User login

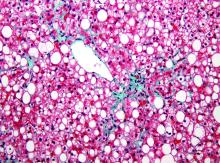

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease accelerates brain aging

TORONTO – Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease seems to accelerate physical brain aging by up to 7 years, according to a new subanalysis of the ongoing Framingham Heart Study.

However, while finding that the liver disorder directly endangers brains, the study also offers hope, Galit Weinstein, PhD, said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2016. “If indeed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is a risk factor for brain aging and subsequent dementia, then it is a modifiable one,” said Dr. Weinstein of Boston University. “We have reason to hope that NAFLD remission could possibly improve cognitive outcomes” as patients age.

For this study, the researchers assessed the presence of NAFLD by abdominal CT scans and white-matter hyperintensities and brain volume (total, frontal, and hippocampal) by MRI. The resulting associations were then adjusted for age, sex, alcohol consumption, visceral adipose tissue, body mass index, menopausal status, systolic blood pressure, current smoking, diabetes, history of cardiovascular disease, physical activity, insulin resistance, and C-reactive protein.

There were no significant associations with white-matter hyperintensities or with hippocampal volume, but the researches did find a significant association with total brain volume: Even after adjustment for all of the covariates, patients with NAFLD had smaller-than-normal brains for their age. This can be seen as a pathologic acceleration of the brain aging process, Dr. Weinstein said.

The finding was most striking among the youngest subjects, she said, accounting for about a 7-year advance in brain aging for those younger than 60 years. Older patients with NAFLD showed about a 2-year advance in brain aging.

The effect is probably mediated by the liver’s complex interplay in metabolism and vascular functions, Dr. Weinstein said.

She had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

TORONTO – Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease seems to accelerate physical brain aging by up to 7 years, according to a new subanalysis of the ongoing Framingham Heart Study.

However, while finding that the liver disorder directly endangers brains, the study also offers hope, Galit Weinstein, PhD, said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2016. “If indeed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is a risk factor for brain aging and subsequent dementia, then it is a modifiable one,” said Dr. Weinstein of Boston University. “We have reason to hope that NAFLD remission could possibly improve cognitive outcomes” as patients age.

For this study, the researchers assessed the presence of NAFLD by abdominal CT scans and white-matter hyperintensities and brain volume (total, frontal, and hippocampal) by MRI. The resulting associations were then adjusted for age, sex, alcohol consumption, visceral adipose tissue, body mass index, menopausal status, systolic blood pressure, current smoking, diabetes, history of cardiovascular disease, physical activity, insulin resistance, and C-reactive protein.

There were no significant associations with white-matter hyperintensities or with hippocampal volume, but the researches did find a significant association with total brain volume: Even after adjustment for all of the covariates, patients with NAFLD had smaller-than-normal brains for their age. This can be seen as a pathologic acceleration of the brain aging process, Dr. Weinstein said.

The finding was most striking among the youngest subjects, she said, accounting for about a 7-year advance in brain aging for those younger than 60 years. Older patients with NAFLD showed about a 2-year advance in brain aging.

The effect is probably mediated by the liver’s complex interplay in metabolism and vascular functions, Dr. Weinstein said.

She had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

TORONTO – Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease seems to accelerate physical brain aging by up to 7 years, according to a new subanalysis of the ongoing Framingham Heart Study.

However, while finding that the liver disorder directly endangers brains, the study also offers hope, Galit Weinstein, PhD, said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2016. “If indeed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is a risk factor for brain aging and subsequent dementia, then it is a modifiable one,” said Dr. Weinstein of Boston University. “We have reason to hope that NAFLD remission could possibly improve cognitive outcomes” as patients age.

For this study, the researchers assessed the presence of NAFLD by abdominal CT scans and white-matter hyperintensities and brain volume (total, frontal, and hippocampal) by MRI. The resulting associations were then adjusted for age, sex, alcohol consumption, visceral adipose tissue, body mass index, menopausal status, systolic blood pressure, current smoking, diabetes, history of cardiovascular disease, physical activity, insulin resistance, and C-reactive protein.

There were no significant associations with white-matter hyperintensities or with hippocampal volume, but the researches did find a significant association with total brain volume: Even after adjustment for all of the covariates, patients with NAFLD had smaller-than-normal brains for their age. This can be seen as a pathologic acceleration of the brain aging process, Dr. Weinstein said.

The finding was most striking among the youngest subjects, she said, accounting for about a 7-year advance in brain aging for those younger than 60 years. Older patients with NAFLD showed about a 2-year advance in brain aging.

The effect is probably mediated by the liver’s complex interplay in metabolism and vascular functions, Dr. Weinstein said.

She had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

AT AAIC 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: NAFLD was associated with a 7-year advance in brain aging in people younger than 60 years.

Data source: An analysis of 906 members of the Framingham Offspring Cohort.

Disclosures: Dr. Weinstein had no financial declarations.

Amyloid pathology associated with neuropsychiatric symptoms in MCI

TORONTO – Patients with mild cognitive impairment have a greater likelihood of having neuropsychiatric symptoms if they test positive for amyloid pathology on PET imaging, according to a study of patients in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative.

Amyloid-positive patients were significantly more likely to develop agitation, anxiety, apathy, and other symptoms over 4 years than were amyloid-negative patients, Naira Goukasian said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2016.

“In MCI [mild cognitive impairment], we found that amyloid pathology was a significant risk factor for developing these symptoms,” said Ms. Goukasian, a researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles.

She investigated the presence and development of neuropsychiatric symptoms in 1,077 subjects drawn from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) cohort. The cohort comprised 275 cognitively normal subjects, 100 with subjective memory complaint, 559 with MCI, and 143 with Alzheimer’s disease. As part of ADNI, all patients had baseline neurocognitive and neuropsychiatric testing, and florbetapir F 18 (Amyvid) scans to determine brain amyloid status. Neuropsychiatric symptoms were measured with the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q) at baseline and during every annual visit. Patients were followed for up to 4 years.

At baseline, amyloid pathology was associated with some neuropsychiatric symptomatology in every group except those with subjective memory complaints.

Amyloid-positive control subjects were significantly more likely to present with depression than were amyloid-negative controls. Amyloid-positive MCI patients were significantly more likely to present with anxiety when they had amyloid pathology than when they did not. Amyloid-positive dementia patients were significantly more likely to present with apathy than were amyloid-negative dementia patients.

There were no amyloid-dependent differences in neuropsychiatric symptoms among those with subjective memory complaints.

Over the 4-year follow-up period, no new neuropsychiatric symptoms developed in the control, subjective memory complaint, or dementia groups, whether they were amyloid positive or negative.

Amyloid-positive MCI patients, however, were significantly more likely to develop new symptoms than were amyloid-negative MCI patients, including delusions (13% vs. 2%), hallucinations (8% vs. 2%), anxiety (36% vs. 25%), apathy (38% vs. 22%), agitation (36% vs. 27%), disinhibition (24% vs. 15%), irritability (46% vs. 33%), and motor disturbances (18% vs. 9%).

Ms. Goukasian did not elaborate on the pathophysiologic relationship between amyloid and these symptoms. However, a 2015 study using a similar ADNI cohort localized some of them to specific amyloid-burdened brain regions (J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;49[2]:387-98).

The study by David Bensamoun, MD, and colleagues comprised 657 ADNI participants (230 controls, 308 MCI patients, and 119 Alzheimer’s patients).

In the entire group, Dr. Bensamoun, of the Regional Memory Center, Nice, France, found positive significant correlations between anxiety and global cerebral florbetapir F 18 uptake, as well as uptake in the frontal and cingulate regions. Irritability was associated with global florbetapir F 18 uptake and increased signal in the frontal, cingulate, and parietal regions.

In the MCI subgroup, there was an association between anxiety and frontal and global cerebral uptake. In the Alzheimer’s subgroup, there was an association between irritability and parietal uptake.

“Anxiety and irritability appear to be associated with greater amyloid deposition in the neurodegenerative process leading to Alzheimer’s,” the investigators said.

Ms. Goukasian had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @alz_gal

TORONTO – Patients with mild cognitive impairment have a greater likelihood of having neuropsychiatric symptoms if they test positive for amyloid pathology on PET imaging, according to a study of patients in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative.

Amyloid-positive patients were significantly more likely to develop agitation, anxiety, apathy, and other symptoms over 4 years than were amyloid-negative patients, Naira Goukasian said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2016.

“In MCI [mild cognitive impairment], we found that amyloid pathology was a significant risk factor for developing these symptoms,” said Ms. Goukasian, a researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles.

She investigated the presence and development of neuropsychiatric symptoms in 1,077 subjects drawn from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) cohort. The cohort comprised 275 cognitively normal subjects, 100 with subjective memory complaint, 559 with MCI, and 143 with Alzheimer’s disease. As part of ADNI, all patients had baseline neurocognitive and neuropsychiatric testing, and florbetapir F 18 (Amyvid) scans to determine brain amyloid status. Neuropsychiatric symptoms were measured with the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q) at baseline and during every annual visit. Patients were followed for up to 4 years.

At baseline, amyloid pathology was associated with some neuropsychiatric symptomatology in every group except those with subjective memory complaints.

Amyloid-positive control subjects were significantly more likely to present with depression than were amyloid-negative controls. Amyloid-positive MCI patients were significantly more likely to present with anxiety when they had amyloid pathology than when they did not. Amyloid-positive dementia patients were significantly more likely to present with apathy than were amyloid-negative dementia patients.

There were no amyloid-dependent differences in neuropsychiatric symptoms among those with subjective memory complaints.

Over the 4-year follow-up period, no new neuropsychiatric symptoms developed in the control, subjective memory complaint, or dementia groups, whether they were amyloid positive or negative.

Amyloid-positive MCI patients, however, were significantly more likely to develop new symptoms than were amyloid-negative MCI patients, including delusions (13% vs. 2%), hallucinations (8% vs. 2%), anxiety (36% vs. 25%), apathy (38% vs. 22%), agitation (36% vs. 27%), disinhibition (24% vs. 15%), irritability (46% vs. 33%), and motor disturbances (18% vs. 9%).

Ms. Goukasian did not elaborate on the pathophysiologic relationship between amyloid and these symptoms. However, a 2015 study using a similar ADNI cohort localized some of them to specific amyloid-burdened brain regions (J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;49[2]:387-98).

The study by David Bensamoun, MD, and colleagues comprised 657 ADNI participants (230 controls, 308 MCI patients, and 119 Alzheimer’s patients).

In the entire group, Dr. Bensamoun, of the Regional Memory Center, Nice, France, found positive significant correlations between anxiety and global cerebral florbetapir F 18 uptake, as well as uptake in the frontal and cingulate regions. Irritability was associated with global florbetapir F 18 uptake and increased signal in the frontal, cingulate, and parietal regions.

In the MCI subgroup, there was an association between anxiety and frontal and global cerebral uptake. In the Alzheimer’s subgroup, there was an association between irritability and parietal uptake.

“Anxiety and irritability appear to be associated with greater amyloid deposition in the neurodegenerative process leading to Alzheimer’s,” the investigators said.

Ms. Goukasian had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @alz_gal

TORONTO – Patients with mild cognitive impairment have a greater likelihood of having neuropsychiatric symptoms if they test positive for amyloid pathology on PET imaging, according to a study of patients in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative.

Amyloid-positive patients were significantly more likely to develop agitation, anxiety, apathy, and other symptoms over 4 years than were amyloid-negative patients, Naira Goukasian said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2016.

“In MCI [mild cognitive impairment], we found that amyloid pathology was a significant risk factor for developing these symptoms,” said Ms. Goukasian, a researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles.

She investigated the presence and development of neuropsychiatric symptoms in 1,077 subjects drawn from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) cohort. The cohort comprised 275 cognitively normal subjects, 100 with subjective memory complaint, 559 with MCI, and 143 with Alzheimer’s disease. As part of ADNI, all patients had baseline neurocognitive and neuropsychiatric testing, and florbetapir F 18 (Amyvid) scans to determine brain amyloid status. Neuropsychiatric symptoms were measured with the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q) at baseline and during every annual visit. Patients were followed for up to 4 years.

At baseline, amyloid pathology was associated with some neuropsychiatric symptomatology in every group except those with subjective memory complaints.

Amyloid-positive control subjects were significantly more likely to present with depression than were amyloid-negative controls. Amyloid-positive MCI patients were significantly more likely to present with anxiety when they had amyloid pathology than when they did not. Amyloid-positive dementia patients were significantly more likely to present with apathy than were amyloid-negative dementia patients.

There were no amyloid-dependent differences in neuropsychiatric symptoms among those with subjective memory complaints.

Over the 4-year follow-up period, no new neuropsychiatric symptoms developed in the control, subjective memory complaint, or dementia groups, whether they were amyloid positive or negative.

Amyloid-positive MCI patients, however, were significantly more likely to develop new symptoms than were amyloid-negative MCI patients, including delusions (13% vs. 2%), hallucinations (8% vs. 2%), anxiety (36% vs. 25%), apathy (38% vs. 22%), agitation (36% vs. 27%), disinhibition (24% vs. 15%), irritability (46% vs. 33%), and motor disturbances (18% vs. 9%).

Ms. Goukasian did not elaborate on the pathophysiologic relationship between amyloid and these symptoms. However, a 2015 study using a similar ADNI cohort localized some of them to specific amyloid-burdened brain regions (J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;49[2]:387-98).

The study by David Bensamoun, MD, and colleagues comprised 657 ADNI participants (230 controls, 308 MCI patients, and 119 Alzheimer’s patients).

In the entire group, Dr. Bensamoun, of the Regional Memory Center, Nice, France, found positive significant correlations between anxiety and global cerebral florbetapir F 18 uptake, as well as uptake in the frontal and cingulate regions. Irritability was associated with global florbetapir F 18 uptake and increased signal in the frontal, cingulate, and parietal regions.

In the MCI subgroup, there was an association between anxiety and frontal and global cerebral uptake. In the Alzheimer’s subgroup, there was an association between irritability and parietal uptake.

“Anxiety and irritability appear to be associated with greater amyloid deposition in the neurodegenerative process leading to Alzheimer’s,” the investigators said.

Ms. Goukasian had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT AAIC 2016

Key clinical point: Amyloid pathology is a risk factor for neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment.

Major finding: Amyloid-positive patients with MCI were more likely than were amyloid-negative patients to develop anxiety (36% vs. 25%), apathy (38% vs. 22%), agitation (36% vs. 27%), and other symptoms.

Data source: The study comprised 1,077 patients drawn from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative.

Disclosures: Ms. Goukasian had no financial disclosures.

VIDEO: Withdrawing antipsychotics is safe and feasible in long-term care

TORONTO – Antipsychotics can be safely withdrawn from many dementia patients in long-term care facilities, two new studies from Australia and Canada have determined.

When the drugs were withdrawn and supplanted with behavior-centered care in the Australian study, 80% of patients experienced no relapse of symptoms, Henry Brodaty, MD, DSc, said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2016.

“We saw no significant changes at all in agitation, aggression, delusions, or hallucinations,” Dr. Brodaty, the Scientia Professor of Ageing and Mental Health, University of New South Wales, Australia, said in an interview. “Were we surprised at this? No. Because for the majority of these patients, the medications were inappropriately prescribed.”

The 12-month Australian study is still in the process of tracking outcomes after antipsychotic withdrawal. But the Canadian study found great benefits, said Selma Didic, an improvement analyst with the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement in Ottawa. “We saw falls decrease by 20%. The incidence of verbal abuse and socially disruptive behavior actually decreased as well.”

In fact, she said, patients who discontinued the medications actually started behaving better than the comparator group that stayed on them.

The Australian experience

Dr. Brodaty discussed the HALT (Halting Antipsychotic Use in Long-Term Care) study. HALT is a single-arm, 12-month longitudinal study carried out in 23 nursing homes in New South Wales.

The study team worked with nursing leadership in each facility to identify patients who might be eligible for the program. In order to enroll, each patient’s family and general physician had to agree to a trial of deprescribing. Physicians were instructed to wean patients off the medication by decreasing the dose by half once a week. Most patients were able to stop within a couple of weeks, Dr. Brodaty said.

Getting buy-in wasn’t always easy, he noted. “Some families didn’t want to rock the boat, and some physicians were resistant,” to the idea. Overall, “Families and nurses were very, very worried” about the prospect of dropping drugs that were seen as helpful in everyday patient management.

But getting rid of the medications was just half the picture. Training nurses and care staff to intervene in problematic behaviors without resorting to drugs was just as important. A nurse-leader at each facility received training in person-centered care, and then trained the rest of the staff. This wasn’t always an easy idea to embrace, either, Dr. Brodaty said, especially since nursing staff often leads the discussion about the need for drugs to manage behavioral problems.

“Nursing staff are very task oriented, focused on dressing, bathing, eating, and toileting. They work very hard, and they don’t always have time to sit down and talk to resistant patients. It takes a much different attitude to show that you can actually save time by spending time and engaging the patient.”

He related one of his favorite illustrative stories – the milkman who caused a ruckus at bath time. “He got upset and aggressive every night when being put to bed and every morning when being given a shower. The staff spoke to his wife about it. She said that for 40 years, he was accustomed to getting up at 4 a.m. to deliver the milk. He would take a bath at night and get on his track suit and go to bed. Then at 4 a.m., he would get up and be ready to jump in the truck and go.”

When the staff started letting him shower at night and go to bed in his track suit, the milkman’s behavior improved without the need for antipsychotic medications.

“This is what we mean by ‘person-centered care,’ ” Dr. Brodaty said. “We use the ABC paradigm: Addressing the antecedent to the behavior, then the behavior, and then the consequences of the behavior.”

The intervention cohort comprised 139 patients with a mean age of 85 years; most were women. The vast majority (93%) had a diagnosis of dementia. About one-third had Alzheimer’s and one-third vascular dementia. The remainder had other diagnoses, including frontotemporal dementia, Lewy body dementia, and Parkinson’s disease. Common comorbid conditions included depression (56%) and previous stroke (36%). None of the patients had a diagnosis of psychosis.

Risperidone was the most common antipsychotic medication (85%). Other medications were olanzapine, quetiapine, and haloperidol. About 30% had come to the facility on the medication; the others had received it since admission.

Despite the national recommendation to review antipsychotic use every 12 weeks, patients had been on their current antipsychotic for an average of 2 years, and on their current dose for 1 year. In reviewing medications, Dr. Brodaty also found a “concerning” lack of informed consent. In Australia, informed consent for antipsychotic drugs can be given by a family member, but 84% of patients had no documented consent at all.

Of the original group, 125 entered the deprescribing protocol. Of these, 26 (21%) have since resumed their medications, but 79% have done well and are without a relapse of their symptoms or problematic behaviors. An ongoing medication review suggests there has been no concomitant upswing in other psychotropic medications, including benzodiazepines.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms remained stable from baseline. The mean total group score on the Neuropsychiatric Index (NPI) has not changed from its baseline of 30. The mean agitation/aggression NPI subscale has remained about 6, and the mean group score on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory about 56. The NPI delusion subscale increased, but the change was nonsignificant, Dr. Brodaty said. The NPI hallucinations subscale decreased slightly, but again the change was nonsignificant.

“Look, we all know antipsychotics are bad for old people, and we all know they are overprescribed,” he said. “Inappropriate use of these medications is an old story, yet we’re still talking about it. Why is this? We have the knowledge now, and we have to build on this knowledge so that we can change practice.”

The Canadian experience

Ms. Didic shared a year-long quality improvement process at 24 long-term care facilities that wanted to improve antipsychotic prescribing for their dementia patients.

The program, which was sponsored by the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement, used a “train-the-trainer” approach to spread support for antipsychotic deprescribing.

The foundation deployed 15 interdisciplinary teams, which comprised 180 members, including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, recreational therapists, and “clinical champions” who took the methodology directly into participating facilities. Interactive webinars on patient-centered care and deprescribing protocols were part of the process, Ms. Didic said.

In all, 416 patients were included in the outcomes report. Within 12 months, antipsychotics were eliminated in 74 patients (18%) and in 148 (36%), the dosage was reduced.

The benefits of these changes were striking, Ms. Didic said. There were fewer falls and reductions in verbal abuse, care resistance, and socially inappropriate behaviors. These issues either remained the same or got worse in patients who did not decrease antipsychotics. Again, there was no concomitant increase in other psychotropic medications.

The results show that changing the focus from medication-first to behavior-first care is institutionally feasible, Ms. Didic said.

Staff members’ assessments of the program and its personal and institutional impact were positive:

• 91% said they instituted regular medication reviews for every resident.

• 92% said old ways of doing things were adjusted to accommodate the new type of care.

• 94% said the new person-centered care was now a standard way of working.

• 84% said the project improved their ability to lead.

• 80% said it improved their ability to communicate.

“Currently, our teams are now spreading and sharing these resources and tools, serving as advisers, and organizing clinical training and workshops,” for other Canadian nursing homes that want to adopt the strategy.

Dr. Richard Caselli, professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., commented on the issues surrounding antipsychotic prescribing in long-term care facilities in a video interview.

Neither Ms. Didic nor Dr. Brodaty had any financial declarations.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @alz_gal

TORONTO – Antipsychotics can be safely withdrawn from many dementia patients in long-term care facilities, two new studies from Australia and Canada have determined.

When the drugs were withdrawn and supplanted with behavior-centered care in the Australian study, 80% of patients experienced no relapse of symptoms, Henry Brodaty, MD, DSc, said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2016.

“We saw no significant changes at all in agitation, aggression, delusions, or hallucinations,” Dr. Brodaty, the Scientia Professor of Ageing and Mental Health, University of New South Wales, Australia, said in an interview. “Were we surprised at this? No. Because for the majority of these patients, the medications were inappropriately prescribed.”

The 12-month Australian study is still in the process of tracking outcomes after antipsychotic withdrawal. But the Canadian study found great benefits, said Selma Didic, an improvement analyst with the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement in Ottawa. “We saw falls decrease by 20%. The incidence of verbal abuse and socially disruptive behavior actually decreased as well.”

In fact, she said, patients who discontinued the medications actually started behaving better than the comparator group that stayed on them.

The Australian experience

Dr. Brodaty discussed the HALT (Halting Antipsychotic Use in Long-Term Care) study. HALT is a single-arm, 12-month longitudinal study carried out in 23 nursing homes in New South Wales.

The study team worked with nursing leadership in each facility to identify patients who might be eligible for the program. In order to enroll, each patient’s family and general physician had to agree to a trial of deprescribing. Physicians were instructed to wean patients off the medication by decreasing the dose by half once a week. Most patients were able to stop within a couple of weeks, Dr. Brodaty said.

Getting buy-in wasn’t always easy, he noted. “Some families didn’t want to rock the boat, and some physicians were resistant,” to the idea. Overall, “Families and nurses were very, very worried” about the prospect of dropping drugs that were seen as helpful in everyday patient management.

But getting rid of the medications was just half the picture. Training nurses and care staff to intervene in problematic behaviors without resorting to drugs was just as important. A nurse-leader at each facility received training in person-centered care, and then trained the rest of the staff. This wasn’t always an easy idea to embrace, either, Dr. Brodaty said, especially since nursing staff often leads the discussion about the need for drugs to manage behavioral problems.

“Nursing staff are very task oriented, focused on dressing, bathing, eating, and toileting. They work very hard, and they don’t always have time to sit down and talk to resistant patients. It takes a much different attitude to show that you can actually save time by spending time and engaging the patient.”

He related one of his favorite illustrative stories – the milkman who caused a ruckus at bath time. “He got upset and aggressive every night when being put to bed and every morning when being given a shower. The staff spoke to his wife about it. She said that for 40 years, he was accustomed to getting up at 4 a.m. to deliver the milk. He would take a bath at night and get on his track suit and go to bed. Then at 4 a.m., he would get up and be ready to jump in the truck and go.”

When the staff started letting him shower at night and go to bed in his track suit, the milkman’s behavior improved without the need for antipsychotic medications.

“This is what we mean by ‘person-centered care,’ ” Dr. Brodaty said. “We use the ABC paradigm: Addressing the antecedent to the behavior, then the behavior, and then the consequences of the behavior.”

The intervention cohort comprised 139 patients with a mean age of 85 years; most were women. The vast majority (93%) had a diagnosis of dementia. About one-third had Alzheimer’s and one-third vascular dementia. The remainder had other diagnoses, including frontotemporal dementia, Lewy body dementia, and Parkinson’s disease. Common comorbid conditions included depression (56%) and previous stroke (36%). None of the patients had a diagnosis of psychosis.

Risperidone was the most common antipsychotic medication (85%). Other medications were olanzapine, quetiapine, and haloperidol. About 30% had come to the facility on the medication; the others had received it since admission.

Despite the national recommendation to review antipsychotic use every 12 weeks, patients had been on their current antipsychotic for an average of 2 years, and on their current dose for 1 year. In reviewing medications, Dr. Brodaty also found a “concerning” lack of informed consent. In Australia, informed consent for antipsychotic drugs can be given by a family member, but 84% of patients had no documented consent at all.

Of the original group, 125 entered the deprescribing protocol. Of these, 26 (21%) have since resumed their medications, but 79% have done well and are without a relapse of their symptoms or problematic behaviors. An ongoing medication review suggests there has been no concomitant upswing in other psychotropic medications, including benzodiazepines.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms remained stable from baseline. The mean total group score on the Neuropsychiatric Index (NPI) has not changed from its baseline of 30. The mean agitation/aggression NPI subscale has remained about 6, and the mean group score on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory about 56. The NPI delusion subscale increased, but the change was nonsignificant, Dr. Brodaty said. The NPI hallucinations subscale decreased slightly, but again the change was nonsignificant.

“Look, we all know antipsychotics are bad for old people, and we all know they are overprescribed,” he said. “Inappropriate use of these medications is an old story, yet we’re still talking about it. Why is this? We have the knowledge now, and we have to build on this knowledge so that we can change practice.”

The Canadian experience

Ms. Didic shared a year-long quality improvement process at 24 long-term care facilities that wanted to improve antipsychotic prescribing for their dementia patients.

The program, which was sponsored by the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement, used a “train-the-trainer” approach to spread support for antipsychotic deprescribing.

The foundation deployed 15 interdisciplinary teams, which comprised 180 members, including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, recreational therapists, and “clinical champions” who took the methodology directly into participating facilities. Interactive webinars on patient-centered care and deprescribing protocols were part of the process, Ms. Didic said.

In all, 416 patients were included in the outcomes report. Within 12 months, antipsychotics were eliminated in 74 patients (18%) and in 148 (36%), the dosage was reduced.

The benefits of these changes were striking, Ms. Didic said. There were fewer falls and reductions in verbal abuse, care resistance, and socially inappropriate behaviors. These issues either remained the same or got worse in patients who did not decrease antipsychotics. Again, there was no concomitant increase in other psychotropic medications.

The results show that changing the focus from medication-first to behavior-first care is institutionally feasible, Ms. Didic said.

Staff members’ assessments of the program and its personal and institutional impact were positive:

• 91% said they instituted regular medication reviews for every resident.

• 92% said old ways of doing things were adjusted to accommodate the new type of care.

• 94% said the new person-centered care was now a standard way of working.

• 84% said the project improved their ability to lead.

• 80% said it improved their ability to communicate.

“Currently, our teams are now spreading and sharing these resources and tools, serving as advisers, and organizing clinical training and workshops,” for other Canadian nursing homes that want to adopt the strategy.

Dr. Richard Caselli, professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., commented on the issues surrounding antipsychotic prescribing in long-term care facilities in a video interview.

Neither Ms. Didic nor Dr. Brodaty had any financial declarations.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @alz_gal

TORONTO – Antipsychotics can be safely withdrawn from many dementia patients in long-term care facilities, two new studies from Australia and Canada have determined.

When the drugs were withdrawn and supplanted with behavior-centered care in the Australian study, 80% of patients experienced no relapse of symptoms, Henry Brodaty, MD, DSc, said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2016.

“We saw no significant changes at all in agitation, aggression, delusions, or hallucinations,” Dr. Brodaty, the Scientia Professor of Ageing and Mental Health, University of New South Wales, Australia, said in an interview. “Were we surprised at this? No. Because for the majority of these patients, the medications were inappropriately prescribed.”

The 12-month Australian study is still in the process of tracking outcomes after antipsychotic withdrawal. But the Canadian study found great benefits, said Selma Didic, an improvement analyst with the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement in Ottawa. “We saw falls decrease by 20%. The incidence of verbal abuse and socially disruptive behavior actually decreased as well.”

In fact, she said, patients who discontinued the medications actually started behaving better than the comparator group that stayed on them.

The Australian experience

Dr. Brodaty discussed the HALT (Halting Antipsychotic Use in Long-Term Care) study. HALT is a single-arm, 12-month longitudinal study carried out in 23 nursing homes in New South Wales.

The study team worked with nursing leadership in each facility to identify patients who might be eligible for the program. In order to enroll, each patient’s family and general physician had to agree to a trial of deprescribing. Physicians were instructed to wean patients off the medication by decreasing the dose by half once a week. Most patients were able to stop within a couple of weeks, Dr. Brodaty said.

Getting buy-in wasn’t always easy, he noted. “Some families didn’t want to rock the boat, and some physicians were resistant,” to the idea. Overall, “Families and nurses were very, very worried” about the prospect of dropping drugs that were seen as helpful in everyday patient management.

But getting rid of the medications was just half the picture. Training nurses and care staff to intervene in problematic behaviors without resorting to drugs was just as important. A nurse-leader at each facility received training in person-centered care, and then trained the rest of the staff. This wasn’t always an easy idea to embrace, either, Dr. Brodaty said, especially since nursing staff often leads the discussion about the need for drugs to manage behavioral problems.

“Nursing staff are very task oriented, focused on dressing, bathing, eating, and toileting. They work very hard, and they don’t always have time to sit down and talk to resistant patients. It takes a much different attitude to show that you can actually save time by spending time and engaging the patient.”

He related one of his favorite illustrative stories – the milkman who caused a ruckus at bath time. “He got upset and aggressive every night when being put to bed and every morning when being given a shower. The staff spoke to his wife about it. She said that for 40 years, he was accustomed to getting up at 4 a.m. to deliver the milk. He would take a bath at night and get on his track suit and go to bed. Then at 4 a.m., he would get up and be ready to jump in the truck and go.”

When the staff started letting him shower at night and go to bed in his track suit, the milkman’s behavior improved without the need for antipsychotic medications.

“This is what we mean by ‘person-centered care,’ ” Dr. Brodaty said. “We use the ABC paradigm: Addressing the antecedent to the behavior, then the behavior, and then the consequences of the behavior.”

The intervention cohort comprised 139 patients with a mean age of 85 years; most were women. The vast majority (93%) had a diagnosis of dementia. About one-third had Alzheimer’s and one-third vascular dementia. The remainder had other diagnoses, including frontotemporal dementia, Lewy body dementia, and Parkinson’s disease. Common comorbid conditions included depression (56%) and previous stroke (36%). None of the patients had a diagnosis of psychosis.

Risperidone was the most common antipsychotic medication (85%). Other medications were olanzapine, quetiapine, and haloperidol. About 30% had come to the facility on the medication; the others had received it since admission.

Despite the national recommendation to review antipsychotic use every 12 weeks, patients had been on their current antipsychotic for an average of 2 years, and on their current dose for 1 year. In reviewing medications, Dr. Brodaty also found a “concerning” lack of informed consent. In Australia, informed consent for antipsychotic drugs can be given by a family member, but 84% of patients had no documented consent at all.

Of the original group, 125 entered the deprescribing protocol. Of these, 26 (21%) have since resumed their medications, but 79% have done well and are without a relapse of their symptoms or problematic behaviors. An ongoing medication review suggests there has been no concomitant upswing in other psychotropic medications, including benzodiazepines.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms remained stable from baseline. The mean total group score on the Neuropsychiatric Index (NPI) has not changed from its baseline of 30. The mean agitation/aggression NPI subscale has remained about 6, and the mean group score on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory about 56. The NPI delusion subscale increased, but the change was nonsignificant, Dr. Brodaty said. The NPI hallucinations subscale decreased slightly, but again the change was nonsignificant.

“Look, we all know antipsychotics are bad for old people, and we all know they are overprescribed,” he said. “Inappropriate use of these medications is an old story, yet we’re still talking about it. Why is this? We have the knowledge now, and we have to build on this knowledge so that we can change practice.”

The Canadian experience

Ms. Didic shared a year-long quality improvement process at 24 long-term care facilities that wanted to improve antipsychotic prescribing for their dementia patients.

The program, which was sponsored by the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement, used a “train-the-trainer” approach to spread support for antipsychotic deprescribing.

The foundation deployed 15 interdisciplinary teams, which comprised 180 members, including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, recreational therapists, and “clinical champions” who took the methodology directly into participating facilities. Interactive webinars on patient-centered care and deprescribing protocols were part of the process, Ms. Didic said.

In all, 416 patients were included in the outcomes report. Within 12 months, antipsychotics were eliminated in 74 patients (18%) and in 148 (36%), the dosage was reduced.

The benefits of these changes were striking, Ms. Didic said. There were fewer falls and reductions in verbal abuse, care resistance, and socially inappropriate behaviors. These issues either remained the same or got worse in patients who did not decrease antipsychotics. Again, there was no concomitant increase in other psychotropic medications.

The results show that changing the focus from medication-first to behavior-first care is institutionally feasible, Ms. Didic said.

Staff members’ assessments of the program and its personal and institutional impact were positive:

• 91% said they instituted regular medication reviews for every resident.

• 92% said old ways of doing things were adjusted to accommodate the new type of care.

• 94% said the new person-centered care was now a standard way of working.

• 84% said the project improved their ability to lead.

• 80% said it improved their ability to communicate.

“Currently, our teams are now spreading and sharing these resources and tools, serving as advisers, and organizing clinical training and workshops,” for other Canadian nursing homes that want to adopt the strategy.

Dr. Richard Caselli, professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., commented on the issues surrounding antipsychotic prescribing in long-term care facilities in a video interview.

Neither Ms. Didic nor Dr. Brodaty had any financial declarations.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @alz_gal

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAIC 2016

VIDEO: Smell test reflects brain pathologies, risk of Alzheimer’s progression

TORONTO – A scratch-and-sniff test that asks subjects to identify 40 odors and ranks olfaction is almost as powerful a predictor of Alzheimer’s disease as is a positive test for amyloid.

Low scores on the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) are linked to a thinning of the entorhinal cortex – the brain region where amyloid plaques are thought to first appear as Alzheimer’s disease takes hold, Seonjoo Lee, PhD, reported at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

“The findings indirectly suggest that impairment in odor identification may precede thinning in the entorhinal cortex in the early clinical stage of AD,” she concluded.

According to William Kriesl, MD, poor UPSIT sores are also related to brain levels of amyloid beta and are almost as predictive of cognitive decline.

These sensory changes appear to be one of the earliest manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease, the researchers said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. Their studies also suggest that the test has a place in the clinic as an easy and inexpensive screening tool for patients with memory complaints, Dr. Kreisl said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

The amyloid biomarker tests currently available are not suitable for wide dissemination. Amyloid brain scans are currently investigative; they are also invasive, expensive, and not covered by Medicare or any private insurance. Lumbar punctures are also invasive and expensive, and almost universally disliked by patients. Additionally, there is little consensus on how to interpret CSF amyloid levels.

“We need easy, noninvasive biomarkers that can be deployed in the clinic for patients who are concerned about their risk of memory decline,” said Dr. Kreisl of Columbia University Medical Center, New York. “Odor identification testing may provide to be a useful tool in helping physicians counsel patients who are concerned about this.”

His study concluded that the UPSIT predicted Alzheimer’s disease almost as well as invasive amyloid biomarkers. The scratch-and-sniff test asks subjects to identify 40 odors and ranks olfaction as normal, or mildly, moderately or severely impaired.

Dr. Kreisl examined the relationship between UPSIT and brain amyloid beta in 84 subjects, 58 of whom had mild cognitive impairment (MCI) at baseline. All of these subjects had either an amyloid brain scan or a lumbar puncture to measure amyloid in cerebrospinal fluid. They were followed for at least 6 months.

At follow-up, 67% of the group of participants showed cognitive decline. After correcting for age, gender, and education, patients who were amyloid-positive on imaging or in CSF were more than 7 times as likely to have experienced cognitive decline [Odds Ratio (OR) 7.3]. Overall, UPSIT score alone didn’t predict cognitive decline, Dr. Kreisl said. However, when it was imputed as a continuous variable, patients with a score of less than 35 on the 40-item test were four times more likely to show cognitive decline than those with a score of 35 or higher (OR 4).

In fact, these low UPSIT scores were much more common among amyloid-positive patients. Of the 38 patients who were positive for amyloid beta on either diagnostic test, 32 had an UPSIT score of less than 35 while six had a score of 35 or higher. Among the 46 amyloid-negative patients, 28 had low UPSIT scores and 18 had normal UPSIT scores.

Combining amyloid status and UPSIT in a single predictive model didn’t increase accuracy above that of either variable alone, which suggests olfactory dysfunction is not being completely driven by amyloid brain pathology.

“This makes sense because other factors like neurofibrillary tangle burden and other neurodegeneration are also involved in influencing how the UPSIT score predicts memory decline,” he said.

In a separate study, Dr. Lee examined the relationship of UPSIT performance to entorhinal cortical thickness in 397 cognitively normal subjects who were involved in the Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project. These subjects took the UPSIT and had magnetic resonance brain imaging both at baseline and at 4 years’ follow-up. Over that time, 50 transitioned to dementia, and 49 of them were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Another 79 subjects experienced cognitive decline, which was defined as a decline of at least one standard deviation in the average of the three cognitive composite scores of memory, language and visuospatial domains.

In comparing the groups with and without dementia, Dr. Lee found significant differences in the follow-up UPSIT score (23 vs. 27) and entorhinal cortical thickness (2.9 vs. 3.1 mm).

One standard deviation in performance on the UPSIT score was associated with a significant 47% increase in the risk of dementia, while one standard deviation in entorhinal cortical thickness was associated with a 22% increase in the risk. However, Dr. Lee said, the interaction of entorhinal thickness and UPSIT score was only significant in the group of subjects who transitioned to dementia.

Dr. Richard Caselli, professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., commented on the limited clinical utility of the UPSIT in a video interview.

Neither Dr. Lee nor Dr. Kreisl had any financial declarations.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @alz_gal

TORONTO – A scratch-and-sniff test that asks subjects to identify 40 odors and ranks olfaction is almost as powerful a predictor of Alzheimer’s disease as is a positive test for amyloid.

Low scores on the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) are linked to a thinning of the entorhinal cortex – the brain region where amyloid plaques are thought to first appear as Alzheimer’s disease takes hold, Seonjoo Lee, PhD, reported at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

“The findings indirectly suggest that impairment in odor identification may precede thinning in the entorhinal cortex in the early clinical stage of AD,” she concluded.

According to William Kriesl, MD, poor UPSIT sores are also related to brain levels of amyloid beta and are almost as predictive of cognitive decline.

These sensory changes appear to be one of the earliest manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease, the researchers said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. Their studies also suggest that the test has a place in the clinic as an easy and inexpensive screening tool for patients with memory complaints, Dr. Kreisl said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

The amyloid biomarker tests currently available are not suitable for wide dissemination. Amyloid brain scans are currently investigative; they are also invasive, expensive, and not covered by Medicare or any private insurance. Lumbar punctures are also invasive and expensive, and almost universally disliked by patients. Additionally, there is little consensus on how to interpret CSF amyloid levels.

“We need easy, noninvasive biomarkers that can be deployed in the clinic for patients who are concerned about their risk of memory decline,” said Dr. Kreisl of Columbia University Medical Center, New York. “Odor identification testing may provide to be a useful tool in helping physicians counsel patients who are concerned about this.”

His study concluded that the UPSIT predicted Alzheimer’s disease almost as well as invasive amyloid biomarkers. The scratch-and-sniff test asks subjects to identify 40 odors and ranks olfaction as normal, or mildly, moderately or severely impaired.

Dr. Kreisl examined the relationship between UPSIT and brain amyloid beta in 84 subjects, 58 of whom had mild cognitive impairment (MCI) at baseline. All of these subjects had either an amyloid brain scan or a lumbar puncture to measure amyloid in cerebrospinal fluid. They were followed for at least 6 months.

At follow-up, 67% of the group of participants showed cognitive decline. After correcting for age, gender, and education, patients who were amyloid-positive on imaging or in CSF were more than 7 times as likely to have experienced cognitive decline [Odds Ratio (OR) 7.3]. Overall, UPSIT score alone didn’t predict cognitive decline, Dr. Kreisl said. However, when it was imputed as a continuous variable, patients with a score of less than 35 on the 40-item test were four times more likely to show cognitive decline than those with a score of 35 or higher (OR 4).

In fact, these low UPSIT scores were much more common among amyloid-positive patients. Of the 38 patients who were positive for amyloid beta on either diagnostic test, 32 had an UPSIT score of less than 35 while six had a score of 35 or higher. Among the 46 amyloid-negative patients, 28 had low UPSIT scores and 18 had normal UPSIT scores.

Combining amyloid status and UPSIT in a single predictive model didn’t increase accuracy above that of either variable alone, which suggests olfactory dysfunction is not being completely driven by amyloid brain pathology.

“This makes sense because other factors like neurofibrillary tangle burden and other neurodegeneration are also involved in influencing how the UPSIT score predicts memory decline,” he said.

In a separate study, Dr. Lee examined the relationship of UPSIT performance to entorhinal cortical thickness in 397 cognitively normal subjects who were involved in the Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project. These subjects took the UPSIT and had magnetic resonance brain imaging both at baseline and at 4 years’ follow-up. Over that time, 50 transitioned to dementia, and 49 of them were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Another 79 subjects experienced cognitive decline, which was defined as a decline of at least one standard deviation in the average of the three cognitive composite scores of memory, language and visuospatial domains.

In comparing the groups with and without dementia, Dr. Lee found significant differences in the follow-up UPSIT score (23 vs. 27) and entorhinal cortical thickness (2.9 vs. 3.1 mm).

One standard deviation in performance on the UPSIT score was associated with a significant 47% increase in the risk of dementia, while one standard deviation in entorhinal cortical thickness was associated with a 22% increase in the risk. However, Dr. Lee said, the interaction of entorhinal thickness and UPSIT score was only significant in the group of subjects who transitioned to dementia.

Dr. Richard Caselli, professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., commented on the limited clinical utility of the UPSIT in a video interview.

Neither Dr. Lee nor Dr. Kreisl had any financial declarations.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @alz_gal

TORONTO – A scratch-and-sniff test that asks subjects to identify 40 odors and ranks olfaction is almost as powerful a predictor of Alzheimer’s disease as is a positive test for amyloid.

Low scores on the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) are linked to a thinning of the entorhinal cortex – the brain region where amyloid plaques are thought to first appear as Alzheimer’s disease takes hold, Seonjoo Lee, PhD, reported at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

“The findings indirectly suggest that impairment in odor identification may precede thinning in the entorhinal cortex in the early clinical stage of AD,” she concluded.

According to William Kriesl, MD, poor UPSIT sores are also related to brain levels of amyloid beta and are almost as predictive of cognitive decline.

These sensory changes appear to be one of the earliest manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease, the researchers said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. Their studies also suggest that the test has a place in the clinic as an easy and inexpensive screening tool for patients with memory complaints, Dr. Kreisl said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

The amyloid biomarker tests currently available are not suitable for wide dissemination. Amyloid brain scans are currently investigative; they are also invasive, expensive, and not covered by Medicare or any private insurance. Lumbar punctures are also invasive and expensive, and almost universally disliked by patients. Additionally, there is little consensus on how to interpret CSF amyloid levels.

“We need easy, noninvasive biomarkers that can be deployed in the clinic for patients who are concerned about their risk of memory decline,” said Dr. Kreisl of Columbia University Medical Center, New York. “Odor identification testing may provide to be a useful tool in helping physicians counsel patients who are concerned about this.”

His study concluded that the UPSIT predicted Alzheimer’s disease almost as well as invasive amyloid biomarkers. The scratch-and-sniff test asks subjects to identify 40 odors and ranks olfaction as normal, or mildly, moderately or severely impaired.

Dr. Kreisl examined the relationship between UPSIT and brain amyloid beta in 84 subjects, 58 of whom had mild cognitive impairment (MCI) at baseline. All of these subjects had either an amyloid brain scan or a lumbar puncture to measure amyloid in cerebrospinal fluid. They were followed for at least 6 months.

At follow-up, 67% of the group of participants showed cognitive decline. After correcting for age, gender, and education, patients who were amyloid-positive on imaging or in CSF were more than 7 times as likely to have experienced cognitive decline [Odds Ratio (OR) 7.3]. Overall, UPSIT score alone didn’t predict cognitive decline, Dr. Kreisl said. However, when it was imputed as a continuous variable, patients with a score of less than 35 on the 40-item test were four times more likely to show cognitive decline than those with a score of 35 or higher (OR 4).

In fact, these low UPSIT scores were much more common among amyloid-positive patients. Of the 38 patients who were positive for amyloid beta on either diagnostic test, 32 had an UPSIT score of less than 35 while six had a score of 35 or higher. Among the 46 amyloid-negative patients, 28 had low UPSIT scores and 18 had normal UPSIT scores.

Combining amyloid status and UPSIT in a single predictive model didn’t increase accuracy above that of either variable alone, which suggests olfactory dysfunction is not being completely driven by amyloid brain pathology.

“This makes sense because other factors like neurofibrillary tangle burden and other neurodegeneration are also involved in influencing how the UPSIT score predicts memory decline,” he said.

In a separate study, Dr. Lee examined the relationship of UPSIT performance to entorhinal cortical thickness in 397 cognitively normal subjects who were involved in the Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project. These subjects took the UPSIT and had magnetic resonance brain imaging both at baseline and at 4 years’ follow-up. Over that time, 50 transitioned to dementia, and 49 of them were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Another 79 subjects experienced cognitive decline, which was defined as a decline of at least one standard deviation in the average of the three cognitive composite scores of memory, language and visuospatial domains.

In comparing the groups with and without dementia, Dr. Lee found significant differences in the follow-up UPSIT score (23 vs. 27) and entorhinal cortical thickness (2.9 vs. 3.1 mm).

One standard deviation in performance on the UPSIT score was associated with a significant 47% increase in the risk of dementia, while one standard deviation in entorhinal cortical thickness was associated with a 22% increase in the risk. However, Dr. Lee said, the interaction of entorhinal thickness and UPSIT score was only significant in the group of subjects who transitioned to dementia.

Dr. Richard Caselli, professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., commented on the limited clinical utility of the UPSIT in a video interview.

Neither Dr. Lee nor Dr. Kreisl had any financial declarations.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT AAIC 2016

Retinal nerve fiber layer thinning predicts cognitive decline

TORONTO – A thinner-than-normal layer of retinal nerve fibers in the eye is now linked with cognitive decline – another suggestion that extracranial physical findings could be leveraged into dementia screening tools.

The findings were seen in a cohort of 32,000 people enrolled in the U.K. Biobank– an ongoing prospective study following half a million people and collecting data on cancer, heart diseases, stroke, diabetes, arthritis, osteoporosis, eye disorders, depression, and dementia.

The correlation between retinal nerve fiber thickness and cognition was observed in the large cohort at baseline, Fang Sarah Ko, MD, said during a press briefing at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2016. But after following 1,251 of these subjects for 3 years, she and her colleagues found that the correlation continued unabated.

“It’s amazing that we found this in such a healthy population,” Dr. Ko said during the briefing. “We wouldn’t have expected in just 3 years to see any cognitive decline in this cohort, much less measurable cognitive decline with a significant association with retinal nerve fiber layer thickness.”

Dr. Ko, an ophthalmologist in private practice in Tallahassee, Fla., said later during her main presentation of the study that the finding suggests a possible role for retinal imaging as a cognitive health screen.

“Thinner nerve fiber layer was associated with worse performance on memory, reasoning, and reaction time at baseline, and with a decline in each of these tests over time,” she said. “It may be that the nerve fiber layer could be used as a biomarker,” because it is easy to observe and measure with equipment available in most ophthalmology offices. “I would say the potential for clinical use is quite high.”

The U.K. Biobank recruits all of its subjects through the U.K. National Health Service patient registry. All undergo a standard battery of numerous tests; among them are tests of cognitive function and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (S-DOCT) of the eye. S-DOCT is an increasingly common method of imaging the retina. It produces three-dimensional images of extremely fine resolution.

The 32,000 subjects included in the baseline cohort were all free of diabetes and ocular or neurological disease, and they had normal intraocular pressure. They undertook four tests of cognition: prospective memory, pairs matching, numeric and verbal reasoning, and reaction time. The relationship between these test results and retinal nerve fiber thickness was adjusted for age, sex, race, socioeconomic status, height, refraction, and intraocular pressure.

At baseline, the mean retinal nerve fiber layer was significantly thinner among subjects with abnormal scores on any of the cognitive tests. On the prospective memory test, the layer was an average of 53.3 micrometers for subjects who had correct first-time recall, 52.5 micrometers for those with correct second-time recall, and 51.9 micrometers for those who did not recall. The layer was also significantly thinner in subjects who had low scores on pairs matching, numeric and verbal reasoning, and reaction times.

And the relationship between test results and retinal nerve fiber thinning appeared additive, Dr. Ko said. For each test that a subject failed, the layer was about 1 micrometer thinner. In the multivariate analysis, thinner retinal nerve fiber layer was associated with worse performance on all of the tests: The layer was 0.13 micrometer thinner for each incorrect match on pairs matching; 0.14 micrometer thinner for every 2 points lower in score on numeric and verbal reasoning; and 0.14 micrometer thinner for every 100 millisecond slower reaction time.

The 3-year follow-up data confirmed that these baseline findings persisted, and predicted cognitive decline. “Again, this was true after controlling for all the variables,” Dr. Ko said. “We found that those with the thinnest layers at baseline got worse on more of the tests, compared to those who had the thickest nerve fiber layers at baseline.”

Although this is the first time retinal nerve fiber thickness has predicted cognitive decline, the association with cognition has been studied for a few years. A 2015 meta-analysis found 17 studies comparing the marker between patients with Alzheimer’s and healthy controls and 5 studies of patients with mild cognitive impairment MCI) and healthy controls (Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2015 Apr 23;1[2]:136-43). All of these found significant retinal nerve fiber thinning in Alzheimer’s and MCI patients.

The lead author of that paper, Kelsey Thompson of the University of Edinburgh (United Kingdom), said the retinal ganglion cell axons can be seen as a sentinel marker for neurodegeneration in the brain.

“Retinal nerve fiber layer thinning in [Alzheimer’s disease] has been hypothesized to occur because of retrograde degeneration of the retinal ganglion cell axons, and these changes have been suggested to occur even before memory is affected. There is also a suggestion that neuroretinal atrophy may occur as a result of amyloid-beta plaque deposits within the retina, although this hypothesis remains more speculative.”

Dr. Ko had no financial declarations.

On Twitter @alz_gal

TORONTO – A thinner-than-normal layer of retinal nerve fibers in the eye is now linked with cognitive decline – another suggestion that extracranial physical findings could be leveraged into dementia screening tools.

The findings were seen in a cohort of 32,000 people enrolled in the U.K. Biobank– an ongoing prospective study following half a million people and collecting data on cancer, heart diseases, stroke, diabetes, arthritis, osteoporosis, eye disorders, depression, and dementia.

The correlation between retinal nerve fiber thickness and cognition was observed in the large cohort at baseline, Fang Sarah Ko, MD, said during a press briefing at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2016. But after following 1,251 of these subjects for 3 years, she and her colleagues found that the correlation continued unabated.

“It’s amazing that we found this in such a healthy population,” Dr. Ko said during the briefing. “We wouldn’t have expected in just 3 years to see any cognitive decline in this cohort, much less measurable cognitive decline with a significant association with retinal nerve fiber layer thickness.”

Dr. Ko, an ophthalmologist in private practice in Tallahassee, Fla., said later during her main presentation of the study that the finding suggests a possible role for retinal imaging as a cognitive health screen.

“Thinner nerve fiber layer was associated with worse performance on memory, reasoning, and reaction time at baseline, and with a decline in each of these tests over time,” she said. “It may be that the nerve fiber layer could be used as a biomarker,” because it is easy to observe and measure with equipment available in most ophthalmology offices. “I would say the potential for clinical use is quite high.”

The U.K. Biobank recruits all of its subjects through the U.K. National Health Service patient registry. All undergo a standard battery of numerous tests; among them are tests of cognitive function and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (S-DOCT) of the eye. S-DOCT is an increasingly common method of imaging the retina. It produces three-dimensional images of extremely fine resolution.

The 32,000 subjects included in the baseline cohort were all free of diabetes and ocular or neurological disease, and they had normal intraocular pressure. They undertook four tests of cognition: prospective memory, pairs matching, numeric and verbal reasoning, and reaction time. The relationship between these test results and retinal nerve fiber thickness was adjusted for age, sex, race, socioeconomic status, height, refraction, and intraocular pressure.

At baseline, the mean retinal nerve fiber layer was significantly thinner among subjects with abnormal scores on any of the cognitive tests. On the prospective memory test, the layer was an average of 53.3 micrometers for subjects who had correct first-time recall, 52.5 micrometers for those with correct second-time recall, and 51.9 micrometers for those who did not recall. The layer was also significantly thinner in subjects who had low scores on pairs matching, numeric and verbal reasoning, and reaction times.

And the relationship between test results and retinal nerve fiber thinning appeared additive, Dr. Ko said. For each test that a subject failed, the layer was about 1 micrometer thinner. In the multivariate analysis, thinner retinal nerve fiber layer was associated with worse performance on all of the tests: The layer was 0.13 micrometer thinner for each incorrect match on pairs matching; 0.14 micrometer thinner for every 2 points lower in score on numeric and verbal reasoning; and 0.14 micrometer thinner for every 100 millisecond slower reaction time.

The 3-year follow-up data confirmed that these baseline findings persisted, and predicted cognitive decline. “Again, this was true after controlling for all the variables,” Dr. Ko said. “We found that those with the thinnest layers at baseline got worse on more of the tests, compared to those who had the thickest nerve fiber layers at baseline.”

Although this is the first time retinal nerve fiber thickness has predicted cognitive decline, the association with cognition has been studied for a few years. A 2015 meta-analysis found 17 studies comparing the marker between patients with Alzheimer’s and healthy controls and 5 studies of patients with mild cognitive impairment MCI) and healthy controls (Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2015 Apr 23;1[2]:136-43). All of these found significant retinal nerve fiber thinning in Alzheimer’s and MCI patients.

The lead author of that paper, Kelsey Thompson of the University of Edinburgh (United Kingdom), said the retinal ganglion cell axons can be seen as a sentinel marker for neurodegeneration in the brain.

“Retinal nerve fiber layer thinning in [Alzheimer’s disease] has been hypothesized to occur because of retrograde degeneration of the retinal ganglion cell axons, and these changes have been suggested to occur even before memory is affected. There is also a suggestion that neuroretinal atrophy may occur as a result of amyloid-beta plaque deposits within the retina, although this hypothesis remains more speculative.”

Dr. Ko had no financial declarations.

On Twitter @alz_gal

TORONTO – A thinner-than-normal layer of retinal nerve fibers in the eye is now linked with cognitive decline – another suggestion that extracranial physical findings could be leveraged into dementia screening tools.

The findings were seen in a cohort of 32,000 people enrolled in the U.K. Biobank– an ongoing prospective study following half a million people and collecting data on cancer, heart diseases, stroke, diabetes, arthritis, osteoporosis, eye disorders, depression, and dementia.

The correlation between retinal nerve fiber thickness and cognition was observed in the large cohort at baseline, Fang Sarah Ko, MD, said during a press briefing at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2016. But after following 1,251 of these subjects for 3 years, she and her colleagues found that the correlation continued unabated.

“It’s amazing that we found this in such a healthy population,” Dr. Ko said during the briefing. “We wouldn’t have expected in just 3 years to see any cognitive decline in this cohort, much less measurable cognitive decline with a significant association with retinal nerve fiber layer thickness.”

Dr. Ko, an ophthalmologist in private practice in Tallahassee, Fla., said later during her main presentation of the study that the finding suggests a possible role for retinal imaging as a cognitive health screen.

“Thinner nerve fiber layer was associated with worse performance on memory, reasoning, and reaction time at baseline, and with a decline in each of these tests over time,” she said. “It may be that the nerve fiber layer could be used as a biomarker,” because it is easy to observe and measure with equipment available in most ophthalmology offices. “I would say the potential for clinical use is quite high.”

The U.K. Biobank recruits all of its subjects through the U.K. National Health Service patient registry. All undergo a standard battery of numerous tests; among them are tests of cognitive function and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (S-DOCT) of the eye. S-DOCT is an increasingly common method of imaging the retina. It produces three-dimensional images of extremely fine resolution.

The 32,000 subjects included in the baseline cohort were all free of diabetes and ocular or neurological disease, and they had normal intraocular pressure. They undertook four tests of cognition: prospective memory, pairs matching, numeric and verbal reasoning, and reaction time. The relationship between these test results and retinal nerve fiber thickness was adjusted for age, sex, race, socioeconomic status, height, refraction, and intraocular pressure.

At baseline, the mean retinal nerve fiber layer was significantly thinner among subjects with abnormal scores on any of the cognitive tests. On the prospective memory test, the layer was an average of 53.3 micrometers for subjects who had correct first-time recall, 52.5 micrometers for those with correct second-time recall, and 51.9 micrometers for those who did not recall. The layer was also significantly thinner in subjects who had low scores on pairs matching, numeric and verbal reasoning, and reaction times.

And the relationship between test results and retinal nerve fiber thinning appeared additive, Dr. Ko said. For each test that a subject failed, the layer was about 1 micrometer thinner. In the multivariate analysis, thinner retinal nerve fiber layer was associated with worse performance on all of the tests: The layer was 0.13 micrometer thinner for each incorrect match on pairs matching; 0.14 micrometer thinner for every 2 points lower in score on numeric and verbal reasoning; and 0.14 micrometer thinner for every 100 millisecond slower reaction time.

The 3-year follow-up data confirmed that these baseline findings persisted, and predicted cognitive decline. “Again, this was true after controlling for all the variables,” Dr. Ko said. “We found that those with the thinnest layers at baseline got worse on more of the tests, compared to those who had the thickest nerve fiber layers at baseline.”

Although this is the first time retinal nerve fiber thickness has predicted cognitive decline, the association with cognition has been studied for a few years. A 2015 meta-analysis found 17 studies comparing the marker between patients with Alzheimer’s and healthy controls and 5 studies of patients with mild cognitive impairment MCI) and healthy controls (Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2015 Apr 23;1[2]:136-43). All of these found significant retinal nerve fiber thinning in Alzheimer’s and MCI patients.

The lead author of that paper, Kelsey Thompson of the University of Edinburgh (United Kingdom), said the retinal ganglion cell axons can be seen as a sentinel marker for neurodegeneration in the brain.

“Retinal nerve fiber layer thinning in [Alzheimer’s disease] has been hypothesized to occur because of retrograde degeneration of the retinal ganglion cell axons, and these changes have been suggested to occur even before memory is affected. There is also a suggestion that neuroretinal atrophy may occur as a result of amyloid-beta plaque deposits within the retina, although this hypothesis remains more speculative.”

Dr. Ko had no financial declarations.

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT AAIC 2016

Key clinical point: Thinning of the retinal nerve fiber layer was associated with poorer cognitive performance and predicted cognitive decline as well.

Major finding: On a prospective memory test, the layer was an average of 53.3 micrometers for subjects who had correct first-time recall, vs. 51.9 micrometers for those who did not recall.

Data source: The study comprised 32,000 patients at baseline, of whom 1,251 were followed for 3 years.

Disclosures: Dr. Ko had no financial disclosures.

Early Alzheimer’s Treatment Decreases Both Costs and Mortality

TORONTO – For patients with Alzheimer’s disease, early treatment may translate into lower health care costs and better survival, based on study results reported at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2016.

A review of Medicare claims data from more than 1,300 patients who received a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease during 2010-2013 found that patients who got standard anti-dementia therapy within a month of an Alzheimer’s diagnosis had a 28% lower risk of dying by 6 months than did patients who weren’t treated. And while their health care costs spiked at the time of diagnosis, monthly costs were consistently lower, yielding an overall savings of about $1,700 by the end of the study.

It’s not that the drugs themselves exerted any lifesaving effects, said study co-author Christopher Black, associate director of outcomes research at Merck Research Laboratories, Rahway, N.J. Rather, the observed benefit is probably because the patients who got treated also then got consistent medical attention for health-threatening comorbidities.

“This is an important caveat,” Mr. Black said in an interview at the meeting. “We are not saying that anti-dementia treatment is causing longer survival. It’s a proxy for better care. Typically, dementia patients die of complications from comorbidities that are exacerbated by Alzheimer’s symptoms.”