User login

Biennial vs annual mammography: How I manage my patients

Controversy surrounds the issue of mammographic screening intervals for older women, with conflicting recommendations from professional organizations and governmental bodies. For example, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends biennial screening for women aged 50 to 74 years,1 whereas the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists2 and the American Cancer Society3 both recommend annual screening for women aged 40 years and older, with no upper age limit. It also has been unclear how patient comorbidities affect screening.

Recently, Braithwaite and colleagues addressed both issues in a prospective trial of 3,000 women with breast cancer and 138,000 women without breast cancer—all of them aged 66 to 89 years.4

What did they find?

Details of the trial. This study was conducted between January 1999 and December 2006. Using logistic-regression analyses, the study authors calculated the odds of advanced tumors and the 10-year cumulative probability of false-positive findings by the frequency of screening (1 vs 2 years), age, and comorbidity score, as determined using the Klabunde approximation of the Charlson score.1

All women underwent mammography at a facility that participated in data linkage between the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium and Medicare claims.

Screening interval had no effect on odds of advanced tumors. The study authors found no difference in the rate of advanced breast cancer (adverse characteristics included stage IIb or higher, tumor size greater than 20 mm, or positive lymph nodes) when screening was biennial versus annual, and no effect of comorbidities on this percentage.4

Annual screening led to more false-positives. In fact, Braithwaite and colleagues found that 48% of women aged 66 to 74 years had at least one false-positive screen in the annual-screening group (95% confidence interval [CI], 46.1–49.9), compared with 29% of biennial screeners (95% CI, 28.1–29.9).1

Balance of data seems to tilt toward biennial screening

In this study, Braithwaite and colleagues observe that their findings are consistent with those of earlier studies indicating that biennial screening retains the benefits of annual assessment and reduces the false-positive rate.

RELATED ARTICLE: Update on Breast Health

Guiding my patients. Although I expect most of my patients aged 50 and older to continue to seek annual mammograms for the foreseeable future, I plan to be flexible about mammography intervals, given these findings. Therefore, if a patient aged 50 years or older is receptive to being screened less often than annually, I would encourage her to be screened every 2 years, provided she is not at elevated risk of breast cancer by virtue of family or personal history, genetic testing, or earlier findings.

1. US Preventive Services Task Force Screening for Breast Cancer. http://www.uspreventiveservicestask force.org/uspstf/uspsbrca.htm. Accessed May 17, 2013.

2. American College of Obstetricians-Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 122: Breast cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 pt 1):372-82.

3. Breast cancer: early detection. American Cancer Society Web site. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/breastcancer/moreinformation/breastcancerearlydetection/breast-cancer-early-detection-acs-recs. Accessed May 17, 2013.

4. Braithwaite D, Zhu W, Hubbard RA, et al. Screening outcomes in older US women undergoing multiple mammograms in community practice: Does interval, age, or comorbidity score affect tumor characteristics or false positive rates? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(5):334–341.

Controversy surrounds the issue of mammographic screening intervals for older women, with conflicting recommendations from professional organizations and governmental bodies. For example, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends biennial screening for women aged 50 to 74 years,1 whereas the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists2 and the American Cancer Society3 both recommend annual screening for women aged 40 years and older, with no upper age limit. It also has been unclear how patient comorbidities affect screening.

Recently, Braithwaite and colleagues addressed both issues in a prospective trial of 3,000 women with breast cancer and 138,000 women without breast cancer—all of them aged 66 to 89 years.4

What did they find?

Details of the trial. This study was conducted between January 1999 and December 2006. Using logistic-regression analyses, the study authors calculated the odds of advanced tumors and the 10-year cumulative probability of false-positive findings by the frequency of screening (1 vs 2 years), age, and comorbidity score, as determined using the Klabunde approximation of the Charlson score.1

All women underwent mammography at a facility that participated in data linkage between the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium and Medicare claims.

Screening interval had no effect on odds of advanced tumors. The study authors found no difference in the rate of advanced breast cancer (adverse characteristics included stage IIb or higher, tumor size greater than 20 mm, or positive lymph nodes) when screening was biennial versus annual, and no effect of comorbidities on this percentage.4

Annual screening led to more false-positives. In fact, Braithwaite and colleagues found that 48% of women aged 66 to 74 years had at least one false-positive screen in the annual-screening group (95% confidence interval [CI], 46.1–49.9), compared with 29% of biennial screeners (95% CI, 28.1–29.9).1

Balance of data seems to tilt toward biennial screening

In this study, Braithwaite and colleagues observe that their findings are consistent with those of earlier studies indicating that biennial screening retains the benefits of annual assessment and reduces the false-positive rate.

RELATED ARTICLE: Update on Breast Health

Guiding my patients. Although I expect most of my patients aged 50 and older to continue to seek annual mammograms for the foreseeable future, I plan to be flexible about mammography intervals, given these findings. Therefore, if a patient aged 50 years or older is receptive to being screened less often than annually, I would encourage her to be screened every 2 years, provided she is not at elevated risk of breast cancer by virtue of family or personal history, genetic testing, or earlier findings.

Controversy surrounds the issue of mammographic screening intervals for older women, with conflicting recommendations from professional organizations and governmental bodies. For example, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends biennial screening for women aged 50 to 74 years,1 whereas the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists2 and the American Cancer Society3 both recommend annual screening for women aged 40 years and older, with no upper age limit. It also has been unclear how patient comorbidities affect screening.

Recently, Braithwaite and colleagues addressed both issues in a prospective trial of 3,000 women with breast cancer and 138,000 women without breast cancer—all of them aged 66 to 89 years.4

What did they find?

Details of the trial. This study was conducted between January 1999 and December 2006. Using logistic-regression analyses, the study authors calculated the odds of advanced tumors and the 10-year cumulative probability of false-positive findings by the frequency of screening (1 vs 2 years), age, and comorbidity score, as determined using the Klabunde approximation of the Charlson score.1

All women underwent mammography at a facility that participated in data linkage between the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium and Medicare claims.

Screening interval had no effect on odds of advanced tumors. The study authors found no difference in the rate of advanced breast cancer (adverse characteristics included stage IIb or higher, tumor size greater than 20 mm, or positive lymph nodes) when screening was biennial versus annual, and no effect of comorbidities on this percentage.4

Annual screening led to more false-positives. In fact, Braithwaite and colleagues found that 48% of women aged 66 to 74 years had at least one false-positive screen in the annual-screening group (95% confidence interval [CI], 46.1–49.9), compared with 29% of biennial screeners (95% CI, 28.1–29.9).1

Balance of data seems to tilt toward biennial screening

In this study, Braithwaite and colleagues observe that their findings are consistent with those of earlier studies indicating that biennial screening retains the benefits of annual assessment and reduces the false-positive rate.

RELATED ARTICLE: Update on Breast Health

Guiding my patients. Although I expect most of my patients aged 50 and older to continue to seek annual mammograms for the foreseeable future, I plan to be flexible about mammography intervals, given these findings. Therefore, if a patient aged 50 years or older is receptive to being screened less often than annually, I would encourage her to be screened every 2 years, provided she is not at elevated risk of breast cancer by virtue of family or personal history, genetic testing, or earlier findings.

1. US Preventive Services Task Force Screening for Breast Cancer. http://www.uspreventiveservicestask force.org/uspstf/uspsbrca.htm. Accessed May 17, 2013.

2. American College of Obstetricians-Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 122: Breast cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 pt 1):372-82.

3. Breast cancer: early detection. American Cancer Society Web site. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/breastcancer/moreinformation/breastcancerearlydetection/breast-cancer-early-detection-acs-recs. Accessed May 17, 2013.

4. Braithwaite D, Zhu W, Hubbard RA, et al. Screening outcomes in older US women undergoing multiple mammograms in community practice: Does interval, age, or comorbidity score affect tumor characteristics or false positive rates? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(5):334–341.

1. US Preventive Services Task Force Screening for Breast Cancer. http://www.uspreventiveservicestask force.org/uspstf/uspsbrca.htm. Accessed May 17, 2013.

2. American College of Obstetricians-Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 122: Breast cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 pt 1):372-82.

3. Breast cancer: early detection. American Cancer Society Web site. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/breastcancer/moreinformation/breastcancerearlydetection/breast-cancer-early-detection-acs-recs. Accessed May 17, 2013.

4. Braithwaite D, Zhu W, Hubbard RA, et al. Screening outcomes in older US women undergoing multiple mammograms in community practice: Does interval, age, or comorbidity score affect tumor characteristics or false positive rates? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(5):334–341.

Four pillars of a successful practice: 3. Obtain and maintain physician referrals

READ THE REST OF THE SERIES

Pillar 1: Keep your current patients happy (March 2013)

Dr. Baum describes his number one strategy to retain patients (Audiocast, March 2013)

Pillar 2: Attract new patients (May 2013)

Pillar 4: Motivate your staff (August 2013)

Discussions of medical marketing often begin with the three As: availability, affability, and affordability. But most physicians already think of themselves as available, likeable, and offering appropriately priced services.

How do you differentiate yourself from the competition?

Fancy stationery; a slick, three-color brochure; a catchy logo; and a Web site will not do the trick. In fact, these are the last things you need.

One of the biggest misconceptions about marketing is that, to do it well, you must spend lots of money on peripherals. In truth, there are many other actions that are far more effective and essential to marketing than merely polishing your public relations image. The most essential element of your marketing plan is to make your practice user-friendly.

Nowhere is this need greater than when it comes to working with colleagues who are capable of referring patients to you—or are already doing so. In this article, I describe 10 strategies you can use to enhance your relationships with referring physicians.

1. WRITE AN EFFECTIVE REFERRAL LETTER

To obtain referrals from your colleagues, you need to ensure that your name crosses their mind and desk as frequently as possible—and in a positive fashion.

If you interview referring physicians, you will find that prompt communication is one of the most important reasons they refer a patient to a particular provider. According to the Annals of Family Medicine, more than 50% of physicians state that effective communication is the reason they select a doctor for referral (TABLE).1

| How primary care physicians select a doctor for referral | |

| Medical skill of the specialist | 87.5% |

| Access to the practice and acceptance of insurance | 59.0% |

| Previous experience with the specialist | 59.2% |

| Quality of communication | 52.5% |

| Board certification of the specialist | 33.9% |

| Medical school, residency | <1% |

Source: Kinchen et al1

Keep your referral letter short

The traditional referral letter is far too long, often 2 or 3 pages. It usually arrives 10 to 14 days after the patient was seen and is very expensive, costing a practice $12–$15 for each letter sent. The goal of an effective referral letter: Get it there before the patient returns to the primary care provider.

The key ingredients of an effective referral letter are:

diagnosis

medications you have prescribed for the patient

your treatment plan.

The referring doctor is not interested in the nuances of your history or physical exam. They just want the three ingredients listed above.

For example, let’s say that Dr. Bill Smith refers Jane Doe, who has an overactive bladder and cystocele. Her urinalysis is negative, so you prescribe an anticholinergic agent and schedule a follow-up visit in 1 month to check symptoms and to conduct a urodynamic study if she has not improved. Your letter to Dr. Smith would read as follows:

Now the letter can be faxed to the referring doctor, often before the patient leaves the office. That way you can be certain that the letter arrives before the patient calls the physician with questions or concerns.

This is the best way to keep the referring physician informed and to function as the captain of the patient’s health-care ship.

EHRs can smooth the referral process

Most electronic health records (EHRs) have the capability to fax the entire note to the referring physician. However, if you were to ask a referring physician if she would like to read your entire note, the answer would probably be “No.” Most EHRs will allow you to select fields that contain the diagnosis, medications prescribed, and the treatment plan. A sample of this kind of letter appears in the FIGURE.

2. MAKE AN EFFORT TO PERSONALLY MEET EVERY PHYSICIAN WHO REFERS A PATIENT

Not only that, but try to meet all new physicians in your area. It is important to coddle your existing sources of referrals, but don’t forget to reach out to new physicians to let them know about your areas of interest or expertise.

3. REFER YOUR NEW PATIENTS TO REFERRING PHYSICIANS

Don’t refer to the same colleagues time after time. If a doctor starts sending new patients your way, it’s in your best interest to “reverse-refer” when a patient needs a primary care doctor, endocrinologist, or cardiologist.

You can be sure these referring doctors will appreciate your recommendations.

Related Article Complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia: When to refer

4. CREATE A LUNCH-AND-LEARN PROGRAM

You want other offices and medical staffs to get to know your staff and to be familiar with what you do. There’s no better way than to create a lunch-and-learn program in your office and extend an invitation to other offices in the area. At the program, have all of the staff members introduce themselves. Provide a tour of your office and give a 3- to 5-minute lecture on areas of your gynecologic interest and expertise.

5. ACKNOWLEDGE THE ACCOMPLISHMENTS OF REFERRING PHYSICIANS AND THEIR FAMILIES

If you see that one of your referring physicians has received an honor or award, send him a congratulatory note. If her children have been recognized for academic or athletic achievement, acknowledge this accomplishment with a note. You can be sure it will be one of the only acknowledgments they receive and will be deeply appreciated.

6. SHARE INFORMATION WITH A NO-MEETING JOURNAL CLUB

It’s very difficult to keep up with the medical literature. It’s challenging enough to keep up with the literature in your own specialty, let alone articles appearing in other specialty publications. One of the nicest gestures you can make is to copy any article that may be of interest to your colleagues and send it to them. Include a sticky note indicating where you would like them to look so that they don’t have to read the entire article.

7. SHARE NONMEDICAL INFORMATION, TOO

Your colleagues will appreciate it when you share nonmedical information to let them know you are thinking of them even when you are not discussing patient care. For example, one of my colleagues collects fine pens. When I saw an article about a very expensive pen made with diamonds, I sent the story to my friend, suggesting that he tell his wife what was on his wish list.

8. KEEP THE REFERRING DOCTOR IN THE MEDICAL LOOP

If you are caring for a patient and plan to discharge her from the hospital, make sure that you or someone in your office contacts the referring doctor to inform him that the patient is being discharged so he doesn’t make unnecessary rounds. Other times to notify the referring doctor:

upon admission of her patient to the hospital

after surgery or a procedure

when you receive a significant laboratory or pathology report.

9. BE USER-FRIENDLY

If you perform gynecologic surgery on a referred patient, be sure to dictate a discharge summary. If the patient is to be discharged with gynecologic medications, give the patient their names in writing. Another convenience for the patient: Arrange your follow-up appointment on the same day she is to return to see the referring physician.

10. DON’T FORGET NONPHYSICIAN REFERRAL SOURCES

Nurses, pharmacists, pharmaceutical representatives, social workers, lawyers, beauticians, and manicurists—all of these professionals are likely to refer patients to you if you keep them in the loop.

11. BOTTOM LINE

You can build a practice by word of mouth by doing a great job of caring for patients, hoping that they will tell others about their positive experience. However, there are other opportunities to enhance your practice—notably, by nurturing your relationship with referring physicians. Try a few of these ideas and you will certainly see your referrals increase significantly.

READ THE REST OF THE SERIES

Pillar 1: Keep your current patients happy (March 2013)

Dr. Baum describes his number one strategy to retain patients (Audiocast, March 2013)

Pillar 2: Attract new patients (May 2013)

Pillar 4: Motivate your staff (August 2013)

Discussions of medical marketing often begin with the three As: availability, affability, and affordability. But most physicians already think of themselves as available, likeable, and offering appropriately priced services.

How do you differentiate yourself from the competition?

Fancy stationery; a slick, three-color brochure; a catchy logo; and a Web site will not do the trick. In fact, these are the last things you need.

One of the biggest misconceptions about marketing is that, to do it well, you must spend lots of money on peripherals. In truth, there are many other actions that are far more effective and essential to marketing than merely polishing your public relations image. The most essential element of your marketing plan is to make your practice user-friendly.

Nowhere is this need greater than when it comes to working with colleagues who are capable of referring patients to you—or are already doing so. In this article, I describe 10 strategies you can use to enhance your relationships with referring physicians.

1. WRITE AN EFFECTIVE REFERRAL LETTER

To obtain referrals from your colleagues, you need to ensure that your name crosses their mind and desk as frequently as possible—and in a positive fashion.

If you interview referring physicians, you will find that prompt communication is one of the most important reasons they refer a patient to a particular provider. According to the Annals of Family Medicine, more than 50% of physicians state that effective communication is the reason they select a doctor for referral (TABLE).1

| How primary care physicians select a doctor for referral | |

| Medical skill of the specialist | 87.5% |

| Access to the practice and acceptance of insurance | 59.0% |

| Previous experience with the specialist | 59.2% |

| Quality of communication | 52.5% |

| Board certification of the specialist | 33.9% |

| Medical school, residency | <1% |

Source: Kinchen et al1

Keep your referral letter short

The traditional referral letter is far too long, often 2 or 3 pages. It usually arrives 10 to 14 days after the patient was seen and is very expensive, costing a practice $12–$15 for each letter sent. The goal of an effective referral letter: Get it there before the patient returns to the primary care provider.

The key ingredients of an effective referral letter are:

diagnosis

medications you have prescribed for the patient

your treatment plan.

The referring doctor is not interested in the nuances of your history or physical exam. They just want the three ingredients listed above.

For example, let’s say that Dr. Bill Smith refers Jane Doe, who has an overactive bladder and cystocele. Her urinalysis is negative, so you prescribe an anticholinergic agent and schedule a follow-up visit in 1 month to check symptoms and to conduct a urodynamic study if she has not improved. Your letter to Dr. Smith would read as follows:

Now the letter can be faxed to the referring doctor, often before the patient leaves the office. That way you can be certain that the letter arrives before the patient calls the physician with questions or concerns.

This is the best way to keep the referring physician informed and to function as the captain of the patient’s health-care ship.

EHRs can smooth the referral process

Most electronic health records (EHRs) have the capability to fax the entire note to the referring physician. However, if you were to ask a referring physician if she would like to read your entire note, the answer would probably be “No.” Most EHRs will allow you to select fields that contain the diagnosis, medications prescribed, and the treatment plan. A sample of this kind of letter appears in the FIGURE.

2. MAKE AN EFFORT TO PERSONALLY MEET EVERY PHYSICIAN WHO REFERS A PATIENT

Not only that, but try to meet all new physicians in your area. It is important to coddle your existing sources of referrals, but don’t forget to reach out to new physicians to let them know about your areas of interest or expertise.

3. REFER YOUR NEW PATIENTS TO REFERRING PHYSICIANS

Don’t refer to the same colleagues time after time. If a doctor starts sending new patients your way, it’s in your best interest to “reverse-refer” when a patient needs a primary care doctor, endocrinologist, or cardiologist.

You can be sure these referring doctors will appreciate your recommendations.

Related Article Complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia: When to refer

4. CREATE A LUNCH-AND-LEARN PROGRAM

You want other offices and medical staffs to get to know your staff and to be familiar with what you do. There’s no better way than to create a lunch-and-learn program in your office and extend an invitation to other offices in the area. At the program, have all of the staff members introduce themselves. Provide a tour of your office and give a 3- to 5-minute lecture on areas of your gynecologic interest and expertise.

5. ACKNOWLEDGE THE ACCOMPLISHMENTS OF REFERRING PHYSICIANS AND THEIR FAMILIES

If you see that one of your referring physicians has received an honor or award, send him a congratulatory note. If her children have been recognized for academic or athletic achievement, acknowledge this accomplishment with a note. You can be sure it will be one of the only acknowledgments they receive and will be deeply appreciated.

6. SHARE INFORMATION WITH A NO-MEETING JOURNAL CLUB

It’s very difficult to keep up with the medical literature. It’s challenging enough to keep up with the literature in your own specialty, let alone articles appearing in other specialty publications. One of the nicest gestures you can make is to copy any article that may be of interest to your colleagues and send it to them. Include a sticky note indicating where you would like them to look so that they don’t have to read the entire article.

7. SHARE NONMEDICAL INFORMATION, TOO

Your colleagues will appreciate it when you share nonmedical information to let them know you are thinking of them even when you are not discussing patient care. For example, one of my colleagues collects fine pens. When I saw an article about a very expensive pen made with diamonds, I sent the story to my friend, suggesting that he tell his wife what was on his wish list.

8. KEEP THE REFERRING DOCTOR IN THE MEDICAL LOOP

If you are caring for a patient and plan to discharge her from the hospital, make sure that you or someone in your office contacts the referring doctor to inform him that the patient is being discharged so he doesn’t make unnecessary rounds. Other times to notify the referring doctor:

upon admission of her patient to the hospital

after surgery or a procedure

when you receive a significant laboratory or pathology report.

9. BE USER-FRIENDLY

If you perform gynecologic surgery on a referred patient, be sure to dictate a discharge summary. If the patient is to be discharged with gynecologic medications, give the patient their names in writing. Another convenience for the patient: Arrange your follow-up appointment on the same day she is to return to see the referring physician.

10. DON’T FORGET NONPHYSICIAN REFERRAL SOURCES

Nurses, pharmacists, pharmaceutical representatives, social workers, lawyers, beauticians, and manicurists—all of these professionals are likely to refer patients to you if you keep them in the loop.

11. BOTTOM LINE

You can build a practice by word of mouth by doing a great job of caring for patients, hoping that they will tell others about their positive experience. However, there are other opportunities to enhance your practice—notably, by nurturing your relationship with referring physicians. Try a few of these ideas and you will certainly see your referrals increase significantly.

READ THE REST OF THE SERIES

Pillar 1: Keep your current patients happy (March 2013)

Dr. Baum describes his number one strategy to retain patients (Audiocast, March 2013)

Pillar 2: Attract new patients (May 2013)

Pillar 4: Motivate your staff (August 2013)

Discussions of medical marketing often begin with the three As: availability, affability, and affordability. But most physicians already think of themselves as available, likeable, and offering appropriately priced services.

How do you differentiate yourself from the competition?

Fancy stationery; a slick, three-color brochure; a catchy logo; and a Web site will not do the trick. In fact, these are the last things you need.

One of the biggest misconceptions about marketing is that, to do it well, you must spend lots of money on peripherals. In truth, there are many other actions that are far more effective and essential to marketing than merely polishing your public relations image. The most essential element of your marketing plan is to make your practice user-friendly.

Nowhere is this need greater than when it comes to working with colleagues who are capable of referring patients to you—or are already doing so. In this article, I describe 10 strategies you can use to enhance your relationships with referring physicians.

1. WRITE AN EFFECTIVE REFERRAL LETTER

To obtain referrals from your colleagues, you need to ensure that your name crosses their mind and desk as frequently as possible—and in a positive fashion.

If you interview referring physicians, you will find that prompt communication is one of the most important reasons they refer a patient to a particular provider. According to the Annals of Family Medicine, more than 50% of physicians state that effective communication is the reason they select a doctor for referral (TABLE).1

| How primary care physicians select a doctor for referral | |

| Medical skill of the specialist | 87.5% |

| Access to the practice and acceptance of insurance | 59.0% |

| Previous experience with the specialist | 59.2% |

| Quality of communication | 52.5% |

| Board certification of the specialist | 33.9% |

| Medical school, residency | <1% |

Source: Kinchen et al1

Keep your referral letter short

The traditional referral letter is far too long, often 2 or 3 pages. It usually arrives 10 to 14 days after the patient was seen and is very expensive, costing a practice $12–$15 for each letter sent. The goal of an effective referral letter: Get it there before the patient returns to the primary care provider.

The key ingredients of an effective referral letter are:

diagnosis

medications you have prescribed for the patient

your treatment plan.

The referring doctor is not interested in the nuances of your history or physical exam. They just want the three ingredients listed above.

For example, let’s say that Dr. Bill Smith refers Jane Doe, who has an overactive bladder and cystocele. Her urinalysis is negative, so you prescribe an anticholinergic agent and schedule a follow-up visit in 1 month to check symptoms and to conduct a urodynamic study if she has not improved. Your letter to Dr. Smith would read as follows:

Now the letter can be faxed to the referring doctor, often before the patient leaves the office. That way you can be certain that the letter arrives before the patient calls the physician with questions or concerns.

This is the best way to keep the referring physician informed and to function as the captain of the patient’s health-care ship.

EHRs can smooth the referral process

Most electronic health records (EHRs) have the capability to fax the entire note to the referring physician. However, if you were to ask a referring physician if she would like to read your entire note, the answer would probably be “No.” Most EHRs will allow you to select fields that contain the diagnosis, medications prescribed, and the treatment plan. A sample of this kind of letter appears in the FIGURE.

2. MAKE AN EFFORT TO PERSONALLY MEET EVERY PHYSICIAN WHO REFERS A PATIENT

Not only that, but try to meet all new physicians in your area. It is important to coddle your existing sources of referrals, but don’t forget to reach out to new physicians to let them know about your areas of interest or expertise.

3. REFER YOUR NEW PATIENTS TO REFERRING PHYSICIANS

Don’t refer to the same colleagues time after time. If a doctor starts sending new patients your way, it’s in your best interest to “reverse-refer” when a patient needs a primary care doctor, endocrinologist, or cardiologist.

You can be sure these referring doctors will appreciate your recommendations.

Related Article Complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia: When to refer

4. CREATE A LUNCH-AND-LEARN PROGRAM

You want other offices and medical staffs to get to know your staff and to be familiar with what you do. There’s no better way than to create a lunch-and-learn program in your office and extend an invitation to other offices in the area. At the program, have all of the staff members introduce themselves. Provide a tour of your office and give a 3- to 5-minute lecture on areas of your gynecologic interest and expertise.

5. ACKNOWLEDGE THE ACCOMPLISHMENTS OF REFERRING PHYSICIANS AND THEIR FAMILIES

If you see that one of your referring physicians has received an honor or award, send him a congratulatory note. If her children have been recognized for academic or athletic achievement, acknowledge this accomplishment with a note. You can be sure it will be one of the only acknowledgments they receive and will be deeply appreciated.

6. SHARE INFORMATION WITH A NO-MEETING JOURNAL CLUB

It’s very difficult to keep up with the medical literature. It’s challenging enough to keep up with the literature in your own specialty, let alone articles appearing in other specialty publications. One of the nicest gestures you can make is to copy any article that may be of interest to your colleagues and send it to them. Include a sticky note indicating where you would like them to look so that they don’t have to read the entire article.

7. SHARE NONMEDICAL INFORMATION, TOO

Your colleagues will appreciate it when you share nonmedical information to let them know you are thinking of them even when you are not discussing patient care. For example, one of my colleagues collects fine pens. When I saw an article about a very expensive pen made with diamonds, I sent the story to my friend, suggesting that he tell his wife what was on his wish list.

8. KEEP THE REFERRING DOCTOR IN THE MEDICAL LOOP

If you are caring for a patient and plan to discharge her from the hospital, make sure that you or someone in your office contacts the referring doctor to inform him that the patient is being discharged so he doesn’t make unnecessary rounds. Other times to notify the referring doctor:

upon admission of her patient to the hospital

after surgery or a procedure

when you receive a significant laboratory or pathology report.

9. BE USER-FRIENDLY

If you perform gynecologic surgery on a referred patient, be sure to dictate a discharge summary. If the patient is to be discharged with gynecologic medications, give the patient their names in writing. Another convenience for the patient: Arrange your follow-up appointment on the same day she is to return to see the referring physician.

10. DON’T FORGET NONPHYSICIAN REFERRAL SOURCES

Nurses, pharmacists, pharmaceutical representatives, social workers, lawyers, beauticians, and manicurists—all of these professionals are likely to refer patients to you if you keep them in the loop.

11. BOTTOM LINE

You can build a practice by word of mouth by doing a great job of caring for patients, hoping that they will tell others about their positive experience. However, there are other opportunities to enhance your practice—notably, by nurturing your relationship with referring physicians. Try a few of these ideas and you will certainly see your referrals increase significantly.

STOP performing dilation and curettage for the evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding

CASE: In-office hysteroscopy spies previously missed polyp

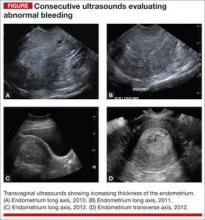

A 51-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer completed 5 years of tamoxifen. During her treatment she had a 3-year history of abnormal vaginal bleeding. Results from consecutive pelvic ultrasounds indicated that the patient had progressively thickening endometrium (from 1.4 cm to 2.5 cm to 4.7 cm). In-office biopsy was negative for endometrial pathology. An ultimate dilation and curettage (D&C) was performed with negative histologic diagnosis. The patient is seen in consultation, and the ultrasound images are reviewed (FIGURE).

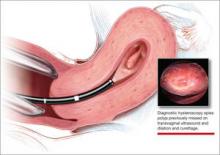

These images show an increasing thickness of the ednometrium with definitive intracavitary pathology that was missed with the prevous clinical evaluation with enodmetrial biopsy and D&C. An in-office hysteroscopy is performed, and a large 5 x 4 x 7 cm cystic and fibrous polyp is identified with normal endometrium (VIDEO 1).

Hysteroscopy reveals massive polyp extending into a dilated lower uterine segment

Abnormal uterine bleeding

The evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding. (AUB), as described in this clinical scenario, is quite common. As a consequence, many patients have a missed or inaccurate diagnosis and undergo unnecessary invasive procedures under general anesthesia.

AUB is one of the primary indications for a gynecologic consultation, accounting for approximately 33% of all gynecology visits, and for 69% of visits among postmenopausal women.1 Confirming the etiology and planning appropriate intervention is important in the clinical management of AUB because accurate diagnosis may result in avoiding major gynecologic surgery in favor of minimally invasive hysteroscopic management.

Diagnostic hysteroscopy is proven in AUB evaluation

Drawbacks of other diagnostic tools. It is generally accepted that the initial evaluation of women with AUB is performed with noninvasive transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS).1-3 As illustrated by the opening case, however, the accuracy of TVUS is limited in the diagnosis of focal endometrial lesions, and further investigation of the uterine cavity is warranted.

Evaluation of the uterine cavity with sonohysterography (SH)—vaginal ultrasound with the instillation of saline into the uterine cavity—is more accurate than TVUS alone. Yet, diagnostic hysteroscopy (DH) has proven to be superior to either modality for the accurate evaluation of intracavitary pathology.1-3

Evidence of DH superiority. Farquhar and colleagues reported results of a systematic review of studies published from 1980 to July 2001 that examined TVUS versus SH and DH for the investigation of AUB in premenopausal women. The researchers found that TVUS had a higher rate of false negatives for detecting intrauterine pathology, compared with SH and DH. They also found that DH was superior to SH in diagnosing submucous myomas.2

In 2010, results of a prospective comparison of TVUS, SH, and DH for detecting endometrial pathology, showed that DH had a significantly better diagnostic performance than SH and TVUS and that hysteroscopy was significantly more precise in the diagnosis of intracavitary masses.3

Again, in 2012, a prospective comparison of TVUS, SH, and DH in the diagnosis of AUB revealed that hysteroscopy provided the most accurate diagnosis.1

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, van Dongen found the accuracy of DH to be estimated at 96.9%.4

Hysteroscopy is also considered to be more comfortable for patients than SH.2

blinded sampling missed intracavitary lesions such as polyps and myomas that accounted for bleeding abnormalities.5

A procedure performed “blind” limits its usefulness in AUB evaluation

This statement is not a new realization. As far back as 1989, Loffer showed that blind D&C was less accurate for diagnosing AUB than was hysteroscopy with visually directed biopsy. The sensitivity of diagnosing the etiology of AUB with D&C was 65%, compared to a sensitivity of 98% with hysteroscopy with directed biopsy. Hysteroscopy was shown to be better because blinded sampling missed intracavitary lesions such as polyps and myomas that accounted for bleeding abnormalities.5

The limitations of D&C are evident in the opening case, as the D&C performed in the operating room under general anesthesia, without visualization of the uterine cavity, failed to identify the patient’s intrauterine pathology. D&C is seldom necessary to evaluate AUB and has significant surgical risks beyond general anesthesia, including cervical or uterine trauma that can occur with cervical dilation and instrumentation of the uterus.

As with D&C, endometrial biopsy has limitations in diagnosing abnormalities within the uterine cavity. In a 2008 prospective comparative study of hysteroscopy versus blind biopsy with a suction biopsy curette, Angioni and colleagues showed a significant difference in the capability of these two procedures to accurately diagnose the etiology of bleeding for menopausal women. Blinded biopsy had a sensitivity for diagnosing polyps, myomas, and hyperplasia of 11%, 13%, and 25%, respectively. The sensitivity of hysteroscopy to diagnose the same intracavitary pathology was 89%, 100%, and 74%, respectively.6

This does not mean, however, that the endometrial biopsy is not beneficial in the evaluation of AUB. Several authors recommend that in a clinically relevant situation, endometrial biopsy with a small suction curette should be performed concomitantly with hysteroscopy to improve the sensitivity of the overall evaluation with histology.7,8 And, as Loffer showed, the hysteroscopic evaluation with a visually directed biopsy is extremely accurate (VIDEO 2, VIDEO 3).5

The bottom line for D&C use in AUB evaluation

Sometimes a D&C is needed. For instance, when more tissue is needed for histologic evaluation than can be obtained with small suction curette at endometrial biopsy. However, there are several shortcomings of D&C for the evaluation of AUB:

- Most clinicians perform D&C in the operating room under general anesthesia.

- It is often done without concomitant hysteroscopy.

- There is significant potential to miss pathology, such as polyps or myomas.

- There is risk of uterine perforation with cervical dilation and uterine instrumentation.

- Hysteroscopy with visually directed biopsy provides a method that offers a more accurate diagnosis, and the procedure can be performed in the office.

In-office AUB evaluation using hysteroscopy is possible and advantageous

Hysteroscopy not only has increased accuracy for identifying the etiology of AUB, compared with D&C, but also offers the possibility of in-office use. Newer hysteroscopes with small diameters and decreasing costs of hysteroscopic equipment allow gynecologists to perform hysteroscopy economically and safely in the office.

Office evaluation of the uterine cavity and preoperative decision-making before a patient is taken to the operating room (OR) improve the likelihood that the appropriate procedure will be performed. They also provide an opportunity for the patient to see inside her own uterine cavity and for the surgeon to discuss management options with her (VIDEO 4: Diagnostic hysteroscopy with fundal myoma, VIDEO 5: Diagnostic hysteroscopy in a menopausal patient with atypical hyperplasia, VIDEO 6: Diagnostic hysteroscopy in a menopausal patient with polyps). If pathology is noted, there is a potential to treat abnormalities such as endometrial polyps at the same time, thus avoiding the OR altogether (VIDEO 7).

The small diameter of the hysteroscope allows evaluation in most menopausal and nulliparous patients comfortably without first having to dilate or soften the cervix. Paracervical placement of local anesthetic can be used as needed for patient comfort (VIDEO 8).9 A vaginoscopic approach will eliminate the discomfort of having to place a speculum (VIDEO 9).

It offers:

- a familiar and comfortable environment for the procedure

- saved time for patient and physician

- saved money for the patient with a large deductible or coinsurance

- no requirement for general anesthesia

- local anesthesia can be used but is not necessary

- immediate visual affirmation for the patient and physician

- a see and treat possibility

- possibility of preoperative decision-making

- saved trip to the OR if significant precancer or cancer is identified

- use in menopausal and nulliparous patients with no cervical preparation necessary when a small-diameter hysteroscope or flexible hysteroscope is used

- minimized discomfort from a speculum with the vaginoscopic approach for awake patients

- possibility of cervical access when needed (VIDEO 10).

My clinical recommendation

Use office hysteroscopy with endometrial biopsy as needed with the opportunity to perform a directed biopsy.

Coding for in-office hysteroscopy

Some procedures now can be performed in the office setting. Among these is operative hysteroscopy, for things such as abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), foreign body removal, and tubal occlusion. When performing hysteroscopic evaluation of AUB, the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 58558 (Hysteroscopy, surgical; with sampling (biopsy) of endometrium and/or polypectomy, with or without D&C) should be reported. This code is reported whether polyp(s) are removed or a sampling of the uterine lining or a full D&C is performed.

Under the Resource-Based Relative Value System (RBRVS), used by the majority of payers for reimbursement, there is a payment differential for site of service. In other words, when performed in the office setting, reimbursement will be higher than in the hospital setting to offset the increased practice expenses incurred. In the office setting, 58558 has 11.93 relative value units. In comparison, a D&C performed without hysteroscopy has 7.75 relative value units in the office setting. Keep in mind, however, that all supplies used in performing this procedure are included in the reimbursement amount.

Some payers will reimburse separately for administering a regional anesthetic, but a local anesthetic is considered integral to the procedure. Under CPT rules, you may bill separately for regional anesthesia. When performing office hysteroscopy, the most common regional anesthesia would be a paracervical nerve block (CPT code 66435—Injection, anesthetic agent; paracervical [uterine] nerve). Under CPT rules, coding should go in as 58558-47, 64435-51. The modifier -47 lets the payer know that the physician performed the regional block, and the modifier -51 identifies the regional block as a multiple procedure.

Medicare, however, will never reimburse separately for regional anesthesia performed by the operating physician, and because of this, Medicare’s Correct Coding Initiative (CCI) permanently bundles 64435 when billed with 58558. Medicare will not permit a modifier to be used to bypass this bundling edit, and separate payment is never allowed. If your payer has adopted this Medicare policy, separate payment will also not be made.

—Melanie Witt, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

Ms. Witt is an independent coding and documentation consultant and former program manager, department of coding and nomenclature, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

- Soguktas S, Cogendez E, Kayatas SE, Asoglu MR, Selcuk S, Ertekin A. Comparison of saline infusion sonohysterography and hysteroscopy in diagnosis of premenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Repro Biol. 2012;161(1):66−70.

- Farquhar C, Ekeroma A, Furness S, Arroll B. A systematic review of transvaginal ultrasonography, sonohysterography and hysteroscopy for the investigation of abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal bleeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(6):493–504.

- Grimbizis GF, Tsolakidis D, Mikos T, et al. A prospective comparison of transvaginal ultrasound, saline infusion sonohysterography, and diagnostic hysteroscopy in the evaluation of endometrial pathology. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(7):2721−2725.

- van Dongen H, de Kroon CD, Jacobi CE, Trimbos JB, Jansen FW. Diagnostic hysteroscopy in abnormal uterine bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2007;114(6):664–75.

- Loffer FD. Hysteroscopy with selective endometrial sampling compared with D & C for abnormal uterine bleeding: the value of a negative hysteroscopic view. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73(1):16–20.

- Angioni S, Loddo A, Milano F, Piras B, Minerba L, Melis GB. Detection of benign intracavitary lesions in postmenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding: a prospective comparative study on outpatient hysteroscopy and blind biopsy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(1):87–91.

- Lo KY, Yuen PM. The role of outpatient diagnostic hysteroscopy in identifying anatomic pathology and histopathology in the endometrial cavity. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7(3):381–385.

- Garuti G, Sambruni I, Colonneli M, Luerti M. Accuracy of hysteroscopy in predicting histopathology of endometrium in 1500 women. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2001;8(2):207–213.

- Munro MG, Brooks PG. Use of local anesthesia for office diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(6):709–718.

CASE: In-office hysteroscopy spies previously missed polyp

A 51-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer completed 5 years of tamoxifen. During her treatment she had a 3-year history of abnormal vaginal bleeding. Results from consecutive pelvic ultrasounds indicated that the patient had progressively thickening endometrium (from 1.4 cm to 2.5 cm to 4.7 cm). In-office biopsy was negative for endometrial pathology. An ultimate dilation and curettage (D&C) was performed with negative histologic diagnosis. The patient is seen in consultation, and the ultrasound images are reviewed (FIGURE).

These images show an increasing thickness of the ednometrium with definitive intracavitary pathology that was missed with the prevous clinical evaluation with enodmetrial biopsy and D&C. An in-office hysteroscopy is performed, and a large 5 x 4 x 7 cm cystic and fibrous polyp is identified with normal endometrium (VIDEO 1).

Hysteroscopy reveals massive polyp extending into a dilated lower uterine segment

Abnormal uterine bleeding

The evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding. (AUB), as described in this clinical scenario, is quite common. As a consequence, many patients have a missed or inaccurate diagnosis and undergo unnecessary invasive procedures under general anesthesia.

AUB is one of the primary indications for a gynecologic consultation, accounting for approximately 33% of all gynecology visits, and for 69% of visits among postmenopausal women.1 Confirming the etiology and planning appropriate intervention is important in the clinical management of AUB because accurate diagnosis may result in avoiding major gynecologic surgery in favor of minimally invasive hysteroscopic management.

Diagnostic hysteroscopy is proven in AUB evaluation

Drawbacks of other diagnostic tools. It is generally accepted that the initial evaluation of women with AUB is performed with noninvasive transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS).1-3 As illustrated by the opening case, however, the accuracy of TVUS is limited in the diagnosis of focal endometrial lesions, and further investigation of the uterine cavity is warranted.

Evaluation of the uterine cavity with sonohysterography (SH)—vaginal ultrasound with the instillation of saline into the uterine cavity—is more accurate than TVUS alone. Yet, diagnostic hysteroscopy (DH) has proven to be superior to either modality for the accurate evaluation of intracavitary pathology.1-3

Evidence of DH superiority. Farquhar and colleagues reported results of a systematic review of studies published from 1980 to July 2001 that examined TVUS versus SH and DH for the investigation of AUB in premenopausal women. The researchers found that TVUS had a higher rate of false negatives for detecting intrauterine pathology, compared with SH and DH. They also found that DH was superior to SH in diagnosing submucous myomas.2

In 2010, results of a prospective comparison of TVUS, SH, and DH for detecting endometrial pathology, showed that DH had a significantly better diagnostic performance than SH and TVUS and that hysteroscopy was significantly more precise in the diagnosis of intracavitary masses.3

Again, in 2012, a prospective comparison of TVUS, SH, and DH in the diagnosis of AUB revealed that hysteroscopy provided the most accurate diagnosis.1

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, van Dongen found the accuracy of DH to be estimated at 96.9%.4

Hysteroscopy is also considered to be more comfortable for patients than SH.2

blinded sampling missed intracavitary lesions such as polyps and myomas that accounted for bleeding abnormalities.5

A procedure performed “blind” limits its usefulness in AUB evaluation

This statement is not a new realization. As far back as 1989, Loffer showed that blind D&C was less accurate for diagnosing AUB than was hysteroscopy with visually directed biopsy. The sensitivity of diagnosing the etiology of AUB with D&C was 65%, compared to a sensitivity of 98% with hysteroscopy with directed biopsy. Hysteroscopy was shown to be better because blinded sampling missed intracavitary lesions such as polyps and myomas that accounted for bleeding abnormalities.5

The limitations of D&C are evident in the opening case, as the D&C performed in the operating room under general anesthesia, without visualization of the uterine cavity, failed to identify the patient’s intrauterine pathology. D&C is seldom necessary to evaluate AUB and has significant surgical risks beyond general anesthesia, including cervical or uterine trauma that can occur with cervical dilation and instrumentation of the uterus.

As with D&C, endometrial biopsy has limitations in diagnosing abnormalities within the uterine cavity. In a 2008 prospective comparative study of hysteroscopy versus blind biopsy with a suction biopsy curette, Angioni and colleagues showed a significant difference in the capability of these two procedures to accurately diagnose the etiology of bleeding for menopausal women. Blinded biopsy had a sensitivity for diagnosing polyps, myomas, and hyperplasia of 11%, 13%, and 25%, respectively. The sensitivity of hysteroscopy to diagnose the same intracavitary pathology was 89%, 100%, and 74%, respectively.6

This does not mean, however, that the endometrial biopsy is not beneficial in the evaluation of AUB. Several authors recommend that in a clinically relevant situation, endometrial biopsy with a small suction curette should be performed concomitantly with hysteroscopy to improve the sensitivity of the overall evaluation with histology.7,8 And, as Loffer showed, the hysteroscopic evaluation with a visually directed biopsy is extremely accurate (VIDEO 2, VIDEO 3).5

The bottom line for D&C use in AUB evaluation

Sometimes a D&C is needed. For instance, when more tissue is needed for histologic evaluation than can be obtained with small suction curette at endometrial biopsy. However, there are several shortcomings of D&C for the evaluation of AUB:

- Most clinicians perform D&C in the operating room under general anesthesia.

- It is often done without concomitant hysteroscopy.

- There is significant potential to miss pathology, such as polyps or myomas.

- There is risk of uterine perforation with cervical dilation and uterine instrumentation.

- Hysteroscopy with visually directed biopsy provides a method that offers a more accurate diagnosis, and the procedure can be performed in the office.

In-office AUB evaluation using hysteroscopy is possible and advantageous

Hysteroscopy not only has increased accuracy for identifying the etiology of AUB, compared with D&C, but also offers the possibility of in-office use. Newer hysteroscopes with small diameters and decreasing costs of hysteroscopic equipment allow gynecologists to perform hysteroscopy economically and safely in the office.

Office evaluation of the uterine cavity and preoperative decision-making before a patient is taken to the operating room (OR) improve the likelihood that the appropriate procedure will be performed. They also provide an opportunity for the patient to see inside her own uterine cavity and for the surgeon to discuss management options with her (VIDEO 4: Diagnostic hysteroscopy with fundal myoma, VIDEO 5: Diagnostic hysteroscopy in a menopausal patient with atypical hyperplasia, VIDEO 6: Diagnostic hysteroscopy in a menopausal patient with polyps). If pathology is noted, there is a potential to treat abnormalities such as endometrial polyps at the same time, thus avoiding the OR altogether (VIDEO 7).

The small diameter of the hysteroscope allows evaluation in most menopausal and nulliparous patients comfortably without first having to dilate or soften the cervix. Paracervical placement of local anesthetic can be used as needed for patient comfort (VIDEO 8).9 A vaginoscopic approach will eliminate the discomfort of having to place a speculum (VIDEO 9).

It offers:

- a familiar and comfortable environment for the procedure

- saved time for patient and physician

- saved money for the patient with a large deductible or coinsurance

- no requirement for general anesthesia

- local anesthesia can be used but is not necessary

- immediate visual affirmation for the patient and physician

- a see and treat possibility

- possibility of preoperative decision-making

- saved trip to the OR if significant precancer or cancer is identified

- use in menopausal and nulliparous patients with no cervical preparation necessary when a small-diameter hysteroscope or flexible hysteroscope is used

- minimized discomfort from a speculum with the vaginoscopic approach for awake patients

- possibility of cervical access when needed (VIDEO 10).

My clinical recommendation

Use office hysteroscopy with endometrial biopsy as needed with the opportunity to perform a directed biopsy.

Coding for in-office hysteroscopy

Some procedures now can be performed in the office setting. Among these is operative hysteroscopy, for things such as abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), foreign body removal, and tubal occlusion. When performing hysteroscopic evaluation of AUB, the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 58558 (Hysteroscopy, surgical; with sampling (biopsy) of endometrium and/or polypectomy, with or without D&C) should be reported. This code is reported whether polyp(s) are removed or a sampling of the uterine lining or a full D&C is performed.

Under the Resource-Based Relative Value System (RBRVS), used by the majority of payers for reimbursement, there is a payment differential for site of service. In other words, when performed in the office setting, reimbursement will be higher than in the hospital setting to offset the increased practice expenses incurred. In the office setting, 58558 has 11.93 relative value units. In comparison, a D&C performed without hysteroscopy has 7.75 relative value units in the office setting. Keep in mind, however, that all supplies used in performing this procedure are included in the reimbursement amount.

Some payers will reimburse separately for administering a regional anesthetic, but a local anesthetic is considered integral to the procedure. Under CPT rules, you may bill separately for regional anesthesia. When performing office hysteroscopy, the most common regional anesthesia would be a paracervical nerve block (CPT code 66435—Injection, anesthetic agent; paracervical [uterine] nerve). Under CPT rules, coding should go in as 58558-47, 64435-51. The modifier -47 lets the payer know that the physician performed the regional block, and the modifier -51 identifies the regional block as a multiple procedure.

Medicare, however, will never reimburse separately for regional anesthesia performed by the operating physician, and because of this, Medicare’s Correct Coding Initiative (CCI) permanently bundles 64435 when billed with 58558. Medicare will not permit a modifier to be used to bypass this bundling edit, and separate payment is never allowed. If your payer has adopted this Medicare policy, separate payment will also not be made.

—Melanie Witt, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

Ms. Witt is an independent coding and documentation consultant and former program manager, department of coding and nomenclature, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

CASE: In-office hysteroscopy spies previously missed polyp

A 51-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer completed 5 years of tamoxifen. During her treatment she had a 3-year history of abnormal vaginal bleeding. Results from consecutive pelvic ultrasounds indicated that the patient had progressively thickening endometrium (from 1.4 cm to 2.5 cm to 4.7 cm). In-office biopsy was negative for endometrial pathology. An ultimate dilation and curettage (D&C) was performed with negative histologic diagnosis. The patient is seen in consultation, and the ultrasound images are reviewed (FIGURE).

These images show an increasing thickness of the ednometrium with definitive intracavitary pathology that was missed with the prevous clinical evaluation with enodmetrial biopsy and D&C. An in-office hysteroscopy is performed, and a large 5 x 4 x 7 cm cystic and fibrous polyp is identified with normal endometrium (VIDEO 1).

Hysteroscopy reveals massive polyp extending into a dilated lower uterine segment

Abnormal uterine bleeding

The evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding. (AUB), as described in this clinical scenario, is quite common. As a consequence, many patients have a missed or inaccurate diagnosis and undergo unnecessary invasive procedures under general anesthesia.

AUB is one of the primary indications for a gynecologic consultation, accounting for approximately 33% of all gynecology visits, and for 69% of visits among postmenopausal women.1 Confirming the etiology and planning appropriate intervention is important in the clinical management of AUB because accurate diagnosis may result in avoiding major gynecologic surgery in favor of minimally invasive hysteroscopic management.

Diagnostic hysteroscopy is proven in AUB evaluation

Drawbacks of other diagnostic tools. It is generally accepted that the initial evaluation of women with AUB is performed with noninvasive transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS).1-3 As illustrated by the opening case, however, the accuracy of TVUS is limited in the diagnosis of focal endometrial lesions, and further investigation of the uterine cavity is warranted.

Evaluation of the uterine cavity with sonohysterography (SH)—vaginal ultrasound with the instillation of saline into the uterine cavity—is more accurate than TVUS alone. Yet, diagnostic hysteroscopy (DH) has proven to be superior to either modality for the accurate evaluation of intracavitary pathology.1-3

Evidence of DH superiority. Farquhar and colleagues reported results of a systematic review of studies published from 1980 to July 2001 that examined TVUS versus SH and DH for the investigation of AUB in premenopausal women. The researchers found that TVUS had a higher rate of false negatives for detecting intrauterine pathology, compared with SH and DH. They also found that DH was superior to SH in diagnosing submucous myomas.2

In 2010, results of a prospective comparison of TVUS, SH, and DH for detecting endometrial pathology, showed that DH had a significantly better diagnostic performance than SH and TVUS and that hysteroscopy was significantly more precise in the diagnosis of intracavitary masses.3

Again, in 2012, a prospective comparison of TVUS, SH, and DH in the diagnosis of AUB revealed that hysteroscopy provided the most accurate diagnosis.1

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, van Dongen found the accuracy of DH to be estimated at 96.9%.4

Hysteroscopy is also considered to be more comfortable for patients than SH.2

blinded sampling missed intracavitary lesions such as polyps and myomas that accounted for bleeding abnormalities.5

A procedure performed “blind” limits its usefulness in AUB evaluation

This statement is not a new realization. As far back as 1989, Loffer showed that blind D&C was less accurate for diagnosing AUB than was hysteroscopy with visually directed biopsy. The sensitivity of diagnosing the etiology of AUB with D&C was 65%, compared to a sensitivity of 98% with hysteroscopy with directed biopsy. Hysteroscopy was shown to be better because blinded sampling missed intracavitary lesions such as polyps and myomas that accounted for bleeding abnormalities.5

The limitations of D&C are evident in the opening case, as the D&C performed in the operating room under general anesthesia, without visualization of the uterine cavity, failed to identify the patient’s intrauterine pathology. D&C is seldom necessary to evaluate AUB and has significant surgical risks beyond general anesthesia, including cervical or uterine trauma that can occur with cervical dilation and instrumentation of the uterus.

As with D&C, endometrial biopsy has limitations in diagnosing abnormalities within the uterine cavity. In a 2008 prospective comparative study of hysteroscopy versus blind biopsy with a suction biopsy curette, Angioni and colleagues showed a significant difference in the capability of these two procedures to accurately diagnose the etiology of bleeding for menopausal women. Blinded biopsy had a sensitivity for diagnosing polyps, myomas, and hyperplasia of 11%, 13%, and 25%, respectively. The sensitivity of hysteroscopy to diagnose the same intracavitary pathology was 89%, 100%, and 74%, respectively.6

This does not mean, however, that the endometrial biopsy is not beneficial in the evaluation of AUB. Several authors recommend that in a clinically relevant situation, endometrial biopsy with a small suction curette should be performed concomitantly with hysteroscopy to improve the sensitivity of the overall evaluation with histology.7,8 And, as Loffer showed, the hysteroscopic evaluation with a visually directed biopsy is extremely accurate (VIDEO 2, VIDEO 3).5

The bottom line for D&C use in AUB evaluation

Sometimes a D&C is needed. For instance, when more tissue is needed for histologic evaluation than can be obtained with small suction curette at endometrial biopsy. However, there are several shortcomings of D&C for the evaluation of AUB:

- Most clinicians perform D&C in the operating room under general anesthesia.

- It is often done without concomitant hysteroscopy.

- There is significant potential to miss pathology, such as polyps or myomas.

- There is risk of uterine perforation with cervical dilation and uterine instrumentation.

- Hysteroscopy with visually directed biopsy provides a method that offers a more accurate diagnosis, and the procedure can be performed in the office.

In-office AUB evaluation using hysteroscopy is possible and advantageous

Hysteroscopy not only has increased accuracy for identifying the etiology of AUB, compared with D&C, but also offers the possibility of in-office use. Newer hysteroscopes with small diameters and decreasing costs of hysteroscopic equipment allow gynecologists to perform hysteroscopy economically and safely in the office.

Office evaluation of the uterine cavity and preoperative decision-making before a patient is taken to the operating room (OR) improve the likelihood that the appropriate procedure will be performed. They also provide an opportunity for the patient to see inside her own uterine cavity and for the surgeon to discuss management options with her (VIDEO 4: Diagnostic hysteroscopy with fundal myoma, VIDEO 5: Diagnostic hysteroscopy in a menopausal patient with atypical hyperplasia, VIDEO 6: Diagnostic hysteroscopy in a menopausal patient with polyps). If pathology is noted, there is a potential to treat abnormalities such as endometrial polyps at the same time, thus avoiding the OR altogether (VIDEO 7).

The small diameter of the hysteroscope allows evaluation in most menopausal and nulliparous patients comfortably without first having to dilate or soften the cervix. Paracervical placement of local anesthetic can be used as needed for patient comfort (VIDEO 8).9 A vaginoscopic approach will eliminate the discomfort of having to place a speculum (VIDEO 9).

It offers:

- a familiar and comfortable environment for the procedure

- saved time for patient and physician

- saved money for the patient with a large deductible or coinsurance

- no requirement for general anesthesia

- local anesthesia can be used but is not necessary

- immediate visual affirmation for the patient and physician

- a see and treat possibility

- possibility of preoperative decision-making

- saved trip to the OR if significant precancer or cancer is identified

- use in menopausal and nulliparous patients with no cervical preparation necessary when a small-diameter hysteroscope or flexible hysteroscope is used

- minimized discomfort from a speculum with the vaginoscopic approach for awake patients

- possibility of cervical access when needed (VIDEO 10).

My clinical recommendation

Use office hysteroscopy with endometrial biopsy as needed with the opportunity to perform a directed biopsy.

Coding for in-office hysteroscopy

Some procedures now can be performed in the office setting. Among these is operative hysteroscopy, for things such as abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), foreign body removal, and tubal occlusion. When performing hysteroscopic evaluation of AUB, the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 58558 (Hysteroscopy, surgical; with sampling (biopsy) of endometrium and/or polypectomy, with or without D&C) should be reported. This code is reported whether polyp(s) are removed or a sampling of the uterine lining or a full D&C is performed.

Under the Resource-Based Relative Value System (RBRVS), used by the majority of payers for reimbursement, there is a payment differential for site of service. In other words, when performed in the office setting, reimbursement will be higher than in the hospital setting to offset the increased practice expenses incurred. In the office setting, 58558 has 11.93 relative value units. In comparison, a D&C performed without hysteroscopy has 7.75 relative value units in the office setting. Keep in mind, however, that all supplies used in performing this procedure are included in the reimbursement amount.

Some payers will reimburse separately for administering a regional anesthetic, but a local anesthetic is considered integral to the procedure. Under CPT rules, you may bill separately for regional anesthesia. When performing office hysteroscopy, the most common regional anesthesia would be a paracervical nerve block (CPT code 66435—Injection, anesthetic agent; paracervical [uterine] nerve). Under CPT rules, coding should go in as 58558-47, 64435-51. The modifier -47 lets the payer know that the physician performed the regional block, and the modifier -51 identifies the regional block as a multiple procedure.

Medicare, however, will never reimburse separately for regional anesthesia performed by the operating physician, and because of this, Medicare’s Correct Coding Initiative (CCI) permanently bundles 64435 when billed with 58558. Medicare will not permit a modifier to be used to bypass this bundling edit, and separate payment is never allowed. If your payer has adopted this Medicare policy, separate payment will also not be made.

—Melanie Witt, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

Ms. Witt is an independent coding and documentation consultant and former program manager, department of coding and nomenclature, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

- Soguktas S, Cogendez E, Kayatas SE, Asoglu MR, Selcuk S, Ertekin A. Comparison of saline infusion sonohysterography and hysteroscopy in diagnosis of premenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Repro Biol. 2012;161(1):66−70.

- Farquhar C, Ekeroma A, Furness S, Arroll B. A systematic review of transvaginal ultrasonography, sonohysterography and hysteroscopy for the investigation of abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal bleeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(6):493–504.

- Grimbizis GF, Tsolakidis D, Mikos T, et al. A prospective comparison of transvaginal ultrasound, saline infusion sonohysterography, and diagnostic hysteroscopy in the evaluation of endometrial pathology. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(7):2721−2725.

- van Dongen H, de Kroon CD, Jacobi CE, Trimbos JB, Jansen FW. Diagnostic hysteroscopy in abnormal uterine bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2007;114(6):664–75.

- Loffer FD. Hysteroscopy with selective endometrial sampling compared with D & C for abnormal uterine bleeding: the value of a negative hysteroscopic view. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73(1):16–20.

- Angioni S, Loddo A, Milano F, Piras B, Minerba L, Melis GB. Detection of benign intracavitary lesions in postmenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding: a prospective comparative study on outpatient hysteroscopy and blind biopsy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(1):87–91.

- Lo KY, Yuen PM. The role of outpatient diagnostic hysteroscopy in identifying anatomic pathology and histopathology in the endometrial cavity. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7(3):381–385.

- Garuti G, Sambruni I, Colonneli M, Luerti M. Accuracy of hysteroscopy in predicting histopathology of endometrium in 1500 women. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2001;8(2):207–213.

- Munro MG, Brooks PG. Use of local anesthesia for office diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(6):709–718.

- Soguktas S, Cogendez E, Kayatas SE, Asoglu MR, Selcuk S, Ertekin A. Comparison of saline infusion sonohysterography and hysteroscopy in diagnosis of premenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Repro Biol. 2012;161(1):66−70.

- Farquhar C, Ekeroma A, Furness S, Arroll B. A systematic review of transvaginal ultrasonography, sonohysterography and hysteroscopy for the investigation of abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal bleeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(6):493–504.

- Grimbizis GF, Tsolakidis D, Mikos T, et al. A prospective comparison of transvaginal ultrasound, saline infusion sonohysterography, and diagnostic hysteroscopy in the evaluation of endometrial pathology. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(7):2721−2725.

- van Dongen H, de Kroon CD, Jacobi CE, Trimbos JB, Jansen FW. Diagnostic hysteroscopy in abnormal uterine bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2007;114(6):664–75.

- Loffer FD. Hysteroscopy with selective endometrial sampling compared with D & C for abnormal uterine bleeding: the value of a negative hysteroscopic view. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73(1):16–20.

- Angioni S, Loddo A, Milano F, Piras B, Minerba L, Melis GB. Detection of benign intracavitary lesions in postmenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding: a prospective comparative study on outpatient hysteroscopy and blind biopsy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(1):87–91.

- Lo KY, Yuen PM. The role of outpatient diagnostic hysteroscopy in identifying anatomic pathology and histopathology in the endometrial cavity. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7(3):381–385.

- Garuti G, Sambruni I, Colonneli M, Luerti M. Accuracy of hysteroscopy in predicting histopathology of endometrium in 1500 women. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2001;8(2):207–213.

- Munro MG, Brooks PG. Use of local anesthesia for office diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(6):709–718.