User login

Caution with IVC filters in elderly

Background: Acute pulmonary embolism is a common cause of morbidity and mortality in older adults, and IVC filters have historically and frequently been used to prevent subsequent PE. Almost one in six elderly Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries with PE currently receives an IVC filter.

Study design: Retrospective, matched cohort study.

Setting: United States inpatients during 2011-2014.

Synopsis: Of 214,579 Medicare FFS patients aged 65 years or older who were hospitalized for acute PE, 13.4% received an IVC filter. Mortality was higher in those receiving an IVC filter (11.6%), compared with those who did not receive an IVC filter (9.3%), with an adjusted odds ratio of 30-day mortality of 1.02 (95% CI, 0.98-1.06). One-year mortality rates were 20.5% in the IVC filter group and 13.4% in the group with no IVC filter, with an adjusted OR of 1.35 (95% CI, 1.31-1.40).

In the 76,198 Medicare FFS patients hospitalized with acute PE in the matched cohort group, 18.2% received an IVC filter. The IVC-filter group had higher odds for 30-day mortality, compared with the no–IVC filter group (OR, 2.19; 95% CI, 2.06-2.33).

Bottom line: In patients aged 65 years or older, use caution when considering IVC filter placement for prevention of subsequent PE. Future studies across patient subgroups are needed to analyze the safety and value of IVC filters.

Citation: Bikdeli B et al. Association of inferior vena cava filter use with mortality rates in older adults with acute pulmonary embolism. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(2):263-5.

Dr. Trammell Velasquez is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System.

Background: Acute pulmonary embolism is a common cause of morbidity and mortality in older adults, and IVC filters have historically and frequently been used to prevent subsequent PE. Almost one in six elderly Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries with PE currently receives an IVC filter.

Study design: Retrospective, matched cohort study.

Setting: United States inpatients during 2011-2014.

Synopsis: Of 214,579 Medicare FFS patients aged 65 years or older who were hospitalized for acute PE, 13.4% received an IVC filter. Mortality was higher in those receiving an IVC filter (11.6%), compared with those who did not receive an IVC filter (9.3%), with an adjusted odds ratio of 30-day mortality of 1.02 (95% CI, 0.98-1.06). One-year mortality rates were 20.5% in the IVC filter group and 13.4% in the group with no IVC filter, with an adjusted OR of 1.35 (95% CI, 1.31-1.40).

In the 76,198 Medicare FFS patients hospitalized with acute PE in the matched cohort group, 18.2% received an IVC filter. The IVC-filter group had higher odds for 30-day mortality, compared with the no–IVC filter group (OR, 2.19; 95% CI, 2.06-2.33).

Bottom line: In patients aged 65 years or older, use caution when considering IVC filter placement for prevention of subsequent PE. Future studies across patient subgroups are needed to analyze the safety and value of IVC filters.

Citation: Bikdeli B et al. Association of inferior vena cava filter use with mortality rates in older adults with acute pulmonary embolism. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(2):263-5.

Dr. Trammell Velasquez is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System.

Background: Acute pulmonary embolism is a common cause of morbidity and mortality in older adults, and IVC filters have historically and frequently been used to prevent subsequent PE. Almost one in six elderly Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries with PE currently receives an IVC filter.

Study design: Retrospective, matched cohort study.

Setting: United States inpatients during 2011-2014.

Synopsis: Of 214,579 Medicare FFS patients aged 65 years or older who were hospitalized for acute PE, 13.4% received an IVC filter. Mortality was higher in those receiving an IVC filter (11.6%), compared with those who did not receive an IVC filter (9.3%), with an adjusted odds ratio of 30-day mortality of 1.02 (95% CI, 0.98-1.06). One-year mortality rates were 20.5% in the IVC filter group and 13.4% in the group with no IVC filter, with an adjusted OR of 1.35 (95% CI, 1.31-1.40).

In the 76,198 Medicare FFS patients hospitalized with acute PE in the matched cohort group, 18.2% received an IVC filter. The IVC-filter group had higher odds for 30-day mortality, compared with the no–IVC filter group (OR, 2.19; 95% CI, 2.06-2.33).

Bottom line: In patients aged 65 years or older, use caution when considering IVC filter placement for prevention of subsequent PE. Future studies across patient subgroups are needed to analyze the safety and value of IVC filters.

Citation: Bikdeli B et al. Association of inferior vena cava filter use with mortality rates in older adults with acute pulmonary embolism. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(2):263-5.

Dr. Trammell Velasquez is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System.

Palliative care programs continue growth in U.S. hospitals

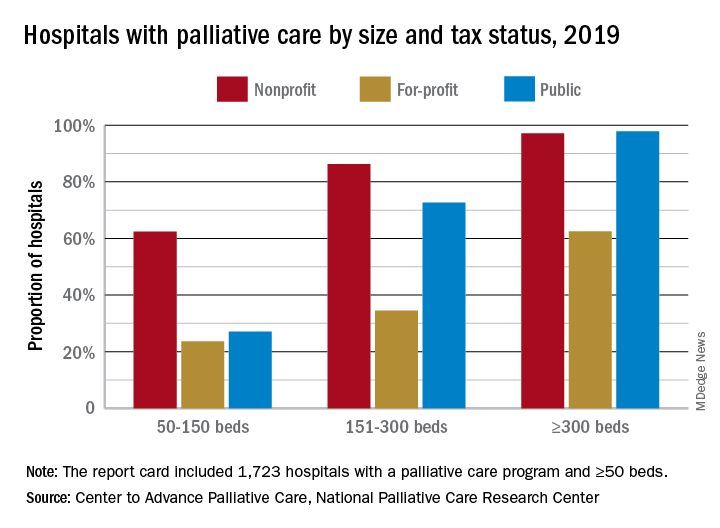

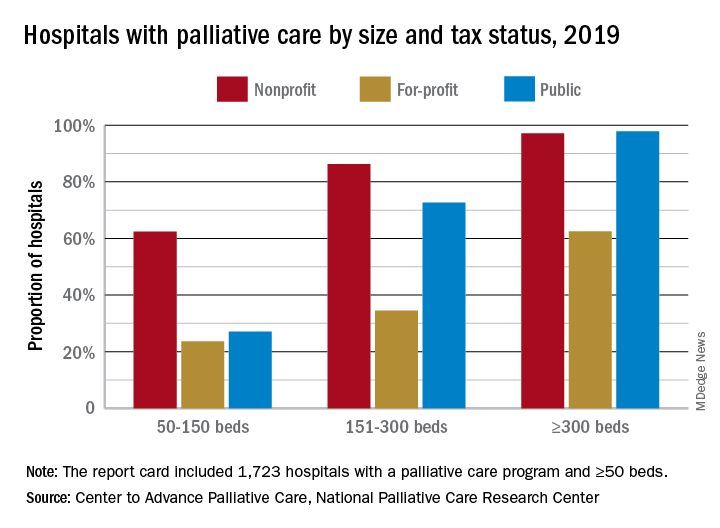

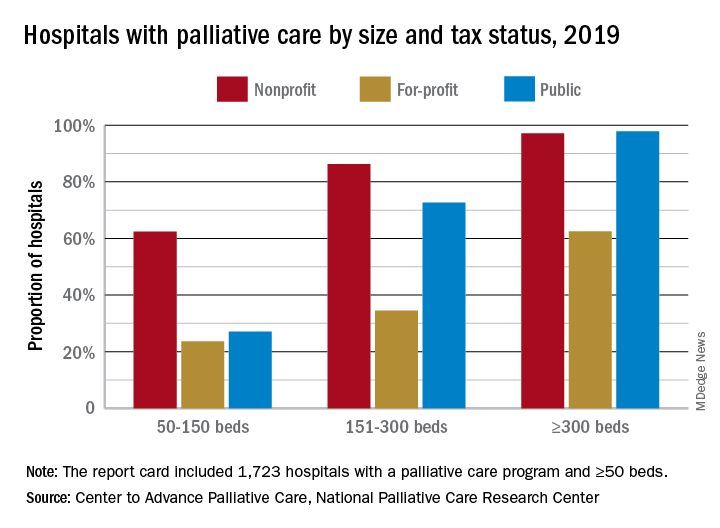

Growth continues among palliative care programs in the United States, although access often depends “more upon accidents of geography than it does upon the needs of patients,” according to the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

“As is true for many aspects of health care, geography is destiny. Where you live determines your access to the best quality of life and highest quality of care during a serious illness,” said Diane E. Meier, MD, director of the Center to Advance Palliative Care, in a written statement.

the two organizations said in their 2019 report card on palliative care access. What hasn’t changed since 2015, however, is the country’s overall grade, which remains a B.

Delaware, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont have a palliative care program in all of their hospitals with 50 or more beds and each earned a grade of A (palliative care rate of greater than 80%), along with 17 other states. The lowest-performing states – Alabama, Mississippi, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Wyoming – all received Ds for having a rate below 40%, the CAPC said.

The urban/rural divide also is prominent in palliative care: “90% of hospitals with palliative care are in urban areas. Only 17% of rural hospitals with fifty or more beds report palliative care programs,” the report said.

Hospital type is another source of disparity. Small, nonprofit hospitals are much more likely to offer access to palliative care than either for-profit or public facilities of the same size, but the gap closes as size increases, at least between nonprofit and public hospitals. For the largest institutions, the public hospitals pull into the lead, 98% versus 97%, over the nonprofits, with the for-profit facilities well behind at 63%.

“High quality palliative care has been shown to improve patient and family quality of life, improve patients’ and families’ health care experiences, and in certain diseases, prolong life. Palliative care has also been shown to improve hospital efficiency and reduce unnecessary spending,” said R. Sean Morrison, MD, director of the National Palliative Care Research Center.

The report card is based on data from the American Hospital Association’s Annual Survey Database, with additional data from the National Palliative Care Registry and Center to Advance Palliative Care’s Mapping Community Palliative Care initiative. The final sample included 2,409 hospitals with 50 or more beds.

Growth continues among palliative care programs in the United States, although access often depends “more upon accidents of geography than it does upon the needs of patients,” according to the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

“As is true for many aspects of health care, geography is destiny. Where you live determines your access to the best quality of life and highest quality of care during a serious illness,” said Diane E. Meier, MD, director of the Center to Advance Palliative Care, in a written statement.

the two organizations said in their 2019 report card on palliative care access. What hasn’t changed since 2015, however, is the country’s overall grade, which remains a B.

Delaware, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont have a palliative care program in all of their hospitals with 50 or more beds and each earned a grade of A (palliative care rate of greater than 80%), along with 17 other states. The lowest-performing states – Alabama, Mississippi, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Wyoming – all received Ds for having a rate below 40%, the CAPC said.

The urban/rural divide also is prominent in palliative care: “90% of hospitals with palliative care are in urban areas. Only 17% of rural hospitals with fifty or more beds report palliative care programs,” the report said.

Hospital type is another source of disparity. Small, nonprofit hospitals are much more likely to offer access to palliative care than either for-profit or public facilities of the same size, but the gap closes as size increases, at least between nonprofit and public hospitals. For the largest institutions, the public hospitals pull into the lead, 98% versus 97%, over the nonprofits, with the for-profit facilities well behind at 63%.

“High quality palliative care has been shown to improve patient and family quality of life, improve patients’ and families’ health care experiences, and in certain diseases, prolong life. Palliative care has also been shown to improve hospital efficiency and reduce unnecessary spending,” said R. Sean Morrison, MD, director of the National Palliative Care Research Center.

The report card is based on data from the American Hospital Association’s Annual Survey Database, with additional data from the National Palliative Care Registry and Center to Advance Palliative Care’s Mapping Community Palliative Care initiative. The final sample included 2,409 hospitals with 50 or more beds.

Growth continues among palliative care programs in the United States, although access often depends “more upon accidents of geography than it does upon the needs of patients,” according to the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

“As is true for many aspects of health care, geography is destiny. Where you live determines your access to the best quality of life and highest quality of care during a serious illness,” said Diane E. Meier, MD, director of the Center to Advance Palliative Care, in a written statement.

the two organizations said in their 2019 report card on palliative care access. What hasn’t changed since 2015, however, is the country’s overall grade, which remains a B.

Delaware, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont have a palliative care program in all of their hospitals with 50 or more beds and each earned a grade of A (palliative care rate of greater than 80%), along with 17 other states. The lowest-performing states – Alabama, Mississippi, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Wyoming – all received Ds for having a rate below 40%, the CAPC said.

The urban/rural divide also is prominent in palliative care: “90% of hospitals with palliative care are in urban areas. Only 17% of rural hospitals with fifty or more beds report palliative care programs,” the report said.

Hospital type is another source of disparity. Small, nonprofit hospitals are much more likely to offer access to palliative care than either for-profit or public facilities of the same size, but the gap closes as size increases, at least between nonprofit and public hospitals. For the largest institutions, the public hospitals pull into the lead, 98% versus 97%, over the nonprofits, with the for-profit facilities well behind at 63%.

“High quality palliative care has been shown to improve patient and family quality of life, improve patients’ and families’ health care experiences, and in certain diseases, prolong life. Palliative care has also been shown to improve hospital efficiency and reduce unnecessary spending,” said R. Sean Morrison, MD, director of the National Palliative Care Research Center.

The report card is based on data from the American Hospital Association’s Annual Survey Database, with additional data from the National Palliative Care Registry and Center to Advance Palliative Care’s Mapping Community Palliative Care initiative. The final sample included 2,409 hospitals with 50 or more beds.

Apixaban prevents clots with cancer

Background: Active cancer places patients at increased risk for VTE. Ambulatory patients can be risk stratified using the validated Khorana score to assess risk for VTE, a complication resulting in significant morbidity, mortality, and health care costs.

Study design: Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial.

Setting: Ambulatory; Canada.

Synopsis: A total of 1,809 patients were assessed for eligibility, 1,235 were excluded, and 574 with a Khorana score of 2 or higher were randomized to apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily or placebo. Treatment or placebo was given within 24 hours after the initiation of chemotherapy and continued for 180 days. The primary efficacy outcome – first episode of major VTE within 180 days of randomization – occurred in 4.2% of the apixaban group and in 10.2% of the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.41; 95% confidence interval, 0.26-0.65; P less than .001). Major bleeding in the modified intention-to-treat analysis occurred in 3.5% in the apixaban group and 1.8% in the placebo group (HR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.01-3.95; P = .046).

There was no significant difference in overall survival, with 87% of deaths were related to cancer or cancer progression.

Bottom line: VTE is significantly lower with the use of apixaban, compared with placebo, in intermediate- to high-risk ambulatory patients with active cancer who are initiating chemotherapy.

Citation: Carrier M et al. Apixaban to prevent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018 Dec 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814468.

Dr. Trammell Velasquez is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System.

Background: Active cancer places patients at increased risk for VTE. Ambulatory patients can be risk stratified using the validated Khorana score to assess risk for VTE, a complication resulting in significant morbidity, mortality, and health care costs.

Study design: Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial.

Setting: Ambulatory; Canada.

Synopsis: A total of 1,809 patients were assessed for eligibility, 1,235 were excluded, and 574 with a Khorana score of 2 or higher were randomized to apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily or placebo. Treatment or placebo was given within 24 hours after the initiation of chemotherapy and continued for 180 days. The primary efficacy outcome – first episode of major VTE within 180 days of randomization – occurred in 4.2% of the apixaban group and in 10.2% of the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.41; 95% confidence interval, 0.26-0.65; P less than .001). Major bleeding in the modified intention-to-treat analysis occurred in 3.5% in the apixaban group and 1.8% in the placebo group (HR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.01-3.95; P = .046).

There was no significant difference in overall survival, with 87% of deaths were related to cancer or cancer progression.

Bottom line: VTE is significantly lower with the use of apixaban, compared with placebo, in intermediate- to high-risk ambulatory patients with active cancer who are initiating chemotherapy.

Citation: Carrier M et al. Apixaban to prevent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018 Dec 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814468.

Dr. Trammell Velasquez is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System.

Background: Active cancer places patients at increased risk for VTE. Ambulatory patients can be risk stratified using the validated Khorana score to assess risk for VTE, a complication resulting in significant morbidity, mortality, and health care costs.

Study design: Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial.

Setting: Ambulatory; Canada.

Synopsis: A total of 1,809 patients were assessed for eligibility, 1,235 were excluded, and 574 with a Khorana score of 2 or higher were randomized to apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily or placebo. Treatment or placebo was given within 24 hours after the initiation of chemotherapy and continued for 180 days. The primary efficacy outcome – first episode of major VTE within 180 days of randomization – occurred in 4.2% of the apixaban group and in 10.2% of the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.41; 95% confidence interval, 0.26-0.65; P less than .001). Major bleeding in the modified intention-to-treat analysis occurred in 3.5% in the apixaban group and 1.8% in the placebo group (HR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.01-3.95; P = .046).

There was no significant difference in overall survival, with 87% of deaths were related to cancer or cancer progression.

Bottom line: VTE is significantly lower with the use of apixaban, compared with placebo, in intermediate- to high-risk ambulatory patients with active cancer who are initiating chemotherapy.

Citation: Carrier M et al. Apixaban to prevent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018 Dec 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814468.

Dr. Trammell Velasquez is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System.

SHM and Jefferson College of Population Health partner to provide vital education for hospitalists

Both the Society of Hospital Medicine and Jefferson College of Population Health, of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, share a goal to educate physicians to be effective leaders and managers in the pursuit of health care quality, safety, and population health, and they have entered into a partnership with this in mind.

Alexis Skoufalos, EdD, associate dean, strategic development, for Jefferson College of Population Health, recently spoke with The Hospitalist to discuss the importance of population health to hospital medicine professionals, the health care landscape as a whole, and the benefits of this new partnership with SHM.

Can you explain the importance of population health in the current health care landscape?

Many people confuse population health with public health. While they are related, they are different disciplines. Public health focuses on prevention and health promotion (clean water, vaccines, exercise, using seat belts, and so on), but it stops there.

Population health builds on the foundation of public health and goes a step further, working to connect health and health care delivery. It takes a more holistic approach, looking at what we need to do inside and outside the delivery system to help people to get and stay healthy, as well as take better care of them when they do get sick.

We work to identify and understand the health impact of social and environmental factors, while also looking for ways to make health care delivery safer, better, and more affordable and accessible.

This can get complicated. It involves sorting through lots of information to uncover the best way to meet the needs of a specific group, whether that is a community, a neighborhood, or a patient with a particular condition.

It’s about taking the time to really look at things from different vantage points. You won’t see the same view if you are looking at something through a telescope as you would looking through a microscope. That information can help you to adjust your perspective to identify the best course of action.

In order to be successful in improving population health, providers need to understand how to work with the other stakeholders in the health care ecosystem. Collaboration and coordination are the best ways to optimize the resources available.

It is important for delivery systems to establish good working relationships with community nonprofit and service organizations, faith-based organizations, social service providers, school systems, and federal, state, and local government.

At Jefferson, we thought it was important to create a college and programs that would prepare professionals across the workforce for this new challenge.

How did this partnership between SHM and Jefferson College of Population Health come to fruition?

Hospitalists are an important link with a person’s primary care team. The work they do to prepare a person and their family for successful discharge to the community after a hospital stay can make all the difference in a person’s recovery, condition management, and preventing readmission to the hospital.

Because both of our organizations are based in Philadelphia, we have had longstanding connections with SHM leadership. It was only natural for us to talk with SHM about how we can build upon the society’s excellent continuing education offerings and work together to provide members with additional content that can equip them to advance their careers.

How did SHM and Jefferson College of Population Health identify the mutually beneficial educational offerings in each institution that are included in this partnership?

Members of our respective leadership teams got together to complete a detailed review of the offerings from each organization. SHM’s Leadership Academy and JCPH’s Population Health Academy are rigorous continuing education programs that can provide physicians with excellent just-in-time information they can put to use right away.

After a careful examination of the curriculum, JCPH determined that SHM members can apply the credits they earn from completing two qualified sessions from the Leadership Academy to satisfy the elective course requirement for a Master’s degree. (Note: This does not apply to the Population Health Intelligence Program, which does not include an elective course.)

How will this partnership benefit Jefferson College of Population Health?

Our mission is to prepare health care leaders with the skills and tools they need to be effective in improving population health. Clinicians who work in a hospital setting have a key role to play.

We are also dedicated to making a difference right here in Philadelphia. The more students we have in our programs, the more of an impact we (and they) will have in improving outcomes in our own community.

We need to move the needle and get Philadelphia County out of the basement in terms of health rankings. We have a responsibility to do what we can to make a difference, and we appreciate the partnership with SHM to make it happen.

What other components of the partnership are especially noteworthy to highlight?

In addition to what I’ve already discussed, the following are some of the significant benefits that SHM members are entitled to as a result of the partnership with JCPH:

- 15% discount on tuition for any JCPH online graduate degree program.

- Registration discount for JCPH’s Population Health Academy in Philadelphia.

- Special registration rate for Annual Population Health Colloquium.

For more information about this partnership, visit hospitalmedicine.org/jefferson.

Both the Society of Hospital Medicine and Jefferson College of Population Health, of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, share a goal to educate physicians to be effective leaders and managers in the pursuit of health care quality, safety, and population health, and they have entered into a partnership with this in mind.

Alexis Skoufalos, EdD, associate dean, strategic development, for Jefferson College of Population Health, recently spoke with The Hospitalist to discuss the importance of population health to hospital medicine professionals, the health care landscape as a whole, and the benefits of this new partnership with SHM.

Can you explain the importance of population health in the current health care landscape?

Many people confuse population health with public health. While they are related, they are different disciplines. Public health focuses on prevention and health promotion (clean water, vaccines, exercise, using seat belts, and so on), but it stops there.

Population health builds on the foundation of public health and goes a step further, working to connect health and health care delivery. It takes a more holistic approach, looking at what we need to do inside and outside the delivery system to help people to get and stay healthy, as well as take better care of them when they do get sick.

We work to identify and understand the health impact of social and environmental factors, while also looking for ways to make health care delivery safer, better, and more affordable and accessible.

This can get complicated. It involves sorting through lots of information to uncover the best way to meet the needs of a specific group, whether that is a community, a neighborhood, or a patient with a particular condition.

It’s about taking the time to really look at things from different vantage points. You won’t see the same view if you are looking at something through a telescope as you would looking through a microscope. That information can help you to adjust your perspective to identify the best course of action.

In order to be successful in improving population health, providers need to understand how to work with the other stakeholders in the health care ecosystem. Collaboration and coordination are the best ways to optimize the resources available.

It is important for delivery systems to establish good working relationships with community nonprofit and service organizations, faith-based organizations, social service providers, school systems, and federal, state, and local government.

At Jefferson, we thought it was important to create a college and programs that would prepare professionals across the workforce for this new challenge.

How did this partnership between SHM and Jefferson College of Population Health come to fruition?

Hospitalists are an important link with a person’s primary care team. The work they do to prepare a person and their family for successful discharge to the community after a hospital stay can make all the difference in a person’s recovery, condition management, and preventing readmission to the hospital.

Because both of our organizations are based in Philadelphia, we have had longstanding connections with SHM leadership. It was only natural for us to talk with SHM about how we can build upon the society’s excellent continuing education offerings and work together to provide members with additional content that can equip them to advance their careers.

How did SHM and Jefferson College of Population Health identify the mutually beneficial educational offerings in each institution that are included in this partnership?

Members of our respective leadership teams got together to complete a detailed review of the offerings from each organization. SHM’s Leadership Academy and JCPH’s Population Health Academy are rigorous continuing education programs that can provide physicians with excellent just-in-time information they can put to use right away.

After a careful examination of the curriculum, JCPH determined that SHM members can apply the credits they earn from completing two qualified sessions from the Leadership Academy to satisfy the elective course requirement for a Master’s degree. (Note: This does not apply to the Population Health Intelligence Program, which does not include an elective course.)

How will this partnership benefit Jefferson College of Population Health?

Our mission is to prepare health care leaders with the skills and tools they need to be effective in improving population health. Clinicians who work in a hospital setting have a key role to play.

We are also dedicated to making a difference right here in Philadelphia. The more students we have in our programs, the more of an impact we (and they) will have in improving outcomes in our own community.

We need to move the needle and get Philadelphia County out of the basement in terms of health rankings. We have a responsibility to do what we can to make a difference, and we appreciate the partnership with SHM to make it happen.

What other components of the partnership are especially noteworthy to highlight?

In addition to what I’ve already discussed, the following are some of the significant benefits that SHM members are entitled to as a result of the partnership with JCPH:

- 15% discount on tuition for any JCPH online graduate degree program.

- Registration discount for JCPH’s Population Health Academy in Philadelphia.

- Special registration rate for Annual Population Health Colloquium.

For more information about this partnership, visit hospitalmedicine.org/jefferson.

Both the Society of Hospital Medicine and Jefferson College of Population Health, of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, share a goal to educate physicians to be effective leaders and managers in the pursuit of health care quality, safety, and population health, and they have entered into a partnership with this in mind.

Alexis Skoufalos, EdD, associate dean, strategic development, for Jefferson College of Population Health, recently spoke with The Hospitalist to discuss the importance of population health to hospital medicine professionals, the health care landscape as a whole, and the benefits of this new partnership with SHM.

Can you explain the importance of population health in the current health care landscape?

Many people confuse population health with public health. While they are related, they are different disciplines. Public health focuses on prevention and health promotion (clean water, vaccines, exercise, using seat belts, and so on), but it stops there.

Population health builds on the foundation of public health and goes a step further, working to connect health and health care delivery. It takes a more holistic approach, looking at what we need to do inside and outside the delivery system to help people to get and stay healthy, as well as take better care of them when they do get sick.

We work to identify and understand the health impact of social and environmental factors, while also looking for ways to make health care delivery safer, better, and more affordable and accessible.

This can get complicated. It involves sorting through lots of information to uncover the best way to meet the needs of a specific group, whether that is a community, a neighborhood, or a patient with a particular condition.

It’s about taking the time to really look at things from different vantage points. You won’t see the same view if you are looking at something through a telescope as you would looking through a microscope. That information can help you to adjust your perspective to identify the best course of action.

In order to be successful in improving population health, providers need to understand how to work with the other stakeholders in the health care ecosystem. Collaboration and coordination are the best ways to optimize the resources available.

It is important for delivery systems to establish good working relationships with community nonprofit and service organizations, faith-based organizations, social service providers, school systems, and federal, state, and local government.

At Jefferson, we thought it was important to create a college and programs that would prepare professionals across the workforce for this new challenge.

How did this partnership between SHM and Jefferson College of Population Health come to fruition?

Hospitalists are an important link with a person’s primary care team. The work they do to prepare a person and their family for successful discharge to the community after a hospital stay can make all the difference in a person’s recovery, condition management, and preventing readmission to the hospital.

Because both of our organizations are based in Philadelphia, we have had longstanding connections with SHM leadership. It was only natural for us to talk with SHM about how we can build upon the society’s excellent continuing education offerings and work together to provide members with additional content that can equip them to advance their careers.

How did SHM and Jefferson College of Population Health identify the mutually beneficial educational offerings in each institution that are included in this partnership?

Members of our respective leadership teams got together to complete a detailed review of the offerings from each organization. SHM’s Leadership Academy and JCPH’s Population Health Academy are rigorous continuing education programs that can provide physicians with excellent just-in-time information they can put to use right away.

After a careful examination of the curriculum, JCPH determined that SHM members can apply the credits they earn from completing two qualified sessions from the Leadership Academy to satisfy the elective course requirement for a Master’s degree. (Note: This does not apply to the Population Health Intelligence Program, which does not include an elective course.)

How will this partnership benefit Jefferson College of Population Health?

Our mission is to prepare health care leaders with the skills and tools they need to be effective in improving population health. Clinicians who work in a hospital setting have a key role to play.

We are also dedicated to making a difference right here in Philadelphia. The more students we have in our programs, the more of an impact we (and they) will have in improving outcomes in our own community.

We need to move the needle and get Philadelphia County out of the basement in terms of health rankings. We have a responsibility to do what we can to make a difference, and we appreciate the partnership with SHM to make it happen.

What other components of the partnership are especially noteworthy to highlight?

In addition to what I’ve already discussed, the following are some of the significant benefits that SHM members are entitled to as a result of the partnership with JCPH:

- 15% discount on tuition for any JCPH online graduate degree program.

- Registration discount for JCPH’s Population Health Academy in Philadelphia.

- Special registration rate for Annual Population Health Colloquium.

For more information about this partnership, visit hospitalmedicine.org/jefferson.

POCUS for hospitalists: The SHM position statement

Background: POCUS is becoming more prevalent in the daily practice of hospitalists; however, there are currently no established standards or guidelines for the use of POCUS for hospitalists.

Study design: Position statement.

Setting: SHM Executive Committee and Multi-Institutional POCUS faculty meeting through the Society of Hospital Medicine 2018 Annual Conference reviewed and approved this statement.

Synopsis: In contrast to the comprehensive ultrasound exam, POCUS is used by hospitalists to answer focused questions, by the same clinician who is generating the clinical question, to evaluate multiple body systems, or to serially investigate changes clinical status or evaluate responses to therapy.

This position statement provides guidance on the use of POCUS by hospitalists and the administrators who oversee it by outlining POCUS in terms of common diagnostic and procedural applications; training; assessments by the categories of basic knowledge, image acquisition, interpretation, clinical integration, and certification and maintenance of skills; and program management.

Bottom line: This position statement by the SHM provides guidance for hospitalists and administrators on the use and oversight of POCUS.

Citation: Soni NJ et al. Point-of-care ultrasound for hospitalists: A position statement of the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019 Jan 2;14:E1-E6.

Dr. Wang is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System.

Background: POCUS is becoming more prevalent in the daily practice of hospitalists; however, there are currently no established standards or guidelines for the use of POCUS for hospitalists.

Study design: Position statement.

Setting: SHM Executive Committee and Multi-Institutional POCUS faculty meeting through the Society of Hospital Medicine 2018 Annual Conference reviewed and approved this statement.

Synopsis: In contrast to the comprehensive ultrasound exam, POCUS is used by hospitalists to answer focused questions, by the same clinician who is generating the clinical question, to evaluate multiple body systems, or to serially investigate changes clinical status or evaluate responses to therapy.

This position statement provides guidance on the use of POCUS by hospitalists and the administrators who oversee it by outlining POCUS in terms of common diagnostic and procedural applications; training; assessments by the categories of basic knowledge, image acquisition, interpretation, clinical integration, and certification and maintenance of skills; and program management.

Bottom line: This position statement by the SHM provides guidance for hospitalists and administrators on the use and oversight of POCUS.

Citation: Soni NJ et al. Point-of-care ultrasound for hospitalists: A position statement of the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019 Jan 2;14:E1-E6.

Dr. Wang is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System.

Background: POCUS is becoming more prevalent in the daily practice of hospitalists; however, there are currently no established standards or guidelines for the use of POCUS for hospitalists.

Study design: Position statement.

Setting: SHM Executive Committee and Multi-Institutional POCUS faculty meeting through the Society of Hospital Medicine 2018 Annual Conference reviewed and approved this statement.

Synopsis: In contrast to the comprehensive ultrasound exam, POCUS is used by hospitalists to answer focused questions, by the same clinician who is generating the clinical question, to evaluate multiple body systems, or to serially investigate changes clinical status or evaluate responses to therapy.

This position statement provides guidance on the use of POCUS by hospitalists and the administrators who oversee it by outlining POCUS in terms of common diagnostic and procedural applications; training; assessments by the categories of basic knowledge, image acquisition, interpretation, clinical integration, and certification and maintenance of skills; and program management.

Bottom line: This position statement by the SHM provides guidance for hospitalists and administrators on the use and oversight of POCUS.

Citation: Soni NJ et al. Point-of-care ultrasound for hospitalists: A position statement of the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019 Jan 2;14:E1-E6.

Dr. Wang is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System.

Effects of hospitalization on readmission rate

Background: There is increasing concern that the patient experience in the hospital may be associated with post-hospital adverse outcomes, including new or recurrent illnesses after discharge or unplanned return to the hospital or readmission.

Study design: Prospective cohort that included 207 patients.

Setting: Two academic hospitals in Toronto.

Synopsis: These patients had been admitted to the internal medicine ward for more than 48 hours and were interviewed at discharge using a standardized questionnaire to assess four domains of the trauma of hospitalization defined as the cumulative effects of patient-reported sleep disturbance, mobility, nutrition, and mood. Among these patients, 64.3% experienced disturbance in more than one domain, and patients who experienced disturbance in three to four domains had a 15.8% greater absolute risk of 30-day readmission or ED visit.

Because this is an observational study, causal inferences were not possible; however, hospitalists should keep in mind the possible association of the patient experience and the link to clinical outcomes.

Bottom line: Trauma of hospitalization is common and may be associated with an increased 30-day risk of readmission or ED visit.

Citation: Rawal J et al. Association of the trauma of hospitalization with 30-day readmission or emergency department visit. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(1):38-45.

Dr. Wang is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System.

Background: There is increasing concern that the patient experience in the hospital may be associated with post-hospital adverse outcomes, including new or recurrent illnesses after discharge or unplanned return to the hospital or readmission.

Study design: Prospective cohort that included 207 patients.

Setting: Two academic hospitals in Toronto.

Synopsis: These patients had been admitted to the internal medicine ward for more than 48 hours and were interviewed at discharge using a standardized questionnaire to assess four domains of the trauma of hospitalization defined as the cumulative effects of patient-reported sleep disturbance, mobility, nutrition, and mood. Among these patients, 64.3% experienced disturbance in more than one domain, and patients who experienced disturbance in three to four domains had a 15.8% greater absolute risk of 30-day readmission or ED visit.

Because this is an observational study, causal inferences were not possible; however, hospitalists should keep in mind the possible association of the patient experience and the link to clinical outcomes.

Bottom line: Trauma of hospitalization is common and may be associated with an increased 30-day risk of readmission or ED visit.

Citation: Rawal J et al. Association of the trauma of hospitalization with 30-day readmission or emergency department visit. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(1):38-45.

Dr. Wang is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System.

Background: There is increasing concern that the patient experience in the hospital may be associated with post-hospital adverse outcomes, including new or recurrent illnesses after discharge or unplanned return to the hospital or readmission.

Study design: Prospective cohort that included 207 patients.

Setting: Two academic hospitals in Toronto.

Synopsis: These patients had been admitted to the internal medicine ward for more than 48 hours and were interviewed at discharge using a standardized questionnaire to assess four domains of the trauma of hospitalization defined as the cumulative effects of patient-reported sleep disturbance, mobility, nutrition, and mood. Among these patients, 64.3% experienced disturbance in more than one domain, and patients who experienced disturbance in three to four domains had a 15.8% greater absolute risk of 30-day readmission or ED visit.

Because this is an observational study, causal inferences were not possible; however, hospitalists should keep in mind the possible association of the patient experience and the link to clinical outcomes.

Bottom line: Trauma of hospitalization is common and may be associated with an increased 30-day risk of readmission or ED visit.

Citation: Rawal J et al. Association of the trauma of hospitalization with 30-day readmission or emergency department visit. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(1):38-45.

Dr. Wang is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System.

Using ultrasound guidance for adult abdominal paracentesis

Background: Abdominal paracentesis is a commonly performed procedure, and with appropriate training, hospitalists can deliver similar outcomes when compared to interventional radiologists.

Study design: Position statement.

Setting: The Society of Hospital Medicine Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS) Task Force developed these guidelines after reviewing available literature and voted on the appropriateness and consensus of a recommendation.

Synopsis: A total of 794 articles were screened, and 91 articles were included and incorporated into the recommendations. The 12 recommendations fall into three categories (clinical outcomes, technique, and training), and all 12 recommendations achieved consensus as strong recommendations.

To improve clinical outcomes, the authors recommended ultrasound guidance in performing paracentesis to reduce the risk of serious complications, to avoid attempting paracentesis with insufficient fluid, and to improve overall procedure success.

The authors advocated for several technique recommendations, including using the ultrasound to assess volume and location of intraperitoneal fluid, to identify the needle insertion site and confirm in multiple planes, to use color flow Doppler to identify abdominal wall vessels, to mark the insertion site immediately prior to the procedure, and to consider real-time ultrasound guidance.

When health care professionals are learning ultrasound-guided paracentesis, the authors recommended use of dedicated training sessions with simulation if available and that competency should be demonstrated before independently attempting the procedure.

Bottom line: These recommendations from SHM POCUS Task Force provides consensus guidelines on the use of ultrasound guidance when performing or learning abdominal paracentesis.

Citation: Cho J et al. Recommendations on the use of ultrasound guidance for adult abdominal paracentesis: A position statement of the Society of Hospital Medicine. 2019 Jan 2. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3095.

Dr. Schmit is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System, also in San Antonio.

Background: Abdominal paracentesis is a commonly performed procedure, and with appropriate training, hospitalists can deliver similar outcomes when compared to interventional radiologists.

Study design: Position statement.

Setting: The Society of Hospital Medicine Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS) Task Force developed these guidelines after reviewing available literature and voted on the appropriateness and consensus of a recommendation.

Synopsis: A total of 794 articles were screened, and 91 articles were included and incorporated into the recommendations. The 12 recommendations fall into three categories (clinical outcomes, technique, and training), and all 12 recommendations achieved consensus as strong recommendations.

To improve clinical outcomes, the authors recommended ultrasound guidance in performing paracentesis to reduce the risk of serious complications, to avoid attempting paracentesis with insufficient fluid, and to improve overall procedure success.

The authors advocated for several technique recommendations, including using the ultrasound to assess volume and location of intraperitoneal fluid, to identify the needle insertion site and confirm in multiple planes, to use color flow Doppler to identify abdominal wall vessels, to mark the insertion site immediately prior to the procedure, and to consider real-time ultrasound guidance.

When health care professionals are learning ultrasound-guided paracentesis, the authors recommended use of dedicated training sessions with simulation if available and that competency should be demonstrated before independently attempting the procedure.

Bottom line: These recommendations from SHM POCUS Task Force provides consensus guidelines on the use of ultrasound guidance when performing or learning abdominal paracentesis.

Citation: Cho J et al. Recommendations on the use of ultrasound guidance for adult abdominal paracentesis: A position statement of the Society of Hospital Medicine. 2019 Jan 2. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3095.

Dr. Schmit is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System, also in San Antonio.

Background: Abdominal paracentesis is a commonly performed procedure, and with appropriate training, hospitalists can deliver similar outcomes when compared to interventional radiologists.

Study design: Position statement.

Setting: The Society of Hospital Medicine Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS) Task Force developed these guidelines after reviewing available literature and voted on the appropriateness and consensus of a recommendation.

Synopsis: A total of 794 articles were screened, and 91 articles were included and incorporated into the recommendations. The 12 recommendations fall into three categories (clinical outcomes, technique, and training), and all 12 recommendations achieved consensus as strong recommendations.

To improve clinical outcomes, the authors recommended ultrasound guidance in performing paracentesis to reduce the risk of serious complications, to avoid attempting paracentesis with insufficient fluid, and to improve overall procedure success.

The authors advocated for several technique recommendations, including using the ultrasound to assess volume and location of intraperitoneal fluid, to identify the needle insertion site and confirm in multiple planes, to use color flow Doppler to identify abdominal wall vessels, to mark the insertion site immediately prior to the procedure, and to consider real-time ultrasound guidance.

When health care professionals are learning ultrasound-guided paracentesis, the authors recommended use of dedicated training sessions with simulation if available and that competency should be demonstrated before independently attempting the procedure.

Bottom line: These recommendations from SHM POCUS Task Force provides consensus guidelines on the use of ultrasound guidance when performing or learning abdominal paracentesis.

Citation: Cho J et al. Recommendations on the use of ultrasound guidance for adult abdominal paracentesis: A position statement of the Society of Hospital Medicine. 2019 Jan 2. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3095.

Dr. Schmit is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System, also in San Antonio.

Is it safe to discharge patients with anemia?

Background: Anemia is common in hospitalized patients and is associated with short- and long-term morbidity and mortality. Current evidence shows that reduced red blood cell (RBC) use and more restrictive transfusion practices do not increase short-term mortality; however, few data exist on the long-term outcomes of anemia.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Integrated health care system (Kaiser Permanente) with 21 hospitals located in Northern California.

Synopsis: From 2010 to 2014, there were 801,261 hospitalizations among 445,371 patients who survived to discharge. The prevalence of moderate anemia (hemoglobin between 7 and 10 g/dL) at hospital discharge increased from 20% to 25% (P less than .001) while RBC transfusions decreased by 28% (P less than .001). Resolution of moderate anemia within 6 months of hospital discharge decreased from 42% to 34% (P less than .001). RBC transfusion and rehospitalization rates at 6 months decreased as well. During the study period, adjusted 6-month mortality decreased from 16.1% to 15.6% (P = .04) in patients with moderate anemia.

Given the retrospective design of this study, data must be interpreted with caution in determining a causal relationship. The authors also acknowledge that there may be unmeasured confounding variables not accounted for in the study results.

Bottom line: Despite higher rates of moderate anemia at discharge, there was not an associated rise in subsequent RBC transfusions, readmissions, or mortality in the 6 months after hospital discharge.

Citation: Roubinian NH et al. Long-term outcomes among patients discharged from the hospital with moderate anemia: A retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.7326/M17-3253.

Dr. Schmit is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System, also in San Antonio.

Background: Anemia is common in hospitalized patients and is associated with short- and long-term morbidity and mortality. Current evidence shows that reduced red blood cell (RBC) use and more restrictive transfusion practices do not increase short-term mortality; however, few data exist on the long-term outcomes of anemia.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Integrated health care system (Kaiser Permanente) with 21 hospitals located in Northern California.

Synopsis: From 2010 to 2014, there were 801,261 hospitalizations among 445,371 patients who survived to discharge. The prevalence of moderate anemia (hemoglobin between 7 and 10 g/dL) at hospital discharge increased from 20% to 25% (P less than .001) while RBC transfusions decreased by 28% (P less than .001). Resolution of moderate anemia within 6 months of hospital discharge decreased from 42% to 34% (P less than .001). RBC transfusion and rehospitalization rates at 6 months decreased as well. During the study period, adjusted 6-month mortality decreased from 16.1% to 15.6% (P = .04) in patients with moderate anemia.

Given the retrospective design of this study, data must be interpreted with caution in determining a causal relationship. The authors also acknowledge that there may be unmeasured confounding variables not accounted for in the study results.

Bottom line: Despite higher rates of moderate anemia at discharge, there was not an associated rise in subsequent RBC transfusions, readmissions, or mortality in the 6 months after hospital discharge.

Citation: Roubinian NH et al. Long-term outcomes among patients discharged from the hospital with moderate anemia: A retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.7326/M17-3253.

Dr. Schmit is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System, also in San Antonio.

Background: Anemia is common in hospitalized patients and is associated with short- and long-term morbidity and mortality. Current evidence shows that reduced red blood cell (RBC) use and more restrictive transfusion practices do not increase short-term mortality; however, few data exist on the long-term outcomes of anemia.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Integrated health care system (Kaiser Permanente) with 21 hospitals located in Northern California.

Synopsis: From 2010 to 2014, there were 801,261 hospitalizations among 445,371 patients who survived to discharge. The prevalence of moderate anemia (hemoglobin between 7 and 10 g/dL) at hospital discharge increased from 20% to 25% (P less than .001) while RBC transfusions decreased by 28% (P less than .001). Resolution of moderate anemia within 6 months of hospital discharge decreased from 42% to 34% (P less than .001). RBC transfusion and rehospitalization rates at 6 months decreased as well. During the study period, adjusted 6-month mortality decreased from 16.1% to 15.6% (P = .04) in patients with moderate anemia.

Given the retrospective design of this study, data must be interpreted with caution in determining a causal relationship. The authors also acknowledge that there may be unmeasured confounding variables not accounted for in the study results.

Bottom line: Despite higher rates of moderate anemia at discharge, there was not an associated rise in subsequent RBC transfusions, readmissions, or mortality in the 6 months after hospital discharge.

Citation: Roubinian NH et al. Long-term outcomes among patients discharged from the hospital with moderate anemia: A retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.7326/M17-3253.

Dr. Schmit is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System, also in San Antonio.

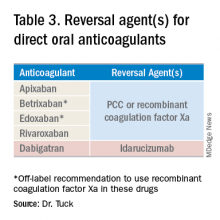

Reversal agents for direct-acting oral anticoagulants

Summary of guidelines published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine

When on call for admissions, a hospitalist receives a request from a colleague to admit an octogenarian man with an acute uncomplicated deep vein thrombosis to start heparin, bridging to warfarin. The patient has no evidence of postphlebitic syndrome, pulmonary embolism, or right-sided heart strain. The hospitalist asks her colleague if he had considered treating the patient in the ambulatory setting using a direct-acting oral anticoagulant (DOAC). After all, this would save the patient an unnecessary hospitalization, weekly international normalized ratio checks, and other important lifestyle changes. In response, the colleague voices concern that the “new drugs don’t have antidotes.”

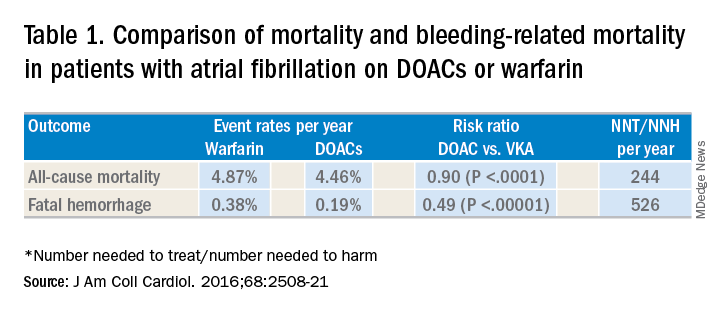

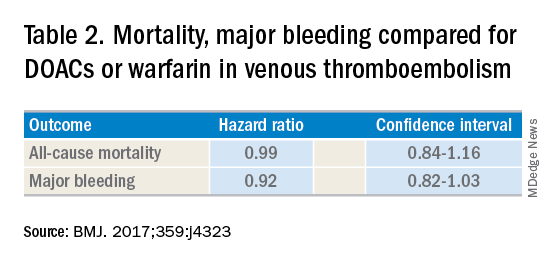

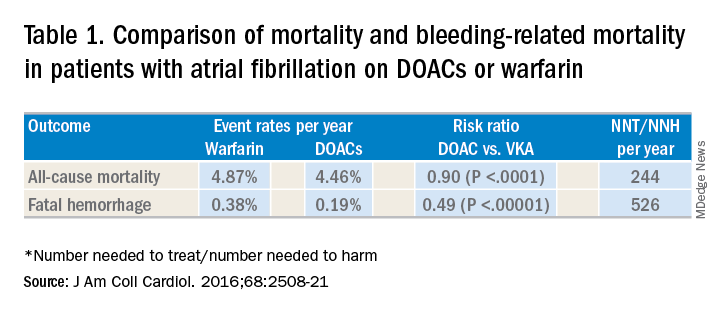

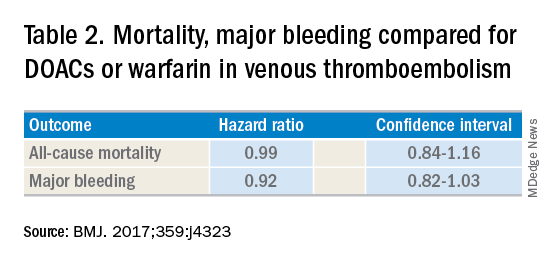

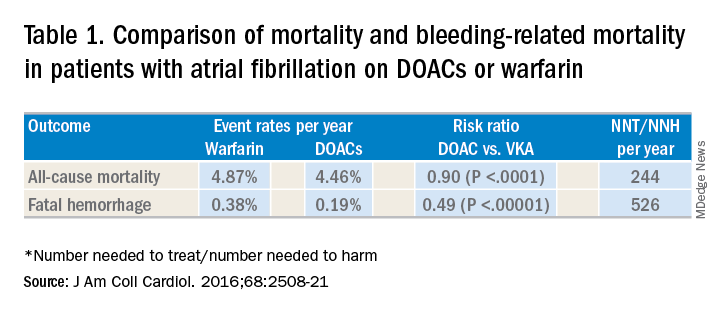

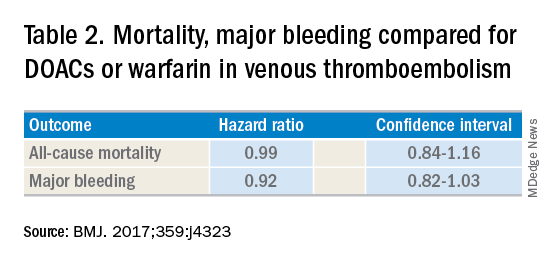

DOACs have several benefits over vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) and heparins. DOACs have quicker onset of action, can be taken by mouth, in general do not require dosage adjustment, and have fewer dietary and lifestyle modifications, compared with VKAs and heparins. In atrial fibrillation, DOACs have been shown to have lower all-cause and bleeding-related mortality than warfarin (see Table 1).1 Observational studies also suggest less risk of major bleeding with DOACs over warfarin but no difference in overall mortality when used to treat venous thromboembolism (see Table 2).2 Because of these combined advantages, DOACs are increasingly prescribed, accounting for approximately half of all oral anticoagulant prescriptions in 2014.3

Although DOACs have been shown to be as good if not superior to VKAs and heparins in these circumstances, there are situations where a DOAC should not be used. There is limited data on the safety of DOACs in patients with mechanical heart valves, liver failure, and chronic kidney disease with a creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min.4 Therefore, warfarin is still the preferred agent in these settings. There is some data that apixaban may be safe in patients with a creatinine clearance of greater than 10 mL/min, but long-term safety studies have not been performed in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis.5 Finally, in patients requiring concomitant inducers or inhibitors of the P-glycoprotein or cytochrome P450 enzymes like antiepileptics and protease inhibitors, VKAs and heparins are favored.4

Notwithstanding their advantages, when DOACs first hit the market there were concerns that reversal agents were not available. In the August issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine’s Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist, Emily Gottenborg, MD, and Gregory Misky, MD, summarized guideline recommendations for reversal of the newer agents.6 This includes use of idarucizumab for patients on dabigatran and use of prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) or recombinant coagulation factor Xa (andexanet alfa) for patients on apixaban or rivaroxaban for the treatment of life-threatening bleeding.

Idarucizumab is a monoclonal antibody developed to reverse the effects of dabigatran, the only DOAC that directly inhibits thrombin. In 2017, researchers reported on a cohort of subjects receiving idarucizumab for uncontrolled bleeding or who were on dabigatran and about to undergo an urgent procedure.7 Of those with uncontrolled bleeding, two-thirds had confirmed bleeding cessation within 24 hours. Periprocedural hemostasis was achieved in 93.4% of patients undergoing urgent procedures. However, it should be noted that use of idarucizumab conferred an increase risk (6.3%) of thrombosis within 90 days. Based on these findings, guidelines recommend use of idarucizumab in patients experiencing life-threatening bleeding, balanced against the risk of thrombosis.8

In 2018, the Food and Drug Administration approved recombinant coagulation factor Xa for treatment of life-threatening or uncontrolled bleeding in patients on apixaban or rivaroxaban.9 The approval came after a study by the ANNEXA-4 investigators showed that recombinant coagulation factor Xa quickly and effectively achieved hemostasis.10 Full study results were published in April 2019, demonstrating 82% of patients receiving the drug attained clinical hemostasis.11 However, as with idarucizumab, up to 10% of patients had a thrombotic event in the follow-up period. Use of recombinant coagulation factor Xa for treatment of life-threatening bleeding related to betrixaban and edoxaban is considered off label but is recommended by guidelines.8 Studies on investigational reversal agents for betrixaban and edoxaban are ongoing.

Both unactivated and activated PCC contain clotting factor X. Their use to control bleeding related to DOAC use is based on observational studies. In a systematic review of the nonrandomized studies, the efficacy of PCC to stem major bleeding was 69% and the risk for thromboembolism was 4%.12 There are no head-to-head studies comparing use of recombinant coagulation factor Xa and PCC. Therefore, guidelines are to use either recombinant factor Xa or PCC for the treatment of life-threatening bleeding related to DOAC use.7

As thrombosis risk heightens after use of any reversal agent, the recommendations are to resume anticoagulation within 90 days if the patient is at moderate or high risk for recurrent thromboembolism.8

After discussion with the hospitalist about the new agents available to reverse anticoagulation, the colleague decided to place the patient on a DOAC and keep the patient in his nursing home. Thankfully, the patient did not thereafter experience sustained bleeding necessitating use of these reversal agents. More importantly for the patient, he was able to stay in the comfort of his home.

Dr. Tuck is associate section chief for hospital medicine at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Washington, D.C.

References

1. Gómez-Outes A et al. Causes of death in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2508-21.

2. Jun M et al. Comparative safety of direct oral anticoagulants and warfarin in venous thromboembolism: multicentre, population-based, observational study. BMJ. 2017;359:j4323.

3. Barnes GD et al. National trends in ambulatory oral anticoagulant use. Am J Med. 2015;128:(1300-5).e2.

4. Reddy P et al. Practical approach to VTE management in hospitalized patients. Am J Ther. 2017;24(4):e442-67.

5. Kimachi M et al. Direct oral anticoagulants versus warfarin for preventing stroke and systemic embolic events among atrial fibrillation patients with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Nov 6;11:CD011373.

6. Gottenborg E et al. Clinical guideline highlights for the hospitalist: The management of anticoagulation in the hospitalized adult. J Hosp Med. 2019; 14(8):499-500.

7. Pollack CV Jr et al. Idarucizumab for dabigatran reversal – full cohort analysis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):431-41.

8. Witt DM et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Optimal management of anticoagulation therapy. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3257-91.

9. Malarky M et al. FDA accelerated approval letter. Retrieved July 15, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/113285/download

10. Connolly SJ et al. Andexanet alfa for acute major bleeding associated with factor Xa inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(12):1131-41.

11. Connolly SJ et al. Full study report of andexanet alfa for bleeding associated with factor xa inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(14):1326-35.

12. Piran S et al. Management of direct factor Xa inhibitor–related major bleeding with prothrombin complex concentrate: A meta-analysis. Blood Adv. 2019;3(2):158-67.

Summary of guidelines published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine

Summary of guidelines published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine

When on call for admissions, a hospitalist receives a request from a colleague to admit an octogenarian man with an acute uncomplicated deep vein thrombosis to start heparin, bridging to warfarin. The patient has no evidence of postphlebitic syndrome, pulmonary embolism, or right-sided heart strain. The hospitalist asks her colleague if he had considered treating the patient in the ambulatory setting using a direct-acting oral anticoagulant (DOAC). After all, this would save the patient an unnecessary hospitalization, weekly international normalized ratio checks, and other important lifestyle changes. In response, the colleague voices concern that the “new drugs don’t have antidotes.”

DOACs have several benefits over vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) and heparins. DOACs have quicker onset of action, can be taken by mouth, in general do not require dosage adjustment, and have fewer dietary and lifestyle modifications, compared with VKAs and heparins. In atrial fibrillation, DOACs have been shown to have lower all-cause and bleeding-related mortality than warfarin (see Table 1).1 Observational studies also suggest less risk of major bleeding with DOACs over warfarin but no difference in overall mortality when used to treat venous thromboembolism (see Table 2).2 Because of these combined advantages, DOACs are increasingly prescribed, accounting for approximately half of all oral anticoagulant prescriptions in 2014.3

Although DOACs have been shown to be as good if not superior to VKAs and heparins in these circumstances, there are situations where a DOAC should not be used. There is limited data on the safety of DOACs in patients with mechanical heart valves, liver failure, and chronic kidney disease with a creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min.4 Therefore, warfarin is still the preferred agent in these settings. There is some data that apixaban may be safe in patients with a creatinine clearance of greater than 10 mL/min, but long-term safety studies have not been performed in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis.5 Finally, in patients requiring concomitant inducers or inhibitors of the P-glycoprotein or cytochrome P450 enzymes like antiepileptics and protease inhibitors, VKAs and heparins are favored.4

Notwithstanding their advantages, when DOACs first hit the market there were concerns that reversal agents were not available. In the August issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine’s Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist, Emily Gottenborg, MD, and Gregory Misky, MD, summarized guideline recommendations for reversal of the newer agents.6 This includes use of idarucizumab for patients on dabigatran and use of prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) or recombinant coagulation factor Xa (andexanet alfa) for patients on apixaban or rivaroxaban for the treatment of life-threatening bleeding.

Idarucizumab is a monoclonal antibody developed to reverse the effects of dabigatran, the only DOAC that directly inhibits thrombin. In 2017, researchers reported on a cohort of subjects receiving idarucizumab for uncontrolled bleeding or who were on dabigatran and about to undergo an urgent procedure.7 Of those with uncontrolled bleeding, two-thirds had confirmed bleeding cessation within 24 hours. Periprocedural hemostasis was achieved in 93.4% of patients undergoing urgent procedures. However, it should be noted that use of idarucizumab conferred an increase risk (6.3%) of thrombosis within 90 days. Based on these findings, guidelines recommend use of idarucizumab in patients experiencing life-threatening bleeding, balanced against the risk of thrombosis.8

In 2018, the Food and Drug Administration approved recombinant coagulation factor Xa for treatment of life-threatening or uncontrolled bleeding in patients on apixaban or rivaroxaban.9 The approval came after a study by the ANNEXA-4 investigators showed that recombinant coagulation factor Xa quickly and effectively achieved hemostasis.10 Full study results were published in April 2019, demonstrating 82% of patients receiving the drug attained clinical hemostasis.11 However, as with idarucizumab, up to 10% of patients had a thrombotic event in the follow-up period. Use of recombinant coagulation factor Xa for treatment of life-threatening bleeding related to betrixaban and edoxaban is considered off label but is recommended by guidelines.8 Studies on investigational reversal agents for betrixaban and edoxaban are ongoing.

Both unactivated and activated PCC contain clotting factor X. Their use to control bleeding related to DOAC use is based on observational studies. In a systematic review of the nonrandomized studies, the efficacy of PCC to stem major bleeding was 69% and the risk for thromboembolism was 4%.12 There are no head-to-head studies comparing use of recombinant coagulation factor Xa and PCC. Therefore, guidelines are to use either recombinant factor Xa or PCC for the treatment of life-threatening bleeding related to DOAC use.7

As thrombosis risk heightens after use of any reversal agent, the recommendations are to resume anticoagulation within 90 days if the patient is at moderate or high risk for recurrent thromboembolism.8

After discussion with the hospitalist about the new agents available to reverse anticoagulation, the colleague decided to place the patient on a DOAC and keep the patient in his nursing home. Thankfully, the patient did not thereafter experience sustained bleeding necessitating use of these reversal agents. More importantly for the patient, he was able to stay in the comfort of his home.

Dr. Tuck is associate section chief for hospital medicine at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Washington, D.C.

References

1. Gómez-Outes A et al. Causes of death in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2508-21.

2. Jun M et al. Comparative safety of direct oral anticoagulants and warfarin in venous thromboembolism: multicentre, population-based, observational study. BMJ. 2017;359:j4323.

3. Barnes GD et al. National trends in ambulatory oral anticoagulant use. Am J Med. 2015;128:(1300-5).e2.

4. Reddy P et al. Practical approach to VTE management in hospitalized patients. Am J Ther. 2017;24(4):e442-67.

5. Kimachi M et al. Direct oral anticoagulants versus warfarin for preventing stroke and systemic embolic events among atrial fibrillation patients with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Nov 6;11:CD011373.

6. Gottenborg E et al. Clinical guideline highlights for the hospitalist: The management of anticoagulation in the hospitalized adult. J Hosp Med. 2019; 14(8):499-500.

7. Pollack CV Jr et al. Idarucizumab for dabigatran reversal – full cohort analysis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):431-41.

8. Witt DM et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Optimal management of anticoagulation therapy. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3257-91.

9. Malarky M et al. FDA accelerated approval letter. Retrieved July 15, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/113285/download

10. Connolly SJ et al. Andexanet alfa for acute major bleeding associated with factor Xa inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(12):1131-41.

11. Connolly SJ et al. Full study report of andexanet alfa for bleeding associated with factor xa inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(14):1326-35.

12. Piran S et al. Management of direct factor Xa inhibitor–related major bleeding with prothrombin complex concentrate: A meta-analysis. Blood Adv. 2019;3(2):158-67.

When on call for admissions, a hospitalist receives a request from a colleague to admit an octogenarian man with an acute uncomplicated deep vein thrombosis to start heparin, bridging to warfarin. The patient has no evidence of postphlebitic syndrome, pulmonary embolism, or right-sided heart strain. The hospitalist asks her colleague if he had considered treating the patient in the ambulatory setting using a direct-acting oral anticoagulant (DOAC). After all, this would save the patient an unnecessary hospitalization, weekly international normalized ratio checks, and other important lifestyle changes. In response, the colleague voices concern that the “new drugs don’t have antidotes.”

DOACs have several benefits over vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) and heparins. DOACs have quicker onset of action, can be taken by mouth, in general do not require dosage adjustment, and have fewer dietary and lifestyle modifications, compared with VKAs and heparins. In atrial fibrillation, DOACs have been shown to have lower all-cause and bleeding-related mortality than warfarin (see Table 1).1 Observational studies also suggest less risk of major bleeding with DOACs over warfarin but no difference in overall mortality when used to treat venous thromboembolism (see Table 2).2 Because of these combined advantages, DOACs are increasingly prescribed, accounting for approximately half of all oral anticoagulant prescriptions in 2014.3

Although DOACs have been shown to be as good if not superior to VKAs and heparins in these circumstances, there are situations where a DOAC should not be used. There is limited data on the safety of DOACs in patients with mechanical heart valves, liver failure, and chronic kidney disease with a creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min.4 Therefore, warfarin is still the preferred agent in these settings. There is some data that apixaban may be safe in patients with a creatinine clearance of greater than 10 mL/min, but long-term safety studies have not been performed in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis.5 Finally, in patients requiring concomitant inducers or inhibitors of the P-glycoprotein or cytochrome P450 enzymes like antiepileptics and protease inhibitors, VKAs and heparins are favored.4

Notwithstanding their advantages, when DOACs first hit the market there were concerns that reversal agents were not available. In the August issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine’s Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist, Emily Gottenborg, MD, and Gregory Misky, MD, summarized guideline recommendations for reversal of the newer agents.6 This includes use of idarucizumab for patients on dabigatran and use of prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) or recombinant coagulation factor Xa (andexanet alfa) for patients on apixaban or rivaroxaban for the treatment of life-threatening bleeding.

Idarucizumab is a monoclonal antibody developed to reverse the effects of dabigatran, the only DOAC that directly inhibits thrombin. In 2017, researchers reported on a cohort of subjects receiving idarucizumab for uncontrolled bleeding or who were on dabigatran and about to undergo an urgent procedure.7 Of those with uncontrolled bleeding, two-thirds had confirmed bleeding cessation within 24 hours. Periprocedural hemostasis was achieved in 93.4% of patients undergoing urgent procedures. However, it should be noted that use of idarucizumab conferred an increase risk (6.3%) of thrombosis within 90 days. Based on these findings, guidelines recommend use of idarucizumab in patients experiencing life-threatening bleeding, balanced against the risk of thrombosis.8

In 2018, the Food and Drug Administration approved recombinant coagulation factor Xa for treatment of life-threatening or uncontrolled bleeding in patients on apixaban or rivaroxaban.9 The approval came after a study by the ANNEXA-4 investigators showed that recombinant coagulation factor Xa quickly and effectively achieved hemostasis.10 Full study results were published in April 2019, demonstrating 82% of patients receiving the drug attained clinical hemostasis.11 However, as with idarucizumab, up to 10% of patients had a thrombotic event in the follow-up period. Use of recombinant coagulation factor Xa for treatment of life-threatening bleeding related to betrixaban and edoxaban is considered off label but is recommended by guidelines.8 Studies on investigational reversal agents for betrixaban and edoxaban are ongoing.

Both unactivated and activated PCC contain clotting factor X. Their use to control bleeding related to DOAC use is based on observational studies. In a systematic review of the nonrandomized studies, the efficacy of PCC to stem major bleeding was 69% and the risk for thromboembolism was 4%.12 There are no head-to-head studies comparing use of recombinant coagulation factor Xa and PCC. Therefore, guidelines are to use either recombinant factor Xa or PCC for the treatment of life-threatening bleeding related to DOAC use.7

As thrombosis risk heightens after use of any reversal agent, the recommendations are to resume anticoagulation within 90 days if the patient is at moderate or high risk for recurrent thromboembolism.8

After discussion with the hospitalist about the new agents available to reverse anticoagulation, the colleague decided to place the patient on a DOAC and keep the patient in his nursing home. Thankfully, the patient did not thereafter experience sustained bleeding necessitating use of these reversal agents. More importantly for the patient, he was able to stay in the comfort of his home.

Dr. Tuck is associate section chief for hospital medicine at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Washington, D.C.

References

1. Gómez-Outes A et al. Causes of death in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2508-21.

2. Jun M et al. Comparative safety of direct oral anticoagulants and warfarin in venous thromboembolism: multicentre, population-based, observational study. BMJ. 2017;359:j4323.