User login

Fast and Furious

Every May, Mayo Clinic hospitalist Jason Persoff, MD, SFHM, sheds his doctor’s gear, grabs his camera and camcorder, and heads to the Midwest in search of ferocious weather for two weeks. “My wife jokingly calls it my ‘midlife crisis prevention program,’ ” says Dr. Persoff, who works in Jacksonville, Fla.

This year, he put his doctor’s gear back on sooner than he expected.

After 20 years of chasing storms, Dr. Persoff found himself in what might have been considered an inevitable situation: helping people injured in a tornado. When a monstrous twister with winds of more than 200 mph barreled through Joplin, Mo., on May 22, Dr. Persoff was less than a mile from its path. He and a “chase partner,” Robert Balogh, MD, an Oklahoma-based internist and former hospitalist, were able to rush to the scene and assist in the aftermath.

In the moments after the fast-forming storm, Dr. Persoff hoped that the damage wouldn’t be so devastating, despite the first ominous signs he saw along the highway.

“We were dealing with a raining sky of debris,” he says. “There was Styrofoam insulation falling from the sky, papers, there was a Barbie doll in the middle of the road, but I have no idea where that came from. There were trees and twigs and leaves, so I knew that the destruction to Joplin had been significant. But I hoped that it would be very limited.”

As he traveled along another road, he saw two dozen flipped-over semi-trucks.

“There was no decision,” Dr. Balogh says. “We knew right then that the chase was over for us.”

One hospital serving the area, St. John’s Regional Medical Center, was destroyed, its roof ripped off, he learned. At press time, the tornado had killed more than 150 and caused an estimated $3 billion in damage.

Dr. Persoff checked in at the ED of another hospital, Freeman Health System, and offered his help. He spent 10 hours there, first treating trauma patients.

“We were immediately put to work because there were just so many people coming in,” he says. “The initial trauma that came in was pretty fast and furious. If somebody could be saved, and it wasn’t going to require an effort that would jeopardize resources, they did everything they could to save people. They put in chest tubes, ventilated them, [performed] other procedures.

"If somebody was dying and that was pretty obvious, it required us to rethink how we were going to approach things. And I made a diligent effort to help the dying with low doses of pain medication to help them through.”

There were amputations, impalements, eviscerations.

“We had patients who were covered in glass, and by covered I don’t mean they just had glass in their skin—they were covered with it,” he says. “When you’d examine them, there was a risk of your glove getting torn doing an exam.”

Dr. Balogh describes the patient influx as an “absolutely overwhelming” onslaught, with ambulances, cars, and pickup trucks that had rescued strangers on the roadside arriving seemingly nonstop.

It was so frantic, he says, that he was worried “if I even take time to talk to one patient .. I’ve missed the next 15.”

When the patients from St. John’s began to arrive at Freeman, Dr. Persoff treated them, too. He wrote admission orders on 24 patients.

“The patients weren’t able to provide history,” he says. “Some of the medical records fell as far as, I think, Kansas City (160 miles to the north), from the air,” he explains. “So we had no medical records. We had patients who were demented or delirious. We had patients who’d undergone routine procedures, several patients who were postoperative.”

Leaving the hospital, he said, was gut-wrenching.

“I felt like a loser. I felt like I was handing patient-care responsibilities to a completely overtaxed system because I was tired,” he says. “When I started not making good decisions, I knew that I wasn’t helping anybody and it was time for me to step aside. But that was a very hard decision to make.”

Dr. Persoff says he’ll never forget the triage nurse on duty. She was there when he arrived, about 6:30 p.m., and was perfectly orchestrating the trauma care, even though there was no way for any of the hospital staff to know what had become of their own families and homes. And she was still there when he left at 4 a.m., so efficient and fresh it was as if she’d “just come in from having showered.”

“I don’t know what she knew or where her house was or where her family was,” he says. “I just knew that she was there working like there was no tomorrow and doing it in a way that I couldn’t. That was one of the times where I was like, ‘Wow, this is really humbling.’ ”

Dr. Persoff, who writes about his hobby at Stormdoctor.blogspot.com, continued his storm chasing; he even helped provide assistance two days later, after storms near Oklahoma City exacted a human toll that was not nearly as severe. But first, he says, he had to do some soul-searching. After all, he had hoped for a tornado to form in the Joplin area.

“My chase partners and I were talking about how can the rational person want to continue storm-chasing after having seen what we’d seen. And it took me a while to sort of figure out where my own conscience was on this,” he says. “I felt very guilty for having even wanted [a tornado] earlier in the day. Then I also felt like, had the storm not formed where it did, I wouldn’t have been there, my partner Dr. Balogh wouldn’t have been there, and we would not have been able to assist in that disaster.

“So in many ways it was karma. It happened. We were there at a time when Joplin needed some help.”

After the storm, Dr. Persoff received words of thanks from the town.

Jane Culver, a floor nurse with whom he worked, told him via email: “People often say to me, ‘Doctors are just in it for the money, they really don’t really care about me.’ Well, I say they don’t know the Dr. Jason Persoffs of the world. You are a true humanitarian, and the people of Joplin are lucky you were in our midst at our hour of need.”

Stephanie Conrad, whose grandmother Clara had her broken hip cared for by Dr. Persoff, called him “the angel doctor.”

“Thank you so much for using your knowledge, skills, and expertise during this crisis,” Conrad wrote in an email. “It is physicians like you that make a difference in the lives of others. You were truly a blessing that night.”

Tom Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

Every May, Mayo Clinic hospitalist Jason Persoff, MD, SFHM, sheds his doctor’s gear, grabs his camera and camcorder, and heads to the Midwest in search of ferocious weather for two weeks. “My wife jokingly calls it my ‘midlife crisis prevention program,’ ” says Dr. Persoff, who works in Jacksonville, Fla.

This year, he put his doctor’s gear back on sooner than he expected.

After 20 years of chasing storms, Dr. Persoff found himself in what might have been considered an inevitable situation: helping people injured in a tornado. When a monstrous twister with winds of more than 200 mph barreled through Joplin, Mo., on May 22, Dr. Persoff was less than a mile from its path. He and a “chase partner,” Robert Balogh, MD, an Oklahoma-based internist and former hospitalist, were able to rush to the scene and assist in the aftermath.

In the moments after the fast-forming storm, Dr. Persoff hoped that the damage wouldn’t be so devastating, despite the first ominous signs he saw along the highway.

“We were dealing with a raining sky of debris,” he says. “There was Styrofoam insulation falling from the sky, papers, there was a Barbie doll in the middle of the road, but I have no idea where that came from. There were trees and twigs and leaves, so I knew that the destruction to Joplin had been significant. But I hoped that it would be very limited.”

As he traveled along another road, he saw two dozen flipped-over semi-trucks.

“There was no decision,” Dr. Balogh says. “We knew right then that the chase was over for us.”

One hospital serving the area, St. John’s Regional Medical Center, was destroyed, its roof ripped off, he learned. At press time, the tornado had killed more than 150 and caused an estimated $3 billion in damage.

Dr. Persoff checked in at the ED of another hospital, Freeman Health System, and offered his help. He spent 10 hours there, first treating trauma patients.

“We were immediately put to work because there were just so many people coming in,” he says. “The initial trauma that came in was pretty fast and furious. If somebody could be saved, and it wasn’t going to require an effort that would jeopardize resources, they did everything they could to save people. They put in chest tubes, ventilated them, [performed] other procedures.

"If somebody was dying and that was pretty obvious, it required us to rethink how we were going to approach things. And I made a diligent effort to help the dying with low doses of pain medication to help them through.”

There were amputations, impalements, eviscerations.

“We had patients who were covered in glass, and by covered I don’t mean they just had glass in their skin—they were covered with it,” he says. “When you’d examine them, there was a risk of your glove getting torn doing an exam.”

Dr. Balogh describes the patient influx as an “absolutely overwhelming” onslaught, with ambulances, cars, and pickup trucks that had rescued strangers on the roadside arriving seemingly nonstop.

It was so frantic, he says, that he was worried “if I even take time to talk to one patient .. I’ve missed the next 15.”

When the patients from St. John’s began to arrive at Freeman, Dr. Persoff treated them, too. He wrote admission orders on 24 patients.

“The patients weren’t able to provide history,” he says. “Some of the medical records fell as far as, I think, Kansas City (160 miles to the north), from the air,” he explains. “So we had no medical records. We had patients who were demented or delirious. We had patients who’d undergone routine procedures, several patients who were postoperative.”

Leaving the hospital, he said, was gut-wrenching.

“I felt like a loser. I felt like I was handing patient-care responsibilities to a completely overtaxed system because I was tired,” he says. “When I started not making good decisions, I knew that I wasn’t helping anybody and it was time for me to step aside. But that was a very hard decision to make.”

Dr. Persoff says he’ll never forget the triage nurse on duty. She was there when he arrived, about 6:30 p.m., and was perfectly orchestrating the trauma care, even though there was no way for any of the hospital staff to know what had become of their own families and homes. And she was still there when he left at 4 a.m., so efficient and fresh it was as if she’d “just come in from having showered.”

“I don’t know what she knew or where her house was or where her family was,” he says. “I just knew that she was there working like there was no tomorrow and doing it in a way that I couldn’t. That was one of the times where I was like, ‘Wow, this is really humbling.’ ”

Dr. Persoff, who writes about his hobby at Stormdoctor.blogspot.com, continued his storm chasing; he even helped provide assistance two days later, after storms near Oklahoma City exacted a human toll that was not nearly as severe. But first, he says, he had to do some soul-searching. After all, he had hoped for a tornado to form in the Joplin area.

“My chase partners and I were talking about how can the rational person want to continue storm-chasing after having seen what we’d seen. And it took me a while to sort of figure out where my own conscience was on this,” he says. “I felt very guilty for having even wanted [a tornado] earlier in the day. Then I also felt like, had the storm not formed where it did, I wouldn’t have been there, my partner Dr. Balogh wouldn’t have been there, and we would not have been able to assist in that disaster.

“So in many ways it was karma. It happened. We were there at a time when Joplin needed some help.”

After the storm, Dr. Persoff received words of thanks from the town.

Jane Culver, a floor nurse with whom he worked, told him via email: “People often say to me, ‘Doctors are just in it for the money, they really don’t really care about me.’ Well, I say they don’t know the Dr. Jason Persoffs of the world. You are a true humanitarian, and the people of Joplin are lucky you were in our midst at our hour of need.”

Stephanie Conrad, whose grandmother Clara had her broken hip cared for by Dr. Persoff, called him “the angel doctor.”

“Thank you so much for using your knowledge, skills, and expertise during this crisis,” Conrad wrote in an email. “It is physicians like you that make a difference in the lives of others. You were truly a blessing that night.”

Tom Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

Every May, Mayo Clinic hospitalist Jason Persoff, MD, SFHM, sheds his doctor’s gear, grabs his camera and camcorder, and heads to the Midwest in search of ferocious weather for two weeks. “My wife jokingly calls it my ‘midlife crisis prevention program,’ ” says Dr. Persoff, who works in Jacksonville, Fla.

This year, he put his doctor’s gear back on sooner than he expected.

After 20 years of chasing storms, Dr. Persoff found himself in what might have been considered an inevitable situation: helping people injured in a tornado. When a monstrous twister with winds of more than 200 mph barreled through Joplin, Mo., on May 22, Dr. Persoff was less than a mile from its path. He and a “chase partner,” Robert Balogh, MD, an Oklahoma-based internist and former hospitalist, were able to rush to the scene and assist in the aftermath.

In the moments after the fast-forming storm, Dr. Persoff hoped that the damage wouldn’t be so devastating, despite the first ominous signs he saw along the highway.

“We were dealing with a raining sky of debris,” he says. “There was Styrofoam insulation falling from the sky, papers, there was a Barbie doll in the middle of the road, but I have no idea where that came from. There were trees and twigs and leaves, so I knew that the destruction to Joplin had been significant. But I hoped that it would be very limited.”

As he traveled along another road, he saw two dozen flipped-over semi-trucks.

“There was no decision,” Dr. Balogh says. “We knew right then that the chase was over for us.”

One hospital serving the area, St. John’s Regional Medical Center, was destroyed, its roof ripped off, he learned. At press time, the tornado had killed more than 150 and caused an estimated $3 billion in damage.

Dr. Persoff checked in at the ED of another hospital, Freeman Health System, and offered his help. He spent 10 hours there, first treating trauma patients.

“We were immediately put to work because there were just so many people coming in,” he says. “The initial trauma that came in was pretty fast and furious. If somebody could be saved, and it wasn’t going to require an effort that would jeopardize resources, they did everything they could to save people. They put in chest tubes, ventilated them, [performed] other procedures.

"If somebody was dying and that was pretty obvious, it required us to rethink how we were going to approach things. And I made a diligent effort to help the dying with low doses of pain medication to help them through.”

There were amputations, impalements, eviscerations.

“We had patients who were covered in glass, and by covered I don’t mean they just had glass in their skin—they were covered with it,” he says. “When you’d examine them, there was a risk of your glove getting torn doing an exam.”

Dr. Balogh describes the patient influx as an “absolutely overwhelming” onslaught, with ambulances, cars, and pickup trucks that had rescued strangers on the roadside arriving seemingly nonstop.

It was so frantic, he says, that he was worried “if I even take time to talk to one patient .. I’ve missed the next 15.”

When the patients from St. John’s began to arrive at Freeman, Dr. Persoff treated them, too. He wrote admission orders on 24 patients.

“The patients weren’t able to provide history,” he says. “Some of the medical records fell as far as, I think, Kansas City (160 miles to the north), from the air,” he explains. “So we had no medical records. We had patients who were demented or delirious. We had patients who’d undergone routine procedures, several patients who were postoperative.”

Leaving the hospital, he said, was gut-wrenching.

“I felt like a loser. I felt like I was handing patient-care responsibilities to a completely overtaxed system because I was tired,” he says. “When I started not making good decisions, I knew that I wasn’t helping anybody and it was time for me to step aside. But that was a very hard decision to make.”

Dr. Persoff says he’ll never forget the triage nurse on duty. She was there when he arrived, about 6:30 p.m., and was perfectly orchestrating the trauma care, even though there was no way for any of the hospital staff to know what had become of their own families and homes. And she was still there when he left at 4 a.m., so efficient and fresh it was as if she’d “just come in from having showered.”

“I don’t know what she knew or where her house was or where her family was,” he says. “I just knew that she was there working like there was no tomorrow and doing it in a way that I couldn’t. That was one of the times where I was like, ‘Wow, this is really humbling.’ ”

Dr. Persoff, who writes about his hobby at Stormdoctor.blogspot.com, continued his storm chasing; he even helped provide assistance two days later, after storms near Oklahoma City exacted a human toll that was not nearly as severe. But first, he says, he had to do some soul-searching. After all, he had hoped for a tornado to form in the Joplin area.

“My chase partners and I were talking about how can the rational person want to continue storm-chasing after having seen what we’d seen. And it took me a while to sort of figure out where my own conscience was on this,” he says. “I felt very guilty for having even wanted [a tornado] earlier in the day. Then I also felt like, had the storm not formed where it did, I wouldn’t have been there, my partner Dr. Balogh wouldn’t have been there, and we would not have been able to assist in that disaster.

“So in many ways it was karma. It happened. We were there at a time when Joplin needed some help.”

After the storm, Dr. Persoff received words of thanks from the town.

Jane Culver, a floor nurse with whom he worked, told him via email: “People often say to me, ‘Doctors are just in it for the money, they really don’t really care about me.’ Well, I say they don’t know the Dr. Jason Persoffs of the world. You are a true humanitarian, and the people of Joplin are lucky you were in our midst at our hour of need.”

Stephanie Conrad, whose grandmother Clara had her broken hip cared for by Dr. Persoff, called him “the angel doctor.”

“Thank you so much for using your knowledge, skills, and expertise during this crisis,” Conrad wrote in an email. “It is physicians like you that make a difference in the lives of others. You were truly a blessing that night.”

Tom Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

Cause For Concern

When a drug is in short supply at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, a message goes out to the physicians on the hospital’s intranet system. When the shortage gets close to being critically short in supply, a message will be embedded into the physician order-entry system recommending that the physicians use an alternate drug—if there is an alternate.

It’s an alert system that has been put to frequent use lately, says Joseph Li, MD, SFHM, director of the hospital medicine program at Beth Israel Deaconess, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and president of SHM.

The rate of drug shortages has been rising steadily in recent years due to quality questions at manufacturers, consolidation in the drug-manufacturing industry, and other factors, according to data from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and other sources.

“It does seem like there’s more today than previous years,” says Dr. Li, who was a pharmacist before he trained in internal medicine.

Some of the recent shortages at Beth Israel Deaconess have involved the diuretic furosemide, the antiemetic Compazine, and the anticoagulant heparin. “More often than not, there’s a reasonable alternative that can be chosen,” he says. “Not necessarily exactly the same drug, but usually in the same therapeutic class.”

While actual cases of patient harm due to drug shortages appear to be relatively uncommon, having drugs in short supply can lead to a safety problem hovering over a medical center and its hospitalists. In addition to the potential of simply not having an alternate to give to a patient, hospitalists and their pharmacists sometimes have to adjust to a new dosage that comes with a replacement medication.

Plus, having to manage the problem when a drug shortage hits can be a headache, with time and resources spent trying to obtain updates from drug manufacturers and find other drugs that can be used in the meantime, experts say.

With hospitalists now treating so many patients, many of them complex and on multiple medications, it is an important issue for hospitalists to stay aware of and to be prepared for, Dr. Li says. More than 90% of all medical patients at Beth Israel Deaconess are now cared for by hospitalists, he says, and it’s a similar situation for many acute-care hospitals around the country.

If a drug is in short supply, balancing availability with patient needs can be especially tricky for a hospitalist caring for patients with a multitude of demands, Dr. Li says. “There is an effort to make sure that our most vulnerable population of patients receive these treatments before the general population of patients have access to it,” he adds.

However, the very existence of hospitalists makes it easier to navigate a shortage compared to the days when hundreds of providers would be caring for a pool of patients.

“If you’re trying to notify a group of providers about shortages and have an impact on their prescribing habits, I think it’s easier today,” he says.

Troubled Waters

The FDA says it confirmed a record 178 cases of drug shortages in 2010 (www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/drugshortages/default.htm). That was up from 55 shortages five years ago. And according to the University of Utah Drug Information Service, the problem is actually more pervasive than that, reporting 120 shortages in the U.S. in 2001, with a reported 211 in 2010. And through March of this year, there were 80 reported cases of shortages, on pace for another record year.

“In the past couple of years, it’s just been exponential,” says Diane Ginsburg, president of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists and clinical professor and assistant dean for student affairs at the University of Texas’ College of Pharmacy in Austin.

According to the FDA, 77% of the shortages in 2010 involved sterile injectable drugs.

“There are fewer and fewer firms making these older sterile injectables, and they are often discontinued for newer, more profitable agents,” FDA spokeswoman Yolanda Fultz-Morris said in an email. “When one firm has a delay or a manufacturing problem, it is extremely difficult for the remaining firms to quickly increase production.”

The biggest cause for the shortages in those drugs has been product quality issues, namely microbial contamination and newly identified impurities, according to the FDA. From January to October of 2010, 42% of drug shortages were due to quality problems.

Eighteen percent were due to product discontinuation by the manufacturer and another 18% were due to delays and capacity problems. Nine percent were due to difficulties getting raw materials, and 4% of the sterile injectable shortages were due to increased demand because there was a shortage of another injectable medication. In other words, one shortage led directly to another.

Kevin Schweers, a spokesman for the National Community Pharmacists Association, says generic drugs, especially Schedule II substances, have been in short supply. But there can be problems even when one generic is available to replace another generic.

An example, he says, is when a “new generic substituted in place of the old one is made by a different manufacturer and may come in a different color or shape. That can leave patients”—including those just released from hospitals—“wondering and asking the pharmacist why their medication is different or if a mistake was made.”

Patient Safety and Communication Errors

Lalit Verma, MD, director of the hospital medicine program at Durham Regional Medical Center in North Carolina and assistant professor of medicine at the Duke University School of Medicine, is unaware of any situations in which a shortage put patients in jeopardy at his hospital. He says the pharmacy at Durham Regional, which has seen recent shortages in morphine and heparin, among other drugs, keeps doctors up to date and has adjusted doses appropriately when replacements are used.

“It’s probably been more than I’ve experienced in my 10 years as a hospitalist,” Dr. Verma says. “We have a very good pharmacy program that updates us regularly on drug shortages and offers alternatives.”

Dr. Li also says no patient’s safety has been jeopardized by a shortage.

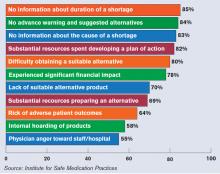

Others say patient safety has been affected, according to 1,800 healthcare practitioners who participated in a survey last year conducted by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), a nonprofit group. Twenty percent of the respondents said drug-shortage-related errors were made, while 32% said they had “near misses” related to drug shortages. Nineteen percent said there had been adverse patient outcomes as a result of drug shortages.

The study noted two instances in which patients died when they were switched to dilaudid because morphine was in short supply; both patients were given morphine doses instead of adjusted doses for dilaudid.

“It’s about six- or sevenfold more potent than morphine,” says Michael Cohen, ISMP president. “And so when that drug is prescribed in a morphine dose, that would be a massive overdose for some patients.”

He adds that hospitals have tried to stay on top of the drug shortage problem, but that “it’s very difficult.”

“A lot of this happens last-minute,” Cohen says. “Physicians aren’t given a chance to even realize that a certain drug isn’t available, so it causes an interruption in the whole flow of things in the hospital.” Some hospitals have had to hire staffers who handle just the inevitable daily drug shortages, he adds.

A law has been proposed in the U.S. Senate that would require drug manufacturers to notify the FDA when circumstances arise that might reasonably lead to a drug shortage (see “Senate Bill Would Require Advance Notice of Potential Shortages,” p. 41).

Cohen says another concern is that some hospitals, faced with shortages in electrolytes, such as potassium phosphate and sodium acetate, have been turning to less-regulated sterile compounding pharmacies for the products.

Dr. Verma, of Durham Regional, says perhaps the biggest challenge is staying on top of changing doses. “I think there was a learning curve for physicians in using dilaudid [rather than morphine] because the dosing is quite different, so that can cause challenges for patient care when you’re switching in and out of drug classes,” he says. “It’s not a perfect science. It doesn’t cripple us, but it does make it more challenging to fine-tune patient care.”

Ginsburg, of the ASHP, urges hospitalists to stay in close contact with the pharmacists at their hospitals and to be diligent about reporting shortages to the ASHP.

“Please work closely with the pharmacists, because we’re the ones that can really help,” she says. “We’re in it together with them, in terms of trying to provide care for their patients.” TH

Thomas R. Collins a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

When a drug is in short supply at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, a message goes out to the physicians on the hospital’s intranet system. When the shortage gets close to being critically short in supply, a message will be embedded into the physician order-entry system recommending that the physicians use an alternate drug—if there is an alternate.

It’s an alert system that has been put to frequent use lately, says Joseph Li, MD, SFHM, director of the hospital medicine program at Beth Israel Deaconess, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and president of SHM.

The rate of drug shortages has been rising steadily in recent years due to quality questions at manufacturers, consolidation in the drug-manufacturing industry, and other factors, according to data from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and other sources.

“It does seem like there’s more today than previous years,” says Dr. Li, who was a pharmacist before he trained in internal medicine.

Some of the recent shortages at Beth Israel Deaconess have involved the diuretic furosemide, the antiemetic Compazine, and the anticoagulant heparin. “More often than not, there’s a reasonable alternative that can be chosen,” he says. “Not necessarily exactly the same drug, but usually in the same therapeutic class.”

While actual cases of patient harm due to drug shortages appear to be relatively uncommon, having drugs in short supply can lead to a safety problem hovering over a medical center and its hospitalists. In addition to the potential of simply not having an alternate to give to a patient, hospitalists and their pharmacists sometimes have to adjust to a new dosage that comes with a replacement medication.

Plus, having to manage the problem when a drug shortage hits can be a headache, with time and resources spent trying to obtain updates from drug manufacturers and find other drugs that can be used in the meantime, experts say.

With hospitalists now treating so many patients, many of them complex and on multiple medications, it is an important issue for hospitalists to stay aware of and to be prepared for, Dr. Li says. More than 90% of all medical patients at Beth Israel Deaconess are now cared for by hospitalists, he says, and it’s a similar situation for many acute-care hospitals around the country.

If a drug is in short supply, balancing availability with patient needs can be especially tricky for a hospitalist caring for patients with a multitude of demands, Dr. Li says. “There is an effort to make sure that our most vulnerable population of patients receive these treatments before the general population of patients have access to it,” he adds.

However, the very existence of hospitalists makes it easier to navigate a shortage compared to the days when hundreds of providers would be caring for a pool of patients.

“If you’re trying to notify a group of providers about shortages and have an impact on their prescribing habits, I think it’s easier today,” he says.

Troubled Waters

The FDA says it confirmed a record 178 cases of drug shortages in 2010 (www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/drugshortages/default.htm). That was up from 55 shortages five years ago. And according to the University of Utah Drug Information Service, the problem is actually more pervasive than that, reporting 120 shortages in the U.S. in 2001, with a reported 211 in 2010. And through March of this year, there were 80 reported cases of shortages, on pace for another record year.

“In the past couple of years, it’s just been exponential,” says Diane Ginsburg, president of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists and clinical professor and assistant dean for student affairs at the University of Texas’ College of Pharmacy in Austin.

According to the FDA, 77% of the shortages in 2010 involved sterile injectable drugs.

“There are fewer and fewer firms making these older sterile injectables, and they are often discontinued for newer, more profitable agents,” FDA spokeswoman Yolanda Fultz-Morris said in an email. “When one firm has a delay or a manufacturing problem, it is extremely difficult for the remaining firms to quickly increase production.”

The biggest cause for the shortages in those drugs has been product quality issues, namely microbial contamination and newly identified impurities, according to the FDA. From January to October of 2010, 42% of drug shortages were due to quality problems.

Eighteen percent were due to product discontinuation by the manufacturer and another 18% were due to delays and capacity problems. Nine percent were due to difficulties getting raw materials, and 4% of the sterile injectable shortages were due to increased demand because there was a shortage of another injectable medication. In other words, one shortage led directly to another.

Kevin Schweers, a spokesman for the National Community Pharmacists Association, says generic drugs, especially Schedule II substances, have been in short supply. But there can be problems even when one generic is available to replace another generic.

An example, he says, is when a “new generic substituted in place of the old one is made by a different manufacturer and may come in a different color or shape. That can leave patients”—including those just released from hospitals—“wondering and asking the pharmacist why their medication is different or if a mistake was made.”

Patient Safety and Communication Errors

Lalit Verma, MD, director of the hospital medicine program at Durham Regional Medical Center in North Carolina and assistant professor of medicine at the Duke University School of Medicine, is unaware of any situations in which a shortage put patients in jeopardy at his hospital. He says the pharmacy at Durham Regional, which has seen recent shortages in morphine and heparin, among other drugs, keeps doctors up to date and has adjusted doses appropriately when replacements are used.

“It’s probably been more than I’ve experienced in my 10 years as a hospitalist,” Dr. Verma says. “We have a very good pharmacy program that updates us regularly on drug shortages and offers alternatives.”

Dr. Li also says no patient’s safety has been jeopardized by a shortage.

Others say patient safety has been affected, according to 1,800 healthcare practitioners who participated in a survey last year conducted by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), a nonprofit group. Twenty percent of the respondents said drug-shortage-related errors were made, while 32% said they had “near misses” related to drug shortages. Nineteen percent said there had been adverse patient outcomes as a result of drug shortages.

The study noted two instances in which patients died when they were switched to dilaudid because morphine was in short supply; both patients were given morphine doses instead of adjusted doses for dilaudid.

“It’s about six- or sevenfold more potent than morphine,” says Michael Cohen, ISMP president. “And so when that drug is prescribed in a morphine dose, that would be a massive overdose for some patients.”

He adds that hospitals have tried to stay on top of the drug shortage problem, but that “it’s very difficult.”

“A lot of this happens last-minute,” Cohen says. “Physicians aren’t given a chance to even realize that a certain drug isn’t available, so it causes an interruption in the whole flow of things in the hospital.” Some hospitals have had to hire staffers who handle just the inevitable daily drug shortages, he adds.

A law has been proposed in the U.S. Senate that would require drug manufacturers to notify the FDA when circumstances arise that might reasonably lead to a drug shortage (see “Senate Bill Would Require Advance Notice of Potential Shortages,” p. 41).

Cohen says another concern is that some hospitals, faced with shortages in electrolytes, such as potassium phosphate and sodium acetate, have been turning to less-regulated sterile compounding pharmacies for the products.

Dr. Verma, of Durham Regional, says perhaps the biggest challenge is staying on top of changing doses. “I think there was a learning curve for physicians in using dilaudid [rather than morphine] because the dosing is quite different, so that can cause challenges for patient care when you’re switching in and out of drug classes,” he says. “It’s not a perfect science. It doesn’t cripple us, but it does make it more challenging to fine-tune patient care.”

Ginsburg, of the ASHP, urges hospitalists to stay in close contact with the pharmacists at their hospitals and to be diligent about reporting shortages to the ASHP.

“Please work closely with the pharmacists, because we’re the ones that can really help,” she says. “We’re in it together with them, in terms of trying to provide care for their patients.” TH

Thomas R. Collins a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

When a drug is in short supply at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, a message goes out to the physicians on the hospital’s intranet system. When the shortage gets close to being critically short in supply, a message will be embedded into the physician order-entry system recommending that the physicians use an alternate drug—if there is an alternate.

It’s an alert system that has been put to frequent use lately, says Joseph Li, MD, SFHM, director of the hospital medicine program at Beth Israel Deaconess, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and president of SHM.

The rate of drug shortages has been rising steadily in recent years due to quality questions at manufacturers, consolidation in the drug-manufacturing industry, and other factors, according to data from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and other sources.

“It does seem like there’s more today than previous years,” says Dr. Li, who was a pharmacist before he trained in internal medicine.

Some of the recent shortages at Beth Israel Deaconess have involved the diuretic furosemide, the antiemetic Compazine, and the anticoagulant heparin. “More often than not, there’s a reasonable alternative that can be chosen,” he says. “Not necessarily exactly the same drug, but usually in the same therapeutic class.”

While actual cases of patient harm due to drug shortages appear to be relatively uncommon, having drugs in short supply can lead to a safety problem hovering over a medical center and its hospitalists. In addition to the potential of simply not having an alternate to give to a patient, hospitalists and their pharmacists sometimes have to adjust to a new dosage that comes with a replacement medication.

Plus, having to manage the problem when a drug shortage hits can be a headache, with time and resources spent trying to obtain updates from drug manufacturers and find other drugs that can be used in the meantime, experts say.

With hospitalists now treating so many patients, many of them complex and on multiple medications, it is an important issue for hospitalists to stay aware of and to be prepared for, Dr. Li says. More than 90% of all medical patients at Beth Israel Deaconess are now cared for by hospitalists, he says, and it’s a similar situation for many acute-care hospitals around the country.

If a drug is in short supply, balancing availability with patient needs can be especially tricky for a hospitalist caring for patients with a multitude of demands, Dr. Li says. “There is an effort to make sure that our most vulnerable population of patients receive these treatments before the general population of patients have access to it,” he adds.

However, the very existence of hospitalists makes it easier to navigate a shortage compared to the days when hundreds of providers would be caring for a pool of patients.

“If you’re trying to notify a group of providers about shortages and have an impact on their prescribing habits, I think it’s easier today,” he says.

Troubled Waters

The FDA says it confirmed a record 178 cases of drug shortages in 2010 (www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/drugshortages/default.htm). That was up from 55 shortages five years ago. And according to the University of Utah Drug Information Service, the problem is actually more pervasive than that, reporting 120 shortages in the U.S. in 2001, with a reported 211 in 2010. And through March of this year, there were 80 reported cases of shortages, on pace for another record year.

“In the past couple of years, it’s just been exponential,” says Diane Ginsburg, president of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists and clinical professor and assistant dean for student affairs at the University of Texas’ College of Pharmacy in Austin.

According to the FDA, 77% of the shortages in 2010 involved sterile injectable drugs.

“There are fewer and fewer firms making these older sterile injectables, and they are often discontinued for newer, more profitable agents,” FDA spokeswoman Yolanda Fultz-Morris said in an email. “When one firm has a delay or a manufacturing problem, it is extremely difficult for the remaining firms to quickly increase production.”

The biggest cause for the shortages in those drugs has been product quality issues, namely microbial contamination and newly identified impurities, according to the FDA. From January to October of 2010, 42% of drug shortages were due to quality problems.

Eighteen percent were due to product discontinuation by the manufacturer and another 18% were due to delays and capacity problems. Nine percent were due to difficulties getting raw materials, and 4% of the sterile injectable shortages were due to increased demand because there was a shortage of another injectable medication. In other words, one shortage led directly to another.

Kevin Schweers, a spokesman for the National Community Pharmacists Association, says generic drugs, especially Schedule II substances, have been in short supply. But there can be problems even when one generic is available to replace another generic.

An example, he says, is when a “new generic substituted in place of the old one is made by a different manufacturer and may come in a different color or shape. That can leave patients”—including those just released from hospitals—“wondering and asking the pharmacist why their medication is different or if a mistake was made.”

Patient Safety and Communication Errors

Lalit Verma, MD, director of the hospital medicine program at Durham Regional Medical Center in North Carolina and assistant professor of medicine at the Duke University School of Medicine, is unaware of any situations in which a shortage put patients in jeopardy at his hospital. He says the pharmacy at Durham Regional, which has seen recent shortages in morphine and heparin, among other drugs, keeps doctors up to date and has adjusted doses appropriately when replacements are used.

“It’s probably been more than I’ve experienced in my 10 years as a hospitalist,” Dr. Verma says. “We have a very good pharmacy program that updates us regularly on drug shortages and offers alternatives.”

Dr. Li also says no patient’s safety has been jeopardized by a shortage.

Others say patient safety has been affected, according to 1,800 healthcare practitioners who participated in a survey last year conducted by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), a nonprofit group. Twenty percent of the respondents said drug-shortage-related errors were made, while 32% said they had “near misses” related to drug shortages. Nineteen percent said there had been adverse patient outcomes as a result of drug shortages.

The study noted two instances in which patients died when they were switched to dilaudid because morphine was in short supply; both patients were given morphine doses instead of adjusted doses for dilaudid.

“It’s about six- or sevenfold more potent than morphine,” says Michael Cohen, ISMP president. “And so when that drug is prescribed in a morphine dose, that would be a massive overdose for some patients.”

He adds that hospitals have tried to stay on top of the drug shortage problem, but that “it’s very difficult.”

“A lot of this happens last-minute,” Cohen says. “Physicians aren’t given a chance to even realize that a certain drug isn’t available, so it causes an interruption in the whole flow of things in the hospital.” Some hospitals have had to hire staffers who handle just the inevitable daily drug shortages, he adds.

A law has been proposed in the U.S. Senate that would require drug manufacturers to notify the FDA when circumstances arise that might reasonably lead to a drug shortage (see “Senate Bill Would Require Advance Notice of Potential Shortages,” p. 41).

Cohen says another concern is that some hospitals, faced with shortages in electrolytes, such as potassium phosphate and sodium acetate, have been turning to less-regulated sterile compounding pharmacies for the products.

Dr. Verma, of Durham Regional, says perhaps the biggest challenge is staying on top of changing doses. “I think there was a learning curve for physicians in using dilaudid [rather than morphine] because the dosing is quite different, so that can cause challenges for patient care when you’re switching in and out of drug classes,” he says. “It’s not a perfect science. It doesn’t cripple us, but it does make it more challenging to fine-tune patient care.”

Ginsburg, of the ASHP, urges hospitalists to stay in close contact with the pharmacists at their hospitals and to be diligent about reporting shortages to the ASHP.

“Please work closely with the pharmacists, because we’re the ones that can really help,” she says. “We’re in it together with them, in terms of trying to provide care for their patients.” TH

Thomas R. Collins a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

What Is Your Value?

For those of you who attended Bob Wachter’s talk at HM11 in Dallas, you learned that Bob drives a particular model of a popular SUV made by a well-known Japanese manufacturer. When he was in the market for a vehicle, he decided he wanted to buy an SUV. He acknowledged there were certainly less expensive SUVs on the market, along with more expensive alternatives.

So why did he choose to purchase that particular model? Was it the color, the seat warmers, or the keyless entry system? The answer is simple: He decided to purchase the popular SUV because he thought it was the best value for his dollar.

I have this vision of Bob, head cocked to one side, with his index finger resting against his chin and a text bubble above his head reading, “What is the quality of this vehicle and what is the price tag?”

These are decisions all of us make in our everyday lives. I make the same value judgment when I pull into the gasoline station to purchase gas (regular or premium?) or when I go to the grocery store (brand-name or generic orange juice?). But we know that higher cost doesn’t always mean higher quality. Think American-made automobiles versus Japanese-made vehicles in the 1970s and ’80s.

Along those same lines, let’s think about the U.S. healthcare system in 2011. America is trying to move its healthcare toward a value-based system. How do we receive the best healthcare for the—many times taxpayer—dollar? I am a taxpayer and I am all for higher-quality healthcare for my dollars.

At HM11, I heard from many supporters of healthcare reform, but I also heard many people vilify the government’s efforts at reforming our healthcare system. Just about everyone agreed that the future is uncertain. The current healthcare system certainly values hospitalists. It is hard to argue with the facts. In less than 15 years, our healthcare system has created jobs for more than 30,000 hospitalists, the majority of whom require nonclinical revenue from hospitals to meet expenses. The latest SHM-MGMA data show that the average hospitalist full-time equivalent (FTE) receives more than $131,500 of nonclinical revenue (primarily from hospitals) annually.

Payors of healthcare are no different than Bob when it comes to purchasing a car, or me when it comes to purchasing orange juice. Payors will pay for hospitalists as long as they perceive value in their investment.

But what is the basis of this notion that hospitalists are high-value healthcare providers, and is it justified? At HM11, I heard about the continued rise in hospitalist salaries. Higher costs mean we will have to increase quality if we hope to achieve the same value (value=quality/cost).

Don’t Worry, Share Your Data

I have listened to many presentations about healthcare value, quality, and cost. My perception is that it makes the most sense if it is personal. I live in Massachusetts, and my state government has been aggressive at helping everyone understand the quality and the cost of care being delivered at our hospitals. For example, our state government generates a massive annual report that describes the quality and cost of healthcare being delivered at individual hospitals; a PDF of the report is available at www.mass.gov. (For full disclosure, I work at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center [BIDMC] in Boston and I serve on a Massachusetts Department of Public Health Stroke Advisory Committee.)

The annual report shows there is not as much of a direct relationship between quality and cost as one would like to see. But I applaud Massachusetts for producing this report. Recognizing and understanding a problem is the first step in creating a solution to the problem. One cannot create a value-based system without understanding the existing quality and cost.

This is one of the reasons why, several years ago, the BIDMC leadership posted my hospital’s quality data online for public consumption (www.bidmc.org/QualityandSafety.aspx). The BIDMC website even features a short video of hospitalist Ken Sands, MD, who also happens to be the vice president of quality at BIDMC, telling you about the hospital quality data. Before the hospital posted this data online, most of our hospital staff and providers, let alone our patients and their families, were unaware of the data. BIDMC is not the only hospital who does this. I understand Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles and Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in New Hampshire have long shared their quality data publicly.

But the truth is, if you look hard enough, you can find these data for just about all acute-care hospitals in the country. Start with Medicare’s Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). However, BIDMC and others have simply made it easier to find the data by putting it directly on their websites.

Policy of Transparency

An interesting thing happened over the past decade at BIDMC. In 1997, there were no hospitalists who cared for BIDMC patients. Today, hospitalists manage nearly 100% of the patients hospitalized on our large medical service.

When you look at the data being reported by BIDMC and the state of Massachusetts about nonsurgical conditions, doesn’t that reflect the care being provided by the hospitalists who work at BIDMC? I imagine that is what will run through my CEO and CFO’s minds when we discuss the hospitalist budget this summer. They will ask themselves, “What is the value of our hospitalists? What is the quality of their care? How much do they cost us?”

Some of you might be in a similar position. Do your hospitalists now provide the bulk of the care at your hospital? Are your hospital’s data being publicly reported? I think the answer is a resounding “yes” for many of you.

Allow me to ask this question: What are you doing to collect data to understand the quality and cost of your hospitalist program? Wouldn’t you rather know this information before your hospital or state government tells you?

As the director of my hospitalist group, I spearhead our group efforts to better understand the quality of care we provide. This proactive, introspective approach is essential, especially if hospitalist groups around the country hope to continue being perceived as “high value” providers.

I am interested in hearing from you about your efforts to understand the care being provided by your hospitalists. Feel free to email me at [email protected]. TH

Dr. Li is president of SHM.

For those of you who attended Bob Wachter’s talk at HM11 in Dallas, you learned that Bob drives a particular model of a popular SUV made by a well-known Japanese manufacturer. When he was in the market for a vehicle, he decided he wanted to buy an SUV. He acknowledged there were certainly less expensive SUVs on the market, along with more expensive alternatives.

So why did he choose to purchase that particular model? Was it the color, the seat warmers, or the keyless entry system? The answer is simple: He decided to purchase the popular SUV because he thought it was the best value for his dollar.

I have this vision of Bob, head cocked to one side, with his index finger resting against his chin and a text bubble above his head reading, “What is the quality of this vehicle and what is the price tag?”

These are decisions all of us make in our everyday lives. I make the same value judgment when I pull into the gasoline station to purchase gas (regular or premium?) or when I go to the grocery store (brand-name or generic orange juice?). But we know that higher cost doesn’t always mean higher quality. Think American-made automobiles versus Japanese-made vehicles in the 1970s and ’80s.

Along those same lines, let’s think about the U.S. healthcare system in 2011. America is trying to move its healthcare toward a value-based system. How do we receive the best healthcare for the—many times taxpayer—dollar? I am a taxpayer and I am all for higher-quality healthcare for my dollars.

At HM11, I heard from many supporters of healthcare reform, but I also heard many people vilify the government’s efforts at reforming our healthcare system. Just about everyone agreed that the future is uncertain. The current healthcare system certainly values hospitalists. It is hard to argue with the facts. In less than 15 years, our healthcare system has created jobs for more than 30,000 hospitalists, the majority of whom require nonclinical revenue from hospitals to meet expenses. The latest SHM-MGMA data show that the average hospitalist full-time equivalent (FTE) receives more than $131,500 of nonclinical revenue (primarily from hospitals) annually.

Payors of healthcare are no different than Bob when it comes to purchasing a car, or me when it comes to purchasing orange juice. Payors will pay for hospitalists as long as they perceive value in their investment.

But what is the basis of this notion that hospitalists are high-value healthcare providers, and is it justified? At HM11, I heard about the continued rise in hospitalist salaries. Higher costs mean we will have to increase quality if we hope to achieve the same value (value=quality/cost).

Don’t Worry, Share Your Data

I have listened to many presentations about healthcare value, quality, and cost. My perception is that it makes the most sense if it is personal. I live in Massachusetts, and my state government has been aggressive at helping everyone understand the quality and the cost of care being delivered at our hospitals. For example, our state government generates a massive annual report that describes the quality and cost of healthcare being delivered at individual hospitals; a PDF of the report is available at www.mass.gov. (For full disclosure, I work at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center [BIDMC] in Boston and I serve on a Massachusetts Department of Public Health Stroke Advisory Committee.)

The annual report shows there is not as much of a direct relationship between quality and cost as one would like to see. But I applaud Massachusetts for producing this report. Recognizing and understanding a problem is the first step in creating a solution to the problem. One cannot create a value-based system without understanding the existing quality and cost.

This is one of the reasons why, several years ago, the BIDMC leadership posted my hospital’s quality data online for public consumption (www.bidmc.org/QualityandSafety.aspx). The BIDMC website even features a short video of hospitalist Ken Sands, MD, who also happens to be the vice president of quality at BIDMC, telling you about the hospital quality data. Before the hospital posted this data online, most of our hospital staff and providers, let alone our patients and their families, were unaware of the data. BIDMC is not the only hospital who does this. I understand Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles and Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in New Hampshire have long shared their quality data publicly.

But the truth is, if you look hard enough, you can find these data for just about all acute-care hospitals in the country. Start with Medicare’s Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). However, BIDMC and others have simply made it easier to find the data by putting it directly on their websites.

Policy of Transparency

An interesting thing happened over the past decade at BIDMC. In 1997, there were no hospitalists who cared for BIDMC patients. Today, hospitalists manage nearly 100% of the patients hospitalized on our large medical service.

When you look at the data being reported by BIDMC and the state of Massachusetts about nonsurgical conditions, doesn’t that reflect the care being provided by the hospitalists who work at BIDMC? I imagine that is what will run through my CEO and CFO’s minds when we discuss the hospitalist budget this summer. They will ask themselves, “What is the value of our hospitalists? What is the quality of their care? How much do they cost us?”

Some of you might be in a similar position. Do your hospitalists now provide the bulk of the care at your hospital? Are your hospital’s data being publicly reported? I think the answer is a resounding “yes” for many of you.

Allow me to ask this question: What are you doing to collect data to understand the quality and cost of your hospitalist program? Wouldn’t you rather know this information before your hospital or state government tells you?

As the director of my hospitalist group, I spearhead our group efforts to better understand the quality of care we provide. This proactive, introspective approach is essential, especially if hospitalist groups around the country hope to continue being perceived as “high value” providers.

I am interested in hearing from you about your efforts to understand the care being provided by your hospitalists. Feel free to email me at [email protected]. TH

Dr. Li is president of SHM.

For those of you who attended Bob Wachter’s talk at HM11 in Dallas, you learned that Bob drives a particular model of a popular SUV made by a well-known Japanese manufacturer. When he was in the market for a vehicle, he decided he wanted to buy an SUV. He acknowledged there were certainly less expensive SUVs on the market, along with more expensive alternatives.

So why did he choose to purchase that particular model? Was it the color, the seat warmers, or the keyless entry system? The answer is simple: He decided to purchase the popular SUV because he thought it was the best value for his dollar.

I have this vision of Bob, head cocked to one side, with his index finger resting against his chin and a text bubble above his head reading, “What is the quality of this vehicle and what is the price tag?”

These are decisions all of us make in our everyday lives. I make the same value judgment when I pull into the gasoline station to purchase gas (regular or premium?) or when I go to the grocery store (brand-name or generic orange juice?). But we know that higher cost doesn’t always mean higher quality. Think American-made automobiles versus Japanese-made vehicles in the 1970s and ’80s.

Along those same lines, let’s think about the U.S. healthcare system in 2011. America is trying to move its healthcare toward a value-based system. How do we receive the best healthcare for the—many times taxpayer—dollar? I am a taxpayer and I am all for higher-quality healthcare for my dollars.

At HM11, I heard from many supporters of healthcare reform, but I also heard many people vilify the government’s efforts at reforming our healthcare system. Just about everyone agreed that the future is uncertain. The current healthcare system certainly values hospitalists. It is hard to argue with the facts. In less than 15 years, our healthcare system has created jobs for more than 30,000 hospitalists, the majority of whom require nonclinical revenue from hospitals to meet expenses. The latest SHM-MGMA data show that the average hospitalist full-time equivalent (FTE) receives more than $131,500 of nonclinical revenue (primarily from hospitals) annually.

Payors of healthcare are no different than Bob when it comes to purchasing a car, or me when it comes to purchasing orange juice. Payors will pay for hospitalists as long as they perceive value in their investment.

But what is the basis of this notion that hospitalists are high-value healthcare providers, and is it justified? At HM11, I heard about the continued rise in hospitalist salaries. Higher costs mean we will have to increase quality if we hope to achieve the same value (value=quality/cost).

Don’t Worry, Share Your Data

I have listened to many presentations about healthcare value, quality, and cost. My perception is that it makes the most sense if it is personal. I live in Massachusetts, and my state government has been aggressive at helping everyone understand the quality and the cost of care being delivered at our hospitals. For example, our state government generates a massive annual report that describes the quality and cost of healthcare being delivered at individual hospitals; a PDF of the report is available at www.mass.gov. (For full disclosure, I work at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center [BIDMC] in Boston and I serve on a Massachusetts Department of Public Health Stroke Advisory Committee.)

The annual report shows there is not as much of a direct relationship between quality and cost as one would like to see. But I applaud Massachusetts for producing this report. Recognizing and understanding a problem is the first step in creating a solution to the problem. One cannot create a value-based system without understanding the existing quality and cost.

This is one of the reasons why, several years ago, the BIDMC leadership posted my hospital’s quality data online for public consumption (www.bidmc.org/QualityandSafety.aspx). The BIDMC website even features a short video of hospitalist Ken Sands, MD, who also happens to be the vice president of quality at BIDMC, telling you about the hospital quality data. Before the hospital posted this data online, most of our hospital staff and providers, let alone our patients and their families, were unaware of the data. BIDMC is not the only hospital who does this. I understand Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles and Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in New Hampshire have long shared their quality data publicly.

But the truth is, if you look hard enough, you can find these data for just about all acute-care hospitals in the country. Start with Medicare’s Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). However, BIDMC and others have simply made it easier to find the data by putting it directly on their websites.

Policy of Transparency

An interesting thing happened over the past decade at BIDMC. In 1997, there were no hospitalists who cared for BIDMC patients. Today, hospitalists manage nearly 100% of the patients hospitalized on our large medical service.

When you look at the data being reported by BIDMC and the state of Massachusetts about nonsurgical conditions, doesn’t that reflect the care being provided by the hospitalists who work at BIDMC? I imagine that is what will run through my CEO and CFO’s minds when we discuss the hospitalist budget this summer. They will ask themselves, “What is the value of our hospitalists? What is the quality of their care? How much do they cost us?”

Some of you might be in a similar position. Do your hospitalists now provide the bulk of the care at your hospital? Are your hospital’s data being publicly reported? I think the answer is a resounding “yes” for many of you.

Allow me to ask this question: What are you doing to collect data to understand the quality and cost of your hospitalist program? Wouldn’t you rather know this information before your hospital or state government tells you?

As the director of my hospitalist group, I spearhead our group efforts to better understand the quality of care we provide. This proactive, introspective approach is essential, especially if hospitalist groups around the country hope to continue being perceived as “high value” providers.

I am interested in hearing from you about your efforts to understand the care being provided by your hospitalists. Feel free to email me at [email protected]. TH

Dr. Li is president of SHM.

Subsidy or Payment?

Question: Before hospitalists, who cared for hospitalized patients?

Answer: Generalists—in other words, internists, family physicians, pediatricians.

Q: How much did that system cost hospitals?

A: Nothing, or very little. In some cases, support dollars were available for weekend, night, or uninsured patient coverage, but by and large this system cost hospitals little. Physicians admitted their patients to the hospital because the alternatives (sending a hypoxic pneumonia patient home from clinic, turning out the office lights and hoping the patient survived the night, or bringing the patient home with them) offered uncomfortable ethical, malpractice, or alimony consequences. So doctors admitted these patients to the hospital and visited them daily.

Q: The average amount of support per hospitalist is $131,564, or about $1.7 million per HM group seeing adult patients. The bulk of those dollars come from the hospital. If we assume that the people running hospitals are smart, then why would those smart businesspeople pay $1.7 million for something they used to get for free?

A: Because there is something they get in return for that money. Or, perhaps, something they think they are getting in return for those dollars.

Q: What?

A: I often go through this exercise with the residents in our hospitalist training program when we discuss the drivers of the HM movement. I usually discuss the reasons why a hospital should fund these groups; it always seems like such a no-brainer to me.

Enter a recent news item from Montana. The story from the Helena Independent Record (see “Unsustainable Growth?” p. 1) noted that a multispecialty group practice in Helena announced they were no longer admitting their patients to a local hospital in protest over a new hospital policy to charge the clinic practice. The fee was to defray some of the costs of the HM program. A hospital representative was quoted as saying “physicians are responsible for obtaining hospital coverage for their own patients, not the hospital.”

I can’t really argue with the logic of that statement. Surely a clinic has responsibility to ensure that their patients get cared for while they are inpatients. If an internist is going to see a patient in the clinic and admit them to the hospital, shouldn’t an internist then see the patient in the hospital?

If I’m a hospital CEO, the answer is no.

To retrench a bit, yes, I’d want a board-certified internal-medicine (or pediatric or family medicine) physician to see the hospitalized patient. But in the process, I wouldn’t want them to only practice internal medicine. That was the model hospitals had 25 years ago—a model that cost them very little, a model that they played a large part in exterminating. The fact that most hospitals are willing to pay millions or more per year to not have that system tells me that they don’t want that system.

Q: So, what do hospitals want?

A: Hospitalists, not internists in the hospital.

What’s the difference? Well, it’s a perception issue. Many, if not most, believe that all it takes to be a great hospitalist is to show up for your shift, provide great care to your 15 patients, and go home. That is, the job is defined by the clinical effort—the internist part. Although there is tremendous benefit to this and I recognize its importance (and let’s not forget the weekend, night, and holiday coverage), this sells us short and puts our financial stability in peril.

To be great, to best help our patients, to give our hospitals what they want and need, we have to evolve from “internists in the hospital” to hospitalists. Hospitalists are defined not by our clinical effort but rather by our nonclinical effort. This is what hospitals are paying $1.7 million per year for. They had the internist in the hospital model and chose to pay more—they chose the hospitalist model.

To be a great hospitalist group means embracing the nonclinical work that envelops the clinical practice—the process and quality improvement (QI). That is, fundamentally changing the unsafe systems that surround our patients. Making them safer, more efficient and of higher quality.

This takes time.

Time = Money

It takes time to implement a QI project to reduce central line infections in the ICU. Or to develop and implement a VTE prophylaxis order set or an insulin or heparin drip protocol. Or to work closely with nursing to reduce falls on a medical unit. It takes time to be at the pneumonia core measures meeting every Monday at 7 a.m. and the hospital credentialing committee meeting every other Friday at 3 p.m. It also takes time to implement a new electronic health record or roll out the new LEAN project to reduce ED wait times.

This takes time, effort, and bandwidth—the kind that can’t be shoehorned into the average clinical day. This is work that needs to be done primarily during nonclinical hours. It’s the kind of work that defines HM as a field; the kind of work that increasingly determines your hospital’s bottom line; the kind of work that has tremendous value; the kind of work that requires remuneration.

In paying for the hospitalist model, your hospital is paying for the clinical (internist) and nonclinical (hospitalist) work you do. The $1.7 million per year is not a subsidy they pay to keep you in business. It’s the price they must pay to compensate your group for all the nonclinical work you do around quality, safety, efficiency, and leadership.

Q: But what if my group isn’t doing these kinds of things?

A: Then your hospital funding is at risk. The Montana story addresses just such a scenario. Clearly the hospital C-suite in this instance only valued (or was presented with) clinical work. Therefore, they felt that others should subsidize the hospitalist salaries—in this case, the clinic. I don’t know the particulars of this case but deduce this because it would be ludicrous to expect the clinic to pay for the part of the hospitalists’ time spent improving the hospital’s systems of care.

Writing the Final Chapter

At the core of the HM funding model is the concept of subsidy versus compensation. If we are only providing clinical care, then the offset dollars from the hospital to support our salaries is functionally a subsidy—a dollar amount to make up for our collections shortfall. However, if it is support for the nonclinical work we are doing, then it is compensation.

As the story of hospitalist funding is written, the report from Montana should serve as a cautionary tale. Hospital financial pressures likely will focus more scrutiny on the hospitalist financial support model. And as this story plays out, HM groups will be expected to bring more to the table than patient care.

Those that do will live happily ever after.

Those that don’t will be forced to answer the tough question: What’s the difference between an internist in the hospital and a hospitalist? If the answer is nothing, that story will have a decidedly and predictably less happy ending. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

Question: Before hospitalists, who cared for hospitalized patients?

Answer: Generalists—in other words, internists, family physicians, pediatricians.

Q: How much did that system cost hospitals?

A: Nothing, or very little. In some cases, support dollars were available for weekend, night, or uninsured patient coverage, but by and large this system cost hospitals little. Physicians admitted their patients to the hospital because the alternatives (sending a hypoxic pneumonia patient home from clinic, turning out the office lights and hoping the patient survived the night, or bringing the patient home with them) offered uncomfortable ethical, malpractice, or alimony consequences. So doctors admitted these patients to the hospital and visited them daily.

Q: The average amount of support per hospitalist is $131,564, or about $1.7 million per HM group seeing adult patients. The bulk of those dollars come from the hospital. If we assume that the people running hospitals are smart, then why would those smart businesspeople pay $1.7 million for something they used to get for free?

A: Because there is something they get in return for that money. Or, perhaps, something they think they are getting in return for those dollars.

Q: What?

A: I often go through this exercise with the residents in our hospitalist training program when we discuss the drivers of the HM movement. I usually discuss the reasons why a hospital should fund these groups; it always seems like such a no-brainer to me.

Enter a recent news item from Montana. The story from the Helena Independent Record (see “Unsustainable Growth?” p. 1) noted that a multispecialty group practice in Helena announced they were no longer admitting their patients to a local hospital in protest over a new hospital policy to charge the clinic practice. The fee was to defray some of the costs of the HM program. A hospital representative was quoted as saying “physicians are responsible for obtaining hospital coverage for their own patients, not the hospital.”

I can’t really argue with the logic of that statement. Surely a clinic has responsibility to ensure that their patients get cared for while they are inpatients. If an internist is going to see a patient in the clinic and admit them to the hospital, shouldn’t an internist then see the patient in the hospital?

If I’m a hospital CEO, the answer is no.

To retrench a bit, yes, I’d want a board-certified internal-medicine (or pediatric or family medicine) physician to see the hospitalized patient. But in the process, I wouldn’t want them to only practice internal medicine. That was the model hospitals had 25 years ago—a model that cost them very little, a model that they played a large part in exterminating. The fact that most hospitals are willing to pay millions or more per year to not have that system tells me that they don’t want that system.

Q: So, what do hospitals want?

A: Hospitalists, not internists in the hospital.

What’s the difference? Well, it’s a perception issue. Many, if not most, believe that all it takes to be a great hospitalist is to show up for your shift, provide great care to your 15 patients, and go home. That is, the job is defined by the clinical effort—the internist part. Although there is tremendous benefit to this and I recognize its importance (and let’s not forget the weekend, night, and holiday coverage), this sells us short and puts our financial stability in peril.

To be great, to best help our patients, to give our hospitals what they want and need, we have to evolve from “internists in the hospital” to hospitalists. Hospitalists are defined not by our clinical effort but rather by our nonclinical effort. This is what hospitals are paying $1.7 million per year for. They had the internist in the hospital model and chose to pay more—they chose the hospitalist model.

To be a great hospitalist group means embracing the nonclinical work that envelops the clinical practice—the process and quality improvement (QI). That is, fundamentally changing the unsafe systems that surround our patients. Making them safer, more efficient and of higher quality.

This takes time.

Time = Money

It takes time to implement a QI project to reduce central line infections in the ICU. Or to develop and implement a VTE prophylaxis order set or an insulin or heparin drip protocol. Or to work closely with nursing to reduce falls on a medical unit. It takes time to be at the pneumonia core measures meeting every Monday at 7 a.m. and the hospital credentialing committee meeting every other Friday at 3 p.m. It also takes time to implement a new electronic health record or roll out the new LEAN project to reduce ED wait times.

This takes time, effort, and bandwidth—the kind that can’t be shoehorned into the average clinical day. This is work that needs to be done primarily during nonclinical hours. It’s the kind of work that defines HM as a field; the kind of work that increasingly determines your hospital’s bottom line; the kind of work that has tremendous value; the kind of work that requires remuneration.

In paying for the hospitalist model, your hospital is paying for the clinical (internist) and nonclinical (hospitalist) work you do. The $1.7 million per year is not a subsidy they pay to keep you in business. It’s the price they must pay to compensate your group for all the nonclinical work you do around quality, safety, efficiency, and leadership.

Q: But what if my group isn’t doing these kinds of things?

A: Then your hospital funding is at risk. The Montana story addresses just such a scenario. Clearly the hospital C-suite in this instance only valued (or was presented with) clinical work. Therefore, they felt that others should subsidize the hospitalist salaries—in this case, the clinic. I don’t know the particulars of this case but deduce this because it would be ludicrous to expect the clinic to pay for the part of the hospitalists’ time spent improving the hospital’s systems of care.

Writing the Final Chapter