User login

Pigmentation on foot

The FP suspected that this was an acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM).

The FP considered the various ways to biopsy this lesion. Doing a biopsy of the whole lesion was neither practical, nor desirable, given that the lesion was >2 cm and located on the bottom of the patient’s foot. And while incomplete sampling could result in a false negative result, this lesion was so suspicious for melanoma that any well-performed biopsy would likely produce a diagnosis of melanoma. (Of course if melanoma was not diagnosable with partial sampling, a full excisional biopsy would be needed.)

The FP also debated doing a 6-mm punch biopsy vs a shave biopsy; his intent was to get below some of the deeper pigment. Incisional biopsy done as a small ellipse with suturing was also an option. It would also be the most time consuming.

The FP presented the biopsy options to the patient and explained that the shave biopsy would require a dressing and the punch biopsy would require sutures, which would need to be removed at the next visit. Both biopsy methods would likely cause the foot to be uncomfortable to walk on for several days.

The FP and patient decided to do a deep shave biopsy (saucerization). After administering local anesthesia with lidocaine and epinephrine, the FP performed a deep shave biopsy that included about 1 cm of the darkest and thickest portion of the suspected melanoma.

The biopsy results indicated that the patient had an acral lentiginous melanoma, which measured 0.7 mm at its deepest point in the biopsied portion. The patient was referred to Orthopedics for a wide excision and repair. A sentinel node biopsy was not needed because the lesion was less than 1 mm in depth and there was no ulceration. The surgery and healing time were challenging for the patient, but she did not lose her foot and has remained cancer free.

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1103-1111.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this was an acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM).

The FP considered the various ways to biopsy this lesion. Doing a biopsy of the whole lesion was neither practical, nor desirable, given that the lesion was >2 cm and located on the bottom of the patient’s foot. And while incomplete sampling could result in a false negative result, this lesion was so suspicious for melanoma that any well-performed biopsy would likely produce a diagnosis of melanoma. (Of course if melanoma was not diagnosable with partial sampling, a full excisional biopsy would be needed.)

The FP also debated doing a 6-mm punch biopsy vs a shave biopsy; his intent was to get below some of the deeper pigment. Incisional biopsy done as a small ellipse with suturing was also an option. It would also be the most time consuming.

The FP presented the biopsy options to the patient and explained that the shave biopsy would require a dressing and the punch biopsy would require sutures, which would need to be removed at the next visit. Both biopsy methods would likely cause the foot to be uncomfortable to walk on for several days.

The FP and patient decided to do a deep shave biopsy (saucerization). After administering local anesthesia with lidocaine and epinephrine, the FP performed a deep shave biopsy that included about 1 cm of the darkest and thickest portion of the suspected melanoma.

The biopsy results indicated that the patient had an acral lentiginous melanoma, which measured 0.7 mm at its deepest point in the biopsied portion. The patient was referred to Orthopedics for a wide excision and repair. A sentinel node biopsy was not needed because the lesion was less than 1 mm in depth and there was no ulceration. The surgery and healing time were challenging for the patient, but she did not lose her foot and has remained cancer free.

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1103-1111.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this was an acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM).

The FP considered the various ways to biopsy this lesion. Doing a biopsy of the whole lesion was neither practical, nor desirable, given that the lesion was >2 cm and located on the bottom of the patient’s foot. And while incomplete sampling could result in a false negative result, this lesion was so suspicious for melanoma that any well-performed biopsy would likely produce a diagnosis of melanoma. (Of course if melanoma was not diagnosable with partial sampling, a full excisional biopsy would be needed.)

The FP also debated doing a 6-mm punch biopsy vs a shave biopsy; his intent was to get below some of the deeper pigment. Incisional biopsy done as a small ellipse with suturing was also an option. It would also be the most time consuming.

The FP presented the biopsy options to the patient and explained that the shave biopsy would require a dressing and the punch biopsy would require sutures, which would need to be removed at the next visit. Both biopsy methods would likely cause the foot to be uncomfortable to walk on for several days.

The FP and patient decided to do a deep shave biopsy (saucerization). After administering local anesthesia with lidocaine and epinephrine, the FP performed a deep shave biopsy that included about 1 cm of the darkest and thickest portion of the suspected melanoma.

The biopsy results indicated that the patient had an acral lentiginous melanoma, which measured 0.7 mm at its deepest point in the biopsied portion. The patient was referred to Orthopedics for a wide excision and repair. A sentinel node biopsy was not needed because the lesion was less than 1 mm in depth and there was no ulceration. The surgery and healing time were challenging for the patient, but she did not lose her foot and has remained cancer free.

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1103-1111.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

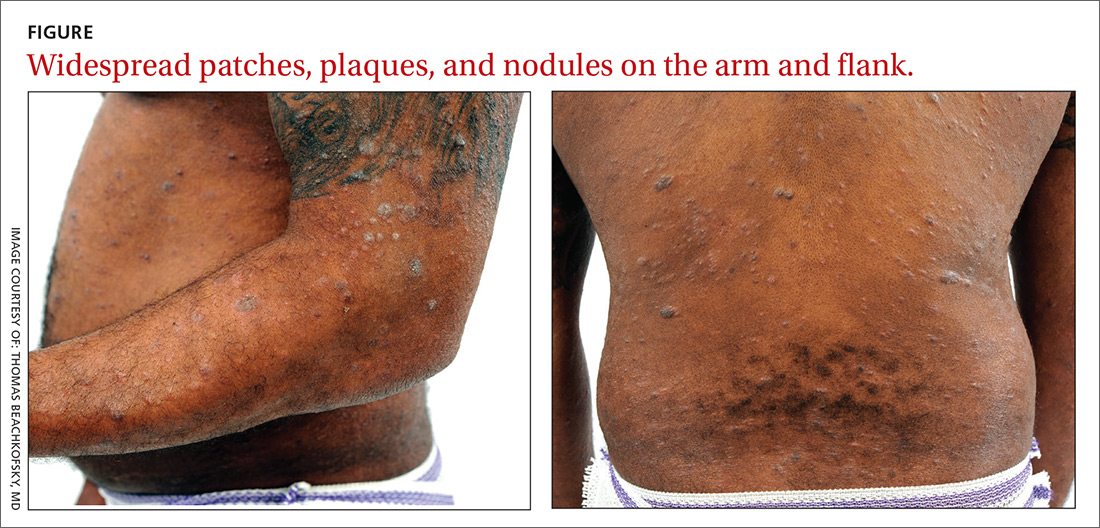

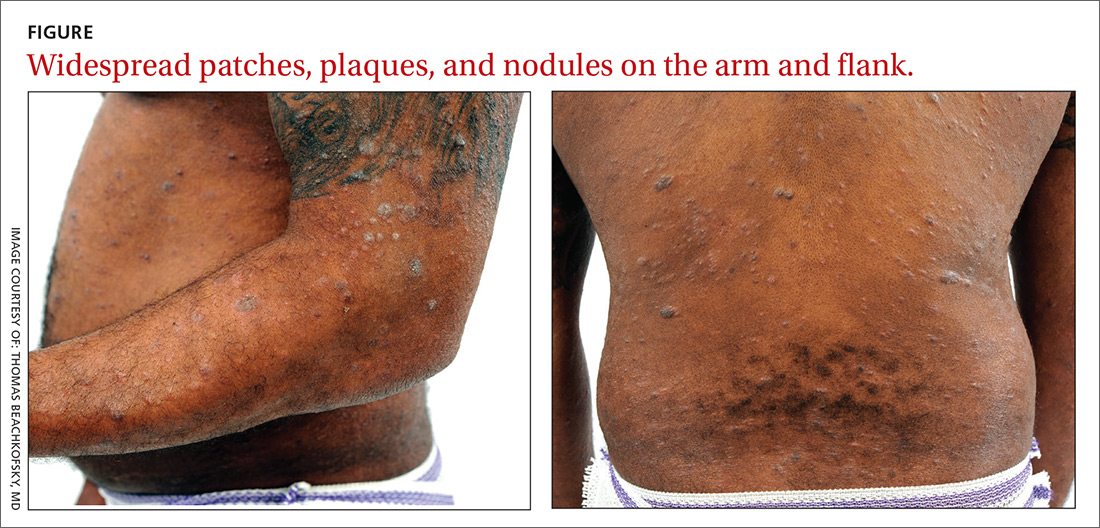

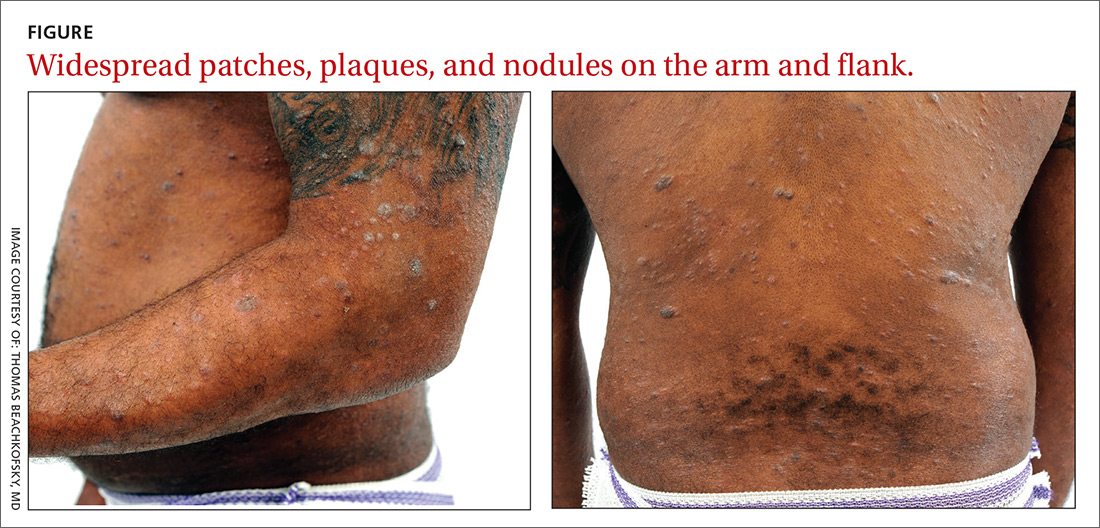

Nodules, tumors, and hyperpigmented patches

A 36-year-old African-American man presented to our clinic for evaluation of a chronic “rash” on his trunk, arms, and legs that had been present for 3 years. Empiric therapy for tinea corporis, nummular eczema, and confluent and reticulated papillomatosis had failed to improve his lesions.

Physical examination revealed a widespread skin eruption consisting of well-demarcated, hyperpigmented, scaly patches and plaques distributed throughout the patient’s trunk and extremities. Initial biopsies of the skin lesions (performed at an outside institution prior to current presentation) were nondiagnostic.

Over the next several months, the patient developed numerous cutaneous nodules and tumors within the background of his persistent patches and plaques (FIGURE). These nodules and tumors intermittently disappeared and recurred, seemingly independent of therapies including psoralen and ultraviolet A phototherapy (PUVA), interferon, and methotrexate.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: CD30+ transformed mycosis fungoides

Repeat biopsies ultimately confirmed a diagnosis of mycosis fungoides (MF), a primary cutaneous non-Hodgkin lymphoma of T-cell origin.

Lymphomas occurring in the skin without evidence of disease in other areas of the body at the time of diagnosis are referred to as primary cutaneous lymphomas. They are broadly divided by their cell of origin into cutaneous T-cell and cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Differentiating primary cutaneous lymphoma from systemic lymphomas with secondary skin involvement is an important distinction, as primary cutaneous lymphomas have different clinical courses and prognoses and require different treatments.1

MF is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), yet it remains an uncommon diagnosis as cutaneous lymphomas comprise only 3.9% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas.2 The CD30+ transformed variant identified in this patient is a rare subtype of MF that is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.3 Other types of CTCL include primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma, lymphomatoid papulosis, and adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, all of which can resemble MF clinically and are diagnosed by histopathology.

A nonspecific presentation

Patients with MF typically present with a complaint of chronic, slowly progressive skin lesions of various sizes and morphologies including scaly patches, plaques, and tumors, often in skin distributions that are not directly exposed to the sun (often referred to as a “bathing suit” distribution).4 Pruritus typically accompanies these skin lesions, and alopecia and poikiloderma are common findings. Patients with more advanced cases may present with generalized erythroderma. This finding should raise concern for progression to Sézary syndrome, a more aggressive type of CTCL that manifests with leukemic involvement of malignant T-cells matching the T-cell clones found in the skin.2

Alopecia is a common manifestation of MF that can be clinically indistinguishable from alopecia areata.5 While isolated alopecia is unlikely to be a consequence of MF, alopecia in the setting of widespread patches and plaques should raise suspicion for a diagnosis of MF.

Continue to: Diagnostic dilemma

Diagnostic dilemma: Condition mimics benign disorders

This case illustrates the diagnostic dilemma posed by MF due to its propensity to mimic more benign skin disorders, both clinically and histologically.2 One literature review of MF cases in which the diagnosis was not suspected clinically but was eventually confirmed histopathologically found that 25 unique dermatoses can be mimicked clinically by MF.6 The more common conditions that MF can be mistaken for are discussed below. In light of the diagnostic challenge posed by this multitude of morphologic presentations, referral to Dermatology for histopathologic evaluation is a reasonable next step when empiric treatment fails to improve symptoms of these common skin disorders.

Chronic atopic dermatitis (eczema) is characterized by dry skin and severe pruritis, usually associated with lichenified plaques and a history of atopic disease. The pruritic, scaly plaques typical of MF may be misdiagnosed as eczema; however, a distribution involving the “bathing suit” area is more suggestive of MF. Patients with atopic dermatitis are more likely to display a flexural distribution.2

Tinea corporis typically presents as annular, erythematous, pruritic, scaly patches or plaques that are similar to the scaling lesions of MF. Tinea corporis can be distinguished from MF via potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scrapings from an active lesion, which should demonstrate the segmented hyphae characteristic of this infection. If lesions of this type fail to respond to topical antifungal therapy, a skin biopsy may be warranted for further evaluation.

Nummular eczema, like tinea corporis, presents with round, coin-shaped patches that are highly pruritic and can be difficult to distinguish from the pruritic patches of MF. Unlike MF, however, nummular eczema typically is observed in patients with diffusely dry skin7; the lack of this finding should prompt consideration of alternative diagnoses, including MF.

Psoriasis classically presents with symmetrically distributed, well-demarcated plaques with prominent scaling that are usually asymptomatic, but may be associated with pruritis. Psoriatic plaques may be difficult to distinguish clinically from the plaques of MF, but their distribution may offer clues; psoriasis typically follows an extensor surface distribution, whereas MF is more commonly identified in a “bathing suit” or generalized distribution.4

Continue to: Tx based on disease extent, impact on quality of life

Tx based on disease extent, impact on quality of life

Staging of MF is the primary determinant of treatment and involves evaluation of skin, lymph node, viscera, and blood involvement. Early-stage MF has a favorable prognosis and can be effectively managed with skin-directed treatments. These include topical corticosteroids, topical nitrogen mustard agents, topical retinoids, and phototherapy (PUVA).8 Total skin electron beam therapy has been proven effective in the treatment of refractory and extensive MF, and local radiation therapy also is an effective treatment for isolated cutaneous tumors. Prolonged complete remissions of early-stage MF have been achieved using skin-directed treatments.8

In contrast, advanced MF often is treatment refractory and carries a poor prognosis. Systemic treatments such as interferon therapy, oral retinoids, extracorporeal photopheresis, and chemotherapy are added in patients with advanced disease after skin-directed therapy fails to adequately control tumor burden.

Our patient initially was treated with PUVA as well as 6 million U of interferon alfa-2B 3 times weekly, which he eventually elected to discontinue after 8 months because he wanted to father a child. His disease became more widespread after discontinuing these treatments despite interim therapy with clobetasol ointment .05%. His larger nodules and tumors were intermittently treated with local radiation with good response. Methotrexate 15 mg weekly was initiated following his decline after discontinuing PUVA and interferon treatment. Treatment with methotrexate resulted in an overall decrease in his tumor burden and several months of clinical stability.

Approximately 6 months after initiating methotrexate, his condition notably worsened. He developed generalized erythroderma, systemic symptoms including fever, chills, and unintentional 9.07-kg weight loss, in addition to new findings of palmoplantar keratoderma and nail dystrophy. In light of this systemic progression and concern for developing Sézary syndrome, extracorporeal photopheresis, bexarotene (an oral retinoid) 75 mg twice daily, and interferon alfa-2B 5 million U 3 times weekly were initiated. His condition continued to decline despite these therapies, culminating in a hospital admission for sepsis.

The patient recovered, and his regimen was changed to PUVA 3 times weekly in addition to treatment with intravenous brentuximab 1.8 mg/kg, a monoclonal antibody that targets CD30 receptors. Unfortunately, his condition continued to decline on this treatment regimen, which was subsequently abandoned in favor of chemotherapy with gemcitabine 1980 mg/250 mL normal saline. The patient was improving clinically with each cycle of gemcitabine and the plan was to transition him to extracorporeal photopheresis and bexarotene for maintenance therapy; however, the patient succumbed to his disease and passed away at the age of 37.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Banta, MD, PSC 103, Box 3613, APO, AE 09603 [email protected]

1. Whittaker S, Knobler R, Ortiz P, et al. Major achievements of the EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force (CLTF). EJC Suppl. 2012;10:46-50.

2. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part I. diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:205.e1-205.e16.

3. Kadin ME, Hughey LC, Wood GS. Large-cell transformation of mycosis fungoides-differential diagnosis with implications for clinical management: a consensus statement of the US Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:374-376.

4. Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, et al; International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma. Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1053-1063.

5. Bi MY, Curry JL, Christiano AM, et al. The spectrum of hair loss in patients with mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:53-63.

6. Zackheim HS, McCalmont TH. Mycosis fungoides: the great imitator. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:914-918.

7. Jiamton S, Tangjaturonrusamee C, Kulthanan K. Clinical features and aggravating factors in nummular eczema in Thais. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2013;31:36-42.

8. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:223.e1-223.e17.

A 36-year-old African-American man presented to our clinic for evaluation of a chronic “rash” on his trunk, arms, and legs that had been present for 3 years. Empiric therapy for tinea corporis, nummular eczema, and confluent and reticulated papillomatosis had failed to improve his lesions.

Physical examination revealed a widespread skin eruption consisting of well-demarcated, hyperpigmented, scaly patches and plaques distributed throughout the patient’s trunk and extremities. Initial biopsies of the skin lesions (performed at an outside institution prior to current presentation) were nondiagnostic.

Over the next several months, the patient developed numerous cutaneous nodules and tumors within the background of his persistent patches and plaques (FIGURE). These nodules and tumors intermittently disappeared and recurred, seemingly independent of therapies including psoralen and ultraviolet A phototherapy (PUVA), interferon, and methotrexate.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: CD30+ transformed mycosis fungoides

Repeat biopsies ultimately confirmed a diagnosis of mycosis fungoides (MF), a primary cutaneous non-Hodgkin lymphoma of T-cell origin.

Lymphomas occurring in the skin without evidence of disease in other areas of the body at the time of diagnosis are referred to as primary cutaneous lymphomas. They are broadly divided by their cell of origin into cutaneous T-cell and cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Differentiating primary cutaneous lymphoma from systemic lymphomas with secondary skin involvement is an important distinction, as primary cutaneous lymphomas have different clinical courses and prognoses and require different treatments.1

MF is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), yet it remains an uncommon diagnosis as cutaneous lymphomas comprise only 3.9% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas.2 The CD30+ transformed variant identified in this patient is a rare subtype of MF that is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.3 Other types of CTCL include primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma, lymphomatoid papulosis, and adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, all of which can resemble MF clinically and are diagnosed by histopathology.

A nonspecific presentation

Patients with MF typically present with a complaint of chronic, slowly progressive skin lesions of various sizes and morphologies including scaly patches, plaques, and tumors, often in skin distributions that are not directly exposed to the sun (often referred to as a “bathing suit” distribution).4 Pruritus typically accompanies these skin lesions, and alopecia and poikiloderma are common findings. Patients with more advanced cases may present with generalized erythroderma. This finding should raise concern for progression to Sézary syndrome, a more aggressive type of CTCL that manifests with leukemic involvement of malignant T-cells matching the T-cell clones found in the skin.2

Alopecia is a common manifestation of MF that can be clinically indistinguishable from alopecia areata.5 While isolated alopecia is unlikely to be a consequence of MF, alopecia in the setting of widespread patches and plaques should raise suspicion for a diagnosis of MF.

Continue to: Diagnostic dilemma

Diagnostic dilemma: Condition mimics benign disorders

This case illustrates the diagnostic dilemma posed by MF due to its propensity to mimic more benign skin disorders, both clinically and histologically.2 One literature review of MF cases in which the diagnosis was not suspected clinically but was eventually confirmed histopathologically found that 25 unique dermatoses can be mimicked clinically by MF.6 The more common conditions that MF can be mistaken for are discussed below. In light of the diagnostic challenge posed by this multitude of morphologic presentations, referral to Dermatology for histopathologic evaluation is a reasonable next step when empiric treatment fails to improve symptoms of these common skin disorders.

Chronic atopic dermatitis (eczema) is characterized by dry skin and severe pruritis, usually associated with lichenified plaques and a history of atopic disease. The pruritic, scaly plaques typical of MF may be misdiagnosed as eczema; however, a distribution involving the “bathing suit” area is more suggestive of MF. Patients with atopic dermatitis are more likely to display a flexural distribution.2

Tinea corporis typically presents as annular, erythematous, pruritic, scaly patches or plaques that are similar to the scaling lesions of MF. Tinea corporis can be distinguished from MF via potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scrapings from an active lesion, which should demonstrate the segmented hyphae characteristic of this infection. If lesions of this type fail to respond to topical antifungal therapy, a skin biopsy may be warranted for further evaluation.

Nummular eczema, like tinea corporis, presents with round, coin-shaped patches that are highly pruritic and can be difficult to distinguish from the pruritic patches of MF. Unlike MF, however, nummular eczema typically is observed in patients with diffusely dry skin7; the lack of this finding should prompt consideration of alternative diagnoses, including MF.

Psoriasis classically presents with symmetrically distributed, well-demarcated plaques with prominent scaling that are usually asymptomatic, but may be associated with pruritis. Psoriatic plaques may be difficult to distinguish clinically from the plaques of MF, but their distribution may offer clues; psoriasis typically follows an extensor surface distribution, whereas MF is more commonly identified in a “bathing suit” or generalized distribution.4

Continue to: Tx based on disease extent, impact on quality of life

Tx based on disease extent, impact on quality of life

Staging of MF is the primary determinant of treatment and involves evaluation of skin, lymph node, viscera, and blood involvement. Early-stage MF has a favorable prognosis and can be effectively managed with skin-directed treatments. These include topical corticosteroids, topical nitrogen mustard agents, topical retinoids, and phototherapy (PUVA).8 Total skin electron beam therapy has been proven effective in the treatment of refractory and extensive MF, and local radiation therapy also is an effective treatment for isolated cutaneous tumors. Prolonged complete remissions of early-stage MF have been achieved using skin-directed treatments.8

In contrast, advanced MF often is treatment refractory and carries a poor prognosis. Systemic treatments such as interferon therapy, oral retinoids, extracorporeal photopheresis, and chemotherapy are added in patients with advanced disease after skin-directed therapy fails to adequately control tumor burden.

Our patient initially was treated with PUVA as well as 6 million U of interferon alfa-2B 3 times weekly, which he eventually elected to discontinue after 8 months because he wanted to father a child. His disease became more widespread after discontinuing these treatments despite interim therapy with clobetasol ointment .05%. His larger nodules and tumors were intermittently treated with local radiation with good response. Methotrexate 15 mg weekly was initiated following his decline after discontinuing PUVA and interferon treatment. Treatment with methotrexate resulted in an overall decrease in his tumor burden and several months of clinical stability.

Approximately 6 months after initiating methotrexate, his condition notably worsened. He developed generalized erythroderma, systemic symptoms including fever, chills, and unintentional 9.07-kg weight loss, in addition to new findings of palmoplantar keratoderma and nail dystrophy. In light of this systemic progression and concern for developing Sézary syndrome, extracorporeal photopheresis, bexarotene (an oral retinoid) 75 mg twice daily, and interferon alfa-2B 5 million U 3 times weekly were initiated. His condition continued to decline despite these therapies, culminating in a hospital admission for sepsis.

The patient recovered, and his regimen was changed to PUVA 3 times weekly in addition to treatment with intravenous brentuximab 1.8 mg/kg, a monoclonal antibody that targets CD30 receptors. Unfortunately, his condition continued to decline on this treatment regimen, which was subsequently abandoned in favor of chemotherapy with gemcitabine 1980 mg/250 mL normal saline. The patient was improving clinically with each cycle of gemcitabine and the plan was to transition him to extracorporeal photopheresis and bexarotene for maintenance therapy; however, the patient succumbed to his disease and passed away at the age of 37.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Banta, MD, PSC 103, Box 3613, APO, AE 09603 [email protected]

A 36-year-old African-American man presented to our clinic for evaluation of a chronic “rash” on his trunk, arms, and legs that had been present for 3 years. Empiric therapy for tinea corporis, nummular eczema, and confluent and reticulated papillomatosis had failed to improve his lesions.

Physical examination revealed a widespread skin eruption consisting of well-demarcated, hyperpigmented, scaly patches and plaques distributed throughout the patient’s trunk and extremities. Initial biopsies of the skin lesions (performed at an outside institution prior to current presentation) were nondiagnostic.

Over the next several months, the patient developed numerous cutaneous nodules and tumors within the background of his persistent patches and plaques (FIGURE). These nodules and tumors intermittently disappeared and recurred, seemingly independent of therapies including psoralen and ultraviolet A phototherapy (PUVA), interferon, and methotrexate.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: CD30+ transformed mycosis fungoides

Repeat biopsies ultimately confirmed a diagnosis of mycosis fungoides (MF), a primary cutaneous non-Hodgkin lymphoma of T-cell origin.

Lymphomas occurring in the skin without evidence of disease in other areas of the body at the time of diagnosis are referred to as primary cutaneous lymphomas. They are broadly divided by their cell of origin into cutaneous T-cell and cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Differentiating primary cutaneous lymphoma from systemic lymphomas with secondary skin involvement is an important distinction, as primary cutaneous lymphomas have different clinical courses and prognoses and require different treatments.1

MF is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), yet it remains an uncommon diagnosis as cutaneous lymphomas comprise only 3.9% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas.2 The CD30+ transformed variant identified in this patient is a rare subtype of MF that is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.3 Other types of CTCL include primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma, lymphomatoid papulosis, and adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, all of which can resemble MF clinically and are diagnosed by histopathology.

A nonspecific presentation

Patients with MF typically present with a complaint of chronic, slowly progressive skin lesions of various sizes and morphologies including scaly patches, plaques, and tumors, often in skin distributions that are not directly exposed to the sun (often referred to as a “bathing suit” distribution).4 Pruritus typically accompanies these skin lesions, and alopecia and poikiloderma are common findings. Patients with more advanced cases may present with generalized erythroderma. This finding should raise concern for progression to Sézary syndrome, a more aggressive type of CTCL that manifests with leukemic involvement of malignant T-cells matching the T-cell clones found in the skin.2

Alopecia is a common manifestation of MF that can be clinically indistinguishable from alopecia areata.5 While isolated alopecia is unlikely to be a consequence of MF, alopecia in the setting of widespread patches and plaques should raise suspicion for a diagnosis of MF.

Continue to: Diagnostic dilemma

Diagnostic dilemma: Condition mimics benign disorders

This case illustrates the diagnostic dilemma posed by MF due to its propensity to mimic more benign skin disorders, both clinically and histologically.2 One literature review of MF cases in which the diagnosis was not suspected clinically but was eventually confirmed histopathologically found that 25 unique dermatoses can be mimicked clinically by MF.6 The more common conditions that MF can be mistaken for are discussed below. In light of the diagnostic challenge posed by this multitude of morphologic presentations, referral to Dermatology for histopathologic evaluation is a reasonable next step when empiric treatment fails to improve symptoms of these common skin disorders.

Chronic atopic dermatitis (eczema) is characterized by dry skin and severe pruritis, usually associated with lichenified plaques and a history of atopic disease. The pruritic, scaly plaques typical of MF may be misdiagnosed as eczema; however, a distribution involving the “bathing suit” area is more suggestive of MF. Patients with atopic dermatitis are more likely to display a flexural distribution.2

Tinea corporis typically presents as annular, erythematous, pruritic, scaly patches or plaques that are similar to the scaling lesions of MF. Tinea corporis can be distinguished from MF via potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scrapings from an active lesion, which should demonstrate the segmented hyphae characteristic of this infection. If lesions of this type fail to respond to topical antifungal therapy, a skin biopsy may be warranted for further evaluation.

Nummular eczema, like tinea corporis, presents with round, coin-shaped patches that are highly pruritic and can be difficult to distinguish from the pruritic patches of MF. Unlike MF, however, nummular eczema typically is observed in patients with diffusely dry skin7; the lack of this finding should prompt consideration of alternative diagnoses, including MF.

Psoriasis classically presents with symmetrically distributed, well-demarcated plaques with prominent scaling that are usually asymptomatic, but may be associated with pruritis. Psoriatic plaques may be difficult to distinguish clinically from the plaques of MF, but their distribution may offer clues; psoriasis typically follows an extensor surface distribution, whereas MF is more commonly identified in a “bathing suit” or generalized distribution.4

Continue to: Tx based on disease extent, impact on quality of life

Tx based on disease extent, impact on quality of life

Staging of MF is the primary determinant of treatment and involves evaluation of skin, lymph node, viscera, and blood involvement. Early-stage MF has a favorable prognosis and can be effectively managed with skin-directed treatments. These include topical corticosteroids, topical nitrogen mustard agents, topical retinoids, and phototherapy (PUVA).8 Total skin electron beam therapy has been proven effective in the treatment of refractory and extensive MF, and local radiation therapy also is an effective treatment for isolated cutaneous tumors. Prolonged complete remissions of early-stage MF have been achieved using skin-directed treatments.8

In contrast, advanced MF often is treatment refractory and carries a poor prognosis. Systemic treatments such as interferon therapy, oral retinoids, extracorporeal photopheresis, and chemotherapy are added in patients with advanced disease after skin-directed therapy fails to adequately control tumor burden.

Our patient initially was treated with PUVA as well as 6 million U of interferon alfa-2B 3 times weekly, which he eventually elected to discontinue after 8 months because he wanted to father a child. His disease became more widespread after discontinuing these treatments despite interim therapy with clobetasol ointment .05%. His larger nodules and tumors were intermittently treated with local radiation with good response. Methotrexate 15 mg weekly was initiated following his decline after discontinuing PUVA and interferon treatment. Treatment with methotrexate resulted in an overall decrease in his tumor burden and several months of clinical stability.

Approximately 6 months after initiating methotrexate, his condition notably worsened. He developed generalized erythroderma, systemic symptoms including fever, chills, and unintentional 9.07-kg weight loss, in addition to new findings of palmoplantar keratoderma and nail dystrophy. In light of this systemic progression and concern for developing Sézary syndrome, extracorporeal photopheresis, bexarotene (an oral retinoid) 75 mg twice daily, and interferon alfa-2B 5 million U 3 times weekly were initiated. His condition continued to decline despite these therapies, culminating in a hospital admission for sepsis.

The patient recovered, and his regimen was changed to PUVA 3 times weekly in addition to treatment with intravenous brentuximab 1.8 mg/kg, a monoclonal antibody that targets CD30 receptors. Unfortunately, his condition continued to decline on this treatment regimen, which was subsequently abandoned in favor of chemotherapy with gemcitabine 1980 mg/250 mL normal saline. The patient was improving clinically with each cycle of gemcitabine and the plan was to transition him to extracorporeal photopheresis and bexarotene for maintenance therapy; however, the patient succumbed to his disease and passed away at the age of 37.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Banta, MD, PSC 103, Box 3613, APO, AE 09603 [email protected]

1. Whittaker S, Knobler R, Ortiz P, et al. Major achievements of the EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force (CLTF). EJC Suppl. 2012;10:46-50.

2. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part I. diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:205.e1-205.e16.

3. Kadin ME, Hughey LC, Wood GS. Large-cell transformation of mycosis fungoides-differential diagnosis with implications for clinical management: a consensus statement of the US Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:374-376.

4. Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, et al; International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma. Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1053-1063.

5. Bi MY, Curry JL, Christiano AM, et al. The spectrum of hair loss in patients with mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:53-63.

6. Zackheim HS, McCalmont TH. Mycosis fungoides: the great imitator. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:914-918.

7. Jiamton S, Tangjaturonrusamee C, Kulthanan K. Clinical features and aggravating factors in nummular eczema in Thais. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2013;31:36-42.

8. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:223.e1-223.e17.

1. Whittaker S, Knobler R, Ortiz P, et al. Major achievements of the EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force (CLTF). EJC Suppl. 2012;10:46-50.

2. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part I. diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:205.e1-205.e16.

3. Kadin ME, Hughey LC, Wood GS. Large-cell transformation of mycosis fungoides-differential diagnosis with implications for clinical management: a consensus statement of the US Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:374-376.

4. Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, et al; International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma. Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1053-1063.

5. Bi MY, Curry JL, Christiano AM, et al. The spectrum of hair loss in patients with mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:53-63.

6. Zackheim HS, McCalmont TH. Mycosis fungoides: the great imitator. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:914-918.

7. Jiamton S, Tangjaturonrusamee C, Kulthanan K. Clinical features and aggravating factors in nummular eczema in Thais. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2013;31:36-42.

8. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:223.e1-223.e17.

Pruritic rash on chest and back

A 26-year-old woman presented to our clinic with pruritic, hyperpigmented, symmetric edematous plaques on her upper flank, chest, and lower back (FIGURE) 3 weeks after starting a strict ketogenic (high fat/low carbohydrate) diet for postpartum weight loss. The patient was an otherwise healthy stay-at-home mother with an unremarkable medical history.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Prurigo pigmentosa

We recognized that this was a case of prurigo pigmentosa based on the characteristic pruritic rash that had developed after the patient started a strict ketogenic diet.

Prurigo pigmentosa is a benign, pruritic rash that most commonly presents with erythematous or hyperpigmented, symmetrically distributed urticarial papules and plaques on the chest and back. Females represent approximately 70% of cases with a predominant age range of 11 to 30.1

While the pathophysiology remains unknown, the rash most often is reported in association with ketogenic diets.1 Despite occurring in only a fraction of patients on the ketogenic diet, the characteristic presentation has led to the alternative name of the “keto rash” in online nutritional forums and blogs.

Although prurigo pigmentosa is relatively uncommon (with an unknown incidence), primary care physicians may begin to encounter the characteristic rash more frequently, given the number of articles over the past 5 years in the primary care and nutritional literature highlighting the diet’s health benefits.2 The ketogenic diet is a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet with preliminary evidence of improved weight loss, cardiovascular health, and glycemic control suggested by a meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials.3 Additionally, the popular press and general public’s rising interest are likely to increase the number of patients on this diet.

A clinical diagnosis

The diagnosis is made clinically, so the appearance of a symmetric pruritic, hyperpigmented rash on the chest and back should prompt the physician to ask about any recent changes in diet. Laboratory analysis is unnecessary, as a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and liver function panel are almost always normal. Urinary ketones are present in only 30% to 50% of patients; there is, however, an absence of blood ketones.

Continue to: Other conditions can mimic prurigo pigmentosa

Other conditions can mimic prurigo pigmentosa

Urticaria presents as individual lesions that often have a pale center. The lesions may occur anywhere on the body and generally last less than 24 hours. History may reveal a trigger including drugs, infection, food, or emotional stress in up to 50% of cases.

Irritant contact dermatitis often is associated with a stinging or burning sensation. Irritant and allergic contact dermatitis may have a geometric, or “outside job,” distribution suggestive of external contact, potentially with plants, alkalis, acids, or solvents.5

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is a rare asymptomatic dermatosis of unknown etiology that presents as hyperpigmented papules on the upper trunk, neck, and axillae. Most patients lack associated pruritis which is in contrast to prurigo pigmentosa.6

Pityriasis rosea is a viral exanthem that may be associated with constitutional symptoms and often presents initially with a herald patch progressing to a classic “Christmas tree” distribution with a fine collarette of scale. It often is asymptomatic, although some cases may be pruritic.5

Treatment focuses on dietary modification

Primary treatment includes resumption of a normal diet. This often leads to rapid resolution of pruritis. Residual hyperpigmentation may take months to fade.

Continue to: Pharmaceutical intervention may be necessary

Pharmaceutical intervention may be necessary

If additional treatment is required, minocycline 100 to 200 mg/d has been reported most effective, likely due to its anti-inflammatory properties.1,4 Topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines provide symptomatic relief in some patients.1,4

Our patient had resolution of the pruritis and urticarial lesions within 2 days of resuming a normal diet; however, residual asymptomatic hyperpigmentation persisted. A retrial of the ketogenic diet initiated a flare of the rash in the same distribution. It rapidly resolved with carbohydrate intake.

CORRESPONDENCE

Daniel Croom, MD, 34520 Bob Wilson Dr, Naval Medical Center San Diego, San Diego, CA 92134; [email protected]

1. Kim JK, Chung WK, Chang SE, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: clinicopathological study and analysis of 50 cases in Korea. J Dermatol. 2012;39:891-897.

2. Abbasi J. Interest in the ketogenic diet grows for weight loss and type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2018;319:215-217.

3. Bueno NB, de Melo IS, de Oliveira SL, et al. Very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet v. low-fat diet for long-term weight loss: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Nutr. 2013;110:1178-1187.

4. Oh YJ, Lee MH. Prurigo pigmentosa: a clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1149-1153.

5. James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Diseases of the skin appendages. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2015:747-788.

6. Shevchenko A, Valdes-Rodriguez R, Hsu S, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: case series and differentiation from confluent and reticulated papillomatosis. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:77-80.

A 26-year-old woman presented to our clinic with pruritic, hyperpigmented, symmetric edematous plaques on her upper flank, chest, and lower back (FIGURE) 3 weeks after starting a strict ketogenic (high fat/low carbohydrate) diet for postpartum weight loss. The patient was an otherwise healthy stay-at-home mother with an unremarkable medical history.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Prurigo pigmentosa

We recognized that this was a case of prurigo pigmentosa based on the characteristic pruritic rash that had developed after the patient started a strict ketogenic diet.

Prurigo pigmentosa is a benign, pruritic rash that most commonly presents with erythematous or hyperpigmented, symmetrically distributed urticarial papules and plaques on the chest and back. Females represent approximately 70% of cases with a predominant age range of 11 to 30.1

While the pathophysiology remains unknown, the rash most often is reported in association with ketogenic diets.1 Despite occurring in only a fraction of patients on the ketogenic diet, the characteristic presentation has led to the alternative name of the “keto rash” in online nutritional forums and blogs.

Although prurigo pigmentosa is relatively uncommon (with an unknown incidence), primary care physicians may begin to encounter the characteristic rash more frequently, given the number of articles over the past 5 years in the primary care and nutritional literature highlighting the diet’s health benefits.2 The ketogenic diet is a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet with preliminary evidence of improved weight loss, cardiovascular health, and glycemic control suggested by a meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials.3 Additionally, the popular press and general public’s rising interest are likely to increase the number of patients on this diet.

A clinical diagnosis

The diagnosis is made clinically, so the appearance of a symmetric pruritic, hyperpigmented rash on the chest and back should prompt the physician to ask about any recent changes in diet. Laboratory analysis is unnecessary, as a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and liver function panel are almost always normal. Urinary ketones are present in only 30% to 50% of patients; there is, however, an absence of blood ketones.

Continue to: Other conditions can mimic prurigo pigmentosa

Other conditions can mimic prurigo pigmentosa

Urticaria presents as individual lesions that often have a pale center. The lesions may occur anywhere on the body and generally last less than 24 hours. History may reveal a trigger including drugs, infection, food, or emotional stress in up to 50% of cases.

Irritant contact dermatitis often is associated with a stinging or burning sensation. Irritant and allergic contact dermatitis may have a geometric, or “outside job,” distribution suggestive of external contact, potentially with plants, alkalis, acids, or solvents.5

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is a rare asymptomatic dermatosis of unknown etiology that presents as hyperpigmented papules on the upper trunk, neck, and axillae. Most patients lack associated pruritis which is in contrast to prurigo pigmentosa.6

Pityriasis rosea is a viral exanthem that may be associated with constitutional symptoms and often presents initially with a herald patch progressing to a classic “Christmas tree” distribution with a fine collarette of scale. It often is asymptomatic, although some cases may be pruritic.5

Treatment focuses on dietary modification

Primary treatment includes resumption of a normal diet. This often leads to rapid resolution of pruritis. Residual hyperpigmentation may take months to fade.

Continue to: Pharmaceutical intervention may be necessary

Pharmaceutical intervention may be necessary

If additional treatment is required, minocycline 100 to 200 mg/d has been reported most effective, likely due to its anti-inflammatory properties.1,4 Topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines provide symptomatic relief in some patients.1,4

Our patient had resolution of the pruritis and urticarial lesions within 2 days of resuming a normal diet; however, residual asymptomatic hyperpigmentation persisted. A retrial of the ketogenic diet initiated a flare of the rash in the same distribution. It rapidly resolved with carbohydrate intake.

CORRESPONDENCE

Daniel Croom, MD, 34520 Bob Wilson Dr, Naval Medical Center San Diego, San Diego, CA 92134; [email protected]

A 26-year-old woman presented to our clinic with pruritic, hyperpigmented, symmetric edematous plaques on her upper flank, chest, and lower back (FIGURE) 3 weeks after starting a strict ketogenic (high fat/low carbohydrate) diet for postpartum weight loss. The patient was an otherwise healthy stay-at-home mother with an unremarkable medical history.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Prurigo pigmentosa

We recognized that this was a case of prurigo pigmentosa based on the characteristic pruritic rash that had developed after the patient started a strict ketogenic diet.

Prurigo pigmentosa is a benign, pruritic rash that most commonly presents with erythematous or hyperpigmented, symmetrically distributed urticarial papules and plaques on the chest and back. Females represent approximately 70% of cases with a predominant age range of 11 to 30.1

While the pathophysiology remains unknown, the rash most often is reported in association with ketogenic diets.1 Despite occurring in only a fraction of patients on the ketogenic diet, the characteristic presentation has led to the alternative name of the “keto rash” in online nutritional forums and blogs.

Although prurigo pigmentosa is relatively uncommon (with an unknown incidence), primary care physicians may begin to encounter the characteristic rash more frequently, given the number of articles over the past 5 years in the primary care and nutritional literature highlighting the diet’s health benefits.2 The ketogenic diet is a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet with preliminary evidence of improved weight loss, cardiovascular health, and glycemic control suggested by a meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials.3 Additionally, the popular press and general public’s rising interest are likely to increase the number of patients on this diet.

A clinical diagnosis

The diagnosis is made clinically, so the appearance of a symmetric pruritic, hyperpigmented rash on the chest and back should prompt the physician to ask about any recent changes in diet. Laboratory analysis is unnecessary, as a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and liver function panel are almost always normal. Urinary ketones are present in only 30% to 50% of patients; there is, however, an absence of blood ketones.

Continue to: Other conditions can mimic prurigo pigmentosa

Other conditions can mimic prurigo pigmentosa

Urticaria presents as individual lesions that often have a pale center. The lesions may occur anywhere on the body and generally last less than 24 hours. History may reveal a trigger including drugs, infection, food, or emotional stress in up to 50% of cases.

Irritant contact dermatitis often is associated with a stinging or burning sensation. Irritant and allergic contact dermatitis may have a geometric, or “outside job,” distribution suggestive of external contact, potentially with plants, alkalis, acids, or solvents.5

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is a rare asymptomatic dermatosis of unknown etiology that presents as hyperpigmented papules on the upper trunk, neck, and axillae. Most patients lack associated pruritis which is in contrast to prurigo pigmentosa.6

Pityriasis rosea is a viral exanthem that may be associated with constitutional symptoms and often presents initially with a herald patch progressing to a classic “Christmas tree” distribution with a fine collarette of scale. It often is asymptomatic, although some cases may be pruritic.5

Treatment focuses on dietary modification

Primary treatment includes resumption of a normal diet. This often leads to rapid resolution of pruritis. Residual hyperpigmentation may take months to fade.

Continue to: Pharmaceutical intervention may be necessary

Pharmaceutical intervention may be necessary

If additional treatment is required, minocycline 100 to 200 mg/d has been reported most effective, likely due to its anti-inflammatory properties.1,4 Topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines provide symptomatic relief in some patients.1,4

Our patient had resolution of the pruritis and urticarial lesions within 2 days of resuming a normal diet; however, residual asymptomatic hyperpigmentation persisted. A retrial of the ketogenic diet initiated a flare of the rash in the same distribution. It rapidly resolved with carbohydrate intake.

CORRESPONDENCE

Daniel Croom, MD, 34520 Bob Wilson Dr, Naval Medical Center San Diego, San Diego, CA 92134; [email protected]

1. Kim JK, Chung WK, Chang SE, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: clinicopathological study and analysis of 50 cases in Korea. J Dermatol. 2012;39:891-897.

2. Abbasi J. Interest in the ketogenic diet grows for weight loss and type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2018;319:215-217.

3. Bueno NB, de Melo IS, de Oliveira SL, et al. Very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet v. low-fat diet for long-term weight loss: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Nutr. 2013;110:1178-1187.

4. Oh YJ, Lee MH. Prurigo pigmentosa: a clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1149-1153.

5. James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Diseases of the skin appendages. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2015:747-788.

6. Shevchenko A, Valdes-Rodriguez R, Hsu S, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: case series and differentiation from confluent and reticulated papillomatosis. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:77-80.

1. Kim JK, Chung WK, Chang SE, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: clinicopathological study and analysis of 50 cases in Korea. J Dermatol. 2012;39:891-897.

2. Abbasi J. Interest in the ketogenic diet grows for weight loss and type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2018;319:215-217.

3. Bueno NB, de Melo IS, de Oliveira SL, et al. Very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet v. low-fat diet for long-term weight loss: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Nutr. 2013;110:1178-1187.

4. Oh YJ, Lee MH. Prurigo pigmentosa: a clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1149-1153.

5. James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Diseases of the skin appendages. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2015:747-788.

6. Shevchenko A, Valdes-Rodriguez R, Hsu S, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: case series and differentiation from confluent and reticulated papillomatosis. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:77-80.

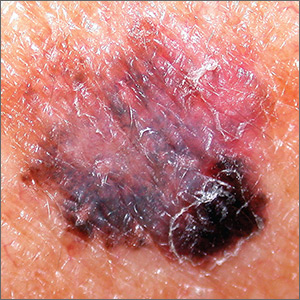

Sore on head

The FP suspected that this was a skin cancer with ulceration and pigmentation. The differential diagnosis included pigmented basal cell carcinoma, melanoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. If this were a melanoma, there would appear to be areas of regression between the islands of pigmentation. The FP explained that a biopsy was needed and suggested a broad shave biopsy because this technique would provide adequate tissue to the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The FP performed the broad shave biopsy and saw some remaining pigment at the base of the initial cut. He performed a second pass with the DermaBlade and explained this in the pathology requisition. (It is acceptable to send a deeper section of tissue if it appears that there is some remaining tumor below the initial biopsy.)

The biopsy report revealed lentigo maligna melanoma, which was approximately 2 mm thick—much deeper than the clinical appearance suggested. The pathologist combined the depths from the 2 specimens to get an approximate Breslow level. In this case, the most important information was that this was >1 mm in depth, which suggested that a sentinel lymph node biopsy would be needed for prognostic information. The patient was referred to Surgical Oncology for wide excision and sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Fortunately, the nodes were negative for metastasis. The wide excision was closed with a graft that healed well over time. The patient was followed with regular skin exams and careful lymph node exams of the neck and supraclavicular areas. He now wears a hat whenever he is outdoors.

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1103-1111.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this was a skin cancer with ulceration and pigmentation. The differential diagnosis included pigmented basal cell carcinoma, melanoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. If this were a melanoma, there would appear to be areas of regression between the islands of pigmentation. The FP explained that a biopsy was needed and suggested a broad shave biopsy because this technique would provide adequate tissue to the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The FP performed the broad shave biopsy and saw some remaining pigment at the base of the initial cut. He performed a second pass with the DermaBlade and explained this in the pathology requisition. (It is acceptable to send a deeper section of tissue if it appears that there is some remaining tumor below the initial biopsy.)

The biopsy report revealed lentigo maligna melanoma, which was approximately 2 mm thick—much deeper than the clinical appearance suggested. The pathologist combined the depths from the 2 specimens to get an approximate Breslow level. In this case, the most important information was that this was >1 mm in depth, which suggested that a sentinel lymph node biopsy would be needed for prognostic information. The patient was referred to Surgical Oncology for wide excision and sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Fortunately, the nodes were negative for metastasis. The wide excision was closed with a graft that healed well over time. The patient was followed with regular skin exams and careful lymph node exams of the neck and supraclavicular areas. He now wears a hat whenever he is outdoors.

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1103-1111.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this was a skin cancer with ulceration and pigmentation. The differential diagnosis included pigmented basal cell carcinoma, melanoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. If this were a melanoma, there would appear to be areas of regression between the islands of pigmentation. The FP explained that a biopsy was needed and suggested a broad shave biopsy because this technique would provide adequate tissue to the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The FP performed the broad shave biopsy and saw some remaining pigment at the base of the initial cut. He performed a second pass with the DermaBlade and explained this in the pathology requisition. (It is acceptable to send a deeper section of tissue if it appears that there is some remaining tumor below the initial biopsy.)

The biopsy report revealed lentigo maligna melanoma, which was approximately 2 mm thick—much deeper than the clinical appearance suggested. The pathologist combined the depths from the 2 specimens to get an approximate Breslow level. In this case, the most important information was that this was >1 mm in depth, which suggested that a sentinel lymph node biopsy would be needed for prognostic information. The patient was referred to Surgical Oncology for wide excision and sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Fortunately, the nodes were negative for metastasis. The wide excision was closed with a graft that healed well over time. The patient was followed with regular skin exams and careful lymph node exams of the neck and supraclavicular areas. He now wears a hat whenever he is outdoors.

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1103-1111.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Growing spot on nose

The FP was concerned that this could be melanoma.

He used his dermatoscope and saw suspicious patterns that included polygonal lines and circle-within-circle patterns. He informed the patient about his concerns for melanoma and discussed the need for a biopsy. After obtaining informed consent, the FP injected the patient’s nose with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine for anesthesia and to prevent bleeding. Remember, it is safe to use injectable epinephrine along with lidocaine when doing surgery on the nose. (See “Biopsies for skin cancer detection: Dispelling the myths”). The FP used a Dermablade to perform a broad shave biopsy, which revealed a lentigo maligna melanoma in situ (also known as lentigo maligna). (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy”)

During the follow-up visit, the FP presented the patient with 2 options for treatment: topical imiquimod for 3 months or Mohs surgery. The FP recommended Mohs surgery because the data for topical imiquimod in the treatment of lentigo maligna indicate that it is less effective on the nose than other areas of the face. The patient agreed to surgery, and the FP sent the referral and the photo of the original lesion to the Mohs surgeon. The outcome was good, and the need for ongoing sun safety and regular skin surveillance was explained to the patient.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP was concerned that this could be melanoma.

He used his dermatoscope and saw suspicious patterns that included polygonal lines and circle-within-circle patterns. He informed the patient about his concerns for melanoma and discussed the need for a biopsy. After obtaining informed consent, the FP injected the patient’s nose with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine for anesthesia and to prevent bleeding. Remember, it is safe to use injectable epinephrine along with lidocaine when doing surgery on the nose. (See “Biopsies for skin cancer detection: Dispelling the myths”). The FP used a Dermablade to perform a broad shave biopsy, which revealed a lentigo maligna melanoma in situ (also known as lentigo maligna). (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy”)

During the follow-up visit, the FP presented the patient with 2 options for treatment: topical imiquimod for 3 months or Mohs surgery. The FP recommended Mohs surgery because the data for topical imiquimod in the treatment of lentigo maligna indicate that it is less effective on the nose than other areas of the face. The patient agreed to surgery, and the FP sent the referral and the photo of the original lesion to the Mohs surgeon. The outcome was good, and the need for ongoing sun safety and regular skin surveillance was explained to the patient.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP was concerned that this could be melanoma.

He used his dermatoscope and saw suspicious patterns that included polygonal lines and circle-within-circle patterns. He informed the patient about his concerns for melanoma and discussed the need for a biopsy. After obtaining informed consent, the FP injected the patient’s nose with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine for anesthesia and to prevent bleeding. Remember, it is safe to use injectable epinephrine along with lidocaine when doing surgery on the nose. (See “Biopsies for skin cancer detection: Dispelling the myths”). The FP used a Dermablade to perform a broad shave biopsy, which revealed a lentigo maligna melanoma in situ (also known as lentigo maligna). (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy”)

During the follow-up visit, the FP presented the patient with 2 options for treatment: topical imiquimod for 3 months or Mohs surgery. The FP recommended Mohs surgery because the data for topical imiquimod in the treatment of lentigo maligna indicate that it is less effective on the nose than other areas of the face. The patient agreed to surgery, and the FP sent the referral and the photo of the original lesion to the Mohs surgeon. The outcome was good, and the need for ongoing sun safety and regular skin surveillance was explained to the patient.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

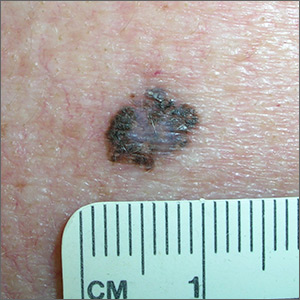

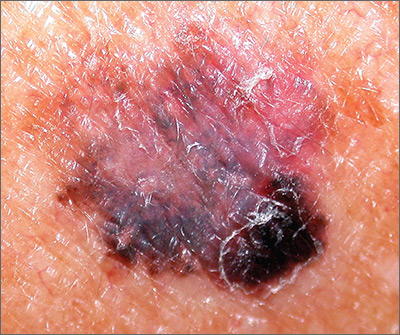

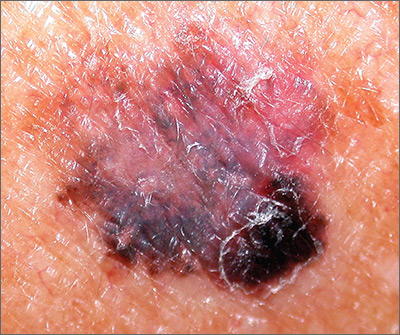

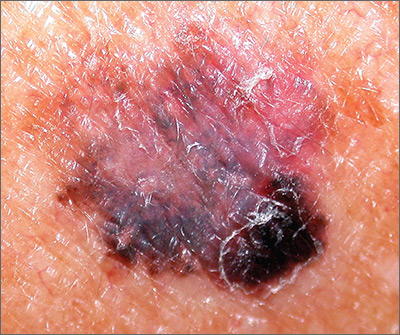

Dark spot on arm

The FP suspected that this was a melanoma or a pigmented basal cell carcinoma.

Going through the ABCDE criteria, the FP noted that the spot was Asymmetric, the Border was irregular, the Colors were varied, the Diameter was >6 mm, and the history was positive for an Enlarging lesion. With 5 out of the 5 criteria positive, it was likely that this was a melanoma. The FP performed a deep shave biopsy (saucerization) with 1- to 2-mm margins to provide full sampling for the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The depth of the tissue biopsy was approximately 1 to 1.5 mm (a dime is 1.4 mm in depth), which was adequate for a lesion of this type. The pathology report came back as invasive melanoma with a 0.25 mm Breslow depth.

The FP referred the patient to a local dermatologist, who agreed to see the patient within the next 2 weeks rather than the standard 3- to 4-month wait time for a new patient. The dermatologist performed a wide local excision with a 1-cm margin down to the fascia. While this melanoma was invasive, this depth did not require sentinel lymph node biopsy for staging. On a follow-up visit, the FP counseled the patient about sun protection and the need for regular skin exams. Note that while brown skin and regular sun exposure may be less risky for melanoma than fair skin with multiple sunburns, anyone can get a melanoma.

Photo courtesy of Eric Kraus, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this was a melanoma or a pigmented basal cell carcinoma.

Going through the ABCDE criteria, the FP noted that the spot was Asymmetric, the Border was irregular, the Colors were varied, the Diameter was >6 mm, and the history was positive for an Enlarging lesion. With 5 out of the 5 criteria positive, it was likely that this was a melanoma. The FP performed a deep shave biopsy (saucerization) with 1- to 2-mm margins to provide full sampling for the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The depth of the tissue biopsy was approximately 1 to 1.5 mm (a dime is 1.4 mm in depth), which was adequate for a lesion of this type. The pathology report came back as invasive melanoma with a 0.25 mm Breslow depth.

The FP referred the patient to a local dermatologist, who agreed to see the patient within the next 2 weeks rather than the standard 3- to 4-month wait time for a new patient. The dermatologist performed a wide local excision with a 1-cm margin down to the fascia. While this melanoma was invasive, this depth did not require sentinel lymph node biopsy for staging. On a follow-up visit, the FP counseled the patient about sun protection and the need for regular skin exams. Note that while brown skin and regular sun exposure may be less risky for melanoma than fair skin with multiple sunburns, anyone can get a melanoma.

Photo courtesy of Eric Kraus, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this was a melanoma or a pigmented basal cell carcinoma.

Going through the ABCDE criteria, the FP noted that the spot was Asymmetric, the Border was irregular, the Colors were varied, the Diameter was >6 mm, and the history was positive for an Enlarging lesion. With 5 out of the 5 criteria positive, it was likely that this was a melanoma. The FP performed a deep shave biopsy (saucerization) with 1- to 2-mm margins to provide full sampling for the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The depth of the tissue biopsy was approximately 1 to 1.5 mm (a dime is 1.4 mm in depth), which was adequate for a lesion of this type. The pathology report came back as invasive melanoma with a 0.25 mm Breslow depth.

The FP referred the patient to a local dermatologist, who agreed to see the patient within the next 2 weeks rather than the standard 3- to 4-month wait time for a new patient. The dermatologist performed a wide local excision with a 1-cm margin down to the fascia. While this melanoma was invasive, this depth did not require sentinel lymph node biopsy for staging. On a follow-up visit, the FP counseled the patient about sun protection and the need for regular skin exams. Note that while brown skin and regular sun exposure may be less risky for melanoma than fair skin with multiple sunburns, anyone can get a melanoma.

Photo courtesy of Eric Kraus, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Irregular macule on back

The FP suspected that this could be a melanoma and took out his dermatoscope. (See “Dermoscopy in family medicine: A primer.”) The FP was initially concerned about melanoma because the lesion appeared chaotic, with multiple colors and an irregular border. Going through the ABCDE criteria, he noted that the macule was Asymmetric, the Border was irregular, the Colors were varied, the Diameter was >6 mm, but the history was insufficient to say whether it was Enlarging. Of course, 4 out of 5 positive criteria requires a tissue diagnosis.

Dermoscopy added evidence for regression in the center and an atypical network in the brown and black areas. The FP performed a deep shave biopsy (saucerization) with 2 mm margins to provide full sampling for the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The depth of the tissue biopsy was approximately 1 to 1.5 mm, which was adequate for a lesion of this type. The pathology report confirmed melanoma in situ.

On a return visit, the FP performed a local wide excision with 5 mm margins down to the deep fat. The surgical specimen revealed only the scar at the biopsy site with no remaining cancer. This reassured the patient because it should provide a cure very near 100%. The FP provided counseling about sun protection and the need for regular skin exams.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this could be a melanoma and took out his dermatoscope. (See “Dermoscopy in family medicine: A primer.”) The FP was initially concerned about melanoma because the lesion appeared chaotic, with multiple colors and an irregular border. Going through the ABCDE criteria, he noted that the macule was Asymmetric, the Border was irregular, the Colors were varied, the Diameter was >6 mm, but the history was insufficient to say whether it was Enlarging. Of course, 4 out of 5 positive criteria requires a tissue diagnosis.

Dermoscopy added evidence for regression in the center and an atypical network in the brown and black areas. The FP performed a deep shave biopsy (saucerization) with 2 mm margins to provide full sampling for the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The depth of the tissue biopsy was approximately 1 to 1.5 mm, which was adequate for a lesion of this type. The pathology report confirmed melanoma in situ.

On a return visit, the FP performed a local wide excision with 5 mm margins down to the deep fat. The surgical specimen revealed only the scar at the biopsy site with no remaining cancer. This reassured the patient because it should provide a cure very near 100%. The FP provided counseling about sun protection and the need for regular skin exams.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this could be a melanoma and took out his dermatoscope. (See “Dermoscopy in family medicine: A primer.”) The FP was initially concerned about melanoma because the lesion appeared chaotic, with multiple colors and an irregular border. Going through the ABCDE criteria, he noted that the macule was Asymmetric, the Border was irregular, the Colors were varied, the Diameter was >6 mm, but the history was insufficient to say whether it was Enlarging. Of course, 4 out of 5 positive criteria requires a tissue diagnosis.

Dermoscopy added evidence for regression in the center and an atypical network in the brown and black areas. The FP performed a deep shave biopsy (saucerization) with 2 mm margins to provide full sampling for the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The depth of the tissue biopsy was approximately 1 to 1.5 mm, which was adequate for a lesion of this type. The pathology report confirmed melanoma in situ.

On a return visit, the FP performed a local wide excision with 5 mm margins down to the deep fat. The surgical specimen revealed only the scar at the biopsy site with no remaining cancer. This reassured the patient because it should provide a cure very near 100%. The FP provided counseling about sun protection and the need for regular skin exams.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Black lesion on arm

Due to the dark and rapidly growing nodule, the FP immediately worried about melanoma.