User login

New and Updated FDA Boxed Warnings

The FDA’s MedWatch program safety labeling changes for boxed warnings are compiled quarterly for drugs and therapeutic biologics where important changes have been made to the safety information. These and other label changes are searchable in the Drug Safety Labeling Changes (SLC) database, where data are available to the public in downloadable and searchable formats. Boxed warnings are ordinarily used to highlight either adverse reactions so serious in proportion to the potential bene t from the drug that it is essential that it be considered in assessing the risks and bene ts of using the drug; or serious adverse reactions that can be prevented/reduced in frequency or severity by appropriate use of the drug; or FDA approved the drug with restrictions to ensure safe use because FDA concluded that the drug can be safely used only if distribution or use is restricted.

IMODIUM (LOPERAMIDE HYDROCHLORIDE):

- New warning December 2016

WARNING: TORSADES DE POINTES AND SUDDEN DEATH

Cases of Torsades de Pointes, cardiac arrest, and death have been reported with the use of a higher than recommended dosages of Imodium (see WARNINGS and OVERDOSAGE).

Imodium is contraindicated in pediatric patients less than 2 years of age (see CONTRANIDICATIONS).

Avoid Imodium dosages higher than recommended in adults and pediatric patients 2 years of age and older due to the risk of serious cardiac adverse reactions (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

AUBAGIO (TERIFLUNOMIDE) TABLETS:

- Edited and updated warning December 2016

Risk of Teratogenicity

Aubagio is contraindicated for use in pregnant women and in women of reproductive potential who are not using effective contraception because of the potential for fetal harm. Teratogenicity and embryolethality occurred in animals at plasma teriflunomide exposures lower than that in humans. Exclude pregnancy before the start of treatment with Aubagio in females of reproductive potential. Advise females of reproductive potential to use effective contraception during Aubagio treatment and during an accelerated drug elimination procedure after Aubagio treatment. Stop Aubagio and use an accelerated drug elimination procedure if the patient becomes pregnant.

PROMACTA (ELTROMBOPAG) TABLETS, FOR ORAL USE AND ORAL SUSPENSION:

- Edited and updated warning December 2016

Chronic Hepatitis C

Promacta may increase the risk of severe and potentially lifethreatening hepatotoxicity. Monitor hepatic function and discontinue dosing as recommended.

ICLUSIG (PONATINIB HYDROCHLORIDE):

- Edited and updated warning December 2016

WARNING: ARTERIAL OCCLUSION, VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM, HEART FAILURE, and HEPATOTOXICITY

Arterial Occlusion

Arterial occlusions have occurred in at least 35% of Iclusig-treated patients. Some patients experienced more than 1 type of event. Events observed included fatal myocardial infarction, stroke, stenosis of large arterial vessels of the brain, severe peripheral vascular disease, and the need for urgent revascularization procedures. Patients with and without cardiovascular risk factors, including patients age 50 years or younger, experienced these events. Monitor for evidence of arterial occlusion. Interrupt or stop Iclusig immediately for arterial occlusion.

Venous Thromboembolism

Venous occlusive events have occurred in 6% of Iclusig-treated patients. Monitor for evidence of venous thromboembolism. Consider dose modification or discontinuation of Iclusig in patients who develop serious venous thromboembolism.

Heart Failure

Heart failure, including fatalities, occurred in 9% of Iclusig-treated patients.

The FDA’s MedWatch program safety labeling changes for boxed warnings are compiled quarterly for drugs and therapeutic biologics where important changes have been made to the safety information. These and other label changes are searchable in the Drug Safety Labeling Changes (SLC) database, where data are available to the public in downloadable and searchable formats. Boxed warnings are ordinarily used to highlight either adverse reactions so serious in proportion to the potential bene t from the drug that it is essential that it be considered in assessing the risks and bene ts of using the drug; or serious adverse reactions that can be prevented/reduced in frequency or severity by appropriate use of the drug; or FDA approved the drug with restrictions to ensure safe use because FDA concluded that the drug can be safely used only if distribution or use is restricted.

IMODIUM (LOPERAMIDE HYDROCHLORIDE):

- New warning December 2016

WARNING: TORSADES DE POINTES AND SUDDEN DEATH

Cases of Torsades de Pointes, cardiac arrest, and death have been reported with the use of a higher than recommended dosages of Imodium (see WARNINGS and OVERDOSAGE).

Imodium is contraindicated in pediatric patients less than 2 years of age (see CONTRANIDICATIONS).

Avoid Imodium dosages higher than recommended in adults and pediatric patients 2 years of age and older due to the risk of serious cardiac adverse reactions (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

AUBAGIO (TERIFLUNOMIDE) TABLETS:

- Edited and updated warning December 2016

Risk of Teratogenicity

Aubagio is contraindicated for use in pregnant women and in women of reproductive potential who are not using effective contraception because of the potential for fetal harm. Teratogenicity and embryolethality occurred in animals at plasma teriflunomide exposures lower than that in humans. Exclude pregnancy before the start of treatment with Aubagio in females of reproductive potential. Advise females of reproductive potential to use effective contraception during Aubagio treatment and during an accelerated drug elimination procedure after Aubagio treatment. Stop Aubagio and use an accelerated drug elimination procedure if the patient becomes pregnant.

PROMACTA (ELTROMBOPAG) TABLETS, FOR ORAL USE AND ORAL SUSPENSION:

- Edited and updated warning December 2016

Chronic Hepatitis C

Promacta may increase the risk of severe and potentially lifethreatening hepatotoxicity. Monitor hepatic function and discontinue dosing as recommended.

ICLUSIG (PONATINIB HYDROCHLORIDE):

- Edited and updated warning December 2016

WARNING: ARTERIAL OCCLUSION, VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM, HEART FAILURE, and HEPATOTOXICITY

Arterial Occlusion

Arterial occlusions have occurred in at least 35% of Iclusig-treated patients. Some patients experienced more than 1 type of event. Events observed included fatal myocardial infarction, stroke, stenosis of large arterial vessels of the brain, severe peripheral vascular disease, and the need for urgent revascularization procedures. Patients with and without cardiovascular risk factors, including patients age 50 years or younger, experienced these events. Monitor for evidence of arterial occlusion. Interrupt or stop Iclusig immediately for arterial occlusion.

Venous Thromboembolism

Venous occlusive events have occurred in 6% of Iclusig-treated patients. Monitor for evidence of venous thromboembolism. Consider dose modification or discontinuation of Iclusig in patients who develop serious venous thromboembolism.

Heart Failure

Heart failure, including fatalities, occurred in 9% of Iclusig-treated patients.

The FDA’s MedWatch program safety labeling changes for boxed warnings are compiled quarterly for drugs and therapeutic biologics where important changes have been made to the safety information. These and other label changes are searchable in the Drug Safety Labeling Changes (SLC) database, where data are available to the public in downloadable and searchable formats. Boxed warnings are ordinarily used to highlight either adverse reactions so serious in proportion to the potential bene t from the drug that it is essential that it be considered in assessing the risks and bene ts of using the drug; or serious adverse reactions that can be prevented/reduced in frequency or severity by appropriate use of the drug; or FDA approved the drug with restrictions to ensure safe use because FDA concluded that the drug can be safely used only if distribution or use is restricted.

IMODIUM (LOPERAMIDE HYDROCHLORIDE):

- New warning December 2016

WARNING: TORSADES DE POINTES AND SUDDEN DEATH

Cases of Torsades de Pointes, cardiac arrest, and death have been reported with the use of a higher than recommended dosages of Imodium (see WARNINGS and OVERDOSAGE).

Imodium is contraindicated in pediatric patients less than 2 years of age (see CONTRANIDICATIONS).

Avoid Imodium dosages higher than recommended in adults and pediatric patients 2 years of age and older due to the risk of serious cardiac adverse reactions (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

AUBAGIO (TERIFLUNOMIDE) TABLETS:

- Edited and updated warning December 2016

Risk of Teratogenicity

Aubagio is contraindicated for use in pregnant women and in women of reproductive potential who are not using effective contraception because of the potential for fetal harm. Teratogenicity and embryolethality occurred in animals at plasma teriflunomide exposures lower than that in humans. Exclude pregnancy before the start of treatment with Aubagio in females of reproductive potential. Advise females of reproductive potential to use effective contraception during Aubagio treatment and during an accelerated drug elimination procedure after Aubagio treatment. Stop Aubagio and use an accelerated drug elimination procedure if the patient becomes pregnant.

PROMACTA (ELTROMBOPAG) TABLETS, FOR ORAL USE AND ORAL SUSPENSION:

- Edited and updated warning December 2016

Chronic Hepatitis C

Promacta may increase the risk of severe and potentially lifethreatening hepatotoxicity. Monitor hepatic function and discontinue dosing as recommended.

ICLUSIG (PONATINIB HYDROCHLORIDE):

- Edited and updated warning December 2016

WARNING: ARTERIAL OCCLUSION, VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM, HEART FAILURE, and HEPATOTOXICITY

Arterial Occlusion

Arterial occlusions have occurred in at least 35% of Iclusig-treated patients. Some patients experienced more than 1 type of event. Events observed included fatal myocardial infarction, stroke, stenosis of large arterial vessels of the brain, severe peripheral vascular disease, and the need for urgent revascularization procedures. Patients with and without cardiovascular risk factors, including patients age 50 years or younger, experienced these events. Monitor for evidence of arterial occlusion. Interrupt or stop Iclusig immediately for arterial occlusion.

Venous Thromboembolism

Venous occlusive events have occurred in 6% of Iclusig-treated patients. Monitor for evidence of venous thromboembolism. Consider dose modification or discontinuation of Iclusig in patients who develop serious venous thromboembolism.

Heart Failure

Heart failure, including fatalities, occurred in 9% of Iclusig-treated patients.

IHS Gives Pharmacy Students Hands-On Experience

The IHS has partnered with 3 top American universities to give pharmacy students an opportunity to get real-life work experience and potentially careers at IHS facilities.

Related: Dangerous Staff Shortages in the IHS

In the IHS Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experience Program, PharmD candidates at Howard University, Purdue University, and the University of Southern California will join students from more than 80 universities in 39 states to complete rotations at IHS direct service facilities. “Many return to start their career in providing quality health care to the American Indian and Alaska Native community,” said Mary Smith, IHS principal deputy director.

“My experience with IHS as a student inspired me to apply to work here when I graduated,” said Fengyee Zhou, now a pharmacist at the IHS Whiteriver Indian Hospital in Arizona. “The level of teamwork among all health care disciplines and the extent to which pharmacists engage in patient care activities brought me back to Whiteriver.”

Related: What s the VA? The Largest Educator of Health Care Professionals in the U.S.

The IHS also offers internships, externships, rotations, and residencies to pharmacy, behavioral health, dentistry, optometry, nursing, and medical students.

The IHS has partnered with 3 top American universities to give pharmacy students an opportunity to get real-life work experience and potentially careers at IHS facilities.

Related: Dangerous Staff Shortages in the IHS

In the IHS Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experience Program, PharmD candidates at Howard University, Purdue University, and the University of Southern California will join students from more than 80 universities in 39 states to complete rotations at IHS direct service facilities. “Many return to start their career in providing quality health care to the American Indian and Alaska Native community,” said Mary Smith, IHS principal deputy director.

“My experience with IHS as a student inspired me to apply to work here when I graduated,” said Fengyee Zhou, now a pharmacist at the IHS Whiteriver Indian Hospital in Arizona. “The level of teamwork among all health care disciplines and the extent to which pharmacists engage in patient care activities brought me back to Whiteriver.”

Related: What s the VA? The Largest Educator of Health Care Professionals in the U.S.

The IHS also offers internships, externships, rotations, and residencies to pharmacy, behavioral health, dentistry, optometry, nursing, and medical students.

The IHS has partnered with 3 top American universities to give pharmacy students an opportunity to get real-life work experience and potentially careers at IHS facilities.

Related: Dangerous Staff Shortages in the IHS

In the IHS Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experience Program, PharmD candidates at Howard University, Purdue University, and the University of Southern California will join students from more than 80 universities in 39 states to complete rotations at IHS direct service facilities. “Many return to start their career in providing quality health care to the American Indian and Alaska Native community,” said Mary Smith, IHS principal deputy director.

“My experience with IHS as a student inspired me to apply to work here when I graduated,” said Fengyee Zhou, now a pharmacist at the IHS Whiteriver Indian Hospital in Arizona. “The level of teamwork among all health care disciplines and the extent to which pharmacists engage in patient care activities brought me back to Whiteriver.”

Related: What s the VA? The Largest Educator of Health Care Professionals in the U.S.

The IHS also offers internships, externships, rotations, and residencies to pharmacy, behavioral health, dentistry, optometry, nursing, and medical students.

Recent FDA Boxed Warnings

The FDA’s MedWatch program safety labeling changes for boxed warnings are compiled quarterly for drugs and therapeutic biologics where important changes have been made to the safety information. You can search these and other label changes in the Drug Safety Labeling Changes (SLC) database, where data are available to the public in downloadable and searchable formats. Boxed warnings are ordinarily used to highlight either adverse reactions so serious in proportion to the potential bene t from the drug that it is essential that it be considered in assessing the risks and bene ts of using the drug; or serious adverse reactions that can be prevented/reduced in frequency or severity by appropriate use of the drug; or FDA approved the drug with restrictions to ensure safe use because FDA concluded that the drug can be safely used only if distribution or use is restricted.

QUINOLONE:

- Edited and updated warning September 2016

WARNING: SERIOUS ADVERSE REACTIONS INCLUDING TENDINITIS, TENDON RUPTURE, PERIPHERAL NEUROPATHY, CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM EFFECTS AND EXACERBATION OF MYASTHENIA GRAVIS

Fluoroquinolones have been associated with disabling and potentially irreversible serious adverse reactions that have occurred together including:

- Tendinitis and tendon rupture

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Central nervous system effects

Discontinue immediately and avoid the use of fluoroquinolones in patients who experience any of these serious adverse reactions. Fluoroquinolones may exacerbate muscle weakness in patients with myasthenia gravis. Avoid quinolones in patients with known history of myasthenia gravis. Because fluoroquinolones

have been associated with serious adverse reactions, reserve quinolones for use in patients who have no alternative treatment options for the following

indications:

Avelox (moxifloxacin hydrochloride): Avelox in sodium chloride 0.8% in plastic container; moxifloxacin hydrochloride; Cipro in dextrose 5% in plastic container):

Acute bacterial sinusitis, acute bacterial exacerbation of chronic bronchitis.

Cipro (ciprofloxacin; ciprofloxacin hydrochloride): Acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis, acute uncomplicated cystitis, and acute sinusitis.

Cipro XR; Noroxin (norfloxacin): Uncomplicated urinary tract infections.

Factive (gemifloxacin mesylate): Acute bacterial exacerbation of chronic bronchitis.

Levaquin (levofloxacin): Uncomplicated urinary tract infection, acute bacterial exacerbation of chronic bronchitis, and acute bacterial sinusitis.

KRYSTEXXA (PEGLOTICASE):

- Added section to warning September 2016

WARNING: ANAPHYLAXIS AND INFUSION REACTIONS; G6PD DEFICIENCY ASSOCIATED HEMOLYSIS AND METHEMOGLOBINEMIA (Title Updated)

Addition of: Screen patients at risk for G6PD deficiency prior to starting Krystexxa. Hemolysis and methemoglobinemia have been reported with Krystexxa in patients with G6PD deficiency. Do not administer Krystexxa to patients with G6PD deficiency.

PLAVIX (CLOPIDOGREL BISULFATE):

- Edited and updated warning September 2016

WARNING: DIMINISHED ANTIPLATELET EFFECT IN PATIENTS WITH TWO LOSS-OF-FUNCTION ALLELES OF THE CYP2C19 GENE

The effectiveness of Plavix results from its antiplatelet activity, which is dependent on its conversion to an active metabolite by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system, principally CYP2C19. Plavix at recommended doses forms less of the active metabolite and so has a reduced effect on platelet activity in patients who are homozygous for nonfunctional alleles of the CYP2C19 gene, (termed “CYP2C19 poor metabolizers”). Tests are available to identify patients who are CYP2C19 poor metabolizers. Consider use of another platelet P2Y12 inhibitor in patients identified as CYP2C19 poor metabolizers.

SYNJARDY (EMPAGLIFLOZIN; METFORMIN HYDROCHLORIDE):

- Edited and updated warning September 2016

Postmarketing cases of metformin-associated lactic acidosis have resulted in death, hypothermia, hypotension, and resistant bradyarrhythmias. The onset of metformin-associated lactic acidosis is often subtle, accompanied only by nonspecific symptoms such as malaise, myalgias, respiratory distress, somnolence, and abdominal pain. Metforminassociated lactic acidosis was characterized by elevated blood lactate levels (> 5 mmol/Liter), anion gap acidosis (without evidence of ketonuria or ketonemia), an increased lactate/pyruvate ratio; and metformin plasma levels generally > 5 mcg/mL.

Risk factors for metformin-associated lactic acidosis include renal impairment, concomitant use of certain drugs (e.g., carbonic anhydrase inhibitors such as topiramate), age 65 years old or greater, having a radiological study with contrast, surgery and other procedures, hypoxic states (e.g., acute congestive heart failure), excessive alcohol intake, and hepatic impairment.

Steps to reduce the risk of and manage metformin-associated lactic acidosis in these high-risk groups are provided in the full prescribing information.

If metformin-associated lactic acidosis is suspected, immediately discontinue Synjardy and institute general supportive measures in a hospital setting. Prompt hemodialysis is recommended.

ZYDELIG (IDELALISIB)

- Edited and updated warning September 2016

WARNING: FATAL AND SERIOUS TOXICITIES: HEPATIC, SEVERE DIARRHEA, COLITIS, PNEUMONITIS, INFECTIONS, AND INTESTINAL PERFORATION

- Fatal and/or serious hepatotoxicity occurred in 11 % to 18% of Zydelig-treated patients. Monitor hepatic function prior to and during treatment. Interrupt and then reduce or discontinue Zydelig as recommended.

- Fatal and/or serious and severe diarrhea or colitis occurred in 14% to 19% of Zydelig-treated patients. Monitor for the development of severe diarrhea or colitis. Interrupt and then reduce or discontinue Zydelig as recommended.

- Fatal and/or serious pneumonitis occurred in 4% of Zydelig-treated patients. Monitor for pulmonary symptoms and bilateral interstitial infiltrates. Interrupt or discontinue Zydelig as recommended.

- Fatal and/or serious infections occurred in 21% to 36% of Zydelig-treated patients. Monitor for signs and symptoms of infection. Interrupt Zydelig if infection is suspected.

- Fatal and serious intestinal perforation can occur in Zydelig-treated patients across clinical trials. Discontinue Zydelig for intestinal perforation.

The FDA’s MedWatch program safety labeling changes for boxed warnings are compiled quarterly for drugs and therapeutic biologics where important changes have been made to the safety information. You can search these and other label changes in the Drug Safety Labeling Changes (SLC) database, where data are available to the public in downloadable and searchable formats. Boxed warnings are ordinarily used to highlight either adverse reactions so serious in proportion to the potential bene t from the drug that it is essential that it be considered in assessing the risks and bene ts of using the drug; or serious adverse reactions that can be prevented/reduced in frequency or severity by appropriate use of the drug; or FDA approved the drug with restrictions to ensure safe use because FDA concluded that the drug can be safely used only if distribution or use is restricted.

QUINOLONE:

- Edited and updated warning September 2016

WARNING: SERIOUS ADVERSE REACTIONS INCLUDING TENDINITIS, TENDON RUPTURE, PERIPHERAL NEUROPATHY, CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM EFFECTS AND EXACERBATION OF MYASTHENIA GRAVIS

Fluoroquinolones have been associated with disabling and potentially irreversible serious adverse reactions that have occurred together including:

- Tendinitis and tendon rupture

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Central nervous system effects

Discontinue immediately and avoid the use of fluoroquinolones in patients who experience any of these serious adverse reactions. Fluoroquinolones may exacerbate muscle weakness in patients with myasthenia gravis. Avoid quinolones in patients with known history of myasthenia gravis. Because fluoroquinolones

have been associated with serious adverse reactions, reserve quinolones for use in patients who have no alternative treatment options for the following

indications:

Avelox (moxifloxacin hydrochloride): Avelox in sodium chloride 0.8% in plastic container; moxifloxacin hydrochloride; Cipro in dextrose 5% in plastic container):

Acute bacterial sinusitis, acute bacterial exacerbation of chronic bronchitis.

Cipro (ciprofloxacin; ciprofloxacin hydrochloride): Acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis, acute uncomplicated cystitis, and acute sinusitis.

Cipro XR; Noroxin (norfloxacin): Uncomplicated urinary tract infections.

Factive (gemifloxacin mesylate): Acute bacterial exacerbation of chronic bronchitis.

Levaquin (levofloxacin): Uncomplicated urinary tract infection, acute bacterial exacerbation of chronic bronchitis, and acute bacterial sinusitis.

KRYSTEXXA (PEGLOTICASE):

- Added section to warning September 2016

WARNING: ANAPHYLAXIS AND INFUSION REACTIONS; G6PD DEFICIENCY ASSOCIATED HEMOLYSIS AND METHEMOGLOBINEMIA (Title Updated)

Addition of: Screen patients at risk for G6PD deficiency prior to starting Krystexxa. Hemolysis and methemoglobinemia have been reported with Krystexxa in patients with G6PD deficiency. Do not administer Krystexxa to patients with G6PD deficiency.

PLAVIX (CLOPIDOGREL BISULFATE):

- Edited and updated warning September 2016

WARNING: DIMINISHED ANTIPLATELET EFFECT IN PATIENTS WITH TWO LOSS-OF-FUNCTION ALLELES OF THE CYP2C19 GENE

The effectiveness of Plavix results from its antiplatelet activity, which is dependent on its conversion to an active metabolite by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system, principally CYP2C19. Plavix at recommended doses forms less of the active metabolite and so has a reduced effect on platelet activity in patients who are homozygous for nonfunctional alleles of the CYP2C19 gene, (termed “CYP2C19 poor metabolizers”). Tests are available to identify patients who are CYP2C19 poor metabolizers. Consider use of another platelet P2Y12 inhibitor in patients identified as CYP2C19 poor metabolizers.

SYNJARDY (EMPAGLIFLOZIN; METFORMIN HYDROCHLORIDE):

- Edited and updated warning September 2016

Postmarketing cases of metformin-associated lactic acidosis have resulted in death, hypothermia, hypotension, and resistant bradyarrhythmias. The onset of metformin-associated lactic acidosis is often subtle, accompanied only by nonspecific symptoms such as malaise, myalgias, respiratory distress, somnolence, and abdominal pain. Metforminassociated lactic acidosis was characterized by elevated blood lactate levels (> 5 mmol/Liter), anion gap acidosis (without evidence of ketonuria or ketonemia), an increased lactate/pyruvate ratio; and metformin plasma levels generally > 5 mcg/mL.

Risk factors for metformin-associated lactic acidosis include renal impairment, concomitant use of certain drugs (e.g., carbonic anhydrase inhibitors such as topiramate), age 65 years old or greater, having a radiological study with contrast, surgery and other procedures, hypoxic states (e.g., acute congestive heart failure), excessive alcohol intake, and hepatic impairment.

Steps to reduce the risk of and manage metformin-associated lactic acidosis in these high-risk groups are provided in the full prescribing information.

If metformin-associated lactic acidosis is suspected, immediately discontinue Synjardy and institute general supportive measures in a hospital setting. Prompt hemodialysis is recommended.

ZYDELIG (IDELALISIB)

- Edited and updated warning September 2016

WARNING: FATAL AND SERIOUS TOXICITIES: HEPATIC, SEVERE DIARRHEA, COLITIS, PNEUMONITIS, INFECTIONS, AND INTESTINAL PERFORATION

- Fatal and/or serious hepatotoxicity occurred in 11 % to 18% of Zydelig-treated patients. Monitor hepatic function prior to and during treatment. Interrupt and then reduce or discontinue Zydelig as recommended.

- Fatal and/or serious and severe diarrhea or colitis occurred in 14% to 19% of Zydelig-treated patients. Monitor for the development of severe diarrhea or colitis. Interrupt and then reduce or discontinue Zydelig as recommended.

- Fatal and/or serious pneumonitis occurred in 4% of Zydelig-treated patients. Monitor for pulmonary symptoms and bilateral interstitial infiltrates. Interrupt or discontinue Zydelig as recommended.

- Fatal and/or serious infections occurred in 21% to 36% of Zydelig-treated patients. Monitor for signs and symptoms of infection. Interrupt Zydelig if infection is suspected.

- Fatal and serious intestinal perforation can occur in Zydelig-treated patients across clinical trials. Discontinue Zydelig for intestinal perforation.

The FDA’s MedWatch program safety labeling changes for boxed warnings are compiled quarterly for drugs and therapeutic biologics where important changes have been made to the safety information. You can search these and other label changes in the Drug Safety Labeling Changes (SLC) database, where data are available to the public in downloadable and searchable formats. Boxed warnings are ordinarily used to highlight either adverse reactions so serious in proportion to the potential bene t from the drug that it is essential that it be considered in assessing the risks and bene ts of using the drug; or serious adverse reactions that can be prevented/reduced in frequency or severity by appropriate use of the drug; or FDA approved the drug with restrictions to ensure safe use because FDA concluded that the drug can be safely used only if distribution or use is restricted.

QUINOLONE:

- Edited and updated warning September 2016

WARNING: SERIOUS ADVERSE REACTIONS INCLUDING TENDINITIS, TENDON RUPTURE, PERIPHERAL NEUROPATHY, CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM EFFECTS AND EXACERBATION OF MYASTHENIA GRAVIS

Fluoroquinolones have been associated with disabling and potentially irreversible serious adverse reactions that have occurred together including:

- Tendinitis and tendon rupture

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Central nervous system effects

Discontinue immediately and avoid the use of fluoroquinolones in patients who experience any of these serious adverse reactions. Fluoroquinolones may exacerbate muscle weakness in patients with myasthenia gravis. Avoid quinolones in patients with known history of myasthenia gravis. Because fluoroquinolones

have been associated with serious adverse reactions, reserve quinolones for use in patients who have no alternative treatment options for the following

indications:

Avelox (moxifloxacin hydrochloride): Avelox in sodium chloride 0.8% in plastic container; moxifloxacin hydrochloride; Cipro in dextrose 5% in plastic container):

Acute bacterial sinusitis, acute bacterial exacerbation of chronic bronchitis.

Cipro (ciprofloxacin; ciprofloxacin hydrochloride): Acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis, acute uncomplicated cystitis, and acute sinusitis.

Cipro XR; Noroxin (norfloxacin): Uncomplicated urinary tract infections.

Factive (gemifloxacin mesylate): Acute bacterial exacerbation of chronic bronchitis.

Levaquin (levofloxacin): Uncomplicated urinary tract infection, acute bacterial exacerbation of chronic bronchitis, and acute bacterial sinusitis.

KRYSTEXXA (PEGLOTICASE):

- Added section to warning September 2016

WARNING: ANAPHYLAXIS AND INFUSION REACTIONS; G6PD DEFICIENCY ASSOCIATED HEMOLYSIS AND METHEMOGLOBINEMIA (Title Updated)

Addition of: Screen patients at risk for G6PD deficiency prior to starting Krystexxa. Hemolysis and methemoglobinemia have been reported with Krystexxa in patients with G6PD deficiency. Do not administer Krystexxa to patients with G6PD deficiency.

PLAVIX (CLOPIDOGREL BISULFATE):

- Edited and updated warning September 2016

WARNING: DIMINISHED ANTIPLATELET EFFECT IN PATIENTS WITH TWO LOSS-OF-FUNCTION ALLELES OF THE CYP2C19 GENE

The effectiveness of Plavix results from its antiplatelet activity, which is dependent on its conversion to an active metabolite by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system, principally CYP2C19. Plavix at recommended doses forms less of the active metabolite and so has a reduced effect on platelet activity in patients who are homozygous for nonfunctional alleles of the CYP2C19 gene, (termed “CYP2C19 poor metabolizers”). Tests are available to identify patients who are CYP2C19 poor metabolizers. Consider use of another platelet P2Y12 inhibitor in patients identified as CYP2C19 poor metabolizers.

SYNJARDY (EMPAGLIFLOZIN; METFORMIN HYDROCHLORIDE):

- Edited and updated warning September 2016

Postmarketing cases of metformin-associated lactic acidosis have resulted in death, hypothermia, hypotension, and resistant bradyarrhythmias. The onset of metformin-associated lactic acidosis is often subtle, accompanied only by nonspecific symptoms such as malaise, myalgias, respiratory distress, somnolence, and abdominal pain. Metforminassociated lactic acidosis was characterized by elevated blood lactate levels (> 5 mmol/Liter), anion gap acidosis (without evidence of ketonuria or ketonemia), an increased lactate/pyruvate ratio; and metformin plasma levels generally > 5 mcg/mL.

Risk factors for metformin-associated lactic acidosis include renal impairment, concomitant use of certain drugs (e.g., carbonic anhydrase inhibitors such as topiramate), age 65 years old or greater, having a radiological study with contrast, surgery and other procedures, hypoxic states (e.g., acute congestive heart failure), excessive alcohol intake, and hepatic impairment.

Steps to reduce the risk of and manage metformin-associated lactic acidosis in these high-risk groups are provided in the full prescribing information.

If metformin-associated lactic acidosis is suspected, immediately discontinue Synjardy and institute general supportive measures in a hospital setting. Prompt hemodialysis is recommended.

ZYDELIG (IDELALISIB)

- Edited and updated warning September 2016

WARNING: FATAL AND SERIOUS TOXICITIES: HEPATIC, SEVERE DIARRHEA, COLITIS, PNEUMONITIS, INFECTIONS, AND INTESTINAL PERFORATION

- Fatal and/or serious hepatotoxicity occurred in 11 % to 18% of Zydelig-treated patients. Monitor hepatic function prior to and during treatment. Interrupt and then reduce or discontinue Zydelig as recommended.

- Fatal and/or serious and severe diarrhea or colitis occurred in 14% to 19% of Zydelig-treated patients. Monitor for the development of severe diarrhea or colitis. Interrupt and then reduce or discontinue Zydelig as recommended.

- Fatal and/or serious pneumonitis occurred in 4% of Zydelig-treated patients. Monitor for pulmonary symptoms and bilateral interstitial infiltrates. Interrupt or discontinue Zydelig as recommended.

- Fatal and/or serious infections occurred in 21% to 36% of Zydelig-treated patients. Monitor for signs and symptoms of infection. Interrupt Zydelig if infection is suspected.

- Fatal and serious intestinal perforation can occur in Zydelig-treated patients across clinical trials. Discontinue Zydelig for intestinal perforation.

A Primary Hospital Antimicrobial Stewardship Intervention on Pneumonia Treatment Duration

The safety and the efficacy of shorter durations of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated pneumonia have been clearly established in the past decade.1,2 Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Thoracic Society have been available since 2007. These expert consensus statements recommend that uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) should be treated for 5 to 7 days, as long as the patient exhibits signs and symptoms of clinical stability.3 Similarly, recently updated guidelines for hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonias call for short-course therapy.4 Despite this guidance, pneumonia treatment duration is often discordant.5 Unnecessary antimicrobial use is associated with greater selection pressure on pathogens, increased risk of adverse events (AEs), and elevated treatment costs.6 The growing burden of antibiotic resistance coupled with limited availability of new antibiotics requires judicious use of these agents.

The IDSA guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) note that exposure to antimicrobial agents is the most important modifiable risk factor for the development of CDI.7 Longer durations of antibiotics increase the risk of CDI compared with shorter durations.8,9 Antibiotics are a frequent cause of drug-associated AEs and likely are underestimated.10 To decrease the unwanted effects of excessive therapy, IDSA and CDC suggest that antimicrobial stewardship interventions should be implemented.11-13

Antimicrobial stewardship efforts in small community hospitals (also known as district, rural, general, and primary hospitals) are varied and can be challenging due to limited staff and resources.14,15 The World Health Organization defines a primary care facility as having few specialties, mainly internal medicine and general surgery with limited laboratory services for general (but not specialized) pathologic analysis, and bed size ranging from 30 to 200 beds.16 Although guidance is available for effective intervention strategies in smaller hospitals, there are limited data in the literature regarding successful outcomes.17-22

The purpose of this study was to establish the need and evaluate the impact of a pharmacy-initiated 3-part intervention targeting treatment duration in patients hospitalized with uncomplicated pneumonia in a primary hospital setting. The Veterans Health Care System of the Ozarks (VHSO) in Fayetteville, Arkansas, has 50 acute care beds, including 7 intensive care unit beds and excluding 15 mental health beds. The pharmacy is staffed 24 hours a day. Acute-care providers consist of 7 full-time hospitalists, not including nocturnists and contract physicians. The VHSO does not have an infectious disease physician on staff.

The antimicrobial stewardship committee consists of 3 clinical pharmacists, a pulmonologist, a pathologist, and 2 infection-control nurses. There is 1 full-time equivalent allotted for inpatient clinical pharmacy activities in the acute care areas, including enforcement of all antimicrobial stewardship policies, which are conducted by a single pharmacist.

Methods

This was a retrospective chart review of two 12-month periods using a before and after study design. Medical records were reviewed during October 2012 through September 2013 (before the stewardship implementation) and December 2014 through November 2015 (after implementation). Inclusion criteria consisted of a primary discharge diagnosis of pneumonia as documented by the provider (or secondary diagnosis if sepsis was primary), hospitalization for at least 48 hours, administration of antibiotics for a minimum of 24 hours, and survival to discharge.

Exclusion criteria consisted of direct transfer from another facility, inappropriate empiric therapy as evidenced by culture data (isolated pathogens not covered by prescribed antibiotics), pneumonia that developed 48 hours after admission, extrapulmonary sources of infection, hospitalization > 14 days, discharge without a known duration of outpatient antibiotics, discharge for pneumonia within 28 days prior to admission, documented infection caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa or other nonlactose fermenting Gram-negative rod, and complicated pneumonias defined as lung abscess, empyema, or severe immunosuppression (eg, cancer with chemotherapy within the previous 30 days, transplant recipients, HIV infection, acquired or congenital immunodeficiency, or absolute neutrophil count 1,500 cell/mm3 within past 28 days).

Patients were designated with health care-associated pneumonia (HCAP) if they were hospitalized ≥ 2 days or resided in a skilled nursing or extended-care facility within the previous 90 days; on chronic dialysis; or had wound care, tracheostomy care, or ventilator care from a health care professional within the previous 28 days. Criteria for clinical stability were defined as ≤ 100.4º F temperature, ≤ 100 beats/min heart rate, ≤ 24 breaths/min respiratory rate, ≥ 90 mm Hg systolic blood pressure, ≥ 90% or PaO2 ≥ 60 mm Hg oxygen saturation on room air (or baseline oxygen requirements), and return to baseline mental status. To compare groups, researchers tabulated the pneumonia severity index on hospital day 1.

The intervention consisted of a 3-part process. First, hospitalists were educated on VHSO’s baseline treatment duration data, and these were compared with current IDSA recommendations. The education was followed by an open-discussion component to solicit feedback from providers on perceived barriers to following guidelines. Provider feedback was used to tailor an antimicrobial stewardship intervention to address perceived barriers to optimal antibiotic treatment duration.

After the education component, prospective intervention and feedback were provided for hospitalized patients by a single clinical pharmacist. This pharmacist interacted verbally and in writing with the patients’ providers, discussing antimicrobial appropriateness, de-escalation, duration of therapy, and intravenous to oral switching. Finally, a stewardship note for the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) was generated and included a template with reminders of clinical stability, duration of current therapy, and a request to discontinue therapy if the patient met criteria. For patients who remained hospitalized, this note was entered into CPRS on or about day 7 of antibiotic therapy; this required an electronic signature from the provider.

The VHSO Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee approved both the provider education and the stewardship note in November 2014, and implementation of the stewardship intervention occurred immediately afterward. The pharmacy staff also was educated on the VHSO baseline data and stewardship efforts.

The primary outcome of the study was the change in days of total antibiotic treatment. Secondary outcomes included days of intravenous antibiotic therapy, days of inpatient oral therapy, mean length of stay (LOS), and number of outpatient antibiotic days once discharged. Incidence of CDI and 28-day readmissions were also evaluated. The VHSO Institutional Review Board approved these methods and the procedures that followed were in accord with the ethical standards of the VHSO Committee on Human Experimentation.

Statistical Analysis

All continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation. Data analysis for significance was performed using a Student t test for continuous variables and a χ2 test (or Fisher exact test) for categorical variables in R Foundation for Statistical Computing version 3.1.0. All samples were 2-tailed. A P value < .05 was considered statistically significant. Using the smaller of the 2 study populations, the investigators calculated that the given sample size of 88 in each group would provide 99% power to detect a 2-day difference in the primary endpoint at a 2-sided significance level of 5%.

Results

During the baseline assessment (group 1), 192 cases were reviewed with 103 meeting the inclusion criteria. Group 1 consisted of 85 cases of CAP and 18 cases of HCAP (mean age, 70.7 years). During the follow-up assessment (group 2), 168 cases were reviewed with 88 meeting the inclusion criteria. Group 2 consisted of 68 cases of CAP and 20 cases of HCAP (mean age, 70.8 years).

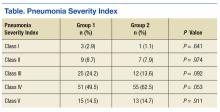

There was no difference in inpatient mortality rates between groups (3.1% vs 3.0%, P = .99). This mortality rate is consistent with published reports.23 Empiric antibiotic selection was appropriate because there were no exclusions for drug/pathogen mismatch. Pneumonia severity was similar in both groups (Table).

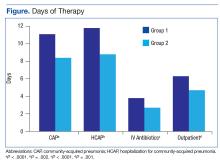

The total duration of antibiotic treatment decreased significantly for CAP and HCAP (Figure). The observed median treatment days for groups 1 and 2 were 11 days and 8 days, respectively. Outpatient antibiotic days also decreased. Mean LOS was shorter in the follow-up group (4.9 ± 2.6 days vs 4.0 ± 2.6 days, P = .02). Length of IV antibiotic duration decreased. Oral antibiotic days while inpatient were not statistically different (1.5 ± 1.8 days vs 1.1 ± 1.5 days, P = .15). During the follow-up period, 26 stewardship notes were entered into CPRS; antibiotics were stopped in 65% of cases.

There were no recorded cases of CDI in either group. There were eleven 28-day readmissions in group 1, only 3 of which were due to infectious causes. One patient had a primary diagnosis of necrotizing pneumonia, 1 had Pseudomonas pneumonia, and 1 patient had a new lung mass and was diagnosed with postobstructive pneumonia. Of eight 28-day readmissions in group 2, only 2 resulted from infectious causes. One readmission primary diagnosis was sinusitis and 1 was recurrent pneumonia (of note, this patient received a 10-day treatment course for pneumonia on initial admission). Two patients died within 28 days of discharge in each group.

Discussion

Other multifaceted single-center interventions have been shown to be effective in large, teaching hospitals,24,25 and it has been suggested that smaller, rural hospitals may be underserved in antimicrobial stewardship activities.26,27 In the global struggle with antimicrobial resistance, McGregor and colleagues highlighted the importance of evaluating successful stewardship methods in an array of clinical settings to help tailor an approach for a specific type of facility.28 To the authors knowledge, this is the first publication showing efficacy of such antimicrobial stewardship interventions specific to pneumonia therapy in a small, primary facility.

The intervention methods used at VHSO are supported by recent IDSA and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for effective stewardship implementation.29 Prospective audit and feedback is considered a core recommendation, whereas didactic education is recommended only in conjunction with other stewardship activities. Additionally, the guidelines recommend evaluating specific infectious disease syndromes, in this case uncomplicated pneumonia, to focus on specific treatment guidelines. Last, the results of the 3-part intervention can be used to aid in demonstrating facility improvement and encourage continued success.

Of note, VHSO has had established inpatient and outpatient clinical pharmacy roles for several years. Stewardship interventions already in place included an intravenous-to-oral antibiotic switch policy, automatic antibiotic stop dates, as well as pharmacist-driven vancomycin and aminoglycoside dosing. Prior to this multifaceted intervention specific to pneumonia duration, prospective audit and feedback interventions (verbal and written) also were common. The number of interventions specific to this study outside of the stewardship note was not recorded. Using rapid diagnostic testing and biomarkers to aid in stewardship activities at VHSO have been considered, but these tools are not available due to a lab personnel shortage.

Soliciting feedback from providers on their preferred stewardship strategy and perceived barriers was a key component of the educational intervention. Of equal importance was presenting providers with their baseline prescribing data to provide objective evidence of a problem. While all were familiar with existing treatment guidelines, some feedback indicated that it can be difficult to determine accurate antibiotic duration in CPRS. Prescribers reported that identifying antibiotic duration was especially challenging when antibiotics as well as providers change during an admission. Also frequently overlooked were antibiotics given in the emergency department. This could be a key area for clinical pharmacists’ intervention given their familiarity with the CPRS medication sections.

Charani and colleagues suggest that recognizing barriers to implementing best practices and adapting to the local facility culture is paramount for changing prescribing behaviors and developing a successful stewardship intervention.30 At VHSO, the providers were presented with multiple stewardship options but agreed to the new note and template. This process gave providers a voice in selecting their own stewardship intervention. In a culture with no infectious disease physician to champion initiatives, the investigators felt that provider involvement in the intervention selection was unique and may have encouraged provider concurrence.

Although not directly targeted by the intervention strategies, average LOS was shorter in the follow-up group. According to investigators, frequent reminders of clinical stability in the stewardship notes may have influenced this. Even though the note was used only in patients who remained hospitalized for their entire treatment course, investigators felt that it still served as a reminder for prescribing habits as they were also able to show a decrease in outpatient prescription duration.

Limitations

Potential weaknesses of the study include changes in providers. During the transition between group 1 and group 2, 2 hospitalists left and 2 new hospitalists arrived. Given the small size of the staff, this could significantly impact prescribing trends. Another potential weakness is the high exclusion rate, although these rates were similar in both groups (46% group 1, 47% group 2). Furthermore, similar exclusion rates have been reported elsewhere.24,25,31 The most common reasons for exclusion were complicated pneumonias (36%) and immunocompromised patients (18%). These patient populations were not evaluated in the current study, and optimal treatment durations are unknown. Hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonias also were excluded. Therefore, limitations in applicability of the results should be noted.

The authors acknowledge that, prior to this publication, the IDSA guidelines have removed the designation of HCAP as a separate clinical entity.4 However, this should not affect the significance of the intervention for treatment duration.

The study facility experienced a hiring freeze resulting in a 9.3% decrease in overall admissions from fiscal year 2013 to fiscal year 2015. This is likely why there were fewer admissions for pneumonia in group 2. Regardless, power analysis revealed the study was of adequate sample size to detect its primary outcome. It is possible that patients in either group could have sought health care at other facilities, making the CDI and readmission endpoints less inclusive.

The study was not of a scale to detect changes in antimicrobial resistance pressure or clinical outcomes. Cost savings were not analyzed. However, this study adds to the growing body of evidence that a structured intervention can result in positive outcomes at the facility level. This study shows that interventions targeting pneumonia treatment duration could feasibly be added to the menu of stewardship options available to smaller facilities.

Like other stewardship studies in the literature, the follow-up treatment duration, while improved, still exceeded those recommended in the IDSA guidelines. The investigators noted that not all providers were equal regarding change in prescribing habits, perhaps making the average duration longer. Additionally, the request to discontinue antibiotic therapy through the stewardship note could have been entered earlier (eg, as early as day 5 of therapy) to target the shortest effective date as recommended in the recent stewardship guidelines.29 Future steps include continued feedback to providers on their progress in this area and encouragement to document day of antibiotic treatment in their daily progress notes.

Conclusion

This study showed a significant decrease in antibiotic duration for the treatment of uncomplicated pneumonia using a 3-part pharmacy intervention in a primary hospital setting. The investigators feel that each arm of the strategy was equally important and fewer interventions were not likely to be as effective.32 Although data collection for baseline prescribing and follow-up on outcomes may be a time-consuming task, it can be a valuable component of successful stewardship interventions.

1. Li JZ, Winston LG, Moore DH, Bent S. Efficacy of short-course antibiotic regimens for community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2007;120(9):783-790.

2. Dimopoulos G, Matthaiou DK, Karageorgopoulos DE, Grammatikos AP, Athanassa Z, Falagas ME. Short- versus long-course antibacterial therapy of community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Drugs. 2008;68(13):1841-1854.

3. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America; American Thoracic Society. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(suppl 2):S27-S72.

4. Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(5):e61-e111.

5. Jenkins TC, Stella SA, Cervantes L, et al. Targets for antibiotic and healthcare resource stewardship in inpatient community-acquired pneumonia: a comparison of management practices with National Guideline Recommendations. Infection. 2013; 41(1):135-144.

6. Shlaes DM, Gerding DN, John JF Jr, et al. Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, and Infectious Diseases Society of America Joint Committee on the Prevention of Antimicrobial Resistance: guidelines for the prevention of antimicrobial resistance in hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25(3):584-599.

7. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(5):431-455.

8. Brown E, Talbot GH, Axelrod P, Provencher M, Hoegg C. Risk factors for Clostridium-difficile toxin-associated diarrhea. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1990;11(6):283-290.

9. McFarland LV, Surawicz CM, Stamm WE. Risk factors for Clostridium-difficile carriage and C. difficile-associated diarrhea in a cohort of hospitalized patients. J Infect Dis. 1990;162(3):678-684.

10. Shehab N, Patel PR, Srinivasan A, Budnitz DS. Emergency department visits for antibiotic-associated adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(6):735-743.

11. Dellit TH, Owens RC, McGowan JE Jr, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America Guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(2):159-177.

12. Fridkin S, Baggs J, Fagan R, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: improving antibiotic use among hospitalized patients. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(9):194-200.

13. Nussenblatt V, Avdic E, Cosgrove S. What is the role of antimicrobial stewardship in improving outcomes of patients with CAP? Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2013;27(1):211-228.

14. Septimus EJ, Owens RC Jr. Need and potential of antimicrobial stewardship in community hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(suppl 1):S8-S14.

15. Hensher M, Price M, Adomakoh S. Referral hospitals. In Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, eds, et al. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006:1230.

16. Mulligan J, Fox-Rushby JA, Adam T, Johns B, Mills A. Unit costs of health care inputs in low and middle income regions. 2003. Working Paper 9, Disease Control Priorities Project. Published September 2003. Revised June 2005.

17. Ohl CA, Dodds Ashley ES. Antimicrobial stewardship programs in community hospitals: the evidence base and case studies. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53(suppl 1):S23-S28.

18. Trevidi KK, Kuper K. Hospital antimicrobial stewardship in the nonuniversity setting. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2014;28(2):281-289.

19. Yam P, Fales D, Jemison J, Gillum M, Bernstein M. Implementation of an antimicrobial stewardship program in a rural hospital. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69(13);1142-1148.

20. LaRocco A Jr. Concurrent antibiotic review programs—a role for infectious diseases specialists at small community hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(5):742-743.

21. Bartlett JM, Siola PL. Implementation and first-year results of an antimicrobial stewardship program at a community hospital. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(11):943-949.

22. Storey DF, Pate PG, Nguyen AT, Chang F. Implementation of an antimicrobial stewardship program on the medical-surgical service of a 100-bed community hospital. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2012;1(1):32.

23. Fine MJ, Smith MA, Carson CA, et al. Prognosis and outcomes of patients with community-acquired pneumonia. A meta-analysis. JAMA. 1996;275(2):134-141.

24. Advic E, Cushinotto LA, Hughes AH, et al. Impact of an antimicrobial stewardship intervention on shortening the duration of therapy for community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(11):1581-1587.

25. Carratallà J, Garcia-Vidal C, Ortega L, et al. Effect of a 3-step critical pathway to reduce duration of intravenous antibiotic therapy and length of stay in community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(12):922-928.

26. Stevenson KB, Samore M, Barbera J, et al. Pharmacist involvement in antimicrobial use at rural community hospitals in four Western states. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(8):787-792.

27. Reese SM, Gilmartin H, Rich KL, Price CS. Infection prevention needs assessment in Colorado hospitals: rural and urban settings. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(6):597-601.

28. McGregor JC, Furuno JP. Optimizing research methods used for the evaluation of antimicrobial stewardship programs. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(suppl 3):S185-S192.

29. Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, et al. Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(10):e51-e77.

30. Charani E, Castro-Sánchez E, Holmes A. The role of behavior change in antimicrobial stewardship. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2014;28(2):169-175.

31. Attridge RT, Frei CR, Restrepo MI, et al. Guideline-concordant therapy and outcomes in healthcare-associated pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2011;38(4):878-887.

32. MacDougal C, Polk RE. Antimicrobial stewardship programs in health care systems. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18(4):638-656.

The safety and the efficacy of shorter durations of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated pneumonia have been clearly established in the past decade.1,2 Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Thoracic Society have been available since 2007. These expert consensus statements recommend that uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) should be treated for 5 to 7 days, as long as the patient exhibits signs and symptoms of clinical stability.3 Similarly, recently updated guidelines for hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonias call for short-course therapy.4 Despite this guidance, pneumonia treatment duration is often discordant.5 Unnecessary antimicrobial use is associated with greater selection pressure on pathogens, increased risk of adverse events (AEs), and elevated treatment costs.6 The growing burden of antibiotic resistance coupled with limited availability of new antibiotics requires judicious use of these agents.

The IDSA guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) note that exposure to antimicrobial agents is the most important modifiable risk factor for the development of CDI.7 Longer durations of antibiotics increase the risk of CDI compared with shorter durations.8,9 Antibiotics are a frequent cause of drug-associated AEs and likely are underestimated.10 To decrease the unwanted effects of excessive therapy, IDSA and CDC suggest that antimicrobial stewardship interventions should be implemented.11-13

Antimicrobial stewardship efforts in small community hospitals (also known as district, rural, general, and primary hospitals) are varied and can be challenging due to limited staff and resources.14,15 The World Health Organization defines a primary care facility as having few specialties, mainly internal medicine and general surgery with limited laboratory services for general (but not specialized) pathologic analysis, and bed size ranging from 30 to 200 beds.16 Although guidance is available for effective intervention strategies in smaller hospitals, there are limited data in the literature regarding successful outcomes.17-22

The purpose of this study was to establish the need and evaluate the impact of a pharmacy-initiated 3-part intervention targeting treatment duration in patients hospitalized with uncomplicated pneumonia in a primary hospital setting. The Veterans Health Care System of the Ozarks (VHSO) in Fayetteville, Arkansas, has 50 acute care beds, including 7 intensive care unit beds and excluding 15 mental health beds. The pharmacy is staffed 24 hours a day. Acute-care providers consist of 7 full-time hospitalists, not including nocturnists and contract physicians. The VHSO does not have an infectious disease physician on staff.

The antimicrobial stewardship committee consists of 3 clinical pharmacists, a pulmonologist, a pathologist, and 2 infection-control nurses. There is 1 full-time equivalent allotted for inpatient clinical pharmacy activities in the acute care areas, including enforcement of all antimicrobial stewardship policies, which are conducted by a single pharmacist.

Methods

This was a retrospective chart review of two 12-month periods using a before and after study design. Medical records were reviewed during October 2012 through September 2013 (before the stewardship implementation) and December 2014 through November 2015 (after implementation). Inclusion criteria consisted of a primary discharge diagnosis of pneumonia as documented by the provider (or secondary diagnosis if sepsis was primary), hospitalization for at least 48 hours, administration of antibiotics for a minimum of 24 hours, and survival to discharge.

Exclusion criteria consisted of direct transfer from another facility, inappropriate empiric therapy as evidenced by culture data (isolated pathogens not covered by prescribed antibiotics), pneumonia that developed 48 hours after admission, extrapulmonary sources of infection, hospitalization > 14 days, discharge without a known duration of outpatient antibiotics, discharge for pneumonia within 28 days prior to admission, documented infection caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa or other nonlactose fermenting Gram-negative rod, and complicated pneumonias defined as lung abscess, empyema, or severe immunosuppression (eg, cancer with chemotherapy within the previous 30 days, transplant recipients, HIV infection, acquired or congenital immunodeficiency, or absolute neutrophil count 1,500 cell/mm3 within past 28 days).

Patients were designated with health care-associated pneumonia (HCAP) if they were hospitalized ≥ 2 days or resided in a skilled nursing or extended-care facility within the previous 90 days; on chronic dialysis; or had wound care, tracheostomy care, or ventilator care from a health care professional within the previous 28 days. Criteria for clinical stability were defined as ≤ 100.4º F temperature, ≤ 100 beats/min heart rate, ≤ 24 breaths/min respiratory rate, ≥ 90 mm Hg systolic blood pressure, ≥ 90% or PaO2 ≥ 60 mm Hg oxygen saturation on room air (or baseline oxygen requirements), and return to baseline mental status. To compare groups, researchers tabulated the pneumonia severity index on hospital day 1.

The intervention consisted of a 3-part process. First, hospitalists were educated on VHSO’s baseline treatment duration data, and these were compared with current IDSA recommendations. The education was followed by an open-discussion component to solicit feedback from providers on perceived barriers to following guidelines. Provider feedback was used to tailor an antimicrobial stewardship intervention to address perceived barriers to optimal antibiotic treatment duration.

After the education component, prospective intervention and feedback were provided for hospitalized patients by a single clinical pharmacist. This pharmacist interacted verbally and in writing with the patients’ providers, discussing antimicrobial appropriateness, de-escalation, duration of therapy, and intravenous to oral switching. Finally, a stewardship note for the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) was generated and included a template with reminders of clinical stability, duration of current therapy, and a request to discontinue therapy if the patient met criteria. For patients who remained hospitalized, this note was entered into CPRS on or about day 7 of antibiotic therapy; this required an electronic signature from the provider.

The VHSO Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee approved both the provider education and the stewardship note in November 2014, and implementation of the stewardship intervention occurred immediately afterward. The pharmacy staff also was educated on the VHSO baseline data and stewardship efforts.

The primary outcome of the study was the change in days of total antibiotic treatment. Secondary outcomes included days of intravenous antibiotic therapy, days of inpatient oral therapy, mean length of stay (LOS), and number of outpatient antibiotic days once discharged. Incidence of CDI and 28-day readmissions were also evaluated. The VHSO Institutional Review Board approved these methods and the procedures that followed were in accord with the ethical standards of the VHSO Committee on Human Experimentation.

Statistical Analysis

All continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation. Data analysis for significance was performed using a Student t test for continuous variables and a χ2 test (or Fisher exact test) for categorical variables in R Foundation for Statistical Computing version 3.1.0. All samples were 2-tailed. A P value < .05 was considered statistically significant. Using the smaller of the 2 study populations, the investigators calculated that the given sample size of 88 in each group would provide 99% power to detect a 2-day difference in the primary endpoint at a 2-sided significance level of 5%.

Results

During the baseline assessment (group 1), 192 cases were reviewed with 103 meeting the inclusion criteria. Group 1 consisted of 85 cases of CAP and 18 cases of HCAP (mean age, 70.7 years). During the follow-up assessment (group 2), 168 cases were reviewed with 88 meeting the inclusion criteria. Group 2 consisted of 68 cases of CAP and 20 cases of HCAP (mean age, 70.8 years).

There was no difference in inpatient mortality rates between groups (3.1% vs 3.0%, P = .99). This mortality rate is consistent with published reports.23 Empiric antibiotic selection was appropriate because there were no exclusions for drug/pathogen mismatch. Pneumonia severity was similar in both groups (Table).

The total duration of antibiotic treatment decreased significantly for CAP and HCAP (Figure). The observed median treatment days for groups 1 and 2 were 11 days and 8 days, respectively. Outpatient antibiotic days also decreased. Mean LOS was shorter in the follow-up group (4.9 ± 2.6 days vs 4.0 ± 2.6 days, P = .02). Length of IV antibiotic duration decreased. Oral antibiotic days while inpatient were not statistically different (1.5 ± 1.8 days vs 1.1 ± 1.5 days, P = .15). During the follow-up period, 26 stewardship notes were entered into CPRS; antibiotics were stopped in 65% of cases.

There were no recorded cases of CDI in either group. There were eleven 28-day readmissions in group 1, only 3 of which were due to infectious causes. One patient had a primary diagnosis of necrotizing pneumonia, 1 had Pseudomonas pneumonia, and 1 patient had a new lung mass and was diagnosed with postobstructive pneumonia. Of eight 28-day readmissions in group 2, only 2 resulted from infectious causes. One readmission primary diagnosis was sinusitis and 1 was recurrent pneumonia (of note, this patient received a 10-day treatment course for pneumonia on initial admission). Two patients died within 28 days of discharge in each group.

Discussion

Other multifaceted single-center interventions have been shown to be effective in large, teaching hospitals,24,25 and it has been suggested that smaller, rural hospitals may be underserved in antimicrobial stewardship activities.26,27 In the global struggle with antimicrobial resistance, McGregor and colleagues highlighted the importance of evaluating successful stewardship methods in an array of clinical settings to help tailor an approach for a specific type of facility.28 To the authors knowledge, this is the first publication showing efficacy of such antimicrobial stewardship interventions specific to pneumonia therapy in a small, primary facility.

The intervention methods used at VHSO are supported by recent IDSA and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for effective stewardship implementation.29 Prospective audit and feedback is considered a core recommendation, whereas didactic education is recommended only in conjunction with other stewardship activities. Additionally, the guidelines recommend evaluating specific infectious disease syndromes, in this case uncomplicated pneumonia, to focus on specific treatment guidelines. Last, the results of the 3-part intervention can be used to aid in demonstrating facility improvement and encourage continued success.

Of note, VHSO has had established inpatient and outpatient clinical pharmacy roles for several years. Stewardship interventions already in place included an intravenous-to-oral antibiotic switch policy, automatic antibiotic stop dates, as well as pharmacist-driven vancomycin and aminoglycoside dosing. Prior to this multifaceted intervention specific to pneumonia duration, prospective audit and feedback interventions (verbal and written) also were common. The number of interventions specific to this study outside of the stewardship note was not recorded. Using rapid diagnostic testing and biomarkers to aid in stewardship activities at VHSO have been considered, but these tools are not available due to a lab personnel shortage.

Soliciting feedback from providers on their preferred stewardship strategy and perceived barriers was a key component of the educational intervention. Of equal importance was presenting providers with their baseline prescribing data to provide objective evidence of a problem. While all were familiar with existing treatment guidelines, some feedback indicated that it can be difficult to determine accurate antibiotic duration in CPRS. Prescribers reported that identifying antibiotic duration was especially challenging when antibiotics as well as providers change during an admission. Also frequently overlooked were antibiotics given in the emergency department. This could be a key area for clinical pharmacists’ intervention given their familiarity with the CPRS medication sections.

Charani and colleagues suggest that recognizing barriers to implementing best practices and adapting to the local facility culture is paramount for changing prescribing behaviors and developing a successful stewardship intervention.30 At VHSO, the providers were presented with multiple stewardship options but agreed to the new note and template. This process gave providers a voice in selecting their own stewardship intervention. In a culture with no infectious disease physician to champion initiatives, the investigators felt that provider involvement in the intervention selection was unique and may have encouraged provider concurrence.

Although not directly targeted by the intervention strategies, average LOS was shorter in the follow-up group. According to investigators, frequent reminders of clinical stability in the stewardship notes may have influenced this. Even though the note was used only in patients who remained hospitalized for their entire treatment course, investigators felt that it still served as a reminder for prescribing habits as they were also able to show a decrease in outpatient prescription duration.

Limitations

Potential weaknesses of the study include changes in providers. During the transition between group 1 and group 2, 2 hospitalists left and 2 new hospitalists arrived. Given the small size of the staff, this could significantly impact prescribing trends. Another potential weakness is the high exclusion rate, although these rates were similar in both groups (46% group 1, 47% group 2). Furthermore, similar exclusion rates have been reported elsewhere.24,25,31 The most common reasons for exclusion were complicated pneumonias (36%) and immunocompromised patients (18%). These patient populations were not evaluated in the current study, and optimal treatment durations are unknown. Hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonias also were excluded. Therefore, limitations in applicability of the results should be noted.

The authors acknowledge that, prior to this publication, the IDSA guidelines have removed the designation of HCAP as a separate clinical entity.4 However, this should not affect the significance of the intervention for treatment duration.

The study facility experienced a hiring freeze resulting in a 9.3% decrease in overall admissions from fiscal year 2013 to fiscal year 2015. This is likely why there were fewer admissions for pneumonia in group 2. Regardless, power analysis revealed the study was of adequate sample size to detect its primary outcome. It is possible that patients in either group could have sought health care at other facilities, making the CDI and readmission endpoints less inclusive.

The study was not of a scale to detect changes in antimicrobial resistance pressure or clinical outcomes. Cost savings were not analyzed. However, this study adds to the growing body of evidence that a structured intervention can result in positive outcomes at the facility level. This study shows that interventions targeting pneumonia treatment duration could feasibly be added to the menu of stewardship options available to smaller facilities.

Like other stewardship studies in the literature, the follow-up treatment duration, while improved, still exceeded those recommended in the IDSA guidelines. The investigators noted that not all providers were equal regarding change in prescribing habits, perhaps making the average duration longer. Additionally, the request to discontinue antibiotic therapy through the stewardship note could have been entered earlier (eg, as early as day 5 of therapy) to target the shortest effective date as recommended in the recent stewardship guidelines.29 Future steps include continued feedback to providers on their progress in this area and encouragement to document day of antibiotic treatment in their daily progress notes.

Conclusion

This study showed a significant decrease in antibiotic duration for the treatment of uncomplicated pneumonia using a 3-part pharmacy intervention in a primary hospital setting. The investigators feel that each arm of the strategy was equally important and fewer interventions were not likely to be as effective.32 Although data collection for baseline prescribing and follow-up on outcomes may be a time-consuming task, it can be a valuable component of successful stewardship interventions.

The safety and the efficacy of shorter durations of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated pneumonia have been clearly established in the past decade.1,2 Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Thoracic Society have been available since 2007. These expert consensus statements recommend that uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) should be treated for 5 to 7 days, as long as the patient exhibits signs and symptoms of clinical stability.3 Similarly, recently updated guidelines for hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonias call for short-course therapy.4 Despite this guidance, pneumonia treatment duration is often discordant.5 Unnecessary antimicrobial use is associated with greater selection pressure on pathogens, increased risk of adverse events (AEs), and elevated treatment costs.6 The growing burden of antibiotic resistance coupled with limited availability of new antibiotics requires judicious use of these agents.

The IDSA guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) note that exposure to antimicrobial agents is the most important modifiable risk factor for the development of CDI.7 Longer durations of antibiotics increase the risk of CDI compared with shorter durations.8,9 Antibiotics are a frequent cause of drug-associated AEs and likely are underestimated.10 To decrease the unwanted effects of excessive therapy, IDSA and CDC suggest that antimicrobial stewardship interventions should be implemented.11-13

Antimicrobial stewardship efforts in small community hospitals (also known as district, rural, general, and primary hospitals) are varied and can be challenging due to limited staff and resources.14,15 The World Health Organization defines a primary care facility as having few specialties, mainly internal medicine and general surgery with limited laboratory services for general (but not specialized) pathologic analysis, and bed size ranging from 30 to 200 beds.16 Although guidance is available for effective intervention strategies in smaller hospitals, there are limited data in the literature regarding successful outcomes.17-22

The purpose of this study was to establish the need and evaluate the impact of a pharmacy-initiated 3-part intervention targeting treatment duration in patients hospitalized with uncomplicated pneumonia in a primary hospital setting. The Veterans Health Care System of the Ozarks (VHSO) in Fayetteville, Arkansas, has 50 acute care beds, including 7 intensive care unit beds and excluding 15 mental health beds. The pharmacy is staffed 24 hours a day. Acute-care providers consist of 7 full-time hospitalists, not including nocturnists and contract physicians. The VHSO does not have an infectious disease physician on staff.

The antimicrobial stewardship committee consists of 3 clinical pharmacists, a pulmonologist, a pathologist, and 2 infection-control nurses. There is 1 full-time equivalent allotted for inpatient clinical pharmacy activities in the acute care areas, including enforcement of all antimicrobial stewardship policies, which are conducted by a single pharmacist.

Methods

This was a retrospective chart review of two 12-month periods using a before and after study design. Medical records were reviewed during October 2012 through September 2013 (before the stewardship implementation) and December 2014 through November 2015 (after implementation). Inclusion criteria consisted of a primary discharge diagnosis of pneumonia as documented by the provider (or secondary diagnosis if sepsis was primary), hospitalization for at least 48 hours, administration of antibiotics for a minimum of 24 hours, and survival to discharge.