User login

Boy with slightly impaired coordination

This young patient is probably presenting with pediatric multiple sclerosis (MS). It is estimated that MS onset before the age of 18 years accounts for 3%-5% of the general population of patients with this autoimmune disease. The condition represents the most common nontraumatic, disabling neurologic disorder among young adults. Disease prevalence is highest between the ages of 13 and 16. In children older than 10, a female predominance is seen, suggesting a hormonal role in pathogenesis. The vast majority (up to 98%) of children and adolescents with MS have a relapsing-remitting course. Overall, pediatric MS has a milder course than adult MS but can lead to significant disability at an early age. Although pediatric patients may experience more frequent relapses, data also suggest that children seem to recover more quickly from episodes than adults.

In children and adolescents, MS most typically manifests with sensory disturbances and impaired coordination. The most commonly reported symptoms in pediatric MS are sensory, motor, and brainstem dysfunction, though cognitive and emotional disorders can emerge over time.

Younger children will often show multifocal symptoms but with the onset of adolescence may begin to present with only a single focal symptom, as is often the case with adult patients.

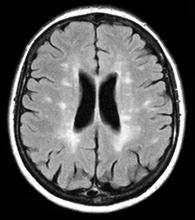

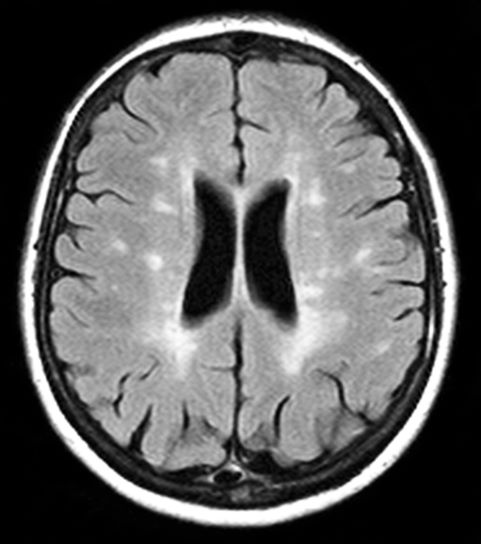

Diagnosis of pediatric MS goes hand-in-hand with a diagnosis of clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) or sporadic acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). CIS is diagnosed when symptoms last for over 24 hours with possible inflammatory demyelination but without encephalopathy. To confirm an MS diagnosis, two or more clinical episodes must occur at least 30 days apart. MRI can both confirm diagnosis and offer great value in monitoring disease progression in the brain and spinal cord. Of note, differentiating the first episode of juvenile MS from ADEM is a significant clinical challenge.

When it comes to treating relapses, the approach in children is similar to that of adults. Therapy may consist of an intravenous pulse of methylprednisolone (20-30 mg/kg/day for 3-5 days). In 2018, the FDA approved the use of the oral MS therapy Gilenya (fingolimod) for the treatment of patients 10 years of age or older with relapsing forms of MS. Providers can also adapt treatments approved for adults for pediatric patients.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme

This young patient is probably presenting with pediatric multiple sclerosis (MS). It is estimated that MS onset before the age of 18 years accounts for 3%-5% of the general population of patients with this autoimmune disease. The condition represents the most common nontraumatic, disabling neurologic disorder among young adults. Disease prevalence is highest between the ages of 13 and 16. In children older than 10, a female predominance is seen, suggesting a hormonal role in pathogenesis. The vast majority (up to 98%) of children and adolescents with MS have a relapsing-remitting course. Overall, pediatric MS has a milder course than adult MS but can lead to significant disability at an early age. Although pediatric patients may experience more frequent relapses, data also suggest that children seem to recover more quickly from episodes than adults.

In children and adolescents, MS most typically manifests with sensory disturbances and impaired coordination. The most commonly reported symptoms in pediatric MS are sensory, motor, and brainstem dysfunction, though cognitive and emotional disorders can emerge over time.

Younger children will often show multifocal symptoms but with the onset of adolescence may begin to present with only a single focal symptom, as is often the case with adult patients.

Diagnosis of pediatric MS goes hand-in-hand with a diagnosis of clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) or sporadic acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). CIS is diagnosed when symptoms last for over 24 hours with possible inflammatory demyelination but without encephalopathy. To confirm an MS diagnosis, two or more clinical episodes must occur at least 30 days apart. MRI can both confirm diagnosis and offer great value in monitoring disease progression in the brain and spinal cord. Of note, differentiating the first episode of juvenile MS from ADEM is a significant clinical challenge.

When it comes to treating relapses, the approach in children is similar to that of adults. Therapy may consist of an intravenous pulse of methylprednisolone (20-30 mg/kg/day for 3-5 days). In 2018, the FDA approved the use of the oral MS therapy Gilenya (fingolimod) for the treatment of patients 10 years of age or older with relapsing forms of MS. Providers can also adapt treatments approved for adults for pediatric patients.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme

This young patient is probably presenting with pediatric multiple sclerosis (MS). It is estimated that MS onset before the age of 18 years accounts for 3%-5% of the general population of patients with this autoimmune disease. The condition represents the most common nontraumatic, disabling neurologic disorder among young adults. Disease prevalence is highest between the ages of 13 and 16. In children older than 10, a female predominance is seen, suggesting a hormonal role in pathogenesis. The vast majority (up to 98%) of children and adolescents with MS have a relapsing-remitting course. Overall, pediatric MS has a milder course than adult MS but can lead to significant disability at an early age. Although pediatric patients may experience more frequent relapses, data also suggest that children seem to recover more quickly from episodes than adults.

In children and adolescents, MS most typically manifests with sensory disturbances and impaired coordination. The most commonly reported symptoms in pediatric MS are sensory, motor, and brainstem dysfunction, though cognitive and emotional disorders can emerge over time.

Younger children will often show multifocal symptoms but with the onset of adolescence may begin to present with only a single focal symptom, as is often the case with adult patients.

Diagnosis of pediatric MS goes hand-in-hand with a diagnosis of clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) or sporadic acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). CIS is diagnosed when symptoms last for over 24 hours with possible inflammatory demyelination but without encephalopathy. To confirm an MS diagnosis, two or more clinical episodes must occur at least 30 days apart. MRI can both confirm diagnosis and offer great value in monitoring disease progression in the brain and spinal cord. Of note, differentiating the first episode of juvenile MS from ADEM is a significant clinical challenge.

When it comes to treating relapses, the approach in children is similar to that of adults. Therapy may consist of an intravenous pulse of methylprednisolone (20-30 mg/kg/day for 3-5 days). In 2018, the FDA approved the use of the oral MS therapy Gilenya (fingolimod) for the treatment of patients 10 years of age or older with relapsing forms of MS. Providers can also adapt treatments approved for adults for pediatric patients.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme

A 10-year-old boy, typically active, presents with slightly impaired coordination and facial weakness. His parents noticed that his gait in particular seems impaired, though to his knowledge he had not been injured. His mother reports a history of meningoencephalitis. A sagittal T2-weighted MRI sequence shows a portion of the brainstem with a large demyelinating plaque in the dorsal part of the medulla and several other lesions in the periventricular regions of the brain. Spinal fluid is normal.

Fatigued absent of medical history

The patient is probably presenting with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS). MS is characterized by symptomatic episodes that are heralded by symptoms of central nervous system involvement. These attacks last longer than 24 hours and may occur months or years apart and affect different anatomic locations. Consistent with other autoimmune conditions, MS is more common in women. Patients are usually diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 49 years. The condition presents differently from patient to patient; some experience cognitive changes or visual symptoms, while others may have numbness, ataxia, clumsiness, hemiparesis, paraparesis, depression, or seizures. Symptoms can also include fatigue, impaired mobility, mood diagnosed changes, elimination dysfunction, and pain.

Of the four disease courses identified in MS, the most common is RRMS, characterized by a cycle of relapse and remission. In the initial stages, RRMS is characterized largely by an inflammatory pathology which, over time, becomes largely neurodegenerative. Most cases of RRMS evolve to secondary progressive MS after about 15 years. Early in the spectrum of demyelinating disease is clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), defined by a single episode of neurologic symptoms and MRI showing more than two classic lesions seen in MS. CIS patients subsequently will present with a second episode or relapse, at which point the diagnosis of RRMS is usually confirmed.

MS is diagnosed on the basis of clinical findings, exclusion of mimickers, and supporting evidence from the workup, namely MRI of the brain and spinal cord as well as cerebrospinal fluid examination. From a clinical perspective, presentation must align with the constellation of neurologic deficits seen in MS. Typically, the duration of deficit is days to weeks, as seen in the present case. While MRI alone cannot be used to diagnose MS, imaging may confirm diagnosis and offer value in monitoring disease progression in the brain and spinal cord. New lesions on MRI usually occur with relapses in RRMS.

Treatment of MS encompasses immunomodulatory therapy to address the underlying immune disorder together with therapies to relieve symptoms. In general, disease-modifying therapy (DMT) should be considered for patients who have experienced a single demyelinating event and exhibit two or more brain lesions on MRI testing. This recommendation holds true even for patients with CIS or those who have experienced their first clinical event and have MRI features consistent with MS, so long as all other conditions in the differential are ruled out. Pivotal trials support the early initiation of DMT with CIS to delay disability.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme

The patient is probably presenting with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS). MS is characterized by symptomatic episodes that are heralded by symptoms of central nervous system involvement. These attacks last longer than 24 hours and may occur months or years apart and affect different anatomic locations. Consistent with other autoimmune conditions, MS is more common in women. Patients are usually diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 49 years. The condition presents differently from patient to patient; some experience cognitive changes or visual symptoms, while others may have numbness, ataxia, clumsiness, hemiparesis, paraparesis, depression, or seizures. Symptoms can also include fatigue, impaired mobility, mood diagnosed changes, elimination dysfunction, and pain.

Of the four disease courses identified in MS, the most common is RRMS, characterized by a cycle of relapse and remission. In the initial stages, RRMS is characterized largely by an inflammatory pathology which, over time, becomes largely neurodegenerative. Most cases of RRMS evolve to secondary progressive MS after about 15 years. Early in the spectrum of demyelinating disease is clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), defined by a single episode of neurologic symptoms and MRI showing more than two classic lesions seen in MS. CIS patients subsequently will present with a second episode or relapse, at which point the diagnosis of RRMS is usually confirmed.

MS is diagnosed on the basis of clinical findings, exclusion of mimickers, and supporting evidence from the workup, namely MRI of the brain and spinal cord as well as cerebrospinal fluid examination. From a clinical perspective, presentation must align with the constellation of neurologic deficits seen in MS. Typically, the duration of deficit is days to weeks, as seen in the present case. While MRI alone cannot be used to diagnose MS, imaging may confirm diagnosis and offer value in monitoring disease progression in the brain and spinal cord. New lesions on MRI usually occur with relapses in RRMS.

Treatment of MS encompasses immunomodulatory therapy to address the underlying immune disorder together with therapies to relieve symptoms. In general, disease-modifying therapy (DMT) should be considered for patients who have experienced a single demyelinating event and exhibit two or more brain lesions on MRI testing. This recommendation holds true even for patients with CIS or those who have experienced their first clinical event and have MRI features consistent with MS, so long as all other conditions in the differential are ruled out. Pivotal trials support the early initiation of DMT with CIS to delay disability.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme

The patient is probably presenting with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS). MS is characterized by symptomatic episodes that are heralded by symptoms of central nervous system involvement. These attacks last longer than 24 hours and may occur months or years apart and affect different anatomic locations. Consistent with other autoimmune conditions, MS is more common in women. Patients are usually diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 49 years. The condition presents differently from patient to patient; some experience cognitive changes or visual symptoms, while others may have numbness, ataxia, clumsiness, hemiparesis, paraparesis, depression, or seizures. Symptoms can also include fatigue, impaired mobility, mood diagnosed changes, elimination dysfunction, and pain.

Of the four disease courses identified in MS, the most common is RRMS, characterized by a cycle of relapse and remission. In the initial stages, RRMS is characterized largely by an inflammatory pathology which, over time, becomes largely neurodegenerative. Most cases of RRMS evolve to secondary progressive MS after about 15 years. Early in the spectrum of demyelinating disease is clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), defined by a single episode of neurologic symptoms and MRI showing more than two classic lesions seen in MS. CIS patients subsequently will present with a second episode or relapse, at which point the diagnosis of RRMS is usually confirmed.

MS is diagnosed on the basis of clinical findings, exclusion of mimickers, and supporting evidence from the workup, namely MRI of the brain and spinal cord as well as cerebrospinal fluid examination. From a clinical perspective, presentation must align with the constellation of neurologic deficits seen in MS. Typically, the duration of deficit is days to weeks, as seen in the present case. While MRI alone cannot be used to diagnose MS, imaging may confirm diagnosis and offer value in monitoring disease progression in the brain and spinal cord. New lesions on MRI usually occur with relapses in RRMS.

Treatment of MS encompasses immunomodulatory therapy to address the underlying immune disorder together with therapies to relieve symptoms. In general, disease-modifying therapy (DMT) should be considered for patients who have experienced a single demyelinating event and exhibit two or more brain lesions on MRI testing. This recommendation holds true even for patients with CIS or those who have experienced their first clinical event and have MRI features consistent with MS, so long as all other conditions in the differential are ruled out. Pivotal trials support the early initiation of DMT with CIS to delay disability.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme

A 51-year-old woman reports that she has been feeling fatigued despite the absence of any significant medical history. Although she usually walks to work, lately she has not had the energy to participate in her daily routine. She notes that over the past 2 weeks, colleagues have asked her if she is feeling well due to unusual ocular symptoms. She explains that several months ago she felt similarly unwell, with fatigue and generalized weakness, but her symptoms seemed to resolve. Upon presentation, she has diplopia on lateral gaze. MRI reveals lesions with high T2 signal intensity.

6-year-old with loud wheezing, difficulty breathing

The patient is probably presenting with a moderate asthma exacerbation. To confirm the diagnosis, spirometry assessments should be performed to establish the presence of baseline airway obstruction and determine its severity. Measurements should be obtained before and after inhalation of a short-acting bronchodilator. In addition, chest radiography can help to exclude other diagnoses, and pulse oximetry can exclude hypoxemia.

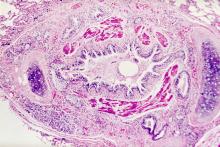

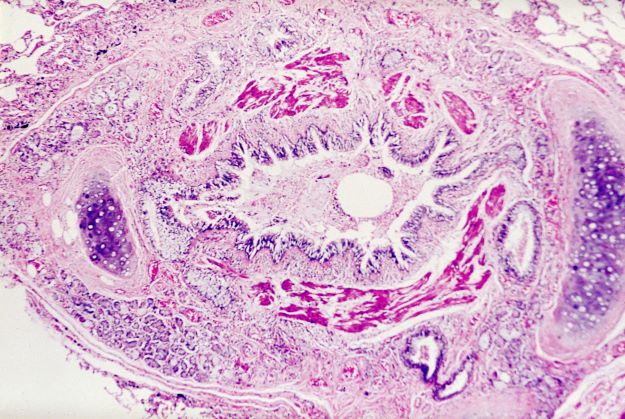

Asthma is a heterogeneous inflammatory disease and the most common chronic condition among children. Histologically, it is marked by vascular congestion, increased vascular permeability, increased tissue volume, and the presence of an exudate. Because the asthmatic lung undergoes a cycle of injury, repair, and regeneration, inflammation creates histologic changes and functional abnormalities in the airway mucosal epithelium. It is hypothesized that these changes play a major role in the pathophysiology of asthma.

Eosinophilic infiltration is a hallmark of this inflammatory activity. Histologic evaluations of the large airways may also reveal narrowing of lumina, bronchial and bronchiolar epithelial denudation, and mucus plugs. Other relevant findings can include epithelial desquamation and hyperplasia, goblet cell metaplasia, subbasement membrane thickening, smooth muscle hypertrophy or hyperplasia, and submucosal gland hypertrophy. In patients with severe asthma, the basement membrane may be significantly thickened. In terms of the small airways, pathologic study from the lungs of living patients is rarely undertaken, and therefore the histopathologic findings of asthma at the level of the distal airways and alveolated lung parenchyma remains largely unknown.

Asthma is treated using a stepwise approach. As directed for pediatric patients younger than 5 years, the patient in this case may be provided with an as-needed inhaled short-acting beta2-agonist (SABA) and should be followed up every 2-6 weeks while gaining control of her symptoms.

Nathan L. Boyer, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland; Chief of Critical Care, Landstuhl Regional Medical Center, Landstuhl, Germany.

Nathan L. Boyer, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The patient is probably presenting with a moderate asthma exacerbation. To confirm the diagnosis, spirometry assessments should be performed to establish the presence of baseline airway obstruction and determine its severity. Measurements should be obtained before and after inhalation of a short-acting bronchodilator. In addition, chest radiography can help to exclude other diagnoses, and pulse oximetry can exclude hypoxemia.

Asthma is a heterogeneous inflammatory disease and the most common chronic condition among children. Histologically, it is marked by vascular congestion, increased vascular permeability, increased tissue volume, and the presence of an exudate. Because the asthmatic lung undergoes a cycle of injury, repair, and regeneration, inflammation creates histologic changes and functional abnormalities in the airway mucosal epithelium. It is hypothesized that these changes play a major role in the pathophysiology of asthma.

Eosinophilic infiltration is a hallmark of this inflammatory activity. Histologic evaluations of the large airways may also reveal narrowing of lumina, bronchial and bronchiolar epithelial denudation, and mucus plugs. Other relevant findings can include epithelial desquamation and hyperplasia, goblet cell metaplasia, subbasement membrane thickening, smooth muscle hypertrophy or hyperplasia, and submucosal gland hypertrophy. In patients with severe asthma, the basement membrane may be significantly thickened. In terms of the small airways, pathologic study from the lungs of living patients is rarely undertaken, and therefore the histopathologic findings of asthma at the level of the distal airways and alveolated lung parenchyma remains largely unknown.

Asthma is treated using a stepwise approach. As directed for pediatric patients younger than 5 years, the patient in this case may be provided with an as-needed inhaled short-acting beta2-agonist (SABA) and should be followed up every 2-6 weeks while gaining control of her symptoms.

Nathan L. Boyer, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland; Chief of Critical Care, Landstuhl Regional Medical Center, Landstuhl, Germany.

Nathan L. Boyer, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The patient is probably presenting with a moderate asthma exacerbation. To confirm the diagnosis, spirometry assessments should be performed to establish the presence of baseline airway obstruction and determine its severity. Measurements should be obtained before and after inhalation of a short-acting bronchodilator. In addition, chest radiography can help to exclude other diagnoses, and pulse oximetry can exclude hypoxemia.

Asthma is a heterogeneous inflammatory disease and the most common chronic condition among children. Histologically, it is marked by vascular congestion, increased vascular permeability, increased tissue volume, and the presence of an exudate. Because the asthmatic lung undergoes a cycle of injury, repair, and regeneration, inflammation creates histologic changes and functional abnormalities in the airway mucosal epithelium. It is hypothesized that these changes play a major role in the pathophysiology of asthma.

Eosinophilic infiltration is a hallmark of this inflammatory activity. Histologic evaluations of the large airways may also reveal narrowing of lumina, bronchial and bronchiolar epithelial denudation, and mucus plugs. Other relevant findings can include epithelial desquamation and hyperplasia, goblet cell metaplasia, subbasement membrane thickening, smooth muscle hypertrophy or hyperplasia, and submucosal gland hypertrophy. In patients with severe asthma, the basement membrane may be significantly thickened. In terms of the small airways, pathologic study from the lungs of living patients is rarely undertaken, and therefore the histopathologic findings of asthma at the level of the distal airways and alveolated lung parenchyma remains largely unknown.

Asthma is treated using a stepwise approach. As directed for pediatric patients younger than 5 years, the patient in this case may be provided with an as-needed inhaled short-acting beta2-agonist (SABA) and should be followed up every 2-6 weeks while gaining control of her symptoms.

Nathan L. Boyer, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland; Chief of Critical Care, Landstuhl Regional Medical Center, Landstuhl, Germany.

Nathan L. Boyer, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 6-year-old girl presents with loud wheezing, difficulty breathing, and nasal flaring. She becomes particularly breathless while talking. The only abnormalities on chest CT are reduced airway luminal area and mucus plugs. Heart rate is 110 beats/min. Oxyhemoglobin saturation with room air is 94%. Skin examination is nonrevealing. The patient's mother cannot identify any factors that may have precipitated the episode.

Inflamed skin lesions on legs

Superinfected eczema is an inflammation of the skin accompanied by itchy, weeping, oozing lesions. Secondary infection of the open skin can occur as a result of scratching. In this case, the infection was a consequence of sensitivity to wearing shin pads.

Although superinfected eczema is a complication of eczema, it can produce separate challenges. With damaged protective skin function and disturbance of quantity and quality of skin lipids, patients with eczema may have secondary bacterial infections. Staphylococcus aureus organisms are the most common etiologic agents; up to 90% of patients with eczema have staphylococcal colonization. Streptococcus is less commonly a cause. The progression from colonization to infection often is associated with a flare of eczema, and increased severity of the eczema is associated with more colonization. More erythema may be noted when the infection begins; then, the affected areas become encrusted or show a serous drainage. A clinical clue to superinfection of any kind is when patients stop responding to therapies that they are normally responsive to (eg, topical steroids).

With the recent increase in methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), treatment of a secondary infection of eczema with these organisms can be tricky. Patients with eczema and secondary bacterial skin infections should be treated with topical steroids or other anti-inflammatory medications and moisturizers to repair the skin barrier. The level of skin colonization with S. aureus is decreased with use of these agents alone. Topical or systemic antibiotics appropriate for specific or community-based sensitivities may be needed in severe infections.

Because of the damaged protective skin function, cutaneous inoculation of herpes simplex virus (HSV) can occur. Eczema herpeticum, or HSV-associated Kaposi varicelliform eruption, describes eczema secondarily infected with HSV (type 1 or type 2). The eczema may become more erythematous; then, vesicles develop that are arranged in a grouped pattern. Accompanying symptoms include fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. The condition can be diagnosed by a Tzanck smear (seeking multinucleated giant cells), a fluorescent antibody smear, or culture of a vesicular lesion. Patients with eczema herpeticum should be treated with acyclovir. More severe involvement may require hospitalization and use of systemic antivirals. In addition, topical steroids and moisturizers should be continued to repair the skin barrier.

Children with eczema are more likely than adults to acquire molluscum contagiosum infection, and the disease tends to be widespread. The lesions are generally smooth papules, sometimes with umbilicated skin. The lesions can spread by auto-inoculation to surrounding areas. Molluscum dermatitis accompanies 10% of molluscum lesions, and the dermatitis can be difficult to distinguish from eczema lesions. Untreated, molluscum lesions may resolve on their own; if necessary, the lesions can be treated with cantharidin, liquid nitrogen, or curettage.

Molluscum dermatitis is treated with topical steroids. Early recognition of infections associated with a diagnosis of eczema is critical for timely initiation of appropriate treatment.

Brian S. Kim, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Dermatology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri

Brian S. Kim, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Superinfected eczema is an inflammation of the skin accompanied by itchy, weeping, oozing lesions. Secondary infection of the open skin can occur as a result of scratching. In this case, the infection was a consequence of sensitivity to wearing shin pads.

Although superinfected eczema is a complication of eczema, it can produce separate challenges. With damaged protective skin function and disturbance of quantity and quality of skin lipids, patients with eczema may have secondary bacterial infections. Staphylococcus aureus organisms are the most common etiologic agents; up to 90% of patients with eczema have staphylococcal colonization. Streptococcus is less commonly a cause. The progression from colonization to infection often is associated with a flare of eczema, and increased severity of the eczema is associated with more colonization. More erythema may be noted when the infection begins; then, the affected areas become encrusted or show a serous drainage. A clinical clue to superinfection of any kind is when patients stop responding to therapies that they are normally responsive to (eg, topical steroids).

With the recent increase in methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), treatment of a secondary infection of eczema with these organisms can be tricky. Patients with eczema and secondary bacterial skin infections should be treated with topical steroids or other anti-inflammatory medications and moisturizers to repair the skin barrier. The level of skin colonization with S. aureus is decreased with use of these agents alone. Topical or systemic antibiotics appropriate for specific or community-based sensitivities may be needed in severe infections.

Because of the damaged protective skin function, cutaneous inoculation of herpes simplex virus (HSV) can occur. Eczema herpeticum, or HSV-associated Kaposi varicelliform eruption, describes eczema secondarily infected with HSV (type 1 or type 2). The eczema may become more erythematous; then, vesicles develop that are arranged in a grouped pattern. Accompanying symptoms include fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. The condition can be diagnosed by a Tzanck smear (seeking multinucleated giant cells), a fluorescent antibody smear, or culture of a vesicular lesion. Patients with eczema herpeticum should be treated with acyclovir. More severe involvement may require hospitalization and use of systemic antivirals. In addition, topical steroids and moisturizers should be continued to repair the skin barrier.

Children with eczema are more likely than adults to acquire molluscum contagiosum infection, and the disease tends to be widespread. The lesions are generally smooth papules, sometimes with umbilicated skin. The lesions can spread by auto-inoculation to surrounding areas. Molluscum dermatitis accompanies 10% of molluscum lesions, and the dermatitis can be difficult to distinguish from eczema lesions. Untreated, molluscum lesions may resolve on their own; if necessary, the lesions can be treated with cantharidin, liquid nitrogen, or curettage.

Molluscum dermatitis is treated with topical steroids. Early recognition of infections associated with a diagnosis of eczema is critical for timely initiation of appropriate treatment.

Brian S. Kim, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Dermatology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri

Brian S. Kim, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Superinfected eczema is an inflammation of the skin accompanied by itchy, weeping, oozing lesions. Secondary infection of the open skin can occur as a result of scratching. In this case, the infection was a consequence of sensitivity to wearing shin pads.

Although superinfected eczema is a complication of eczema, it can produce separate challenges. With damaged protective skin function and disturbance of quantity and quality of skin lipids, patients with eczema may have secondary bacterial infections. Staphylococcus aureus organisms are the most common etiologic agents; up to 90% of patients with eczema have staphylococcal colonization. Streptococcus is less commonly a cause. The progression from colonization to infection often is associated with a flare of eczema, and increased severity of the eczema is associated with more colonization. More erythema may be noted when the infection begins; then, the affected areas become encrusted or show a serous drainage. A clinical clue to superinfection of any kind is when patients stop responding to therapies that they are normally responsive to (eg, topical steroids).

With the recent increase in methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), treatment of a secondary infection of eczema with these organisms can be tricky. Patients with eczema and secondary bacterial skin infections should be treated with topical steroids or other anti-inflammatory medications and moisturizers to repair the skin barrier. The level of skin colonization with S. aureus is decreased with use of these agents alone. Topical or systemic antibiotics appropriate for specific or community-based sensitivities may be needed in severe infections.

Because of the damaged protective skin function, cutaneous inoculation of herpes simplex virus (HSV) can occur. Eczema herpeticum, or HSV-associated Kaposi varicelliform eruption, describes eczema secondarily infected with HSV (type 1 or type 2). The eczema may become more erythematous; then, vesicles develop that are arranged in a grouped pattern. Accompanying symptoms include fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. The condition can be diagnosed by a Tzanck smear (seeking multinucleated giant cells), a fluorescent antibody smear, or culture of a vesicular lesion. Patients with eczema herpeticum should be treated with acyclovir. More severe involvement may require hospitalization and use of systemic antivirals. In addition, topical steroids and moisturizers should be continued to repair the skin barrier.

Children with eczema are more likely than adults to acquire molluscum contagiosum infection, and the disease tends to be widespread. The lesions are generally smooth papules, sometimes with umbilicated skin. The lesions can spread by auto-inoculation to surrounding areas. Molluscum dermatitis accompanies 10% of molluscum lesions, and the dermatitis can be difficult to distinguish from eczema lesions. Untreated, molluscum lesions may resolve on their own; if necessary, the lesions can be treated with cantharidin, liquid nitrogen, or curettage.

Molluscum dermatitis is treated with topical steroids. Early recognition of infections associated with a diagnosis of eczema is critical for timely initiation of appropriate treatment.

Brian S. Kim, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Dermatology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri

Brian S. Kim, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

An 11-year-old boy presents with diffuse, inflamed lesions on both shins. His mother first noticed the abrasions when he was scratching them to the point where they bled. He doesn't remember any insect bites, but as a catcher on his Little League baseball team, he noticed that the lesions are always worse after a game and after practice. He is generally healthy and of normal weight for his height. He has no history of allergies or asthma.

Abdominal pain and urinary frequency

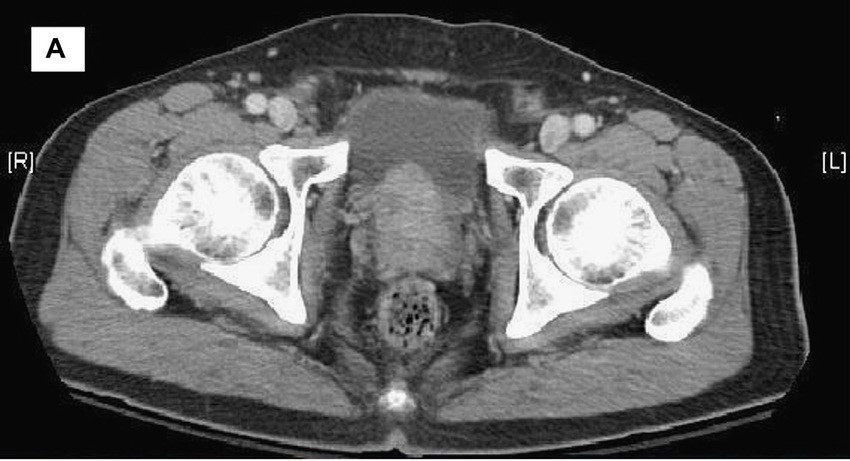

Transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS)–guided needle biopsy of the prostate confirms a diagnosis of high-grade prostate cancer, and the digital rectal exam and CT scan are concerning for extracapsular invasion. Genetic and molecular biomarker testing is recommended.

According to GLOBOCAN 2020 data, prostate cancer is the second most common type of cancer in men (second only to lung cancer) and the fifth leading cause of death globally. Compared with other races, the incidence of prostate cancer in the United States is highest in Black men, and mortality rates are more than double than those reported in White men. In its early stages, prostate cancer is often asymptomatic and has an indolent course. Locally advanced prostate cancer is a clinical scenario in which the cancer has extended beyond the prostatic capsule. It involves invasion of the pericapsular tissue, bladder neck, or seminal vesicles, without lymph node involvement or distant metastases. Biological recurrence, metastatic progression, and poor survival are associated with locally advanced prostate cancer.

In the presence of advanced disease, troublesome lower urinary tract symptoms — particularly abnormal growth of prostate cancer–induced bladder outlet obstruction — are often reported. Such symptoms have a significant impact on patients' quality of life. Other symptoms of locally advanced disease may include hematuria, pain, urinary retention, urinary incontinence, hematospermia, painful ejaculation, anejaculation, constipation, and hematochezia.

Guideline-based approaches to the management of prostate cancer begin with appropriate risk stratification based on biopsy, physical examination, and imaging evaluation. In patients with advanced prostate cancer, treatment decisions should incorporate a multidisciplinary approach and include consideration of life expectancy, comorbidities, patient preferences, and tumor characteristics. Establishing whether the patient has widely advanced disease vs locally advanced disease (clinical stage T3) is helpful for ascertaining which treatment options are available. Pain control and other supportive therapies should be optimized in cases involving advanced prostate cancer.

Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), combined with luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists or surgical castration, is considered first-line treatment for advanced metastatic prostate cancer. Abundant data show that ADT in advanced symptomatic metastatic prostate cancer, either in the form of surgical castration or LHRH analogues, is beneficial chiefly for palliation of symptoms. However, the combination of ADT with radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy has been shown to improve overall and cancer-specific survival in selected patients with nonmetastatic but locally advanced prostate cancer. Recently, a prospective study showed a significant improvement in urodynamic variables and International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) questionnaire results, including IPSS-related quality of life, in patients with advanced cancer who received ADT, although lower urinary tract symptoms persist in some patients.

For patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC), continued treatment with ADT in combination with either androgen pathway–directed therapy (abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, apalutamide, enzalutamide) or chemotherapy (docetaxel) is generally recommended. A recent meta-analysis found that the next-generation androgen receptor inhibitors abiraterone, apalutamide, and enzalutamide appear to be significantly more effective than ADT and more effective than docetaxel for mHSPC; apalutamide was the best tolerated. For selected patients with mHSPC with low-volume metastatic disease, primary radiation therapy to the prostate in combination with ADT may be offered. First-generation antiandrogens (bicalutamide, flutamide, nilutamide) in combination with LHRH agonists are not recommended for patients with mHSPC, unless needed to block testosterone flare. In addition, oral androgen pathway–directed therapy (eg, abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, apalutamide, bicalutamide, darolutamide, enzalutamide, flutamide, nilutamide) without ADT is not recommended for patients with mHSPC.

In patients with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC), darolutamide, apalutamide, and enzalutamide with continued ADT have been shown to postpone the onset of metastases and death. Unless within the context of a clinical trial, systemic chemotherapy or immunotherapy should not be offered to patients with nmCRPC.

For patients with newly diagnosed metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), continued ADT with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, docetaxel, or enzalutamide is recommended. For patients with mCRPC who are asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic, sipuleucel-T may be offered. At present, radium-223 is the only available therapy for mCRPC that specifically targets bone metastases, delays development of skeletal-related events, and improves survival. On the basis of results of the ALSYMPCA study, radium-223 in combination with systemic therapies is now considered an effective, efficient, and well-tolerated therapy for patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer with bone lesions. The effects of local radiation therapy for men with metastatic prostate cancer and the optimal combination of systemic therapies in the metastatic setting are still under investigation.

Complete recommendations on sequencing agents and selecting therapies for patients with advanced prostate cancer can be found in guidelines from the American Urological Association, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the European Association of Urology.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS)–guided needle biopsy of the prostate confirms a diagnosis of high-grade prostate cancer, and the digital rectal exam and CT scan are concerning for extracapsular invasion. Genetic and molecular biomarker testing is recommended.

According to GLOBOCAN 2020 data, prostate cancer is the second most common type of cancer in men (second only to lung cancer) and the fifth leading cause of death globally. Compared with other races, the incidence of prostate cancer in the United States is highest in Black men, and mortality rates are more than double than those reported in White men. In its early stages, prostate cancer is often asymptomatic and has an indolent course. Locally advanced prostate cancer is a clinical scenario in which the cancer has extended beyond the prostatic capsule. It involves invasion of the pericapsular tissue, bladder neck, or seminal vesicles, without lymph node involvement or distant metastases. Biological recurrence, metastatic progression, and poor survival are associated with locally advanced prostate cancer.

In the presence of advanced disease, troublesome lower urinary tract symptoms — particularly abnormal growth of prostate cancer–induced bladder outlet obstruction — are often reported. Such symptoms have a significant impact on patients' quality of life. Other symptoms of locally advanced disease may include hematuria, pain, urinary retention, urinary incontinence, hematospermia, painful ejaculation, anejaculation, constipation, and hematochezia.

Guideline-based approaches to the management of prostate cancer begin with appropriate risk stratification based on biopsy, physical examination, and imaging evaluation. In patients with advanced prostate cancer, treatment decisions should incorporate a multidisciplinary approach and include consideration of life expectancy, comorbidities, patient preferences, and tumor characteristics. Establishing whether the patient has widely advanced disease vs locally advanced disease (clinical stage T3) is helpful for ascertaining which treatment options are available. Pain control and other supportive therapies should be optimized in cases involving advanced prostate cancer.

Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), combined with luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists or surgical castration, is considered first-line treatment for advanced metastatic prostate cancer. Abundant data show that ADT in advanced symptomatic metastatic prostate cancer, either in the form of surgical castration or LHRH analogues, is beneficial chiefly for palliation of symptoms. However, the combination of ADT with radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy has been shown to improve overall and cancer-specific survival in selected patients with nonmetastatic but locally advanced prostate cancer. Recently, a prospective study showed a significant improvement in urodynamic variables and International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) questionnaire results, including IPSS-related quality of life, in patients with advanced cancer who received ADT, although lower urinary tract symptoms persist in some patients.

For patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC), continued treatment with ADT in combination with either androgen pathway–directed therapy (abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, apalutamide, enzalutamide) or chemotherapy (docetaxel) is generally recommended. A recent meta-analysis found that the next-generation androgen receptor inhibitors abiraterone, apalutamide, and enzalutamide appear to be significantly more effective than ADT and more effective than docetaxel for mHSPC; apalutamide was the best tolerated. For selected patients with mHSPC with low-volume metastatic disease, primary radiation therapy to the prostate in combination with ADT may be offered. First-generation antiandrogens (bicalutamide, flutamide, nilutamide) in combination with LHRH agonists are not recommended for patients with mHSPC, unless needed to block testosterone flare. In addition, oral androgen pathway–directed therapy (eg, abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, apalutamide, bicalutamide, darolutamide, enzalutamide, flutamide, nilutamide) without ADT is not recommended for patients with mHSPC.

In patients with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC), darolutamide, apalutamide, and enzalutamide with continued ADT have been shown to postpone the onset of metastases and death. Unless within the context of a clinical trial, systemic chemotherapy or immunotherapy should not be offered to patients with nmCRPC.

For patients with newly diagnosed metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), continued ADT with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, docetaxel, or enzalutamide is recommended. For patients with mCRPC who are asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic, sipuleucel-T may be offered. At present, radium-223 is the only available therapy for mCRPC that specifically targets bone metastases, delays development of skeletal-related events, and improves survival. On the basis of results of the ALSYMPCA study, radium-223 in combination with systemic therapies is now considered an effective, efficient, and well-tolerated therapy for patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer with bone lesions. The effects of local radiation therapy for men with metastatic prostate cancer and the optimal combination of systemic therapies in the metastatic setting are still under investigation.

Complete recommendations on sequencing agents and selecting therapies for patients with advanced prostate cancer can be found in guidelines from the American Urological Association, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the European Association of Urology.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS)–guided needle biopsy of the prostate confirms a diagnosis of high-grade prostate cancer, and the digital rectal exam and CT scan are concerning for extracapsular invasion. Genetic and molecular biomarker testing is recommended.

According to GLOBOCAN 2020 data, prostate cancer is the second most common type of cancer in men (second only to lung cancer) and the fifth leading cause of death globally. Compared with other races, the incidence of prostate cancer in the United States is highest in Black men, and mortality rates are more than double than those reported in White men. In its early stages, prostate cancer is often asymptomatic and has an indolent course. Locally advanced prostate cancer is a clinical scenario in which the cancer has extended beyond the prostatic capsule. It involves invasion of the pericapsular tissue, bladder neck, or seminal vesicles, without lymph node involvement or distant metastases. Biological recurrence, metastatic progression, and poor survival are associated with locally advanced prostate cancer.

In the presence of advanced disease, troublesome lower urinary tract symptoms — particularly abnormal growth of prostate cancer–induced bladder outlet obstruction — are often reported. Such symptoms have a significant impact on patients' quality of life. Other symptoms of locally advanced disease may include hematuria, pain, urinary retention, urinary incontinence, hematospermia, painful ejaculation, anejaculation, constipation, and hematochezia.

Guideline-based approaches to the management of prostate cancer begin with appropriate risk stratification based on biopsy, physical examination, and imaging evaluation. In patients with advanced prostate cancer, treatment decisions should incorporate a multidisciplinary approach and include consideration of life expectancy, comorbidities, patient preferences, and tumor characteristics. Establishing whether the patient has widely advanced disease vs locally advanced disease (clinical stage T3) is helpful for ascertaining which treatment options are available. Pain control and other supportive therapies should be optimized in cases involving advanced prostate cancer.

Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), combined with luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists or surgical castration, is considered first-line treatment for advanced metastatic prostate cancer. Abundant data show that ADT in advanced symptomatic metastatic prostate cancer, either in the form of surgical castration or LHRH analogues, is beneficial chiefly for palliation of symptoms. However, the combination of ADT with radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy has been shown to improve overall and cancer-specific survival in selected patients with nonmetastatic but locally advanced prostate cancer. Recently, a prospective study showed a significant improvement in urodynamic variables and International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) questionnaire results, including IPSS-related quality of life, in patients with advanced cancer who received ADT, although lower urinary tract symptoms persist in some patients.

For patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC), continued treatment with ADT in combination with either androgen pathway–directed therapy (abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, apalutamide, enzalutamide) or chemotherapy (docetaxel) is generally recommended. A recent meta-analysis found that the next-generation androgen receptor inhibitors abiraterone, apalutamide, and enzalutamide appear to be significantly more effective than ADT and more effective than docetaxel for mHSPC; apalutamide was the best tolerated. For selected patients with mHSPC with low-volume metastatic disease, primary radiation therapy to the prostate in combination with ADT may be offered. First-generation antiandrogens (bicalutamide, flutamide, nilutamide) in combination with LHRH agonists are not recommended for patients with mHSPC, unless needed to block testosterone flare. In addition, oral androgen pathway–directed therapy (eg, abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, apalutamide, bicalutamide, darolutamide, enzalutamide, flutamide, nilutamide) without ADT is not recommended for patients with mHSPC.

In patients with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC), darolutamide, apalutamide, and enzalutamide with continued ADT have been shown to postpone the onset of metastases and death. Unless within the context of a clinical trial, systemic chemotherapy or immunotherapy should not be offered to patients with nmCRPC.

For patients with newly diagnosed metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), continued ADT with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, docetaxel, or enzalutamide is recommended. For patients with mCRPC who are asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic, sipuleucel-T may be offered. At present, radium-223 is the only available therapy for mCRPC that specifically targets bone metastases, delays development of skeletal-related events, and improves survival. On the basis of results of the ALSYMPCA study, radium-223 in combination with systemic therapies is now considered an effective, efficient, and well-tolerated therapy for patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer with bone lesions. The effects of local radiation therapy for men with metastatic prostate cancer and the optimal combination of systemic therapies in the metastatic setting are still under investigation.

Complete recommendations on sequencing agents and selecting therapies for patients with advanced prostate cancer can be found in guidelines from the American Urological Association, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the European Association of Urology.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

A 58-year-old Black man presents with abdominal pain, urinary frequency and urgency, dysuria, incomplete voiding, and postmicturition dribble. The patient's medical history is unremarkable apart from stage 1 hypertension, for which he receives losartan plus amlodipine. Physical examination findings reveal an overdistended bladder with associated tenderness and a mildly enlarged prostate with a large, firm nodule on digital rectal exam. Urinalysis shows hematuria. Complete blood count and chemistry panel are normal. The total prostate-specific antigen level is 22 ng/mL.

History of asthma presents with wheezing and coughing

Subcutaneous emphysema is a rare complication of asthma exacerbation. The condition develops when air becomes trapped in the soft tissues under the skin. It can arise from surgical, traumatic, or infectious causes, but sometimes occurs spontaneously. Air accumulates in subcutaneous areas, dissecting along planes of the mediastinum to the tissues of the thorax, neck, and upper limbs. With pressure, the air may dissect to other planes, causing extensive subcutaneous spread which may lead to respiratory or cardiovascular collapse. Clinical findings include swelling and crepitus over the involved site, which is usually painless. Subcutaneous emphysema is closely linked with pneumomediastinum, which is characterized by chest pain, dyspnea, and the neck swelling associated with subcutaneous emphysema.

In children, exacerbations of asthma constitute the most common cause of subcutaneous emphysema, thought to be spurred by forced inhalation. It has also been suggested that patients who use inhaled corticosteroids may be at increased risk for tracheal injury with endotracheal intubation because mucosa is friable and thin.

Coupled with clinical symptoms, chest radiography can usually confirm subcutaneous emphysema, revealing air within the mediastinal space. Striations may be noted in the pectoralis major muscle group, a pattern which is referred to as a ginkgo leaf sign of the chest.

Subcutaneous emphysema is generally self-limiting and should resolve with treatment of the underlying cause. Conservative treatment with oxygen therapy may be beneficial.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Subcutaneous emphysema is a rare complication of asthma exacerbation. The condition develops when air becomes trapped in the soft tissues under the skin. It can arise from surgical, traumatic, or infectious causes, but sometimes occurs spontaneously. Air accumulates in subcutaneous areas, dissecting along planes of the mediastinum to the tissues of the thorax, neck, and upper limbs. With pressure, the air may dissect to other planes, causing extensive subcutaneous spread which may lead to respiratory or cardiovascular collapse. Clinical findings include swelling and crepitus over the involved site, which is usually painless. Subcutaneous emphysema is closely linked with pneumomediastinum, which is characterized by chest pain, dyspnea, and the neck swelling associated with subcutaneous emphysema.

In children, exacerbations of asthma constitute the most common cause of subcutaneous emphysema, thought to be spurred by forced inhalation. It has also been suggested that patients who use inhaled corticosteroids may be at increased risk for tracheal injury with endotracheal intubation because mucosa is friable and thin.

Coupled with clinical symptoms, chest radiography can usually confirm subcutaneous emphysema, revealing air within the mediastinal space. Striations may be noted in the pectoralis major muscle group, a pattern which is referred to as a ginkgo leaf sign of the chest.

Subcutaneous emphysema is generally self-limiting and should resolve with treatment of the underlying cause. Conservative treatment with oxygen therapy may be beneficial.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Subcutaneous emphysema is a rare complication of asthma exacerbation. The condition develops when air becomes trapped in the soft tissues under the skin. It can arise from surgical, traumatic, or infectious causes, but sometimes occurs spontaneously. Air accumulates in subcutaneous areas, dissecting along planes of the mediastinum to the tissues of the thorax, neck, and upper limbs. With pressure, the air may dissect to other planes, causing extensive subcutaneous spread which may lead to respiratory or cardiovascular collapse. Clinical findings include swelling and crepitus over the involved site, which is usually painless. Subcutaneous emphysema is closely linked with pneumomediastinum, which is characterized by chest pain, dyspnea, and the neck swelling associated with subcutaneous emphysema.

In children, exacerbations of asthma constitute the most common cause of subcutaneous emphysema, thought to be spurred by forced inhalation. It has also been suggested that patients who use inhaled corticosteroids may be at increased risk for tracheal injury with endotracheal intubation because mucosa is friable and thin.

Coupled with clinical symptoms, chest radiography can usually confirm subcutaneous emphysema, revealing air within the mediastinal space. Striations may be noted in the pectoralis major muscle group, a pattern which is referred to as a ginkgo leaf sign of the chest.

Subcutaneous emphysema is generally self-limiting and should resolve with treatment of the underlying cause. Conservative treatment with oxygen therapy may be beneficial.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

A 16-year-old female patient with a history of asthma presents with wheezing and coughing. Initial oxygen saturation is 89% and respiratory rate is 33 breaths/min. On physical examination, it is noted that the patient is using accessory muscles of ventilation. She was deemed to be having a severe asthma exacerbation and was treated with an inhaled bronchodilator. Several hours later, the patient's breathing frequency increased. Examination of the neck and chest revealed symmetrical swelling.

Man presents with diffuse pruritus

This patient has atopic dermatitis (AD), but on the basis of the image and description above, by no means would this be an intuitive diagnosis; the findings are not characteristic of those in younger patients with AD. Further, clinicians might find it difficult to diagnose AD in an older patient because older patients generally tend to have more comorbidities and medication side effects, including chronic pruritus of unknown origin and xerosis, which could confound the diagnosis.

Finally, specific guidelines are lacking for clinicians to distinguish AD from other pruritic skin conditions in the older patient. Currently, according to one report, older patients are diagnosed with AD after at least 6 months of symptom assessment and exclusion of other conditions, including cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, allergic contact dermatitis, psoriasis, drug reactions, and chronic idiopathic or secondary erythroderma.

AD arising de novo in older persons is a discrete form of the disease that characteristically involves the face, neck, trunk, and hands, while sparing the flexural areas, which are prominently involved in younger patients. The eczema can become erythrodermic. Older men are affected threefold more often than older women.

Skin manifestations in older patients with AD generally match those of adolescents and young adults with AD, but the reverse sign of lichenified eczema around unaffected folds of the elbows and knees is more common than the classic sign of localized lichenified eczema at those folds.

Factors rendering older people susceptible to AD include innate physiologic changes of aging, notably a decline in skin barrier function, dysregulation of innate immune cells, and skewing of adaptive immunity to a Th2 response.

Much about how to best treat AD in older patients remains unclear. It is a challenge to treat older patients according to standardized guidelines for general AD treatment because dermatologists and others need to consider comorbidities and the medications that these patients might already be taking. Some examples: Dermatologists might limit cyclosporine use in patients with hypertension and reduced kidney function, or limit systemic steroid use in patients with osteoporosis. Older patients have a greater propensity for infection, which might cause dermatologists to limit systemic immunosuppressant drugs. And skin thinning and diffuse photoaging might cause doctors to limit even topical steroid treatment in these patients.

As in other age groups, regular application of moisturizers in combination with calcineurin inhibitors, adjunctive administration of oral antihistamines and avoidance of exacerbating factors comprise basic treatments for AD in older patients.

Although antihistamines such as hydroxyzine can work for itching in some individuals, they are generally lacking in efficacy in most patients with AD.

Brian S. Kim, MD, is Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Dermatology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri

Brian S. Kim, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This patient has atopic dermatitis (AD), but on the basis of the image and description above, by no means would this be an intuitive diagnosis; the findings are not characteristic of those in younger patients with AD. Further, clinicians might find it difficult to diagnose AD in an older patient because older patients generally tend to have more comorbidities and medication side effects, including chronic pruritus of unknown origin and xerosis, which could confound the diagnosis.

Finally, specific guidelines are lacking for clinicians to distinguish AD from other pruritic skin conditions in the older patient. Currently, according to one report, older patients are diagnosed with AD after at least 6 months of symptom assessment and exclusion of other conditions, including cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, allergic contact dermatitis, psoriasis, drug reactions, and chronic idiopathic or secondary erythroderma.

AD arising de novo in older persons is a discrete form of the disease that characteristically involves the face, neck, trunk, and hands, while sparing the flexural areas, which are prominently involved in younger patients. The eczema can become erythrodermic. Older men are affected threefold more often than older women.

Skin manifestations in older patients with AD generally match those of adolescents and young adults with AD, but the reverse sign of lichenified eczema around unaffected folds of the elbows and knees is more common than the classic sign of localized lichenified eczema at those folds.

Factors rendering older people susceptible to AD include innate physiologic changes of aging, notably a decline in skin barrier function, dysregulation of innate immune cells, and skewing of adaptive immunity to a Th2 response.

Much about how to best treat AD in older patients remains unclear. It is a challenge to treat older patients according to standardized guidelines for general AD treatment because dermatologists and others need to consider comorbidities and the medications that these patients might already be taking. Some examples: Dermatologists might limit cyclosporine use in patients with hypertension and reduced kidney function, or limit systemic steroid use in patients with osteoporosis. Older patients have a greater propensity for infection, which might cause dermatologists to limit systemic immunosuppressant drugs. And skin thinning and diffuse photoaging might cause doctors to limit even topical steroid treatment in these patients.

As in other age groups, regular application of moisturizers in combination with calcineurin inhibitors, adjunctive administration of oral antihistamines and avoidance of exacerbating factors comprise basic treatments for AD in older patients.

Although antihistamines such as hydroxyzine can work for itching in some individuals, they are generally lacking in efficacy in most patients with AD.

Brian S. Kim, MD, is Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Dermatology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri

Brian S. Kim, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This patient has atopic dermatitis (AD), but on the basis of the image and description above, by no means would this be an intuitive diagnosis; the findings are not characteristic of those in younger patients with AD. Further, clinicians might find it difficult to diagnose AD in an older patient because older patients generally tend to have more comorbidities and medication side effects, including chronic pruritus of unknown origin and xerosis, which could confound the diagnosis.

Finally, specific guidelines are lacking for clinicians to distinguish AD from other pruritic skin conditions in the older patient. Currently, according to one report, older patients are diagnosed with AD after at least 6 months of symptom assessment and exclusion of other conditions, including cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, allergic contact dermatitis, psoriasis, drug reactions, and chronic idiopathic or secondary erythroderma.

AD arising de novo in older persons is a discrete form of the disease that characteristically involves the face, neck, trunk, and hands, while sparing the flexural areas, which are prominently involved in younger patients. The eczema can become erythrodermic. Older men are affected threefold more often than older women.

Skin manifestations in older patients with AD generally match those of adolescents and young adults with AD, but the reverse sign of lichenified eczema around unaffected folds of the elbows and knees is more common than the classic sign of localized lichenified eczema at those folds.

Factors rendering older people susceptible to AD include innate physiologic changes of aging, notably a decline in skin barrier function, dysregulation of innate immune cells, and skewing of adaptive immunity to a Th2 response.

Much about how to best treat AD in older patients remains unclear. It is a challenge to treat older patients according to standardized guidelines for general AD treatment because dermatologists and others need to consider comorbidities and the medications that these patients might already be taking. Some examples: Dermatologists might limit cyclosporine use in patients with hypertension and reduced kidney function, or limit systemic steroid use in patients with osteoporosis. Older patients have a greater propensity for infection, which might cause dermatologists to limit systemic immunosuppressant drugs. And skin thinning and diffuse photoaging might cause doctors to limit even topical steroid treatment in these patients.

As in other age groups, regular application of moisturizers in combination with calcineurin inhibitors, adjunctive administration of oral antihistamines and avoidance of exacerbating factors comprise basic treatments for AD in older patients.

Although antihistamines such as hydroxyzine can work for itching in some individuals, they are generally lacking in efficacy in most patients with AD.

Brian S. Kim, MD, is Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Dermatology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri

Brian S. Kim, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A 59-year-old man presents with diffuse pruritus that first appeared 6 months earlier. He developed worsening eczematous, erythematous papules on his hands and face which waxed and waned. The areas of eczema on his hands and face were erythrodermic. The pruritus was intermittently controlled with the antihistamine hydroxyzine, a potent topical corticosteroid, and over-the-counter skin lotions. The patient said he had no history of allergies or asthma.

Sudden onset of severe pain in left thigh

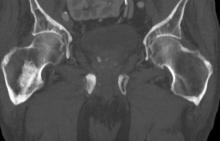

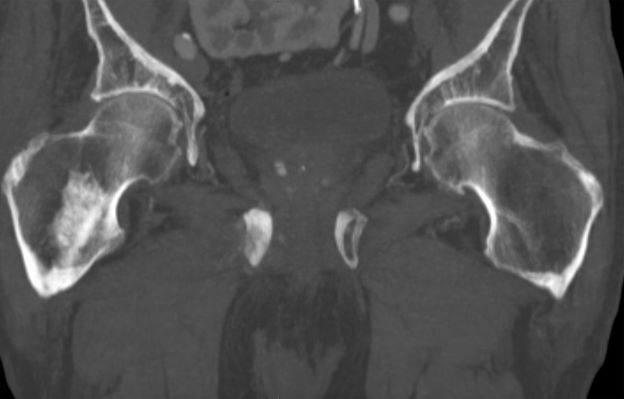

On the basis of the patient's physical examination, laboratory findings, and radiographic findings, a diagnosis of de novo metastatic prostate cancer is suspected and later confirmed by transrectal ultrasonography–guided needle biopsy of the prostate.

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer and the second most common cause of cancer-associated death in men in the United States. Among men diagnosed with prostate cancer in the United States, approximately three quarters have localized-stage disease at diagnosis; however, recent data show that an increasing number and percentage of men are being diagnosed with distant-stage prostate cancer. Despite advancements in treatment, less than one third of men survive 5 years after the diagnosis of distant-stage prostate cancer.

Prostate cancer frequently metastasizes to the bone. In fact, as many as 90% of patients with advanced prostate cancer have bone involvement. The morbidity from bone metastases is considerable and includes bone pain, immobility, pathologic fractures, hypercalcemia, hematologic disorders, and spinal cord compression. Bone metastases also have a considerable impact on mortality.

In patients with metastatic prostate cancer, determining the presence and extent of metastatic disease is essential for appropriate treatment to be selected. Studies have shown that the extent of metastatic disease affects treatment response. In a recent exploratory analysis of the STAMPEDE trial, survival benefit associated with prostate radiation therapy decreased continuously as the number of bone metastases rose, with the most benefit being seen in patients with up to three bone metastases.

Guidelines recommend that imaging studies be conducted in all patients with advanced prostate cancer. This may include conventional imaging (ie, CT, bone scan, and/or prostate MRI) and/or next-generation imaging (ie, PET, PET/CT, PET/MRI, whole-body MRI). In cases involving hormone-sensitive disease with obvious metastatic disease on conventional imaging at presentation, next-generation imaging may be useful for illuminating the disease burden and possibly shifting the treatment intent from multimodality management of oligometastatic disease to systemic anticancer therapy, either alone or in combination with targeted therapy for palliative purposes. However, prospective data on this are lacking.

Clinicians should also assess symptoms in patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer at presentation, because symptoms have been shown to have prognostic value. In addition, understanding symptoms related to cancer is essential for optimizing pain and other symptom management in addition to anticancer therapy.

Metastatic prostate cancer remains incurable. Immediate systemic treatment with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) combined with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone or apalutamide or enzalutamide should be offered to symptomatic patients who have distant metastases on diagnosis, both to alleviate symptoms and to lessen the risk for potential serious complications, such as spinal cord compression. ADT combined with docetaxel can also be offered to patients who are able to tolerate docetaxel.

ADT combined with prostate radiation therapy may be offered to patients with distant metastases and low-volume disease. However, when patients present with high-volume disease, referral to a clinical trial is recommended.

Surgery and/or local radiation therapy can be considered for patients with distant metastases and evidence of impending complications (eg, spinal cord compression or pathologic fracture).

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

On the basis of the patient's physical examination, laboratory findings, and radiographic findings, a diagnosis of de novo metastatic prostate cancer is suspected and later confirmed by transrectal ultrasonography–guided needle biopsy of the prostate.

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer and the second most common cause of cancer-associated death in men in the United States. Among men diagnosed with prostate cancer in the United States, approximately three quarters have localized-stage disease at diagnosis; however, recent data show that an increasing number and percentage of men are being diagnosed with distant-stage prostate cancer. Despite advancements in treatment, less than one third of men survive 5 years after the diagnosis of distant-stage prostate cancer.

Prostate cancer frequently metastasizes to the bone. In fact, as many as 90% of patients with advanced prostate cancer have bone involvement. The morbidity from bone metastases is considerable and includes bone pain, immobility, pathologic fractures, hypercalcemia, hematologic disorders, and spinal cord compression. Bone metastases also have a considerable impact on mortality.

In patients with metastatic prostate cancer, determining the presence and extent of metastatic disease is essential for appropriate treatment to be selected. Studies have shown that the extent of metastatic disease affects treatment response. In a recent exploratory analysis of the STAMPEDE trial, survival benefit associated with prostate radiation therapy decreased continuously as the number of bone metastases rose, with the most benefit being seen in patients with up to three bone metastases.

Guidelines recommend that imaging studies be conducted in all patients with advanced prostate cancer. This may include conventional imaging (ie, CT, bone scan, and/or prostate MRI) and/or next-generation imaging (ie, PET, PET/CT, PET/MRI, whole-body MRI). In cases involving hormone-sensitive disease with obvious metastatic disease on conventional imaging at presentation, next-generation imaging may be useful for illuminating the disease burden and possibly shifting the treatment intent from multimodality management of oligometastatic disease to systemic anticancer therapy, either alone or in combination with targeted therapy for palliative purposes. However, prospective data on this are lacking.

Clinicians should also assess symptoms in patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer at presentation, because symptoms have been shown to have prognostic value. In addition, understanding symptoms related to cancer is essential for optimizing pain and other symptom management in addition to anticancer therapy.

Metastatic prostate cancer remains incurable. Immediate systemic treatment with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) combined with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone or apalutamide or enzalutamide should be offered to symptomatic patients who have distant metastases on diagnosis, both to alleviate symptoms and to lessen the risk for potential serious complications, such as spinal cord compression. ADT combined with docetaxel can also be offered to patients who are able to tolerate docetaxel.

ADT combined with prostate radiation therapy may be offered to patients with distant metastases and low-volume disease. However, when patients present with high-volume disease, referral to a clinical trial is recommended.

Surgery and/or local radiation therapy can be considered for patients with distant metastases and evidence of impending complications (eg, spinal cord compression or pathologic fracture).