User login

Cutis Tricolor

Circumscribed Acral Hypokeratosis

Paranoid, agitated, and manipulative

CASE: Agitation

Mrs. M, age 39, presents to the emergency department (ED) with altered mental status. She is escorted by her husband and the police. She has a history of severe alcohol dependence, bipolar disorder (BD), anxiety, borderline personality disorder (BPD), hypothyroidism, and bulimia, and had gastric bypass surgery 4 years ago. Her husband called 911 when he could no longer manage Mrs. M’s agitated state. The police found her to be extremely paranoid, restless, and disoriented. Her husband reports that she shouted “the world is going to end” before she escaped naked into her neighborhood streets.

On several occasions Mrs. M had been admitted to the same hospital for alcohol withdrawal and dependence with subsequent liver failure, leading to jaundice, coagulopathy, and ascites. During these hospitalizations, she exhibited poor behavioral tendencies, unhealthy psychological defenses, and chronic maladaptive coping and defense mechanisms congruent with her BPD diagnosis. Specifically, she engaged in splitting of hospital staff, ranging from extreme flattery to overt devaluation and hostility. Other defense mechanisms included denial, distortion, acting out, and passive-aggressive behavior. During these admissions, Mrs. M often displayed deficits in recall and attention on Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), but these deficits were associated with concurrent alcohol use and improved rapidly during her stay.

In her current presentation, Mrs. M’s mental status change is more pronounced and atypical compared with earlier admissions. Her outpatient medication regimen includes lamotrigine, 100 mg/d, levothyroxine, 88 mcg/d, venlafaxine extended release (XR), 75 mg/d, clonazepam, 3 mg/d, docusate as needed for constipation, and a daily multivitamin.

The authors’ observations

Delirium is a disturbance of consciousness manifested by a reduced clarity of awareness (impairment in attention) and change in cognition (impairment in orientation, memory, and language).1,2 The disturbance develops over a short time and tends to fluctuate during the day. Delirium is a direct physiological consequence of a general medical condition, substance use (intoxication or withdrawal), or both (Table).3

Delirium generally is a reversible mental disorder but can progress to irreversible brain damage. Prompt and accurate diagnosis of delirium is essential,4 although the condition often is underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed because of lack of recognition.

Table

DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for delirium

|

| Source: Reference 3 |

Patients who have convoluted histories, such as Mrs. M, are common and difficult to manage and treat. These patients become substantially more complex when they are admitted to inpatient medical or surgical services. The need to clarify between delirium (primarily medical) and depression (primarily psychiatric) becomes paramount when administering treatment and evaluating decision-making capacity.5 In Mrs. M’s case, internal medicine, neurology, and psychiatry teams each had a different approach to altered mental status. Each team’s different terminology, assessment, and objectives further complicated an already challenging case.6

EVALUATION: Confounding results

The ED physicians offer a working diagnosis of acute mental status change, administer IV lorazepam, 4 mg, and order restraints for Mrs. M’s severe agitation. Her initial vital signs reveal slightly elevated blood pressure (140/90 mm Hg) and tachycardia (115 beats per minute). Internal medicine clinicians note that Mrs. M is not in acute distress, although she refuses to speak and has a small amount of dried blood on her lips, presumably from a struggle with the police before coming to the hospital, but this is not certain. Her abdomen is not tender; she has normal bowel sounds, and no asterixis is noted on neurologic exam. Physical exam is otherwise normal. A noncontrast head CT scan shows no acute process. Initial lab values show elevations in ammonia (277 μg/dL) and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (68 U/L). Thyroid-stimulating hormone is 1.45 mlU/L, prothrombin time is 19.5 s, partial thromboplastin time is 40.3 s, and international normalized ratio is 1.67. The internal medicine team admits Mrs. M to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further management of her mental status change with alcohol withdrawal or hepatic encephalopathy as the most likely etiologies.

Mrs. M’s husband says that his wife has not consumed alcohol in the last 4 months in preparation for a possible liver transplant; however, past interactions with Mrs. M’s family suggest they are unreliable. The Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment (CIWA) protocol is implemented in case her symptoms are caused by alcohol withdrawal. Her vital signs are stable and IV lorazepam, 4 mg, is administered once for agitation. Mrs. M’s husband also reports that 1 month ago his wife underwent a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure for portal hypertension. Outpatient psychotropics (lamotrigine, 100 mg/d, and venlafaxine XR, 75 mg/d) are restarted because withdrawal from these drugs may exacerbate her symptoms. In the ICU Mrs. M experiences a tonic-clonic seizure with fecal incontinence and bitten tongue, which results in a consultation from neurology and the psychiatry consultation-liaison service.

Psychiatry recommends withholding psychotropics, stopping CIWA, and using vital sign parameters along with objective signs of diaphoresis and tremors as indicators of alcohol withdrawal for lorazepam administration. Mrs. M receives IV haloperidol, 1 mg, once during her second day in the hospital for severe agitation, but this medication is discontinued because of concern about lowering her seizure threshold.7 After treatment with lactulose, her ammonia levels trend down to 33 μg/dL, but her altered mental state persists with significant deficits in attention and orientation.

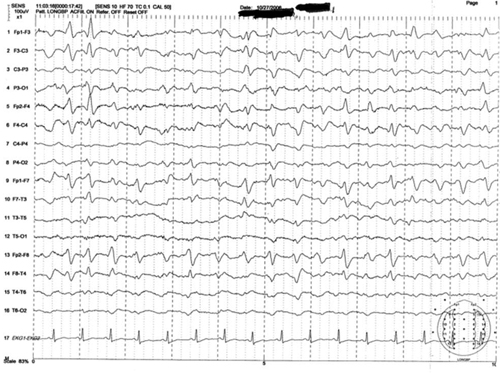

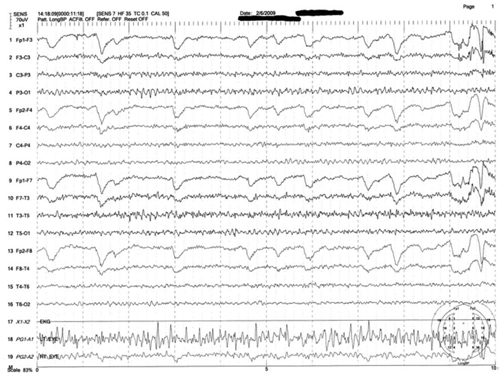

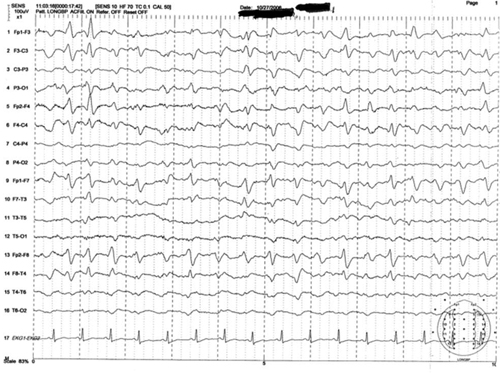

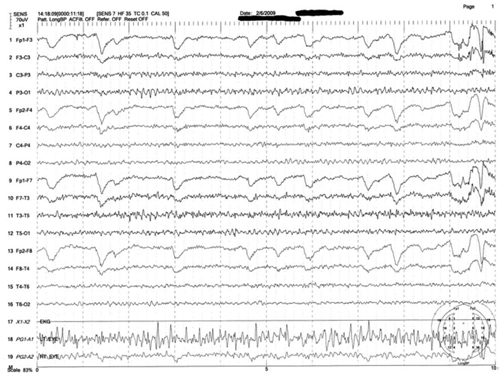

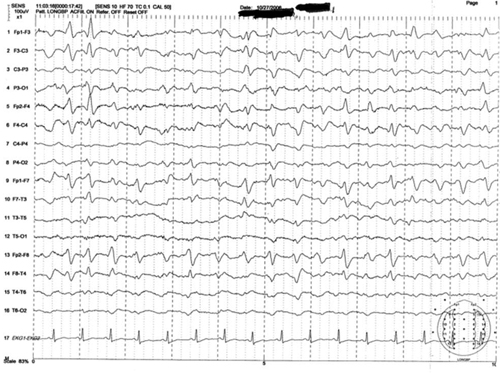

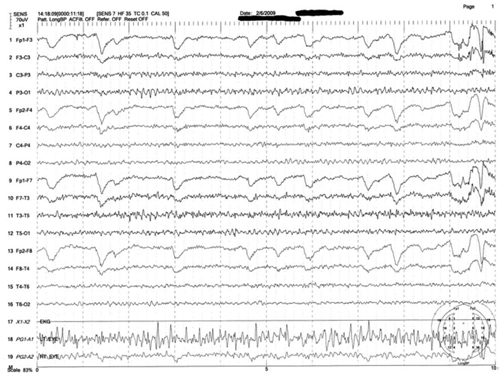

The neurology service performs an EEG that shows no slow-wave, triphasic waves, or epileptiform activity, which likely would be present in delirium or seizures. See Figure 1 for an example of triphasic waves on an EEG and Figure 2 for Mrs. M's EEG results. Subsequent lumbar puncture, MRI, and a second EEG are unremarkable. By the fifth hospital day, Mrs. M is calm and her paranoia has subsided, but she still is confused and disoriented. Psychiatry orders a third EEG while she is in this confused state; it shows no pathologic process. Based on these examinations, neurology posits that Mrs. M is not encephalopathic.

Figure 1: Representative sample of triphasic waves

This EEG tracing is from a 54-year-old woman who underwent prolonged abdominal surgery for lysis of adhesions during which she suffered an intraoperative left subinsular stroke followed by nonconvulsive status epilepticus. The tracing demonstrates typical morphology with the positive sharp transient preceded and followed by smaller amplitude negative deflections. Symmetric, frontal predominance of findings seen is this tracing is common

Figure 2: Mrs. M’s EEG results

This is a representative tracing of Mrs. M’s 3 EEGs revealing an 8.5 to 9 Hz dominant alpha rhythm. There is superimposed frontally dominant beta fast activity, which is consistent with known administration of benzodiazepines

The authors’ observations

Mrs. M had repeated admissions for alcohol dependence and subsequent liver failure. Her recent hospitalization was complicated by a TIPS procedure done 1 month ago. The incidence of hepatic encephalopathy in patients undergoing TIPS is >30%, especially in the first month post-procedure, which raised suspicion that hepatic encephalopathy played a significant role in Mrs. M’s delirium.8

Because of frequent hospitalization, Mrs. M was well known to the internal medicine, neurology, and psychiatry teams, and each used different terms to describe her mental state. Internal medicine used the phrase “acute mental status change,” which covers a broad differential. Neurology used “encephalopathy,” which also is a general term. Psychiatry used “delirium,” which has narrower and more specific diagnostic criteria. Engel et al9 described the delirious patient as having “cerebral insufficiency” with universally abnormal EEG. Regardless of terminology, based on Mrs. M’s acute confusion, one would expect an abnormal EEG, but repeat EEGs were unremarkable.

Interpreting EEG

EEG is one of the few tools available for measuring acute changes in cerebral function, and an EEG slowing remains a hallmark in encephalopathic processes.10,11 Initially, the 3 specialties agreed that Mrs. M’s presentation likely was caused by underlying medical issues or substances (alcohol or others). EEG can help recognize delirium, and, in some cases, elucidate the underlying cause.10,12 It was surprising that Mrs. M’s EEGs were normal despite a clinical presentation of delirium. Because of the normal EEG findings, neurology leaned toward a primary psychiatric (“functional”) etiology as the cause of her delirium vs a general medical condition or alcohol withdrawal (“organic”).

A literature search in regards to sensitivity of EEG in delirium revealed conflicting statements and data. A standard textbook in neurology and psychiatry states that “a normal EEG virtually excludes a toxic-metabolic encephalopathy.”13 The American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) practice guidelines for delirium states: “The presence of EEG abnormalities has fairly good sensitivities for delirium (in one study, the sensitivity was found to be 75%), but the absence does not rule out the diagnosis; thus the EEG is no substitute for careful clinical observation.”6

At the beginning of Mrs. M’s care, in discussion with the neurology and internal medicine teams, we argued that Mrs. M was experiencing delirium despite her initial normal EEG. We did not expect that 2 subsequent EEGs would be normal, especially because the teams witnessed the final EEG being performed while Mrs. M was clinically evaluated and observed to be in a state of delirium.

OUTCOME: Cause still unknown

By the 6th day of hospitalization, Mrs. M’s vitals are normal and she remains hemodynamically stable. Differential diagnosis remains wide and unclear. The psychiatry team feels she could have atypical catatonia due to an underlying mood disorder. One hour after a trial of IV lorazepam, 1 mg, Mrs. M is more lucid and fully oriented, with MMSE of 28/30 (recall was 1/3), indicating normal cognition. During the exam, a psychiatry resident notes Mrs. M winks and feigns a yawn at the medical students and nurses in the room, displaying her boredom with the interview and simplicity of the mental status exam questions. Later that evening, Mrs. M exhibits bizarre sexual gestures toward male hospital staff, including licking a male nursing staff member’s hand.

Although Mrs. M’s initial confusion resolved, the severity of her comorbid psychiatric history warrants inpatient psychiatric hospitalization. She agrees to transfer to the psychiatric ward after she confesses anxiety regarding death, intense demoralization, and guilt related to her condition and her relationship with her 12-year-old daughter. She tearfully reports that she discontinued her psychotropic medications shortly after stopping alcohol 4 months ago. Shortly before her transfer, psychiatry is called back to the medicine floor because of Mrs. M’s disruptive behavior.

The team finds Mrs. M in her hospital gown, pursuing her husband in the hallway as he is leaving, yelling profanities and blaming him for her horrible experience in the hospital. Based on her demeanor, the team determines that she is back to her baseline mental state despite her mood disorder, and that her upcoming inpatient psychiatric stay likely would be too short to address her comorbid personality disorder. The next day she signs out of the hospital against medical advice.

The authors’ observations

We never clearly identified the specific etiology responsible for Mrs. M’s delirium. We assume at the initial presentation she had toxic-metabolic encephalopathy that rapidly resolved with lactulose treatment and lowering her ammonia. She then had a single tonic-clonic seizure, perhaps related to stopping and then restarting her psychotropics. Her subsequent confusion, bizarre sexual behavior, and demeanor on her final hospital days were more indicative of her psychiatric diagnoses. We now suspect that Mrs. M’s delirium was briefer than presumed and she returned to her baseline borderline personality, resulting in some factitious staging of delirium to confuse her 3 treating teams (a psychoanalyst may say this was a form of projective identification).

We felt that if Mrs. M truly was delirious due to metabolic or hepatic dysfunction or alcohol withdrawal, she would have had abnormal EEG findings. We discovered that the notion of “75% sensitivity” of EEG abnormalities cited in the APA guidelines comes from studies that include patients with “psychogenic” and “organic” delirium. Acute manias and agitated psychoses were termed “psychogenic delirium” and acute confusion due to medical conditions or substance issues was termed “organic delirium.”9,12,14-16

This poses a circular reasoning in the diagnostic criteria and clinical approach to delirium. The fallacy is that, according to DSM-IV-TR, delirium is supposed to be the result of a direct physiological consequence of a general medical condition or substance use (criterion D), and cannot be due to psychosis (eg, schizophrenia) or mania (eg, BD). We question the presumptive 75% sensitivity of EEG abnormalities in patients with delirium because it is possible that when some of these studies were conducted the definition of delirium was not solidified or fully understood. We suspect the sensitivity would be much higher if the correct definition of delirium according to DSM-IV-TR is used in future studies. To improve interdisciplinary communication and future research, it would be constructive if all disciplines could agree on a single term, with the same diagnostic criteria, when evaluating a patient with acute confusion.

Related Resources

- Meagher D. Delirium: the role of psychiatry. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2001;7:433-442.

- Casey DA, DeFazio JV Jr, Vansickle K, et al. Delirium. Quick recognition, careful evaluation, and appropriate treatment. Postgrad Med. 1996;100(1):121-4, 128, 133-134.

Drug Brand Names

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Docusate • Surfak

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Levothyroxine • Levoxyl, Synthtoid

- Venlafaxine XR • Effexor XR

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgment

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. The authors are employees of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. 105 provides that “Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the U.S. Government.” Title 17 U.S.C. 101 defines a U.S. Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person’s official duties.

1. Katz IR, Mossey J, Sussman N, et al. Bedside clinical and electrophysiological assessment: assessment of change in vulnerable patients. Int Psychogeriatr. 1991;3(2):289-300.

2. Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(11):1157-1165.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

4. McPhee SJ, Papadakis M, Rabow MW. CURRENT medical diagnosis and treatment. New York NY: McGraw Hill Medical; 2012.

5. Brody B. Who has capacity? N Engl J Med. 2009;361(3):232-233.

6. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(5 suppl):1-20.

7. Fricchione GL, Nejad SH, Esses JA, et al. Postoperative delirium. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(7):803-812.

8. Sanyal AJ, Freedman AM, Shiffman ML, et al. Portosystemic encephalopathy after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: results of a prospective controlled study. Hepatology. 1994;20(1 pt 1):46-55.

9. Engel GL, Romano J. Delirium a syndrome of cerebral insufficiency. 1959. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;16(4):526-538.

10. Pro JD, Wells CE. The use of the electroencephalogram in the diagnosis of delirium. Dis Nerv Syst. 1977;38(10):804-808.

11. Sidhu KS, Balon R, Ajluni V, et al. Standard EEG and the difficult-to-assess mental status. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2009;21(2):103-108.

12. Brenner RP. Utility of EEG in delirium: past views and current practice. Int Psychogeriatr. 1991;3(2):211-229.

13. Kaufman DM. Clinical neurology for psychiatrists. 5th ed. Philadelphia PA: Saunders; 2001: 230-232.

14. Bond TC. Recognition of acute delirious mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37(5):553-554.

15. Krauthammer C, Klerman GL. Secondary mania: manic syndromes associated with antecedent physical illness or drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35(11):1333-1339.

16. Larson EW, Richelson E. Organic causes of mania. Mayo Clin Proc. 1988;63(9):906-912.

CASE: Agitation

Mrs. M, age 39, presents to the emergency department (ED) with altered mental status. She is escorted by her husband and the police. She has a history of severe alcohol dependence, bipolar disorder (BD), anxiety, borderline personality disorder (BPD), hypothyroidism, and bulimia, and had gastric bypass surgery 4 years ago. Her husband called 911 when he could no longer manage Mrs. M’s agitated state. The police found her to be extremely paranoid, restless, and disoriented. Her husband reports that she shouted “the world is going to end” before she escaped naked into her neighborhood streets.

On several occasions Mrs. M had been admitted to the same hospital for alcohol withdrawal and dependence with subsequent liver failure, leading to jaundice, coagulopathy, and ascites. During these hospitalizations, she exhibited poor behavioral tendencies, unhealthy psychological defenses, and chronic maladaptive coping and defense mechanisms congruent with her BPD diagnosis. Specifically, she engaged in splitting of hospital staff, ranging from extreme flattery to overt devaluation and hostility. Other defense mechanisms included denial, distortion, acting out, and passive-aggressive behavior. During these admissions, Mrs. M often displayed deficits in recall and attention on Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), but these deficits were associated with concurrent alcohol use and improved rapidly during her stay.

In her current presentation, Mrs. M’s mental status change is more pronounced and atypical compared with earlier admissions. Her outpatient medication regimen includes lamotrigine, 100 mg/d, levothyroxine, 88 mcg/d, venlafaxine extended release (XR), 75 mg/d, clonazepam, 3 mg/d, docusate as needed for constipation, and a daily multivitamin.

The authors’ observations

Delirium is a disturbance of consciousness manifested by a reduced clarity of awareness (impairment in attention) and change in cognition (impairment in orientation, memory, and language).1,2 The disturbance develops over a short time and tends to fluctuate during the day. Delirium is a direct physiological consequence of a general medical condition, substance use (intoxication or withdrawal), or both (Table).3

Delirium generally is a reversible mental disorder but can progress to irreversible brain damage. Prompt and accurate diagnosis of delirium is essential,4 although the condition often is underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed because of lack of recognition.

Table

DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for delirium

|

| Source: Reference 3 |

Patients who have convoluted histories, such as Mrs. M, are common and difficult to manage and treat. These patients become substantially more complex when they are admitted to inpatient medical or surgical services. The need to clarify between delirium (primarily medical) and depression (primarily psychiatric) becomes paramount when administering treatment and evaluating decision-making capacity.5 In Mrs. M’s case, internal medicine, neurology, and psychiatry teams each had a different approach to altered mental status. Each team’s different terminology, assessment, and objectives further complicated an already challenging case.6

EVALUATION: Confounding results

The ED physicians offer a working diagnosis of acute mental status change, administer IV lorazepam, 4 mg, and order restraints for Mrs. M’s severe agitation. Her initial vital signs reveal slightly elevated blood pressure (140/90 mm Hg) and tachycardia (115 beats per minute). Internal medicine clinicians note that Mrs. M is not in acute distress, although she refuses to speak and has a small amount of dried blood on her lips, presumably from a struggle with the police before coming to the hospital, but this is not certain. Her abdomen is not tender; she has normal bowel sounds, and no asterixis is noted on neurologic exam. Physical exam is otherwise normal. A noncontrast head CT scan shows no acute process. Initial lab values show elevations in ammonia (277 μg/dL) and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (68 U/L). Thyroid-stimulating hormone is 1.45 mlU/L, prothrombin time is 19.5 s, partial thromboplastin time is 40.3 s, and international normalized ratio is 1.67. The internal medicine team admits Mrs. M to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further management of her mental status change with alcohol withdrawal or hepatic encephalopathy as the most likely etiologies.

Mrs. M’s husband says that his wife has not consumed alcohol in the last 4 months in preparation for a possible liver transplant; however, past interactions with Mrs. M’s family suggest they are unreliable. The Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment (CIWA) protocol is implemented in case her symptoms are caused by alcohol withdrawal. Her vital signs are stable and IV lorazepam, 4 mg, is administered once for agitation. Mrs. M’s husband also reports that 1 month ago his wife underwent a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure for portal hypertension. Outpatient psychotropics (lamotrigine, 100 mg/d, and venlafaxine XR, 75 mg/d) are restarted because withdrawal from these drugs may exacerbate her symptoms. In the ICU Mrs. M experiences a tonic-clonic seizure with fecal incontinence and bitten tongue, which results in a consultation from neurology and the psychiatry consultation-liaison service.

Psychiatry recommends withholding psychotropics, stopping CIWA, and using vital sign parameters along with objective signs of diaphoresis and tremors as indicators of alcohol withdrawal for lorazepam administration. Mrs. M receives IV haloperidol, 1 mg, once during her second day in the hospital for severe agitation, but this medication is discontinued because of concern about lowering her seizure threshold.7 After treatment with lactulose, her ammonia levels trend down to 33 μg/dL, but her altered mental state persists with significant deficits in attention and orientation.

The neurology service performs an EEG that shows no slow-wave, triphasic waves, or epileptiform activity, which likely would be present in delirium or seizures. See Figure 1 for an example of triphasic waves on an EEG and Figure 2 for Mrs. M's EEG results. Subsequent lumbar puncture, MRI, and a second EEG are unremarkable. By the fifth hospital day, Mrs. M is calm and her paranoia has subsided, but she still is confused and disoriented. Psychiatry orders a third EEG while she is in this confused state; it shows no pathologic process. Based on these examinations, neurology posits that Mrs. M is not encephalopathic.

Figure 1: Representative sample of triphasic waves

This EEG tracing is from a 54-year-old woman who underwent prolonged abdominal surgery for lysis of adhesions during which she suffered an intraoperative left subinsular stroke followed by nonconvulsive status epilepticus. The tracing demonstrates typical morphology with the positive sharp transient preceded and followed by smaller amplitude negative deflections. Symmetric, frontal predominance of findings seen is this tracing is common

Figure 2: Mrs. M’s EEG results

This is a representative tracing of Mrs. M’s 3 EEGs revealing an 8.5 to 9 Hz dominant alpha rhythm. There is superimposed frontally dominant beta fast activity, which is consistent with known administration of benzodiazepines

The authors’ observations

Mrs. M had repeated admissions for alcohol dependence and subsequent liver failure. Her recent hospitalization was complicated by a TIPS procedure done 1 month ago. The incidence of hepatic encephalopathy in patients undergoing TIPS is >30%, especially in the first month post-procedure, which raised suspicion that hepatic encephalopathy played a significant role in Mrs. M’s delirium.8

Because of frequent hospitalization, Mrs. M was well known to the internal medicine, neurology, and psychiatry teams, and each used different terms to describe her mental state. Internal medicine used the phrase “acute mental status change,” which covers a broad differential. Neurology used “encephalopathy,” which also is a general term. Psychiatry used “delirium,” which has narrower and more specific diagnostic criteria. Engel et al9 described the delirious patient as having “cerebral insufficiency” with universally abnormal EEG. Regardless of terminology, based on Mrs. M’s acute confusion, one would expect an abnormal EEG, but repeat EEGs were unremarkable.

Interpreting EEG

EEG is one of the few tools available for measuring acute changes in cerebral function, and an EEG slowing remains a hallmark in encephalopathic processes.10,11 Initially, the 3 specialties agreed that Mrs. M’s presentation likely was caused by underlying medical issues or substances (alcohol or others). EEG can help recognize delirium, and, in some cases, elucidate the underlying cause.10,12 It was surprising that Mrs. M’s EEGs were normal despite a clinical presentation of delirium. Because of the normal EEG findings, neurology leaned toward a primary psychiatric (“functional”) etiology as the cause of her delirium vs a general medical condition or alcohol withdrawal (“organic”).

A literature search in regards to sensitivity of EEG in delirium revealed conflicting statements and data. A standard textbook in neurology and psychiatry states that “a normal EEG virtually excludes a toxic-metabolic encephalopathy.”13 The American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) practice guidelines for delirium states: “The presence of EEG abnormalities has fairly good sensitivities for delirium (in one study, the sensitivity was found to be 75%), but the absence does not rule out the diagnosis; thus the EEG is no substitute for careful clinical observation.”6

At the beginning of Mrs. M’s care, in discussion with the neurology and internal medicine teams, we argued that Mrs. M was experiencing delirium despite her initial normal EEG. We did not expect that 2 subsequent EEGs would be normal, especially because the teams witnessed the final EEG being performed while Mrs. M was clinically evaluated and observed to be in a state of delirium.

OUTCOME: Cause still unknown

By the 6th day of hospitalization, Mrs. M’s vitals are normal and she remains hemodynamically stable. Differential diagnosis remains wide and unclear. The psychiatry team feels she could have atypical catatonia due to an underlying mood disorder. One hour after a trial of IV lorazepam, 1 mg, Mrs. M is more lucid and fully oriented, with MMSE of 28/30 (recall was 1/3), indicating normal cognition. During the exam, a psychiatry resident notes Mrs. M winks and feigns a yawn at the medical students and nurses in the room, displaying her boredom with the interview and simplicity of the mental status exam questions. Later that evening, Mrs. M exhibits bizarre sexual gestures toward male hospital staff, including licking a male nursing staff member’s hand.

Although Mrs. M’s initial confusion resolved, the severity of her comorbid psychiatric history warrants inpatient psychiatric hospitalization. She agrees to transfer to the psychiatric ward after she confesses anxiety regarding death, intense demoralization, and guilt related to her condition and her relationship with her 12-year-old daughter. She tearfully reports that she discontinued her psychotropic medications shortly after stopping alcohol 4 months ago. Shortly before her transfer, psychiatry is called back to the medicine floor because of Mrs. M’s disruptive behavior.

The team finds Mrs. M in her hospital gown, pursuing her husband in the hallway as he is leaving, yelling profanities and blaming him for her horrible experience in the hospital. Based on her demeanor, the team determines that she is back to her baseline mental state despite her mood disorder, and that her upcoming inpatient psychiatric stay likely would be too short to address her comorbid personality disorder. The next day she signs out of the hospital against medical advice.

The authors’ observations

We never clearly identified the specific etiology responsible for Mrs. M’s delirium. We assume at the initial presentation she had toxic-metabolic encephalopathy that rapidly resolved with lactulose treatment and lowering her ammonia. She then had a single tonic-clonic seizure, perhaps related to stopping and then restarting her psychotropics. Her subsequent confusion, bizarre sexual behavior, and demeanor on her final hospital days were more indicative of her psychiatric diagnoses. We now suspect that Mrs. M’s delirium was briefer than presumed and she returned to her baseline borderline personality, resulting in some factitious staging of delirium to confuse her 3 treating teams (a psychoanalyst may say this was a form of projective identification).

We felt that if Mrs. M truly was delirious due to metabolic or hepatic dysfunction or alcohol withdrawal, she would have had abnormal EEG findings. We discovered that the notion of “75% sensitivity” of EEG abnormalities cited in the APA guidelines comes from studies that include patients with “psychogenic” and “organic” delirium. Acute manias and agitated psychoses were termed “psychogenic delirium” and acute confusion due to medical conditions or substance issues was termed “organic delirium.”9,12,14-16

This poses a circular reasoning in the diagnostic criteria and clinical approach to delirium. The fallacy is that, according to DSM-IV-TR, delirium is supposed to be the result of a direct physiological consequence of a general medical condition or substance use (criterion D), and cannot be due to psychosis (eg, schizophrenia) or mania (eg, BD). We question the presumptive 75% sensitivity of EEG abnormalities in patients with delirium because it is possible that when some of these studies were conducted the definition of delirium was not solidified or fully understood. We suspect the sensitivity would be much higher if the correct definition of delirium according to DSM-IV-TR is used in future studies. To improve interdisciplinary communication and future research, it would be constructive if all disciplines could agree on a single term, with the same diagnostic criteria, when evaluating a patient with acute confusion.

Related Resources

- Meagher D. Delirium: the role of psychiatry. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2001;7:433-442.

- Casey DA, DeFazio JV Jr, Vansickle K, et al. Delirium. Quick recognition, careful evaluation, and appropriate treatment. Postgrad Med. 1996;100(1):121-4, 128, 133-134.

Drug Brand Names

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Docusate • Surfak

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Levothyroxine • Levoxyl, Synthtoid

- Venlafaxine XR • Effexor XR

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgment

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. The authors are employees of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. 105 provides that “Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the U.S. Government.” Title 17 U.S.C. 101 defines a U.S. Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person’s official duties.

CASE: Agitation

Mrs. M, age 39, presents to the emergency department (ED) with altered mental status. She is escorted by her husband and the police. She has a history of severe alcohol dependence, bipolar disorder (BD), anxiety, borderline personality disorder (BPD), hypothyroidism, and bulimia, and had gastric bypass surgery 4 years ago. Her husband called 911 when he could no longer manage Mrs. M’s agitated state. The police found her to be extremely paranoid, restless, and disoriented. Her husband reports that she shouted “the world is going to end” before she escaped naked into her neighborhood streets.

On several occasions Mrs. M had been admitted to the same hospital for alcohol withdrawal and dependence with subsequent liver failure, leading to jaundice, coagulopathy, and ascites. During these hospitalizations, she exhibited poor behavioral tendencies, unhealthy psychological defenses, and chronic maladaptive coping and defense mechanisms congruent with her BPD diagnosis. Specifically, she engaged in splitting of hospital staff, ranging from extreme flattery to overt devaluation and hostility. Other defense mechanisms included denial, distortion, acting out, and passive-aggressive behavior. During these admissions, Mrs. M often displayed deficits in recall and attention on Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), but these deficits were associated with concurrent alcohol use and improved rapidly during her stay.

In her current presentation, Mrs. M’s mental status change is more pronounced and atypical compared with earlier admissions. Her outpatient medication regimen includes lamotrigine, 100 mg/d, levothyroxine, 88 mcg/d, venlafaxine extended release (XR), 75 mg/d, clonazepam, 3 mg/d, docusate as needed for constipation, and a daily multivitamin.

The authors’ observations

Delirium is a disturbance of consciousness manifested by a reduced clarity of awareness (impairment in attention) and change in cognition (impairment in orientation, memory, and language).1,2 The disturbance develops over a short time and tends to fluctuate during the day. Delirium is a direct physiological consequence of a general medical condition, substance use (intoxication or withdrawal), or both (Table).3

Delirium generally is a reversible mental disorder but can progress to irreversible brain damage. Prompt and accurate diagnosis of delirium is essential,4 although the condition often is underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed because of lack of recognition.

Table

DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for delirium

|

| Source: Reference 3 |

Patients who have convoluted histories, such as Mrs. M, are common and difficult to manage and treat. These patients become substantially more complex when they are admitted to inpatient medical or surgical services. The need to clarify between delirium (primarily medical) and depression (primarily psychiatric) becomes paramount when administering treatment and evaluating decision-making capacity.5 In Mrs. M’s case, internal medicine, neurology, and psychiatry teams each had a different approach to altered mental status. Each team’s different terminology, assessment, and objectives further complicated an already challenging case.6

EVALUATION: Confounding results

The ED physicians offer a working diagnosis of acute mental status change, administer IV lorazepam, 4 mg, and order restraints for Mrs. M’s severe agitation. Her initial vital signs reveal slightly elevated blood pressure (140/90 mm Hg) and tachycardia (115 beats per minute). Internal medicine clinicians note that Mrs. M is not in acute distress, although she refuses to speak and has a small amount of dried blood on her lips, presumably from a struggle with the police before coming to the hospital, but this is not certain. Her abdomen is not tender; she has normal bowel sounds, and no asterixis is noted on neurologic exam. Physical exam is otherwise normal. A noncontrast head CT scan shows no acute process. Initial lab values show elevations in ammonia (277 μg/dL) and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (68 U/L). Thyroid-stimulating hormone is 1.45 mlU/L, prothrombin time is 19.5 s, partial thromboplastin time is 40.3 s, and international normalized ratio is 1.67. The internal medicine team admits Mrs. M to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further management of her mental status change with alcohol withdrawal or hepatic encephalopathy as the most likely etiologies.

Mrs. M’s husband says that his wife has not consumed alcohol in the last 4 months in preparation for a possible liver transplant; however, past interactions with Mrs. M’s family suggest they are unreliable. The Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment (CIWA) protocol is implemented in case her symptoms are caused by alcohol withdrawal. Her vital signs are stable and IV lorazepam, 4 mg, is administered once for agitation. Mrs. M’s husband also reports that 1 month ago his wife underwent a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure for portal hypertension. Outpatient psychotropics (lamotrigine, 100 mg/d, and venlafaxine XR, 75 mg/d) are restarted because withdrawal from these drugs may exacerbate her symptoms. In the ICU Mrs. M experiences a tonic-clonic seizure with fecal incontinence and bitten tongue, which results in a consultation from neurology and the psychiatry consultation-liaison service.

Psychiatry recommends withholding psychotropics, stopping CIWA, and using vital sign parameters along with objective signs of diaphoresis and tremors as indicators of alcohol withdrawal for lorazepam administration. Mrs. M receives IV haloperidol, 1 mg, once during her second day in the hospital for severe agitation, but this medication is discontinued because of concern about lowering her seizure threshold.7 After treatment with lactulose, her ammonia levels trend down to 33 μg/dL, but her altered mental state persists with significant deficits in attention and orientation.

The neurology service performs an EEG that shows no slow-wave, triphasic waves, or epileptiform activity, which likely would be present in delirium or seizures. See Figure 1 for an example of triphasic waves on an EEG and Figure 2 for Mrs. M's EEG results. Subsequent lumbar puncture, MRI, and a second EEG are unremarkable. By the fifth hospital day, Mrs. M is calm and her paranoia has subsided, but she still is confused and disoriented. Psychiatry orders a third EEG while she is in this confused state; it shows no pathologic process. Based on these examinations, neurology posits that Mrs. M is not encephalopathic.

Figure 1: Representative sample of triphasic waves

This EEG tracing is from a 54-year-old woman who underwent prolonged abdominal surgery for lysis of adhesions during which she suffered an intraoperative left subinsular stroke followed by nonconvulsive status epilepticus. The tracing demonstrates typical morphology with the positive sharp transient preceded and followed by smaller amplitude negative deflections. Symmetric, frontal predominance of findings seen is this tracing is common

Figure 2: Mrs. M’s EEG results

This is a representative tracing of Mrs. M’s 3 EEGs revealing an 8.5 to 9 Hz dominant alpha rhythm. There is superimposed frontally dominant beta fast activity, which is consistent with known administration of benzodiazepines

The authors’ observations

Mrs. M had repeated admissions for alcohol dependence and subsequent liver failure. Her recent hospitalization was complicated by a TIPS procedure done 1 month ago. The incidence of hepatic encephalopathy in patients undergoing TIPS is >30%, especially in the first month post-procedure, which raised suspicion that hepatic encephalopathy played a significant role in Mrs. M’s delirium.8

Because of frequent hospitalization, Mrs. M was well known to the internal medicine, neurology, and psychiatry teams, and each used different terms to describe her mental state. Internal medicine used the phrase “acute mental status change,” which covers a broad differential. Neurology used “encephalopathy,” which also is a general term. Psychiatry used “delirium,” which has narrower and more specific diagnostic criteria. Engel et al9 described the delirious patient as having “cerebral insufficiency” with universally abnormal EEG. Regardless of terminology, based on Mrs. M’s acute confusion, one would expect an abnormal EEG, but repeat EEGs were unremarkable.

Interpreting EEG

EEG is one of the few tools available for measuring acute changes in cerebral function, and an EEG slowing remains a hallmark in encephalopathic processes.10,11 Initially, the 3 specialties agreed that Mrs. M’s presentation likely was caused by underlying medical issues or substances (alcohol or others). EEG can help recognize delirium, and, in some cases, elucidate the underlying cause.10,12 It was surprising that Mrs. M’s EEGs were normal despite a clinical presentation of delirium. Because of the normal EEG findings, neurology leaned toward a primary psychiatric (“functional”) etiology as the cause of her delirium vs a general medical condition or alcohol withdrawal (“organic”).

A literature search in regards to sensitivity of EEG in delirium revealed conflicting statements and data. A standard textbook in neurology and psychiatry states that “a normal EEG virtually excludes a toxic-metabolic encephalopathy.”13 The American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) practice guidelines for delirium states: “The presence of EEG abnormalities has fairly good sensitivities for delirium (in one study, the sensitivity was found to be 75%), but the absence does not rule out the diagnosis; thus the EEG is no substitute for careful clinical observation.”6

At the beginning of Mrs. M’s care, in discussion with the neurology and internal medicine teams, we argued that Mrs. M was experiencing delirium despite her initial normal EEG. We did not expect that 2 subsequent EEGs would be normal, especially because the teams witnessed the final EEG being performed while Mrs. M was clinically evaluated and observed to be in a state of delirium.

OUTCOME: Cause still unknown

By the 6th day of hospitalization, Mrs. M’s vitals are normal and she remains hemodynamically stable. Differential diagnosis remains wide and unclear. The psychiatry team feels she could have atypical catatonia due to an underlying mood disorder. One hour after a trial of IV lorazepam, 1 mg, Mrs. M is more lucid and fully oriented, with MMSE of 28/30 (recall was 1/3), indicating normal cognition. During the exam, a psychiatry resident notes Mrs. M winks and feigns a yawn at the medical students and nurses in the room, displaying her boredom with the interview and simplicity of the mental status exam questions. Later that evening, Mrs. M exhibits bizarre sexual gestures toward male hospital staff, including licking a male nursing staff member’s hand.

Although Mrs. M’s initial confusion resolved, the severity of her comorbid psychiatric history warrants inpatient psychiatric hospitalization. She agrees to transfer to the psychiatric ward after she confesses anxiety regarding death, intense demoralization, and guilt related to her condition and her relationship with her 12-year-old daughter. She tearfully reports that she discontinued her psychotropic medications shortly after stopping alcohol 4 months ago. Shortly before her transfer, psychiatry is called back to the medicine floor because of Mrs. M’s disruptive behavior.

The team finds Mrs. M in her hospital gown, pursuing her husband in the hallway as he is leaving, yelling profanities and blaming him for her horrible experience in the hospital. Based on her demeanor, the team determines that she is back to her baseline mental state despite her mood disorder, and that her upcoming inpatient psychiatric stay likely would be too short to address her comorbid personality disorder. The next day she signs out of the hospital against medical advice.

The authors’ observations

We never clearly identified the specific etiology responsible for Mrs. M’s delirium. We assume at the initial presentation she had toxic-metabolic encephalopathy that rapidly resolved with lactulose treatment and lowering her ammonia. She then had a single tonic-clonic seizure, perhaps related to stopping and then restarting her psychotropics. Her subsequent confusion, bizarre sexual behavior, and demeanor on her final hospital days were more indicative of her psychiatric diagnoses. We now suspect that Mrs. M’s delirium was briefer than presumed and she returned to her baseline borderline personality, resulting in some factitious staging of delirium to confuse her 3 treating teams (a psychoanalyst may say this was a form of projective identification).

We felt that if Mrs. M truly was delirious due to metabolic or hepatic dysfunction or alcohol withdrawal, she would have had abnormal EEG findings. We discovered that the notion of “75% sensitivity” of EEG abnormalities cited in the APA guidelines comes from studies that include patients with “psychogenic” and “organic” delirium. Acute manias and agitated psychoses were termed “psychogenic delirium” and acute confusion due to medical conditions or substance issues was termed “organic delirium.”9,12,14-16

This poses a circular reasoning in the diagnostic criteria and clinical approach to delirium. The fallacy is that, according to DSM-IV-TR, delirium is supposed to be the result of a direct physiological consequence of a general medical condition or substance use (criterion D), and cannot be due to psychosis (eg, schizophrenia) or mania (eg, BD). We question the presumptive 75% sensitivity of EEG abnormalities in patients with delirium because it is possible that when some of these studies were conducted the definition of delirium was not solidified or fully understood. We suspect the sensitivity would be much higher if the correct definition of delirium according to DSM-IV-TR is used in future studies. To improve interdisciplinary communication and future research, it would be constructive if all disciplines could agree on a single term, with the same diagnostic criteria, when evaluating a patient with acute confusion.

Related Resources

- Meagher D. Delirium: the role of psychiatry. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2001;7:433-442.

- Casey DA, DeFazio JV Jr, Vansickle K, et al. Delirium. Quick recognition, careful evaluation, and appropriate treatment. Postgrad Med. 1996;100(1):121-4, 128, 133-134.

Drug Brand Names

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Docusate • Surfak

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Levothyroxine • Levoxyl, Synthtoid

- Venlafaxine XR • Effexor XR

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgment

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. The authors are employees of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. 105 provides that “Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the U.S. Government.” Title 17 U.S.C. 101 defines a U.S. Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person’s official duties.

1. Katz IR, Mossey J, Sussman N, et al. Bedside clinical and electrophysiological assessment: assessment of change in vulnerable patients. Int Psychogeriatr. 1991;3(2):289-300.

2. Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(11):1157-1165.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

4. McPhee SJ, Papadakis M, Rabow MW. CURRENT medical diagnosis and treatment. New York NY: McGraw Hill Medical; 2012.

5. Brody B. Who has capacity? N Engl J Med. 2009;361(3):232-233.

6. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(5 suppl):1-20.

7. Fricchione GL, Nejad SH, Esses JA, et al. Postoperative delirium. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(7):803-812.

8. Sanyal AJ, Freedman AM, Shiffman ML, et al. Portosystemic encephalopathy after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: results of a prospective controlled study. Hepatology. 1994;20(1 pt 1):46-55.

9. Engel GL, Romano J. Delirium a syndrome of cerebral insufficiency. 1959. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;16(4):526-538.

10. Pro JD, Wells CE. The use of the electroencephalogram in the diagnosis of delirium. Dis Nerv Syst. 1977;38(10):804-808.

11. Sidhu KS, Balon R, Ajluni V, et al. Standard EEG and the difficult-to-assess mental status. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2009;21(2):103-108.

12. Brenner RP. Utility of EEG in delirium: past views and current practice. Int Psychogeriatr. 1991;3(2):211-229.

13. Kaufman DM. Clinical neurology for psychiatrists. 5th ed. Philadelphia PA: Saunders; 2001: 230-232.

14. Bond TC. Recognition of acute delirious mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37(5):553-554.

15. Krauthammer C, Klerman GL. Secondary mania: manic syndromes associated with antecedent physical illness or drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35(11):1333-1339.

16. Larson EW, Richelson E. Organic causes of mania. Mayo Clin Proc. 1988;63(9):906-912.

1. Katz IR, Mossey J, Sussman N, et al. Bedside clinical and electrophysiological assessment: assessment of change in vulnerable patients. Int Psychogeriatr. 1991;3(2):289-300.

2. Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(11):1157-1165.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

4. McPhee SJ, Papadakis M, Rabow MW. CURRENT medical diagnosis and treatment. New York NY: McGraw Hill Medical; 2012.

5. Brody B. Who has capacity? N Engl J Med. 2009;361(3):232-233.

6. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(5 suppl):1-20.

7. Fricchione GL, Nejad SH, Esses JA, et al. Postoperative delirium. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(7):803-812.

8. Sanyal AJ, Freedman AM, Shiffman ML, et al. Portosystemic encephalopathy after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: results of a prospective controlled study. Hepatology. 1994;20(1 pt 1):46-55.

9. Engel GL, Romano J. Delirium a syndrome of cerebral insufficiency. 1959. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;16(4):526-538.

10. Pro JD, Wells CE. The use of the electroencephalogram in the diagnosis of delirium. Dis Nerv Syst. 1977;38(10):804-808.

11. Sidhu KS, Balon R, Ajluni V, et al. Standard EEG and the difficult-to-assess mental status. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2009;21(2):103-108.

12. Brenner RP. Utility of EEG in delirium: past views and current practice. Int Psychogeriatr. 1991;3(2):211-229.

13. Kaufman DM. Clinical neurology for psychiatrists. 5th ed. Philadelphia PA: Saunders; 2001: 230-232.

14. Bond TC. Recognition of acute delirious mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37(5):553-554.

15. Krauthammer C, Klerman GL. Secondary mania: manic syndromes associated with antecedent physical illness or drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35(11):1333-1339.

16. Larson EW, Richelson E. Organic causes of mania. Mayo Clin Proc. 1988;63(9):906-912.

One twin has cerebral palsy; $103M verdict … and more

AFTER PREMATURE RUPTURE OF MEMBRANES at 25 weeks’ gestation, a woman went to the emergency department (ED) and was later released. Eight days later, she returned to the ED with abdominal pain; a soporific drug was administered. After several hours, it was determined that she was in labor. Twins were delivered vaginally. One child has cerebral palsy and requires assistance in daily activities, although her cognitive function is intact.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The mother should not have been released after premature rupture of her membranes. The nurses and ObGyns failed to timely recognize that the mother was in labor, and failed to prevent premature delivery. Proper recognition of contractions would have allowed for administration of a tocolytic to delay delivery. That drug had been effectively administered during the first two trimesters of the pregnancy. A cesarean delivery should have been performed.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE There was no negligence. The hospital argued that fetal heart-rate monitors did not suggest contractions.

VERDICT A $103 million New York verdict was returned against the hospital; a defense verdict was returned for the physicians.

Perforated uterus and severed iliac artery after D&C

A GYNECOLOGIC SURGEON performed a dilation and curettage (D&C) on a 47-year-old woman. During surgery, the patient suffered a perforated uterus and a severed iliac artery, resulting in a myocardial infarction.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The surgeon failed to dilate the cervix appropriately to assess the cervical and endometrial cavity length, and then failed to use proper instrumentation in the uterus. He did not assess uterine shape before the D&C. The patient suffered cognitive and emotional injuries, and will require additional surgery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The patient’s anatomy is abnormal. A perforation is a known complication of a D&C.

VERDICT A $350,000 Wisconsin settlement was reached.

Failure to monitor a high-risk patient

A WOMAN WITH A HEART CONDITION who routinely took a beta-blocker plus migraine medication also had lupus. Her pregnancy was therefore at high risk for developing intrauterine growth restriction. Her US Navy ObGyn was advised by a maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) specialist to monitor the pregnancy closely with frequent ultrasonography and other tests that were never performed.

The baby was born by emergency cesarean delivery at 36 weeks’ gestation. The child suffered severe hypoxia and a brain hemorrhage just before delivery, which caused serious, permanent physical and neurologic injuries. He needs 24-hour care, is confined to a wheelchair, and requires a feeding tube.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn failed to monitor the mother for fetal growth restriction as recommended by the MFM specialist.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE There was no negligence; the mother was treated properly.

VERDICT After a $28 million Virginia verdict was awarded, the parties continued to dispute whether the judgment would be paid under California law (where the child was born) or Virginia law (where the case was filed). Prior to a rehearing, a $25 million settlement was reached.

Uterine cancer went undiagnosed

A WOMAN IN HER 50s saw her gynecologist in March 2004 to report vaginal staining. She did not return to the physician’s office until January 2005, when she reported daily vaginal bleeding. Ultrasonography showed a 4-cm mass in the endometrial cavity, consistent with a large polyp. A hysteroscopy and biopsy revealed that the woman had uterine cancer. She underwent a hysterectomy and radiation therapy, but the cancer metastasized to her lungs and she died in October 2006.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The gynecologist failed to diagnose uterine cancer in a timely manner.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The patient’s cancer was aggressive; an earlier diagnosis would not have changed the outcome.

VERDICT A $820,000 Massachusetts settlement was reached.

WHEN A 51-YEAR-OLD WOMAN NOTICED A BULGE in her vagina, she consulted her gynecologist. He determined the cause to be a cystocele and rectocele, and recommended a tension-free vaginal tape–obturator (TVT-O) procedure with anterior and posterior colporrhaphy.

The patient awoke from surgery in severe pain and was told that she had lost a lot of blood. Two weeks later, the physician explained that the stitches, not yet absorbed, were causing an abrasion, and that more vaginal tissue had been removed than planned.

Two more weeks passed, and the patient used a mirror to look at her vagina but could not see the opening. The TVT-O tape had created a ridge of tissue in the anterior vagina, causing severe stenosis. Vaginal dilators were required to expand the vagina. Entrapment of the dorsal clitoral nerve by the TVT-O tape was also discovered. The patient continues to experience dyspareunia and groin pain.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The gynecologist failed to tell her that, 2 months before surgery, the FDA had issued a public health warning about complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh during prolapse and urinary incontinence repair. Nor was she informed that the defendant had just completed training in TVT-O surgery, was not fully credentialed, and was proctored during the procedure.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The case was settled before the trial concluded.

VERDICT A $390,000 Virginia settlement was reached.

Lumpectomy, though no mass palpated

A 52-YEAR-OLD WOMAN FOUND A LUMP in her left breast. Her internist ordered mammography, which identified a 2-cm oval, asymmetrical density in the upper inner quadrant of the left breast. The radiologist recommended ultrasonography (US).

The patient consulted a surgical oncologist, who performed fine-needle aspiration. Pathology identified “clusters of malignant cells consistent with carcinoma,” and suggested a confirmatory biopsy. The oncologist recommended lumpectomy and sentinel node biopsy.

On the day of surgery, the patient could not locate the mass. The oncologist testified that he had palpated it. During surgery, gross examination did not show a mass or tumor. Frozen sections of sentinel nodes did not reveal evidence of cancer.

The patient suffered postsurgical seromas and lymphedema. The lymphedema has partially resolved, but causes pain in her left arm and breast.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The surgical oncologist should have performed US before surgery. It was negligent to continue with surgery when there were negative intraoperative findings for cancer or a mass.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE Proper care was provided.

VERDICT A $950,000 Illinois verdict was returned.

Genetic testing fails to identify cystic fibrosis in one twin

AFTER HAVING ONE CHILD with cystic fibrosis (CF), parents underwent genetic testing. Embryos were prepared for in vitro fertilization (IVF) and sent to a genetic-testing laboratory. The lab reported that the embryos were negative for CF. Two embryos were implanted, and the mother gave birth to twins, one of which has CF.

PARENTS’ CLAIM Multiple errors by the genetic-testing laboratory led to an incorrect report on the embryos. The parents claimed wrongful birth.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The testing laboratory and physician owner argued that amniocentesis should have been performed during the pregnancy to rule out CF.

VERDICT The trial judge denied the use of the amniocentesis defense because an abortion would have been the only option available, and abortion is against the public policy of Tennessee. The court entered summary judgment on liability for the parents.

A $13 million verdict was returned, including $7 million to the parents for emotional distress.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

AFTER PREMATURE RUPTURE OF MEMBRANES at 25 weeks’ gestation, a woman went to the emergency department (ED) and was later released. Eight days later, she returned to the ED with abdominal pain; a soporific drug was administered. After several hours, it was determined that she was in labor. Twins were delivered vaginally. One child has cerebral palsy and requires assistance in daily activities, although her cognitive function is intact.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The mother should not have been released after premature rupture of her membranes. The nurses and ObGyns failed to timely recognize that the mother was in labor, and failed to prevent premature delivery. Proper recognition of contractions would have allowed for administration of a tocolytic to delay delivery. That drug had been effectively administered during the first two trimesters of the pregnancy. A cesarean delivery should have been performed.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE There was no negligence. The hospital argued that fetal heart-rate monitors did not suggest contractions.

VERDICT A $103 million New York verdict was returned against the hospital; a defense verdict was returned for the physicians.

Perforated uterus and severed iliac artery after D&C

A GYNECOLOGIC SURGEON performed a dilation and curettage (D&C) on a 47-year-old woman. During surgery, the patient suffered a perforated uterus and a severed iliac artery, resulting in a myocardial infarction.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The surgeon failed to dilate the cervix appropriately to assess the cervical and endometrial cavity length, and then failed to use proper instrumentation in the uterus. He did not assess uterine shape before the D&C. The patient suffered cognitive and emotional injuries, and will require additional surgery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The patient’s anatomy is abnormal. A perforation is a known complication of a D&C.

VERDICT A $350,000 Wisconsin settlement was reached.

Failure to monitor a high-risk patient

A WOMAN WITH A HEART CONDITION who routinely took a beta-blocker plus migraine medication also had lupus. Her pregnancy was therefore at high risk for developing intrauterine growth restriction. Her US Navy ObGyn was advised by a maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) specialist to monitor the pregnancy closely with frequent ultrasonography and other tests that were never performed.

The baby was born by emergency cesarean delivery at 36 weeks’ gestation. The child suffered severe hypoxia and a brain hemorrhage just before delivery, which caused serious, permanent physical and neurologic injuries. He needs 24-hour care, is confined to a wheelchair, and requires a feeding tube.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn failed to monitor the mother for fetal growth restriction as recommended by the MFM specialist.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE There was no negligence; the mother was treated properly.

VERDICT After a $28 million Virginia verdict was awarded, the parties continued to dispute whether the judgment would be paid under California law (where the child was born) or Virginia law (where the case was filed). Prior to a rehearing, a $25 million settlement was reached.

Uterine cancer went undiagnosed

A WOMAN IN HER 50s saw her gynecologist in March 2004 to report vaginal staining. She did not return to the physician’s office until January 2005, when she reported daily vaginal bleeding. Ultrasonography showed a 4-cm mass in the endometrial cavity, consistent with a large polyp. A hysteroscopy and biopsy revealed that the woman had uterine cancer. She underwent a hysterectomy and radiation therapy, but the cancer metastasized to her lungs and she died in October 2006.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The gynecologist failed to diagnose uterine cancer in a timely manner.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The patient’s cancer was aggressive; an earlier diagnosis would not have changed the outcome.

VERDICT A $820,000 Massachusetts settlement was reached.

WHEN A 51-YEAR-OLD WOMAN NOTICED A BULGE in her vagina, she consulted her gynecologist. He determined the cause to be a cystocele and rectocele, and recommended a tension-free vaginal tape–obturator (TVT-O) procedure with anterior and posterior colporrhaphy.

The patient awoke from surgery in severe pain and was told that she had lost a lot of blood. Two weeks later, the physician explained that the stitches, not yet absorbed, were causing an abrasion, and that more vaginal tissue had been removed than planned.

Two more weeks passed, and the patient used a mirror to look at her vagina but could not see the opening. The TVT-O tape had created a ridge of tissue in the anterior vagina, causing severe stenosis. Vaginal dilators were required to expand the vagina. Entrapment of the dorsal clitoral nerve by the TVT-O tape was also discovered. The patient continues to experience dyspareunia and groin pain.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The gynecologist failed to tell her that, 2 months before surgery, the FDA had issued a public health warning about complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh during prolapse and urinary incontinence repair. Nor was she informed that the defendant had just completed training in TVT-O surgery, was not fully credentialed, and was proctored during the procedure.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The case was settled before the trial concluded.

VERDICT A $390,000 Virginia settlement was reached.

Lumpectomy, though no mass palpated

A 52-YEAR-OLD WOMAN FOUND A LUMP in her left breast. Her internist ordered mammography, which identified a 2-cm oval, asymmetrical density in the upper inner quadrant of the left breast. The radiologist recommended ultrasonography (US).

The patient consulted a surgical oncologist, who performed fine-needle aspiration. Pathology identified “clusters of malignant cells consistent with carcinoma,” and suggested a confirmatory biopsy. The oncologist recommended lumpectomy and sentinel node biopsy.

On the day of surgery, the patient could not locate the mass. The oncologist testified that he had palpated it. During surgery, gross examination did not show a mass or tumor. Frozen sections of sentinel nodes did not reveal evidence of cancer.

The patient suffered postsurgical seromas and lymphedema. The lymphedema has partially resolved, but causes pain in her left arm and breast.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The surgical oncologist should have performed US before surgery. It was negligent to continue with surgery when there were negative intraoperative findings for cancer or a mass.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE Proper care was provided.

VERDICT A $950,000 Illinois verdict was returned.

Genetic testing fails to identify cystic fibrosis in one twin

AFTER HAVING ONE CHILD with cystic fibrosis (CF), parents underwent genetic testing. Embryos were prepared for in vitro fertilization (IVF) and sent to a genetic-testing laboratory. The lab reported that the embryos were negative for CF. Two embryos were implanted, and the mother gave birth to twins, one of which has CF.

PARENTS’ CLAIM Multiple errors by the genetic-testing laboratory led to an incorrect report on the embryos. The parents claimed wrongful birth.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The testing laboratory and physician owner argued that amniocentesis should have been performed during the pregnancy to rule out CF.

VERDICT The trial judge denied the use of the amniocentesis defense because an abortion would have been the only option available, and abortion is against the public policy of Tennessee. The court entered summary judgment on liability for the parents.

A $13 million verdict was returned, including $7 million to the parents for emotional distress.

AFTER PREMATURE RUPTURE OF MEMBRANES at 25 weeks’ gestation, a woman went to the emergency department (ED) and was later released. Eight days later, she returned to the ED with abdominal pain; a soporific drug was administered. After several hours, it was determined that she was in labor. Twins were delivered vaginally. One child has cerebral palsy and requires assistance in daily activities, although her cognitive function is intact.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The mother should not have been released after premature rupture of her membranes. The nurses and ObGyns failed to timely recognize that the mother was in labor, and failed to prevent premature delivery. Proper recognition of contractions would have allowed for administration of a tocolytic to delay delivery. That drug had been effectively administered during the first two trimesters of the pregnancy. A cesarean delivery should have been performed.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE There was no negligence. The hospital argued that fetal heart-rate monitors did not suggest contractions.

VERDICT A $103 million New York verdict was returned against the hospital; a defense verdict was returned for the physicians.

Perforated uterus and severed iliac artery after D&C

A GYNECOLOGIC SURGEON performed a dilation and curettage (D&C) on a 47-year-old woman. During surgery, the patient suffered a perforated uterus and a severed iliac artery, resulting in a myocardial infarction.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The surgeon failed to dilate the cervix appropriately to assess the cervical and endometrial cavity length, and then failed to use proper instrumentation in the uterus. He did not assess uterine shape before the D&C. The patient suffered cognitive and emotional injuries, and will require additional surgery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The patient’s anatomy is abnormal. A perforation is a known complication of a D&C.

VERDICT A $350,000 Wisconsin settlement was reached.

Failure to monitor a high-risk patient

A WOMAN WITH A HEART CONDITION who routinely took a beta-blocker plus migraine medication also had lupus. Her pregnancy was therefore at high risk for developing intrauterine growth restriction. Her US Navy ObGyn was advised by a maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) specialist to monitor the pregnancy closely with frequent ultrasonography and other tests that were never performed.

The baby was born by emergency cesarean delivery at 36 weeks’ gestation. The child suffered severe hypoxia and a brain hemorrhage just before delivery, which caused serious, permanent physical and neurologic injuries. He needs 24-hour care, is confined to a wheelchair, and requires a feeding tube.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn failed to monitor the mother for fetal growth restriction as recommended by the MFM specialist.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE There was no negligence; the mother was treated properly.

VERDICT After a $28 million Virginia verdict was awarded, the parties continued to dispute whether the judgment would be paid under California law (where the child was born) or Virginia law (where the case was filed). Prior to a rehearing, a $25 million settlement was reached.

Uterine cancer went undiagnosed

A WOMAN IN HER 50s saw her gynecologist in March 2004 to report vaginal staining. She did not return to the physician’s office until January 2005, when she reported daily vaginal bleeding. Ultrasonography showed a 4-cm mass in the endometrial cavity, consistent with a large polyp. A hysteroscopy and biopsy revealed that the woman had uterine cancer. She underwent a hysterectomy and radiation therapy, but the cancer metastasized to her lungs and she died in October 2006.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The gynecologist failed to diagnose uterine cancer in a timely manner.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The patient’s cancer was aggressive; an earlier diagnosis would not have changed the outcome.

VERDICT A $820,000 Massachusetts settlement was reached.

WHEN A 51-YEAR-OLD WOMAN NOTICED A BULGE in her vagina, she consulted her gynecologist. He determined the cause to be a cystocele and rectocele, and recommended a tension-free vaginal tape–obturator (TVT-O) procedure with anterior and posterior colporrhaphy.

The patient awoke from surgery in severe pain and was told that she had lost a lot of blood. Two weeks later, the physician explained that the stitches, not yet absorbed, were causing an abrasion, and that more vaginal tissue had been removed than planned.

Two more weeks passed, and the patient used a mirror to look at her vagina but could not see the opening. The TVT-O tape had created a ridge of tissue in the anterior vagina, causing severe stenosis. Vaginal dilators were required to expand the vagina. Entrapment of the dorsal clitoral nerve by the TVT-O tape was also discovered. The patient continues to experience dyspareunia and groin pain.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The gynecologist failed to tell her that, 2 months before surgery, the FDA had issued a public health warning about complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh during prolapse and urinary incontinence repair. Nor was she informed that the defendant had just completed training in TVT-O surgery, was not fully credentialed, and was proctored during the procedure.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The case was settled before the trial concluded.

VERDICT A $390,000 Virginia settlement was reached.

Lumpectomy, though no mass palpated

A 52-YEAR-OLD WOMAN FOUND A LUMP in her left breast. Her internist ordered mammography, which identified a 2-cm oval, asymmetrical density in the upper inner quadrant of the left breast. The radiologist recommended ultrasonography (US).

The patient consulted a surgical oncologist, who performed fine-needle aspiration. Pathology identified “clusters of malignant cells consistent with carcinoma,” and suggested a confirmatory biopsy. The oncologist recommended lumpectomy and sentinel node biopsy.

On the day of surgery, the patient could not locate the mass. The oncologist testified that he had palpated it. During surgery, gross examination did not show a mass or tumor. Frozen sections of sentinel nodes did not reveal evidence of cancer.

The patient suffered postsurgical seromas and lymphedema. The lymphedema has partially resolved, but causes pain in her left arm and breast.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The surgical oncologist should have performed US before surgery. It was negligent to continue with surgery when there were negative intraoperative findings for cancer or a mass.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE Proper care was provided.

VERDICT A $950,000 Illinois verdict was returned.

Genetic testing fails to identify cystic fibrosis in one twin

AFTER HAVING ONE CHILD with cystic fibrosis (CF), parents underwent genetic testing. Embryos were prepared for in vitro fertilization (IVF) and sent to a genetic-testing laboratory. The lab reported that the embryos were negative for CF. Two embryos were implanted, and the mother gave birth to twins, one of which has CF.

PARENTS’ CLAIM Multiple errors by the genetic-testing laboratory led to an incorrect report on the embryos. The parents claimed wrongful birth.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The testing laboratory and physician owner argued that amniocentesis should have been performed during the pregnancy to rule out CF.

VERDICT The trial judge denied the use of the amniocentesis defense because an abortion would have been the only option available, and abortion is against the public policy of Tennessee. The court entered summary judgment on liability for the parents.

A $13 million verdict was returned, including $7 million to the parents for emotional distress.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

The new year brings refinements to CPT and Medicare codes

Ms. Witt reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Among changes to Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) that took effect on January 1 are several of interest to our specialty:

- the addition of “typical” times to the evaluation and management (E/M) codes for same-day admission and discharge

- a new code for bladder injection

- bundling of imaging guidance associated with percutaneous implantation of a neurostimulator electrode array, if performed, using code 64561, Percutaneous implantation of neurostimulator electrode array; sacral nerve (transforaminal placement).

In addition, CPT made it clear that all E/M codes can be reported by qualified nonphysician health-care providers, as well as physicians. As for Medicare, coding for administration of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera) has been modified, as has the billing process for interpretation of ultrasonography performed outside of the office.

Because of requirements in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), insurers were required to accept the new codes and revisions on January 1.

Providers can now characterize their level of service by how long it took to provide