User login

Providing Pain and Palliative Care Education Internationally

Volume 9, Issue 4, July-August 2011, Pages 129-133

How we do it

Judith A. Paice PhD, RN![]()

Available online 2 July 2011.

Article Outline

For many clinicians in oncology, educating other health-care professionals about cancer pain and palliative care is part of their professional life. The need for education exists across clinical settings around the world. Improved education is an urgent need as the prevalence of cancer is increasing. This burden is largely carried by the developing world, where resources are often limited.[1] Global educational efforts, including managing common symptoms, communication, care at the time of death, grief, and other topics, are imperative to reduce pain and suffering.[2] International training efforts require additional expertise and preparation beyond the standard teaching skills needed for all professional education.

The goal of international training efforts in pain and palliative care is to provide useful, culturally relevant programs while empowering participants to sustain these efforts in the long term. Global efforts in palliative care have demonstrated that sharing educational materials, resources, support and encouragement with our international colleagues can provide mentorship to go beyond simply attending a course to developing and expanding their own programs of palliative care in oncology.[3] and [4] To do this well, the following provides specific suggestions for before, during, and after international palliative care training experiences.

Do Your Homework

Before a course, it is essential to learn as much as possible about the region, the culture(s), and the health-care system. Several resources for this information are listed in Table 1. Additionally, speaking with colleagues who have traveled to the country or to those who have emigrated from the country can provide valuable insight. These individuals can provide a wealth of information to assist in developing an appropriate curriculum and specific presentations. As demographics vary, it is important to know the common cancers and other leading causes of death in the region. Issues that may be seen as “competing” issues HIV/AIDS, malaria, immunizations, lack of clean water, or maternal–infant mortality.[5] and [6] Literature, including fiction and nonfiction, as well as movies and other media, can enlighten the traveler regarding life in the region. Local consulates offer opportunities for learning, as do organizations such as the Council on Global Relations. There are rapid changes in global politics, health-care systems, and governments, so it is also vital to have current information.

| American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) | Offers international cancer courses as well as fellowships and other awards. |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/ | Provides information regarding common infectious illnesses, traveler's alerts. |

| Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), The World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/ | Excellent review of a country's political, demographic, geographic, and other attributes. |

| City of Hope Pain & Palliative Care Resource Center, http://prc.coh.org/ | Provides a clearinghouse that includes a wide array of resources and references to enhance pain and palliative care education and research. |

| End of Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC), http://www.aacn.nche.edu/elnec/ | Includes relevant articles, resources, and a summary of current international ELNEC training programs. |

| International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care (IAHPC), http://www.hospicecare.com/ | Numerous global palliative care resources, including List of Essential Medicines, Global Directory of Educational Programs in Palliative Care, Global Directory of Palliative Care Providers/Services/Organizations, as well as Palliative Care in the Developing World: Principles and Practice. |

| International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), http://www.iasp-pain.org/ | Strong emphasis on support of developing countries with research and educational grants; publishes a Guide to Pain Management in Low-Resource Settings offered without cost. |

| Open Society Institute–International Palliative Care Initiative, http://www.soros.org/initiatives/health/focus/ipci/about | Offers support for training, clinical care, and research in palliative care, alone and in collaboration with other organizations. |

| Pain & Policy Studies Group, http://www.painpolicy.wisc.edu/ | Excellent resource for information regarding opioid consumption by country as well as guidelines for policies that allow access to necessary medications. |

| U.S. Department of State, http://www.usembassy.gov/ Bureau of Consular Affairs, http://travel.state.gov/travel/travel_1744.html | Comprehensive lists of US embassies, consulates, and diplomatic missions; information to assist travelers from the United States to other countries, including visa requirements and safety alerts. |

| World Health Organization, http://www.who.int | Many useful resources, including Access to Analgesics and to other Controlled Medicines, as well as statistics regarding common illnesses by country. |

Health-Care Structure

Understand the existing health-care structure and what health care is available to all or for select populations. What is the extent of health-care services? Are there clinics for preventive care, or is most care obtained in the hospital? Is home care available with support from nurses and other professionals? Are emergency services available (eg, does the region have ambulances to transport and emergency departments to accept critically ill patients)? Where do patients obtain medications, and do they have to pay out of pocket for these? Do most people die in the hospital or at home? While websites and government sources are valuable, verify this information with clinicians since the clinical reality may be quite different.

Available Medications

To provide useful guidance in symptom management, it is necessary to have a list of available medications used to treat pain, nausea, dyspnea, constipation/diarrhea, wounds, and other symptoms commonly seen in oncology. Your presentation may need to be modified based upon these available drugs (Table 2). Where do patients obtain medications, and do they pay out of pocket for these? There are limitations on availability and access to opioids around the world.[7] Which opioids are available and actually used? What is the process for obtaining a supply of an opioid for a person with cancer? For example, in some countries, physicians can order only one week's worth of medication at a time. In other countries, patients must obtain opioids from the police station rather than a pharmacy. In several settings, only the patient, not family members, can pick up the medication from the dispensing site. And in a few countries, only parenteral opioids are available. It is also helpful to understand issues such as the prevalence of drug trafficking in the region and how this might affect local drug laws. Are traditional medicines, such as herbal therapies, or other techniques commonly used? It is helpful to be aware of these practices and incorporate them into teaching plans where appropriate.

Education of Health-Care Professionals

International education in palliative care should consider how physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and others are educated. Is the educational system very traditional and formal, with little interaction between students and teachers? Professionals trained in this manner may be less comfortable when faced with role-play, learning through discussion, or other Socratic educational methods. That does not mean that one should exclude these methods when planning the curriculum but, rather, be prepared for silence and possibly even discomfort when first introduced. Seek guidance from local educators as to what methods will be acceptable.

Who is included in the health-care team? Are psychologists available, and are chaplains considered part of health-care services? What is the relationship between physicians, nurses, and other team members? Is collegiality accepted, or is there a hierarchy that limits true teamwork? What is the status of physicians, nurses, and other professionals in the region? In some areas, physicians are highly regarded and financially compensated accordingly. In other parts of the world, physicians have very low social status, respect, and compensation. Within diverse cultures, compensation and acceptance of tips (or bribes) to see a patient or perform an intervention may be accepted practice. Attitudes toward work hours may differ from the Western perspective. In some cultures, socialization and development of personal relationships may be considered more important than other aspects of the workload.[8]

Planning in advance to know the targeted attendees is helpful. It is advisable to inquire if the hosts might consider inviting representatives from the ministry of health, the appropriate drug institutes, other key government officials, as well as medical, nursing, and pharmacy leaders who can become champions for access to pain relief and palliative care. Having multiple disciplines and leaders from health care and government at the same program can foster ongoing communication and understanding. Include chief educators as they can incorporate this content into their respective curricula.

Plan the Curriculum and the Program

The importance of cultural issues when developing content cannot be overstated.[9] Factors that might affect pain expression and language or cultural beliefs about death and dying will greatly impact content for teaching. Be aware of local religious and spiritual beliefs impacting pain and palliative care. Consider issues surrounding disclosure of diagnosis and prognosis. Autonomy may not be the prevailing perspective as seen in North America. Ensure that slides are culturally correct and that pictures and illustrations are appropriate. Having the host country leaders review the curriculum in advance is advisable. Avoid cartoons as these may not translate well. Use case examples, but ensure that they represent the types of patients and scenarios seen by the audience. It is also important to avoid being ethnocentric as Western medicine has much to learn from other approaches. It is very helpful to use case studies from the host country. In some settings, trainers will not have access to computers and projectors, limiting the role of PowerPoint slides. Paper presentations or the use of flip-charts may be more accessible.

Consider the need for translation and, if so, which type will be used. Simultaneous interpretation generally requires a sound booth and headphones for participants, and may be more expensive. Consecutive interpretation requires that the instructor present blocks of information, usually a sentence or two, followed by the interpreter providing the content in the appropriate language. This requires speakers to plan much shorter presentations with up to 50% less content being delivered. In either case, trained interpreters can benefit from seeing the slides in advance so they can prepare and clarify prior to the presentation.

When developing an agenda, inquire about the usual times for breaks and meals, as well as time for prayers or other activities. What is considered a “full day” varies around the world, as does the value of adhering rigidly to a schedule. International education generally means that the agenda is fluid; once you are actually in the country and providing the course, other needs may arise. A common mistake is trying to squeeze in too much content. Ask your host to meet prior to the program and, optimally, plan for time before the course to tour health-care facilities. Arrange for a time to meet with key medical, nursing, pharmacy, and governmental leaders who are not scheduled to attend the meeting but might somehow influence curricula and practice. In some settings, local media may be alerted to generate local interest in the topic. Communicate with your host about these opportunities so that arrangements can be made in advance.

For resource-poor countries, consider asking for donations from colleagues before leaving, including books, CDs, and medical supplies. Check local regulations first, particularly if bringing in medications or equipment. If sending books, some countries require high tariff fees to be paid by the receiver when accepting these packages, creating a financial burden for your hosts. Inquire ahead of time if they have to pay to accept these packages. Additionally, in some resource-poor countries, professionals do not have access to personal or work computers and internet café computers often do not have CD drives. Information on jump drives may be more easily accessible.

Finally, visiting educators may want to pack small gifts to give to hosts and others. These should be easily transported and may include items that represent your city or institution. We have also found bringing candy and small toys to be universally appreciated when visiting pediatric settings. A small portable color printer can be used to print photographs of pediatric patients as some of these children have never seen pictures of themselves. You can also print photographs of participants in the training courses.

Personal Considerations

Several months prior to departure, you should contact your traveler's health information resource to identify which vaccinations and what documents are needed to enter the country. To avoid lost time due to illness, ciprofloxacin and antidiarrheal medicines should be obtained before traveling. It is advisable to update your passport. Some countries require you to have sufficient blank pages in your passport to allow entry into their country. An entry fee paid in cash may be required upon arrival. Travelers should consider the political climate of the country and check the U.S. Department of State website (included in Table 1) for alerts or precautions.

Consider appropriate attire when packing. Clothing should reflect respect for the cultural and religious beliefs of the attendees.

During the Experience

It is very useful to meet with interpreters prior to the presentations to clarify any questions. Translation can be quite complicated. For example, a slide that used the term “caring” was interpreted as “romantic love,” and concepts about suffering and death can take on a cultural meaning. Check with interpreters regularly to determine if the speed of delivery is acceptable. Also, translators may have difficulty with this emotional content. In some instances, interpreters have become tearful and required debriefing after palliative care education events. Consider nonverbal communication and personal space. In some cultures, it may not be appropriate to shake hands or to use two hands. Gestures may have very different meanings in other cultures, so avoid these forms of communication. For example, the “OK” sign commonly used in North America, with the tip of the finger touching the tip of the thumb and the other three fingers extended, is considered an obscene gesture in Brazil.

When using teaching strategies other than lecture, respect that some students may not be comfortable at first with nontraditional approaches. Informal teaching strategies that are valued in North America may be viewed as of poor academic quality in other cultures. Debate and discussion, which may make it seem that the student is questioning a teacher's view, may be seen as disrespectful. At times, eliciting personal reflection and experience can engage the audience. For example, when introducing the topic of communication, health-care professionals in the audience can be asked the following questions:

- • If you had cancer, would you want to know?

• Would you want to know that you had a disease that you could die from?

Following these with “What do you tell your patients?” usually engenders excellent discussion.

We have also found that asking participants to do “homework” can be useful, particularly if the students have been quiet or reluctant to communicate during class. Suggested assignments might include listing the five top barriers to cancer pain management in your setting, describing a difficult death or a death that you made better, or related issues. Reticence to speak during class may be due to discomfort with language skills. Some students feel more comfortable sharing ideas in writing, and these assignments have yielded valuable stories that have helped us to understand their experiences and perspectives.

Since the goal of these educational efforts should be sustained, it is helpful to develop a plan for the future with students. Assist them in identifying goals, as well as action items to meet these goals. Allow time for individual meetings between faculty and students to fine-tune these efforts. This ensures that the educational experience will have a greater likelihood of translation into action. To provide practical assistance, if Internet access is available, spend time with small groups to demonstrate literature searches, useful websites, and other information that will foster continuity.

Faculty should meet after each day of training to modify the planned agenda as needed, to optimally meet the needs of the participants. This also provides needed time to debrief about the day's activities and provide support. Particularly when new to international education, the experience may be overwhelming as the status of health-care in developing countries can cause deep personal reflection.

Finally, celebrate. We have found that many students appreciate the opportunity to have some type of closing ceremony to receive certificates and pins, acknowledge their accomplishments, and encourage their future efforts.

Afterward

E-mail, voiceover Internet services, and videoconferencing software have significantly enhanced global communication. Faculty can make themselves available to the trainees after leaving the country using these technologies. Group conversations via e-mail can help solve problems, provide encouragement, and celebrate successes. Connect attendees with international professional organizations to support ongoing educational efforts. It is very useful to identify the leaders or champions and to plan ongoing support to help sustain their commitment. Many countries do not have professional organizations or support networks. These leaders can exist in isolation and suffer great personal sacrifice to lead palliative care efforts in their country.

Conclusion

When educating about pain and palliative care to a worldwide audience, never make assumptions, expect the unexpected, and be flexible. We have found many of these international teaching experiences to be some of the most exhilarating of our professional lives, providing insight to our own practices and creating lasting relationships with colleagues from around the globe. Ultimately, these efforts will improve care for people with cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the American Association of Colleges of Nursing and the City of Hope for their ongoing support of the End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium training activities, as well as the Oncology Nursing Society Foundation and the Open Society Institute for their support of international educational efforts. They also thank Marian Grant for her input.

References [Pub Med ID in Brackets]

1 A.L. Taylor, L.O. Gostin and K.A. Pagonis, Ensuring effective pain treatment: a national and global perspective, JAMA 299 (2008), pp. 89–91 [18167410].

2 K. Crane, Palliative care gains ground in developing countries, J Natl Cancer Inst 102 (21) (2010), pp. 1613–1615 [20966432].

3 J.A. Paice, B.R. Ferrell, N. Coyle, P. Coyne and M. Callaway, Global efforts to improve palliative care: the International End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium training programme, J Adv Nurs 61 (2007), pp. 173–180 [18186909].

4 J.A. Paice, B. Ferrell, N. Coyle, P. Coyne and T. Smith, Living and dying in East Africa: implementing the End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium curriculum in Tanzania, Clin J Oncol Nurs 14 (2010), pp. 161–166 [20350889].

5 C. Olweny, C. Sepulveda, A. Merriman, S. Fonn, M. Borok, T. Ngoma, A. Doh and J. Stjernsward, Desirable services and guidelines for the treatment and palliative care of HIV disease patients with cancer in Africa: a World Health Organization consultation, J Palliat Care 19 (2003), pp. 198–205 [14606333].

6 C. Sepulveda, V. Habiyatmbete, J. Amandua, M. Borok, E. Kikule, B. Mudanga and B. Solomon, Quality care at the end of life in Africa, BMJ 327 (2003), pp. 209–213 [12881267].

7 E.L. Krakauer, R. Wenk, R. Buitrago, P. Jenkins and W. Scholten, Opioid inaccessibility and its human consequences: reports from the field, J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 24 (2010), pp. 239–243 [20718644].

8 C.M. Bolin, Developing a postbasic gerontology program for international learners: considerations for the process, J Contin Educ Nurs 34 (2003), pp. 177–183 [12887229].

9 K.D. Meneses and C.H. Yarbro, Cultural perspectives of international breast health and breast cancer education, J Nurs Scholarsh 39 (2) (2007), pp. 105–112 [19058079].

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and none were reported.

![]()

Vitae

Dr. Paice is Director of the Cancer Pain Program, Division of Hematology-Oncology, Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois.

Carma Erickson-Hurt is a faculty member at Grand Canyon University, Phoenix, Arizona.

Dr. Ferrell is a Professor and Research Scientist at the City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, California.

Nessa Coyle is on the Pain and Palliative Care Service, Department of Medicine, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

Dr. Coyne is Clinical Director of the Thomas Palliative Care Program, Virginia Commonwealth University/Massey Cancer Center, Richmond, Virginia.

Dr. Long is a geriatric nursing consultant and codirector of the Palliative Care for Advanced Dementia, Beatitudes Campus, Phoenix, Arizona.

Dr. Mazanec is a clinical nurse specialist at the University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center, Cleveland, Ohio.

Pam Malloy is ELNEC Project Director, American Association of Colleges of Nursing, Washington, DC.

Dr. Smith is Professor of Medicine and Palliative Care Research, Virginia Commonwealth University/Massey Cancer Center, Richmond.

Volume 9, Issue 4, July-August 2011, Pages 129-133

How we do it

Judith A. Paice PhD, RN![]()

Available online 2 July 2011.

Article Outline

For many clinicians in oncology, educating other health-care professionals about cancer pain and palliative care is part of their professional life. The need for education exists across clinical settings around the world. Improved education is an urgent need as the prevalence of cancer is increasing. This burden is largely carried by the developing world, where resources are often limited.[1] Global educational efforts, including managing common symptoms, communication, care at the time of death, grief, and other topics, are imperative to reduce pain and suffering.[2] International training efforts require additional expertise and preparation beyond the standard teaching skills needed for all professional education.

The goal of international training efforts in pain and palliative care is to provide useful, culturally relevant programs while empowering participants to sustain these efforts in the long term. Global efforts in palliative care have demonstrated that sharing educational materials, resources, support and encouragement with our international colleagues can provide mentorship to go beyond simply attending a course to developing and expanding their own programs of palliative care in oncology.[3] and [4] To do this well, the following provides specific suggestions for before, during, and after international palliative care training experiences.

Do Your Homework

Before a course, it is essential to learn as much as possible about the region, the culture(s), and the health-care system. Several resources for this information are listed in Table 1. Additionally, speaking with colleagues who have traveled to the country or to those who have emigrated from the country can provide valuable insight. These individuals can provide a wealth of information to assist in developing an appropriate curriculum and specific presentations. As demographics vary, it is important to know the common cancers and other leading causes of death in the region. Issues that may be seen as “competing” issues HIV/AIDS, malaria, immunizations, lack of clean water, or maternal–infant mortality.[5] and [6] Literature, including fiction and nonfiction, as well as movies and other media, can enlighten the traveler regarding life in the region. Local consulates offer opportunities for learning, as do organizations such as the Council on Global Relations. There are rapid changes in global politics, health-care systems, and governments, so it is also vital to have current information.

| American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) | Offers international cancer courses as well as fellowships and other awards. |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/ | Provides information regarding common infectious illnesses, traveler's alerts. |

| Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), The World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/ | Excellent review of a country's political, demographic, geographic, and other attributes. |

| City of Hope Pain & Palliative Care Resource Center, http://prc.coh.org/ | Provides a clearinghouse that includes a wide array of resources and references to enhance pain and palliative care education and research. |

| End of Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC), http://www.aacn.nche.edu/elnec/ | Includes relevant articles, resources, and a summary of current international ELNEC training programs. |

| International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care (IAHPC), http://www.hospicecare.com/ | Numerous global palliative care resources, including List of Essential Medicines, Global Directory of Educational Programs in Palliative Care, Global Directory of Palliative Care Providers/Services/Organizations, as well as Palliative Care in the Developing World: Principles and Practice. |

| International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), http://www.iasp-pain.org/ | Strong emphasis on support of developing countries with research and educational grants; publishes a Guide to Pain Management in Low-Resource Settings offered without cost. |

| Open Society Institute–International Palliative Care Initiative, http://www.soros.org/initiatives/health/focus/ipci/about | Offers support for training, clinical care, and research in palliative care, alone and in collaboration with other organizations. |

| Pain & Policy Studies Group, http://www.painpolicy.wisc.edu/ | Excellent resource for information regarding opioid consumption by country as well as guidelines for policies that allow access to necessary medications. |

| U.S. Department of State, http://www.usembassy.gov/ Bureau of Consular Affairs, http://travel.state.gov/travel/travel_1744.html | Comprehensive lists of US embassies, consulates, and diplomatic missions; information to assist travelers from the United States to other countries, including visa requirements and safety alerts. |

| World Health Organization, http://www.who.int | Many useful resources, including Access to Analgesics and to other Controlled Medicines, as well as statistics regarding common illnesses by country. |

Health-Care Structure

Understand the existing health-care structure and what health care is available to all or for select populations. What is the extent of health-care services? Are there clinics for preventive care, or is most care obtained in the hospital? Is home care available with support from nurses and other professionals? Are emergency services available (eg, does the region have ambulances to transport and emergency departments to accept critically ill patients)? Where do patients obtain medications, and do they have to pay out of pocket for these? Do most people die in the hospital or at home? While websites and government sources are valuable, verify this information with clinicians since the clinical reality may be quite different.

Available Medications

To provide useful guidance in symptom management, it is necessary to have a list of available medications used to treat pain, nausea, dyspnea, constipation/diarrhea, wounds, and other symptoms commonly seen in oncology. Your presentation may need to be modified based upon these available drugs (Table 2). Where do patients obtain medications, and do they pay out of pocket for these? There are limitations on availability and access to opioids around the world.[7] Which opioids are available and actually used? What is the process for obtaining a supply of an opioid for a person with cancer? For example, in some countries, physicians can order only one week's worth of medication at a time. In other countries, patients must obtain opioids from the police station rather than a pharmacy. In several settings, only the patient, not family members, can pick up the medication from the dispensing site. And in a few countries, only parenteral opioids are available. It is also helpful to understand issues such as the prevalence of drug trafficking in the region and how this might affect local drug laws. Are traditional medicines, such as herbal therapies, or other techniques commonly used? It is helpful to be aware of these practices and incorporate them into teaching plans where appropriate.

Education of Health-Care Professionals

International education in palliative care should consider how physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and others are educated. Is the educational system very traditional and formal, with little interaction between students and teachers? Professionals trained in this manner may be less comfortable when faced with role-play, learning through discussion, or other Socratic educational methods. That does not mean that one should exclude these methods when planning the curriculum but, rather, be prepared for silence and possibly even discomfort when first introduced. Seek guidance from local educators as to what methods will be acceptable.

Who is included in the health-care team? Are psychologists available, and are chaplains considered part of health-care services? What is the relationship between physicians, nurses, and other team members? Is collegiality accepted, or is there a hierarchy that limits true teamwork? What is the status of physicians, nurses, and other professionals in the region? In some areas, physicians are highly regarded and financially compensated accordingly. In other parts of the world, physicians have very low social status, respect, and compensation. Within diverse cultures, compensation and acceptance of tips (or bribes) to see a patient or perform an intervention may be accepted practice. Attitudes toward work hours may differ from the Western perspective. In some cultures, socialization and development of personal relationships may be considered more important than other aspects of the workload.[8]

Planning in advance to know the targeted attendees is helpful. It is advisable to inquire if the hosts might consider inviting representatives from the ministry of health, the appropriate drug institutes, other key government officials, as well as medical, nursing, and pharmacy leaders who can become champions for access to pain relief and palliative care. Having multiple disciplines and leaders from health care and government at the same program can foster ongoing communication and understanding. Include chief educators as they can incorporate this content into their respective curricula.

Plan the Curriculum and the Program

The importance of cultural issues when developing content cannot be overstated.[9] Factors that might affect pain expression and language or cultural beliefs about death and dying will greatly impact content for teaching. Be aware of local religious and spiritual beliefs impacting pain and palliative care. Consider issues surrounding disclosure of diagnosis and prognosis. Autonomy may not be the prevailing perspective as seen in North America. Ensure that slides are culturally correct and that pictures and illustrations are appropriate. Having the host country leaders review the curriculum in advance is advisable. Avoid cartoons as these may not translate well. Use case examples, but ensure that they represent the types of patients and scenarios seen by the audience. It is also important to avoid being ethnocentric as Western medicine has much to learn from other approaches. It is very helpful to use case studies from the host country. In some settings, trainers will not have access to computers and projectors, limiting the role of PowerPoint slides. Paper presentations or the use of flip-charts may be more accessible.

Consider the need for translation and, if so, which type will be used. Simultaneous interpretation generally requires a sound booth and headphones for participants, and may be more expensive. Consecutive interpretation requires that the instructor present blocks of information, usually a sentence or two, followed by the interpreter providing the content in the appropriate language. This requires speakers to plan much shorter presentations with up to 50% less content being delivered. In either case, trained interpreters can benefit from seeing the slides in advance so they can prepare and clarify prior to the presentation.

When developing an agenda, inquire about the usual times for breaks and meals, as well as time for prayers or other activities. What is considered a “full day” varies around the world, as does the value of adhering rigidly to a schedule. International education generally means that the agenda is fluid; once you are actually in the country and providing the course, other needs may arise. A common mistake is trying to squeeze in too much content. Ask your host to meet prior to the program and, optimally, plan for time before the course to tour health-care facilities. Arrange for a time to meet with key medical, nursing, pharmacy, and governmental leaders who are not scheduled to attend the meeting but might somehow influence curricula and practice. In some settings, local media may be alerted to generate local interest in the topic. Communicate with your host about these opportunities so that arrangements can be made in advance.

For resource-poor countries, consider asking for donations from colleagues before leaving, including books, CDs, and medical supplies. Check local regulations first, particularly if bringing in medications or equipment. If sending books, some countries require high tariff fees to be paid by the receiver when accepting these packages, creating a financial burden for your hosts. Inquire ahead of time if they have to pay to accept these packages. Additionally, in some resource-poor countries, professionals do not have access to personal or work computers and internet café computers often do not have CD drives. Information on jump drives may be more easily accessible.

Finally, visiting educators may want to pack small gifts to give to hosts and others. These should be easily transported and may include items that represent your city or institution. We have also found bringing candy and small toys to be universally appreciated when visiting pediatric settings. A small portable color printer can be used to print photographs of pediatric patients as some of these children have never seen pictures of themselves. You can also print photographs of participants in the training courses.

Personal Considerations

Several months prior to departure, you should contact your traveler's health information resource to identify which vaccinations and what documents are needed to enter the country. To avoid lost time due to illness, ciprofloxacin and antidiarrheal medicines should be obtained before traveling. It is advisable to update your passport. Some countries require you to have sufficient blank pages in your passport to allow entry into their country. An entry fee paid in cash may be required upon arrival. Travelers should consider the political climate of the country and check the U.S. Department of State website (included in Table 1) for alerts or precautions.

Consider appropriate attire when packing. Clothing should reflect respect for the cultural and religious beliefs of the attendees.

During the Experience

It is very useful to meet with interpreters prior to the presentations to clarify any questions. Translation can be quite complicated. For example, a slide that used the term “caring” was interpreted as “romantic love,” and concepts about suffering and death can take on a cultural meaning. Check with interpreters regularly to determine if the speed of delivery is acceptable. Also, translators may have difficulty with this emotional content. In some instances, interpreters have become tearful and required debriefing after palliative care education events. Consider nonverbal communication and personal space. In some cultures, it may not be appropriate to shake hands or to use two hands. Gestures may have very different meanings in other cultures, so avoid these forms of communication. For example, the “OK” sign commonly used in North America, with the tip of the finger touching the tip of the thumb and the other three fingers extended, is considered an obscene gesture in Brazil.

When using teaching strategies other than lecture, respect that some students may not be comfortable at first with nontraditional approaches. Informal teaching strategies that are valued in North America may be viewed as of poor academic quality in other cultures. Debate and discussion, which may make it seem that the student is questioning a teacher's view, may be seen as disrespectful. At times, eliciting personal reflection and experience can engage the audience. For example, when introducing the topic of communication, health-care professionals in the audience can be asked the following questions:

- • If you had cancer, would you want to know?

• Would you want to know that you had a disease that you could die from?

Following these with “What do you tell your patients?” usually engenders excellent discussion.

We have also found that asking participants to do “homework” can be useful, particularly if the students have been quiet or reluctant to communicate during class. Suggested assignments might include listing the five top barriers to cancer pain management in your setting, describing a difficult death or a death that you made better, or related issues. Reticence to speak during class may be due to discomfort with language skills. Some students feel more comfortable sharing ideas in writing, and these assignments have yielded valuable stories that have helped us to understand their experiences and perspectives.

Since the goal of these educational efforts should be sustained, it is helpful to develop a plan for the future with students. Assist them in identifying goals, as well as action items to meet these goals. Allow time for individual meetings between faculty and students to fine-tune these efforts. This ensures that the educational experience will have a greater likelihood of translation into action. To provide practical assistance, if Internet access is available, spend time with small groups to demonstrate literature searches, useful websites, and other information that will foster continuity.

Faculty should meet after each day of training to modify the planned agenda as needed, to optimally meet the needs of the participants. This also provides needed time to debrief about the day's activities and provide support. Particularly when new to international education, the experience may be overwhelming as the status of health-care in developing countries can cause deep personal reflection.

Finally, celebrate. We have found that many students appreciate the opportunity to have some type of closing ceremony to receive certificates and pins, acknowledge their accomplishments, and encourage their future efforts.

Afterward

E-mail, voiceover Internet services, and videoconferencing software have significantly enhanced global communication. Faculty can make themselves available to the trainees after leaving the country using these technologies. Group conversations via e-mail can help solve problems, provide encouragement, and celebrate successes. Connect attendees with international professional organizations to support ongoing educational efforts. It is very useful to identify the leaders or champions and to plan ongoing support to help sustain their commitment. Many countries do not have professional organizations or support networks. These leaders can exist in isolation and suffer great personal sacrifice to lead palliative care efforts in their country.

Conclusion

When educating about pain and palliative care to a worldwide audience, never make assumptions, expect the unexpected, and be flexible. We have found many of these international teaching experiences to be some of the most exhilarating of our professional lives, providing insight to our own practices and creating lasting relationships with colleagues from around the globe. Ultimately, these efforts will improve care for people with cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the American Association of Colleges of Nursing and the City of Hope for their ongoing support of the End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium training activities, as well as the Oncology Nursing Society Foundation and the Open Society Institute for their support of international educational efforts. They also thank Marian Grant for her input.

References [Pub Med ID in Brackets]

1 A.L. Taylor, L.O. Gostin and K.A. Pagonis, Ensuring effective pain treatment: a national and global perspective, JAMA 299 (2008), pp. 89–91 [18167410].

2 K. Crane, Palliative care gains ground in developing countries, J Natl Cancer Inst 102 (21) (2010), pp. 1613–1615 [20966432].

3 J.A. Paice, B.R. Ferrell, N. Coyle, P. Coyne and M. Callaway, Global efforts to improve palliative care: the International End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium training programme, J Adv Nurs 61 (2007), pp. 173–180 [18186909].

4 J.A. Paice, B. Ferrell, N. Coyle, P. Coyne and T. Smith, Living and dying in East Africa: implementing the End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium curriculum in Tanzania, Clin J Oncol Nurs 14 (2010), pp. 161–166 [20350889].

5 C. Olweny, C. Sepulveda, A. Merriman, S. Fonn, M. Borok, T. Ngoma, A. Doh and J. Stjernsward, Desirable services and guidelines for the treatment and palliative care of HIV disease patients with cancer in Africa: a World Health Organization consultation, J Palliat Care 19 (2003), pp. 198–205 [14606333].

6 C. Sepulveda, V. Habiyatmbete, J. Amandua, M. Borok, E. Kikule, B. Mudanga and B. Solomon, Quality care at the end of life in Africa, BMJ 327 (2003), pp. 209–213 [12881267].

7 E.L. Krakauer, R. Wenk, R. Buitrago, P. Jenkins and W. Scholten, Opioid inaccessibility and its human consequences: reports from the field, J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 24 (2010), pp. 239–243 [20718644].

8 C.M. Bolin, Developing a postbasic gerontology program for international learners: considerations for the process, J Contin Educ Nurs 34 (2003), pp. 177–183 [12887229].

9 K.D. Meneses and C.H. Yarbro, Cultural perspectives of international breast health and breast cancer education, J Nurs Scholarsh 39 (2) (2007), pp. 105–112 [19058079].

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and none were reported.

![]()

Vitae

Dr. Paice is Director of the Cancer Pain Program, Division of Hematology-Oncology, Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois.

Carma Erickson-Hurt is a faculty member at Grand Canyon University, Phoenix, Arizona.

Dr. Ferrell is a Professor and Research Scientist at the City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, California.

Nessa Coyle is on the Pain and Palliative Care Service, Department of Medicine, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

Dr. Coyne is Clinical Director of the Thomas Palliative Care Program, Virginia Commonwealth University/Massey Cancer Center, Richmond, Virginia.

Dr. Long is a geriatric nursing consultant and codirector of the Palliative Care for Advanced Dementia, Beatitudes Campus, Phoenix, Arizona.

Dr. Mazanec is a clinical nurse specialist at the University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center, Cleveland, Ohio.

Pam Malloy is ELNEC Project Director, American Association of Colleges of Nursing, Washington, DC.

Dr. Smith is Professor of Medicine and Palliative Care Research, Virginia Commonwealth University/Massey Cancer Center, Richmond.

Volume 9, Issue 4, July-August 2011, Pages 129-133

How we do it

Judith A. Paice PhD, RN![]()

Available online 2 July 2011.

Article Outline

For many clinicians in oncology, educating other health-care professionals about cancer pain and palliative care is part of their professional life. The need for education exists across clinical settings around the world. Improved education is an urgent need as the prevalence of cancer is increasing. This burden is largely carried by the developing world, where resources are often limited.[1] Global educational efforts, including managing common symptoms, communication, care at the time of death, grief, and other topics, are imperative to reduce pain and suffering.[2] International training efforts require additional expertise and preparation beyond the standard teaching skills needed for all professional education.

The goal of international training efforts in pain and palliative care is to provide useful, culturally relevant programs while empowering participants to sustain these efforts in the long term. Global efforts in palliative care have demonstrated that sharing educational materials, resources, support and encouragement with our international colleagues can provide mentorship to go beyond simply attending a course to developing and expanding their own programs of palliative care in oncology.[3] and [4] To do this well, the following provides specific suggestions for before, during, and after international palliative care training experiences.

Do Your Homework

Before a course, it is essential to learn as much as possible about the region, the culture(s), and the health-care system. Several resources for this information are listed in Table 1. Additionally, speaking with colleagues who have traveled to the country or to those who have emigrated from the country can provide valuable insight. These individuals can provide a wealth of information to assist in developing an appropriate curriculum and specific presentations. As demographics vary, it is important to know the common cancers and other leading causes of death in the region. Issues that may be seen as “competing” issues HIV/AIDS, malaria, immunizations, lack of clean water, or maternal–infant mortality.[5] and [6] Literature, including fiction and nonfiction, as well as movies and other media, can enlighten the traveler regarding life in the region. Local consulates offer opportunities for learning, as do organizations such as the Council on Global Relations. There are rapid changes in global politics, health-care systems, and governments, so it is also vital to have current information.

| American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) | Offers international cancer courses as well as fellowships and other awards. |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/ | Provides information regarding common infectious illnesses, traveler's alerts. |

| Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), The World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/ | Excellent review of a country's political, demographic, geographic, and other attributes. |

| City of Hope Pain & Palliative Care Resource Center, http://prc.coh.org/ | Provides a clearinghouse that includes a wide array of resources and references to enhance pain and palliative care education and research. |

| End of Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC), http://www.aacn.nche.edu/elnec/ | Includes relevant articles, resources, and a summary of current international ELNEC training programs. |

| International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care (IAHPC), http://www.hospicecare.com/ | Numerous global palliative care resources, including List of Essential Medicines, Global Directory of Educational Programs in Palliative Care, Global Directory of Palliative Care Providers/Services/Organizations, as well as Palliative Care in the Developing World: Principles and Practice. |

| International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), http://www.iasp-pain.org/ | Strong emphasis on support of developing countries with research and educational grants; publishes a Guide to Pain Management in Low-Resource Settings offered without cost. |

| Open Society Institute–International Palliative Care Initiative, http://www.soros.org/initiatives/health/focus/ipci/about | Offers support for training, clinical care, and research in palliative care, alone and in collaboration with other organizations. |

| Pain & Policy Studies Group, http://www.painpolicy.wisc.edu/ | Excellent resource for information regarding opioid consumption by country as well as guidelines for policies that allow access to necessary medications. |

| U.S. Department of State, http://www.usembassy.gov/ Bureau of Consular Affairs, http://travel.state.gov/travel/travel_1744.html | Comprehensive lists of US embassies, consulates, and diplomatic missions; information to assist travelers from the United States to other countries, including visa requirements and safety alerts. |

| World Health Organization, http://www.who.int | Many useful resources, including Access to Analgesics and to other Controlled Medicines, as well as statistics regarding common illnesses by country. |

Health-Care Structure

Understand the existing health-care structure and what health care is available to all or for select populations. What is the extent of health-care services? Are there clinics for preventive care, or is most care obtained in the hospital? Is home care available with support from nurses and other professionals? Are emergency services available (eg, does the region have ambulances to transport and emergency departments to accept critically ill patients)? Where do patients obtain medications, and do they have to pay out of pocket for these? Do most people die in the hospital or at home? While websites and government sources are valuable, verify this information with clinicians since the clinical reality may be quite different.

Available Medications

To provide useful guidance in symptom management, it is necessary to have a list of available medications used to treat pain, nausea, dyspnea, constipation/diarrhea, wounds, and other symptoms commonly seen in oncology. Your presentation may need to be modified based upon these available drugs (Table 2). Where do patients obtain medications, and do they pay out of pocket for these? There are limitations on availability and access to opioids around the world.[7] Which opioids are available and actually used? What is the process for obtaining a supply of an opioid for a person with cancer? For example, in some countries, physicians can order only one week's worth of medication at a time. In other countries, patients must obtain opioids from the police station rather than a pharmacy. In several settings, only the patient, not family members, can pick up the medication from the dispensing site. And in a few countries, only parenteral opioids are available. It is also helpful to understand issues such as the prevalence of drug trafficking in the region and how this might affect local drug laws. Are traditional medicines, such as herbal therapies, or other techniques commonly used? It is helpful to be aware of these practices and incorporate them into teaching plans where appropriate.

Education of Health-Care Professionals

International education in palliative care should consider how physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and others are educated. Is the educational system very traditional and formal, with little interaction between students and teachers? Professionals trained in this manner may be less comfortable when faced with role-play, learning through discussion, or other Socratic educational methods. That does not mean that one should exclude these methods when planning the curriculum but, rather, be prepared for silence and possibly even discomfort when first introduced. Seek guidance from local educators as to what methods will be acceptable.

Who is included in the health-care team? Are psychologists available, and are chaplains considered part of health-care services? What is the relationship between physicians, nurses, and other team members? Is collegiality accepted, or is there a hierarchy that limits true teamwork? What is the status of physicians, nurses, and other professionals in the region? In some areas, physicians are highly regarded and financially compensated accordingly. In other parts of the world, physicians have very low social status, respect, and compensation. Within diverse cultures, compensation and acceptance of tips (or bribes) to see a patient or perform an intervention may be accepted practice. Attitudes toward work hours may differ from the Western perspective. In some cultures, socialization and development of personal relationships may be considered more important than other aspects of the workload.[8]

Planning in advance to know the targeted attendees is helpful. It is advisable to inquire if the hosts might consider inviting representatives from the ministry of health, the appropriate drug institutes, other key government officials, as well as medical, nursing, and pharmacy leaders who can become champions for access to pain relief and palliative care. Having multiple disciplines and leaders from health care and government at the same program can foster ongoing communication and understanding. Include chief educators as they can incorporate this content into their respective curricula.

Plan the Curriculum and the Program

The importance of cultural issues when developing content cannot be overstated.[9] Factors that might affect pain expression and language or cultural beliefs about death and dying will greatly impact content for teaching. Be aware of local religious and spiritual beliefs impacting pain and palliative care. Consider issues surrounding disclosure of diagnosis and prognosis. Autonomy may not be the prevailing perspective as seen in North America. Ensure that slides are culturally correct and that pictures and illustrations are appropriate. Having the host country leaders review the curriculum in advance is advisable. Avoid cartoons as these may not translate well. Use case examples, but ensure that they represent the types of patients and scenarios seen by the audience. It is also important to avoid being ethnocentric as Western medicine has much to learn from other approaches. It is very helpful to use case studies from the host country. In some settings, trainers will not have access to computers and projectors, limiting the role of PowerPoint slides. Paper presentations or the use of flip-charts may be more accessible.

Consider the need for translation and, if so, which type will be used. Simultaneous interpretation generally requires a sound booth and headphones for participants, and may be more expensive. Consecutive interpretation requires that the instructor present blocks of information, usually a sentence or two, followed by the interpreter providing the content in the appropriate language. This requires speakers to plan much shorter presentations with up to 50% less content being delivered. In either case, trained interpreters can benefit from seeing the slides in advance so they can prepare and clarify prior to the presentation.

When developing an agenda, inquire about the usual times for breaks and meals, as well as time for prayers or other activities. What is considered a “full day” varies around the world, as does the value of adhering rigidly to a schedule. International education generally means that the agenda is fluid; once you are actually in the country and providing the course, other needs may arise. A common mistake is trying to squeeze in too much content. Ask your host to meet prior to the program and, optimally, plan for time before the course to tour health-care facilities. Arrange for a time to meet with key medical, nursing, pharmacy, and governmental leaders who are not scheduled to attend the meeting but might somehow influence curricula and practice. In some settings, local media may be alerted to generate local interest in the topic. Communicate with your host about these opportunities so that arrangements can be made in advance.

For resource-poor countries, consider asking for donations from colleagues before leaving, including books, CDs, and medical supplies. Check local regulations first, particularly if bringing in medications or equipment. If sending books, some countries require high tariff fees to be paid by the receiver when accepting these packages, creating a financial burden for your hosts. Inquire ahead of time if they have to pay to accept these packages. Additionally, in some resource-poor countries, professionals do not have access to personal or work computers and internet café computers often do not have CD drives. Information on jump drives may be more easily accessible.

Finally, visiting educators may want to pack small gifts to give to hosts and others. These should be easily transported and may include items that represent your city or institution. We have also found bringing candy and small toys to be universally appreciated when visiting pediatric settings. A small portable color printer can be used to print photographs of pediatric patients as some of these children have never seen pictures of themselves. You can also print photographs of participants in the training courses.

Personal Considerations

Several months prior to departure, you should contact your traveler's health information resource to identify which vaccinations and what documents are needed to enter the country. To avoid lost time due to illness, ciprofloxacin and antidiarrheal medicines should be obtained before traveling. It is advisable to update your passport. Some countries require you to have sufficient blank pages in your passport to allow entry into their country. An entry fee paid in cash may be required upon arrival. Travelers should consider the political climate of the country and check the U.S. Department of State website (included in Table 1) for alerts or precautions.

Consider appropriate attire when packing. Clothing should reflect respect for the cultural and religious beliefs of the attendees.

During the Experience

It is very useful to meet with interpreters prior to the presentations to clarify any questions. Translation can be quite complicated. For example, a slide that used the term “caring” was interpreted as “romantic love,” and concepts about suffering and death can take on a cultural meaning. Check with interpreters regularly to determine if the speed of delivery is acceptable. Also, translators may have difficulty with this emotional content. In some instances, interpreters have become tearful and required debriefing after palliative care education events. Consider nonverbal communication and personal space. In some cultures, it may not be appropriate to shake hands or to use two hands. Gestures may have very different meanings in other cultures, so avoid these forms of communication. For example, the “OK” sign commonly used in North America, with the tip of the finger touching the tip of the thumb and the other three fingers extended, is considered an obscene gesture in Brazil.

When using teaching strategies other than lecture, respect that some students may not be comfortable at first with nontraditional approaches. Informal teaching strategies that are valued in North America may be viewed as of poor academic quality in other cultures. Debate and discussion, which may make it seem that the student is questioning a teacher's view, may be seen as disrespectful. At times, eliciting personal reflection and experience can engage the audience. For example, when introducing the topic of communication, health-care professionals in the audience can be asked the following questions:

- • If you had cancer, would you want to know?

• Would you want to know that you had a disease that you could die from?

Following these with “What do you tell your patients?” usually engenders excellent discussion.

We have also found that asking participants to do “homework” can be useful, particularly if the students have been quiet or reluctant to communicate during class. Suggested assignments might include listing the five top barriers to cancer pain management in your setting, describing a difficult death or a death that you made better, or related issues. Reticence to speak during class may be due to discomfort with language skills. Some students feel more comfortable sharing ideas in writing, and these assignments have yielded valuable stories that have helped us to understand their experiences and perspectives.

Since the goal of these educational efforts should be sustained, it is helpful to develop a plan for the future with students. Assist them in identifying goals, as well as action items to meet these goals. Allow time for individual meetings between faculty and students to fine-tune these efforts. This ensures that the educational experience will have a greater likelihood of translation into action. To provide practical assistance, if Internet access is available, spend time with small groups to demonstrate literature searches, useful websites, and other information that will foster continuity.

Faculty should meet after each day of training to modify the planned agenda as needed, to optimally meet the needs of the participants. This also provides needed time to debrief about the day's activities and provide support. Particularly when new to international education, the experience may be overwhelming as the status of health-care in developing countries can cause deep personal reflection.

Finally, celebrate. We have found that many students appreciate the opportunity to have some type of closing ceremony to receive certificates and pins, acknowledge their accomplishments, and encourage their future efforts.

Afterward

E-mail, voiceover Internet services, and videoconferencing software have significantly enhanced global communication. Faculty can make themselves available to the trainees after leaving the country using these technologies. Group conversations via e-mail can help solve problems, provide encouragement, and celebrate successes. Connect attendees with international professional organizations to support ongoing educational efforts. It is very useful to identify the leaders or champions and to plan ongoing support to help sustain their commitment. Many countries do not have professional organizations or support networks. These leaders can exist in isolation and suffer great personal sacrifice to lead palliative care efforts in their country.

Conclusion

When educating about pain and palliative care to a worldwide audience, never make assumptions, expect the unexpected, and be flexible. We have found many of these international teaching experiences to be some of the most exhilarating of our professional lives, providing insight to our own practices and creating lasting relationships with colleagues from around the globe. Ultimately, these efforts will improve care for people with cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the American Association of Colleges of Nursing and the City of Hope for their ongoing support of the End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium training activities, as well as the Oncology Nursing Society Foundation and the Open Society Institute for their support of international educational efforts. They also thank Marian Grant for her input.

References [Pub Med ID in Brackets]

1 A.L. Taylor, L.O. Gostin and K.A. Pagonis, Ensuring effective pain treatment: a national and global perspective, JAMA 299 (2008), pp. 89–91 [18167410].

2 K. Crane, Palliative care gains ground in developing countries, J Natl Cancer Inst 102 (21) (2010), pp. 1613–1615 [20966432].

3 J.A. Paice, B.R. Ferrell, N. Coyle, P. Coyne and M. Callaway, Global efforts to improve palliative care: the International End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium training programme, J Adv Nurs 61 (2007), pp. 173–180 [18186909].

4 J.A. Paice, B. Ferrell, N. Coyle, P. Coyne and T. Smith, Living and dying in East Africa: implementing the End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium curriculum in Tanzania, Clin J Oncol Nurs 14 (2010), pp. 161–166 [20350889].

5 C. Olweny, C. Sepulveda, A. Merriman, S. Fonn, M. Borok, T. Ngoma, A. Doh and J. Stjernsward, Desirable services and guidelines for the treatment and palliative care of HIV disease patients with cancer in Africa: a World Health Organization consultation, J Palliat Care 19 (2003), pp. 198–205 [14606333].

6 C. Sepulveda, V. Habiyatmbete, J. Amandua, M. Borok, E. Kikule, B. Mudanga and B. Solomon, Quality care at the end of life in Africa, BMJ 327 (2003), pp. 209–213 [12881267].

7 E.L. Krakauer, R. Wenk, R. Buitrago, P. Jenkins and W. Scholten, Opioid inaccessibility and its human consequences: reports from the field, J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 24 (2010), pp. 239–243 [20718644].

8 C.M. Bolin, Developing a postbasic gerontology program for international learners: considerations for the process, J Contin Educ Nurs 34 (2003), pp. 177–183 [12887229].

9 K.D. Meneses and C.H. Yarbro, Cultural perspectives of international breast health and breast cancer education, J Nurs Scholarsh 39 (2) (2007), pp. 105–112 [19058079].

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and none were reported.

![]()

Vitae

Dr. Paice is Director of the Cancer Pain Program, Division of Hematology-Oncology, Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois.

Carma Erickson-Hurt is a faculty member at Grand Canyon University, Phoenix, Arizona.

Dr. Ferrell is a Professor and Research Scientist at the City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, California.

Nessa Coyle is on the Pain and Palliative Care Service, Department of Medicine, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

Dr. Coyne is Clinical Director of the Thomas Palliative Care Program, Virginia Commonwealth University/Massey Cancer Center, Richmond, Virginia.

Dr. Long is a geriatric nursing consultant and codirector of the Palliative Care for Advanced Dementia, Beatitudes Campus, Phoenix, Arizona.

Dr. Mazanec is a clinical nurse specialist at the University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center, Cleveland, Ohio.

Pam Malloy is ELNEC Project Director, American Association of Colleges of Nursing, Washington, DC.

Dr. Smith is Professor of Medicine and Palliative Care Research, Virginia Commonwealth University/Massey Cancer Center, Richmond.

For many clinicians in oncology, educating other health-care professionals about cancer pain and palliative care is part of their professional life. The need for education exists across clinical settings around the world. Improved education is an urgent need as the prevalence of cancer is increasing.

How High Can Your Support Payments Go?

Last December, St. Peter’s Hospital, a 122-bed acute-care facility in Helena, Mont., crossed a symbolic line in the decade-long evolution of the financial payments that hospitals have provided to HM groups to make up the gap that exists between the expenses of running a hospitalist service and the professional fees that generate its revenue.

Hospital administrators asked the outpatient providers at the Helena Physicians’ Clinic to pay nearly $400,000 per year to support the in-house HM service at St. Peter’s, according to a series of stories in the local paper, the Helena Independent Record. The fee was never instituted and, in fact, some Helena patients and physicians have questioned whether the high-stakes payment was part of a broader campaign for the hospital to take over the clinic, a process that culminated in March with the hospital’s purchase of the clinic’s building.

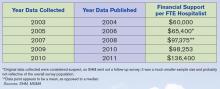

Still, the Montana case focused a spotlight on the doughnut hole of HM ledger sheets: hospital subsidies. More than 80% of HM groups took financial support from their host institutions in fiscal year 2010, according to new data from SHM and the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA), which will be released in September. And the amount of that support has more than doubled, from $60,000 per full-time equivalent (FTE) in 2003-2004 to $136,400 per FTE in the latest data, according to a presentation at HM11 in May.

HM leaders agree the growth is unsustainable, particularly in the new world of healthcare reform, but they also concur that satisfaction with the benefits a hospitalist service offers make it unlikely other institutions will implement a fee-for-service system similar to that of St. Peter’s (see “Pay to Play?,” p. 38). As hospital administrators struggle to dole out pieces of their ever-shrinking financial pie, hospitalists also agree that they will find it more and more difficult to ask their C-suite for continually larger payments (see Figure 1, “Growth in Hospitalist Financial Support,” p. 37). Even when portrayed as “investments” in physicians that provide more than clinical care (e.g. hospitalists assuming leadership roles on hospital committees and pushing quality-improvement initiatives), a hospital’s bottom line can only afford so much.

“It’s not sustainable,” says Burke Kealey, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital specialties at HealthPartners in Minneapolis and an SHM board member. “I think hospitals are pretty much tapped out by and large.

“What we’ve been seeing is practices have been able to ramp up their productivity, but people have also found other revenue streams, be it perioperative clinics, be it trying to find direct subsidies from specialty practices, be it educational funds for teaching. … We’re kind of entering a time when payment reform of some sort is going to have to come into play.”

History Lesson

Support payments have been around since HM’s earliest days, Dr. Kealey says. From the outset, it was difficult for most practices to cover their own salaries and expenses with reimbursement to the charges that make up the bulk of the field’s billing opportunities. “The economics of the situation are such that it is pretty difficult for a hospitalist to cover their own salary with the standard E/M codes,” he adds.

Hospitals, though, quickly realized that hospitalist practices were a valuable presence and created a payment stream to help offset the difference.

John Laverty, DHA, vice president of hospital-based physicians at HCA Physician Services in Nashville, Tenn., says four main factors drive the need for the hospitalist subsidy:

- Physician productivity. How many patients can a practice see on a daily or a monthly basis? Most averages teeter between 15 and 20 patients per day, often less in academic models. There is a mathematical point at which a group can generate enough revenue to cover costs, but many HM leaders say that comes at the cost of quality care delivery and physician satisfaction.

- Nonclinical/non-revenue-generating activities performed by hospitalists. HM groups usually are involved in QI and patient-safety initiatives, which, while important, are not necessarily captured by billing codes. Some HM contracts call for compensation tied to those activities, but many still do not, leaving groups with a gap to cover.

- Payor mix. A particularly difficult mix with high charity care and uninsured patients can lower the average net collected revenue per visit. There also is the choice between being a Medicaid participating provider or a nonparticipating provider with managed-care payors. So-called “non-par” providers typically have the ability to negotiate higher rates.

- Expenses. “How rich is your benefit package for your physicians?” Laverty asks. “Do you provide a retirement plan? Health, dental and vision? … Do you pay for CME?”

Dr. Kealey says it’s not “impossible” to cover all of a hospitalist’s costs through professional fees; however, “it usually requires a hospitalist be in an area with a very good payor mix or a hospital of very high efficiency, where they can see lots of patients. And often, there might be a setup where they aren’t covering unproductive times or tasks.”

Another Point of View

Not everyone thinks the subsidy is a fait accompli. Jeff Taylor, president and chief operating officer of IPC: The Hospitalist Co., a national physician group practice based in North Hollywood, Calif., says subsidies do not need to be a factor in a practice’s bottom line. Taylor says that IPC generates just 5% of its revenues from subsidies, with the remaining 95% financed by professional fees.

He attributes much of that to the work schedule, particularly the popular model of seven days on clinical duty followed by seven days off. He says that model has led to increased practice costs that then require financial support from their hospital. The schedule’s popularity is fueled by the balance it offers physicians between their work and personal lives, Taylor says, but it also means that practitioners working under it lose two weeks a month of billing opportunities.

He’s right about the popularity, as more than 70% of hospitalist groups use a shift-based staffing model, according to the State of Hospital Medicine: 2010 Report Based on 2009 Data. The number of HM groups employing call-based and hybrid coverage (some shift, some call) is 30%.

—Todd Nelson, MBA, technical director, Healthcare Financial Management Association, Chicago

“There is nothing else inherent in hospital medicine that makes this expensive, other than scheduling,” Taylor says. “Absent a very difficult payor mix, it’s the scheduling and the number of days worked that drives the cost. … We have been saying that for years, but we haven’t seen much of a waver yet. Once hospitals realize—some of them are starting to get it—that it’s the underlying work schedule that drives cost, they’re not going to continue to do it.”

Todd Nelson, MBA, a technical director at the Healthcare Financial Management Association in Chicago, agrees that the upward trajectory of hospital support payments will have to end, likely in concert with the expected payment reform of the next five years. But, he adds, the mere fact that hospital administrators have allowed the payments to double suggests that they view the support as an investment. In return for that money, though, C-suite members should contract for and then demand adherence to performance measures, he notes.

“Many specialties say, ‘We’re valuable; help us out,’ ” says Nelson, a former chief financial officer at Grinnell Regional Medical Center in Iowa. “In the hospital world, you can’t just ‘help out.’ They need to be providing a service you’re paying them for.”

SHM President Joseph Li, MD, SFHM, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the hospital medicine division at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, could not agree more. “The way I view monies that are sent to a group for nonclinical work is exactly that,” he says. “It’s compensation for nonclinical work. Subsidy, to me, seems to mean that despite whatever you’re doing, you need some more to pay because you can’t make your ends meet. That’s not true. What that figure is, for my group and for the vast majority of groups in this country, is really compensation for nonclinical efforts.”

HM groups should take it upon themselves to discuss their value contribution with their chief financial officer, as many in that position view hospitalist services as a “cost center” rather than as a means to the end of better financial performance for the institution as a whole, says Beth Hawley, senior vice president with Brentwood, Tenn.-based Cogent HMG.

“You need to look at it from the viewpoint of your CFO,” she says. “It is really important to educate your CFO on the myriad ways that your hospitalist program can create value for the hospital.”

—Jeff Taylor, president, COO, IPC: The Hospitalist Co., North Hollywood, Calif.

Hospitalist John Bulger, DO, FACP, FHM, of Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pa., says such education should highlight the intangible values of HM services, but it also needs to include firm, eye-opening data points. Put another way: “Have true ROI [return on investment], not soft ROI,” he says.

Dr. Bulger suggests pointing out that what some call a subsidy, he views as simply a payment, no different from the lump-sum check a hospital or healthcare system might cut for the group running its ED, or the check it writes for a cardiology specialty.

“There’s a subsidy for all those groups, but it’s never been looked at as a subsidy,” he adds. “But from a business perspective, it’s the same thing.”

The Future of Support

The relative value, justification, and existence of the support aside, the question remains: What is its future?