User login

Can a vaccine prevent Alzheimer’s disease?

Deposition of amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) is believed to contribute to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathogenesis. Derived from a larger precursor protein, Aβ aggregates into plaques, and may promote neuronal death and, ultimately, dementia.

Current treatments alleviate symptoms without slowing underlying neurodegeneration. The prospect of harnessing the immune system to target the Aβ peptide offers an intriguing option for preventing this devastating, increasingly common disease.

Anti-a BETA antibodies

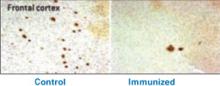

Transgenic mice bred to overexpress AD genes have responded remarkably in studies using the immune system to target the amyloid-β peptide.3 Several mouse groups have shown plaque reduction (Figure 1) and improved cognitive performance. These findings substantiate the amyloid hypothesis in AD pathogenesis.

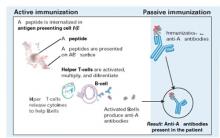

A host could acquire anti-Aβ antibodies though two basic approaches (Figure 2):2

Figure 1 Differences in amyloid deposition between control and immunized mice

Frontal cortex of an unvaccinated mouse (left) shows more amyloid deposits (dark spots) than that of a mouse producing antibodies against the amyloid-β peptide (right).

Source: Image by Cynthia A. Lemere, PhD. Used with permission.Active immunization exposes the subject to the antigen (in this case the Aβ peptide) and allows T cells and B cells to produce anti-Aβ antibodies. This approach has been studied in humans, but adverse effects have stymied its development.

Passive immunization, which involves developing anti-Aβ antibodies in a separate source, aims to clear Aβ peptide without requiring an immunologic response from the host. Large doses of antibodies administered weekly or monthly would be needed to build adequate plasma levels in the CNS, and large quantities of circulating antibodies could cause hemorrhagic stroke.

A troublesome trial

After successful preclinical and phase 1 testing of a vaccine against the Aβ peptide (called AN-1792), a phase 2a placebo-controlled trial in 2001 followed patients with mild to moderate AD. Drug administration was halted after 18 patients (6%) developed meningoencephalitis after several months.4 However, 300 patients with AD and 72 control patients had received at least one injection, and double-blind assessments were maintained for 12 months.

Figure 2 Methods for immunizing against Aβ peptide

Active immunization produces anti-Aβ antibodies via immunologic response to vaccination. With passive immunization, anti-Aβ antibodies are administered directly.

Illustration by Rich LaRocco.All patients with meningoencephalitis had received the vaccine but not all developed an immune response, suggesting that something other than the antibodies—such as T cells—caused the encephalitis. Twelve patients recovered, but six had persistent cognitive and neurologic deficits.

More-optimistic news

Of the 300 patients who received an active vaccine, 20% developed an adequate antibody response.5

The responders showed no significant difference from the placebo group in most outcome measures but showed less worsening in the nine-component Neuropsychological Test Battery (NTB) (P=0.02). Of particular interest, antibody responders showed significant improvement in the NTB—s memory domain (P=0.03). Further, subjects with higher IgG antibody titers showed greater improvement than did other responders.

More work ahead

Although the outcome of this initial AN-1792 trial is disappointing because of its discontinuation and mixed results, T cell infiltration and amyloid depletion were found during postmortem examinations of two vaccine recipients.6

Pharmaceutical companies are testing two compounds for AD immunotherapy:7

- AAB-001, a human monoclonal antibody, targets all 42 Aβ amino acids via passive immunization and has entered phase 2 trials.

- ACC-001, an Aβ immuno-conjugate designed to elicit an active antibody response, began phase 1 testing last fall.

These efforts suggest that an “Alzheimer’s vaccine” could be produced, provided it could attack the Aβ peptide without inducing a significant cellular reaction.

1. Neugroschl JA, Kolevzor A, Samuels SC, Marir DB. Dementia. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA (eds). Kaplan & Sadock’s comprehensive text-book of psychiatry (8th ed). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:1068-93.

2. Schenk D. Amyloid-beta immunotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease: the end of the beginning. Nat Rev Neurosci 2002;3:824-8.

3. Schenk D, Hagen M, Seubert P. Current progress in beta-amyloid immunotherapy. Current Opin Immunol 2004;16:599-606.

4. Orgogozo JM, Gilman S, Dartigues JF, et al. Subacute meningoen-cephalitis in a subset of patients with AD after Abeta42 immunization. Neurology 2003;61:46-54.

5. Gilman S, Koller M, Black RS, et al. Clinical effects of Abeta immunization (AN1792) in patients with AD in an interrupted trial. Neurology 2005;64:1553-62.

6. Ferrer I, Boada Rovira M, Sanchez Guerra ML, et al. Neuropathology and pathogenesis of encephalitis following amyloid-beta immunization in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathology 2004;14(1):11-20.

7. Sullivan MG. Immunotherapy studies for AD back on track. Psychiatry News 2005;33(11):69.-

Deposition of amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) is believed to contribute to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathogenesis. Derived from a larger precursor protein, Aβ aggregates into plaques, and may promote neuronal death and, ultimately, dementia.

Current treatments alleviate symptoms without slowing underlying neurodegeneration. The prospect of harnessing the immune system to target the Aβ peptide offers an intriguing option for preventing this devastating, increasingly common disease.

Anti-a BETA antibodies

Transgenic mice bred to overexpress AD genes have responded remarkably in studies using the immune system to target the amyloid-β peptide.3 Several mouse groups have shown plaque reduction (Figure 1) and improved cognitive performance. These findings substantiate the amyloid hypothesis in AD pathogenesis.

A host could acquire anti-Aβ antibodies though two basic approaches (Figure 2):2

Figure 1 Differences in amyloid deposition between control and immunized mice

Frontal cortex of an unvaccinated mouse (left) shows more amyloid deposits (dark spots) than that of a mouse producing antibodies against the amyloid-β peptide (right).

Source: Image by Cynthia A. Lemere, PhD. Used with permission.Active immunization exposes the subject to the antigen (in this case the Aβ peptide) and allows T cells and B cells to produce anti-Aβ antibodies. This approach has been studied in humans, but adverse effects have stymied its development.

Passive immunization, which involves developing anti-Aβ antibodies in a separate source, aims to clear Aβ peptide without requiring an immunologic response from the host. Large doses of antibodies administered weekly or monthly would be needed to build adequate plasma levels in the CNS, and large quantities of circulating antibodies could cause hemorrhagic stroke.

A troublesome trial

After successful preclinical and phase 1 testing of a vaccine against the Aβ peptide (called AN-1792), a phase 2a placebo-controlled trial in 2001 followed patients with mild to moderate AD. Drug administration was halted after 18 patients (6%) developed meningoencephalitis after several months.4 However, 300 patients with AD and 72 control patients had received at least one injection, and double-blind assessments were maintained for 12 months.

Figure 2 Methods for immunizing against Aβ peptide

Active immunization produces anti-Aβ antibodies via immunologic response to vaccination. With passive immunization, anti-Aβ antibodies are administered directly.

Illustration by Rich LaRocco.All patients with meningoencephalitis had received the vaccine but not all developed an immune response, suggesting that something other than the antibodies—such as T cells—caused the encephalitis. Twelve patients recovered, but six had persistent cognitive and neurologic deficits.

More-optimistic news

Of the 300 patients who received an active vaccine, 20% developed an adequate antibody response.5

The responders showed no significant difference from the placebo group in most outcome measures but showed less worsening in the nine-component Neuropsychological Test Battery (NTB) (P=0.02). Of particular interest, antibody responders showed significant improvement in the NTB—s memory domain (P=0.03). Further, subjects with higher IgG antibody titers showed greater improvement than did other responders.

More work ahead

Although the outcome of this initial AN-1792 trial is disappointing because of its discontinuation and mixed results, T cell infiltration and amyloid depletion were found during postmortem examinations of two vaccine recipients.6

Pharmaceutical companies are testing two compounds for AD immunotherapy:7

- AAB-001, a human monoclonal antibody, targets all 42 Aβ amino acids via passive immunization and has entered phase 2 trials.

- ACC-001, an Aβ immuno-conjugate designed to elicit an active antibody response, began phase 1 testing last fall.

These efforts suggest that an “Alzheimer’s vaccine” could be produced, provided it could attack the Aβ peptide without inducing a significant cellular reaction.

Deposition of amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) is believed to contribute to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathogenesis. Derived from a larger precursor protein, Aβ aggregates into plaques, and may promote neuronal death and, ultimately, dementia.

Current treatments alleviate symptoms without slowing underlying neurodegeneration. The prospect of harnessing the immune system to target the Aβ peptide offers an intriguing option for preventing this devastating, increasingly common disease.

Anti-a BETA antibodies

Transgenic mice bred to overexpress AD genes have responded remarkably in studies using the immune system to target the amyloid-β peptide.3 Several mouse groups have shown plaque reduction (Figure 1) and improved cognitive performance. These findings substantiate the amyloid hypothesis in AD pathogenesis.

A host could acquire anti-Aβ antibodies though two basic approaches (Figure 2):2

Figure 1 Differences in amyloid deposition between control and immunized mice

Frontal cortex of an unvaccinated mouse (left) shows more amyloid deposits (dark spots) than that of a mouse producing antibodies against the amyloid-β peptide (right).

Source: Image by Cynthia A. Lemere, PhD. Used with permission.Active immunization exposes the subject to the antigen (in this case the Aβ peptide) and allows T cells and B cells to produce anti-Aβ antibodies. This approach has been studied in humans, but adverse effects have stymied its development.

Passive immunization, which involves developing anti-Aβ antibodies in a separate source, aims to clear Aβ peptide without requiring an immunologic response from the host. Large doses of antibodies administered weekly or monthly would be needed to build adequate plasma levels in the CNS, and large quantities of circulating antibodies could cause hemorrhagic stroke.

A troublesome trial

After successful preclinical and phase 1 testing of a vaccine against the Aβ peptide (called AN-1792), a phase 2a placebo-controlled trial in 2001 followed patients with mild to moderate AD. Drug administration was halted after 18 patients (6%) developed meningoencephalitis after several months.4 However, 300 patients with AD and 72 control patients had received at least one injection, and double-blind assessments were maintained for 12 months.

Figure 2 Methods for immunizing against Aβ peptide

Active immunization produces anti-Aβ antibodies via immunologic response to vaccination. With passive immunization, anti-Aβ antibodies are administered directly.

Illustration by Rich LaRocco.All patients with meningoencephalitis had received the vaccine but not all developed an immune response, suggesting that something other than the antibodies—such as T cells—caused the encephalitis. Twelve patients recovered, but six had persistent cognitive and neurologic deficits.

More-optimistic news

Of the 300 patients who received an active vaccine, 20% developed an adequate antibody response.5

The responders showed no significant difference from the placebo group in most outcome measures but showed less worsening in the nine-component Neuropsychological Test Battery (NTB) (P=0.02). Of particular interest, antibody responders showed significant improvement in the NTB—s memory domain (P=0.03). Further, subjects with higher IgG antibody titers showed greater improvement than did other responders.

More work ahead

Although the outcome of this initial AN-1792 trial is disappointing because of its discontinuation and mixed results, T cell infiltration and amyloid depletion were found during postmortem examinations of two vaccine recipients.6

Pharmaceutical companies are testing two compounds for AD immunotherapy:7

- AAB-001, a human monoclonal antibody, targets all 42 Aβ amino acids via passive immunization and has entered phase 2 trials.

- ACC-001, an Aβ immuno-conjugate designed to elicit an active antibody response, began phase 1 testing last fall.

These efforts suggest that an “Alzheimer’s vaccine” could be produced, provided it could attack the Aβ peptide without inducing a significant cellular reaction.

1. Neugroschl JA, Kolevzor A, Samuels SC, Marir DB. Dementia. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA (eds). Kaplan & Sadock’s comprehensive text-book of psychiatry (8th ed). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:1068-93.

2. Schenk D. Amyloid-beta immunotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease: the end of the beginning. Nat Rev Neurosci 2002;3:824-8.

3. Schenk D, Hagen M, Seubert P. Current progress in beta-amyloid immunotherapy. Current Opin Immunol 2004;16:599-606.

4. Orgogozo JM, Gilman S, Dartigues JF, et al. Subacute meningoen-cephalitis in a subset of patients with AD after Abeta42 immunization. Neurology 2003;61:46-54.

5. Gilman S, Koller M, Black RS, et al. Clinical effects of Abeta immunization (AN1792) in patients with AD in an interrupted trial. Neurology 2005;64:1553-62.

6. Ferrer I, Boada Rovira M, Sanchez Guerra ML, et al. Neuropathology and pathogenesis of encephalitis following amyloid-beta immunization in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathology 2004;14(1):11-20.

7. Sullivan MG. Immunotherapy studies for AD back on track. Psychiatry News 2005;33(11):69.-

1. Neugroschl JA, Kolevzor A, Samuels SC, Marir DB. Dementia. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA (eds). Kaplan & Sadock’s comprehensive text-book of psychiatry (8th ed). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:1068-93.

2. Schenk D. Amyloid-beta immunotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease: the end of the beginning. Nat Rev Neurosci 2002;3:824-8.

3. Schenk D, Hagen M, Seubert P. Current progress in beta-amyloid immunotherapy. Current Opin Immunol 2004;16:599-606.

4. Orgogozo JM, Gilman S, Dartigues JF, et al. Subacute meningoen-cephalitis in a subset of patients with AD after Abeta42 immunization. Neurology 2003;61:46-54.

5. Gilman S, Koller M, Black RS, et al. Clinical effects of Abeta immunization (AN1792) in patients with AD in an interrupted trial. Neurology 2005;64:1553-62.

6. Ferrer I, Boada Rovira M, Sanchez Guerra ML, et al. Neuropathology and pathogenesis of encephalitis following amyloid-beta immunization in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathology 2004;14(1):11-20.

7. Sullivan MG. Immunotherapy studies for AD back on track. Psychiatry News 2005;33(11):69.-

CATIE’s surprises: In antipsychotics’ square-off, were there winners or losers?

Investigators faced a dilemma while designing the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE). More than 200 enrollees with chronic schizophrenia had pre-existing tardive dyskinesia (TD). Would it be ethical to give them the antipsychotic most likely to worsen their TD? Would exempting them from taking that drug influence the trial’s outcome?

This issue and others had to be resolved before the largest controlled study of “real world” schizophrenia could begin. Now that data are unfolding, groups with diverse agendas are debating CATIE’s methods and surprising results. This article describes how the trial’s design and findings could transform public policy and clinical practice.

poll here

Efficacy vs Effectiveness

The National Institute of Mental Health funded the prospective CATIE schizophrenia study to compare the effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics versus each other and versus a first-generation (typical) antipsychotic.

All approved atypicals have shown similar efficacy compared with placebo in short-term trials (usually 6 weeks).1 The CATIE trial’s rationale is that short-term efficacy studies required for FDA approval may not necessarily reflect the drugs’ effectiveness in long-term schizophrenia management. Effectiveness measures take into account efficacy as well as safety, tolerability, and unpredictable patient behaviors in the real world.

CATIE’s ‘Real World’ Patients

CATIE investigators enrolled a community sample of chronic schizophrenia patients similar to those many psychiatrists see. Very liberal inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1) allowed enrollees to have a history of substance abuse, comorbid psychiatric or medical disorders, be receiving other medications, or show evidence of TD. Their schizophrenia ranged from minimal to severe.2,3

The 1,493 patients who completed the study (Table 2) were enrolled at 57 outpatient treatment settings. One site’s 33 patients were eliminated from analysis because of doubts about the integrity of the data, leaving a total of 1,460 subjects.4

Table 1

Criteria for enrolling patients in the CATIE schizophrenia trial

| Inclusion criteria | Ages 18 to 65 yrs |

| DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia | |

| Able to take oral medication | |

| Able to give informed consent | |

| Exclusion criteria | Diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, mental retardation, or other cognitive disorders |

| History of serious adverse reactions to one of the study medications | |

| Had only one schizophrenic episode | |

| History of treatment resistance, defined as persistence of severe symptoms despite adequate trials of one of the study antipsychotics or prior treatment with clozapine | |

| Pregnant or breast feeding | |

| Serious and unstable medical conditions |

Table 2

CATIE’s 1,460 ‘real world’ schizophrenia patients at trial entry

| Mean age | 40.6±11.1 yrs |

| Mean age of first treatment | 24.0±8.9 yrs |

| Mean duration of treatment | 14.4±10.7 yrs |

| Gender | 74% male |

| Race | 60% white, 35% black, 5% other |

| Mean education | 12.1±2.3 years |

| Marital status | 59% never married |

| 29% previously married | |

| 11% married | |

| Employment status | 85% unemployed |

| Mean PANSS total score | 75.7±17.6 |

| Mean CGI | 4.0±0.9 |

| Psychiatric comorbidities | 29% drug dependence/abuse |

| 28% depression | |

| 25% alcohol dependence/abuse | |

| 14% anxiety disorder | |

| 5% obsessive-compulsive disorder | |

| Illness severity | 4% severe |

| 20% marked | |

| 47% moderate | |

| 23% mild | |

| 6% minimal | |

| PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale | |

| CGI: Clinician-rated Clinical Global Impressions severity score | |

| Source: Reference 5. | |

Medications. Before randomization, 28% of enrollees were not receiving antipsychotics. The remainder were receiving:

- olanzapine (22%)

- risperidone (19%)

- quetiapine (7%)

- ziprasidone (0%; approved after the trial began)

- any combination of olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine (7%)

- typical antipsychotics (16%).

Metabolic profile. These outpatients had a high rate of metabolic disorders: 42%—twice the rate in the general population—met criteria for metabolic syndrome,5 putting them at high risk to die of cardiovascular causes within 10 years.6 They had relatively poor physical health self-ratings and increased somatic preoccupation.7 Most worrisome, many were receiving no medications for their metabolic disorders, including 45% of those with diabetes, 89% with hyperlipidemia, and 62% with hypertension.8

Substance abuse. At enrollment, 40% of patients were abstinent from substance use, 22% were using substances without abuse or dependence, and 37% had substance abuse or dependence. Compared with nonusers, substance abusers tended to be male with more childhood problems, higher positive symptoms on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), and more likely to have had a recent illness exacerbation.9

Tardive dyskinesia. The 231 subjects who met criteria for probable TD10 were older than the overall sample with more years of antipsychotic treatment, especially with conventional neuroleptics and anticholinergics. Substance abuse was associated with TD, as were severity of psychopathology, extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), and akathisia.11

Violent behavior. A history of serious violent behavior was reported in:

- 5.4% of patients with high positive and low negative PANSS symptom scores

- 1.7% of patients with low positive and high negative PANSS symptom scores.

Consent. Patients’ capacity to give consent to participate in the study was assessed with the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research (MacCAT-CR). Psychosis severity (PANSS positive symptom scale) was not found to affect decision-making capacity, but negative symptoms and diminished working memory did.12

CATIE’s Unique Design

Defining effectiveness. CATIE was designed in three phases (Figure). Phase 1—discussed here—was a blinded, controlled comparison of four atypical antipsychotics and perphenazine. Results of phases 2 and 3 have yet to be published. The primary effectiveness endpoint, “all-cause discontinuation,” was defined as:

- lack of efficacy (patient was switched to another drug assigned at random)

- lack of tolerability (patient requested a drug change)

- safety problem (investigator initiated a switch)

- patient’s decision for any reason (often dropping out of the study).

The longer subjects stayed on the first antipsychotic they received, the more effective that drug was considered to be.

Figure CATIE schizophrenia trial design

* Phase 1A: participants with tardive dyskinesia (N=231) do not get randomized to perphenazine; phase 1B: participants who fail perphenazine will be randomized to an atypical (olanzapine, quetiapine, or risperidone) before eligibility for phase 2.

Source: Reference 2.Medications. Three atypicals—risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine—were approved for schizophrenia when the trial began in 1999. Recruitment ended in June 2003, the last subject completed the 18-month trial in December 2004, and data analysis began in January 2005. Ziprasidone was added to phase 1 after 40% of the sample had been enrolled, and aripiprazole was included as an option in the unblinded phase 3.

Perphenazine was chosen to represent typical antipsychotics because it has medium potency and less risk of EPS than high-potency drugs such as haloperidol and is associated with less weight gain than low-potency drugs such as thioridazine.

Dosing. Pharmaceutical manufacturers donated the antipsychotics and were invited to recommend their respective drugs’ starting dosages, dose increments, and maximum dosages. Olanzapine’s maker requested a higher starting dosage (7.5 mg/d instead of 5.0 mg/d) and a maximum dosage 50% higher than the FDA-approved range (30 mg/d instead of 20 mg/d). The others recommended the FDA-approved dosage ranges or less:

- quetiapine, 200 to 800 mg/d

- risperidone, 1.5 to 6 mg/d

- ziprasidone, 40 to 160 mg/d

- perphenazine, 8 to 32 mg/d.

The study team accepted their recommendations.

The medications were packaged in identical capsules. Quetiapine and ziprasidone were given twice daily because of product labeling; risperidone, olanzapine, and perphenazine were given once daily to one-half the patients assigned to them and twice daily to the others to prevent raters from guessing which drug a patient was receiving.

Tardive dyskinesia. For ethical reasons, the 231 patients with TD at enrollment were randomly assigned in phase 1 to atypicals but not to perphenazine because of the well-established link between typical antipsychotics and TD. This exception could have contributed to the closer-than-expected differences in EPS and perhaps in efficacy, given reports that TD patients have more negative symptoms and cognitive dysfunction.13 However, a statistical analysis took that into account.

CATIE’s Key Findings

Discontinuation. A disappointingly high discontinuation rate (74% overall) within a few months was the most important finding (Table 3). A recent effectiveness study with a design similar to the CATIE trial found a similarly high rate of all-cause discontinuation (70%) in patients with first-episode psychosis.14 Thus, patient-initiated drug discontinuation appears to be a core illness behavior from schizophrenia onset to chronic illness.

The high discontinuation rate shows that we need to modify our approach to schizophrenia, emphasizing full adherence to antipsychotic therapy from the onset of the illness.

Table 3

All-cause discontinuation rates in the CATIE trial

| Antipsychotic | Percent discontinued | Duration on antipsychotic (months)* | Dosage (mg/d)* |

| Olanzapine | 64% | 9.2 | 20.1 |

| Perphenazine | 75% | 4.6 | 20.8 |

| Quetiapine | 82% | 4.8 | 543.4 |

| Risperidone | 74% | 5.6 | 3.9 |

| Ziprasidone | 79% | 3.5 | 112.8 |

| Overall | 74% | Median 6.0; mean 8.3 | |

| Notes | |||

| *Mean modal | |||

| Olanzapine’s discontinuation rate was significantly lower than those of perphenazine, quetiapine, and risperidone but not of ziprasidone. | |||

| Olanzapine’s maximum dosage was 30 mg/d (50% higher than FDA-approved 20 mg/d); other agents were dosed within approved ranges. | |||

| Patients reached maximum daily antipsychotic dosages at these rates: 40% with olanzapine, 40% with perphenazine, 44% with quetiapine, 40% with risperidone, and 48% with ziprasidone. | |||

Effectiveness—measured as all-cause discontinuation or switching—was the primary outcome of phase 1. The unexpected finding that perphenazine and the atypicals had similar effectiveness could influence clinical practice. Insurers, for example, might consider promoting cheaper typical antipsychotics for first-line use. CATIE’s cost-effectiveness arm (Rosenheck et al, submitted for publication) will provide additional data on this issue.

Before rushing to use older antipsychotics as first-line treatments for schizophrenia, however, policymakers should consider three factors in the study design that could have enhanced perphenazine’s efficacy and safety profiles.

First, perphenazine was given at lower dosages (up to 32 mg/d) than “real world” clinicians used a decade ago (up to 64 mg/d). Thus, lower rates of serious side effects, especially TD, might have occurred in the study than in past clinical practice. Since atypical antipsychotics were approved, clinicians see far fewer psychiatric patients with pill-rolling tremors, rigid posture, or a shuffling gait, compared with 10 to 15 years ago when typical antipsychotics were widely used.

Second, perphenazine was associated with the highest EPS rate (17%), though its mean modal dosage (20.8 mg/d) is considered moderate. Discontinuation because of EPS was highest with perphenazine and lowest with quetiapine.

Third, excluding enrollees with TD from perphenazine may have increased perphenazine’s effectiveness, whereas including them in the atypicals groups may have reduced the atypicals’ effectiveness. TD patients are at increased risk to develop EPS; they had more-severe illness and a higher substance abuse rate among CATIE patients.11 Even so, investigators did control for TD in the data analysis and found no significant difference between typical and atypical antipsychotics.

No ‘Winners’ or ‘Losers’

Effectiveness, tolerability, and safety findings for each antipsychotic are compared in Tables 4A and 4B. Careful review shows no clear “winners” or “losers;” each agent has weaknesses but also strengths that may benefit individual patients.

Efficacy. Olanzapine showed a relatively higher efficacy and lower discontinuation rate but also had the highest risk of adverse metabolic effects. Some have attributed its greater efficacy to its higher dosing compared with the other antipsychotics. Some also have argued that the antipsychotics that showed lower efficacy, such as quetiapine and ziprasidone, were underdosed in this chronic schizophrenia population with a mean duration of illness of 14 years. Perphenazine, too, was dosed at the lower end of its range (mean modal dose 20.8 mg/d) compared with the old community standard of 36 to 64 mg/d.

Generally, a mean modal dosage of 20.1 mg/d for olanzapine is considered equivalent to ziprasidone, 160 mg; quetiapine, 800 mg; and risperidone, 6 mg. In CATIE phase 1, mean modal dosages were:

- ziprasidone, 112.8 mg/d (30% below 160 mg)

- quetiapine, 543.4 mg/d (32% below 800)

- risperidone, 3.9 mg/d (35% below 6 mg).

Olanzapine’s starting dosage of 7.5 mg/d was relatively higher than those of the other atypicals, which may have produced more-rapid onset of efficacy.

Switching. Another potential “advantage” for olanzapine was that 22% of subjects were taking it when they enrolled. By random assignment, 23% of patients who were taking olanzapine stayed on olanzapine and did not switch. By comparison:

- No patients assigned to ziprasidone were taking it before entering the trial.

- Only 5% of those taking quetiapine stayed on that drug after randomization.

- Few were receiving perphenazine before enrollment.

Switching antipsychotics may increase side effect risk or efficacy problems. For example, a patient switched from olanzapine or quetiapine to ziprasidone or perphenazine may experience insomnia during the transition, which may lead to tolerability complaints.

Metabolic side effects seen in this trial support past observations and reports that olanzapine is associated with higher risk for weight gain, hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia than other antipsychotics.15 Data on metabolic changes in CATIE patients taking olanzapine are being analyzed.

Hyperprolactinemia was most common with risperidone and practically nonexistent with other antipsychotics—even perphenazine. On the other hand, risperidone had the most favorable tolerability profile. This implies that elevated prolactin does not necessarily lead to antipsychotic discontinuation because of tolerability among patients with schizophrenia.

QTC interval and cataract data were benign across all antipsychotics. These findings appear to exonerate ziprasidone and quetiapine, respectively, which have been perceived as associated with these side effects.

When data become available, the next article in this series will discuss CATIE phase 2 findings. This phase includes patients who did not improve with the phase 1 regimens because of efficacy or tolerability problems and were switched to other antipsychotic therapies.

Related resources

- Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia study. www.catie.unc.edu/schizophrenia

- Schizophrenia Research Forum. NARSAD, The Mental Health Research Association.www.schizophreniaforum.org

Drug brand names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Perphenazine • Trilafon

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

Dr Nasrallah receives grants/research support from AstraZeneca, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Eli Lilly & Co., and Pfizer. He is a consultant, advisory board member, and speaker for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Pfizer, and Shire Pharmaceuticals Group.

1. Tandon R, Jibson MD. Efficacy of newer generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychoneuroendocrinol 2003;28(suppl 1):9-26.

2. Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, et al. The National Institute of Mental Health Clinical Antipsychotic Trial of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE). Project: schizophrenia trial design and protocol development. Schizophr Bull 2003;29:15-31.

3. Swartz MS, Perkins DO, Stroup TS, et al. Assessing clinical and functional outcomes in the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial. Schizophr Bull 2003;29:33-43.

4. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1209-23.

5. McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: baseline results from the CATIE schizophrenia trial and comparison with national estimates from NHANES III. Schizophr Res 2005;80:19-32.

6. Goff D, Sullivan LM, McEvoy JP, et al. A comparison of ten-year cardiac risk estimates in schizophrenia patients from the CATIE study and matched controls. Schizophr Res 2005;80:45-53.

7. Meyer JM, Nasrallah HA, McEvoy JP, et al. The Clinical Antipsychotic Trial of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial: clinical comparison of subgroups with and without the metabolic syndrome. Schizophr Res 2005;80:9-18.

8. Nasrallah HA, McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, et al. Low rates of treatment for metabolic disorders in the CATIE schizophrenia trial. Neuropsychopharmacol 2005;(suppl 1):204.-

9. Swartz MS, et al. (unpublished data).

10. Schooler NR, Kane JM. Research diagnosis for tardive dyskinesia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982;39:486-7.

11. Miller DD, McEvoy JP, Davis SM, et al. Clinical correlates of tardive dyskinesia in schizophrenia: baseline data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial. Schizophr Res 2005;80:33-43.

12. Stroup TS, Applebaum P, Swartz M, et al. Decision-making capacity for research participation among individuals in the CATIE schizophrenia trial. Schizophr Res 2005;80:1-8.

13. Waddington JL, Youssef HA, Dolphin C, et al. Cognitive function, negative symptoms and tardive dyskinesia in schizophrenia. Their association in relation to topography of involuntary movements and criterion of their abnormality. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987;44:907-12.

14. Keefe R. The CAFÉ effectiveness study. Amsterdam: European College of Neuropsychopharmacology annual meeting, 2005;

15. American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs, obesity, and diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004;27:596-601.

Investigators faced a dilemma while designing the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE). More than 200 enrollees with chronic schizophrenia had pre-existing tardive dyskinesia (TD). Would it be ethical to give them the antipsychotic most likely to worsen their TD? Would exempting them from taking that drug influence the trial’s outcome?

This issue and others had to be resolved before the largest controlled study of “real world” schizophrenia could begin. Now that data are unfolding, groups with diverse agendas are debating CATIE’s methods and surprising results. This article describes how the trial’s design and findings could transform public policy and clinical practice.

poll here

Efficacy vs Effectiveness

The National Institute of Mental Health funded the prospective CATIE schizophrenia study to compare the effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics versus each other and versus a first-generation (typical) antipsychotic.

All approved atypicals have shown similar efficacy compared with placebo in short-term trials (usually 6 weeks).1 The CATIE trial’s rationale is that short-term efficacy studies required for FDA approval may not necessarily reflect the drugs’ effectiveness in long-term schizophrenia management. Effectiveness measures take into account efficacy as well as safety, tolerability, and unpredictable patient behaviors in the real world.

CATIE’s ‘Real World’ Patients

CATIE investigators enrolled a community sample of chronic schizophrenia patients similar to those many psychiatrists see. Very liberal inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1) allowed enrollees to have a history of substance abuse, comorbid psychiatric or medical disorders, be receiving other medications, or show evidence of TD. Their schizophrenia ranged from minimal to severe.2,3

The 1,493 patients who completed the study (Table 2) were enrolled at 57 outpatient treatment settings. One site’s 33 patients were eliminated from analysis because of doubts about the integrity of the data, leaving a total of 1,460 subjects.4

Table 1

Criteria for enrolling patients in the CATIE schizophrenia trial

| Inclusion criteria | Ages 18 to 65 yrs |

| DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia | |

| Able to take oral medication | |

| Able to give informed consent | |

| Exclusion criteria | Diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, mental retardation, or other cognitive disorders |

| History of serious adverse reactions to one of the study medications | |

| Had only one schizophrenic episode | |

| History of treatment resistance, defined as persistence of severe symptoms despite adequate trials of one of the study antipsychotics or prior treatment with clozapine | |

| Pregnant or breast feeding | |

| Serious and unstable medical conditions |

Table 2

CATIE’s 1,460 ‘real world’ schizophrenia patients at trial entry

| Mean age | 40.6±11.1 yrs |

| Mean age of first treatment | 24.0±8.9 yrs |

| Mean duration of treatment | 14.4±10.7 yrs |

| Gender | 74% male |

| Race | 60% white, 35% black, 5% other |

| Mean education | 12.1±2.3 years |

| Marital status | 59% never married |

| 29% previously married | |

| 11% married | |

| Employment status | 85% unemployed |

| Mean PANSS total score | 75.7±17.6 |

| Mean CGI | 4.0±0.9 |

| Psychiatric comorbidities | 29% drug dependence/abuse |

| 28% depression | |

| 25% alcohol dependence/abuse | |

| 14% anxiety disorder | |

| 5% obsessive-compulsive disorder | |

| Illness severity | 4% severe |

| 20% marked | |

| 47% moderate | |

| 23% mild | |

| 6% minimal | |

| PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale | |

| CGI: Clinician-rated Clinical Global Impressions severity score | |

| Source: Reference 5. | |

Medications. Before randomization, 28% of enrollees were not receiving antipsychotics. The remainder were receiving:

- olanzapine (22%)

- risperidone (19%)

- quetiapine (7%)

- ziprasidone (0%; approved after the trial began)

- any combination of olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine (7%)

- typical antipsychotics (16%).

Metabolic profile. These outpatients had a high rate of metabolic disorders: 42%—twice the rate in the general population—met criteria for metabolic syndrome,5 putting them at high risk to die of cardiovascular causes within 10 years.6 They had relatively poor physical health self-ratings and increased somatic preoccupation.7 Most worrisome, many were receiving no medications for their metabolic disorders, including 45% of those with diabetes, 89% with hyperlipidemia, and 62% with hypertension.8

Substance abuse. At enrollment, 40% of patients were abstinent from substance use, 22% were using substances without abuse or dependence, and 37% had substance abuse or dependence. Compared with nonusers, substance abusers tended to be male with more childhood problems, higher positive symptoms on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), and more likely to have had a recent illness exacerbation.9

Tardive dyskinesia. The 231 subjects who met criteria for probable TD10 were older than the overall sample with more years of antipsychotic treatment, especially with conventional neuroleptics and anticholinergics. Substance abuse was associated with TD, as were severity of psychopathology, extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), and akathisia.11

Violent behavior. A history of serious violent behavior was reported in:

- 5.4% of patients with high positive and low negative PANSS symptom scores

- 1.7% of patients with low positive and high negative PANSS symptom scores.

Consent. Patients’ capacity to give consent to participate in the study was assessed with the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research (MacCAT-CR). Psychosis severity (PANSS positive symptom scale) was not found to affect decision-making capacity, but negative symptoms and diminished working memory did.12

CATIE’s Unique Design

Defining effectiveness. CATIE was designed in three phases (Figure). Phase 1—discussed here—was a blinded, controlled comparison of four atypical antipsychotics and perphenazine. Results of phases 2 and 3 have yet to be published. The primary effectiveness endpoint, “all-cause discontinuation,” was defined as:

- lack of efficacy (patient was switched to another drug assigned at random)

- lack of tolerability (patient requested a drug change)

- safety problem (investigator initiated a switch)

- patient’s decision for any reason (often dropping out of the study).

The longer subjects stayed on the first antipsychotic they received, the more effective that drug was considered to be.

Figure CATIE schizophrenia trial design

* Phase 1A: participants with tardive dyskinesia (N=231) do not get randomized to perphenazine; phase 1B: participants who fail perphenazine will be randomized to an atypical (olanzapine, quetiapine, or risperidone) before eligibility for phase 2.

Source: Reference 2.Medications. Three atypicals—risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine—were approved for schizophrenia when the trial began in 1999. Recruitment ended in June 2003, the last subject completed the 18-month trial in December 2004, and data analysis began in January 2005. Ziprasidone was added to phase 1 after 40% of the sample had been enrolled, and aripiprazole was included as an option in the unblinded phase 3.

Perphenazine was chosen to represent typical antipsychotics because it has medium potency and less risk of EPS than high-potency drugs such as haloperidol and is associated with less weight gain than low-potency drugs such as thioridazine.

Dosing. Pharmaceutical manufacturers donated the antipsychotics and were invited to recommend their respective drugs’ starting dosages, dose increments, and maximum dosages. Olanzapine’s maker requested a higher starting dosage (7.5 mg/d instead of 5.0 mg/d) and a maximum dosage 50% higher than the FDA-approved range (30 mg/d instead of 20 mg/d). The others recommended the FDA-approved dosage ranges or less:

- quetiapine, 200 to 800 mg/d

- risperidone, 1.5 to 6 mg/d

- ziprasidone, 40 to 160 mg/d

- perphenazine, 8 to 32 mg/d.

The study team accepted their recommendations.

The medications were packaged in identical capsules. Quetiapine and ziprasidone were given twice daily because of product labeling; risperidone, olanzapine, and perphenazine were given once daily to one-half the patients assigned to them and twice daily to the others to prevent raters from guessing which drug a patient was receiving.

Tardive dyskinesia. For ethical reasons, the 231 patients with TD at enrollment were randomly assigned in phase 1 to atypicals but not to perphenazine because of the well-established link between typical antipsychotics and TD. This exception could have contributed to the closer-than-expected differences in EPS and perhaps in efficacy, given reports that TD patients have more negative symptoms and cognitive dysfunction.13 However, a statistical analysis took that into account.

CATIE’s Key Findings

Discontinuation. A disappointingly high discontinuation rate (74% overall) within a few months was the most important finding (Table 3). A recent effectiveness study with a design similar to the CATIE trial found a similarly high rate of all-cause discontinuation (70%) in patients with first-episode psychosis.14 Thus, patient-initiated drug discontinuation appears to be a core illness behavior from schizophrenia onset to chronic illness.

The high discontinuation rate shows that we need to modify our approach to schizophrenia, emphasizing full adherence to antipsychotic therapy from the onset of the illness.

Table 3

All-cause discontinuation rates in the CATIE trial

| Antipsychotic | Percent discontinued | Duration on antipsychotic (months)* | Dosage (mg/d)* |

| Olanzapine | 64% | 9.2 | 20.1 |

| Perphenazine | 75% | 4.6 | 20.8 |

| Quetiapine | 82% | 4.8 | 543.4 |

| Risperidone | 74% | 5.6 | 3.9 |

| Ziprasidone | 79% | 3.5 | 112.8 |

| Overall | 74% | Median 6.0; mean 8.3 | |

| Notes | |||

| *Mean modal | |||

| Olanzapine’s discontinuation rate was significantly lower than those of perphenazine, quetiapine, and risperidone but not of ziprasidone. | |||

| Olanzapine’s maximum dosage was 30 mg/d (50% higher than FDA-approved 20 mg/d); other agents were dosed within approved ranges. | |||

| Patients reached maximum daily antipsychotic dosages at these rates: 40% with olanzapine, 40% with perphenazine, 44% with quetiapine, 40% with risperidone, and 48% with ziprasidone. | |||

Effectiveness—measured as all-cause discontinuation or switching—was the primary outcome of phase 1. The unexpected finding that perphenazine and the atypicals had similar effectiveness could influence clinical practice. Insurers, for example, might consider promoting cheaper typical antipsychotics for first-line use. CATIE’s cost-effectiveness arm (Rosenheck et al, submitted for publication) will provide additional data on this issue.

Before rushing to use older antipsychotics as first-line treatments for schizophrenia, however, policymakers should consider three factors in the study design that could have enhanced perphenazine’s efficacy and safety profiles.

First, perphenazine was given at lower dosages (up to 32 mg/d) than “real world” clinicians used a decade ago (up to 64 mg/d). Thus, lower rates of serious side effects, especially TD, might have occurred in the study than in past clinical practice. Since atypical antipsychotics were approved, clinicians see far fewer psychiatric patients with pill-rolling tremors, rigid posture, or a shuffling gait, compared with 10 to 15 years ago when typical antipsychotics were widely used.

Second, perphenazine was associated with the highest EPS rate (17%), though its mean modal dosage (20.8 mg/d) is considered moderate. Discontinuation because of EPS was highest with perphenazine and lowest with quetiapine.

Third, excluding enrollees with TD from perphenazine may have increased perphenazine’s effectiveness, whereas including them in the atypicals groups may have reduced the atypicals’ effectiveness. TD patients are at increased risk to develop EPS; they had more-severe illness and a higher substance abuse rate among CATIE patients.11 Even so, investigators did control for TD in the data analysis and found no significant difference between typical and atypical antipsychotics.

No ‘Winners’ or ‘Losers’

Effectiveness, tolerability, and safety findings for each antipsychotic are compared in Tables 4A and 4B. Careful review shows no clear “winners” or “losers;” each agent has weaknesses but also strengths that may benefit individual patients.

Efficacy. Olanzapine showed a relatively higher efficacy and lower discontinuation rate but also had the highest risk of adverse metabolic effects. Some have attributed its greater efficacy to its higher dosing compared with the other antipsychotics. Some also have argued that the antipsychotics that showed lower efficacy, such as quetiapine and ziprasidone, were underdosed in this chronic schizophrenia population with a mean duration of illness of 14 years. Perphenazine, too, was dosed at the lower end of its range (mean modal dose 20.8 mg/d) compared with the old community standard of 36 to 64 mg/d.

Generally, a mean modal dosage of 20.1 mg/d for olanzapine is considered equivalent to ziprasidone, 160 mg; quetiapine, 800 mg; and risperidone, 6 mg. In CATIE phase 1, mean modal dosages were:

- ziprasidone, 112.8 mg/d (30% below 160 mg)

- quetiapine, 543.4 mg/d (32% below 800)

- risperidone, 3.9 mg/d (35% below 6 mg).

Olanzapine’s starting dosage of 7.5 mg/d was relatively higher than those of the other atypicals, which may have produced more-rapid onset of efficacy.

Switching. Another potential “advantage” for olanzapine was that 22% of subjects were taking it when they enrolled. By random assignment, 23% of patients who were taking olanzapine stayed on olanzapine and did not switch. By comparison:

- No patients assigned to ziprasidone were taking it before entering the trial.

- Only 5% of those taking quetiapine stayed on that drug after randomization.

- Few were receiving perphenazine before enrollment.

Switching antipsychotics may increase side effect risk or efficacy problems. For example, a patient switched from olanzapine or quetiapine to ziprasidone or perphenazine may experience insomnia during the transition, which may lead to tolerability complaints.

Metabolic side effects seen in this trial support past observations and reports that olanzapine is associated with higher risk for weight gain, hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia than other antipsychotics.15 Data on metabolic changes in CATIE patients taking olanzapine are being analyzed.

Hyperprolactinemia was most common with risperidone and practically nonexistent with other antipsychotics—even perphenazine. On the other hand, risperidone had the most favorable tolerability profile. This implies that elevated prolactin does not necessarily lead to antipsychotic discontinuation because of tolerability among patients with schizophrenia.

QTC interval and cataract data were benign across all antipsychotics. These findings appear to exonerate ziprasidone and quetiapine, respectively, which have been perceived as associated with these side effects.

When data become available, the next article in this series will discuss CATIE phase 2 findings. This phase includes patients who did not improve with the phase 1 regimens because of efficacy or tolerability problems and were switched to other antipsychotic therapies.

Related resources

- Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia study. www.catie.unc.edu/schizophrenia

- Schizophrenia Research Forum. NARSAD, The Mental Health Research Association.www.schizophreniaforum.org

Drug brand names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Perphenazine • Trilafon

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

Dr Nasrallah receives grants/research support from AstraZeneca, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Eli Lilly & Co., and Pfizer. He is a consultant, advisory board member, and speaker for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Pfizer, and Shire Pharmaceuticals Group.

Investigators faced a dilemma while designing the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE). More than 200 enrollees with chronic schizophrenia had pre-existing tardive dyskinesia (TD). Would it be ethical to give them the antipsychotic most likely to worsen their TD? Would exempting them from taking that drug influence the trial’s outcome?

This issue and others had to be resolved before the largest controlled study of “real world” schizophrenia could begin. Now that data are unfolding, groups with diverse agendas are debating CATIE’s methods and surprising results. This article describes how the trial’s design and findings could transform public policy and clinical practice.

poll here

Efficacy vs Effectiveness

The National Institute of Mental Health funded the prospective CATIE schizophrenia study to compare the effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics versus each other and versus a first-generation (typical) antipsychotic.

All approved atypicals have shown similar efficacy compared with placebo in short-term trials (usually 6 weeks).1 The CATIE trial’s rationale is that short-term efficacy studies required for FDA approval may not necessarily reflect the drugs’ effectiveness in long-term schizophrenia management. Effectiveness measures take into account efficacy as well as safety, tolerability, and unpredictable patient behaviors in the real world.

CATIE’s ‘Real World’ Patients

CATIE investigators enrolled a community sample of chronic schizophrenia patients similar to those many psychiatrists see. Very liberal inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1) allowed enrollees to have a history of substance abuse, comorbid psychiatric or medical disorders, be receiving other medications, or show evidence of TD. Their schizophrenia ranged from minimal to severe.2,3

The 1,493 patients who completed the study (Table 2) were enrolled at 57 outpatient treatment settings. One site’s 33 patients were eliminated from analysis because of doubts about the integrity of the data, leaving a total of 1,460 subjects.4

Table 1

Criteria for enrolling patients in the CATIE schizophrenia trial

| Inclusion criteria | Ages 18 to 65 yrs |

| DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia | |

| Able to take oral medication | |

| Able to give informed consent | |

| Exclusion criteria | Diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, mental retardation, or other cognitive disorders |

| History of serious adverse reactions to one of the study medications | |

| Had only one schizophrenic episode | |

| History of treatment resistance, defined as persistence of severe symptoms despite adequate trials of one of the study antipsychotics or prior treatment with clozapine | |

| Pregnant or breast feeding | |

| Serious and unstable medical conditions |

Table 2

CATIE’s 1,460 ‘real world’ schizophrenia patients at trial entry

| Mean age | 40.6±11.1 yrs |

| Mean age of first treatment | 24.0±8.9 yrs |

| Mean duration of treatment | 14.4±10.7 yrs |

| Gender | 74% male |

| Race | 60% white, 35% black, 5% other |

| Mean education | 12.1±2.3 years |

| Marital status | 59% never married |

| 29% previously married | |

| 11% married | |

| Employment status | 85% unemployed |

| Mean PANSS total score | 75.7±17.6 |

| Mean CGI | 4.0±0.9 |

| Psychiatric comorbidities | 29% drug dependence/abuse |

| 28% depression | |

| 25% alcohol dependence/abuse | |

| 14% anxiety disorder | |

| 5% obsessive-compulsive disorder | |

| Illness severity | 4% severe |

| 20% marked | |

| 47% moderate | |

| 23% mild | |

| 6% minimal | |

| PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale | |

| CGI: Clinician-rated Clinical Global Impressions severity score | |

| Source: Reference 5. | |

Medications. Before randomization, 28% of enrollees were not receiving antipsychotics. The remainder were receiving:

- olanzapine (22%)

- risperidone (19%)

- quetiapine (7%)

- ziprasidone (0%; approved after the trial began)

- any combination of olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine (7%)

- typical antipsychotics (16%).

Metabolic profile. These outpatients had a high rate of metabolic disorders: 42%—twice the rate in the general population—met criteria for metabolic syndrome,5 putting them at high risk to die of cardiovascular causes within 10 years.6 They had relatively poor physical health self-ratings and increased somatic preoccupation.7 Most worrisome, many were receiving no medications for their metabolic disorders, including 45% of those with diabetes, 89% with hyperlipidemia, and 62% with hypertension.8

Substance abuse. At enrollment, 40% of patients were abstinent from substance use, 22% were using substances without abuse or dependence, and 37% had substance abuse or dependence. Compared with nonusers, substance abusers tended to be male with more childhood problems, higher positive symptoms on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), and more likely to have had a recent illness exacerbation.9

Tardive dyskinesia. The 231 subjects who met criteria for probable TD10 were older than the overall sample with more years of antipsychotic treatment, especially with conventional neuroleptics and anticholinergics. Substance abuse was associated with TD, as were severity of psychopathology, extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), and akathisia.11

Violent behavior. A history of serious violent behavior was reported in:

- 5.4% of patients with high positive and low negative PANSS symptom scores

- 1.7% of patients with low positive and high negative PANSS symptom scores.

Consent. Patients’ capacity to give consent to participate in the study was assessed with the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research (MacCAT-CR). Psychosis severity (PANSS positive symptom scale) was not found to affect decision-making capacity, but negative symptoms and diminished working memory did.12

CATIE’s Unique Design

Defining effectiveness. CATIE was designed in three phases (Figure). Phase 1—discussed here—was a blinded, controlled comparison of four atypical antipsychotics and perphenazine. Results of phases 2 and 3 have yet to be published. The primary effectiveness endpoint, “all-cause discontinuation,” was defined as:

- lack of efficacy (patient was switched to another drug assigned at random)

- lack of tolerability (patient requested a drug change)

- safety problem (investigator initiated a switch)

- patient’s decision for any reason (often dropping out of the study).

The longer subjects stayed on the first antipsychotic they received, the more effective that drug was considered to be.

Figure CATIE schizophrenia trial design

* Phase 1A: participants with tardive dyskinesia (N=231) do not get randomized to perphenazine; phase 1B: participants who fail perphenazine will be randomized to an atypical (olanzapine, quetiapine, or risperidone) before eligibility for phase 2.

Source: Reference 2.Medications. Three atypicals—risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine—were approved for schizophrenia when the trial began in 1999. Recruitment ended in June 2003, the last subject completed the 18-month trial in December 2004, and data analysis began in January 2005. Ziprasidone was added to phase 1 after 40% of the sample had been enrolled, and aripiprazole was included as an option in the unblinded phase 3.

Perphenazine was chosen to represent typical antipsychotics because it has medium potency and less risk of EPS than high-potency drugs such as haloperidol and is associated with less weight gain than low-potency drugs such as thioridazine.

Dosing. Pharmaceutical manufacturers donated the antipsychotics and were invited to recommend their respective drugs’ starting dosages, dose increments, and maximum dosages. Olanzapine’s maker requested a higher starting dosage (7.5 mg/d instead of 5.0 mg/d) and a maximum dosage 50% higher than the FDA-approved range (30 mg/d instead of 20 mg/d). The others recommended the FDA-approved dosage ranges or less:

- quetiapine, 200 to 800 mg/d

- risperidone, 1.5 to 6 mg/d

- ziprasidone, 40 to 160 mg/d

- perphenazine, 8 to 32 mg/d.

The study team accepted their recommendations.

The medications were packaged in identical capsules. Quetiapine and ziprasidone were given twice daily because of product labeling; risperidone, olanzapine, and perphenazine were given once daily to one-half the patients assigned to them and twice daily to the others to prevent raters from guessing which drug a patient was receiving.

Tardive dyskinesia. For ethical reasons, the 231 patients with TD at enrollment were randomly assigned in phase 1 to atypicals but not to perphenazine because of the well-established link between typical antipsychotics and TD. This exception could have contributed to the closer-than-expected differences in EPS and perhaps in efficacy, given reports that TD patients have more negative symptoms and cognitive dysfunction.13 However, a statistical analysis took that into account.

CATIE’s Key Findings

Discontinuation. A disappointingly high discontinuation rate (74% overall) within a few months was the most important finding (Table 3). A recent effectiveness study with a design similar to the CATIE trial found a similarly high rate of all-cause discontinuation (70%) in patients with first-episode psychosis.14 Thus, patient-initiated drug discontinuation appears to be a core illness behavior from schizophrenia onset to chronic illness.

The high discontinuation rate shows that we need to modify our approach to schizophrenia, emphasizing full adherence to antipsychotic therapy from the onset of the illness.

Table 3

All-cause discontinuation rates in the CATIE trial

| Antipsychotic | Percent discontinued | Duration on antipsychotic (months)* | Dosage (mg/d)* |

| Olanzapine | 64% | 9.2 | 20.1 |

| Perphenazine | 75% | 4.6 | 20.8 |

| Quetiapine | 82% | 4.8 | 543.4 |

| Risperidone | 74% | 5.6 | 3.9 |

| Ziprasidone | 79% | 3.5 | 112.8 |

| Overall | 74% | Median 6.0; mean 8.3 | |

| Notes | |||

| *Mean modal | |||

| Olanzapine’s discontinuation rate was significantly lower than those of perphenazine, quetiapine, and risperidone but not of ziprasidone. | |||

| Olanzapine’s maximum dosage was 30 mg/d (50% higher than FDA-approved 20 mg/d); other agents were dosed within approved ranges. | |||

| Patients reached maximum daily antipsychotic dosages at these rates: 40% with olanzapine, 40% with perphenazine, 44% with quetiapine, 40% with risperidone, and 48% with ziprasidone. | |||

Effectiveness—measured as all-cause discontinuation or switching—was the primary outcome of phase 1. The unexpected finding that perphenazine and the atypicals had similar effectiveness could influence clinical practice. Insurers, for example, might consider promoting cheaper typical antipsychotics for first-line use. CATIE’s cost-effectiveness arm (Rosenheck et al, submitted for publication) will provide additional data on this issue.

Before rushing to use older antipsychotics as first-line treatments for schizophrenia, however, policymakers should consider three factors in the study design that could have enhanced perphenazine’s efficacy and safety profiles.

First, perphenazine was given at lower dosages (up to 32 mg/d) than “real world” clinicians used a decade ago (up to 64 mg/d). Thus, lower rates of serious side effects, especially TD, might have occurred in the study than in past clinical practice. Since atypical antipsychotics were approved, clinicians see far fewer psychiatric patients with pill-rolling tremors, rigid posture, or a shuffling gait, compared with 10 to 15 years ago when typical antipsychotics were widely used.

Second, perphenazine was associated with the highest EPS rate (17%), though its mean modal dosage (20.8 mg/d) is considered moderate. Discontinuation because of EPS was highest with perphenazine and lowest with quetiapine.

Third, excluding enrollees with TD from perphenazine may have increased perphenazine’s effectiveness, whereas including them in the atypicals groups may have reduced the atypicals’ effectiveness. TD patients are at increased risk to develop EPS; they had more-severe illness and a higher substance abuse rate among CATIE patients.11 Even so, investigators did control for TD in the data analysis and found no significant difference between typical and atypical antipsychotics.

No ‘Winners’ or ‘Losers’

Effectiveness, tolerability, and safety findings for each antipsychotic are compared in Tables 4A and 4B. Careful review shows no clear “winners” or “losers;” each agent has weaknesses but also strengths that may benefit individual patients.

Efficacy. Olanzapine showed a relatively higher efficacy and lower discontinuation rate but also had the highest risk of adverse metabolic effects. Some have attributed its greater efficacy to its higher dosing compared with the other antipsychotics. Some also have argued that the antipsychotics that showed lower efficacy, such as quetiapine and ziprasidone, were underdosed in this chronic schizophrenia population with a mean duration of illness of 14 years. Perphenazine, too, was dosed at the lower end of its range (mean modal dose 20.8 mg/d) compared with the old community standard of 36 to 64 mg/d.

Generally, a mean modal dosage of 20.1 mg/d for olanzapine is considered equivalent to ziprasidone, 160 mg; quetiapine, 800 mg; and risperidone, 6 mg. In CATIE phase 1, mean modal dosages were:

- ziprasidone, 112.8 mg/d (30% below 160 mg)

- quetiapine, 543.4 mg/d (32% below 800)

- risperidone, 3.9 mg/d (35% below 6 mg).

Olanzapine’s starting dosage of 7.5 mg/d was relatively higher than those of the other atypicals, which may have produced more-rapid onset of efficacy.

Switching. Another potential “advantage” for olanzapine was that 22% of subjects were taking it when they enrolled. By random assignment, 23% of patients who were taking olanzapine stayed on olanzapine and did not switch. By comparison:

- No patients assigned to ziprasidone were taking it before entering the trial.

- Only 5% of those taking quetiapine stayed on that drug after randomization.

- Few were receiving perphenazine before enrollment.

Switching antipsychotics may increase side effect risk or efficacy problems. For example, a patient switched from olanzapine or quetiapine to ziprasidone or perphenazine may experience insomnia during the transition, which may lead to tolerability complaints.

Metabolic side effects seen in this trial support past observations and reports that olanzapine is associated with higher risk for weight gain, hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia than other antipsychotics.15 Data on metabolic changes in CATIE patients taking olanzapine are being analyzed.

Hyperprolactinemia was most common with risperidone and practically nonexistent with other antipsychotics—even perphenazine. On the other hand, risperidone had the most favorable tolerability profile. This implies that elevated prolactin does not necessarily lead to antipsychotic discontinuation because of tolerability among patients with schizophrenia.

QTC interval and cataract data were benign across all antipsychotics. These findings appear to exonerate ziprasidone and quetiapine, respectively, which have been perceived as associated with these side effects.

When data become available, the next article in this series will discuss CATIE phase 2 findings. This phase includes patients who did not improve with the phase 1 regimens because of efficacy or tolerability problems and were switched to other antipsychotic therapies.

Related resources

- Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia study. www.catie.unc.edu/schizophrenia

- Schizophrenia Research Forum. NARSAD, The Mental Health Research Association.www.schizophreniaforum.org

Drug brand names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Perphenazine • Trilafon

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

Dr Nasrallah receives grants/research support from AstraZeneca, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Eli Lilly & Co., and Pfizer. He is a consultant, advisory board member, and speaker for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Pfizer, and Shire Pharmaceuticals Group.

1. Tandon R, Jibson MD. Efficacy of newer generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychoneuroendocrinol 2003;28(suppl 1):9-26.

2. Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, et al. The National Institute of Mental Health Clinical Antipsychotic Trial of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE). Project: schizophrenia trial design and protocol development. Schizophr Bull 2003;29:15-31.

3. Swartz MS, Perkins DO, Stroup TS, et al. Assessing clinical and functional outcomes in the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial. Schizophr Bull 2003;29:33-43.

4. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1209-23.

5. McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: baseline results from the CATIE schizophrenia trial and comparison with national estimates from NHANES III. Schizophr Res 2005;80:19-32.

6. Goff D, Sullivan LM, McEvoy JP, et al. A comparison of ten-year cardiac risk estimates in schizophrenia patients from the CATIE study and matched controls. Schizophr Res 2005;80:45-53.

7. Meyer JM, Nasrallah HA, McEvoy JP, et al. The Clinical Antipsychotic Trial of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial: clinical comparison of subgroups with and without the metabolic syndrome. Schizophr Res 2005;80:9-18.

8. Nasrallah HA, McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, et al. Low rates of treatment for metabolic disorders in the CATIE schizophrenia trial. Neuropsychopharmacol 2005;(suppl 1):204.-

9. Swartz MS, et al. (unpublished data).

10. Schooler NR, Kane JM. Research diagnosis for tardive dyskinesia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982;39:486-7.

11. Miller DD, McEvoy JP, Davis SM, et al. Clinical correlates of tardive dyskinesia in schizophrenia: baseline data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial. Schizophr Res 2005;80:33-43.

12. Stroup TS, Applebaum P, Swartz M, et al. Decision-making capacity for research participation among individuals in the CATIE schizophrenia trial. Schizophr Res 2005;80:1-8.

13. Waddington JL, Youssef HA, Dolphin C, et al. Cognitive function, negative symptoms and tardive dyskinesia in schizophrenia. Their association in relation to topography of involuntary movements and criterion of their abnormality. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987;44:907-12.

14. Keefe R. The CAFÉ effectiveness study. Amsterdam: European College of Neuropsychopharmacology annual meeting, 2005;

15. American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs, obesity, and diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004;27:596-601.

1. Tandon R, Jibson MD. Efficacy of newer generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychoneuroendocrinol 2003;28(suppl 1):9-26.

2. Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, et al. The National Institute of Mental Health Clinical Antipsychotic Trial of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE). Project: schizophrenia trial design and protocol development. Schizophr Bull 2003;29:15-31.

3. Swartz MS, Perkins DO, Stroup TS, et al. Assessing clinical and functional outcomes in the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial. Schizophr Bull 2003;29:33-43.

4. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1209-23.

5. McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: baseline results from the CATIE schizophrenia trial and comparison with national estimates from NHANES III. Schizophr Res 2005;80:19-32.

6. Goff D, Sullivan LM, McEvoy JP, et al. A comparison of ten-year cardiac risk estimates in schizophrenia patients from the CATIE study and matched controls. Schizophr Res 2005;80:45-53.

7. Meyer JM, Nasrallah HA, McEvoy JP, et al. The Clinical Antipsychotic Trial of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial: clinical comparison of subgroups with and without the metabolic syndrome. Schizophr Res 2005;80:9-18.

8. Nasrallah HA, McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, et al. Low rates of treatment for metabolic disorders in the CATIE schizophrenia trial. Neuropsychopharmacol 2005;(suppl 1):204.-

9. Swartz MS, et al. (unpublished data).

10. Schooler NR, Kane JM. Research diagnosis for tardive dyskinesia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982;39:486-7.

11. Miller DD, McEvoy JP, Davis SM, et al. Clinical correlates of tardive dyskinesia in schizophrenia: baseline data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial. Schizophr Res 2005;80:33-43.

12. Stroup TS, Applebaum P, Swartz M, et al. Decision-making capacity for research participation among individuals in the CATIE schizophrenia trial. Schizophr Res 2005;80:1-8.

13. Waddington JL, Youssef HA, Dolphin C, et al. Cognitive function, negative symptoms and tardive dyskinesia in schizophrenia. Their association in relation to topography of involuntary movements and criterion of their abnormality. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987;44:907-12.

14. Keefe R. The CAFÉ effectiveness study. Amsterdam: European College of Neuropsychopharmacology annual meeting, 2005;

15. American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs, obesity, and diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004;27:596-601.

Psychosis: 6 steps rule out medical causes in kids

John, age 16, is admitted to our inpatient psychiatric unit, complaining of “a 2-week constant headache” caused by “voices arguing in my head.” He has lived in Mexico with an uncle for 6 months but returned home last week for medical evaluation of his headaches.

His parents report that John developed normally until 3 years ago, when he gradually lost interest in his favorite activities and became socially withdrawn. He has not attended school in 2 years. He has no history of illicit drug use and is not taking prescription or over the-counter medications.

Complete physical examination, neurologic exam, and routine screening lab test results are normal. Thinking that a high lead content of cookware used in Mexico might be causing John’s symptoms, we order a lead level: result-0.2 mg/dL (

We diagnose schizophreniform disorder, but John’s parents refuse to accept this diagnosis. They repeatedly ask if we can do more to identify a medical cause of their son’s psychiatric symptoms.

As in John’s case, young patients or their parents may resist the diagnosis of a chronic mental illness such as schizophrenia. Understandably, they may be invested in trying to identify “medically treatable” causes. You can address their anxieties by showing them that you have systematically evaluated medical causes of psychosis.

We offer such a tool: an algorithm and tables to help you identify common and rare medical conditions that may cause or exacerbate psychotic symptoms in patients ages 3 to 18.

An evidence-based algorithm

Multiple factors—developmental, psychological, family, environmental, or medical—typically cause psychotic symptoms in a child or adolescent. Evaluating all possibilities is essential, but guidelines tend to minimize medical causes. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry guidelines, for example, recommend that “all medical disorders (including general medical conditions and substance-induced disorders) are ruled out,”1 but they do not specify which medical conditions to consider.

To supplement existing guidelines, we searched the literature and developed an evidence-based algorithm to help you systematically consider medical causes of pediatric psychotic symptoms. We excluded children age 2

How to use it. The algorithm walks you through a medical systems review. You begin with a complete history, then address six causes of psychotic symptoms: substance abuse, medication reactions, general medical conditions, unexplained somatic symptoms (such as from toxic environmental exposures), developmental and learning disabilities, and atypical presentations.

Don’t stop if you find one possible cause of psychotic symptoms; continue to the end of the algorithm. The more factors you identify, the greater your chance of finding a treatable cause that may ameliorate your patient’s symptoms.

To make the algorithm clinically useful, we listed conditions in order of decreasing probability of causing psychotic symptoms. For example, the first cause listed is substance-induced disorders,3 which are most common among adolescent patients. We also “triaged” medical conditions from common to rare (based on estimated prevalence of association with psychotic symptoms), listing rare causes only in cases of atypical presentation or treatment resistance.

Supporting tables. The following discussion summarizes data that support the algorithm and its tables:

- medications reported to cause psychosis (Table 1)

- medical conditions most likely to cause psychosis (Table 2)

- medical conditions that rarely cause psychosis (Table 3).

Drugs that may cause psychotic symptoms

| Drug class | Psychotic symptoms | |

|---|---|---|

| Bizarre behavior/delusions | Auditory or visual hallucinations | |

| Amphetamine-like drugs | X | X |

| Anabolic steroids | X | |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors | X | |

| Anticholinergics and atropine | X | X |

| Antidepressants, tricyclic | X | |

| Antiepileptics | X | |

| Barbiturates | X | X |

| Benzodiazepines | X | X |

| Beta-adrenergic blockers | X | X |

| Calcium channel blockers | X | |

| Cephalosporins | X | X |

| Corticosteroids | X | |

| Dopamine receptor agonists | X | X |

| Fluoroquinolone antibiotics | X | X |

| Histamine H1 receptor blockers | X | |

| Histamine H2 receptor blockers | X | |

| HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors | X | |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | X | |

| Opioids | X | X |