User login

AGA News

Ten tips to help you get a research grant

It’s almost time to submit your application for the American Gastroenterological Association Research Scholar Award, the application deadline is Nov. 13, 2019. Review these tips for writing and preparing your application.

1. Start early. Allow plenty of time to complete your application, give it multiple reviews, and get feedback from others. Most applicants start working on the Specific Aims for the project 6 months in advance of the deadline.

2. Look at examples. Ask your division if there are any templates/prior grant submissions that you can review. There’s no recipe for a successful grant, so the only way to compose one is to have a sense of what has worked in the past. In general, prior awardees are happy to share their applications if you contact them.

3. Request feedback. Ask mentors and colleagues for early feedback on your Specific Aims page. If it makes sense and is interesting to them, reviewers will likely feel the same way.

4. Ask your collaborators for letters of support. In addition to your preceptor, consider including letters of support from prior researchers that you have worked with or any collaborators for the current project, especially if they will help you with a new technique or reagents.

5. Contact the grants staff with questions and concerns early on. If you don’t understand part of the application, aren’t sure if you’re eligible or are having problems with submission, contact the grant staff right away. Don’t wait until the week or day the grant is due when staff may be flooded with calls. They can assist you much better with advance notice, which will allow you to avoid last-minute stress.

6. Each application should be different. Keep in mind the scope of the grant and amount of funding. Don’t just recycle an R01-level application for a 1-year AGA pilot award.

7. More is better than less when it comes to preliminary data. If your expertise in a technique you are proposing is established, you will not need to demonstrate the capability to do the work but will likely need to show preliminary data. If you are looking to build expertise (as a part of your career development), you may need to show that the infrastructure that enables you to do the work is accessible.

8. Don’t take constructive feedback personally. As you share your draft with mentors and colleagues for feedback, you may receive some unanticipated criticism. Try not to take this personally. If you can detach yourself emotionally, you’ll be in a better position to answer critiques and make adjustments.

9. Remember your end goal: To help patients! Even the most basic science proposals are rooted in a clear potential to benefit patients.

10. Stay positive. If you do not succeed on your first application, believe in your work, make it better, and apply again.

Thanks to the following AGA Research Foundation grant recipients for sharing their advice, which resulted in the above 10 tips:

- Arthur Beyder, MD, PhD, 2015 AGA Research Scholar Award

- Barbara Jung, MD, AGAF, 2016 AGA-Elsevier Pilot Research Award

- Benjamin Lebwohl, MD, 2014 AGA Research Scholar Award

- Josephine Ni, MD, 2017 AGA-Takeda Pharmaceuticals Research Scholar Award in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Sahar Nissim, MD, PhD, 2017 AGA-Caroline Craig Augustyn and Damian Augustyn Award in Digestive Cancer

- Jatin Roper, MD, 2011 AGA Fellowship-to-Faculty Transition Award

- Christina Twyman-Saint Victor, MD, 2015 AGA Research Scholar Award

Visit www.gastro.org/research-funding to review the AGA Research Foundation research grants now open for applications. If you have questions about the AGA awards program, please contact [email protected].

The importance of getting involved for gastroenterology

On Sept. 20, 2019, I had the opportunity to participate in AGA’s Advocacy Day for the second time, joining 40 of our gastroenterology colleagues from across the United States on Capitol Hill to advocate for our profession and our patients.

The evening before Advocacy Day, we discussed strategies for having a successful meeting on Capitol Hill with AGA staff (including Kathleen Teixeira, AGA vice president of government affairs, and Jonathan Sollish, AGA senior coordinator, public policy). We discussed having our “asks” supported with evidence, and “getting personal” about how these policy issues directly affect us and our patients. We also had the chance to hear from Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.) and Sen. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.), both of whom invited our questions. Both congressmen are friends of AGA, with Rep. McGovern serving as chair of the House Rules Committee, and Sen. Blunt serving as chair of the Senate Labor–Health & Human Services Subcommittee on Appropriations.

Advocacy Day began with a group breakfast during which we reviewed some of the policy issues of central importance to gastroenterology:

- Removing Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Act (HR1570/S668), which enjoys strong bipartisan support, would correct the “cost-sharing” problem of screening colonoscopies turning therapeutic (with polypectomy) for our Medicare patients, by waiving the coinsurance for screening colonoscopies — regardless of whether we remove polyps during these colonoscopies.

- Safe Step Act, HR2279, legislation introduced in the House, facilitates a common-sense and timely (72 hours or 24 hours if life threatening) appeals process when our patients are subjected to step therapy (“fail first”) by insurers.

- Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act of 2019, HR3107, legislation in the House, eases onerous prior authorization burdens by promoting an electronic prior authorization process, ensuring requests are approved by qualified medical professionals who have specialty-specific experience, and mandating that plans report their rates of delays and denials.

- National Institutes of Health research funding facilitates innovative research and supports young investigators in our field.

Full of enthusiasm, our six-strong North Carolina contingent (pictured L-R, Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, AGAF; David Leiman, MD, MSPH; Animesh Jain, MD; Anne Finefrock Peery, MD; Lisa Gangarosa, MD, AGAF, chair of the AGA Government Affairs Committee; and Amit Patel, MD) met with the offices of Rep. David Price (D-N.C.), and both North Carolina senators, Richard Burr (R) and Thom Tillis (R), on Capitol Hill to convey our “asks.”

At Rep. Price’s office in the stately Rayburn House Office Building, we thanked his team for cosponsorship of H.R. 1570 and H.R. 2279. We also discussed the importance of increasing research funding by the AGA’s goal of $2.5 billion for NIH for fiscal year 2020, noting that a majority of our delegation has received NIH funding for our training and/or research activities. We also encouraged Price’s office to cosponsor H.R. 3107, sharing our personal experiences about the administrative toll of the prior authorization process for obtaining appropriate and recommended medications for our patients – in my case, swallowed topical corticosteroids for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis.

We moved on to Sen. Tillis’s office, where we thanked his office for cosponsorship of S. 668 but encouraged his office to cosponsor upcoming companion Senate legislation for H.R. 2279 and H.R. 3107. Our colleague capably conveyed how an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patient he saw recently may require a colectomy because of delays in appropriate treatment stemming from these regulatory processes. We also showed Tillis’s office how NIH funding generates significant economic activity in North Carolina, supporting jobs in our state.

After a quick stop at the U.S. Senate gift shop in the basement to buy souvenirs for our kids, our last meeting was with Sen. Burr’s office. There, we also thanked his office for cosponsorship of S. 668 but encouraged him to sign the “Dear Colleague” letter that Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) has circulated asking the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to address the colonoscopy cost-sharing “loophole.” We discussed the importance of cosponsoring upcoming companion Senate legislation for H.R. 2279 and H.R. 3107, sharing stories from our clinical practices about how these regulatory burdens have delayed treatment for our patients.

You can get involved, too.

AGA Advocacy Day was a tremendous experience, but it is not the only way AGA members can get involved and take action. The AGA Advocacy website, gastro.org/advocacy, provides more information on multiple avenues for advocacy. These include an online advocacy tool for sending templated letters on these issues to your elected officials.

Perhaps now more than ever, it is crucial that we get involved to support gastroenterology and advocate for our patients.

Dr. Patel is assistant professor, division of gastroenterology, Duke University, Durham, N.C.; member, AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee.

GI of the week: Arthur Beyder, MD, PhD

Congrats to Arthur Beyder, MD, PhD, who was selected for an NIH Director’s New Innovator Award, part of the NIH director’s high-risk, high-reward research award program. The NIH Director’s New Innovator Award will provide Dr. Beyder with more than $2 million in funding over a 5-year period to continue his project: Does the gut have a sense of touch?

Dr. Beyder’s lab at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., recently discovered a novel population of mechanosensitive epithelial sensory cells that are similar to skin’s touch sensors, which prompted a potentially transformative question: “Does the gut have a sense of touch?” We look forward to seeing the results of future research on this topic.

Dr. Beyder – a physician-scientist at the Mayo Clinic – is a 2015 AGA Research Scholar Award recipient and graduate of the 2018 AGA Future Leaders Program. Dr. Beyder currently serves on the AGA Nominating Committee.

Please join us in congratulating Dr. Beyder on Twitter (@BeyderLab) or in the AGA Community.

The NIH director’s high-risk, high-reward research program funds highly innovative, high-impact biomedical research proposed by extraordinarily creative scientists – these awards have one of the lowest funding rates for NIH. Congrats to two additional AGA members who also received a 2019 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award: Maayan Levy, PhD, and Christoph A. Thaiss, PhD, both from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Eight new insights about diet and gut health

During your 4 years of medical school, you likely received only 4 hours of nutrition training. Yet we know diet is so integral to the care of GI patients. That’s why AGA focused the 2019 James W. Freston Conference on the topic: Food at the Intersection of Gut Health and Disease.

Our course directors William Chey, MD, AGAF, Sheila E. Crowe, MD, AGAF, and Gerard E. Mullin, MD, AGAF, share eight points from the meeting that stuck with them and can help all practicing GIs as they consider dietary treatments for their patients.

1. Personalized nutrition is important. Genetic differences lead to differences in health outcomes. One size or recommendation does not fit all. This is why certain diets only work on certain people. There is no one diet for all and for all disease states. Genetic tests can be helpful, but they rely on reporting that isn’t readily available yet.

2. Dietary therapy is key to managing eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). EoE is becoming more and more prevalent. Genes can’t change that fast, but epigenetic factors can, and the evidence seems to be in food. EoE is not an IgE-mediated disease and therefore most allergy tests will not prove useful; however, food is often the trigger – most common, dairy. Dietary therapy is likely the best way to manage. You want to reduce the number of eliminated foods by way of a reintroduction protocol. The six-food elimination diet is standard, though some are moving to a four-food elimination diet (dairy, wheat, egg, and soy).

3. There has been a reported increase in those with food allergies, sensitivities, celiac disease, and other adverse reactions to food. Many of the food allergy tests available are not helpful. In addition, many afflicted patients are using self-imposed diets rather than working with a GI, allergist, or dietitian. This needs to change.

4. There is currently insufficient evidence to support a gluten-free diet for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). It is possible that fructans, more than gluten, are causing the GI issues. Typically, the low-FODMAP diet is beneficial to IBS patients if done correctly with the guidance of a dietitian; however, not everyone with IBS improves on it. All the steps are important though, including reintroduction and maintenance.

5. When working with patients on the low-FODMAP or other restrictive diets, it is important to know their food and eating history. Avoidance/restrictive food intake disorder is something we need to be aware of when it comes to patients with a history or likelihood to develop disordered eating/eating disorders. The patient team may need to include an eating disorder therapist.

6. The general population in the United States has increased the adoption of a gluten-free diet although the number of cases of celiac disease has not increased. Many have self-reported gluten sensitivities. Those that have removed gluten, following trends, are more at risk of bowel irregularity (low fiber), weight gain, and disordered eating. Celiac disease is not a do-it-yourself disease, patients will be best served working with a dietitian and GI.

7. Food can induce symptoms in patients with IBD. It can also trigger gut inflammation resulting in incident or relapse. There is experimental plausibility for some factors of the relationship to be causal and we may be able to modify the diet to prevent and manage IBD.

8. The focus on nutrition education must continue! Nutrition should be a required part of continuing medical education for physicians. And physicians should work with dietitians to improve the care of GI patients.

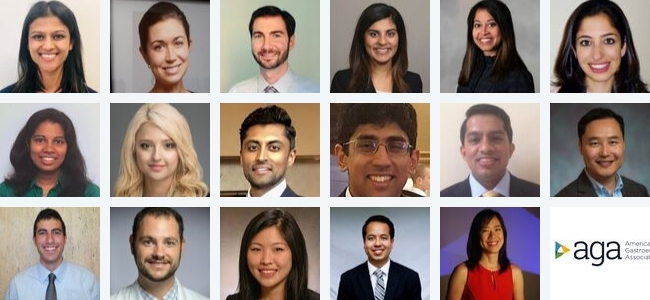

17 fellows advancing GI and patient care

Each year during Digestive Disease Week®, AGA hosts a session titled “Advancing Clinical Practice: GI Fellow-Directed Quality-Improvement Projects.” During the 2019 session, 17 quality improvement initiatives were presented — you can review these abstracts in the July issue of Gastroenterology in the “AGA Section” or review a presenter’s abstract by clicking their name or image. Kudos to the promising fellows featured below, who all served as lead authors for their quality improvement projects.

Manasi Agrawal, MD

Lenox Hill Hospital, New York

@ManasiAgrawalMD

Jessica Breton, MD

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Adam Faye, MD

Columbia University Medical Center, New York

@AdamFaye4

Shelly Gurwara, MD

Wake Forest Baptist Health Medical Center, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Afrin Kamal, MD

Stanford (Calif.) University

Ani Kardashian, MD

University of California, Los Angeles

@AniKardashianMD

Sonali Palchaudhuri, MD

University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

@sopalchaudhuri

Nasim Parsa, MD

University of Missouri Health System, Columbia

Sahil Patel, MD

Drexel University, Philadelphia

@sahilr

Vikram Raghu, MD

Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh

Amit Shah, MD

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Lin Shen, MD

Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

@LinShenMD

Charles Snyder, MD

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York

Brian Sullivan, MD

Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Ashley Vachon, MD

University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora

Ted Walker, MD

Washington University/Barnes Jewish Hospital, St. Louis

Xiao Jing Wang, MD

Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

@IrisWangMD

Ten tips to help you get a research grant

It’s almost time to submit your application for the American Gastroenterological Association Research Scholar Award, the application deadline is Nov. 13, 2019. Review these tips for writing and preparing your application.

1. Start early. Allow plenty of time to complete your application, give it multiple reviews, and get feedback from others. Most applicants start working on the Specific Aims for the project 6 months in advance of the deadline.

2. Look at examples. Ask your division if there are any templates/prior grant submissions that you can review. There’s no recipe for a successful grant, so the only way to compose one is to have a sense of what has worked in the past. In general, prior awardees are happy to share their applications if you contact them.

3. Request feedback. Ask mentors and colleagues for early feedback on your Specific Aims page. If it makes sense and is interesting to them, reviewers will likely feel the same way.

4. Ask your collaborators for letters of support. In addition to your preceptor, consider including letters of support from prior researchers that you have worked with or any collaborators for the current project, especially if they will help you with a new technique or reagents.

5. Contact the grants staff with questions and concerns early on. If you don’t understand part of the application, aren’t sure if you’re eligible or are having problems with submission, contact the grant staff right away. Don’t wait until the week or day the grant is due when staff may be flooded with calls. They can assist you much better with advance notice, which will allow you to avoid last-minute stress.

6. Each application should be different. Keep in mind the scope of the grant and amount of funding. Don’t just recycle an R01-level application for a 1-year AGA pilot award.

7. More is better than less when it comes to preliminary data. If your expertise in a technique you are proposing is established, you will not need to demonstrate the capability to do the work but will likely need to show preliminary data. If you are looking to build expertise (as a part of your career development), you may need to show that the infrastructure that enables you to do the work is accessible.

8. Don’t take constructive feedback personally. As you share your draft with mentors and colleagues for feedback, you may receive some unanticipated criticism. Try not to take this personally. If you can detach yourself emotionally, you’ll be in a better position to answer critiques and make adjustments.

9. Remember your end goal: To help patients! Even the most basic science proposals are rooted in a clear potential to benefit patients.

10. Stay positive. If you do not succeed on your first application, believe in your work, make it better, and apply again.

Thanks to the following AGA Research Foundation grant recipients for sharing their advice, which resulted in the above 10 tips:

- Arthur Beyder, MD, PhD, 2015 AGA Research Scholar Award

- Barbara Jung, MD, AGAF, 2016 AGA-Elsevier Pilot Research Award

- Benjamin Lebwohl, MD, 2014 AGA Research Scholar Award

- Josephine Ni, MD, 2017 AGA-Takeda Pharmaceuticals Research Scholar Award in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Sahar Nissim, MD, PhD, 2017 AGA-Caroline Craig Augustyn and Damian Augustyn Award in Digestive Cancer

- Jatin Roper, MD, 2011 AGA Fellowship-to-Faculty Transition Award

- Christina Twyman-Saint Victor, MD, 2015 AGA Research Scholar Award

Visit www.gastro.org/research-funding to review the AGA Research Foundation research grants now open for applications. If you have questions about the AGA awards program, please contact [email protected].

The importance of getting involved for gastroenterology

On Sept. 20, 2019, I had the opportunity to participate in AGA’s Advocacy Day for the second time, joining 40 of our gastroenterology colleagues from across the United States on Capitol Hill to advocate for our profession and our patients.

The evening before Advocacy Day, we discussed strategies for having a successful meeting on Capitol Hill with AGA staff (including Kathleen Teixeira, AGA vice president of government affairs, and Jonathan Sollish, AGA senior coordinator, public policy). We discussed having our “asks” supported with evidence, and “getting personal” about how these policy issues directly affect us and our patients. We also had the chance to hear from Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.) and Sen. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.), both of whom invited our questions. Both congressmen are friends of AGA, with Rep. McGovern serving as chair of the House Rules Committee, and Sen. Blunt serving as chair of the Senate Labor–Health & Human Services Subcommittee on Appropriations.

Advocacy Day began with a group breakfast during which we reviewed some of the policy issues of central importance to gastroenterology:

- Removing Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Act (HR1570/S668), which enjoys strong bipartisan support, would correct the “cost-sharing” problem of screening colonoscopies turning therapeutic (with polypectomy) for our Medicare patients, by waiving the coinsurance for screening colonoscopies — regardless of whether we remove polyps during these colonoscopies.

- Safe Step Act, HR2279, legislation introduced in the House, facilitates a common-sense and timely (72 hours or 24 hours if life threatening) appeals process when our patients are subjected to step therapy (“fail first”) by insurers.

- Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act of 2019, HR3107, legislation in the House, eases onerous prior authorization burdens by promoting an electronic prior authorization process, ensuring requests are approved by qualified medical professionals who have specialty-specific experience, and mandating that plans report their rates of delays and denials.

- National Institutes of Health research funding facilitates innovative research and supports young investigators in our field.

Full of enthusiasm, our six-strong North Carolina contingent (pictured L-R, Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, AGAF; David Leiman, MD, MSPH; Animesh Jain, MD; Anne Finefrock Peery, MD; Lisa Gangarosa, MD, AGAF, chair of the AGA Government Affairs Committee; and Amit Patel, MD) met with the offices of Rep. David Price (D-N.C.), and both North Carolina senators, Richard Burr (R) and Thom Tillis (R), on Capitol Hill to convey our “asks.”

At Rep. Price’s office in the stately Rayburn House Office Building, we thanked his team for cosponsorship of H.R. 1570 and H.R. 2279. We also discussed the importance of increasing research funding by the AGA’s goal of $2.5 billion for NIH for fiscal year 2020, noting that a majority of our delegation has received NIH funding for our training and/or research activities. We also encouraged Price’s office to cosponsor H.R. 3107, sharing our personal experiences about the administrative toll of the prior authorization process for obtaining appropriate and recommended medications for our patients – in my case, swallowed topical corticosteroids for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis.

We moved on to Sen. Tillis’s office, where we thanked his office for cosponsorship of S. 668 but encouraged his office to cosponsor upcoming companion Senate legislation for H.R. 2279 and H.R. 3107. Our colleague capably conveyed how an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patient he saw recently may require a colectomy because of delays in appropriate treatment stemming from these regulatory processes. We also showed Tillis’s office how NIH funding generates significant economic activity in North Carolina, supporting jobs in our state.

After a quick stop at the U.S. Senate gift shop in the basement to buy souvenirs for our kids, our last meeting was with Sen. Burr’s office. There, we also thanked his office for cosponsorship of S. 668 but encouraged him to sign the “Dear Colleague” letter that Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) has circulated asking the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to address the colonoscopy cost-sharing “loophole.” We discussed the importance of cosponsoring upcoming companion Senate legislation for H.R. 2279 and H.R. 3107, sharing stories from our clinical practices about how these regulatory burdens have delayed treatment for our patients.

You can get involved, too.

AGA Advocacy Day was a tremendous experience, but it is not the only way AGA members can get involved and take action. The AGA Advocacy website, gastro.org/advocacy, provides more information on multiple avenues for advocacy. These include an online advocacy tool for sending templated letters on these issues to your elected officials.

Perhaps now more than ever, it is crucial that we get involved to support gastroenterology and advocate for our patients.

Dr. Patel is assistant professor, division of gastroenterology, Duke University, Durham, N.C.; member, AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee.

GI of the week: Arthur Beyder, MD, PhD

Congrats to Arthur Beyder, MD, PhD, who was selected for an NIH Director’s New Innovator Award, part of the NIH director’s high-risk, high-reward research award program. The NIH Director’s New Innovator Award will provide Dr. Beyder with more than $2 million in funding over a 5-year period to continue his project: Does the gut have a sense of touch?

Dr. Beyder’s lab at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., recently discovered a novel population of mechanosensitive epithelial sensory cells that are similar to skin’s touch sensors, which prompted a potentially transformative question: “Does the gut have a sense of touch?” We look forward to seeing the results of future research on this topic.

Dr. Beyder – a physician-scientist at the Mayo Clinic – is a 2015 AGA Research Scholar Award recipient and graduate of the 2018 AGA Future Leaders Program. Dr. Beyder currently serves on the AGA Nominating Committee.

Please join us in congratulating Dr. Beyder on Twitter (@BeyderLab) or in the AGA Community.

The NIH director’s high-risk, high-reward research program funds highly innovative, high-impact biomedical research proposed by extraordinarily creative scientists – these awards have one of the lowest funding rates for NIH. Congrats to two additional AGA members who also received a 2019 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award: Maayan Levy, PhD, and Christoph A. Thaiss, PhD, both from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Eight new insights about diet and gut health

During your 4 years of medical school, you likely received only 4 hours of nutrition training. Yet we know diet is so integral to the care of GI patients. That’s why AGA focused the 2019 James W. Freston Conference on the topic: Food at the Intersection of Gut Health and Disease.

Our course directors William Chey, MD, AGAF, Sheila E. Crowe, MD, AGAF, and Gerard E. Mullin, MD, AGAF, share eight points from the meeting that stuck with them and can help all practicing GIs as they consider dietary treatments for their patients.

1. Personalized nutrition is important. Genetic differences lead to differences in health outcomes. One size or recommendation does not fit all. This is why certain diets only work on certain people. There is no one diet for all and for all disease states. Genetic tests can be helpful, but they rely on reporting that isn’t readily available yet.

2. Dietary therapy is key to managing eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). EoE is becoming more and more prevalent. Genes can’t change that fast, but epigenetic factors can, and the evidence seems to be in food. EoE is not an IgE-mediated disease and therefore most allergy tests will not prove useful; however, food is often the trigger – most common, dairy. Dietary therapy is likely the best way to manage. You want to reduce the number of eliminated foods by way of a reintroduction protocol. The six-food elimination diet is standard, though some are moving to a four-food elimination diet (dairy, wheat, egg, and soy).

3. There has been a reported increase in those with food allergies, sensitivities, celiac disease, and other adverse reactions to food. Many of the food allergy tests available are not helpful. In addition, many afflicted patients are using self-imposed diets rather than working with a GI, allergist, or dietitian. This needs to change.

4. There is currently insufficient evidence to support a gluten-free diet for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). It is possible that fructans, more than gluten, are causing the GI issues. Typically, the low-FODMAP diet is beneficial to IBS patients if done correctly with the guidance of a dietitian; however, not everyone with IBS improves on it. All the steps are important though, including reintroduction and maintenance.

5. When working with patients on the low-FODMAP or other restrictive diets, it is important to know their food and eating history. Avoidance/restrictive food intake disorder is something we need to be aware of when it comes to patients with a history or likelihood to develop disordered eating/eating disorders. The patient team may need to include an eating disorder therapist.

6. The general population in the United States has increased the adoption of a gluten-free diet although the number of cases of celiac disease has not increased. Many have self-reported gluten sensitivities. Those that have removed gluten, following trends, are more at risk of bowel irregularity (low fiber), weight gain, and disordered eating. Celiac disease is not a do-it-yourself disease, patients will be best served working with a dietitian and GI.

7. Food can induce symptoms in patients with IBD. It can also trigger gut inflammation resulting in incident or relapse. There is experimental plausibility for some factors of the relationship to be causal and we may be able to modify the diet to prevent and manage IBD.

8. The focus on nutrition education must continue! Nutrition should be a required part of continuing medical education for physicians. And physicians should work with dietitians to improve the care of GI patients.

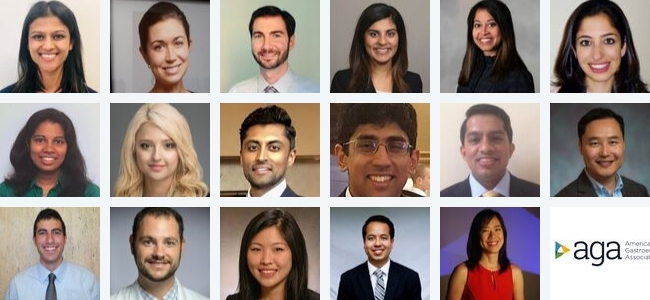

17 fellows advancing GI and patient care

Each year during Digestive Disease Week®, AGA hosts a session titled “Advancing Clinical Practice: GI Fellow-Directed Quality-Improvement Projects.” During the 2019 session, 17 quality improvement initiatives were presented — you can review these abstracts in the July issue of Gastroenterology in the “AGA Section” or review a presenter’s abstract by clicking their name or image. Kudos to the promising fellows featured below, who all served as lead authors for their quality improvement projects.

Manasi Agrawal, MD

Lenox Hill Hospital, New York

@ManasiAgrawalMD

Jessica Breton, MD

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Adam Faye, MD

Columbia University Medical Center, New York

@AdamFaye4

Shelly Gurwara, MD

Wake Forest Baptist Health Medical Center, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Afrin Kamal, MD

Stanford (Calif.) University

Ani Kardashian, MD

University of California, Los Angeles

@AniKardashianMD

Sonali Palchaudhuri, MD

University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

@sopalchaudhuri

Nasim Parsa, MD

University of Missouri Health System, Columbia

Sahil Patel, MD

Drexel University, Philadelphia

@sahilr

Vikram Raghu, MD

Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh

Amit Shah, MD

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Lin Shen, MD

Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

@LinShenMD

Charles Snyder, MD

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York

Brian Sullivan, MD

Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Ashley Vachon, MD

University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora

Ted Walker, MD

Washington University/Barnes Jewish Hospital, St. Louis

Xiao Jing Wang, MD

Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

@IrisWangMD

Ten tips to help you get a research grant

It’s almost time to submit your application for the American Gastroenterological Association Research Scholar Award, the application deadline is Nov. 13, 2019. Review these tips for writing and preparing your application.

1. Start early. Allow plenty of time to complete your application, give it multiple reviews, and get feedback from others. Most applicants start working on the Specific Aims for the project 6 months in advance of the deadline.

2. Look at examples. Ask your division if there are any templates/prior grant submissions that you can review. There’s no recipe for a successful grant, so the only way to compose one is to have a sense of what has worked in the past. In general, prior awardees are happy to share their applications if you contact them.

3. Request feedback. Ask mentors and colleagues for early feedback on your Specific Aims page. If it makes sense and is interesting to them, reviewers will likely feel the same way.

4. Ask your collaborators for letters of support. In addition to your preceptor, consider including letters of support from prior researchers that you have worked with or any collaborators for the current project, especially if they will help you with a new technique or reagents.

5. Contact the grants staff with questions and concerns early on. If you don’t understand part of the application, aren’t sure if you’re eligible or are having problems with submission, contact the grant staff right away. Don’t wait until the week or day the grant is due when staff may be flooded with calls. They can assist you much better with advance notice, which will allow you to avoid last-minute stress.

6. Each application should be different. Keep in mind the scope of the grant and amount of funding. Don’t just recycle an R01-level application for a 1-year AGA pilot award.

7. More is better than less when it comes to preliminary data. If your expertise in a technique you are proposing is established, you will not need to demonstrate the capability to do the work but will likely need to show preliminary data. If you are looking to build expertise (as a part of your career development), you may need to show that the infrastructure that enables you to do the work is accessible.

8. Don’t take constructive feedback personally. As you share your draft with mentors and colleagues for feedback, you may receive some unanticipated criticism. Try not to take this personally. If you can detach yourself emotionally, you’ll be in a better position to answer critiques and make adjustments.

9. Remember your end goal: To help patients! Even the most basic science proposals are rooted in a clear potential to benefit patients.

10. Stay positive. If you do not succeed on your first application, believe in your work, make it better, and apply again.

Thanks to the following AGA Research Foundation grant recipients for sharing their advice, which resulted in the above 10 tips:

- Arthur Beyder, MD, PhD, 2015 AGA Research Scholar Award

- Barbara Jung, MD, AGAF, 2016 AGA-Elsevier Pilot Research Award

- Benjamin Lebwohl, MD, 2014 AGA Research Scholar Award

- Josephine Ni, MD, 2017 AGA-Takeda Pharmaceuticals Research Scholar Award in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Sahar Nissim, MD, PhD, 2017 AGA-Caroline Craig Augustyn and Damian Augustyn Award in Digestive Cancer

- Jatin Roper, MD, 2011 AGA Fellowship-to-Faculty Transition Award

- Christina Twyman-Saint Victor, MD, 2015 AGA Research Scholar Award

Visit www.gastro.org/research-funding to review the AGA Research Foundation research grants now open for applications. If you have questions about the AGA awards program, please contact [email protected].

The importance of getting involved for gastroenterology

On Sept. 20, 2019, I had the opportunity to participate in AGA’s Advocacy Day for the second time, joining 40 of our gastroenterology colleagues from across the United States on Capitol Hill to advocate for our profession and our patients.

The evening before Advocacy Day, we discussed strategies for having a successful meeting on Capitol Hill with AGA staff (including Kathleen Teixeira, AGA vice president of government affairs, and Jonathan Sollish, AGA senior coordinator, public policy). We discussed having our “asks” supported with evidence, and “getting personal” about how these policy issues directly affect us and our patients. We also had the chance to hear from Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.) and Sen. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.), both of whom invited our questions. Both congressmen are friends of AGA, with Rep. McGovern serving as chair of the House Rules Committee, and Sen. Blunt serving as chair of the Senate Labor–Health & Human Services Subcommittee on Appropriations.

Advocacy Day began with a group breakfast during which we reviewed some of the policy issues of central importance to gastroenterology:

- Removing Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Act (HR1570/S668), which enjoys strong bipartisan support, would correct the “cost-sharing” problem of screening colonoscopies turning therapeutic (with polypectomy) for our Medicare patients, by waiving the coinsurance for screening colonoscopies — regardless of whether we remove polyps during these colonoscopies.

- Safe Step Act, HR2279, legislation introduced in the House, facilitates a common-sense and timely (72 hours or 24 hours if life threatening) appeals process when our patients are subjected to step therapy (“fail first”) by insurers.

- Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act of 2019, HR3107, legislation in the House, eases onerous prior authorization burdens by promoting an electronic prior authorization process, ensuring requests are approved by qualified medical professionals who have specialty-specific experience, and mandating that plans report their rates of delays and denials.

- National Institutes of Health research funding facilitates innovative research and supports young investigators in our field.

Full of enthusiasm, our six-strong North Carolina contingent (pictured L-R, Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, AGAF; David Leiman, MD, MSPH; Animesh Jain, MD; Anne Finefrock Peery, MD; Lisa Gangarosa, MD, AGAF, chair of the AGA Government Affairs Committee; and Amit Patel, MD) met with the offices of Rep. David Price (D-N.C.), and both North Carolina senators, Richard Burr (R) and Thom Tillis (R), on Capitol Hill to convey our “asks.”

At Rep. Price’s office in the stately Rayburn House Office Building, we thanked his team for cosponsorship of H.R. 1570 and H.R. 2279. We also discussed the importance of increasing research funding by the AGA’s goal of $2.5 billion for NIH for fiscal year 2020, noting that a majority of our delegation has received NIH funding for our training and/or research activities. We also encouraged Price’s office to cosponsor H.R. 3107, sharing our personal experiences about the administrative toll of the prior authorization process for obtaining appropriate and recommended medications for our patients – in my case, swallowed topical corticosteroids for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis.

We moved on to Sen. Tillis’s office, where we thanked his office for cosponsorship of S. 668 but encouraged his office to cosponsor upcoming companion Senate legislation for H.R. 2279 and H.R. 3107. Our colleague capably conveyed how an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patient he saw recently may require a colectomy because of delays in appropriate treatment stemming from these regulatory processes. We also showed Tillis’s office how NIH funding generates significant economic activity in North Carolina, supporting jobs in our state.

After a quick stop at the U.S. Senate gift shop in the basement to buy souvenirs for our kids, our last meeting was with Sen. Burr’s office. There, we also thanked his office for cosponsorship of S. 668 but encouraged him to sign the “Dear Colleague” letter that Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) has circulated asking the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to address the colonoscopy cost-sharing “loophole.” We discussed the importance of cosponsoring upcoming companion Senate legislation for H.R. 2279 and H.R. 3107, sharing stories from our clinical practices about how these regulatory burdens have delayed treatment for our patients.

You can get involved, too.

AGA Advocacy Day was a tremendous experience, but it is not the only way AGA members can get involved and take action. The AGA Advocacy website, gastro.org/advocacy, provides more information on multiple avenues for advocacy. These include an online advocacy tool for sending templated letters on these issues to your elected officials.

Perhaps now more than ever, it is crucial that we get involved to support gastroenterology and advocate for our patients.

Dr. Patel is assistant professor, division of gastroenterology, Duke University, Durham, N.C.; member, AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee.

GI of the week: Arthur Beyder, MD, PhD

Congrats to Arthur Beyder, MD, PhD, who was selected for an NIH Director’s New Innovator Award, part of the NIH director’s high-risk, high-reward research award program. The NIH Director’s New Innovator Award will provide Dr. Beyder with more than $2 million in funding over a 5-year period to continue his project: Does the gut have a sense of touch?

Dr. Beyder’s lab at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., recently discovered a novel population of mechanosensitive epithelial sensory cells that are similar to skin’s touch sensors, which prompted a potentially transformative question: “Does the gut have a sense of touch?” We look forward to seeing the results of future research on this topic.

Dr. Beyder – a physician-scientist at the Mayo Clinic – is a 2015 AGA Research Scholar Award recipient and graduate of the 2018 AGA Future Leaders Program. Dr. Beyder currently serves on the AGA Nominating Committee.

Please join us in congratulating Dr. Beyder on Twitter (@BeyderLab) or in the AGA Community.

The NIH director’s high-risk, high-reward research program funds highly innovative, high-impact biomedical research proposed by extraordinarily creative scientists – these awards have one of the lowest funding rates for NIH. Congrats to two additional AGA members who also received a 2019 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award: Maayan Levy, PhD, and Christoph A. Thaiss, PhD, both from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Eight new insights about diet and gut health

During your 4 years of medical school, you likely received only 4 hours of nutrition training. Yet we know diet is so integral to the care of GI patients. That’s why AGA focused the 2019 James W. Freston Conference on the topic: Food at the Intersection of Gut Health and Disease.

Our course directors William Chey, MD, AGAF, Sheila E. Crowe, MD, AGAF, and Gerard E. Mullin, MD, AGAF, share eight points from the meeting that stuck with them and can help all practicing GIs as they consider dietary treatments for their patients.

1. Personalized nutrition is important. Genetic differences lead to differences in health outcomes. One size or recommendation does not fit all. This is why certain diets only work on certain people. There is no one diet for all and for all disease states. Genetic tests can be helpful, but they rely on reporting that isn’t readily available yet.

2. Dietary therapy is key to managing eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). EoE is becoming more and more prevalent. Genes can’t change that fast, but epigenetic factors can, and the evidence seems to be in food. EoE is not an IgE-mediated disease and therefore most allergy tests will not prove useful; however, food is often the trigger – most common, dairy. Dietary therapy is likely the best way to manage. You want to reduce the number of eliminated foods by way of a reintroduction protocol. The six-food elimination diet is standard, though some are moving to a four-food elimination diet (dairy, wheat, egg, and soy).

3. There has been a reported increase in those with food allergies, sensitivities, celiac disease, and other adverse reactions to food. Many of the food allergy tests available are not helpful. In addition, many afflicted patients are using self-imposed diets rather than working with a GI, allergist, or dietitian. This needs to change.

4. There is currently insufficient evidence to support a gluten-free diet for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). It is possible that fructans, more than gluten, are causing the GI issues. Typically, the low-FODMAP diet is beneficial to IBS patients if done correctly with the guidance of a dietitian; however, not everyone with IBS improves on it. All the steps are important though, including reintroduction and maintenance.

5. When working with patients on the low-FODMAP or other restrictive diets, it is important to know their food and eating history. Avoidance/restrictive food intake disorder is something we need to be aware of when it comes to patients with a history or likelihood to develop disordered eating/eating disorders. The patient team may need to include an eating disorder therapist.

6. The general population in the United States has increased the adoption of a gluten-free diet although the number of cases of celiac disease has not increased. Many have self-reported gluten sensitivities. Those that have removed gluten, following trends, are more at risk of bowel irregularity (low fiber), weight gain, and disordered eating. Celiac disease is not a do-it-yourself disease, patients will be best served working with a dietitian and GI.

7. Food can induce symptoms in patients with IBD. It can also trigger gut inflammation resulting in incident or relapse. There is experimental plausibility for some factors of the relationship to be causal and we may be able to modify the diet to prevent and manage IBD.

8. The focus on nutrition education must continue! Nutrition should be a required part of continuing medical education for physicians. And physicians should work with dietitians to improve the care of GI patients.

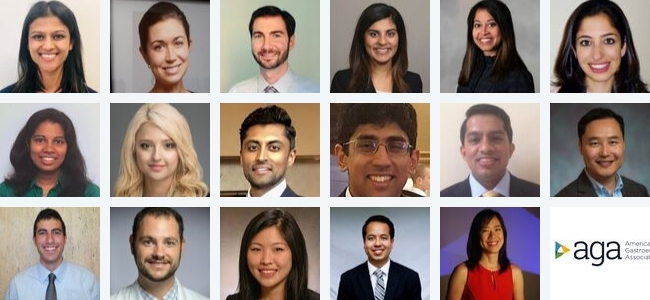

17 fellows advancing GI and patient care

Each year during Digestive Disease Week®, AGA hosts a session titled “Advancing Clinical Practice: GI Fellow-Directed Quality-Improvement Projects.” During the 2019 session, 17 quality improvement initiatives were presented — you can review these abstracts in the July issue of Gastroenterology in the “AGA Section” or review a presenter’s abstract by clicking their name or image. Kudos to the promising fellows featured below, who all served as lead authors for their quality improvement projects.

Manasi Agrawal, MD

Lenox Hill Hospital, New York

@ManasiAgrawalMD

Jessica Breton, MD

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Adam Faye, MD

Columbia University Medical Center, New York

@AdamFaye4

Shelly Gurwara, MD

Wake Forest Baptist Health Medical Center, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Afrin Kamal, MD

Stanford (Calif.) University

Ani Kardashian, MD

University of California, Los Angeles

@AniKardashianMD

Sonali Palchaudhuri, MD

University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

@sopalchaudhuri

Nasim Parsa, MD

University of Missouri Health System, Columbia

Sahil Patel, MD

Drexel University, Philadelphia

@sahilr

Vikram Raghu, MD

Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh

Amit Shah, MD

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Lin Shen, MD

Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

@LinShenMD

Charles Snyder, MD

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York

Brian Sullivan, MD

Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Ashley Vachon, MD

University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora

Ted Walker, MD

Washington University/Barnes Jewish Hospital, St. Louis

Xiao Jing Wang, MD

Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

@IrisWangMD

Calendar

For more information about upcoming events and award deadlines, please visit http://agau.gastro.org and http://www.gastro.org/research-funding.

UPCOMING EVENTS

Dec. 9-10, 11-12, 18-19, 2019; Jan. 15-16, 22-23; Feb. 12-13, Mar. 10-11, 11-12, 25-26; Apr. 15-16; May 13-14, 2020

Two-Day, In-Depth Coding Seminar by McVey Associates, Inc.

Become a certified GI coder with a 2-day, in-depth training course provided by McVey Associates, Inc.

Anaheim, Calif. (12/9-10); Houston, Tex. (12/11-12); New Orleans, La. (12/18-19); Phoenix, Ariz. (12/18-19); Pittsburgh, Pa. (1/15-16); Dallas, Tex. (1/22-23); Hartford, Conn. (2/12-13); Orlando, Fla. (3/10-11); Novi, Mich. (3/11-12); Charlotte, N.C. (3/25-26); Columbus, Ohio (4/15-16); Chicago, Ill. (5/13-14)

Jan. 23–25, 2020

2020 Crohn’s & Colitis Congress®

Gain a multidisciplinary perspective on treating inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). Join health care professionals and researchers at the Crohn’s & Colitis Congress® for the premier conference on IBD. Discover different perspectives, leave with practical information you can immediately implement, and hear about potential treatments on the horizon.

Austin, Tex.

Jan. 23–25, 2020

Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium

Designed for clinicians, scientists, and all other members of the cancer care and research community, the 2020 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium will feature a wide array of multidisciplinary topics and expert faculty will offer insights on the application of gastrointestinal advances in: cancers of the esophagus and stomach, pancreas, small bowel and hepatobiliary tract, and the colon, rectum, and anus.

San Francisco, Calif.

Feb. 8-9, 2020

2020 Academic Skills Workshop

A free biannual meeting for fellows and early-career GIs that is implemented in conjunction with the AASLD. Topics range from leveraging mentor-mentee relationships, promotion strategies, and insights on writing grants. The application deadline is Nov. 18, 2019.

Charlotte, N.C.

Feb. 20; Mar. 24, 2020

Coding and Reimbursement Solutions by McVey Associates, Inc.

Improve the efficiency and performance of your practice by staying current on the latest reimbursement, coding and compliance changes.

Knoxville, Tenn. (2/20); Birmingham, Ala. (3/24)

May 2-5, 2020

Digestive Disease Week® (DDW)

Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) is the world’s leading educational forum for academicians, clinicians, researchers, students, and trainees working in gastroenterology, hepatology, GI endoscopy, gastrointestinal surgery, and related fields. Whether you work in patient care, research, education, or administration, the DDW program offers something for you. Abstract submissions will be due on Dec. 1, and registration will open in January 2020.

Chicago, Ill.

June 3-6, 2020

2020 AGA Tech Summit

Visit https://techsummit.gastro.org/ for more details.

San Francisco, Calif.

AWARDS DEADLINES

AGA Fellow Abstract Award

This $500 travel award supports recipients who are MD, PhD, or equivalent fellows giving abstract-based oral or poster presentations at Digestive Disease Week® (DDW). The top-scoring abstract will be designated the Fellow Abstract of the Year and receive a $1,000 award.

Application Deadline: Feb. 26, 2020

AGA Student Abstract Award

This $500 travel award supports recipients who are graduate students, medical students, or medical residents (residents up to postgraduate year three) giving abstract-based oral or poster presentations at Digestive Disease Week® (DDW).

Application Deadline: Feb. 26, 2020

AGA-Moti L. & Kamla Rustgi International Travel Awards

This $750 travel award supports recipients who are young (i.e., 35 years of age or younger at the time of DDW) basic, translational or clinical investigators residing outside North America to support travel and related expenses to attend Digestive Disease Week® (DDW).

Application Deadline: Feb. 26, 2020

For more information about upcoming events and award deadlines, please visit http://agau.gastro.org and http://www.gastro.org/research-funding.

UPCOMING EVENTS

Dec. 9-10, 11-12, 18-19, 2019; Jan. 15-16, 22-23; Feb. 12-13, Mar. 10-11, 11-12, 25-26; Apr. 15-16; May 13-14, 2020

Two-Day, In-Depth Coding Seminar by McVey Associates, Inc.

Become a certified GI coder with a 2-day, in-depth training course provided by McVey Associates, Inc.

Anaheim, Calif. (12/9-10); Houston, Tex. (12/11-12); New Orleans, La. (12/18-19); Phoenix, Ariz. (12/18-19); Pittsburgh, Pa. (1/15-16); Dallas, Tex. (1/22-23); Hartford, Conn. (2/12-13); Orlando, Fla. (3/10-11); Novi, Mich. (3/11-12); Charlotte, N.C. (3/25-26); Columbus, Ohio (4/15-16); Chicago, Ill. (5/13-14)

Jan. 23–25, 2020

2020 Crohn’s & Colitis Congress®

Gain a multidisciplinary perspective on treating inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). Join health care professionals and researchers at the Crohn’s & Colitis Congress® for the premier conference on IBD. Discover different perspectives, leave with practical information you can immediately implement, and hear about potential treatments on the horizon.

Austin, Tex.

Jan. 23–25, 2020

Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium

Designed for clinicians, scientists, and all other members of the cancer care and research community, the 2020 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium will feature a wide array of multidisciplinary topics and expert faculty will offer insights on the application of gastrointestinal advances in: cancers of the esophagus and stomach, pancreas, small bowel and hepatobiliary tract, and the colon, rectum, and anus.

San Francisco, Calif.

Feb. 8-9, 2020

2020 Academic Skills Workshop

A free biannual meeting for fellows and early-career GIs that is implemented in conjunction with the AASLD. Topics range from leveraging mentor-mentee relationships, promotion strategies, and insights on writing grants. The application deadline is Nov. 18, 2019.

Charlotte, N.C.

Feb. 20; Mar. 24, 2020

Coding and Reimbursement Solutions by McVey Associates, Inc.

Improve the efficiency and performance of your practice by staying current on the latest reimbursement, coding and compliance changes.

Knoxville, Tenn. (2/20); Birmingham, Ala. (3/24)

May 2-5, 2020

Digestive Disease Week® (DDW)

Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) is the world’s leading educational forum for academicians, clinicians, researchers, students, and trainees working in gastroenterology, hepatology, GI endoscopy, gastrointestinal surgery, and related fields. Whether you work in patient care, research, education, or administration, the DDW program offers something for you. Abstract submissions will be due on Dec. 1, and registration will open in January 2020.

Chicago, Ill.

June 3-6, 2020

2020 AGA Tech Summit

Visit https://techsummit.gastro.org/ for more details.

San Francisco, Calif.

AWARDS DEADLINES

AGA Fellow Abstract Award

This $500 travel award supports recipients who are MD, PhD, or equivalent fellows giving abstract-based oral or poster presentations at Digestive Disease Week® (DDW). The top-scoring abstract will be designated the Fellow Abstract of the Year and receive a $1,000 award.

Application Deadline: Feb. 26, 2020

AGA Student Abstract Award

This $500 travel award supports recipients who are graduate students, medical students, or medical residents (residents up to postgraduate year three) giving abstract-based oral or poster presentations at Digestive Disease Week® (DDW).

Application Deadline: Feb. 26, 2020

AGA-Moti L. & Kamla Rustgi International Travel Awards

This $750 travel award supports recipients who are young (i.e., 35 years of age or younger at the time of DDW) basic, translational or clinical investigators residing outside North America to support travel and related expenses to attend Digestive Disease Week® (DDW).

Application Deadline: Feb. 26, 2020

For more information about upcoming events and award deadlines, please visit http://agau.gastro.org and http://www.gastro.org/research-funding.

UPCOMING EVENTS

Dec. 9-10, 11-12, 18-19, 2019; Jan. 15-16, 22-23; Feb. 12-13, Mar. 10-11, 11-12, 25-26; Apr. 15-16; May 13-14, 2020

Two-Day, In-Depth Coding Seminar by McVey Associates, Inc.

Become a certified GI coder with a 2-day, in-depth training course provided by McVey Associates, Inc.

Anaheim, Calif. (12/9-10); Houston, Tex. (12/11-12); New Orleans, La. (12/18-19); Phoenix, Ariz. (12/18-19); Pittsburgh, Pa. (1/15-16); Dallas, Tex. (1/22-23); Hartford, Conn. (2/12-13); Orlando, Fla. (3/10-11); Novi, Mich. (3/11-12); Charlotte, N.C. (3/25-26); Columbus, Ohio (4/15-16); Chicago, Ill. (5/13-14)

Jan. 23–25, 2020

2020 Crohn’s & Colitis Congress®

Gain a multidisciplinary perspective on treating inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). Join health care professionals and researchers at the Crohn’s & Colitis Congress® for the premier conference on IBD. Discover different perspectives, leave with practical information you can immediately implement, and hear about potential treatments on the horizon.

Austin, Tex.

Jan. 23–25, 2020

Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium

Designed for clinicians, scientists, and all other members of the cancer care and research community, the 2020 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium will feature a wide array of multidisciplinary topics and expert faculty will offer insights on the application of gastrointestinal advances in: cancers of the esophagus and stomach, pancreas, small bowel and hepatobiliary tract, and the colon, rectum, and anus.

San Francisco, Calif.

Feb. 8-9, 2020

2020 Academic Skills Workshop

A free biannual meeting for fellows and early-career GIs that is implemented in conjunction with the AASLD. Topics range from leveraging mentor-mentee relationships, promotion strategies, and insights on writing grants. The application deadline is Nov. 18, 2019.

Charlotte, N.C.

Feb. 20; Mar. 24, 2020

Coding and Reimbursement Solutions by McVey Associates, Inc.

Improve the efficiency and performance of your practice by staying current on the latest reimbursement, coding and compliance changes.

Knoxville, Tenn. (2/20); Birmingham, Ala. (3/24)

May 2-5, 2020

Digestive Disease Week® (DDW)

Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) is the world’s leading educational forum for academicians, clinicians, researchers, students, and trainees working in gastroenterology, hepatology, GI endoscopy, gastrointestinal surgery, and related fields. Whether you work in patient care, research, education, or administration, the DDW program offers something for you. Abstract submissions will be due on Dec. 1, and registration will open in January 2020.

Chicago, Ill.

June 3-6, 2020

2020 AGA Tech Summit

Visit https://techsummit.gastro.org/ for more details.

San Francisco, Calif.

AWARDS DEADLINES

AGA Fellow Abstract Award

This $500 travel award supports recipients who are MD, PhD, or equivalent fellows giving abstract-based oral or poster presentations at Digestive Disease Week® (DDW). The top-scoring abstract will be designated the Fellow Abstract of the Year and receive a $1,000 award.

Application Deadline: Feb. 26, 2020

AGA Student Abstract Award

This $500 travel award supports recipients who are graduate students, medical students, or medical residents (residents up to postgraduate year three) giving abstract-based oral or poster presentations at Digestive Disease Week® (DDW).

Application Deadline: Feb. 26, 2020

AGA-Moti L. & Kamla Rustgi International Travel Awards

This $750 travel award supports recipients who are young (i.e., 35 years of age or younger at the time of DDW) basic, translational or clinical investigators residing outside North America to support travel and related expenses to attend Digestive Disease Week® (DDW).

Application Deadline: Feb. 26, 2020

An emerging role for physicians in health policy advocacy

The American Board of Internal Medicine has called for “a commitment to the promotion of public health and preventative medicine, as well as public advocacy on the part of each physician.”1 In our responsibility to preserve and promote human life, physicians are not only uniquely positioned for advocacy but also inherently assume the role of becoming health care activists.

The American Medical Association has defined physician advocacy as promoting “social, economic, educational, and political changes that ameliorate suffering and contribute to human well being.”2 For health care professionals, this translates into ensuring the concerns and best interests of patients are at the core of all decisions.3 For generations, physicians have taken extra steps for patient care in daily practice, including submitting prior authorizations, performing peer review, and taking part in family meetings. Many doctors also participate on hospital committees and boards for quality improvement measures and are leaders in designing strategies to improve patient safety and health care experiences. Although these examples may be viewed as a fundamental part of daily practice, in fact, these roles are consistent with advocacy on a local level. A significant number of physicians participate in medical education, research, and societal duties, which include formulating and reviewing guidelines for medical practice. Participation in conference organizing committees and reviewing medical journals are likewise not uncommon roles among medical practitioners. These efforts to provide education to improve patient care are also forms of advocacy on a national or regional level but often viewed as a standard in professionalism.4

It is on the federal and political level in advocacy where physician representation is critical. Health legislation is enacted by Congress and signed into law by the president of the United States.5 These laws can drastically affect clinical practice and patient care, especially in the realm of preventive medicine and pharmaceuticals. Gastroenterology is a unique field in which a large portion of practice is dedicated to cancer prevention, by screening age-appropriate individuals and monitoring high-risk patients. The field is rapidly expanding in the pharmaceutical area with new medications for inflammatory bowel disease and groundbreaking treatments for viral hepatitis. The breadth of practice in gastroenterology calls for antiquated laws to be changed to accommodate the development of patient care guidelines. With physicians representing less than 3% of Congress,6 the rules that govern our practice are largely left to those unfamiliar with the delivery of health care.

Lack of experience, limited time, and a tradition in medicine that prefers physicians to be apolitical are each contributing factors for reduced participation in federal advocacy.7 Professional GI societies, including the American Gastroenterological Association, American College of Gastroenterology, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and American Association for the Study of Liver Disease, have a presence in public policy to educate lawmakers and promote statutes in gastroenterology. The involvement of these organizations in legislation is critical since public policy directly affects the interests and well-being of patients.

The priority public policy issues for GI societies are listed as follows:

- Reducing the administrative burden of prior authorizations.

- Implementing timely appeals for non–first-line therapies as determined by payers (step therapy).

- Eliminating surprise billing and cost-sharing for screening colonoscopy.

- Preserving patient protections, including for preexisting conditions and preventive services.

- Increasing federal funding and research appropriations for gastrointestinal research.

Communication with and development of relationships with legislators are essential to effective advocacy.7,8 Health professionals should be well-informed resources for members of Congress and therefore it is pivotal to provide factual information when presenting topics. There are various ways to reach congressional representatives, including personal visits, writing letters, making phone calls, or attending town halls.

Of the aforementioned, in-person meetings are the best way to directly connect with legislators. These allow for time to discuss a legislative issue, including the background and societal impact, proposed initiative, and personal accounts relating to the topic. Attending town halls also will give face-time with legislators, although the format to ask questions often is abbreviated. GI societies use letter writing as a way to increase support for a proposed bill or measure. The efficacy of letter writing increases with higher involvement. Letters are often generated in an online forum that requires the user’s zip code (so the letter can be routed to the appropriate legislator) and name with electronic signature, which are designed for easy use to boost participation.

Understanding that physicians are advocates in daily practice and that federal initiatives have significant impact on patients and clinical practice is the first step to getting involved. Participation at the local level includes connecting with the district offices of congressional leaders through letter writing, making phone calls, or in-person visits. On regional and national levels, involvement with state legislators, GI societies, or personal like-minded groups are ways to initiate federal advocacy. GI societies have federal policy committees, political action committees, and opportunities for early-career gastroenterologists to become involved in advocacy, including the Congressional Advocates Program from the AGA and the Young Physician Leadership Scholars Program from the ACG. Be sure to visit AGA’s Advocacy & Policy page to keep informed about current and future opportunities.

As the population grows and human life expectancy increases, the practice of medicine is a prime target for legislative changes, which ultimately affect patient care and clinical practice. Physicians are respected members of society, have expansive knowledge in disease processes and the delivery of health care to patients, and are naturally patient advocates. For these reasons, it is imperative for doctors to rise to the calling of federal advocacy, to continue to preserve the best interests and dignity of our patients.

References

1. ABIM Foundation. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:243-6.

2. Earnest MA et al. Academic Med. 2010;85(1):63-7.

3. Schwartz L. J Med Ethics. 2002;28:37-40.

4. Howell BA et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2019 Aug 5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05184-3. [epub ahead of print]

5. The House of Representatives.

6. AGA News: https://www.gastro.org/news/new-congress-includes-22-health-care-providers

7. Kupfer SS et al. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(4)8:834-7.

8. Grace ND and LB Dennis. Hepatology. 2007;45(6):1337-9.

Dr. Abbasi is a gastroenterologist who works in inflammatory bowel diseases at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and Santa Monica Gastroenterology, Calif.

The American Board of Internal Medicine has called for “a commitment to the promotion of public health and preventative medicine, as well as public advocacy on the part of each physician.”1 In our responsibility to preserve and promote human life, physicians are not only uniquely positioned for advocacy but also inherently assume the role of becoming health care activists.

The American Medical Association has defined physician advocacy as promoting “social, economic, educational, and political changes that ameliorate suffering and contribute to human well being.”2 For health care professionals, this translates into ensuring the concerns and best interests of patients are at the core of all decisions.3 For generations, physicians have taken extra steps for patient care in daily practice, including submitting prior authorizations, performing peer review, and taking part in family meetings. Many doctors also participate on hospital committees and boards for quality improvement measures and are leaders in designing strategies to improve patient safety and health care experiences. Although these examples may be viewed as a fundamental part of daily practice, in fact, these roles are consistent with advocacy on a local level. A significant number of physicians participate in medical education, research, and societal duties, which include formulating and reviewing guidelines for medical practice. Participation in conference organizing committees and reviewing medical journals are likewise not uncommon roles among medical practitioners. These efforts to provide education to improve patient care are also forms of advocacy on a national or regional level but often viewed as a standard in professionalism.4

It is on the federal and political level in advocacy where physician representation is critical. Health legislation is enacted by Congress and signed into law by the president of the United States.5 These laws can drastically affect clinical practice and patient care, especially in the realm of preventive medicine and pharmaceuticals. Gastroenterology is a unique field in which a large portion of practice is dedicated to cancer prevention, by screening age-appropriate individuals and monitoring high-risk patients. The field is rapidly expanding in the pharmaceutical area with new medications for inflammatory bowel disease and groundbreaking treatments for viral hepatitis. The breadth of practice in gastroenterology calls for antiquated laws to be changed to accommodate the development of patient care guidelines. With physicians representing less than 3% of Congress,6 the rules that govern our practice are largely left to those unfamiliar with the delivery of health care.

Lack of experience, limited time, and a tradition in medicine that prefers physicians to be apolitical are each contributing factors for reduced participation in federal advocacy.7 Professional GI societies, including the American Gastroenterological Association, American College of Gastroenterology, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and American Association for the Study of Liver Disease, have a presence in public policy to educate lawmakers and promote statutes in gastroenterology. The involvement of these organizations in legislation is critical since public policy directly affects the interests and well-being of patients.

The priority public policy issues for GI societies are listed as follows:

- Reducing the administrative burden of prior authorizations.

- Implementing timely appeals for non–first-line therapies as determined by payers (step therapy).

- Eliminating surprise billing and cost-sharing for screening colonoscopy.

- Preserving patient protections, including for preexisting conditions and preventive services.

- Increasing federal funding and research appropriations for gastrointestinal research.

Communication with and development of relationships with legislators are essential to effective advocacy.7,8 Health professionals should be well-informed resources for members of Congress and therefore it is pivotal to provide factual information when presenting topics. There are various ways to reach congressional representatives, including personal visits, writing letters, making phone calls, or attending town halls.

Of the aforementioned, in-person meetings are the best way to directly connect with legislators. These allow for time to discuss a legislative issue, including the background and societal impact, proposed initiative, and personal accounts relating to the topic. Attending town halls also will give face-time with legislators, although the format to ask questions often is abbreviated. GI societies use letter writing as a way to increase support for a proposed bill or measure. The efficacy of letter writing increases with higher involvement. Letters are often generated in an online forum that requires the user’s zip code (so the letter can be routed to the appropriate legislator) and name with electronic signature, which are designed for easy use to boost participation.

Understanding that physicians are advocates in daily practice and that federal initiatives have significant impact on patients and clinical practice is the first step to getting involved. Participation at the local level includes connecting with the district offices of congressional leaders through letter writing, making phone calls, or in-person visits. On regional and national levels, involvement with state legislators, GI societies, or personal like-minded groups are ways to initiate federal advocacy. GI societies have federal policy committees, political action committees, and opportunities for early-career gastroenterologists to become involved in advocacy, including the Congressional Advocates Program from the AGA and the Young Physician Leadership Scholars Program from the ACG. Be sure to visit AGA’s Advocacy & Policy page to keep informed about current and future opportunities.

As the population grows and human life expectancy increases, the practice of medicine is a prime target for legislative changes, which ultimately affect patient care and clinical practice. Physicians are respected members of society, have expansive knowledge in disease processes and the delivery of health care to patients, and are naturally patient advocates. For these reasons, it is imperative for doctors to rise to the calling of federal advocacy, to continue to preserve the best interests and dignity of our patients.

References

1. ABIM Foundation. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:243-6.

2. Earnest MA et al. Academic Med. 2010;85(1):63-7.

3. Schwartz L. J Med Ethics. 2002;28:37-40.

4. Howell BA et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2019 Aug 5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05184-3. [epub ahead of print]

5. The House of Representatives.

6. AGA News: https://www.gastro.org/news/new-congress-includes-22-health-care-providers

7. Kupfer SS et al. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(4)8:834-7.

8. Grace ND and LB Dennis. Hepatology. 2007;45(6):1337-9.

Dr. Abbasi is a gastroenterologist who works in inflammatory bowel diseases at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and Santa Monica Gastroenterology, Calif.

The American Board of Internal Medicine has called for “a commitment to the promotion of public health and preventative medicine, as well as public advocacy on the part of each physician.”1 In our responsibility to preserve and promote human life, physicians are not only uniquely positioned for advocacy but also inherently assume the role of becoming health care activists.

The American Medical Association has defined physician advocacy as promoting “social, economic, educational, and political changes that ameliorate suffering and contribute to human well being.”2 For health care professionals, this translates into ensuring the concerns and best interests of patients are at the core of all decisions.3 For generations, physicians have taken extra steps for patient care in daily practice, including submitting prior authorizations, performing peer review, and taking part in family meetings. Many doctors also participate on hospital committees and boards for quality improvement measures and are leaders in designing strategies to improve patient safety and health care experiences. Although these examples may be viewed as a fundamental part of daily practice, in fact, these roles are consistent with advocacy on a local level. A significant number of physicians participate in medical education, research, and societal duties, which include formulating and reviewing guidelines for medical practice. Participation in conference organizing committees and reviewing medical journals are likewise not uncommon roles among medical practitioners. These efforts to provide education to improve patient care are also forms of advocacy on a national or regional level but often viewed as a standard in professionalism.4

It is on the federal and political level in advocacy where physician representation is critical. Health legislation is enacted by Congress and signed into law by the president of the United States.5 These laws can drastically affect clinical practice and patient care, especially in the realm of preventive medicine and pharmaceuticals. Gastroenterology is a unique field in which a large portion of practice is dedicated to cancer prevention, by screening age-appropriate individuals and monitoring high-risk patients. The field is rapidly expanding in the pharmaceutical area with new medications for inflammatory bowel disease and groundbreaking treatments for viral hepatitis. The breadth of practice in gastroenterology calls for antiquated laws to be changed to accommodate the development of patient care guidelines. With physicians representing less than 3% of Congress,6 the rules that govern our practice are largely left to those unfamiliar with the delivery of health care.

Lack of experience, limited time, and a tradition in medicine that prefers physicians to be apolitical are each contributing factors for reduced participation in federal advocacy.7 Professional GI societies, including the American Gastroenterological Association, American College of Gastroenterology, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and American Association for the Study of Liver Disease, have a presence in public policy to educate lawmakers and promote statutes in gastroenterology. The involvement of these organizations in legislation is critical since public policy directly affects the interests and well-being of patients.

The priority public policy issues for GI societies are listed as follows:

- Reducing the administrative burden of prior authorizations.

- Implementing timely appeals for non–first-line therapies as determined by payers (step therapy).

- Eliminating surprise billing and cost-sharing for screening colonoscopy.

- Preserving patient protections, including for preexisting conditions and preventive services.

- Increasing federal funding and research appropriations for gastrointestinal research.

Communication with and development of relationships with legislators are essential to effective advocacy.7,8 Health professionals should be well-informed resources for members of Congress and therefore it is pivotal to provide factual information when presenting topics. There are various ways to reach congressional representatives, including personal visits, writing letters, making phone calls, or attending town halls.