User login

A “Routine” Electrocardiogram (ECG)

Patient Presentation

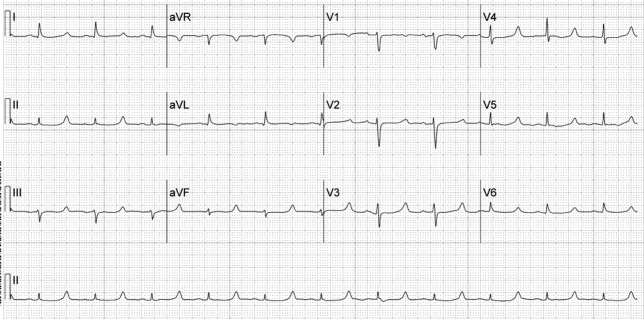

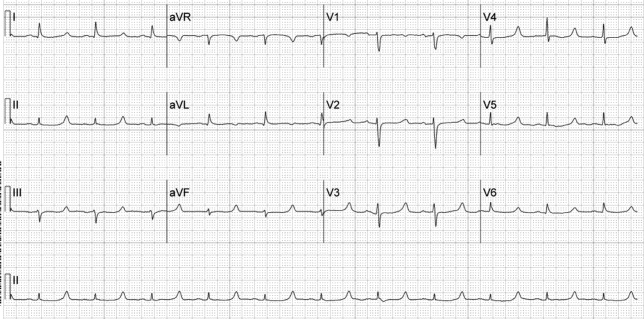

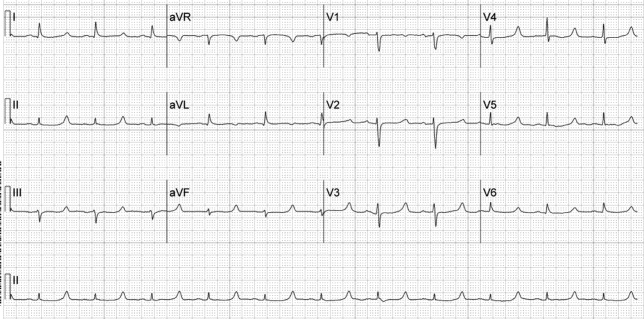

A 52‐year‐old woman with cirrhosis presented with a large‐volume upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleed. After receiving massive volume and blood product resuscitation (18 U packed red blood cells [PRBCs], 17 U fresh frozen plasma [FFP], 2 U cryoprecipitate, 1 U platelets, and 14 L normal saline), a routine admission electrocardiogram (ECG) was obtained (Figure 1).

Discussion

The ECG shows normal sinus rhythm with a prolonged QT interval (specifically due to a long ST segment). The differential diagnosis of this pattern of QT prolongation includes hypocalcemia, long QT syndrome (variant 3), and hypothermia. Massive transfusion can result in the chelation of calcium by citrate resulting in hypocalcemia. This patient's serum calcium was 7 mg/dL (8.9‐10.2) (ionized 0.21 mmol/L; 1.18‐1.38), her pH was 7.03. There were no overt signs or symptoms of hypocalcemia (paresthesias, twitching, tetany, or seizures.) and with aggressive replacement the calcium and the ECG normalized. Transfusions are an uncommon cause of hypocalcemia, with hypomagnesemia or hypermagnesemia, acute pancreatitis, rhabdomyolysis, tumor lysis syndrome, renal failure, vitamin D deficiency, pseudoparathyroidism and hypoparathyroidism being the more common disorders caused.1, 2 This patient's magnesium was normal on admission (2.1 mg/dL) and she did not have any of the other conditions mentioned. It is possible that hemodilution may also have played a role.

Genetic long QT syndrome (variant 3) can manifest with a similar ECG pattern, although the T‐wave is sometimes peaked or biphasic in that condition. Our patient had no personal or family history of syncope or sudden death, and her ECG normalized with calcium replacement.3

Hypothermia can also present with a long QT interval secondary to a long ST segment. Our patient was normothermic, and had no other ECG findings suggestive of hypothermia (Osborn waves: notching of terminal portion of QRS), shivering artifacts, sinus bradycardia, atrial fibrillation, QRS prolongation, or prolongation of the PR interval.4

The differential diagnosis of a long QT interval with a long ST segment is short, and the clinical scenario will provide the etiology in most cases.

- .Hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia. In:Fauci AS,Braunwald E,Kasper DL, et al., eds.Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. Available at: http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=2864354.

- ,,.Massive transfusion.Crit Care Clin.1986;2:791–805.

- ,,,.Novel insights in the congenital long QT syndrome.Ann Intern Med.2002;137:981–992.

- ,,.The clinical value of the ECG in noncardiac conditions.Chest.2004;125:1561–1576.

Patient Presentation

A 52‐year‐old woman with cirrhosis presented with a large‐volume upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleed. After receiving massive volume and blood product resuscitation (18 U packed red blood cells [PRBCs], 17 U fresh frozen plasma [FFP], 2 U cryoprecipitate, 1 U platelets, and 14 L normal saline), a routine admission electrocardiogram (ECG) was obtained (Figure 1).

Discussion

The ECG shows normal sinus rhythm with a prolonged QT interval (specifically due to a long ST segment). The differential diagnosis of this pattern of QT prolongation includes hypocalcemia, long QT syndrome (variant 3), and hypothermia. Massive transfusion can result in the chelation of calcium by citrate resulting in hypocalcemia. This patient's serum calcium was 7 mg/dL (8.9‐10.2) (ionized 0.21 mmol/L; 1.18‐1.38), her pH was 7.03. There were no overt signs or symptoms of hypocalcemia (paresthesias, twitching, tetany, or seizures.) and with aggressive replacement the calcium and the ECG normalized. Transfusions are an uncommon cause of hypocalcemia, with hypomagnesemia or hypermagnesemia, acute pancreatitis, rhabdomyolysis, tumor lysis syndrome, renal failure, vitamin D deficiency, pseudoparathyroidism and hypoparathyroidism being the more common disorders caused.1, 2 This patient's magnesium was normal on admission (2.1 mg/dL) and she did not have any of the other conditions mentioned. It is possible that hemodilution may also have played a role.

Genetic long QT syndrome (variant 3) can manifest with a similar ECG pattern, although the T‐wave is sometimes peaked or biphasic in that condition. Our patient had no personal or family history of syncope or sudden death, and her ECG normalized with calcium replacement.3

Hypothermia can also present with a long QT interval secondary to a long ST segment. Our patient was normothermic, and had no other ECG findings suggestive of hypothermia (Osborn waves: notching of terminal portion of QRS), shivering artifacts, sinus bradycardia, atrial fibrillation, QRS prolongation, or prolongation of the PR interval.4

The differential diagnosis of a long QT interval with a long ST segment is short, and the clinical scenario will provide the etiology in most cases.

Patient Presentation

A 52‐year‐old woman with cirrhosis presented with a large‐volume upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleed. After receiving massive volume and blood product resuscitation (18 U packed red blood cells [PRBCs], 17 U fresh frozen plasma [FFP], 2 U cryoprecipitate, 1 U platelets, and 14 L normal saline), a routine admission electrocardiogram (ECG) was obtained (Figure 1).

Discussion

The ECG shows normal sinus rhythm with a prolonged QT interval (specifically due to a long ST segment). The differential diagnosis of this pattern of QT prolongation includes hypocalcemia, long QT syndrome (variant 3), and hypothermia. Massive transfusion can result in the chelation of calcium by citrate resulting in hypocalcemia. This patient's serum calcium was 7 mg/dL (8.9‐10.2) (ionized 0.21 mmol/L; 1.18‐1.38), her pH was 7.03. There were no overt signs or symptoms of hypocalcemia (paresthesias, twitching, tetany, or seizures.) and with aggressive replacement the calcium and the ECG normalized. Transfusions are an uncommon cause of hypocalcemia, with hypomagnesemia or hypermagnesemia, acute pancreatitis, rhabdomyolysis, tumor lysis syndrome, renal failure, vitamin D deficiency, pseudoparathyroidism and hypoparathyroidism being the more common disorders caused.1, 2 This patient's magnesium was normal on admission (2.1 mg/dL) and she did not have any of the other conditions mentioned. It is possible that hemodilution may also have played a role.

Genetic long QT syndrome (variant 3) can manifest with a similar ECG pattern, although the T‐wave is sometimes peaked or biphasic in that condition. Our patient had no personal or family history of syncope or sudden death, and her ECG normalized with calcium replacement.3

Hypothermia can also present with a long QT interval secondary to a long ST segment. Our patient was normothermic, and had no other ECG findings suggestive of hypothermia (Osborn waves: notching of terminal portion of QRS), shivering artifacts, sinus bradycardia, atrial fibrillation, QRS prolongation, or prolongation of the PR interval.4

The differential diagnosis of a long QT interval with a long ST segment is short, and the clinical scenario will provide the etiology in most cases.

- .Hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia. In:Fauci AS,Braunwald E,Kasper DL, et al., eds.Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. Available at: http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=2864354.

- ,,.Massive transfusion.Crit Care Clin.1986;2:791–805.

- ,,,.Novel insights in the congenital long QT syndrome.Ann Intern Med.2002;137:981–992.

- ,,.The clinical value of the ECG in noncardiac conditions.Chest.2004;125:1561–1576.

- .Hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia. In:Fauci AS,Braunwald E,Kasper DL, et al., eds.Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. Available at: http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=2864354.

- ,,.Massive transfusion.Crit Care Clin.1986;2:791–805.

- ,,,.Novel insights in the congenital long QT syndrome.Ann Intern Med.2002;137:981–992.

- ,,.The clinical value of the ECG in noncardiac conditions.Chest.2004;125:1561–1576.

Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia?

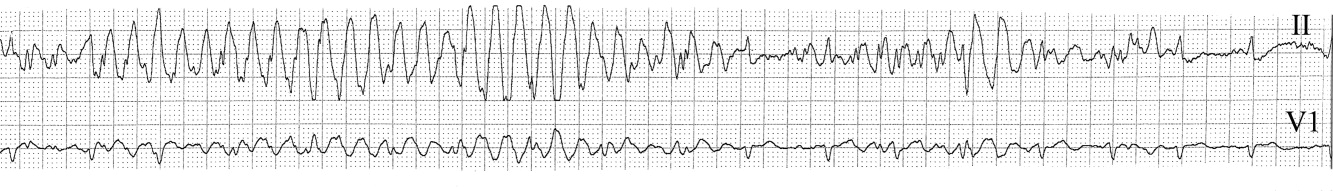

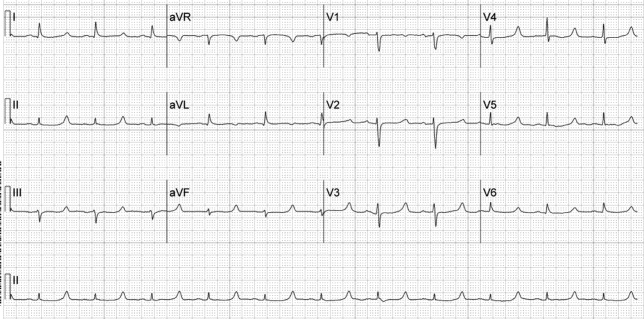

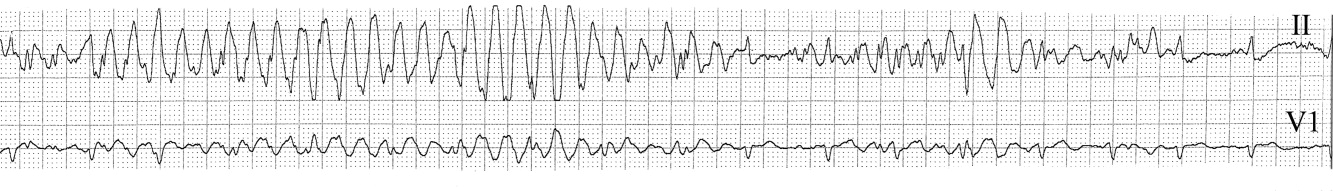

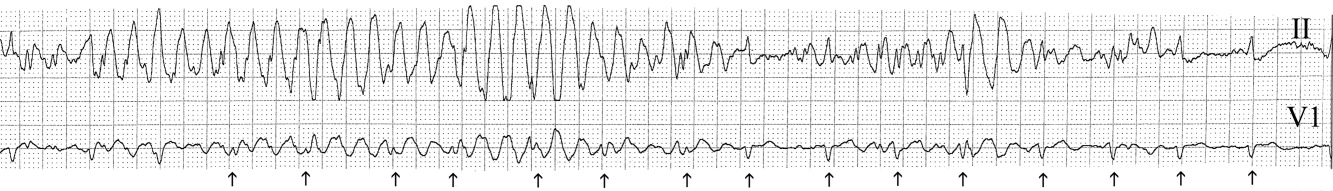

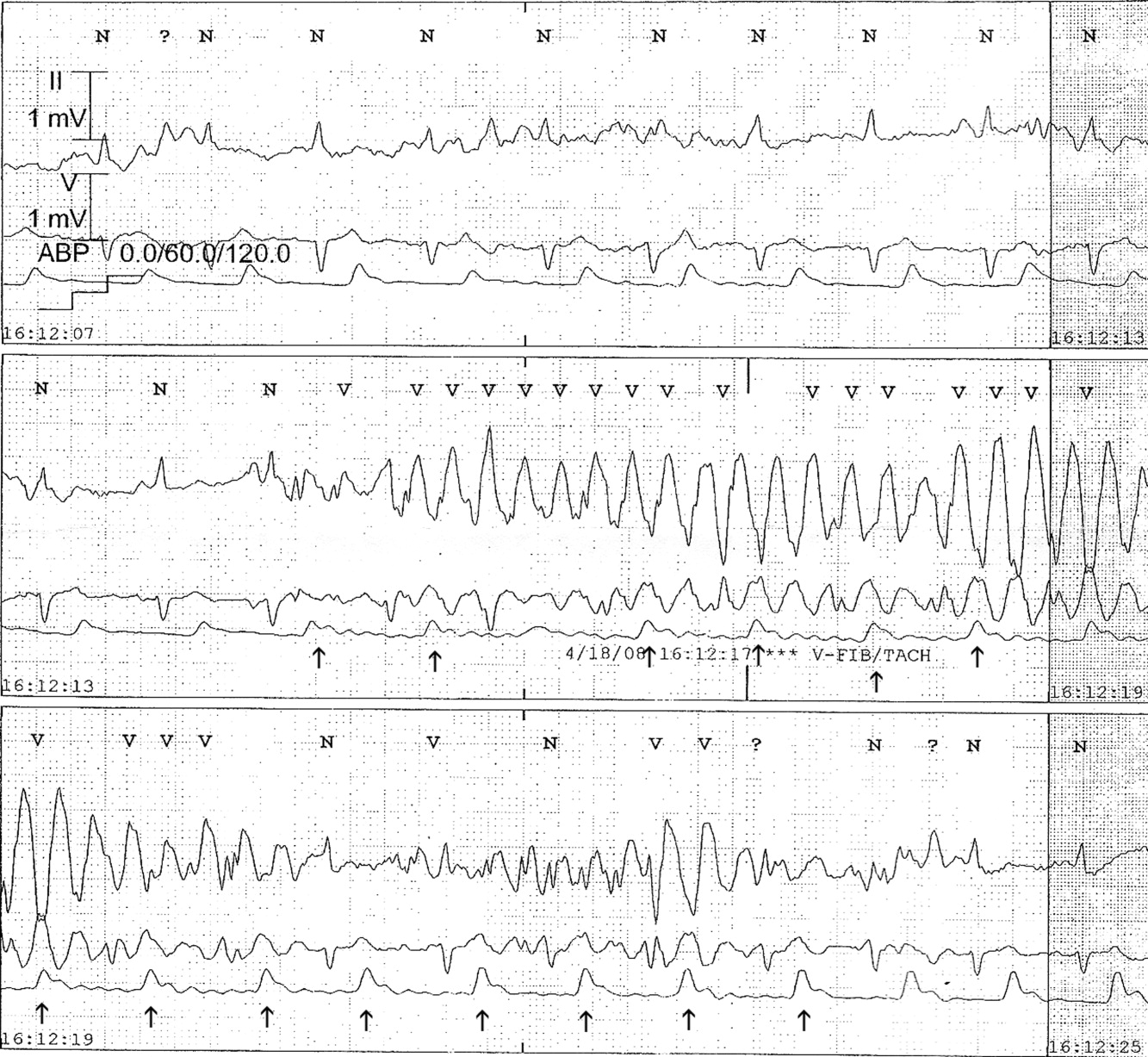

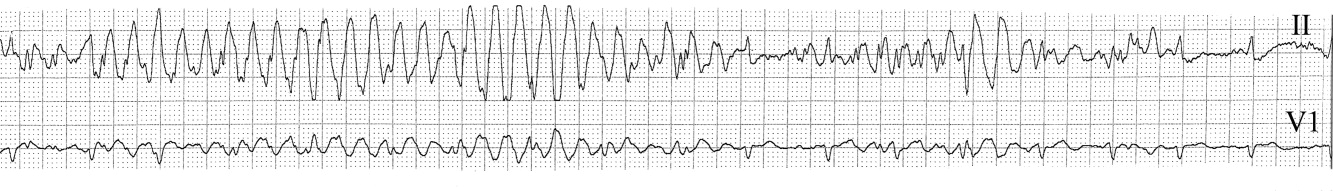

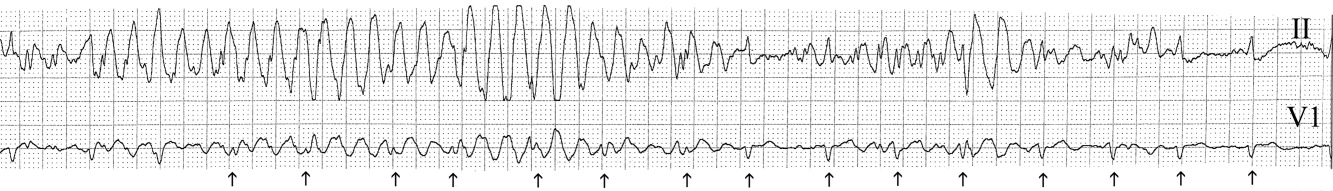

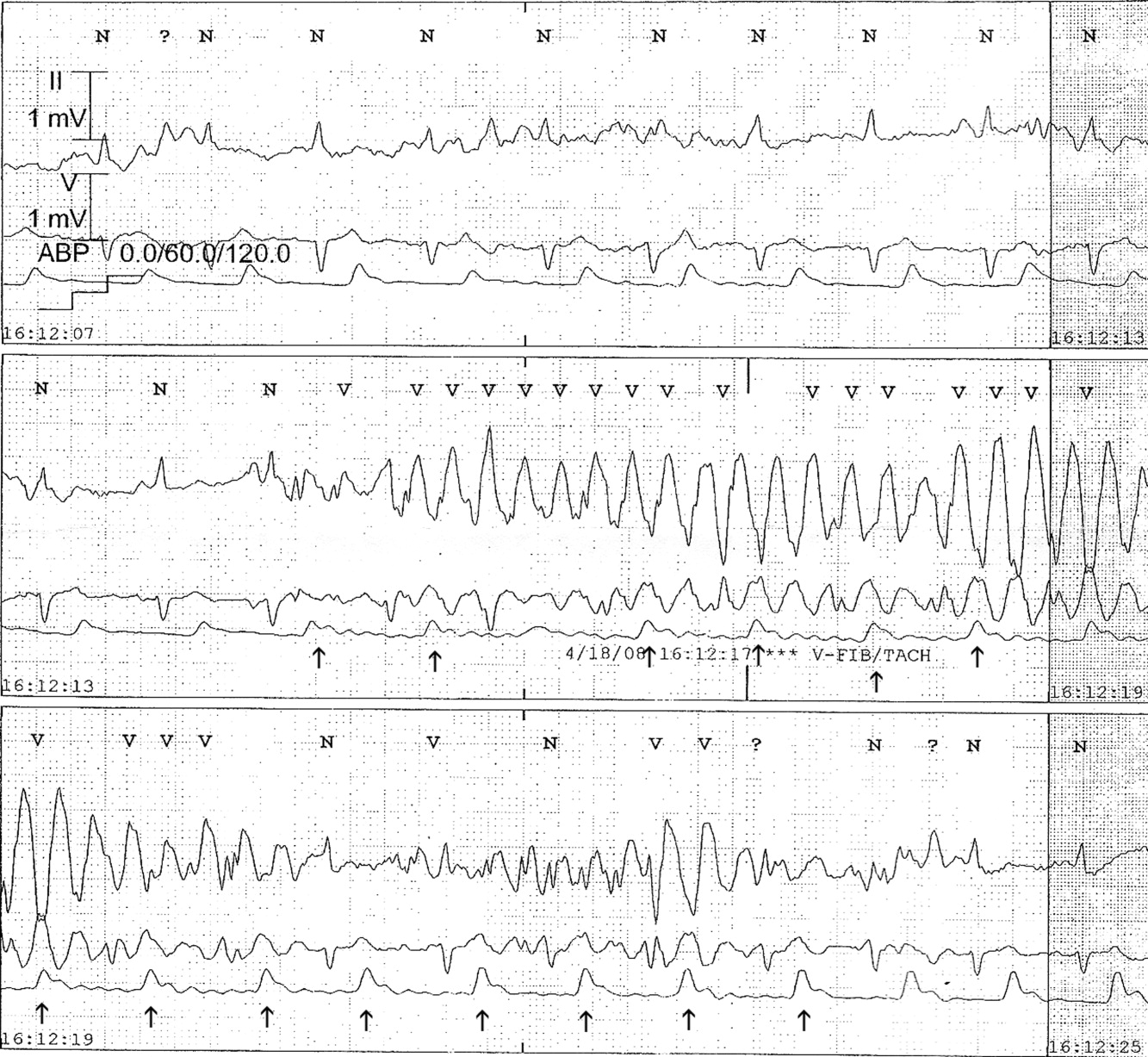

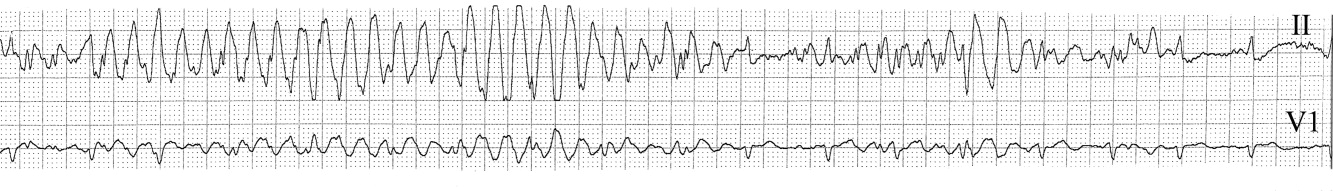

The medical team was called emergently from the telemetry station in response to the tracing shown in Figure 1. The patient was a 65‐year‐old woman with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and no structural heart disease. The medical team arrived at the bedside to find the patient chatting with her family with a heart rate of 95 and blood pressure of 144/92. The patient had been awake and alert throughout the episode. Initial inspection of the rhythm strip (Figure 1) shows what appears to be nonsustained polymorphic ventricular tachycardia followed by normal QRS complexes. Upon careful inspection of the V1 (lower) tracing, the QRS complexes can be marched backward through the wide complexes to the beginning of the strip, as shown in Figure 2 (arrows), indicating that the wide complexes are artifact.

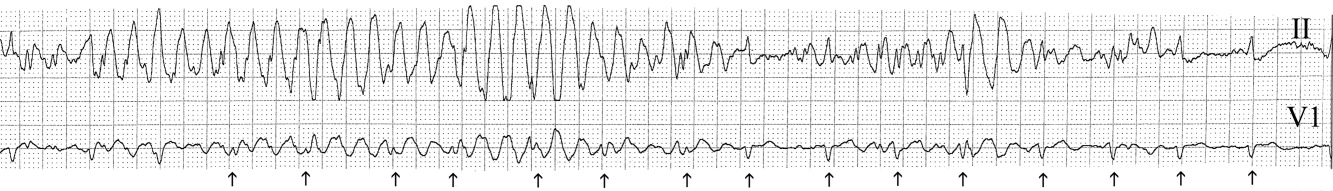

The presence of artifact is confirmed in Figure 3, in which the arterial blood pressure (ABP) waveform follows the QRS complexes. In polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, the ABP would have fallen and the waveform would have been chaotic. Failure to differentiate between artifact and ventricular tachycardia can lead to inappropriate management.1, 2 The artifact in this case is likely due to electrode motion and emphasizes the importance of using all the available data when evaluating rhythm strips. Critical evaluation of multiple electrocardiographic (ECG) leads is the cornerstone of diagnosis; continuous arterial monitoring, if available, can be useful for confirmation.

- ,,.Approach to the diagnosis and initial management of the stable adult patient with a wide complex tachycardia.Am J Cardiol.2008;101(10):1456–1466.

- ,,,,.Physician interpretation of electrocardiographic artifact that mimics ventricular tachycardia.Am J Med.2001;110(5):335–338.

The medical team was called emergently from the telemetry station in response to the tracing shown in Figure 1. The patient was a 65‐year‐old woman with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and no structural heart disease. The medical team arrived at the bedside to find the patient chatting with her family with a heart rate of 95 and blood pressure of 144/92. The patient had been awake and alert throughout the episode. Initial inspection of the rhythm strip (Figure 1) shows what appears to be nonsustained polymorphic ventricular tachycardia followed by normal QRS complexes. Upon careful inspection of the V1 (lower) tracing, the QRS complexes can be marched backward through the wide complexes to the beginning of the strip, as shown in Figure 2 (arrows), indicating that the wide complexes are artifact.

The presence of artifact is confirmed in Figure 3, in which the arterial blood pressure (ABP) waveform follows the QRS complexes. In polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, the ABP would have fallen and the waveform would have been chaotic. Failure to differentiate between artifact and ventricular tachycardia can lead to inappropriate management.1, 2 The artifact in this case is likely due to electrode motion and emphasizes the importance of using all the available data when evaluating rhythm strips. Critical evaluation of multiple electrocardiographic (ECG) leads is the cornerstone of diagnosis; continuous arterial monitoring, if available, can be useful for confirmation.

The medical team was called emergently from the telemetry station in response to the tracing shown in Figure 1. The patient was a 65‐year‐old woman with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and no structural heart disease. The medical team arrived at the bedside to find the patient chatting with her family with a heart rate of 95 and blood pressure of 144/92. The patient had been awake and alert throughout the episode. Initial inspection of the rhythm strip (Figure 1) shows what appears to be nonsustained polymorphic ventricular tachycardia followed by normal QRS complexes. Upon careful inspection of the V1 (lower) tracing, the QRS complexes can be marched backward through the wide complexes to the beginning of the strip, as shown in Figure 2 (arrows), indicating that the wide complexes are artifact.

The presence of artifact is confirmed in Figure 3, in which the arterial blood pressure (ABP) waveform follows the QRS complexes. In polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, the ABP would have fallen and the waveform would have been chaotic. Failure to differentiate between artifact and ventricular tachycardia can lead to inappropriate management.1, 2 The artifact in this case is likely due to electrode motion and emphasizes the importance of using all the available data when evaluating rhythm strips. Critical evaluation of multiple electrocardiographic (ECG) leads is the cornerstone of diagnosis; continuous arterial monitoring, if available, can be useful for confirmation.

- ,,.Approach to the diagnosis and initial management of the stable adult patient with a wide complex tachycardia.Am J Cardiol.2008;101(10):1456–1466.

- ,,,,.Physician interpretation of electrocardiographic artifact that mimics ventricular tachycardia.Am J Med.2001;110(5):335–338.

- ,,.Approach to the diagnosis and initial management of the stable adult patient with a wide complex tachycardia.Am J Cardiol.2008;101(10):1456–1466.

- ,,,,.Physician interpretation of electrocardiographic artifact that mimics ventricular tachycardia.Am J Med.2001;110(5):335–338.

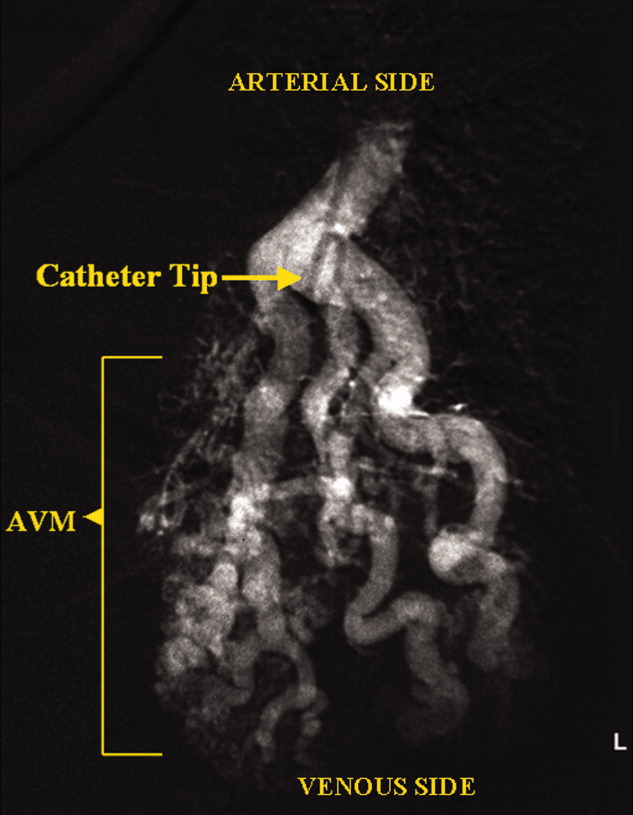

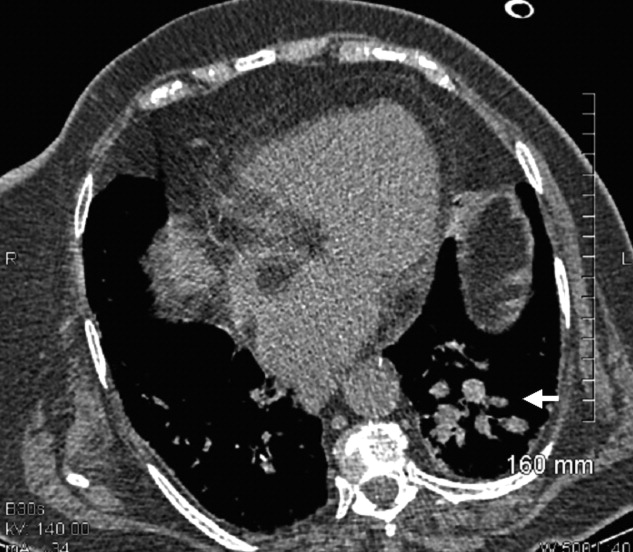

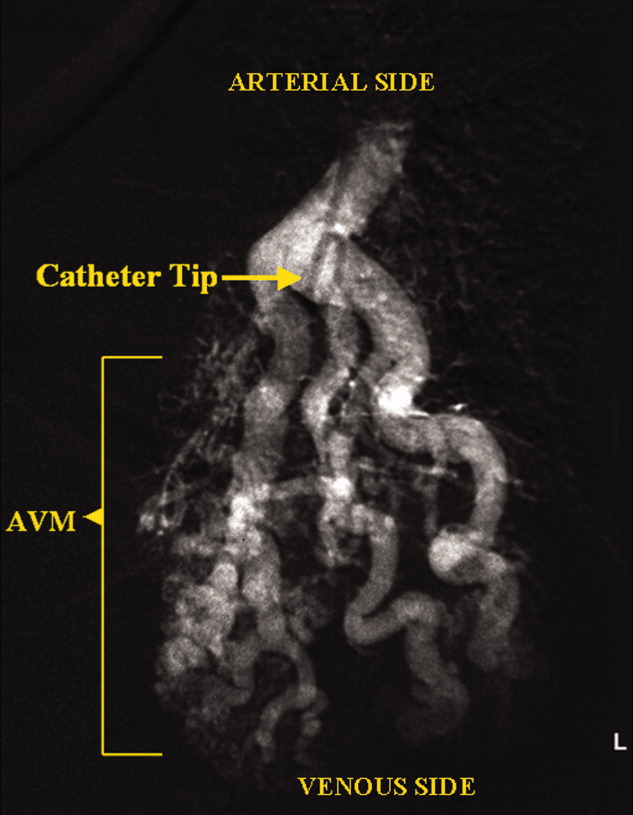

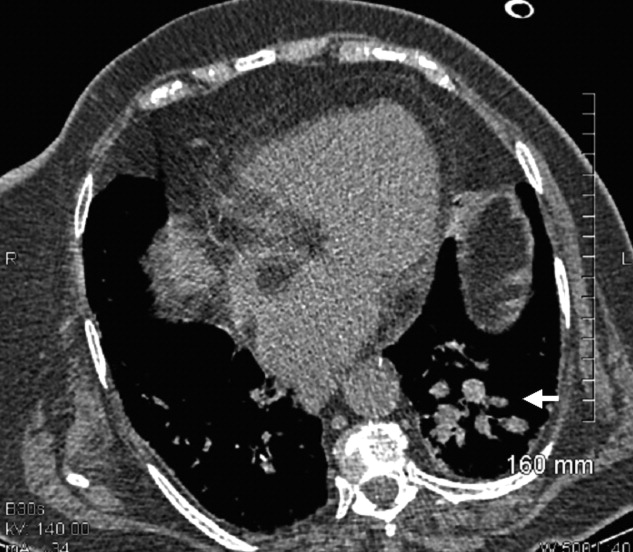

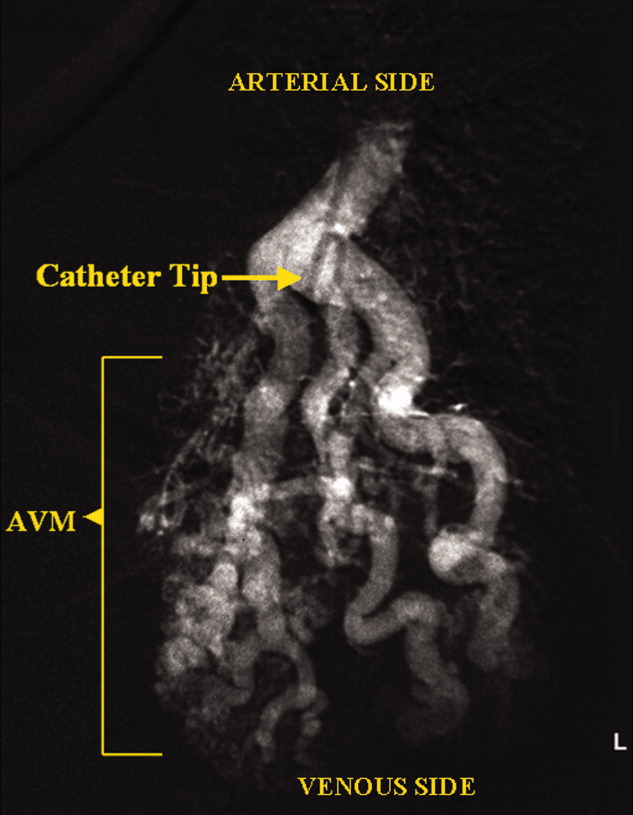

Doctor, my breathing is better when I lie down

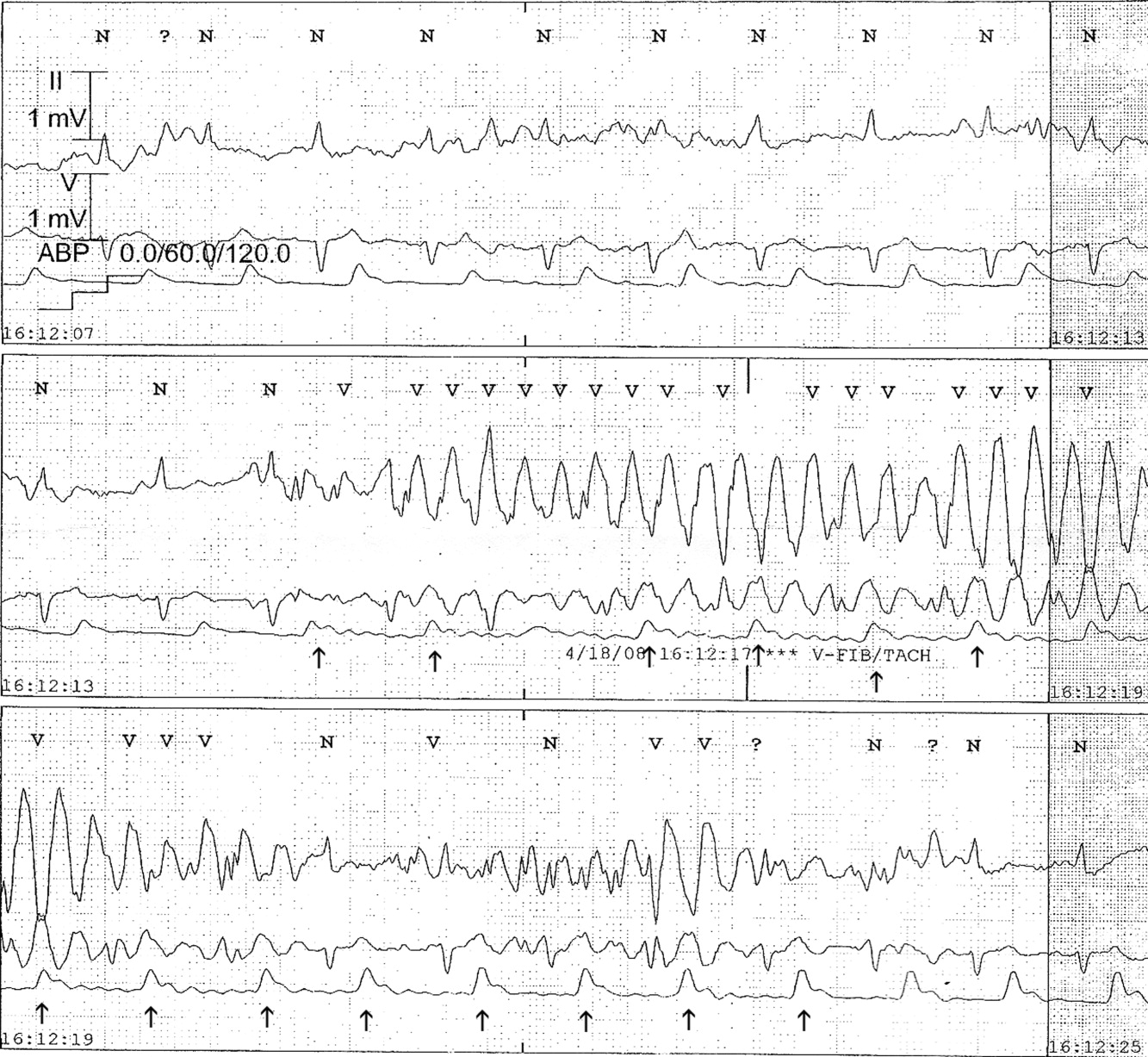

A 73‐year‐old female presented with progressive shortness of breath that was worse in the upright position and was relieved when she was lying flat (platypnea). Arterial blood gas analysis revealed a partial pressure of oxygen of 56 mm Hg in the supine position and 42 mm Hg when the patient was seated upright. Chest radiography revealed an ill‐defined density in the left lung base, and a high‐resolution computed tomography scan of the chest revealed dilated arteries and veins in the left lower lobe (Figure 1). Pulmonary angiography showed a huge pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (PAVM) with a nidus of 7 cm 8 cm involving the left lower lobe (Figure 2; the arrow points to the catheter tip). Embolization therapy was not an option because of the large size of the PAVM, which would have necessitated several coils with an increased risk of systemic embolization. Left lower lobectomy was performed with marked relief of the patient's dyspnea and hypoxemia.

PAVMs are extracardiac shunts caused by abnormal communication between pulmonary arteries and pulmonary veins. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia accounts for nearly 84% of PAVMs. PAVMs as complications of the surgical treatment of complex cyanotic congenital heart disease, trauma, and liver disease and sporadic PAVMs, as in our case, are less common. There were no associated signs of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia or liver disease in our patient, and gradual enlargement over time likely resulted in the late presentation. Common clinical manifestations of PAVMs include dyspnea, hemoptysis, and chest pain. A PAVM may also cause platypnea because of a decrease in blood flow through the PAVM in the dependent portions of the lungs when the patient changes from an upright position to a supine position. This decrease in blood flow though the PAVM causes an improvement in the shortness of breath and hypoxemia as there is decreased right‐to‐left shunting of blood. Treatment is initiated for all symptomatic patients and PAVMs more than 2 cm in diameter. Embolization therapy is preferable because it avoids the risks of major surgery. Surgery is performed for patients with an untreatable allergy to the contrast material and with large PAVMs not technically amenable to embolization therapy, as in our patient.

A 73‐year‐old female presented with progressive shortness of breath that was worse in the upright position and was relieved when she was lying flat (platypnea). Arterial blood gas analysis revealed a partial pressure of oxygen of 56 mm Hg in the supine position and 42 mm Hg when the patient was seated upright. Chest radiography revealed an ill‐defined density in the left lung base, and a high‐resolution computed tomography scan of the chest revealed dilated arteries and veins in the left lower lobe (Figure 1). Pulmonary angiography showed a huge pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (PAVM) with a nidus of 7 cm 8 cm involving the left lower lobe (Figure 2; the arrow points to the catheter tip). Embolization therapy was not an option because of the large size of the PAVM, which would have necessitated several coils with an increased risk of systemic embolization. Left lower lobectomy was performed with marked relief of the patient's dyspnea and hypoxemia.

PAVMs are extracardiac shunts caused by abnormal communication between pulmonary arteries and pulmonary veins. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia accounts for nearly 84% of PAVMs. PAVMs as complications of the surgical treatment of complex cyanotic congenital heart disease, trauma, and liver disease and sporadic PAVMs, as in our case, are less common. There were no associated signs of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia or liver disease in our patient, and gradual enlargement over time likely resulted in the late presentation. Common clinical manifestations of PAVMs include dyspnea, hemoptysis, and chest pain. A PAVM may also cause platypnea because of a decrease in blood flow through the PAVM in the dependent portions of the lungs when the patient changes from an upright position to a supine position. This decrease in blood flow though the PAVM causes an improvement in the shortness of breath and hypoxemia as there is decreased right‐to‐left shunting of blood. Treatment is initiated for all symptomatic patients and PAVMs more than 2 cm in diameter. Embolization therapy is preferable because it avoids the risks of major surgery. Surgery is performed for patients with an untreatable allergy to the contrast material and with large PAVMs not technically amenable to embolization therapy, as in our patient.

A 73‐year‐old female presented with progressive shortness of breath that was worse in the upright position and was relieved when she was lying flat (platypnea). Arterial blood gas analysis revealed a partial pressure of oxygen of 56 mm Hg in the supine position and 42 mm Hg when the patient was seated upright. Chest radiography revealed an ill‐defined density in the left lung base, and a high‐resolution computed tomography scan of the chest revealed dilated arteries and veins in the left lower lobe (Figure 1). Pulmonary angiography showed a huge pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (PAVM) with a nidus of 7 cm 8 cm involving the left lower lobe (Figure 2; the arrow points to the catheter tip). Embolization therapy was not an option because of the large size of the PAVM, which would have necessitated several coils with an increased risk of systemic embolization. Left lower lobectomy was performed with marked relief of the patient's dyspnea and hypoxemia.

PAVMs are extracardiac shunts caused by abnormal communication between pulmonary arteries and pulmonary veins. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia accounts for nearly 84% of PAVMs. PAVMs as complications of the surgical treatment of complex cyanotic congenital heart disease, trauma, and liver disease and sporadic PAVMs, as in our case, are less common. There were no associated signs of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia or liver disease in our patient, and gradual enlargement over time likely resulted in the late presentation. Common clinical manifestations of PAVMs include dyspnea, hemoptysis, and chest pain. A PAVM may also cause platypnea because of a decrease in blood flow through the PAVM in the dependent portions of the lungs when the patient changes from an upright position to a supine position. This decrease in blood flow though the PAVM causes an improvement in the shortness of breath and hypoxemia as there is decreased right‐to‐left shunting of blood. Treatment is initiated for all symptomatic patients and PAVMs more than 2 cm in diameter. Embolization therapy is preferable because it avoids the risks of major surgery. Surgery is performed for patients with an untreatable allergy to the contrast material and with large PAVMs not technically amenable to embolization therapy, as in our patient.

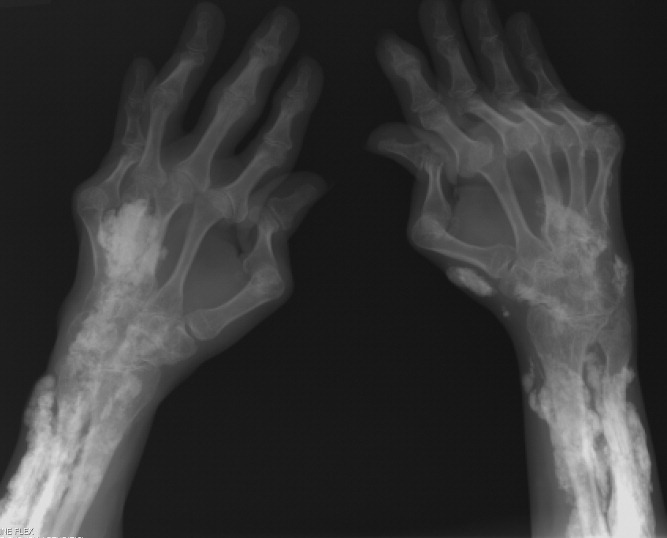

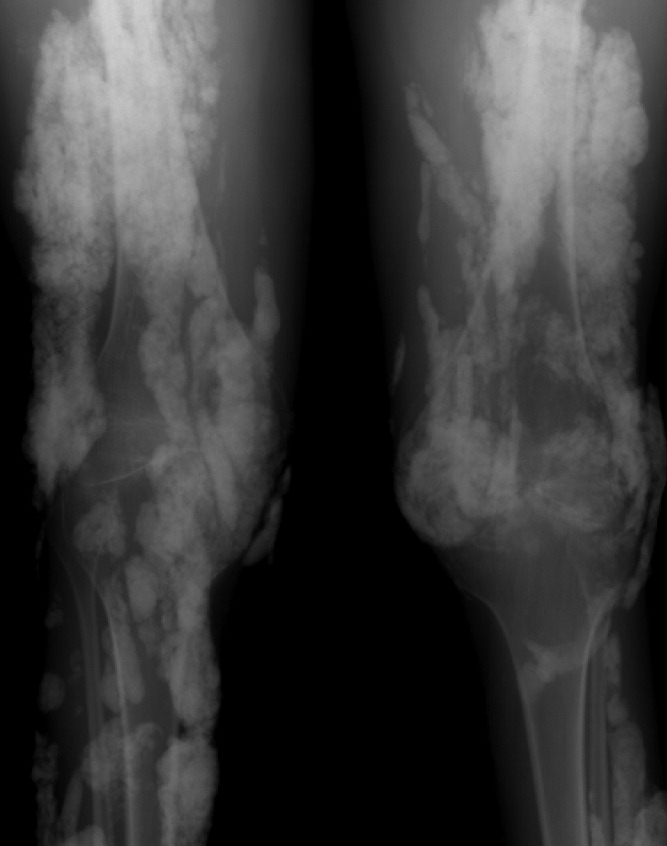

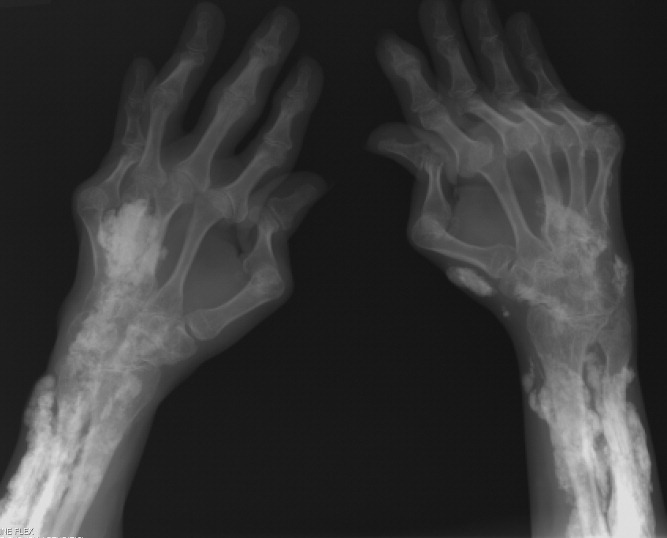

Calcinosis universalis

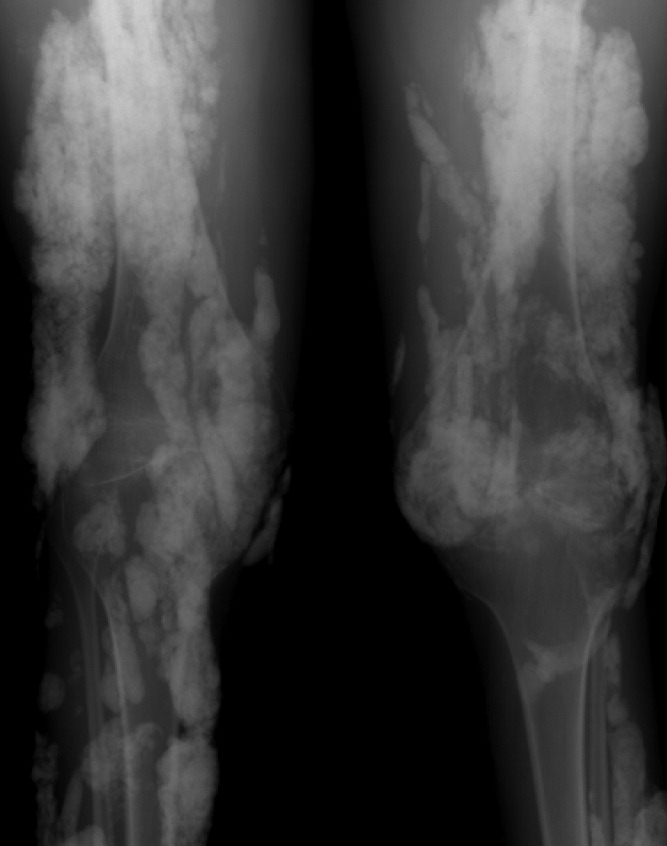

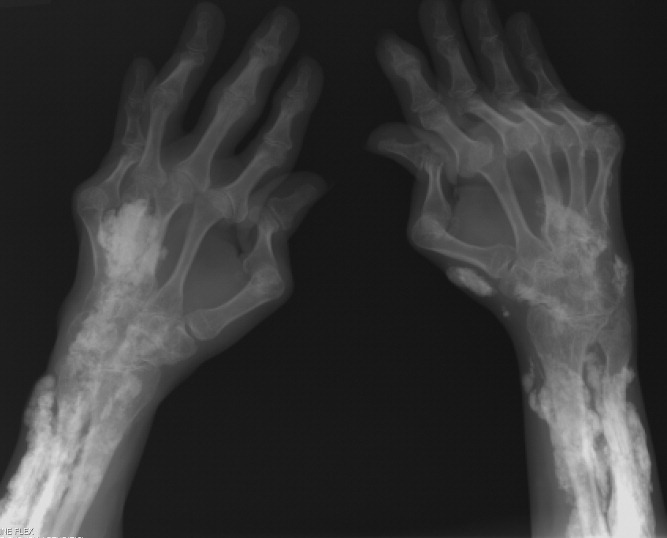

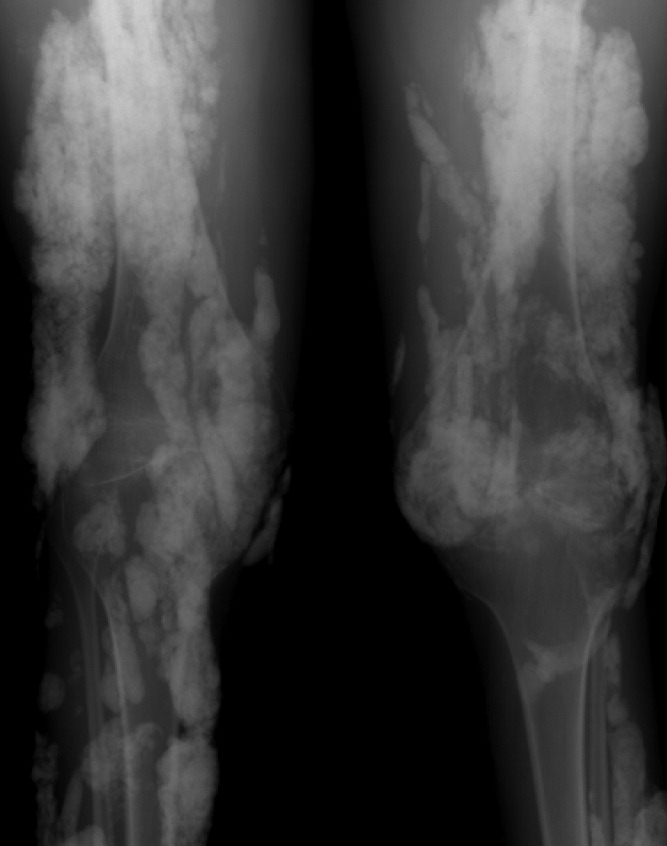

A 38‐year‐old woman with juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) and calcinosis universalis presented with 3 days of drainage from a lesion on her right elbow. An examination of the elbow revealed diffuse and firm subcutaneous nodules with overlying erythema. X‐rays illustrated soft‐tissue calcifications in the forearm and elbow without evidence of osteomyelitis (Figure 1). Wound cultures grew Staphylococcus aureus, and the patient was started on intravenous antibiotics for abscess treatment.

Calcinosis universalis is soft‐tissue calcification presenting as a complication of JDM. It is often detected in childhood in 30% to 70% of patients. It is hypothesized that calcinosis is due to chronic tissue inflammation, as seen in JDM, leading to muscle damage, releasing calcium, and inducing mineralization. Calcinosis universalis often presents as calcified nodules and plaques in areas of repeated trauma, such as joints, extremities, and buttocks (Figures 13). Calcification is localized in subcutaneous tissue, fascial planes, tendons, or intramuscular areas. It can cause debilitating secondary complications such as skin ulcerations expressing calcified material, superimposed infections of skin lesions, joint contractures with severe arthralgias, and muscle atrophy. Calcinosis has been correlated with severity of JDM with presence of cardiac involvement and use of more than one immunosuppression medication.1 It has also been associated with the degree of vasculopathy and delay in initiation of therapy for controlling inflammation in JDM.2

Soft‐tissue calcification can be classified into 5 categories:

-

Dystrophic calcification occurs in injured tissues with normal calcium, phosphorus, and parathyroid hormone levels, as seen in this patient. Calcified nodules or plaques occur in the extremities and buttocks. This is most often seen in JDM, scleroderma, and systemic lupus erythematosus.

-

Metastatic calcification affects normal tissues with abnormal levels of calcium and phosphorus. It is seen in large joints as well as arteries and visceral organs. It is associated with hyperparathyroidism, hypervitaminosis D, and malignancies.

-

Calciphylaxis with abnormal calcium and phosphorus metabolism causes small‐vessel calcification in patients with chronic renal failure.

-

Tumoral calcification is a familial condition with normal calcium levels but elevated phosphorus levels. Large subcutaneous calcifications are seen near high‐pressure areas and joints.

-

Idiopathic calcification is seen in healthy children and young adults with normal calcium metabolism and appears as multiple subcutaneous calcifications.2

Although multiple therapeutic options have been tried for the management or prevention of calcinosis, there is currently no accepted standard of treatment. In patients with calcinosis, warfarin, probenecid, colchicine, bisphosphonates, minocycline, diltiazem, aluminum hydroxide, corticosteroids, and salicylate have been attempted with variable results. Other therapeutic options include carbon dioxide laser treatments and surgical excision of large plaques. Decreasing muscle inflammation with aggressive treatment of JDM may improve outcomes and decrease the incidence of calcification.3 Unfortunately, once calcinosis has occurred, it is highly refractory to medical therapy.

Calcinosis universalis can lead to severe functional impairment. It can be distinguished from other types of calcinosis by diffuse involvement of muscle and fascia in connective tissue disease with normal calcium and phosphorus levels. New management modalities such as cyclosporine, intravenous immunoglobulin, and tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors are currently being evaluated.

- ,,, et al.Risk factors associated with calcinosis of juvenile dermatomyositis.JPediatr (Rio J).2008;84(1):68–74.

- ,,,.Calcinosis in rheumatic diseases.Semin Arthritis Rheum.2005;34(6):805–812.

- ,,, et al.Aggressive management of juvenile dermatomyositis results in improved outcome and decreased incidence of calcinosis.J Am Acad Dermatol.2002;47(4):505–511.

A 38‐year‐old woman with juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) and calcinosis universalis presented with 3 days of drainage from a lesion on her right elbow. An examination of the elbow revealed diffuse and firm subcutaneous nodules with overlying erythema. X‐rays illustrated soft‐tissue calcifications in the forearm and elbow without evidence of osteomyelitis (Figure 1). Wound cultures grew Staphylococcus aureus, and the patient was started on intravenous antibiotics for abscess treatment.

Calcinosis universalis is soft‐tissue calcification presenting as a complication of JDM. It is often detected in childhood in 30% to 70% of patients. It is hypothesized that calcinosis is due to chronic tissue inflammation, as seen in JDM, leading to muscle damage, releasing calcium, and inducing mineralization. Calcinosis universalis often presents as calcified nodules and plaques in areas of repeated trauma, such as joints, extremities, and buttocks (Figures 13). Calcification is localized in subcutaneous tissue, fascial planes, tendons, or intramuscular areas. It can cause debilitating secondary complications such as skin ulcerations expressing calcified material, superimposed infections of skin lesions, joint contractures with severe arthralgias, and muscle atrophy. Calcinosis has been correlated with severity of JDM with presence of cardiac involvement and use of more than one immunosuppression medication.1 It has also been associated with the degree of vasculopathy and delay in initiation of therapy for controlling inflammation in JDM.2

Soft‐tissue calcification can be classified into 5 categories:

-

Dystrophic calcification occurs in injured tissues with normal calcium, phosphorus, and parathyroid hormone levels, as seen in this patient. Calcified nodules or plaques occur in the extremities and buttocks. This is most often seen in JDM, scleroderma, and systemic lupus erythematosus.

-

Metastatic calcification affects normal tissues with abnormal levels of calcium and phosphorus. It is seen in large joints as well as arteries and visceral organs. It is associated with hyperparathyroidism, hypervitaminosis D, and malignancies.

-

Calciphylaxis with abnormal calcium and phosphorus metabolism causes small‐vessel calcification in patients with chronic renal failure.

-

Tumoral calcification is a familial condition with normal calcium levels but elevated phosphorus levels. Large subcutaneous calcifications are seen near high‐pressure areas and joints.

-

Idiopathic calcification is seen in healthy children and young adults with normal calcium metabolism and appears as multiple subcutaneous calcifications.2

Although multiple therapeutic options have been tried for the management or prevention of calcinosis, there is currently no accepted standard of treatment. In patients with calcinosis, warfarin, probenecid, colchicine, bisphosphonates, minocycline, diltiazem, aluminum hydroxide, corticosteroids, and salicylate have been attempted with variable results. Other therapeutic options include carbon dioxide laser treatments and surgical excision of large plaques. Decreasing muscle inflammation with aggressive treatment of JDM may improve outcomes and decrease the incidence of calcification.3 Unfortunately, once calcinosis has occurred, it is highly refractory to medical therapy.

Calcinosis universalis can lead to severe functional impairment. It can be distinguished from other types of calcinosis by diffuse involvement of muscle and fascia in connective tissue disease with normal calcium and phosphorus levels. New management modalities such as cyclosporine, intravenous immunoglobulin, and tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors are currently being evaluated.

A 38‐year‐old woman with juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) and calcinosis universalis presented with 3 days of drainage from a lesion on her right elbow. An examination of the elbow revealed diffuse and firm subcutaneous nodules with overlying erythema. X‐rays illustrated soft‐tissue calcifications in the forearm and elbow without evidence of osteomyelitis (Figure 1). Wound cultures grew Staphylococcus aureus, and the patient was started on intravenous antibiotics for abscess treatment.

Calcinosis universalis is soft‐tissue calcification presenting as a complication of JDM. It is often detected in childhood in 30% to 70% of patients. It is hypothesized that calcinosis is due to chronic tissue inflammation, as seen in JDM, leading to muscle damage, releasing calcium, and inducing mineralization. Calcinosis universalis often presents as calcified nodules and plaques in areas of repeated trauma, such as joints, extremities, and buttocks (Figures 13). Calcification is localized in subcutaneous tissue, fascial planes, tendons, or intramuscular areas. It can cause debilitating secondary complications such as skin ulcerations expressing calcified material, superimposed infections of skin lesions, joint contractures with severe arthralgias, and muscle atrophy. Calcinosis has been correlated with severity of JDM with presence of cardiac involvement and use of more than one immunosuppression medication.1 It has also been associated with the degree of vasculopathy and delay in initiation of therapy for controlling inflammation in JDM.2

Soft‐tissue calcification can be classified into 5 categories:

-

Dystrophic calcification occurs in injured tissues with normal calcium, phosphorus, and parathyroid hormone levels, as seen in this patient. Calcified nodules or plaques occur in the extremities and buttocks. This is most often seen in JDM, scleroderma, and systemic lupus erythematosus.

-

Metastatic calcification affects normal tissues with abnormal levels of calcium and phosphorus. It is seen in large joints as well as arteries and visceral organs. It is associated with hyperparathyroidism, hypervitaminosis D, and malignancies.

-

Calciphylaxis with abnormal calcium and phosphorus metabolism causes small‐vessel calcification in patients with chronic renal failure.

-

Tumoral calcification is a familial condition with normal calcium levels but elevated phosphorus levels. Large subcutaneous calcifications are seen near high‐pressure areas and joints.

-

Idiopathic calcification is seen in healthy children and young adults with normal calcium metabolism and appears as multiple subcutaneous calcifications.2

Although multiple therapeutic options have been tried for the management or prevention of calcinosis, there is currently no accepted standard of treatment. In patients with calcinosis, warfarin, probenecid, colchicine, bisphosphonates, minocycline, diltiazem, aluminum hydroxide, corticosteroids, and salicylate have been attempted with variable results. Other therapeutic options include carbon dioxide laser treatments and surgical excision of large plaques. Decreasing muscle inflammation with aggressive treatment of JDM may improve outcomes and decrease the incidence of calcification.3 Unfortunately, once calcinosis has occurred, it is highly refractory to medical therapy.

Calcinosis universalis can lead to severe functional impairment. It can be distinguished from other types of calcinosis by diffuse involvement of muscle and fascia in connective tissue disease with normal calcium and phosphorus levels. New management modalities such as cyclosporine, intravenous immunoglobulin, and tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors are currently being evaluated.

- ,,, et al.Risk factors associated with calcinosis of juvenile dermatomyositis.JPediatr (Rio J).2008;84(1):68–74.

- ,,,.Calcinosis in rheumatic diseases.Semin Arthritis Rheum.2005;34(6):805–812.

- ,,, et al.Aggressive management of juvenile dermatomyositis results in improved outcome and decreased incidence of calcinosis.J Am Acad Dermatol.2002;47(4):505–511.

- ,,, et al.Risk factors associated with calcinosis of juvenile dermatomyositis.JPediatr (Rio J).2008;84(1):68–74.

- ,,,.Calcinosis in rheumatic diseases.Semin Arthritis Rheum.2005;34(6):805–812.

- ,,, et al.Aggressive management of juvenile dermatomyositis results in improved outcome and decreased incidence of calcinosis.J Am Acad Dermatol.2002;47(4):505–511.

Soft‐tissue gangrene secondary to mixed cryoglobulinemia

A 61‐year‐old Hispanic male with chronic hepatitis C presented with a 4‐week history of a nonpruritic skin rash involving his lower extremities, hands, arms, and right ear. He also reported purple discoloration of his right foot, along with pain in the extremity that worsened with ambulation. Physical examination revealed diffuse purpura of both arms and legs (Figure 1). The right foot was cold to the touch and purple to black in color (Figure 2). There were multiple skin ulcers of various sizes covering the anterior aspect of his legs bilaterally. Pedal pulses were 2/4. Laboratory evaluation revealed positive cryoglobulins with low C4 and CH50 concentrations of 3 mg/dL (10‐40) and 2 units/mL (60‐144), respectively. Other immunological studies were negative. Lower extremity arterial Doppler studies were normal.

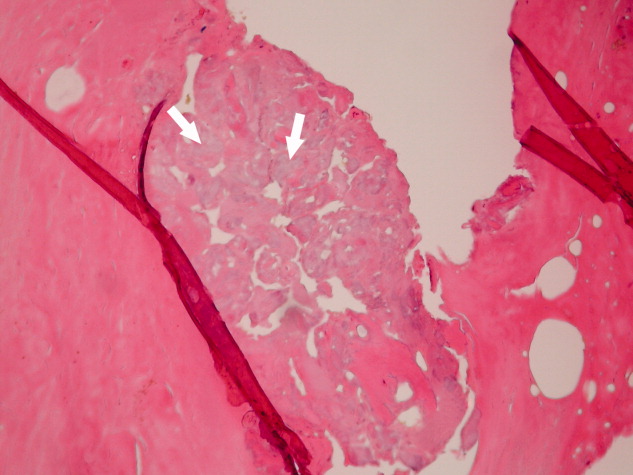

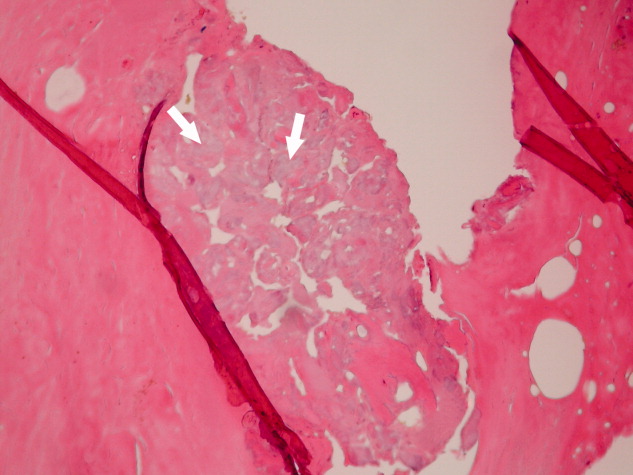

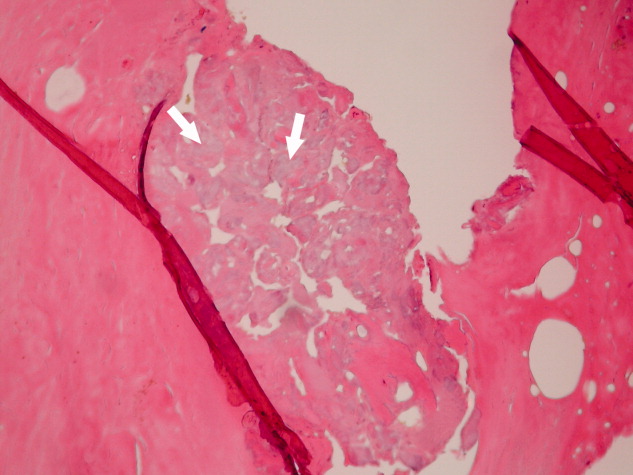

His clinical and laboratory findings were attributed to mixed cryoglobulinemia, and treatment, consisting of daily intravenous methylprednisolone, a single dose of intravenous cyclophosphamide, and plasmapheresis, was initiated. Despite these interventions, 5 days later, he developed severe burning pain in the right extremity with worsening discoloration and a line of demarcation at the level of his proximal midfoot. Eventually, right below the knee, amputation was performed, and histopathological examination showed soft‐tissue gangrene with avascular necrosis of the bone (Figure 3). The patient subsequently had an uneventful course. Plasmapheresis and oral prednisone were continued.

Cryoglobulinemia is a small‐ to medium‐vessel vasculitis due to cryoglobulin‐containing immune complexes. There are 3 types, with the classification based on an immunological analysis of the cryoglobulin composition. Hepatitis C virus infection is closely associated with type II mixed cryoglobulinemia. Cutaneous manifestations are the most common, consisting of palpable purpura, urticaria, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, acrocyanosis, and skin ulcers. A serum cryoglobulin elevation is diagnostic and is usually accompanied by hypocomplementemia.

Treatment of the underlying disease is essential. However, aggressive therapy with plasmapheresis and immunosuppressive medications is warranted in severe cases involving limb‐ or organ‐threatening vasculitis.

A 61‐year‐old Hispanic male with chronic hepatitis C presented with a 4‐week history of a nonpruritic skin rash involving his lower extremities, hands, arms, and right ear. He also reported purple discoloration of his right foot, along with pain in the extremity that worsened with ambulation. Physical examination revealed diffuse purpura of both arms and legs (Figure 1). The right foot was cold to the touch and purple to black in color (Figure 2). There were multiple skin ulcers of various sizes covering the anterior aspect of his legs bilaterally. Pedal pulses were 2/4. Laboratory evaluation revealed positive cryoglobulins with low C4 and CH50 concentrations of 3 mg/dL (10‐40) and 2 units/mL (60‐144), respectively. Other immunological studies were negative. Lower extremity arterial Doppler studies were normal.

His clinical and laboratory findings were attributed to mixed cryoglobulinemia, and treatment, consisting of daily intravenous methylprednisolone, a single dose of intravenous cyclophosphamide, and plasmapheresis, was initiated. Despite these interventions, 5 days later, he developed severe burning pain in the right extremity with worsening discoloration and a line of demarcation at the level of his proximal midfoot. Eventually, right below the knee, amputation was performed, and histopathological examination showed soft‐tissue gangrene with avascular necrosis of the bone (Figure 3). The patient subsequently had an uneventful course. Plasmapheresis and oral prednisone were continued.

Cryoglobulinemia is a small‐ to medium‐vessel vasculitis due to cryoglobulin‐containing immune complexes. There are 3 types, with the classification based on an immunological analysis of the cryoglobulin composition. Hepatitis C virus infection is closely associated with type II mixed cryoglobulinemia. Cutaneous manifestations are the most common, consisting of palpable purpura, urticaria, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, acrocyanosis, and skin ulcers. A serum cryoglobulin elevation is diagnostic and is usually accompanied by hypocomplementemia.

Treatment of the underlying disease is essential. However, aggressive therapy with plasmapheresis and immunosuppressive medications is warranted in severe cases involving limb‐ or organ‐threatening vasculitis.

A 61‐year‐old Hispanic male with chronic hepatitis C presented with a 4‐week history of a nonpruritic skin rash involving his lower extremities, hands, arms, and right ear. He also reported purple discoloration of his right foot, along with pain in the extremity that worsened with ambulation. Physical examination revealed diffuse purpura of both arms and legs (Figure 1). The right foot was cold to the touch and purple to black in color (Figure 2). There were multiple skin ulcers of various sizes covering the anterior aspect of his legs bilaterally. Pedal pulses were 2/4. Laboratory evaluation revealed positive cryoglobulins with low C4 and CH50 concentrations of 3 mg/dL (10‐40) and 2 units/mL (60‐144), respectively. Other immunological studies were negative. Lower extremity arterial Doppler studies were normal.

His clinical and laboratory findings were attributed to mixed cryoglobulinemia, and treatment, consisting of daily intravenous methylprednisolone, a single dose of intravenous cyclophosphamide, and plasmapheresis, was initiated. Despite these interventions, 5 days later, he developed severe burning pain in the right extremity with worsening discoloration and a line of demarcation at the level of his proximal midfoot. Eventually, right below the knee, amputation was performed, and histopathological examination showed soft‐tissue gangrene with avascular necrosis of the bone (Figure 3). The patient subsequently had an uneventful course. Plasmapheresis and oral prednisone were continued.

Cryoglobulinemia is a small‐ to medium‐vessel vasculitis due to cryoglobulin‐containing immune complexes. There are 3 types, with the classification based on an immunological analysis of the cryoglobulin composition. Hepatitis C virus infection is closely associated with type II mixed cryoglobulinemia. Cutaneous manifestations are the most common, consisting of palpable purpura, urticaria, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, acrocyanosis, and skin ulcers. A serum cryoglobulin elevation is diagnostic and is usually accompanied by hypocomplementemia.

Treatment of the underlying disease is essential. However, aggressive therapy with plasmapheresis and immunosuppressive medications is warranted in severe cases involving limb‐ or organ‐threatening vasculitis.

Purple Like a Glove

A 90‐year‐old female nursing home resident was admitted for hyponatremia and altered mental status. A Foley catheter was placed on admission. On hospital day 2, the Foley catheter was found to be draining violet urine. Urinalysis showed a pH of 9.0, numerous white cells, leukocyte esterase, and bacteria. Urine culture grew Proteus mirabilis. Purple Urine Bag Syndrome (PUBS) is a rare phenomenon associated with alkaline urine due to a urinary tract infection. The patient was treated with ciprofloxacin, and her urine returned to a pale yellow color. While alarming to patients and providers alike, PUBS is a benign herald of urinary tract infection, often in an elderly woman with constipation. In normal individuals, tryptophan is metabolized to indole by gut flora, which is in turn conjugated to indoxyl sulfate (IS) by the liver. Urine excretion of IS varies by individual. Sulfatase‐containing bacteria, notably Providencia, Klebsiella, and Proteus species, then catabolize IS to indoxyl. In an alkaline environment indoxyl isomers interact to alternately yield indigo or indirubin which jointly create the urine's characteristic violet color.0

- ,,.Enzymatic degradation of urinary indoxyl sulfate by Providencia stuartii and Klebsiella pneumonia causes the purple urine bag syndrome.J Clin Microbiol.1988;26(10):2152–2156.

A 90‐year‐old female nursing home resident was admitted for hyponatremia and altered mental status. A Foley catheter was placed on admission. On hospital day 2, the Foley catheter was found to be draining violet urine. Urinalysis showed a pH of 9.0, numerous white cells, leukocyte esterase, and bacteria. Urine culture grew Proteus mirabilis. Purple Urine Bag Syndrome (PUBS) is a rare phenomenon associated with alkaline urine due to a urinary tract infection. The patient was treated with ciprofloxacin, and her urine returned to a pale yellow color. While alarming to patients and providers alike, PUBS is a benign herald of urinary tract infection, often in an elderly woman with constipation. In normal individuals, tryptophan is metabolized to indole by gut flora, which is in turn conjugated to indoxyl sulfate (IS) by the liver. Urine excretion of IS varies by individual. Sulfatase‐containing bacteria, notably Providencia, Klebsiella, and Proteus species, then catabolize IS to indoxyl. In an alkaline environment indoxyl isomers interact to alternately yield indigo or indirubin which jointly create the urine's characteristic violet color.0

A 90‐year‐old female nursing home resident was admitted for hyponatremia and altered mental status. A Foley catheter was placed on admission. On hospital day 2, the Foley catheter was found to be draining violet urine. Urinalysis showed a pH of 9.0, numerous white cells, leukocyte esterase, and bacteria. Urine culture grew Proteus mirabilis. Purple Urine Bag Syndrome (PUBS) is a rare phenomenon associated with alkaline urine due to a urinary tract infection. The patient was treated with ciprofloxacin, and her urine returned to a pale yellow color. While alarming to patients and providers alike, PUBS is a benign herald of urinary tract infection, often in an elderly woman with constipation. In normal individuals, tryptophan is metabolized to indole by gut flora, which is in turn conjugated to indoxyl sulfate (IS) by the liver. Urine excretion of IS varies by individual. Sulfatase‐containing bacteria, notably Providencia, Klebsiella, and Proteus species, then catabolize IS to indoxyl. In an alkaline environment indoxyl isomers interact to alternately yield indigo or indirubin which jointly create the urine's characteristic violet color.0

- ,,.Enzymatic degradation of urinary indoxyl sulfate by Providencia stuartii and Klebsiella pneumonia causes the purple urine bag syndrome.J Clin Microbiol.1988;26(10):2152–2156.

- ,,.Enzymatic degradation of urinary indoxyl sulfate by Providencia stuartii and Klebsiella pneumonia causes the purple urine bag syndrome.J Clin Microbiol.1988;26(10):2152–2156.

Streptococcus pneumoniae keratitis

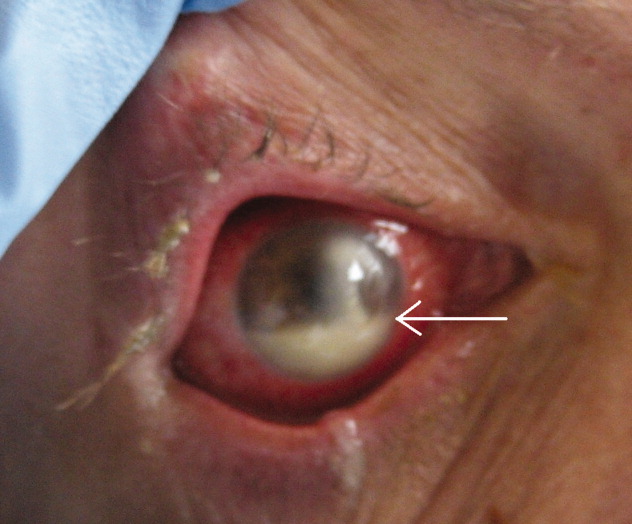

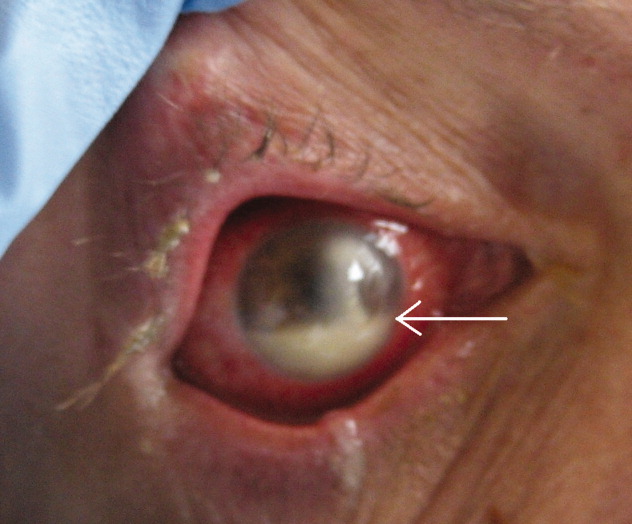

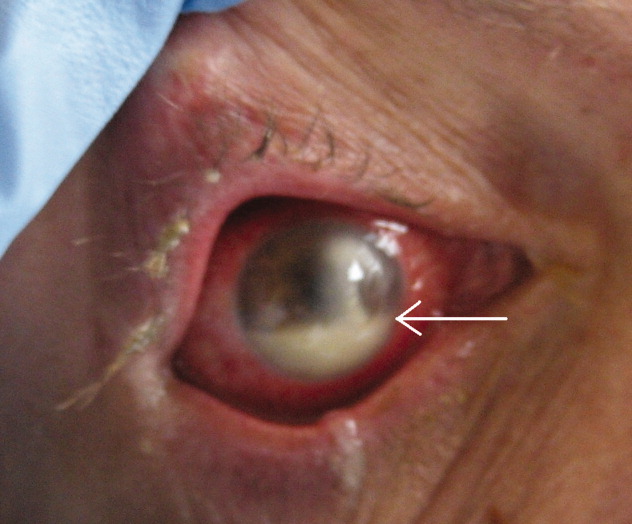

A 45‐year‐old man with HIV infection (CD4 count of 6 cells per cubic millimeter) presented after 2 days of diminishing visual acuity and pain in his right eye. Examination revealed a corneal ulceration and hypopyon (Fig. 1, white arrow). Chest radiograph demonstrated right lower lobe pneumonia. Cultures of the hypopyon, sputum, and blood grew Streptococcus pneumoniae.

The patient was treated with IV ceftriaxone as well as fortified tobramycin, vancomycin, and doxycycline eye drops with intravitreal vancomycin. The patient's vision and eye pain gradually improved, and he was discharged home.

Infectious ulcerative keratitis is a rare entity, most often resulting from direct corneal invasion by bacterial or fungal organisms. This case appears to involve hematogenous spread. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus, and Pseudomonas are the most common bacterial pathogens. Broad‐spectrum topical antibiotics are the cornerstone of therapy. Topical steroids may be administered once the infection is under control.

A 45‐year‐old man with HIV infection (CD4 count of 6 cells per cubic millimeter) presented after 2 days of diminishing visual acuity and pain in his right eye. Examination revealed a corneal ulceration and hypopyon (Fig. 1, white arrow). Chest radiograph demonstrated right lower lobe pneumonia. Cultures of the hypopyon, sputum, and blood grew Streptococcus pneumoniae.

The patient was treated with IV ceftriaxone as well as fortified tobramycin, vancomycin, and doxycycline eye drops with intravitreal vancomycin. The patient's vision and eye pain gradually improved, and he was discharged home.

Infectious ulcerative keratitis is a rare entity, most often resulting from direct corneal invasion by bacterial or fungal organisms. This case appears to involve hematogenous spread. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus, and Pseudomonas are the most common bacterial pathogens. Broad‐spectrum topical antibiotics are the cornerstone of therapy. Topical steroids may be administered once the infection is under control.

A 45‐year‐old man with HIV infection (CD4 count of 6 cells per cubic millimeter) presented after 2 days of diminishing visual acuity and pain in his right eye. Examination revealed a corneal ulceration and hypopyon (Fig. 1, white arrow). Chest radiograph demonstrated right lower lobe pneumonia. Cultures of the hypopyon, sputum, and blood grew Streptococcus pneumoniae.

The patient was treated with IV ceftriaxone as well as fortified tobramycin, vancomycin, and doxycycline eye drops with intravitreal vancomycin. The patient's vision and eye pain gradually improved, and he was discharged home.

Infectious ulcerative keratitis is a rare entity, most often resulting from direct corneal invasion by bacterial or fungal organisms. This case appears to involve hematogenous spread. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus, and Pseudomonas are the most common bacterial pathogens. Broad‐spectrum topical antibiotics are the cornerstone of therapy. Topical steroids may be administered once the infection is under control.

“String‐of‐Pearls”

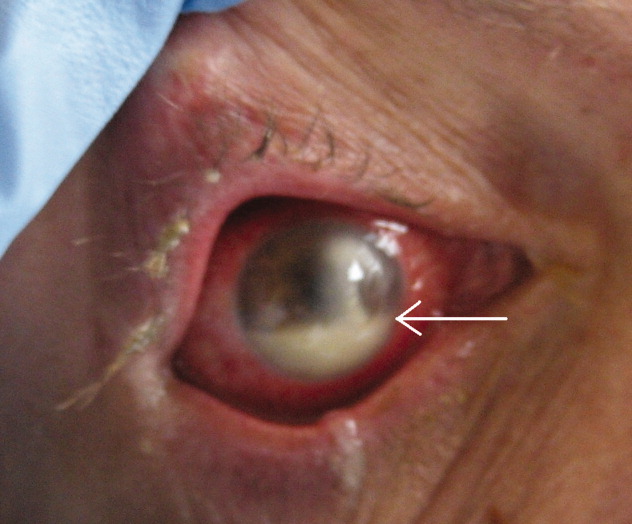

A 41‐year‐old intravenous drug user (IVDU) was admitted with candidal endophthalmitis 6 weeks after a hospitalization for pneumonia. After discharge from his previous hospitalization which were blood cultures grew Candida albicans, attributed to contamination by a covering physician. The patient described looking through spider webs. Fundoscopic examination revealed fluffy, white string‐of‐pearls opacities with retinal obscuration (Fig. 1). There were no findings of endocarditis (negative echocardiogram) or congestive heart failure. Blood and vitreal cultures grew Candida albicans. The patient underwent a pars plana vitrectomy, and was prescribed chronic fluconazole. He was lost to follow‐up.

Candida albicans is the most common organism identified in endogenous endophthalmitis.1 Predisposing factors include IVDU, indwelling catheters, endocarditis, recent surgeries, immunosuppression, broad‐spectrum antibiotics, and parental nutrition.1 The diagnosis is based on retinal findings of white pinpoint opacities (string‐of‐pearls, Fig. 2), with vitreous involvement and positive cultures. Endocarditis occurs in 15%17% of patients with endophthalmitis.2 This case highlights the importance of physician recognition of the significant attributable morbidity and mortality of candidemia.3, 4

- ,,, et al.Endogenous endophthalmitis with azole‐resistant Candida albicans—case report and review of the literature.Infection.2006;34:285–288.

- ,,, et al.Endogenous endophthalmitis: a 13‐year review at a tertiary hospital in south Australia. ScandinavianJ Infect Dis.2005;37:184–189.

- ,,.Attributable mortaility of candidemia: a systematic review of matched cohort and case‐control studies.Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis.2006;25:419–425.

- ,,, et al.Bloodstream infections in a secondary and tertiary care hospital setting.Intern Med J.2006;765–772.

A 41‐year‐old intravenous drug user (IVDU) was admitted with candidal endophthalmitis 6 weeks after a hospitalization for pneumonia. After discharge from his previous hospitalization which were blood cultures grew Candida albicans, attributed to contamination by a covering physician. The patient described looking through spider webs. Fundoscopic examination revealed fluffy, white string‐of‐pearls opacities with retinal obscuration (Fig. 1). There were no findings of endocarditis (negative echocardiogram) or congestive heart failure. Blood and vitreal cultures grew Candida albicans. The patient underwent a pars plana vitrectomy, and was prescribed chronic fluconazole. He was lost to follow‐up.

Candida albicans is the most common organism identified in endogenous endophthalmitis.1 Predisposing factors include IVDU, indwelling catheters, endocarditis, recent surgeries, immunosuppression, broad‐spectrum antibiotics, and parental nutrition.1 The diagnosis is based on retinal findings of white pinpoint opacities (string‐of‐pearls, Fig. 2), with vitreous involvement and positive cultures. Endocarditis occurs in 15%17% of patients with endophthalmitis.2 This case highlights the importance of physician recognition of the significant attributable morbidity and mortality of candidemia.3, 4

A 41‐year‐old intravenous drug user (IVDU) was admitted with candidal endophthalmitis 6 weeks after a hospitalization for pneumonia. After discharge from his previous hospitalization which were blood cultures grew Candida albicans, attributed to contamination by a covering physician. The patient described looking through spider webs. Fundoscopic examination revealed fluffy, white string‐of‐pearls opacities with retinal obscuration (Fig. 1). There were no findings of endocarditis (negative echocardiogram) or congestive heart failure. Blood and vitreal cultures grew Candida albicans. The patient underwent a pars plana vitrectomy, and was prescribed chronic fluconazole. He was lost to follow‐up.

Candida albicans is the most common organism identified in endogenous endophthalmitis.1 Predisposing factors include IVDU, indwelling catheters, endocarditis, recent surgeries, immunosuppression, broad‐spectrum antibiotics, and parental nutrition.1 The diagnosis is based on retinal findings of white pinpoint opacities (string‐of‐pearls, Fig. 2), with vitreous involvement and positive cultures. Endocarditis occurs in 15%17% of patients with endophthalmitis.2 This case highlights the importance of physician recognition of the significant attributable morbidity and mortality of candidemia.3, 4

- ,,, et al.Endogenous endophthalmitis with azole‐resistant Candida albicans—case report and review of the literature.Infection.2006;34:285–288.

- ,,, et al.Endogenous endophthalmitis: a 13‐year review at a tertiary hospital in south Australia. ScandinavianJ Infect Dis.2005;37:184–189.

- ,,.Attributable mortaility of candidemia: a systematic review of matched cohort and case‐control studies.Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis.2006;25:419–425.

- ,,, et al.Bloodstream infections in a secondary and tertiary care hospital setting.Intern Med J.2006;765–772.

- ,,, et al.Endogenous endophthalmitis with azole‐resistant Candida albicans—case report and review of the literature.Infection.2006;34:285–288.

- ,,, et al.Endogenous endophthalmitis: a 13‐year review at a tertiary hospital in south Australia. ScandinavianJ Infect Dis.2005;37:184–189.

- ,,.Attributable mortaility of candidemia: a systematic review of matched cohort and case‐control studies.Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis.2006;25:419–425.

- ,,, et al.Bloodstream infections in a secondary and tertiary care hospital setting.Intern Med J.2006;765–772.

A “Super” case of longevity

A 109‐year‐old woman was admitted to the hospital for mild congestive heart failure and bradycardia. She scored 30 out of 30 on the Mini‐mental status exam. Further conversations revealed that she was a native of San Francisco and that she was 9 years old during the earthquake of 1906. She was 109 years old during hospitalization (Fig. 1). About 5 months after the hospitalization, she celebrated her 110th birthday (Fig. 2).

A centenarian is a person who has lived to the age of 100, and a supercentenarian is a person who has reached the age of 110. The number of centenarians in the United States was counted as 50,454 in the 2000 Census, increased from the 37,306 reported in 1990.1 The US Census Bureau estimates the current number of centenarians to be 79,682 and projects an increase to 580,605 by the year 2040.2 The number of supercentenarians was reported as 1400 in the 2000 Census.3

Hospital physicians can expect to see a growing number of centenarians in their practice as this segment of the population continues to increase.

A 109‐year‐old woman was admitted to the hospital for mild congestive heart failure and bradycardia. She scored 30 out of 30 on the Mini‐mental status exam. Further conversations revealed that she was a native of San Francisco and that she was 9 years old during the earthquake of 1906. She was 109 years old during hospitalization (Fig. 1). About 5 months after the hospitalization, she celebrated her 110th birthday (Fig. 2).

A centenarian is a person who has lived to the age of 100, and a supercentenarian is a person who has reached the age of 110. The number of centenarians in the United States was counted as 50,454 in the 2000 Census, increased from the 37,306 reported in 1990.1 The US Census Bureau estimates the current number of centenarians to be 79,682 and projects an increase to 580,605 by the year 2040.2 The number of supercentenarians was reported as 1400 in the 2000 Census.3

Hospital physicians can expect to see a growing number of centenarians in their practice as this segment of the population continues to increase.

A 109‐year‐old woman was admitted to the hospital for mild congestive heart failure and bradycardia. She scored 30 out of 30 on the Mini‐mental status exam. Further conversations revealed that she was a native of San Francisco and that she was 9 years old during the earthquake of 1906. She was 109 years old during hospitalization (Fig. 1). About 5 months after the hospitalization, she celebrated her 110th birthday (Fig. 2).

A centenarian is a person who has lived to the age of 100, and a supercentenarian is a person who has reached the age of 110. The number of centenarians in the United States was counted as 50,454 in the 2000 Census, increased from the 37,306 reported in 1990.1 The US Census Bureau estimates the current number of centenarians to be 79,682 and projects an increase to 580,605 by the year 2040.2 The number of supercentenarians was reported as 1400 in the 2000 Census.3

Hospital physicians can expect to see a growing number of centenarians in their practice as this segment of the population continues to increase.

Purpuric Rash of Meningococcemia

A previously healthy 62‐year‐old man presented to the emergency department with 4 days of headache, fever, and chills. Within several hours of presentation, he developed septic shock. His temperature was 39C, and his white blood count was 17,000/mm3 with 38% bands. He had acute renal failure (creatinine = 2.5) and mild mental status changes. His blood pressure decreased from 103/63 to 71/46 and was not responsive to intravenous fluid administration. He therefore was begun on pressors. Eight hours after arrival, a petechial and purpuric rash suddenly appeared on the patient's extremities, including the palms of his hands (Fig. 1). Ceftriaxone was added to his initial antibiotics (vancomycin and pipercillin‐tazobactam), and he was treated with stress‐dose hydrocortisone and activated drotrecogin alpha. The following day, blood cultures grew gram‐negative diplococci in pairs, and preventive measures were taken, including treating close contacts and placing the patient under droplet precautions. The cultures eventually confirmed Neisseria meningitidis. The patient made excellent progresshis mental status improved, he was weaned off pressors after 3 days, and his renal failure resolved. Figure 2 demonstrates the evolution of the purpuric lesions, which became more prominent as he otherwise made clinical improvement. He was discharged home after 2 weeks of intravenous ceftriaxone in good condition.

A previously healthy 62‐year‐old man presented to the emergency department with 4 days of headache, fever, and chills. Within several hours of presentation, he developed septic shock. His temperature was 39C, and his white blood count was 17,000/mm3 with 38% bands. He had acute renal failure (creatinine = 2.5) and mild mental status changes. His blood pressure decreased from 103/63 to 71/46 and was not responsive to intravenous fluid administration. He therefore was begun on pressors. Eight hours after arrival, a petechial and purpuric rash suddenly appeared on the patient's extremities, including the palms of his hands (Fig. 1). Ceftriaxone was added to his initial antibiotics (vancomycin and pipercillin‐tazobactam), and he was treated with stress‐dose hydrocortisone and activated drotrecogin alpha. The following day, blood cultures grew gram‐negative diplococci in pairs, and preventive measures were taken, including treating close contacts and placing the patient under droplet precautions. The cultures eventually confirmed Neisseria meningitidis. The patient made excellent progresshis mental status improved, he was weaned off pressors after 3 days, and his renal failure resolved. Figure 2 demonstrates the evolution of the purpuric lesions, which became more prominent as he otherwise made clinical improvement. He was discharged home after 2 weeks of intravenous ceftriaxone in good condition.

A previously healthy 62‐year‐old man presented to the emergency department with 4 days of headache, fever, and chills. Within several hours of presentation, he developed septic shock. His temperature was 39C, and his white blood count was 17,000/mm3 with 38% bands. He had acute renal failure (creatinine = 2.5) and mild mental status changes. His blood pressure decreased from 103/63 to 71/46 and was not responsive to intravenous fluid administration. He therefore was begun on pressors. Eight hours after arrival, a petechial and purpuric rash suddenly appeared on the patient's extremities, including the palms of his hands (Fig. 1). Ceftriaxone was added to his initial antibiotics (vancomycin and pipercillin‐tazobactam), and he was treated with stress‐dose hydrocortisone and activated drotrecogin alpha. The following day, blood cultures grew gram‐negative diplococci in pairs, and preventive measures were taken, including treating close contacts and placing the patient under droplet precautions. The cultures eventually confirmed Neisseria meningitidis. The patient made excellent progresshis mental status improved, he was weaned off pressors after 3 days, and his renal failure resolved. Figure 2 demonstrates the evolution of the purpuric lesions, which became more prominent as he otherwise made clinical improvement. He was discharged home after 2 weeks of intravenous ceftriaxone in good condition.