User login

What Is the Best Management of Hereditary Angioedema?

Case

A 36-year-old man with a known history of hereditary angioedema (HAE) presents with severe orofacial swelling and laryngeal angioedema, requiring expectant management, including endotracheal intubation. His previous angioedema (AE) episodes involved his hands, feet, and genitalia; episodes generally occurred after physical trauma. Ten years prior to admission, he had an episode of secondary small bowel obstruction. The patient had been prescribed prophylactic danazol (Danacrine) 100 mg BID but he had gradually been reducing the dosage due to mood changes; at the time of presentation, he had already tapered to 100 mg danazol three times per week (Monday, Wednesday, and Friday).

Overview

HAE is an autosomal dominant condition characterized by localized, episodic swelling of the deeper dermal layers and/or mucosal tissue. Its acute presentation can vary in severity; presentations can be lethal.

HAE is generally unresponsive to conventional treatments used for other causes of AE (e.g. food or drug reactions) including glucocorticoids, antihistamines, and epinephrine. The pharmacologic treatment of acute attacks, as well as for short- and long-term prophylaxis of HAE, has evolved significantly in recent years and now includes several forms of C1 inhibitor (C1INH) protein replacement, as well as a bradykinin antagonist, and a kallikrein inhibitor.

Review of the Data

Epidemiology. HAE is an autosomal dominant disease with prevalence in the U.S. of 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 50,000 patients. All ethnic groups are equally affected, with no gender predilection. In most cases, a positive family history is present; however, in 25% of cases, spontaneous mutations occur such that an unremarkable family history does not rule out the diagnosis.1

Pathophysiology. In the past decade, there has been substantial advancement in our understanding of HAE pathophysiology. HAE occurs as a result of functional or quantitative C1 esterase inhibitor (C1INH) deficiency.

C1INH belongs to a group of proteins known as serpins (serine protease inhibitors). The C1INH gene is located on chromosome 11, and has several polymorphic sites, which predispose to spontaneous mutations.1

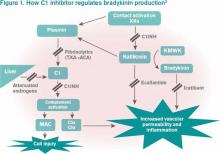

Bradykinin is the core bioactive mediator, which causes vasodilation, smooth muscle contraction, and subsequent edema.1 C1INH regulates bradykinin production by blocking kallikrein’s conversion of factor XII into XIIa, prekallikrein to kallikrein, and cleavage of high-molecular-weight kininogen by activated kallikrein to form bradykinin (see Figure 1).1,2

Clinical Manifestations

HAE is characterized by recurrent episodes of swelling, the frequency and severity of which are quite variable. Virtually all HAE patients have abdominal- and extremity-swelling episodes, and 50% will have episodes of laryngeal swelling; other involved areas might include the face, oropharynx, and genitalia.4 These episodes are usually unilateral; edema is nonpruritic, nonpitting, and often painless. Episodes involving the oropharynx, larynx, and abdomen can be associated with potentially serious morbidity and mortality.1, 3

HAE episodes usually commence during late childhood and early puberty (on average at age 11). Approximately half of HAE patients will have oropharyngeal involvement that might occur many years, even decades, after the initial onset of the disease. The annual rate of severe, life-threatening laryngeal edema was 0.9% in a recent retrospective study.4

Severity of the disease is variable. Attacks are episodic, and occur on average every 10 to 20 days in untreated patients. These attacks typically peak over 24 hours, then usually resolve after 48 to 72 hours. However, the complete resolution of signs and symptoms can last for up to one week after the attacks.5

There is no concomitant pruritus or urticaria that accompanies the AE. However, erythema marginatum, an evanescent nonpruritic rash with serpiginous borders involving the trunk and inner surface of extremities but sparing the face, might herald the onset of an episode. This rash usually has central pallor that blanches with pressure and worsens with heat.

HAE can be triggered by stressful events, including trauma, surgery, menstruation, and viral infections. However, in many instances, HAE attacks occur without an identifiable cause.5

Differential Diagnosis from Other Causes of Angioedema

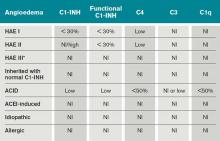

Type I HAE is characterized by a quantitative C1INH deficiency (which is functionally abnormal as well), and occurs in 85% of patients. Type II HAE occurs in 15% of patients, and results from a functionally abnormal C1INH.

In patients with Type I and II HAE, as well as acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency (ACID), C4 levels are low during and between attacks. C2 levels are also low during acute attacks. In ACID, levels of C1q are also reduced; these patients require further workup to rule out an undiagnosed malignancy or an autoimmune process. In contrast, patients with ACE-induced, idiopathic, and allergic AE have normal complement profiles.3,6

Type III is a more recently described type of HAE that is rare, not well understood, and generally affects women.3,6 Clinically, it resembles Type I and Type II HAE but complement levels, including C1 inhibitor, are normal (see Table 1).

Treatment

HAE types I, II, III, and ACID are generally unresponsive to glucocorticoids, antihistamines, and epinephrine. These forms of AE may be exacerbated by exogenous estrogen.1,8 For this reason, HAE patients should avoid oral hormonal contraception and estrogen replacement therapy. In addition, ACE inhibitors should also be avoided based on their effect on bradykinin degradation.

Until the introduction of newer therapeutic choices, as noted in our case, the treatment of acute attacks of AE was essentially supportive. Patients with impending laryngeal obstruction were managed with intubation prior to progression of the AE to limit airway patency. Prior to the modern era, a substantial proportion of HAE patients died of asphyxiation.

Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) has been used to treat acute HAE attacks, but given its content of contact system proteins (in addition to C1INH), FFP might also pose a risk for worsening of HAE; for this reason, it must be given cautiously to patients who are symptomatic.9

In the past decade, there has been significant progress in the available treatments for HAE. Currently in the U.S., there are several agents recently approved by, or have pending approvals from, the FDA, including several forms of C1INH replacement, a bradykinin antagonist, and a kallikrein inhibitor.

The C1 esterase inhibitor (human) drugs are administered intravenously; both have been shown to be efficacious and safe. Nanofiltered C1 inhibitor provided relief in a median time of two hours when used acutely; when used as prophylaxis, it decreased the number of attacks in a three-month period by 50% (six vs. 12 with placebo, P<0.001).11

The other C1INH is rhucin, still not approved in U.S. This drug is characterized by a short half-life (approximately two to four hours) compared with the plasma-derived C1INH agents (24 to 48 hours). It is contraindicated in patients with rabbit hypersensitivity, as it is purified from rabbit breast milk.10

Ecallantide is a kallikrein inhibitor for acute therapy that is administered via three subcutaneous injections. This agent has been linked to allergic/anaphylactic reactions in a minority of patients (approximately 4%); therefore, it should be administered cautiously, by a health-care provider, and in a setting where anaphylaxis can be successfully managed.12 Icatibant is a bradykinin antagonist recently approved in the U.S. and administered SC via a single injection.10

In light of the development of these new agents, there is a need for updated guidelines for the long- and short-term prophylaxis and acute management of HAE. A recent guideline focused on the management of HAE in gynecologic and obstetric patients recommended the use of plasma-derived C1INH C1 esterase inhibitor (human) (Cinryze) for short- and long-term prophylaxis and acute treatment of HAE.13 The effect of pregnancy on HAE is variable: Some women worsen and other women have less swelling during their pregnancy. Swelling at the time of parturition is rare; however, the risk rises during the post-partum period.

Type III HAE. An additional form of HAE has been recognized with a pattern of AE episodes that mimics Type I or Type II HAE but with unremarkable laboratory studies of the complement cascade, including C1 inhibitor level and function. At this time, there is no laboratory test with which a diagnosis of Type III HAE can be confirmed. The diagnosis should be suspected in patients with a strong family history of AE reflecting autosomal dominant inheritance. In some, but not all, cases, the condition is manifest in association with high estrogen levels (e.g. pregnancy or administration of oral contraceptives). Type III HAE patients have a salutary response to the same agents that are efficacious for Type I and II HAE.

Acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency (ACID). ACID generally occurs in adults and is clinically indistinguishable from HAE. ACID is not associated with a remarkable family history of AE. In contrast to HAE, this is a consumptive deficiency of C1 inhibitor and results from enhanced catabolism that exceeds the capacity for regenerating C1 inhibitor protein. It is often associated with neoplastic (usually lymphoproliferative) or autoimmune disorders; treatment of the underlying condition frequently leads to improvement in ACID. Although its management is similar to HAE, it tends to be more responsive to anti-fibrinolytics. A salutary response to C1INH replacement therapy might not occur in patients with autoantibodies to C1 inhibitor, but efficacy of ecallantide and icatibant for the treatment of acquired AE has been reported.14, 15

ACEI angioedema. Treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) has been associated with recurrent AE without urticaria in 0.1 to 0.7% of patients exposed to these drugs.16 Angioedema from ACE-I more frequently occurs within the first few months of therapy, but it might occur even after years of continuous therapy. ACEI-induced AE is secondary to impaired degradation of bradykinin. The main treatment is to discontinue the offending agent and avoid all other ACE-I, as this is a class-specific reaction.17

Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) have been associated less commonly with AE. The mechanism for ARB-associated AE has not been elucidated. A meta-analysis showed that in 2% to 17% of patients who were switched to ARBs, recurrence of AE was observed.18 From the pooling of these data with two randomized controlled trials, it is estimated that approximately 10% or less of patients with ACEI-associated AE who switched to ARBs will develop AE.19 In the majority of cases, patients can be switched to ARBs with no recurrence of AE; however, the decision to prescribe an ARB to a patient who has had AE while receiving ACEI should be made carefully on an individualized risk/benefit basis.19

Preventive Treatment

The 17 α-alkylated androgens that can be used for treatment of HAE are danazol (Danacrine), stanozolol (Winstrol), oxandralone (Oxandrine) and methyltestosterone (Android). In patients with HAE, attenuated androgens can significantly reduce the frequency and severity of attacks; however, their use is limited by risk for untoward effects (virilization, abnormal liver function tests, change in libido, anxiety, etc.).21 There is also a risk for hepatotoxicity, including development of hepatic adenomas and hepatic carcinoma.

Antifibrinolytics also may have efficacy for HAE, but these agents have been associated with a variety of adverse effects, including nausea and diarrhea, postural hypotension, fatigue, enhanced thrombosis, retinal changes, and teratogenicity.8, 22, 23

In 2009, long-term prophylaxis with C1-INH concentrate was recommended for patients with HAE with frequent or disabling attacks, a history of laryngeal attacks, and poor quality of life. The 2007 International Consensus Algorithm for the Diagnosis, Therapy, and Management of HAE recommended long-term prophylaxis in patients with more than one monthly severe HAE attack, more than five days of disability per month, or any history of airway compromise.24, 25

The decision to prescribe long-term prophylaxis, and the dose/frequency of medication required, should be individualized based on clinical parameters, such as frequency and severity of attacks, and not on C1 INH or C4 levels.

Perioperative Considerations

It is well established that any trauma, including dental procedures or surgery, can precipitate HAE attacks. For this reason, short-term prophylactic treatment in HAE patients undergoing procedures is recommended. Ideally, avoiding endotracheal intubation is the best approach; however, if intubation cannot be avoided, then adequate prophylaxis should be administered.2

Attenuated androgens can be given up to seven days before a procedure, or C1 INH can be administered 24 hours in advance. If C1 INH is unavailable, FFP can be given six to 12 hours in advance in patients who are not symptomatic; in case of endotracheal intubation, either FFP or C1 INH should be administered immediately before.2

Several case reports in multiple specialty surgical patients (abdominal surgery, cardiopulmonary bypass, orthopedic surgery, etc.) have confirmed the successful use of C1 INH in the prevention of acute attacks with favorable outcomes.2

There is no need to follow C1 INH levels, as it has no clinical relevance.

Back to the Case

The patient was admitted to the ICU and received a total of eight units of FFP. He was transferred to our institution and was able to be extubated three days after initial presentation. Laboratory studies revealed C4 10mg/dL and C1 esterase inhibitor 10mg/dL (both low).

Danazol was resumed. However, within several months after discharge, Cinryze became available in the U.S. market and was eventually prescribed. The patient has not had further significant attacks requiring inpatient management.

Dr. Auron is an assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University. Dr. Lang is co-director of the Asthma Center and director of the Allergy/Immunology Fellowship Training Program at the Cleveland Clinic.

References

- Bernstein, JA. Update on angioedema: evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011;32(6):408-412.

- Levy JH, Freiberger DJ, Roback J. Hereditary angioedema: current and emerging treatment options. Anesth Analg. 2010;110(5):1271-1280.

- Busse PJ. Angioedema: Differential diagnosis and treatment. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011;32:Suppl 1:S3-S11.

- Khan DA. Hereditary angioedema: historical aspects, classification, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and laboratory diagnosis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011;32(1):1-10.

- Bork K, Meng G, Staubach P, Hardt, J. Hereditary angioedema: new findings concerning symptoms, affected organs, and course. Am J Med. 2006;119(3):267-274.

- Zuraw BL, Christiansen SC. Pathogenesis and laboratory diagnosis of hereditary angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2009;30:487-492.

- Frazer-Abel A, Giclas PC. Update on laboratory tests for the diagnosis and differentiation of hereditary angioedema and acquired angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011;32:Suppl 1:S17-S21.

- Banerjee A. Current treatment of hereditary angioedema: an update on clinical studies. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31:398-406.

- Donaldson VH. Therapy of "the neurotic edema." N Engl J Med. 1972;286(15):835-836.

- Riedl MA. Update on the acute treatment of hereditary angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011;32:11-16.

- Zuraw BL, Busse PJ, White M, et al. Nanofiltered C1 inhibitor concentrate for treatment of hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:513-522.

- Cicardi M, Levy RJ, McNeil DL. Ecallantide for the treatment of acute attacks in hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:523-531.

- Caballero T, Farkas H, Bouillet L, et al. International consensus and practical guidelines on the gynecologic and obstetric management of female patients with hereditary angioedema caused by C1 inhibitor deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(2):308-320.

- Cicardi M, Zanichelli A. Acquired angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;6(1):14.

- Zanichelli A, Badini M, Nataloni I, Montano N, Cicardi M. Treatment of acquired angioedema with icatibant: a case report. Intern Emerg Med. 2011;6(3):279-280.

- Byrd JB, Adam A, Brown NJ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-associated angioedema. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2006;26(4):725-737.

- Haymore BR, Yoon J, Mikita CP, Klote MM, DeZee KJ. Risk of angioedema with angiotensin receptor blockers in patients with prior angioedema associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a meta-analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101(5):495-499.

- Beavers CJ, Dunn SP, Macaulay TE. The role of angiotensin receptor blockers in patients with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(4):520-524.

- Nzeako UC. Diagnosis and management of angioedema with abdominal involvement: a gastroenterology perspective. World J Gastroenterol. 2010; 16(39):4913-4921.

- Banerji A, Sloane DE, Sheffer AL. Hereditary angioedema: a current state-of-the-art review, V: attenuated androgens for the treatment of hereditary angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100(1) (Suppl 2):S19-22.

- Zuraw BL. Clinical practice. Hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359(10):1027-1036.

- Zuraw BL. Hereditary angioedema: a current state-of-the-art review, IV: short- and long-term treatment of hereditary angioedema: out with the old and in with the new? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100(1) (Suppl 2):S13-S18.

- Bowen T, Cicardi M, Bork K, et al. Hereditary angioedema: a current state-of-the-art review, VII: Canadian Hungarian 2007 International Consensus Algorithm for the Diagnosis, Therapy, and Management of Hereditary Angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100(1)(Suppl 2):S30-40.

- Craig T, Riedl M, Dykewicz M, et al. When is prophylaxis for hereditary angioedema necessary? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009.102(5):366-372.

- Frank MM. Update on preventive therapy (prophylaxis) of hereditary angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011;32(1):17-21.

Case

A 36-year-old man with a known history of hereditary angioedema (HAE) presents with severe orofacial swelling and laryngeal angioedema, requiring expectant management, including endotracheal intubation. His previous angioedema (AE) episodes involved his hands, feet, and genitalia; episodes generally occurred after physical trauma. Ten years prior to admission, he had an episode of secondary small bowel obstruction. The patient had been prescribed prophylactic danazol (Danacrine) 100 mg BID but he had gradually been reducing the dosage due to mood changes; at the time of presentation, he had already tapered to 100 mg danazol three times per week (Monday, Wednesday, and Friday).

Overview

HAE is an autosomal dominant condition characterized by localized, episodic swelling of the deeper dermal layers and/or mucosal tissue. Its acute presentation can vary in severity; presentations can be lethal.

HAE is generally unresponsive to conventional treatments used for other causes of AE (e.g. food or drug reactions) including glucocorticoids, antihistamines, and epinephrine. The pharmacologic treatment of acute attacks, as well as for short- and long-term prophylaxis of HAE, has evolved significantly in recent years and now includes several forms of C1 inhibitor (C1INH) protein replacement, as well as a bradykinin antagonist, and a kallikrein inhibitor.

Review of the Data

Epidemiology. HAE is an autosomal dominant disease with prevalence in the U.S. of 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 50,000 patients. All ethnic groups are equally affected, with no gender predilection. In most cases, a positive family history is present; however, in 25% of cases, spontaneous mutations occur such that an unremarkable family history does not rule out the diagnosis.1

Pathophysiology. In the past decade, there has been substantial advancement in our understanding of HAE pathophysiology. HAE occurs as a result of functional or quantitative C1 esterase inhibitor (C1INH) deficiency.

C1INH belongs to a group of proteins known as serpins (serine protease inhibitors). The C1INH gene is located on chromosome 11, and has several polymorphic sites, which predispose to spontaneous mutations.1

Bradykinin is the core bioactive mediator, which causes vasodilation, smooth muscle contraction, and subsequent edema.1 C1INH regulates bradykinin production by blocking kallikrein’s conversion of factor XII into XIIa, prekallikrein to kallikrein, and cleavage of high-molecular-weight kininogen by activated kallikrein to form bradykinin (see Figure 1).1,2

Clinical Manifestations

HAE is characterized by recurrent episodes of swelling, the frequency and severity of which are quite variable. Virtually all HAE patients have abdominal- and extremity-swelling episodes, and 50% will have episodes of laryngeal swelling; other involved areas might include the face, oropharynx, and genitalia.4 These episodes are usually unilateral; edema is nonpruritic, nonpitting, and often painless. Episodes involving the oropharynx, larynx, and abdomen can be associated with potentially serious morbidity and mortality.1, 3

HAE episodes usually commence during late childhood and early puberty (on average at age 11). Approximately half of HAE patients will have oropharyngeal involvement that might occur many years, even decades, after the initial onset of the disease. The annual rate of severe, life-threatening laryngeal edema was 0.9% in a recent retrospective study.4

Severity of the disease is variable. Attacks are episodic, and occur on average every 10 to 20 days in untreated patients. These attacks typically peak over 24 hours, then usually resolve after 48 to 72 hours. However, the complete resolution of signs and symptoms can last for up to one week after the attacks.5

There is no concomitant pruritus or urticaria that accompanies the AE. However, erythema marginatum, an evanescent nonpruritic rash with serpiginous borders involving the trunk and inner surface of extremities but sparing the face, might herald the onset of an episode. This rash usually has central pallor that blanches with pressure and worsens with heat.

HAE can be triggered by stressful events, including trauma, surgery, menstruation, and viral infections. However, in many instances, HAE attacks occur without an identifiable cause.5

Differential Diagnosis from Other Causes of Angioedema

Type I HAE is characterized by a quantitative C1INH deficiency (which is functionally abnormal as well), and occurs in 85% of patients. Type II HAE occurs in 15% of patients, and results from a functionally abnormal C1INH.

In patients with Type I and II HAE, as well as acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency (ACID), C4 levels are low during and between attacks. C2 levels are also low during acute attacks. In ACID, levels of C1q are also reduced; these patients require further workup to rule out an undiagnosed malignancy or an autoimmune process. In contrast, patients with ACE-induced, idiopathic, and allergic AE have normal complement profiles.3,6

Type III is a more recently described type of HAE that is rare, not well understood, and generally affects women.3,6 Clinically, it resembles Type I and Type II HAE but complement levels, including C1 inhibitor, are normal (see Table 1).

Treatment

HAE types I, II, III, and ACID are generally unresponsive to glucocorticoids, antihistamines, and epinephrine. These forms of AE may be exacerbated by exogenous estrogen.1,8 For this reason, HAE patients should avoid oral hormonal contraception and estrogen replacement therapy. In addition, ACE inhibitors should also be avoided based on their effect on bradykinin degradation.

Until the introduction of newer therapeutic choices, as noted in our case, the treatment of acute attacks of AE was essentially supportive. Patients with impending laryngeal obstruction were managed with intubation prior to progression of the AE to limit airway patency. Prior to the modern era, a substantial proportion of HAE patients died of asphyxiation.

Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) has been used to treat acute HAE attacks, but given its content of contact system proteins (in addition to C1INH), FFP might also pose a risk for worsening of HAE; for this reason, it must be given cautiously to patients who are symptomatic.9

In the past decade, there has been significant progress in the available treatments for HAE. Currently in the U.S., there are several agents recently approved by, or have pending approvals from, the FDA, including several forms of C1INH replacement, a bradykinin antagonist, and a kallikrein inhibitor.

The C1 esterase inhibitor (human) drugs are administered intravenously; both have been shown to be efficacious and safe. Nanofiltered C1 inhibitor provided relief in a median time of two hours when used acutely; when used as prophylaxis, it decreased the number of attacks in a three-month period by 50% (six vs. 12 with placebo, P<0.001).11

The other C1INH is rhucin, still not approved in U.S. This drug is characterized by a short half-life (approximately two to four hours) compared with the plasma-derived C1INH agents (24 to 48 hours). It is contraindicated in patients with rabbit hypersensitivity, as it is purified from rabbit breast milk.10

Ecallantide is a kallikrein inhibitor for acute therapy that is administered via three subcutaneous injections. This agent has been linked to allergic/anaphylactic reactions in a minority of patients (approximately 4%); therefore, it should be administered cautiously, by a health-care provider, and in a setting where anaphylaxis can be successfully managed.12 Icatibant is a bradykinin antagonist recently approved in the U.S. and administered SC via a single injection.10

In light of the development of these new agents, there is a need for updated guidelines for the long- and short-term prophylaxis and acute management of HAE. A recent guideline focused on the management of HAE in gynecologic and obstetric patients recommended the use of plasma-derived C1INH C1 esterase inhibitor (human) (Cinryze) for short- and long-term prophylaxis and acute treatment of HAE.13 The effect of pregnancy on HAE is variable: Some women worsen and other women have less swelling during their pregnancy. Swelling at the time of parturition is rare; however, the risk rises during the post-partum period.

Type III HAE. An additional form of HAE has been recognized with a pattern of AE episodes that mimics Type I or Type II HAE but with unremarkable laboratory studies of the complement cascade, including C1 inhibitor level and function. At this time, there is no laboratory test with which a diagnosis of Type III HAE can be confirmed. The diagnosis should be suspected in patients with a strong family history of AE reflecting autosomal dominant inheritance. In some, but not all, cases, the condition is manifest in association with high estrogen levels (e.g. pregnancy or administration of oral contraceptives). Type III HAE patients have a salutary response to the same agents that are efficacious for Type I and II HAE.

Acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency (ACID). ACID generally occurs in adults and is clinically indistinguishable from HAE. ACID is not associated with a remarkable family history of AE. In contrast to HAE, this is a consumptive deficiency of C1 inhibitor and results from enhanced catabolism that exceeds the capacity for regenerating C1 inhibitor protein. It is often associated with neoplastic (usually lymphoproliferative) or autoimmune disorders; treatment of the underlying condition frequently leads to improvement in ACID. Although its management is similar to HAE, it tends to be more responsive to anti-fibrinolytics. A salutary response to C1INH replacement therapy might not occur in patients with autoantibodies to C1 inhibitor, but efficacy of ecallantide and icatibant for the treatment of acquired AE has been reported.14, 15

ACEI angioedema. Treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) has been associated with recurrent AE without urticaria in 0.1 to 0.7% of patients exposed to these drugs.16 Angioedema from ACE-I more frequently occurs within the first few months of therapy, but it might occur even after years of continuous therapy. ACEI-induced AE is secondary to impaired degradation of bradykinin. The main treatment is to discontinue the offending agent and avoid all other ACE-I, as this is a class-specific reaction.17

Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) have been associated less commonly with AE. The mechanism for ARB-associated AE has not been elucidated. A meta-analysis showed that in 2% to 17% of patients who were switched to ARBs, recurrence of AE was observed.18 From the pooling of these data with two randomized controlled trials, it is estimated that approximately 10% or less of patients with ACEI-associated AE who switched to ARBs will develop AE.19 In the majority of cases, patients can be switched to ARBs with no recurrence of AE; however, the decision to prescribe an ARB to a patient who has had AE while receiving ACEI should be made carefully on an individualized risk/benefit basis.19

Preventive Treatment

The 17 α-alkylated androgens that can be used for treatment of HAE are danazol (Danacrine), stanozolol (Winstrol), oxandralone (Oxandrine) and methyltestosterone (Android). In patients with HAE, attenuated androgens can significantly reduce the frequency and severity of attacks; however, their use is limited by risk for untoward effects (virilization, abnormal liver function tests, change in libido, anxiety, etc.).21 There is also a risk for hepatotoxicity, including development of hepatic adenomas and hepatic carcinoma.

Antifibrinolytics also may have efficacy for HAE, but these agents have been associated with a variety of adverse effects, including nausea and diarrhea, postural hypotension, fatigue, enhanced thrombosis, retinal changes, and teratogenicity.8, 22, 23

In 2009, long-term prophylaxis with C1-INH concentrate was recommended for patients with HAE with frequent or disabling attacks, a history of laryngeal attacks, and poor quality of life. The 2007 International Consensus Algorithm for the Diagnosis, Therapy, and Management of HAE recommended long-term prophylaxis in patients with more than one monthly severe HAE attack, more than five days of disability per month, or any history of airway compromise.24, 25

The decision to prescribe long-term prophylaxis, and the dose/frequency of medication required, should be individualized based on clinical parameters, such as frequency and severity of attacks, and not on C1 INH or C4 levels.

Perioperative Considerations

It is well established that any trauma, including dental procedures or surgery, can precipitate HAE attacks. For this reason, short-term prophylactic treatment in HAE patients undergoing procedures is recommended. Ideally, avoiding endotracheal intubation is the best approach; however, if intubation cannot be avoided, then adequate prophylaxis should be administered.2

Attenuated androgens can be given up to seven days before a procedure, or C1 INH can be administered 24 hours in advance. If C1 INH is unavailable, FFP can be given six to 12 hours in advance in patients who are not symptomatic; in case of endotracheal intubation, either FFP or C1 INH should be administered immediately before.2

Several case reports in multiple specialty surgical patients (abdominal surgery, cardiopulmonary bypass, orthopedic surgery, etc.) have confirmed the successful use of C1 INH in the prevention of acute attacks with favorable outcomes.2

There is no need to follow C1 INH levels, as it has no clinical relevance.

Back to the Case

The patient was admitted to the ICU and received a total of eight units of FFP. He was transferred to our institution and was able to be extubated three days after initial presentation. Laboratory studies revealed C4 10mg/dL and C1 esterase inhibitor 10mg/dL (both low).

Danazol was resumed. However, within several months after discharge, Cinryze became available in the U.S. market and was eventually prescribed. The patient has not had further significant attacks requiring inpatient management.

Dr. Auron is an assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University. Dr. Lang is co-director of the Asthma Center and director of the Allergy/Immunology Fellowship Training Program at the Cleveland Clinic.

References

- Bernstein, JA. Update on angioedema: evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011;32(6):408-412.

- Levy JH, Freiberger DJ, Roback J. Hereditary angioedema: current and emerging treatment options. Anesth Analg. 2010;110(5):1271-1280.

- Busse PJ. Angioedema: Differential diagnosis and treatment. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011;32:Suppl 1:S3-S11.

- Khan DA. Hereditary angioedema: historical aspects, classification, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and laboratory diagnosis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011;32(1):1-10.

- Bork K, Meng G, Staubach P, Hardt, J. Hereditary angioedema: new findings concerning symptoms, affected organs, and course. Am J Med. 2006;119(3):267-274.

- Zuraw BL, Christiansen SC. Pathogenesis and laboratory diagnosis of hereditary angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2009;30:487-492.

- Frazer-Abel A, Giclas PC. Update on laboratory tests for the diagnosis and differentiation of hereditary angioedema and acquired angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011;32:Suppl 1:S17-S21.

- Banerjee A. Current treatment of hereditary angioedema: an update on clinical studies. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31:398-406.

- Donaldson VH. Therapy of "the neurotic edema." N Engl J Med. 1972;286(15):835-836.

- Riedl MA. Update on the acute treatment of hereditary angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011;32:11-16.

- Zuraw BL, Busse PJ, White M, et al. Nanofiltered C1 inhibitor concentrate for treatment of hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:513-522.

- Cicardi M, Levy RJ, McNeil DL. Ecallantide for the treatment of acute attacks in hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:523-531.

- Caballero T, Farkas H, Bouillet L, et al. International consensus and practical guidelines on the gynecologic and obstetric management of female patients with hereditary angioedema caused by C1 inhibitor deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(2):308-320.

- Cicardi M, Zanichelli A. Acquired angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;6(1):14.

- Zanichelli A, Badini M, Nataloni I, Montano N, Cicardi M. Treatment of acquired angioedema with icatibant: a case report. Intern Emerg Med. 2011;6(3):279-280.

- Byrd JB, Adam A, Brown NJ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-associated angioedema. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2006;26(4):725-737.

- Haymore BR, Yoon J, Mikita CP, Klote MM, DeZee KJ. Risk of angioedema with angiotensin receptor blockers in patients with prior angioedema associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a meta-analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101(5):495-499.

- Beavers CJ, Dunn SP, Macaulay TE. The role of angiotensin receptor blockers in patients with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(4):520-524.

- Nzeako UC. Diagnosis and management of angioedema with abdominal involvement: a gastroenterology perspective. World J Gastroenterol. 2010; 16(39):4913-4921.

- Banerji A, Sloane DE, Sheffer AL. Hereditary angioedema: a current state-of-the-art review, V: attenuated androgens for the treatment of hereditary angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100(1) (Suppl 2):S19-22.

- Zuraw BL. Clinical practice. Hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359(10):1027-1036.

- Zuraw BL. Hereditary angioedema: a current state-of-the-art review, IV: short- and long-term treatment of hereditary angioedema: out with the old and in with the new? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100(1) (Suppl 2):S13-S18.

- Bowen T, Cicardi M, Bork K, et al. Hereditary angioedema: a current state-of-the-art review, VII: Canadian Hungarian 2007 International Consensus Algorithm for the Diagnosis, Therapy, and Management of Hereditary Angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100(1)(Suppl 2):S30-40.

- Craig T, Riedl M, Dykewicz M, et al. When is prophylaxis for hereditary angioedema necessary? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009.102(5):366-372.

- Frank MM. Update on preventive therapy (prophylaxis) of hereditary angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011;32(1):17-21.

Case

A 36-year-old man with a known history of hereditary angioedema (HAE) presents with severe orofacial swelling and laryngeal angioedema, requiring expectant management, including endotracheal intubation. His previous angioedema (AE) episodes involved his hands, feet, and genitalia; episodes generally occurred after physical trauma. Ten years prior to admission, he had an episode of secondary small bowel obstruction. The patient had been prescribed prophylactic danazol (Danacrine) 100 mg BID but he had gradually been reducing the dosage due to mood changes; at the time of presentation, he had already tapered to 100 mg danazol three times per week (Monday, Wednesday, and Friday).

Overview

HAE is an autosomal dominant condition characterized by localized, episodic swelling of the deeper dermal layers and/or mucosal tissue. Its acute presentation can vary in severity; presentations can be lethal.

HAE is generally unresponsive to conventional treatments used for other causes of AE (e.g. food or drug reactions) including glucocorticoids, antihistamines, and epinephrine. The pharmacologic treatment of acute attacks, as well as for short- and long-term prophylaxis of HAE, has evolved significantly in recent years and now includes several forms of C1 inhibitor (C1INH) protein replacement, as well as a bradykinin antagonist, and a kallikrein inhibitor.

Review of the Data

Epidemiology. HAE is an autosomal dominant disease with prevalence in the U.S. of 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 50,000 patients. All ethnic groups are equally affected, with no gender predilection. In most cases, a positive family history is present; however, in 25% of cases, spontaneous mutations occur such that an unremarkable family history does not rule out the diagnosis.1

Pathophysiology. In the past decade, there has been substantial advancement in our understanding of HAE pathophysiology. HAE occurs as a result of functional or quantitative C1 esterase inhibitor (C1INH) deficiency.

C1INH belongs to a group of proteins known as serpins (serine protease inhibitors). The C1INH gene is located on chromosome 11, and has several polymorphic sites, which predispose to spontaneous mutations.1

Bradykinin is the core bioactive mediator, which causes vasodilation, smooth muscle contraction, and subsequent edema.1 C1INH regulates bradykinin production by blocking kallikrein’s conversion of factor XII into XIIa, prekallikrein to kallikrein, and cleavage of high-molecular-weight kininogen by activated kallikrein to form bradykinin (see Figure 1).1,2

Clinical Manifestations

HAE is characterized by recurrent episodes of swelling, the frequency and severity of which are quite variable. Virtually all HAE patients have abdominal- and extremity-swelling episodes, and 50% will have episodes of laryngeal swelling; other involved areas might include the face, oropharynx, and genitalia.4 These episodes are usually unilateral; edema is nonpruritic, nonpitting, and often painless. Episodes involving the oropharynx, larynx, and abdomen can be associated with potentially serious morbidity and mortality.1, 3

HAE episodes usually commence during late childhood and early puberty (on average at age 11). Approximately half of HAE patients will have oropharyngeal involvement that might occur many years, even decades, after the initial onset of the disease. The annual rate of severe, life-threatening laryngeal edema was 0.9% in a recent retrospective study.4

Severity of the disease is variable. Attacks are episodic, and occur on average every 10 to 20 days in untreated patients. These attacks typically peak over 24 hours, then usually resolve after 48 to 72 hours. However, the complete resolution of signs and symptoms can last for up to one week after the attacks.5

There is no concomitant pruritus or urticaria that accompanies the AE. However, erythema marginatum, an evanescent nonpruritic rash with serpiginous borders involving the trunk and inner surface of extremities but sparing the face, might herald the onset of an episode. This rash usually has central pallor that blanches with pressure and worsens with heat.

HAE can be triggered by stressful events, including trauma, surgery, menstruation, and viral infections. However, in many instances, HAE attacks occur without an identifiable cause.5

Differential Diagnosis from Other Causes of Angioedema

Type I HAE is characterized by a quantitative C1INH deficiency (which is functionally abnormal as well), and occurs in 85% of patients. Type II HAE occurs in 15% of patients, and results from a functionally abnormal C1INH.

In patients with Type I and II HAE, as well as acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency (ACID), C4 levels are low during and between attacks. C2 levels are also low during acute attacks. In ACID, levels of C1q are also reduced; these patients require further workup to rule out an undiagnosed malignancy or an autoimmune process. In contrast, patients with ACE-induced, idiopathic, and allergic AE have normal complement profiles.3,6

Type III is a more recently described type of HAE that is rare, not well understood, and generally affects women.3,6 Clinically, it resembles Type I and Type II HAE but complement levels, including C1 inhibitor, are normal (see Table 1).

Treatment

HAE types I, II, III, and ACID are generally unresponsive to glucocorticoids, antihistamines, and epinephrine. These forms of AE may be exacerbated by exogenous estrogen.1,8 For this reason, HAE patients should avoid oral hormonal contraception and estrogen replacement therapy. In addition, ACE inhibitors should also be avoided based on their effect on bradykinin degradation.

Until the introduction of newer therapeutic choices, as noted in our case, the treatment of acute attacks of AE was essentially supportive. Patients with impending laryngeal obstruction were managed with intubation prior to progression of the AE to limit airway patency. Prior to the modern era, a substantial proportion of HAE patients died of asphyxiation.

Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) has been used to treat acute HAE attacks, but given its content of contact system proteins (in addition to C1INH), FFP might also pose a risk for worsening of HAE; for this reason, it must be given cautiously to patients who are symptomatic.9

In the past decade, there has been significant progress in the available treatments for HAE. Currently in the U.S., there are several agents recently approved by, or have pending approvals from, the FDA, including several forms of C1INH replacement, a bradykinin antagonist, and a kallikrein inhibitor.

The C1 esterase inhibitor (human) drugs are administered intravenously; both have been shown to be efficacious and safe. Nanofiltered C1 inhibitor provided relief in a median time of two hours when used acutely; when used as prophylaxis, it decreased the number of attacks in a three-month period by 50% (six vs. 12 with placebo, P<0.001).11

The other C1INH is rhucin, still not approved in U.S. This drug is characterized by a short half-life (approximately two to four hours) compared with the plasma-derived C1INH agents (24 to 48 hours). It is contraindicated in patients with rabbit hypersensitivity, as it is purified from rabbit breast milk.10

Ecallantide is a kallikrein inhibitor for acute therapy that is administered via three subcutaneous injections. This agent has been linked to allergic/anaphylactic reactions in a minority of patients (approximately 4%); therefore, it should be administered cautiously, by a health-care provider, and in a setting where anaphylaxis can be successfully managed.12 Icatibant is a bradykinin antagonist recently approved in the U.S. and administered SC via a single injection.10

In light of the development of these new agents, there is a need for updated guidelines for the long- and short-term prophylaxis and acute management of HAE. A recent guideline focused on the management of HAE in gynecologic and obstetric patients recommended the use of plasma-derived C1INH C1 esterase inhibitor (human) (Cinryze) for short- and long-term prophylaxis and acute treatment of HAE.13 The effect of pregnancy on HAE is variable: Some women worsen and other women have less swelling during their pregnancy. Swelling at the time of parturition is rare; however, the risk rises during the post-partum period.

Type III HAE. An additional form of HAE has been recognized with a pattern of AE episodes that mimics Type I or Type II HAE but with unremarkable laboratory studies of the complement cascade, including C1 inhibitor level and function. At this time, there is no laboratory test with which a diagnosis of Type III HAE can be confirmed. The diagnosis should be suspected in patients with a strong family history of AE reflecting autosomal dominant inheritance. In some, but not all, cases, the condition is manifest in association with high estrogen levels (e.g. pregnancy or administration of oral contraceptives). Type III HAE patients have a salutary response to the same agents that are efficacious for Type I and II HAE.

Acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency (ACID). ACID generally occurs in adults and is clinically indistinguishable from HAE. ACID is not associated with a remarkable family history of AE. In contrast to HAE, this is a consumptive deficiency of C1 inhibitor and results from enhanced catabolism that exceeds the capacity for regenerating C1 inhibitor protein. It is often associated with neoplastic (usually lymphoproliferative) or autoimmune disorders; treatment of the underlying condition frequently leads to improvement in ACID. Although its management is similar to HAE, it tends to be more responsive to anti-fibrinolytics. A salutary response to C1INH replacement therapy might not occur in patients with autoantibodies to C1 inhibitor, but efficacy of ecallantide and icatibant for the treatment of acquired AE has been reported.14, 15

ACEI angioedema. Treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) has been associated with recurrent AE without urticaria in 0.1 to 0.7% of patients exposed to these drugs.16 Angioedema from ACE-I more frequently occurs within the first few months of therapy, but it might occur even after years of continuous therapy. ACEI-induced AE is secondary to impaired degradation of bradykinin. The main treatment is to discontinue the offending agent and avoid all other ACE-I, as this is a class-specific reaction.17

Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) have been associated less commonly with AE. The mechanism for ARB-associated AE has not been elucidated. A meta-analysis showed that in 2% to 17% of patients who were switched to ARBs, recurrence of AE was observed.18 From the pooling of these data with two randomized controlled trials, it is estimated that approximately 10% or less of patients with ACEI-associated AE who switched to ARBs will develop AE.19 In the majority of cases, patients can be switched to ARBs with no recurrence of AE; however, the decision to prescribe an ARB to a patient who has had AE while receiving ACEI should be made carefully on an individualized risk/benefit basis.19

Preventive Treatment

The 17 α-alkylated androgens that can be used for treatment of HAE are danazol (Danacrine), stanozolol (Winstrol), oxandralone (Oxandrine) and methyltestosterone (Android). In patients with HAE, attenuated androgens can significantly reduce the frequency and severity of attacks; however, their use is limited by risk for untoward effects (virilization, abnormal liver function tests, change in libido, anxiety, etc.).21 There is also a risk for hepatotoxicity, including development of hepatic adenomas and hepatic carcinoma.

Antifibrinolytics also may have efficacy for HAE, but these agents have been associated with a variety of adverse effects, including nausea and diarrhea, postural hypotension, fatigue, enhanced thrombosis, retinal changes, and teratogenicity.8, 22, 23

In 2009, long-term prophylaxis with C1-INH concentrate was recommended for patients with HAE with frequent or disabling attacks, a history of laryngeal attacks, and poor quality of life. The 2007 International Consensus Algorithm for the Diagnosis, Therapy, and Management of HAE recommended long-term prophylaxis in patients with more than one monthly severe HAE attack, more than five days of disability per month, or any history of airway compromise.24, 25

The decision to prescribe long-term prophylaxis, and the dose/frequency of medication required, should be individualized based on clinical parameters, such as frequency and severity of attacks, and not on C1 INH or C4 levels.

Perioperative Considerations

It is well established that any trauma, including dental procedures or surgery, can precipitate HAE attacks. For this reason, short-term prophylactic treatment in HAE patients undergoing procedures is recommended. Ideally, avoiding endotracheal intubation is the best approach; however, if intubation cannot be avoided, then adequate prophylaxis should be administered.2

Attenuated androgens can be given up to seven days before a procedure, or C1 INH can be administered 24 hours in advance. If C1 INH is unavailable, FFP can be given six to 12 hours in advance in patients who are not symptomatic; in case of endotracheal intubation, either FFP or C1 INH should be administered immediately before.2

Several case reports in multiple specialty surgical patients (abdominal surgery, cardiopulmonary bypass, orthopedic surgery, etc.) have confirmed the successful use of C1 INH in the prevention of acute attacks with favorable outcomes.2

There is no need to follow C1 INH levels, as it has no clinical relevance.

Back to the Case

The patient was admitted to the ICU and received a total of eight units of FFP. He was transferred to our institution and was able to be extubated three days after initial presentation. Laboratory studies revealed C4 10mg/dL and C1 esterase inhibitor 10mg/dL (both low).

Danazol was resumed. However, within several months after discharge, Cinryze became available in the U.S. market and was eventually prescribed. The patient has not had further significant attacks requiring inpatient management.

Dr. Auron is an assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University. Dr. Lang is co-director of the Asthma Center and director of the Allergy/Immunology Fellowship Training Program at the Cleveland Clinic.

References

- Bernstein, JA. Update on angioedema: evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011;32(6):408-412.

- Levy JH, Freiberger DJ, Roback J. Hereditary angioedema: current and emerging treatment options. Anesth Analg. 2010;110(5):1271-1280.

- Busse PJ. Angioedema: Differential diagnosis and treatment. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011;32:Suppl 1:S3-S11.

- Khan DA. Hereditary angioedema: historical aspects, classification, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and laboratory diagnosis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011;32(1):1-10.

- Bork K, Meng G, Staubach P, Hardt, J. Hereditary angioedema: new findings concerning symptoms, affected organs, and course. Am J Med. 2006;119(3):267-274.

- Zuraw BL, Christiansen SC. Pathogenesis and laboratory diagnosis of hereditary angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2009;30:487-492.

- Frazer-Abel A, Giclas PC. Update on laboratory tests for the diagnosis and differentiation of hereditary angioedema and acquired angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011;32:Suppl 1:S17-S21.

- Banerjee A. Current treatment of hereditary angioedema: an update on clinical studies. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31:398-406.

- Donaldson VH. Therapy of "the neurotic edema." N Engl J Med. 1972;286(15):835-836.

- Riedl MA. Update on the acute treatment of hereditary angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011;32:11-16.

- Zuraw BL, Busse PJ, White M, et al. Nanofiltered C1 inhibitor concentrate for treatment of hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:513-522.

- Cicardi M, Levy RJ, McNeil DL. Ecallantide for the treatment of acute attacks in hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:523-531.

- Caballero T, Farkas H, Bouillet L, et al. International consensus and practical guidelines on the gynecologic and obstetric management of female patients with hereditary angioedema caused by C1 inhibitor deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(2):308-320.

- Cicardi M, Zanichelli A. Acquired angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;6(1):14.

- Zanichelli A, Badini M, Nataloni I, Montano N, Cicardi M. Treatment of acquired angioedema with icatibant: a case report. Intern Emerg Med. 2011;6(3):279-280.

- Byrd JB, Adam A, Brown NJ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-associated angioedema. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2006;26(4):725-737.

- Haymore BR, Yoon J, Mikita CP, Klote MM, DeZee KJ. Risk of angioedema with angiotensin receptor blockers in patients with prior angioedema associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a meta-analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101(5):495-499.

- Beavers CJ, Dunn SP, Macaulay TE. The role of angiotensin receptor blockers in patients with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(4):520-524.

- Nzeako UC. Diagnosis and management of angioedema with abdominal involvement: a gastroenterology perspective. World J Gastroenterol. 2010; 16(39):4913-4921.

- Banerji A, Sloane DE, Sheffer AL. Hereditary angioedema: a current state-of-the-art review, V: attenuated androgens for the treatment of hereditary angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100(1) (Suppl 2):S19-22.

- Zuraw BL. Clinical practice. Hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359(10):1027-1036.

- Zuraw BL. Hereditary angioedema: a current state-of-the-art review, IV: short- and long-term treatment of hereditary angioedema: out with the old and in with the new? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100(1) (Suppl 2):S13-S18.

- Bowen T, Cicardi M, Bork K, et al. Hereditary angioedema: a current state-of-the-art review, VII: Canadian Hungarian 2007 International Consensus Algorithm for the Diagnosis, Therapy, and Management of Hereditary Angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100(1)(Suppl 2):S30-40.

- Craig T, Riedl M, Dykewicz M, et al. When is prophylaxis for hereditary angioedema necessary? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009.102(5):366-372.

- Frank MM. Update on preventive therapy (prophylaxis) of hereditary angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011;32(1):17-21.

Nonurgent Pediatric Admissions on Weekends Bump Up Hospital Costs

Clinical question: Do weekend admissions for failure to thrive (FTT) result in higher costs and length of stay (LOS)?

Background: FTT accounts for up to 5% of all admissions for children younger than 2 years of age. The optimal approach to inpatient or outpatient care is not well defined. Hospitalizations sometimes are used to facilitate costly and intense workups for organic disease. Given the nonurgent nature of this condition and expected barriers to efficient workup on weekends, it is likely that weekend admissions for FTT might not add much value.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Forty-two tertiary-care pediatric hospitals.

Synopsis: A total of 23,332 children younger than 2 were studied over an eight-year period. Saturday and Sunday admissions resulted in an average increase in LOS by 1.93 days and an increase in cost by $2,785 when compared with weekday admissions. Patients admitted on weekends were more likely to have imaging studies and lab tests performed, but were less likely to have a discharge diagnosis of FTT. The authors estimate that if one-half of the weekend admissions from 2010 with a consistent FTT diagnosis at admission and discharge were converted to a Monday admission, $534,145 in savings to the health-care system would result.

One notable limitation of the authors’ conclusions is that patients admitted on weekends appeared to have more organic diagnoses documented and might in fact have been more acutely ill, requiring more workup and intervention. Researchers were not able to further explore this using the administrative data. Nonetheless, a subset of weekend admissions with a consistent FTT diagnosis appeared to represent no value added to the system, and potentially could have resulted in a $3.5 million cost savings had they simply been admitted instead on a weekday.

Bottom line: Nonurgent weekend admissions for FTT are inefficient.

Citation: Thompson RT, Bennett WE, Finnell SME, Downs SM. Increased length of stay and costs associated with weekend admissions for failure to thrive. Pediatrics. 2012;131:e805-e810.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: Do weekend admissions for failure to thrive (FTT) result in higher costs and length of stay (LOS)?

Background: FTT accounts for up to 5% of all admissions for children younger than 2 years of age. The optimal approach to inpatient or outpatient care is not well defined. Hospitalizations sometimes are used to facilitate costly and intense workups for organic disease. Given the nonurgent nature of this condition and expected barriers to efficient workup on weekends, it is likely that weekend admissions for FTT might not add much value.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Forty-two tertiary-care pediatric hospitals.

Synopsis: A total of 23,332 children younger than 2 were studied over an eight-year period. Saturday and Sunday admissions resulted in an average increase in LOS by 1.93 days and an increase in cost by $2,785 when compared with weekday admissions. Patients admitted on weekends were more likely to have imaging studies and lab tests performed, but were less likely to have a discharge diagnosis of FTT. The authors estimate that if one-half of the weekend admissions from 2010 with a consistent FTT diagnosis at admission and discharge were converted to a Monday admission, $534,145 in savings to the health-care system would result.

One notable limitation of the authors’ conclusions is that patients admitted on weekends appeared to have more organic diagnoses documented and might in fact have been more acutely ill, requiring more workup and intervention. Researchers were not able to further explore this using the administrative data. Nonetheless, a subset of weekend admissions with a consistent FTT diagnosis appeared to represent no value added to the system, and potentially could have resulted in a $3.5 million cost savings had they simply been admitted instead on a weekday.

Bottom line: Nonurgent weekend admissions for FTT are inefficient.

Citation: Thompson RT, Bennett WE, Finnell SME, Downs SM. Increased length of stay and costs associated with weekend admissions for failure to thrive. Pediatrics. 2012;131:e805-e810.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: Do weekend admissions for failure to thrive (FTT) result in higher costs and length of stay (LOS)?

Background: FTT accounts for up to 5% of all admissions for children younger than 2 years of age. The optimal approach to inpatient or outpatient care is not well defined. Hospitalizations sometimes are used to facilitate costly and intense workups for organic disease. Given the nonurgent nature of this condition and expected barriers to efficient workup on weekends, it is likely that weekend admissions for FTT might not add much value.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Forty-two tertiary-care pediatric hospitals.

Synopsis: A total of 23,332 children younger than 2 were studied over an eight-year period. Saturday and Sunday admissions resulted in an average increase in LOS by 1.93 days and an increase in cost by $2,785 when compared with weekday admissions. Patients admitted on weekends were more likely to have imaging studies and lab tests performed, but were less likely to have a discharge diagnosis of FTT. The authors estimate that if one-half of the weekend admissions from 2010 with a consistent FTT diagnosis at admission and discharge were converted to a Monday admission, $534,145 in savings to the health-care system would result.

One notable limitation of the authors’ conclusions is that patients admitted on weekends appeared to have more organic diagnoses documented and might in fact have been more acutely ill, requiring more workup and intervention. Researchers were not able to further explore this using the administrative data. Nonetheless, a subset of weekend admissions with a consistent FTT diagnosis appeared to represent no value added to the system, and potentially could have resulted in a $3.5 million cost savings had they simply been admitted instead on a weekday.

Bottom line: Nonurgent weekend admissions for FTT are inefficient.

Citation: Thompson RT, Bennett WE, Finnell SME, Downs SM. Increased length of stay and costs associated with weekend admissions for failure to thrive. Pediatrics. 2012;131:e805-e810.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Physician Reviews of Hospital Medicine-Related Research

In This Edition

Literature At A Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Prices for common hospital procedures not readily available

- Antibiotics associated with decreased mortality in acute COPD exacerbation

- Endovascular therapy has no benefit to systemic t-PA in acute stroke

- Net harm observed with rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis

- Noninvasive ventilation more effective, safer for AECOPD patients

- Synthetic cannabinoid use and acute kidney injury

- Dabigatran vs. warfarin in the extended treatment of VTE

- Spironolactone improves diastolic function

- Real-time EMR-based prediction tool for clinical deterioration

- Hypothermia protocol and cardiac arrest

Prices for Common Hospital Procedures Not Readily Available

Clinical question: Are patients able to select health-care providers based on price of service?

Background: With health-care costs rising, patients are encouraged to take a more active role in cost containment. Many initiatives call for greater pricing transparency in the health-care system. This study evaluated price availability for a common surgical procedure.

Study design: Telephone inquiries with standardized interview script.

Setting: Twenty top-ranked orthopedic hospitals and 102 non-top-ranked U.S. hospitals.

Synopsis: Hospitals were contacted by phone with a standardized, scripted request for their price of an elective total hip arthroplasty. The script described the patient as a 62-year-old grandmother without insurance who is able to pay out of pocket and wishes to compare hospital prices. On the first or second attempt, 40% of top-ranked and 32% of non-top-ranked hospitals were able to provide their price; after five attempts, authors were unable to obtain full pricing information (both hospital and physician fee) from 40% of top-ranked and 37% of non-top-ranked hospitals. Neither fee was made available by 15% of top-ranked and 16% of non-top-ranked hospitals. Wide variation of pricing was found across hospitals. The authors commented on the difficulties they encountered, such as the transfer of calls between departments and the uncertainty of representatives on how to assist.

Bottom line: For individual patients, applying basic economic principles as a consumer might be tiresome and often impossible, with no major differences between top-ranked and non-top-ranked hospitals.

Citation: Rosenthal JA, Lu X, Cram P. Availability of consumer prices from US hospitals for a common surgical procedure. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(6):427-432.

Antibiotics Associated with Decreased Mortality in Acute COPD Exacerbation

Clinical question: Do antibiotics when added to systemic steroids provide clinical benefit for patients with acute COPD exacerbation?

Background: Despite widespread use of antibiotics in the treatment of acute COPD, their benefit is not clear.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.Setting: Four hundred ten U.S. hospitals participating in Perspective, an inpatient administrative database.

Synopsis: More than 50,000 patients treated with systemic steroids for acute COPD exacerbation were included in this study; 85% of them received empiric antibiotics within the first two hospital days. They were compared with those treated with systemic steroids alone. In-hospital mortality was 1.02% for patients on steroids plus antibiotics versus 1.78% on steroids alone. Use of antibiotics was associated with a 40% reduction in the odds of in-hospital mortality (OR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.50-0.74) and reduced readmissions. In an analysis of matched cohorts, hospital mortality was 1% for patients on antibiotics and 1.8% for patients without antibiotics (OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.40-0.71). The risk for readmission for Clostridium difficile colitis was not different between the groups, but other potential adverse effects of antibiotic use, such as development of resistant micro-organisms, were not studied. In a subset analysis, three groups of antibiotics were compared: macrolides, quinolones, and cephalosporins. None was better than another, but those treated with macrolides had a lower readmission rate for C. diff.

Bottom line: Treatment with antibiotics when added to systemic steroids is associated with improved outcomes in acute COPD exacerbations, but there is no clear advantage of one antibiotic class over another.

Citation: Stefan MS, Rothberg MB, Shieh M, Pekow PS, Lindenauer PK. Association between antibiotic treatment and outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute exacerbation of COPD treated with systemic steroids. Chest. 2013;143(1):82-90.

Endovascular Therapy Added to Systemic t-PA Has No Benefit in Acute Stroke

Clinical question: Does adding endovascular therapy to intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) reduce disability in acute stroke?

Background: Early systemic t-PA is the only proven reperfusion therapy in acute stroke, but it is unknown if adding localized endovascular therapy is beneficial.

Study design: Randomized, open-label, blinded-outcome trial.

Setting: Fifty-eight centers in North America, Europe, and Australia.

Synopsis: Patients aged 18 to 82 with acute ischemic stroke were eligible if they received t-PA within three hours of enrollment and had moderate to severe neurologic deficit (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] >10, or NIHSS 8 or 9 with CT angiographic evidence of specific major artery occlusion). All patients received standard-dose t-PA; those randomized to endovascular treatment underwent angiography, and, if indicated, underwent one of the endovascular treatments chosen by the neurointerventionalist. The primary outcome measure was a modified Rankin score of 2 or lower (indicating functional independence) at 90 days (assessed by a neurologist).

After enrollment of 656 patients, the trial was terminated early for futility. There was no significant difference in the primary outcome, with 40.8% of patients in the endovascular intervention group and 38.7% in the t-PA-only group having a modified Rankin score of 2 or lower. There was also no difference in mortality or other secondary outcomes, even when the analysis was limited to patients presenting with more severe neurologic deficits.

Bottom line: The addition of endovascular therapy to systemic t-PA in acute ischemic stroke does not improve functional outcomes or mortality.

Citation: Broderick JP, Palesch YY, Demchuk AM, et al. Endovascular therapy after intravenous t-PA versus t-PA alone for stroke. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:893-903.

Rivaroxaban Compared with Enoxaparin for Thromboprophylaxis

Clinical question: Is extended-duration rivaroxaban more effective than standard-duration enoxaparin in preventing deep venous thrombosis in acutely ill medical patients?

Background: Trials have shown benefits of thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients at increased risk of venous thrombosis, but the optimal duration and type of anticoagulation is unknown.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, double-blinded, active-comparator controlled trial.

Setting: Five hundred fifty-two centers in 52 countries.

Synopsis: The trial enrolled 8,428 patients hospitalized with an acute medical condition and reduced mobility. Patients were randomized to receive either enoxaparin for 10 (+/-4) days or rivaroxaban for 35 (+/-4) days. The co-primary composite outcomes were the incidence of asymptomatic proximal deep venous thrombosis, symptomatic deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or death related to venous thromboembolism over 10 days and over 35 days.

Both groups had a 2.7% incidence of the primary endpoint over 10 days; over 35 days, the extended-duration rivaroxaban group had a reduced incidence of the primary endpoint of 4.4% compared with 5.7% for enoxaparin. However, there was an increase of clinically relevant bleeding in the rivaroxaban group, occurring in 2.8% and 4.1% of patients over 10 and 35 days, respectively, compared with 1.2% and 1.7% for enoxaparin.

Overall, there was net harm with rivaroxaban over both time periods: 6.6% and 9.4% of patients in the rivaroxaban group had a negative outcome at 10 and 35 days, compared with 4.4% and 7.8% with enoxaparin.

Bottom line: There was net harm with extended-duration rivaroxaban versus standard-duration enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized medical patients.

Citation: Cohen AT, Spiro TE, Büller HR, et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:513-523.

Noninvasive Ventilation More Effective, Safer for Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (AECOPD)

Clinical question: What are the patterns in use of noninvasive ventilation (NIV) and invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) in patients with AECOPD, and which method produces better outcomes?

Background: Multiple randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses have suggested a mortality benefit with NIV compared to standard medical care in AECOPD. However, little evidence exists on head-to-head comparisons of NIV and IMV.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Non-federal, short-term, general, and other specialty hospitals nationwide.

Synopsis: A sample of 67,651 ED visits for AECOPD with acute respiratory failure was analyzed from the National Emergency Department Sample (NEDS) database between 2006 and 2008. The study found that NIV use increased to 16% in 2008 from 14% in 2006. Use varied widely between hospitals and was more utilized in higher-case-volume, nonmetropolitan, and Northeastern hospitals. Compared with IMV, NIV was associated with 46% lower inpatient mortality (risk ratio 0.54, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.50-0.59), shortened hospital length of stay (-3.2 days, 95% CI -3.4 to -2.9), lower hospital charges (-$35,012, 95% CI -$36,848 to -$33,176), and lower risk of iatrogenic pneumothorax (0.05% vs. 0.5%, P<0.001). Causality could not be established given the observational study design.

Bottom line: NIV is associated with better outcomes than IMV in the management of AECOPD, and might be underutilized.

Citation: Tsai CL, Lee WY, Delclos GL, Hanania NA, Camargo CA Jr. Comparative effectiveness of noninvasive ventilation vs. invasive mechanical ventilation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with acute respiratory failure. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(4):165-172.

Synthetic Cannabinoid Use May Cause Acute Kidney Injury

Clinical question: Are synthetic cannabinoids associated with acute kidney injury (AKI)?

Background: Synthetic cannabinoids are designer drugs of abuse with a growing popularity in the U.S.

Study design: Retrospective case series.

Setting: Hospitals in Wyoming, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, New York, Kansas, and Oregon.

Synopsis: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued an alert when 16 cases of unexplained AKI after exposure to synthetic cannabinoids were reported between March and December 2012. Synthetic cannabinoid use is associated with neurologic, sympathomimetic, and cardiovascular toxicity; however, this is the first case series reporting renal toxicity. The 16 patients included 15 males and one female, aged 15-33 years, with no pre-existing renal disease or nephrotoxic medication consumption. All used synthetic cannabinoids within hours to days before developing nausea, vomiting, abdominal, and flank and/or back pain.

Creatinine peaked one to six days after symptom onset. Five patients required hemodialysis, and all 16 recovered. There was no finding specific for all cases on ultrasound and/or biopsy. Toxicologic analysis of specimens was possible in seven cases and revealed a previously unreported fluorinated synthetic cannabinoid compound XLR-11 in all clinical specimens of patients who used the drug within two days of being tested.

Overall, the analysis did not reveal any single compound or brand that could explain all cases.

Bottom line: Clinicians should be aware of the potential for renal or other toxicities in users of synthetic cannabinoid products and should ask about their use in cases of unexplained AKI.

Citation: Murphy TD, Weidenbach KN, Van Houten C, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Acute kidney injury associated with synthetic cannabinoid use—multiple states, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(6):93-98.

Dabigatran versus Warfarin in Extended VTE Treatment

Clinical question: Is dabigatran suitable for extended treatment VTE?

Background: In contrast to warfarin (Coumadin), dabigatran (Pradaxa) is given in a fixed dose and does not require frequent laboratory monitoring. Dabigatran has been shown to be noninferior to warfarin in the initial six-month treatment of VTE.

Study design: Two double-blinded, randomized trials: an active-control study and a placebo-control study.

Setting: Two hundred sixty-five sites in 33 countries for the active-control study, and 147 sites in 21 countries for the placebo-control study.

Synopsis: This study enrolled 4,299 adult patients with objectively confirmed, symptomatic, proximal deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. In the active-control study comparing warfarin and dabigatran, recurrent objectively confirmed symptomatic or fatal VTE was observed in 1.8% of patients in the dabigatran group compared with 1.3% of patients in the warfarin group (P=0.01 for noninferiority). While major or clinically relevant bleeding was less frequent with dabigatran compared to warfarin (hazard ratio, 0.54), more acute coronary syndromes were observed with dabigatran (0.9% vs. 0.2%, P=0.02). In the placebo-control study, symptomatic or fatal VTE was observed in 0.4% of patients in the dabigatran group compared with 5.6% in the placebo group. Clinically relevant bleeding was more common with dabigatran (5.3% vs. 1.8%; hazard ratio 2.92).

Bottom line: Treatment with dabigatran met the pre-specified noninferiority margin in this study. However, it is worth noting that patients with VTE given extended treatment with dabigatran had significantly higher rates of recurrent symptomatic or fatal VTE than patients treated with warfarin.

Citation: Schulman S, Kearson C, Kakkar AK, et al. Extended use of dabigatran, warfarin, or placebo in venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(8):709-718.

Spironolactone Improves Diastolic Function

Clinical question: What is the efficacy of aldosterone receptor blockers on diastolic function and exercise capacity?

Background: Mineralocorticoid receptor activation by aldosterone contributes to the pathophysiology of heart failure (HF) in patients with and without reduced ejection fraction (EF). Aldosterone receptor blockers (spironolactone) reduce overall and cardiovascular mortality in HF patients with reduced EF; however, its effect on HF patients with preserved EF is unknown.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Ten ambulatory sites in Germany and Austria.

Synopsis: This study enrolled 422 men and women, aged 50 or older, with New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class II or III HF and preserved EF, and randomized them to receive spironolactone 25 mg daily or placebo for one year.

The endpoints included echocardiographic measures of diastolic function and remodeling; N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide (NT pro-BNP) levels; exercise capacity; quality of life; and HF symptoms.

In the spironolactone group, there was significant improvement in echocardiographic measures of diastolic function and remodeling as well as NT pro-BNP levels. However, there was no difference in exercise capacity, quality of life, or HF symptoms when compared to placebo.

The spironolactone group had significantly lower blood pressure than the control group, which may account for some of the remodeling effects. The study may have been underpowered, and the study population might not have had severe enough disease to detect a difference in clinical measures. It remains unknown if structural changes on echocardiography will translate into clinical benefits.