User login

When Staying Up Late Should Pay Off

Most people believe that nocturnists should get paid 20% to 33% more than their day-shift counterparts, according to a recent survey at www.the-hospitalist.org. Results of the survey, however, do not necessarily reflect the realities of supply and demand in local markets, according to members of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Practice size, volume of work, and the inconvenience of working at night contribute to the amount nocturnists get paid, says Leslie Flores, MHA, a committee member and partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. “We usually see a range between [a] 15% to 20% premium for nocturnist work,” she adds.

Survey respondents were asked to choose how much of a premium nocturnists should get paid, with the answers ranging from 20% to 60% to the same as everyone else. Two-thirds of the 212 respondents chose 20% or 33% bonus pay for nocturnists; 17% chose “the same as everyone else”; and another 17% chose 50% or 66%.

Committee member Troy Ahlstrom, MD, SFHM, senior chief information officer at Hospitals of Northern Michigan, says the survey does not reflect the reality of important factors that influence the market, such as supply and demand for nocturnists, local and regional factors that impact the level of supply and demand, and economic influence nationally.

“If you ask a practice manager or a hospital administrator that question, they would say nocturnists should make whatever is necessary to meet the demands for filling that job,” Dr. Ahlstrom says. “It’s a market-driven phenomenon.”

Hospitals don’t want to pay more, he notes, but they do want “to pay the right amount for the right job.”

Check out our website for more information about hospitalist compensation.

Most people believe that nocturnists should get paid 20% to 33% more than their day-shift counterparts, according to a recent survey at www.the-hospitalist.org. Results of the survey, however, do not necessarily reflect the realities of supply and demand in local markets, according to members of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Practice size, volume of work, and the inconvenience of working at night contribute to the amount nocturnists get paid, says Leslie Flores, MHA, a committee member and partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. “We usually see a range between [a] 15% to 20% premium for nocturnist work,” she adds.

Survey respondents were asked to choose how much of a premium nocturnists should get paid, with the answers ranging from 20% to 60% to the same as everyone else. Two-thirds of the 212 respondents chose 20% or 33% bonus pay for nocturnists; 17% chose “the same as everyone else”; and another 17% chose 50% or 66%.

Committee member Troy Ahlstrom, MD, SFHM, senior chief information officer at Hospitals of Northern Michigan, says the survey does not reflect the reality of important factors that influence the market, such as supply and demand for nocturnists, local and regional factors that impact the level of supply and demand, and economic influence nationally.

“If you ask a practice manager or a hospital administrator that question, they would say nocturnists should make whatever is necessary to meet the demands for filling that job,” Dr. Ahlstrom says. “It’s a market-driven phenomenon.”

Hospitals don’t want to pay more, he notes, but they do want “to pay the right amount for the right job.”

Check out our website for more information about hospitalist compensation.

Most people believe that nocturnists should get paid 20% to 33% more than their day-shift counterparts, according to a recent survey at www.the-hospitalist.org. Results of the survey, however, do not necessarily reflect the realities of supply and demand in local markets, according to members of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Practice size, volume of work, and the inconvenience of working at night contribute to the amount nocturnists get paid, says Leslie Flores, MHA, a committee member and partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. “We usually see a range between [a] 15% to 20% premium for nocturnist work,” she adds.

Survey respondents were asked to choose how much of a premium nocturnists should get paid, with the answers ranging from 20% to 60% to the same as everyone else. Two-thirds of the 212 respondents chose 20% or 33% bonus pay for nocturnists; 17% chose “the same as everyone else”; and another 17% chose 50% or 66%.

Committee member Troy Ahlstrom, MD, SFHM, senior chief information officer at Hospitals of Northern Michigan, says the survey does not reflect the reality of important factors that influence the market, such as supply and demand for nocturnists, local and regional factors that impact the level of supply and demand, and economic influence nationally.

“If you ask a practice manager or a hospital administrator that question, they would say nocturnists should make whatever is necessary to meet the demands for filling that job,” Dr. Ahlstrom says. “It’s a market-driven phenomenon.”

Hospitals don’t want to pay more, he notes, but they do want “to pay the right amount for the right job.”

Check out our website for more information about hospitalist compensation.

Physician Reviews of HM-Related Research

Clinical question: Does fluid management guided by daily plasma natriuretic peptide-driven (BNP) levels in mechanically ventilated patients improve weaning outcomes compared with usual therapy dictated by clinical acumen?

Background: Ventilator weaning contributes at least 40% of the total duration of mechanical ventilation; strategies aimed at optimizing this process could provide substantial benefit. Previous studies have demonstrated that BNP levels prior to ventilator weaning independently predict weaning failure. No current objective practical guide to fluid management during ventilator weaning exists.

Study design: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Multiple international centers.

Synopsis: Three hundred four patients who met specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were randomized to either a BNP-driven or physician-guided strategy for fluid management during ventilator weaning. Patients with renal failure were excluded because of the influence of renal function on BNP levels.

All patients in both groups were ventilated with an automatic computer-driven weaning system to standardize the weaning process. In the BNP-driven group, diuretic use was higher, resulting in a more negative fluid balance and significantly shorter time to successful extubation (58.6 hours vs. 42.2 hours, P=0.03). The effect on weaning time was strongest in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction, whereas those with COPD seemed less likely to benefit. The two groups did not differ in baseline characteristics, length of stay, mortality, or development of adverse outcomes of renal failure, shock, or electrolyte disturbances.

Bottom line: Compared with physician-guided fluid management, a BNP-driven fluid management protocol decreased duration of ventilator weaning without significant differences in adverse events, mortality rate, or length of stay between the two groups.

Citation: Dessap AM, Roche-Campo F, Kouatchet A, et al. Natriuretic peptide-driven fluid management during ventilator weaning. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(12):1256-1263.

Visit our website for more physician reviews of recent HM-relevant literature.

Clinical question: Does fluid management guided by daily plasma natriuretic peptide-driven (BNP) levels in mechanically ventilated patients improve weaning outcomes compared with usual therapy dictated by clinical acumen?

Background: Ventilator weaning contributes at least 40% of the total duration of mechanical ventilation; strategies aimed at optimizing this process could provide substantial benefit. Previous studies have demonstrated that BNP levels prior to ventilator weaning independently predict weaning failure. No current objective practical guide to fluid management during ventilator weaning exists.

Study design: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Multiple international centers.

Synopsis: Three hundred four patients who met specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were randomized to either a BNP-driven or physician-guided strategy for fluid management during ventilator weaning. Patients with renal failure were excluded because of the influence of renal function on BNP levels.

All patients in both groups were ventilated with an automatic computer-driven weaning system to standardize the weaning process. In the BNP-driven group, diuretic use was higher, resulting in a more negative fluid balance and significantly shorter time to successful extubation (58.6 hours vs. 42.2 hours, P=0.03). The effect on weaning time was strongest in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction, whereas those with COPD seemed less likely to benefit. The two groups did not differ in baseline characteristics, length of stay, mortality, or development of adverse outcomes of renal failure, shock, or electrolyte disturbances.

Bottom line: Compared with physician-guided fluid management, a BNP-driven fluid management protocol decreased duration of ventilator weaning without significant differences in adverse events, mortality rate, or length of stay between the two groups.

Citation: Dessap AM, Roche-Campo F, Kouatchet A, et al. Natriuretic peptide-driven fluid management during ventilator weaning. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(12):1256-1263.

Visit our website for more physician reviews of recent HM-relevant literature.

Clinical question: Does fluid management guided by daily plasma natriuretic peptide-driven (BNP) levels in mechanically ventilated patients improve weaning outcomes compared with usual therapy dictated by clinical acumen?

Background: Ventilator weaning contributes at least 40% of the total duration of mechanical ventilation; strategies aimed at optimizing this process could provide substantial benefit. Previous studies have demonstrated that BNP levels prior to ventilator weaning independently predict weaning failure. No current objective practical guide to fluid management during ventilator weaning exists.

Study design: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Multiple international centers.

Synopsis: Three hundred four patients who met specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were randomized to either a BNP-driven or physician-guided strategy for fluid management during ventilator weaning. Patients with renal failure were excluded because of the influence of renal function on BNP levels.

All patients in both groups were ventilated with an automatic computer-driven weaning system to standardize the weaning process. In the BNP-driven group, diuretic use was higher, resulting in a more negative fluid balance and significantly shorter time to successful extubation (58.6 hours vs. 42.2 hours, P=0.03). The effect on weaning time was strongest in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction, whereas those with COPD seemed less likely to benefit. The two groups did not differ in baseline characteristics, length of stay, mortality, or development of adverse outcomes of renal failure, shock, or electrolyte disturbances.

Bottom line: Compared with physician-guided fluid management, a BNP-driven fluid management protocol decreased duration of ventilator weaning without significant differences in adverse events, mortality rate, or length of stay between the two groups.

Citation: Dessap AM, Roche-Campo F, Kouatchet A, et al. Natriuretic peptide-driven fluid management during ventilator weaning. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(12):1256-1263.

Visit our website for more physician reviews of recent HM-relevant literature.

Risk factors for death in NAFLD patients remain elusive

ORLANDO – The risk factors for death in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease include older age, male sex, truncal obesity, and a low HDL cholesterol level – in other words, the same factors that increase risk for death from cardiovascular disease and other causes, according to Dr. Naga P. Chalasani.

On the other hand, elevations in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels in patients with NAFLD are not associated with an increased risk for death or other poor outcomes, meaning that researchers may have to burrow more deeply through the available data to find risk predictors unique to NAFLD, said Dr Chalasani of Indiana University, Indianapolis.

"How do we identify someone with NAFLD who is at risk for poor outcomes? I think this is the first shot at risk mapping patients," Dr. Chalasani said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Dr. Keith D. Lindor, who moderated the session at which the data were presented, agreed.

"What we’re having trouble with, I think, is defining nonalcoholic fatty liver disease easily, particularly amongst the population," he said. "We saw data that ALT, which we commonly used to use, may not be telling, and there are questions about how well ultrasound detects [NAFLD], particularly given that the amount of steatosis in order to be detected by ultrasound has to be relatively dramatic."

It is still not known whether people with steatosis discovered during biopsy but not visible on ultrasound will have risk factors similar to those of people with more grossly evident steatosis, he said in an interview.

Although Dr. Chalasani and colleagues failed to find unique risk markers in this population, it was not for want of trying. The investigators pored over data from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) for baseline and follow-up information about patients with NAFLD.

The data were collected from 1988 through 1994, and included gallbladder ultrasound with liver images in 14,797 adults aged 20-74. The authors linked the data to the National Death Index in an attempt to determine which factors might be harbingers of early mortality in patients with NAFLD vs. controls.

They defined NAFLD by the presence of moderate to severe hepatic steatosis on ultrasonography, and by the absence of iron overload, hepatitis B or C infections, and excessive alcohol consumption. Controls were participants in the same data set who did not have underlying liver disease and had normal ultrasound and liver function tests.

There were a total of 2,441 people with NAFLD and 8,423 controls. During a median follow-up of 14.3 years, 14% of controls (1,193), and 21% of those with NAFLD (501) died, a difference that was significant in a univariate analysis (P = .0328).

But when they looked at overall mortality, cancer-related mortality, and cardiovascular mortality, they found that all three categories shared male sex, older age, and a low HDL level as independent predictors for death, with cardiovascular mortality having the added bonus of the metabolic syndrome as an additional risk factor.

The authors did not disclose a funding source. Dr. Chalasani and Dr. Lindor reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – The risk factors for death in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease include older age, male sex, truncal obesity, and a low HDL cholesterol level – in other words, the same factors that increase risk for death from cardiovascular disease and other causes, according to Dr. Naga P. Chalasani.

On the other hand, elevations in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels in patients with NAFLD are not associated with an increased risk for death or other poor outcomes, meaning that researchers may have to burrow more deeply through the available data to find risk predictors unique to NAFLD, said Dr Chalasani of Indiana University, Indianapolis.

"How do we identify someone with NAFLD who is at risk for poor outcomes? I think this is the first shot at risk mapping patients," Dr. Chalasani said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Dr. Keith D. Lindor, who moderated the session at which the data were presented, agreed.

"What we’re having trouble with, I think, is defining nonalcoholic fatty liver disease easily, particularly amongst the population," he said. "We saw data that ALT, which we commonly used to use, may not be telling, and there are questions about how well ultrasound detects [NAFLD], particularly given that the amount of steatosis in order to be detected by ultrasound has to be relatively dramatic."

It is still not known whether people with steatosis discovered during biopsy but not visible on ultrasound will have risk factors similar to those of people with more grossly evident steatosis, he said in an interview.

Although Dr. Chalasani and colleagues failed to find unique risk markers in this population, it was not for want of trying. The investigators pored over data from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) for baseline and follow-up information about patients with NAFLD.

The data were collected from 1988 through 1994, and included gallbladder ultrasound with liver images in 14,797 adults aged 20-74. The authors linked the data to the National Death Index in an attempt to determine which factors might be harbingers of early mortality in patients with NAFLD vs. controls.

They defined NAFLD by the presence of moderate to severe hepatic steatosis on ultrasonography, and by the absence of iron overload, hepatitis B or C infections, and excessive alcohol consumption. Controls were participants in the same data set who did not have underlying liver disease and had normal ultrasound and liver function tests.

There were a total of 2,441 people with NAFLD and 8,423 controls. During a median follow-up of 14.3 years, 14% of controls (1,193), and 21% of those with NAFLD (501) died, a difference that was significant in a univariate analysis (P = .0328).

But when they looked at overall mortality, cancer-related mortality, and cardiovascular mortality, they found that all three categories shared male sex, older age, and a low HDL level as independent predictors for death, with cardiovascular mortality having the added bonus of the metabolic syndrome as an additional risk factor.

The authors did not disclose a funding source. Dr. Chalasani and Dr. Lindor reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – The risk factors for death in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease include older age, male sex, truncal obesity, and a low HDL cholesterol level – in other words, the same factors that increase risk for death from cardiovascular disease and other causes, according to Dr. Naga P. Chalasani.

On the other hand, elevations in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels in patients with NAFLD are not associated with an increased risk for death or other poor outcomes, meaning that researchers may have to burrow more deeply through the available data to find risk predictors unique to NAFLD, said Dr Chalasani of Indiana University, Indianapolis.

"How do we identify someone with NAFLD who is at risk for poor outcomes? I think this is the first shot at risk mapping patients," Dr. Chalasani said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Dr. Keith D. Lindor, who moderated the session at which the data were presented, agreed.

"What we’re having trouble with, I think, is defining nonalcoholic fatty liver disease easily, particularly amongst the population," he said. "We saw data that ALT, which we commonly used to use, may not be telling, and there are questions about how well ultrasound detects [NAFLD], particularly given that the amount of steatosis in order to be detected by ultrasound has to be relatively dramatic."

It is still not known whether people with steatosis discovered during biopsy but not visible on ultrasound will have risk factors similar to those of people with more grossly evident steatosis, he said in an interview.

Although Dr. Chalasani and colleagues failed to find unique risk markers in this population, it was not for want of trying. The investigators pored over data from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) for baseline and follow-up information about patients with NAFLD.

The data were collected from 1988 through 1994, and included gallbladder ultrasound with liver images in 14,797 adults aged 20-74. The authors linked the data to the National Death Index in an attempt to determine which factors might be harbingers of early mortality in patients with NAFLD vs. controls.

They defined NAFLD by the presence of moderate to severe hepatic steatosis on ultrasonography, and by the absence of iron overload, hepatitis B or C infections, and excessive alcohol consumption. Controls were participants in the same data set who did not have underlying liver disease and had normal ultrasound and liver function tests.

There were a total of 2,441 people with NAFLD and 8,423 controls. During a median follow-up of 14.3 years, 14% of controls (1,193), and 21% of those with NAFLD (501) died, a difference that was significant in a univariate analysis (P = .0328).

But when they looked at overall mortality, cancer-related mortality, and cardiovascular mortality, they found that all three categories shared male sex, older age, and a low HDL level as independent predictors for death, with cardiovascular mortality having the added bonus of the metabolic syndrome as an additional risk factor.

The authors did not disclose a funding source. Dr. Chalasani and Dr. Lindor reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT DDW 2013

Major finding: Age, male sex, truncal obesity, and a low HDL level are risk factors for death in patients with NAFLD, but are common to other causes of death as well.

Data source: A review of data from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Disclosures: The authors did not disclose a funding source. Dr. Chalasani and Dr. Lindor reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Serum cytokeratin fragments correlate with NASH histology

ORLANDO – Changes in serum levels of cytokeratin fragments appear to reflect changes in liver histology in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, Dr. Raj Vuppalanchi reported at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Among 231 participants in the PIVENS (Pioglitazone versus Vitamin E versus Placebo for the Treatment of Nondiabetic Patients with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis) trial, every 100-U/L decline in serum cytokeratin fragment (CK-18) level was significantly associated with overall histological improvement (P less than .001); resolution of NASH (P = .002); and improvement of at least 1 point in steatosis grade, hepatocellular ballooning, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) score (P less than .001 for all).

"We feel that serum CK-18 is a potentially useful surrogate marker for detection of improvement in clinical trials for NASH," said Dr. Vuppalanchi from Indiana University in Indianapolis.

Dr. Keith D. Lindor, executive vice provost for health at Arizona State University in Phoenix, said in an interview that CK-18 shows promise as a marker for disease activity in NASH but offers only limited information.

"It doesn’t hold the possibility of giving as much detailed information as a biopsy. We look at the amount of fat, amount of inflammation, amount of scarring – the biopsy lets us do that, but I don’t think a single serum assay will allow that," he said.

Dr. Lindor, who was not involved in the study, moderated the session at which the data were presented.

In previous cross-sectional studies, circulating CK-18 levels were shown to be associated with steatohepatitis in people with NAFLD, but it was unclear whether longitudinal changes in CK-18 would reflect changes in liver histology, Dr. Vuppalanchi said.

The investigators looked at CK-18 levels measured at baseline and at 16, 48, and 96 months among 231 of the 247 patients enrolled in the PIVENS trial, which compared vitamin E and/or pioglitazone against placebo in nondiabetic patients with NASH. The participants had liver biopsies at baseline and after 96 weeks of treatment.

The main trial results showed that vitamin E, but not pioglitazone, was significantly better than placebo at improvement of steatohepatitis.

In this substudy, the authors found that, compared with placebo, serum CK-18 levels were significantly lower in vitamin E–treated patients (P = .02 at 16 weeks, and P = .009 at 48 and 96 weeks). Among pioglitazone-treated patients, there was a similar pattern of lower CK-18 levels vs. placebo at all three time intervals (P = .001 for all).

Reductions in CK-18 correlated strongly with disease measures. For each 100-U/L decrease in CK-18 over 96 weeks, the odds ratios (ORs) were as follows: overall histological improvement (OR, 1.41; P less than .001); resolution of NASH (OR, 1.31; P = .002); and 1 point or more improvement in steatosis grade (OR, 1.45; P less than .001), hepatocellular ballooning (OR, 1.36; P less than .001), and NAFLD (OR, 1.41; P less than .001).

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health with additional funding from Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Vuppalanchi and Dr. Lindor reported having no financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – Changes in serum levels of cytokeratin fragments appear to reflect changes in liver histology in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, Dr. Raj Vuppalanchi reported at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Among 231 participants in the PIVENS (Pioglitazone versus Vitamin E versus Placebo for the Treatment of Nondiabetic Patients with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis) trial, every 100-U/L decline in serum cytokeratin fragment (CK-18) level was significantly associated with overall histological improvement (P less than .001); resolution of NASH (P = .002); and improvement of at least 1 point in steatosis grade, hepatocellular ballooning, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) score (P less than .001 for all).

"We feel that serum CK-18 is a potentially useful surrogate marker for detection of improvement in clinical trials for NASH," said Dr. Vuppalanchi from Indiana University in Indianapolis.

Dr. Keith D. Lindor, executive vice provost for health at Arizona State University in Phoenix, said in an interview that CK-18 shows promise as a marker for disease activity in NASH but offers only limited information.

"It doesn’t hold the possibility of giving as much detailed information as a biopsy. We look at the amount of fat, amount of inflammation, amount of scarring – the biopsy lets us do that, but I don’t think a single serum assay will allow that," he said.

Dr. Lindor, who was not involved in the study, moderated the session at which the data were presented.

In previous cross-sectional studies, circulating CK-18 levels were shown to be associated with steatohepatitis in people with NAFLD, but it was unclear whether longitudinal changes in CK-18 would reflect changes in liver histology, Dr. Vuppalanchi said.

The investigators looked at CK-18 levels measured at baseline and at 16, 48, and 96 months among 231 of the 247 patients enrolled in the PIVENS trial, which compared vitamin E and/or pioglitazone against placebo in nondiabetic patients with NASH. The participants had liver biopsies at baseline and after 96 weeks of treatment.

The main trial results showed that vitamin E, but not pioglitazone, was significantly better than placebo at improvement of steatohepatitis.

In this substudy, the authors found that, compared with placebo, serum CK-18 levels were significantly lower in vitamin E–treated patients (P = .02 at 16 weeks, and P = .009 at 48 and 96 weeks). Among pioglitazone-treated patients, there was a similar pattern of lower CK-18 levels vs. placebo at all three time intervals (P = .001 for all).

Reductions in CK-18 correlated strongly with disease measures. For each 100-U/L decrease in CK-18 over 96 weeks, the odds ratios (ORs) were as follows: overall histological improvement (OR, 1.41; P less than .001); resolution of NASH (OR, 1.31; P = .002); and 1 point or more improvement in steatosis grade (OR, 1.45; P less than .001), hepatocellular ballooning (OR, 1.36; P less than .001), and NAFLD (OR, 1.41; P less than .001).

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health with additional funding from Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Vuppalanchi and Dr. Lindor reported having no financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – Changes in serum levels of cytokeratin fragments appear to reflect changes in liver histology in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, Dr. Raj Vuppalanchi reported at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Among 231 participants in the PIVENS (Pioglitazone versus Vitamin E versus Placebo for the Treatment of Nondiabetic Patients with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis) trial, every 100-U/L decline in serum cytokeratin fragment (CK-18) level was significantly associated with overall histological improvement (P less than .001); resolution of NASH (P = .002); and improvement of at least 1 point in steatosis grade, hepatocellular ballooning, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) score (P less than .001 for all).

"We feel that serum CK-18 is a potentially useful surrogate marker for detection of improvement in clinical trials for NASH," said Dr. Vuppalanchi from Indiana University in Indianapolis.

Dr. Keith D. Lindor, executive vice provost for health at Arizona State University in Phoenix, said in an interview that CK-18 shows promise as a marker for disease activity in NASH but offers only limited information.

"It doesn’t hold the possibility of giving as much detailed information as a biopsy. We look at the amount of fat, amount of inflammation, amount of scarring – the biopsy lets us do that, but I don’t think a single serum assay will allow that," he said.

Dr. Lindor, who was not involved in the study, moderated the session at which the data were presented.

In previous cross-sectional studies, circulating CK-18 levels were shown to be associated with steatohepatitis in people with NAFLD, but it was unclear whether longitudinal changes in CK-18 would reflect changes in liver histology, Dr. Vuppalanchi said.

The investigators looked at CK-18 levels measured at baseline and at 16, 48, and 96 months among 231 of the 247 patients enrolled in the PIVENS trial, which compared vitamin E and/or pioglitazone against placebo in nondiabetic patients with NASH. The participants had liver biopsies at baseline and after 96 weeks of treatment.

The main trial results showed that vitamin E, but not pioglitazone, was significantly better than placebo at improvement of steatohepatitis.

In this substudy, the authors found that, compared with placebo, serum CK-18 levels were significantly lower in vitamin E–treated patients (P = .02 at 16 weeks, and P = .009 at 48 and 96 weeks). Among pioglitazone-treated patients, there was a similar pattern of lower CK-18 levels vs. placebo at all three time intervals (P = .001 for all).

Reductions in CK-18 correlated strongly with disease measures. For each 100-U/L decrease in CK-18 over 96 weeks, the odds ratios (ORs) were as follows: overall histological improvement (OR, 1.41; P less than .001); resolution of NASH (OR, 1.31; P = .002); and 1 point or more improvement in steatosis grade (OR, 1.45; P less than .001), hepatocellular ballooning (OR, 1.36; P less than .001), and NAFLD (OR, 1.41; P less than .001).

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health with additional funding from Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Vuppalanchi and Dr. Lindor reported having no financial disclosures.

AT DDW 2013

Major finding: Every 100-U/L decline in serum cytokeratin fragment (CK-18) levels was significantly associated with overall histological improvement of NAFLD.

Data source: Subanalysis of data from the randomized controlled PIVENS trial.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health with additional funding from Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Vuppalanchi and Dr. Lindor reported having no financial disclosures.

Hint of prolonged response to vedoluzimab seen in Crohn's

ORLANDO – In patients with Crohn’s disease, a response to the investigational monoclonal antibody vedoluzimab within 6 weeks of initiating therapy was predictive of a continued response to the drug, even at lower doses.

Among patients in the GEMINI II trial with a documented response to vedoluzimab after 6 weeks, 32% of those who were then randomized to receive the drug once every 8 weeks for an additional 46 weeks had a corticosteroid-free clinical remission of Crohn’s disease (CD), as did 29% of those who continued to receive the same dose every 4 weeks and 16% of those on placebo, said Dr. William Sandborn at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

However, the rate of durable clinical remissions, defined as clinical remissions at 80% or more of study visits, was comparable for both dosing groups and the placebo group.

"Patients who had a clinical response to vedolizumab by week 6 then went on to have stable clinical remission rates throughout the maintenance phase and significantly higher clinical remission rates than placebo by week 52," said Dr. Sandborn of the University of California, San Diego.

Vedolizumab is an investigational, gut-selective monoclonal antibody targeting the alpha-4 beta-7 integrin. In GEMINI II, the drug was shown to be more effective than placebo for induction and maintenance therapy of CD.

For this analysis, the researchers dug deeper into the data from GEMINI II and looked at maintenance-phase outcomes for those patients who had a clinical response to the drug by week 6 of the trial.

Patients in the trial were adults 18-80 years old with a diagnosis of CD at least 3 months before study entry, moderate to severe CD as determined by a CD Activity Index (CDAI) score of 220-450 at screening, and either intolerance of or an inadequate response to purine antimetabolites or anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents.

A clinical response to vedolizumab was defined as at least a 70-point decline in CDAI score from baseline value at week 6 following two induction doses of therapy. Patients were randomized on a 1:1:1 basis to receive vedolizumab via infusion every 8 weeks, the same dose every 4 weeks, or placebo until week 52.

Patients who did not have a clinical response by week 6 were treated with open-label vedolizumab at the 300-mg dose every 8 weeks until week 52, and were assessed with those patients who had been on placebo throughout the induction and maintenance phases.

CDAI scores among 153 patients on placebo stabilized at 26 weeks, but continued to decline through week 52 among patients on vedolizumab at both dosing frequencies (154 patients in each dosing group). Rates of clinical remission (CDAI score of 150 or lower) remained relatively stable among patients on vedolizumab, but declined among those on placebo.

A corticosteroid-free remission was seen at week 52 in 32% of patients on the 8-week schedule and in 16% of those on placebo (P = .015). The remission rate was 29% for those on the 4-week schedule (P vs. placebo = .045).

In addition, 21% of those on vedolizumab every 8 weeks had durable clinical remissions, as did 16% of those on the every-4-week dose and 14% of those on placebo. There were no statistically significant differences among the three groups.

In the question-and-answer session following presentation of the results, an attendee commented that "it’s a little disturbing that the more frequent dose seemed to be numerically inferior to the less-frequent dose at virtually every measured outcome."

Dr. Sandborn said that the investigators have extensively examined that question and determined that "there’s noise around the measurements, but you couldn’t draw any firm statistical conclusions."

The study was funded by Millennium/Takeda. Dr. Sandborn disclosed serving as a consultant and receiving grant and research support from the combined companies.

ORLANDO – In patients with Crohn’s disease, a response to the investigational monoclonal antibody vedoluzimab within 6 weeks of initiating therapy was predictive of a continued response to the drug, even at lower doses.

Among patients in the GEMINI II trial with a documented response to vedoluzimab after 6 weeks, 32% of those who were then randomized to receive the drug once every 8 weeks for an additional 46 weeks had a corticosteroid-free clinical remission of Crohn’s disease (CD), as did 29% of those who continued to receive the same dose every 4 weeks and 16% of those on placebo, said Dr. William Sandborn at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

However, the rate of durable clinical remissions, defined as clinical remissions at 80% or more of study visits, was comparable for both dosing groups and the placebo group.

"Patients who had a clinical response to vedolizumab by week 6 then went on to have stable clinical remission rates throughout the maintenance phase and significantly higher clinical remission rates than placebo by week 52," said Dr. Sandborn of the University of California, San Diego.

Vedolizumab is an investigational, gut-selective monoclonal antibody targeting the alpha-4 beta-7 integrin. In GEMINI II, the drug was shown to be more effective than placebo for induction and maintenance therapy of CD.

For this analysis, the researchers dug deeper into the data from GEMINI II and looked at maintenance-phase outcomes for those patients who had a clinical response to the drug by week 6 of the trial.

Patients in the trial were adults 18-80 years old with a diagnosis of CD at least 3 months before study entry, moderate to severe CD as determined by a CD Activity Index (CDAI) score of 220-450 at screening, and either intolerance of or an inadequate response to purine antimetabolites or anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents.

A clinical response to vedolizumab was defined as at least a 70-point decline in CDAI score from baseline value at week 6 following two induction doses of therapy. Patients were randomized on a 1:1:1 basis to receive vedolizumab via infusion every 8 weeks, the same dose every 4 weeks, or placebo until week 52.

Patients who did not have a clinical response by week 6 were treated with open-label vedolizumab at the 300-mg dose every 8 weeks until week 52, and were assessed with those patients who had been on placebo throughout the induction and maintenance phases.

CDAI scores among 153 patients on placebo stabilized at 26 weeks, but continued to decline through week 52 among patients on vedolizumab at both dosing frequencies (154 patients in each dosing group). Rates of clinical remission (CDAI score of 150 or lower) remained relatively stable among patients on vedolizumab, but declined among those on placebo.

A corticosteroid-free remission was seen at week 52 in 32% of patients on the 8-week schedule and in 16% of those on placebo (P = .015). The remission rate was 29% for those on the 4-week schedule (P vs. placebo = .045).

In addition, 21% of those on vedolizumab every 8 weeks had durable clinical remissions, as did 16% of those on the every-4-week dose and 14% of those on placebo. There were no statistically significant differences among the three groups.

In the question-and-answer session following presentation of the results, an attendee commented that "it’s a little disturbing that the more frequent dose seemed to be numerically inferior to the less-frequent dose at virtually every measured outcome."

Dr. Sandborn said that the investigators have extensively examined that question and determined that "there’s noise around the measurements, but you couldn’t draw any firm statistical conclusions."

The study was funded by Millennium/Takeda. Dr. Sandborn disclosed serving as a consultant and receiving grant and research support from the combined companies.

ORLANDO – In patients with Crohn’s disease, a response to the investigational monoclonal antibody vedoluzimab within 6 weeks of initiating therapy was predictive of a continued response to the drug, even at lower doses.

Among patients in the GEMINI II trial with a documented response to vedoluzimab after 6 weeks, 32% of those who were then randomized to receive the drug once every 8 weeks for an additional 46 weeks had a corticosteroid-free clinical remission of Crohn’s disease (CD), as did 29% of those who continued to receive the same dose every 4 weeks and 16% of those on placebo, said Dr. William Sandborn at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

However, the rate of durable clinical remissions, defined as clinical remissions at 80% or more of study visits, was comparable for both dosing groups and the placebo group.

"Patients who had a clinical response to vedolizumab by week 6 then went on to have stable clinical remission rates throughout the maintenance phase and significantly higher clinical remission rates than placebo by week 52," said Dr. Sandborn of the University of California, San Diego.

Vedolizumab is an investigational, gut-selective monoclonal antibody targeting the alpha-4 beta-7 integrin. In GEMINI II, the drug was shown to be more effective than placebo for induction and maintenance therapy of CD.

For this analysis, the researchers dug deeper into the data from GEMINI II and looked at maintenance-phase outcomes for those patients who had a clinical response to the drug by week 6 of the trial.

Patients in the trial were adults 18-80 years old with a diagnosis of CD at least 3 months before study entry, moderate to severe CD as determined by a CD Activity Index (CDAI) score of 220-450 at screening, and either intolerance of or an inadequate response to purine antimetabolites or anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents.

A clinical response to vedolizumab was defined as at least a 70-point decline in CDAI score from baseline value at week 6 following two induction doses of therapy. Patients were randomized on a 1:1:1 basis to receive vedolizumab via infusion every 8 weeks, the same dose every 4 weeks, or placebo until week 52.

Patients who did not have a clinical response by week 6 were treated with open-label vedolizumab at the 300-mg dose every 8 weeks until week 52, and were assessed with those patients who had been on placebo throughout the induction and maintenance phases.

CDAI scores among 153 patients on placebo stabilized at 26 weeks, but continued to decline through week 52 among patients on vedolizumab at both dosing frequencies (154 patients in each dosing group). Rates of clinical remission (CDAI score of 150 or lower) remained relatively stable among patients on vedolizumab, but declined among those on placebo.

A corticosteroid-free remission was seen at week 52 in 32% of patients on the 8-week schedule and in 16% of those on placebo (P = .015). The remission rate was 29% for those on the 4-week schedule (P vs. placebo = .045).

In addition, 21% of those on vedolizumab every 8 weeks had durable clinical remissions, as did 16% of those on the every-4-week dose and 14% of those on placebo. There were no statistically significant differences among the three groups.

In the question-and-answer session following presentation of the results, an attendee commented that "it’s a little disturbing that the more frequent dose seemed to be numerically inferior to the less-frequent dose at virtually every measured outcome."

Dr. Sandborn said that the investigators have extensively examined that question and determined that "there’s noise around the measurements, but you couldn’t draw any firm statistical conclusions."

The study was funded by Millennium/Takeda. Dr. Sandborn disclosed serving as a consultant and receiving grant and research support from the combined companies.

AT DDW 2013

Major finding: Among patients with a documented response to vedoluzimab after 6 weeks, 32% of those who received it every 8 weeks had a clinical remission at week 52, compared with 29% on an every-4-week dose and 16% of those on placebo.

Data source: Subanalysis of 461 patients in the maintenance phase of a randomized controlled trial.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Millennium/Takeda. Dr. Sandborn disclosed serving as a consultant and receiving grant and research support from the combined companies.

HM13 Session Analysis: Things Hospitalists Do for No Reason

I attended an excellent presentation by Hopkins' Leonard Feldman, MD, FAAP, FACP, SFHM, that challenged some of our practices, most notably unnecessary diagnostic tests that cost the hundreds of billions of dollars per year. Dr. Feldman focused on the evaluation of syncope, seizure prophylaxis for brain tumors, adjusting serum potassium levels in STEMI, and GI prophylaxis outside of the ICU.

Here are the key takeways for hospitalists:

- Using carotid Doppler for the evaluation of syncope adds no value in unveiling the etiology. Even if used in a high-risk group with cardiovascular disease, Doppler is helpful in determining the etiology only in the presence of focal neurological symptoms or carotid bruits. On the other hand, checking orthostatics is very helpful and inexpensive, providing an etiology about 25% to 30% of the time.

- There is no benefit of a 7-day peri-operative seizure prophylaxis in patients undergoing resection for a brain tumor (Wu et al, Journal of Neurosurgery, April 2013). The number of seizures within 30 days was actually slightly higher in the group of patients, who had received prophylaxis.

Watch a 2-minute video clip of Bob Wachter's HM13 keynote address

- In the past, medical societies have published guidelines for target serum potassium levels. These had been developed in the setting of STEMI and date back quite a while, before beta-blockers or reperfusion therapies were utilized in the acute management of STEMI. Target potassium levels of >4.0 or even between 4.5 and 5.5 had been recommended. Review of the literature did not find evidence to support this, but rather suggests that a target range of 3.5 to 4.5 is advisable.

- Hospitalized patients are frequently placed on proton-pump inhibitors (PPI) or H2-blockers for GI prophylaxis. Is there any benefit of this practice outside of the ICU? According to a study by Herzig et al (Archives of Internal Medicine, June 2011) clinically significant GI bleeding occurred in 0.18% of patients without prophylaxis compared to 0.26% with prophylaxis. To look at it from a different angle: The number needed to treat to prevent 1 episode of clinically significant GI bleeding was 834, whereas the number needed to harm was 553 for C. diff and 111 for hospital-acquired pneumonia. According to these data, there is no benefit and, if anything, harm done by providing GI prophylaxis to hospitalized patients outside of the ICU.

This is just a small sample of all the things we do. The results should motivate us to look for many other things we may do for no reason in our daily practice. TH

Dr. Suehler is a hospitalist at Mercy Hospital, Allina Health, in Minneapolis, and Team Hospitalist member.

I attended an excellent presentation by Hopkins' Leonard Feldman, MD, FAAP, FACP, SFHM, that challenged some of our practices, most notably unnecessary diagnostic tests that cost the hundreds of billions of dollars per year. Dr. Feldman focused on the evaluation of syncope, seizure prophylaxis for brain tumors, adjusting serum potassium levels in STEMI, and GI prophylaxis outside of the ICU.

Here are the key takeways for hospitalists:

- Using carotid Doppler for the evaluation of syncope adds no value in unveiling the etiology. Even if used in a high-risk group with cardiovascular disease, Doppler is helpful in determining the etiology only in the presence of focal neurological symptoms or carotid bruits. On the other hand, checking orthostatics is very helpful and inexpensive, providing an etiology about 25% to 30% of the time.

- There is no benefit of a 7-day peri-operative seizure prophylaxis in patients undergoing resection for a brain tumor (Wu et al, Journal of Neurosurgery, April 2013). The number of seizures within 30 days was actually slightly higher in the group of patients, who had received prophylaxis.

Watch a 2-minute video clip of Bob Wachter's HM13 keynote address

- In the past, medical societies have published guidelines for target serum potassium levels. These had been developed in the setting of STEMI and date back quite a while, before beta-blockers or reperfusion therapies were utilized in the acute management of STEMI. Target potassium levels of >4.0 or even between 4.5 and 5.5 had been recommended. Review of the literature did not find evidence to support this, but rather suggests that a target range of 3.5 to 4.5 is advisable.

- Hospitalized patients are frequently placed on proton-pump inhibitors (PPI) or H2-blockers for GI prophylaxis. Is there any benefit of this practice outside of the ICU? According to a study by Herzig et al (Archives of Internal Medicine, June 2011) clinically significant GI bleeding occurred in 0.18% of patients without prophylaxis compared to 0.26% with prophylaxis. To look at it from a different angle: The number needed to treat to prevent 1 episode of clinically significant GI bleeding was 834, whereas the number needed to harm was 553 for C. diff and 111 for hospital-acquired pneumonia. According to these data, there is no benefit and, if anything, harm done by providing GI prophylaxis to hospitalized patients outside of the ICU.

This is just a small sample of all the things we do. The results should motivate us to look for many other things we may do for no reason in our daily practice. TH

Dr. Suehler is a hospitalist at Mercy Hospital, Allina Health, in Minneapolis, and Team Hospitalist member.

I attended an excellent presentation by Hopkins' Leonard Feldman, MD, FAAP, FACP, SFHM, that challenged some of our practices, most notably unnecessary diagnostic tests that cost the hundreds of billions of dollars per year. Dr. Feldman focused on the evaluation of syncope, seizure prophylaxis for brain tumors, adjusting serum potassium levels in STEMI, and GI prophylaxis outside of the ICU.

Here are the key takeways for hospitalists:

- Using carotid Doppler for the evaluation of syncope adds no value in unveiling the etiology. Even if used in a high-risk group with cardiovascular disease, Doppler is helpful in determining the etiology only in the presence of focal neurological symptoms or carotid bruits. On the other hand, checking orthostatics is very helpful and inexpensive, providing an etiology about 25% to 30% of the time.

- There is no benefit of a 7-day peri-operative seizure prophylaxis in patients undergoing resection for a brain tumor (Wu et al, Journal of Neurosurgery, April 2013). The number of seizures within 30 days was actually slightly higher in the group of patients, who had received prophylaxis.

Watch a 2-minute video clip of Bob Wachter's HM13 keynote address

- In the past, medical societies have published guidelines for target serum potassium levels. These had been developed in the setting of STEMI and date back quite a while, before beta-blockers or reperfusion therapies were utilized in the acute management of STEMI. Target potassium levels of >4.0 or even between 4.5 and 5.5 had been recommended. Review of the literature did not find evidence to support this, but rather suggests that a target range of 3.5 to 4.5 is advisable.

- Hospitalized patients are frequently placed on proton-pump inhibitors (PPI) or H2-blockers for GI prophylaxis. Is there any benefit of this practice outside of the ICU? According to a study by Herzig et al (Archives of Internal Medicine, June 2011) clinically significant GI bleeding occurred in 0.18% of patients without prophylaxis compared to 0.26% with prophylaxis. To look at it from a different angle: The number needed to treat to prevent 1 episode of clinically significant GI bleeding was 834, whereas the number needed to harm was 553 for C. diff and 111 for hospital-acquired pneumonia. According to these data, there is no benefit and, if anything, harm done by providing GI prophylaxis to hospitalized patients outside of the ICU.

This is just a small sample of all the things we do. The results should motivate us to look for many other things we may do for no reason in our daily practice. TH

Dr. Suehler is a hospitalist at Mercy Hospital, Allina Health, in Minneapolis, and Team Hospitalist member.

HM13 Session Analysis: Success Stories: How to Integrate NPs and PAs into a Hospitalist Practice

I attended the HM13 breakout session “Success Stories: How to Integrate NPs and PAs into a Hospitalist Practice,” which featured Timothy Capstack, MD, a hospitalist at Maryland Inpatient Care Specialists, James Levy, a physician assistant/hospitalist at Hospitalists of Northern Michigan, Kaine Brown, MD, a hospitalist at Tift Regional Medical Center, and Justin Psaila, MD, a hospitalist at St. Luke’s University Hospital and Health Network. Judging from the attendance, this is a very relevant topic. It seems every group is looking to hire NP/PAs, and most want to learn how to successfully incorporate them into a hospitalist practice.

Dr. Psaila explained the first key to success is hiring “beyond the basics,” meaning that it is not enough to be a good clinician, you must also hire a good fit to your practice culture. Additionally, NPs/PAs need to be part of a team they can rely on. He said critical-thinking skills are a much better asset for an NP/PA than technical procedural skills.

Levy agreed, and noted successful integration starts with getting the “right people on the bus.” HM groups should develop a thoughtful, consistent hiring process—and be willing to cut loose a provider if they are not a good fit. He also thinks it is important to have a lead NP/PA, so new hires know where to turn.

Dr. Brown found successful integration when his group turned to NP/PAs to run the post-discharge transition clinic. His group’s NP/PAs are helping reduce readmissions, improve patient/provider communication, and supporting the social and emotional needs of patients.

Watch a 2-minute video clip of Bob Wachter's HM13 keynote address

Dr. Capstack agreed that HM groups have to “hire right.” Hospitalist NP/PAs need to communicate well and be a team player, but also “know what they don’t know.” If the skill set is right, and you create a culture of collaboration, he said success is guaranteed.

All of the presenters agreed NP/PAs in hospital medicine are here to stay, and that they can be an asset to any HM group. TH

Tracy Cardin is a nurse practitioner in the Section of Hospital Medicine at the University of Chicago.

I attended the HM13 breakout session “Success Stories: How to Integrate NPs and PAs into a Hospitalist Practice,” which featured Timothy Capstack, MD, a hospitalist at Maryland Inpatient Care Specialists, James Levy, a physician assistant/hospitalist at Hospitalists of Northern Michigan, Kaine Brown, MD, a hospitalist at Tift Regional Medical Center, and Justin Psaila, MD, a hospitalist at St. Luke’s University Hospital and Health Network. Judging from the attendance, this is a very relevant topic. It seems every group is looking to hire NP/PAs, and most want to learn how to successfully incorporate them into a hospitalist practice.

Dr. Psaila explained the first key to success is hiring “beyond the basics,” meaning that it is not enough to be a good clinician, you must also hire a good fit to your practice culture. Additionally, NPs/PAs need to be part of a team they can rely on. He said critical-thinking skills are a much better asset for an NP/PA than technical procedural skills.

Levy agreed, and noted successful integration starts with getting the “right people on the bus.” HM groups should develop a thoughtful, consistent hiring process—and be willing to cut loose a provider if they are not a good fit. He also thinks it is important to have a lead NP/PA, so new hires know where to turn.

Dr. Brown found successful integration when his group turned to NP/PAs to run the post-discharge transition clinic. His group’s NP/PAs are helping reduce readmissions, improve patient/provider communication, and supporting the social and emotional needs of patients.

Watch a 2-minute video clip of Bob Wachter's HM13 keynote address

Dr. Capstack agreed that HM groups have to “hire right.” Hospitalist NP/PAs need to communicate well and be a team player, but also “know what they don’t know.” If the skill set is right, and you create a culture of collaboration, he said success is guaranteed.

All of the presenters agreed NP/PAs in hospital medicine are here to stay, and that they can be an asset to any HM group. TH

Tracy Cardin is a nurse practitioner in the Section of Hospital Medicine at the University of Chicago.

I attended the HM13 breakout session “Success Stories: How to Integrate NPs and PAs into a Hospitalist Practice,” which featured Timothy Capstack, MD, a hospitalist at Maryland Inpatient Care Specialists, James Levy, a physician assistant/hospitalist at Hospitalists of Northern Michigan, Kaine Brown, MD, a hospitalist at Tift Regional Medical Center, and Justin Psaila, MD, a hospitalist at St. Luke’s University Hospital and Health Network. Judging from the attendance, this is a very relevant topic. It seems every group is looking to hire NP/PAs, and most want to learn how to successfully incorporate them into a hospitalist practice.

Dr. Psaila explained the first key to success is hiring “beyond the basics,” meaning that it is not enough to be a good clinician, you must also hire a good fit to your practice culture. Additionally, NPs/PAs need to be part of a team they can rely on. He said critical-thinking skills are a much better asset for an NP/PA than technical procedural skills.

Levy agreed, and noted successful integration starts with getting the “right people on the bus.” HM groups should develop a thoughtful, consistent hiring process—and be willing to cut loose a provider if they are not a good fit. He also thinks it is important to have a lead NP/PA, so new hires know where to turn.

Dr. Brown found successful integration when his group turned to NP/PAs to run the post-discharge transition clinic. His group’s NP/PAs are helping reduce readmissions, improve patient/provider communication, and supporting the social and emotional needs of patients.

Watch a 2-minute video clip of Bob Wachter's HM13 keynote address

Dr. Capstack agreed that HM groups have to “hire right.” Hospitalist NP/PAs need to communicate well and be a team player, but also “know what they don’t know.” If the skill set is right, and you create a culture of collaboration, he said success is guaranteed.

All of the presenters agreed NP/PAs in hospital medicine are here to stay, and that they can be an asset to any HM group. TH

Tracy Cardin is a nurse practitioner in the Section of Hospital Medicine at the University of Chicago.

The Heart of the Matter

A 52 year‐old male presented to the emergency department with a 2‐month history of a sensation of fluttering in his chest and rapid heartbeat. The symptoms occurred episodically 6 to 8 times per day and lasted 15 to 60 minutes without associated chest pain, lightheadedness, or syncope. Over the past 2 weeks, he also began to experience dyspnea with minimal exertion.

These symptoms strongly hint at a cardiac dysrhythmia. Premature atrial and ventricular beats are frequent causes of palpitations in outpatients; however, the associated dyspnea on exertion indicates a more serious etiology. The 2‐month duration and absence of more severe sequelae up until now are points against life‐threatening ventricular tachycardia. A supraventricular arrhythmia would be most likely, especially atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, atrioventricular nodal re‐entrant (AVNRT) or atrioventricular re‐entrant tachycardia (AVRT).

Evaluation should proceed along 2 parallel paths: to diagnose the specific type of arrhythmia and to uncover predisposing conditions. Etiologies of supraventricular arrhythmias include hypertensive heart disease, other structural heart disease including cardiomyopathy, pulmonary disease (eg, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary hypertension, or pulmonary embolism), pericardial disease, hyperthyroidism, sympathomimetic drug use, and in the case of AVRT, an underlying accessory pathway.

The patient's past medical history included hyperlipidemia. Two years prior, his electrocardiogram (ECG) at the time of a health insurance screening had demonstrated sinus rhythm with Q waves in leads III and aVF, and T wave inversions in the inferolateral and anterior leads. An exercise treadmill thallium test at that time demonstrated an area of reversibility in the inferior wall of the left ventricle and a normal ejection fraction. Coronary angiography revealed focal inferior and apical hypokinesis, with frequent premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) and normal coronary arteries.

These prior studies reveal an underlying cardiomyopathy. An ischemic etiology is less likely in the face of normal‐appearing coronary arteries, and he lacks a history of hypertension. Hypertrophic and restrictive cardiomyopathies are possibilities, and tachycardia‐induced cardiomyopathy is an uncommon cause to consider. The pattern of wall‐motion abnormalities is not classic for the Takotsubo phenomenon of apical ballooning, which is typically transient, related to stress, and more common in women. Frequent PVCs are associated with an increased risk of sudden death. I would inquire about illicit drug use and family history of sudden death or cardiac disease.

The patient was a married Caucasian male who reported significant stress related to his career at a software company. He drank 4 glasses of red wine weekly and never smoked cigarettes. He last used cocaine 30 years previously and denied ever using intravenous drugs. Prior to this illness he exercised regularly and traveled frequently to Europe, China, and Japan. He had no family history of cardiac disease or sudden cardiac death. On review of systems, he endorsed a dry cough for 3 weeks without fever, chills, or sweats, and he denied rashes or joint pains. Medications included aspirin, metoprolol, ezetimibe/simvastatin, fish oil, vitamin E, saw palmetto, glucosamine, chondroitin, and a multivitamin.

His remote cocaine use may have predisposed him to cardiomyopathy and hints at ongoing unacknowledged use, but otherwise the additional history is not helpful.

On physical examination, the patient appeared ill. His heart rate was 86 beats per minute, blood pressure 114/67 mm Hg, temperature 36.4C, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation was 95% while breathing ambient air. There was no conjunctival erythema or pallor, and the oropharynx was moist. The jugular venous pressure (JVP) was not elevated. The heart rhythm was irregular, with a variable intensity of the first heart sound; there were no murmurs or gallops. The apical impulse was normal. The lungs were clear to auscultation. The abdomen was soft, nontender, and nondistended without hepatosplenomegaly. The extremities were without clubbing, cyanosis, or edema. There was no joint swelling. Neurological examination was normal.

In this ill‐appearing patient with 2 months of palpitations, dry cough, and dyspnea on exertion, 2 diagnostic possibilities leap to the front: primary cardiac disease or a primary pulmonary disorder producing a cardiac arrhythmia. The normal JVP, apical impulse, clear lungs, and absence of edema indicate he does not have decompensated heart failure. However, based on prior studies that demonstrated structural heart disease, a cardiac etiology remains more probable. An oxygen saturation of 95% is not normal in a 52‐year‐old nonsmoker and needs to be investigated.

The white blood cell count was 10,000/mm3 with a normal differential, hemoglobin was 15 g/dL, and platelets were 250,000/mm3. Chemistries including sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, glucose, calcium, magnesium, total protein, albumin, liver enzymes, and troponin‐I were all normal.

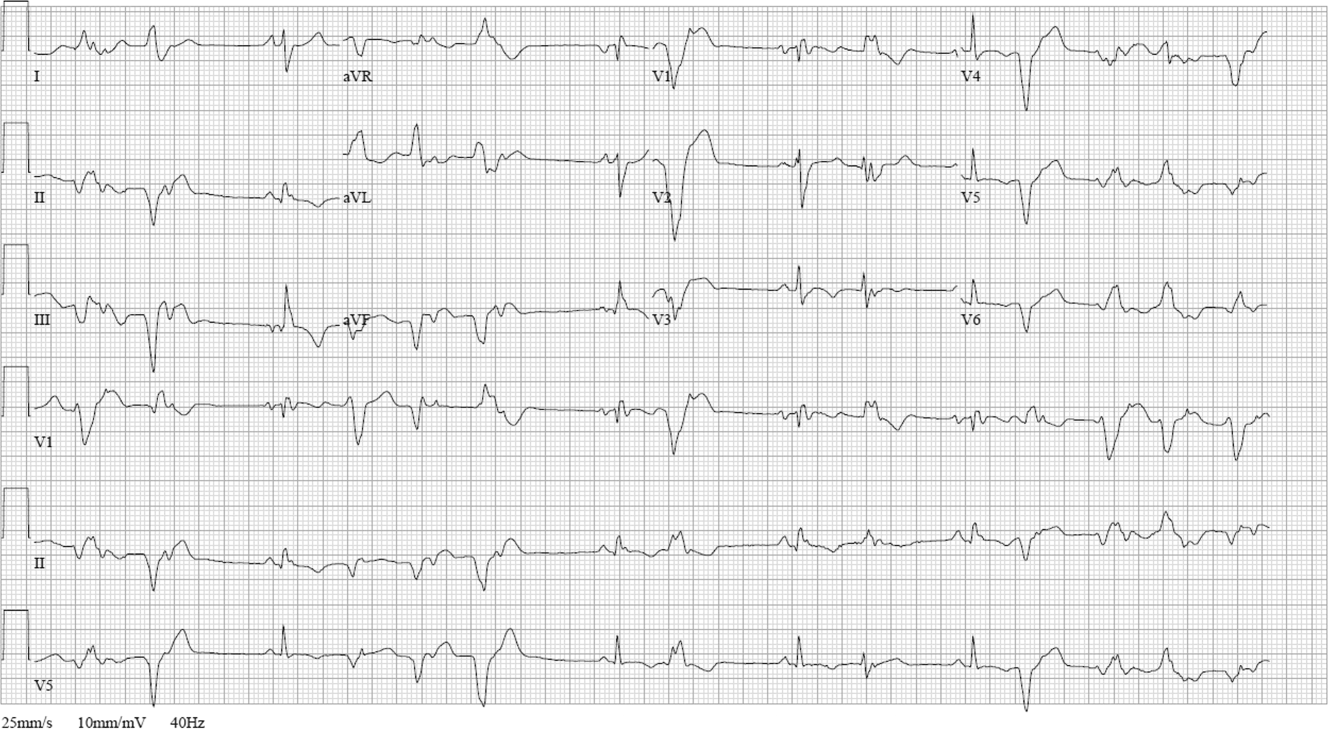

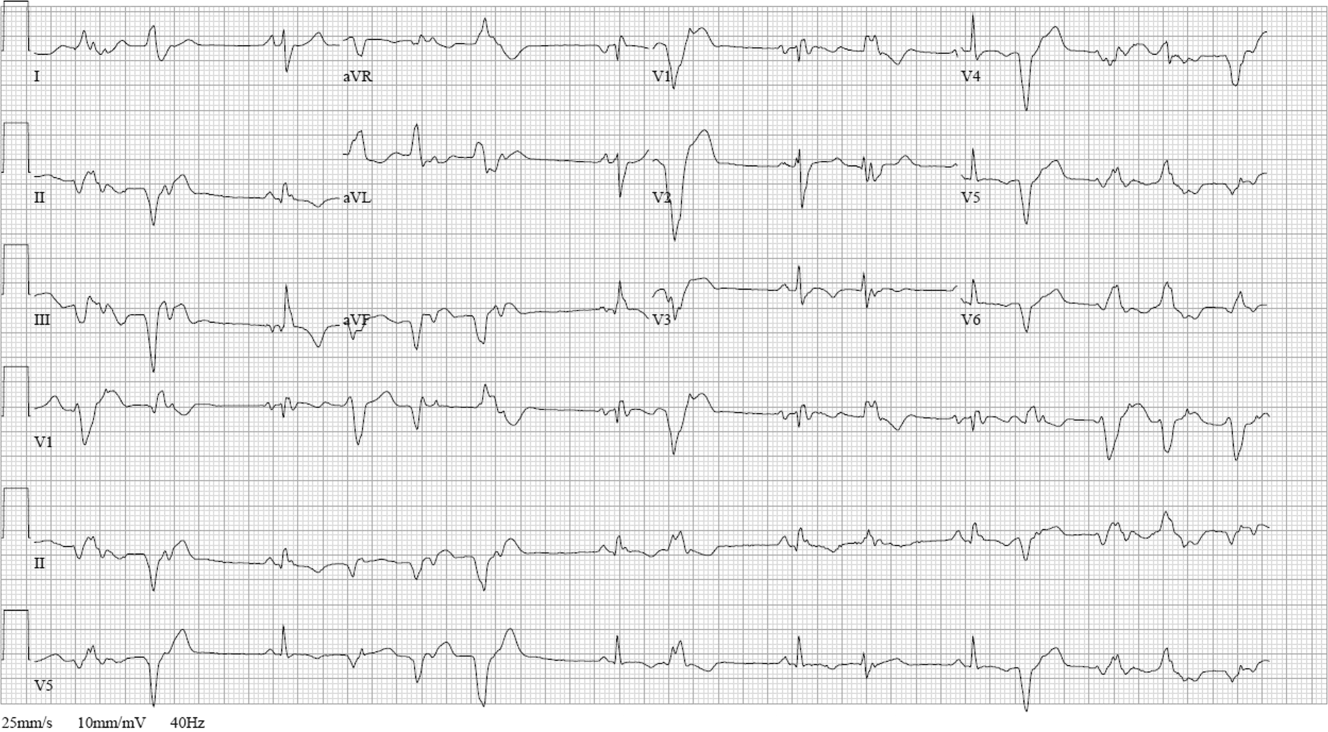

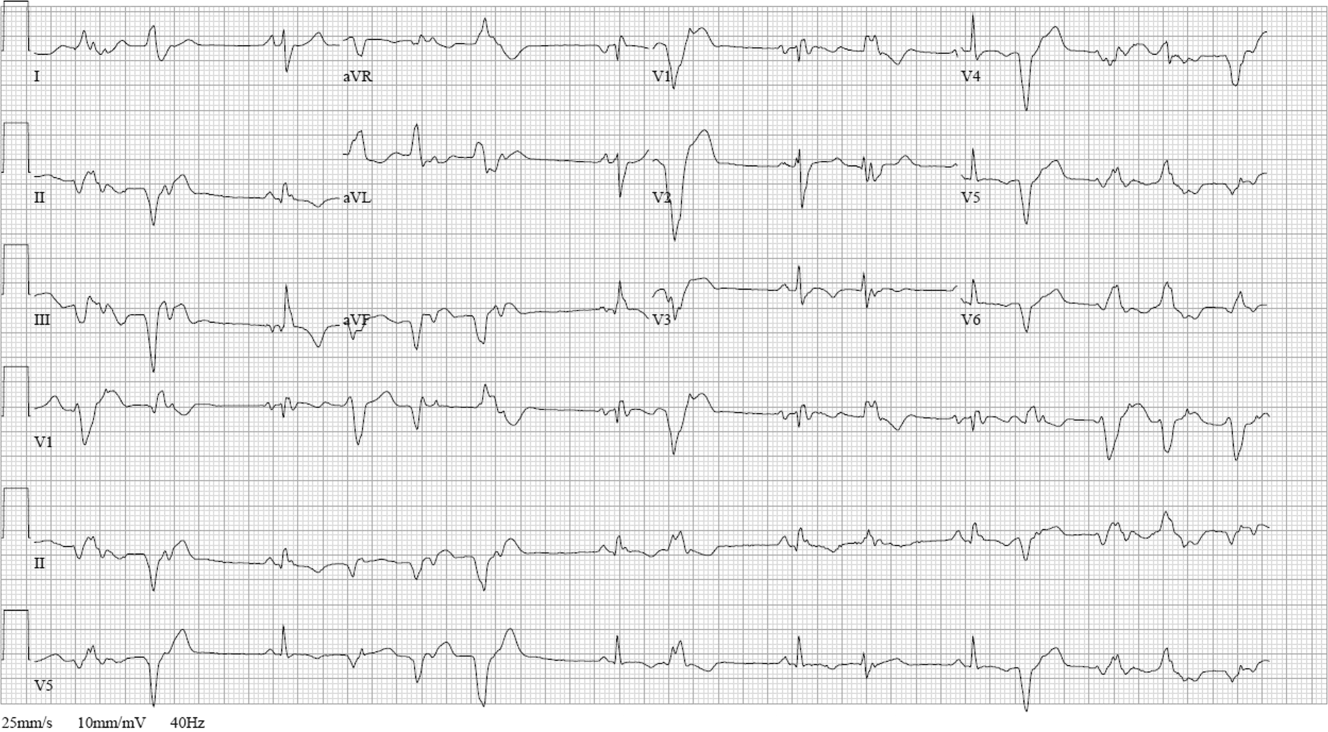

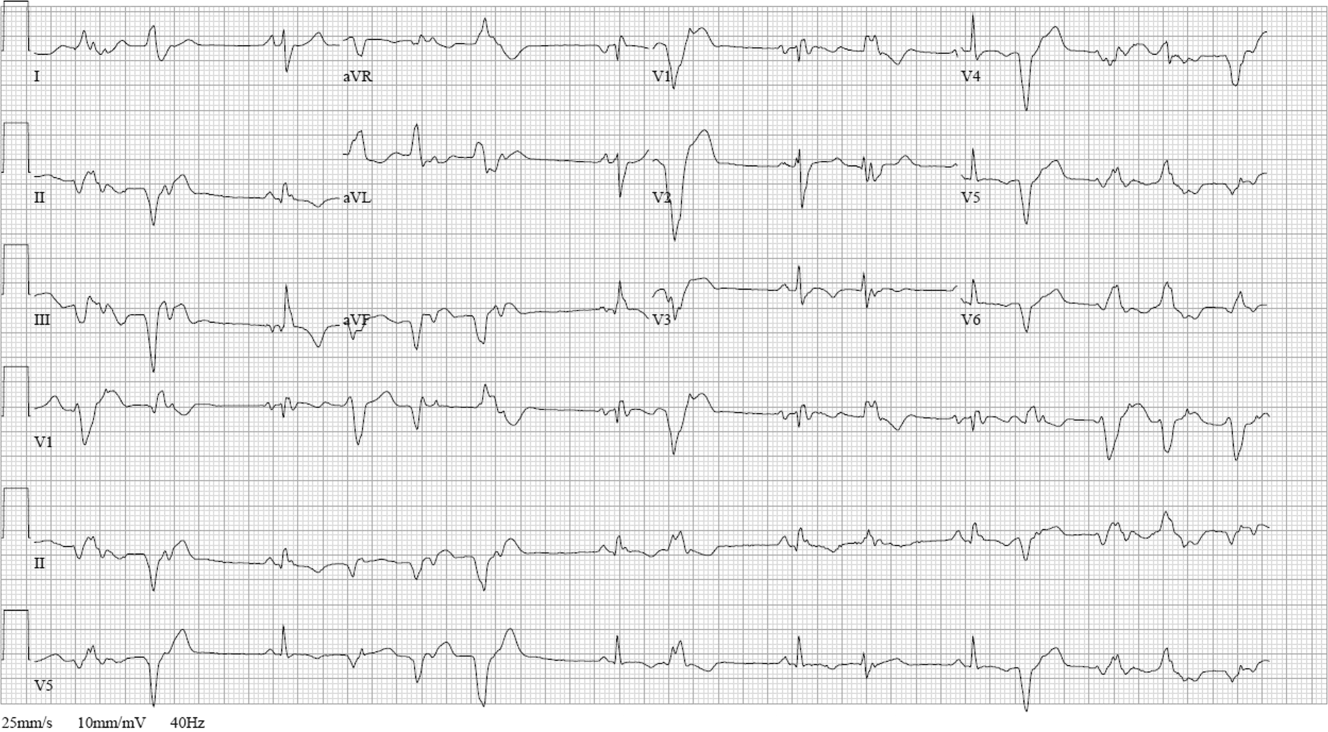

ECG (Figure 11) demonstrated sinus rhythm with an incomplete right bundle branch block, right axis deviation, low voltage, premature atrial contractions, and frequent multiform PVCs with couplets and triplets. Chest radiographs (Figure 22) demonstrated bilateral pleural effusions and a borderline enlarged cardiac silhouette.

The review of systems, physical exam, and laboratory tests provided no evidence of widespread systemic disease, promoting the hypothesis that a primary cardiac or pulmonary disorder is responsible for this patient's illness. The markedly abnormal ECG with conduction disturbance and ventricular ectopy provide further evidence of cardiomyopathy. Cardiomyopathies can be categorized as restrictive, dilated, hypertrophic, arrhythmogenic right ventricular, and miscellaneous causes. Transthoracic echocardiogram is the next key diagnostic test.

The patient was admitted to the hospital. Over the first 24 hours, serial ECGs and telemetry demonstrated runs of ventricular tachycardia at a rate of 169 beats per minute, frequent multiform PVCs, bifascicular block, and runs of supraventricular tachycardia.

Transthoracic echocardiogram showed right and left atrial enlargement, 2+ mitral regurgitation, an estimated right ventricular peak pressure of 35 mm Hg, severe left ventricular global hypokinesis with ejection fraction of 20% to 25%, and moderate right ventricular global hypokinesis. Oral amiodarone was administered, and subsequently an internal cardiac defibrillator (ICD) was placed.

I suspect the pulmonary hypertension and mitral regurgitation are consequences of left ventricular impairment, and therefore are not useful diagnostic clues. By contrast, the presence of severe biventricular failure narrows the diagnostic possibilities considerably. I would attempt to obtain the prior coronary angiography films to confirm the presence of normal coronary arteries. In the absence of coronary artery disease, biventricular failure suggests an advanced infiltrative or dilated cardiomyopathy, because hypertrophic cardiomyopathies are less likely to impair the right ventricle this profoundly.

Causes of restrictive cardiomyopathy in adults include amyloidosis, hemochromatosis, sarcoidosis, and the hypereosinophilic syndrome. Dilated cardiomyopathy may arise from antecedent myocarditis from numerous viruses including parvovirus B19, human herpesvirus 6, coxsackievirus, influenza, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), or from other infections such as Chagas and Lyme disease, toxins (including alcohol and cocaine), autoimmune disease, hypothyroidism, peripartum, genetic causes, nutritional deficiency, or may be idiopathic.

I would check for antibodies to HIV, serum thyrotropin, transferrin saturation, and ferritin, test for serum and urine light chains (looking for evidence of AL amyloid), and obtain a toxicology screen. I would also obtain a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest to look for supportive evidence of sarcoidosis in this mildly hypoxic patient.

Prior coronary angiography films were unobtainable. Repeat cardiac catheterization demonstrated normal coronary arteries, mildly enlarged left ventricle with ejection fraction of 35%. The mean right atrial, right ventricular end‐diastolic, and left ventricular end‐diastolic pressures were equal at 11 mm Hg, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure was 8 mm Hg. Serologies for coxsackie B, HIV, syphilis, cytomegalovirus, Epstein‐Barr virus, and hepatitis B and C were negative. A purified protein derivative was placed and was nonreactive 48 hours later. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C‐reactive protein, antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor, and antibodies to citrullinated peptide were negative. Serum angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) level was normal, lysozyme was elevated at 27 g/mL (normal range, 917), and interleukin (IL)6 was elevated at 27 pg/mL (normal range, 05). Serum protein electrophoresis, serum thyrotropin, transferrin saturation, and ferritin were normal.

The finding of equalization of diastolic pressures at catheterization suggests either constrictive or restrictive physiology; pressure measurements alone cannot distinguish the 2. In the absence of an obvious etiology of constrictive pericarditis (eg, tuberculosis, prior radiation therapy, or cardiac surgery), I remain concerned about infiltrative diseases. Normal iron studies rule out hemochromatosis, and the absence of peripheral eosinophilia removes hypereosinophilic syndrome as a diagnostic consideration. Sarcoidosis can definitely manifest with conduction block as well as biventricular failure, as can amyloidosis. By the time cardiac involvement manifests in sarcoidosis, pulmonary disease is often present, although it may be subclinical. Chest radiography and serum ACE levels are neither sensitive nor specific for screening for pulmonary sarcoidosis. Lysozyme and IL‐6 levels may be elevated in sarcoid, but these too are not specific.

Cardiac involvement in amyloidosis is typically due to AL amyloid light chain deposition associated with a plasma cell dyscrasia. I would expect evidence of organ involvement elsewhere, such as the liver, intestinal tract, tongue, peripheral nerves, or kidneys, none of which are evident in this man. Furthermore, lung involvement in amyloidosis is much less common than in sarcoid. If chest CT fails to demonstrate evidence of sarcoidosis, assays for light chains in the serum and urine might be warranted, as serum protein electrophoresis may fail to detect the abnormal paraprotein.

Chest CT demonstrated bronchial thickening and peribronchovascular bundle ground‐glass opacification, predominantly in the apical lobes with diffuse nodules, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

Taken together with the rest of this patient's illness, the CT findings are highly suspicious for sarcoidosis. Biopsy confirmation is essential prior to initiating immunosuppressive therapy. Endomyocardial biopsy and transbronchial biopsy would both be reasonable options; I would discuss these possibilities with pulmonary and cardiology consultants.

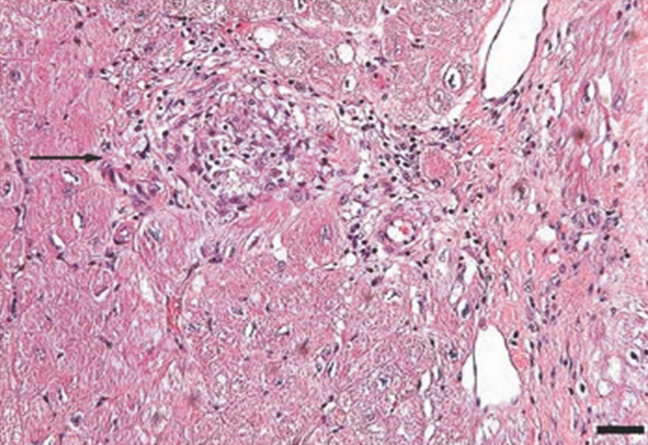

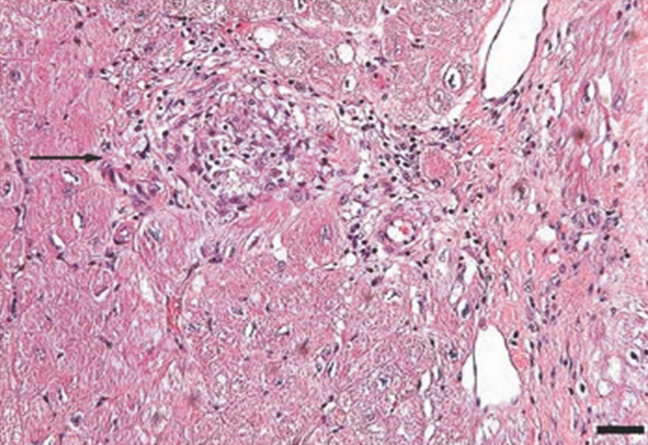

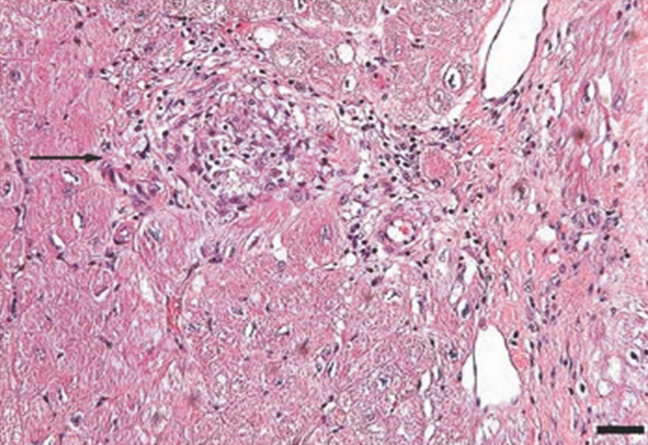

An endomyocardial biopsy was performed. The results (Figure 33) revealed the presence of noncaseating granulomas. A diagnosis of cardiac and pulmonary sarcoidosis was made, and treatment with corticosteroids was initiated. At follow‐up 3 years later, he was stable with New York Heart Association class II symptoms and an ejection fraction of 40% to 45%.

DISCUSSION

In outpatient medical practice, up to 16% of individuals report palpitations.[1] In 1 study, primary cardiac disorders accounted for 43% of palpitations, and clinically significant arrhythmias were found in 19% of patients.[2] A history of cardiac disease substantially raises the probability of an arrhythmic etiology of palpitations; over 90% of cases of palpitations in patients with prior cardiac disease are due to arrhythmias.[3]

In patients with palpitations, the history and physical examination do not reliably differentiate patients with significant arrhythmias from those without arrhythmias or those with benign arrhythmias (PVCs and sinus tachycardia). In a recent systematic review, palpitations awakening patients from sleep or occurring while at work, or a known history of cardiac disease, modestly increase the probability of a cardiac arrhythmia, with positive likelihood ratios of 2.03 to 2.29. On the other hand, palpitations lasting 5 minutes and a known history of panic disorder make an arrhythmia much less likely. Interestingly, palpitations associated with a regular rapid‐pounding sensation in the neck (as opposed to neck fullness) substantially increase the probability of AVNRT with an impressive likelihood ratio of 177.[3]

Sarcoidosis is a rare cause of palpitations and arrhythmias. Most commonly seen in young and middle‐aged adults, sarcoidosis is a disorder of unknown cause characterized by the formation of granulomas in multiple organs. Cardiac involvement is detected in 20% to 30% of sarcoidosis patients at autopsy, but only 5% of patients have clinically significant cardiac involvement.[4] Cardiac involvement can be the presenting and lone feature of sarcoidosis or may occur later in a patient with multisystem disease.

Within the heart, sarcoid granulomas are most abundant in the myocardium of the left ventricular free wall followed by the interventricular septum, right ventricle, and atria. The diffuse cardiac involvement explains the protean clinical and electrocardiographic manifestations seen in cardiac sarcoid. Symptoms of cardiac disease include palpitations, syncope, sudden death, or heart failure. The most common ECG manifestations are heart blocks of all types, followed by ventricular arrhythmias and then supraventricular arrhythmias, the latter attributed to secondary atrial enlargement or direct atrial infiltration by granuloma.[5]

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is challenging. Presenting clinical features, physical exam, routine laboratory tests, ECG, and echocardiography are neither sensitive nor specific. Among the noninvasive tests, serum ACE has been commonly used, but its low sensitivity ranging from 60% to 77%[6, 7, 8] and 50% specificity[8] limit its usefulness in the diagnosis of sarcoid. IL‐6 and lysozyme are other serum markers sometimes obtained in cases of suspected sarcoid, but they too lack adequate sensitivity and specificity to be useful diagnostic tools.[8, 9]

When available, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can enhance clinicians' ability to diagnose cardiac sarcoidosis. It demonstrates zones of thinning and segmental myocardial wall motion abnormalities with increased signal intensity, more pronounced on T2‐weighted images due to inflammation and granulomatous edema. One study reported 100% sensitivity and 78% specificity of MRI in diagnosing cardiac sarcoid.[10]

Because of the limitations of noninvasive tests, tissue biopsy is necessary to diagnose sarcoidosis. If an accessible extracardiac site, such as an enlarged lymph node or skin lesion, is unavailable, a more invasive biopsy is recommended. Transbronchial biopsy is an option if there is obvious thoracic disease. Another alternative is to obtain a 18‐fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18FDG‐PET) scan to identify hypermetabolic granulomas, which can be targeted for biopsy. For cardiac sarcoidosis, endomyocardial biopsy is often performed. This procedure is generally quite safe, with severe complications such as right ventricular perforation occurring in fewer than 1% of procedures.[11] However, the patchy nature of heart involvement in sarcoidosis results in a sensitivity as low as 20%.[12] Despite its low yield, according to guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, patients with unexplained heart failure of 3 months' duration associated with heart block or ventricular arrhythmias have a class I indication for endomyocardial biopsy.[11]

The prognosis of sarcoidosis is generally favorable, with fewer than 5% of patients dying from the disease. Although the impact of cardiac involvement is poorly established, the available literature indicate a worse prognosis for patients with symptomatic heart disease due to sarcoidosis. In 1 series, over half of 19 patients with cardiac involvement were either dead or required an ICD or pacemaker within 2 years of detection, as opposed to none of 82 sarcoid patients without clinically apparent cardiac involvement.[13]

The mainstay of treatment of cardiac sarcoidosis is corticosteroids, which may halt disease progression and improve survival, but do not reduce the incidence of ventricular arrhythmias. Initially, 1 mg/kg doses of prednisone dose are administered daily. Patients should be reassessed for response to treatment, and repeat ejection fraction measurement by echocardiogram should be obtained if symptoms worsen. The use of serial serum ACE levels to monitor disease activity is controversial. For patients responding to prednisone, the dose can be tapered over a period of 6 months to a maintenance daily dose of 10 to 15 mg, with a goal of eventually stopping therapy if disease is quiescent.[14] For patients who do not respond to glucocorticoids or who experience intolerable side effects, other immunosuppressive agents have been tried with reported success based on limited data. Options include methotrexate, azathioprine, hydroxychloroquine, cyclophosphamide, and infliximab.[5] Treatment of asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients with corticosteroids remains controversial.[14]

Adjunctive treatments are often necessary in cardiac sarcoidosis. Permanent pacemaker implantation is indicated if there is complete atrioventricular block or other high‐grade conduction system disease. Survivors of sudden cardiac death, individuals with refractory ventricular arrhythmias, and those with severely impaired systolic function are candidates for ICDs.[15] Catheter radiofrequency ablation may be effective in patients with ventricular tachyarrhythmias.[16]

Cardiac sarcoidosis is important to suspect in a patient with unexplained cardiomyopathy associated with conduction blocks or tachyarrhythmias because it is potentially reversible. Diagnosis can be elusive, as noninvasive tests lack sufficient sensitivity and specificity to establish the presence or absence of the disorder. Biopsy of affected organs is essential to identify the noncaseating granulomas that characterize the disease. When no extracardiac target exists, clinicians may need an endomyocardial biopsy to get to the heart of the matter.

CLINICAL TEACHING POINTS

- A history of cardiac disease substantially raises the possibility of an arrhythmic etiology of palpitations.

- Cardiac involvement in sarcoidosis can be asymptomatic or include conduction blocks, supraventricular and ventricular tachyarrhythmias, or cardiomyopathy.

- Cardiac sarcoid can be an elusive diagnosis to establish, because both noninvasive tests and endomyocardial biopsy demonstrate low sensitivity.

- Cardiac sarcoidosis portends a worse prognosis than sarcoid in general, but is a potentially reversible condition that therefore warrants an aggressive approach to establishing a diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ellen Killebrew, MD, for help with the formal interpretation of the admission ECG.

Disclosures