User login

Can You Nail the Diagnosis? (It’s Not Fungal)

A 50-year-old man is sent to dermatology for evaluation of a “fungal infection” affecting both of his thumbnails. In the past several years, treatment with at least two courses of oral terbinafine and numerous topical antifungal creams has failed to produce any improvement in the problem. The patient denies any nail-related symptoms or trauma to his thumbs.

The patient claims to be otherwise healthy. On further questioning, however, he admits to having intermittent joint pain and swelling, especially in one ankle. He adds that for the past several years, he has experienced severe back pain and stiffness in the morning.

EXAMINATION

The patient looks his stated age, is in no acute distress, and is well developed and well nourished.

Both thumbnails demonstrate identical changes: separation of the distal one-third of the nail plate from the nail bed and yellowish discoloration of that portion of the nails. In and under the nail plate, fine, short, longitudinal black streaks are seen. Proximally, a well-defined brown band is observed in the subungual areas. The patient’s other nails are unaffected.

Broader examination reveals a salmon-pink rash with white scale covering the periumbilical area. A similar rash is seen in the upper intergluteal area.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

All these findings add up to the diagnosis of psoriasis vulgaris, or common psoriasis, a disease that affects almost 3% of the US population and is far less common in persons with darker skin. This inflammatory condition, thought to be of autoimmune origin, manifested in predictable ways in this patient, who most likely inherited the genetic predisposition for the disease.

Although numerous related chromosomal abnormalities have been identified, environmental factors often play a role in psoriasis as well. These include antecedent strep infection, stress, smoking, obesity, alcohol intake, and use of certain medications (eg, beta-blockers, lithium).

Psoriasis is known to affect nails. The changes in this patient are classic: onycholysis (separation of the nail plate from the nail bed), deformed nails (known as dystrophy), yellow-brown discoloration (so-called oil spotting), and often, splinter hemorrhages. Nail pitting, though not seen in this case, is also common.

For some psoriasis patients, nail involvement is the sole manifestation of the disease. But more often, observing these nail changes prompts the provider to look elsewhere for corroborative findings, of which periumbilical and upper intergluteal involvement are typical.

Seen in a diagnostic vacuum, such nail changes are often diagnosed as “fungal infection.” This overlooks the fact that fungal infection is far less common in the fingernails than in toenails. In fact, there are several other items in the differential for nail changes, including lichen planus, eczema, and chronic candidal paronychia.

Had fungal infection (onychomycosis) been a serious possibility, culture or histologic examination of a sample of nail plate could have been confirmatory. First, though, the other items in the differential should have been considered. (I’ve said it before, in a variety of contexts: If your only explanation for discolored and misshapen nails is fungal infection, that’s a problem.)

This patient’s skin disease was initially treated with topical steroids. However, due to his joint symptoms and the possibility of psoriatic arthropathy, he was also referred to rheumatology. It’s entirely possible that he’ll be prescribed a biologic, which will eliminate his otherwise-problematic-to-treat nail psoriasis.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Since fungal infection of the fingernails is distinctly uncommon, other items in the differential should be considered in such cases.

• Other potential diagnostic explanations for nail changes include lichen planus, eczema, and chronic candidal paronychia.

• Nail changes can be the sole manifestation of psoriasis in a given patient.

• Evaluation should include other areas of involvement that exhibit “classic” signs of psoriasis, including extensor surfaces and periumbilical and upper intergluteal skin.

A 50-year-old man is sent to dermatology for evaluation of a “fungal infection” affecting both of his thumbnails. In the past several years, treatment with at least two courses of oral terbinafine and numerous topical antifungal creams has failed to produce any improvement in the problem. The patient denies any nail-related symptoms or trauma to his thumbs.

The patient claims to be otherwise healthy. On further questioning, however, he admits to having intermittent joint pain and swelling, especially in one ankle. He adds that for the past several years, he has experienced severe back pain and stiffness in the morning.

EXAMINATION

The patient looks his stated age, is in no acute distress, and is well developed and well nourished.

Both thumbnails demonstrate identical changes: separation of the distal one-third of the nail plate from the nail bed and yellowish discoloration of that portion of the nails. In and under the nail plate, fine, short, longitudinal black streaks are seen. Proximally, a well-defined brown band is observed in the subungual areas. The patient’s other nails are unaffected.

Broader examination reveals a salmon-pink rash with white scale covering the periumbilical area. A similar rash is seen in the upper intergluteal area.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

All these findings add up to the diagnosis of psoriasis vulgaris, or common psoriasis, a disease that affects almost 3% of the US population and is far less common in persons with darker skin. This inflammatory condition, thought to be of autoimmune origin, manifested in predictable ways in this patient, who most likely inherited the genetic predisposition for the disease.

Although numerous related chromosomal abnormalities have been identified, environmental factors often play a role in psoriasis as well. These include antecedent strep infection, stress, smoking, obesity, alcohol intake, and use of certain medications (eg, beta-blockers, lithium).

Psoriasis is known to affect nails. The changes in this patient are classic: onycholysis (separation of the nail plate from the nail bed), deformed nails (known as dystrophy), yellow-brown discoloration (so-called oil spotting), and often, splinter hemorrhages. Nail pitting, though not seen in this case, is also common.

For some psoriasis patients, nail involvement is the sole manifestation of the disease. But more often, observing these nail changes prompts the provider to look elsewhere for corroborative findings, of which periumbilical and upper intergluteal involvement are typical.

Seen in a diagnostic vacuum, such nail changes are often diagnosed as “fungal infection.” This overlooks the fact that fungal infection is far less common in the fingernails than in toenails. In fact, there are several other items in the differential for nail changes, including lichen planus, eczema, and chronic candidal paronychia.

Had fungal infection (onychomycosis) been a serious possibility, culture or histologic examination of a sample of nail plate could have been confirmatory. First, though, the other items in the differential should have been considered. (I’ve said it before, in a variety of contexts: If your only explanation for discolored and misshapen nails is fungal infection, that’s a problem.)

This patient’s skin disease was initially treated with topical steroids. However, due to his joint symptoms and the possibility of psoriatic arthropathy, he was also referred to rheumatology. It’s entirely possible that he’ll be prescribed a biologic, which will eliminate his otherwise-problematic-to-treat nail psoriasis.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Since fungal infection of the fingernails is distinctly uncommon, other items in the differential should be considered in such cases.

• Other potential diagnostic explanations for nail changes include lichen planus, eczema, and chronic candidal paronychia.

• Nail changes can be the sole manifestation of psoriasis in a given patient.

• Evaluation should include other areas of involvement that exhibit “classic” signs of psoriasis, including extensor surfaces and periumbilical and upper intergluteal skin.

A 50-year-old man is sent to dermatology for evaluation of a “fungal infection” affecting both of his thumbnails. In the past several years, treatment with at least two courses of oral terbinafine and numerous topical antifungal creams has failed to produce any improvement in the problem. The patient denies any nail-related symptoms or trauma to his thumbs.

The patient claims to be otherwise healthy. On further questioning, however, he admits to having intermittent joint pain and swelling, especially in one ankle. He adds that for the past several years, he has experienced severe back pain and stiffness in the morning.

EXAMINATION

The patient looks his stated age, is in no acute distress, and is well developed and well nourished.

Both thumbnails demonstrate identical changes: separation of the distal one-third of the nail plate from the nail bed and yellowish discoloration of that portion of the nails. In and under the nail plate, fine, short, longitudinal black streaks are seen. Proximally, a well-defined brown band is observed in the subungual areas. The patient’s other nails are unaffected.

Broader examination reveals a salmon-pink rash with white scale covering the periumbilical area. A similar rash is seen in the upper intergluteal area.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

All these findings add up to the diagnosis of psoriasis vulgaris, or common psoriasis, a disease that affects almost 3% of the US population and is far less common in persons with darker skin. This inflammatory condition, thought to be of autoimmune origin, manifested in predictable ways in this patient, who most likely inherited the genetic predisposition for the disease.

Although numerous related chromosomal abnormalities have been identified, environmental factors often play a role in psoriasis as well. These include antecedent strep infection, stress, smoking, obesity, alcohol intake, and use of certain medications (eg, beta-blockers, lithium).

Psoriasis is known to affect nails. The changes in this patient are classic: onycholysis (separation of the nail plate from the nail bed), deformed nails (known as dystrophy), yellow-brown discoloration (so-called oil spotting), and often, splinter hemorrhages. Nail pitting, though not seen in this case, is also common.

For some psoriasis patients, nail involvement is the sole manifestation of the disease. But more often, observing these nail changes prompts the provider to look elsewhere for corroborative findings, of which periumbilical and upper intergluteal involvement are typical.

Seen in a diagnostic vacuum, such nail changes are often diagnosed as “fungal infection.” This overlooks the fact that fungal infection is far less common in the fingernails than in toenails. In fact, there are several other items in the differential for nail changes, including lichen planus, eczema, and chronic candidal paronychia.

Had fungal infection (onychomycosis) been a serious possibility, culture or histologic examination of a sample of nail plate could have been confirmatory. First, though, the other items in the differential should have been considered. (I’ve said it before, in a variety of contexts: If your only explanation for discolored and misshapen nails is fungal infection, that’s a problem.)

This patient’s skin disease was initially treated with topical steroids. However, due to his joint symptoms and the possibility of psoriatic arthropathy, he was also referred to rheumatology. It’s entirely possible that he’ll be prescribed a biologic, which will eliminate his otherwise-problematic-to-treat nail psoriasis.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Since fungal infection of the fingernails is distinctly uncommon, other items in the differential should be considered in such cases.

• Other potential diagnostic explanations for nail changes include lichen planus, eczema, and chronic candidal paronychia.

• Nail changes can be the sole manifestation of psoriasis in a given patient.

• Evaluation should include other areas of involvement that exhibit “classic” signs of psoriasis, including extensor surfaces and periumbilical and upper intergluteal skin.

Bluish Pink, Nontender Lesion Worries Patient’s Mother

A 12-year-old girl is brought to dermatology by her mother for evaluation of a lesion on her arm. It’s been there for two years without causing symptoms—but lately it has grown, as has the mother’s concern.

The child is otherwise healthy. The mother reports that the child has neither a personal nor a family history of seizures.

EXAMINATION

A solitary, firm, subcutaneous nodule measuring 2 cm is located on the lateral aspect of the child’s left triceps. It is bluish pink, nontender, and firm on palpation. No other overlying skin changes are seen.

Lateral digital traction toward the center of the lesion produces no dimpling, while lateral traction toward its periphery accentuates the lesion’s central raised portion. The lesion is moderately mobile. No lymph nodes are felt on palpation of nodal sites in the area, and no other such lesions are found elsewhere on the child’s skin.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

At this point, the differential included items such as pilomatricoma, dermatofibroma, calcinosis cutis, or epidermal cyst. The firm feel, bluish color, and shallow subcutaneous location of the lesion lent themselves to a provisional diagnosis of pilomatricoma, as did the patient’s age. But the fact that the lesion was changing was of sufficient concern to prompt removal.

Excision revealed a cystic lesion with cottage-cheese–like contents and a poorly defined wall, extending more than a centimeter into the subcutaneous tissue. It was removed in one piece and submitted to pathology. Primary closure completed the procedure.

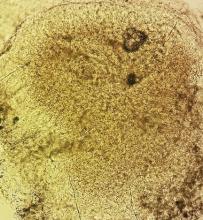

The pathology report showed sheets of anucleate squamous cells (called ghost cells), benign viable nucleated squamous cells, and a center filled with multiple soft calcified granules. A positive von Kossa stain confirmed the expected diagnosis of pilomatricoma (PMC; also spelled pilomatrixoma).

PMCs, also known by their eponymous designation of calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe, are common, benign appendageal tumors derived from hair matrix. They usually manifest (as in this case) as a solitary subcutaneous firm mass, often with bluish discoloration, on the face, neck, or upper extremities. While they average around 2 cm, they can be as large as 15 cm in diameter. They are more common in children and occur slightly more often in girls.

There is some evidence that the tendency to develop PMCs is associated with increased levels of beta-catenin, which encourages cell growth by diminishing apoptosis. This mechanism is thought to promote malignant transformation of PMCs—a rare event.

As is often the case, the main concern about this patient’s lesion related to its unknown source and recent alteration. Aside from scarring, the patient was no worse off for its removal—and her mother was much relieved.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• PMCs are benign cystic lesions of appendageal origin, commonly found on the necks, faces, and upper extremities of children.

• Diagnostic clues for PMC include firm feel, subcutaneous location, bluish discoloration, and patient age.

• PMCs have poorly defined cyst walls and granular calcified contents.

• Except when occurring in multiples, PMCs have no pathologic implications.

• The term calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe is still in use, as is the alternate spelling of pilomatrixoma.

A 12-year-old girl is brought to dermatology by her mother for evaluation of a lesion on her arm. It’s been there for two years without causing symptoms—but lately it has grown, as has the mother’s concern.

The child is otherwise healthy. The mother reports that the child has neither a personal nor a family history of seizures.

EXAMINATION

A solitary, firm, subcutaneous nodule measuring 2 cm is located on the lateral aspect of the child’s left triceps. It is bluish pink, nontender, and firm on palpation. No other overlying skin changes are seen.

Lateral digital traction toward the center of the lesion produces no dimpling, while lateral traction toward its periphery accentuates the lesion’s central raised portion. The lesion is moderately mobile. No lymph nodes are felt on palpation of nodal sites in the area, and no other such lesions are found elsewhere on the child’s skin.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

At this point, the differential included items such as pilomatricoma, dermatofibroma, calcinosis cutis, or epidermal cyst. The firm feel, bluish color, and shallow subcutaneous location of the lesion lent themselves to a provisional diagnosis of pilomatricoma, as did the patient’s age. But the fact that the lesion was changing was of sufficient concern to prompt removal.

Excision revealed a cystic lesion with cottage-cheese–like contents and a poorly defined wall, extending more than a centimeter into the subcutaneous tissue. It was removed in one piece and submitted to pathology. Primary closure completed the procedure.

The pathology report showed sheets of anucleate squamous cells (called ghost cells), benign viable nucleated squamous cells, and a center filled with multiple soft calcified granules. A positive von Kossa stain confirmed the expected diagnosis of pilomatricoma (PMC; also spelled pilomatrixoma).

PMCs, also known by their eponymous designation of calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe, are common, benign appendageal tumors derived from hair matrix. They usually manifest (as in this case) as a solitary subcutaneous firm mass, often with bluish discoloration, on the face, neck, or upper extremities. While they average around 2 cm, they can be as large as 15 cm in diameter. They are more common in children and occur slightly more often in girls.

There is some evidence that the tendency to develop PMCs is associated with increased levels of beta-catenin, which encourages cell growth by diminishing apoptosis. This mechanism is thought to promote malignant transformation of PMCs—a rare event.

As is often the case, the main concern about this patient’s lesion related to its unknown source and recent alteration. Aside from scarring, the patient was no worse off for its removal—and her mother was much relieved.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• PMCs are benign cystic lesions of appendageal origin, commonly found on the necks, faces, and upper extremities of children.

• Diagnostic clues for PMC include firm feel, subcutaneous location, bluish discoloration, and patient age.

• PMCs have poorly defined cyst walls and granular calcified contents.

• Except when occurring in multiples, PMCs have no pathologic implications.

• The term calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe is still in use, as is the alternate spelling of pilomatrixoma.

A 12-year-old girl is brought to dermatology by her mother for evaluation of a lesion on her arm. It’s been there for two years without causing symptoms—but lately it has grown, as has the mother’s concern.

The child is otherwise healthy. The mother reports that the child has neither a personal nor a family history of seizures.

EXAMINATION

A solitary, firm, subcutaneous nodule measuring 2 cm is located on the lateral aspect of the child’s left triceps. It is bluish pink, nontender, and firm on palpation. No other overlying skin changes are seen.

Lateral digital traction toward the center of the lesion produces no dimpling, while lateral traction toward its periphery accentuates the lesion’s central raised portion. The lesion is moderately mobile. No lymph nodes are felt on palpation of nodal sites in the area, and no other such lesions are found elsewhere on the child’s skin.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

At this point, the differential included items such as pilomatricoma, dermatofibroma, calcinosis cutis, or epidermal cyst. The firm feel, bluish color, and shallow subcutaneous location of the lesion lent themselves to a provisional diagnosis of pilomatricoma, as did the patient’s age. But the fact that the lesion was changing was of sufficient concern to prompt removal.

Excision revealed a cystic lesion with cottage-cheese–like contents and a poorly defined wall, extending more than a centimeter into the subcutaneous tissue. It was removed in one piece and submitted to pathology. Primary closure completed the procedure.

The pathology report showed sheets of anucleate squamous cells (called ghost cells), benign viable nucleated squamous cells, and a center filled with multiple soft calcified granules. A positive von Kossa stain confirmed the expected diagnosis of pilomatricoma (PMC; also spelled pilomatrixoma).

PMCs, also known by their eponymous designation of calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe, are common, benign appendageal tumors derived from hair matrix. They usually manifest (as in this case) as a solitary subcutaneous firm mass, often with bluish discoloration, on the face, neck, or upper extremities. While they average around 2 cm, they can be as large as 15 cm in diameter. They are more common in children and occur slightly more often in girls.

There is some evidence that the tendency to develop PMCs is associated with increased levels of beta-catenin, which encourages cell growth by diminishing apoptosis. This mechanism is thought to promote malignant transformation of PMCs—a rare event.

As is often the case, the main concern about this patient’s lesion related to its unknown source and recent alteration. Aside from scarring, the patient was no worse off for its removal—and her mother was much relieved.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• PMCs are benign cystic lesions of appendageal origin, commonly found on the necks, faces, and upper extremities of children.

• Diagnostic clues for PMC include firm feel, subcutaneous location, bluish discoloration, and patient age.

• PMCs have poorly defined cyst walls and granular calcified contents.

• Except when occurring in multiples, PMCs have no pathologic implications.

• The term calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe is still in use, as is the alternate spelling of pilomatrixoma.

Girl, 10, Asks Tough Questions About Skin Problem

A 10-year-old girl is seen in dermatology for evaluation of dry skin. She reports few if any symptoms but expresses frustration at her inability to curb the problem; she’s tried several different moisturizers to no avail.

Additional history-taking reveals that she’s had patches of dry skin since age 4; these have appeared and disappeared on her arms, legs, and neck. None has ever been problematic enough to require medical attention.

But recently, a dry patch manifested on the patient’s forearm that her primary care provider diagnosed as fungal infection. Unfortunately, the prescribed antifungal creams (terbinafine and clotrimazole) had no positive impact on the situation.

The patient and her mother deny any family history of skin disease.

EXAMINATION

The scaly, annular plaque on the patient’s extensor left forearm is distinctly salmon-pink, with a tenacious white scale. Elsewhere, there are scaly areas in both post-auricular sulci. There are no significant changes to the skin on the patient’s knees, elbows, or scalp. Several tiny pits are observed on her fingernails.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

It would be difficult to imagine a more clear-cut case of psoriasis: not only manifesting with a classic plaque on the left extensor forearm but also with corroboratory stigmata behind the ears and classic fingernail pits. Then why, you might ask, was the diagnosis missed?

Psoriasis has a classic look: annular borders, salmon-pink color, and thick, tenacious scale. Distribution matters, since the condition tends to manifest in specific areas, particularly the extensor portions of extremities. It’s helpful to know that psoriasis affects almost 3% of the white population in the United States, meaning that you will see it with considerable frequency. It would also help if you knew the diagnosis can be corroborated by identification of other, lesser known features.

But if you’re unaware of these facts, you won’t look for these things—and if you don’t look specifically for them, you won’t see them. Then, to add insult to injury, when you consult your bag of “diseases that present with annular borders and scaly surfaces,” you’ll find one item in your differential: fungal infection. When antifungal medications don’t work, you’ll find yourself stuck, because you simply don’t have any other diagnoses to consider.

I’ve known internists who have practiced for more than 25 years and still make this diagnostic mistake. So it’s not a matter of lack of intelligence. They simply do not invest the time to expand their knowledge of dermatologic conditions.

My job was to break the news to the patient and her mother about the diagnosis and, perhaps more importantly, her prognosis. The only good news is that the patient is living in the golden age of psoriasis treatment; if her condition flares, and even if she eventually develops psoriatic arthritis (as do almost 25% of psoriasis patients), we have terrific treatment for it.

I prescribed topical fluocinonide 0.05% ointment (for bid application) to address her plaque and scheduled a follow-up visit for one month later. Before she left, though, I had to address her most pressing question: “Why did my doctor say this was a fungal infection?” Good question indeed.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Psoriasis is quite commonly seen in primary care, since it affects almost 3% of the white population.

• Psoriasis is the quintessential papulosquamous disorder, manifesting with salmon-pink scaly patches on extensor extremities, behind ears, and/or in scalp.

• The diagnosis may be corroborated by identification of pits in the fingernails (25% of cases).

• Confirmation of the diagnosis can be made by punch biopsy, which usually shows characteristic changes.

• The overarching learning point: Your differential for “round and scaly” needs more than one item in it.

A 10-year-old girl is seen in dermatology for evaluation of dry skin. She reports few if any symptoms but expresses frustration at her inability to curb the problem; she’s tried several different moisturizers to no avail.

Additional history-taking reveals that she’s had patches of dry skin since age 4; these have appeared and disappeared on her arms, legs, and neck. None has ever been problematic enough to require medical attention.

But recently, a dry patch manifested on the patient’s forearm that her primary care provider diagnosed as fungal infection. Unfortunately, the prescribed antifungal creams (terbinafine and clotrimazole) had no positive impact on the situation.

The patient and her mother deny any family history of skin disease.

EXAMINATION

The scaly, annular plaque on the patient’s extensor left forearm is distinctly salmon-pink, with a tenacious white scale. Elsewhere, there are scaly areas in both post-auricular sulci. There are no significant changes to the skin on the patient’s knees, elbows, or scalp. Several tiny pits are observed on her fingernails.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

It would be difficult to imagine a more clear-cut case of psoriasis: not only manifesting with a classic plaque on the left extensor forearm but also with corroboratory stigmata behind the ears and classic fingernail pits. Then why, you might ask, was the diagnosis missed?

Psoriasis has a classic look: annular borders, salmon-pink color, and thick, tenacious scale. Distribution matters, since the condition tends to manifest in specific areas, particularly the extensor portions of extremities. It’s helpful to know that psoriasis affects almost 3% of the white population in the United States, meaning that you will see it with considerable frequency. It would also help if you knew the diagnosis can be corroborated by identification of other, lesser known features.

But if you’re unaware of these facts, you won’t look for these things—and if you don’t look specifically for them, you won’t see them. Then, to add insult to injury, when you consult your bag of “diseases that present with annular borders and scaly surfaces,” you’ll find one item in your differential: fungal infection. When antifungal medications don’t work, you’ll find yourself stuck, because you simply don’t have any other diagnoses to consider.

I’ve known internists who have practiced for more than 25 years and still make this diagnostic mistake. So it’s not a matter of lack of intelligence. They simply do not invest the time to expand their knowledge of dermatologic conditions.

My job was to break the news to the patient and her mother about the diagnosis and, perhaps more importantly, her prognosis. The only good news is that the patient is living in the golden age of psoriasis treatment; if her condition flares, and even if she eventually develops psoriatic arthritis (as do almost 25% of psoriasis patients), we have terrific treatment for it.

I prescribed topical fluocinonide 0.05% ointment (for bid application) to address her plaque and scheduled a follow-up visit for one month later. Before she left, though, I had to address her most pressing question: “Why did my doctor say this was a fungal infection?” Good question indeed.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Psoriasis is quite commonly seen in primary care, since it affects almost 3% of the white population.

• Psoriasis is the quintessential papulosquamous disorder, manifesting with salmon-pink scaly patches on extensor extremities, behind ears, and/or in scalp.

• The diagnosis may be corroborated by identification of pits in the fingernails (25% of cases).

• Confirmation of the diagnosis can be made by punch biopsy, which usually shows characteristic changes.

• The overarching learning point: Your differential for “round and scaly” needs more than one item in it.

A 10-year-old girl is seen in dermatology for evaluation of dry skin. She reports few if any symptoms but expresses frustration at her inability to curb the problem; she’s tried several different moisturizers to no avail.

Additional history-taking reveals that she’s had patches of dry skin since age 4; these have appeared and disappeared on her arms, legs, and neck. None has ever been problematic enough to require medical attention.

But recently, a dry patch manifested on the patient’s forearm that her primary care provider diagnosed as fungal infection. Unfortunately, the prescribed antifungal creams (terbinafine and clotrimazole) had no positive impact on the situation.

The patient and her mother deny any family history of skin disease.

EXAMINATION

The scaly, annular plaque on the patient’s extensor left forearm is distinctly salmon-pink, with a tenacious white scale. Elsewhere, there are scaly areas in both post-auricular sulci. There are no significant changes to the skin on the patient’s knees, elbows, or scalp. Several tiny pits are observed on her fingernails.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

It would be difficult to imagine a more clear-cut case of psoriasis: not only manifesting with a classic plaque on the left extensor forearm but also with corroboratory stigmata behind the ears and classic fingernail pits. Then why, you might ask, was the diagnosis missed?

Psoriasis has a classic look: annular borders, salmon-pink color, and thick, tenacious scale. Distribution matters, since the condition tends to manifest in specific areas, particularly the extensor portions of extremities. It’s helpful to know that psoriasis affects almost 3% of the white population in the United States, meaning that you will see it with considerable frequency. It would also help if you knew the diagnosis can be corroborated by identification of other, lesser known features.

But if you’re unaware of these facts, you won’t look for these things—and if you don’t look specifically for them, you won’t see them. Then, to add insult to injury, when you consult your bag of “diseases that present with annular borders and scaly surfaces,” you’ll find one item in your differential: fungal infection. When antifungal medications don’t work, you’ll find yourself stuck, because you simply don’t have any other diagnoses to consider.

I’ve known internists who have practiced for more than 25 years and still make this diagnostic mistake. So it’s not a matter of lack of intelligence. They simply do not invest the time to expand their knowledge of dermatologic conditions.

My job was to break the news to the patient and her mother about the diagnosis and, perhaps more importantly, her prognosis. The only good news is that the patient is living in the golden age of psoriasis treatment; if her condition flares, and even if she eventually develops psoriatic arthritis (as do almost 25% of psoriasis patients), we have terrific treatment for it.

I prescribed topical fluocinonide 0.05% ointment (for bid application) to address her plaque and scheduled a follow-up visit for one month later. Before she left, though, I had to address her most pressing question: “Why did my doctor say this was a fungal infection?” Good question indeed.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Psoriasis is quite commonly seen in primary care, since it affects almost 3% of the white population.

• Psoriasis is the quintessential papulosquamous disorder, manifesting with salmon-pink scaly patches on extensor extremities, behind ears, and/or in scalp.

• The diagnosis may be corroborated by identification of pits in the fingernails (25% of cases).

• Confirmation of the diagnosis can be made by punch biopsy, which usually shows characteristic changes.

• The overarching learning point: Your differential for “round and scaly” needs more than one item in it.

Could Lesion Become a Pain in the Neck?

At the insistence of his wife, a 39-year-old man presents to dermatology for evaluation of a lesion on his neck that manifested three years ago. As the lesion has grown, darkened, and become more irregular in outline, she has urged him to have it checked. Her efforts finally succeeded when several of his coworkers also commented on it.

The patient has a history of sun exposure but says he tolerates it well and tans easily. He is otherwise healthy.

EXAMINATION

The irregularly pigmented and bordered dark brown macule, located on the lateral aspect of the left side of his neck, measures about 2 cm in its greatest dimension. The rest of his neck shows definite signs of chronic UV overexposure, in the form of poikilodermatous changes.

Dermatoscopic examination of the lesion shows focal areas of pigment streaming and blue veiling—both indicative of melanoma. In light of these findings and in the context of his heavily sun-damaged skin, the patient is scheduled for excision. This is performed one week later; the lesion is removed with 5-mm margins, producing a curved, elliptiform defect to match local skin lines, with a two-layer closure.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The pathology report showed the lesion to be an early lentigo maligna (LM). Most authorities in the field do not consider this a true melanoma, although it is probably best considered a type of melanoma in situ. LM definitely involves cellular atypia, but at a very superficial level. Only a tiny fraction of LMs ever become invasive—and only after several years of being left in place.

LM isn’t always as obvious as this patient’s lesion is. It can be brown, red, or even bluish and can blend into surrounding mottled skin lesions (eg, solar lentigines, seborrheic keratoses or actinic keratosis). The key to diagnosis is to observe for change in size and/or color, especially on sun-exposed areas of skin in older, sun-damaged patients.

In this case, the decision to excise the lesion was made easier by its size and location. Larger lesions of uncertain dimensions may be assessed with multiple punch biopsies.

Once LM is diagnosed, the problem becomes obtaining adequate margins surgically, given the often ill-defined dimensions of the lesion. Failure rates, even when Mohs surgery is performed, are all too high. Surgery has therefore been combined with the application of immune-enhancing creams (eg, imiquimod), a method that shows promise but yields conflicting results in studies.

Since many LMs appear on truly elderly patients, and since their evolution to invasive status is so slow, they don’t command the same urgency as a truly invasive melanoma. Clinically, however, this patient’s lesion met the criteria by which we judge potentially malignant lesions: asymmetry, irregular borders, odd color, and large size. It could easily have been an invasive melanoma, either at the time or in future. Finding and identifying it not only delivered peace of mind but also provided a warning that the patient had some serious sun damage—and therefore the potential to develop other cutaneous malignancies.

Fortunately, a whole-body check revealed no other worrisome lesions. The patient has, however, been scheduled for twice-yearly skin checks. He also received education on the recognition of melanoma.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• The prognosis for a melanoma is determined by numerous factors, most notably the vertical thickness of the lesion, as measured under the microscope by the examining pathologist.

• The lentigo maligna lesion, as seen in this case, can be so thin and superficial that some experts don’t consider it a true melanoma.

• Nonetheless, the gross appearance of such lesions typifies the main diagnostic features (ABCDs) of melanoma: Asymmetry, odd Borders, odd Colors, and Diameter (large size).

• The finding of an LM means the patient has increased risk for invasive melanoma in the future.

At the insistence of his wife, a 39-year-old man presents to dermatology for evaluation of a lesion on his neck that manifested three years ago. As the lesion has grown, darkened, and become more irregular in outline, she has urged him to have it checked. Her efforts finally succeeded when several of his coworkers also commented on it.

The patient has a history of sun exposure but says he tolerates it well and tans easily. He is otherwise healthy.

EXAMINATION

The irregularly pigmented and bordered dark brown macule, located on the lateral aspect of the left side of his neck, measures about 2 cm in its greatest dimension. The rest of his neck shows definite signs of chronic UV overexposure, in the form of poikilodermatous changes.

Dermatoscopic examination of the lesion shows focal areas of pigment streaming and blue veiling—both indicative of melanoma. In light of these findings and in the context of his heavily sun-damaged skin, the patient is scheduled for excision. This is performed one week later; the lesion is removed with 5-mm margins, producing a curved, elliptiform defect to match local skin lines, with a two-layer closure.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The pathology report showed the lesion to be an early lentigo maligna (LM). Most authorities in the field do not consider this a true melanoma, although it is probably best considered a type of melanoma in situ. LM definitely involves cellular atypia, but at a very superficial level. Only a tiny fraction of LMs ever become invasive—and only after several years of being left in place.

LM isn’t always as obvious as this patient’s lesion is. It can be brown, red, or even bluish and can blend into surrounding mottled skin lesions (eg, solar lentigines, seborrheic keratoses or actinic keratosis). The key to diagnosis is to observe for change in size and/or color, especially on sun-exposed areas of skin in older, sun-damaged patients.

In this case, the decision to excise the lesion was made easier by its size and location. Larger lesions of uncertain dimensions may be assessed with multiple punch biopsies.

Once LM is diagnosed, the problem becomes obtaining adequate margins surgically, given the often ill-defined dimensions of the lesion. Failure rates, even when Mohs surgery is performed, are all too high. Surgery has therefore been combined with the application of immune-enhancing creams (eg, imiquimod), a method that shows promise but yields conflicting results in studies.

Since many LMs appear on truly elderly patients, and since their evolution to invasive status is so slow, they don’t command the same urgency as a truly invasive melanoma. Clinically, however, this patient’s lesion met the criteria by which we judge potentially malignant lesions: asymmetry, irregular borders, odd color, and large size. It could easily have been an invasive melanoma, either at the time or in future. Finding and identifying it not only delivered peace of mind but also provided a warning that the patient had some serious sun damage—and therefore the potential to develop other cutaneous malignancies.

Fortunately, a whole-body check revealed no other worrisome lesions. The patient has, however, been scheduled for twice-yearly skin checks. He also received education on the recognition of melanoma.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• The prognosis for a melanoma is determined by numerous factors, most notably the vertical thickness of the lesion, as measured under the microscope by the examining pathologist.

• The lentigo maligna lesion, as seen in this case, can be so thin and superficial that some experts don’t consider it a true melanoma.

• Nonetheless, the gross appearance of such lesions typifies the main diagnostic features (ABCDs) of melanoma: Asymmetry, odd Borders, odd Colors, and Diameter (large size).

• The finding of an LM means the patient has increased risk for invasive melanoma in the future.

At the insistence of his wife, a 39-year-old man presents to dermatology for evaluation of a lesion on his neck that manifested three years ago. As the lesion has grown, darkened, and become more irregular in outline, she has urged him to have it checked. Her efforts finally succeeded when several of his coworkers also commented on it.

The patient has a history of sun exposure but says he tolerates it well and tans easily. He is otherwise healthy.

EXAMINATION

The irregularly pigmented and bordered dark brown macule, located on the lateral aspect of the left side of his neck, measures about 2 cm in its greatest dimension. The rest of his neck shows definite signs of chronic UV overexposure, in the form of poikilodermatous changes.

Dermatoscopic examination of the lesion shows focal areas of pigment streaming and blue veiling—both indicative of melanoma. In light of these findings and in the context of his heavily sun-damaged skin, the patient is scheduled for excision. This is performed one week later; the lesion is removed with 5-mm margins, producing a curved, elliptiform defect to match local skin lines, with a two-layer closure.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The pathology report showed the lesion to be an early lentigo maligna (LM). Most authorities in the field do not consider this a true melanoma, although it is probably best considered a type of melanoma in situ. LM definitely involves cellular atypia, but at a very superficial level. Only a tiny fraction of LMs ever become invasive—and only after several years of being left in place.

LM isn’t always as obvious as this patient’s lesion is. It can be brown, red, or even bluish and can blend into surrounding mottled skin lesions (eg, solar lentigines, seborrheic keratoses or actinic keratosis). The key to diagnosis is to observe for change in size and/or color, especially on sun-exposed areas of skin in older, sun-damaged patients.

In this case, the decision to excise the lesion was made easier by its size and location. Larger lesions of uncertain dimensions may be assessed with multiple punch biopsies.

Once LM is diagnosed, the problem becomes obtaining adequate margins surgically, given the often ill-defined dimensions of the lesion. Failure rates, even when Mohs surgery is performed, are all too high. Surgery has therefore been combined with the application of immune-enhancing creams (eg, imiquimod), a method that shows promise but yields conflicting results in studies.

Since many LMs appear on truly elderly patients, and since their evolution to invasive status is so slow, they don’t command the same urgency as a truly invasive melanoma. Clinically, however, this patient’s lesion met the criteria by which we judge potentially malignant lesions: asymmetry, irregular borders, odd color, and large size. It could easily have been an invasive melanoma, either at the time or in future. Finding and identifying it not only delivered peace of mind but also provided a warning that the patient had some serious sun damage—and therefore the potential to develop other cutaneous malignancies.

Fortunately, a whole-body check revealed no other worrisome lesions. The patient has, however, been scheduled for twice-yearly skin checks. He also received education on the recognition of melanoma.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• The prognosis for a melanoma is determined by numerous factors, most notably the vertical thickness of the lesion, as measured under the microscope by the examining pathologist.

• The lentigo maligna lesion, as seen in this case, can be so thin and superficial that some experts don’t consider it a true melanoma.

• Nonetheless, the gross appearance of such lesions typifies the main diagnostic features (ABCDs) of melanoma: Asymmetry, odd Borders, odd Colors, and Diameter (large size).

• The finding of an LM means the patient has increased risk for invasive melanoma in the future.

He Tried So Hard to Avoid It …

A 38-year-old man presents to dermatology with what he assumes is poison ivy: an itchy, blistery rash that usually appears in the summer, more years than not. Each year, it’s a bit worse in terms of extent and symptomatology, despite his efforts to avoid the problem altogether.

The rash pretty consistently manifests on his leg, although there are other areas of involvement. Equally predictable, at this point, is his wife’s reaction: She banishes him to the couch for fear of “catching” whatever he has.

After so many years’ experience with the condition, the patient is understandably alert to coming in contact with the offending plant. He has even taken photos of it, to demonstrate how abundantly it grows in his yard.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s lesions are classic collections of vesicles crisscrossing his legs in linear configurations. There is faint underlying erythema. Smaller but similar lesions are scattered over his arms and trunk; the patient is sure he spread the rash with his scratching.

The plant in the patient’s photos has five dart-shaped leaves with uniformly serrated margins extending from a single stem. It grows as a vine on fences and masonry. He has scrupulously avoided contact with it and therefore cannot understand how he keeps developing the rash.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

It has been said that humor is tragedy plus time; certain skin diseases, such as shingles or poison ivy, certainly provide fodder. In the midst of an attack, however, these conditions can produce not only miserable symptoms of itching, pain, and sleeplessness, but also considerable mental anguish regarding contagion.

Repeated polls of the general public reveal an almost universal belief that poison ivy is contagious and that scratching spreads it around the body. Research, and a thorough knowledge of the pathophysiology involved, have long since disproven both concepts. So while the inclination to distance oneself from an affected person is understandable, there is actually no need to do so. For the patient, facing six weeks or more of isolation is no laughing matter (at least, until long after the fact).

This particular case highlights one other pertinent issue with poison ivy: As the photos established, the patient had carefully avoided the wrong plant. The five dart-shaped serrated leaves suggest Virginia creeper—certainly not poison ivy. This may sound like a minor issue, but it is quite possible that while the patient was steering clear of a harmless plant, he was in fact coming in contact with the one he should have been concerned about.

True poison ivy, Toxicodendron radicans, can develop as a bush, a vine that stays low to the ground, a small tree, or even a climbing vine that can reach 30 feet or higher into mature trees, especially along waterways or in low, boggy land. The vines can attain a thickness of more than 3 in and have a surface covered by tiny “rootlets,” giving them a shaggy look.

Regardless of the plant’s form, its leaves are always found in threes, protruding from the same stem. The leaves are diamond shaped, can reach a length of 10 in, and often have a single notch on the margin that is said to resemble the outline of a thumb. The plant produces white berries in late summer or early fall.

It has been estimated that the number of poison ivy plants has doubled since 1960, for at least two reasons. First, an increase in population has led to more land being cleared for housing; many properties now border woodlands, which are an ideal environment for this plant.

Second, and more surprising, poison ivy thrives in a CO2-rich environment. Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has increased significantly in the past 50 years and will continue to do so. Experts predict that the density of poison ivy will double again in the next 20 years as a result. The potency of the urushiol, the offending substance in the stems and leaves, is expected to increase as well.

The patient (height, 6’3” and weight, > 300 lb) was treated with a 60-mg IM injection of triamcinolone, a two-week, 40-mg taper of prednisone, and twice-daily application of betamethasone cream. This, of course, followed a discussion of the risks versus benefits of such a course of action.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Climbing vines with five serrated leaves coming off the same stem are probably Virginia creeper and not poison ivy.

• Poison ivy is not contagious, cannot be spread by scratching, and is not poisonous in any way.

• The rash produced by poison ivy exposure can be severe and can last six weeks or more without treatment.

• The number of poison ivy plants has doubled in the past 50 years and is expected to double again within 20 years. The potency of the plant’s allergen is also expected to increase.

A 38-year-old man presents to dermatology with what he assumes is poison ivy: an itchy, blistery rash that usually appears in the summer, more years than not. Each year, it’s a bit worse in terms of extent and symptomatology, despite his efforts to avoid the problem altogether.

The rash pretty consistently manifests on his leg, although there are other areas of involvement. Equally predictable, at this point, is his wife’s reaction: She banishes him to the couch for fear of “catching” whatever he has.

After so many years’ experience with the condition, the patient is understandably alert to coming in contact with the offending plant. He has even taken photos of it, to demonstrate how abundantly it grows in his yard.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s lesions are classic collections of vesicles crisscrossing his legs in linear configurations. There is faint underlying erythema. Smaller but similar lesions are scattered over his arms and trunk; the patient is sure he spread the rash with his scratching.

The plant in the patient’s photos has five dart-shaped leaves with uniformly serrated margins extending from a single stem. It grows as a vine on fences and masonry. He has scrupulously avoided contact with it and therefore cannot understand how he keeps developing the rash.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

It has been said that humor is tragedy plus time; certain skin diseases, such as shingles or poison ivy, certainly provide fodder. In the midst of an attack, however, these conditions can produce not only miserable symptoms of itching, pain, and sleeplessness, but also considerable mental anguish regarding contagion.

Repeated polls of the general public reveal an almost universal belief that poison ivy is contagious and that scratching spreads it around the body. Research, and a thorough knowledge of the pathophysiology involved, have long since disproven both concepts. So while the inclination to distance oneself from an affected person is understandable, there is actually no need to do so. For the patient, facing six weeks or more of isolation is no laughing matter (at least, until long after the fact).

This particular case highlights one other pertinent issue with poison ivy: As the photos established, the patient had carefully avoided the wrong plant. The five dart-shaped serrated leaves suggest Virginia creeper—certainly not poison ivy. This may sound like a minor issue, but it is quite possible that while the patient was steering clear of a harmless plant, he was in fact coming in contact with the one he should have been concerned about.

True poison ivy, Toxicodendron radicans, can develop as a bush, a vine that stays low to the ground, a small tree, or even a climbing vine that can reach 30 feet or higher into mature trees, especially along waterways or in low, boggy land. The vines can attain a thickness of more than 3 in and have a surface covered by tiny “rootlets,” giving them a shaggy look.

Regardless of the plant’s form, its leaves are always found in threes, protruding from the same stem. The leaves are diamond shaped, can reach a length of 10 in, and often have a single notch on the margin that is said to resemble the outline of a thumb. The plant produces white berries in late summer or early fall.

It has been estimated that the number of poison ivy plants has doubled since 1960, for at least two reasons. First, an increase in population has led to more land being cleared for housing; many properties now border woodlands, which are an ideal environment for this plant.

Second, and more surprising, poison ivy thrives in a CO2-rich environment. Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has increased significantly in the past 50 years and will continue to do so. Experts predict that the density of poison ivy will double again in the next 20 years as a result. The potency of the urushiol, the offending substance in the stems and leaves, is expected to increase as well.

The patient (height, 6’3” and weight, > 300 lb) was treated with a 60-mg IM injection of triamcinolone, a two-week, 40-mg taper of prednisone, and twice-daily application of betamethasone cream. This, of course, followed a discussion of the risks versus benefits of such a course of action.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Climbing vines with five serrated leaves coming off the same stem are probably Virginia creeper and not poison ivy.

• Poison ivy is not contagious, cannot be spread by scratching, and is not poisonous in any way.

• The rash produced by poison ivy exposure can be severe and can last six weeks or more without treatment.

• The number of poison ivy plants has doubled in the past 50 years and is expected to double again within 20 years. The potency of the plant’s allergen is also expected to increase.

A 38-year-old man presents to dermatology with what he assumes is poison ivy: an itchy, blistery rash that usually appears in the summer, more years than not. Each year, it’s a bit worse in terms of extent and symptomatology, despite his efforts to avoid the problem altogether.

The rash pretty consistently manifests on his leg, although there are other areas of involvement. Equally predictable, at this point, is his wife’s reaction: She banishes him to the couch for fear of “catching” whatever he has.

After so many years’ experience with the condition, the patient is understandably alert to coming in contact with the offending plant. He has even taken photos of it, to demonstrate how abundantly it grows in his yard.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s lesions are classic collections of vesicles crisscrossing his legs in linear configurations. There is faint underlying erythema. Smaller but similar lesions are scattered over his arms and trunk; the patient is sure he spread the rash with his scratching.

The plant in the patient’s photos has five dart-shaped leaves with uniformly serrated margins extending from a single stem. It grows as a vine on fences and masonry. He has scrupulously avoided contact with it and therefore cannot understand how he keeps developing the rash.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

It has been said that humor is tragedy plus time; certain skin diseases, such as shingles or poison ivy, certainly provide fodder. In the midst of an attack, however, these conditions can produce not only miserable symptoms of itching, pain, and sleeplessness, but also considerable mental anguish regarding contagion.

Repeated polls of the general public reveal an almost universal belief that poison ivy is contagious and that scratching spreads it around the body. Research, and a thorough knowledge of the pathophysiology involved, have long since disproven both concepts. So while the inclination to distance oneself from an affected person is understandable, there is actually no need to do so. For the patient, facing six weeks or more of isolation is no laughing matter (at least, until long after the fact).

This particular case highlights one other pertinent issue with poison ivy: As the photos established, the patient had carefully avoided the wrong plant. The five dart-shaped serrated leaves suggest Virginia creeper—certainly not poison ivy. This may sound like a minor issue, but it is quite possible that while the patient was steering clear of a harmless plant, he was in fact coming in contact with the one he should have been concerned about.

True poison ivy, Toxicodendron radicans, can develop as a bush, a vine that stays low to the ground, a small tree, or even a climbing vine that can reach 30 feet or higher into mature trees, especially along waterways or in low, boggy land. The vines can attain a thickness of more than 3 in and have a surface covered by tiny “rootlets,” giving them a shaggy look.

Regardless of the plant’s form, its leaves are always found in threes, protruding from the same stem. The leaves are diamond shaped, can reach a length of 10 in, and often have a single notch on the margin that is said to resemble the outline of a thumb. The plant produces white berries in late summer or early fall.

It has been estimated that the number of poison ivy plants has doubled since 1960, for at least two reasons. First, an increase in population has led to more land being cleared for housing; many properties now border woodlands, which are an ideal environment for this plant.

Second, and more surprising, poison ivy thrives in a CO2-rich environment. Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has increased significantly in the past 50 years and will continue to do so. Experts predict that the density of poison ivy will double again in the next 20 years as a result. The potency of the urushiol, the offending substance in the stems and leaves, is expected to increase as well.

The patient (height, 6’3” and weight, > 300 lb) was treated with a 60-mg IM injection of triamcinolone, a two-week, 40-mg taper of prednisone, and twice-daily application of betamethasone cream. This, of course, followed a discussion of the risks versus benefits of such a course of action.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Climbing vines with five serrated leaves coming off the same stem are probably Virginia creeper and not poison ivy.

• Poison ivy is not contagious, cannot be spread by scratching, and is not poisonous in any way.

• The rash produced by poison ivy exposure can be severe and can last six weeks or more without treatment.

• The number of poison ivy plants has doubled in the past 50 years and is expected to double again within 20 years. The potency of the plant’s allergen is also expected to increase.

Wife Says Husband Needs to Use Moisturizer

A 72-year-old man self-refers to dermatology at the insistence of his wife, who wants confirmation of her assertion that he needs to use a moisturizer on his arms. “They’re just so dry!” she says. “They’d look so much better if he’d use moisturizer every day, like I do.”

Her husband says he tried it and it didn’t help, so he stopped. “Besides, I can’t stand the greasy feeling it leaves behind!”

The patient claims to be in decent health aside from mild arthritis. He is retired from his job with the local power company, which kept him outdoors for many years. His employer required workers to wear long-sleeved khaki shirts, but, like all his fellow employees, the patient rolled up the sleeves in hot weather, exposing his forearms.

EXAMINATION

The patient has type II skin, blue eyes, and light brown hair. The skin on the dorsa of both arms is flecked with innumerable tan to orange macules from the mid forearms to (and including) the hands. Many old scars are seen in these same areas.

Closer examination reveals that the skin in these areas is quite thin and dry. Fine telangiectasias and focal scaling are also noted. The effect is much less pronounced from about the elbow up and is totally absent on both volar forearms.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The patient’s admittedly dry skin is not his primary problem, and all the moisturizers in the world will not make much difference. The term we use for his problem is dermatoheliosis , literally “sun condition,” which includes predictable indicators of past overexposure to UV sources. Specific lesions include solar lentigines, the tan to orange freckles that are commonly called “age spots” or “liver spots.” (Given enough sun exposure, a 25-year-old can develop solar lentigines, so age is not the cause. Likewise, the liver is not involved at all.)

Chronic overexposure to the sun thins the skin (solar atrophy), making it more susceptible to minor trauma and resultant scarring and also making the tortuous red blood vessels (telangiectasias) visible. Other indications of sun damage include actinic keratoses (flaky white papules), solar elastosis (creamy yellow to white “chicken skin”), and solar purpura. The combination of these superimposed colors (white, red, tan, orange, pink) in the context of dermatoheliosis is sometimes termed poikilodermatous change.

Although dermatoheliosis is a problem in terms of the potential for skin cancer and for cosmetic reasons, it will not be helped much by moisturizers. Sunscreen, too, will have minimal impact so long after the damage has been done. Laser resurfacing could erase most of these skin changes, but it would also knock out all the normal skin pigment, making the area contrast sharply with the rest of the patient’s skin.

A combination of fade cream (4% hydroquinone, applied bid) and sunscreen could reduce the brown discoloration to a degree. Twice-daily application of 5-fluorouracil cream for two weeks would erase much of the redness, but only for a few months. Various other methods have been tried with modest success.

The main outcome of this patient’s visit was to establish the need for periodic examination. His wife’s opinion notwithstanding, the utility of moisturizers is dubious.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Dermatoheliosis is the collective term for skin changes associated with chronic overexposure to the sun.

• The white, red, pink, and yellow discoloration seen on this kind of sun-damaged skin is known as poikilodermatous change.

• In addition to poikiloderma, patients with advanced dermatoheliosis also have solar atrophy, multiple scars, telangiectasias, actinic keratoses, dry skin, and often solar purpura.

• Moisturizers play a minimal role in treating dermatoheliosis (providing skin-smoothing effects, if anything).

• Such patients need to be examined periodically for skin cancer.

• Younger patients with dermatoheliosis are well advised to use better sun protection.

A 72-year-old man self-refers to dermatology at the insistence of his wife, who wants confirmation of her assertion that he needs to use a moisturizer on his arms. “They’re just so dry!” she says. “They’d look so much better if he’d use moisturizer every day, like I do.”

Her husband says he tried it and it didn’t help, so he stopped. “Besides, I can’t stand the greasy feeling it leaves behind!”

The patient claims to be in decent health aside from mild arthritis. He is retired from his job with the local power company, which kept him outdoors for many years. His employer required workers to wear long-sleeved khaki shirts, but, like all his fellow employees, the patient rolled up the sleeves in hot weather, exposing his forearms.

EXAMINATION

The patient has type II skin, blue eyes, and light brown hair. The skin on the dorsa of both arms is flecked with innumerable tan to orange macules from the mid forearms to (and including) the hands. Many old scars are seen in these same areas.

Closer examination reveals that the skin in these areas is quite thin and dry. Fine telangiectasias and focal scaling are also noted. The effect is much less pronounced from about the elbow up and is totally absent on both volar forearms.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The patient’s admittedly dry skin is not his primary problem, and all the moisturizers in the world will not make much difference. The term we use for his problem is dermatoheliosis , literally “sun condition,” which includes predictable indicators of past overexposure to UV sources. Specific lesions include solar lentigines, the tan to orange freckles that are commonly called “age spots” or “liver spots.” (Given enough sun exposure, a 25-year-old can develop solar lentigines, so age is not the cause. Likewise, the liver is not involved at all.)

Chronic overexposure to the sun thins the skin (solar atrophy), making it more susceptible to minor trauma and resultant scarring and also making the tortuous red blood vessels (telangiectasias) visible. Other indications of sun damage include actinic keratoses (flaky white papules), solar elastosis (creamy yellow to white “chicken skin”), and solar purpura. The combination of these superimposed colors (white, red, tan, orange, pink) in the context of dermatoheliosis is sometimes termed poikilodermatous change.

Although dermatoheliosis is a problem in terms of the potential for skin cancer and for cosmetic reasons, it will not be helped much by moisturizers. Sunscreen, too, will have minimal impact so long after the damage has been done. Laser resurfacing could erase most of these skin changes, but it would also knock out all the normal skin pigment, making the area contrast sharply with the rest of the patient’s skin.

A combination of fade cream (4% hydroquinone, applied bid) and sunscreen could reduce the brown discoloration to a degree. Twice-daily application of 5-fluorouracil cream for two weeks would erase much of the redness, but only for a few months. Various other methods have been tried with modest success.

The main outcome of this patient’s visit was to establish the need for periodic examination. His wife’s opinion notwithstanding, the utility of moisturizers is dubious.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Dermatoheliosis is the collective term for skin changes associated with chronic overexposure to the sun.

• The white, red, pink, and yellow discoloration seen on this kind of sun-damaged skin is known as poikilodermatous change.

• In addition to poikiloderma, patients with advanced dermatoheliosis also have solar atrophy, multiple scars, telangiectasias, actinic keratoses, dry skin, and often solar purpura.

• Moisturizers play a minimal role in treating dermatoheliosis (providing skin-smoothing effects, if anything).

• Such patients need to be examined periodically for skin cancer.

• Younger patients with dermatoheliosis are well advised to use better sun protection.

A 72-year-old man self-refers to dermatology at the insistence of his wife, who wants confirmation of her assertion that he needs to use a moisturizer on his arms. “They’re just so dry!” she says. “They’d look so much better if he’d use moisturizer every day, like I do.”

Her husband says he tried it and it didn’t help, so he stopped. “Besides, I can’t stand the greasy feeling it leaves behind!”

The patient claims to be in decent health aside from mild arthritis. He is retired from his job with the local power company, which kept him outdoors for many years. His employer required workers to wear long-sleeved khaki shirts, but, like all his fellow employees, the patient rolled up the sleeves in hot weather, exposing his forearms.

EXAMINATION

The patient has type II skin, blue eyes, and light brown hair. The skin on the dorsa of both arms is flecked with innumerable tan to orange macules from the mid forearms to (and including) the hands. Many old scars are seen in these same areas.

Closer examination reveals that the skin in these areas is quite thin and dry. Fine telangiectasias and focal scaling are also noted. The effect is much less pronounced from about the elbow up and is totally absent on both volar forearms.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The patient’s admittedly dry skin is not his primary problem, and all the moisturizers in the world will not make much difference. The term we use for his problem is dermatoheliosis , literally “sun condition,” which includes predictable indicators of past overexposure to UV sources. Specific lesions include solar lentigines, the tan to orange freckles that are commonly called “age spots” or “liver spots.” (Given enough sun exposure, a 25-year-old can develop solar lentigines, so age is not the cause. Likewise, the liver is not involved at all.)

Chronic overexposure to the sun thins the skin (solar atrophy), making it more susceptible to minor trauma and resultant scarring and also making the tortuous red blood vessels (telangiectasias) visible. Other indications of sun damage include actinic keratoses (flaky white papules), solar elastosis (creamy yellow to white “chicken skin”), and solar purpura. The combination of these superimposed colors (white, red, tan, orange, pink) in the context of dermatoheliosis is sometimes termed poikilodermatous change.

Although dermatoheliosis is a problem in terms of the potential for skin cancer and for cosmetic reasons, it will not be helped much by moisturizers. Sunscreen, too, will have minimal impact so long after the damage has been done. Laser resurfacing could erase most of these skin changes, but it would also knock out all the normal skin pigment, making the area contrast sharply with the rest of the patient’s skin.

A combination of fade cream (4% hydroquinone, applied bid) and sunscreen could reduce the brown discoloration to a degree. Twice-daily application of 5-fluorouracil cream for two weeks would erase much of the redness, but only for a few months. Various other methods have been tried with modest success.

The main outcome of this patient’s visit was to establish the need for periodic examination. His wife’s opinion notwithstanding, the utility of moisturizers is dubious.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Dermatoheliosis is the collective term for skin changes associated with chronic overexposure to the sun.

• The white, red, pink, and yellow discoloration seen on this kind of sun-damaged skin is known as poikilodermatous change.

• In addition to poikiloderma, patients with advanced dermatoheliosis also have solar atrophy, multiple scars, telangiectasias, actinic keratoses, dry skin, and often solar purpura.

• Moisturizers play a minimal role in treating dermatoheliosis (providing skin-smoothing effects, if anything).

• Such patients need to be examined periodically for skin cancer.

• Younger patients with dermatoheliosis are well advised to use better sun protection.

With Rashes, Consider the Source (Or Lack Thereof)

A 44-year-old man presents with what his primary care provider called “ringworm.” The condition has not responded to topical and oral antifungal medications (clotrimazole and oral terbinafine). Fortunately, the lesions are not particularly symptomatic.

The patient, who works in an oil field, claims to be in otherwise good health. He has no pets at home, and no one else in his household has been similarly affected. He is taking no medications at this time.

EXAMINATION

Multiple arcuate and annular scaly lesions are seen, most densely distributed across the patient’s upper back and posterior shoulders. They thin out inferiorly and are missing entirely below the waist.

Many of the lesions are larger than 10 cm (though on average half that size). They have well-defined, scaly margins and mostly clear centers. There is minimal erythema.

A KOH prep of the lesions does not show fungal elements. A 4-mm punch biopsy is performed, the results of which will be discussed in the next section.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case nicely illustrates a common dilemma in dermatology: “ringworm” that is neither fungal nor any other kind of infection. Presented with this case, the vast majority of primary care providers would do what this man’s clinician did: treat it as fungal. This attempt would fail, for one basic reason: There is an extensive differential for round, scaly lesions, of which dermatophytosis (superficial fungal infection) is but one item.

In this case, there was no source from which our patient could have acquired a fungal infection (animal, child, soil) and no particular susceptibility by virtue of immune suppression. To these facts we add the negative KOH, forcing us to consider other items in the differential, including psoriasis, T-cell lymphoma, erythema annulare centrifugum, chronic cutaneous lupus, and nummular eczema, just to name a few.

One way to settle the issue is to obtain a skin biopsy, which in this case showed results most consistent with eczema and effectively ruled out items such as lupus or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. This provides extremely useful treatment guidance, as well as reassurance to the patient. Stains for fungal organisms were requested and obtained as part of specimen processing—and, of course, results were negative.

In most derm clinics, skin biopsies are routinely done—but what really sets the specialty apart is the fact that a full differential is considered, not just the first (and often only) diagnostic idea that comes to mind. More often than not, a reasonable diagnosis can be found without biopsy, using corroborative history and physical data.

This patient responded nicely to the application of a topical steroid lotion (fluocinonide 0.05%) and the use of emollients. In the process of history-taking, it was discovered that the patient had a habit of taking long, hot showers while standing with his back to the nozzle. Since this certainly can contribute to dry skin, he was advised to reduce the temperature to a more moderate level and limit his time spent in the shower.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Just because a rash presents with round, scaly lesions doesn’t mean it’s fungal.

• The rather extensive differential for such rashes includes lupus, psoriasis, eczema, and a type of skin cancer called cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

• Biopsy, performed under local anesthetic and with a 4-mm punch (closed with two sutures), can be extremely useful in sorting through the differential.

• A KOH prep is a helpful first step (one that would confirm or rule out fungal origin).

• In the absence of a source or indications of susceptibility, fungal infection is an unlikely diagnosis in these cases.

A 44-year-old man presents with what his primary care provider called “ringworm.” The condition has not responded to topical and oral antifungal medications (clotrimazole and oral terbinafine). Fortunately, the lesions are not particularly symptomatic.

The patient, who works in an oil field, claims to be in otherwise good health. He has no pets at home, and no one else in his household has been similarly affected. He is taking no medications at this time.

EXAMINATION

Multiple arcuate and annular scaly lesions are seen, most densely distributed across the patient’s upper back and posterior shoulders. They thin out inferiorly and are missing entirely below the waist.

Many of the lesions are larger than 10 cm (though on average half that size). They have well-defined, scaly margins and mostly clear centers. There is minimal erythema.

A KOH prep of the lesions does not show fungal elements. A 4-mm punch biopsy is performed, the results of which will be discussed in the next section.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case nicely illustrates a common dilemma in dermatology: “ringworm” that is neither fungal nor any other kind of infection. Presented with this case, the vast majority of primary care providers would do what this man’s clinician did: treat it as fungal. This attempt would fail, for one basic reason: There is an extensive differential for round, scaly lesions, of which dermatophytosis (superficial fungal infection) is but one item.

In this case, there was no source from which our patient could have acquired a fungal infection (animal, child, soil) and no particular susceptibility by virtue of immune suppression. To these facts we add the negative KOH, forcing us to consider other items in the differential, including psoriasis, T-cell lymphoma, erythema annulare centrifugum, chronic cutaneous lupus, and nummular eczema, just to name a few.