User login

Heightened Emphasis on Sex-specific Cardiovascular Risk Factors

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Achieving continued reductions in cardiovascular deaths in U.S. women will require that physicians make greater use of sex-specific risk factors that aren’t incorporated in the ACC/AHA atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk score, Dr. Jennifer H. Mieres asserted at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

In the 13-year period beginning in 2000, with the launch of a national initiative to boost the research focus on cardiovascular disease in women, the annual number of women dying from cardiovascular disease has dropped by roughly 30%. That’s a steeper decline than in men. One of the keys to further reductions in women is more widespread physician evaluation of sex-specific risk factors – such as a history of elevated blood pressure in pregnancy, polycystic ovarian syndrome, or radiation therapy for breast cancer – as part of routine cardiovascular risk assessment in women, said Dr. Mieres, senior vice president office of community and public health at Hofstra Northwell in Hempstead, N.Y.

Hypertension in pregnancy as a harbinger of premature cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases has been a topic of particularly fruitful research in the past few years.

“The ongoing hypothesis is that pregnancy is a sort of stress test. Pregnancy-related complications indicate an inability to adequately adapt to the physiologic stress of pregnancy and thus reveal the presence of underlying susceptibility to ischemic heart disease,” according to the cardiologist.

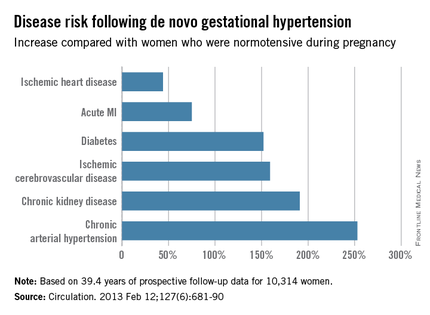

She cited a landmark prospective study of 10,314 women born in Northern Finland in 1966 and followed for an average of more than 39 years after a singleton pregnancy. The investigators showed that any elevation in blood pressure during pregnancy, including isolated systolic or diastolic hypertension that resolved during or shortly after pregnancy, was associated with increased future risks of various forms of cardiovascular disease.

For example, de novo gestational hypertension without proteinuria was associated with significantly increased risks of subsequent ischemic cerebrovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, acute MI, chronic hypertension, and heart failure. The MIs that occurred in Finns with a history of gestational hypertension were more serious, too, with an associated threefold greater risk of being fatal than MIs in women who had been normotensive in pregnancy (Circulation. 2013 Feb 12;127[6]:681-90).

New-onset isolated systolic or diastolic hypertension emerged during pregnancy in about 17% of the Finnish women. Roughly 30% of them had a cardiovascular event before their late 60s. This translated to a 14%-18% greater risk than in women who remained normotensive in pregnancy.

The highest risk of all in the Finnish study was seen in women with preeclampsia/eclampsia superimposed on a background of chronic hypertension. They had a 3.18-fold greater risk of subsequent MI than did women who were normotensive in pregnancy, a 3.32-fold increased risk of heart failure, and a 2.22-fold greater risk of developing diabetes.

In addition to the growing appreciation that it’s important to consider sex-specific cardiovascular risk factors, recent evidence shows that many of the traditional risk factors are stronger predictors of ischemic heart disease in women than men. These include diabetes, smoking, obesity, and hypertension, Dr. Mieres observed.

For example, a recent meta-analysis of 26 studies including more than 214,000 subjects concluded that women with type 1 diabetes had a 2.5-fold greater risk of incident coronary heart disease than did men with type 1 diabetes. The women with type 1 diabetes also had an 86% greater risk of fatal cardiovascular diseases, a 44% increase in the risk of fatal kidney disease, a 37% greater risk of stroke, and a 37% increase in all-cause mortality relative to type 1 diabetic men (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015 Mar;3[3]:198-206).

A wealth of accumulating data indicates that type 2 diabetes, too, is a much stronger risk factor for cardiovascular diseases in women than in men. The evidence prompted a recent formal scientific statement to that effect by the American Heart Association (Circulation. 2015 Dec 22;132[25]:2424-47).

Dr. Mieres reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Achieving continued reductions in cardiovascular deaths in U.S. women will require that physicians make greater use of sex-specific risk factors that aren’t incorporated in the ACC/AHA atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk score, Dr. Jennifer H. Mieres asserted at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

In the 13-year period beginning in 2000, with the launch of a national initiative to boost the research focus on cardiovascular disease in women, the annual number of women dying from cardiovascular disease has dropped by roughly 30%. That’s a steeper decline than in men. One of the keys to further reductions in women is more widespread physician evaluation of sex-specific risk factors – such as a history of elevated blood pressure in pregnancy, polycystic ovarian syndrome, or radiation therapy for breast cancer – as part of routine cardiovascular risk assessment in women, said Dr. Mieres, senior vice president office of community and public health at Hofstra Northwell in Hempstead, N.Y.

Hypertension in pregnancy as a harbinger of premature cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases has been a topic of particularly fruitful research in the past few years.

“The ongoing hypothesis is that pregnancy is a sort of stress test. Pregnancy-related complications indicate an inability to adequately adapt to the physiologic stress of pregnancy and thus reveal the presence of underlying susceptibility to ischemic heart disease,” according to the cardiologist.

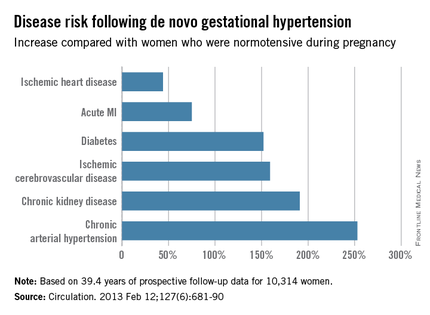

She cited a landmark prospective study of 10,314 women born in Northern Finland in 1966 and followed for an average of more than 39 years after a singleton pregnancy. The investigators showed that any elevation in blood pressure during pregnancy, including isolated systolic or diastolic hypertension that resolved during or shortly after pregnancy, was associated with increased future risks of various forms of cardiovascular disease.

For example, de novo gestational hypertension without proteinuria was associated with significantly increased risks of subsequent ischemic cerebrovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, acute MI, chronic hypertension, and heart failure. The MIs that occurred in Finns with a history of gestational hypertension were more serious, too, with an associated threefold greater risk of being fatal than MIs in women who had been normotensive in pregnancy (Circulation. 2013 Feb 12;127[6]:681-90).

New-onset isolated systolic or diastolic hypertension emerged during pregnancy in about 17% of the Finnish women. Roughly 30% of them had a cardiovascular event before their late 60s. This translated to a 14%-18% greater risk than in women who remained normotensive in pregnancy.

The highest risk of all in the Finnish study was seen in women with preeclampsia/eclampsia superimposed on a background of chronic hypertension. They had a 3.18-fold greater risk of subsequent MI than did women who were normotensive in pregnancy, a 3.32-fold increased risk of heart failure, and a 2.22-fold greater risk of developing diabetes.

In addition to the growing appreciation that it’s important to consider sex-specific cardiovascular risk factors, recent evidence shows that many of the traditional risk factors are stronger predictors of ischemic heart disease in women than men. These include diabetes, smoking, obesity, and hypertension, Dr. Mieres observed.

For example, a recent meta-analysis of 26 studies including more than 214,000 subjects concluded that women with type 1 diabetes had a 2.5-fold greater risk of incident coronary heart disease than did men with type 1 diabetes. The women with type 1 diabetes also had an 86% greater risk of fatal cardiovascular diseases, a 44% increase in the risk of fatal kidney disease, a 37% greater risk of stroke, and a 37% increase in all-cause mortality relative to type 1 diabetic men (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015 Mar;3[3]:198-206).

A wealth of accumulating data indicates that type 2 diabetes, too, is a much stronger risk factor for cardiovascular diseases in women than in men. The evidence prompted a recent formal scientific statement to that effect by the American Heart Association (Circulation. 2015 Dec 22;132[25]:2424-47).

Dr. Mieres reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Achieving continued reductions in cardiovascular deaths in U.S. women will require that physicians make greater use of sex-specific risk factors that aren’t incorporated in the ACC/AHA atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk score, Dr. Jennifer H. Mieres asserted at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

In the 13-year period beginning in 2000, with the launch of a national initiative to boost the research focus on cardiovascular disease in women, the annual number of women dying from cardiovascular disease has dropped by roughly 30%. That’s a steeper decline than in men. One of the keys to further reductions in women is more widespread physician evaluation of sex-specific risk factors – such as a history of elevated blood pressure in pregnancy, polycystic ovarian syndrome, or radiation therapy for breast cancer – as part of routine cardiovascular risk assessment in women, said Dr. Mieres, senior vice president office of community and public health at Hofstra Northwell in Hempstead, N.Y.

Hypertension in pregnancy as a harbinger of premature cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases has been a topic of particularly fruitful research in the past few years.

“The ongoing hypothesis is that pregnancy is a sort of stress test. Pregnancy-related complications indicate an inability to adequately adapt to the physiologic stress of pregnancy and thus reveal the presence of underlying susceptibility to ischemic heart disease,” according to the cardiologist.

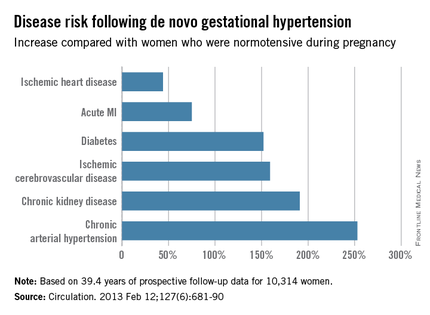

She cited a landmark prospective study of 10,314 women born in Northern Finland in 1966 and followed for an average of more than 39 years after a singleton pregnancy. The investigators showed that any elevation in blood pressure during pregnancy, including isolated systolic or diastolic hypertension that resolved during or shortly after pregnancy, was associated with increased future risks of various forms of cardiovascular disease.

For example, de novo gestational hypertension without proteinuria was associated with significantly increased risks of subsequent ischemic cerebrovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, acute MI, chronic hypertension, and heart failure. The MIs that occurred in Finns with a history of gestational hypertension were more serious, too, with an associated threefold greater risk of being fatal than MIs in women who had been normotensive in pregnancy (Circulation. 2013 Feb 12;127[6]:681-90).

New-onset isolated systolic or diastolic hypertension emerged during pregnancy in about 17% of the Finnish women. Roughly 30% of them had a cardiovascular event before their late 60s. This translated to a 14%-18% greater risk than in women who remained normotensive in pregnancy.

The highest risk of all in the Finnish study was seen in women with preeclampsia/eclampsia superimposed on a background of chronic hypertension. They had a 3.18-fold greater risk of subsequent MI than did women who were normotensive in pregnancy, a 3.32-fold increased risk of heart failure, and a 2.22-fold greater risk of developing diabetes.

In addition to the growing appreciation that it’s important to consider sex-specific cardiovascular risk factors, recent evidence shows that many of the traditional risk factors are stronger predictors of ischemic heart disease in women than men. These include diabetes, smoking, obesity, and hypertension, Dr. Mieres observed.

For example, a recent meta-analysis of 26 studies including more than 214,000 subjects concluded that women with type 1 diabetes had a 2.5-fold greater risk of incident coronary heart disease than did men with type 1 diabetes. The women with type 1 diabetes also had an 86% greater risk of fatal cardiovascular diseases, a 44% increase in the risk of fatal kidney disease, a 37% greater risk of stroke, and a 37% increase in all-cause mortality relative to type 1 diabetic men (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015 Mar;3[3]:198-206).

A wealth of accumulating data indicates that type 2 diabetes, too, is a much stronger risk factor for cardiovascular diseases in women than in men. The evidence prompted a recent formal scientific statement to that effect by the American Heart Association (Circulation. 2015 Dec 22;132[25]:2424-47).

Dr. Mieres reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

Heightened emphasis on sex-specific cardiovascular risk factors

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Achieving continued reductions in cardiovascular deaths in U.S. women will require that physicians make greater use of sex-specific risk factors that aren’t incorporated in the ACC/AHA atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk score, Dr. Jennifer H. Mieres asserted at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

In the 13-year period beginning in 2000, with the launch of a national initiative to boost the research focus on cardiovascular disease in women, the annual number of women dying from cardiovascular disease has dropped by roughly 30%. That’s a steeper decline than in men. One of the keys to further reductions in women is more widespread physician evaluation of sex-specific risk factors – such as a history of elevated blood pressure in pregnancy, polycystic ovarian syndrome, or radiation therapy for breast cancer – as part of routine cardiovascular risk assessment in women, said Dr. Mieres, senior vice president office of community and public health at Hofstra Northwell in Hempstead, N.Y.

Hypertension in pregnancy as a harbinger of premature cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases has been a topic of particularly fruitful research in the past few years.

“The ongoing hypothesis is that pregnancy is a sort of stress test. Pregnancy-related complications indicate an inability to adequately adapt to the physiologic stress of pregnancy and thus reveal the presence of underlying susceptibility to ischemic heart disease,” according to the cardiologist.

She cited a landmark prospective study of 10,314 women born in Northern Finland in 1966 and followed for an average of more than 39 years after a singleton pregnancy. The investigators showed that any elevation in blood pressure during pregnancy, including isolated systolic or diastolic hypertension that resolved during or shortly after pregnancy, was associated with increased future risks of various forms of cardiovascular disease.

For example, de novo gestational hypertension without proteinuria was associated with significantly increased risks of subsequent ischemic cerebrovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, acute MI, chronic hypertension, and heart failure. The MIs that occurred in Finns with a history of gestational hypertension were more serious, too, with an associated threefold greater risk of being fatal than MIs in women who had been normotensive in pregnancy (Circulation. 2013 Feb 12;127[6]:681-90).

New-onset isolated systolic or diastolic hypertension emerged during pregnancy in about 17% of the Finnish women. Roughly 30% of them had a cardiovascular event before their late 60s. This translated to a 14%-18% greater risk than in women who remained normotensive in pregnancy.

The highest risk of all in the Finnish study was seen in women with preeclampsia/eclampsia superimposed on a background of chronic hypertension. They had a 3.18-fold greater risk of subsequent MI than did women who were normotensive in pregnancy, a 3.32-fold increased risk of heart failure, and a 2.22-fold greater risk of developing diabetes.

In addition to the growing appreciation that it’s important to consider sex-specific cardiovascular risk factors, recent evidence shows that many of the traditional risk factors are stronger predictors of ischemic heart disease in women than men. These include diabetes, smoking, obesity, and hypertension, Dr. Mieres observed.

For example, a recent meta-analysis of 26 studies including more than 214,000 subjects concluded that women with type 1 diabetes had a 2.5-fold greater risk of incident coronary heart disease than did men with type 1 diabetes. The women with type 1 diabetes also had an 86% greater risk of fatal cardiovascular diseases, a 44% increase in the risk of fatal kidney disease, a 37% greater risk of stroke, and a 37% increase in all-cause mortality relative to type 1 diabetic men (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015 Mar;3[3]:198-206).

A wealth of accumulating data indicates that type 2 diabetes, too, is a much stronger risk factor for cardiovascular diseases in women than in men. The evidence prompted a recent formal scientific statement to that effect by the American Heart Association (Circulation. 2015 Dec 22;132[25]:2424-47).

Dr. Mieres reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Achieving continued reductions in cardiovascular deaths in U.S. women will require that physicians make greater use of sex-specific risk factors that aren’t incorporated in the ACC/AHA atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk score, Dr. Jennifer H. Mieres asserted at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

In the 13-year period beginning in 2000, with the launch of a national initiative to boost the research focus on cardiovascular disease in women, the annual number of women dying from cardiovascular disease has dropped by roughly 30%. That’s a steeper decline than in men. One of the keys to further reductions in women is more widespread physician evaluation of sex-specific risk factors – such as a history of elevated blood pressure in pregnancy, polycystic ovarian syndrome, or radiation therapy for breast cancer – as part of routine cardiovascular risk assessment in women, said Dr. Mieres, senior vice president office of community and public health at Hofstra Northwell in Hempstead, N.Y.

Hypertension in pregnancy as a harbinger of premature cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases has been a topic of particularly fruitful research in the past few years.

“The ongoing hypothesis is that pregnancy is a sort of stress test. Pregnancy-related complications indicate an inability to adequately adapt to the physiologic stress of pregnancy and thus reveal the presence of underlying susceptibility to ischemic heart disease,” according to the cardiologist.

She cited a landmark prospective study of 10,314 women born in Northern Finland in 1966 and followed for an average of more than 39 years after a singleton pregnancy. The investigators showed that any elevation in blood pressure during pregnancy, including isolated systolic or diastolic hypertension that resolved during or shortly after pregnancy, was associated with increased future risks of various forms of cardiovascular disease.

For example, de novo gestational hypertension without proteinuria was associated with significantly increased risks of subsequent ischemic cerebrovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, acute MI, chronic hypertension, and heart failure. The MIs that occurred in Finns with a history of gestational hypertension were more serious, too, with an associated threefold greater risk of being fatal than MIs in women who had been normotensive in pregnancy (Circulation. 2013 Feb 12;127[6]:681-90).

New-onset isolated systolic or diastolic hypertension emerged during pregnancy in about 17% of the Finnish women. Roughly 30% of them had a cardiovascular event before their late 60s. This translated to a 14%-18% greater risk than in women who remained normotensive in pregnancy.

The highest risk of all in the Finnish study was seen in women with preeclampsia/eclampsia superimposed on a background of chronic hypertension. They had a 3.18-fold greater risk of subsequent MI than did women who were normotensive in pregnancy, a 3.32-fold increased risk of heart failure, and a 2.22-fold greater risk of developing diabetes.

In addition to the growing appreciation that it’s important to consider sex-specific cardiovascular risk factors, recent evidence shows that many of the traditional risk factors are stronger predictors of ischemic heart disease in women than men. These include diabetes, smoking, obesity, and hypertension, Dr. Mieres observed.

For example, a recent meta-analysis of 26 studies including more than 214,000 subjects concluded that women with type 1 diabetes had a 2.5-fold greater risk of incident coronary heart disease than did men with type 1 diabetes. The women with type 1 diabetes also had an 86% greater risk of fatal cardiovascular diseases, a 44% increase in the risk of fatal kidney disease, a 37% greater risk of stroke, and a 37% increase in all-cause mortality relative to type 1 diabetic men (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015 Mar;3[3]:198-206).

A wealth of accumulating data indicates that type 2 diabetes, too, is a much stronger risk factor for cardiovascular diseases in women than in men. The evidence prompted a recent formal scientific statement to that effect by the American Heart Association (Circulation. 2015 Dec 22;132[25]:2424-47).

Dr. Mieres reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Achieving continued reductions in cardiovascular deaths in U.S. women will require that physicians make greater use of sex-specific risk factors that aren’t incorporated in the ACC/AHA atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk score, Dr. Jennifer H. Mieres asserted at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

In the 13-year period beginning in 2000, with the launch of a national initiative to boost the research focus on cardiovascular disease in women, the annual number of women dying from cardiovascular disease has dropped by roughly 30%. That’s a steeper decline than in men. One of the keys to further reductions in women is more widespread physician evaluation of sex-specific risk factors – such as a history of elevated blood pressure in pregnancy, polycystic ovarian syndrome, or radiation therapy for breast cancer – as part of routine cardiovascular risk assessment in women, said Dr. Mieres, senior vice president office of community and public health at Hofstra Northwell in Hempstead, N.Y.

Hypertension in pregnancy as a harbinger of premature cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases has been a topic of particularly fruitful research in the past few years.

“The ongoing hypothesis is that pregnancy is a sort of stress test. Pregnancy-related complications indicate an inability to adequately adapt to the physiologic stress of pregnancy and thus reveal the presence of underlying susceptibility to ischemic heart disease,” according to the cardiologist.

She cited a landmark prospective study of 10,314 women born in Northern Finland in 1966 and followed for an average of more than 39 years after a singleton pregnancy. The investigators showed that any elevation in blood pressure during pregnancy, including isolated systolic or diastolic hypertension that resolved during or shortly after pregnancy, was associated with increased future risks of various forms of cardiovascular disease.

For example, de novo gestational hypertension without proteinuria was associated with significantly increased risks of subsequent ischemic cerebrovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, acute MI, chronic hypertension, and heart failure. The MIs that occurred in Finns with a history of gestational hypertension were more serious, too, with an associated threefold greater risk of being fatal than MIs in women who had been normotensive in pregnancy (Circulation. 2013 Feb 12;127[6]:681-90).

New-onset isolated systolic or diastolic hypertension emerged during pregnancy in about 17% of the Finnish women. Roughly 30% of them had a cardiovascular event before their late 60s. This translated to a 14%-18% greater risk than in women who remained normotensive in pregnancy.

The highest risk of all in the Finnish study was seen in women with preeclampsia/eclampsia superimposed on a background of chronic hypertension. They had a 3.18-fold greater risk of subsequent MI than did women who were normotensive in pregnancy, a 3.32-fold increased risk of heart failure, and a 2.22-fold greater risk of developing diabetes.

In addition to the growing appreciation that it’s important to consider sex-specific cardiovascular risk factors, recent evidence shows that many of the traditional risk factors are stronger predictors of ischemic heart disease in women than men. These include diabetes, smoking, obesity, and hypertension, Dr. Mieres observed.

For example, a recent meta-analysis of 26 studies including more than 214,000 subjects concluded that women with type 1 diabetes had a 2.5-fold greater risk of incident coronary heart disease than did men with type 1 diabetes. The women with type 1 diabetes also had an 86% greater risk of fatal cardiovascular diseases, a 44% increase in the risk of fatal kidney disease, a 37% greater risk of stroke, and a 37% increase in all-cause mortality relative to type 1 diabetic men (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015 Mar;3[3]:198-206).

A wealth of accumulating data indicates that type 2 diabetes, too, is a much stronger risk factor for cardiovascular diseases in women than in men. The evidence prompted a recent formal scientific statement to that effect by the American Heart Association (Circulation. 2015 Dec 22;132[25]:2424-47).

Dr. Mieres reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

Ischemic mitral regurgitation: valve repair vs. replacement

SNOWMASS, COLO. – A clear message from the first-ever randomized trial of surgical mitral valve repair versus replacement for patients with severe ischemic mitral regurgitation is that replacement should be utilized more liberally, Dr. Michael J. Mack said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

The results of prosthetic valve implantation proved far more durable than repair. At 2 years of follow-up in this 251-patient multicenter trial conducted by the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network (CSTN), the incidence of recurrent moderate or severe mitral regurgitation was just 3.8% in the valve replacement group, compared with 58.8% with repair via restrictive annuloplasty. As a result, the repair group had significantly more heart failure–related adverse events and cardiovascular hospitalizations and a lower rate of clinically meaningful improvement in quality of life scores, noted Dr. Mack, an investigator in the trial and medical director of the Baylor Health Care System in Plano, Tex.

“I think surgical mitral valve replacement has had a bad name over the years, and one of the reasons is because of the worse left ventricular function afterwards. However, that was a casualty of excising the mitral valve and the subvalvular apparatus, causing atrial-ventricular disconnection. We’ve gotten smarter about this. The techniques we now use are valve sparing,” the cardiothoracic surgeon said.

He was quick to add, however, that the CSTN study results are by no means the death knell for restrictive mitral annuloplasty. Indeed, participants in the mitral valve repair group who didn’t develop recurrent regurgitation actually experienced significant positive reverse remodeling as reflected by improvement in their left ventricular end-systolic volume index, the primary endpoint of the study (N Engl J Med. 2016;374:344-35).

The key to successful outcomes in mitral valve repair is to save the procedure for patients who are unlikely to develop recurrent regurgitation. And a substudy of the CTSN trial led by Dr. Irving L. Kron, professor of surgery at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, provides practical guidance on that score. The investigators conducted a logistic regression analysis of the mitral valve repair group’s baseline echocardiographic and clinical characteristics and identified a collection of strong predictors of recurrent regurgitation within 2 years (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015 Mar;149[3]:752-61).

“The bottom line is, the more tethering you have of the mitral valve leaflets, the more likely you are to have recurrent mitral regurgitation after mitral valve annuloplasty,” Dr. Mack said.

The predictors of recurrent regurgitation included a coaptation depth greater than 10 mm, a posterior leaflet angle in excess of 45 degrees, a distal anterior leaflet angle greater than 25 degrees, inferior basal aneurysm, mitral annular calcification, and a left ventricular end diastolic diameter greater than 65 mm, as well as other indices of advanced left ventricular remodeling.

No or only mild annular dilation, as occurs, for example, in patients whose mitral regurgitation is caused by atrial fibrillation, is another independent predictor of recurrent regurgitation post repair.

“Shrinking the annulus isn’t going to make a difference if the annulus wasn’t dilated to begin with,” the surgeon observed. “If surgery is performed, we now know those patients who are most likely to recur – and they should have mitral valve replacement. If those factors are not present, then repair is still a viable option,” according to Dr. Mack.

That being said, it’s still not known whether correcting severe ischemic mitral regurgitation prolongs life or improves quality of life long term, compared with guideline-directed medical therapy, he stressed.

“Secondary mitral regurgitation is a disease of the left ventricle, not the mitral valve. So it’s possible that mitral regurgitation reduction has no benefit because the regurgitation is a surrogate marker not causally related to outcome. I don’t think so, but it is a possibility,” Dr. Mack conceded.

This is a clinically important unresolved question because secondary mitral regurgitation is extremely common. In a retrospective echocardiographic study of 558 heart failure patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less and class III-IV symptoms, 90% of them had some degree of mitral regurgitation (J Card Fail. 2004 Aug;10[4]:285-91).

Together with Columbia University cardiologist Dr. Gregg W. Stone, Dr. Mack is coprincipal investigator of the COAPT (Cardiovascular Outcomes Assessment of the MitraClip Percutaneous Therapy for Heart Failure Patients with Functional Mitral Regurgitation) trial, which is expected to provide an answer to this key question. The multicenter U.S. study involves a planned 420 patients with severely symptomatic secondary mitral regurgitation who are deemed at prohibitive risk for surgery. They are to be randomized to guideline-directed medical therapy with or without transcatheter mitral valve repair using the MitraClip device. Enrollment should be completed by May, with initial results available in late 2017.

Dr. Mack reported receiving research grants from Abbott Vascular, which is sponsoring the COAPT trial, as well as from Edwards Lifesciences.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – A clear message from the first-ever randomized trial of surgical mitral valve repair versus replacement for patients with severe ischemic mitral regurgitation is that replacement should be utilized more liberally, Dr. Michael J. Mack said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

The results of prosthetic valve implantation proved far more durable than repair. At 2 years of follow-up in this 251-patient multicenter trial conducted by the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network (CSTN), the incidence of recurrent moderate or severe mitral regurgitation was just 3.8% in the valve replacement group, compared with 58.8% with repair via restrictive annuloplasty. As a result, the repair group had significantly more heart failure–related adverse events and cardiovascular hospitalizations and a lower rate of clinically meaningful improvement in quality of life scores, noted Dr. Mack, an investigator in the trial and medical director of the Baylor Health Care System in Plano, Tex.

“I think surgical mitral valve replacement has had a bad name over the years, and one of the reasons is because of the worse left ventricular function afterwards. However, that was a casualty of excising the mitral valve and the subvalvular apparatus, causing atrial-ventricular disconnection. We’ve gotten smarter about this. The techniques we now use are valve sparing,” the cardiothoracic surgeon said.

He was quick to add, however, that the CSTN study results are by no means the death knell for restrictive mitral annuloplasty. Indeed, participants in the mitral valve repair group who didn’t develop recurrent regurgitation actually experienced significant positive reverse remodeling as reflected by improvement in their left ventricular end-systolic volume index, the primary endpoint of the study (N Engl J Med. 2016;374:344-35).

The key to successful outcomes in mitral valve repair is to save the procedure for patients who are unlikely to develop recurrent regurgitation. And a substudy of the CTSN trial led by Dr. Irving L. Kron, professor of surgery at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, provides practical guidance on that score. The investigators conducted a logistic regression analysis of the mitral valve repair group’s baseline echocardiographic and clinical characteristics and identified a collection of strong predictors of recurrent regurgitation within 2 years (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015 Mar;149[3]:752-61).

“The bottom line is, the more tethering you have of the mitral valve leaflets, the more likely you are to have recurrent mitral regurgitation after mitral valve annuloplasty,” Dr. Mack said.

The predictors of recurrent regurgitation included a coaptation depth greater than 10 mm, a posterior leaflet angle in excess of 45 degrees, a distal anterior leaflet angle greater than 25 degrees, inferior basal aneurysm, mitral annular calcification, and a left ventricular end diastolic diameter greater than 65 mm, as well as other indices of advanced left ventricular remodeling.

No or only mild annular dilation, as occurs, for example, in patients whose mitral regurgitation is caused by atrial fibrillation, is another independent predictor of recurrent regurgitation post repair.

“Shrinking the annulus isn’t going to make a difference if the annulus wasn’t dilated to begin with,” the surgeon observed. “If surgery is performed, we now know those patients who are most likely to recur – and they should have mitral valve replacement. If those factors are not present, then repair is still a viable option,” according to Dr. Mack.

That being said, it’s still not known whether correcting severe ischemic mitral regurgitation prolongs life or improves quality of life long term, compared with guideline-directed medical therapy, he stressed.

“Secondary mitral regurgitation is a disease of the left ventricle, not the mitral valve. So it’s possible that mitral regurgitation reduction has no benefit because the regurgitation is a surrogate marker not causally related to outcome. I don’t think so, but it is a possibility,” Dr. Mack conceded.

This is a clinically important unresolved question because secondary mitral regurgitation is extremely common. In a retrospective echocardiographic study of 558 heart failure patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less and class III-IV symptoms, 90% of them had some degree of mitral regurgitation (J Card Fail. 2004 Aug;10[4]:285-91).

Together with Columbia University cardiologist Dr. Gregg W. Stone, Dr. Mack is coprincipal investigator of the COAPT (Cardiovascular Outcomes Assessment of the MitraClip Percutaneous Therapy for Heart Failure Patients with Functional Mitral Regurgitation) trial, which is expected to provide an answer to this key question. The multicenter U.S. study involves a planned 420 patients with severely symptomatic secondary mitral regurgitation who are deemed at prohibitive risk for surgery. They are to be randomized to guideline-directed medical therapy with or without transcatheter mitral valve repair using the MitraClip device. Enrollment should be completed by May, with initial results available in late 2017.

Dr. Mack reported receiving research grants from Abbott Vascular, which is sponsoring the COAPT trial, as well as from Edwards Lifesciences.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – A clear message from the first-ever randomized trial of surgical mitral valve repair versus replacement for patients with severe ischemic mitral regurgitation is that replacement should be utilized more liberally, Dr. Michael J. Mack said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

The results of prosthetic valve implantation proved far more durable than repair. At 2 years of follow-up in this 251-patient multicenter trial conducted by the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network (CSTN), the incidence of recurrent moderate or severe mitral regurgitation was just 3.8% in the valve replacement group, compared with 58.8% with repair via restrictive annuloplasty. As a result, the repair group had significantly more heart failure–related adverse events and cardiovascular hospitalizations and a lower rate of clinically meaningful improvement in quality of life scores, noted Dr. Mack, an investigator in the trial and medical director of the Baylor Health Care System in Plano, Tex.

“I think surgical mitral valve replacement has had a bad name over the years, and one of the reasons is because of the worse left ventricular function afterwards. However, that was a casualty of excising the mitral valve and the subvalvular apparatus, causing atrial-ventricular disconnection. We’ve gotten smarter about this. The techniques we now use are valve sparing,” the cardiothoracic surgeon said.

He was quick to add, however, that the CSTN study results are by no means the death knell for restrictive mitral annuloplasty. Indeed, participants in the mitral valve repair group who didn’t develop recurrent regurgitation actually experienced significant positive reverse remodeling as reflected by improvement in their left ventricular end-systolic volume index, the primary endpoint of the study (N Engl J Med. 2016;374:344-35).

The key to successful outcomes in mitral valve repair is to save the procedure for patients who are unlikely to develop recurrent regurgitation. And a substudy of the CTSN trial led by Dr. Irving L. Kron, professor of surgery at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, provides practical guidance on that score. The investigators conducted a logistic regression analysis of the mitral valve repair group’s baseline echocardiographic and clinical characteristics and identified a collection of strong predictors of recurrent regurgitation within 2 years (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015 Mar;149[3]:752-61).

“The bottom line is, the more tethering you have of the mitral valve leaflets, the more likely you are to have recurrent mitral regurgitation after mitral valve annuloplasty,” Dr. Mack said.

The predictors of recurrent regurgitation included a coaptation depth greater than 10 mm, a posterior leaflet angle in excess of 45 degrees, a distal anterior leaflet angle greater than 25 degrees, inferior basal aneurysm, mitral annular calcification, and a left ventricular end diastolic diameter greater than 65 mm, as well as other indices of advanced left ventricular remodeling.

No or only mild annular dilation, as occurs, for example, in patients whose mitral regurgitation is caused by atrial fibrillation, is another independent predictor of recurrent regurgitation post repair.

“Shrinking the annulus isn’t going to make a difference if the annulus wasn’t dilated to begin with,” the surgeon observed. “If surgery is performed, we now know those patients who are most likely to recur – and they should have mitral valve replacement. If those factors are not present, then repair is still a viable option,” according to Dr. Mack.

That being said, it’s still not known whether correcting severe ischemic mitral regurgitation prolongs life or improves quality of life long term, compared with guideline-directed medical therapy, he stressed.

“Secondary mitral regurgitation is a disease of the left ventricle, not the mitral valve. So it’s possible that mitral regurgitation reduction has no benefit because the regurgitation is a surrogate marker not causally related to outcome. I don’t think so, but it is a possibility,” Dr. Mack conceded.

This is a clinically important unresolved question because secondary mitral regurgitation is extremely common. In a retrospective echocardiographic study of 558 heart failure patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less and class III-IV symptoms, 90% of them had some degree of mitral regurgitation (J Card Fail. 2004 Aug;10[4]:285-91).

Together with Columbia University cardiologist Dr. Gregg W. Stone, Dr. Mack is coprincipal investigator of the COAPT (Cardiovascular Outcomes Assessment of the MitraClip Percutaneous Therapy for Heart Failure Patients with Functional Mitral Regurgitation) trial, which is expected to provide an answer to this key question. The multicenter U.S. study involves a planned 420 patients with severely symptomatic secondary mitral regurgitation who are deemed at prohibitive risk for surgery. They are to be randomized to guideline-directed medical therapy with or without transcatheter mitral valve repair using the MitraClip device. Enrollment should be completed by May, with initial results available in late 2017.

Dr. Mack reported receiving research grants from Abbott Vascular, which is sponsoring the COAPT trial, as well as from Edwards Lifesciences.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

How to use two new game-changing heart failure drugs

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Ivabradine and sacubitril/valsartan are paradigm-changing drugs approved last year for the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction – and it’s entirely reasonable to begin using them now in the appropriate patients, Dr. Akshay S. Desai said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

The impressive positive results seen in the pivotal trials for these novel agents – the SHIFT trial for ivabradine (Corlanor) and PARADIGM-HF for sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) – have rocked the heart failure world.

The studies showed that, in the right patients, these two medications improve heart failure morbidity and mortality significantly beyond what’s achievable with the current gold standard, guideline-directed medical therapy. That’s exciting because even though great therapeutic strides have been made during the past 15 years, symptomatic patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) treated with optimal guideline-directed pharmacotherapy still have substantial residual risk for heart failure hospitalization and death, noted Dr. Desai, director of heart failure disease management at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The U.S. heart failure guidelines panel hasn’t yet addressed the use of either of these recently approved drugs, but Dr. Desai provided his best sense of the data and how he thinks physicians might start using them now.

Ivabradine and sacubitril/valsartan are first-in-class agents with novel mechanisms of action. Ivabradine’s demonstrated safety and efficacy in the SHIFT trial confirmed the hypothesis that elevated heart rate is a legitimate therapeutic target in HFrEF.

Sacubitril/valsartan, an angiotensin II receptor/neprilysin inhibitor formerly known as LCZ696, provides what is to date a unique ability to enhance the activity of endogenous vasoactive peptides, including natriuretic peptides, bradykinin, substance P, adrenomedullin, and calcitonin gene–related peptide. These peptides are antifibrotic, antihypertrophic, and they promote vasodilation and diuresis, thus counteracting the adverse effects of neurohormonal activation. But in HFrEF, these vasoactive peptides are less active and patients are less sensitive to them.

Ivabradine

This selective sinus node inhibitor decreases heart rate and has essentially no other effects. The drug has been available for years in Europe, and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has had sufficient time to integrate ivabradine into its guidelines for pharmacotherapy in HFrEF.

The ESC treatment algorithm for HFrEF (Eur Heart J. 2012 Jul;33[14]:1787-847) is built upon a foundation of thiazide diuretics to relieve signs and symptoms of congestion along with a beta-blocker and an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB). In a patient who still has New York Heart Association class II-IV symptoms after those drugs are titrated to guideline-recommended target levels or maximally tolerated doses, a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist – either spironolactone or eplerenone – is added. And, in a patient who still remains symptomatic, has a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less, is in sinus rhythm, and has a heart rate of 70 beats per minute or more, it’s time to consider adding ivabradine.

“This is how our own guidelines may elect to incorporate ivabradine, but of course, we don’t know yet,” Dr. Desai observed.

In the randomized, double-blind SHIFT trial involving 6,558 HFrEF patients who fit the description of ivabradine candidates described in the ESC guidelines, those who received ivabradine titrated to a maximum of 7.5 mg twice daily experienced a 26% reduction in hospital admissions for worsening heart failure, compared with placebo, a 26% reduction in deaths from heart failure, and fewer adverse events than the control group (Lancet. 2010 Sep 11;376[9744]:875-85).

The important question is who should get ivabradine and who should just get a little more beta-blocker in order to slow the heart rate. The fact is, many heart failure patients simply can’t tolerate the guideline-recommended target dose of beta-blocker therapy, which is 12.5 mg twice daily of carvedilol or its equivalent. Indeed, only 26% of SHIFT participants were able to do so.

“My interpretation of the SHIFT trial is that the goal is to reduce heart rate by any means necessary; preferentially, with a beta-blocker, and with ivabradine as an adjunct in patients who can’t get to target doses,” the cardiologist said.

Sacubitril/valsartan

In the landmark double-blind, 8,442-patient PARADIGM-HF trial, the group randomized to sacubitril/valsartan had a 20% reduction in the primary endpoint of cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization over 27 months of follow-up, compared with controls on enalapril at the guideline-recommended dose of 10 mg twice a day. The number needed to treat (NNT) was 21. Moreover, all-cause mortality was reduced by 16% (N Engl J Med. 2014 Sep 11;37[11]:993-1004).

In a recent follow-up cause of death analysis, Dr. Desai and his coinvestigators reported that 81% of all deaths in PARADIGM-HF were cardiovascular in nature. The NNT for sacubitril/valsartan in order to prevent one cardiovascular death was 32. The risk of sudden cardiac death was reduced by 80%, while the risk of death due to worsening heart failure was decreased by 21% (Eur Heart J 2015 Aug 7;36[30]:1990-7).

In another secondary analysis from the PARADIGM-HF investigators, the use of the angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitor was shown to prevent clinical progression of surviving patients with heart failure much more effectively than enalapril. The sacubitril/valsartan group was 34% less likely to have an emergency department visit for worsening heart failure, 18% less likely to require intensive care, and 22% less likely to receive an implantable heart failure device or undergo cardiac transplantation. The reduction in the rate of heart failure hospitalization became significant within the first 30 days (Circulation. 2015 Jan 6;131[1]:54-61).

Moreover, the absolute benefit of sacubitril/valsartan in PARADIGM-HF was consistent across the full spectrum of patient risk (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Nov 10;66[19]:2059-71).

To put this into perspective, Dr. Desai continued, for every 1,000 HFrEF patients switched from an ACE inhibitor or ARB to sacubitril/valsartan, the absolute benefit over the course of 27 months includes 31 fewer cardiovascular deaths, 28 fewer hospitalizations for heart failure, and 37 fewer hospitalizations for any reason.

“This is potent therapy for patients with HFrEF who have the right phenotype,” he observed.

While substitution of sacubitril/valsartan for an ACE inhibitor or ARB may be appropriate in many patients with chronic HFrEF who continue to have NYHA Class II-IV symptoms on guideline-directed medical therapy, several caveats apply, according to Dr. Desai.

It’s important to be aware of the PARADIGM-HF eligibility criteria, because it’s only in patients who fit that profile that sacubitril/valsartan provides evidence-based therapy. There are as yet no data to support the drug’s use in patients with new-onset HFrEF, acute decompensated HFrEF, in patients who are immediately post-MI, or in those with advanced chronic kidney disease, he emphasized.

“I think you have to be mindful of eligibility because the label that’s applied to this drug is basically ‘patients with HFrEF who are treated with guideline-directed medical therapy.’ There’s no specific requirement that you follow the detailed eligibility criteria of the PARADIGM-HF trial, but you should realize that the drug is known to be effective only in patients who fit the PARADIGM-HF eligibility profile,” he said.

Dr. Desai gave a few clinical pearls for prescribing sacubitril/valsartan. For most patients, the initial recommended dose is 49/51 mg twice daily. In those with low baseline blood pressure and tenuous hemodynamics, it’s appropriate to initiate therapy at 24/26 mg BID. It’s important to halt ACE inhibitor therapy 36 hours prior to starting sacubitril/valsartan so as to avoid overlap and consequent increased risk of angioedema. And while serum n-terminal prohormone brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) remains a useful biomarker to monitor heart rate severity and response to treatment while a patient is on sacubitril/valsartan, BNP is not because serum levels of that biomarker rise with neprilysin inhibition.

Dr. Desai reported receiving research support from Novartis and St. Jude Medical and serving as a consultant to those companies as well as Merck and Relypsa.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Ivabradine and sacubitril/valsartan are paradigm-changing drugs approved last year for the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction – and it’s entirely reasonable to begin using them now in the appropriate patients, Dr. Akshay S. Desai said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

The impressive positive results seen in the pivotal trials for these novel agents – the SHIFT trial for ivabradine (Corlanor) and PARADIGM-HF for sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) – have rocked the heart failure world.

The studies showed that, in the right patients, these two medications improve heart failure morbidity and mortality significantly beyond what’s achievable with the current gold standard, guideline-directed medical therapy. That’s exciting because even though great therapeutic strides have been made during the past 15 years, symptomatic patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) treated with optimal guideline-directed pharmacotherapy still have substantial residual risk for heart failure hospitalization and death, noted Dr. Desai, director of heart failure disease management at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The U.S. heart failure guidelines panel hasn’t yet addressed the use of either of these recently approved drugs, but Dr. Desai provided his best sense of the data and how he thinks physicians might start using them now.

Ivabradine and sacubitril/valsartan are first-in-class agents with novel mechanisms of action. Ivabradine’s demonstrated safety and efficacy in the SHIFT trial confirmed the hypothesis that elevated heart rate is a legitimate therapeutic target in HFrEF.

Sacubitril/valsartan, an angiotensin II receptor/neprilysin inhibitor formerly known as LCZ696, provides what is to date a unique ability to enhance the activity of endogenous vasoactive peptides, including natriuretic peptides, bradykinin, substance P, adrenomedullin, and calcitonin gene–related peptide. These peptides are antifibrotic, antihypertrophic, and they promote vasodilation and diuresis, thus counteracting the adverse effects of neurohormonal activation. But in HFrEF, these vasoactive peptides are less active and patients are less sensitive to them.

Ivabradine

This selective sinus node inhibitor decreases heart rate and has essentially no other effects. The drug has been available for years in Europe, and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has had sufficient time to integrate ivabradine into its guidelines for pharmacotherapy in HFrEF.

The ESC treatment algorithm for HFrEF (Eur Heart J. 2012 Jul;33[14]:1787-847) is built upon a foundation of thiazide diuretics to relieve signs and symptoms of congestion along with a beta-blocker and an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB). In a patient who still has New York Heart Association class II-IV symptoms after those drugs are titrated to guideline-recommended target levels or maximally tolerated doses, a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist – either spironolactone or eplerenone – is added. And, in a patient who still remains symptomatic, has a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less, is in sinus rhythm, and has a heart rate of 70 beats per minute or more, it’s time to consider adding ivabradine.

“This is how our own guidelines may elect to incorporate ivabradine, but of course, we don’t know yet,” Dr. Desai observed.

In the randomized, double-blind SHIFT trial involving 6,558 HFrEF patients who fit the description of ivabradine candidates described in the ESC guidelines, those who received ivabradine titrated to a maximum of 7.5 mg twice daily experienced a 26% reduction in hospital admissions for worsening heart failure, compared with placebo, a 26% reduction in deaths from heart failure, and fewer adverse events than the control group (Lancet. 2010 Sep 11;376[9744]:875-85).

The important question is who should get ivabradine and who should just get a little more beta-blocker in order to slow the heart rate. The fact is, many heart failure patients simply can’t tolerate the guideline-recommended target dose of beta-blocker therapy, which is 12.5 mg twice daily of carvedilol or its equivalent. Indeed, only 26% of SHIFT participants were able to do so.

“My interpretation of the SHIFT trial is that the goal is to reduce heart rate by any means necessary; preferentially, with a beta-blocker, and with ivabradine as an adjunct in patients who can’t get to target doses,” the cardiologist said.

Sacubitril/valsartan

In the landmark double-blind, 8,442-patient PARADIGM-HF trial, the group randomized to sacubitril/valsartan had a 20% reduction in the primary endpoint of cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization over 27 months of follow-up, compared with controls on enalapril at the guideline-recommended dose of 10 mg twice a day. The number needed to treat (NNT) was 21. Moreover, all-cause mortality was reduced by 16% (N Engl J Med. 2014 Sep 11;37[11]:993-1004).

In a recent follow-up cause of death analysis, Dr. Desai and his coinvestigators reported that 81% of all deaths in PARADIGM-HF were cardiovascular in nature. The NNT for sacubitril/valsartan in order to prevent one cardiovascular death was 32. The risk of sudden cardiac death was reduced by 80%, while the risk of death due to worsening heart failure was decreased by 21% (Eur Heart J 2015 Aug 7;36[30]:1990-7).

In another secondary analysis from the PARADIGM-HF investigators, the use of the angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitor was shown to prevent clinical progression of surviving patients with heart failure much more effectively than enalapril. The sacubitril/valsartan group was 34% less likely to have an emergency department visit for worsening heart failure, 18% less likely to require intensive care, and 22% less likely to receive an implantable heart failure device or undergo cardiac transplantation. The reduction in the rate of heart failure hospitalization became significant within the first 30 days (Circulation. 2015 Jan 6;131[1]:54-61).

Moreover, the absolute benefit of sacubitril/valsartan in PARADIGM-HF was consistent across the full spectrum of patient risk (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Nov 10;66[19]:2059-71).

To put this into perspective, Dr. Desai continued, for every 1,000 HFrEF patients switched from an ACE inhibitor or ARB to sacubitril/valsartan, the absolute benefit over the course of 27 months includes 31 fewer cardiovascular deaths, 28 fewer hospitalizations for heart failure, and 37 fewer hospitalizations for any reason.

“This is potent therapy for patients with HFrEF who have the right phenotype,” he observed.

While substitution of sacubitril/valsartan for an ACE inhibitor or ARB may be appropriate in many patients with chronic HFrEF who continue to have NYHA Class II-IV symptoms on guideline-directed medical therapy, several caveats apply, according to Dr. Desai.

It’s important to be aware of the PARADIGM-HF eligibility criteria, because it’s only in patients who fit that profile that sacubitril/valsartan provides evidence-based therapy. There are as yet no data to support the drug’s use in patients with new-onset HFrEF, acute decompensated HFrEF, in patients who are immediately post-MI, or in those with advanced chronic kidney disease, he emphasized.

“I think you have to be mindful of eligibility because the label that’s applied to this drug is basically ‘patients with HFrEF who are treated with guideline-directed medical therapy.’ There’s no specific requirement that you follow the detailed eligibility criteria of the PARADIGM-HF trial, but you should realize that the drug is known to be effective only in patients who fit the PARADIGM-HF eligibility profile,” he said.

Dr. Desai gave a few clinical pearls for prescribing sacubitril/valsartan. For most patients, the initial recommended dose is 49/51 mg twice daily. In those with low baseline blood pressure and tenuous hemodynamics, it’s appropriate to initiate therapy at 24/26 mg BID. It’s important to halt ACE inhibitor therapy 36 hours prior to starting sacubitril/valsartan so as to avoid overlap and consequent increased risk of angioedema. And while serum n-terminal prohormone brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) remains a useful biomarker to monitor heart rate severity and response to treatment while a patient is on sacubitril/valsartan, BNP is not because serum levels of that biomarker rise with neprilysin inhibition.

Dr. Desai reported receiving research support from Novartis and St. Jude Medical and serving as a consultant to those companies as well as Merck and Relypsa.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Ivabradine and sacubitril/valsartan are paradigm-changing drugs approved last year for the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction – and it’s entirely reasonable to begin using them now in the appropriate patients, Dr. Akshay S. Desai said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

The impressive positive results seen in the pivotal trials for these novel agents – the SHIFT trial for ivabradine (Corlanor) and PARADIGM-HF for sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) – have rocked the heart failure world.

The studies showed that, in the right patients, these two medications improve heart failure morbidity and mortality significantly beyond what’s achievable with the current gold standard, guideline-directed medical therapy. That’s exciting because even though great therapeutic strides have been made during the past 15 years, symptomatic patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) treated with optimal guideline-directed pharmacotherapy still have substantial residual risk for heart failure hospitalization and death, noted Dr. Desai, director of heart failure disease management at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The U.S. heart failure guidelines panel hasn’t yet addressed the use of either of these recently approved drugs, but Dr. Desai provided his best sense of the data and how he thinks physicians might start using them now.

Ivabradine and sacubitril/valsartan are first-in-class agents with novel mechanisms of action. Ivabradine’s demonstrated safety and efficacy in the SHIFT trial confirmed the hypothesis that elevated heart rate is a legitimate therapeutic target in HFrEF.

Sacubitril/valsartan, an angiotensin II receptor/neprilysin inhibitor formerly known as LCZ696, provides what is to date a unique ability to enhance the activity of endogenous vasoactive peptides, including natriuretic peptides, bradykinin, substance P, adrenomedullin, and calcitonin gene–related peptide. These peptides are antifibrotic, antihypertrophic, and they promote vasodilation and diuresis, thus counteracting the adverse effects of neurohormonal activation. But in HFrEF, these vasoactive peptides are less active and patients are less sensitive to them.

Ivabradine

This selective sinus node inhibitor decreases heart rate and has essentially no other effects. The drug has been available for years in Europe, and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has had sufficient time to integrate ivabradine into its guidelines for pharmacotherapy in HFrEF.

The ESC treatment algorithm for HFrEF (Eur Heart J. 2012 Jul;33[14]:1787-847) is built upon a foundation of thiazide diuretics to relieve signs and symptoms of congestion along with a beta-blocker and an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB). In a patient who still has New York Heart Association class II-IV symptoms after those drugs are titrated to guideline-recommended target levels or maximally tolerated doses, a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist – either spironolactone or eplerenone – is added. And, in a patient who still remains symptomatic, has a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less, is in sinus rhythm, and has a heart rate of 70 beats per minute or more, it’s time to consider adding ivabradine.

“This is how our own guidelines may elect to incorporate ivabradine, but of course, we don’t know yet,” Dr. Desai observed.

In the randomized, double-blind SHIFT trial involving 6,558 HFrEF patients who fit the description of ivabradine candidates described in the ESC guidelines, those who received ivabradine titrated to a maximum of 7.5 mg twice daily experienced a 26% reduction in hospital admissions for worsening heart failure, compared with placebo, a 26% reduction in deaths from heart failure, and fewer adverse events than the control group (Lancet. 2010 Sep 11;376[9744]:875-85).

The important question is who should get ivabradine and who should just get a little more beta-blocker in order to slow the heart rate. The fact is, many heart failure patients simply can’t tolerate the guideline-recommended target dose of beta-blocker therapy, which is 12.5 mg twice daily of carvedilol or its equivalent. Indeed, only 26% of SHIFT participants were able to do so.

“My interpretation of the SHIFT trial is that the goal is to reduce heart rate by any means necessary; preferentially, with a beta-blocker, and with ivabradine as an adjunct in patients who can’t get to target doses,” the cardiologist said.

Sacubitril/valsartan

In the landmark double-blind, 8,442-patient PARADIGM-HF trial, the group randomized to sacubitril/valsartan had a 20% reduction in the primary endpoint of cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization over 27 months of follow-up, compared with controls on enalapril at the guideline-recommended dose of 10 mg twice a day. The number needed to treat (NNT) was 21. Moreover, all-cause mortality was reduced by 16% (N Engl J Med. 2014 Sep 11;37[11]:993-1004).

In a recent follow-up cause of death analysis, Dr. Desai and his coinvestigators reported that 81% of all deaths in PARADIGM-HF were cardiovascular in nature. The NNT for sacubitril/valsartan in order to prevent one cardiovascular death was 32. The risk of sudden cardiac death was reduced by 80%, while the risk of death due to worsening heart failure was decreased by 21% (Eur Heart J 2015 Aug 7;36[30]:1990-7).

In another secondary analysis from the PARADIGM-HF investigators, the use of the angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitor was shown to prevent clinical progression of surviving patients with heart failure much more effectively than enalapril. The sacubitril/valsartan group was 34% less likely to have an emergency department visit for worsening heart failure, 18% less likely to require intensive care, and 22% less likely to receive an implantable heart failure device or undergo cardiac transplantation. The reduction in the rate of heart failure hospitalization became significant within the first 30 days (Circulation. 2015 Jan 6;131[1]:54-61).

Moreover, the absolute benefit of sacubitril/valsartan in PARADIGM-HF was consistent across the full spectrum of patient risk (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Nov 10;66[19]:2059-71).

To put this into perspective, Dr. Desai continued, for every 1,000 HFrEF patients switched from an ACE inhibitor or ARB to sacubitril/valsartan, the absolute benefit over the course of 27 months includes 31 fewer cardiovascular deaths, 28 fewer hospitalizations for heart failure, and 37 fewer hospitalizations for any reason.

“This is potent therapy for patients with HFrEF who have the right phenotype,” he observed.

While substitution of sacubitril/valsartan for an ACE inhibitor or ARB may be appropriate in many patients with chronic HFrEF who continue to have NYHA Class II-IV symptoms on guideline-directed medical therapy, several caveats apply, according to Dr. Desai.

It’s important to be aware of the PARADIGM-HF eligibility criteria, because it’s only in patients who fit that profile that sacubitril/valsartan provides evidence-based therapy. There are as yet no data to support the drug’s use in patients with new-onset HFrEF, acute decompensated HFrEF, in patients who are immediately post-MI, or in those with advanced chronic kidney disease, he emphasized.

“I think you have to be mindful of eligibility because the label that’s applied to this drug is basically ‘patients with HFrEF who are treated with guideline-directed medical therapy.’ There’s no specific requirement that you follow the detailed eligibility criteria of the PARADIGM-HF trial, but you should realize that the drug is known to be effective only in patients who fit the PARADIGM-HF eligibility profile,” he said.

Dr. Desai gave a few clinical pearls for prescribing sacubitril/valsartan. For most patients, the initial recommended dose is 49/51 mg twice daily. In those with low baseline blood pressure and tenuous hemodynamics, it’s appropriate to initiate therapy at 24/26 mg BID. It’s important to halt ACE inhibitor therapy 36 hours prior to starting sacubitril/valsartan so as to avoid overlap and consequent increased risk of angioedema. And while serum n-terminal prohormone brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) remains a useful biomarker to monitor heart rate severity and response to treatment while a patient is on sacubitril/valsartan, BNP is not because serum levels of that biomarker rise with neprilysin inhibition.

Dr. Desai reported receiving research support from Novartis and St. Jude Medical and serving as a consultant to those companies as well as Merck and Relypsa.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

Warfarin is best for anticoagulation in prosthetic heart valve pregnancies

SNOWMASS, COLO. – How would you manage anticoagulation in a newly pregnant 23-year-old with a mechanical heart valve who has been on warfarin at 3 mg/day?

A) Weight-adjusted low-molecular-weight heparin during the first trimester, then warfarin in the second and third until switching to unfractionated heparin for delivery.

B) Low-molecular-weight heparin throughout pregnancy.

C) Warfarin throughout pregnancy.

D) Unfractionated heparin in the first trimester, warfarin in the second and third until returning to unfractionated heparin peridelivery.

The correct answer, according to both the ACC/AHA guidelines (Circulation. 2014 Jun 10;129[23]:e521-643) and European Society of Cardiology guidelines (Eur Heart J. 2011 Dec;32[24]:3147-97), is C in women who are on 5 mg/day of warfarin or less.

“Oral anticoagulants throughout pregnancy are much better for the mother, and this is where the guidelines have moved,” Dr. Carole A. Warnes said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

Both sets of guidelines give a class I recommendation to warfarin during the second and third trimesters, because the risk of warfarin embryopathy is confined to weeks 6-12. During the first trimester, warfarin at 5 mg/day or less gets a class IIa rating – making it preferable to unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin – because heparin is a far less effective anticoagulant. Plus, multiple small studies indicate the risk of embryopathy is low – roughly 1%-2% – when the mother is on warfarin at 5 mg/day or less.

In a woman on more than 5 mg/day of warfarin, the risk of warfarin embryopathy is about 6%, so the guidelines recommend replacing the drug with heparin during weeks 6-12.

“It’s not a walk in the park,” said Dr. Warnes, director of the Snowmass conference and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The major concern in using heparin for anticoagulation in pregnancy is valve thrombosis. It doubles the risk.

“Pregnancy is the most prothrombotic state there is,” she said. “It’s not like managing a patient through a hip replacement or prostate surgery. Women with a mechanical prosthetic valve should be managed by a heart valve team with expertise in treatment during pregnancy.”

The alternatives to warfarin are adjusted-dose unfractionated heparin, which must be given in a continuous intravenous infusion with meticulous monitoring of activated partial thromboplastin time, or twice-daily low-molecular-weight heparin with dose adjustment by weight and maintenance of a target anti–Factor Xa level of 1.0-1.2 IU/mL.

“If you use low-molecular-weight heparin, you’re going to be seeing that patient every week to monitor anti–Factor Xa 4-6 hours post injection. You’ll find it’s not that easy to stay in the sweet spot, with excellent anticoagulation without an increased risk of maternal thromboembolism, or at the other extreme, fetal bleeding. What might look initially as a relatively easy strategy with a lot of appeal turns out to entail considerable risk,” Dr. Warnes said.

This was underscored in a cautionary report by highly experienced University of Toronto investigators. In their series of 23 pregnancies in 17 women with mechanical heart valves on low-molecular-weight heparin throughout pregnancy with careful monitoring, there was one maternal thromboembolic event resulting in maternal and fetal death despite a documented therapeutic anti–Factor Xa level (Am J Cardiol. 2009 Nov 1;104[9]:1259-63).

Although warfarin is clearly the better anticoagulant for the mother, the fetus pays the price. This was highlighted in a recent report from the ESC Registry of Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease (ROPAC) that compared pregnancy outcomes in 212 patients with a mechanical heart valve, 134 with a tissue valve, and 2,620 women without a prosthetic heart valve. Use of warfarin or another vitamin K antagonist in the first trimester was associated with a higher rate of miscarriage than heparin – 28.6% vs. 9.2% – as well as a 7.1% incidence of late fetal death, compared with just 0.7% with heparin.

On the other hand, the mechanical valve thrombosis rate was 4.7%, with half of those serious events occurring during the first trimester in patients after they’d been switched to heparin (Circulation. 2015 Jul 14;132[2]:132-42).

Hemorrhagic events occurred in 23.1% of mothers with a mechanical heart valve, 5.1% of those with a bioprosthetic valve, and 4.9% of patients without a prosthetic valve. A point worth incorporating into prepregnancy patient counseling, Dr. Warnes noted, is that only 58% of ROPAC participants with a mechanical heart valve had an uncomplicated pregnancy with a live birth, in contrast to 79% of those with a tissue valve and 78% of controls.

Because warfarin crosses the placenta, and it takes about a week for the fetus to eliminate the drug following maternal discontinuation, the guidelines recommend stopping warfarin at about week 36 and changing to a continuous infusion of dose-adjusted unfractionated heparin peridelivery. The heparin should be stopped for as short a time as possible before delivery and resumed 6-12 hours post delivery in order to protect against valve thrombosis.

Of course, opting for a bioprosthetic rather than a mechanical heart valve avoids all these difficult anticoagulation-related issues. But it poses a different serious problem: The younger the patient at the time of tissue valve implantation, the greater the risk of rapid calcification and structural valve deterioration. Indeed, among patients who are age 16-39 when they receive a bioprosthetic valve, the rate of structural valve deterioration is 50% at 10 years and 90% at 15 years.

“There is no ideal valve prosthesis. If you elect a tissue prosthesis, you have to discuss the risk of reoperation in that young woman,” Dr. Warnes advised.

Recent data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons database indicate the mortality associated with redo elective aortic valve replacement in a 35-year-old woman with no comorbidities averages 1.63%, with a 2% mortality rate for redo mitral valve replacement.

Dr. Warnes reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – How would you manage anticoagulation in a newly pregnant 23-year-old with a mechanical heart valve who has been on warfarin at 3 mg/day?

A) Weight-adjusted low-molecular-weight heparin during the first trimester, then warfarin in the second and third until switching to unfractionated heparin for delivery.

B) Low-molecular-weight heparin throughout pregnancy.

C) Warfarin throughout pregnancy.

D) Unfractionated heparin in the first trimester, warfarin in the second and third until returning to unfractionated heparin peridelivery.

The correct answer, according to both the ACC/AHA guidelines (Circulation. 2014 Jun 10;129[23]:e521-643) and European Society of Cardiology guidelines (Eur Heart J. 2011 Dec;32[24]:3147-97), is C in women who are on 5 mg/day of warfarin or less.

“Oral anticoagulants throughout pregnancy are much better for the mother, and this is where the guidelines have moved,” Dr. Carole A. Warnes said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

Both sets of guidelines give a class I recommendation to warfarin during the second and third trimesters, because the risk of warfarin embryopathy is confined to weeks 6-12. During the first trimester, warfarin at 5 mg/day or less gets a class IIa rating – making it preferable to unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin – because heparin is a far less effective anticoagulant. Plus, multiple small studies indicate the risk of embryopathy is low – roughly 1%-2% – when the mother is on warfarin at 5 mg/day or less.

In a woman on more than 5 mg/day of warfarin, the risk of warfarin embryopathy is about 6%, so the guidelines recommend replacing the drug with heparin during weeks 6-12.

“It’s not a walk in the park,” said Dr. Warnes, director of the Snowmass conference and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The major concern in using heparin for anticoagulation in pregnancy is valve thrombosis. It doubles the risk.

“Pregnancy is the most prothrombotic state there is,” she said. “It’s not like managing a patient through a hip replacement or prostate surgery. Women with a mechanical prosthetic valve should be managed by a heart valve team with expertise in treatment during pregnancy.”

The alternatives to warfarin are adjusted-dose unfractionated heparin, which must be given in a continuous intravenous infusion with meticulous monitoring of activated partial thromboplastin time, or twice-daily low-molecular-weight heparin with dose adjustment by weight and maintenance of a target anti–Factor Xa level of 1.0-1.2 IU/mL.

“If you use low-molecular-weight heparin, you’re going to be seeing that patient every week to monitor anti–Factor Xa 4-6 hours post injection. You’ll find it’s not that easy to stay in the sweet spot, with excellent anticoagulation without an increased risk of maternal thromboembolism, or at the other extreme, fetal bleeding. What might look initially as a relatively easy strategy with a lot of appeal turns out to entail considerable risk,” Dr. Warnes said.

This was underscored in a cautionary report by highly experienced University of Toronto investigators. In their series of 23 pregnancies in 17 women with mechanical heart valves on low-molecular-weight heparin throughout pregnancy with careful monitoring, there was one maternal thromboembolic event resulting in maternal and fetal death despite a documented therapeutic anti–Factor Xa level (Am J Cardiol. 2009 Nov 1;104[9]:1259-63).

Although warfarin is clearly the better anticoagulant for the mother, the fetus pays the price. This was highlighted in a recent report from the ESC Registry of Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease (ROPAC) that compared pregnancy outcomes in 212 patients with a mechanical heart valve, 134 with a tissue valve, and 2,620 women without a prosthetic heart valve. Use of warfarin or another vitamin K antagonist in the first trimester was associated with a higher rate of miscarriage than heparin – 28.6% vs. 9.2% – as well as a 7.1% incidence of late fetal death, compared with just 0.7% with heparin.