User login

More in the Affordable Care Act than the Mandate

As America weighs the value of healthcare and health reform, many moving parts of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) will continue to reshape the healthcare system. And hospitalists continue to be part of the reshaping.

The full title of the bill should serve as a reminder to hospitalists of the dual purposes of the ACA: patient protection and cost control. The bulk of popular consciousness about the ACA focused around the favored positions (no pre-existing conditions and children remaining on parents’ plans until age 26) or around points of contention (the individual mandate and the Medicaid expansion).

The lesser-mentioned provisions centering around cost, quality, and payment reform have the potential to substantively reframe the conversation, particularly from the provider perspective. Hospitalists have a unique expertise that positions them to be critical in shaping these programs and regulations.

Two initiatives aim at moving the traditional fee-for-service models of payment for health services toward pay-for-performance. Both the hospital value-based purchasing and physician value-based payment modifier use quality measures to link the performance of care with payments. Hospitals and associated groups are in the process of working with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as the value-based purchasing program moves forward.

The physician value-based modifier will combine quality measures and reports, similar to the 2010 Quality and Resource Use Reports piloted this year in Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, and Missouri, with a to-be-determined payment adjustment. These reports represent a major step toward Medicare providing large-scale feedback to providers on healthcare quality and costs. When the modifier is enforced, a percentage of payments will reflect quality scores, making the feedback from hospitalists important in creating meaningful and useful measures.

Concurrently, the ACA spurred the development of additional quality-improvement (QI) programs. Quality efforts ranging from reducing hospital-acquired infections, stemming preventable complications, meaningful use of electronic health records (EHRs), and reducing readmissions round out a complement of programs that strive to create safer, more cost-effective care for patients. For example, the Partnership for Patients is a collaborative program between providers, patient groups, and the government that catalyzes care improvement in hospitals. Hospitalists have been QI leaders at the front lines in their hospitals for years, affording an informed perspective on policy development.

The ACA is a constellation of programs and initiatives that seek to test new systems for care delivery and payment reform while providing access and quality protections for patients. Even without the ACA, reforms in quality and payment models are necessary and will occur.

Through SHM, hospitalists actively are sharing their experiences with policymakers in an effort to create responsive and reflective programs. It is precisely this expertise with hospitalized patients that affords hospitalists a ground- and systems-level perspective on healthcare. With so many reforms taking place, it is vital that hospitalists remain connected and informed about these issues and engage the opportunities for policy leadership and feedback.

To get involved with SHM’s advocacy efforts, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/advocacy.

As America weighs the value of healthcare and health reform, many moving parts of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) will continue to reshape the healthcare system. And hospitalists continue to be part of the reshaping.

The full title of the bill should serve as a reminder to hospitalists of the dual purposes of the ACA: patient protection and cost control. The bulk of popular consciousness about the ACA focused around the favored positions (no pre-existing conditions and children remaining on parents’ plans until age 26) or around points of contention (the individual mandate and the Medicaid expansion).

The lesser-mentioned provisions centering around cost, quality, and payment reform have the potential to substantively reframe the conversation, particularly from the provider perspective. Hospitalists have a unique expertise that positions them to be critical in shaping these programs and regulations.

Two initiatives aim at moving the traditional fee-for-service models of payment for health services toward pay-for-performance. Both the hospital value-based purchasing and physician value-based payment modifier use quality measures to link the performance of care with payments. Hospitals and associated groups are in the process of working with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as the value-based purchasing program moves forward.

The physician value-based modifier will combine quality measures and reports, similar to the 2010 Quality and Resource Use Reports piloted this year in Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, and Missouri, with a to-be-determined payment adjustment. These reports represent a major step toward Medicare providing large-scale feedback to providers on healthcare quality and costs. When the modifier is enforced, a percentage of payments will reflect quality scores, making the feedback from hospitalists important in creating meaningful and useful measures.

Concurrently, the ACA spurred the development of additional quality-improvement (QI) programs. Quality efforts ranging from reducing hospital-acquired infections, stemming preventable complications, meaningful use of electronic health records (EHRs), and reducing readmissions round out a complement of programs that strive to create safer, more cost-effective care for patients. For example, the Partnership for Patients is a collaborative program between providers, patient groups, and the government that catalyzes care improvement in hospitals. Hospitalists have been QI leaders at the front lines in their hospitals for years, affording an informed perspective on policy development.

The ACA is a constellation of programs and initiatives that seek to test new systems for care delivery and payment reform while providing access and quality protections for patients. Even without the ACA, reforms in quality and payment models are necessary and will occur.

Through SHM, hospitalists actively are sharing their experiences with policymakers in an effort to create responsive and reflective programs. It is precisely this expertise with hospitalized patients that affords hospitalists a ground- and systems-level perspective on healthcare. With so many reforms taking place, it is vital that hospitalists remain connected and informed about these issues and engage the opportunities for policy leadership and feedback.

To get involved with SHM’s advocacy efforts, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/advocacy.

As America weighs the value of healthcare and health reform, many moving parts of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) will continue to reshape the healthcare system. And hospitalists continue to be part of the reshaping.

The full title of the bill should serve as a reminder to hospitalists of the dual purposes of the ACA: patient protection and cost control. The bulk of popular consciousness about the ACA focused around the favored positions (no pre-existing conditions and children remaining on parents’ plans until age 26) or around points of contention (the individual mandate and the Medicaid expansion).

The lesser-mentioned provisions centering around cost, quality, and payment reform have the potential to substantively reframe the conversation, particularly from the provider perspective. Hospitalists have a unique expertise that positions them to be critical in shaping these programs and regulations.

Two initiatives aim at moving the traditional fee-for-service models of payment for health services toward pay-for-performance. Both the hospital value-based purchasing and physician value-based payment modifier use quality measures to link the performance of care with payments. Hospitals and associated groups are in the process of working with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as the value-based purchasing program moves forward.

The physician value-based modifier will combine quality measures and reports, similar to the 2010 Quality and Resource Use Reports piloted this year in Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, and Missouri, with a to-be-determined payment adjustment. These reports represent a major step toward Medicare providing large-scale feedback to providers on healthcare quality and costs. When the modifier is enforced, a percentage of payments will reflect quality scores, making the feedback from hospitalists important in creating meaningful and useful measures.

Concurrently, the ACA spurred the development of additional quality-improvement (QI) programs. Quality efforts ranging from reducing hospital-acquired infections, stemming preventable complications, meaningful use of electronic health records (EHRs), and reducing readmissions round out a complement of programs that strive to create safer, more cost-effective care for patients. For example, the Partnership for Patients is a collaborative program between providers, patient groups, and the government that catalyzes care improvement in hospitals. Hospitalists have been QI leaders at the front lines in their hospitals for years, affording an informed perspective on policy development.

The ACA is a constellation of programs and initiatives that seek to test new systems for care delivery and payment reform while providing access and quality protections for patients. Even without the ACA, reforms in quality and payment models are necessary and will occur.

Through SHM, hospitalists actively are sharing their experiences with policymakers in an effort to create responsive and reflective programs. It is precisely this expertise with hospitalized patients that affords hospitalists a ground- and systems-level perspective on healthcare. With so many reforms taking place, it is vital that hospitalists remain connected and informed about these issues and engage the opportunities for policy leadership and feedback.

To get involved with SHM’s advocacy efforts, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/advocacy.

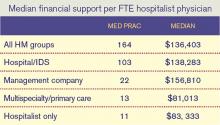

Survey Insights: HM's Financial Support Requirement

One of the most eagerly awaited results from an SHM compensation and productivity survey is the amount of financial support provided by hospitals or other organizations to HM groups (note that we’ve carefully avoided the dreaded “S” word). SHM has been asking this question since at least 2003, when the median annual support per hospitalist FTE was reported at $60,000. By 2007, that number had grown by 62% to $97,375. But the 2007 findings that might have caused the greatest uproar were that fully 37% of responding HM group leaders did not know their program’s annual expenses, and 35% did not know their program’s revenues.

Fast-forward to today. The median annual financial support per FTE reported in the 2011 SHM/MGMA State of Hospital Medicine report is $136,403, a whopping 39% increase over the 2010 median of $98,253.

What caused this big increase in HM’s financial support requirement? Did costs go up that dramatically in just one year? Well, the median compensation for adult medicine hospitalists (the vast majority of hospitalists in the data set) went up by a mere 2.6% during the same period. The amount of support staffing reported by HM groups did not change appreciably. And since labor accounts for the vast majority of virtually every HM practice’s costs, it’s unlikely that the increase in financial support per FTE was caused by a dramatic increase in program costs.

Perhaps program revenues went down significantly, then. It’s true that the median professional fee collections per FTE for adult hospitalists declined between the 2010 and 2011 reports, but only by about 3.3%—probably a result of gearing up for healthcare reform, increases in indigent care and bad debt due to the weak economy, and similar revenue pressures. So it doesn’t appear that declining revenues can explain the big jump in financial support per FTE, either.

I’d like to think that one of the reasons financial support per FTE has increased so much is that we are getting better at how we ask the question. Early on, we simply asked, “If your group receives OTHER INCOME (besides collections for direct patient care), indicate source and amount of payments.” In recent years, the question has been fine-tuned to ask about “financial support over and above professional fee revenues from one or more hospitals or integrated delivery systems (or other sources),” and the survey guide has given even more detailed instructions. But in truth, the question was worded almost identically in 2010 and 2011.

All of this leads me to the unavoidable speculation that HM groups (and/or the hospitals they work for) probably are becoming more sophisticated about how they account for the costs of their hospitalist programs, and that HM group leaders are becoming more knowledgeable about their own programs’ costs and revenues (and, yes, the amount of financial support they receive). We haven’t asked respondents recently whether they know their practice’s costs and revenues, but maybe next time we should. I’ll bet the results will differ a lot from 2007.

—Leslie Flores, MHA, SHM senior advisor

One of the most eagerly awaited results from an SHM compensation and productivity survey is the amount of financial support provided by hospitals or other organizations to HM groups (note that we’ve carefully avoided the dreaded “S” word). SHM has been asking this question since at least 2003, when the median annual support per hospitalist FTE was reported at $60,000. By 2007, that number had grown by 62% to $97,375. But the 2007 findings that might have caused the greatest uproar were that fully 37% of responding HM group leaders did not know their program’s annual expenses, and 35% did not know their program’s revenues.

Fast-forward to today. The median annual financial support per FTE reported in the 2011 SHM/MGMA State of Hospital Medicine report is $136,403, a whopping 39% increase over the 2010 median of $98,253.

What caused this big increase in HM’s financial support requirement? Did costs go up that dramatically in just one year? Well, the median compensation for adult medicine hospitalists (the vast majority of hospitalists in the data set) went up by a mere 2.6% during the same period. The amount of support staffing reported by HM groups did not change appreciably. And since labor accounts for the vast majority of virtually every HM practice’s costs, it’s unlikely that the increase in financial support per FTE was caused by a dramatic increase in program costs.

Perhaps program revenues went down significantly, then. It’s true that the median professional fee collections per FTE for adult hospitalists declined between the 2010 and 2011 reports, but only by about 3.3%—probably a result of gearing up for healthcare reform, increases in indigent care and bad debt due to the weak economy, and similar revenue pressures. So it doesn’t appear that declining revenues can explain the big jump in financial support per FTE, either.

I’d like to think that one of the reasons financial support per FTE has increased so much is that we are getting better at how we ask the question. Early on, we simply asked, “If your group receives OTHER INCOME (besides collections for direct patient care), indicate source and amount of payments.” In recent years, the question has been fine-tuned to ask about “financial support over and above professional fee revenues from one or more hospitals or integrated delivery systems (or other sources),” and the survey guide has given even more detailed instructions. But in truth, the question was worded almost identically in 2010 and 2011.

All of this leads me to the unavoidable speculation that HM groups (and/or the hospitals they work for) probably are becoming more sophisticated about how they account for the costs of their hospitalist programs, and that HM group leaders are becoming more knowledgeable about their own programs’ costs and revenues (and, yes, the amount of financial support they receive). We haven’t asked respondents recently whether they know their practice’s costs and revenues, but maybe next time we should. I’ll bet the results will differ a lot from 2007.

—Leslie Flores, MHA, SHM senior advisor

One of the most eagerly awaited results from an SHM compensation and productivity survey is the amount of financial support provided by hospitals or other organizations to HM groups (note that we’ve carefully avoided the dreaded “S” word). SHM has been asking this question since at least 2003, when the median annual support per hospitalist FTE was reported at $60,000. By 2007, that number had grown by 62% to $97,375. But the 2007 findings that might have caused the greatest uproar were that fully 37% of responding HM group leaders did not know their program’s annual expenses, and 35% did not know their program’s revenues.

Fast-forward to today. The median annual financial support per FTE reported in the 2011 SHM/MGMA State of Hospital Medicine report is $136,403, a whopping 39% increase over the 2010 median of $98,253.

What caused this big increase in HM’s financial support requirement? Did costs go up that dramatically in just one year? Well, the median compensation for adult medicine hospitalists (the vast majority of hospitalists in the data set) went up by a mere 2.6% during the same period. The amount of support staffing reported by HM groups did not change appreciably. And since labor accounts for the vast majority of virtually every HM practice’s costs, it’s unlikely that the increase in financial support per FTE was caused by a dramatic increase in program costs.

Perhaps program revenues went down significantly, then. It’s true that the median professional fee collections per FTE for adult hospitalists declined between the 2010 and 2011 reports, but only by about 3.3%—probably a result of gearing up for healthcare reform, increases in indigent care and bad debt due to the weak economy, and similar revenue pressures. So it doesn’t appear that declining revenues can explain the big jump in financial support per FTE, either.

I’d like to think that one of the reasons financial support per FTE has increased so much is that we are getting better at how we ask the question. Early on, we simply asked, “If your group receives OTHER INCOME (besides collections for direct patient care), indicate source and amount of payments.” In recent years, the question has been fine-tuned to ask about “financial support over and above professional fee revenues from one or more hospitals or integrated delivery systems (or other sources),” and the survey guide has given even more detailed instructions. But in truth, the question was worded almost identically in 2010 and 2011.

All of this leads me to the unavoidable speculation that HM groups (and/or the hospitals they work for) probably are becoming more sophisticated about how they account for the costs of their hospitalist programs, and that HM group leaders are becoming more knowledgeable about their own programs’ costs and revenues (and, yes, the amount of financial support they receive). We haven’t asked respondents recently whether they know their practice’s costs and revenues, but maybe next time we should. I’ll bet the results will differ a lot from 2007.

—Leslie Flores, MHA, SHM senior advisor

Hospitalists On the Move

Kenneth Donovan, MD, FHM and Sarada Sripada, MD, SFHM have been named the 2011 Hospitalists of the Year, and Donald Quinn, MD, MBA, SFHM was named the 2011 Post Acute Hospitalist of the Year by IPC: The Hospitalist Company Inc. Selected by IPC’s senior management team, the award includes an honorarium to each of the recipients. Additionally, IPC will make a $2,500 donation to the charity of their choice for each of the recipients.

Paul Fu Jr., MD, MPH, FAAP, recently was named chief medical informatics officer (CMIO) at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles. He has served as chief of the division of pediatric hospital medicine since July 2011.

Former Cogent HMG senior vice president in charge of quality initiatives Anna-Gene O’Neal has taken a CEO position with Alive Hospice, a Nashville, Tenn.-based end-of-life care and grief support company. As CEO, O’Neal will oversee hospice and palliative care, as well as grief-support programs in a service area of 12 Middle Tennessee counties.

Kasra Djalayer, MD, a hospitalist based in Franklin, N.H., has received the 2011 Patients’ Choice Award from Patients’ Choice, an organization that collects and analyzes rankings from various patient-feedback websites, such as Vitals.com. Dr. Djalayer was honored based on a top ranking among physicians across the nation.

Hospitalist Glenn Rosenbluth, MD, has been appointed director of quality and safety programs for graduate medical education (GME) at University of California at San Francisco Medical Center. In his new role, Dr. Rosenbluth will lead multiple GME-related programs while still continuing his leadership as associated director of the pediatrics residency training program.

Business Moves

Cogent HMG has established a new critical-care program at Saint Francis Hospital in Brentwood, Tenn., which marks the hospitalist management company’s 11th full-service intensivist program. The new program will be operated by The Intensivist Group, recently acquired by Cogent HMG, and will include the development and implementation of literature-based ICU guidelines, a staff intensivist in the hospital seven days a week, and intensivist consultation and comanagement for all ICU patients.

IPC: The Hospitalist Company Inc. has acquired the facility-based practice of Asana Integrated Medical Group, a professional medical corporation that serves Southern California and Phoenix. Headquartered in Agoura Hills, Calif., the acquisition will add approximately 65,000 patient encounters annually to IPC.

IPC: The Hospitalist Company Inc. has entered into agreements to provide hospitalist services to four Methodist Healthcare System hospitals in San Antonio. The agreements are with Methodist Stone Oak Hospital, Methodist Specialty and Transplant Hospital, Northeast Methodist Hospital, and Metropolitan Methodist Hospital.

Apollo Medical Holdings Inc. has appointed Gary Augusta to its board of directors. Augusta brings more than 20 years of experience as an executive to the job.

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center has extended its hospitalist program to three additional Pennsylvania campuses, including the McKeesport, Greenville and Farrell hospitals.

Colquitt Regional Medical Center in Moultrie, Ga., has started a hospitalist program. The new team will be led by Marshall Tanner, MD, and will also include Alan Brown, MD, MBA, Frank Wilson, MD, and Ndubuisi Apu Ndukwe, MD.

—Alexandra Schultz

Kenneth Donovan, MD, FHM and Sarada Sripada, MD, SFHM have been named the 2011 Hospitalists of the Year, and Donald Quinn, MD, MBA, SFHM was named the 2011 Post Acute Hospitalist of the Year by IPC: The Hospitalist Company Inc. Selected by IPC’s senior management team, the award includes an honorarium to each of the recipients. Additionally, IPC will make a $2,500 donation to the charity of their choice for each of the recipients.

Paul Fu Jr., MD, MPH, FAAP, recently was named chief medical informatics officer (CMIO) at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles. He has served as chief of the division of pediatric hospital medicine since July 2011.

Former Cogent HMG senior vice president in charge of quality initiatives Anna-Gene O’Neal has taken a CEO position with Alive Hospice, a Nashville, Tenn.-based end-of-life care and grief support company. As CEO, O’Neal will oversee hospice and palliative care, as well as grief-support programs in a service area of 12 Middle Tennessee counties.

Kasra Djalayer, MD, a hospitalist based in Franklin, N.H., has received the 2011 Patients’ Choice Award from Patients’ Choice, an organization that collects and analyzes rankings from various patient-feedback websites, such as Vitals.com. Dr. Djalayer was honored based on a top ranking among physicians across the nation.

Hospitalist Glenn Rosenbluth, MD, has been appointed director of quality and safety programs for graduate medical education (GME) at University of California at San Francisco Medical Center. In his new role, Dr. Rosenbluth will lead multiple GME-related programs while still continuing his leadership as associated director of the pediatrics residency training program.

Business Moves

Cogent HMG has established a new critical-care program at Saint Francis Hospital in Brentwood, Tenn., which marks the hospitalist management company’s 11th full-service intensivist program. The new program will be operated by The Intensivist Group, recently acquired by Cogent HMG, and will include the development and implementation of literature-based ICU guidelines, a staff intensivist in the hospital seven days a week, and intensivist consultation and comanagement for all ICU patients.

IPC: The Hospitalist Company Inc. has acquired the facility-based practice of Asana Integrated Medical Group, a professional medical corporation that serves Southern California and Phoenix. Headquartered in Agoura Hills, Calif., the acquisition will add approximately 65,000 patient encounters annually to IPC.

IPC: The Hospitalist Company Inc. has entered into agreements to provide hospitalist services to four Methodist Healthcare System hospitals in San Antonio. The agreements are with Methodist Stone Oak Hospital, Methodist Specialty and Transplant Hospital, Northeast Methodist Hospital, and Metropolitan Methodist Hospital.

Apollo Medical Holdings Inc. has appointed Gary Augusta to its board of directors. Augusta brings more than 20 years of experience as an executive to the job.

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center has extended its hospitalist program to three additional Pennsylvania campuses, including the McKeesport, Greenville and Farrell hospitals.

Colquitt Regional Medical Center in Moultrie, Ga., has started a hospitalist program. The new team will be led by Marshall Tanner, MD, and will also include Alan Brown, MD, MBA, Frank Wilson, MD, and Ndubuisi Apu Ndukwe, MD.

—Alexandra Schultz

Kenneth Donovan, MD, FHM and Sarada Sripada, MD, SFHM have been named the 2011 Hospitalists of the Year, and Donald Quinn, MD, MBA, SFHM was named the 2011 Post Acute Hospitalist of the Year by IPC: The Hospitalist Company Inc. Selected by IPC’s senior management team, the award includes an honorarium to each of the recipients. Additionally, IPC will make a $2,500 donation to the charity of their choice for each of the recipients.

Paul Fu Jr., MD, MPH, FAAP, recently was named chief medical informatics officer (CMIO) at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles. He has served as chief of the division of pediatric hospital medicine since July 2011.

Former Cogent HMG senior vice president in charge of quality initiatives Anna-Gene O’Neal has taken a CEO position with Alive Hospice, a Nashville, Tenn.-based end-of-life care and grief support company. As CEO, O’Neal will oversee hospice and palliative care, as well as grief-support programs in a service area of 12 Middle Tennessee counties.

Kasra Djalayer, MD, a hospitalist based in Franklin, N.H., has received the 2011 Patients’ Choice Award from Patients’ Choice, an organization that collects and analyzes rankings from various patient-feedback websites, such as Vitals.com. Dr. Djalayer was honored based on a top ranking among physicians across the nation.

Hospitalist Glenn Rosenbluth, MD, has been appointed director of quality and safety programs for graduate medical education (GME) at University of California at San Francisco Medical Center. In his new role, Dr. Rosenbluth will lead multiple GME-related programs while still continuing his leadership as associated director of the pediatrics residency training program.

Business Moves

Cogent HMG has established a new critical-care program at Saint Francis Hospital in Brentwood, Tenn., which marks the hospitalist management company’s 11th full-service intensivist program. The new program will be operated by The Intensivist Group, recently acquired by Cogent HMG, and will include the development and implementation of literature-based ICU guidelines, a staff intensivist in the hospital seven days a week, and intensivist consultation and comanagement for all ICU patients.

IPC: The Hospitalist Company Inc. has acquired the facility-based practice of Asana Integrated Medical Group, a professional medical corporation that serves Southern California and Phoenix. Headquartered in Agoura Hills, Calif., the acquisition will add approximately 65,000 patient encounters annually to IPC.

IPC: The Hospitalist Company Inc. has entered into agreements to provide hospitalist services to four Methodist Healthcare System hospitals in San Antonio. The agreements are with Methodist Stone Oak Hospital, Methodist Specialty and Transplant Hospital, Northeast Methodist Hospital, and Metropolitan Methodist Hospital.

Apollo Medical Holdings Inc. has appointed Gary Augusta to its board of directors. Augusta brings more than 20 years of experience as an executive to the job.

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center has extended its hospitalist program to three additional Pennsylvania campuses, including the McKeesport, Greenville and Farrell hospitals.

Colquitt Regional Medical Center in Moultrie, Ga., has started a hospitalist program. The new team will be led by Marshall Tanner, MD, and will also include Alan Brown, MD, MBA, Frank Wilson, MD, and Ndubuisi Apu Ndukwe, MD.

—Alexandra Schultz

Adult Hospital Medicine Boot Camp

Physician assistants and other non-physician providers (NPPs) can stay up to date on the fastest-growing specialty in medicine through the Adult Hospital Medicine Boot Camp, Oct. 18-21 in New Orleans, with optional half-day pre-courses on Oct. 17.

Co-hosted by SHM and the American Academy of Physician Assistants, this annual boot-camp-style educational event will immerse clinicians who are practicing in HM or who are interested in an intensive internal-medicine review of commonly encountered diagnoses and diseases of the hospitalized adult patient.

In addition to educating those already practicing in the HM setting, the boot camp provides an ideal introduction for clinicians who plan to practice in HM soon.

The boot camp has been approved for a maximum of 29.5 AAPA Category I CME credits.

For more information, visit the link on the SHM “Events” page at www.hospitalmedicine.org/events.

Physician assistants and other non-physician providers (NPPs) can stay up to date on the fastest-growing specialty in medicine through the Adult Hospital Medicine Boot Camp, Oct. 18-21 in New Orleans, with optional half-day pre-courses on Oct. 17.

Co-hosted by SHM and the American Academy of Physician Assistants, this annual boot-camp-style educational event will immerse clinicians who are practicing in HM or who are interested in an intensive internal-medicine review of commonly encountered diagnoses and diseases of the hospitalized adult patient.

In addition to educating those already practicing in the HM setting, the boot camp provides an ideal introduction for clinicians who plan to practice in HM soon.

The boot camp has been approved for a maximum of 29.5 AAPA Category I CME credits.

For more information, visit the link on the SHM “Events” page at www.hospitalmedicine.org/events.

Physician assistants and other non-physician providers (NPPs) can stay up to date on the fastest-growing specialty in medicine through the Adult Hospital Medicine Boot Camp, Oct. 18-21 in New Orleans, with optional half-day pre-courses on Oct. 17.

Co-hosted by SHM and the American Academy of Physician Assistants, this annual boot-camp-style educational event will immerse clinicians who are practicing in HM or who are interested in an intensive internal-medicine review of commonly encountered diagnoses and diseases of the hospitalized adult patient.

In addition to educating those already practicing in the HM setting, the boot camp provides an ideal introduction for clinicians who plan to practice in HM soon.

The boot camp has been approved for a maximum of 29.5 AAPA Category I CME credits.

For more information, visit the link on the SHM “Events” page at www.hospitalmedicine.org/events.

CER: Friend or Foe?

A key engine of healthcare reform is poised to accelerate, with the potential to improve clinical decision-making and care quality, curtail inappropriate utilization of ineffective treatments, and lower costs. Comparative-effectiveness research (CER), until now, has received relatively meager funding and has occupied a relatively low profile among policymakers, clinicians, and the public.

With a $1.1 billion injection from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (better known as the “stimulus”) and dedicated funding mandated by the Affordable Care Act, a new national center dedicated to CER—the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI)—has recently released a draft of its national priorities and is mobilizing a national research agenda for CER.1

Demonized by critics as a prelude to coverage denials, healthcare rationing, and intrusion upon physicians’ clinical autonomy, CER is reconstituting its reputation as a non-coercive yet powerful tool to reduce uncertainty about which healthcare options work best for which patients, and to encourage adoption of care practices that are truly effective.

“I practice on weekends as a pediatric hospitalist, and it is still far too common to encounter a case for which we don’t have good, evidence-based guidance—such as whether surgery or medical management is best for a neurologically impaired child presenting with aspiration and gastroesophageal reflux disease,” says Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, SFHM, chief medical officer of the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and director of its Office of Clinical Standards and Quality.

SHM strongly supported the creation of PCORI during the health reform debate, and hospitalists have important opportunities to be part of the nation’s CER agenda, as well as key beneficiaries of its results, according to Dr. Conway.

Efficacy vs. Effectiveness

While the traditional “gold standard” of clinical research is the randomized controlled trial, its focus on efficacy typically involves comparing some treatment to no treatment at all (a placebo), and requires highly controlled, ideal conditions, often with narrow patient-inclusion criteria. All of those requirements sacrifice generalizability to patients whom physicians encounter daily in clinical settings who often have multiple chronic conditions and comorbidities and might require multiple therapies, Dr. Conway says.

CER studies larger, more representative patient populations treated in real-world clinical circumstances, explains SHM Research Committee chairman David Meltzer, MD, PhD, FHM, who is a member of the PCORI’s Methodology Committee. “One of the big initial tasks of the PCORI is to produce a translation table of what research study designs—randomized controlled trials, head-to-head, observational studies, and others—can best answer which kinds of questions,” he says.

The PCORI’s ultimate goal, says Dr. Conway, is to enable better-informed decision-making between physicians and their patients by allowing for the “right treatments to the right patients at the right time.”

The Case for CER

The unrelenting reality of an unsustainable healthcare cost spiral that threatens to bankrupt the national economy might be changing the conversation about CER (see “PCORI: Built to Reject the Myth of Coercive Rationing,” at left). Add to that increasing gravitation by government and private insurers toward reimbursement models that reward providers for better outcomes, more efficient care, and evidence-based practices (and penalizes the opposite), and CER makes a lot of sense.

An estimated $158 billion to $226 billion in wasteful healthcare spending last year came from “subjecting patients to care that, according to sound science and the patients’ own preferences, cannot possibly help them—care rooted in outmoded habits, supply-driven behaviors, and ignoring science,” wrote former CMS administrator Donald Berwick, MD, MPP, and RAND researcher Andrew Hackbarth, MPhil.2

It appears as though physicians are becoming more receptive to their role as responsible stewards of finite healthcare resources, and are willing to abandon some common clinical practices that add little value to patient care when given credible evidence. In the recent Choosing Wisely campaign (www.ChoosingWisely.org), for example, nine medical specialty societies worked with the ABIM Foundation and Consumer Reports to publicize 45 tests and procedures—five from each society—that are commonly used in their field, but which evidence suggests might be unnecessary and inappropriate for many patients.

Physicians who in the past might have resisted traditional evidence-based guidelines as “cookie cutter” algorithms that “don’t apply to my particular patient” will find it harder to dismiss CER findings on that basis, Dr. Meltzer notes, because CER is designed at the outset to be relevant to specific subsets of patients in actual clinical settings.

Nevertheless, incentives will be required to drive rapid and widespread adoption of CER findings, Dr. Conway believes.

“Just creating evidence doesn’t create change,” he says. “Cycle time from research finding to implementation matters, and the typical 17 years [time lag from bench to bedside] is not going to cut it. We need to work with clinicians and patients to take new findings and implement them sooner.”

CMS already has selected some evidence-based process and outcome metrics for its value-based purchasing program. “As CER identifies new evidence-based process and outcome metrics, we could incorporate them,” Dr. Conway adds.

Private insurers could use CER findings when making coverage decisions for their health plans. By law, CMS is obligated to provide coverage to Medicare beneficiaries for healthcare services that are “reasonable and necessary,” and cannot exclude coverage based on the cost of services.

“CMS could use CER findings to make coverage determinations based on ineffectiveness, when there is compelling evidence that a service is ‘not reasonable and necessary,’” Dr. Conway states.

HM Opportunity

Dr. Conway says hospitalists are uniquely poised to seek funding for CER that builds upon several critically important topics, such as examining the best discharge planning processes and transition-of-care protocols for certain types of patients. Dr. Meltzer, who is chief of the section of hospital medicine at University of Chicago, says he is seeking funding for a study of alternative transfusion thresholds for older patients with anemia across different levels of patients’ functional status.

“That’s the type of patient-centered study that CER is especially equipped to handle,” Dr. Meltzer says.

CER promises to produce important evidence for clinical questions that hospitalists struggle with day to day, Dr. Conway says. “Hospitalists should take the lead in developing effective ways to disseminate those findings, to teach medical trainees about them, and to spearhead CER-based QI [quality improvement] implementation and tracking efforts at their institutions,” he adds.

Christopher Guadagnino is a freelance medical writer in Philadelphia.

References

- Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute. Draft National Priorities for Research and Research Agenda, Version 1. Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute website. Available at: http://interactive.snm.org/docs/PCORI-Draft-National-Priorities-and-Research-Agenda2.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2012.

- Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in U.S. health care. Journal of the American Medical Association website. Available at: http://jama.ama-assn.org/content/307/14/1513.full. Accessed April 15, 2012.

- Selby JV. The researcher-in-chief at the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Inverview by Susan Dentzer. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(12):2252-2258.

A key engine of healthcare reform is poised to accelerate, with the potential to improve clinical decision-making and care quality, curtail inappropriate utilization of ineffective treatments, and lower costs. Comparative-effectiveness research (CER), until now, has received relatively meager funding and has occupied a relatively low profile among policymakers, clinicians, and the public.

With a $1.1 billion injection from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (better known as the “stimulus”) and dedicated funding mandated by the Affordable Care Act, a new national center dedicated to CER—the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI)—has recently released a draft of its national priorities and is mobilizing a national research agenda for CER.1

Demonized by critics as a prelude to coverage denials, healthcare rationing, and intrusion upon physicians’ clinical autonomy, CER is reconstituting its reputation as a non-coercive yet powerful tool to reduce uncertainty about which healthcare options work best for which patients, and to encourage adoption of care practices that are truly effective.

“I practice on weekends as a pediatric hospitalist, and it is still far too common to encounter a case for which we don’t have good, evidence-based guidance—such as whether surgery or medical management is best for a neurologically impaired child presenting with aspiration and gastroesophageal reflux disease,” says Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, SFHM, chief medical officer of the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and director of its Office of Clinical Standards and Quality.

SHM strongly supported the creation of PCORI during the health reform debate, and hospitalists have important opportunities to be part of the nation’s CER agenda, as well as key beneficiaries of its results, according to Dr. Conway.

Efficacy vs. Effectiveness

While the traditional “gold standard” of clinical research is the randomized controlled trial, its focus on efficacy typically involves comparing some treatment to no treatment at all (a placebo), and requires highly controlled, ideal conditions, often with narrow patient-inclusion criteria. All of those requirements sacrifice generalizability to patients whom physicians encounter daily in clinical settings who often have multiple chronic conditions and comorbidities and might require multiple therapies, Dr. Conway says.

CER studies larger, more representative patient populations treated in real-world clinical circumstances, explains SHM Research Committee chairman David Meltzer, MD, PhD, FHM, who is a member of the PCORI’s Methodology Committee. “One of the big initial tasks of the PCORI is to produce a translation table of what research study designs—randomized controlled trials, head-to-head, observational studies, and others—can best answer which kinds of questions,” he says.

The PCORI’s ultimate goal, says Dr. Conway, is to enable better-informed decision-making between physicians and their patients by allowing for the “right treatments to the right patients at the right time.”

The Case for CER

The unrelenting reality of an unsustainable healthcare cost spiral that threatens to bankrupt the national economy might be changing the conversation about CER (see “PCORI: Built to Reject the Myth of Coercive Rationing,” at left). Add to that increasing gravitation by government and private insurers toward reimbursement models that reward providers for better outcomes, more efficient care, and evidence-based practices (and penalizes the opposite), and CER makes a lot of sense.

An estimated $158 billion to $226 billion in wasteful healthcare spending last year came from “subjecting patients to care that, according to sound science and the patients’ own preferences, cannot possibly help them—care rooted in outmoded habits, supply-driven behaviors, and ignoring science,” wrote former CMS administrator Donald Berwick, MD, MPP, and RAND researcher Andrew Hackbarth, MPhil.2

It appears as though physicians are becoming more receptive to their role as responsible stewards of finite healthcare resources, and are willing to abandon some common clinical practices that add little value to patient care when given credible evidence. In the recent Choosing Wisely campaign (www.ChoosingWisely.org), for example, nine medical specialty societies worked with the ABIM Foundation and Consumer Reports to publicize 45 tests and procedures—five from each society—that are commonly used in their field, but which evidence suggests might be unnecessary and inappropriate for many patients.

Physicians who in the past might have resisted traditional evidence-based guidelines as “cookie cutter” algorithms that “don’t apply to my particular patient” will find it harder to dismiss CER findings on that basis, Dr. Meltzer notes, because CER is designed at the outset to be relevant to specific subsets of patients in actual clinical settings.

Nevertheless, incentives will be required to drive rapid and widespread adoption of CER findings, Dr. Conway believes.

“Just creating evidence doesn’t create change,” he says. “Cycle time from research finding to implementation matters, and the typical 17 years [time lag from bench to bedside] is not going to cut it. We need to work with clinicians and patients to take new findings and implement them sooner.”

CMS already has selected some evidence-based process and outcome metrics for its value-based purchasing program. “As CER identifies new evidence-based process and outcome metrics, we could incorporate them,” Dr. Conway adds.

Private insurers could use CER findings when making coverage decisions for their health plans. By law, CMS is obligated to provide coverage to Medicare beneficiaries for healthcare services that are “reasonable and necessary,” and cannot exclude coverage based on the cost of services.

“CMS could use CER findings to make coverage determinations based on ineffectiveness, when there is compelling evidence that a service is ‘not reasonable and necessary,’” Dr. Conway states.

HM Opportunity

Dr. Conway says hospitalists are uniquely poised to seek funding for CER that builds upon several critically important topics, such as examining the best discharge planning processes and transition-of-care protocols for certain types of patients. Dr. Meltzer, who is chief of the section of hospital medicine at University of Chicago, says he is seeking funding for a study of alternative transfusion thresholds for older patients with anemia across different levels of patients’ functional status.

“That’s the type of patient-centered study that CER is especially equipped to handle,” Dr. Meltzer says.

CER promises to produce important evidence for clinical questions that hospitalists struggle with day to day, Dr. Conway says. “Hospitalists should take the lead in developing effective ways to disseminate those findings, to teach medical trainees about them, and to spearhead CER-based QI [quality improvement] implementation and tracking efforts at their institutions,” he adds.

Christopher Guadagnino is a freelance medical writer in Philadelphia.

References

- Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute. Draft National Priorities for Research and Research Agenda, Version 1. Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute website. Available at: http://interactive.snm.org/docs/PCORI-Draft-National-Priorities-and-Research-Agenda2.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2012.

- Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in U.S. health care. Journal of the American Medical Association website. Available at: http://jama.ama-assn.org/content/307/14/1513.full. Accessed April 15, 2012.

- Selby JV. The researcher-in-chief at the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Inverview by Susan Dentzer. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(12):2252-2258.

A key engine of healthcare reform is poised to accelerate, with the potential to improve clinical decision-making and care quality, curtail inappropriate utilization of ineffective treatments, and lower costs. Comparative-effectiveness research (CER), until now, has received relatively meager funding and has occupied a relatively low profile among policymakers, clinicians, and the public.

With a $1.1 billion injection from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (better known as the “stimulus”) and dedicated funding mandated by the Affordable Care Act, a new national center dedicated to CER—the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI)—has recently released a draft of its national priorities and is mobilizing a national research agenda for CER.1

Demonized by critics as a prelude to coverage denials, healthcare rationing, and intrusion upon physicians’ clinical autonomy, CER is reconstituting its reputation as a non-coercive yet powerful tool to reduce uncertainty about which healthcare options work best for which patients, and to encourage adoption of care practices that are truly effective.

“I practice on weekends as a pediatric hospitalist, and it is still far too common to encounter a case for which we don’t have good, evidence-based guidance—such as whether surgery or medical management is best for a neurologically impaired child presenting with aspiration and gastroesophageal reflux disease,” says Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, SFHM, chief medical officer of the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and director of its Office of Clinical Standards and Quality.

SHM strongly supported the creation of PCORI during the health reform debate, and hospitalists have important opportunities to be part of the nation’s CER agenda, as well as key beneficiaries of its results, according to Dr. Conway.

Efficacy vs. Effectiveness

While the traditional “gold standard” of clinical research is the randomized controlled trial, its focus on efficacy typically involves comparing some treatment to no treatment at all (a placebo), and requires highly controlled, ideal conditions, often with narrow patient-inclusion criteria. All of those requirements sacrifice generalizability to patients whom physicians encounter daily in clinical settings who often have multiple chronic conditions and comorbidities and might require multiple therapies, Dr. Conway says.

CER studies larger, more representative patient populations treated in real-world clinical circumstances, explains SHM Research Committee chairman David Meltzer, MD, PhD, FHM, who is a member of the PCORI’s Methodology Committee. “One of the big initial tasks of the PCORI is to produce a translation table of what research study designs—randomized controlled trials, head-to-head, observational studies, and others—can best answer which kinds of questions,” he says.

The PCORI’s ultimate goal, says Dr. Conway, is to enable better-informed decision-making between physicians and their patients by allowing for the “right treatments to the right patients at the right time.”

The Case for CER

The unrelenting reality of an unsustainable healthcare cost spiral that threatens to bankrupt the national economy might be changing the conversation about CER (see “PCORI: Built to Reject the Myth of Coercive Rationing,” at left). Add to that increasing gravitation by government and private insurers toward reimbursement models that reward providers for better outcomes, more efficient care, and evidence-based practices (and penalizes the opposite), and CER makes a lot of sense.

An estimated $158 billion to $226 billion in wasteful healthcare spending last year came from “subjecting patients to care that, according to sound science and the patients’ own preferences, cannot possibly help them—care rooted in outmoded habits, supply-driven behaviors, and ignoring science,” wrote former CMS administrator Donald Berwick, MD, MPP, and RAND researcher Andrew Hackbarth, MPhil.2

It appears as though physicians are becoming more receptive to their role as responsible stewards of finite healthcare resources, and are willing to abandon some common clinical practices that add little value to patient care when given credible evidence. In the recent Choosing Wisely campaign (www.ChoosingWisely.org), for example, nine medical specialty societies worked with the ABIM Foundation and Consumer Reports to publicize 45 tests and procedures—five from each society—that are commonly used in their field, but which evidence suggests might be unnecessary and inappropriate for many patients.

Physicians who in the past might have resisted traditional evidence-based guidelines as “cookie cutter” algorithms that “don’t apply to my particular patient” will find it harder to dismiss CER findings on that basis, Dr. Meltzer notes, because CER is designed at the outset to be relevant to specific subsets of patients in actual clinical settings.

Nevertheless, incentives will be required to drive rapid and widespread adoption of CER findings, Dr. Conway believes.

“Just creating evidence doesn’t create change,” he says. “Cycle time from research finding to implementation matters, and the typical 17 years [time lag from bench to bedside] is not going to cut it. We need to work with clinicians and patients to take new findings and implement them sooner.”

CMS already has selected some evidence-based process and outcome metrics for its value-based purchasing program. “As CER identifies new evidence-based process and outcome metrics, we could incorporate them,” Dr. Conway adds.

Private insurers could use CER findings when making coverage decisions for their health plans. By law, CMS is obligated to provide coverage to Medicare beneficiaries for healthcare services that are “reasonable and necessary,” and cannot exclude coverage based on the cost of services.

“CMS could use CER findings to make coverage determinations based on ineffectiveness, when there is compelling evidence that a service is ‘not reasonable and necessary,’” Dr. Conway states.

HM Opportunity

Dr. Conway says hospitalists are uniquely poised to seek funding for CER that builds upon several critically important topics, such as examining the best discharge planning processes and transition-of-care protocols for certain types of patients. Dr. Meltzer, who is chief of the section of hospital medicine at University of Chicago, says he is seeking funding for a study of alternative transfusion thresholds for older patients with anemia across different levels of patients’ functional status.

“That’s the type of patient-centered study that CER is especially equipped to handle,” Dr. Meltzer says.

CER promises to produce important evidence for clinical questions that hospitalists struggle with day to day, Dr. Conway says. “Hospitalists should take the lead in developing effective ways to disseminate those findings, to teach medical trainees about them, and to spearhead CER-based QI [quality improvement] implementation and tracking efforts at their institutions,” he adds.

Christopher Guadagnino is a freelance medical writer in Philadelphia.

References

- Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute. Draft National Priorities for Research and Research Agenda, Version 1. Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute website. Available at: http://interactive.snm.org/docs/PCORI-Draft-National-Priorities-and-Research-Agenda2.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2012.

- Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in U.S. health care. Journal of the American Medical Association website. Available at: http://jama.ama-assn.org/content/307/14/1513.full. Accessed April 15, 2012.

- Selby JV. The researcher-in-chief at the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Inverview by Susan Dentzer. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(12):2252-2258.

Hospitalists Match PCPs in Patient Satisfaction Scores

A recent study in the Journal of Hospital Medicine that found inpatients are similarly satisfied with the care provided by hospitalists and the care of primary-care physicians (PCPs) should be considered a positive for HM, says lead author Adrianne Seiler, MD, of the Division of Healthcare Quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass.1

The results are drawn from scripted patient-satisfaction telephone interviews of 8,295 patients discharged from three Massachusetts hospitals from 2003 to 2009. Starting in 2007, questions were added from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) federal quality reporting system. Multivariate-adjusted satisfaction scores for physician care quality were only slightly higher for PCPs (4.24 on a five-point scale) than for hospitalists (4.20), with no statistical difference for individual hospitals or for different hospitalist groups.

“What has been passed down as dogma is the discontinuity in care introduced by the hospitalist model,” Dr. Seiler says. But actual data on the effects of the hospitalist model on patient satisfaction are scant. “Our finding that patients essentially were equally satisfied with either model of medical care—that’s huge.”

HCAHPS scores have not been validated to evaluate patient satisfaction with individual hospitalist providers specifically, Dr. Seiler says, but they are standardized nationwide. “Is this the best way to measure patient experience?” she asks. “It’s the best tool we have at this time.”

Another wrinkle in patient satisfaction was presented as an oral research abstract at HM12. Researchers from the Veterans Administration and the University of Michigan examined the association between hospitalist staffing levels and patient satisfaction.2 Hospitals with the highest hospitalist staffing had modestly higher patient satisfaction scores than those with the lowest hospitalist staffing. Overall satisfaction was 65.6 for hospitals in the highest tertile of hospitalist staffing versus 62.7 those in the lowest tertile.

References

- Seiler A, Visintainer P, Brzostek R, et al. Patient satisfaction with hospital care provided by hospitalists and primary care physicians. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:131-136.

- Chen L, Birkmeyer J, Saint S, Ashish J. Hospitalist staffing and patient satisfaction in the national Medicare population. Abstract presented at HM12, April 2, 2012, San Diego.

A recent study in the Journal of Hospital Medicine that found inpatients are similarly satisfied with the care provided by hospitalists and the care of primary-care physicians (PCPs) should be considered a positive for HM, says lead author Adrianne Seiler, MD, of the Division of Healthcare Quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass.1

The results are drawn from scripted patient-satisfaction telephone interviews of 8,295 patients discharged from three Massachusetts hospitals from 2003 to 2009. Starting in 2007, questions were added from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) federal quality reporting system. Multivariate-adjusted satisfaction scores for physician care quality were only slightly higher for PCPs (4.24 on a five-point scale) than for hospitalists (4.20), with no statistical difference for individual hospitals or for different hospitalist groups.

“What has been passed down as dogma is the discontinuity in care introduced by the hospitalist model,” Dr. Seiler says. But actual data on the effects of the hospitalist model on patient satisfaction are scant. “Our finding that patients essentially were equally satisfied with either model of medical care—that’s huge.”

HCAHPS scores have not been validated to evaluate patient satisfaction with individual hospitalist providers specifically, Dr. Seiler says, but they are standardized nationwide. “Is this the best way to measure patient experience?” she asks. “It’s the best tool we have at this time.”

Another wrinkle in patient satisfaction was presented as an oral research abstract at HM12. Researchers from the Veterans Administration and the University of Michigan examined the association between hospitalist staffing levels and patient satisfaction.2 Hospitals with the highest hospitalist staffing had modestly higher patient satisfaction scores than those with the lowest hospitalist staffing. Overall satisfaction was 65.6 for hospitals in the highest tertile of hospitalist staffing versus 62.7 those in the lowest tertile.

References

- Seiler A, Visintainer P, Brzostek R, et al. Patient satisfaction with hospital care provided by hospitalists and primary care physicians. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:131-136.

- Chen L, Birkmeyer J, Saint S, Ashish J. Hospitalist staffing and patient satisfaction in the national Medicare population. Abstract presented at HM12, April 2, 2012, San Diego.

A recent study in the Journal of Hospital Medicine that found inpatients are similarly satisfied with the care provided by hospitalists and the care of primary-care physicians (PCPs) should be considered a positive for HM, says lead author Adrianne Seiler, MD, of the Division of Healthcare Quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass.1

The results are drawn from scripted patient-satisfaction telephone interviews of 8,295 patients discharged from three Massachusetts hospitals from 2003 to 2009. Starting in 2007, questions were added from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) federal quality reporting system. Multivariate-adjusted satisfaction scores for physician care quality were only slightly higher for PCPs (4.24 on a five-point scale) than for hospitalists (4.20), with no statistical difference for individual hospitals or for different hospitalist groups.

“What has been passed down as dogma is the discontinuity in care introduced by the hospitalist model,” Dr. Seiler says. But actual data on the effects of the hospitalist model on patient satisfaction are scant. “Our finding that patients essentially were equally satisfied with either model of medical care—that’s huge.”

HCAHPS scores have not been validated to evaluate patient satisfaction with individual hospitalist providers specifically, Dr. Seiler says, but they are standardized nationwide. “Is this the best way to measure patient experience?” she asks. “It’s the best tool we have at this time.”

Another wrinkle in patient satisfaction was presented as an oral research abstract at HM12. Researchers from the Veterans Administration and the University of Michigan examined the association between hospitalist staffing levels and patient satisfaction.2 Hospitals with the highest hospitalist staffing had modestly higher patient satisfaction scores than those with the lowest hospitalist staffing. Overall satisfaction was 65.6 for hospitals in the highest tertile of hospitalist staffing versus 62.7 those in the lowest tertile.

References

- Seiler A, Visintainer P, Brzostek R, et al. Patient satisfaction with hospital care provided by hospitalists and primary care physicians. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:131-136.

- Chen L, Birkmeyer J, Saint S, Ashish J. Hospitalist staffing and patient satisfaction in the national Medicare population. Abstract presented at HM12, April 2, 2012, San Diego.

By the Numbers: -0.44

Average difference in length of stay (LOS) between hospitalist groups and non-hospitalist groups, according to a meta-analysis of 17 studies of outcomes from the hospitalist approach.1 The authors, from Cooper University Hospital in Camden, N.J., and elsewhere, searched medical literature through February 2011 for studies comparing length of stay or cost outcomes of hospitalist groups with non-hospitalist “comparator groups.” In studies comparing non-resident hospitalist services with non-resident, non-hospitalist services, LOS was shorter by 0.69 days for the hospitalist model. A total of 137,561 patients were included in the meta-analysis. No significant difference was found in cost between the hospitalist and comparison groups.

Reference

Average difference in length of stay (LOS) between hospitalist groups and non-hospitalist groups, according to a meta-analysis of 17 studies of outcomes from the hospitalist approach.1 The authors, from Cooper University Hospital in Camden, N.J., and elsewhere, searched medical literature through February 2011 for studies comparing length of stay or cost outcomes of hospitalist groups with non-hospitalist “comparator groups.” In studies comparing non-resident hospitalist services with non-resident, non-hospitalist services, LOS was shorter by 0.69 days for the hospitalist model. A total of 137,561 patients were included in the meta-analysis. No significant difference was found in cost between the hospitalist and comparison groups.

Reference

Average difference in length of stay (LOS) between hospitalist groups and non-hospitalist groups, according to a meta-analysis of 17 studies of outcomes from the hospitalist approach.1 The authors, from Cooper University Hospital in Camden, N.J., and elsewhere, searched medical literature through February 2011 for studies comparing length of stay or cost outcomes of hospitalist groups with non-hospitalist “comparator groups.” In studies comparing non-resident hospitalist services with non-resident, non-hospitalist services, LOS was shorter by 0.69 days for the hospitalist model. A total of 137,561 patients were included in the meta-analysis. No significant difference was found in cost between the hospitalist and comparison groups.

Reference

HIT Continues Spread Across Health Networks

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius recently announced that the proportion of U.S. hospitals using health information technology (HIT), such as electronic health records (EHRs), has doubled in the past two years, reaching 35% in 2011, up from 16% in 2009, based on data from an American Hospital Association survey.

Nearly 2,000 hospitals and 41,000 physicians have taken advantage of $3.12 billion in EHR incentive payments from Medicare and Medicaid for ensuring meaningful use of HIT. Fully 85% of hospitals now report that they intend by 2015 to take advantage of HIT incentive payments, which were funded under the HITECH Act provisions of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.

The government also has created a network of 62 regional extension centers to provide technical guidance and resources. Individual HIT training is available at more than 90 community colleges and universities nationwide. For more information on the incentives, visit www.cms.gov/EHRIncentivePrograms.

A recent study of the “connected health maturity index”—systematic leveraging of HIT applications and health information exchanges—in eight countries finds the U.S. leading in several aspects of HIT use and adoption.1 The Reston, Va., consulting firm Accenture interviewed and surveyed health-policy makers, HIT experts, and physicians in the U.S., Australia, Canada, England, France, Germany, Singapore, and Spain.

The U.S. led the way in computerized physician order entry, and 65% of its primary-care physicians (PCPs) use e-prescribing versus 20% in the other surveyed countries. Sixty-two percent of U.S. medical specialists use electronic tools to improve administrative efficiency. However, the report notes, the eight surveyed countries continue to lag behind such acknowledged HIT leaders as Denmark, Sweden, and New Zealand.

Reference

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius recently announced that the proportion of U.S. hospitals using health information technology (HIT), such as electronic health records (EHRs), has doubled in the past two years, reaching 35% in 2011, up from 16% in 2009, based on data from an American Hospital Association survey.

Nearly 2,000 hospitals and 41,000 physicians have taken advantage of $3.12 billion in EHR incentive payments from Medicare and Medicaid for ensuring meaningful use of HIT. Fully 85% of hospitals now report that they intend by 2015 to take advantage of HIT incentive payments, which were funded under the HITECH Act provisions of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.

The government also has created a network of 62 regional extension centers to provide technical guidance and resources. Individual HIT training is available at more than 90 community colleges and universities nationwide. For more information on the incentives, visit www.cms.gov/EHRIncentivePrograms.

A recent study of the “connected health maturity index”—systematic leveraging of HIT applications and health information exchanges—in eight countries finds the U.S. leading in several aspects of HIT use and adoption.1 The Reston, Va., consulting firm Accenture interviewed and surveyed health-policy makers, HIT experts, and physicians in the U.S., Australia, Canada, England, France, Germany, Singapore, and Spain.

The U.S. led the way in computerized physician order entry, and 65% of its primary-care physicians (PCPs) use e-prescribing versus 20% in the other surveyed countries. Sixty-two percent of U.S. medical specialists use electronic tools to improve administrative efficiency. However, the report notes, the eight surveyed countries continue to lag behind such acknowledged HIT leaders as Denmark, Sweden, and New Zealand.

Reference

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius recently announced that the proportion of U.S. hospitals using health information technology (HIT), such as electronic health records (EHRs), has doubled in the past two years, reaching 35% in 2011, up from 16% in 2009, based on data from an American Hospital Association survey.

Nearly 2,000 hospitals and 41,000 physicians have taken advantage of $3.12 billion in EHR incentive payments from Medicare and Medicaid for ensuring meaningful use of HIT. Fully 85% of hospitals now report that they intend by 2015 to take advantage of HIT incentive payments, which were funded under the HITECH Act provisions of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.

The government also has created a network of 62 regional extension centers to provide technical guidance and resources. Individual HIT training is available at more than 90 community colleges and universities nationwide. For more information on the incentives, visit www.cms.gov/EHRIncentivePrograms.

A recent study of the “connected health maturity index”—systematic leveraging of HIT applications and health information exchanges—in eight countries finds the U.S. leading in several aspects of HIT use and adoption.1 The Reston, Va., consulting firm Accenture interviewed and surveyed health-policy makers, HIT experts, and physicians in the U.S., Australia, Canada, England, France, Germany, Singapore, and Spain.

The U.S. led the way in computerized physician order entry, and 65% of its primary-care physicians (PCPs) use e-prescribing versus 20% in the other surveyed countries. Sixty-two percent of U.S. medical specialists use electronic tools to improve administrative efficiency. However, the report notes, the eight surveyed countries continue to lag behind such acknowledged HIT leaders as Denmark, Sweden, and New Zealand.

Reference

Residents Plug Gaps in Professionalism Training

Residents can play a lead role in a program aimed at teaching commitment to the highest standards of excellence in medicine, to the welfare of patients, and to the best interests of the larger society, according to an innovations poster presentation at HM12.1

Professionalism is important to physicians and medical trainees, says Pablo Garcia, MD, a critical-care fellow at the University of New Mexico (UNM) School of Medicine in Albuquerque and one of the project investigators who presented the results in San Diego.

“It directly impacts on patient care and the patient experience,” Dr. Garcia says. “But if we don’t police ourselves as a profession and set our own high standards, we may find that others outside of medicine will take notice.”

Academic medical centers have a particular interest in teaching professionalism to their trainees, not only because the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires it, but also because of the profound impact of positive or negative examples by teachers—the “hidden curriculum”— on trainees, Dr. Garcia says.

The UNM project began with a lecture on elements of and threats to professionalism. A nine-item survey was completed by about half of the 70-member internal-medicine residency program. The results showed some less-than-ideal standards by residents. A team then met to develop nine vignettes involving real-world ethical situations, and small groups of four to six participants came together to discuss the vignettes and how they should be handled.

In some cases, attending physicians observed the groups and posed questions but did not lead the discussions, Dr. Garcia says. Over 12 months, all of the ethical scenarios were discussed at least once. Dr. Garcia was invited to speak to two other residency programs at UNM, pediatrics and emergency medicine, both of which developed their own vignettes for small-group discussion.

Reference

Residents can play a lead role in a program aimed at teaching commitment to the highest standards of excellence in medicine, to the welfare of patients, and to the best interests of the larger society, according to an innovations poster presentation at HM12.1

Professionalism is important to physicians and medical trainees, says Pablo Garcia, MD, a critical-care fellow at the University of New Mexico (UNM) School of Medicine in Albuquerque and one of the project investigators who presented the results in San Diego.

“It directly impacts on patient care and the patient experience,” Dr. Garcia says. “But if we don’t police ourselves as a profession and set our own high standards, we may find that others outside of medicine will take notice.”

Academic medical centers have a particular interest in teaching professionalism to their trainees, not only because the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires it, but also because of the profound impact of positive or negative examples by teachers—the “hidden curriculum”— on trainees, Dr. Garcia says.

The UNM project began with a lecture on elements of and threats to professionalism. A nine-item survey was completed by about half of the 70-member internal-medicine residency program. The results showed some less-than-ideal standards by residents. A team then met to develop nine vignettes involving real-world ethical situations, and small groups of four to six participants came together to discuss the vignettes and how they should be handled.

In some cases, attending physicians observed the groups and posed questions but did not lead the discussions, Dr. Garcia says. Over 12 months, all of the ethical scenarios were discussed at least once. Dr. Garcia was invited to speak to two other residency programs at UNM, pediatrics and emergency medicine, both of which developed their own vignettes for small-group discussion.

Reference

Residents can play a lead role in a program aimed at teaching commitment to the highest standards of excellence in medicine, to the welfare of patients, and to the best interests of the larger society, according to an innovations poster presentation at HM12.1

Professionalism is important to physicians and medical trainees, says Pablo Garcia, MD, a critical-care fellow at the University of New Mexico (UNM) School of Medicine in Albuquerque and one of the project investigators who presented the results in San Diego.

“It directly impacts on patient care and the patient experience,” Dr. Garcia says. “But if we don’t police ourselves as a profession and set our own high standards, we may find that others outside of medicine will take notice.”

Academic medical centers have a particular interest in teaching professionalism to their trainees, not only because the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires it, but also because of the profound impact of positive or negative examples by teachers—the “hidden curriculum”— on trainees, Dr. Garcia says.

The UNM project began with a lecture on elements of and threats to professionalism. A nine-item survey was completed by about half of the 70-member internal-medicine residency program. The results showed some less-than-ideal standards by residents. A team then met to develop nine vignettes involving real-world ethical situations, and small groups of four to six participants came together to discuss the vignettes and how they should be handled.

In some cases, attending physicians observed the groups and posed questions but did not lead the discussions, Dr. Garcia says. Over 12 months, all of the ethical scenarios were discussed at least once. Dr. Garcia was invited to speak to two other residency programs at UNM, pediatrics and emergency medicine, both of which developed their own vignettes for small-group discussion.

Reference

End-of-Life Discussions Don’t Decrease Rate of Survival

Engaging in advance-care-planning discussions with their physicians or having advance directives filed in their medical records resulted in no significant difference in survival time for patients at three Colorado hospitals, according to a report in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.1

A total of 458 adult patients admitted to general IM services at the hospitals were asked whether they’d had discussions with their physicians about advance directives, which are legal documents allowing patients to spell out treatment preferences (including a desire for more aggressive treatment) in advance of situations in which they are no longer able to communicate them. Charts were reviewed for the presence of advance directives, and the patients were then stratified based on low, medium, or high risk of death within a year. The high-risk patients were excluded from the study, and those in the low- and medium-risk groups were followed from 2003 to 2009.

“In regard to the current national debate about the merits of advance-care planning, this study suggests that honoring patients’ wishes to engage in advance directive discussions and documentation does not lead to harm,” the study concludes.