User login

Developments and issues in prenatal screening and diagnosis

Prenatal assessments for major chromosomal abnormalities have, like a pendulum, swung over the last 50 years between advancements in screening tests and diagnostic procedures.

In the 1960s, screening for advanced maternal age gave way to diagnostic amniocentesis. Maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein screening for neural tube defects came on the scene in the 1970s, and Down syndrome screening and chorionic villus sampling (CVS) followed in the 1980s. Better ultrasound screening markers were used in combination with biochemistry to advance first-trimester screening in the 1990s and 2000s, leading to a significant decline in diagnostic procedures. Now, free fetal DNA measurement, known as noninvasive prenatal screening, or NIPS, has entered the scene. This development, along with advances in the accuracy of diagnostic lab testing through microarray analysis, will soon lead the pendulum to swing back toward more definitive diagnostic procedures that require either CVS or amniocentesis.

Screening tests provide us with odds adjustments, not definitive answers, and are meant for everyone. Diagnostic tests are meant to give us definitive answers, may have risks, and therefore have traditionally been done on "at-risk" patients. Fundamentally, a screening test gives us an impression, while a diagnostic test gives us harsh reality. As always, there will be trade-offs. No approach is perfect, and no one size fits everyone.

Risks beyond Down syndrome

During the prenatal period, patients will often say, "I’m concerned about having a baby with Down syndrome." What they really mean is that they’re concerned about having a baby with a serious problem, and Down syndrome is the name they know.

Serious problems – a Mendelian disorder, a multifactorial disorder, or a major chromosomal abnormality – affect 2%-3% of all births. Less serious chromosomal abnormalities affect 5%-6% of births. Although advanced maternal age is no longer the sole criterion for deciding who should be offered diagnostic testing, age still is a principal factor for risk determination.

At age 35, the chance of having a baby with Down syndrome is 1 in 380, but the chance of having any chromosomal abnormality detectable by karyotype is 1 in 190. For a 30-year-old, the chance of having a baby with any chromosomal abnormality is 1 in 380, and for a 40-year-old, the risk is 1 in 65.

With the first-trimester screening approach that combines maternal serum free beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (free beta-HCG) and pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) with fetal nuchal translucency measurement, we are able to detect upward of 85% of fetuses with Down syndrome, or trisomy 21. Yet the disorder is only one of a large number of chromosomal abnormalities observed.

In a recent single-center study of more than 20,000 first-trimester screenings, 5.6% were positive for Down syndrome risk. Of those who subsequently had an amniocentesis or CVS, we found 4% had an abnormal karyotype. Interestingly, 40% of the time the abnormality was not Down syndrome, but another chromosomal abnormality. Similar analyses for trisomies 13 and 18 – the other major abnormalities targeted in first-trimester combined screening – yielded similar statistics (Prenat. Diagn. 2013;33:251-6).

All told, of the screen-positive pregnancies found to have an abnormal karyotype, at least 30% had chromosomal abnormalities outside of those for which they were screen positive. Such findings speak to the limitations of screening as opposed to diagnostic testing, and have implications for patient counseling. Patients should be counseled about the possibility of all chromosome abnormalities – not just Down syndrome.

The NIPS rollout

We have known for well over 100 years that fetal cells cross the placental barrier in small numbers, driving the development of what’s currently known as NIPS. The future of NIPS actually lies in an ever-expanding number of disorders, and will eventually end with sequencing the entire genome.

There are two main methods by which NIPS is done. The original and predominant method uses massive parallel shotgun sequencing, known as next-generation sequencing. This method involves whole-genome amplification and collects enormous amounts of information. Investigators are now attempting to direct amplification at the subchromosome level, mimicking some of what microarray analysis can do.

The second approach uses selected probes, or targeted sequencing, to focus on those sections of DNA that are of interest. Although this method may be cheaper in the short run, one drawback is that new probes will need to be created for each new disorder.

Initially, investigators attempted to isolate nucleated fetal cells from the maternal blood and use them for aneuploidy detection. However, a National Institutes of Health–funded fetal-cell isolation study that ended in 2002 reported disappointing results: Fetal-cell isolation methods had low sensitivity and other technological shortcomings. Subsequently, a number of companies attempted to replicate and improve the work, also without much success.

Concurrent with efforts to use fetal-cell isolation to perform NIPS was the discovery, in the late 1990s by Dr. Dennis Lo, upon whose work next-generation sequencing for NIPS is based, of the presence of circulating cell-free fetal DNA in maternal plasma. The concentration of cell-free fetal DNA may be as much as 5%-8% of the total circulating cell-free DNA in maternal plasma, making free fetal DNA a promising source of fetal genetic material for noninvasive prenatal investigation.

The first high-quality trials on the use of free fetal DNA measurement for detection of trisomy 21 were published in the fall of 2011, and demonstrated up to a 99% detection rate for Down syndrome (less for trisomies 18 and 13). Companies subsequently began to manufacture free fetal DNA tests as off-label products, The tests were initially designated as "noninvasive prenatal diagnosis" tools, but experts around the world objected to the "diagnosis" label, and the terminology shifted to "noninvasive prenatal testing" and finally to "noninvasive prenatal screening"– a designation that I believe accurately reflects its current role.

The uptake in utilization of NIPS has been faster than anyone could have predicted: In just over 2 years, several hundred thousand screening tests have been performed. With 98% to 99% sensitivity, NIPS is an excellent screening test for Down syndrome. However, 99% sensitivity does not equate to 99% positive predictive value, that is, the risk that a patient with a positive screen actually has Down syndrome is much lower.

The published studies of NIPS cite false positive rates of 0.2%-1.0%, but this rate will increase as more disorders are screened. Positive predictive value is directly proportional to the underlying risk. For example, a test with 99% sensitivity and 99% specificity (1% false positive rate) means that a 26-year-old woman who has a positive free fetal DNA test actually has as low as an 11% chance of having a baby with Down syndrome. In older women, who have a higher incidence of having a baby with Down syndrome, a positive NIPS result will have a higher positive predictive value of giving birth to a baby with Down syndrome. However, at the current time, NIPS is an excellent screening test for Down syndrome, but it is not ready for universal primary screening in younger women.

Falsely reassuring are the hyped marketing claims in the United States that NIPS "replaces amnio" and eliminates the need for a nuchal translucency (NT) test. When clinicians abandon performing or referring for a high-quality NT measurement, they can miss or significantly delay the diagnosis of twins/zygosity, growth abnormalities and placentation, cardiac defects, and numerous other anomalies. Similarly, when patients who otherwise would have opted to have CVS or amniocentesis forego having the procedure and have NIPS performed instead, they may regret this decision.

The danger that overreliance on screening tests may paradoxically increase the number of births of babies with otherwise detectable problems was raised in a study led by the late Dr. George Henry, an obstetrician-geneticist in Denver. Curious about declining rates of diagnostic testing in his own practice, Dr. Henry examined trends in his state and found that while the utilization of diagnostic tests had plummeted by 70% over about 15 years, the birth rate of babies born with Down syndrome during this time had doubled among mothers over age 35, and stayed the same among mothers under age 35.

A sociologist-researcher examined the trend that Dr. Henry identified and found that the rise in Down syndrome births was not due to an increase in women electing to keep these pregnancies, but to the fact that the abnormality was not detected in the first place (Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2008;23:308-15). The same risk of screening tests replacing definitive diagnosis exists today with the uptake of NIPS.

The impact of microarray

Microarray technologies have been developed over the past decade. The National Institutes of Health study on chromosomal microarray versus karyotyping, published a year ago, is a game changer. The microarray is analogous to a 15-fold magnifying glass on the karyotype. While the smallest piece of a chromosome that can be evaluated by karyotype analysis is about 5 million base pairs, microarray analysis zooms in on about 200,000 base pairs, allowing us to see small genomic deletions and duplications (copy number variants) that we’ve never seen before.

The trial looked at upward of 4,000 women undergoing CVS or amniocentesis at one of 29 centers. Each diagnostic sample was split in two, with standard karyotyping performed on one portion and chromosomal microarray on the other (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:2175-84).

There were several significant findings: One is that almost one-third of patients have a copy variation now known to be benign. Another is that 2.5% of women who had ultrasound-identified anomalies and normal karyotypes had microdeletion/duplications on the microarray that were clearly associated with a known clinical problem. Moreover, another 3.2% had gains and losses of potential clinical significance. As such, close to 6% of women with ultrasound-identified anomalies and a normal karyotype had clinically relevant copy number variants that only the microarray could find.

When microarray analysis was performed in women whose only indication for prenatal diagnosis was advanced age or an abnormal result on Down syndrome screening, as opposed to an ultrasound-detected anomaly, 0.5%, or 1 in 200, were found to have a pathogenic abnormality that otherwise would have been missed. This is significant: Previously, with karyotyping, we quoted patients a minimum of 1/500 risk of finding a clinically relevant chromosomal anomaly even if the combined report suggested much lower risks of Down syndrome. Now, with microarray, that risk is 1/200. Other studies already published or about to be published show this same level of risk determined by microarray.

With any new technological advance, we get our numerators of the problem before our denominators. The first cases published are those in which clinical or laboratory findings are associated with an abnormality. Only then do researchers go back and look at cases with those findings to test these associations – and only then are the markers sometimes found not to be associated. It will take a number of years to acquire a sizable database on microarray-detected copy number variants. In the end, microarray may help us to explain many of the approximately 1% of serious problems that we have been unable to diagnose until now.

Current decision-making

Ultimately, the future lies with routine, complete genomic sequencing that provides a detailed view of the fetal genome. This is likely to be about 7-10 years away, and the main question on the table is whether it will be performed invasively or with a maternal blood sample.

Today, when a 35-year-old woman comes into my office early in her pregnancy, I will tell her that the risk of having a baby with a chromosomal abnormality is 1 in 190. If she wants to know more, I will explain that the second-trimester quad screen will detect 60% of Down syndrome cases, that the first-trimester combined screen can identify 85% or more, and that the free fetal DNA test will get closer to 99%.

Despite the significant advances in screening, all of these options are still the fundamental equivalent of a Gallup poll. If the patient wants a definitive answer, she will need either an amniocentesis or a CVS, which, in experienced hands, have been shown through an increasing number of studies to be of equal risk. Because there is no such thing as "no" risk when it comes to prenatal diagnostic testing, the question that each patient must answer is, "Where do you want to put that risk – in the test or gambling on the outcome?"

We also have a great cultural divide in the United States. Some people want to know everything, others want to know nothing. Our affluent patients are getting older. Our poorer patients are getting younger. Some people will pay whatever it takes to get the answers they want, while others can or will not pay a dime beyond what their insurance will cover.

There is no one algorithm that can handle these two extremes of patients. Right now, many programs around the country have seen a diminishing number of patients having diagnostic testing – a phenomenon I believe is the result of a false sense of confidence, of people being lulled by the faulty argument that screening protocols can find Down syndrome, so what else is there to know?

Ultimately, a model for younger women would start with "contingent screening," in which patients could start with first-trimester combined screening and move straight to CVS if found to be at "high risk," and end testing if found to be at "low risk." Women who fall in the middle could undergo either free fetal DNA analysis or CVS, and we are developing methods to improve the mathematical processing of data to improve the sensitivity and specificity of all screening programs.

In my program, CVS and microarray are now offered to all patients regardless of age, as the risk that a microarray will find a significant abnormality is at least 1/200, which is the risk we have been quoting to 35-year-old patients for nearly 50 years.

Dr. Evans is president of the Fetal Medicine Foundation and International Fetal Medicine and Surgery Society Foundation, and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Dr. Evans disclosed that he is a consultant for PerkinElmer, a genetics company based in Waltham, Mass.

Prenatal assessments for major chromosomal abnormalities have, like a pendulum, swung over the last 50 years between advancements in screening tests and diagnostic procedures.

In the 1960s, screening for advanced maternal age gave way to diagnostic amniocentesis. Maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein screening for neural tube defects came on the scene in the 1970s, and Down syndrome screening and chorionic villus sampling (CVS) followed in the 1980s. Better ultrasound screening markers were used in combination with biochemistry to advance first-trimester screening in the 1990s and 2000s, leading to a significant decline in diagnostic procedures. Now, free fetal DNA measurement, known as noninvasive prenatal screening, or NIPS, has entered the scene. This development, along with advances in the accuracy of diagnostic lab testing through microarray analysis, will soon lead the pendulum to swing back toward more definitive diagnostic procedures that require either CVS or amniocentesis.

Screening tests provide us with odds adjustments, not definitive answers, and are meant for everyone. Diagnostic tests are meant to give us definitive answers, may have risks, and therefore have traditionally been done on "at-risk" patients. Fundamentally, a screening test gives us an impression, while a diagnostic test gives us harsh reality. As always, there will be trade-offs. No approach is perfect, and no one size fits everyone.

Risks beyond Down syndrome

During the prenatal period, patients will often say, "I’m concerned about having a baby with Down syndrome." What they really mean is that they’re concerned about having a baby with a serious problem, and Down syndrome is the name they know.

Serious problems – a Mendelian disorder, a multifactorial disorder, or a major chromosomal abnormality – affect 2%-3% of all births. Less serious chromosomal abnormalities affect 5%-6% of births. Although advanced maternal age is no longer the sole criterion for deciding who should be offered diagnostic testing, age still is a principal factor for risk determination.

At age 35, the chance of having a baby with Down syndrome is 1 in 380, but the chance of having any chromosomal abnormality detectable by karyotype is 1 in 190. For a 30-year-old, the chance of having a baby with any chromosomal abnormality is 1 in 380, and for a 40-year-old, the risk is 1 in 65.

With the first-trimester screening approach that combines maternal serum free beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (free beta-HCG) and pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) with fetal nuchal translucency measurement, we are able to detect upward of 85% of fetuses with Down syndrome, or trisomy 21. Yet the disorder is only one of a large number of chromosomal abnormalities observed.

In a recent single-center study of more than 20,000 first-trimester screenings, 5.6% were positive for Down syndrome risk. Of those who subsequently had an amniocentesis or CVS, we found 4% had an abnormal karyotype. Interestingly, 40% of the time the abnormality was not Down syndrome, but another chromosomal abnormality. Similar analyses for trisomies 13 and 18 – the other major abnormalities targeted in first-trimester combined screening – yielded similar statistics (Prenat. Diagn. 2013;33:251-6).

All told, of the screen-positive pregnancies found to have an abnormal karyotype, at least 30% had chromosomal abnormalities outside of those for which they were screen positive. Such findings speak to the limitations of screening as opposed to diagnostic testing, and have implications for patient counseling. Patients should be counseled about the possibility of all chromosome abnormalities – not just Down syndrome.

The NIPS rollout

We have known for well over 100 years that fetal cells cross the placental barrier in small numbers, driving the development of what’s currently known as NIPS. The future of NIPS actually lies in an ever-expanding number of disorders, and will eventually end with sequencing the entire genome.

There are two main methods by which NIPS is done. The original and predominant method uses massive parallel shotgun sequencing, known as next-generation sequencing. This method involves whole-genome amplification and collects enormous amounts of information. Investigators are now attempting to direct amplification at the subchromosome level, mimicking some of what microarray analysis can do.

The second approach uses selected probes, or targeted sequencing, to focus on those sections of DNA that are of interest. Although this method may be cheaper in the short run, one drawback is that new probes will need to be created for each new disorder.

Initially, investigators attempted to isolate nucleated fetal cells from the maternal blood and use them for aneuploidy detection. However, a National Institutes of Health–funded fetal-cell isolation study that ended in 2002 reported disappointing results: Fetal-cell isolation methods had low sensitivity and other technological shortcomings. Subsequently, a number of companies attempted to replicate and improve the work, also without much success.

Concurrent with efforts to use fetal-cell isolation to perform NIPS was the discovery, in the late 1990s by Dr. Dennis Lo, upon whose work next-generation sequencing for NIPS is based, of the presence of circulating cell-free fetal DNA in maternal plasma. The concentration of cell-free fetal DNA may be as much as 5%-8% of the total circulating cell-free DNA in maternal plasma, making free fetal DNA a promising source of fetal genetic material for noninvasive prenatal investigation.

The first high-quality trials on the use of free fetal DNA measurement for detection of trisomy 21 were published in the fall of 2011, and demonstrated up to a 99% detection rate for Down syndrome (less for trisomies 18 and 13). Companies subsequently began to manufacture free fetal DNA tests as off-label products, The tests were initially designated as "noninvasive prenatal diagnosis" tools, but experts around the world objected to the "diagnosis" label, and the terminology shifted to "noninvasive prenatal testing" and finally to "noninvasive prenatal screening"– a designation that I believe accurately reflects its current role.

The uptake in utilization of NIPS has been faster than anyone could have predicted: In just over 2 years, several hundred thousand screening tests have been performed. With 98% to 99% sensitivity, NIPS is an excellent screening test for Down syndrome. However, 99% sensitivity does not equate to 99% positive predictive value, that is, the risk that a patient with a positive screen actually has Down syndrome is much lower.

The published studies of NIPS cite false positive rates of 0.2%-1.0%, but this rate will increase as more disorders are screened. Positive predictive value is directly proportional to the underlying risk. For example, a test with 99% sensitivity and 99% specificity (1% false positive rate) means that a 26-year-old woman who has a positive free fetal DNA test actually has as low as an 11% chance of having a baby with Down syndrome. In older women, who have a higher incidence of having a baby with Down syndrome, a positive NIPS result will have a higher positive predictive value of giving birth to a baby with Down syndrome. However, at the current time, NIPS is an excellent screening test for Down syndrome, but it is not ready for universal primary screening in younger women.

Falsely reassuring are the hyped marketing claims in the United States that NIPS "replaces amnio" and eliminates the need for a nuchal translucency (NT) test. When clinicians abandon performing or referring for a high-quality NT measurement, they can miss or significantly delay the diagnosis of twins/zygosity, growth abnormalities and placentation, cardiac defects, and numerous other anomalies. Similarly, when patients who otherwise would have opted to have CVS or amniocentesis forego having the procedure and have NIPS performed instead, they may regret this decision.

The danger that overreliance on screening tests may paradoxically increase the number of births of babies with otherwise detectable problems was raised in a study led by the late Dr. George Henry, an obstetrician-geneticist in Denver. Curious about declining rates of diagnostic testing in his own practice, Dr. Henry examined trends in his state and found that while the utilization of diagnostic tests had plummeted by 70% over about 15 years, the birth rate of babies born with Down syndrome during this time had doubled among mothers over age 35, and stayed the same among mothers under age 35.

A sociologist-researcher examined the trend that Dr. Henry identified and found that the rise in Down syndrome births was not due to an increase in women electing to keep these pregnancies, but to the fact that the abnormality was not detected in the first place (Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2008;23:308-15). The same risk of screening tests replacing definitive diagnosis exists today with the uptake of NIPS.

The impact of microarray

Microarray technologies have been developed over the past decade. The National Institutes of Health study on chromosomal microarray versus karyotyping, published a year ago, is a game changer. The microarray is analogous to a 15-fold magnifying glass on the karyotype. While the smallest piece of a chromosome that can be evaluated by karyotype analysis is about 5 million base pairs, microarray analysis zooms in on about 200,000 base pairs, allowing us to see small genomic deletions and duplications (copy number variants) that we’ve never seen before.

The trial looked at upward of 4,000 women undergoing CVS or amniocentesis at one of 29 centers. Each diagnostic sample was split in two, with standard karyotyping performed on one portion and chromosomal microarray on the other (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:2175-84).

There were several significant findings: One is that almost one-third of patients have a copy variation now known to be benign. Another is that 2.5% of women who had ultrasound-identified anomalies and normal karyotypes had microdeletion/duplications on the microarray that were clearly associated with a known clinical problem. Moreover, another 3.2% had gains and losses of potential clinical significance. As such, close to 6% of women with ultrasound-identified anomalies and a normal karyotype had clinically relevant copy number variants that only the microarray could find.

When microarray analysis was performed in women whose only indication for prenatal diagnosis was advanced age or an abnormal result on Down syndrome screening, as opposed to an ultrasound-detected anomaly, 0.5%, or 1 in 200, were found to have a pathogenic abnormality that otherwise would have been missed. This is significant: Previously, with karyotyping, we quoted patients a minimum of 1/500 risk of finding a clinically relevant chromosomal anomaly even if the combined report suggested much lower risks of Down syndrome. Now, with microarray, that risk is 1/200. Other studies already published or about to be published show this same level of risk determined by microarray.

With any new technological advance, we get our numerators of the problem before our denominators. The first cases published are those in which clinical or laboratory findings are associated with an abnormality. Only then do researchers go back and look at cases with those findings to test these associations – and only then are the markers sometimes found not to be associated. It will take a number of years to acquire a sizable database on microarray-detected copy number variants. In the end, microarray may help us to explain many of the approximately 1% of serious problems that we have been unable to diagnose until now.

Current decision-making

Ultimately, the future lies with routine, complete genomic sequencing that provides a detailed view of the fetal genome. This is likely to be about 7-10 years away, and the main question on the table is whether it will be performed invasively or with a maternal blood sample.

Today, when a 35-year-old woman comes into my office early in her pregnancy, I will tell her that the risk of having a baby with a chromosomal abnormality is 1 in 190. If she wants to know more, I will explain that the second-trimester quad screen will detect 60% of Down syndrome cases, that the first-trimester combined screen can identify 85% or more, and that the free fetal DNA test will get closer to 99%.

Despite the significant advances in screening, all of these options are still the fundamental equivalent of a Gallup poll. If the patient wants a definitive answer, she will need either an amniocentesis or a CVS, which, in experienced hands, have been shown through an increasing number of studies to be of equal risk. Because there is no such thing as "no" risk when it comes to prenatal diagnostic testing, the question that each patient must answer is, "Where do you want to put that risk – in the test or gambling on the outcome?"

We also have a great cultural divide in the United States. Some people want to know everything, others want to know nothing. Our affluent patients are getting older. Our poorer patients are getting younger. Some people will pay whatever it takes to get the answers they want, while others can or will not pay a dime beyond what their insurance will cover.

There is no one algorithm that can handle these two extremes of patients. Right now, many programs around the country have seen a diminishing number of patients having diagnostic testing – a phenomenon I believe is the result of a false sense of confidence, of people being lulled by the faulty argument that screening protocols can find Down syndrome, so what else is there to know?

Ultimately, a model for younger women would start with "contingent screening," in which patients could start with first-trimester combined screening and move straight to CVS if found to be at "high risk," and end testing if found to be at "low risk." Women who fall in the middle could undergo either free fetal DNA analysis or CVS, and we are developing methods to improve the mathematical processing of data to improve the sensitivity and specificity of all screening programs.

In my program, CVS and microarray are now offered to all patients regardless of age, as the risk that a microarray will find a significant abnormality is at least 1/200, which is the risk we have been quoting to 35-year-old patients for nearly 50 years.

Dr. Evans is president of the Fetal Medicine Foundation and International Fetal Medicine and Surgery Society Foundation, and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Dr. Evans disclosed that he is a consultant for PerkinElmer, a genetics company based in Waltham, Mass.

Prenatal assessments for major chromosomal abnormalities have, like a pendulum, swung over the last 50 years between advancements in screening tests and diagnostic procedures.

In the 1960s, screening for advanced maternal age gave way to diagnostic amniocentesis. Maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein screening for neural tube defects came on the scene in the 1970s, and Down syndrome screening and chorionic villus sampling (CVS) followed in the 1980s. Better ultrasound screening markers were used in combination with biochemistry to advance first-trimester screening in the 1990s and 2000s, leading to a significant decline in diagnostic procedures. Now, free fetal DNA measurement, known as noninvasive prenatal screening, or NIPS, has entered the scene. This development, along with advances in the accuracy of diagnostic lab testing through microarray analysis, will soon lead the pendulum to swing back toward more definitive diagnostic procedures that require either CVS or amniocentesis.

Screening tests provide us with odds adjustments, not definitive answers, and are meant for everyone. Diagnostic tests are meant to give us definitive answers, may have risks, and therefore have traditionally been done on "at-risk" patients. Fundamentally, a screening test gives us an impression, while a diagnostic test gives us harsh reality. As always, there will be trade-offs. No approach is perfect, and no one size fits everyone.

Risks beyond Down syndrome

During the prenatal period, patients will often say, "I’m concerned about having a baby with Down syndrome." What they really mean is that they’re concerned about having a baby with a serious problem, and Down syndrome is the name they know.

Serious problems – a Mendelian disorder, a multifactorial disorder, or a major chromosomal abnormality – affect 2%-3% of all births. Less serious chromosomal abnormalities affect 5%-6% of births. Although advanced maternal age is no longer the sole criterion for deciding who should be offered diagnostic testing, age still is a principal factor for risk determination.

At age 35, the chance of having a baby with Down syndrome is 1 in 380, but the chance of having any chromosomal abnormality detectable by karyotype is 1 in 190. For a 30-year-old, the chance of having a baby with any chromosomal abnormality is 1 in 380, and for a 40-year-old, the risk is 1 in 65.

With the first-trimester screening approach that combines maternal serum free beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (free beta-HCG) and pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) with fetal nuchal translucency measurement, we are able to detect upward of 85% of fetuses with Down syndrome, or trisomy 21. Yet the disorder is only one of a large number of chromosomal abnormalities observed.

In a recent single-center study of more than 20,000 first-trimester screenings, 5.6% were positive for Down syndrome risk. Of those who subsequently had an amniocentesis or CVS, we found 4% had an abnormal karyotype. Interestingly, 40% of the time the abnormality was not Down syndrome, but another chromosomal abnormality. Similar analyses for trisomies 13 and 18 – the other major abnormalities targeted in first-trimester combined screening – yielded similar statistics (Prenat. Diagn. 2013;33:251-6).

All told, of the screen-positive pregnancies found to have an abnormal karyotype, at least 30% had chromosomal abnormalities outside of those for which they were screen positive. Such findings speak to the limitations of screening as opposed to diagnostic testing, and have implications for patient counseling. Patients should be counseled about the possibility of all chromosome abnormalities – not just Down syndrome.

The NIPS rollout

We have known for well over 100 years that fetal cells cross the placental barrier in small numbers, driving the development of what’s currently known as NIPS. The future of NIPS actually lies in an ever-expanding number of disorders, and will eventually end with sequencing the entire genome.

There are two main methods by which NIPS is done. The original and predominant method uses massive parallel shotgun sequencing, known as next-generation sequencing. This method involves whole-genome amplification and collects enormous amounts of information. Investigators are now attempting to direct amplification at the subchromosome level, mimicking some of what microarray analysis can do.

The second approach uses selected probes, or targeted sequencing, to focus on those sections of DNA that are of interest. Although this method may be cheaper in the short run, one drawback is that new probes will need to be created for each new disorder.

Initially, investigators attempted to isolate nucleated fetal cells from the maternal blood and use them for aneuploidy detection. However, a National Institutes of Health–funded fetal-cell isolation study that ended in 2002 reported disappointing results: Fetal-cell isolation methods had low sensitivity and other technological shortcomings. Subsequently, a number of companies attempted to replicate and improve the work, also without much success.

Concurrent with efforts to use fetal-cell isolation to perform NIPS was the discovery, in the late 1990s by Dr. Dennis Lo, upon whose work next-generation sequencing for NIPS is based, of the presence of circulating cell-free fetal DNA in maternal plasma. The concentration of cell-free fetal DNA may be as much as 5%-8% of the total circulating cell-free DNA in maternal plasma, making free fetal DNA a promising source of fetal genetic material for noninvasive prenatal investigation.

The first high-quality trials on the use of free fetal DNA measurement for detection of trisomy 21 were published in the fall of 2011, and demonstrated up to a 99% detection rate for Down syndrome (less for trisomies 18 and 13). Companies subsequently began to manufacture free fetal DNA tests as off-label products, The tests were initially designated as "noninvasive prenatal diagnosis" tools, but experts around the world objected to the "diagnosis" label, and the terminology shifted to "noninvasive prenatal testing" and finally to "noninvasive prenatal screening"– a designation that I believe accurately reflects its current role.

The uptake in utilization of NIPS has been faster than anyone could have predicted: In just over 2 years, several hundred thousand screening tests have been performed. With 98% to 99% sensitivity, NIPS is an excellent screening test for Down syndrome. However, 99% sensitivity does not equate to 99% positive predictive value, that is, the risk that a patient with a positive screen actually has Down syndrome is much lower.

The published studies of NIPS cite false positive rates of 0.2%-1.0%, but this rate will increase as more disorders are screened. Positive predictive value is directly proportional to the underlying risk. For example, a test with 99% sensitivity and 99% specificity (1% false positive rate) means that a 26-year-old woman who has a positive free fetal DNA test actually has as low as an 11% chance of having a baby with Down syndrome. In older women, who have a higher incidence of having a baby with Down syndrome, a positive NIPS result will have a higher positive predictive value of giving birth to a baby with Down syndrome. However, at the current time, NIPS is an excellent screening test for Down syndrome, but it is not ready for universal primary screening in younger women.

Falsely reassuring are the hyped marketing claims in the United States that NIPS "replaces amnio" and eliminates the need for a nuchal translucency (NT) test. When clinicians abandon performing or referring for a high-quality NT measurement, they can miss or significantly delay the diagnosis of twins/zygosity, growth abnormalities and placentation, cardiac defects, and numerous other anomalies. Similarly, when patients who otherwise would have opted to have CVS or amniocentesis forego having the procedure and have NIPS performed instead, they may regret this decision.

The danger that overreliance on screening tests may paradoxically increase the number of births of babies with otherwise detectable problems was raised in a study led by the late Dr. George Henry, an obstetrician-geneticist in Denver. Curious about declining rates of diagnostic testing in his own practice, Dr. Henry examined trends in his state and found that while the utilization of diagnostic tests had plummeted by 70% over about 15 years, the birth rate of babies born with Down syndrome during this time had doubled among mothers over age 35, and stayed the same among mothers under age 35.

A sociologist-researcher examined the trend that Dr. Henry identified and found that the rise in Down syndrome births was not due to an increase in women electing to keep these pregnancies, but to the fact that the abnormality was not detected in the first place (Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2008;23:308-15). The same risk of screening tests replacing definitive diagnosis exists today with the uptake of NIPS.

The impact of microarray

Microarray technologies have been developed over the past decade. The National Institutes of Health study on chromosomal microarray versus karyotyping, published a year ago, is a game changer. The microarray is analogous to a 15-fold magnifying glass on the karyotype. While the smallest piece of a chromosome that can be evaluated by karyotype analysis is about 5 million base pairs, microarray analysis zooms in on about 200,000 base pairs, allowing us to see small genomic deletions and duplications (copy number variants) that we’ve never seen before.

The trial looked at upward of 4,000 women undergoing CVS or amniocentesis at one of 29 centers. Each diagnostic sample was split in two, with standard karyotyping performed on one portion and chromosomal microarray on the other (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:2175-84).

There were several significant findings: One is that almost one-third of patients have a copy variation now known to be benign. Another is that 2.5% of women who had ultrasound-identified anomalies and normal karyotypes had microdeletion/duplications on the microarray that were clearly associated with a known clinical problem. Moreover, another 3.2% had gains and losses of potential clinical significance. As such, close to 6% of women with ultrasound-identified anomalies and a normal karyotype had clinically relevant copy number variants that only the microarray could find.

When microarray analysis was performed in women whose only indication for prenatal diagnosis was advanced age or an abnormal result on Down syndrome screening, as opposed to an ultrasound-detected anomaly, 0.5%, or 1 in 200, were found to have a pathogenic abnormality that otherwise would have been missed. This is significant: Previously, with karyotyping, we quoted patients a minimum of 1/500 risk of finding a clinically relevant chromosomal anomaly even if the combined report suggested much lower risks of Down syndrome. Now, with microarray, that risk is 1/200. Other studies already published or about to be published show this same level of risk determined by microarray.

With any new technological advance, we get our numerators of the problem before our denominators. The first cases published are those in which clinical or laboratory findings are associated with an abnormality. Only then do researchers go back and look at cases with those findings to test these associations – and only then are the markers sometimes found not to be associated. It will take a number of years to acquire a sizable database on microarray-detected copy number variants. In the end, microarray may help us to explain many of the approximately 1% of serious problems that we have been unable to diagnose until now.

Current decision-making

Ultimately, the future lies with routine, complete genomic sequencing that provides a detailed view of the fetal genome. This is likely to be about 7-10 years away, and the main question on the table is whether it will be performed invasively or with a maternal blood sample.

Today, when a 35-year-old woman comes into my office early in her pregnancy, I will tell her that the risk of having a baby with a chromosomal abnormality is 1 in 190. If she wants to know more, I will explain that the second-trimester quad screen will detect 60% of Down syndrome cases, that the first-trimester combined screen can identify 85% or more, and that the free fetal DNA test will get closer to 99%.

Despite the significant advances in screening, all of these options are still the fundamental equivalent of a Gallup poll. If the patient wants a definitive answer, she will need either an amniocentesis or a CVS, which, in experienced hands, have been shown through an increasing number of studies to be of equal risk. Because there is no such thing as "no" risk when it comes to prenatal diagnostic testing, the question that each patient must answer is, "Where do you want to put that risk – in the test or gambling on the outcome?"

We also have a great cultural divide in the United States. Some people want to know everything, others want to know nothing. Our affluent patients are getting older. Our poorer patients are getting younger. Some people will pay whatever it takes to get the answers they want, while others can or will not pay a dime beyond what their insurance will cover.

There is no one algorithm that can handle these two extremes of patients. Right now, many programs around the country have seen a diminishing number of patients having diagnostic testing – a phenomenon I believe is the result of a false sense of confidence, of people being lulled by the faulty argument that screening protocols can find Down syndrome, so what else is there to know?

Ultimately, a model for younger women would start with "contingent screening," in which patients could start with first-trimester combined screening and move straight to CVS if found to be at "high risk," and end testing if found to be at "low risk." Women who fall in the middle could undergo either free fetal DNA analysis or CVS, and we are developing methods to improve the mathematical processing of data to improve the sensitivity and specificity of all screening programs.

In my program, CVS and microarray are now offered to all patients regardless of age, as the risk that a microarray will find a significant abnormality is at least 1/200, which is the risk we have been quoting to 35-year-old patients for nearly 50 years.

Dr. Evans is president of the Fetal Medicine Foundation and International Fetal Medicine and Surgery Society Foundation, and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Dr. Evans disclosed that he is a consultant for PerkinElmer, a genetics company based in Waltham, Mass.

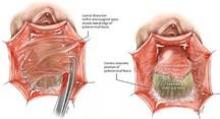

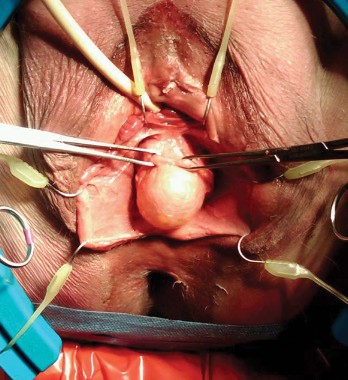

Biologic mesh in pelvic organ prolapse

Adverse events associated with the use of synthetic mesh in pelvic organ prolapse (POP) reparative surgery – and the Food and Drug Administration’s safety communication in 2011 warning physicians and patients about transvaginal placement of mesh for the repair of POP and stress urinary incontinence – have had a significant impact on gynecologic surgery.

Many physicians have become reluctant to use synthetic mesh products because of the risks of mesh erosion, exposure, pain and dyspareunia, and litigation. Patients also are concerned or even alarmed by reported risks. Moreover, some manufacturers have become increasingly concerned with the production of mesh products for POP repair, lessening the availability of synthetic mesh, and possibly some biologic mesh as well, for POP reparative surgery. Overall, the future of mesh augmentation in POP repair is uncertain.

Vaginal mesh procedures had surged in the decade prior to 2011 despite the lack of good randomized studies to determine whether mesh augmentation was truly efficacious. And unfortunately, the FDA has grouped synthetic and biologic material together in its reviews and notices of mesh products for POP repair. Not classifying and investigating them separately can mislead patients and hinder the development of randomized controlled trials needed to determine if augmentation with biologic material is truly superior to traditional POP repair using native tissue.

Comparing biologic mesh products to synthetic materials for pelvic organ prolapse repairs is like comparing apples to oranges: Synthetic mesh is permanent, while most biologics break down and remain in the body no longer than 6 months. From the standpoint of complications, this gives biologic materials an advantage. In my practice, biologic grafts have not eroded or caused pain, dyspareunia, or postoperative infections in any of my patients who have had surgical repair for POP.

There remains a real need for augmentation of weakened collagen tissue in the repair of POP. The native tissue in these patients is faulty tissue. Without reinforcement of defective tissue, we cannot expect excellent repairs. Data from nonrandomized studies have borne this out. When I talk with my patients about the options for surgical correction of POP, I tell them that success rates without the use of any augmentation are low, and that only about 60% of patients achieve a satisfactory result with traditional repairs.

Increasingly, I and other gynecologic surgeons are having success with biologic materials in our POP repairs. Efficacy needs to be measured in well-controlled randomized clinical trials, but at this point it appears anecdotally and from nonrandomized case reports that we can achieve good anatomic outcomes – upwards of 80% success rates – with biologic grafts, without the complications of synthetic mesh.

A recent survey of members of the American Urogynecologic Society shows that the use of synthetic mesh in transvaginal POP surgery decreased significantly after the 2011 FDA safety update, while there was no significant change in the use of biologic graft for POP (Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg 2013;19:191-8). It may be that the tide will shift toward greater use of biologic grafts. At the least, gynecologic surgeons should appreciate the differences between the two types of materials.

In the meantime, transvaginal placement of synthetic mesh should be used carefully and sparingly, with proper attention paid to patient selection and technique to reduce as much as possible the risk of erosion and pain.

In either case, more attention should be paid to the prevention of postoperative infections. Postoperative infection is an underappreciated risk with pelvic reconstructive surgery overall, and the use of synthetic mesh significantly increases this risk. Biologics are safer from an infection standpoint, but proper prevention – including evaluating each patient’s vaginal microflora immediately preoperatively and treating patients accordingly – is important for any surgery.

My advice on synthetics

Selecting patients for POP repair with no mesh, biologic mesh, or synthetic mesh requires thorough patient counseling. This is best done over multiple visits, with the patient reviewing information and coming back for a subsequent visit 1-2 weeks later with questions. She must be prepared psychologically and have realistic expectations.

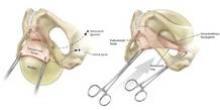

In its 2011 safety communication, the FDA stated that the main role for mesh with POP repair is in the anterior compartment, and that traditional apical or posterior repair with mesh does not appear to provide any added benefit, compared with traditional surgery without mesh. Rectocele repair should not preclude the use of mesh, however, especially when a prior nonmesh repair has failed. For a patient with a small rectocele, I would advise repair with native tissue, and a second surgery with augmentation if the initial repair fails.

Synthetic mesh should be reserved for patients who have had multiple failures with traditional repairs and who are not sexually active. Sexual behavior is key to the decision-making process I undertake with my patients because synthetic mesh can cause a loss of elasticity in the vagina and consequent dyspareunia. When synthetic meshes are selected, the surgeon should use a minimal amount of material to cover as small an area as possible. It should not be used concomitantly in both the anterior and posterior compartments, as the risk of mesh contraction, rigidity, and vaginal shrinkage is too great.

Incisions in a mesh-augmented anterior or posterior repair should be 3-4 mm thick, passing through the full thickness of the vagina. Posterior compartment incisions should be kept as small in length as possible to reduce the risk of erosion/exposure and hematoma. In the anterior compartment, for similar reasons, surgeons are increasingly moving toward using small semilunar incisions.

In addition to the well-reported risks of erosion, exposure, and extrusion, synthetic meshes pose a problem from an infection point of view. Not uncommonly, synthetic grafts are found upon removal to be covered with biofilms – matrices produced by bacteria or fungi that colonize the material and house the organisms. Biofilm formation can lead to both acute, significant infection and long-term chronic infection; it also can result in metastatic infection if the biofilm breaks off, fragments, and is transported to other areas of the body.

Minimizing infection risk

Biofilms have been known and studied for some time, but there is growing appreciation for the role they play in infections that are chronic, recurrent, or hard to detect and treat. It has been shown, for instance, that patients with recurrent bacterial vaginosis have Gardnerella vaginalis–generated biofilms that house the bacteria and keep it from being adequately penetrated by white blood cells or antibiotics.

Ongoing research is looking for agents to break down biofilms so that antibiotics can reach the infectious organisms embedded within them. At the current time, we do not have any tools available, other than the benefit of understanding how biofilms form, work, and can be prevented. Biofilms can form on a variety of surfaces, synthetic or natural, but clearly, permanent synthetic meshes are more likely to house biofilms than are biologic meshes.

In any case, every patient undergoing POP repair – any surgery, for that matter – should be evaluated prior to the procedure to determine if she is at higher risk of infection. The patient’s vaginal microflora should be evaluated, and conditions such as bacterial vaginosis or aerobic vaginitis should be treated presurgically to reduce her risk of postoperative infection.

Infections rates for POP surgery are not published, to my knowledge, but there is reason to believe the rate is substantive (the infection rate associated with hysterectomy, depending on the population, is 5%-9%, and we do know that most postsurgical pelvic infections are derived from the vaginal microflora.

I also advocate checking the vaginal pH in the operating room before the vagina is prepped. In my surgeries, if the pH is 4.5 or lower, a standard regimen for antibiotic prophylaxis (1-2 g cefazolin) is administered. If the pH is greater than 4.5, then 500 mg metronidazole is added to this standard regimen. This covers pathogenic obligate anaerobes, whose growth is favored in an environment with a higher pH. Antibiotic prophylaxis should be administered one time only.

It is important to recognize as early as possible the patient who is developing an infection or has an infection. There are no definitive signs of developing or early infection. Therefore, any patient who develops postoperative fever (101°F or higher) and has a pulse rate of 100 or higher and an elevated WBC count should be evaluated (physical examination including a pelvic exam). It is important to rule out infection involving the respiratory system, urinary tract, and pelvis.

If there is no evidence of infection, further observation is acceptable. If there is strong suspicion of infection, further evaluation is warranted (ultrasound or CT scan) and broad-spectrum antibiotics should be administered. The patient should be evaluated daily to determine the response to treatment.

Contrary to popular belief, some infections (such as group A streptococcus, group B streptococcus, Escherichia coli) can set in early, within 24-48 hours after surgery.

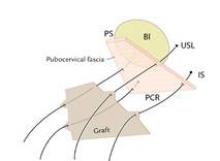

My experience with biologics

Pelvic reconstructive surgeons became interested in biologic material because both animal studies and clinical experience in other surgical areas, such as hernia repair, have demonstrated a high degree of neovascularization and reepithelialization at the implantation area. When non–cross-linked biologic material is implanted onto or near fascia, new fascia is generated. When it is placed at the site of skin dissection, skin is regenerated. Over 3-6 months, the graft materials break down and are excreted from the body. The risks of complications and infection with non–cross-linked biologic meshes are low in comparison with the synthetic nonabsorbable meshes.

Biologic materials that are cross linked, or treated in an effort to improve strength and durability, tend to have inadequate elasticity and are not porous enough for adequate transmission of white blood cells and macrophages. Cross-linked biologics also may become encapsulated, which makes them more permanent and prone to erosion and other problems seen with the synthetic graft materials.

The non–cross-linked biologics are porous and do not present a barrier to white blood cells and macrophages. At least one of the available biologics in this category has an active antimicrobial component.

Most importantly, the non–cross-linked biologic materials give us much of what we are trying to achieve with augmentation, which is not to have a permanent prosthetic device but rather an extracellular matrix that acts like a cluster of stem cells, stimulating the body to regenerate tissue at the site of implantation.

I have used biologic mesh in approximately 200 surgeries over the past 5 years; many of these surgeries have been POP repairs. My success rate in terms of anatomic outcome and symptom resolution (anecdotally, per nonrandomized evaluation) has been about 85%. I have not hesitated to place biologic mesh concomitantly in both the anterior and posterior compartments, and I have used it to lengthen the vagina. I have not seen any infection or any rejection or allergic issues, and there have been no cases of erosion/exposure.

On occasion, a suture migrates through the vaginal epithelium and creates chronic discharge and/or pain. When the granulation tissue and the suture are both removed, the patient’s symptoms resolve. I have had two patients in whom the suture line has spontaneously opened along the anterior-posterior wall. In both patients, the vaginal discharge resolved once the tissue reepithelialized in 6-8 weeks.

Many patients today tell me immediately in their initial visit that they do not want mesh. It takes some time and thorough explanation to help each patient understand that adverse outcomes are associated mainly with the synthetic meshes, and that biologic materials are worth considering.

Dr. Faro is professor and vice chairman of ob.gyn. at Lyndon Baines Johnson Hospital and professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Texas, both in Houston. He has led infectious disease sections at Baylor College of Medicine and Louisiana State University, is a past president of the Infectious Diseases Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology, has published on postoperative and other infections, and has otherwise been an expert and leader in this realm of gynecologic care. *Dr. Faro is a scientific advisor for the research arm of Medical Diagnostic Laboratories in Hamilton, N.J.

*CORRECTION (11/25/13): A previous version of this story reported an incorrect financial disclosure of Dr. Sebastian Faro. This article has been updated.

Adverse events associated with the use of synthetic mesh in pelvic organ prolapse (POP) reparative surgery – and the Food and Drug Administration’s safety communication in 2011 warning physicians and patients about transvaginal placement of mesh for the repair of POP and stress urinary incontinence – have had a significant impact on gynecologic surgery.

Many physicians have become reluctant to use synthetic mesh products because of the risks of mesh erosion, exposure, pain and dyspareunia, and litigation. Patients also are concerned or even alarmed by reported risks. Moreover, some manufacturers have become increasingly concerned with the production of mesh products for POP repair, lessening the availability of synthetic mesh, and possibly some biologic mesh as well, for POP reparative surgery. Overall, the future of mesh augmentation in POP repair is uncertain.

Vaginal mesh procedures had surged in the decade prior to 2011 despite the lack of good randomized studies to determine whether mesh augmentation was truly efficacious. And unfortunately, the FDA has grouped synthetic and biologic material together in its reviews and notices of mesh products for POP repair. Not classifying and investigating them separately can mislead patients and hinder the development of randomized controlled trials needed to determine if augmentation with biologic material is truly superior to traditional POP repair using native tissue.

Comparing biologic mesh products to synthetic materials for pelvic organ prolapse repairs is like comparing apples to oranges: Synthetic mesh is permanent, while most biologics break down and remain in the body no longer than 6 months. From the standpoint of complications, this gives biologic materials an advantage. In my practice, biologic grafts have not eroded or caused pain, dyspareunia, or postoperative infections in any of my patients who have had surgical repair for POP.

There remains a real need for augmentation of weakened collagen tissue in the repair of POP. The native tissue in these patients is faulty tissue. Without reinforcement of defective tissue, we cannot expect excellent repairs. Data from nonrandomized studies have borne this out. When I talk with my patients about the options for surgical correction of POP, I tell them that success rates without the use of any augmentation are low, and that only about 60% of patients achieve a satisfactory result with traditional repairs.

Increasingly, I and other gynecologic surgeons are having success with biologic materials in our POP repairs. Efficacy needs to be measured in well-controlled randomized clinical trials, but at this point it appears anecdotally and from nonrandomized case reports that we can achieve good anatomic outcomes – upwards of 80% success rates – with biologic grafts, without the complications of synthetic mesh.

A recent survey of members of the American Urogynecologic Society shows that the use of synthetic mesh in transvaginal POP surgery decreased significantly after the 2011 FDA safety update, while there was no significant change in the use of biologic graft for POP (Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg 2013;19:191-8). It may be that the tide will shift toward greater use of biologic grafts. At the least, gynecologic surgeons should appreciate the differences between the two types of materials.

In the meantime, transvaginal placement of synthetic mesh should be used carefully and sparingly, with proper attention paid to patient selection and technique to reduce as much as possible the risk of erosion and pain.

In either case, more attention should be paid to the prevention of postoperative infections. Postoperative infection is an underappreciated risk with pelvic reconstructive surgery overall, and the use of synthetic mesh significantly increases this risk. Biologics are safer from an infection standpoint, but proper prevention – including evaluating each patient’s vaginal microflora immediately preoperatively and treating patients accordingly – is important for any surgery.

My advice on synthetics

Selecting patients for POP repair with no mesh, biologic mesh, or synthetic mesh requires thorough patient counseling. This is best done over multiple visits, with the patient reviewing information and coming back for a subsequent visit 1-2 weeks later with questions. She must be prepared psychologically and have realistic expectations.

In its 2011 safety communication, the FDA stated that the main role for mesh with POP repair is in the anterior compartment, and that traditional apical or posterior repair with mesh does not appear to provide any added benefit, compared with traditional surgery without mesh. Rectocele repair should not preclude the use of mesh, however, especially when a prior nonmesh repair has failed. For a patient with a small rectocele, I would advise repair with native tissue, and a second surgery with augmentation if the initial repair fails.

Synthetic mesh should be reserved for patients who have had multiple failures with traditional repairs and who are not sexually active. Sexual behavior is key to the decision-making process I undertake with my patients because synthetic mesh can cause a loss of elasticity in the vagina and consequent dyspareunia. When synthetic meshes are selected, the surgeon should use a minimal amount of material to cover as small an area as possible. It should not be used concomitantly in both the anterior and posterior compartments, as the risk of mesh contraction, rigidity, and vaginal shrinkage is too great.

Incisions in a mesh-augmented anterior or posterior repair should be 3-4 mm thick, passing through the full thickness of the vagina. Posterior compartment incisions should be kept as small in length as possible to reduce the risk of erosion/exposure and hematoma. In the anterior compartment, for similar reasons, surgeons are increasingly moving toward using small semilunar incisions.

In addition to the well-reported risks of erosion, exposure, and extrusion, synthetic meshes pose a problem from an infection point of view. Not uncommonly, synthetic grafts are found upon removal to be covered with biofilms – matrices produced by bacteria or fungi that colonize the material and house the organisms. Biofilm formation can lead to both acute, significant infection and long-term chronic infection; it also can result in metastatic infection if the biofilm breaks off, fragments, and is transported to other areas of the body.

Minimizing infection risk

Biofilms have been known and studied for some time, but there is growing appreciation for the role they play in infections that are chronic, recurrent, or hard to detect and treat. It has been shown, for instance, that patients with recurrent bacterial vaginosis have Gardnerella vaginalis–generated biofilms that house the bacteria and keep it from being adequately penetrated by white blood cells or antibiotics.

Ongoing research is looking for agents to break down biofilms so that antibiotics can reach the infectious organisms embedded within them. At the current time, we do not have any tools available, other than the benefit of understanding how biofilms form, work, and can be prevented. Biofilms can form on a variety of surfaces, synthetic or natural, but clearly, permanent synthetic meshes are more likely to house biofilms than are biologic meshes.

In any case, every patient undergoing POP repair – any surgery, for that matter – should be evaluated prior to the procedure to determine if she is at higher risk of infection. The patient’s vaginal microflora should be evaluated, and conditions such as bacterial vaginosis or aerobic vaginitis should be treated presurgically to reduce her risk of postoperative infection.

Infections rates for POP surgery are not published, to my knowledge, but there is reason to believe the rate is substantive (the infection rate associated with hysterectomy, depending on the population, is 5%-9%, and we do know that most postsurgical pelvic infections are derived from the vaginal microflora.

I also advocate checking the vaginal pH in the operating room before the vagina is prepped. In my surgeries, if the pH is 4.5 or lower, a standard regimen for antibiotic prophylaxis (1-2 g cefazolin) is administered. If the pH is greater than 4.5, then 500 mg metronidazole is added to this standard regimen. This covers pathogenic obligate anaerobes, whose growth is favored in an environment with a higher pH. Antibiotic prophylaxis should be administered one time only.

It is important to recognize as early as possible the patient who is developing an infection or has an infection. There are no definitive signs of developing or early infection. Therefore, any patient who develops postoperative fever (101°F or higher) and has a pulse rate of 100 or higher and an elevated WBC count should be evaluated (physical examination including a pelvic exam). It is important to rule out infection involving the respiratory system, urinary tract, and pelvis.

If there is no evidence of infection, further observation is acceptable. If there is strong suspicion of infection, further evaluation is warranted (ultrasound or CT scan) and broad-spectrum antibiotics should be administered. The patient should be evaluated daily to determine the response to treatment.

Contrary to popular belief, some infections (such as group A streptococcus, group B streptococcus, Escherichia coli) can set in early, within 24-48 hours after surgery.

My experience with biologics

Pelvic reconstructive surgeons became interested in biologic material because both animal studies and clinical experience in other surgical areas, such as hernia repair, have demonstrated a high degree of neovascularization and reepithelialization at the implantation area. When non–cross-linked biologic material is implanted onto or near fascia, new fascia is generated. When it is placed at the site of skin dissection, skin is regenerated. Over 3-6 months, the graft materials break down and are excreted from the body. The risks of complications and infection with non–cross-linked biologic meshes are low in comparison with the synthetic nonabsorbable meshes.

Biologic materials that are cross linked, or treated in an effort to improve strength and durability, tend to have inadequate elasticity and are not porous enough for adequate transmission of white blood cells and macrophages. Cross-linked biologics also may become encapsulated, which makes them more permanent and prone to erosion and other problems seen with the synthetic graft materials.

The non–cross-linked biologics are porous and do not present a barrier to white blood cells and macrophages. At least one of the available biologics in this category has an active antimicrobial component.

Most importantly, the non–cross-linked biologic materials give us much of what we are trying to achieve with augmentation, which is not to have a permanent prosthetic device but rather an extracellular matrix that acts like a cluster of stem cells, stimulating the body to regenerate tissue at the site of implantation.

I have used biologic mesh in approximately 200 surgeries over the past 5 years; many of these surgeries have been POP repairs. My success rate in terms of anatomic outcome and symptom resolution (anecdotally, per nonrandomized evaluation) has been about 85%. I have not hesitated to place biologic mesh concomitantly in both the anterior and posterior compartments, and I have used it to lengthen the vagina. I have not seen any infection or any rejection or allergic issues, and there have been no cases of erosion/exposure.

On occasion, a suture migrates through the vaginal epithelium and creates chronic discharge and/or pain. When the granulation tissue and the suture are both removed, the patient’s symptoms resolve. I have had two patients in whom the suture line has spontaneously opened along the anterior-posterior wall. In both patients, the vaginal discharge resolved once the tissue reepithelialized in 6-8 weeks.

Many patients today tell me immediately in their initial visit that they do not want mesh. It takes some time and thorough explanation to help each patient understand that adverse outcomes are associated mainly with the synthetic meshes, and that biologic materials are worth considering.

Dr. Faro is professor and vice chairman of ob.gyn. at Lyndon Baines Johnson Hospital and professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Texas, both in Houston. He has led infectious disease sections at Baylor College of Medicine and Louisiana State University, is a past president of the Infectious Diseases Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology, has published on postoperative and other infections, and has otherwise been an expert and leader in this realm of gynecologic care. *Dr. Faro is a scientific advisor for the research arm of Medical Diagnostic Laboratories in Hamilton, N.J.

*CORRECTION (11/25/13): A previous version of this story reported an incorrect financial disclosure of Dr. Sebastian Faro. This article has been updated.

Adverse events associated with the use of synthetic mesh in pelvic organ prolapse (POP) reparative surgery – and the Food and Drug Administration’s safety communication in 2011 warning physicians and patients about transvaginal placement of mesh for the repair of POP and stress urinary incontinence – have had a significant impact on gynecologic surgery.

Many physicians have become reluctant to use synthetic mesh products because of the risks of mesh erosion, exposure, pain and dyspareunia, and litigation. Patients also are concerned or even alarmed by reported risks. Moreover, some manufacturers have become increasingly concerned with the production of mesh products for POP repair, lessening the availability of synthetic mesh, and possibly some biologic mesh as well, for POP reparative surgery. Overall, the future of mesh augmentation in POP repair is uncertain.

Vaginal mesh procedures had surged in the decade prior to 2011 despite the lack of good randomized studies to determine whether mesh augmentation was truly efficacious. And unfortunately, the FDA has grouped synthetic and biologic material together in its reviews and notices of mesh products for POP repair. Not classifying and investigating them separately can mislead patients and hinder the development of randomized controlled trials needed to determine if augmentation with biologic material is truly superior to traditional POP repair using native tissue.

Comparing biologic mesh products to synthetic materials for pelvic organ prolapse repairs is like comparing apples to oranges: Synthetic mesh is permanent, while most biologics break down and remain in the body no longer than 6 months. From the standpoint of complications, this gives biologic materials an advantage. In my practice, biologic grafts have not eroded or caused pain, dyspareunia, or postoperative infections in any of my patients who have had surgical repair for POP.

There remains a real need for augmentation of weakened collagen tissue in the repair of POP. The native tissue in these patients is faulty tissue. Without reinforcement of defective tissue, we cannot expect excellent repairs. Data from nonrandomized studies have borne this out. When I talk with my patients about the options for surgical correction of POP, I tell them that success rates without the use of any augmentation are low, and that only about 60% of patients achieve a satisfactory result with traditional repairs.

Increasingly, I and other gynecologic surgeons are having success with biologic materials in our POP repairs. Efficacy needs to be measured in well-controlled randomized clinical trials, but at this point it appears anecdotally and from nonrandomized case reports that we can achieve good anatomic outcomes – upwards of 80% success rates – with biologic grafts, without the complications of synthetic mesh.

A recent survey of members of the American Urogynecologic Society shows that the use of synthetic mesh in transvaginal POP surgery decreased significantly after the 2011 FDA safety update, while there was no significant change in the use of biologic graft for POP (Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg 2013;19:191-8). It may be that the tide will shift toward greater use of biologic grafts. At the least, gynecologic surgeons should appreciate the differences between the two types of materials.

In the meantime, transvaginal placement of synthetic mesh should be used carefully and sparingly, with proper attention paid to patient selection and technique to reduce as much as possible the risk of erosion and pain.

In either case, more attention should be paid to the prevention of postoperative infections. Postoperative infection is an underappreciated risk with pelvic reconstructive surgery overall, and the use of synthetic mesh significantly increases this risk. Biologics are safer from an infection standpoint, but proper prevention – including evaluating each patient’s vaginal microflora immediately preoperatively and treating patients accordingly – is important for any surgery.

My advice on synthetics

Selecting patients for POP repair with no mesh, biologic mesh, or synthetic mesh requires thorough patient counseling. This is best done over multiple visits, with the patient reviewing information and coming back for a subsequent visit 1-2 weeks later with questions. She must be prepared psychologically and have realistic expectations.

In its 2011 safety communication, the FDA stated that the main role for mesh with POP repair is in the anterior compartment, and that traditional apical or posterior repair with mesh does not appear to provide any added benefit, compared with traditional surgery without mesh. Rectocele repair should not preclude the use of mesh, however, especially when a prior nonmesh repair has failed. For a patient with a small rectocele, I would advise repair with native tissue, and a second surgery with augmentation if the initial repair fails.

Synthetic mesh should be reserved for patients who have had multiple failures with traditional repairs and who are not sexually active. Sexual behavior is key to the decision-making process I undertake with my patients because synthetic mesh can cause a loss of elasticity in the vagina and consequent dyspareunia. When synthetic meshes are selected, the surgeon should use a minimal amount of material to cover as small an area as possible. It should not be used concomitantly in both the anterior and posterior compartments, as the risk of mesh contraction, rigidity, and vaginal shrinkage is too great.

Incisions in a mesh-augmented anterior or posterior repair should be 3-4 mm thick, passing through the full thickness of the vagina. Posterior compartment incisions should be kept as small in length as possible to reduce the risk of erosion/exposure and hematoma. In the anterior compartment, for similar reasons, surgeons are increasingly moving toward using small semilunar incisions.

In addition to the well-reported risks of erosion, exposure, and extrusion, synthetic meshes pose a problem from an infection point of view. Not uncommonly, synthetic grafts are found upon removal to be covered with biofilms – matrices produced by bacteria or fungi that colonize the material and house the organisms. Biofilm formation can lead to both acute, significant infection and long-term chronic infection; it also can result in metastatic infection if the biofilm breaks off, fragments, and is transported to other areas of the body.

Minimizing infection risk

Biofilms have been known and studied for some time, but there is growing appreciation for the role they play in infections that are chronic, recurrent, or hard to detect and treat. It has been shown, for instance, that patients with recurrent bacterial vaginosis have Gardnerella vaginalis–generated biofilms that house the bacteria and keep it from being adequately penetrated by white blood cells or antibiotics.

Ongoing research is looking for agents to break down biofilms so that antibiotics can reach the infectious organisms embedded within them. At the current time, we do not have any tools available, other than the benefit of understanding how biofilms form, work, and can be prevented. Biofilms can form on a variety of surfaces, synthetic or natural, but clearly, permanent synthetic meshes are more likely to house biofilms than are biologic meshes.

In any case, every patient undergoing POP repair – any surgery, for that matter – should be evaluated prior to the procedure to determine if she is at higher risk of infection. The patient’s vaginal microflora should be evaluated, and conditions such as bacterial vaginosis or aerobic vaginitis should be treated presurgically to reduce her risk of postoperative infection.

Infections rates for POP surgery are not published, to my knowledge, but there is reason to believe the rate is substantive (the infection rate associated with hysterectomy, depending on the population, is 5%-9%, and we do know that most postsurgical pelvic infections are derived from the vaginal microflora.