User login

New SoHM Report Brings Important Changes

It’s a little like giving birth: A nine-month-long process that started last January with the excitement and anticipation of launching the survey and encouraging as many hospital medicine groups (HMGs) as possible to participate. Then the long, drawn-out process of analyzing data, organizing everything into tables and charts, drafting the report, and reviewing it over and over until our eyes crossed. Watching it grow and take shape before our eyes, with a few small hiccups along the way. Then the agonizing process of copyediting, designing (both print and digital versions), and printing—a point at which, like all expectant parents, we said, “Enough already. When will this ever end?”

But we (that is, SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee) finally have a baby, and what proud parents we are! SHM’s 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report (SoHM) should be available in early October, and the cover story for this issue of The Hospitalist previews some of the key findings.

I want to let you know what’s new and different about this year’s report and to explain why we made some of the changes we did. First, we had an opportunity this year to ask some questions that haven’t appeared in previous surveys, including:

- The percentage of the hospital’s total patient volume the HMG was responsible for caring for

- The presence of hospitalists within the HMG focusing their practice in a specific medical subspecialty, such as critical care, neurology, or oncology

- The annual dollar value of CME allowances for hospitalists

- The utilization of prolonged service codes by hospitalists

- Charge capture methodologies being used by HMGs

- For academic HMGs, the dollar amount of financial support provided for nonclinical work

- Questions regarding non-physician practice administrators that were asked in 2012 but not in 2014

One big change that users of the digital version will see is a much more user-friendly interface with vastly improved search and navigation features. This will be an enormous improvement over the essentially static PDF versions of previous years, and we’re very excited about it.

The other major change that all users will note is that beginning this year, SHM will no longer report findings broken out by employment model (e.g., hospital/IDS-employed versus management companies versus private local hospitalist groups, etc.). We know this will be a disappointment to some, but with the consolidation that has occurred in the management company space over the last couple of years, we found it would be difficult, if not impossible, to protect the confidentiality of information supplied by the largest management companies if the data are reported separately. Because of their sheer size, these mega-companies will be disproportionately represented in the survey results, and their identities and operational details might become apparent.

It’s crucial that management companies continue to be represented in SHM survey data because they represent an important and growing segment of the hospital medicine workforce. SoHM wouldn’t present a true picture of the hospital medicine field without them. We hope to continue to protect the confidentiality of all data and encourage more management companies to participate in future surveys while still providing meaningful information to our users. TH

Leslie Flores is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee and a partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants.

It’s a little like giving birth: A nine-month-long process that started last January with the excitement and anticipation of launching the survey and encouraging as many hospital medicine groups (HMGs) as possible to participate. Then the long, drawn-out process of analyzing data, organizing everything into tables and charts, drafting the report, and reviewing it over and over until our eyes crossed. Watching it grow and take shape before our eyes, with a few small hiccups along the way. Then the agonizing process of copyediting, designing (both print and digital versions), and printing—a point at which, like all expectant parents, we said, “Enough already. When will this ever end?”

But we (that is, SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee) finally have a baby, and what proud parents we are! SHM’s 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report (SoHM) should be available in early October, and the cover story for this issue of The Hospitalist previews some of the key findings.

I want to let you know what’s new and different about this year’s report and to explain why we made some of the changes we did. First, we had an opportunity this year to ask some questions that haven’t appeared in previous surveys, including:

- The percentage of the hospital’s total patient volume the HMG was responsible for caring for

- The presence of hospitalists within the HMG focusing their practice in a specific medical subspecialty, such as critical care, neurology, or oncology

- The annual dollar value of CME allowances for hospitalists

- The utilization of prolonged service codes by hospitalists

- Charge capture methodologies being used by HMGs

- For academic HMGs, the dollar amount of financial support provided for nonclinical work

- Questions regarding non-physician practice administrators that were asked in 2012 but not in 2014

One big change that users of the digital version will see is a much more user-friendly interface with vastly improved search and navigation features. This will be an enormous improvement over the essentially static PDF versions of previous years, and we’re very excited about it.

The other major change that all users will note is that beginning this year, SHM will no longer report findings broken out by employment model (e.g., hospital/IDS-employed versus management companies versus private local hospitalist groups, etc.). We know this will be a disappointment to some, but with the consolidation that has occurred in the management company space over the last couple of years, we found it would be difficult, if not impossible, to protect the confidentiality of information supplied by the largest management companies if the data are reported separately. Because of their sheer size, these mega-companies will be disproportionately represented in the survey results, and their identities and operational details might become apparent.

It’s crucial that management companies continue to be represented in SHM survey data because they represent an important and growing segment of the hospital medicine workforce. SoHM wouldn’t present a true picture of the hospital medicine field without them. We hope to continue to protect the confidentiality of all data and encourage more management companies to participate in future surveys while still providing meaningful information to our users. TH

Leslie Flores is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee and a partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants.

It’s a little like giving birth: A nine-month-long process that started last January with the excitement and anticipation of launching the survey and encouraging as many hospital medicine groups (HMGs) as possible to participate. Then the long, drawn-out process of analyzing data, organizing everything into tables and charts, drafting the report, and reviewing it over and over until our eyes crossed. Watching it grow and take shape before our eyes, with a few small hiccups along the way. Then the agonizing process of copyediting, designing (both print and digital versions), and printing—a point at which, like all expectant parents, we said, “Enough already. When will this ever end?”

But we (that is, SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee) finally have a baby, and what proud parents we are! SHM’s 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report (SoHM) should be available in early October, and the cover story for this issue of The Hospitalist previews some of the key findings.

I want to let you know what’s new and different about this year’s report and to explain why we made some of the changes we did. First, we had an opportunity this year to ask some questions that haven’t appeared in previous surveys, including:

- The percentage of the hospital’s total patient volume the HMG was responsible for caring for

- The presence of hospitalists within the HMG focusing their practice in a specific medical subspecialty, such as critical care, neurology, or oncology

- The annual dollar value of CME allowances for hospitalists

- The utilization of prolonged service codes by hospitalists

- Charge capture methodologies being used by HMGs

- For academic HMGs, the dollar amount of financial support provided for nonclinical work

- Questions regarding non-physician practice administrators that were asked in 2012 but not in 2014

One big change that users of the digital version will see is a much more user-friendly interface with vastly improved search and navigation features. This will be an enormous improvement over the essentially static PDF versions of previous years, and we’re very excited about it.

The other major change that all users will note is that beginning this year, SHM will no longer report findings broken out by employment model (e.g., hospital/IDS-employed versus management companies versus private local hospitalist groups, etc.). We know this will be a disappointment to some, but with the consolidation that has occurred in the management company space over the last couple of years, we found it would be difficult, if not impossible, to protect the confidentiality of information supplied by the largest management companies if the data are reported separately. Because of their sheer size, these mega-companies will be disproportionately represented in the survey results, and their identities and operational details might become apparent.

It’s crucial that management companies continue to be represented in SHM survey data because they represent an important and growing segment of the hospital medicine workforce. SoHM wouldn’t present a true picture of the hospital medicine field without them. We hope to continue to protect the confidentiality of all data and encourage more management companies to participate in future surveys while still providing meaningful information to our users. TH

Leslie Flores is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee and a partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants.

Hospitalists' Evolving Scope of Practice

Last month The Hospitalist reported new 2012 State of Hospital Medicine survey data showing that 57% of those adult medicine hospitalist groups providing surgical comanagement services typically do so as admitting/attending physician, as opposed to serving in a consultant role. For groups providing medical subspecialty comanagement, the admitting/attending rate was a whopping 85%.

But just how common is comanagement these days, and what else do we know about hospitalists’ evolving scope of practice? It’s hard to compare this year’s survey results with those presented in last year’s report because previously this information was reported for all HM groups combined while this year adult and pediatric groups are reported separately. In addition, the survey population was different this year since MGMA survey participants were no longer included. But if you ask almost anyone working in HM today, they probably will tell you that the pressure to assume increased comanagement responsibilities for more and more types of patients is intense.

One of the new questions this year asked respondents to characterize their scope of services by selecting one of the following three options:

- We maintain a scope of practice that resembles traditional hospital-based internal medicine (or pediatrics, if applicable).

- Our practice scope has evolved to include some services that are outside of traditional internal medicine practice (or pediatrics, if applicable), e.g., admitting/managing patients with intracranial hemorrhage, small bowel obstruction or hip fracture.

- Our practice scope has evolved to encompass admitting a full range of hospital patients in the age group for which we are responsible, with the exception of OB and emergency surgery patients (i.e. nearly “universal admitter”).

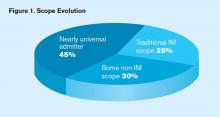

A remarkable 45% of adult medicine hospitalist groups reported that their scope has evolved toward a nearly universal admitter role, while only a quarter of such groups reported maintaining a traditional internal medicine scope (see Figure 1, below). The broader scope of practice was more common in the Midwest, among private hospitalist-only groups and those employed by management companies, and in non-teaching hospitals. Not surprisingly, academic hospital medicine groups and those employed by university/medical schools tended to maintain narrower internal medicine-focused scopes.

As to the prevalence of comanagement, this year 94% of groups serving adults only reported providing surgical comanagement services (either admitting or consulting), while 70% reported providing comanagement for medical subspecialty patients. Seven years ago, SHM’s 2005 survey found that 87% of adult medicine groups provided surgical comanagement (SHM didn’t ask about medical comanagement).

So yes, the proportion of groups providing surgical comanagement has increased, but not dramatically.

Although we don’t know for sure since the question wasn’t asked in 2005, I suspect we’d find that most groups providing surgical (and probably medical subspecialty) comanagement in 2005 served as consultants; today the preponderance serve as admitting/attending physician for such patients. That’s a significant scope evolution that’s not obvious from just looking at the percent of groups that provide comanagement.

A comprehensive list of services routinely provided by HM groups is available in the new 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report, with breakdowns by group type, geographic region, employment model, and academic/teaching status. Hopefully, SHM will continue to survey this important topic so that scope evolution can be tracked going forward.

Last month The Hospitalist reported new 2012 State of Hospital Medicine survey data showing that 57% of those adult medicine hospitalist groups providing surgical comanagement services typically do so as admitting/attending physician, as opposed to serving in a consultant role. For groups providing medical subspecialty comanagement, the admitting/attending rate was a whopping 85%.

But just how common is comanagement these days, and what else do we know about hospitalists’ evolving scope of practice? It’s hard to compare this year’s survey results with those presented in last year’s report because previously this information was reported for all HM groups combined while this year adult and pediatric groups are reported separately. In addition, the survey population was different this year since MGMA survey participants were no longer included. But if you ask almost anyone working in HM today, they probably will tell you that the pressure to assume increased comanagement responsibilities for more and more types of patients is intense.

One of the new questions this year asked respondents to characterize their scope of services by selecting one of the following three options:

- We maintain a scope of practice that resembles traditional hospital-based internal medicine (or pediatrics, if applicable).

- Our practice scope has evolved to include some services that are outside of traditional internal medicine practice (or pediatrics, if applicable), e.g., admitting/managing patients with intracranial hemorrhage, small bowel obstruction or hip fracture.

- Our practice scope has evolved to encompass admitting a full range of hospital patients in the age group for which we are responsible, with the exception of OB and emergency surgery patients (i.e. nearly “universal admitter”).

A remarkable 45% of adult medicine hospitalist groups reported that their scope has evolved toward a nearly universal admitter role, while only a quarter of such groups reported maintaining a traditional internal medicine scope (see Figure 1, below). The broader scope of practice was more common in the Midwest, among private hospitalist-only groups and those employed by management companies, and in non-teaching hospitals. Not surprisingly, academic hospital medicine groups and those employed by university/medical schools tended to maintain narrower internal medicine-focused scopes.

As to the prevalence of comanagement, this year 94% of groups serving adults only reported providing surgical comanagement services (either admitting or consulting), while 70% reported providing comanagement for medical subspecialty patients. Seven years ago, SHM’s 2005 survey found that 87% of adult medicine groups provided surgical comanagement (SHM didn’t ask about medical comanagement).

So yes, the proportion of groups providing surgical comanagement has increased, but not dramatically.

Although we don’t know for sure since the question wasn’t asked in 2005, I suspect we’d find that most groups providing surgical (and probably medical subspecialty) comanagement in 2005 served as consultants; today the preponderance serve as admitting/attending physician for such patients. That’s a significant scope evolution that’s not obvious from just looking at the percent of groups that provide comanagement.

A comprehensive list of services routinely provided by HM groups is available in the new 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report, with breakdowns by group type, geographic region, employment model, and academic/teaching status. Hopefully, SHM will continue to survey this important topic so that scope evolution can be tracked going forward.

Last month The Hospitalist reported new 2012 State of Hospital Medicine survey data showing that 57% of those adult medicine hospitalist groups providing surgical comanagement services typically do so as admitting/attending physician, as opposed to serving in a consultant role. For groups providing medical subspecialty comanagement, the admitting/attending rate was a whopping 85%.

But just how common is comanagement these days, and what else do we know about hospitalists’ evolving scope of practice? It’s hard to compare this year’s survey results with those presented in last year’s report because previously this information was reported for all HM groups combined while this year adult and pediatric groups are reported separately. In addition, the survey population was different this year since MGMA survey participants were no longer included. But if you ask almost anyone working in HM today, they probably will tell you that the pressure to assume increased comanagement responsibilities for more and more types of patients is intense.

One of the new questions this year asked respondents to characterize their scope of services by selecting one of the following three options:

- We maintain a scope of practice that resembles traditional hospital-based internal medicine (or pediatrics, if applicable).

- Our practice scope has evolved to include some services that are outside of traditional internal medicine practice (or pediatrics, if applicable), e.g., admitting/managing patients with intracranial hemorrhage, small bowel obstruction or hip fracture.

- Our practice scope has evolved to encompass admitting a full range of hospital patients in the age group for which we are responsible, with the exception of OB and emergency surgery patients (i.e. nearly “universal admitter”).

A remarkable 45% of adult medicine hospitalist groups reported that their scope has evolved toward a nearly universal admitter role, while only a quarter of such groups reported maintaining a traditional internal medicine scope (see Figure 1, below). The broader scope of practice was more common in the Midwest, among private hospitalist-only groups and those employed by management companies, and in non-teaching hospitals. Not surprisingly, academic hospital medicine groups and those employed by university/medical schools tended to maintain narrower internal medicine-focused scopes.

As to the prevalence of comanagement, this year 94% of groups serving adults only reported providing surgical comanagement services (either admitting or consulting), while 70% reported providing comanagement for medical subspecialty patients. Seven years ago, SHM’s 2005 survey found that 87% of adult medicine groups provided surgical comanagement (SHM didn’t ask about medical comanagement).

So yes, the proportion of groups providing surgical comanagement has increased, but not dramatically.

Although we don’t know for sure since the question wasn’t asked in 2005, I suspect we’d find that most groups providing surgical (and probably medical subspecialty) comanagement in 2005 served as consultants; today the preponderance serve as admitting/attending physician for such patients. That’s a significant scope evolution that’s not obvious from just looking at the percent of groups that provide comanagement.

A comprehensive list of services routinely provided by HM groups is available in the new 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report, with breakdowns by group type, geographic region, employment model, and academic/teaching status. Hopefully, SHM will continue to survey this important topic so that scope evolution can be tracked going forward.

Survey Insights: Better Understand CPT Coding Intensity

Many of the practice-management-related questions we field from members here at SHM are about documentation and coding issues; members are looking for ways to benchmark their group’s coding performance against other similar groups. One helpful metric reported in the SHM/MGMA State of Hospital Medicine report is the ratio of work-RVUs to total encounters, which I refer to as “coding intensity.”

Median coding intensity for adult medicine hospitalists in the 2011 report was 1.90, up slightly from 2010 levels.

The most obvious factor that influences coding intensity is the distribution of CPT codes within specific evaluation and management code sets, such as inpatient admissions (99221-99223) or follow-up visits (99231-99233). Other considerations include the degree to which hospitalists provide high-wRVU services, such as critical care or procedures, the ratio of inpatient vs. observation patients, and the group’s average length of stay.

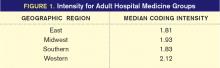

One interesting finding was that coding intensity varies greatly by geographic region (see Figure 1, right).

What’s going on out there in the Western states? Are those folks receiving different training than the rest of us? Or are they just mavericks, more interested in generating professional fee revenues than hospitalists elsewhere are? It’s hard to say. One big factor is that length of stay (LOS) tends to be shorter in the West than in other parts of the country. That means the typical Western hospitalist will have a larger proportion of high-wRVU value admission and discharge codes relative to their proportion of low-wRVU value subsequent visit codes.

This isn’t the whole story, though. Hospitalists in the West actually did report a significantly more aggressive code distribution for all three CPT code sets for which data were collected (inpatient admissions, subsequent visits, and discharges). And hospitalists in the South, where LOS tends to be longer, also reported the least aggressive code distributions.

Unfortunately, we don’t have a lot of clues as to why these differences exist. We don’t know, for example, whether more hospitalists in the West work in the ICU or perform more procedures compared to other parts of the country. One possibility suggested by report data is that hospitalists in Western states have the highest average proportion of their total compensation allocated to productivity incentives. Hospitalists in the East have the lowest proportion of their compensation based on productivity. So productivity-based compensation might cause hospitalists to care a lot more about doing a good job with documentation and CPT coding.

Other interesting findings include the fact that hospitalists employed by multistate hospitalist-management companies had the lowest median coding intensity, while hospitalists employed by private hospitalist-only groups had the highest coding intensity. And, perhaps not surprisingly, the small proportion of practices that did not receive any financial support had a higher average coding intensity than practices receiving financial support.

While there are no clear answers about variations in CPT coding intensity among hospitalist practices, the State of Hospital Medicine report does offer some intriguing pointers, along with a variety of useful benchmarks about hospitalist CPT coding practices. And stay tuned: The new report, due out in August, will offer even more ways of looking at coding intensity and CPT code distribution.

Leslie Flores, SHM senior advisor

Many of the practice-management-related questions we field from members here at SHM are about documentation and coding issues; members are looking for ways to benchmark their group’s coding performance against other similar groups. One helpful metric reported in the SHM/MGMA State of Hospital Medicine report is the ratio of work-RVUs to total encounters, which I refer to as “coding intensity.”

Median coding intensity for adult medicine hospitalists in the 2011 report was 1.90, up slightly from 2010 levels.

The most obvious factor that influences coding intensity is the distribution of CPT codes within specific evaluation and management code sets, such as inpatient admissions (99221-99223) or follow-up visits (99231-99233). Other considerations include the degree to which hospitalists provide high-wRVU services, such as critical care or procedures, the ratio of inpatient vs. observation patients, and the group’s average length of stay.

One interesting finding was that coding intensity varies greatly by geographic region (see Figure 1, right).

What’s going on out there in the Western states? Are those folks receiving different training than the rest of us? Or are they just mavericks, more interested in generating professional fee revenues than hospitalists elsewhere are? It’s hard to say. One big factor is that length of stay (LOS) tends to be shorter in the West than in other parts of the country. That means the typical Western hospitalist will have a larger proportion of high-wRVU value admission and discharge codes relative to their proportion of low-wRVU value subsequent visit codes.

This isn’t the whole story, though. Hospitalists in the West actually did report a significantly more aggressive code distribution for all three CPT code sets for which data were collected (inpatient admissions, subsequent visits, and discharges). And hospitalists in the South, where LOS tends to be longer, also reported the least aggressive code distributions.

Unfortunately, we don’t have a lot of clues as to why these differences exist. We don’t know, for example, whether more hospitalists in the West work in the ICU or perform more procedures compared to other parts of the country. One possibility suggested by report data is that hospitalists in Western states have the highest average proportion of their total compensation allocated to productivity incentives. Hospitalists in the East have the lowest proportion of their compensation based on productivity. So productivity-based compensation might cause hospitalists to care a lot more about doing a good job with documentation and CPT coding.

Other interesting findings include the fact that hospitalists employed by multistate hospitalist-management companies had the lowest median coding intensity, while hospitalists employed by private hospitalist-only groups had the highest coding intensity. And, perhaps not surprisingly, the small proportion of practices that did not receive any financial support had a higher average coding intensity than practices receiving financial support.

While there are no clear answers about variations in CPT coding intensity among hospitalist practices, the State of Hospital Medicine report does offer some intriguing pointers, along with a variety of useful benchmarks about hospitalist CPT coding practices. And stay tuned: The new report, due out in August, will offer even more ways of looking at coding intensity and CPT code distribution.

Leslie Flores, SHM senior advisor

Many of the practice-management-related questions we field from members here at SHM are about documentation and coding issues; members are looking for ways to benchmark their group’s coding performance against other similar groups. One helpful metric reported in the SHM/MGMA State of Hospital Medicine report is the ratio of work-RVUs to total encounters, which I refer to as “coding intensity.”

Median coding intensity for adult medicine hospitalists in the 2011 report was 1.90, up slightly from 2010 levels.

The most obvious factor that influences coding intensity is the distribution of CPT codes within specific evaluation and management code sets, such as inpatient admissions (99221-99223) or follow-up visits (99231-99233). Other considerations include the degree to which hospitalists provide high-wRVU services, such as critical care or procedures, the ratio of inpatient vs. observation patients, and the group’s average length of stay.

One interesting finding was that coding intensity varies greatly by geographic region (see Figure 1, right).

What’s going on out there in the Western states? Are those folks receiving different training than the rest of us? Or are they just mavericks, more interested in generating professional fee revenues than hospitalists elsewhere are? It’s hard to say. One big factor is that length of stay (LOS) tends to be shorter in the West than in other parts of the country. That means the typical Western hospitalist will have a larger proportion of high-wRVU value admission and discharge codes relative to their proportion of low-wRVU value subsequent visit codes.

This isn’t the whole story, though. Hospitalists in the West actually did report a significantly more aggressive code distribution for all three CPT code sets for which data were collected (inpatient admissions, subsequent visits, and discharges). And hospitalists in the South, where LOS tends to be longer, also reported the least aggressive code distributions.

Unfortunately, we don’t have a lot of clues as to why these differences exist. We don’t know, for example, whether more hospitalists in the West work in the ICU or perform more procedures compared to other parts of the country. One possibility suggested by report data is that hospitalists in Western states have the highest average proportion of their total compensation allocated to productivity incentives. Hospitalists in the East have the lowest proportion of their compensation based on productivity. So productivity-based compensation might cause hospitalists to care a lot more about doing a good job with documentation and CPT coding.

Other interesting findings include the fact that hospitalists employed by multistate hospitalist-management companies had the lowest median coding intensity, while hospitalists employed by private hospitalist-only groups had the highest coding intensity. And, perhaps not surprisingly, the small proportion of practices that did not receive any financial support had a higher average coding intensity than practices receiving financial support.

While there are no clear answers about variations in CPT coding intensity among hospitalist practices, the State of Hospital Medicine report does offer some intriguing pointers, along with a variety of useful benchmarks about hospitalist CPT coding practices. And stay tuned: The new report, due out in August, will offer even more ways of looking at coding intensity and CPT code distribution.

Leslie Flores, SHM senior advisor

Survey Insights: The Scoop on Pediatric Hospital Medicine

The SHM/MGMA 2011 State of Hospital Medicine report offers some intriguing glimpses into the world of pediatric hospital medicine. Last year, we received responses from 31 pediatric HM groups, more than half of which were academic (an additional 29 groups reported caring for both adults and children).

SHM Pediatrics Committee chair Doug Carlson, MD, SFHM, professor of pediatrics and director of the Division of Pediatric Hospital Medicine at Washington University in St. Louis, believes that the number of community hospitals with pediatric hospitalists is growing, based on his work with the workforce group of the Pediatric Hospital Medicine leadership group. Hopefully we will see more community pediatric HM groups in future surveys.

As is the case in adult HM, academic pediatric practices tend to be larger than their nonacademic counterparts, with a median size of 6.0 FTEs vs. 4.0 FTEs in nonacademic groups. In both cases, this is well below the median size of comparable adult HM groups.

“Community hospital programs are often started to improve the quality of care around the clock,” Dr. Carlson says. “But the minimum number of FTEs needed for a sustainable 24-hour program is about five—even in very small units. Group size can often be larger in academic settings because pediatric units are larger, and their tertiary nature creates more opportunities for involvement in surgical comanagement and other types of complex care.”

The report shows turnover was higher for both academic and nonacademic pediatric HM practices than for adult medicine practices. The median turnover for nonacademic pediatric groups was 15.5%, for example, compared with 8.2% for the nonacademic adult groups. The sample size for pediatric groups was much smaller, however.

Pediatric hospitalist Dan Rauch, MD, FAAP, FHM, associate professor of pediatrics at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, N.Y., and a former SHM Practice Analysis Committee member, notes that because the typical pediatric group size is much smaller than an adult practice, the loss of only a single hospitalist will result in a much higher turnover rate.

“It’s also my sense that community-based pediatric hospitalist positions are more likely to be transient spots as opposed to academic positions, which are more likely to lead to sustained careers,” he says.

Table 1 (above) presents some key median indicators for nonacademic HM practices. As is true for pediatricians in traditional practice, the typical pediatric hospitalist earned quite a bit less than her colleagues in adult medicine.

Even so, the finances of a pediatric HM program are more challenging than for adult hospitalists. Although professional fee collections per work relative value unit (wRVU) were slightly higher for pediatric groups than for adult groups (a surprising finding as the primary payor for many pediatric hospitalist groups is Medicaid), pediatric hospitalists’ typical annual wRVU production was about 53% lower than that of adult hospitalists, according to the 2011 report. As a result, the compensation-to-collections ratio for pediatric hospitalists was 1.75, which means that pediatric hospitalists collected only about 57 cents in professional fee revenues for every dollar of compensation paid. Adult hospitalists, by comparison, collected about 80 cents for each dollar of compensation.

Dr. Rauch isn’t particularly surprised by those figures. “The goals of nonacademic pediatric hospital medicine programs are more about providing service and expertise than about volume,” he says. “Most community hospital-based pediatric programs simply don’t have the consistent volume to support hospitalists on a billing basis, especially since they typically experience seasonal census variations that academic children’s hospitals don’t have.”

Leslie Flores, SHM senior advisor, practice management

Last chance for both pediatric and adult HM practices to participate in the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine survey: The survey closes March 9. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

The SHM/MGMA 2011 State of Hospital Medicine report offers some intriguing glimpses into the world of pediatric hospital medicine. Last year, we received responses from 31 pediatric HM groups, more than half of which were academic (an additional 29 groups reported caring for both adults and children).

SHM Pediatrics Committee chair Doug Carlson, MD, SFHM, professor of pediatrics and director of the Division of Pediatric Hospital Medicine at Washington University in St. Louis, believes that the number of community hospitals with pediatric hospitalists is growing, based on his work with the workforce group of the Pediatric Hospital Medicine leadership group. Hopefully we will see more community pediatric HM groups in future surveys.

As is the case in adult HM, academic pediatric practices tend to be larger than their nonacademic counterparts, with a median size of 6.0 FTEs vs. 4.0 FTEs in nonacademic groups. In both cases, this is well below the median size of comparable adult HM groups.

“Community hospital programs are often started to improve the quality of care around the clock,” Dr. Carlson says. “But the minimum number of FTEs needed for a sustainable 24-hour program is about five—even in very small units. Group size can often be larger in academic settings because pediatric units are larger, and their tertiary nature creates more opportunities for involvement in surgical comanagement and other types of complex care.”

The report shows turnover was higher for both academic and nonacademic pediatric HM practices than for adult medicine practices. The median turnover for nonacademic pediatric groups was 15.5%, for example, compared with 8.2% for the nonacademic adult groups. The sample size for pediatric groups was much smaller, however.

Pediatric hospitalist Dan Rauch, MD, FAAP, FHM, associate professor of pediatrics at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, N.Y., and a former SHM Practice Analysis Committee member, notes that because the typical pediatric group size is much smaller than an adult practice, the loss of only a single hospitalist will result in a much higher turnover rate.

“It’s also my sense that community-based pediatric hospitalist positions are more likely to be transient spots as opposed to academic positions, which are more likely to lead to sustained careers,” he says.

Table 1 (above) presents some key median indicators for nonacademic HM practices. As is true for pediatricians in traditional practice, the typical pediatric hospitalist earned quite a bit less than her colleagues in adult medicine.

Even so, the finances of a pediatric HM program are more challenging than for adult hospitalists. Although professional fee collections per work relative value unit (wRVU) were slightly higher for pediatric groups than for adult groups (a surprising finding as the primary payor for many pediatric hospitalist groups is Medicaid), pediatric hospitalists’ typical annual wRVU production was about 53% lower than that of adult hospitalists, according to the 2011 report. As a result, the compensation-to-collections ratio for pediatric hospitalists was 1.75, which means that pediatric hospitalists collected only about 57 cents in professional fee revenues for every dollar of compensation paid. Adult hospitalists, by comparison, collected about 80 cents for each dollar of compensation.

Dr. Rauch isn’t particularly surprised by those figures. “The goals of nonacademic pediatric hospital medicine programs are more about providing service and expertise than about volume,” he says. “Most community hospital-based pediatric programs simply don’t have the consistent volume to support hospitalists on a billing basis, especially since they typically experience seasonal census variations that academic children’s hospitals don’t have.”

Leslie Flores, SHM senior advisor, practice management

Last chance for both pediatric and adult HM practices to participate in the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine survey: The survey closes March 9. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

The SHM/MGMA 2011 State of Hospital Medicine report offers some intriguing glimpses into the world of pediatric hospital medicine. Last year, we received responses from 31 pediatric HM groups, more than half of which were academic (an additional 29 groups reported caring for both adults and children).

SHM Pediatrics Committee chair Doug Carlson, MD, SFHM, professor of pediatrics and director of the Division of Pediatric Hospital Medicine at Washington University in St. Louis, believes that the number of community hospitals with pediatric hospitalists is growing, based on his work with the workforce group of the Pediatric Hospital Medicine leadership group. Hopefully we will see more community pediatric HM groups in future surveys.

As is the case in adult HM, academic pediatric practices tend to be larger than their nonacademic counterparts, with a median size of 6.0 FTEs vs. 4.0 FTEs in nonacademic groups. In both cases, this is well below the median size of comparable adult HM groups.

“Community hospital programs are often started to improve the quality of care around the clock,” Dr. Carlson says. “But the minimum number of FTEs needed for a sustainable 24-hour program is about five—even in very small units. Group size can often be larger in academic settings because pediatric units are larger, and their tertiary nature creates more opportunities for involvement in surgical comanagement and other types of complex care.”

The report shows turnover was higher for both academic and nonacademic pediatric HM practices than for adult medicine practices. The median turnover for nonacademic pediatric groups was 15.5%, for example, compared with 8.2% for the nonacademic adult groups. The sample size for pediatric groups was much smaller, however.

Pediatric hospitalist Dan Rauch, MD, FAAP, FHM, associate professor of pediatrics at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, N.Y., and a former SHM Practice Analysis Committee member, notes that because the typical pediatric group size is much smaller than an adult practice, the loss of only a single hospitalist will result in a much higher turnover rate.

“It’s also my sense that community-based pediatric hospitalist positions are more likely to be transient spots as opposed to academic positions, which are more likely to lead to sustained careers,” he says.

Table 1 (above) presents some key median indicators for nonacademic HM practices. As is true for pediatricians in traditional practice, the typical pediatric hospitalist earned quite a bit less than her colleagues in adult medicine.

Even so, the finances of a pediatric HM program are more challenging than for adult hospitalists. Although professional fee collections per work relative value unit (wRVU) were slightly higher for pediatric groups than for adult groups (a surprising finding as the primary payor for many pediatric hospitalist groups is Medicaid), pediatric hospitalists’ typical annual wRVU production was about 53% lower than that of adult hospitalists, according to the 2011 report. As a result, the compensation-to-collections ratio for pediatric hospitalists was 1.75, which means that pediatric hospitalists collected only about 57 cents in professional fee revenues for every dollar of compensation paid. Adult hospitalists, by comparison, collected about 80 cents for each dollar of compensation.

Dr. Rauch isn’t particularly surprised by those figures. “The goals of nonacademic pediatric hospital medicine programs are more about providing service and expertise than about volume,” he says. “Most community hospital-based pediatric programs simply don’t have the consistent volume to support hospitalists on a billing basis, especially since they typically experience seasonal census variations that academic children’s hospitals don’t have.”

Leslie Flores, SHM senior advisor, practice management

Last chance for both pediatric and adult HM practices to participate in the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine survey: The survey closes March 9. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

Survey Insights: NPs and PAs in Hospital Medicine

One of the most intriguing changes in hospitalist practice staffing over the past few years is the increase in the number of groups integrating nurse practitioners (NPs) and/or physician assistants (PAs) into workflows. When SHM surveyed HM groups in 2005, only 29% of respondents reported having NPs and/or PAs in their practices. In 2011, nearly half (49%) of respondents to the SHM-MGMA nonacademic survey have NPs/PAs in their practices; academic hospital medicine practices were only slightly lower, at 47%.

Of course, it is always important to keep in mind that the respondent pool for the SHM-MGMA surveys is broader than SHM’s historical survey base, which could lead to different results.

Nevertheless, my anecdotal experience from talking with hospitalists around the country, and the experience of SHM Practice Analysis Committee members, supports the conclusion that the proportion of practices using NPs/PAs is growing, and that the number of NPs/PAs per practice is also growing.

Last year, MGMA created new NP/PA specialties just for HM—“Nurse Practitioner: Hospitalist” and “Physician Assistant: Hospitalist.” Data were submitted for only 26 NPs and 23 PAs in these specialties—but hey, it’s a start. Very few practices submitted encounters or wRVUs for hospitalist NPs or PAs, so the only item for which enough data were submitted to report results was compensation, as shown in the table.

NPs in the sample were about evenly divided between hospital-employed and not hospital-employed; however, most of the PAs were hospital-employed. The only region in which enough of the NPs and PAs were located to separately report data was the Southern section. And the vast majority of both NPs and PAs in the sample worked in practices with a shift-based staffing model.

Practice Analysis Committee (PAC) member Scarlett Blue, RN, MSN, vice president of quality and clinical development at Atlanta-based Eagle Hospital Physicians, believes the growing number of NPs and PAs is an indication not only of the continued shortage of physician resources, but also of growing recognition of the value that NPs/PAs can bring to a hospitalist practice. She notes that although Eagle has had NPs/PAs in its practices for some time, the company recently responded to this growth by appointing a national director for hospitalist NP-PA services who is an acute-care nurse practitioner (ACNP) and a doctor of nursing practice (DNP).

Dan Fuller, president of IN Compass Health and a PAC member, concurs. “We’ve had varying success incorporating NPs and PAs so far,” he says. “But as a model, it makes sense. We need to find ways to extend the abilities of our physicians without sacrificing quality.”

The 2012 MGMA surveys are again requesting compensation and productivity data for hospitalist NPs and PAs, and we’re hoping for a robust response. SHM’s new, independent State of Hospital Medicine survey includes questions about NPs and PAs as well. The questionnaires, which only take a few minutes to complete, are available through March 9 at www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

Leslie Flores, SHM senior advisor, practice management

MGMA and SHM compensation and productivity surveys are available through March 9; to participate, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey

One of the most intriguing changes in hospitalist practice staffing over the past few years is the increase in the number of groups integrating nurse practitioners (NPs) and/or physician assistants (PAs) into workflows. When SHM surveyed HM groups in 2005, only 29% of respondents reported having NPs and/or PAs in their practices. In 2011, nearly half (49%) of respondents to the SHM-MGMA nonacademic survey have NPs/PAs in their practices; academic hospital medicine practices were only slightly lower, at 47%.

Of course, it is always important to keep in mind that the respondent pool for the SHM-MGMA surveys is broader than SHM’s historical survey base, which could lead to different results.

Nevertheless, my anecdotal experience from talking with hospitalists around the country, and the experience of SHM Practice Analysis Committee members, supports the conclusion that the proportion of practices using NPs/PAs is growing, and that the number of NPs/PAs per practice is also growing.

Last year, MGMA created new NP/PA specialties just for HM—“Nurse Practitioner: Hospitalist” and “Physician Assistant: Hospitalist.” Data were submitted for only 26 NPs and 23 PAs in these specialties—but hey, it’s a start. Very few practices submitted encounters or wRVUs for hospitalist NPs or PAs, so the only item for which enough data were submitted to report results was compensation, as shown in the table.

NPs in the sample were about evenly divided between hospital-employed and not hospital-employed; however, most of the PAs were hospital-employed. The only region in which enough of the NPs and PAs were located to separately report data was the Southern section. And the vast majority of both NPs and PAs in the sample worked in practices with a shift-based staffing model.

Practice Analysis Committee (PAC) member Scarlett Blue, RN, MSN, vice president of quality and clinical development at Atlanta-based Eagle Hospital Physicians, believes the growing number of NPs and PAs is an indication not only of the continued shortage of physician resources, but also of growing recognition of the value that NPs/PAs can bring to a hospitalist practice. She notes that although Eagle has had NPs/PAs in its practices for some time, the company recently responded to this growth by appointing a national director for hospitalist NP-PA services who is an acute-care nurse practitioner (ACNP) and a doctor of nursing practice (DNP).

Dan Fuller, president of IN Compass Health and a PAC member, concurs. “We’ve had varying success incorporating NPs and PAs so far,” he says. “But as a model, it makes sense. We need to find ways to extend the abilities of our physicians without sacrificing quality.”

The 2012 MGMA surveys are again requesting compensation and productivity data for hospitalist NPs and PAs, and we’re hoping for a robust response. SHM’s new, independent State of Hospital Medicine survey includes questions about NPs and PAs as well. The questionnaires, which only take a few minutes to complete, are available through March 9 at www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

Leslie Flores, SHM senior advisor, practice management

MGMA and SHM compensation and productivity surveys are available through March 9; to participate, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey

One of the most intriguing changes in hospitalist practice staffing over the past few years is the increase in the number of groups integrating nurse practitioners (NPs) and/or physician assistants (PAs) into workflows. When SHM surveyed HM groups in 2005, only 29% of respondents reported having NPs and/or PAs in their practices. In 2011, nearly half (49%) of respondents to the SHM-MGMA nonacademic survey have NPs/PAs in their practices; academic hospital medicine practices were only slightly lower, at 47%.

Of course, it is always important to keep in mind that the respondent pool for the SHM-MGMA surveys is broader than SHM’s historical survey base, which could lead to different results.

Nevertheless, my anecdotal experience from talking with hospitalists around the country, and the experience of SHM Practice Analysis Committee members, supports the conclusion that the proportion of practices using NPs/PAs is growing, and that the number of NPs/PAs per practice is also growing.

Last year, MGMA created new NP/PA specialties just for HM—“Nurse Practitioner: Hospitalist” and “Physician Assistant: Hospitalist.” Data were submitted for only 26 NPs and 23 PAs in these specialties—but hey, it’s a start. Very few practices submitted encounters or wRVUs for hospitalist NPs or PAs, so the only item for which enough data were submitted to report results was compensation, as shown in the table.

NPs in the sample were about evenly divided between hospital-employed and not hospital-employed; however, most of the PAs were hospital-employed. The only region in which enough of the NPs and PAs were located to separately report data was the Southern section. And the vast majority of both NPs and PAs in the sample worked in practices with a shift-based staffing model.

Practice Analysis Committee (PAC) member Scarlett Blue, RN, MSN, vice president of quality and clinical development at Atlanta-based Eagle Hospital Physicians, believes the growing number of NPs and PAs is an indication not only of the continued shortage of physician resources, but also of growing recognition of the value that NPs/PAs can bring to a hospitalist practice. She notes that although Eagle has had NPs/PAs in its practices for some time, the company recently responded to this growth by appointing a national director for hospitalist NP-PA services who is an acute-care nurse practitioner (ACNP) and a doctor of nursing practice (DNP).

Dan Fuller, president of IN Compass Health and a PAC member, concurs. “We’ve had varying success incorporating NPs and PAs so far,” he says. “But as a model, it makes sense. We need to find ways to extend the abilities of our physicians without sacrificing quality.”

The 2012 MGMA surveys are again requesting compensation and productivity data for hospitalist NPs and PAs, and we’re hoping for a robust response. SHM’s new, independent State of Hospital Medicine survey includes questions about NPs and PAs as well. The questionnaires, which only take a few minutes to complete, are available through March 9 at www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

Leslie Flores, SHM senior advisor, practice management

MGMA and SHM compensation and productivity surveys are available through March 9; to participate, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey

Survey Insights: Peeking under the Hood of Academic HM

The 2011 State of Hospital Medicine report offers some tantalizing insights into the operation of academic hospital medicine practices and how they compare with their nonacademic peers. Some results are not surprising, such as the fact that academic hospital medicine groups tend to be larger than nonacademic groups, and that compensation and clinical-FTE-adjusted productivity both tend to be lower for academic hospitalists. Interestingly, turnover rates were about the same in academic and nonacademic practices.

Among the more unexpected findings, however, is that academic HM practices tend to employ a higher proportion of women (44%) than nonacademic practices (35%). In addition, academic practices employed a wider range of staffing models, with only 43% of practices using shift-based staffing, compared with 78% of nonacademic respondents. Similarly, only 47% of academic groups provided on-site coverage at night, compared with 81% of nonacademic groups.

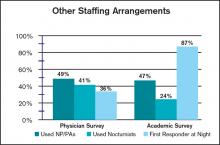

Additional differences between the way academic and nonacademic HM groups staff their programs are shown in the table, “Other Staffing Arrangements.” While the use of nurse practitioners and physician assistants (PA) was similar for academic and nonacademic practices, academic groups were much less likely to utilize nocturnists, and far more likely to have a nonphysician first responder at night (resident, nonphysician provider/PA, or other) than nonacademic groups.

It will be interesting to follow these trends over time. Because of new resident work-hour limits that went into effect in July, SHM Practice Analysis Committee (PAC) member Andrew White, MD, expects that there will be very few places that continue to use residents to cross-cover at night. “I suspect most academic centers have or will hire nocturnists,” he says, “but we’ll see.”

On the other hand, PAC member Scarlett Blue, RN, believes that continued growth in HM, coupled with a competitive job market, could result in increased use of nonphysician first responders at night—and in general. “Hospital medicine group leaders who are looking for alternative ways to meet the supply-demand conundrum may find a blended physician-NP/PA team to be one such answer,” she says.

Finally, the clinical services provided by academic HM groups vary from their nonacademic counterparts in some other important ways. Only 25% of academic practices provide care for ICU patients, compared with 78% of nonacademic practices, while 75% of academic groups perform procedures, compared with only 52% of nonacademic groups. And while the overwhelming majority of both academic and nonacademic practices provide surgical comanagement, academic practices were more than twice as likely to provide comanagement for medical subspecialty patients (45%, compared with 20% for nonacademic practices).

PAC member Troy Ahlstrom, MD, explains, tongue-in-cheek, that “academic hospitalists don’t do procedures because they have oodles of residents, fellows, and interventional radiologists to do them instead, and academics do more medical comanagement because the subspecialist who only does Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia probably doesn’t do diabetes.”

Whatever the reason, there are meaningful differences between academic and nonacademic HM practices that bear watching over time. You can help us identify and track these differences by ensuring that your group participates in SHM’s annual State of Hospital Medicine survey, launching this month.

The 2011 State of Hospital Medicine report offers some tantalizing insights into the operation of academic hospital medicine practices and how they compare with their nonacademic peers. Some results are not surprising, such as the fact that academic hospital medicine groups tend to be larger than nonacademic groups, and that compensation and clinical-FTE-adjusted productivity both tend to be lower for academic hospitalists. Interestingly, turnover rates were about the same in academic and nonacademic practices.

Among the more unexpected findings, however, is that academic HM practices tend to employ a higher proportion of women (44%) than nonacademic practices (35%). In addition, academic practices employed a wider range of staffing models, with only 43% of practices using shift-based staffing, compared with 78% of nonacademic respondents. Similarly, only 47% of academic groups provided on-site coverage at night, compared with 81% of nonacademic groups.

Additional differences between the way academic and nonacademic HM groups staff their programs are shown in the table, “Other Staffing Arrangements.” While the use of nurse practitioners and physician assistants (PA) was similar for academic and nonacademic practices, academic groups were much less likely to utilize nocturnists, and far more likely to have a nonphysician first responder at night (resident, nonphysician provider/PA, or other) than nonacademic groups.

It will be interesting to follow these trends over time. Because of new resident work-hour limits that went into effect in July, SHM Practice Analysis Committee (PAC) member Andrew White, MD, expects that there will be very few places that continue to use residents to cross-cover at night. “I suspect most academic centers have or will hire nocturnists,” he says, “but we’ll see.”

On the other hand, PAC member Scarlett Blue, RN, believes that continued growth in HM, coupled with a competitive job market, could result in increased use of nonphysician first responders at night—and in general. “Hospital medicine group leaders who are looking for alternative ways to meet the supply-demand conundrum may find a blended physician-NP/PA team to be one such answer,” she says.

Finally, the clinical services provided by academic HM groups vary from their nonacademic counterparts in some other important ways. Only 25% of academic practices provide care for ICU patients, compared with 78% of nonacademic practices, while 75% of academic groups perform procedures, compared with only 52% of nonacademic groups. And while the overwhelming majority of both academic and nonacademic practices provide surgical comanagement, academic practices were more than twice as likely to provide comanagement for medical subspecialty patients (45%, compared with 20% for nonacademic practices).

PAC member Troy Ahlstrom, MD, explains, tongue-in-cheek, that “academic hospitalists don’t do procedures because they have oodles of residents, fellows, and interventional radiologists to do them instead, and academics do more medical comanagement because the subspecialist who only does Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia probably doesn’t do diabetes.”

Whatever the reason, there are meaningful differences between academic and nonacademic HM practices that bear watching over time. You can help us identify and track these differences by ensuring that your group participates in SHM’s annual State of Hospital Medicine survey, launching this month.

The 2011 State of Hospital Medicine report offers some tantalizing insights into the operation of academic hospital medicine practices and how they compare with their nonacademic peers. Some results are not surprising, such as the fact that academic hospital medicine groups tend to be larger than nonacademic groups, and that compensation and clinical-FTE-adjusted productivity both tend to be lower for academic hospitalists. Interestingly, turnover rates were about the same in academic and nonacademic practices.

Among the more unexpected findings, however, is that academic HM practices tend to employ a higher proportion of women (44%) than nonacademic practices (35%). In addition, academic practices employed a wider range of staffing models, with only 43% of practices using shift-based staffing, compared with 78% of nonacademic respondents. Similarly, only 47% of academic groups provided on-site coverage at night, compared with 81% of nonacademic groups.

Additional differences between the way academic and nonacademic HM groups staff their programs are shown in the table, “Other Staffing Arrangements.” While the use of nurse practitioners and physician assistants (PA) was similar for academic and nonacademic practices, academic groups were much less likely to utilize nocturnists, and far more likely to have a nonphysician first responder at night (resident, nonphysician provider/PA, or other) than nonacademic groups.

It will be interesting to follow these trends over time. Because of new resident work-hour limits that went into effect in July, SHM Practice Analysis Committee (PAC) member Andrew White, MD, expects that there will be very few places that continue to use residents to cross-cover at night. “I suspect most academic centers have or will hire nocturnists,” he says, “but we’ll see.”

On the other hand, PAC member Scarlett Blue, RN, believes that continued growth in HM, coupled with a competitive job market, could result in increased use of nonphysician first responders at night—and in general. “Hospital medicine group leaders who are looking for alternative ways to meet the supply-demand conundrum may find a blended physician-NP/PA team to be one such answer,” she says.

Finally, the clinical services provided by academic HM groups vary from their nonacademic counterparts in some other important ways. Only 25% of academic practices provide care for ICU patients, compared with 78% of nonacademic practices, while 75% of academic groups perform procedures, compared with only 52% of nonacademic groups. And while the overwhelming majority of both academic and nonacademic practices provide surgical comanagement, academic practices were more than twice as likely to provide comanagement for medical subspecialty patients (45%, compared with 20% for nonacademic practices).

PAC member Troy Ahlstrom, MD, explains, tongue-in-cheek, that “academic hospitalists don’t do procedures because they have oodles of residents, fellows, and interventional radiologists to do them instead, and academics do more medical comanagement because the subspecialist who only does Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia probably doesn’t do diabetes.”

Whatever the reason, there are meaningful differences between academic and nonacademic HM practices that bear watching over time. You can help us identify and track these differences by ensuring that your group participates in SHM’s annual State of Hospital Medicine survey, launching this month.

Survey Insights: It's All Written in Code

One of the questions I am often asked is “What is the typical distribution of CPT codes for hospitalists?” Prior to publication of the 2011 State of Hospital Medicine report, no one could answer that question with any authority. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) publishes some Healthcare Procedure Code (HCPC) distribution information by specialty, but because CMS does not recognize HM as a specialty, the closest proxies are the reported distributions for internal medicine (or pediatrics). And hospitalists argue that because their patient population and the work they do are different, typical distributions for those specialties might not be applicable to hospitalists.

“Coding for hospitalists has to be different from other internists,” says SHM Practice Analysis Committee (PAC) member Rachel Lovins, MD, SFHM. “Because we take responsibility for unfamiliar patients that we hand back to other providers, our level of admission and discharge documentation in particular needs to be higher, in order to ensure excellent communication between hospitalists and PCPs.”

We finally have information about hospitalist coding practices, because both the academic and non-academic Hospital Medicine Supplements captured information about the distribution of inpatient admissions (CPT codes 99221, 99222, and 99223), subsequent visits (99231, 99232, and 99233), and discharges (99238 and 99239). Figure 1 shows the average CPT code distribution for non-academic HM groups serving adults only.

Figure 1. CPT code distribution for non-academic HM groups serving adults

The 2011 State of Hospital Medicine report also shows how CPT distribution varied based on some key practice characteristics. For example, HM practices that are not owned by hospitals/integrated delivery systems tend to code more of their services at higher service levels than do hospital-owned practices. And practices in the Western section of the country tend to code more services at higher levels than other parts of the country.

Other factors are certainly at play as well. “Whether a physician receives training in documentation and coding can have a tremendous impact on CPT distributions,” PAC member Beth Papetti says. “Historically, there has been a tendency for hospitalists to under-code, but through education and enhancements like electronic charge capture, hospitalists can more accurately substantiate the services they provided to the patient.”

Other committee members have speculated that a hospitalist’s compensation model might influence coding patterns, with those who receive less of their total compensation in the form of base salary (and more in the form of productivity and/or performance-based pay) tending to code more of their services at higher levels. But, in fact, the survey data don’t reveal any clear relationship between compensation structure and the average number of work RVUs (relative value units) per encounter.

Interestingly, coding patterns of academic HM practices were similar to those of non-academic practices for admissions and subsequent visits, but academic hospitalists tend to code a higher proportion of discharges at the <30-minute level (99238). PAC members speculate that residents and hospital support staff might perform a larger portion of the discharge coordination and paperwork in academic centers, and attendings can only bill based on their personal time, not time spent by others.

To contribute to a robust CPT distribution database, be sure to participate in the next State of Hospital Medicine survey, scheduled to launch in January 2012.

Leslie Flores, SHM senior advisor, practice management

One of the questions I am often asked is “What is the typical distribution of CPT codes for hospitalists?” Prior to publication of the 2011 State of Hospital Medicine report, no one could answer that question with any authority. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) publishes some Healthcare Procedure Code (HCPC) distribution information by specialty, but because CMS does not recognize HM as a specialty, the closest proxies are the reported distributions for internal medicine (or pediatrics). And hospitalists argue that because their patient population and the work they do are different, typical distributions for those specialties might not be applicable to hospitalists.

“Coding for hospitalists has to be different from other internists,” says SHM Practice Analysis Committee (PAC) member Rachel Lovins, MD, SFHM. “Because we take responsibility for unfamiliar patients that we hand back to other providers, our level of admission and discharge documentation in particular needs to be higher, in order to ensure excellent communication between hospitalists and PCPs.”

We finally have information about hospitalist coding practices, because both the academic and non-academic Hospital Medicine Supplements captured information about the distribution of inpatient admissions (CPT codes 99221, 99222, and 99223), subsequent visits (99231, 99232, and 99233), and discharges (99238 and 99239). Figure 1 shows the average CPT code distribution for non-academic HM groups serving adults only.

Figure 1. CPT code distribution for non-academic HM groups serving adults

The 2011 State of Hospital Medicine report also shows how CPT distribution varied based on some key practice characteristics. For example, HM practices that are not owned by hospitals/integrated delivery systems tend to code more of their services at higher service levels than do hospital-owned practices. And practices in the Western section of the country tend to code more services at higher levels than other parts of the country.

Other factors are certainly at play as well. “Whether a physician receives training in documentation and coding can have a tremendous impact on CPT distributions,” PAC member Beth Papetti says. “Historically, there has been a tendency for hospitalists to under-code, but through education and enhancements like electronic charge capture, hospitalists can more accurately substantiate the services they provided to the patient.”

Other committee members have speculated that a hospitalist’s compensation model might influence coding patterns, with those who receive less of their total compensation in the form of base salary (and more in the form of productivity and/or performance-based pay) tending to code more of their services at higher levels. But, in fact, the survey data don’t reveal any clear relationship between compensation structure and the average number of work RVUs (relative value units) per encounter.

Interestingly, coding patterns of academic HM practices were similar to those of non-academic practices for admissions and subsequent visits, but academic hospitalists tend to code a higher proportion of discharges at the <30-minute level (99238). PAC members speculate that residents and hospital support staff might perform a larger portion of the discharge coordination and paperwork in academic centers, and attendings can only bill based on their personal time, not time spent by others.

To contribute to a robust CPT distribution database, be sure to participate in the next State of Hospital Medicine survey, scheduled to launch in January 2012.

Leslie Flores, SHM senior advisor, practice management

One of the questions I am often asked is “What is the typical distribution of CPT codes for hospitalists?” Prior to publication of the 2011 State of Hospital Medicine report, no one could answer that question with any authority. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) publishes some Healthcare Procedure Code (HCPC) distribution information by specialty, but because CMS does not recognize HM as a specialty, the closest proxies are the reported distributions for internal medicine (or pediatrics). And hospitalists argue that because their patient population and the work they do are different, typical distributions for those specialties might not be applicable to hospitalists.

“Coding for hospitalists has to be different from other internists,” says SHM Practice Analysis Committee (PAC) member Rachel Lovins, MD, SFHM. “Because we take responsibility for unfamiliar patients that we hand back to other providers, our level of admission and discharge documentation in particular needs to be higher, in order to ensure excellent communication between hospitalists and PCPs.”

We finally have information about hospitalist coding practices, because both the academic and non-academic Hospital Medicine Supplements captured information about the distribution of inpatient admissions (CPT codes 99221, 99222, and 99223), subsequent visits (99231, 99232, and 99233), and discharges (99238 and 99239). Figure 1 shows the average CPT code distribution for non-academic HM groups serving adults only.

Figure 1. CPT code distribution for non-academic HM groups serving adults

The 2011 State of Hospital Medicine report also shows how CPT distribution varied based on some key practice characteristics. For example, HM practices that are not owned by hospitals/integrated delivery systems tend to code more of their services at higher service levels than do hospital-owned practices. And practices in the Western section of the country tend to code more services at higher levels than other parts of the country.

Other factors are certainly at play as well. “Whether a physician receives training in documentation and coding can have a tremendous impact on CPT distributions,” PAC member Beth Papetti says. “Historically, there has been a tendency for hospitalists to under-code, but through education and enhancements like electronic charge capture, hospitalists can more accurately substantiate the services they provided to the patient.”

Other committee members have speculated that a hospitalist’s compensation model might influence coding patterns, with those who receive less of their total compensation in the form of base salary (and more in the form of productivity and/or performance-based pay) tending to code more of their services at higher levels. But, in fact, the survey data don’t reveal any clear relationship between compensation structure and the average number of work RVUs (relative value units) per encounter.

Interestingly, coding patterns of academic HM practices were similar to those of non-academic practices for admissions and subsequent visits, but academic hospitalists tend to code a higher proportion of discharges at the <30-minute level (99238). PAC members speculate that residents and hospital support staff might perform a larger portion of the discharge coordination and paperwork in academic centers, and attendings can only bill based on their personal time, not time spent by others.

To contribute to a robust CPT distribution database, be sure to participate in the next State of Hospital Medicine survey, scheduled to launch in January 2012.

Leslie Flores, SHM senior advisor, practice management

Survey Insights

SHM and the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) have enjoyed a successful survey collaboration for the past two years. Working together under a survey collaboration agreement to jointly conduct comprehensive annual surveys of HM groups, the two entities have been able to provide an unprecedented amount of high-quality information for members—not only data about hospitalist compensation and productivity, but also about many other aspects of the ways hospitalists and HM groups function.

And while SHM’s relationship with MGMA remains strong, all good things must come to an end—or at least change considerably.

MGMA is headed in new strategic directions that require a reallocation of its existing survey operations department resources. As a result, SHM and MGMA have agreed to change the way they work together, and this will have some important implications for the types of compensation and productivity data that will be available to hospitalists in the future.

MGMA will continue to conduct its regular surveys, including capturing compensation and productivity data for hospitalists. But instead of incorporating a hospital medicine supplement as it has for the last two years, SHM will instead conduct a separate survey each year to collect additional information about the characteristics of HM practices.

The SHM survey will be launched in January to coincide with the launch of MGMA’s Physician Compensation and Production Survey; in fact, academic groups that participated in MGMA’s Academic Practice Compensation and Production Survey for Faculty and Management this fall might already have noticed that the survey no longer included a hospital medicine supplement. SHM is encouraging hospitalists to participate in both the applicable MGMA survey and the companion SHM survey.

SHM will then license MGMA’s compensation and productivity data for both academic and nonacademic hospitalists, then will combine it with the results of its separate SHM survey to create the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report.

The good news is that this approach will enable SHM to have greater flexibility to design surveys and analyze results in ways that best meet the needs of its constituents, and SHM will also be able to continue to provide survey information annually, rather than going back to the old biannual format.

However, some of the more detailed looks at compensation and productivity data will be lost; those data glimpses only were possible when the supplemental survey was integrated with MGMA’s survey instruments. Such data for 2012 will only be available for national, hospital-employed vs. not-hospital-employed, and geographic region cohorts.

Like the hospitalists it surveys, this report has changed every time it has been conducted. And SHM depends on its members to make sure it is delivering the kind of information that effectively, efficiently, and profitably guides hospitalists’ decisions.

Together, SHM and MGMA have been working to find the right balance that enables MGMA to pursue new strategies and still gives hospitalists the data they need. Ultimately, hospitalists will be the judges of whether the right balance has been struck.