User login

Hospitalist movers and shakers

Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, SFHM, and Vineet Arora, MD, MPP, MHM, recently were elected to the new member class of American Society for Clinical Investigation (ASCI) for 2017. Members must have “accomplished meritorious, original, creative, and independent investigations in the clinical or allied sciences of medicine and enjoy an unimpeachable moral standing in the medical profession.”

Dr. Auerbach and Dr. Arora are just the third and fourth hospitalists to become ASCI members. Dr. Auerbach is the professor of medicine in residence and director of the research division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Aurora is associate professor of medicine, assistant dean for scholarship and discovery, and director of graduate medical education’s clinical learning environment innovation at the University of Chicago.

Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, MHM, director of the University of Kentucky’s Center for Health Services Research (CHSR), recently presented at the International Conference of Hospital Medicine held in Taiwan.

Olevia M. Pitts, MD, SFHM, made history at Research Medical Center in Kansas City, becoming the first woman and the first person of color to be named the facility’s chief medical officer. Dr. Pitts assumed her role at the 131-year-old RMC on January 30.

Greta Boynton, MD, SFHM, was promoted to the role of associate chief medical officer of Sound Physicians’ northeast region. She was elevated from her position as regional medical director for Sound Physicians, a health care organization that serves as a provider practice in 225 hospitals in 38 states.

Dr. Boynton will be charged with overseeing clinical operation of 13 programs, 120 providers, and a team of regional medical directors. She joined Sound Physicians in 2013 as chief hospitalist and divisional chief at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. She was, previously, chief of hospital medicine for Eastern Connecticut Health Network, Manchester, from 2008-2013.

Business Moves

Sound Physicians, Tacoma, Wash., added to its list of partners on March 1, when Eagle Hospital Medicine Practices, Atlanta, joined the Sound group’s organization. Eagle’s 150 providers in 16 hospitals across the United States raises Sound’s resume to more than 2,500 providers.

Eagle will continue to run its own Locum Connections and Telemedicine divisions.

The Society of Hospital Medicine’s Center for Quality Improvement recently was recognized and honored by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for its patient-safety partnership with CMS. The two entities have maintained a relationship since August 2016.

SHM’s Center for QI has participated in weekly CMS webinars to generate strategies intended to limit opioid use, including SHM’s pilot RADEO – Reducing Adverse Drug Events Related to Opioids – program. In January 2017, CMS contacted SHM to provide best practices for patients receiving opioids and better use data to monitor those patients.

University of Iowa Health Care, Iowa City, and Van Buren County Hospital, Keosauqua, Iowa, have created a partnership, allowing patients at VBCH access to UI hospitalists through a telemedicine connection. The relationship will allow VBCH patients to remain at their local hospital – located 90 minutes from Iowa City – while getting care and treatment advice from UI hospitalists through videoconferencing and a shared electronic health record.

With their VBCH provider bedside, patients meet face-to–virtual face with the UI hospitalist during twice-daily virtual rounding.

Unity Medical Center, Manchester, Tenn., recently partnered with physician-owned and -operated Concord Medical Group, Knoxville, Tenn., to provide hospitalist services at its facility in Manchester. Unity now will have hospitalists on duty 24 hours per day thanks to the relationship with Concord, a hospital management and staffing specialist group.

Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, SFHM, and Vineet Arora, MD, MPP, MHM, recently were elected to the new member class of American Society for Clinical Investigation (ASCI) for 2017. Members must have “accomplished meritorious, original, creative, and independent investigations in the clinical or allied sciences of medicine and enjoy an unimpeachable moral standing in the medical profession.”

Dr. Auerbach and Dr. Arora are just the third and fourth hospitalists to become ASCI members. Dr. Auerbach is the professor of medicine in residence and director of the research division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Aurora is associate professor of medicine, assistant dean for scholarship and discovery, and director of graduate medical education’s clinical learning environment innovation at the University of Chicago.

Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, MHM, director of the University of Kentucky’s Center for Health Services Research (CHSR), recently presented at the International Conference of Hospital Medicine held in Taiwan.

Olevia M. Pitts, MD, SFHM, made history at Research Medical Center in Kansas City, becoming the first woman and the first person of color to be named the facility’s chief medical officer. Dr. Pitts assumed her role at the 131-year-old RMC on January 30.

Greta Boynton, MD, SFHM, was promoted to the role of associate chief medical officer of Sound Physicians’ northeast region. She was elevated from her position as regional medical director for Sound Physicians, a health care organization that serves as a provider practice in 225 hospitals in 38 states.

Dr. Boynton will be charged with overseeing clinical operation of 13 programs, 120 providers, and a team of regional medical directors. She joined Sound Physicians in 2013 as chief hospitalist and divisional chief at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. She was, previously, chief of hospital medicine for Eastern Connecticut Health Network, Manchester, from 2008-2013.

Business Moves

Sound Physicians, Tacoma, Wash., added to its list of partners on March 1, when Eagle Hospital Medicine Practices, Atlanta, joined the Sound group’s organization. Eagle’s 150 providers in 16 hospitals across the United States raises Sound’s resume to more than 2,500 providers.

Eagle will continue to run its own Locum Connections and Telemedicine divisions.

The Society of Hospital Medicine’s Center for Quality Improvement recently was recognized and honored by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for its patient-safety partnership with CMS. The two entities have maintained a relationship since August 2016.

SHM’s Center for QI has participated in weekly CMS webinars to generate strategies intended to limit opioid use, including SHM’s pilot RADEO – Reducing Adverse Drug Events Related to Opioids – program. In January 2017, CMS contacted SHM to provide best practices for patients receiving opioids and better use data to monitor those patients.

University of Iowa Health Care, Iowa City, and Van Buren County Hospital, Keosauqua, Iowa, have created a partnership, allowing patients at VBCH access to UI hospitalists through a telemedicine connection. The relationship will allow VBCH patients to remain at their local hospital – located 90 minutes from Iowa City – while getting care and treatment advice from UI hospitalists through videoconferencing and a shared electronic health record.

With their VBCH provider bedside, patients meet face-to–virtual face with the UI hospitalist during twice-daily virtual rounding.

Unity Medical Center, Manchester, Tenn., recently partnered with physician-owned and -operated Concord Medical Group, Knoxville, Tenn., to provide hospitalist services at its facility in Manchester. Unity now will have hospitalists on duty 24 hours per day thanks to the relationship with Concord, a hospital management and staffing specialist group.

Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, SFHM, and Vineet Arora, MD, MPP, MHM, recently were elected to the new member class of American Society for Clinical Investigation (ASCI) for 2017. Members must have “accomplished meritorious, original, creative, and independent investigations in the clinical or allied sciences of medicine and enjoy an unimpeachable moral standing in the medical profession.”

Dr. Auerbach and Dr. Arora are just the third and fourth hospitalists to become ASCI members. Dr. Auerbach is the professor of medicine in residence and director of the research division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Aurora is associate professor of medicine, assistant dean for scholarship and discovery, and director of graduate medical education’s clinical learning environment innovation at the University of Chicago.

Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, MHM, director of the University of Kentucky’s Center for Health Services Research (CHSR), recently presented at the International Conference of Hospital Medicine held in Taiwan.

Olevia M. Pitts, MD, SFHM, made history at Research Medical Center in Kansas City, becoming the first woman and the first person of color to be named the facility’s chief medical officer. Dr. Pitts assumed her role at the 131-year-old RMC on January 30.

Greta Boynton, MD, SFHM, was promoted to the role of associate chief medical officer of Sound Physicians’ northeast region. She was elevated from her position as regional medical director for Sound Physicians, a health care organization that serves as a provider practice in 225 hospitals in 38 states.

Dr. Boynton will be charged with overseeing clinical operation of 13 programs, 120 providers, and a team of regional medical directors. She joined Sound Physicians in 2013 as chief hospitalist and divisional chief at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. She was, previously, chief of hospital medicine for Eastern Connecticut Health Network, Manchester, from 2008-2013.

Business Moves

Sound Physicians, Tacoma, Wash., added to its list of partners on March 1, when Eagle Hospital Medicine Practices, Atlanta, joined the Sound group’s organization. Eagle’s 150 providers in 16 hospitals across the United States raises Sound’s resume to more than 2,500 providers.

Eagle will continue to run its own Locum Connections and Telemedicine divisions.

The Society of Hospital Medicine’s Center for Quality Improvement recently was recognized and honored by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for its patient-safety partnership with CMS. The two entities have maintained a relationship since August 2016.

SHM’s Center for QI has participated in weekly CMS webinars to generate strategies intended to limit opioid use, including SHM’s pilot RADEO – Reducing Adverse Drug Events Related to Opioids – program. In January 2017, CMS contacted SHM to provide best practices for patients receiving opioids and better use data to monitor those patients.

University of Iowa Health Care, Iowa City, and Van Buren County Hospital, Keosauqua, Iowa, have created a partnership, allowing patients at VBCH access to UI hospitalists through a telemedicine connection. The relationship will allow VBCH patients to remain at their local hospital – located 90 minutes from Iowa City – while getting care and treatment advice from UI hospitalists through videoconferencing and a shared electronic health record.

With their VBCH provider bedside, patients meet face-to–virtual face with the UI hospitalist during twice-daily virtual rounding.

Unity Medical Center, Manchester, Tenn., recently partnered with physician-owned and -operated Concord Medical Group, Knoxville, Tenn., to provide hospitalist services at its facility in Manchester. Unity now will have hospitalists on duty 24 hours per day thanks to the relationship with Concord, a hospital management and staffing specialist group.

Survey insights: Unwrapping the compensation package

When approached for advice regarding the evaluation of job offers after completion of training, specific day-to-day duties (for example, shift length, teaching time, ICU coverage, and so on), and the overall gestalt of the interview experience, I find that location, lifestyle, and pay are the most consistent and common themes.

People often assume that pay is relatively straightforward, since it can be summarized in a number in the offer, whereas the other factors are harder to evaluate. However, it turns out pay is more complex. As a result, the last several State of Hospital Medicine reports have sought to evaluate compensation packages more thoroughly.

In 2016, the survey started including pay increases by years of experience, as well as CME dollars allotted per year per hospitalist. The goal was to gain deeper insight into the entire financial package, which is tied to a particular hospitalist job.

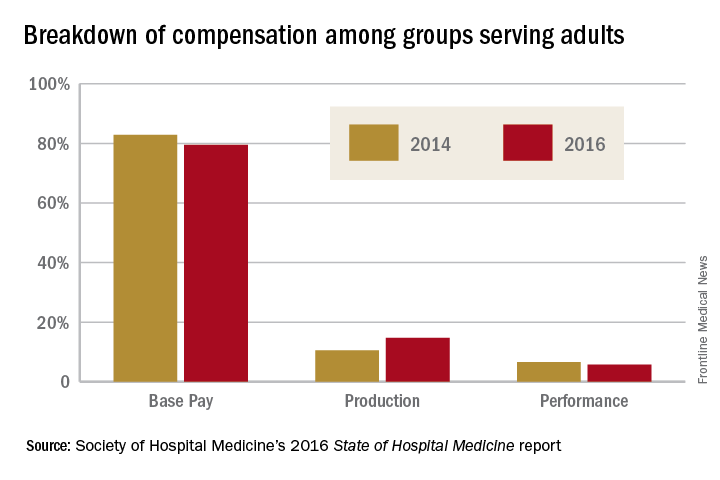

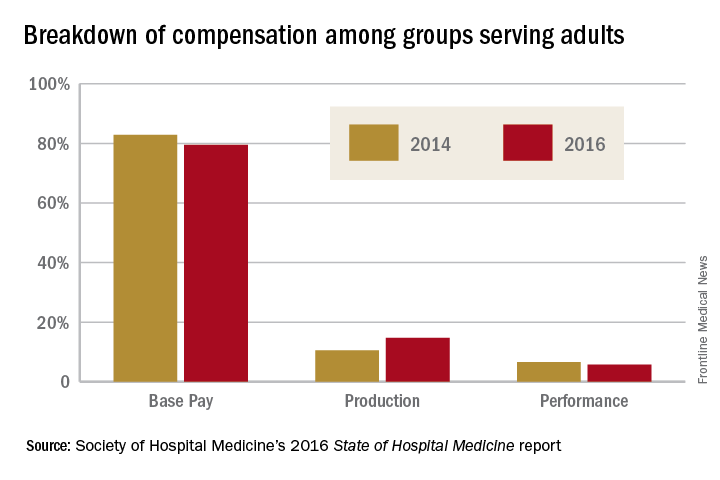

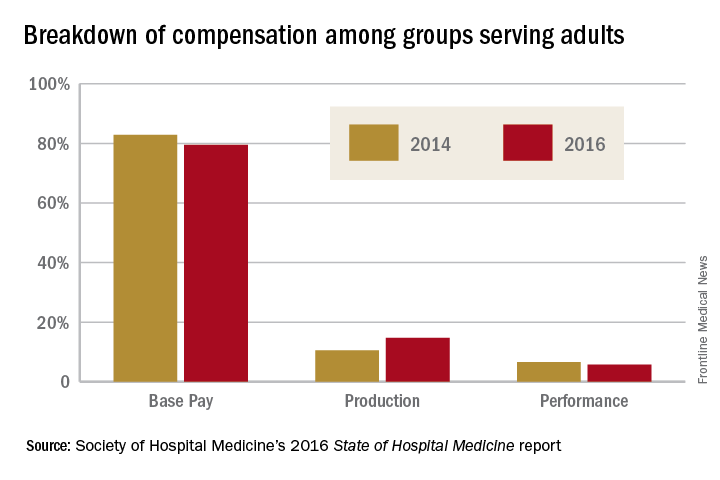

When looking at the 2014 and 2016 SHM survey results, there are several interesting findings. Base pay makes up the majority of earnings for all types of hospitalists (those seeing adults only, children only, and a mix of adults and children). In academic hospitalist groups, more of the total package of compensation comes from base pay, compared with nonacademic groups, where production and performance pay play a bigger role.

Of interest, despite the increased national attention on quality of care, productivity-based pay increased again (10.5%-14.7%), while performance-based pay (usually tied to quality and safety metrics) decreased (6.6%-5.7%) among groups serving adults. Consistent with prior trends for adults-only hospitalists, the Southern region of the country had the highest percentage of pay derived from productivity (18.8%), as well as of overall compensation in the 2016 report.

For hospitalists serving both adults and children, there was a smaller increase in pay derived from production (12.4%-13.2%), while pay derived from performance dropped more dramatically (8.9%-3.9%).

For hospitalists serving only children, the opposite occurred: Pay derived from production fell from 10.7% to 2.8%. While it is not yet clear why compensation, overall, is moving into closer alignment with productivity, rather than performance on quality and safety metrics, one hypothesis is that work relative value units used for calculating productivity are easier to tie to an individual hospitalist than are quality and safety outcomes.

Employee benefits, as previously defined, increased among hospitalists caring for adults only and those caring for adults and children, with a mean increase in both groups of $5,000. The most generous benefits were typically seen at university-based academic medical centers. Amongst adult-only hospitalists, academic groups offer benefits worth $8,000-$9,000 more per year than in nonacademic groups. Lower benefits were common among practices in the Eastern region and in groups with four or fewer full-time hospitalists. The 2016 survey data on CME dollars revealed a median of $3,000-$4,000 per year, with higher amounts provided in nonacademic groups.

Paid time off (PTO) from work is an ongoing topic of interest on venues such as HMX forum, and, in the surveys, PTO remained fairly consistent among groups caring for adults only and those caring for adults and children, with only 30%-40% of groups offering PTO. The number of PTO hours offered vary substantially, however, ranging from a mean of 126 hours up to 216.4 hours annually. Future analysis of PTO will benefit from a deeper understanding of how many hours equate to a shift (the practical definition of a “day off” for most hospitalists).

Finally, the 2016 survey asked about automatic pay increases based strictly on overall experience or length of employment with the group. Roughly one-fifth to one-third of groups provided some sort of salary increase based on experience in 2015. This practice was more common in the Southern region and in nonteaching hospitals. These data raise the complex topic of seniority among hospitalists and how to define it: years since completing training, years with a particular hospital or group, academic rank, leadership roles, other? Further, if seniority is not recognized in pay, how commonly are groups recognizing it in other ways, such as in preferences related to time on certain services, shift type, or vacation requests?

The expanded survey on hospitalist pay, in addition to the biannual comparison of prior data, will likely continue to add value in assessing and exploring the entire package of compensation. Additional topics of interest moving forward might include better understanding of parental leave, sick time, and the comparison between compensation packages for physician hospitalists and those for inpatient Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants. Stay tuned for the next report.

Dr. Anoff is associate professor of clinical practice, division of hospital medicine, department of medicine, University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

References

1. (2014). The State of Hospital Medicine Report. Philadelphia: Society of Hospital Medicine. Retrieved from www.hospitalmedicine.org/Survey2014.

2. (2016). The State of Hospital Medicine Report. Philadelphia: Society of Hospital Medicine. Retrieved from www.hospitalmedicine.org/Survey2016.

When approached for advice regarding the evaluation of job offers after completion of training, specific day-to-day duties (for example, shift length, teaching time, ICU coverage, and so on), and the overall gestalt of the interview experience, I find that location, lifestyle, and pay are the most consistent and common themes.

People often assume that pay is relatively straightforward, since it can be summarized in a number in the offer, whereas the other factors are harder to evaluate. However, it turns out pay is more complex. As a result, the last several State of Hospital Medicine reports have sought to evaluate compensation packages more thoroughly.

In 2016, the survey started including pay increases by years of experience, as well as CME dollars allotted per year per hospitalist. The goal was to gain deeper insight into the entire financial package, which is tied to a particular hospitalist job.

When looking at the 2014 and 2016 SHM survey results, there are several interesting findings. Base pay makes up the majority of earnings for all types of hospitalists (those seeing adults only, children only, and a mix of adults and children). In academic hospitalist groups, more of the total package of compensation comes from base pay, compared with nonacademic groups, where production and performance pay play a bigger role.

Of interest, despite the increased national attention on quality of care, productivity-based pay increased again (10.5%-14.7%), while performance-based pay (usually tied to quality and safety metrics) decreased (6.6%-5.7%) among groups serving adults. Consistent with prior trends for adults-only hospitalists, the Southern region of the country had the highest percentage of pay derived from productivity (18.8%), as well as of overall compensation in the 2016 report.

For hospitalists serving both adults and children, there was a smaller increase in pay derived from production (12.4%-13.2%), while pay derived from performance dropped more dramatically (8.9%-3.9%).

For hospitalists serving only children, the opposite occurred: Pay derived from production fell from 10.7% to 2.8%. While it is not yet clear why compensation, overall, is moving into closer alignment with productivity, rather than performance on quality and safety metrics, one hypothesis is that work relative value units used for calculating productivity are easier to tie to an individual hospitalist than are quality and safety outcomes.

Employee benefits, as previously defined, increased among hospitalists caring for adults only and those caring for adults and children, with a mean increase in both groups of $5,000. The most generous benefits were typically seen at university-based academic medical centers. Amongst adult-only hospitalists, academic groups offer benefits worth $8,000-$9,000 more per year than in nonacademic groups. Lower benefits were common among practices in the Eastern region and in groups with four or fewer full-time hospitalists. The 2016 survey data on CME dollars revealed a median of $3,000-$4,000 per year, with higher amounts provided in nonacademic groups.

Paid time off (PTO) from work is an ongoing topic of interest on venues such as HMX forum, and, in the surveys, PTO remained fairly consistent among groups caring for adults only and those caring for adults and children, with only 30%-40% of groups offering PTO. The number of PTO hours offered vary substantially, however, ranging from a mean of 126 hours up to 216.4 hours annually. Future analysis of PTO will benefit from a deeper understanding of how many hours equate to a shift (the practical definition of a “day off” for most hospitalists).

Finally, the 2016 survey asked about automatic pay increases based strictly on overall experience or length of employment with the group. Roughly one-fifth to one-third of groups provided some sort of salary increase based on experience in 2015. This practice was more common in the Southern region and in nonteaching hospitals. These data raise the complex topic of seniority among hospitalists and how to define it: years since completing training, years with a particular hospital or group, academic rank, leadership roles, other? Further, if seniority is not recognized in pay, how commonly are groups recognizing it in other ways, such as in preferences related to time on certain services, shift type, or vacation requests?

The expanded survey on hospitalist pay, in addition to the biannual comparison of prior data, will likely continue to add value in assessing and exploring the entire package of compensation. Additional topics of interest moving forward might include better understanding of parental leave, sick time, and the comparison between compensation packages for physician hospitalists and those for inpatient Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants. Stay tuned for the next report.

Dr. Anoff is associate professor of clinical practice, division of hospital medicine, department of medicine, University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

References

1. (2014). The State of Hospital Medicine Report. Philadelphia: Society of Hospital Medicine. Retrieved from www.hospitalmedicine.org/Survey2014.

2. (2016). The State of Hospital Medicine Report. Philadelphia: Society of Hospital Medicine. Retrieved from www.hospitalmedicine.org/Survey2016.

When approached for advice regarding the evaluation of job offers after completion of training, specific day-to-day duties (for example, shift length, teaching time, ICU coverage, and so on), and the overall gestalt of the interview experience, I find that location, lifestyle, and pay are the most consistent and common themes.

People often assume that pay is relatively straightforward, since it can be summarized in a number in the offer, whereas the other factors are harder to evaluate. However, it turns out pay is more complex. As a result, the last several State of Hospital Medicine reports have sought to evaluate compensation packages more thoroughly.

In 2016, the survey started including pay increases by years of experience, as well as CME dollars allotted per year per hospitalist. The goal was to gain deeper insight into the entire financial package, which is tied to a particular hospitalist job.

When looking at the 2014 and 2016 SHM survey results, there are several interesting findings. Base pay makes up the majority of earnings for all types of hospitalists (those seeing adults only, children only, and a mix of adults and children). In academic hospitalist groups, more of the total package of compensation comes from base pay, compared with nonacademic groups, where production and performance pay play a bigger role.

Of interest, despite the increased national attention on quality of care, productivity-based pay increased again (10.5%-14.7%), while performance-based pay (usually tied to quality and safety metrics) decreased (6.6%-5.7%) among groups serving adults. Consistent with prior trends for adults-only hospitalists, the Southern region of the country had the highest percentage of pay derived from productivity (18.8%), as well as of overall compensation in the 2016 report.

For hospitalists serving both adults and children, there was a smaller increase in pay derived from production (12.4%-13.2%), while pay derived from performance dropped more dramatically (8.9%-3.9%).

For hospitalists serving only children, the opposite occurred: Pay derived from production fell from 10.7% to 2.8%. While it is not yet clear why compensation, overall, is moving into closer alignment with productivity, rather than performance on quality and safety metrics, one hypothesis is that work relative value units used for calculating productivity are easier to tie to an individual hospitalist than are quality and safety outcomes.

Employee benefits, as previously defined, increased among hospitalists caring for adults only and those caring for adults and children, with a mean increase in both groups of $5,000. The most generous benefits were typically seen at university-based academic medical centers. Amongst adult-only hospitalists, academic groups offer benefits worth $8,000-$9,000 more per year than in nonacademic groups. Lower benefits were common among practices in the Eastern region and in groups with four or fewer full-time hospitalists. The 2016 survey data on CME dollars revealed a median of $3,000-$4,000 per year, with higher amounts provided in nonacademic groups.

Paid time off (PTO) from work is an ongoing topic of interest on venues such as HMX forum, and, in the surveys, PTO remained fairly consistent among groups caring for adults only and those caring for adults and children, with only 30%-40% of groups offering PTO. The number of PTO hours offered vary substantially, however, ranging from a mean of 126 hours up to 216.4 hours annually. Future analysis of PTO will benefit from a deeper understanding of how many hours equate to a shift (the practical definition of a “day off” for most hospitalists).

Finally, the 2016 survey asked about automatic pay increases based strictly on overall experience or length of employment with the group. Roughly one-fifth to one-third of groups provided some sort of salary increase based on experience in 2015. This practice was more common in the Southern region and in nonteaching hospitals. These data raise the complex topic of seniority among hospitalists and how to define it: years since completing training, years with a particular hospital or group, academic rank, leadership roles, other? Further, if seniority is not recognized in pay, how commonly are groups recognizing it in other ways, such as in preferences related to time on certain services, shift type, or vacation requests?

The expanded survey on hospitalist pay, in addition to the biannual comparison of prior data, will likely continue to add value in assessing and exploring the entire package of compensation. Additional topics of interest moving forward might include better understanding of parental leave, sick time, and the comparison between compensation packages for physician hospitalists and those for inpatient Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants. Stay tuned for the next report.

Dr. Anoff is associate professor of clinical practice, division of hospital medicine, department of medicine, University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

References

1. (2014). The State of Hospital Medicine Report. Philadelphia: Society of Hospital Medicine. Retrieved from www.hospitalmedicine.org/Survey2014.

2. (2016). The State of Hospital Medicine Report. Philadelphia: Society of Hospital Medicine. Retrieved from www.hospitalmedicine.org/Survey2016.

Set a goal, or two, or three

In today’s health care space, tracking progress and achieving specified metrics are all part of the job. Most fast-paced physician groups incentivize clinicians for efficiency, consistency, quality, and loyalty. Setting and achieving goals, although it might sound somewhat cliche, can play an important role in daily performance, as well as have an impact on long-term satisfaction with an HM career, according to experts in the field.

“Health care insurers and individuals choosing where to obtain health care want evidence that hospitalists are delivering the best care possible,” says Judith S. Treharne, consulting executive at Halley Consulting Group in Westerville, Ohio. “This requires goal setting, measuring performance related to those goals, and continually developing processes that enhance performance in order to achieve goals.”

Hospitalists are at the forefront of healthcare transformations taking place both inside the hospital and when patients are discharged to different settings. The opportunities for setting goals – personal and group-wide – are endless.

For employed hospitalists, goal setting – and achievement – can counter career stagnation, says Sanjay Bhatia, MD, FHM, CDIP.

“They show up, do a job, and go home. Many are not encouraged to develop their careers,” says Dr. Bhatia, chief medical officer, Prime Healthcare–Lower Bucks Hospital, Bristol, Pa.; founding partner, First Docs/Mercer Bucks Medical, Levittown, Pa.; and CEO/president, Prime Clinical Solutions, Freehold, N.J.

Setting goals will help hospitalists establish skill sets and achieve accomplishments that will keep their career growth on track, adds Surinder Yadav, MD, SFHM, vice president of hospital medicine at Emeryville, Calif.–based CEP America, a national organization specializing in acute-care staffing, including hospitalist, intensivist, and emergency medicine programs.

when someone consistently reaches their goals (that is, improving outcomes) and feels accomplished, it enhances engagement of their work, says Treharne, who advises hospitalist groups.

Determine, pursue goals

There are many reasons why goal setting is important. So what guidelines can a hospitalist use to set goals? In order to establish goals for your current role, Treharne advises reviewing your job description – which should be updated as your role evolves.

“Determine what you need to do in order to progress toward meeting these requirements,” she says. “Find out what resources are available to support your efforts.”

Regarding setting career goals, Dr. Jaffer says hospitalists should consider things that really move them.

“For hospitalists in the early stages of their careers, it may take some time to determine them,” he says. “But when a passion develops, hospitalists can identify opportunities which will allow them to create a niche for themselves or an area of expertise.”

Then, hospitalists can work with individuals within their organization and beyond to increase their expertise.

“Find one or more mentors, take educational courses or even pursue an advanced degree, and write about your area of expertise either by publishing articles or abstracts, giving poster presentations, or lecturing,” Dr. Jaffer advises. “That will establish you as an expert and lead to promotions.”

Dr. Bhatia believes it’s natural and important for hospitalists to pursue administrative roles and become experts on how hospitals and post–acute care facilities work, because they transition patients to these institutions and they employ hospitalists. He has also seen hospitalists pursue entrepreneurial goals, such as becoming involved in information technology by developing apps or becoming C-suite executives, and starting other medical-based businesses such as home-based physician visits and telemedicine ventures and even nonmedical-based businesses such as real estate investing. Another avenue is teaching residency programs and developing an academic career.

“The key is to have good teammates, partners, and ancillary staff in each endeavor,” Dr. Bhatia says. “You can learn a lot from them as well. My experiences beyond being a hospitalist make me very valuable as a hospitalist. I’ve found that varied experiences create a synergistic and value-added service to a hospital.”

Stay on target

In order to reach your goals, Dr. Bhatia recommends creating daily task lists as well as setting goals quarterly and annually and evaluating them at those intervals. Determine action steps to reach long-term goals. “I keep these lists on my smartphone, so they’re always in my mind’s eye,” he says. “I look at the big picture on a daily basis and work toward my goals.”

In an effort to help faculty members reach their goals, Dr. Jaffer, when he was a division director at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, scheduled biannual professional reviews with each team member. It was a formal process adapted from the annual professional review that he learned while at the Cleveland Clinic. Members were asked to complete a faculty self-reflection assessment and answer questions such as:

- Since our last meeting, what committees and educational opportunities have you participated in?

- What types of quality improvement projects and presentations have you done?

- What achievements are you most proud of?

- Regarding the goals you listed at your last review, where have you had the most growth? What would you define as opportunities for growth?

At Rush, Dr. Jaffer asked members of his division to set one or two professional goals each year. “I suggested they set goals that will make them feel fulfilled professionally, so their careers remain gratifying,” he says.

Group goals

Hospitalists should play an integral role in developing a hospital’s strategic and operational plan. “By having hospitalists provide feedback in the planning process, prior to annual finalization of the plan, the hospital’s and hospitalist program’s objectives can be aligned,” Treharne says. “It’s important that their goals align, in order for both to be successful.”

Dr. Jaffer suggests starting at the beginning of each fiscal year. HM groups should, as a team, create quality, operational, and efficiency goals, which align closely with the hospital’s goals. Some examples: clinical productivity work relative value units (wRVUs), doctor-patient communication scores, observed-to-expected length of stay, readmission rates, and percentage of patients discharged by 1 p.m.

“We set goals both as individuals and as a group,” Dr. Jaffer says. “Then, we create a scorecard for each hospitalist on a quarterly basis and share each hospitalist’s data with them, as well as create a group dashboard. As a group, hospitalists can view both individual data and the group’s data. This feedback helps them identify where they need to improve their performance.”

Dr. Bhatia has found that setting group goals on a quarterly basis works well. Goals involve recruitment needs, patient satisfaction, case mix index, Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS), utilization, and length of stay.

“Metrics should be recorded and shared monthly by either the hospital’s information technology department or the hospitalist group’s software,” he says.

Data: top of mind

Each provider needs to understand that success for the team also means individual success.

“Focus on helping each other to achieve high performance and high quality care,” Dr. Yadav says. “Engage with each other and with the hospital at large. Aim to be involved in projects and to help find solutions to problems or barriers within the system.”

When you implement a change in a process and expect to see improvement regarding a particular measure, be sure to give the new process adequate time to shift the outcome.

“Many good ideas have been cast aside because they were deemed unsuccessful before there was sufficient time for the process to stabilize and the improvement to be seen,” Treharne says.

When setting targets and measures, set expectations regarding how long the new process will need to be in place prior to evaluating the change.

“Pilot programs are often a good way to try something out before completely changing a process with potential unwanted outcomes,” she says.

If a clinical operational or efficiency goal that involves the whole group and performance is below target, look to best practices to help you achieve success, Dr. Jaffer says. Create a work group and appoint a champion.

Hopefully, reaching your goals will translate into success.

“Success for me is about having a positive impact on people and processes, and being content with my personal life and having time and resources to pursue my passions,” Dr. Jaffer concludes.

Setting Goals for Now and Then

When looking to set goals, Treharne recommends starting with long-term goal setting.

“Set goals for the next year, or five years and beyond, by establishing a vision – dream to be more than you are today,” she says. “Envision a future that gets you excited to participate in change and come to work every day.”

- I could become more valued in my job by doing _____.

- I could make more income by _____.

- I’d like to increase my knowledge of _____.

Then, develop short-term goals that will help you work toward achieving your long-term goals.

“Map out a path from today using the metrics available and applicable to the future state,” Treharne says. “Creating that path allows you to determine the short-term goals. How far can you get in what period of time? Be realistic, but stretch yourself so you’re not complacent.”

Document this path in a quarterly action plan with a complementary monthly tactical plan. Plans should identify accountable parties, resources needed, data requirements, and timelines, Treharne says. Review your progress monthly.

Check in and articulate your goals with those in your inner circle – seek their advice on a regular basis, Uy says. Measure results and be willing to adapt if you’re not progressing as you’ve envisioned.

Karen Appold is a freelance writer in Pennsylvania.

In today’s health care space, tracking progress and achieving specified metrics are all part of the job. Most fast-paced physician groups incentivize clinicians for efficiency, consistency, quality, and loyalty. Setting and achieving goals, although it might sound somewhat cliche, can play an important role in daily performance, as well as have an impact on long-term satisfaction with an HM career, according to experts in the field.

“Health care insurers and individuals choosing where to obtain health care want evidence that hospitalists are delivering the best care possible,” says Judith S. Treharne, consulting executive at Halley Consulting Group in Westerville, Ohio. “This requires goal setting, measuring performance related to those goals, and continually developing processes that enhance performance in order to achieve goals.”

Hospitalists are at the forefront of healthcare transformations taking place both inside the hospital and when patients are discharged to different settings. The opportunities for setting goals – personal and group-wide – are endless.

For employed hospitalists, goal setting – and achievement – can counter career stagnation, says Sanjay Bhatia, MD, FHM, CDIP.

“They show up, do a job, and go home. Many are not encouraged to develop their careers,” says Dr. Bhatia, chief medical officer, Prime Healthcare–Lower Bucks Hospital, Bristol, Pa.; founding partner, First Docs/Mercer Bucks Medical, Levittown, Pa.; and CEO/president, Prime Clinical Solutions, Freehold, N.J.

Setting goals will help hospitalists establish skill sets and achieve accomplishments that will keep their career growth on track, adds Surinder Yadav, MD, SFHM, vice president of hospital medicine at Emeryville, Calif.–based CEP America, a national organization specializing in acute-care staffing, including hospitalist, intensivist, and emergency medicine programs.

when someone consistently reaches their goals (that is, improving outcomes) and feels accomplished, it enhances engagement of their work, says Treharne, who advises hospitalist groups.

Determine, pursue goals

There are many reasons why goal setting is important. So what guidelines can a hospitalist use to set goals? In order to establish goals for your current role, Treharne advises reviewing your job description – which should be updated as your role evolves.

“Determine what you need to do in order to progress toward meeting these requirements,” she says. “Find out what resources are available to support your efforts.”

Regarding setting career goals, Dr. Jaffer says hospitalists should consider things that really move them.

“For hospitalists in the early stages of their careers, it may take some time to determine them,” he says. “But when a passion develops, hospitalists can identify opportunities which will allow them to create a niche for themselves or an area of expertise.”

Then, hospitalists can work with individuals within their organization and beyond to increase their expertise.

“Find one or more mentors, take educational courses or even pursue an advanced degree, and write about your area of expertise either by publishing articles or abstracts, giving poster presentations, or lecturing,” Dr. Jaffer advises. “That will establish you as an expert and lead to promotions.”

Dr. Bhatia believes it’s natural and important for hospitalists to pursue administrative roles and become experts on how hospitals and post–acute care facilities work, because they transition patients to these institutions and they employ hospitalists. He has also seen hospitalists pursue entrepreneurial goals, such as becoming involved in information technology by developing apps or becoming C-suite executives, and starting other medical-based businesses such as home-based physician visits and telemedicine ventures and even nonmedical-based businesses such as real estate investing. Another avenue is teaching residency programs and developing an academic career.

“The key is to have good teammates, partners, and ancillary staff in each endeavor,” Dr. Bhatia says. “You can learn a lot from them as well. My experiences beyond being a hospitalist make me very valuable as a hospitalist. I’ve found that varied experiences create a synergistic and value-added service to a hospital.”

Stay on target

In order to reach your goals, Dr. Bhatia recommends creating daily task lists as well as setting goals quarterly and annually and evaluating them at those intervals. Determine action steps to reach long-term goals. “I keep these lists on my smartphone, so they’re always in my mind’s eye,” he says. “I look at the big picture on a daily basis and work toward my goals.”

In an effort to help faculty members reach their goals, Dr. Jaffer, when he was a division director at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, scheduled biannual professional reviews with each team member. It was a formal process adapted from the annual professional review that he learned while at the Cleveland Clinic. Members were asked to complete a faculty self-reflection assessment and answer questions such as:

- Since our last meeting, what committees and educational opportunities have you participated in?

- What types of quality improvement projects and presentations have you done?

- What achievements are you most proud of?

- Regarding the goals you listed at your last review, where have you had the most growth? What would you define as opportunities for growth?

At Rush, Dr. Jaffer asked members of his division to set one or two professional goals each year. “I suggested they set goals that will make them feel fulfilled professionally, so their careers remain gratifying,” he says.

Group goals

Hospitalists should play an integral role in developing a hospital’s strategic and operational plan. “By having hospitalists provide feedback in the planning process, prior to annual finalization of the plan, the hospital’s and hospitalist program’s objectives can be aligned,” Treharne says. “It’s important that their goals align, in order for both to be successful.”

Dr. Jaffer suggests starting at the beginning of each fiscal year. HM groups should, as a team, create quality, operational, and efficiency goals, which align closely with the hospital’s goals. Some examples: clinical productivity work relative value units (wRVUs), doctor-patient communication scores, observed-to-expected length of stay, readmission rates, and percentage of patients discharged by 1 p.m.

“We set goals both as individuals and as a group,” Dr. Jaffer says. “Then, we create a scorecard for each hospitalist on a quarterly basis and share each hospitalist’s data with them, as well as create a group dashboard. As a group, hospitalists can view both individual data and the group’s data. This feedback helps them identify where they need to improve their performance.”

Dr. Bhatia has found that setting group goals on a quarterly basis works well. Goals involve recruitment needs, patient satisfaction, case mix index, Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS), utilization, and length of stay.

“Metrics should be recorded and shared monthly by either the hospital’s information technology department or the hospitalist group’s software,” he says.

Data: top of mind

Each provider needs to understand that success for the team also means individual success.

“Focus on helping each other to achieve high performance and high quality care,” Dr. Yadav says. “Engage with each other and with the hospital at large. Aim to be involved in projects and to help find solutions to problems or barriers within the system.”

When you implement a change in a process and expect to see improvement regarding a particular measure, be sure to give the new process adequate time to shift the outcome.

“Many good ideas have been cast aside because they were deemed unsuccessful before there was sufficient time for the process to stabilize and the improvement to be seen,” Treharne says.

When setting targets and measures, set expectations regarding how long the new process will need to be in place prior to evaluating the change.

“Pilot programs are often a good way to try something out before completely changing a process with potential unwanted outcomes,” she says.

If a clinical operational or efficiency goal that involves the whole group and performance is below target, look to best practices to help you achieve success, Dr. Jaffer says. Create a work group and appoint a champion.

Hopefully, reaching your goals will translate into success.

“Success for me is about having a positive impact on people and processes, and being content with my personal life and having time and resources to pursue my passions,” Dr. Jaffer concludes.

Setting Goals for Now and Then

When looking to set goals, Treharne recommends starting with long-term goal setting.

“Set goals for the next year, or five years and beyond, by establishing a vision – dream to be more than you are today,” she says. “Envision a future that gets you excited to participate in change and come to work every day.”

- I could become more valued in my job by doing _____.

- I could make more income by _____.

- I’d like to increase my knowledge of _____.

Then, develop short-term goals that will help you work toward achieving your long-term goals.

“Map out a path from today using the metrics available and applicable to the future state,” Treharne says. “Creating that path allows you to determine the short-term goals. How far can you get in what period of time? Be realistic, but stretch yourself so you’re not complacent.”

Document this path in a quarterly action plan with a complementary monthly tactical plan. Plans should identify accountable parties, resources needed, data requirements, and timelines, Treharne says. Review your progress monthly.

Check in and articulate your goals with those in your inner circle – seek their advice on a regular basis, Uy says. Measure results and be willing to adapt if you’re not progressing as you’ve envisioned.

Karen Appold is a freelance writer in Pennsylvania.

In today’s health care space, tracking progress and achieving specified metrics are all part of the job. Most fast-paced physician groups incentivize clinicians for efficiency, consistency, quality, and loyalty. Setting and achieving goals, although it might sound somewhat cliche, can play an important role in daily performance, as well as have an impact on long-term satisfaction with an HM career, according to experts in the field.

“Health care insurers and individuals choosing where to obtain health care want evidence that hospitalists are delivering the best care possible,” says Judith S. Treharne, consulting executive at Halley Consulting Group in Westerville, Ohio. “This requires goal setting, measuring performance related to those goals, and continually developing processes that enhance performance in order to achieve goals.”

Hospitalists are at the forefront of healthcare transformations taking place both inside the hospital and when patients are discharged to different settings. The opportunities for setting goals – personal and group-wide – are endless.

For employed hospitalists, goal setting – and achievement – can counter career stagnation, says Sanjay Bhatia, MD, FHM, CDIP.

“They show up, do a job, and go home. Many are not encouraged to develop their careers,” says Dr. Bhatia, chief medical officer, Prime Healthcare–Lower Bucks Hospital, Bristol, Pa.; founding partner, First Docs/Mercer Bucks Medical, Levittown, Pa.; and CEO/president, Prime Clinical Solutions, Freehold, N.J.

Setting goals will help hospitalists establish skill sets and achieve accomplishments that will keep their career growth on track, adds Surinder Yadav, MD, SFHM, vice president of hospital medicine at Emeryville, Calif.–based CEP America, a national organization specializing in acute-care staffing, including hospitalist, intensivist, and emergency medicine programs.

when someone consistently reaches their goals (that is, improving outcomes) and feels accomplished, it enhances engagement of their work, says Treharne, who advises hospitalist groups.

Determine, pursue goals

There are many reasons why goal setting is important. So what guidelines can a hospitalist use to set goals? In order to establish goals for your current role, Treharne advises reviewing your job description – which should be updated as your role evolves.

“Determine what you need to do in order to progress toward meeting these requirements,” she says. “Find out what resources are available to support your efforts.”

Regarding setting career goals, Dr. Jaffer says hospitalists should consider things that really move them.

“For hospitalists in the early stages of their careers, it may take some time to determine them,” he says. “But when a passion develops, hospitalists can identify opportunities which will allow them to create a niche for themselves or an area of expertise.”

Then, hospitalists can work with individuals within their organization and beyond to increase their expertise.

“Find one or more mentors, take educational courses or even pursue an advanced degree, and write about your area of expertise either by publishing articles or abstracts, giving poster presentations, or lecturing,” Dr. Jaffer advises. “That will establish you as an expert and lead to promotions.”

Dr. Bhatia believes it’s natural and important for hospitalists to pursue administrative roles and become experts on how hospitals and post–acute care facilities work, because they transition patients to these institutions and they employ hospitalists. He has also seen hospitalists pursue entrepreneurial goals, such as becoming involved in information technology by developing apps or becoming C-suite executives, and starting other medical-based businesses such as home-based physician visits and telemedicine ventures and even nonmedical-based businesses such as real estate investing. Another avenue is teaching residency programs and developing an academic career.

“The key is to have good teammates, partners, and ancillary staff in each endeavor,” Dr. Bhatia says. “You can learn a lot from them as well. My experiences beyond being a hospitalist make me very valuable as a hospitalist. I’ve found that varied experiences create a synergistic and value-added service to a hospital.”

Stay on target

In order to reach your goals, Dr. Bhatia recommends creating daily task lists as well as setting goals quarterly and annually and evaluating them at those intervals. Determine action steps to reach long-term goals. “I keep these lists on my smartphone, so they’re always in my mind’s eye,” he says. “I look at the big picture on a daily basis and work toward my goals.”

In an effort to help faculty members reach their goals, Dr. Jaffer, when he was a division director at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, scheduled biannual professional reviews with each team member. It was a formal process adapted from the annual professional review that he learned while at the Cleveland Clinic. Members were asked to complete a faculty self-reflection assessment and answer questions such as:

- Since our last meeting, what committees and educational opportunities have you participated in?

- What types of quality improvement projects and presentations have you done?

- What achievements are you most proud of?

- Regarding the goals you listed at your last review, where have you had the most growth? What would you define as opportunities for growth?

At Rush, Dr. Jaffer asked members of his division to set one or two professional goals each year. “I suggested they set goals that will make them feel fulfilled professionally, so their careers remain gratifying,” he says.

Group goals

Hospitalists should play an integral role in developing a hospital’s strategic and operational plan. “By having hospitalists provide feedback in the planning process, prior to annual finalization of the plan, the hospital’s and hospitalist program’s objectives can be aligned,” Treharne says. “It’s important that their goals align, in order for both to be successful.”

Dr. Jaffer suggests starting at the beginning of each fiscal year. HM groups should, as a team, create quality, operational, and efficiency goals, which align closely with the hospital’s goals. Some examples: clinical productivity work relative value units (wRVUs), doctor-patient communication scores, observed-to-expected length of stay, readmission rates, and percentage of patients discharged by 1 p.m.

“We set goals both as individuals and as a group,” Dr. Jaffer says. “Then, we create a scorecard for each hospitalist on a quarterly basis and share each hospitalist’s data with them, as well as create a group dashboard. As a group, hospitalists can view both individual data and the group’s data. This feedback helps them identify where they need to improve their performance.”

Dr. Bhatia has found that setting group goals on a quarterly basis works well. Goals involve recruitment needs, patient satisfaction, case mix index, Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS), utilization, and length of stay.

“Metrics should be recorded and shared monthly by either the hospital’s information technology department or the hospitalist group’s software,” he says.

Data: top of mind

Each provider needs to understand that success for the team also means individual success.

“Focus on helping each other to achieve high performance and high quality care,” Dr. Yadav says. “Engage with each other and with the hospital at large. Aim to be involved in projects and to help find solutions to problems or barriers within the system.”

When you implement a change in a process and expect to see improvement regarding a particular measure, be sure to give the new process adequate time to shift the outcome.

“Many good ideas have been cast aside because they were deemed unsuccessful before there was sufficient time for the process to stabilize and the improvement to be seen,” Treharne says.

When setting targets and measures, set expectations regarding how long the new process will need to be in place prior to evaluating the change.

“Pilot programs are often a good way to try something out before completely changing a process with potential unwanted outcomes,” she says.

If a clinical operational or efficiency goal that involves the whole group and performance is below target, look to best practices to help you achieve success, Dr. Jaffer says. Create a work group and appoint a champion.

Hopefully, reaching your goals will translate into success.

“Success for me is about having a positive impact on people and processes, and being content with my personal life and having time and resources to pursue my passions,” Dr. Jaffer concludes.

Setting Goals for Now and Then

When looking to set goals, Treharne recommends starting with long-term goal setting.

“Set goals for the next year, or five years and beyond, by establishing a vision – dream to be more than you are today,” she says. “Envision a future that gets you excited to participate in change and come to work every day.”

- I could become more valued in my job by doing _____.

- I could make more income by _____.

- I’d like to increase my knowledge of _____.

Then, develop short-term goals that will help you work toward achieving your long-term goals.

“Map out a path from today using the metrics available and applicable to the future state,” Treharne says. “Creating that path allows you to determine the short-term goals. How far can you get in what period of time? Be realistic, but stretch yourself so you’re not complacent.”

Document this path in a quarterly action plan with a complementary monthly tactical plan. Plans should identify accountable parties, resources needed, data requirements, and timelines, Treharne says. Review your progress monthly.

Check in and articulate your goals with those in your inner circle – seek their advice on a regular basis, Uy says. Measure results and be willing to adapt if you’re not progressing as you’ve envisioned.

Karen Appold is a freelance writer in Pennsylvania.

Hospitalist movers and shakers

O’Neil Pike, MD, SFHM, has been promoted to chief medical officer with healthcare staffing company Medicus Healthcare Solutions (MHS) of Windham, N.H. Formerly a hospitalist consultant and chief practice advisor with MHS, Dr. Pike is a practicing hospitalist and serves as an assistant professor of medicine at Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine in Scranton, Pa.

Timothy D. Bode, MD, MBA, SFHM, has been named appointed medical officer at Saint Thomas Rutherford Hospital in Murfreesboro, Tenn., as well as several regional hospitals in the Saint Thomas system. Previously, Dr. Bode served as senior vice president and CMO at Memorial Health in Jacksonville, Fla.

Joseph Perras, MD, has been named chief executive officer at Mt. Ascutney Hospital and Health Center (MAHHC) in Windsor, Vt. Dr. Perras will continue as the center’s CMO, as well. He previously held the role of MAHHC’s director of hospital medicine.

Alamjit Virk, MD, has been promoted to medical director of Emergency Medicine and Hospitalist Services at Martha’s Vineyard Hospital in Oak Bluffs, Mass. Dr. Virk was a MVH staff physician for a year and half prior to the elevation, and he previously served as an attending physician in emergency medicine at Emerson Hospital in Concord, Mass.

Business Moves

Dearborn County Hospital (DCH) in Lawrenceburg, Ind., has partnered with TriHealth to provide hospitalist services for its inpatients. TriHealth’s team of more than 30 hospitalists is led by chief of hospital medicine Bryan Strader, MD. TriHealth also provides care for patients at Ohio’s Bethesda North, Good Samaritan and Bethesda Butler Hospitals.

MidMichigan Medical Centers in Alma, Gladwin, and Midland have been recognized with Five Star Excellence Awards by national health care research leader Professional Research Consultants. Awards were received for excellence in providing patients discharge information and pain management.

Pediatric Associates, located in Broward County, Fla., has expanded its pediatric hospitalist program thanks to the success of a pilot program run at Palm Beach Children’s Hospital at St. Mary’s Medical Center (West Palm Beach). Jamilah Grant-Guimaraes, MD, FAAP, and Nina Phillips Bernstein, DO, FAAP, will provide care to Pediatrics Associates patients at Broward General Medical Center.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System announced that it will add Princeton HealthCare System (PHCS) to the UPHS family. Located just 40 miles from Philadelphia, PHCS serves more than 1.3 million people in central New Jersey and includes the University Medical Center of Princeton, which opened in 2012 in Plainsboro, N.J.

Lehigh Valley Health Network, based out of Allentown, Pa., has absorbed Pocono Health System (East Stroudsburg, Pa.) in a move effective Jan. 1. Under the deal’s terms, Pocono Medical Center (the system’s only hospital) now will be known as Lehigh Valley Hospital–Pocono. LVH also absorbs Pocono’s three health centers. LVH now operates 8 hospital campuses and 19 health centers.

O’Neil Pike, MD, SFHM, has been promoted to chief medical officer with healthcare staffing company Medicus Healthcare Solutions (MHS) of Windham, N.H. Formerly a hospitalist consultant and chief practice advisor with MHS, Dr. Pike is a practicing hospitalist and serves as an assistant professor of medicine at Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine in Scranton, Pa.

Timothy D. Bode, MD, MBA, SFHM, has been named appointed medical officer at Saint Thomas Rutherford Hospital in Murfreesboro, Tenn., as well as several regional hospitals in the Saint Thomas system. Previously, Dr. Bode served as senior vice president and CMO at Memorial Health in Jacksonville, Fla.

Joseph Perras, MD, has been named chief executive officer at Mt. Ascutney Hospital and Health Center (MAHHC) in Windsor, Vt. Dr. Perras will continue as the center’s CMO, as well. He previously held the role of MAHHC’s director of hospital medicine.

Alamjit Virk, MD, has been promoted to medical director of Emergency Medicine and Hospitalist Services at Martha’s Vineyard Hospital in Oak Bluffs, Mass. Dr. Virk was a MVH staff physician for a year and half prior to the elevation, and he previously served as an attending physician in emergency medicine at Emerson Hospital in Concord, Mass.

Business Moves

Dearborn County Hospital (DCH) in Lawrenceburg, Ind., has partnered with TriHealth to provide hospitalist services for its inpatients. TriHealth’s team of more than 30 hospitalists is led by chief of hospital medicine Bryan Strader, MD. TriHealth also provides care for patients at Ohio’s Bethesda North, Good Samaritan and Bethesda Butler Hospitals.

MidMichigan Medical Centers in Alma, Gladwin, and Midland have been recognized with Five Star Excellence Awards by national health care research leader Professional Research Consultants. Awards were received for excellence in providing patients discharge information and pain management.

Pediatric Associates, located in Broward County, Fla., has expanded its pediatric hospitalist program thanks to the success of a pilot program run at Palm Beach Children’s Hospital at St. Mary’s Medical Center (West Palm Beach). Jamilah Grant-Guimaraes, MD, FAAP, and Nina Phillips Bernstein, DO, FAAP, will provide care to Pediatrics Associates patients at Broward General Medical Center.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System announced that it will add Princeton HealthCare System (PHCS) to the UPHS family. Located just 40 miles from Philadelphia, PHCS serves more than 1.3 million people in central New Jersey and includes the University Medical Center of Princeton, which opened in 2012 in Plainsboro, N.J.

Lehigh Valley Health Network, based out of Allentown, Pa., has absorbed Pocono Health System (East Stroudsburg, Pa.) in a move effective Jan. 1. Under the deal’s terms, Pocono Medical Center (the system’s only hospital) now will be known as Lehigh Valley Hospital–Pocono. LVH also absorbs Pocono’s three health centers. LVH now operates 8 hospital campuses and 19 health centers.

O’Neil Pike, MD, SFHM, has been promoted to chief medical officer with healthcare staffing company Medicus Healthcare Solutions (MHS) of Windham, N.H. Formerly a hospitalist consultant and chief practice advisor with MHS, Dr. Pike is a practicing hospitalist and serves as an assistant professor of medicine at Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine in Scranton, Pa.

Timothy D. Bode, MD, MBA, SFHM, has been named appointed medical officer at Saint Thomas Rutherford Hospital in Murfreesboro, Tenn., as well as several regional hospitals in the Saint Thomas system. Previously, Dr. Bode served as senior vice president and CMO at Memorial Health in Jacksonville, Fla.

Joseph Perras, MD, has been named chief executive officer at Mt. Ascutney Hospital and Health Center (MAHHC) in Windsor, Vt. Dr. Perras will continue as the center’s CMO, as well. He previously held the role of MAHHC’s director of hospital medicine.

Alamjit Virk, MD, has been promoted to medical director of Emergency Medicine and Hospitalist Services at Martha’s Vineyard Hospital in Oak Bluffs, Mass. Dr. Virk was a MVH staff physician for a year and half prior to the elevation, and he previously served as an attending physician in emergency medicine at Emerson Hospital in Concord, Mass.

Business Moves

Dearborn County Hospital (DCH) in Lawrenceburg, Ind., has partnered with TriHealth to provide hospitalist services for its inpatients. TriHealth’s team of more than 30 hospitalists is led by chief of hospital medicine Bryan Strader, MD. TriHealth also provides care for patients at Ohio’s Bethesda North, Good Samaritan and Bethesda Butler Hospitals.

MidMichigan Medical Centers in Alma, Gladwin, and Midland have been recognized with Five Star Excellence Awards by national health care research leader Professional Research Consultants. Awards were received for excellence in providing patients discharge information and pain management.

Pediatric Associates, located in Broward County, Fla., has expanded its pediatric hospitalist program thanks to the success of a pilot program run at Palm Beach Children’s Hospital at St. Mary’s Medical Center (West Palm Beach). Jamilah Grant-Guimaraes, MD, FAAP, and Nina Phillips Bernstein, DO, FAAP, will provide care to Pediatrics Associates patients at Broward General Medical Center.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System announced that it will add Princeton HealthCare System (PHCS) to the UPHS family. Located just 40 miles from Philadelphia, PHCS serves more than 1.3 million people in central New Jersey and includes the University Medical Center of Princeton, which opened in 2012 in Plainsboro, N.J.

Lehigh Valley Health Network, based out of Allentown, Pa., has absorbed Pocono Health System (East Stroudsburg, Pa.) in a move effective Jan. 1. Under the deal’s terms, Pocono Medical Center (the system’s only hospital) now will be known as Lehigh Valley Hospital–Pocono. LVH also absorbs Pocono’s three health centers. LVH now operates 8 hospital campuses and 19 health centers.

Burnout: No laughing matter

Much has been written about burnout in U.S. physicians over the course of many years. Burnout is a syndrome that is exemplified by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a low sense of personal accomplishment. It appears that hospitalists are particularly prone to burnout, being at the very front line of patient care. In addition, the prevalence of burnout appears to be getting worse. According to a survey from the American Medical Association, the prevalence of burnout in 2011 was 45%. Three years later in 2014 the prevalence was up to 55%.1,2

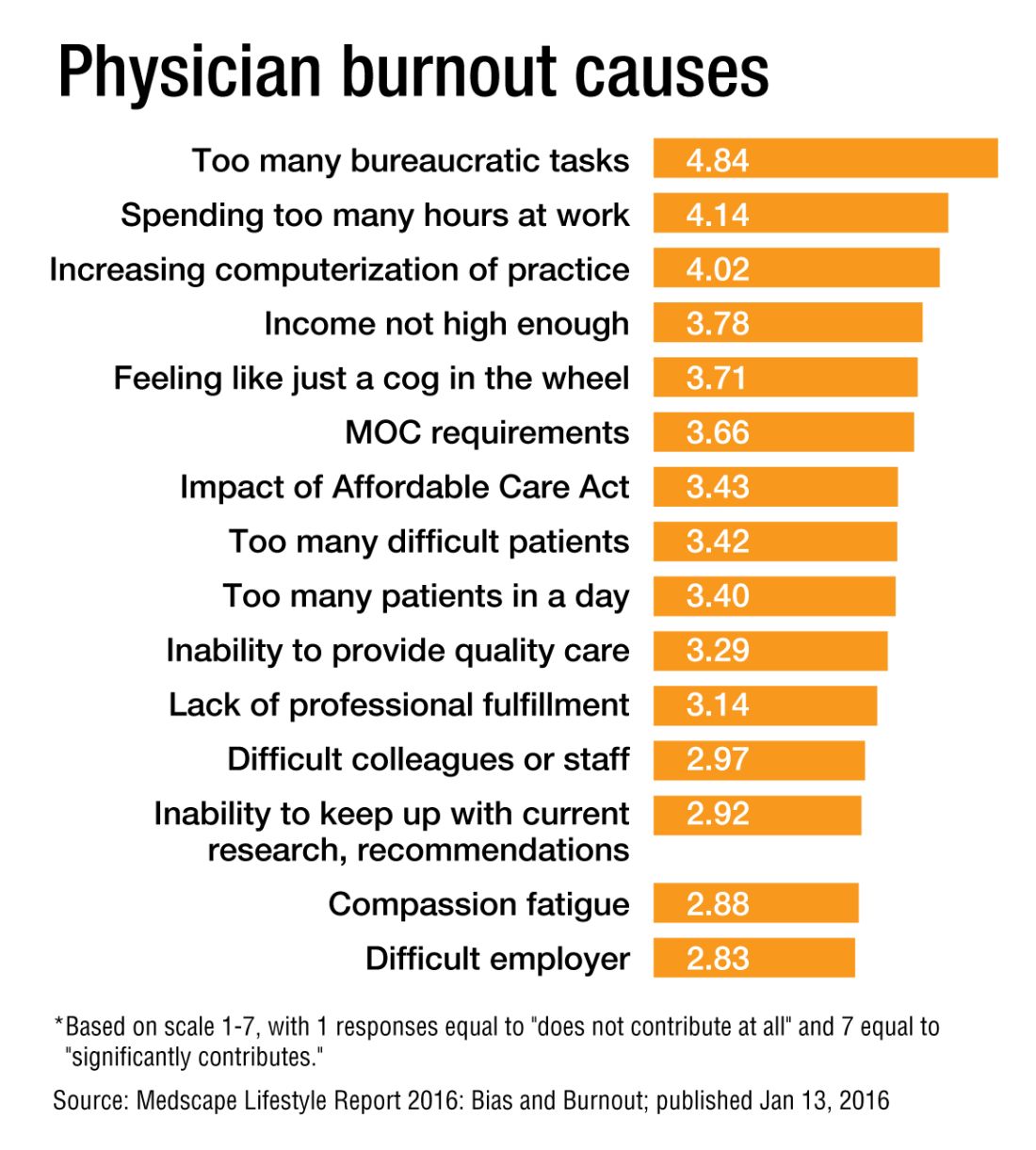

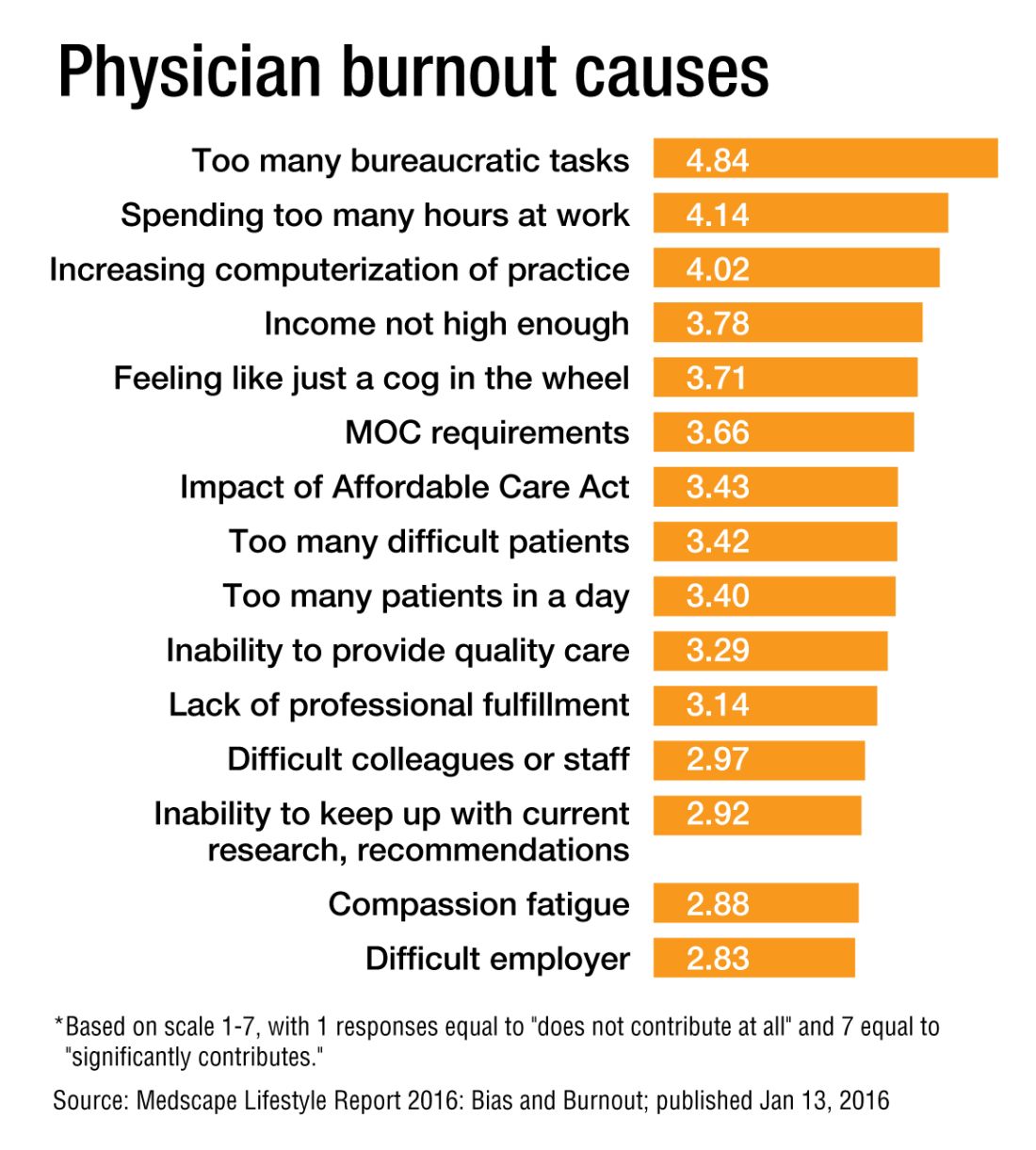

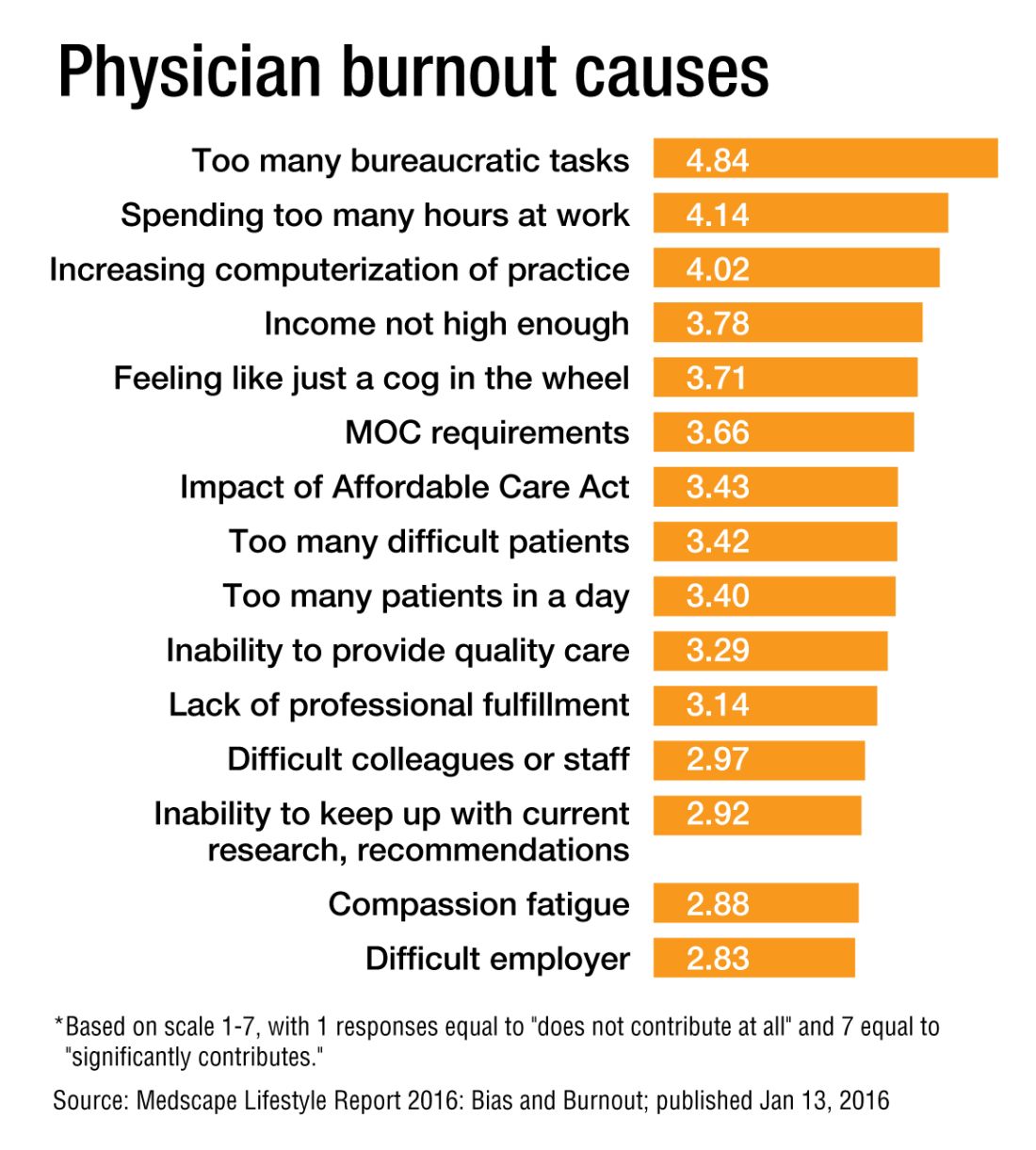

Although triggers for the onset and intensity of burnout likely vary by specialty, a recent Medscape Lifestyle Report found the most common causes of burnout among physicians included (see graphic):3

• Bureaucratic tasks.

• Work hours.

• Computerization.

• Compensation.

• Lower work satisfaction.

• Disrupted personal relationships.

• Substance misuse.

• Depression.

• Suicide.

Burnout also leads to lower productivity, higher job turnover, and early retirement. In addition, from a systems perspective, burnout is associated with higher medical errors, reduced quality of patient care, and lower patient satisfaction. And, at its most extreme, burnout is deadly: Sadly, every year, 300-400 physicians in the United States commit suicide. Female physicians are 2.3 times more likely to commit suicide than are female nonphysicians; for males, the risk is 1.4 times higher among physicians compared to the general population.1

Proactive approaches

Despite all these sobering statistics on the prevalence and outcomes of burnout among physicians, the ongoing question is, what can we do about it? Although awareness and recognition of burnout has grown substantially over time, successful interventions to prevent or mitigate burnout have not. Many potential interventions and ideas have surfaced and have been published, but none have had impressive impacts or have been adopted widely within or across institutions. According to a Modern Healthcare survey of approximately 100 health care CEOs, only about one-third reported that their organization had programs to address physician burnout, although about another one-third reported attempts to develop such programs.1

The good news is that at least there is a lot of activity around trying new interventions to reduce burnout, including in medical schools and graduate training programs. The thought is that if you can employ healthy resilience tactics during training, these can be carried throughout a career to diminish the risk and/or severity of burnout, despite any challenges that arise along the way.

Some of these interventions are aimed at individuals (to enhance personal resilience and coping skills) while others are aimed at the level of organizations (to reduce organizational stress and/or workload). A recent Modern Healthcare article found several good examples:1

• New York’s Albert Einstein College of Medicine’s WellMed program has been designed to help students develop healthy and balanced habits and attitudes, and to enhance their personal resilience, for the short and the long term.

• Baystate Health in Massachusetts hosts a physician leadership academy that offers training in communication, unconscious bias, strategy, and other management skills, to enhance individual resilience and organizational engagement.

• HealthPartners, a not-for-profit, Minnesota-based health care organization, has specific programs to engage physicians and allow them to have organizational impact, as well as programs to simplify technology use.

Organization efforts are key to prevent, treat

The key to reducing burnout does seem to be employing a combination of self-directed and organization-directed interventions, each of which enhances resilience and reduces workplace stressors (i.e., administrative tasks and workload). Specific to hospitalists, Leslie Flores, MBA, recently wrote about burnout at The Hospital Leader blog. Her list included several specific examples to reduce the top causes of burnout among busy hospitalists:4

• Modifying the skill mix in hospital medicine groups so that less costly support staff are doing much of the work not requiring a physician’s expertise, freeing up hospitalists to provide better care to more patients.

• Reducing unnecessary interruptions and the stress they cause, via both technology and process improvement.

• Paying deliberate attention to hospitalist personal and professional well-being.

• Adjusting hospitalist schedules and work flow so that hospitalists can be more efficient (that is, do less low-value work and re-work) and have better work-life balance.

• Ensuring that hospitalists have the training, clinical competencies, and support to comfortably perform in expanded clinical roles.

Many of these systemic solutions were recently validated as likely able to have an impact on burnout (and seem to be more effective than interventions focused on individual resilience).5 A recent meta-analysis found that physician-directed interventions were associated with small but significant reductions in burnout; these were primarily mindfulness-based stress reduction techniques, educational interventions targeting physicians self-confidence and communication skills, exercise, or a combination of these features. More impactful were organization-directed interventions, which were associated with more significant reductions in burnout; these were primarily aimed at reducing workload and enhancing teamwork and leadership.

In sum

It is important for all of us hospitalists to understand and try to mitigate burnout within our teams. Although individual-focused interventions can have some effect, most efforts should primarily be focused on system-based interventions, to reduce administrative burdens and workload. Through such system design and redesign, we can likely reduce burnout amongst our teams, and therefore improve the sustainability of our specialty.

References

1.http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20161029/MAGAZINE/310299983

2. http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196(15)00716-8/abstract

3.http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2016/public/overview#page=5

4. http://blogs.hospitalmedicine.org/Blog/making-hospital-medicine-a-sustainable-specialty/

5.http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2588814

Much has been written about burnout in U.S. physicians over the course of many years. Burnout is a syndrome that is exemplified by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a low sense of personal accomplishment. It appears that hospitalists are particularly prone to burnout, being at the very front line of patient care. In addition, the prevalence of burnout appears to be getting worse. According to a survey from the American Medical Association, the prevalence of burnout in 2011 was 45%. Three years later in 2014 the prevalence was up to 55%.1,2

Although triggers for the onset and intensity of burnout likely vary by specialty, a recent Medscape Lifestyle Report found the most common causes of burnout among physicians included (see graphic):3

• Bureaucratic tasks.

• Work hours.

• Computerization.

• Compensation.

• Lower work satisfaction.

• Disrupted personal relationships.

• Substance misuse.

• Depression.

• Suicide.

Burnout also leads to lower productivity, higher job turnover, and early retirement. In addition, from a systems perspective, burnout is associated with higher medical errors, reduced quality of patient care, and lower patient satisfaction. And, at its most extreme, burnout is deadly: Sadly, every year, 300-400 physicians in the United States commit suicide. Female physicians are 2.3 times more likely to commit suicide than are female nonphysicians; for males, the risk is 1.4 times higher among physicians compared to the general population.1

Proactive approaches

Despite all these sobering statistics on the prevalence and outcomes of burnout among physicians, the ongoing question is, what can we do about it? Although awareness and recognition of burnout has grown substantially over time, successful interventions to prevent or mitigate burnout have not. Many potential interventions and ideas have surfaced and have been published, but none have had impressive impacts or have been adopted widely within or across institutions. According to a Modern Healthcare survey of approximately 100 health care CEOs, only about one-third reported that their organization had programs to address physician burnout, although about another one-third reported attempts to develop such programs.1

The good news is that at least there is a lot of activity around trying new interventions to reduce burnout, including in medical schools and graduate training programs. The thought is that if you can employ healthy resilience tactics during training, these can be carried throughout a career to diminish the risk and/or severity of burnout, despite any challenges that arise along the way.

Some of these interventions are aimed at individuals (to enhance personal resilience and coping skills) while others are aimed at the level of organizations (to reduce organizational stress and/or workload). A recent Modern Healthcare article found several good examples:1

• New York’s Albert Einstein College of Medicine’s WellMed program has been designed to help students develop healthy and balanced habits and attitudes, and to enhance their personal resilience, for the short and the long term.

• Baystate Health in Massachusetts hosts a physician leadership academy that offers training in communication, unconscious bias, strategy, and other management skills, to enhance individual resilience and organizational engagement.

• HealthPartners, a not-for-profit, Minnesota-based health care organization, has specific programs to engage physicians and allow them to have organizational impact, as well as programs to simplify technology use.

Organization efforts are key to prevent, treat

The key to reducing burnout does seem to be employing a combination of self-directed and organization-directed interventions, each of which enhances resilience and reduces workplace stressors (i.e., administrative tasks and workload). Specific to hospitalists, Leslie Flores, MBA, recently wrote about burnout at The Hospital Leader blog. Her list included several specific examples to reduce the top causes of burnout among busy hospitalists:4

• Modifying the skill mix in hospital medicine groups so that less costly support staff are doing much of the work not requiring a physician’s expertise, freeing up hospitalists to provide better care to more patients.

• Reducing unnecessary interruptions and the stress they cause, via both technology and process improvement.

• Paying deliberate attention to hospitalist personal and professional well-being.