User login

New Year’s resolutions

The holiday season has come and gone with alarming speed; and now, ’tis the season for resolutions, turning over a new leaf, promising – yet again – to break all those bad habits once and for all.

I can’t presume to know what your professional bad habits are, but I do know the ones I get asked about the most. The following "top ten list" might provide some inspiration for assembling a list of your own:

1. Start on time. So many doctors complain of running behind. Guess what? Your patients complain about that too. Waiting is the most common patient complaint, and you can’t hope to run on time if you don’t start on time. No single change will improve your efficiency more than this.

2. Organize your Internet time. I confess, this one is on my own list most years. E-mail needs to be answered, and your office’s Twitter feed and Facebook page need updating; but do it before or after office hours. It’s just too easy to start clicking that mouse, and suddenly you’re half an hour behind.

3. Permit fewer interruptions. Phone calls and pharmaceutical reps seem to be the big interrupters in most offices. Make some rules, and stick to them. I’ll stop to take an emergency call, or one from an immediate family member; all others get routed to the nurses or are returned at lunch or after hours. Reps make appointments, like everybody else – and only if they have something new to talk about.

4. Organize samples. See my column on this subject. We strip all the space-wasting packaging off our samples and store them, alphabetically, in cardboard "parts" bins, available in many industrial catalogs. Besides always knowing what you have, you’ll always know what you’re out of; and your staff will waste far less time tracking samples down. Also, a bin system makes logging samples in and out much easier, should that become a requirement – as the FDA keeps promising.

5. Clear your "horizontal file cabinet." That’s the mess on your desk, all the paperwork you never seem to get to (probably because you’re tweeting or answering e-mail). Set aside an hour or two and get it all done. You’ll find some interesting stuff in there. Then, for every piece of paper that arrives on your desk from now on, follow the DDD Rule: Do it, Delegate it, or Destroy it. Don’t start a new mess.

6. Keep a closer eye on your office finances. Most physicians delegate the bookkeeping, and that’s fine. But ignoring the financial side creates an atmosphere that facilitates embezzlement. Set aside a couple of hours each month to review the books personally. And make sure your employees know you’re doing it.

7. Make sure your long-range financial planning is on track. This is another task physicians tend to "set and forget," but the Great Recession was an eye-opener for many of us. Once a year, sit down with your accountant and planner, and make sure your investments are well diversified and all other aspects of your finances – budgets, credit ratings, insurance coverage, tax situations, college savings, estate plans, and retirement accounts – are in the best shape possible. Now would be a good time.

8. Pay down your debt. Debt can destroy the best-laid retirement plans; many learned this the hard way when the "bubble" burst. If you carry significant debt, set up a plan to pay it off as soon as you can.

9. Take more vacations. Remember Eastern’s First Law: Your last words will NOT be, "I wish I had spent more time in the office." This is the year to start spending more time enjoying your life, your friends and family, and the world. As John Lennon said, "Life is what happens to you while you’re busy making other plans."

10. Look at yourself. A private practice lives or dies on the personalities of its physicians, and your staff copies your personality and style. Take a hard, honest look at yourself. Identify your negative personality traits and work to eliminate them. If you have any difficulty finding the things that need changing . . . ask your spouse. He or she will be happy to outline them for you, in great detail.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. T

The holiday season has come and gone with alarming speed; and now, ’tis the season for resolutions, turning over a new leaf, promising – yet again – to break all those bad habits once and for all.

I can’t presume to know what your professional bad habits are, but I do know the ones I get asked about the most. The following "top ten list" might provide some inspiration for assembling a list of your own:

1. Start on time. So many doctors complain of running behind. Guess what? Your patients complain about that too. Waiting is the most common patient complaint, and you can’t hope to run on time if you don’t start on time. No single change will improve your efficiency more than this.

2. Organize your Internet time. I confess, this one is on my own list most years. E-mail needs to be answered, and your office’s Twitter feed and Facebook page need updating; but do it before or after office hours. It’s just too easy to start clicking that mouse, and suddenly you’re half an hour behind.

3. Permit fewer interruptions. Phone calls and pharmaceutical reps seem to be the big interrupters in most offices. Make some rules, and stick to them. I’ll stop to take an emergency call, or one from an immediate family member; all others get routed to the nurses or are returned at lunch or after hours. Reps make appointments, like everybody else – and only if they have something new to talk about.

4. Organize samples. See my column on this subject. We strip all the space-wasting packaging off our samples and store them, alphabetically, in cardboard "parts" bins, available in many industrial catalogs. Besides always knowing what you have, you’ll always know what you’re out of; and your staff will waste far less time tracking samples down. Also, a bin system makes logging samples in and out much easier, should that become a requirement – as the FDA keeps promising.

5. Clear your "horizontal file cabinet." That’s the mess on your desk, all the paperwork you never seem to get to (probably because you’re tweeting or answering e-mail). Set aside an hour or two and get it all done. You’ll find some interesting stuff in there. Then, for every piece of paper that arrives on your desk from now on, follow the DDD Rule: Do it, Delegate it, or Destroy it. Don’t start a new mess.

6. Keep a closer eye on your office finances. Most physicians delegate the bookkeeping, and that’s fine. But ignoring the financial side creates an atmosphere that facilitates embezzlement. Set aside a couple of hours each month to review the books personally. And make sure your employees know you’re doing it.

7. Make sure your long-range financial planning is on track. This is another task physicians tend to "set and forget," but the Great Recession was an eye-opener for many of us. Once a year, sit down with your accountant and planner, and make sure your investments are well diversified and all other aspects of your finances – budgets, credit ratings, insurance coverage, tax situations, college savings, estate plans, and retirement accounts – are in the best shape possible. Now would be a good time.

8. Pay down your debt. Debt can destroy the best-laid retirement plans; many learned this the hard way when the "bubble" burst. If you carry significant debt, set up a plan to pay it off as soon as you can.

9. Take more vacations. Remember Eastern’s First Law: Your last words will NOT be, "I wish I had spent more time in the office." This is the year to start spending more time enjoying your life, your friends and family, and the world. As John Lennon said, "Life is what happens to you while you’re busy making other plans."

10. Look at yourself. A private practice lives or dies on the personalities of its physicians, and your staff copies your personality and style. Take a hard, honest look at yourself. Identify your negative personality traits and work to eliminate them. If you have any difficulty finding the things that need changing . . . ask your spouse. He or she will be happy to outline them for you, in great detail.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. T

The holiday season has come and gone with alarming speed; and now, ’tis the season for resolutions, turning over a new leaf, promising – yet again – to break all those bad habits once and for all.

I can’t presume to know what your professional bad habits are, but I do know the ones I get asked about the most. The following "top ten list" might provide some inspiration for assembling a list of your own:

1. Start on time. So many doctors complain of running behind. Guess what? Your patients complain about that too. Waiting is the most common patient complaint, and you can’t hope to run on time if you don’t start on time. No single change will improve your efficiency more than this.

2. Organize your Internet time. I confess, this one is on my own list most years. E-mail needs to be answered, and your office’s Twitter feed and Facebook page need updating; but do it before or after office hours. It’s just too easy to start clicking that mouse, and suddenly you’re half an hour behind.

3. Permit fewer interruptions. Phone calls and pharmaceutical reps seem to be the big interrupters in most offices. Make some rules, and stick to them. I’ll stop to take an emergency call, or one from an immediate family member; all others get routed to the nurses or are returned at lunch or after hours. Reps make appointments, like everybody else – and only if they have something new to talk about.

4. Organize samples. See my column on this subject. We strip all the space-wasting packaging off our samples and store them, alphabetically, in cardboard "parts" bins, available in many industrial catalogs. Besides always knowing what you have, you’ll always know what you’re out of; and your staff will waste far less time tracking samples down. Also, a bin system makes logging samples in and out much easier, should that become a requirement – as the FDA keeps promising.

5. Clear your "horizontal file cabinet." That’s the mess on your desk, all the paperwork you never seem to get to (probably because you’re tweeting or answering e-mail). Set aside an hour or two and get it all done. You’ll find some interesting stuff in there. Then, for every piece of paper that arrives on your desk from now on, follow the DDD Rule: Do it, Delegate it, or Destroy it. Don’t start a new mess.

6. Keep a closer eye on your office finances. Most physicians delegate the bookkeeping, and that’s fine. But ignoring the financial side creates an atmosphere that facilitates embezzlement. Set aside a couple of hours each month to review the books personally. And make sure your employees know you’re doing it.

7. Make sure your long-range financial planning is on track. This is another task physicians tend to "set and forget," but the Great Recession was an eye-opener for many of us. Once a year, sit down with your accountant and planner, and make sure your investments are well diversified and all other aspects of your finances – budgets, credit ratings, insurance coverage, tax situations, college savings, estate plans, and retirement accounts – are in the best shape possible. Now would be a good time.

8. Pay down your debt. Debt can destroy the best-laid retirement plans; many learned this the hard way when the "bubble" burst. If you carry significant debt, set up a plan to pay it off as soon as you can.

9. Take more vacations. Remember Eastern’s First Law: Your last words will NOT be, "I wish I had spent more time in the office." This is the year to start spending more time enjoying your life, your friends and family, and the world. As John Lennon said, "Life is what happens to you while you’re busy making other plans."

10. Look at yourself. A private practice lives or dies on the personalities of its physicians, and your staff copies your personality and style. Take a hard, honest look at yourself. Identify your negative personality traits and work to eliminate them. If you have any difficulty finding the things that need changing . . . ask your spouse. He or she will be happy to outline them for you, in great detail.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. T

Marijuana most popular drug of abuse among teens

WASHINGTON – Marijuana remains popular with U.S. teenagers, with steady and even rising rates of use, according to a key federal survey.

This year’s data from the annual Monitoring the Future survey found that marijuana was the No. 1 drug used by students in the 8th, 10th, and 12th grades. About 35% of high school seniors said they smoked pot in the past year, consistent with 2011 usage. Daily use among seniors also stayed flat, at around 7%.

Of concern is the declining number of seniors who view marijuana use as risky. Only 20% of seniors said occasional use was harmful, the lowest rate recorded since 1983. Higher numbers of 8th and 10th graders consider pot smoking to be risky, but those figures declined as well.

Dr. Nora D. Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, said that teen perception of harm might be decreasing in part because of the ongoing debate over legalized medical marijuana and recent state efforts that decriminalized recreational use.

Previous NIDA studies have shown that teens believe that anything used for medicinal purposes – such as prescription painkillers – are inherently less dangerous. Also, many teens will not use drugs because they are illegal. Without laws prohibiting use, "that deterrent is not present," Dr. Volkow said at a press conference called by NIDA.

But marijuana is not harmless, Dr. Volkow noted. A study published earlier this year found that heavy marijuana use in the teen years contributed to lower IQs and impaired mental abilities (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012;109:E2657-64 [doi:10.1073/pnas.1206820109]).

"We are increasingly concerned that regular or daily use of marijuana is robbing many young people of their potential to achieve and excel in school or other aspects of life," she said.

Synthetic marijuana, also known as spice or K-2, was the second most popular drug among high school seniors, with 11% reporting they had used it in the past year. A little more than 4% of 8th graders said they’d used the substance.

Dr. Volkow cautioned that synthetic cannabinoids were just as dangerous as is the plant form, and possibly more so, given that the active drug could be concentrated. Many ingredients that can be found in synthetic marijuana have been banned by the Drug Enforcement Administration.

Prescription drug abuse continues to be of concern. Among seniors, Adderall was the third most used drug. About 8% said they had used the prescription stimulant in the previous year, often for a nonmedical use. Vicodin was close behind, with 7.5% of seniors having used it within the past year. The majority of 12th graders (68%) said they were given the prescription medications by friends or relatives; 38% said they had bought the drug from friends or relatives, about a third said they had gotten it by prescription, and 22% said they took it from friends or relatives.

So called "bath salts" were included in the Monitoring the Future survey this year for the first time. "Bath salts" is the street name for a group of designer amphetamine-like stimulants that are sold over the counter. Only 1.3% of seniors reported using the products, a relatively low rate that may reflect heavy publicity about their dangers, Gil Kerlikowske, director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, said at the briefing.

The survey also showed that both tobacco and alcohol use have declined significantly over the years. Alcohol use is at its lowest since the survey began in 1975. About 70% of high school seniors said they’d ever used alcohol, down from a peak of 90%.

For tobacco, there were significant declines in lifetime use among 8th graders: 16% in 2012 compared with a peak of 50% in 1996. For 10th graders, 28% said they had ever smoked tobacco, down from a peak of 61% in 1996. Rates of use of smokeless tobacco and other tobacco products continued to stay steady.

"So as we look at these numbers and we look again in trying to determine what they tell us, I think they identify the areas where we need to pay attention and don’t become complacent," Dr. Volkow said.

More than 45,000 students from 395 public and private schools took part in the Monitoring the Future survey this year. Since 1975, the survey has measured the drug, alcohol, and cigarette use and related attitudes of U.S. high school seniors; 8th and 10th graders were added to the survey in 1991. The survey is funded by NIDA and conducted by University of Michigan investigators led by Lloyd Johnston, Ph.D.

WASHINGTON – Marijuana remains popular with U.S. teenagers, with steady and even rising rates of use, according to a key federal survey.

This year’s data from the annual Monitoring the Future survey found that marijuana was the No. 1 drug used by students in the 8th, 10th, and 12th grades. About 35% of high school seniors said they smoked pot in the past year, consistent with 2011 usage. Daily use among seniors also stayed flat, at around 7%.

Of concern is the declining number of seniors who view marijuana use as risky. Only 20% of seniors said occasional use was harmful, the lowest rate recorded since 1983. Higher numbers of 8th and 10th graders consider pot smoking to be risky, but those figures declined as well.

Dr. Nora D. Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, said that teen perception of harm might be decreasing in part because of the ongoing debate over legalized medical marijuana and recent state efforts that decriminalized recreational use.

Previous NIDA studies have shown that teens believe that anything used for medicinal purposes – such as prescription painkillers – are inherently less dangerous. Also, many teens will not use drugs because they are illegal. Without laws prohibiting use, "that deterrent is not present," Dr. Volkow said at a press conference called by NIDA.

But marijuana is not harmless, Dr. Volkow noted. A study published earlier this year found that heavy marijuana use in the teen years contributed to lower IQs and impaired mental abilities (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012;109:E2657-64 [doi:10.1073/pnas.1206820109]).

"We are increasingly concerned that regular or daily use of marijuana is robbing many young people of their potential to achieve and excel in school or other aspects of life," she said.

Synthetic marijuana, also known as spice or K-2, was the second most popular drug among high school seniors, with 11% reporting they had used it in the past year. A little more than 4% of 8th graders said they’d used the substance.

Dr. Volkow cautioned that synthetic cannabinoids were just as dangerous as is the plant form, and possibly more so, given that the active drug could be concentrated. Many ingredients that can be found in synthetic marijuana have been banned by the Drug Enforcement Administration.

Prescription drug abuse continues to be of concern. Among seniors, Adderall was the third most used drug. About 8% said they had used the prescription stimulant in the previous year, often for a nonmedical use. Vicodin was close behind, with 7.5% of seniors having used it within the past year. The majority of 12th graders (68%) said they were given the prescription medications by friends or relatives; 38% said they had bought the drug from friends or relatives, about a third said they had gotten it by prescription, and 22% said they took it from friends or relatives.

So called "bath salts" were included in the Monitoring the Future survey this year for the first time. "Bath salts" is the street name for a group of designer amphetamine-like stimulants that are sold over the counter. Only 1.3% of seniors reported using the products, a relatively low rate that may reflect heavy publicity about their dangers, Gil Kerlikowske, director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, said at the briefing.

The survey also showed that both tobacco and alcohol use have declined significantly over the years. Alcohol use is at its lowest since the survey began in 1975. About 70% of high school seniors said they’d ever used alcohol, down from a peak of 90%.

For tobacco, there were significant declines in lifetime use among 8th graders: 16% in 2012 compared with a peak of 50% in 1996. For 10th graders, 28% said they had ever smoked tobacco, down from a peak of 61% in 1996. Rates of use of smokeless tobacco and other tobacco products continued to stay steady.

"So as we look at these numbers and we look again in trying to determine what they tell us, I think they identify the areas where we need to pay attention and don’t become complacent," Dr. Volkow said.

More than 45,000 students from 395 public and private schools took part in the Monitoring the Future survey this year. Since 1975, the survey has measured the drug, alcohol, and cigarette use and related attitudes of U.S. high school seniors; 8th and 10th graders were added to the survey in 1991. The survey is funded by NIDA and conducted by University of Michigan investigators led by Lloyd Johnston, Ph.D.

WASHINGTON – Marijuana remains popular with U.S. teenagers, with steady and even rising rates of use, according to a key federal survey.

This year’s data from the annual Monitoring the Future survey found that marijuana was the No. 1 drug used by students in the 8th, 10th, and 12th grades. About 35% of high school seniors said they smoked pot in the past year, consistent with 2011 usage. Daily use among seniors also stayed flat, at around 7%.

Of concern is the declining number of seniors who view marijuana use as risky. Only 20% of seniors said occasional use was harmful, the lowest rate recorded since 1983. Higher numbers of 8th and 10th graders consider pot smoking to be risky, but those figures declined as well.

Dr. Nora D. Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, said that teen perception of harm might be decreasing in part because of the ongoing debate over legalized medical marijuana and recent state efforts that decriminalized recreational use.

Previous NIDA studies have shown that teens believe that anything used for medicinal purposes – such as prescription painkillers – are inherently less dangerous. Also, many teens will not use drugs because they are illegal. Without laws prohibiting use, "that deterrent is not present," Dr. Volkow said at a press conference called by NIDA.

But marijuana is not harmless, Dr. Volkow noted. A study published earlier this year found that heavy marijuana use in the teen years contributed to lower IQs and impaired mental abilities (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012;109:E2657-64 [doi:10.1073/pnas.1206820109]).

"We are increasingly concerned that regular or daily use of marijuana is robbing many young people of their potential to achieve and excel in school or other aspects of life," she said.

Synthetic marijuana, also known as spice or K-2, was the second most popular drug among high school seniors, with 11% reporting they had used it in the past year. A little more than 4% of 8th graders said they’d used the substance.

Dr. Volkow cautioned that synthetic cannabinoids were just as dangerous as is the plant form, and possibly more so, given that the active drug could be concentrated. Many ingredients that can be found in synthetic marijuana have been banned by the Drug Enforcement Administration.

Prescription drug abuse continues to be of concern. Among seniors, Adderall was the third most used drug. About 8% said they had used the prescription stimulant in the previous year, often for a nonmedical use. Vicodin was close behind, with 7.5% of seniors having used it within the past year. The majority of 12th graders (68%) said they were given the prescription medications by friends or relatives; 38% said they had bought the drug from friends or relatives, about a third said they had gotten it by prescription, and 22% said they took it from friends or relatives.

So called "bath salts" were included in the Monitoring the Future survey this year for the first time. "Bath salts" is the street name for a group of designer amphetamine-like stimulants that are sold over the counter. Only 1.3% of seniors reported using the products, a relatively low rate that may reflect heavy publicity about their dangers, Gil Kerlikowske, director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, said at the briefing.

The survey also showed that both tobacco and alcohol use have declined significantly over the years. Alcohol use is at its lowest since the survey began in 1975. About 70% of high school seniors said they’d ever used alcohol, down from a peak of 90%.

For tobacco, there were significant declines in lifetime use among 8th graders: 16% in 2012 compared with a peak of 50% in 1996. For 10th graders, 28% said they had ever smoked tobacco, down from a peak of 61% in 1996. Rates of use of smokeless tobacco and other tobacco products continued to stay steady.

"So as we look at these numbers and we look again in trying to determine what they tell us, I think they identify the areas where we need to pay attention and don’t become complacent," Dr. Volkow said.

More than 45,000 students from 395 public and private schools took part in the Monitoring the Future survey this year. Since 1975, the survey has measured the drug, alcohol, and cigarette use and related attitudes of U.S. high school seniors; 8th and 10th graders were added to the survey in 1991. The survey is funded by NIDA and conducted by University of Michigan investigators led by Lloyd Johnston, Ph.D.

AT A PRESS CONFERENCE CALLED BY THE NATIONAL INSTITUTE ON DRUG ABUSE

Major Finding: One in five high school seniors believe marijuana use is harmful.

Data Source: Monitoring the Future, a survey of 45,449 U.S. teens in the 8th, 10th, and 12th grades.

Disclosures: The study is funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Pediatric Hospitalist Certification Options Still Up for Debate

While the debate about whether pediatric hospitalists should obtain certification is alive and well, the majority of hospitalists favor further education through fellowships, or a recognition of focused practice for the subspecialty.

When asked in a recent poll by The Hospitalist which certification options pediatric hospital medicine should pursue, 40% of respondents preferred having a recognition of focused practice for pediatric hospitalists, similar to that of adult hospitalists; 25% thought a one-year fellowship should be in place; and 9% would keep the status quo. Currently, there is no specific certification option for pediatric hospitalists. Still, the topic has raised some strong opinions and remains popular fodder for debate among hospitalists.

"I think it is clear the vast majority of pediatric hospitalists believe there are skills necessary to function at a high level in pediatric hospitalist medicine that are not gained during just three years of pediatric residency," says Douglas W. Carlson, MD, SFHM, SHM's representative to the Joint Council of Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Dr. Carlson says he considers two-year fellowships the best option. However, he does see the possible negative consequences to further education. "If we go to a fellowship, I am worried we will turn off that pipeline [of bright young physicians] … particularly when so many medical students in residency are coming out with such huge debt," he adds.

Rather than debating which result is best, Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center in Austin, Texas, is more interested in the "why"of the matter."Whatever result comes out will be well thought through," he says. "In my mind, I would be more interested in what the underlying thought process is in the decision more than anything else."

Visit our website for more information about pediatric hospitalist certification.

While the debate about whether pediatric hospitalists should obtain certification is alive and well, the majority of hospitalists favor further education through fellowships, or a recognition of focused practice for the subspecialty.

When asked in a recent poll by The Hospitalist which certification options pediatric hospital medicine should pursue, 40% of respondents preferred having a recognition of focused practice for pediatric hospitalists, similar to that of adult hospitalists; 25% thought a one-year fellowship should be in place; and 9% would keep the status quo. Currently, there is no specific certification option for pediatric hospitalists. Still, the topic has raised some strong opinions and remains popular fodder for debate among hospitalists.

"I think it is clear the vast majority of pediatric hospitalists believe there are skills necessary to function at a high level in pediatric hospitalist medicine that are not gained during just three years of pediatric residency," says Douglas W. Carlson, MD, SFHM, SHM's representative to the Joint Council of Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Dr. Carlson says he considers two-year fellowships the best option. However, he does see the possible negative consequences to further education. "If we go to a fellowship, I am worried we will turn off that pipeline [of bright young physicians] … particularly when so many medical students in residency are coming out with such huge debt," he adds.

Rather than debating which result is best, Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center in Austin, Texas, is more interested in the "why"of the matter."Whatever result comes out will be well thought through," he says. "In my mind, I would be more interested in what the underlying thought process is in the decision more than anything else."

Visit our website for more information about pediatric hospitalist certification.

While the debate about whether pediatric hospitalists should obtain certification is alive and well, the majority of hospitalists favor further education through fellowships, or a recognition of focused practice for the subspecialty.

When asked in a recent poll by The Hospitalist which certification options pediatric hospital medicine should pursue, 40% of respondents preferred having a recognition of focused practice for pediatric hospitalists, similar to that of adult hospitalists; 25% thought a one-year fellowship should be in place; and 9% would keep the status quo. Currently, there is no specific certification option for pediatric hospitalists. Still, the topic has raised some strong opinions and remains popular fodder for debate among hospitalists.

"I think it is clear the vast majority of pediatric hospitalists believe there are skills necessary to function at a high level in pediatric hospitalist medicine that are not gained during just three years of pediatric residency," says Douglas W. Carlson, MD, SFHM, SHM's representative to the Joint Council of Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Dr. Carlson says he considers two-year fellowships the best option. However, he does see the possible negative consequences to further education. "If we go to a fellowship, I am worried we will turn off that pipeline [of bright young physicians] … particularly when so many medical students in residency are coming out with such huge debt," he adds.

Rather than debating which result is best, Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center in Austin, Texas, is more interested in the "why"of the matter."Whatever result comes out will be well thought through," he says. "In my mind, I would be more interested in what the underlying thought process is in the decision more than anything else."

Visit our website for more information about pediatric hospitalist certification.

ITL: Physician Reviews of HM-Relevant Research

Clinical question: What are the relative predictive values of the HEMORR2HAGES, ATRIA, and HAS-BLED risk-prediction schemes?

Background: The tools predict bleeding risk in patients anticoagulated for atrial fibrillation (afib), but it is unknown which is the best for predicting clinically relevant bleeding.

Study design: Post-hoc analysis.

Setting: Data previously collected for the AMADEUS trial (2,293 patients taking warfarin; 251 had at least one clinically relevant bleeding event) were used to test each of the three bleeding-risk-prediction schemes on the same data set.

Synopsis: Using three analysis methods (net reclassification improvement, receiver-operating characteristic [ROC], and decision-curve analysis), the researchers compared the three schemes’ performance. HAS-BLED performed best in all three of the analysis methods.

The HAS-BLED score calculation requires the following patient information: history of hypertension, renal disease, liver disease, stroke, prior major bleeding event, and labile INR; age >65; and use of antiplatelet agents, aspirin, and alcohol.

Bottom line: HAS-BLED was the best of the three schemes, although all three had only modest ability to predict clinically relevant bleeding.

Citation: Apostolakis S, Lane DA, Guo Y, et al. Performance of the HEMORR2HAGES, ATRIA and HAS-BLED bleeding risk-prediction scores in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing anticoagulation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(9):861-867.

Visit our website for more physician reviews of recent HM-relevant literature.

Clinical question: What are the relative predictive values of the HEMORR2HAGES, ATRIA, and HAS-BLED risk-prediction schemes?

Background: The tools predict bleeding risk in patients anticoagulated for atrial fibrillation (afib), but it is unknown which is the best for predicting clinically relevant bleeding.

Study design: Post-hoc analysis.

Setting: Data previously collected for the AMADEUS trial (2,293 patients taking warfarin; 251 had at least one clinically relevant bleeding event) were used to test each of the three bleeding-risk-prediction schemes on the same data set.

Synopsis: Using three analysis methods (net reclassification improvement, receiver-operating characteristic [ROC], and decision-curve analysis), the researchers compared the three schemes’ performance. HAS-BLED performed best in all three of the analysis methods.

The HAS-BLED score calculation requires the following patient information: history of hypertension, renal disease, liver disease, stroke, prior major bleeding event, and labile INR; age >65; and use of antiplatelet agents, aspirin, and alcohol.

Bottom line: HAS-BLED was the best of the three schemes, although all three had only modest ability to predict clinically relevant bleeding.

Citation: Apostolakis S, Lane DA, Guo Y, et al. Performance of the HEMORR2HAGES, ATRIA and HAS-BLED bleeding risk-prediction scores in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing anticoagulation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(9):861-867.

Visit our website for more physician reviews of recent HM-relevant literature.

Clinical question: What are the relative predictive values of the HEMORR2HAGES, ATRIA, and HAS-BLED risk-prediction schemes?

Background: The tools predict bleeding risk in patients anticoagulated for atrial fibrillation (afib), but it is unknown which is the best for predicting clinically relevant bleeding.

Study design: Post-hoc analysis.

Setting: Data previously collected for the AMADEUS trial (2,293 patients taking warfarin; 251 had at least one clinically relevant bleeding event) were used to test each of the three bleeding-risk-prediction schemes on the same data set.

Synopsis: Using three analysis methods (net reclassification improvement, receiver-operating characteristic [ROC], and decision-curve analysis), the researchers compared the three schemes’ performance. HAS-BLED performed best in all three of the analysis methods.

The HAS-BLED score calculation requires the following patient information: history of hypertension, renal disease, liver disease, stroke, prior major bleeding event, and labile INR; age >65; and use of antiplatelet agents, aspirin, and alcohol.

Bottom line: HAS-BLED was the best of the three schemes, although all three had only modest ability to predict clinically relevant bleeding.

Citation: Apostolakis S, Lane DA, Guo Y, et al. Performance of the HEMORR2HAGES, ATRIA and HAS-BLED bleeding risk-prediction scores in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing anticoagulation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(9):861-867.

Visit our website for more physician reviews of recent HM-relevant literature.

Changes in Hospital Glycemic Control

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus continues to increase, now affecting almost 26 million people in the United States alone.[1] Hospitalizations associated with diabetes also continue to rise,[2] and nearly 50% of the $174 billion annual costs related to diabetes care in the United States are for inpatient hospital stays.[3] In recent years, inpatient glucose control has received considerable attention, and consensus statements for glucose targets have been published.[4, 5, 6]

A number of developments support the rationale for tracking and reporting inpatient glucose control. For instance, there are clinical scenarios where treatment of hyperglycemia has been shown to lead to better patient outcomes.[6, 7, 8, 9] Second, several organizations have recognized the value of better inpatient glucose management and have developed educational resources to assist practitioners and their institutions toward achieving that goal.[10, 11, 12, 13, 14] Finally, pay‐for‐performance requirements are emerging that are relevant to inpatient diabetes management.[15, 16]

Reports on the status of inpatient glucose control in large samples of US hospitals are now becoming available, and their findings suggest differences on the basis of hospital size, hospital type, and geographic location.[17, 18] However, these reports represent cross‐sectional studies, and little is known about trends in hospital glucose control over time. To determine whether changes were occurring, we obtained inpatient point‐of‐care blood glucose (POC‐BG) data from 126 hospitals for January to December 2009 and compared these with glycemic control data collected from the same hospitals for January to December 2007,[19] separately analyzing measurements from the intensive care unit (ICU) and the non‐intensive care unit (non‐ICU).

METHODS

Data Collection

The methods we used for data collection have been described previously.[18, 19, 20] Hospitals in the study used standard bedside glucose meters downloaded to the Remote Automated Laboratory System‐Plus (RALS‐Plus) (Medical Automation Systems, Charlottesville, VA). We originally evaluated data for adult inpatients for the period from January to December 2007[19]; for this study, we extracted POC‐BG from the same hospitals for the period from January to December 2009. Data excluded measurements obtained in emergency departments. Patient‐specific data (age, sex, race, and diagnoses) were not provided by hospitals, but individual patients could be distinguished by a unique identifier and also by location (ICU vs non‐ICU).

Hospital Selection

The characteristics of the 126 hospitals have been published previously.[19] However, hospital characteristics for 2009 were reevaluated for this analysis using the same methods already described for 2007[19] to determine whether any changes had occurred. Briefly, hospital characteristics during 2009 were determined via a combination of accessing the hospital Web site, consulting the Hospital Blue Book (Billian's HealthDATA; Billian Publishing Inc., Atlanta, Georgia), and determining membership in the Council of Teaching Hospitals and Health Systems of the Association of American Medical Colleges. The characteristics of the hospitals were size (number of beds), type (academic, urban community, or rural), and geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, or West). Per the Hospital Blue Book, a rural hospital is a hospital that operates outside of a metropolitan statistical area, typically with fewer than 100 beds, whereas an urban hospital is located within a metropolitan statistical area, typically with more than 100 beds. Institutions provided written permission to remotely access their glucose data and combine it with other hospitals into a single database for analysis. Patient data were deidentified, and consent to retrospective analysis and reporting was waived. The analysis was considered exempt by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. Participating hospitals were guaranteed confidentiality regarding their data.

Statistical Analysis

ICU and non‐ICU glucose datasets were differentiated on the basis of the download location designated by the RALS‐Plus database. As previously described, patient‐day‐weighted mean POC‐BG values were calculated as means of daily POC‐BG averaged per patient across all days during the hospital stay.[18, 19] We determined the overall patient‐day‐weighted mean values, and also the proportion of patient‐day‐weighted mean values greater than 180, 200, 250, 300, 350, and 400 mg/dL.[18, 19] We also examined the data to determine if there were any changes in the proportion of patient hospital days when there was at least 1 value <70 mg/dL or <40 mg/dL.

Differences in patient‐day‐weighted mean POC‐BG values between the years 2007 and 2009 were assessed in a mixed‐effects model with the term of year as the fixed effect and hospital characteristics as the random effect. The glucose trends between years 2007 and 2009 were examined to identify any differentiation by hospital characteristics by conducting mixed‐effects models using the terms of year, hospital characteristics (hospital size by bed capacity, hospital type, or geographic region), and interaction between year as the fixed effects and hospital characteristics as the random effect. These analyses were performed separately for ICU patients and non‐ICU patients. Values were compared between data obtained in 2009 and that obtained previously in 2007 using the Pearson [2] test. The means within the same category of hospital characteristics were compared for the years 2007 and 2009.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Participating Hospitals

Fewer than half of the 126 hospitals had changes in characteristics from 2007 to 2009 (size and type [Table 1]). There were 71 hospitals whose characteristics did not change compared to when the previous analysis was performed. The rest (n = 55) had changes in their characteristics that resulted in a net redistribution in the number of beds in the <200 and 200 to 299 categories, and a change in the rural/urban categories. These changes slightly altered the distributions by hospital size and hospital type compared to those in the previous analysis (Table 1). The regional distribution of the 126 hospitals was 41 (32.5%) in the South, 37 (29.4%) in the Midwest, 28 (22.2%) in the West, and 20 (15.9%) in the Northeast.[19]

| Characteristic | 2007, No. (%) [N = 126] | 2009, No. (%) [N = 126] |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital size, no. of beds | ||

| <200 | 48 (38.1) | 45 (35.7) |

| 200299 | 25 (19.8) | 28 (22.2) |

| 300399 | 17 (13.5) | 17 (13.5) |

| 400 | 36 (28.6) | 36 (28.6) |

| Hospital type | ||

| Academic | 11 (8.7) | 11 (8.7) |

| Urban | 69 (54.8) | 79 (62.7) |

| Rural | 46 (36.5) | 36 (28.6) |

Changes in Glycemic Control

For 2007, we analyzed a total of 12,541,929 POC‐BG measurements for 1,010,705 patients, and for 2009, we analyzed a total of 10,659,418 measurements for 656,206 patients. For ICU patients, a mean of 4.6 POC‐BG measurements per day was obtained in 2009 compared to a mean of 4.7 POC‐BG measurements per day in 2007. For non‐ICU patients, the POC‐BG mean was 3.1 per day in 2009 vs 2.9 per day in 2007.

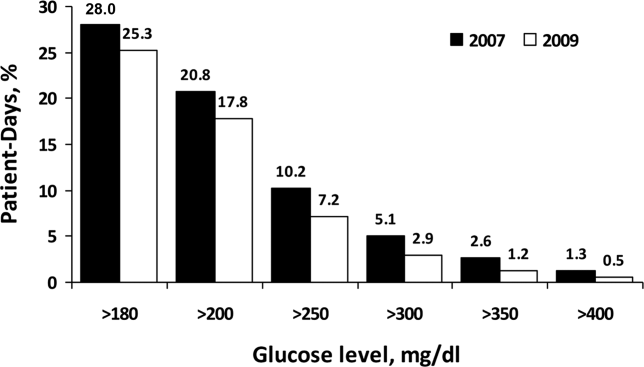

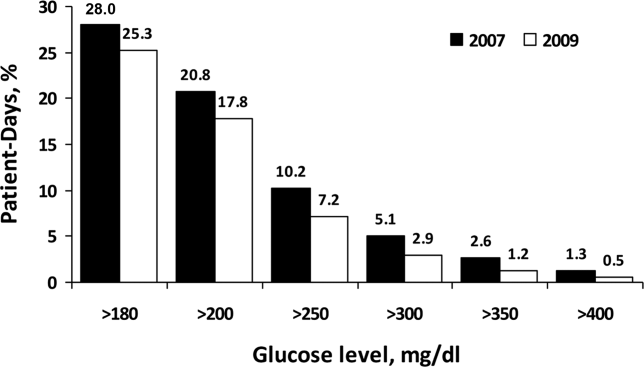

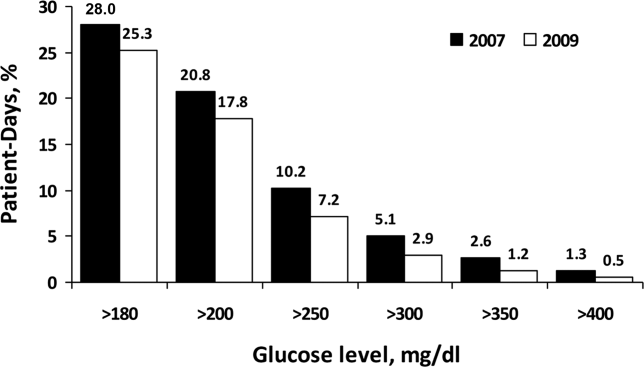

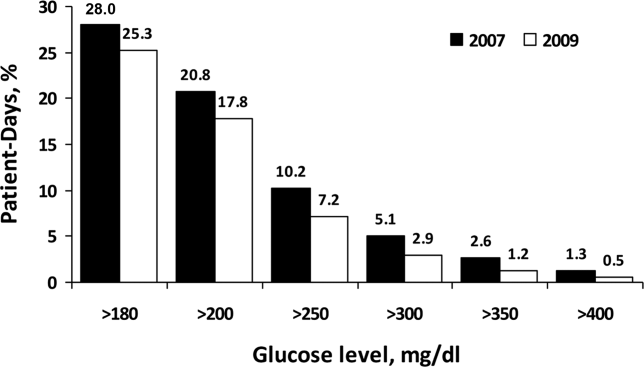

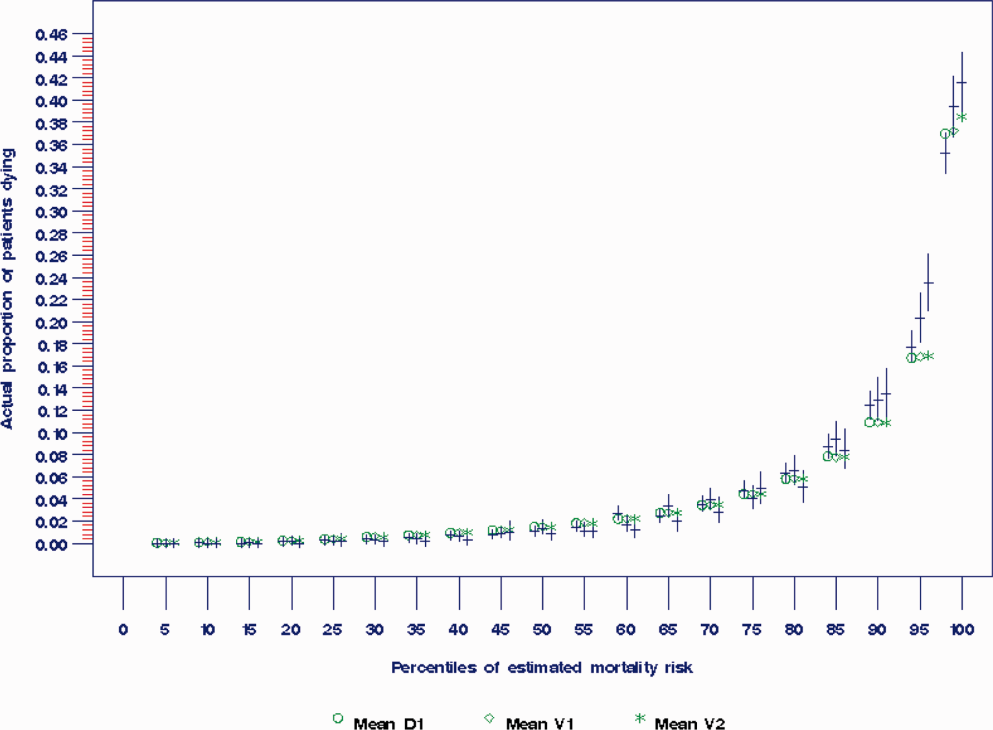

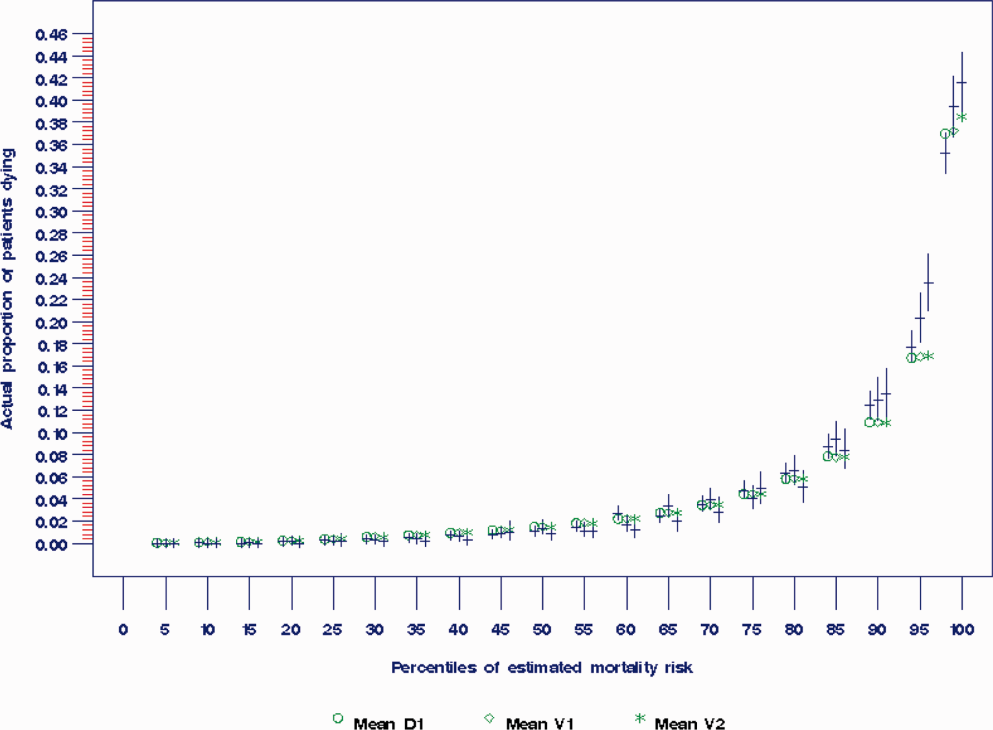

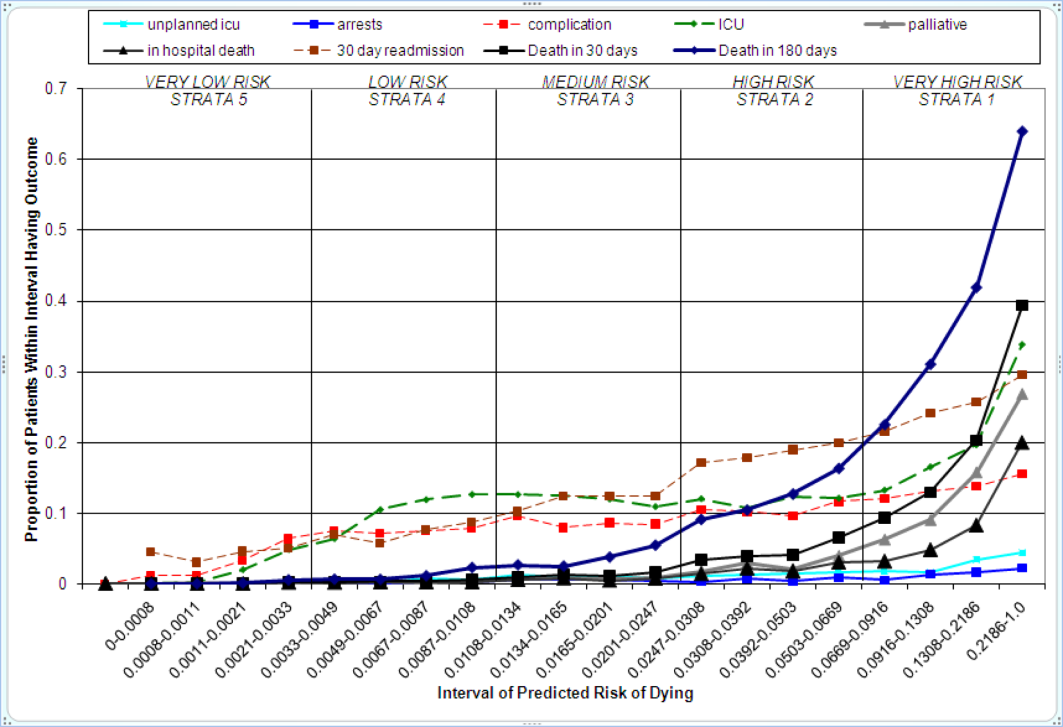

For non‐ICU data, the patient‐day‐weighted mean POC‐BG values decreased in 2009 by 5 mg/dL compared with the 2007 values (154 mg/dL vs 159 mg/dL, respectively; P < 0.001), and were clinically unchanged in the ICU data (167 mg/dL vs 166 mg/dL, respectively; P < 0.001). For non‐ICU data, the proportion of patient‐day‐weighted mean POC‐BG values in any hyperglycemia category decreased in 2009 compared with those in 2007 among all patients (all P < 0.001) (Figure 1). For the ICU data, there was no significant difference (all P > 0.20; not shown) from 2007 to 2009.

In the ICU data, 2.9% of patient days on average had at least 1 POC‐BG value <70 mg/dL in both 2007 and 2009 (P = 0.67). There were fewer patient days with values <40 mg/dL in 2009 (1.1%) compared to 2007 (1.4%) in the ICU (P < 0.001). In the non‐ICU data, the mean percentage of patient days with a value <70 mg/dL was higher in 2009 (5.1%) than in 2007 (4.7%) (P < 0.001); however, there were actually fewer patient days in 2009 on average with a value <40 mg/dL (0.84% vs 1.1% for 2009 vs 2007; P < 0.001).

Changes in Glycemic Control by Hospital Characteristics

Next, changes in glucose levels between the 2 analytic periods were evaluated according to hospital characteristics. Significant interactions were found between the year and each of the hospital characteristics both for the ICU group (Table 2) and for the non‐ICU group (Table 3) (all P < 0.001 for interaction terms). In the ICU data, changes were generally small but significant on the basis of hospital size, hospital type, and geographic region, and these changes were not necessarily in the same direction, because there were increases in patient‐day‐weighted mean glucose values in some categories, whereas there were decreases in others. For instance, hospitals with <200 inpatient beds experienced no significant change in ICU glycemic control, whereas those with 200 to 299 beds or >400 beds had an increase in patient‐day‐weighted mean values, and ones with 300 to 399 beds had a decrease. In regard to hospital type, only ICUs in academic medical institutions had a significant change over time in patient‐day‐weighted mean glucose levels, and these changes were toward higher values. ICUs in institutions in the Northeast and West had significantly higher glucose levels between the 2 periods, whereas those in the Midwest and South demonstrated lower glucose levels. In contrast to the different trends in ICU data by hospital characteristics, non‐ICU glucose control improved for hospitals of all sizes and types, and in all regions, over time.

| Characteristic | Year 2007, mg/dL | Year 2009, mg/dL | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Overall | 166 (1) | 167 (1) | <0.001 |

| Hospital size, no. of beds | |||

| <200 | 175 (2) | 174 (2) | 0.19 |

| 200299 | 164 (2) | 165 (2) | 0.009 |

| 300399 | 166 (3) | 164 (3) | <0.002 |

| 400 | 157 (2) | 160 (2) | <0.001 |

| Hospital type | |||

| Academic | 150 (3) | 156 (4) | <0.001 |

| Rural | 172 (2) | 172 (2) | 0.94 |

| Urban | 166 (1) | 166 (1) | 0.61 |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | 165 (3) | 167 (3) | 0.003 |

| Midwest | 169 (2) | 168 (2) | 0.007 |

| South | 168 (2) | 167 (2) | <0.001 |

| West | 160 (2) | 165 (2) | <0.001 |

| Characteristic | Year 2007, mg/dL | Year 2009, mg/dL | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Overall | 159 (1) | 154 (1) | <0.001 |

| Hospital size, no. of beds | |||

| <200 | 162 (2) | 158 (2) | <0.001 |

| 200299 | 156 (2) | 152 (2) | <0.001 |

| 300399 | 158 (3) | 151 (3) | <0.001 |

| 400 | 156 (2) | 151 (2) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital type | |||

| Academic | 162 (3) | 159 (3) | <0.001 |

| Rural | 161 (2) | 156 (2) | <0.001 |

| Urban | 157 (1) | 152 (1) | <0.001 |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | 162 (3) | 158 (3) | <0.001 |

| Midwest | 157 (2) | 149 (2) | <0.001 |

| South | 160 (2) | 157 (2) | <0.001 |

| West | 156 (2) | 151 (2) | <0.001 |

DISCUSSION

Optimal management of hospital hyperglycemia is now advocated by a number of professional societies and organizations.[10, 11, 12, 13] One of the next major tasks in the area of inpatient diabetes management will be how to identify and evaluate changes in glycemic control among US hospitals over time. Respondents to a recent survey of hospitals indicated that most institutions are now attempting to initiate quality improvement programs for the management of inpatients with diabetes.[21] These initiatives may translate into objective changes that could be monitored on a national level. However, few data exist on trends in glucose control in US hospitals. In our analysis, POC‐BG data from 126 hospitals collected in 2009 were compared to data obtained from the same hospitals in 2007. Our findings, and the methods of data collection and analysis described previously,[18, 19] demonstrate how such data can be used as a national benchmarking process for inpatient glucose control.

At all levels of hyperglycemia, significant decreases in patient‐day‐weighted mean values were found in non‐ICU data but not in ICU data. During the time these data were collected, recommendations about glucose targets in the critically ill were in a state of flux.[22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27] Thus, the lack of hyperglycemia improvement in the ICU data between 2007 and 2009 may reflect the reluctance of providers to aggressively manage hyperglycemia because of recent reports linking increased mortality to tight glucose control.[25, 28, 29, 30] The differences in patient‐day‐weighted mean glucose values detected in the non‐ICU data between the 2 analytic periods were statistically significant, but were otherwise small and may not have clinical implications as far as an association with improved patient outcomes. Ongoing longitudinal analysis is required to establish whether these improvements in non‐ICU glucose control will persist over time.

Changes in glycemic control between the 2 periods were also noted when data were stratified according to hospital characteristics. Differences in glucose control in ICU data were not consistently better or worse, but varied by category of hospital characteristics (hospital size, hospital type, and geographic region). Other than academic hospitals and hospitals in the West, changes in the ICU data were small and likely do not have clinical importance. Analysis of non‐ICU data, however, showed consistent improvement within all 3 categories. Some hospital characteristics did change between the 2 study periods: there were fewer hospitals with <200 beds, more hospitals with 200 to 299 beds, a decrease in hospitals identified as rural, and an increase in hospitals designated as urban. Our previous analyses have indicated that hospital characteristics should be considered when examining national inpatient glucose data.[18, 19] In this analysis there was a statistically significant interaction between the year for which data were analyzed and each category of hospital characteristics. It is unclear how these evolving characteristics could have impacted inpatient glucose control. A change in hospital characteristics may in fact represent a change in resources to manage inpatient hyperglycemia. Future studies with nationally aggregated inpatient glucose data that assess longitudinal changes in glucose data may also have to account for variations in hospital characteristics over time in addition to the characteristics of the hospitals themselves.

Differences in hypoglycemia frequency, as calculated as the proportion of patient hospital days, were also detected. In the ICU data, the percentage of days with at least 1 value <70 mg/dL was similar between 2007 and 2009, but the proportion of days with at least 1 value <40 mg/dL was less in 2009, suggesting that institutions as a whole in this analysis may have been more focused on reducing the frequency of severe hypoglycemia. However, in the non‐ICU, there were more days in 2009 with a value <70 mg/dL, but fewer with a value <40 mg/dL. In noncritically ill patients, institutions likely continue to attempt to find the best balance between optimizing glycemic control while minimizing the risk of hypoglycemia. It should be pointed out, however, that overall, the frequency of hypoglycemia, particularly severe hypoglycemia, was quite low in this analysis, as it has been in our previous reports.[18, 19] An examination of hypoglycemia frequency by hospital characteristic to evaluate differences in this metric would be of interest in a future analysis.

The limitations of these data have been previously outlined,[18, 19] and they include the lack of patient‐level data such as demographics and the lack of information on diagnoses that allow adjustment of comparisons by the severity of illness. Moreover, without detailed treatment‐specific information (such as type of insulin protocol), one cannot establish the basis for longitudinal differences in glucose control. Volunteer‐dependent hospital involvement that creates selection bias may skew data toward those who are aware that they are witnessing a successful reduction in hyperglycemia. Finally, POC‐BG may not be the optimal method for assessing glycemic control. The limitations of current methods of evaluating inpatient glycemic control were recently reviewed.[31] Nonetheless, POC‐BG measurements remain the richest source of data on hospital hyperglycemia because of their widespread use and large sample size. A data warehouse of nearly 600 hospitals now exists,[18] which will permit future longitudinal analyses of glucose control in even larger samples.

Despite such limitations, our findings do represent the first analysis of trends in glucose control in a large cross‐section of US hospitals. Over 2 years, non‐ICU hyperglycemia improved among hospitals of all sizes and types and in all regions, whereas similar improvement did not occur in ICU hyperglycemia. Continued analysis will determine whether these trends continue. For those hospitals that are achieving better glucose control in non‐ICU patients, more information is needed on how they are accomplishing this so that protocols can be standardized and disseminated.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: This project was supported entirely by The Epsilon Group Virginia, LLC, Charlottesville, Virginia, and a contractual arrangement is in place between the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona, and The Epsilon Group. The Mayo Clinic does not endorse the products mentioned in this article. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- 2011 National Diabetes Fact Sheet.Diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes in the United States, all ages, 2010.Atlanta, GA:Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2011 [updated 2011]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/estimates11.htm#2. Accessed November 23, 2012.

- Diabetes Data and Trends.Atlanta, GA:Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2009 [updated 2009]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/dmany/fig1.htm. Accessed November 23, 2012.

- American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. In 2007 [published correction appears in Diabetes Care. 2008;31(6):1271.]. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(3):596–615.

- , , , et al.;American College of Endocrinology Task Force on Inpatient Diabetes Metabolic Control. American College of Endocrinology position statement on inpatient diabetes and metabolic control. Endocr Pract. 2004;10(1):77–82.

- ACE/ADA Task Force on Inpatient Diabetes. American College of Endocrinology and American Diabetes Association consensus statement on inpatient diabetes and glycemic control. Endocr Pract. 2006;12(4):458–468.

- , , , et al.;American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; American Diabetes Association. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Diabetes Association consensus statement on inpatient glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(6):1119–1131.

- ;DIGAMI (Diabetes Mellitus, Insulin Glucose Infusion in Acute Myocardial Infarction) Study Group. Prospective randomised study of intensive insulin treatment on long term survival after acute myocardial infarction in patients with diabetes mellitus. BMJ. 1997;314(7093):1512–1515.

- , , , et al.;American Diabetes Association Diabetes in Hospitals Writing Committee. Management of diabetes and hyperglycemia in hospitals [published correction appears in Diabetes Care. 2004;27(5):1255; Diabetes Care. 2004;27(3):856]. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):553–591.

- , , , , . Inpatient management of diabetes and hyperglycemia among general medicine patients at a large teaching hospital. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(3):145–150.

- , , , , ;Society of Hospital Medicine Glycemic Control Task Force. Society of Hospital Medicine Glycemic Control Task Force summary: practical recommendations for assessing the impact of glycemic control efforts. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5 suppl):66–75.

- , , , , , . Adherence to surgical care improvement project measures and the association with postoperative infections. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2479–2485.

- Glycemic Control Resource Room.Philadelphia, PA:Society of Hospital Medicine;2008. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/ResourceRoomRedesign/GlycemicControl.cfm. Accessed November 23, 2012.

- Inpatient Glycemic Control Resource Center.Jacksonville, FL:American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists;2011. Available at: http://resources.aace.com. Accessed November 23, 2012.

- , , , et al.;Endocrine Society. Management of hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients in non‐critical care setting: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(1):16–38.

- Hospital Quality Initiative.Baltimore, MD:Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services;2012 [updated 2012]. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/HospitalQualityInits/08_HospitalRHQDAPU.asp. Accessed November 23, 2012.

- Hospital‐Acquired Conditions (Present on Admission Indicator).Baltimore, MD:Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services;2012 [updated 2012]. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/hospitalacqcond/06_hospital‐acquired_conditions.asp. Accessed November 23, 2012.

- , , , et al. Evaluation of hospital glycemic control at US academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(1):35–44.

- , , , . Update on inpatient glycemic control in hospitals in the United States. Endocr Pract. 2011;17(6):853–861.

- , , , , , . Inpatient glucose control: a glycemic survey of 126 U.S. hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(9):E7–E14.

- , , , , . Inpatient point‐of‐care bedside glucose testing: preliminary data on use of connectivity informatics to measure hospital glycemic control. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2007;9(6):493–500.

- , , , , , . Diabetes and hyperglycemia quality improvement efforts in hospitals in the United States: current status, practice variation, and barriers to implementation. Endocr Pract. 2010;16(2):219–230.

- , , , et al. Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(19):1359–1367.

- , , , et al. Intensive insulin therapy in the medical ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(5):449–461.

- , , , et al.;German Competence Network Sepsis (SepNet). Intensive insulin therapy and pentastarch resuscitation in severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(2):125–139.

- , , , et al.;NICE‐SUGAR Study Investigators. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(13):1283–1297.

- , , , et al. A prospective randomised multi‐centre controlled trial on tight glucose control by intensive insulin therapy in adult intensive care units: the Glucontrol study. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(10):1738–1748.

- , , . Benefits and risks of tight glucose control in critically ill adults: a meta‐analysis [published correction appears in JAMA. 2009;301(9):936]. JAMA. 2008;300(8):933–944.

- , . Severe hypoglycemia in critically ill patients: risk factors and outcomes. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(10):2262–2267.

- , , , et al. Relationship between spontaneous and iatrogenic hypoglycemia and mortality in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2009;301(15):1556–1564.

- , , , et al. Hypoglycemia and outcome in critically ill patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(3):217–224.

- , , , . Assessing inpatient glycemic control: what are the next steps?J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2012;6(2):421–427.

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus continues to increase, now affecting almost 26 million people in the United States alone.[1] Hospitalizations associated with diabetes also continue to rise,[2] and nearly 50% of the $174 billion annual costs related to diabetes care in the United States are for inpatient hospital stays.[3] In recent years, inpatient glucose control has received considerable attention, and consensus statements for glucose targets have been published.[4, 5, 6]

A number of developments support the rationale for tracking and reporting inpatient glucose control. For instance, there are clinical scenarios where treatment of hyperglycemia has been shown to lead to better patient outcomes.[6, 7, 8, 9] Second, several organizations have recognized the value of better inpatient glucose management and have developed educational resources to assist practitioners and their institutions toward achieving that goal.[10, 11, 12, 13, 14] Finally, pay‐for‐performance requirements are emerging that are relevant to inpatient diabetes management.[15, 16]

Reports on the status of inpatient glucose control in large samples of US hospitals are now becoming available, and their findings suggest differences on the basis of hospital size, hospital type, and geographic location.[17, 18] However, these reports represent cross‐sectional studies, and little is known about trends in hospital glucose control over time. To determine whether changes were occurring, we obtained inpatient point‐of‐care blood glucose (POC‐BG) data from 126 hospitals for January to December 2009 and compared these with glycemic control data collected from the same hospitals for January to December 2007,[19] separately analyzing measurements from the intensive care unit (ICU) and the non‐intensive care unit (non‐ICU).

METHODS

Data Collection

The methods we used for data collection have been described previously.[18, 19, 20] Hospitals in the study used standard bedside glucose meters downloaded to the Remote Automated Laboratory System‐Plus (RALS‐Plus) (Medical Automation Systems, Charlottesville, VA). We originally evaluated data for adult inpatients for the period from January to December 2007[19]; for this study, we extracted POC‐BG from the same hospitals for the period from January to December 2009. Data excluded measurements obtained in emergency departments. Patient‐specific data (age, sex, race, and diagnoses) were not provided by hospitals, but individual patients could be distinguished by a unique identifier and also by location (ICU vs non‐ICU).

Hospital Selection

The characteristics of the 126 hospitals have been published previously.[19] However, hospital characteristics for 2009 were reevaluated for this analysis using the same methods already described for 2007[19] to determine whether any changes had occurred. Briefly, hospital characteristics during 2009 were determined via a combination of accessing the hospital Web site, consulting the Hospital Blue Book (Billian's HealthDATA; Billian Publishing Inc., Atlanta, Georgia), and determining membership in the Council of Teaching Hospitals and Health Systems of the Association of American Medical Colleges. The characteristics of the hospitals were size (number of beds), type (academic, urban community, or rural), and geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, or West). Per the Hospital Blue Book, a rural hospital is a hospital that operates outside of a metropolitan statistical area, typically with fewer than 100 beds, whereas an urban hospital is located within a metropolitan statistical area, typically with more than 100 beds. Institutions provided written permission to remotely access their glucose data and combine it with other hospitals into a single database for analysis. Patient data were deidentified, and consent to retrospective analysis and reporting was waived. The analysis was considered exempt by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. Participating hospitals were guaranteed confidentiality regarding their data.

Statistical Analysis

ICU and non‐ICU glucose datasets were differentiated on the basis of the download location designated by the RALS‐Plus database. As previously described, patient‐day‐weighted mean POC‐BG values were calculated as means of daily POC‐BG averaged per patient across all days during the hospital stay.[18, 19] We determined the overall patient‐day‐weighted mean values, and also the proportion of patient‐day‐weighted mean values greater than 180, 200, 250, 300, 350, and 400 mg/dL.[18, 19] We also examined the data to determine if there were any changes in the proportion of patient hospital days when there was at least 1 value <70 mg/dL or <40 mg/dL.

Differences in patient‐day‐weighted mean POC‐BG values between the years 2007 and 2009 were assessed in a mixed‐effects model with the term of year as the fixed effect and hospital characteristics as the random effect. The glucose trends between years 2007 and 2009 were examined to identify any differentiation by hospital characteristics by conducting mixed‐effects models using the terms of year, hospital characteristics (hospital size by bed capacity, hospital type, or geographic region), and interaction between year as the fixed effects and hospital characteristics as the random effect. These analyses were performed separately for ICU patients and non‐ICU patients. Values were compared between data obtained in 2009 and that obtained previously in 2007 using the Pearson [2] test. The means within the same category of hospital characteristics were compared for the years 2007 and 2009.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Participating Hospitals

Fewer than half of the 126 hospitals had changes in characteristics from 2007 to 2009 (size and type [Table 1]). There were 71 hospitals whose characteristics did not change compared to when the previous analysis was performed. The rest (n = 55) had changes in their characteristics that resulted in a net redistribution in the number of beds in the <200 and 200 to 299 categories, and a change in the rural/urban categories. These changes slightly altered the distributions by hospital size and hospital type compared to those in the previous analysis (Table 1). The regional distribution of the 126 hospitals was 41 (32.5%) in the South, 37 (29.4%) in the Midwest, 28 (22.2%) in the West, and 20 (15.9%) in the Northeast.[19]

| Characteristic | 2007, No. (%) [N = 126] | 2009, No. (%) [N = 126] |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital size, no. of beds | ||

| <200 | 48 (38.1) | 45 (35.7) |

| 200299 | 25 (19.8) | 28 (22.2) |

| 300399 | 17 (13.5) | 17 (13.5) |

| 400 | 36 (28.6) | 36 (28.6) |

| Hospital type | ||

| Academic | 11 (8.7) | 11 (8.7) |

| Urban | 69 (54.8) | 79 (62.7) |

| Rural | 46 (36.5) | 36 (28.6) |

Changes in Glycemic Control

For 2007, we analyzed a total of 12,541,929 POC‐BG measurements for 1,010,705 patients, and for 2009, we analyzed a total of 10,659,418 measurements for 656,206 patients. For ICU patients, a mean of 4.6 POC‐BG measurements per day was obtained in 2009 compared to a mean of 4.7 POC‐BG measurements per day in 2007. For non‐ICU patients, the POC‐BG mean was 3.1 per day in 2009 vs 2.9 per day in 2007.

For non‐ICU data, the patient‐day‐weighted mean POC‐BG values decreased in 2009 by 5 mg/dL compared with the 2007 values (154 mg/dL vs 159 mg/dL, respectively; P < 0.001), and were clinically unchanged in the ICU data (167 mg/dL vs 166 mg/dL, respectively; P < 0.001). For non‐ICU data, the proportion of patient‐day‐weighted mean POC‐BG values in any hyperglycemia category decreased in 2009 compared with those in 2007 among all patients (all P < 0.001) (Figure 1). For the ICU data, there was no significant difference (all P > 0.20; not shown) from 2007 to 2009.

In the ICU data, 2.9% of patient days on average had at least 1 POC‐BG value <70 mg/dL in both 2007 and 2009 (P = 0.67). There were fewer patient days with values <40 mg/dL in 2009 (1.1%) compared to 2007 (1.4%) in the ICU (P < 0.001). In the non‐ICU data, the mean percentage of patient days with a value <70 mg/dL was higher in 2009 (5.1%) than in 2007 (4.7%) (P < 0.001); however, there were actually fewer patient days in 2009 on average with a value <40 mg/dL (0.84% vs 1.1% for 2009 vs 2007; P < 0.001).

Changes in Glycemic Control by Hospital Characteristics

Next, changes in glucose levels between the 2 analytic periods were evaluated according to hospital characteristics. Significant interactions were found between the year and each of the hospital characteristics both for the ICU group (Table 2) and for the non‐ICU group (Table 3) (all P < 0.001 for interaction terms). In the ICU data, changes were generally small but significant on the basis of hospital size, hospital type, and geographic region, and these changes were not necessarily in the same direction, because there were increases in patient‐day‐weighted mean glucose values in some categories, whereas there were decreases in others. For instance, hospitals with <200 inpatient beds experienced no significant change in ICU glycemic control, whereas those with 200 to 299 beds or >400 beds had an increase in patient‐day‐weighted mean values, and ones with 300 to 399 beds had a decrease. In regard to hospital type, only ICUs in academic medical institutions had a significant change over time in patient‐day‐weighted mean glucose levels, and these changes were toward higher values. ICUs in institutions in the Northeast and West had significantly higher glucose levels between the 2 periods, whereas those in the Midwest and South demonstrated lower glucose levels. In contrast to the different trends in ICU data by hospital characteristics, non‐ICU glucose control improved for hospitals of all sizes and types, and in all regions, over time.

| Characteristic | Year 2007, mg/dL | Year 2009, mg/dL | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Overall | 166 (1) | 167 (1) | <0.001 |

| Hospital size, no. of beds | |||

| <200 | 175 (2) | 174 (2) | 0.19 |

| 200299 | 164 (2) | 165 (2) | 0.009 |

| 300399 | 166 (3) | 164 (3) | <0.002 |

| 400 | 157 (2) | 160 (2) | <0.001 |

| Hospital type | |||

| Academic | 150 (3) | 156 (4) | <0.001 |

| Rural | 172 (2) | 172 (2) | 0.94 |

| Urban | 166 (1) | 166 (1) | 0.61 |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | 165 (3) | 167 (3) | 0.003 |

| Midwest | 169 (2) | 168 (2) | 0.007 |

| South | 168 (2) | 167 (2) | <0.001 |

| West | 160 (2) | 165 (2) | <0.001 |

| Characteristic | Year 2007, mg/dL | Year 2009, mg/dL | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Overall | 159 (1) | 154 (1) | <0.001 |

| Hospital size, no. of beds | |||

| <200 | 162 (2) | 158 (2) | <0.001 |

| 200299 | 156 (2) | 152 (2) | <0.001 |

| 300399 | 158 (3) | 151 (3) | <0.001 |

| 400 | 156 (2) | 151 (2) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital type | |||

| Academic | 162 (3) | 159 (3) | <0.001 |

| Rural | 161 (2) | 156 (2) | <0.001 |

| Urban | 157 (1) | 152 (1) | <0.001 |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | 162 (3) | 158 (3) | <0.001 |

| Midwest | 157 (2) | 149 (2) | <0.001 |

| South | 160 (2) | 157 (2) | <0.001 |

| West | 156 (2) | 151 (2) | <0.001 |

DISCUSSION

Optimal management of hospital hyperglycemia is now advocated by a number of professional societies and organizations.[10, 11, 12, 13] One of the next major tasks in the area of inpatient diabetes management will be how to identify and evaluate changes in glycemic control among US hospitals over time. Respondents to a recent survey of hospitals indicated that most institutions are now attempting to initiate quality improvement programs for the management of inpatients with diabetes.[21] These initiatives may translate into objective changes that could be monitored on a national level. However, few data exist on trends in glucose control in US hospitals. In our analysis, POC‐BG data from 126 hospitals collected in 2009 were compared to data obtained from the same hospitals in 2007. Our findings, and the methods of data collection and analysis described previously,[18, 19] demonstrate how such data can be used as a national benchmarking process for inpatient glucose control.

At all levels of hyperglycemia, significant decreases in patient‐day‐weighted mean values were found in non‐ICU data but not in ICU data. During the time these data were collected, recommendations about glucose targets in the critically ill were in a state of flux.[22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27] Thus, the lack of hyperglycemia improvement in the ICU data between 2007 and 2009 may reflect the reluctance of providers to aggressively manage hyperglycemia because of recent reports linking increased mortality to tight glucose control.[25, 28, 29, 30] The differences in patient‐day‐weighted mean glucose values detected in the non‐ICU data between the 2 analytic periods were statistically significant, but were otherwise small and may not have clinical implications as far as an association with improved patient outcomes. Ongoing longitudinal analysis is required to establish whether these improvements in non‐ICU glucose control will persist over time.

Changes in glycemic control between the 2 periods were also noted when data were stratified according to hospital characteristics. Differences in glucose control in ICU data were not consistently better or worse, but varied by category of hospital characteristics (hospital size, hospital type, and geographic region). Other than academic hospitals and hospitals in the West, changes in the ICU data were small and likely do not have clinical importance. Analysis of non‐ICU data, however, showed consistent improvement within all 3 categories. Some hospital characteristics did change between the 2 study periods: there were fewer hospitals with <200 beds, more hospitals with 200 to 299 beds, a decrease in hospitals identified as rural, and an increase in hospitals designated as urban. Our previous analyses have indicated that hospital characteristics should be considered when examining national inpatient glucose data.[18, 19] In this analysis there was a statistically significant interaction between the year for which data were analyzed and each category of hospital characteristics. It is unclear how these evolving characteristics could have impacted inpatient glucose control. A change in hospital characteristics may in fact represent a change in resources to manage inpatient hyperglycemia. Future studies with nationally aggregated inpatient glucose data that assess longitudinal changes in glucose data may also have to account for variations in hospital characteristics over time in addition to the characteristics of the hospitals themselves.

Differences in hypoglycemia frequency, as calculated as the proportion of patient hospital days, were also detected. In the ICU data, the percentage of days with at least 1 value <70 mg/dL was similar between 2007 and 2009, but the proportion of days with at least 1 value <40 mg/dL was less in 2009, suggesting that institutions as a whole in this analysis may have been more focused on reducing the frequency of severe hypoglycemia. However, in the non‐ICU, there were more days in 2009 with a value <70 mg/dL, but fewer with a value <40 mg/dL. In noncritically ill patients, institutions likely continue to attempt to find the best balance between optimizing glycemic control while minimizing the risk of hypoglycemia. It should be pointed out, however, that overall, the frequency of hypoglycemia, particularly severe hypoglycemia, was quite low in this analysis, as it has been in our previous reports.[18, 19] An examination of hypoglycemia frequency by hospital characteristic to evaluate differences in this metric would be of interest in a future analysis.

The limitations of these data have been previously outlined,[18, 19] and they include the lack of patient‐level data such as demographics and the lack of information on diagnoses that allow adjustment of comparisons by the severity of illness. Moreover, without detailed treatment‐specific information (such as type of insulin protocol), one cannot establish the basis for longitudinal differences in glucose control. Volunteer‐dependent hospital involvement that creates selection bias may skew data toward those who are aware that they are witnessing a successful reduction in hyperglycemia. Finally, POC‐BG may not be the optimal method for assessing glycemic control. The limitations of current methods of evaluating inpatient glycemic control were recently reviewed.[31] Nonetheless, POC‐BG measurements remain the richest source of data on hospital hyperglycemia because of their widespread use and large sample size. A data warehouse of nearly 600 hospitals now exists,[18] which will permit future longitudinal analyses of glucose control in even larger samples.

Despite such limitations, our findings do represent the first analysis of trends in glucose control in a large cross‐section of US hospitals. Over 2 years, non‐ICU hyperglycemia improved among hospitals of all sizes and types and in all regions, whereas similar improvement did not occur in ICU hyperglycemia. Continued analysis will determine whether these trends continue. For those hospitals that are achieving better glucose control in non‐ICU patients, more information is needed on how they are accomplishing this so that protocols can be standardized and disseminated.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: This project was supported entirely by The Epsilon Group Virginia, LLC, Charlottesville, Virginia, and a contractual arrangement is in place between the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona, and The Epsilon Group. The Mayo Clinic does not endorse the products mentioned in this article. The authors report no conflicts of interest.