User login

Preexposure prophylaxis among LGBT youth

Every prevention effort or treatment has its own risks. Gynecologists must consider the risk for blood clots from using estrogen-containing oral contraceptives versus the risk of blood clots from pregnancy. Endocrinologists must weigh the risk of decreased bone mineral density versus premature closure of growth plates when starting pubertal blockers for children suffering from precocious puberty. Psychologists and primary care providers must consider the risk for increased suicidal thoughts while on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus the risk of completed suicide if the depression remains untreated.

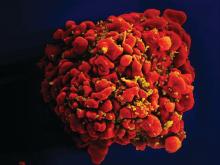

In the United States alone, 22% of HIV infections occur in people aged 13-24 years. Among those with HIV infection, 81% are young men who have sex with men (MSM).1 Among those new infections, young MSM of color are nearly four times as likely to have HIV, compared with white young MSM.2 Moreover, the incidence of HIV infection among transgender individuals is three times higher than the national average.3

What further hampers public health prevention efforts is the stigma and discrimination LGBT youth face in trying to prevent HIV infections: 84% of those aged 15-24 years report recognizing stigma around HIV in the United States.4 In addition, black MSM were more likely than other MSMs to report this kind of stigma.5 And it isn’t enough that LGBT youth have to face stigma and discrimination. In fact, because of it, they often face serious financial challenges. It is estimated that 50% of homeless youth identify as LGBT, and 40% of them were forced out of their homes because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.6 Also, transgender youth have difficulty finding employment because of their gender identity.7 A combination of homelessness or chronic unemployment has driven many LGBT youth to survival sex or sex for money, which puts them at higher risk for HIV infection.7,8 The risk for HIV infection is so high that we should be using all available resources, including PrEP, to address these profound health disparities.

Studies, however, are forthcoming. One study by Hosek et al. that was published in September suggested that PrEP among adolescents can be safe and well tolerated, may not increase the rate of high-risk sexual behaviors, and may not increase the risk of other STDs such as gonorrhea and chlamydia. It must be noted, however, that incidence of HIV was fairly high – the HIV seroconversion rate was 6.4 per 100 person-years. Nevertheless, researchers found the rate of HIV seroconversion was higher among those with lower levels of Truvada in their bodies, compared with the seroconversion rate in those with higher levels of the medication. This suggests that adherence is key in using PrEP to prevent HIV infection.10 Although far from definitive, this small study provides some solid evidence that PrEP is safe and effective in preventing HIV among LGBT youth. More studies that will eventually support its effectiveness and safety are on the way.11

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. Email him at [email protected].

Resource

CDC website on PrEP: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/prep/index.html, with provider guidelines.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Youth fact sheet, April 2017.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2015; vol. 27.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Transgender People.

4. Kaiser Family Foundation. National survey of teens and young adults on HIV/AIDS, Nov. 1, 2012. .

5. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(5):547-55.

6. Serving our youth: Findings from a national survey of services providers working with lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless (The Williams Institute with True Colors and The Palette Fund, 2012).

7. Injustice at every turn: A report of the national transgender discrimination survey (National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011).

8. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010 Apr;53(5):661-4.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States: A clinical practice guideline, 2014.

10. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(11):1063-71.

11. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.7.21107.

Every prevention effort or treatment has its own risks. Gynecologists must consider the risk for blood clots from using estrogen-containing oral contraceptives versus the risk of blood clots from pregnancy. Endocrinologists must weigh the risk of decreased bone mineral density versus premature closure of growth plates when starting pubertal blockers for children suffering from precocious puberty. Psychologists and primary care providers must consider the risk for increased suicidal thoughts while on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus the risk of completed suicide if the depression remains untreated.

In the United States alone, 22% of HIV infections occur in people aged 13-24 years. Among those with HIV infection, 81% are young men who have sex with men (MSM).1 Among those new infections, young MSM of color are nearly four times as likely to have HIV, compared with white young MSM.2 Moreover, the incidence of HIV infection among transgender individuals is three times higher than the national average.3

What further hampers public health prevention efforts is the stigma and discrimination LGBT youth face in trying to prevent HIV infections: 84% of those aged 15-24 years report recognizing stigma around HIV in the United States.4 In addition, black MSM were more likely than other MSMs to report this kind of stigma.5 And it isn’t enough that LGBT youth have to face stigma and discrimination. In fact, because of it, they often face serious financial challenges. It is estimated that 50% of homeless youth identify as LGBT, and 40% of them were forced out of their homes because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.6 Also, transgender youth have difficulty finding employment because of their gender identity.7 A combination of homelessness or chronic unemployment has driven many LGBT youth to survival sex or sex for money, which puts them at higher risk for HIV infection.7,8 The risk for HIV infection is so high that we should be using all available resources, including PrEP, to address these profound health disparities.

Studies, however, are forthcoming. One study by Hosek et al. that was published in September suggested that PrEP among adolescents can be safe and well tolerated, may not increase the rate of high-risk sexual behaviors, and may not increase the risk of other STDs such as gonorrhea and chlamydia. It must be noted, however, that incidence of HIV was fairly high – the HIV seroconversion rate was 6.4 per 100 person-years. Nevertheless, researchers found the rate of HIV seroconversion was higher among those with lower levels of Truvada in their bodies, compared with the seroconversion rate in those with higher levels of the medication. This suggests that adherence is key in using PrEP to prevent HIV infection.10 Although far from definitive, this small study provides some solid evidence that PrEP is safe and effective in preventing HIV among LGBT youth. More studies that will eventually support its effectiveness and safety are on the way.11

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. Email him at [email protected].

Resource

CDC website on PrEP: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/prep/index.html, with provider guidelines.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Youth fact sheet, April 2017.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2015; vol. 27.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Transgender People.

4. Kaiser Family Foundation. National survey of teens and young adults on HIV/AIDS, Nov. 1, 2012. .

5. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(5):547-55.

6. Serving our youth: Findings from a national survey of services providers working with lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless (The Williams Institute with True Colors and The Palette Fund, 2012).

7. Injustice at every turn: A report of the national transgender discrimination survey (National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011).

8. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010 Apr;53(5):661-4.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States: A clinical practice guideline, 2014.

10. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(11):1063-71.

11. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.7.21107.

Every prevention effort or treatment has its own risks. Gynecologists must consider the risk for blood clots from using estrogen-containing oral contraceptives versus the risk of blood clots from pregnancy. Endocrinologists must weigh the risk of decreased bone mineral density versus premature closure of growth plates when starting pubertal blockers for children suffering from precocious puberty. Psychologists and primary care providers must consider the risk for increased suicidal thoughts while on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus the risk of completed suicide if the depression remains untreated.

In the United States alone, 22% of HIV infections occur in people aged 13-24 years. Among those with HIV infection, 81% are young men who have sex with men (MSM).1 Among those new infections, young MSM of color are nearly four times as likely to have HIV, compared with white young MSM.2 Moreover, the incidence of HIV infection among transgender individuals is three times higher than the national average.3

What further hampers public health prevention efforts is the stigma and discrimination LGBT youth face in trying to prevent HIV infections: 84% of those aged 15-24 years report recognizing stigma around HIV in the United States.4 In addition, black MSM were more likely than other MSMs to report this kind of stigma.5 And it isn’t enough that LGBT youth have to face stigma and discrimination. In fact, because of it, they often face serious financial challenges. It is estimated that 50% of homeless youth identify as LGBT, and 40% of them were forced out of their homes because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.6 Also, transgender youth have difficulty finding employment because of their gender identity.7 A combination of homelessness or chronic unemployment has driven many LGBT youth to survival sex or sex for money, which puts them at higher risk for HIV infection.7,8 The risk for HIV infection is so high that we should be using all available resources, including PrEP, to address these profound health disparities.

Studies, however, are forthcoming. One study by Hosek et al. that was published in September suggested that PrEP among adolescents can be safe and well tolerated, may not increase the rate of high-risk sexual behaviors, and may not increase the risk of other STDs such as gonorrhea and chlamydia. It must be noted, however, that incidence of HIV was fairly high – the HIV seroconversion rate was 6.4 per 100 person-years. Nevertheless, researchers found the rate of HIV seroconversion was higher among those with lower levels of Truvada in their bodies, compared with the seroconversion rate in those with higher levels of the medication. This suggests that adherence is key in using PrEP to prevent HIV infection.10 Although far from definitive, this small study provides some solid evidence that PrEP is safe and effective in preventing HIV among LGBT youth. More studies that will eventually support its effectiveness and safety are on the way.11

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. Email him at [email protected].

Resource

CDC website on PrEP: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/prep/index.html, with provider guidelines.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Youth fact sheet, April 2017.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2015; vol. 27.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Transgender People.

4. Kaiser Family Foundation. National survey of teens and young adults on HIV/AIDS, Nov. 1, 2012. .

5. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(5):547-55.

6. Serving our youth: Findings from a national survey of services providers working with lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless (The Williams Institute with True Colors and The Palette Fund, 2012).

7. Injustice at every turn: A report of the national transgender discrimination survey (National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011).

8. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010 Apr;53(5):661-4.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States: A clinical practice guideline, 2014.

10. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(11):1063-71.

11. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.7.21107.

Eating disorders over the holidays

For many, the holiday season is a time to celebrate, relax, and enjoy the company of family. Much of this celebrating centers on eating and food. Historically, eating disorders were associated with young, straight, cisgender, white females. Data collected over the past 15 years suggest that eating disorders can affect youth of all ethnicities and genders.

Below are some tips from the National Eating Disorder Association that may be helpful for youth struggling with an eating disorder over the holiday season:

• Eat regularly and in a consistent pattern. Avoid skipping meals or restricting intake in preparation for a holiday meal.

• Discuss any anticipated struggles around food or family with your parents, therapist, health care provider, dietitian, or other members of your support group. This can allow you to plan ahead for any challenges that may arise, and could prevent potential negative or harmful coping behaviors

• Consider choosing a loved one to be your “reality check” with food, to either help fix a plate for you or to give you sound feedback on the food portion sizes you make for yourself.

• Have a game plan before you go to a holiday event. Know who your support people are and how you’ll recognize when it may be time to make a quick exit and get connected with needed support.

• Avoid overextending yourself. A lower stress level can decrease the need to turn to eating-disordered behaviors or other unhelpful coping strategies.

• Work on being flexible in your thoughts. Learn to be flexible when setting guidelines for yourself and expectations of yourself and others. Strive to be flexible in what you can eat during the holidays. Take a holiday from self-imposed criticism, rigidity, and perfectionism.

Dr. Chelvakumar is an attending physician in the division of adolescent medicine at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and an assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at the Ohio State University, both in Columbus. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Resources

National Eating Disorders Association: www.nationaleatingdisorders.org

“Body image and eating disorders among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth” (Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016 Dec;63[6]:1079-90.

References

1. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008 Oct;5(4):A114.

2. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011 Jul;68(7):714-23.

3. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016 Dec;63(6):1079-90.

4. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012 Aug;14(4):391-7.

5. J Adolesc Health. 2015 Aug;57(2):144-9.

6. Am J Public Health. 2013 Feb;103(2):e16-22.

7. J Adolesc Health. 2009 Sep;45(3):238-45.

For many, the holiday season is a time to celebrate, relax, and enjoy the company of family. Much of this celebrating centers on eating and food. Historically, eating disorders were associated with young, straight, cisgender, white females. Data collected over the past 15 years suggest that eating disorders can affect youth of all ethnicities and genders.

Below are some tips from the National Eating Disorder Association that may be helpful for youth struggling with an eating disorder over the holiday season:

• Eat regularly and in a consistent pattern. Avoid skipping meals or restricting intake in preparation for a holiday meal.

• Discuss any anticipated struggles around food or family with your parents, therapist, health care provider, dietitian, or other members of your support group. This can allow you to plan ahead for any challenges that may arise, and could prevent potential negative or harmful coping behaviors

• Consider choosing a loved one to be your “reality check” with food, to either help fix a plate for you or to give you sound feedback on the food portion sizes you make for yourself.

• Have a game plan before you go to a holiday event. Know who your support people are and how you’ll recognize when it may be time to make a quick exit and get connected with needed support.

• Avoid overextending yourself. A lower stress level can decrease the need to turn to eating-disordered behaviors or other unhelpful coping strategies.

• Work on being flexible in your thoughts. Learn to be flexible when setting guidelines for yourself and expectations of yourself and others. Strive to be flexible in what you can eat during the holidays. Take a holiday from self-imposed criticism, rigidity, and perfectionism.

Dr. Chelvakumar is an attending physician in the division of adolescent medicine at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and an assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at the Ohio State University, both in Columbus. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Resources

National Eating Disorders Association: www.nationaleatingdisorders.org

“Body image and eating disorders among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth” (Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016 Dec;63[6]:1079-90.

References

1. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008 Oct;5(4):A114.

2. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011 Jul;68(7):714-23.

3. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016 Dec;63(6):1079-90.

4. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012 Aug;14(4):391-7.

5. J Adolesc Health. 2015 Aug;57(2):144-9.

6. Am J Public Health. 2013 Feb;103(2):e16-22.

7. J Adolesc Health. 2009 Sep;45(3):238-45.

For many, the holiday season is a time to celebrate, relax, and enjoy the company of family. Much of this celebrating centers on eating and food. Historically, eating disorders were associated with young, straight, cisgender, white females. Data collected over the past 15 years suggest that eating disorders can affect youth of all ethnicities and genders.

Below are some tips from the National Eating Disorder Association that may be helpful for youth struggling with an eating disorder over the holiday season:

• Eat regularly and in a consistent pattern. Avoid skipping meals or restricting intake in preparation for a holiday meal.

• Discuss any anticipated struggles around food or family with your parents, therapist, health care provider, dietitian, or other members of your support group. This can allow you to plan ahead for any challenges that may arise, and could prevent potential negative or harmful coping behaviors

• Consider choosing a loved one to be your “reality check” with food, to either help fix a plate for you or to give you sound feedback on the food portion sizes you make for yourself.

• Have a game plan before you go to a holiday event. Know who your support people are and how you’ll recognize when it may be time to make a quick exit and get connected with needed support.

• Avoid overextending yourself. A lower stress level can decrease the need to turn to eating-disordered behaviors or other unhelpful coping strategies.

• Work on being flexible in your thoughts. Learn to be flexible when setting guidelines for yourself and expectations of yourself and others. Strive to be flexible in what you can eat during the holidays. Take a holiday from self-imposed criticism, rigidity, and perfectionism.

Dr. Chelvakumar is an attending physician in the division of adolescent medicine at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and an assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at the Ohio State University, both in Columbus. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Resources

National Eating Disorders Association: www.nationaleatingdisorders.org

“Body image and eating disorders among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth” (Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016 Dec;63[6]:1079-90.

References

1. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008 Oct;5(4):A114.

2. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011 Jul;68(7):714-23.

3. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016 Dec;63(6):1079-90.

4. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012 Aug;14(4):391-7.

5. J Adolesc Health. 2015 Aug;57(2):144-9.

6. Am J Public Health. 2013 Feb;103(2):e16-22.

7. J Adolesc Health. 2009 Sep;45(3):238-45.

Inclusive sexual health counseling and care

Sexual health screening and counseling is an important part of wellness care for all adolescents, and transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC) youth are no exception. TGNC youth may avoid routine health visits and sexual health conversations because they fear discrimination in the health care setting and feel uncomfortable about physical exams.1 Providers should be aware of the potential anxiety patients may feel during health care visits and work to establish an environment of respect and inclusiveness. Below are some tips to help provide care that is inclusive of the diverse gender and sexual identities of the patients we see.

Obtaining a sexual history

1. Clearly explain the reasons for asking sexually explicit questions.

TGNC youth experiencing dysphoria may have heightened levels of anxiety when discussing sexuality. Before asking these questions, acknowledge the sensitivity of this topic and explain that this information is important for providers to know so that they can provide appropriate counseling and screening recommendations. This may alleviate some of their discomfort.

2. Ensure confidentiality.

When obtaining sexual health histories, it is crucial to ensure confidential patient encounters, as described by the American Academy of Pediatrics and Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine.2,3 The Guttmacher Institute provides information about minors’ consent law in each state.4

3. Do not assume identity equals behavior.

Here are some sexual health questions you need to ask:

- Who are you attracted to? What is/are the gender(s) of your partner(s)?

- Have you ever had anal, genital, or oral sex? If yes:

Do you give, receive, or both?

When was the last time you had sex?

How many partners have you had in past 6 months?

Do you use barrier protection most of the time, some of the time, always, or never?

Do you have symptoms of an infection, such as burning when you pee, abnormal genital discharge, pain with sex, or irregular bleeding?

- Have you ever been forced/coerced into having sex?

Starting with open-ended questions about attraction can give patients an opportunity to describe their pattern of attraction. If needed, patients can be prompted with more specific questions about their partners’ genders. It is important to ask explicitly about genital, oral, and anal sex because patients sometimes do not realize that the term sex includes oral and anal sex. Patients also may not be aware that it is possible to spread infections through oral and anal sex.

4. Anatomy and behavior may change over time, and it is important to reassess sexually transmitted infection risk at each visit

Studies suggest that, as gender dysphoria decreases, sexual desires may increase; this is true for all adolescents but of particular interest with TGNC youth. This may affect behaviors.5 For youth on hormone therapy, testosterone can increase libido, whereas estrogen may decrease libido and affect sexual function.6

Physical exam

Dysphoria related to primary and secondary sex characteristics may make exams particularly distressing. Providers should clearly explain reasons for performing various parts of the physical exam. When performing the physical exam, providers should use a gender-affirming approach. This includes using the patient’s identified name and pronouns throughout the visit and asking patients preference for terminology when discussing body parts (some patients may prefer the use of the term “front hole” to vagina).1,7,8 The exam and evaluation may need to be modified based on comfort. If a patient refuses a speculum exam after the need for the its use has been discussed, consider offering an external genital exam and bimanual exam instead. If a patient refuses to allow a provider to obtain a rectal or vaginal swab, consider allowing patients to self-swab. Providers also should consider whether genital exams can be deferred to subsequent visits. These techniques offer an opportunity to build trust and rapport with patients so that they remain engaged in care and may become comfortable with the necessary tests and procedures at future visits.

Sexual health counseling

Sexual health counseling should address reducing risk and optimizing physical and emotional satisfaction in relationships and encounters.9 In addition to assessing risky behaviors and screening for sexually transmitted infections, providers also should provide counseling on safer-sex practices. This includes the use of lubrication to reduce trauma to genital tissues, which can potentiate the spread of infections, and the use of barrier protection, such as external condoms (often referred to as male condoms), internal condoms (often referred to as female condoms), dental dams during oral sex, and gloves for digital penetration. Patients at risk for pregnancy should receive comprehensive contraceptive counseling. TGNC patients may be at increased risk of sexual victimization, and honest discussions about safety in relationships is important. The goal of sexual health counseling should be to promote safe, satisfying experiences for all patients.

Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People, in Center of Excellence for Transgender Health, Department of Family and Community Medicine, 2nd ed. (San Francisco: University of California, 2016).

2. Pediatrics. 2008. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0694.

3. J Adol Health. 2004;35:160-7.

4. An Overview of Minors’ Consent Law: State Laws and Policies. 2017, by the Guttmacher Institute.

5. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011 Aug;165(2):331-7.

6. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009 Sep;94(9):3132-54.

7. Sex Roles. 2013 Jun 1;68(11-12):675-89.

8. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2008 Jul-Aug;53(4):331-7.

9. “The Fenway Guide to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health,” 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: American College of Physicians Press, 2008).

Sexual health screening and counseling is an important part of wellness care for all adolescents, and transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC) youth are no exception. TGNC youth may avoid routine health visits and sexual health conversations because they fear discrimination in the health care setting and feel uncomfortable about physical exams.1 Providers should be aware of the potential anxiety patients may feel during health care visits and work to establish an environment of respect and inclusiveness. Below are some tips to help provide care that is inclusive of the diverse gender and sexual identities of the patients we see.

Obtaining a sexual history

1. Clearly explain the reasons for asking sexually explicit questions.

TGNC youth experiencing dysphoria may have heightened levels of anxiety when discussing sexuality. Before asking these questions, acknowledge the sensitivity of this topic and explain that this information is important for providers to know so that they can provide appropriate counseling and screening recommendations. This may alleviate some of their discomfort.

2. Ensure confidentiality.

When obtaining sexual health histories, it is crucial to ensure confidential patient encounters, as described by the American Academy of Pediatrics and Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine.2,3 The Guttmacher Institute provides information about minors’ consent law in each state.4

3. Do not assume identity equals behavior.

Here are some sexual health questions you need to ask:

- Who are you attracted to? What is/are the gender(s) of your partner(s)?

- Have you ever had anal, genital, or oral sex? If yes:

Do you give, receive, or both?

When was the last time you had sex?

How many partners have you had in past 6 months?

Do you use barrier protection most of the time, some of the time, always, or never?

Do you have symptoms of an infection, such as burning when you pee, abnormal genital discharge, pain with sex, or irregular bleeding?

- Have you ever been forced/coerced into having sex?

Starting with open-ended questions about attraction can give patients an opportunity to describe their pattern of attraction. If needed, patients can be prompted with more specific questions about their partners’ genders. It is important to ask explicitly about genital, oral, and anal sex because patients sometimes do not realize that the term sex includes oral and anal sex. Patients also may not be aware that it is possible to spread infections through oral and anal sex.

4. Anatomy and behavior may change over time, and it is important to reassess sexually transmitted infection risk at each visit

Studies suggest that, as gender dysphoria decreases, sexual desires may increase; this is true for all adolescents but of particular interest with TGNC youth. This may affect behaviors.5 For youth on hormone therapy, testosterone can increase libido, whereas estrogen may decrease libido and affect sexual function.6

Physical exam

Dysphoria related to primary and secondary sex characteristics may make exams particularly distressing. Providers should clearly explain reasons for performing various parts of the physical exam. When performing the physical exam, providers should use a gender-affirming approach. This includes using the patient’s identified name and pronouns throughout the visit and asking patients preference for terminology when discussing body parts (some patients may prefer the use of the term “front hole” to vagina).1,7,8 The exam and evaluation may need to be modified based on comfort. If a patient refuses a speculum exam after the need for the its use has been discussed, consider offering an external genital exam and bimanual exam instead. If a patient refuses to allow a provider to obtain a rectal or vaginal swab, consider allowing patients to self-swab. Providers also should consider whether genital exams can be deferred to subsequent visits. These techniques offer an opportunity to build trust and rapport with patients so that they remain engaged in care and may become comfortable with the necessary tests and procedures at future visits.

Sexual health counseling

Sexual health counseling should address reducing risk and optimizing physical and emotional satisfaction in relationships and encounters.9 In addition to assessing risky behaviors and screening for sexually transmitted infections, providers also should provide counseling on safer-sex practices. This includes the use of lubrication to reduce trauma to genital tissues, which can potentiate the spread of infections, and the use of barrier protection, such as external condoms (often referred to as male condoms), internal condoms (often referred to as female condoms), dental dams during oral sex, and gloves for digital penetration. Patients at risk for pregnancy should receive comprehensive contraceptive counseling. TGNC patients may be at increased risk of sexual victimization, and honest discussions about safety in relationships is important. The goal of sexual health counseling should be to promote safe, satisfying experiences for all patients.

Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People, in Center of Excellence for Transgender Health, Department of Family and Community Medicine, 2nd ed. (San Francisco: University of California, 2016).

2. Pediatrics. 2008. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0694.

3. J Adol Health. 2004;35:160-7.

4. An Overview of Minors’ Consent Law: State Laws and Policies. 2017, by the Guttmacher Institute.

5. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011 Aug;165(2):331-7.

6. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009 Sep;94(9):3132-54.

7. Sex Roles. 2013 Jun 1;68(11-12):675-89.

8. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2008 Jul-Aug;53(4):331-7.

9. “The Fenway Guide to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health,” 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: American College of Physicians Press, 2008).

Sexual health screening and counseling is an important part of wellness care for all adolescents, and transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC) youth are no exception. TGNC youth may avoid routine health visits and sexual health conversations because they fear discrimination in the health care setting and feel uncomfortable about physical exams.1 Providers should be aware of the potential anxiety patients may feel during health care visits and work to establish an environment of respect and inclusiveness. Below are some tips to help provide care that is inclusive of the diverse gender and sexual identities of the patients we see.

Obtaining a sexual history

1. Clearly explain the reasons for asking sexually explicit questions.

TGNC youth experiencing dysphoria may have heightened levels of anxiety when discussing sexuality. Before asking these questions, acknowledge the sensitivity of this topic and explain that this information is important for providers to know so that they can provide appropriate counseling and screening recommendations. This may alleviate some of their discomfort.

2. Ensure confidentiality.

When obtaining sexual health histories, it is crucial to ensure confidential patient encounters, as described by the American Academy of Pediatrics and Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine.2,3 The Guttmacher Institute provides information about minors’ consent law in each state.4

3. Do not assume identity equals behavior.

Here are some sexual health questions you need to ask:

- Who are you attracted to? What is/are the gender(s) of your partner(s)?

- Have you ever had anal, genital, or oral sex? If yes:

Do you give, receive, or both?

When was the last time you had sex?

How many partners have you had in past 6 months?

Do you use barrier protection most of the time, some of the time, always, or never?

Do you have symptoms of an infection, such as burning when you pee, abnormal genital discharge, pain with sex, or irregular bleeding?

- Have you ever been forced/coerced into having sex?

Starting with open-ended questions about attraction can give patients an opportunity to describe their pattern of attraction. If needed, patients can be prompted with more specific questions about their partners’ genders. It is important to ask explicitly about genital, oral, and anal sex because patients sometimes do not realize that the term sex includes oral and anal sex. Patients also may not be aware that it is possible to spread infections through oral and anal sex.

4. Anatomy and behavior may change over time, and it is important to reassess sexually transmitted infection risk at each visit

Studies suggest that, as gender dysphoria decreases, sexual desires may increase; this is true for all adolescents but of particular interest with TGNC youth. This may affect behaviors.5 For youth on hormone therapy, testosterone can increase libido, whereas estrogen may decrease libido and affect sexual function.6

Physical exam

Dysphoria related to primary and secondary sex characteristics may make exams particularly distressing. Providers should clearly explain reasons for performing various parts of the physical exam. When performing the physical exam, providers should use a gender-affirming approach. This includes using the patient’s identified name and pronouns throughout the visit and asking patients preference for terminology when discussing body parts (some patients may prefer the use of the term “front hole” to vagina).1,7,8 The exam and evaluation may need to be modified based on comfort. If a patient refuses a speculum exam after the need for the its use has been discussed, consider offering an external genital exam and bimanual exam instead. If a patient refuses to allow a provider to obtain a rectal or vaginal swab, consider allowing patients to self-swab. Providers also should consider whether genital exams can be deferred to subsequent visits. These techniques offer an opportunity to build trust and rapport with patients so that they remain engaged in care and may become comfortable with the necessary tests and procedures at future visits.

Sexual health counseling

Sexual health counseling should address reducing risk and optimizing physical and emotional satisfaction in relationships and encounters.9 In addition to assessing risky behaviors and screening for sexually transmitted infections, providers also should provide counseling on safer-sex practices. This includes the use of lubrication to reduce trauma to genital tissues, which can potentiate the spread of infections, and the use of barrier protection, such as external condoms (often referred to as male condoms), internal condoms (often referred to as female condoms), dental dams during oral sex, and gloves for digital penetration. Patients at risk for pregnancy should receive comprehensive contraceptive counseling. TGNC patients may be at increased risk of sexual victimization, and honest discussions about safety in relationships is important. The goal of sexual health counseling should be to promote safe, satisfying experiences for all patients.

Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People, in Center of Excellence for Transgender Health, Department of Family and Community Medicine, 2nd ed. (San Francisco: University of California, 2016).

2. Pediatrics. 2008. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0694.

3. J Adol Health. 2004;35:160-7.

4. An Overview of Minors’ Consent Law: State Laws and Policies. 2017, by the Guttmacher Institute.

5. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011 Aug;165(2):331-7.

6. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009 Sep;94(9):3132-54.

7. Sex Roles. 2013 Jun 1;68(11-12):675-89.

8. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2008 Jul-Aug;53(4):331-7.

9. “The Fenway Guide to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health,” 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: American College of Physicians Press, 2008).

Confronting hate and violence against the LGBT community

It may be unusual for an LGBT health columnist to mention the horrendous events that occurred in Charlottesville, Va., in August 2017. It clearly was a demonstration of hate and violence against racial and ethnic minorities. Unfortunately, the LGBT community – especially LGBT communities of color – are often a target of that kind of hate and violence. This has a detrimental effect on the health of the LGBT community, and I believe that health care providers have a responsibility to address this hate and violence to promote the well-being of this marginalized community.

It cannot be overstated that LGBT individuals frequently experience anti-gay and anti-trans violence. According to the 2015 Federal Bureau of Investigation Hate Crime Statistics, about a fifth of hate crimes reported were based on sexual orientation or gender identity.1 In addition, LGBT youth are eight times as likely to experience bullying at school because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.2 Furthermore, on many surveys on anti-LGBT violence, people of color comprise more than half of the victims.3 There is a strong association between exposure to this violence and the health outcomes of LGBT youth. A study by Russell et al. showed that LGBT youth who were victims of physical violence at school are more likely to be depressed and suicidal and more likely to be diagnosed with an STD,4 and another study showed that LGBT youth who experienced anti-LGBT violence are more likely to engage in substance use.5 The health outcomes from anti-LGBT violence are not limited to the adolescent period – adolescents who experienced this kind of violence are more likely to report higher levels of depression as adults.6 Although researchers still are trying to determine the exact mechanism for these relationships, the most cited (and sensible) explanation is that exposure to anti-LGBT stigma, discrimination, and violence leads to a toxic environment, which in turn increases the risk for mental health problems and maladaptive coping mechanisms (such as substance use) as a response to such an environment.7

What can we do to stand up to the hate and violence against marginalized groups, such as the LGBT community? First, make your office a safe space. With the recent brazen display of hate and violence going around, members the LGBT community are desperate to feel protected. A good place to start is a guide by Advocates for Youth. Second, educate yourself and others. The title physician means “teacher,” and I feel it is your responsibility to teach your peers, colleagues, and the public about how anti-LGBT violence affects the health of LGBT individuals. To be an effective teacher, you need to be up to date on the research on how hatred and intolerance affects the health of the LGBT community. A good place to start is the Human Rights Campaign, which has accurate statistics on anti-LGBT violence and resources to address this problem. Finally, be an advocate. You don’t need to be in the streets with picket signs, nor do you necessarily need to lead the charge against anti-LGBT hate and violence – others will be at the front lines. What you can do is to call for your local, state, and federal government to institute policies that address anti-LGBT violence. Many medical organizations have resources that help health care providers engage with policy makers (check out the American Academy of Pediatrics advocacy page for these resources). Many of our elected officials take our professional opinions seriously.

Anti-gay and anti-trans violence is all too common in the LGBT community, especially violence against LGBT people of color, and this violence can adversely affect their health. Health care providers have a responsibility and the influence to confront these nexuses of hate and intolerance. You don’t need to do something heroic to accomplish this. You are members of a privileged and respected group of professionals, so small actions can coalesce into something that has a large impact on the health and well-being of the communities you serve.

Resources

• Advocates for Youth. Creating Safe Space for GLBTQ Youth: A Toolkit

• Human Rights Campaign. www.hrc.org/resources/

• American Academy of Pediatrics advocacy page: www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/

References

1. U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation. Uniform Crime Report Hate Crime Statistics, 2015.

2. J Interpers Violence. 2017. doi: 10.1177/0886260517718830.

3. National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs (NCAVP). Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and HIV-Affected Hate Violence in 2016.

4. J Sch Health. 2011 May;81(5):223-30.

5. Prev Sci. 2015 Jul;16(5):734-43.

6. Dev Psychol. 2010 Nov;46(6):1580-9.

7. Psychol Bull. 2003 Sep;129(5):674-97.

8. Gallup. Americans Rate Healthcare Providers High on Honesty, Ethics. 2016.

9. The Hippocratic Oath Today. 2001 or Do. No. Harm.

It may be unusual for an LGBT health columnist to mention the horrendous events that occurred in Charlottesville, Va., in August 2017. It clearly was a demonstration of hate and violence against racial and ethnic minorities. Unfortunately, the LGBT community – especially LGBT communities of color – are often a target of that kind of hate and violence. This has a detrimental effect on the health of the LGBT community, and I believe that health care providers have a responsibility to address this hate and violence to promote the well-being of this marginalized community.

It cannot be overstated that LGBT individuals frequently experience anti-gay and anti-trans violence. According to the 2015 Federal Bureau of Investigation Hate Crime Statistics, about a fifth of hate crimes reported were based on sexual orientation or gender identity.1 In addition, LGBT youth are eight times as likely to experience bullying at school because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.2 Furthermore, on many surveys on anti-LGBT violence, people of color comprise more than half of the victims.3 There is a strong association between exposure to this violence and the health outcomes of LGBT youth. A study by Russell et al. showed that LGBT youth who were victims of physical violence at school are more likely to be depressed and suicidal and more likely to be diagnosed with an STD,4 and another study showed that LGBT youth who experienced anti-LGBT violence are more likely to engage in substance use.5 The health outcomes from anti-LGBT violence are not limited to the adolescent period – adolescents who experienced this kind of violence are more likely to report higher levels of depression as adults.6 Although researchers still are trying to determine the exact mechanism for these relationships, the most cited (and sensible) explanation is that exposure to anti-LGBT stigma, discrimination, and violence leads to a toxic environment, which in turn increases the risk for mental health problems and maladaptive coping mechanisms (such as substance use) as a response to such an environment.7

What can we do to stand up to the hate and violence against marginalized groups, such as the LGBT community? First, make your office a safe space. With the recent brazen display of hate and violence going around, members the LGBT community are desperate to feel protected. A good place to start is a guide by Advocates for Youth. Second, educate yourself and others. The title physician means “teacher,” and I feel it is your responsibility to teach your peers, colleagues, and the public about how anti-LGBT violence affects the health of LGBT individuals. To be an effective teacher, you need to be up to date on the research on how hatred and intolerance affects the health of the LGBT community. A good place to start is the Human Rights Campaign, which has accurate statistics on anti-LGBT violence and resources to address this problem. Finally, be an advocate. You don’t need to be in the streets with picket signs, nor do you necessarily need to lead the charge against anti-LGBT hate and violence – others will be at the front lines. What you can do is to call for your local, state, and federal government to institute policies that address anti-LGBT violence. Many medical organizations have resources that help health care providers engage with policy makers (check out the American Academy of Pediatrics advocacy page for these resources). Many of our elected officials take our professional opinions seriously.

Anti-gay and anti-trans violence is all too common in the LGBT community, especially violence against LGBT people of color, and this violence can adversely affect their health. Health care providers have a responsibility and the influence to confront these nexuses of hate and intolerance. You don’t need to do something heroic to accomplish this. You are members of a privileged and respected group of professionals, so small actions can coalesce into something that has a large impact on the health and well-being of the communities you serve.

Resources

• Advocates for Youth. Creating Safe Space for GLBTQ Youth: A Toolkit

• Human Rights Campaign. www.hrc.org/resources/

• American Academy of Pediatrics advocacy page: www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/

References

1. U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation. Uniform Crime Report Hate Crime Statistics, 2015.

2. J Interpers Violence. 2017. doi: 10.1177/0886260517718830.

3. National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs (NCAVP). Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and HIV-Affected Hate Violence in 2016.

4. J Sch Health. 2011 May;81(5):223-30.

5. Prev Sci. 2015 Jul;16(5):734-43.

6. Dev Psychol. 2010 Nov;46(6):1580-9.

7. Psychol Bull. 2003 Sep;129(5):674-97.

8. Gallup. Americans Rate Healthcare Providers High on Honesty, Ethics. 2016.

9. The Hippocratic Oath Today. 2001 or Do. No. Harm.

It may be unusual for an LGBT health columnist to mention the horrendous events that occurred in Charlottesville, Va., in August 2017. It clearly was a demonstration of hate and violence against racial and ethnic minorities. Unfortunately, the LGBT community – especially LGBT communities of color – are often a target of that kind of hate and violence. This has a detrimental effect on the health of the LGBT community, and I believe that health care providers have a responsibility to address this hate and violence to promote the well-being of this marginalized community.

It cannot be overstated that LGBT individuals frequently experience anti-gay and anti-trans violence. According to the 2015 Federal Bureau of Investigation Hate Crime Statistics, about a fifth of hate crimes reported were based on sexual orientation or gender identity.1 In addition, LGBT youth are eight times as likely to experience bullying at school because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.2 Furthermore, on many surveys on anti-LGBT violence, people of color comprise more than half of the victims.3 There is a strong association between exposure to this violence and the health outcomes of LGBT youth. A study by Russell et al. showed that LGBT youth who were victims of physical violence at school are more likely to be depressed and suicidal and more likely to be diagnosed with an STD,4 and another study showed that LGBT youth who experienced anti-LGBT violence are more likely to engage in substance use.5 The health outcomes from anti-LGBT violence are not limited to the adolescent period – adolescents who experienced this kind of violence are more likely to report higher levels of depression as adults.6 Although researchers still are trying to determine the exact mechanism for these relationships, the most cited (and sensible) explanation is that exposure to anti-LGBT stigma, discrimination, and violence leads to a toxic environment, which in turn increases the risk for mental health problems and maladaptive coping mechanisms (such as substance use) as a response to such an environment.7

What can we do to stand up to the hate and violence against marginalized groups, such as the LGBT community? First, make your office a safe space. With the recent brazen display of hate and violence going around, members the LGBT community are desperate to feel protected. A good place to start is a guide by Advocates for Youth. Second, educate yourself and others. The title physician means “teacher,” and I feel it is your responsibility to teach your peers, colleagues, and the public about how anti-LGBT violence affects the health of LGBT individuals. To be an effective teacher, you need to be up to date on the research on how hatred and intolerance affects the health of the LGBT community. A good place to start is the Human Rights Campaign, which has accurate statistics on anti-LGBT violence and resources to address this problem. Finally, be an advocate. You don’t need to be in the streets with picket signs, nor do you necessarily need to lead the charge against anti-LGBT hate and violence – others will be at the front lines. What you can do is to call for your local, state, and federal government to institute policies that address anti-LGBT violence. Many medical organizations have resources that help health care providers engage with policy makers (check out the American Academy of Pediatrics advocacy page for these resources). Many of our elected officials take our professional opinions seriously.

Anti-gay and anti-trans violence is all too common in the LGBT community, especially violence against LGBT people of color, and this violence can adversely affect their health. Health care providers have a responsibility and the influence to confront these nexuses of hate and intolerance. You don’t need to do something heroic to accomplish this. You are members of a privileged and respected group of professionals, so small actions can coalesce into something that has a large impact on the health and well-being of the communities you serve.

Resources

• Advocates for Youth. Creating Safe Space for GLBTQ Youth: A Toolkit

• Human Rights Campaign. www.hrc.org/resources/

• American Academy of Pediatrics advocacy page: www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/

References

1. U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation. Uniform Crime Report Hate Crime Statistics, 2015.

2. J Interpers Violence. 2017. doi: 10.1177/0886260517718830.

3. National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs (NCAVP). Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and HIV-Affected Hate Violence in 2016.

4. J Sch Health. 2011 May;81(5):223-30.

5. Prev Sci. 2015 Jul;16(5):734-43.

6. Dev Psychol. 2010 Nov;46(6):1580-9.

7. Psychol Bull. 2003 Sep;129(5):674-97.

8. Gallup. Americans Rate Healthcare Providers High on Honesty, Ethics. 2016.

9. The Hippocratic Oath Today. 2001 or Do. No. Harm.

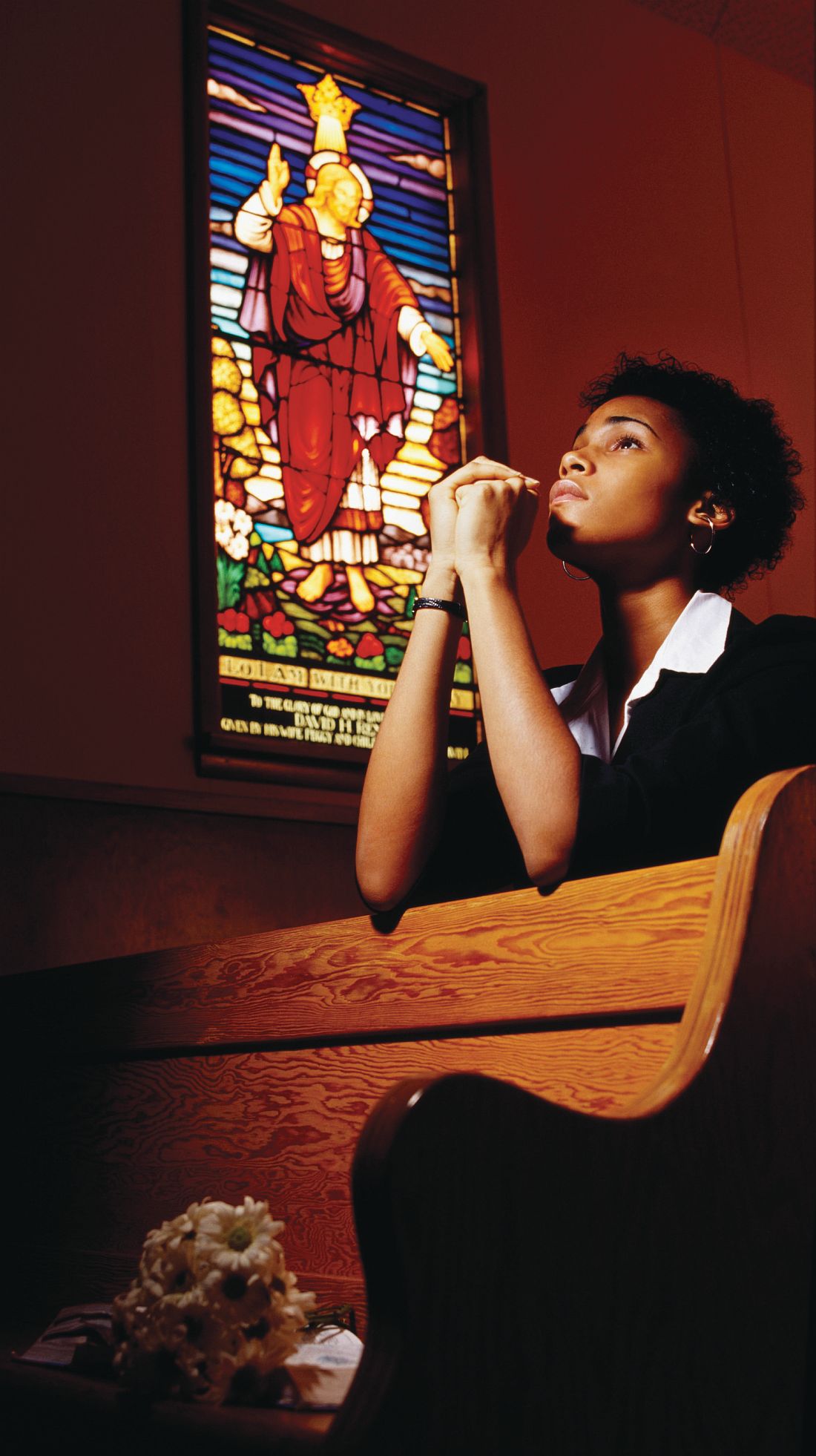

Religion and LGBTQ identities

JB is a 15-year-old female who presents to your office for a wellness check. Mom is concerned because she has seemed more depressed and withdrawn over the past few months. During the confidential portion of your visit, JB discloses that, while she has had boyfriends in the past, she is realizing that she is romantically and sexually attracted to females. Many members of her religious faith, which she is strongly connected to, believe that homosexuality is a sin. She has been secretly researching therapies to help her “not be gay” and asks you for advice.

Adolescence is a time of rapid growth and development. Two important developmental tasks of adolescence are to establish key aspects of identity and identify meaningful moral standards, values, and belief systems.1 For some LGBTQ adolescents, these tasks can become more complicated when the value system or religious faith in which they were raised views homosexuality or gender nonconformity as a sin.

- Identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender is normal, just different.

- LGBT people exist in almost every faith group across the country.

- Many religious groups have wrestled with homosexuality, gender identity, and religion and decided to be more welcoming to LGBT communities.

- Within most faiths, there are many interpretations of religious texts, such as the Bible and the Koran, on all issues, including homosexuality.

- While every religion has different teachings, almost all religions advocate love and compassion.

- Clergy and other faith leaders can be a source of support. However, every faith community is different and may not always be supportive. Safely investigate your individual community’s approach. You have the right to question and explore your faith, sexuality, and/or gender identity and reconcile these in a way that is true to you.

- Remember this is your journey. You get to decide the path and the pace.

- Recognize that this may involve working for change within your community or it may mean leaving it.

- Referral for “conversion” or “reparative therapy” is never indicated. Such therapy is not effective and may be harmful to LGBTQ individuals by increasing internalized stigma, distress, and depression.

Dr. Chelvakumar is an attending physician in the division of adolescent medicine at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and an assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at the Ohio State University, both in Columbus. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Spirituality resources

- LGBTQ and Religion: Your Relationship with Religion is Completely Up to You, the FAQ Page by the Trevor Project, a national organization that provides crisis intervention and suicide prevention resources to LGBTQ young people ages 13-24 years. www.thetrevorproject.org/pages/lgbtq-and-religion

- Faith in Our Families: Parents, Families and Friends Talk About Religion and Homosexuality, a resource from PFLAG (Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays). www.pflag.org/sites/default/files/Faith%20In%20Our%20Families.pdf

- LGBT Center UNC Chapel Hill: Religion and Spirituality, a page with a link to nondenominational and denomination-specific resources with various religious and spiritual communities’ beliefs regarding faith and LGBTQIA+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual). lgbtq.unc.edu/resources/exploring-identities/religion-and-spirituality

- HRC: Explore Religion and Faith, a Human Rights Campaign page containing links to resources on religion and faith. It also has links to the Coming Home Series, guides aimed at those who hope to lead their faith communities toward a more welcoming stance and those seeking a path back to beloved traditions. www.hrc.org/explore/topic/religion-faith

References

1. Raising teens: A synthesis or research and a foundation for action. (Boston: Center for Health Communication, Harvard School of Public Health, 2001).

2. Faith in Our Families: Parents, Families and Friends Talk About Religion and Homosexuality (Washington, D.C.: Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays, 1997)

3. Pediatrics. 2013 Jul;132(1):198-203.

4. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. (Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2011)

5. Coming Home: To Faith, to Spirit, to Self. Pamphlet by the Human Rights Campaign.

JB is a 15-year-old female who presents to your office for a wellness check. Mom is concerned because she has seemed more depressed and withdrawn over the past few months. During the confidential portion of your visit, JB discloses that, while she has had boyfriends in the past, she is realizing that she is romantically and sexually attracted to females. Many members of her religious faith, which she is strongly connected to, believe that homosexuality is a sin. She has been secretly researching therapies to help her “not be gay” and asks you for advice.

Adolescence is a time of rapid growth and development. Two important developmental tasks of adolescence are to establish key aspects of identity and identify meaningful moral standards, values, and belief systems.1 For some LGBTQ adolescents, these tasks can become more complicated when the value system or religious faith in which they were raised views homosexuality or gender nonconformity as a sin.

- Identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender is normal, just different.

- LGBT people exist in almost every faith group across the country.

- Many religious groups have wrestled with homosexuality, gender identity, and religion and decided to be more welcoming to LGBT communities.

- Within most faiths, there are many interpretations of religious texts, such as the Bible and the Koran, on all issues, including homosexuality.

- While every religion has different teachings, almost all religions advocate love and compassion.

- Clergy and other faith leaders can be a source of support. However, every faith community is different and may not always be supportive. Safely investigate your individual community’s approach. You have the right to question and explore your faith, sexuality, and/or gender identity and reconcile these in a way that is true to you.

- Remember this is your journey. You get to decide the path and the pace.

- Recognize that this may involve working for change within your community or it may mean leaving it.

- Referral for “conversion” or “reparative therapy” is never indicated. Such therapy is not effective and may be harmful to LGBTQ individuals by increasing internalized stigma, distress, and depression.

Dr. Chelvakumar is an attending physician in the division of adolescent medicine at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and an assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at the Ohio State University, both in Columbus. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Spirituality resources

- LGBTQ and Religion: Your Relationship with Religion is Completely Up to You, the FAQ Page by the Trevor Project, a national organization that provides crisis intervention and suicide prevention resources to LGBTQ young people ages 13-24 years. www.thetrevorproject.org/pages/lgbtq-and-religion

- Faith in Our Families: Parents, Families and Friends Talk About Religion and Homosexuality, a resource from PFLAG (Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays). www.pflag.org/sites/default/files/Faith%20In%20Our%20Families.pdf

- LGBT Center UNC Chapel Hill: Religion and Spirituality, a page with a link to nondenominational and denomination-specific resources with various religious and spiritual communities’ beliefs regarding faith and LGBTQIA+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual). lgbtq.unc.edu/resources/exploring-identities/religion-and-spirituality

- HRC: Explore Religion and Faith, a Human Rights Campaign page containing links to resources on religion and faith. It also has links to the Coming Home Series, guides aimed at those who hope to lead their faith communities toward a more welcoming stance and those seeking a path back to beloved traditions. www.hrc.org/explore/topic/religion-faith

References

1. Raising teens: A synthesis or research and a foundation for action. (Boston: Center for Health Communication, Harvard School of Public Health, 2001).

2. Faith in Our Families: Parents, Families and Friends Talk About Religion and Homosexuality (Washington, D.C.: Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays, 1997)

3. Pediatrics. 2013 Jul;132(1):198-203.

4. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. (Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2011)

5. Coming Home: To Faith, to Spirit, to Self. Pamphlet by the Human Rights Campaign.

JB is a 15-year-old female who presents to your office for a wellness check. Mom is concerned because she has seemed more depressed and withdrawn over the past few months. During the confidential portion of your visit, JB discloses that, while she has had boyfriends in the past, she is realizing that she is romantically and sexually attracted to females. Many members of her religious faith, which she is strongly connected to, believe that homosexuality is a sin. She has been secretly researching therapies to help her “not be gay” and asks you for advice.

Adolescence is a time of rapid growth and development. Two important developmental tasks of adolescence are to establish key aspects of identity and identify meaningful moral standards, values, and belief systems.1 For some LGBTQ adolescents, these tasks can become more complicated when the value system or religious faith in which they were raised views homosexuality or gender nonconformity as a sin.

- Identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender is normal, just different.

- LGBT people exist in almost every faith group across the country.

- Many religious groups have wrestled with homosexuality, gender identity, and religion and decided to be more welcoming to LGBT communities.

- Within most faiths, there are many interpretations of religious texts, such as the Bible and the Koran, on all issues, including homosexuality.

- While every religion has different teachings, almost all religions advocate love and compassion.

- Clergy and other faith leaders can be a source of support. However, every faith community is different and may not always be supportive. Safely investigate your individual community’s approach. You have the right to question and explore your faith, sexuality, and/or gender identity and reconcile these in a way that is true to you.

- Remember this is your journey. You get to decide the path and the pace.

- Recognize that this may involve working for change within your community or it may mean leaving it.

- Referral for “conversion” or “reparative therapy” is never indicated. Such therapy is not effective and may be harmful to LGBTQ individuals by increasing internalized stigma, distress, and depression.

Dr. Chelvakumar is an attending physician in the division of adolescent medicine at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and an assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at the Ohio State University, both in Columbus. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Spirituality resources

- LGBTQ and Religion: Your Relationship with Religion is Completely Up to You, the FAQ Page by the Trevor Project, a national organization that provides crisis intervention and suicide prevention resources to LGBTQ young people ages 13-24 years. www.thetrevorproject.org/pages/lgbtq-and-religion

- Faith in Our Families: Parents, Families and Friends Talk About Religion and Homosexuality, a resource from PFLAG (Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays). www.pflag.org/sites/default/files/Faith%20In%20Our%20Families.pdf

- LGBT Center UNC Chapel Hill: Religion and Spirituality, a page with a link to nondenominational and denomination-specific resources with various religious and spiritual communities’ beliefs regarding faith and LGBTQIA+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual). lgbtq.unc.edu/resources/exploring-identities/religion-and-spirituality

- HRC: Explore Religion and Faith, a Human Rights Campaign page containing links to resources on religion and faith. It also has links to the Coming Home Series, guides aimed at those who hope to lead their faith communities toward a more welcoming stance and those seeking a path back to beloved traditions. www.hrc.org/explore/topic/religion-faith

References

1. Raising teens: A synthesis or research and a foundation for action. (Boston: Center for Health Communication, Harvard School of Public Health, 2001).

2. Faith in Our Families: Parents, Families and Friends Talk About Religion and Homosexuality (Washington, D.C.: Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays, 1997)

3. Pediatrics. 2013 Jul;132(1):198-203.

4. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. (Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2011)

5. Coming Home: To Faith, to Spirit, to Self. Pamphlet by the Human Rights Campaign.

Obtaining coverage for transgender and gender-expansive youth

Transgender and gender-expansive youth face many barriers to health care. (Gender-expansive youth are defined as “youth who do not identify with traditional gender roles but are otherwise not confined to one gender narrative or experience.”) Although some of these youth may be fortunate to have a supportive family and access to health care providers proficient in transgender health care, they still face difficulties in having their insurance cover transgender-related services. This is not an impossible task, but it is a constant struggle for many clinicians.

In this column, I will provide some tips and strategies to help clinicians get insurance companies to cover these critical services. However, keep in mind that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to obtaining insurance coverage. In addition, growing uncertainty over the repeal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) – which was critical in lifting many of the barriers to insurance coverage for transgender individuals – will make this task challenging.

Health insurance is extraordinarily complex. There are multiple private and public plans that vary in the services they cover. This variation is state dependent. And even within states, there is additional variability. Most health insurance plans are purchased by employers, and employers have a choice of what can be covered in their health plans. So even though an insurance company may state that it covers transgender-related services, the patient’s employer may pay for a plan that doesn’t cover such services. The only way to be sure whether a patient’s insurance will cover transgender-related services or not is to contact the insurance provider directly, but with extremely busy schedules and heavy patient loads, this is easier said than done. It would be helpful to have a social worker perform this task, but even having a social worker can be a luxury for some clinics.

The ACA made it easier for transgender individuals to obtain insurance coverage. Three years ago, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services stated that Medicare’s longstanding exclusion of “transsexual surgical procedures” was no longer valid.1 Although it did not universally ban transgender exclusion policies, it did allow individual states to do so. Thirteen states have explicit policies that ban exclusions of transgender-related services in both private insurance and in Medicaid, and an additional five states have some policies that discourage such practices.2 This allowed some insurance providers and state Medicaid plans to offer coverage of transgender-related services.

Another challenge in obtaining insurance coverage for transgender and gender-expansive youth is claims denial for sex-specific procedures. For example, if a transwoman is designated as “male” in the electronic medical record and requires a breast ultrasound, the insurance company may automatically reject this claim because this procedure is covered for bodies designated as “female.” If the patient’s insurance plan covers transgender-related services, the clinic can notify the insurance company that the patient is transgender; if the patient’s plan does not, then the clinic will need to appeal to the insurance provider. Alternatively, for clinics associated with federally-funded institutions (e.g., most hospitals), the clinician can use Condition Code 45 in the billing to override the sex mismatch, although not all hospitals have implemented this code.3

1. Patient’s identifying information. Usually the patient’s name and date of birth is sufficient. Clinicians should use the patient’s preferred name in the letter, but provide the insurance or legal name of the patient so that the insurance provider can locate the patient’s records.

2. Result of a psychosocial evaluation and diagnosis (if any). Many insurance providers are looking specifically for the gender dysphoria diagnosis.

3. The duration of the referring health professional’s relationship with the patient, which includes the type of evaluation and therapy or counseling (e.g., cognitive behavior therapy or gender coaching).

4. An explanation that the criteria (usually from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health standard of care4 or the Endocrine Society Guidelines titled Endocrine Treatment of Transsexual Persons5) for hormone therapy have been met, and a brief description of the clinical rationale for supporting the client’s request for hormone therapy.

5. A statement that informed consent has been obtained from the patient (or parental permission if the patient is younger than 18 years).

6. A statement that the referring health professional is available for coordination of care.

If the clinician fails to convince the insurance provider of the necessity of covering transgender-related services, the patient still can pay out of pocket. Some hormones can be affordable to certain patients. In the state of Pennsylvania, for example, a 10-mL vial of testosterone can cost anywhere from $60 to $80, and may generally last anywhere from 10 weeks to a year, depending on dosage. Nevertheless, these costs still may be prohibitive for many transgender youth. Many are chronically unemployed or underemployed, or struggle with homelessness.6 Some transgender youth have to the face the excruciatingly difficult choice between having something to eat for the day or living another day with gender dysphoria.

Clinicians should work very hard to make sure that their transgender and gender-expansive patients obtain the care they need. The above strategies may help navigate the complex insurance system. However, insurance policies vary by state, and anti-trans discrimination creates additional barriers to health care. Therefore, clinicians who take care of transgender youth also should advocate for policies that protect these patients from discrimination, and they should advocate for policies that expand medical coverage for this vulnerable population.

Resources

• The Human Rights Campaign keeps a list of insurance plans that cover transgender-related services, but this list is far from comprehensive.

• Healthcare.gov provides some guidance on how to obtain coverage and navigate the insurance system for transgender individuals.

• UCSF Center of Excellence for Transgender Health provides some excellent resources and guidance on obtaining insurance coverage for transgender individuals.

References

1. LGBT Health 2014;1(4):256-8.

2. Map: State Health Insurance Rules: National Center for Transgender Equality, 2016 [Available from: www.transequality.org/issues/resources/map-state-health-insurance-rules].

3. Health insurance coverage issues for transgender people in the United States: University of California, San Fransisco Center of Excellence for Transgender Health, 2017 [Available from: http://transhealth.ucsf.edu/trans?page=guidelines-insurance].

4. International Journal of Transgenderism 2012;13(4):165-232.

5. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94(9):3132-54.

6. Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011.

Transgender and gender-expansive youth face many barriers to health care. (Gender-expansive youth are defined as “youth who do not identify with traditional gender roles but are otherwise not confined to one gender narrative or experience.”) Although some of these youth may be fortunate to have a supportive family and access to health care providers proficient in transgender health care, they still face difficulties in having their insurance cover transgender-related services. This is not an impossible task, but it is a constant struggle for many clinicians.

In this column, I will provide some tips and strategies to help clinicians get insurance companies to cover these critical services. However, keep in mind that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to obtaining insurance coverage. In addition, growing uncertainty over the repeal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) – which was critical in lifting many of the barriers to insurance coverage for transgender individuals – will make this task challenging.

Health insurance is extraordinarily complex. There are multiple private and public plans that vary in the services they cover. This variation is state dependent. And even within states, there is additional variability. Most health insurance plans are purchased by employers, and employers have a choice of what can be covered in their health plans. So even though an insurance company may state that it covers transgender-related services, the patient’s employer may pay for a plan that doesn’t cover such services. The only way to be sure whether a patient’s insurance will cover transgender-related services or not is to contact the insurance provider directly, but with extremely busy schedules and heavy patient loads, this is easier said than done. It would be helpful to have a social worker perform this task, but even having a social worker can be a luxury for some clinics.

The ACA made it easier for transgender individuals to obtain insurance coverage. Three years ago, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services stated that Medicare’s longstanding exclusion of “transsexual surgical procedures” was no longer valid.1 Although it did not universally ban transgender exclusion policies, it did allow individual states to do so. Thirteen states have explicit policies that ban exclusions of transgender-related services in both private insurance and in Medicaid, and an additional five states have some policies that discourage such practices.2 This allowed some insurance providers and state Medicaid plans to offer coverage of transgender-related services.

Another challenge in obtaining insurance coverage for transgender and gender-expansive youth is claims denial for sex-specific procedures. For example, if a transwoman is designated as “male” in the electronic medical record and requires a breast ultrasound, the insurance company may automatically reject this claim because this procedure is covered for bodies designated as “female.” If the patient’s insurance plan covers transgender-related services, the clinic can notify the insurance company that the patient is transgender; if the patient’s plan does not, then the clinic will need to appeal to the insurance provider. Alternatively, for clinics associated with federally-funded institutions (e.g., most hospitals), the clinician can use Condition Code 45 in the billing to override the sex mismatch, although not all hospitals have implemented this code.3