User login

Life in Romanian village offers lessons for our patients

BREB, ROMANIA – While strolling through this village in the Maramures region in the northwest corner of Romania, I ask Ileana, "How many live in this village?" Ileana has just come home from high school in the nearest town and is wearing brightly colored sneakers, blue jeans, and a pink sweatshirt with the word "LOVE" emblazed in sparkles across her chest. She is touring us proudly around her village.

"400."

"400 people?"

"No, 400 families."

"How many in each family?"

"About six or seven."

On the large ornate wooden gate to the family homestead is the inscription: "Familie Hermann." All seven members of the Hermann family live in a three-room traditional wooden house. The house has a large porch, where the family eats, works, and sometimes sleeps in the warm weather.

Maria, the 82-year-old grandmother, sits outside the gate on a small bench and watches the villagers stroll home from the fields with scythes and rakes on their shoulders. She welcomes her daughter and son-in-law back home. It is spring, and the villagers are cleaning the fields in preparation for the summer grass growing. In the fall, they will harvest the grass to feed their animals throughout the winter.

On the porch, in the quiet of a late afternoon, as 9-year-old Ioanna is doing her homework, her mother, Raluca, works on the intricacies of beading the border of Ioanna’s traditional costume to be worn on Easter Sunday. Ioanna watches her mother pin the black velvet jacket to her skirt and load the needle with the gold beads to make the stems for the purple and red flowers. She sees how to turn the green rows into leaves. She shows her mother her school work, as equally neat and carefully calligraphied as her mother’s beading. Concern for accuracy and aesthetics are the skills and values passed down through the generations.

Maria comes in from the gate and resumes shelling beans on the front porch. She doesn’t do as much work in the fields anymore. Instead, she sweeps the house, tends to the flower garden, and helps with the two children. Maria takes the clothes down from the clothesline that stretches across the front of the porch. These handmade, intricately stitched works of art have been washed in preparation for Easter.

Maria shows us the gown she will wear at her funeral. She wove the linen, and smocked the neck and wrists with traditional village colors. She is proud of her work, and we admire it. She takes her gown inside, along with all the other freshly laundered white blouses that men and women will wear during the traditional events throughout the year.

After Easter, when the weather warms, most of the village will make the pilgrimage up the mountain accompanying the shepherds taking the sheep to summer grazing. The milking of the sheep is a defining village event, and precise measures are recorded in a book or on a stick to indicate each person’s anticipated portion of future milkings. This is Stina, a serious celebration, and the villagers wear traditional dress for the feasting, drinking, and dancing.

Life in rural villages is physically hard, and family and communal living are not idyllic. There is no privacy in the village, perhaps no secrets.

There is no privileging of the individual over the family. The family functions as a unit, getting work done by the seasons, so the family can eat throughout the year. The sense of belonging is irrefutable.

There is room for individual pride, however, and this is expressed as skill in raking a straight row, making the best plum brandy, wood carving, and doing embroidery. Everyone has an opinion on which family is the best at their craft in the village. The Hermann family is recognized for their skill in textiles – particularly their embroidery.

The village has its characters: the most devout, the "bad boy," the lazy person, and the man who can’t hold his liquor. This man, the village drunk, frequently makes a trip to the psychiatric hospital in the town of Sighetu Marmatieti, when he gets out of hand. After a few weeks, he comes home quieter, and his good behavior will last for the best part of a year. There is no physician or nurse in the village, only a veterinarian who visits, when called, to care for the animals.

The darker stories of the village lie hidden, because for now, it is early spring, and the village flows with optimism, celebration, and courtship. The white, hand-crafted blouses manifest the feelings of anticipation as they billow and dance on each clothesline throughout the village. Belonging to the village means feeling the seasons unfold intuitively. These feelings sustain and nourish the village families throughout their lives.

Outside of the village, in the "real world," we try to create a sense of belonging. As a country of immigrants, we in America have sense of belonging that is scattered. Still, connecting with our past is too often beyond our grasp. What is belonging? What are its components?

Ways to think about belonging

Studies on belonging extend across many disciplines: psychoanalysis, attachment psychology, social and cultural studies to philosophy. How does a family psychiatrist think about belonging? What aspects of belonging can be incorporated into psychiatric care?

An unmet need for belonging leads to loneliness and lower life satisfaction. This finding came from a study of 436 participants from the Australian Unity Wellbeing database who completed several measurements, including the Need to Belong Scale according to David Mellor, Ph.D., and his colleagues(Pers. Individ. Dif. 2008;45:213-8). Dr. Vincenzo Di Nicola, a psychiatrist who has written extensively about family relationships, also has offered valuable perspective on belongingness: "Belonging is a way of rethinking relational being, how we define mental health, how we understand the expression of its vicissitudes, and how we organize care and healing for sufferers. To do this, we need to recognize how belonging is experienced and negotiated, free of the constraints of our habitual patterns of practice and thought, to imagine belonging without borders for settlers, sojourners, and travelers in the 21st century."

Belongingness traditionally has been seen as a core of family life. If your values are different from those of your family, if you have moved from the village to the city and don’t want to be a farmer, what values do you uphold? Do you now have a new set of people and values? Do you belong to a group/club/school? Belonging to a guild or religious order means that the guild or order becomes your new family. However, belongingness is more transient and a less substantial part of life, as people change jobs and careers, get divorced and remarried, move to other countries.

Who serves as the family for people with psychiatric illness? In a recent study, people with serious mental illness were interviewed and asked about the "communities" to which they belonged (Psychiatr. Serv. [doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200235]). The researchers found four "patterns of experience" that made up communities for the respondents. Communities were places where people with mental illness could receive help, especially in times of vulnerability.

In addition, communities were places to manage risk and minimize the anxiety felt in public setting by people with mental illness. The stigma experienced in the general community or even within their families led many respondents to identify more strongly with peers who had mental illness.

Communities also were seen as places where those with serious mental illness could "give back" and help others. So perhaps, in the same way as these respondents defined belongingness for themselves, we can define belongingness for all our patients.

Several components must be satisfied for a person to have a sense of belongingness.

• A community in which the person’s beliefs and values are upheld as sacred (meaningfulness).

• Rituals that bring people together and support the meaningfulness of their lives (meaningfulness).

• People who provide emotional and practical support for others (attachment).

• People who allow others to provide them with support (sense of self-efficacy).

• Generational transmission of skills, crafts, values, and beliefs (generativity).

A sense of place is another component that has been associated with a sense of belonging. After the Boston Marathon bombings, some people affirmed that their sense of belonging was consolidated by that event. For others, a sense of belonging becomes fixed in their sense of tragedy as a victim of an event. We see many patients with posttraumatic stress disorder who have been bound by the traumatizing event(s), and who find it difficult or impossible to move beyond that experience.

For Americans, perhaps the notion of "family values" can be parsed to include the idea and study of belongingness. Understanding what belongingness encompasses can help us discuss relational being with our patients. Where do you find that sense of belonging? For Ioanna, her sense of belonging is felt in the seasonal ebb and flow of village life. Her sense of belonging shows in her skill as she works with her crafts with her hands. Breb belongs to her, even as it opens its large wooden doors to the world.

Dr. Heru is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of the recently published book, "Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals" (New York: Routledge, 2013.

BREB, ROMANIA – While strolling through this village in the Maramures region in the northwest corner of Romania, I ask Ileana, "How many live in this village?" Ileana has just come home from high school in the nearest town and is wearing brightly colored sneakers, blue jeans, and a pink sweatshirt with the word "LOVE" emblazed in sparkles across her chest. She is touring us proudly around her village.

"400."

"400 people?"

"No, 400 families."

"How many in each family?"

"About six or seven."

On the large ornate wooden gate to the family homestead is the inscription: "Familie Hermann." All seven members of the Hermann family live in a three-room traditional wooden house. The house has a large porch, where the family eats, works, and sometimes sleeps in the warm weather.

Maria, the 82-year-old grandmother, sits outside the gate on a small bench and watches the villagers stroll home from the fields with scythes and rakes on their shoulders. She welcomes her daughter and son-in-law back home. It is spring, and the villagers are cleaning the fields in preparation for the summer grass growing. In the fall, they will harvest the grass to feed their animals throughout the winter.

On the porch, in the quiet of a late afternoon, as 9-year-old Ioanna is doing her homework, her mother, Raluca, works on the intricacies of beading the border of Ioanna’s traditional costume to be worn on Easter Sunday. Ioanna watches her mother pin the black velvet jacket to her skirt and load the needle with the gold beads to make the stems for the purple and red flowers. She sees how to turn the green rows into leaves. She shows her mother her school work, as equally neat and carefully calligraphied as her mother’s beading. Concern for accuracy and aesthetics are the skills and values passed down through the generations.

Maria comes in from the gate and resumes shelling beans on the front porch. She doesn’t do as much work in the fields anymore. Instead, she sweeps the house, tends to the flower garden, and helps with the two children. Maria takes the clothes down from the clothesline that stretches across the front of the porch. These handmade, intricately stitched works of art have been washed in preparation for Easter.

Maria shows us the gown she will wear at her funeral. She wove the linen, and smocked the neck and wrists with traditional village colors. She is proud of her work, and we admire it. She takes her gown inside, along with all the other freshly laundered white blouses that men and women will wear during the traditional events throughout the year.

After Easter, when the weather warms, most of the village will make the pilgrimage up the mountain accompanying the shepherds taking the sheep to summer grazing. The milking of the sheep is a defining village event, and precise measures are recorded in a book or on a stick to indicate each person’s anticipated portion of future milkings. This is Stina, a serious celebration, and the villagers wear traditional dress for the feasting, drinking, and dancing.

Life in rural villages is physically hard, and family and communal living are not idyllic. There is no privacy in the village, perhaps no secrets.

There is no privileging of the individual over the family. The family functions as a unit, getting work done by the seasons, so the family can eat throughout the year. The sense of belonging is irrefutable.

There is room for individual pride, however, and this is expressed as skill in raking a straight row, making the best plum brandy, wood carving, and doing embroidery. Everyone has an opinion on which family is the best at their craft in the village. The Hermann family is recognized for their skill in textiles – particularly their embroidery.

The village has its characters: the most devout, the "bad boy," the lazy person, and the man who can’t hold his liquor. This man, the village drunk, frequently makes a trip to the psychiatric hospital in the town of Sighetu Marmatieti, when he gets out of hand. After a few weeks, he comes home quieter, and his good behavior will last for the best part of a year. There is no physician or nurse in the village, only a veterinarian who visits, when called, to care for the animals.

The darker stories of the village lie hidden, because for now, it is early spring, and the village flows with optimism, celebration, and courtship. The white, hand-crafted blouses manifest the feelings of anticipation as they billow and dance on each clothesline throughout the village. Belonging to the village means feeling the seasons unfold intuitively. These feelings sustain and nourish the village families throughout their lives.

Outside of the village, in the "real world," we try to create a sense of belonging. As a country of immigrants, we in America have sense of belonging that is scattered. Still, connecting with our past is too often beyond our grasp. What is belonging? What are its components?

Ways to think about belonging

Studies on belonging extend across many disciplines: psychoanalysis, attachment psychology, social and cultural studies to philosophy. How does a family psychiatrist think about belonging? What aspects of belonging can be incorporated into psychiatric care?

An unmet need for belonging leads to loneliness and lower life satisfaction. This finding came from a study of 436 participants from the Australian Unity Wellbeing database who completed several measurements, including the Need to Belong Scale according to David Mellor, Ph.D., and his colleagues(Pers. Individ. Dif. 2008;45:213-8). Dr. Vincenzo Di Nicola, a psychiatrist who has written extensively about family relationships, also has offered valuable perspective on belongingness: "Belonging is a way of rethinking relational being, how we define mental health, how we understand the expression of its vicissitudes, and how we organize care and healing for sufferers. To do this, we need to recognize how belonging is experienced and negotiated, free of the constraints of our habitual patterns of practice and thought, to imagine belonging without borders for settlers, sojourners, and travelers in the 21st century."

Belongingness traditionally has been seen as a core of family life. If your values are different from those of your family, if you have moved from the village to the city and don’t want to be a farmer, what values do you uphold? Do you now have a new set of people and values? Do you belong to a group/club/school? Belonging to a guild or religious order means that the guild or order becomes your new family. However, belongingness is more transient and a less substantial part of life, as people change jobs and careers, get divorced and remarried, move to other countries.

Who serves as the family for people with psychiatric illness? In a recent study, people with serious mental illness were interviewed and asked about the "communities" to which they belonged (Psychiatr. Serv. [doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200235]). The researchers found four "patterns of experience" that made up communities for the respondents. Communities were places where people with mental illness could receive help, especially in times of vulnerability.

In addition, communities were places to manage risk and minimize the anxiety felt in public setting by people with mental illness. The stigma experienced in the general community or even within their families led many respondents to identify more strongly with peers who had mental illness.

Communities also were seen as places where those with serious mental illness could "give back" and help others. So perhaps, in the same way as these respondents defined belongingness for themselves, we can define belongingness for all our patients.

Several components must be satisfied for a person to have a sense of belongingness.

• A community in which the person’s beliefs and values are upheld as sacred (meaningfulness).

• Rituals that bring people together and support the meaningfulness of their lives (meaningfulness).

• People who provide emotional and practical support for others (attachment).

• People who allow others to provide them with support (sense of self-efficacy).

• Generational transmission of skills, crafts, values, and beliefs (generativity).

A sense of place is another component that has been associated with a sense of belonging. After the Boston Marathon bombings, some people affirmed that their sense of belonging was consolidated by that event. For others, a sense of belonging becomes fixed in their sense of tragedy as a victim of an event. We see many patients with posttraumatic stress disorder who have been bound by the traumatizing event(s), and who find it difficult or impossible to move beyond that experience.

For Americans, perhaps the notion of "family values" can be parsed to include the idea and study of belongingness. Understanding what belongingness encompasses can help us discuss relational being with our patients. Where do you find that sense of belonging? For Ioanna, her sense of belonging is felt in the seasonal ebb and flow of village life. Her sense of belonging shows in her skill as she works with her crafts with her hands. Breb belongs to her, even as it opens its large wooden doors to the world.

Dr. Heru is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of the recently published book, "Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals" (New York: Routledge, 2013.

BREB, ROMANIA – While strolling through this village in the Maramures region in the northwest corner of Romania, I ask Ileana, "How many live in this village?" Ileana has just come home from high school in the nearest town and is wearing brightly colored sneakers, blue jeans, and a pink sweatshirt with the word "LOVE" emblazed in sparkles across her chest. She is touring us proudly around her village.

"400."

"400 people?"

"No, 400 families."

"How many in each family?"

"About six or seven."

On the large ornate wooden gate to the family homestead is the inscription: "Familie Hermann." All seven members of the Hermann family live in a three-room traditional wooden house. The house has a large porch, where the family eats, works, and sometimes sleeps in the warm weather.

Maria, the 82-year-old grandmother, sits outside the gate on a small bench and watches the villagers stroll home from the fields with scythes and rakes on their shoulders. She welcomes her daughter and son-in-law back home. It is spring, and the villagers are cleaning the fields in preparation for the summer grass growing. In the fall, they will harvest the grass to feed their animals throughout the winter.

On the porch, in the quiet of a late afternoon, as 9-year-old Ioanna is doing her homework, her mother, Raluca, works on the intricacies of beading the border of Ioanna’s traditional costume to be worn on Easter Sunday. Ioanna watches her mother pin the black velvet jacket to her skirt and load the needle with the gold beads to make the stems for the purple and red flowers. She sees how to turn the green rows into leaves. She shows her mother her school work, as equally neat and carefully calligraphied as her mother’s beading. Concern for accuracy and aesthetics are the skills and values passed down through the generations.

Maria comes in from the gate and resumes shelling beans on the front porch. She doesn’t do as much work in the fields anymore. Instead, she sweeps the house, tends to the flower garden, and helps with the two children. Maria takes the clothes down from the clothesline that stretches across the front of the porch. These handmade, intricately stitched works of art have been washed in preparation for Easter.

Maria shows us the gown she will wear at her funeral. She wove the linen, and smocked the neck and wrists with traditional village colors. She is proud of her work, and we admire it. She takes her gown inside, along with all the other freshly laundered white blouses that men and women will wear during the traditional events throughout the year.

After Easter, when the weather warms, most of the village will make the pilgrimage up the mountain accompanying the shepherds taking the sheep to summer grazing. The milking of the sheep is a defining village event, and precise measures are recorded in a book or on a stick to indicate each person’s anticipated portion of future milkings. This is Stina, a serious celebration, and the villagers wear traditional dress for the feasting, drinking, and dancing.

Life in rural villages is physically hard, and family and communal living are not idyllic. There is no privacy in the village, perhaps no secrets.

There is no privileging of the individual over the family. The family functions as a unit, getting work done by the seasons, so the family can eat throughout the year. The sense of belonging is irrefutable.

There is room for individual pride, however, and this is expressed as skill in raking a straight row, making the best plum brandy, wood carving, and doing embroidery. Everyone has an opinion on which family is the best at their craft in the village. The Hermann family is recognized for their skill in textiles – particularly their embroidery.

The village has its characters: the most devout, the "bad boy," the lazy person, and the man who can’t hold his liquor. This man, the village drunk, frequently makes a trip to the psychiatric hospital in the town of Sighetu Marmatieti, when he gets out of hand. After a few weeks, he comes home quieter, and his good behavior will last for the best part of a year. There is no physician or nurse in the village, only a veterinarian who visits, when called, to care for the animals.

The darker stories of the village lie hidden, because for now, it is early spring, and the village flows with optimism, celebration, and courtship. The white, hand-crafted blouses manifest the feelings of anticipation as they billow and dance on each clothesline throughout the village. Belonging to the village means feeling the seasons unfold intuitively. These feelings sustain and nourish the village families throughout their lives.

Outside of the village, in the "real world," we try to create a sense of belonging. As a country of immigrants, we in America have sense of belonging that is scattered. Still, connecting with our past is too often beyond our grasp. What is belonging? What are its components?

Ways to think about belonging

Studies on belonging extend across many disciplines: psychoanalysis, attachment psychology, social and cultural studies to philosophy. How does a family psychiatrist think about belonging? What aspects of belonging can be incorporated into psychiatric care?

An unmet need for belonging leads to loneliness and lower life satisfaction. This finding came from a study of 436 participants from the Australian Unity Wellbeing database who completed several measurements, including the Need to Belong Scale according to David Mellor, Ph.D., and his colleagues(Pers. Individ. Dif. 2008;45:213-8). Dr. Vincenzo Di Nicola, a psychiatrist who has written extensively about family relationships, also has offered valuable perspective on belongingness: "Belonging is a way of rethinking relational being, how we define mental health, how we understand the expression of its vicissitudes, and how we organize care and healing for sufferers. To do this, we need to recognize how belonging is experienced and negotiated, free of the constraints of our habitual patterns of practice and thought, to imagine belonging without borders for settlers, sojourners, and travelers in the 21st century."

Belongingness traditionally has been seen as a core of family life. If your values are different from those of your family, if you have moved from the village to the city and don’t want to be a farmer, what values do you uphold? Do you now have a new set of people and values? Do you belong to a group/club/school? Belonging to a guild or religious order means that the guild or order becomes your new family. However, belongingness is more transient and a less substantial part of life, as people change jobs and careers, get divorced and remarried, move to other countries.

Who serves as the family for people with psychiatric illness? In a recent study, people with serious mental illness were interviewed and asked about the "communities" to which they belonged (Psychiatr. Serv. [doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200235]). The researchers found four "patterns of experience" that made up communities for the respondents. Communities were places where people with mental illness could receive help, especially in times of vulnerability.

In addition, communities were places to manage risk and minimize the anxiety felt in public setting by people with mental illness. The stigma experienced in the general community or even within their families led many respondents to identify more strongly with peers who had mental illness.

Communities also were seen as places where those with serious mental illness could "give back" and help others. So perhaps, in the same way as these respondents defined belongingness for themselves, we can define belongingness for all our patients.

Several components must be satisfied for a person to have a sense of belongingness.

• A community in which the person’s beliefs and values are upheld as sacred (meaningfulness).

• Rituals that bring people together and support the meaningfulness of their lives (meaningfulness).

• People who provide emotional and practical support for others (attachment).

• People who allow others to provide them with support (sense of self-efficacy).

• Generational transmission of skills, crafts, values, and beliefs (generativity).

A sense of place is another component that has been associated with a sense of belonging. After the Boston Marathon bombings, some people affirmed that their sense of belonging was consolidated by that event. For others, a sense of belonging becomes fixed in their sense of tragedy as a victim of an event. We see many patients with posttraumatic stress disorder who have been bound by the traumatizing event(s), and who find it difficult or impossible to move beyond that experience.

For Americans, perhaps the notion of "family values" can be parsed to include the idea and study of belongingness. Understanding what belongingness encompasses can help us discuss relational being with our patients. Where do you find that sense of belonging? For Ioanna, her sense of belonging is felt in the seasonal ebb and flow of village life. Her sense of belonging shows in her skill as she works with her crafts with her hands. Breb belongs to her, even as it opens its large wooden doors to the world.

Dr. Heru is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of the recently published book, "Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals" (New York: Routledge, 2013.

Dogs and heart attacks

We have recently been informed by an American Heart Association committee that owning a pet decreases your cardiovascular risk. Since I am of the age when a coronary event is almost inevitable, the opinion of the committee caught my attention.

I am not much into pets, and I am not what you would call a dog lover; but I have had a dog that I really loved. Her name was Cassiopeia, "Cassie" for short, named after my then–10-year-old son’s favorite constellation. She was a warm and attentive golden retriever who jumped up on my car to greet me every evening when I came home from the hospital. My wife, who dutifully walked her every day, rarely got so much as a tail wag. She was clearly "my" dog and, like any person or animal that comes up to you at the end of the day with a lick or a kiss, was someone to be cherished.

In her 10th year, Cassie’s kidneys failed. After several weeks of daily administration of intravenous fluids, I gave up and took her to the vet to be euthanized. I freely admit that I was mildly depressed for a few weeks after she died. We never got another dog because my wife refused to continue to take care of an animal that never showed any appreciation.

The American Heart Association’s position on the benefit of pet ownership in the reduction of cardiovascular risk is one of at least three scientific statements that the organization makes each month. It did bring to mind the effect of Cassie on my psyche and the potentially beneficial effect that she had on my coronary arteries. However, I would have to admit I have failed to pay much attention to previous proclamations by well-meaning scientific bodies like the AHA committees. I have ignored the advice about my large coffee intake, my lack of daily exercise, and the amount of salt I put on my steak.

This particular statement by the AHA, however, was cautious about the justification of the canine-human interaction and indicated that there are scant randomized data to support the claim, and what existed related to cats, a species to which my wife is allergic. The recent dog–heart disease statement had come about as a result of a "growing number of news reports and medical studies" that purported to show a beneficial relationship between pet ownership and heart disease. It is amazing how one fails to notice a brouhaha right in our own midst. According to the New York Times account, the public uproar had reached such a "point that it would be reasonable to formally investigate" the issue.

But how would you ever try to design a trial testing the hypothesis that owning a dog was a panacea for cardiovascular disease? It is not clear what mechanism of action could be attributed to the presence of the dog. Was it exercise or depression? Of course, members of the committee jumped to the obvious relationship between exercising the dog and exercising the human. The particular species of dog certainly could have importance. Should it be a big friendly golden lab, a huge Great Dane, or a little Pekingese? Did its weight or disposition have any importance? How could you ever get rid of all of the variables? Forget the idea of a randomized trial; let’s just deal with the science of the matter.

I still could not forget Cassie and I tried to see how a new dog could help me. I thought about how my wife would take this, but I decided that her unhappiness would tip the balance against getting another dog. Another Cassie to bolster my psyche just doesn’t seem to be in the cards. In my own situation I wasn’t going to exercise the dog anyway. I had already assigned that responsibility to my wife, and I am not prepared to take that from her, even though she was willing to pass it on to someone else. I think that I will do without a dog and just try to carry on.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

We have recently been informed by an American Heart Association committee that owning a pet decreases your cardiovascular risk. Since I am of the age when a coronary event is almost inevitable, the opinion of the committee caught my attention.

I am not much into pets, and I am not what you would call a dog lover; but I have had a dog that I really loved. Her name was Cassiopeia, "Cassie" for short, named after my then–10-year-old son’s favorite constellation. She was a warm and attentive golden retriever who jumped up on my car to greet me every evening when I came home from the hospital. My wife, who dutifully walked her every day, rarely got so much as a tail wag. She was clearly "my" dog and, like any person or animal that comes up to you at the end of the day with a lick or a kiss, was someone to be cherished.

In her 10th year, Cassie’s kidneys failed. After several weeks of daily administration of intravenous fluids, I gave up and took her to the vet to be euthanized. I freely admit that I was mildly depressed for a few weeks after she died. We never got another dog because my wife refused to continue to take care of an animal that never showed any appreciation.

The American Heart Association’s position on the benefit of pet ownership in the reduction of cardiovascular risk is one of at least three scientific statements that the organization makes each month. It did bring to mind the effect of Cassie on my psyche and the potentially beneficial effect that she had on my coronary arteries. However, I would have to admit I have failed to pay much attention to previous proclamations by well-meaning scientific bodies like the AHA committees. I have ignored the advice about my large coffee intake, my lack of daily exercise, and the amount of salt I put on my steak.

This particular statement by the AHA, however, was cautious about the justification of the canine-human interaction and indicated that there are scant randomized data to support the claim, and what existed related to cats, a species to which my wife is allergic. The recent dog–heart disease statement had come about as a result of a "growing number of news reports and medical studies" that purported to show a beneficial relationship between pet ownership and heart disease. It is amazing how one fails to notice a brouhaha right in our own midst. According to the New York Times account, the public uproar had reached such a "point that it would be reasonable to formally investigate" the issue.

But how would you ever try to design a trial testing the hypothesis that owning a dog was a panacea for cardiovascular disease? It is not clear what mechanism of action could be attributed to the presence of the dog. Was it exercise or depression? Of course, members of the committee jumped to the obvious relationship between exercising the dog and exercising the human. The particular species of dog certainly could have importance. Should it be a big friendly golden lab, a huge Great Dane, or a little Pekingese? Did its weight or disposition have any importance? How could you ever get rid of all of the variables? Forget the idea of a randomized trial; let’s just deal with the science of the matter.

I still could not forget Cassie and I tried to see how a new dog could help me. I thought about how my wife would take this, but I decided that her unhappiness would tip the balance against getting another dog. Another Cassie to bolster my psyche just doesn’t seem to be in the cards. In my own situation I wasn’t going to exercise the dog anyway. I had already assigned that responsibility to my wife, and I am not prepared to take that from her, even though she was willing to pass it on to someone else. I think that I will do without a dog and just try to carry on.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

We have recently been informed by an American Heart Association committee that owning a pet decreases your cardiovascular risk. Since I am of the age when a coronary event is almost inevitable, the opinion of the committee caught my attention.

I am not much into pets, and I am not what you would call a dog lover; but I have had a dog that I really loved. Her name was Cassiopeia, "Cassie" for short, named after my then–10-year-old son’s favorite constellation. She was a warm and attentive golden retriever who jumped up on my car to greet me every evening when I came home from the hospital. My wife, who dutifully walked her every day, rarely got so much as a tail wag. She was clearly "my" dog and, like any person or animal that comes up to you at the end of the day with a lick or a kiss, was someone to be cherished.

In her 10th year, Cassie’s kidneys failed. After several weeks of daily administration of intravenous fluids, I gave up and took her to the vet to be euthanized. I freely admit that I was mildly depressed for a few weeks after she died. We never got another dog because my wife refused to continue to take care of an animal that never showed any appreciation.

The American Heart Association’s position on the benefit of pet ownership in the reduction of cardiovascular risk is one of at least three scientific statements that the organization makes each month. It did bring to mind the effect of Cassie on my psyche and the potentially beneficial effect that she had on my coronary arteries. However, I would have to admit I have failed to pay much attention to previous proclamations by well-meaning scientific bodies like the AHA committees. I have ignored the advice about my large coffee intake, my lack of daily exercise, and the amount of salt I put on my steak.

This particular statement by the AHA, however, was cautious about the justification of the canine-human interaction and indicated that there are scant randomized data to support the claim, and what existed related to cats, a species to which my wife is allergic. The recent dog–heart disease statement had come about as a result of a "growing number of news reports and medical studies" that purported to show a beneficial relationship between pet ownership and heart disease. It is amazing how one fails to notice a brouhaha right in our own midst. According to the New York Times account, the public uproar had reached such a "point that it would be reasonable to formally investigate" the issue.

But how would you ever try to design a trial testing the hypothesis that owning a dog was a panacea for cardiovascular disease? It is not clear what mechanism of action could be attributed to the presence of the dog. Was it exercise or depression? Of course, members of the committee jumped to the obvious relationship between exercising the dog and exercising the human. The particular species of dog certainly could have importance. Should it be a big friendly golden lab, a huge Great Dane, or a little Pekingese? Did its weight or disposition have any importance? How could you ever get rid of all of the variables? Forget the idea of a randomized trial; let’s just deal with the science of the matter.

I still could not forget Cassie and I tried to see how a new dog could help me. I thought about how my wife would take this, but I decided that her unhappiness would tip the balance against getting another dog. Another Cassie to bolster my psyche just doesn’t seem to be in the cards. In my own situation I wasn’t going to exercise the dog anyway. I had already assigned that responsibility to my wife, and I am not prepared to take that from her, even though she was willing to pass it on to someone else. I think that I will do without a dog and just try to carry on.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

Applied molecular profiling: evidence-based decision-making for anticancer therapy

Applied molecular profiling is a method for helping clinicians select the most appropriate therapy for a patient with cancer by determining the level of gene and/or protein expression within the cancer and comparing that expression pattern with the expression profiles of cancers with known outcomes. This approach facilitates the development and selection of tumor-specific therapies based on the identification of biomarkers within a tumor. Molecular characterization techniques such as immunohistochemistry, microarray analysis, and fluorescence in situ hybridization have facilitated identification and validation of a number of important solid tumor biomarkers, including HER2/neu, EGFR, EML4/ALK, and KIT, and can also be used to identify biomarkers (eg, BCR-ABL, CD20, CD30) in various hematologic malignancies. It is of note that molecular profiling can be used to identify targets in tumors for which a therapeutic agent may already be available, thus avoiding the administration of an unproven investigational agent. As the field of molecular profiling continues to evolve and next-generation techniques such as exome sequencing – sequencing 1% of the genome – and whole gene sequencing gain currency, biomarker identification and analysis will become less expensive and more efficient, and possibly allow for a pathway-oriented approach to treatment selection. Wider acceptance and use of molecular profiling should therefore help practicing physicians and oncology researchers keep pace with advances in the understanding of oncogenic expression in various malignancies and encourage the use of molecular profiling in earlier stages of cancer rather than as an option of last resort...

*Click on the link to the left for a PDF of the full article.

Applied molecular profiling is a method for helping clinicians select the most appropriate therapy for a patient with cancer by determining the level of gene and/or protein expression within the cancer and comparing that expression pattern with the expression profiles of cancers with known outcomes. This approach facilitates the development and selection of tumor-specific therapies based on the identification of biomarkers within a tumor. Molecular characterization techniques such as immunohistochemistry, microarray analysis, and fluorescence in situ hybridization have facilitated identification and validation of a number of important solid tumor biomarkers, including HER2/neu, EGFR, EML4/ALK, and KIT, and can also be used to identify biomarkers (eg, BCR-ABL, CD20, CD30) in various hematologic malignancies. It is of note that molecular profiling can be used to identify targets in tumors for which a therapeutic agent may already be available, thus avoiding the administration of an unproven investigational agent. As the field of molecular profiling continues to evolve and next-generation techniques such as exome sequencing – sequencing 1% of the genome – and whole gene sequencing gain currency, biomarker identification and analysis will become less expensive and more efficient, and possibly allow for a pathway-oriented approach to treatment selection. Wider acceptance and use of molecular profiling should therefore help practicing physicians and oncology researchers keep pace with advances in the understanding of oncogenic expression in various malignancies and encourage the use of molecular profiling in earlier stages of cancer rather than as an option of last resort...

*Click on the link to the left for a PDF of the full article.

Applied molecular profiling is a method for helping clinicians select the most appropriate therapy for a patient with cancer by determining the level of gene and/or protein expression within the cancer and comparing that expression pattern with the expression profiles of cancers with known outcomes. This approach facilitates the development and selection of tumor-specific therapies based on the identification of biomarkers within a tumor. Molecular characterization techniques such as immunohistochemistry, microarray analysis, and fluorescence in situ hybridization have facilitated identification and validation of a number of important solid tumor biomarkers, including HER2/neu, EGFR, EML4/ALK, and KIT, and can also be used to identify biomarkers (eg, BCR-ABL, CD20, CD30) in various hematologic malignancies. It is of note that molecular profiling can be used to identify targets in tumors for which a therapeutic agent may already be available, thus avoiding the administration of an unproven investigational agent. As the field of molecular profiling continues to evolve and next-generation techniques such as exome sequencing – sequencing 1% of the genome – and whole gene sequencing gain currency, biomarker identification and analysis will become less expensive and more efficient, and possibly allow for a pathway-oriented approach to treatment selection. Wider acceptance and use of molecular profiling should therefore help practicing physicians and oncology researchers keep pace with advances in the understanding of oncogenic expression in various malignancies and encourage the use of molecular profiling in earlier stages of cancer rather than as an option of last resort...

*Click on the link to the left for a PDF of the full article.

Anti-TNFs for ulcerative colitis up sepsis risk after some proctocolectomies

PHOENIX – Among patients with ulcerative colitis, preoperative therapy targeting tumor necrosis factor increases the risk of postoperative complications after two-stage restorative proctocolectomy procedures but not after three-stage ones, a study has shown.

A team at the Cleveland Clinic retrospectively assessed outcomes in more than 500 patients who underwent a restorative proctocolectomy for medically refractory ulcerative colitis during a recent 5-year period. Overall, 28% were receiving an agent that targets tumor necrosis factor (TNF) before their surgery.

The main results, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, showed that among patients having an initial total proctocolectomy (TPC) with ileoanal pouch–anal anastomosis, preoperative anti-TNF therapy more than doubled the risk of pelvic sepsis in the subsequent year.

In contrast, among patients having an initial subtotal colectomy (STC) with end ileostomy, preoperative anti-TNF therapy did not significantly affect the risk of complications overall, or in the subset who went on to have completion proctectomy and ileoanal pouch–anal anastomosis.

"Considering the lack of [a randomized controlled trial], our conclusion is that preoperative exposure to biologics is associated with an increased risk of pelvic sepsis after TPC with ileoanal pouch–anal anastomosis," commented lead investigator Dr. Jinyu Gu, a colorectal surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic. "This risk can be mitigated by the performance of initial STC."

The study’s senior investigator, Dr. P. Ravi Kiran, noted the importance of studying late complications in this population.

"We consciously decided to include patients who developed complications up to 1 year after surgery because quite often, these patients will not manifest their pelvic sepsis until the stoma is closed," he explained. "Some of the previous data from our institution have also shown that if someone were to get pelvic complications or septic complications that resemble Crohn’s disease, it is unlikely that it is really the disease that does it within 1 year after surgery; it is usually septic complications that manifest in a delayed fashion. ... A problem with any study that does not include patients for a prolonged follow-up is that you cannot really know what are the long-term complications because the presence of a stoma sometimes keeps the pelvic infection hidden."

"We, as colorectal surgeons, have been questioning what to do with patients who are on anti-TNF therapy when we operate on them," session comoderator Dr. Janice Rafferty, chief of the division of colon and rectal surgery at the University of Cincinnati, commented in an interview.

"I think this tells us that if we do a pouch procedure on them, and they are on anti-TNF therapy, their risk for pelvic sepsis is higher than if they had a three-stage procedure and we get them off of anti-TNF therapy," she said. "That probably supports what most colorectal surgeons suspect and want to do, but I think the gastroenterologists are currently pushing us, saying there is not a lot of evidence to say that they have a worse outcome."

Session comoderator Dr. Bruce Robb of Indiana University in Indianapolis agreed and noted that the findings support a recent shift toward multistage procedures in this population.

"For a long time, we were talking about two- versus one-stage procedures, and now we are going back, I think, especially with the advent of laparoscopy; people are much happier to do a three-stage procedure than they were even 10 years ago," he said. "This study sort of validates a change in practice pattern that’s already in place."

Dr. Gu’s team retrospectively assessed outcomes in 588 patients who underwent a restorative proctocolectomy for medically refractory ulcerative colitis between 2006 and 2010. Patients with complicated colitis, colitis-associated neoplasia, and Crohn’s disease were excluded.

The investigators assessed the rates of a variety of postoperative complications: pelvic sepsis, leaking of the colorectal stump, wound infection, postoperative hemorrhage, thromboembolism, urinary tract infection, and pneumonia.

Patients were defined as receiving anti-TNF therapy preoperatively if they had received at least 12 weeks of infliximab (Remicade) or at least 4 weeks of adalimumab (Humira) or certolizumab (Cimzia).

Of the 181 patients whose initial surgery was TPC with ileoanal pouch–anal anastomosis, 14% were receiving anti-TNF therapy preoperatively.

Within this group, the 30-day rate of complications did not differ significantly between patients who were and were not receiving preoperative anti-TNF therapy.

But the cumulative 1-year rate of pelvic sepsis was twice as high in patients receiving anti-TNF therapy (32% vs. 16%, P = .012). In adjusted analyses, these patients still had a more than doubling of the risk of pelvic sepsis (hazard ratio, 2.62; P = .027).

Of the 407 patients whose initial surgery was STC with end ileostomy, 35% were receiving anti-TNF agents preoperatively.

Within this group, patients taking anti-TNF agents preoperatively did not have an elevated risk of any of the complications studied at either 30 days or 1 year. The findings were similar among the subset who went on to have a completion proctectomy and ileoanal pouch–anal anastomosis.

Dr. Gu and Dr. Kiran both disclosed no relevant financial conflicts.

PHOENIX – Among patients with ulcerative colitis, preoperative therapy targeting tumor necrosis factor increases the risk of postoperative complications after two-stage restorative proctocolectomy procedures but not after three-stage ones, a study has shown.

A team at the Cleveland Clinic retrospectively assessed outcomes in more than 500 patients who underwent a restorative proctocolectomy for medically refractory ulcerative colitis during a recent 5-year period. Overall, 28% were receiving an agent that targets tumor necrosis factor (TNF) before their surgery.

The main results, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, showed that among patients having an initial total proctocolectomy (TPC) with ileoanal pouch–anal anastomosis, preoperative anti-TNF therapy more than doubled the risk of pelvic sepsis in the subsequent year.

In contrast, among patients having an initial subtotal colectomy (STC) with end ileostomy, preoperative anti-TNF therapy did not significantly affect the risk of complications overall, or in the subset who went on to have completion proctectomy and ileoanal pouch–anal anastomosis.

"Considering the lack of [a randomized controlled trial], our conclusion is that preoperative exposure to biologics is associated with an increased risk of pelvic sepsis after TPC with ileoanal pouch–anal anastomosis," commented lead investigator Dr. Jinyu Gu, a colorectal surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic. "This risk can be mitigated by the performance of initial STC."

The study’s senior investigator, Dr. P. Ravi Kiran, noted the importance of studying late complications in this population.

"We consciously decided to include patients who developed complications up to 1 year after surgery because quite often, these patients will not manifest their pelvic sepsis until the stoma is closed," he explained. "Some of the previous data from our institution have also shown that if someone were to get pelvic complications or septic complications that resemble Crohn’s disease, it is unlikely that it is really the disease that does it within 1 year after surgery; it is usually septic complications that manifest in a delayed fashion. ... A problem with any study that does not include patients for a prolonged follow-up is that you cannot really know what are the long-term complications because the presence of a stoma sometimes keeps the pelvic infection hidden."

"We, as colorectal surgeons, have been questioning what to do with patients who are on anti-TNF therapy when we operate on them," session comoderator Dr. Janice Rafferty, chief of the division of colon and rectal surgery at the University of Cincinnati, commented in an interview.

"I think this tells us that if we do a pouch procedure on them, and they are on anti-TNF therapy, their risk for pelvic sepsis is higher than if they had a three-stage procedure and we get them off of anti-TNF therapy," she said. "That probably supports what most colorectal surgeons suspect and want to do, but I think the gastroenterologists are currently pushing us, saying there is not a lot of evidence to say that they have a worse outcome."

Session comoderator Dr. Bruce Robb of Indiana University in Indianapolis agreed and noted that the findings support a recent shift toward multistage procedures in this population.

"For a long time, we were talking about two- versus one-stage procedures, and now we are going back, I think, especially with the advent of laparoscopy; people are much happier to do a three-stage procedure than they were even 10 years ago," he said. "This study sort of validates a change in practice pattern that’s already in place."

Dr. Gu’s team retrospectively assessed outcomes in 588 patients who underwent a restorative proctocolectomy for medically refractory ulcerative colitis between 2006 and 2010. Patients with complicated colitis, colitis-associated neoplasia, and Crohn’s disease were excluded.

The investigators assessed the rates of a variety of postoperative complications: pelvic sepsis, leaking of the colorectal stump, wound infection, postoperative hemorrhage, thromboembolism, urinary tract infection, and pneumonia.

Patients were defined as receiving anti-TNF therapy preoperatively if they had received at least 12 weeks of infliximab (Remicade) or at least 4 weeks of adalimumab (Humira) or certolizumab (Cimzia).

Of the 181 patients whose initial surgery was TPC with ileoanal pouch–anal anastomosis, 14% were receiving anti-TNF therapy preoperatively.

Within this group, the 30-day rate of complications did not differ significantly between patients who were and were not receiving preoperative anti-TNF therapy.

But the cumulative 1-year rate of pelvic sepsis was twice as high in patients receiving anti-TNF therapy (32% vs. 16%, P = .012). In adjusted analyses, these patients still had a more than doubling of the risk of pelvic sepsis (hazard ratio, 2.62; P = .027).

Of the 407 patients whose initial surgery was STC with end ileostomy, 35% were receiving anti-TNF agents preoperatively.

Within this group, patients taking anti-TNF agents preoperatively did not have an elevated risk of any of the complications studied at either 30 days or 1 year. The findings were similar among the subset who went on to have a completion proctectomy and ileoanal pouch–anal anastomosis.

Dr. Gu and Dr. Kiran both disclosed no relevant financial conflicts.

PHOENIX – Among patients with ulcerative colitis, preoperative therapy targeting tumor necrosis factor increases the risk of postoperative complications after two-stage restorative proctocolectomy procedures but not after three-stage ones, a study has shown.

A team at the Cleveland Clinic retrospectively assessed outcomes in more than 500 patients who underwent a restorative proctocolectomy for medically refractory ulcerative colitis during a recent 5-year period. Overall, 28% were receiving an agent that targets tumor necrosis factor (TNF) before their surgery.

The main results, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, showed that among patients having an initial total proctocolectomy (TPC) with ileoanal pouch–anal anastomosis, preoperative anti-TNF therapy more than doubled the risk of pelvic sepsis in the subsequent year.

In contrast, among patients having an initial subtotal colectomy (STC) with end ileostomy, preoperative anti-TNF therapy did not significantly affect the risk of complications overall, or in the subset who went on to have completion proctectomy and ileoanal pouch–anal anastomosis.

"Considering the lack of [a randomized controlled trial], our conclusion is that preoperative exposure to biologics is associated with an increased risk of pelvic sepsis after TPC with ileoanal pouch–anal anastomosis," commented lead investigator Dr. Jinyu Gu, a colorectal surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic. "This risk can be mitigated by the performance of initial STC."

The study’s senior investigator, Dr. P. Ravi Kiran, noted the importance of studying late complications in this population.

"We consciously decided to include patients who developed complications up to 1 year after surgery because quite often, these patients will not manifest their pelvic sepsis until the stoma is closed," he explained. "Some of the previous data from our institution have also shown that if someone were to get pelvic complications or septic complications that resemble Crohn’s disease, it is unlikely that it is really the disease that does it within 1 year after surgery; it is usually septic complications that manifest in a delayed fashion. ... A problem with any study that does not include patients for a prolonged follow-up is that you cannot really know what are the long-term complications because the presence of a stoma sometimes keeps the pelvic infection hidden."

"We, as colorectal surgeons, have been questioning what to do with patients who are on anti-TNF therapy when we operate on them," session comoderator Dr. Janice Rafferty, chief of the division of colon and rectal surgery at the University of Cincinnati, commented in an interview.

"I think this tells us that if we do a pouch procedure on them, and they are on anti-TNF therapy, their risk for pelvic sepsis is higher than if they had a three-stage procedure and we get them off of anti-TNF therapy," she said. "That probably supports what most colorectal surgeons suspect and want to do, but I think the gastroenterologists are currently pushing us, saying there is not a lot of evidence to say that they have a worse outcome."

Session comoderator Dr. Bruce Robb of Indiana University in Indianapolis agreed and noted that the findings support a recent shift toward multistage procedures in this population.

"For a long time, we were talking about two- versus one-stage procedures, and now we are going back, I think, especially with the advent of laparoscopy; people are much happier to do a three-stage procedure than they were even 10 years ago," he said. "This study sort of validates a change in practice pattern that’s already in place."

Dr. Gu’s team retrospectively assessed outcomes in 588 patients who underwent a restorative proctocolectomy for medically refractory ulcerative colitis between 2006 and 2010. Patients with complicated colitis, colitis-associated neoplasia, and Crohn’s disease were excluded.

The investigators assessed the rates of a variety of postoperative complications: pelvic sepsis, leaking of the colorectal stump, wound infection, postoperative hemorrhage, thromboembolism, urinary tract infection, and pneumonia.

Patients were defined as receiving anti-TNF therapy preoperatively if they had received at least 12 weeks of infliximab (Remicade) or at least 4 weeks of adalimumab (Humira) or certolizumab (Cimzia).

Of the 181 patients whose initial surgery was TPC with ileoanal pouch–anal anastomosis, 14% were receiving anti-TNF therapy preoperatively.

Within this group, the 30-day rate of complications did not differ significantly between patients who were and were not receiving preoperative anti-TNF therapy.

But the cumulative 1-year rate of pelvic sepsis was twice as high in patients receiving anti-TNF therapy (32% vs. 16%, P = .012). In adjusted analyses, these patients still had a more than doubling of the risk of pelvic sepsis (hazard ratio, 2.62; P = .027).

Of the 407 patients whose initial surgery was STC with end ileostomy, 35% were receiving anti-TNF agents preoperatively.

Within this group, patients taking anti-TNF agents preoperatively did not have an elevated risk of any of the complications studied at either 30 days or 1 year. The findings were similar among the subset who went on to have a completion proctectomy and ileoanal pouch–anal anastomosis.

Dr. Gu and Dr. Kiran both disclosed no relevant financial conflicts.

AT THE ASCRS ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Preoperative anti-TNF therapy increased the risk of sepsis after initial total proctocolectomy with ileoanal pouch–anal anastomosis (HR, 2.62). In contrast, it did not increase the risk of any complications after initial subtotal colectomy with end ileostomy.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 588 patients with ulcerative colitis

Disclosures: Dr. Gu and Dr. Kiran disclosed no relevant financial conflicts.

Hand Slammed in Door

A 48-year-old woman presents to the urgent care center with complaints of right hand pain second-ary to an injury she sustained earlier in the day. Her hand was accidentally caught in a metal door as it was being shut by someone else. The door struck her in the middorsal aspect of her hand. She is now complaining of pain and swelling. She is healthy except for mild but well-controlled hypertension. Her vital signs are normal. Examina-tion of her right hand shows mild to moderate soft tissue swelling and some early bruising. There is extreme tenderness over the fourth and fifth metacarpal bones. Good capillary refill time is noted, and sensation is intact. She is able to flex her fingers somewhat, although this is limited by the swelling. Radiograph of the right hand is obtained. What is your impression?

Do Nausea and Vomiting Have Cardiac Cause?

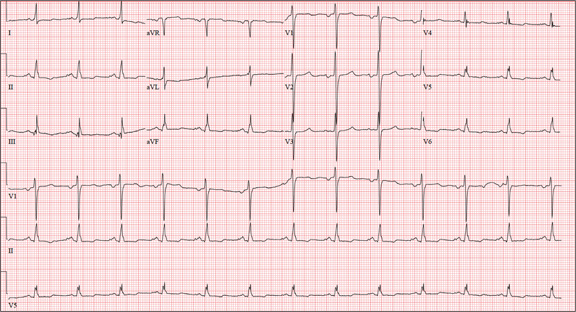

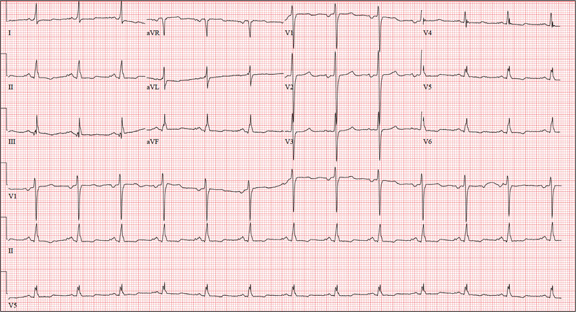

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes normal sinus rhythm, left atrial enlargement, and nonspecific T-wave abnormalities.

Normal sinus rhythm is evidenced by an atrial and ventricular rate of 77 beats/min with one-to-one association. Left atrial enlargement is evidenced by the presence of a biphasic P wave in lead V1 with a negative terminal portion of the P wave ≥ 1 mm2. (P waves in lead I ≥ 110 ms are also seen in left atrial enlargement, but are not evident in this ECG.) The small or inverted appearance of T waves in the inferior and lateral leads indicates nonspecific T waves.

These ECG findings are typical of patients with mitral valve disease, but were of no benefit in diagnosing acute pancreatitis in this patient. By the time she had the ECG done, she had been given sedation sufficient to reduce her heart rate from the 118 beats/min it had been at the time of examination.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes normal sinus rhythm, left atrial enlargement, and nonspecific T-wave abnormalities.

Normal sinus rhythm is evidenced by an atrial and ventricular rate of 77 beats/min with one-to-one association. Left atrial enlargement is evidenced by the presence of a biphasic P wave in lead V1 with a negative terminal portion of the P wave ≥ 1 mm2. (P waves in lead I ≥ 110 ms are also seen in left atrial enlargement, but are not evident in this ECG.) The small or inverted appearance of T waves in the inferior and lateral leads indicates nonspecific T waves.

These ECG findings are typical of patients with mitral valve disease, but were of no benefit in diagnosing acute pancreatitis in this patient. By the time she had the ECG done, she had been given sedation sufficient to reduce her heart rate from the 118 beats/min it had been at the time of examination.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes normal sinus rhythm, left atrial enlargement, and nonspecific T-wave abnormalities.

Normal sinus rhythm is evidenced by an atrial and ventricular rate of 77 beats/min with one-to-one association. Left atrial enlargement is evidenced by the presence of a biphasic P wave in lead V1 with a negative terminal portion of the P wave ≥ 1 mm2. (P waves in lead I ≥ 110 ms are also seen in left atrial enlargement, but are not evident in this ECG.) The small or inverted appearance of T waves in the inferior and lateral leads indicates nonspecific T waves.

These ECG findings are typical of patients with mitral valve disease, but were of no benefit in diagnosing acute pancreatitis in this patient. By the time she had the ECG done, she had been given sedation sufficient to reduce her heart rate from the 118 beats/min it had been at the time of examination.

A 58-year-old woman presents with epigastric pain that began gradually about four hours ago, re-maining constant for the past two. She describes it as a “dull, steady, aching” pain directly beneath her lower sternum. It is neither exacerbated by exertion nor relieved by rest, but it does improve if she bends from the waist. She denies radiation of pain into her neck or upper extremities but describes a band of pain radiating to her back. Additionally, she has experienced nausea and vomiting, starting about 12 hours before her pain, with a single episode of emesis immediately upon presentation. She has a history of mitral valve prolapse, which was surgically corrected with a mechanical heart valve two years ago. She also has a history of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation for which she has been cardioverted on two separate occasions. Her last episode was six months ago. Social history reveals that she is divorced, has smoked one pack of cigarettes a day for the past 30 years, and is a heavy alcohol user. She states she went on a binge last weekend (72 hours ago), drinking one bottle of whiskey and half a bottle of vodka over the course of one day. She has tried heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamines in the past and currently uses marijuana when she can get it. The patient has a primary care provider who prescribed aspirin, atorvastatin, clonidine, gabapentin, metoprolol, and warfarin; however, she hasn’t taken or refilled any of these prescriptions for approx-imately six months. She is allergic to codeine, erythromycin, and azithromycin. The review of sys-tems is positive for difficulty sleeping, anxiety, diffuse abdominal pain not related to her current symp-toms, dyspnea on exertion, “typical smoker’s cough,” and burning with urination. The physical examination reveals an unkempt, thin woman who is restless and easily agitated. Her weight is 125 lb, and her height, 64”. Her vital signs include a blood pressure of 168/102 mm Hg; pulse, 118 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min-1; and temperature, 99.9°F. She has poor den-tition. There is no thyromegaly or jugular venous distention. Her respirations are shallow, and there are coarse rhonchi in both bases that change with coughing. The cardiac exam reveals a regular tachy-cardia with mechanical heart sounds and a grade II/VI systolic murmur. A well-healed median ster-notomy scar is present. The abdominal exam is remarkable for tenderness to palpation in the epigas-trium, with no evidence of rebound. There are no palpable masses. Bowel tones are present in all quadrants. The extremities are positive for 2+ pitting edema to the knees bilaterally. The neurologic exam is grossly intact. Following acute management of her pain, laboratory blood work, abdominal ultrasound and CT, chest x-ray, and ECG are ordered. The ECG is the last test to be obtained and reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 77 beats/min; PR interval, 142 ms; QRS duration, 104 ms; QT/QTc interval, 402/454 ms; P axis, 66°; R axis, 57°; and T axis, –11°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Striking rise in accidental marijuana poisonings

The number of unintentional marijuana poisonings in children rose markedly in Colorado after medical marijuana was decriminalized in 2009, with visits to one emergency department climbing from zero to 2.4% of all poisoning cases in just 2 years, according to a report published online May 27 in JAMA Pediatrics.

The toxic effects in these children were more serious than those typically reported for marijuana exposures in the past, most likely because tetrahydrocannabinol concentrations are higher in today’s medical marijuana products than in the plant parts involved in most previous exposures. So now, even when the amount ingested is small, it still produces significant adverse effects in the pediatric population, including respiratory insufficiency requiring care in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), said Dr. George Sam Wang of Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center, Denver, and his associates.

In addition, medical marijuana is sold in a variety of forms that are more palatable to children than plant parts are, such as baked goods, soft drinks, and candies. So more children are attracted to eating the drug now, and they likely eat larger amounts than in the past.

"Physicians, especially in states that have decriminalized medical marijuana, need to be cognizant of the potential for marijuana exposures and be familiar with the symptoms of marijuana ingestion," the investigators said.

After Colorado decriminalized medical marijuana, both the number of dispensaries and the number of patients authorized to use the drug increased rapidly. As of 2010, more than 300 such dispensaries were licensed in Denver alone, "roughly twice the number of the city’s public schools," Dr. Wang and his colleagues noted.

They performed the first U.S. study to asses the impact of this legislation on pediatric poisonings: a retrospective cohort study at a tertiary children’s hospital that had approximately 65,000 annual visits to its emergency department. The researchers focused on children under age 12 who were evaluated for possible toxic exposures, comparing the 790 patients seen from 2005 to Sept. 30, 2009, before legalization with the 588 seen from Oct. 1, 2009, to the end of 2011 after medical marijuana was legalized.

There were no cases of marijuana poisoning during the first time period, compared with 14 in the second time period. The proportion of such visits in relation to all pediatric ED visits for toxic exposures thus rose from 0% to 2.4% after the drug was decriminalized.

Children as young as 8 months of age were exposed to marijuana. Most presented with central nervous system (CNS) effects such as lethargy or somnolence, and some displayed rigidity, ataxia, hypoxia, or respiratory insufficiency, the researchers reported (JAMA Ped. 2013 May 27 [doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.140]).

Only two patients were known to have been exposed to marijuana on arrival at the ED; they underwent a urine toxicology screen. The rest underwent extensive workups to determine the cause of their symptoms, which included urine toxicology screens; blood work; CT and x-ray imaging of the head, spine, and abdomen; and lumbar punctures.

Only one patient, a 13-year-old girl with minimal symptoms, was discharged after being assessed. The rest were observed in the ED (5) or admitted for hospitalization (8), including 2 children who required admission to the PICU.

This 93% rate of hospitalization reinforces the hypothesis that current marijuana exposures induce more serious effects than past exposures did, because historically only 1.3% of marijuana poisoning cases required hospitalization, Dr. Wang and his associates said.

Eight of these 14 (57%) marijuana exposures were from food products that incorporated the drug. "Currently, there are no regulations on storing medical marijuana products in child-resistant containers, including labels with warnings or precautions, or providing counseling on safe storage practices," the investigators said.

As is the case with many accidental pediatric exposures to other medications, the source of the medical marijuana in several of the cases in this study was the child’s grandparent.

Dr. Wang and his colleagues added that proponents of legalizing marijuana often claim that it is "safer" than alcohol. However, only two patients under age 12 were evaluated for alcohol exposure at this ED since 2009. One, an 11-year-old, intentionally drank alcohol and only required observation for intoxication; the other, a 2-year-old who accidentally drank a household product containing ethanol, was discharged after failing to develop any symptoms.

In comparison, the symptoms, invasive assessments, and hospitalizations described in this study can hardly be considered "safer." These findings clearly demonstrate that "the consequences of marijuana exposure in children should be part of the ongoing debate on legalizing marijuana," the researchers said.

Seventeen states and Washington, D.C., have passed laws to decriminalize medical marijuana at the state level, even though marijuana is a schedule I drug under the Controlled Substances Act. "In November 2012, Colorado and Washington [State] passed amendments legalizing the recreational use of marijuana," Dr. Wang and his associates said.

No financial conflicts of interest were reported.

Another reason for the rise in accidental marijuana poisonings is the increased potency of the drug currently available in the United States, compared with 40 years ago. THC levels have risen from 2% to nearly 8% during that time, said Dr. William Hurley and Dr. Suzan Mazor.

Physicians may now need additional training to recognize and manage toxic reactions to marijuana. Children can present with anxiety, hallucinations, panic episodes, dyspnea, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, somnolence, CNS depression, respiratory depression, and coma, which unfortunately are the same signs and symptoms for other toxicities and disorders.

Emergency medicine, pediatric emergency medicine, and primary care pediatric providers will be the first to see patients accidentally exposed to marijuana. They should be alert to "investigating the availability of marijuana in the child’s environment" and should use a rapid urine test to confirm the diagnosis. "No antidote exists for marijuana toxic reactions, and supportive care should be provided, including control of anxiety, control of vomiting, airway control, and ventilation as needed," they said.

Dr. Hurley is at the University of Washington and the Washington Poison Center, both in Seattle. Dr. Mazor is in the division of emergency medicine at Seattle Children’s Hospital. Neither Dr. Hurley nor Dr. Mazor reported any financial conflicts of interest. These remarks were taken from their editorial accompanying Dr. Wang’s report (JAMA Ped. 2013 May 27 [doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2273]).

Another reason for the rise in accidental marijuana poisonings is the increased potency of the drug currently available in the United States, compared with 40 years ago. THC levels have risen from 2% to nearly 8% during that time, said Dr. William Hurley and Dr. Suzan Mazor.

Physicians may now need additional training to recognize and manage toxic reactions to marijuana. Children can present with anxiety, hallucinations, panic episodes, dyspnea, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, somnolence, CNS depression, respiratory depression, and coma, which unfortunately are the same signs and symptoms for other toxicities and disorders.

Emergency medicine, pediatric emergency medicine, and primary care pediatric providers will be the first to see patients accidentally exposed to marijuana. They should be alert to "investigating the availability of marijuana in the child’s environment" and should use a rapid urine test to confirm the diagnosis. "No antidote exists for marijuana toxic reactions, and supportive care should be provided, including control of anxiety, control of vomiting, airway control, and ventilation as needed," they said.

Dr. Hurley is at the University of Washington and the Washington Poison Center, both in Seattle. Dr. Mazor is in the division of emergency medicine at Seattle Children’s Hospital. Neither Dr. Hurley nor Dr. Mazor reported any financial conflicts of interest. These remarks were taken from their editorial accompanying Dr. Wang’s report (JAMA Ped. 2013 May 27 [doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2273]).

Another reason for the rise in accidental marijuana poisonings is the increased potency of the drug currently available in the United States, compared with 40 years ago. THC levels have risen from 2% to nearly 8% during that time, said Dr. William Hurley and Dr. Suzan Mazor.