User login

How do new BP guidelines affect identifying risk for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy?

Hauspurg A, Parry S, Mercer BM, et al. Blood pressure trajectory and category and risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in nulliparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019. pii: S0002-9378(19)30807-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.06.031.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Hauspurg and colleagues set out to determine whether redefined BP category (normal, < 120/80 mm Hg) and trajectory (a difference of ≥ 5 mm Hg systolic, diastolic, or mean arterial pressure between the first and second prenatal visit) helps to identify women at increased risk for developing hypertensive disorders of pregnancy or preeclampsia.

With respect to the former variable, such an association was demonstrated in the first National Institutes of Health–funded preeclampsia prevention trial published in 1993, which used low-dose aspirin.1 In that trial, low-dose aspirin was not found to be effective in preventing preeclampsia in young, healthy nulliparous women. Interestingly, the 2 factors most associated with developing preeclampsia were an initial systolic BP of 120 to 134 mm Hg and an initial weight of >60 kg. For most clinicians, these findings would not be helpful in trying to better identify a high-risk group.

Details of the study

The idea of BP “trajectory” is interesting in the Hauspurg and colleagues’ study. The authors analyzed data from the Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: Monitoring Mothers-to-Be (nuMoM2b), a prospective cohort study, and included a very large population of almost 9,000 women in the analysis. Participants were classified according to their BP measurement at the first study visit, with BP categories based on updated American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines. The primary outcome was the risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including gestational hypertension and preeclampsia.

The data analysis found that elevated BP was associated with an adjusted risk ratio (aRR) of 1.54 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.18–2.02). Stage 1 hypertension was associated with an aRR of 2.16 (95% CI, 1.31–3.57). Compared with women whose BP had a downward systolic trajectory, women with normal BP and an upward systolic trajectory had a 41% increased risk of any hypertensive disorder of pregnancy (aRR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.20–1.65).

Study strengths and limitations

While the large study population is a strength of this study, there are a number of limitations, such as the use of BP measurements during pregnancy only, without having pre-pregnancy measurements available. Further, a single BP measurement during each visit is also a drawback, although the standardized measurement by study staff is a strength.

Anticlimactic conclusions. The conclusions of the study, however, are either not surprising, not clinically meaningful, or of little value to clinicians at present, at least with respect to patient management.

Continue to: Conclusions that were not surprising included...

Conclusions that were not surprising included a statistically lower chance of indicated preterm delivery in the normal BP group than in the elevated BP or stage 1 hypertension groups. Conclusions that were not meaningful included a statistically significant lower birthweight in the elevated BP group (3,269 g) and in the stage 1 hypertension group (3,258 g) compared with the normal BP group (3,279 g), but the clinical significance of these differences is arguable.

Lastly is the issue of what these data mean for clinical practice. The idea of identifying high-risk groups is attractive, provided that there are effective intervention strategies available. If one follows the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations for preeclampsia prevention,2 then virtually every nulliparous woman is a candidate for low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prophylaxis. Beyond that, the current data do not support any change in the standard clinical practice of managing these “now identified” high-risk women. Increasing prenatal visits, using biomarkers to further delineate risk, and using uterine artery Doppler studies are all strategies that have been or are being investigated, but as yet they are not supported by conclusive data documenting improved outcomes—a sentiment supported by both the USPSTF3 and the authors of the study.

Until further data are available, my advice to clinicians is to pay close attention to all risk factors for any of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Initial BP and BP trajectory are important but probably something that sound clinical judgment would identify anyway. My recommendation is to continue to use those methods of prophylaxis, fetal surveillance, and indications for delivery that are supported by current data and await the additional investigations that Hauspurg and colleagues suggest need to be done before altering your management of women at increased risk for any of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

JOHN T. REPKE, MD

- Sibai BM, Caritis SN, Thom E, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Prevention of preeclampsia with low-dose aspirin in healthy nulliparous pregnant women. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1213-1218.

- United States Preventive Services Task Force. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: preventive medication. September 2014. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/low-dose-aspirin-use-for-the-prevention-of-morbidity-and-mortality-from-preeclampsia-preventive-medication. Accessed July 30, 2019.

- United States Preventive Service Task Force, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for preeclampsia: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;387:1661-1667.

Hauspurg A, Parry S, Mercer BM, et al. Blood pressure trajectory and category and risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in nulliparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019. pii: S0002-9378(19)30807-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.06.031.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Hauspurg and colleagues set out to determine whether redefined BP category (normal, < 120/80 mm Hg) and trajectory (a difference of ≥ 5 mm Hg systolic, diastolic, or mean arterial pressure between the first and second prenatal visit) helps to identify women at increased risk for developing hypertensive disorders of pregnancy or preeclampsia.

With respect to the former variable, such an association was demonstrated in the first National Institutes of Health–funded preeclampsia prevention trial published in 1993, which used low-dose aspirin.1 In that trial, low-dose aspirin was not found to be effective in preventing preeclampsia in young, healthy nulliparous women. Interestingly, the 2 factors most associated with developing preeclampsia were an initial systolic BP of 120 to 134 mm Hg and an initial weight of >60 kg. For most clinicians, these findings would not be helpful in trying to better identify a high-risk group.

Details of the study

The idea of BP “trajectory” is interesting in the Hauspurg and colleagues’ study. The authors analyzed data from the Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: Monitoring Mothers-to-Be (nuMoM2b), a prospective cohort study, and included a very large population of almost 9,000 women in the analysis. Participants were classified according to their BP measurement at the first study visit, with BP categories based on updated American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines. The primary outcome was the risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including gestational hypertension and preeclampsia.

The data analysis found that elevated BP was associated with an adjusted risk ratio (aRR) of 1.54 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.18–2.02). Stage 1 hypertension was associated with an aRR of 2.16 (95% CI, 1.31–3.57). Compared with women whose BP had a downward systolic trajectory, women with normal BP and an upward systolic trajectory had a 41% increased risk of any hypertensive disorder of pregnancy (aRR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.20–1.65).

Study strengths and limitations

While the large study population is a strength of this study, there are a number of limitations, such as the use of BP measurements during pregnancy only, without having pre-pregnancy measurements available. Further, a single BP measurement during each visit is also a drawback, although the standardized measurement by study staff is a strength.

Anticlimactic conclusions. The conclusions of the study, however, are either not surprising, not clinically meaningful, or of little value to clinicians at present, at least with respect to patient management.

Continue to: Conclusions that were not surprising included...

Conclusions that were not surprising included a statistically lower chance of indicated preterm delivery in the normal BP group than in the elevated BP or stage 1 hypertension groups. Conclusions that were not meaningful included a statistically significant lower birthweight in the elevated BP group (3,269 g) and in the stage 1 hypertension group (3,258 g) compared with the normal BP group (3,279 g), but the clinical significance of these differences is arguable.

Lastly is the issue of what these data mean for clinical practice. The idea of identifying high-risk groups is attractive, provided that there are effective intervention strategies available. If one follows the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations for preeclampsia prevention,2 then virtually every nulliparous woman is a candidate for low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prophylaxis. Beyond that, the current data do not support any change in the standard clinical practice of managing these “now identified” high-risk women. Increasing prenatal visits, using biomarkers to further delineate risk, and using uterine artery Doppler studies are all strategies that have been or are being investigated, but as yet they are not supported by conclusive data documenting improved outcomes—a sentiment supported by both the USPSTF3 and the authors of the study.

Until further data are available, my advice to clinicians is to pay close attention to all risk factors for any of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Initial BP and BP trajectory are important but probably something that sound clinical judgment would identify anyway. My recommendation is to continue to use those methods of prophylaxis, fetal surveillance, and indications for delivery that are supported by current data and await the additional investigations that Hauspurg and colleagues suggest need to be done before altering your management of women at increased risk for any of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

JOHN T. REPKE, MD

Hauspurg A, Parry S, Mercer BM, et al. Blood pressure trajectory and category and risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in nulliparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019. pii: S0002-9378(19)30807-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.06.031.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Hauspurg and colleagues set out to determine whether redefined BP category (normal, < 120/80 mm Hg) and trajectory (a difference of ≥ 5 mm Hg systolic, diastolic, or mean arterial pressure between the first and second prenatal visit) helps to identify women at increased risk for developing hypertensive disorders of pregnancy or preeclampsia.

With respect to the former variable, such an association was demonstrated in the first National Institutes of Health–funded preeclampsia prevention trial published in 1993, which used low-dose aspirin.1 In that trial, low-dose aspirin was not found to be effective in preventing preeclampsia in young, healthy nulliparous women. Interestingly, the 2 factors most associated with developing preeclampsia were an initial systolic BP of 120 to 134 mm Hg and an initial weight of >60 kg. For most clinicians, these findings would not be helpful in trying to better identify a high-risk group.

Details of the study

The idea of BP “trajectory” is interesting in the Hauspurg and colleagues’ study. The authors analyzed data from the Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: Monitoring Mothers-to-Be (nuMoM2b), a prospective cohort study, and included a very large population of almost 9,000 women in the analysis. Participants were classified according to their BP measurement at the first study visit, with BP categories based on updated American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines. The primary outcome was the risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including gestational hypertension and preeclampsia.

The data analysis found that elevated BP was associated with an adjusted risk ratio (aRR) of 1.54 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.18–2.02). Stage 1 hypertension was associated with an aRR of 2.16 (95% CI, 1.31–3.57). Compared with women whose BP had a downward systolic trajectory, women with normal BP and an upward systolic trajectory had a 41% increased risk of any hypertensive disorder of pregnancy (aRR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.20–1.65).

Study strengths and limitations

While the large study population is a strength of this study, there are a number of limitations, such as the use of BP measurements during pregnancy only, without having pre-pregnancy measurements available. Further, a single BP measurement during each visit is also a drawback, although the standardized measurement by study staff is a strength.

Anticlimactic conclusions. The conclusions of the study, however, are either not surprising, not clinically meaningful, or of little value to clinicians at present, at least with respect to patient management.

Continue to: Conclusions that were not surprising included...

Conclusions that were not surprising included a statistically lower chance of indicated preterm delivery in the normal BP group than in the elevated BP or stage 1 hypertension groups. Conclusions that were not meaningful included a statistically significant lower birthweight in the elevated BP group (3,269 g) and in the stage 1 hypertension group (3,258 g) compared with the normal BP group (3,279 g), but the clinical significance of these differences is arguable.

Lastly is the issue of what these data mean for clinical practice. The idea of identifying high-risk groups is attractive, provided that there are effective intervention strategies available. If one follows the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations for preeclampsia prevention,2 then virtually every nulliparous woman is a candidate for low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prophylaxis. Beyond that, the current data do not support any change in the standard clinical practice of managing these “now identified” high-risk women. Increasing prenatal visits, using biomarkers to further delineate risk, and using uterine artery Doppler studies are all strategies that have been or are being investigated, but as yet they are not supported by conclusive data documenting improved outcomes—a sentiment supported by both the USPSTF3 and the authors of the study.

Until further data are available, my advice to clinicians is to pay close attention to all risk factors for any of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Initial BP and BP trajectory are important but probably something that sound clinical judgment would identify anyway. My recommendation is to continue to use those methods of prophylaxis, fetal surveillance, and indications for delivery that are supported by current data and await the additional investigations that Hauspurg and colleagues suggest need to be done before altering your management of women at increased risk for any of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

JOHN T. REPKE, MD

- Sibai BM, Caritis SN, Thom E, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Prevention of preeclampsia with low-dose aspirin in healthy nulliparous pregnant women. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1213-1218.

- United States Preventive Services Task Force. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: preventive medication. September 2014. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/low-dose-aspirin-use-for-the-prevention-of-morbidity-and-mortality-from-preeclampsia-preventive-medication. Accessed July 30, 2019.

- United States Preventive Service Task Force, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for preeclampsia: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;387:1661-1667.

- Sibai BM, Caritis SN, Thom E, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Prevention of preeclampsia with low-dose aspirin in healthy nulliparous pregnant women. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1213-1218.

- United States Preventive Services Task Force. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: preventive medication. September 2014. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/low-dose-aspirin-use-for-the-prevention-of-morbidity-and-mortality-from-preeclampsia-preventive-medication. Accessed July 30, 2019.

- United States Preventive Service Task Force, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for preeclampsia: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;387:1661-1667.

Tips to improve immunization rates in your office

In October 2018 the US Food and Drug Administration expanded the approved use of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine (Gardasil 9) to adults aged 27 through 45.1 In June 2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted to extend catch-up HPV vaccination to include all individuals through age 26 and to catch-up HPV vaccination, based on shared clinical decision making, for all adults aged 27 through 45.2 HPV viruses are associated with cervical cancer, as well as several other forms of cancer that affect both women and men. Approval for the expanded use of the HPV vaccine was based on data of the vaccine’s use in women.1,3

Unfortunately, adult immunization rates, including among pregnant women, do not equal the higher rates in childhood vaccine uptake, according to Kevin A. Ault, MD, and colleagues. Less than half of women (46.6%) receive influenza vaccination prior to and during pregnancy, for instance.4 Dr. Ault has identified the need for an “immunization champion”—someone who can manage one-on-one conversations with patients in the office setting to enhance the acceptance and uptake of adult and maternal vaccines.

OBG Management:

Dr. Kevin A. Ault, MD: The main thing a practice needs to do is to identify someone who is interested, and this person does not have to be a physician. In fact, he or she can frequently be a member of your nursing staff or office staff. And the word “champion” involves a lot of nuts and bolts: such details as how do you store the vaccine, how do you keep track of it, where are the vaccine information statements filed, where can the provider get more information if there is a question about contraindications? One person should organize all these details. The mechanics of vaccine administration are important as well, as the research shows that the more automated the process is, the better and more smoothly it is carried out. There is certainly a role for “standing orders” for adult vaccines.

OBG Management: What communication approach do you take with patients to enhance vaccination acceptance and uptake?

Dr. Ault: There are multiple research studies that show that provider recommendation is the most important way to get both nonpregnant and pregnant adults to receive vaccinations. Take the pertussis vaccine (the whooping cough booster) as an example. It is a relatively new vaccine recommendation during pregnancy. Your approach is relatively straightforward when explaining it to pregnant women. Make the point that we do not want your newborn to have whooping cough in those first few months of life before the newborn or infant vaccine becomes effective. Most people know they had a whooping cough, or pertussis, vaccine when they were younger, and the concept of the booster is well-known to patients. You should explain that the maternal antibodies pass through the placenta to the fetus, and they provide benefit for the first few months of life after birth.

The pertussis vaccine does not have all the “baggage” of the influenza vaccine. Talking with patients about the flu vaccine may present more challenges. Typically, each fall there is a popular press publication that explains “the 10, or 20, most common myths about influenza vaccine.” Every fall I try to find one of those articles, print it out, and even carry it in my jacket pocket and talk about all the myths. For example, there is a myth that “I always get sick when I get the flu shot.” Obstetricians should be giving patients an inactivated vaccine that does not contain any live flu virus. We should be able to explain to patients, your arm will be sore, and you may have some muscle aches, but you will not have the flu from your flu vaccine.

I think another reason that pregnant women do not always take the flu vaccine is that we do not yet have normalized influenza vaccination in the adult population. Women in their twenties and thirties are generally very healthy and have other concerns when they are pregnant, and they perhaps do not realize that they are more vulnerable to devastating effects of influenza while pregnant. Additionally, maternal influenza vaccination does protect the newborn from flu for the first few months. It is vital that those patients who are due during the dark winter months, when the flu is in season, get vaccinated.

Combat the myths and tell your patients the reasons for flu vaccination. Also tell them that you got your flu shot, like most health care professionals do every fall. You should be prepared to talk about safety. There are wonderful safety data, even some published in 2017 and 2018, about pertussis vaccine safety during pregnancy, and it is very reassuring to patients. For flu, the idea of vaccinating women against influenza has been around for decades, and so we have reliable information about that as well. Certainly, the risks are very minor, and the benefits are potentially huge for the pregnant woman and for the newborn.

OBG Management: When do you recommend that ObGyns administer the flu vaccine for pregnant women?

Dr. Ault: There are 2 issues to this question: when throughout the year and when during the pregnancy to administer the vaccine. First, you want to give the flu vaccine during the usual influenza season during the fall. As soon as the vaccine is available, you will recommend that pregnant women, even in their late pregnancy, get vaccinated so that their newborns who are 3 and 4 months old in the peak flu season are protected. The patients who deliver over the summer, who are coming in for their postpartum visit during the fall, should be getting vaccinated as well, because they are still vulnerable to influenza and pneumonia for several months postpartum.

If you have patients that come in for preconception visits, you could say: “Let’s get this out of the way. You could be pregnant by the time flu season really gets cranked up.”

Because we see patients 10 or 12 times during pregnancy, we certainly have plenty of opportunities to educate patients about and administer the flu vaccine. There are older data that demonstrate if patients do not get the flu vaccine done during early pregnancy, the opportunity may be lost. It is different now because there is more emphasis on vaccinating all adults. Your patients certainly can get their vaccine at the pharmacy or at their primary care doctor; however, delaying until later pregnancy usually means not getting the vaccine.

I would like to address one recent study from Donahue and colleagues that showed a potentially increased risk of miscarriage with flu vaccination.5 That study was an anomaly, as there are many other studies into the issue. Yes, there are not a lot of first trimester data, but there are other studies, including studies by the same authors, that did not find this to be the case.6-10

The 2017 study by Donahue and colleagues was an anomaly because the group of women they were vaccinating were already at high risk for miscarriage. The women were older, had diabetes, or a history of miscarriages. There is selection bias in the study because the pregnant women who were vaccinated were already at higher risk for miscarriage. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists are not going to change any of their recommendations based on a single study that is different than our previous data.11

Current recommended adult (anyone over 18 years old) immunization schedule

ACOG Immunization Champions (ACOG members who have demonstrated exceptional progress in increasing immunization rates among adults and pregnant women in their communities through leadership, innovation, collaboration, and educational activities aimed at following ACOG and CDC guidance.)

Summary of Maternal Immunization Recommendations is a provider resource from ACOG and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Maternal Immunization Toolkit contains materials, including the Vaccines During Pregnancy Poster, to support ObGyns on recommending the influenza vaccine and the Tdap vaccine to all pregnant patients.

Influenza Immunization During Pregnancy Toolkit

CDC vaccine schedules app for health care providers

CDC Vaccine Information Statements (available for clinician or patient download)

- FDA approves expanded use of Gardasil 9 to include individuals 27 through 45 years old [press release]. Washington, DC: Food and Drug Administration; October 5, 2018.

- Color/Blue2. Splete H. ACIP extends HPV vaccine coverage. June 27, 2019. https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/article/203656/vaccines/acip-extends-hpv-vaccine-coverage. Accessed July 5, 2019.

- Levy BS, Downs Jr L. The HPV vaccine is now recommended for adults aged 27–45: Counseling implications. OBG Manag. 2019;31(1):9-11.

- Frew PM, Randall LA, Malik F, et al. Clinician perspectives on strategies to improve patient maternal immunization acceptability in obstetrics and gynecology practice settings. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(7):1548–1557.

- Donahue JG, Kieke BA, King JP, et al. Association of spontaneous abortion with receipt of inactivated influenza vaccine containing H1N1pdm09 in 2010-11 and 2011-12. Vaccine. 2017;35(40):5314-5322.

- Moro PL, Broder K, Zheteyeva Y, et al. Adverse events in pregnant women following administration of trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine and live attenuated influenza vaccine in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, 1990-2009. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:146.e1-146.e7.

- Irving SA, Kieke BA, Donahue JG, et al; Vaccine Safety Datalink. Trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine and spontaneous abortion. 2013;121:159-165.

- Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, Lipkind H, et al; Vaccine Safety Datalink Team. Inactivated influenza vaccine during pregnancy and risks for adverse obstetric events. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:659-667.

- Nordin JD, Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, et al; Vaccine Safety Datalink. Maternal Influenza vaccine and risks for preterm or small for gestational age birth. J Pediatrics. 2014;164:1051-1057.e2.

- Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, Romitti PA, et al; Vaccine Safety Datalink. First trimester influenza vaccination and risks for major structural birth defects in offspring. 2017;187:234-239.e4.

- Flu vaccination and possible safety signal. CDC website. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/vaccination-possible-safety-signal.html. Last reviewed September 13, 2017. Accessed May 15, 2019.

In October 2018 the US Food and Drug Administration expanded the approved use of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine (Gardasil 9) to adults aged 27 through 45.1 In June 2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted to extend catch-up HPV vaccination to include all individuals through age 26 and to catch-up HPV vaccination, based on shared clinical decision making, for all adults aged 27 through 45.2 HPV viruses are associated with cervical cancer, as well as several other forms of cancer that affect both women and men. Approval for the expanded use of the HPV vaccine was based on data of the vaccine’s use in women.1,3

Unfortunately, adult immunization rates, including among pregnant women, do not equal the higher rates in childhood vaccine uptake, according to Kevin A. Ault, MD, and colleagues. Less than half of women (46.6%) receive influenza vaccination prior to and during pregnancy, for instance.4 Dr. Ault has identified the need for an “immunization champion”—someone who can manage one-on-one conversations with patients in the office setting to enhance the acceptance and uptake of adult and maternal vaccines.

OBG Management:

Dr. Kevin A. Ault, MD: The main thing a practice needs to do is to identify someone who is interested, and this person does not have to be a physician. In fact, he or she can frequently be a member of your nursing staff or office staff. And the word “champion” involves a lot of nuts and bolts: such details as how do you store the vaccine, how do you keep track of it, where are the vaccine information statements filed, where can the provider get more information if there is a question about contraindications? One person should organize all these details. The mechanics of vaccine administration are important as well, as the research shows that the more automated the process is, the better and more smoothly it is carried out. There is certainly a role for “standing orders” for adult vaccines.

OBG Management: What communication approach do you take with patients to enhance vaccination acceptance and uptake?

Dr. Ault: There are multiple research studies that show that provider recommendation is the most important way to get both nonpregnant and pregnant adults to receive vaccinations. Take the pertussis vaccine (the whooping cough booster) as an example. It is a relatively new vaccine recommendation during pregnancy. Your approach is relatively straightforward when explaining it to pregnant women. Make the point that we do not want your newborn to have whooping cough in those first few months of life before the newborn or infant vaccine becomes effective. Most people know they had a whooping cough, or pertussis, vaccine when they were younger, and the concept of the booster is well-known to patients. You should explain that the maternal antibodies pass through the placenta to the fetus, and they provide benefit for the first few months of life after birth.

The pertussis vaccine does not have all the “baggage” of the influenza vaccine. Talking with patients about the flu vaccine may present more challenges. Typically, each fall there is a popular press publication that explains “the 10, or 20, most common myths about influenza vaccine.” Every fall I try to find one of those articles, print it out, and even carry it in my jacket pocket and talk about all the myths. For example, there is a myth that “I always get sick when I get the flu shot.” Obstetricians should be giving patients an inactivated vaccine that does not contain any live flu virus. We should be able to explain to patients, your arm will be sore, and you may have some muscle aches, but you will not have the flu from your flu vaccine.

I think another reason that pregnant women do not always take the flu vaccine is that we do not yet have normalized influenza vaccination in the adult population. Women in their twenties and thirties are generally very healthy and have other concerns when they are pregnant, and they perhaps do not realize that they are more vulnerable to devastating effects of influenza while pregnant. Additionally, maternal influenza vaccination does protect the newborn from flu for the first few months. It is vital that those patients who are due during the dark winter months, when the flu is in season, get vaccinated.

Combat the myths and tell your patients the reasons for flu vaccination. Also tell them that you got your flu shot, like most health care professionals do every fall. You should be prepared to talk about safety. There are wonderful safety data, even some published in 2017 and 2018, about pertussis vaccine safety during pregnancy, and it is very reassuring to patients. For flu, the idea of vaccinating women against influenza has been around for decades, and so we have reliable information about that as well. Certainly, the risks are very minor, and the benefits are potentially huge for the pregnant woman and for the newborn.

OBG Management: When do you recommend that ObGyns administer the flu vaccine for pregnant women?

Dr. Ault: There are 2 issues to this question: when throughout the year and when during the pregnancy to administer the vaccine. First, you want to give the flu vaccine during the usual influenza season during the fall. As soon as the vaccine is available, you will recommend that pregnant women, even in their late pregnancy, get vaccinated so that their newborns who are 3 and 4 months old in the peak flu season are protected. The patients who deliver over the summer, who are coming in for their postpartum visit during the fall, should be getting vaccinated as well, because they are still vulnerable to influenza and pneumonia for several months postpartum.

If you have patients that come in for preconception visits, you could say: “Let’s get this out of the way. You could be pregnant by the time flu season really gets cranked up.”

Because we see patients 10 or 12 times during pregnancy, we certainly have plenty of opportunities to educate patients about and administer the flu vaccine. There are older data that demonstrate if patients do not get the flu vaccine done during early pregnancy, the opportunity may be lost. It is different now because there is more emphasis on vaccinating all adults. Your patients certainly can get their vaccine at the pharmacy or at their primary care doctor; however, delaying until later pregnancy usually means not getting the vaccine.

I would like to address one recent study from Donahue and colleagues that showed a potentially increased risk of miscarriage with flu vaccination.5 That study was an anomaly, as there are many other studies into the issue. Yes, there are not a lot of first trimester data, but there are other studies, including studies by the same authors, that did not find this to be the case.6-10

The 2017 study by Donahue and colleagues was an anomaly because the group of women they were vaccinating were already at high risk for miscarriage. The women were older, had diabetes, or a history of miscarriages. There is selection bias in the study because the pregnant women who were vaccinated were already at higher risk for miscarriage. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists are not going to change any of their recommendations based on a single study that is different than our previous data.11

Current recommended adult (anyone over 18 years old) immunization schedule

ACOG Immunization Champions (ACOG members who have demonstrated exceptional progress in increasing immunization rates among adults and pregnant women in their communities through leadership, innovation, collaboration, and educational activities aimed at following ACOG and CDC guidance.)

Summary of Maternal Immunization Recommendations is a provider resource from ACOG and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Maternal Immunization Toolkit contains materials, including the Vaccines During Pregnancy Poster, to support ObGyns on recommending the influenza vaccine and the Tdap vaccine to all pregnant patients.

Influenza Immunization During Pregnancy Toolkit

CDC vaccine schedules app for health care providers

CDC Vaccine Information Statements (available for clinician or patient download)

In October 2018 the US Food and Drug Administration expanded the approved use of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine (Gardasil 9) to adults aged 27 through 45.1 In June 2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted to extend catch-up HPV vaccination to include all individuals through age 26 and to catch-up HPV vaccination, based on shared clinical decision making, for all adults aged 27 through 45.2 HPV viruses are associated with cervical cancer, as well as several other forms of cancer that affect both women and men. Approval for the expanded use of the HPV vaccine was based on data of the vaccine’s use in women.1,3

Unfortunately, adult immunization rates, including among pregnant women, do not equal the higher rates in childhood vaccine uptake, according to Kevin A. Ault, MD, and colleagues. Less than half of women (46.6%) receive influenza vaccination prior to and during pregnancy, for instance.4 Dr. Ault has identified the need for an “immunization champion”—someone who can manage one-on-one conversations with patients in the office setting to enhance the acceptance and uptake of adult and maternal vaccines.

OBG Management:

Dr. Kevin A. Ault, MD: The main thing a practice needs to do is to identify someone who is interested, and this person does not have to be a physician. In fact, he or she can frequently be a member of your nursing staff or office staff. And the word “champion” involves a lot of nuts and bolts: such details as how do you store the vaccine, how do you keep track of it, where are the vaccine information statements filed, where can the provider get more information if there is a question about contraindications? One person should organize all these details. The mechanics of vaccine administration are important as well, as the research shows that the more automated the process is, the better and more smoothly it is carried out. There is certainly a role for “standing orders” for adult vaccines.

OBG Management: What communication approach do you take with patients to enhance vaccination acceptance and uptake?

Dr. Ault: There are multiple research studies that show that provider recommendation is the most important way to get both nonpregnant and pregnant adults to receive vaccinations. Take the pertussis vaccine (the whooping cough booster) as an example. It is a relatively new vaccine recommendation during pregnancy. Your approach is relatively straightforward when explaining it to pregnant women. Make the point that we do not want your newborn to have whooping cough in those first few months of life before the newborn or infant vaccine becomes effective. Most people know they had a whooping cough, or pertussis, vaccine when they were younger, and the concept of the booster is well-known to patients. You should explain that the maternal antibodies pass through the placenta to the fetus, and they provide benefit for the first few months of life after birth.

The pertussis vaccine does not have all the “baggage” of the influenza vaccine. Talking with patients about the flu vaccine may present more challenges. Typically, each fall there is a popular press publication that explains “the 10, or 20, most common myths about influenza vaccine.” Every fall I try to find one of those articles, print it out, and even carry it in my jacket pocket and talk about all the myths. For example, there is a myth that “I always get sick when I get the flu shot.” Obstetricians should be giving patients an inactivated vaccine that does not contain any live flu virus. We should be able to explain to patients, your arm will be sore, and you may have some muscle aches, but you will not have the flu from your flu vaccine.

I think another reason that pregnant women do not always take the flu vaccine is that we do not yet have normalized influenza vaccination in the adult population. Women in their twenties and thirties are generally very healthy and have other concerns when they are pregnant, and they perhaps do not realize that they are more vulnerable to devastating effects of influenza while pregnant. Additionally, maternal influenza vaccination does protect the newborn from flu for the first few months. It is vital that those patients who are due during the dark winter months, when the flu is in season, get vaccinated.

Combat the myths and tell your patients the reasons for flu vaccination. Also tell them that you got your flu shot, like most health care professionals do every fall. You should be prepared to talk about safety. There are wonderful safety data, even some published in 2017 and 2018, about pertussis vaccine safety during pregnancy, and it is very reassuring to patients. For flu, the idea of vaccinating women against influenza has been around for decades, and so we have reliable information about that as well. Certainly, the risks are very minor, and the benefits are potentially huge for the pregnant woman and for the newborn.

OBG Management: When do you recommend that ObGyns administer the flu vaccine for pregnant women?

Dr. Ault: There are 2 issues to this question: when throughout the year and when during the pregnancy to administer the vaccine. First, you want to give the flu vaccine during the usual influenza season during the fall. As soon as the vaccine is available, you will recommend that pregnant women, even in their late pregnancy, get vaccinated so that their newborns who are 3 and 4 months old in the peak flu season are protected. The patients who deliver over the summer, who are coming in for their postpartum visit during the fall, should be getting vaccinated as well, because they are still vulnerable to influenza and pneumonia for several months postpartum.

If you have patients that come in for preconception visits, you could say: “Let’s get this out of the way. You could be pregnant by the time flu season really gets cranked up.”

Because we see patients 10 or 12 times during pregnancy, we certainly have plenty of opportunities to educate patients about and administer the flu vaccine. There are older data that demonstrate if patients do not get the flu vaccine done during early pregnancy, the opportunity may be lost. It is different now because there is more emphasis on vaccinating all adults. Your patients certainly can get their vaccine at the pharmacy or at their primary care doctor; however, delaying until later pregnancy usually means not getting the vaccine.

I would like to address one recent study from Donahue and colleagues that showed a potentially increased risk of miscarriage with flu vaccination.5 That study was an anomaly, as there are many other studies into the issue. Yes, there are not a lot of first trimester data, but there are other studies, including studies by the same authors, that did not find this to be the case.6-10

The 2017 study by Donahue and colleagues was an anomaly because the group of women they were vaccinating were already at high risk for miscarriage. The women were older, had diabetes, or a history of miscarriages. There is selection bias in the study because the pregnant women who were vaccinated were already at higher risk for miscarriage. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists are not going to change any of their recommendations based on a single study that is different than our previous data.11

Current recommended adult (anyone over 18 years old) immunization schedule

ACOG Immunization Champions (ACOG members who have demonstrated exceptional progress in increasing immunization rates among adults and pregnant women in their communities through leadership, innovation, collaboration, and educational activities aimed at following ACOG and CDC guidance.)

Summary of Maternal Immunization Recommendations is a provider resource from ACOG and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Maternal Immunization Toolkit contains materials, including the Vaccines During Pregnancy Poster, to support ObGyns on recommending the influenza vaccine and the Tdap vaccine to all pregnant patients.

Influenza Immunization During Pregnancy Toolkit

CDC vaccine schedules app for health care providers

CDC Vaccine Information Statements (available for clinician or patient download)

- FDA approves expanded use of Gardasil 9 to include individuals 27 through 45 years old [press release]. Washington, DC: Food and Drug Administration; October 5, 2018.

- Color/Blue2. Splete H. ACIP extends HPV vaccine coverage. June 27, 2019. https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/article/203656/vaccines/acip-extends-hpv-vaccine-coverage. Accessed July 5, 2019.

- Levy BS, Downs Jr L. The HPV vaccine is now recommended for adults aged 27–45: Counseling implications. OBG Manag. 2019;31(1):9-11.

- Frew PM, Randall LA, Malik F, et al. Clinician perspectives on strategies to improve patient maternal immunization acceptability in obstetrics and gynecology practice settings. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(7):1548–1557.

- Donahue JG, Kieke BA, King JP, et al. Association of spontaneous abortion with receipt of inactivated influenza vaccine containing H1N1pdm09 in 2010-11 and 2011-12. Vaccine. 2017;35(40):5314-5322.

- Moro PL, Broder K, Zheteyeva Y, et al. Adverse events in pregnant women following administration of trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine and live attenuated influenza vaccine in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, 1990-2009. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:146.e1-146.e7.

- Irving SA, Kieke BA, Donahue JG, et al; Vaccine Safety Datalink. Trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine and spontaneous abortion. 2013;121:159-165.

- Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, Lipkind H, et al; Vaccine Safety Datalink Team. Inactivated influenza vaccine during pregnancy and risks for adverse obstetric events. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:659-667.

- Nordin JD, Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, et al; Vaccine Safety Datalink. Maternal Influenza vaccine and risks for preterm or small for gestational age birth. J Pediatrics. 2014;164:1051-1057.e2.

- Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, Romitti PA, et al; Vaccine Safety Datalink. First trimester influenza vaccination and risks for major structural birth defects in offspring. 2017;187:234-239.e4.

- Flu vaccination and possible safety signal. CDC website. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/vaccination-possible-safety-signal.html. Last reviewed September 13, 2017. Accessed May 15, 2019.

- FDA approves expanded use of Gardasil 9 to include individuals 27 through 45 years old [press release]. Washington, DC: Food and Drug Administration; October 5, 2018.

- Color/Blue2. Splete H. ACIP extends HPV vaccine coverage. June 27, 2019. https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/article/203656/vaccines/acip-extends-hpv-vaccine-coverage. Accessed July 5, 2019.

- Levy BS, Downs Jr L. The HPV vaccine is now recommended for adults aged 27–45: Counseling implications. OBG Manag. 2019;31(1):9-11.

- Frew PM, Randall LA, Malik F, et al. Clinician perspectives on strategies to improve patient maternal immunization acceptability in obstetrics and gynecology practice settings. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(7):1548–1557.

- Donahue JG, Kieke BA, King JP, et al. Association of spontaneous abortion with receipt of inactivated influenza vaccine containing H1N1pdm09 in 2010-11 and 2011-12. Vaccine. 2017;35(40):5314-5322.

- Moro PL, Broder K, Zheteyeva Y, et al. Adverse events in pregnant women following administration of trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine and live attenuated influenza vaccine in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, 1990-2009. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:146.e1-146.e7.

- Irving SA, Kieke BA, Donahue JG, et al; Vaccine Safety Datalink. Trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine and spontaneous abortion. 2013;121:159-165.

- Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, Lipkind H, et al; Vaccine Safety Datalink Team. Inactivated influenza vaccine during pregnancy and risks for adverse obstetric events. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:659-667.

- Nordin JD, Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, et al; Vaccine Safety Datalink. Maternal Influenza vaccine and risks for preterm or small for gestational age birth. J Pediatrics. 2014;164:1051-1057.e2.

- Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, Romitti PA, et al; Vaccine Safety Datalink. First trimester influenza vaccination and risks for major structural birth defects in offspring. 2017;187:234-239.e4.

- Flu vaccination and possible safety signal. CDC website. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/vaccination-possible-safety-signal.html. Last reviewed September 13, 2017. Accessed May 15, 2019.

Expert advice for immediate postpartum LARC insertion

Evidence-based education about long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) for women in the postpartum period can result in the increased continuation of and satisfaction with LARC.1 However, nearly 40% of women do not attend a postpartum visit.2 And up to 57% of women report having unprotected intercourse before the 6-week postpartum visit, which increases the risk of unplanned pregnancy.3 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) supports immediate postpartum LARC insertion as best practice,3 and clinicians providing care for women during the peripartum period can counsel women regarding informed contraceptive decisions and provide guidance regarding both short-acting contraception and LARC.1

Immediate postpartum LARC, using intrauterine devices (IUDs) in particular, has been used around the world for a long time, says Lisa Hofler, MD, MPH, MBA, Chief in the Division of Family Planning at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque. “Much of our initial data came from other countries, but eventually people in the United States said, ‘This is a great option, why aren't we doing this?’" In addition, although women considering immediate postpartum LARC should be counseled about the theoretical risk of reduced duration of breastfeeding, the evidence overwhelmingly has not shown a negative effect on actual breastfeeding outcomes according to ACOG.3 OBG MANAGEMENT recently met up with Dr. Hofler to ask her which patients are ideal for postpartum LARC, how to troubleshoot common pitfalls, and how to implement the practice within one’s own institution.

OBG Management: Who do you consider to be the ideal patient for immediate postpartum LARC?

Lisa Hofler, MD: The great thing about immediate postpartum LARC (including IUDs and implants) is that any woman is an ideal candidate. We are simply talking about the timing of when a woman chooses to get an IUD or an implant after the birth of her child. There is no one perfect woman; it is the person who chooses the method and wants to use that method immediately after birth. When a woman chooses a LARC, she can be assured that after the birth of her child she will be protected against pregnancy. If she chooses an IUD as her LARC method, she will be comfortable at insertion because the cervix is already dilated when it is inserted.

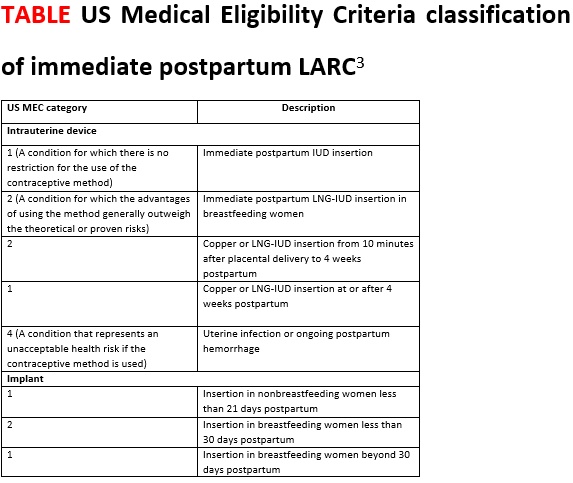

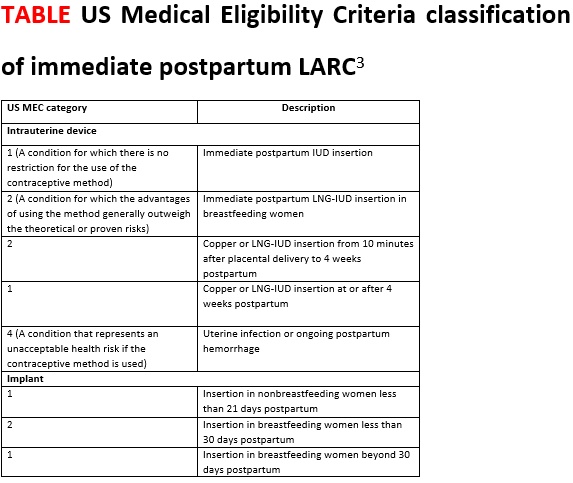

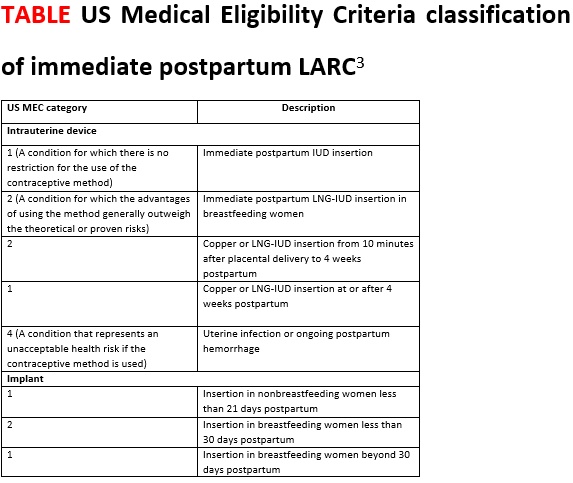

For the implant, the contraindications are the same as in the outpatient setting. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use covers many medical conditions and whether or not a person might be a candidate for different birth control methods.4 Those same considerations apply for the implant postpartum (TABLE).3

For the IUD, similarly, anyone who would not be a candidate for the IUD in the outpatient setting is not a candidate for immediate postpartum IUD. For instance, if the person has an intrauterine infection, you should not place an IUD. Also, if a patient is hemorrhaging and you are managing the hemorrhage (say she has retained placenta or membranes or she has uterine atony), you are not going to put an IUD in, as you need to attend to her bleeding.

OBG Management: What is your approach to counseling a patient for immediate postpartum LARC?

Dr. Hofler: The ideal time to counsel about postbirth contraception is in the prenatal period, when the patient is making decisions about what method she wants to use after the birth. Once she chooses her preferred method, address timing if appropriate. It is less ideal to talk to a woman about the option of immediate postpartum LARC when she comes to labor and delivery, especially if that is the first time she has heard about it. Certainly, the time to talk about postpartum LARC options is not immediately after the baby is born. Approaching your patient with, "What do you want for birth control? Do you want this IUD? I can put it in right now," can feel coercive. This approach does not put the woman in a position in which she has enough decision-making time or time to ask questions.

OBG Management: What problems do clinicians run into when placing an immediate postpartum IUD, and can you offer solutions?

Dr. Hofler: When placing an immediate postpartum IUD, people might run into a few problems. The first relates to preplacement counseling. Perhaps when making the plan for the postpartum IUD the clinician did not counsel the woman that there are certain conditions that could preclude IUD placement—such as intrauterine infection or postpartum hemorrhage. When dealing with those types of issues, a patient is not eligible for an IUD, and she should be mentally prepared for this type of situation. Let her know during the counseling before the birth that immediately postpartum is a great time and opportunity for effective contraception placement. Tell her that hopefully IUD placement will be possible but that occasionally it is not, and make a back-up plan in case the IUD cannot be placed immediately postpartum.

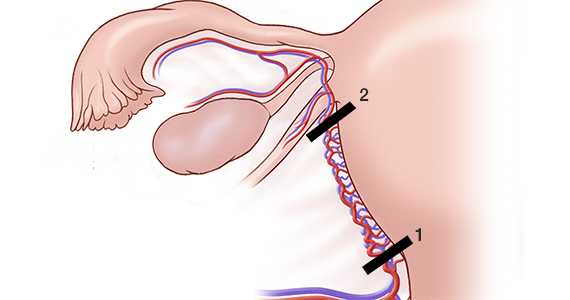

The second unique area for counseling with immediate postpartum IUDs is a slightly increased risk of expulsion of an IUD placed immediately postpartum compared with in the office. The risk of expulsion varies by type of delivery. For instance, cesarean delivery births have a lower expulsion rate than vaginal births. The expulsion rate seems to vary by type of IUD as well. Copper IUDs seem to have a slightly lower expulsion rate than hormonal IUDs. (See “Levonorgestrel vs copper IUD expulsion rates after immediate postpartum insertion.”) This consideration should be talked about ahead of time, too. Provider training in IUD placement does impact the likelihood of expulsion, and if you place the IUD at the fundus, it is less likely to expel. (See “Inserting the immediate postpartum IUD after vaginal and cesarean birth step by step.”)

A third issue that clinicians run into is actually the systems of care—making sure that the IUD or implant is available when you need it, making sure that documentation happens the way it should, and ensuring that the follow-up billing and revenue cycle happens so that the woman gets the device that she wants and the providers get paid for having provided it. These issues require a multidisciplinary team to work through in order to ensure that postpartum LARC placement is a sustainable process in the long run.

Often, when people think of immediate postpartum LARC they think of postplacental IUDs. However, an implant also is an option, and that too is immediate postpartum LARC. Placing an implant is often a lot easier to do after the birth than placing an IUD. As clinicians work toward bringing an immediate postpartum LARC program to their hospital system, starting with implants is a smart thing to do because clinicians do not have to learn or teach new clinical skills. Because of that, immediate postpartum implants are a good troubleshooting mechanism for opening up the conversation about immediate postpartum LARC at your institution.

OBG MANAGEMENT: What advice do you have for administrators or physicians looking to implement an immediate postpartum LARC program into a hospital setting?

Dr. Hofler: Probably the best single resource is the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Postpartum Contraception Access Initiative (PCAI). They have a dedicated website and offer a lot of support and resources that include site-specific training at the hospital or the institution; clinician training on implants and IUDs; and administrator training on some of the systems of care, the billing process, the stocking process, and pharmacy education. They also provide information on all the things that should be included beyond the clinical aspects. I strongly recommend looking at what they offer.

Also, because many hospitals say, "We love this idea. We would support immediate postpartum LARC, we just want to make sure we get paid," the ACOG LARC Program website includes state-specific guidance for how Medicaid pays for LARC devices. There is state-specific guidance about how the device payment can be separated from the global payment for delivery—specific things for each institution to do to get reimbursed.

A 2017 prospective cohort study was the first to directly compare expulsion rates of the levonorgestrel (LNG) intrauterine device (IUD) and the copper IUD placed postplacentally (within 10 minutes of placental delivery). The study investigators found that, among 96 women at 12 weeks, 38% of the LNG-IUD users and 20% of the copper IUD users experienced IUD expulsion (odds ratio, 2.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.99-6.55; P = .05). Women were aged 18 to 40 and had a singleton vaginal delivery at ≥ 35 weeks’ gestation.1 The two study groups were similar except that more copper IUD users were Hispanic (66% vs 38%) and fewer were primiparous (16% vs 31%). The study authors found the only independent predictor of device expulsion to be IUD type.

In a 2019 prospective cohort study, Hinz and colleagues compared the 6-month expulsion rate of IUDs inserted in the immediate postpartum period (within 10 to 15 minutes of placental delivery) after vaginal or cesarean delivery.2 Women were aged 18 to 45 years and selected a LNG 52-mg IUD (75 women) or copper IUD (58 women) for postpartum contraception. They completed a survey from weeks 0 to 5 and on weeks 12 and 24 postpartum regarding IUD expulsion, IUD removal, vaginal bleeding, and breastfeeding. A total of 58 women had a vaginal delivery, and 56 had a cesarean delivery.

At 6 months, the expulsion rates were similar in the two groups: 26.7% of the LNG IUDs expelled, compared with 20.5% of the copper IUDs (P = .38). The study groups were similar, point out the study investigators, except that the copper IUD users had a higher median parity (3 vs. 2; P = .03). In addition, the copper IUDs were inserted by more senior than junior residents (46.2% vs 22.7%, P = .02).

A 2018 systematic review pooled absolute rates of IUD expulsion and estimated adjusted relative risk (RR) for IUD type. A total of 48 studies (rated level I to II-3 of poor to good quality) were included in the analysis, and results indicated that the LNG-IUD was associated with a higher risk of expulsion at less than 4 weeks postpartum than the copper IUD (adjusted RR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.50-2.43).3

References

1. Goldthwaite LM, Sheeder J, Hyer J, et al. Postplacental intrauterine device expulsion by 12 weeks: a prospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:674.e1-674.e8.

2. Hinz EK, Murthy A, Wang B, Ryan N, Ades V. A prospective cohort study comparing expulsion after postplacental insertion: the levonorgestrel versus the copper intrauterine device. Contraception. May 17, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.04.011.

3. Jatlaoui TC, Whiteman MK, Jeng G, et al. Intrauterine device expulsion after postpartum placement. Obstet Gynecol. 2018:895-905.

Technique for placing an IUD immediately after vaginal birth

1. Bring supplies for intrauterine device (IUD) insertion: the IUD, posterior blade of a speculum or retractor for posterior vagina, ring forceps, curved Kelly placenta forceps, and scissors.

2. Determine that the patient still wants the IUD and is still medically eligible for the IUD. Place the IUD as soon as possible following placenta delivery; in most studies IUD placement occurred within 10 minutes of the placenta. Any perineal lacerations should be repaired after IUD placement.

3. Break down the bed to facilitate placement. If the perineum or vagina is soiled with stool or meconium then consider povodine-iodine prep.

4. Place the posterior blade of the speculum into the vagina and grasp the anterior cervix with the ring forceps.

5. Set up the IUD for insertion: Change into new sterile gloves. Remove the IUD from the inserter. For levonorgestrel IUDs, cut the strings so that the length of the IUD and strings together is approximately 10 to 12 cm; copper IUDs do not need strings trimmed. Hold one arm of the IUD with the long Kelly placenta forceps so that the stem of the IUD is approximately parallel to the shaft of the forceps.

6. Insert the IUD: Guide the IUD into the lower uterine segment with the left hand on the cervix ring forceps and the right hand on the IUD forceps. After passing the IUD through the cervix, move the left hand to the abdomen and press the fundus posterior and caudad to straighten the endometrial canal and to feel the IUD at the fundus. With the right hand, guide the IUD to the fundus; this often entails dropping the hand significantly and guiding the IUD much more anteriorly than first expected.

7. Release the IUD with forceps wide open, sweeping the forceps to one side to avoid pulling the IUD out with the forceps. 8. Consider use of ultrasound guidance and ultrasound verification of fundal location, especially when first performing postplacental IUD placements.

8. Consider use of ultrasound guidance and ultrasound verification of fundal location, especially when first performing postplacental IUD placements.

Troubleshooting tips:

- If you are unable to visualize the anterior cervix, try to place the ring forceps by palpation.

- If you are unable to grasp the cervix with ring forceps by palpation, you may try to place the IUD manually. Hold the IUD between the first and second fingers of the right hand and place the IUD at the fundus. Release the IUD with the fingers wide open and remove the hand without removing the IUD.

Technique for placing an IUD immediately after cesarean birth

1. Determine that the patient still wants the IUD and is still medically eligible for the IUD. Place the IUD as soon as possible following placenta delivery; in most studies IUD placement occurred within 10 minutes of the placenta.

2. For levonorgestrel IUDs: Remove the IUD from the inserter. Cut the strings so that the length of the IUD and strings together is approximately 10 to 12 cm. Place the IUD at the fundus with a ring forceps and tuck the strings toward the cervix. It is not necessary to open the cervix or to place the strings through the cervix.

3. For copper IUDs: String trimming is not necessary. Place the IUD at the fundus with the IUD inserter or a ring forceps and tuck the strings toward the cervix. It is not necessary to open the cervix or to place the strings through the cervix.

4. Repair the hysterotomy as usual.

1. Dole DM, Martin J. What nurses need to know about immediate postpartum initiation of long-acting reversible contraception. Nurs Womens Health. 2017;21:186-195.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion no. 736: optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e140-e150.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology, Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Work Group. Practice Bulletin no. 186: long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e251-e269.

4. Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-104.

Evidence-based education about long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) for women in the postpartum period can result in the increased continuation of and satisfaction with LARC.1 However, nearly 40% of women do not attend a postpartum visit.2 And up to 57% of women report having unprotected intercourse before the 6-week postpartum visit, which increases the risk of unplanned pregnancy.3 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) supports immediate postpartum LARC insertion as best practice,3 and clinicians providing care for women during the peripartum period can counsel women regarding informed contraceptive decisions and provide guidance regarding both short-acting contraception and LARC.1

Immediate postpartum LARC, using intrauterine devices (IUDs) in particular, has been used around the world for a long time, says Lisa Hofler, MD, MPH, MBA, Chief in the Division of Family Planning at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque. “Much of our initial data came from other countries, but eventually people in the United States said, ‘This is a great option, why aren't we doing this?’" In addition, although women considering immediate postpartum LARC should be counseled about the theoretical risk of reduced duration of breastfeeding, the evidence overwhelmingly has not shown a negative effect on actual breastfeeding outcomes according to ACOG.3 OBG MANAGEMENT recently met up with Dr. Hofler to ask her which patients are ideal for postpartum LARC, how to troubleshoot common pitfalls, and how to implement the practice within one’s own institution.

OBG Management: Who do you consider to be the ideal patient for immediate postpartum LARC?

Lisa Hofler, MD: The great thing about immediate postpartum LARC (including IUDs and implants) is that any woman is an ideal candidate. We are simply talking about the timing of when a woman chooses to get an IUD or an implant after the birth of her child. There is no one perfect woman; it is the person who chooses the method and wants to use that method immediately after birth. When a woman chooses a LARC, she can be assured that after the birth of her child she will be protected against pregnancy. If she chooses an IUD as her LARC method, she will be comfortable at insertion because the cervix is already dilated when it is inserted.

For the implant, the contraindications are the same as in the outpatient setting. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use covers many medical conditions and whether or not a person might be a candidate for different birth control methods.4 Those same considerations apply for the implant postpartum (TABLE).3

For the IUD, similarly, anyone who would not be a candidate for the IUD in the outpatient setting is not a candidate for immediate postpartum IUD. For instance, if the person has an intrauterine infection, you should not place an IUD. Also, if a patient is hemorrhaging and you are managing the hemorrhage (say she has retained placenta or membranes or she has uterine atony), you are not going to put an IUD in, as you need to attend to her bleeding.

OBG Management: What is your approach to counseling a patient for immediate postpartum LARC?

Dr. Hofler: The ideal time to counsel about postbirth contraception is in the prenatal period, when the patient is making decisions about what method she wants to use after the birth. Once she chooses her preferred method, address timing if appropriate. It is less ideal to talk to a woman about the option of immediate postpartum LARC when she comes to labor and delivery, especially if that is the first time she has heard about it. Certainly, the time to talk about postpartum LARC options is not immediately after the baby is born. Approaching your patient with, "What do you want for birth control? Do you want this IUD? I can put it in right now," can feel coercive. This approach does not put the woman in a position in which she has enough decision-making time or time to ask questions.

OBG Management: What problems do clinicians run into when placing an immediate postpartum IUD, and can you offer solutions?

Dr. Hofler: When placing an immediate postpartum IUD, people might run into a few problems. The first relates to preplacement counseling. Perhaps when making the plan for the postpartum IUD the clinician did not counsel the woman that there are certain conditions that could preclude IUD placement—such as intrauterine infection or postpartum hemorrhage. When dealing with those types of issues, a patient is not eligible for an IUD, and she should be mentally prepared for this type of situation. Let her know during the counseling before the birth that immediately postpartum is a great time and opportunity for effective contraception placement. Tell her that hopefully IUD placement will be possible but that occasionally it is not, and make a back-up plan in case the IUD cannot be placed immediately postpartum.

The second unique area for counseling with immediate postpartum IUDs is a slightly increased risk of expulsion of an IUD placed immediately postpartum compared with in the office. The risk of expulsion varies by type of delivery. For instance, cesarean delivery births have a lower expulsion rate than vaginal births. The expulsion rate seems to vary by type of IUD as well. Copper IUDs seem to have a slightly lower expulsion rate than hormonal IUDs. (See “Levonorgestrel vs copper IUD expulsion rates after immediate postpartum insertion.”) This consideration should be talked about ahead of time, too. Provider training in IUD placement does impact the likelihood of expulsion, and if you place the IUD at the fundus, it is less likely to expel. (See “Inserting the immediate postpartum IUD after vaginal and cesarean birth step by step.”)

A third issue that clinicians run into is actually the systems of care—making sure that the IUD or implant is available when you need it, making sure that documentation happens the way it should, and ensuring that the follow-up billing and revenue cycle happens so that the woman gets the device that she wants and the providers get paid for having provided it. These issues require a multidisciplinary team to work through in order to ensure that postpartum LARC placement is a sustainable process in the long run.

Often, when people think of immediate postpartum LARC they think of postplacental IUDs. However, an implant also is an option, and that too is immediate postpartum LARC. Placing an implant is often a lot easier to do after the birth than placing an IUD. As clinicians work toward bringing an immediate postpartum LARC program to their hospital system, starting with implants is a smart thing to do because clinicians do not have to learn or teach new clinical skills. Because of that, immediate postpartum implants are a good troubleshooting mechanism for opening up the conversation about immediate postpartum LARC at your institution.

OBG MANAGEMENT: What advice do you have for administrators or physicians looking to implement an immediate postpartum LARC program into a hospital setting?

Dr. Hofler: Probably the best single resource is the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Postpartum Contraception Access Initiative (PCAI). They have a dedicated website and offer a lot of support and resources that include site-specific training at the hospital or the institution; clinician training on implants and IUDs; and administrator training on some of the systems of care, the billing process, the stocking process, and pharmacy education. They also provide information on all the things that should be included beyond the clinical aspects. I strongly recommend looking at what they offer.

Also, because many hospitals say, "We love this idea. We would support immediate postpartum LARC, we just want to make sure we get paid," the ACOG LARC Program website includes state-specific guidance for how Medicaid pays for LARC devices. There is state-specific guidance about how the device payment can be separated from the global payment for delivery—specific things for each institution to do to get reimbursed.

A 2017 prospective cohort study was the first to directly compare expulsion rates of the levonorgestrel (LNG) intrauterine device (IUD) and the copper IUD placed postplacentally (within 10 minutes of placental delivery). The study investigators found that, among 96 women at 12 weeks, 38% of the LNG-IUD users and 20% of the copper IUD users experienced IUD expulsion (odds ratio, 2.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.99-6.55; P = .05). Women were aged 18 to 40 and had a singleton vaginal delivery at ≥ 35 weeks’ gestation.1 The two study groups were similar except that more copper IUD users were Hispanic (66% vs 38%) and fewer were primiparous (16% vs 31%). The study authors found the only independent predictor of device expulsion to be IUD type.

In a 2019 prospective cohort study, Hinz and colleagues compared the 6-month expulsion rate of IUDs inserted in the immediate postpartum period (within 10 to 15 minutes of placental delivery) after vaginal or cesarean delivery.2 Women were aged 18 to 45 years and selected a LNG 52-mg IUD (75 women) or copper IUD (58 women) for postpartum contraception. They completed a survey from weeks 0 to 5 and on weeks 12 and 24 postpartum regarding IUD expulsion, IUD removal, vaginal bleeding, and breastfeeding. A total of 58 women had a vaginal delivery, and 56 had a cesarean delivery.

At 6 months, the expulsion rates were similar in the two groups: 26.7% of the LNG IUDs expelled, compared with 20.5% of the copper IUDs (P = .38). The study groups were similar, point out the study investigators, except that the copper IUD users had a higher median parity (3 vs. 2; P = .03). In addition, the copper IUDs were inserted by more senior than junior residents (46.2% vs 22.7%, P = .02).

A 2018 systematic review pooled absolute rates of IUD expulsion and estimated adjusted relative risk (RR) for IUD type. A total of 48 studies (rated level I to II-3 of poor to good quality) were included in the analysis, and results indicated that the LNG-IUD was associated with a higher risk of expulsion at less than 4 weeks postpartum than the copper IUD (adjusted RR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.50-2.43).3

References

1. Goldthwaite LM, Sheeder J, Hyer J, et al. Postplacental intrauterine device expulsion by 12 weeks: a prospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:674.e1-674.e8.

2. Hinz EK, Murthy A, Wang B, Ryan N, Ades V. A prospective cohort study comparing expulsion after postplacental insertion: the levonorgestrel versus the copper intrauterine device. Contraception. May 17, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.04.011.

3. Jatlaoui TC, Whiteman MK, Jeng G, et al. Intrauterine device expulsion after postpartum placement. Obstet Gynecol. 2018:895-905.

Technique for placing an IUD immediately after vaginal birth

1. Bring supplies for intrauterine device (IUD) insertion: the IUD, posterior blade of a speculum or retractor for posterior vagina, ring forceps, curved Kelly placenta forceps, and scissors.

2. Determine that the patient still wants the IUD and is still medically eligible for the IUD. Place the IUD as soon as possible following placenta delivery; in most studies IUD placement occurred within 10 minutes of the placenta. Any perineal lacerations should be repaired after IUD placement.

3. Break down the bed to facilitate placement. If the perineum or vagina is soiled with stool or meconium then consider povodine-iodine prep.

4. Place the posterior blade of the speculum into the vagina and grasp the anterior cervix with the ring forceps.

5. Set up the IUD for insertion: Change into new sterile gloves. Remove the IUD from the inserter. For levonorgestrel IUDs, cut the strings so that the length of the IUD and strings together is approximately 10 to 12 cm; copper IUDs do not need strings trimmed. Hold one arm of the IUD with the long Kelly placenta forceps so that the stem of the IUD is approximately parallel to the shaft of the forceps.

6. Insert the IUD: Guide the IUD into the lower uterine segment with the left hand on the cervix ring forceps and the right hand on the IUD forceps. After passing the IUD through the cervix, move the left hand to the abdomen and press the fundus posterior and caudad to straighten the endometrial canal and to feel the IUD at the fundus. With the right hand, guide the IUD to the fundus; this often entails dropping the hand significantly and guiding the IUD much more anteriorly than first expected.

7. Release the IUD with forceps wide open, sweeping the forceps to one side to avoid pulling the IUD out with the forceps. 8. Consider use of ultrasound guidance and ultrasound verification of fundal location, especially when first performing postplacental IUD placements.

8. Consider use of ultrasound guidance and ultrasound verification of fundal location, especially when first performing postplacental IUD placements.

Troubleshooting tips:

- If you are unable to visualize the anterior cervix, try to place the ring forceps by palpation.

- If you are unable to grasp the cervix with ring forceps by palpation, you may try to place the IUD manually. Hold the IUD between the first and second fingers of the right hand and place the IUD at the fundus. Release the IUD with the fingers wide open and remove the hand without removing the IUD.

Technique for placing an IUD immediately after cesarean birth

1. Determine that the patient still wants the IUD and is still medically eligible for the IUD. Place the IUD as soon as possible following placenta delivery; in most studies IUD placement occurred within 10 minutes of the placenta.

2. For levonorgestrel IUDs: Remove the IUD from the inserter. Cut the strings so that the length of the IUD and strings together is approximately 10 to 12 cm. Place the IUD at the fundus with a ring forceps and tuck the strings toward the cervix. It is not necessary to open the cervix or to place the strings through the cervix.

3. For copper IUDs: String trimming is not necessary. Place the IUD at the fundus with the IUD inserter or a ring forceps and tuck the strings toward the cervix. It is not necessary to open the cervix or to place the strings through the cervix.

4. Repair the hysterotomy as usual.