User login

Daily aspirin use may not improve CV outcomes in healthy elderly

Clinical question: What are the benefits and risks of daily aspirin use for primary prevention in healthy elderly adults?

Background: Prior studies have shown the efficacy of aspirin for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease and stroke, but the evidence supporting the use of aspirin for primary prevention is less certain.

Study design: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled prospective study with a 5-year study period.

Setting: Australia and the United States.

Synopsis: The Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) trial included 19,114 community-dwelling healthy people (aged 70 years and older overall and aged 65 years and older if black or Hispanic), without cardiovascular disease, dementia or disability. The goal was to investigate the effect of daily low-dose aspirin (100 mg, enteric coated) on healthy life span (without dementia or disability), with prespecified secondary outcomes (cardiovascular events and major hemorrhage).

Analysis was by intention-to-treat. Participants were predominantly Caucasian, approximately 10% of patients had diabetes, 74% had hypertension, and 65% had dyslipidemia. There was high adherence to the intervention. There was no significant difference in the primary outcome (disability-free survival) or in the secondary outcome of cardiovascular event (fatal or nonfatal MI or stroke, or hospitalization for heart failure.) The rate of major hemorrhage (hemorrhagic stroke, symptomatic intracranial bleeding, clinically significant extracranial bleeding) was higher in the aspirin group (P less than .001). In contrast to prior studies, subgroup analysis showed higher mortality in the aspirin group (attributed to an increase in the risk of cancer-related death.) The authors warn that this finding should be interpreted with caution.

Bottom line: Aspirin use for primary prevention in healthy elderly persons over a 5-year period did not change disability-free survival, did not decrease cardiovascular risk, and increased the rate of major hemorrhage.

Citation: McNeil JJ et al. Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1519-28.

Dr. Linker is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Clinical question: What are the benefits and risks of daily aspirin use for primary prevention in healthy elderly adults?

Background: Prior studies have shown the efficacy of aspirin for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease and stroke, but the evidence supporting the use of aspirin for primary prevention is less certain.

Study design: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled prospective study with a 5-year study period.

Setting: Australia and the United States.

Synopsis: The Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) trial included 19,114 community-dwelling healthy people (aged 70 years and older overall and aged 65 years and older if black or Hispanic), without cardiovascular disease, dementia or disability. The goal was to investigate the effect of daily low-dose aspirin (100 mg, enteric coated) on healthy life span (without dementia or disability), with prespecified secondary outcomes (cardiovascular events and major hemorrhage).

Analysis was by intention-to-treat. Participants were predominantly Caucasian, approximately 10% of patients had diabetes, 74% had hypertension, and 65% had dyslipidemia. There was high adherence to the intervention. There was no significant difference in the primary outcome (disability-free survival) or in the secondary outcome of cardiovascular event (fatal or nonfatal MI or stroke, or hospitalization for heart failure.) The rate of major hemorrhage (hemorrhagic stroke, symptomatic intracranial bleeding, clinically significant extracranial bleeding) was higher in the aspirin group (P less than .001). In contrast to prior studies, subgroup analysis showed higher mortality in the aspirin group (attributed to an increase in the risk of cancer-related death.) The authors warn that this finding should be interpreted with caution.

Bottom line: Aspirin use for primary prevention in healthy elderly persons over a 5-year period did not change disability-free survival, did not decrease cardiovascular risk, and increased the rate of major hemorrhage.

Citation: McNeil JJ et al. Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1519-28.

Dr. Linker is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Clinical question: What are the benefits and risks of daily aspirin use for primary prevention in healthy elderly adults?

Background: Prior studies have shown the efficacy of aspirin for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease and stroke, but the evidence supporting the use of aspirin for primary prevention is less certain.

Study design: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled prospective study with a 5-year study period.

Setting: Australia and the United States.

Synopsis: The Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) trial included 19,114 community-dwelling healthy people (aged 70 years and older overall and aged 65 years and older if black or Hispanic), without cardiovascular disease, dementia or disability. The goal was to investigate the effect of daily low-dose aspirin (100 mg, enteric coated) on healthy life span (without dementia or disability), with prespecified secondary outcomes (cardiovascular events and major hemorrhage).

Analysis was by intention-to-treat. Participants were predominantly Caucasian, approximately 10% of patients had diabetes, 74% had hypertension, and 65% had dyslipidemia. There was high adherence to the intervention. There was no significant difference in the primary outcome (disability-free survival) or in the secondary outcome of cardiovascular event (fatal or nonfatal MI or stroke, or hospitalization for heart failure.) The rate of major hemorrhage (hemorrhagic stroke, symptomatic intracranial bleeding, clinically significant extracranial bleeding) was higher in the aspirin group (P less than .001). In contrast to prior studies, subgroup analysis showed higher mortality in the aspirin group (attributed to an increase in the risk of cancer-related death.) The authors warn that this finding should be interpreted with caution.

Bottom line: Aspirin use for primary prevention in healthy elderly persons over a 5-year period did not change disability-free survival, did not decrease cardiovascular risk, and increased the rate of major hemorrhage.

Citation: McNeil JJ et al. Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1519-28.

Dr. Linker is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Short Takes

Restrictive transfusion strategy for cardiac surgery patients remains noninferior at 6 months post op

The authors previously reported that, in moderate- to high-risk cardiac surgery patients, a restrictive transfusion strategy was noninferior to a liberal strategy based on the clinical outcomes of all-cause mortality, MI, stroke, or new renal failure with dialysis. The groups continued to show no significant difference in outcomes at 6 months post op.

Citation: Mazer CD et al. Six-month outcomes after restrictive or liberal transfusion for cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1224-33.

Restrictive transfusion strategy for cardiac surgery patients remains noninferior at 6 months post op

The authors previously reported that, in moderate- to high-risk cardiac surgery patients, a restrictive transfusion strategy was noninferior to a liberal strategy based on the clinical outcomes of all-cause mortality, MI, stroke, or new renal failure with dialysis. The groups continued to show no significant difference in outcomes at 6 months post op.

Citation: Mazer CD et al. Six-month outcomes after restrictive or liberal transfusion for cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1224-33.

Restrictive transfusion strategy for cardiac surgery patients remains noninferior at 6 months post op

The authors previously reported that, in moderate- to high-risk cardiac surgery patients, a restrictive transfusion strategy was noninferior to a liberal strategy based on the clinical outcomes of all-cause mortality, MI, stroke, or new renal failure with dialysis. The groups continued to show no significant difference in outcomes at 6 months post op.

Citation: Mazer CD et al. Six-month outcomes after restrictive or liberal transfusion for cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1224-33.

Becoming a high-value care physician

‘Culture shift’ comes from collective efforts

It’s Monday morning, and Mrs. Jones still has abdominal pain. Your ward team decides to order a CT. On chart review you notice she’s had three other abdominal CTs for the same indication this year. How did this happen? What should you do?

High-value care has been defined by the Institute of Medicine as “the best care for the patient, with the optimal result for the circumstances, delivered at the right price.”1 With an estimated $700 billion dollars – 30% of medical expenditures – spent on wasted care, there are rising calls for a transformational shift.2

You are now asked to consider not just everything you can do for a patient, but also the benefits, harms, and costs associated with those choices. But where to start? We recommend that trainees integrate these tips for high-value care into their routine practice.

1. Use evidence-based resources that highlight value

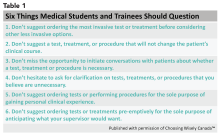

A great place to begin is the “Six Things Medical Students and Trainees Should Question,” originally published in Academic Medicine and created by Choosing Wisely Canada™. Recommendations range from avoiding tests or treatments that will not change a patient’s clinical course to holding off on ordering tests solely based on what you assume your preceptor will want (see the full list in Table 1).3

Other ways to avoid low-value care include following the United States Choosing Wisely™ campaign, which has collected more than 500 specialty society recommendations. Likewise, the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria are designed to assist providers with ordering the appropriate imaging tests (for a more extensive list see Table 2).

2. Express your clinical reasoning

One driver of health care expenditures that is especially prevalent in academia is the pressure to demonstrate knowledge by recommending extensive testing. While these tests may rule out obscure diagnoses, they often do not change management.

You can still demonstrate a mastery of your patients’ care by expressing your thought process overtly. For instance, “I considered secondary causes of the patient’s severe hypertension but felt it was most reasonable to first treat her pain and restart her home medications before pursuing a larger work-up. If the patient’s blood pressure remains elevated and she is hypokalemic, we could consider testing for hyperaldosteronism.” If you explain why you think a diagnosis is less likely and order tests accordingly, others will be encouraged to consider value in their own medical decision making.

3. Hone your communication skills

One of the most cited reasons for providing unnecessary care is the time required to discuss treatment plans with patients – it’s much faster to just order the test than to explain why it isn’t needed. Research, however, shows that these cost conversations take 68 seconds on average.4 Costs of Care (see Table 2) has an excellent video series that highlights how effective communication allows for shared decision making, which promotes both patient engagement and helps avoid wasteful care.

Physicians’ first instincts are often defensive when a patient asks for care we perceive as unnecessary. However, exploring what the patient hopes to gain from said test or treatment frequently reveals concern for a specific, missed diagnosis or complication. Addressing this underlying fear, rather than defending your ordering patterns, can create improved rapport and may serve to provide more reassurance than a test ever could.5

As a physician-in-training, try to observe others having these conversations and take every opportunity to practice. By focusing on this key skill set, you will increase your comfort with in-depth discussions on the value of care.

4. Get involved in a project related to high-value care

While you are developing your own practice patterns, you may be inspired to tackle areas of overuse and underuse at a more systemwide level. If your hospital does not have a committee for high-value care, perhaps a quality improvement leader can support your ideas to launch a project or participate in an ongoing initiative. Physicians-in-training have been identified as crucial to these projects’ success – your frontline insight can highlight potential problems and the nuances of workflow that are key to effective solutions.6

5. Embrace lifelong learning and reflection

The process of becoming a physician and of practicing high-value care is not a sprint but a marathon. Multiple barriers to high-value care exist, and you may feel these pressures differently at various points in your career. These include malpractice concerns, addressing patient expectations, and the desire to take action “just to be safe.”6

Interestingly, fear of malpractice does not seem to dissipate in areas where tort reform has provided stronger provider protections.7 Practitioners may also inaccurately assume a patient’s desire for additional work-up or treatment.8 Furthermore, be aware of the role of “commission bias” by which a provider regrets not doing something that could have helped a previous patient. This regret can prove to be a stronger motivator than the potential harm related to unnecessary diagnostic tests or treatments.9

While these barriers cannot be removed easily, learners and providers can practice active reflection by examining their own fears, biases, and motivations before and after they order additional testing or treatment.

As a physician-in-training, you may feel that your decisions do not have a major impact on the health care system as a whole. However, the culture shift needed to “bend the cost curve” will come from the collective efforts of individuals like you. Practicing high-value care is not just a matter of ordering fewer tests – appropriate ordering of an expensive test that expedites a diagnosis may be more cost-effective and enhance the quality of care provided. Increasing your own awareness of both necessary and unnecessary practices is a major step toward realizing system change. Your efforts to resist and reform the medical culture that propagates low value care will encourage your colleagues to follow suit.

Dr. Lacy is assistant professor and associate clerkship director at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, as well as division director of high-value care for the division of hospital medicine. Dr. Goetz is assistant professor at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. They met as 2015 Copello Fellows at the National Physician Alliance. Both have been involved in numerous high-value care initiatives, curricular development, and medical education at their respective institutions.

References

1. Committee on the Learning Health Care System in America, Institute of Medicine. “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Edited by Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, and McGinnis JM. (Washington: National Academies Press, 2013). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207225/.

2. Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513-6.

3. Lakhani A et al. Choosing Wisely for Medical Education: Six things medical students and trainees should question. Acad Med. 2016 Oct;91(10):1374-8.

4. Hunter WG et al. Patient-physician discussions about costs: Definitions and impact on cost conversation incidence estimates. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:108.

5. van Ravesteijn H et al. The reassuring value of diagnostic tests: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):3-8.

6. Moriates C, Wong BM. High-value care programmes from the bottom-up… and the top-down. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(11):821-3.

7. Snyder Sulmasy L, Weinberger SE. Better care is the best defense: High-value clinical practice vs. defensive medicine. Cleve Clin J Med. 2014;81(8):464-7.

8. Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: Patients’ preferences matter. BMJ. 2012;345:e6572.

9. Scott IA. Cognitive challenges to minimising low value care. Intern Med J. 2017;47(9):1079-1083.

‘Culture shift’ comes from collective efforts

‘Culture shift’ comes from collective efforts

It’s Monday morning, and Mrs. Jones still has abdominal pain. Your ward team decides to order a CT. On chart review you notice she’s had three other abdominal CTs for the same indication this year. How did this happen? What should you do?

High-value care has been defined by the Institute of Medicine as “the best care for the patient, with the optimal result for the circumstances, delivered at the right price.”1 With an estimated $700 billion dollars – 30% of medical expenditures – spent on wasted care, there are rising calls for a transformational shift.2

You are now asked to consider not just everything you can do for a patient, but also the benefits, harms, and costs associated with those choices. But where to start? We recommend that trainees integrate these tips for high-value care into their routine practice.

1. Use evidence-based resources that highlight value

A great place to begin is the “Six Things Medical Students and Trainees Should Question,” originally published in Academic Medicine and created by Choosing Wisely Canada™. Recommendations range from avoiding tests or treatments that will not change a patient’s clinical course to holding off on ordering tests solely based on what you assume your preceptor will want (see the full list in Table 1).3

Other ways to avoid low-value care include following the United States Choosing Wisely™ campaign, which has collected more than 500 specialty society recommendations. Likewise, the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria are designed to assist providers with ordering the appropriate imaging tests (for a more extensive list see Table 2).

2. Express your clinical reasoning

One driver of health care expenditures that is especially prevalent in academia is the pressure to demonstrate knowledge by recommending extensive testing. While these tests may rule out obscure diagnoses, they often do not change management.

You can still demonstrate a mastery of your patients’ care by expressing your thought process overtly. For instance, “I considered secondary causes of the patient’s severe hypertension but felt it was most reasonable to first treat her pain and restart her home medications before pursuing a larger work-up. If the patient’s blood pressure remains elevated and she is hypokalemic, we could consider testing for hyperaldosteronism.” If you explain why you think a diagnosis is less likely and order tests accordingly, others will be encouraged to consider value in their own medical decision making.

3. Hone your communication skills

One of the most cited reasons for providing unnecessary care is the time required to discuss treatment plans with patients – it’s much faster to just order the test than to explain why it isn’t needed. Research, however, shows that these cost conversations take 68 seconds on average.4 Costs of Care (see Table 2) has an excellent video series that highlights how effective communication allows for shared decision making, which promotes both patient engagement and helps avoid wasteful care.

Physicians’ first instincts are often defensive when a patient asks for care we perceive as unnecessary. However, exploring what the patient hopes to gain from said test or treatment frequently reveals concern for a specific, missed diagnosis or complication. Addressing this underlying fear, rather than defending your ordering patterns, can create improved rapport and may serve to provide more reassurance than a test ever could.5

As a physician-in-training, try to observe others having these conversations and take every opportunity to practice. By focusing on this key skill set, you will increase your comfort with in-depth discussions on the value of care.

4. Get involved in a project related to high-value care

While you are developing your own practice patterns, you may be inspired to tackle areas of overuse and underuse at a more systemwide level. If your hospital does not have a committee for high-value care, perhaps a quality improvement leader can support your ideas to launch a project or participate in an ongoing initiative. Physicians-in-training have been identified as crucial to these projects’ success – your frontline insight can highlight potential problems and the nuances of workflow that are key to effective solutions.6

5. Embrace lifelong learning and reflection

The process of becoming a physician and of practicing high-value care is not a sprint but a marathon. Multiple barriers to high-value care exist, and you may feel these pressures differently at various points in your career. These include malpractice concerns, addressing patient expectations, and the desire to take action “just to be safe.”6

Interestingly, fear of malpractice does not seem to dissipate in areas where tort reform has provided stronger provider protections.7 Practitioners may also inaccurately assume a patient’s desire for additional work-up or treatment.8 Furthermore, be aware of the role of “commission bias” by which a provider regrets not doing something that could have helped a previous patient. This regret can prove to be a stronger motivator than the potential harm related to unnecessary diagnostic tests or treatments.9

While these barriers cannot be removed easily, learners and providers can practice active reflection by examining their own fears, biases, and motivations before and after they order additional testing or treatment.

As a physician-in-training, you may feel that your decisions do not have a major impact on the health care system as a whole. However, the culture shift needed to “bend the cost curve” will come from the collective efforts of individuals like you. Practicing high-value care is not just a matter of ordering fewer tests – appropriate ordering of an expensive test that expedites a diagnosis may be more cost-effective and enhance the quality of care provided. Increasing your own awareness of both necessary and unnecessary practices is a major step toward realizing system change. Your efforts to resist and reform the medical culture that propagates low value care will encourage your colleagues to follow suit.

Dr. Lacy is assistant professor and associate clerkship director at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, as well as division director of high-value care for the division of hospital medicine. Dr. Goetz is assistant professor at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. They met as 2015 Copello Fellows at the National Physician Alliance. Both have been involved in numerous high-value care initiatives, curricular development, and medical education at their respective institutions.

References

1. Committee on the Learning Health Care System in America, Institute of Medicine. “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Edited by Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, and McGinnis JM. (Washington: National Academies Press, 2013). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207225/.

2. Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513-6.

3. Lakhani A et al. Choosing Wisely for Medical Education: Six things medical students and trainees should question. Acad Med. 2016 Oct;91(10):1374-8.

4. Hunter WG et al. Patient-physician discussions about costs: Definitions and impact on cost conversation incidence estimates. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:108.

5. van Ravesteijn H et al. The reassuring value of diagnostic tests: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):3-8.

6. Moriates C, Wong BM. High-value care programmes from the bottom-up… and the top-down. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(11):821-3.

7. Snyder Sulmasy L, Weinberger SE. Better care is the best defense: High-value clinical practice vs. defensive medicine. Cleve Clin J Med. 2014;81(8):464-7.

8. Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: Patients’ preferences matter. BMJ. 2012;345:e6572.

9. Scott IA. Cognitive challenges to minimising low value care. Intern Med J. 2017;47(9):1079-1083.

It’s Monday morning, and Mrs. Jones still has abdominal pain. Your ward team decides to order a CT. On chart review you notice she’s had three other abdominal CTs for the same indication this year. How did this happen? What should you do?

High-value care has been defined by the Institute of Medicine as “the best care for the patient, with the optimal result for the circumstances, delivered at the right price.”1 With an estimated $700 billion dollars – 30% of medical expenditures – spent on wasted care, there are rising calls for a transformational shift.2

You are now asked to consider not just everything you can do for a patient, but also the benefits, harms, and costs associated with those choices. But where to start? We recommend that trainees integrate these tips for high-value care into their routine practice.

1. Use evidence-based resources that highlight value

A great place to begin is the “Six Things Medical Students and Trainees Should Question,” originally published in Academic Medicine and created by Choosing Wisely Canada™. Recommendations range from avoiding tests or treatments that will not change a patient’s clinical course to holding off on ordering tests solely based on what you assume your preceptor will want (see the full list in Table 1).3

Other ways to avoid low-value care include following the United States Choosing Wisely™ campaign, which has collected more than 500 specialty society recommendations. Likewise, the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria are designed to assist providers with ordering the appropriate imaging tests (for a more extensive list see Table 2).

2. Express your clinical reasoning

One driver of health care expenditures that is especially prevalent in academia is the pressure to demonstrate knowledge by recommending extensive testing. While these tests may rule out obscure diagnoses, they often do not change management.

You can still demonstrate a mastery of your patients’ care by expressing your thought process overtly. For instance, “I considered secondary causes of the patient’s severe hypertension but felt it was most reasonable to first treat her pain and restart her home medications before pursuing a larger work-up. If the patient’s blood pressure remains elevated and she is hypokalemic, we could consider testing for hyperaldosteronism.” If you explain why you think a diagnosis is less likely and order tests accordingly, others will be encouraged to consider value in their own medical decision making.

3. Hone your communication skills

One of the most cited reasons for providing unnecessary care is the time required to discuss treatment plans with patients – it’s much faster to just order the test than to explain why it isn’t needed. Research, however, shows that these cost conversations take 68 seconds on average.4 Costs of Care (see Table 2) has an excellent video series that highlights how effective communication allows for shared decision making, which promotes both patient engagement and helps avoid wasteful care.

Physicians’ first instincts are often defensive when a patient asks for care we perceive as unnecessary. However, exploring what the patient hopes to gain from said test or treatment frequently reveals concern for a specific, missed diagnosis or complication. Addressing this underlying fear, rather than defending your ordering patterns, can create improved rapport and may serve to provide more reassurance than a test ever could.5

As a physician-in-training, try to observe others having these conversations and take every opportunity to practice. By focusing on this key skill set, you will increase your comfort with in-depth discussions on the value of care.

4. Get involved in a project related to high-value care

While you are developing your own practice patterns, you may be inspired to tackle areas of overuse and underuse at a more systemwide level. If your hospital does not have a committee for high-value care, perhaps a quality improvement leader can support your ideas to launch a project or participate in an ongoing initiative. Physicians-in-training have been identified as crucial to these projects’ success – your frontline insight can highlight potential problems and the nuances of workflow that are key to effective solutions.6

5. Embrace lifelong learning and reflection

The process of becoming a physician and of practicing high-value care is not a sprint but a marathon. Multiple barriers to high-value care exist, and you may feel these pressures differently at various points in your career. These include malpractice concerns, addressing patient expectations, and the desire to take action “just to be safe.”6

Interestingly, fear of malpractice does not seem to dissipate in areas where tort reform has provided stronger provider protections.7 Practitioners may also inaccurately assume a patient’s desire for additional work-up or treatment.8 Furthermore, be aware of the role of “commission bias” by which a provider regrets not doing something that could have helped a previous patient. This regret can prove to be a stronger motivator than the potential harm related to unnecessary diagnostic tests or treatments.9

While these barriers cannot be removed easily, learners and providers can practice active reflection by examining their own fears, biases, and motivations before and after they order additional testing or treatment.

As a physician-in-training, you may feel that your decisions do not have a major impact on the health care system as a whole. However, the culture shift needed to “bend the cost curve” will come from the collective efforts of individuals like you. Practicing high-value care is not just a matter of ordering fewer tests – appropriate ordering of an expensive test that expedites a diagnosis may be more cost-effective and enhance the quality of care provided. Increasing your own awareness of both necessary and unnecessary practices is a major step toward realizing system change. Your efforts to resist and reform the medical culture that propagates low value care will encourage your colleagues to follow suit.

Dr. Lacy is assistant professor and associate clerkship director at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, as well as division director of high-value care for the division of hospital medicine. Dr. Goetz is assistant professor at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. They met as 2015 Copello Fellows at the National Physician Alliance. Both have been involved in numerous high-value care initiatives, curricular development, and medical education at their respective institutions.

References

1. Committee on the Learning Health Care System in America, Institute of Medicine. “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Edited by Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, and McGinnis JM. (Washington: National Academies Press, 2013). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207225/.

2. Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513-6.

3. Lakhani A et al. Choosing Wisely for Medical Education: Six things medical students and trainees should question. Acad Med. 2016 Oct;91(10):1374-8.

4. Hunter WG et al. Patient-physician discussions about costs: Definitions and impact on cost conversation incidence estimates. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:108.

5. van Ravesteijn H et al. The reassuring value of diagnostic tests: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):3-8.

6. Moriates C, Wong BM. High-value care programmes from the bottom-up… and the top-down. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(11):821-3.

7. Snyder Sulmasy L, Weinberger SE. Better care is the best defense: High-value clinical practice vs. defensive medicine. Cleve Clin J Med. 2014;81(8):464-7.

8. Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: Patients’ preferences matter. BMJ. 2012;345:e6572.

9. Scott IA. Cognitive challenges to minimising low value care. Intern Med J. 2017;47(9):1079-1083.

Repeated qSOFA measurements better predict in-hospital mortality from sepsis

Clinical question: Do repeated quick Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) measurements improve predictive validity for sepsis using in-hospital mortality, compared with a single qSOFA measurement at the time a clinician first suspects infection?

Background: Sepsis in hospitalized patients is associated with poor outcomes, but it is not clear how to best identify patients at risk. For non-ICU patients, the qSOFA score (made up of three simple clinical variables: respiratory rate greater than or equal to 22 breaths/minute, systolic blood pressure less than or equal to 100 mm Hg, and Glasgow Coma Scale score less than 15) has predictive validity for important outcomes including in-hospital mortality. qSOFA is relatively new in clinical practice, and the optimal utilization of the score has not yet been defined.

Study design: Retrospective Cohort Study.

Setting: All adult medical and surgical encounters in the ED, hospital ward, postanesthesia care unit (PACU), and ICU at 12 hospitals in Pennsylvania in 2012.

Synopsis: Kievlan et al. studied whether repeated qSOFA scores improved prediction of in-hospital mortality and allowed identification of specific clinical trajectories. The study included approximately 37,600 encounters. Authors abstracted demographic data, vital signs, laboratory results, and antibiotic/culture orders. An infection cohort was identified by a combination of orders for body fluid culture and antibiotics. The qSOFA scores were gathered at 6-hour intervals from the culture/antibiotic event (suspected sepsis). Scores were low (0), moderate (1), or high (greater than or equal to 2). Mean initial qSOFA scores were greater for patients who died, and remained higher during the 48-hours after suspected infection. Mortality was less than 2% in patients with an initial low qSOFA. 25% of patients with an initial moderate qSOFA had subsequent higher qSOFAs, and they had higher mortality, compared with patients with subsequent low qSOFA scores (16% vs. 4%).

Only those patients with initial qSOFA scores at the time of suspected infection were included, and missing data was common. The results may not be applicable to hospitals with a different sepsis case mix from the those of study institutions.

Bottom line: Repeated qSOFA measurements improve predictive validity for in-hospital mortality for patients with sepsis. Patients with low initial qSOFA scores have a low chance (less than 2%) of in-hospital mortality. Further studies are needed to determine how repeat qSOFA measurements can be used to improve management of patients with sepsis.

Citation: Kievlan DR et al. Evaluation of repeated quick sepsis-related organ failure assessment measurements among patients with suspected infection. Crit Care Med. 2018. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003360.

Dr. Linker is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Clinical question: Do repeated quick Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) measurements improve predictive validity for sepsis using in-hospital mortality, compared with a single qSOFA measurement at the time a clinician first suspects infection?

Background: Sepsis in hospitalized patients is associated with poor outcomes, but it is not clear how to best identify patients at risk. For non-ICU patients, the qSOFA score (made up of three simple clinical variables: respiratory rate greater than or equal to 22 breaths/minute, systolic blood pressure less than or equal to 100 mm Hg, and Glasgow Coma Scale score less than 15) has predictive validity for important outcomes including in-hospital mortality. qSOFA is relatively new in clinical practice, and the optimal utilization of the score has not yet been defined.

Study design: Retrospective Cohort Study.

Setting: All adult medical and surgical encounters in the ED, hospital ward, postanesthesia care unit (PACU), and ICU at 12 hospitals in Pennsylvania in 2012.

Synopsis: Kievlan et al. studied whether repeated qSOFA scores improved prediction of in-hospital mortality and allowed identification of specific clinical trajectories. The study included approximately 37,600 encounters. Authors abstracted demographic data, vital signs, laboratory results, and antibiotic/culture orders. An infection cohort was identified by a combination of orders for body fluid culture and antibiotics. The qSOFA scores were gathered at 6-hour intervals from the culture/antibiotic event (suspected sepsis). Scores were low (0), moderate (1), or high (greater than or equal to 2). Mean initial qSOFA scores were greater for patients who died, and remained higher during the 48-hours after suspected infection. Mortality was less than 2% in patients with an initial low qSOFA. 25% of patients with an initial moderate qSOFA had subsequent higher qSOFAs, and they had higher mortality, compared with patients with subsequent low qSOFA scores (16% vs. 4%).

Only those patients with initial qSOFA scores at the time of suspected infection were included, and missing data was common. The results may not be applicable to hospitals with a different sepsis case mix from the those of study institutions.

Bottom line: Repeated qSOFA measurements improve predictive validity for in-hospital mortality for patients with sepsis. Patients with low initial qSOFA scores have a low chance (less than 2%) of in-hospital mortality. Further studies are needed to determine how repeat qSOFA measurements can be used to improve management of patients with sepsis.

Citation: Kievlan DR et al. Evaluation of repeated quick sepsis-related organ failure assessment measurements among patients with suspected infection. Crit Care Med. 2018. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003360.

Dr. Linker is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Clinical question: Do repeated quick Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) measurements improve predictive validity for sepsis using in-hospital mortality, compared with a single qSOFA measurement at the time a clinician first suspects infection?

Background: Sepsis in hospitalized patients is associated with poor outcomes, but it is not clear how to best identify patients at risk. For non-ICU patients, the qSOFA score (made up of three simple clinical variables: respiratory rate greater than or equal to 22 breaths/minute, systolic blood pressure less than or equal to 100 mm Hg, and Glasgow Coma Scale score less than 15) has predictive validity for important outcomes including in-hospital mortality. qSOFA is relatively new in clinical practice, and the optimal utilization of the score has not yet been defined.

Study design: Retrospective Cohort Study.

Setting: All adult medical and surgical encounters in the ED, hospital ward, postanesthesia care unit (PACU), and ICU at 12 hospitals in Pennsylvania in 2012.

Synopsis: Kievlan et al. studied whether repeated qSOFA scores improved prediction of in-hospital mortality and allowed identification of specific clinical trajectories. The study included approximately 37,600 encounters. Authors abstracted demographic data, vital signs, laboratory results, and antibiotic/culture orders. An infection cohort was identified by a combination of orders for body fluid culture and antibiotics. The qSOFA scores were gathered at 6-hour intervals from the culture/antibiotic event (suspected sepsis). Scores were low (0), moderate (1), or high (greater than or equal to 2). Mean initial qSOFA scores were greater for patients who died, and remained higher during the 48-hours after suspected infection. Mortality was less than 2% in patients with an initial low qSOFA. 25% of patients with an initial moderate qSOFA had subsequent higher qSOFAs, and they had higher mortality, compared with patients with subsequent low qSOFA scores (16% vs. 4%).

Only those patients with initial qSOFA scores at the time of suspected infection were included, and missing data was common. The results may not be applicable to hospitals with a different sepsis case mix from the those of study institutions.

Bottom line: Repeated qSOFA measurements improve predictive validity for in-hospital mortality for patients with sepsis. Patients with low initial qSOFA scores have a low chance (less than 2%) of in-hospital mortality. Further studies are needed to determine how repeat qSOFA measurements can be used to improve management of patients with sepsis.

Citation: Kievlan DR et al. Evaluation of repeated quick sepsis-related organ failure assessment measurements among patients with suspected infection. Crit Care Med. 2018. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003360.

Dr. Linker is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

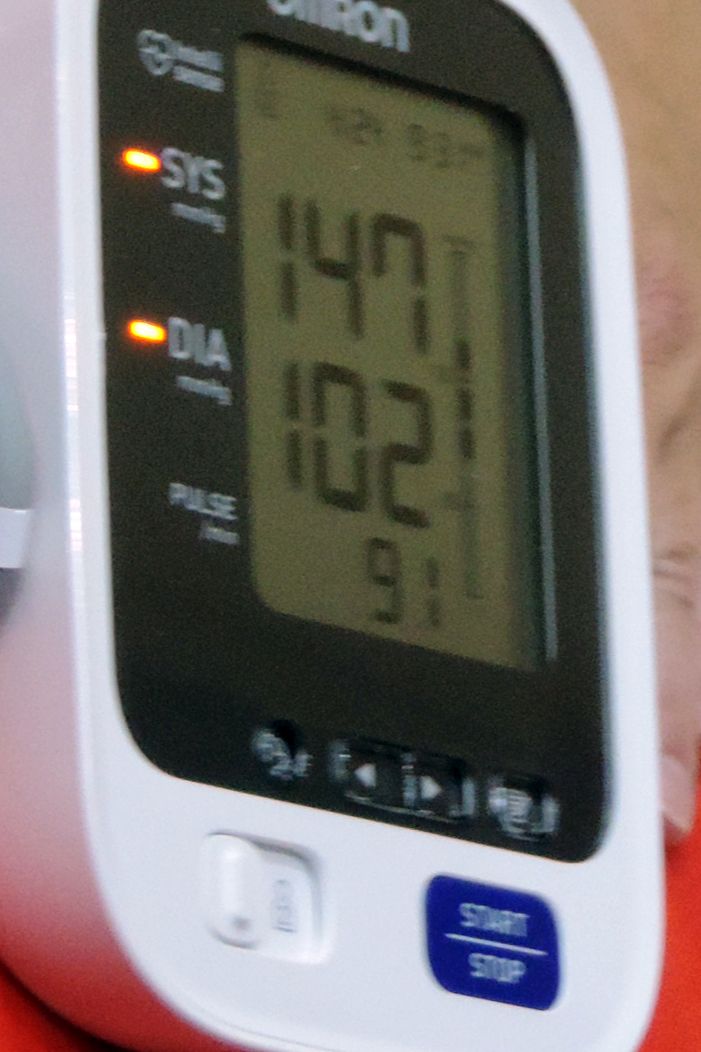

What drives intensification of antihypertensive therapy at discharge?

Background: Transient elevations in blood pressure are common among adult patients, yet there are no data or guidelines that support long-term medication changes based on these readings. Tight control of blood pressure is likely to improve outcomes among patients with heart failure), myocardial infarction, and stroke. Patients with reduced life expectancy, dementia, or metastatic cancer are less likely to benefit from tight control.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: U.S. Veterans Administration (VA) Health System.

Synopsis: The investigators reviewed data from 14,915 adults over 65 (median age, 76 years) admitted to the VA with a diagnosis of pneumonia, urinary tract infection, or venous thromboembolism. Most patients (65%) had well-controlled blood pressure prior to admission.

A total of 2,074 (14%) patients were discharged with an intensified hypertension regimen (additional medication or higher dose). While both elevated inpatient and outpatient blood pressures were predictive of intensification, the association with elevated inpatient blood pressure was much stronger (odds ratio, 3.66; 95% confidence interval, 3.29-4.08) than it was with elevated outpatient blood pressure (OR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.58-1.93).

In a multivariate regression analysis, the investigators found no significant differences in intensification by life expectancy (P = .07), diagnosis of dementia (P = .95), or metastatic malignancy (P = .13). There was a small increased probability of intensification among patients with heart failure, but no such difference for patients with history of MI (P = .53), stroke (P = .37), or renal disease (P = .73).

The generalizability of this trial may be limited given the cohort was predominantly male (97%), white (77%), and 53% had at least four major comorbidities.

Bottom line: Intensification of antihypertensive therapy at discharge is often driven by inpatient blood pressure readings rather than the broader context of their disease, such as prior long-term outpatient blood pressure control or major comorbidities.

Citation: Anderson TS et al. Intensification of older adults’ outpatient blood pressure treatment at hospital discharge: A national retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2018:362:k3503.

Dr. Holzer is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Background: Transient elevations in blood pressure are common among adult patients, yet there are no data or guidelines that support long-term medication changes based on these readings. Tight control of blood pressure is likely to improve outcomes among patients with heart failure), myocardial infarction, and stroke. Patients with reduced life expectancy, dementia, or metastatic cancer are less likely to benefit from tight control.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: U.S. Veterans Administration (VA) Health System.

Synopsis: The investigators reviewed data from 14,915 adults over 65 (median age, 76 years) admitted to the VA with a diagnosis of pneumonia, urinary tract infection, or venous thromboembolism. Most patients (65%) had well-controlled blood pressure prior to admission.

A total of 2,074 (14%) patients were discharged with an intensified hypertension regimen (additional medication or higher dose). While both elevated inpatient and outpatient blood pressures were predictive of intensification, the association with elevated inpatient blood pressure was much stronger (odds ratio, 3.66; 95% confidence interval, 3.29-4.08) than it was with elevated outpatient blood pressure (OR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.58-1.93).

In a multivariate regression analysis, the investigators found no significant differences in intensification by life expectancy (P = .07), diagnosis of dementia (P = .95), or metastatic malignancy (P = .13). There was a small increased probability of intensification among patients with heart failure, but no such difference for patients with history of MI (P = .53), stroke (P = .37), or renal disease (P = .73).

The generalizability of this trial may be limited given the cohort was predominantly male (97%), white (77%), and 53% had at least four major comorbidities.

Bottom line: Intensification of antihypertensive therapy at discharge is often driven by inpatient blood pressure readings rather than the broader context of their disease, such as prior long-term outpatient blood pressure control or major comorbidities.

Citation: Anderson TS et al. Intensification of older adults’ outpatient blood pressure treatment at hospital discharge: A national retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2018:362:k3503.

Dr. Holzer is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Background: Transient elevations in blood pressure are common among adult patients, yet there are no data or guidelines that support long-term medication changes based on these readings. Tight control of blood pressure is likely to improve outcomes among patients with heart failure), myocardial infarction, and stroke. Patients with reduced life expectancy, dementia, or metastatic cancer are less likely to benefit from tight control.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: U.S. Veterans Administration (VA) Health System.

Synopsis: The investigators reviewed data from 14,915 adults over 65 (median age, 76 years) admitted to the VA with a diagnosis of pneumonia, urinary tract infection, or venous thromboembolism. Most patients (65%) had well-controlled blood pressure prior to admission.

A total of 2,074 (14%) patients were discharged with an intensified hypertension regimen (additional medication or higher dose). While both elevated inpatient and outpatient blood pressures were predictive of intensification, the association with elevated inpatient blood pressure was much stronger (odds ratio, 3.66; 95% confidence interval, 3.29-4.08) than it was with elevated outpatient blood pressure (OR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.58-1.93).

In a multivariate regression analysis, the investigators found no significant differences in intensification by life expectancy (P = .07), diagnosis of dementia (P = .95), or metastatic malignancy (P = .13). There was a small increased probability of intensification among patients with heart failure, but no such difference for patients with history of MI (P = .53), stroke (P = .37), or renal disease (P = .73).

The generalizability of this trial may be limited given the cohort was predominantly male (97%), white (77%), and 53% had at least four major comorbidities.

Bottom line: Intensification of antihypertensive therapy at discharge is often driven by inpatient blood pressure readings rather than the broader context of their disease, such as prior long-term outpatient blood pressure control or major comorbidities.

Citation: Anderson TS et al. Intensification of older adults’ outpatient blood pressure treatment at hospital discharge: A national retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2018:362:k3503.

Dr. Holzer is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

New single-dose influenza therapy effective among outpatients

Clinical question: Is baloxavir marboxil, a selective inhibitor of influenza cap-dependent endonuclease, a safe and effective treatment for acute uncomplicated influenza?

Background: The emergence of oseltamivir-resistant influenza A(H1NI) infection in 2007 highlights the risk of future neuraminidase-resistant global pandemics. Baloxavir represents a new class of antiviral agent that may help treat such outbreaks.

Study design: Phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Outpatients in the United States and Japan.

Synopsis: The trial recruited 1,436 otherwise healthy patients aged 12-64 years of age (median age, 33 years) with a clinical diagnosis of acute uncomplicated influenza pneumonia. The patients were randomly assigned to receive either a single dose of oral baloxavir, oseltamivir 75 mg twice daily for 5 days, or matching placebo within 48 hours of symptom onset. The primary outcome was patient self-assessment of symptomatology.

Among the 1,064 adult patients (age 20-64) with influenza diagnosis confirmed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), the median time to alleviation of symptoms was lower in the baloxavir group than it was in the placebo group (53.7 hours vs. 80.2 hours; P less than .001). There was no significant difference in time to alleviation of symptoms in the baloxavir group when compared with the oseltamivir group. Adverse events were reported in 21% of baloxavir patients, 25% of placebo patients, and 25% of oseltamivir patients.

The enrolled patients were predominantly young, healthy, and treated as an outpatient. Patients hospitalized with influenza pneumonia are often older, have significant comorbidities, and are at higher risk of poor outcomes. This trial does not directly support the safety or efficacy of baloxavir in this population.

Bottom line: A single dose of baloxavir provides similar clinical benefit as 5 days of oseltamivir therapy in the early treatment of healthy patients with acute influenza.

Citation: Hayden FG et al. Baloxavir marboxil for uncomplicated influenza in adults and adolescents. N Eng J Med. 2018:379(10):914-23.

Dr. Holzer is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Clinical question: Is baloxavir marboxil, a selective inhibitor of influenza cap-dependent endonuclease, a safe and effective treatment for acute uncomplicated influenza?

Background: The emergence of oseltamivir-resistant influenza A(H1NI) infection in 2007 highlights the risk of future neuraminidase-resistant global pandemics. Baloxavir represents a new class of antiviral agent that may help treat such outbreaks.

Study design: Phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Outpatients in the United States and Japan.

Synopsis: The trial recruited 1,436 otherwise healthy patients aged 12-64 years of age (median age, 33 years) with a clinical diagnosis of acute uncomplicated influenza pneumonia. The patients were randomly assigned to receive either a single dose of oral baloxavir, oseltamivir 75 mg twice daily for 5 days, or matching placebo within 48 hours of symptom onset. The primary outcome was patient self-assessment of symptomatology.

Among the 1,064 adult patients (age 20-64) with influenza diagnosis confirmed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), the median time to alleviation of symptoms was lower in the baloxavir group than it was in the placebo group (53.7 hours vs. 80.2 hours; P less than .001). There was no significant difference in time to alleviation of symptoms in the baloxavir group when compared with the oseltamivir group. Adverse events were reported in 21% of baloxavir patients, 25% of placebo patients, and 25% of oseltamivir patients.

The enrolled patients were predominantly young, healthy, and treated as an outpatient. Patients hospitalized with influenza pneumonia are often older, have significant comorbidities, and are at higher risk of poor outcomes. This trial does not directly support the safety or efficacy of baloxavir in this population.

Bottom line: A single dose of baloxavir provides similar clinical benefit as 5 days of oseltamivir therapy in the early treatment of healthy patients with acute influenza.

Citation: Hayden FG et al. Baloxavir marboxil for uncomplicated influenza in adults and adolescents. N Eng J Med. 2018:379(10):914-23.

Dr. Holzer is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Clinical question: Is baloxavir marboxil, a selective inhibitor of influenza cap-dependent endonuclease, a safe and effective treatment for acute uncomplicated influenza?

Background: The emergence of oseltamivir-resistant influenza A(H1NI) infection in 2007 highlights the risk of future neuraminidase-resistant global pandemics. Baloxavir represents a new class of antiviral agent that may help treat such outbreaks.

Study design: Phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Outpatients in the United States and Japan.

Synopsis: The trial recruited 1,436 otherwise healthy patients aged 12-64 years of age (median age, 33 years) with a clinical diagnosis of acute uncomplicated influenza pneumonia. The patients were randomly assigned to receive either a single dose of oral baloxavir, oseltamivir 75 mg twice daily for 5 days, or matching placebo within 48 hours of symptom onset. The primary outcome was patient self-assessment of symptomatology.

Among the 1,064 adult patients (age 20-64) with influenza diagnosis confirmed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), the median time to alleviation of symptoms was lower in the baloxavir group than it was in the placebo group (53.7 hours vs. 80.2 hours; P less than .001). There was no significant difference in time to alleviation of symptoms in the baloxavir group when compared with the oseltamivir group. Adverse events were reported in 21% of baloxavir patients, 25% of placebo patients, and 25% of oseltamivir patients.

The enrolled patients were predominantly young, healthy, and treated as an outpatient. Patients hospitalized with influenza pneumonia are often older, have significant comorbidities, and are at higher risk of poor outcomes. This trial does not directly support the safety or efficacy of baloxavir in this population.

Bottom line: A single dose of baloxavir provides similar clinical benefit as 5 days of oseltamivir therapy in the early treatment of healthy patients with acute influenza.

Citation: Hayden FG et al. Baloxavir marboxil for uncomplicated influenza in adults and adolescents. N Eng J Med. 2018:379(10):914-23.

Dr. Holzer is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

No Pip/Tazo for patients with ESBL blood stream infections

Background: ESBL-producing gram-negative bacilli are becoming increasingly common. Carbapenems are considered the treatment of choice for these infections, but they may in turn select for carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacilli.

Study design: Open-label, noninferiority, randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Adult inpatients from nine countries (not including the United States).

Synopsis: Patients with at least one positive blood culture for ESBL E. coli or K. pneumoniae were screened. Of the initial 1,646 patients assessed, only 391 were enrolled (866 met exclusion criteria, 218 patients declined, and 123 treating physicians declined). Patients were randomized within 72 hours of the positive blood culture collection to either piperacillin/tazobactam 4.5 g every 6 hours or meropenem 1 g every 8 hours. Patients were treated from 4 to 14 days, with the total duration of antibiotics left up to the treating physician.

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality at 30 days after randomization. The study was stopped early because of a significant mortality difference between the two groups (12.3% in the piperacillin/tazobactam group versus 3.7% in the meropenem group).

The overall mortality rate was lower than expected. The sickest patients may have been excluded because the treating physician needed to approve enrollment. Because of the necessity for empiric antibiotic therapy, there was substantial crossover in antibiotics between the groups, although this would have biased the study toward noninferiority.

Bottom line: For patients with ESBL E. coli or K. pneumoniae blood stream infections, treatment with piperacillin/tazobactam was inferior to meropenem for 30-day mortality.

Citation: Harris PNA et al. Effect of piperacillin-tazobactam vs meropenem on 30-day mortality for patients with E coli or Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infection and ceftriaxone resistance: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(10):984-94.

Dr. Gabriel is assistant professor of medicine and director of Preoperative Medicine and Medicine Consult Service in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Background: ESBL-producing gram-negative bacilli are becoming increasingly common. Carbapenems are considered the treatment of choice for these infections, but they may in turn select for carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacilli.

Study design: Open-label, noninferiority, randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Adult inpatients from nine countries (not including the United States).

Synopsis: Patients with at least one positive blood culture for ESBL E. coli or K. pneumoniae were screened. Of the initial 1,646 patients assessed, only 391 were enrolled (866 met exclusion criteria, 218 patients declined, and 123 treating physicians declined). Patients were randomized within 72 hours of the positive blood culture collection to either piperacillin/tazobactam 4.5 g every 6 hours or meropenem 1 g every 8 hours. Patients were treated from 4 to 14 days, with the total duration of antibiotics left up to the treating physician.

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality at 30 days after randomization. The study was stopped early because of a significant mortality difference between the two groups (12.3% in the piperacillin/tazobactam group versus 3.7% in the meropenem group).

The overall mortality rate was lower than expected. The sickest patients may have been excluded because the treating physician needed to approve enrollment. Because of the necessity for empiric antibiotic therapy, there was substantial crossover in antibiotics between the groups, although this would have biased the study toward noninferiority.

Bottom line: For patients with ESBL E. coli or K. pneumoniae blood stream infections, treatment with piperacillin/tazobactam was inferior to meropenem for 30-day mortality.

Citation: Harris PNA et al. Effect of piperacillin-tazobactam vs meropenem on 30-day mortality for patients with E coli or Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infection and ceftriaxone resistance: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(10):984-94.

Dr. Gabriel is assistant professor of medicine and director of Preoperative Medicine and Medicine Consult Service in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Background: ESBL-producing gram-negative bacilli are becoming increasingly common. Carbapenems are considered the treatment of choice for these infections, but they may in turn select for carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacilli.

Study design: Open-label, noninferiority, randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Adult inpatients from nine countries (not including the United States).

Synopsis: Patients with at least one positive blood culture for ESBL E. coli or K. pneumoniae were screened. Of the initial 1,646 patients assessed, only 391 were enrolled (866 met exclusion criteria, 218 patients declined, and 123 treating physicians declined). Patients were randomized within 72 hours of the positive blood culture collection to either piperacillin/tazobactam 4.5 g every 6 hours or meropenem 1 g every 8 hours. Patients were treated from 4 to 14 days, with the total duration of antibiotics left up to the treating physician.

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality at 30 days after randomization. The study was stopped early because of a significant mortality difference between the two groups (12.3% in the piperacillin/tazobactam group versus 3.7% in the meropenem group).

The overall mortality rate was lower than expected. The sickest patients may have been excluded because the treating physician needed to approve enrollment. Because of the necessity for empiric antibiotic therapy, there was substantial crossover in antibiotics between the groups, although this would have biased the study toward noninferiority.

Bottom line: For patients with ESBL E. coli or K. pneumoniae blood stream infections, treatment with piperacillin/tazobactam was inferior to meropenem for 30-day mortality.

Citation: Harris PNA et al. Effect of piperacillin-tazobactam vs meropenem on 30-day mortality for patients with E coli or Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infection and ceftriaxone resistance: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(10):984-94.

Dr. Gabriel is assistant professor of medicine and director of Preoperative Medicine and Medicine Consult Service in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Physician burnout may be jeopardizing patient care

Clinical question: Is physician burnout associated with more patient safety issues, low professionalism, or poor patient satisfaction?

Background: Burnout is common among physicians and has a negative effect on their personal lives. It is unclear whether physician burnout is associated with poor outcomes for patients.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Forty-seven published studies from 19 countries assessing inpatient and outpatient physicians and the relationship between physician burnout and patient care.

Synopsis: After a systematic review of the published literature, 47 studies were included to pool data from 42,473 physicians. Study subjects included residents, early-career and late-career physicians, and both hospital and outpatient physicians. All studies used validated measures of physician burnout.

Burnout was associated with a two-fold increased risk of physician-reported safety incidents (odds ratio, 1.96; 95% confidence interval, 1.59-2.40), low professionalism (OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.87-2.85), and likelihood of low patient-reported satisfaction (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.42-3.68). There were no significant differences in these results based on country of origin of the study. Early-career physicians were more likely to have burnout associated with low professionalism than were late-career physicians.

Of the components of burnout, depersonalization was most strongly associated with these negative outcomes. Interestingly, the increased risk of patient safety incidents was associated with physician-reported, but not health care system–reported, patient safety outcomes. This raises concerns that the health care systems may not be capturing “near misses” in their metrics.

Bottom line: Physician burnout doubles the risk of being involved in a patient safety incident, low professionalism, and poor patient satisfaction.

Citation: Panagioti M et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1317-30.

Dr. Gabriel is assistant professor of medicine and director of Pre-operative Medicine and Medicine Consult Service in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Clinical question: Is physician burnout associated with more patient safety issues, low professionalism, or poor patient satisfaction?

Background: Burnout is common among physicians and has a negative effect on their personal lives. It is unclear whether physician burnout is associated with poor outcomes for patients.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Forty-seven published studies from 19 countries assessing inpatient and outpatient physicians and the relationship between physician burnout and patient care.

Synopsis: After a systematic review of the published literature, 47 studies were included to pool data from 42,473 physicians. Study subjects included residents, early-career and late-career physicians, and both hospital and outpatient physicians. All studies used validated measures of physician burnout.

Burnout was associated with a two-fold increased risk of physician-reported safety incidents (odds ratio, 1.96; 95% confidence interval, 1.59-2.40), low professionalism (OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.87-2.85), and likelihood of low patient-reported satisfaction (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.42-3.68). There were no significant differences in these results based on country of origin of the study. Early-career physicians were more likely to have burnout associated with low professionalism than were late-career physicians.

Of the components of burnout, depersonalization was most strongly associated with these negative outcomes. Interestingly, the increased risk of patient safety incidents was associated with physician-reported, but not health care system–reported, patient safety outcomes. This raises concerns that the health care systems may not be capturing “near misses” in their metrics.

Bottom line: Physician burnout doubles the risk of being involved in a patient safety incident, low professionalism, and poor patient satisfaction.

Citation: Panagioti M et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1317-30.

Dr. Gabriel is assistant professor of medicine and director of Pre-operative Medicine and Medicine Consult Service in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Clinical question: Is physician burnout associated with more patient safety issues, low professionalism, or poor patient satisfaction?

Background: Burnout is common among physicians and has a negative effect on their personal lives. It is unclear whether physician burnout is associated with poor outcomes for patients.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Forty-seven published studies from 19 countries assessing inpatient and outpatient physicians and the relationship between physician burnout and patient care.

Synopsis: After a systematic review of the published literature, 47 studies were included to pool data from 42,473 physicians. Study subjects included residents, early-career and late-career physicians, and both hospital and outpatient physicians. All studies used validated measures of physician burnout.

Burnout was associated with a two-fold increased risk of physician-reported safety incidents (odds ratio, 1.96; 95% confidence interval, 1.59-2.40), low professionalism (OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.87-2.85), and likelihood of low patient-reported satisfaction (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.42-3.68). There were no significant differences in these results based on country of origin of the study. Early-career physicians were more likely to have burnout associated with low professionalism than were late-career physicians.

Of the components of burnout, depersonalization was most strongly associated with these negative outcomes. Interestingly, the increased risk of patient safety incidents was associated with physician-reported, but not health care system–reported, patient safety outcomes. This raises concerns that the health care systems may not be capturing “near misses” in their metrics.

Bottom line: Physician burnout doubles the risk of being involved in a patient safety incident, low professionalism, and poor patient satisfaction.

Citation: Panagioti M et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1317-30.

Dr. Gabriel is assistant professor of medicine and director of Pre-operative Medicine and Medicine Consult Service in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Quick Byte: Conversations about cost

Patients want to talk

Seventy percent of Americans would like to have conversations about the costs of care with their health care providers, but only 28% do so, according to polling conducted for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) by Avalere Health.

With those polling results in hand, 2 years ago RWJF and Avalere Health launched the Cost Conversation projects to help. Practice briefs for these kinds of conversations are now available on America’s Essential Hospitals’ website (https://essentialhospitals.org/cost-care/practice-briefs/).

Reference

1. Ganos E, Steinberg K, Seidman J, Masi D, Gomez-Rexode A, Fraser A. Talking About Costs: Innovation In Clinician-Patient Conversations. Health Affairs. Published online Nov. 27, 2018. doi: 10.1377/hblog20181126.366161. Accessed Dec. 11, 2018.

Patients want to talk

Patients want to talk

Seventy percent of Americans would like to have conversations about the costs of care with their health care providers, but only 28% do so, according to polling conducted for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) by Avalere Health.

With those polling results in hand, 2 years ago RWJF and Avalere Health launched the Cost Conversation projects to help. Practice briefs for these kinds of conversations are now available on America’s Essential Hospitals’ website (https://essentialhospitals.org/cost-care/practice-briefs/).

Reference

1. Ganos E, Steinberg K, Seidman J, Masi D, Gomez-Rexode A, Fraser A. Talking About Costs: Innovation In Clinician-Patient Conversations. Health Affairs. Published online Nov. 27, 2018. doi: 10.1377/hblog20181126.366161. Accessed Dec. 11, 2018.

Seventy percent of Americans would like to have conversations about the costs of care with their health care providers, but only 28% do so, according to polling conducted for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) by Avalere Health.

With those polling results in hand, 2 years ago RWJF and Avalere Health launched the Cost Conversation projects to help. Practice briefs for these kinds of conversations are now available on America’s Essential Hospitals’ website (https://essentialhospitals.org/cost-care/practice-briefs/).

Reference

1. Ganos E, Steinberg K, Seidman J, Masi D, Gomez-Rexode A, Fraser A. Talking About Costs: Innovation In Clinician-Patient Conversations. Health Affairs. Published online Nov. 27, 2018. doi: 10.1377/hblog20181126.366161. Accessed Dec. 11, 2018.

Adjuvant corticosteroids in hospitalized patients with CAP

When is it appropriate to treat?

Case

A 55-year-old male with a history of tobacco use disorder presents with 2 days of productive cough, fever, chills, and mild shortness of breath. T 38.4, HR 89, RR 32, BP 100/65, 02 sat 86% on room air. Exam reveals diminished breath sounds and positive egophony over the right lung base. WBC is 16,000 and BUN 22. Chest x-ray reveals right lower lobe consolidation. He is given ceftriaxone and azithromycin.

Brief overview of the issue

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is the leading cause of infectious disease–related death in the United States. Mortality associated with CAP is estimated at 57,000 deaths annually and occurs largely in patients requiring hospitalization.1 The 30-day mortality rate in patients who are hospitalized for CAP is approximately 10%-12%.2 After discharge from the hospital, about 18% of patients are readmitted within 30 days.3 An excessive inflammatory cytokine response may be a major contributor to the high mortality rate in CAP and systemic corticosteroids may reduce the inflammatory response from the infection by down-regulating this proinflammatory cytokine production.

Almost all of the major decisions regarding management of CAP, including diagnostic and treatment issues, revolve around the initial assessment of severity of illness. Between 40% and 60% of patients who present to the emergency department with CAP are admitted4 and approximately 10% of hospitalized patients with CAP require ICU admission.5 Validated instruments such as CURB-65, the pneumonia severity index (PSI), and guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)/American Thoracic Society (ATS) may predict severity of illness but should always be supplemented with physician determination of subjective factors when determining treatment.5 Although there is no census definition of severe pneumonia, studies generally define the condition in the following order of preference: PSI score of IV or V followed by CURB-65 score of two or greater. If these scoring modalities were not available, the IDSA/ATS criteria was used (1 major or 3 minor). Others define severe CAP as pneumonia requiring supportive therapy within a critical care environment.

Overview of the data

The use of corticosteroids in addition to antibiotics in the treatment of CAP was proposed as early as the 1950s and yet only in the last decade has the body of evidence grown significantly.5 There is evidence that corticosteroids suppress inflammation without acutely impairing the immune response as evidenced by a rapid and sustained decrease in circulating inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein and interleukin 6 and no effect on the anti-inflammatory interleukin 10.6 Within the last year, three meta-analyses, one by the Cochrane Library, one by the IDSA, and a third in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine, addressed the role of routine low dose (20-60 mg of prednisone or equivalent), short-course (3-7 days) systemic corticosteroids in hospitalized patients with CAP of varying severities.

The Cochrane meta-analysis, the largest and most recent dataset, included 13 trials with a combined 1,954 adult patients and found that corticosteroids significantly lowered mortality in hospitalized patients with severe CAP with a number needed to treat of 19.7 In this group with severe CAP, mortality was lowered from 13% to 8% and there were significantly fewer episodes of respiratory failure and shock with the addition of corticosteroids. No effect was seen on mortality in patients with less severe CAP. In those patients who received adjuvant corticosteroids, length of hospital stay decreased by 3 days, regardless of CAP severity.7

The IDSA meta-analysis was similar and included 1,506 patients from six trials.8 In contrast with the Cochrane study, this analysis found corticosteroids did not significantly lower mortality in patients with severe CAP but did reduce time to clinical stability and length of hospital stay by over 1 day. This study also found significantly more CAP-related, 30-day rehospitalizations (5% vs. 3%; defined as recurrent pneumonia, other infection, pleuritic pain, adverse cardiovascular event, or diarrhea) in patient with non-severe CAP treated with corticosteroids.

The study in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine involved ten trials involving more than 700 patients admitted with severe CAP and found in-hospital mortality was cut in half (RR 0.49) and length of hospital stay was reduced when patients were treated with corticosteroids in addition to standard antibiotic therapy.9

In 2015, two randomized clinical trials, one in the Lancet and the other in JAMA, and a meta-analysis in Annals of Internal Medicine assessed the impact of adjuvant corticosteroids in the treatment of hospitalized patients with CAP. The Lancet study of 785 patients hospitalized with CAP of any severity found shortened time to clinical stability (3.0 vs. 4.4 days) as defined by stable vital signs, improved oral intake, and normalized mental status for greater than 24 hours when oral prednisone 50 mg for 7 days was added to standard therapy.10 Patients in the treatment group were also discharged 1 day earlier compared with the placebo control group.

The study in JAMA was small, with only 100 patients at three teaching hospitals in Spain, but found that patients hospitalized with severe CAP and high inflammatory response based on elevated C-reactive protein were less likely to experience a treatment failure, defined as shock, mechanical ventilation, death, or radiographic progression, when intravenous methylprednisolone 0.5 mg/kg was added to standard antibiotic therapy.11

Finally, the meta-analysis in Annals of Internal Medicine assessed 13 randomized controlled placebo trials of 1,974 patients and found that adjuvant corticosteroids in a dose of 20-60 mg of prednisone or equivalent total daily dose significantly lowered mortality in patients with severe CAP and incidence of respiratory distress syndrome, and need for mechanical ventilation in all patients hospitalized with CAP.12

Importantly, nearly all of the described studies showed a significantly higher incidence of hyperglycemia in patients who received corticosteroids.

Application of the data to our patients

The benefit of adjuvant corticosteroids is most clear in hospitalized patients with severe CAP. Recent, strong evidence supports decreased mortality, decreased time to clinical stability, and decreased length of stay in our patient, with severe CAP, if treated with 20-60 mg of prednisone or equivalent total daily dose for 3-7 days. For patients with non-severe CAP, we suggest taking a risk-benefit approach based on other comorbidities, as the risk for CAP-related rehospitalizations may be higher.