User login

How to address reviewer criticism

Authors of manuscripts typically receive one of three responses from journals: 1. Accepted as submitted; 2. Accepted pending revisions (major or minor); and 3. Rejected. Receiving an unconditional acceptance is an unusual fate worth documenting and celebrating. On the other hand, irreversible rejections are so common that authors need to get accustomed to them. Upon receiving an unqualified editorial rejection without a formal review (usually described as priority-related rejection), send the same manuscript out the next day to another journal (with electronic submissions you can do this on the same day).

If your manuscript is rejected after being reviewed, consider seriously the comments given and try to learn from them. Was your study design flawed? Do you need additional data? Were your analyses incomplete or did you employ suboptimal statistical methods? Was your interpretation of the findings far reaching and out of proportion to the actual data? Use this experience and feedback, revise your manuscript, and submit it to a different journal. It is not uncommon to encounter the same reviewer at the next journal; fixing major issues seems responsive and gets you in the door.

To receive a “conditional acceptance” or “rejection with hope” is the most likely “good” editorial response. Avoid a very quick response, because it may be hasty or create an impression of a hasty response. Because most manuscripts with substantial reviews are sent back to the reviewers, the turnaround time in most journals is several weeks and, therefore, there is little to be gained by sending the revised manuscript in 1 day rather than 1 week. The best course of action is to cool down for 1-2 days and then decide and draft responses in 1 week, including planned additional analyses. In the case of seemingly contradictory or numerous requests from reviewers, it is best to carefully examine clues from the editors or associate editors as to the nature and extent of the revision needed. In most instances, we draft the response letter before revising the manuscript. We use the draft letter to obtain specific input from other authors and ‘brainstorm’ about additional analyses that can best address reviewers concerns.

Do the best that you can to fully address all reviewers’ comments. Adequate time should be spent making real changes, including adding additional data or analyses to the manuscript, and taking utmost care in describing and highlighting these changes. If you believe that the reviewers missed a point that was already included in the paper, then point this out as politely as possible as part of the response letter (see below).

In addition to revising your manuscript, you will be asked to prepare a point-by-point response to each of the reviewers’ comments you receive. Thank the editors and reviewers sincerely for their comments and explain how changes based on the comments have made the paper better; they did spend time reviewing your manuscript, and they have not rejected it yet. Reviewers are usually recognized experts, or their apprentices, in the content or method of research employed in your paper. Reviewers are also likely to be authors on papers cited in your manuscript. Avoid unnecessary arguments when possible, especially about noncore issues or about changes that you already conceded. If you are compelled to contest any of the reviewers’ comments, provide substantial evidence that supports your position and be respectful with your responses. Address each comment separately, beginning with the comments raised by the editors followed by those from reviewer one, two, and so on. After each response, clearly point the reviewers and the editors to the revised sections in the manuscript. In case of similar comments, it is acceptable to direct the second (or the third) reviewer to your previous response. Provide new tables, figures, data elements, and references as part of the response letter to make it a stand-alone document. It can be difficult (and annoying) if the reviewer has to flip back and forth between documents to understand the full story.

Appealing editorial decisions consumes a lot of energy, annoys editors and reviewers, and is generally futile. If it is needed, then write a polite, brief appeal letter that summarizes the reasons for the appeal. The most common editorial response to an appeal, which usually follows a several-week delay, is an equally polite affirmation of the original decision. The second and arguably worse outcome is for the manuscript to be sent to two to three new reviewers with another rejection after a several-month delay.

Have colleagues read and comment on your revised paper and use these comments to improve the draft. There is evidence that writing groups are effective in providing suggestions for improving papers: A writing group also keeps the momentum going during the revision process. Setting realistic time lines with the coauthors of the paper is a useful strategy to maintain momentum during revisions.

Writing (and revising) papers can be a highly rewarding activity. Start early, plan carefully, and do not delay the process. Reviewers’ comments are mostly geared toward enhancing the manuscript. Take them seriously, address them fully, and you will have an improved (and we hope, an accepted) manuscript.

Additional reading

El-Serag HB. Writing and publishing scientific papers. Gastroenterology. 2012 Feb;142(2):197-200. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.021. Epub 2011 Dec 16.

Downey SMet al. Manuscript development and publishing: A 5-step approach. Am J Med Sci. 2017 Feb;353(2):132-6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.12.005. Epub 2016 Dec 9.

Sullivan GM. What to do when your paper is rejected. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7:1-3. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-14-00686.1

Kotz Det al. Effective writing and publishing scientific papers, part XII: responding to reviewers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:243. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.10.003. Epub 2014 Jan 9.

Dr. El-Serag is chairman of the Margaret M. and Albert B. Alkek department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; incoming president of the American Gastroenterological Association Institute; and past Editor in Chief, Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Dr. Kanwal is professor of medicine and chief of the section of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine and Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Houston, and Editor in Chief, Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. This material is based on work supported by Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas grant (RP150587). The work is also supported in part by the Center for Gastrointestinal Development, Infection and Injury (NIDDK P30 DK 56338).

Authors of manuscripts typically receive one of three responses from journals: 1. Accepted as submitted; 2. Accepted pending revisions (major or minor); and 3. Rejected. Receiving an unconditional acceptance is an unusual fate worth documenting and celebrating. On the other hand, irreversible rejections are so common that authors need to get accustomed to them. Upon receiving an unqualified editorial rejection without a formal review (usually described as priority-related rejection), send the same manuscript out the next day to another journal (with electronic submissions you can do this on the same day).

If your manuscript is rejected after being reviewed, consider seriously the comments given and try to learn from them. Was your study design flawed? Do you need additional data? Were your analyses incomplete or did you employ suboptimal statistical methods? Was your interpretation of the findings far reaching and out of proportion to the actual data? Use this experience and feedback, revise your manuscript, and submit it to a different journal. It is not uncommon to encounter the same reviewer at the next journal; fixing major issues seems responsive and gets you in the door.

To receive a “conditional acceptance” or “rejection with hope” is the most likely “good” editorial response. Avoid a very quick response, because it may be hasty or create an impression of a hasty response. Because most manuscripts with substantial reviews are sent back to the reviewers, the turnaround time in most journals is several weeks and, therefore, there is little to be gained by sending the revised manuscript in 1 day rather than 1 week. The best course of action is to cool down for 1-2 days and then decide and draft responses in 1 week, including planned additional analyses. In the case of seemingly contradictory or numerous requests from reviewers, it is best to carefully examine clues from the editors or associate editors as to the nature and extent of the revision needed. In most instances, we draft the response letter before revising the manuscript. We use the draft letter to obtain specific input from other authors and ‘brainstorm’ about additional analyses that can best address reviewers concerns.

Do the best that you can to fully address all reviewers’ comments. Adequate time should be spent making real changes, including adding additional data or analyses to the manuscript, and taking utmost care in describing and highlighting these changes. If you believe that the reviewers missed a point that was already included in the paper, then point this out as politely as possible as part of the response letter (see below).

In addition to revising your manuscript, you will be asked to prepare a point-by-point response to each of the reviewers’ comments you receive. Thank the editors and reviewers sincerely for their comments and explain how changes based on the comments have made the paper better; they did spend time reviewing your manuscript, and they have not rejected it yet. Reviewers are usually recognized experts, or their apprentices, in the content or method of research employed in your paper. Reviewers are also likely to be authors on papers cited in your manuscript. Avoid unnecessary arguments when possible, especially about noncore issues or about changes that you already conceded. If you are compelled to contest any of the reviewers’ comments, provide substantial evidence that supports your position and be respectful with your responses. Address each comment separately, beginning with the comments raised by the editors followed by those from reviewer one, two, and so on. After each response, clearly point the reviewers and the editors to the revised sections in the manuscript. In case of similar comments, it is acceptable to direct the second (or the third) reviewer to your previous response. Provide new tables, figures, data elements, and references as part of the response letter to make it a stand-alone document. It can be difficult (and annoying) if the reviewer has to flip back and forth between documents to understand the full story.

Appealing editorial decisions consumes a lot of energy, annoys editors and reviewers, and is generally futile. If it is needed, then write a polite, brief appeal letter that summarizes the reasons for the appeal. The most common editorial response to an appeal, which usually follows a several-week delay, is an equally polite affirmation of the original decision. The second and arguably worse outcome is for the manuscript to be sent to two to three new reviewers with another rejection after a several-month delay.

Have colleagues read and comment on your revised paper and use these comments to improve the draft. There is evidence that writing groups are effective in providing suggestions for improving papers: A writing group also keeps the momentum going during the revision process. Setting realistic time lines with the coauthors of the paper is a useful strategy to maintain momentum during revisions.

Writing (and revising) papers can be a highly rewarding activity. Start early, plan carefully, and do not delay the process. Reviewers’ comments are mostly geared toward enhancing the manuscript. Take them seriously, address them fully, and you will have an improved (and we hope, an accepted) manuscript.

Additional reading

El-Serag HB. Writing and publishing scientific papers. Gastroenterology. 2012 Feb;142(2):197-200. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.021. Epub 2011 Dec 16.

Downey SMet al. Manuscript development and publishing: A 5-step approach. Am J Med Sci. 2017 Feb;353(2):132-6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.12.005. Epub 2016 Dec 9.

Sullivan GM. What to do when your paper is rejected. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7:1-3. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-14-00686.1

Kotz Det al. Effective writing and publishing scientific papers, part XII: responding to reviewers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:243. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.10.003. Epub 2014 Jan 9.

Dr. El-Serag is chairman of the Margaret M. and Albert B. Alkek department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; incoming president of the American Gastroenterological Association Institute; and past Editor in Chief, Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Dr. Kanwal is professor of medicine and chief of the section of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine and Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Houston, and Editor in Chief, Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. This material is based on work supported by Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas grant (RP150587). The work is also supported in part by the Center for Gastrointestinal Development, Infection and Injury (NIDDK P30 DK 56338).

Authors of manuscripts typically receive one of three responses from journals: 1. Accepted as submitted; 2. Accepted pending revisions (major or minor); and 3. Rejected. Receiving an unconditional acceptance is an unusual fate worth documenting and celebrating. On the other hand, irreversible rejections are so common that authors need to get accustomed to them. Upon receiving an unqualified editorial rejection without a formal review (usually described as priority-related rejection), send the same manuscript out the next day to another journal (with electronic submissions you can do this on the same day).

If your manuscript is rejected after being reviewed, consider seriously the comments given and try to learn from them. Was your study design flawed? Do you need additional data? Were your analyses incomplete or did you employ suboptimal statistical methods? Was your interpretation of the findings far reaching and out of proportion to the actual data? Use this experience and feedback, revise your manuscript, and submit it to a different journal. It is not uncommon to encounter the same reviewer at the next journal; fixing major issues seems responsive and gets you in the door.

To receive a “conditional acceptance” or “rejection with hope” is the most likely “good” editorial response. Avoid a very quick response, because it may be hasty or create an impression of a hasty response. Because most manuscripts with substantial reviews are sent back to the reviewers, the turnaround time in most journals is several weeks and, therefore, there is little to be gained by sending the revised manuscript in 1 day rather than 1 week. The best course of action is to cool down for 1-2 days and then decide and draft responses in 1 week, including planned additional analyses. In the case of seemingly contradictory or numerous requests from reviewers, it is best to carefully examine clues from the editors or associate editors as to the nature and extent of the revision needed. In most instances, we draft the response letter before revising the manuscript. We use the draft letter to obtain specific input from other authors and ‘brainstorm’ about additional analyses that can best address reviewers concerns.

Do the best that you can to fully address all reviewers’ comments. Adequate time should be spent making real changes, including adding additional data or analyses to the manuscript, and taking utmost care in describing and highlighting these changes. If you believe that the reviewers missed a point that was already included in the paper, then point this out as politely as possible as part of the response letter (see below).

In addition to revising your manuscript, you will be asked to prepare a point-by-point response to each of the reviewers’ comments you receive. Thank the editors and reviewers sincerely for their comments and explain how changes based on the comments have made the paper better; they did spend time reviewing your manuscript, and they have not rejected it yet. Reviewers are usually recognized experts, or their apprentices, in the content or method of research employed in your paper. Reviewers are also likely to be authors on papers cited in your manuscript. Avoid unnecessary arguments when possible, especially about noncore issues or about changes that you already conceded. If you are compelled to contest any of the reviewers’ comments, provide substantial evidence that supports your position and be respectful with your responses. Address each comment separately, beginning with the comments raised by the editors followed by those from reviewer one, two, and so on. After each response, clearly point the reviewers and the editors to the revised sections in the manuscript. In case of similar comments, it is acceptable to direct the second (or the third) reviewer to your previous response. Provide new tables, figures, data elements, and references as part of the response letter to make it a stand-alone document. It can be difficult (and annoying) if the reviewer has to flip back and forth between documents to understand the full story.

Appealing editorial decisions consumes a lot of energy, annoys editors and reviewers, and is generally futile. If it is needed, then write a polite, brief appeal letter that summarizes the reasons for the appeal. The most common editorial response to an appeal, which usually follows a several-week delay, is an equally polite affirmation of the original decision. The second and arguably worse outcome is for the manuscript to be sent to two to three new reviewers with another rejection after a several-month delay.

Have colleagues read and comment on your revised paper and use these comments to improve the draft. There is evidence that writing groups are effective in providing suggestions for improving papers: A writing group also keeps the momentum going during the revision process. Setting realistic time lines with the coauthors of the paper is a useful strategy to maintain momentum during revisions.

Writing (and revising) papers can be a highly rewarding activity. Start early, plan carefully, and do not delay the process. Reviewers’ comments are mostly geared toward enhancing the manuscript. Take them seriously, address them fully, and you will have an improved (and we hope, an accepted) manuscript.

Additional reading

El-Serag HB. Writing and publishing scientific papers. Gastroenterology. 2012 Feb;142(2):197-200. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.021. Epub 2011 Dec 16.

Downey SMet al. Manuscript development and publishing: A 5-step approach. Am J Med Sci. 2017 Feb;353(2):132-6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.12.005. Epub 2016 Dec 9.

Sullivan GM. What to do when your paper is rejected. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7:1-3. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-14-00686.1

Kotz Det al. Effective writing and publishing scientific papers, part XII: responding to reviewers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:243. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.10.003. Epub 2014 Jan 9.

Dr. El-Serag is chairman of the Margaret M. and Albert B. Alkek department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; incoming president of the American Gastroenterological Association Institute; and past Editor in Chief, Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Dr. Kanwal is professor of medicine and chief of the section of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine and Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Houston, and Editor in Chief, Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. This material is based on work supported by Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas grant (RP150587). The work is also supported in part by the Center for Gastrointestinal Development, Infection and Injury (NIDDK P30 DK 56338).

Junior faculty guide to preparing a research grant

A wise person once said, “Research is a marathon and not a sprint.” Grant writing is the training for the marathon, and it requires discipline and fortitude to succeed. We are junior faculty members with mentored career development awards who are transitioning to independence. Below, we provide for our junior faculty colleagues some tips that have helped us train for our marathon in research.

Identify great mentors

We all understand that outstanding mentorship is critical to success. With that said, we often struggle to understand what a good mentor is. In regard to grant writing, you need someone who is willing to use red ink. While positive reinforcement may be good for your self-esteem, your mentor needs to be critical so that you can learn how to present the best possible product. In return, you must be an invested mentee who is respectful of the mentor’s time, is prepared for meetings, and responds appropriately to feedback.

Attend workshops

Your home institution and professional societies hold outstanding workshops that provide didactic lessons on both the logistics and mechanics of grant writing and allow you to network with like-minded peers, potential mentors, and staff from the funding organization. One excellent example is the American Gastroenterological Association/American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AGA/AASLD) Academic Skills workshop.

Decide on a grant mechanism

There are many different grants available through the government, industry, foundations, and your institution. Each grantor may have a variety of mechanisms from pilot awards to larger multiprovider and institution grants. Deciding which grants to apply for can be more of an art than it is a science. Research the opportunities available to you and develop a long-term plan with your mentors.

Start early and have a plan

An effective grant application is prepared in steps, and every step takes longer than anticipated. About 6 months prior to the deadline, read the instructions and consider using something like a Gantt chart to identify all required sections, special requirements (font, spacing, page limits), and anticipated time of completion. Then, structure a reasonable timeline – and stick to it! Remember to allow ample time for all sections, including the career development plan and research environment. Your institution will probably request the documents early, anywhere from 1 to 2 weeks prior to the deadline so that it can be circulated for institutional signatures. Steady progress wins most races.

Specific aims

There is no grant without a great idea, but not all great ideas are funded. So, the first step is to polish your idea, which must be clearly described on the Specific Aims page, which is a one-page summary that lays the framework for the rest of the grant. For the primary reviewers, it should entice them to read the proposal. For others on the review panel, it may be the only section of your grant that they read. Make sure it is clear and concise. If possible, construct a visually pleasing and easy-to-follow figure that encapsulates your proposal.

Circulate

Ideally, every section of the grant will be circulated but it is critical to have others review the Specific Aims at the very least. Ask not only your mentors and those in the field to critique but also those outside of your area and even your friends and unsuspecting family members; they may not know (or care) about the content but should be able to follow the flow and identify grammatical errors. Remember that everyone is busy, so give ample time for people to review the documents.

Read other proposals

Practice makes perfect. So you can either apply for many grants and make the mistakes yourself or read and review as many proposals as you can to learn from your colleagues’ successes and mistakes. Many institutions, mentors, and colleagues will provide copies of prior applications if you ask. Make sure you know which were successful and try to understand why the others were not successful.

When reading the aims and research strategy, pay close attention to how significance and innovation are detailed. Also, some things like the research environment, which is especially important for career development grants, may be directly applicable to your grant.

Help the reviewer

In general, reviewing grants is a voluntary undertaking. Imagine the reviewer reading your grant at a home filled with screaming children or, alternatively, flying in cramped quarters. Neither situation is stress-free, so put yourself in those positions and decide what you can do to make the reviewer’s job easier.

Use figures and tables to summarize the text, and consider coming back to the figure from your Specific Aims to refer to the specific parts of the proposal. You can decrease reviewer fatigue by using line breaks and fonts to break up sections and highlight important details. This will also be helpful to the reviewers on the panel who were not assigned to your grant and possibly first seeing it during the session.

Learn from rejection

You are either a savant or have not applied for enough grants if you have not received a rejection letter. Often, reviewers provide you with constructive comments, which (after a session of crying in the corner in a fetal position), you can use to improve your grant. Resubmission works!

Apply widely

Identify different possible grants, and work with your mentors on a strategy that allows you to make your idea versatile and package it for various funding mechanisms. Once you have a grant, you can tailor it to other grants as needed. However, remember that quantity does not replace quality, so many poor grants that are not funded will not replace one good one that is funded.

There are multiple approaches to training for the marathon of research, so these tips are not a comprehensive list or mandatory commandments. They have, however, proven invaluable to our mentors and us. Our institutions, societies and government agencies have identified the decline of young scientists and physician-scientists as a major leak in the research pipeline, so there are excellent funding mechanisms that are available to you. Good luck!

We would like to acknowledge Jennifer Weiss, MD, and Sumera Rizvi, MD, for their constructive comments.

Dr. Beyder is with the enteric neuroscience program, a consultant for the department of gastroenterology and hepatology, and an assistant professor of biomedical engineering and physiology at the Mayo Clinic School of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.; Dr. Twyman-Saint Victor is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

A wise person once said, “Research is a marathon and not a sprint.” Grant writing is the training for the marathon, and it requires discipline and fortitude to succeed. We are junior faculty members with mentored career development awards who are transitioning to independence. Below, we provide for our junior faculty colleagues some tips that have helped us train for our marathon in research.

Identify great mentors

We all understand that outstanding mentorship is critical to success. With that said, we often struggle to understand what a good mentor is. In regard to grant writing, you need someone who is willing to use red ink. While positive reinforcement may be good for your self-esteem, your mentor needs to be critical so that you can learn how to present the best possible product. In return, you must be an invested mentee who is respectful of the mentor’s time, is prepared for meetings, and responds appropriately to feedback.

Attend workshops

Your home institution and professional societies hold outstanding workshops that provide didactic lessons on both the logistics and mechanics of grant writing and allow you to network with like-minded peers, potential mentors, and staff from the funding organization. One excellent example is the American Gastroenterological Association/American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AGA/AASLD) Academic Skills workshop.

Decide on a grant mechanism

There are many different grants available through the government, industry, foundations, and your institution. Each grantor may have a variety of mechanisms from pilot awards to larger multiprovider and institution grants. Deciding which grants to apply for can be more of an art than it is a science. Research the opportunities available to you and develop a long-term plan with your mentors.

Start early and have a plan

An effective grant application is prepared in steps, and every step takes longer than anticipated. About 6 months prior to the deadline, read the instructions and consider using something like a Gantt chart to identify all required sections, special requirements (font, spacing, page limits), and anticipated time of completion. Then, structure a reasonable timeline – and stick to it! Remember to allow ample time for all sections, including the career development plan and research environment. Your institution will probably request the documents early, anywhere from 1 to 2 weeks prior to the deadline so that it can be circulated for institutional signatures. Steady progress wins most races.

Specific aims

There is no grant without a great idea, but not all great ideas are funded. So, the first step is to polish your idea, which must be clearly described on the Specific Aims page, which is a one-page summary that lays the framework for the rest of the grant. For the primary reviewers, it should entice them to read the proposal. For others on the review panel, it may be the only section of your grant that they read. Make sure it is clear and concise. If possible, construct a visually pleasing and easy-to-follow figure that encapsulates your proposal.

Circulate

Ideally, every section of the grant will be circulated but it is critical to have others review the Specific Aims at the very least. Ask not only your mentors and those in the field to critique but also those outside of your area and even your friends and unsuspecting family members; they may not know (or care) about the content but should be able to follow the flow and identify grammatical errors. Remember that everyone is busy, so give ample time for people to review the documents.

Read other proposals

Practice makes perfect. So you can either apply for many grants and make the mistakes yourself or read and review as many proposals as you can to learn from your colleagues’ successes and mistakes. Many institutions, mentors, and colleagues will provide copies of prior applications if you ask. Make sure you know which were successful and try to understand why the others were not successful.

When reading the aims and research strategy, pay close attention to how significance and innovation are detailed. Also, some things like the research environment, which is especially important for career development grants, may be directly applicable to your grant.

Help the reviewer

In general, reviewing grants is a voluntary undertaking. Imagine the reviewer reading your grant at a home filled with screaming children or, alternatively, flying in cramped quarters. Neither situation is stress-free, so put yourself in those positions and decide what you can do to make the reviewer’s job easier.

Use figures and tables to summarize the text, and consider coming back to the figure from your Specific Aims to refer to the specific parts of the proposal. You can decrease reviewer fatigue by using line breaks and fonts to break up sections and highlight important details. This will also be helpful to the reviewers on the panel who were not assigned to your grant and possibly first seeing it during the session.

Learn from rejection

You are either a savant or have not applied for enough grants if you have not received a rejection letter. Often, reviewers provide you with constructive comments, which (after a session of crying in the corner in a fetal position), you can use to improve your grant. Resubmission works!

Apply widely

Identify different possible grants, and work with your mentors on a strategy that allows you to make your idea versatile and package it for various funding mechanisms. Once you have a grant, you can tailor it to other grants as needed. However, remember that quantity does not replace quality, so many poor grants that are not funded will not replace one good one that is funded.

There are multiple approaches to training for the marathon of research, so these tips are not a comprehensive list or mandatory commandments. They have, however, proven invaluable to our mentors and us. Our institutions, societies and government agencies have identified the decline of young scientists and physician-scientists as a major leak in the research pipeline, so there are excellent funding mechanisms that are available to you. Good luck!

We would like to acknowledge Jennifer Weiss, MD, and Sumera Rizvi, MD, for their constructive comments.

Dr. Beyder is with the enteric neuroscience program, a consultant for the department of gastroenterology and hepatology, and an assistant professor of biomedical engineering and physiology at the Mayo Clinic School of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.; Dr. Twyman-Saint Victor is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

A wise person once said, “Research is a marathon and not a sprint.” Grant writing is the training for the marathon, and it requires discipline and fortitude to succeed. We are junior faculty members with mentored career development awards who are transitioning to independence. Below, we provide for our junior faculty colleagues some tips that have helped us train for our marathon in research.

Identify great mentors

We all understand that outstanding mentorship is critical to success. With that said, we often struggle to understand what a good mentor is. In regard to grant writing, you need someone who is willing to use red ink. While positive reinforcement may be good for your self-esteem, your mentor needs to be critical so that you can learn how to present the best possible product. In return, you must be an invested mentee who is respectful of the mentor’s time, is prepared for meetings, and responds appropriately to feedback.

Attend workshops

Your home institution and professional societies hold outstanding workshops that provide didactic lessons on both the logistics and mechanics of grant writing and allow you to network with like-minded peers, potential mentors, and staff from the funding organization. One excellent example is the American Gastroenterological Association/American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AGA/AASLD) Academic Skills workshop.

Decide on a grant mechanism

There are many different grants available through the government, industry, foundations, and your institution. Each grantor may have a variety of mechanisms from pilot awards to larger multiprovider and institution grants. Deciding which grants to apply for can be more of an art than it is a science. Research the opportunities available to you and develop a long-term plan with your mentors.

Start early and have a plan

An effective grant application is prepared in steps, and every step takes longer than anticipated. About 6 months prior to the deadline, read the instructions and consider using something like a Gantt chart to identify all required sections, special requirements (font, spacing, page limits), and anticipated time of completion. Then, structure a reasonable timeline – and stick to it! Remember to allow ample time for all sections, including the career development plan and research environment. Your institution will probably request the documents early, anywhere from 1 to 2 weeks prior to the deadline so that it can be circulated for institutional signatures. Steady progress wins most races.

Specific aims

There is no grant without a great idea, but not all great ideas are funded. So, the first step is to polish your idea, which must be clearly described on the Specific Aims page, which is a one-page summary that lays the framework for the rest of the grant. For the primary reviewers, it should entice them to read the proposal. For others on the review panel, it may be the only section of your grant that they read. Make sure it is clear and concise. If possible, construct a visually pleasing and easy-to-follow figure that encapsulates your proposal.

Circulate

Ideally, every section of the grant will be circulated but it is critical to have others review the Specific Aims at the very least. Ask not only your mentors and those in the field to critique but also those outside of your area and even your friends and unsuspecting family members; they may not know (or care) about the content but should be able to follow the flow and identify grammatical errors. Remember that everyone is busy, so give ample time for people to review the documents.

Read other proposals

Practice makes perfect. So you can either apply for many grants and make the mistakes yourself or read and review as many proposals as you can to learn from your colleagues’ successes and mistakes. Many institutions, mentors, and colleagues will provide copies of prior applications if you ask. Make sure you know which were successful and try to understand why the others were not successful.

When reading the aims and research strategy, pay close attention to how significance and innovation are detailed. Also, some things like the research environment, which is especially important for career development grants, may be directly applicable to your grant.

Help the reviewer

In general, reviewing grants is a voluntary undertaking. Imagine the reviewer reading your grant at a home filled with screaming children or, alternatively, flying in cramped quarters. Neither situation is stress-free, so put yourself in those positions and decide what you can do to make the reviewer’s job easier.

Use figures and tables to summarize the text, and consider coming back to the figure from your Specific Aims to refer to the specific parts of the proposal. You can decrease reviewer fatigue by using line breaks and fonts to break up sections and highlight important details. This will also be helpful to the reviewers on the panel who were not assigned to your grant and possibly first seeing it during the session.

Learn from rejection

You are either a savant or have not applied for enough grants if you have not received a rejection letter. Often, reviewers provide you with constructive comments, which (after a session of crying in the corner in a fetal position), you can use to improve your grant. Resubmission works!

Apply widely

Identify different possible grants, and work with your mentors on a strategy that allows you to make your idea versatile and package it for various funding mechanisms. Once you have a grant, you can tailor it to other grants as needed. However, remember that quantity does not replace quality, so many poor grants that are not funded will not replace one good one that is funded.

There are multiple approaches to training for the marathon of research, so these tips are not a comprehensive list or mandatory commandments. They have, however, proven invaluable to our mentors and us. Our institutions, societies and government agencies have identified the decline of young scientists and physician-scientists as a major leak in the research pipeline, so there are excellent funding mechanisms that are available to you. Good luck!

We would like to acknowledge Jennifer Weiss, MD, and Sumera Rizvi, MD, for their constructive comments.

Dr. Beyder is with the enteric neuroscience program, a consultant for the department of gastroenterology and hepatology, and an assistant professor of biomedical engineering and physiology at the Mayo Clinic School of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.; Dr. Twyman-Saint Victor is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

November 2018

Gastroenterology

How and when to consider genetic testing for colon cancer? Ballester V; Cruz-Correa M. 2018 Oct;155(4):955-9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.031.

How to approach a patient with eosinophilic esophagitis. Hirano I. 2018 Sept;155(3):601-6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.001.

How to ensure patient adherence to colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in your practice. Hassan C; Kaminski MF; Repici A. 2018 Aug;155(2):252-7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.06.051.

How to approach difficult patient encounters: ROAR. McCarthy JG; Cheatham JG; Singla M. 2018 Aug;155(2):258-61. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.06.052.

An inside view: AGA advocacy priorities. Jain R. 2018 Aug;155(2):572-3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.06.028.

Clin Gastro Hepatol

Adding value to the conversation about colorectal cancer screening: Practical pearls for gastroenterologists. Maratt JK; Naylor K; Saini SD. 2018 Oct;16(10):1545–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.07.002.

Credentialing for endoscopic practice: The Mayo Clinic model. Kane SV; Chandrasekhara V; Sedlack RE; Buttar NS. 2018 Sept;16(9):1370–3.e1 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.06.020.

Gastroenterology

How and when to consider genetic testing for colon cancer? Ballester V; Cruz-Correa M. 2018 Oct;155(4):955-9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.031.

How to approach a patient with eosinophilic esophagitis. Hirano I. 2018 Sept;155(3):601-6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.001.

How to ensure patient adherence to colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in your practice. Hassan C; Kaminski MF; Repici A. 2018 Aug;155(2):252-7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.06.051.

How to approach difficult patient encounters: ROAR. McCarthy JG; Cheatham JG; Singla M. 2018 Aug;155(2):258-61. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.06.052.

An inside view: AGA advocacy priorities. Jain R. 2018 Aug;155(2):572-3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.06.028.

Clin Gastro Hepatol

Adding value to the conversation about colorectal cancer screening: Practical pearls for gastroenterologists. Maratt JK; Naylor K; Saini SD. 2018 Oct;16(10):1545–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.07.002.

Credentialing for endoscopic practice: The Mayo Clinic model. Kane SV; Chandrasekhara V; Sedlack RE; Buttar NS. 2018 Sept;16(9):1370–3.e1 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.06.020.

Gastroenterology

How and when to consider genetic testing for colon cancer? Ballester V; Cruz-Correa M. 2018 Oct;155(4):955-9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.031.

How to approach a patient with eosinophilic esophagitis. Hirano I. 2018 Sept;155(3):601-6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.001.

How to ensure patient adherence to colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in your practice. Hassan C; Kaminski MF; Repici A. 2018 Aug;155(2):252-7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.06.051.

How to approach difficult patient encounters: ROAR. McCarthy JG; Cheatham JG; Singla M. 2018 Aug;155(2):258-61. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.06.052.

An inside view: AGA advocacy priorities. Jain R. 2018 Aug;155(2):572-3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.06.028.

Clin Gastro Hepatol

Adding value to the conversation about colorectal cancer screening: Practical pearls for gastroenterologists. Maratt JK; Naylor K; Saini SD. 2018 Oct;16(10):1545–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.07.002.

Credentialing for endoscopic practice: The Mayo Clinic model. Kane SV; Chandrasekhara V; Sedlack RE; Buttar NS. 2018 Sept;16(9):1370–3.e1 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.06.020.

Quality metrics in colonoscopy

Editor's Note:

As quality metrics are becoming increasingly significant throughout all of medicine, our field is no exception. Recent evidence has demonstrated the importance of quality measures in colonoscopy; understanding, reporting, and improving these metrics has become a hot topic of discussion.

In this month’s In Focus article, brought to you by The New Gastroenterologist, Nabiha Shamsi, Ashish Malhotra, and Aasma Shaukat (University of Minnesota/Minneapolis VAMC) provide an outstanding overview of the evidence as well as recommended goals for important quality metrics in colonoscopy. Ultimately, improving colonoscopy quality amongst all gastroenterologists will increase colonoscopy value and lead to further decreases in the incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer.

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief, The New Gastroenterologist

Introduction

Colonoscopy is a widely used modality to evaluate colorectal cancer because it allows for both identification of early malignancies and removal of precancerous lesions. The increased use of colonoscopy in the last 20 years has been associated with a decline in the incidence and mortality from colorectal cancer.1,2 However, colonoscopy has its limitations. It is an invasive test with inherent risks. Additionally, studies have reported rates of post-colonoscopy cancers, also referred to as interval cancers, of 2%-7%, and miss-rates for adenomas by tandem colonoscopy of 2%-26%.3-5

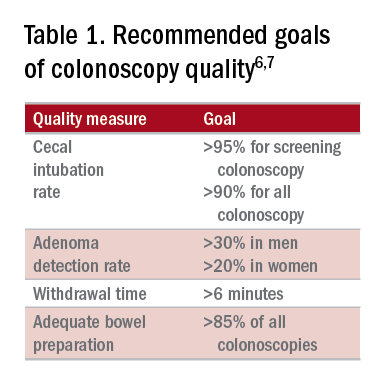

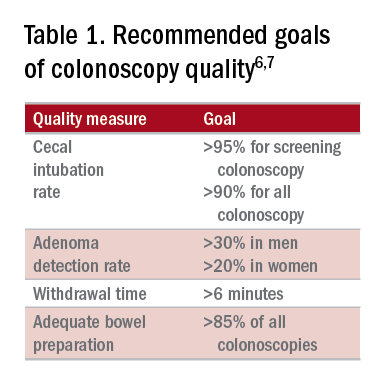

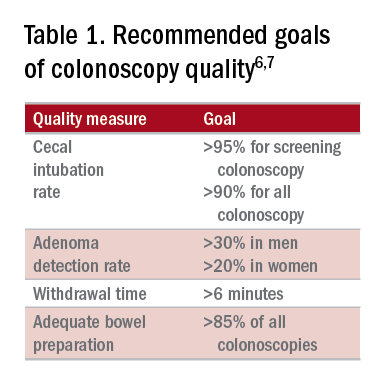

High-quality exams can maximize the value of colonoscopy, and it is important to consider the factors that contribute to high-quality colonoscopies. While there are many metrics proposed,6,7 here we discuss the most evidence-based ones, outlined in Table 1, along with their goal values.

Cecal intubation rate

A high-quality colonoscopy should include a complete examination of the colon. To achieve this, it is necessary to fully intubate the cecum, passing the colonoscope past the ileocecal valve to examine the medial wall of the cecum.8

There are several factors that may contribute to an incomplete colonoscopy, including bowel preparation, anatomy, body habitus, and endoscopist’s skill. To calculate cecal intubation rate as a quality measure, colonoscopies that are incomplete because of poor bowel preparation, severe colitis, or known obstructing lesion are usually excluded.

The U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer recommends a cecal intubation rate of at least 95% for screening colonoscopy and 90% for all colonoscopies.6 There is an expectation of photodocumentation of the ileocecal valve and appendiceal orifice to establish completion of the colonoscopy.6

Some methods used to assist with cecal intubation include changing patient position, applying abdominal pressure, stiffening the colonoscope, and alternating between adult or pediatric colonoscopes.

Adenoma detection rate

Adenoma detection rate (ADR), is defined as the proportion of patients over the age of 50 years undergoing first-time screening colonoscopies in which at least one adenomatous polyp is detected for a given endoscopist in a given time period.

Adenomas are tracked because clearing the colon of neoplasm is the goal of screening colonoscopies; adenomas are tracked instead of more advanced lesions because the higher frequency of adenomas allows for better tracking of variation between endoscopists. Tracking ADR also utilizes the assumption that, if small lesions are identified, larger ones will be as well.

ADR is the only current quality indicator reported to be significantly associated with the risk of interval cancers. In 2010, a study of 45,000 screening colonoscopies by 186 endoscopists validated the use of ADR, finding that patients who underwent colonoscopy by physicians with ADRs below 20% had hazard ratios for development of postcolonoscopy cancer greater than 10 times higher than patients of physicians with ADRs above 20%.9 However, this study had limited power to establish that cancer protection continues to improve when ADRs rise above 20%. Another study, which evaluated the association of ADR in 224,000 patients undergoing colonoscopies by 136 gastroenterologists, showed each 1% increase in ADR is associated with 3% decrease in the risk of interval CRC and 5% decrease in the risk of fatal interval cancers.10

Most recent guidelines propose an adequate ADR for asymptomatic individuals aged 50 years or older undergoing screening colonoscopy should be greater than 30% in men and greater than 20% in women.6 It remains unknown whether there is a threshold for maximum benefit of ADR, in which a very high ADR is not associated with further protective benefit. The answer to this question may depend on why a low ADR is associated with a higher rate of interval cancers and whether every missed polyp, independent of size, is a potential interval cancer or whether hasty, inadequate, or incomplete examinations of the colon are the underlying concern.

Withdrawal time

Optimizing identification of colonic lesions requires a careful and thorough exam of the colon on withdrawal. While this may seem obvious, there is often little focus on the approach to withdrawal. In four chapters on colonoscopy technique from textbooks, the number of pages describing insertion ranged from 20 to 38, while the number of pages focused on withdrawal ranged from 0.5 to 1.5.11-14

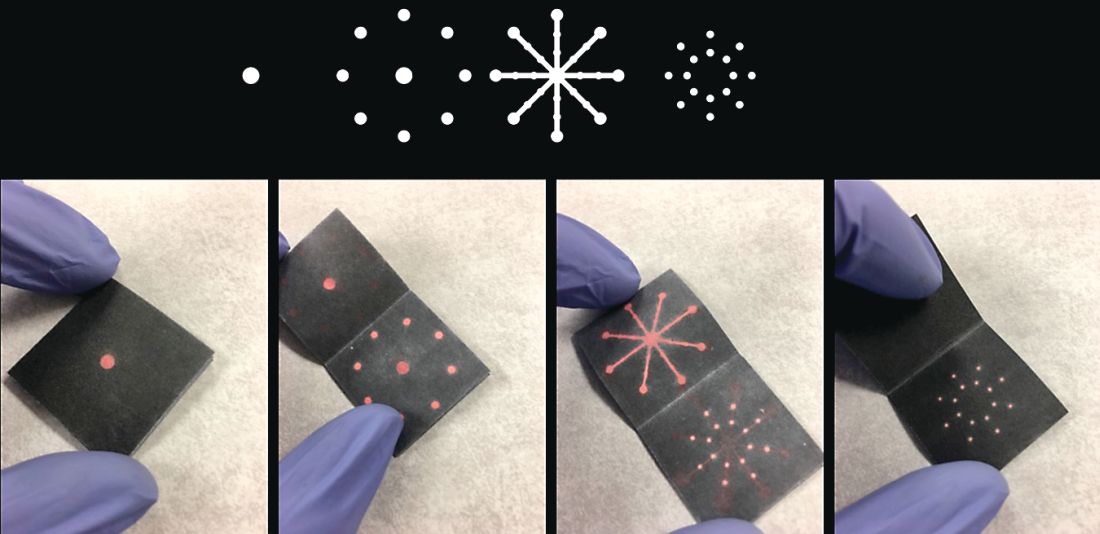

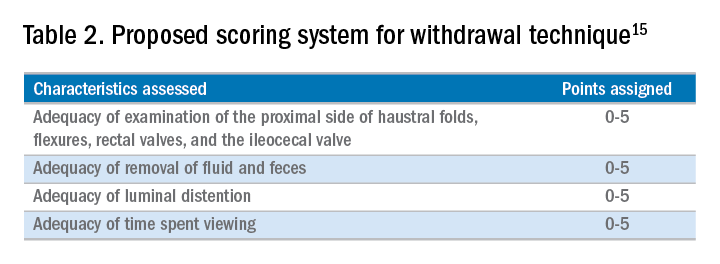

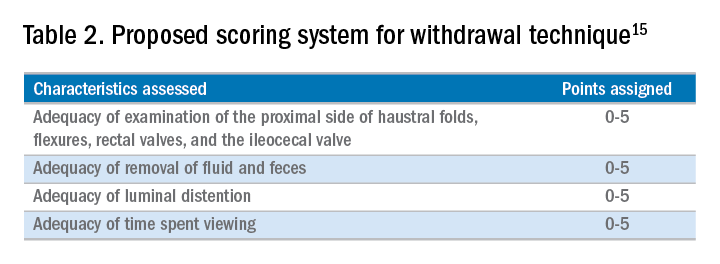

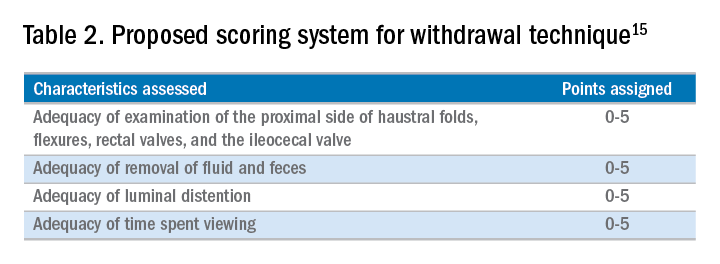

A study examining the difference in withdrawal technique between two endoscopists who were known to differ in adenoma miss rates by tandem colonoscopy proposed the scoring system listed in Table 2 that can assess quality of examination on withdrawal. There was a statistically significant difference in quality scores for the two endoscopists, as assessed by expert review of video recordings of their colonoscopies.15

The endoscopist with the lower adenoma miss rate was also found to have an average withdrawal time of 8 minutes and 55 seconds versus 6 minutes and 41 seconds for the endoscopist with the higher adenoma miss rate. A large, community-based study with over 76,000 colonoscopies found a statistically significant correlation between interval colorectal cancer and withdrawal times shorter than 6 minutes.16 However, there was no association between ADR and colorectal cancer, suggesting that, for practices with optimal ADRs (that is, rates greater than 25%), withdrawal time may be a more sensitive marker of quality of colonoscopy than ADR is.16Intuitively, adequate examination of the colon that includes examining the proximal side of folds, washing and suctioning stool, and even repositioning the patient would likely increase withdrawal time. In a 2008 study examining 2,000 screening colonoscopies of 12 endoscopists, those with withdrawal times greater than 6 minutes had significantly higher rates of detecting adenomas and advanced neoplasia, compared with those with faster withdrawal times.17 The average ADR in this group was 28.3%, compared with 11.8% for physicians who had a withdrawal time less than 6 minutes.17 An evaluation of nearly 11,000 colonoscopies done by 43 endoscopists also identified an increase polyp yield with increased withdrawal time.18 These data drive the recommendation for a minimum withdrawal time of 6 minutes, with 2 minutes spent examining each colonic segment.

Bowel preparation

Diagnosis of colonic lesions is dependent on adequate visualization of the colon. Poor bowel preparation can limit the yield of colonoscopy and lead to missed lesions. It also leads to canceled and rescheduled procedures that reduce efficiency, increase cost, and pose an undue burden on the patient.

The quality of bowel preparation should be assessed after washing and suctioning of colonic mucosa has been completed. Adequate preparation is that which allows identification of lesions greater than 5 mm in size.19

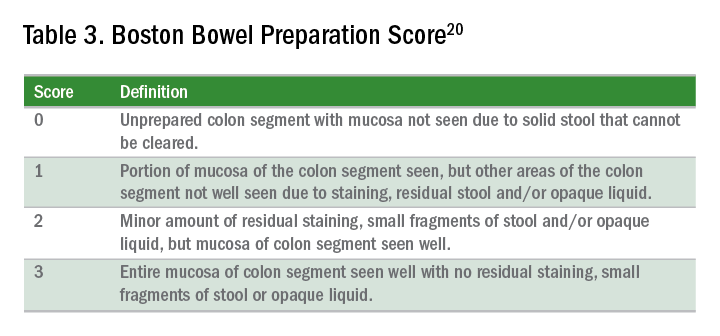

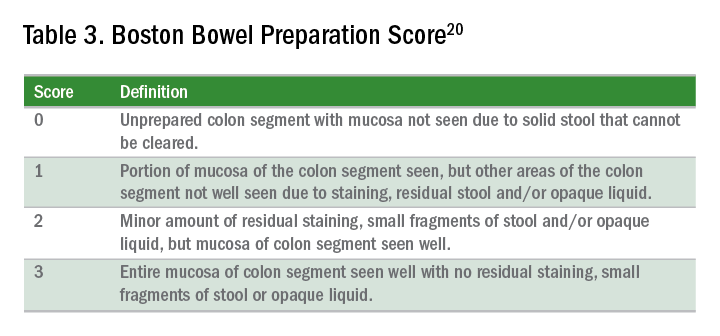

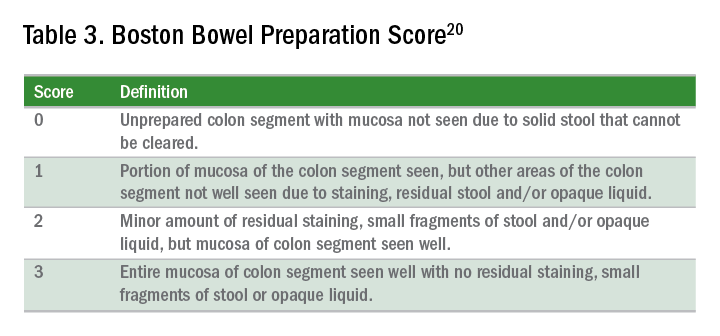

Quality of preparation is assessed subjectively by the endoscopists and often listed as excellent, good, fair, or poor. An alternative method of reporting bowel preparation quality is the Boston Bowel Preparation Score (BBPS) (Table 3).20 This scoring system allows for a more descriptive assessment of each colonic segment by assigning a score from 0 to 3 for the right, transverse, and left colon, leading to a total score between 0 and 9. The BBPS also helps standardize reporting of bowel preparation. The polyp detection rate associated with a BBPS of 5 or greater was 40%, compared with 24% associated with BBPS less than 5.19 A split-dose bowel preparation regimen with at least half of the preparation ingested on the day of the procedure is recommended to optimize quality of bowel preparation.6

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and American College of Gastroenterology task force on quality assurance in endoscopy recommends that bowel preparation should be adequate in 85% of all colonoscopy exams on a per-provider basis.7 One study of completed colonoscopy with inadequate preparation showed an adenoma miss rate of 48%.21 In the setting of inadequate bowel preparation, another study reported 42% of all adenomas detected were only found on repeat colonoscopy. When considering advanced adenomas, there was a 27% miss rate, a relatively high percentage.22

When poor bowel preparation precludes the exam, colonoscopy is appropriately aborted, and the patient asked to return. However, there are situations in which the exam can be completed but the bowel preparation is still inadequate to identify polyps larger than 5 mm. In this setting, the colonoscopy should be repeated with a more aggressive bowel preparation regimen within 1 year.19 Shorter intervals are recommended if advanced neoplasm is detected within an inadequate bowel preparation.19

The appropriate surveillance interval can be unclear when bowel preparation is considered adequate to identify polyps greater than or equal to 5 mm, yet still suboptimal. “Adequate” or “fair” bowel preparation often leads to shorter-than-recommended surveillance intervals because of the concern for small missed lesions. For example, patients with normal colonoscopy results and a fair prep were recommended to undergo a screening colonoscopy in 5 years at 57.4%, while only 23.1% received a 10-year recommendation.23 This increased frequency of colonoscopy leads to increased costs and procedural risks for the patient. Furthermore, a meta-analysis evaluating the effects of bowel preparation reported no significant difference in ADR between adequate and excellent prep.24 These findings suggest that patients with adequate bowel preparation may be followed at guideline-recommended surveillance intervals without significantly affecting colonoscopy quality as measured by ADR.

Endoscopist feedback and report cards

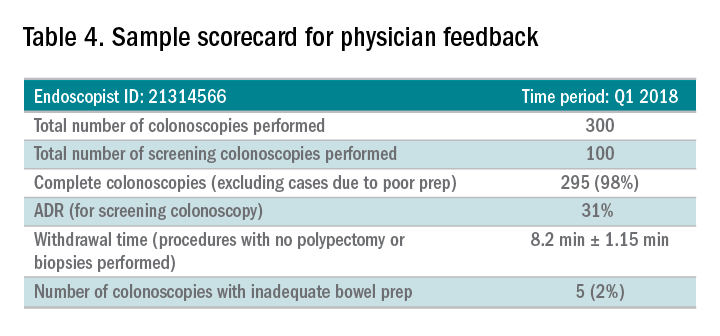

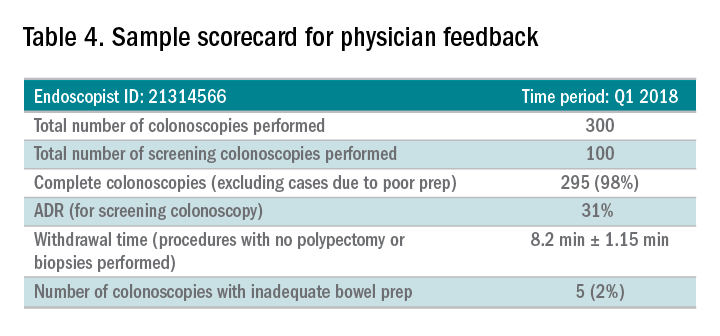

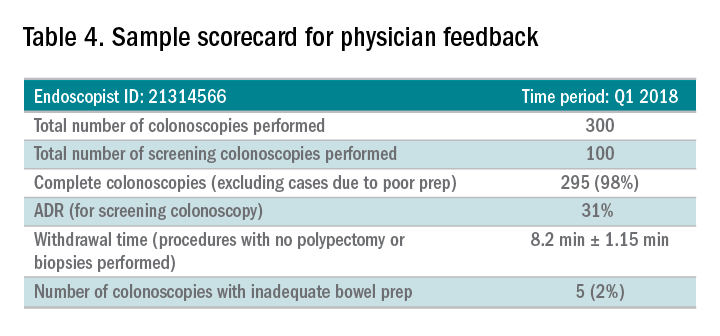

Awareness of quality metrics among individuals and endoscopy practices is crucial to ensuring adequate performance. Several studies have shown improvement with feedback and monitoring of endoscopists.25,26 Some strategies to improve colonoscopy technique and efficiency include having recorded or observed procedures, computer software that measures image resolution/velocity, and scorecards with quality measures. A representation of the scorecards used in our practice is shown in Table 4. Feedback measures both make endoscopists aware of how their performance compares with recommended goals for colonoscopy and help track their improvement. We recommend such feedback should be provided quarterly for most providers and more frequently for providers not meeting benchmarks.

Conclusion

Given we rely on colonoscopy to identify and clear the colon of potential malignancy, it is imperative that we provide high-value exams for our patients. The basis for a quality colonoscopy is complete intubation and careful inspection of the mucosa on withdrawal. Several quality measures are used as surrogates of a good exam such that endoscopists can assess themselves in relation to their peers. These metrics can help us in our goal of remaining mindful during each procedure we are completing and providing the best exam possible.

Dr. Shamsi is a third-year GI fellow. Dr. Malhotra is an assistant professor in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Dr. Shaukat is a professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and the GI Section Chief at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center.

References

1. Siegel R et al. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012 Jan-Feb;62(1):10-29.

2. Edwards BK et al. Cancer. 2010 Feb 1;116(3):544-73.

3. Hosokawa O et al. Endoscopy. 2003 Jun;35(6):506-10.

4. Morris EJ et al. Gut. 2015(Aug);64(2):1248-56.

5. Bressler B et al. Gastroenterology. 2004 Aug;127(2):452-6.

6. Rex DK et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 July;12(7):1016-30.

7. Rex DK et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015 Jan;81(1):31-53.

8. Anderson J et al. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2015 Feb 26;6:e77.

9. Kaminski M et al. N Engl J Med. 2010 May 13;362(19):1795-803.

10. Corley DA et al. N Engl J Med. 2014 Apr 3;370(4):1298-306.

11. Hunt RH. Colonoscopy intubation techniques without fluoroscopy. In: Colonoscopy techniques clinical practice and color atlas. Edited by Hunt RH, Waye JD. London: Chapman and Hall; 1981. p. 109-46.

12. Waye JD. Colonoscopy intubation techniques without fluoroscopy. In: Colonoscopy techniques clinical practice and color atlas. Edited by Hunt RH, Waye JD. London: Chapman and Hall; 1981. p. 147-78.

13. Williams CB et al. In: Colonoscopy principles & techniques. Edited by Raskin J, Juergen NH. New York: Igaku-Shoin Medical Publishers; 1995. p. 121-42.

14. Baillie J. Colonoscopy. In: Gastrointestinal endoscopy basic principles and practice. Oxford (UK): Butterworth-Heinemann; 1992. p. 63-92.

15. Rex DK. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000 Jan;51(1):33-6.

16. Shaukat A et al. Gastroenterol. 2015;149(4):952-7.

17. Barclay R et al. N Engl J Med. 2006 Dec 14;355(24):2533-41.

18. Simmons DT et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65(5):AB94.

19. Johnson DA et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80(4):543-62.

20. Calderwood A et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010 Oct;72(4):686-92.

21. Chokshi R et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012 Jun;75(6):1197-203.

22. Lebwohl B et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011 Jun;73(6):1207-14.

23. Menees SB et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013 Sep;78(3): 510-6.

24. Clark B et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Nov;109(11):1714-23.

25. Nielson A et al. BMJ Open Gastro. 2017 Jun. doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2017-000142.

26. Gurudu S et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Mar;33(3):645-9.

Editor's Note:

As quality metrics are becoming increasingly significant throughout all of medicine, our field is no exception. Recent evidence has demonstrated the importance of quality measures in colonoscopy; understanding, reporting, and improving these metrics has become a hot topic of discussion.

In this month’s In Focus article, brought to you by The New Gastroenterologist, Nabiha Shamsi, Ashish Malhotra, and Aasma Shaukat (University of Minnesota/Minneapolis VAMC) provide an outstanding overview of the evidence as well as recommended goals for important quality metrics in colonoscopy. Ultimately, improving colonoscopy quality amongst all gastroenterologists will increase colonoscopy value and lead to further decreases in the incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer.

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief, The New Gastroenterologist

Introduction

Colonoscopy is a widely used modality to evaluate colorectal cancer because it allows for both identification of early malignancies and removal of precancerous lesions. The increased use of colonoscopy in the last 20 years has been associated with a decline in the incidence and mortality from colorectal cancer.1,2 However, colonoscopy has its limitations. It is an invasive test with inherent risks. Additionally, studies have reported rates of post-colonoscopy cancers, also referred to as interval cancers, of 2%-7%, and miss-rates for adenomas by tandem colonoscopy of 2%-26%.3-5

High-quality exams can maximize the value of colonoscopy, and it is important to consider the factors that contribute to high-quality colonoscopies. While there are many metrics proposed,6,7 here we discuss the most evidence-based ones, outlined in Table 1, along with their goal values.

Cecal intubation rate

A high-quality colonoscopy should include a complete examination of the colon. To achieve this, it is necessary to fully intubate the cecum, passing the colonoscope past the ileocecal valve to examine the medial wall of the cecum.8

There are several factors that may contribute to an incomplete colonoscopy, including bowel preparation, anatomy, body habitus, and endoscopist’s skill. To calculate cecal intubation rate as a quality measure, colonoscopies that are incomplete because of poor bowel preparation, severe colitis, or known obstructing lesion are usually excluded.

The U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer recommends a cecal intubation rate of at least 95% for screening colonoscopy and 90% for all colonoscopies.6 There is an expectation of photodocumentation of the ileocecal valve and appendiceal orifice to establish completion of the colonoscopy.6

Some methods used to assist with cecal intubation include changing patient position, applying abdominal pressure, stiffening the colonoscope, and alternating between adult or pediatric colonoscopes.

Adenoma detection rate

Adenoma detection rate (ADR), is defined as the proportion of patients over the age of 50 years undergoing first-time screening colonoscopies in which at least one adenomatous polyp is detected for a given endoscopist in a given time period.

Adenomas are tracked because clearing the colon of neoplasm is the goal of screening colonoscopies; adenomas are tracked instead of more advanced lesions because the higher frequency of adenomas allows for better tracking of variation between endoscopists. Tracking ADR also utilizes the assumption that, if small lesions are identified, larger ones will be as well.

ADR is the only current quality indicator reported to be significantly associated with the risk of interval cancers. In 2010, a study of 45,000 screening colonoscopies by 186 endoscopists validated the use of ADR, finding that patients who underwent colonoscopy by physicians with ADRs below 20% had hazard ratios for development of postcolonoscopy cancer greater than 10 times higher than patients of physicians with ADRs above 20%.9 However, this study had limited power to establish that cancer protection continues to improve when ADRs rise above 20%. Another study, which evaluated the association of ADR in 224,000 patients undergoing colonoscopies by 136 gastroenterologists, showed each 1% increase in ADR is associated with 3% decrease in the risk of interval CRC and 5% decrease in the risk of fatal interval cancers.10

Most recent guidelines propose an adequate ADR for asymptomatic individuals aged 50 years or older undergoing screening colonoscopy should be greater than 30% in men and greater than 20% in women.6 It remains unknown whether there is a threshold for maximum benefit of ADR, in which a very high ADR is not associated with further protective benefit. The answer to this question may depend on why a low ADR is associated with a higher rate of interval cancers and whether every missed polyp, independent of size, is a potential interval cancer or whether hasty, inadequate, or incomplete examinations of the colon are the underlying concern.

Withdrawal time

Optimizing identification of colonic lesions requires a careful and thorough exam of the colon on withdrawal. While this may seem obvious, there is often little focus on the approach to withdrawal. In four chapters on colonoscopy technique from textbooks, the number of pages describing insertion ranged from 20 to 38, while the number of pages focused on withdrawal ranged from 0.5 to 1.5.11-14

A study examining the difference in withdrawal technique between two endoscopists who were known to differ in adenoma miss rates by tandem colonoscopy proposed the scoring system listed in Table 2 that can assess quality of examination on withdrawal. There was a statistically significant difference in quality scores for the two endoscopists, as assessed by expert review of video recordings of their colonoscopies.15

The endoscopist with the lower adenoma miss rate was also found to have an average withdrawal time of 8 minutes and 55 seconds versus 6 minutes and 41 seconds for the endoscopist with the higher adenoma miss rate. A large, community-based study with over 76,000 colonoscopies found a statistically significant correlation between interval colorectal cancer and withdrawal times shorter than 6 minutes.16 However, there was no association between ADR and colorectal cancer, suggesting that, for practices with optimal ADRs (that is, rates greater than 25%), withdrawal time may be a more sensitive marker of quality of colonoscopy than ADR is.16Intuitively, adequate examination of the colon that includes examining the proximal side of folds, washing and suctioning stool, and even repositioning the patient would likely increase withdrawal time. In a 2008 study examining 2,000 screening colonoscopies of 12 endoscopists, those with withdrawal times greater than 6 minutes had significantly higher rates of detecting adenomas and advanced neoplasia, compared with those with faster withdrawal times.17 The average ADR in this group was 28.3%, compared with 11.8% for physicians who had a withdrawal time less than 6 minutes.17 An evaluation of nearly 11,000 colonoscopies done by 43 endoscopists also identified an increase polyp yield with increased withdrawal time.18 These data drive the recommendation for a minimum withdrawal time of 6 minutes, with 2 minutes spent examining each colonic segment.

Bowel preparation

Diagnosis of colonic lesions is dependent on adequate visualization of the colon. Poor bowel preparation can limit the yield of colonoscopy and lead to missed lesions. It also leads to canceled and rescheduled procedures that reduce efficiency, increase cost, and pose an undue burden on the patient.

The quality of bowel preparation should be assessed after washing and suctioning of colonic mucosa has been completed. Adequate preparation is that which allows identification of lesions greater than 5 mm in size.19

Quality of preparation is assessed subjectively by the endoscopists and often listed as excellent, good, fair, or poor. An alternative method of reporting bowel preparation quality is the Boston Bowel Preparation Score (BBPS) (Table 3).20 This scoring system allows for a more descriptive assessment of each colonic segment by assigning a score from 0 to 3 for the right, transverse, and left colon, leading to a total score between 0 and 9. The BBPS also helps standardize reporting of bowel preparation. The polyp detection rate associated with a BBPS of 5 or greater was 40%, compared with 24% associated with BBPS less than 5.19 A split-dose bowel preparation regimen with at least half of the preparation ingested on the day of the procedure is recommended to optimize quality of bowel preparation.6

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and American College of Gastroenterology task force on quality assurance in endoscopy recommends that bowel preparation should be adequate in 85% of all colonoscopy exams on a per-provider basis.7 One study of completed colonoscopy with inadequate preparation showed an adenoma miss rate of 48%.21 In the setting of inadequate bowel preparation, another study reported 42% of all adenomas detected were only found on repeat colonoscopy. When considering advanced adenomas, there was a 27% miss rate, a relatively high percentage.22

When poor bowel preparation precludes the exam, colonoscopy is appropriately aborted, and the patient asked to return. However, there are situations in which the exam can be completed but the bowel preparation is still inadequate to identify polyps larger than 5 mm. In this setting, the colonoscopy should be repeated with a more aggressive bowel preparation regimen within 1 year.19 Shorter intervals are recommended if advanced neoplasm is detected within an inadequate bowel preparation.19

The appropriate surveillance interval can be unclear when bowel preparation is considered adequate to identify polyps greater than or equal to 5 mm, yet still suboptimal. “Adequate” or “fair” bowel preparation often leads to shorter-than-recommended surveillance intervals because of the concern for small missed lesions. For example, patients with normal colonoscopy results and a fair prep were recommended to undergo a screening colonoscopy in 5 years at 57.4%, while only 23.1% received a 10-year recommendation.23 This increased frequency of colonoscopy leads to increased costs and procedural risks for the patient. Furthermore, a meta-analysis evaluating the effects of bowel preparation reported no significant difference in ADR between adequate and excellent prep.24 These findings suggest that patients with adequate bowel preparation may be followed at guideline-recommended surveillance intervals without significantly affecting colonoscopy quality as measured by ADR.

Endoscopist feedback and report cards

Awareness of quality metrics among individuals and endoscopy practices is crucial to ensuring adequate performance. Several studies have shown improvement with feedback and monitoring of endoscopists.25,26 Some strategies to improve colonoscopy technique and efficiency include having recorded or observed procedures, computer software that measures image resolution/velocity, and scorecards with quality measures. A representation of the scorecards used in our practice is shown in Table 4. Feedback measures both make endoscopists aware of how their performance compares with recommended goals for colonoscopy and help track their improvement. We recommend such feedback should be provided quarterly for most providers and more frequently for providers not meeting benchmarks.

Conclusion

Given we rely on colonoscopy to identify and clear the colon of potential malignancy, it is imperative that we provide high-value exams for our patients. The basis for a quality colonoscopy is complete intubation and careful inspection of the mucosa on withdrawal. Several quality measures are used as surrogates of a good exam such that endoscopists can assess themselves in relation to their peers. These metrics can help us in our goal of remaining mindful during each procedure we are completing and providing the best exam possible.

Dr. Shamsi is a third-year GI fellow. Dr. Malhotra is an assistant professor in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Dr. Shaukat is a professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and the GI Section Chief at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center.

References

1. Siegel R et al. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012 Jan-Feb;62(1):10-29.

2. Edwards BK et al. Cancer. 2010 Feb 1;116(3):544-73.

3. Hosokawa O et al. Endoscopy. 2003 Jun;35(6):506-10.

4. Morris EJ et al. Gut. 2015(Aug);64(2):1248-56.

5. Bressler B et al. Gastroenterology. 2004 Aug;127(2):452-6.

6. Rex DK et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 July;12(7):1016-30.

7. Rex DK et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015 Jan;81(1):31-53.

8. Anderson J et al. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2015 Feb 26;6:e77.

9. Kaminski M et al. N Engl J Med. 2010 May 13;362(19):1795-803.

10. Corley DA et al. N Engl J Med. 2014 Apr 3;370(4):1298-306.

11. Hunt RH. Colonoscopy intubation techniques without fluoroscopy. In: Colonoscopy techniques clinical practice and color atlas. Edited by Hunt RH, Waye JD. London: Chapman and Hall; 1981. p. 109-46.

12. Waye JD. Colonoscopy intubation techniques without fluoroscopy. In: Colonoscopy techniques clinical practice and color atlas. Edited by Hunt RH, Waye JD. London: Chapman and Hall; 1981. p. 147-78.

13. Williams CB et al. In: Colonoscopy principles & techniques. Edited by Raskin J, Juergen NH. New York: Igaku-Shoin Medical Publishers; 1995. p. 121-42.

14. Baillie J. Colonoscopy. In: Gastrointestinal endoscopy basic principles and practice. Oxford (UK): Butterworth-Heinemann; 1992. p. 63-92.

15. Rex DK. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000 Jan;51(1):33-6.

16. Shaukat A et al. Gastroenterol. 2015;149(4):952-7.

17. Barclay R et al. N Engl J Med. 2006 Dec 14;355(24):2533-41.

18. Simmons DT et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65(5):AB94.

19. Johnson DA et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80(4):543-62.

20. Calderwood A et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010 Oct;72(4):686-92.

21. Chokshi R et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012 Jun;75(6):1197-203.

22. Lebwohl B et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011 Jun;73(6):1207-14.

23. Menees SB et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013 Sep;78(3): 510-6.

24. Clark B et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Nov;109(11):1714-23.

25. Nielson A et al. BMJ Open Gastro. 2017 Jun. doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2017-000142.

26. Gurudu S et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Mar;33(3):645-9.

Editor's Note:

As quality metrics are becoming increasingly significant throughout all of medicine, our field is no exception. Recent evidence has demonstrated the importance of quality measures in colonoscopy; understanding, reporting, and improving these metrics has become a hot topic of discussion.

In this month’s In Focus article, brought to you by The New Gastroenterologist, Nabiha Shamsi, Ashish Malhotra, and Aasma Shaukat (University of Minnesota/Minneapolis VAMC) provide an outstanding overview of the evidence as well as recommended goals for important quality metrics in colonoscopy. Ultimately, improving colonoscopy quality amongst all gastroenterologists will increase colonoscopy value and lead to further decreases in the incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer.

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief, The New Gastroenterologist

Introduction

Colonoscopy is a widely used modality to evaluate colorectal cancer because it allows for both identification of early malignancies and removal of precancerous lesions. The increased use of colonoscopy in the last 20 years has been associated with a decline in the incidence and mortality from colorectal cancer.1,2 However, colonoscopy has its limitations. It is an invasive test with inherent risks. Additionally, studies have reported rates of post-colonoscopy cancers, also referred to as interval cancers, of 2%-7%, and miss-rates for adenomas by tandem colonoscopy of 2%-26%.3-5

High-quality exams can maximize the value of colonoscopy, and it is important to consider the factors that contribute to high-quality colonoscopies. While there are many metrics proposed,6,7 here we discuss the most evidence-based ones, outlined in Table 1, along with their goal values.

Cecal intubation rate

A high-quality colonoscopy should include a complete examination of the colon. To achieve this, it is necessary to fully intubate the cecum, passing the colonoscope past the ileocecal valve to examine the medial wall of the cecum.8

There are several factors that may contribute to an incomplete colonoscopy, including bowel preparation, anatomy, body habitus, and endoscopist’s skill. To calculate cecal intubation rate as a quality measure, colonoscopies that are incomplete because of poor bowel preparation, severe colitis, or known obstructing lesion are usually excluded.

The U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer recommends a cecal intubation rate of at least 95% for screening colonoscopy and 90% for all colonoscopies.6 There is an expectation of photodocumentation of the ileocecal valve and appendiceal orifice to establish completion of the colonoscopy.6

Some methods used to assist with cecal intubation include changing patient position, applying abdominal pressure, stiffening the colonoscope, and alternating between adult or pediatric colonoscopes.

Adenoma detection rate

Adenoma detection rate (ADR), is defined as the proportion of patients over the age of 50 years undergoing first-time screening colonoscopies in which at least one adenomatous polyp is detected for a given endoscopist in a given time period.

Adenomas are tracked because clearing the colon of neoplasm is the goal of screening colonoscopies; adenomas are tracked instead of more advanced lesions because the higher frequency of adenomas allows for better tracking of variation between endoscopists. Tracking ADR also utilizes the assumption that, if small lesions are identified, larger ones will be as well.

ADR is the only current quality indicator reported to be significantly associated with the risk of interval cancers. In 2010, a study of 45,000 screening colonoscopies by 186 endoscopists validated the use of ADR, finding that patients who underwent colonoscopy by physicians with ADRs below 20% had hazard ratios for development of postcolonoscopy cancer greater than 10 times higher than patients of physicians with ADRs above 20%.9 However, this study had limited power to establish that cancer protection continues to improve when ADRs rise above 20%. Another study, which evaluated the association of ADR in 224,000 patients undergoing colonoscopies by 136 gastroenterologists, showed each 1% increase in ADR is associated with 3% decrease in the risk of interval CRC and 5% decrease in the risk of fatal interval cancers.10

Most recent guidelines propose an adequate ADR for asymptomatic individuals aged 50 years or older undergoing screening colonoscopy should be greater than 30% in men and greater than 20% in women.6 It remains unknown whether there is a threshold for maximum benefit of ADR, in which a very high ADR is not associated with further protective benefit. The answer to this question may depend on why a low ADR is associated with a higher rate of interval cancers and whether every missed polyp, independent of size, is a potential interval cancer or whether hasty, inadequate, or incomplete examinations of the colon are the underlying concern.

Withdrawal time

Optimizing identification of colonic lesions requires a careful and thorough exam of the colon on withdrawal. While this may seem obvious, there is often little focus on the approach to withdrawal. In four chapters on colonoscopy technique from textbooks, the number of pages describing insertion ranged from 20 to 38, while the number of pages focused on withdrawal ranged from 0.5 to 1.5.11-14