User login

Personalizing depression treatment: 2 clinical tools

Approximately one-half of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) will have partial or nonresponse to first-line antidepressant monotherapy, despite receiving an adequate dosage and sufficient duration of treatment.1 This has led to the definition of treatment-resistant depression (TRD) as a depressive episode that has shown insufficient response to ≥1 trial of an antidepressant that has demonstrated efficacy in clinical trials.1 Depressed patients should be treated to full remission because absence of complete remission is associated with:

- a more recurrent and chronic illness course2,3

- increased medical and psychiatric comorbidities

- greater functional burden

- increased social and economic costs linked with impaired social functioning.4

Clinicians need to properly identify MDD and treatment resistance to guide optimal treatment choices. Additional tools are necessary to accurately identify, document, and communicate about symptoms commonly experienced by depressed patients but not fully characterized by DSM-IV-TR MDD criteria.5 Finally, in many cases, trait or situational factors might obfuscate accurate diagnosis and the natural course of illness, and tools that can be implemented practically will help identify patients with MDD.

Our group has created and implemented 2 clinician-administered tools—the SAFER Interview and the Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ)—to enrich the qualitative assessment of MDD and treatment resistance.

SAFER: Assessing the diagnosis, symptom severity

The SAFER interview refines the diagnosis of depressed patients by assessing the state vs trait nature of the symptoms, their assessability, their face and ecological validity, and if they pass the rule of the 3 Ps: pervasiveness, persistence, and pathological nature of the current MDD episode (Table 1 and Table 2).6 This reliable assessment of the patient’s diagnosis and symptom severity is made in a way that reflects the illness in a real-world setting.

Clinical application of SAFER. Implementing SAFER in clinical settings promotes a personalized, dimensional approach by taking into account a varying degree of symptom severity in depressed patients, in contrast to relying on symptom lists as found in the DSM-IV-TR. Using the SAFER interview deepens the typical psychiatric diagnostic process, allows for a more precise understanding of the patient’s situation, and may help clinicians select effective treatments that target specific symptoms, thus resulting in more rapid alleviation of MDD.6

Table 1

The SAFER interview: Assessing depression in a real-world setting

State vs trait nature of the symptoms

|

Assessability

|

Face validity

|

Ecological validity

|

Rule of the 3 Ps

|

| © Massachusetts General Hospital Source: Reference 6 |

Table 2

The SAFER criteria: Rule of the 3 Ps

| Pervasive—Do the major symptoms affect the patient across multiple arenas of life (work, relationships, school, chores, etc.)? |

| Persistent—Do the main symptoms occur most days, most of the day during the current episode? |

| Pathological—Do the symptoms of the present episode interfere with functioning? |

| © Massachusetts General Hospital Source: Reference 6 |

CASE REPORT: Worsening symptoms

Ms. Y, age 53, has been depressed for 30 years. She hardly remembers a time in her life when she felt good for more than a few days. However, 2 months ago she noted her symptoms got worse. She presents with many MDD symptoms as assessed by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, eg, ongoing depressive mood, feelings of guilt, major sleep disturbances, and work impairments.

Using SAFER to evaluate Ms. Y, a clinician would ask: Does she have symptoms that are present primarily during an episode of acute illness? Does the episode constitute a measurable exacerbation of preexisting symptoms? This clinical vignette illustrates the importance of the first SAFER criterion, state vs trait nature of the symptoms. Ms. Y is a SAFER “pass”—meaning consistent with a major depressive episode—because exacerbation of preexisting symptoms is measurable. However, if her symptoms represented a chronic, long-standing trait, she would be a SAFER “fail” based on this criterion, and her symptoms likely would not improve during a brief pharmacologic intervention. For such patients, SAFER would have oriented the clinician toward alternative therapies such as psychotherapy or a combination of longer, more complex pharmacologic treatment and psychotherapy.

By helping clinicians refine MDD diagnoses, SAFER draws attention to specific depression entities (eg, MDD or dysthymia) and directs them toward appropriate guidelines, treatment algorithms, and precautions (eg, when treated with pharmacotherapy, dysthymic patients are particularly sensitive to unwanted effects and adherence is a serious issue).7 The SAFER interview also can help identify when what appears to be a depressive episode clearly is precipitated by situational factors, and is more likely to be influenced by changes in the patient’s life than by treatment. For such patients, first consider nonpharmacologic interventions to avoid unnecessary medication exposure.

ATRQ: Efficacy and adequacy

The ATRQ examines the efficacy (improvement from 0% [not improved at all] to 100% [completely improved]), and adequacy (adequate duration and dose) of any antidepressant treatment in a step-by-step procedure.1,8,9 For a copy of the ATRQ, click here.

While conducting the interview, clinicians ask about treatment adherence to each medication trial. A treatment-resistant patient may go through many types of trials, from monotherapy to combination to augmentation.10 For each trial, the ATRQ systematically reviews 4 strategies to enhance treatment response:

- increasing the initial antidepressant dosage11

- combining the initial antidepressant with another antidepressant, typically from another class12

- augmenting the initial antidepressant with a nonantidepressant12

- switching from the initial antidepressant to another antidepressant.13

These strategies also are applied in cases of lost sustained antidepressant efficacy or depressive relapse/recurrence, although empirical evidence supporting these strategies is lacking, with the possible exception of dose increase.14,15

In the convention our group adopted, an adequate antidepressant trial must be ≥6 weeks in total length, with a dose within an adequate range as specified in the medication’s package insert. In addition, for the purposes of conducting TRD trials, we have considered a patient treatment-resistant if response to adequate dose and duration is <50%. On the ATRQ, 50% improvement refers to 50% symptom reduction from baseline without achieving remission. In an initial clinical trial that lasts ≥6 weeks, any dose increase (for ≥4 weeks) represents optimization and is not considered a new or separate trial, whereas augmentation or combination therapy (for ≥3 weeks) or a switch to another antidepressant (for ≥6 weeks) are considered new trials/treatments.

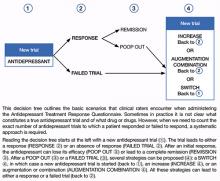

Decision tree for ATRQ. Because antidepressant treatment always is constrained by personal (eg, adherence, insurance coverage, etc.) and clinical (eg, contraindications due to comorbid conditions, side effects, etc.) considerations, we propose a decision tree to help clinicians determine the number of failed antidepressant trials their patient experienced (Figure). Although this tree does not represent all treatment scenarios, we hope it could help clinicians implement TRD treatment strategies because it highlights proper assessment of treatment duration, dosage, and changes before applying a TRD diagnosis.

The ATRQ meticulously examines patients’ antidepressant history to identify:

- pseudo-resistance, to guide adequate dosing and/or duration, and

- resistance, to propose next-step treatment.

Pseudo-resistance refers to treatment failures that can be attributed to factors such as inadequate treatment dosing or duration, atypical pharmacokinetics that reduce agents’ effectiveness, patient nonadherence (eg, due to adverse effects), or misdiagnosis of the primary disorder (ie, other mood disorders or depressive subsets such as dysthymia or minor depression mistreated as unipolar depression).16,17 Studies show that many patients with MDD referred to specialty settings are undertreated and receive inadequate antidepressant doses,18 which suggests that many referrals for TRD are in fact pseudo-resistance.19 Despite the lack of consensus on criteria for TRD,1 standardization of what constitutes treatment adequacy during antidepressant trials (eg, adherence, dose, duration) is indispensable.

Clinical application of the ATRQ. Because TRD may require specific interventions, we first need to properly identify treatment resistance. Also, systematic use of a classification system enhances the ability of clinicians and patients to provide meaningful descriptions of antidepressant resistance.

In clinical practice, choice of treatment strategy is based on factors that include partial or nonresponse, tolerability, avoiding withdrawal symptoms, the need to target side effects of a current antidepressant by administering another drug, cost, avoiding drug-drug interactions, and patient preference. Because a treatment-resistant patient may go through many types of trials, it is essential to obtain information about all treatments to determine the number of failed clinical trials a patient may have had for the current MDD episode and lifetime episodes. The importance of asking about adherence to each trial cannot be overemphasized.

Figure: Using the Massachusetts General Hospital Antidepressant Treatment History Questionnaire: A decision tree

CASE REPORT: Limited improvement

Mr. T, age 45, reported that his current depressive episode started several years ago. The first antidepressant trial he received, sertraline, 100 mg/d for 3 months, resulted in 0% improvement. Next he received citalopram, 20 mg/d, for 1 month, without any improvement. The next trial, venlafaxine, 75 mg/d, for 7 weeks, resulted in a 30% response. More recently Mr. B tried duloxetine, up to 90 mg/d, for 2 years with an 80% improvement during the first 3 months and then a decrease of response to <40%. He then received aripiprazole, 10 mg/d, in combination with duloxetine for approximately 4 weeks with no response.

Using the ATRQ to evaluate Mr. B, a clinician would consider the sertraline trial as a failed trial. The citalopram treatment would not be considered an adequate trial because it was too short. The venlafaxine course wouldn’t count as an adequate trial because the dosage was too low. The trial with duloxetine would count as a response (80% improvement) followed by a “poop out” or tachyphylaxis (40% improvement). The fifth trial with the combination of duloxetine and aripiprazole would count as a failed trial. The ATRQ highlights which drugs have been used for too short a duration or at too low a dosage. In Mr. B’s case, using the ATRQ revealed that of 5 trials, only 2 showed antidepressant resistance.

The ATRQ and decision tree are meant to provide clinicians with user-friendly tools to more precisely determine the number of failed antidepressant trials a patient experienced. By assessing if an antidepressant trial had an adequate dose and duration, the ATRQ can help suggest the next treatment options. For example, if a trial was inadequate in dose and/or duration but the patient tolerated the medication, then optimizing treatment with the current drug would be a logical next step. If a patient does not respond to an adequate trial, clinicians have several options, such as switching to another antidepressant, using a combination of medications or an augmentation strategy, or increasing the dose of the original antidepressant.

Limitations of the ATRQ. Historical rating of treatment is not as accurate as a prospective trial. Another limitation of the ATRQ is that the minimum effective dose is accepted as adequate; many clinicians would suggest that such a dose is inadequate. Also, the duration specified for augmentation, dose increase, and monotherapy are based on expert consensus1 rather than systematic research. Nonetheless, this method of documenting prior trials and treatment adequacy is an important advance.

The ATRQ lacks a place to indicate discontinuation due to intolerance. Knowing if adverse events caused treatment nonadherence or discontinuation is relevant to selecting treatment.

The ATRQ considers only pharmacotherapy and electroconvulsive therapy. Comprehensive assessment of treatment resistance requires asking about depression-specific, evidence-based psychotherapies, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy. Another precaution is that the ATRQ and SAFER should be used in conjunction with structured or semi-structured clinical interviews and other clinical tools to rule out other primary diagnoses (eg, bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or surreptitious substance abuse).20

Using SAFER and ATRQ allows clinicians to make a proper MDD diagnosis with an accurate, reliable assessment of symptom severity and a precise count of antidepressant trials of adequate duration and dose. SAFER helps differentiate MDD from other depressive disorders and can be used to separate MDD from a similar presentation of a reaction to external circumstances that may remit if these circumstances change.

These 2 clinical tools focus on MDD and TRD. Compared with treatment resistance in MDD, treatment resistance in other forms of depression, such as minor depressive disorder or dysthymia, has been inadequately researched21,22 and should be addressed in large studies. However, to help patients achieve remission of depressive disorders—especially MDD—clinicians should use patient information gathered via measurement-based care in combination with algorithm recommendations.23 Persistence of clinical care of MDD is essential because several treatment steps might be necessary for some patients to achieve remission. Throughout treatment, patients’ symptoms, adverse events secondary to ongoing treatment, and medication adherence should be assessed with appropriate tools. ATRQ and SAFER offer a clinician support in assessing treatment resistance history and a patient’s likelihood to respond to pharmacologic treatment.

Related Resources

- Desseilles M, Witte J, Chang TE, et al. Assessing the adequacy of past antidepressant trials: a clinician’s guide to the Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ). J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(8):1152-1154.

- Targum SD, Pollack MH, Fava M. Redefining affective disorders: relevance for drug development. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2008;14(1):2-9.

- Depression Clinical and Research Program. www.massgeneral.org/psychiatry/services/dcrp_home.aspx.

Drug Brand Names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosures

Dr. Desseilles was supported by the National Funds for Scientific Research of Belgium. Additional support came from the Belgian American Educational Foundation.

Dr. Fava receives grant/research support from, is a consultant to, and/or is a speaker for Abbott Laboratories, Adamed, Advanced Meeting Partners, Affectis Pharmaceuticals, Alkermes, Amarin Pharma, American Psychiatric Association, American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, Aspect Medical Systems, AstraZeneca, Auspex Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Belvoir Media Group, Best Practice Project Management, BioMarin, BioResearch, Biovail, Boehringer Ingelheim, BrainCells, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CeNeRx BioPharma, Cephalon, Clinical Trials Solutions, Clintara, CME Institute/Physicians Postgraduate Press, CNS Response, Compellis Pharmaceuticals, Covance, Covidien, Cypress Pharmaceutical, DiagnoSearch Life Sciences, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Dov Pharmaceuticals, Edgemont Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, Eli Lilly and Company, EnVivo Pharmaceuticals, ePharmaSolutions, EPIX Pharmaceuticals, Euthymics Bioscience, Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Ganeden Biotech, GenOmind, GlaxoSmithKline, Grünenthal GmbH, Icon Clinical Research, Imedex, i3 Innovus/Ingenix, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, Knoll Pharmaceuticals, Labopharm, Lichtwer Pharma GmbH, Lorex Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, MedAvante, Merck, MGH Psychiatry Academy/Primedia, MGH Psychiatry Academy/Reed Elsevier, MSI Methylation Sciences, National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia & Depression, National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, National Institute of Drug Abuse, National Institute of Mental Health, Naurex, Neuronetics, NextWave Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Nutrition 21, Orexigen Therapeutics, Organon Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, PamLab, Pfizer, PharmaStar, Pharmavite®, PharmoRx Therapeutics, Photothera, Precision Human Biolaboratory, Prexa Pharmaceuticals, Puretech Ventures, PsychoGenics, Psylin Neurosciences, RCT Logic, Rexahn Pharmaceuticals, Ridge Diagnostics, Roche Pharmaceuticals, sanofi-aventis US, Schering-Plough, Sepracor, Servier Laboratories, Shire, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Somaxon Pharmaceuticals, Somerset Pharmaceuticals, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Synthelabo, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Tal Medical, Tetragenex Pharmaceuticals, Transcept Pharmaceuticals, TransForm Pharmaceuticals, United BioSource, Vanda Pharmaceuticals, and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories.

Over the past year, Dr. Mischoulon has received research support from the Bowman Family Foundation, FisherWallace, Ganeden, and Nordic Naturals. He has received honoraria for speaking from Nordic Naturals. He has received royalties from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins for the book Natural medications for psychiatric disorders: Considering the alternatives. No payment has exceeded $10,000.

Dr. Freeman has received research support from Eli Lilly and Company, Forest Laboratories, and GlaxoSmithKline, and served on a one-time advisory board to Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge Janet Witte, MD, MPH, Trina E. Chang, MD, MPH, Nadia Iovieno, MD, PhD, Christina Dording, MD, Heidi Ashih, MD, PhD, Maren Nyer, PhD, and Marasha-Fiona De Jong, MD from the Clinical Trials Network and Institute at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA.

1. Fava M. Diagnosis and definition of treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(8):649-659.

2. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Maser JD, et al. Major depressive disorder: a prospective study of residual subthreshold depressive symptoms as predictor of rapid relapse. J Affect Disord. 1998;50(2-3):97-108.

3. Van Londen L, Molenaar RP, Goekoop JG, et al. Three- to 5-year prospective follow-up of outcome in major depression. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):731-735.

4. Paykel ES. Achieving gains beyond response. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2002;(415):12-17.

5. Cassano P, Fava M. Depression and public health: an overview. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(4):849-857.

6. Targum SD, Pollack MH, Fava M. Redefining affective disorders: relevance for drug development. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2008;14(1):2-9.

7. Versiani M, Nardi AE, Figueira I. Pharmacotherapy of dysthymia: review and new findings. Eur Psychiatry. 1998;13(4):203-209.

8. Chandler GM, Iosifescu DV, Pollack MH, et al. RESEARCH: validation of the Massachusetts General Hospital Antidepressant Treatment History Questionnaire (ATRQ). CNS Neurosci Ther. 2010;16(5):322-325.

9. Desseilles M, Witte J, Chang TE, et al. Assessing the adequacy of past antidepressant trials: a clinician’s guide to the antidepressant treatment response questionnaire. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(8):1152-1154.

10. Fava M. Augmentation and combination strategies for complicated depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(11):e40.-

11. Adli M, Baethge C, Heinz A, et al. Is dose escalation of antidepressants a rational strategy after a medium-dose treatment has failed? A systematic review. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255(6):387-400.

12. Fava M, Rush AJ. Current status of augmentation and combination treatments for major depressive disorder: a literature review and a proposal for a novel approach to improve practice. Psychother Psychosom. 2006;75(3):139-153.

13. Wohlreich MM, Mallinckrodt CH, Watkin JG, et al. Immediate switching of antidepressant therapy: results from a clinical trial of duloxetine. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2005;17(4):259-268.

14. Schmidt ME, Fava M, Zhang S, et al. Treatment approaches to major depressive disorder relapse. Part 1: dose increase. Psychother Psychosom. 2002;71(4):190-194.

15. Fava M, Detke MJ, Balestrieri M, et al. Management of depression relapse: re-initiation of duloxetine treatment or dose increase. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40(4):328-336.

16. Kornstein SG, Schneider RK. Clinical features of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 16):18-25.

17. Souery D, Papakostas GI, Trivedi MH. Treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 6):16-22.

18. Hirschfeld RM, Keller MB, Panico S, et al. The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA. 1997;277(4):333-340.

19. Sackeim HA. The definition and meaning of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 16):10-17.

20. Parker G, Malhi GS, Crawford JG, et al. Identifying “paradigm failures” contributing to treatment-resistant depression. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(2-3):185-191.

21. Harris SJ, Parent M. Patient with chronic and apparently treatment-resistant dysthymia. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(2):260-261.

22. Amsterdam J, Hornig M, Nierenberg AA. Treatment-resistant mood disorders. Cambridge United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2001.

23. Trivedi MH. Tools and strategies for ongoing assessment of depression: a measurement-based approach to remission. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 6):26-31.

Approximately one-half of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) will have partial or nonresponse to first-line antidepressant monotherapy, despite receiving an adequate dosage and sufficient duration of treatment.1 This has led to the definition of treatment-resistant depression (TRD) as a depressive episode that has shown insufficient response to ≥1 trial of an antidepressant that has demonstrated efficacy in clinical trials.1 Depressed patients should be treated to full remission because absence of complete remission is associated with:

- a more recurrent and chronic illness course2,3

- increased medical and psychiatric comorbidities

- greater functional burden

- increased social and economic costs linked with impaired social functioning.4

Clinicians need to properly identify MDD and treatment resistance to guide optimal treatment choices. Additional tools are necessary to accurately identify, document, and communicate about symptoms commonly experienced by depressed patients but not fully characterized by DSM-IV-TR MDD criteria.5 Finally, in many cases, trait or situational factors might obfuscate accurate diagnosis and the natural course of illness, and tools that can be implemented practically will help identify patients with MDD.

Our group has created and implemented 2 clinician-administered tools—the SAFER Interview and the Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ)—to enrich the qualitative assessment of MDD and treatment resistance.

SAFER: Assessing the diagnosis, symptom severity

The SAFER interview refines the diagnosis of depressed patients by assessing the state vs trait nature of the symptoms, their assessability, their face and ecological validity, and if they pass the rule of the 3 Ps: pervasiveness, persistence, and pathological nature of the current MDD episode (Table 1 and Table 2).6 This reliable assessment of the patient’s diagnosis and symptom severity is made in a way that reflects the illness in a real-world setting.

Clinical application of SAFER. Implementing SAFER in clinical settings promotes a personalized, dimensional approach by taking into account a varying degree of symptom severity in depressed patients, in contrast to relying on symptom lists as found in the DSM-IV-TR. Using the SAFER interview deepens the typical psychiatric diagnostic process, allows for a more precise understanding of the patient’s situation, and may help clinicians select effective treatments that target specific symptoms, thus resulting in more rapid alleviation of MDD.6

Table 1

The SAFER interview: Assessing depression in a real-world setting

State vs trait nature of the symptoms

|

Assessability

|

Face validity

|

Ecological validity

|

Rule of the 3 Ps

|

| © Massachusetts General Hospital Source: Reference 6 |

Table 2

The SAFER criteria: Rule of the 3 Ps

| Pervasive—Do the major symptoms affect the patient across multiple arenas of life (work, relationships, school, chores, etc.)? |

| Persistent—Do the main symptoms occur most days, most of the day during the current episode? |

| Pathological—Do the symptoms of the present episode interfere with functioning? |

| © Massachusetts General Hospital Source: Reference 6 |

CASE REPORT: Worsening symptoms

Ms. Y, age 53, has been depressed for 30 years. She hardly remembers a time in her life when she felt good for more than a few days. However, 2 months ago she noted her symptoms got worse. She presents with many MDD symptoms as assessed by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, eg, ongoing depressive mood, feelings of guilt, major sleep disturbances, and work impairments.

Using SAFER to evaluate Ms. Y, a clinician would ask: Does she have symptoms that are present primarily during an episode of acute illness? Does the episode constitute a measurable exacerbation of preexisting symptoms? This clinical vignette illustrates the importance of the first SAFER criterion, state vs trait nature of the symptoms. Ms. Y is a SAFER “pass”—meaning consistent with a major depressive episode—because exacerbation of preexisting symptoms is measurable. However, if her symptoms represented a chronic, long-standing trait, she would be a SAFER “fail” based on this criterion, and her symptoms likely would not improve during a brief pharmacologic intervention. For such patients, SAFER would have oriented the clinician toward alternative therapies such as psychotherapy or a combination of longer, more complex pharmacologic treatment and psychotherapy.

By helping clinicians refine MDD diagnoses, SAFER draws attention to specific depression entities (eg, MDD or dysthymia) and directs them toward appropriate guidelines, treatment algorithms, and precautions (eg, when treated with pharmacotherapy, dysthymic patients are particularly sensitive to unwanted effects and adherence is a serious issue).7 The SAFER interview also can help identify when what appears to be a depressive episode clearly is precipitated by situational factors, and is more likely to be influenced by changes in the patient’s life than by treatment. For such patients, first consider nonpharmacologic interventions to avoid unnecessary medication exposure.

ATRQ: Efficacy and adequacy

The ATRQ examines the efficacy (improvement from 0% [not improved at all] to 100% [completely improved]), and adequacy (adequate duration and dose) of any antidepressant treatment in a step-by-step procedure.1,8,9 For a copy of the ATRQ, click here.

While conducting the interview, clinicians ask about treatment adherence to each medication trial. A treatment-resistant patient may go through many types of trials, from monotherapy to combination to augmentation.10 For each trial, the ATRQ systematically reviews 4 strategies to enhance treatment response:

- increasing the initial antidepressant dosage11

- combining the initial antidepressant with another antidepressant, typically from another class12

- augmenting the initial antidepressant with a nonantidepressant12

- switching from the initial antidepressant to another antidepressant.13

These strategies also are applied in cases of lost sustained antidepressant efficacy or depressive relapse/recurrence, although empirical evidence supporting these strategies is lacking, with the possible exception of dose increase.14,15

In the convention our group adopted, an adequate antidepressant trial must be ≥6 weeks in total length, with a dose within an adequate range as specified in the medication’s package insert. In addition, for the purposes of conducting TRD trials, we have considered a patient treatment-resistant if response to adequate dose and duration is <50%. On the ATRQ, 50% improvement refers to 50% symptom reduction from baseline without achieving remission. In an initial clinical trial that lasts ≥6 weeks, any dose increase (for ≥4 weeks) represents optimization and is not considered a new or separate trial, whereas augmentation or combination therapy (for ≥3 weeks) or a switch to another antidepressant (for ≥6 weeks) are considered new trials/treatments.

Decision tree for ATRQ. Because antidepressant treatment always is constrained by personal (eg, adherence, insurance coverage, etc.) and clinical (eg, contraindications due to comorbid conditions, side effects, etc.) considerations, we propose a decision tree to help clinicians determine the number of failed antidepressant trials their patient experienced (Figure). Although this tree does not represent all treatment scenarios, we hope it could help clinicians implement TRD treatment strategies because it highlights proper assessment of treatment duration, dosage, and changes before applying a TRD diagnosis.

The ATRQ meticulously examines patients’ antidepressant history to identify:

- pseudo-resistance, to guide adequate dosing and/or duration, and

- resistance, to propose next-step treatment.

Pseudo-resistance refers to treatment failures that can be attributed to factors such as inadequate treatment dosing or duration, atypical pharmacokinetics that reduce agents’ effectiveness, patient nonadherence (eg, due to adverse effects), or misdiagnosis of the primary disorder (ie, other mood disorders or depressive subsets such as dysthymia or minor depression mistreated as unipolar depression).16,17 Studies show that many patients with MDD referred to specialty settings are undertreated and receive inadequate antidepressant doses,18 which suggests that many referrals for TRD are in fact pseudo-resistance.19 Despite the lack of consensus on criteria for TRD,1 standardization of what constitutes treatment adequacy during antidepressant trials (eg, adherence, dose, duration) is indispensable.

Clinical application of the ATRQ. Because TRD may require specific interventions, we first need to properly identify treatment resistance. Also, systematic use of a classification system enhances the ability of clinicians and patients to provide meaningful descriptions of antidepressant resistance.

In clinical practice, choice of treatment strategy is based on factors that include partial or nonresponse, tolerability, avoiding withdrawal symptoms, the need to target side effects of a current antidepressant by administering another drug, cost, avoiding drug-drug interactions, and patient preference. Because a treatment-resistant patient may go through many types of trials, it is essential to obtain information about all treatments to determine the number of failed clinical trials a patient may have had for the current MDD episode and lifetime episodes. The importance of asking about adherence to each trial cannot be overemphasized.

Figure: Using the Massachusetts General Hospital Antidepressant Treatment History Questionnaire: A decision tree

CASE REPORT: Limited improvement

Mr. T, age 45, reported that his current depressive episode started several years ago. The first antidepressant trial he received, sertraline, 100 mg/d for 3 months, resulted in 0% improvement. Next he received citalopram, 20 mg/d, for 1 month, without any improvement. The next trial, venlafaxine, 75 mg/d, for 7 weeks, resulted in a 30% response. More recently Mr. B tried duloxetine, up to 90 mg/d, for 2 years with an 80% improvement during the first 3 months and then a decrease of response to <40%. He then received aripiprazole, 10 mg/d, in combination with duloxetine for approximately 4 weeks with no response.

Using the ATRQ to evaluate Mr. B, a clinician would consider the sertraline trial as a failed trial. The citalopram treatment would not be considered an adequate trial because it was too short. The venlafaxine course wouldn’t count as an adequate trial because the dosage was too low. The trial with duloxetine would count as a response (80% improvement) followed by a “poop out” or tachyphylaxis (40% improvement). The fifth trial with the combination of duloxetine and aripiprazole would count as a failed trial. The ATRQ highlights which drugs have been used for too short a duration or at too low a dosage. In Mr. B’s case, using the ATRQ revealed that of 5 trials, only 2 showed antidepressant resistance.

The ATRQ and decision tree are meant to provide clinicians with user-friendly tools to more precisely determine the number of failed antidepressant trials a patient experienced. By assessing if an antidepressant trial had an adequate dose and duration, the ATRQ can help suggest the next treatment options. For example, if a trial was inadequate in dose and/or duration but the patient tolerated the medication, then optimizing treatment with the current drug would be a logical next step. If a patient does not respond to an adequate trial, clinicians have several options, such as switching to another antidepressant, using a combination of medications or an augmentation strategy, or increasing the dose of the original antidepressant.

Limitations of the ATRQ. Historical rating of treatment is not as accurate as a prospective trial. Another limitation of the ATRQ is that the minimum effective dose is accepted as adequate; many clinicians would suggest that such a dose is inadequate. Also, the duration specified for augmentation, dose increase, and monotherapy are based on expert consensus1 rather than systematic research. Nonetheless, this method of documenting prior trials and treatment adequacy is an important advance.

The ATRQ lacks a place to indicate discontinuation due to intolerance. Knowing if adverse events caused treatment nonadherence or discontinuation is relevant to selecting treatment.

The ATRQ considers only pharmacotherapy and electroconvulsive therapy. Comprehensive assessment of treatment resistance requires asking about depression-specific, evidence-based psychotherapies, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy. Another precaution is that the ATRQ and SAFER should be used in conjunction with structured or semi-structured clinical interviews and other clinical tools to rule out other primary diagnoses (eg, bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or surreptitious substance abuse).20

Using SAFER and ATRQ allows clinicians to make a proper MDD diagnosis with an accurate, reliable assessment of symptom severity and a precise count of antidepressant trials of adequate duration and dose. SAFER helps differentiate MDD from other depressive disorders and can be used to separate MDD from a similar presentation of a reaction to external circumstances that may remit if these circumstances change.

These 2 clinical tools focus on MDD and TRD. Compared with treatment resistance in MDD, treatment resistance in other forms of depression, such as minor depressive disorder or dysthymia, has been inadequately researched21,22 and should be addressed in large studies. However, to help patients achieve remission of depressive disorders—especially MDD—clinicians should use patient information gathered via measurement-based care in combination with algorithm recommendations.23 Persistence of clinical care of MDD is essential because several treatment steps might be necessary for some patients to achieve remission. Throughout treatment, patients’ symptoms, adverse events secondary to ongoing treatment, and medication adherence should be assessed with appropriate tools. ATRQ and SAFER offer a clinician support in assessing treatment resistance history and a patient’s likelihood to respond to pharmacologic treatment.

Related Resources

- Desseilles M, Witte J, Chang TE, et al. Assessing the adequacy of past antidepressant trials: a clinician’s guide to the Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ). J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(8):1152-1154.

- Targum SD, Pollack MH, Fava M. Redefining affective disorders: relevance for drug development. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2008;14(1):2-9.

- Depression Clinical and Research Program. www.massgeneral.org/psychiatry/services/dcrp_home.aspx.

Drug Brand Names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosures

Dr. Desseilles was supported by the National Funds for Scientific Research of Belgium. Additional support came from the Belgian American Educational Foundation.

Dr. Fava receives grant/research support from, is a consultant to, and/or is a speaker for Abbott Laboratories, Adamed, Advanced Meeting Partners, Affectis Pharmaceuticals, Alkermes, Amarin Pharma, American Psychiatric Association, American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, Aspect Medical Systems, AstraZeneca, Auspex Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Belvoir Media Group, Best Practice Project Management, BioMarin, BioResearch, Biovail, Boehringer Ingelheim, BrainCells, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CeNeRx BioPharma, Cephalon, Clinical Trials Solutions, Clintara, CME Institute/Physicians Postgraduate Press, CNS Response, Compellis Pharmaceuticals, Covance, Covidien, Cypress Pharmaceutical, DiagnoSearch Life Sciences, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Dov Pharmaceuticals, Edgemont Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, Eli Lilly and Company, EnVivo Pharmaceuticals, ePharmaSolutions, EPIX Pharmaceuticals, Euthymics Bioscience, Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Ganeden Biotech, GenOmind, GlaxoSmithKline, Grünenthal GmbH, Icon Clinical Research, Imedex, i3 Innovus/Ingenix, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, Knoll Pharmaceuticals, Labopharm, Lichtwer Pharma GmbH, Lorex Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, MedAvante, Merck, MGH Psychiatry Academy/Primedia, MGH Psychiatry Academy/Reed Elsevier, MSI Methylation Sciences, National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia & Depression, National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, National Institute of Drug Abuse, National Institute of Mental Health, Naurex, Neuronetics, NextWave Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Nutrition 21, Orexigen Therapeutics, Organon Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, PamLab, Pfizer, PharmaStar, Pharmavite®, PharmoRx Therapeutics, Photothera, Precision Human Biolaboratory, Prexa Pharmaceuticals, Puretech Ventures, PsychoGenics, Psylin Neurosciences, RCT Logic, Rexahn Pharmaceuticals, Ridge Diagnostics, Roche Pharmaceuticals, sanofi-aventis US, Schering-Plough, Sepracor, Servier Laboratories, Shire, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Somaxon Pharmaceuticals, Somerset Pharmaceuticals, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Synthelabo, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Tal Medical, Tetragenex Pharmaceuticals, Transcept Pharmaceuticals, TransForm Pharmaceuticals, United BioSource, Vanda Pharmaceuticals, and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories.

Over the past year, Dr. Mischoulon has received research support from the Bowman Family Foundation, FisherWallace, Ganeden, and Nordic Naturals. He has received honoraria for speaking from Nordic Naturals. He has received royalties from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins for the book Natural medications for psychiatric disorders: Considering the alternatives. No payment has exceeded $10,000.

Dr. Freeman has received research support from Eli Lilly and Company, Forest Laboratories, and GlaxoSmithKline, and served on a one-time advisory board to Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge Janet Witte, MD, MPH, Trina E. Chang, MD, MPH, Nadia Iovieno, MD, PhD, Christina Dording, MD, Heidi Ashih, MD, PhD, Maren Nyer, PhD, and Marasha-Fiona De Jong, MD from the Clinical Trials Network and Institute at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA.

Approximately one-half of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) will have partial or nonresponse to first-line antidepressant monotherapy, despite receiving an adequate dosage and sufficient duration of treatment.1 This has led to the definition of treatment-resistant depression (TRD) as a depressive episode that has shown insufficient response to ≥1 trial of an antidepressant that has demonstrated efficacy in clinical trials.1 Depressed patients should be treated to full remission because absence of complete remission is associated with:

- a more recurrent and chronic illness course2,3

- increased medical and psychiatric comorbidities

- greater functional burden

- increased social and economic costs linked with impaired social functioning.4

Clinicians need to properly identify MDD and treatment resistance to guide optimal treatment choices. Additional tools are necessary to accurately identify, document, and communicate about symptoms commonly experienced by depressed patients but not fully characterized by DSM-IV-TR MDD criteria.5 Finally, in many cases, trait or situational factors might obfuscate accurate diagnosis and the natural course of illness, and tools that can be implemented practically will help identify patients with MDD.

Our group has created and implemented 2 clinician-administered tools—the SAFER Interview and the Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ)—to enrich the qualitative assessment of MDD and treatment resistance.

SAFER: Assessing the diagnosis, symptom severity

The SAFER interview refines the diagnosis of depressed patients by assessing the state vs trait nature of the symptoms, their assessability, their face and ecological validity, and if they pass the rule of the 3 Ps: pervasiveness, persistence, and pathological nature of the current MDD episode (Table 1 and Table 2).6 This reliable assessment of the patient’s diagnosis and symptom severity is made in a way that reflects the illness in a real-world setting.

Clinical application of SAFER. Implementing SAFER in clinical settings promotes a personalized, dimensional approach by taking into account a varying degree of symptom severity in depressed patients, in contrast to relying on symptom lists as found in the DSM-IV-TR. Using the SAFER interview deepens the typical psychiatric diagnostic process, allows for a more precise understanding of the patient’s situation, and may help clinicians select effective treatments that target specific symptoms, thus resulting in more rapid alleviation of MDD.6

Table 1

The SAFER interview: Assessing depression in a real-world setting

State vs trait nature of the symptoms

|

Assessability

|

Face validity

|

Ecological validity

|

Rule of the 3 Ps

|

| © Massachusetts General Hospital Source: Reference 6 |

Table 2

The SAFER criteria: Rule of the 3 Ps

| Pervasive—Do the major symptoms affect the patient across multiple arenas of life (work, relationships, school, chores, etc.)? |

| Persistent—Do the main symptoms occur most days, most of the day during the current episode? |

| Pathological—Do the symptoms of the present episode interfere with functioning? |

| © Massachusetts General Hospital Source: Reference 6 |

CASE REPORT: Worsening symptoms

Ms. Y, age 53, has been depressed for 30 years. She hardly remembers a time in her life when she felt good for more than a few days. However, 2 months ago she noted her symptoms got worse. She presents with many MDD symptoms as assessed by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, eg, ongoing depressive mood, feelings of guilt, major sleep disturbances, and work impairments.

Using SAFER to evaluate Ms. Y, a clinician would ask: Does she have symptoms that are present primarily during an episode of acute illness? Does the episode constitute a measurable exacerbation of preexisting symptoms? This clinical vignette illustrates the importance of the first SAFER criterion, state vs trait nature of the symptoms. Ms. Y is a SAFER “pass”—meaning consistent with a major depressive episode—because exacerbation of preexisting symptoms is measurable. However, if her symptoms represented a chronic, long-standing trait, she would be a SAFER “fail” based on this criterion, and her symptoms likely would not improve during a brief pharmacologic intervention. For such patients, SAFER would have oriented the clinician toward alternative therapies such as psychotherapy or a combination of longer, more complex pharmacologic treatment and psychotherapy.

By helping clinicians refine MDD diagnoses, SAFER draws attention to specific depression entities (eg, MDD or dysthymia) and directs them toward appropriate guidelines, treatment algorithms, and precautions (eg, when treated with pharmacotherapy, dysthymic patients are particularly sensitive to unwanted effects and adherence is a serious issue).7 The SAFER interview also can help identify when what appears to be a depressive episode clearly is precipitated by situational factors, and is more likely to be influenced by changes in the patient’s life than by treatment. For such patients, first consider nonpharmacologic interventions to avoid unnecessary medication exposure.

ATRQ: Efficacy and adequacy

The ATRQ examines the efficacy (improvement from 0% [not improved at all] to 100% [completely improved]), and adequacy (adequate duration and dose) of any antidepressant treatment in a step-by-step procedure.1,8,9 For a copy of the ATRQ, click here.

While conducting the interview, clinicians ask about treatment adherence to each medication trial. A treatment-resistant patient may go through many types of trials, from monotherapy to combination to augmentation.10 For each trial, the ATRQ systematically reviews 4 strategies to enhance treatment response:

- increasing the initial antidepressant dosage11

- combining the initial antidepressant with another antidepressant, typically from another class12

- augmenting the initial antidepressant with a nonantidepressant12

- switching from the initial antidepressant to another antidepressant.13

These strategies also are applied in cases of lost sustained antidepressant efficacy or depressive relapse/recurrence, although empirical evidence supporting these strategies is lacking, with the possible exception of dose increase.14,15

In the convention our group adopted, an adequate antidepressant trial must be ≥6 weeks in total length, with a dose within an adequate range as specified in the medication’s package insert. In addition, for the purposes of conducting TRD trials, we have considered a patient treatment-resistant if response to adequate dose and duration is <50%. On the ATRQ, 50% improvement refers to 50% symptom reduction from baseline without achieving remission. In an initial clinical trial that lasts ≥6 weeks, any dose increase (for ≥4 weeks) represents optimization and is not considered a new or separate trial, whereas augmentation or combination therapy (for ≥3 weeks) or a switch to another antidepressant (for ≥6 weeks) are considered new trials/treatments.

Decision tree for ATRQ. Because antidepressant treatment always is constrained by personal (eg, adherence, insurance coverage, etc.) and clinical (eg, contraindications due to comorbid conditions, side effects, etc.) considerations, we propose a decision tree to help clinicians determine the number of failed antidepressant trials their patient experienced (Figure). Although this tree does not represent all treatment scenarios, we hope it could help clinicians implement TRD treatment strategies because it highlights proper assessment of treatment duration, dosage, and changes before applying a TRD diagnosis.

The ATRQ meticulously examines patients’ antidepressant history to identify:

- pseudo-resistance, to guide adequate dosing and/or duration, and

- resistance, to propose next-step treatment.

Pseudo-resistance refers to treatment failures that can be attributed to factors such as inadequate treatment dosing or duration, atypical pharmacokinetics that reduce agents’ effectiveness, patient nonadherence (eg, due to adverse effects), or misdiagnosis of the primary disorder (ie, other mood disorders or depressive subsets such as dysthymia or minor depression mistreated as unipolar depression).16,17 Studies show that many patients with MDD referred to specialty settings are undertreated and receive inadequate antidepressant doses,18 which suggests that many referrals for TRD are in fact pseudo-resistance.19 Despite the lack of consensus on criteria for TRD,1 standardization of what constitutes treatment adequacy during antidepressant trials (eg, adherence, dose, duration) is indispensable.

Clinical application of the ATRQ. Because TRD may require specific interventions, we first need to properly identify treatment resistance. Also, systematic use of a classification system enhances the ability of clinicians and patients to provide meaningful descriptions of antidepressant resistance.

In clinical practice, choice of treatment strategy is based on factors that include partial or nonresponse, tolerability, avoiding withdrawal symptoms, the need to target side effects of a current antidepressant by administering another drug, cost, avoiding drug-drug interactions, and patient preference. Because a treatment-resistant patient may go through many types of trials, it is essential to obtain information about all treatments to determine the number of failed clinical trials a patient may have had for the current MDD episode and lifetime episodes. The importance of asking about adherence to each trial cannot be overemphasized.

Figure: Using the Massachusetts General Hospital Antidepressant Treatment History Questionnaire: A decision tree

CASE REPORT: Limited improvement

Mr. T, age 45, reported that his current depressive episode started several years ago. The first antidepressant trial he received, sertraline, 100 mg/d for 3 months, resulted in 0% improvement. Next he received citalopram, 20 mg/d, for 1 month, without any improvement. The next trial, venlafaxine, 75 mg/d, for 7 weeks, resulted in a 30% response. More recently Mr. B tried duloxetine, up to 90 mg/d, for 2 years with an 80% improvement during the first 3 months and then a decrease of response to <40%. He then received aripiprazole, 10 mg/d, in combination with duloxetine for approximately 4 weeks with no response.

Using the ATRQ to evaluate Mr. B, a clinician would consider the sertraline trial as a failed trial. The citalopram treatment would not be considered an adequate trial because it was too short. The venlafaxine course wouldn’t count as an adequate trial because the dosage was too low. The trial with duloxetine would count as a response (80% improvement) followed by a “poop out” or tachyphylaxis (40% improvement). The fifth trial with the combination of duloxetine and aripiprazole would count as a failed trial. The ATRQ highlights which drugs have been used for too short a duration or at too low a dosage. In Mr. B’s case, using the ATRQ revealed that of 5 trials, only 2 showed antidepressant resistance.

The ATRQ and decision tree are meant to provide clinicians with user-friendly tools to more precisely determine the number of failed antidepressant trials a patient experienced. By assessing if an antidepressant trial had an adequate dose and duration, the ATRQ can help suggest the next treatment options. For example, if a trial was inadequate in dose and/or duration but the patient tolerated the medication, then optimizing treatment with the current drug would be a logical next step. If a patient does not respond to an adequate trial, clinicians have several options, such as switching to another antidepressant, using a combination of medications or an augmentation strategy, or increasing the dose of the original antidepressant.

Limitations of the ATRQ. Historical rating of treatment is not as accurate as a prospective trial. Another limitation of the ATRQ is that the minimum effective dose is accepted as adequate; many clinicians would suggest that such a dose is inadequate. Also, the duration specified for augmentation, dose increase, and monotherapy are based on expert consensus1 rather than systematic research. Nonetheless, this method of documenting prior trials and treatment adequacy is an important advance.

The ATRQ lacks a place to indicate discontinuation due to intolerance. Knowing if adverse events caused treatment nonadherence or discontinuation is relevant to selecting treatment.

The ATRQ considers only pharmacotherapy and electroconvulsive therapy. Comprehensive assessment of treatment resistance requires asking about depression-specific, evidence-based psychotherapies, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy. Another precaution is that the ATRQ and SAFER should be used in conjunction with structured or semi-structured clinical interviews and other clinical tools to rule out other primary diagnoses (eg, bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or surreptitious substance abuse).20

Using SAFER and ATRQ allows clinicians to make a proper MDD diagnosis with an accurate, reliable assessment of symptom severity and a precise count of antidepressant trials of adequate duration and dose. SAFER helps differentiate MDD from other depressive disorders and can be used to separate MDD from a similar presentation of a reaction to external circumstances that may remit if these circumstances change.

These 2 clinical tools focus on MDD and TRD. Compared with treatment resistance in MDD, treatment resistance in other forms of depression, such as minor depressive disorder or dysthymia, has been inadequately researched21,22 and should be addressed in large studies. However, to help patients achieve remission of depressive disorders—especially MDD—clinicians should use patient information gathered via measurement-based care in combination with algorithm recommendations.23 Persistence of clinical care of MDD is essential because several treatment steps might be necessary for some patients to achieve remission. Throughout treatment, patients’ symptoms, adverse events secondary to ongoing treatment, and medication adherence should be assessed with appropriate tools. ATRQ and SAFER offer a clinician support in assessing treatment resistance history and a patient’s likelihood to respond to pharmacologic treatment.

Related Resources

- Desseilles M, Witte J, Chang TE, et al. Assessing the adequacy of past antidepressant trials: a clinician’s guide to the Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ). J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(8):1152-1154.

- Targum SD, Pollack MH, Fava M. Redefining affective disorders: relevance for drug development. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2008;14(1):2-9.

- Depression Clinical and Research Program. www.massgeneral.org/psychiatry/services/dcrp_home.aspx.

Drug Brand Names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosures

Dr. Desseilles was supported by the National Funds for Scientific Research of Belgium. Additional support came from the Belgian American Educational Foundation.

Dr. Fava receives grant/research support from, is a consultant to, and/or is a speaker for Abbott Laboratories, Adamed, Advanced Meeting Partners, Affectis Pharmaceuticals, Alkermes, Amarin Pharma, American Psychiatric Association, American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, Aspect Medical Systems, AstraZeneca, Auspex Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Belvoir Media Group, Best Practice Project Management, BioMarin, BioResearch, Biovail, Boehringer Ingelheim, BrainCells, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CeNeRx BioPharma, Cephalon, Clinical Trials Solutions, Clintara, CME Institute/Physicians Postgraduate Press, CNS Response, Compellis Pharmaceuticals, Covance, Covidien, Cypress Pharmaceutical, DiagnoSearch Life Sciences, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Dov Pharmaceuticals, Edgemont Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, Eli Lilly and Company, EnVivo Pharmaceuticals, ePharmaSolutions, EPIX Pharmaceuticals, Euthymics Bioscience, Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Ganeden Biotech, GenOmind, GlaxoSmithKline, Grünenthal GmbH, Icon Clinical Research, Imedex, i3 Innovus/Ingenix, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, Knoll Pharmaceuticals, Labopharm, Lichtwer Pharma GmbH, Lorex Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, MedAvante, Merck, MGH Psychiatry Academy/Primedia, MGH Psychiatry Academy/Reed Elsevier, MSI Methylation Sciences, National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia & Depression, National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, National Institute of Drug Abuse, National Institute of Mental Health, Naurex, Neuronetics, NextWave Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Nutrition 21, Orexigen Therapeutics, Organon Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, PamLab, Pfizer, PharmaStar, Pharmavite®, PharmoRx Therapeutics, Photothera, Precision Human Biolaboratory, Prexa Pharmaceuticals, Puretech Ventures, PsychoGenics, Psylin Neurosciences, RCT Logic, Rexahn Pharmaceuticals, Ridge Diagnostics, Roche Pharmaceuticals, sanofi-aventis US, Schering-Plough, Sepracor, Servier Laboratories, Shire, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Somaxon Pharmaceuticals, Somerset Pharmaceuticals, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Synthelabo, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Tal Medical, Tetragenex Pharmaceuticals, Transcept Pharmaceuticals, TransForm Pharmaceuticals, United BioSource, Vanda Pharmaceuticals, and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories.

Over the past year, Dr. Mischoulon has received research support from the Bowman Family Foundation, FisherWallace, Ganeden, and Nordic Naturals. He has received honoraria for speaking from Nordic Naturals. He has received royalties from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins for the book Natural medications for psychiatric disorders: Considering the alternatives. No payment has exceeded $10,000.

Dr. Freeman has received research support from Eli Lilly and Company, Forest Laboratories, and GlaxoSmithKline, and served on a one-time advisory board to Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge Janet Witte, MD, MPH, Trina E. Chang, MD, MPH, Nadia Iovieno, MD, PhD, Christina Dording, MD, Heidi Ashih, MD, PhD, Maren Nyer, PhD, and Marasha-Fiona De Jong, MD from the Clinical Trials Network and Institute at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA.

1. Fava M. Diagnosis and definition of treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(8):649-659.

2. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Maser JD, et al. Major depressive disorder: a prospective study of residual subthreshold depressive symptoms as predictor of rapid relapse. J Affect Disord. 1998;50(2-3):97-108.

3. Van Londen L, Molenaar RP, Goekoop JG, et al. Three- to 5-year prospective follow-up of outcome in major depression. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):731-735.

4. Paykel ES. Achieving gains beyond response. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2002;(415):12-17.

5. Cassano P, Fava M. Depression and public health: an overview. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(4):849-857.

6. Targum SD, Pollack MH, Fava M. Redefining affective disorders: relevance for drug development. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2008;14(1):2-9.

7. Versiani M, Nardi AE, Figueira I. Pharmacotherapy of dysthymia: review and new findings. Eur Psychiatry. 1998;13(4):203-209.

8. Chandler GM, Iosifescu DV, Pollack MH, et al. RESEARCH: validation of the Massachusetts General Hospital Antidepressant Treatment History Questionnaire (ATRQ). CNS Neurosci Ther. 2010;16(5):322-325.

9. Desseilles M, Witte J, Chang TE, et al. Assessing the adequacy of past antidepressant trials: a clinician’s guide to the antidepressant treatment response questionnaire. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(8):1152-1154.

10. Fava M. Augmentation and combination strategies for complicated depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(11):e40.-

11. Adli M, Baethge C, Heinz A, et al. Is dose escalation of antidepressants a rational strategy after a medium-dose treatment has failed? A systematic review. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255(6):387-400.

12. Fava M, Rush AJ. Current status of augmentation and combination treatments for major depressive disorder: a literature review and a proposal for a novel approach to improve practice. Psychother Psychosom. 2006;75(3):139-153.

13. Wohlreich MM, Mallinckrodt CH, Watkin JG, et al. Immediate switching of antidepressant therapy: results from a clinical trial of duloxetine. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2005;17(4):259-268.

14. Schmidt ME, Fava M, Zhang S, et al. Treatment approaches to major depressive disorder relapse. Part 1: dose increase. Psychother Psychosom. 2002;71(4):190-194.

15. Fava M, Detke MJ, Balestrieri M, et al. Management of depression relapse: re-initiation of duloxetine treatment or dose increase. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40(4):328-336.

16. Kornstein SG, Schneider RK. Clinical features of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 16):18-25.

17. Souery D, Papakostas GI, Trivedi MH. Treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 6):16-22.

18. Hirschfeld RM, Keller MB, Panico S, et al. The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA. 1997;277(4):333-340.

19. Sackeim HA. The definition and meaning of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 16):10-17.

20. Parker G, Malhi GS, Crawford JG, et al. Identifying “paradigm failures” contributing to treatment-resistant depression. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(2-3):185-191.

21. Harris SJ, Parent M. Patient with chronic and apparently treatment-resistant dysthymia. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(2):260-261.

22. Amsterdam J, Hornig M, Nierenberg AA. Treatment-resistant mood disorders. Cambridge United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2001.

23. Trivedi MH. Tools and strategies for ongoing assessment of depression: a measurement-based approach to remission. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 6):26-31.

1. Fava M. Diagnosis and definition of treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(8):649-659.

2. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Maser JD, et al. Major depressive disorder: a prospective study of residual subthreshold depressive symptoms as predictor of rapid relapse. J Affect Disord. 1998;50(2-3):97-108.

3. Van Londen L, Molenaar RP, Goekoop JG, et al. Three- to 5-year prospective follow-up of outcome in major depression. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):731-735.

4. Paykel ES. Achieving gains beyond response. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2002;(415):12-17.

5. Cassano P, Fava M. Depression and public health: an overview. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(4):849-857.

6. Targum SD, Pollack MH, Fava M. Redefining affective disorders: relevance for drug development. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2008;14(1):2-9.

7. Versiani M, Nardi AE, Figueira I. Pharmacotherapy of dysthymia: review and new findings. Eur Psychiatry. 1998;13(4):203-209.

8. Chandler GM, Iosifescu DV, Pollack MH, et al. RESEARCH: validation of the Massachusetts General Hospital Antidepressant Treatment History Questionnaire (ATRQ). CNS Neurosci Ther. 2010;16(5):322-325.

9. Desseilles M, Witte J, Chang TE, et al. Assessing the adequacy of past antidepressant trials: a clinician’s guide to the antidepressant treatment response questionnaire. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(8):1152-1154.

10. Fava M. Augmentation and combination strategies for complicated depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(11):e40.-

11. Adli M, Baethge C, Heinz A, et al. Is dose escalation of antidepressants a rational strategy after a medium-dose treatment has failed? A systematic review. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255(6):387-400.

12. Fava M, Rush AJ. Current status of augmentation and combination treatments for major depressive disorder: a literature review and a proposal for a novel approach to improve practice. Psychother Psychosom. 2006;75(3):139-153.

13. Wohlreich MM, Mallinckrodt CH, Watkin JG, et al. Immediate switching of antidepressant therapy: results from a clinical trial of duloxetine. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2005;17(4):259-268.

14. Schmidt ME, Fava M, Zhang S, et al. Treatment approaches to major depressive disorder relapse. Part 1: dose increase. Psychother Psychosom. 2002;71(4):190-194.

15. Fava M, Detke MJ, Balestrieri M, et al. Management of depression relapse: re-initiation of duloxetine treatment or dose increase. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40(4):328-336.

16. Kornstein SG, Schneider RK. Clinical features of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 16):18-25.

17. Souery D, Papakostas GI, Trivedi MH. Treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 6):16-22.

18. Hirschfeld RM, Keller MB, Panico S, et al. The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA. 1997;277(4):333-340.

19. Sackeim HA. The definition and meaning of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 16):10-17.

20. Parker G, Malhi GS, Crawford JG, et al. Identifying “paradigm failures” contributing to treatment-resistant depression. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(2-3):185-191.

21. Harris SJ, Parent M. Patient with chronic and apparently treatment-resistant dysthymia. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(2):260-261.

22. Amsterdam J, Hornig M, Nierenberg AA. Treatment-resistant mood disorders. Cambridge United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2001.

23. Trivedi MH. Tools and strategies for ongoing assessment of depression: a measurement-based approach to remission. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 6):26-31.

New Alzheimer’s disease guidelines: Implications for clinicians

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

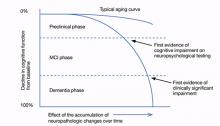

In 2011, a workgroup of experts from the Alzheimer’s Association and the National Institute on Aging published new criteria and guidelines for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the first new AD guidelines since 1984.1-4 These criteria reflect data that suggest AD is not synonymous with dementia of the Alzheimer’s type (DAT) but is a disease that slowly develops over many years as a result of accumulated neuropathologic changes, with dementia representing only the final phase of the disease (Figure).1-4

Figure: Cognitive decline in AD over time

AD: Alzheimer’s disease; MCI: mild cognitive impairment

Source: Adapted from reference 2

This article highlights the similarities and differences of the 1984 and 2011 AD diagnosis guidelines. We also discuss the new guidelines’ limitations and clinical implications.

The 1984 AD criteria

Both the 1984 AD criteria5 and DSM-IV-TR criteria6 rely on the concept that AD is a clinical diagnosis made after a patient develops dementia. That is, diagnosis rests on the physician’s clinical judgment about the etiology of the patient’s symptoms, taking into account reports from the patient, family, and friends, as well as results of neurocognitive testing and mental status evaluation. The 1984 criteria were developed with the expectation that if a patient who met clinical criteria for AD were to undergo an autopsy, he or she likely would have evidence of AD pathology as the underlying etiology. These criteria were developed before researchers discovered that in AD, pathologic changes occur over many years and clinical dementia is the end product of accumulated pathology. The 1984 criteria did not address important phases that precede clinical dementia—such as mild cognitive impairment (MCI). See the Table for a summary of the 1984 AD criteria.

Table

The 1984 NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for clinical diagnosis of AD

|

| AD: Alzheimer’s disease; NINCDS-ADRDA: National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Diseases and Stroke/Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association Source: McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939-944 |

The 2011 AD criteria

The new AD criteria differ from the 1984 criteria in 2 major ways:

- expansion of AD into 3 phases, only 1 of which is characterized by dementia

- incorporation of biomarkers to provide information regarding pathophysiologic changes underlying the disease state (Table 1).1-5

The 3 phases. The 2011 criteria expand the definition of AD to include an asymptomatic, preclinical phase; a symptomatic, pre-dementia phase; and a dementia phase. In the initial phase, neuronal toxins such as beta-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and elevated tau first become detectable. Patients in this phase are asymptomatic or have subtle symptoms. This phase should be viewed as part of a continuum and includes patients who may, for instance, develop Aβ plaques but do not progress to further neurodegeneration.2 The diagnostic criteria of this phase are intended for research purposes only.1,2

Patients in the symptomatic, pre-dementia phase—also known as the MCI phase—exhibit mild decline in memory, attention, and thinking. Although this decline is more than what is expected for the patient’s age and education, it does not compromise everyday activity and functioning.

A patient who develops cognitive or behavioral problems that interfere with his or her ability to function at work or in everyday activities has entered the dementia phase. Similar to the 1984 guidelines, the 2011 criteria classify patients into probable and possible AD dementia. All patients who would have satisfied criteria for probable AD under the 1984 guidelines will satisfy criteria for probable AD dementia under the 2011 criteria.4 The same is not true for possible AD dementia. The 2011 criteria include 2 other major categories for patients with AD dementia: probable and possible AD dementia with evidence of the AD pathophysiological process. These categories are intended for research purposes only, whereas the criteria for the MCI and dementia phases are intended to guide diagnosis in the clinical setting.

By incorporating phases of AD that precede dementia into the disease spectrum, the new guidelines are designed to move clinicians toward earlier diagnosis and treatment.1-3 Similar to how early, pre-symptomatic detection and treatment of conditions such as diabetes and cancer can reduce mortality, improving diagnosis of AD in its early phases may allow clinicians to better test potential therapies and eventually use them to treat at-risk individuals.2,3 Most pharmacotherapies for AD are FDA-approved only for patients diagnosed with clinical dementia. Furthermore, current pharmacotherapies do not alter the course of AD; they have a modest effect in slowing cognitive and functional decline.7,8 If patients in the earlier phases of AD could be recruited for research studies, we may be able to develop new treatments to stop or reverse AD pathology and its clinical manifestations.

Biomarkers. The new criteria incorporate biomarkers to provide information about pathophysiologic changes underlying the disease process. These criteria define biomarkers as physiologic, biochemical, or anatomic parameters that can be measured in vivo and reflect specific features of disease-related pathophysiologic processes.1 Presently, there are no cutoff values to demarcate “normal” levels from “abnormal,” and biomarkers are proposed primarily as research tools because they have not been studied adequately in community settings and laboratory techniques to measure biomarkers have not been standardized.1-4,9

The 5 biomarkers incorporated into the new criteria are divided into 2 categories: biomarkers of Aβ accumulation and those of neuronal degeneration or injury (Table 2).1-4 In the initial, preclinical phase, biomarkers are used to detect changes in the brain—such as amyloid accumulation and nerve cell degeneration—that may already be in process in an individual whose clinical symptoms are subtle or not yet evident.1,2 In this phase, progressive evidence of biomarkers, such as both Aβ accumulation and neuronal injury rather than Aβ accumulation alone, may increase the probability that a patient will decline quickly into the MCI phase.2 Biomarkers of neuronal degeneration or injury especially correlate with the likelihood that the disease will progress to clinical dementia.1 Subtle cognitive symptoms in the preclinical phase also might predict rapid decline into MCI.2

In the MCI and dementia phases, biomarkers are used to determine the level of certainty that AD is responsible for the patient’s symptoms.1,3,4 For example, a patient could meet criteria for a non-AD dementia such as dementia with Lewy bodies, but also meet pathologic criteria for AD on autopsy.3 The diagnostic category of possible AD dementia with evidence of the AD pathophysiologic process is intended for this type of scenario.4 For the MCI phase, the criteria propose levels of certainty that a patient’s MCI syndrome is caused by AD, ranging from MCI due to AD-high likelihood to MCI-unlikely due to AD.3

Research has demonstrated that a patient’s clinical picture doesn’t necessarily reflect the extent of the underlying pathology. For example, a patient could have extensive AD pathology, such as diffuse amyloid plaques, without any obvious clinical symptoms.3 Conversely, although both Aβ deposition and elevated tau are hallmarks of AD, variations in these proteins can be seen in neuropsychiatric disorders other than AD.10 That said, it appears that worsening of clinical symptoms often parallels worsening of neurodegenerative biomarkers.1

Under the 2011 guidelines, biomarkers would not be used to diagnose or exclude AD or MCI, but instead would help improve diagnostic accuracy in individuals with cognitive decline.1,3,4 In other words, AD remains a clinical diagnosis, but these biomarkers could raise or lower the positive predictive value of a clinician’s judgment about the etiology of a patient’s symptoms.

See the Box for a description of the potential risks and benefits of using the new diagnostic criteria.

Table 1

Comparing the 1984 and 2011 AD criteria

| 1984 criteria | 2011 criteria |

|---|---|

| AD is a clinical diagnosis | AD remains a clinical diagnosis but biomarkers serve to improve the accuracy of diagnosis of the disease |

| There is only 1 phase of AD—dementia. | AD is expanded into 3 phases: an asymptomatic, preclinical phase; a symptomatic, pre-dementia phase; and a dementia phase |

| A patient who meets the clinical criteria for AD would be expected to have AD pathology as the underlying etiology were he/she to undergo a brain autopsy | Presently, biomarkers are proposed as research tools only and are not intended to be applied in the clinical setting. However, eventually clinicians will be able to diagnose AD in all 3 phases, as biomarker testing becomes standardized and reliable enough to be accurately applied in clinical settings |

| Little consideration is given to specific neuropathologic changes underlying the disease process | Biomarkers provide information regarding the pathophysiologic changes underlying the disease state |

| Little consideration is given to the idea that pathologic changes occur over many years | Inherent in dividing AD into 3 phases is the concept that AD develops slowly over many years and has a long prodromal phase that is clinically silent |

| AD: Alzheimer’s disease Source: References 1-5 | |

Table 2

5 biomarkers incorporated into the 2011 AD criteria

| Category | Biomarkers |

|---|---|

| Biomarkers of Aβ accumulation | Abnormal tracer retention on amyloid PET imaging |

| Low CSF Aβ42 | |

| Biomarkers of neuronal degeneration or injury | Elevated CSF tau (total and phosphorylated tau) |

| Decreased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake on PET | |

| Atrophy on structural magnetic resonance imaging | |

| Aβ: beta-amyloid; AD: Alzheimer’s disease; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; PET: positron emission tomography Source: References 1-4 | |

The earlier an Alzheimer’s disease (AD) diagnosis is made, the less certain it is AD.a Biomarkers typically found in individuals with AD also can be found in patients with dementia not caused by AD, such as vascular dementia, as well as in individuals who may never develop dementia.b Additionally, there is no certainty that a patient in an early phase of AD will develop clinical dementia. Falsely diagnosing a patient with AD may lead the individual and their family to feel helpless, hopeless, depressed, anxious, or ashamed and to spend money and other resources preparing for a prognosis that may never come to fruition. Clinicians may feel compelled to assess for biomarkers using expensive, invasive tests that are not yet standardized in an attempt to support the AD diagnosis.

Early diagnosis of AD has many benefits that should not be overlooked, however. It provides patients and their families an opportunity to become familiar with the disease course, which may help some patients cope with the diagnosis. Patients diagnosed in the early stages would be able to make important decisions regarding health care, social, and financial planning before they develop pathology that limits their executive planning abilities or become functionally impaired.