User login

Sore on nose

The FP suspected that it could be a skin cancer because any nonhealing lesion in sun-exposed areas could be skin cancer (especially basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma).

He explained this to the patient and obtained written consent for a shave biopsy. He told the patient that the biopsy would likely leave an indentation in the involved area, but since treating the sore would likely require a second surgery, this indented area could be cut out and repaired with sutures. The patient indicated that he was more concerned about getting a proper diagnosis than he was about the appearance of the biopsy site.

The physician injected the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine for anesthesia and to prevent bleeding. (Remember, it is safe to use injectable epinephrine along with lidocaine when doing surgery on the nose. See “Biopsies for skin cancer detection: Dispelling the myths.”) The shave biopsy was performed using a Dermablade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathology report revealed squamous cell carcinoma. The patient was referred for Mohs surgery to get the best cure and cosmetic result.

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1103-1111.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that it could be a skin cancer because any nonhealing lesion in sun-exposed areas could be skin cancer (especially basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma).

He explained this to the patient and obtained written consent for a shave biopsy. He told the patient that the biopsy would likely leave an indentation in the involved area, but since treating the sore would likely require a second surgery, this indented area could be cut out and repaired with sutures. The patient indicated that he was more concerned about getting a proper diagnosis than he was about the appearance of the biopsy site.

The physician injected the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine for anesthesia and to prevent bleeding. (Remember, it is safe to use injectable epinephrine along with lidocaine when doing surgery on the nose. See “Biopsies for skin cancer detection: Dispelling the myths.”) The shave biopsy was performed using a Dermablade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathology report revealed squamous cell carcinoma. The patient was referred for Mohs surgery to get the best cure and cosmetic result.

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1103-1111.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that it could be a skin cancer because any nonhealing lesion in sun-exposed areas could be skin cancer (especially basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma).

He explained this to the patient and obtained written consent for a shave biopsy. He told the patient that the biopsy would likely leave an indentation in the involved area, but since treating the sore would likely require a second surgery, this indented area could be cut out and repaired with sutures. The patient indicated that he was more concerned about getting a proper diagnosis than he was about the appearance of the biopsy site.

The physician injected the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine for anesthesia and to prevent bleeding. (Remember, it is safe to use injectable epinephrine along with lidocaine when doing surgery on the nose. See “Biopsies for skin cancer detection: Dispelling the myths.”) The shave biopsy was performed using a Dermablade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathology report revealed squamous cell carcinoma. The patient was referred for Mohs surgery to get the best cure and cosmetic result.

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1103-1111.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

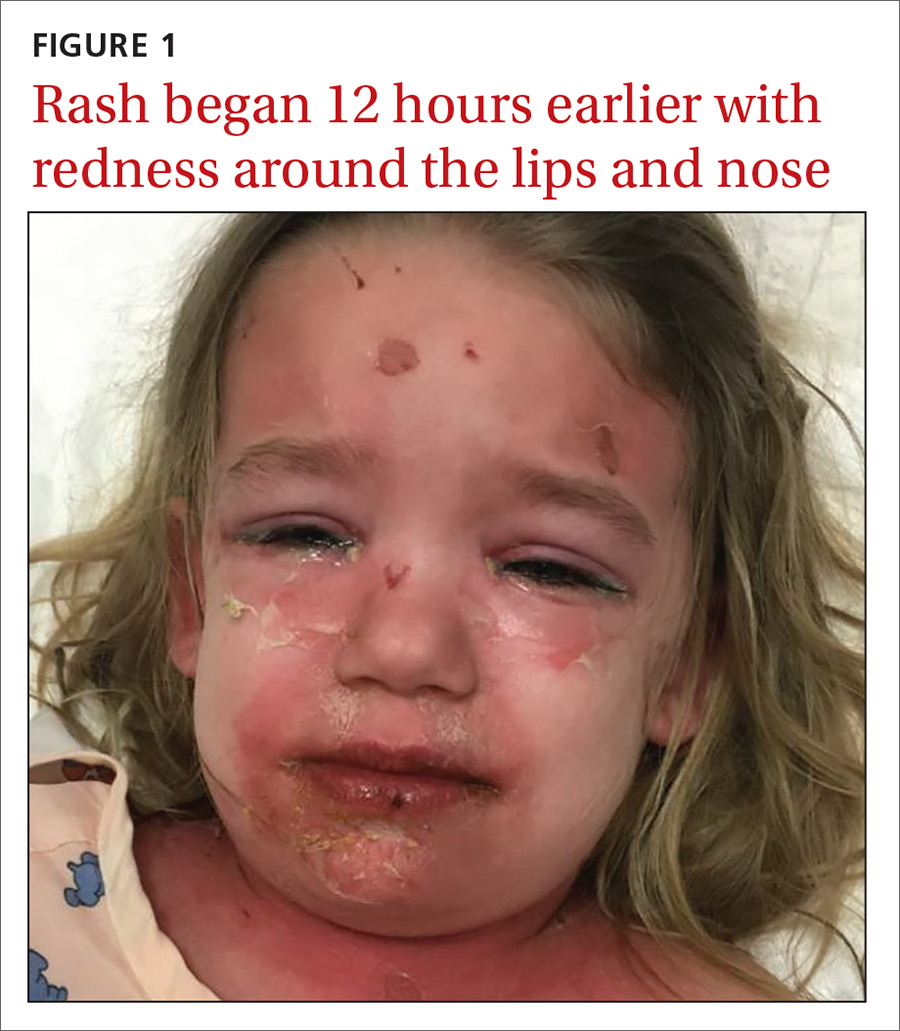

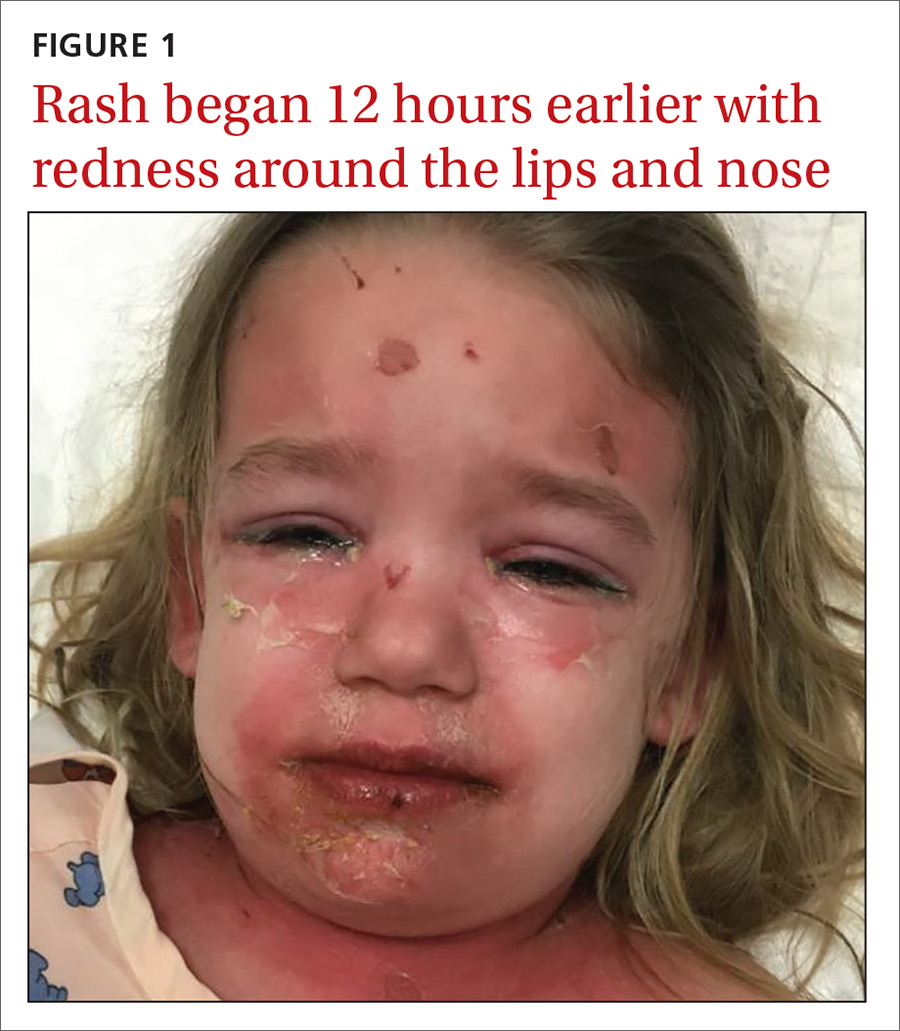

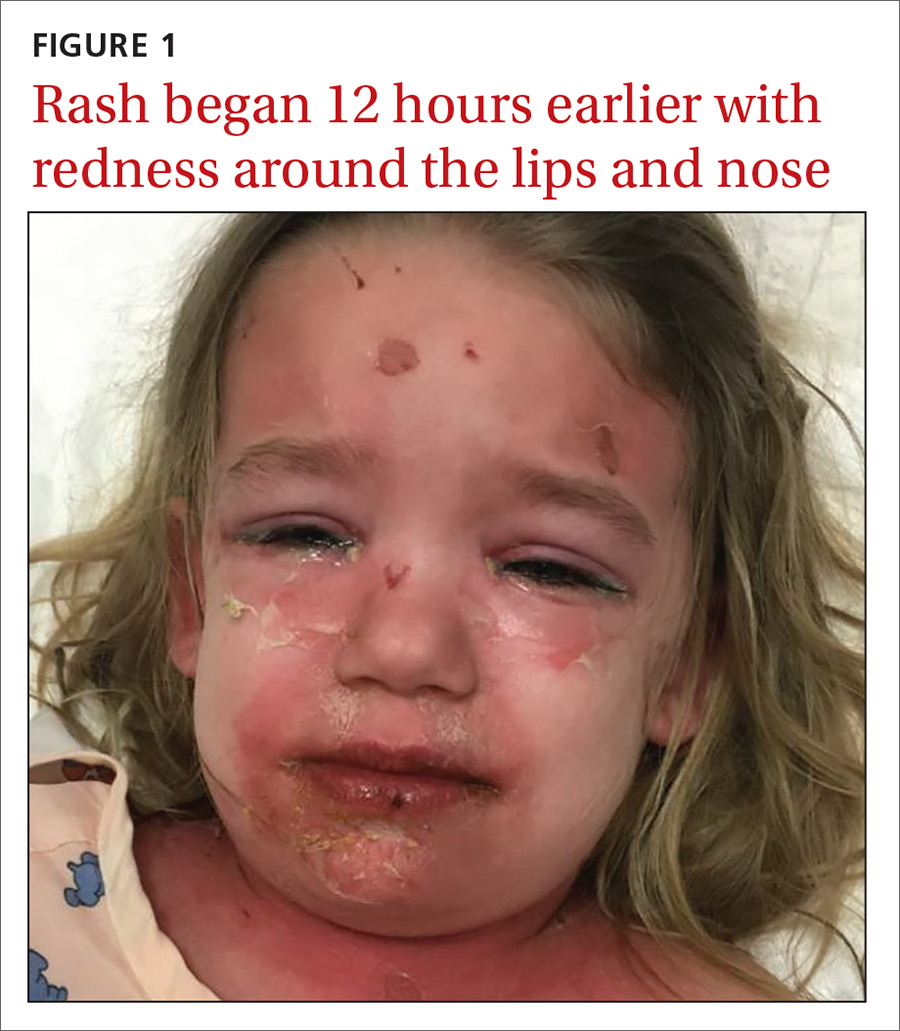

A young girl with a painful rash

A 3-year-old girl presented with a rapidly progressing rash. The rash began the previous day with redness around her lips and nose (FIGURE 1). Twelve hours later, the rash had progressed to involve her neck, trunk, and inguinal area (FIGURE 2). The child’s parents reported that she had no recent illnesses or treatment with antibiotics.

On physical examination, she was febrile (101.8° F) and irritable throughout the encounter. She had perioral and nasolabial erythema and dryness. Her lips were dry with no intraoral mucosal lesions, and her conjunctiva was clear.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Based on the patient’s classic presentation and exam findings, the physician suspected staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. SSSS is a rare but serious condition that progresses quickly with high fevers and diffuse painful erythema. The exact epidemiology of SSSS is unclear; some articles report incidences between 0.09 and 0.13 cases per 1 million people.1 The mortality rate is about 5% due to complications of sepsis, superinfection, and electrolyte disturbances.2

SSSS is caused by Staphylococcus aureus from a localized source that produces exfoliative toxins A and B that spread hematogenously, causing extensive epidermal damage. Exotoxins bind to desmosomes, causing skin cells to lose adherence.3 Histopathology shows intraepidermal cleavage through the stratum granulosum.

Infants and younger children appear more likely to be affected by SSSS, although it may occur in older children or adults who are immunocompromised. It may be that younger children are most susceptible due to a lack of antibodies to the toxin produced or because of a delayed clearance of the toxin-antibody complex from an immature renal system.

What you’ll see. Patients with SSSS may have a prodrome of irritability, malaise, and fever. The rash is first noticeable as erythema in the flexural areas.4 The erythematous tender patches spread and coalesce into a scarlatiniform erythema. Fragile bullae become large sheets of epidermis that slough (a positive Nikolsky’s sign).5 The desquamated areas can exhibit a scalded appearance.3

Differential diagnosis includes TEN and SJS

There is a broad differential for vesiculobullous rashes, ranging from self-limiting conditions to those that are life threatening.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS), and erythema multiforme major (EMM) are immunological reactions to certain drugs or infections varying in the severity of their presentation. EMM, SJS, and TEN involve the mucosal surfaces, while SSSS does not. The histopathology of these conditions also differs from SSSS as they have keratinocyte necrosis of varying levels of the skin, whereas SSSS only involves the epidermis.

SSSS also may be confused with drug reactions, such as DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome. DRESS typically is associated with anticonvulsants and sulfonamides and may have peripheral eosinophilia and a transaminitis.4

Continue to: Other more self-limited vesiculobullous rashes...

Other more self-limited vesiculobullous rashes include human enteroviruses such as coxsackie virus (hand-foot-mouth disease), echovirus, and enterovirus. However, unlike SSSS, which only affects the epidermis, these disorders may produce epidermal necrosis resulting in epidermal-dermal separation and mucocutaneous blistering.4

Making the diagnosis

When a patient has classic SSSS, the diagnosis can be made based on exam findings and the patient’s history. Families will usually report a generalized rash in neonates with desquamation of the entire skin. Fever is often present. Recent exposures to other family members with skin and soft-tissue infections is a possibility. If there is doubt, a skin biopsy can be obtained for histology. Lab work may reveal an elevated white blood cell count; blood culture is often negative.

The primary site of S aureus infection is usually the nasopharynx, causing a mild upper respiratory tract infection; therefore, nasopharyngeal cultures may be positive.4 Cultures can also be drawn from blood, wounds, nares, and ocular exudates if there is suspicion. Cultures from the actual blisters are typically negative, as the toxin—not the actual bacteria—is responsible for the blistering. Unlike adults who experience SSSS, children typically have negative blood cultures.4

Prompt treatment is essential

Swift diagnosis and management of SSSS is important due to the risk of severe disease. It is important to start antibiotics early because methicillin-sensitive S aureus is a predominant cause of SSSS.2 The epidemiology of methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) continues to shift. A recent study suggests that empiric therapy with penicillinase-resistant penicillins, along with clindamycin, be employed until culture sensitivities are available to guide therapy.2 Local resistance patterns to S aureus should help guide initial empiric antibiotic treatment. Patients should receive intravenous (IV) fluids to compensate for insensible fluid losses similar to an extensive burn wound. Wound dressings placed over sloughed skin can help prevent secondary infection.2 Lastly, the use of anti-inflammatory drugs and opiates often depends upon the extent of pain the patient experiences.

Our patient was immediately started on IV clindamycin 10 mg/kg tid and IV fluids. She was given morphine 0.01 mg/kg for pain control. As expected, cultures of her nasopharynx, blood, and vulva did not grow S aureus. Although no organism was isolated, her rash rapidly improved, and she was discharged home to complete a 10-day oral course of clindamycin 10 mg/kg tid.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nicholas M. Potisek, MD, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Medical Center Blvd, Winston-Salem, NC 27157; [email protected]

1. Mockenhaupt M, Idzko M, Grosber M, et al. Epidemiology of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in Germany. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:700-703.

2. Braunstein I, Wanat K, Abuabara K, et al. Antibiotic sensitivity and resistance patterns in pediatric staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:305-308.

3. Mishra AK, Yadav, P, Mishra A. A systemic review on Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome (SSSS): A rare and critical disease of neonates. Open Microbiol J. 2016;10: 150-159.

4. Handler MZ, Schwarz RA. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome: diagnosis and management in children and adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1418-1423.

5. Franco L, Pereira P. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Indian Pediatr. 2016. 53:939.

A 3-year-old girl presented with a rapidly progressing rash. The rash began the previous day with redness around her lips and nose (FIGURE 1). Twelve hours later, the rash had progressed to involve her neck, trunk, and inguinal area (FIGURE 2). The child’s parents reported that she had no recent illnesses or treatment with antibiotics.

On physical examination, she was febrile (101.8° F) and irritable throughout the encounter. She had perioral and nasolabial erythema and dryness. Her lips were dry with no intraoral mucosal lesions, and her conjunctiva was clear.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Based on the patient’s classic presentation and exam findings, the physician suspected staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. SSSS is a rare but serious condition that progresses quickly with high fevers and diffuse painful erythema. The exact epidemiology of SSSS is unclear; some articles report incidences between 0.09 and 0.13 cases per 1 million people.1 The mortality rate is about 5% due to complications of sepsis, superinfection, and electrolyte disturbances.2

SSSS is caused by Staphylococcus aureus from a localized source that produces exfoliative toxins A and B that spread hematogenously, causing extensive epidermal damage. Exotoxins bind to desmosomes, causing skin cells to lose adherence.3 Histopathology shows intraepidermal cleavage through the stratum granulosum.

Infants and younger children appear more likely to be affected by SSSS, although it may occur in older children or adults who are immunocompromised. It may be that younger children are most susceptible due to a lack of antibodies to the toxin produced or because of a delayed clearance of the toxin-antibody complex from an immature renal system.

What you’ll see. Patients with SSSS may have a prodrome of irritability, malaise, and fever. The rash is first noticeable as erythema in the flexural areas.4 The erythematous tender patches spread and coalesce into a scarlatiniform erythema. Fragile bullae become large sheets of epidermis that slough (a positive Nikolsky’s sign).5 The desquamated areas can exhibit a scalded appearance.3

Differential diagnosis includes TEN and SJS

There is a broad differential for vesiculobullous rashes, ranging from self-limiting conditions to those that are life threatening.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS), and erythema multiforme major (EMM) are immunological reactions to certain drugs or infections varying in the severity of their presentation. EMM, SJS, and TEN involve the mucosal surfaces, while SSSS does not. The histopathology of these conditions also differs from SSSS as they have keratinocyte necrosis of varying levels of the skin, whereas SSSS only involves the epidermis.

SSSS also may be confused with drug reactions, such as DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome. DRESS typically is associated with anticonvulsants and sulfonamides and may have peripheral eosinophilia and a transaminitis.4

Continue to: Other more self-limited vesiculobullous rashes...

Other more self-limited vesiculobullous rashes include human enteroviruses such as coxsackie virus (hand-foot-mouth disease), echovirus, and enterovirus. However, unlike SSSS, which only affects the epidermis, these disorders may produce epidermal necrosis resulting in epidermal-dermal separation and mucocutaneous blistering.4

Making the diagnosis

When a patient has classic SSSS, the diagnosis can be made based on exam findings and the patient’s history. Families will usually report a generalized rash in neonates with desquamation of the entire skin. Fever is often present. Recent exposures to other family members with skin and soft-tissue infections is a possibility. If there is doubt, a skin biopsy can be obtained for histology. Lab work may reveal an elevated white blood cell count; blood culture is often negative.

The primary site of S aureus infection is usually the nasopharynx, causing a mild upper respiratory tract infection; therefore, nasopharyngeal cultures may be positive.4 Cultures can also be drawn from blood, wounds, nares, and ocular exudates if there is suspicion. Cultures from the actual blisters are typically negative, as the toxin—not the actual bacteria—is responsible for the blistering. Unlike adults who experience SSSS, children typically have negative blood cultures.4

Prompt treatment is essential

Swift diagnosis and management of SSSS is important due to the risk of severe disease. It is important to start antibiotics early because methicillin-sensitive S aureus is a predominant cause of SSSS.2 The epidemiology of methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) continues to shift. A recent study suggests that empiric therapy with penicillinase-resistant penicillins, along with clindamycin, be employed until culture sensitivities are available to guide therapy.2 Local resistance patterns to S aureus should help guide initial empiric antibiotic treatment. Patients should receive intravenous (IV) fluids to compensate for insensible fluid losses similar to an extensive burn wound. Wound dressings placed over sloughed skin can help prevent secondary infection.2 Lastly, the use of anti-inflammatory drugs and opiates often depends upon the extent of pain the patient experiences.

Our patient was immediately started on IV clindamycin 10 mg/kg tid and IV fluids. She was given morphine 0.01 mg/kg for pain control. As expected, cultures of her nasopharynx, blood, and vulva did not grow S aureus. Although no organism was isolated, her rash rapidly improved, and she was discharged home to complete a 10-day oral course of clindamycin 10 mg/kg tid.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nicholas M. Potisek, MD, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Medical Center Blvd, Winston-Salem, NC 27157; [email protected]

A 3-year-old girl presented with a rapidly progressing rash. The rash began the previous day with redness around her lips and nose (FIGURE 1). Twelve hours later, the rash had progressed to involve her neck, trunk, and inguinal area (FIGURE 2). The child’s parents reported that she had no recent illnesses or treatment with antibiotics.

On physical examination, she was febrile (101.8° F) and irritable throughout the encounter. She had perioral and nasolabial erythema and dryness. Her lips were dry with no intraoral mucosal lesions, and her conjunctiva was clear.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Based on the patient’s classic presentation and exam findings, the physician suspected staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. SSSS is a rare but serious condition that progresses quickly with high fevers and diffuse painful erythema. The exact epidemiology of SSSS is unclear; some articles report incidences between 0.09 and 0.13 cases per 1 million people.1 The mortality rate is about 5% due to complications of sepsis, superinfection, and electrolyte disturbances.2

SSSS is caused by Staphylococcus aureus from a localized source that produces exfoliative toxins A and B that spread hematogenously, causing extensive epidermal damage. Exotoxins bind to desmosomes, causing skin cells to lose adherence.3 Histopathology shows intraepidermal cleavage through the stratum granulosum.

Infants and younger children appear more likely to be affected by SSSS, although it may occur in older children or adults who are immunocompromised. It may be that younger children are most susceptible due to a lack of antibodies to the toxin produced or because of a delayed clearance of the toxin-antibody complex from an immature renal system.

What you’ll see. Patients with SSSS may have a prodrome of irritability, malaise, and fever. The rash is first noticeable as erythema in the flexural areas.4 The erythematous tender patches spread and coalesce into a scarlatiniform erythema. Fragile bullae become large sheets of epidermis that slough (a positive Nikolsky’s sign).5 The desquamated areas can exhibit a scalded appearance.3

Differential diagnosis includes TEN and SJS

There is a broad differential for vesiculobullous rashes, ranging from self-limiting conditions to those that are life threatening.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS), and erythema multiforme major (EMM) are immunological reactions to certain drugs or infections varying in the severity of their presentation. EMM, SJS, and TEN involve the mucosal surfaces, while SSSS does not. The histopathology of these conditions also differs from SSSS as they have keratinocyte necrosis of varying levels of the skin, whereas SSSS only involves the epidermis.

SSSS also may be confused with drug reactions, such as DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome. DRESS typically is associated with anticonvulsants and sulfonamides and may have peripheral eosinophilia and a transaminitis.4

Continue to: Other more self-limited vesiculobullous rashes...

Other more self-limited vesiculobullous rashes include human enteroviruses such as coxsackie virus (hand-foot-mouth disease), echovirus, and enterovirus. However, unlike SSSS, which only affects the epidermis, these disorders may produce epidermal necrosis resulting in epidermal-dermal separation and mucocutaneous blistering.4

Making the diagnosis

When a patient has classic SSSS, the diagnosis can be made based on exam findings and the patient’s history. Families will usually report a generalized rash in neonates with desquamation of the entire skin. Fever is often present. Recent exposures to other family members with skin and soft-tissue infections is a possibility. If there is doubt, a skin biopsy can be obtained for histology. Lab work may reveal an elevated white blood cell count; blood culture is often negative.

The primary site of S aureus infection is usually the nasopharynx, causing a mild upper respiratory tract infection; therefore, nasopharyngeal cultures may be positive.4 Cultures can also be drawn from blood, wounds, nares, and ocular exudates if there is suspicion. Cultures from the actual blisters are typically negative, as the toxin—not the actual bacteria—is responsible for the blistering. Unlike adults who experience SSSS, children typically have negative blood cultures.4

Prompt treatment is essential

Swift diagnosis and management of SSSS is important due to the risk of severe disease. It is important to start antibiotics early because methicillin-sensitive S aureus is a predominant cause of SSSS.2 The epidemiology of methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) continues to shift. A recent study suggests that empiric therapy with penicillinase-resistant penicillins, along with clindamycin, be employed until culture sensitivities are available to guide therapy.2 Local resistance patterns to S aureus should help guide initial empiric antibiotic treatment. Patients should receive intravenous (IV) fluids to compensate for insensible fluid losses similar to an extensive burn wound. Wound dressings placed over sloughed skin can help prevent secondary infection.2 Lastly, the use of anti-inflammatory drugs and opiates often depends upon the extent of pain the patient experiences.

Our patient was immediately started on IV clindamycin 10 mg/kg tid and IV fluids. She was given morphine 0.01 mg/kg for pain control. As expected, cultures of her nasopharynx, blood, and vulva did not grow S aureus. Although no organism was isolated, her rash rapidly improved, and she was discharged home to complete a 10-day oral course of clindamycin 10 mg/kg tid.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nicholas M. Potisek, MD, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Medical Center Blvd, Winston-Salem, NC 27157; [email protected]

1. Mockenhaupt M, Idzko M, Grosber M, et al. Epidemiology of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in Germany. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:700-703.

2. Braunstein I, Wanat K, Abuabara K, et al. Antibiotic sensitivity and resistance patterns in pediatric staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:305-308.

3. Mishra AK, Yadav, P, Mishra A. A systemic review on Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome (SSSS): A rare and critical disease of neonates. Open Microbiol J. 2016;10: 150-159.

4. Handler MZ, Schwarz RA. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome: diagnosis and management in children and adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1418-1423.

5. Franco L, Pereira P. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Indian Pediatr. 2016. 53:939.

1. Mockenhaupt M, Idzko M, Grosber M, et al. Epidemiology of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in Germany. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:700-703.

2. Braunstein I, Wanat K, Abuabara K, et al. Antibiotic sensitivity and resistance patterns in pediatric staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:305-308.

3. Mishra AK, Yadav, P, Mishra A. A systemic review on Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome (SSSS): A rare and critical disease of neonates. Open Microbiol J. 2016;10: 150-159.

4. Handler MZ, Schwarz RA. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome: diagnosis and management in children and adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1418-1423.

5. Franco L, Pereira P. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Indian Pediatr. 2016. 53:939.

Persistent facial hyperpigmentation

A 59-year-old woman presented to a dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic brown facial hyperpigmentation that had developed several years earlier, and had persisted, despite regular face washing. Physicians who previously treated this patient interpreted this as melasma and advised her to wear sunscreen. The condition was not aggravated by sun exposure. The patient reported that she was otherwise healthy.

Physical examination revealed a brown discoloration with a slightly rough texture. Upon rubbing the affected area with a 70% isopropyl alcohol pad, normal skin was revealed (FIGURE 1A) and brown flakes were apparent on the gauze (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Terra firma-forme dermatosis

The physician diagnosed terra firma-forme dermatosis (TFFD) in this patient, noting the “dirty brown coloration” and distribution that did not suggest post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation or melasma. TFFD is a rare and benign form of acquired hyperpigmentation characterized by “velvety, pigmented patches or plaques.”1 A simple bedside test, known as an “alcohol wipe test,” both confirms and treats TFFD; it involves rubbing the affected area with a 70% isopropyl alcohol pad.1

TFFD typically affects the face, neck, trunk, or ankles, but the scalp, axilla, back, and pubis also can be affected.1 Histopathology will show negligible amounts of dermal inflammation, hyperkeratosis with mild acanthosis, and hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis.1 Most patients diagnosed with TFFD report that the hyperpigmentation does not improve despite washing with soap and water.2

Hygiene is not a factor

In 2015, Greywal and Cohen followed the case presentations of 10 Caucasian patients with TFFD who presented with “brown and/or black plaques or papules or both.”2 Many of the individuals followed in this case series reported “[practicing] good hygiene and showered a minimum of every other day or daily.”2 The same was reported by the patient in this case. This suggests that TFFD is not a consequence of poor hygiene but perhaps a result of “sticky” sebum that produces a buildup of keratin debris, sebum, and bacteria on the skin.3 This produces the hyperpigmentation seen clinically.

Differential includes post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation

Several other hyperpigmentation disorders were considered on the initial differential diagnosis for this case, including melasma and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. However, these 2 conditions are macular, whereas this hyperpigmented condition had a rough, mildly papular texture. Additionally, melasma flares up in the summer with UV exposure, and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation presents with pruritus and/or a pre-existing rash.4 This patient reported that the condition did not itch nor change with increased sunlight, thus making melasma and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation unlikely diagnoses.

Acanthosis nigricans also was considered because it presents with a velvety brown pigmentation similar to what was seen with this patient. Acanthosis nigricans, however, primarily affects flexural areas, not the face, making it improbable.

Continue to: Our patient

Our patient. A “wipe test” was performed on the patient. This removed the brown flaky scaling and revealed the underlying normal skin. We instructed the patient to wash daily with a soapy wash cloth and scrub with 70% isopropyl alcohol should the hyperpigmentation recur. The patient did not return.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected]

1. Lunge S, Supraja C. Terra firma-forme dermatosis—a dirty dermatosis: report of two cases. Our Dermatol Online. 2016;7:338-340.

2. Greywal T, Cohen PR. Terra firma-forme dermatosis: A report of ten individuals with Duncan’s dirty dermatosis and literature review. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2015;5:29-33.

3. Alonso-Usero V, Gavrilova M, et al. Dermatosis neglecta or terra firma-forme dermatosis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:932-934.

4. Lucas J, Brodell RT, Feldman SR. Dermatosis neglecta: a series of case reports and review of other dirty-appearing dermatoses. Dermatol Online J. 2006;12:5.

A 59-year-old woman presented to a dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic brown facial hyperpigmentation that had developed several years earlier, and had persisted, despite regular face washing. Physicians who previously treated this patient interpreted this as melasma and advised her to wear sunscreen. The condition was not aggravated by sun exposure. The patient reported that she was otherwise healthy.

Physical examination revealed a brown discoloration with a slightly rough texture. Upon rubbing the affected area with a 70% isopropyl alcohol pad, normal skin was revealed (FIGURE 1A) and brown flakes were apparent on the gauze (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Terra firma-forme dermatosis

The physician diagnosed terra firma-forme dermatosis (TFFD) in this patient, noting the “dirty brown coloration” and distribution that did not suggest post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation or melasma. TFFD is a rare and benign form of acquired hyperpigmentation characterized by “velvety, pigmented patches or plaques.”1 A simple bedside test, known as an “alcohol wipe test,” both confirms and treats TFFD; it involves rubbing the affected area with a 70% isopropyl alcohol pad.1

TFFD typically affects the face, neck, trunk, or ankles, but the scalp, axilla, back, and pubis also can be affected.1 Histopathology will show negligible amounts of dermal inflammation, hyperkeratosis with mild acanthosis, and hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis.1 Most patients diagnosed with TFFD report that the hyperpigmentation does not improve despite washing with soap and water.2

Hygiene is not a factor

In 2015, Greywal and Cohen followed the case presentations of 10 Caucasian patients with TFFD who presented with “brown and/or black plaques or papules or both.”2 Many of the individuals followed in this case series reported “[practicing] good hygiene and showered a minimum of every other day or daily.”2 The same was reported by the patient in this case. This suggests that TFFD is not a consequence of poor hygiene but perhaps a result of “sticky” sebum that produces a buildup of keratin debris, sebum, and bacteria on the skin.3 This produces the hyperpigmentation seen clinically.

Differential includes post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation

Several other hyperpigmentation disorders were considered on the initial differential diagnosis for this case, including melasma and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. However, these 2 conditions are macular, whereas this hyperpigmented condition had a rough, mildly papular texture. Additionally, melasma flares up in the summer with UV exposure, and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation presents with pruritus and/or a pre-existing rash.4 This patient reported that the condition did not itch nor change with increased sunlight, thus making melasma and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation unlikely diagnoses.

Acanthosis nigricans also was considered because it presents with a velvety brown pigmentation similar to what was seen with this patient. Acanthosis nigricans, however, primarily affects flexural areas, not the face, making it improbable.

Continue to: Our patient

Our patient. A “wipe test” was performed on the patient. This removed the brown flaky scaling and revealed the underlying normal skin. We instructed the patient to wash daily with a soapy wash cloth and scrub with 70% isopropyl alcohol should the hyperpigmentation recur. The patient did not return.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected]

A 59-year-old woman presented to a dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic brown facial hyperpigmentation that had developed several years earlier, and had persisted, despite regular face washing. Physicians who previously treated this patient interpreted this as melasma and advised her to wear sunscreen. The condition was not aggravated by sun exposure. The patient reported that she was otherwise healthy.

Physical examination revealed a brown discoloration with a slightly rough texture. Upon rubbing the affected area with a 70% isopropyl alcohol pad, normal skin was revealed (FIGURE 1A) and brown flakes were apparent on the gauze (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Terra firma-forme dermatosis

The physician diagnosed terra firma-forme dermatosis (TFFD) in this patient, noting the “dirty brown coloration” and distribution that did not suggest post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation or melasma. TFFD is a rare and benign form of acquired hyperpigmentation characterized by “velvety, pigmented patches or plaques.”1 A simple bedside test, known as an “alcohol wipe test,” both confirms and treats TFFD; it involves rubbing the affected area with a 70% isopropyl alcohol pad.1

TFFD typically affects the face, neck, trunk, or ankles, but the scalp, axilla, back, and pubis also can be affected.1 Histopathology will show negligible amounts of dermal inflammation, hyperkeratosis with mild acanthosis, and hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis.1 Most patients diagnosed with TFFD report that the hyperpigmentation does not improve despite washing with soap and water.2

Hygiene is not a factor

In 2015, Greywal and Cohen followed the case presentations of 10 Caucasian patients with TFFD who presented with “brown and/or black plaques or papules or both.”2 Many of the individuals followed in this case series reported “[practicing] good hygiene and showered a minimum of every other day or daily.”2 The same was reported by the patient in this case. This suggests that TFFD is not a consequence of poor hygiene but perhaps a result of “sticky” sebum that produces a buildup of keratin debris, sebum, and bacteria on the skin.3 This produces the hyperpigmentation seen clinically.

Differential includes post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation

Several other hyperpigmentation disorders were considered on the initial differential diagnosis for this case, including melasma and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. However, these 2 conditions are macular, whereas this hyperpigmented condition had a rough, mildly papular texture. Additionally, melasma flares up in the summer with UV exposure, and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation presents with pruritus and/or a pre-existing rash.4 This patient reported that the condition did not itch nor change with increased sunlight, thus making melasma and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation unlikely diagnoses.

Acanthosis nigricans also was considered because it presents with a velvety brown pigmentation similar to what was seen with this patient. Acanthosis nigricans, however, primarily affects flexural areas, not the face, making it improbable.

Continue to: Our patient

Our patient. A “wipe test” was performed on the patient. This removed the brown flaky scaling and revealed the underlying normal skin. We instructed the patient to wash daily with a soapy wash cloth and scrub with 70% isopropyl alcohol should the hyperpigmentation recur. The patient did not return.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected]

1. Lunge S, Supraja C. Terra firma-forme dermatosis—a dirty dermatosis: report of two cases. Our Dermatol Online. 2016;7:338-340.

2. Greywal T, Cohen PR. Terra firma-forme dermatosis: A report of ten individuals with Duncan’s dirty dermatosis and literature review. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2015;5:29-33.

3. Alonso-Usero V, Gavrilova M, et al. Dermatosis neglecta or terra firma-forme dermatosis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:932-934.

4. Lucas J, Brodell RT, Feldman SR. Dermatosis neglecta: a series of case reports and review of other dirty-appearing dermatoses. Dermatol Online J. 2006;12:5.

1. Lunge S, Supraja C. Terra firma-forme dermatosis—a dirty dermatosis: report of two cases. Our Dermatol Online. 2016;7:338-340.

2. Greywal T, Cohen PR. Terra firma-forme dermatosis: A report of ten individuals with Duncan’s dirty dermatosis and literature review. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2015;5:29-33.

3. Alonso-Usero V, Gavrilova M, et al. Dermatosis neglecta or terra firma-forme dermatosis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:932-934.

4. Lucas J, Brodell RT, Feldman SR. Dermatosis neglecta: a series of case reports and review of other dirty-appearing dermatoses. Dermatol Online J. 2006;12:5.

Growing cyst on face

The FP suspected this was more than just a simple cyst, and his differential diagnosis included basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). The FP advised the patient that a punch biopsy was needed to determine the diagnosis and that it was not possible to just remove the cyst. The patient consented to the biopsy, and the FP performed a 4-mm punch biopsy. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The pathology showed an invasive SCC. Note that cutaneous SCCs can appear cystic on presentation. Due to the location and size of the SCC, the patient was referred to Head and Neck Surgery for resection of the tumor and flap repair. The temporal branch of the facial nerve was spared. And, while it appeared that the red lines radiating down the cheek from the tumor were lymphangitic spread, the pathology at the time of the tumor resection did not show this. The surgery achieved clear margins, and the patient recovered well.

On a follow-up visit, the FP performed a total body skin exam to look for other skin cancers and found none. He also counseled the patient on sun avoidance, the consistent use of a hat outdoors, and the use of sunscreen when exposed to the sun.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected this was more than just a simple cyst, and his differential diagnosis included basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). The FP advised the patient that a punch biopsy was needed to determine the diagnosis and that it was not possible to just remove the cyst. The patient consented to the biopsy, and the FP performed a 4-mm punch biopsy. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The pathology showed an invasive SCC. Note that cutaneous SCCs can appear cystic on presentation. Due to the location and size of the SCC, the patient was referred to Head and Neck Surgery for resection of the tumor and flap repair. The temporal branch of the facial nerve was spared. And, while it appeared that the red lines radiating down the cheek from the tumor were lymphangitic spread, the pathology at the time of the tumor resection did not show this. The surgery achieved clear margins, and the patient recovered well.

On a follow-up visit, the FP performed a total body skin exam to look for other skin cancers and found none. He also counseled the patient on sun avoidance, the consistent use of a hat outdoors, and the use of sunscreen when exposed to the sun.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected this was more than just a simple cyst, and his differential diagnosis included basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). The FP advised the patient that a punch biopsy was needed to determine the diagnosis and that it was not possible to just remove the cyst. The patient consented to the biopsy, and the FP performed a 4-mm punch biopsy. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The pathology showed an invasive SCC. Note that cutaneous SCCs can appear cystic on presentation. Due to the location and size of the SCC, the patient was referred to Head and Neck Surgery for resection of the tumor and flap repair. The temporal branch of the facial nerve was spared. And, while it appeared that the red lines radiating down the cheek from the tumor were lymphangitic spread, the pathology at the time of the tumor resection did not show this. The surgery achieved clear margins, and the patient recovered well.

On a follow-up visit, the FP performed a total body skin exam to look for other skin cancers and found none. He also counseled the patient on sun avoidance, the consistent use of a hat outdoors, and the use of sunscreen when exposed to the sun.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Lesions around anus

The FP suspected invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) related to human papillomavirus. He recognized that the patient was at a higher risk of this secondary to the HIV/AIDS diagnosis.

The FP recommended a shave biopsy (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) of the ulcerated lesion, and the patient consented to this procedure. The FP used a surgical marker to mark an area at the edge of the ulcer including some tissue outside of the ulcer. (This is recommended for biopsy of any ulcerated skin lesion.) He then injected 1% lidocaine with epinephrine into the edge of the ulcer for anesthesia and to minimize bleeding during the shave biopsy. The shave was performed and aluminum chloride, along with electrosurgery, was used to stop the bleeding.

The pathology showed an invasive SCC. Due to the size and location of the lesions, the patient was referred to Colorectal Surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) related to human papillomavirus. He recognized that the patient was at a higher risk of this secondary to the HIV/AIDS diagnosis.

The FP recommended a shave biopsy (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) of the ulcerated lesion, and the patient consented to this procedure. The FP used a surgical marker to mark an area at the edge of the ulcer including some tissue outside of the ulcer. (This is recommended for biopsy of any ulcerated skin lesion.) He then injected 1% lidocaine with epinephrine into the edge of the ulcer for anesthesia and to minimize bleeding during the shave biopsy. The shave was performed and aluminum chloride, along with electrosurgery, was used to stop the bleeding.

The pathology showed an invasive SCC. Due to the size and location of the lesions, the patient was referred to Colorectal Surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) related to human papillomavirus. He recognized that the patient was at a higher risk of this secondary to the HIV/AIDS diagnosis.

The FP recommended a shave biopsy (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) of the ulcerated lesion, and the patient consented to this procedure. The FP used a surgical marker to mark an area at the edge of the ulcer including some tissue outside of the ulcer. (This is recommended for biopsy of any ulcerated skin lesion.) He then injected 1% lidocaine with epinephrine into the edge of the ulcer for anesthesia and to minimize bleeding during the shave biopsy. The shave was performed and aluminum chloride, along with electrosurgery, was used to stop the bleeding.

The pathology showed an invasive SCC. Due to the size and location of the lesions, the patient was referred to Colorectal Surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Growing lesion

The FP recognized this as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the penis.

The FP knew that a biopsy would be needed to confirm his clinical impression and obtained informed consent for a shave biopsy of a portion of the lesion. While the FP was taught in medical school to never use epinephrine on the penis, he realized that this was merely a myth (see “Biopsies for skin cancer detection: Dispelling the myths”). He injected 1% lidocaine with epinephrine into the lesion for anesthesia and to minimize bleeding during the shave biopsy. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The FP performed a shave biopsy of a small portion of the lesion farthest from the urethra.

Aluminum chloride was used to stop most of the bleeding, but since the penis is very vascular, some electrocoagulation was needed to stop all of the bleeding. The pathology came back as an invasive SCC. Due to the location of the lesion on the glans and around the urethra, the patient was referred to Urology.

A partial penectomy was performed and clear surgical margins were achieved. If the lesion had been on the shaft of the penis (rather than the glans penis), a Mohs surgeon would have attempted to save the whole penis with tissue sparing surgery.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Meffert, MD, and text courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized this as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the penis.

The FP knew that a biopsy would be needed to confirm his clinical impression and obtained informed consent for a shave biopsy of a portion of the lesion. While the FP was taught in medical school to never use epinephrine on the penis, he realized that this was merely a myth (see “Biopsies for skin cancer detection: Dispelling the myths”). He injected 1% lidocaine with epinephrine into the lesion for anesthesia and to minimize bleeding during the shave biopsy. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The FP performed a shave biopsy of a small portion of the lesion farthest from the urethra.

Aluminum chloride was used to stop most of the bleeding, but since the penis is very vascular, some electrocoagulation was needed to stop all of the bleeding. The pathology came back as an invasive SCC. Due to the location of the lesion on the glans and around the urethra, the patient was referred to Urology.

A partial penectomy was performed and clear surgical margins were achieved. If the lesion had been on the shaft of the penis (rather than the glans penis), a Mohs surgeon would have attempted to save the whole penis with tissue sparing surgery.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Meffert, MD, and text courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized this as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the penis.

The FP knew that a biopsy would be needed to confirm his clinical impression and obtained informed consent for a shave biopsy of a portion of the lesion. While the FP was taught in medical school to never use epinephrine on the penis, he realized that this was merely a myth (see “Biopsies for skin cancer detection: Dispelling the myths”). He injected 1% lidocaine with epinephrine into the lesion for anesthesia and to minimize bleeding during the shave biopsy. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The FP performed a shave biopsy of a small portion of the lesion farthest from the urethra.

Aluminum chloride was used to stop most of the bleeding, but since the penis is very vascular, some electrocoagulation was needed to stop all of the bleeding. The pathology came back as an invasive SCC. Due to the location of the lesion on the glans and around the urethra, the patient was referred to Urology.

A partial penectomy was performed and clear surgical margins were achieved. If the lesion had been on the shaft of the penis (rather than the glans penis), a Mohs surgeon would have attempted to save the whole penis with tissue sparing surgery.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Meffert, MD, and text courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Painful lesion on lower lip

The FP recognized this as a probable squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) arising in a burn, known as a Marjolin ulcer.

The combination of the burn and the location on the lower lip made it extremely likely that this lesion was an SCC. The FP suggested the patient get a biopsy and have surgery for treatment. Unfortunately, the patient lived in poverty with no health insurance, financial means, running water, or electricity and stated that she could not afford any medical treatment. Her local hospital required cash payments, and she did not believe they would help her without funding and hoped that the medical mission team could help her. The FP was saddened by this news, but suggested that she do her best to access treatment in the near future. The FP did not have access to a pathologist (even if he could do the biopsy). Ultimately, the patient would need an experienced surgeon to excise this SCC.

With close to 1 billion people living in extreme poverty in the world, this is one sad example of a person that likely went without medical care for a serious, but treatable, illness.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized this as a probable squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) arising in a burn, known as a Marjolin ulcer.

The combination of the burn and the location on the lower lip made it extremely likely that this lesion was an SCC. The FP suggested the patient get a biopsy and have surgery for treatment. Unfortunately, the patient lived in poverty with no health insurance, financial means, running water, or electricity and stated that she could not afford any medical treatment. Her local hospital required cash payments, and she did not believe they would help her without funding and hoped that the medical mission team could help her. The FP was saddened by this news, but suggested that she do her best to access treatment in the near future. The FP did not have access to a pathologist (even if he could do the biopsy). Ultimately, the patient would need an experienced surgeon to excise this SCC.

With close to 1 billion people living in extreme poverty in the world, this is one sad example of a person that likely went without medical care for a serious, but treatable, illness.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized this as a probable squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) arising in a burn, known as a Marjolin ulcer.

The combination of the burn and the location on the lower lip made it extremely likely that this lesion was an SCC. The FP suggested the patient get a biopsy and have surgery for treatment. Unfortunately, the patient lived in poverty with no health insurance, financial means, running water, or electricity and stated that she could not afford any medical treatment. Her local hospital required cash payments, and she did not believe they would help her without funding and hoped that the medical mission team could help her. The FP was saddened by this news, but suggested that she do her best to access treatment in the near future. The FP did not have access to a pathologist (even if he could do the biopsy). Ultimately, the patient would need an experienced surgeon to excise this SCC.

With close to 1 billion people living in extreme poverty in the world, this is one sad example of a person that likely went without medical care for a serious, but treatable, illness.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Growth on right hand

The FP recognized that this could be a wart but was concerned that it might be a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) related to HPV and sun exposure.

He performed a shave biopsy and the pathology report indicated it was an SCC in situ. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) At the follow-up visit, the FP reviewed the patient’s treatment options, which included topical 5% fluorouracil, topical imiquimod, and surgical excision. He also explained that the topical treatments were off label, so these options might have a lower success rate than the surgery.

The patient chose to have the surgery, even though he’d be out of work while the excision site was healing. The FP provided counseling about sun avoidance, the consistent use of a hat outdoors, and the use of sunscreens when exposed to the sun. He also referred the patient to a dermatologist who had extensive experience doing skin cancer surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

The new third edition will be available in January 2019: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/.

You can also get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized that this could be a wart but was concerned that it might be a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) related to HPV and sun exposure.

He performed a shave biopsy and the pathology report indicated it was an SCC in situ. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) At the follow-up visit, the FP reviewed the patient’s treatment options, which included topical 5% fluorouracil, topical imiquimod, and surgical excision. He also explained that the topical treatments were off label, so these options might have a lower success rate than the surgery.

The patient chose to have the surgery, even though he’d be out of work while the excision site was healing. The FP provided counseling about sun avoidance, the consistent use of a hat outdoors, and the use of sunscreens when exposed to the sun. He also referred the patient to a dermatologist who had extensive experience doing skin cancer surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

The new third edition will be available in January 2019: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/.

You can also get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized that this could be a wart but was concerned that it might be a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) related to HPV and sun exposure.

He performed a shave biopsy and the pathology report indicated it was an SCC in situ. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) At the follow-up visit, the FP reviewed the patient’s treatment options, which included topical 5% fluorouracil, topical imiquimod, and surgical excision. He also explained that the topical treatments were off label, so these options might have a lower success rate than the surgery.

The patient chose to have the surgery, even though he’d be out of work while the excision site was healing. The FP provided counseling about sun avoidance, the consistent use of a hat outdoors, and the use of sunscreens when exposed to the sun. He also referred the patient to a dermatologist who had extensive experience doing skin cancer surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

The new third edition will be available in January 2019: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/.

You can also get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Wart on scalp

The FP had seen many recalcitrant warts before, but rather than repeat the cryotherapy, he performed a shave biopsy to get a definitive diagnosis. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The biopsy revealed a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

This lesion may have started with a wart, as human papillomavirus (HPV) is both the cause of warts and a risk factor for cutaneous SCC. The FP referred the patient to a Mohs surgeon for complete excision of the SCC. He also provided counseling about sun avoidance, the consistent use of a hat outdoors, and the use of sunscreens when exposed to the sun.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

The new third edition will be available in January 2019: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/.

You can also get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP had seen many recalcitrant warts before, but rather than repeat the cryotherapy, he performed a shave biopsy to get a definitive diagnosis. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The biopsy revealed a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

This lesion may have started with a wart, as human papillomavirus (HPV) is both the cause of warts and a risk factor for cutaneous SCC. The FP referred the patient to a Mohs surgeon for complete excision of the SCC. He also provided counseling about sun avoidance, the consistent use of a hat outdoors, and the use of sunscreens when exposed to the sun.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

The new third edition will be available in January 2019: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/.

You can also get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP had seen many recalcitrant warts before, but rather than repeat the cryotherapy, he performed a shave biopsy to get a definitive diagnosis. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The biopsy revealed a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

This lesion may have started with a wart, as human papillomavirus (HPV) is both the cause of warts and a risk factor for cutaneous SCC. The FP referred the patient to a Mohs surgeon for complete excision of the SCC. He also provided counseling about sun avoidance, the consistent use of a hat outdoors, and the use of sunscreens when exposed to the sun.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

The new third edition will be available in January 2019: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/.

You can also get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.