User login

Development, implementation, and evaluation of a prostate cancer supportive care program

Prostate cancer is the most common malignancy diagnosed in Canadian men. An estimated 21,300 Canadian men were diagnosed with the disease in 2017, representing 21% of all new cancer cases.1 There are about 176,000 men living with prostate cancer in Canada.1 In the United States, there were 2,778,630 survivors of prostate cancer as of 2012 and that population is expected to increase by more than 1 million (40%) to 3,922,600 by 2022.2

Although 96% of men diagnosed with prostate cancer now survive longer than 5 years3, many will suffer from treatment-related sequelae that can have a profound effect on quality of life for themselves and their partners.4,5 Impacts include sexual, urinary, and bowel dysfunctions6 owing to treatment of the primary tumor as well as reduced muscle and bone mass, osteoporosis, fatigue, obesity, and glucose intolerance or diabetes7 owing to androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT). Many men also suffer from psychological issues such as depression, anxiety, anger and irritability, sense of isolation, grief, and loss of masculinity.8,9 The psychological impacts also continue well beyond the completion of treatment and can be significant for both patients and their partners.5,8

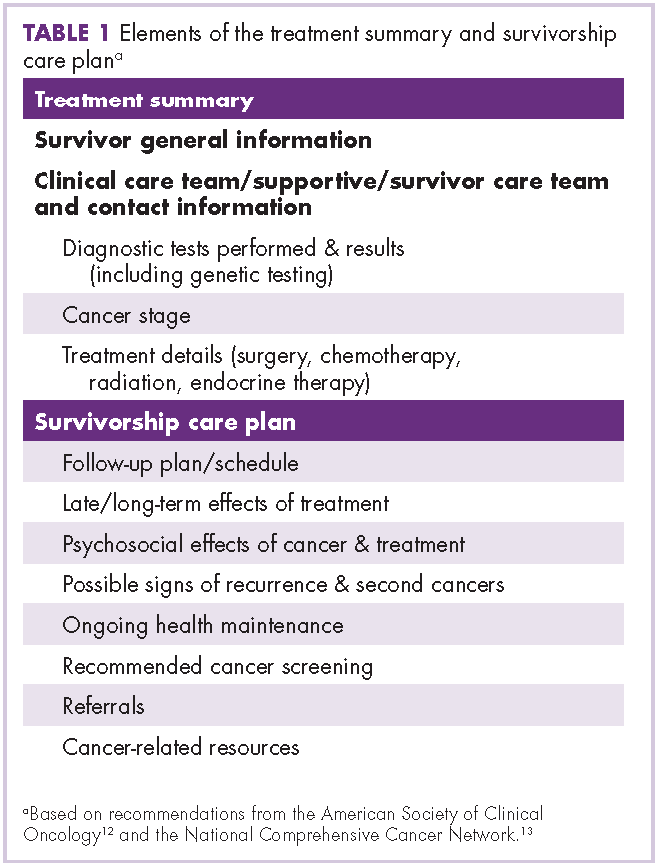

With posttreatment longevity and the associated complex sequelae, prostate cancer is being viewed increasingly as a chronic disease whose effects must be managed for many years after the completion of primary treatment. Supportive care that “[manages] symptoms and side effects, enables adaptation and coping, optimizes understanding and informed decision-making, and minimizes decrements in functioning”10 is becoming recognized as a critical component of direct oncologic care before, during, and after treatment. Health care professionals, scientists, governments, and patient advocates are increasingly calling for the development of comprehensive supportive care programs improve the quality of life for people diagnosed with cancer. A common model for survivorship care is a general program for all cancer survivors that provides disease- and patient-specific care plans. These care plans outline patients’ prior therapies, potential side effects, recommendations for monitoring (for side effects or relapse of cancer), and advice on how patients can maintain a healthy lifestyle.11 However, there are few survivorship programs for men with prostate cancer and their partners, and the evidence base around best practices for these programs is scant.12 Furthermore, up to 87% of men with a prostate cancer diagnosis report specific and significant unmet supportive care needs,10,13 with sexuality-related and psychological issues10,14 being the areas of greatest concern.

To address the complex supportive care needs of men with prostate cancer in British Columbia, Canada, the Vancouver Prostate Centre (VPC) and Department of Urologic Sciences at the University of British Columbia developed the multidisciplinary Prostate Cancer Supportive Care (PCSC) Program. The program aims to address the challenges of decision-making and coping faced by men with prostate cancer and their partners and family members along the entire disease trajectory. Services are provided at no cost to participants. Here, we outline the guiding principles for the PCSC program and its scope, delivery, and evaluation. We provide information on the more than 1,200 patients who have participated in the program since its inception in January of 2013, the rates of participation across the different program modules, and a selection of patient satisfaction measures. We also discuss successes and limitations and ongoing research and evaluation efforts, providing lessons learned to support the development of other supportive care programs in Canada and internationally.

Program description

Guiding principles

The PCSC Program is a clinical, educational, and research-based program, with 4 guiding principles: it is comprehensive, patient- and partner-centered, evidence-based, and supports new research. The program serves patients, partners, and families along the entire disease trajectory, recognizing that cancer is a family disease, affecting both the individual and social network, and that the psychological stress associated with a diagnosis of prostate cancer is borne heavily by partners. It has been designed, implemented, and refined with the best available evidence and with the intention to undergo consistent and repeated evaluation. Finally, it was designed to provide opportunities for targeted research efforts, supporting the growth of the evidence base in this area.

Patient entry and module descriptions

Patients can be referred to the program by a physician or other allied health professional. They may also self-refer, having been made aware of the program through our website, a variety of print materials, or by word of mouth. On referral, the program coordinator collects patients’ basic clinical and demographic data, assesses health literacy and lifestyle factors, and provides them with information on the program modules. As of December 2015, the program consisted of 6 distinct modules, each focusing on different elements of the disease trajectory or on addressing specific physical or mental health concerns. Modules are led by licensed health professionals with experience in oncology. No elements of the program are mandatory, and participants are free to pick and choose the components that are most relevant to them and their partners.

Introduction to prostate cancer and primary treatment options. This is a group-based module that focuses on educating newly diagnosed patients (and those going on or off active surveillance) on the basic biology of prostate cancer, the primary treatment options for localized disease, and the main side effects associated with the treatments. It also includes information about the other services offered by the program and any ongoing research studies. The session is held twice a month in the early evening and is run collectively by a urologist, radiation oncologist, patient representative, and program coordinator. It includes a brief one-on-one discussion between each patient and their partner or family member and the urologist and radiation oncologist to address any remaining questions. A copy of the patient’s biopsy report is on hand for the physician(s). Attendance of this session has been shown to significantly reduce pretreatment distress in both patients and their partners.15

Managing sexual function and intimacy. Sexual intimacy is tied to overall health outcomes, relationship satisfaction, and quality of life.16 Primary therapy for prostate cancer can be associated with substantial side-effects (eg, erectile dysfunction, incontinence, altered libido, penile shortening) that negatively affect sexual intimacy and have an impact on the patient individually as well as the sexual relationship he has with his partner.17

The program’s Sexual Health Service (SHS) provides patients and partners with information on the impact of treatment on sexual health.18 The SHS offers educational sessions led by a sexual rehabilitation nurse and clinical psychologist with a specialization in sexual health. Sessions focus on the impact of prostate cancer treatments on sexual function and therapeutic modalities, promote an understanding of the barriers to sexual adaptation posttreatment, and present options for sexual activity that are not solely dependent on the ability to achieve an erection. Once participants have attended an educational session, they are offered individual consultations with the sexual health nurse every 3 to 6 months for 2 years or longer, depending on the patient’s or couple’s needs. They are referred to the SHS’s sexual medicine physician if further medical intervention is warranted. The sexual health nurse works with the patient and partner to develop an individualized Sexual Health Rehabilitation Action Plan (SHRAP), which assists the couple in sexual adaptation going forward. The SHRAP is a tool devised by the sexual health nurse based on her clinical experience with couples affected by prostate cancer.

Couples who have been evaluated within the SHS are also invited to attend a second workshop on intimacy that is offered quarterly. Workshop participants discuss the impact of sexual changes on relationships, and strategies on how to enhance intimacy and sexual communication are presented. A resource package is provided to each couple to help re-establish and/or strengthen their various dimensions of intimacy.

Lifestyle management. The lifestyle management modules include separate nutrition and physical activity or exercise components. Referral to the smoking cessation program in the Vancouver Coastal Health Authority is made at program registration, if appropriate. The nutrition group-based education session is delivered by a registered dietitian from the British Columbia Cancer Agency who specializes in prostate cancer. The session focuses on evidence-based recommendations on diet after a diagnosis of prostate cancer, the use of dietary supplements, body weight and health, and practical nutrition tips. The exercise session is delivered by an exercise physiologist who specializes in working with cancer patients. It covers the value of exercise in terms of safety, prevention and reduction of treatment side effects (including from ADT), treatment prehabilitation and recovery, advanced cancer management, and long-term survival. A one-on-one exercise counseling clinic is also offered and aims to increase exercise adoption and long-term adherence in line with Canadian Physical Activity guidelines and exercise oncology guidelines,19,20 with follow-up appointments at 3, 6, and 12 months to help patients stay motivated and ensure they are exercising correctly. The individual consultations with the exercise physiologist include physical measures, exercise volume, treatment side effects, and coconstructed goal setting with an individualized formal exercise regimen (exercise prescription).

Adapting to ADT. This is an educational module offered to patients with metastatic prostate cancer who are starting hormone therapy treatments that lower serum testosterone into the castrate range. This program was one of several available through TrueNTH, a portfolio of projects funded by the Movember Foundation, through Prostate Cancer Canada. The session is delivered by a patient facilitator and focuses on strategies to recognize and adapt to the side effects of ADT21 while maintaining a good quality of life and strong intimate relationships with partners.22,23

Pelvic-floor physical therapy for urinary incontinence. This module includes a group-based and individualized education session for patients (either pre- or posttreatment) focused on reducing the effects of surgery and/or radiation therapy on urinary and sexual continence as well as on how to cope with these symptoms and minimize the effect they have on quality of life.24 The session is conducted by a physical therapist who is certified as a pelvic-floor specialist. Supervised pelvic-floor re-education and/or exercise has been shown to successfully reduce the degree of incontinence in this population.25 The module therefore also includes 3 one-on-one clinical appointments for patients who are still experiencing bother from incontinence 12 weeks after a radical prostatectomy or postradiation treatment.

Psycho-oncology. In recognition of the emotional and psychological burden associated with prostate cancer and the important role partners play in facilitating treatment of these psychological and/or psychosocial issues, the program offers appointments with a registered clinical counselor to address acute emotional distress. These are usually 1-hour appointments offered to both patients and partners, either separately or together. Appointments can be attended in person or conducted by telephone. When appropriate, patients are referred for further long-term individual support or couple support with their partners. A group therapy workshop was also initiated in 2016. In this program, men participate in a guided autobiographical life review through a process that focuses on developing a cohesive working group, learning strategic communication skills, and understanding and learning how to manage difficult emotions and transitional life stressors associated with prostate cancer. It also focuses on processing and integrating critical events that contribute to the men’s identity and psychological function and involves the consolidation of the personal learning that occurs. Postgroup referral plans are developed on an individual basis as needed.

Methods

Data

We obtained sociodemographic, diagnostic, and treatment information as well as clinic visit records for all PCSC Program registrants from the electronic medical record held at the VPC. Clinical variables included age at diagnosis, Gleason score, and primary treatment modality (including active surveillance and ADT use). The Gleason score determines the aggressiveness of a patient’s prostate cancer based on biopsy results. A score of 6 or less indicates that the disease is likely to grow slowly. A grade of 7 is considered intermediate risk (with primary score of 3 and secondary 4 being lower risk than those with a primary score of 4 and secondary of 3). A Gleason score of 8 or higher indicates aggressive disease that is poorly differentiated or high grade. Sociodemographic characteristics included age, travel distance to the clinic, and income quintile. We obtained attendance records for the modular education sessions from the program’s database. Patients who did not have any medical visits at the VPC (referred to henceforth as non-VPC patients) did not have a clinic record, so we excluded them from the subset of the analyses that depended on specific clinical variables.

All patients and partners who participate in any PCSC Program education sessions (introduction to prostate cancer, sexual health, nutrition, exercise, ADT, and pelvic-floor physical therapy) are asked to complete voluntary, anonymous feedback forms. These forms assess participant satisfaction using a series of Likert-based and Boolean response items as well as qualitative commentary. They include questions that assess the timing, structure, and content of each session.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Statistical approach

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze participant characteristics, program participation rates, and participant satisfaction. For each module’s education session, we compared the overall satisfaction between patients and partners using t tests. We also compared the level of satisfaction across the different modules using a 1-way analysis of variance. For the sexual health and pelvic-floor physical therapy sessions, we compared satisfaction between participants who attended the education sessions before to those who attended following their primary treatment using t tests. We provide the eta squared (for analyses of variance) and Cohen d (for t tests) to provide an effect size estimate of any significant differences observed.

Results

Participants

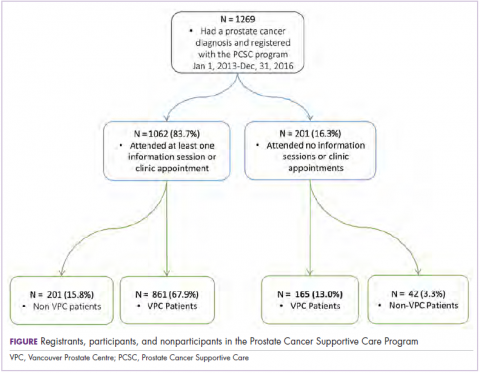

From the program’s founding in January of 2013 to December 31, 2016, a total of 1,269 patients registered (an average of 317 patients a year). Of those, 1,026 (80.9%) had at least 1 prostate cancer–related visit at the VPC. The remaining 243 (19.1%) were non-VPC patients (Figure). Overall, 1,062 men (83.4%) who registered with the program went on to attend at least 1 education session or clinic appointment.

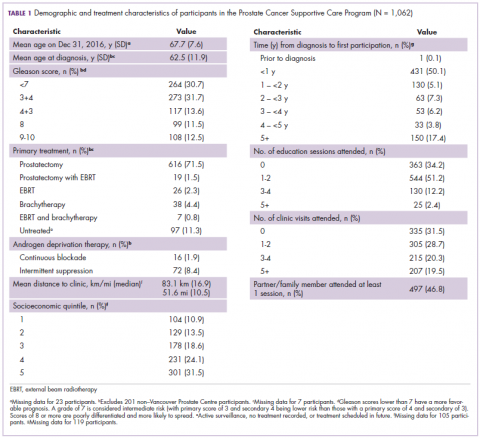

Average age among male program participants was 67.7 years, and age at diagnosis was 62.5 years (Table 1). In all, 273 men (31.7%) had Gleason 3+4, and 117 (13.7%) had Gleason 4+3. Most of the participants (76.9%) elected to undergo radical prostatectomy for primary treatment. Ninety-five men (8.9%) received at least some ADT treatment as an adjunct to radiation or to treat recurrent disease. Participants traveled an average of 83.1 km (51.6 miles; median, 6.9 km and 10.5 miles, respectively) to attend the program; 10% of participants traveled further than 112 km (70 mi) to the clinic. One hundred and four (10.9%) and 301 (31.5%) of registrants were in the lowest and highest income quintiles respectively. Four hundred and ninety-seven (46.8%) attended at lesson 1 session or clinic appointment with a partner or family member.

Program participation

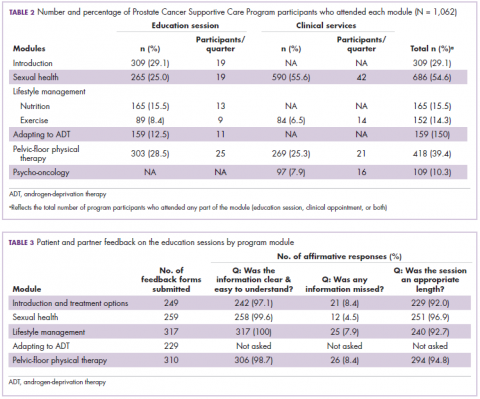

Of the 1,062 men who participated in the program, 867 (80.1%) were patients of the VPC, and 205 (19.1%) were non-VPC patients. The education sessions for the introduction to prostate cancer and sexual health modules had the largest numbers of participants (309 and 265, respectively; Table 2); however, pelvic-floor physical therapy had the highest participation rate per quarter (25 patients). The clinical services offered within the sexual health module had the larger number of participants and highest participation rate per quarter (590 total patients, 42/quarter). Timing of program participation was highly variable, ranging from 6 days to 18.5 years after diagnosis (SD, 1,301 days). More than half of participants attended a session or clinic visit within the first year of their diagnosis. A total of 17% of patients who registered did not attend any part of the program.

Satisfaction

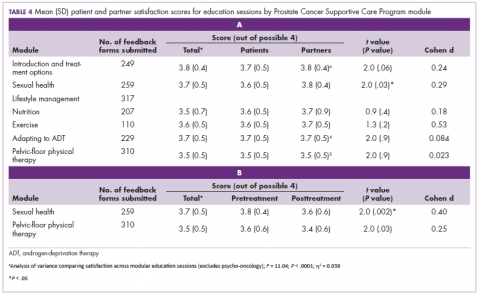

Most patients and partners said that they found the information presented at the modular education sessions comprehensive, clear, and easy to understand (Table 3). Although the overall average satisfaction score varied significantly across sessions, ranging from 3.5 (out of a possible 4) for pelvic-floor physical therapy to 3.8 for introduction to prostate cancer (F = 3.8, P < .001), the effect size of this difference was small (η2 = .039; Table 4A). We found no difference in the level of satisfaction between patients and partners, with the exception of the sexual health module, which was rated better by partners than by patients (patients: 3.6, partners: 3.8; t = 2.0; P = .03); however, the effect size of this difference was again small (Cohen d = .29). A total of 86% of patients found the inclusion of their partners at the sessions useful. For both pelvic-floor physical therapy and sexual health, attendees were more satisfied if they attended before treatment initiation rather than after completion (Table 4B).

Discussion

The purpose of this descriptive analysis was to outline a comprehensive, multidisciplinary supportive care program for men with prostate cancer and to present initial data on the population that has used the program and their satisfaction with the services provided. Within the first 5 years of the PCSC Program, 1,269 patients registered to participate. However, nearly 1 in 6 men who registered for the program did not subsequently attend any education sessions or use any clinical services offered, despite the fact that all services were free of charge. It is possible that nonparticipation may be related to men on active surveillance choosing not to engage with the program until they are faced with making a treatment decision, which may not happen until several years after an initial positive biopsy.26 This and other factors that affect a patient’s decision not to participate will be investigated in a future study. There is existing evidence documenting high levels of distress and anxiety for patients and their partners resulting from decision-making around prostate cancer treatment,27,28 and many face both decisional conflict and subsequent regret.15,29 Further work to help patients access the program could include defining a prehabilitation program for which patients can sign up that automatically selects the education sessions and clinical services most relevant to them.

The number of attendees varied across the 6 education sessions, with introduction to prostate cancer and sexual health being the best attended. This is consistent with the literature concerning the specific unmet supportive care and information needs in this population10,13 and with the value that men have placed on taking an active role in the decisions around their prostate cancer treatment.30 It is also possible that attendance varied because modules were introduced in a stepwise fashion and were offered on different schedules. Patients and partners both reported a high degree of satisfaction with all of the modules’ education sessions, reporting that the length, content, and delivery were appropriate.

Since 2013, a wide research portfolio has grown alongside the program. It has acted as a recruitment site for multicenter national studies and has attracted funding for several in-house research projects and evaluations. In addition, the VPC has implemented clinic-wide electronic collection of several patient-reported outcome measures using iPads. Patients have the option of contributing their data to Canadian (PC360o) and Global (TrueNTH Global Registry – Prostate Cancer Outcomes) registries for prostate cancer. The program has also created educational opportunities by supporting postdoctoral fellows. It has also provided a rich environment for urology and radiation oncology residents and fellows to participate in a multidisciplinary supportive care team, ensuring that the next generation of surgeons and oncologists recognize the importance of this approach to care.

Limitations

This is a brief descriptive study that relies on a mixture of anonymized survey and clinical chart data. Because the program’s patient feedback forms are anonymous, we are not able to link satisfaction scores to differences in sociodemographic, clinical, or prognostic factors. We also have not directly measured clinical, psychological, or quality of life outcomes; however, all 3 will be included in future studies of the program. An additional limitation is that not all program modules were offered for the entirety of the study duration and are offered at different frequencies. Thus, some modules have disproportionally higher participation rates than others. Lastly, we are missing clinical information for 16% of our participants who are not patients at the VPC.

The program is offered within an academic and teaching hospital in a major metropolitan center and depends on the work of a large interdisciplinary team. Cancer programs that are not embedded within a similar environment, such as those located in smaller rural communities, may not have access to the specialized clinical professionals who run our program, affecting its direct generalizability to these locations. Other specialists, such as palliative care teams, could be well positioned to provide support in locations that do not have a similar level of resource available. Furthermore, some program elements will be adapted to be delivered using telemedicine technology, which is an additional approach to improving access for patients who are beyond the reach of a tertiary care facility.

Conclusions

There is a growing need to provide consistent and comprehensive supportive care to patients with prostate cancer and their partners and families throughout the disease and treatment journey. The PCSC Program uses a multidisciplinary, evidenced-based, disease-focused approach to support informed treatment decision-making and address the physical, psychological, and psychosocial effects of prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment. We proactively collect data on disease, personal demographic details, and symptoms or quality of life, supporting opportunities to partner with researchers with the goal of further improving quality of life based on evidenced-based practices. Going forward, we will conduct detailed examinations of the costs and benefits (in terms of symptom management and quality of life) of the PCSC Program, further contributing to the development of evidence-based best practices for supportive care for men with prostate cancer and their families.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the urologists and radiation oncologists who referred their patients to the program and participated in delivering education sessions, including Dr Martin Gleave, Dr Peter Black, Dr Alan So, Dr Scott Tyldesley, and Dr Mira Keyes. They also thank Dr Richard Wassersug for his contributions to the initial program design and implementation. They thank the patients and their families for participating, and all of their current or past staff and collaborators. Lastly, they thank the funders of the program: the Specialist Services Committee, the BC Ministry of Health, the Prostate Cancer Foundation of BC, and philanthropic donors. They acknowledge Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute and the University of British Columbia for their institutional support.

1. Cancer Research UK. Prostate cancer statistics. http://www.cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-type/prostate/statistics/?region=sk. Published 2015. Accessed June 22, 2017.

2. Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(4):220-241.

3. Canadian Cancer Society. Canadian cancer statistics special topic: predictions of the future burden of cancer in Canada. Ottawa, Canada: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2015.

4. Roth AJ, Weinberger MI, Nelson CJ. Prostate cancer: psychosocial implications and management. Future Oncol. 2008;4(4):561-568.

5. Couper J, Bloch S, Love A, Macvean M, Duchesne GM, Kissane D. Psychosocial adjustment of female partners of men with prostate cancer: a review of the literature. Psychooncology 2006;15(11):937-953.

6. Wilt TJ, MacDonald R, Rutks I, Shamliyan TA, Taylor BC, Kane RL. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness and harms of treatments for clinically localized prostate cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(6):435-448.

7. Galvão DA, Spry NA, Taaffe DR, et al. Changes in muscle, fat and bone mass after 36 weeks of maximal androgen blockade for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2008;102(1):44-47.

8. Watts S, Leydon G, Birch B, et al. Depression and anxiety in prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence rates. BMJ Open. 2014;4(3):e003901.

9. Zaider T, Manne S, Nelson C, Mulhall J, Kissane D. Loss of masculine identity, marital affection, and sexual bother in men with localized prostate cancer. J Sex Med. 2012;9(10):2724-2732.

10. Ream E, Quennell A, Fincham L, et al. Supportive care needs of men living with prostate cancer in England: a survey. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(12):1903-1909.

11. Howell D, Hack TF, Oliver TK, et al. Models of care for post-treatment follow-up of adult cancer survivors: a systematic review and quality appraisal of the evidence. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(4):359-371.

12. Halpern MT, Viswanathan M, Evans TS, Birken SA, Basch E, Mayer DK. Models of cancer survivorship care: overview and summary of current evidence. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(1):e19-e27.

13. Smith DP, Supramaniam R, King MT, Ward J, Berry M, Armstrong BK. Age, health, and education determine supportive care needs of men younger than 70 years with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(18):2560-2566.

14. Northouse LL, Mood DW, Montie JE, et al. Living with prostate cancer: patients’ and spouses’ psychosocial status and quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(27):4171-4177.

15. Hedden L, Wassersug R, Mahovlich S, et al. Evaluating an educational intervention to alleviate distress amongst men with newly diagnosed prostate cancer and their partners. BJU Int. 2017;120(5B):E21-E29.

16. Bradley EB, Bissonette EA, Theodorescu D. Determinants of long-term quality of life and voiding function of patients treated with radical prostatectomy or permanent brachytherapy for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2004;94(7):1003-1009.

17. Ramsey SD, Zeliadt SB, Blough DK, et al. Impact of prostate cancer on sexual relationships: a longitudinal perspective on intimate partners’ experiences. J Sex Med. 2013;10(12):3135-3143.

18. Wittmann D, Carolan M, Given B, et al. Exploring the role of the partner in couples’ sexual recovery after surgery for prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(9):2509-2515.

19. Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, et al. American college of sports medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(7):1409-1426.

20. Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(4):243-274.

21. Elliott S, Latini DM, Walker LM, Wassersug R, Robinson JW; ADT Suvivorship Working Group. Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: recommendations to improve patient and partner quality of life. J Sex Med. 2010;7(9):2996-3010.

22. Wassersug RJ, Walker LM, Robinson JW. Androgen deprivation therapy: an essential guide for prostate cancer patients and their loved ones. New York, NY: Demos Health; 2014.

23. Wibowo E, Walker LM, Wilyman S, et al. Androgen deprivation therapy educational program: a Canadian True NTH initiative. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl 3):243.

24. Stanford JL, Feng Z, Hamilton AS, et al. Urinary and sexual function after radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 2000;283(3):354-360.

25. Overgård M, Angelsen A, Lydersen S, Mørkved S. Does physiotherapist-guided pelvic floor muscle training reduce urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy? A randomised controlled trial. Eur Urol. 2008;54(2):438-448.

26. Godtman RA, Holmberg E, Khatami A, Pihl CG, Stranne J, Hugosson J. Long-term results of active surveillance in the Göteborg randomized, population-based prostate cancer screening trial. Eur Urol. 2016;70(5):760-766.

27. Cohen H, Britten N. Who decides about prostate cancer treatment? A qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2003;20(6):724-729.

28. Denberg TD, Melhado TV, Steiner JF. Patient treatment preferences in localized prostate carcinoma: the influence of emotion, misconception, and anecdote. Cancer. 2006;107(3):620-630.

29. Morris BB, Farnan L, Song L, et al. Treatment decisional regret among men with prostate cancer: racial differences and influential factors in the North Carolina health access and prostate cancer treatment project (HCaP-NC). Cancer. 2015;121(12):2029-2035.

30. Feldman-Stewart D, Capirci C, Brennenstuhl S, et al. Information for decision making by patients with early-stage prostate cancer: a comparison across 9 countries. Med Decis Making. 2011;31(5):754-766.

Prostate cancer is the most common malignancy diagnosed in Canadian men. An estimated 21,300 Canadian men were diagnosed with the disease in 2017, representing 21% of all new cancer cases.1 There are about 176,000 men living with prostate cancer in Canada.1 In the United States, there were 2,778,630 survivors of prostate cancer as of 2012 and that population is expected to increase by more than 1 million (40%) to 3,922,600 by 2022.2

Although 96% of men diagnosed with prostate cancer now survive longer than 5 years3, many will suffer from treatment-related sequelae that can have a profound effect on quality of life for themselves and their partners.4,5 Impacts include sexual, urinary, and bowel dysfunctions6 owing to treatment of the primary tumor as well as reduced muscle and bone mass, osteoporosis, fatigue, obesity, and glucose intolerance or diabetes7 owing to androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT). Many men also suffer from psychological issues such as depression, anxiety, anger and irritability, sense of isolation, grief, and loss of masculinity.8,9 The psychological impacts also continue well beyond the completion of treatment and can be significant for both patients and their partners.5,8

With posttreatment longevity and the associated complex sequelae, prostate cancer is being viewed increasingly as a chronic disease whose effects must be managed for many years after the completion of primary treatment. Supportive care that “[manages] symptoms and side effects, enables adaptation and coping, optimizes understanding and informed decision-making, and minimizes decrements in functioning”10 is becoming recognized as a critical component of direct oncologic care before, during, and after treatment. Health care professionals, scientists, governments, and patient advocates are increasingly calling for the development of comprehensive supportive care programs improve the quality of life for people diagnosed with cancer. A common model for survivorship care is a general program for all cancer survivors that provides disease- and patient-specific care plans. These care plans outline patients’ prior therapies, potential side effects, recommendations for monitoring (for side effects or relapse of cancer), and advice on how patients can maintain a healthy lifestyle.11 However, there are few survivorship programs for men with prostate cancer and their partners, and the evidence base around best practices for these programs is scant.12 Furthermore, up to 87% of men with a prostate cancer diagnosis report specific and significant unmet supportive care needs,10,13 with sexuality-related and psychological issues10,14 being the areas of greatest concern.

To address the complex supportive care needs of men with prostate cancer in British Columbia, Canada, the Vancouver Prostate Centre (VPC) and Department of Urologic Sciences at the University of British Columbia developed the multidisciplinary Prostate Cancer Supportive Care (PCSC) Program. The program aims to address the challenges of decision-making and coping faced by men with prostate cancer and their partners and family members along the entire disease trajectory. Services are provided at no cost to participants. Here, we outline the guiding principles for the PCSC program and its scope, delivery, and evaluation. We provide information on the more than 1,200 patients who have participated in the program since its inception in January of 2013, the rates of participation across the different program modules, and a selection of patient satisfaction measures. We also discuss successes and limitations and ongoing research and evaluation efforts, providing lessons learned to support the development of other supportive care programs in Canada and internationally.

Program description

Guiding principles

The PCSC Program is a clinical, educational, and research-based program, with 4 guiding principles: it is comprehensive, patient- and partner-centered, evidence-based, and supports new research. The program serves patients, partners, and families along the entire disease trajectory, recognizing that cancer is a family disease, affecting both the individual and social network, and that the psychological stress associated with a diagnosis of prostate cancer is borne heavily by partners. It has been designed, implemented, and refined with the best available evidence and with the intention to undergo consistent and repeated evaluation. Finally, it was designed to provide opportunities for targeted research efforts, supporting the growth of the evidence base in this area.

Patient entry and module descriptions

Patients can be referred to the program by a physician or other allied health professional. They may also self-refer, having been made aware of the program through our website, a variety of print materials, or by word of mouth. On referral, the program coordinator collects patients’ basic clinical and demographic data, assesses health literacy and lifestyle factors, and provides them with information on the program modules. As of December 2015, the program consisted of 6 distinct modules, each focusing on different elements of the disease trajectory or on addressing specific physical or mental health concerns. Modules are led by licensed health professionals with experience in oncology. No elements of the program are mandatory, and participants are free to pick and choose the components that are most relevant to them and their partners.

Introduction to prostate cancer and primary treatment options. This is a group-based module that focuses on educating newly diagnosed patients (and those going on or off active surveillance) on the basic biology of prostate cancer, the primary treatment options for localized disease, and the main side effects associated with the treatments. It also includes information about the other services offered by the program and any ongoing research studies. The session is held twice a month in the early evening and is run collectively by a urologist, radiation oncologist, patient representative, and program coordinator. It includes a brief one-on-one discussion between each patient and their partner or family member and the urologist and radiation oncologist to address any remaining questions. A copy of the patient’s biopsy report is on hand for the physician(s). Attendance of this session has been shown to significantly reduce pretreatment distress in both patients and their partners.15

Managing sexual function and intimacy. Sexual intimacy is tied to overall health outcomes, relationship satisfaction, and quality of life.16 Primary therapy for prostate cancer can be associated with substantial side-effects (eg, erectile dysfunction, incontinence, altered libido, penile shortening) that negatively affect sexual intimacy and have an impact on the patient individually as well as the sexual relationship he has with his partner.17

The program’s Sexual Health Service (SHS) provides patients and partners with information on the impact of treatment on sexual health.18 The SHS offers educational sessions led by a sexual rehabilitation nurse and clinical psychologist with a specialization in sexual health. Sessions focus on the impact of prostate cancer treatments on sexual function and therapeutic modalities, promote an understanding of the barriers to sexual adaptation posttreatment, and present options for sexual activity that are not solely dependent on the ability to achieve an erection. Once participants have attended an educational session, they are offered individual consultations with the sexual health nurse every 3 to 6 months for 2 years or longer, depending on the patient’s or couple’s needs. They are referred to the SHS’s sexual medicine physician if further medical intervention is warranted. The sexual health nurse works with the patient and partner to develop an individualized Sexual Health Rehabilitation Action Plan (SHRAP), which assists the couple in sexual adaptation going forward. The SHRAP is a tool devised by the sexual health nurse based on her clinical experience with couples affected by prostate cancer.

Couples who have been evaluated within the SHS are also invited to attend a second workshop on intimacy that is offered quarterly. Workshop participants discuss the impact of sexual changes on relationships, and strategies on how to enhance intimacy and sexual communication are presented. A resource package is provided to each couple to help re-establish and/or strengthen their various dimensions of intimacy.

Lifestyle management. The lifestyle management modules include separate nutrition and physical activity or exercise components. Referral to the smoking cessation program in the Vancouver Coastal Health Authority is made at program registration, if appropriate. The nutrition group-based education session is delivered by a registered dietitian from the British Columbia Cancer Agency who specializes in prostate cancer. The session focuses on evidence-based recommendations on diet after a diagnosis of prostate cancer, the use of dietary supplements, body weight and health, and practical nutrition tips. The exercise session is delivered by an exercise physiologist who specializes in working with cancer patients. It covers the value of exercise in terms of safety, prevention and reduction of treatment side effects (including from ADT), treatment prehabilitation and recovery, advanced cancer management, and long-term survival. A one-on-one exercise counseling clinic is also offered and aims to increase exercise adoption and long-term adherence in line with Canadian Physical Activity guidelines and exercise oncology guidelines,19,20 with follow-up appointments at 3, 6, and 12 months to help patients stay motivated and ensure they are exercising correctly. The individual consultations with the exercise physiologist include physical measures, exercise volume, treatment side effects, and coconstructed goal setting with an individualized formal exercise regimen (exercise prescription).

Adapting to ADT. This is an educational module offered to patients with metastatic prostate cancer who are starting hormone therapy treatments that lower serum testosterone into the castrate range. This program was one of several available through TrueNTH, a portfolio of projects funded by the Movember Foundation, through Prostate Cancer Canada. The session is delivered by a patient facilitator and focuses on strategies to recognize and adapt to the side effects of ADT21 while maintaining a good quality of life and strong intimate relationships with partners.22,23

Pelvic-floor physical therapy for urinary incontinence. This module includes a group-based and individualized education session for patients (either pre- or posttreatment) focused on reducing the effects of surgery and/or radiation therapy on urinary and sexual continence as well as on how to cope with these symptoms and minimize the effect they have on quality of life.24 The session is conducted by a physical therapist who is certified as a pelvic-floor specialist. Supervised pelvic-floor re-education and/or exercise has been shown to successfully reduce the degree of incontinence in this population.25 The module therefore also includes 3 one-on-one clinical appointments for patients who are still experiencing bother from incontinence 12 weeks after a radical prostatectomy or postradiation treatment.

Psycho-oncology. In recognition of the emotional and psychological burden associated with prostate cancer and the important role partners play in facilitating treatment of these psychological and/or psychosocial issues, the program offers appointments with a registered clinical counselor to address acute emotional distress. These are usually 1-hour appointments offered to both patients and partners, either separately or together. Appointments can be attended in person or conducted by telephone. When appropriate, patients are referred for further long-term individual support or couple support with their partners. A group therapy workshop was also initiated in 2016. In this program, men participate in a guided autobiographical life review through a process that focuses on developing a cohesive working group, learning strategic communication skills, and understanding and learning how to manage difficult emotions and transitional life stressors associated with prostate cancer. It also focuses on processing and integrating critical events that contribute to the men’s identity and psychological function and involves the consolidation of the personal learning that occurs. Postgroup referral plans are developed on an individual basis as needed.

Methods

Data

We obtained sociodemographic, diagnostic, and treatment information as well as clinic visit records for all PCSC Program registrants from the electronic medical record held at the VPC. Clinical variables included age at diagnosis, Gleason score, and primary treatment modality (including active surveillance and ADT use). The Gleason score determines the aggressiveness of a patient’s prostate cancer based on biopsy results. A score of 6 or less indicates that the disease is likely to grow slowly. A grade of 7 is considered intermediate risk (with primary score of 3 and secondary 4 being lower risk than those with a primary score of 4 and secondary of 3). A Gleason score of 8 or higher indicates aggressive disease that is poorly differentiated or high grade. Sociodemographic characteristics included age, travel distance to the clinic, and income quintile. We obtained attendance records for the modular education sessions from the program’s database. Patients who did not have any medical visits at the VPC (referred to henceforth as non-VPC patients) did not have a clinic record, so we excluded them from the subset of the analyses that depended on specific clinical variables.

All patients and partners who participate in any PCSC Program education sessions (introduction to prostate cancer, sexual health, nutrition, exercise, ADT, and pelvic-floor physical therapy) are asked to complete voluntary, anonymous feedback forms. These forms assess participant satisfaction using a series of Likert-based and Boolean response items as well as qualitative commentary. They include questions that assess the timing, structure, and content of each session.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Statistical approach

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze participant characteristics, program participation rates, and participant satisfaction. For each module’s education session, we compared the overall satisfaction between patients and partners using t tests. We also compared the level of satisfaction across the different modules using a 1-way analysis of variance. For the sexual health and pelvic-floor physical therapy sessions, we compared satisfaction between participants who attended the education sessions before to those who attended following their primary treatment using t tests. We provide the eta squared (for analyses of variance) and Cohen d (for t tests) to provide an effect size estimate of any significant differences observed.

Results

Participants

From the program’s founding in January of 2013 to December 31, 2016, a total of 1,269 patients registered (an average of 317 patients a year). Of those, 1,026 (80.9%) had at least 1 prostate cancer–related visit at the VPC. The remaining 243 (19.1%) were non-VPC patients (Figure). Overall, 1,062 men (83.4%) who registered with the program went on to attend at least 1 education session or clinic appointment.

Average age among male program participants was 67.7 years, and age at diagnosis was 62.5 years (Table 1). In all, 273 men (31.7%) had Gleason 3+4, and 117 (13.7%) had Gleason 4+3. Most of the participants (76.9%) elected to undergo radical prostatectomy for primary treatment. Ninety-five men (8.9%) received at least some ADT treatment as an adjunct to radiation or to treat recurrent disease. Participants traveled an average of 83.1 km (51.6 miles; median, 6.9 km and 10.5 miles, respectively) to attend the program; 10% of participants traveled further than 112 km (70 mi) to the clinic. One hundred and four (10.9%) and 301 (31.5%) of registrants were in the lowest and highest income quintiles respectively. Four hundred and ninety-seven (46.8%) attended at lesson 1 session or clinic appointment with a partner or family member.

Program participation

Of the 1,062 men who participated in the program, 867 (80.1%) were patients of the VPC, and 205 (19.1%) were non-VPC patients. The education sessions for the introduction to prostate cancer and sexual health modules had the largest numbers of participants (309 and 265, respectively; Table 2); however, pelvic-floor physical therapy had the highest participation rate per quarter (25 patients). The clinical services offered within the sexual health module had the larger number of participants and highest participation rate per quarter (590 total patients, 42/quarter). Timing of program participation was highly variable, ranging from 6 days to 18.5 years after diagnosis (SD, 1,301 days). More than half of participants attended a session or clinic visit within the first year of their diagnosis. A total of 17% of patients who registered did not attend any part of the program.

Satisfaction

Most patients and partners said that they found the information presented at the modular education sessions comprehensive, clear, and easy to understand (Table 3). Although the overall average satisfaction score varied significantly across sessions, ranging from 3.5 (out of a possible 4) for pelvic-floor physical therapy to 3.8 for introduction to prostate cancer (F = 3.8, P < .001), the effect size of this difference was small (η2 = .039; Table 4A). We found no difference in the level of satisfaction between patients and partners, with the exception of the sexual health module, which was rated better by partners than by patients (patients: 3.6, partners: 3.8; t = 2.0; P = .03); however, the effect size of this difference was again small (Cohen d = .29). A total of 86% of patients found the inclusion of their partners at the sessions useful. For both pelvic-floor physical therapy and sexual health, attendees were more satisfied if they attended before treatment initiation rather than after completion (Table 4B).

Discussion

The purpose of this descriptive analysis was to outline a comprehensive, multidisciplinary supportive care program for men with prostate cancer and to present initial data on the population that has used the program and their satisfaction with the services provided. Within the first 5 years of the PCSC Program, 1,269 patients registered to participate. However, nearly 1 in 6 men who registered for the program did not subsequently attend any education sessions or use any clinical services offered, despite the fact that all services were free of charge. It is possible that nonparticipation may be related to men on active surveillance choosing not to engage with the program until they are faced with making a treatment decision, which may not happen until several years after an initial positive biopsy.26 This and other factors that affect a patient’s decision not to participate will be investigated in a future study. There is existing evidence documenting high levels of distress and anxiety for patients and their partners resulting from decision-making around prostate cancer treatment,27,28 and many face both decisional conflict and subsequent regret.15,29 Further work to help patients access the program could include defining a prehabilitation program for which patients can sign up that automatically selects the education sessions and clinical services most relevant to them.

The number of attendees varied across the 6 education sessions, with introduction to prostate cancer and sexual health being the best attended. This is consistent with the literature concerning the specific unmet supportive care and information needs in this population10,13 and with the value that men have placed on taking an active role in the decisions around their prostate cancer treatment.30 It is also possible that attendance varied because modules were introduced in a stepwise fashion and were offered on different schedules. Patients and partners both reported a high degree of satisfaction with all of the modules’ education sessions, reporting that the length, content, and delivery were appropriate.

Since 2013, a wide research portfolio has grown alongside the program. It has acted as a recruitment site for multicenter national studies and has attracted funding for several in-house research projects and evaluations. In addition, the VPC has implemented clinic-wide electronic collection of several patient-reported outcome measures using iPads. Patients have the option of contributing their data to Canadian (PC360o) and Global (TrueNTH Global Registry – Prostate Cancer Outcomes) registries for prostate cancer. The program has also created educational opportunities by supporting postdoctoral fellows. It has also provided a rich environment for urology and radiation oncology residents and fellows to participate in a multidisciplinary supportive care team, ensuring that the next generation of surgeons and oncologists recognize the importance of this approach to care.

Limitations

This is a brief descriptive study that relies on a mixture of anonymized survey and clinical chart data. Because the program’s patient feedback forms are anonymous, we are not able to link satisfaction scores to differences in sociodemographic, clinical, or prognostic factors. We also have not directly measured clinical, psychological, or quality of life outcomes; however, all 3 will be included in future studies of the program. An additional limitation is that not all program modules were offered for the entirety of the study duration and are offered at different frequencies. Thus, some modules have disproportionally higher participation rates than others. Lastly, we are missing clinical information for 16% of our participants who are not patients at the VPC.

The program is offered within an academic and teaching hospital in a major metropolitan center and depends on the work of a large interdisciplinary team. Cancer programs that are not embedded within a similar environment, such as those located in smaller rural communities, may not have access to the specialized clinical professionals who run our program, affecting its direct generalizability to these locations. Other specialists, such as palliative care teams, could be well positioned to provide support in locations that do not have a similar level of resource available. Furthermore, some program elements will be adapted to be delivered using telemedicine technology, which is an additional approach to improving access for patients who are beyond the reach of a tertiary care facility.

Conclusions

There is a growing need to provide consistent and comprehensive supportive care to patients with prostate cancer and their partners and families throughout the disease and treatment journey. The PCSC Program uses a multidisciplinary, evidenced-based, disease-focused approach to support informed treatment decision-making and address the physical, psychological, and psychosocial effects of prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment. We proactively collect data on disease, personal demographic details, and symptoms or quality of life, supporting opportunities to partner with researchers with the goal of further improving quality of life based on evidenced-based practices. Going forward, we will conduct detailed examinations of the costs and benefits (in terms of symptom management and quality of life) of the PCSC Program, further contributing to the development of evidence-based best practices for supportive care for men with prostate cancer and their families.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the urologists and radiation oncologists who referred their patients to the program and participated in delivering education sessions, including Dr Martin Gleave, Dr Peter Black, Dr Alan So, Dr Scott Tyldesley, and Dr Mira Keyes. They also thank Dr Richard Wassersug for his contributions to the initial program design and implementation. They thank the patients and their families for participating, and all of their current or past staff and collaborators. Lastly, they thank the funders of the program: the Specialist Services Committee, the BC Ministry of Health, the Prostate Cancer Foundation of BC, and philanthropic donors. They acknowledge Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute and the University of British Columbia for their institutional support.

Prostate cancer is the most common malignancy diagnosed in Canadian men. An estimated 21,300 Canadian men were diagnosed with the disease in 2017, representing 21% of all new cancer cases.1 There are about 176,000 men living with prostate cancer in Canada.1 In the United States, there were 2,778,630 survivors of prostate cancer as of 2012 and that population is expected to increase by more than 1 million (40%) to 3,922,600 by 2022.2

Although 96% of men diagnosed with prostate cancer now survive longer than 5 years3, many will suffer from treatment-related sequelae that can have a profound effect on quality of life for themselves and their partners.4,5 Impacts include sexual, urinary, and bowel dysfunctions6 owing to treatment of the primary tumor as well as reduced muscle and bone mass, osteoporosis, fatigue, obesity, and glucose intolerance or diabetes7 owing to androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT). Many men also suffer from psychological issues such as depression, anxiety, anger and irritability, sense of isolation, grief, and loss of masculinity.8,9 The psychological impacts also continue well beyond the completion of treatment and can be significant for both patients and their partners.5,8

With posttreatment longevity and the associated complex sequelae, prostate cancer is being viewed increasingly as a chronic disease whose effects must be managed for many years after the completion of primary treatment. Supportive care that “[manages] symptoms and side effects, enables adaptation and coping, optimizes understanding and informed decision-making, and minimizes decrements in functioning”10 is becoming recognized as a critical component of direct oncologic care before, during, and after treatment. Health care professionals, scientists, governments, and patient advocates are increasingly calling for the development of comprehensive supportive care programs improve the quality of life for people diagnosed with cancer. A common model for survivorship care is a general program for all cancer survivors that provides disease- and patient-specific care plans. These care plans outline patients’ prior therapies, potential side effects, recommendations for monitoring (for side effects or relapse of cancer), and advice on how patients can maintain a healthy lifestyle.11 However, there are few survivorship programs for men with prostate cancer and their partners, and the evidence base around best practices for these programs is scant.12 Furthermore, up to 87% of men with a prostate cancer diagnosis report specific and significant unmet supportive care needs,10,13 with sexuality-related and psychological issues10,14 being the areas of greatest concern.

To address the complex supportive care needs of men with prostate cancer in British Columbia, Canada, the Vancouver Prostate Centre (VPC) and Department of Urologic Sciences at the University of British Columbia developed the multidisciplinary Prostate Cancer Supportive Care (PCSC) Program. The program aims to address the challenges of decision-making and coping faced by men with prostate cancer and their partners and family members along the entire disease trajectory. Services are provided at no cost to participants. Here, we outline the guiding principles for the PCSC program and its scope, delivery, and evaluation. We provide information on the more than 1,200 patients who have participated in the program since its inception in January of 2013, the rates of participation across the different program modules, and a selection of patient satisfaction measures. We also discuss successes and limitations and ongoing research and evaluation efforts, providing lessons learned to support the development of other supportive care programs in Canada and internationally.

Program description

Guiding principles

The PCSC Program is a clinical, educational, and research-based program, with 4 guiding principles: it is comprehensive, patient- and partner-centered, evidence-based, and supports new research. The program serves patients, partners, and families along the entire disease trajectory, recognizing that cancer is a family disease, affecting both the individual and social network, and that the psychological stress associated with a diagnosis of prostate cancer is borne heavily by partners. It has been designed, implemented, and refined with the best available evidence and with the intention to undergo consistent and repeated evaluation. Finally, it was designed to provide opportunities for targeted research efforts, supporting the growth of the evidence base in this area.

Patient entry and module descriptions

Patients can be referred to the program by a physician or other allied health professional. They may also self-refer, having been made aware of the program through our website, a variety of print materials, or by word of mouth. On referral, the program coordinator collects patients’ basic clinical and demographic data, assesses health literacy and lifestyle factors, and provides them with information on the program modules. As of December 2015, the program consisted of 6 distinct modules, each focusing on different elements of the disease trajectory or on addressing specific physical or mental health concerns. Modules are led by licensed health professionals with experience in oncology. No elements of the program are mandatory, and participants are free to pick and choose the components that are most relevant to them and their partners.

Introduction to prostate cancer and primary treatment options. This is a group-based module that focuses on educating newly diagnosed patients (and those going on or off active surveillance) on the basic biology of prostate cancer, the primary treatment options for localized disease, and the main side effects associated with the treatments. It also includes information about the other services offered by the program and any ongoing research studies. The session is held twice a month in the early evening and is run collectively by a urologist, radiation oncologist, patient representative, and program coordinator. It includes a brief one-on-one discussion between each patient and their partner or family member and the urologist and radiation oncologist to address any remaining questions. A copy of the patient’s biopsy report is on hand for the physician(s). Attendance of this session has been shown to significantly reduce pretreatment distress in both patients and their partners.15

Managing sexual function and intimacy. Sexual intimacy is tied to overall health outcomes, relationship satisfaction, and quality of life.16 Primary therapy for prostate cancer can be associated with substantial side-effects (eg, erectile dysfunction, incontinence, altered libido, penile shortening) that negatively affect sexual intimacy and have an impact on the patient individually as well as the sexual relationship he has with his partner.17

The program’s Sexual Health Service (SHS) provides patients and partners with information on the impact of treatment on sexual health.18 The SHS offers educational sessions led by a sexual rehabilitation nurse and clinical psychologist with a specialization in sexual health. Sessions focus on the impact of prostate cancer treatments on sexual function and therapeutic modalities, promote an understanding of the barriers to sexual adaptation posttreatment, and present options for sexual activity that are not solely dependent on the ability to achieve an erection. Once participants have attended an educational session, they are offered individual consultations with the sexual health nurse every 3 to 6 months for 2 years or longer, depending on the patient’s or couple’s needs. They are referred to the SHS’s sexual medicine physician if further medical intervention is warranted. The sexual health nurse works with the patient and partner to develop an individualized Sexual Health Rehabilitation Action Plan (SHRAP), which assists the couple in sexual adaptation going forward. The SHRAP is a tool devised by the sexual health nurse based on her clinical experience with couples affected by prostate cancer.

Couples who have been evaluated within the SHS are also invited to attend a second workshop on intimacy that is offered quarterly. Workshop participants discuss the impact of sexual changes on relationships, and strategies on how to enhance intimacy and sexual communication are presented. A resource package is provided to each couple to help re-establish and/or strengthen their various dimensions of intimacy.

Lifestyle management. The lifestyle management modules include separate nutrition and physical activity or exercise components. Referral to the smoking cessation program in the Vancouver Coastal Health Authority is made at program registration, if appropriate. The nutrition group-based education session is delivered by a registered dietitian from the British Columbia Cancer Agency who specializes in prostate cancer. The session focuses on evidence-based recommendations on diet after a diagnosis of prostate cancer, the use of dietary supplements, body weight and health, and practical nutrition tips. The exercise session is delivered by an exercise physiologist who specializes in working with cancer patients. It covers the value of exercise in terms of safety, prevention and reduction of treatment side effects (including from ADT), treatment prehabilitation and recovery, advanced cancer management, and long-term survival. A one-on-one exercise counseling clinic is also offered and aims to increase exercise adoption and long-term adherence in line with Canadian Physical Activity guidelines and exercise oncology guidelines,19,20 with follow-up appointments at 3, 6, and 12 months to help patients stay motivated and ensure they are exercising correctly. The individual consultations with the exercise physiologist include physical measures, exercise volume, treatment side effects, and coconstructed goal setting with an individualized formal exercise regimen (exercise prescription).

Adapting to ADT. This is an educational module offered to patients with metastatic prostate cancer who are starting hormone therapy treatments that lower serum testosterone into the castrate range. This program was one of several available through TrueNTH, a portfolio of projects funded by the Movember Foundation, through Prostate Cancer Canada. The session is delivered by a patient facilitator and focuses on strategies to recognize and adapt to the side effects of ADT21 while maintaining a good quality of life and strong intimate relationships with partners.22,23

Pelvic-floor physical therapy for urinary incontinence. This module includes a group-based and individualized education session for patients (either pre- or posttreatment) focused on reducing the effects of surgery and/or radiation therapy on urinary and sexual continence as well as on how to cope with these symptoms and minimize the effect they have on quality of life.24 The session is conducted by a physical therapist who is certified as a pelvic-floor specialist. Supervised pelvic-floor re-education and/or exercise has been shown to successfully reduce the degree of incontinence in this population.25 The module therefore also includes 3 one-on-one clinical appointments for patients who are still experiencing bother from incontinence 12 weeks after a radical prostatectomy or postradiation treatment.

Psycho-oncology. In recognition of the emotional and psychological burden associated with prostate cancer and the important role partners play in facilitating treatment of these psychological and/or psychosocial issues, the program offers appointments with a registered clinical counselor to address acute emotional distress. These are usually 1-hour appointments offered to both patients and partners, either separately or together. Appointments can be attended in person or conducted by telephone. When appropriate, patients are referred for further long-term individual support or couple support with their partners. A group therapy workshop was also initiated in 2016. In this program, men participate in a guided autobiographical life review through a process that focuses on developing a cohesive working group, learning strategic communication skills, and understanding and learning how to manage difficult emotions and transitional life stressors associated with prostate cancer. It also focuses on processing and integrating critical events that contribute to the men’s identity and psychological function and involves the consolidation of the personal learning that occurs. Postgroup referral plans are developed on an individual basis as needed.

Methods

Data

We obtained sociodemographic, diagnostic, and treatment information as well as clinic visit records for all PCSC Program registrants from the electronic medical record held at the VPC. Clinical variables included age at diagnosis, Gleason score, and primary treatment modality (including active surveillance and ADT use). The Gleason score determines the aggressiveness of a patient’s prostate cancer based on biopsy results. A score of 6 or less indicates that the disease is likely to grow slowly. A grade of 7 is considered intermediate risk (with primary score of 3 and secondary 4 being lower risk than those with a primary score of 4 and secondary of 3). A Gleason score of 8 or higher indicates aggressive disease that is poorly differentiated or high grade. Sociodemographic characteristics included age, travel distance to the clinic, and income quintile. We obtained attendance records for the modular education sessions from the program’s database. Patients who did not have any medical visits at the VPC (referred to henceforth as non-VPC patients) did not have a clinic record, so we excluded them from the subset of the analyses that depended on specific clinical variables.

All patients and partners who participate in any PCSC Program education sessions (introduction to prostate cancer, sexual health, nutrition, exercise, ADT, and pelvic-floor physical therapy) are asked to complete voluntary, anonymous feedback forms. These forms assess participant satisfaction using a series of Likert-based and Boolean response items as well as qualitative commentary. They include questions that assess the timing, structure, and content of each session.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Statistical approach

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze participant characteristics, program participation rates, and participant satisfaction. For each module’s education session, we compared the overall satisfaction between patients and partners using t tests. We also compared the level of satisfaction across the different modules using a 1-way analysis of variance. For the sexual health and pelvic-floor physical therapy sessions, we compared satisfaction between participants who attended the education sessions before to those who attended following their primary treatment using t tests. We provide the eta squared (for analyses of variance) and Cohen d (for t tests) to provide an effect size estimate of any significant differences observed.

Results

Participants

From the program’s founding in January of 2013 to December 31, 2016, a total of 1,269 patients registered (an average of 317 patients a year). Of those, 1,026 (80.9%) had at least 1 prostate cancer–related visit at the VPC. The remaining 243 (19.1%) were non-VPC patients (Figure). Overall, 1,062 men (83.4%) who registered with the program went on to attend at least 1 education session or clinic appointment.

Average age among male program participants was 67.7 years, and age at diagnosis was 62.5 years (Table 1). In all, 273 men (31.7%) had Gleason 3+4, and 117 (13.7%) had Gleason 4+3. Most of the participants (76.9%) elected to undergo radical prostatectomy for primary treatment. Ninety-five men (8.9%) received at least some ADT treatment as an adjunct to radiation or to treat recurrent disease. Participants traveled an average of 83.1 km (51.6 miles; median, 6.9 km and 10.5 miles, respectively) to attend the program; 10% of participants traveled further than 112 km (70 mi) to the clinic. One hundred and four (10.9%) and 301 (31.5%) of registrants were in the lowest and highest income quintiles respectively. Four hundred and ninety-seven (46.8%) attended at lesson 1 session or clinic appointment with a partner or family member.

Program participation

Of the 1,062 men who participated in the program, 867 (80.1%) were patients of the VPC, and 205 (19.1%) were non-VPC patients. The education sessions for the introduction to prostate cancer and sexual health modules had the largest numbers of participants (309 and 265, respectively; Table 2); however, pelvic-floor physical therapy had the highest participation rate per quarter (25 patients). The clinical services offered within the sexual health module had the larger number of participants and highest participation rate per quarter (590 total patients, 42/quarter). Timing of program participation was highly variable, ranging from 6 days to 18.5 years after diagnosis (SD, 1,301 days). More than half of participants attended a session or clinic visit within the first year of their diagnosis. A total of 17% of patients who registered did not attend any part of the program.

Satisfaction

Most patients and partners said that they found the information presented at the modular education sessions comprehensive, clear, and easy to understand (Table 3). Although the overall average satisfaction score varied significantly across sessions, ranging from 3.5 (out of a possible 4) for pelvic-floor physical therapy to 3.8 for introduction to prostate cancer (F = 3.8, P < .001), the effect size of this difference was small (η2 = .039; Table 4A). We found no difference in the level of satisfaction between patients and partners, with the exception of the sexual health module, which was rated better by partners than by patients (patients: 3.6, partners: 3.8; t = 2.0; P = .03); however, the effect size of this difference was again small (Cohen d = .29). A total of 86% of patients found the inclusion of their partners at the sessions useful. For both pelvic-floor physical therapy and sexual health, attendees were more satisfied if they attended before treatment initiation rather than after completion (Table 4B).

Discussion

The purpose of this descriptive analysis was to outline a comprehensive, multidisciplinary supportive care program for men with prostate cancer and to present initial data on the population that has used the program and their satisfaction with the services provided. Within the first 5 years of the PCSC Program, 1,269 patients registered to participate. However, nearly 1 in 6 men who registered for the program did not subsequently attend any education sessions or use any clinical services offered, despite the fact that all services were free of charge. It is possible that nonparticipation may be related to men on active surveillance choosing not to engage with the program until they are faced with making a treatment decision, which may not happen until several years after an initial positive biopsy.26 This and other factors that affect a patient’s decision not to participate will be investigated in a future study. There is existing evidence documenting high levels of distress and anxiety for patients and their partners resulting from decision-making around prostate cancer treatment,27,28 and many face both decisional conflict and subsequent regret.15,29 Further work to help patients access the program could include defining a prehabilitation program for which patients can sign up that automatically selects the education sessions and clinical services most relevant to them.

The number of attendees varied across the 6 education sessions, with introduction to prostate cancer and sexual health being the best attended. This is consistent with the literature concerning the specific unmet supportive care and information needs in this population10,13 and with the value that men have placed on taking an active role in the decisions around their prostate cancer treatment.30 It is also possible that attendance varied because modules were introduced in a stepwise fashion and were offered on different schedules. Patients and partners both reported a high degree of satisfaction with all of the modules’ education sessions, reporting that the length, content, and delivery were appropriate.

Since 2013, a wide research portfolio has grown alongside the program. It has acted as a recruitment site for multicenter national studies and has attracted funding for several in-house research projects and evaluations. In addition, the VPC has implemented clinic-wide electronic collection of several patient-reported outcome measures using iPads. Patients have the option of contributing their data to Canadian (PC360o) and Global (TrueNTH Global Registry – Prostate Cancer Outcomes) registries for prostate cancer. The program has also created educational opportunities by supporting postdoctoral fellows. It has also provided a rich environment for urology and radiation oncology residents and fellows to participate in a multidisciplinary supportive care team, ensuring that the next generation of surgeons and oncologists recognize the importance of this approach to care.

Limitations

This is a brief descriptive study that relies on a mixture of anonymized survey and clinical chart data. Because the program’s patient feedback forms are anonymous, we are not able to link satisfaction scores to differences in sociodemographic, clinical, or prognostic factors. We also have not directly measured clinical, psychological, or quality of life outcomes; however, all 3 will be included in future studies of the program. An additional limitation is that not all program modules were offered for the entirety of the study duration and are offered at different frequencies. Thus, some modules have disproportionally higher participation rates than others. Lastly, we are missing clinical information for 16% of our participants who are not patients at the VPC.

The program is offered within an academic and teaching hospital in a major metropolitan center and depends on the work of a large interdisciplinary team. Cancer programs that are not embedded within a similar environment, such as those located in smaller rural communities, may not have access to the specialized clinical professionals who run our program, affecting its direct generalizability to these locations. Other specialists, such as palliative care teams, could be well positioned to provide support in locations that do not have a similar level of resource available. Furthermore, some program elements will be adapted to be delivered using telemedicine technology, which is an additional approach to improving access for patients who are beyond the reach of a tertiary care facility.

Conclusions