’ve got a person who comes in with tophi all over the place, and they’re having a lot of acute gout attacks – maybe six or more per year – this is a great drug to try to get the total body urate pool decreased rapidly," Dr. Wortmann explained. "Once the tophi are gone, I think you can switch the patient to an oral agent. That’s how I use it. There have been people who’ve taken pegloticase for 2 years and continued to tolerate it, but if the tophi are gone, to me it’s time to move on to one of the other drugs."

Before utilizing pegloticase, it’s important to ensure that a patient doesn’t have hereditary glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Pretreatment with an antihistamine and a corticosteroid is recommended to help guard against infusion reactions.

Gout flares occur in close to three-quarters of pegloticase-treated patients in the first few months, so prophylaxis with colchicine and/or NSAIDs is a must, he said.

"Anything that lowers serum urate can trigger an attack, and the faster and further urate goes down, the more likely are flares. So these people need to have a lot of prophylaxis initially. Over time the flare rate goes down," Dr. Wortmann said.

He reported that he serves as a consultant to Savient, which markets pegloticase, as well as to Ardea Biosciences, Novartis, Takeda, and URL Pharmaceuticals.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Many rheumatologists may have been scared off from using pegloticase in chronic refractory gout because of the much-publicized risk of infusion reactions – needlessly so, according to Dr. Robert L. Wortmann.

That safety concern has been resolved. Patients on pegloticase who are headed for an infusion reaction can now reliably be identified in advance so that the drug gets stopped before this complication ever occurs, Dr. Wortmann said at the symposium.

Pegloticase (Krystexxa) is a porcinelike pegylated uricase. A uric acid–lowering drug of unprecedented effectiveness, pegloticase converts urate to allantoin. Given intravenously at a dosage of 8 mg every 2 weeks, it quickly drives serum urate to close to 0 and keeps it there.

"Tophi will melt away before your eyes within about 12 weeks," said Dr. Wortmann, professor of medicine at Dartmouth Medical School, Hanover, N.H.

In the major clinical trials, 25%-42% of treated patients had infusion reactions of varied severity. Those statistics have understandably put off a lot of rheumatologists. However, patients experience infusion reactions only when they develop blocking antibodies against the uricase. So as long as the most recent dose they received was effective, they will not have an infusion reaction to the next one.

"When using this agent, get a urate level in the morning, before the patient gets the infusion. If it’s less than 1 mg/dL, it’s okay to proceed," the rheumatologist said.

On the other hand, if the urate level is above about 4 mg/dL, the drug is no longer working. Blocking antibodies have formed, and the patient is at risk for an infusion reaction. It’s time to stop pegloticase for good and move on to other therapy, he continued.

"Pegloticase, to me, is an induction drug. If you’ve got a person who comes in with tophi all over the place, and they’re having a lot of acute gout attacks – maybe six or more per year – this is a great drug to try to get the total body urate pool decreased rapidly," Dr. Wortmann explained. "Once the tophi are gone, I think you can switch the patient to an oral agent. That’s how I use it. There have been people who’ve taken pegloticase for 2 years and continued to tolerate it, but if the tophi are gone, to me it’s time to move on to one of the other drugs."

Before utilizing pegloticase, it’s important to ensure that a patient doesn’t have hereditary glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Pretreatment with an antihistamine and a corticosteroid is recommended to help guard against infusion reactions.

Gout flares occur in close to three-quarters of pegloticase-treated patients in the first few months, so prophylaxis with colchicine and/or NSAIDs is a must, he said.

"Anything that lowers serum urate can trigger an attack, and the faster and further urate goes down, the more likely are flares. So these people need to have a lot of prophylaxis initially. Over time the flare rate goes down," Dr. Wortmann said.

He reported that he serves as a consultant to Savient, which markets pegloticase, as well as to Ardea Biosciences, Novartis, Takeda, and URL Pharmaceuticals.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Many rheumatologists may have been scared off from using pegloticase in chronic refractory gout because of the much-publicized risk of infusion reactions – needlessly so, according to Dr. Robert L. Wortmann.

That safety concern has been resolved. Patients on pegloticase who are headed for an infusion reaction can now reliably be identified in advance so that the drug gets stopped before this complication ever occurs, Dr. Wortmann said at the symposium.

Pegloticase (Krystexxa) is a porcinelike pegylated uricase. A uric acid–lowering drug of unprecedented effectiveness, pegloticase converts urate to allantoin. Given intravenously at a dosage of 8 mg every 2 weeks, it quickly drives serum urate to close to 0 and keeps it there.

"Tophi will melt away before your eyes within about 12 weeks," said Dr. Wortmann, professor of medicine at Dartmouth Medical School, Hanover, N.H.

In the major clinical trials, 25%-42% of treated patients had infusion reactions of varied severity. Those statistics have understandably put off a lot of rheumatologists. However, patients experience infusion reactions only when they develop blocking antibodies against the uricase. So as long as the most recent dose they received was effective, they will not have an infusion reaction to the next one.

"When using this agent, get a urate level in the morning, before the patient gets the infusion. If it’s less than 1 mg/dL, it’s okay to proceed," the rheumatologist said.

On the other hand, if the urate level is above about 4 mg/dL, the drug is no longer working. Blocking antibodies have formed, and the patient is at risk for an infusion reaction. It’s time to stop pegloticase for good and move on to other therapy, he continued.

"Pegloticase, to me, is an induction drug. If you’ve got a person who comes in with tophi all over the place, and they’re having a lot of acute gout attacks – maybe six or more per year – this is a great drug to try to get the total body urate pool decreased rapidly," Dr. Wortmann explained. "Once the tophi are gone, I think you can switch the patient to an oral agent. That’s how I use it. There have been people who’ve taken pegloticase for 2 years and continued to tolerate it, but if the tophi are gone, to me it’s time to move on to one of the other drugs."

Before utilizing pegloticase, it’s important to ensure that a patient doesn’t have hereditary glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Pretreatment with an antihistamine and a corticosteroid is recommended to help guard against infusion reactions.

Gout flares occur in close to three-quarters of pegloticase-treated patients in the first few months, so prophylaxis with colchicine and/or NSAIDs is a must, he said.

"Anything that lowers serum urate can trigger an attack, and the faster and further urate goes down, the more likely are flares. So these people need to have a lot of prophylaxis initially. Over time the flare rate goes down," Dr. Wortmann said.

He reported that he serves as a consultant to Savient, which markets pegloticase, as well as to Ardea Biosciences, Novartis, Takeda, and URL Pharmaceuticals.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A SYMPOSIUM SPONSORED BY THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF RHEUMATOLOGY

Anticipate Mycobacterial Lung Disease in Anti-TNF Users

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Rheumatoid arthritis patients on tumor necrosis factor inhibitors are at markedly increased risk for both tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease, as highlighted in data not yet published from Kaiser Permanente of Northern California that was discussed by investigator Dr. Kevin L. Winthrop at the symposium.

The crude incidence rate of nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in this 3.1-million-member health plan during the study years of 2000-2008 was 4.1 cases/100,000 person-years. The risk rose with age such that among plan members aged 50 years or older the rate was 11.8 cases/100,000 person-years. Plan members with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who’d never been on a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor had a moderately higher rate of 19.2 cases/100,000 person-years, probably because of their use of prednisone. But among 8,418 RA patients on TNF inhibitor therapy, the incidence of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease shot up to 112 cases/100,000 person-years.

The tuberculosis incidence followed a similar pattern: 2.8 cases/100,000 person-years among the general Kaiser membership, 5.2 in those aged 50 years or older, 8.7 in RA patients never exposed to a TNF inhibitor, jumping to 56 cases/100,000 person-years among RA patients on an anti-TNF biologic, according to Dr. Winthrop.

In light of these data, physicians need to be on the lookout for nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease arising in RA patients using a TNF inhibitor.

"You will have patients with this. It’s best to diagnose them early, if possible, and get them off their biologic and also limit or discontinue prednisone," said Dr. Winthrop, an infectious diseases specialist at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

It’s his clinical impression, as well as that of other physicians participating in the Infectious Diseases Society of America’s Emerging Infections Network, that people who develop nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease while on a TNF inhibitor tend to experience more rapid progression of their lung disease, he said at the meeting.

He and his coinvestigators at Kaiser also examined the pulmonary disease rates associated with individual TNF inhibitors. The nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease rate in patients on etanercept was 35 cases/100,000 person-years of exposure, significantly less than the 116 cases/100,000 person-years with infliximab or 122 with adalimumab.

Similarly, the tuberculosis rate was lowest with etanercept at 17 cases/100,000 person-years as compared to 83 with infliximab and 61 with adalimumab.

The Kaiser experience confirms a 2010 report from the British Society for Rheumatology biologic registry that provided the first solid epidemiologic data showing that TNF inhibitors carry an increased tuberculosis risk. In the U.K. study, etanercept use was associated with a tuberculosis incidence of 39 cases per 100,000 person-years, significantly lower than the 136 cases per 100,000 person-years with infliximab or 144 with adalimumab. In contrast, the tuberculosis rate among more than 3,200 RA patients on a conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug was zero. The background tuberculosis incidence in the United Kingdom during that time period was about 12 cases/100,000 person-years (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010;69:522-8).

"I’m convinced that the monoclonal antibody TNF inhibitors [infliximab and adalimumab] cause more tuberculosis than [does] etanercept. I’m not convinced I know why," Dr. Winthrop admitted.

Numerous potential mechanisms have been floated to explain this differential effect. The two he finds most plausible are that etanercept is less able to penetrate tuberculosis granulomas than are the monoclonal antibody TNF inhibitors, as shown in a mouse model, and the possibility – as yet unproven – that etanercept might also cause less downregulation of CD8 cells producing the antimicrobial peptides perforin and granulysin, which are directed against Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Dr. Winthrop said the epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease is changing. Decades ago, it was viewed as a disease of elderly men. As the incidence has climbed during the past 2 decades, however, the disease has come to be recognized as mainly one of postmenopausal women, typically with no history of underlying lung disease or smoking. The phenotype is one of an elderly woman who is tall, slender, and underweight, often with mitral valve prolapse, scoliosis, or pectus defects.

In a large study conducted at four geographically diverse large health plans, the annual prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease among persons age 60 years or older rose from 19.6 cases/100,000 in 1994-1996 to 26.7 cases/100,000 person-years in 2004-2006, a rate two- to threefold greater than the prevalence of tuberculosis at those sites during 2004-2006 (Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010;182:970-6).

Nontuberculous mycobacteria are ubiquitous in tap water and soil. Unlike tuberculosis, which is spread from person to person by coughing, nontuberculous mycobacterial infections are acquired directly from the environment.

Dr. Winthrop said he is reluctant to recommend resuming biologic therapy after a RA patient has been treated for nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease or coccidioidomycosis.

Dr. Winthrop reported having received consultant fees from Abbott, Amgen, and Pfizer as well as research funding from Pfizer.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Rheumatoid arthritis patients on tumor necrosis factor inhibitors are at markedly increased risk for both tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease, as highlighted in data not yet published from Kaiser Permanente of Northern California that was discussed by investigator Dr. Kevin L. Winthrop at the symposium.

The crude incidence rate of nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in this 3.1-million-member health plan during the study years of 2000-2008 was 4.1 cases/100,000 person-years. The risk rose with age such that among plan members aged 50 years or older the rate was 11.8 cases/100,000 person-years. Plan members with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who’d never been on a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor had a moderately higher rate of 19.2 cases/100,000 person-years, probably because of their use of prednisone. But among 8,418 RA patients on TNF inhibitor therapy, the incidence of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease shot up to 112 cases/100,000 person-years.

The tuberculosis incidence followed a similar pattern: 2.8 cases/100,000 person-years among the general Kaiser membership, 5.2 in those aged 50 years or older, 8.7 in RA patients never exposed to a TNF inhibitor, jumping to 56 cases/100,000 person-years among RA patients on an anti-TNF biologic, according to Dr. Winthrop.

In light of these data, physicians need to be on the lookout for nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease arising in RA patients using a TNF inhibitor.

"You will have patients with this. It’s best to diagnose them early, if possible, and get them off their biologic and also limit or discontinue prednisone," said Dr. Winthrop, an infectious diseases specialist at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

It’s his clinical impression, as well as that of other physicians participating in the Infectious Diseases Society of America’s Emerging Infections Network, that people who develop nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease while on a TNF inhibitor tend to experience more rapid progression of their lung disease, he said at the meeting.

He and his coinvestigators at Kaiser also examined the pulmonary disease rates associated with individual TNF inhibitors. The nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease rate in patients on etanercept was 35 cases/100,000 person-years of exposure, significantly less than the 116 cases/100,000 person-years with infliximab or 122 with adalimumab.

Similarly, the tuberculosis rate was lowest with etanercept at 17 cases/100,000 person-years as compared to 83 with infliximab and 61 with adalimumab.

The Kaiser experience confirms a 2010 report from the British Society for Rheumatology biologic registry that provided the first solid epidemiologic data showing that TNF inhibitors carry an increased tuberculosis risk. In the U.K. study, etanercept use was associated with a tuberculosis incidence of 39 cases per 100,000 person-years, significantly lower than the 136 cases per 100,000 person-years with infliximab or 144 with adalimumab. In contrast, the tuberculosis rate among more than 3,200 RA patients on a conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug was zero. The background tuberculosis incidence in the United Kingdom during that time period was about 12 cases/100,000 person-years (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010;69:522-8).

"I’m convinced that the monoclonal antibody TNF inhibitors [infliximab and adalimumab] cause more tuberculosis than [does] etanercept. I’m not convinced I know why," Dr. Winthrop admitted.

Numerous potential mechanisms have been floated to explain this differential effect. The two he finds most plausible are that etanercept is less able to penetrate tuberculosis granulomas than are the monoclonal antibody TNF inhibitors, as shown in a mouse model, and the possibility – as yet unproven – that etanercept might also cause less downregulation of CD8 cells producing the antimicrobial peptides perforin and granulysin, which are directed against Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Dr. Winthrop said the epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease is changing. Decades ago, it was viewed as a disease of elderly men. As the incidence has climbed during the past 2 decades, however, the disease has come to be recognized as mainly one of postmenopausal women, typically with no history of underlying lung disease or smoking. The phenotype is one of an elderly woman who is tall, slender, and underweight, often with mitral valve prolapse, scoliosis, or pectus defects.

In a large study conducted at four geographically diverse large health plans, the annual prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease among persons age 60 years or older rose from 19.6 cases/100,000 in 1994-1996 to 26.7 cases/100,000 person-years in 2004-2006, a rate two- to threefold greater than the prevalence of tuberculosis at those sites during 2004-2006 (Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010;182:970-6).

Nontuberculous mycobacteria are ubiquitous in tap water and soil. Unlike tuberculosis, which is spread from person to person by coughing, nontuberculous mycobacterial infections are acquired directly from the environment.

Dr. Winthrop said he is reluctant to recommend resuming biologic therapy after a RA patient has been treated for nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease or coccidioidomycosis.

Dr. Winthrop reported having received consultant fees from Abbott, Amgen, and Pfizer as well as research funding from Pfizer.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Rheumatoid arthritis patients on tumor necrosis factor inhibitors are at markedly increased risk for both tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease, as highlighted in data not yet published from Kaiser Permanente of Northern California that was discussed by investigator Dr. Kevin L. Winthrop at the symposium.

The crude incidence rate of nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in this 3.1-million-member health plan during the study years of 2000-2008 was 4.1 cases/100,000 person-years. The risk rose with age such that among plan members aged 50 years or older the rate was 11.8 cases/100,000 person-years. Plan members with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who’d never been on a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor had a moderately higher rate of 19.2 cases/100,000 person-years, probably because of their use of prednisone. But among 8,418 RA patients on TNF inhibitor therapy, the incidence of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease shot up to 112 cases/100,000 person-years.

The tuberculosis incidence followed a similar pattern: 2.8 cases/100,000 person-years among the general Kaiser membership, 5.2 in those aged 50 years or older, 8.7 in RA patients never exposed to a TNF inhibitor, jumping to 56 cases/100,000 person-years among RA patients on an anti-TNF biologic, according to Dr. Winthrop.

In light of these data, physicians need to be on the lookout for nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease arising in RA patients using a TNF inhibitor.

"You will have patients with this. It’s best to diagnose them early, if possible, and get them off their biologic and also limit or discontinue prednisone," said Dr. Winthrop, an infectious diseases specialist at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

It’s his clinical impression, as well as that of other physicians participating in the Infectious Diseases Society of America’s Emerging Infections Network, that people who develop nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease while on a TNF inhibitor tend to experience more rapid progression of their lung disease, he said at the meeting.

He and his coinvestigators at Kaiser also examined the pulmonary disease rates associated with individual TNF inhibitors. The nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease rate in patients on etanercept was 35 cases/100,000 person-years of exposure, significantly less than the 116 cases/100,000 person-years with infliximab or 122 with adalimumab.

Similarly, the tuberculosis rate was lowest with etanercept at 17 cases/100,000 person-years as compared to 83 with infliximab and 61 with adalimumab.

The Kaiser experience confirms a 2010 report from the British Society for Rheumatology biologic registry that provided the first solid epidemiologic data showing that TNF inhibitors carry an increased tuberculosis risk. In the U.K. study, etanercept use was associated with a tuberculosis incidence of 39 cases per 100,000 person-years, significantly lower than the 136 cases per 100,000 person-years with infliximab or 144 with adalimumab. In contrast, the tuberculosis rate among more than 3,200 RA patients on a conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug was zero. The background tuberculosis incidence in the United Kingdom during that time period was about 12 cases/100,000 person-years (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010;69:522-8).

"I’m convinced that the monoclonal antibody TNF inhibitors [infliximab and adalimumab] cause more tuberculosis than [does] etanercept. I’m not convinced I know why," Dr. Winthrop admitted.

Numerous potential mechanisms have been floated to explain this differential effect. The two he finds most plausible are that etanercept is less able to penetrate tuberculosis granulomas than are the monoclonal antibody TNF inhibitors, as shown in a mouse model, and the possibility – as yet unproven – that etanercept might also cause less downregulation of CD8 cells producing the antimicrobial peptides perforin and granulysin, which are directed against Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Dr. Winthrop said the epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease is changing. Decades ago, it was viewed as a disease of elderly men. As the incidence has climbed during the past 2 decades, however, the disease has come to be recognized as mainly one of postmenopausal women, typically with no history of underlying lung disease or smoking. The phenotype is one of an elderly woman who is tall, slender, and underweight, often with mitral valve prolapse, scoliosis, or pectus defects.

In a large study conducted at four geographically diverse large health plans, the annual prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease among persons age 60 years or older rose from 19.6 cases/100,000 in 1994-1996 to 26.7 cases/100,000 person-years in 2004-2006, a rate two- to threefold greater than the prevalence of tuberculosis at those sites during 2004-2006 (Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010;182:970-6).

Nontuberculous mycobacteria are ubiquitous in tap water and soil. Unlike tuberculosis, which is spread from person to person by coughing, nontuberculous mycobacterial infections are acquired directly from the environment.

Dr. Winthrop said he is reluctant to recommend resuming biologic therapy after a RA patient has been treated for nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease or coccidioidomycosis.

Dr. Winthrop reported having received consultant fees from Abbott, Amgen, and Pfizer as well as research funding from Pfizer.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A SYMPOSIUM SPONSORED BY THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF RHEUMATOLOGY

Physicians Often Missing Boat on Gout Therapy

SNOWMASS, COLO. – A disturbing proportion of gout cases are mismanaged by primary care physicians, and the blame falls squarely upon rheumatologists, according to one prominent gout expert.

"As rheumatologists, gout is our disease. The cause and pathophysiology are well understood, we can make the diagnosis with absolute certainty, and we’ve got great medicines. Yet today we all see people with tophi. That’s tragic. It shouldn’t exist. One of our biggest mistakes has been not being able to educate primary care physicians that having a tophus is bad, that it’s eroding cartilage and bone, and that it’s something we can prevent if we start urate-lowering therapy soon enough," Dr. Robert L. Wortmann said at the conference.

An estimated 8.3 million Americans have gout. Yet, the pharmaceutical industry says only 3.1 million of them are prescribed urate-lowering drugs. Five different studies show that a mere 40% of those on allopurinol are prescribed a dose sufficient to drive serum uric acid below 6 mg/dL, a key tenet of gout management, noted Dr. Wortmann, professor of medicine at Dartmouth Medical School in Hanover, N.H.

Moreover, poor treatment adherence is a huge problem in gout. A study of close to 4,200 gout patients started on urate-lowering drug therapy found that 56% of them were nonadherent (Arthritis Res. Ther. 2009;11(2):R46).

"I charge you all to go back from this meeting and try to communicate with all the primary care physicians you can about the principles of managing gout. People shouldn’t suffer from this," the rheumatologist declared.

He offered these major take home points:

Don’t prescribe urate-lowering drugs for asymptomatic hyperuricemia: This practice hasn’t been shown to prevent the future development of gout, yet it exposes patients to the risk of drug toxicities.

But don’t ignore asymptomatic hyperuricemia, either: Epidemiologic studies have linked asymptomatic hyperuricemia, defined by a serum urate in excess of 6.8 mg/dL, to increased risks of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and all-cause mortality. The big unanswered question is whether using medications to lower serum urate in individuals with asymptomatic hyperuricemia reduces the risk of any of these conditions. That’s the subject of ongoing large clinical trials in high-risk patients. If those studies prove positive, clinical practice will change.

While awaiting the outcome of the prevention trials, it’s worth bearing in mind that Framingham Heart Study data indicate that individuals with a serum uric acid level above 9 mg/dL have a 22% chance of developing gout within the next 5 years. The major contributors to asymptomatic hyperuricemia include obesity, metabolic syndrome, and heavy consumption of fructose-containing beverages or alcohol. Those issues should be addressed.

Losartan is the only antihypertensive agent that’s uricosuric. Fenofibrate is the sole uricosuric drug indicated for dyslipidemia. Preferential consideration could be given to the use of these drugs in hypertensive and/or hyperlipidemic patients with asymptomatic hyperuricemia.

The important thing is not which oral agent you use for treatment of acute gout, it’s to initiate therapy as early as possible, at the first hint of an attack. Colchicine, maximum-dose NSAIDs, and oral prednisone dosed at 20 mg BID until symptoms have been gone for 1 week followed by another week at 20 mg/day – they’re all effective. And since they work by different mechanisms, they can beneficially be combined in refractory patients.

The old-school colchicine dosing regimen most physicians were taught has been cast aside of late. It had a high rate of diarrhea, an inhumane side effect in gout patients hobbled by a foot too sore to walk on. The former regimen has been replaced by 1.2 mg, given in a single dose, followed by 0.6 mg 1 hour later.

"This lower dose is just as effective as the old high-dose regimen of two 0.6-mg pills given at once and then one per hour for the next 5 hours. And the lower-dose program has the same side effect profile as placebo," Dr. Wortmann said.

Get the gout patient’s serum urate below 6 mg/dL using the lowest effective dose of the urate-lowering drug you’ve selected. Physicians have traditionally started gout patients on allopurinol at the standard dose of 300 mg/day. Recently, it has been demonstrated that the risk of developing allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome is greatly reduced by starting off at 150 mg/day, checking the urate level 2 weeks later, then increasing to 300 mg/day if the serum urate isn’t below 6 mg/dL. After 2 weeks at 300 mg/day, check the urate again, and if it still isn’t below 6 mg/dL then bump the dose to 400 mg/day. Continue testing and titrating every 2 weeks until the serum urate is less than 6 mg/dL – and preferably less than 4 mg/dL if the patient has tophi – or until the maximum approved dose of 800 mg/day is reached.

The same start-low-and-titrate strategy applies to febuxostat, with a maximum approved dose of 80 mg/day.

"We have to educate primary care physicians to check the serum urate after starting therapy, and that, if it’s not below 6 mg/dL, they need to increase the dose. And if they don’t feel comfortable with that, they need to send the patient to us," the rheumatologist said.

Fortunately, patients who have a hypersensitivity reaction to allopurinol are very unlikely to experience one with febuxostat, and vice versa.

For patients who can’t reach the target serum urate with maximum-dose therapy, take heart: Second-line agents with impressive potency are well-along in the developmental pipeline.

Many labs now list the upper limit of normal for serum urate as 8 mg/dL or 8.5 mg/dL. Ignore that. This raised ceiling is simply the result of the changing demographics among the increasingly obese U.S. population in the last several decades. The definition of asymptomatic hyperuricemia remains unchanged: a serum urate greater than 6.8 mg/dL. And the target in patients with gout is still a serum urate less than 6 mg/dL. Merely dropping a gout patient’s urate from 10 to 8 or even 6.6 mg/dL isn’t doing any favors; the disease will continue to progress if the urate is above 6 mg/dL.

All gout is tophaceous. Even if tophi aren’t apparent on clinical examination, often they are radiographically. "This is a message that has to get out," Dr. Wortmann insisted.

Proposed American College of Rheumatology gout management guidelines call for starting urate-lowering drug therapy when a patient is experiencing three attacks per year. Dr. Wortmann takes issue with that.

"I would argue that once you’ve had a third attack of gout, period, you should be treated. Maybe even sooner. We need to prevent the erosion and bony destruction that occur with tophi," he said.

One audience member complained that his gout patients with comorbid renal insufficiency and/or cardiovascular disease often get caught in a revolving door. He titrates their allopurinol to an effective dose, but when they are later admitted to the hospital because of their comorbid condition the hospitalists, nephrologists, and/or cardiologists are shocked at the allopurinol dose and either reduce it or stop it altogether. The first that the rheumatologist learns of it is when patients reappear in his office with active gout. He then resumes their allopurinol at the previous dose, and they remain well controlled until the next hospitalization, when the same thing happens.

Dr. Wortmann responded that the solution requires convincing the nonrheumatologists in one-on-one conversation that urate-lowering therapy is not a one-size-fits-all matter. They need to understand that to get rid of gout, it’s necessary to drive the serum urate to the target of less than 6 mg/dL, and it helps to reassure them that that this will be accomplished using the lowest effective dose.

He reported serving as a consultant to Savient, Takeda, URL Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, and Ardea Biosciences.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – A disturbing proportion of gout cases are mismanaged by primary care physicians, and the blame falls squarely upon rheumatologists, according to one prominent gout expert.

"As rheumatologists, gout is our disease. The cause and pathophysiology are well understood, we can make the diagnosis with absolute certainty, and we’ve got great medicines. Yet today we all see people with tophi. That’s tragic. It shouldn’t exist. One of our biggest mistakes has been not being able to educate primary care physicians that having a tophus is bad, that it’s eroding cartilage and bone, and that it’s something we can prevent if we start urate-lowering therapy soon enough," Dr. Robert L. Wortmann said at the conference.

An estimated 8.3 million Americans have gout. Yet, the pharmaceutical industry says only 3.1 million of them are prescribed urate-lowering drugs. Five different studies show that a mere 40% of those on allopurinol are prescribed a dose sufficient to drive serum uric acid below 6 mg/dL, a key tenet of gout management, noted Dr. Wortmann, professor of medicine at Dartmouth Medical School in Hanover, N.H.

Moreover, poor treatment adherence is a huge problem in gout. A study of close to 4,200 gout patients started on urate-lowering drug therapy found that 56% of them were nonadherent (Arthritis Res. Ther. 2009;11(2):R46).

"I charge you all to go back from this meeting and try to communicate with all the primary care physicians you can about the principles of managing gout. People shouldn’t suffer from this," the rheumatologist declared.

He offered these major take home points:

Don’t prescribe urate-lowering drugs for asymptomatic hyperuricemia: This practice hasn’t been shown to prevent the future development of gout, yet it exposes patients to the risk of drug toxicities.

But don’t ignore asymptomatic hyperuricemia, either: Epidemiologic studies have linked asymptomatic hyperuricemia, defined by a serum urate in excess of 6.8 mg/dL, to increased risks of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and all-cause mortality. The big unanswered question is whether using medications to lower serum urate in individuals with asymptomatic hyperuricemia reduces the risk of any of these conditions. That’s the subject of ongoing large clinical trials in high-risk patients. If those studies prove positive, clinical practice will change.

While awaiting the outcome of the prevention trials, it’s worth bearing in mind that Framingham Heart Study data indicate that individuals with a serum uric acid level above 9 mg/dL have a 22% chance of developing gout within the next 5 years. The major contributors to asymptomatic hyperuricemia include obesity, metabolic syndrome, and heavy consumption of fructose-containing beverages or alcohol. Those issues should be addressed.

Losartan is the only antihypertensive agent that’s uricosuric. Fenofibrate is the sole uricosuric drug indicated for dyslipidemia. Preferential consideration could be given to the use of these drugs in hypertensive and/or hyperlipidemic patients with asymptomatic hyperuricemia.

The important thing is not which oral agent you use for treatment of acute gout, it’s to initiate therapy as early as possible, at the first hint of an attack. Colchicine, maximum-dose NSAIDs, and oral prednisone dosed at 20 mg BID until symptoms have been gone for 1 week followed by another week at 20 mg/day – they’re all effective. And since they work by different mechanisms, they can beneficially be combined in refractory patients.

The old-school colchicine dosing regimen most physicians were taught has been cast aside of late. It had a high rate of diarrhea, an inhumane side effect in gout patients hobbled by a foot too sore to walk on. The former regimen has been replaced by 1.2 mg, given in a single dose, followed by 0.6 mg 1 hour later.

"This lower dose is just as effective as the old high-dose regimen of two 0.6-mg pills given at once and then one per hour for the next 5 hours. And the lower-dose program has the same side effect profile as placebo," Dr. Wortmann said.

Get the gout patient’s serum urate below 6 mg/dL using the lowest effective dose of the urate-lowering drug you’ve selected. Physicians have traditionally started gout patients on allopurinol at the standard dose of 300 mg/day. Recently, it has been demonstrated that the risk of developing allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome is greatly reduced by starting off at 150 mg/day, checking the urate level 2 weeks later, then increasing to 300 mg/day if the serum urate isn’t below 6 mg/dL. After 2 weeks at 300 mg/day, check the urate again, and if it still isn’t below 6 mg/dL then bump the dose to 400 mg/day. Continue testing and titrating every 2 weeks until the serum urate is less than 6 mg/dL – and preferably less than 4 mg/dL if the patient has tophi – or until the maximum approved dose of 800 mg/day is reached.

The same start-low-and-titrate strategy applies to febuxostat, with a maximum approved dose of 80 mg/day.

"We have to educate primary care physicians to check the serum urate after starting therapy, and that, if it’s not below 6 mg/dL, they need to increase the dose. And if they don’t feel comfortable with that, they need to send the patient to us," the rheumatologist said.

Fortunately, patients who have a hypersensitivity reaction to allopurinol are very unlikely to experience one with febuxostat, and vice versa.

For patients who can’t reach the target serum urate with maximum-dose therapy, take heart: Second-line agents with impressive potency are well-along in the developmental pipeline.

Many labs now list the upper limit of normal for serum urate as 8 mg/dL or 8.5 mg/dL. Ignore that. This raised ceiling is simply the result of the changing demographics among the increasingly obese U.S. population in the last several decades. The definition of asymptomatic hyperuricemia remains unchanged: a serum urate greater than 6.8 mg/dL. And the target in patients with gout is still a serum urate less than 6 mg/dL. Merely dropping a gout patient’s urate from 10 to 8 or even 6.6 mg/dL isn’t doing any favors; the disease will continue to progress if the urate is above 6 mg/dL.

All gout is tophaceous. Even if tophi aren’t apparent on clinical examination, often they are radiographically. "This is a message that has to get out," Dr. Wortmann insisted.

Proposed American College of Rheumatology gout management guidelines call for starting urate-lowering drug therapy when a patient is experiencing three attacks per year. Dr. Wortmann takes issue with that.

"I would argue that once you’ve had a third attack of gout, period, you should be treated. Maybe even sooner. We need to prevent the erosion and bony destruction that occur with tophi," he said.

One audience member complained that his gout patients with comorbid renal insufficiency and/or cardiovascular disease often get caught in a revolving door. He titrates their allopurinol to an effective dose, but when they are later admitted to the hospital because of their comorbid condition the hospitalists, nephrologists, and/or cardiologists are shocked at the allopurinol dose and either reduce it or stop it altogether. The first that the rheumatologist learns of it is when patients reappear in his office with active gout. He then resumes their allopurinol at the previous dose, and they remain well controlled until the next hospitalization, when the same thing happens.

Dr. Wortmann responded that the solution requires convincing the nonrheumatologists in one-on-one conversation that urate-lowering therapy is not a one-size-fits-all matter. They need to understand that to get rid of gout, it’s necessary to drive the serum urate to the target of less than 6 mg/dL, and it helps to reassure them that that this will be accomplished using the lowest effective dose.

He reported serving as a consultant to Savient, Takeda, URL Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, and Ardea Biosciences.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – A disturbing proportion of gout cases are mismanaged by primary care physicians, and the blame falls squarely upon rheumatologists, according to one prominent gout expert.

"As rheumatologists, gout is our disease. The cause and pathophysiology are well understood, we can make the diagnosis with absolute certainty, and we’ve got great medicines. Yet today we all see people with tophi. That’s tragic. It shouldn’t exist. One of our biggest mistakes has been not being able to educate primary care physicians that having a tophus is bad, that it’s eroding cartilage and bone, and that it’s something we can prevent if we start urate-lowering therapy soon enough," Dr. Robert L. Wortmann said at the conference.

An estimated 8.3 million Americans have gout. Yet, the pharmaceutical industry says only 3.1 million of them are prescribed urate-lowering drugs. Five different studies show that a mere 40% of those on allopurinol are prescribed a dose sufficient to drive serum uric acid below 6 mg/dL, a key tenet of gout management, noted Dr. Wortmann, professor of medicine at Dartmouth Medical School in Hanover, N.H.

Moreover, poor treatment adherence is a huge problem in gout. A study of close to 4,200 gout patients started on urate-lowering drug therapy found that 56% of them were nonadherent (Arthritis Res. Ther. 2009;11(2):R46).

"I charge you all to go back from this meeting and try to communicate with all the primary care physicians you can about the principles of managing gout. People shouldn’t suffer from this," the rheumatologist declared.

He offered these major take home points:

Don’t prescribe urate-lowering drugs for asymptomatic hyperuricemia: This practice hasn’t been shown to prevent the future development of gout, yet it exposes patients to the risk of drug toxicities.

But don’t ignore asymptomatic hyperuricemia, either: Epidemiologic studies have linked asymptomatic hyperuricemia, defined by a serum urate in excess of 6.8 mg/dL, to increased risks of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and all-cause mortality. The big unanswered question is whether using medications to lower serum urate in individuals with asymptomatic hyperuricemia reduces the risk of any of these conditions. That’s the subject of ongoing large clinical trials in high-risk patients. If those studies prove positive, clinical practice will change.

While awaiting the outcome of the prevention trials, it’s worth bearing in mind that Framingham Heart Study data indicate that individuals with a serum uric acid level above 9 mg/dL have a 22% chance of developing gout within the next 5 years. The major contributors to asymptomatic hyperuricemia include obesity, metabolic syndrome, and heavy consumption of fructose-containing beverages or alcohol. Those issues should be addressed.

Losartan is the only antihypertensive agent that’s uricosuric. Fenofibrate is the sole uricosuric drug indicated for dyslipidemia. Preferential consideration could be given to the use of these drugs in hypertensive and/or hyperlipidemic patients with asymptomatic hyperuricemia.

The important thing is not which oral agent you use for treatment of acute gout, it’s to initiate therapy as early as possible, at the first hint of an attack. Colchicine, maximum-dose NSAIDs, and oral prednisone dosed at 20 mg BID until symptoms have been gone for 1 week followed by another week at 20 mg/day – they’re all effective. And since they work by different mechanisms, they can beneficially be combined in refractory patients.

The old-school colchicine dosing regimen most physicians were taught has been cast aside of late. It had a high rate of diarrhea, an inhumane side effect in gout patients hobbled by a foot too sore to walk on. The former regimen has been replaced by 1.2 mg, given in a single dose, followed by 0.6 mg 1 hour later.

"This lower dose is just as effective as the old high-dose regimen of two 0.6-mg pills given at once and then one per hour for the next 5 hours. And the lower-dose program has the same side effect profile as placebo," Dr. Wortmann said.

Get the gout patient’s serum urate below 6 mg/dL using the lowest effective dose of the urate-lowering drug you’ve selected. Physicians have traditionally started gout patients on allopurinol at the standard dose of 300 mg/day. Recently, it has been demonstrated that the risk of developing allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome is greatly reduced by starting off at 150 mg/day, checking the urate level 2 weeks later, then increasing to 300 mg/day if the serum urate isn’t below 6 mg/dL. After 2 weeks at 300 mg/day, check the urate again, and if it still isn’t below 6 mg/dL then bump the dose to 400 mg/day. Continue testing and titrating every 2 weeks until the serum urate is less than 6 mg/dL – and preferably less than 4 mg/dL if the patient has tophi – or until the maximum approved dose of 800 mg/day is reached.

The same start-low-and-titrate strategy applies to febuxostat, with a maximum approved dose of 80 mg/day.

"We have to educate primary care physicians to check the serum urate after starting therapy, and that, if it’s not below 6 mg/dL, they need to increase the dose. And if they don’t feel comfortable with that, they need to send the patient to us," the rheumatologist said.

Fortunately, patients who have a hypersensitivity reaction to allopurinol are very unlikely to experience one with febuxostat, and vice versa.

For patients who can’t reach the target serum urate with maximum-dose therapy, take heart: Second-line agents with impressive potency are well-along in the developmental pipeline.

Many labs now list the upper limit of normal for serum urate as 8 mg/dL or 8.5 mg/dL. Ignore that. This raised ceiling is simply the result of the changing demographics among the increasingly obese U.S. population in the last several decades. The definition of asymptomatic hyperuricemia remains unchanged: a serum urate greater than 6.8 mg/dL. And the target in patients with gout is still a serum urate less than 6 mg/dL. Merely dropping a gout patient’s urate from 10 to 8 or even 6.6 mg/dL isn’t doing any favors; the disease will continue to progress if the urate is above 6 mg/dL.

All gout is tophaceous. Even if tophi aren’t apparent on clinical examination, often they are radiographically. "This is a message that has to get out," Dr. Wortmann insisted.

Proposed American College of Rheumatology gout management guidelines call for starting urate-lowering drug therapy when a patient is experiencing three attacks per year. Dr. Wortmann takes issue with that.

"I would argue that once you’ve had a third attack of gout, period, you should be treated. Maybe even sooner. We need to prevent the erosion and bony destruction that occur with tophi," he said.

One audience member complained that his gout patients with comorbid renal insufficiency and/or cardiovascular disease often get caught in a revolving door. He titrates their allopurinol to an effective dose, but when they are later admitted to the hospital because of their comorbid condition the hospitalists, nephrologists, and/or cardiologists are shocked at the allopurinol dose and either reduce it or stop it altogether. The first that the rheumatologist learns of it is when patients reappear in his office with active gout. He then resumes their allopurinol at the previous dose, and they remain well controlled until the next hospitalization, when the same thing happens.

Dr. Wortmann responded that the solution requires convincing the nonrheumatologists in one-on-one conversation that urate-lowering therapy is not a one-size-fits-all matter. They need to understand that to get rid of gout, it’s necessary to drive the serum urate to the target of less than 6 mg/dL, and it helps to reassure them that that this will be accomplished using the lowest effective dose.

He reported serving as a consultant to Savient, Takeda, URL Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, and Ardea Biosciences.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A SYMPOSIUM SPONSORED BY THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF RHEUMATOLOGY

Obesity Epidemic Is Skewing Face of Gout

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The epidemiology of gout has changed considerably in the past several decades, rendering treatment more challenging.

For example, today fully 21.4% of all U.S. adults are hyperuricemic as defined by a serum uric acid in excess of 6.8 mg/dL.

"When I was a fellow it was 5%. There’s a lot more uric acid in the world today," Dr. Robert L. Wortmann observed at the symposium.

Major contributing factors include metabolic syndrome, the obesity epidemic, increased consumption of high-fructose drinks and processed foods, and alcohol. Liquor has a twofold stronger urate-boosting effect than does wine, and beer’s impact is fourfold greater than wine, according to Dr. Wortmann, professor of medicine at Dartmouth Medical School in Hanover, N.H.

"When I was in training uric acids above 9 mg/dL weren’t common; now, when I see a newly diagnosed gout patient with a uric acid level below 9, it’s exceptional. Gout patients today have uric acids of 10, 11, and 12 mg/dL as opposed to 7.5, 8, and 9 in decades past," he said.

Since 1964 the standard dose of allopurinol has been 300 mg/day. Back then, that was sufficient to reach the serum uric acid target of less than 6.0 mg/dL in about 90% of gout patients. Today, 300 mg/day gets only about 40% of patients to target, as has been shown in numerous studies.

Dr. Wortmann reported serving as a consultant to Ardea Biosciences, Novartis, Savient, Takeda, and URL Pharmaceuticals.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The epidemiology of gout has changed considerably in the past several decades, rendering treatment more challenging.

For example, today fully 21.4% of all U.S. adults are hyperuricemic as defined by a serum uric acid in excess of 6.8 mg/dL.

"When I was a fellow it was 5%. There’s a lot more uric acid in the world today," Dr. Robert L. Wortmann observed at the symposium.

Major contributing factors include metabolic syndrome, the obesity epidemic, increased consumption of high-fructose drinks and processed foods, and alcohol. Liquor has a twofold stronger urate-boosting effect than does wine, and beer’s impact is fourfold greater than wine, according to Dr. Wortmann, professor of medicine at Dartmouth Medical School in Hanover, N.H.

"When I was in training uric acids above 9 mg/dL weren’t common; now, when I see a newly diagnosed gout patient with a uric acid level below 9, it’s exceptional. Gout patients today have uric acids of 10, 11, and 12 mg/dL as opposed to 7.5, 8, and 9 in decades past," he said.

Since 1964 the standard dose of allopurinol has been 300 mg/day. Back then, that was sufficient to reach the serum uric acid target of less than 6.0 mg/dL in about 90% of gout patients. Today, 300 mg/day gets only about 40% of patients to target, as has been shown in numerous studies.

Dr. Wortmann reported serving as a consultant to Ardea Biosciences, Novartis, Savient, Takeda, and URL Pharmaceuticals.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The epidemiology of gout has changed considerably in the past several decades, rendering treatment more challenging.

For example, today fully 21.4% of all U.S. adults are hyperuricemic as defined by a serum uric acid in excess of 6.8 mg/dL.

"When I was a fellow it was 5%. There’s a lot more uric acid in the world today," Dr. Robert L. Wortmann observed at the symposium.

Major contributing factors include metabolic syndrome, the obesity epidemic, increased consumption of high-fructose drinks and processed foods, and alcohol. Liquor has a twofold stronger urate-boosting effect than does wine, and beer’s impact is fourfold greater than wine, according to Dr. Wortmann, professor of medicine at Dartmouth Medical School in Hanover, N.H.

"When I was in training uric acids above 9 mg/dL weren’t common; now, when I see a newly diagnosed gout patient with a uric acid level below 9, it’s exceptional. Gout patients today have uric acids of 10, 11, and 12 mg/dL as opposed to 7.5, 8, and 9 in decades past," he said.

Since 1964 the standard dose of allopurinol has been 300 mg/day. Back then, that was sufficient to reach the serum uric acid target of less than 6.0 mg/dL in about 90% of gout patients. Today, 300 mg/day gets only about 40% of patients to target, as has been shown in numerous studies.

Dr. Wortmann reported serving as a consultant to Ardea Biosciences, Novartis, Savient, Takeda, and URL Pharmaceuticals.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A SYMPOSIUM SPONSORED BY THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF RHEUMATOLOGY

Spot Lumbar Spinal Stenosis From Across the Room

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Patients with lumbar spinal stenosis display a distinctive gait and posture that are of great assistance in diagnosing this common low back/leg pain syndrome.

"I find that in the supermarket I can identify persons with symptomatic lumbar stenosis because they lean forward on the cart and have a characteristic wide-based gait. The gait reflects poor balance. In essence the feet are not communicating effectively with the brain because of compression of proprioceptive fibers," Dr. Jeffrey N. Katz explained at the meeting.

The clinical syndrome of lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) requires both the appropriate clinical picture and the radiographic finding of lumbar spinal canal narrowing on cross-sectional imaging. The radiographic narrowing typically is caused by three pathoanatomic abnormalities occurring together: thickening of the normally paper-thin ligamentum flavum, facet joint osteoarthritis, and disc protrusion.

Radiographic evidence of lumbar spinal canal narrowing is necessary but not sufficient to diagnose the clinical syndrome of LSS. That’s because many individuals with anatomic stenosis don’t have the signs and symptoms of LSS, much as MRI studies have shown that a herniated lumbar disc is present in close to one-third of asymptomatic individuals, according to Dr. Katz, professor of medicine, orthopedic surgery, and epidemiology at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

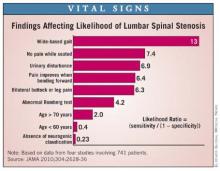

The clinical history and physical examination are invaluable in helping establish the diagnosis of LSS. Dr. Katz and coworkers analyzed data from four published studies involving 741 patients with radiographic evidence of anatomic stenosis to generate a list of predictors of increased likelihood of the syndrome of LSS in an individual patient (JAMA 2010;304:2628-36).

This analysis showed that among the most useful findings for ruling in the diagnosis are a wide-based gait, which confers a likelihood ratio of 13; lack of pain when seated, with an associated likelihood ratio of 7.4; and improvement of symptoms when bending forward, with a likelihood ratio of 6.4.