User login

Panic attacks: Help sufferers recover with cognitive-behavioral therapy

With panic attacks, alarming physiologic symptoms mount swiftly—tachycardia, chest pain, sweating, trembling, smothering or choking, dizziness, fear of losing control or going crazy—even fear of dying.1 Patients constantly fear the next attack, worry about its consequences, and change their behaviors to avoid or withdraw from anxiety-provoking situations.

To relieve their suffering, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) may offer benefits you would not realize with medication alone. CBT can:

- improve long-term patient outcomes

- enhance medication management

- boost treatment response when medication alone is inadequate

- ease drug discontinuation.2

Whether you or a CBT-trained psychotherapist guides the sessions, you can achieve optimal results for your patients with panic disorder.

How Effective is CBT?

Panic disorder is chronic, often disabling, and characterized by spontaneous, unpredictable panic attacks (Boxes 1 and 23-11). When treated with CBT, about three-quarters of patients become panic-free and maintain treatment gains at follow-up, and one-half become both panic-free and free of excess anxiety.9

Typical therapy is 12 individual, once-weekly visits for psycho-education, relaxation, and breathing training; cognitive restructuring; and exposure therapies.

Briefer protocols, “reduced therapist contact,”12 and group therapy13 also can help patients and in some studies have been as beneficial as 12 weeks of individual therapy. Although trained psychotherapists have higher success rates than nonbehaviorists when treating panic patients, nonbehaviorists also can provide effective therapy after relatively brief training.14

American Psychiatric Association15 treatment guidelines recommend medications—such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and benzodiazepines—as well as CBT as first-line therapies for panic disorder. Other treatment guidelines concur16 and note that CBT is more cost-effective than medications.

In comparison studies, CBT has been at least as effective for panic symptoms as SSRIs,17,18 TCAs,19 and alprazolam.20 Antidepressants are the preferred drug for panic disorder16 because they lack benzodiazepines’ dependence and abuse potential.

Providing medication during CBT may maintain patients’ therapeutic gains better than CBT alone if the medication is continued after CBT is completed. Interestingly, patients who use benzodiazepines during CBT may have higher relapse rates than those who do not use benzodiazepines, particularly when the benzodiazepines are withdrawn.9

CBT produces improvement rates similar to those of pharmacologic treatment at one-quarter to one-half the cost in the first year. Patients also appear to have better clinical outcomes if they receive CBT while SSRIs or benzodiazepines are being discontinued, compared with simply stopping the medications.8

Panic attacks typically begin between ages 10 and 40. The cause is unknown, but evidence points to multiple factors, including heredity, neurobiology, provocations, and psychological conditioning (Box 2).3-9 prevalence is approximately 5%,10 and about three-fourths of panic disorder patients are female.11

Comorbidity. Up to 50% of persons with panic disorder also experience agoraphobia.1 Depression, other anxiety disorders, and substance abuse may complicate the clinical picture.

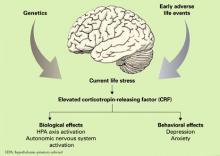

BIOLOGICAL THEORIES

Genetics. About 10% of persons who experience panic attacks have first-degree relatives with panic disorder. Twin studies suggest heritability of up to 43%

Neurobiology. Anxiety responses appear to be organized at different neuroanatomic levels:

- automatic responses by periaqueductal grey matter or locus coeruleus

- practiced responses by the amygdala and septohippocampal regions

- cognitively complex responses by higher cortical regions.

The hypothalamus mediates neurohormonal responses. Panic disorder patients’ response to SSRIs, tricyclic antidepressants, and benzodiazepines suggest a link with neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine, and GABA. Adenosine, cannabinoids, neuropeptides, hormones, neurotrophins, cytokines, and cellular mediators may also be involved.

Provocation. Panic disorder may have a physiologic mechanism. When exposed in the laboratory to panicogenic substances (such as carbon dioxide, sodium lactate, yohimbine, and caffeine), persons with panic disorders experience greater numbers of panic attacks than do those without panic disorders. These laboratory-induced panic attacks resemble real attacks, and anti-panic medications block the induced panic attacks.

PSYCHOLOGICAL THEORIES

The cognitive-behavioral model postulates that panic disorder patients:

- have a predisposed vulnerability to respond with physiologic arousal to negative stressors

- tend to see anxiety symptoms as harmful

- have negative and catastrophizing cognitions about those symptoms.

With conditioning, patients associate early physiologic arousal with other panic symptoms as the arousal progresses. Ultimately, they become hypervigilant for symptoms and develop a learned escalation of anxiety and apprehension (with accompanying negative cognitions) when the early symptoms re-occur.

Source: References 3-9

CBT Candidates

To diagnose panic disorder, conduct a thorough psychiatric evaluation that includes assessing for comorbid mental and substance use disorders. The history and physical exam are essential to rule out medical causes of the patient’s symptoms, such as heart disease causing dizziness or palpitations. Asking patients to keep panic attack records can help you identify panic symptoms’ frequency and triggers.9

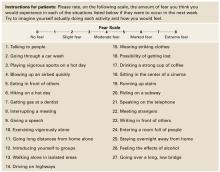

An assessment tool such as the Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire (Figure) can be a useful starting point. It has 27 items and three subscales to quantify a patient’s fear of agoraphobic situations, social phobia situations, and situations that produce bodily sensations (interoceptive symptoms). Items on the interoceptive subscale include activities such as exercising vigorously, ingesting caffeine, and experiencing intense emotion.21 Using the Anxiety Sensitivity Index is another assessment option.22

Not all patients with panic attacks respond well to CBT; predictors of poor response in clinical trials have included:

- severe baseline panic symptoms, personality disorders, and possibly depressed mood

- marital dissatisfaction

- low motivation for treatment.2,9

Figure Patient assessment: Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire

Source: Reprinted with permission from Rapee RM, Craske MG, Barlow DH. Assessment instrument for panic disorder that includes fear of sensation-producing activities: The Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire. Anxiety 1995;1:114-22. Copyright 1995, Wiley-Liss, Inc.

Cognitive Therapies for Panic Disorder

Psychoeducation. Begin by defining and explaining anxiety, panic attacks, panic disorder, and any comorbid psychopathology the patient may have (agoraphobia, depression). Explain panic symptoms as physiologic and psychological responses to stressors.

Address the patient’s fears that anxiety’s physiologic symptoms represent a serious or undiagnosed medical disorder or that a panic attack could cause serious harm. Assign self-help and reading materials to reinforce this discussion (see Related resources). Finally, explain the rationale for using CBT to treat panic symptoms.

Use cognitive restructuring to address faulty or irrational information-processing patterns that underlie pathologic anxiety. Identify automatic thought patterns (such as catastrophizing, overgeneralization, all-or-nothing thinking, and personalization), then provide a careful “reality check,” in which you systematically substitute a more-rational thought process.

Have the patient keep a self-monitoring diary to help you assess thought patterns and re-direct irrational thoughts. A diary may identify anxiety-provoking scenarios on which to focus therapy. Encourage patients to document anxiety events using the “triple-column” technique:23

- column 1: circumstances of the anxiety or panic

- column 2: their emotional state at the time

- column 3: any thoughts they can identify.

Instruct them to log this data while experiencing symptoms or immediately afterward. Later, during the intervention phase, patients can record how they tried to restructure their thoughts and any consequent mood changes. Review diary entries with them during subsequent sessions.

Exposure Therapy

Graduated exposure and response prevention (ERP) is the core component of CBT for panic disorder. ERP exercises require the patient to confront anxiety-producing stimuli while agreeing not to engage in maladaptive behavior that avoids, prematurely reduces, or prevents the anxiety. The stimuli may be external cues—such as bridges, stores, or heights—or interoceptive cues such as dizziness, tachycardia, or tachypnea.

Creating fear hierarchies. To begin, we recommend that you work with the patient to create lists of all external situations and interoceptive stimuli that cause him or her anxiety. Separating the stimuli into two lists helps patients recognize that their bodily stimuli are at least as important as environmental stimuli in promoting a panic attack.

The patient then rates each stimulus using a Subjective Units of Distress scale (SUDS)—assigning 0 to 100 points from no anxiety to overwhelming anxiety—and ranks items on the lists from mildest to worst anxiety. Instruct patients to rate the distress they would feel if they could not escape from the stimuli.

First experience. After the hierarchies are created, the therapist introduces the patient to exposure therapy by choosing an item that causes mild to moderate anxiety. Starting at this anxiety level, patients are likely to succeed with their first exercise without feeling overwhelmed. The therapist teaches the patient about the process, then begins the exposure by helping the patient create and confront the very scenario (or a representation of that scenario) that causes anxiety.

When working on interoceptive cues, various exercises can be used to reproduce bother-some bodily symptoms, such as:

- running up a flight of stairs or running in place to generate tachycardia

- purposefully hyperventilating to produce lightheadedness.

- spinning in place to create dizziness.

The patient agrees not to actively attempt to escape the scenario but to tolerate and perhaps even focus on the anxiety (Box 3). Using “safety cues”—such as leaning against a wall or keeping eyes closed—is also forbidden. Patients soon see that the anxiety does not last indefinitely but begins to diminish fairly rapidly.

Reaching the goal. After repeated exposure sessions, anxiety associated with a stimulus begins to extinguish. Having experienced the success of tolerating a previously difficult stimuli and feeling much less anxious, the patient is ready to take on increasingly difficult tasks. The therapist also assigns the patient “homework” to practice exposure exercises already mastered during sessions. As exposure therapy progresses, the patient takes a larger role in designing and executing sessions. The goal is for the patient to learn to become his or her own behaviorist and to intervene early when panic symptoms begin.

Resist temptation to rescue patients from their anxiety during exposure sessions, such as by chatting about the weather or current events or providing other distractions. To extinguish the link between the stimuli and anxiety, the patient must experience anxiety all the way through the exercise—preferably giving ongoing Subjective Units of Distress (SUDS) ratings—until symptoms inevitably wane and cease.

Similarly, avoid assigning exposure homework to be done “until you can’t stand it anymore, then take a rest.” Although well-intentioned, allowing the patient to escape the exposure when anxiety peaks increases conditioned anxiety and strongly reinforces avoidance behaviors.

Other Behavioral Techniques

Imaginal exposure sessions can be created using visualizations of feared stimuli, gradually presented as with in vivo exposure. For example, as you recount a target scenario, ask the patient to imagine a progression of events or bodily cues that have led to panic attacks. The patient supplies SUDS ratings and refrains from imagining an avoidance or maladaptive response. You can tape-record the session for homework and assign the patient to listen to it and participate daily.

Imaginal exposure may help treat phobic avoidance (such as agoraphobic symptoms), but study results have been disappointing in panic symptoms.24 However, this approach may help reluctant patients initiate in vivo exposure therapy.

Relaxation training—such as progressive muscle relaxation, visual imagery, or autogenic protocols—has shown mixed results in treating panic.25,26 Relaxation may help patients cope with panic’s physiologic arousal, but it is not suitable as a singular intervention.

Breathing retraining. Because hyperventilation and panic symptoms are related, instruction and practice in slow, diaphragmatic breathing has long been a component of CBT for panic symptoms. Little evidence supports breathing retraining,9 although Meuret et al27,28 have described a respiratory feedback paradigm that may reduce panic symptoms in appropriately selected patients.

Many studies that have assessed breathing retraining as monotherapy for panic have had methodologic flaws.27

Building a Therapeutic Alliance

Successful therapists have been found to use empathic listening more than directives and explanations in the first therapy session.9 They understand the suffering from panic disorder and the value of listening as patients explain their symptoms, thoughts, and feelings. The rapport built during this initial interaction can help sustain motivation as the therapist then takes charge of subsequent sessions.

Among important skills for CBT therapists, Seligman29 includes empathy, caring, warmth, and active listening, as well as the ability to:

- be a teacher, scientist, and co-investigator

- demystify treatment

- engage clients as “active, knowledgeable, and responsible partners” in their therapy.

Finally, although CBT clinicians suggest tasks and interventions for this “shared endeavor,” patients are primarily responsible for change.

- Anxiety Disorders Association of America. www.adaa.org.

- Craske M, Barlow D, Cary NC. Mastery of your anxiety and panic, (3rd ed). Therapist guide and client workbook. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2000.

- Otto MW. Stopping anxiety medication: panic control therapy for benzodiazepine discontinuation. Therapist guide and patient workbook. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2004.

- The Panic Center. Patient diaries and other self-help resources. www.paniccenter.net

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed, text rev). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

2. Otto MW, Deckersbach T. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder: Theory, strategies, and outcome. In: Rosenbaum JF, Pollack M (eds). Panic disorder and its treatment. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1998.

3. Hettema, JM, Neale, MC, Kendler, KS. A review and meta-analysis of the genetic epidemiology of anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158(10):1568-78.

4. Kendler KS, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. Panic syndromes in a population-based sample of male and female twins. Psychol Med 2001;31:989-1000.

5. Sandford JJ, Argyropoulos SV, Nutt DJ. The psychobiology of anxiolytic drugs. Part I: basic neurobiology. Pharmacol Ther 2000;88:197-212.

6. Millan MJ. The neurobiology and control of anxious states. Prog Neurobiol 2003;70:83-244.

7. Sanderson WC, Rego SA. Empirically supported psychological treatment of panic disorder and agoraphobia. Medscape. Available at www.medscape.com/viewprogram/350_pnt. Accessed Nov. 8, 2005.

8. Rayburn NR, Otto MW. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder: a review of treatment elements, strategies, and outcomes. CNS Spectr 2003;8(5):356-62.

9. Craske MG, Barlow DH. Panic disorder and agoraphobia. In: Barlow DH (ed). Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual. New York: Guilford Press; 2001;1-59.

10. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:593-602.

11. Rapee RM, Barlow DH. Generalized anxiety disorders, panic disorders, and phobias. In: Sutker PB, Adams HE (eds). Comprehensive handbook of psychopathology (3rd ed). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2001.

12. Cote G, Gauthier JG, Laberge B, et al. Reduced therapist contact in the cognitive behavioral treatment of panic disorder. Behav Ther 1994;25:123-45.

13. Telch MJ, Lucas JA, Schmidt NB, et al. Group cognitive-behavioral treatment of panic disorder. Behav Res Ther 1993;31:279-28.

14. Welkowitz LA, Papp LA, Cloitre M, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder delivered by psychopharmacologically oriented clinicians. J Nerv Ment Dis 1991;179:473-77.

15. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1998.

16. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. Australian and New Zealand clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of panic disorder and agoraphobia. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2003;37:641-56.Available at: www.ranzcp.org/publicarea/cpg.asp. Accessed Aug. 24, 2005.

17. Black DW, Wesner R, Bowers W, Gabel J. A comparison of fluvoxamine, cognitive therapy, and placebo in the treatment of panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993;31:383-94.

18. Dannon PN, Gon-Usishkin M, Gelbert A, et al. Cognitive behavioral group therapy in panic disorder patients: The efficacy of CBGT versus drug treatment. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2004;16:41-6.

19. Clark DM, Salkovskis PM, Hackmann A, et al. A comparison of cognitive therapy, applied relaxation, and imipramine in the treatment of panic disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1994;164:759-69.

20. Klosko JS, Barlow DH, Tassinari R, Cerny JA. A comparison of alprazolam and behavior therapy in treatment of panic disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 1990;58:77-84.

21. Rapee RM, Craske MG, Barlow DH. Assessment instrument for panic disorder that includes fear of sensation-producing activities: The Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire. Anxiety 1995;1:114-22.

22. Reiss S, Peterson R, Gursky D, McNally R. Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency, and the prediction of fearfulness. Behav Res Ther 1986;24:1-8.

23. Burns DD. Feeling good: The new mood therapy. New York: William Morrow and Co.; 1980.

24. Clum GA, Watkins PL, Borden JW, et al. A comparison of guided imaginal coping and imaginal exposure in the treatment of panic disorder. J Rational-Emotive & Cognitive Behavior Therapy 1993;11(4):179-93.

25. Craske MG, Brown TA, Barlow DH. Behavioral treatment of panic disorder: A two year follow-up. Behav Ther 1991;22:289-304.

26. Ost LG, Westling BE. Applied relaxation vs cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of panic disorder. Behav Res Ther 1995;33:145-58.

27. Meuret AE, Wilhelm FH, Ritz T, Roth WT. Breathing training for treating panic disorder: useful intervention or impediment. Behav Mod 2003;27(5):731-54.

28. Meuret AE, Wilhelm FH, Roth WT. Respiratory feedback for treating panic disorder. J Clin Psychol 2004;60:197-207.

29. Seligman L. Systems, strategies, and skills of counseling and psychotherapy. Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 2001.

With panic attacks, alarming physiologic symptoms mount swiftly—tachycardia, chest pain, sweating, trembling, smothering or choking, dizziness, fear of losing control or going crazy—even fear of dying.1 Patients constantly fear the next attack, worry about its consequences, and change their behaviors to avoid or withdraw from anxiety-provoking situations.

To relieve their suffering, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) may offer benefits you would not realize with medication alone. CBT can:

- improve long-term patient outcomes

- enhance medication management

- boost treatment response when medication alone is inadequate

- ease drug discontinuation.2

Whether you or a CBT-trained psychotherapist guides the sessions, you can achieve optimal results for your patients with panic disorder.

How Effective is CBT?

Panic disorder is chronic, often disabling, and characterized by spontaneous, unpredictable panic attacks (Boxes 1 and 23-11). When treated with CBT, about three-quarters of patients become panic-free and maintain treatment gains at follow-up, and one-half become both panic-free and free of excess anxiety.9

Typical therapy is 12 individual, once-weekly visits for psycho-education, relaxation, and breathing training; cognitive restructuring; and exposure therapies.

Briefer protocols, “reduced therapist contact,”12 and group therapy13 also can help patients and in some studies have been as beneficial as 12 weeks of individual therapy. Although trained psychotherapists have higher success rates than nonbehaviorists when treating panic patients, nonbehaviorists also can provide effective therapy after relatively brief training.14

American Psychiatric Association15 treatment guidelines recommend medications—such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and benzodiazepines—as well as CBT as first-line therapies for panic disorder. Other treatment guidelines concur16 and note that CBT is more cost-effective than medications.

In comparison studies, CBT has been at least as effective for panic symptoms as SSRIs,17,18 TCAs,19 and alprazolam.20 Antidepressants are the preferred drug for panic disorder16 because they lack benzodiazepines’ dependence and abuse potential.

Providing medication during CBT may maintain patients’ therapeutic gains better than CBT alone if the medication is continued after CBT is completed. Interestingly, patients who use benzodiazepines during CBT may have higher relapse rates than those who do not use benzodiazepines, particularly when the benzodiazepines are withdrawn.9

CBT produces improvement rates similar to those of pharmacologic treatment at one-quarter to one-half the cost in the first year. Patients also appear to have better clinical outcomes if they receive CBT while SSRIs or benzodiazepines are being discontinued, compared with simply stopping the medications.8

Panic attacks typically begin between ages 10 and 40. The cause is unknown, but evidence points to multiple factors, including heredity, neurobiology, provocations, and psychological conditioning (Box 2).3-9 prevalence is approximately 5%,10 and about three-fourths of panic disorder patients are female.11

Comorbidity. Up to 50% of persons with panic disorder also experience agoraphobia.1 Depression, other anxiety disorders, and substance abuse may complicate the clinical picture.

BIOLOGICAL THEORIES

Genetics. About 10% of persons who experience panic attacks have first-degree relatives with panic disorder. Twin studies suggest heritability of up to 43%

Neurobiology. Anxiety responses appear to be organized at different neuroanatomic levels:

- automatic responses by periaqueductal grey matter or locus coeruleus

- practiced responses by the amygdala and septohippocampal regions

- cognitively complex responses by higher cortical regions.

The hypothalamus mediates neurohormonal responses. Panic disorder patients’ response to SSRIs, tricyclic antidepressants, and benzodiazepines suggest a link with neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine, and GABA. Adenosine, cannabinoids, neuropeptides, hormones, neurotrophins, cytokines, and cellular mediators may also be involved.

Provocation. Panic disorder may have a physiologic mechanism. When exposed in the laboratory to panicogenic substances (such as carbon dioxide, sodium lactate, yohimbine, and caffeine), persons with panic disorders experience greater numbers of panic attacks than do those without panic disorders. These laboratory-induced panic attacks resemble real attacks, and anti-panic medications block the induced panic attacks.

PSYCHOLOGICAL THEORIES

The cognitive-behavioral model postulates that panic disorder patients:

- have a predisposed vulnerability to respond with physiologic arousal to negative stressors

- tend to see anxiety symptoms as harmful

- have negative and catastrophizing cognitions about those symptoms.

With conditioning, patients associate early physiologic arousal with other panic symptoms as the arousal progresses. Ultimately, they become hypervigilant for symptoms and develop a learned escalation of anxiety and apprehension (with accompanying negative cognitions) when the early symptoms re-occur.

Source: References 3-9

CBT Candidates

To diagnose panic disorder, conduct a thorough psychiatric evaluation that includes assessing for comorbid mental and substance use disorders. The history and physical exam are essential to rule out medical causes of the patient’s symptoms, such as heart disease causing dizziness or palpitations. Asking patients to keep panic attack records can help you identify panic symptoms’ frequency and triggers.9

An assessment tool such as the Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire (Figure) can be a useful starting point. It has 27 items and three subscales to quantify a patient’s fear of agoraphobic situations, social phobia situations, and situations that produce bodily sensations (interoceptive symptoms). Items on the interoceptive subscale include activities such as exercising vigorously, ingesting caffeine, and experiencing intense emotion.21 Using the Anxiety Sensitivity Index is another assessment option.22

Not all patients with panic attacks respond well to CBT; predictors of poor response in clinical trials have included:

- severe baseline panic symptoms, personality disorders, and possibly depressed mood

- marital dissatisfaction

- low motivation for treatment.2,9

Figure Patient assessment: Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire

Source: Reprinted with permission from Rapee RM, Craske MG, Barlow DH. Assessment instrument for panic disorder that includes fear of sensation-producing activities: The Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire. Anxiety 1995;1:114-22. Copyright 1995, Wiley-Liss, Inc.

Cognitive Therapies for Panic Disorder

Psychoeducation. Begin by defining and explaining anxiety, panic attacks, panic disorder, and any comorbid psychopathology the patient may have (agoraphobia, depression). Explain panic symptoms as physiologic and psychological responses to stressors.

Address the patient’s fears that anxiety’s physiologic symptoms represent a serious or undiagnosed medical disorder or that a panic attack could cause serious harm. Assign self-help and reading materials to reinforce this discussion (see Related resources). Finally, explain the rationale for using CBT to treat panic symptoms.

Use cognitive restructuring to address faulty or irrational information-processing patterns that underlie pathologic anxiety. Identify automatic thought patterns (such as catastrophizing, overgeneralization, all-or-nothing thinking, and personalization), then provide a careful “reality check,” in which you systematically substitute a more-rational thought process.

Have the patient keep a self-monitoring diary to help you assess thought patterns and re-direct irrational thoughts. A diary may identify anxiety-provoking scenarios on which to focus therapy. Encourage patients to document anxiety events using the “triple-column” technique:23

- column 1: circumstances of the anxiety or panic

- column 2: their emotional state at the time

- column 3: any thoughts they can identify.

Instruct them to log this data while experiencing symptoms or immediately afterward. Later, during the intervention phase, patients can record how they tried to restructure their thoughts and any consequent mood changes. Review diary entries with them during subsequent sessions.

Exposure Therapy

Graduated exposure and response prevention (ERP) is the core component of CBT for panic disorder. ERP exercises require the patient to confront anxiety-producing stimuli while agreeing not to engage in maladaptive behavior that avoids, prematurely reduces, or prevents the anxiety. The stimuli may be external cues—such as bridges, stores, or heights—or interoceptive cues such as dizziness, tachycardia, or tachypnea.

Creating fear hierarchies. To begin, we recommend that you work with the patient to create lists of all external situations and interoceptive stimuli that cause him or her anxiety. Separating the stimuli into two lists helps patients recognize that their bodily stimuli are at least as important as environmental stimuli in promoting a panic attack.

The patient then rates each stimulus using a Subjective Units of Distress scale (SUDS)—assigning 0 to 100 points from no anxiety to overwhelming anxiety—and ranks items on the lists from mildest to worst anxiety. Instruct patients to rate the distress they would feel if they could not escape from the stimuli.

First experience. After the hierarchies are created, the therapist introduces the patient to exposure therapy by choosing an item that causes mild to moderate anxiety. Starting at this anxiety level, patients are likely to succeed with their first exercise without feeling overwhelmed. The therapist teaches the patient about the process, then begins the exposure by helping the patient create and confront the very scenario (or a representation of that scenario) that causes anxiety.

When working on interoceptive cues, various exercises can be used to reproduce bother-some bodily symptoms, such as:

- running up a flight of stairs or running in place to generate tachycardia

- purposefully hyperventilating to produce lightheadedness.

- spinning in place to create dizziness.

The patient agrees not to actively attempt to escape the scenario but to tolerate and perhaps even focus on the anxiety (Box 3). Using “safety cues”—such as leaning against a wall or keeping eyes closed—is also forbidden. Patients soon see that the anxiety does not last indefinitely but begins to diminish fairly rapidly.

Reaching the goal. After repeated exposure sessions, anxiety associated with a stimulus begins to extinguish. Having experienced the success of tolerating a previously difficult stimuli and feeling much less anxious, the patient is ready to take on increasingly difficult tasks. The therapist also assigns the patient “homework” to practice exposure exercises already mastered during sessions. As exposure therapy progresses, the patient takes a larger role in designing and executing sessions. The goal is for the patient to learn to become his or her own behaviorist and to intervene early when panic symptoms begin.

Resist temptation to rescue patients from their anxiety during exposure sessions, such as by chatting about the weather or current events or providing other distractions. To extinguish the link between the stimuli and anxiety, the patient must experience anxiety all the way through the exercise—preferably giving ongoing Subjective Units of Distress (SUDS) ratings—until symptoms inevitably wane and cease.

Similarly, avoid assigning exposure homework to be done “until you can’t stand it anymore, then take a rest.” Although well-intentioned, allowing the patient to escape the exposure when anxiety peaks increases conditioned anxiety and strongly reinforces avoidance behaviors.

Other Behavioral Techniques

Imaginal exposure sessions can be created using visualizations of feared stimuli, gradually presented as with in vivo exposure. For example, as you recount a target scenario, ask the patient to imagine a progression of events or bodily cues that have led to panic attacks. The patient supplies SUDS ratings and refrains from imagining an avoidance or maladaptive response. You can tape-record the session for homework and assign the patient to listen to it and participate daily.

Imaginal exposure may help treat phobic avoidance (such as agoraphobic symptoms), but study results have been disappointing in panic symptoms.24 However, this approach may help reluctant patients initiate in vivo exposure therapy.

Relaxation training—such as progressive muscle relaxation, visual imagery, or autogenic protocols—has shown mixed results in treating panic.25,26 Relaxation may help patients cope with panic’s physiologic arousal, but it is not suitable as a singular intervention.

Breathing retraining. Because hyperventilation and panic symptoms are related, instruction and practice in slow, diaphragmatic breathing has long been a component of CBT for panic symptoms. Little evidence supports breathing retraining,9 although Meuret et al27,28 have described a respiratory feedback paradigm that may reduce panic symptoms in appropriately selected patients.

Many studies that have assessed breathing retraining as monotherapy for panic have had methodologic flaws.27

Building a Therapeutic Alliance

Successful therapists have been found to use empathic listening more than directives and explanations in the first therapy session.9 They understand the suffering from panic disorder and the value of listening as patients explain their symptoms, thoughts, and feelings. The rapport built during this initial interaction can help sustain motivation as the therapist then takes charge of subsequent sessions.

Among important skills for CBT therapists, Seligman29 includes empathy, caring, warmth, and active listening, as well as the ability to:

- be a teacher, scientist, and co-investigator

- demystify treatment

- engage clients as “active, knowledgeable, and responsible partners” in their therapy.

Finally, although CBT clinicians suggest tasks and interventions for this “shared endeavor,” patients are primarily responsible for change.

- Anxiety Disorders Association of America. www.adaa.org.

- Craske M, Barlow D, Cary NC. Mastery of your anxiety and panic, (3rd ed). Therapist guide and client workbook. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2000.

- Otto MW. Stopping anxiety medication: panic control therapy for benzodiazepine discontinuation. Therapist guide and patient workbook. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2004.

- The Panic Center. Patient diaries and other self-help resources. www.paniccenter.net

With panic attacks, alarming physiologic symptoms mount swiftly—tachycardia, chest pain, sweating, trembling, smothering or choking, dizziness, fear of losing control or going crazy—even fear of dying.1 Patients constantly fear the next attack, worry about its consequences, and change their behaviors to avoid or withdraw from anxiety-provoking situations.

To relieve their suffering, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) may offer benefits you would not realize with medication alone. CBT can:

- improve long-term patient outcomes

- enhance medication management

- boost treatment response when medication alone is inadequate

- ease drug discontinuation.2

Whether you or a CBT-trained psychotherapist guides the sessions, you can achieve optimal results for your patients with panic disorder.

How Effective is CBT?

Panic disorder is chronic, often disabling, and characterized by spontaneous, unpredictable panic attacks (Boxes 1 and 23-11). When treated with CBT, about three-quarters of patients become panic-free and maintain treatment gains at follow-up, and one-half become both panic-free and free of excess anxiety.9

Typical therapy is 12 individual, once-weekly visits for psycho-education, relaxation, and breathing training; cognitive restructuring; and exposure therapies.

Briefer protocols, “reduced therapist contact,”12 and group therapy13 also can help patients and in some studies have been as beneficial as 12 weeks of individual therapy. Although trained psychotherapists have higher success rates than nonbehaviorists when treating panic patients, nonbehaviorists also can provide effective therapy after relatively brief training.14

American Psychiatric Association15 treatment guidelines recommend medications—such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and benzodiazepines—as well as CBT as first-line therapies for panic disorder. Other treatment guidelines concur16 and note that CBT is more cost-effective than medications.

In comparison studies, CBT has been at least as effective for panic symptoms as SSRIs,17,18 TCAs,19 and alprazolam.20 Antidepressants are the preferred drug for panic disorder16 because they lack benzodiazepines’ dependence and abuse potential.

Providing medication during CBT may maintain patients’ therapeutic gains better than CBT alone if the medication is continued after CBT is completed. Interestingly, patients who use benzodiazepines during CBT may have higher relapse rates than those who do not use benzodiazepines, particularly when the benzodiazepines are withdrawn.9

CBT produces improvement rates similar to those of pharmacologic treatment at one-quarter to one-half the cost in the first year. Patients also appear to have better clinical outcomes if they receive CBT while SSRIs or benzodiazepines are being discontinued, compared with simply stopping the medications.8

Panic attacks typically begin between ages 10 and 40. The cause is unknown, but evidence points to multiple factors, including heredity, neurobiology, provocations, and psychological conditioning (Box 2).3-9 prevalence is approximately 5%,10 and about three-fourths of panic disorder patients are female.11

Comorbidity. Up to 50% of persons with panic disorder also experience agoraphobia.1 Depression, other anxiety disorders, and substance abuse may complicate the clinical picture.

BIOLOGICAL THEORIES

Genetics. About 10% of persons who experience panic attacks have first-degree relatives with panic disorder. Twin studies suggest heritability of up to 43%

Neurobiology. Anxiety responses appear to be organized at different neuroanatomic levels:

- automatic responses by periaqueductal grey matter or locus coeruleus

- practiced responses by the amygdala and septohippocampal regions

- cognitively complex responses by higher cortical regions.

The hypothalamus mediates neurohormonal responses. Panic disorder patients’ response to SSRIs, tricyclic antidepressants, and benzodiazepines suggest a link with neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine, and GABA. Adenosine, cannabinoids, neuropeptides, hormones, neurotrophins, cytokines, and cellular mediators may also be involved.

Provocation. Panic disorder may have a physiologic mechanism. When exposed in the laboratory to panicogenic substances (such as carbon dioxide, sodium lactate, yohimbine, and caffeine), persons with panic disorders experience greater numbers of panic attacks than do those without panic disorders. These laboratory-induced panic attacks resemble real attacks, and anti-panic medications block the induced panic attacks.

PSYCHOLOGICAL THEORIES

The cognitive-behavioral model postulates that panic disorder patients:

- have a predisposed vulnerability to respond with physiologic arousal to negative stressors

- tend to see anxiety symptoms as harmful

- have negative and catastrophizing cognitions about those symptoms.

With conditioning, patients associate early physiologic arousal with other panic symptoms as the arousal progresses. Ultimately, they become hypervigilant for symptoms and develop a learned escalation of anxiety and apprehension (with accompanying negative cognitions) when the early symptoms re-occur.

Source: References 3-9

CBT Candidates

To diagnose panic disorder, conduct a thorough psychiatric evaluation that includes assessing for comorbid mental and substance use disorders. The history and physical exam are essential to rule out medical causes of the patient’s symptoms, such as heart disease causing dizziness or palpitations. Asking patients to keep panic attack records can help you identify panic symptoms’ frequency and triggers.9

An assessment tool such as the Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire (Figure) can be a useful starting point. It has 27 items and three subscales to quantify a patient’s fear of agoraphobic situations, social phobia situations, and situations that produce bodily sensations (interoceptive symptoms). Items on the interoceptive subscale include activities such as exercising vigorously, ingesting caffeine, and experiencing intense emotion.21 Using the Anxiety Sensitivity Index is another assessment option.22

Not all patients with panic attacks respond well to CBT; predictors of poor response in clinical trials have included:

- severe baseline panic symptoms, personality disorders, and possibly depressed mood

- marital dissatisfaction

- low motivation for treatment.2,9

Figure Patient assessment: Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire

Source: Reprinted with permission from Rapee RM, Craske MG, Barlow DH. Assessment instrument for panic disorder that includes fear of sensation-producing activities: The Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire. Anxiety 1995;1:114-22. Copyright 1995, Wiley-Liss, Inc.

Cognitive Therapies for Panic Disorder

Psychoeducation. Begin by defining and explaining anxiety, panic attacks, panic disorder, and any comorbid psychopathology the patient may have (agoraphobia, depression). Explain panic symptoms as physiologic and psychological responses to stressors.

Address the patient’s fears that anxiety’s physiologic symptoms represent a serious or undiagnosed medical disorder or that a panic attack could cause serious harm. Assign self-help and reading materials to reinforce this discussion (see Related resources). Finally, explain the rationale for using CBT to treat panic symptoms.

Use cognitive restructuring to address faulty or irrational information-processing patterns that underlie pathologic anxiety. Identify automatic thought patterns (such as catastrophizing, overgeneralization, all-or-nothing thinking, and personalization), then provide a careful “reality check,” in which you systematically substitute a more-rational thought process.

Have the patient keep a self-monitoring diary to help you assess thought patterns and re-direct irrational thoughts. A diary may identify anxiety-provoking scenarios on which to focus therapy. Encourage patients to document anxiety events using the “triple-column” technique:23

- column 1: circumstances of the anxiety or panic

- column 2: their emotional state at the time

- column 3: any thoughts they can identify.

Instruct them to log this data while experiencing symptoms or immediately afterward. Later, during the intervention phase, patients can record how they tried to restructure their thoughts and any consequent mood changes. Review diary entries with them during subsequent sessions.

Exposure Therapy

Graduated exposure and response prevention (ERP) is the core component of CBT for panic disorder. ERP exercises require the patient to confront anxiety-producing stimuli while agreeing not to engage in maladaptive behavior that avoids, prematurely reduces, or prevents the anxiety. The stimuli may be external cues—such as bridges, stores, or heights—or interoceptive cues such as dizziness, tachycardia, or tachypnea.

Creating fear hierarchies. To begin, we recommend that you work with the patient to create lists of all external situations and interoceptive stimuli that cause him or her anxiety. Separating the stimuli into two lists helps patients recognize that their bodily stimuli are at least as important as environmental stimuli in promoting a panic attack.

The patient then rates each stimulus using a Subjective Units of Distress scale (SUDS)—assigning 0 to 100 points from no anxiety to overwhelming anxiety—and ranks items on the lists from mildest to worst anxiety. Instruct patients to rate the distress they would feel if they could not escape from the stimuli.

First experience. After the hierarchies are created, the therapist introduces the patient to exposure therapy by choosing an item that causes mild to moderate anxiety. Starting at this anxiety level, patients are likely to succeed with their first exercise without feeling overwhelmed. The therapist teaches the patient about the process, then begins the exposure by helping the patient create and confront the very scenario (or a representation of that scenario) that causes anxiety.

When working on interoceptive cues, various exercises can be used to reproduce bother-some bodily symptoms, such as:

- running up a flight of stairs or running in place to generate tachycardia

- purposefully hyperventilating to produce lightheadedness.

- spinning in place to create dizziness.

The patient agrees not to actively attempt to escape the scenario but to tolerate and perhaps even focus on the anxiety (Box 3). Using “safety cues”—such as leaning against a wall or keeping eyes closed—is also forbidden. Patients soon see that the anxiety does not last indefinitely but begins to diminish fairly rapidly.

Reaching the goal. After repeated exposure sessions, anxiety associated with a stimulus begins to extinguish. Having experienced the success of tolerating a previously difficult stimuli and feeling much less anxious, the patient is ready to take on increasingly difficult tasks. The therapist also assigns the patient “homework” to practice exposure exercises already mastered during sessions. As exposure therapy progresses, the patient takes a larger role in designing and executing sessions. The goal is for the patient to learn to become his or her own behaviorist and to intervene early when panic symptoms begin.

Resist temptation to rescue patients from their anxiety during exposure sessions, such as by chatting about the weather or current events or providing other distractions. To extinguish the link between the stimuli and anxiety, the patient must experience anxiety all the way through the exercise—preferably giving ongoing Subjective Units of Distress (SUDS) ratings—until symptoms inevitably wane and cease.

Similarly, avoid assigning exposure homework to be done “until you can’t stand it anymore, then take a rest.” Although well-intentioned, allowing the patient to escape the exposure when anxiety peaks increases conditioned anxiety and strongly reinforces avoidance behaviors.

Other Behavioral Techniques

Imaginal exposure sessions can be created using visualizations of feared stimuli, gradually presented as with in vivo exposure. For example, as you recount a target scenario, ask the patient to imagine a progression of events or bodily cues that have led to panic attacks. The patient supplies SUDS ratings and refrains from imagining an avoidance or maladaptive response. You can tape-record the session for homework and assign the patient to listen to it and participate daily.

Imaginal exposure may help treat phobic avoidance (such as agoraphobic symptoms), but study results have been disappointing in panic symptoms.24 However, this approach may help reluctant patients initiate in vivo exposure therapy.

Relaxation training—such as progressive muscle relaxation, visual imagery, or autogenic protocols—has shown mixed results in treating panic.25,26 Relaxation may help patients cope with panic’s physiologic arousal, but it is not suitable as a singular intervention.

Breathing retraining. Because hyperventilation and panic symptoms are related, instruction and practice in slow, diaphragmatic breathing has long been a component of CBT for panic symptoms. Little evidence supports breathing retraining,9 although Meuret et al27,28 have described a respiratory feedback paradigm that may reduce panic symptoms in appropriately selected patients.

Many studies that have assessed breathing retraining as monotherapy for panic have had methodologic flaws.27

Building a Therapeutic Alliance

Successful therapists have been found to use empathic listening more than directives and explanations in the first therapy session.9 They understand the suffering from panic disorder and the value of listening as patients explain their symptoms, thoughts, and feelings. The rapport built during this initial interaction can help sustain motivation as the therapist then takes charge of subsequent sessions.

Among important skills for CBT therapists, Seligman29 includes empathy, caring, warmth, and active listening, as well as the ability to:

- be a teacher, scientist, and co-investigator

- demystify treatment

- engage clients as “active, knowledgeable, and responsible partners” in their therapy.

Finally, although CBT clinicians suggest tasks and interventions for this “shared endeavor,” patients are primarily responsible for change.

- Anxiety Disorders Association of America. www.adaa.org.

- Craske M, Barlow D, Cary NC. Mastery of your anxiety and panic, (3rd ed). Therapist guide and client workbook. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2000.

- Otto MW. Stopping anxiety medication: panic control therapy for benzodiazepine discontinuation. Therapist guide and patient workbook. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2004.

- The Panic Center. Patient diaries and other self-help resources. www.paniccenter.net

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed, text rev). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

2. Otto MW, Deckersbach T. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder: Theory, strategies, and outcome. In: Rosenbaum JF, Pollack M (eds). Panic disorder and its treatment. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1998.

3. Hettema, JM, Neale, MC, Kendler, KS. A review and meta-analysis of the genetic epidemiology of anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158(10):1568-78.

4. Kendler KS, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. Panic syndromes in a population-based sample of male and female twins. Psychol Med 2001;31:989-1000.

5. Sandford JJ, Argyropoulos SV, Nutt DJ. The psychobiology of anxiolytic drugs. Part I: basic neurobiology. Pharmacol Ther 2000;88:197-212.

6. Millan MJ. The neurobiology and control of anxious states. Prog Neurobiol 2003;70:83-244.

7. Sanderson WC, Rego SA. Empirically supported psychological treatment of panic disorder and agoraphobia. Medscape. Available at www.medscape.com/viewprogram/350_pnt. Accessed Nov. 8, 2005.

8. Rayburn NR, Otto MW. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder: a review of treatment elements, strategies, and outcomes. CNS Spectr 2003;8(5):356-62.

9. Craske MG, Barlow DH. Panic disorder and agoraphobia. In: Barlow DH (ed). Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual. New York: Guilford Press; 2001;1-59.

10. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:593-602.

11. Rapee RM, Barlow DH. Generalized anxiety disorders, panic disorders, and phobias. In: Sutker PB, Adams HE (eds). Comprehensive handbook of psychopathology (3rd ed). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2001.

12. Cote G, Gauthier JG, Laberge B, et al. Reduced therapist contact in the cognitive behavioral treatment of panic disorder. Behav Ther 1994;25:123-45.

13. Telch MJ, Lucas JA, Schmidt NB, et al. Group cognitive-behavioral treatment of panic disorder. Behav Res Ther 1993;31:279-28.

14. Welkowitz LA, Papp LA, Cloitre M, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder delivered by psychopharmacologically oriented clinicians. J Nerv Ment Dis 1991;179:473-77.

15. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1998.

16. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. Australian and New Zealand clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of panic disorder and agoraphobia. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2003;37:641-56.Available at: www.ranzcp.org/publicarea/cpg.asp. Accessed Aug. 24, 2005.

17. Black DW, Wesner R, Bowers W, Gabel J. A comparison of fluvoxamine, cognitive therapy, and placebo in the treatment of panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993;31:383-94.

18. Dannon PN, Gon-Usishkin M, Gelbert A, et al. Cognitive behavioral group therapy in panic disorder patients: The efficacy of CBGT versus drug treatment. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2004;16:41-6.

19. Clark DM, Salkovskis PM, Hackmann A, et al. A comparison of cognitive therapy, applied relaxation, and imipramine in the treatment of panic disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1994;164:759-69.

20. Klosko JS, Barlow DH, Tassinari R, Cerny JA. A comparison of alprazolam and behavior therapy in treatment of panic disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 1990;58:77-84.

21. Rapee RM, Craske MG, Barlow DH. Assessment instrument for panic disorder that includes fear of sensation-producing activities: The Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire. Anxiety 1995;1:114-22.

22. Reiss S, Peterson R, Gursky D, McNally R. Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency, and the prediction of fearfulness. Behav Res Ther 1986;24:1-8.

23. Burns DD. Feeling good: The new mood therapy. New York: William Morrow and Co.; 1980.

24. Clum GA, Watkins PL, Borden JW, et al. A comparison of guided imaginal coping and imaginal exposure in the treatment of panic disorder. J Rational-Emotive & Cognitive Behavior Therapy 1993;11(4):179-93.

25. Craske MG, Brown TA, Barlow DH. Behavioral treatment of panic disorder: A two year follow-up. Behav Ther 1991;22:289-304.

26. Ost LG, Westling BE. Applied relaxation vs cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of panic disorder. Behav Res Ther 1995;33:145-58.

27. Meuret AE, Wilhelm FH, Ritz T, Roth WT. Breathing training for treating panic disorder: useful intervention or impediment. Behav Mod 2003;27(5):731-54.

28. Meuret AE, Wilhelm FH, Roth WT. Respiratory feedback for treating panic disorder. J Clin Psychol 2004;60:197-207.

29. Seligman L. Systems, strategies, and skills of counseling and psychotherapy. Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 2001.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed, text rev). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

2. Otto MW, Deckersbach T. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder: Theory, strategies, and outcome. In: Rosenbaum JF, Pollack M (eds). Panic disorder and its treatment. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1998.

3. Hettema, JM, Neale, MC, Kendler, KS. A review and meta-analysis of the genetic epidemiology of anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158(10):1568-78.

4. Kendler KS, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. Panic syndromes in a population-based sample of male and female twins. Psychol Med 2001;31:989-1000.

5. Sandford JJ, Argyropoulos SV, Nutt DJ. The psychobiology of anxiolytic drugs. Part I: basic neurobiology. Pharmacol Ther 2000;88:197-212.

6. Millan MJ. The neurobiology and control of anxious states. Prog Neurobiol 2003;70:83-244.

7. Sanderson WC, Rego SA. Empirically supported psychological treatment of panic disorder and agoraphobia. Medscape. Available at www.medscape.com/viewprogram/350_pnt. Accessed Nov. 8, 2005.

8. Rayburn NR, Otto MW. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder: a review of treatment elements, strategies, and outcomes. CNS Spectr 2003;8(5):356-62.

9. Craske MG, Barlow DH. Panic disorder and agoraphobia. In: Barlow DH (ed). Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual. New York: Guilford Press; 2001;1-59.

10. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:593-602.

11. Rapee RM, Barlow DH. Generalized anxiety disorders, panic disorders, and phobias. In: Sutker PB, Adams HE (eds). Comprehensive handbook of psychopathology (3rd ed). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2001.

12. Cote G, Gauthier JG, Laberge B, et al. Reduced therapist contact in the cognitive behavioral treatment of panic disorder. Behav Ther 1994;25:123-45.

13. Telch MJ, Lucas JA, Schmidt NB, et al. Group cognitive-behavioral treatment of panic disorder. Behav Res Ther 1993;31:279-28.

14. Welkowitz LA, Papp LA, Cloitre M, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder delivered by psychopharmacologically oriented clinicians. J Nerv Ment Dis 1991;179:473-77.

15. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1998.

16. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. Australian and New Zealand clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of panic disorder and agoraphobia. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2003;37:641-56.Available at: www.ranzcp.org/publicarea/cpg.asp. Accessed Aug. 24, 2005.

17. Black DW, Wesner R, Bowers W, Gabel J. A comparison of fluvoxamine, cognitive therapy, and placebo in the treatment of panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993;31:383-94.

18. Dannon PN, Gon-Usishkin M, Gelbert A, et al. Cognitive behavioral group therapy in panic disorder patients: The efficacy of CBGT versus drug treatment. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2004;16:41-6.

19. Clark DM, Salkovskis PM, Hackmann A, et al. A comparison of cognitive therapy, applied relaxation, and imipramine in the treatment of panic disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1994;164:759-69.

20. Klosko JS, Barlow DH, Tassinari R, Cerny JA. A comparison of alprazolam and behavior therapy in treatment of panic disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 1990;58:77-84.

21. Rapee RM, Craske MG, Barlow DH. Assessment instrument for panic disorder that includes fear of sensation-producing activities: The Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire. Anxiety 1995;1:114-22.

22. Reiss S, Peterson R, Gursky D, McNally R. Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency, and the prediction of fearfulness. Behav Res Ther 1986;24:1-8.

23. Burns DD. Feeling good: The new mood therapy. New York: William Morrow and Co.; 1980.

24. Clum GA, Watkins PL, Borden JW, et al. A comparison of guided imaginal coping and imaginal exposure in the treatment of panic disorder. J Rational-Emotive & Cognitive Behavior Therapy 1993;11(4):179-93.

25. Craske MG, Brown TA, Barlow DH. Behavioral treatment of panic disorder: A two year follow-up. Behav Ther 1991;22:289-304.

26. Ost LG, Westling BE. Applied relaxation vs cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of panic disorder. Behav Res Ther 1995;33:145-58.

27. Meuret AE, Wilhelm FH, Ritz T, Roth WT. Breathing training for treating panic disorder: useful intervention or impediment. Behav Mod 2003;27(5):731-54.

28. Meuret AE, Wilhelm FH, Roth WT. Respiratory feedback for treating panic disorder. J Clin Psychol 2004;60:197-207.

29. Seligman L. Systems, strategies, and skills of counseling and psychotherapy. Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 2001.

Bipolar disorder: New strategy for checking serum valproate

Valproate’s well-accepted therapeutic range for treating epilepsy—50 to 100 mcg/mL—was adopted for bipolar disorder treatment without rigorous evaluation of serum levels and response relationships. Because most literature on monitoring serum valproate refers to its use as an anticonvulsant, you may wonder:

- When should I measure serum valproate in bipolar patients?

- What do serum valproate levels mean in their clinical care?

To answer these questions, we discuss when to monitor serum valproate, whether routinely or in specific situations. We then review studies that show how serum levels affect valproate’s efficacy and safety in three phases of bipolar disorder management: acute mania, maintenance therapy, and acute depression.

Is monitoring overused?

Some neurologists consider serum levels nonessential—and, in some cases, overused—when valproate is used as an anticonvulsant for healthy patients.1,2 A multicenter, randomized controlled trial evaluating the impact of antiepileptic drug monitoring on patient outcomes3 supports this notion, at least in part. Serum monitoring did not improve therapeutic outcome, suggesting that patients with epilepsy could be satisfactorily treated by adjusting dosages based on clinical response.

On the other hand, American Psychiatric Association (APA) guidelines for bipolar disorder suggest routine serum monitoring every 6 months along with other hematologic and hepatic assessments, or more frequently if necessary. The APA recommends maintaining serum valproate levels of 50 to 125 mcg/mL when treating:

- acutely manic patients

- outpatients

- the elderly

- patients who are hypomanic or euthymic.4

Table 1

4 situations where serum valproate monitoring may be clinically useful

| To establish a baseline effective level in individual patients |

| To assess lack or loss of efficacy, including patient adherence |

| When drug-drug interactions increase or decrease valproate clearance (such as with aspirin, carbamazepine, felbamate, or phenytoin)5 |

| When dose-dependent side effects occur (such as alopecia, elevated liver function, thrombocytopenia, or pancreatitis) |

Effective levels in acute mania

In one of the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials to examine valproate use in adults with acute mania, Pope et al6 used the epilepsy reference range to adjust dosages. Patients (n=17) initially received valproate, 750 mg/d, and dosages were then adjusted to serum levels of 50 to 100 mcg/mL. Nineteen patients received placebo. Mean (SD) baseline Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) scores for the valproate and placebo groups were 28.2 (5.8) and 28.6 (6.9), respectively.

Patients receiving valproate showed the greatest symptomatic improvement—as indicated by YMRS scores—within 1 to 4 days of achieving a serum level ≥50 mcg/mL. Serum valproate for all patients was maintained at >50 mcg/mL, which limits our ability to draw conclusions about a minimum level associated with efficacy.

Minimum threshold for efficacy. In another randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of acute mania, Bowden et al7 compared the efficacy of divalproex (n=69) versus lithium (n=36) or placebo (n=74) given for 3 weeks. Patients met criteria for manic disorder using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) and had Mania Rating Scale scores (derived from the SADS) of at least 14.

Those in the divalproex group received 750 mg/d for 2 days, then 1,000 mg/d for 3 days. Dosages were then adjusted to target a serum level of 150 mcg/mL, unless limited by side effects. Mean serum valproate levels on days 8 and 21 were 77 and 93.2 mcg/mL, respectively. Marked improvement, defined as ≥50% reduction in Mania Rating Scale scores, was seen in 48% of the divalproex group, compared with 25% of the placebo group.

The authors then analyzed the relationship between serum valproate levels and clinical response and tolerability.8 At day 5, patients with serum valproate ≥45 mcg/mL were 2 to 7 times more likely to show 20% or greater improvement in SADS mania subscales (manic syndrome, and behavior and ideation).

This study provided a minimum threshold for valproate efficacy in bipolar mania—45 to 50 mcg/mL—but not a level above which further clinical benefit would not be gained.

Optimum serum ranges. Allen et al9 recently conducted a post hoc analysis of pooled intent-to-treat data from three randomized, fixed dose, placebo-controlled studies of divalproex for acute mania. Subjects were stratified into a placebo group (n=171) and six serum valproate ranges:

- ≤55 mcg/mL (n=35)

- >55 to 71.3 mcg/mL (n=32)

- >71.3 to 85 mcg/mL (n=36)

- >85 to 94 mcg/mL (n=34)

- >94 to 107 mcg/mL (n=33)

- >107 mcg/mL (n=33).

Loading for rapid response. Patients with acute mania may respond sooner when loading doses are used to attain therapeutic serum valproate levels.

Keck et al10 examined time to onset of improvement in adults with acute mania (N=19) receiving oral loading doses of valproate (20 mg/kg/d in divided doses for 5 days) to rapidly attain valproate levels ≥50 mcg/mL. Ten (53%) patients who received at least 1 loading dose showed a ≥50% reduction in MRS scores and the greatest improvement across the first 3 days.

Hirschfeld et al11 also reported that patients’ symptoms began to improve sooner when divalproex was given at 30 mg/kg/d on days 1 and 2, and 20 mg/kg/d on days 3 to 10 (n=20), compared with standard titration (750 mg/d on days 1 and 2, and gradual dose titration on days 3 to 10 [n=20]).

Discussion. In acute mania, evidence suggests that patients with serum valproate ≥45 to 50 mcg/mL may show greater clinical improvement than patients with lower serum levels. Loading doses may achieve a minimum therapeutic serum level more quickly, yielding faster clinical improvement. A serum level >90 mcg/mL may confer additional benefit.

Although a minimum serum level has been recommended, no data have established a maximum level beyond which further clinical improvement would not be observed.

In maintenance therapy

What serum valproate levels are most effective for bipolar maintenance therapy? Some evidence is emerging.

Bowden et al12 compared divalproex (n=187), lithium (n=90), and placebo (n=92) in a 52-week, double-blind, parallel-group study of bipolar adult outpatients who met recovery criteria 3 months after an index manic episode. Divalproex dosages were adjusted to achieve trough serum concentrations between 71 and 125 mcg/mL. Mean (SD) and median serum valproate levels were 84.8 (29.9) mcg/mL and 83.9 mcg/mL, respectively. Serum valproate levels significantly correlated with Mania Rating Scale scores. No minimum threshold for efficacy was reported.

Thirteen subjects in the divalproex group were then stratified into 4 categories:

- nontherapeutic (

- low therapeutic (50 to 74.9 mcg/mL)

- medium therapeutic (75 to 99.9 mcg/mL)

- high therapeutic (>100 mcg/mL).

Discussion. Serum valproate levels of 75 to 100 mcg/mL may be most effective in preventing subsequent mood episodes with acceptable tolerability. Prospective, longitudinal studies are needed to better establish a therapeutic range for valproate in bipolar maintenance therapy.

In bipolar depression

Little evidence supports a therapeutic serum valproate range for treating acute bipolar depression.

In an 8-week, double-blind study, Davis et al14 randomly assigned adults with bipolar depression to divalproex (n=13) or placebo (n=12). Bipolar depression diagnoses were confirmed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, and patients were required to have a Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) score ≥16.

Valproate was started at 500 mg/d and titrated to serum levels of 50 to 150 mcg/mL. Mean (SD) serum valproate levels at weeks 4 and 8 were 80 (9.3) mcg/mL and 81 (19.2) mcg/mL, respectively. Remission rate (defined a priori as a >50% improvement and total HRSD score 15 In Sachs’ 8-week study, the mean (SD) valproate level was 61.5 (42.8) mcg/mL.

Discussion. The relationship between serum valproate and therapeutic efficacy in acute bipolar depression—and the range of levels considered therapeutic—are undefined. For now we recommend that individual patients’ clinical response and tolerability guide optimum serum valproate in acute bipolar depression (Box).16

When evaluating serum valproate levels–especially for assessing adherence–be careful to:

- obtain blood samples 12 hours after the most recent dose to accurately assess serum trough concentrations

- account for valproate’s saturation of protein binding sites and increased free fraction with increased serum concentration.16

Valproate clearance is increased when more free drug is available for metabolism, and this may result in disproportionately lower steady-state serum concentrations. Smaller increases in total valproate after dosage increases may be misinterpreted as medication nonadherence.

High levels and safety

High serum valproate levels may increase the risk and frequency of side effects. For example, serum levels >125 mcg/mL have been associated with:

- increased nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and sedation in acutely manic patients8

- weight gain and reduced platelets and white blood cells in patients receiving valproate as maintenance treatment.12

In the loading dose study by Hirschfeld et al,11 patients receiving divalproex, 20 to 30 mg/kg/d, did not experience a higher frequency or severity of side effects compared with patients receiving standard titration. Keck et al10 also reported minimal valproate-related side effects in their open-label study. Neither study suggested an upper-limit valproate level associated with increased side effects.

Discussion. Serum valproate >125 mcg/mL has been associated with increased side effects (Table 2), but more studies are needed.

Table 2

For bipolar disorder, suggested serum valproate therapeutic ranges*

| Serum valproate (mcg/mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower level | Upper level | Comments | |

| Acute mania | 45 to 50 | 125 | Upper level based on tolerability, not efficacy |

| Maintenance | 75 | 100 | Levels based primarily on retrospective analysis |

| Acute bipolar | Not established | Not established | |

| * Based on available data | |||

Clinical recommendations

Carefully consider when to monitor serum valproate levels in your patients with bipolar disorder:

- Obtaining routine serum levels can be expensive, and no data support the cost-effectiveness of this approach in bipolar disorder.

- Individualize valproate dosing; a specific patient’s therapeutic range may differ from another’s or from those published in the literature or used by a clinical laboratory.

- Monitoring serum valproate levels does not replace the need to adjust dosages based on patients’ therapeutic response and tolerance.

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry2002; 159(suppl 4):1–50.

- Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance. www.dbsalliance.org.

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol, Equetro

- Divalproex sodium • Depakote

- Felbamate • Felbatol

- Phenytoin • Dilantin

Dr. Kaneria reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Patel is a consultant to and speaker for Eli Lilly and Co. and a speaker for Pfizer.

Dr. Keck receives research support from or is a consultant to or advisor for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Eli Lilly and Co., Organon, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Merck & Co., Pfizer, Shire, and UCB Pharma.

1. Glauser TA, Pippenger CE. Controversies in blood-level monitoring: reexamining its role in the treatment of epilepsy. Epilepsia 2000;41(suppl 8):S6-S15.

2. Pellock JM, Willmore LJ. A rational guide to routine blood monitoring in patients receiving antiepileptic drugs. Neurology 1991;41:961-4.

3. Jannuzzi G, Cian P, Fattore C, et al. A multicenter randomized controlled trial on the clinical impact of therapeutic drug monitoring in patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy. The Italian TDM Study Group in Epilepsy. Epilepsia 2000;41:222-30.

4. AmericanPsychiatric Association Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry 2002;159(suppl 4):1-50.

5. Depakote (divalproex sodium) package insert Abbott Park, IL: Abbott Laboratories; October 2005.

6. Pope HG, Jr, McElroy SL, Keck PE, Jr, Hudson JI. Valproate in the treatment of acute mania. A placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991;48:62-8.

7. Bowden CL, Brugger AM, Swann AC, et al. Efficacy of divalproex vs lithium and placebo in the treatment of mania. The Depakote Mania Study Group. JAMA 1994;271:918-24.

8. Bowden CL, Janicak PG, Orsulak P, et al. Relation of serum valproate concentration to response in mania. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:765-70.

9. Allen MH, Baker J, Wozniak PJ. Relationship of serum valproate level to response in mania (abstract presentation). New York: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2004.

10. Keck PE, Jr, McElroy SL, Tugrul KC, Bennett JA. Valproate oral loading in the treatment of acute mania. J Clin Psychiatry 1993;54:305-8.

11. Hirschfeld RM, Allen MH, McEvoy JP, et al. Safety and tolerability of oral loading divalproex sodium in acutely manic bipolar patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60:815-18.

12. Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, McElroy SL, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled 12-month trial of divalproex and lithium in treatment of outpatients with bipolar I disorder. Divalproex Maintenance Study Group. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57:481-9.

13. Keck PE, Jr, Bowden CL, Meinhold JM, et al. Relationship between serum valproate and lithium levels and efficacy and tolerability in bipolar maintenance therapy. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract (in press).

14. Davis LL, Bartolucci A, Petty F. Divalproex in the treatment of bipolar depression: a placebo-controlled study. J Affect Disord 2005;85:259-66.

15. Sachs GS, Collins MA, Altshuler LL, et al. Divalproex sodium versus placebo for the treatment of bipolar depression (abstract presentation). San Juan, PR: American College of Neuropsychopharmacology annual meeting, 2001.

16. Wilder BJ. Pharmacokinetics of valproate and carbamazepine. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1992;12(suppl 1):64S-68S.

Valproate’s well-accepted therapeutic range for treating epilepsy—50 to 100 mcg/mL—was adopted for bipolar disorder treatment without rigorous evaluation of serum levels and response relationships. Because most literature on monitoring serum valproate refers to its use as an anticonvulsant, you may wonder:

- When should I measure serum valproate in bipolar patients?

- What do serum valproate levels mean in their clinical care?

To answer these questions, we discuss when to monitor serum valproate, whether routinely or in specific situations. We then review studies that show how serum levels affect valproate’s efficacy and safety in three phases of bipolar disorder management: acute mania, maintenance therapy, and acute depression.

Is monitoring overused?

Some neurologists consider serum levels nonessential—and, in some cases, overused—when valproate is used as an anticonvulsant for healthy patients.1,2 A multicenter, randomized controlled trial evaluating the impact of antiepileptic drug monitoring on patient outcomes3 supports this notion, at least in part. Serum monitoring did not improve therapeutic outcome, suggesting that patients with epilepsy could be satisfactorily treated by adjusting dosages based on clinical response.

On the other hand, American Psychiatric Association (APA) guidelines for bipolar disorder suggest routine serum monitoring every 6 months along with other hematologic and hepatic assessments, or more frequently if necessary. The APA recommends maintaining serum valproate levels of 50 to 125 mcg/mL when treating:

- acutely manic patients

- outpatients

- the elderly

- patients who are hypomanic or euthymic.4

Table 1

4 situations where serum valproate monitoring may be clinically useful

| To establish a baseline effective level in individual patients |

| To assess lack or loss of efficacy, including patient adherence |

| When drug-drug interactions increase or decrease valproate clearance (such as with aspirin, carbamazepine, felbamate, or phenytoin)5 |

| When dose-dependent side effects occur (such as alopecia, elevated liver function, thrombocytopenia, or pancreatitis) |

Effective levels in acute mania

In one of the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials to examine valproate use in adults with acute mania, Pope et al6 used the epilepsy reference range to adjust dosages. Patients (n=17) initially received valproate, 750 mg/d, and dosages were then adjusted to serum levels of 50 to 100 mcg/mL. Nineteen patients received placebo. Mean (SD) baseline Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) scores for the valproate and placebo groups were 28.2 (5.8) and 28.6 (6.9), respectively.

Patients receiving valproate showed the greatest symptomatic improvement—as indicated by YMRS scores—within 1 to 4 days of achieving a serum level ≥50 mcg/mL. Serum valproate for all patients was maintained at >50 mcg/mL, which limits our ability to draw conclusions about a minimum level associated with efficacy.

Minimum threshold for efficacy. In another randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of acute mania, Bowden et al7 compared the efficacy of divalproex (n=69) versus lithium (n=36) or placebo (n=74) given for 3 weeks. Patients met criteria for manic disorder using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) and had Mania Rating Scale scores (derived from the SADS) of at least 14.

Those in the divalproex group received 750 mg/d for 2 days, then 1,000 mg/d for 3 days. Dosages were then adjusted to target a serum level of 150 mcg/mL, unless limited by side effects. Mean serum valproate levels on days 8 and 21 were 77 and 93.2 mcg/mL, respectively. Marked improvement, defined as ≥50% reduction in Mania Rating Scale scores, was seen in 48% of the divalproex group, compared with 25% of the placebo group.

The authors then analyzed the relationship between serum valproate levels and clinical response and tolerability.8 At day 5, patients with serum valproate ≥45 mcg/mL were 2 to 7 times more likely to show 20% or greater improvement in SADS mania subscales (manic syndrome, and behavior and ideation).