User login

Wedding dermatology

Planning a wedding doesn’t just involve decisions on venues, vows, guests, food, and décor, but also on the betrothed couple’s appearance. Memories and photographs from this day last a lifetime, so it is understandable that people may want to and feel pressured to look their best on this important day – which along with the pressures of planning a wedding, can lead to unnecessary stress, increased cortisol, and unexpected acne and other skin issues.

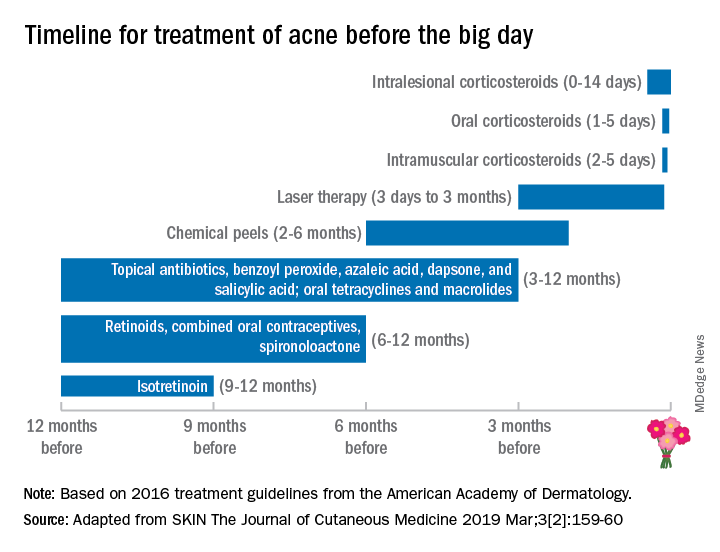

Because of a complete absence of wedding skin recommendations in the dermatology literature, Winklemann R et al. recently published a paper titled “Wedding Dermatology: A proposed timeline to optimize skin clearance and the avoidance of a true dermatologic emergency” (SKIN The Journal of Cutaneous Medicine 2019 Mar;3[2]:159-60). He focused on acne, using the American Academy of Dermatology acne treatment guidelines and expert opinion, they point out that other than intralesional corticosteroids (which take 0-14 days to have an effect), the majority of acne treatments require at least 3-12 months to achieve clearance or improvement.

This proposed treatment timeline makes sense given that skin cell turnover on the face takes about 6-8 weeks; therefore, it may take that long for acne lesions to resolve or for treatment to have an effect.

Besides acne treatment, cosmetic treatments also have varying healing times and may require multiple sessions with time in between treatments for optimal results. For instance, treatment of photoaging with intense pulsed light or nonablative fractionated resurfacing may require three to six treatments, typically spaced 1 month apart.

Botulinum toxin treatments may take up to 2 weeks to kick in fully, then last 3-4 months. While the lead time for botulinum toxin to kick in is relatively short, I advise people not to get their first botulinum toxin 2 weeks before their wedding. Sometimes, having this treatment 4-6 weeks prior to the wedding date provides enough time for botulinum toxin to kick in – and to start wearing off to the point that the patient has the desired cosmetic effect, but still has some movement for the desired emotional facial expressions on the wedding day. Some patients also may require touch-ups, optimally at the 2-week window, once the botulinum toxin effect has fully kicked in.

With any injectable, there may be bruising and swelling that can take a week or so to heal, even when the bruises are treated with pulse dye laser used to make bruises resolve more quickly. Even a facial may result in blemishes that take a few days to 1-2 weeks to heal, especially with extractions. As such, a facial, especially a hydrafacial, may be beneficial before one’s wedding, but I would recommend having them done at least once or twice to assess an individual’s recovery time (if any) prior to the actual wedding date.

Treatment needs will vary considerably depending on the patient’s baseline skin health. As dermatologists, our patients depend greatly on us to help them look and feel their best, especially during a time when they are about to embark on a new journey like marriage. Patients need to be given realistic treatment options and time frames to achieve their goals. Whether the goal is treating acne or acne scars, starting or fine-tuning cosmetic treatments, or deciding on a skin-care regimen, the bottom line is making an appointment with the dermatologist early – 6-12 months in advance, if possible – to figure out the right plan.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

Planning a wedding doesn’t just involve decisions on venues, vows, guests, food, and décor, but also on the betrothed couple’s appearance. Memories and photographs from this day last a lifetime, so it is understandable that people may want to and feel pressured to look their best on this important day – which along with the pressures of planning a wedding, can lead to unnecessary stress, increased cortisol, and unexpected acne and other skin issues.

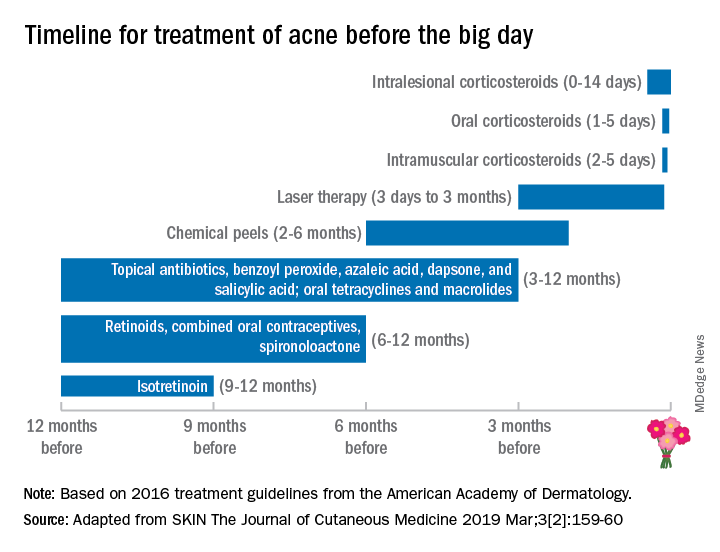

Because of a complete absence of wedding skin recommendations in the dermatology literature, Winklemann R et al. recently published a paper titled “Wedding Dermatology: A proposed timeline to optimize skin clearance and the avoidance of a true dermatologic emergency” (SKIN The Journal of Cutaneous Medicine 2019 Mar;3[2]:159-60). He focused on acne, using the American Academy of Dermatology acne treatment guidelines and expert opinion, they point out that other than intralesional corticosteroids (which take 0-14 days to have an effect), the majority of acne treatments require at least 3-12 months to achieve clearance or improvement.

This proposed treatment timeline makes sense given that skin cell turnover on the face takes about 6-8 weeks; therefore, it may take that long for acne lesions to resolve or for treatment to have an effect.

Besides acne treatment, cosmetic treatments also have varying healing times and may require multiple sessions with time in between treatments for optimal results. For instance, treatment of photoaging with intense pulsed light or nonablative fractionated resurfacing may require three to six treatments, typically spaced 1 month apart.

Botulinum toxin treatments may take up to 2 weeks to kick in fully, then last 3-4 months. While the lead time for botulinum toxin to kick in is relatively short, I advise people not to get their first botulinum toxin 2 weeks before their wedding. Sometimes, having this treatment 4-6 weeks prior to the wedding date provides enough time for botulinum toxin to kick in – and to start wearing off to the point that the patient has the desired cosmetic effect, but still has some movement for the desired emotional facial expressions on the wedding day. Some patients also may require touch-ups, optimally at the 2-week window, once the botulinum toxin effect has fully kicked in.

With any injectable, there may be bruising and swelling that can take a week or so to heal, even when the bruises are treated with pulse dye laser used to make bruises resolve more quickly. Even a facial may result in blemishes that take a few days to 1-2 weeks to heal, especially with extractions. As such, a facial, especially a hydrafacial, may be beneficial before one’s wedding, but I would recommend having them done at least once or twice to assess an individual’s recovery time (if any) prior to the actual wedding date.

Treatment needs will vary considerably depending on the patient’s baseline skin health. As dermatologists, our patients depend greatly on us to help them look and feel their best, especially during a time when they are about to embark on a new journey like marriage. Patients need to be given realistic treatment options and time frames to achieve their goals. Whether the goal is treating acne or acne scars, starting or fine-tuning cosmetic treatments, or deciding on a skin-care regimen, the bottom line is making an appointment with the dermatologist early – 6-12 months in advance, if possible – to figure out the right plan.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

Planning a wedding doesn’t just involve decisions on venues, vows, guests, food, and décor, but also on the betrothed couple’s appearance. Memories and photographs from this day last a lifetime, so it is understandable that people may want to and feel pressured to look their best on this important day – which along with the pressures of planning a wedding, can lead to unnecessary stress, increased cortisol, and unexpected acne and other skin issues.

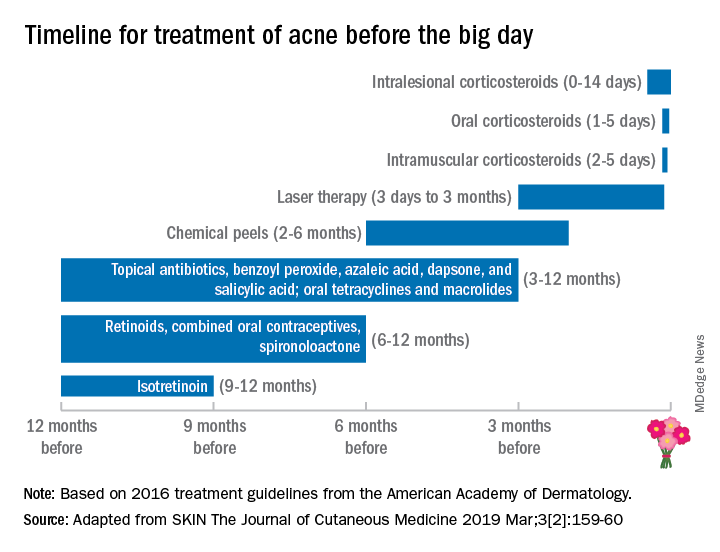

Because of a complete absence of wedding skin recommendations in the dermatology literature, Winklemann R et al. recently published a paper titled “Wedding Dermatology: A proposed timeline to optimize skin clearance and the avoidance of a true dermatologic emergency” (SKIN The Journal of Cutaneous Medicine 2019 Mar;3[2]:159-60). He focused on acne, using the American Academy of Dermatology acne treatment guidelines and expert opinion, they point out that other than intralesional corticosteroids (which take 0-14 days to have an effect), the majority of acne treatments require at least 3-12 months to achieve clearance or improvement.

This proposed treatment timeline makes sense given that skin cell turnover on the face takes about 6-8 weeks; therefore, it may take that long for acne lesions to resolve or for treatment to have an effect.

Besides acne treatment, cosmetic treatments also have varying healing times and may require multiple sessions with time in between treatments for optimal results. For instance, treatment of photoaging with intense pulsed light or nonablative fractionated resurfacing may require three to six treatments, typically spaced 1 month apart.

Botulinum toxin treatments may take up to 2 weeks to kick in fully, then last 3-4 months. While the lead time for botulinum toxin to kick in is relatively short, I advise people not to get their first botulinum toxin 2 weeks before their wedding. Sometimes, having this treatment 4-6 weeks prior to the wedding date provides enough time for botulinum toxin to kick in – and to start wearing off to the point that the patient has the desired cosmetic effect, but still has some movement for the desired emotional facial expressions on the wedding day. Some patients also may require touch-ups, optimally at the 2-week window, once the botulinum toxin effect has fully kicked in.

With any injectable, there may be bruising and swelling that can take a week or so to heal, even when the bruises are treated with pulse dye laser used to make bruises resolve more quickly. Even a facial may result in blemishes that take a few days to 1-2 weeks to heal, especially with extractions. As such, a facial, especially a hydrafacial, may be beneficial before one’s wedding, but I would recommend having them done at least once or twice to assess an individual’s recovery time (if any) prior to the actual wedding date.

Treatment needs will vary considerably depending on the patient’s baseline skin health. As dermatologists, our patients depend greatly on us to help them look and feel their best, especially during a time when they are about to embark on a new journey like marriage. Patients need to be given realistic treatment options and time frames to achieve their goals. Whether the goal is treating acne or acne scars, starting or fine-tuning cosmetic treatments, or deciding on a skin-care regimen, the bottom line is making an appointment with the dermatologist early – 6-12 months in advance, if possible – to figure out the right plan.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

Probiotic, prebiotic, and postbiotic skin care

A decade ago, I gave my senior expert talk at the University of California, San Francisco, department of dermatology on skin care and brought up the controversial topic that sterile or clean skin is bad. At the time, I initiated the conversation on the Today, I not only preach this message to my patients, but I also practice the “less-is-more” philosophy every day. It is my hope that this brief summary of the skin microbiome and the importance of skin bacteria will affect the development of the next generation of skin care products.

The normal human skin is a microbiome colonized by 10,000-1,000,000 bacteria units/cm2 that prevent the growth of pathogenic organisms and maintain the immunity of the skin. The diversity and type of skin bacteria (that is, Staphylococcus or Propionibacterium acnes), as well as their concentration, varies by person, body location, and environment. Symbiotic with bacteria on the skin are yeasts, such as Malassezia, and parasites, such as Demodex. When the composition and diversity of microorganisms are disrupted, the skin can no longer protect its barrier functions, leading to pathogenic bacterial infections, altered skin pH, decreased production of antimicrobial peptides, and increased inflammation. The microbiome also serves to shield the skin from environmental stressors, such as free radicals, UV radiation, and pollution.

What can lead to disruption of our skin is hygiene. Over-washing; stripping of the skin with lathering cleaner; overexfoliation; long, hot showers; and the use of products with antibacterial properties have increased over the last 50 years, and so has skin disease. The removal of these microorganisms, either by overcleansing or with antibiotic use, disrupts the microflora and leads to pH-imbalanced and inflamed skin. Our microflora contains prebiotics, probiotics, and postbiotics. Prebiotics are the “fertilizer” or “food,” so to speak, that encourages these essential microorganisms to grow; probiotics are the microorganisms themselves; and postbiotics are the chemical byproducts of bacteria, such as antimicrobial peptides and fragments of dead bacterial cells that remain on the skin.

Skin care tailored to our unique microbiome is in its infancy. On the frontier of microflora-rich skin care are organisms like Bifidobacterium longum, which increases the skin’s resistance to temperature and product-related irritation. Streptococcus thermophilus has been shown to increase the production of ceramides in the skin, which could help atopic dermatitis. Lactobacillus paracasei has been shown to inhibit the neuropeptide substance P, which increases inflammation and oil production. Enterococcus faecalis, Streptococcus salivarius, and Lactobacillus plantarum have all been shown to decrease Propionibacterium acnes. Bacillus coagulans and Bifidobacterium breve have been shown to decrease free radicals and protect against UV rays.

Probiotic, prebiotic, and postbiotic skin care, however, does have its challenges. Probiotics are live bacteria, and thus need refrigeration. These products are also not intended for use in anyone who is immunosuppressed or neutropenic. Another complexity in the development of probiotic, prebiotic, and postbiotic skin care is that each person may have a different need in terms of their skin microflora and that microflora is inherently different in different body parts. Furthermore, people with skin inflammation may require a different concentration or population of that flora.

In 2007, the National Institutes of Health initiated the Human Microbiome Project, and in 2016, the White House announced the creation of a new National Microbiome Initiative (NMI). Through this research, the identification and importance of our gut bacteria has led to a vast increase in development and near obsession with probiotic supplements, foods, and drinks (examples include Kombucha tea, kimchi, miso, and Kefir). Although oral consumption of prebiotics and probiotics may prove to be helpful, the skin does have its own unique flora and will benefit from targeted skin care. In the meantime, fostering the skins’s microflora is as important or more important than the replacement of it. My recommendations include using “microflora friendly” products that are lather-free, cream- or oil-based cleansers with acidic pH’s, and moisturizing heavily and consistently. I recommend staying away from antibacterial wipes, antibacterial soaps, and sanitizers.

Fostering this bacterial rich environment will help maintain your skin integrity. Squeaky clean skin is damaged skin.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Al-Ghazzewi F et al. Benef Microbes. 2014 Jun 1;5(2):99-107.

Baquerizo Nole K et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Oct;71(4):814-21.

Chen Y et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Jul;69(1):143-55.e3.

Grice E et al. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011 Apr;9(4):244-53.

Kong H et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2012 Mar;132(3, part 2):933-9.

Hutkins R et al. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2016 Feb;37:1-7.

Kober MM et al. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015 Apr 6;1(2):85-9.

Maquire M. et al. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017 Aug;309(6):411-421.

Sugimoto S. et al. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2012 Dec;28(6): 312-9.

A decade ago, I gave my senior expert talk at the University of California, San Francisco, department of dermatology on skin care and brought up the controversial topic that sterile or clean skin is bad. At the time, I initiated the conversation on the Today, I not only preach this message to my patients, but I also practice the “less-is-more” philosophy every day. It is my hope that this brief summary of the skin microbiome and the importance of skin bacteria will affect the development of the next generation of skin care products.

The normal human skin is a microbiome colonized by 10,000-1,000,000 bacteria units/cm2 that prevent the growth of pathogenic organisms and maintain the immunity of the skin. The diversity and type of skin bacteria (that is, Staphylococcus or Propionibacterium acnes), as well as their concentration, varies by person, body location, and environment. Symbiotic with bacteria on the skin are yeasts, such as Malassezia, and parasites, such as Demodex. When the composition and diversity of microorganisms are disrupted, the skin can no longer protect its barrier functions, leading to pathogenic bacterial infections, altered skin pH, decreased production of antimicrobial peptides, and increased inflammation. The microbiome also serves to shield the skin from environmental stressors, such as free radicals, UV radiation, and pollution.

What can lead to disruption of our skin is hygiene. Over-washing; stripping of the skin with lathering cleaner; overexfoliation; long, hot showers; and the use of products with antibacterial properties have increased over the last 50 years, and so has skin disease. The removal of these microorganisms, either by overcleansing or with antibiotic use, disrupts the microflora and leads to pH-imbalanced and inflamed skin. Our microflora contains prebiotics, probiotics, and postbiotics. Prebiotics are the “fertilizer” or “food,” so to speak, that encourages these essential microorganisms to grow; probiotics are the microorganisms themselves; and postbiotics are the chemical byproducts of bacteria, such as antimicrobial peptides and fragments of dead bacterial cells that remain on the skin.

Skin care tailored to our unique microbiome is in its infancy. On the frontier of microflora-rich skin care are organisms like Bifidobacterium longum, which increases the skin’s resistance to temperature and product-related irritation. Streptococcus thermophilus has been shown to increase the production of ceramides in the skin, which could help atopic dermatitis. Lactobacillus paracasei has been shown to inhibit the neuropeptide substance P, which increases inflammation and oil production. Enterococcus faecalis, Streptococcus salivarius, and Lactobacillus plantarum have all been shown to decrease Propionibacterium acnes. Bacillus coagulans and Bifidobacterium breve have been shown to decrease free radicals and protect against UV rays.

Probiotic, prebiotic, and postbiotic skin care, however, does have its challenges. Probiotics are live bacteria, and thus need refrigeration. These products are also not intended for use in anyone who is immunosuppressed or neutropenic. Another complexity in the development of probiotic, prebiotic, and postbiotic skin care is that each person may have a different need in terms of their skin microflora and that microflora is inherently different in different body parts. Furthermore, people with skin inflammation may require a different concentration or population of that flora.

In 2007, the National Institutes of Health initiated the Human Microbiome Project, and in 2016, the White House announced the creation of a new National Microbiome Initiative (NMI). Through this research, the identification and importance of our gut bacteria has led to a vast increase in development and near obsession with probiotic supplements, foods, and drinks (examples include Kombucha tea, kimchi, miso, and Kefir). Although oral consumption of prebiotics and probiotics may prove to be helpful, the skin does have its own unique flora and will benefit from targeted skin care. In the meantime, fostering the skins’s microflora is as important or more important than the replacement of it. My recommendations include using “microflora friendly” products that are lather-free, cream- or oil-based cleansers with acidic pH’s, and moisturizing heavily and consistently. I recommend staying away from antibacterial wipes, antibacterial soaps, and sanitizers.

Fostering this bacterial rich environment will help maintain your skin integrity. Squeaky clean skin is damaged skin.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Al-Ghazzewi F et al. Benef Microbes. 2014 Jun 1;5(2):99-107.

Baquerizo Nole K et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Oct;71(4):814-21.

Chen Y et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Jul;69(1):143-55.e3.

Grice E et al. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011 Apr;9(4):244-53.

Kong H et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2012 Mar;132(3, part 2):933-9.

Hutkins R et al. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2016 Feb;37:1-7.

Kober MM et al. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015 Apr 6;1(2):85-9.

Maquire M. et al. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017 Aug;309(6):411-421.

Sugimoto S. et al. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2012 Dec;28(6): 312-9.

A decade ago, I gave my senior expert talk at the University of California, San Francisco, department of dermatology on skin care and brought up the controversial topic that sterile or clean skin is bad. At the time, I initiated the conversation on the Today, I not only preach this message to my patients, but I also practice the “less-is-more” philosophy every day. It is my hope that this brief summary of the skin microbiome and the importance of skin bacteria will affect the development of the next generation of skin care products.

The normal human skin is a microbiome colonized by 10,000-1,000,000 bacteria units/cm2 that prevent the growth of pathogenic organisms and maintain the immunity of the skin. The diversity and type of skin bacteria (that is, Staphylococcus or Propionibacterium acnes), as well as their concentration, varies by person, body location, and environment. Symbiotic with bacteria on the skin are yeasts, such as Malassezia, and parasites, such as Demodex. When the composition and diversity of microorganisms are disrupted, the skin can no longer protect its barrier functions, leading to pathogenic bacterial infections, altered skin pH, decreased production of antimicrobial peptides, and increased inflammation. The microbiome also serves to shield the skin from environmental stressors, such as free radicals, UV radiation, and pollution.

What can lead to disruption of our skin is hygiene. Over-washing; stripping of the skin with lathering cleaner; overexfoliation; long, hot showers; and the use of products with antibacterial properties have increased over the last 50 years, and so has skin disease. The removal of these microorganisms, either by overcleansing or with antibiotic use, disrupts the microflora and leads to pH-imbalanced and inflamed skin. Our microflora contains prebiotics, probiotics, and postbiotics. Prebiotics are the “fertilizer” or “food,” so to speak, that encourages these essential microorganisms to grow; probiotics are the microorganisms themselves; and postbiotics are the chemical byproducts of bacteria, such as antimicrobial peptides and fragments of dead bacterial cells that remain on the skin.

Skin care tailored to our unique microbiome is in its infancy. On the frontier of microflora-rich skin care are organisms like Bifidobacterium longum, which increases the skin’s resistance to temperature and product-related irritation. Streptococcus thermophilus has been shown to increase the production of ceramides in the skin, which could help atopic dermatitis. Lactobacillus paracasei has been shown to inhibit the neuropeptide substance P, which increases inflammation and oil production. Enterococcus faecalis, Streptococcus salivarius, and Lactobacillus plantarum have all been shown to decrease Propionibacterium acnes. Bacillus coagulans and Bifidobacterium breve have been shown to decrease free radicals and protect against UV rays.

Probiotic, prebiotic, and postbiotic skin care, however, does have its challenges. Probiotics are live bacteria, and thus need refrigeration. These products are also not intended for use in anyone who is immunosuppressed or neutropenic. Another complexity in the development of probiotic, prebiotic, and postbiotic skin care is that each person may have a different need in terms of their skin microflora and that microflora is inherently different in different body parts. Furthermore, people with skin inflammation may require a different concentration or population of that flora.

In 2007, the National Institutes of Health initiated the Human Microbiome Project, and in 2016, the White House announced the creation of a new National Microbiome Initiative (NMI). Through this research, the identification and importance of our gut bacteria has led to a vast increase in development and near obsession with probiotic supplements, foods, and drinks (examples include Kombucha tea, kimchi, miso, and Kefir). Although oral consumption of prebiotics and probiotics may prove to be helpful, the skin does have its own unique flora and will benefit from targeted skin care. In the meantime, fostering the skins’s microflora is as important or more important than the replacement of it. My recommendations include using “microflora friendly” products that are lather-free, cream- or oil-based cleansers with acidic pH’s, and moisturizing heavily and consistently. I recommend staying away from antibacterial wipes, antibacterial soaps, and sanitizers.

Fostering this bacterial rich environment will help maintain your skin integrity. Squeaky clean skin is damaged skin.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Al-Ghazzewi F et al. Benef Microbes. 2014 Jun 1;5(2):99-107.

Baquerizo Nole K et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Oct;71(4):814-21.

Chen Y et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Jul;69(1):143-55.e3.

Grice E et al. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011 Apr;9(4):244-53.

Kong H et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2012 Mar;132(3, part 2):933-9.

Hutkins R et al. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2016 Feb;37:1-7.

Kober MM et al. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015 Apr 6;1(2):85-9.

Maquire M. et al. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017 Aug;309(6):411-421.

Sugimoto S. et al. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2012 Dec;28(6): 312-9.

Winter exfoliation: A multicultural approach

Winter or postwinter exfoliation may seem counterintuitive to some patients because skin is often more dry because of cold weather and dry heat from heaters in the home, car, and workplace. Some patients even admit to using emollients less frequently in the winter because they are too cold to do it after bathing or are covering more of their body. But winter exfoliation can be an important method for improving skin hydration by aiding skin cell turnover, removing surface flaky skin, and enhancing penetration of moisturizers and active ingredients applied afterward. Here we explore exfoliation techniques used in various cultures around the world.

Ancient Egypt: Egyptians are credited with the first exfoliation techniques. Mechanical exfoliation was practiced in ancient Egypt via pumice stones, as well as alabaster particles, and scrubs made from sand or plants, such as aloe vera. (Although the subject is beyond the scope of this article, the first use of chemical exfoliation, using sour milk, which contains lactic acid, has been credited to ancient Egypt.)

Iran: Most traditional Iranian households are familiar with kiseh and sefidab, used for exfoliation as often as once a week. Kiseh is a special loofah-like exfoliating mitt, often hand woven. Sefidab is a whitish ball that looks like a dense piece of chalk made from animal fats and natural minerals that is rubbed on the kiseh, which is then rubbed on the skin. Exfoliation results as the sefidab and top layers of skin come off in gray white rolls, which are then rinsed off. The dead skin left on the mitt is known as “chairk.” Archaeological excavations have provided evidence that sefidab may have been used in Persian cosmetics as long ago as 2000 BC–4500 BC, as part of Zoroastrian traditions.

Korea: Koreans have long been known for practicing skin exfoliation. Here in Los Angeles, especially in Koreatown, many Korean spas or bathhouses, known as jjimjilbang, can be found; these provide various therapies, particularly “detoxification” in hot tubs, saunas (many with different stones and crystal minerals for healing properties), computer rooms, restaurants, theater rooms. They also provide body scrubs, or seshin: A soak in the hot tub for at least 30 minutes is recommended, followed by a hot water rinse and a scrub by a “ddemiri” (a scrub practitioner), who intensely scrubs the skin from head to toe using a roughened cloth. Going into a hot room or sauna is recommended after the scrub for relaxation, with the belief that the sweat won’t be blocked by dirty or clogged pores. Scrubs in jjimjilbang are recommended as often as once per week.

Indigenous people of the Americas and Caribbean: Sea salt is used commonly as an exfoliant among people from Caribbean countries and those of indigenous ancestry in the Americas (North America, including Hawaii, and Central and South America). Finer-grained sea salt is commonly found in the showers of my friends of Afro-Caribbean and indigenous American descent. While sugar is less coarse and easy to wash off in warm water, finer-grained sea salt provides more friction but is not as rough as coarse sea salt. Fine sea salt, because it is less coarse, can also be used on the face, if used carefully. While the effect of topical salt on skin microbes is unknown, cutaneous sodium storage has been found to strengthen the antimicrobial barrier function and boost macrophage host defense (Cell Metab. 2015 Mar 3;21[3]:493-501). Additionally, it has been noted that some Native Americans used dried corncobs for exfoliation. The people of the Comanche tribe would use sand from the bottom of a river bed to scrub the skin (similarly, Polynesian people have been known to use crushed sea shells for this purpose).

India (Ayurveda): Garshana is a dry brushing technique performed in Ayurvedic medicine. Dry brushing may be performed with a bristle brush or with slightly roughened silk gloves. The motion of dry brushing is intended to stimulate lymphatic drainage for elimination of toxins from the body. Circular strokes are used on the stomach and joints (shoulders, elbows, knees, wrists, hips, and ankles), and long sweeping strokes are used on the arms and legs. It is recommended for the morning, upon awakening and before a shower, because it is a stimulating practice. Sometimes oils, specific to an individual’s “dosha” (constitutional type or energy as defined by Ayurveda) – are applied afterward in a similar head-to-toe motion as a self-massage called Abhyanga.

Japan: Shaving, particularly facial shaving, is frequently done not just among men in Japan, but also among women who have shaved their faces and skin for years as a method of exfoliation for skin rejuvenation. In the United States, facial shaving among women has evolved to a method of exfoliation called “dermaplaning,” which involves dry shaving hairs (including facial vellus hairs) as well as top layers of stratum corneum. The procedure uses of a 25-centimeter (10-inch) scalpel, which curves into a sharp point. Potential risks include irritation from friction, as well as folliculitis.

France: It is not certain whether “gommage” originated in France, but in French, it means “to erase” because the rubbing action is similar to erasing a word. In gommage, a paste is applied to the skin and allowed to dry slightly while gentle enzymes digest dead skin cells on the surface; then it is rubbed off, taking skin cells with it. Most of what comes off is the product itself, but this may include some skin cells. One commonly used enzyme in gommage is papain, derived from the papaya fruit. Gommage was popular with facials before stronger chemical exfoliants like alpha-hydroxy acids became widely available commercially.

West Africa (Ghana, Nigeria): A long mesh body exfoliator, much like a tightly woven fishing net made of nylon, is common in Ghanaian and Nigerian households. The textured washcloth typically stretches up to 3 times the size of a regular washcloth, making it easy to scrub hard-to-reach places like the back.

Worldwide: Around the world in places where coffee beans are native, including Kenya and other parts of Africa, the Middle East, South America, Australia, and Hawaii, coffee beans are used as a skin exfoliant. Coffee grounds can however, should be used cautiously in showers as they can coagulate in water and clog drains and pipes. One tradition in Kenya is to crush and rub coffee beans on the skin with a piece of sugarcane to remove top layers of skin. Often too harsh to use directly, coffee grounds in cosmetic formulations are often mixed with oils or shea butter to create a smoother texture.

May this list grow as we continue to learn from the skin care techniques practiced in different cultures around the world.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

Winter or postwinter exfoliation may seem counterintuitive to some patients because skin is often more dry because of cold weather and dry heat from heaters in the home, car, and workplace. Some patients even admit to using emollients less frequently in the winter because they are too cold to do it after bathing or are covering more of their body. But winter exfoliation can be an important method for improving skin hydration by aiding skin cell turnover, removing surface flaky skin, and enhancing penetration of moisturizers and active ingredients applied afterward. Here we explore exfoliation techniques used in various cultures around the world.

Ancient Egypt: Egyptians are credited with the first exfoliation techniques. Mechanical exfoliation was practiced in ancient Egypt via pumice stones, as well as alabaster particles, and scrubs made from sand or plants, such as aloe vera. (Although the subject is beyond the scope of this article, the first use of chemical exfoliation, using sour milk, which contains lactic acid, has been credited to ancient Egypt.)

Iran: Most traditional Iranian households are familiar with kiseh and sefidab, used for exfoliation as often as once a week. Kiseh is a special loofah-like exfoliating mitt, often hand woven. Sefidab is a whitish ball that looks like a dense piece of chalk made from animal fats and natural minerals that is rubbed on the kiseh, which is then rubbed on the skin. Exfoliation results as the sefidab and top layers of skin come off in gray white rolls, which are then rinsed off. The dead skin left on the mitt is known as “chairk.” Archaeological excavations have provided evidence that sefidab may have been used in Persian cosmetics as long ago as 2000 BC–4500 BC, as part of Zoroastrian traditions.

Korea: Koreans have long been known for practicing skin exfoliation. Here in Los Angeles, especially in Koreatown, many Korean spas or bathhouses, known as jjimjilbang, can be found; these provide various therapies, particularly “detoxification” in hot tubs, saunas (many with different stones and crystal minerals for healing properties), computer rooms, restaurants, theater rooms. They also provide body scrubs, or seshin: A soak in the hot tub for at least 30 minutes is recommended, followed by a hot water rinse and a scrub by a “ddemiri” (a scrub practitioner), who intensely scrubs the skin from head to toe using a roughened cloth. Going into a hot room or sauna is recommended after the scrub for relaxation, with the belief that the sweat won’t be blocked by dirty or clogged pores. Scrubs in jjimjilbang are recommended as often as once per week.

Indigenous people of the Americas and Caribbean: Sea salt is used commonly as an exfoliant among people from Caribbean countries and those of indigenous ancestry in the Americas (North America, including Hawaii, and Central and South America). Finer-grained sea salt is commonly found in the showers of my friends of Afro-Caribbean and indigenous American descent. While sugar is less coarse and easy to wash off in warm water, finer-grained sea salt provides more friction but is not as rough as coarse sea salt. Fine sea salt, because it is less coarse, can also be used on the face, if used carefully. While the effect of topical salt on skin microbes is unknown, cutaneous sodium storage has been found to strengthen the antimicrobial barrier function and boost macrophage host defense (Cell Metab. 2015 Mar 3;21[3]:493-501). Additionally, it has been noted that some Native Americans used dried corncobs for exfoliation. The people of the Comanche tribe would use sand from the bottom of a river bed to scrub the skin (similarly, Polynesian people have been known to use crushed sea shells for this purpose).

India (Ayurveda): Garshana is a dry brushing technique performed in Ayurvedic medicine. Dry brushing may be performed with a bristle brush or with slightly roughened silk gloves. The motion of dry brushing is intended to stimulate lymphatic drainage for elimination of toxins from the body. Circular strokes are used on the stomach and joints (shoulders, elbows, knees, wrists, hips, and ankles), and long sweeping strokes are used on the arms and legs. It is recommended for the morning, upon awakening and before a shower, because it is a stimulating practice. Sometimes oils, specific to an individual’s “dosha” (constitutional type or energy as defined by Ayurveda) – are applied afterward in a similar head-to-toe motion as a self-massage called Abhyanga.

Japan: Shaving, particularly facial shaving, is frequently done not just among men in Japan, but also among women who have shaved their faces and skin for years as a method of exfoliation for skin rejuvenation. In the United States, facial shaving among women has evolved to a method of exfoliation called “dermaplaning,” which involves dry shaving hairs (including facial vellus hairs) as well as top layers of stratum corneum. The procedure uses of a 25-centimeter (10-inch) scalpel, which curves into a sharp point. Potential risks include irritation from friction, as well as folliculitis.

France: It is not certain whether “gommage” originated in France, but in French, it means “to erase” because the rubbing action is similar to erasing a word. In gommage, a paste is applied to the skin and allowed to dry slightly while gentle enzymes digest dead skin cells on the surface; then it is rubbed off, taking skin cells with it. Most of what comes off is the product itself, but this may include some skin cells. One commonly used enzyme in gommage is papain, derived from the papaya fruit. Gommage was popular with facials before stronger chemical exfoliants like alpha-hydroxy acids became widely available commercially.

West Africa (Ghana, Nigeria): A long mesh body exfoliator, much like a tightly woven fishing net made of nylon, is common in Ghanaian and Nigerian households. The textured washcloth typically stretches up to 3 times the size of a regular washcloth, making it easy to scrub hard-to-reach places like the back.

Worldwide: Around the world in places where coffee beans are native, including Kenya and other parts of Africa, the Middle East, South America, Australia, and Hawaii, coffee beans are used as a skin exfoliant. Coffee grounds can however, should be used cautiously in showers as they can coagulate in water and clog drains and pipes. One tradition in Kenya is to crush and rub coffee beans on the skin with a piece of sugarcane to remove top layers of skin. Often too harsh to use directly, coffee grounds in cosmetic formulations are often mixed with oils or shea butter to create a smoother texture.

May this list grow as we continue to learn from the skin care techniques practiced in different cultures around the world.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

Winter or postwinter exfoliation may seem counterintuitive to some patients because skin is often more dry because of cold weather and dry heat from heaters in the home, car, and workplace. Some patients even admit to using emollients less frequently in the winter because they are too cold to do it after bathing or are covering more of their body. But winter exfoliation can be an important method for improving skin hydration by aiding skin cell turnover, removing surface flaky skin, and enhancing penetration of moisturizers and active ingredients applied afterward. Here we explore exfoliation techniques used in various cultures around the world.

Ancient Egypt: Egyptians are credited with the first exfoliation techniques. Mechanical exfoliation was practiced in ancient Egypt via pumice stones, as well as alabaster particles, and scrubs made from sand or plants, such as aloe vera. (Although the subject is beyond the scope of this article, the first use of chemical exfoliation, using sour milk, which contains lactic acid, has been credited to ancient Egypt.)

Iran: Most traditional Iranian households are familiar with kiseh and sefidab, used for exfoliation as often as once a week. Kiseh is a special loofah-like exfoliating mitt, often hand woven. Sefidab is a whitish ball that looks like a dense piece of chalk made from animal fats and natural minerals that is rubbed on the kiseh, which is then rubbed on the skin. Exfoliation results as the sefidab and top layers of skin come off in gray white rolls, which are then rinsed off. The dead skin left on the mitt is known as “chairk.” Archaeological excavations have provided evidence that sefidab may have been used in Persian cosmetics as long ago as 2000 BC–4500 BC, as part of Zoroastrian traditions.

Korea: Koreans have long been known for practicing skin exfoliation. Here in Los Angeles, especially in Koreatown, many Korean spas or bathhouses, known as jjimjilbang, can be found; these provide various therapies, particularly “detoxification” in hot tubs, saunas (many with different stones and crystal minerals for healing properties), computer rooms, restaurants, theater rooms. They also provide body scrubs, or seshin: A soak in the hot tub for at least 30 minutes is recommended, followed by a hot water rinse and a scrub by a “ddemiri” (a scrub practitioner), who intensely scrubs the skin from head to toe using a roughened cloth. Going into a hot room or sauna is recommended after the scrub for relaxation, with the belief that the sweat won’t be blocked by dirty or clogged pores. Scrubs in jjimjilbang are recommended as often as once per week.

Indigenous people of the Americas and Caribbean: Sea salt is used commonly as an exfoliant among people from Caribbean countries and those of indigenous ancestry in the Americas (North America, including Hawaii, and Central and South America). Finer-grained sea salt is commonly found in the showers of my friends of Afro-Caribbean and indigenous American descent. While sugar is less coarse and easy to wash off in warm water, finer-grained sea salt provides more friction but is not as rough as coarse sea salt. Fine sea salt, because it is less coarse, can also be used on the face, if used carefully. While the effect of topical salt on skin microbes is unknown, cutaneous sodium storage has been found to strengthen the antimicrobial barrier function and boost macrophage host defense (Cell Metab. 2015 Mar 3;21[3]:493-501). Additionally, it has been noted that some Native Americans used dried corncobs for exfoliation. The people of the Comanche tribe would use sand from the bottom of a river bed to scrub the skin (similarly, Polynesian people have been known to use crushed sea shells for this purpose).

India (Ayurveda): Garshana is a dry brushing technique performed in Ayurvedic medicine. Dry brushing may be performed with a bristle brush or with slightly roughened silk gloves. The motion of dry brushing is intended to stimulate lymphatic drainage for elimination of toxins from the body. Circular strokes are used on the stomach and joints (shoulders, elbows, knees, wrists, hips, and ankles), and long sweeping strokes are used on the arms and legs. It is recommended for the morning, upon awakening and before a shower, because it is a stimulating practice. Sometimes oils, specific to an individual’s “dosha” (constitutional type or energy as defined by Ayurveda) – are applied afterward in a similar head-to-toe motion as a self-massage called Abhyanga.

Japan: Shaving, particularly facial shaving, is frequently done not just among men in Japan, but also among women who have shaved their faces and skin for years as a method of exfoliation for skin rejuvenation. In the United States, facial shaving among women has evolved to a method of exfoliation called “dermaplaning,” which involves dry shaving hairs (including facial vellus hairs) as well as top layers of stratum corneum. The procedure uses of a 25-centimeter (10-inch) scalpel, which curves into a sharp point. Potential risks include irritation from friction, as well as folliculitis.

France: It is not certain whether “gommage” originated in France, but in French, it means “to erase” because the rubbing action is similar to erasing a word. In gommage, a paste is applied to the skin and allowed to dry slightly while gentle enzymes digest dead skin cells on the surface; then it is rubbed off, taking skin cells with it. Most of what comes off is the product itself, but this may include some skin cells. One commonly used enzyme in gommage is papain, derived from the papaya fruit. Gommage was popular with facials before stronger chemical exfoliants like alpha-hydroxy acids became widely available commercially.

West Africa (Ghana, Nigeria): A long mesh body exfoliator, much like a tightly woven fishing net made of nylon, is common in Ghanaian and Nigerian households. The textured washcloth typically stretches up to 3 times the size of a regular washcloth, making it easy to scrub hard-to-reach places like the back.

Worldwide: Around the world in places where coffee beans are native, including Kenya and other parts of Africa, the Middle East, South America, Australia, and Hawaii, coffee beans are used as a skin exfoliant. Coffee grounds can however, should be used cautiously in showers as they can coagulate in water and clog drains and pipes. One tradition in Kenya is to crush and rub coffee beans on the skin with a piece of sugarcane to remove top layers of skin. Often too harsh to use directly, coffee grounds in cosmetic formulations are often mixed with oils or shea butter to create a smoother texture.

May this list grow as we continue to learn from the skin care techniques practiced in different cultures around the world.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

Knee and elbow rejuvenation

The cosmetic industry improves techniques for tightening faces, hands, necks, and decolletes; meanwhile, sagging elbows and knees, once ignored, also are a visible sign of aging. Modifying techniques commonly used for the face and neck can yield significant improvements in the elbows and knees. The elbows and knees naturally have looser skin to allow for joint movement; over time, the skin over these joints is exposed to sun damage, friction, and recurrent extension and flexion, which cause skin laxity and aging.

A combination approach addressing skin texture, collagen damage, rhytides, and fat deposition is the most effective method for knee and elbow rejuvenation.

For knees and elbows with loose skin and rhytides, in-office noninvasive and minimally invasive radio-frequency and light energy treatments are helpful in increasing collagen production and tissue tightening. Similarly, microfocused ultrasound has been shown to be a safe and effective skin tightening treatment for the knees. In comparison to the face, however, the skin around the elbows and knees can be thinner and has fewer sebaceous glands. Caution should be used particularly with minimally invasive radio-frequency techniques in order to protect the epidermal skin. Often, treatments have to be repeated to give optimal results, which are not apparent until 3-6 months after the initial procedure.

For knee skin with severe laxity, a comprehensive approach using polydioxanone (PDO) or poly-l-lactic acid (PLLA) threads in both the upper thighs and circumferentially around the knees provides collagen production and tightening of the loose skin. Treatment of the upper thighs is essential in providing a vector that lifts the skin of the knees. Treatments can be repeated, with results seen after 90 days. Thread lifts of the knees and thighs are highly effective, noninvasive procedures with little to no downtime and can be used for severe skin laxity, wrinkling, and thinning of the knee skin.

Loose, roughened knee and elbow skin can also be treated with nonablative factional resurfacing, radio-frequency microneedling, or a series of monthly treatments with PLLA and hyaluronic acid fillers injected in the superficial to mid-dermis. Both fractional resurfacing and dermal filler injections help stimulate collagen production and improve both fine rhytides and dermatoheliosis.

Adipose tissue around the knees can be treated with monthly deoxycholic acid injections (for a video of this procedure, go to https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rhw-nESy15AoDhKUrc25DDjKEun7RL4i/view). The volume of injection, however, is significantly higher than that recommended in the submental area. Two to four times the volume is needed per knee over a series of 3-6 treatments, depending on the amount of fat in the knees.

Cryolipolysis is also an effective option for fat pockets around the knees; however, in my experience, it can be difficult to fit the applicators onto the area of concern appropriately unless smaller applicators are applied.

With the increasing demand for body rejuvenation techniques, providers are adapting techniques used for the face and neck to lift, tighten, thin, and sculpt the knees and elbows. A combination approach using lasers, ultrasound, fillers, threads, and cryolipolysis can be effective for these areas. Results are obtainable when repeat treatments are performed; however, one must be patient because results are not seen for 6 months or more.

Dr. Lily Talakoub and Dr. Naissan Wesley are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Macedo O. et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(Suppl 1), Abstract P800, page AB193.

The cosmetic industry improves techniques for tightening faces, hands, necks, and decolletes; meanwhile, sagging elbows and knees, once ignored, also are a visible sign of aging. Modifying techniques commonly used for the face and neck can yield significant improvements in the elbows and knees. The elbows and knees naturally have looser skin to allow for joint movement; over time, the skin over these joints is exposed to sun damage, friction, and recurrent extension and flexion, which cause skin laxity and aging.

A combination approach addressing skin texture, collagen damage, rhytides, and fat deposition is the most effective method for knee and elbow rejuvenation.

For knees and elbows with loose skin and rhytides, in-office noninvasive and minimally invasive radio-frequency and light energy treatments are helpful in increasing collagen production and tissue tightening. Similarly, microfocused ultrasound has been shown to be a safe and effective skin tightening treatment for the knees. In comparison to the face, however, the skin around the elbows and knees can be thinner and has fewer sebaceous glands. Caution should be used particularly with minimally invasive radio-frequency techniques in order to protect the epidermal skin. Often, treatments have to be repeated to give optimal results, which are not apparent until 3-6 months after the initial procedure.

For knee skin with severe laxity, a comprehensive approach using polydioxanone (PDO) or poly-l-lactic acid (PLLA) threads in both the upper thighs and circumferentially around the knees provides collagen production and tightening of the loose skin. Treatment of the upper thighs is essential in providing a vector that lifts the skin of the knees. Treatments can be repeated, with results seen after 90 days. Thread lifts of the knees and thighs are highly effective, noninvasive procedures with little to no downtime and can be used for severe skin laxity, wrinkling, and thinning of the knee skin.

Loose, roughened knee and elbow skin can also be treated with nonablative factional resurfacing, radio-frequency microneedling, or a series of monthly treatments with PLLA and hyaluronic acid fillers injected in the superficial to mid-dermis. Both fractional resurfacing and dermal filler injections help stimulate collagen production and improve both fine rhytides and dermatoheliosis.

Adipose tissue around the knees can be treated with monthly deoxycholic acid injections (for a video of this procedure, go to https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rhw-nESy15AoDhKUrc25DDjKEun7RL4i/view). The volume of injection, however, is significantly higher than that recommended in the submental area. Two to four times the volume is needed per knee over a series of 3-6 treatments, depending on the amount of fat in the knees.

Cryolipolysis is also an effective option for fat pockets around the knees; however, in my experience, it can be difficult to fit the applicators onto the area of concern appropriately unless smaller applicators are applied.

With the increasing demand for body rejuvenation techniques, providers are adapting techniques used for the face and neck to lift, tighten, thin, and sculpt the knees and elbows. A combination approach using lasers, ultrasound, fillers, threads, and cryolipolysis can be effective for these areas. Results are obtainable when repeat treatments are performed; however, one must be patient because results are not seen for 6 months or more.

Dr. Lily Talakoub and Dr. Naissan Wesley are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Macedo O. et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(Suppl 1), Abstract P800, page AB193.

The cosmetic industry improves techniques for tightening faces, hands, necks, and decolletes; meanwhile, sagging elbows and knees, once ignored, also are a visible sign of aging. Modifying techniques commonly used for the face and neck can yield significant improvements in the elbows and knees. The elbows and knees naturally have looser skin to allow for joint movement; over time, the skin over these joints is exposed to sun damage, friction, and recurrent extension and flexion, which cause skin laxity and aging.

A combination approach addressing skin texture, collagen damage, rhytides, and fat deposition is the most effective method for knee and elbow rejuvenation.

For knees and elbows with loose skin and rhytides, in-office noninvasive and minimally invasive radio-frequency and light energy treatments are helpful in increasing collagen production and tissue tightening. Similarly, microfocused ultrasound has been shown to be a safe and effective skin tightening treatment for the knees. In comparison to the face, however, the skin around the elbows and knees can be thinner and has fewer sebaceous glands. Caution should be used particularly with minimally invasive radio-frequency techniques in order to protect the epidermal skin. Often, treatments have to be repeated to give optimal results, which are not apparent until 3-6 months after the initial procedure.

For knee skin with severe laxity, a comprehensive approach using polydioxanone (PDO) or poly-l-lactic acid (PLLA) threads in both the upper thighs and circumferentially around the knees provides collagen production and tightening of the loose skin. Treatment of the upper thighs is essential in providing a vector that lifts the skin of the knees. Treatments can be repeated, with results seen after 90 days. Thread lifts of the knees and thighs are highly effective, noninvasive procedures with little to no downtime and can be used for severe skin laxity, wrinkling, and thinning of the knee skin.

Loose, roughened knee and elbow skin can also be treated with nonablative factional resurfacing, radio-frequency microneedling, or a series of monthly treatments with PLLA and hyaluronic acid fillers injected in the superficial to mid-dermis. Both fractional resurfacing and dermal filler injections help stimulate collagen production and improve both fine rhytides and dermatoheliosis.

Adipose tissue around the knees can be treated with monthly deoxycholic acid injections (for a video of this procedure, go to https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rhw-nESy15AoDhKUrc25DDjKEun7RL4i/view). The volume of injection, however, is significantly higher than that recommended in the submental area. Two to four times the volume is needed per knee over a series of 3-6 treatments, depending on the amount of fat in the knees.

Cryolipolysis is also an effective option for fat pockets around the knees; however, in my experience, it can be difficult to fit the applicators onto the area of concern appropriately unless smaller applicators are applied.

With the increasing demand for body rejuvenation techniques, providers are adapting techniques used for the face and neck to lift, tighten, thin, and sculpt the knees and elbows. A combination approach using lasers, ultrasound, fillers, threads, and cryolipolysis can be effective for these areas. Results are obtainable when repeat treatments are performed; however, one must be patient because results are not seen for 6 months or more.

Dr. Lily Talakoub and Dr. Naissan Wesley are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Macedo O. et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(Suppl 1), Abstract P800, page AB193.

Integrative dermatology

In October of this year, the , and practitioners of Ayurvedic, Naturopathic, and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), in one place. This was the first time in the United States that practitioners from these different areas of medicine were brought together to discuss and learn different approaches to skin care and treatment of dermatologic diseases.

Of all the medical specialties, it is presumed that dermatology is the most inherently holistic. By examining the hair, skin, and nails, we are able to diagnose internal organ diseases such as liver failure (jaundice, veins on stomach), thyroid disease (madarosis), sarcoidosis, and infectious diseases (cutaneous manifestations of HIV), diabetes (acanthosis nigricans, tripe palm), polycystic ovary syndrome (acne, hirsutism), and porphyria, just to name a few. We are also able to treat cutaneous conditions, such as psoriasis, with biologic medications, treatment that in turn, also benefits internal manifestations such as joint, cardiovascular, and metabolic disease. In TCM and Ayurveda, the skin, hair, body type, and tongue can also be analyzed to diagnose and treat disease.

Salves and skin care routines that would be considered natural or holistic have been “prescribed” by Western dermatologists with an MD license for many years. Most medicines initially come from nature, and it is only in the past century, with the boom in the pharmaceutical industry and development of synthetic prescription medications, that people have forgotten this. Some of this boom has been needed to treat enormous populations, as natural resources can be scarce, and in some cases, only an extract of the plant may be needed for treatment, where other elements may be ineffective or even harmful.

Domeboro solution, Epsom salt soaks, and wet to dry soaks are used to draw out and treat infections. Bleach baths are often used to decrease bacterial load and calm inflammation when treating eczema. In Mohs surgery, Fredrick Mohs initially used a zinc chloride paste on nonmelanoma skin cancers in between stages, before frozen section processing and cosmetic reconstruction made Mohs what it is today. In the days of Hippocrates, food was medicine. If you were “red in the face” your blood was deemed too acidic and alkaline-forming foods or “cold foods” were given. This has now again come full circle with rosacea and evidence supporting a link between disease flares or improvement related to foods and the gut microbiome.

On a photography trip to Wyoming, I learned how Native Americans in the United States wiped the white powder from the bark of aspen trees on their skin and used it as sunscreen. In Mongolia, I learned how fat from a sheep’s bottom was used in beauty skin care routines. It is from native and nomadic people that we can often learn how effective natural methods can be used, especially in cases where the treatment regimens may not be written down. With Ayurveda and TCM, we are lucky that textbooks thousands of years old and professors and schools are available to educate us about these ancient practices.

The rediscovery of ancient treatments through the study of ethnobotany, Ayurveda, and TCM has been fascinating, as most of these approaches focus not just on the skin, but on treating the patient as a whole, inside and out (often depending on the discipline treating mind, body, and spirit), with the effects ultimately benefiting the skin. With the many advances in Western medicine over the past 2,000 years, starting with Hippocrates, it will be interesting to see how we, in the field of dermatology, can still learn from and potentially integrate medicine that originated 3,000-5,000 plus years ago in Ayurveda and 2,000-plus years ago in TCM that is still practiced today. In the future, we hope to have more columns about these specialties and how they are used in skin and beauty.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

In October of this year, the , and practitioners of Ayurvedic, Naturopathic, and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), in one place. This was the first time in the United States that practitioners from these different areas of medicine were brought together to discuss and learn different approaches to skin care and treatment of dermatologic diseases.

Of all the medical specialties, it is presumed that dermatology is the most inherently holistic. By examining the hair, skin, and nails, we are able to diagnose internal organ diseases such as liver failure (jaundice, veins on stomach), thyroid disease (madarosis), sarcoidosis, and infectious diseases (cutaneous manifestations of HIV), diabetes (acanthosis nigricans, tripe palm), polycystic ovary syndrome (acne, hirsutism), and porphyria, just to name a few. We are also able to treat cutaneous conditions, such as psoriasis, with biologic medications, treatment that in turn, also benefits internal manifestations such as joint, cardiovascular, and metabolic disease. In TCM and Ayurveda, the skin, hair, body type, and tongue can also be analyzed to diagnose and treat disease.

Salves and skin care routines that would be considered natural or holistic have been “prescribed” by Western dermatologists with an MD license for many years. Most medicines initially come from nature, and it is only in the past century, with the boom in the pharmaceutical industry and development of synthetic prescription medications, that people have forgotten this. Some of this boom has been needed to treat enormous populations, as natural resources can be scarce, and in some cases, only an extract of the plant may be needed for treatment, where other elements may be ineffective or even harmful.

Domeboro solution, Epsom salt soaks, and wet to dry soaks are used to draw out and treat infections. Bleach baths are often used to decrease bacterial load and calm inflammation when treating eczema. In Mohs surgery, Fredrick Mohs initially used a zinc chloride paste on nonmelanoma skin cancers in between stages, before frozen section processing and cosmetic reconstruction made Mohs what it is today. In the days of Hippocrates, food was medicine. If you were “red in the face” your blood was deemed too acidic and alkaline-forming foods or “cold foods” were given. This has now again come full circle with rosacea and evidence supporting a link between disease flares or improvement related to foods and the gut microbiome.

On a photography trip to Wyoming, I learned how Native Americans in the United States wiped the white powder from the bark of aspen trees on their skin and used it as sunscreen. In Mongolia, I learned how fat from a sheep’s bottom was used in beauty skin care routines. It is from native and nomadic people that we can often learn how effective natural methods can be used, especially in cases where the treatment regimens may not be written down. With Ayurveda and TCM, we are lucky that textbooks thousands of years old and professors and schools are available to educate us about these ancient practices.

The rediscovery of ancient treatments through the study of ethnobotany, Ayurveda, and TCM has been fascinating, as most of these approaches focus not just on the skin, but on treating the patient as a whole, inside and out (often depending on the discipline treating mind, body, and spirit), with the effects ultimately benefiting the skin. With the many advances in Western medicine over the past 2,000 years, starting with Hippocrates, it will be interesting to see how we, in the field of dermatology, can still learn from and potentially integrate medicine that originated 3,000-5,000 plus years ago in Ayurveda and 2,000-plus years ago in TCM that is still practiced today. In the future, we hope to have more columns about these specialties and how they are used in skin and beauty.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

In October of this year, the , and practitioners of Ayurvedic, Naturopathic, and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), in one place. This was the first time in the United States that practitioners from these different areas of medicine were brought together to discuss and learn different approaches to skin care and treatment of dermatologic diseases.

Of all the medical specialties, it is presumed that dermatology is the most inherently holistic. By examining the hair, skin, and nails, we are able to diagnose internal organ diseases such as liver failure (jaundice, veins on stomach), thyroid disease (madarosis), sarcoidosis, and infectious diseases (cutaneous manifestations of HIV), diabetes (acanthosis nigricans, tripe palm), polycystic ovary syndrome (acne, hirsutism), and porphyria, just to name a few. We are also able to treat cutaneous conditions, such as psoriasis, with biologic medications, treatment that in turn, also benefits internal manifestations such as joint, cardiovascular, and metabolic disease. In TCM and Ayurveda, the skin, hair, body type, and tongue can also be analyzed to diagnose and treat disease.

Salves and skin care routines that would be considered natural or holistic have been “prescribed” by Western dermatologists with an MD license for many years. Most medicines initially come from nature, and it is only in the past century, with the boom in the pharmaceutical industry and development of synthetic prescription medications, that people have forgotten this. Some of this boom has been needed to treat enormous populations, as natural resources can be scarce, and in some cases, only an extract of the plant may be needed for treatment, where other elements may be ineffective or even harmful.

Domeboro solution, Epsom salt soaks, and wet to dry soaks are used to draw out and treat infections. Bleach baths are often used to decrease bacterial load and calm inflammation when treating eczema. In Mohs surgery, Fredrick Mohs initially used a zinc chloride paste on nonmelanoma skin cancers in between stages, before frozen section processing and cosmetic reconstruction made Mohs what it is today. In the days of Hippocrates, food was medicine. If you were “red in the face” your blood was deemed too acidic and alkaline-forming foods or “cold foods” were given. This has now again come full circle with rosacea and evidence supporting a link between disease flares or improvement related to foods and the gut microbiome.

On a photography trip to Wyoming, I learned how Native Americans in the United States wiped the white powder from the bark of aspen trees on their skin and used it as sunscreen. In Mongolia, I learned how fat from a sheep’s bottom was used in beauty skin care routines. It is from native and nomadic people that we can often learn how effective natural methods can be used, especially in cases where the treatment regimens may not be written down. With Ayurveda and TCM, we are lucky that textbooks thousands of years old and professors and schools are available to educate us about these ancient practices.

The rediscovery of ancient treatments through the study of ethnobotany, Ayurveda, and TCM has been fascinating, as most of these approaches focus not just on the skin, but on treating the patient as a whole, inside and out (often depending on the discipline treating mind, body, and spirit), with the effects ultimately benefiting the skin. With the many advances in Western medicine over the past 2,000 years, starting with Hippocrates, it will be interesting to see how we, in the field of dermatology, can still learn from and potentially integrate medicine that originated 3,000-5,000 plus years ago in Ayurveda and 2,000-plus years ago in TCM that is still practiced today. In the future, we hope to have more columns about these specialties and how they are used in skin and beauty.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

Hypopigmentation

Hypopigmentation or depigmentation of the skin is very challenging to treat. The loss of melanin in the skin is often a frustrating problem, resulting from acne, burn scars, vitiligo, topically applied chemicals, or cryotherapy. To date, there is no universally accepted treatment that restores skin pigmentation. In our clinic, the induction of trauma to the skin via a series of microneedling or subcision treatments has shown promise in increasing the pigmentation of skin with localized hypo- or depigmented patches.

to improve the appearance of fine lines, acne scars, photoaging, stretch marks, enlarged pores, and other cosmetic issues characterized by loss of collagen or altered collagen remodeling. The skin-needling technique involves fine sterile needles 0.1 mm–2.5 mm in length that repeatedly pierce the stratum corneum producing microscopic “holes” in the dermis. These microscopic wounds lead to the release of growth factors stimulating the formation of new collagen, elastin, and neovascularization in the dermis. Similar to microneedling, subcision uses repeat trauma to the dermis and subcutis through the insertion and repeat movement of a needle.

In our practice, patients presenting with hypopigmentation of the skin from a variety of causes have been treated with a series of five subcision or microneedling procedures, resulting in rapid repigmentation of the skin with minimal to no side effects. Trauma to the skin causes regenerative mechanisms and wound healing. The release of cytokines that induce neoangiogenesis, neocollagenesis, and the deposition of hemosiderin from dermal bleeding induce the activation of melanocytes and stimulate skin pigmentation.

Subcision and microneedling are safe, effective, in-office procedures with vast indications that now can be applied to depigmented and hypopigmented skin. Patients have little to no downtime and results are permanent.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Dermatol Surg. 1995 Jun;21(6):543-9.

Aesthet Plast Surg. 1997 Jan-Feb;21(1):48-51.

Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2005 Feb;17(1):51-63.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 Apr;121(4):1421-9.

Clin Dermatol. 2008 Mar-Apr;26(2):192-9.Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 Nov;122(5):1553-63.

J Dermatolog Treat. 2012 Apr;23(2):144-52.

J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2009 Jan;2(1):26-30.

J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2009 Jul;2(2):110-1.

J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014 Sep;13(3):180-7.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Nov;75(5):e195-e197.

Hypopigmentation or depigmentation of the skin is very challenging to treat. The loss of melanin in the skin is often a frustrating problem, resulting from acne, burn scars, vitiligo, topically applied chemicals, or cryotherapy. To date, there is no universally accepted treatment that restores skin pigmentation. In our clinic, the induction of trauma to the skin via a series of microneedling or subcision treatments has shown promise in increasing the pigmentation of skin with localized hypo- or depigmented patches.

to improve the appearance of fine lines, acne scars, photoaging, stretch marks, enlarged pores, and other cosmetic issues characterized by loss of collagen or altered collagen remodeling. The skin-needling technique involves fine sterile needles 0.1 mm–2.5 mm in length that repeatedly pierce the stratum corneum producing microscopic “holes” in the dermis. These microscopic wounds lead to the release of growth factors stimulating the formation of new collagen, elastin, and neovascularization in the dermis. Similar to microneedling, subcision uses repeat trauma to the dermis and subcutis through the insertion and repeat movement of a needle.

In our practice, patients presenting with hypopigmentation of the skin from a variety of causes have been treated with a series of five subcision or microneedling procedures, resulting in rapid repigmentation of the skin with minimal to no side effects. Trauma to the skin causes regenerative mechanisms and wound healing. The release of cytokines that induce neoangiogenesis, neocollagenesis, and the deposition of hemosiderin from dermal bleeding induce the activation of melanocytes and stimulate skin pigmentation.

Subcision and microneedling are safe, effective, in-office procedures with vast indications that now can be applied to depigmented and hypopigmented skin. Patients have little to no downtime and results are permanent.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Dermatol Surg. 1995 Jun;21(6):543-9.

Aesthet Plast Surg. 1997 Jan-Feb;21(1):48-51.

Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2005 Feb;17(1):51-63.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 Apr;121(4):1421-9.

Clin Dermatol. 2008 Mar-Apr;26(2):192-9.Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 Nov;122(5):1553-63.

J Dermatolog Treat. 2012 Apr;23(2):144-52.

J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2009 Jan;2(1):26-30.

J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2009 Jul;2(2):110-1.

J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014 Sep;13(3):180-7.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Nov;75(5):e195-e197.

Hypopigmentation or depigmentation of the skin is very challenging to treat. The loss of melanin in the skin is often a frustrating problem, resulting from acne, burn scars, vitiligo, topically applied chemicals, or cryotherapy. To date, there is no universally accepted treatment that restores skin pigmentation. In our clinic, the induction of trauma to the skin via a series of microneedling or subcision treatments has shown promise in increasing the pigmentation of skin with localized hypo- or depigmented patches.