User login

Diagnosis and treatment of uterine isthmocele

In recent years, uterine isthmocele has increasingly been included as part of the differential in women with a history of a cesarean section who present with postmenstrual bleeding, pelvic pain, or secondary infertility.

The defect appears as a fluid-filled, pouch-like abnormality in the anterior uterine wall at the site of a prior cesarean section. The best method for diagnosis is usually a saline-infused sonogram. It can be treated in various ways, depending on the patient’s symptoms and desire for future fertility. Although we have treated isthmoceles with hysteroscopic desiccation, or resection, our best success has occurred with laparoscopic resection and reapproximation of normal tissue in a small series of patients.

There is no standard definition of the defect that fully describes its size, depth, and other characteristics. Many words and phrases have been used to describe the defect: It is commonly referred to as an isthmocele, because of its usual location at the uterine isthmus, but others have referred to it as a cesarean scar defect or niche, as the defect may be found at the endocervical canal or in the lower uterine segment. In any case, while diagnoses appear to be increasing, the incidence of the defect is unknown.

More research on risk factors and treatment is needed, but the literature, as well as our own experience, has demonstrated that this treatable defect should be considered in the differential diagnosis for women who have undergone cesarean section and subsequently have abnormal bleeding or staining, pelvic pain, or secondary infertility, especially when fluid is clearly visible in the cesarean section defect.

Diagnosis, symptoms

An isthmocele forms in the first place, it is thought, after an incision scar forms and causes retraction and dilation in the thinner, lower segment of the anterior wall and a thickening in the upper portion. There is a deficient scar, in other words, with disparate wound healing on the sides of the incision site.

The defect and its consequences were described in 1995 by Dr. Hugh Morris, who studied hysterectomy specimens in 51 women with a history of cesarean section (in most cases, more than one). Dr. Morris concluded that scar tissue in these patients contributed to significant pathological changes and anatomical abnormalities that, in turn, gave rise to a variety of clinical symptoms including menorrhagia, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and lower abdominal pain refractory to medical management.

Distortion and widening of the lower uterine segment and “free” red blood cells in endometrial stroma of the scar were the most frequently identified pathological changes, followed by fragmentation and breakdown of the endometrium of the scar, and iatrogenic adenomyosis (Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol.1995;14:16-20).

Several small reports and case series published in the late 1990s offered additional support for a cause-and-effect correlation between cesarean scar defects and abnormal vaginal bleeding. Several years later, the link was strengthened as more investigators reported connections between the defects and various symptoms. These reports were followed by published comparisons of imaging techniques for the diagnosis of isthmoceles.

Diagnosis of the defects can be made with transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS), saline infused sonohysterogram (SIS), hysterosalpingogram, hysteroscopy, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). With any modality, imaging is best performed in the early proliferative phase, right after the menstrual cycle has ended.

Comparisons of unenhanced TVUS and SIS – both of which may be easily performed in the office and at a much lower cost than MRI – have shown the latter technique to be superior for evaluating isthmoceles. Distension of the endometrial cavity makes the borders of the defects easier to delineate, which enables detection of more subtle defects and improves our ability to measure the size of defects.

This advantage was described by in 2010 by Dr. O. Vikhareva Osser and colleagues, who performed both TVUS and SIS in 108 women with a history of one or more cesarean sections. They identified more scar defects with SIS than with TVUS (Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;35:75-83).

Another benefit of SIS over TVUS and hysterosalpingogram is that one can measure the thickness of the remaining myometrium overlying the isthmocele, which is especially important knowledge for patients considering another pregnancy. As a result, we have relied on this technique to diagnose every case within our practice. I will perform SIS in a patient who has a history of one or multiple cesarean sections and symptoms of abnormal bleeding, pelvic pain, or secondary infertility as part of the basic work-up.

Similarly, an observational prospective cohort study of 225 women who had undergone a cesarean section 6-12 months prior compared TVUS and gel-infused sonohysterogram (GIS), and found that the prevalence of a niche – defined as an anechoic area at the site of the cesarean scar, with a depth of at least 1 mm on GIS – was 24% with TVUS and 56% with GIS (Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;37:93-9).

The abnormal bleeding is often described by patients as spotting or bleeding that continues for days or weeks after menstrual flow has ended; it is believed to result from an accumulation of blood in the defect and a lack of coordinated muscle contractions, which leads to continued accumulation of blood and menstrual debris. Dysmenorrhea and chronic pelvic pain are thought to be associated with iatrogenic adenomyosis and/or a chronic inflammatory state created when accumulated blood and mucus are intermittently expelled. Secondary infertility can occur, it is believed, as accumulated fluid and blood interfere with the endocervical and even the endometrial environment and disrupt sperm transport, sperm quality, and embryo implantation. Difficulty in embryo transfer may also occur because of the distortion caused to the endometrial cavity. Many of the isthmoceles that we and others have diagnosed have been in patients undergoing invitro fertilization. The patients are often found to have an accumulation of fluid in the endometrial canal and isthmocele during stimulation for either a fresh or frozen embryo transfer, thus necessitating the cancellation of their cycle.

Treatment

The choice of treatment depends upon the patient’s symptoms and desire for future fertility, but it can include hormonal treatment, hysteroscopic resection, transvaginal repair, a laparoscopic or robot-assisted approach, and hysterectomy.

Little has been published on nonsurgical treatment, but this may be considered for patients whose primary symptoms are bleeding or pain and who desire the least invasive option. In a small observational study of women with an isthmocele and bleeding, symptoms were eliminated with several cycles of oral contraceptive pills (Fertil. Steril. 2006;86: 477-9).

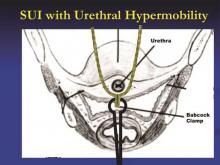

Hysteroscopic isthmocele correction or resection are the surgical techniques most frequently described in the literature, but, as with other surgical approaches, studies are small. Hysteroscopic repair has typically involved the use of electrical energy to desiccate or cauterize abnormal tissue and eliminate the outpouching in which blood and fluid accumulate. Hysteroscopic resection is another technique that has also been championed.

However, for patients who desire future pregnancy, we do not recommend a hysteroscopic approach because it does not reinforce the often-thinning myometrium covering the defect. We are concerned that if this area is simply desiccated or resected, and not reapproximated, the patient will be at greater risk of pregnancy-related complications, including cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy with potential uterine dehiscence.

Laparoscopic repair was first described by Dr. Olivier Donnez, who rightly pointed out that the laparoscopic approach offers an optimal view from above during dissection of the vesico-vaginal space. Dr. Donnez used a CO2 laser to excise fibrotic tissue, followed by laparoscopic closure (Fertil. Steril. 2008;89:974-80).

We have had success with a laparoscopic approach that uses concomitant hysteroscopy. The vesico-uterine peritoneum is incised over the anterior uterine wall, and the bladder is backfilled so that its boundaries may be identified prior to further dissection. With the area exposed, we perform a hysteroscopy to determine the exact location of the isthmocele. As the hysteroscope enters the thinned out isthmocele, the light will be more visible via laparoscopic visualization.

When performing conventional laparoscopy, the isthmocele is excised with an ultrasonic curved blade. We use this instrument because it has no opposing arm and because it enables precise tissue dissection in multiple planes. With harmonic energy, we can limit tissue dessication and destruction, lowering the risk of future pregnancy-related complications. Monopolar scissors are best when a robotic approach is used.

Once the isthmocele is resected, the clean edges are sutured together in two layers. The first layer is sutured in an interrupted mattress-style fashion, to prevent tissue strangulation and necrosis. We use a monofilament nonbarbed delayed-absorbable 3-0 PDS suture on a CT-1 needle – a choice that limits tissue trauma and postoperative inflammation.

Sutures are initially placed at each angle with one or two sutures placed between. These sutures must be placed deep to close the bottom of the defect. A second layer of suture is then placed to imbricate over the initial layer of closure. We utilize 3-0 PDS in a running or mattress style, or a running 3-0 V-Loc suture. Our patients return after 1-3 months for a postoperative image, and are instructed to wait at least 3 months after surgery before attempting conception.

In our experience, of more than 10 patients, symptoms ceased in all patients whose surgery was performed for the indication of abnormal uterine bleeding. The follow-up on our series of patients who underwent the procedure for secondary infertility is ongoing, but the preliminary results are very positive, with resolution of intrauterine fluid in all of the patients, as well as several successful pregnancy outcomes.

A recent systematic review of minimally invasive therapy for symptoms related to an isthmocele shows good outcomes across the 12 included studies but does not offer evidence to favor one treatment over another. The studies show significant reductions in abnormal uterine bleeding and pain, as well as a high rate of satisfaction in most patients after hysteroscopic niche resection or vaginal or laparoscopic niche repair, with a low complication rate (BJOG 2014;121:145-6).

Pregnancies were reported after treatment, but sample sizes and follow-up were insufficient to draw conclusions on pregnancy and delivery outcomes, according to the review. As the reviewers wrote, following patients through their next delivery in larger, higher-quality studies will help provide more guidance for selecting the best isthmocele treatments and implementing these treatments into practice.

Dr. Sasaki reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

In recent years, uterine isthmocele has increasingly been included as part of the differential in women with a history of a cesarean section who present with postmenstrual bleeding, pelvic pain, or secondary infertility.

The defect appears as a fluid-filled, pouch-like abnormality in the anterior uterine wall at the site of a prior cesarean section. The best method for diagnosis is usually a saline-infused sonogram. It can be treated in various ways, depending on the patient’s symptoms and desire for future fertility. Although we have treated isthmoceles with hysteroscopic desiccation, or resection, our best success has occurred with laparoscopic resection and reapproximation of normal tissue in a small series of patients.

There is no standard definition of the defect that fully describes its size, depth, and other characteristics. Many words and phrases have been used to describe the defect: It is commonly referred to as an isthmocele, because of its usual location at the uterine isthmus, but others have referred to it as a cesarean scar defect or niche, as the defect may be found at the endocervical canal or in the lower uterine segment. In any case, while diagnoses appear to be increasing, the incidence of the defect is unknown.

More research on risk factors and treatment is needed, but the literature, as well as our own experience, has demonstrated that this treatable defect should be considered in the differential diagnosis for women who have undergone cesarean section and subsequently have abnormal bleeding or staining, pelvic pain, or secondary infertility, especially when fluid is clearly visible in the cesarean section defect.

Diagnosis, symptoms

An isthmocele forms in the first place, it is thought, after an incision scar forms and causes retraction and dilation in the thinner, lower segment of the anterior wall and a thickening in the upper portion. There is a deficient scar, in other words, with disparate wound healing on the sides of the incision site.

The defect and its consequences were described in 1995 by Dr. Hugh Morris, who studied hysterectomy specimens in 51 women with a history of cesarean section (in most cases, more than one). Dr. Morris concluded that scar tissue in these patients contributed to significant pathological changes and anatomical abnormalities that, in turn, gave rise to a variety of clinical symptoms including menorrhagia, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and lower abdominal pain refractory to medical management.

Distortion and widening of the lower uterine segment and “free” red blood cells in endometrial stroma of the scar were the most frequently identified pathological changes, followed by fragmentation and breakdown of the endometrium of the scar, and iatrogenic adenomyosis (Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol.1995;14:16-20).

Several small reports and case series published in the late 1990s offered additional support for a cause-and-effect correlation between cesarean scar defects and abnormal vaginal bleeding. Several years later, the link was strengthened as more investigators reported connections between the defects and various symptoms. These reports were followed by published comparisons of imaging techniques for the diagnosis of isthmoceles.

Diagnosis of the defects can be made with transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS), saline infused sonohysterogram (SIS), hysterosalpingogram, hysteroscopy, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). With any modality, imaging is best performed in the early proliferative phase, right after the menstrual cycle has ended.

Comparisons of unenhanced TVUS and SIS – both of which may be easily performed in the office and at a much lower cost than MRI – have shown the latter technique to be superior for evaluating isthmoceles. Distension of the endometrial cavity makes the borders of the defects easier to delineate, which enables detection of more subtle defects and improves our ability to measure the size of defects.

This advantage was described by in 2010 by Dr. O. Vikhareva Osser and colleagues, who performed both TVUS and SIS in 108 women with a history of one or more cesarean sections. They identified more scar defects with SIS than with TVUS (Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;35:75-83).

Another benefit of SIS over TVUS and hysterosalpingogram is that one can measure the thickness of the remaining myometrium overlying the isthmocele, which is especially important knowledge for patients considering another pregnancy. As a result, we have relied on this technique to diagnose every case within our practice. I will perform SIS in a patient who has a history of one or multiple cesarean sections and symptoms of abnormal bleeding, pelvic pain, or secondary infertility as part of the basic work-up.

Similarly, an observational prospective cohort study of 225 women who had undergone a cesarean section 6-12 months prior compared TVUS and gel-infused sonohysterogram (GIS), and found that the prevalence of a niche – defined as an anechoic area at the site of the cesarean scar, with a depth of at least 1 mm on GIS – was 24% with TVUS and 56% with GIS (Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;37:93-9).

The abnormal bleeding is often described by patients as spotting or bleeding that continues for days or weeks after menstrual flow has ended; it is believed to result from an accumulation of blood in the defect and a lack of coordinated muscle contractions, which leads to continued accumulation of blood and menstrual debris. Dysmenorrhea and chronic pelvic pain are thought to be associated with iatrogenic adenomyosis and/or a chronic inflammatory state created when accumulated blood and mucus are intermittently expelled. Secondary infertility can occur, it is believed, as accumulated fluid and blood interfere with the endocervical and even the endometrial environment and disrupt sperm transport, sperm quality, and embryo implantation. Difficulty in embryo transfer may also occur because of the distortion caused to the endometrial cavity. Many of the isthmoceles that we and others have diagnosed have been in patients undergoing invitro fertilization. The patients are often found to have an accumulation of fluid in the endometrial canal and isthmocele during stimulation for either a fresh or frozen embryo transfer, thus necessitating the cancellation of their cycle.

Treatment

The choice of treatment depends upon the patient’s symptoms and desire for future fertility, but it can include hormonal treatment, hysteroscopic resection, transvaginal repair, a laparoscopic or robot-assisted approach, and hysterectomy.

Little has been published on nonsurgical treatment, but this may be considered for patients whose primary symptoms are bleeding or pain and who desire the least invasive option. In a small observational study of women with an isthmocele and bleeding, symptoms were eliminated with several cycles of oral contraceptive pills (Fertil. Steril. 2006;86: 477-9).

Hysteroscopic isthmocele correction or resection are the surgical techniques most frequently described in the literature, but, as with other surgical approaches, studies are small. Hysteroscopic repair has typically involved the use of electrical energy to desiccate or cauterize abnormal tissue and eliminate the outpouching in which blood and fluid accumulate. Hysteroscopic resection is another technique that has also been championed.

However, for patients who desire future pregnancy, we do not recommend a hysteroscopic approach because it does not reinforce the often-thinning myometrium covering the defect. We are concerned that if this area is simply desiccated or resected, and not reapproximated, the patient will be at greater risk of pregnancy-related complications, including cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy with potential uterine dehiscence.

Laparoscopic repair was first described by Dr. Olivier Donnez, who rightly pointed out that the laparoscopic approach offers an optimal view from above during dissection of the vesico-vaginal space. Dr. Donnez used a CO2 laser to excise fibrotic tissue, followed by laparoscopic closure (Fertil. Steril. 2008;89:974-80).

We have had success with a laparoscopic approach that uses concomitant hysteroscopy. The vesico-uterine peritoneum is incised over the anterior uterine wall, and the bladder is backfilled so that its boundaries may be identified prior to further dissection. With the area exposed, we perform a hysteroscopy to determine the exact location of the isthmocele. As the hysteroscope enters the thinned out isthmocele, the light will be more visible via laparoscopic visualization.

When performing conventional laparoscopy, the isthmocele is excised with an ultrasonic curved blade. We use this instrument because it has no opposing arm and because it enables precise tissue dissection in multiple planes. With harmonic energy, we can limit tissue dessication and destruction, lowering the risk of future pregnancy-related complications. Monopolar scissors are best when a robotic approach is used.

Once the isthmocele is resected, the clean edges are sutured together in two layers. The first layer is sutured in an interrupted mattress-style fashion, to prevent tissue strangulation and necrosis. We use a monofilament nonbarbed delayed-absorbable 3-0 PDS suture on a CT-1 needle – a choice that limits tissue trauma and postoperative inflammation.

Sutures are initially placed at each angle with one or two sutures placed between. These sutures must be placed deep to close the bottom of the defect. A second layer of suture is then placed to imbricate over the initial layer of closure. We utilize 3-0 PDS in a running or mattress style, or a running 3-0 V-Loc suture. Our patients return after 1-3 months for a postoperative image, and are instructed to wait at least 3 months after surgery before attempting conception.

In our experience, of more than 10 patients, symptoms ceased in all patients whose surgery was performed for the indication of abnormal uterine bleeding. The follow-up on our series of patients who underwent the procedure for secondary infertility is ongoing, but the preliminary results are very positive, with resolution of intrauterine fluid in all of the patients, as well as several successful pregnancy outcomes.

A recent systematic review of minimally invasive therapy for symptoms related to an isthmocele shows good outcomes across the 12 included studies but does not offer evidence to favor one treatment over another. The studies show significant reductions in abnormal uterine bleeding and pain, as well as a high rate of satisfaction in most patients after hysteroscopic niche resection or vaginal or laparoscopic niche repair, with a low complication rate (BJOG 2014;121:145-6).

Pregnancies were reported after treatment, but sample sizes and follow-up were insufficient to draw conclusions on pregnancy and delivery outcomes, according to the review. As the reviewers wrote, following patients through their next delivery in larger, higher-quality studies will help provide more guidance for selecting the best isthmocele treatments and implementing these treatments into practice.

Dr. Sasaki reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

In recent years, uterine isthmocele has increasingly been included as part of the differential in women with a history of a cesarean section who present with postmenstrual bleeding, pelvic pain, or secondary infertility.

The defect appears as a fluid-filled, pouch-like abnormality in the anterior uterine wall at the site of a prior cesarean section. The best method for diagnosis is usually a saline-infused sonogram. It can be treated in various ways, depending on the patient’s symptoms and desire for future fertility. Although we have treated isthmoceles with hysteroscopic desiccation, or resection, our best success has occurred with laparoscopic resection and reapproximation of normal tissue in a small series of patients.

There is no standard definition of the defect that fully describes its size, depth, and other characteristics. Many words and phrases have been used to describe the defect: It is commonly referred to as an isthmocele, because of its usual location at the uterine isthmus, but others have referred to it as a cesarean scar defect or niche, as the defect may be found at the endocervical canal or in the lower uterine segment. In any case, while diagnoses appear to be increasing, the incidence of the defect is unknown.

More research on risk factors and treatment is needed, but the literature, as well as our own experience, has demonstrated that this treatable defect should be considered in the differential diagnosis for women who have undergone cesarean section and subsequently have abnormal bleeding or staining, pelvic pain, or secondary infertility, especially when fluid is clearly visible in the cesarean section defect.

Diagnosis, symptoms

An isthmocele forms in the first place, it is thought, after an incision scar forms and causes retraction and dilation in the thinner, lower segment of the anterior wall and a thickening in the upper portion. There is a deficient scar, in other words, with disparate wound healing on the sides of the incision site.

The defect and its consequences were described in 1995 by Dr. Hugh Morris, who studied hysterectomy specimens in 51 women with a history of cesarean section (in most cases, more than one). Dr. Morris concluded that scar tissue in these patients contributed to significant pathological changes and anatomical abnormalities that, in turn, gave rise to a variety of clinical symptoms including menorrhagia, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and lower abdominal pain refractory to medical management.

Distortion and widening of the lower uterine segment and “free” red blood cells in endometrial stroma of the scar were the most frequently identified pathological changes, followed by fragmentation and breakdown of the endometrium of the scar, and iatrogenic adenomyosis (Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol.1995;14:16-20).

Several small reports and case series published in the late 1990s offered additional support for a cause-and-effect correlation between cesarean scar defects and abnormal vaginal bleeding. Several years later, the link was strengthened as more investigators reported connections between the defects and various symptoms. These reports were followed by published comparisons of imaging techniques for the diagnosis of isthmoceles.

Diagnosis of the defects can be made with transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS), saline infused sonohysterogram (SIS), hysterosalpingogram, hysteroscopy, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). With any modality, imaging is best performed in the early proliferative phase, right after the menstrual cycle has ended.

Comparisons of unenhanced TVUS and SIS – both of which may be easily performed in the office and at a much lower cost than MRI – have shown the latter technique to be superior for evaluating isthmoceles. Distension of the endometrial cavity makes the borders of the defects easier to delineate, which enables detection of more subtle defects and improves our ability to measure the size of defects.

This advantage was described by in 2010 by Dr. O. Vikhareva Osser and colleagues, who performed both TVUS and SIS in 108 women with a history of one or more cesarean sections. They identified more scar defects with SIS than with TVUS (Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;35:75-83).

Another benefit of SIS over TVUS and hysterosalpingogram is that one can measure the thickness of the remaining myometrium overlying the isthmocele, which is especially important knowledge for patients considering another pregnancy. As a result, we have relied on this technique to diagnose every case within our practice. I will perform SIS in a patient who has a history of one or multiple cesarean sections and symptoms of abnormal bleeding, pelvic pain, or secondary infertility as part of the basic work-up.

Similarly, an observational prospective cohort study of 225 women who had undergone a cesarean section 6-12 months prior compared TVUS and gel-infused sonohysterogram (GIS), and found that the prevalence of a niche – defined as an anechoic area at the site of the cesarean scar, with a depth of at least 1 mm on GIS – was 24% with TVUS and 56% with GIS (Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;37:93-9).

The abnormal bleeding is often described by patients as spotting or bleeding that continues for days or weeks after menstrual flow has ended; it is believed to result from an accumulation of blood in the defect and a lack of coordinated muscle contractions, which leads to continued accumulation of blood and menstrual debris. Dysmenorrhea and chronic pelvic pain are thought to be associated with iatrogenic adenomyosis and/or a chronic inflammatory state created when accumulated blood and mucus are intermittently expelled. Secondary infertility can occur, it is believed, as accumulated fluid and blood interfere with the endocervical and even the endometrial environment and disrupt sperm transport, sperm quality, and embryo implantation. Difficulty in embryo transfer may also occur because of the distortion caused to the endometrial cavity. Many of the isthmoceles that we and others have diagnosed have been in patients undergoing invitro fertilization. The patients are often found to have an accumulation of fluid in the endometrial canal and isthmocele during stimulation for either a fresh or frozen embryo transfer, thus necessitating the cancellation of their cycle.

Treatment

The choice of treatment depends upon the patient’s symptoms and desire for future fertility, but it can include hormonal treatment, hysteroscopic resection, transvaginal repair, a laparoscopic or robot-assisted approach, and hysterectomy.

Little has been published on nonsurgical treatment, but this may be considered for patients whose primary symptoms are bleeding or pain and who desire the least invasive option. In a small observational study of women with an isthmocele and bleeding, symptoms were eliminated with several cycles of oral contraceptive pills (Fertil. Steril. 2006;86: 477-9).

Hysteroscopic isthmocele correction or resection are the surgical techniques most frequently described in the literature, but, as with other surgical approaches, studies are small. Hysteroscopic repair has typically involved the use of electrical energy to desiccate or cauterize abnormal tissue and eliminate the outpouching in which blood and fluid accumulate. Hysteroscopic resection is another technique that has also been championed.

However, for patients who desire future pregnancy, we do not recommend a hysteroscopic approach because it does not reinforce the often-thinning myometrium covering the defect. We are concerned that if this area is simply desiccated or resected, and not reapproximated, the patient will be at greater risk of pregnancy-related complications, including cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy with potential uterine dehiscence.

Laparoscopic repair was first described by Dr. Olivier Donnez, who rightly pointed out that the laparoscopic approach offers an optimal view from above during dissection of the vesico-vaginal space. Dr. Donnez used a CO2 laser to excise fibrotic tissue, followed by laparoscopic closure (Fertil. Steril. 2008;89:974-80).

We have had success with a laparoscopic approach that uses concomitant hysteroscopy. The vesico-uterine peritoneum is incised over the anterior uterine wall, and the bladder is backfilled so that its boundaries may be identified prior to further dissection. With the area exposed, we perform a hysteroscopy to determine the exact location of the isthmocele. As the hysteroscope enters the thinned out isthmocele, the light will be more visible via laparoscopic visualization.

When performing conventional laparoscopy, the isthmocele is excised with an ultrasonic curved blade. We use this instrument because it has no opposing arm and because it enables precise tissue dissection in multiple planes. With harmonic energy, we can limit tissue dessication and destruction, lowering the risk of future pregnancy-related complications. Monopolar scissors are best when a robotic approach is used.

Once the isthmocele is resected, the clean edges are sutured together in two layers. The first layer is sutured in an interrupted mattress-style fashion, to prevent tissue strangulation and necrosis. We use a monofilament nonbarbed delayed-absorbable 3-0 PDS suture on a CT-1 needle – a choice that limits tissue trauma and postoperative inflammation.

Sutures are initially placed at each angle with one or two sutures placed between. These sutures must be placed deep to close the bottom of the defect. A second layer of suture is then placed to imbricate over the initial layer of closure. We utilize 3-0 PDS in a running or mattress style, or a running 3-0 V-Loc suture. Our patients return after 1-3 months for a postoperative image, and are instructed to wait at least 3 months after surgery before attempting conception.

In our experience, of more than 10 patients, symptoms ceased in all patients whose surgery was performed for the indication of abnormal uterine bleeding. The follow-up on our series of patients who underwent the procedure for secondary infertility is ongoing, but the preliminary results are very positive, with resolution of intrauterine fluid in all of the patients, as well as several successful pregnancy outcomes.

A recent systematic review of minimally invasive therapy for symptoms related to an isthmocele shows good outcomes across the 12 included studies but does not offer evidence to favor one treatment over another. The studies show significant reductions in abnormal uterine bleeding and pain, as well as a high rate of satisfaction in most patients after hysteroscopic niche resection or vaginal or laparoscopic niche repair, with a low complication rate (BJOG 2014;121:145-6).

Pregnancies were reported after treatment, but sample sizes and follow-up were insufficient to draw conclusions on pregnancy and delivery outcomes, according to the review. As the reviewers wrote, following patients through their next delivery in larger, higher-quality studies will help provide more guidance for selecting the best isthmocele treatments and implementing these treatments into practice.

Dr. Sasaki reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Using cervical length screening to predict preterm birth

One of the key indicators of a nation’s health is how well it can care for its young. Despite many advances in medical care and improvements in access to care, infant mortality remains a significant concern worldwide. According to the World Health Organization, the leading cause of death among children under age 5 is preterm birth complications. With an estimated 15 million babies born prematurely (prior to 37 weeks’ gestation) globally each year, it is vital for ob.gyns. to uncover ways to predict, diagnose early, and treat the causes of preterm birth.

While the challenges to infant health could be considered more of an issue in developing countries, here in the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 1 in 9 babies is born prematurely. Preterm birth-related causes of death (i.e., breathing and feeding problems and disabilities) accounted for 35% of all infant deaths in 2010.

The World Health Organization (WHO) lists the United States as one of the top 10 countries with the greatest number of preterm births, despite the fact that we spend approximately 17.1% of our gross domestic product in total health care expenditures – the highest rate among our peer nations.

In the April 2014 edition of Master Class, we discussed one of the primary causes of preterm birth, bacterial infections, and specifically the need for ob.gyns. to rigorously screen patients for asymptomatic bacteriuria, which can lead to pyelonephritis. This month, we examine another biologic marker of preterm birth, cervical length.

Seminal studies of transvaginal sonography to measure cervical length during pregnancy and predict premature birth were published more than 2 decades ago. This work showed that a short cervix at 24 and 28 weeks’ gestation predicted preterm birth. Since then, clinical studies have demonstrated the utility of cervical length screening in women with prior preterm pregnancies. In the last decade, three large, randomized human trials have examined the usefulness of universal cervical length screening (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;207:101-6). However, the results of these trials have given practitioners a confusing picture of the predictability of this biologic marker.

Given the complexity of the “to screen or not to screen” issue, we have devoted this Master Class to a discussion on the role of cervical length screening and the prediction of preterm birth. Our guest author this month is Dr. Erika Werner, an assistant professor in ob.gyn (maternal-fetal medicine) in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Brown University, in Providence, R.I., and an expert in the area of preterm birth.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

One of the key indicators of a nation’s health is how well it can care for its young. Despite many advances in medical care and improvements in access to care, infant mortality remains a significant concern worldwide. According to the World Health Organization, the leading cause of death among children under age 5 is preterm birth complications. With an estimated 15 million babies born prematurely (prior to 37 weeks’ gestation) globally each year, it is vital for ob.gyns. to uncover ways to predict, diagnose early, and treat the causes of preterm birth.

While the challenges to infant health could be considered more of an issue in developing countries, here in the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 1 in 9 babies is born prematurely. Preterm birth-related causes of death (i.e., breathing and feeding problems and disabilities) accounted for 35% of all infant deaths in 2010.

The World Health Organization (WHO) lists the United States as one of the top 10 countries with the greatest number of preterm births, despite the fact that we spend approximately 17.1% of our gross domestic product in total health care expenditures – the highest rate among our peer nations.

In the April 2014 edition of Master Class, we discussed one of the primary causes of preterm birth, bacterial infections, and specifically the need for ob.gyns. to rigorously screen patients for asymptomatic bacteriuria, which can lead to pyelonephritis. This month, we examine another biologic marker of preterm birth, cervical length.

Seminal studies of transvaginal sonography to measure cervical length during pregnancy and predict premature birth were published more than 2 decades ago. This work showed that a short cervix at 24 and 28 weeks’ gestation predicted preterm birth. Since then, clinical studies have demonstrated the utility of cervical length screening in women with prior preterm pregnancies. In the last decade, three large, randomized human trials have examined the usefulness of universal cervical length screening (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;207:101-6). However, the results of these trials have given practitioners a confusing picture of the predictability of this biologic marker.

Given the complexity of the “to screen or not to screen” issue, we have devoted this Master Class to a discussion on the role of cervical length screening and the prediction of preterm birth. Our guest author this month is Dr. Erika Werner, an assistant professor in ob.gyn (maternal-fetal medicine) in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Brown University, in Providence, R.I., and an expert in the area of preterm birth.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

One of the key indicators of a nation’s health is how well it can care for its young. Despite many advances in medical care and improvements in access to care, infant mortality remains a significant concern worldwide. According to the World Health Organization, the leading cause of death among children under age 5 is preterm birth complications. With an estimated 15 million babies born prematurely (prior to 37 weeks’ gestation) globally each year, it is vital for ob.gyns. to uncover ways to predict, diagnose early, and treat the causes of preterm birth.

While the challenges to infant health could be considered more of an issue in developing countries, here in the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 1 in 9 babies is born prematurely. Preterm birth-related causes of death (i.e., breathing and feeding problems and disabilities) accounted for 35% of all infant deaths in 2010.

The World Health Organization (WHO) lists the United States as one of the top 10 countries with the greatest number of preterm births, despite the fact that we spend approximately 17.1% of our gross domestic product in total health care expenditures – the highest rate among our peer nations.

In the April 2014 edition of Master Class, we discussed one of the primary causes of preterm birth, bacterial infections, and specifically the need for ob.gyns. to rigorously screen patients for asymptomatic bacteriuria, which can lead to pyelonephritis. This month, we examine another biologic marker of preterm birth, cervical length.

Seminal studies of transvaginal sonography to measure cervical length during pregnancy and predict premature birth were published more than 2 decades ago. This work showed that a short cervix at 24 and 28 weeks’ gestation predicted preterm birth. Since then, clinical studies have demonstrated the utility of cervical length screening in women with prior preterm pregnancies. In the last decade, three large, randomized human trials have examined the usefulness of universal cervical length screening (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;207:101-6). However, the results of these trials have given practitioners a confusing picture of the predictability of this biologic marker.

Given the complexity of the “to screen or not to screen” issue, we have devoted this Master Class to a discussion on the role of cervical length screening and the prediction of preterm birth. Our guest author this month is Dr. Erika Werner, an assistant professor in ob.gyn (maternal-fetal medicine) in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Brown University, in Providence, R.I., and an expert in the area of preterm birth.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

The benefits, costs of universal cervical length screening

Rates of preterm birth in the United States have been falling since 2006, but the rates of early preterm birth in singletons (those under 34 weeks’ gestation), specifically, have not trended downward as dramatically as have late preterm birth in singletons (34-36 weeks). According to 2015 data from the National Vital Statistics Reports, the rate of early preterm births is still 3.4% in all pregnancies and 2.7% among singletons.

While the number of neonates born before 37 weeks of gestation remains high – approximately 11% in 2013 – and signifies a continuing public health problem, the rate of early preterm birth is particularly concerning because early preterm birth is more significantly associated with neonatal mortality, long-term morbidity and extended neonatal intensive care unit stays, all leading to increased health care expenditures.

Finding predictors for preterm birth that are stronger than traditional clinical factors has long been a goal of ob.gyns. because the vast majority of all spontaneous preterm births occur to women without known risk factors (i.e., multiple gestations or prior preterm birth).

Cervical length in the midtrimester is now a well-verified predictor of preterm birth, for both low- and high-risk women. Furthermore, vaginal progesterone has been shown to be a safe and beneficial intervention for women with no known risk factors who are diagnosed with a shortened cervical length (< 2 cm), and cervical cerclage has been suggested to reduce the risk of preterm birth for women with a history of prior preterm birth who also have a shortened cervical length.

Some are now advocating universal cervical length screening for women with singleton gestations, but before universal screening is mandated, the downstream effect of such a change in practice must be considered.

Backdrop to screening

Cervical length measurement was first investigated more than 25 years ago as a possible predictor of preterm birth. In 1996, a prospective multicenter study of almost 3,000 women with singleton pregnancies showed that the risk of preterm delivery is inversely and directly related to the length of the cervix, as measured with vaginal ultrasonography (N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;334:567-72).

In fact, at 24 weeks’ gestation, every 1 mm of additional cervical length equates to a significant decrease in preterm birth risk (odds ratio, 0.91). Several other studies, in addition to the landmark 1996 study, have similarly demonstrated this inverse relationship between preterm birth risk and cervical length between 18 and 24 weeks’ gestation.

However, the use of cervical measurement did not achieve widespread use until more than a decade later, when researchers began to identify interventions that could prolong pregnancy if a short cervix was diagnosed in the second trimester.

For example, Dr. E.B. Fonseca’s study of almost 25,000 asymptomatic pregnant women, demonstrated that daily vaginal progesterone reduced the risk of spontaneous delivery before 34 weeks by approximately 44% in women identified with a cervical length of 1.5 cm or less (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:462-9). The vast majority of the women in this study had singleton pregnancies.

Shortly thereafter, Dr. S.S. Hassan and her colleagues completed a similar trial in women with singleton gestations and transvaginal cervical lengths between 1.0 and 2.0 cm at 20-23 weeks’ gestation. In this trial, nightly progesterone gel (with 90 mg progesterone per application) was associated with a 45% reduction in preterm birth before 33 weeks and a 38% reduction in preterm birth before 35 weeks (Ultrasound. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;38:18-31).

A meta-analysis led by Dr. Roberto Romero, which included the Fonseca and Hassan trials, looked specifically at 775 women with a midtrimester cervical length of 2.5 cm or less. Women with a singleton gestation who had no history of preterm birth had a 40% reduction in the rate of early preterm birth when they were treated with vaginal progesterone (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;206:124-e1-19).

The benefits of identifying a short cervix likely extend to women with a history of prior preterm birth. A patient-level meta-analysis published in 2011 demonstrated that cervical cerclage placement was associated with a significant reduction in preterm birth before 35 weeks’ gestation in women with singleton gestations, previous spontaneous preterm birth, and cervical length less than 2.5 cm before 24 weeks’ gestation (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;117:663-71).

The possible benefits of diagnosing and intervening for a shortened cervix have tipped many experts and clinicians toward the practice of universal cervical length screening of all singleton pregnancies. Research has shown that we can accurately obtain a cervical-length measurement before 24 weeks, and that we have effective and safe interventions for cases of short cervix: cerclage in women with a history of preterm birth who are already receiving progesterone, and vaginal progesterone in women without such a history.

Screening certainties and doubts

In 2011, my colleagues and I compared the cost effectiveness of two approaches to preterm birth prevention in low-risk pregnancies: no screening versus a single transvaginal ultrasound cervical-length measurement in all asymptomatic, low-risk singleton pregnant individuals between 18 and 24 weeks’ gestation.

In our model, women identified as having a cervical length less than 1.5 cm would be offered vaginal progesterone. Based on published data, we assumed there would be a 92% adherence rate, and a 45% reduction in deliveries before 34 weeks with progesterone treatment.

We found that in low-risk pregnancies, universal transvaginal cervical-length ultrasound screening and progesterone intervention would be cost effective and in many cases cost saving. We estimated that screening would prevent 248 early preterm births – as well as 22 neonatal deaths or neonates with long-term neurologic deficits – per 100,000 deliveries.

Our sensitivity analyses showed that screening remained cost saving under a range of clinical scenarios, including varied preterm birth rates and predictive values of a shortened cervix. Screening was not cost saving, but remained cost effective, when the expense of a transvaginal ultrasound scan exceeds $187 or when vaginal progesterone is assumed to reduce the risk of early preterm delivery by less than 20% (Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;38;32-37).

Neither the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists nor the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine support mandated universal transvaginal ultrasound cervical length screening. Both organizations state, however, that the approach may be considered in women with singleton gestations without prior spontaneous preterm birth.

Interestingly, Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, which uses a universal screening program for singleton gestations without prior preterm birth, has recently published data that complicate the growing trend toward universal cervical length screening.

The Philadelphia clinicians followed a strategy whereby women with a transvaginal cervical length of 2 cm or less were prescribed vaginal progesterone (90 mg vaginal progesterone gel, or 200 mg micronized progesterone gel capsules). Those with a cervical length between approximately 2 cm and 2.5 cm were asked to return for a follow-up cervical length measurement before 24 weeks’ gestation.

What they found in this cohort was surprising: a rate of short cervix that is significantly lower than what previous research has shown.

Among those screened, 0.8% of women had a cervical length of 2 cm or less on an initial transvaginal ultrasonogram. Previously, a prevalence of 1%-2% for an even shorter cervical length (less than 1.5 cm) was fairly consistent in the literature.

As Dr. Kelly M. Orzechowski and her colleagues point out, the low incidence of short cervix “raises questions regarding whether universal transvaginal ultrasonogram cervical length screening in low-risk asymptomatic women is beneficial” (Obstet. Gynecol. 2014;124:520-5).

In our 2011 cost-effectiveness analysis, we found that screening was no longer a cost-saving practice when the incidence of cervical length less than 1.5 cm falls below 0.8%. Screening remained cost effective, however.

Recently, we found that if the Philadelphia protocol is followed and the U.S. population has an incidence of shortened cervix similar to that described by Dr. Orzechowski and her colleagues, universal cervical length screening in low-risk singleton pregnancies is cost effective but not cost saving. Furthermore, we found several additional plausible situations in this unpublished analysis in which universal screening ceased to be cost effective.

Thus, before we move to a strategy of mandated universal screening, we need better population-based estimates of the incidence of short cervix in a truly low-risk population.

We also must consider the future costs of progesterone. It is possible that costs may increase significantly if vaginal progesterone wins approval from the Food and Drug Administration for this indication.

Finally, if universal cervical length screening is to become the standard of care, we need policies in place to prevent misuse of the screening technology that would inevitably drive up costs without improving outcomes. For example, we must ensure that one cervical length measurement does not transition into serial cervical length measurements over the course of pregnancy, since measurement after 24 weeks has limited clinical utility. Similarly, progesterone use for a cervical length less than or equal to 2.0 cm cannot progress to progesterone for anyone approaching 2.0 cm (i.e. 2.5 cm or even 3 cm) as there is no evidence to suggest a benefit for women with longer cervixes.

Over time, it would be beneficial to have additional data on how best to manage patients who have a cervical length of 2 cm-2.5 cm before 24 weeks’ gestation. Many of us ask these women to return for a follow-up measurement and some may prescribe progesterone. However, we lack evidence for either approach; while a cervical length measurement less than 2.5 cm is clearly associated with an increased risk of preterm birth, the benefit of treatment has been demonstrated only with a cervical length of 2 cm or less.

Today and the future

For women with a history of preterm birth, cervical length screening is now routine. For low-risk pregnant women – those without a history of previous spontaneous preterm delivery – various approaches are currently taken. Most physicians recommend assessing the cervical length transabdominally at the time of the 18-20-week ultrasound, and proceeding to transvaginal ultrasonography if the cervical length is less than 3 cm or 3.5 cm.

To reliably image the cervix with transabdominal ultrasound, it should be performed with a full bladder and with the understanding that the cervix appears longer (6 mm longer, on average) when the bladder is full (Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2014;54:250-55).

Transvaginal ultrasound has been widely recognized as a sensitive and reproducible method for detecting shortened cervical length. Overall, this tool has several advantages over the transabdominal approach. However, the lack of universal access to transvaginal ultrasound and to consistently reliable cervical length measurements have been valid concerns of those who oppose universal transvaginal ultrasound cervical length screening.

Such concerns likely will lessen over time as transvaginal ultrasound continues to become more pervasive. Several years ago, the Perinatal Quality Foundation set standards for measuring the cervix and launched the Cervical Length Education and Review (CLEAR) program. When sonographers and physicians obtain training and credentialing, there appears to be only a 5%-10% intraobserver variability in cervical length measurement. (The PQF’s initial focus in 2005 was the Nuchal Translucency Quality Review program.)

Increasingly, I believe, transvaginal ultrasound cervical length measurement will be utilized to identify women at high risk for early preterm birth so that low-risk women can receive progesterone and high-risk women (those with a history of preterm birth) can be considered as candidates for cerclage placement. In the process, the quality of clinical care as well as the quality of our research data will improve. Whether and when such screening will become universal, however, is still uncertain.

Dr. Werner reported that she has no financial disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Rates of preterm birth in the United States have been falling since 2006, but the rates of early preterm birth in singletons (those under 34 weeks’ gestation), specifically, have not trended downward as dramatically as have late preterm birth in singletons (34-36 weeks). According to 2015 data from the National Vital Statistics Reports, the rate of early preterm births is still 3.4% in all pregnancies and 2.7% among singletons.

While the number of neonates born before 37 weeks of gestation remains high – approximately 11% in 2013 – and signifies a continuing public health problem, the rate of early preterm birth is particularly concerning because early preterm birth is more significantly associated with neonatal mortality, long-term morbidity and extended neonatal intensive care unit stays, all leading to increased health care expenditures.

Finding predictors for preterm birth that are stronger than traditional clinical factors has long been a goal of ob.gyns. because the vast majority of all spontaneous preterm births occur to women without known risk factors (i.e., multiple gestations or prior preterm birth).

Cervical length in the midtrimester is now a well-verified predictor of preterm birth, for both low- and high-risk women. Furthermore, vaginal progesterone has been shown to be a safe and beneficial intervention for women with no known risk factors who are diagnosed with a shortened cervical length (< 2 cm), and cervical cerclage has been suggested to reduce the risk of preterm birth for women with a history of prior preterm birth who also have a shortened cervical length.

Some are now advocating universal cervical length screening for women with singleton gestations, but before universal screening is mandated, the downstream effect of such a change in practice must be considered.

Backdrop to screening

Cervical length measurement was first investigated more than 25 years ago as a possible predictor of preterm birth. In 1996, a prospective multicenter study of almost 3,000 women with singleton pregnancies showed that the risk of preterm delivery is inversely and directly related to the length of the cervix, as measured with vaginal ultrasonography (N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;334:567-72).

In fact, at 24 weeks’ gestation, every 1 mm of additional cervical length equates to a significant decrease in preterm birth risk (odds ratio, 0.91). Several other studies, in addition to the landmark 1996 study, have similarly demonstrated this inverse relationship between preterm birth risk and cervical length between 18 and 24 weeks’ gestation.

However, the use of cervical measurement did not achieve widespread use until more than a decade later, when researchers began to identify interventions that could prolong pregnancy if a short cervix was diagnosed in the second trimester.

For example, Dr. E.B. Fonseca’s study of almost 25,000 asymptomatic pregnant women, demonstrated that daily vaginal progesterone reduced the risk of spontaneous delivery before 34 weeks by approximately 44% in women identified with a cervical length of 1.5 cm or less (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:462-9). The vast majority of the women in this study had singleton pregnancies.

Shortly thereafter, Dr. S.S. Hassan and her colleagues completed a similar trial in women with singleton gestations and transvaginal cervical lengths between 1.0 and 2.0 cm at 20-23 weeks’ gestation. In this trial, nightly progesterone gel (with 90 mg progesterone per application) was associated with a 45% reduction in preterm birth before 33 weeks and a 38% reduction in preterm birth before 35 weeks (Ultrasound. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;38:18-31).

A meta-analysis led by Dr. Roberto Romero, which included the Fonseca and Hassan trials, looked specifically at 775 women with a midtrimester cervical length of 2.5 cm or less. Women with a singleton gestation who had no history of preterm birth had a 40% reduction in the rate of early preterm birth when they were treated with vaginal progesterone (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;206:124-e1-19).

The benefits of identifying a short cervix likely extend to women with a history of prior preterm birth. A patient-level meta-analysis published in 2011 demonstrated that cervical cerclage placement was associated with a significant reduction in preterm birth before 35 weeks’ gestation in women with singleton gestations, previous spontaneous preterm birth, and cervical length less than 2.5 cm before 24 weeks’ gestation (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;117:663-71).

The possible benefits of diagnosing and intervening for a shortened cervix have tipped many experts and clinicians toward the practice of universal cervical length screening of all singleton pregnancies. Research has shown that we can accurately obtain a cervical-length measurement before 24 weeks, and that we have effective and safe interventions for cases of short cervix: cerclage in women with a history of preterm birth who are already receiving progesterone, and vaginal progesterone in women without such a history.

Screening certainties and doubts

In 2011, my colleagues and I compared the cost effectiveness of two approaches to preterm birth prevention in low-risk pregnancies: no screening versus a single transvaginal ultrasound cervical-length measurement in all asymptomatic, low-risk singleton pregnant individuals between 18 and 24 weeks’ gestation.

In our model, women identified as having a cervical length less than 1.5 cm would be offered vaginal progesterone. Based on published data, we assumed there would be a 92% adherence rate, and a 45% reduction in deliveries before 34 weeks with progesterone treatment.

We found that in low-risk pregnancies, universal transvaginal cervical-length ultrasound screening and progesterone intervention would be cost effective and in many cases cost saving. We estimated that screening would prevent 248 early preterm births – as well as 22 neonatal deaths or neonates with long-term neurologic deficits – per 100,000 deliveries.

Our sensitivity analyses showed that screening remained cost saving under a range of clinical scenarios, including varied preterm birth rates and predictive values of a shortened cervix. Screening was not cost saving, but remained cost effective, when the expense of a transvaginal ultrasound scan exceeds $187 or when vaginal progesterone is assumed to reduce the risk of early preterm delivery by less than 20% (Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;38;32-37).

Neither the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists nor the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine support mandated universal transvaginal ultrasound cervical length screening. Both organizations state, however, that the approach may be considered in women with singleton gestations without prior spontaneous preterm birth.

Interestingly, Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, which uses a universal screening program for singleton gestations without prior preterm birth, has recently published data that complicate the growing trend toward universal cervical length screening.

The Philadelphia clinicians followed a strategy whereby women with a transvaginal cervical length of 2 cm or less were prescribed vaginal progesterone (90 mg vaginal progesterone gel, or 200 mg micronized progesterone gel capsules). Those with a cervical length between approximately 2 cm and 2.5 cm were asked to return for a follow-up cervical length measurement before 24 weeks’ gestation.

What they found in this cohort was surprising: a rate of short cervix that is significantly lower than what previous research has shown.

Among those screened, 0.8% of women had a cervical length of 2 cm or less on an initial transvaginal ultrasonogram. Previously, a prevalence of 1%-2% for an even shorter cervical length (less than 1.5 cm) was fairly consistent in the literature.

As Dr. Kelly M. Orzechowski and her colleagues point out, the low incidence of short cervix “raises questions regarding whether universal transvaginal ultrasonogram cervical length screening in low-risk asymptomatic women is beneficial” (Obstet. Gynecol. 2014;124:520-5).

In our 2011 cost-effectiveness analysis, we found that screening was no longer a cost-saving practice when the incidence of cervical length less than 1.5 cm falls below 0.8%. Screening remained cost effective, however.

Recently, we found that if the Philadelphia protocol is followed and the U.S. population has an incidence of shortened cervix similar to that described by Dr. Orzechowski and her colleagues, universal cervical length screening in low-risk singleton pregnancies is cost effective but not cost saving. Furthermore, we found several additional plausible situations in this unpublished analysis in which universal screening ceased to be cost effective.

Thus, before we move to a strategy of mandated universal screening, we need better population-based estimates of the incidence of short cervix in a truly low-risk population.

We also must consider the future costs of progesterone. It is possible that costs may increase significantly if vaginal progesterone wins approval from the Food and Drug Administration for this indication.

Finally, if universal cervical length screening is to become the standard of care, we need policies in place to prevent misuse of the screening technology that would inevitably drive up costs without improving outcomes. For example, we must ensure that one cervical length measurement does not transition into serial cervical length measurements over the course of pregnancy, since measurement after 24 weeks has limited clinical utility. Similarly, progesterone use for a cervical length less than or equal to 2.0 cm cannot progress to progesterone for anyone approaching 2.0 cm (i.e. 2.5 cm or even 3 cm) as there is no evidence to suggest a benefit for women with longer cervixes.

Over time, it would be beneficial to have additional data on how best to manage patients who have a cervical length of 2 cm-2.5 cm before 24 weeks’ gestation. Many of us ask these women to return for a follow-up measurement and some may prescribe progesterone. However, we lack evidence for either approach; while a cervical length measurement less than 2.5 cm is clearly associated with an increased risk of preterm birth, the benefit of treatment has been demonstrated only with a cervical length of 2 cm or less.

Today and the future

For women with a history of preterm birth, cervical length screening is now routine. For low-risk pregnant women – those without a history of previous spontaneous preterm delivery – various approaches are currently taken. Most physicians recommend assessing the cervical length transabdominally at the time of the 18-20-week ultrasound, and proceeding to transvaginal ultrasonography if the cervical length is less than 3 cm or 3.5 cm.

To reliably image the cervix with transabdominal ultrasound, it should be performed with a full bladder and with the understanding that the cervix appears longer (6 mm longer, on average) when the bladder is full (Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2014;54:250-55).

Transvaginal ultrasound has been widely recognized as a sensitive and reproducible method for detecting shortened cervical length. Overall, this tool has several advantages over the transabdominal approach. However, the lack of universal access to transvaginal ultrasound and to consistently reliable cervical length measurements have been valid concerns of those who oppose universal transvaginal ultrasound cervical length screening.

Such concerns likely will lessen over time as transvaginal ultrasound continues to become more pervasive. Several years ago, the Perinatal Quality Foundation set standards for measuring the cervix and launched the Cervical Length Education and Review (CLEAR) program. When sonographers and physicians obtain training and credentialing, there appears to be only a 5%-10% intraobserver variability in cervical length measurement. (The PQF’s initial focus in 2005 was the Nuchal Translucency Quality Review program.)

Increasingly, I believe, transvaginal ultrasound cervical length measurement will be utilized to identify women at high risk for early preterm birth so that low-risk women can receive progesterone and high-risk women (those with a history of preterm birth) can be considered as candidates for cerclage placement. In the process, the quality of clinical care as well as the quality of our research data will improve. Whether and when such screening will become universal, however, is still uncertain.

Dr. Werner reported that she has no financial disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Rates of preterm birth in the United States have been falling since 2006, but the rates of early preterm birth in singletons (those under 34 weeks’ gestation), specifically, have not trended downward as dramatically as have late preterm birth in singletons (34-36 weeks). According to 2015 data from the National Vital Statistics Reports, the rate of early preterm births is still 3.4% in all pregnancies and 2.7% among singletons.

While the number of neonates born before 37 weeks of gestation remains high – approximately 11% in 2013 – and signifies a continuing public health problem, the rate of early preterm birth is particularly concerning because early preterm birth is more significantly associated with neonatal mortality, long-term morbidity and extended neonatal intensive care unit stays, all leading to increased health care expenditures.

Finding predictors for preterm birth that are stronger than traditional clinical factors has long been a goal of ob.gyns. because the vast majority of all spontaneous preterm births occur to women without known risk factors (i.e., multiple gestations or prior preterm birth).

Cervical length in the midtrimester is now a well-verified predictor of preterm birth, for both low- and high-risk women. Furthermore, vaginal progesterone has been shown to be a safe and beneficial intervention for women with no known risk factors who are diagnosed with a shortened cervical length (< 2 cm), and cervical cerclage has been suggested to reduce the risk of preterm birth for women with a history of prior preterm birth who also have a shortened cervical length.

Some are now advocating universal cervical length screening for women with singleton gestations, but before universal screening is mandated, the downstream effect of such a change in practice must be considered.

Backdrop to screening

Cervical length measurement was first investigated more than 25 years ago as a possible predictor of preterm birth. In 1996, a prospective multicenter study of almost 3,000 women with singleton pregnancies showed that the risk of preterm delivery is inversely and directly related to the length of the cervix, as measured with vaginal ultrasonography (N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;334:567-72).

In fact, at 24 weeks’ gestation, every 1 mm of additional cervical length equates to a significant decrease in preterm birth risk (odds ratio, 0.91). Several other studies, in addition to the landmark 1996 study, have similarly demonstrated this inverse relationship between preterm birth risk and cervical length between 18 and 24 weeks’ gestation.

However, the use of cervical measurement did not achieve widespread use until more than a decade later, when researchers began to identify interventions that could prolong pregnancy if a short cervix was diagnosed in the second trimester.

For example, Dr. E.B. Fonseca’s study of almost 25,000 asymptomatic pregnant women, demonstrated that daily vaginal progesterone reduced the risk of spontaneous delivery before 34 weeks by approximately 44% in women identified with a cervical length of 1.5 cm or less (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:462-9). The vast majority of the women in this study had singleton pregnancies.

Shortly thereafter, Dr. S.S. Hassan and her colleagues completed a similar trial in women with singleton gestations and transvaginal cervical lengths between 1.0 and 2.0 cm at 20-23 weeks’ gestation. In this trial, nightly progesterone gel (with 90 mg progesterone per application) was associated with a 45% reduction in preterm birth before 33 weeks and a 38% reduction in preterm birth before 35 weeks (Ultrasound. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;38:18-31).

A meta-analysis led by Dr. Roberto Romero, which included the Fonseca and Hassan trials, looked specifically at 775 women with a midtrimester cervical length of 2.5 cm or less. Women with a singleton gestation who had no history of preterm birth had a 40% reduction in the rate of early preterm birth when they were treated with vaginal progesterone (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;206:124-e1-19).

The benefits of identifying a short cervix likely extend to women with a history of prior preterm birth. A patient-level meta-analysis published in 2011 demonstrated that cervical cerclage placement was associated with a significant reduction in preterm birth before 35 weeks’ gestation in women with singleton gestations, previous spontaneous preterm birth, and cervical length less than 2.5 cm before 24 weeks’ gestation (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;117:663-71).

The possible benefits of diagnosing and intervening for a shortened cervix have tipped many experts and clinicians toward the practice of universal cervical length screening of all singleton pregnancies. Research has shown that we can accurately obtain a cervical-length measurement before 24 weeks, and that we have effective and safe interventions for cases of short cervix: cerclage in women with a history of preterm birth who are already receiving progesterone, and vaginal progesterone in women without such a history.

Screening certainties and doubts

In 2011, my colleagues and I compared the cost effectiveness of two approaches to preterm birth prevention in low-risk pregnancies: no screening versus a single transvaginal ultrasound cervical-length measurement in all asymptomatic, low-risk singleton pregnant individuals between 18 and 24 weeks’ gestation.

In our model, women identified as having a cervical length less than 1.5 cm would be offered vaginal progesterone. Based on published data, we assumed there would be a 92% adherence rate, and a 45% reduction in deliveries before 34 weeks with progesterone treatment.

We found that in low-risk pregnancies, universal transvaginal cervical-length ultrasound screening and progesterone intervention would be cost effective and in many cases cost saving. We estimated that screening would prevent 248 early preterm births – as well as 22 neonatal deaths or neonates with long-term neurologic deficits – per 100,000 deliveries.

Our sensitivity analyses showed that screening remained cost saving under a range of clinical scenarios, including varied preterm birth rates and predictive values of a shortened cervix. Screening was not cost saving, but remained cost effective, when the expense of a transvaginal ultrasound scan exceeds $187 or when vaginal progesterone is assumed to reduce the risk of early preterm delivery by less than 20% (Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;38;32-37).

Neither the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists nor the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine support mandated universal transvaginal ultrasound cervical length screening. Both organizations state, however, that the approach may be considered in women with singleton gestations without prior spontaneous preterm birth.

Interestingly, Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, which uses a universal screening program for singleton gestations without prior preterm birth, has recently published data that complicate the growing trend toward universal cervical length screening.

The Philadelphia clinicians followed a strategy whereby women with a transvaginal cervical length of 2 cm or less were prescribed vaginal progesterone (90 mg vaginal progesterone gel, or 200 mg micronized progesterone gel capsules). Those with a cervical length between approximately 2 cm and 2.5 cm were asked to return for a follow-up cervical length measurement before 24 weeks’ gestation.

What they found in this cohort was surprising: a rate of short cervix that is significantly lower than what previous research has shown.

Among those screened, 0.8% of women had a cervical length of 2 cm or less on an initial transvaginal ultrasonogram. Previously, a prevalence of 1%-2% for an even shorter cervical length (less than 1.5 cm) was fairly consistent in the literature.

As Dr. Kelly M. Orzechowski and her colleagues point out, the low incidence of short cervix “raises questions regarding whether universal transvaginal ultrasonogram cervical length screening in low-risk asymptomatic women is beneficial” (Obstet. Gynecol. 2014;124:520-5).

In our 2011 cost-effectiveness analysis, we found that screening was no longer a cost-saving practice when the incidence of cervical length less than 1.5 cm falls below 0.8%. Screening remained cost effective, however.

Recently, we found that if the Philadelphia protocol is followed and the U.S. population has an incidence of shortened cervix similar to that described by Dr. Orzechowski and her colleagues, universal cervical length screening in low-risk singleton pregnancies is cost effective but not cost saving. Furthermore, we found several additional plausible situations in this unpublished analysis in which universal screening ceased to be cost effective.

Thus, before we move to a strategy of mandated universal screening, we need better population-based estimates of the incidence of short cervix in a truly low-risk population.

We also must consider the future costs of progesterone. It is possible that costs may increase significantly if vaginal progesterone wins approval from the Food and Drug Administration for this indication.

Finally, if universal cervical length screening is to become the standard of care, we need policies in place to prevent misuse of the screening technology that would inevitably drive up costs without improving outcomes. For example, we must ensure that one cervical length measurement does not transition into serial cervical length measurements over the course of pregnancy, since measurement after 24 weeks has limited clinical utility. Similarly, progesterone use for a cervical length less than or equal to 2.0 cm cannot progress to progesterone for anyone approaching 2.0 cm (i.e. 2.5 cm or even 3 cm) as there is no evidence to suggest a benefit for women with longer cervixes.

Over time, it would be beneficial to have additional data on how best to manage patients who have a cervical length of 2 cm-2.5 cm before 24 weeks’ gestation. Many of us ask these women to return for a follow-up measurement and some may prescribe progesterone. However, we lack evidence for either approach; while a cervical length measurement less than 2.5 cm is clearly associated with an increased risk of preterm birth, the benefit of treatment has been demonstrated only with a cervical length of 2 cm or less.

Today and the future