User login

Man with distal flexion deformities

On the basis of history and presentation, this patient's psoriatic disease has probably evolved to psoriatic arthritis mutilans (PAM). PAM is considered the most severe form of psoriatic arthritis (PsA), causing joint destruction and functional disability. It is estimated to affect about 5% of patients with PsA, with an equal sex distribution. Psoriatic nail dystrophy, a hallmark of PsA, appears to be a clinical biomarker of PAM development. Patients with PAM are generally younger at diagnosis than those with less severe forms of disease. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and anti-TNF therapy do not appear to prevent the development of PAM, as evidenced by the present case.

In general, clinical presentation of PsA is heterogeneous and can be similar to that of other rheumatic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis, complicating the differential diagnosis. The Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) are considered the most sensitive diagnostic criteria, encompassing evidence of psoriasis; nail dystrophy; lab findings of typical autoantibodies (negative rheumatoid factor); and phenomena that are characteristic of PsA, like dactylitis.

Workup for PAM often includes radiography, ultrasound, and MRI or CT. With no established consensus, classification systems for the condition vary clinically and radiographically. Radiographic features suggestive of PAM include osteolysis or extended bone resorption; pencil-in-cup changes; joint subluxation; and, less often, ankylosis. Osteolysis has been defined as bone resorption with more than 50% loss of joint surface on both sides of the joint. Clinically, dissolution of the joint causes redundant, overlying skin with a telescoping motion of the digit. Other clinical features of PAM include digital shortening and flail joints. Of note, involvement of one small joint in the hands or feet is diagnostic of PAM.

In the setting of PsA, multiple genetic factors have been described, including presence of HLA-B27 and HLA-DRB1, but none are considered defining factors for the disease. A recent population-based study shows that presence of HLA-B27 was significantly increased among patients with PAM (45%) compared with patients with less severe PsA (13%) and healthy controls (13%).

According to the American College of Rheumatology guidelines, first-line therapy in adult patients who have active PsA and are treatment-naive is a TNFi biologic agent. For the patient in this case, who has active PsA despite treatment with TNFi biologic monotherapy, switching to a different TNFi biologic may be appropriate; however, switching to an interleukin-17 inhibitor may also be considered because this patient has severe disease. Data on the comparative efficacy of different biological agents for treatment of PAM are not yet available.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of history and presentation, this patient's psoriatic disease has probably evolved to psoriatic arthritis mutilans (PAM). PAM is considered the most severe form of psoriatic arthritis (PsA), causing joint destruction and functional disability. It is estimated to affect about 5% of patients with PsA, with an equal sex distribution. Psoriatic nail dystrophy, a hallmark of PsA, appears to be a clinical biomarker of PAM development. Patients with PAM are generally younger at diagnosis than those with less severe forms of disease. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and anti-TNF therapy do not appear to prevent the development of PAM, as evidenced by the present case.

In general, clinical presentation of PsA is heterogeneous and can be similar to that of other rheumatic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis, complicating the differential diagnosis. The Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) are considered the most sensitive diagnostic criteria, encompassing evidence of psoriasis; nail dystrophy; lab findings of typical autoantibodies (negative rheumatoid factor); and phenomena that are characteristic of PsA, like dactylitis.

Workup for PAM often includes radiography, ultrasound, and MRI or CT. With no established consensus, classification systems for the condition vary clinically and radiographically. Radiographic features suggestive of PAM include osteolysis or extended bone resorption; pencil-in-cup changes; joint subluxation; and, less often, ankylosis. Osteolysis has been defined as bone resorption with more than 50% loss of joint surface on both sides of the joint. Clinically, dissolution of the joint causes redundant, overlying skin with a telescoping motion of the digit. Other clinical features of PAM include digital shortening and flail joints. Of note, involvement of one small joint in the hands or feet is diagnostic of PAM.

In the setting of PsA, multiple genetic factors have been described, including presence of HLA-B27 and HLA-DRB1, but none are considered defining factors for the disease. A recent population-based study shows that presence of HLA-B27 was significantly increased among patients with PAM (45%) compared with patients with less severe PsA (13%) and healthy controls (13%).

According to the American College of Rheumatology guidelines, first-line therapy in adult patients who have active PsA and are treatment-naive is a TNFi biologic agent. For the patient in this case, who has active PsA despite treatment with TNFi biologic monotherapy, switching to a different TNFi biologic may be appropriate; however, switching to an interleukin-17 inhibitor may also be considered because this patient has severe disease. Data on the comparative efficacy of different biological agents for treatment of PAM are not yet available.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of history and presentation, this patient's psoriatic disease has probably evolved to psoriatic arthritis mutilans (PAM). PAM is considered the most severe form of psoriatic arthritis (PsA), causing joint destruction and functional disability. It is estimated to affect about 5% of patients with PsA, with an equal sex distribution. Psoriatic nail dystrophy, a hallmark of PsA, appears to be a clinical biomarker of PAM development. Patients with PAM are generally younger at diagnosis than those with less severe forms of disease. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and anti-TNF therapy do not appear to prevent the development of PAM, as evidenced by the present case.

In general, clinical presentation of PsA is heterogeneous and can be similar to that of other rheumatic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis, complicating the differential diagnosis. The Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) are considered the most sensitive diagnostic criteria, encompassing evidence of psoriasis; nail dystrophy; lab findings of typical autoantibodies (negative rheumatoid factor); and phenomena that are characteristic of PsA, like dactylitis.

Workup for PAM often includes radiography, ultrasound, and MRI or CT. With no established consensus, classification systems for the condition vary clinically and radiographically. Radiographic features suggestive of PAM include osteolysis or extended bone resorption; pencil-in-cup changes; joint subluxation; and, less often, ankylosis. Osteolysis has been defined as bone resorption with more than 50% loss of joint surface on both sides of the joint. Clinically, dissolution of the joint causes redundant, overlying skin with a telescoping motion of the digit. Other clinical features of PAM include digital shortening and flail joints. Of note, involvement of one small joint in the hands or feet is diagnostic of PAM.

In the setting of PsA, multiple genetic factors have been described, including presence of HLA-B27 and HLA-DRB1, but none are considered defining factors for the disease. A recent population-based study shows that presence of HLA-B27 was significantly increased among patients with PAM (45%) compared with patients with less severe PsA (13%) and healthy controls (13%).

According to the American College of Rheumatology guidelines, first-line therapy in adult patients who have active PsA and are treatment-naive is a TNFi biologic agent. For the patient in this case, who has active PsA despite treatment with TNFi biologic monotherapy, switching to a different TNFi biologic may be appropriate; however, switching to an interleukin-17 inhibitor may also be considered because this patient has severe disease. Data on the comparative efficacy of different biological agents for treatment of PAM are not yet available.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 43-year-old man presents with distal flexion deformities and telescoping of the digits. The patient was diagnosed with psoriasis at age 31 and he has several immediate family members who previously received the same diagnosis. He has been treated intermittently with tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) biologic monotherapy but admits to nonadherence when disease activity seems to quiet down. Radiography shows osteolysis and dissolution of the joint.

Hormones account for 10% of lipid changes after menopause

The transition from perimenopause to menopause is accompanied by a proatherogenic shift in lipids and other circulating metabolites that potentially predispose women to cardiovascular disease (CVD). Now, for the first time, a new prospective cohort study quantifies the link between hormonal shifts and these lipid changes.

However, hormone therapy (HT) somewhat mitigates the shift and may help protect menopausal women from some elevated CVD risk, the same study suggests.

“Menopause is not avoidable, but perhaps the negative metabolite shift can be diminished by lifestyle choices such as eating healthily and being physically active,” senior author Eija Laakkonen, MD, University of Jyväskylä, Finland, told this news organization in an email.

“And women should especially pay attention to the quality of dietary fats and amount of exercise [they get] to maintain cardiorespiratory fitness,” she said, adding that women should discuss the option of HT with their health care providers.

Asked to comment, JoAnn Manson, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and past president of the North American Menopause Society, said there is strong evidence that women undergo negative cardiometabolic changes during the menopausal transition.

Changes include those in body composition (an increase in visceral fat and waist circumference), as well as unfavorable shifts in the lipid profile, as reflected by increases in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and triglycerides and a decrease in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C).

It’s also clear from a variety of cohort studies that HT blunts menopausal-related increases in body weight, percentage of body fat, as well as visceral fat, she said.

So the new findings do seem to “parallel” those of other perimenopausal to menopausal transition studies, which include HT having “favorable effects on lipids,” Dr. Manson said. HT “lowers LDL-C and increases HDL-C, and this is especially true when it is given orally,” but even transdermal delivery has shown some benefits, she observed.

Shift in hormones causes 10% of lipid changes after menopause

The new study, by Jari E. Karppinen, also of the University of Jyväskylä, and colleagues, was recently published in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. The data are from the Estrogenic Regulation of Muscle Apoptosis (ERMA) prospective cohort study.

In total, 218 women were tracked from perimenopause through to early postmenopause, 35 of whom started HT, mostly oral preparations. The women were followed for a median of 14 months. Their mean age was 51.7 years when their hormone and metabolite profiles were first measured.

Previous studies have shown that menopause is associated with levels of metabolites that promote CVD, but this study is the first to specifically link this shift with changes in female sex hormones, the researchers stress.

“Menopause was associated with a statistically significant change in 85 metabolite measures,” Mr. Karppinen and colleagues report.

Analyses showed that the menopausal hormonal shift directly explained the change in 64 of the 85 metabolites, with effect sizes ranging from 2.1% to 11.2%.

These included increases in LDL-C, triglycerides, and fatty acids. Analyses were adjusted for age at baseline, duration of follow-up, education level, smoking status, alcohol use, physical activity, and diet quality.

More specifically, investigators found that all apoB-containing particle counts as well as particle diameters increased over follow-up, although no change occurred in HDL particles.

They also found cholesterol concentrations in all apoB-containing lipoprotein classes to increase and triglyceride concentrations to increase in very low-density lipoprotein and HDL particles.

“These findings, including HDL triglycerides, can be interpreted as signs of poor metabolic health since, despite higher HDL-C being good for health, high HDL triglyceride levels are associated with a higher risk of coronary heart disease,” Dr. Laakkonen emphasized.

Among the 35 women who initiated HT on study enrollment, investigators did note, on exploratory analysis, increases in HDL-C and reductions in LDL-C.

“The number of women starting HT was small, and the type of HT was not controlled,” Dr. Laakkonen cautioned, however.

“Nevertheless, our observations support clinical guidelines to initiate HT early into menopause, as this timing offers the greatest cardioprotective effect,” she added.

The study was supported by the Academy of Finland. The authors and Dr. Manson have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Manson is a contributor to Medscape.

This article was updated on 5/20/2022.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The transition from perimenopause to menopause is accompanied by a proatherogenic shift in lipids and other circulating metabolites that potentially predispose women to cardiovascular disease (CVD). Now, for the first time, a new prospective cohort study quantifies the link between hormonal shifts and these lipid changes.

However, hormone therapy (HT) somewhat mitigates the shift and may help protect menopausal women from some elevated CVD risk, the same study suggests.

“Menopause is not avoidable, but perhaps the negative metabolite shift can be diminished by lifestyle choices such as eating healthily and being physically active,” senior author Eija Laakkonen, MD, University of Jyväskylä, Finland, told this news organization in an email.

“And women should especially pay attention to the quality of dietary fats and amount of exercise [they get] to maintain cardiorespiratory fitness,” she said, adding that women should discuss the option of HT with their health care providers.

Asked to comment, JoAnn Manson, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and past president of the North American Menopause Society, said there is strong evidence that women undergo negative cardiometabolic changes during the menopausal transition.

Changes include those in body composition (an increase in visceral fat and waist circumference), as well as unfavorable shifts in the lipid profile, as reflected by increases in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and triglycerides and a decrease in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C).

It’s also clear from a variety of cohort studies that HT blunts menopausal-related increases in body weight, percentage of body fat, as well as visceral fat, she said.

So the new findings do seem to “parallel” those of other perimenopausal to menopausal transition studies, which include HT having “favorable effects on lipids,” Dr. Manson said. HT “lowers LDL-C and increases HDL-C, and this is especially true when it is given orally,” but even transdermal delivery has shown some benefits, she observed.

Shift in hormones causes 10% of lipid changes after menopause

The new study, by Jari E. Karppinen, also of the University of Jyväskylä, and colleagues, was recently published in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. The data are from the Estrogenic Regulation of Muscle Apoptosis (ERMA) prospective cohort study.

In total, 218 women were tracked from perimenopause through to early postmenopause, 35 of whom started HT, mostly oral preparations. The women were followed for a median of 14 months. Their mean age was 51.7 years when their hormone and metabolite profiles were first measured.

Previous studies have shown that menopause is associated with levels of metabolites that promote CVD, but this study is the first to specifically link this shift with changes in female sex hormones, the researchers stress.

“Menopause was associated with a statistically significant change in 85 metabolite measures,” Mr. Karppinen and colleagues report.

Analyses showed that the menopausal hormonal shift directly explained the change in 64 of the 85 metabolites, with effect sizes ranging from 2.1% to 11.2%.

These included increases in LDL-C, triglycerides, and fatty acids. Analyses were adjusted for age at baseline, duration of follow-up, education level, smoking status, alcohol use, physical activity, and diet quality.

More specifically, investigators found that all apoB-containing particle counts as well as particle diameters increased over follow-up, although no change occurred in HDL particles.

They also found cholesterol concentrations in all apoB-containing lipoprotein classes to increase and triglyceride concentrations to increase in very low-density lipoprotein and HDL particles.

“These findings, including HDL triglycerides, can be interpreted as signs of poor metabolic health since, despite higher HDL-C being good for health, high HDL triglyceride levels are associated with a higher risk of coronary heart disease,” Dr. Laakkonen emphasized.

Among the 35 women who initiated HT on study enrollment, investigators did note, on exploratory analysis, increases in HDL-C and reductions in LDL-C.

“The number of women starting HT was small, and the type of HT was not controlled,” Dr. Laakkonen cautioned, however.

“Nevertheless, our observations support clinical guidelines to initiate HT early into menopause, as this timing offers the greatest cardioprotective effect,” she added.

The study was supported by the Academy of Finland. The authors and Dr. Manson have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Manson is a contributor to Medscape.

This article was updated on 5/20/2022.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The transition from perimenopause to menopause is accompanied by a proatherogenic shift in lipids and other circulating metabolites that potentially predispose women to cardiovascular disease (CVD). Now, for the first time, a new prospective cohort study quantifies the link between hormonal shifts and these lipid changes.

However, hormone therapy (HT) somewhat mitigates the shift and may help protect menopausal women from some elevated CVD risk, the same study suggests.

“Menopause is not avoidable, but perhaps the negative metabolite shift can be diminished by lifestyle choices such as eating healthily and being physically active,” senior author Eija Laakkonen, MD, University of Jyväskylä, Finland, told this news organization in an email.

“And women should especially pay attention to the quality of dietary fats and amount of exercise [they get] to maintain cardiorespiratory fitness,” she said, adding that women should discuss the option of HT with their health care providers.

Asked to comment, JoAnn Manson, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and past president of the North American Menopause Society, said there is strong evidence that women undergo negative cardiometabolic changes during the menopausal transition.

Changes include those in body composition (an increase in visceral fat and waist circumference), as well as unfavorable shifts in the lipid profile, as reflected by increases in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and triglycerides and a decrease in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C).

It’s also clear from a variety of cohort studies that HT blunts menopausal-related increases in body weight, percentage of body fat, as well as visceral fat, she said.

So the new findings do seem to “parallel” those of other perimenopausal to menopausal transition studies, which include HT having “favorable effects on lipids,” Dr. Manson said. HT “lowers LDL-C and increases HDL-C, and this is especially true when it is given orally,” but even transdermal delivery has shown some benefits, she observed.

Shift in hormones causes 10% of lipid changes after menopause

The new study, by Jari E. Karppinen, also of the University of Jyväskylä, and colleagues, was recently published in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. The data are from the Estrogenic Regulation of Muscle Apoptosis (ERMA) prospective cohort study.

In total, 218 women were tracked from perimenopause through to early postmenopause, 35 of whom started HT, mostly oral preparations. The women were followed for a median of 14 months. Their mean age was 51.7 years when their hormone and metabolite profiles were first measured.

Previous studies have shown that menopause is associated with levels of metabolites that promote CVD, but this study is the first to specifically link this shift with changes in female sex hormones, the researchers stress.

“Menopause was associated with a statistically significant change in 85 metabolite measures,” Mr. Karppinen and colleagues report.

Analyses showed that the menopausal hormonal shift directly explained the change in 64 of the 85 metabolites, with effect sizes ranging from 2.1% to 11.2%.

These included increases in LDL-C, triglycerides, and fatty acids. Analyses were adjusted for age at baseline, duration of follow-up, education level, smoking status, alcohol use, physical activity, and diet quality.

More specifically, investigators found that all apoB-containing particle counts as well as particle diameters increased over follow-up, although no change occurred in HDL particles.

They also found cholesterol concentrations in all apoB-containing lipoprotein classes to increase and triglyceride concentrations to increase in very low-density lipoprotein and HDL particles.

“These findings, including HDL triglycerides, can be interpreted as signs of poor metabolic health since, despite higher HDL-C being good for health, high HDL triglyceride levels are associated with a higher risk of coronary heart disease,” Dr. Laakkonen emphasized.

Among the 35 women who initiated HT on study enrollment, investigators did note, on exploratory analysis, increases in HDL-C and reductions in LDL-C.

“The number of women starting HT was small, and the type of HT was not controlled,” Dr. Laakkonen cautioned, however.

“Nevertheless, our observations support clinical guidelines to initiate HT early into menopause, as this timing offers the greatest cardioprotective effect,” she added.

The study was supported by the Academy of Finland. The authors and Dr. Manson have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Manson is a contributor to Medscape.

This article was updated on 5/20/2022.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PREVENTIVE CARDIOLOGY

Improved cancer survival in states with ACA Medicaid expansion

compared with patients in states that did not adopt the expansion.

The finding comes from an American Cancer Society study of more than 2 million patients with newly diagnosed cancer, published online in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

The analysis also showed that the evidence was strongest for malignancies with poor prognosis such as lung, pancreatic, and liver cancer, and also for colorectal cancer.

Importantly, improvements in survival were larger in non-Hispanic Black patients and individuals residing in rural areas, suggesting there was a narrowing of disparities in cancer survival by race and rurality.

“Our findings provide further evidence of the importance of expanding Medicaid eligibility in all states, particularly considering the economic crisis and health care disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic,” said lead author Xuesong Han, PhD, scientific director of health services research at the American Cancer Society, in a statement. “What’s encouraging is the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 provides new incentives for Medicaid expansion in states that have yet to increase eligibility.”

The ACA provided states with incentives to expand Medicaid eligibility to all low-income adults under 138% federal poverty level, regardless of parental status.

As of last month, just 12 states have not yet opted for Medicaid expansion, even though the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 provides new incentives for those remaining jurisdictions. But to date, none of the remaining states have taken advantage of these new incentives.

An interactive map showing the status of Medicare expansion by state is available here. The 12 states that have not adopted Medicare expansion (as of April) are Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

The benefit of Medicaid expansion on cancer outcomes has already been observed in other studies. The first study to show a survival benefit was presented at the 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting. That analysis showed that cancer mortality declined by 29% in states that expanded Medicaid and by 25% in those that did not. The authors also noted that the greatest mortality benefit was observed in Hispanic patients.

Improved survival with expansion

In the current paper, Dr. Han and colleagues used population-based cancer registries from 42 states and compared data on patients aged 18-62 years who were diagnosed with cancer in a period of 2 years before (2010-2012) and after (2014-2016) ACA Medicaid expansion. They were followed through Sept. 30, 2013, and Dec. 31, 2017, respectively.

The analysis involved a total of 2.5 million patients, of whom 1.52 million lived in states that adopted Medicaid expansion and compared with 1 million patients were in states that did not.

Patients with grouped by sex, race and ethnicity, census tract-level poverty, and rurality. The authors note that non-Hispanic Black patients and those from high poverty areas and nonmetropolitan areas were disproportionately represented in nonexpansion states.

During the 2-year follow-up period, a total of 453,487 deaths occurred (257,950 in expansion states and 195,537 in nonexpansion states).

Overall, patients in expansion states generally had better survival versus those in nonexpansion states, the authors comment. However, for most cancer types, overall survival improved after the ACA for both groups of states.

The 2-year overall survival increased from 80.6% before the ACA to 82.2% post ACA in expansion states and from 78.7% to 80% in nonexpansion states.

This extrapolated to net increase of 0.44 percentage points in expansion states after adjusting for sociodemographic factors. By cancer site, the net increase was greater for colorectal cancer, lung cancer, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, pancreatic cancer, and liver cancer.

For Hispanic patients, 2-year survival also increased but was similar in expansion and nonexpansion states, and little net change was associated with Medicaid expansion.

“Our study shows that the increase was largely driven by improvements in survival for cancer types with poor prognosis, suggesting improved access to timely and effective treatments,” said Dr. Han. “It adds to accumulating evidence of the multiple benefits of Medicaid expansion.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

compared with patients in states that did not adopt the expansion.

The finding comes from an American Cancer Society study of more than 2 million patients with newly diagnosed cancer, published online in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

The analysis also showed that the evidence was strongest for malignancies with poor prognosis such as lung, pancreatic, and liver cancer, and also for colorectal cancer.

Importantly, improvements in survival were larger in non-Hispanic Black patients and individuals residing in rural areas, suggesting there was a narrowing of disparities in cancer survival by race and rurality.

“Our findings provide further evidence of the importance of expanding Medicaid eligibility in all states, particularly considering the economic crisis and health care disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic,” said lead author Xuesong Han, PhD, scientific director of health services research at the American Cancer Society, in a statement. “What’s encouraging is the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 provides new incentives for Medicaid expansion in states that have yet to increase eligibility.”

The ACA provided states with incentives to expand Medicaid eligibility to all low-income adults under 138% federal poverty level, regardless of parental status.

As of last month, just 12 states have not yet opted for Medicaid expansion, even though the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 provides new incentives for those remaining jurisdictions. But to date, none of the remaining states have taken advantage of these new incentives.

An interactive map showing the status of Medicare expansion by state is available here. The 12 states that have not adopted Medicare expansion (as of April) are Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

The benefit of Medicaid expansion on cancer outcomes has already been observed in other studies. The first study to show a survival benefit was presented at the 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting. That analysis showed that cancer mortality declined by 29% in states that expanded Medicaid and by 25% in those that did not. The authors also noted that the greatest mortality benefit was observed in Hispanic patients.

Improved survival with expansion

In the current paper, Dr. Han and colleagues used population-based cancer registries from 42 states and compared data on patients aged 18-62 years who were diagnosed with cancer in a period of 2 years before (2010-2012) and after (2014-2016) ACA Medicaid expansion. They were followed through Sept. 30, 2013, and Dec. 31, 2017, respectively.

The analysis involved a total of 2.5 million patients, of whom 1.52 million lived in states that adopted Medicaid expansion and compared with 1 million patients were in states that did not.

Patients with grouped by sex, race and ethnicity, census tract-level poverty, and rurality. The authors note that non-Hispanic Black patients and those from high poverty areas and nonmetropolitan areas were disproportionately represented in nonexpansion states.

During the 2-year follow-up period, a total of 453,487 deaths occurred (257,950 in expansion states and 195,537 in nonexpansion states).

Overall, patients in expansion states generally had better survival versus those in nonexpansion states, the authors comment. However, for most cancer types, overall survival improved after the ACA for both groups of states.

The 2-year overall survival increased from 80.6% before the ACA to 82.2% post ACA in expansion states and from 78.7% to 80% in nonexpansion states.

This extrapolated to net increase of 0.44 percentage points in expansion states after adjusting for sociodemographic factors. By cancer site, the net increase was greater for colorectal cancer, lung cancer, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, pancreatic cancer, and liver cancer.

For Hispanic patients, 2-year survival also increased but was similar in expansion and nonexpansion states, and little net change was associated with Medicaid expansion.

“Our study shows that the increase was largely driven by improvements in survival for cancer types with poor prognosis, suggesting improved access to timely and effective treatments,” said Dr. Han. “It adds to accumulating evidence of the multiple benefits of Medicaid expansion.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

compared with patients in states that did not adopt the expansion.

The finding comes from an American Cancer Society study of more than 2 million patients with newly diagnosed cancer, published online in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

The analysis also showed that the evidence was strongest for malignancies with poor prognosis such as lung, pancreatic, and liver cancer, and also for colorectal cancer.

Importantly, improvements in survival were larger in non-Hispanic Black patients and individuals residing in rural areas, suggesting there was a narrowing of disparities in cancer survival by race and rurality.

“Our findings provide further evidence of the importance of expanding Medicaid eligibility in all states, particularly considering the economic crisis and health care disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic,” said lead author Xuesong Han, PhD, scientific director of health services research at the American Cancer Society, in a statement. “What’s encouraging is the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 provides new incentives for Medicaid expansion in states that have yet to increase eligibility.”

The ACA provided states with incentives to expand Medicaid eligibility to all low-income adults under 138% federal poverty level, regardless of parental status.

As of last month, just 12 states have not yet opted for Medicaid expansion, even though the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 provides new incentives for those remaining jurisdictions. But to date, none of the remaining states have taken advantage of these new incentives.

An interactive map showing the status of Medicare expansion by state is available here. The 12 states that have not adopted Medicare expansion (as of April) are Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

The benefit of Medicaid expansion on cancer outcomes has already been observed in other studies. The first study to show a survival benefit was presented at the 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting. That analysis showed that cancer mortality declined by 29% in states that expanded Medicaid and by 25% in those that did not. The authors also noted that the greatest mortality benefit was observed in Hispanic patients.

Improved survival with expansion

In the current paper, Dr. Han and colleagues used population-based cancer registries from 42 states and compared data on patients aged 18-62 years who were diagnosed with cancer in a period of 2 years before (2010-2012) and after (2014-2016) ACA Medicaid expansion. They were followed through Sept. 30, 2013, and Dec. 31, 2017, respectively.

The analysis involved a total of 2.5 million patients, of whom 1.52 million lived in states that adopted Medicaid expansion and compared with 1 million patients were in states that did not.

Patients with grouped by sex, race and ethnicity, census tract-level poverty, and rurality. The authors note that non-Hispanic Black patients and those from high poverty areas and nonmetropolitan areas were disproportionately represented in nonexpansion states.

During the 2-year follow-up period, a total of 453,487 deaths occurred (257,950 in expansion states and 195,537 in nonexpansion states).

Overall, patients in expansion states generally had better survival versus those in nonexpansion states, the authors comment. However, for most cancer types, overall survival improved after the ACA for both groups of states.

The 2-year overall survival increased from 80.6% before the ACA to 82.2% post ACA in expansion states and from 78.7% to 80% in nonexpansion states.

This extrapolated to net increase of 0.44 percentage points in expansion states after adjusting for sociodemographic factors. By cancer site, the net increase was greater for colorectal cancer, lung cancer, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, pancreatic cancer, and liver cancer.

For Hispanic patients, 2-year survival also increased but was similar in expansion and nonexpansion states, and little net change was associated with Medicaid expansion.

“Our study shows that the increase was largely driven by improvements in survival for cancer types with poor prognosis, suggesting improved access to timely and effective treatments,” said Dr. Han. “It adds to accumulating evidence of the multiple benefits of Medicaid expansion.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Steroid use associated with higher relapse risk in some UC

Patients who have histologically active ulcerative colitis (UC) with a Mayo endoscopic subscore (MES) of 1 and a history of steroid use may be at increased risk for clinical relapse, according to a new single-center, retrospective analysis.

In recent years, treat-to-target approaches in UC have incorporated clinician and patient-reported outcomes, along with endoscopic remission, defined as MES 1 or less. However, additional studies showed a higher risk of relapse with MES 1, and the STRIDE-II (Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease) guidelines released in 2021 suggest that only MES 0 indicates endoscopic healing.

Nevertheless, there is concern that striving to achieve MES 0 could lead to overtreatment, since MES values are somewhat subjective, and patients with MES 1 sometimes report few or no symptoms. This led to the current study by Gyeol Seong, MD, and colleagues, published in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases.

Commenting on the study, Miguel Regueiro, MD, chair for the Digestive Disease and Surgery Institute and a professor of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic said “the question has always been, if the patient is in endoscopic remission and clinically feels well, how important is it to have histologically normal mucosa?”

In their retrospective study, Dr. Seong and colleagues analyzed data from 492 patients. The median age was 48, and 51.6% were male. The median duration of disease was 78 months. During a median follow-up of 549 days, 18.7% experienced a relapse, defined as “change or escalation of medication, hospitalization due to the aggravation of UC, or total colectomy.” Of these patients, 39.4% had used steroids and 51.4% had a MES score of 0 at the index endoscopy, and 70.5% had histologic improvement, as defined by a Geboes score of less than 3.1.

A Geboes score of 3.1 or higher and a history of steroid use was associated with an increased cumulative incidence of clinical relapse, compared with a Geboes score lower than 3.1 and no steroid use (P = .001). In a multivariate analysis, histologic activity alone was not a predictor of relapse. Among patients with an MES score of 1, a history of steroid use predicted risk of relapse (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.102; P = .006).

Although Dr. Regueiro said the new findings would not change his current practice, he does incorporate histopathology in clinical decision-making. In cases where a patient is in endoscopic remission but has histologic activity, he will consider adjusting the current medication rather than changing to a different therapeutic. “I wouldn’t recommend that we switch patients off one therapy to another just because of histologic activity.”

That’s because patients often improve dramatically after effective therapy. Dr. Regueiro said: “The one concern is whether the next medicine works as well as what the patient is already on? I’m also worried that we burn through our biologics too quickly. We go from one to another and another, sometimes I think we just need to optimize the one they’re on.”

The study does have the potential to influence surveillance for dysplasia, according to Dr. Regueiro, noting that a recent retrospective analysis showed an increased risk of dysplasia in UC with persistent histologic activity. “This suggests the need for a colonoscopy in a patient who has had ulcerative colitis for a number of years, even if there’s improvement but, on biopsy, there’s evidence of inflammation.”

According to Dr. Regueiro, such patients might benefit from a fecal calprotectin measurement in 3-6 months to monitor for colonic inflammation. Increased levels might be a sign that the patient is skipping medication doses, although other factors, like respiratory infections, can also explain the results. If the patient’s medication adherence is good, another therapy can be added or the dose increased, and the next endoscopy can be pushed up.

A key limitation to the study by Dr. Seong and colleagues is that it was based in South Korea. “Would this be the same in different countries and different populations? That is still a question,” said Dr. Regueiro.

Dr. Regueiro has received unrestricted educational grants from Abbvie, Janssen, UCB, Pfizer, Takeda, Celgene, Genentech, Gilead, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Lilly. He has been on advisory boards or consulted for numerous companies. He also has relationships with the following CME companies: CME Outfitters, Imedex, GI Health Foundation, Cornerstones, Remedy, MJH Life Sciences, Medscape, MDEducation, WebMD, and HMPGlobal.

Patients who have histologically active ulcerative colitis (UC) with a Mayo endoscopic subscore (MES) of 1 and a history of steroid use may be at increased risk for clinical relapse, according to a new single-center, retrospective analysis.

In recent years, treat-to-target approaches in UC have incorporated clinician and patient-reported outcomes, along with endoscopic remission, defined as MES 1 or less. However, additional studies showed a higher risk of relapse with MES 1, and the STRIDE-II (Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease) guidelines released in 2021 suggest that only MES 0 indicates endoscopic healing.

Nevertheless, there is concern that striving to achieve MES 0 could lead to overtreatment, since MES values are somewhat subjective, and patients with MES 1 sometimes report few or no symptoms. This led to the current study by Gyeol Seong, MD, and colleagues, published in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases.

Commenting on the study, Miguel Regueiro, MD, chair for the Digestive Disease and Surgery Institute and a professor of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic said “the question has always been, if the patient is in endoscopic remission and clinically feels well, how important is it to have histologically normal mucosa?”

In their retrospective study, Dr. Seong and colleagues analyzed data from 492 patients. The median age was 48, and 51.6% were male. The median duration of disease was 78 months. During a median follow-up of 549 days, 18.7% experienced a relapse, defined as “change or escalation of medication, hospitalization due to the aggravation of UC, or total colectomy.” Of these patients, 39.4% had used steroids and 51.4% had a MES score of 0 at the index endoscopy, and 70.5% had histologic improvement, as defined by a Geboes score of less than 3.1.

A Geboes score of 3.1 or higher and a history of steroid use was associated with an increased cumulative incidence of clinical relapse, compared with a Geboes score lower than 3.1 and no steroid use (P = .001). In a multivariate analysis, histologic activity alone was not a predictor of relapse. Among patients with an MES score of 1, a history of steroid use predicted risk of relapse (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.102; P = .006).

Although Dr. Regueiro said the new findings would not change his current practice, he does incorporate histopathology in clinical decision-making. In cases where a patient is in endoscopic remission but has histologic activity, he will consider adjusting the current medication rather than changing to a different therapeutic. “I wouldn’t recommend that we switch patients off one therapy to another just because of histologic activity.”

That’s because patients often improve dramatically after effective therapy. Dr. Regueiro said: “The one concern is whether the next medicine works as well as what the patient is already on? I’m also worried that we burn through our biologics too quickly. We go from one to another and another, sometimes I think we just need to optimize the one they’re on.”

The study does have the potential to influence surveillance for dysplasia, according to Dr. Regueiro, noting that a recent retrospective analysis showed an increased risk of dysplasia in UC with persistent histologic activity. “This suggests the need for a colonoscopy in a patient who has had ulcerative colitis for a number of years, even if there’s improvement but, on biopsy, there’s evidence of inflammation.”

According to Dr. Regueiro, such patients might benefit from a fecal calprotectin measurement in 3-6 months to monitor for colonic inflammation. Increased levels might be a sign that the patient is skipping medication doses, although other factors, like respiratory infections, can also explain the results. If the patient’s medication adherence is good, another therapy can be added or the dose increased, and the next endoscopy can be pushed up.

A key limitation to the study by Dr. Seong and colleagues is that it was based in South Korea. “Would this be the same in different countries and different populations? That is still a question,” said Dr. Regueiro.

Dr. Regueiro has received unrestricted educational grants from Abbvie, Janssen, UCB, Pfizer, Takeda, Celgene, Genentech, Gilead, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Lilly. He has been on advisory boards or consulted for numerous companies. He also has relationships with the following CME companies: CME Outfitters, Imedex, GI Health Foundation, Cornerstones, Remedy, MJH Life Sciences, Medscape, MDEducation, WebMD, and HMPGlobal.

Patients who have histologically active ulcerative colitis (UC) with a Mayo endoscopic subscore (MES) of 1 and a history of steroid use may be at increased risk for clinical relapse, according to a new single-center, retrospective analysis.

In recent years, treat-to-target approaches in UC have incorporated clinician and patient-reported outcomes, along with endoscopic remission, defined as MES 1 or less. However, additional studies showed a higher risk of relapse with MES 1, and the STRIDE-II (Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease) guidelines released in 2021 suggest that only MES 0 indicates endoscopic healing.

Nevertheless, there is concern that striving to achieve MES 0 could lead to overtreatment, since MES values are somewhat subjective, and patients with MES 1 sometimes report few or no symptoms. This led to the current study by Gyeol Seong, MD, and colleagues, published in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases.

Commenting on the study, Miguel Regueiro, MD, chair for the Digestive Disease and Surgery Institute and a professor of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic said “the question has always been, if the patient is in endoscopic remission and clinically feels well, how important is it to have histologically normal mucosa?”

In their retrospective study, Dr. Seong and colleagues analyzed data from 492 patients. The median age was 48, and 51.6% were male. The median duration of disease was 78 months. During a median follow-up of 549 days, 18.7% experienced a relapse, defined as “change or escalation of medication, hospitalization due to the aggravation of UC, or total colectomy.” Of these patients, 39.4% had used steroids and 51.4% had a MES score of 0 at the index endoscopy, and 70.5% had histologic improvement, as defined by a Geboes score of less than 3.1.

A Geboes score of 3.1 or higher and a history of steroid use was associated with an increased cumulative incidence of clinical relapse, compared with a Geboes score lower than 3.1 and no steroid use (P = .001). In a multivariate analysis, histologic activity alone was not a predictor of relapse. Among patients with an MES score of 1, a history of steroid use predicted risk of relapse (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.102; P = .006).

Although Dr. Regueiro said the new findings would not change his current practice, he does incorporate histopathology in clinical decision-making. In cases where a patient is in endoscopic remission but has histologic activity, he will consider adjusting the current medication rather than changing to a different therapeutic. “I wouldn’t recommend that we switch patients off one therapy to another just because of histologic activity.”

That’s because patients often improve dramatically after effective therapy. Dr. Regueiro said: “The one concern is whether the next medicine works as well as what the patient is already on? I’m also worried that we burn through our biologics too quickly. We go from one to another and another, sometimes I think we just need to optimize the one they’re on.”

The study does have the potential to influence surveillance for dysplasia, according to Dr. Regueiro, noting that a recent retrospective analysis showed an increased risk of dysplasia in UC with persistent histologic activity. “This suggests the need for a colonoscopy in a patient who has had ulcerative colitis for a number of years, even if there’s improvement but, on biopsy, there’s evidence of inflammation.”

According to Dr. Regueiro, such patients might benefit from a fecal calprotectin measurement in 3-6 months to monitor for colonic inflammation. Increased levels might be a sign that the patient is skipping medication doses, although other factors, like respiratory infections, can also explain the results. If the patient’s medication adherence is good, another therapy can be added or the dose increased, and the next endoscopy can be pushed up.

A key limitation to the study by Dr. Seong and colleagues is that it was based in South Korea. “Would this be the same in different countries and different populations? That is still a question,” said Dr. Regueiro.

Dr. Regueiro has received unrestricted educational grants from Abbvie, Janssen, UCB, Pfizer, Takeda, Celgene, Genentech, Gilead, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Lilly. He has been on advisory boards or consulted for numerous companies. He also has relationships with the following CME companies: CME Outfitters, Imedex, GI Health Foundation, Cornerstones, Remedy, MJH Life Sciences, Medscape, MDEducation, WebMD, and HMPGlobal.

FROM INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASES

NAVIGATOR steers uncontrolled asthma toward calmer seas

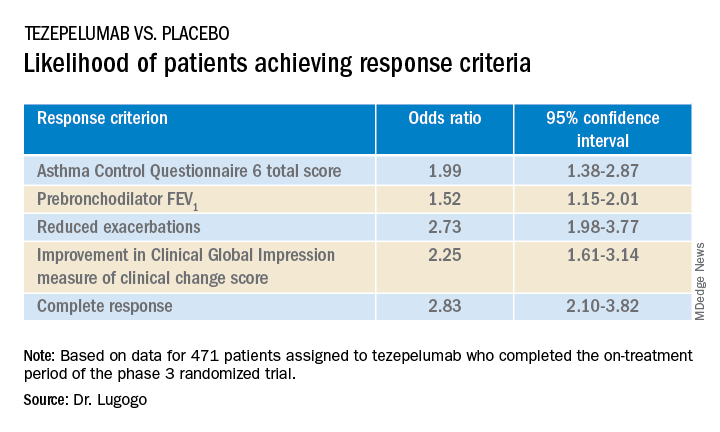

SAN FRANCISCO – Nearly half of all patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma who received a full course of the biologic agent tezepelumab (Tezspire) in the NAVIGATOR trial had a complete response to treatment at 1 year, results of a prespecified exploratory analysis indicated.

Among 471 patients assigned to tezepelumab who completed the on-treatment period of the phase 3 randomized trial, 46% had a complete response at 52 weeks, compared with 24% of patients assigned to placebo.

Complete response was defined as reduction in exacerbations of at least 50% over the previous year, improvement from baseline in Asthma Control Questionnaire 6 (ACQ-6) total score of at least 0.5 points, improvement in prebronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (pre-BD FEV1), and physician-assessed Clinical Global Impression measure of clinical change (CGI-C) score.

“These data further support the efficacy of tezepelumab in a broad population of patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma,” said Njira Lugogo, MD, of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Dr. Lugogo presented results of the exploratory analysis at the American Thoracic Society’s international conference.

Exacerbations reduced, lung function improved

Primary results from NAVIGATOR, published in The New England Journal of Medicine, showed that patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma randomly assigned to tezepelumab had fewer exacerbations and better lung function, asthma control, and health-related quality of life compared with patients assigned to placebo.

The investigators noted that approximately 10% of patients with asthma have symptoms and exacerbations despite maximal standard-of-care controller therapy.

Tezepelumab is a human monoclonal antibody that inhibits action of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), an epithelial cytokine that is released in response to airborne triggers of asthma. TSLP is a major contributor to initiation and persistence of airway inflammation, Dr. Lugogo said.

The on-treatment analysis looked at all patients in the trial who completed 52 weeks of treatment and had complete data for all criteria studied.

The odds ratios (OR) for patients on tezepelumab achieving each of the response criteria are shown in the table.

Exacerbations explored

In a separate presentation, Christopher S. Ambrose, MD, MBA, of AstraZeneca in Gaithersburg, Md., presented information from investigator-narrative descriptions of all hospitalization events related to asthma exacerbations (mild, moderate, or severe) that occurred while the investigator was blinded to each patient’s treatment assignment in NAVIGATOR.

In all, 39 of 531 patients (7.3%) assigned to placebo had a total of 78 exacerbations requiring hospitalization, compared with 13 of 528 patients (2.5%) assigned to tezepelumab. The latter group had a total of 14 exacerbations requiring hospitalization during the study.

Among hospitalized patients, 32 of the 39 assigned to placebo had severe, incapacitating exacerbations, compared with 5 of 13 assigned to tezepelumab.

Reported symptoms were generally similar between hospitalized patients in the two treatment groups, although there appeared to be trends toward lower incidence of dyspnea, fever, and tachycardia with tezepelumab.

Health care resource utilization, a surrogate marker for disease burden, was substantially lower for patients assigned to tezepelumab.

Infections were the most common triggers of exacerbations in both groups.

“These data provide further evidence that tezepelumab can reduce the burden of disease of severe uncontrolled asthma, both to patients and to health care systems,” Dr. Ambrose said.

Head-to-head studies needed

Although there have been no head-to-head comparisons of biologic agents for asthma to date, results of these studies suggest that tezepelumab has efficacy similar to that of other agents for reducing exacerbation, said Fernando Holguin, MD, MPH, from the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, who comoderated the oral session where the data were presented but was not involved in the study.

Biologic agents appear to be slightly more effective against type 2 inflammation in asthma, “but in general I think we give it to a broader severe population, so that’s exciting,” he told this news organization.

Comoderator Amisha Barochia, MBBS, MHS, of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., told this news organization that head-to-head trials of biologic agents would provide important clinical information going forward.

“Should we switch to a different biologic or add a second biologic? Those are questions we need answers for,” she said.

The NAVIGATOR trial is funded by AstraZeneca and Amgen. Dr. Lugogo disclosed financial relationships with both companies. Dr. Holguin and Dr. Barochia have disclosed no financial relationships relevant to the studies presented.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

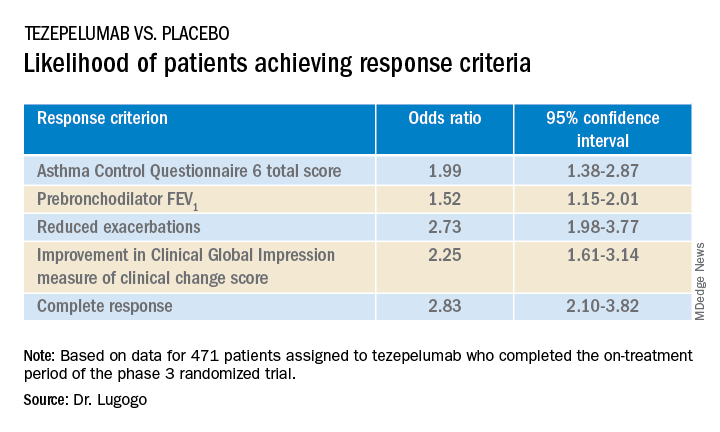

SAN FRANCISCO – Nearly half of all patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma who received a full course of the biologic agent tezepelumab (Tezspire) in the NAVIGATOR trial had a complete response to treatment at 1 year, results of a prespecified exploratory analysis indicated.

Among 471 patients assigned to tezepelumab who completed the on-treatment period of the phase 3 randomized trial, 46% had a complete response at 52 weeks, compared with 24% of patients assigned to placebo.

Complete response was defined as reduction in exacerbations of at least 50% over the previous year, improvement from baseline in Asthma Control Questionnaire 6 (ACQ-6) total score of at least 0.5 points, improvement in prebronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (pre-BD FEV1), and physician-assessed Clinical Global Impression measure of clinical change (CGI-C) score.

“These data further support the efficacy of tezepelumab in a broad population of patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma,” said Njira Lugogo, MD, of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Dr. Lugogo presented results of the exploratory analysis at the American Thoracic Society’s international conference.

Exacerbations reduced, lung function improved

Primary results from NAVIGATOR, published in The New England Journal of Medicine, showed that patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma randomly assigned to tezepelumab had fewer exacerbations and better lung function, asthma control, and health-related quality of life compared with patients assigned to placebo.

The investigators noted that approximately 10% of patients with asthma have symptoms and exacerbations despite maximal standard-of-care controller therapy.

Tezepelumab is a human monoclonal antibody that inhibits action of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), an epithelial cytokine that is released in response to airborne triggers of asthma. TSLP is a major contributor to initiation and persistence of airway inflammation, Dr. Lugogo said.

The on-treatment analysis looked at all patients in the trial who completed 52 weeks of treatment and had complete data for all criteria studied.

The odds ratios (OR) for patients on tezepelumab achieving each of the response criteria are shown in the table.

Exacerbations explored

In a separate presentation, Christopher S. Ambrose, MD, MBA, of AstraZeneca in Gaithersburg, Md., presented information from investigator-narrative descriptions of all hospitalization events related to asthma exacerbations (mild, moderate, or severe) that occurred while the investigator was blinded to each patient’s treatment assignment in NAVIGATOR.

In all, 39 of 531 patients (7.3%) assigned to placebo had a total of 78 exacerbations requiring hospitalization, compared with 13 of 528 patients (2.5%) assigned to tezepelumab. The latter group had a total of 14 exacerbations requiring hospitalization during the study.

Among hospitalized patients, 32 of the 39 assigned to placebo had severe, incapacitating exacerbations, compared with 5 of 13 assigned to tezepelumab.

Reported symptoms were generally similar between hospitalized patients in the two treatment groups, although there appeared to be trends toward lower incidence of dyspnea, fever, and tachycardia with tezepelumab.

Health care resource utilization, a surrogate marker for disease burden, was substantially lower for patients assigned to tezepelumab.

Infections were the most common triggers of exacerbations in both groups.

“These data provide further evidence that tezepelumab can reduce the burden of disease of severe uncontrolled asthma, both to patients and to health care systems,” Dr. Ambrose said.

Head-to-head studies needed

Although there have been no head-to-head comparisons of biologic agents for asthma to date, results of these studies suggest that tezepelumab has efficacy similar to that of other agents for reducing exacerbation, said Fernando Holguin, MD, MPH, from the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, who comoderated the oral session where the data were presented but was not involved in the study.

Biologic agents appear to be slightly more effective against type 2 inflammation in asthma, “but in general I think we give it to a broader severe population, so that’s exciting,” he told this news organization.

Comoderator Amisha Barochia, MBBS, MHS, of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., told this news organization that head-to-head trials of biologic agents would provide important clinical information going forward.

“Should we switch to a different biologic or add a second biologic? Those are questions we need answers for,” she said.

The NAVIGATOR trial is funded by AstraZeneca and Amgen. Dr. Lugogo disclosed financial relationships with both companies. Dr. Holguin and Dr. Barochia have disclosed no financial relationships relevant to the studies presented.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

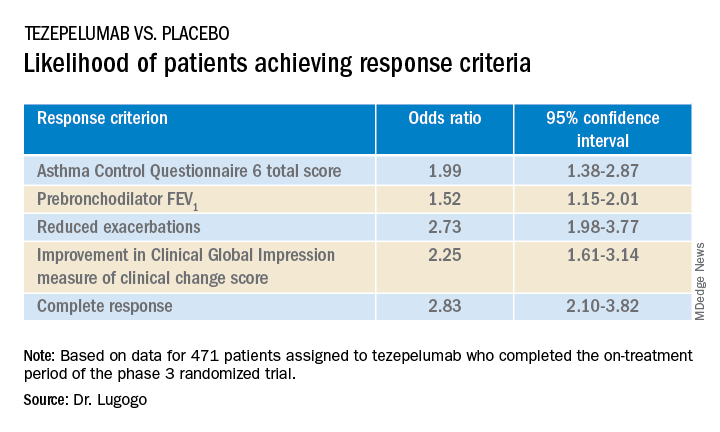

SAN FRANCISCO – Nearly half of all patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma who received a full course of the biologic agent tezepelumab (Tezspire) in the NAVIGATOR trial had a complete response to treatment at 1 year, results of a prespecified exploratory analysis indicated.

Among 471 patients assigned to tezepelumab who completed the on-treatment period of the phase 3 randomized trial, 46% had a complete response at 52 weeks, compared with 24% of patients assigned to placebo.

Complete response was defined as reduction in exacerbations of at least 50% over the previous year, improvement from baseline in Asthma Control Questionnaire 6 (ACQ-6) total score of at least 0.5 points, improvement in prebronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (pre-BD FEV1), and physician-assessed Clinical Global Impression measure of clinical change (CGI-C) score.

“These data further support the efficacy of tezepelumab in a broad population of patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma,” said Njira Lugogo, MD, of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Dr. Lugogo presented results of the exploratory analysis at the American Thoracic Society’s international conference.

Exacerbations reduced, lung function improved

Primary results from NAVIGATOR, published in The New England Journal of Medicine, showed that patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma randomly assigned to tezepelumab had fewer exacerbations and better lung function, asthma control, and health-related quality of life compared with patients assigned to placebo.

The investigators noted that approximately 10% of patients with asthma have symptoms and exacerbations despite maximal standard-of-care controller therapy.

Tezepelumab is a human monoclonal antibody that inhibits action of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), an epithelial cytokine that is released in response to airborne triggers of asthma. TSLP is a major contributor to initiation and persistence of airway inflammation, Dr. Lugogo said.

The on-treatment analysis looked at all patients in the trial who completed 52 weeks of treatment and had complete data for all criteria studied.

The odds ratios (OR) for patients on tezepelumab achieving each of the response criteria are shown in the table.

Exacerbations explored

In a separate presentation, Christopher S. Ambrose, MD, MBA, of AstraZeneca in Gaithersburg, Md., presented information from investigator-narrative descriptions of all hospitalization events related to asthma exacerbations (mild, moderate, or severe) that occurred while the investigator was blinded to each patient’s treatment assignment in NAVIGATOR.

In all, 39 of 531 patients (7.3%) assigned to placebo had a total of 78 exacerbations requiring hospitalization, compared with 13 of 528 patients (2.5%) assigned to tezepelumab. The latter group had a total of 14 exacerbations requiring hospitalization during the study.

Among hospitalized patients, 32 of the 39 assigned to placebo had severe, incapacitating exacerbations, compared with 5 of 13 assigned to tezepelumab.

Reported symptoms were generally similar between hospitalized patients in the two treatment groups, although there appeared to be trends toward lower incidence of dyspnea, fever, and tachycardia with tezepelumab.

Health care resource utilization, a surrogate marker for disease burden, was substantially lower for patients assigned to tezepelumab.

Infections were the most common triggers of exacerbations in both groups.

“These data provide further evidence that tezepelumab can reduce the burden of disease of severe uncontrolled asthma, both to patients and to health care systems,” Dr. Ambrose said.

Head-to-head studies needed

Although there have been no head-to-head comparisons of biologic agents for asthma to date, results of these studies suggest that tezepelumab has efficacy similar to that of other agents for reducing exacerbation, said Fernando Holguin, MD, MPH, from the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, who comoderated the oral session where the data were presented but was not involved in the study.

Biologic agents appear to be slightly more effective against type 2 inflammation in asthma, “but in general I think we give it to a broader severe population, so that’s exciting,” he told this news organization.

Comoderator Amisha Barochia, MBBS, MHS, of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., told this news organization that head-to-head trials of biologic agents would provide important clinical information going forward.

“Should we switch to a different biologic or add a second biologic? Those are questions we need answers for,” she said.

The NAVIGATOR trial is funded by AstraZeneca and Amgen. Dr. Lugogo disclosed financial relationships with both companies. Dr. Holguin and Dr. Barochia have disclosed no financial relationships relevant to the studies presented.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ATS 2022

Jury is in? Survival benefit with lap surgery for rectal cancer

, according to findings from a large meta-analysis.

The estimated 5-year OS rate for patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery was 76.2%, vs. 72.7% for those who had open surgery.

“The survival benefit of laparoscopic surgery is encouraging and supports the routine use of laparoscopic surgery for adult patients with rectal cancer in the era of minimally invasive surgery,” wrote the authors, led by Leping Li, MD, of the department of gastrointestinal surgery, Shandong (China) Provincial Hospital.

The article was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Surgery is an essential component in treating rectal cancer, but the benefits of laparoscopic vs. open surgery are not clear. Over the past 15 years, randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have shown comparable long-term outcomes for laparoscopic and open surgery. However, in most meta-analyses that assessed the evidence more broadly, researchers used an “inappropriate” method for the pooled analysis. Dr. Li and colleagues wanted to perform their own meta-analysis to more definitively understand whether the evidence on long-term outcomes supports or opposes the use of laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer.

In the current study, the authors conducted an individual participant data meta-analysis using time-to-event data and focused on the long-term survival outcomes after laparoscopic or open surgery for adult patients with rectal cancer.

Ten articles involving 12 RCTs and 3,709 participants were included. In these, 2,097 patients were randomly assigned to undergo laparoscopic surgery, and 1,612 were randomly assigned to undergo open surgery. The studies covered a global population, with participants from Europe, North America, and East Asia.

In a one-stage analysis, the authors found that disease-free survival was slightly better among patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery, but the results were statistically similar (hazard ratio [HR], 0.92; P = .26).

However, when it came to OS, those who had undergone laparoscopic surgery fared significantly better (HR, 0.85; P = .02).

These results held up in the two-stage analysis for both disease-free survival (HR, 0.92; P = .25) and OS (HR, 0.85; P = .02). A sensitivity analyses conducted with large RCTs yielded similar pooled effect sizes for disease-free survival (HR, 0.91; P = .20) and OS (HR, 0.84; P = .03).

The authors highlighted several reasons why laparoscopic surgery may be associated with better survival. First, the faster recovery from the minimally invasive procedure could allow patients to begin adjuvant therapy earlier. In addition, the reduced stress responses and higher levels of immune function among patients undergoing minimally invasive surgery may contribute to a long-term survival advantage.

“These findings address concerns regarding the effectiveness of laparoscopic surgery,” the authors wrote. However, “further studies are necessary to explore the specific mechanisms underlying the positive effect of laparoscopic surgery on OS.”

No outside funding source was noted. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to findings from a large meta-analysis.

The estimated 5-year OS rate for patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery was 76.2%, vs. 72.7% for those who had open surgery.

“The survival benefit of laparoscopic surgery is encouraging and supports the routine use of laparoscopic surgery for adult patients with rectal cancer in the era of minimally invasive surgery,” wrote the authors, led by Leping Li, MD, of the department of gastrointestinal surgery, Shandong (China) Provincial Hospital.

The article was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Surgery is an essential component in treating rectal cancer, but the benefits of laparoscopic vs. open surgery are not clear. Over the past 15 years, randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have shown comparable long-term outcomes for laparoscopic and open surgery. However, in most meta-analyses that assessed the evidence more broadly, researchers used an “inappropriate” method for the pooled analysis. Dr. Li and colleagues wanted to perform their own meta-analysis to more definitively understand whether the evidence on long-term outcomes supports or opposes the use of laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer.

In the current study, the authors conducted an individual participant data meta-analysis using time-to-event data and focused on the long-term survival outcomes after laparoscopic or open surgery for adult patients with rectal cancer.

Ten articles involving 12 RCTs and 3,709 participants were included. In these, 2,097 patients were randomly assigned to undergo laparoscopic surgery, and 1,612 were randomly assigned to undergo open surgery. The studies covered a global population, with participants from Europe, North America, and East Asia.

In a one-stage analysis, the authors found that disease-free survival was slightly better among patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery, but the results were statistically similar (hazard ratio [HR], 0.92; P = .26).

However, when it came to OS, those who had undergone laparoscopic surgery fared significantly better (HR, 0.85; P = .02).

These results held up in the two-stage analysis for both disease-free survival (HR, 0.92; P = .25) and OS (HR, 0.85; P = .02). A sensitivity analyses conducted with large RCTs yielded similar pooled effect sizes for disease-free survival (HR, 0.91; P = .20) and OS (HR, 0.84; P = .03).

The authors highlighted several reasons why laparoscopic surgery may be associated with better survival. First, the faster recovery from the minimally invasive procedure could allow patients to begin adjuvant therapy earlier. In addition, the reduced stress responses and higher levels of immune function among patients undergoing minimally invasive surgery may contribute to a long-term survival advantage.

“These findings address concerns regarding the effectiveness of laparoscopic surgery,” the authors wrote. However, “further studies are necessary to explore the specific mechanisms underlying the positive effect of laparoscopic surgery on OS.”

No outside funding source was noted. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to findings from a large meta-analysis.

The estimated 5-year OS rate for patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery was 76.2%, vs. 72.7% for those who had open surgery.

“The survival benefit of laparoscopic surgery is encouraging and supports the routine use of laparoscopic surgery for adult patients with rectal cancer in the era of minimally invasive surgery,” wrote the authors, led by Leping Li, MD, of the department of gastrointestinal surgery, Shandong (China) Provincial Hospital.

The article was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Surgery is an essential component in treating rectal cancer, but the benefits of laparoscopic vs. open surgery are not clear. Over the past 15 years, randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have shown comparable long-term outcomes for laparoscopic and open surgery. However, in most meta-analyses that assessed the evidence more broadly, researchers used an “inappropriate” method for the pooled analysis. Dr. Li and colleagues wanted to perform their own meta-analysis to more definitively understand whether the evidence on long-term outcomes supports or opposes the use of laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer.

In the current study, the authors conducted an individual participant data meta-analysis using time-to-event data and focused on the long-term survival outcomes after laparoscopic or open surgery for adult patients with rectal cancer.

Ten articles involving 12 RCTs and 3,709 participants were included. In these, 2,097 patients were randomly assigned to undergo laparoscopic surgery, and 1,612 were randomly assigned to undergo open surgery. The studies covered a global population, with participants from Europe, North America, and East Asia.

In a one-stage analysis, the authors found that disease-free survival was slightly better among patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery, but the results were statistically similar (hazard ratio [HR], 0.92; P = .26).

However, when it came to OS, those who had undergone laparoscopic surgery fared significantly better (HR, 0.85; P = .02).

These results held up in the two-stage analysis for both disease-free survival (HR, 0.92; P = .25) and OS (HR, 0.85; P = .02). A sensitivity analyses conducted with large RCTs yielded similar pooled effect sizes for disease-free survival (HR, 0.91; P = .20) and OS (HR, 0.84; P = .03).

The authors highlighted several reasons why laparoscopic surgery may be associated with better survival. First, the faster recovery from the minimally invasive procedure could allow patients to begin adjuvant therapy earlier. In addition, the reduced stress responses and higher levels of immune function among patients undergoing minimally invasive surgery may contribute to a long-term survival advantage.

“These findings address concerns regarding the effectiveness of laparoscopic surgery,” the authors wrote. However, “further studies are necessary to explore the specific mechanisms underlying the positive effect of laparoscopic surgery on OS.”

No outside funding source was noted. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Male breast cancer risk linked with infertility

, according to new research funded by the charity Breast Cancer Now and published in Breast Cancer Research. The study is one of the largest ever into male breast cancer, enabling the team to show a highly statistically significant association.

A link with infertility had been suspected, since parity markedly reduces the risk of female breast cancer; there are known genetic links in both sexes, and a high risk of both breast cancer and infertility among men with Klinefelter syndrome, suggesting some sex hormone-related involvement. However, the rarity of breast cancer in men – with an annual incidence of about 370 cases and 80 deaths per year in the United Kingdom – meant that past studies were necessarily small and yielded mixed results.

“Compared with previous studies, our study of male breast cancer is large,” said study coauthor Michael Jones, PhD, of the division of genetics and epidemiology at the Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) in London. “It was carried out nationwide across England and Wales and was set in motion more than 15 years ago. Because of how rare male breast cancer is, it took us over 12 years to identify and interview the nearly 2,000 men with breast cancer who were part of this study.”

The latest research is part of the wider Breast Cancer Now Male Breast Cancer Study, launched by the charity in 2007. For the new study, the ICR team interviewed 1,998 males living in England and Wales who had been diagnosed with breast cancer between 2005 and 2017. All were aged under 80 but most 60 or older at diagnosis; 92% of their tumors were invasive, and almost all were estrogen receptor positive (98.5% of those with known status).

Their responses were compared with those of a control group of 1,597 men without breast cancer, matched by age at diagnosis and geographic region, recruited from male non-blood relatives of cases and from husbands of women participating in the Generations cohort study of breast cancer etiology.

Raised risk with history of male infertility