User login

Welcome to the final week of HM20 Virtual!

Hospitalists, welcome to the final week of HM20 Virtual – the first virtual annual conference in the history of SHM. We hope you have enjoyed your experience thus far. What is most exciting about HM20 Virtual is how it exemplifies the agility and innovation that is in the hearts and minds of SHM and hospitalists all around the country and beyond. Because 2020 is shaping up to be anything but ordinary, SHM and its members have had to embrace changes on a scale that has surpassed anything we have seen in most of our careers. SHM is committed to keeping pace with the needs of hospitalists, including the use of virtual meetings to keep us all connected, informed, and engaged.

The full course of sessions for HM20 has a vast array of topics, aimed at quickly and concisely updating our members on core topics. These include clinical updates on common conditions, a half-dozen sessions dedicated to COVID-19, the ever-popular Rapid Fire sessions, an Update in Pediatric Top Articles, a High Value Care session, and special sessions on immigrant hospitalist issues and structural racism. Also included is the Best of Research and Innovations and the Annual Update in Hospital Medicine.

In addition, the “Simulive” sessions offer additional Q&A with the experts; our lineup this week includes many important clinical topics, including heart failure, glucose management, GI emergencies, drug allergies, endocrine emergencies, and balancing being a hospitalist and a parent. (Particularly challenging with COVID-19!) Of note, if you are unable to join any of these sessions live, all 3 weeks of the Simulive sessions will be available on demand after Aug. 31.

We are hopeful this new virtual format will exceed expectations for our members. Our dedicated HM20 faculty and SHM staff have worked tirelessly to make HM20 Virtual a success, and for that, we owe them our gratitude and appreciation. Since this is our “first rodeo,” we are very eager for your feedback on all aspects of this new format. The more we learn now, the better off we will all be with future offerings, so please be candid and honest. With so much change and uncertainty, we hope you continue to find SHM to be a place of consistency and stability, and the “source of truth” for all things hospital medicine.

Dr. Scheurer is chief quality officer and professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. She is president of SHM.

Hospitalists, welcome to the final week of HM20 Virtual – the first virtual annual conference in the history of SHM. We hope you have enjoyed your experience thus far. What is most exciting about HM20 Virtual is how it exemplifies the agility and innovation that is in the hearts and minds of SHM and hospitalists all around the country and beyond. Because 2020 is shaping up to be anything but ordinary, SHM and its members have had to embrace changes on a scale that has surpassed anything we have seen in most of our careers. SHM is committed to keeping pace with the needs of hospitalists, including the use of virtual meetings to keep us all connected, informed, and engaged.

The full course of sessions for HM20 has a vast array of topics, aimed at quickly and concisely updating our members on core topics. These include clinical updates on common conditions, a half-dozen sessions dedicated to COVID-19, the ever-popular Rapid Fire sessions, an Update in Pediatric Top Articles, a High Value Care session, and special sessions on immigrant hospitalist issues and structural racism. Also included is the Best of Research and Innovations and the Annual Update in Hospital Medicine.

In addition, the “Simulive” sessions offer additional Q&A with the experts; our lineup this week includes many important clinical topics, including heart failure, glucose management, GI emergencies, drug allergies, endocrine emergencies, and balancing being a hospitalist and a parent. (Particularly challenging with COVID-19!) Of note, if you are unable to join any of these sessions live, all 3 weeks of the Simulive sessions will be available on demand after Aug. 31.

We are hopeful this new virtual format will exceed expectations for our members. Our dedicated HM20 faculty and SHM staff have worked tirelessly to make HM20 Virtual a success, and for that, we owe them our gratitude and appreciation. Since this is our “first rodeo,” we are very eager for your feedback on all aspects of this new format. The more we learn now, the better off we will all be with future offerings, so please be candid and honest. With so much change and uncertainty, we hope you continue to find SHM to be a place of consistency and stability, and the “source of truth” for all things hospital medicine.

Dr. Scheurer is chief quality officer and professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. She is president of SHM.

Hospitalists, welcome to the final week of HM20 Virtual – the first virtual annual conference in the history of SHM. We hope you have enjoyed your experience thus far. What is most exciting about HM20 Virtual is how it exemplifies the agility and innovation that is in the hearts and minds of SHM and hospitalists all around the country and beyond. Because 2020 is shaping up to be anything but ordinary, SHM and its members have had to embrace changes on a scale that has surpassed anything we have seen in most of our careers. SHM is committed to keeping pace with the needs of hospitalists, including the use of virtual meetings to keep us all connected, informed, and engaged.

The full course of sessions for HM20 has a vast array of topics, aimed at quickly and concisely updating our members on core topics. These include clinical updates on common conditions, a half-dozen sessions dedicated to COVID-19, the ever-popular Rapid Fire sessions, an Update in Pediatric Top Articles, a High Value Care session, and special sessions on immigrant hospitalist issues and structural racism. Also included is the Best of Research and Innovations and the Annual Update in Hospital Medicine.

In addition, the “Simulive” sessions offer additional Q&A with the experts; our lineup this week includes many important clinical topics, including heart failure, glucose management, GI emergencies, drug allergies, endocrine emergencies, and balancing being a hospitalist and a parent. (Particularly challenging with COVID-19!) Of note, if you are unable to join any of these sessions live, all 3 weeks of the Simulive sessions will be available on demand after Aug. 31.

We are hopeful this new virtual format will exceed expectations for our members. Our dedicated HM20 faculty and SHM staff have worked tirelessly to make HM20 Virtual a success, and for that, we owe them our gratitude and appreciation. Since this is our “first rodeo,” we are very eager for your feedback on all aspects of this new format. The more we learn now, the better off we will all be with future offerings, so please be candid and honest. With so much change and uncertainty, we hope you continue to find SHM to be a place of consistency and stability, and the “source of truth” for all things hospital medicine.

Dr. Scheurer is chief quality officer and professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. She is president of SHM.

Performance status, molecular testing key to metastatic cancer prognosis

according to Sam Brondfield, MD, MA, an inpatient medical oncologist at the University of California, San Francisco.

Oncologists have at their fingertips a voluminous and ever-growing body of clinical trials data to draw on for prognostication. Yet many hospitalists will be surprised to learn that this wealth of information is of little value in the inpatient settings where they work, he said at HM20 Virtual, hosted by the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“The applicability of clinical trials data to hospitalized patients is generally poor. That’s an important caveat to keep in mind,” Dr. Brondfield said.

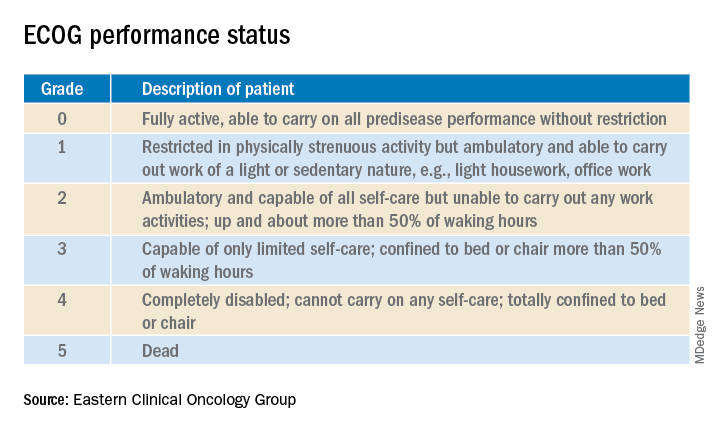

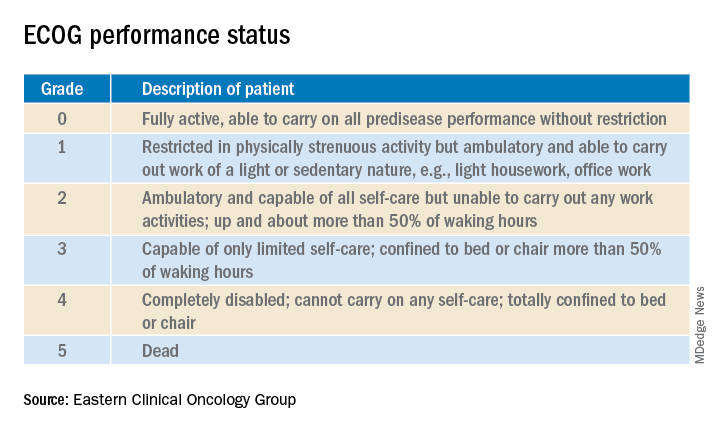

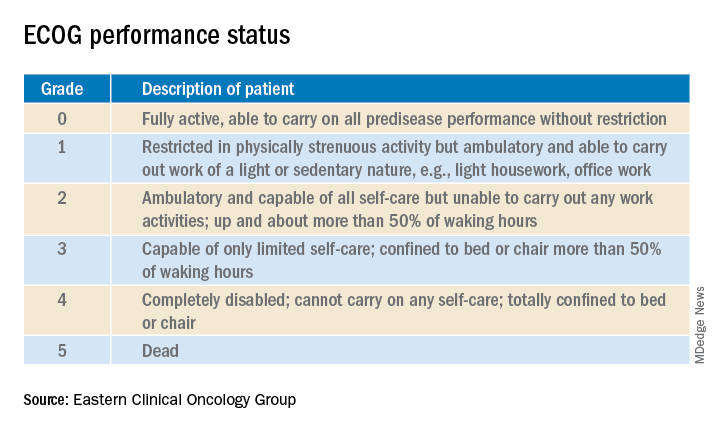

Enrollment in clinical trials is usually restricted to patients with a score of 0 or 1 on the Eastern Clinical Oncology Group Performance Status, meaning their cancer is causing minimal or no disruption to their life (see graphic). Sometimes trials will include patients with a performance status of 2 on the ECOG scale, a tool developed nearly 40 years ago, but clinical trials virtually never enroll those with an ECOG status of 3 or 4. Yet most hospitalized patients with metastatic cancer have an ECOG performance status of 3 or worse. Thus, the clinical trials outcome data are of little relevance.

“In oncology the distinction between ECOG 2 and 3 is very important,” Dr. Brondfield emphasized.

When he talks about treatment options with hospitalized patients who have metastatic cancer and poor performance status – that is, ECOG 3 or 4 – he’ll often say: “Assuming you feel better and can go home, that’s when these clinical trial data may apply better to you.”

Dr. Brondfield cautioned against quoting the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) 5-year overall survival data when hospitalized patients with advanced cancer ask how long they have to live. For one thing, the national average 5-year overall survival figure is hardly an individualized assessment. Plus, oncology is a fast-moving field in which important treatment advances occur all the time, and the SEER data lag far behind. For example, when Dr. Brondfield recently looked up the current SEER 5-year survival for patients diagnosed with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the figure quoted was less than 6%, and it was drawn from data accrued in 2009-2015. That simply doesn’t reflect contemporary practice.

Indeed, it’s no longer true that the average survival of patients with metastatic NSCLC is less than a year. In the practice-changing KEYNOTE-189 randomized trial, which accrued participants in 2016-2017, the median overall survival of patients randomized to pembrolizumab (Keytruda) plus standard cytotoxic chemotherapy was 22 months, compared with 11 months with chemotherapy plus placebo (J Clin Oncol. 2020 May 10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03136). As a result, immunotherapy with a programmed death–1 inhibitor such as pembrolizumab in combination with chemotherapy is now standard practice in patients with metastatic NSCLC without targetable mutations.

Performance status guides treatment decision-making

Hospitalists can help oncologists in decision-making regarding whether to offer palliative systemic therapy to patients with advanced metastatic cancer and poor performance status by determining whether that status is caused by the cancer itself or some other cause that’s not easily reversible, such as liver failure.

Take, for example, the inpatient with advanced SCLC. This is an aggressive and chemosensitive cancer. Dr. Brondfield said he is among many medical oncologists who are convinced that, if poor performance status in a patient with advanced SCLC is caused by the cancer itself, prompt initiation of inpatient chemotherapy should be recommended to elicit a response that improves quality of life and performance status in the short term. If, on the other hand, the poor performance status is caused by organ failure or some other issue that can’t easily be improved, hospice may be more appropriate.

“The contour of SCLC over time is that despite its treatment responsiveness it inevitably recurs. But with chemotherapy you can give people in this situation months of quality time, so we generally try to treat these sorts of patients,” Dr. Brondfield explained.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines upon which oncologists rely leave lots of room for interpretation regarding the appropriateness of inpatient chemotherapy in patients with advanced cancer and poor patient performance status. Citing “knowledge that’s been passed down across oncology generations,” Dr. Brondfield said he and many of his colleagues believe early palliative supportive care rather than systemic cytotoxic cancer-directed therapy is appropriate for patients with poor performance status who have one of several specific relatively nonchemoresponsive types of metastatic cancer. These include esophageal, gastric, and head and neck cancers.

On the other hand, advanced SCLC isn’t the only type of metastatic cancer that’s so chemosensitive that he and many other oncologists believe aggressive chemotherapy should be offered even in the face of poor patient performance status attributable to the cancer itself.

Take, for example, colorectal cancer with no more than five metastases to the lung or liver, provided those metastases are treatable with resection or radiation. “Those patients are actually curable at a high rate. They have about a 30%-40% cure rate. So those patients, even if they have poor performance status, if we can get them up for surgery or radiation, we usually do try to treat them aggressively,” Dr. Brondfield said.

There are other often chemoresponsive metastatic cancers for which oncologists frequently recommend aggressive treatment to improve quality of life in patients with poor performance status. These cancers include aggressive lymphomas, which are actually often curable; multiple myeloma; testicular and germ cell cancers; NSCLC with a targetable mutation, which is often responsive to oral medications; and prostate and well-differentiated thyroid cancers, which can usually be treated with hormone- or iodine-based therapies rather than more toxic intravenous cytotoxic chemotherapy.

The impact of inpatient palliative chemotherapy in patients with poor performance status and advanced solid cancers not on the short list of highly chemosensitive cancers has not been well studied. A recent retrospective study of 228 such patients who received inpatient palliative chemotherapy at a large Brazilian academic medical center provided little reason for enthusiasm regarding the practice. Survival was short, with 30- and 60-day survival rates of 56% and 39%, respectively. Plus, 30% of patients were admitted to the ICU, where they received aggressive and costly end-of-life care. The investigators found these results suggestive of overprescribing of inpatient palliative chemotherapy (BMC Palliat Care. 2019 May 20;18[1]:42. doi: 10.1186/s12904-019-0427-4).

Of note, the investigators found in a multivariate analysis that an elevated bilirubin was associated with a 217% increased risk of 30-day mortality, and hypercalcemia was associated with a 119% increased risk.

“That’s something to take into account when these decisions are being made,” Dr. Brondfield advised.

In response to an audience comment that oncologists often seem overly optimistic about prognosis, Dr. Brondfield observed, “I think it’s very common for there to be a disagreement between the oncologist wanting to be aggressive for a sick inpatient and the hospitalist or generalist provider thinking: ‘This person looks way too sick for chemotherapy.’ ”

For this reason he is a firm believer in having multidisciplinary conversations regarding prognosis in challenging situations involving hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. An oncologist can bring to such discussions a detailed understanding of clinical trial and molecular data as well as information about the patient’s response to the first round of therapy. But lots of other factors are relevant to prognosis, including nutritional status, comorbidities, and the intuitive eyeball test of how a patient might do. The patient’s family, primary care provider, oncologist, the hospitalist, and the palliative care team will have perspectives of their own.

Molecular testing is now the norm in metastatic cancers

These days oncologists order molecular testing for most patients with metastatic carcinomas to determine eligibility for targeted therapy, suitability for participation in clinical trials, prognostication, and/or assistance in determining the site of origin if that’s unclear.

A single-pass fine needle aspiration biopsy doesn’t provide enough tissue for molecular testing. It’s therefore important to order initially a multipass fine needle aspiration to avoid the need for a repeat biopsy, which is uncomfortable for the patient and can delay diagnosis and treatment.

Dr. Brondfield advised waiting for molecular testing results to come in before trying to prognosticate in patients with a metastatic cancer for which targetable mutations might be present. Survival rates can vary substantially depending upon those test results. Take, for example, metastatic NSCLC: Just within the past year, clinical trials have been published reporting overall survival rates of 39 months in patients with treatable mutations in epidermal growth factor receptor, 42 months with anaplastic lymphoma kinase mutations, and 51 months in patients whose tumor signature features mutations in c-ros oncogene 1, as compared with 22 months with no targetable mutations in the KEYNOTE-189 trial.

“There’s a lot of heterogeneity around how metastatic tumors behave and respond to therapy. Not all metastatic cancers are the same,” the oncologist emphasized.

according to Sam Brondfield, MD, MA, an inpatient medical oncologist at the University of California, San Francisco.

Oncologists have at their fingertips a voluminous and ever-growing body of clinical trials data to draw on for prognostication. Yet many hospitalists will be surprised to learn that this wealth of information is of little value in the inpatient settings where they work, he said at HM20 Virtual, hosted by the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“The applicability of clinical trials data to hospitalized patients is generally poor. That’s an important caveat to keep in mind,” Dr. Brondfield said.

Enrollment in clinical trials is usually restricted to patients with a score of 0 or 1 on the Eastern Clinical Oncology Group Performance Status, meaning their cancer is causing minimal or no disruption to their life (see graphic). Sometimes trials will include patients with a performance status of 2 on the ECOG scale, a tool developed nearly 40 years ago, but clinical trials virtually never enroll those with an ECOG status of 3 or 4. Yet most hospitalized patients with metastatic cancer have an ECOG performance status of 3 or worse. Thus, the clinical trials outcome data are of little relevance.

“In oncology the distinction between ECOG 2 and 3 is very important,” Dr. Brondfield emphasized.

When he talks about treatment options with hospitalized patients who have metastatic cancer and poor performance status – that is, ECOG 3 or 4 – he’ll often say: “Assuming you feel better and can go home, that’s when these clinical trial data may apply better to you.”

Dr. Brondfield cautioned against quoting the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) 5-year overall survival data when hospitalized patients with advanced cancer ask how long they have to live. For one thing, the national average 5-year overall survival figure is hardly an individualized assessment. Plus, oncology is a fast-moving field in which important treatment advances occur all the time, and the SEER data lag far behind. For example, when Dr. Brondfield recently looked up the current SEER 5-year survival for patients diagnosed with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the figure quoted was less than 6%, and it was drawn from data accrued in 2009-2015. That simply doesn’t reflect contemporary practice.

Indeed, it’s no longer true that the average survival of patients with metastatic NSCLC is less than a year. In the practice-changing KEYNOTE-189 randomized trial, which accrued participants in 2016-2017, the median overall survival of patients randomized to pembrolizumab (Keytruda) plus standard cytotoxic chemotherapy was 22 months, compared with 11 months with chemotherapy plus placebo (J Clin Oncol. 2020 May 10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03136). As a result, immunotherapy with a programmed death–1 inhibitor such as pembrolizumab in combination with chemotherapy is now standard practice in patients with metastatic NSCLC without targetable mutations.

Performance status guides treatment decision-making

Hospitalists can help oncologists in decision-making regarding whether to offer palliative systemic therapy to patients with advanced metastatic cancer and poor performance status by determining whether that status is caused by the cancer itself or some other cause that’s not easily reversible, such as liver failure.

Take, for example, the inpatient with advanced SCLC. This is an aggressive and chemosensitive cancer. Dr. Brondfield said he is among many medical oncologists who are convinced that, if poor performance status in a patient with advanced SCLC is caused by the cancer itself, prompt initiation of inpatient chemotherapy should be recommended to elicit a response that improves quality of life and performance status in the short term. If, on the other hand, the poor performance status is caused by organ failure or some other issue that can’t easily be improved, hospice may be more appropriate.

“The contour of SCLC over time is that despite its treatment responsiveness it inevitably recurs. But with chemotherapy you can give people in this situation months of quality time, so we generally try to treat these sorts of patients,” Dr. Brondfield explained.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines upon which oncologists rely leave lots of room for interpretation regarding the appropriateness of inpatient chemotherapy in patients with advanced cancer and poor patient performance status. Citing “knowledge that’s been passed down across oncology generations,” Dr. Brondfield said he and many of his colleagues believe early palliative supportive care rather than systemic cytotoxic cancer-directed therapy is appropriate for patients with poor performance status who have one of several specific relatively nonchemoresponsive types of metastatic cancer. These include esophageal, gastric, and head and neck cancers.

On the other hand, advanced SCLC isn’t the only type of metastatic cancer that’s so chemosensitive that he and many other oncologists believe aggressive chemotherapy should be offered even in the face of poor patient performance status attributable to the cancer itself.

Take, for example, colorectal cancer with no more than five metastases to the lung or liver, provided those metastases are treatable with resection or radiation. “Those patients are actually curable at a high rate. They have about a 30%-40% cure rate. So those patients, even if they have poor performance status, if we can get them up for surgery or radiation, we usually do try to treat them aggressively,” Dr. Brondfield said.

There are other often chemoresponsive metastatic cancers for which oncologists frequently recommend aggressive treatment to improve quality of life in patients with poor performance status. These cancers include aggressive lymphomas, which are actually often curable; multiple myeloma; testicular and germ cell cancers; NSCLC with a targetable mutation, which is often responsive to oral medications; and prostate and well-differentiated thyroid cancers, which can usually be treated with hormone- or iodine-based therapies rather than more toxic intravenous cytotoxic chemotherapy.

The impact of inpatient palliative chemotherapy in patients with poor performance status and advanced solid cancers not on the short list of highly chemosensitive cancers has not been well studied. A recent retrospective study of 228 such patients who received inpatient palliative chemotherapy at a large Brazilian academic medical center provided little reason for enthusiasm regarding the practice. Survival was short, with 30- and 60-day survival rates of 56% and 39%, respectively. Plus, 30% of patients were admitted to the ICU, where they received aggressive and costly end-of-life care. The investigators found these results suggestive of overprescribing of inpatient palliative chemotherapy (BMC Palliat Care. 2019 May 20;18[1]:42. doi: 10.1186/s12904-019-0427-4).

Of note, the investigators found in a multivariate analysis that an elevated bilirubin was associated with a 217% increased risk of 30-day mortality, and hypercalcemia was associated with a 119% increased risk.

“That’s something to take into account when these decisions are being made,” Dr. Brondfield advised.

In response to an audience comment that oncologists often seem overly optimistic about prognosis, Dr. Brondfield observed, “I think it’s very common for there to be a disagreement between the oncologist wanting to be aggressive for a sick inpatient and the hospitalist or generalist provider thinking: ‘This person looks way too sick for chemotherapy.’ ”

For this reason he is a firm believer in having multidisciplinary conversations regarding prognosis in challenging situations involving hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. An oncologist can bring to such discussions a detailed understanding of clinical trial and molecular data as well as information about the patient’s response to the first round of therapy. But lots of other factors are relevant to prognosis, including nutritional status, comorbidities, and the intuitive eyeball test of how a patient might do. The patient’s family, primary care provider, oncologist, the hospitalist, and the palliative care team will have perspectives of their own.

Molecular testing is now the norm in metastatic cancers

These days oncologists order molecular testing for most patients with metastatic carcinomas to determine eligibility for targeted therapy, suitability for participation in clinical trials, prognostication, and/or assistance in determining the site of origin if that’s unclear.

A single-pass fine needle aspiration biopsy doesn’t provide enough tissue for molecular testing. It’s therefore important to order initially a multipass fine needle aspiration to avoid the need for a repeat biopsy, which is uncomfortable for the patient and can delay diagnosis and treatment.

Dr. Brondfield advised waiting for molecular testing results to come in before trying to prognosticate in patients with a metastatic cancer for which targetable mutations might be present. Survival rates can vary substantially depending upon those test results. Take, for example, metastatic NSCLC: Just within the past year, clinical trials have been published reporting overall survival rates of 39 months in patients with treatable mutations in epidermal growth factor receptor, 42 months with anaplastic lymphoma kinase mutations, and 51 months in patients whose tumor signature features mutations in c-ros oncogene 1, as compared with 22 months with no targetable mutations in the KEYNOTE-189 trial.

“There’s a lot of heterogeneity around how metastatic tumors behave and respond to therapy. Not all metastatic cancers are the same,” the oncologist emphasized.

according to Sam Brondfield, MD, MA, an inpatient medical oncologist at the University of California, San Francisco.

Oncologists have at their fingertips a voluminous and ever-growing body of clinical trials data to draw on for prognostication. Yet many hospitalists will be surprised to learn that this wealth of information is of little value in the inpatient settings where they work, he said at HM20 Virtual, hosted by the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“The applicability of clinical trials data to hospitalized patients is generally poor. That’s an important caveat to keep in mind,” Dr. Brondfield said.

Enrollment in clinical trials is usually restricted to patients with a score of 0 or 1 on the Eastern Clinical Oncology Group Performance Status, meaning their cancer is causing minimal or no disruption to their life (see graphic). Sometimes trials will include patients with a performance status of 2 on the ECOG scale, a tool developed nearly 40 years ago, but clinical trials virtually never enroll those with an ECOG status of 3 or 4. Yet most hospitalized patients with metastatic cancer have an ECOG performance status of 3 or worse. Thus, the clinical trials outcome data are of little relevance.

“In oncology the distinction between ECOG 2 and 3 is very important,” Dr. Brondfield emphasized.

When he talks about treatment options with hospitalized patients who have metastatic cancer and poor performance status – that is, ECOG 3 or 4 – he’ll often say: “Assuming you feel better and can go home, that’s when these clinical trial data may apply better to you.”

Dr. Brondfield cautioned against quoting the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) 5-year overall survival data when hospitalized patients with advanced cancer ask how long they have to live. For one thing, the national average 5-year overall survival figure is hardly an individualized assessment. Plus, oncology is a fast-moving field in which important treatment advances occur all the time, and the SEER data lag far behind. For example, when Dr. Brondfield recently looked up the current SEER 5-year survival for patients diagnosed with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the figure quoted was less than 6%, and it was drawn from data accrued in 2009-2015. That simply doesn’t reflect contemporary practice.

Indeed, it’s no longer true that the average survival of patients with metastatic NSCLC is less than a year. In the practice-changing KEYNOTE-189 randomized trial, which accrued participants in 2016-2017, the median overall survival of patients randomized to pembrolizumab (Keytruda) plus standard cytotoxic chemotherapy was 22 months, compared with 11 months with chemotherapy plus placebo (J Clin Oncol. 2020 May 10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03136). As a result, immunotherapy with a programmed death–1 inhibitor such as pembrolizumab in combination with chemotherapy is now standard practice in patients with metastatic NSCLC without targetable mutations.

Performance status guides treatment decision-making

Hospitalists can help oncologists in decision-making regarding whether to offer palliative systemic therapy to patients with advanced metastatic cancer and poor performance status by determining whether that status is caused by the cancer itself or some other cause that’s not easily reversible, such as liver failure.

Take, for example, the inpatient with advanced SCLC. This is an aggressive and chemosensitive cancer. Dr. Brondfield said he is among many medical oncologists who are convinced that, if poor performance status in a patient with advanced SCLC is caused by the cancer itself, prompt initiation of inpatient chemotherapy should be recommended to elicit a response that improves quality of life and performance status in the short term. If, on the other hand, the poor performance status is caused by organ failure or some other issue that can’t easily be improved, hospice may be more appropriate.

“The contour of SCLC over time is that despite its treatment responsiveness it inevitably recurs. But with chemotherapy you can give people in this situation months of quality time, so we generally try to treat these sorts of patients,” Dr. Brondfield explained.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines upon which oncologists rely leave lots of room for interpretation regarding the appropriateness of inpatient chemotherapy in patients with advanced cancer and poor patient performance status. Citing “knowledge that’s been passed down across oncology generations,” Dr. Brondfield said he and many of his colleagues believe early palliative supportive care rather than systemic cytotoxic cancer-directed therapy is appropriate for patients with poor performance status who have one of several specific relatively nonchemoresponsive types of metastatic cancer. These include esophageal, gastric, and head and neck cancers.

On the other hand, advanced SCLC isn’t the only type of metastatic cancer that’s so chemosensitive that he and many other oncologists believe aggressive chemotherapy should be offered even in the face of poor patient performance status attributable to the cancer itself.

Take, for example, colorectal cancer with no more than five metastases to the lung or liver, provided those metastases are treatable with resection or radiation. “Those patients are actually curable at a high rate. They have about a 30%-40% cure rate. So those patients, even if they have poor performance status, if we can get them up for surgery or radiation, we usually do try to treat them aggressively,” Dr. Brondfield said.

There are other often chemoresponsive metastatic cancers for which oncologists frequently recommend aggressive treatment to improve quality of life in patients with poor performance status. These cancers include aggressive lymphomas, which are actually often curable; multiple myeloma; testicular and germ cell cancers; NSCLC with a targetable mutation, which is often responsive to oral medications; and prostate and well-differentiated thyroid cancers, which can usually be treated with hormone- or iodine-based therapies rather than more toxic intravenous cytotoxic chemotherapy.

The impact of inpatient palliative chemotherapy in patients with poor performance status and advanced solid cancers not on the short list of highly chemosensitive cancers has not been well studied. A recent retrospective study of 228 such patients who received inpatient palliative chemotherapy at a large Brazilian academic medical center provided little reason for enthusiasm regarding the practice. Survival was short, with 30- and 60-day survival rates of 56% and 39%, respectively. Plus, 30% of patients were admitted to the ICU, where they received aggressive and costly end-of-life care. The investigators found these results suggestive of overprescribing of inpatient palliative chemotherapy (BMC Palliat Care. 2019 May 20;18[1]:42. doi: 10.1186/s12904-019-0427-4).

Of note, the investigators found in a multivariate analysis that an elevated bilirubin was associated with a 217% increased risk of 30-day mortality, and hypercalcemia was associated with a 119% increased risk.

“That’s something to take into account when these decisions are being made,” Dr. Brondfield advised.

In response to an audience comment that oncologists often seem overly optimistic about prognosis, Dr. Brondfield observed, “I think it’s very common for there to be a disagreement between the oncologist wanting to be aggressive for a sick inpatient and the hospitalist or generalist provider thinking: ‘This person looks way too sick for chemotherapy.’ ”

For this reason he is a firm believer in having multidisciplinary conversations regarding prognosis in challenging situations involving hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. An oncologist can bring to such discussions a detailed understanding of clinical trial and molecular data as well as information about the patient’s response to the first round of therapy. But lots of other factors are relevant to prognosis, including nutritional status, comorbidities, and the intuitive eyeball test of how a patient might do. The patient’s family, primary care provider, oncologist, the hospitalist, and the palliative care team will have perspectives of their own.

Molecular testing is now the norm in metastatic cancers

These days oncologists order molecular testing for most patients with metastatic carcinomas to determine eligibility for targeted therapy, suitability for participation in clinical trials, prognostication, and/or assistance in determining the site of origin if that’s unclear.

A single-pass fine needle aspiration biopsy doesn’t provide enough tissue for molecular testing. It’s therefore important to order initially a multipass fine needle aspiration to avoid the need for a repeat biopsy, which is uncomfortable for the patient and can delay diagnosis and treatment.

Dr. Brondfield advised waiting for molecular testing results to come in before trying to prognosticate in patients with a metastatic cancer for which targetable mutations might be present. Survival rates can vary substantially depending upon those test results. Take, for example, metastatic NSCLC: Just within the past year, clinical trials have been published reporting overall survival rates of 39 months in patients with treatable mutations in epidermal growth factor receptor, 42 months with anaplastic lymphoma kinase mutations, and 51 months in patients whose tumor signature features mutations in c-ros oncogene 1, as compared with 22 months with no targetable mutations in the KEYNOTE-189 trial.

“There’s a lot of heterogeneity around how metastatic tumors behave and respond to therapy. Not all metastatic cancers are the same,” the oncologist emphasized.

FROM HM20 VIRTUAL

Hospitalists share work-parent experience during pandemic

The week of March 13, Heather Nye, MD, PhD, SFHM, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, got word that schools were closing because of COVID-19.

“My first thought was, ‘You’re kidding, right?’ ” she said. That was the start of a series of reactions that included denial and bargaining and, finally, some semblance of acceptance.

In a session at HM20 Virtual, hosted by the Society of Hospital Medicine, she and David J. Alfandre, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine at New York University Langone, described the complicated logistics and emotional and psychological strain that has come from working during a time of such great health care need while balancing home responsibilities and parenting.

At the time schools closed, Dr. Alfandre said, he was busy with clinical work while his wife’s work as an academic psychiatrist, including research activities, stopped for a time, allowing her to manage many of the family duties. Ever since her work picked back up, though, it’s been a juggling act.

“Our roles were dynamic and changing, sometimes week to week,” he said. “It was quite a shock to the system.”

Well before the pandemic struck, Dr. Nye and Dr. Alfandre had been scheduled to talk during the annual conference about work-parenting challenges. The pandemic has further underscored those challenges, they said. although they did make suggestions in that vein.

Child care and odd hours always have been a challenge for hospitalists, they said, and for those in academia, any “wiggle room” in the schedule is often taken up by education, administration, and research projects.

“And then, of course, there are those ever-important baseball games and ballet recitals and any number of school-related activities to help support your kids,” Dr. Nye said.

COVID-19 has brought a new degree of strain, she said. There is the concern that hospitalists’ very work brings a higher infection risk to their children. Extra work responsibilities have brought on guilt about perhaps not doing a well enough job helping their children with schoolwork “without having any definition of what ‘well enough’ actually looks like.” At the same time, she said, she’s felt “incredibly grateful to have a stable job.

“There is this spectrum of guilt and gratitude that is constant – it’s an undulating, never-stopping pendulum,” she said.

Dr. Alfandre noted that it was a “tremendously proud moment” to have people cheering for his colleagues and him at shift change in New York. Still, after several days off, he “felt guilty that I wasn’t in the hospital.”

Dr. Nye observed that, while working from home on nonclinical work, “recognizing how little I got done was a big surprise,” and she had to “grow comfortable with that” and learn to live with the uncertainty about when that was going to change.

Both physicians described the emotional toll of worrying about their children if they have to continue distance learning.

At work, her center seems to be in a constant state of instability – they’re either dealing with a surge or a reopening.

“It just goes on and on and on and on,” she said. “I find it overwhelming.”

Dr. Alfandre said that a shared Google calendar for his wife and him – with appointments, work obligations, children’s doctor’s appointments, recitals – has been helpful, removing the strain of having to remind each other.

“It’s really about cooperation with your partner,” he said. “I really think this is the most important aspect.”

He said that there are skills used at work that hospitalists can use at home – such as not getting upset with a child for crying about a spilled drink – in the same way that a physician wouldn’t get upset with a patient concerned about a test.

“We empathize with our patients, and we empathize with our kids and what their experience is,” he said. Similarly, seeing family members crowd around a smartphone video call to check in with a COVID-19 patient can be a helpful reminder to appreciate going home to family at the end of the day.

When her children get upset that she has to go in to work, Dr. Nye said, it has been helpful to explain that her many patients are suffering and scared and need her help.

“I feel like sharing that part of our job to our kids helps them understand that there are very, very big problems out there – that they don’t have to know too much about and be frightened about – but [that knowledge] just gives them a little perspective.”

Dr. Nye and Dr. Alfandre said they had no financial conflicts of interest.

The week of March 13, Heather Nye, MD, PhD, SFHM, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, got word that schools were closing because of COVID-19.

“My first thought was, ‘You’re kidding, right?’ ” she said. That was the start of a series of reactions that included denial and bargaining and, finally, some semblance of acceptance.

In a session at HM20 Virtual, hosted by the Society of Hospital Medicine, she and David J. Alfandre, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine at New York University Langone, described the complicated logistics and emotional and psychological strain that has come from working during a time of such great health care need while balancing home responsibilities and parenting.

At the time schools closed, Dr. Alfandre said, he was busy with clinical work while his wife’s work as an academic psychiatrist, including research activities, stopped for a time, allowing her to manage many of the family duties. Ever since her work picked back up, though, it’s been a juggling act.

“Our roles were dynamic and changing, sometimes week to week,” he said. “It was quite a shock to the system.”

Well before the pandemic struck, Dr. Nye and Dr. Alfandre had been scheduled to talk during the annual conference about work-parenting challenges. The pandemic has further underscored those challenges, they said. although they did make suggestions in that vein.

Child care and odd hours always have been a challenge for hospitalists, they said, and for those in academia, any “wiggle room” in the schedule is often taken up by education, administration, and research projects.

“And then, of course, there are those ever-important baseball games and ballet recitals and any number of school-related activities to help support your kids,” Dr. Nye said.

COVID-19 has brought a new degree of strain, she said. There is the concern that hospitalists’ very work brings a higher infection risk to their children. Extra work responsibilities have brought on guilt about perhaps not doing a well enough job helping their children with schoolwork “without having any definition of what ‘well enough’ actually looks like.” At the same time, she said, she’s felt “incredibly grateful to have a stable job.

“There is this spectrum of guilt and gratitude that is constant – it’s an undulating, never-stopping pendulum,” she said.

Dr. Alfandre noted that it was a “tremendously proud moment” to have people cheering for his colleagues and him at shift change in New York. Still, after several days off, he “felt guilty that I wasn’t in the hospital.”

Dr. Nye observed that, while working from home on nonclinical work, “recognizing how little I got done was a big surprise,” and she had to “grow comfortable with that” and learn to live with the uncertainty about when that was going to change.

Both physicians described the emotional toll of worrying about their children if they have to continue distance learning.

At work, her center seems to be in a constant state of instability – they’re either dealing with a surge or a reopening.

“It just goes on and on and on and on,” she said. “I find it overwhelming.”

Dr. Alfandre said that a shared Google calendar for his wife and him – with appointments, work obligations, children’s doctor’s appointments, recitals – has been helpful, removing the strain of having to remind each other.

“It’s really about cooperation with your partner,” he said. “I really think this is the most important aspect.”

He said that there are skills used at work that hospitalists can use at home – such as not getting upset with a child for crying about a spilled drink – in the same way that a physician wouldn’t get upset with a patient concerned about a test.

“We empathize with our patients, and we empathize with our kids and what their experience is,” he said. Similarly, seeing family members crowd around a smartphone video call to check in with a COVID-19 patient can be a helpful reminder to appreciate going home to family at the end of the day.

When her children get upset that she has to go in to work, Dr. Nye said, it has been helpful to explain that her many patients are suffering and scared and need her help.

“I feel like sharing that part of our job to our kids helps them understand that there are very, very big problems out there – that they don’t have to know too much about and be frightened about – but [that knowledge] just gives them a little perspective.”

Dr. Nye and Dr. Alfandre said they had no financial conflicts of interest.

The week of March 13, Heather Nye, MD, PhD, SFHM, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, got word that schools were closing because of COVID-19.

“My first thought was, ‘You’re kidding, right?’ ” she said. That was the start of a series of reactions that included denial and bargaining and, finally, some semblance of acceptance.

In a session at HM20 Virtual, hosted by the Society of Hospital Medicine, she and David J. Alfandre, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine at New York University Langone, described the complicated logistics and emotional and psychological strain that has come from working during a time of such great health care need while balancing home responsibilities and parenting.

At the time schools closed, Dr. Alfandre said, he was busy with clinical work while his wife’s work as an academic psychiatrist, including research activities, stopped for a time, allowing her to manage many of the family duties. Ever since her work picked back up, though, it’s been a juggling act.

“Our roles were dynamic and changing, sometimes week to week,” he said. “It was quite a shock to the system.”

Well before the pandemic struck, Dr. Nye and Dr. Alfandre had been scheduled to talk during the annual conference about work-parenting challenges. The pandemic has further underscored those challenges, they said. although they did make suggestions in that vein.

Child care and odd hours always have been a challenge for hospitalists, they said, and for those in academia, any “wiggle room” in the schedule is often taken up by education, administration, and research projects.

“And then, of course, there are those ever-important baseball games and ballet recitals and any number of school-related activities to help support your kids,” Dr. Nye said.

COVID-19 has brought a new degree of strain, she said. There is the concern that hospitalists’ very work brings a higher infection risk to their children. Extra work responsibilities have brought on guilt about perhaps not doing a well enough job helping their children with schoolwork “without having any definition of what ‘well enough’ actually looks like.” At the same time, she said, she’s felt “incredibly grateful to have a stable job.

“There is this spectrum of guilt and gratitude that is constant – it’s an undulating, never-stopping pendulum,” she said.

Dr. Alfandre noted that it was a “tremendously proud moment” to have people cheering for his colleagues and him at shift change in New York. Still, after several days off, he “felt guilty that I wasn’t in the hospital.”

Dr. Nye observed that, while working from home on nonclinical work, “recognizing how little I got done was a big surprise,” and she had to “grow comfortable with that” and learn to live with the uncertainty about when that was going to change.

Both physicians described the emotional toll of worrying about their children if they have to continue distance learning.

At work, her center seems to be in a constant state of instability – they’re either dealing with a surge or a reopening.

“It just goes on and on and on and on,” she said. “I find it overwhelming.”

Dr. Alfandre said that a shared Google calendar for his wife and him – with appointments, work obligations, children’s doctor’s appointments, recitals – has been helpful, removing the strain of having to remind each other.

“It’s really about cooperation with your partner,” he said. “I really think this is the most important aspect.”

He said that there are skills used at work that hospitalists can use at home – such as not getting upset with a child for crying about a spilled drink – in the same way that a physician wouldn’t get upset with a patient concerned about a test.

“We empathize with our patients, and we empathize with our kids and what their experience is,” he said. Similarly, seeing family members crowd around a smartphone video call to check in with a COVID-19 patient can be a helpful reminder to appreciate going home to family at the end of the day.

When her children get upset that she has to go in to work, Dr. Nye said, it has been helpful to explain that her many patients are suffering and scared and need her help.

“I feel like sharing that part of our job to our kids helps them understand that there are very, very big problems out there – that they don’t have to know too much about and be frightened about – but [that knowledge] just gives them a little perspective.”

Dr. Nye and Dr. Alfandre said they had no financial conflicts of interest.

FROM HM20 VIRTUAL

Risk stratification key in acute pulmonary embolism

All intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism is not the same, Victor F. Tapson, MD, declared at HM20 Virtual, hosted by the Society of Hospital Medicine.

This additional classification is worthwhile because it has important treatment implications.

Patients with intermediate- to low-risk PE, along with those who have truly low-risk PE, require anticoagulation only. In contrast, patients with intermediate- to high-risk PE are at increased risk of decompensation. They have a much higher in-hospital mortality than those with intermediate- to low-risk PE. So hospitalists may want to consult their hospitals’ PE response team (PERT), if there is one, or whoever on staff is involved in helping make decisions about the appropriateness of more aggressive interventions, such as catheter-directed thrombolysis or catheter-directed clot extraction, said Dr. Tapson, director of the venous thromboembolism and pulmonary vascular disease research program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

“We don’t have evidence of any real proven mortality difference yet in the intermediate-high risk PE group by being more aggressive. I think if the right patients were studied we could see a mortality difference. But one thing I’ve noted is that by being more aggressive – in a cautious manner, in selected patients – we clearly shorten the hospital stay by doing catheter-directed therapy in some of these folks. It saves money,” he observed.

Once the diagnosis of PE is confirmed, the first priority is to get anticoagulation started in all patients with an acceptable bleeding risk, since there is convincing evidence that anticoagulation reduces mortality in PE. The 2019 European Society of Cardiology guidelines recommend a direct-acting oral anticoagulant over warfarin on the basis of persuasive evidence of lower risk of major bleeding coupled with equal or better effectiveness in preventing recurrent PE.

Dr. Tapson said it’s worthwhile for hospitalists to take a close look at these European guidelines (Eur Respir J. 2019 Oct 9. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01647-2019).

“I think our Europeans friends did a really nice job with those guidelines. They’re great guidelines, better than many of the others out there. I think they’re very, very usable,” he said. “I took part in the ACCP [American College of Chest Physicians] guidelines for years. I think they’re very rigorous in terms of the evidence base, but because they’re so rigorous there’s just tons of 2C recommendations, which are basically suggestions. The ESC guidelines are more robust.”

Risk stratification

Once anticoagulation is on board, the next task is risk stratification to determine the need for more aggressive therapy. A high-risk PE is best defined hemodynamically as one causing a systolic blood pressure below 90 mm Hg for at least 15 minutes. The term “high risk” is increasingly replacing “massive” PE, because the size of the clot doesn’t necessarily correlate with its hemodynamic impact.

An intermediate-risk PE is marked by a simplified Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (sPESI) score of 1 or more, right ventricular dysfunction on echocardiography or CT angiography, or an elevated cardiac troponin level.

The sPESI is a validated, user-friendly tool that grants 1 point each for age over 80, background cardiopulmonary disease, a systolic blood pressure below 100 mm Hg, cancer, a heart rate of 110 bpm or more, and an oxygen saturation level below 90%.

“All you really need to know about a patient’s sPESI score is: Is it more than zero?” he explained.

Indeed, patients with an sPESI score of 0 have a 30-day mortality of 1%. With a score of 1 or more, however, that risk jumps to 10.9%.

No scoring system is 100% accurate, though, and Dr. Tapson emphasized that clinician gestalt plays an important role in PE risk stratification. In terms of clinical indicators of risk, he pays special attention to heart rate.

“I think if I had to pick the one thing that drives my decision the most about whether someone needs more aggressive therapy than anticoagulation, it’s probably heart rate,” he said. “If the heart rate is 70, the patient is probably very stable. Of course, that might not hold up in a patient with conduction problems or who is on a beta blocker, but in general if I see someone who looks good, has a relatively small PE, and a low heart rate, it makes me feel much better. If the heart rate is 130 or 120, I’m much more concerned.”

Both the European guidelines and the PERT Consortium guidelines on the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of acute PE (Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2019 Jun 17. doi: 10.1177/1076029619853037), which Dr. Tapson coauthored, recommend substratifying intermediate-risk PE into intermediate to low or intermediate to high risk. It’s a straightforward matter: If a patient has either right ventricular dysfunction on imaging or an elevated cardiac troponin, that’s an intermediate- to low-risk PE warranting anticoagulation only. On the other hand, if both right ventricular dysfunction and an elevated troponin are present, the patient has an intermediate- to high-risk PE. Since this distinction translates to a difference in outcome, a consultation with PERT or an experienced PE interventionalist is in order for the intermediate- to high-risk PE, he said.

Dr. Tapson reported receiving research funding from Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, BiO2, EKOS/BTG, and Daiichi. He is also a consultant to Janssen and BiO2, and on speakers’ bureaus for EKOS/BTG and Janssen.

All intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism is not the same, Victor F. Tapson, MD, declared at HM20 Virtual, hosted by the Society of Hospital Medicine.

This additional classification is worthwhile because it has important treatment implications.

Patients with intermediate- to low-risk PE, along with those who have truly low-risk PE, require anticoagulation only. In contrast, patients with intermediate- to high-risk PE are at increased risk of decompensation. They have a much higher in-hospital mortality than those with intermediate- to low-risk PE. So hospitalists may want to consult their hospitals’ PE response team (PERT), if there is one, or whoever on staff is involved in helping make decisions about the appropriateness of more aggressive interventions, such as catheter-directed thrombolysis or catheter-directed clot extraction, said Dr. Tapson, director of the venous thromboembolism and pulmonary vascular disease research program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

“We don’t have evidence of any real proven mortality difference yet in the intermediate-high risk PE group by being more aggressive. I think if the right patients were studied we could see a mortality difference. But one thing I’ve noted is that by being more aggressive – in a cautious manner, in selected patients – we clearly shorten the hospital stay by doing catheter-directed therapy in some of these folks. It saves money,” he observed.

Once the diagnosis of PE is confirmed, the first priority is to get anticoagulation started in all patients with an acceptable bleeding risk, since there is convincing evidence that anticoagulation reduces mortality in PE. The 2019 European Society of Cardiology guidelines recommend a direct-acting oral anticoagulant over warfarin on the basis of persuasive evidence of lower risk of major bleeding coupled with equal or better effectiveness in preventing recurrent PE.

Dr. Tapson said it’s worthwhile for hospitalists to take a close look at these European guidelines (Eur Respir J. 2019 Oct 9. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01647-2019).

“I think our Europeans friends did a really nice job with those guidelines. They’re great guidelines, better than many of the others out there. I think they’re very, very usable,” he said. “I took part in the ACCP [American College of Chest Physicians] guidelines for years. I think they’re very rigorous in terms of the evidence base, but because they’re so rigorous there’s just tons of 2C recommendations, which are basically suggestions. The ESC guidelines are more robust.”

Risk stratification

Once anticoagulation is on board, the next task is risk stratification to determine the need for more aggressive therapy. A high-risk PE is best defined hemodynamically as one causing a systolic blood pressure below 90 mm Hg for at least 15 minutes. The term “high risk” is increasingly replacing “massive” PE, because the size of the clot doesn’t necessarily correlate with its hemodynamic impact.

An intermediate-risk PE is marked by a simplified Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (sPESI) score of 1 or more, right ventricular dysfunction on echocardiography or CT angiography, or an elevated cardiac troponin level.

The sPESI is a validated, user-friendly tool that grants 1 point each for age over 80, background cardiopulmonary disease, a systolic blood pressure below 100 mm Hg, cancer, a heart rate of 110 bpm or more, and an oxygen saturation level below 90%.

“All you really need to know about a patient’s sPESI score is: Is it more than zero?” he explained.

Indeed, patients with an sPESI score of 0 have a 30-day mortality of 1%. With a score of 1 or more, however, that risk jumps to 10.9%.

No scoring system is 100% accurate, though, and Dr. Tapson emphasized that clinician gestalt plays an important role in PE risk stratification. In terms of clinical indicators of risk, he pays special attention to heart rate.

“I think if I had to pick the one thing that drives my decision the most about whether someone needs more aggressive therapy than anticoagulation, it’s probably heart rate,” he said. “If the heart rate is 70, the patient is probably very stable. Of course, that might not hold up in a patient with conduction problems or who is on a beta blocker, but in general if I see someone who looks good, has a relatively small PE, and a low heart rate, it makes me feel much better. If the heart rate is 130 or 120, I’m much more concerned.”

Both the European guidelines and the PERT Consortium guidelines on the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of acute PE (Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2019 Jun 17. doi: 10.1177/1076029619853037), which Dr. Tapson coauthored, recommend substratifying intermediate-risk PE into intermediate to low or intermediate to high risk. It’s a straightforward matter: If a patient has either right ventricular dysfunction on imaging or an elevated cardiac troponin, that’s an intermediate- to low-risk PE warranting anticoagulation only. On the other hand, if both right ventricular dysfunction and an elevated troponin are present, the patient has an intermediate- to high-risk PE. Since this distinction translates to a difference in outcome, a consultation with PERT or an experienced PE interventionalist is in order for the intermediate- to high-risk PE, he said.

Dr. Tapson reported receiving research funding from Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, BiO2, EKOS/BTG, and Daiichi. He is also a consultant to Janssen and BiO2, and on speakers’ bureaus for EKOS/BTG and Janssen.

All intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism is not the same, Victor F. Tapson, MD, declared at HM20 Virtual, hosted by the Society of Hospital Medicine.

This additional classification is worthwhile because it has important treatment implications.

Patients with intermediate- to low-risk PE, along with those who have truly low-risk PE, require anticoagulation only. In contrast, patients with intermediate- to high-risk PE are at increased risk of decompensation. They have a much higher in-hospital mortality than those with intermediate- to low-risk PE. So hospitalists may want to consult their hospitals’ PE response team (PERT), if there is one, or whoever on staff is involved in helping make decisions about the appropriateness of more aggressive interventions, such as catheter-directed thrombolysis or catheter-directed clot extraction, said Dr. Tapson, director of the venous thromboembolism and pulmonary vascular disease research program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

“We don’t have evidence of any real proven mortality difference yet in the intermediate-high risk PE group by being more aggressive. I think if the right patients were studied we could see a mortality difference. But one thing I’ve noted is that by being more aggressive – in a cautious manner, in selected patients – we clearly shorten the hospital stay by doing catheter-directed therapy in some of these folks. It saves money,” he observed.

Once the diagnosis of PE is confirmed, the first priority is to get anticoagulation started in all patients with an acceptable bleeding risk, since there is convincing evidence that anticoagulation reduces mortality in PE. The 2019 European Society of Cardiology guidelines recommend a direct-acting oral anticoagulant over warfarin on the basis of persuasive evidence of lower risk of major bleeding coupled with equal or better effectiveness in preventing recurrent PE.

Dr. Tapson said it’s worthwhile for hospitalists to take a close look at these European guidelines (Eur Respir J. 2019 Oct 9. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01647-2019).

“I think our Europeans friends did a really nice job with those guidelines. They’re great guidelines, better than many of the others out there. I think they’re very, very usable,” he said. “I took part in the ACCP [American College of Chest Physicians] guidelines for years. I think they’re very rigorous in terms of the evidence base, but because they’re so rigorous there’s just tons of 2C recommendations, which are basically suggestions. The ESC guidelines are more robust.”

Risk stratification

Once anticoagulation is on board, the next task is risk stratification to determine the need for more aggressive therapy. A high-risk PE is best defined hemodynamically as one causing a systolic blood pressure below 90 mm Hg for at least 15 minutes. The term “high risk” is increasingly replacing “massive” PE, because the size of the clot doesn’t necessarily correlate with its hemodynamic impact.

An intermediate-risk PE is marked by a simplified Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (sPESI) score of 1 or more, right ventricular dysfunction on echocardiography or CT angiography, or an elevated cardiac troponin level.

The sPESI is a validated, user-friendly tool that grants 1 point each for age over 80, background cardiopulmonary disease, a systolic blood pressure below 100 mm Hg, cancer, a heart rate of 110 bpm or more, and an oxygen saturation level below 90%.

“All you really need to know about a patient’s sPESI score is: Is it more than zero?” he explained.

Indeed, patients with an sPESI score of 0 have a 30-day mortality of 1%. With a score of 1 or more, however, that risk jumps to 10.9%.

No scoring system is 100% accurate, though, and Dr. Tapson emphasized that clinician gestalt plays an important role in PE risk stratification. In terms of clinical indicators of risk, he pays special attention to heart rate.

“I think if I had to pick the one thing that drives my decision the most about whether someone needs more aggressive therapy than anticoagulation, it’s probably heart rate,” he said. “If the heart rate is 70, the patient is probably very stable. Of course, that might not hold up in a patient with conduction problems or who is on a beta blocker, but in general if I see someone who looks good, has a relatively small PE, and a low heart rate, it makes me feel much better. If the heart rate is 130 or 120, I’m much more concerned.”

Both the European guidelines and the PERT Consortium guidelines on the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of acute PE (Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2019 Jun 17. doi: 10.1177/1076029619853037), which Dr. Tapson coauthored, recommend substratifying intermediate-risk PE into intermediate to low or intermediate to high risk. It’s a straightforward matter: If a patient has either right ventricular dysfunction on imaging or an elevated cardiac troponin, that’s an intermediate- to low-risk PE warranting anticoagulation only. On the other hand, if both right ventricular dysfunction and an elevated troponin are present, the patient has an intermediate- to high-risk PE. Since this distinction translates to a difference in outcome, a consultation with PERT or an experienced PE interventionalist is in order for the intermediate- to high-risk PE, he said.

Dr. Tapson reported receiving research funding from Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, BiO2, EKOS/BTG, and Daiichi. He is also a consultant to Janssen and BiO2, and on speakers’ bureaus for EKOS/BTG and Janssen.

FROM HM20 VIRTUAL

A ‘foolproof’ way to diagnose narrow complex tachycardias on EKGs

A hospitalist looking at an EKG showing a narrow complex tachycardia needs to be able to come up with an accurate diagnosis of the rhythm pronto. And hospitalist Meghan Mary Walsh, MD, MPH, has developed a simple and efficient method for doing so within a minute or two that she’s used with great success on the wards and in teaching medical students and residents for nearly a decade.

she promised at HM20 Virtual, hosted by the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Her method involves asking three questions about the 12-lead EKG:

1) What’s the rate?

A narrow complex tachycardia by definition needs to be both narrow and fast, with a QRS complex of less than 0.12 seconds and a heart rate above 100 bpm. Knowing how far above 100 bpm the rate is will help with the differential diagnosis.

2) Is the rhythm regular or irregular?

“If I put the EKG 10 feet away from you, you should still be able to look at it and say the QRS is either systematically marching out – boom, boom, boom – or there is an irregular sea of QRS complexes where the RR intervals are variable and inconsistent,” said Dr. Walsh, a hospitalist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and chief academic officer at Hennepin Healthcare, where she oversees all medical students and residents training in the health system.

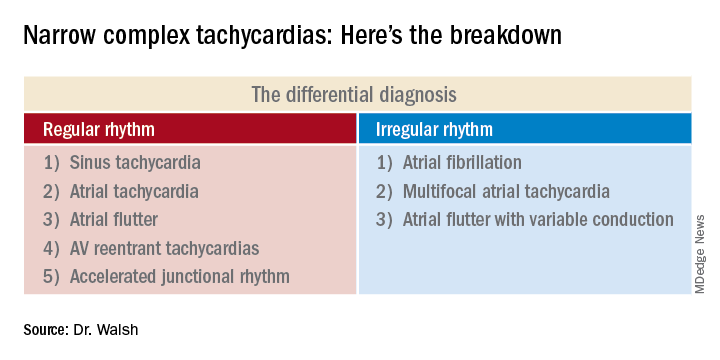

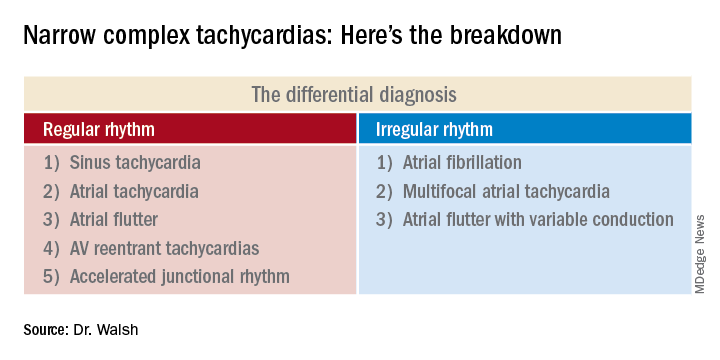

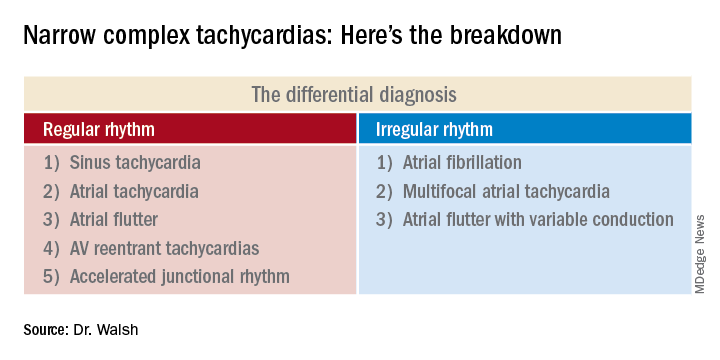

This distinction between a regular and irregular rhythm immediately narrows the differential by dividing the diagnostic possibilities into two columns (See chart). She urged her audience to commit the list to memory or keep it handy on their cell phone or in a notebook.

“If it’s irregular I’m going down the right column; if it’s regular I’m going down the left. And then I’m systematically running the drill,” she explained.

3) Are upright p waves present before each QRS complex in leads II and V1?

This information rules out some of the eight items in the differential diagnosis and rules in others.

Narrow complex tachycardias with an irregular rhythm

There are only three:

Atrial fibrillation: The heart rate is typically 110-160 bpm, although it can occasionally go higher. The rhythm is irregularly irregular: No two RR intervals on the EKG are exactly the same. And there are no p waves.

“If it’s faster than 100 bpm, irregularly irregular, and no p waves, the conclusion is very simple: It’s AFib,” Dr. Walsh said.

Multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT): The heart rate is generally 100-150 bpm but can sometimes climb to about 180 bpm. The PP, PR, and RR intervals are varied, inconsistent, and don’t repeat. Most importantly, there are three or more different p wave morphologies in the same lead. One p wave might look like a tall mountain peak, another could be short and flat, and perhaps the next is big and broad.

MAT often occurs in patients with a structurally abnormal atrium – for example, in the setting of pulmonary hypertension leading to right atrial enlargement, with resultant depolarization occurring all over the atrium.

“Don’t confuse MAT with AFib: One has p waves, one does not. Otherwise they can look very similar,” she said.

Atrial flutter with variable conduction: A hallmark of this reentrant tachycardia is the atrial flutter waves occurring at about 300 bpm between each QRS complex.

“On board renewal exams, the question is often asked, ‘Which leads are the best identifiers of atrial flutter?’ And the answer is the inferior leads II, III, and aVF,” she said.

Another classic feature of atrial flutter with variable conduction is cluster beating attributable to a varied ventricular response. This results in a repeated pattern of irregular RR intervals: There might be a 2:1 block in AV conduction for several beats, then maybe a 4:1 block for several more, with resultant lengthening of the RR interval, then 3:1, with shortening of RR. This regularly irregular sequence is repeated throughout the EKG.

“Look for a pattern amidst the chaos,” the hospitalist advised.

The heart rate might be roughly 150 bpm with a 2:1 block, or 100 bpm with a 3:1 block. The p waves in atrial flutter with variable conduction can be either negatively or positively deflected.

Narrow complex tachycardias with a regular rhythm*

Sinus tachycardia: The heart rate is typically less than 160 bpm, the QRS complexes show a regular pattern, and upright p waves are clearly visible in leads II and V1.

The distinguishing feature of this arrhythmia is the ramping up and ramping down of the heart rate. The tachycardia is typically less than 160 bpm. But the rate doesn’t suddenly jump from, say, 70 to140 bpm in a flash while the patient is lying in the hospital bed. A trip to the telemetry room for a look at the telemetry strip will tell the tale: The heart rate will have progressively ramped up from 70, to 80, then 90, then 100, 110, 120, 130, to perhaps 140 bpm. And then it will similarly ramp back down in stages, with the up/down pattern being repeated.

Sinus tachycardia is generally a reflection of underlying significant systemic illness, such as sepsis, hypotension, or anemia.

Atrial tachycardia: The heart rate is generally 100-140 bpm, and p waves are present. But unlike in sinus tachycardia, the patient with atrial tachycardia lying in bed with a heart rate of 140 bpm is not in a state of profound neurohormonal activation and is not all that sick.

Another diagnostic clue is provided by a look at the telemonitoring strip. Unlike in sinus tachycardia, where the heart rate ramps up and then back down repeatedly, in atrial tachycardia the heart rate very quickly ramps up in stages to, say, 140 bpm, and then hangs there.

Atrial flutter: This is the only narrow complex tachycardia that appears in both the regular and irregular rhythm columns. It belongs in the irregular rhythm column when there is variable conduction and cluster beating, with a regularly irregular pattern of RR intervals. In contrast, when atrial flutter is in the regular rhythm column, it’s because the atrioventricular node is steadily conducting the atrial depolarizations at a rate of about 300 bpm. So there’s no cluster beating. As in atrial flutter with variable conduction, the flutter waves are visible most often in leads II, III, and aVF, where they can be either positively or negatively deflected.

AV reentrant tachycardias: These reentrant tachycardias can take two forms. In atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVnRT), the aberrant pathway is found entirely within the AV node, whereas in atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia (AVRT) the aberrant pathway is found outside the AV node. AVnRT is more common than AVRT. As in atrial flutter, there is no ramp up in heart rate. Patients will be lying in their hospital bed with a heart rate of, say, 80 bpm, and then suddenly it jumps to 180, 200, or even as high as 240 bpm “almost in a split second,” Dr. Walsh said.

No other narrow complex tachycardia reaches so high a heart rate. In both of these reentrant tachycardias the p waves are often buried in the QRS complex and can be tough to see. It’s very difficult to differentiate AVnRT from AVRT except by an electrophysiologic study.

Accelerated junctional tachycardia: This is most commonly the slowest of the narrow complex tachycardias, with a heart rate of less than 120 bpm.

“In the case of accelerated junctional tachycardia, think slow, think ‘regular,’ think of a rate often just over 100, usually with p waves after the QRS that are inverted because there’s retrograde conduction,” she advised.

She reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

Correction, 8/19/20: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized the type of rhythm noted in this subhead.

A hospitalist looking at an EKG showing a narrow complex tachycardia needs to be able to come up with an accurate diagnosis of the rhythm pronto. And hospitalist Meghan Mary Walsh, MD, MPH, has developed a simple and efficient method for doing so within a minute or two that she’s used with great success on the wards and in teaching medical students and residents for nearly a decade.

she promised at HM20 Virtual, hosted by the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Her method involves asking three questions about the 12-lead EKG:

1) What’s the rate?

A narrow complex tachycardia by definition needs to be both narrow and fast, with a QRS complex of less than 0.12 seconds and a heart rate above 100 bpm. Knowing how far above 100 bpm the rate is will help with the differential diagnosis.

2) Is the rhythm regular or irregular?

“If I put the EKG 10 feet away from you, you should still be able to look at it and say the QRS is either systematically marching out – boom, boom, boom – or there is an irregular sea of QRS complexes where the RR intervals are variable and inconsistent,” said Dr. Walsh, a hospitalist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and chief academic officer at Hennepin Healthcare, where she oversees all medical students and residents training in the health system.

This distinction between a regular and irregular rhythm immediately narrows the differential by dividing the diagnostic possibilities into two columns (See chart). She urged her audience to commit the list to memory or keep it handy on their cell phone or in a notebook.

“If it’s irregular I’m going down the right column; if it’s regular I’m going down the left. And then I’m systematically running the drill,” she explained.

3) Are upright p waves present before each QRS complex in leads II and V1?

This information rules out some of the eight items in the differential diagnosis and rules in others.

Narrow complex tachycardias with an irregular rhythm

There are only three:

Atrial fibrillation: The heart rate is typically 110-160 bpm, although it can occasionally go higher. The rhythm is irregularly irregular: No two RR intervals on the EKG are exactly the same. And there are no p waves.

“If it’s faster than 100 bpm, irregularly irregular, and no p waves, the conclusion is very simple: It’s AFib,” Dr. Walsh said.

Multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT): The heart rate is generally 100-150 bpm but can sometimes climb to about 180 bpm. The PP, PR, and RR intervals are varied, inconsistent, and don’t repeat. Most importantly, there are three or more different p wave morphologies in the same lead. One p wave might look like a tall mountain peak, another could be short and flat, and perhaps the next is big and broad.

MAT often occurs in patients with a structurally abnormal atrium – for example, in the setting of pulmonary hypertension leading to right atrial enlargement, with resultant depolarization occurring all over the atrium.

“Don’t confuse MAT with AFib: One has p waves, one does not. Otherwise they can look very similar,” she said.

Atrial flutter with variable conduction: A hallmark of this reentrant tachycardia is the atrial flutter waves occurring at about 300 bpm between each QRS complex.

“On board renewal exams, the question is often asked, ‘Which leads are the best identifiers of atrial flutter?’ And the answer is the inferior leads II, III, and aVF,” she said.