User login

Tuberculosis: In and out of the airways

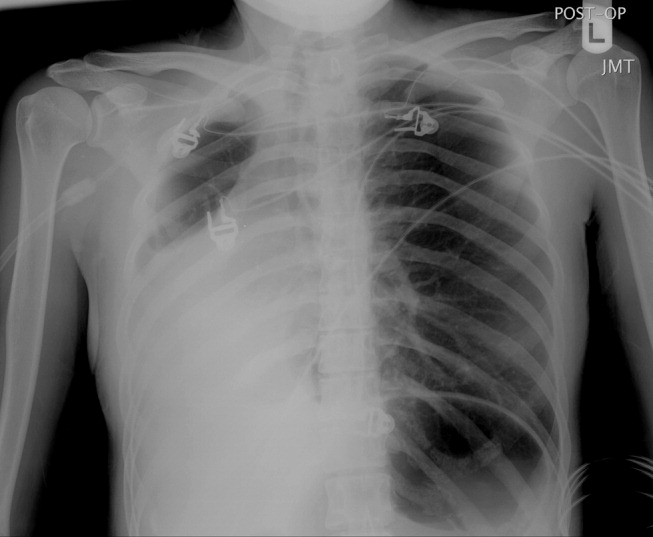

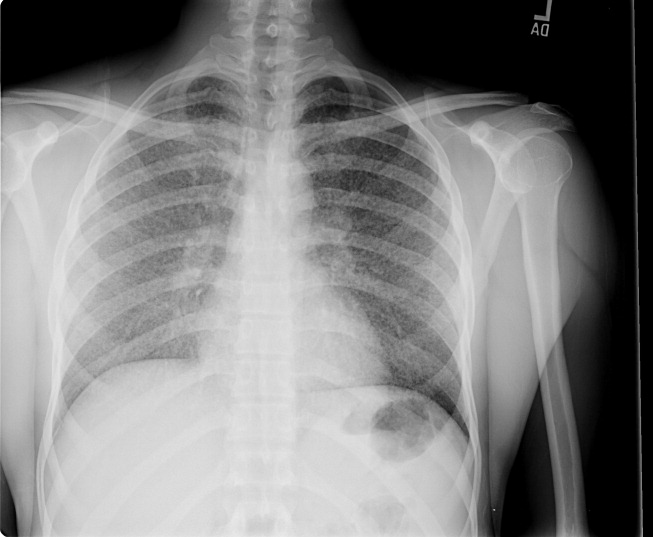

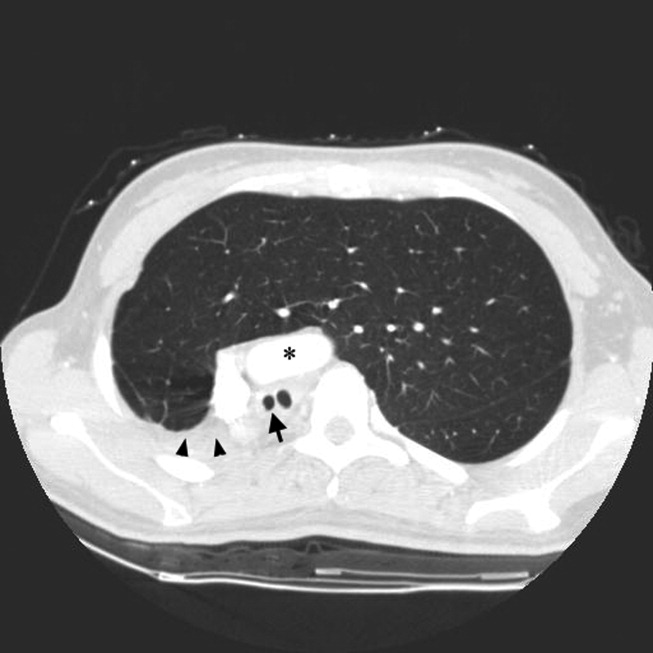

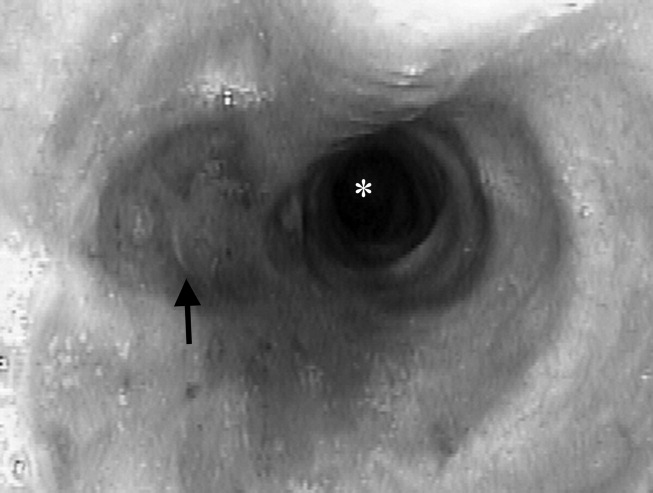

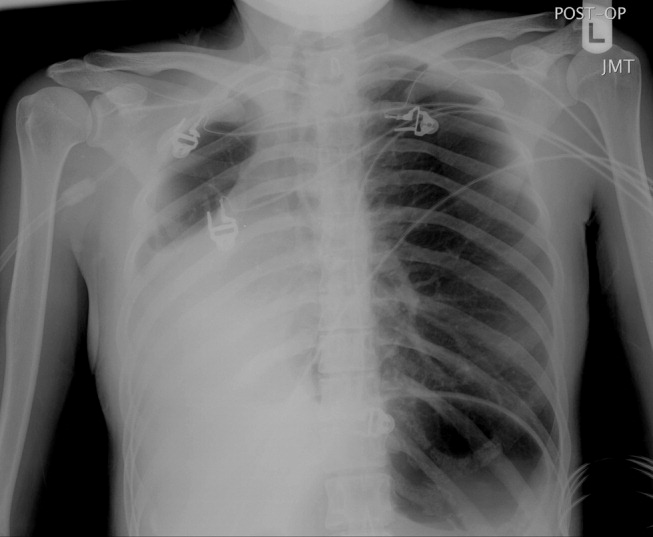

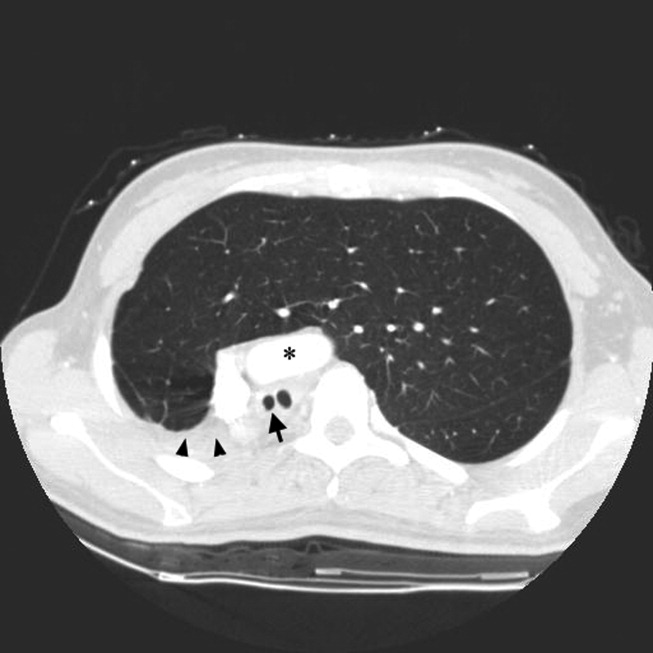

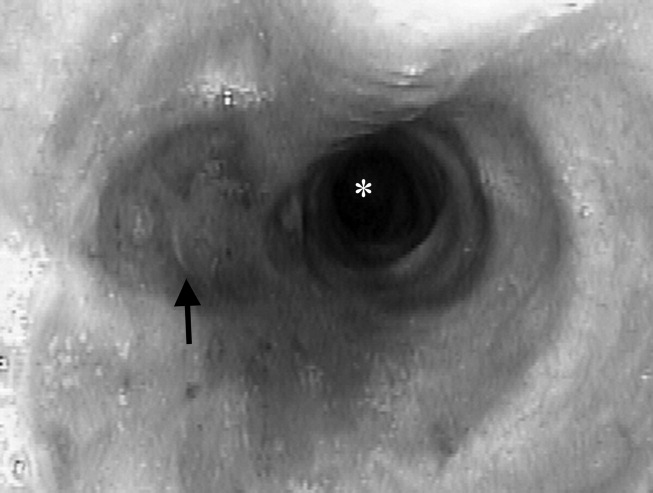

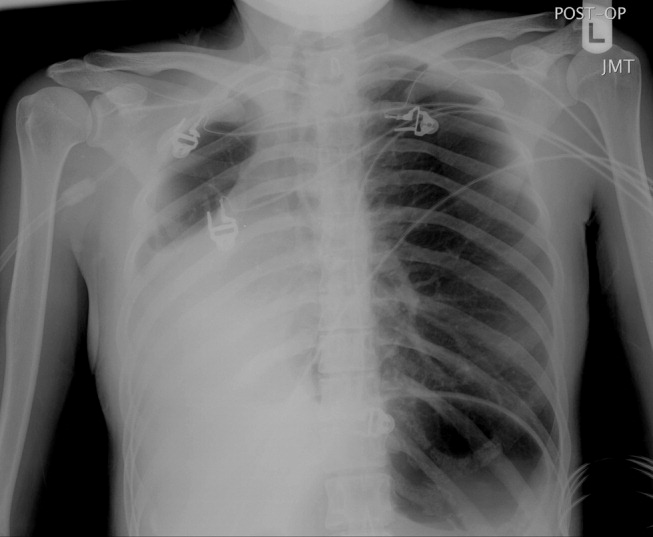

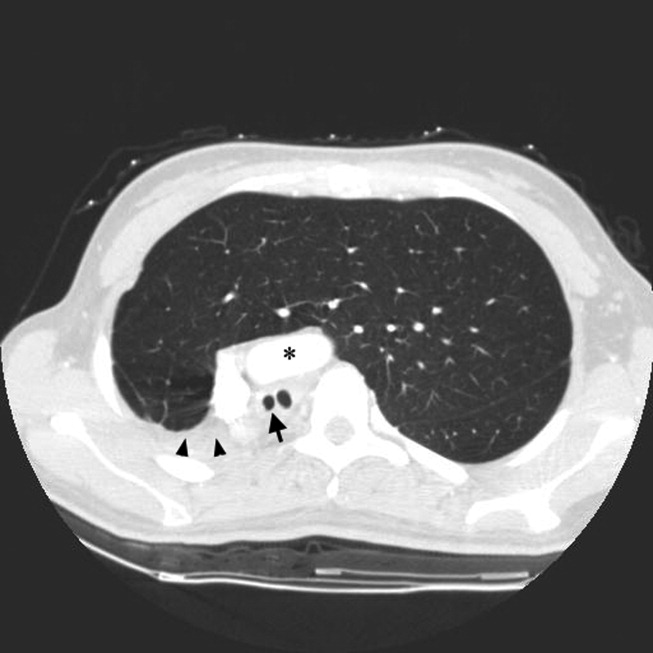

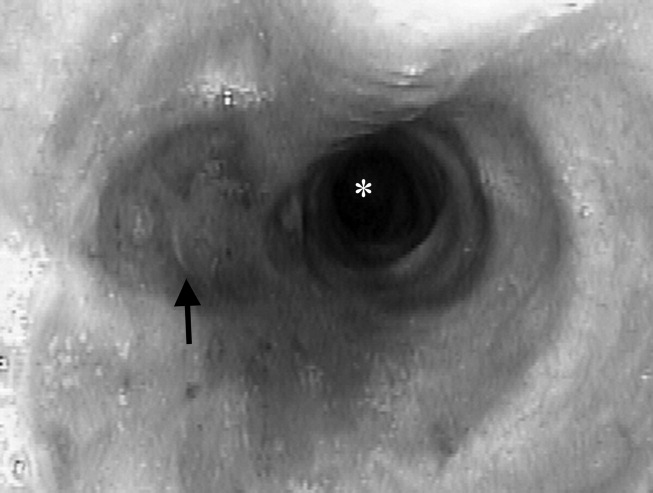

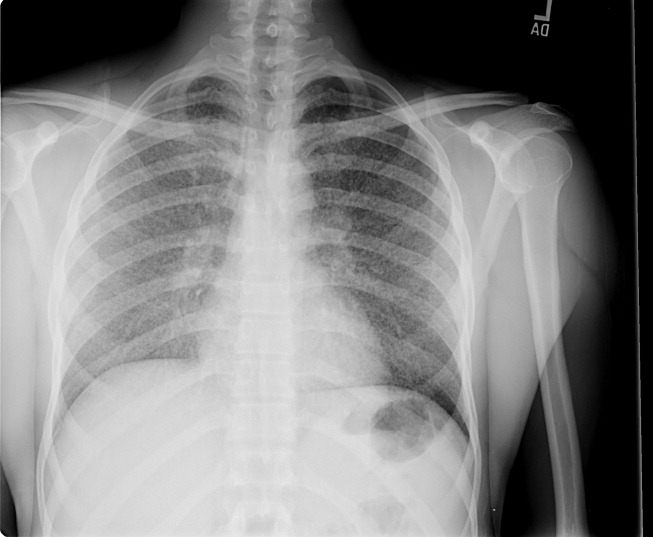

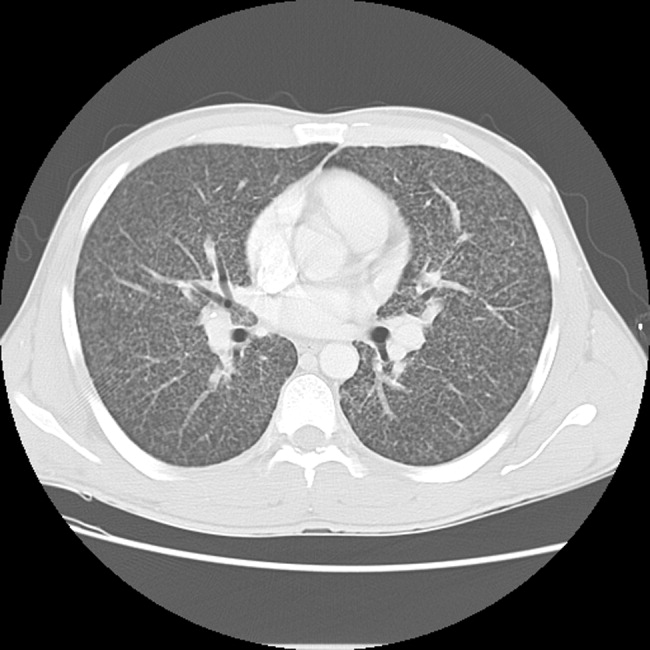

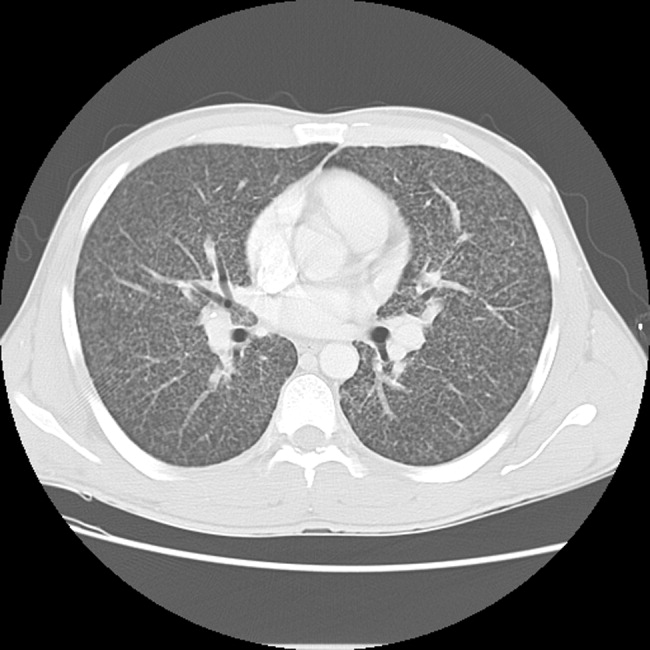

A 23‐year‐old Chinese woman presented with worsening exertional dyspnea. Her medical history was notable for pulmonary tuberculosis treated at the age of 16. Over the past 3 years, she reported progressive respiratory symptoms resulting in marked exercise intolerance. She denied any fevers, cough, or weight loss. On examination, she had right‐sided tracheal deviation but spoke comfortably. Her heart sounds were displaced and right‐sided breath sounds nearly absent. Chest x‐ray (Fig. 1) and subsequent CT revealed complete collapse of the right lung with associated hyperexpansion of the left lung and left‐to‐right mediastinal shift (Fig. 2, with an asterisk denoting the aortic arch; an arrow, the right main‐stem bronchus, which would soon terminate; and arrowheads, the collapsed right lung). No lung masses or effusions were noted; active TB had been ruled out with AFB sputums. Bronchoscopy revealed a fibrotic and stenotic right main‐stem bronchus (Fig. 3, with an asterisk denoting a patent left main‐stem bronchus and an arrow denoting a stenotic right main‐stem bronchus). Pulmonary manifestations of TB include parenchymal and endobronchial disease. Patients more likely to develop endobronchial disease include those with extensive pulmonary involvement, particularly cavitary lesions. Between 10% and 20% of patients with endobronchial disease will have normal CXRs, though CT scans may reveal endobronchial lesions or narrowing. Complications of endobronchial disease include obstruction, bronchiectasis, and tracheal or bronchial stenosis. Some airway obstructions may be associated with enlarging peribronchial nodes, which may erode into the airways as broncholiths. Steroids have been used to prevent long‐term complications, but their efficacy is still unclear. Repeated dilation, stenting, and resection all serve as management options for advanced endobronchial disease. In our patient, the extensive bronchial scarring and stenosis were most likely complications from past endobronchial infection. Unfortunately, attempts at balloon dilatation of her right main‐stem bronchus were unsuccessful, and she continues to have considerable exercise limitation. More prompt recognition of the disease may have allowed for an earlier and more successful intervention.

A 23‐year‐old Chinese woman presented with worsening exertional dyspnea. Her medical history was notable for pulmonary tuberculosis treated at the age of 16. Over the past 3 years, she reported progressive respiratory symptoms resulting in marked exercise intolerance. She denied any fevers, cough, or weight loss. On examination, she had right‐sided tracheal deviation but spoke comfortably. Her heart sounds were displaced and right‐sided breath sounds nearly absent. Chest x‐ray (Fig. 1) and subsequent CT revealed complete collapse of the right lung with associated hyperexpansion of the left lung and left‐to‐right mediastinal shift (Fig. 2, with an asterisk denoting the aortic arch; an arrow, the right main‐stem bronchus, which would soon terminate; and arrowheads, the collapsed right lung). No lung masses or effusions were noted; active TB had been ruled out with AFB sputums. Bronchoscopy revealed a fibrotic and stenotic right main‐stem bronchus (Fig. 3, with an asterisk denoting a patent left main‐stem bronchus and an arrow denoting a stenotic right main‐stem bronchus). Pulmonary manifestations of TB include parenchymal and endobronchial disease. Patients more likely to develop endobronchial disease include those with extensive pulmonary involvement, particularly cavitary lesions. Between 10% and 20% of patients with endobronchial disease will have normal CXRs, though CT scans may reveal endobronchial lesions or narrowing. Complications of endobronchial disease include obstruction, bronchiectasis, and tracheal or bronchial stenosis. Some airway obstructions may be associated with enlarging peribronchial nodes, which may erode into the airways as broncholiths. Steroids have been used to prevent long‐term complications, but their efficacy is still unclear. Repeated dilation, stenting, and resection all serve as management options for advanced endobronchial disease. In our patient, the extensive bronchial scarring and stenosis were most likely complications from past endobronchial infection. Unfortunately, attempts at balloon dilatation of her right main‐stem bronchus were unsuccessful, and she continues to have considerable exercise limitation. More prompt recognition of the disease may have allowed for an earlier and more successful intervention.

A 23‐year‐old Chinese woman presented with worsening exertional dyspnea. Her medical history was notable for pulmonary tuberculosis treated at the age of 16. Over the past 3 years, she reported progressive respiratory symptoms resulting in marked exercise intolerance. She denied any fevers, cough, or weight loss. On examination, she had right‐sided tracheal deviation but spoke comfortably. Her heart sounds were displaced and right‐sided breath sounds nearly absent. Chest x‐ray (Fig. 1) and subsequent CT revealed complete collapse of the right lung with associated hyperexpansion of the left lung and left‐to‐right mediastinal shift (Fig. 2, with an asterisk denoting the aortic arch; an arrow, the right main‐stem bronchus, which would soon terminate; and arrowheads, the collapsed right lung). No lung masses or effusions were noted; active TB had been ruled out with AFB sputums. Bronchoscopy revealed a fibrotic and stenotic right main‐stem bronchus (Fig. 3, with an asterisk denoting a patent left main‐stem bronchus and an arrow denoting a stenotic right main‐stem bronchus). Pulmonary manifestations of TB include parenchymal and endobronchial disease. Patients more likely to develop endobronchial disease include those with extensive pulmonary involvement, particularly cavitary lesions. Between 10% and 20% of patients with endobronchial disease will have normal CXRs, though CT scans may reveal endobronchial lesions or narrowing. Complications of endobronchial disease include obstruction, bronchiectasis, and tracheal or bronchial stenosis. Some airway obstructions may be associated with enlarging peribronchial nodes, which may erode into the airways as broncholiths. Steroids have been used to prevent long‐term complications, but their efficacy is still unclear. Repeated dilation, stenting, and resection all serve as management options for advanced endobronchial disease. In our patient, the extensive bronchial scarring and stenosis were most likely complications from past endobronchial infection. Unfortunately, attempts at balloon dilatation of her right main‐stem bronchus were unsuccessful, and she continues to have considerable exercise limitation. More prompt recognition of the disease may have allowed for an earlier and more successful intervention.

Erythema multiforme secondary to HSV labialis precipitating sickle cell pain crisis

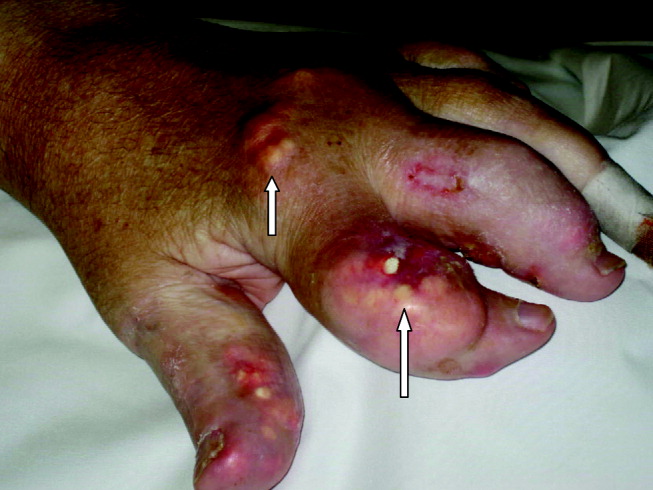

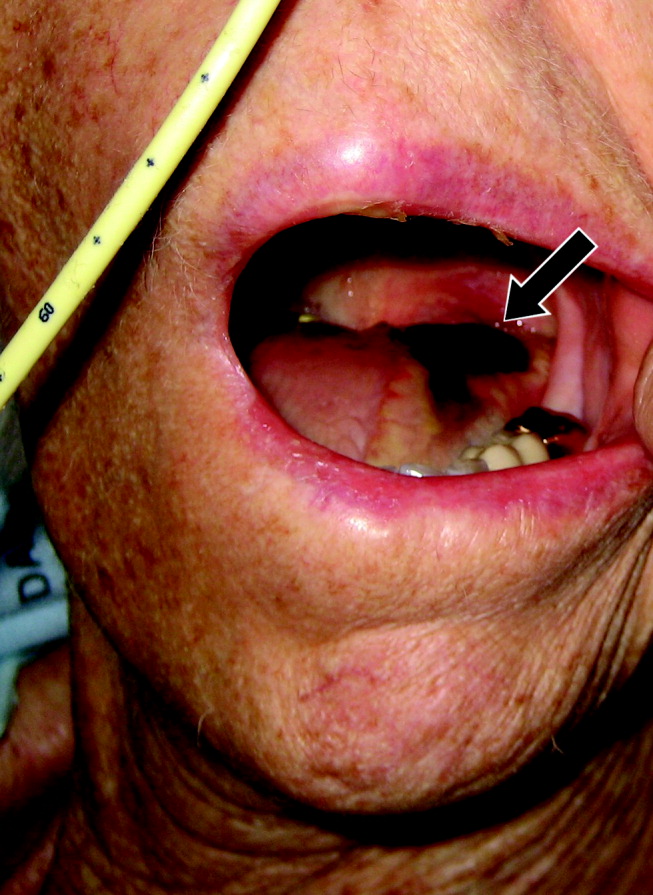

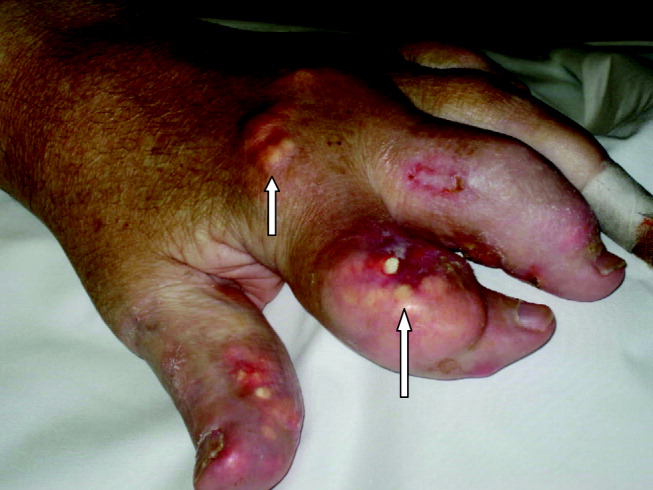

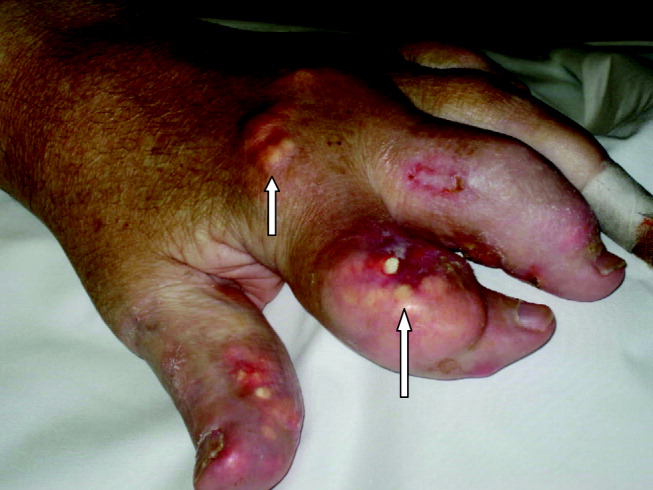

A 28‐year‐old man with sickle cell anemia was admitted with generalized pain. He noted an upper lip lesion 2 weeks prior to admission. He subsequently developed generalized pain in his legs, chest, and back typical of his pain crises. At admission he noted subjective fevers without chills for a week. Vital signs revealed a blood pressure of 135/80, a pulse of 81, a respiratory rate of 16, and an initial temperature of 37.7C. On examination he had scleral icterus and a large upper lip ulcer (Fig. 1). His hospital course was complicated by persistent fevers, a hepatic sequestration crisis, persistent hemolytic anemia requiring blood transfusion, and ultimately the identification of iris‐shaped targetoid lesions on the palms (Fig. 2).These lesions were believed to be consistent with erythema multiforme (EM) secondary to his recent HSV labialis, confirmed by a herpes culture. The patient recovered uneventfully after a 10‐day hospitalization. Erythema multiforme is an acute, self‐limited, but sometimes recurrent dermatologic condition considered to be a distinct hypersensitivity reaction.1 It is associated with certain infections such as herpes simplex 1 and 2, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and fungal infections, and a number of medications in the classes barbiturates, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, penicillins, hydantoins, phenothiazines, and sulfonamides.2 EM is diagnosed clinically by the characteristic rash on the hands and feet, with some cases involving the oral cavity. Treatment is typically focused on resolving the underlying infection or removing the offending drug. Dermatologic manifestations usually improve over 3‐5 weeks without residual sequelae.

- ,,.Understanding the pathogenesis of HSV‐associated erythema multiforme.Dermatology.1998;197:219–222.

- ,,.Erythema multiforme.Am Fam Physician.2006;74:1883–1888.

A 28‐year‐old man with sickle cell anemia was admitted with generalized pain. He noted an upper lip lesion 2 weeks prior to admission. He subsequently developed generalized pain in his legs, chest, and back typical of his pain crises. At admission he noted subjective fevers without chills for a week. Vital signs revealed a blood pressure of 135/80, a pulse of 81, a respiratory rate of 16, and an initial temperature of 37.7C. On examination he had scleral icterus and a large upper lip ulcer (Fig. 1). His hospital course was complicated by persistent fevers, a hepatic sequestration crisis, persistent hemolytic anemia requiring blood transfusion, and ultimately the identification of iris‐shaped targetoid lesions on the palms (Fig. 2).These lesions were believed to be consistent with erythema multiforme (EM) secondary to his recent HSV labialis, confirmed by a herpes culture. The patient recovered uneventfully after a 10‐day hospitalization. Erythema multiforme is an acute, self‐limited, but sometimes recurrent dermatologic condition considered to be a distinct hypersensitivity reaction.1 It is associated with certain infections such as herpes simplex 1 and 2, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and fungal infections, and a number of medications in the classes barbiturates, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, penicillins, hydantoins, phenothiazines, and sulfonamides.2 EM is diagnosed clinically by the characteristic rash on the hands and feet, with some cases involving the oral cavity. Treatment is typically focused on resolving the underlying infection or removing the offending drug. Dermatologic manifestations usually improve over 3‐5 weeks without residual sequelae.

A 28‐year‐old man with sickle cell anemia was admitted with generalized pain. He noted an upper lip lesion 2 weeks prior to admission. He subsequently developed generalized pain in his legs, chest, and back typical of his pain crises. At admission he noted subjective fevers without chills for a week. Vital signs revealed a blood pressure of 135/80, a pulse of 81, a respiratory rate of 16, and an initial temperature of 37.7C. On examination he had scleral icterus and a large upper lip ulcer (Fig. 1). His hospital course was complicated by persistent fevers, a hepatic sequestration crisis, persistent hemolytic anemia requiring blood transfusion, and ultimately the identification of iris‐shaped targetoid lesions on the palms (Fig. 2).These lesions were believed to be consistent with erythema multiforme (EM) secondary to his recent HSV labialis, confirmed by a herpes culture. The patient recovered uneventfully after a 10‐day hospitalization. Erythema multiforme is an acute, self‐limited, but sometimes recurrent dermatologic condition considered to be a distinct hypersensitivity reaction.1 It is associated with certain infections such as herpes simplex 1 and 2, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and fungal infections, and a number of medications in the classes barbiturates, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, penicillins, hydantoins, phenothiazines, and sulfonamides.2 EM is diagnosed clinically by the characteristic rash on the hands and feet, with some cases involving the oral cavity. Treatment is typically focused on resolving the underlying infection or removing the offending drug. Dermatologic manifestations usually improve over 3‐5 weeks without residual sequelae.

- ,,.Understanding the pathogenesis of HSV‐associated erythema multiforme.Dermatology.1998;197:219–222.

- ,,.Erythema multiforme.Am Fam Physician.2006;74:1883–1888.

- ,,.Understanding the pathogenesis of HSV‐associated erythema multiforme.Dermatology.1998;197:219–222.

- ,,.Erythema multiforme.Am Fam Physician.2006;74:1883–1888.

Asymmetric muscle atrophy from childhood polio

A 45‐year‐old Vietnamese woman presented to the emergency department reporting 4 days of vomiting, diarrhea, and epigastric pain. Other than poliomyelitis as a child, she had an unremarkable medical history. A slight left‐sided limp was noted on exam. Although she was diagnosed with gastroenteritis, laboratory studies revealed her blood urea nitrogen was low, at 4 mg/dL, and her creatinine was 0.2 mg/dL, raising concern for an intercurrent abdominal malignancy. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained.

The CT scan did not reveal any abdominal pathology but, incidentally, showed near‐complete atrophy of the left pelvic girdle and proximal femur. Specifically noted was near‐complete fatty atrophy and involution of the left iliacus, piriformis, and gluteus muscles (Fig. 1). Atrophy also involved muscles surrounding the left proximal femur (Fig. 2). The CT and laboratory findings were attributed to childhood poliomyelitis. The patient was discharged home in good condition.

Poliovirus, a small RNA enterovirus, causes destruction of the motor neuron ganglia of the brain stem and anterior horn cells of the spine. Resultant Wallerian degeneration leads to muscle atrophy, as seen here.

A 45‐year‐old Vietnamese woman presented to the emergency department reporting 4 days of vomiting, diarrhea, and epigastric pain. Other than poliomyelitis as a child, she had an unremarkable medical history. A slight left‐sided limp was noted on exam. Although she was diagnosed with gastroenteritis, laboratory studies revealed her blood urea nitrogen was low, at 4 mg/dL, and her creatinine was 0.2 mg/dL, raising concern for an intercurrent abdominal malignancy. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained.

The CT scan did not reveal any abdominal pathology but, incidentally, showed near‐complete atrophy of the left pelvic girdle and proximal femur. Specifically noted was near‐complete fatty atrophy and involution of the left iliacus, piriformis, and gluteus muscles (Fig. 1). Atrophy also involved muscles surrounding the left proximal femur (Fig. 2). The CT and laboratory findings were attributed to childhood poliomyelitis. The patient was discharged home in good condition.

Poliovirus, a small RNA enterovirus, causes destruction of the motor neuron ganglia of the brain stem and anterior horn cells of the spine. Resultant Wallerian degeneration leads to muscle atrophy, as seen here.

A 45‐year‐old Vietnamese woman presented to the emergency department reporting 4 days of vomiting, diarrhea, and epigastric pain. Other than poliomyelitis as a child, she had an unremarkable medical history. A slight left‐sided limp was noted on exam. Although she was diagnosed with gastroenteritis, laboratory studies revealed her blood urea nitrogen was low, at 4 mg/dL, and her creatinine was 0.2 mg/dL, raising concern for an intercurrent abdominal malignancy. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained.

The CT scan did not reveal any abdominal pathology but, incidentally, showed near‐complete atrophy of the left pelvic girdle and proximal femur. Specifically noted was near‐complete fatty atrophy and involution of the left iliacus, piriformis, and gluteus muscles (Fig. 1). Atrophy also involved muscles surrounding the left proximal femur (Fig. 2). The CT and laboratory findings were attributed to childhood poliomyelitis. The patient was discharged home in good condition.

Poliovirus, a small RNA enterovirus, causes destruction of the motor neuron ganglia of the brain stem and anterior horn cells of the spine. Resultant Wallerian degeneration leads to muscle atrophy, as seen here.

Color‐coded wristbands: Promoting safety or confusion?

A 62‐year‐old man was transferred from an outside hospital for evaluation of a complicated spinal infection. Like many patients, he had color‐coded wristbands to help identify potential safety hazards (see Fig. 1). The patient, an educated and alert individual, could describe the indications for only 3 of the 5 wristbands, and the transferring hospital supplied no legend. As it turned out, the green band represented a fall risk, the red one a drug allergy alert, and the purple one a tape allergy, whereas the white one was for patient identification. We're still not certain what the yellow one represented, but it was not a Lance Armstrong Livestrong bracelet; such wristbands have been reported to cause confusion in hospitals that have adopted yellow for their do not resuscitate wristbands.1 Although attempts at ensuring patient safety by using color‐coded wristbands are a common practice, the lack of standardization may pose an unknown hazard. Elsewhere in this journal, we present findings from a survey reinforcing the need for standardization around this issue.

- .Wristbands called patient safety risk.St. Petersburg Times 10 Dec2004. p1A.

A 62‐year‐old man was transferred from an outside hospital for evaluation of a complicated spinal infection. Like many patients, he had color‐coded wristbands to help identify potential safety hazards (see Fig. 1). The patient, an educated and alert individual, could describe the indications for only 3 of the 5 wristbands, and the transferring hospital supplied no legend. As it turned out, the green band represented a fall risk, the red one a drug allergy alert, and the purple one a tape allergy, whereas the white one was for patient identification. We're still not certain what the yellow one represented, but it was not a Lance Armstrong Livestrong bracelet; such wristbands have been reported to cause confusion in hospitals that have adopted yellow for their do not resuscitate wristbands.1 Although attempts at ensuring patient safety by using color‐coded wristbands are a common practice, the lack of standardization may pose an unknown hazard. Elsewhere in this journal, we present findings from a survey reinforcing the need for standardization around this issue.

A 62‐year‐old man was transferred from an outside hospital for evaluation of a complicated spinal infection. Like many patients, he had color‐coded wristbands to help identify potential safety hazards (see Fig. 1). The patient, an educated and alert individual, could describe the indications for only 3 of the 5 wristbands, and the transferring hospital supplied no legend. As it turned out, the green band represented a fall risk, the red one a drug allergy alert, and the purple one a tape allergy, whereas the white one was for patient identification. We're still not certain what the yellow one represented, but it was not a Lance Armstrong Livestrong bracelet; such wristbands have been reported to cause confusion in hospitals that have adopted yellow for their do not resuscitate wristbands.1 Although attempts at ensuring patient safety by using color‐coded wristbands are a common practice, the lack of standardization may pose an unknown hazard. Elsewhere in this journal, we present findings from a survey reinforcing the need for standardization around this issue.

- .Wristbands called patient safety risk.St. Petersburg Times 10 Dec2004. p1A.

- .Wristbands called patient safety risk.St. Petersburg Times 10 Dec2004. p1A.

Tongue necrosis from temporal arteritis

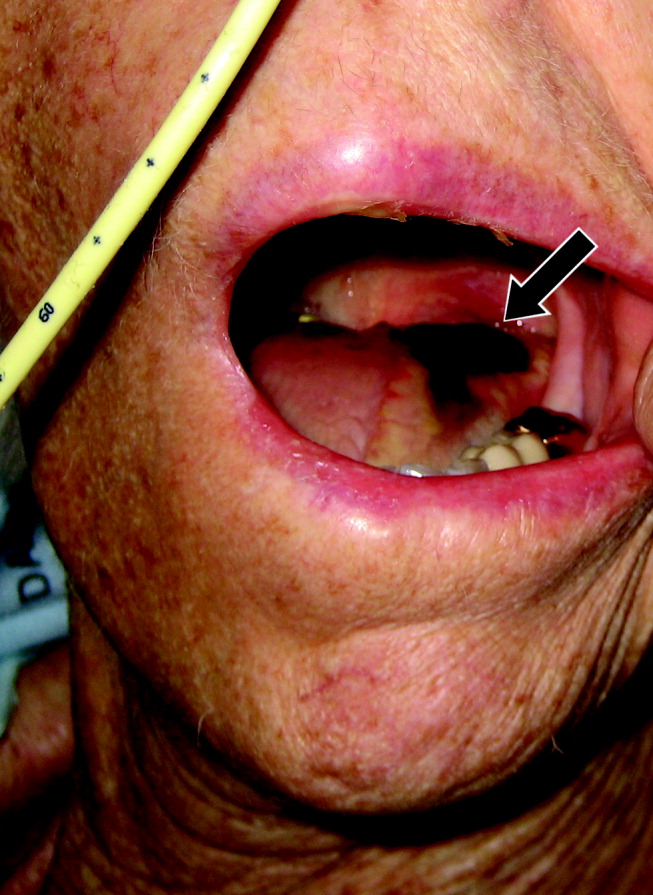

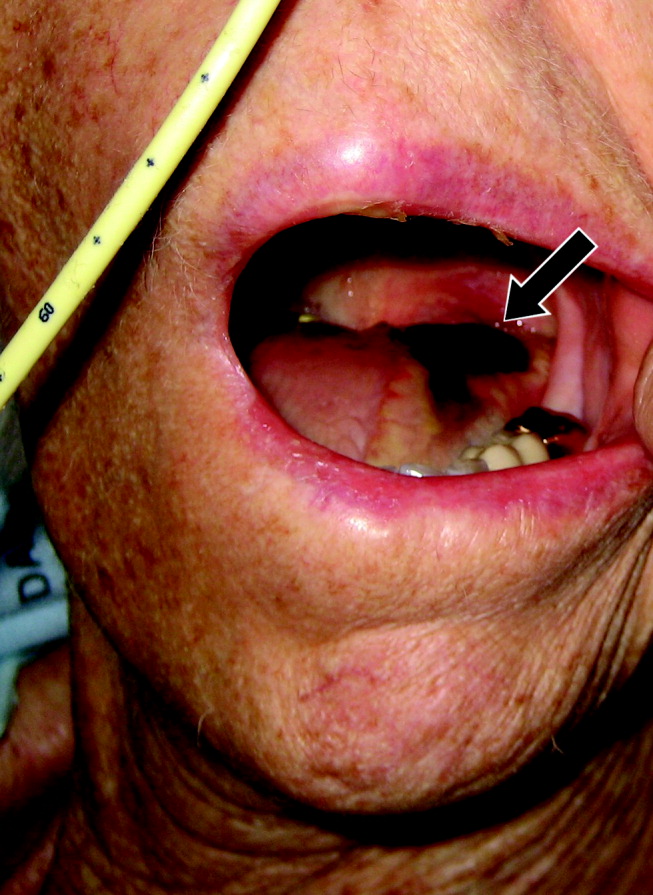

A 77‐year‐old woman with hypothyroidism presented with a 2‐week history of head, neck, jaw, and tongue pain. She had also developed slurred speech and difficulty chewing. On examination she had a temperature of 38.0C. She was without neurological deficits. However, she did have difficulty protruding her tongue, which had a cyanotic appearance and was painful. Laboratory findings showed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 68 mm/hr. Temporal arteritis was suspected, and the patient was started on corticosteroids. A subsequent temporal artery biopsy revealed inflammation and thrombus formation consistent with temporal arteritis. On hospital day 3, she developed unilateral ischemia in her tongue, which eventually became necrotic (Fig. 1). Although tongue necrosis is rare, temporal arteritis is the most frequent cause. It is usually unilateral and caused by compromised blood supply as a result of vasculitis in one of the lingual arteries. Other causes of tongue necrosis such as embolus, abscess, syphilis, tongue carcinoma, and Hodgkin's disease should be excluded.1, 2 Although necrotic tongue tissue must sometimes be extensively debrided or resected, our patient required minimal debridement. At follow‐up 1 month later, she was recovering at home with ongoing speech therapy and a corticosteroid taper.

- ,,.Lingual infarction: a review of the literature.Ann Vasc Surg.1992;6:450–452.

- ,.The ESR in the diagnosis and management of the polymyalgia rheumatica/giant cell arteritis syndrome.Ann Rheum Dis.1983;42:168–170.

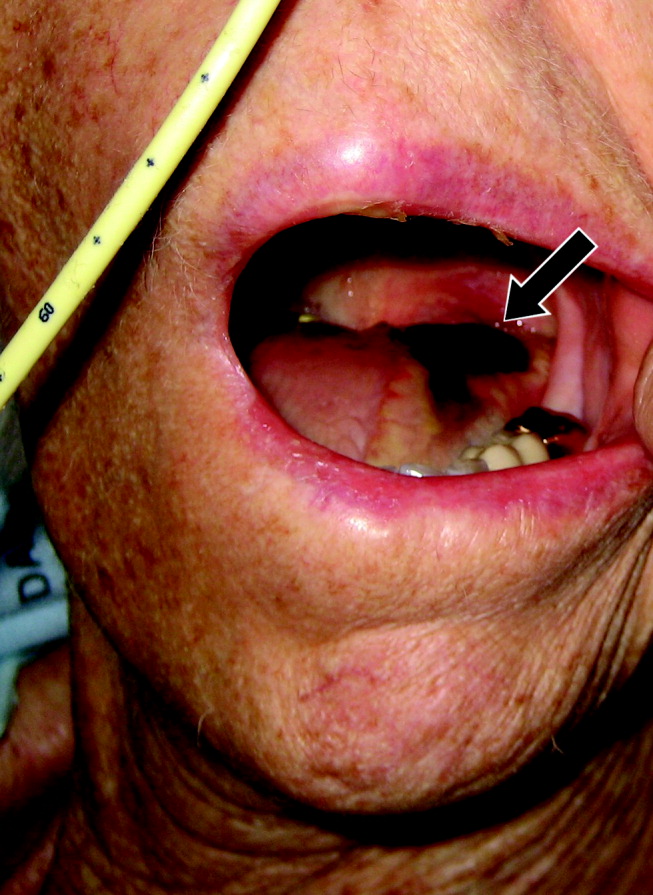

A 77‐year‐old woman with hypothyroidism presented with a 2‐week history of head, neck, jaw, and tongue pain. She had also developed slurred speech and difficulty chewing. On examination she had a temperature of 38.0C. She was without neurological deficits. However, she did have difficulty protruding her tongue, which had a cyanotic appearance and was painful. Laboratory findings showed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 68 mm/hr. Temporal arteritis was suspected, and the patient was started on corticosteroids. A subsequent temporal artery biopsy revealed inflammation and thrombus formation consistent with temporal arteritis. On hospital day 3, she developed unilateral ischemia in her tongue, which eventually became necrotic (Fig. 1). Although tongue necrosis is rare, temporal arteritis is the most frequent cause. It is usually unilateral and caused by compromised blood supply as a result of vasculitis in one of the lingual arteries. Other causes of tongue necrosis such as embolus, abscess, syphilis, tongue carcinoma, and Hodgkin's disease should be excluded.1, 2 Although necrotic tongue tissue must sometimes be extensively debrided or resected, our patient required minimal debridement. At follow‐up 1 month later, she was recovering at home with ongoing speech therapy and a corticosteroid taper.

A 77‐year‐old woman with hypothyroidism presented with a 2‐week history of head, neck, jaw, and tongue pain. She had also developed slurred speech and difficulty chewing. On examination she had a temperature of 38.0C. She was without neurological deficits. However, she did have difficulty protruding her tongue, which had a cyanotic appearance and was painful. Laboratory findings showed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 68 mm/hr. Temporal arteritis was suspected, and the patient was started on corticosteroids. A subsequent temporal artery biopsy revealed inflammation and thrombus formation consistent with temporal arteritis. On hospital day 3, she developed unilateral ischemia in her tongue, which eventually became necrotic (Fig. 1). Although tongue necrosis is rare, temporal arteritis is the most frequent cause. It is usually unilateral and caused by compromised blood supply as a result of vasculitis in one of the lingual arteries. Other causes of tongue necrosis such as embolus, abscess, syphilis, tongue carcinoma, and Hodgkin's disease should be excluded.1, 2 Although necrotic tongue tissue must sometimes be extensively debrided or resected, our patient required minimal debridement. At follow‐up 1 month later, she was recovering at home with ongoing speech therapy and a corticosteroid taper.

- ,,.Lingual infarction: a review of the literature.Ann Vasc Surg.1992;6:450–452.

- ,.The ESR in the diagnosis and management of the polymyalgia rheumatica/giant cell arteritis syndrome.Ann Rheum Dis.1983;42:168–170.

- ,,.Lingual infarction: a review of the literature.Ann Vasc Surg.1992;6:450–452.

- ,.The ESR in the diagnosis and management of the polymyalgia rheumatica/giant cell arteritis syndrome.Ann Rheum Dis.1983;42:168–170.

Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum

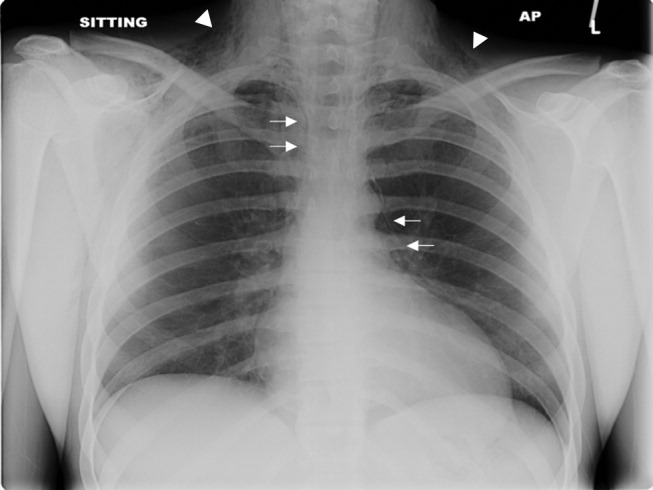

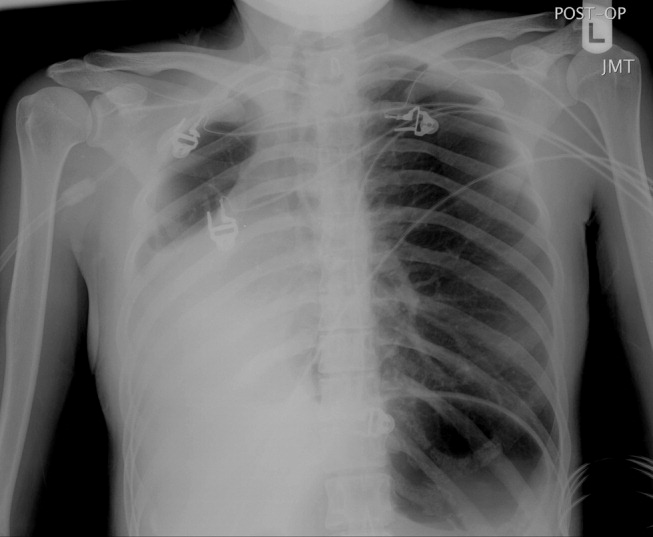

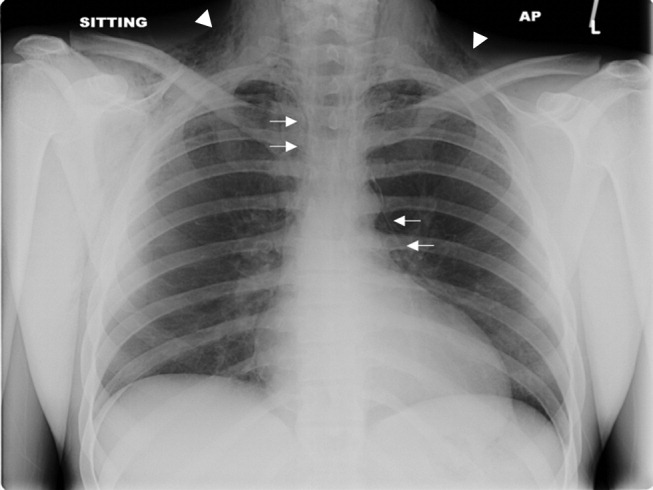

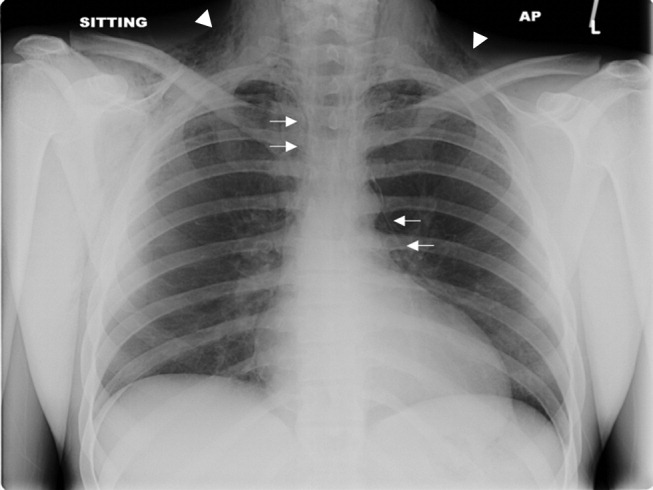

A previously healthy 22‐year‐old white man presented with acute psychosis after an 11‐day binge of smoking and injecting methamphetamine. The physical exam revealed crepitus over the anterior neck and Hamman's crunch (a crunching sound synchronous with the cardiac cycle and best heard with patient positioned in the left lateral decubitus position). Chest film (Fig. 1) and computerized tomography (Fig. 2) showed pneumomediastinum with extensive subcutaneous emphysema and pneumorrhachis (air in the epidural space).1 An esophogram was normal. Following 48 hours of inpatient observation and oxygen therapy, the neumomediastinum and psychosis resolved.

Spontaneous pneumomediastinum is rare, accounting for 1 in 30,000 emergency department referrals. It is more common among users of illicit substances (ie, amphetamine and methylenedioxymethamphetamine [MDMA/ecstasy]).2 Patients present with chest pain, dyspnea, and the typical physical findings described above.3 Chest imaging confirms the diagnosis.4 Vigorous inhalation during a Valsalva maneuver is thought to rupture terminal alveoli. Gas then enters the lung interstitium and dissects along fascial planes into the hilum and mediastinum and occasionally into the epidural space.5 Thorough investigation rules out other sources of air from the neck, abdomen, or ruptured esophagus (Boerhaave syndrome). Treatment is generally supportive and includes oxygen therapy, reassurance, analgesics, and close monitoring for complications (eg, pneumothorax). Surgical intervention is only necessary if a pneumothorax develops.6 Prognosis is excellent.

- .Spontaneous mediastinal emphysema.Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp.1939;64:1–21.

- ,.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: a benign curiosity or a significant problem?Chest.2005;3298–3302128.

- ,.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax and ecstasy abuse.Emerg Med.:2001;13:121–123.

- ,,,,.“Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum.Ann Thorac Surg.2004;78:711–713.

- ,,.Pneumorrhachis secondary to traumatic pneumomediastinum in a child.Pediatr Radiol.2006;36:711–713.

- ,,.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum.Curr Surg.2006;63:351–353.

A previously healthy 22‐year‐old white man presented with acute psychosis after an 11‐day binge of smoking and injecting methamphetamine. The physical exam revealed crepitus over the anterior neck and Hamman's crunch (a crunching sound synchronous with the cardiac cycle and best heard with patient positioned in the left lateral decubitus position). Chest film (Fig. 1) and computerized tomography (Fig. 2) showed pneumomediastinum with extensive subcutaneous emphysema and pneumorrhachis (air in the epidural space).1 An esophogram was normal. Following 48 hours of inpatient observation and oxygen therapy, the neumomediastinum and psychosis resolved.

Spontaneous pneumomediastinum is rare, accounting for 1 in 30,000 emergency department referrals. It is more common among users of illicit substances (ie, amphetamine and methylenedioxymethamphetamine [MDMA/ecstasy]).2 Patients present with chest pain, dyspnea, and the typical physical findings described above.3 Chest imaging confirms the diagnosis.4 Vigorous inhalation during a Valsalva maneuver is thought to rupture terminal alveoli. Gas then enters the lung interstitium and dissects along fascial planes into the hilum and mediastinum and occasionally into the epidural space.5 Thorough investigation rules out other sources of air from the neck, abdomen, or ruptured esophagus (Boerhaave syndrome). Treatment is generally supportive and includes oxygen therapy, reassurance, analgesics, and close monitoring for complications (eg, pneumothorax). Surgical intervention is only necessary if a pneumothorax develops.6 Prognosis is excellent.

A previously healthy 22‐year‐old white man presented with acute psychosis after an 11‐day binge of smoking and injecting methamphetamine. The physical exam revealed crepitus over the anterior neck and Hamman's crunch (a crunching sound synchronous with the cardiac cycle and best heard with patient positioned in the left lateral decubitus position). Chest film (Fig. 1) and computerized tomography (Fig. 2) showed pneumomediastinum with extensive subcutaneous emphysema and pneumorrhachis (air in the epidural space).1 An esophogram was normal. Following 48 hours of inpatient observation and oxygen therapy, the neumomediastinum and psychosis resolved.

Spontaneous pneumomediastinum is rare, accounting for 1 in 30,000 emergency department referrals. It is more common among users of illicit substances (ie, amphetamine and methylenedioxymethamphetamine [MDMA/ecstasy]).2 Patients present with chest pain, dyspnea, and the typical physical findings described above.3 Chest imaging confirms the diagnosis.4 Vigorous inhalation during a Valsalva maneuver is thought to rupture terminal alveoli. Gas then enters the lung interstitium and dissects along fascial planes into the hilum and mediastinum and occasionally into the epidural space.5 Thorough investigation rules out other sources of air from the neck, abdomen, or ruptured esophagus (Boerhaave syndrome). Treatment is generally supportive and includes oxygen therapy, reassurance, analgesics, and close monitoring for complications (eg, pneumothorax). Surgical intervention is only necessary if a pneumothorax develops.6 Prognosis is excellent.

- .Spontaneous mediastinal emphysema.Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp.1939;64:1–21.

- ,.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: a benign curiosity or a significant problem?Chest.2005;3298–3302128.

- ,.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax and ecstasy abuse.Emerg Med.:2001;13:121–123.

- ,,,,.“Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum.Ann Thorac Surg.2004;78:711–713.

- ,,.Pneumorrhachis secondary to traumatic pneumomediastinum in a child.Pediatr Radiol.2006;36:711–713.

- ,,.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum.Curr Surg.2006;63:351–353.

- .Spontaneous mediastinal emphysema.Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp.1939;64:1–21.

- ,.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: a benign curiosity or a significant problem?Chest.2005;3298–3302128.

- ,.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax and ecstasy abuse.Emerg Med.:2001;13:121–123.

- ,,,,.“Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum.Ann Thorac Surg.2004;78:711–713.

- ,,.Pneumorrhachis secondary to traumatic pneumomediastinum in a child.Pediatr Radiol.2006;36:711–713.

- ,,.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum.Curr Surg.2006;63:351–353.

Suppurative complications and upper airway obstruction in infectious mononucleosis

A 17‐year‐old female patient presented to the emergency department reporting having fever, sore throat, and pain with swallowing for several days. The result of her rapid strep screen was negative. She had an elevated white blood cell count, mildly elevated AST and ALT levels, and a positive result from a heterophile antibody test (BBL Monoslide). She was diagnosed with infectious mononucleosis. Given her inability to tolerate oral fluids, she was admitted to the hospital for intravenous hydration. After 3 days of receiving methylprednisolone intravenously, she had worsening throat pain, progressive neck swelling, difficulty handling her secretions, and new respiratory symptoms. During the examination, she was sitting upright in bed in moderate respiratory distress. She had kissing, exudative tonsils with palatal and uvular edema. Examination of her neck showed significantly enlarged anterior and posterior cervical lymph nodes without fluctuance. Her lung exam revealed subcostal retractions with transmitted upper airway sounds but good aeration. The edge of her liver and spleen tip were palpable.

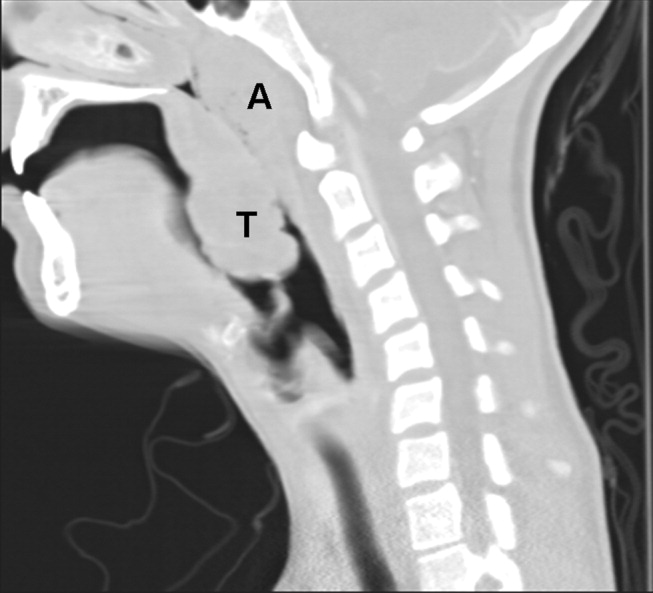

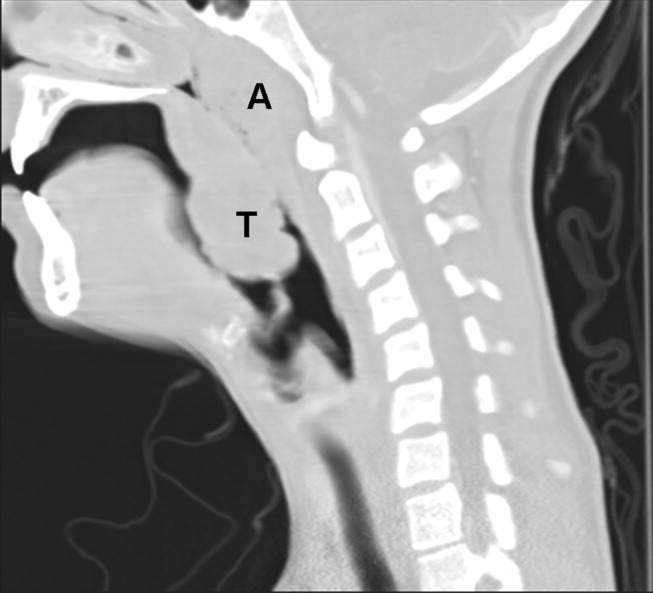

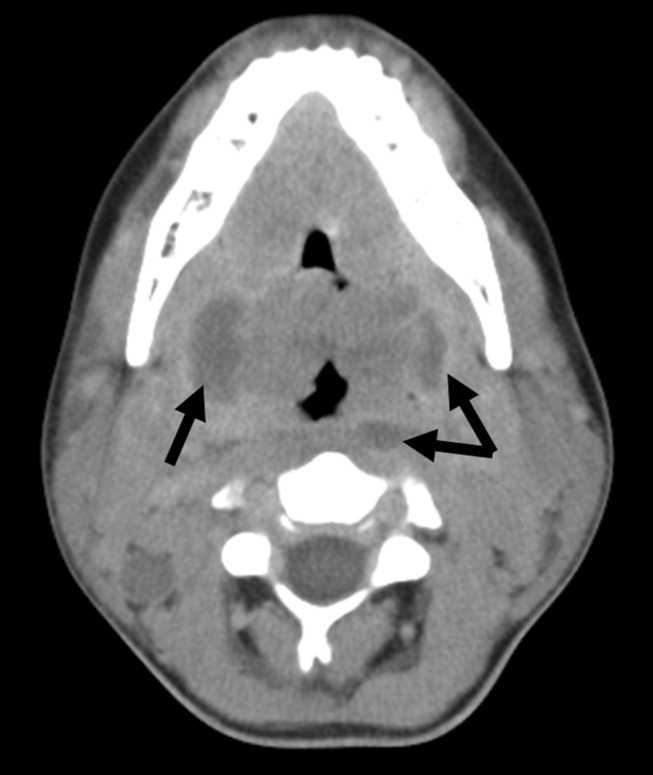

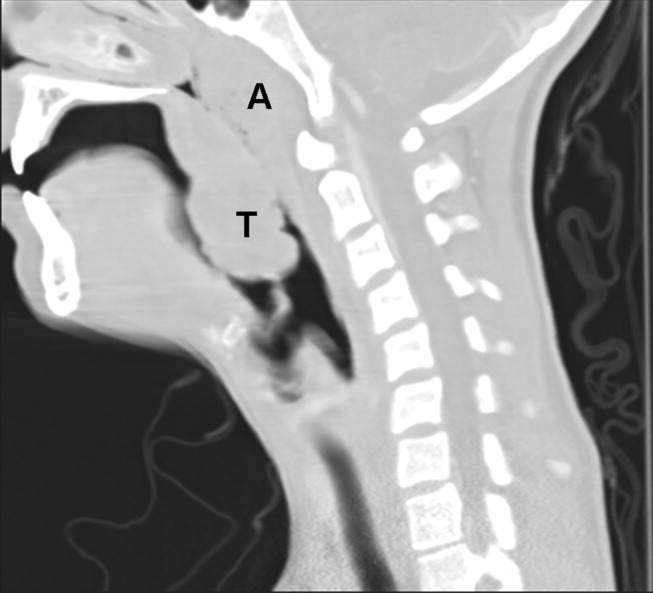

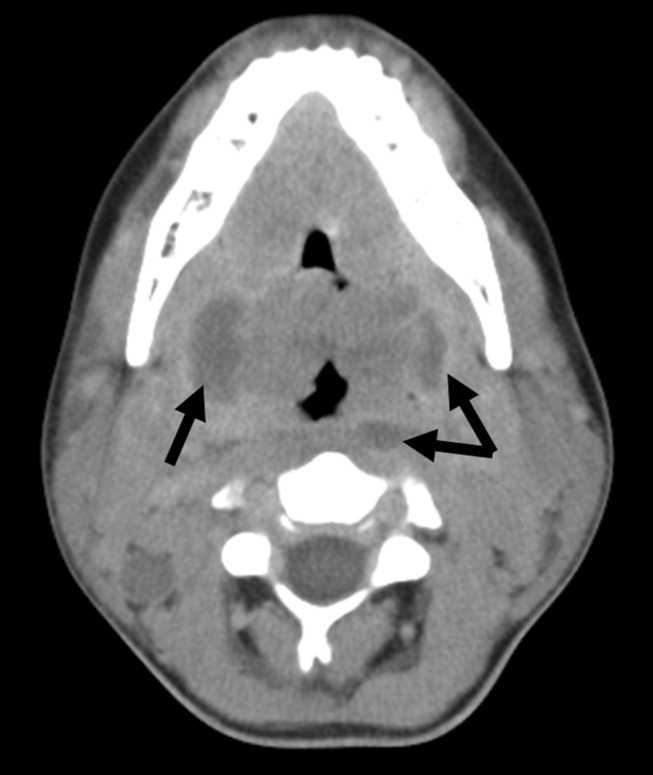

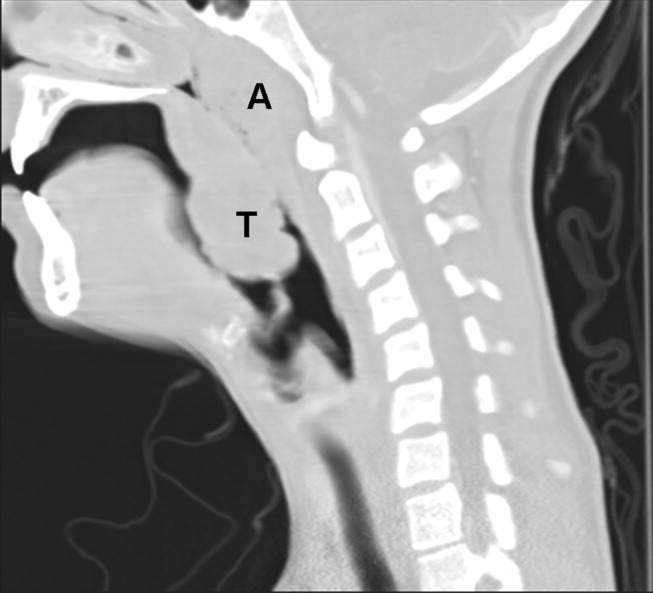

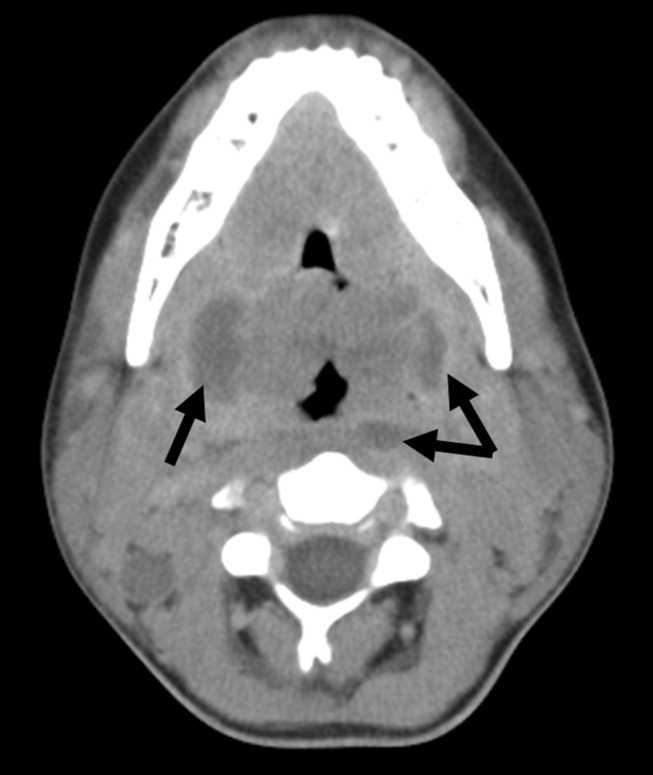

Because of the rapid progression of symptoms while on medical therapy, computed tomography (CT) of the neck was performed. Sagittal reconstructions showed adenoidal hypertrophy compromising her nasopharynx, and massive tonsillar enlargement causing nearly complete obstruction of her oropharyngeal airway (Fig. 1), with airway narrowing to less than 2.5 mm in axial images. Bilateral low‐density lesions within the paratonsillar regions were suggestive of abscesses and retropharyngeal soft‐tissue swelling was consistent with phlegmon (Fig. 2). The patient was taken to the operating room for an emergent tonsillectomy. Bilateral peritonsillar abscesses were drained, pus was sent for culture, and her tonsils were excised. Cultures from the abscesses grew Streptococcus milleri. The patient was discharged home 2 days later to complete a 2‐week course of oral clindamycin.

Most patients with infectious mononucleosis (IM) have a benign, self‐limited course. However, a wide range of severe complications have been described including airway obstruction, splenic rupture, meningoencephalitis, Guillain‐Barr syndrome, peritonsillar abscess, and hemolytic anemia.1, 2 Upper‐airway obstruction results from lymphoid hyperplasia throughout Waldeyer's ring, with associated soft‐tissue edema. As many as 25% of patients hospitalized for IM will have some degree of airway obstruction.2, 3 Peritonsillar abscesses (PTAs) occur in approximately 1% of hospitalized patients with IM and may further obstruct the airway.4 Most commonly, peritonsillar abscesses are polymicrobial, having both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. In a study of young adults with peritonsillar abscesses from all causes, Streptococcus pyogenes was the most common aerobe, found in nearly half of isolates; Streptococcus milleri, the bacterium isolated from our patient, was the second most common organism, found in approximately 25% of these abscesses.5 One prior case of airway obstruction from IM complicated by bilateral peritonsillar abscesses has been reported6; however, this patient was not reported to have concomitant retropharyngeal infection, as was noted in our patient.

Guidelines suggest that patients with mild, uncomplicated IM should be managed with supportive care alone; current recommendations are that steroids be prescribed only for specific complications of IM, including upper‐airway obstruction.7 Protocols for steroid regimens include initial prednisone doses ranging from 20 to 80 mg/day, with most advocating that they be tapered off over 1‐2 weeks.7, 8

Some of the controversy about the routine use of steroids in IM is related to concern for potential infectious complications associated with immunosuppression. In a small case series, Handler et al. proposed that there is an association between steroid therapy and the development of peritonsillar abscesses.9 However, this has not been tested in controlled trials, and the results of more recent studies do not support an increased likelihood of PTA in patients with infectious mononucleosis treated with corticosteroids.10, 11 Therefore, given that it has documented benefits and no proven adverse consequences, steroid therapy is uniformly recommended for patients with upper‐airway obstruction secondary to infectious mononucleosis. However, use of steroids also mandates careful monitoring for signs or symptoms suggestive of secondary bacterial infection.

For patients whose symptoms progress despite medical management including steroid therapy, surgical intervention may be required. Both tracheostomy and tonsillectomy during acute infection, sometimes referred to as hot tonsillectomy, have been reported as surgical options for airway obstruction in IM, the latter having emerged as the preferred treatment.3 Such treatment allows for drainage of any infectious collections, as well as removal of obstructing lymphoid tissue as indicated.

In conclusion, enlargement of tonsils and adenoids with associated edema in infectious mononucleosis can lead to upper‐airway obstruction. Patients with evidence of such obstruction should be treated with a tapering course of corticosteroids. Peritonsillar abscesses and deep neck infections are also severe complications of IM and can cause further respiratory compromise. In cases where medical therapy is not effective, such as with our patient, evaluation for peritonsillar abscess and need for possible acute tonsillectomy may be required.

- .Acute complications of Epstein‐Barr virus infectious mononucleosis.Curr Opin Pediatr.2000;12(3):263–268.

- ,.Complications of infection with Epstein‐Barr virus during childhood: a study of children admitted to the hospital.Pediatr Infect Dis.1984;3:304–307.

- ,.The management of severe infectious mononucleosis tonsillitis and upper airway obstruction.J Laryngol Otol.2001;115:973–977.

- ,,.Otolaryngological complications in infectious mononucleosis.J Laryngol Otol.1984;98:999–1001.

- ,,.Bacteriologic findings in peritonsillar abscesses in young adults.Clin Infect Dis.1993;16(suppl 4):S292–S298.

- ,.Infectious mononucleosis and bilateral peritonsillar abscesses resulting in airway obstruction.J Laryngol Otol.1998;112:1186–1188.

- ,,, et al.Guidelines for the use of systemic glucocorticosteroids in the management of selected infections.Working Group on Steroid Use, Antimicrobial Agents Committee, Infectious Diseases Society of America.J Infect Dis.1992;165(1):1–13.

- ,Narula AA Steroids for airway problems in glandular fever.J Laryngol Otol.1987;10:673–675.

- ,.Peritonsillar abscess: a complication of corticosteroid treatment in infectious mononucleosis.Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol.1979;1(3):265–268.

- ,,.Corticosteroids and peritonsillar abscess formation in infectious mononucleosis.J Laryngol Otol.2004;118:459–461.

- ,,.Otolaryngologic Clinical Patterns in Pediatric Infectious Mononucleosis.Am J Otolaryngol.1996;17:397–400.

A 17‐year‐old female patient presented to the emergency department reporting having fever, sore throat, and pain with swallowing for several days. The result of her rapid strep screen was negative. She had an elevated white blood cell count, mildly elevated AST and ALT levels, and a positive result from a heterophile antibody test (BBL Monoslide). She was diagnosed with infectious mononucleosis. Given her inability to tolerate oral fluids, she was admitted to the hospital for intravenous hydration. After 3 days of receiving methylprednisolone intravenously, she had worsening throat pain, progressive neck swelling, difficulty handling her secretions, and new respiratory symptoms. During the examination, she was sitting upright in bed in moderate respiratory distress. She had kissing, exudative tonsils with palatal and uvular edema. Examination of her neck showed significantly enlarged anterior and posterior cervical lymph nodes without fluctuance. Her lung exam revealed subcostal retractions with transmitted upper airway sounds but good aeration. The edge of her liver and spleen tip were palpable.

Because of the rapid progression of symptoms while on medical therapy, computed tomography (CT) of the neck was performed. Sagittal reconstructions showed adenoidal hypertrophy compromising her nasopharynx, and massive tonsillar enlargement causing nearly complete obstruction of her oropharyngeal airway (Fig. 1), with airway narrowing to less than 2.5 mm in axial images. Bilateral low‐density lesions within the paratonsillar regions were suggestive of abscesses and retropharyngeal soft‐tissue swelling was consistent with phlegmon (Fig. 2). The patient was taken to the operating room for an emergent tonsillectomy. Bilateral peritonsillar abscesses were drained, pus was sent for culture, and her tonsils were excised. Cultures from the abscesses grew Streptococcus milleri. The patient was discharged home 2 days later to complete a 2‐week course of oral clindamycin.

Most patients with infectious mononucleosis (IM) have a benign, self‐limited course. However, a wide range of severe complications have been described including airway obstruction, splenic rupture, meningoencephalitis, Guillain‐Barr syndrome, peritonsillar abscess, and hemolytic anemia.1, 2 Upper‐airway obstruction results from lymphoid hyperplasia throughout Waldeyer's ring, with associated soft‐tissue edema. As many as 25% of patients hospitalized for IM will have some degree of airway obstruction.2, 3 Peritonsillar abscesses (PTAs) occur in approximately 1% of hospitalized patients with IM and may further obstruct the airway.4 Most commonly, peritonsillar abscesses are polymicrobial, having both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. In a study of young adults with peritonsillar abscesses from all causes, Streptococcus pyogenes was the most common aerobe, found in nearly half of isolates; Streptococcus milleri, the bacterium isolated from our patient, was the second most common organism, found in approximately 25% of these abscesses.5 One prior case of airway obstruction from IM complicated by bilateral peritonsillar abscesses has been reported6; however, this patient was not reported to have concomitant retropharyngeal infection, as was noted in our patient.

Guidelines suggest that patients with mild, uncomplicated IM should be managed with supportive care alone; current recommendations are that steroids be prescribed only for specific complications of IM, including upper‐airway obstruction.7 Protocols for steroid regimens include initial prednisone doses ranging from 20 to 80 mg/day, with most advocating that they be tapered off over 1‐2 weeks.7, 8

Some of the controversy about the routine use of steroids in IM is related to concern for potential infectious complications associated with immunosuppression. In a small case series, Handler et al. proposed that there is an association between steroid therapy and the development of peritonsillar abscesses.9 However, this has not been tested in controlled trials, and the results of more recent studies do not support an increased likelihood of PTA in patients with infectious mononucleosis treated with corticosteroids.10, 11 Therefore, given that it has documented benefits and no proven adverse consequences, steroid therapy is uniformly recommended for patients with upper‐airway obstruction secondary to infectious mononucleosis. However, use of steroids also mandates careful monitoring for signs or symptoms suggestive of secondary bacterial infection.

For patients whose symptoms progress despite medical management including steroid therapy, surgical intervention may be required. Both tracheostomy and tonsillectomy during acute infection, sometimes referred to as hot tonsillectomy, have been reported as surgical options for airway obstruction in IM, the latter having emerged as the preferred treatment.3 Such treatment allows for drainage of any infectious collections, as well as removal of obstructing lymphoid tissue as indicated.

In conclusion, enlargement of tonsils and adenoids with associated edema in infectious mononucleosis can lead to upper‐airway obstruction. Patients with evidence of such obstruction should be treated with a tapering course of corticosteroids. Peritonsillar abscesses and deep neck infections are also severe complications of IM and can cause further respiratory compromise. In cases where medical therapy is not effective, such as with our patient, evaluation for peritonsillar abscess and need for possible acute tonsillectomy may be required.

A 17‐year‐old female patient presented to the emergency department reporting having fever, sore throat, and pain with swallowing for several days. The result of her rapid strep screen was negative. She had an elevated white blood cell count, mildly elevated AST and ALT levels, and a positive result from a heterophile antibody test (BBL Monoslide). She was diagnosed with infectious mononucleosis. Given her inability to tolerate oral fluids, she was admitted to the hospital for intravenous hydration. After 3 days of receiving methylprednisolone intravenously, she had worsening throat pain, progressive neck swelling, difficulty handling her secretions, and new respiratory symptoms. During the examination, she was sitting upright in bed in moderate respiratory distress. She had kissing, exudative tonsils with palatal and uvular edema. Examination of her neck showed significantly enlarged anterior and posterior cervical lymph nodes without fluctuance. Her lung exam revealed subcostal retractions with transmitted upper airway sounds but good aeration. The edge of her liver and spleen tip were palpable.

Because of the rapid progression of symptoms while on medical therapy, computed tomography (CT) of the neck was performed. Sagittal reconstructions showed adenoidal hypertrophy compromising her nasopharynx, and massive tonsillar enlargement causing nearly complete obstruction of her oropharyngeal airway (Fig. 1), with airway narrowing to less than 2.5 mm in axial images. Bilateral low‐density lesions within the paratonsillar regions were suggestive of abscesses and retropharyngeal soft‐tissue swelling was consistent with phlegmon (Fig. 2). The patient was taken to the operating room for an emergent tonsillectomy. Bilateral peritonsillar abscesses were drained, pus was sent for culture, and her tonsils were excised. Cultures from the abscesses grew Streptococcus milleri. The patient was discharged home 2 days later to complete a 2‐week course of oral clindamycin.

Most patients with infectious mononucleosis (IM) have a benign, self‐limited course. However, a wide range of severe complications have been described including airway obstruction, splenic rupture, meningoencephalitis, Guillain‐Barr syndrome, peritonsillar abscess, and hemolytic anemia.1, 2 Upper‐airway obstruction results from lymphoid hyperplasia throughout Waldeyer's ring, with associated soft‐tissue edema. As many as 25% of patients hospitalized for IM will have some degree of airway obstruction.2, 3 Peritonsillar abscesses (PTAs) occur in approximately 1% of hospitalized patients with IM and may further obstruct the airway.4 Most commonly, peritonsillar abscesses are polymicrobial, having both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. In a study of young adults with peritonsillar abscesses from all causes, Streptococcus pyogenes was the most common aerobe, found in nearly half of isolates; Streptococcus milleri, the bacterium isolated from our patient, was the second most common organism, found in approximately 25% of these abscesses.5 One prior case of airway obstruction from IM complicated by bilateral peritonsillar abscesses has been reported6; however, this patient was not reported to have concomitant retropharyngeal infection, as was noted in our patient.

Guidelines suggest that patients with mild, uncomplicated IM should be managed with supportive care alone; current recommendations are that steroids be prescribed only for specific complications of IM, including upper‐airway obstruction.7 Protocols for steroid regimens include initial prednisone doses ranging from 20 to 80 mg/day, with most advocating that they be tapered off over 1‐2 weeks.7, 8

Some of the controversy about the routine use of steroids in IM is related to concern for potential infectious complications associated with immunosuppression. In a small case series, Handler et al. proposed that there is an association between steroid therapy and the development of peritonsillar abscesses.9 However, this has not been tested in controlled trials, and the results of more recent studies do not support an increased likelihood of PTA in patients with infectious mononucleosis treated with corticosteroids.10, 11 Therefore, given that it has documented benefits and no proven adverse consequences, steroid therapy is uniformly recommended for patients with upper‐airway obstruction secondary to infectious mononucleosis. However, use of steroids also mandates careful monitoring for signs or symptoms suggestive of secondary bacterial infection.

For patients whose symptoms progress despite medical management including steroid therapy, surgical intervention may be required. Both tracheostomy and tonsillectomy during acute infection, sometimes referred to as hot tonsillectomy, have been reported as surgical options for airway obstruction in IM, the latter having emerged as the preferred treatment.3 Such treatment allows for drainage of any infectious collections, as well as removal of obstructing lymphoid tissue as indicated.

In conclusion, enlargement of tonsils and adenoids with associated edema in infectious mononucleosis can lead to upper‐airway obstruction. Patients with evidence of such obstruction should be treated with a tapering course of corticosteroids. Peritonsillar abscesses and deep neck infections are also severe complications of IM and can cause further respiratory compromise. In cases where medical therapy is not effective, such as with our patient, evaluation for peritonsillar abscess and need for possible acute tonsillectomy may be required.

- .Acute complications of Epstein‐Barr virus infectious mononucleosis.Curr Opin Pediatr.2000;12(3):263–268.

- ,.Complications of infection with Epstein‐Barr virus during childhood: a study of children admitted to the hospital.Pediatr Infect Dis.1984;3:304–307.

- ,.The management of severe infectious mononucleosis tonsillitis and upper airway obstruction.J Laryngol Otol.2001;115:973–977.

- ,,.Otolaryngological complications in infectious mononucleosis.J Laryngol Otol.1984;98:999–1001.

- ,,.Bacteriologic findings in peritonsillar abscesses in young adults.Clin Infect Dis.1993;16(suppl 4):S292–S298.

- ,.Infectious mononucleosis and bilateral peritonsillar abscesses resulting in airway obstruction.J Laryngol Otol.1998;112:1186–1188.

- ,,, et al.Guidelines for the use of systemic glucocorticosteroids in the management of selected infections.Working Group on Steroid Use, Antimicrobial Agents Committee, Infectious Diseases Society of America.J Infect Dis.1992;165(1):1–13.

- ,Narula AA Steroids for airway problems in glandular fever.J Laryngol Otol.1987;10:673–675.

- ,.Peritonsillar abscess: a complication of corticosteroid treatment in infectious mononucleosis.Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol.1979;1(3):265–268.

- ,,.Corticosteroids and peritonsillar abscess formation in infectious mononucleosis.J Laryngol Otol.2004;118:459–461.

- ,,.Otolaryngologic Clinical Patterns in Pediatric Infectious Mononucleosis.Am J Otolaryngol.1996;17:397–400.

- .Acute complications of Epstein‐Barr virus infectious mononucleosis.Curr Opin Pediatr.2000;12(3):263–268.

- ,.Complications of infection with Epstein‐Barr virus during childhood: a study of children admitted to the hospital.Pediatr Infect Dis.1984;3:304–307.

- ,.The management of severe infectious mononucleosis tonsillitis and upper airway obstruction.J Laryngol Otol.2001;115:973–977.

- ,,.Otolaryngological complications in infectious mononucleosis.J Laryngol Otol.1984;98:999–1001.

- ,,.Bacteriologic findings in peritonsillar abscesses in young adults.Clin Infect Dis.1993;16(suppl 4):S292–S298.

- ,.Infectious mononucleosis and bilateral peritonsillar abscesses resulting in airway obstruction.J Laryngol Otol.1998;112:1186–1188.

- ,,, et al.Guidelines for the use of systemic glucocorticosteroids in the management of selected infections.Working Group on Steroid Use, Antimicrobial Agents Committee, Infectious Diseases Society of America.J Infect Dis.1992;165(1):1–13.

- ,Narula AA Steroids for airway problems in glandular fever.J Laryngol Otol.1987;10:673–675.

- ,.Peritonsillar abscess: a complication of corticosteroid treatment in infectious mononucleosis.Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol.1979;1(3):265–268.

- ,,.Corticosteroids and peritonsillar abscess formation in infectious mononucleosis.J Laryngol Otol.2004;118:459–461.

- ,,.Otolaryngologic Clinical Patterns in Pediatric Infectious Mononucleosis.Am J Otolaryngol.1996;17:397–400.

Severe tophaceous gout

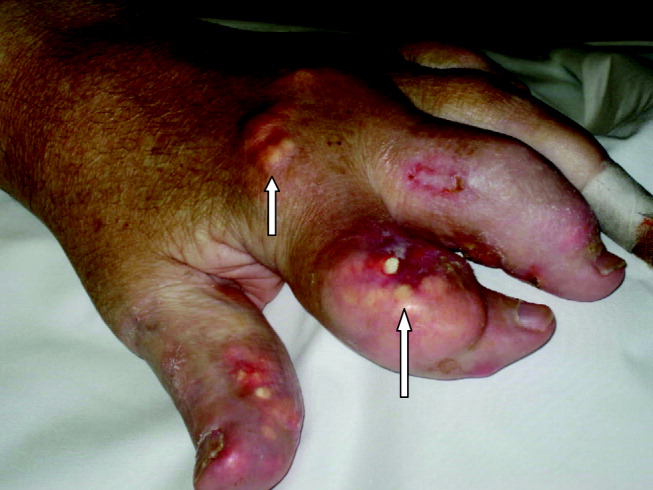

A 55‐year‐old man was admitted to the hospital for amputation of multiple toes secondarily infected in the setting of severe tophaceous gout. He had been wheelchair bound for several years because of severe gouty arthritis. His medical history was remarkable for previous arthroscopies of his hands, knees, and Achilles tendons to remove uric acid deposits, in addition to multiple episodes of nephrolithiasis from uric acid stones. His family history was remarkable for severe, debilitating gout in multiple first‐degree relatives. On further examination he was noted to have severe tophaceous gouty involvement of numerous joints (arrows in Figs. 1 and 2). His uric acid level was 11.6 mg/dL despite receiving 900 mg of allopurinol daily. Because his creatinine was 1.7 mg/dL on admission, his dose of allopurinol was reduced. Renal ultrasound revealed multiple bilateral renal stones (arrows in Fig. 3).

He underwent surgery, and was subsequently transferred to a skilled nursing facility for wound care and physical therapy, where he recuperated uneventfully.

A 55‐year‐old man was admitted to the hospital for amputation of multiple toes secondarily infected in the setting of severe tophaceous gout. He had been wheelchair bound for several years because of severe gouty arthritis. His medical history was remarkable for previous arthroscopies of his hands, knees, and Achilles tendons to remove uric acid deposits, in addition to multiple episodes of nephrolithiasis from uric acid stones. His family history was remarkable for severe, debilitating gout in multiple first‐degree relatives. On further examination he was noted to have severe tophaceous gouty involvement of numerous joints (arrows in Figs. 1 and 2). His uric acid level was 11.6 mg/dL despite receiving 900 mg of allopurinol daily. Because his creatinine was 1.7 mg/dL on admission, his dose of allopurinol was reduced. Renal ultrasound revealed multiple bilateral renal stones (arrows in Fig. 3).

He underwent surgery, and was subsequently transferred to a skilled nursing facility for wound care and physical therapy, where he recuperated uneventfully.

A 55‐year‐old man was admitted to the hospital for amputation of multiple toes secondarily infected in the setting of severe tophaceous gout. He had been wheelchair bound for several years because of severe gouty arthritis. His medical history was remarkable for previous arthroscopies of his hands, knees, and Achilles tendons to remove uric acid deposits, in addition to multiple episodes of nephrolithiasis from uric acid stones. His family history was remarkable for severe, debilitating gout in multiple first‐degree relatives. On further examination he was noted to have severe tophaceous gouty involvement of numerous joints (arrows in Figs. 1 and 2). His uric acid level was 11.6 mg/dL despite receiving 900 mg of allopurinol daily. Because his creatinine was 1.7 mg/dL on admission, his dose of allopurinol was reduced. Renal ultrasound revealed multiple bilateral renal stones (arrows in Fig. 3).

He underwent surgery, and was subsequently transferred to a skilled nursing facility for wound care and physical therapy, where he recuperated uneventfully.

Bony Metastatic Disease

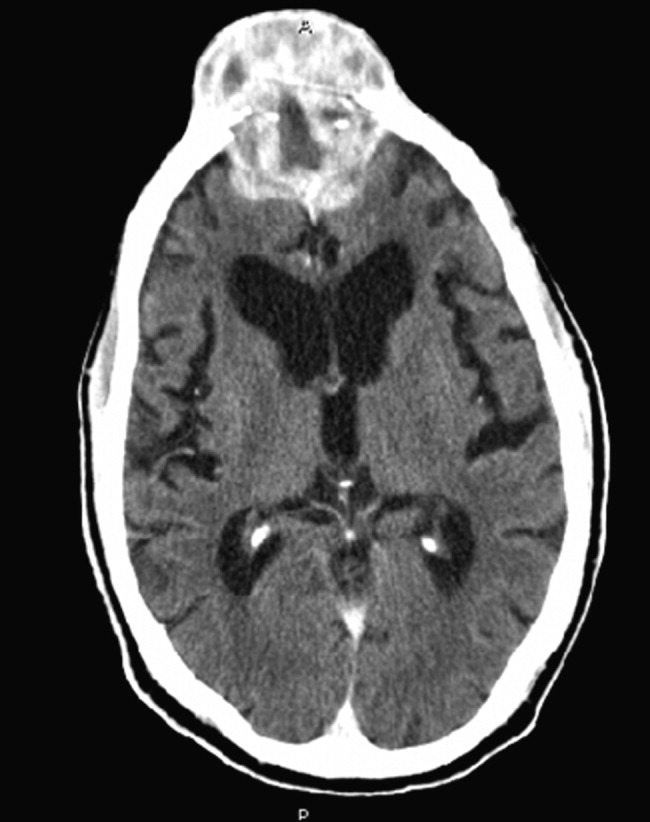

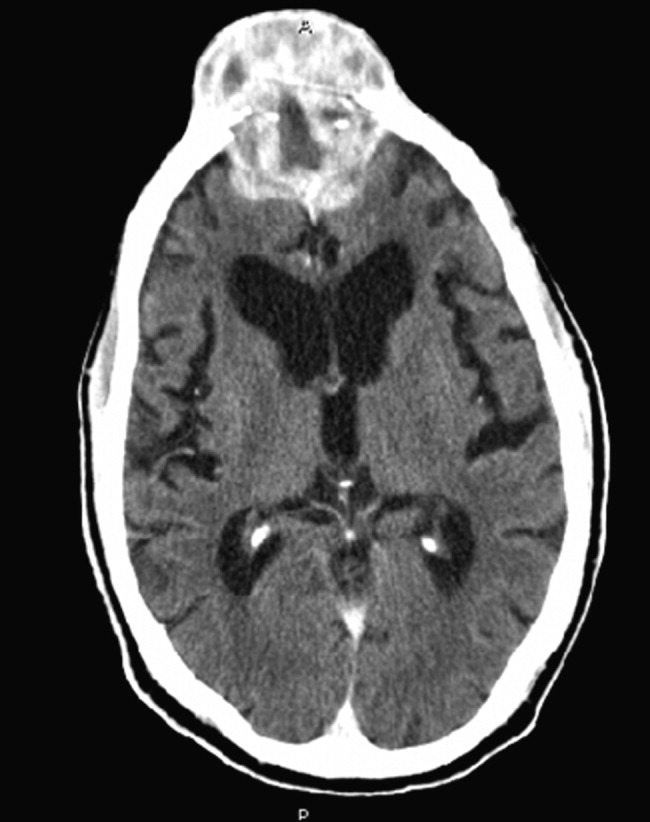

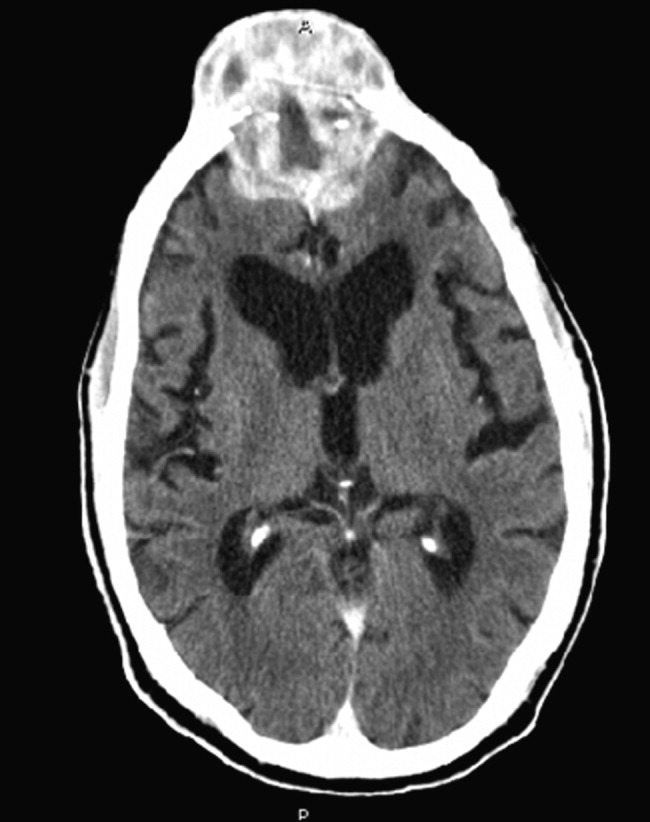

A60‐year‐old man presented with agitation and a forehead mass (Figs. 1 and 2). His wife had noticed its rapid growth over several weeks and said he had recently become extremely confused and hostile. He had a history of smoking and exposures to silica and Agent Orange. His vitals and oxygen saturation were normal. He was cachectic but in no distress, and although he was uncooperative, his examination did not demonstrate an obvious neurological deficit. Routine electrolytes were within normal limits.

Noncontrast computed tomography of the skull revealed a 5.5 5.4 7.7cm frontal soft‐tissue density eroding his frontal bone and extending intracranially, with extensive displacement of both frontal lobes and invasion into his superior sagittal sinus (Fig. 3) and possible involvement of the brain parenchyma. A subsequent CT scan of the chest demonstrated a 7.8 7.9cm right mass in the lower lobe of the lung encasing the right pulmonary artery and 2 left renal masses.

Biopsy of the forehead mass demonstrated a necrotic, poorly differentiated carcinoma with focal clear‐cell features. Immunohistochemical staining was consistent with squamous cell carcinoma.

The forehead mass was painless, and the lung mass unresectable. His behavioral changes persisted and were attributed to the tumor compressing and possibly invading both frontal lobes. At his wife's request, he was discharged on dexamethasone with home hospice and died 2 weeks later.

Although there is little literature on the epidemiology of skull metastases, the most common malignancies to metastasize to the skull are breast and lung carcinomas. Others include prostate, thyroid, myeloma, and melanoma. Symptomatic metastases, including neurological findings, are unusual, except for tumors that metastasize to the skull base and cause cranial nerve deficits. Skeletal metastasis as the first manifestation of lung cancer occurs in about 2% of lung cancer patients and is a marker of poor prognosis. Received 2 November 2006; revision received 15 December 2006; accepted 16 January 2007.

A60‐year‐old man presented with agitation and a forehead mass (Figs. 1 and 2). His wife had noticed its rapid growth over several weeks and said he had recently become extremely confused and hostile. He had a history of smoking and exposures to silica and Agent Orange. His vitals and oxygen saturation were normal. He was cachectic but in no distress, and although he was uncooperative, his examination did not demonstrate an obvious neurological deficit. Routine electrolytes were within normal limits.

Noncontrast computed tomography of the skull revealed a 5.5 5.4 7.7cm frontal soft‐tissue density eroding his frontal bone and extending intracranially, with extensive displacement of both frontal lobes and invasion into his superior sagittal sinus (Fig. 3) and possible involvement of the brain parenchyma. A subsequent CT scan of the chest demonstrated a 7.8 7.9cm right mass in the lower lobe of the lung encasing the right pulmonary artery and 2 left renal masses.

Biopsy of the forehead mass demonstrated a necrotic, poorly differentiated carcinoma with focal clear‐cell features. Immunohistochemical staining was consistent with squamous cell carcinoma.

The forehead mass was painless, and the lung mass unresectable. His behavioral changes persisted and were attributed to the tumor compressing and possibly invading both frontal lobes. At his wife's request, he was discharged on dexamethasone with home hospice and died 2 weeks later.

Although there is little literature on the epidemiology of skull metastases, the most common malignancies to metastasize to the skull are breast and lung carcinomas. Others include prostate, thyroid, myeloma, and melanoma. Symptomatic metastases, including neurological findings, are unusual, except for tumors that metastasize to the skull base and cause cranial nerve deficits. Skeletal metastasis as the first manifestation of lung cancer occurs in about 2% of lung cancer patients and is a marker of poor prognosis. Received 2 November 2006; revision received 15 December 2006; accepted 16 January 2007.

A60‐year‐old man presented with agitation and a forehead mass (Figs. 1 and 2). His wife had noticed its rapid growth over several weeks and said he had recently become extremely confused and hostile. He had a history of smoking and exposures to silica and Agent Orange. His vitals and oxygen saturation were normal. He was cachectic but in no distress, and although he was uncooperative, his examination did not demonstrate an obvious neurological deficit. Routine electrolytes were within normal limits.

Noncontrast computed tomography of the skull revealed a 5.5 5.4 7.7cm frontal soft‐tissue density eroding his frontal bone and extending intracranially, with extensive displacement of both frontal lobes and invasion into his superior sagittal sinus (Fig. 3) and possible involvement of the brain parenchyma. A subsequent CT scan of the chest demonstrated a 7.8 7.9cm right mass in the lower lobe of the lung encasing the right pulmonary artery and 2 left renal masses.

Biopsy of the forehead mass demonstrated a necrotic, poorly differentiated carcinoma with focal clear‐cell features. Immunohistochemical staining was consistent with squamous cell carcinoma.

The forehead mass was painless, and the lung mass unresectable. His behavioral changes persisted and were attributed to the tumor compressing and possibly invading both frontal lobes. At his wife's request, he was discharged on dexamethasone with home hospice and died 2 weeks later.

Although there is little literature on the epidemiology of skull metastases, the most common malignancies to metastasize to the skull are breast and lung carcinomas. Others include prostate, thyroid, myeloma, and melanoma. Symptomatic metastases, including neurological findings, are unusual, except for tumors that metastasize to the skull base and cause cranial nerve deficits. Skeletal metastasis as the first manifestation of lung cancer occurs in about 2% of lung cancer patients and is a marker of poor prognosis. Received 2 November 2006; revision received 15 December 2006; accepted 16 January 2007.

Disseminated histoplasmosis

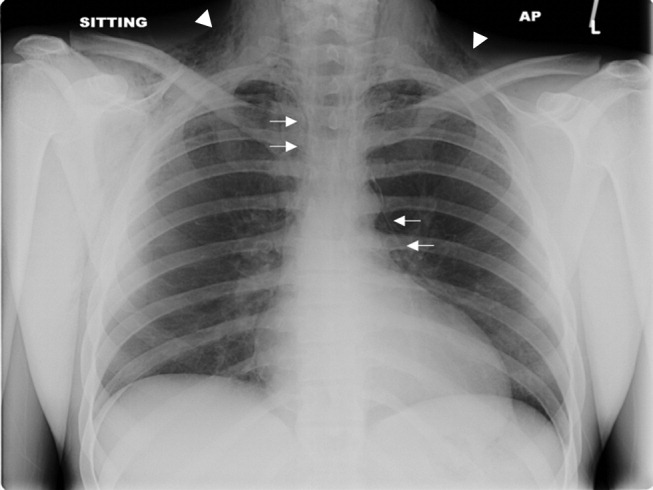

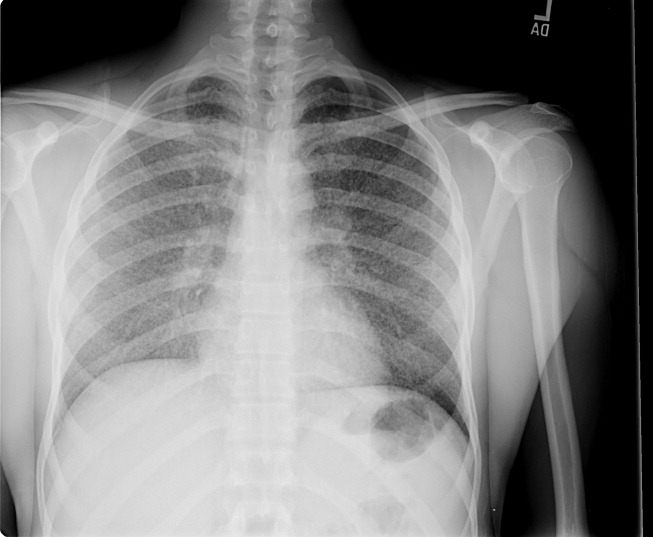

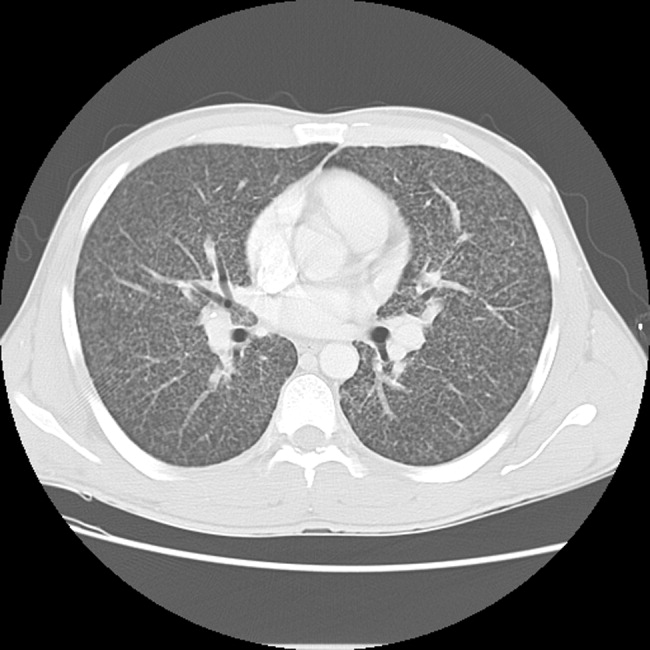

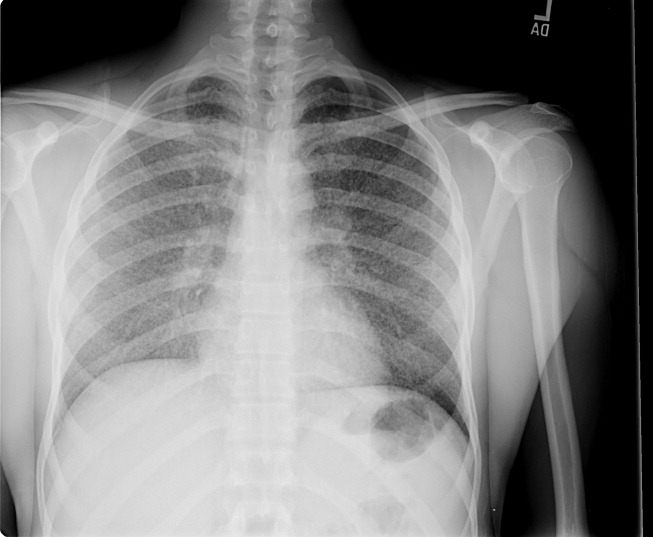

A previously healthy 27‐year‐old El Salvadoran immigrant presented with a 2‐week history of cough, fever, rigors, prostration, anorexia, weight loss, and scant hemoptysis. Physical examination revealed a thin, febrile, toxic‐appearing man in respiratory distress with bibasilar rales and scattered wheezes. Laboratory data showed a sodium of 126 mEq/L, lactate dehydrogenase of 617 U/L, ferritin of 3570 ng/mL, and liver test abnormalities suggestive of cholestasis. Chest film (Fig. 1) and computed tomography (Fig. 2) demonstrated a diffuse miliary air space pattern. Sputum smears for mycobacterium tuberculosis were negative. A urine histoplasmosis antigen level was markedly positive (7.6 EIA units), and bone marrow cultures eventually grew Histoplasma capsulatum. The HIV test result was positive, and his CD4 count was 34 cells/mm3. He was successfully treated with liposomal amphotericin B followed by itraconazole.

Histoplasmosis is the most prevalent endemic mycosis in Latin America. Most infections are asymptomatic or self‐limited, but immunodeficient individuals may develop acute pulmonary or severe, progressive disseminated infection, usually from reactivation of latent disease. Although nonspecific, the serum lactate dehydrogenase and ferritin levels are often markedly elevated. Chest imaging may be normal or show a diffuse reticulonodular pattern (with nodules less than 3 mm in diameter), indistinguishable from miliary tuberculosis. In HIV‐infected individuals, disseminated histoplasmosis usually develops when the CD4 count is less than 75 cells/mm3. Treatment is generally lifelong.

A previously healthy 27‐year‐old El Salvadoran immigrant presented with a 2‐week history of cough, fever, rigors, prostration, anorexia, weight loss, and scant hemoptysis. Physical examination revealed a thin, febrile, toxic‐appearing man in respiratory distress with bibasilar rales and scattered wheezes. Laboratory data showed a sodium of 126 mEq/L, lactate dehydrogenase of 617 U/L, ferritin of 3570 ng/mL, and liver test abnormalities suggestive of cholestasis. Chest film (Fig. 1) and computed tomography (Fig. 2) demonstrated a diffuse miliary air space pattern. Sputum smears for mycobacterium tuberculosis were negative. A urine histoplasmosis antigen level was markedly positive (7.6 EIA units), and bone marrow cultures eventually grew Histoplasma capsulatum. The HIV test result was positive, and his CD4 count was 34 cells/mm3. He was successfully treated with liposomal amphotericin B followed by itraconazole.

Histoplasmosis is the most prevalent endemic mycosis in Latin America. Most infections are asymptomatic or self‐limited, but immunodeficient individuals may develop acute pulmonary or severe, progressive disseminated infection, usually from reactivation of latent disease. Although nonspecific, the serum lactate dehydrogenase and ferritin levels are often markedly elevated. Chest imaging may be normal or show a diffuse reticulonodular pattern (with nodules less than 3 mm in diameter), indistinguishable from miliary tuberculosis. In HIV‐infected individuals, disseminated histoplasmosis usually develops when the CD4 count is less than 75 cells/mm3. Treatment is generally lifelong.

A previously healthy 27‐year‐old El Salvadoran immigrant presented with a 2‐week history of cough, fever, rigors, prostration, anorexia, weight loss, and scant hemoptysis. Physical examination revealed a thin, febrile, toxic‐appearing man in respiratory distress with bibasilar rales and scattered wheezes. Laboratory data showed a sodium of 126 mEq/L, lactate dehydrogenase of 617 U/L, ferritin of 3570 ng/mL, and liver test abnormalities suggestive of cholestasis. Chest film (Fig. 1) and computed tomography (Fig. 2) demonstrated a diffuse miliary air space pattern. Sputum smears for mycobacterium tuberculosis were negative. A urine histoplasmosis antigen level was markedly positive (7.6 EIA units), and bone marrow cultures eventually grew Histoplasma capsulatum. The HIV test result was positive, and his CD4 count was 34 cells/mm3. He was successfully treated with liposomal amphotericin B followed by itraconazole.

Histoplasmosis is the most prevalent endemic mycosis in Latin America. Most infections are asymptomatic or self‐limited, but immunodeficient individuals may develop acute pulmonary or severe, progressive disseminated infection, usually from reactivation of latent disease. Although nonspecific, the serum lactate dehydrogenase and ferritin levels are often markedly elevated. Chest imaging may be normal or show a diffuse reticulonodular pattern (with nodules less than 3 mm in diameter), indistinguishable from miliary tuberculosis. In HIV‐infected individuals, disseminated histoplasmosis usually develops when the CD4 count is less than 75 cells/mm3. Treatment is generally lifelong.