User login

Pediatric Hospitalist Role in Transition

Optimal health care is achieved when every person at every age receives health care that is medically and developmentally appropriate.1 For healthy patients, medically and developmentally appropriate care is usually available, but for children with special healthcare needs (SHCN), receiving this care can be a challenge that is magnified as a child with SHCN grows into a teenager and then a young adult. For these children, simply transferring care, which is essentially a handoff of responsibility, to adult providers is insufficient to meet the needs of a special healthcare population.1 Transition is the purposeful planned movement of adolescents and young adults with chronic medical conditions and disabilities from pediatric (child‐centered) to adult‐oriented providers and facilities.2

The 2005‐2006 National Survey of Children with SHCN identified 4 component measures of transition which included discussions between the patient and the healthcare provider about: 1) shifting to adult providers, 2) adult healthcare needs, 3) health insurance, and 4) encouraging the patient to take responsibility for his/her care.34 Overall, only 41% of youth with SHCN met the core outcomes.4 The survey also found that those most affected by their health conditions were less likely to have transition discussions compared with less‐affected youth.3

The importance of healthcare transition also resonates with pediatric hospitalists. The results of a 1988 National Health Survey revealed that 4% of all children with SHCN were hospitalized, and 2% of those with severe chronic conditions accounted for 27% of all hospital bed days.5 Or, stated differently, a small percentage of patients are admitted most frequently and stay the longest in the hospital. Further, transition for those with significant cognitive delay was more difficult, because of the lack of adult‐oriented providers who are willing to care for the patient and work collaboratively with the family.6 This has a significant implication for pediatric hospitalists, because it increases the likelihood that a severely affected 21 to 25‐year‐old patient will be admitted to the pediatric hospitalist service having not yet made a successful transition to an adult‐oriented provider.

Clearly, transition of care should have its roots in the outpatient medical home; however, often a patient with a chronic medical condition will spend extended periods of time in the hospital and away from their identified medical home. Although not a widely accepted concept, some may consider the pediatric hospitalist service to be an extension of the medical home for inpatients. The pediatric hospitalist is often the physician who cares for inpatients with SHCN because of their complexity. There are components of the transition process that specifically deal with hospitalization. Pediatric hospitalists should understand transition and their role in it, so that the process does not stop when patients are hospitalized.

Our hypothesis is that pediatric hospitalists are well poised to provide inpatient transition services, but insufficient understanding of the concepts and practical processes related to transition limit involvement. Through this exploratory survey, we hope to understand current attitudes and knowledge about transition. We survey the degree to which pediatric hospitalists want to participate in the process, the level of support that healthcare transition services receive from the institutions in which pediatric hospitalists practice, and potential barriers and benefits of their participation.

METHODS

Participants

After a review of current literature, we developed an exploratory survey for pediatric hospitalists that was approved by our institutional review board, and was reviewed for content and face validity by a qualitative expert on transition of care. Using Survey Monkey, the survey was piloted with a small group of pediatric hospitalists for feedback regarding the clarity of the survey questions before it was introduced to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)/Pediatric Hospital Medicine Listserv. The Listserv is available to any pediatric hospitalist that joins. The exact number of pediatric hospitalists is unknown. A reasonable approximation of Listserv members at the time the survey was introduced is 1800. A fraction of that number is active on the Listserv, as defined by multiple postings during the course of an academic year. Pediatric hospitalists were the targeted group because of their expertise in the care of the adolescent and, often, young adult, with SHCN. The survey was voluntary and anonymous, and was reintroduced 3 times to capture as many participants as possible. The purpose of the survey was to gauge the interest, attitudes, and understanding of healthcare transition in a cross section of pediatric hospitalists.

Definitions

For clarity, in this survey, transfer is defined as an event, a handoff of responsibility for the management of a patient from one physician to another. Transition is defined as the purposeful planned movement of adolescents and young adults, with chronic medical conditions and disabilities, from pediatric (child‐centered) to adult‐oriented providers and facilities.2

Survey

This questionnaire contained 33 items and included a mixture of open‐ended questions, yes and no questions, and questions with responses that used a modified Likert scale. The survey questions were not adapted from another study or survey; they were developed in conjunction with 2 well‐published experts on the subject of transition. The demographic questions were used to help determine whether patterns related to transition services and knowledge could be detected based on age, gender, or type of practice, whether academic or community. The survey content included several areas: 1) Who is responsible for the care of young adults and adolescents; 2) Hospital‐based transition services; 3) Benefits or challenges for pediatric hospitalists who become involved in health care transition (HCT); 4) Knowledge of HCT and education opportunities. Informed consent was the first page; if consent was obtained, the participant could move forward in the survey (Table 1).

| Who is primarily responsible for inpatient care of patients 16‐21? |

| Please rate your knowledge of healthcare transition. |

| Are there healthcare transition services in your hospital? |

| How old are patients when they first receive inpatient‐oriented healthcare transition services? |

| How beneficial are these services to the patient and the provider if available? |

| Does your hospital have a policy that mandates the age by which an adolescent/young adult patient must be transferred from Pediatrics to adult providers and facilities? |

| What factors determine age of transfer? |

| How big a problem is it transferring adolescent/young adult patients from Pediatrics to adult providers and facilities? |

| How prepared are adolescents and young adults in your institution for transition to adult services? |

| Should pediatric hospitalists be involved in providing healthcare transition services and supports to patients with chronic healthcare conditions in the inpatient setting? |

| How often have you been asked by a subspecialist to provide healthcare transition services and supports to patients with chronic health conditions in the inpatient setting? |

| Who is best qualified to provide healthcare transition services? |

| What are the biggest impediments and benefits to hospitalist involvement in healthcare transition services? |

| If there was an online educational training module about healthcare transitions, would you take it? |

RESULTS

There were 131 participants who consented to participate in, and completed, the survey.

Demographics

Of all participants, 42.5% identified their primary practice site as a pediatric hospital; 40.8% identified their primary practice setting as a children's hospital within a general hospital, and 15.8% identified their primary practice setting as a general hospital with pediatric beds but no designation as a children's hospital. The participants came from nearly every state in the United States; 69.2% were women and 30.8% were men. The ages ranged from 27 to 67, with the majority of participants in their mid‐30s and 40s. Most were boarded in Pediatrics and/or Internal Medicine with some subspecialties such as Physical Medical and Rehabilitation, Cardiology, Critical Care, Pulmonology, and Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics represented. Although the sample size is small, it is representative of the larger population of pediatric hospitalists. There were no patterns detected based on demographics relative to the knowledge or participation in healthcare transition (Table 2).

| Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|

| Age range | 3267 years | 2761 years |

| Boarded in Pediatrics/Pediatric subspecialty | 92% | 99% |

| Practice setting | ||

| Pediatric hospital | 51.4% | 38.6% |

| General hospital with a pediatric hospital within it | 27% | 47% |

| General hospital with pediatric beds but no children's hospital designation | 21.6% | 13.3% |

| Other | 8.1% | 7.2% |

Which Groups of Physicians Are Caring for Adolescent and Young Adult Patients?

Establishing whether pediatric subspecialists, adult providers, or pediatric hospitalists are the primary caregivers for adolescents and young adults with SCHN is important to determine whether the pediatric hospitalist is really well poised to deal with transition issues. If the pediatric hospitalist does not care for these patients, then developing modules to educate them about healthcare transition may not be necessary. As expected, pediatric hospitalists believe they care for adolescent and young adult patients with special healthcare needs in the vast majority of cases. Table 3 illustrates in more detail who is specifically responsible for their care.

| Patient Age | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1617 | 1820 | |

| ||

| Inpatient care provider | ||

| Pediatric hospitalist | 70.1%* | 36.8% |

| Adult hospitalist | 0.9% | 27.4% |

| Pediatric subspecialist | 27.4% | 25.6% |

| Adult subspecialist | 0.9% | 2.6% |

| Other/not sure | 7.7% | 0.9% |

Knowledge of Healthcare Transition

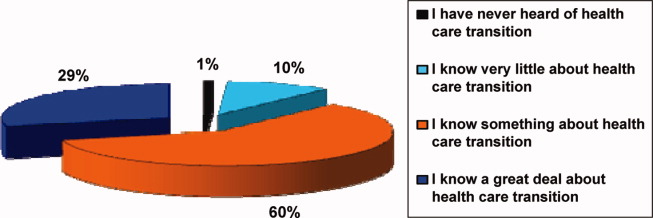

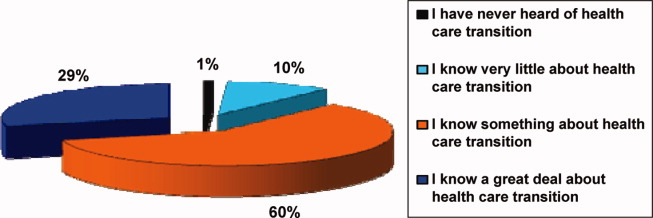

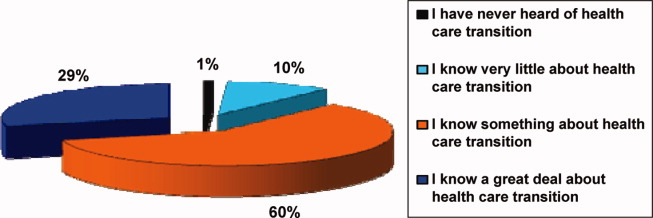

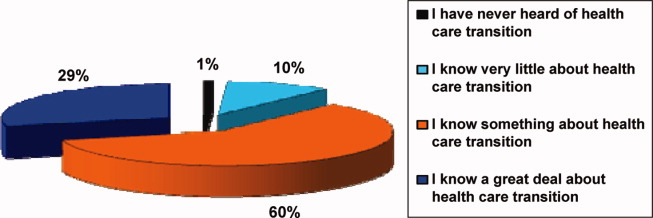

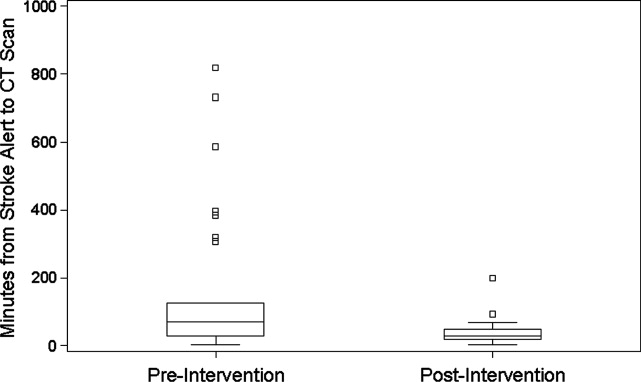

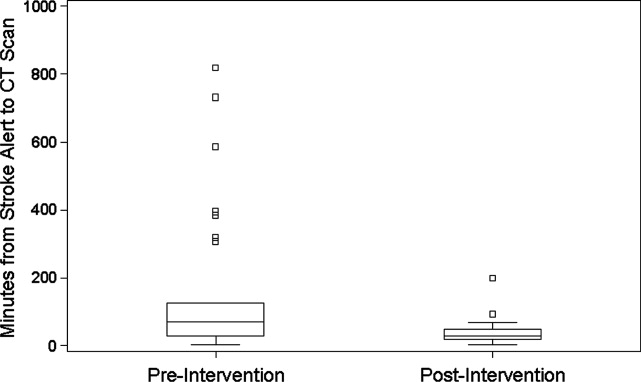

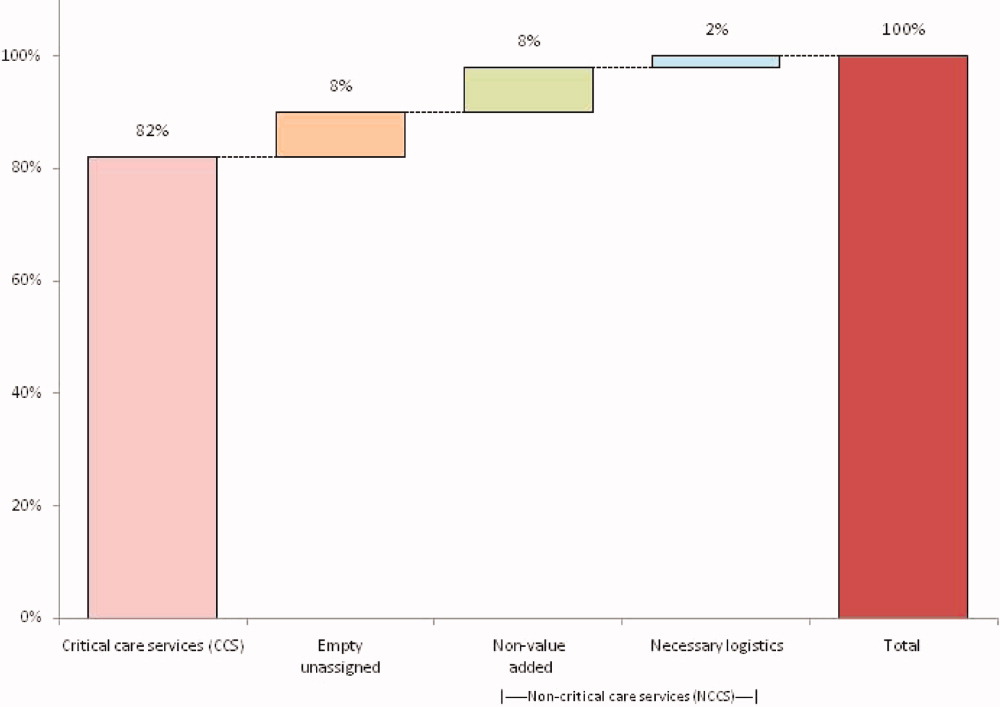

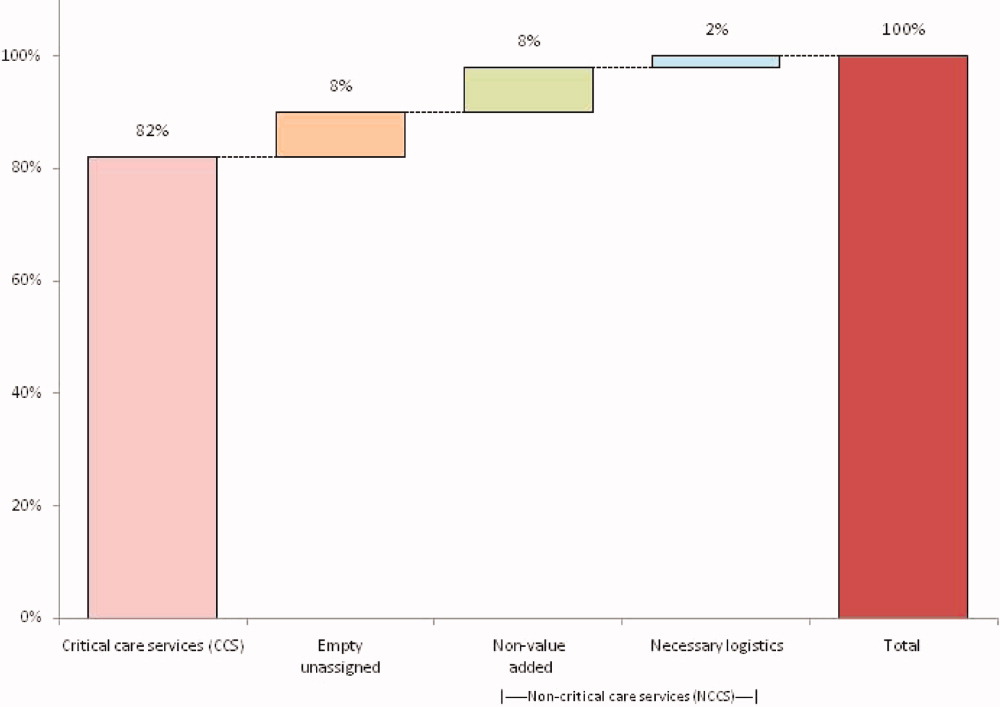

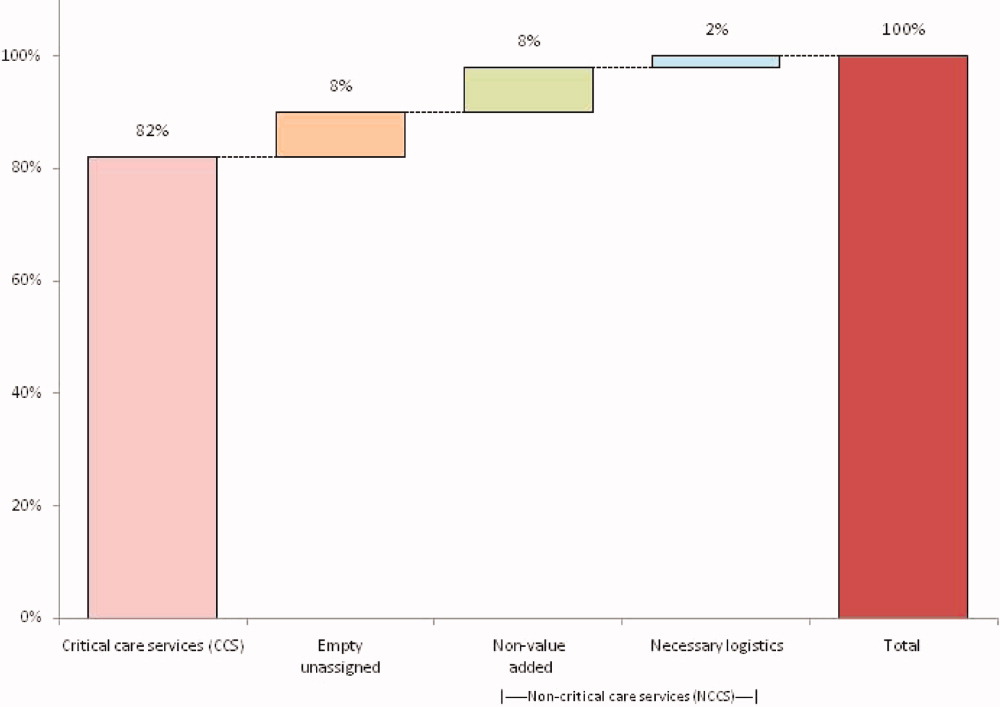

Participants in the survey were provided definitions of healthcare transition; they were asked to rate their knowledge of healthcare transition on a modified Likert scale, given the definition provided. The results can be seen in Figure 1.

Transition Programs

Of all participants, 60.9% did not know if their hospital had inpatient‐oriented healthcare transition services. Another 27.8% only had informal or unstructured services for some patients with a chronic condition, and less than 1% of all respondents said they had a formal or structured program at their institution for inpatients with any chronic medical condition. Eighty percent thought transferring adolescent or young adult patients from pediatric to adult providers was a moderate to major problem.

Of those who responded to the survey, 97.6% feel that inpatient‐oriented healthcare transition services would be beneficial to adolescent and young adult patients, and 92.2% felt that these supports would be beneficial to pediatric providers. This is consistent with the data from another question in which respondents felt that only 1% of patients were quite a bit prepared for transition to inpatient adult providers, and that over half were only a little bit or not at all prepared.

Institutional Mandates

Nearly 40% of institutions have a mandated age by which adolescent and young adult patients must be transferred to adult providers and facilities. Additionally, only 5.2% of those institutions have a written procedure or protocol that describes how these pediatric patients will be transferred to adult providers and institutions.

Pediatric Hospitalist Participation in Transition

Sixty‐eight percent of respondents believe that the patient's primary care provider is the most qualified to discuss healthcare transition issues, followed by their pediatric subspecialists. However, more than 75% of respondents agree or strongly agree that pediatric hospitalists should be involved in providing healthcare transition services and supports to inpatients with chronic health conditions. Please refer to Table 4. Despite this, 58% of pediatric hospitalists are rarely, if ever, asked to participate in healthcare transition by their subspecialist counterparts.

| Respondents, % (No.) | |

|---|---|

| Strongly agree | 28.6 (28) |

| Agree | 50.0 (49) |

| Neither agree or disagree | 12.2 (12) |

| Disagree | 6.1 (6) |

| Strongly disagree | 3.1 (3) |

Barriers to Pediatric Hospitalist Participation in Transition

The survey participants were given a list of potential barriers to participation in healthcare transition and were asked to rank 3 of the choices in order of significance, with 1 being the biggest perceived impediment and 3 being the least significant. Seventeen percent ranked lack of familiarity with healthcare transition resources as the biggest barrier in their setting. Thirteen percent indicated that lack of support from pediatric and adult subspecialists is the major barrier, and 13% felt that insufficient time to provide transition services and supports would be the most significant barrier to their participation in transition. Interestingly, billing and reimbursement issues were not seen as obstacles (see Supporting Information 1/Table 5 in the online version of this article).

Advantages to Pediatric Hospitalist Participation in Transition

The participants were given a set of potential benefits that might result from the pediatric hospitalist participation in transition of care. They were asked to rank 3 of the choices in order of importance, with 1 being the most important positive outcome to 3 being a lesser, but still positive, outcome. Twenty‐three percent of respondents ranked improved communication between pediatric and adult providers and facilities as being the most significant advantage. Twenty‐one percent ranked both better continuity of care in the inpatient setting, and better quality of care for adolescents and young adults with chronic healthcare conditions, as the most important potential advantages of pediatric hospitalist involvement in healthcare transition. However, most felt that improved cost effectiveness would not be an important result (see Supporting Information 2/Table 6 in the online version of this article).

Educational Process

If an educational module was offered, over half of the respondents would definitely or probably take the training, and another 22% might take the training.

LIMITATIONS

This is an exploratory study which is limited by the small number of participants. Although the demographics of the participants include both young and experienced hospitalists, as well as academic and community institutions, it is difficult to determine whether the results are truly representative of the larger pediatric hospitalist population. The survey was also too long which may have deterred participation. Given the lack of experience and literature on pediatric hospitalist involvement in transition of care, it is difficult to construct a concise survey that addresses all of the concerns of the diverse hospitalist population. This is a new area of exploration for pediatric hospitalists, and ideally new questions will arise out of these preliminary findings, despite the limitations in the survey. Future surveys should focus on singular issues related to transition, and every attempt should be made to increase participation in the survey.

DISCUSSION

The survey demonstrates that the majority of the pediatric hospitalists believe providing transition services is important, but that transition programs are, for all practical purposes, nonexistent. Hospitalists believe the primary care doctor or the subspecialists should direct the transition process, but most clearly believe that their participation in the process would be beneficial for their patients, as evidenced by a 97.6% positive response to that question in the survey. Transition of care should be handled predominantly in the medical home.1 At this point, there is no literature that describes a pediatric hospitalist service as an inpatient medical home. However, pediatric hospitalists, not pediatric subspecialists, care for the majority of patients with SHCN in the transition age range while they are hospitalized; therefore, continuing the transition discussion while a patient is hospitalized may be a key component to its success. Better quality and continuity of care for the inpatient with SHCN is a potential advantage, as is coordination of services. Having the support of the pediatric subspecialists and the pediatric primary care provider is not only important, but it is critical in successful transition. Further, most pediatric hospitalists identify transfer of pediatric patients to adult providers as a major problem, and the perception is that only 1% of patients are adequately prepared for this transfer of care. Few institutions have a formalized process by which patients are transferred to adult care providers; however, many institutions have a mandated age at which they expect transfer of care to occur.

The literature about transition of care highlights the issues in the outpatient setting. Reiss and Gibson used focus groups comprised of caregivers, and youth and young adults with SHCN, to explore the issues related to transition of care.7 They identified several factors associated with successful transition that are pertinent to inpatient pediatrics. Involving the patient as a responsible member of the treatment team is important because it fosters independence and problem solving.7 Advocating this in the inpatient setting gives the patient and caregivers confidence that the patient can participate in the healthcare process, thereby making it a habit.7 A second important factor is attending to the patient's personal preferences and interpersonal dynamics.7 Many adolescents and young adult patients prefer to be cared for by their pediatric providers on adult wards away from crying infants and children.7 This may be their first indication that they'd like to explore the adult medical world.7

Pediatric hospitalists should be prepared to meet the needs of adolescent and young adult patients with SCHN by becoming familiar with the components of the transition process. Saidi and Kovacs provide a checklist of practical transition strategies that are helpful to review, and many are quite pertinent to the practice of pediatric hospital medicine.8 Education is a fundamental aspect of the identity of the pediatric hospitalist and is also the foundation of the transition process. Identifying established institutional transition resources, developing educational tools for faculty and residents to learn about transition, as well as adapting the transition checklist to inpatient needs are useful tools for developing a culture of effective healthcare transition. Simple strategies, such as speaking to young patients on their own, and displaying a public commitment to transition are other easy changes that can be made to the everyday activities of the pediatric hospitalist.8

Other key issues that would be important for the pediatric hospitalist to address are the adolescents' understanding of his/her disease, current treatments, long‐term complications, and the impact of healthy and unhealthy behaviors.9 Because these issues can directly affect his/her hospitalization, the pediatric hospitalist should play a role in discussing these issues and reaffirming their importance in the overall health of the patient. This affirmation will also support the process of transition, and will give further confidence to the patient and family that the patient is becoming a responsible member of the healthcare team.

Many of the strategies espoused by experts in transition are part of what the pediatric hospitalist does regularly. The pediatric hospitalist is a resource for patients, families, and subspecialists, because of their comfort and expertise managing complex pediatric patients and because of their understanding of the hospital and how it functions. The process of transition of care should be part of what pediatric hospitalists are prepared to teach, because of the numbers of adolescent and young adult patients that are in their care. The current knowledge base for most pediatric hospitalists seems to be a basic understanding of what transition of care means, but little knowledge about how to go about engaging in the process. More and more transition is relevant to primary care doctors and hospitalists, as the medically complex patient survives into adolescence and adulthood.

CONCLUSION

The survey provides a snapshot of the current attitudes and beliefs of pediatric hospitalists relative to involvement in healthcare transition. This article addresses what we believe to be important questions for the pediatric hospitalist to ask, prior to becoming involved in healthcare transition. Our hypothesis, that pediatric hospitalists are well poised to provide inpatient transition services but are limited by lack of understanding of the concepts and process, is supported by the responses in the survey which show that pediatric hospitalists are interested in participating in healthcare transition but feel impeded by time, support, and understanding of the process of transition. A larger sample size is needed to strengthen the data and lend support to these observations. Additionally, more research to compare current models of transition services and a hospitalist model could be important in realizing the potential positive outcomes predicted in this survey. Education and resources for transition of care are inadequate. Targeted educational modules might provide a foundation for pediatric hospitalists to build their scope of practice to include transition services. The next step for interested pediatric hospitalists might be developing a web‐based module that addresses the unique needs of the inpatient provider and the chronically ill pediatric patient who spends a great deal of time as an inpatient. The measurable outcomes for such an intervention might well be the feeling of preparation that the family and patient have as they move into the adult provider world.

- A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs.Pediatrics.2002;110(6 pt 2):1304–1306.

- ,,,,,.Perceptions of transitional care needs and experiences in pediatric heart transplant recipients.Am J Transplant.2009;9(3):614–619.

- ,,,,,.Planning for health care transitions: results from the 2005–2006 National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs.Pediatrics.2009;123(1):e145–e152.

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau.The National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs, Chartbook 2005–2006.Rockville, MD:US Department of Health and Human Services;2008.

- ,,,,,.Changes in hospitalization patterns among patients with congenital heart disease during the transition from adolescence to adulthood.J Am Coll Cardiol.2007;49(8):875–882.

- ,,.Health care transition: youth, family, and provider perspectives.Pediatrics.2005;115(1):112–120.

- ,.Health care transition: destinations unknown.Pediatrics.2002;110(6 pt 2):1307–1314.

- ,.Developing a transition program from pediatric‐ to adult‐focused cardiology care: practical considerations.Congenit Heart Dis.2009;4(4):204–215.

- .Transition for youth with chronic conditions: primary care physicians' approaches.Pediatrics.2002;110(6 pt 2):1315–1321.

Optimal health care is achieved when every person at every age receives health care that is medically and developmentally appropriate.1 For healthy patients, medically and developmentally appropriate care is usually available, but for children with special healthcare needs (SHCN), receiving this care can be a challenge that is magnified as a child with SHCN grows into a teenager and then a young adult. For these children, simply transferring care, which is essentially a handoff of responsibility, to adult providers is insufficient to meet the needs of a special healthcare population.1 Transition is the purposeful planned movement of adolescents and young adults with chronic medical conditions and disabilities from pediatric (child‐centered) to adult‐oriented providers and facilities.2

The 2005‐2006 National Survey of Children with SHCN identified 4 component measures of transition which included discussions between the patient and the healthcare provider about: 1) shifting to adult providers, 2) adult healthcare needs, 3) health insurance, and 4) encouraging the patient to take responsibility for his/her care.34 Overall, only 41% of youth with SHCN met the core outcomes.4 The survey also found that those most affected by their health conditions were less likely to have transition discussions compared with less‐affected youth.3

The importance of healthcare transition also resonates with pediatric hospitalists. The results of a 1988 National Health Survey revealed that 4% of all children with SHCN were hospitalized, and 2% of those with severe chronic conditions accounted for 27% of all hospital bed days.5 Or, stated differently, a small percentage of patients are admitted most frequently and stay the longest in the hospital. Further, transition for those with significant cognitive delay was more difficult, because of the lack of adult‐oriented providers who are willing to care for the patient and work collaboratively with the family.6 This has a significant implication for pediatric hospitalists, because it increases the likelihood that a severely affected 21 to 25‐year‐old patient will be admitted to the pediatric hospitalist service having not yet made a successful transition to an adult‐oriented provider.

Clearly, transition of care should have its roots in the outpatient medical home; however, often a patient with a chronic medical condition will spend extended periods of time in the hospital and away from their identified medical home. Although not a widely accepted concept, some may consider the pediatric hospitalist service to be an extension of the medical home for inpatients. The pediatric hospitalist is often the physician who cares for inpatients with SHCN because of their complexity. There are components of the transition process that specifically deal with hospitalization. Pediatric hospitalists should understand transition and their role in it, so that the process does not stop when patients are hospitalized.

Our hypothesis is that pediatric hospitalists are well poised to provide inpatient transition services, but insufficient understanding of the concepts and practical processes related to transition limit involvement. Through this exploratory survey, we hope to understand current attitudes and knowledge about transition. We survey the degree to which pediatric hospitalists want to participate in the process, the level of support that healthcare transition services receive from the institutions in which pediatric hospitalists practice, and potential barriers and benefits of their participation.

METHODS

Participants

After a review of current literature, we developed an exploratory survey for pediatric hospitalists that was approved by our institutional review board, and was reviewed for content and face validity by a qualitative expert on transition of care. Using Survey Monkey, the survey was piloted with a small group of pediatric hospitalists for feedback regarding the clarity of the survey questions before it was introduced to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)/Pediatric Hospital Medicine Listserv. The Listserv is available to any pediatric hospitalist that joins. The exact number of pediatric hospitalists is unknown. A reasonable approximation of Listserv members at the time the survey was introduced is 1800. A fraction of that number is active on the Listserv, as defined by multiple postings during the course of an academic year. Pediatric hospitalists were the targeted group because of their expertise in the care of the adolescent and, often, young adult, with SHCN. The survey was voluntary and anonymous, and was reintroduced 3 times to capture as many participants as possible. The purpose of the survey was to gauge the interest, attitudes, and understanding of healthcare transition in a cross section of pediatric hospitalists.

Definitions

For clarity, in this survey, transfer is defined as an event, a handoff of responsibility for the management of a patient from one physician to another. Transition is defined as the purposeful planned movement of adolescents and young adults, with chronic medical conditions and disabilities, from pediatric (child‐centered) to adult‐oriented providers and facilities.2

Survey

This questionnaire contained 33 items and included a mixture of open‐ended questions, yes and no questions, and questions with responses that used a modified Likert scale. The survey questions were not adapted from another study or survey; they were developed in conjunction with 2 well‐published experts on the subject of transition. The demographic questions were used to help determine whether patterns related to transition services and knowledge could be detected based on age, gender, or type of practice, whether academic or community. The survey content included several areas: 1) Who is responsible for the care of young adults and adolescents; 2) Hospital‐based transition services; 3) Benefits or challenges for pediatric hospitalists who become involved in health care transition (HCT); 4) Knowledge of HCT and education opportunities. Informed consent was the first page; if consent was obtained, the participant could move forward in the survey (Table 1).

| Who is primarily responsible for inpatient care of patients 16‐21? |

| Please rate your knowledge of healthcare transition. |

| Are there healthcare transition services in your hospital? |

| How old are patients when they first receive inpatient‐oriented healthcare transition services? |

| How beneficial are these services to the patient and the provider if available? |

| Does your hospital have a policy that mandates the age by which an adolescent/young adult patient must be transferred from Pediatrics to adult providers and facilities? |

| What factors determine age of transfer? |

| How big a problem is it transferring adolescent/young adult patients from Pediatrics to adult providers and facilities? |

| How prepared are adolescents and young adults in your institution for transition to adult services? |

| Should pediatric hospitalists be involved in providing healthcare transition services and supports to patients with chronic healthcare conditions in the inpatient setting? |

| How often have you been asked by a subspecialist to provide healthcare transition services and supports to patients with chronic health conditions in the inpatient setting? |

| Who is best qualified to provide healthcare transition services? |

| What are the biggest impediments and benefits to hospitalist involvement in healthcare transition services? |

| If there was an online educational training module about healthcare transitions, would you take it? |

RESULTS

There were 131 participants who consented to participate in, and completed, the survey.

Demographics

Of all participants, 42.5% identified their primary practice site as a pediatric hospital; 40.8% identified their primary practice setting as a children's hospital within a general hospital, and 15.8% identified their primary practice setting as a general hospital with pediatric beds but no designation as a children's hospital. The participants came from nearly every state in the United States; 69.2% were women and 30.8% were men. The ages ranged from 27 to 67, with the majority of participants in their mid‐30s and 40s. Most were boarded in Pediatrics and/or Internal Medicine with some subspecialties such as Physical Medical and Rehabilitation, Cardiology, Critical Care, Pulmonology, and Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics represented. Although the sample size is small, it is representative of the larger population of pediatric hospitalists. There were no patterns detected based on demographics relative to the knowledge or participation in healthcare transition (Table 2).

| Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|

| Age range | 3267 years | 2761 years |

| Boarded in Pediatrics/Pediatric subspecialty | 92% | 99% |

| Practice setting | ||

| Pediatric hospital | 51.4% | 38.6% |

| General hospital with a pediatric hospital within it | 27% | 47% |

| General hospital with pediatric beds but no children's hospital designation | 21.6% | 13.3% |

| Other | 8.1% | 7.2% |

Which Groups of Physicians Are Caring for Adolescent and Young Adult Patients?

Establishing whether pediatric subspecialists, adult providers, or pediatric hospitalists are the primary caregivers for adolescents and young adults with SCHN is important to determine whether the pediatric hospitalist is really well poised to deal with transition issues. If the pediatric hospitalist does not care for these patients, then developing modules to educate them about healthcare transition may not be necessary. As expected, pediatric hospitalists believe they care for adolescent and young adult patients with special healthcare needs in the vast majority of cases. Table 3 illustrates in more detail who is specifically responsible for their care.

| Patient Age | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1617 | 1820 | |

| ||

| Inpatient care provider | ||

| Pediatric hospitalist | 70.1%* | 36.8% |

| Adult hospitalist | 0.9% | 27.4% |

| Pediatric subspecialist | 27.4% | 25.6% |

| Adult subspecialist | 0.9% | 2.6% |

| Other/not sure | 7.7% | 0.9% |

Knowledge of Healthcare Transition

Participants in the survey were provided definitions of healthcare transition; they were asked to rate their knowledge of healthcare transition on a modified Likert scale, given the definition provided. The results can be seen in Figure 1.

Transition Programs

Of all participants, 60.9% did not know if their hospital had inpatient‐oriented healthcare transition services. Another 27.8% only had informal or unstructured services for some patients with a chronic condition, and less than 1% of all respondents said they had a formal or structured program at their institution for inpatients with any chronic medical condition. Eighty percent thought transferring adolescent or young adult patients from pediatric to adult providers was a moderate to major problem.

Of those who responded to the survey, 97.6% feel that inpatient‐oriented healthcare transition services would be beneficial to adolescent and young adult patients, and 92.2% felt that these supports would be beneficial to pediatric providers. This is consistent with the data from another question in which respondents felt that only 1% of patients were quite a bit prepared for transition to inpatient adult providers, and that over half were only a little bit or not at all prepared.

Institutional Mandates

Nearly 40% of institutions have a mandated age by which adolescent and young adult patients must be transferred to adult providers and facilities. Additionally, only 5.2% of those institutions have a written procedure or protocol that describes how these pediatric patients will be transferred to adult providers and institutions.

Pediatric Hospitalist Participation in Transition

Sixty‐eight percent of respondents believe that the patient's primary care provider is the most qualified to discuss healthcare transition issues, followed by their pediatric subspecialists. However, more than 75% of respondents agree or strongly agree that pediatric hospitalists should be involved in providing healthcare transition services and supports to inpatients with chronic health conditions. Please refer to Table 4. Despite this, 58% of pediatric hospitalists are rarely, if ever, asked to participate in healthcare transition by their subspecialist counterparts.

| Respondents, % (No.) | |

|---|---|

| Strongly agree | 28.6 (28) |

| Agree | 50.0 (49) |

| Neither agree or disagree | 12.2 (12) |

| Disagree | 6.1 (6) |

| Strongly disagree | 3.1 (3) |

Barriers to Pediatric Hospitalist Participation in Transition

The survey participants were given a list of potential barriers to participation in healthcare transition and were asked to rank 3 of the choices in order of significance, with 1 being the biggest perceived impediment and 3 being the least significant. Seventeen percent ranked lack of familiarity with healthcare transition resources as the biggest barrier in their setting. Thirteen percent indicated that lack of support from pediatric and adult subspecialists is the major barrier, and 13% felt that insufficient time to provide transition services and supports would be the most significant barrier to their participation in transition. Interestingly, billing and reimbursement issues were not seen as obstacles (see Supporting Information 1/Table 5 in the online version of this article).

Advantages to Pediatric Hospitalist Participation in Transition

The participants were given a set of potential benefits that might result from the pediatric hospitalist participation in transition of care. They were asked to rank 3 of the choices in order of importance, with 1 being the most important positive outcome to 3 being a lesser, but still positive, outcome. Twenty‐three percent of respondents ranked improved communication between pediatric and adult providers and facilities as being the most significant advantage. Twenty‐one percent ranked both better continuity of care in the inpatient setting, and better quality of care for adolescents and young adults with chronic healthcare conditions, as the most important potential advantages of pediatric hospitalist involvement in healthcare transition. However, most felt that improved cost effectiveness would not be an important result (see Supporting Information 2/Table 6 in the online version of this article).

Educational Process

If an educational module was offered, over half of the respondents would definitely or probably take the training, and another 22% might take the training.

LIMITATIONS

This is an exploratory study which is limited by the small number of participants. Although the demographics of the participants include both young and experienced hospitalists, as well as academic and community institutions, it is difficult to determine whether the results are truly representative of the larger pediatric hospitalist population. The survey was also too long which may have deterred participation. Given the lack of experience and literature on pediatric hospitalist involvement in transition of care, it is difficult to construct a concise survey that addresses all of the concerns of the diverse hospitalist population. This is a new area of exploration for pediatric hospitalists, and ideally new questions will arise out of these preliminary findings, despite the limitations in the survey. Future surveys should focus on singular issues related to transition, and every attempt should be made to increase participation in the survey.

DISCUSSION

The survey demonstrates that the majority of the pediatric hospitalists believe providing transition services is important, but that transition programs are, for all practical purposes, nonexistent. Hospitalists believe the primary care doctor or the subspecialists should direct the transition process, but most clearly believe that their participation in the process would be beneficial for their patients, as evidenced by a 97.6% positive response to that question in the survey. Transition of care should be handled predominantly in the medical home.1 At this point, there is no literature that describes a pediatric hospitalist service as an inpatient medical home. However, pediatric hospitalists, not pediatric subspecialists, care for the majority of patients with SHCN in the transition age range while they are hospitalized; therefore, continuing the transition discussion while a patient is hospitalized may be a key component to its success. Better quality and continuity of care for the inpatient with SHCN is a potential advantage, as is coordination of services. Having the support of the pediatric subspecialists and the pediatric primary care provider is not only important, but it is critical in successful transition. Further, most pediatric hospitalists identify transfer of pediatric patients to adult providers as a major problem, and the perception is that only 1% of patients are adequately prepared for this transfer of care. Few institutions have a formalized process by which patients are transferred to adult care providers; however, many institutions have a mandated age at which they expect transfer of care to occur.

The literature about transition of care highlights the issues in the outpatient setting. Reiss and Gibson used focus groups comprised of caregivers, and youth and young adults with SHCN, to explore the issues related to transition of care.7 They identified several factors associated with successful transition that are pertinent to inpatient pediatrics. Involving the patient as a responsible member of the treatment team is important because it fosters independence and problem solving.7 Advocating this in the inpatient setting gives the patient and caregivers confidence that the patient can participate in the healthcare process, thereby making it a habit.7 A second important factor is attending to the patient's personal preferences and interpersonal dynamics.7 Many adolescents and young adult patients prefer to be cared for by their pediatric providers on adult wards away from crying infants and children.7 This may be their first indication that they'd like to explore the adult medical world.7

Pediatric hospitalists should be prepared to meet the needs of adolescent and young adult patients with SCHN by becoming familiar with the components of the transition process. Saidi and Kovacs provide a checklist of practical transition strategies that are helpful to review, and many are quite pertinent to the practice of pediatric hospital medicine.8 Education is a fundamental aspect of the identity of the pediatric hospitalist and is also the foundation of the transition process. Identifying established institutional transition resources, developing educational tools for faculty and residents to learn about transition, as well as adapting the transition checklist to inpatient needs are useful tools for developing a culture of effective healthcare transition. Simple strategies, such as speaking to young patients on their own, and displaying a public commitment to transition are other easy changes that can be made to the everyday activities of the pediatric hospitalist.8

Other key issues that would be important for the pediatric hospitalist to address are the adolescents' understanding of his/her disease, current treatments, long‐term complications, and the impact of healthy and unhealthy behaviors.9 Because these issues can directly affect his/her hospitalization, the pediatric hospitalist should play a role in discussing these issues and reaffirming their importance in the overall health of the patient. This affirmation will also support the process of transition, and will give further confidence to the patient and family that the patient is becoming a responsible member of the healthcare team.

Many of the strategies espoused by experts in transition are part of what the pediatric hospitalist does regularly. The pediatric hospitalist is a resource for patients, families, and subspecialists, because of their comfort and expertise managing complex pediatric patients and because of their understanding of the hospital and how it functions. The process of transition of care should be part of what pediatric hospitalists are prepared to teach, because of the numbers of adolescent and young adult patients that are in their care. The current knowledge base for most pediatric hospitalists seems to be a basic understanding of what transition of care means, but little knowledge about how to go about engaging in the process. More and more transition is relevant to primary care doctors and hospitalists, as the medically complex patient survives into adolescence and adulthood.

CONCLUSION

The survey provides a snapshot of the current attitudes and beliefs of pediatric hospitalists relative to involvement in healthcare transition. This article addresses what we believe to be important questions for the pediatric hospitalist to ask, prior to becoming involved in healthcare transition. Our hypothesis, that pediatric hospitalists are well poised to provide inpatient transition services but are limited by lack of understanding of the concepts and process, is supported by the responses in the survey which show that pediatric hospitalists are interested in participating in healthcare transition but feel impeded by time, support, and understanding of the process of transition. A larger sample size is needed to strengthen the data and lend support to these observations. Additionally, more research to compare current models of transition services and a hospitalist model could be important in realizing the potential positive outcomes predicted in this survey. Education and resources for transition of care are inadequate. Targeted educational modules might provide a foundation for pediatric hospitalists to build their scope of practice to include transition services. The next step for interested pediatric hospitalists might be developing a web‐based module that addresses the unique needs of the inpatient provider and the chronically ill pediatric patient who spends a great deal of time as an inpatient. The measurable outcomes for such an intervention might well be the feeling of preparation that the family and patient have as they move into the adult provider world.

Optimal health care is achieved when every person at every age receives health care that is medically and developmentally appropriate.1 For healthy patients, medically and developmentally appropriate care is usually available, but for children with special healthcare needs (SHCN), receiving this care can be a challenge that is magnified as a child with SHCN grows into a teenager and then a young adult. For these children, simply transferring care, which is essentially a handoff of responsibility, to adult providers is insufficient to meet the needs of a special healthcare population.1 Transition is the purposeful planned movement of adolescents and young adults with chronic medical conditions and disabilities from pediatric (child‐centered) to adult‐oriented providers and facilities.2

The 2005‐2006 National Survey of Children with SHCN identified 4 component measures of transition which included discussions between the patient and the healthcare provider about: 1) shifting to adult providers, 2) adult healthcare needs, 3) health insurance, and 4) encouraging the patient to take responsibility for his/her care.34 Overall, only 41% of youth with SHCN met the core outcomes.4 The survey also found that those most affected by their health conditions were less likely to have transition discussions compared with less‐affected youth.3

The importance of healthcare transition also resonates with pediatric hospitalists. The results of a 1988 National Health Survey revealed that 4% of all children with SHCN were hospitalized, and 2% of those with severe chronic conditions accounted for 27% of all hospital bed days.5 Or, stated differently, a small percentage of patients are admitted most frequently and stay the longest in the hospital. Further, transition for those with significant cognitive delay was more difficult, because of the lack of adult‐oriented providers who are willing to care for the patient and work collaboratively with the family.6 This has a significant implication for pediatric hospitalists, because it increases the likelihood that a severely affected 21 to 25‐year‐old patient will be admitted to the pediatric hospitalist service having not yet made a successful transition to an adult‐oriented provider.

Clearly, transition of care should have its roots in the outpatient medical home; however, often a patient with a chronic medical condition will spend extended periods of time in the hospital and away from their identified medical home. Although not a widely accepted concept, some may consider the pediatric hospitalist service to be an extension of the medical home for inpatients. The pediatric hospitalist is often the physician who cares for inpatients with SHCN because of their complexity. There are components of the transition process that specifically deal with hospitalization. Pediatric hospitalists should understand transition and their role in it, so that the process does not stop when patients are hospitalized.

Our hypothesis is that pediatric hospitalists are well poised to provide inpatient transition services, but insufficient understanding of the concepts and practical processes related to transition limit involvement. Through this exploratory survey, we hope to understand current attitudes and knowledge about transition. We survey the degree to which pediatric hospitalists want to participate in the process, the level of support that healthcare transition services receive from the institutions in which pediatric hospitalists practice, and potential barriers and benefits of their participation.

METHODS

Participants

After a review of current literature, we developed an exploratory survey for pediatric hospitalists that was approved by our institutional review board, and was reviewed for content and face validity by a qualitative expert on transition of care. Using Survey Monkey, the survey was piloted with a small group of pediatric hospitalists for feedback regarding the clarity of the survey questions before it was introduced to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)/Pediatric Hospital Medicine Listserv. The Listserv is available to any pediatric hospitalist that joins. The exact number of pediatric hospitalists is unknown. A reasonable approximation of Listserv members at the time the survey was introduced is 1800. A fraction of that number is active on the Listserv, as defined by multiple postings during the course of an academic year. Pediatric hospitalists were the targeted group because of their expertise in the care of the adolescent and, often, young adult, with SHCN. The survey was voluntary and anonymous, and was reintroduced 3 times to capture as many participants as possible. The purpose of the survey was to gauge the interest, attitudes, and understanding of healthcare transition in a cross section of pediatric hospitalists.

Definitions

For clarity, in this survey, transfer is defined as an event, a handoff of responsibility for the management of a patient from one physician to another. Transition is defined as the purposeful planned movement of adolescents and young adults, with chronic medical conditions and disabilities, from pediatric (child‐centered) to adult‐oriented providers and facilities.2

Survey

This questionnaire contained 33 items and included a mixture of open‐ended questions, yes and no questions, and questions with responses that used a modified Likert scale. The survey questions were not adapted from another study or survey; they were developed in conjunction with 2 well‐published experts on the subject of transition. The demographic questions were used to help determine whether patterns related to transition services and knowledge could be detected based on age, gender, or type of practice, whether academic or community. The survey content included several areas: 1) Who is responsible for the care of young adults and adolescents; 2) Hospital‐based transition services; 3) Benefits or challenges for pediatric hospitalists who become involved in health care transition (HCT); 4) Knowledge of HCT and education opportunities. Informed consent was the first page; if consent was obtained, the participant could move forward in the survey (Table 1).

| Who is primarily responsible for inpatient care of patients 16‐21? |

| Please rate your knowledge of healthcare transition. |

| Are there healthcare transition services in your hospital? |

| How old are patients when they first receive inpatient‐oriented healthcare transition services? |

| How beneficial are these services to the patient and the provider if available? |

| Does your hospital have a policy that mandates the age by which an adolescent/young adult patient must be transferred from Pediatrics to adult providers and facilities? |

| What factors determine age of transfer? |

| How big a problem is it transferring adolescent/young adult patients from Pediatrics to adult providers and facilities? |

| How prepared are adolescents and young adults in your institution for transition to adult services? |

| Should pediatric hospitalists be involved in providing healthcare transition services and supports to patients with chronic healthcare conditions in the inpatient setting? |

| How often have you been asked by a subspecialist to provide healthcare transition services and supports to patients with chronic health conditions in the inpatient setting? |

| Who is best qualified to provide healthcare transition services? |

| What are the biggest impediments and benefits to hospitalist involvement in healthcare transition services? |

| If there was an online educational training module about healthcare transitions, would you take it? |

RESULTS

There were 131 participants who consented to participate in, and completed, the survey.

Demographics

Of all participants, 42.5% identified their primary practice site as a pediatric hospital; 40.8% identified their primary practice setting as a children's hospital within a general hospital, and 15.8% identified their primary practice setting as a general hospital with pediatric beds but no designation as a children's hospital. The participants came from nearly every state in the United States; 69.2% were women and 30.8% were men. The ages ranged from 27 to 67, with the majority of participants in their mid‐30s and 40s. Most were boarded in Pediatrics and/or Internal Medicine with some subspecialties such as Physical Medical and Rehabilitation, Cardiology, Critical Care, Pulmonology, and Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics represented. Although the sample size is small, it is representative of the larger population of pediatric hospitalists. There were no patterns detected based on demographics relative to the knowledge or participation in healthcare transition (Table 2).

| Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|

| Age range | 3267 years | 2761 years |

| Boarded in Pediatrics/Pediatric subspecialty | 92% | 99% |

| Practice setting | ||

| Pediatric hospital | 51.4% | 38.6% |

| General hospital with a pediatric hospital within it | 27% | 47% |

| General hospital with pediatric beds but no children's hospital designation | 21.6% | 13.3% |

| Other | 8.1% | 7.2% |

Which Groups of Physicians Are Caring for Adolescent and Young Adult Patients?

Establishing whether pediatric subspecialists, adult providers, or pediatric hospitalists are the primary caregivers for adolescents and young adults with SCHN is important to determine whether the pediatric hospitalist is really well poised to deal with transition issues. If the pediatric hospitalist does not care for these patients, then developing modules to educate them about healthcare transition may not be necessary. As expected, pediatric hospitalists believe they care for adolescent and young adult patients with special healthcare needs in the vast majority of cases. Table 3 illustrates in more detail who is specifically responsible for their care.

| Patient Age | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1617 | 1820 | |

| ||

| Inpatient care provider | ||

| Pediatric hospitalist | 70.1%* | 36.8% |

| Adult hospitalist | 0.9% | 27.4% |

| Pediatric subspecialist | 27.4% | 25.6% |

| Adult subspecialist | 0.9% | 2.6% |

| Other/not sure | 7.7% | 0.9% |

Knowledge of Healthcare Transition

Participants in the survey were provided definitions of healthcare transition; they were asked to rate their knowledge of healthcare transition on a modified Likert scale, given the definition provided. The results can be seen in Figure 1.

Transition Programs

Of all participants, 60.9% did not know if their hospital had inpatient‐oriented healthcare transition services. Another 27.8% only had informal or unstructured services for some patients with a chronic condition, and less than 1% of all respondents said they had a formal or structured program at their institution for inpatients with any chronic medical condition. Eighty percent thought transferring adolescent or young adult patients from pediatric to adult providers was a moderate to major problem.

Of those who responded to the survey, 97.6% feel that inpatient‐oriented healthcare transition services would be beneficial to adolescent and young adult patients, and 92.2% felt that these supports would be beneficial to pediatric providers. This is consistent with the data from another question in which respondents felt that only 1% of patients were quite a bit prepared for transition to inpatient adult providers, and that over half were only a little bit or not at all prepared.

Institutional Mandates

Nearly 40% of institutions have a mandated age by which adolescent and young adult patients must be transferred to adult providers and facilities. Additionally, only 5.2% of those institutions have a written procedure or protocol that describes how these pediatric patients will be transferred to adult providers and institutions.

Pediatric Hospitalist Participation in Transition

Sixty‐eight percent of respondents believe that the patient's primary care provider is the most qualified to discuss healthcare transition issues, followed by their pediatric subspecialists. However, more than 75% of respondents agree or strongly agree that pediatric hospitalists should be involved in providing healthcare transition services and supports to inpatients with chronic health conditions. Please refer to Table 4. Despite this, 58% of pediatric hospitalists are rarely, if ever, asked to participate in healthcare transition by their subspecialist counterparts.

| Respondents, % (No.) | |

|---|---|

| Strongly agree | 28.6 (28) |

| Agree | 50.0 (49) |

| Neither agree or disagree | 12.2 (12) |

| Disagree | 6.1 (6) |

| Strongly disagree | 3.1 (3) |

Barriers to Pediatric Hospitalist Participation in Transition

The survey participants were given a list of potential barriers to participation in healthcare transition and were asked to rank 3 of the choices in order of significance, with 1 being the biggest perceived impediment and 3 being the least significant. Seventeen percent ranked lack of familiarity with healthcare transition resources as the biggest barrier in their setting. Thirteen percent indicated that lack of support from pediatric and adult subspecialists is the major barrier, and 13% felt that insufficient time to provide transition services and supports would be the most significant barrier to their participation in transition. Interestingly, billing and reimbursement issues were not seen as obstacles (see Supporting Information 1/Table 5 in the online version of this article).

Advantages to Pediatric Hospitalist Participation in Transition

The participants were given a set of potential benefits that might result from the pediatric hospitalist participation in transition of care. They were asked to rank 3 of the choices in order of importance, with 1 being the most important positive outcome to 3 being a lesser, but still positive, outcome. Twenty‐three percent of respondents ranked improved communication between pediatric and adult providers and facilities as being the most significant advantage. Twenty‐one percent ranked both better continuity of care in the inpatient setting, and better quality of care for adolescents and young adults with chronic healthcare conditions, as the most important potential advantages of pediatric hospitalist involvement in healthcare transition. However, most felt that improved cost effectiveness would not be an important result (see Supporting Information 2/Table 6 in the online version of this article).

Educational Process

If an educational module was offered, over half of the respondents would definitely or probably take the training, and another 22% might take the training.

LIMITATIONS

This is an exploratory study which is limited by the small number of participants. Although the demographics of the participants include both young and experienced hospitalists, as well as academic and community institutions, it is difficult to determine whether the results are truly representative of the larger pediatric hospitalist population. The survey was also too long which may have deterred participation. Given the lack of experience and literature on pediatric hospitalist involvement in transition of care, it is difficult to construct a concise survey that addresses all of the concerns of the diverse hospitalist population. This is a new area of exploration for pediatric hospitalists, and ideally new questions will arise out of these preliminary findings, despite the limitations in the survey. Future surveys should focus on singular issues related to transition, and every attempt should be made to increase participation in the survey.

DISCUSSION

The survey demonstrates that the majority of the pediatric hospitalists believe providing transition services is important, but that transition programs are, for all practical purposes, nonexistent. Hospitalists believe the primary care doctor or the subspecialists should direct the transition process, but most clearly believe that their participation in the process would be beneficial for their patients, as evidenced by a 97.6% positive response to that question in the survey. Transition of care should be handled predominantly in the medical home.1 At this point, there is no literature that describes a pediatric hospitalist service as an inpatient medical home. However, pediatric hospitalists, not pediatric subspecialists, care for the majority of patients with SHCN in the transition age range while they are hospitalized; therefore, continuing the transition discussion while a patient is hospitalized may be a key component to its success. Better quality and continuity of care for the inpatient with SHCN is a potential advantage, as is coordination of services. Having the support of the pediatric subspecialists and the pediatric primary care provider is not only important, but it is critical in successful transition. Further, most pediatric hospitalists identify transfer of pediatric patients to adult providers as a major problem, and the perception is that only 1% of patients are adequately prepared for this transfer of care. Few institutions have a formalized process by which patients are transferred to adult care providers; however, many institutions have a mandated age at which they expect transfer of care to occur.

The literature about transition of care highlights the issues in the outpatient setting. Reiss and Gibson used focus groups comprised of caregivers, and youth and young adults with SHCN, to explore the issues related to transition of care.7 They identified several factors associated with successful transition that are pertinent to inpatient pediatrics. Involving the patient as a responsible member of the treatment team is important because it fosters independence and problem solving.7 Advocating this in the inpatient setting gives the patient and caregivers confidence that the patient can participate in the healthcare process, thereby making it a habit.7 A second important factor is attending to the patient's personal preferences and interpersonal dynamics.7 Many adolescents and young adult patients prefer to be cared for by their pediatric providers on adult wards away from crying infants and children.7 This may be their first indication that they'd like to explore the adult medical world.7

Pediatric hospitalists should be prepared to meet the needs of adolescent and young adult patients with SCHN by becoming familiar with the components of the transition process. Saidi and Kovacs provide a checklist of practical transition strategies that are helpful to review, and many are quite pertinent to the practice of pediatric hospital medicine.8 Education is a fundamental aspect of the identity of the pediatric hospitalist and is also the foundation of the transition process. Identifying established institutional transition resources, developing educational tools for faculty and residents to learn about transition, as well as adapting the transition checklist to inpatient needs are useful tools for developing a culture of effective healthcare transition. Simple strategies, such as speaking to young patients on their own, and displaying a public commitment to transition are other easy changes that can be made to the everyday activities of the pediatric hospitalist.8

Other key issues that would be important for the pediatric hospitalist to address are the adolescents' understanding of his/her disease, current treatments, long‐term complications, and the impact of healthy and unhealthy behaviors.9 Because these issues can directly affect his/her hospitalization, the pediatric hospitalist should play a role in discussing these issues and reaffirming their importance in the overall health of the patient. This affirmation will also support the process of transition, and will give further confidence to the patient and family that the patient is becoming a responsible member of the healthcare team.

Many of the strategies espoused by experts in transition are part of what the pediatric hospitalist does regularly. The pediatric hospitalist is a resource for patients, families, and subspecialists, because of their comfort and expertise managing complex pediatric patients and because of their understanding of the hospital and how it functions. The process of transition of care should be part of what pediatric hospitalists are prepared to teach, because of the numbers of adolescent and young adult patients that are in their care. The current knowledge base for most pediatric hospitalists seems to be a basic understanding of what transition of care means, but little knowledge about how to go about engaging in the process. More and more transition is relevant to primary care doctors and hospitalists, as the medically complex patient survives into adolescence and adulthood.

CONCLUSION

The survey provides a snapshot of the current attitudes and beliefs of pediatric hospitalists relative to involvement in healthcare transition. This article addresses what we believe to be important questions for the pediatric hospitalist to ask, prior to becoming involved in healthcare transition. Our hypothesis, that pediatric hospitalists are well poised to provide inpatient transition services but are limited by lack of understanding of the concepts and process, is supported by the responses in the survey which show that pediatric hospitalists are interested in participating in healthcare transition but feel impeded by time, support, and understanding of the process of transition. A larger sample size is needed to strengthen the data and lend support to these observations. Additionally, more research to compare current models of transition services and a hospitalist model could be important in realizing the potential positive outcomes predicted in this survey. Education and resources for transition of care are inadequate. Targeted educational modules might provide a foundation for pediatric hospitalists to build their scope of practice to include transition services. The next step for interested pediatric hospitalists might be developing a web‐based module that addresses the unique needs of the inpatient provider and the chronically ill pediatric patient who spends a great deal of time as an inpatient. The measurable outcomes for such an intervention might well be the feeling of preparation that the family and patient have as they move into the adult provider world.

- A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs.Pediatrics.2002;110(6 pt 2):1304–1306.

- ,,,,,.Perceptions of transitional care needs and experiences in pediatric heart transplant recipients.Am J Transplant.2009;9(3):614–619.

- ,,,,,.Planning for health care transitions: results from the 2005–2006 National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs.Pediatrics.2009;123(1):e145–e152.

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau.The National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs, Chartbook 2005–2006.Rockville, MD:US Department of Health and Human Services;2008.

- ,,,,,.Changes in hospitalization patterns among patients with congenital heart disease during the transition from adolescence to adulthood.J Am Coll Cardiol.2007;49(8):875–882.

- ,,.Health care transition: youth, family, and provider perspectives.Pediatrics.2005;115(1):112–120.

- ,.Health care transition: destinations unknown.Pediatrics.2002;110(6 pt 2):1307–1314.

- ,.Developing a transition program from pediatric‐ to adult‐focused cardiology care: practical considerations.Congenit Heart Dis.2009;4(4):204–215.

- .Transition for youth with chronic conditions: primary care physicians' approaches.Pediatrics.2002;110(6 pt 2):1315–1321.

- A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs.Pediatrics.2002;110(6 pt 2):1304–1306.

- ,,,,,.Perceptions of transitional care needs and experiences in pediatric heart transplant recipients.Am J Transplant.2009;9(3):614–619.

- ,,,,,.Planning for health care transitions: results from the 2005–2006 National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs.Pediatrics.2009;123(1):e145–e152.

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau.The National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs, Chartbook 2005–2006.Rockville, MD:US Department of Health and Human Services;2008.

- ,,,,,.Changes in hospitalization patterns among patients with congenital heart disease during the transition from adolescence to adulthood.J Am Coll Cardiol.2007;49(8):875–882.

- ,,.Health care transition: youth, family, and provider perspectives.Pediatrics.2005;115(1):112–120.

- ,.Health care transition: destinations unknown.Pediatrics.2002;110(6 pt 2):1307–1314.

- ,.Developing a transition program from pediatric‐ to adult‐focused cardiology care: practical considerations.Congenit Heart Dis.2009;4(4):204–215.

- .Transition for youth with chronic conditions: primary care physicians' approaches.Pediatrics.2002;110(6 pt 2):1315–1321.

Copyright © 2011 Society of Hospital Medicine

HPS: Benefits, Safety Persist With Long-Term Statin Use

The protection against vascular morbidity and mortality that resulted from lowering LDL cholesterol with simvastatin over a period of about 5 years in the Heart Protection Study persisted for nearly 6 additional years after study treatment ended, according to findings from an extended follow-up of the large randomized controlled trial.

Furthermore, no evidence of emerging safety concerns was apparent during the follow-up, the Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group reported online on Nov. 23 in the Lancet.

Participants in the Medical Research Council and British Heart Foundation Heart Protection Study (HPS) was composed of 20,536 adults aged 40-80 years who were at increased risk of vascular events and who were enrolled between July 1994 and May 1997. Those allocated to receive simvastatin experienced a mean reduction in LDL cholesterol of 1.0 mmol/L and a proportional reduction of 23% in major cardiovascular events during the 5-year study period.

The findings, along with those from other major trials of statins, provided "compelling evidence" of the value of lowering LDL cholesterol – and led to the widespread use of long-term statin treatment – but evidence from observational studies has raised concerns about possible increases in the risk of certain types of cancer and other nonvascular morbidity and mortality in patients with lower blood cholesterol concentrations, according to the study group.

The findings of the HPS extended follow-up appear to lay those concerns to rest.

At a mean of 5.3 years (for a total HPS follow-up of 11 years), the rate of first vascular events in previously event-free participants was similar in both the initial simvastatin group and the initial placebo (21.7% and 22.5%, respectively; risk ratio 0.95), the investigators said (Lancet 2011 Nov. 23 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61125-2]).

Although a further 14% decrease in vascular events occurred in the first year in the simvastatin group, little difference was seen between the treatment and placebo groups thereafter. Similar patterns were seen for major coronary events, strokes, and revascularization procedures.

Vascular mortality was also similar in the two groups during the post-trial follow-up (11.5% and 11.6% in the simvastatin and placebo groups). During the in-trial period, an 18% proportional reduction in vascular mortality was seen in the treatment group, so the follow-up findings indicate that the in-trial survival gains persisted, they investigators said.

Nonvascular mortality rates were also similar in the two groups during the post-trial follow-up (10.6% and 10.9%). There were no differences in deaths from cancer, respiratory disease, or nonmedical causes.

"When the 11 years of in-trial and post-trial follow-up are considered together, allocation to about 5 years of statin treatment was not associated with any increase in nonvascular mortality, either overall [14.8% vs. 15.1%] or for any prespecified category of death," they said.

As for first diagnoses of any type of cancer, rates were also similar in the in-trial and post-trial periods, for a combined incidence of 17% in each group.

"Indeed, even during the later years of this prolonged follow-up, no suggestion was noted of any emerging difference in the overall incidence of cancer," the investigators said, noting that the large numbers of incident cancer that occurred during the entire in-trial and post-trial period allowed for reliable assessment of the effects of the substantial 5-year reduction in cholesterol on 11-year risks of common cancer types. No significant differences were seen in the incidences of genitourinary, gastrointestinal, respiratory, hematologic, or any other malignant disease, even in those aged 70 years or older at baseline, and in those with below-average pretreatment cholesterol concentrations.

Statin use was encouraged in all HPS participants following the initial study treatment period and was similar in both treatment groups during the post-trial follow-up at about 59% in the first year and increasing to about 84% in the fifth year. LDL cholesterol concentrations were also similar at 2.6 mmol/L in both groups at 3.2 years, the investigators noted.

Although 11 years might not be long enough to fully discern all cancer and other risks in this study population, it is notable that no adverse trend was noted, even during the later years of follow-up, the researchers wrote.

The findings are consistent with those from four other large randomized trials of statin treatment, and, taken together, the data support the prompt initiation and long-term continuation of statin treatment in individuals at increased risk of vascular events, they concluded.

This study was supported by the UK Medical Research Council, the British Heart Foundation, Merck & Co., and Roche Vitamins. The HPS Collaborative Study Group is bound by a policy of not accepting honoraria or other payments from the pharmaceutical industry other than reimbursement of costs to participate in scientific meetings. As a result, the only disclosures of the group relate to such reimbursement.

In light of the findings of the HPS Collaborative Study Group, doctors should feel reassured about the long-term safety of statin use to lower LDL cholesterol, Dr. Payal Kohli and Dr. Christopher P. Cannon wrote in an editorial.

Given that follow-up in most prior studies did not extend beyond 5 years and that some data have suggested an increase in cancer risk in patients with very-low cholesterol levels – and possibly with prolonged statin treatment – concerns about an increased risk of cancers that take longer than 5 years to emerge have persisted, they said.

The finding of the HPS extended follow-up, however, provide "contemporary and confirmatory" evidence to the contrary, they added (Lancet 2011 Nov. 23[doi.10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61544-4]).

The findings indicate the risk of cancer and nonvascular mortality is not increased with extended statin use, even among elderly patients.

The original concerns about statin safety were from observational data, which were most likely heavily confounded, they said.

"We now have strong evidence from HPS and several other randomized controlled trials that prolonged treatment with statins is indeed efficacious, safe, and has long-lasting beneficial effects, even after discontinuation of therapy," they concluded.

Dr. Kohli and Dr. Cannon are with the TIMI Study Group, Cardiovascular Division, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. Dr. Cannon disclosed that he has received research funding from Accumetrics, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Takeda, and that he has received honoraria from Pfizer and AstraZeneca. He has also participated in advisory boards for Bristol-Myers Squibb/Sanofi, Novartis, and Alnylam, and he has equity in Automedics Medical Systems. Dr. Kohli had no disclosures.