User login

Multiple Sclerosis Hub

Neurofilaments: A Biomarker of Long-Term Outcome in MS?

Baseline measurement of CSF-NfL may add prognostic information and help identify patients who should start high-efficacy therapy as early as possible.

In patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), levels of light-chain neurofilament (NfL) in CSF at diagnosis seem to predict long-term clinical outcome and conversion from the relapsing-remitting phase of the disease to the secondary progressive phase, according to a study published in the September issue of Multiple Sclerosis Journal. “NfL is thought to reflect ongoing axonal degeneration, which dominates early in the disease phase, and our results support that increased early disease activity, as identified by increased levels of CSF-NfL, has a prognostic effect several years later,” said lead author Alok Bhan, MD, and colleagues. Dr. Bhan works in the Department of Neurology at Stavanger University Hospital in Norway.

Searching for Prognostic Markers

To test whether CSF-NfL levels in patients with MS could predict clinical outcome, Dr. Bhan and colleagues conducted standardized clinical assessments of patients with newly diagnosed MS at baseline and at five- and 10-year follow-up. Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) progression between assessments was defined as an increase of 1 point or more for scores less than 6 and of 0.5 points or more for scores of 6 or greater. CSF obtained at baseline was analyzed for levels of NfL using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay technology.

The study cohort included 44 patients, of whom 35 (80%) had relapsing-remitting MS, seven (16%) had secondary progressive MS, and two (4%) had primary progressive MS at baseline. Patients who progressed on EDSS tended to have higher median baseline CSF-NfL levels than patients who did not progress after five years (947 ng/L vs 246 ng/L, respectively) and those who did not progress after 10 years (708 ng/L vs 265 ng/L, respectively), although the latter difference was not statistically significant. Patients who converted from relapsing-remitting MS to secondary progressive MS at five years had a significantly higher median CSF level of NfL (2,122 ng/L), compared with those who did not convert (246 ng/L).

“We found a statistically significant correlation between NfL levels at baseline and EDSS progression and conversion from relapsing-remitting MS to secondary progressive MS at the five-year follow-up, but a weaker correlation at the 10-year follow-up,” the researchers said. “This [finding] may be due to the increasing number of patients on disease-modifying therapy throughout the study period, as only 16% received therapy at baseline, but 54% [did] at 10-year follow-up.”

The Predictive Value of NfL

“This is now another important report underscoring the predictive value of NfL levels for the evolution of future disability in MS, but the … study clearly suffers from the relatively low number of patients investigated,” said Michael Khalil, MD, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. Dr. Khalil is an Associate Professor of General Neurology at the Medical University of Graz in Austria. “Nevertheless, neurofilaments are currently the most promising markers to indicate neuro-axonal damage in MS and other neurologic diseases. The availability of a highly sensitive blood assay now facilitates its use for further research and in clinical practice.”

—Glenn S. Williams

Suggested Reading

Bhan A, Jacobsen C, Myhr KM, et al. Neurofilaments and 10-year follow-up in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2018; 24(10):1301-1307.

Khalil M. Are neurofilaments valuable biomarkers for long-term disease prognostication in MS? Mult Scler. 2018; 24(10):1270-1271.

Baseline measurement of CSF-NfL may add prognostic information and help identify patients who should start high-efficacy therapy as early as possible.

Baseline measurement of CSF-NfL may add prognostic information and help identify patients who should start high-efficacy therapy as early as possible.

In patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), levels of light-chain neurofilament (NfL) in CSF at diagnosis seem to predict long-term clinical outcome and conversion from the relapsing-remitting phase of the disease to the secondary progressive phase, according to a study published in the September issue of Multiple Sclerosis Journal. “NfL is thought to reflect ongoing axonal degeneration, which dominates early in the disease phase, and our results support that increased early disease activity, as identified by increased levels of CSF-NfL, has a prognostic effect several years later,” said lead author Alok Bhan, MD, and colleagues. Dr. Bhan works in the Department of Neurology at Stavanger University Hospital in Norway.

Searching for Prognostic Markers

To test whether CSF-NfL levels in patients with MS could predict clinical outcome, Dr. Bhan and colleagues conducted standardized clinical assessments of patients with newly diagnosed MS at baseline and at five- and 10-year follow-up. Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) progression between assessments was defined as an increase of 1 point or more for scores less than 6 and of 0.5 points or more for scores of 6 or greater. CSF obtained at baseline was analyzed for levels of NfL using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay technology.

The study cohort included 44 patients, of whom 35 (80%) had relapsing-remitting MS, seven (16%) had secondary progressive MS, and two (4%) had primary progressive MS at baseline. Patients who progressed on EDSS tended to have higher median baseline CSF-NfL levels than patients who did not progress after five years (947 ng/L vs 246 ng/L, respectively) and those who did not progress after 10 years (708 ng/L vs 265 ng/L, respectively), although the latter difference was not statistically significant. Patients who converted from relapsing-remitting MS to secondary progressive MS at five years had a significantly higher median CSF level of NfL (2,122 ng/L), compared with those who did not convert (246 ng/L).

“We found a statistically significant correlation between NfL levels at baseline and EDSS progression and conversion from relapsing-remitting MS to secondary progressive MS at the five-year follow-up, but a weaker correlation at the 10-year follow-up,” the researchers said. “This [finding] may be due to the increasing number of patients on disease-modifying therapy throughout the study period, as only 16% received therapy at baseline, but 54% [did] at 10-year follow-up.”

The Predictive Value of NfL

“This is now another important report underscoring the predictive value of NfL levels for the evolution of future disability in MS, but the … study clearly suffers from the relatively low number of patients investigated,” said Michael Khalil, MD, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. Dr. Khalil is an Associate Professor of General Neurology at the Medical University of Graz in Austria. “Nevertheless, neurofilaments are currently the most promising markers to indicate neuro-axonal damage in MS and other neurologic diseases. The availability of a highly sensitive blood assay now facilitates its use for further research and in clinical practice.”

—Glenn S. Williams

Suggested Reading

Bhan A, Jacobsen C, Myhr KM, et al. Neurofilaments and 10-year follow-up in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2018; 24(10):1301-1307.

Khalil M. Are neurofilaments valuable biomarkers for long-term disease prognostication in MS? Mult Scler. 2018; 24(10):1270-1271.

In patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), levels of light-chain neurofilament (NfL) in CSF at diagnosis seem to predict long-term clinical outcome and conversion from the relapsing-remitting phase of the disease to the secondary progressive phase, according to a study published in the September issue of Multiple Sclerosis Journal. “NfL is thought to reflect ongoing axonal degeneration, which dominates early in the disease phase, and our results support that increased early disease activity, as identified by increased levels of CSF-NfL, has a prognostic effect several years later,” said lead author Alok Bhan, MD, and colleagues. Dr. Bhan works in the Department of Neurology at Stavanger University Hospital in Norway.

Searching for Prognostic Markers

To test whether CSF-NfL levels in patients with MS could predict clinical outcome, Dr. Bhan and colleagues conducted standardized clinical assessments of patients with newly diagnosed MS at baseline and at five- and 10-year follow-up. Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) progression between assessments was defined as an increase of 1 point or more for scores less than 6 and of 0.5 points or more for scores of 6 or greater. CSF obtained at baseline was analyzed for levels of NfL using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay technology.

The study cohort included 44 patients, of whom 35 (80%) had relapsing-remitting MS, seven (16%) had secondary progressive MS, and two (4%) had primary progressive MS at baseline. Patients who progressed on EDSS tended to have higher median baseline CSF-NfL levels than patients who did not progress after five years (947 ng/L vs 246 ng/L, respectively) and those who did not progress after 10 years (708 ng/L vs 265 ng/L, respectively), although the latter difference was not statistically significant. Patients who converted from relapsing-remitting MS to secondary progressive MS at five years had a significantly higher median CSF level of NfL (2,122 ng/L), compared with those who did not convert (246 ng/L).

“We found a statistically significant correlation between NfL levels at baseline and EDSS progression and conversion from relapsing-remitting MS to secondary progressive MS at the five-year follow-up, but a weaker correlation at the 10-year follow-up,” the researchers said. “This [finding] may be due to the increasing number of patients on disease-modifying therapy throughout the study period, as only 16% received therapy at baseline, but 54% [did] at 10-year follow-up.”

The Predictive Value of NfL

“This is now another important report underscoring the predictive value of NfL levels for the evolution of future disability in MS, but the … study clearly suffers from the relatively low number of patients investigated,” said Michael Khalil, MD, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. Dr. Khalil is an Associate Professor of General Neurology at the Medical University of Graz in Austria. “Nevertheless, neurofilaments are currently the most promising markers to indicate neuro-axonal damage in MS and other neurologic diseases. The availability of a highly sensitive blood assay now facilitates its use for further research and in clinical practice.”

—Glenn S. Williams

Suggested Reading

Bhan A, Jacobsen C, Myhr KM, et al. Neurofilaments and 10-year follow-up in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2018; 24(10):1301-1307.

Khalil M. Are neurofilaments valuable biomarkers for long-term disease prognostication in MS? Mult Scler. 2018; 24(10):1270-1271.

How Many Patients Have Benign MS?

Patients and physicians interpret the term differently, thus making its use in the clinical setting problematic.

An estimated 3% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) have a benign course of disease, according to findings from a population-based UK study published online ahead of print September 3 in Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. The term “benign MS” remains problematic, however.

“The study of the individuals with extremely favorable outcomes may uncover insights about disease pathogenesis or repair. However, the insensitivity of Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS]–based definitions of benign MS and the discrepancy between patient and clinician perception of benign MS undermine use of the term ‘benign’ in the clinical setting,” said Emma Clare Tallantyre, BMBS, PhD, Clinical Senior Lecturer in Neurosciences at Cardiff University in the UK, and her colleagues.

The investigators found that of 1,049 patients with a disease duration of longer than 15 years, 200 had a recent EDSS score of less than 4.0. Of those patients, 60 were clinically assessed, and nine (15%) had benign MS, which was defined as an EDSS score less than 3.0 and lack of significant fatigue, mood disturbance, cognitive impairment, and disruption to employment in the absence of disease-modifying therapy at at least 15 years after symptom onset.

Extrapolating these data, the investigators estimated that 30 patients in the study population of 1,049 had benign MS, yielding a prevalence of 2.9%. Of the 60 patients who were clinically assessed, 39 thought they had benign MS, based on the following definition: “When referring to illness, ‘benign’ usually means a condition which has little or no harmful effects on a person. There are no complications, and there is a good outcome or prognosis.”

Patients who self-reported benign MS had significantly lower EDSS scores, fewer depressive symptoms, lower fatigue severity, and lower reported MS impact than did patients who did not report benign MS. “Self-reported benign MS status showed poor agreement with our composite definition of benign MS status and only fair agreement with EDSS-based definitions of benign MS status,” said the investigators.

—Jeff Evans

Suggested Reading

Tallantyre EC, Major PC, Atherton MJ, et al. How common is truly benign MS in a UK population? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Sep 3 [Epub ahead of print].

Patients and physicians interpret the term differently, thus making its use in the clinical setting problematic.

Patients and physicians interpret the term differently, thus making its use in the clinical setting problematic.

An estimated 3% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) have a benign course of disease, according to findings from a population-based UK study published online ahead of print September 3 in Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. The term “benign MS” remains problematic, however.

“The study of the individuals with extremely favorable outcomes may uncover insights about disease pathogenesis or repair. However, the insensitivity of Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS]–based definitions of benign MS and the discrepancy between patient and clinician perception of benign MS undermine use of the term ‘benign’ in the clinical setting,” said Emma Clare Tallantyre, BMBS, PhD, Clinical Senior Lecturer in Neurosciences at Cardiff University in the UK, and her colleagues.

The investigators found that of 1,049 patients with a disease duration of longer than 15 years, 200 had a recent EDSS score of less than 4.0. Of those patients, 60 were clinically assessed, and nine (15%) had benign MS, which was defined as an EDSS score less than 3.0 and lack of significant fatigue, mood disturbance, cognitive impairment, and disruption to employment in the absence of disease-modifying therapy at at least 15 years after symptom onset.

Extrapolating these data, the investigators estimated that 30 patients in the study population of 1,049 had benign MS, yielding a prevalence of 2.9%. Of the 60 patients who were clinically assessed, 39 thought they had benign MS, based on the following definition: “When referring to illness, ‘benign’ usually means a condition which has little or no harmful effects on a person. There are no complications, and there is a good outcome or prognosis.”

Patients who self-reported benign MS had significantly lower EDSS scores, fewer depressive symptoms, lower fatigue severity, and lower reported MS impact than did patients who did not report benign MS. “Self-reported benign MS status showed poor agreement with our composite definition of benign MS status and only fair agreement with EDSS-based definitions of benign MS status,” said the investigators.

—Jeff Evans

Suggested Reading

Tallantyre EC, Major PC, Atherton MJ, et al. How common is truly benign MS in a UK population? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Sep 3 [Epub ahead of print].

An estimated 3% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) have a benign course of disease, according to findings from a population-based UK study published online ahead of print September 3 in Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. The term “benign MS” remains problematic, however.

“The study of the individuals with extremely favorable outcomes may uncover insights about disease pathogenesis or repair. However, the insensitivity of Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS]–based definitions of benign MS and the discrepancy between patient and clinician perception of benign MS undermine use of the term ‘benign’ in the clinical setting,” said Emma Clare Tallantyre, BMBS, PhD, Clinical Senior Lecturer in Neurosciences at Cardiff University in the UK, and her colleagues.

The investigators found that of 1,049 patients with a disease duration of longer than 15 years, 200 had a recent EDSS score of less than 4.0. Of those patients, 60 were clinically assessed, and nine (15%) had benign MS, which was defined as an EDSS score less than 3.0 and lack of significant fatigue, mood disturbance, cognitive impairment, and disruption to employment in the absence of disease-modifying therapy at at least 15 years after symptom onset.

Extrapolating these data, the investigators estimated that 30 patients in the study population of 1,049 had benign MS, yielding a prevalence of 2.9%. Of the 60 patients who were clinically assessed, 39 thought they had benign MS, based on the following definition: “When referring to illness, ‘benign’ usually means a condition which has little or no harmful effects on a person. There are no complications, and there is a good outcome or prognosis.”

Patients who self-reported benign MS had significantly lower EDSS scores, fewer depressive symptoms, lower fatigue severity, and lower reported MS impact than did patients who did not report benign MS. “Self-reported benign MS status showed poor agreement with our composite definition of benign MS status and only fair agreement with EDSS-based definitions of benign MS status,” said the investigators.

—Jeff Evans

Suggested Reading

Tallantyre EC, Major PC, Atherton MJ, et al. How common is truly benign MS in a UK population? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Sep 3 [Epub ahead of print].

Benign MS is real in small minority of patients

Nearly 3% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) are estimated to have a truly benign course of disease over at least 15 years without the use of disease-modifying therapy, based on findings from a U.K. population-based study that also showed how poorly benign disease tracks with disability measures and lacks agreement between patients and physicians.

“The study of the individuals with extremely favorable outcomes may uncover insights about disease pathogenesis or repair. However, the insensitivity of EDSS [Expanded Disability Status Scale]–based definitions of benign MS and the discrepancy between patient and clinician perception of benign MS undermine use of the term ‘benign’ in the clinical setting,” Emma Clare Tallantyre, MD, of Cardiff (Wales) University, and her colleagues wrote in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

Dr. Tallantyre and her colleagues found that, of 1,049 patients with disease duration longer than 15 years, 200 had a recent EDSS score of less than 4.0. Of those 200, 60 were clinically assessed and 9 (15%) were found to have truly benign MS, defined as having an EDSS less than 3.0 and having no significant fatigue, mood disturbance, cognitive impairment, or disruption to employment in the absence of disease-modifying therapy at least 15 years after symptom onset.

The investigators extrapolated these data to estimate that 30 patients in the study population of 1,049 had truly benign MS, for a prevalence of 2.9%. However, of the 60 patients who were clinically assessed, 39 thought they had benign MS based on the lay definition provided: “When referring to illness, ‘benign’ usually means a condition which has little or no harmful effects on a person. There are no complications and there is a good outcome or prognosis.”

Patients who self-reported benign MS had significantly lower EDSS scores, fewer depressive symptoms, lower fatigue severity, and lower reported MS impact than did patients who did not report benign MS. “Self-reported benign MS status showed poor agreement with our composite definition of benign MS status and only fair agreement with EDSS-based definitions of benign MS status,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Tallantyre EC et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Sep 3. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-318802.

Nearly 3% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) are estimated to have a truly benign course of disease over at least 15 years without the use of disease-modifying therapy, based on findings from a U.K. population-based study that also showed how poorly benign disease tracks with disability measures and lacks agreement between patients and physicians.

“The study of the individuals with extremely favorable outcomes may uncover insights about disease pathogenesis or repair. However, the insensitivity of EDSS [Expanded Disability Status Scale]–based definitions of benign MS and the discrepancy between patient and clinician perception of benign MS undermine use of the term ‘benign’ in the clinical setting,” Emma Clare Tallantyre, MD, of Cardiff (Wales) University, and her colleagues wrote in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

Dr. Tallantyre and her colleagues found that, of 1,049 patients with disease duration longer than 15 years, 200 had a recent EDSS score of less than 4.0. Of those 200, 60 were clinically assessed and 9 (15%) were found to have truly benign MS, defined as having an EDSS less than 3.0 and having no significant fatigue, mood disturbance, cognitive impairment, or disruption to employment in the absence of disease-modifying therapy at least 15 years after symptom onset.

The investigators extrapolated these data to estimate that 30 patients in the study population of 1,049 had truly benign MS, for a prevalence of 2.9%. However, of the 60 patients who were clinically assessed, 39 thought they had benign MS based on the lay definition provided: “When referring to illness, ‘benign’ usually means a condition which has little or no harmful effects on a person. There are no complications and there is a good outcome or prognosis.”

Patients who self-reported benign MS had significantly lower EDSS scores, fewer depressive symptoms, lower fatigue severity, and lower reported MS impact than did patients who did not report benign MS. “Self-reported benign MS status showed poor agreement with our composite definition of benign MS status and only fair agreement with EDSS-based definitions of benign MS status,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Tallantyre EC et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Sep 3. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-318802.

Nearly 3% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) are estimated to have a truly benign course of disease over at least 15 years without the use of disease-modifying therapy, based on findings from a U.K. population-based study that also showed how poorly benign disease tracks with disability measures and lacks agreement between patients and physicians.

“The study of the individuals with extremely favorable outcomes may uncover insights about disease pathogenesis or repair. However, the insensitivity of EDSS [Expanded Disability Status Scale]–based definitions of benign MS and the discrepancy between patient and clinician perception of benign MS undermine use of the term ‘benign’ in the clinical setting,” Emma Clare Tallantyre, MD, of Cardiff (Wales) University, and her colleagues wrote in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

Dr. Tallantyre and her colleagues found that, of 1,049 patients with disease duration longer than 15 years, 200 had a recent EDSS score of less than 4.0. Of those 200, 60 were clinically assessed and 9 (15%) were found to have truly benign MS, defined as having an EDSS less than 3.0 and having no significant fatigue, mood disturbance, cognitive impairment, or disruption to employment in the absence of disease-modifying therapy at least 15 years after symptom onset.

The investigators extrapolated these data to estimate that 30 patients in the study population of 1,049 had truly benign MS, for a prevalence of 2.9%. However, of the 60 patients who were clinically assessed, 39 thought they had benign MS based on the lay definition provided: “When referring to illness, ‘benign’ usually means a condition which has little or no harmful effects on a person. There are no complications and there is a good outcome or prognosis.”

Patients who self-reported benign MS had significantly lower EDSS scores, fewer depressive symptoms, lower fatigue severity, and lower reported MS impact than did patients who did not report benign MS. “Self-reported benign MS status showed poor agreement with our composite definition of benign MS status and only fair agreement with EDSS-based definitions of benign MS status,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Tallantyre EC et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Sep 3. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-318802.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF NEUROLOGY, NEUROSURGERY & PSYCHIATRY

Serum Nf-L shows promise as biomarker for BMT response in MS

LOS ANGELES – Serum neurofilament light chain shows promise as a biomarker for disease severity and response to treatment with autologous bone marrow transplant in patients with multiple sclerosis, according to findings from an analysis of paired samples.

Serum neurofilament light chain (Nf-L) levels were found to be significantly elevated in both the serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of 23 patients with aggressive multiple sclerosis (MS), compared with samples from 5 controls with noninflammatory neurologic conditions such as chronic fatigue syndrome or migraine. The levels in the patients with MS were significantly reduced following autologous bone marrow transplant (BMT), Simon Thebault, MD, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Nf-L has been shown to be a biomarker for neuronal damage and to have potential for denoting disease severity and treatment response in MS; for this analysis, samples from patients were collected at baseline and annually for 3 years after transplant. Samples from controls were obtained for comparison.

“Our objective, really, was [to determine if we could] detect a treatment response in neurofilament light chain, and secondly, did the degree of neurofilament light chain being high at baseline predict anything about subsequent disease outcome?” Dr. Thebault, a third-year resident at the University of Ottawa, reported in the poster.

Indeed, a treatment response was detected; baseline levels were high, and levels in both serum and CSF were down significantly (P = .05) at both 1 and 3 years following bone marrow transplant, and they stayed down. “In fact, they were so low, they were not significantly different from [the levels] in noninflammatory controls,” he said, noting that serum and CSF NfL levels were highly correlated (r = .833; P less than .001).

Study subjects were patients with aggressive MS, characterized by early disease onset, rapid progression, frequent relapses, and poor treatment responses. Such patients who have received autologous BMT represent an interesting group for examining treatment responses, he said.

At baseline, these patients presumably have a high burden of tissue injury, which would be representative of high levels of Nf-L; good, prospective data show these patients have no evidence of ongoing inflammatory disease following an intensive regimen that includes chemoablation and reinfusion of autologous stem cells, which is representative of a significant reduction of neurofilament levels, he explained.

Importantly, serum and CSF levels were correlated in this study, he said, noting that most prior work has involved CSF, but “the real clinical utility in neurofilament light chain is probably in the serum, because patients don’t like having lumbar punctures too often.”

With respect to the second question pertaining to disease outcomes, the study did show that patients with baseline Nf-L levels above the median for the group had worse T1 lesion volumes at baseline and after transplant (P = .0021 at 36 months), and also had worsening brain atrophy even after transplant (P = .0389 at 60 months).

The curves appeared to be diverging, suggesting that, in the absence of inflammatory disease activity, patients with high Nf-L levels at baseline continue to have ongoing atrophy at a differential rate, compared with those with low baseline levels, Dr. Thebault said.

Other findings included better Expanded Disability Status Scale outcomes after transplant in patients with lower baseline Nf-L, and a trend toward worsening outcomes among those with higher baseline Nf-L levels, although the study may have been underpowered for this. Additionally, lower baseline Nf-L predicted significantly lower T1 and T2 lesion volume, number of gadolinium-enhancing lesions, and a reduction in brain atrophy, whereas higher baseline Nf-L predicted the opposite, he noted, adding that N-acetylaspartate-to-creatinine ratios also tended to vary inversely with Nf-L levels.

The most important findings of the study are “the sustained reduction in Nf-L levels after BMT, and that higher baseline levels predicted worse MRI outcomes,” Dr. Thebault noted. “Together these data add to a growing body of evidence that suggests that serum Nf-L has a role in monitoring treatment responses and even a predictive value in determining disease severity.”

This study was supported by Quanterix, which provided Nf-L assay kits. Dr. Thebault reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Thebault S et al. Neurology. 2018 Apr;90(15 Suppl.):P5.036.

LOS ANGELES – Serum neurofilament light chain shows promise as a biomarker for disease severity and response to treatment with autologous bone marrow transplant in patients with multiple sclerosis, according to findings from an analysis of paired samples.

Serum neurofilament light chain (Nf-L) levels were found to be significantly elevated in both the serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of 23 patients with aggressive multiple sclerosis (MS), compared with samples from 5 controls with noninflammatory neurologic conditions such as chronic fatigue syndrome or migraine. The levels in the patients with MS were significantly reduced following autologous bone marrow transplant (BMT), Simon Thebault, MD, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Nf-L has been shown to be a biomarker for neuronal damage and to have potential for denoting disease severity and treatment response in MS; for this analysis, samples from patients were collected at baseline and annually for 3 years after transplant. Samples from controls were obtained for comparison.

“Our objective, really, was [to determine if we could] detect a treatment response in neurofilament light chain, and secondly, did the degree of neurofilament light chain being high at baseline predict anything about subsequent disease outcome?” Dr. Thebault, a third-year resident at the University of Ottawa, reported in the poster.

Indeed, a treatment response was detected; baseline levels were high, and levels in both serum and CSF were down significantly (P = .05) at both 1 and 3 years following bone marrow transplant, and they stayed down. “In fact, they were so low, they were not significantly different from [the levels] in noninflammatory controls,” he said, noting that serum and CSF NfL levels were highly correlated (r = .833; P less than .001).

Study subjects were patients with aggressive MS, characterized by early disease onset, rapid progression, frequent relapses, and poor treatment responses. Such patients who have received autologous BMT represent an interesting group for examining treatment responses, he said.

At baseline, these patients presumably have a high burden of tissue injury, which would be representative of high levels of Nf-L; good, prospective data show these patients have no evidence of ongoing inflammatory disease following an intensive regimen that includes chemoablation and reinfusion of autologous stem cells, which is representative of a significant reduction of neurofilament levels, he explained.

Importantly, serum and CSF levels were correlated in this study, he said, noting that most prior work has involved CSF, but “the real clinical utility in neurofilament light chain is probably in the serum, because patients don’t like having lumbar punctures too often.”

With respect to the second question pertaining to disease outcomes, the study did show that patients with baseline Nf-L levels above the median for the group had worse T1 lesion volumes at baseline and after transplant (P = .0021 at 36 months), and also had worsening brain atrophy even after transplant (P = .0389 at 60 months).

The curves appeared to be diverging, suggesting that, in the absence of inflammatory disease activity, patients with high Nf-L levels at baseline continue to have ongoing atrophy at a differential rate, compared with those with low baseline levels, Dr. Thebault said.

Other findings included better Expanded Disability Status Scale outcomes after transplant in patients with lower baseline Nf-L, and a trend toward worsening outcomes among those with higher baseline Nf-L levels, although the study may have been underpowered for this. Additionally, lower baseline Nf-L predicted significantly lower T1 and T2 lesion volume, number of gadolinium-enhancing lesions, and a reduction in brain atrophy, whereas higher baseline Nf-L predicted the opposite, he noted, adding that N-acetylaspartate-to-creatinine ratios also tended to vary inversely with Nf-L levels.

The most important findings of the study are “the sustained reduction in Nf-L levels after BMT, and that higher baseline levels predicted worse MRI outcomes,” Dr. Thebault noted. “Together these data add to a growing body of evidence that suggests that serum Nf-L has a role in monitoring treatment responses and even a predictive value in determining disease severity.”

This study was supported by Quanterix, which provided Nf-L assay kits. Dr. Thebault reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Thebault S et al. Neurology. 2018 Apr;90(15 Suppl.):P5.036.

LOS ANGELES – Serum neurofilament light chain shows promise as a biomarker for disease severity and response to treatment with autologous bone marrow transplant in patients with multiple sclerosis, according to findings from an analysis of paired samples.

Serum neurofilament light chain (Nf-L) levels were found to be significantly elevated in both the serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of 23 patients with aggressive multiple sclerosis (MS), compared with samples from 5 controls with noninflammatory neurologic conditions such as chronic fatigue syndrome or migraine. The levels in the patients with MS were significantly reduced following autologous bone marrow transplant (BMT), Simon Thebault, MD, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Nf-L has been shown to be a biomarker for neuronal damage and to have potential for denoting disease severity and treatment response in MS; for this analysis, samples from patients were collected at baseline and annually for 3 years after transplant. Samples from controls were obtained for comparison.

“Our objective, really, was [to determine if we could] detect a treatment response in neurofilament light chain, and secondly, did the degree of neurofilament light chain being high at baseline predict anything about subsequent disease outcome?” Dr. Thebault, a third-year resident at the University of Ottawa, reported in the poster.

Indeed, a treatment response was detected; baseline levels were high, and levels in both serum and CSF were down significantly (P = .05) at both 1 and 3 years following bone marrow transplant, and they stayed down. “In fact, they were so low, they were not significantly different from [the levels] in noninflammatory controls,” he said, noting that serum and CSF NfL levels were highly correlated (r = .833; P less than .001).

Study subjects were patients with aggressive MS, characterized by early disease onset, rapid progression, frequent relapses, and poor treatment responses. Such patients who have received autologous BMT represent an interesting group for examining treatment responses, he said.

At baseline, these patients presumably have a high burden of tissue injury, which would be representative of high levels of Nf-L; good, prospective data show these patients have no evidence of ongoing inflammatory disease following an intensive regimen that includes chemoablation and reinfusion of autologous stem cells, which is representative of a significant reduction of neurofilament levels, he explained.

Importantly, serum and CSF levels were correlated in this study, he said, noting that most prior work has involved CSF, but “the real clinical utility in neurofilament light chain is probably in the serum, because patients don’t like having lumbar punctures too often.”

With respect to the second question pertaining to disease outcomes, the study did show that patients with baseline Nf-L levels above the median for the group had worse T1 lesion volumes at baseline and after transplant (P = .0021 at 36 months), and also had worsening brain atrophy even after transplant (P = .0389 at 60 months).

The curves appeared to be diverging, suggesting that, in the absence of inflammatory disease activity, patients with high Nf-L levels at baseline continue to have ongoing atrophy at a differential rate, compared with those with low baseline levels, Dr. Thebault said.

Other findings included better Expanded Disability Status Scale outcomes after transplant in patients with lower baseline Nf-L, and a trend toward worsening outcomes among those with higher baseline Nf-L levels, although the study may have been underpowered for this. Additionally, lower baseline Nf-L predicted significantly lower T1 and T2 lesion volume, number of gadolinium-enhancing lesions, and a reduction in brain atrophy, whereas higher baseline Nf-L predicted the opposite, he noted, adding that N-acetylaspartate-to-creatinine ratios also tended to vary inversely with Nf-L levels.

The most important findings of the study are “the sustained reduction in Nf-L levels after BMT, and that higher baseline levels predicted worse MRI outcomes,” Dr. Thebault noted. “Together these data add to a growing body of evidence that suggests that serum Nf-L has a role in monitoring treatment responses and even a predictive value in determining disease severity.”

This study was supported by Quanterix, which provided Nf-L assay kits. Dr. Thebault reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Thebault S et al. Neurology. 2018 Apr;90(15 Suppl.):P5.036.

REPORTING FROM AAN 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Serum and cerebrospinal fluid Nf-L levels declines significantly after bone marrow transplant (P less than .05) and did not differ from the levels in controls.

Study details: An analysis of paired samples from 23 patients with multiple sclerosis and 5 controls.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Quanterix, which provided Nf-L assay kits. Dr. Thebault reported having no disclosures.

Source: Thebault S et al. Neurology. 2018 Apr;90(15 Suppl.):P5.036.

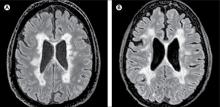

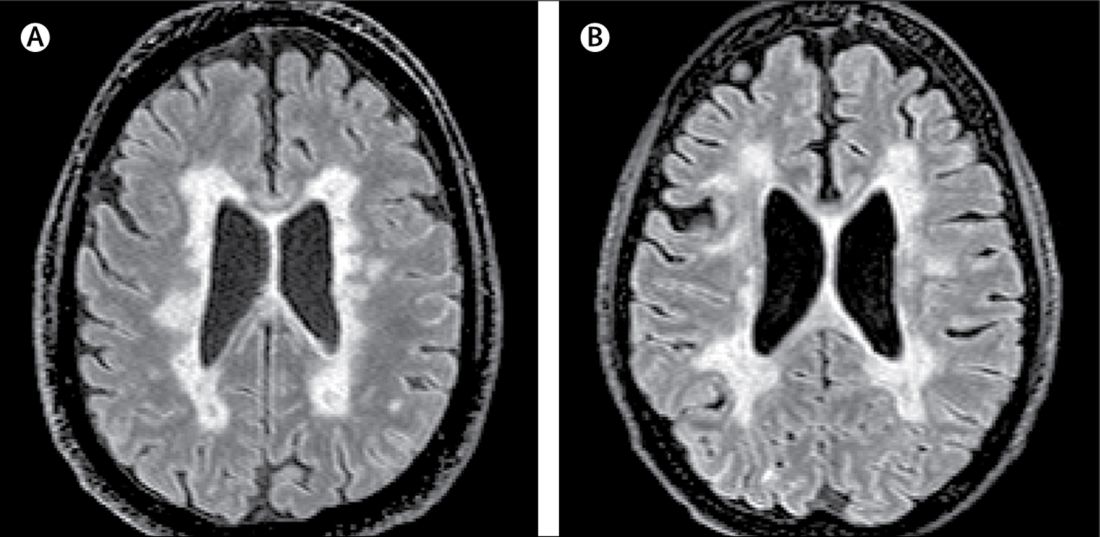

New MS subtype shows absence of cerebral white matter demyelination

A new subtype of multiple sclerosis called myelocortical multiple sclerosis is characterized by demyelination only in the spinal cord and cerebral cortex and not in the cerebral white matter.

A paper published online Aug. 21 in Lancet Neurology presents the results of a study of the brains and spinal cords of 100 patients who died of multiple sclerosis.

Bruce D. Trapp, PhD, of the Lerner Research Institute at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, and his coauthors wrote that while the demyelination of cerebral white matter is a pathologic hallmark of multiple sclerosis, previous research has found only around half of cerebral T2-weighted hyperintense white matter lesions are demyelinated, and these lesions account for less than a third of variance in the rate of brain atrophy.

“In the absence of specific MRI metrics for demyelination, the relationship between cerebral white-matter demyelination and neurodegeneration remains speculative,” they wrote.

In this study, researchers scanned the brains with MRI before autopsy, then took centimeter-thick hemispheric slices to study the white-matter lesions. They identified 12 individuals as having what they describe as ‘myelocortical multiple sclerosis,’ characterized by the absence of areas of cerebral white-matter discoloration indicative of demyelinated lesions.

The authors then compared these individuals to 12 individuals with typical multiple sclerosis matched by age, sex, MRI protocol, multiple sclerosis disease subtype, disease duration, and Expanded Disability Status Scale.

They found that while individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis did not have demyelinated lesions in the cerebral white matter, they had similar areas of demyelinated lesions in the cerebral cortex to individuals with typical multiple sclerosis (median 4.45% vs. 9.74% respectively, P = .5512).

However, the individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis had a significantly smaller area of spinal cord demyelination (median 3.81% vs. 13.81%, P = .0083).

Individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis also had significantly lower mean cortical neuronal densities, compared with healthy control brains in layer III, layer V, and layer VI. But individuals with typical multiple sclerosis only had a lower cortical neuronal density in layer V when compared with controls.

Researchers also saw that in typical multiple sclerosis, neuronal density decreased as the area of brain white-matter demyelination increased. However, this negative linear correlation was not seen in myelocortical multiple sclerosis.

On MRI, researchers were still able to see abnormalities in the cerebral white matter in individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis, in T2-weighted, T1-weighted and magnetization transfer ratios (MTR) images.

They also found similar total T2-weighted and T1-weighted lesion volumes in individuals with myelocortical and with typical multiple sclerosis, although individuals with typical multiple sclerosis had significantly greater MTR lesion volumes.

“We propose that myelocortical multiple sclerosis is characterized by spinal cord demyelination, subpial cortical demyelination, and an absence of cerebral white-matter demyelination,” the authors wrote. “Our findings indicate that abnormal cerebral white-matter T2-T1-MTR regions of interest are not always demyelinated, and this pathological evidence suggests that cerebral white-matter demyelination and cortical neuronal degeneration can be independent events in myelocortical multiple sclerosis.”

The authors noted that their study may have been affected by selection bias, as all the patients in the study had died from complications of advanced multiple sclerosis. They suggested that it was therefore not appropriate to conclude that the prevalence of myelocortical multiple sclerosis seen in their sample would be similar across the multiple sclerosis population, nor were the findings likely to apply to people with earlier stage disease.

The study was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health and National Multiple Sclerosis Society. One author was an employee of Renovo Neural, and three authors were employees of Biogen. One author declared a pending patent related to automated lesion segmentation from MRI images, and four authors declared funding, fees, and non-financial support from pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Trapp B et al. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Aug 21. doi: 10.1016/ S1474-4422(18)30245-X.

A new subtype of multiple sclerosis called myelocortical multiple sclerosis is characterized by demyelination only in the spinal cord and cerebral cortex and not in the cerebral white matter.

A paper published online Aug. 21 in Lancet Neurology presents the results of a study of the brains and spinal cords of 100 patients who died of multiple sclerosis.

Bruce D. Trapp, PhD, of the Lerner Research Institute at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, and his coauthors wrote that while the demyelination of cerebral white matter is a pathologic hallmark of multiple sclerosis, previous research has found only around half of cerebral T2-weighted hyperintense white matter lesions are demyelinated, and these lesions account for less than a third of variance in the rate of brain atrophy.

“In the absence of specific MRI metrics for demyelination, the relationship between cerebral white-matter demyelination and neurodegeneration remains speculative,” they wrote.

In this study, researchers scanned the brains with MRI before autopsy, then took centimeter-thick hemispheric slices to study the white-matter lesions. They identified 12 individuals as having what they describe as ‘myelocortical multiple sclerosis,’ characterized by the absence of areas of cerebral white-matter discoloration indicative of demyelinated lesions.

The authors then compared these individuals to 12 individuals with typical multiple sclerosis matched by age, sex, MRI protocol, multiple sclerosis disease subtype, disease duration, and Expanded Disability Status Scale.

They found that while individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis did not have demyelinated lesions in the cerebral white matter, they had similar areas of demyelinated lesions in the cerebral cortex to individuals with typical multiple sclerosis (median 4.45% vs. 9.74% respectively, P = .5512).

However, the individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis had a significantly smaller area of spinal cord demyelination (median 3.81% vs. 13.81%, P = .0083).

Individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis also had significantly lower mean cortical neuronal densities, compared with healthy control brains in layer III, layer V, and layer VI. But individuals with typical multiple sclerosis only had a lower cortical neuronal density in layer V when compared with controls.

Researchers also saw that in typical multiple sclerosis, neuronal density decreased as the area of brain white-matter demyelination increased. However, this negative linear correlation was not seen in myelocortical multiple sclerosis.

On MRI, researchers were still able to see abnormalities in the cerebral white matter in individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis, in T2-weighted, T1-weighted and magnetization transfer ratios (MTR) images.

They also found similar total T2-weighted and T1-weighted lesion volumes in individuals with myelocortical and with typical multiple sclerosis, although individuals with typical multiple sclerosis had significantly greater MTR lesion volumes.

“We propose that myelocortical multiple sclerosis is characterized by spinal cord demyelination, subpial cortical demyelination, and an absence of cerebral white-matter demyelination,” the authors wrote. “Our findings indicate that abnormal cerebral white-matter T2-T1-MTR regions of interest are not always demyelinated, and this pathological evidence suggests that cerebral white-matter demyelination and cortical neuronal degeneration can be independent events in myelocortical multiple sclerosis.”

The authors noted that their study may have been affected by selection bias, as all the patients in the study had died from complications of advanced multiple sclerosis. They suggested that it was therefore not appropriate to conclude that the prevalence of myelocortical multiple sclerosis seen in their sample would be similar across the multiple sclerosis population, nor were the findings likely to apply to people with earlier stage disease.

The study was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health and National Multiple Sclerosis Society. One author was an employee of Renovo Neural, and three authors were employees of Biogen. One author declared a pending patent related to automated lesion segmentation from MRI images, and four authors declared funding, fees, and non-financial support from pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Trapp B et al. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Aug 21. doi: 10.1016/ S1474-4422(18)30245-X.

A new subtype of multiple sclerosis called myelocortical multiple sclerosis is characterized by demyelination only in the spinal cord and cerebral cortex and not in the cerebral white matter.

A paper published online Aug. 21 in Lancet Neurology presents the results of a study of the brains and spinal cords of 100 patients who died of multiple sclerosis.

Bruce D. Trapp, PhD, of the Lerner Research Institute at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, and his coauthors wrote that while the demyelination of cerebral white matter is a pathologic hallmark of multiple sclerosis, previous research has found only around half of cerebral T2-weighted hyperintense white matter lesions are demyelinated, and these lesions account for less than a third of variance in the rate of brain atrophy.

“In the absence of specific MRI metrics for demyelination, the relationship between cerebral white-matter demyelination and neurodegeneration remains speculative,” they wrote.

In this study, researchers scanned the brains with MRI before autopsy, then took centimeter-thick hemispheric slices to study the white-matter lesions. They identified 12 individuals as having what they describe as ‘myelocortical multiple sclerosis,’ characterized by the absence of areas of cerebral white-matter discoloration indicative of demyelinated lesions.

The authors then compared these individuals to 12 individuals with typical multiple sclerosis matched by age, sex, MRI protocol, multiple sclerosis disease subtype, disease duration, and Expanded Disability Status Scale.

They found that while individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis did not have demyelinated lesions in the cerebral white matter, they had similar areas of demyelinated lesions in the cerebral cortex to individuals with typical multiple sclerosis (median 4.45% vs. 9.74% respectively, P = .5512).

However, the individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis had a significantly smaller area of spinal cord demyelination (median 3.81% vs. 13.81%, P = .0083).

Individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis also had significantly lower mean cortical neuronal densities, compared with healthy control brains in layer III, layer V, and layer VI. But individuals with typical multiple sclerosis only had a lower cortical neuronal density in layer V when compared with controls.

Researchers also saw that in typical multiple sclerosis, neuronal density decreased as the area of brain white-matter demyelination increased. However, this negative linear correlation was not seen in myelocortical multiple sclerosis.

On MRI, researchers were still able to see abnormalities in the cerebral white matter in individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis, in T2-weighted, T1-weighted and magnetization transfer ratios (MTR) images.

They also found similar total T2-weighted and T1-weighted lesion volumes in individuals with myelocortical and with typical multiple sclerosis, although individuals with typical multiple sclerosis had significantly greater MTR lesion volumes.

“We propose that myelocortical multiple sclerosis is characterized by spinal cord demyelination, subpial cortical demyelination, and an absence of cerebral white-matter demyelination,” the authors wrote. “Our findings indicate that abnormal cerebral white-matter T2-T1-MTR regions of interest are not always demyelinated, and this pathological evidence suggests that cerebral white-matter demyelination and cortical neuronal degeneration can be independent events in myelocortical multiple sclerosis.”

The authors noted that their study may have been affected by selection bias, as all the patients in the study had died from complications of advanced multiple sclerosis. They suggested that it was therefore not appropriate to conclude that the prevalence of myelocortical multiple sclerosis seen in their sample would be similar across the multiple sclerosis population, nor were the findings likely to apply to people with earlier stage disease.

The study was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health and National Multiple Sclerosis Society. One author was an employee of Renovo Neural, and three authors were employees of Biogen. One author declared a pending patent related to automated lesion segmentation from MRI images, and four authors declared funding, fees, and non-financial support from pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Trapp B et al. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Aug 21. doi: 10.1016/ S1474-4422(18)30245-X.

FROM LANCET NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point: Researchers have identified a new subtype of multiple sclerosis.

Major finding: Individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis show demyelination in the spinal cord and cortex only.

Study details: Post-mortem study of brains and spinal cords of 100 individuals with multiple sclerosis.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health and National Multiple Sclerosis Society. One author was an employee of Renovo Neural, three authors were employees of Biogen. One author declared a pending patent related to automated lesion segmentation from MRI images, and four authors declared funding, fees and non-financial support from pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Trapp B et al. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Aug 21. doi: 10.1016/ S1474-4422(18)30245-X.

New MS criteria may create more false positives

The revised McDonald criteria for multiple sclerosis (MS) has led to more diagnoses in patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), but a new study of the criteria has suggested that they may lead to a number of false positive MS diagnoses among patients with a less severe disease state.

“In our data, specificity of the 2017 criteria was significantly lower than for the 2010 criteria,” Roos M. van der Vuurst de Vries, MD, from the department of neurology at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and her colleagues wrote in JAMA Neurology. “Earlier data showed that the previous McDonald criteria lead to a higher number of MS diagnoses in patients who will not have a second attack.”

Dr. van der Vuurst de Vries and her colleagues analyzed data from 229 patients with a CIS who underwent an MRI of the spinal cord to assess for dissemination in space (DIS); of these, 180 patients were scored for both DIS and dissemination in time (DIT) and had a “baseline MRI scan that included T1 images after gadolinium administration or scans that did not show any T2 hyperintense lesions.” Some patients also underwent a baseline lumbar puncture if clinically required.

Patients were assessed using both the 2010 and 2017 McDonald criteria for MS, and results were measured using sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive and negative predictive values, and accuracy at 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year follow-up. “The most important addition is that the new criteria allow MS diagnosis when the MRI scan meets criteria for DIS and unique oligoclonal bands (OCB) are present in [cerebrospinal fluid], even in absence of DIT on the MRI scan,” the researchers wrote. “The other major difference is that not only asymptomatic but also symptomatic lesions can be used to demonstrate DIS and DIT on MRI. Furthermore, cortical lesions can be used to demonstrate dissemination in space.”

The researchers found that 124 patients met 2010 DIS criteria (54%) and that 74 patients (60%) went on to develop clinically definite MS, while 149 patients (65%) met 2017 DIS criteria, and 89 patients (60%) went on to clinically definite MS. There were 46 patients (26%) who met 2010 DIT criteria, and 33 of those patients (72%) were diagnosed with clinically definite MS; 126 patients (70%) met 2017 DIT criteria, and 76 of those patients (60%) had clinically definite MS. The sensitivity for the 2010 criteria was 36% (95% confidence interval, 27%-47%)versus 68% for the 2017 criteria (95% CI, 57%-77%; P less than .001). However, specificity for the 2017 criteria was lower (61%; 95% CI, 50%-71%) when compared with the 2010 criteria (85%; 95% CI, 76%-92%; P less than .001). Researchers found more baseline MS diagnoses with the 2017 criteria than with the 2010 criteria, but they noted that 14 of 22 patients (64%) under the 2010 criteria and 26 of 48 patients (54%) under the 2017 criteria with MS had a second attack within 5 years.

The study was supported by the Dutch Multiple Sclerosis Research Foundation. One or more authors received compensation from Teva, Merck, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, Biogen, and Novartis in the form of honoraria, for advisory board membership, as travel grants, or for participation in trials.

SOURCE: van der Vuurst de Vries RM, et al. JAMA Neurol. 2018 Aug 6. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2160.

The revised McDonald criteria for multiple sclerosis (MS) has led to more diagnoses in patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), but a new study of the criteria has suggested that they may lead to a number of false positive MS diagnoses among patients with a less severe disease state.

“In our data, specificity of the 2017 criteria was significantly lower than for the 2010 criteria,” Roos M. van der Vuurst de Vries, MD, from the department of neurology at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and her colleagues wrote in JAMA Neurology. “Earlier data showed that the previous McDonald criteria lead to a higher number of MS diagnoses in patients who will not have a second attack.”

Dr. van der Vuurst de Vries and her colleagues analyzed data from 229 patients with a CIS who underwent an MRI of the spinal cord to assess for dissemination in space (DIS); of these, 180 patients were scored for both DIS and dissemination in time (DIT) and had a “baseline MRI scan that included T1 images after gadolinium administration or scans that did not show any T2 hyperintense lesions.” Some patients also underwent a baseline lumbar puncture if clinically required.

Patients were assessed using both the 2010 and 2017 McDonald criteria for MS, and results were measured using sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive and negative predictive values, and accuracy at 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year follow-up. “The most important addition is that the new criteria allow MS diagnosis when the MRI scan meets criteria for DIS and unique oligoclonal bands (OCB) are present in [cerebrospinal fluid], even in absence of DIT on the MRI scan,” the researchers wrote. “The other major difference is that not only asymptomatic but also symptomatic lesions can be used to demonstrate DIS and DIT on MRI. Furthermore, cortical lesions can be used to demonstrate dissemination in space.”

The researchers found that 124 patients met 2010 DIS criteria (54%) and that 74 patients (60%) went on to develop clinically definite MS, while 149 patients (65%) met 2017 DIS criteria, and 89 patients (60%) went on to clinically definite MS. There were 46 patients (26%) who met 2010 DIT criteria, and 33 of those patients (72%) were diagnosed with clinically definite MS; 126 patients (70%) met 2017 DIT criteria, and 76 of those patients (60%) had clinically definite MS. The sensitivity for the 2010 criteria was 36% (95% confidence interval, 27%-47%)versus 68% for the 2017 criteria (95% CI, 57%-77%; P less than .001). However, specificity for the 2017 criteria was lower (61%; 95% CI, 50%-71%) when compared with the 2010 criteria (85%; 95% CI, 76%-92%; P less than .001). Researchers found more baseline MS diagnoses with the 2017 criteria than with the 2010 criteria, but they noted that 14 of 22 patients (64%) under the 2010 criteria and 26 of 48 patients (54%) under the 2017 criteria with MS had a second attack within 5 years.

The study was supported by the Dutch Multiple Sclerosis Research Foundation. One or more authors received compensation from Teva, Merck, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, Biogen, and Novartis in the form of honoraria, for advisory board membership, as travel grants, or for participation in trials.

SOURCE: van der Vuurst de Vries RM, et al. JAMA Neurol. 2018 Aug 6. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2160.

The revised McDonald criteria for multiple sclerosis (MS) has led to more diagnoses in patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), but a new study of the criteria has suggested that they may lead to a number of false positive MS diagnoses among patients with a less severe disease state.

“In our data, specificity of the 2017 criteria was significantly lower than for the 2010 criteria,” Roos M. van der Vuurst de Vries, MD, from the department of neurology at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and her colleagues wrote in JAMA Neurology. “Earlier data showed that the previous McDonald criteria lead to a higher number of MS diagnoses in patients who will not have a second attack.”

Dr. van der Vuurst de Vries and her colleagues analyzed data from 229 patients with a CIS who underwent an MRI of the spinal cord to assess for dissemination in space (DIS); of these, 180 patients were scored for both DIS and dissemination in time (DIT) and had a “baseline MRI scan that included T1 images after gadolinium administration or scans that did not show any T2 hyperintense lesions.” Some patients also underwent a baseline lumbar puncture if clinically required.

Patients were assessed using both the 2010 and 2017 McDonald criteria for MS, and results were measured using sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive and negative predictive values, and accuracy at 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year follow-up. “The most important addition is that the new criteria allow MS diagnosis when the MRI scan meets criteria for DIS and unique oligoclonal bands (OCB) are present in [cerebrospinal fluid], even in absence of DIT on the MRI scan,” the researchers wrote. “The other major difference is that not only asymptomatic but also symptomatic lesions can be used to demonstrate DIS and DIT on MRI. Furthermore, cortical lesions can be used to demonstrate dissemination in space.”

The researchers found that 124 patients met 2010 DIS criteria (54%) and that 74 patients (60%) went on to develop clinically definite MS, while 149 patients (65%) met 2017 DIS criteria, and 89 patients (60%) went on to clinically definite MS. There were 46 patients (26%) who met 2010 DIT criteria, and 33 of those patients (72%) were diagnosed with clinically definite MS; 126 patients (70%) met 2017 DIT criteria, and 76 of those patients (60%) had clinically definite MS. The sensitivity for the 2010 criteria was 36% (95% confidence interval, 27%-47%)versus 68% for the 2017 criteria (95% CI, 57%-77%; P less than .001). However, specificity for the 2017 criteria was lower (61%; 95% CI, 50%-71%) when compared with the 2010 criteria (85%; 95% CI, 76%-92%; P less than .001). Researchers found more baseline MS diagnoses with the 2017 criteria than with the 2010 criteria, but they noted that 14 of 22 patients (64%) under the 2010 criteria and 26 of 48 patients (54%) under the 2017 criteria with MS had a second attack within 5 years.

The study was supported by the Dutch Multiple Sclerosis Research Foundation. One or more authors received compensation from Teva, Merck, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, Biogen, and Novartis in the form of honoraria, for advisory board membership, as travel grants, or for participation in trials.

SOURCE: van der Vuurst de Vries RM, et al. JAMA Neurol. 2018 Aug 6. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2160.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point: The 2017 McDonald criteria for MS may diagnose more patients with a clinically isolated syndrome, but a lower specificity may also capture more patients who do not have a second CIS event.

Major finding: The sensitivity for the 2017 criteria was greater at 68%, compared with 36% in the 2010 criteria; however, specificity was significantly lower in the 2017 criteria at 61%, compared with 85% in the 2010 criteria.

Data source: An original study of 229 patients from the Netherlands with CIS who underwent an MRI scan within 3 months of symptoms.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Dutch Multiple Sclerosis Research Foundation. One or more authors received compensation from Teva, Merck, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, Biogen, and Novartis in the form of honoraria, for advisory board membership, as travel grants, or for participation in trials.

Source: van der Vuurst de Vries RM et al. JAMA Neurol. 2018 Aug 6. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2160.

Aspirin May Be an Effective Pretreatment for Exercise in Patients With MS

Time to exhaustion was significantly greater after pretreatment with aspirin versus placebo.

LOS ANGELES—Aspirin may be an effective pretreatment for exercise in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), according to a study described at the 70th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“Exercise in MS we know to be beneficial on multiple levels,” said Victoria M. Leavitt, PhD, Assistant Professor of Neuropsychology at Columbia University Medical Center in New York. “In addition to physical benefits like gait, balance, and improved cardiovascular fitness, exercise is also associated with improved mood, reduced fatigue, and improved memory performance. The challenge, of course, is that exercise is only beneficial if people actually do it.”

Exercise-induced overheating, exhaustion, and symptom worsening (Uhtoff’s phenomenon) deter many patients with MS from exercise, and patients may have elevated resting body temperatures that are associated with worse fatigue.

To test whether aspirin pretreatment improves exercise performance in people with MS, Dr. Leavitt and colleagues conducted a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover pilot study. The researchers studied aspirin because of its antipyretic effects and its efficacy in reducing fatigue in nonexercising patients with MS. The primary outcome was total time spent exercising. Change in exercise-induced body temperature was a secondary outcome.

In all, 12 patients participated in the study (nine females; mean age, 39.8; mean disease duration, 7.7 years; Expanded Disability Status Scale scores of 6.5 or less). Eight patients reported heat sensitivity during exercise.

Participants completed two maximal progressive ramped lower body cycle ergometer exercise tests one week apart after taking 650 mg of aspirin or placebo one hour before each test.

Patients exercised an average of 16.4 seconds longer after taking aspirin (9 minutes 28.6 seconds), versus placebo (9 minutes 12.2 seconds). In heat-sensitive patients, average body temperature increase after exercise with aspirin (0.41°F) was lower than the increase with placebo (0.88°F). This difference was not statistically significant.

Larger studies are needed, but the results are encouraging, Dr. Leavitt said. “The next thing we want to look at is how this translates to everyday exercise,” she said. “Does aspirin use in people with MS result in increased physical activity levels or increased adherence to exercise regimens?”

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Leavitt VM, Blanchard AR, Guo CY, et al. Aspirin is an effective pretreatment for exercise in multiple sclerosis: a double-blin

Wingerchuk DM, Benarroch EE, O’Brien PC, et al. A randomized controlled crossover trial of aspirin for fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2005;64(7):1267-1269.

Time to exhaustion was significantly greater after pretreatment with aspirin versus placebo.

Time to exhaustion was significantly greater after pretreatment with aspirin versus placebo.

LOS ANGELES—Aspirin may be an effective pretreatment for exercise in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), according to a study described at the 70th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“Exercise in MS we know to be beneficial on multiple levels,” said Victoria M. Leavitt, PhD, Assistant Professor of Neuropsychology at Columbia University Medical Center in New York. “In addition to physical benefits like gait, balance, and improved cardiovascular fitness, exercise is also associated with improved mood, reduced fatigue, and improved memory performance. The challenge, of course, is that exercise is only beneficial if people actually do it.”

Exercise-induced overheating, exhaustion, and symptom worsening (Uhtoff’s phenomenon) deter many patients with MS from exercise, and patients may have elevated resting body temperatures that are associated with worse fatigue.

To test whether aspirin pretreatment improves exercise performance in people with MS, Dr. Leavitt and colleagues conducted a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover pilot study. The researchers studied aspirin because of its antipyretic effects and its efficacy in reducing fatigue in nonexercising patients with MS. The primary outcome was total time spent exercising. Change in exercise-induced body temperature was a secondary outcome.

In all, 12 patients participated in the study (nine females; mean age, 39.8; mean disease duration, 7.7 years; Expanded Disability Status Scale scores of 6.5 or less). Eight patients reported heat sensitivity during exercise.

Participants completed two maximal progressive ramped lower body cycle ergometer exercise tests one week apart after taking 650 mg of aspirin or placebo one hour before each test.

Patients exercised an average of 16.4 seconds longer after taking aspirin (9 minutes 28.6 seconds), versus placebo (9 minutes 12.2 seconds). In heat-sensitive patients, average body temperature increase after exercise with aspirin (0.41°F) was lower than the increase with placebo (0.88°F). This difference was not statistically significant.

Larger studies are needed, but the results are encouraging, Dr. Leavitt said. “The next thing we want to look at is how this translates to everyday exercise,” she said. “Does aspirin use in people with MS result in increased physical activity levels or increased adherence to exercise regimens?”

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Leavitt VM, Blanchard AR, Guo CY, et al. Aspirin is an effective pretreatment for exercise in multiple sclerosis: a double-blin

Wingerchuk DM, Benarroch EE, O’Brien PC, et al. A randomized controlled crossover trial of aspirin for fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2005;64(7):1267-1269.

LOS ANGELES—Aspirin may be an effective pretreatment for exercise in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), according to a study described at the 70th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“Exercise in MS we know to be beneficial on multiple levels,” said Victoria M. Leavitt, PhD, Assistant Professor of Neuropsychology at Columbia University Medical Center in New York. “In addition to physical benefits like gait, balance, and improved cardiovascular fitness, exercise is also associated with improved mood, reduced fatigue, and improved memory performance. The challenge, of course, is that exercise is only beneficial if people actually do it.”

Exercise-induced overheating, exhaustion, and symptom worsening (Uhtoff’s phenomenon) deter many patients with MS from exercise, and patients may have elevated resting body temperatures that are associated with worse fatigue.

To test whether aspirin pretreatment improves exercise performance in people with MS, Dr. Leavitt and colleagues conducted a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover pilot study. The researchers studied aspirin because of its antipyretic effects and its efficacy in reducing fatigue in nonexercising patients with MS. The primary outcome was total time spent exercising. Change in exercise-induced body temperature was a secondary outcome.

In all, 12 patients participated in the study (nine females; mean age, 39.8; mean disease duration, 7.7 years; Expanded Disability Status Scale scores of 6.5 or less). Eight patients reported heat sensitivity during exercise.

Participants completed two maximal progressive ramped lower body cycle ergometer exercise tests one week apart after taking 650 mg of aspirin or placebo one hour before each test.

Patients exercised an average of 16.4 seconds longer after taking aspirin (9 minutes 28.6 seconds), versus placebo (9 minutes 12.2 seconds). In heat-sensitive patients, average body temperature increase after exercise with aspirin (0.41°F) was lower than the increase with placebo (0.88°F). This difference was not statistically significant.

Larger studies are needed, but the results are encouraging, Dr. Leavitt said. “The next thing we want to look at is how this translates to everyday exercise,” she said. “Does aspirin use in people with MS result in increased physical activity levels or increased adherence to exercise regimens?”

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Leavitt VM, Blanchard AR, Guo CY, et al. Aspirin is an effective pretreatment for exercise in multiple sclerosis: a double-blin

Wingerchuk DM, Benarroch EE, O’Brien PC, et al. A randomized controlled crossover trial of aspirin for fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2005;64(7):1267-1269.

Treatment of relapsing progressive MS may reduce disability progression

Superimposed relapses were associated with a significantly reduced risk of disability progression in a longitudinal, prospective cohort study of 1,419 multiple sclerosis patients (MS) of the progressive-onset type.

To determine the role of inflammatory relapses on disability in the progressive-relapsing phenotype of progressive-onset MS, the researchers collected data from MSBase, an international, observational cohort of MS patients, from January 1995 to February 2017. The study population included 1,419 adults with MS (553 in the relapse subgroup, 866 in a nonrelapse subgroup) from 83 centers in 28 countries; the median prospective follow-up period was 5 years. The patients included in the analysis had adult-onset disease, at least three clinic visits with Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score recorded, and a time frame of more than 3 months between the second and last visit.

Overall, patients with relapses had significantly less risk of disability progression after adjusting for confounding variables (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.74-0.94; P = .003). Disease progression was defined as worsening of the EDSS score.

In addition, the researchers examined the data in a stratified model and found a 4% relative decrease in the hazard of confirmed disability progression events for each 10% increment of follow-up time for receiving disease-modifying therapy (DMT). However, DMT did not reduce disease progression risk in progressive-onset MS patients without relapse.

“This suggests that relapses in progressive-onset MS, as a clinical correlate of episodic inflammatory activity, represent a positive prognostic marker and provide an opportunity to improve disease outcomes through prevention of relapse-related disability accrual,” the researchers wrote.

Interferon-beta was the most common DMT, given to 73% of the relapse patients and 56% of the nonrelapse patients, followed by glatiramer acetate (20% and 13%, respectively), and fingolimod (12% and 16%, respectively).

The study’s main limitation was the use of the EDSS as a measure of disability, as well as the absence of quantifiable disability change to confirm relapse, the researchers noted. However, “these findings provide further evidence for a progressive-onset MS phenotype with acute episodic inflammatory changes, thereby identifying patients who may respond to existing immunotherapies.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the MSBase Foundation, a nonprofit organization that itself receives support from multiple companies, including Merck, Novartis, and Sanofi. Dr. Hughes had no financial conflicts to disclose, but most coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including Merck, Novartis, Sanofi. Genzyme, and Biogen.

SOURCE: Hughes J et al. JAMA Neurol. 2018 Aug 6. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2109.

This study is important because it addresses an area of controversy in management of patients with a progressive multiple sclerosis (MS) phenotype. The role of superimposed relapses in patients with progressive MS has long been debated, with some studies reporting no impact on long-term disability accrual and other reporting a negative impact of relapses. Treatment of progressive MS remains controversial as well, with only one therapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration for any form of progressive MS. There is considerable ongoing debate about whether MS disease-modifying therapies (MSDMT) are effective in progressive forms of MS, and whether clinical or MRI evidence of active inflammation predicts a better chance of response.

This study has several important strengths and limitations. The large sample size allowed statistical power to detect relatively small differences in disability progression risk between progressive MS subtypes. The better prognosis in progressive patients with superimposed relapses contradicts some earlier studies that suggested a worse prognosis or no difference in prognosis between progressive patients with and without relapses. This study also supports a role for MSDMT in progressive MS patients, at least those with clinical evidence of relapses, and possibly MRI evidence of inflammatory disease activity (although this was not specifically addressed in the current study). Limitations of the study include the observational nature of the database, variable periods of follow-up, lack of objective verification of recorded relapses either with EDSS scores or MRI confirmation, and lack of an untreated control group. Therefore, no conclusions can be drawn as to whether MSDMT exposure had a favorable impact on the whole cohort of progressive patients versus no treatment.

Jonathan L. Carter, MD , is an MS specialist at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz. He had no relevant disclosures to report.