User login

National Jewish Health: Annual Pulmonary and Allergy Update at Keystone

Expert: Choose your sinus surgeon carefully

KEYSTONE, COLO. – Surgical treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis has come a long way from the earlier "grab and tear" days, but referring physicians need to understand that not all otolaryngologists are providing state-of-the-art care.

"I am critical of some of my colleagues," Dr. Todd T. Kingdom said at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

"If I leave you with one message, it’s to set high expectations of your consultants in otolaryngology. You should find colleagues who are interested in sinus disease, who are committed to it, and who are excellent," added Dr. Kingdom, professor and vice chairman of the department of otolaryngology, head and neck surgery, at the University of Colorado, Denver, and immediate past president of the American Rhinologic Society.

One fine source is the pool of graduates of U.S. subspecialty surgical rhinology fellowship programs. Each year, 30 surgeons complete one of these fellowships, he said.

Technical innovations over the past 15 years have driven major advances in endoscopic sinus surgery. Powered microdebriders are used to precisely and efficiently remove hyperplastic mucosal disease and restore mucociliary clearance. Mucosal preservation is now a central tenet. Forward-thinking surgeons place a priority on creating exposure for delivery of topical medications. The procedures are routinely done on an outpatient basis, and they are less invasive than in former times. The outcomes are better, too, with this modern patient-centered, symptom-based approach.

"We have efficient ways now to take care of very severe disease atraumatically," Dr. Kingdom explained.

He emphasized that postoperative care is critical to successful sinus surgery outcomes. "My biggest criticism of my colleagues in otolaryngology is that many of them cut and go. There isn’t an emphasis on postoperative care," he said. "That’s a clear, clear deficiency in our approach.

"My postop schedule is to see patients at 1, 3, and 6 weeks and 3 and 6 months after surgery – and that’s if they’re doing perfectly. My point is you should have your otolaryngologist really fussing over these people. It’s not, ‘Well, it’s been a couple of weeks, you look fine, you can go back to your allergist now, I’ll see you later.’ It shouldn’t be that way," Dr. Kingdom said.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Dr. Todd T. Kingdom, allergy and respiratory diseases, National Jewish Health, sinus disease, American Rhinologic Society, U.S. subspecialty surgical rhinology fellowship programs, endoscopic sinus surgery, Powered microdebriders, hyperplastic mucosal disease, restore mucociliary clearance, Mucosal preservation,

KEYSTONE, COLO. – Surgical treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis has come a long way from the earlier "grab and tear" days, but referring physicians need to understand that not all otolaryngologists are providing state-of-the-art care.

"I am critical of some of my colleagues," Dr. Todd T. Kingdom said at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

"If I leave you with one message, it’s to set high expectations of your consultants in otolaryngology. You should find colleagues who are interested in sinus disease, who are committed to it, and who are excellent," added Dr. Kingdom, professor and vice chairman of the department of otolaryngology, head and neck surgery, at the University of Colorado, Denver, and immediate past president of the American Rhinologic Society.

One fine source is the pool of graduates of U.S. subspecialty surgical rhinology fellowship programs. Each year, 30 surgeons complete one of these fellowships, he said.

Technical innovations over the past 15 years have driven major advances in endoscopic sinus surgery. Powered microdebriders are used to precisely and efficiently remove hyperplastic mucosal disease and restore mucociliary clearance. Mucosal preservation is now a central tenet. Forward-thinking surgeons place a priority on creating exposure for delivery of topical medications. The procedures are routinely done on an outpatient basis, and they are less invasive than in former times. The outcomes are better, too, with this modern patient-centered, symptom-based approach.

"We have efficient ways now to take care of very severe disease atraumatically," Dr. Kingdom explained.

He emphasized that postoperative care is critical to successful sinus surgery outcomes. "My biggest criticism of my colleagues in otolaryngology is that many of them cut and go. There isn’t an emphasis on postoperative care," he said. "That’s a clear, clear deficiency in our approach.

"My postop schedule is to see patients at 1, 3, and 6 weeks and 3 and 6 months after surgery – and that’s if they’re doing perfectly. My point is you should have your otolaryngologist really fussing over these people. It’s not, ‘Well, it’s been a couple of weeks, you look fine, you can go back to your allergist now, I’ll see you later.’ It shouldn’t be that way," Dr. Kingdom said.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

KEYSTONE, COLO. – Surgical treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis has come a long way from the earlier "grab and tear" days, but referring physicians need to understand that not all otolaryngologists are providing state-of-the-art care.

"I am critical of some of my colleagues," Dr. Todd T. Kingdom said at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

"If I leave you with one message, it’s to set high expectations of your consultants in otolaryngology. You should find colleagues who are interested in sinus disease, who are committed to it, and who are excellent," added Dr. Kingdom, professor and vice chairman of the department of otolaryngology, head and neck surgery, at the University of Colorado, Denver, and immediate past president of the American Rhinologic Society.

One fine source is the pool of graduates of U.S. subspecialty surgical rhinology fellowship programs. Each year, 30 surgeons complete one of these fellowships, he said.

Technical innovations over the past 15 years have driven major advances in endoscopic sinus surgery. Powered microdebriders are used to precisely and efficiently remove hyperplastic mucosal disease and restore mucociliary clearance. Mucosal preservation is now a central tenet. Forward-thinking surgeons place a priority on creating exposure for delivery of topical medications. The procedures are routinely done on an outpatient basis, and they are less invasive than in former times. The outcomes are better, too, with this modern patient-centered, symptom-based approach.

"We have efficient ways now to take care of very severe disease atraumatically," Dr. Kingdom explained.

He emphasized that postoperative care is critical to successful sinus surgery outcomes. "My biggest criticism of my colleagues in otolaryngology is that many of them cut and go. There isn’t an emphasis on postoperative care," he said. "That’s a clear, clear deficiency in our approach.

"My postop schedule is to see patients at 1, 3, and 6 weeks and 3 and 6 months after surgery – and that’s if they’re doing perfectly. My point is you should have your otolaryngologist really fussing over these people. It’s not, ‘Well, it’s been a couple of weeks, you look fine, you can go back to your allergist now, I’ll see you later.’ It shouldn’t be that way," Dr. Kingdom said.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Dr. Todd T. Kingdom, allergy and respiratory diseases, National Jewish Health, sinus disease, American Rhinologic Society, U.S. subspecialty surgical rhinology fellowship programs, endoscopic sinus surgery, Powered microdebriders, hyperplastic mucosal disease, restore mucociliary clearance, Mucosal preservation,

Dr. Todd T. Kingdom, allergy and respiratory diseases, National Jewish Health, sinus disease, American Rhinologic Society, U.S. subspecialty surgical rhinology fellowship programs, endoscopic sinus surgery, Powered microdebriders, hyperplastic mucosal disease, restore mucociliary clearance, Mucosal preservation,

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE PULMONARY AND ALLERGY UPDATE

Misery, thy name is chronic rhinosinusitis

KEYSTONE, COLO. – Just how lousy do patients with medically refractory chronic rhinosinusitis feel in daily life? A lot worse than you might guess.

Patients who elected to undergo endoscopic sinus surgery after failing medical therapy for chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) rated their own baseline health state on standardized measures as being well below U.S. population norms. Their degree of impairment was similar to the self-rated scores among age- and gender-matched individuals with end-stage renal disease or Parkinson’s disease, according to Dr. Todd T. Kingdom, professor and vice chairman of the department of otolaryngology, head and neck surgery, at the University of Colorado, Denver, and immediate past president of the American Rhinologic Society.

He cited a 5-year study that prospectively followed 232 adults with CRS who elected to undergo endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) after failing to improve on medical therapy (Laryngoscope 2011;121:2672-8). Their mean presurgical health state utility value – derived using the Short Form 6D via methods routinely employed by health economists – was 0.65, on a scale in which 0 is death and 1.0 is perfect health.

That was worse than the self-rated scores among patients with heart failure or moderate COPD, as reported in other studies, and only slightly better than the self-rated health of patients awaiting hip replacement or liver transplantation. The U.S. population norm was a score of 0.81, Dr. Kingdom noted at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

When self-rated health status scores were determined again 6 months or longer after ESS, patients who underwent a revision procedure had a statistically and clinically significant 0.06-point improvement on the 0-1 scale, while those with no prior sinus surgery showed an even more robust 0.09-point gain.

Those are markedly larger improvements than documented in other studies following initiation of drug therapy for Parkinson’s disease, for example, or tumor necrosis factor–inhibitor therapy for psoriasis. Of the specific interventions assessed, only total hip replacement and bariatric surgery resulted in greater self-rated gains in health status than ESS.

In this and other studies, a patient’s baseline clinical phenotype didn’t predict the degree of improvement on quality of life measures following ESS, and gender, age, comorbid asthma, or aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease did not influence how much benefit a patient would receive from ESS.

Patients with baseline self-reported depression, however, were slightly, albeit statistically significantly, less likely than nondepressed patients to experience significant improvement. And patients who presented without nasal polyps showed significantly more improvement in self-reported health status after ESS than did those with polyps.

Dr. Kingdom reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

KEYSTONE, COLO. – Just how lousy do patients with medically refractory chronic rhinosinusitis feel in daily life? A lot worse than you might guess.

Patients who elected to undergo endoscopic sinus surgery after failing medical therapy for chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) rated their own baseline health state on standardized measures as being well below U.S. population norms. Their degree of impairment was similar to the self-rated scores among age- and gender-matched individuals with end-stage renal disease or Parkinson’s disease, according to Dr. Todd T. Kingdom, professor and vice chairman of the department of otolaryngology, head and neck surgery, at the University of Colorado, Denver, and immediate past president of the American Rhinologic Society.

He cited a 5-year study that prospectively followed 232 adults with CRS who elected to undergo endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) after failing to improve on medical therapy (Laryngoscope 2011;121:2672-8). Their mean presurgical health state utility value – derived using the Short Form 6D via methods routinely employed by health economists – was 0.65, on a scale in which 0 is death and 1.0 is perfect health.

That was worse than the self-rated scores among patients with heart failure or moderate COPD, as reported in other studies, and only slightly better than the self-rated health of patients awaiting hip replacement or liver transplantation. The U.S. population norm was a score of 0.81, Dr. Kingdom noted at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

When self-rated health status scores were determined again 6 months or longer after ESS, patients who underwent a revision procedure had a statistically and clinically significant 0.06-point improvement on the 0-1 scale, while those with no prior sinus surgery showed an even more robust 0.09-point gain.

Those are markedly larger improvements than documented in other studies following initiation of drug therapy for Parkinson’s disease, for example, or tumor necrosis factor–inhibitor therapy for psoriasis. Of the specific interventions assessed, only total hip replacement and bariatric surgery resulted in greater self-rated gains in health status than ESS.

In this and other studies, a patient’s baseline clinical phenotype didn’t predict the degree of improvement on quality of life measures following ESS, and gender, age, comorbid asthma, or aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease did not influence how much benefit a patient would receive from ESS.

Patients with baseline self-reported depression, however, were slightly, albeit statistically significantly, less likely than nondepressed patients to experience significant improvement. And patients who presented without nasal polyps showed significantly more improvement in self-reported health status after ESS than did those with polyps.

Dr. Kingdom reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

KEYSTONE, COLO. – Just how lousy do patients with medically refractory chronic rhinosinusitis feel in daily life? A lot worse than you might guess.

Patients who elected to undergo endoscopic sinus surgery after failing medical therapy for chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) rated their own baseline health state on standardized measures as being well below U.S. population norms. Their degree of impairment was similar to the self-rated scores among age- and gender-matched individuals with end-stage renal disease or Parkinson’s disease, according to Dr. Todd T. Kingdom, professor and vice chairman of the department of otolaryngology, head and neck surgery, at the University of Colorado, Denver, and immediate past president of the American Rhinologic Society.

He cited a 5-year study that prospectively followed 232 adults with CRS who elected to undergo endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) after failing to improve on medical therapy (Laryngoscope 2011;121:2672-8). Their mean presurgical health state utility value – derived using the Short Form 6D via methods routinely employed by health economists – was 0.65, on a scale in which 0 is death and 1.0 is perfect health.

That was worse than the self-rated scores among patients with heart failure or moderate COPD, as reported in other studies, and only slightly better than the self-rated health of patients awaiting hip replacement or liver transplantation. The U.S. population norm was a score of 0.81, Dr. Kingdom noted at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

When self-rated health status scores were determined again 6 months or longer after ESS, patients who underwent a revision procedure had a statistically and clinically significant 0.06-point improvement on the 0-1 scale, while those with no prior sinus surgery showed an even more robust 0.09-point gain.

Those are markedly larger improvements than documented in other studies following initiation of drug therapy for Parkinson’s disease, for example, or tumor necrosis factor–inhibitor therapy for psoriasis. Of the specific interventions assessed, only total hip replacement and bariatric surgery resulted in greater self-rated gains in health status than ESS.

In this and other studies, a patient’s baseline clinical phenotype didn’t predict the degree of improvement on quality of life measures following ESS, and gender, age, comorbid asthma, or aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease did not influence how much benefit a patient would receive from ESS.

Patients with baseline self-reported depression, however, were slightly, albeit statistically significantly, less likely than nondepressed patients to experience significant improvement. And patients who presented without nasal polyps showed significantly more improvement in self-reported health status after ESS than did those with polyps.

Dr. Kingdom reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE PULMONARY AND ALLERGY UPDATE

Steroid-sparing therapy is promising for allergic asthma

KEYSTONE, COLO. – A novel toll-like receptor-9 agonist showed impressive clinical efficacy in persistent allergic asthma in a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial.

"This is really interesting," Dr. Harold S. Nelson commented in highlighting the European study as one of the most promising new developments in immunology during the past year in his talk at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

The toll-like receptor-9 agonist under study is known as QbG10. It consists of a protein shell derived from the Q-beta bacteriophage which is wrapped around a core of DNA oligomer G10 rich in A-type CpG motifs. The protein shell protects the G10 CpG so that when the antigen-presenting cell digests that outer coat, the CpG sits like a Trojan horse inside the T cell or macrophage. The G10 CpG induces interferon-alpha production, which in turn causes degradation of transcription factor GATA-3, explained Dr. Nelson, professor of medicine and of pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Denver, and National Jewish Health.

Allergic asthma is a disease in which allergen-specific Th2 responses figure prominently. QbG10 therapy is designed to nudge the immune system toward a Th1-mediated protective response.

What’s particularly intriguing about this novel immunotherapy, he added, is that the clinical efficacy is achieved without administering any allergen. The results are achieved simply by showing the CpG to asthma patients. CpGs are DNA oligonucleotides containing unmethylated deoxycytidylyl-deoxyguanosine dinucleotides.

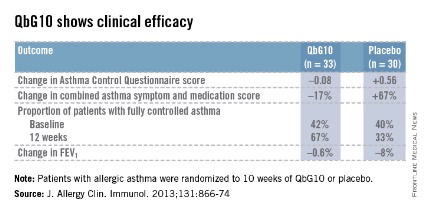

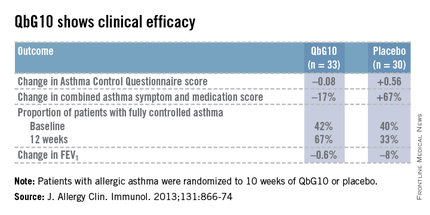

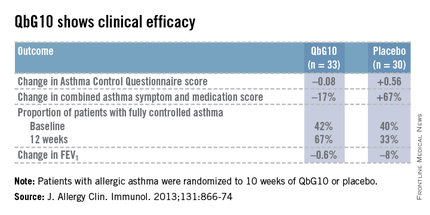

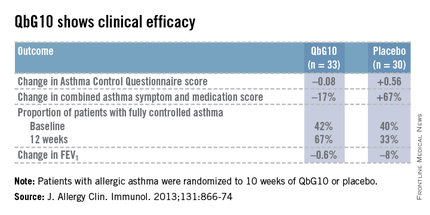

The European proof-of-concept study included 63 patients with allergic asthma being treated with moderate- or high-dose inhaled corticosteroids. They were randomized to receive seven injections of QbG10 or placebo over the course of 10 weeks, during which a controlled steroid withdrawal was carried out. After 4 weeks, the patients’ inhaled steroid dose was cut by 50%. After 8 weeks, the inhaled steroid was discontinued altogether. At evaluation at 12 weeks – 4 weeks after inhaled steroids were halted – two-thirds of QbG10-treated patients had well-controlled asthma as defined by an Asthma Control Questionnaire score of 0.75 or less, compared with one-third of controls. The QbG10 group showed similar advantages on other measures of asthma control, in spite of the steroid taper (see chart).

Local injection site reactions were common in the QbG10 group. The reactions were generally mild to moderate and were most pronounced 1-2 days post injection. The biggest reactions were noted after the third of the seven injections. No systemic reactions occurred (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013;131:866-74).

Dr. Nelson reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this work.

KEYSTONE, COLO. – A novel toll-like receptor-9 agonist showed impressive clinical efficacy in persistent allergic asthma in a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial.

"This is really interesting," Dr. Harold S. Nelson commented in highlighting the European study as one of the most promising new developments in immunology during the past year in his talk at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

The toll-like receptor-9 agonist under study is known as QbG10. It consists of a protein shell derived from the Q-beta bacteriophage which is wrapped around a core of DNA oligomer G10 rich in A-type CpG motifs. The protein shell protects the G10 CpG so that when the antigen-presenting cell digests that outer coat, the CpG sits like a Trojan horse inside the T cell or macrophage. The G10 CpG induces interferon-alpha production, which in turn causes degradation of transcription factor GATA-3, explained Dr. Nelson, professor of medicine and of pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Denver, and National Jewish Health.

Allergic asthma is a disease in which allergen-specific Th2 responses figure prominently. QbG10 therapy is designed to nudge the immune system toward a Th1-mediated protective response.

What’s particularly intriguing about this novel immunotherapy, he added, is that the clinical efficacy is achieved without administering any allergen. The results are achieved simply by showing the CpG to asthma patients. CpGs are DNA oligonucleotides containing unmethylated deoxycytidylyl-deoxyguanosine dinucleotides.

The European proof-of-concept study included 63 patients with allergic asthma being treated with moderate- or high-dose inhaled corticosteroids. They were randomized to receive seven injections of QbG10 or placebo over the course of 10 weeks, during which a controlled steroid withdrawal was carried out. After 4 weeks, the patients’ inhaled steroid dose was cut by 50%. After 8 weeks, the inhaled steroid was discontinued altogether. At evaluation at 12 weeks – 4 weeks after inhaled steroids were halted – two-thirds of QbG10-treated patients had well-controlled asthma as defined by an Asthma Control Questionnaire score of 0.75 or less, compared with one-third of controls. The QbG10 group showed similar advantages on other measures of asthma control, in spite of the steroid taper (see chart).

Local injection site reactions were common in the QbG10 group. The reactions were generally mild to moderate and were most pronounced 1-2 days post injection. The biggest reactions were noted after the third of the seven injections. No systemic reactions occurred (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013;131:866-74).

Dr. Nelson reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this work.

KEYSTONE, COLO. – A novel toll-like receptor-9 agonist showed impressive clinical efficacy in persistent allergic asthma in a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial.

"This is really interesting," Dr. Harold S. Nelson commented in highlighting the European study as one of the most promising new developments in immunology during the past year in his talk at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

The toll-like receptor-9 agonist under study is known as QbG10. It consists of a protein shell derived from the Q-beta bacteriophage which is wrapped around a core of DNA oligomer G10 rich in A-type CpG motifs. The protein shell protects the G10 CpG so that when the antigen-presenting cell digests that outer coat, the CpG sits like a Trojan horse inside the T cell or macrophage. The G10 CpG induces interferon-alpha production, which in turn causes degradation of transcription factor GATA-3, explained Dr. Nelson, professor of medicine and of pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Denver, and National Jewish Health.

Allergic asthma is a disease in which allergen-specific Th2 responses figure prominently. QbG10 therapy is designed to nudge the immune system toward a Th1-mediated protective response.

What’s particularly intriguing about this novel immunotherapy, he added, is that the clinical efficacy is achieved without administering any allergen. The results are achieved simply by showing the CpG to asthma patients. CpGs are DNA oligonucleotides containing unmethylated deoxycytidylyl-deoxyguanosine dinucleotides.

The European proof-of-concept study included 63 patients with allergic asthma being treated with moderate- or high-dose inhaled corticosteroids. They were randomized to receive seven injections of QbG10 or placebo over the course of 10 weeks, during which a controlled steroid withdrawal was carried out. After 4 weeks, the patients’ inhaled steroid dose was cut by 50%. After 8 weeks, the inhaled steroid was discontinued altogether. At evaluation at 12 weeks – 4 weeks after inhaled steroids were halted – two-thirds of QbG10-treated patients had well-controlled asthma as defined by an Asthma Control Questionnaire score of 0.75 or less, compared with one-third of controls. The QbG10 group showed similar advantages on other measures of asthma control, in spite of the steroid taper (see chart).

Local injection site reactions were common in the QbG10 group. The reactions were generally mild to moderate and were most pronounced 1-2 days post injection. The biggest reactions were noted after the third of the seven injections. No systemic reactions occurred (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013;131:866-74).

Dr. Nelson reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this work.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE PULMONARY AND ALLERGY UPDATE

Sinus surgery: new rigor in research

KEYSTONE, COLO. – Research-minded otolaryngologists have gotten serious about conducting high-quality, patient-centered outcomes studies of endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis, which more than 250,000 Americans undergo each year. And the results are eye opening.

Mounting evidence documents that endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) in properly selected patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) results in markedly improved quality of life, functional status, and reduced use of medications, compared with medical management, Dr. Todd T. Kingdom said at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

These studies utilize validated measures of patient-centered quality of life and symptoms. They are nothing like the lightweight, less-than-persuasive ESS research published in the 1990s, which reported glowing ‘success’ rates of 80%-97% in single-institution retrospective studies using variable inclusion criteria and often-sketchy definitions of success.

"Those data are not acceptable, but that’s what we had. This was before evidence-based medicine with an emphasis on rigorously designed studies took hold," explained Dr. Kingdom, professor and vice chairman of the department of otolaryngology – head and neck surgery, at the University of Colorado, Denver, and immediate past president of the American Rhinologic Society.

Current research emphasizes the use of modern, validated patient-centered quality of life tools and symptom scores because CRS is a symptom-based diagnosis and it is symptom severity that drives patients to seek treatment. Also, objective measures, such as the Lund-Mackay CT staging system, fail to capture the full experience of disease burden. Nor do objective measures necessarily correlate with patient symptoms, according to the otolaryngologist.

A low point in the field of sinus surgery, in Dr. Kingdom’s view, was the 2006 Cochrane systematic review which concluded ESS "has not been demonstrated to confer additional benefit to that obtained by medical therapy" (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006:CD004458).

"This review was a disservice," he asserted.

The review was based entirely on three older randomized trials, which not only did not use current treatment paradigms but also did not study the key research question, which Dr. Kingdom believes is this: What’s the comparative effectiveness of ESS vs. continued medical therapy in patients who’ve failed initial medical therapy?

He offered as an example of the contemporary approach to comparative outcomes research in the field of ESS a recent multicenter prospective study led by otolaryngologists at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. It involved 1 year of prospective follow-up of patients with CRS who had failed initial medical therapy, at which point they elected to undergo ESS or further medical management.

The 65 patients who opted for ESS and the 50 whose chose more medical management were comparable in terms of baseline CRS severity and comorbidities. Both groups showed durable improvement at 12 months, compared with baseline. But ESS was the clear winner, with a mean 71% improvement in the validated Chronic Sinusitis Survey total score, compared with a 46% improvement in the medically managed group. Moreover, during the year of follow-up 17 patients switched over from medical management to ESS and they, too, showed significantly greater improvement than those who remained on medical management (Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3:236-41).

An earlier interim report featuring 6 months of followup showed the surgical group experienced roughly twofold greater improvement, compared with the medical cohort in endpoints including number of days on oral antibiotics or oral corticosteroids and missed days of work or school (Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2011;1:235-41).

Cost-effectiveness studies by various research groups are in the pipeline. The early indication is that the data will show an economic advantage for ESS over medical therapy in patients with recalcitrant disease, according to Dr. Kingdom.

The next research frontier in surgical outcomes in CRS is identification of cellular and molecular markers of disease activity and their genetic underpinnings, which it’s hoped can be used to select the best candidates for ESS, he added.

Dr. Kingdom reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

KEYSTONE, COLO. – Research-minded otolaryngologists have gotten serious about conducting high-quality, patient-centered outcomes studies of endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis, which more than 250,000 Americans undergo each year. And the results are eye opening.

Mounting evidence documents that endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) in properly selected patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) results in markedly improved quality of life, functional status, and reduced use of medications, compared with medical management, Dr. Todd T. Kingdom said at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

These studies utilize validated measures of patient-centered quality of life and symptoms. They are nothing like the lightweight, less-than-persuasive ESS research published in the 1990s, which reported glowing ‘success’ rates of 80%-97% in single-institution retrospective studies using variable inclusion criteria and often-sketchy definitions of success.

"Those data are not acceptable, but that’s what we had. This was before evidence-based medicine with an emphasis on rigorously designed studies took hold," explained Dr. Kingdom, professor and vice chairman of the department of otolaryngology – head and neck surgery, at the University of Colorado, Denver, and immediate past president of the American Rhinologic Society.

Current research emphasizes the use of modern, validated patient-centered quality of life tools and symptom scores because CRS is a symptom-based diagnosis and it is symptom severity that drives patients to seek treatment. Also, objective measures, such as the Lund-Mackay CT staging system, fail to capture the full experience of disease burden. Nor do objective measures necessarily correlate with patient symptoms, according to the otolaryngologist.

A low point in the field of sinus surgery, in Dr. Kingdom’s view, was the 2006 Cochrane systematic review which concluded ESS "has not been demonstrated to confer additional benefit to that obtained by medical therapy" (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006:CD004458).

"This review was a disservice," he asserted.

The review was based entirely on three older randomized trials, which not only did not use current treatment paradigms but also did not study the key research question, which Dr. Kingdom believes is this: What’s the comparative effectiveness of ESS vs. continued medical therapy in patients who’ve failed initial medical therapy?

He offered as an example of the contemporary approach to comparative outcomes research in the field of ESS a recent multicenter prospective study led by otolaryngologists at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. It involved 1 year of prospective follow-up of patients with CRS who had failed initial medical therapy, at which point they elected to undergo ESS or further medical management.

The 65 patients who opted for ESS and the 50 whose chose more medical management were comparable in terms of baseline CRS severity and comorbidities. Both groups showed durable improvement at 12 months, compared with baseline. But ESS was the clear winner, with a mean 71% improvement in the validated Chronic Sinusitis Survey total score, compared with a 46% improvement in the medically managed group. Moreover, during the year of follow-up 17 patients switched over from medical management to ESS and they, too, showed significantly greater improvement than those who remained on medical management (Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3:236-41).

An earlier interim report featuring 6 months of followup showed the surgical group experienced roughly twofold greater improvement, compared with the medical cohort in endpoints including number of days on oral antibiotics or oral corticosteroids and missed days of work or school (Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2011;1:235-41).

Cost-effectiveness studies by various research groups are in the pipeline. The early indication is that the data will show an economic advantage for ESS over medical therapy in patients with recalcitrant disease, according to Dr. Kingdom.

The next research frontier in surgical outcomes in CRS is identification of cellular and molecular markers of disease activity and their genetic underpinnings, which it’s hoped can be used to select the best candidates for ESS, he added.

Dr. Kingdom reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

KEYSTONE, COLO. – Research-minded otolaryngologists have gotten serious about conducting high-quality, patient-centered outcomes studies of endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis, which more than 250,000 Americans undergo each year. And the results are eye opening.

Mounting evidence documents that endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) in properly selected patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) results in markedly improved quality of life, functional status, and reduced use of medications, compared with medical management, Dr. Todd T. Kingdom said at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

These studies utilize validated measures of patient-centered quality of life and symptoms. They are nothing like the lightweight, less-than-persuasive ESS research published in the 1990s, which reported glowing ‘success’ rates of 80%-97% in single-institution retrospective studies using variable inclusion criteria and often-sketchy definitions of success.

"Those data are not acceptable, but that’s what we had. This was before evidence-based medicine with an emphasis on rigorously designed studies took hold," explained Dr. Kingdom, professor and vice chairman of the department of otolaryngology – head and neck surgery, at the University of Colorado, Denver, and immediate past president of the American Rhinologic Society.

Current research emphasizes the use of modern, validated patient-centered quality of life tools and symptom scores because CRS is a symptom-based diagnosis and it is symptom severity that drives patients to seek treatment. Also, objective measures, such as the Lund-Mackay CT staging system, fail to capture the full experience of disease burden. Nor do objective measures necessarily correlate with patient symptoms, according to the otolaryngologist.

A low point in the field of sinus surgery, in Dr. Kingdom’s view, was the 2006 Cochrane systematic review which concluded ESS "has not been demonstrated to confer additional benefit to that obtained by medical therapy" (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006:CD004458).

"This review was a disservice," he asserted.

The review was based entirely on three older randomized trials, which not only did not use current treatment paradigms but also did not study the key research question, which Dr. Kingdom believes is this: What’s the comparative effectiveness of ESS vs. continued medical therapy in patients who’ve failed initial medical therapy?

He offered as an example of the contemporary approach to comparative outcomes research in the field of ESS a recent multicenter prospective study led by otolaryngologists at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. It involved 1 year of prospective follow-up of patients with CRS who had failed initial medical therapy, at which point they elected to undergo ESS or further medical management.

The 65 patients who opted for ESS and the 50 whose chose more medical management were comparable in terms of baseline CRS severity and comorbidities. Both groups showed durable improvement at 12 months, compared with baseline. But ESS was the clear winner, with a mean 71% improvement in the validated Chronic Sinusitis Survey total score, compared with a 46% improvement in the medically managed group. Moreover, during the year of follow-up 17 patients switched over from medical management to ESS and they, too, showed significantly greater improvement than those who remained on medical management (Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3:236-41).

An earlier interim report featuring 6 months of followup showed the surgical group experienced roughly twofold greater improvement, compared with the medical cohort in endpoints including number of days on oral antibiotics or oral corticosteroids and missed days of work or school (Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2011;1:235-41).

Cost-effectiveness studies by various research groups are in the pipeline. The early indication is that the data will show an economic advantage for ESS over medical therapy in patients with recalcitrant disease, according to Dr. Kingdom.

The next research frontier in surgical outcomes in CRS is identification of cellular and molecular markers of disease activity and their genetic underpinnings, which it’s hoped can be used to select the best candidates for ESS, he added.

Dr. Kingdom reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE PULMONARY AND ALLERGY UPDATE

Be wary of asthma’s masqueraders

KEYSTONE, COLO. – The diagnosis of asthma isn’t as simple as it may seem.

Asthma is a clinical syndrome with no specific diagnostic test. So, the response to therapy becomes a key element in finalizing the diagnosis, Dr. Gary R. Cott emphasized at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

"If you have features that make you think of asthma, particularly mild to moderate asthma, and you initiate therapy, you should expect a therapeutic response in 80%-85% of cases. If you don’t get a response, step back and think about whether you made the right diagnosis before you start escalating care," advised Dr. Cott, a pulmonologist and executive vice president of medical and clinical services at National Jewish Health, Denver.

How often do physicians on the front lines get the diagnosis of asthma wrong? The National Jewish experience is illuminating.

In a series of 305 consecutive patients referred to the tertiary center with a preestablished diagnosis of asthma, all of whom were already on treatment for the disease, fully 25% didn’t have asthma at all. A mere 5% were found to have asthma only. A total of 38% had asthma plus an associated contributory respiratory condition, such as allergic rhinitis, rhinosinusitis, or aspirin sensitivity. Another 32% had asthma plus a cardiopulmonary condition that contributed to their symptoms, such as valvular dysfunction, a vascular ring, or pulmonary embolus.

"This experience has been duplicated at other specialty centers. It’s not unique to what we see," according to Dr. Cott.

He defined asthma as a syndrome characterized by increased airway responsiveness to various stimuli, along with variable obstruction of expiratory flow. It’s a physiologic definition. Four elements are essential in establishing the diagnosis: the history, physical exam, spirometry, and response to therapy. A variety of other tests are often helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis – for example, chest imaging, blood eosinophil measurement, allergy testing, bronchial challenges, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, lung volumes, and elasticity. But they’re not specific for asthma.

"All that wheezes is not asthma. But most is," Dr. Cott observed. "I must say, I’m not very critical of the outside docs who send patients in and say, ‘I think they have asthma,’ and we then say, ‘No, they’ve got something else.’ Asthma is a common disorder. In Colorado, as much as 11% of the population can have asthma. It’s probably the most common thing that will cause an otherwise healthy individual to present with recurring or persistent symptoms.

"I think that sometimes leads us down a path – not always incorrect – of thinking, ‘Let’s try treating for asthma,’ " Dr. Cott noted. "The problem is that when they’re not responding, it’s time to rethink the differential carefully."

The list of disorders involving lower airways obstruction that can mimic asthma is extensive. The top two masqueraders are emphysema and chronic bronchitis. What’s more, asthma, emphysema, and chronic bronchitis aren’t mutually exclusive diseases. A given patient can have any two or even all three.

In contrast to asthma, which is defined physiologically, chronic bronchitis has a historical definition: It’s a condition involving cough with excessive sputum production for at least 3 months per year in at least 2 consecutive years. And emphysema is defined anatomically: permanent enlargement of air spaces distal to the terminal bronchiole with alveolar septae destruction.

It’s important to differentiate these conditions, because their guideline-recommended management strategies differ, as do their prognoses, Dr. Cott continued.

In addition to emphysema and chronic bronchitis, other lower airways disorders that can mimic asthma include infection, sarcoidosis, interstitial lung disease, cystic fibrosis, a tumor or foreign body, and bronchiolitis.

The list of upper airways disorders that can be mistaken for asthma includes vocal cord dysfunction, infection, laryngeal spasm, and laryngeal edema secondary to angioedema. The most useful spirometric clue to upper airways obstruction, in Dr. Cott’s view, is a ratio of the forced expiratory flow at 50% volume to forced inspiratory volume at 50% of 1 or greater.

"That’s virtually always present with upper airway or extrathoracic airways obstruction," he said.

Dr. Cott reported having no conflicts of interest.

KEYSTONE, COLO. – The diagnosis of asthma isn’t as simple as it may seem.

Asthma is a clinical syndrome with no specific diagnostic test. So, the response to therapy becomes a key element in finalizing the diagnosis, Dr. Gary R. Cott emphasized at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

"If you have features that make you think of asthma, particularly mild to moderate asthma, and you initiate therapy, you should expect a therapeutic response in 80%-85% of cases. If you don’t get a response, step back and think about whether you made the right diagnosis before you start escalating care," advised Dr. Cott, a pulmonologist and executive vice president of medical and clinical services at National Jewish Health, Denver.

How often do physicians on the front lines get the diagnosis of asthma wrong? The National Jewish experience is illuminating.

In a series of 305 consecutive patients referred to the tertiary center with a preestablished diagnosis of asthma, all of whom were already on treatment for the disease, fully 25% didn’t have asthma at all. A mere 5% were found to have asthma only. A total of 38% had asthma plus an associated contributory respiratory condition, such as allergic rhinitis, rhinosinusitis, or aspirin sensitivity. Another 32% had asthma plus a cardiopulmonary condition that contributed to their symptoms, such as valvular dysfunction, a vascular ring, or pulmonary embolus.

"This experience has been duplicated at other specialty centers. It’s not unique to what we see," according to Dr. Cott.

He defined asthma as a syndrome characterized by increased airway responsiveness to various stimuli, along with variable obstruction of expiratory flow. It’s a physiologic definition. Four elements are essential in establishing the diagnosis: the history, physical exam, spirometry, and response to therapy. A variety of other tests are often helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis – for example, chest imaging, blood eosinophil measurement, allergy testing, bronchial challenges, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, lung volumes, and elasticity. But they’re not specific for asthma.

"All that wheezes is not asthma. But most is," Dr. Cott observed. "I must say, I’m not very critical of the outside docs who send patients in and say, ‘I think they have asthma,’ and we then say, ‘No, they’ve got something else.’ Asthma is a common disorder. In Colorado, as much as 11% of the population can have asthma. It’s probably the most common thing that will cause an otherwise healthy individual to present with recurring or persistent symptoms.

"I think that sometimes leads us down a path – not always incorrect – of thinking, ‘Let’s try treating for asthma,’ " Dr. Cott noted. "The problem is that when they’re not responding, it’s time to rethink the differential carefully."

The list of disorders involving lower airways obstruction that can mimic asthma is extensive. The top two masqueraders are emphysema and chronic bronchitis. What’s more, asthma, emphysema, and chronic bronchitis aren’t mutually exclusive diseases. A given patient can have any two or even all three.

In contrast to asthma, which is defined physiologically, chronic bronchitis has a historical definition: It’s a condition involving cough with excessive sputum production for at least 3 months per year in at least 2 consecutive years. And emphysema is defined anatomically: permanent enlargement of air spaces distal to the terminal bronchiole with alveolar septae destruction.

It’s important to differentiate these conditions, because their guideline-recommended management strategies differ, as do their prognoses, Dr. Cott continued.

In addition to emphysema and chronic bronchitis, other lower airways disorders that can mimic asthma include infection, sarcoidosis, interstitial lung disease, cystic fibrosis, a tumor or foreign body, and bronchiolitis.

The list of upper airways disorders that can be mistaken for asthma includes vocal cord dysfunction, infection, laryngeal spasm, and laryngeal edema secondary to angioedema. The most useful spirometric clue to upper airways obstruction, in Dr. Cott’s view, is a ratio of the forced expiratory flow at 50% volume to forced inspiratory volume at 50% of 1 or greater.

"That’s virtually always present with upper airway or extrathoracic airways obstruction," he said.

Dr. Cott reported having no conflicts of interest.

KEYSTONE, COLO. – The diagnosis of asthma isn’t as simple as it may seem.

Asthma is a clinical syndrome with no specific diagnostic test. So, the response to therapy becomes a key element in finalizing the diagnosis, Dr. Gary R. Cott emphasized at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

"If you have features that make you think of asthma, particularly mild to moderate asthma, and you initiate therapy, you should expect a therapeutic response in 80%-85% of cases. If you don’t get a response, step back and think about whether you made the right diagnosis before you start escalating care," advised Dr. Cott, a pulmonologist and executive vice president of medical and clinical services at National Jewish Health, Denver.

How often do physicians on the front lines get the diagnosis of asthma wrong? The National Jewish experience is illuminating.

In a series of 305 consecutive patients referred to the tertiary center with a preestablished diagnosis of asthma, all of whom were already on treatment for the disease, fully 25% didn’t have asthma at all. A mere 5% were found to have asthma only. A total of 38% had asthma plus an associated contributory respiratory condition, such as allergic rhinitis, rhinosinusitis, or aspirin sensitivity. Another 32% had asthma plus a cardiopulmonary condition that contributed to their symptoms, such as valvular dysfunction, a vascular ring, or pulmonary embolus.

"This experience has been duplicated at other specialty centers. It’s not unique to what we see," according to Dr. Cott.

He defined asthma as a syndrome characterized by increased airway responsiveness to various stimuli, along with variable obstruction of expiratory flow. It’s a physiologic definition. Four elements are essential in establishing the diagnosis: the history, physical exam, spirometry, and response to therapy. A variety of other tests are often helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis – for example, chest imaging, blood eosinophil measurement, allergy testing, bronchial challenges, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, lung volumes, and elasticity. But they’re not specific for asthma.

"All that wheezes is not asthma. But most is," Dr. Cott observed. "I must say, I’m not very critical of the outside docs who send patients in and say, ‘I think they have asthma,’ and we then say, ‘No, they’ve got something else.’ Asthma is a common disorder. In Colorado, as much as 11% of the population can have asthma. It’s probably the most common thing that will cause an otherwise healthy individual to present with recurring or persistent symptoms.

"I think that sometimes leads us down a path – not always incorrect – of thinking, ‘Let’s try treating for asthma,’ " Dr. Cott noted. "The problem is that when they’re not responding, it’s time to rethink the differential carefully."

The list of disorders involving lower airways obstruction that can mimic asthma is extensive. The top two masqueraders are emphysema and chronic bronchitis. What’s more, asthma, emphysema, and chronic bronchitis aren’t mutually exclusive diseases. A given patient can have any two or even all three.

In contrast to asthma, which is defined physiologically, chronic bronchitis has a historical definition: It’s a condition involving cough with excessive sputum production for at least 3 months per year in at least 2 consecutive years. And emphysema is defined anatomically: permanent enlargement of air spaces distal to the terminal bronchiole with alveolar septae destruction.

It’s important to differentiate these conditions, because their guideline-recommended management strategies differ, as do their prognoses, Dr. Cott continued.

In addition to emphysema and chronic bronchitis, other lower airways disorders that can mimic asthma include infection, sarcoidosis, interstitial lung disease, cystic fibrosis, a tumor or foreign body, and bronchiolitis.

The list of upper airways disorders that can be mistaken for asthma includes vocal cord dysfunction, infection, laryngeal spasm, and laryngeal edema secondary to angioedema. The most useful spirometric clue to upper airways obstruction, in Dr. Cott’s view, is a ratio of the forced expiratory flow at 50% volume to forced inspiratory volume at 50% of 1 or greater.

"That’s virtually always present with upper airway or extrathoracic airways obstruction," he said.

Dr. Cott reported having no conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE PULMONARY AND ALLERGY UPDATE

Abdominal pain during aspirin desensitization? Think pancreatitis

KEYSTONE, COLO – Pancreatitis may be a rare complication of aspirin desensitization therapy – and perhaps actually not so rare – in patients with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease.

"Be aware: If you’re doing desensitization and a patient reports severe abdominal pain, please check the pancreatic enzyme levels," Dr. Rohit K. Katial urged at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

He and his coworkers were the first to describe this novel complication in a report detailing three cases. Two occurred during the 2-day aspirin desensitization procedure, with pancreatic lipase levels of 425 and 789 U/L, respectively, with normal defined as 13-63 U/L. The third involved a subacute presentation beginning 4 days after finishing desensitization, with a lipase level of 207 U/L while the patient was on standard postdensensitization high-dose aspirin therapy at 650 mg b.i.d. (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012;129:1684-6).

Gallbladder disease, alcohol, drugs, and other secondary causes of pancreatitis were ruled out in all three cases, noted Dr. Katial, professor of medicine at the University of Colorado, Denver, and director of allergy and immunology clinical services at National Jewish Health.

This previously unreported close temporal association between pancreatitis and aspirin desensitization is of particular interest because it may actually not be all that uncommon. Indeed, other investigators, in a study of 172 aspirin-desensitized patients, reported that 27% of them discontinued high-dose maintenance aspirin therapy during the first year. The most common reason for doing so was the emergence of epigastric pain, accounting for 14 discontinuations. Another two patients discontinued therapy because of GI bleeding (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003;111:180-6).

These gastrointestinal reactions weren’t extensively investigated, since it’s well known that high-dose aspirin is associated with gastritis and peptic ulcer disease. So it’s quite possible that some of these cases of what was classified clinically as gastritis were actually pancreatitis, according to Dr. Katial.

The mechanism involved in pancreatitis in the setting of aspirin desensitization is unknown. Animal studies suggest the marked increase in leukotriene levels occurring during aspirin desensitization may play a role. Even though all three patients were on prophylactic montelukast (Singulair) at the time of aspirin challenge, the leukotriene receptor antagonist may not provide complete protection in a subset of vulnerable patients.

Dr. Katial reported serving as an adviser to and on the speakers bureau for Teva Pharmaceuticals.

KEYSTONE, COLO – Pancreatitis may be a rare complication of aspirin desensitization therapy – and perhaps actually not so rare – in patients with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease.

"Be aware: If you’re doing desensitization and a patient reports severe abdominal pain, please check the pancreatic enzyme levels," Dr. Rohit K. Katial urged at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

He and his coworkers were the first to describe this novel complication in a report detailing three cases. Two occurred during the 2-day aspirin desensitization procedure, with pancreatic lipase levels of 425 and 789 U/L, respectively, with normal defined as 13-63 U/L. The third involved a subacute presentation beginning 4 days after finishing desensitization, with a lipase level of 207 U/L while the patient was on standard postdensensitization high-dose aspirin therapy at 650 mg b.i.d. (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012;129:1684-6).

Gallbladder disease, alcohol, drugs, and other secondary causes of pancreatitis were ruled out in all three cases, noted Dr. Katial, professor of medicine at the University of Colorado, Denver, and director of allergy and immunology clinical services at National Jewish Health.

This previously unreported close temporal association between pancreatitis and aspirin desensitization is of particular interest because it may actually not be all that uncommon. Indeed, other investigators, in a study of 172 aspirin-desensitized patients, reported that 27% of them discontinued high-dose maintenance aspirin therapy during the first year. The most common reason for doing so was the emergence of epigastric pain, accounting for 14 discontinuations. Another two patients discontinued therapy because of GI bleeding (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003;111:180-6).

These gastrointestinal reactions weren’t extensively investigated, since it’s well known that high-dose aspirin is associated with gastritis and peptic ulcer disease. So it’s quite possible that some of these cases of what was classified clinically as gastritis were actually pancreatitis, according to Dr. Katial.

The mechanism involved in pancreatitis in the setting of aspirin desensitization is unknown. Animal studies suggest the marked increase in leukotriene levels occurring during aspirin desensitization may play a role. Even though all three patients were on prophylactic montelukast (Singulair) at the time of aspirin challenge, the leukotriene receptor antagonist may not provide complete protection in a subset of vulnerable patients.

Dr. Katial reported serving as an adviser to and on the speakers bureau for Teva Pharmaceuticals.

KEYSTONE, COLO – Pancreatitis may be a rare complication of aspirin desensitization therapy – and perhaps actually not so rare – in patients with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease.

"Be aware: If you’re doing desensitization and a patient reports severe abdominal pain, please check the pancreatic enzyme levels," Dr. Rohit K. Katial urged at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

He and his coworkers were the first to describe this novel complication in a report detailing three cases. Two occurred during the 2-day aspirin desensitization procedure, with pancreatic lipase levels of 425 and 789 U/L, respectively, with normal defined as 13-63 U/L. The third involved a subacute presentation beginning 4 days after finishing desensitization, with a lipase level of 207 U/L while the patient was on standard postdensensitization high-dose aspirin therapy at 650 mg b.i.d. (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012;129:1684-6).

Gallbladder disease, alcohol, drugs, and other secondary causes of pancreatitis were ruled out in all three cases, noted Dr. Katial, professor of medicine at the University of Colorado, Denver, and director of allergy and immunology clinical services at National Jewish Health.

This previously unreported close temporal association between pancreatitis and aspirin desensitization is of particular interest because it may actually not be all that uncommon. Indeed, other investigators, in a study of 172 aspirin-desensitized patients, reported that 27% of them discontinued high-dose maintenance aspirin therapy during the first year. The most common reason for doing so was the emergence of epigastric pain, accounting for 14 discontinuations. Another two patients discontinued therapy because of GI bleeding (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003;111:180-6).

These gastrointestinal reactions weren’t extensively investigated, since it’s well known that high-dose aspirin is associated with gastritis and peptic ulcer disease. So it’s quite possible that some of these cases of what was classified clinically as gastritis were actually pancreatitis, according to Dr. Katial.

The mechanism involved in pancreatitis in the setting of aspirin desensitization is unknown. Animal studies suggest the marked increase in leukotriene levels occurring during aspirin desensitization may play a role. Even though all three patients were on prophylactic montelukast (Singulair) at the time of aspirin challenge, the leukotriene receptor antagonist may not provide complete protection in a subset of vulnerable patients.

Dr. Katial reported serving as an adviser to and on the speakers bureau for Teva Pharmaceuticals.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE PULMONARY AND ALLERGY UPDATE

Exhaled nitric oxide’s merits in childhood asthma

KEYSTONE, COLO. – Fractional exhaled nitric oxide as a tool for patient care in pediatric asthma has often gotten a bad rap, according to a long-time researcher in the field.

"You’re either an exhaled nitric oxide fan or you’re not, it seems like, in the medical community. Some people expect it to be all things when in fact it’s just one measure. It measures atopic eosinophilic inflammation. We know that asthma is more than one disease, so we need more than one tool. This is a tool that’s useful in a subgroup of asthmatics, but I think the subgroup it’s useful in is big enough that it’s a valuable tool," Dr. Joseph D. Spahn declared at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

The pediatric allergist published his first study demonstrating the clinical benefits of measuring fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) well before the technology won Food and Drug Administration approval and became commercially available.

An American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline addressing the clinical utility of the test was a long time coming. Finally, several years ago, the ATS issued an official guideline declaring "FeNO offers added advantages for patient care" over conventional tests for asthma, such as FEV1 [forced expiratory volume in 1 second] reversibility and provocation tests (Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011;184:602-15).

The guideline describes three major clinical uses for FeNO testing: diagnosing asthma, predicting response to inhaled corticosteroids, and monitoring adherence to this cornerstone therapy.

FeNO’s role in diagnosing asthma

FeNO is significantly elevated in allergic asthma but not in other neutrophilic diseases that can masquerade as asthma, including primary immunodeficiencies, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, alpha-1antitrypsin deficiency, and cystic fibrosis, all of which feature either low or normal FeNO levels.

But it’s important to understand where the test is most likely to prove useful.

"FeNO is the only noninvasive tool we have for assessing airway inflammation. It’s a marker of atopic and Th2-driven inflammation. Many severe adult asthmatics don’t seem to have a Th2-driven disease process. Many little kids with nonatopic asthma and viral-induced wheezing don’t have Th2-driven inflammation. As a result, FeNO is not going to be a great tool in those situations. But for those individuals in which atopy plays a role, it’s a great measure of active airway inflammation," explained Dr. Spahn of the University of Colorado, Denver, and National Jewish Health.

In one representative head-to-head comparative study, a 15% or greater improvement in FEV1 in response to an inhaled corticosteroid – widely considered a gold standard test in support of a diagnosis of asthma – had a 12% sensitivity for the diagnosis, while a reduction of greater than 20 ppb in FeNO had an 88% sensitivity (Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2004;169:473-8).

Predicting response to steroid therapy

The ATS guidelines state that symptomatic patients who present initially with a high FeNO – more than 35 ppb in children or 50 ppb in adults – are likely to benefit from a trial of inhaled corticosteroids, and that it’s appropriate to probe for allergen exposure in such patients. The guidelines further recommend that patients with a low baseline FeNO of less than 20 ppb in children or 25 ppb in adults are less likely to have eosinophilic inflammation and are unlikely to benefit from inhaled corticosteroid therapy. Consideration of a therapeutic trial with serial FeNO monitoring is recommended in patients with intermediate levels.

Years ago, Dr. Spahn and his coworkers showed in a double-blind, randomized, crossover study that FeNO values could predict whether children with mild to moderate asthma were more likely to respond to fluticasone (Flonase) or montelukast (Singulair); the higher the initial FeNO, the more likely fluticasone was the more effective option (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2005;115:233-42).

Dr. Spahn also finds FeNO results helpful in combating parental steroid phobia. "Steroid phobia still exists in the pediatric world. I know we as health care providers don’t really worry about inhaled corticosteroids having significant side effects, but parents do," he observed.

He shared a story of a 10-year-old with a severe chronic cough and newly diagnosed asthma.

"This kid was extremely disabled from his cough. If you’re coughing every 30 seconds, it’s not going to be easy for you to function normally in school. But when I mentioned that he needed to be on inhaled corticosteroid therapy, the mom acted like I’d just given her kid a death sentence. So the FeNO was a tool that I used to help convince her that there was inflammation in his airways and the way to treat it was with an inhaled corticosteroid.

"After spending half an hour convincing her of the benefits and safety of inhaled corticosteroids, she agreed. I saw him back 6 weeks later. His cough was pretty much gone, his lung function was completely normalized, and his FeNO had fallen 90%. That’s my record: A 90% reduction is about as good as it gets," Dr. Spahn said.

Assessing steroid adherence

Placing an allergic asthma patient on inhaled corticosteroid therapy should result in at least a 50% reduction in an elevated baseline FeNO. A lesser response, or an increasing FeNO during follow-up visits, is an indicator of an adherence problem.

"I like to tell people who’ve been in practice 20 years or longer that FeNO is to inhaled steroids as the theophylline blood level was to theophylline therapy. Back in the day when we used theophylline, our measure of adherence was checking someone’s theophylline level. If it was low and the patient was poorly controlled, we could blame their poor control on their poor adherence to theophylline. Up until FeNO, we didn’t have that ability with inhaled steroids. We can’t measure inhaled steroid levels due to the fact that they’re so small in the bloodstream," Dr. Spahn explained.

He reported receiving honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline as well as from Aerocrine, which markets an FeNO analyzer.

KEYSTONE, COLO. – Fractional exhaled nitric oxide as a tool for patient care in pediatric asthma has often gotten a bad rap, according to a long-time researcher in the field.

"You’re either an exhaled nitric oxide fan or you’re not, it seems like, in the medical community. Some people expect it to be all things when in fact it’s just one measure. It measures atopic eosinophilic inflammation. We know that asthma is more than one disease, so we need more than one tool. This is a tool that’s useful in a subgroup of asthmatics, but I think the subgroup it’s useful in is big enough that it’s a valuable tool," Dr. Joseph D. Spahn declared at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

The pediatric allergist published his first study demonstrating the clinical benefits of measuring fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) well before the technology won Food and Drug Administration approval and became commercially available.

An American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline addressing the clinical utility of the test was a long time coming. Finally, several years ago, the ATS issued an official guideline declaring "FeNO offers added advantages for patient care" over conventional tests for asthma, such as FEV1 [forced expiratory volume in 1 second] reversibility and provocation tests (Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011;184:602-15).

The guideline describes three major clinical uses for FeNO testing: diagnosing asthma, predicting response to inhaled corticosteroids, and monitoring adherence to this cornerstone therapy.

FeNO’s role in diagnosing asthma

FeNO is significantly elevated in allergic asthma but not in other neutrophilic diseases that can masquerade as asthma, including primary immunodeficiencies, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, alpha-1antitrypsin deficiency, and cystic fibrosis, all of which feature either low or normal FeNO levels.

But it’s important to understand where the test is most likely to prove useful.

"FeNO is the only noninvasive tool we have for assessing airway inflammation. It’s a marker of atopic and Th2-driven inflammation. Many severe adult asthmatics don’t seem to have a Th2-driven disease process. Many little kids with nonatopic asthma and viral-induced wheezing don’t have Th2-driven inflammation. As a result, FeNO is not going to be a great tool in those situations. But for those individuals in which atopy plays a role, it’s a great measure of active airway inflammation," explained Dr. Spahn of the University of Colorado, Denver, and National Jewish Health.

In one representative head-to-head comparative study, a 15% or greater improvement in FEV1 in response to an inhaled corticosteroid – widely considered a gold standard test in support of a diagnosis of asthma – had a 12% sensitivity for the diagnosis, while a reduction of greater than 20 ppb in FeNO had an 88% sensitivity (Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2004;169:473-8).

Predicting response to steroid therapy

The ATS guidelines state that symptomatic patients who present initially with a high FeNO – more than 35 ppb in children or 50 ppb in adults – are likely to benefit from a trial of inhaled corticosteroids, and that it’s appropriate to probe for allergen exposure in such patients. The guidelines further recommend that patients with a low baseline FeNO of less than 20 ppb in children or 25 ppb in adults are less likely to have eosinophilic inflammation and are unlikely to benefit from inhaled corticosteroid therapy. Consideration of a therapeutic trial with serial FeNO monitoring is recommended in patients with intermediate levels.

Years ago, Dr. Spahn and his coworkers showed in a double-blind, randomized, crossover study that FeNO values could predict whether children with mild to moderate asthma were more likely to respond to fluticasone (Flonase) or montelukast (Singulair); the higher the initial FeNO, the more likely fluticasone was the more effective option (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2005;115:233-42).

Dr. Spahn also finds FeNO results helpful in combating parental steroid phobia. "Steroid phobia still exists in the pediatric world. I know we as health care providers don’t really worry about inhaled corticosteroids having significant side effects, but parents do," he observed.

He shared a story of a 10-year-old with a severe chronic cough and newly diagnosed asthma.

"This kid was extremely disabled from his cough. If you’re coughing every 30 seconds, it’s not going to be easy for you to function normally in school. But when I mentioned that he needed to be on inhaled corticosteroid therapy, the mom acted like I’d just given her kid a death sentence. So the FeNO was a tool that I used to help convince her that there was inflammation in his airways and the way to treat it was with an inhaled corticosteroid.

"After spending half an hour convincing her of the benefits and safety of inhaled corticosteroids, she agreed. I saw him back 6 weeks later. His cough was pretty much gone, his lung function was completely normalized, and his FeNO had fallen 90%. That’s my record: A 90% reduction is about as good as it gets," Dr. Spahn said.

Assessing steroid adherence

Placing an allergic asthma patient on inhaled corticosteroid therapy should result in at least a 50% reduction in an elevated baseline FeNO. A lesser response, or an increasing FeNO during follow-up visits, is an indicator of an adherence problem.

"I like to tell people who’ve been in practice 20 years or longer that FeNO is to inhaled steroids as the theophylline blood level was to theophylline therapy. Back in the day when we used theophylline, our measure of adherence was checking someone’s theophylline level. If it was low and the patient was poorly controlled, we could blame their poor control on their poor adherence to theophylline. Up until FeNO, we didn’t have that ability with inhaled steroids. We can’t measure inhaled steroid levels due to the fact that they’re so small in the bloodstream," Dr. Spahn explained.

He reported receiving honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline as well as from Aerocrine, which markets an FeNO analyzer.

KEYSTONE, COLO. – Fractional exhaled nitric oxide as a tool for patient care in pediatric asthma has often gotten a bad rap, according to a long-time researcher in the field.

"You’re either an exhaled nitric oxide fan or you’re not, it seems like, in the medical community. Some people expect it to be all things when in fact it’s just one measure. It measures atopic eosinophilic inflammation. We know that asthma is more than one disease, so we need more than one tool. This is a tool that’s useful in a subgroup of asthmatics, but I think the subgroup it’s useful in is big enough that it’s a valuable tool," Dr. Joseph D. Spahn declared at a meeting on allergy and respiratory diseases sponsored by National Jewish Health.

The pediatric allergist published his first study demonstrating the clinical benefits of measuring fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) well before the technology won Food and Drug Administration approval and became commercially available.

An American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline addressing the clinical utility of the test was a long time coming. Finally, several years ago, the ATS issued an official guideline declaring "FeNO offers added advantages for patient care" over conventional tests for asthma, such as FEV1 [forced expiratory volume in 1 second] reversibility and provocation tests (Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011;184:602-15).

The guideline describes three major clinical uses for FeNO testing: diagnosing asthma, predicting response to inhaled corticosteroids, and monitoring adherence to this cornerstone therapy.

FeNO’s role in diagnosing asthma

FeNO is significantly elevated in allergic asthma but not in other neutrophilic diseases that can masquerade as asthma, including primary immunodeficiencies, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, alpha-1antitrypsin deficiency, and cystic fibrosis, all of which feature either low or normal FeNO levels.

But it’s important to understand where the test is most likely to prove useful.

"FeNO is the only noninvasive tool we have for assessing airway inflammation. It’s a marker of atopic and Th2-driven inflammation. Many severe adult asthmatics don’t seem to have a Th2-driven disease process. Many little kids with nonatopic asthma and viral-induced wheezing don’t have Th2-driven inflammation. As a result, FeNO is not going to be a great tool in those situations. But for those individuals in which atopy plays a role, it’s a great measure of active airway inflammation," explained Dr. Spahn of the University of Colorado, Denver, and National Jewish Health.

In one representative head-to-head comparative study, a 15% or greater improvement in FEV1 in response to an inhaled corticosteroid – widely considered a gold standard test in support of a diagnosis of asthma – had a 12% sensitivity for the diagnosis, while a reduction of greater than 20 ppb in FeNO had an 88% sensitivity (Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2004;169:473-8).

Predicting response to steroid therapy

The ATS guidelines state that symptomatic patients who present initially with a high FeNO – more than 35 ppb in children or 50 ppb in adults – are likely to benefit from a trial of inhaled corticosteroids, and that it’s appropriate to probe for allergen exposure in such patients. The guidelines further recommend that patients with a low baseline FeNO of less than 20 ppb in children or 25 ppb in adults are less likely to have eosinophilic inflammation and are unlikely to benefit from inhaled corticosteroid therapy. Consideration of a therapeutic trial with serial FeNO monitoring is recommended in patients with intermediate levels.

Years ago, Dr. Spahn and his coworkers showed in a double-blind, randomized, crossover study that FeNO values could predict whether children with mild to moderate asthma were more likely to respond to fluticasone (Flonase) or montelukast (Singulair); the higher the initial FeNO, the more likely fluticasone was the more effective option (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2005;115:233-42).

Dr. Spahn also finds FeNO results helpful in combating parental steroid phobia. "Steroid phobia still exists in the pediatric world. I know we as health care providers don’t really worry about inhaled corticosteroids having significant side effects, but parents do," he observed.

He shared a story of a 10-year-old with a severe chronic cough and newly diagnosed asthma.

"This kid was extremely disabled from his cough. If you’re coughing every 30 seconds, it’s not going to be easy for you to function normally in school. But when I mentioned that he needed to be on inhaled corticosteroid therapy, the mom acted like I’d just given her kid a death sentence. So the FeNO was a tool that I used to help convince her that there was inflammation in his airways and the way to treat it was with an inhaled corticosteroid.

"After spending half an hour convincing her of the benefits and safety of inhaled corticosteroids, she agreed. I saw him back 6 weeks later. His cough was pretty much gone, his lung function was completely normalized, and his FeNO had fallen 90%. That’s my record: A 90% reduction is about as good as it gets," Dr. Spahn said.

Assessing steroid adherence

Placing an allergic asthma patient on inhaled corticosteroid therapy should result in at least a 50% reduction in an elevated baseline FeNO. A lesser response, or an increasing FeNO during follow-up visits, is an indicator of an adherence problem.