User login

Home-grown apps for ObGyn clerkship students

Technology has revolutionized how we access information. One example is the increased use of mobile applications (apps). On the surface, building a new app may seem a daunting and intimidating task. However, new software—such as Glide (glideapps.com)—make it easy for anyone to design, build, and launch a custom web app within hours. This software is free for basic apps but does offer an upgrade for those wanting more professional services (glide-apps.com/pro). Here, by way of example, we identify an area of need and walk the reader

through the process of making an app.

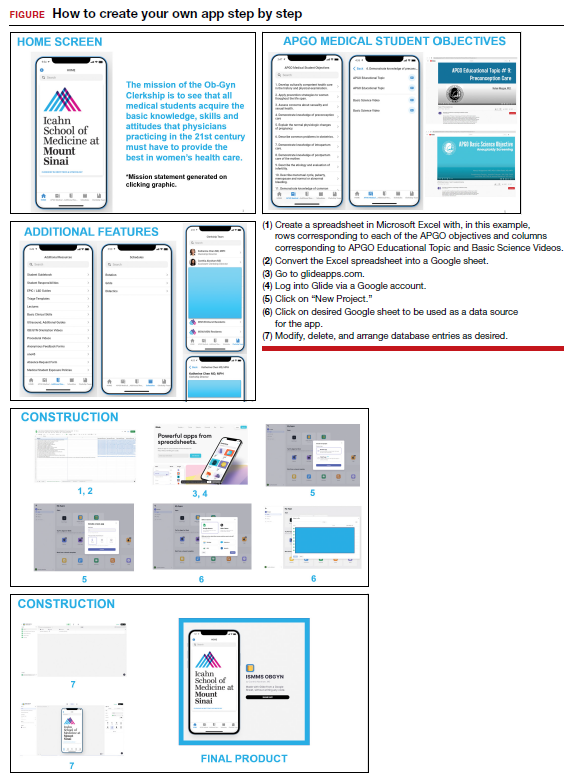

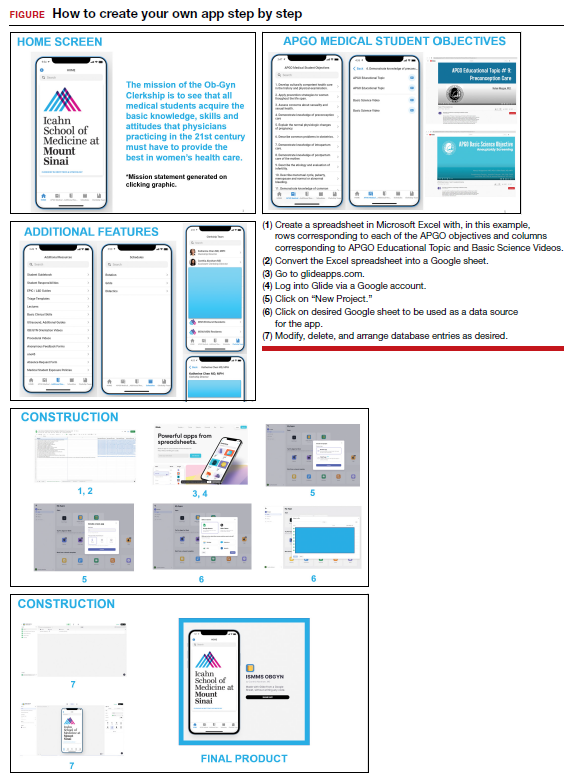

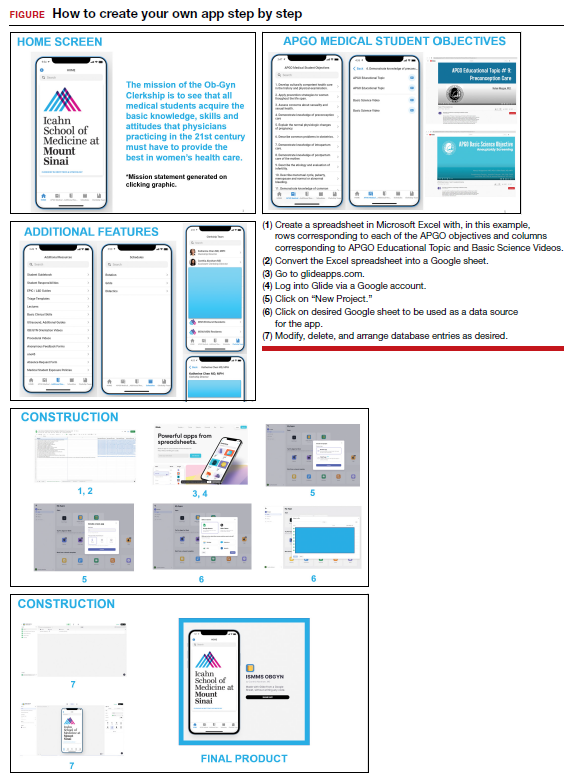

Although there are many apps aimed at educating users on different aspects of obstetrics and gynecology, few are focused on undergraduate medical education (UME). With the assistance of Glide app building software, we created an app focused on providing rapid access to resources aimed at fulfilling medical student objectives from the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO).1 We included 16 of the APGO objectives. On clicking an objective, the user is taken to a screen with links to associated APGO Educational Topic Video and Basic Science Videos. Basic Science Video links were included in order to provide longitudinal learning between the pre-clinical and clinical years of UME. We also created a tab for additional educational resources (including excerpts from the APGO Basic Clinical Skills Curriculum).2 We eventually added two other tabs: one for clerkship schedules that allows students to organize their daily schedule and another that facilitates quick contact with members of the clerkship team. As expected, the app was well-received by our students.

The steps needed for you to make your own app are listed in the FIGURE along with accompanying images for easy navigation. ●

- Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO) Medical Student Educational Objectives, 11th ed;2019.

- Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO) Basic Clinical Skills Curriculum. Updated 2017.

Technology has revolutionized how we access information. One example is the increased use of mobile applications (apps). On the surface, building a new app may seem a daunting and intimidating task. However, new software—such as Glide (glideapps.com)—make it easy for anyone to design, build, and launch a custom web app within hours. This software is free for basic apps but does offer an upgrade for those wanting more professional services (glide-apps.com/pro). Here, by way of example, we identify an area of need and walk the reader

through the process of making an app.

Although there are many apps aimed at educating users on different aspects of obstetrics and gynecology, few are focused on undergraduate medical education (UME). With the assistance of Glide app building software, we created an app focused on providing rapid access to resources aimed at fulfilling medical student objectives from the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO).1 We included 16 of the APGO objectives. On clicking an objective, the user is taken to a screen with links to associated APGO Educational Topic Video and Basic Science Videos. Basic Science Video links were included in order to provide longitudinal learning between the pre-clinical and clinical years of UME. We also created a tab for additional educational resources (including excerpts from the APGO Basic Clinical Skills Curriculum).2 We eventually added two other tabs: one for clerkship schedules that allows students to organize their daily schedule and another that facilitates quick contact with members of the clerkship team. As expected, the app was well-received by our students.

The steps needed for you to make your own app are listed in the FIGURE along with accompanying images for easy navigation. ●

Technology has revolutionized how we access information. One example is the increased use of mobile applications (apps). On the surface, building a new app may seem a daunting and intimidating task. However, new software—such as Glide (glideapps.com)—make it easy for anyone to design, build, and launch a custom web app within hours. This software is free for basic apps but does offer an upgrade for those wanting more professional services (glide-apps.com/pro). Here, by way of example, we identify an area of need and walk the reader

through the process of making an app.

Although there are many apps aimed at educating users on different aspects of obstetrics and gynecology, few are focused on undergraduate medical education (UME). With the assistance of Glide app building software, we created an app focused on providing rapid access to resources aimed at fulfilling medical student objectives from the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO).1 We included 16 of the APGO objectives. On clicking an objective, the user is taken to a screen with links to associated APGO Educational Topic Video and Basic Science Videos. Basic Science Video links were included in order to provide longitudinal learning between the pre-clinical and clinical years of UME. We also created a tab for additional educational resources (including excerpts from the APGO Basic Clinical Skills Curriculum).2 We eventually added two other tabs: one for clerkship schedules that allows students to organize their daily schedule and another that facilitates quick contact with members of the clerkship team. As expected, the app was well-received by our students.

The steps needed for you to make your own app are listed in the FIGURE along with accompanying images for easy navigation. ●

- Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO) Medical Student Educational Objectives, 11th ed;2019.

- Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO) Basic Clinical Skills Curriculum. Updated 2017.

- Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO) Medical Student Educational Objectives, 11th ed;2019.

- Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO) Basic Clinical Skills Curriculum. Updated 2017.

Immunosuppressed rheumatic patients not at high risk of breakthrough COVID-19

COPENHAGEN – Most patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMID) should not be considered at high risk for severe COVID-19 breakthrough infections, but those on anti-CD20 therapy are the exception, data from a large prospective, cohort study show.

“Overall, the data are reassuring, with conventional risk factors, such as age, and comorbidities seeming to be more important regarding risk of severe COVID-19 breakthrough infections than rheumatic disease or immunosuppressant medication,” said Laura Boekel, MD, from Amsterdam UMC, who presented the study at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology.

But, she added, there was an exception for anti-CD20 therapy. “This is especially relevant for patients with conventional risk factors that might accumulate, and rheumatologists might want to consider alternative treatment options if possible. It is important to inform patients about the risks of anti-CD20.”

Another study, presented during the same session at the congress by Rebecca Hasseli, MD, from the University of Giessen (Germany) saw no deaths and no COVID-19 related complications in a cohort of triple-vaccinated patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases, despite a higher median age and a higher rate of comorbidities compared to double-vaccinated and unvaccinated cohorts.

Ingrid Jyssum, MD, from Diakonhjemmet Hospital, Oslo, who presented results of the Nor-vaC study investigating the impact of different DMARDs on the immunogenicity of a third COVID-19 vaccine dose, welcomed the research by Dr. Boekel and Dr. Hasseli.

“The findings of Hasseli are interesting in the light of our data on serological response after the third dose, with a lack of breakthrough infections after three doses corresponding well to the robust antibody response that we found in our cohort,” she remarked. “This is very reassuring for our patients. Our own work together with the findings of Hasseli and Boekel demonstrate that additional vaccine doses are important to keep this population well protected against severe COVID-19 infections.”

The Nor-vaC study was conducted with a cohort of 1,100 patients with inflammatory joint and bowel diseases. “These patients had attenuated antibody responses after two vaccine doses; however, we found that a third vaccine dose brought the humoral response in patients up to the antibody levels that healthy controls had after two doses,” said Dr. Jyssum. “In addition, we found that the decline in antibodies after the third dose was less than the decline seen after the second dose. Importantly, the third dose was safe in our patients, with no new safety issues.”

Breakthrough infections and immunosuppressants

“Like the rest of the world, we were wondering if our patients were at increased risk of COVID-19, and if the immunosuppressants used by these patients influenced their risk,” said Dr. Boekel.

The researchers compared both the incidence and severity of COVID-19 breakthrough infections with the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant in a population of fully vaccinated IMID patients taking immunosuppressants and controls (IMID patients not taking immunosuppressants and healthy controls).

Two large ongoing, prospective, multicenter cohort studies provided pooled data collected between February and December 2021 using digital questionnaires, standardized electronic case record forms, and medical files.

Finger-prick tests were used to collect blood samples that were analyzed after vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 for anti–receptor-binding domain (RBD) antibodies, and antinucleocapsid antibodies to identify asymptomatic breakthrough infections. Any associations between antibodies and the incidence of breakthrough infections were generated, and results were adjusted for sex, cardiovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, obesity, and vaccine type.

The analysis included 3,207 IMID patients taking immunosuppressants, and 1,810 controls (985 IMID patients not on immunosuppressants and 825 healthy controls).

Initially, Dr. Boekel and her colleagues looked at incidence of infections and hospitalizations prior to vaccination, and then after vaccination, which was the main aim of the study.

Prior to vaccination, hospitalization risk for COVID-19 was somewhat higher for IMID patients overall compared with controls, reported Dr. Boekel. “But those treated with anti-CD20 therapy, demonstrated much greater risk for severe disease.”

After the SARS-CoV-2 vaccination campaign began, the researchers then looked at how immunosuppressants influenced humoral response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.

“Anti-CD20 therapy showed the greatest impact on humoral immune response after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination,” said Dr. Boekel. Other immunosuppressant drugs had variable effects on humoral and cellular immunity.

Once they had established that immunosuppressant drugs impaired immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, the researchers wanted to determine if this affected clinical outcomes. Blood samples taken 28 days after the second vaccination enabled Dr. Boekel and her colleagues to see if antibody production was associated with breakthrough infections.

Breakthrough infections were seen in 5% of patients on immunosuppressants, 5% of patients not on immunosuppressants, and 4% of healthy controls. Also, asymptomatic COVID-19 breakthrough cases were comparable between IMID patients taking immunosuppressants and controls, at 10% in each group.

“We saw that the incidence [of getting COVID-19] was comparable between groups, independent of whether they were receiving immunosuppressants or not, or healthy controls. However, if they developed antibodies against the two vaccinations the chance of getting infected was lower,” reported Dr. Boekel.

Hospitalization (severe disease) rates were also comparable between groups. “Patients with rheumatic diseases, even when treated with immunosuppressants were not at increased risk of severe disease from Delta breakthrough infections,” added the researcher. “Cases that were hospitalized were mainly elderly and those with comorbidities, for example cardiovascular disease and cardiopulmonary disease.”

Hospital admissions were 5.4% in patients on immunosuppressants, 5.7% in those not on immunosuppressants, and 6% in health controls.

However, once again, there was one exception, Dr. Boekel stressed. “Patients treated with anti-CD20 therapy were at increased risk of severe disease and hospitalization.”

Omicron variant has a different transmissibility than Delta, so the researchers continued the study looking at the Omicron variant. The data “were mostly reassuring,” said Dr. Boekel. “As expected, hospitalization rates decreased overall, with the exception of patients on anti-CD20 therapy where, despite overall reduced pathogenicity, patients remain at increased risk.”

She said that they were awaiting long-term data so the data reflect only short-term immunity against Omicron. “However, we included many elderly and patients with comorbidities, so this made the analysis very sensitive to detect severe cases,” she added.

Breakthrough infection among double- and triple-vaccinated patients

A lower rate of COVID-19 related complications and deaths were seen in patients who were triple-vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2, than in double-vaccinated or unvaccinated patients, despite the former having more comorbidities and use of rituximab (Rituxan), said Dr. Hasseli.

“These data support the recommendation of booster vaccination to reduce COVID-19-related mortality in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases [IRDs],” she said.

“A small number of COVID-19 cases were seen in patients with IRD after vaccinations, and in a few cases, hospitalizations were required. Breakthrough infections were mostly seen in patients on B-cell depletion therapy,” she added.

Dr. Hasseli and her colleagues looked at the characteristics and outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections among double- and triple-vaccinated patients with IRD.

“We wanted to understand if patients with IRD are protected in the same way as the general population following vaccination, given that these patients receive drugs that might impair the immune response,” she explained.

Data for analysis were drawn from the German COVID-19-IRD registry covering February 2021 and January 2022, and patients who were double- or triple- vaccinated against COVID-19 either 14 days or more prior to a SARS-CoV-2 infection were included. Type of IRD, vaccine, immunomodulation, comorbidities, and outcome of the infection were compared with 737 unvaccinated IRD patients with COVID-19. Those with prior COVID-19 were excluded.

Cases were stratified by vaccinations status: unvaccinated (1,388 patients, median age 57 years); double vaccinated (462, 56 years) and triple vaccinated (301, 53 years). Body mass index was similar across groups (25-26 kg/m2), and time between SARS-CoV-2 infection and last vaccination was 156 days in double-vaccinated patients, and 62 days in triple-vaccinated patients.

Patients had rheumatoid arthritis in 44.7% and 44.4% of unvaccinated and double-vaccinated patients respectively, but fewer triple-vaccinated patients had RA (37.2%). Triple vaccination was seen in 32.2% of patients with spondyloarthritis, 16.6% connective tissue diseases, 5.3% other vasculitis, and 3.3% ANCA-associated vasculitis. Of triple-vaccinated patients, 26.2% were treated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) inhibitors, and 6.3% with rituximab, while 5.3% were not on immunomodulation. At least 25% were treated with glucocorticoids, reported Dr. Hasseli.

“Arterial hypertension and diabetes, that might be risk factors for COVID-19, were less frequently reported in triple-vaccinated patients. More patients in the double-vaccinated group [42.9%] than the triple-vaccinated [23.8%] reported absence of relevant comorbidities,” she said.

COVID-19 related complications were less often reported in double- and triple-vaccinated groups with hospitalizations at 9.5% and 4.3% in double and triple-vaccinated people respectively.

Dr. Boekel and Dr. Hasseli report no relevant conflicts of interest.

COPENHAGEN – Most patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMID) should not be considered at high risk for severe COVID-19 breakthrough infections, but those on anti-CD20 therapy are the exception, data from a large prospective, cohort study show.

“Overall, the data are reassuring, with conventional risk factors, such as age, and comorbidities seeming to be more important regarding risk of severe COVID-19 breakthrough infections than rheumatic disease or immunosuppressant medication,” said Laura Boekel, MD, from Amsterdam UMC, who presented the study at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology.

But, she added, there was an exception for anti-CD20 therapy. “This is especially relevant for patients with conventional risk factors that might accumulate, and rheumatologists might want to consider alternative treatment options if possible. It is important to inform patients about the risks of anti-CD20.”

Another study, presented during the same session at the congress by Rebecca Hasseli, MD, from the University of Giessen (Germany) saw no deaths and no COVID-19 related complications in a cohort of triple-vaccinated patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases, despite a higher median age and a higher rate of comorbidities compared to double-vaccinated and unvaccinated cohorts.

Ingrid Jyssum, MD, from Diakonhjemmet Hospital, Oslo, who presented results of the Nor-vaC study investigating the impact of different DMARDs on the immunogenicity of a third COVID-19 vaccine dose, welcomed the research by Dr. Boekel and Dr. Hasseli.

“The findings of Hasseli are interesting in the light of our data on serological response after the third dose, with a lack of breakthrough infections after three doses corresponding well to the robust antibody response that we found in our cohort,” she remarked. “This is very reassuring for our patients. Our own work together with the findings of Hasseli and Boekel demonstrate that additional vaccine doses are important to keep this population well protected against severe COVID-19 infections.”

The Nor-vaC study was conducted with a cohort of 1,100 patients with inflammatory joint and bowel diseases. “These patients had attenuated antibody responses after two vaccine doses; however, we found that a third vaccine dose brought the humoral response in patients up to the antibody levels that healthy controls had after two doses,” said Dr. Jyssum. “In addition, we found that the decline in antibodies after the third dose was less than the decline seen after the second dose. Importantly, the third dose was safe in our patients, with no new safety issues.”

Breakthrough infections and immunosuppressants

“Like the rest of the world, we were wondering if our patients were at increased risk of COVID-19, and if the immunosuppressants used by these patients influenced their risk,” said Dr. Boekel.

The researchers compared both the incidence and severity of COVID-19 breakthrough infections with the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant in a population of fully vaccinated IMID patients taking immunosuppressants and controls (IMID patients not taking immunosuppressants and healthy controls).

Two large ongoing, prospective, multicenter cohort studies provided pooled data collected between February and December 2021 using digital questionnaires, standardized electronic case record forms, and medical files.

Finger-prick tests were used to collect blood samples that were analyzed after vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 for anti–receptor-binding domain (RBD) antibodies, and antinucleocapsid antibodies to identify asymptomatic breakthrough infections. Any associations between antibodies and the incidence of breakthrough infections were generated, and results were adjusted for sex, cardiovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, obesity, and vaccine type.

The analysis included 3,207 IMID patients taking immunosuppressants, and 1,810 controls (985 IMID patients not on immunosuppressants and 825 healthy controls).

Initially, Dr. Boekel and her colleagues looked at incidence of infections and hospitalizations prior to vaccination, and then after vaccination, which was the main aim of the study.

Prior to vaccination, hospitalization risk for COVID-19 was somewhat higher for IMID patients overall compared with controls, reported Dr. Boekel. “But those treated with anti-CD20 therapy, demonstrated much greater risk for severe disease.”

After the SARS-CoV-2 vaccination campaign began, the researchers then looked at how immunosuppressants influenced humoral response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.

“Anti-CD20 therapy showed the greatest impact on humoral immune response after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination,” said Dr. Boekel. Other immunosuppressant drugs had variable effects on humoral and cellular immunity.

Once they had established that immunosuppressant drugs impaired immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, the researchers wanted to determine if this affected clinical outcomes. Blood samples taken 28 days after the second vaccination enabled Dr. Boekel and her colleagues to see if antibody production was associated with breakthrough infections.

Breakthrough infections were seen in 5% of patients on immunosuppressants, 5% of patients not on immunosuppressants, and 4% of healthy controls. Also, asymptomatic COVID-19 breakthrough cases were comparable between IMID patients taking immunosuppressants and controls, at 10% in each group.

“We saw that the incidence [of getting COVID-19] was comparable between groups, independent of whether they were receiving immunosuppressants or not, or healthy controls. However, if they developed antibodies against the two vaccinations the chance of getting infected was lower,” reported Dr. Boekel.

Hospitalization (severe disease) rates were also comparable between groups. “Patients with rheumatic diseases, even when treated with immunosuppressants were not at increased risk of severe disease from Delta breakthrough infections,” added the researcher. “Cases that were hospitalized were mainly elderly and those with comorbidities, for example cardiovascular disease and cardiopulmonary disease.”

Hospital admissions were 5.4% in patients on immunosuppressants, 5.7% in those not on immunosuppressants, and 6% in health controls.

However, once again, there was one exception, Dr. Boekel stressed. “Patients treated with anti-CD20 therapy were at increased risk of severe disease and hospitalization.”

Omicron variant has a different transmissibility than Delta, so the researchers continued the study looking at the Omicron variant. The data “were mostly reassuring,” said Dr. Boekel. “As expected, hospitalization rates decreased overall, with the exception of patients on anti-CD20 therapy where, despite overall reduced pathogenicity, patients remain at increased risk.”

She said that they were awaiting long-term data so the data reflect only short-term immunity against Omicron. “However, we included many elderly and patients with comorbidities, so this made the analysis very sensitive to detect severe cases,” she added.

Breakthrough infection among double- and triple-vaccinated patients

A lower rate of COVID-19 related complications and deaths were seen in patients who were triple-vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2, than in double-vaccinated or unvaccinated patients, despite the former having more comorbidities and use of rituximab (Rituxan), said Dr. Hasseli.

“These data support the recommendation of booster vaccination to reduce COVID-19-related mortality in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases [IRDs],” she said.

“A small number of COVID-19 cases were seen in patients with IRD after vaccinations, and in a few cases, hospitalizations were required. Breakthrough infections were mostly seen in patients on B-cell depletion therapy,” she added.

Dr. Hasseli and her colleagues looked at the characteristics and outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections among double- and triple-vaccinated patients with IRD.

“We wanted to understand if patients with IRD are protected in the same way as the general population following vaccination, given that these patients receive drugs that might impair the immune response,” she explained.

Data for analysis were drawn from the German COVID-19-IRD registry covering February 2021 and January 2022, and patients who were double- or triple- vaccinated against COVID-19 either 14 days or more prior to a SARS-CoV-2 infection were included. Type of IRD, vaccine, immunomodulation, comorbidities, and outcome of the infection were compared with 737 unvaccinated IRD patients with COVID-19. Those with prior COVID-19 were excluded.

Cases were stratified by vaccinations status: unvaccinated (1,388 patients, median age 57 years); double vaccinated (462, 56 years) and triple vaccinated (301, 53 years). Body mass index was similar across groups (25-26 kg/m2), and time between SARS-CoV-2 infection and last vaccination was 156 days in double-vaccinated patients, and 62 days in triple-vaccinated patients.

Patients had rheumatoid arthritis in 44.7% and 44.4% of unvaccinated and double-vaccinated patients respectively, but fewer triple-vaccinated patients had RA (37.2%). Triple vaccination was seen in 32.2% of patients with spondyloarthritis, 16.6% connective tissue diseases, 5.3% other vasculitis, and 3.3% ANCA-associated vasculitis. Of triple-vaccinated patients, 26.2% were treated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) inhibitors, and 6.3% with rituximab, while 5.3% were not on immunomodulation. At least 25% were treated with glucocorticoids, reported Dr. Hasseli.

“Arterial hypertension and diabetes, that might be risk factors for COVID-19, were less frequently reported in triple-vaccinated patients. More patients in the double-vaccinated group [42.9%] than the triple-vaccinated [23.8%] reported absence of relevant comorbidities,” she said.

COVID-19 related complications were less often reported in double- and triple-vaccinated groups with hospitalizations at 9.5% and 4.3% in double and triple-vaccinated people respectively.

Dr. Boekel and Dr. Hasseli report no relevant conflicts of interest.

COPENHAGEN – Most patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMID) should not be considered at high risk for severe COVID-19 breakthrough infections, but those on anti-CD20 therapy are the exception, data from a large prospective, cohort study show.

“Overall, the data are reassuring, with conventional risk factors, such as age, and comorbidities seeming to be more important regarding risk of severe COVID-19 breakthrough infections than rheumatic disease or immunosuppressant medication,” said Laura Boekel, MD, from Amsterdam UMC, who presented the study at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology.

But, she added, there was an exception for anti-CD20 therapy. “This is especially relevant for patients with conventional risk factors that might accumulate, and rheumatologists might want to consider alternative treatment options if possible. It is important to inform patients about the risks of anti-CD20.”

Another study, presented during the same session at the congress by Rebecca Hasseli, MD, from the University of Giessen (Germany) saw no deaths and no COVID-19 related complications in a cohort of triple-vaccinated patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases, despite a higher median age and a higher rate of comorbidities compared to double-vaccinated and unvaccinated cohorts.

Ingrid Jyssum, MD, from Diakonhjemmet Hospital, Oslo, who presented results of the Nor-vaC study investigating the impact of different DMARDs on the immunogenicity of a third COVID-19 vaccine dose, welcomed the research by Dr. Boekel and Dr. Hasseli.

“The findings of Hasseli are interesting in the light of our data on serological response after the third dose, with a lack of breakthrough infections after three doses corresponding well to the robust antibody response that we found in our cohort,” she remarked. “This is very reassuring for our patients. Our own work together with the findings of Hasseli and Boekel demonstrate that additional vaccine doses are important to keep this population well protected against severe COVID-19 infections.”

The Nor-vaC study was conducted with a cohort of 1,100 patients with inflammatory joint and bowel diseases. “These patients had attenuated antibody responses after two vaccine doses; however, we found that a third vaccine dose brought the humoral response in patients up to the antibody levels that healthy controls had after two doses,” said Dr. Jyssum. “In addition, we found that the decline in antibodies after the third dose was less than the decline seen after the second dose. Importantly, the third dose was safe in our patients, with no new safety issues.”

Breakthrough infections and immunosuppressants

“Like the rest of the world, we were wondering if our patients were at increased risk of COVID-19, and if the immunosuppressants used by these patients influenced their risk,” said Dr. Boekel.

The researchers compared both the incidence and severity of COVID-19 breakthrough infections with the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant in a population of fully vaccinated IMID patients taking immunosuppressants and controls (IMID patients not taking immunosuppressants and healthy controls).

Two large ongoing, prospective, multicenter cohort studies provided pooled data collected between February and December 2021 using digital questionnaires, standardized electronic case record forms, and medical files.

Finger-prick tests were used to collect blood samples that were analyzed after vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 for anti–receptor-binding domain (RBD) antibodies, and antinucleocapsid antibodies to identify asymptomatic breakthrough infections. Any associations between antibodies and the incidence of breakthrough infections were generated, and results were adjusted for sex, cardiovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, obesity, and vaccine type.

The analysis included 3,207 IMID patients taking immunosuppressants, and 1,810 controls (985 IMID patients not on immunosuppressants and 825 healthy controls).

Initially, Dr. Boekel and her colleagues looked at incidence of infections and hospitalizations prior to vaccination, and then after vaccination, which was the main aim of the study.

Prior to vaccination, hospitalization risk for COVID-19 was somewhat higher for IMID patients overall compared with controls, reported Dr. Boekel. “But those treated with anti-CD20 therapy, demonstrated much greater risk for severe disease.”

After the SARS-CoV-2 vaccination campaign began, the researchers then looked at how immunosuppressants influenced humoral response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.

“Anti-CD20 therapy showed the greatest impact on humoral immune response after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination,” said Dr. Boekel. Other immunosuppressant drugs had variable effects on humoral and cellular immunity.

Once they had established that immunosuppressant drugs impaired immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, the researchers wanted to determine if this affected clinical outcomes. Blood samples taken 28 days after the second vaccination enabled Dr. Boekel and her colleagues to see if antibody production was associated with breakthrough infections.

Breakthrough infections were seen in 5% of patients on immunosuppressants, 5% of patients not on immunosuppressants, and 4% of healthy controls. Also, asymptomatic COVID-19 breakthrough cases were comparable between IMID patients taking immunosuppressants and controls, at 10% in each group.

“We saw that the incidence [of getting COVID-19] was comparable between groups, independent of whether they were receiving immunosuppressants or not, or healthy controls. However, if they developed antibodies against the two vaccinations the chance of getting infected was lower,” reported Dr. Boekel.

Hospitalization (severe disease) rates were also comparable between groups. “Patients with rheumatic diseases, even when treated with immunosuppressants were not at increased risk of severe disease from Delta breakthrough infections,” added the researcher. “Cases that were hospitalized were mainly elderly and those with comorbidities, for example cardiovascular disease and cardiopulmonary disease.”

Hospital admissions were 5.4% in patients on immunosuppressants, 5.7% in those not on immunosuppressants, and 6% in health controls.

However, once again, there was one exception, Dr. Boekel stressed. “Patients treated with anti-CD20 therapy were at increased risk of severe disease and hospitalization.”

Omicron variant has a different transmissibility than Delta, so the researchers continued the study looking at the Omicron variant. The data “were mostly reassuring,” said Dr. Boekel. “As expected, hospitalization rates decreased overall, with the exception of patients on anti-CD20 therapy where, despite overall reduced pathogenicity, patients remain at increased risk.”

She said that they were awaiting long-term data so the data reflect only short-term immunity against Omicron. “However, we included many elderly and patients with comorbidities, so this made the analysis very sensitive to detect severe cases,” she added.

Breakthrough infection among double- and triple-vaccinated patients

A lower rate of COVID-19 related complications and deaths were seen in patients who were triple-vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2, than in double-vaccinated or unvaccinated patients, despite the former having more comorbidities and use of rituximab (Rituxan), said Dr. Hasseli.

“These data support the recommendation of booster vaccination to reduce COVID-19-related mortality in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases [IRDs],” she said.

“A small number of COVID-19 cases were seen in patients with IRD after vaccinations, and in a few cases, hospitalizations were required. Breakthrough infections were mostly seen in patients on B-cell depletion therapy,” she added.

Dr. Hasseli and her colleagues looked at the characteristics and outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections among double- and triple-vaccinated patients with IRD.

“We wanted to understand if patients with IRD are protected in the same way as the general population following vaccination, given that these patients receive drugs that might impair the immune response,” she explained.

Data for analysis were drawn from the German COVID-19-IRD registry covering February 2021 and January 2022, and patients who were double- or triple- vaccinated against COVID-19 either 14 days or more prior to a SARS-CoV-2 infection were included. Type of IRD, vaccine, immunomodulation, comorbidities, and outcome of the infection were compared with 737 unvaccinated IRD patients with COVID-19. Those with prior COVID-19 were excluded.

Cases were stratified by vaccinations status: unvaccinated (1,388 patients, median age 57 years); double vaccinated (462, 56 years) and triple vaccinated (301, 53 years). Body mass index was similar across groups (25-26 kg/m2), and time between SARS-CoV-2 infection and last vaccination was 156 days in double-vaccinated patients, and 62 days in triple-vaccinated patients.

Patients had rheumatoid arthritis in 44.7% and 44.4% of unvaccinated and double-vaccinated patients respectively, but fewer triple-vaccinated patients had RA (37.2%). Triple vaccination was seen in 32.2% of patients with spondyloarthritis, 16.6% connective tissue diseases, 5.3% other vasculitis, and 3.3% ANCA-associated vasculitis. Of triple-vaccinated patients, 26.2% were treated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) inhibitors, and 6.3% with rituximab, while 5.3% were not on immunomodulation. At least 25% were treated with glucocorticoids, reported Dr. Hasseli.

“Arterial hypertension and diabetes, that might be risk factors for COVID-19, were less frequently reported in triple-vaccinated patients. More patients in the double-vaccinated group [42.9%] than the triple-vaccinated [23.8%] reported absence of relevant comorbidities,” she said.

COVID-19 related complications were less often reported in double- and triple-vaccinated groups with hospitalizations at 9.5% and 4.3% in double and triple-vaccinated people respectively.

Dr. Boekel and Dr. Hasseli report no relevant conflicts of interest.

AT THE EULAR 2022 CONGRESS

Lupus Erythematosus Tumidus Clinical Characteristics and Treatment: A Retrospective Review of 25 Patients

Lupus erythematosus tumidus (LET) is a rare photosensitive dermatosis1 that previously was considered a subtype of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus; however, the clinical course and favorable prognosis of LET led to its reclassification into another category, called intermittent cutaneous lupus erythematosus.2 Although known about for more than 100 years, the association of LET with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), its autoantibody profile, and its prognosis are not well characterized. The purpose of this study was to describe the demographics, clinical characteristics, autoantibody profile, comorbidities, and treatment of LET based on a retrospective review of patients with LET.

Methods

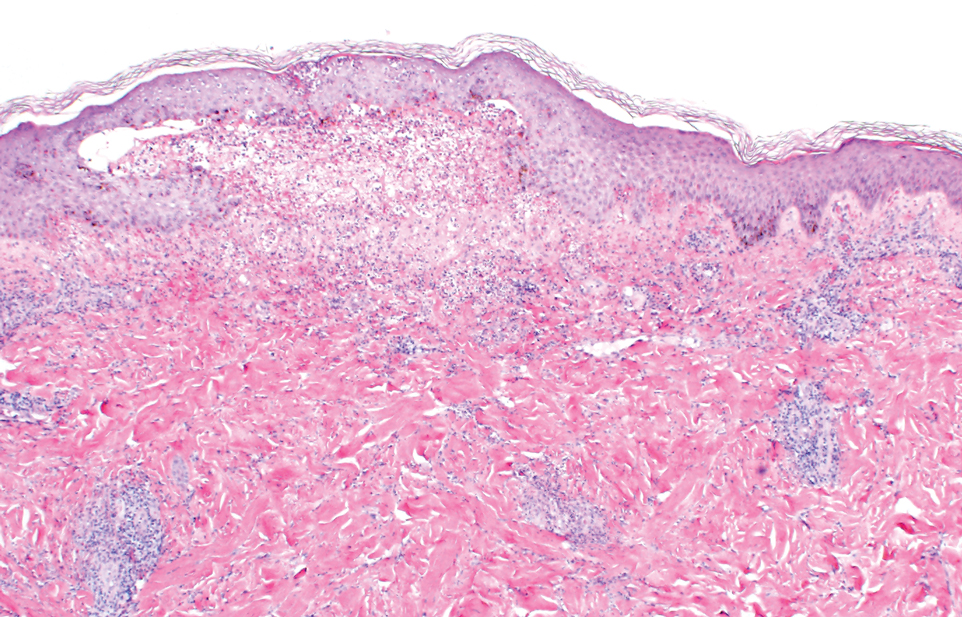

A retrospective review was conducted in patients with histologically diagnosed LET who presented to the Department of Dermatology at the Wake Forest School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) over 6 years (July 2012 to July 2018). Inclusion criteria included males or females aged 18 to 75 years with clinical and histopathology-proven LET, which was defined as a superficial and deep lymphocytic infiltrate with abundant mucin deposition in the reticular dermis and absent or focal dermoepidermal junction alterations. Exclusion criteria included males or females younger than 18 years or older than 75 years or patients without clinical and histopathologically proven LET. Medical records were evaluated for demographics, clinical characteristics, diagnoses, autoantibodies, treatment, and recurrence. Photosensitivity was confirmed by clinical history. This study was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine institutional review board.

Results

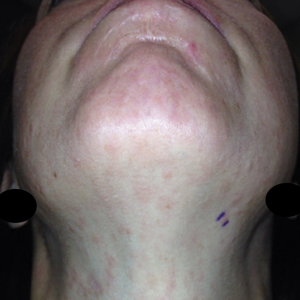

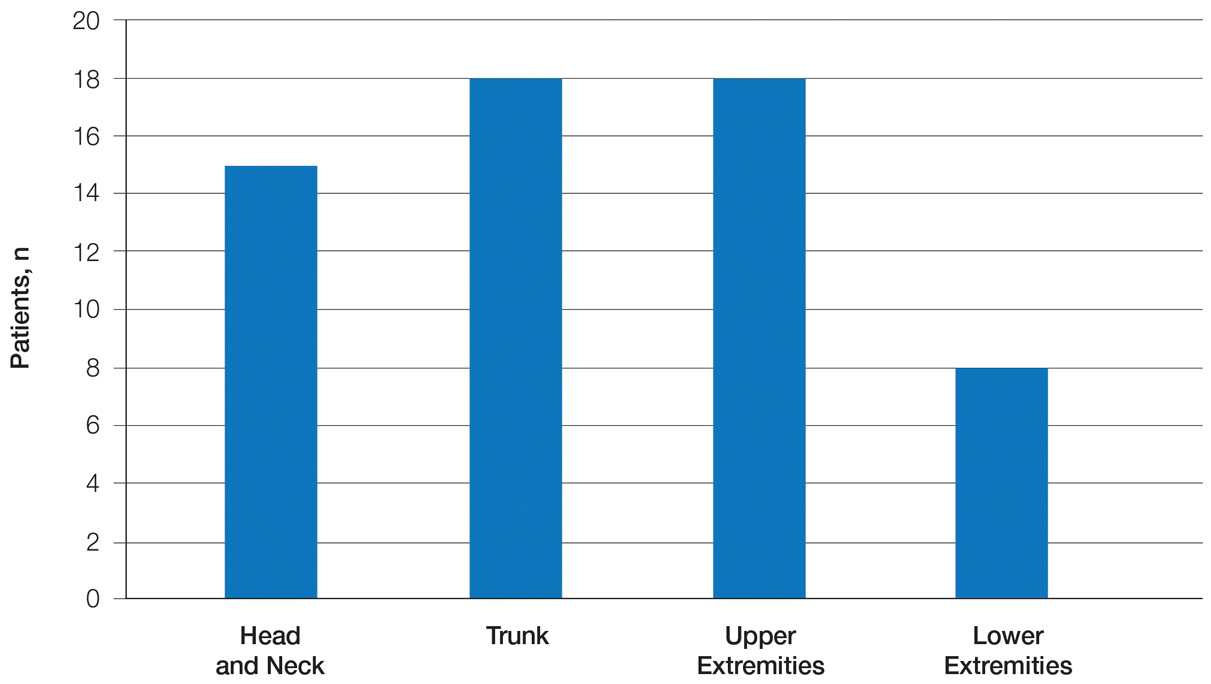

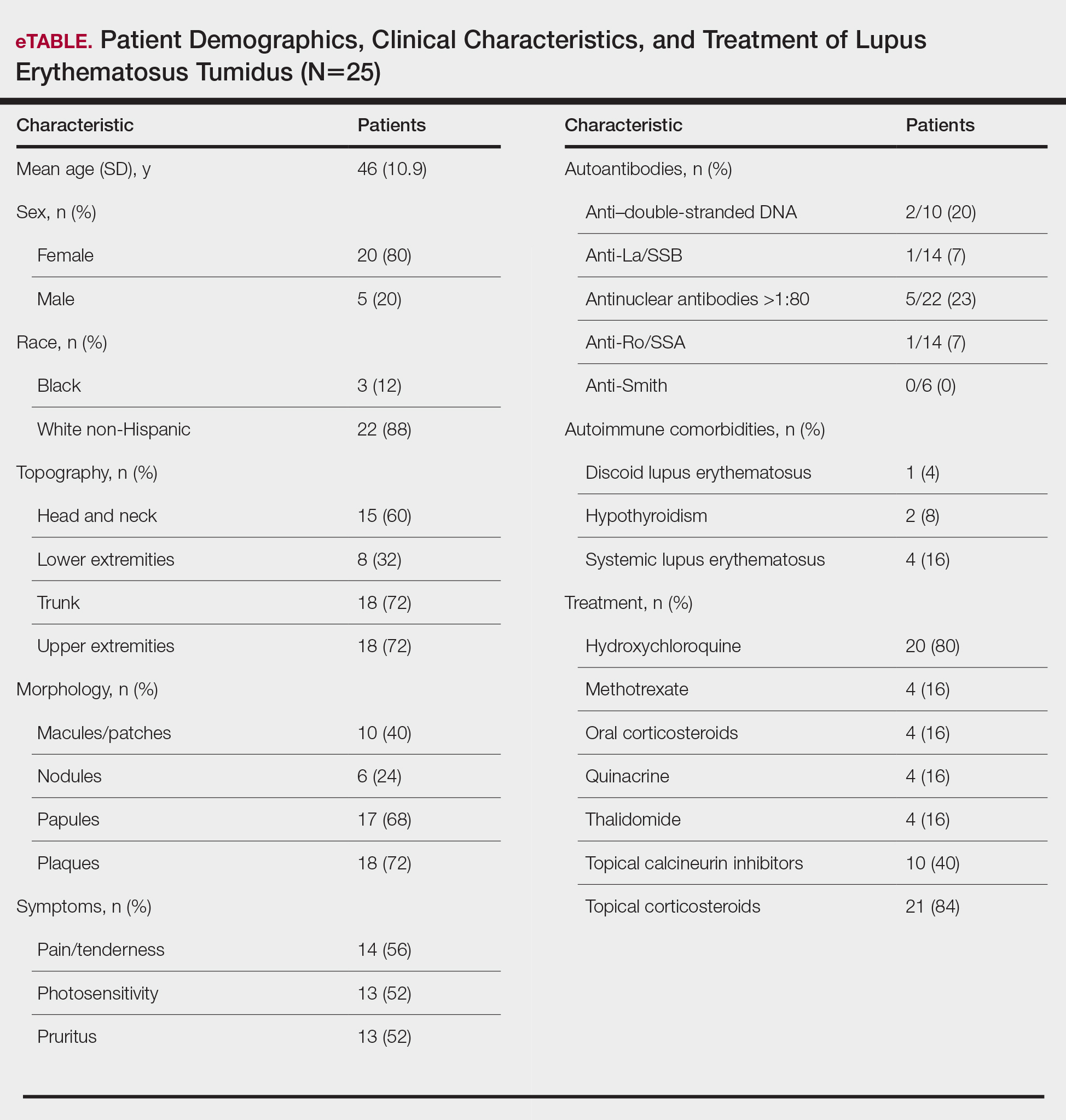

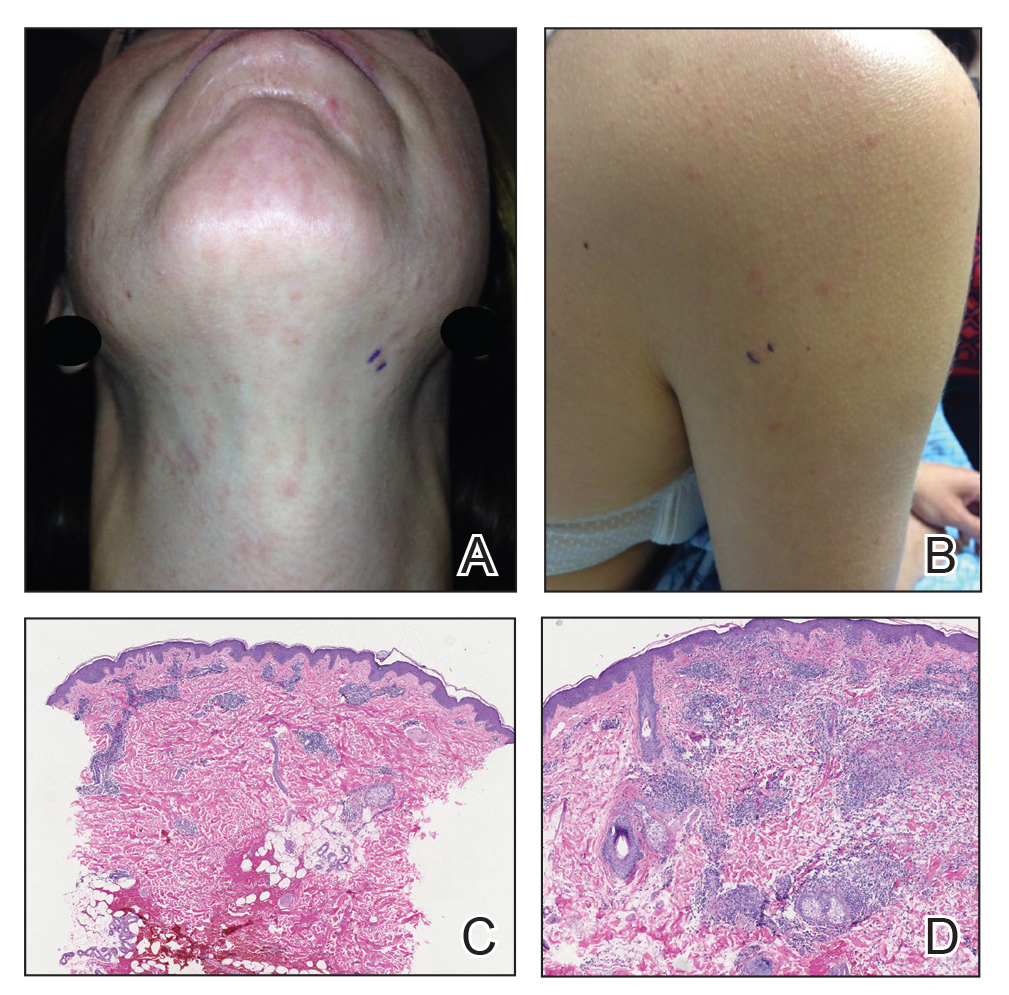

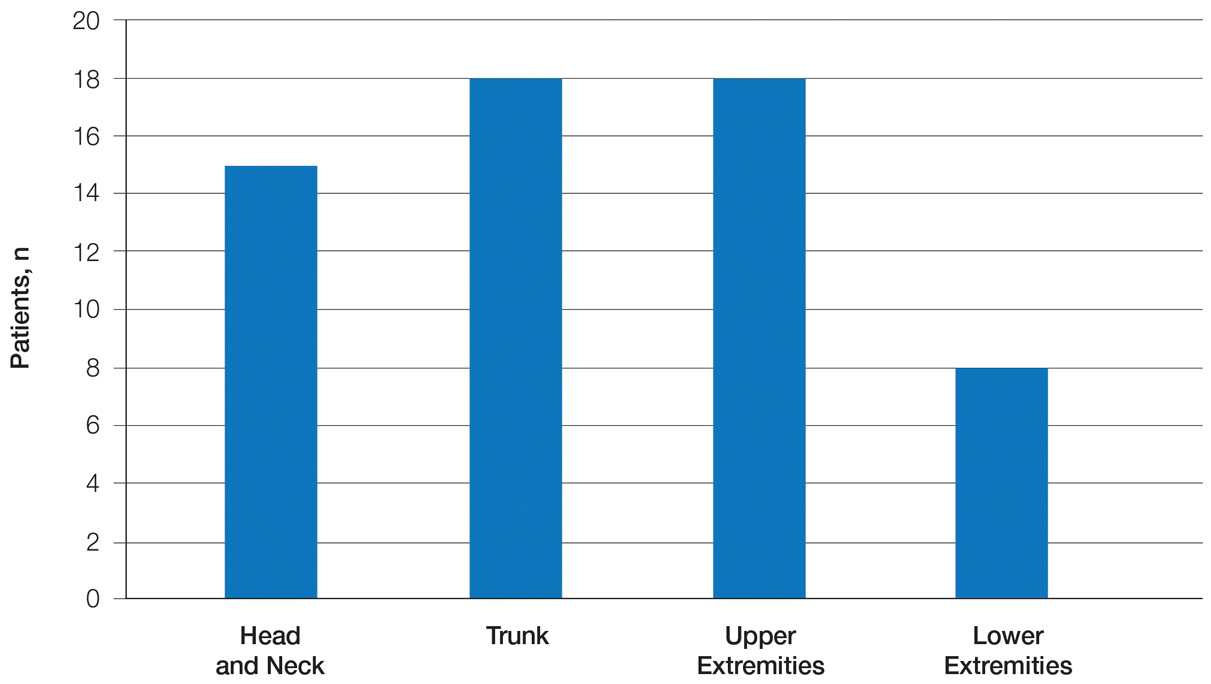

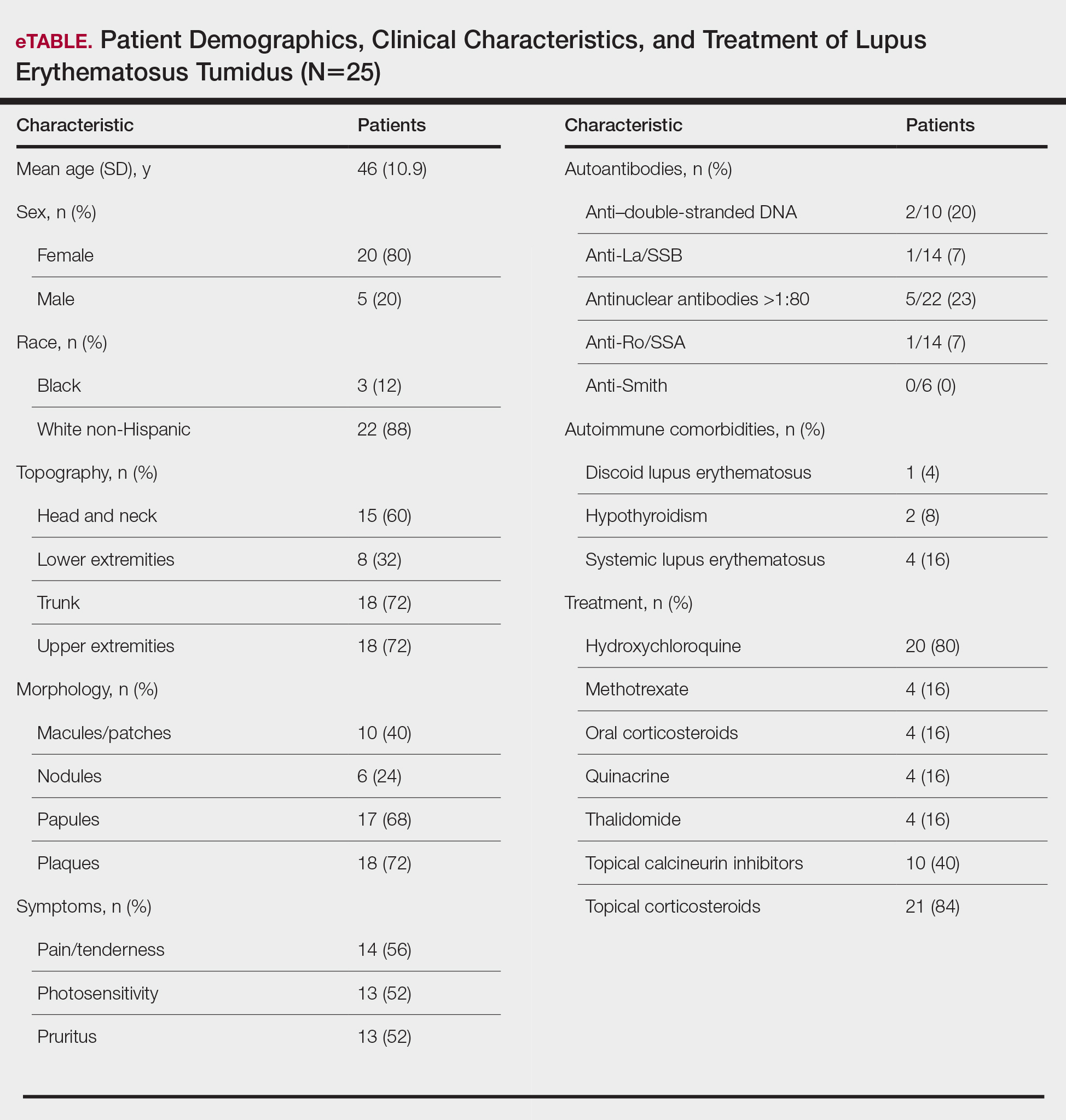

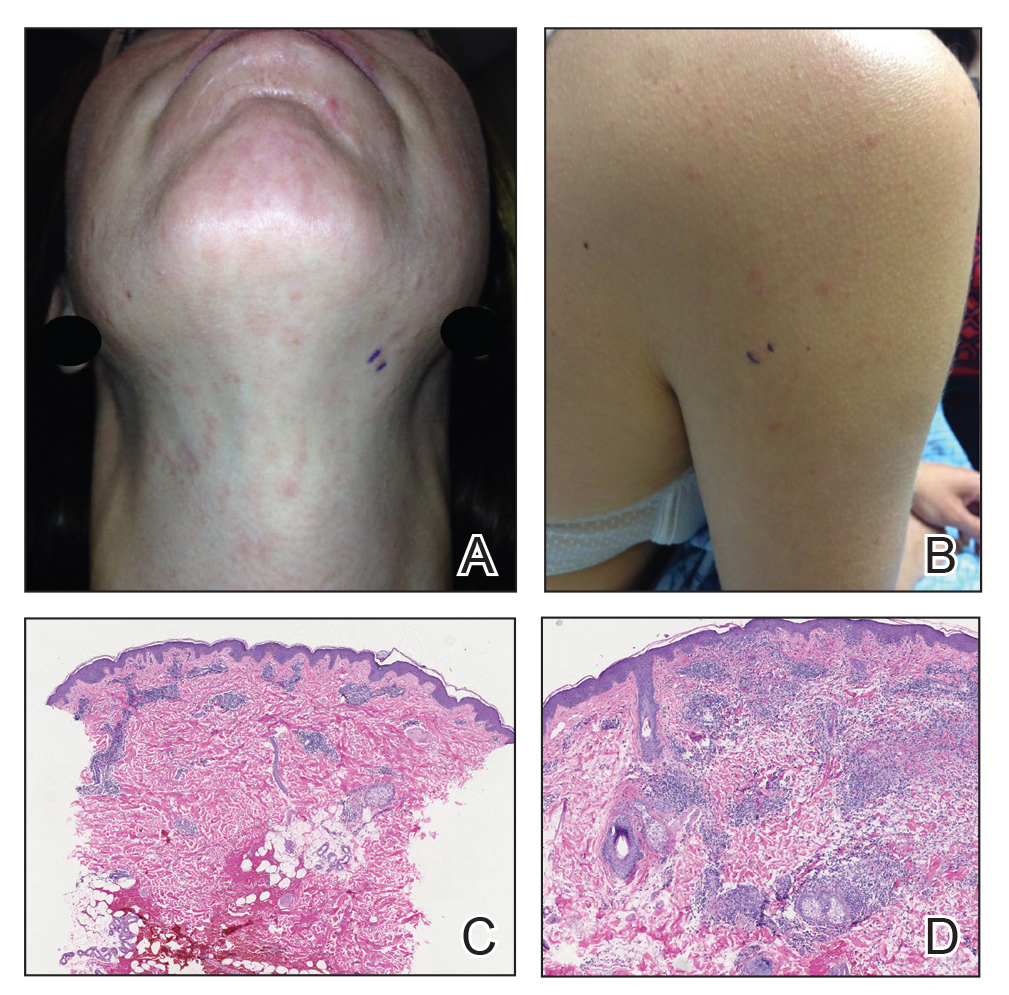

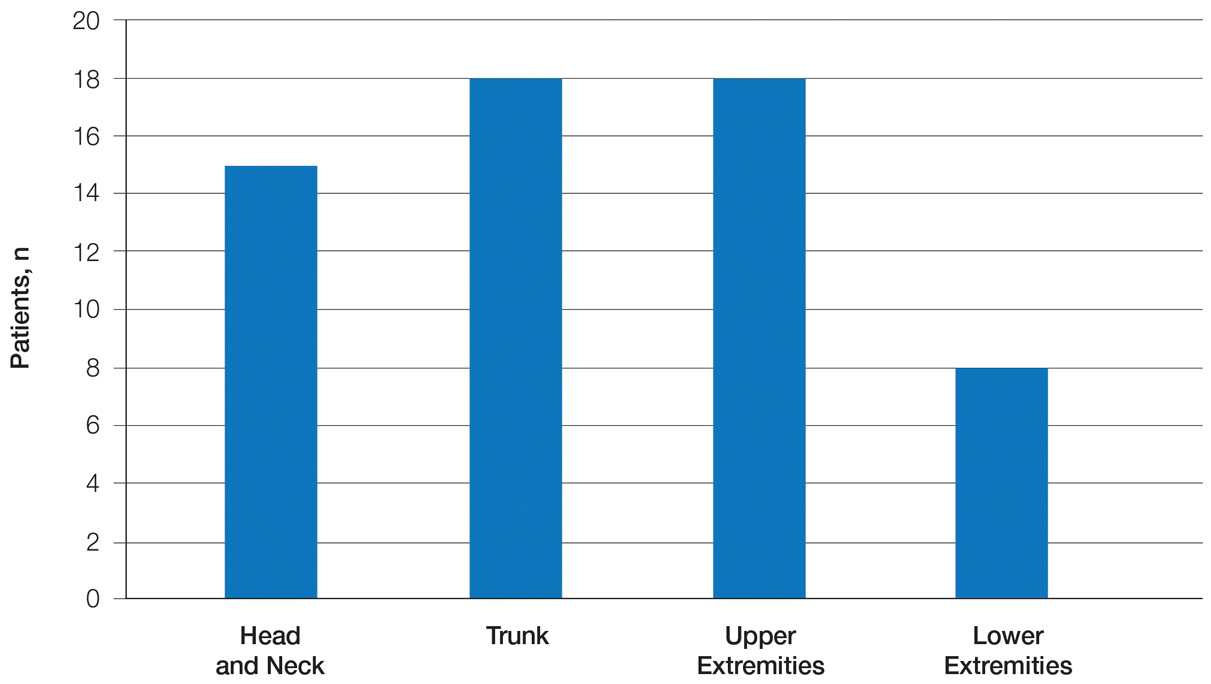

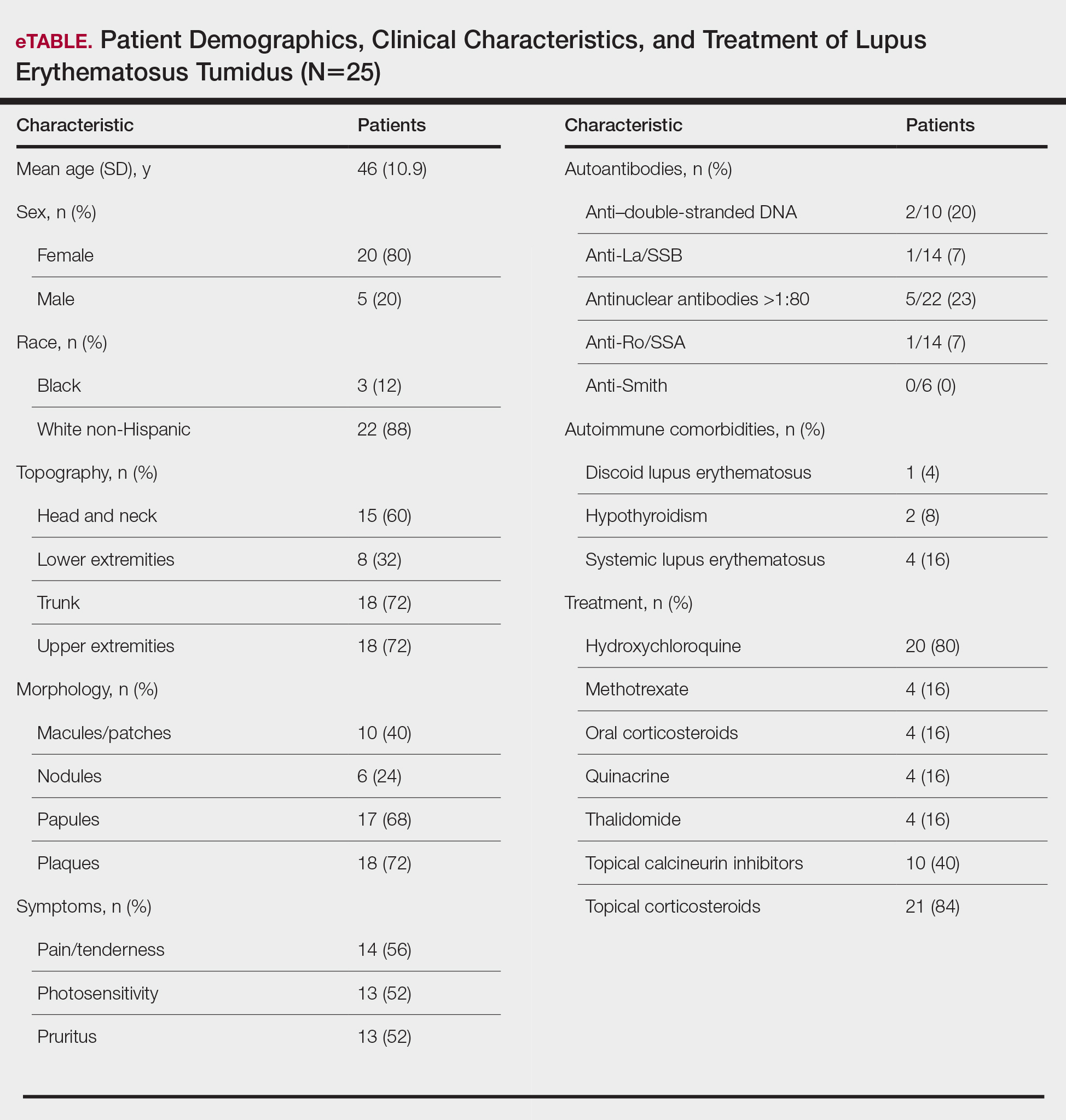

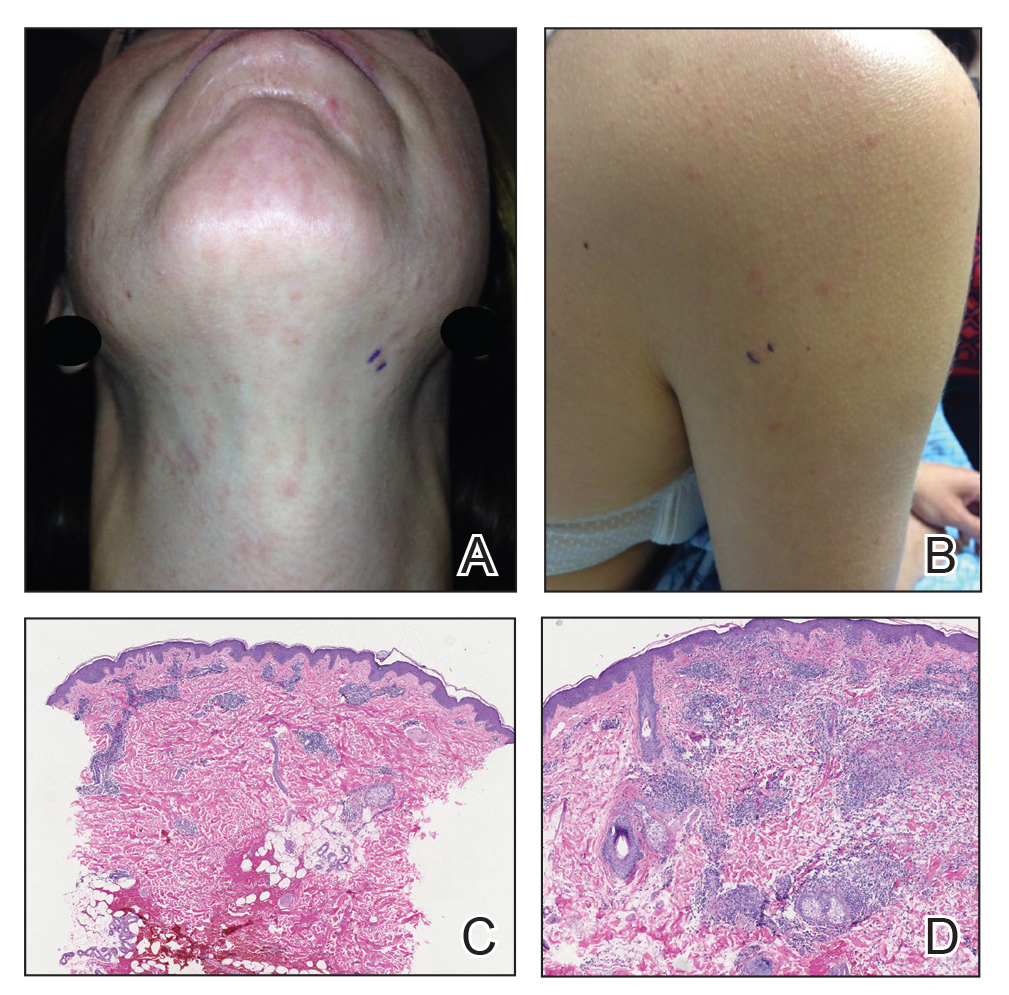

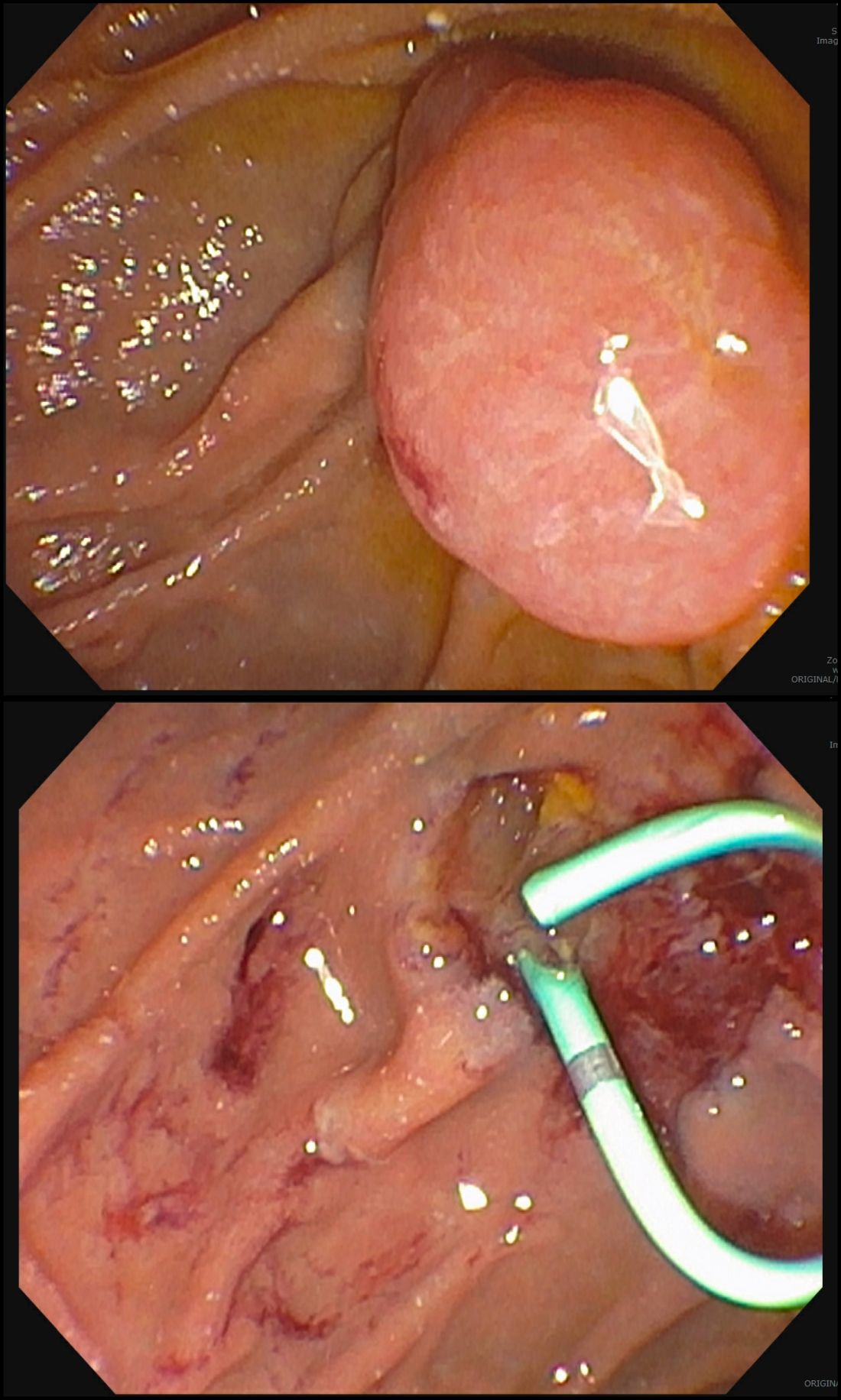

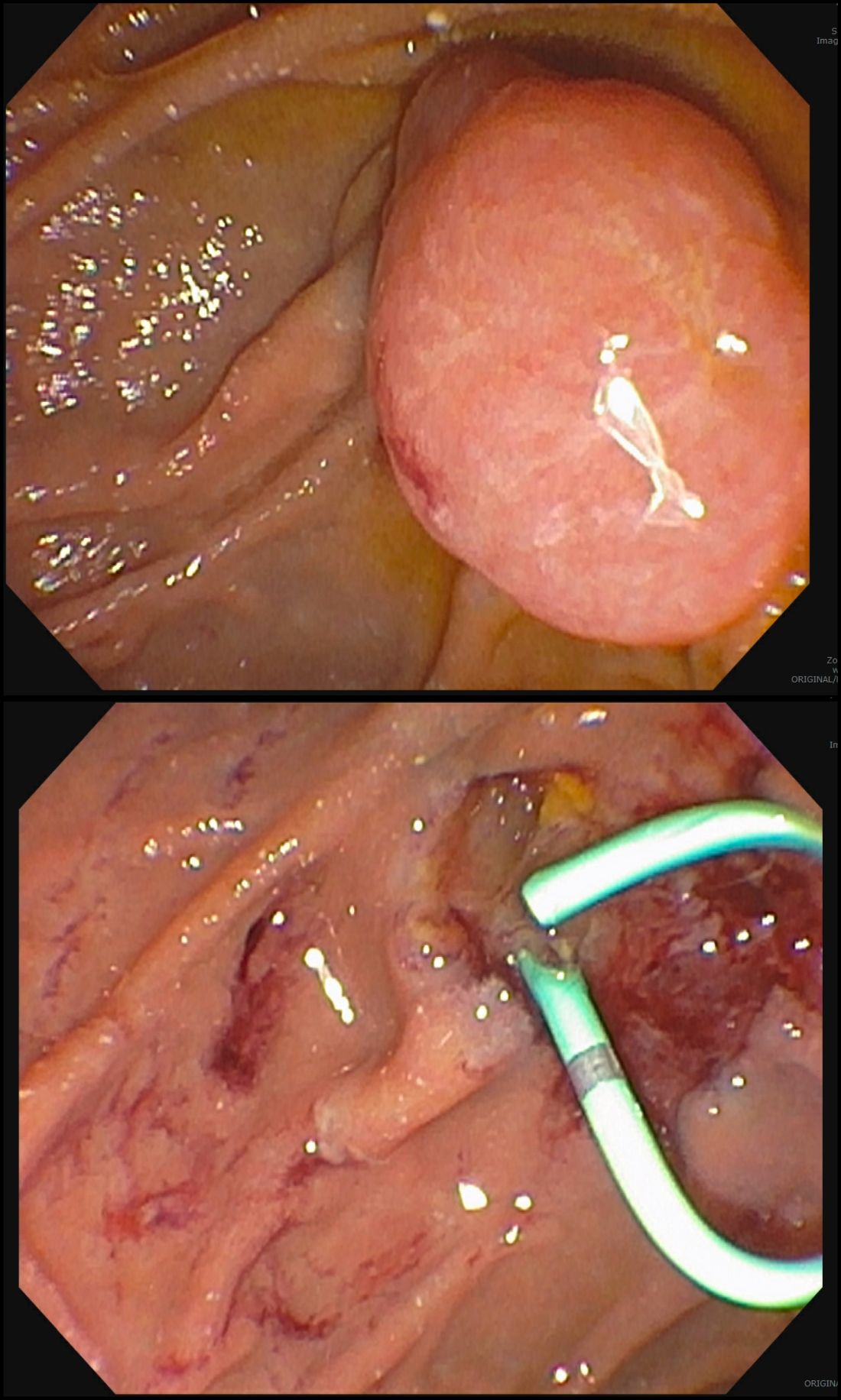

Twenty-five patients were included in the study (eTable). The mean age (SD) at diagnosis was 46 (10.9) years, with a male to female ratio of 1:4. Twenty-two (88%) patients were White non-Hispanic, whereas 3 (12%) were Black. Lupus erythematosus tumidus most commonly affected the trunk (18/25 [72%]) and upper extremities (18/25 [72%]), followed by the head and neck (15/25 [60%]) and lower extremities (8/25 [32%])(Figure 1). The most common morphologies were plaques (18/25 [72%]), papules (17/25 [68%]), and nodules (6/25 [24%])(Figures 2 and 3). Most patients experienced painful (14/25 [56%]) or pruritic (13/25 [52%]) lesions as well as photosensitivity (13/25 [52%]). Of all measured autoantibodies, 5 of 22 (23%) patients had positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) titers greater than 1:80, 1 of 14 (7%) patients had positive anti-Ro (anti-SSA), 1 of 14 (7%) had positive anti-La (anti-SSB), 2 of 10 (20%) had positive anti–double-stranded DNA, and 0 of 6 (0%) patients had positive anti-Smith antibodies. Four (16%) patients with SLE had skin and joint involvement, whereas 1 had lupus nephritis. One (4%) patient had discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). Seventeen (68%) patients reported recurrences or flares. The mean duration of symptoms (SD) was 28 (44) months.

Topical corticosteroids (21/25 [84%]) and hydroxychloroquine (20/25 [80%]) were the most commonly prescribed treatments. Hydroxychloroquine monotherapy achieved clearance or almost clearance in 12 (60%) patients. Four patients were prescribed thalidomide after hydroxychloroquine monotherapy failed; 2 achieved complete clearance with thalidomide and hydroxychloroquine, 1 achieved complete clearance with thalidomide monotherapy, and 1 improved but did not clear. Four patients were concurrently started on quinacrine (mepacrine) after hydroxychloroquine monotherapy failed; 1 patient had no clearance, 1 discontinued because of allergy, 1 improved, and 1 cleared. Four patients had short courses of prednisone lasting 1 to 4 weeks. Three of 4 patients treated with methotrexate discontinued because of adverse effects, and 1 patient improved. Other prescribed treatments included topical calcineurin inhibitors (10/25 [40%]), dapsone (1/25 [4%]), and clofazimine (1/25 [4%]).

Comment

Prevalence of LET—Although other European LET case series reported a male predominance or equal male to female ratio, our case series reported female predominance (1:4).1,3-5 Our male to female ratio resembles similar ratios in DLE and subacute lupus erythematosus, whereas relative to our study, SLE male to female ratios favored females over males.6,7

Clinical Distribution of LET—In one study enrolling 24 patients with LET, 79% (19/24) of patients had facial involvement, 50% (12/24) had V-neck involvement, 50% (12/24) had back involvement, and 46% (11/24) had arm involvement,2 whereas our study reported 72% involvement of the trunk, 72% involvement of the upper extremities, 60% involvement of the head and neck region, and 32% involvement of the lower extremities. Although our study reported more lower extremity involvement, the aforementioned study used precise topographic locations, whereas we used more generalized topographic locations. Therefore, it was difficult to compare disease distribution between both studies.2

Presence of Autoantibodies and Comorbidities—Of the 22 patients tested for ANA, 23% reported titers greater than 1:80, similar to the 20% positive ANA prevalence in an LET case series of 25 patients.5 Of 4 patients diagnosed with SLE, 3 had articular and skin involvement, and 1 had renal involvement. These findings resemble a similar LET case series.2 Nonetheless, given the numerous skin criteria in the American College of Rheumatology SLE classification criteria, patients with predominant skin disease and positive autoantibodies are diagnosed as having SLE without notable extracutaneous involvement.2 Therefore, SLE diagnosis in the setting of LET could be reassessed periodically in this population. One patient in our study was diagnosed with DLE several years later. It is uncommon for LET to be reported concomitantly with DLE.8

Treatment of LET—Evidence supporting efficacious treatment options for LET is limited to case series. Sun protection is recommended in all patients with LET. Earlier case series reported a high response rate with sun protection and topical corticosteroids, with 19% to 55% of patients requiring subsequent systemic antimalarials.3,4 However, one case series presented a need for systemic antimalarials,5 similar to our study. Hydroxychloroquine 200 to 400 mg daily is considered the first-line systemic treatment for LET. Its response rate varies among studies and may be influenced by dosage.1,3 Second-line treatments include methotrexate 7.5 to 25 mg once weekly, thalidomide 50 to 100 mg daily, and quinacrine. However, quinacrine is not currently commercially available. Thalidomide and quinacrine represented useful alternatives when hydroxychloroquine monotherapy failed. As with other immunomodulators, adverse effects should be monitored periodically.

Conclusion

Lupus erythematosus tumidus is characterized by erythematous papules and plaques that may be tender or pruritic. It follows an intermittent course and rarely is associated with SLE. Hydroxychloroquine is considered the first-line systemic treatment; however, recalcitrant disease could be managed with other immunomodulators, including methotrexate, thalidomide, or quinacrine.

- Kuhn A, Bein D, Bonsmann G. The 100th anniversary of lupus erythematosus tumidus. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8:441-448.

- Schmitt V, Meuth AM, Amler S, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus is a separate subtype of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:64-73.

- Kuhn A, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus—a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

- Vieira V, Del Pozo J, Yebra-Pimentel MT, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: a series of 26 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:512-517.

- Rodriguez-Caruncho C, Bielsa I, Fernandez-Figueras MT, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: a clinical and histological study of 25 cases. Lupus. 2015;24:751-755.

- Patsinakidis N, Gambichler T, Lahner N, et al. Cutaneous characteristics and association with antinuclear antibodies in 402 patients with different subtypes of lupus erythematosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:2097-2104.

- Petersen MP, Moller S, Bygum A, et al. Epidemiology of cutaneous lupus erythematosus and the associated risk of systemic lupus erythematosus: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Lupus. 2018;27:1424-1430.

- Dekle CL, Mannes KD, Davis LS, et al. Lupus tumidus. J Am AcadDermatol. 1999;41:250-253.

Lupus erythematosus tumidus (LET) is a rare photosensitive dermatosis1 that previously was considered a subtype of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus; however, the clinical course and favorable prognosis of LET led to its reclassification into another category, called intermittent cutaneous lupus erythematosus.2 Although known about for more than 100 years, the association of LET with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), its autoantibody profile, and its prognosis are not well characterized. The purpose of this study was to describe the demographics, clinical characteristics, autoantibody profile, comorbidities, and treatment of LET based on a retrospective review of patients with LET.

Methods

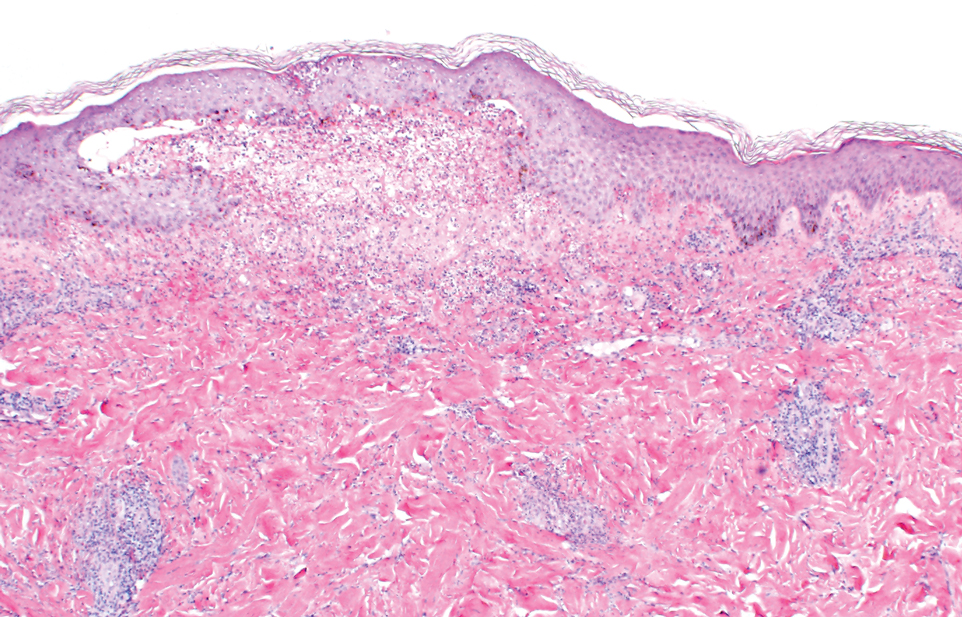

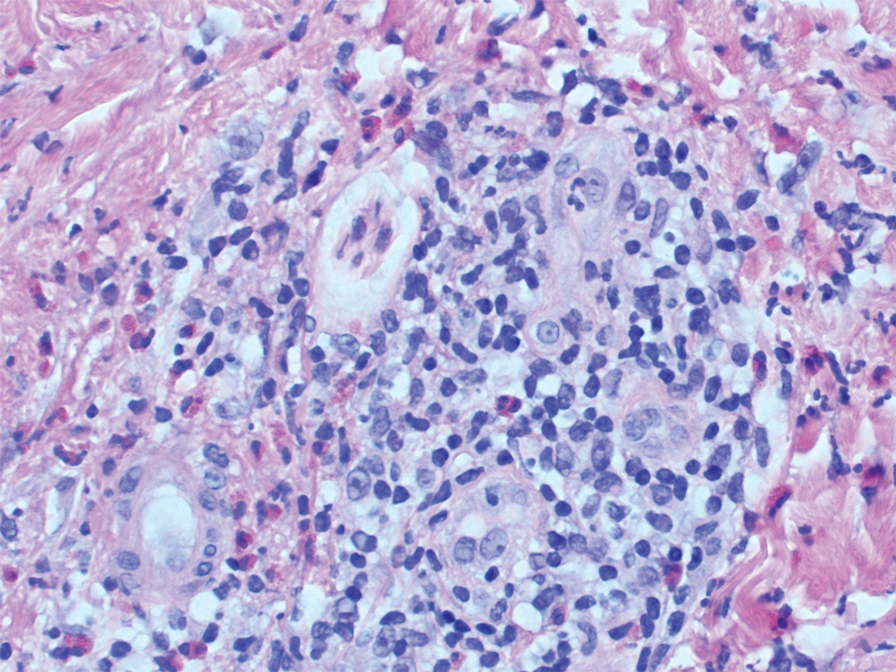

A retrospective review was conducted in patients with histologically diagnosed LET who presented to the Department of Dermatology at the Wake Forest School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) over 6 years (July 2012 to July 2018). Inclusion criteria included males or females aged 18 to 75 years with clinical and histopathology-proven LET, which was defined as a superficial and deep lymphocytic infiltrate with abundant mucin deposition in the reticular dermis and absent or focal dermoepidermal junction alterations. Exclusion criteria included males or females younger than 18 years or older than 75 years or patients without clinical and histopathologically proven LET. Medical records were evaluated for demographics, clinical characteristics, diagnoses, autoantibodies, treatment, and recurrence. Photosensitivity was confirmed by clinical history. This study was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine institutional review board.

Results

Twenty-five patients were included in the study (eTable). The mean age (SD) at diagnosis was 46 (10.9) years, with a male to female ratio of 1:4. Twenty-two (88%) patients were White non-Hispanic, whereas 3 (12%) were Black. Lupus erythematosus tumidus most commonly affected the trunk (18/25 [72%]) and upper extremities (18/25 [72%]), followed by the head and neck (15/25 [60%]) and lower extremities (8/25 [32%])(Figure 1). The most common morphologies were plaques (18/25 [72%]), papules (17/25 [68%]), and nodules (6/25 [24%])(Figures 2 and 3). Most patients experienced painful (14/25 [56%]) or pruritic (13/25 [52%]) lesions as well as photosensitivity (13/25 [52%]). Of all measured autoantibodies, 5 of 22 (23%) patients had positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) titers greater than 1:80, 1 of 14 (7%) patients had positive anti-Ro (anti-SSA), 1 of 14 (7%) had positive anti-La (anti-SSB), 2 of 10 (20%) had positive anti–double-stranded DNA, and 0 of 6 (0%) patients had positive anti-Smith antibodies. Four (16%) patients with SLE had skin and joint involvement, whereas 1 had lupus nephritis. One (4%) patient had discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). Seventeen (68%) patients reported recurrences or flares. The mean duration of symptoms (SD) was 28 (44) months.

Topical corticosteroids (21/25 [84%]) and hydroxychloroquine (20/25 [80%]) were the most commonly prescribed treatments. Hydroxychloroquine monotherapy achieved clearance or almost clearance in 12 (60%) patients. Four patients were prescribed thalidomide after hydroxychloroquine monotherapy failed; 2 achieved complete clearance with thalidomide and hydroxychloroquine, 1 achieved complete clearance with thalidomide monotherapy, and 1 improved but did not clear. Four patients were concurrently started on quinacrine (mepacrine) after hydroxychloroquine monotherapy failed; 1 patient had no clearance, 1 discontinued because of allergy, 1 improved, and 1 cleared. Four patients had short courses of prednisone lasting 1 to 4 weeks. Three of 4 patients treated with methotrexate discontinued because of adverse effects, and 1 patient improved. Other prescribed treatments included topical calcineurin inhibitors (10/25 [40%]), dapsone (1/25 [4%]), and clofazimine (1/25 [4%]).

Comment

Prevalence of LET—Although other European LET case series reported a male predominance or equal male to female ratio, our case series reported female predominance (1:4).1,3-5 Our male to female ratio resembles similar ratios in DLE and subacute lupus erythematosus, whereas relative to our study, SLE male to female ratios favored females over males.6,7

Clinical Distribution of LET—In one study enrolling 24 patients with LET, 79% (19/24) of patients had facial involvement, 50% (12/24) had V-neck involvement, 50% (12/24) had back involvement, and 46% (11/24) had arm involvement,2 whereas our study reported 72% involvement of the trunk, 72% involvement of the upper extremities, 60% involvement of the head and neck region, and 32% involvement of the lower extremities. Although our study reported more lower extremity involvement, the aforementioned study used precise topographic locations, whereas we used more generalized topographic locations. Therefore, it was difficult to compare disease distribution between both studies.2

Presence of Autoantibodies and Comorbidities—Of the 22 patients tested for ANA, 23% reported titers greater than 1:80, similar to the 20% positive ANA prevalence in an LET case series of 25 patients.5 Of 4 patients diagnosed with SLE, 3 had articular and skin involvement, and 1 had renal involvement. These findings resemble a similar LET case series.2 Nonetheless, given the numerous skin criteria in the American College of Rheumatology SLE classification criteria, patients with predominant skin disease and positive autoantibodies are diagnosed as having SLE without notable extracutaneous involvement.2 Therefore, SLE diagnosis in the setting of LET could be reassessed periodically in this population. One patient in our study was diagnosed with DLE several years later. It is uncommon for LET to be reported concomitantly with DLE.8

Treatment of LET—Evidence supporting efficacious treatment options for LET is limited to case series. Sun protection is recommended in all patients with LET. Earlier case series reported a high response rate with sun protection and topical corticosteroids, with 19% to 55% of patients requiring subsequent systemic antimalarials.3,4 However, one case series presented a need for systemic antimalarials,5 similar to our study. Hydroxychloroquine 200 to 400 mg daily is considered the first-line systemic treatment for LET. Its response rate varies among studies and may be influenced by dosage.1,3 Second-line treatments include methotrexate 7.5 to 25 mg once weekly, thalidomide 50 to 100 mg daily, and quinacrine. However, quinacrine is not currently commercially available. Thalidomide and quinacrine represented useful alternatives when hydroxychloroquine monotherapy failed. As with other immunomodulators, adverse effects should be monitored periodically.

Conclusion

Lupus erythematosus tumidus is characterized by erythematous papules and plaques that may be tender or pruritic. It follows an intermittent course and rarely is associated with SLE. Hydroxychloroquine is considered the first-line systemic treatment; however, recalcitrant disease could be managed with other immunomodulators, including methotrexate, thalidomide, or quinacrine.

Lupus erythematosus tumidus (LET) is a rare photosensitive dermatosis1 that previously was considered a subtype of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus; however, the clinical course and favorable prognosis of LET led to its reclassification into another category, called intermittent cutaneous lupus erythematosus.2 Although known about for more than 100 years, the association of LET with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), its autoantibody profile, and its prognosis are not well characterized. The purpose of this study was to describe the demographics, clinical characteristics, autoantibody profile, comorbidities, and treatment of LET based on a retrospective review of patients with LET.

Methods

A retrospective review was conducted in patients with histologically diagnosed LET who presented to the Department of Dermatology at the Wake Forest School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) over 6 years (July 2012 to July 2018). Inclusion criteria included males or females aged 18 to 75 years with clinical and histopathology-proven LET, which was defined as a superficial and deep lymphocytic infiltrate with abundant mucin deposition in the reticular dermis and absent or focal dermoepidermal junction alterations. Exclusion criteria included males or females younger than 18 years or older than 75 years or patients without clinical and histopathologically proven LET. Medical records were evaluated for demographics, clinical characteristics, diagnoses, autoantibodies, treatment, and recurrence. Photosensitivity was confirmed by clinical history. This study was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine institutional review board.

Results

Twenty-five patients were included in the study (eTable). The mean age (SD) at diagnosis was 46 (10.9) years, with a male to female ratio of 1:4. Twenty-two (88%) patients were White non-Hispanic, whereas 3 (12%) were Black. Lupus erythematosus tumidus most commonly affected the trunk (18/25 [72%]) and upper extremities (18/25 [72%]), followed by the head and neck (15/25 [60%]) and lower extremities (8/25 [32%])(Figure 1). The most common morphologies were plaques (18/25 [72%]), papules (17/25 [68%]), and nodules (6/25 [24%])(Figures 2 and 3). Most patients experienced painful (14/25 [56%]) or pruritic (13/25 [52%]) lesions as well as photosensitivity (13/25 [52%]). Of all measured autoantibodies, 5 of 22 (23%) patients had positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) titers greater than 1:80, 1 of 14 (7%) patients had positive anti-Ro (anti-SSA), 1 of 14 (7%) had positive anti-La (anti-SSB), 2 of 10 (20%) had positive anti–double-stranded DNA, and 0 of 6 (0%) patients had positive anti-Smith antibodies. Four (16%) patients with SLE had skin and joint involvement, whereas 1 had lupus nephritis. One (4%) patient had discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). Seventeen (68%) patients reported recurrences or flares. The mean duration of symptoms (SD) was 28 (44) months.

Topical corticosteroids (21/25 [84%]) and hydroxychloroquine (20/25 [80%]) were the most commonly prescribed treatments. Hydroxychloroquine monotherapy achieved clearance or almost clearance in 12 (60%) patients. Four patients were prescribed thalidomide after hydroxychloroquine monotherapy failed; 2 achieved complete clearance with thalidomide and hydroxychloroquine, 1 achieved complete clearance with thalidomide monotherapy, and 1 improved but did not clear. Four patients were concurrently started on quinacrine (mepacrine) after hydroxychloroquine monotherapy failed; 1 patient had no clearance, 1 discontinued because of allergy, 1 improved, and 1 cleared. Four patients had short courses of prednisone lasting 1 to 4 weeks. Three of 4 patients treated with methotrexate discontinued because of adverse effects, and 1 patient improved. Other prescribed treatments included topical calcineurin inhibitors (10/25 [40%]), dapsone (1/25 [4%]), and clofazimine (1/25 [4%]).

Comment

Prevalence of LET—Although other European LET case series reported a male predominance or equal male to female ratio, our case series reported female predominance (1:4).1,3-5 Our male to female ratio resembles similar ratios in DLE and subacute lupus erythematosus, whereas relative to our study, SLE male to female ratios favored females over males.6,7

Clinical Distribution of LET—In one study enrolling 24 patients with LET, 79% (19/24) of patients had facial involvement, 50% (12/24) had V-neck involvement, 50% (12/24) had back involvement, and 46% (11/24) had arm involvement,2 whereas our study reported 72% involvement of the trunk, 72% involvement of the upper extremities, 60% involvement of the head and neck region, and 32% involvement of the lower extremities. Although our study reported more lower extremity involvement, the aforementioned study used precise topographic locations, whereas we used more generalized topographic locations. Therefore, it was difficult to compare disease distribution between both studies.2

Presence of Autoantibodies and Comorbidities—Of the 22 patients tested for ANA, 23% reported titers greater than 1:80, similar to the 20% positive ANA prevalence in an LET case series of 25 patients.5 Of 4 patients diagnosed with SLE, 3 had articular and skin involvement, and 1 had renal involvement. These findings resemble a similar LET case series.2 Nonetheless, given the numerous skin criteria in the American College of Rheumatology SLE classification criteria, patients with predominant skin disease and positive autoantibodies are diagnosed as having SLE without notable extracutaneous involvement.2 Therefore, SLE diagnosis in the setting of LET could be reassessed periodically in this population. One patient in our study was diagnosed with DLE several years later. It is uncommon for LET to be reported concomitantly with DLE.8

Treatment of LET—Evidence supporting efficacious treatment options for LET is limited to case series. Sun protection is recommended in all patients with LET. Earlier case series reported a high response rate with sun protection and topical corticosteroids, with 19% to 55% of patients requiring subsequent systemic antimalarials.3,4 However, one case series presented a need for systemic antimalarials,5 similar to our study. Hydroxychloroquine 200 to 400 mg daily is considered the first-line systemic treatment for LET. Its response rate varies among studies and may be influenced by dosage.1,3 Second-line treatments include methotrexate 7.5 to 25 mg once weekly, thalidomide 50 to 100 mg daily, and quinacrine. However, quinacrine is not currently commercially available. Thalidomide and quinacrine represented useful alternatives when hydroxychloroquine monotherapy failed. As with other immunomodulators, adverse effects should be monitored periodically.

Conclusion

Lupus erythematosus tumidus is characterized by erythematous papules and plaques that may be tender or pruritic. It follows an intermittent course and rarely is associated with SLE. Hydroxychloroquine is considered the first-line systemic treatment; however, recalcitrant disease could be managed with other immunomodulators, including methotrexate, thalidomide, or quinacrine.

- Kuhn A, Bein D, Bonsmann G. The 100th anniversary of lupus erythematosus tumidus. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8:441-448.

- Schmitt V, Meuth AM, Amler S, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus is a separate subtype of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:64-73.

- Kuhn A, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus—a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

- Vieira V, Del Pozo J, Yebra-Pimentel MT, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: a series of 26 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:512-517.

- Rodriguez-Caruncho C, Bielsa I, Fernandez-Figueras MT, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: a clinical and histological study of 25 cases. Lupus. 2015;24:751-755.

- Patsinakidis N, Gambichler T, Lahner N, et al. Cutaneous characteristics and association with antinuclear antibodies in 402 patients with different subtypes of lupus erythematosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:2097-2104.

- Petersen MP, Moller S, Bygum A, et al. Epidemiology of cutaneous lupus erythematosus and the associated risk of systemic lupus erythematosus: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Lupus. 2018;27:1424-1430.

- Dekle CL, Mannes KD, Davis LS, et al. Lupus tumidus. J Am AcadDermatol. 1999;41:250-253.

- Kuhn A, Bein D, Bonsmann G. The 100th anniversary of lupus erythematosus tumidus. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8:441-448.

- Schmitt V, Meuth AM, Amler S, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus is a separate subtype of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:64-73.

- Kuhn A, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus—a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

- Vieira V, Del Pozo J, Yebra-Pimentel MT, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: a series of 26 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:512-517.

- Rodriguez-Caruncho C, Bielsa I, Fernandez-Figueras MT, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: a clinical and histological study of 25 cases. Lupus. 2015;24:751-755.

- Patsinakidis N, Gambichler T, Lahner N, et al. Cutaneous characteristics and association with antinuclear antibodies in 402 patients with different subtypes of lupus erythematosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:2097-2104.

- Petersen MP, Moller S, Bygum A, et al. Epidemiology of cutaneous lupus erythematosus and the associated risk of systemic lupus erythematosus: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Lupus. 2018;27:1424-1430.

- Dekle CL, Mannes KD, Davis LS, et al. Lupus tumidus. J Am AcadDermatol. 1999;41:250-253.

Practice Points

- Approximately 20% of patients with lupus erythematosus tumidus (LET) will have positive antinuclear antibody titers.

- Along with cutaneous manifestations, approximately 50% of patients with LET also will have pruritus, tenderness, and photosensitivity.

- If LET is resistant to hydroxychloroquine, consider using quinacrine, methotrexate, or thalidomide.

Deployed Airbag Causes Bullous Reaction Following a Motor Vehicle Accident

Airbags are lifesaving during motor vehicle accidents (MVAs), but their deployment has been associated with skin issues such as irritant dermatitis1; lacerations2; abrasions3; and thermal, friction, and chemical burns.4-6 Ocular issues such as alkaline chemical keratitis7 and ocular alkali injuries8 also have been described.

Airbag deployment is triggered by rapid deceleration and impact, which ignite a sodium azide cartridge, causing the woven nylon bag to inflate with hydrocarbon gases.8 This leads to release of sodium hydroxide, sodium bicarbonate, and metallic oxides in an aerosolized form. If a tear in the meshwork of the airbag occurs, exposure to an even larger amount of powder containing caustic alkali chemicals can occur.8

We describe a patient who developed a bullous reaction to airbag contents after he was involved in an MVA in which the airbag deployed.

Case Report

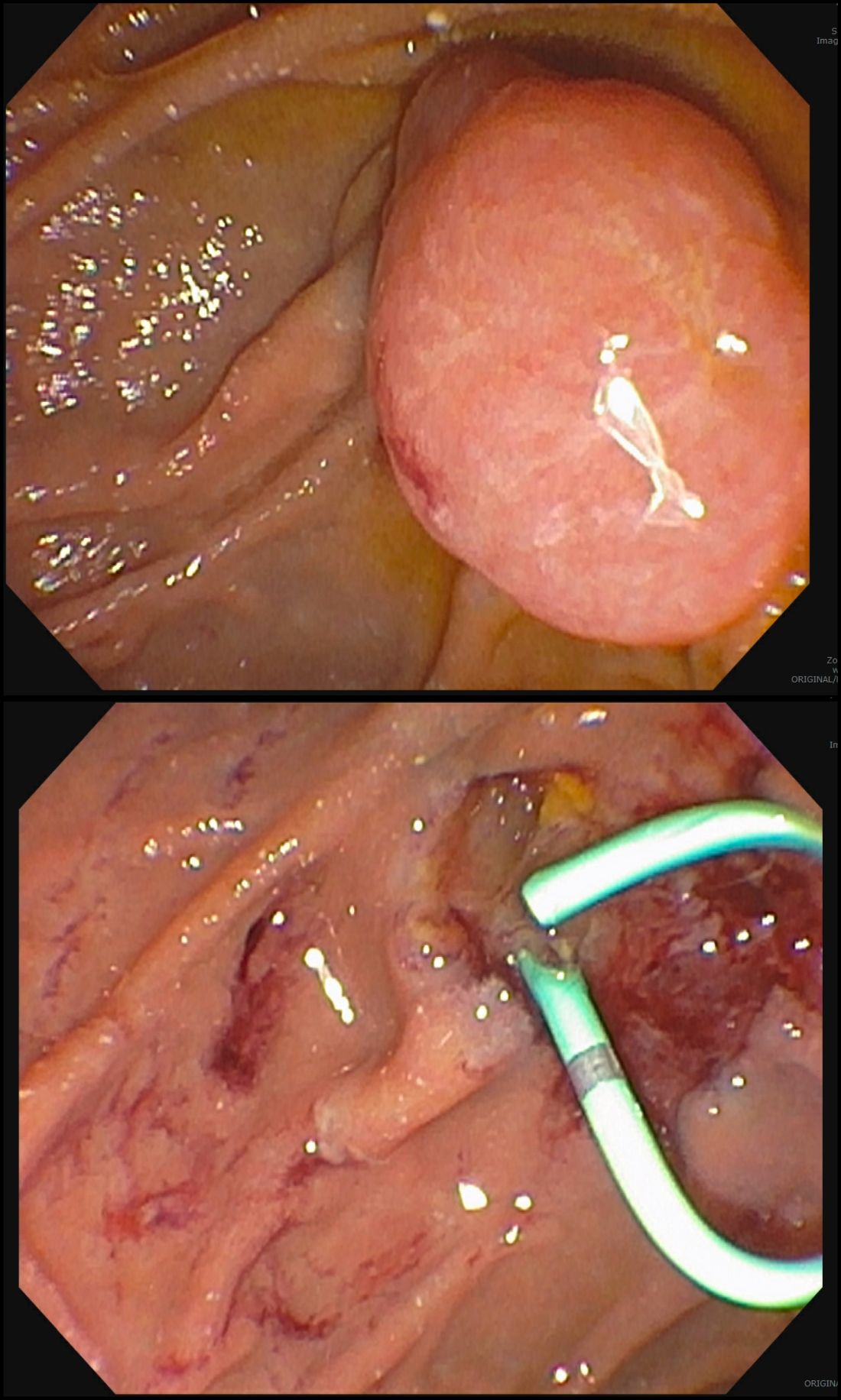

A 35-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic hepatitis B presented to the dermatology clinic for an evaluation of new-onset blisters. The rash occurred 1 day after the patient was involved in an MVA in which he was exposed to the airbag’s contents after it burst. He had been evaluated twice in the emergency department for the skin eruption before being referred to dermatology. He noted the lesions were pruritic and painful. Prior treatments included silver sulfadiazine cream 1% and clobetasol cream 0.05%, though he discontinued using the latter because of burning with application. Physical examination revealed tense vesicles and bullae on an erythematous base on the right lower flank, forearms, and legs, with the exception of the lower right leg where a cast had been from a prior injury (Figure 1).

Two punch biopsies of the left arm were performed and sent for hematoxylin and eosin staining and direct immunofluorescence to rule out bullous diseases, such as bullous pemphigoid, linear IgA, and bullous lupus. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed extensive spongiosis with blister formation and a dense perivascular infiltrate in the superficial and mid dermis composed of lymphocytes with numerous scattered eosinophils (Figures 2 and 3). Direct immunofluorescence studies were negative. Treatment with oral prednisone and oral antihistamines was initiated.

At 10-day follow-up, the patient had a few residual bullae; most lesions were demonstrating various stages of healing (Figure 4). The patient’s cast had been removed, and there were no lesions in this previously covered area. At 6-week follow-up he had continued healing of the bullae and erosions as well as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (Figure 5).

Comment

With the advent of airbags for safety purposes, these potentially lifesaving devices also have been known to cause injury.9 In 1998, the most commonly reported airbag injuries were ocular injuries.10 Cutaneous manifestations of airbag injury are less well known.11

Two cases of airbag deployment with skin blistering have been reported in the literature based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms airbag blistering or airbag bullae12,13; however, the blistering was described in the context of a burn. One case of the effects of airbag deployment residue highlights a patient arriving to the emergency department with erythema and blisters on the hands within 48 hours of airbag deployment in an MVA, and the treatment was standard burn therapy.12 Another case report described a patient with a second-degree burn with a 12-cm blister occurring on the radial side of the hand and distal forearm following an MVA and airbag deployment, which was treated conservatively.13 Cases of thermal burns, chemical burns, and irritant contact dermatitis after airbag deployment have been described in the literature.4-6,11,12,14,15 Our patient’s distal right lower leg was covered with a cast for osteomyelitis, and no blisters had developed in this area. It is likely that the transfer of airbag contents occurred during the process of unbuckling his seatbelt, which could explain the bullae that developed on the right flank. Per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, individuals should quickly remove clothing and wash their body with large amounts of soap and water following exposure to sodium azide.16

In 1989, the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard No. 208 (occupant crash protection) became effective, stating all cars must have vehicle crash protection.12 Prior to 1993, it was reported that there had been no associated chemical injuries with airbag deployment. Subsequently, a 6-month retrospective study in 1993 showed that dermal injuries were found in connection with the presence of sodium hydroxide in automobile airbags.12 By 2004, it was known that airbags could cause chemical and thermal burns in addition to traumatic injuries from deployment.1 Since 2007, all motor vehicles have been required to have advanced airbags, which are engineered to sense the presence of passengers and determine if the airbag will deploy, and if so, how much to deploy to minimize airbag-related injury.3

The brand of car that our patient drove during the MVA is one with known airbag recalls due to safety defects; however, the year and actual model of the vehicle are not known, so specific information about the airbag in question is not available. It has been noted that some defective airbag inflators that were exposed to excess moisture during the manufacturing process could explode during deployment, causing shrapnel and airbag rupture, which has been linked to nearly 300 injuries worldwide.17

Conclusion

It is evident that the use of airbag devices reduces morbidity and mortality due to MVAs.9 It also had been reported that up to 96% of airbag-related injuries are relatively minor, which many would argue justifies their use.18 Furthermore, it has been reported that 99.8% of skin injuries following airbag deployment are minor.19 In the United States, it is mandated that every vehicle have functional airbags installed.8

This case highlights the potential for substantial airbag-induced skin reactions, specifically a bullous reaction, following airbag deployment. The persistent pruritus and lasting postinflammatory hyperpigmentation seen in this case were certainly worrisome for our patient. We also present this case to remind dermatology providers of possible treatment approaches to these skin reactions. Immediate cleansing of the affected areas of skin may help avoid such reactions.

- Corazza M, Trincone S, Zampino MR, et al. Air bags and the skin. Skinmed. 2004;3:256-258.

- Corazza M, Trincone S, Virgili A. Effects of airbag deployment: lesions, epidemiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:295-300.

- Kuska TC. Air bag safety: an update. J Emerg Nurs. 2016;42:438-441.

- Ulrich D, Noah EM, Fuchs P, et al. Burn injuries caused by air bag deployment. Burns. 2001;27:196-199.

- Erpenbeck SP, Roy E, Ziembicki JA, et al. A systematic review on airbag-induced burns. J Burn Care Res. 2021;42:481-487.

- Skibba KEH, Cleveland CN, Bell DE. Airbag burns: an unfortunate consequence of motor vehicle safety. J Burn Care Res. 2021;42:71-73.

- Smally AJ, Binzer A, Dolin S, et al. Alkaline chemical keratitis: eye injury from airbags. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:1400-1402.

- Barnes SS, Wong W Jr, Affeldt JC. A case of severe airbag related ocular alkali injury. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2012;71:229-231.

- Wallis LA, Greaves I. Injuries associated with airbag deployment. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:490-493.

- Mohamed AA, Banerjee A. Patterns of injury associated with automobile airbag use. Postgrad Med J. 1998;74:455-458.

- Foley E, Helm TN. Air bag injury and the dermatologist. Cutis. 2000;66:251-252.

- Swanson-Biearman B, Mrvos R, Dean BS, et al. Air bags: lifesaving with toxic potential? Am J Emerg Med. 1993;11:38-39.

- Roth T, Meredith P. Traumatic lesions caused by the “air-bag” system [in French]. Z Unfallchir Versicherungsmed. 1993;86:189-193.

- Wu JJ, Sanchez-Palacios C, Brieva J, et al. A case of air bag dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1383-1384.

- Vitello W, Kim M, Johnson RM, et al. Full-thickness burn to the hand from an automobile airbag. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1999;20:212-215.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facts about sodium azide. Updated April 4, 2018. Accessed May 15, 2022. https://emergency.cdc.gov/agent/sodiumazide/basics/facts.asp

- Shepardson D. Honda to recall 1.2 million vehicles in North America to replace Takata airbags. March 12, 2019. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-honda-takata-recall/honda-to-recall-1-2-million-vehicles-in-north-america-to-replace-takata-airbags-idUSKBN1QT1C9

- Gabauer DJ, Gabler HC. The effects of airbags and seatbelts on occupant injury in longitudinal barrier crashes. J Safety Res. 2010;41:9-15.

- Rath AL, Jernigan MV, Stitzel JD, et al. The effects of depowered airbags on skin injuries in frontal automobile crashes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:428-435.

Airbags are lifesaving during motor vehicle accidents (MVAs), but their deployment has been associated with skin issues such as irritant dermatitis1; lacerations2; abrasions3; and thermal, friction, and chemical burns.4-6 Ocular issues such as alkaline chemical keratitis7 and ocular alkali injuries8 also have been described.

Airbag deployment is triggered by rapid deceleration and impact, which ignite a sodium azide cartridge, causing the woven nylon bag to inflate with hydrocarbon gases.8 This leads to release of sodium hydroxide, sodium bicarbonate, and metallic oxides in an aerosolized form. If a tear in the meshwork of the airbag occurs, exposure to an even larger amount of powder containing caustic alkali chemicals can occur.8

We describe a patient who developed a bullous reaction to airbag contents after he was involved in an MVA in which the airbag deployed.

Case Report

A 35-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic hepatitis B presented to the dermatology clinic for an evaluation of new-onset blisters. The rash occurred 1 day after the patient was involved in an MVA in which he was exposed to the airbag’s contents after it burst. He had been evaluated twice in the emergency department for the skin eruption before being referred to dermatology. He noted the lesions were pruritic and painful. Prior treatments included silver sulfadiazine cream 1% and clobetasol cream 0.05%, though he discontinued using the latter because of burning with application. Physical examination revealed tense vesicles and bullae on an erythematous base on the right lower flank, forearms, and legs, with the exception of the lower right leg where a cast had been from a prior injury (Figure 1).

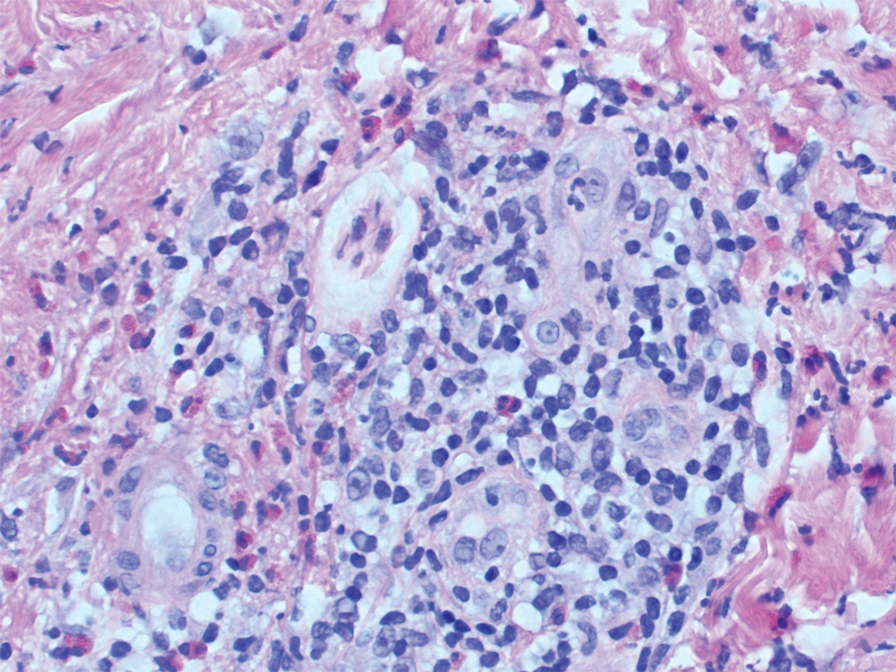

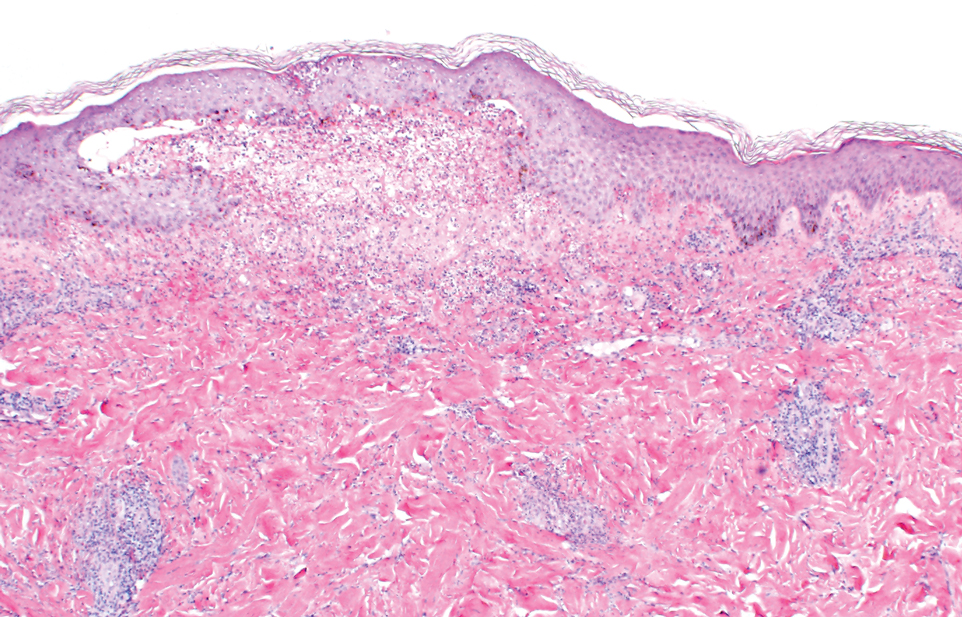

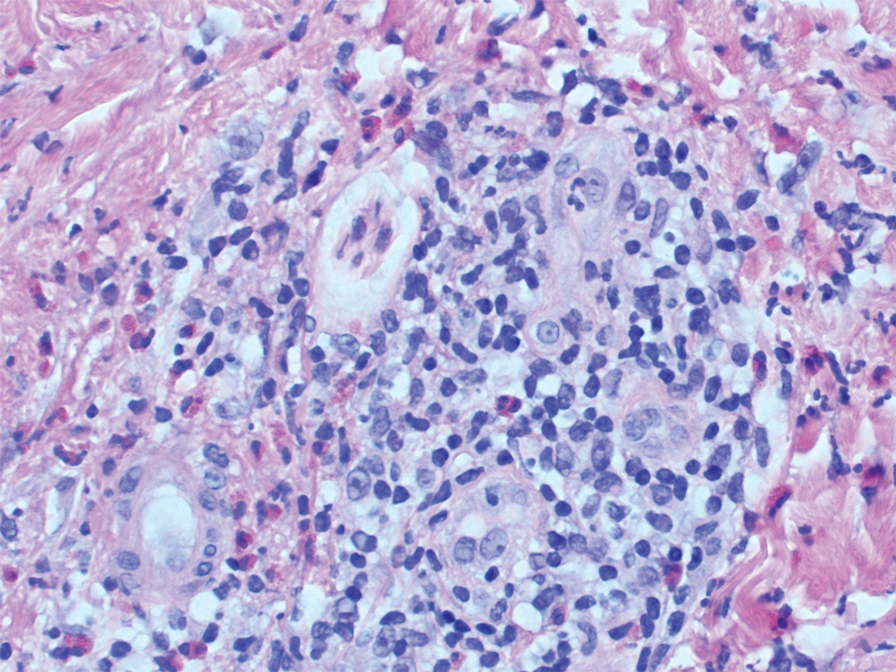

Two punch biopsies of the left arm were performed and sent for hematoxylin and eosin staining and direct immunofluorescence to rule out bullous diseases, such as bullous pemphigoid, linear IgA, and bullous lupus. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed extensive spongiosis with blister formation and a dense perivascular infiltrate in the superficial and mid dermis composed of lymphocytes with numerous scattered eosinophils (Figures 2 and 3). Direct immunofluorescence studies were negative. Treatment with oral prednisone and oral antihistamines was initiated.

At 10-day follow-up, the patient had a few residual bullae; most lesions were demonstrating various stages of healing (Figure 4). The patient’s cast had been removed, and there were no lesions in this previously covered area. At 6-week follow-up he had continued healing of the bullae and erosions as well as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (Figure 5).

Comment

With the advent of airbags for safety purposes, these potentially lifesaving devices also have been known to cause injury.9 In 1998, the most commonly reported airbag injuries were ocular injuries.10 Cutaneous manifestations of airbag injury are less well known.11

Two cases of airbag deployment with skin blistering have been reported in the literature based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms airbag blistering or airbag bullae12,13; however, the blistering was described in the context of a burn. One case of the effects of airbag deployment residue highlights a patient arriving to the emergency department with erythema and blisters on the hands within 48 hours of airbag deployment in an MVA, and the treatment was standard burn therapy.12 Another case report described a patient with a second-degree burn with a 12-cm blister occurring on the radial side of the hand and distal forearm following an MVA and airbag deployment, which was treated conservatively.13 Cases of thermal burns, chemical burns, and irritant contact dermatitis after airbag deployment have been described in the literature.4-6,11,12,14,15 Our patient’s distal right lower leg was covered with a cast for osteomyelitis, and no blisters had developed in this area. It is likely that the transfer of airbag contents occurred during the process of unbuckling his seatbelt, which could explain the bullae that developed on the right flank. Per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, individuals should quickly remove clothing and wash their body with large amounts of soap and water following exposure to sodium azide.16

In 1989, the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard No. 208 (occupant crash protection) became effective, stating all cars must have vehicle crash protection.12 Prior to 1993, it was reported that there had been no associated chemical injuries with airbag deployment. Subsequently, a 6-month retrospective study in 1993 showed that dermal injuries were found in connection with the presence of sodium hydroxide in automobile airbags.12 By 2004, it was known that airbags could cause chemical and thermal burns in addition to traumatic injuries from deployment.1 Since 2007, all motor vehicles have been required to have advanced airbags, which are engineered to sense the presence of passengers and determine if the airbag will deploy, and if so, how much to deploy to minimize airbag-related injury.3

The brand of car that our patient drove during the MVA is one with known airbag recalls due to safety defects; however, the year and actual model of the vehicle are not known, so specific information about the airbag in question is not available. It has been noted that some defective airbag inflators that were exposed to excess moisture during the manufacturing process could explode during deployment, causing shrapnel and airbag rupture, which has been linked to nearly 300 injuries worldwide.17

Conclusion

It is evident that the use of airbag devices reduces morbidity and mortality due to MVAs.9 It also had been reported that up to 96% of airbag-related injuries are relatively minor, which many would argue justifies their use.18 Furthermore, it has been reported that 99.8% of skin injuries following airbag deployment are minor.19 In the United States, it is mandated that every vehicle have functional airbags installed.8

This case highlights the potential for substantial airbag-induced skin reactions, specifically a bullous reaction, following airbag deployment. The persistent pruritus and lasting postinflammatory hyperpigmentation seen in this case were certainly worrisome for our patient. We also present this case to remind dermatology providers of possible treatment approaches to these skin reactions. Immediate cleansing of the affected areas of skin may help avoid such reactions.

Airbags are lifesaving during motor vehicle accidents (MVAs), but their deployment has been associated with skin issues such as irritant dermatitis1; lacerations2; abrasions3; and thermal, friction, and chemical burns.4-6 Ocular issues such as alkaline chemical keratitis7 and ocular alkali injuries8 also have been described.