User login

Yellow pruritic eruption

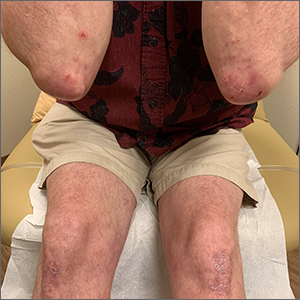

This pruritic, eruption with yellowing atrophy and telangiectasias on the lower extremities is a classic presentation for necrobiosis lipoidica (NL).

NL is a chronic granulomatous disorder with a predilection for the lower extremities. Patients with NL present with progressive, yellow-brown atrophic plaques on the pretibial aspect of the legs. The plaques have underlying telangiectasias, revealed by the atrophy, and may ulcerate. While these lesions are primarily asymptomatic, associated symptoms may include pruritus, pain, or altered sensation on the affected skin. The classic pathology of NL is notable for altered collagen bundles layered with palisading granulomas extending deep into the dermis. Other notable findings may include mixed inflammatory cells, multinucleated giant cells, and plasma cells; mucin is notably absent.

There is an established relationship between NL and diabetes. When these 2 entities are present, the skin eruption may be referred to as “necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum” or “NLD.” Only a small percentage of patients with diabetes will develop NL. Furthermore, there is growing evidence to suggest that NL may be associated with other comorbidities, such as obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and thyroid disease.1 Additionally, squamous cell carcinoma has been reported as arising within skin affected by NL.2

The etiology of NL is not completely understood. Current theories suggest that blood vessel inflammation related to autoimmune factors may be at work.2 The differential diagnosis of NL includes granuloma annulare, pretibial myxedema, stasis dermatitis, panniculitis, morphea, and lichen sclerosis.

NL can be refractory to therapy. Paramount to management is the avoidance of trauma to the affected skin. Topical therapies include corticosteroids, tretinoin, and tacrolimus. Systemic immunomodulation with infliximab, etanercept, thalidomide, and cyclosporine has also been trialed. There is evidence for the utility of pentoxifylline (400 mg po tid), a xanthine derivative often used for peripheral artery disease, to reverse ulceration that can arise in NL.

The patient in this case opted for topical therapy with clobetasol 0.05% ointment and tacrolimus 0.1% ointment. She was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Image courtesy of Cyrelle Fermin, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque. Text courtesy of Cyrelle Fermin, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Hashemi DA, Brown-Joel ZO, Tkachenko E, et al. Clinical features and comorbidities of patients with necrobiosis lipoidica with or without diabetes. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:455-459. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5635

2. Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2015.03.003

This pruritic, eruption with yellowing atrophy and telangiectasias on the lower extremities is a classic presentation for necrobiosis lipoidica (NL).

NL is a chronic granulomatous disorder with a predilection for the lower extremities. Patients with NL present with progressive, yellow-brown atrophic plaques on the pretibial aspect of the legs. The plaques have underlying telangiectasias, revealed by the atrophy, and may ulcerate. While these lesions are primarily asymptomatic, associated symptoms may include pruritus, pain, or altered sensation on the affected skin. The classic pathology of NL is notable for altered collagen bundles layered with palisading granulomas extending deep into the dermis. Other notable findings may include mixed inflammatory cells, multinucleated giant cells, and plasma cells; mucin is notably absent.

There is an established relationship between NL and diabetes. When these 2 entities are present, the skin eruption may be referred to as “necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum” or “NLD.” Only a small percentage of patients with diabetes will develop NL. Furthermore, there is growing evidence to suggest that NL may be associated with other comorbidities, such as obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and thyroid disease.1 Additionally, squamous cell carcinoma has been reported as arising within skin affected by NL.2

The etiology of NL is not completely understood. Current theories suggest that blood vessel inflammation related to autoimmune factors may be at work.2 The differential diagnosis of NL includes granuloma annulare, pretibial myxedema, stasis dermatitis, panniculitis, morphea, and lichen sclerosis.

NL can be refractory to therapy. Paramount to management is the avoidance of trauma to the affected skin. Topical therapies include corticosteroids, tretinoin, and tacrolimus. Systemic immunomodulation with infliximab, etanercept, thalidomide, and cyclosporine has also been trialed. There is evidence for the utility of pentoxifylline (400 mg po tid), a xanthine derivative often used for peripheral artery disease, to reverse ulceration that can arise in NL.

The patient in this case opted for topical therapy with clobetasol 0.05% ointment and tacrolimus 0.1% ointment. She was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Image courtesy of Cyrelle Fermin, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque. Text courtesy of Cyrelle Fermin, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

This pruritic, eruption with yellowing atrophy and telangiectasias on the lower extremities is a classic presentation for necrobiosis lipoidica (NL).

NL is a chronic granulomatous disorder with a predilection for the lower extremities. Patients with NL present with progressive, yellow-brown atrophic plaques on the pretibial aspect of the legs. The plaques have underlying telangiectasias, revealed by the atrophy, and may ulcerate. While these lesions are primarily asymptomatic, associated symptoms may include pruritus, pain, or altered sensation on the affected skin. The classic pathology of NL is notable for altered collagen bundles layered with palisading granulomas extending deep into the dermis. Other notable findings may include mixed inflammatory cells, multinucleated giant cells, and plasma cells; mucin is notably absent.

There is an established relationship between NL and diabetes. When these 2 entities are present, the skin eruption may be referred to as “necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum” or “NLD.” Only a small percentage of patients with diabetes will develop NL. Furthermore, there is growing evidence to suggest that NL may be associated with other comorbidities, such as obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and thyroid disease.1 Additionally, squamous cell carcinoma has been reported as arising within skin affected by NL.2

The etiology of NL is not completely understood. Current theories suggest that blood vessel inflammation related to autoimmune factors may be at work.2 The differential diagnosis of NL includes granuloma annulare, pretibial myxedema, stasis dermatitis, panniculitis, morphea, and lichen sclerosis.

NL can be refractory to therapy. Paramount to management is the avoidance of trauma to the affected skin. Topical therapies include corticosteroids, tretinoin, and tacrolimus. Systemic immunomodulation with infliximab, etanercept, thalidomide, and cyclosporine has also been trialed. There is evidence for the utility of pentoxifylline (400 mg po tid), a xanthine derivative often used for peripheral artery disease, to reverse ulceration that can arise in NL.

The patient in this case opted for topical therapy with clobetasol 0.05% ointment and tacrolimus 0.1% ointment. She was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Image courtesy of Cyrelle Fermin, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque. Text courtesy of Cyrelle Fermin, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Hashemi DA, Brown-Joel ZO, Tkachenko E, et al. Clinical features and comorbidities of patients with necrobiosis lipoidica with or without diabetes. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:455-459. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5635

2. Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2015.03.003

1. Hashemi DA, Brown-Joel ZO, Tkachenko E, et al. Clinical features and comorbidities of patients with necrobiosis lipoidica with or without diabetes. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:455-459. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5635

2. Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2015.03.003

Painful facial abscess

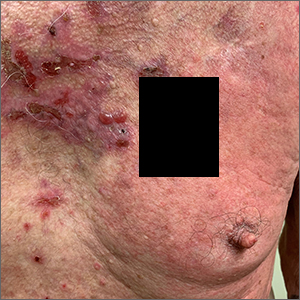

A 35-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a purple-red cyst on her right cheek that had been present for about 4 years but had worsened over the prior 2 weeks (FIGURE 1). She said she was experiencing excruciating pain and that the cyst had purulent drainage. She denied any history of diabetes, dental problems, recent trauma, or an inciting event.

On physical examination, there was no cervical lymphadenopathy, and her vital signs were normal. An incision and drainage procedure was performed. About 2 mL of purulent fluid was extracted and sent for aerobic and anaerobic cultures.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Cervicofacial actinomycosis

Direct Gram stain showed gram-positive cocci, so the patient was started on a 7-day course of cephalexin 500 mg tid. Five days later, the anaerobic culture grew Actinomyces neuii, revealing the diagnosis as cervicofacial actinomycosis; the patient stopped taking cephalexin. The patient was then switched to a 3-month course of amoxicillin 875 mg bid.

Actinomyces are natural inhabitants of the human oropharynx and gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts.1-4 They are filamentous, gram-positive rods with characteristic sulfur granules (although these are not always present).1-4 It is believed that actinomycosis is endogenously acquired from deep tissue either through dental trauma, penetrating wounds, or compound fractures.2,4

The most common presentations of actinomycosis include cervicofacial (sometimes referred to as “lumpy jaw syndrome”), followed by abdominopelvic and thoracic/pulmonary, manifestations.2-4 Primary cutaneous actinomycosis is rare.5-9 Actinomycosis infection often manifests with indolent constitutional symptoms such as fatigue and anorexia.1 Most cases occur in men ages 20 to 60 years, although cases in women are increasingly being reported.2-4

Risk factors include poor dental hygiene or dental procedures, alcoholism, intrauterine device use, immunosuppression, appendicitis, and diverticulitis.2-4 The exact cause of this patient’s actinomycosis was unknown, as she did not have any known risk factors.

Furunculosis and sporotrichosis are part of the differential

Actinomycosis is often called a “great mimicker” due to its ability to masquerade as infection, malignancy, or fungus.1 The differential diagnosis for this patient’s presentation included bacterial soft-tissue infection (eg, furunculosis), infected epidermoid cyst, cutaneous tuberculosis, sporotrichosis, deep fungal infection, and nocardiosis.

Continue to: Furunculosis was initially suspected

Furunculosis was initially suspected, but the original wound culture demonstrated actinomycoses instead of traditional gram-positive bacteria.

A clinical diagnosis

The diagnosis of actinomycosis is usually made clinically, but definitive confirmation requires culture, which can be challenging with a slow-growing facultative or strict anaerobe that may take up to 14 days to appear.2-4 A Gram stain can aid in the diagnosis, but overall, there is a high false-negative rate in identifying actinomycosis.1,3,4

Treatment time can be lengthy, but prognosis is favorable

Unfortunately, there are no randomized controlled studies for treatment of actinomycosis. The majority of evidence for treatment comes from in vitro and clinical case studies.2-4,10 In general, prognosis of actinomycosis is favorable with low mortality, but chronic infection without complete resolution of symptoms can occur.1-4,7,8,10

First-line therapy for actinomycosis is a beta-lactam antibiotic, typically penicillin G or amoxicillin.2-4,10 High doses of prolonged intravenous (IV) and oral antibiotic therapy (2 to 12 months) based on location and complexity are standard.3,11 However, if there is minimal bone involvement and the patient shows rapid improvement, treatment could be shortened to a 4 to 6–week oral regimen.1,11 Surgical intervention can also shorten the required length of antibiotic duration.1,10

Cutaneous actinomycosis Tx. Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid has been shown to be an effective treatment for cutaneous actinomycosis, especially if polymicrobial infection is suspected.5,6 Individualized regimens for cutaneous actinomycosis—based on severity, location, and treatment response—are acceptable with close monitoring.1,2,11

Continue to: A lengthy recovery for our patient

A lengthy recovery for our patient

Seven weeks after the initial visit, the patient reported that she had taken only 20 days’ worth of the recommended 3-month course of amoxicillin. Fortunately, the lesion appeared to be healing well with no apparent fluid collection (FIGURE 2).

The patient was then prescribed, and completed, a 3-month course of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid

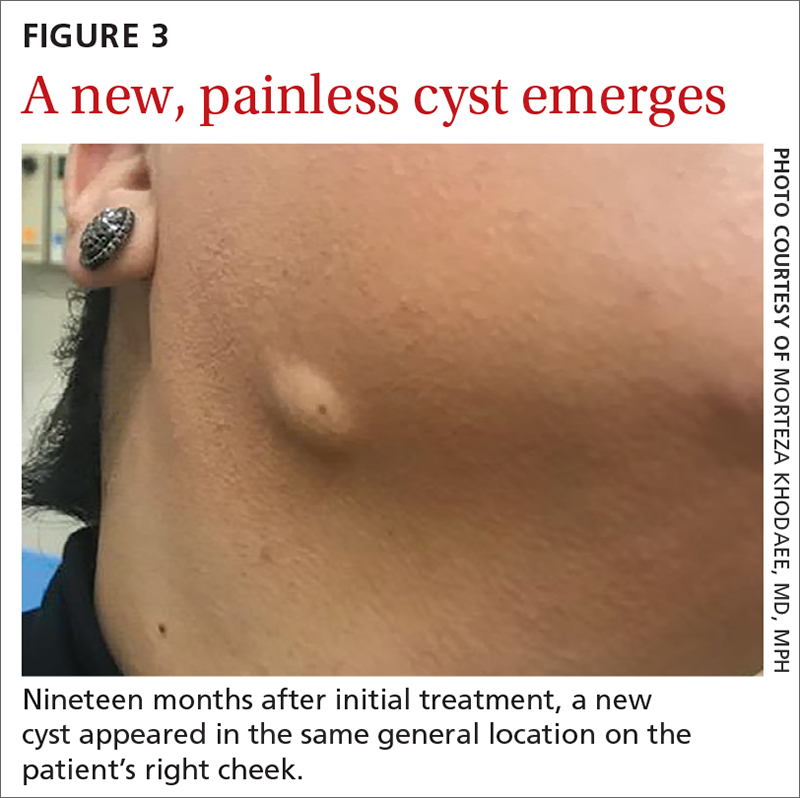

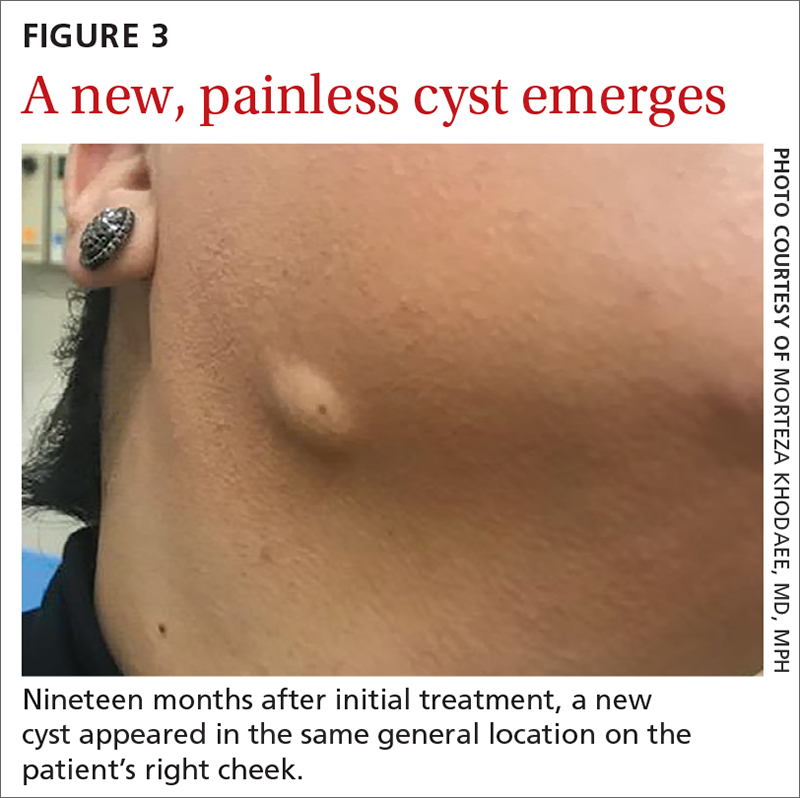

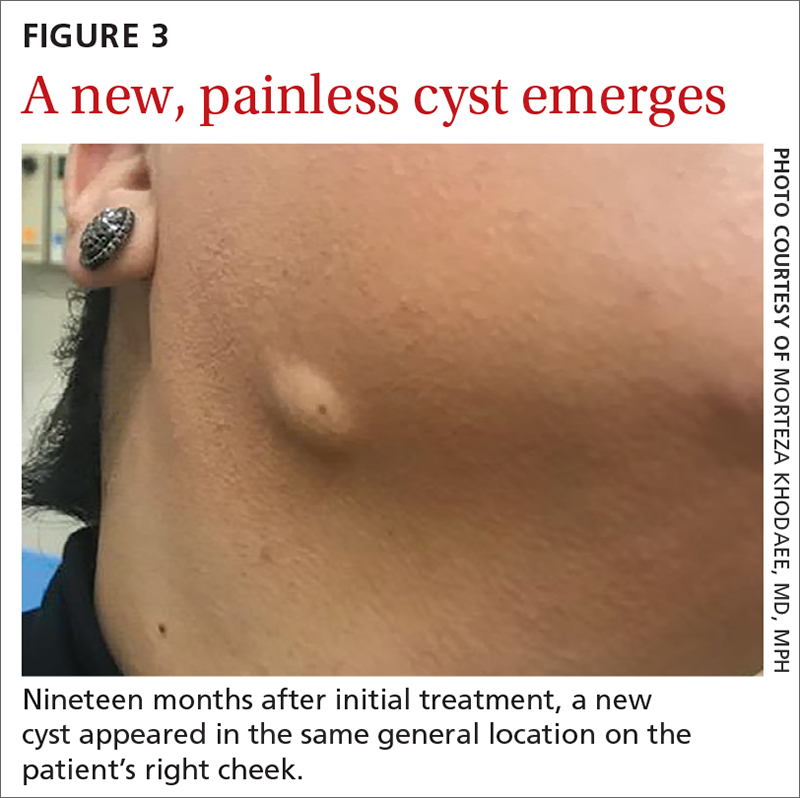

Nineteen months after initial treatment, the lesion reappeared as a painless cyst in a similar location (FIGURE 3). Plastic Surgery incised and drained the lesion and Infectious Diseases continued her on 3 months of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875 mg/125 mg bid, which she did complete.

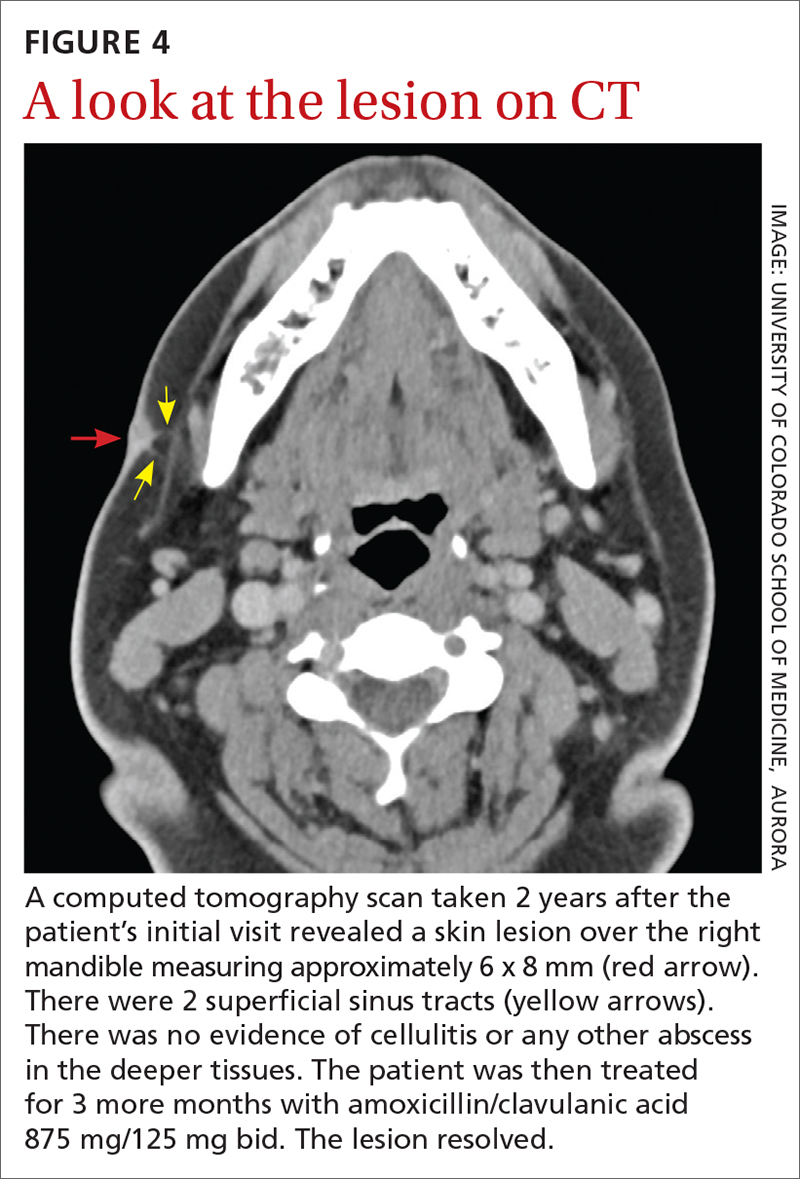

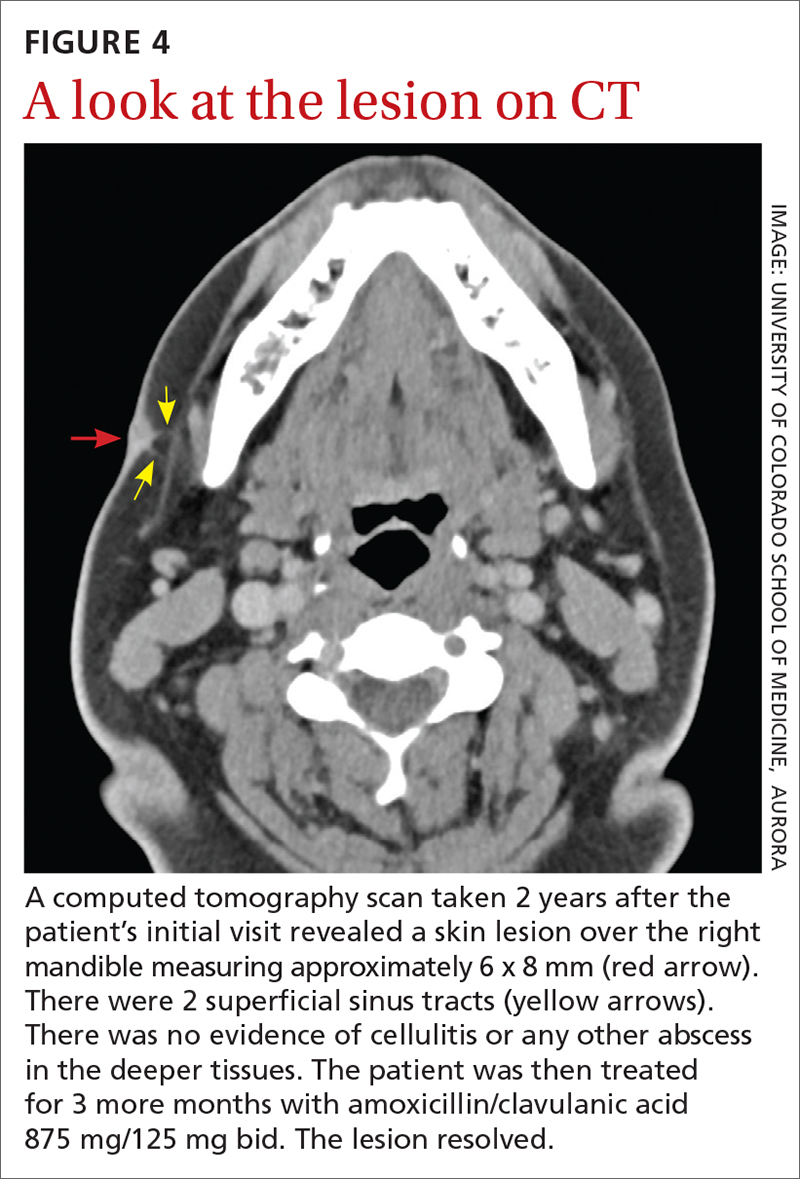

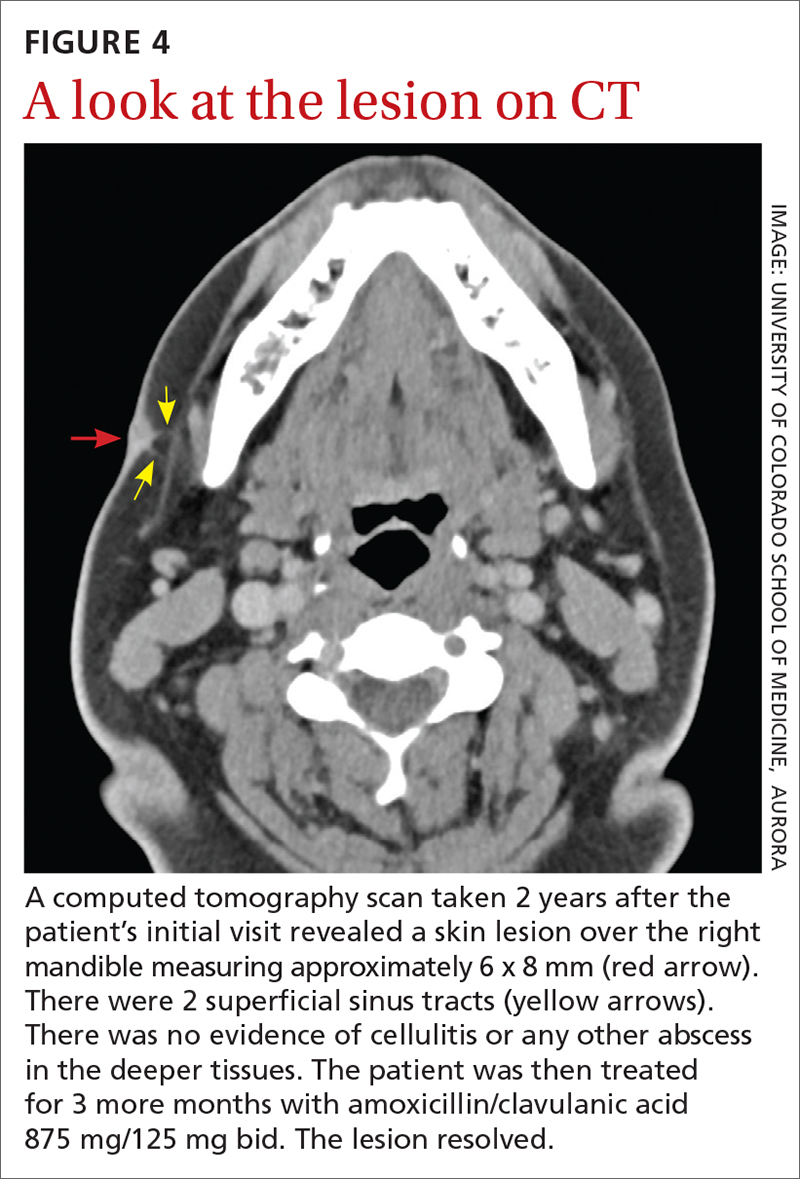

Due to the continued presence of the lesion, a computed tomography scan of the face was ordered 2 years after the initial visit and demonstrated a superficial skin lesion with no mandibular involvement (FIGURE 4). She was then treated with 3 more months of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875 mg/125 mg bid, with the possibility of deep debridement if not improved. However, debridement was unnecessary as the cyst did not recur.

We believe that the course of this patient’s treatment was protracted because she never took oral antibiotics for more than 3 months at a time, and thus, her infection never completely resolved. In retrospect, we would have treated her more aggressively from the outset.

1. Najmi AH, Najmi IH, Tawhari MMH, et al. Cutaneous actinomycosis and long-term management through using oral and topical antibiotics: a case report. Clin Pract. 2018;8:1102. doi: 10.4081/ cp.2018.1102

2. Sharma S, Hashmi MF, Valentino ID. Actinomycosis. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

3. Valour F, Sénécha A, Dupieux C, et al. Actinomycosis: etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;7:183-97. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S39601

4. Wong VK, Turmezei TD, Weston VC. Actinomycosis. BMJ. 2011;343:d6099. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6099

5. Akhtar M, Zade MP, Shahane PL, et al. Scalp actinomycosis presenting as soft tissue tumour: a case report with literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;16:99-101. doi: 10.1016/ j.ijscr.2015.09.030

6. Bose M, Ghosh R, Mukherjee K, et al. Primary cutaneous actinomycosis:a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:YD03-5. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8286.4591

7. Cataño JC, Gómez Villegas SI. Images in clinical medicine. Cutaneous actinomycosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1773. doi: 10.1056/ NEJMicm1511213

8. Mehta V, Balachandran C. Primary cutaneous actinomycosis on the chest wall. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:13.

9. Piggott SA, Khodaee M. A bump in the groin: cutaneous actinomycosis. J Family Community Med. 2017;24:203. doi: 10.4103/jfcm.JFCM_79_17

10. Bonifaz A, Tirado-Sánchez A, Calderón L, et al. Treatment of cutaneous actinomycosis with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;28:59-64. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2016.1178373

11. Valour F, Sénéchal A, Dupieux C, et al. Actinomycosis: etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;;7:183-197. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S39601

A 35-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a purple-red cyst on her right cheek that had been present for about 4 years but had worsened over the prior 2 weeks (FIGURE 1). She said she was experiencing excruciating pain and that the cyst had purulent drainage. She denied any history of diabetes, dental problems, recent trauma, or an inciting event.

On physical examination, there was no cervical lymphadenopathy, and her vital signs were normal. An incision and drainage procedure was performed. About 2 mL of purulent fluid was extracted and sent for aerobic and anaerobic cultures.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Cervicofacial actinomycosis

Direct Gram stain showed gram-positive cocci, so the patient was started on a 7-day course of cephalexin 500 mg tid. Five days later, the anaerobic culture grew Actinomyces neuii, revealing the diagnosis as cervicofacial actinomycosis; the patient stopped taking cephalexin. The patient was then switched to a 3-month course of amoxicillin 875 mg bid.

Actinomyces are natural inhabitants of the human oropharynx and gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts.1-4 They are filamentous, gram-positive rods with characteristic sulfur granules (although these are not always present).1-4 It is believed that actinomycosis is endogenously acquired from deep tissue either through dental trauma, penetrating wounds, or compound fractures.2,4

The most common presentations of actinomycosis include cervicofacial (sometimes referred to as “lumpy jaw syndrome”), followed by abdominopelvic and thoracic/pulmonary, manifestations.2-4 Primary cutaneous actinomycosis is rare.5-9 Actinomycosis infection often manifests with indolent constitutional symptoms such as fatigue and anorexia.1 Most cases occur in men ages 20 to 60 years, although cases in women are increasingly being reported.2-4

Risk factors include poor dental hygiene or dental procedures, alcoholism, intrauterine device use, immunosuppression, appendicitis, and diverticulitis.2-4 The exact cause of this patient’s actinomycosis was unknown, as she did not have any known risk factors.

Furunculosis and sporotrichosis are part of the differential

Actinomycosis is often called a “great mimicker” due to its ability to masquerade as infection, malignancy, or fungus.1 The differential diagnosis for this patient’s presentation included bacterial soft-tissue infection (eg, furunculosis), infected epidermoid cyst, cutaneous tuberculosis, sporotrichosis, deep fungal infection, and nocardiosis.

Continue to: Furunculosis was initially suspected

Furunculosis was initially suspected, but the original wound culture demonstrated actinomycoses instead of traditional gram-positive bacteria.

A clinical diagnosis

The diagnosis of actinomycosis is usually made clinically, but definitive confirmation requires culture, which can be challenging with a slow-growing facultative or strict anaerobe that may take up to 14 days to appear.2-4 A Gram stain can aid in the diagnosis, but overall, there is a high false-negative rate in identifying actinomycosis.1,3,4

Treatment time can be lengthy, but prognosis is favorable

Unfortunately, there are no randomized controlled studies for treatment of actinomycosis. The majority of evidence for treatment comes from in vitro and clinical case studies.2-4,10 In general, prognosis of actinomycosis is favorable with low mortality, but chronic infection without complete resolution of symptoms can occur.1-4,7,8,10

First-line therapy for actinomycosis is a beta-lactam antibiotic, typically penicillin G or amoxicillin.2-4,10 High doses of prolonged intravenous (IV) and oral antibiotic therapy (2 to 12 months) based on location and complexity are standard.3,11 However, if there is minimal bone involvement and the patient shows rapid improvement, treatment could be shortened to a 4 to 6–week oral regimen.1,11 Surgical intervention can also shorten the required length of antibiotic duration.1,10

Cutaneous actinomycosis Tx. Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid has been shown to be an effective treatment for cutaneous actinomycosis, especially if polymicrobial infection is suspected.5,6 Individualized regimens for cutaneous actinomycosis—based on severity, location, and treatment response—are acceptable with close monitoring.1,2,11

Continue to: A lengthy recovery for our patient

A lengthy recovery for our patient

Seven weeks after the initial visit, the patient reported that she had taken only 20 days’ worth of the recommended 3-month course of amoxicillin. Fortunately, the lesion appeared to be healing well with no apparent fluid collection (FIGURE 2).

The patient was then prescribed, and completed, a 3-month course of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid

Nineteen months after initial treatment, the lesion reappeared as a painless cyst in a similar location (FIGURE 3). Plastic Surgery incised and drained the lesion and Infectious Diseases continued her on 3 months of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875 mg/125 mg bid, which she did complete.

Due to the continued presence of the lesion, a computed tomography scan of the face was ordered 2 years after the initial visit and demonstrated a superficial skin lesion with no mandibular involvement (FIGURE 4). She was then treated with 3 more months of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875 mg/125 mg bid, with the possibility of deep debridement if not improved. However, debridement was unnecessary as the cyst did not recur.

We believe that the course of this patient’s treatment was protracted because she never took oral antibiotics for more than 3 months at a time, and thus, her infection never completely resolved. In retrospect, we would have treated her more aggressively from the outset.

A 35-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a purple-red cyst on her right cheek that had been present for about 4 years but had worsened over the prior 2 weeks (FIGURE 1). She said she was experiencing excruciating pain and that the cyst had purulent drainage. She denied any history of diabetes, dental problems, recent trauma, or an inciting event.

On physical examination, there was no cervical lymphadenopathy, and her vital signs were normal. An incision and drainage procedure was performed. About 2 mL of purulent fluid was extracted and sent for aerobic and anaerobic cultures.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Cervicofacial actinomycosis

Direct Gram stain showed gram-positive cocci, so the patient was started on a 7-day course of cephalexin 500 mg tid. Five days later, the anaerobic culture grew Actinomyces neuii, revealing the diagnosis as cervicofacial actinomycosis; the patient stopped taking cephalexin. The patient was then switched to a 3-month course of amoxicillin 875 mg bid.

Actinomyces are natural inhabitants of the human oropharynx and gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts.1-4 They are filamentous, gram-positive rods with characteristic sulfur granules (although these are not always present).1-4 It is believed that actinomycosis is endogenously acquired from deep tissue either through dental trauma, penetrating wounds, or compound fractures.2,4

The most common presentations of actinomycosis include cervicofacial (sometimes referred to as “lumpy jaw syndrome”), followed by abdominopelvic and thoracic/pulmonary, manifestations.2-4 Primary cutaneous actinomycosis is rare.5-9 Actinomycosis infection often manifests with indolent constitutional symptoms such as fatigue and anorexia.1 Most cases occur in men ages 20 to 60 years, although cases in women are increasingly being reported.2-4

Risk factors include poor dental hygiene or dental procedures, alcoholism, intrauterine device use, immunosuppression, appendicitis, and diverticulitis.2-4 The exact cause of this patient’s actinomycosis was unknown, as she did not have any known risk factors.

Furunculosis and sporotrichosis are part of the differential

Actinomycosis is often called a “great mimicker” due to its ability to masquerade as infection, malignancy, or fungus.1 The differential diagnosis for this patient’s presentation included bacterial soft-tissue infection (eg, furunculosis), infected epidermoid cyst, cutaneous tuberculosis, sporotrichosis, deep fungal infection, and nocardiosis.

Continue to: Furunculosis was initially suspected

Furunculosis was initially suspected, but the original wound culture demonstrated actinomycoses instead of traditional gram-positive bacteria.

A clinical diagnosis

The diagnosis of actinomycosis is usually made clinically, but definitive confirmation requires culture, which can be challenging with a slow-growing facultative or strict anaerobe that may take up to 14 days to appear.2-4 A Gram stain can aid in the diagnosis, but overall, there is a high false-negative rate in identifying actinomycosis.1,3,4

Treatment time can be lengthy, but prognosis is favorable

Unfortunately, there are no randomized controlled studies for treatment of actinomycosis. The majority of evidence for treatment comes from in vitro and clinical case studies.2-4,10 In general, prognosis of actinomycosis is favorable with low mortality, but chronic infection without complete resolution of symptoms can occur.1-4,7,8,10

First-line therapy for actinomycosis is a beta-lactam antibiotic, typically penicillin G or amoxicillin.2-4,10 High doses of prolonged intravenous (IV) and oral antibiotic therapy (2 to 12 months) based on location and complexity are standard.3,11 However, if there is minimal bone involvement and the patient shows rapid improvement, treatment could be shortened to a 4 to 6–week oral regimen.1,11 Surgical intervention can also shorten the required length of antibiotic duration.1,10

Cutaneous actinomycosis Tx. Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid has been shown to be an effective treatment for cutaneous actinomycosis, especially if polymicrobial infection is suspected.5,6 Individualized regimens for cutaneous actinomycosis—based on severity, location, and treatment response—are acceptable with close monitoring.1,2,11

Continue to: A lengthy recovery for our patient

A lengthy recovery for our patient

Seven weeks after the initial visit, the patient reported that she had taken only 20 days’ worth of the recommended 3-month course of amoxicillin. Fortunately, the lesion appeared to be healing well with no apparent fluid collection (FIGURE 2).

The patient was then prescribed, and completed, a 3-month course of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid

Nineteen months after initial treatment, the lesion reappeared as a painless cyst in a similar location (FIGURE 3). Plastic Surgery incised and drained the lesion and Infectious Diseases continued her on 3 months of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875 mg/125 mg bid, which she did complete.

Due to the continued presence of the lesion, a computed tomography scan of the face was ordered 2 years after the initial visit and demonstrated a superficial skin lesion with no mandibular involvement (FIGURE 4). She was then treated with 3 more months of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875 mg/125 mg bid, with the possibility of deep debridement if not improved. However, debridement was unnecessary as the cyst did not recur.

We believe that the course of this patient’s treatment was protracted because she never took oral antibiotics for more than 3 months at a time, and thus, her infection never completely resolved. In retrospect, we would have treated her more aggressively from the outset.

1. Najmi AH, Najmi IH, Tawhari MMH, et al. Cutaneous actinomycosis and long-term management through using oral and topical antibiotics: a case report. Clin Pract. 2018;8:1102. doi: 10.4081/ cp.2018.1102

2. Sharma S, Hashmi MF, Valentino ID. Actinomycosis. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

3. Valour F, Sénécha A, Dupieux C, et al. Actinomycosis: etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;7:183-97. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S39601

4. Wong VK, Turmezei TD, Weston VC. Actinomycosis. BMJ. 2011;343:d6099. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6099

5. Akhtar M, Zade MP, Shahane PL, et al. Scalp actinomycosis presenting as soft tissue tumour: a case report with literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;16:99-101. doi: 10.1016/ j.ijscr.2015.09.030

6. Bose M, Ghosh R, Mukherjee K, et al. Primary cutaneous actinomycosis:a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:YD03-5. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8286.4591

7. Cataño JC, Gómez Villegas SI. Images in clinical medicine. Cutaneous actinomycosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1773. doi: 10.1056/ NEJMicm1511213

8. Mehta V, Balachandran C. Primary cutaneous actinomycosis on the chest wall. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:13.

9. Piggott SA, Khodaee M. A bump in the groin: cutaneous actinomycosis. J Family Community Med. 2017;24:203. doi: 10.4103/jfcm.JFCM_79_17

10. Bonifaz A, Tirado-Sánchez A, Calderón L, et al. Treatment of cutaneous actinomycosis with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;28:59-64. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2016.1178373

11. Valour F, Sénéchal A, Dupieux C, et al. Actinomycosis: etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;;7:183-197. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S39601

1. Najmi AH, Najmi IH, Tawhari MMH, et al. Cutaneous actinomycosis and long-term management through using oral and topical antibiotics: a case report. Clin Pract. 2018;8:1102. doi: 10.4081/ cp.2018.1102

2. Sharma S, Hashmi MF, Valentino ID. Actinomycosis. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

3. Valour F, Sénécha A, Dupieux C, et al. Actinomycosis: etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;7:183-97. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S39601

4. Wong VK, Turmezei TD, Weston VC. Actinomycosis. BMJ. 2011;343:d6099. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6099

5. Akhtar M, Zade MP, Shahane PL, et al. Scalp actinomycosis presenting as soft tissue tumour: a case report with literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;16:99-101. doi: 10.1016/ j.ijscr.2015.09.030

6. Bose M, Ghosh R, Mukherjee K, et al. Primary cutaneous actinomycosis:a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:YD03-5. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8286.4591

7. Cataño JC, Gómez Villegas SI. Images in clinical medicine. Cutaneous actinomycosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1773. doi: 10.1056/ NEJMicm1511213

8. Mehta V, Balachandran C. Primary cutaneous actinomycosis on the chest wall. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:13.

9. Piggott SA, Khodaee M. A bump in the groin: cutaneous actinomycosis. J Family Community Med. 2017;24:203. doi: 10.4103/jfcm.JFCM_79_17

10. Bonifaz A, Tirado-Sánchez A, Calderón L, et al. Treatment of cutaneous actinomycosis with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;28:59-64. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2016.1178373

11. Valour F, Sénéchal A, Dupieux C, et al. Actinomycosis: etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;;7:183-197. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S39601

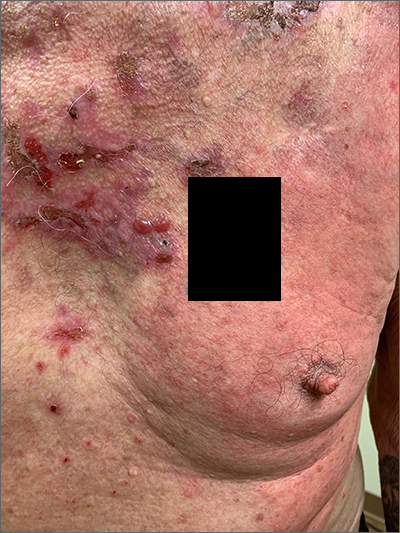

Painful lumps in the axilla

A 30-year-old man presented to the clinic with a complaint of small painful lumps in his armpit. He stated that he initially experienced some itching and discomfort, but after a while he noticed some red, tender, swollen areas. He also mentioned an odorous yellow fluid that would sometimes drain from the lumps. Since first noticing them 2 years earlier, he reported that the nodules had disappeared and reappeared on their own several times.

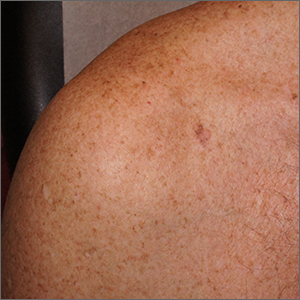

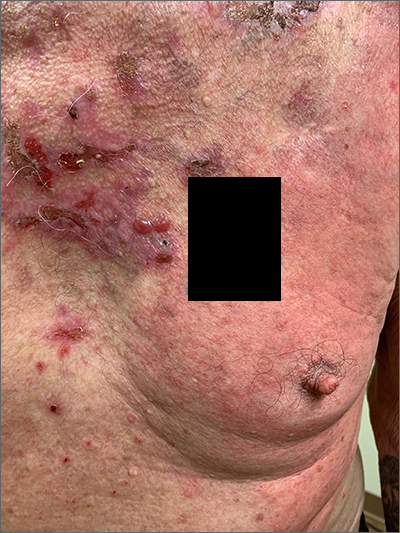

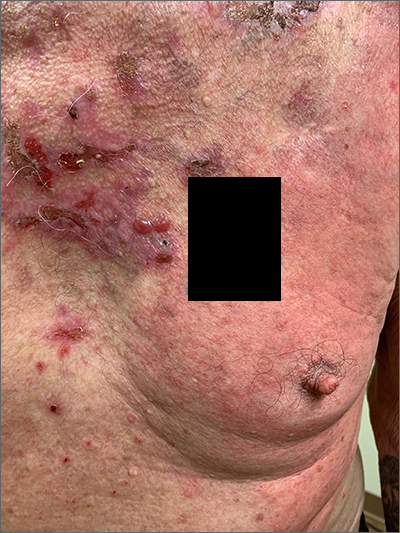

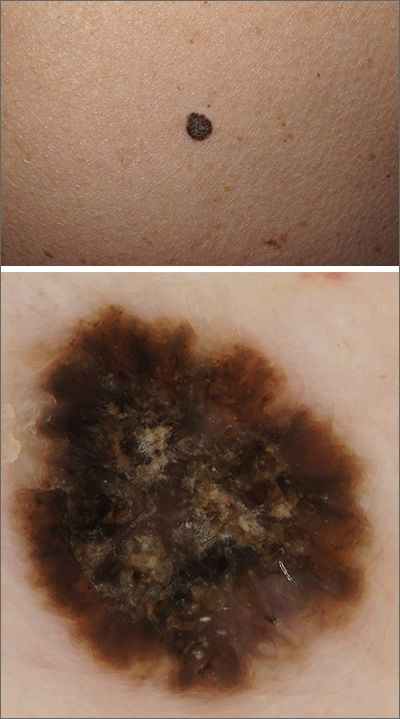

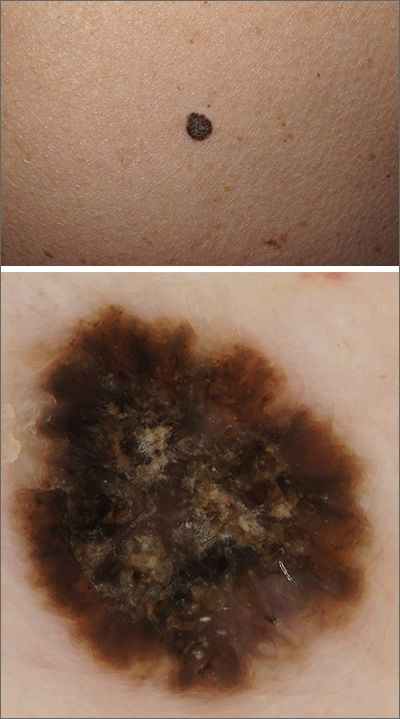

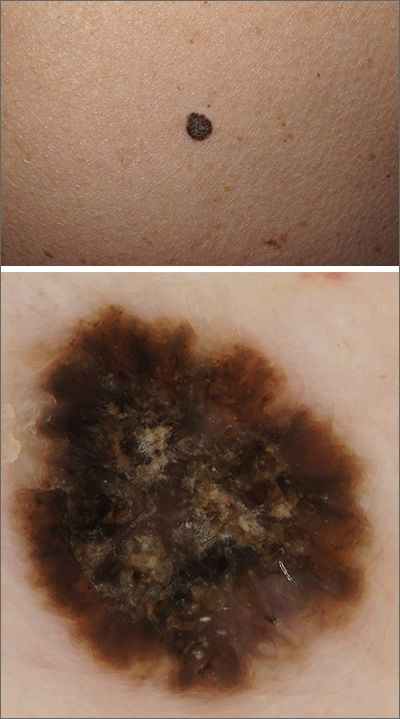

On physical exam, several small red subcutaneous nodules were present in the axilla and tender to palpation (FIGURE 1A). The patient also had comedonal acne on his back (FIGURE 1B). The patient’s body mass index was 31, and he was a nonsmoker.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Hidradenitis suppurativa

The characteristic location and morphology of the lesions, along with the chronicity and odor, were critical in arriving at a diagnosis of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS).

HS is a chronic, inflammatory skin condition that normally manifests in areas of apocrine sweat glands, including the axilla, groin, and perianal, perineal, and inframammary locations.1 It begins when an abnormal hair follicle gets occluded and ruptures, spilling keratin and bacteria into the dermis. An inflammatory response can ensue with surrounding neutrophils and lymphocytes, which leads to abscess formation and destruction of the pilosebaceous unit. Sinus tracts form between the lesions, and a cycle of scarring, fistulas, and contractures can occur.

In this case, the comedones from acne conglobata on the patient’s back indicated a more global follicular occlusion disorder. The characteristic triad is hidradenitis suppurativa, acne conglobata, and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp—of which the patient had 2.

Other potential causes of the pathology include abnormal secretion of apocrine glands, abnormal antimicrobial peptides, deficient numbers of sebaceous glands, and abnormal invaginations of the epidermis.2 Increased levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha and other cytokines have been detected in HS lesions and are a potential target for therapy.

The prevalence of HS in the United States is approximately 0.1%.3 The condition typically begins between the ages of 18 and 39 years. The ratio of women to men affected by the condition is 3:1.2 There is no evident racial or ethnic predilection. There is an association with diabetes and Crohn disease.3 Obesity and smoking are risk factors.1

Continue to: The differential includes an array of common skin conditions

The differential includes an array of common skin conditions

The differential diagnosis in this case included carbuncles, cysts, acne, and abscesses.

A furuncle or carbuncle can result from an infection of hair follicles that can manifest as individual (furuncle) or clusters of (carbuncle) red, painful boils. They form on parts of the skin where hair grows, including the face, neck, armpits, shoulders, and buttocks. They respond well to treatment with antibiotics and incision and drainage. They can be recurrent but usually don’t cluster together in apocrine-rich areas, as seen with HS.

Epidermal inclusion cysts are keratin-filled inclusion cysts with epithelial-lined cyst walls. The cysts are subcutaneous and occasionally more superficial. They can occur almost anywhere but are most often found on the back, scalp, neck, face, and chest. They are usually solitary; however, when there are multiple cysts, they are not linked by sinus tracts as found in HS.

Inflammatory acne lesions tend to form on the face, neck, back, chest, and shoulders, while HS lesions appear most often in apocrine-rich intertriginous areas.

Skin abscesses are local deep infections of the skin caused by bacterial pathogens. The most common agent is Staphylococcus aureus (frequently methicillin resistant). Injection drug use and immunosuppression are risk factors. Although bacteria do not cause HS lesions, bacteria can exacerbate HS through colonization.

Continue to: No lab test needed to diagnosis hidradenitis suppurativa

No lab test needed to diagnose hidradenitis suppurativa

Diagnosis of HS is largely clinical and based on a patient’s history and physical exam findings.2 No specific laboratory test is needed.

Although the patient in this case did have comedonal acne on his back, the lesions that prompted his visit were in an apocrine-rich area, were recurrent, and broke open on their own to release foul-smelling contents—all typical characteristics of HS.

Treatment depends on the severity of the condition

There are 3 stages of HS: Hurley stage I involves abscess formation without tracts or scars. Hurley stage II involves recurrent abscesses with sinus tracts and scarring. Hurley stage III has diffuse involvement with multiple interconnected sinus tracts and abscesses across an entire area.2 Our patient fits into Hurley stage III.

Evidence-based treatment of mild disease (Hurley stage I) includes topical clindamycin 1% solution/gel bid or doxycycline 100 mg bid for widespread disease (Hurley stage II or resistant stage I).2 Chlorhexidine and benzoyl peroxide washes are also often recommended.3 If a patient does not respond to this treatment or the condition is moderate to severe, then clindamycin 300 po bid (with or without rifampin 600/d po) for 10 weeks should be considered.4,5 In a randomized placebo-controlled trial that compared the efficacy of oral clindamycin vs clindamycin plus rifampin in patients with HS, both therapeutic options were statistically equivalent.5 One small, randomized controlled study of patients with mild-to-moderate HS showed that tetracycline 500 mg bid for 3 months resulted in fewer abscesses and nodules but was not superior to topical clindamycin.3

If the patient doesn’t show improvement (Hurley stage III), then adalimumab is an option, as follows: 160 mg subcutaneously at Week 0, 80 mg at Week 2, and then 40 mg weekly, if needed.4 Adalimumab is currently the only FDA-approved treatment for HS. Infliximab by IV infusion can be effective in improving pain, disease severity, and quality of life in patients with moderate-to-severe HS.3 This patient was also a candidate for treatment with systemic retinoids (isotretinoin or acitretin), which could have helped both the HS and the acne conglobata.

Continue to: Intralesional steroid injectiosn with triamcinolone

Intralesional steroid injections with triamcinolone 10 mg/mL can reduce local pain and inflammation rapidly. Pain management is also critical, as HS is painful. First-line therapy includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, atypical anticonvulsants, and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.2 Opiate analgesics may be needed for breakthrough pain in patients with severe disease. Avoiding tight clothing, harsh products, and adhesive dressings, as well as using clear petroleum jelly, can prevent skin trauma and help with healing. Weight loss and smoking cessation are also associated with better outcomes.6,7

If medical management fails …

If there is no improvement with medical management, it may be time to consider local procedures such as unroofing/deroofing, punch debridement, skin-tissue-sparing excision with electrosurgical peeling, and laser excision. Incision and drainage may be necessary for acutely inflamed, painful abscesses but should not be routinely performed because lesions can recur.3

Referral to a plastic surgeon is necessary when patients are considering wide excisions of largely affected areas. Even when surgical excisions are performed, medical treatment is needed to prevent new lesions and recurrences.

Our patient was treated initially with oral doxycycline 100 mg bid and intralesional triamcinolone (10 mg/mL) in the most tender lesions. He was also provided with a prescription for ibuprofen 800 mg tid to be taken with meals. The family physician encouraged the patient to lose weight. The patient derived some benefit from treatment but continued to experience new painful lesions.

The physician prescribed oral clindamycin 300 mg bid at a follow-up visit to replace the oral doxycycline. When this failed, the patient was sent for labs to determine if he would be a candidate for adalimumab. When the screening labs were normal, a prescription for adalimumab was provided: 160 mg subcutaneously at Week 0, 80 mg at Week 2, and then 40 mg weekly.4

1. Napolitano M, Megna M, Timoshchuk EA, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: from pathogenesis to diagnosis and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:105-115. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S111019

2. Ballard K, Shuman VL. Hidradenitis Suppurativa. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

3. Wipperman J, Bragg DA, Litzner B. Hidradenitis suppurativa: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:562-569.

4. Alikhan A, Lymch PJ, Eisen DB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a comprehensive review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:539-561. doi:10.10126/j.jaad.2008.11.911

5. Caro RDC, Cannizzaro MV, Botti E, et al. Clindamycin versus clindamycin plus rifampicin in hidradenitis suppurativa treatment: clinical and ultrasound observations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1314-1321. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.035

6. Hendricks AJ, Hirt PA, Sekhon S, et al. Non-pharmacologic approaches for hidradenitis suppurativa - a systematic review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:11-18. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1621981

7. Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part I: diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:76-90. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.067

A 30-year-old man presented to the clinic with a complaint of small painful lumps in his armpit. He stated that he initially experienced some itching and discomfort, but after a while he noticed some red, tender, swollen areas. He also mentioned an odorous yellow fluid that would sometimes drain from the lumps. Since first noticing them 2 years earlier, he reported that the nodules had disappeared and reappeared on their own several times.

On physical exam, several small red subcutaneous nodules were present in the axilla and tender to palpation (FIGURE 1A). The patient also had comedonal acne on his back (FIGURE 1B). The patient’s body mass index was 31, and he was a nonsmoker.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Hidradenitis suppurativa

The characteristic location and morphology of the lesions, along with the chronicity and odor, were critical in arriving at a diagnosis of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS).

HS is a chronic, inflammatory skin condition that normally manifests in areas of apocrine sweat glands, including the axilla, groin, and perianal, perineal, and inframammary locations.1 It begins when an abnormal hair follicle gets occluded and ruptures, spilling keratin and bacteria into the dermis. An inflammatory response can ensue with surrounding neutrophils and lymphocytes, which leads to abscess formation and destruction of the pilosebaceous unit. Sinus tracts form between the lesions, and a cycle of scarring, fistulas, and contractures can occur.

In this case, the comedones from acne conglobata on the patient’s back indicated a more global follicular occlusion disorder. The characteristic triad is hidradenitis suppurativa, acne conglobata, and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp—of which the patient had 2.

Other potential causes of the pathology include abnormal secretion of apocrine glands, abnormal antimicrobial peptides, deficient numbers of sebaceous glands, and abnormal invaginations of the epidermis.2 Increased levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha and other cytokines have been detected in HS lesions and are a potential target for therapy.

The prevalence of HS in the United States is approximately 0.1%.3 The condition typically begins between the ages of 18 and 39 years. The ratio of women to men affected by the condition is 3:1.2 There is no evident racial or ethnic predilection. There is an association with diabetes and Crohn disease.3 Obesity and smoking are risk factors.1

Continue to: The differential includes an array of common skin conditions

The differential includes an array of common skin conditions

The differential diagnosis in this case included carbuncles, cysts, acne, and abscesses.

A furuncle or carbuncle can result from an infection of hair follicles that can manifest as individual (furuncle) or clusters of (carbuncle) red, painful boils. They form on parts of the skin where hair grows, including the face, neck, armpits, shoulders, and buttocks. They respond well to treatment with antibiotics and incision and drainage. They can be recurrent but usually don’t cluster together in apocrine-rich areas, as seen with HS.

Epidermal inclusion cysts are keratin-filled inclusion cysts with epithelial-lined cyst walls. The cysts are subcutaneous and occasionally more superficial. They can occur almost anywhere but are most often found on the back, scalp, neck, face, and chest. They are usually solitary; however, when there are multiple cysts, they are not linked by sinus tracts as found in HS.

Inflammatory acne lesions tend to form on the face, neck, back, chest, and shoulders, while HS lesions appear most often in apocrine-rich intertriginous areas.

Skin abscesses are local deep infections of the skin caused by bacterial pathogens. The most common agent is Staphylococcus aureus (frequently methicillin resistant). Injection drug use and immunosuppression are risk factors. Although bacteria do not cause HS lesions, bacteria can exacerbate HS through colonization.

Continue to: No lab test needed to diagnosis hidradenitis suppurativa

No lab test needed to diagnose hidradenitis suppurativa

Diagnosis of HS is largely clinical and based on a patient’s history and physical exam findings.2 No specific laboratory test is needed.

Although the patient in this case did have comedonal acne on his back, the lesions that prompted his visit were in an apocrine-rich area, were recurrent, and broke open on their own to release foul-smelling contents—all typical characteristics of HS.

Treatment depends on the severity of the condition

There are 3 stages of HS: Hurley stage I involves abscess formation without tracts or scars. Hurley stage II involves recurrent abscesses with sinus tracts and scarring. Hurley stage III has diffuse involvement with multiple interconnected sinus tracts and abscesses across an entire area.2 Our patient fits into Hurley stage III.

Evidence-based treatment of mild disease (Hurley stage I) includes topical clindamycin 1% solution/gel bid or doxycycline 100 mg bid for widespread disease (Hurley stage II or resistant stage I).2 Chlorhexidine and benzoyl peroxide washes are also often recommended.3 If a patient does not respond to this treatment or the condition is moderate to severe, then clindamycin 300 po bid (with or without rifampin 600/d po) for 10 weeks should be considered.4,5 In a randomized placebo-controlled trial that compared the efficacy of oral clindamycin vs clindamycin plus rifampin in patients with HS, both therapeutic options were statistically equivalent.5 One small, randomized controlled study of patients with mild-to-moderate HS showed that tetracycline 500 mg bid for 3 months resulted in fewer abscesses and nodules but was not superior to topical clindamycin.3

If the patient doesn’t show improvement (Hurley stage III), then adalimumab is an option, as follows: 160 mg subcutaneously at Week 0, 80 mg at Week 2, and then 40 mg weekly, if needed.4 Adalimumab is currently the only FDA-approved treatment for HS. Infliximab by IV infusion can be effective in improving pain, disease severity, and quality of life in patients with moderate-to-severe HS.3 This patient was also a candidate for treatment with systemic retinoids (isotretinoin or acitretin), which could have helped both the HS and the acne conglobata.

Continue to: Intralesional steroid injectiosn with triamcinolone

Intralesional steroid injections with triamcinolone 10 mg/mL can reduce local pain and inflammation rapidly. Pain management is also critical, as HS is painful. First-line therapy includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, atypical anticonvulsants, and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.2 Opiate analgesics may be needed for breakthrough pain in patients with severe disease. Avoiding tight clothing, harsh products, and adhesive dressings, as well as using clear petroleum jelly, can prevent skin trauma and help with healing. Weight loss and smoking cessation are also associated with better outcomes.6,7

If medical management fails …

If there is no improvement with medical management, it may be time to consider local procedures such as unroofing/deroofing, punch debridement, skin-tissue-sparing excision with electrosurgical peeling, and laser excision. Incision and drainage may be necessary for acutely inflamed, painful abscesses but should not be routinely performed because lesions can recur.3

Referral to a plastic surgeon is necessary when patients are considering wide excisions of largely affected areas. Even when surgical excisions are performed, medical treatment is needed to prevent new lesions and recurrences.

Our patient was treated initially with oral doxycycline 100 mg bid and intralesional triamcinolone (10 mg/mL) in the most tender lesions. He was also provided with a prescription for ibuprofen 800 mg tid to be taken with meals. The family physician encouraged the patient to lose weight. The patient derived some benefit from treatment but continued to experience new painful lesions.

The physician prescribed oral clindamycin 300 mg bid at a follow-up visit to replace the oral doxycycline. When this failed, the patient was sent for labs to determine if he would be a candidate for adalimumab. When the screening labs were normal, a prescription for adalimumab was provided: 160 mg subcutaneously at Week 0, 80 mg at Week 2, and then 40 mg weekly.4

A 30-year-old man presented to the clinic with a complaint of small painful lumps in his armpit. He stated that he initially experienced some itching and discomfort, but after a while he noticed some red, tender, swollen areas. He also mentioned an odorous yellow fluid that would sometimes drain from the lumps. Since first noticing them 2 years earlier, he reported that the nodules had disappeared and reappeared on their own several times.

On physical exam, several small red subcutaneous nodules were present in the axilla and tender to palpation (FIGURE 1A). The patient also had comedonal acne on his back (FIGURE 1B). The patient’s body mass index was 31, and he was a nonsmoker.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Hidradenitis suppurativa

The characteristic location and morphology of the lesions, along with the chronicity and odor, were critical in arriving at a diagnosis of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS).

HS is a chronic, inflammatory skin condition that normally manifests in areas of apocrine sweat glands, including the axilla, groin, and perianal, perineal, and inframammary locations.1 It begins when an abnormal hair follicle gets occluded and ruptures, spilling keratin and bacteria into the dermis. An inflammatory response can ensue with surrounding neutrophils and lymphocytes, which leads to abscess formation and destruction of the pilosebaceous unit. Sinus tracts form between the lesions, and a cycle of scarring, fistulas, and contractures can occur.

In this case, the comedones from acne conglobata on the patient’s back indicated a more global follicular occlusion disorder. The characteristic triad is hidradenitis suppurativa, acne conglobata, and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp—of which the patient had 2.

Other potential causes of the pathology include abnormal secretion of apocrine glands, abnormal antimicrobial peptides, deficient numbers of sebaceous glands, and abnormal invaginations of the epidermis.2 Increased levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha and other cytokines have been detected in HS lesions and are a potential target for therapy.

The prevalence of HS in the United States is approximately 0.1%.3 The condition typically begins between the ages of 18 and 39 years. The ratio of women to men affected by the condition is 3:1.2 There is no evident racial or ethnic predilection. There is an association with diabetes and Crohn disease.3 Obesity and smoking are risk factors.1

Continue to: The differential includes an array of common skin conditions

The differential includes an array of common skin conditions

The differential diagnosis in this case included carbuncles, cysts, acne, and abscesses.

A furuncle or carbuncle can result from an infection of hair follicles that can manifest as individual (furuncle) or clusters of (carbuncle) red, painful boils. They form on parts of the skin where hair grows, including the face, neck, armpits, shoulders, and buttocks. They respond well to treatment with antibiotics and incision and drainage. They can be recurrent but usually don’t cluster together in apocrine-rich areas, as seen with HS.

Epidermal inclusion cysts are keratin-filled inclusion cysts with epithelial-lined cyst walls. The cysts are subcutaneous and occasionally more superficial. They can occur almost anywhere but are most often found on the back, scalp, neck, face, and chest. They are usually solitary; however, when there are multiple cysts, they are not linked by sinus tracts as found in HS.

Inflammatory acne lesions tend to form on the face, neck, back, chest, and shoulders, while HS lesions appear most often in apocrine-rich intertriginous areas.

Skin abscesses are local deep infections of the skin caused by bacterial pathogens. The most common agent is Staphylococcus aureus (frequently methicillin resistant). Injection drug use and immunosuppression are risk factors. Although bacteria do not cause HS lesions, bacteria can exacerbate HS through colonization.

Continue to: No lab test needed to diagnosis hidradenitis suppurativa

No lab test needed to diagnose hidradenitis suppurativa

Diagnosis of HS is largely clinical and based on a patient’s history and physical exam findings.2 No specific laboratory test is needed.

Although the patient in this case did have comedonal acne on his back, the lesions that prompted his visit were in an apocrine-rich area, were recurrent, and broke open on their own to release foul-smelling contents—all typical characteristics of HS.

Treatment depends on the severity of the condition

There are 3 stages of HS: Hurley stage I involves abscess formation without tracts or scars. Hurley stage II involves recurrent abscesses with sinus tracts and scarring. Hurley stage III has diffuse involvement with multiple interconnected sinus tracts and abscesses across an entire area.2 Our patient fits into Hurley stage III.

Evidence-based treatment of mild disease (Hurley stage I) includes topical clindamycin 1% solution/gel bid or doxycycline 100 mg bid for widespread disease (Hurley stage II or resistant stage I).2 Chlorhexidine and benzoyl peroxide washes are also often recommended.3 If a patient does not respond to this treatment or the condition is moderate to severe, then clindamycin 300 po bid (with or without rifampin 600/d po) for 10 weeks should be considered.4,5 In a randomized placebo-controlled trial that compared the efficacy of oral clindamycin vs clindamycin plus rifampin in patients with HS, both therapeutic options were statistically equivalent.5 One small, randomized controlled study of patients with mild-to-moderate HS showed that tetracycline 500 mg bid for 3 months resulted in fewer abscesses and nodules but was not superior to topical clindamycin.3

If the patient doesn’t show improvement (Hurley stage III), then adalimumab is an option, as follows: 160 mg subcutaneously at Week 0, 80 mg at Week 2, and then 40 mg weekly, if needed.4 Adalimumab is currently the only FDA-approved treatment for HS. Infliximab by IV infusion can be effective in improving pain, disease severity, and quality of life in patients with moderate-to-severe HS.3 This patient was also a candidate for treatment with systemic retinoids (isotretinoin or acitretin), which could have helped both the HS and the acne conglobata.

Continue to: Intralesional steroid injectiosn with triamcinolone

Intralesional steroid injections with triamcinolone 10 mg/mL can reduce local pain and inflammation rapidly. Pain management is also critical, as HS is painful. First-line therapy includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, atypical anticonvulsants, and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.2 Opiate analgesics may be needed for breakthrough pain in patients with severe disease. Avoiding tight clothing, harsh products, and adhesive dressings, as well as using clear petroleum jelly, can prevent skin trauma and help with healing. Weight loss and smoking cessation are also associated with better outcomes.6,7

If medical management fails …

If there is no improvement with medical management, it may be time to consider local procedures such as unroofing/deroofing, punch debridement, skin-tissue-sparing excision with electrosurgical peeling, and laser excision. Incision and drainage may be necessary for acutely inflamed, painful abscesses but should not be routinely performed because lesions can recur.3

Referral to a plastic surgeon is necessary when patients are considering wide excisions of largely affected areas. Even when surgical excisions are performed, medical treatment is needed to prevent new lesions and recurrences.

Our patient was treated initially with oral doxycycline 100 mg bid and intralesional triamcinolone (10 mg/mL) in the most tender lesions. He was also provided with a prescription for ibuprofen 800 mg tid to be taken with meals. The family physician encouraged the patient to lose weight. The patient derived some benefit from treatment but continued to experience new painful lesions.

The physician prescribed oral clindamycin 300 mg bid at a follow-up visit to replace the oral doxycycline. When this failed, the patient was sent for labs to determine if he would be a candidate for adalimumab. When the screening labs were normal, a prescription for adalimumab was provided: 160 mg subcutaneously at Week 0, 80 mg at Week 2, and then 40 mg weekly.4

1. Napolitano M, Megna M, Timoshchuk EA, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: from pathogenesis to diagnosis and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:105-115. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S111019

2. Ballard K, Shuman VL. Hidradenitis Suppurativa. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

3. Wipperman J, Bragg DA, Litzner B. Hidradenitis suppurativa: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:562-569.

4. Alikhan A, Lymch PJ, Eisen DB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a comprehensive review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:539-561. doi:10.10126/j.jaad.2008.11.911

5. Caro RDC, Cannizzaro MV, Botti E, et al. Clindamycin versus clindamycin plus rifampicin in hidradenitis suppurativa treatment: clinical and ultrasound observations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1314-1321. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.035

6. Hendricks AJ, Hirt PA, Sekhon S, et al. Non-pharmacologic approaches for hidradenitis suppurativa - a systematic review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:11-18. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1621981

7. Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part I: diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:76-90. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.067

1. Napolitano M, Megna M, Timoshchuk EA, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: from pathogenesis to diagnosis and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:105-115. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S111019

2. Ballard K, Shuman VL. Hidradenitis Suppurativa. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

3. Wipperman J, Bragg DA, Litzner B. Hidradenitis suppurativa: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:562-569.

4. Alikhan A, Lymch PJ, Eisen DB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a comprehensive review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:539-561. doi:10.10126/j.jaad.2008.11.911

5. Caro RDC, Cannizzaro MV, Botti E, et al. Clindamycin versus clindamycin plus rifampicin in hidradenitis suppurativa treatment: clinical and ultrasound observations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1314-1321. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.035

6. Hendricks AJ, Hirt PA, Sekhon S, et al. Non-pharmacologic approaches for hidradenitis suppurativa - a systematic review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:11-18. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1621981

7. Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part I: diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:76-90. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.067

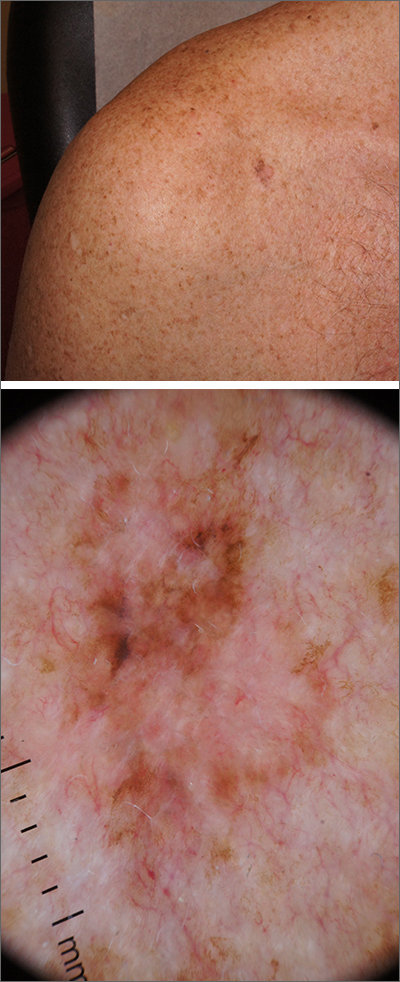

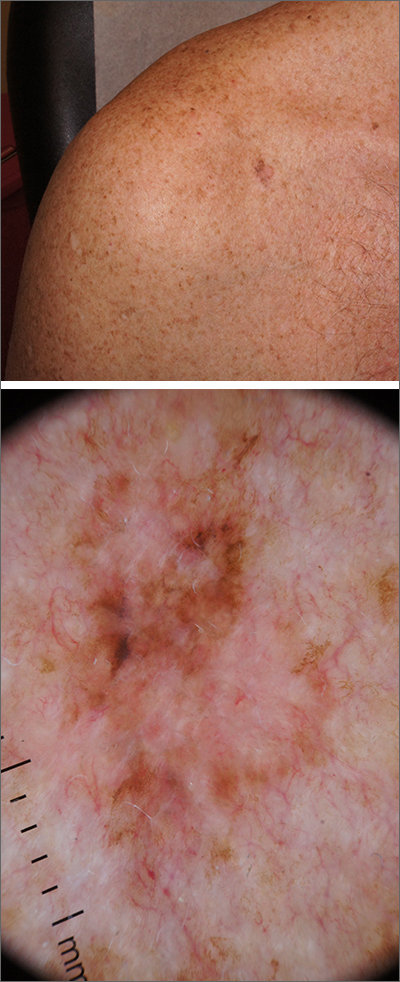

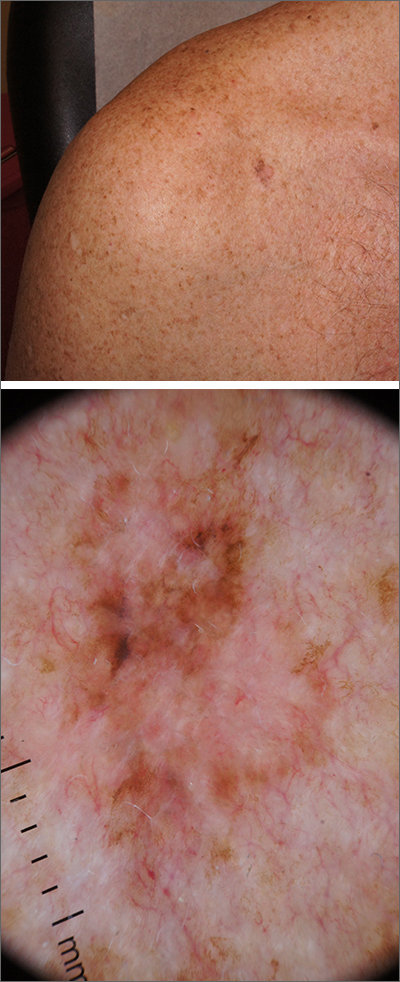

Itchy vesicles

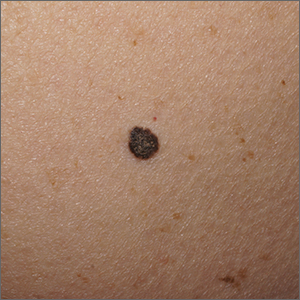

The patient’s history of celiac disease and the presence of vesicular lesions affecting primarily extensor surfaces pointed to a diagnosis of dermatitis herpetiformis (DH).

DH is an autoimmune skin condition that is associated with gluten sensitivity. It is more frequent in individuals of northern European heritage.1

The lesions associated with DH are intensely pruritic grouped papules, vesicles, and tense blisters that appear more commonly on extensor areas of the lower limbs, elbows, buttocks, and sacral region. Involvement of the oral mucosa is rare and not all patients with DH experience the intestinal symptoms of gluten sensitivity.

Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin is the gold standard to confirm the diagnosis. Histology of the lesions is also performed, but findings may vary depending on the age of the lesion. Additionally, serology can help to confirm the diagnosis. Both tissue and epidermal transglutaminase antibodies are often present in the serum but may be negative if the patient is following a gluten-free diet. In this case, biopsy was not ordered because the patient already had a biopsy-confirmed diagnosis of celiac disease and a classic presentation of lesions.

Treatment of DH consists of a strict gluten-free diet and dapsone as first-line pharmacologic therapy. Typically, dapsone is started at doses of 25 to 50 mg daily and increased, as needed and tolerated, to 100 to 200 mg per day. Improvement is usually seen within 2 days of treatment initiation. Dapsone has multiple potential adverse effects; the most common is hemolysis. Since individuals with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency can develop severe hemolysis if treated with dapsone, it is necessary to screen for this condition prior to initiation of treatment. A complete blood count and liver and renal function testing are typically done before, and during, treatment with dapsone.1

This patient had normal levels of G6PD and his screening labs were also normal. He was started on dapsone orally 25 mg/d and follow-up was pending.

Image courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Marcella Colom, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Mendes FBR, Hissa-Elian A, de Abreu MAMM, et al. Review: dermatitis herpetiformis. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:594-599. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20131775

The patient’s history of celiac disease and the presence of vesicular lesions affecting primarily extensor surfaces pointed to a diagnosis of dermatitis herpetiformis (DH).

DH is an autoimmune skin condition that is associated with gluten sensitivity. It is more frequent in individuals of northern European heritage.1

The lesions associated with DH are intensely pruritic grouped papules, vesicles, and tense blisters that appear more commonly on extensor areas of the lower limbs, elbows, buttocks, and sacral region. Involvement of the oral mucosa is rare and not all patients with DH experience the intestinal symptoms of gluten sensitivity.

Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin is the gold standard to confirm the diagnosis. Histology of the lesions is also performed, but findings may vary depending on the age of the lesion. Additionally, serology can help to confirm the diagnosis. Both tissue and epidermal transglutaminase antibodies are often present in the serum but may be negative if the patient is following a gluten-free diet. In this case, biopsy was not ordered because the patient already had a biopsy-confirmed diagnosis of celiac disease and a classic presentation of lesions.

Treatment of DH consists of a strict gluten-free diet and dapsone as first-line pharmacologic therapy. Typically, dapsone is started at doses of 25 to 50 mg daily and increased, as needed and tolerated, to 100 to 200 mg per day. Improvement is usually seen within 2 days of treatment initiation. Dapsone has multiple potential adverse effects; the most common is hemolysis. Since individuals with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency can develop severe hemolysis if treated with dapsone, it is necessary to screen for this condition prior to initiation of treatment. A complete blood count and liver and renal function testing are typically done before, and during, treatment with dapsone.1

This patient had normal levels of G6PD and his screening labs were also normal. He was started on dapsone orally 25 mg/d and follow-up was pending.

Image courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Marcella Colom, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

The patient’s history of celiac disease and the presence of vesicular lesions affecting primarily extensor surfaces pointed to a diagnosis of dermatitis herpetiformis (DH).

DH is an autoimmune skin condition that is associated with gluten sensitivity. It is more frequent in individuals of northern European heritage.1

The lesions associated with DH are intensely pruritic grouped papules, vesicles, and tense blisters that appear more commonly on extensor areas of the lower limbs, elbows, buttocks, and sacral region. Involvement of the oral mucosa is rare and not all patients with DH experience the intestinal symptoms of gluten sensitivity.

Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin is the gold standard to confirm the diagnosis. Histology of the lesions is also performed, but findings may vary depending on the age of the lesion. Additionally, serology can help to confirm the diagnosis. Both tissue and epidermal transglutaminase antibodies are often present in the serum but may be negative if the patient is following a gluten-free diet. In this case, biopsy was not ordered because the patient already had a biopsy-confirmed diagnosis of celiac disease and a classic presentation of lesions.

Treatment of DH consists of a strict gluten-free diet and dapsone as first-line pharmacologic therapy. Typically, dapsone is started at doses of 25 to 50 mg daily and increased, as needed and tolerated, to 100 to 200 mg per day. Improvement is usually seen within 2 days of treatment initiation. Dapsone has multiple potential adverse effects; the most common is hemolysis. Since individuals with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency can develop severe hemolysis if treated with dapsone, it is necessary to screen for this condition prior to initiation of treatment. A complete blood count and liver and renal function testing are typically done before, and during, treatment with dapsone.1

This patient had normal levels of G6PD and his screening labs were also normal. He was started on dapsone orally 25 mg/d and follow-up was pending.

Image courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Marcella Colom, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Mendes FBR, Hissa-Elian A, de Abreu MAMM, et al. Review: dermatitis herpetiformis. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:594-599. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20131775

1. Mendes FBR, Hissa-Elian A, de Abreu MAMM, et al. Review: dermatitis herpetiformis. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:594-599. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20131775

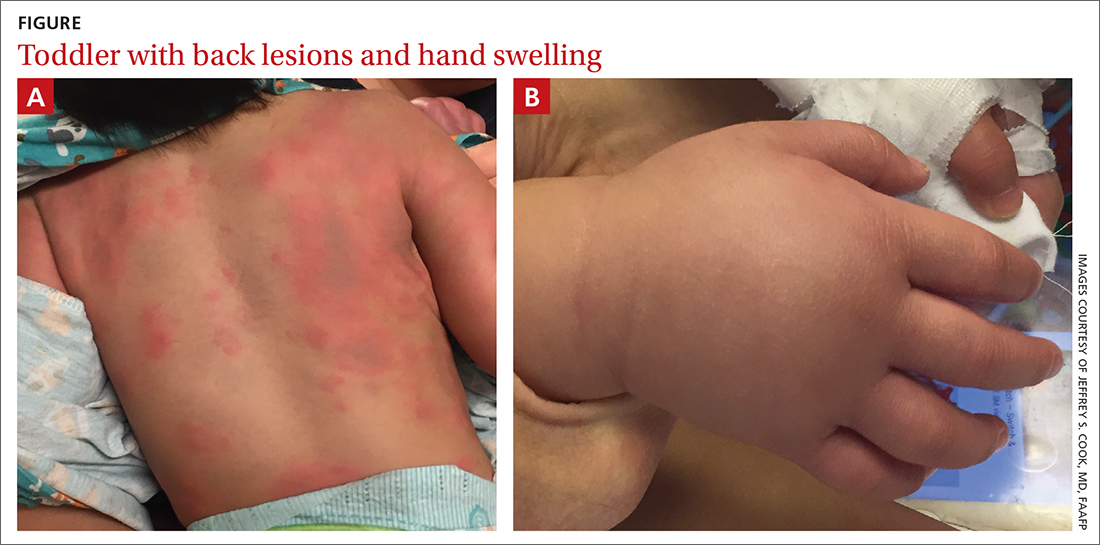

Infant with edematous, erythematous toe

History, presentation, and clinical suspicion led to the diagnosis of hair tourniquet syndrome.

Hair tourniquet syndrome was first described in 1612 by French surgeon Jacques Guillemeau.1 It typically occurs in infants when a long hair gets tightly wrapped around tissue. It most commonly affects the digits, but the penis, labia, or clitoris may also be involved. If left untreated, this condition may lead to serious complications including ischemia and necrosis of the site, and more rarely, bone erosion.

Clinicians who work with children should be aware of this condition, as early diagnosis and treatment can prevent adverse outcomes. Diagnosis requires a high-level of clinical suspicion. Use of ultrasound guidance to confirm the presence of a foreign body may aid in prompt diagnosis.2

Treatment involves release of the constricting hair(s). Hair removal cream may be used if the skin barrier is not compromised. If the hair is visible, clinicians may also attempt to remove it with tweezers. If the hair is deeply embedded within the skin, as in this case, surgical dissection may be necessary.

For this patient, the physician used local anesthesia and surgical loupes to remove 3 strands of hair from beneath newly epithelialized tissue. The digit immediately turned warm and pink. Two minutes later, capillary-refill time was normal. The mother was counseled that women often lose more hair than usual during the postpartum period, and that as a result, it’s important to watch for strands of hair that may get wrapped around the baby’s fingers or toes. Follow-up, 1 month later, showed a healed lesion on a well-perfused and nontender toe.

Image courtesy of Omar Osmani, MD, Spine and Orthopedic Center of New Mexico, Roswell. Text courtesy of Sabah Osmani, BA, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Zimmerman LN, Wagner AJ. Clitoral hair tourniquet: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Pediatr Res. 2015;1:1-2. doi: 10.23937/2469-5769/1510007

2. Sebaratnam DF, Hernández‐Martín Á. Utility of ultrasonography in hair-thread tourniquet syndrome. Pediatr Dermatolo. 2018;35:e138–e139. doi: 10.1111/pde.13400

History, presentation, and clinical suspicion led to the diagnosis of hair tourniquet syndrome.

Hair tourniquet syndrome was first described in 1612 by French surgeon Jacques Guillemeau.1 It typically occurs in infants when a long hair gets tightly wrapped around tissue. It most commonly affects the digits, but the penis, labia, or clitoris may also be involved. If left untreated, this condition may lead to serious complications including ischemia and necrosis of the site, and more rarely, bone erosion.

Clinicians who work with children should be aware of this condition, as early diagnosis and treatment can prevent adverse outcomes. Diagnosis requires a high-level of clinical suspicion. Use of ultrasound guidance to confirm the presence of a foreign body may aid in prompt diagnosis.2

Treatment involves release of the constricting hair(s). Hair removal cream may be used if the skin barrier is not compromised. If the hair is visible, clinicians may also attempt to remove it with tweezers. If the hair is deeply embedded within the skin, as in this case, surgical dissection may be necessary.

For this patient, the physician used local anesthesia and surgical loupes to remove 3 strands of hair from beneath newly epithelialized tissue. The digit immediately turned warm and pink. Two minutes later, capillary-refill time was normal. The mother was counseled that women often lose more hair than usual during the postpartum period, and that as a result, it’s important to watch for strands of hair that may get wrapped around the baby’s fingers or toes. Follow-up, 1 month later, showed a healed lesion on a well-perfused and nontender toe.

Image courtesy of Omar Osmani, MD, Spine and Orthopedic Center of New Mexico, Roswell. Text courtesy of Sabah Osmani, BA, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

History, presentation, and clinical suspicion led to the diagnosis of hair tourniquet syndrome.

Hair tourniquet syndrome was first described in 1612 by French surgeon Jacques Guillemeau.1 It typically occurs in infants when a long hair gets tightly wrapped around tissue. It most commonly affects the digits, but the penis, labia, or clitoris may also be involved. If left untreated, this condition may lead to serious complications including ischemia and necrosis of the site, and more rarely, bone erosion.

Clinicians who work with children should be aware of this condition, as early diagnosis and treatment can prevent adverse outcomes. Diagnosis requires a high-level of clinical suspicion. Use of ultrasound guidance to confirm the presence of a foreign body may aid in prompt diagnosis.2

Treatment involves release of the constricting hair(s). Hair removal cream may be used if the skin barrier is not compromised. If the hair is visible, clinicians may also attempt to remove it with tweezers. If the hair is deeply embedded within the skin, as in this case, surgical dissection may be necessary.

For this patient, the physician used local anesthesia and surgical loupes to remove 3 strands of hair from beneath newly epithelialized tissue. The digit immediately turned warm and pink. Two minutes later, capillary-refill time was normal. The mother was counseled that women often lose more hair than usual during the postpartum period, and that as a result, it’s important to watch for strands of hair that may get wrapped around the baby’s fingers or toes. Follow-up, 1 month later, showed a healed lesion on a well-perfused and nontender toe.

Image courtesy of Omar Osmani, MD, Spine and Orthopedic Center of New Mexico, Roswell. Text courtesy of Sabah Osmani, BA, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Zimmerman LN, Wagner AJ. Clitoral hair tourniquet: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Pediatr Res. 2015;1:1-2. doi: 10.23937/2469-5769/1510007

2. Sebaratnam DF, Hernández‐Martín Á. Utility of ultrasonography in hair-thread tourniquet syndrome. Pediatr Dermatolo. 2018;35:e138–e139. doi: 10.1111/pde.13400

1. Zimmerman LN, Wagner AJ. Clitoral hair tourniquet: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Pediatr Res. 2015;1:1-2. doi: 10.23937/2469-5769/1510007

2. Sebaratnam DF, Hernández‐Martín Á. Utility of ultrasonography in hair-thread tourniquet syndrome. Pediatr Dermatolo. 2018;35:e138–e139. doi: 10.1111/pde.13400

Pruritic blistering rash

This patient was given a diagnosis of linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD) based on biopsy results. (Biopsy is extremely helpful in differentiating bullous disorders.) A shave biopsy of 1 of the mid-chest 3-mm vesicles and a perilesional punch biopsy sent in Michel media showed linear deposition of IgA and IgG along the basement membrane zone and subepidermal blister with neutrophils and eosinophils. The IgA appeared stronger in the direct immunofluorescence study and there were numerous neutrophils on histology, which confirmed the diagnosis.

LABD is one of the less common blistering disorders. It has a bimodal distribution occurring mostly in adults around 60 years of age and a lower peak incidence in young children.1 It often manifests with an acute onset of tense vesicles and bullae. The lesions can be extremely pruritic and can appear on mucous membranes, normal skin, or inflamed skin. Lesion formation is often sudden and manifests in clusters with an erythematous base on the trunk, extensor extremities, buttocks, and face—especially the area in and around the mouth.1

LABD is diagnosed by linear deposits of IgA at the dermo-epidermal interface by direct immunofluorescence. The mechanism for lesion formation is still not well known. It can occur spontaneously or can be drug-induced. In many individuals with LABD (such as this one), the precipitating event for the disease is unknown.

It is important to differentiate LABD from other blistering diseases that can also affect the oral mucosa. Bullous pemphigoid has tense vesicles, as well, but often has a prodromal phase before lesions appear in a nonclustered pattern on the skin.2 Pemphigus vulgaris, which is also in the differential, is characterized by soft blisters and almost always includes the oral mucosa, which is usually where lesions first develop.

Dapsone is first-line therapy. However, due to the risk of hemolysis with dapsone treatment in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6DP) deficiency, the physician confirmed that the patient had normal levels of G6DP before starting the patient on dapsone 25 mg/d po. After starting dapsone, the patient reported unexplained syncopal episodes and falls and stopped the medication. (This was not an anticipated adverse effect.) The patient was then started on colchicine 0.6 mg orally tid. (Other second-line therapies include sulfapyridine and sulfamethoxypyridazine.1) Follow-up in 1 month was scheduled.

Image courtesy Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Riley Diehl, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque. Photo courtesy Daniel Stulberg, MD.

1. Hall III RP, Rao C. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Uptodate. Updated September 24, 2020. Accessed September 26, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/linear-iga-bullous-dermatosis#!

2. Leiferman K. Clinical features and diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid and mucous membrane pemphigoid. Uptodate. Updated June 30, 2021. Accessed September, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-features-and-diagnosis-of-bullous-pemphigoid-and-mucous-membrane-pemphigoid#!

This patient was given a diagnosis of linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD) based on biopsy results. (Biopsy is extremely helpful in differentiating bullous disorders.) A shave biopsy of 1 of the mid-chest 3-mm vesicles and a perilesional punch biopsy sent in Michel media showed linear deposition of IgA and IgG along the basement membrane zone and subepidermal blister with neutrophils and eosinophils. The IgA appeared stronger in the direct immunofluorescence study and there were numerous neutrophils on histology, which confirmed the diagnosis.