User login

HM Embraces Smartphones

The Schumacher Group, which bills itself as the third-largest emergency and HM management firm in the U.S., is incorporating the use of smartphone applications, or apps, through its EDs nationwide. A similar technology could soon be in the offing for its HM operation.

The Lafayette, La.-based firm announced late last month that it was partnering with iTriage, a company that produces a free healthcare app for consumers, at its ED operation at North Okaloosa Medical Center in Crestview, Fla. The app will let patients and others learn details about the hospital and its services. And while David Grace, MD, FHM, the firm’s senior medical officer for hospital medicine, says there are no immediate plans to expand the usage to HM, the topic is being discussed.

"We're investigating it," he says, adding he sees a multitude of potential uses for healthcare apps, especially if they empower HM patients to become more involved in their care.

"I think any information that we can supply patients, whether we supply it or it's supplied through some other media, I think is a good thing," he says. "It increases their engagement. And any time the patient is more engaged in their healthcare, I think you develop better plans, better outcomes."

He cautions that there are potential pitfalls for physicians and patients. Patients need to be realistic about their breadth of knowledge, and doctors need to understand that a patient is not second-guessing them, just being interactive in the process.

It can "almost be one more line of safety checks in the whole healthcare continuum," Dr. Grace says. "The last time I looked, I've not seen too many practices of individuals out there hit 100% of everything 100% of the time. And while the errors numbers may be small, if you're the one discharged after a stroke not on an anti-platelet agent and have a massive stroke, that 1% was a pretty substantial number in your case."

The Schumacher Group, which bills itself as the third-largest emergency and HM management firm in the U.S., is incorporating the use of smartphone applications, or apps, through its EDs nationwide. A similar technology could soon be in the offing for its HM operation.

The Lafayette, La.-based firm announced late last month that it was partnering with iTriage, a company that produces a free healthcare app for consumers, at its ED operation at North Okaloosa Medical Center in Crestview, Fla. The app will let patients and others learn details about the hospital and its services. And while David Grace, MD, FHM, the firm’s senior medical officer for hospital medicine, says there are no immediate plans to expand the usage to HM, the topic is being discussed.

"We're investigating it," he says, adding he sees a multitude of potential uses for healthcare apps, especially if they empower HM patients to become more involved in their care.

"I think any information that we can supply patients, whether we supply it or it's supplied through some other media, I think is a good thing," he says. "It increases their engagement. And any time the patient is more engaged in their healthcare, I think you develop better plans, better outcomes."

He cautions that there are potential pitfalls for physicians and patients. Patients need to be realistic about their breadth of knowledge, and doctors need to understand that a patient is not second-guessing them, just being interactive in the process.

It can "almost be one more line of safety checks in the whole healthcare continuum," Dr. Grace says. "The last time I looked, I've not seen too many practices of individuals out there hit 100% of everything 100% of the time. And while the errors numbers may be small, if you're the one discharged after a stroke not on an anti-platelet agent and have a massive stroke, that 1% was a pretty substantial number in your case."

The Schumacher Group, which bills itself as the third-largest emergency and HM management firm in the U.S., is incorporating the use of smartphone applications, or apps, through its EDs nationwide. A similar technology could soon be in the offing for its HM operation.

The Lafayette, La.-based firm announced late last month that it was partnering with iTriage, a company that produces a free healthcare app for consumers, at its ED operation at North Okaloosa Medical Center in Crestview, Fla. The app will let patients and others learn details about the hospital and its services. And while David Grace, MD, FHM, the firm’s senior medical officer for hospital medicine, says there are no immediate plans to expand the usage to HM, the topic is being discussed.

"We're investigating it," he says, adding he sees a multitude of potential uses for healthcare apps, especially if they empower HM patients to become more involved in their care.

"I think any information that we can supply patients, whether we supply it or it's supplied through some other media, I think is a good thing," he says. "It increases their engagement. And any time the patient is more engaged in their healthcare, I think you develop better plans, better outcomes."

He cautions that there are potential pitfalls for physicians and patients. Patients need to be realistic about their breadth of knowledge, and doctors need to understand that a patient is not second-guessing them, just being interactive in the process.

It can "almost be one more line of safety checks in the whole healthcare continuum," Dr. Grace says. "The last time I looked, I've not seen too many practices of individuals out there hit 100% of everything 100% of the time. And while the errors numbers may be small, if you're the one discharged after a stroke not on an anti-platelet agent and have a massive stroke, that 1% was a pretty substantial number in your case."

In the Literature: Research You Need to Know

Clinical question: In patients with candidemia, what are the incidence, risk factors, and antifungal treatment outcomes for ocular candidiasis?

Background: The incidence and treatment outcomes of ocular candidiasis have not been studied extensively.

Study design: Randomized noninferiority trial.

Setting: Multicenter study of 370 patients.

Synopsis: This study randomized 370 non-neutropenic patients with candidemia in a 2:1 ratio to receive voriconazole monotherapy or amphotericin B followed by fluconazole. Patients were treated for at least two weeks after the last positive blood culture, for a maximum duration of eight weeks. Baseline and follow-up fundoscopic examinations were performed.

Sixty (16%) patients were diagnosed with ocular candidiasis, of which six (1.6%) were diagnosed with endophthalmitis and 34 (9%) with chorioretinitis. Patients with ocular candidiasis had a longer duration of candidemia, and were more likely to be infected with Candida albicans.

Outcomes were not available in 19 patients with ocular candidiasis due to death or loss of follow-up. There was no significant difference between the cure rate of voriconazole (93.5% [29/31]), compared with the amphotericin B group (100% [10/10]).

Bottom line: Ocular candidiasis occurs in approximately 16% of non-neutropenic patients with candidemia. A longer duration of candidemia and infection with C. albicans were associated with ocular candidiasis. Both voriconazole and amphotericin B/fluconazole are effective in patients with ocular candidiasis.

Citation: Oude Lashof AM, Rothova A, Sobel JD, et al. Ocular manifestations of candidemia. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:262-268.

For more physician reviews of HM-related literature, check out our website.

Clinical question: In patients with candidemia, what are the incidence, risk factors, and antifungal treatment outcomes for ocular candidiasis?

Background: The incidence and treatment outcomes of ocular candidiasis have not been studied extensively.

Study design: Randomized noninferiority trial.

Setting: Multicenter study of 370 patients.

Synopsis: This study randomized 370 non-neutropenic patients with candidemia in a 2:1 ratio to receive voriconazole monotherapy or amphotericin B followed by fluconazole. Patients were treated for at least two weeks after the last positive blood culture, for a maximum duration of eight weeks. Baseline and follow-up fundoscopic examinations were performed.

Sixty (16%) patients were diagnosed with ocular candidiasis, of which six (1.6%) were diagnosed with endophthalmitis and 34 (9%) with chorioretinitis. Patients with ocular candidiasis had a longer duration of candidemia, and were more likely to be infected with Candida albicans.

Outcomes were not available in 19 patients with ocular candidiasis due to death or loss of follow-up. There was no significant difference between the cure rate of voriconazole (93.5% [29/31]), compared with the amphotericin B group (100% [10/10]).

Bottom line: Ocular candidiasis occurs in approximately 16% of non-neutropenic patients with candidemia. A longer duration of candidemia and infection with C. albicans were associated with ocular candidiasis. Both voriconazole and amphotericin B/fluconazole are effective in patients with ocular candidiasis.

Citation: Oude Lashof AM, Rothova A, Sobel JD, et al. Ocular manifestations of candidemia. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:262-268.

For more physician reviews of HM-related literature, check out our website.

Clinical question: In patients with candidemia, what are the incidence, risk factors, and antifungal treatment outcomes for ocular candidiasis?

Background: The incidence and treatment outcomes of ocular candidiasis have not been studied extensively.

Study design: Randomized noninferiority trial.

Setting: Multicenter study of 370 patients.

Synopsis: This study randomized 370 non-neutropenic patients with candidemia in a 2:1 ratio to receive voriconazole monotherapy or amphotericin B followed by fluconazole. Patients were treated for at least two weeks after the last positive blood culture, for a maximum duration of eight weeks. Baseline and follow-up fundoscopic examinations were performed.

Sixty (16%) patients were diagnosed with ocular candidiasis, of which six (1.6%) were diagnosed with endophthalmitis and 34 (9%) with chorioretinitis. Patients with ocular candidiasis had a longer duration of candidemia, and were more likely to be infected with Candida albicans.

Outcomes were not available in 19 patients with ocular candidiasis due to death or loss of follow-up. There was no significant difference between the cure rate of voriconazole (93.5% [29/31]), compared with the amphotericin B group (100% [10/10]).

Bottom line: Ocular candidiasis occurs in approximately 16% of non-neutropenic patients with candidemia. A longer duration of candidemia and infection with C. albicans were associated with ocular candidiasis. Both voriconazole and amphotericin B/fluconazole are effective in patients with ocular candidiasis.

Citation: Oude Lashof AM, Rothova A, Sobel JD, et al. Ocular manifestations of candidemia. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:262-268.

For more physician reviews of HM-related literature, check out our website.

Professional-Growth Planning Is Essential to HM Group Success

In the changing healthcare landscape, hospitalists are being asked to be leaders and managers in their day-to-day activities. Often, the HM director will need to help provide hospitalists in their groups with the skills they need to succeed, says Bryce Gartland, MD, FHM, associate director of the hospital medicine division and medical director of care coordination at Emory Healthcare in Atlanta.

“Critical to that is making sure you’ve got a standardized structure in place for ensuring their professional growth and development,” he says.

HM group directors can invite experts to conduct feedback sessions on particular areas of concern or send their hospitalists to outside training, he says. For example, SHM hosts a Leadership Academy that offers a “Foundation for Effective Leadership” course, along with two more advanced leadership seminars.

The American College of Physicians offers the “Leadership Enhancement and Development” (LEAD) program, and the Center for the Health Professions at the University of California at San Francisco offers several leadership initiatives.

—John Bulger, DO, FACP, FHM, chief quality officer, director, HM service line, Geisinger Health System, Danville, Pa.

It also is incumbent on HM directors to get their physicians training in quality improvement (QI), asserts John Bulger, DO, FACP, FHM, chief quality officer and director of the HM service line for Geisinger Health System in Danville, Pa. “In my view, quality improvement is really where hospitalists make their hay in being a value added to the hospital,” he says.

SHM’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement offers a wide variety of tools and resources to educate hospitalists on QI. SHM also has a Quality Improvement Skills pre-course at its annual meeting in April in San Diego.

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement, a nonprofit organization based in Cambridge, Mass., that focuses on healthcare best practices, and the Institute for Health Care Delivery Research at InterMountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, Utah, have respected QI training programs.

QI training also comes from mentorship and putting hospitalists on QI-related committees. “That really has a twofold benefit for the hospital medicine group, because you are also able to stretch your reach,” Dr. Bulger says. “Now you’ve got a hospitalist on that committee who can report back to you and tell you what’s going on, and help you be involved in the changes going on in the hospital.”

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

In the changing healthcare landscape, hospitalists are being asked to be leaders and managers in their day-to-day activities. Often, the HM director will need to help provide hospitalists in their groups with the skills they need to succeed, says Bryce Gartland, MD, FHM, associate director of the hospital medicine division and medical director of care coordination at Emory Healthcare in Atlanta.

“Critical to that is making sure you’ve got a standardized structure in place for ensuring their professional growth and development,” he says.

HM group directors can invite experts to conduct feedback sessions on particular areas of concern or send their hospitalists to outside training, he says. For example, SHM hosts a Leadership Academy that offers a “Foundation for Effective Leadership” course, along with two more advanced leadership seminars.

The American College of Physicians offers the “Leadership Enhancement and Development” (LEAD) program, and the Center for the Health Professions at the University of California at San Francisco offers several leadership initiatives.

—John Bulger, DO, FACP, FHM, chief quality officer, director, HM service line, Geisinger Health System, Danville, Pa.

It also is incumbent on HM directors to get their physicians training in quality improvement (QI), asserts John Bulger, DO, FACP, FHM, chief quality officer and director of the HM service line for Geisinger Health System in Danville, Pa. “In my view, quality improvement is really where hospitalists make their hay in being a value added to the hospital,” he says.

SHM’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement offers a wide variety of tools and resources to educate hospitalists on QI. SHM also has a Quality Improvement Skills pre-course at its annual meeting in April in San Diego.

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement, a nonprofit organization based in Cambridge, Mass., that focuses on healthcare best practices, and the Institute for Health Care Delivery Research at InterMountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, Utah, have respected QI training programs.

QI training also comes from mentorship and putting hospitalists on QI-related committees. “That really has a twofold benefit for the hospital medicine group, because you are also able to stretch your reach,” Dr. Bulger says. “Now you’ve got a hospitalist on that committee who can report back to you and tell you what’s going on, and help you be involved in the changes going on in the hospital.”

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

In the changing healthcare landscape, hospitalists are being asked to be leaders and managers in their day-to-day activities. Often, the HM director will need to help provide hospitalists in their groups with the skills they need to succeed, says Bryce Gartland, MD, FHM, associate director of the hospital medicine division and medical director of care coordination at Emory Healthcare in Atlanta.

“Critical to that is making sure you’ve got a standardized structure in place for ensuring their professional growth and development,” he says.

HM group directors can invite experts to conduct feedback sessions on particular areas of concern or send their hospitalists to outside training, he says. For example, SHM hosts a Leadership Academy that offers a “Foundation for Effective Leadership” course, along with two more advanced leadership seminars.

The American College of Physicians offers the “Leadership Enhancement and Development” (LEAD) program, and the Center for the Health Professions at the University of California at San Francisco offers several leadership initiatives.

—John Bulger, DO, FACP, FHM, chief quality officer, director, HM service line, Geisinger Health System, Danville, Pa.

It also is incumbent on HM directors to get their physicians training in quality improvement (QI), asserts John Bulger, DO, FACP, FHM, chief quality officer and director of the HM service line for Geisinger Health System in Danville, Pa. “In my view, quality improvement is really where hospitalists make their hay in being a value added to the hospital,” he says.

SHM’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement offers a wide variety of tools and resources to educate hospitalists on QI. SHM also has a Quality Improvement Skills pre-course at its annual meeting in April in San Diego.

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement, a nonprofit organization based in Cambridge, Mass., that focuses on healthcare best practices, and the Institute for Health Care Delivery Research at InterMountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, Utah, have respected QI training programs.

QI training also comes from mentorship and putting hospitalists on QI-related committees. “That really has a twofold benefit for the hospital medicine group, because you are also able to stretch your reach,” Dr. Bulger says. “Now you’ve got a hospitalist on that committee who can report back to you and tell you what’s going on, and help you be involved in the changes going on in the hospital.”

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Health Plans, Physician Groups Show Interest in Post-Discharge Clinics

Not all post-discharge clinics are established by hospitalist groups or their parent hospitals. As Tallahassee (Fla.) Memorial Hospital’s experience with a collaborative approach shows (see “Is a Post-Discharge Clinic in Your Hospital’s Future?”), health plans might take an interest in successful discharge protocols to prevent unnecessary readmissions. In other cases, medical specialty practices have established clinics for patients with specific diseases—CHF, COPD, even post-ICU delirium.

In Southern California, two large, established physician groups that assume financial risk or insurance functions see the potential benefit, given that their financial incentives are more obviously aligned to such clinics than are hospitals’. Cerritos, Calif.-based CareMore is a Medicare health plan that started out as a medical group and remains a care delivery system for Medicare Advantage patients, making significant use of hospitalists.

“We call ourselves ‘extensivists,’” says CareMore medical director and hospitalist Hyong Kim, MD. The company’s hospitalists generally

“This approach wouldn’t work in fee-for-service, but it works well in pre-paid environments. We pay our PCPs a capitated rate, and they continue to receive capitation after the hospitalist takes over the care,” he explains. “Our extensivists are salaried, with incentives based on readmissions.”

The company uses chronic-disease managers, who check in daily with the hospitalists. “We also have a house-call physician program, sending physicians and social workers to patients’ homes after discharge,” Dr. Kim says.

Torrance, Calif.-based HealthCare Partners, a large, physician-owned multispecialty medical group, operates in many ways like a health plan, says Tyler Jung, MD, medical director for hospitalists, high-risk groups, and post-discharge clinics. “We’re fully delegated. We accept financial risk from virtually all of the major health plans in the area,” he explains.

—Tyler Jung, MD, medical director, hospitalists, high-risk groups, and post-discharge clinics, HealthCare Partners, Torrance, Calif.

Dr. Jung’s team views the first 30 days after patients leave the hospital as “the riskiest time period for our members. We’ve had hospitalists for 15 to 20 years, and just recently we began looking at the post-discharge clinic option,” he says. “I’m still undecided: Is it a Band-Aid or something we need to intervene in the post-discharge period?”

HealthCare Partners operates six community care and disease management centers across Southern California, each of which houses a post-discharge clinic staffed by a doctor, social worker, and case manager. The post-discharge physicians are internists, not necessarily hospitalists, “although many moonlight in our hospitalist program and the most successful ones have hospitalist experience,” Dr. Jung says. “Our clinics are designed for 45-minute appointments: The patient meets with the doctor and maybe the social worker and case manager—a real multidisciplinary approach.”

Three-fourths of referrals are patients coming home from the hospital and a quarter are high-risk patients identified in primary-care clinics. “The first visit deals with medically complicated issues, but the next couple may have more to do with reinforcing the care plan that was established,” as well as looking at social issues, he says.

Finding the right physician is no easy task. “They’ve got to get it,” he says. “You need to be judicious about how long to keep the patient—versus referring them back to primary care—and setting limits is hard. We don’t have magic criteria for this. It’s mostly subjective right now.”

Another challenge is measuring success. “These clinics can be expensive to run, and we need to show the return on investment,” he says.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer based in Oakland, Calif.

Not all post-discharge clinics are established by hospitalist groups or their parent hospitals. As Tallahassee (Fla.) Memorial Hospital’s experience with a collaborative approach shows (see “Is a Post-Discharge Clinic in Your Hospital’s Future?”), health plans might take an interest in successful discharge protocols to prevent unnecessary readmissions. In other cases, medical specialty practices have established clinics for patients with specific diseases—CHF, COPD, even post-ICU delirium.

In Southern California, two large, established physician groups that assume financial risk or insurance functions see the potential benefit, given that their financial incentives are more obviously aligned to such clinics than are hospitals’. Cerritos, Calif.-based CareMore is a Medicare health plan that started out as a medical group and remains a care delivery system for Medicare Advantage patients, making significant use of hospitalists.

“We call ourselves ‘extensivists,’” says CareMore medical director and hospitalist Hyong Kim, MD. The company’s hospitalists generally

“This approach wouldn’t work in fee-for-service, but it works well in pre-paid environments. We pay our PCPs a capitated rate, and they continue to receive capitation after the hospitalist takes over the care,” he explains. “Our extensivists are salaried, with incentives based on readmissions.”

The company uses chronic-disease managers, who check in daily with the hospitalists. “We also have a house-call physician program, sending physicians and social workers to patients’ homes after discharge,” Dr. Kim says.

Torrance, Calif.-based HealthCare Partners, a large, physician-owned multispecialty medical group, operates in many ways like a health plan, says Tyler Jung, MD, medical director for hospitalists, high-risk groups, and post-discharge clinics. “We’re fully delegated. We accept financial risk from virtually all of the major health plans in the area,” he explains.

—Tyler Jung, MD, medical director, hospitalists, high-risk groups, and post-discharge clinics, HealthCare Partners, Torrance, Calif.

Dr. Jung’s team views the first 30 days after patients leave the hospital as “the riskiest time period for our members. We’ve had hospitalists for 15 to 20 years, and just recently we began looking at the post-discharge clinic option,” he says. “I’m still undecided: Is it a Band-Aid or something we need to intervene in the post-discharge period?”

HealthCare Partners operates six community care and disease management centers across Southern California, each of which houses a post-discharge clinic staffed by a doctor, social worker, and case manager. The post-discharge physicians are internists, not necessarily hospitalists, “although many moonlight in our hospitalist program and the most successful ones have hospitalist experience,” Dr. Jung says. “Our clinics are designed for 45-minute appointments: The patient meets with the doctor and maybe the social worker and case manager—a real multidisciplinary approach.”

Three-fourths of referrals are patients coming home from the hospital and a quarter are high-risk patients identified in primary-care clinics. “The first visit deals with medically complicated issues, but the next couple may have more to do with reinforcing the care plan that was established,” as well as looking at social issues, he says.

Finding the right physician is no easy task. “They’ve got to get it,” he says. “You need to be judicious about how long to keep the patient—versus referring them back to primary care—and setting limits is hard. We don’t have magic criteria for this. It’s mostly subjective right now.”

Another challenge is measuring success. “These clinics can be expensive to run, and we need to show the return on investment,” he says.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer based in Oakland, Calif.

Not all post-discharge clinics are established by hospitalist groups or their parent hospitals. As Tallahassee (Fla.) Memorial Hospital’s experience with a collaborative approach shows (see “Is a Post-Discharge Clinic in Your Hospital’s Future?”), health plans might take an interest in successful discharge protocols to prevent unnecessary readmissions. In other cases, medical specialty practices have established clinics for patients with specific diseases—CHF, COPD, even post-ICU delirium.

In Southern California, two large, established physician groups that assume financial risk or insurance functions see the potential benefit, given that their financial incentives are more obviously aligned to such clinics than are hospitals’. Cerritos, Calif.-based CareMore is a Medicare health plan that started out as a medical group and remains a care delivery system for Medicare Advantage patients, making significant use of hospitalists.

“We call ourselves ‘extensivists,’” says CareMore medical director and hospitalist Hyong Kim, MD. The company’s hospitalists generally

“This approach wouldn’t work in fee-for-service, but it works well in pre-paid environments. We pay our PCPs a capitated rate, and they continue to receive capitation after the hospitalist takes over the care,” he explains. “Our extensivists are salaried, with incentives based on readmissions.”

The company uses chronic-disease managers, who check in daily with the hospitalists. “We also have a house-call physician program, sending physicians and social workers to patients’ homes after discharge,” Dr. Kim says.

Torrance, Calif.-based HealthCare Partners, a large, physician-owned multispecialty medical group, operates in many ways like a health plan, says Tyler Jung, MD, medical director for hospitalists, high-risk groups, and post-discharge clinics. “We’re fully delegated. We accept financial risk from virtually all of the major health plans in the area,” he explains.

—Tyler Jung, MD, medical director, hospitalists, high-risk groups, and post-discharge clinics, HealthCare Partners, Torrance, Calif.

Dr. Jung’s team views the first 30 days after patients leave the hospital as “the riskiest time period for our members. We’ve had hospitalists for 15 to 20 years, and just recently we began looking at the post-discharge clinic option,” he says. “I’m still undecided: Is it a Band-Aid or something we need to intervene in the post-discharge period?”

HealthCare Partners operates six community care and disease management centers across Southern California, each of which houses a post-discharge clinic staffed by a doctor, social worker, and case manager. The post-discharge physicians are internists, not necessarily hospitalists, “although many moonlight in our hospitalist program and the most successful ones have hospitalist experience,” Dr. Jung says. “Our clinics are designed for 45-minute appointments: The patient meets with the doctor and maybe the social worker and case manager—a real multidisciplinary approach.”

Three-fourths of referrals are patients coming home from the hospital and a quarter are high-risk patients identified in primary-care clinics. “The first visit deals with medically complicated issues, but the next couple may have more to do with reinforcing the care plan that was established,” as well as looking at social issues, he says.

Finding the right physician is no easy task. “They’ve got to get it,” he says. “You need to be judicious about how long to keep the patient—versus referring them back to primary care—and setting limits is hard. We don’t have magic criteria for this. It’s mostly subjective right now.”

Another challenge is measuring success. “These clinics can be expensive to run, and we need to show the return on investment,” he says.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer based in Oakland, Calif.

San Fran General’s Transitional Care Clinic Undergoes Makeover

San Francisco General Hospital opened its post-discharge transitional care clinic for many of the same reasons as other safety net hospitals, but through staff transitions a new role has emerged: the training of medicine residents. A nurse practitioner (NP), hired in 2007, first identified the large

In 2009, the NP established a “bridge clinic” five half-days a week within an existing hospital-based general medicine clinic. She encouraged referrals of any patients who needed post-discharge services and then triaged those at greatest risk into available clinic slots. But when she went on maternity leave, the clinic’s presence shrank to one half-day per week.

“It really made us take a step back and think philosophically about whether this was a necessary Band-Aid, or whether the system had changed enough that we no longer needed it,” Dr. Schneidermann says. “We found out through our assessment that things, unfortunately, hadn’t changed that much, and the need was still there for a bridge clinic.”

The “mini” bridge clinic collaborates with a new cadre of care coordinators working on discharge planning and with a new group of hospitalists to create an opportunity for medical residents to learn the challenges of care transitions hands-on. “What’s been interesting about this scaled-down version, which we call the mini-bridge clinic, is that it has made us more resourceful,” says SFGH’s Larissa Thomas, MD, MPH.

Dr. Schneidermann says the NP is planning to return in January, which will mean a new set of challenges. “We’ll need to coordinate with her around how to integrate these two approaches. But we find this is an incredible opportunity to teach future physicians about care transitions,” she says.

—Michelle Schneidermann, MD, hospitalist at San Francisco General Hospital.

The challenge now, Dr. Thomas says, is to view transitional medicine in the 30 days following hospital discharge as an essential part of HM, and then build that into the training of residents. “We’re trying to reframe how we think about medicine and looking to create an integrated curriculum,” she says. “Not only will residents have the experience of the transitional care clinic, but when they’re on an inpatient rotation, they’ll be more mindful of the things that affect patient well-being after discharge.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer based in Oakland, Calif.

San Francisco General Hospital opened its post-discharge transitional care clinic for many of the same reasons as other safety net hospitals, but through staff transitions a new role has emerged: the training of medicine residents. A nurse practitioner (NP), hired in 2007, first identified the large

In 2009, the NP established a “bridge clinic” five half-days a week within an existing hospital-based general medicine clinic. She encouraged referrals of any patients who needed post-discharge services and then triaged those at greatest risk into available clinic slots. But when she went on maternity leave, the clinic’s presence shrank to one half-day per week.

“It really made us take a step back and think philosophically about whether this was a necessary Band-Aid, or whether the system had changed enough that we no longer needed it,” Dr. Schneidermann says. “We found out through our assessment that things, unfortunately, hadn’t changed that much, and the need was still there for a bridge clinic.”

The “mini” bridge clinic collaborates with a new cadre of care coordinators working on discharge planning and with a new group of hospitalists to create an opportunity for medical residents to learn the challenges of care transitions hands-on. “What’s been interesting about this scaled-down version, which we call the mini-bridge clinic, is that it has made us more resourceful,” says SFGH’s Larissa Thomas, MD, MPH.

Dr. Schneidermann says the NP is planning to return in January, which will mean a new set of challenges. “We’ll need to coordinate with her around how to integrate these two approaches. But we find this is an incredible opportunity to teach future physicians about care transitions,” she says.

—Michelle Schneidermann, MD, hospitalist at San Francisco General Hospital.

The challenge now, Dr. Thomas says, is to view transitional medicine in the 30 days following hospital discharge as an essential part of HM, and then build that into the training of residents. “We’re trying to reframe how we think about medicine and looking to create an integrated curriculum,” she says. “Not only will residents have the experience of the transitional care clinic, but when they’re on an inpatient rotation, they’ll be more mindful of the things that affect patient well-being after discharge.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer based in Oakland, Calif.

San Francisco General Hospital opened its post-discharge transitional care clinic for many of the same reasons as other safety net hospitals, but through staff transitions a new role has emerged: the training of medicine residents. A nurse practitioner (NP), hired in 2007, first identified the large

In 2009, the NP established a “bridge clinic” five half-days a week within an existing hospital-based general medicine clinic. She encouraged referrals of any patients who needed post-discharge services and then triaged those at greatest risk into available clinic slots. But when she went on maternity leave, the clinic’s presence shrank to one half-day per week.

“It really made us take a step back and think philosophically about whether this was a necessary Band-Aid, or whether the system had changed enough that we no longer needed it,” Dr. Schneidermann says. “We found out through our assessment that things, unfortunately, hadn’t changed that much, and the need was still there for a bridge clinic.”

The “mini” bridge clinic collaborates with a new cadre of care coordinators working on discharge planning and with a new group of hospitalists to create an opportunity for medical residents to learn the challenges of care transitions hands-on. “What’s been interesting about this scaled-down version, which we call the mini-bridge clinic, is that it has made us more resourceful,” says SFGH’s Larissa Thomas, MD, MPH.

Dr. Schneidermann says the NP is planning to return in January, which will mean a new set of challenges. “We’ll need to coordinate with her around how to integrate these two approaches. But we find this is an incredible opportunity to teach future physicians about care transitions,” she says.

—Michelle Schneidermann, MD, hospitalist at San Francisco General Hospital.

The challenge now, Dr. Thomas says, is to view transitional medicine in the 30 days following hospital discharge as an essential part of HM, and then build that into the training of residents. “We’re trying to reframe how we think about medicine and looking to create an integrated curriculum,” she says. “Not only will residents have the experience of the transitional care clinic, but when they’re on an inpatient rotation, they’ll be more mindful of the things that affect patient well-being after discharge.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer based in Oakland, Calif.

Chronic Headache Persists in Children With Head Injury

In a study of children who had traumatic brain injury, almost half of them experienced chronic headache months later.

Moreover, adolescents and girls are particularly likely to develop posttraumatic chronic headache, an "intriguing" pattern which parallels that for migraine and lends "support to the theory that the pathophysiology of posttraumatic headaches after TBI [traumatic brain injury] may share similarities with the pathophysiology" of primary headache disorders such as migraine, said Dr. Heidi K. Blume of the division of pediatric neurology at the University of Washington, Seattle, and her associates.

Given that more than 500,000 children and adolescents are assessed for TBI in hospitals every year in the United States, the study findings indicate that many pediatric patients suffer from TBI-associated chronic headaches, they noted in the report published online Dec. 5 in Pediatrics.

Chronic headaches that affect children "interfere with school, social function, [and] parental productivity, and are associated with poor quality of life," the researchers said.

Until now, little has been known about posttraumatic headache in children because most studies in the pediatric population have been small, retrospective, lacking a control population, or of short duration. Dr. Blume and her colleagues addressed these issues by analyzing data from the Child Health After Injury Study, a large, prospective study with 12 months of follow-up that included a control group of children who had sustained arm injuries (Pediatrics 2011 Dec. 5 [doi:10.1542/peds.2011-1742]).

The investigators determined the prevalence of chronic headache at 3 months and 12 months following mild, moderate, or severe TBI in 512 study subjects and 137 controls aged 5-17 years who were treated in the emergency departments at nine hospitals during an 18-month period. The facilities included two children’s, two university, and six community hospitals.

Postconcussive symptoms were common among children, and women are at higher risk of posttraumatic chronic headache than are men.

The researchers used the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s definition of TBI (a blunt or penetrating injury to the head that was documented in the medical record and was associated with a decreased level of consciousness, amnesia, an objective neurologic or neuropsychological abnormality, and/or an intracranial lesion).

Most TBIs in this study were sustained either in a fall or when the head struck an object; most of the moderate or severe TBIs were sustained in falls or in motor vehicle or bicycle accidents. Similarly, most arm injuries in the control group were sustained in falls.

At 3 months and 12 months after TBI, the subjects’ head pain during the preceding week was assessed by questioning the parents as well as the subjects themselves if they were aged 14 years or older and able to complete a short survey.

At 3 months, the overall prevalence of headache was 43% among children with mild TBI and 37% among those with moderate or severe TBI, compared with 26% among the control subjects.

At 3 months, chronic headache also was significantly more likely to affect adolescents than younger children, and to affect girls rather than boys. The frequency of headache also was elevated in children of all ages in the TBI group at 3 months, but was significantly elevated only in adolescents.

Similarly, serious headache was more common in children of all ages in the mild TBI group than it was in controls at 3 months, but only significantly so in girls, and it became more prevalent with increasing age. For example, the prevalence of serious headache among girls with mild TBI was 7% at age 5-7 years, 20% at age 8-10 years, 29% at age 11-13 years, and 45% at age 14-18 years, the investigators said. The prevalence of serious headache after moderate/severe TBI was significantly greater only for younger children, at 32%.

The findings were different at 12 months after TBI, with chronic headache reported in 41% of children with mild TBI, 34% of those with moderate or severe TBI, and 34% in the control group, which were nonsignificant differences. Girls were found to have a higher prevalence of headache (52%) than were boys (36%), but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

The subgroup of girls with mild TBI had a higher prevalence of severe headache (27%) than did controls (10%) at 12 months. Adolescent girls also reported more frequent headaches and more severe headaches than did adolescent control subjects, but although these differences were "substantial," they did not reach statistical significance because of small sample sizes in these subgroups.

Overall, the study results accord with those of other recent studies reporting that postconcussive symptoms were common among children and that women are at higher risk of posttraumatic chronic headache than are men.

"Although only a fraction of children and adolescents with TBI develop chronic headaches related to their injury, because thousands of children sustain TBI each year, our findings indicate that many children and adolescents suffer from TBI-associated headaches each year," Dr. Blume and her associates said.

This study was limited in that it could not account for the possibility that because of anxiety or cultural expectations about head injuries, parents of children with TBI might be more likely to report headaches – and to rate them as severe or frequent – than were parents of children with arm injuries. In addition, the survey in this study asked about headaches during the preceding week, and may have missed important information about less-frequent but more-significant headaches that occurred outside that 7-day window, the researchers noted.

Dr. Blume and her associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

In a study of children who had traumatic brain injury, almost half of them experienced chronic headache months later.

Moreover, adolescents and girls are particularly likely to develop posttraumatic chronic headache, an "intriguing" pattern which parallels that for migraine and lends "support to the theory that the pathophysiology of posttraumatic headaches after TBI [traumatic brain injury] may share similarities with the pathophysiology" of primary headache disorders such as migraine, said Dr. Heidi K. Blume of the division of pediatric neurology at the University of Washington, Seattle, and her associates.

Given that more than 500,000 children and adolescents are assessed for TBI in hospitals every year in the United States, the study findings indicate that many pediatric patients suffer from TBI-associated chronic headaches, they noted in the report published online Dec. 5 in Pediatrics.

Chronic headaches that affect children "interfere with school, social function, [and] parental productivity, and are associated with poor quality of life," the researchers said.

Until now, little has been known about posttraumatic headache in children because most studies in the pediatric population have been small, retrospective, lacking a control population, or of short duration. Dr. Blume and her colleagues addressed these issues by analyzing data from the Child Health After Injury Study, a large, prospective study with 12 months of follow-up that included a control group of children who had sustained arm injuries (Pediatrics 2011 Dec. 5 [doi:10.1542/peds.2011-1742]).

The investigators determined the prevalence of chronic headache at 3 months and 12 months following mild, moderate, or severe TBI in 512 study subjects and 137 controls aged 5-17 years who were treated in the emergency departments at nine hospitals during an 18-month period. The facilities included two children’s, two university, and six community hospitals.

Postconcussive symptoms were common among children, and women are at higher risk of posttraumatic chronic headache than are men.

The researchers used the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s definition of TBI (a blunt or penetrating injury to the head that was documented in the medical record and was associated with a decreased level of consciousness, amnesia, an objective neurologic or neuropsychological abnormality, and/or an intracranial lesion).

Most TBIs in this study were sustained either in a fall or when the head struck an object; most of the moderate or severe TBIs were sustained in falls or in motor vehicle or bicycle accidents. Similarly, most arm injuries in the control group were sustained in falls.

At 3 months and 12 months after TBI, the subjects’ head pain during the preceding week was assessed by questioning the parents as well as the subjects themselves if they were aged 14 years or older and able to complete a short survey.

At 3 months, the overall prevalence of headache was 43% among children with mild TBI and 37% among those with moderate or severe TBI, compared with 26% among the control subjects.

At 3 months, chronic headache also was significantly more likely to affect adolescents than younger children, and to affect girls rather than boys. The frequency of headache also was elevated in children of all ages in the TBI group at 3 months, but was significantly elevated only in adolescents.

Similarly, serious headache was more common in children of all ages in the mild TBI group than it was in controls at 3 months, but only significantly so in girls, and it became more prevalent with increasing age. For example, the prevalence of serious headache among girls with mild TBI was 7% at age 5-7 years, 20% at age 8-10 years, 29% at age 11-13 years, and 45% at age 14-18 years, the investigators said. The prevalence of serious headache after moderate/severe TBI was significantly greater only for younger children, at 32%.

The findings were different at 12 months after TBI, with chronic headache reported in 41% of children with mild TBI, 34% of those with moderate or severe TBI, and 34% in the control group, which were nonsignificant differences. Girls were found to have a higher prevalence of headache (52%) than were boys (36%), but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

The subgroup of girls with mild TBI had a higher prevalence of severe headache (27%) than did controls (10%) at 12 months. Adolescent girls also reported more frequent headaches and more severe headaches than did adolescent control subjects, but although these differences were "substantial," they did not reach statistical significance because of small sample sizes in these subgroups.

Overall, the study results accord with those of other recent studies reporting that postconcussive symptoms were common among children and that women are at higher risk of posttraumatic chronic headache than are men.

"Although only a fraction of children and adolescents with TBI develop chronic headaches related to their injury, because thousands of children sustain TBI each year, our findings indicate that many children and adolescents suffer from TBI-associated headaches each year," Dr. Blume and her associates said.

This study was limited in that it could not account for the possibility that because of anxiety or cultural expectations about head injuries, parents of children with TBI might be more likely to report headaches – and to rate them as severe or frequent – than were parents of children with arm injuries. In addition, the survey in this study asked about headaches during the preceding week, and may have missed important information about less-frequent but more-significant headaches that occurred outside that 7-day window, the researchers noted.

Dr. Blume and her associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

In a study of children who had traumatic brain injury, almost half of them experienced chronic headache months later.

Moreover, adolescents and girls are particularly likely to develop posttraumatic chronic headache, an "intriguing" pattern which parallels that for migraine and lends "support to the theory that the pathophysiology of posttraumatic headaches after TBI [traumatic brain injury] may share similarities with the pathophysiology" of primary headache disorders such as migraine, said Dr. Heidi K. Blume of the division of pediatric neurology at the University of Washington, Seattle, and her associates.

Given that more than 500,000 children and adolescents are assessed for TBI in hospitals every year in the United States, the study findings indicate that many pediatric patients suffer from TBI-associated chronic headaches, they noted in the report published online Dec. 5 in Pediatrics.

Chronic headaches that affect children "interfere with school, social function, [and] parental productivity, and are associated with poor quality of life," the researchers said.

Until now, little has been known about posttraumatic headache in children because most studies in the pediatric population have been small, retrospective, lacking a control population, or of short duration. Dr. Blume and her colleagues addressed these issues by analyzing data from the Child Health After Injury Study, a large, prospective study with 12 months of follow-up that included a control group of children who had sustained arm injuries (Pediatrics 2011 Dec. 5 [doi:10.1542/peds.2011-1742]).

The investigators determined the prevalence of chronic headache at 3 months and 12 months following mild, moderate, or severe TBI in 512 study subjects and 137 controls aged 5-17 years who were treated in the emergency departments at nine hospitals during an 18-month period. The facilities included two children’s, two university, and six community hospitals.

Postconcussive symptoms were common among children, and women are at higher risk of posttraumatic chronic headache than are men.

The researchers used the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s definition of TBI (a blunt or penetrating injury to the head that was documented in the medical record and was associated with a decreased level of consciousness, amnesia, an objective neurologic or neuropsychological abnormality, and/or an intracranial lesion).

Most TBIs in this study were sustained either in a fall or when the head struck an object; most of the moderate or severe TBIs were sustained in falls or in motor vehicle or bicycle accidents. Similarly, most arm injuries in the control group were sustained in falls.

At 3 months and 12 months after TBI, the subjects’ head pain during the preceding week was assessed by questioning the parents as well as the subjects themselves if they were aged 14 years or older and able to complete a short survey.

At 3 months, the overall prevalence of headache was 43% among children with mild TBI and 37% among those with moderate or severe TBI, compared with 26% among the control subjects.

At 3 months, chronic headache also was significantly more likely to affect adolescents than younger children, and to affect girls rather than boys. The frequency of headache also was elevated in children of all ages in the TBI group at 3 months, but was significantly elevated only in adolescents.

Similarly, serious headache was more common in children of all ages in the mild TBI group than it was in controls at 3 months, but only significantly so in girls, and it became more prevalent with increasing age. For example, the prevalence of serious headache among girls with mild TBI was 7% at age 5-7 years, 20% at age 8-10 years, 29% at age 11-13 years, and 45% at age 14-18 years, the investigators said. The prevalence of serious headache after moderate/severe TBI was significantly greater only for younger children, at 32%.

The findings were different at 12 months after TBI, with chronic headache reported in 41% of children with mild TBI, 34% of those with moderate or severe TBI, and 34% in the control group, which were nonsignificant differences. Girls were found to have a higher prevalence of headache (52%) than were boys (36%), but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

The subgroup of girls with mild TBI had a higher prevalence of severe headache (27%) than did controls (10%) at 12 months. Adolescent girls also reported more frequent headaches and more severe headaches than did adolescent control subjects, but although these differences were "substantial," they did not reach statistical significance because of small sample sizes in these subgroups.

Overall, the study results accord with those of other recent studies reporting that postconcussive symptoms were common among children and that women are at higher risk of posttraumatic chronic headache than are men.

"Although only a fraction of children and adolescents with TBI develop chronic headaches related to their injury, because thousands of children sustain TBI each year, our findings indicate that many children and adolescents suffer from TBI-associated headaches each year," Dr. Blume and her associates said.

This study was limited in that it could not account for the possibility that because of anxiety or cultural expectations about head injuries, parents of children with TBI might be more likely to report headaches – and to rate them as severe or frequent – than were parents of children with arm injuries. In addition, the survey in this study asked about headaches during the preceding week, and may have missed important information about less-frequent but more-significant headaches that occurred outside that 7-day window, the researchers noted.

Dr. Blume and her associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Major Finding: At 3 months after injury, the prevalence of chronic headache was 43% in children with mild TBI and 37% in those with moderate or severe TBI, compared with 26% in those with arm injuries.

Data Source: The Child Health After Injury Study is a prospective cohort study assessing health outcomes after pediatric TBI (512 subjects), compared with a control group of children who sustained arm injuries (137 subjects).

Disclosures: Dr. Blume and her associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

Exporting Science

On a recent visit to the campus of my alma mater, I had a chance to visit some of the biomedical research laboratories. One of those is under the direction of a tenured professor who is making new biodegradable blood vessels the size of a coronary artery that will last long enough to allow for new fibrous tissue to form and replace the degrading substance. Even more exciting is the fact that the new vessel does not initiate an inflammatory reaction, since the vessel lumen will not be a site for platelet activation and in-situ thrombosis.

The professor was just as excited that a venture capitalist had just obtained the license to develop the technology and was about to begin human testing of the vessel in Asia.

Unfortunately, that is where a host of new devices and drugs are being tested.

Compared with the pharmaceutical industry trials, which have used a mixture of domestic and international sites for new drugs research, device trials have used international and particularly European sites for the development of new products. The development of new stents, for instance, was almost exclusive to Europe, and provided this therapy to Europeans far earlier than to Americans. This migration is a result of a more-receptive approval environment and the fact that human testing in Europe and Asia is recruitment for trials is faster and less expensive.

Since 1999, the number of new Premarket Approvals (PMAs) – the Food and Drug Administration’s regulatory process that is required before a novel device with significant patient health risks can get to market – has decrease significantly. In 2000, the FDA approved approximately 60 PMAs; by 2009, the number of approvals had decreased to 15. According to a device industry–supported survey of 176 of 750 potential medical technology companies (FDA Impact on U.S. Medical Technology Innovation, November 2010), the approval process for a PMA was 54 months in the United States and 11 months in Europe. The survey enumerates a number of process problems that confront the FDA, but the major issue noted by the companies surveyed was that the FDA has become much more risk averse and concerned about safety.

The rush to market, of course, is the driving force behind the increased concern of these delays. Venture capitalists that provide the resources for many small device companies see time as money. They are driven more by their desire to get their product to market quickly and they have a limited concern or appreciation for patient safety. Despite the spate of recent safety problems both in cardiology and orthopedics, they tend to minimize the importance of those problems. The safety aspects of many devices may not, of course, be knowable in the short term and not be measurable in the time frame of an 18- or 24-month clinical trial, but may lie in the distant future.

Much of this overseas migration of science is a result of the significantly lower infrastructure costs in Europe and – especially – in Asia. The per-patient costs in India, for instance, are a fraction of what they are in the United States, and the access to patients who can participate in trials is much more easily obtained. This is largely a result of closer physician involvement in the recruiting of patients, and the reluctance of both patients and doctors in the United States to participate in the clinical research trials. Patients hesitate because of a suspicious environment about clinical trials, and doctors are reluctant because they are too busy and are underpaid for their participation. The paradox of this process is that devices and drugs that are tested outside the United States may, because of their cost, be available only to U.S. patients. Whether clinical data obtained in foreign populations are applicable to the U.S. population is also uncertain.

A recent letter from 41 members of Congress, including 6 from Minnesota (which is the U.S. capital of new device companies), has placed increased pressure on the FDA to expedite the approval process and to bring the testing home to the United States ("Members of Minn. delegation urge FDA to speed medical device approvals," Minnesota Independent, Nov. 8, 2011). Of course the return of testing to our shores would be very advantageous to the approval process, but that same acceleration of the process could result in significant patient hazards. The balance between expeditious approval and safety has been an issue that has been going back and forth for the last 20 years, and will continue to be played out in the future.

On a recent visit to the campus of my alma mater, I had a chance to visit some of the biomedical research laboratories. One of those is under the direction of a tenured professor who is making new biodegradable blood vessels the size of a coronary artery that will last long enough to allow for new fibrous tissue to form and replace the degrading substance. Even more exciting is the fact that the new vessel does not initiate an inflammatory reaction, since the vessel lumen will not be a site for platelet activation and in-situ thrombosis.

The professor was just as excited that a venture capitalist had just obtained the license to develop the technology and was about to begin human testing of the vessel in Asia.

Unfortunately, that is where a host of new devices and drugs are being tested.

Compared with the pharmaceutical industry trials, which have used a mixture of domestic and international sites for new drugs research, device trials have used international and particularly European sites for the development of new products. The development of new stents, for instance, was almost exclusive to Europe, and provided this therapy to Europeans far earlier than to Americans. This migration is a result of a more-receptive approval environment and the fact that human testing in Europe and Asia is recruitment for trials is faster and less expensive.

Since 1999, the number of new Premarket Approvals (PMAs) – the Food and Drug Administration’s regulatory process that is required before a novel device with significant patient health risks can get to market – has decrease significantly. In 2000, the FDA approved approximately 60 PMAs; by 2009, the number of approvals had decreased to 15. According to a device industry–supported survey of 176 of 750 potential medical technology companies (FDA Impact on U.S. Medical Technology Innovation, November 2010), the approval process for a PMA was 54 months in the United States and 11 months in Europe. The survey enumerates a number of process problems that confront the FDA, but the major issue noted by the companies surveyed was that the FDA has become much more risk averse and concerned about safety.

The rush to market, of course, is the driving force behind the increased concern of these delays. Venture capitalists that provide the resources for many small device companies see time as money. They are driven more by their desire to get their product to market quickly and they have a limited concern or appreciation for patient safety. Despite the spate of recent safety problems both in cardiology and orthopedics, they tend to minimize the importance of those problems. The safety aspects of many devices may not, of course, be knowable in the short term and not be measurable in the time frame of an 18- or 24-month clinical trial, but may lie in the distant future.

Much of this overseas migration of science is a result of the significantly lower infrastructure costs in Europe and – especially – in Asia. The per-patient costs in India, for instance, are a fraction of what they are in the United States, and the access to patients who can participate in trials is much more easily obtained. This is largely a result of closer physician involvement in the recruiting of patients, and the reluctance of both patients and doctors in the United States to participate in the clinical research trials. Patients hesitate because of a suspicious environment about clinical trials, and doctors are reluctant because they are too busy and are underpaid for their participation. The paradox of this process is that devices and drugs that are tested outside the United States may, because of their cost, be available only to U.S. patients. Whether clinical data obtained in foreign populations are applicable to the U.S. population is also uncertain.

A recent letter from 41 members of Congress, including 6 from Minnesota (which is the U.S. capital of new device companies), has placed increased pressure on the FDA to expedite the approval process and to bring the testing home to the United States ("Members of Minn. delegation urge FDA to speed medical device approvals," Minnesota Independent, Nov. 8, 2011). Of course the return of testing to our shores would be very advantageous to the approval process, but that same acceleration of the process could result in significant patient hazards. The balance between expeditious approval and safety has been an issue that has been going back and forth for the last 20 years, and will continue to be played out in the future.

On a recent visit to the campus of my alma mater, I had a chance to visit some of the biomedical research laboratories. One of those is under the direction of a tenured professor who is making new biodegradable blood vessels the size of a coronary artery that will last long enough to allow for new fibrous tissue to form and replace the degrading substance. Even more exciting is the fact that the new vessel does not initiate an inflammatory reaction, since the vessel lumen will not be a site for platelet activation and in-situ thrombosis.

The professor was just as excited that a venture capitalist had just obtained the license to develop the technology and was about to begin human testing of the vessel in Asia.

Unfortunately, that is where a host of new devices and drugs are being tested.

Compared with the pharmaceutical industry trials, which have used a mixture of domestic and international sites for new drugs research, device trials have used international and particularly European sites for the development of new products. The development of new stents, for instance, was almost exclusive to Europe, and provided this therapy to Europeans far earlier than to Americans. This migration is a result of a more-receptive approval environment and the fact that human testing in Europe and Asia is recruitment for trials is faster and less expensive.

Since 1999, the number of new Premarket Approvals (PMAs) – the Food and Drug Administration’s regulatory process that is required before a novel device with significant patient health risks can get to market – has decrease significantly. In 2000, the FDA approved approximately 60 PMAs; by 2009, the number of approvals had decreased to 15. According to a device industry–supported survey of 176 of 750 potential medical technology companies (FDA Impact on U.S. Medical Technology Innovation, November 2010), the approval process for a PMA was 54 months in the United States and 11 months in Europe. The survey enumerates a number of process problems that confront the FDA, but the major issue noted by the companies surveyed was that the FDA has become much more risk averse and concerned about safety.

The rush to market, of course, is the driving force behind the increased concern of these delays. Venture capitalists that provide the resources for many small device companies see time as money. They are driven more by their desire to get their product to market quickly and they have a limited concern or appreciation for patient safety. Despite the spate of recent safety problems both in cardiology and orthopedics, they tend to minimize the importance of those problems. The safety aspects of many devices may not, of course, be knowable in the short term and not be measurable in the time frame of an 18- or 24-month clinical trial, but may lie in the distant future.

Much of this overseas migration of science is a result of the significantly lower infrastructure costs in Europe and – especially – in Asia. The per-patient costs in India, for instance, are a fraction of what they are in the United States, and the access to patients who can participate in trials is much more easily obtained. This is largely a result of closer physician involvement in the recruiting of patients, and the reluctance of both patients and doctors in the United States to participate in the clinical research trials. Patients hesitate because of a suspicious environment about clinical trials, and doctors are reluctant because they are too busy and are underpaid for their participation. The paradox of this process is that devices and drugs that are tested outside the United States may, because of their cost, be available only to U.S. patients. Whether clinical data obtained in foreign populations are applicable to the U.S. population is also uncertain.

A recent letter from 41 members of Congress, including 6 from Minnesota (which is the U.S. capital of new device companies), has placed increased pressure on the FDA to expedite the approval process and to bring the testing home to the United States ("Members of Minn. delegation urge FDA to speed medical device approvals," Minnesota Independent, Nov. 8, 2011). Of course the return of testing to our shores would be very advantageous to the approval process, but that same acceleration of the process could result in significant patient hazards. The balance between expeditious approval and safety has been an issue that has been going back and forth for the last 20 years, and will continue to be played out in the future.

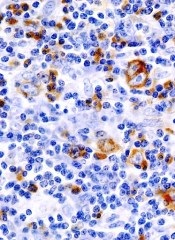

HL drug demonstrates activity and toxicity

A novel agent has shown activity in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), but it can cause severe adverse events and even death at a high dosage.

Researchers found that mocetinostat, an oral isotype-selective histone deacetylase inhibitor, was somewhat effective against HL when given at 85 mg or 110 mg.

However, patients in both treatment arms experienced adverse events, some of which led to treatment discontinuation. And 2 of the 4 deaths that occurred in the 110-mg arm could be attributed to treatment.

Anas Younes, MD, of M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, and his colleagues reported these results in the December print issue of The Lancet Oncology.

Dr Younes’s team began this study by enrolling 51 patients with relapsed or refractory classical HL who were 18 years of age or older. Patients received mocetinostat orally 3 times a week, in 28-day cycles.

Twenty-three patients received 110 mg of the drug, and 28 patients received 85 mg.

The study’s primary outcome was disease control rate. This was defined as complete response, partial response, or stable disease for at least 6 treatment cycles.

In the 110-mg arm, 35% of patients (8/23) met the disease control criteria. In the 85-mg arm, the disease control rate was 25% (7/28).

A total of 12 patients (24%) discontinued treatment due to adverse events. Nine patients discontinued in the 85-mg cohort, as did 3 patients in the 110-mg cohort.

The most frequent grade 3 and 4 adverse events were neutropenia, fatigue, and pneumonia. In the 110-mg arm, 4 patients experienced neutropenia, 5 reported fatigue, and 4 developed pneumonia. In the 85-mg group, 3 patients experienced neutropenia, 3 reported fatigue, and 2 developed pneumonia.

Four patients in the 110-mg arm died, and the researchers said 2 of these deaths may have been related to treatment.

The team therefore concluded that 85 mg of mocetinostat 3 times per week could be a promising treatment option for patients with relapsed or refractory HL.

The researchers received funding from the maker of mocetinostat, MethylGene Inc., of Montreal, Canada, as well as Celgene Corporation, of Summit, New Jersey. ![]()

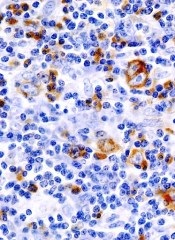

A novel agent has shown activity in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), but it can cause severe adverse events and even death at a high dosage.

Researchers found that mocetinostat, an oral isotype-selective histone deacetylase inhibitor, was somewhat effective against HL when given at 85 mg or 110 mg.

However, patients in both treatment arms experienced adverse events, some of which led to treatment discontinuation. And 2 of the 4 deaths that occurred in the 110-mg arm could be attributed to treatment.

Anas Younes, MD, of M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, and his colleagues reported these results in the December print issue of The Lancet Oncology.

Dr Younes’s team began this study by enrolling 51 patients with relapsed or refractory classical HL who were 18 years of age or older. Patients received mocetinostat orally 3 times a week, in 28-day cycles.

Twenty-three patients received 110 mg of the drug, and 28 patients received 85 mg.

The study’s primary outcome was disease control rate. This was defined as complete response, partial response, or stable disease for at least 6 treatment cycles.

In the 110-mg arm, 35% of patients (8/23) met the disease control criteria. In the 85-mg arm, the disease control rate was 25% (7/28).

A total of 12 patients (24%) discontinued treatment due to adverse events. Nine patients discontinued in the 85-mg cohort, as did 3 patients in the 110-mg cohort.

The most frequent grade 3 and 4 adverse events were neutropenia, fatigue, and pneumonia. In the 110-mg arm, 4 patients experienced neutropenia, 5 reported fatigue, and 4 developed pneumonia. In the 85-mg group, 3 patients experienced neutropenia, 3 reported fatigue, and 2 developed pneumonia.

Four patients in the 110-mg arm died, and the researchers said 2 of these deaths may have been related to treatment.

The team therefore concluded that 85 mg of mocetinostat 3 times per week could be a promising treatment option for patients with relapsed or refractory HL.

The researchers received funding from the maker of mocetinostat, MethylGene Inc., of Montreal, Canada, as well as Celgene Corporation, of Summit, New Jersey. ![]()

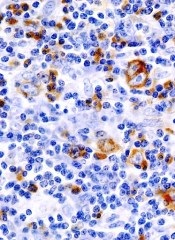

A novel agent has shown activity in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), but it can cause severe adverse events and even death at a high dosage.

Researchers found that mocetinostat, an oral isotype-selective histone deacetylase inhibitor, was somewhat effective against HL when given at 85 mg or 110 mg.

However, patients in both treatment arms experienced adverse events, some of which led to treatment discontinuation. And 2 of the 4 deaths that occurred in the 110-mg arm could be attributed to treatment.

Anas Younes, MD, of M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, and his colleagues reported these results in the December print issue of The Lancet Oncology.

Dr Younes’s team began this study by enrolling 51 patients with relapsed or refractory classical HL who were 18 years of age or older. Patients received mocetinostat orally 3 times a week, in 28-day cycles.

Twenty-three patients received 110 mg of the drug, and 28 patients received 85 mg.

The study’s primary outcome was disease control rate. This was defined as complete response, partial response, or stable disease for at least 6 treatment cycles.

In the 110-mg arm, 35% of patients (8/23) met the disease control criteria. In the 85-mg arm, the disease control rate was 25% (7/28).

A total of 12 patients (24%) discontinued treatment due to adverse events. Nine patients discontinued in the 85-mg cohort, as did 3 patients in the 110-mg cohort.

The most frequent grade 3 and 4 adverse events were neutropenia, fatigue, and pneumonia. In the 110-mg arm, 4 patients experienced neutropenia, 5 reported fatigue, and 4 developed pneumonia. In the 85-mg group, 3 patients experienced neutropenia, 3 reported fatigue, and 2 developed pneumonia.

Four patients in the 110-mg arm died, and the researchers said 2 of these deaths may have been related to treatment.

The team therefore concluded that 85 mg of mocetinostat 3 times per week could be a promising treatment option for patients with relapsed or refractory HL.

The researchers received funding from the maker of mocetinostat, MethylGene Inc., of Montreal, Canada, as well as Celgene Corporation, of Summit, New Jersey. ![]()

Health literacy and medication understanding among hospitalized adults

If you wish to receive credit for this activity, please refer to the website:

Accreditation and Designation Statement

Blackwell Futura Media Services designates this journal‐based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit. Physicians should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Blackwell Futura Media Services is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Educational Objectives

Upon completion of this activity, participants will be better able to:

-

Assess the factors associated with reduced medication adherence.

-

Distinguish which components of medication understanding are assessed by the Medication Understanding Questionnaire.

This manuscript underwent peer review in line with the standards of editorial integrity and publication ethics maintained by Journal of Hospital Medicine. The peer reviewers have no relevant financial relationships. The peer review process for Journal of Hospital Medicine is single‐blinded. As such, the identities of the reviewers are not disclosed in line with the standard accepted practices of medical journal peer review.

Conflicts of interest have been identified and resolved in accordance with Blackwell Futura Media Services's Policy on Activity Disclosure and Conflict of Interest. The primary resolution method used was peer review and review by a non‐conflicted expert.

Instructions on Receiving Credit

For information on applicability and acceptance of CME credit for this activity, please consult your professional licensing board.

This activity is designed to be completed within an hour; physicians should claim only those credits that reflect the time actually spent in the activity. To successfully earn credit, participants must complete the activity during the valid credit period, which is up to two years from initial publication.

Follow these steps to earn credit:

-

Log on to www.wileyblackwellcme.com

-

Read the target audience, learning objectives, and author disclosures.

-

Read the article in print or online format.

-

Reflect on the article.

-

Access the CME Exam, and choose the best answer to each question.

-

Complete the required evaluation component of the activity.

This activity will be available for CME credit for twelve months following its publication date. At that time, it will be reviewed and potentially updated and extended for an additional twelve months.