User login

Out-of-state telehealth visits could help more patients if restrictions eased: Study

About 5% of traditional Medicare patients who had telehealth visits were seen virtually by out-of-state clinicians in the first half of 2021, according to a new study in JAMA Health Forum.

Since then, however, many states have restored restrictions that prevent physicians who are licensed in one state from having telehealth visits with patients unless they’re licensed in the state where the patients live.

This is not fair to many people who live in areas near state borders, the authors argued. For those patients, it is much more convenient to see their primary care physician in a virtual visit from home than to travel to the doctor’s office in another state. This convenience is enjoyed by most patients who reside elsewhere in their state because they’re seeing physicians who are licensed there.

Moreover, the paper said, patients who live in rural areas and in counties with relatively few physicians per capita would also benefit from relaxed telemedicine restrictions.

Using Medicare claims data, the researchers examined the characteristics of out-of-state (OOS) telemedicine visits for the 6 months from January to June 2021. They chose that period for two reasons: by then, health care had stabilized after the chaotic early phase of the pandemic, and in most states, the relaxation of licensing rules for OOS telehealth had not yet lapsed. Earlier periods of time were also used for certain types of comparisons.

Among fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries, the number of OOS telemedicine visits peaked at 451,086 in April 2020 and slowly fell to 175,545 in June 2021, according to the study. The fraction of OOS telehealth visits among all virtual visits was 4.5% in April 2020 and increased to 5.6% by June 2021.

Staying close to home

Of all beneficiaries with a telemedicine visit in the study period, 33% lived within 15 miles of a state border. That cohort accounted for 57.2% of all OOS telemedicine visits.

The highest rates of OOS telehealth visits were seen in the District of Columbia (38.5%), Wyoming (25.6%), and North Dakota (21.1%). California (1%), Texas (2%), and Massachusetts (2.1%) had the lowest rates.

Though intuitive in retrospect, the correlation of OOS telemedicine use with proximity to state borders was one of the study’s most important findings, lead author Ateev Mehrotra, MD, a professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview. “It makes sense,” he said. “If you’re in D.C. and you need a cardiologist, you don’t think: ‘I’ll stay in D.C.’ No, Maryland is right there, so you might use a Maryland cardiologist. Now you’re out of state, even though that office might be only half a mile away from you.”

Similar dynamics, he noted, are seen in many metropolitan areas that border on other states, such as Cincinnati; Philadelphia; and Portland, Ore.

This finding lines up with another result of the study: The majority of patients who had OOS telemedicine visits had previously seen in person the doctor who conducted the virtual visit.

Across all OOS telemedicine visits in the first half of 2021, the researchers observed a prior in-person visit between March 2019 and the date of the virtual visit with the same patient and the same clinician in 62.8% of those visits. Across all in-state telehealth visits, 75.8% of them were made by patients who had seen the same clinician in person since March 2019. This preponderance of virtual visits to clinicians whom the patients had already seen in person reflects the fact that, during the pandemic, most physicians began conducting telehealth visits with their own patients, Dr. Mehrotra said.

It also lays to rest the concern that some states have had about allowing OOS telemedicine visits to physicians not licensed in those states, he added. “They think that all these docs from far away are going to start taking care of patients they don’t even know. But our study shows that isn’t the case. Most of the time, doctors are seeing a patient who’s switching over from in-person visits to out-of-state telemedicine.”

More specialty care sought

The dominant conditions that patients presented with were the same in OOS telemedicine and within-state virtual visits. However, the use of OOS telemedicine was higher for some types of specialized care.

For example, the rate of OOS telemedicine use, compared with all telemedicine use, was highest for cancer care (9.8%). Drilling down to more specific conditions, the top three in OOS telemedicine visits were assessment of organ transplant (13%); male reproductive cancers, such as prostate cancer (11.3%); and graft-related issues (10.2%).

The specialty trend was also evident in the types of OOS clinicians from whom Medicare patients sought virtual care. The rates of OOS telemedicine use as a percentage of all telemedicine use in particular specialties were highest for uncommon specialties, such as hematology/oncology, rheumatology, urology, medical oncology, and orthopedic surgery (8.5%). There was less use of OOS telemedicine as a percentage of all telemedicine among more common medical specialties (6.4%), mental health specialties (4.4%), and primary care (4.4%).

Despite its relatively low showing in this category, however, behavioral health was the leading condition treated in both within-state and OOS telemedicine visits, accounting for 30.7% and 25.8%, respectively, of those encounters.

States backslide on OOS telehealth

Since the end of the study period, over half of the states have restored some or all of the restrictions on OOS telemedicine that they had lifted during the pandemic.

According to Dr. Mehrotra, 22 states have some kind of regulation in place to allow an OOS clinician to conduct telehealth visits without being licensed in the state. This varies all the way from complete reciprocity with other states’ licenses to “emergency” telemedicine licenses. The other 28 states and Washington, D.C., require an OOS telemedicine practitioner to get a state license.

Various proposals have been floated to ameliorate this situation, the JAMA paper noted. These proposals include an expansion of the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact that the Federation of State Medical Boards organized in 2014. Since the pact became effective in 2014, at least 35 states and the District of Columbia have joined it. Those states have made it simpler for physicians to gain licensure in states other than their original state of licensure. However, Mehrotra said, it’s still not easy, and not many physicians have taken advantage of it.

One new wrinkle has emerged in this policy debate as a result of the Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade, he noted. Because people are using OOS telemedicine visits to get prescriptions to abort their fetuses, “that has changed the enthusiasm level for it among many states,” he said.

Dr. Mehrotra reported personal fees from the Pew Charitable Trust, Sanofi Pasteur, and Black Opal Ventures outside the submitted work. One coauthor reported receiving grants from Patient-Centered Outcomes Research, National Institute on Aging, Roundtrip, Independence Blue Cross; personal fees or salary from RAND Corporation from Verily Life Sciences; and that the American Telemedicine Association covered a conference fee. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

About 5% of traditional Medicare patients who had telehealth visits were seen virtually by out-of-state clinicians in the first half of 2021, according to a new study in JAMA Health Forum.

Since then, however, many states have restored restrictions that prevent physicians who are licensed in one state from having telehealth visits with patients unless they’re licensed in the state where the patients live.

This is not fair to many people who live in areas near state borders, the authors argued. For those patients, it is much more convenient to see their primary care physician in a virtual visit from home than to travel to the doctor’s office in another state. This convenience is enjoyed by most patients who reside elsewhere in their state because they’re seeing physicians who are licensed there.

Moreover, the paper said, patients who live in rural areas and in counties with relatively few physicians per capita would also benefit from relaxed telemedicine restrictions.

Using Medicare claims data, the researchers examined the characteristics of out-of-state (OOS) telemedicine visits for the 6 months from January to June 2021. They chose that period for two reasons: by then, health care had stabilized after the chaotic early phase of the pandemic, and in most states, the relaxation of licensing rules for OOS telehealth had not yet lapsed. Earlier periods of time were also used for certain types of comparisons.

Among fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries, the number of OOS telemedicine visits peaked at 451,086 in April 2020 and slowly fell to 175,545 in June 2021, according to the study. The fraction of OOS telehealth visits among all virtual visits was 4.5% in April 2020 and increased to 5.6% by June 2021.

Staying close to home

Of all beneficiaries with a telemedicine visit in the study period, 33% lived within 15 miles of a state border. That cohort accounted for 57.2% of all OOS telemedicine visits.

The highest rates of OOS telehealth visits were seen in the District of Columbia (38.5%), Wyoming (25.6%), and North Dakota (21.1%). California (1%), Texas (2%), and Massachusetts (2.1%) had the lowest rates.

Though intuitive in retrospect, the correlation of OOS telemedicine use with proximity to state borders was one of the study’s most important findings, lead author Ateev Mehrotra, MD, a professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview. “It makes sense,” he said. “If you’re in D.C. and you need a cardiologist, you don’t think: ‘I’ll stay in D.C.’ No, Maryland is right there, so you might use a Maryland cardiologist. Now you’re out of state, even though that office might be only half a mile away from you.”

Similar dynamics, he noted, are seen in many metropolitan areas that border on other states, such as Cincinnati; Philadelphia; and Portland, Ore.

This finding lines up with another result of the study: The majority of patients who had OOS telemedicine visits had previously seen in person the doctor who conducted the virtual visit.

Across all OOS telemedicine visits in the first half of 2021, the researchers observed a prior in-person visit between March 2019 and the date of the virtual visit with the same patient and the same clinician in 62.8% of those visits. Across all in-state telehealth visits, 75.8% of them were made by patients who had seen the same clinician in person since March 2019. This preponderance of virtual visits to clinicians whom the patients had already seen in person reflects the fact that, during the pandemic, most physicians began conducting telehealth visits with their own patients, Dr. Mehrotra said.

It also lays to rest the concern that some states have had about allowing OOS telemedicine visits to physicians not licensed in those states, he added. “They think that all these docs from far away are going to start taking care of patients they don’t even know. But our study shows that isn’t the case. Most of the time, doctors are seeing a patient who’s switching over from in-person visits to out-of-state telemedicine.”

More specialty care sought

The dominant conditions that patients presented with were the same in OOS telemedicine and within-state virtual visits. However, the use of OOS telemedicine was higher for some types of specialized care.

For example, the rate of OOS telemedicine use, compared with all telemedicine use, was highest for cancer care (9.8%). Drilling down to more specific conditions, the top three in OOS telemedicine visits were assessment of organ transplant (13%); male reproductive cancers, such as prostate cancer (11.3%); and graft-related issues (10.2%).

The specialty trend was also evident in the types of OOS clinicians from whom Medicare patients sought virtual care. The rates of OOS telemedicine use as a percentage of all telemedicine use in particular specialties were highest for uncommon specialties, such as hematology/oncology, rheumatology, urology, medical oncology, and orthopedic surgery (8.5%). There was less use of OOS telemedicine as a percentage of all telemedicine among more common medical specialties (6.4%), mental health specialties (4.4%), and primary care (4.4%).

Despite its relatively low showing in this category, however, behavioral health was the leading condition treated in both within-state and OOS telemedicine visits, accounting for 30.7% and 25.8%, respectively, of those encounters.

States backslide on OOS telehealth

Since the end of the study period, over half of the states have restored some or all of the restrictions on OOS telemedicine that they had lifted during the pandemic.

According to Dr. Mehrotra, 22 states have some kind of regulation in place to allow an OOS clinician to conduct telehealth visits without being licensed in the state. This varies all the way from complete reciprocity with other states’ licenses to “emergency” telemedicine licenses. The other 28 states and Washington, D.C., require an OOS telemedicine practitioner to get a state license.

Various proposals have been floated to ameliorate this situation, the JAMA paper noted. These proposals include an expansion of the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact that the Federation of State Medical Boards organized in 2014. Since the pact became effective in 2014, at least 35 states and the District of Columbia have joined it. Those states have made it simpler for physicians to gain licensure in states other than their original state of licensure. However, Mehrotra said, it’s still not easy, and not many physicians have taken advantage of it.

One new wrinkle has emerged in this policy debate as a result of the Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade, he noted. Because people are using OOS telemedicine visits to get prescriptions to abort their fetuses, “that has changed the enthusiasm level for it among many states,” he said.

Dr. Mehrotra reported personal fees from the Pew Charitable Trust, Sanofi Pasteur, and Black Opal Ventures outside the submitted work. One coauthor reported receiving grants from Patient-Centered Outcomes Research, National Institute on Aging, Roundtrip, Independence Blue Cross; personal fees or salary from RAND Corporation from Verily Life Sciences; and that the American Telemedicine Association covered a conference fee. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

About 5% of traditional Medicare patients who had telehealth visits were seen virtually by out-of-state clinicians in the first half of 2021, according to a new study in JAMA Health Forum.

Since then, however, many states have restored restrictions that prevent physicians who are licensed in one state from having telehealth visits with patients unless they’re licensed in the state where the patients live.

This is not fair to many people who live in areas near state borders, the authors argued. For those patients, it is much more convenient to see their primary care physician in a virtual visit from home than to travel to the doctor’s office in another state. This convenience is enjoyed by most patients who reside elsewhere in their state because they’re seeing physicians who are licensed there.

Moreover, the paper said, patients who live in rural areas and in counties with relatively few physicians per capita would also benefit from relaxed telemedicine restrictions.

Using Medicare claims data, the researchers examined the characteristics of out-of-state (OOS) telemedicine visits for the 6 months from January to June 2021. They chose that period for two reasons: by then, health care had stabilized after the chaotic early phase of the pandemic, and in most states, the relaxation of licensing rules for OOS telehealth had not yet lapsed. Earlier periods of time were also used for certain types of comparisons.

Among fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries, the number of OOS telemedicine visits peaked at 451,086 in April 2020 and slowly fell to 175,545 in June 2021, according to the study. The fraction of OOS telehealth visits among all virtual visits was 4.5% in April 2020 and increased to 5.6% by June 2021.

Staying close to home

Of all beneficiaries with a telemedicine visit in the study period, 33% lived within 15 miles of a state border. That cohort accounted for 57.2% of all OOS telemedicine visits.

The highest rates of OOS telehealth visits were seen in the District of Columbia (38.5%), Wyoming (25.6%), and North Dakota (21.1%). California (1%), Texas (2%), and Massachusetts (2.1%) had the lowest rates.

Though intuitive in retrospect, the correlation of OOS telemedicine use with proximity to state borders was one of the study’s most important findings, lead author Ateev Mehrotra, MD, a professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview. “It makes sense,” he said. “If you’re in D.C. and you need a cardiologist, you don’t think: ‘I’ll stay in D.C.’ No, Maryland is right there, so you might use a Maryland cardiologist. Now you’re out of state, even though that office might be only half a mile away from you.”

Similar dynamics, he noted, are seen in many metropolitan areas that border on other states, such as Cincinnati; Philadelphia; and Portland, Ore.

This finding lines up with another result of the study: The majority of patients who had OOS telemedicine visits had previously seen in person the doctor who conducted the virtual visit.

Across all OOS telemedicine visits in the first half of 2021, the researchers observed a prior in-person visit between March 2019 and the date of the virtual visit with the same patient and the same clinician in 62.8% of those visits. Across all in-state telehealth visits, 75.8% of them were made by patients who had seen the same clinician in person since March 2019. This preponderance of virtual visits to clinicians whom the patients had already seen in person reflects the fact that, during the pandemic, most physicians began conducting telehealth visits with their own patients, Dr. Mehrotra said.

It also lays to rest the concern that some states have had about allowing OOS telemedicine visits to physicians not licensed in those states, he added. “They think that all these docs from far away are going to start taking care of patients they don’t even know. But our study shows that isn’t the case. Most of the time, doctors are seeing a patient who’s switching over from in-person visits to out-of-state telemedicine.”

More specialty care sought

The dominant conditions that patients presented with were the same in OOS telemedicine and within-state virtual visits. However, the use of OOS telemedicine was higher for some types of specialized care.

For example, the rate of OOS telemedicine use, compared with all telemedicine use, was highest for cancer care (9.8%). Drilling down to more specific conditions, the top three in OOS telemedicine visits were assessment of organ transplant (13%); male reproductive cancers, such as prostate cancer (11.3%); and graft-related issues (10.2%).

The specialty trend was also evident in the types of OOS clinicians from whom Medicare patients sought virtual care. The rates of OOS telemedicine use as a percentage of all telemedicine use in particular specialties were highest for uncommon specialties, such as hematology/oncology, rheumatology, urology, medical oncology, and orthopedic surgery (8.5%). There was less use of OOS telemedicine as a percentage of all telemedicine among more common medical specialties (6.4%), mental health specialties (4.4%), and primary care (4.4%).

Despite its relatively low showing in this category, however, behavioral health was the leading condition treated in both within-state and OOS telemedicine visits, accounting for 30.7% and 25.8%, respectively, of those encounters.

States backslide on OOS telehealth

Since the end of the study period, over half of the states have restored some or all of the restrictions on OOS telemedicine that they had lifted during the pandemic.

According to Dr. Mehrotra, 22 states have some kind of regulation in place to allow an OOS clinician to conduct telehealth visits without being licensed in the state. This varies all the way from complete reciprocity with other states’ licenses to “emergency” telemedicine licenses. The other 28 states and Washington, D.C., require an OOS telemedicine practitioner to get a state license.

Various proposals have been floated to ameliorate this situation, the JAMA paper noted. These proposals include an expansion of the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact that the Federation of State Medical Boards organized in 2014. Since the pact became effective in 2014, at least 35 states and the District of Columbia have joined it. Those states have made it simpler for physicians to gain licensure in states other than their original state of licensure. However, Mehrotra said, it’s still not easy, and not many physicians have taken advantage of it.

One new wrinkle has emerged in this policy debate as a result of the Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade, he noted. Because people are using OOS telemedicine visits to get prescriptions to abort their fetuses, “that has changed the enthusiasm level for it among many states,” he said.

Dr. Mehrotra reported personal fees from the Pew Charitable Trust, Sanofi Pasteur, and Black Opal Ventures outside the submitted work. One coauthor reported receiving grants from Patient-Centered Outcomes Research, National Institute on Aging, Roundtrip, Independence Blue Cross; personal fees or salary from RAND Corporation from Verily Life Sciences; and that the American Telemedicine Association covered a conference fee. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA HEALTH FORUM

Despite benefits, extended-interval pembro uptake remains low

In April 2020, the Food and Drug Administration approved extended dosing for standalone pembrolizumab – 400 mg every 6 weeks instead of the standard dosing of 200 mg every 3 weeks. The shift came, in part, to reduce patient health care encounters during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, but also because fewer infusions save patients time and out-of-pocket costs and reduce the burden on the health care system.

The FDA deemed this move safe after pharmacologic studies and a small melanoma study found that responses and adverse events were equivalent in comparison with standard dosing.

Given the benefits, one would expect “brisk adoption” of extended-interval dosing, Garth Strohbehn, MD, an oncologist at the VA Medical Center in Ann Arbor, Mich., and colleagues wrote in a recent report in JAMA Oncology.

However, when the team reviewed data on 835 veterans from the Veterans Health Administration who began taking single-agent pembrolizumab between April 1, 2020, and July 1, 2021, only about one-third received extended-interval dosing.

Between April and January 2021, use of extended-interval dosing rose steadily to about 35% of patients but then hovered in that range through August 2021.

Among the patients, age, sex, Charlson comorbidity index, and pembrolizumab indications were well balanced between the standard-dosing and the extended-interval dosing groups.

Notably, Dr. Strohbehn and colleagues also found no difference in time-to-treatment discontinuation between patients receiving extended dosing in comparison with patients receiving standard dosing, which is “a real-world measure of clinical effectiveness,” the team said.

And there was no difference in immune-related side effects between the two regimens, as assessed by incident levothyroxine and prednisone prescriptions.

The real-world near equivalence of extended and standard dosing intervals that was demonstrated in the study is “reassuring” and helps make the case for considering it “as a best practice” for single-agent pembrolizumab, the investigators wrote.

Dr. Strohbehn remained somewhat puzzled by the low uptake of the extended-dosing option.

“I was frankly surprised by the small number of patients who received the extended-interval regimen,” Dr. Strohbehn said in an interview.

“Admittedly, there are patients who would prefer to receive standard-interval therapy, and that preference should of course be accommodated whenever possible, but in my experience, those numbers are small,” at least in the VA system, he noted.

In addition, the authors noted, there is no direct financial incentive for more frequent dosing in the VA system.

It’s possible that low uptake could stem from clinicians’ doubts about switching to an extended-interval dose, given that the FDA’s approval was based largely on a study of 44 patients with melanoma in a single-arm trial.

If that is indeed the case, the new findings – which represent the first health system–level, real-world comparative effectiveness data for standard vs. extended-interval pembrolizumab – should help address these concerns, the team said.

“This observational dataset lends further credence to [the dosing] regimens being clinically equivalent,” said Zachery Reichert, MD, PhD, a urologic oncologist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who was not involved in the study.

To address the issue, Dr. Strohbehn and his team suggested “clinical guideline promotion to overcome some of the barriers to the adoption of extended-interval pembrolizumab.”

Dr. Riechert suggested further validation of equivalent outcomes for the two regimens, more advocacy to encourage patients to ask about the 6-week option, as well as incentives from insurers to adopt it.

Dr. Strohbehn added that the situation highlights a broader issue in oncology, namely that many drugs “end up on the market with dosing regimens that haven’t necessarily been optimized.”

Across the world, investigators are conducting clinical trials “to identify the minimum dosages, frequencies, and durations patients need in order to achieve their best outcome,” Dr. Strohbehn said. In oncology, much of this effort is being led by Project Optimus, from the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, he said.

The study was funded by the VA National Oncology Program. Dr. Reichert and Dr. Strohbehn have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. One investigator has received grants from Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Regeneron, and Genentech.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In April 2020, the Food and Drug Administration approved extended dosing for standalone pembrolizumab – 400 mg every 6 weeks instead of the standard dosing of 200 mg every 3 weeks. The shift came, in part, to reduce patient health care encounters during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, but also because fewer infusions save patients time and out-of-pocket costs and reduce the burden on the health care system.

The FDA deemed this move safe after pharmacologic studies and a small melanoma study found that responses and adverse events were equivalent in comparison with standard dosing.

Given the benefits, one would expect “brisk adoption” of extended-interval dosing, Garth Strohbehn, MD, an oncologist at the VA Medical Center in Ann Arbor, Mich., and colleagues wrote in a recent report in JAMA Oncology.

However, when the team reviewed data on 835 veterans from the Veterans Health Administration who began taking single-agent pembrolizumab between April 1, 2020, and July 1, 2021, only about one-third received extended-interval dosing.

Between April and January 2021, use of extended-interval dosing rose steadily to about 35% of patients but then hovered in that range through August 2021.

Among the patients, age, sex, Charlson comorbidity index, and pembrolizumab indications were well balanced between the standard-dosing and the extended-interval dosing groups.

Notably, Dr. Strohbehn and colleagues also found no difference in time-to-treatment discontinuation between patients receiving extended dosing in comparison with patients receiving standard dosing, which is “a real-world measure of clinical effectiveness,” the team said.

And there was no difference in immune-related side effects between the two regimens, as assessed by incident levothyroxine and prednisone prescriptions.

The real-world near equivalence of extended and standard dosing intervals that was demonstrated in the study is “reassuring” and helps make the case for considering it “as a best practice” for single-agent pembrolizumab, the investigators wrote.

Dr. Strohbehn remained somewhat puzzled by the low uptake of the extended-dosing option.

“I was frankly surprised by the small number of patients who received the extended-interval regimen,” Dr. Strohbehn said in an interview.

“Admittedly, there are patients who would prefer to receive standard-interval therapy, and that preference should of course be accommodated whenever possible, but in my experience, those numbers are small,” at least in the VA system, he noted.

In addition, the authors noted, there is no direct financial incentive for more frequent dosing in the VA system.

It’s possible that low uptake could stem from clinicians’ doubts about switching to an extended-interval dose, given that the FDA’s approval was based largely on a study of 44 patients with melanoma in a single-arm trial.

If that is indeed the case, the new findings – which represent the first health system–level, real-world comparative effectiveness data for standard vs. extended-interval pembrolizumab – should help address these concerns, the team said.

“This observational dataset lends further credence to [the dosing] regimens being clinically equivalent,” said Zachery Reichert, MD, PhD, a urologic oncologist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who was not involved in the study.

To address the issue, Dr. Strohbehn and his team suggested “clinical guideline promotion to overcome some of the barriers to the adoption of extended-interval pembrolizumab.”

Dr. Riechert suggested further validation of equivalent outcomes for the two regimens, more advocacy to encourage patients to ask about the 6-week option, as well as incentives from insurers to adopt it.

Dr. Strohbehn added that the situation highlights a broader issue in oncology, namely that many drugs “end up on the market with dosing regimens that haven’t necessarily been optimized.”

Across the world, investigators are conducting clinical trials “to identify the minimum dosages, frequencies, and durations patients need in order to achieve their best outcome,” Dr. Strohbehn said. In oncology, much of this effort is being led by Project Optimus, from the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, he said.

The study was funded by the VA National Oncology Program. Dr. Reichert and Dr. Strohbehn have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. One investigator has received grants from Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Regeneron, and Genentech.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In April 2020, the Food and Drug Administration approved extended dosing for standalone pembrolizumab – 400 mg every 6 weeks instead of the standard dosing of 200 mg every 3 weeks. The shift came, in part, to reduce patient health care encounters during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, but also because fewer infusions save patients time and out-of-pocket costs and reduce the burden on the health care system.

The FDA deemed this move safe after pharmacologic studies and a small melanoma study found that responses and adverse events were equivalent in comparison with standard dosing.

Given the benefits, one would expect “brisk adoption” of extended-interval dosing, Garth Strohbehn, MD, an oncologist at the VA Medical Center in Ann Arbor, Mich., and colleagues wrote in a recent report in JAMA Oncology.

However, when the team reviewed data on 835 veterans from the Veterans Health Administration who began taking single-agent pembrolizumab between April 1, 2020, and July 1, 2021, only about one-third received extended-interval dosing.

Between April and January 2021, use of extended-interval dosing rose steadily to about 35% of patients but then hovered in that range through August 2021.

Among the patients, age, sex, Charlson comorbidity index, and pembrolizumab indications were well balanced between the standard-dosing and the extended-interval dosing groups.

Notably, Dr. Strohbehn and colleagues also found no difference in time-to-treatment discontinuation between patients receiving extended dosing in comparison with patients receiving standard dosing, which is “a real-world measure of clinical effectiveness,” the team said.

And there was no difference in immune-related side effects between the two regimens, as assessed by incident levothyroxine and prednisone prescriptions.

The real-world near equivalence of extended and standard dosing intervals that was demonstrated in the study is “reassuring” and helps make the case for considering it “as a best practice” for single-agent pembrolizumab, the investigators wrote.

Dr. Strohbehn remained somewhat puzzled by the low uptake of the extended-dosing option.

“I was frankly surprised by the small number of patients who received the extended-interval regimen,” Dr. Strohbehn said in an interview.

“Admittedly, there are patients who would prefer to receive standard-interval therapy, and that preference should of course be accommodated whenever possible, but in my experience, those numbers are small,” at least in the VA system, he noted.

In addition, the authors noted, there is no direct financial incentive for more frequent dosing in the VA system.

It’s possible that low uptake could stem from clinicians’ doubts about switching to an extended-interval dose, given that the FDA’s approval was based largely on a study of 44 patients with melanoma in a single-arm trial.

If that is indeed the case, the new findings – which represent the first health system–level, real-world comparative effectiveness data for standard vs. extended-interval pembrolizumab – should help address these concerns, the team said.

“This observational dataset lends further credence to [the dosing] regimens being clinically equivalent,” said Zachery Reichert, MD, PhD, a urologic oncologist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who was not involved in the study.

To address the issue, Dr. Strohbehn and his team suggested “clinical guideline promotion to overcome some of the barriers to the adoption of extended-interval pembrolizumab.”

Dr. Riechert suggested further validation of equivalent outcomes for the two regimens, more advocacy to encourage patients to ask about the 6-week option, as well as incentives from insurers to adopt it.

Dr. Strohbehn added that the situation highlights a broader issue in oncology, namely that many drugs “end up on the market with dosing regimens that haven’t necessarily been optimized.”

Across the world, investigators are conducting clinical trials “to identify the minimum dosages, frequencies, and durations patients need in order to achieve their best outcome,” Dr. Strohbehn said. In oncology, much of this effort is being led by Project Optimus, from the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, he said.

The study was funded by the VA National Oncology Program. Dr. Reichert and Dr. Strohbehn have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. One investigator has received grants from Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Regeneron, and Genentech.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

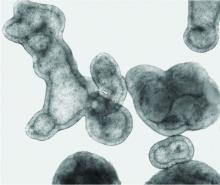

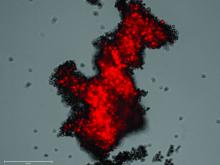

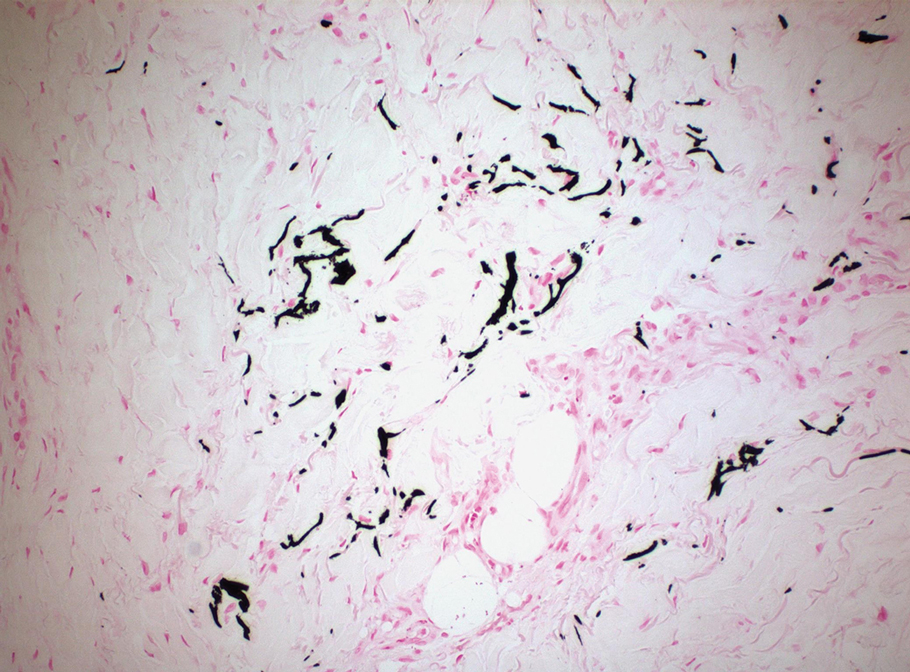

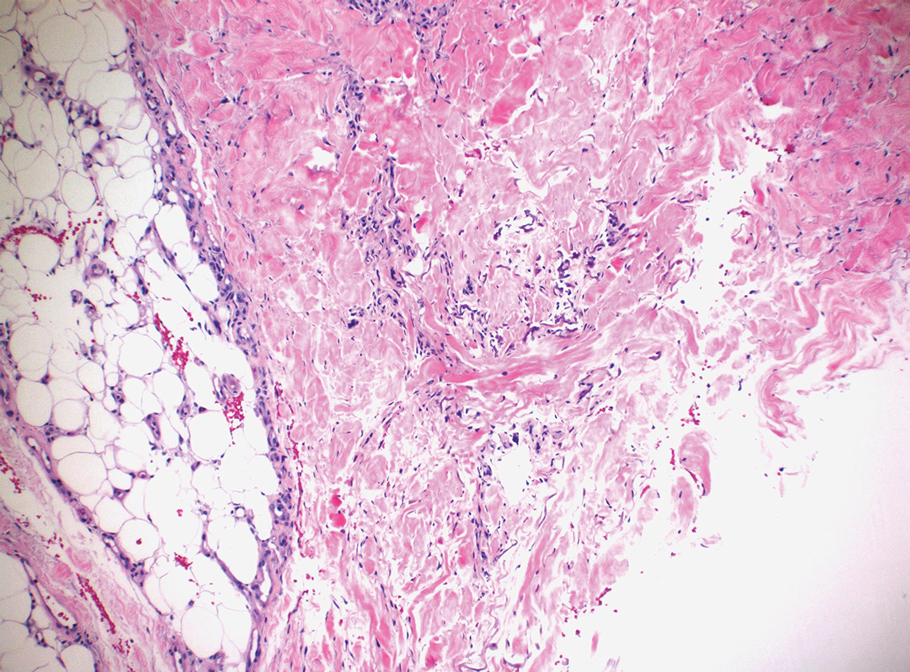

Fast growing hand lesion

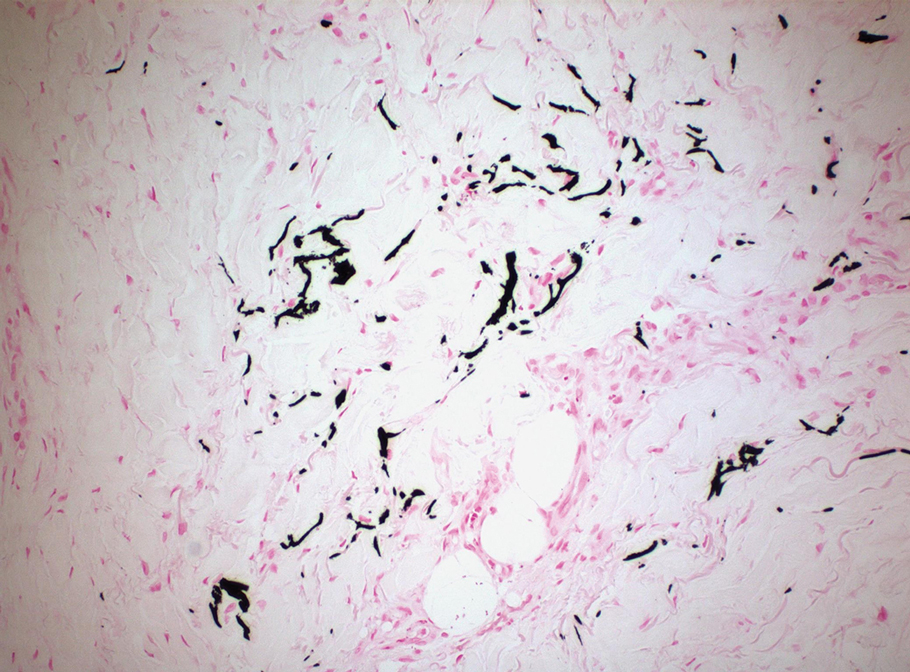

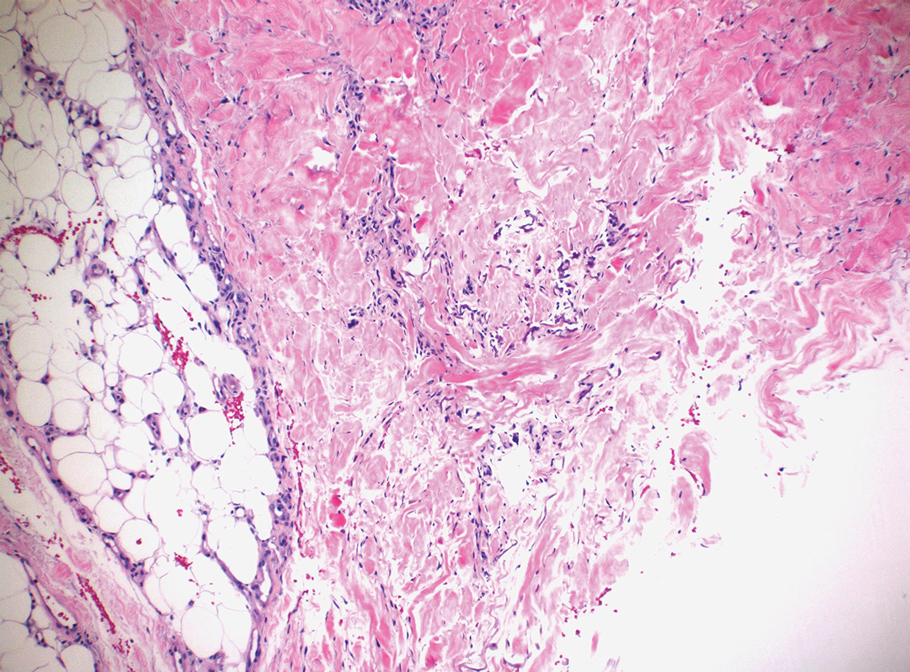

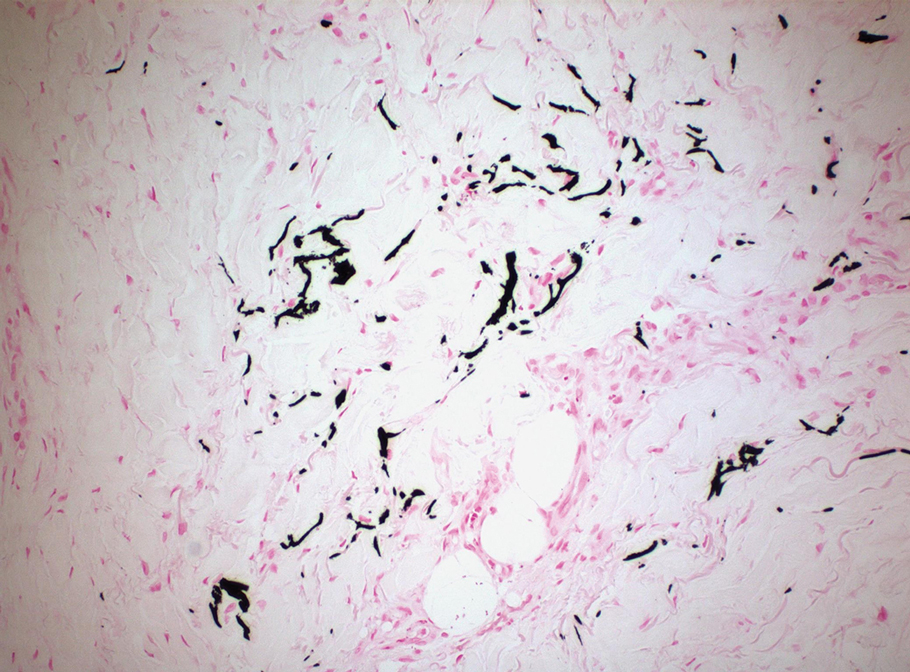

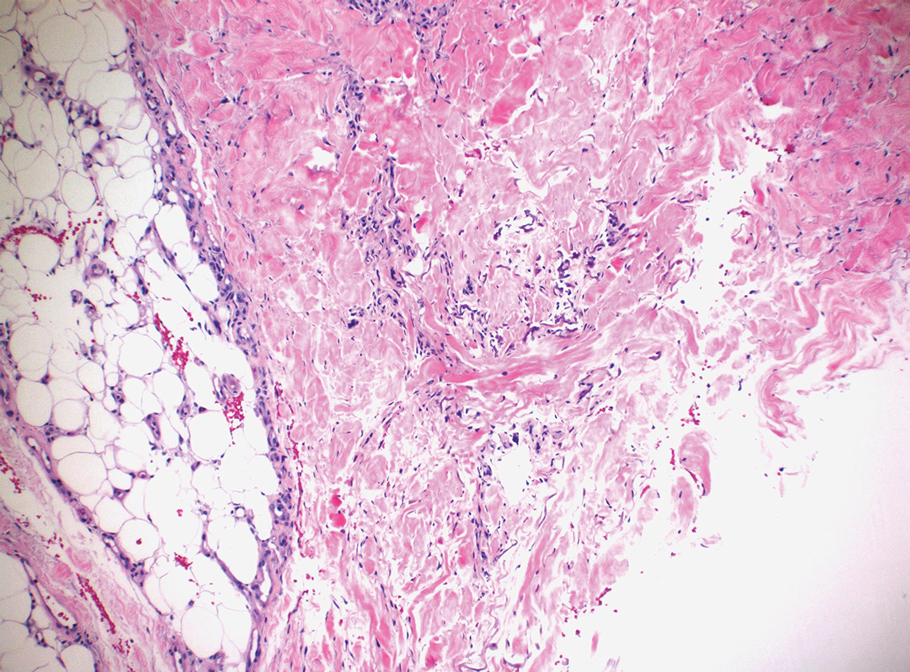

A scoop shave biopsy at the lower edge of the lesion revealed that this was a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma.

Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common cancer in the United States and the most common skin cancer in Black people.1 A patient’s age and their accumulated UV radiation from sun exposure or artificial tanning is a major contributing factor. Lesions may manifest as precancers characterized as rough pink or brown papules with a sandpaper-like texture on sun-exposed skin. These lesions may clear spontaneously or develop into invasive disease, as occurred in this case.

Surgical treatment is often curative. Fusiform excision and Mohs micrographic surgery are 2 common options. More advanced squamous cell carcinomas that are large or found to have poorly differentiated cells or large perineural invasion carry a risk of metastasis.

In elderly patients, optimal treatment isn’t always straightforward.1 Nonsurgical options include radiation and intralesional chemotherapy. These nonsurgical choices may seem less aggressive, but total inconvenience, wound care, and discomfort can be equal to or worse than a single session of curative surgery.

This patient’s lesion was excised with a 5-mm margin. The patient tolerated an in-office procedure lasting about 45 minutes but would have struggled with a longer session with Mohs microsurgery. The postoperative period required limiting full use of his left hand for about 2 weeks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Bradford PT. Skin cancer in skin of color. Dermatol Nurs. 2009;21:170-177, 206; quiz 178. 2. Renzi M Jr, Schimmel J, Decker A, et al. Management of skin cancer in the elderly. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:279-286. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2019.02.003

A scoop shave biopsy at the lower edge of the lesion revealed that this was a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma.

Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common cancer in the United States and the most common skin cancer in Black people.1 A patient’s age and their accumulated UV radiation from sun exposure or artificial tanning is a major contributing factor. Lesions may manifest as precancers characterized as rough pink or brown papules with a sandpaper-like texture on sun-exposed skin. These lesions may clear spontaneously or develop into invasive disease, as occurred in this case.

Surgical treatment is often curative. Fusiform excision and Mohs micrographic surgery are 2 common options. More advanced squamous cell carcinomas that are large or found to have poorly differentiated cells or large perineural invasion carry a risk of metastasis.

In elderly patients, optimal treatment isn’t always straightforward.1 Nonsurgical options include radiation and intralesional chemotherapy. These nonsurgical choices may seem less aggressive, but total inconvenience, wound care, and discomfort can be equal to or worse than a single session of curative surgery.

This patient’s lesion was excised with a 5-mm margin. The patient tolerated an in-office procedure lasting about 45 minutes but would have struggled with a longer session with Mohs microsurgery. The postoperative period required limiting full use of his left hand for about 2 weeks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

A scoop shave biopsy at the lower edge of the lesion revealed that this was a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma.

Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common cancer in the United States and the most common skin cancer in Black people.1 A patient’s age and their accumulated UV radiation from sun exposure or artificial tanning is a major contributing factor. Lesions may manifest as precancers characterized as rough pink or brown papules with a sandpaper-like texture on sun-exposed skin. These lesions may clear spontaneously or develop into invasive disease, as occurred in this case.

Surgical treatment is often curative. Fusiform excision and Mohs micrographic surgery are 2 common options. More advanced squamous cell carcinomas that are large or found to have poorly differentiated cells or large perineural invasion carry a risk of metastasis.

In elderly patients, optimal treatment isn’t always straightforward.1 Nonsurgical options include radiation and intralesional chemotherapy. These nonsurgical choices may seem less aggressive, but total inconvenience, wound care, and discomfort can be equal to or worse than a single session of curative surgery.

This patient’s lesion was excised with a 5-mm margin. The patient tolerated an in-office procedure lasting about 45 minutes but would have struggled with a longer session with Mohs microsurgery. The postoperative period required limiting full use of his left hand for about 2 weeks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Bradford PT. Skin cancer in skin of color. Dermatol Nurs. 2009;21:170-177, 206; quiz 178. 2. Renzi M Jr, Schimmel J, Decker A, et al. Management of skin cancer in the elderly. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:279-286. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2019.02.003

1. Bradford PT. Skin cancer in skin of color. Dermatol Nurs. 2009;21:170-177, 206; quiz 178. 2. Renzi M Jr, Schimmel J, Decker A, et al. Management of skin cancer in the elderly. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:279-286. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2019.02.003

How well are we doing with adolescent vaccination?

Every year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducts a national survey to provide an estimate of vaccination rates among adolescents ages 13 to 17 years. The results for 2021, published recently, illustrate the progress that we’ve made and the areas in which improvement is still needed; notably, human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is an example of both.1

First, what’s recommended? The CDC recommends the following vaccines at age 11 to 12 years: tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap); HPV vaccine series (2 doses if the first dose is received prior to age 15 years; 3 doses if the first dose is received at age 15 years or older); and quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY). A second (booster) dose of MenACWY is recommended at age 16 years. Adolescents should also receive an annual influenza vaccine and a COVID-19 vaccine series.2

For adolescents not fully vaccinated in childhood, catch-up vaccination is recommended for hepatitis A (HepA); hepatitis B (HepB); measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR); and varicella (VAR).2

How are we doing? In 2021, 89.6% of adolescents had received ≥ 1 Tdap dose and 89.0% had received ≥ 1 MenACWY dose; both these rates remained stable from the year before. For HPV vaccine, 76.9% had received ≥ 1 dose (an increase of 1.8 percentage points from 2020); 61.7% were HPV vaccine “up to date” (an increase of 3.1 percentage points). The teen HPV vaccination rate has increased slowly but progressively since the first recommendation for routine HPV vaccination was made for females in 2006 and for males in 2011.1

Among those age 17 years, coverage with ≥ 2 MenACWY doses was 60.0% (an increase of 5.6 percentage points from 2020). Coverage was 85% for ≥ 2 HepA doses (an increase of 2.9 percentage points from 2020) and remained stable at > 90% for each of the following: ≥ 2 doses of MMR, ≥ 3 doses of HepB, and both VAR doses.1

Keeping the momentum. As a country, we continue to make progress at increasing vaccination rates among US adolescents—but there is still plenty of room for improvement. Family physicians should check vaccine status at each clinical encounter and encourage parents and caregivers to schedule future wellness and vaccine visits for these young patients. This may be especially important among adolescents who were due for and missed a vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, et al. National vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—National Immunization Survey-Teen, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1101-1108.

2. Wodi AP, Murthy N, Bernstein H, et al. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended immunization schedule for children and adolescents aged 18 years or younger—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:234-237.

Every year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducts a national survey to provide an estimate of vaccination rates among adolescents ages 13 to 17 years. The results for 2021, published recently, illustrate the progress that we’ve made and the areas in which improvement is still needed; notably, human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is an example of both.1

First, what’s recommended? The CDC recommends the following vaccines at age 11 to 12 years: tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap); HPV vaccine series (2 doses if the first dose is received prior to age 15 years; 3 doses if the first dose is received at age 15 years or older); and quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY). A second (booster) dose of MenACWY is recommended at age 16 years. Adolescents should also receive an annual influenza vaccine and a COVID-19 vaccine series.2

For adolescents not fully vaccinated in childhood, catch-up vaccination is recommended for hepatitis A (HepA); hepatitis B (HepB); measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR); and varicella (VAR).2

How are we doing? In 2021, 89.6% of adolescents had received ≥ 1 Tdap dose and 89.0% had received ≥ 1 MenACWY dose; both these rates remained stable from the year before. For HPV vaccine, 76.9% had received ≥ 1 dose (an increase of 1.8 percentage points from 2020); 61.7% were HPV vaccine “up to date” (an increase of 3.1 percentage points). The teen HPV vaccination rate has increased slowly but progressively since the first recommendation for routine HPV vaccination was made for females in 2006 and for males in 2011.1

Among those age 17 years, coverage with ≥ 2 MenACWY doses was 60.0% (an increase of 5.6 percentage points from 2020). Coverage was 85% for ≥ 2 HepA doses (an increase of 2.9 percentage points from 2020) and remained stable at > 90% for each of the following: ≥ 2 doses of MMR, ≥ 3 doses of HepB, and both VAR doses.1

Keeping the momentum. As a country, we continue to make progress at increasing vaccination rates among US adolescents—but there is still plenty of room for improvement. Family physicians should check vaccine status at each clinical encounter and encourage parents and caregivers to schedule future wellness and vaccine visits for these young patients. This may be especially important among adolescents who were due for and missed a vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Every year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducts a national survey to provide an estimate of vaccination rates among adolescents ages 13 to 17 years. The results for 2021, published recently, illustrate the progress that we’ve made and the areas in which improvement is still needed; notably, human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is an example of both.1

First, what’s recommended? The CDC recommends the following vaccines at age 11 to 12 years: tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap); HPV vaccine series (2 doses if the first dose is received prior to age 15 years; 3 doses if the first dose is received at age 15 years or older); and quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY). A second (booster) dose of MenACWY is recommended at age 16 years. Adolescents should also receive an annual influenza vaccine and a COVID-19 vaccine series.2

For adolescents not fully vaccinated in childhood, catch-up vaccination is recommended for hepatitis A (HepA); hepatitis B (HepB); measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR); and varicella (VAR).2

How are we doing? In 2021, 89.6% of adolescents had received ≥ 1 Tdap dose and 89.0% had received ≥ 1 MenACWY dose; both these rates remained stable from the year before. For HPV vaccine, 76.9% had received ≥ 1 dose (an increase of 1.8 percentage points from 2020); 61.7% were HPV vaccine “up to date” (an increase of 3.1 percentage points). The teen HPV vaccination rate has increased slowly but progressively since the first recommendation for routine HPV vaccination was made for females in 2006 and for males in 2011.1

Among those age 17 years, coverage with ≥ 2 MenACWY doses was 60.0% (an increase of 5.6 percentage points from 2020). Coverage was 85% for ≥ 2 HepA doses (an increase of 2.9 percentage points from 2020) and remained stable at > 90% for each of the following: ≥ 2 doses of MMR, ≥ 3 doses of HepB, and both VAR doses.1

Keeping the momentum. As a country, we continue to make progress at increasing vaccination rates among US adolescents—but there is still plenty of room for improvement. Family physicians should check vaccine status at each clinical encounter and encourage parents and caregivers to schedule future wellness and vaccine visits for these young patients. This may be especially important among adolescents who were due for and missed a vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, et al. National vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—National Immunization Survey-Teen, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1101-1108.

2. Wodi AP, Murthy N, Bernstein H, et al. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended immunization schedule for children and adolescents aged 18 years or younger—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:234-237.

1. Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, et al. National vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—National Immunization Survey-Teen, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1101-1108.

2. Wodi AP, Murthy N, Bernstein H, et al. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended immunization schedule for children and adolescents aged 18 years or younger—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:234-237.

Britain’s hard lessons from handing elder care over to private equity

Domestic and global private equity investors had supercharged the company’s growth, betting that the rising needs of aging Britons would yield big returns.

Within weeks, the Four Seasons brand may be finished.

Christie & Co., a commercial real estate broker, splashed a summer sale across its website that signaled the demise: The last 111 Four Seasons facilities in England, Scotland, and Jersey were on the market. Already sold were its 29 homes in Northern Ireland.

Four Seasons collapsed after years of private equity investors rolling in one after another to buy its business, sell its real estate, and at times wrest multimillion-dollar profits through complex debt schemes – until the last big equity fund, Terra Firma, which in 2012 paid about $1.3 billion for the company, was caught short.

In a country where government health care is a right, the Four Seasons story exemplifies the high-stakes rise – and, ultimately, fall – of private equity investment in health and social services. Hanging over society’s most vulnerable patients, these heavily leveraged deals failed to account for the cost of their care. Private equity firms are known for making a profit on quick-turnaround investments.

“People often say: ‘Why have American investors, as well as professional investors here and in other countries, poured so much into this sector?’ I think they were dazzled by the potential of the demographics,” said Nick Hood, an analyst at Opus Restructuring & Insolvency in London, which advises care homes – the British equivalent of U.S. nursing homes or assisted living facilities. They “saw the baby boomers aging and thought there would be infinite demands.”

What they missed, Mr. Hood said, “was that about half of all the residents in U.K. homes are funded by the government in one way or another. They aren’t private pay – and they’ve got no money.”

Residents as ‘revenue streams’

As in the United States, long-term care homes in Britain serve a mixed market of public- and private-pay residents, and those whose balance sheets rest heavily on government payments are stressed even in better economic times. Andrew Dobbie, a community officer for Unison, a union that represents care home workers, said private equity investors often see homes like Four Seasons as having “two revenue streams, the properties themselves and the residents,” with efficiencies to exploit.

But investors don’t always understand what caregivers do, he said, or that older residents require more time than spreadsheets have calculated. “That’s a problem when you are looking at operating care homes,” Mr. Dobbie said. “Care workers need to have soft skills to work with a vulnerable group of people. It’s not the same skills as stocking shelves in a supermarket.”

A recent study, funded in part by Unison and conducted by University of Surrey researchers, found big changes in the quality of care after private equity investments. More than a dozen staff members, who weren’t identified by name or facility, said companies were “cutting corners” to curb costs because their priority was profit. Staffers said “these changes meant residents sometimes went without the appropriate care, timely medication or sufficient sanitary supplies.”

In August, the House of Commons received a sobering account: The number of adults 65 and older who will need care is speedily rising, estimated to go from 3.5 million in 2018 to 5.2 million in 2038. Yet workers at care homes are among the lowest paid in health care.

“The covid-19 pandemic shone a light on the adult social care sector,” according to the parliamentary report, which noted that “many frustrated and burnt out care workers left” for better-paying jobs. The report’s advice in a year of soaring inflation and energy costs? The government should add “at least £7 billion a year” – more than $8 billion – or risk deterioration of care.

Britain’s care homes are separate from the much-lauded National Health Service, funded by the government. Care homes rely on support from local authorities, akin to counties in the United States. But they have seen a sharp drop in funding from the British government, which cut a third of its payments in the past decade. When the pandemic hit, the differences were apparent: Care home workers were not afforded masks, gloves, or gowns to shield them from the deadly virus.

Years ago, care homes were largely run by families or local entities. In the 1990s, the government promoted privatization, triggering investments and consolidations. Today, private equity firms own three of the country’s five biggest care home providers.

Chris Thomas, a research fellow at the Institute for Public Policy Research, said investors benefited from scant financial oversight. “The accounting practices are horrendously complicated and meant to be complicated,” he said. Local authorities try “to regulate more, but they don’t have the expertise.”

The financial shuffle

At Four Seasons, the speed of change was dizzying. From 2004 to 2017, big money came and went, with revenue at times threaded through multiple offshore vehicles. Among the groups that owned Four Seasons, in part or in its entirety: British private equity firm Alchemy Partners; Allianz Capital Partners, a German private equity firm; Three Delta, an investment fund backed by Qatar; the American hedge fund Monarch Alternative Capital; and Terra Firma, the British private equity group that wallowed in debt demands. H/2 Capital Partners, a hedge fund in Connecticut, was Four Seasons’ main creditor and took over. By 2019, Four Seasons was managed by insolvency experts.

Pressed on whether Four Seasons would exist in any form after the current sale of its property and businesses, MHP Communications, representing the company, said in an email: “It is too early in the process to speculate about the future of the brand.”

Vivek Kotecha, an accountant who has examined the Four Seasons financial shuffle and coauthored the Unison report, said private equity investment – in homes for older residents and, increasingly, in facilities for troubled children – is now part of the financial mainstream. The consulting firm McKinsey in 2022estimated that private markets manage nearly $10 trillion in assets, making them a dominant force in global markets.

“What you find in America with private equity is much the same here,” said Mr. Kotecha, the founder of Trinava Consulting in London. “They are often the same firms, doing the same things.” What was remarkable about Four Seasons was the enormous liability from high-yield bonds that underpinned the deal – one equaling $514 million at 8.75% interest and another for $277 million at 12.75% interest.

Guy Hands, the high-flying British founder of Terra Firma, bought Four Seasons in 2012, soon after losing an epic court battle with Citigroup over the purchase price of the music company EMI Group. Terra Firma acquired the care homes and then a gardening business with more than 100 stores. Neither proved easy, or good, bets. Hands, a Londoner who moved offshore to Guernsey, declined through a representative to discuss Four Seasons.

Mr. Kotecha, however, helped the BBC try to make sense of Four Seasons’ holdings by tracking financial filings. It was “the most complicated spreadsheet I’ve ever seen,” Mr. Kotecha said. “I think there were more subsidiaries involved in Four Seasons’ care homes than there were with General Motors in Europe.”

As Britain’s small homes were swept up in consolidations, some financial practices were dubious. At times, businesses sold the buildings as lease-back deals – not a problem at first – that, after multiple purchases, left operators paying rent with heavy interest that sapped operating budgets. By 2020, some care homes were estimated to be spending as much as 16% of their bed fees on debt payments, according to parliamentary testimony this year.

How could that happen? In part, for-profit providers – backed by private-equity groups and other corporations – had subsidiaries of their parent companies act as lender, setting the rates.

Britain’s elder care was unrecognizable within a generation. By 2022, private-equity companies alone accounted for 55,000 beds, or about 12.6% of the total for-profit care beds for older people in the United Kingdom, according to LaingBuisson, a health care consultancy. LaingBuisson calculated that the average residential care home fee as of February 2022 was about $44,700 a year; the average nursing home fee was $62,275 a year.

From 1980 to 2018, the number of residential care beds provided by local authorities fell 88% – from 141,719 to 17,100, according to the nonprofit Centre for Health and the Public Interest. Independent operators – nonprofits and for-profits – moved in, it said, controlling 243,000 beds by 2018. Nursing homes saw a similar shift: Private providers accounted for 194,100 beds in 2018, compared with 25,500 decades earlier.

Beyond government control

British lawmakers in the winter of 2021-2022 tried – and failed – to bolster financial reporting rules for care homes, including banning the use of government funds to pay off debt.

“I don’t have a problem with offshore companies that make profits if they offer good services. I don’t have a problem with private equity and hedge funds who deliver good returns to their shareholders,” Ros Altmann, a Conservative Party member in the House of Lords and a pension expert, said in a February debate. “I do have a problem if those companies are taking advantage of some of the most vulnerable people in our society without oversight, without controls.”

She cited Four Seasons as an example of how regulators “have no control over the financial models that are used.” Ms. Altmann warned that economic headwinds could worsen matters: “We now have very heavily debt-laden [homes] in an environment where interest rates are heading upward.”

In August, the Bank of England raised borrowing rates. It now forecasts double-digit inflation – as much as 11% – through 2023.

And that leaves care home owner Robert Kilgour pensive about whether government grasps the risks and possibilities that the sector is facing. “It’s a struggle, and it’s becoming more of a struggle,” he said. A global energy crisis is the latest unexpected emergency. Mr. Kilgour said he recently signed electricity contracts, for April 2023, at rates that will rise by 200%. That means an extra $2,400 a day in utility costs for his homes.

Mr. Kilgour founded Four Seasons, opening its first home, in Fife, Scotland, in 1989. His ambition for its growth was modest: “Ten by 2000.” That changed in 1999 when Alchemy swooped in to expand nationally. Mr. Kilgour had left Four Seasons by 2004, turning to other ventures.

Still, he saw opportunity in elder care and opened Renaissance Care, which now operates 16 homes with 750 beds in Scotland. “I missed it,” he said in an interview in London. “It’s people and it’s property, and I like that.”

“People asked me if I had any regrets about selling to private equity. Well, no, the people I dealt with were very fair, very straight. There were no shenanigans,” Mr. Kilgour said, noting that Alchemy made money but invested as well.

Mr. Kilgour said the pandemic motivated him to improve his business. He is spending millions on new LED lighting and boilers, as well as training staffers on digital record-keeping, all to winnow costs. He increased hourly wages by 5%, but employees have suggested other ways to retain staff: shorter shifts and workdays that fit school schedules or allow them to care for their own older relatives.

Debates over whether the government should move back into elder care make little sense to Mr. Kilgour. Britain has had private care for decades, and he doesn’t see that changing. Instead, operators need help balancing private and publicly funded beds “so you have a blended rate for care and some certainty in the business.”

Consolidations are slowing, he said, which might be part of a long-overdue reckoning. “The idea of 200, 300, 400 care homes – that big is good and big is best – those days are gone,” Mr. Kilgour said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Domestic and global private equity investors had supercharged the company’s growth, betting that the rising needs of aging Britons would yield big returns.

Within weeks, the Four Seasons brand may be finished.

Christie & Co., a commercial real estate broker, splashed a summer sale across its website that signaled the demise: The last 111 Four Seasons facilities in England, Scotland, and Jersey were on the market. Already sold were its 29 homes in Northern Ireland.

Four Seasons collapsed after years of private equity investors rolling in one after another to buy its business, sell its real estate, and at times wrest multimillion-dollar profits through complex debt schemes – until the last big equity fund, Terra Firma, which in 2012 paid about $1.3 billion for the company, was caught short.

In a country where government health care is a right, the Four Seasons story exemplifies the high-stakes rise – and, ultimately, fall – of private equity investment in health and social services. Hanging over society’s most vulnerable patients, these heavily leveraged deals failed to account for the cost of their care. Private equity firms are known for making a profit on quick-turnaround investments.

“People often say: ‘Why have American investors, as well as professional investors here and in other countries, poured so much into this sector?’ I think they were dazzled by the potential of the demographics,” said Nick Hood, an analyst at Opus Restructuring & Insolvency in London, which advises care homes – the British equivalent of U.S. nursing homes or assisted living facilities. They “saw the baby boomers aging and thought there would be infinite demands.”

What they missed, Mr. Hood said, “was that about half of all the residents in U.K. homes are funded by the government in one way or another. They aren’t private pay – and they’ve got no money.”

Residents as ‘revenue streams’

As in the United States, long-term care homes in Britain serve a mixed market of public- and private-pay residents, and those whose balance sheets rest heavily on government payments are stressed even in better economic times. Andrew Dobbie, a community officer for Unison, a union that represents care home workers, said private equity investors often see homes like Four Seasons as having “two revenue streams, the properties themselves and the residents,” with efficiencies to exploit.

But investors don’t always understand what caregivers do, he said, or that older residents require more time than spreadsheets have calculated. “That’s a problem when you are looking at operating care homes,” Mr. Dobbie said. “Care workers need to have soft skills to work with a vulnerable group of people. It’s not the same skills as stocking shelves in a supermarket.”

A recent study, funded in part by Unison and conducted by University of Surrey researchers, found big changes in the quality of care after private equity investments. More than a dozen staff members, who weren’t identified by name or facility, said companies were “cutting corners” to curb costs because their priority was profit. Staffers said “these changes meant residents sometimes went without the appropriate care, timely medication or sufficient sanitary supplies.”

In August, the House of Commons received a sobering account: The number of adults 65 and older who will need care is speedily rising, estimated to go from 3.5 million in 2018 to 5.2 million in 2038. Yet workers at care homes are among the lowest paid in health care.

“The covid-19 pandemic shone a light on the adult social care sector,” according to the parliamentary report, which noted that “many frustrated and burnt out care workers left” for better-paying jobs. The report’s advice in a year of soaring inflation and energy costs? The government should add “at least £7 billion a year” – more than $8 billion – or risk deterioration of care.

Britain’s care homes are separate from the much-lauded National Health Service, funded by the government. Care homes rely on support from local authorities, akin to counties in the United States. But they have seen a sharp drop in funding from the British government, which cut a third of its payments in the past decade. When the pandemic hit, the differences were apparent: Care home workers were not afforded masks, gloves, or gowns to shield them from the deadly virus.

Years ago, care homes were largely run by families or local entities. In the 1990s, the government promoted privatization, triggering investments and consolidations. Today, private equity firms own three of the country’s five biggest care home providers.

Chris Thomas, a research fellow at the Institute for Public Policy Research, said investors benefited from scant financial oversight. “The accounting practices are horrendously complicated and meant to be complicated,” he said. Local authorities try “to regulate more, but they don’t have the expertise.”

The financial shuffle

At Four Seasons, the speed of change was dizzying. From 2004 to 2017, big money came and went, with revenue at times threaded through multiple offshore vehicles. Among the groups that owned Four Seasons, in part or in its entirety: British private equity firm Alchemy Partners; Allianz Capital Partners, a German private equity firm; Three Delta, an investment fund backed by Qatar; the American hedge fund Monarch Alternative Capital; and Terra Firma, the British private equity group that wallowed in debt demands. H/2 Capital Partners, a hedge fund in Connecticut, was Four Seasons’ main creditor and took over. By 2019, Four Seasons was managed by insolvency experts.

Pressed on whether Four Seasons would exist in any form after the current sale of its property and businesses, MHP Communications, representing the company, said in an email: “It is too early in the process to speculate about the future of the brand.”

Vivek Kotecha, an accountant who has examined the Four Seasons financial shuffle and coauthored the Unison report, said private equity investment – in homes for older residents and, increasingly, in facilities for troubled children – is now part of the financial mainstream. The consulting firm McKinsey in 2022estimated that private markets manage nearly $10 trillion in assets, making them a dominant force in global markets.

“What you find in America with private equity is much the same here,” said Mr. Kotecha, the founder of Trinava Consulting in London. “They are often the same firms, doing the same things.” What was remarkable about Four Seasons was the enormous liability from high-yield bonds that underpinned the deal – one equaling $514 million at 8.75% interest and another for $277 million at 12.75% interest.

Guy Hands, the high-flying British founder of Terra Firma, bought Four Seasons in 2012, soon after losing an epic court battle with Citigroup over the purchase price of the music company EMI Group. Terra Firma acquired the care homes and then a gardening business with more than 100 stores. Neither proved easy, or good, bets. Hands, a Londoner who moved offshore to Guernsey, declined through a representative to discuss Four Seasons.

Mr. Kotecha, however, helped the BBC try to make sense of Four Seasons’ holdings by tracking financial filings. It was “the most complicated spreadsheet I’ve ever seen,” Mr. Kotecha said. “I think there were more subsidiaries involved in Four Seasons’ care homes than there were with General Motors in Europe.”

As Britain’s small homes were swept up in consolidations, some financial practices were dubious. At times, businesses sold the buildings as lease-back deals – not a problem at first – that, after multiple purchases, left operators paying rent with heavy interest that sapped operating budgets. By 2020, some care homes were estimated to be spending as much as 16% of their bed fees on debt payments, according to parliamentary testimony this year.

How could that happen? In part, for-profit providers – backed by private-equity groups and other corporations – had subsidiaries of their parent companies act as lender, setting the rates.

Britain’s elder care was unrecognizable within a generation. By 2022, private-equity companies alone accounted for 55,000 beds, or about 12.6% of the total for-profit care beds for older people in the United Kingdom, according to LaingBuisson, a health care consultancy. LaingBuisson calculated that the average residential care home fee as of February 2022 was about $44,700 a year; the average nursing home fee was $62,275 a year.

From 1980 to 2018, the number of residential care beds provided by local authorities fell 88% – from 141,719 to 17,100, according to the nonprofit Centre for Health and the Public Interest. Independent operators – nonprofits and for-profits – moved in, it said, controlling 243,000 beds by 2018. Nursing homes saw a similar shift: Private providers accounted for 194,100 beds in 2018, compared with 25,500 decades earlier.

Beyond government control

British lawmakers in the winter of 2021-2022 tried – and failed – to bolster financial reporting rules for care homes, including banning the use of government funds to pay off debt.

“I don’t have a problem with offshore companies that make profits if they offer good services. I don’t have a problem with private equity and hedge funds who deliver good returns to their shareholders,” Ros Altmann, a Conservative Party member in the House of Lords and a pension expert, said in a February debate. “I do have a problem if those companies are taking advantage of some of the most vulnerable people in our society without oversight, without controls.”

She cited Four Seasons as an example of how regulators “have no control over the financial models that are used.” Ms. Altmann warned that economic headwinds could worsen matters: “We now have very heavily debt-laden [homes] in an environment where interest rates are heading upward.”

In August, the Bank of England raised borrowing rates. It now forecasts double-digit inflation – as much as 11% – through 2023.

And that leaves care home owner Robert Kilgour pensive about whether government grasps the risks and possibilities that the sector is facing. “It’s a struggle, and it’s becoming more of a struggle,” he said. A global energy crisis is the latest unexpected emergency. Mr. Kilgour said he recently signed electricity contracts, for April 2023, at rates that will rise by 200%. That means an extra $2,400 a day in utility costs for his homes.

Mr. Kilgour founded Four Seasons, opening its first home, in Fife, Scotland, in 1989. His ambition for its growth was modest: “Ten by 2000.” That changed in 1999 when Alchemy swooped in to expand nationally. Mr. Kilgour had left Four Seasons by 2004, turning to other ventures.

Still, he saw opportunity in elder care and opened Renaissance Care, which now operates 16 homes with 750 beds in Scotland. “I missed it,” he said in an interview in London. “It’s people and it’s property, and I like that.”

“People asked me if I had any regrets about selling to private equity. Well, no, the people I dealt with were very fair, very straight. There were no shenanigans,” Mr. Kilgour said, noting that Alchemy made money but invested as well.

Mr. Kilgour said the pandemic motivated him to improve his business. He is spending millions on new LED lighting and boilers, as well as training staffers on digital record-keeping, all to winnow costs. He increased hourly wages by 5%, but employees have suggested other ways to retain staff: shorter shifts and workdays that fit school schedules or allow them to care for their own older relatives.

Debates over whether the government should move back into elder care make little sense to Mr. Kilgour. Britain has had private care for decades, and he doesn’t see that changing. Instead, operators need help balancing private and publicly funded beds “so you have a blended rate for care and some certainty in the business.”

Consolidations are slowing, he said, which might be part of a long-overdue reckoning. “The idea of 200, 300, 400 care homes – that big is good and big is best – those days are gone,” Mr. Kilgour said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Domestic and global private equity investors had supercharged the company’s growth, betting that the rising needs of aging Britons would yield big returns.

Within weeks, the Four Seasons brand may be finished.

Christie & Co., a commercial real estate broker, splashed a summer sale across its website that signaled the demise: The last 111 Four Seasons facilities in England, Scotland, and Jersey were on the market. Already sold were its 29 homes in Northern Ireland.

Four Seasons collapsed after years of private equity investors rolling in one after another to buy its business, sell its real estate, and at times wrest multimillion-dollar profits through complex debt schemes – until the last big equity fund, Terra Firma, which in 2012 paid about $1.3 billion for the company, was caught short.

In a country where government health care is a right, the Four Seasons story exemplifies the high-stakes rise – and, ultimately, fall – of private equity investment in health and social services. Hanging over society’s most vulnerable patients, these heavily leveraged deals failed to account for the cost of their care. Private equity firms are known for making a profit on quick-turnaround investments.

“People often say: ‘Why have American investors, as well as professional investors here and in other countries, poured so much into this sector?’ I think they were dazzled by the potential of the demographics,” said Nick Hood, an analyst at Opus Restructuring & Insolvency in London, which advises care homes – the British equivalent of U.S. nursing homes or assisted living facilities. They “saw the baby boomers aging and thought there would be infinite demands.”

What they missed, Mr. Hood said, “was that about half of all the residents in U.K. homes are funded by the government in one way or another. They aren’t private pay – and they’ve got no money.”

Residents as ‘revenue streams’

As in the United States, long-term care homes in Britain serve a mixed market of public- and private-pay residents, and those whose balance sheets rest heavily on government payments are stressed even in better economic times. Andrew Dobbie, a community officer for Unison, a union that represents care home workers, said private equity investors often see homes like Four Seasons as having “two revenue streams, the properties themselves and the residents,” with efficiencies to exploit.

But investors don’t always understand what caregivers do, he said, or that older residents require more time than spreadsheets have calculated. “That’s a problem when you are looking at operating care homes,” Mr. Dobbie said. “Care workers need to have soft skills to work with a vulnerable group of people. It’s not the same skills as stocking shelves in a supermarket.”

A recent study, funded in part by Unison and conducted by University of Surrey researchers, found big changes in the quality of care after private equity investments. More than a dozen staff members, who weren’t identified by name or facility, said companies were “cutting corners” to curb costs because their priority was profit. Staffers said “these changes meant residents sometimes went without the appropriate care, timely medication or sufficient sanitary supplies.”