User login

Erythematous swollen ear

A 25-year-old woman presented with an exceedingly tender right ear. She’d had the helix of her ear pierced 3 days prior to presentation and 2 days after that, the ear had become tender. The tenderness was progressively worsening and associated with throbbing pain. The patient, who’d had her ears pierced before, was otherwise in good health and denied fever, chills, or travel outside of the country. She had been going to the gym regularly and took frequent showers. Physical examination revealed an erythematous swollen ear that was tender to the touch (FIGURE). The entire auricle was swollen except for the earlobe. The patient also reported purulent material draining from the helical piercing site.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Auricular perichondritis

Auricular perichondritis is an inflammation of the connective tissue surrounding the cartilage of the ear. Infectious and autoimmune factors may play a role. The underlying cartilage also may become involved. A useful clinical clue to the diagnosis of auricular perichondritis is sparing of the earlobe, which does not contain cartilage. Autoimmune causes typically have bilateral involvement. Infectious causes are usually associated with trauma and purulent drainage at the wound site. Ear piercings are an increasingly common cause, but perichondritis due to minor trauma, as a surgical complication, or in the absence of an obvious inciting trigger can occur. A careful history usually will reveal the cause.

In this case, the patient indicated that an open piercing gun at a shopping mall kiosk had been used to pierce her ear. Piercing with a sterile straight needle would have been preferable and less likely to be associated with secondary infection, as the shearing trauma to the perichondrium experienced with a piercing gun is thought to predispose to infection.1 Exposure to fresh water from the shower could have been a source for Pseudomonas infection.1

Differential: Pinpointing the diagnosis early is vital

A red and tender ear can raise a differential diagnosis that includes erysipelas, relapsing polychondritis, and auricular perichondritis. Erysipelas is a bacterial infection that spreads through the lymphatic system and is associated with intense and well-demarcated erythema. Erysipelas typically involves the face or lower legs. Infection after piercing or traumatic injury should raise suspicion of pseudomonal infection.2-5 Untreated infection can spread quickly and lead to permanent ear deformity. Although the same pattern of inflammation can be seen in relapsing polychondritis, relapsing polychondritis typically involves both ears as well as the eyes and joints.

Prompt treatment is necessary to avoid cosmetic disfigurement

The timing of the reaction in our patient made infection obvious because Pseudomonas aeruginosa seems to have a particular affinity for damaged cartilage.2

Ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily is the treatment of choice. Although many skin infections can be empirically treated with oral cephalosporin, penicillin, or erythromycin, it is important to recognize that infected piercing sites and auricular perichondritis due to pseudomonal infection will not respond to these agents. That’s because these agents do not provide as good coverage for Pseudomonas as they do for Staphylococci or other bacteria more often associated with skin infection. Treatment with an agent such as amoxicillin and clavulanic acid or oral cephalexin can mean the loss of valuable time and subsequent cosmetic disfigurement.6

Continue to: When fluctuance is present...

When fluctuance is present, incision and drainage, or even debridement, may be necessary. When extensive infection leads to cartilage necrosis and liquefaction, treatment is difficult and may result in lasting disfigurement. Prompt empiric treatment currently is considered the best option.6

Our patient was prescribed a course of ciprofloxacin 500 mg every 12 hours for 10 days. She noted improvement within 2 days, and the infection resolved without complication.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, Penn State Health Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Dr, HU14, Hershey, PA 17033; [email protected]

1. Sandhu A, Gross M, Wylie J, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa necrotizing chondritis complicating high helical ear piercing case report: clinical and public health perspectives. Can J Public Health. 2007;98:74-77.

2. Prasad HK, Sreedharan S, Prasad HS, et al. Perichondritis of the auricle and its management. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:530-534.

3. Fisher CG, Kacica MA, Bennett NM. Risk factors for cartilage infections of the ear. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:204-209.

4. Lee TC, Gold WL. Necrotizing Pseudomonas chondritis after piercing of the upper ear. CMAJ. 2011;183:819-821.

5. Rowshan HH, Keith K, Baur D, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection of the auricular cartilage caused by “high ear piercing”: a case report and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:543-546.

6. Liu ZW, Chokkalingam P. Piercing associated perichondritis of the pinna: are we treating it correctly? J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127:505-508.

A 25-year-old woman presented with an exceedingly tender right ear. She’d had the helix of her ear pierced 3 days prior to presentation and 2 days after that, the ear had become tender. The tenderness was progressively worsening and associated with throbbing pain. The patient, who’d had her ears pierced before, was otherwise in good health and denied fever, chills, or travel outside of the country. She had been going to the gym regularly and took frequent showers. Physical examination revealed an erythematous swollen ear that was tender to the touch (FIGURE). The entire auricle was swollen except for the earlobe. The patient also reported purulent material draining from the helical piercing site.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Auricular perichondritis

Auricular perichondritis is an inflammation of the connective tissue surrounding the cartilage of the ear. Infectious and autoimmune factors may play a role. The underlying cartilage also may become involved. A useful clinical clue to the diagnosis of auricular perichondritis is sparing of the earlobe, which does not contain cartilage. Autoimmune causes typically have bilateral involvement. Infectious causes are usually associated with trauma and purulent drainage at the wound site. Ear piercings are an increasingly common cause, but perichondritis due to minor trauma, as a surgical complication, or in the absence of an obvious inciting trigger can occur. A careful history usually will reveal the cause.

In this case, the patient indicated that an open piercing gun at a shopping mall kiosk had been used to pierce her ear. Piercing with a sterile straight needle would have been preferable and less likely to be associated with secondary infection, as the shearing trauma to the perichondrium experienced with a piercing gun is thought to predispose to infection.1 Exposure to fresh water from the shower could have been a source for Pseudomonas infection.1

Differential: Pinpointing the diagnosis early is vital

A red and tender ear can raise a differential diagnosis that includes erysipelas, relapsing polychondritis, and auricular perichondritis. Erysipelas is a bacterial infection that spreads through the lymphatic system and is associated with intense and well-demarcated erythema. Erysipelas typically involves the face or lower legs. Infection after piercing or traumatic injury should raise suspicion of pseudomonal infection.2-5 Untreated infection can spread quickly and lead to permanent ear deformity. Although the same pattern of inflammation can be seen in relapsing polychondritis, relapsing polychondritis typically involves both ears as well as the eyes and joints.

Prompt treatment is necessary to avoid cosmetic disfigurement

The timing of the reaction in our patient made infection obvious because Pseudomonas aeruginosa seems to have a particular affinity for damaged cartilage.2

Ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily is the treatment of choice. Although many skin infections can be empirically treated with oral cephalosporin, penicillin, or erythromycin, it is important to recognize that infected piercing sites and auricular perichondritis due to pseudomonal infection will not respond to these agents. That’s because these agents do not provide as good coverage for Pseudomonas as they do for Staphylococci or other bacteria more often associated with skin infection. Treatment with an agent such as amoxicillin and clavulanic acid or oral cephalexin can mean the loss of valuable time and subsequent cosmetic disfigurement.6

Continue to: When fluctuance is present...

When fluctuance is present, incision and drainage, or even debridement, may be necessary. When extensive infection leads to cartilage necrosis and liquefaction, treatment is difficult and may result in lasting disfigurement. Prompt empiric treatment currently is considered the best option.6

Our patient was prescribed a course of ciprofloxacin 500 mg every 12 hours for 10 days. She noted improvement within 2 days, and the infection resolved without complication.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, Penn State Health Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Dr, HU14, Hershey, PA 17033; [email protected]

A 25-year-old woman presented with an exceedingly tender right ear. She’d had the helix of her ear pierced 3 days prior to presentation and 2 days after that, the ear had become tender. The tenderness was progressively worsening and associated with throbbing pain. The patient, who’d had her ears pierced before, was otherwise in good health and denied fever, chills, or travel outside of the country. She had been going to the gym regularly and took frequent showers. Physical examination revealed an erythematous swollen ear that was tender to the touch (FIGURE). The entire auricle was swollen except for the earlobe. The patient also reported purulent material draining from the helical piercing site.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Auricular perichondritis

Auricular perichondritis is an inflammation of the connective tissue surrounding the cartilage of the ear. Infectious and autoimmune factors may play a role. The underlying cartilage also may become involved. A useful clinical clue to the diagnosis of auricular perichondritis is sparing of the earlobe, which does not contain cartilage. Autoimmune causes typically have bilateral involvement. Infectious causes are usually associated with trauma and purulent drainage at the wound site. Ear piercings are an increasingly common cause, but perichondritis due to minor trauma, as a surgical complication, or in the absence of an obvious inciting trigger can occur. A careful history usually will reveal the cause.

In this case, the patient indicated that an open piercing gun at a shopping mall kiosk had been used to pierce her ear. Piercing with a sterile straight needle would have been preferable and less likely to be associated with secondary infection, as the shearing trauma to the perichondrium experienced with a piercing gun is thought to predispose to infection.1 Exposure to fresh water from the shower could have been a source for Pseudomonas infection.1

Differential: Pinpointing the diagnosis early is vital

A red and tender ear can raise a differential diagnosis that includes erysipelas, relapsing polychondritis, and auricular perichondritis. Erysipelas is a bacterial infection that spreads through the lymphatic system and is associated with intense and well-demarcated erythema. Erysipelas typically involves the face or lower legs. Infection after piercing or traumatic injury should raise suspicion of pseudomonal infection.2-5 Untreated infection can spread quickly and lead to permanent ear deformity. Although the same pattern of inflammation can be seen in relapsing polychondritis, relapsing polychondritis typically involves both ears as well as the eyes and joints.

Prompt treatment is necessary to avoid cosmetic disfigurement

The timing of the reaction in our patient made infection obvious because Pseudomonas aeruginosa seems to have a particular affinity for damaged cartilage.2

Ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily is the treatment of choice. Although many skin infections can be empirically treated with oral cephalosporin, penicillin, or erythromycin, it is important to recognize that infected piercing sites and auricular perichondritis due to pseudomonal infection will not respond to these agents. That’s because these agents do not provide as good coverage for Pseudomonas as they do for Staphylococci or other bacteria more often associated with skin infection. Treatment with an agent such as amoxicillin and clavulanic acid or oral cephalexin can mean the loss of valuable time and subsequent cosmetic disfigurement.6

Continue to: When fluctuance is present...

When fluctuance is present, incision and drainage, or even debridement, may be necessary. When extensive infection leads to cartilage necrosis and liquefaction, treatment is difficult and may result in lasting disfigurement. Prompt empiric treatment currently is considered the best option.6

Our patient was prescribed a course of ciprofloxacin 500 mg every 12 hours for 10 days. She noted improvement within 2 days, and the infection resolved without complication.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, Penn State Health Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Dr, HU14, Hershey, PA 17033; [email protected]

1. Sandhu A, Gross M, Wylie J, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa necrotizing chondritis complicating high helical ear piercing case report: clinical and public health perspectives. Can J Public Health. 2007;98:74-77.

2. Prasad HK, Sreedharan S, Prasad HS, et al. Perichondritis of the auricle and its management. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:530-534.

3. Fisher CG, Kacica MA, Bennett NM. Risk factors for cartilage infections of the ear. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:204-209.

4. Lee TC, Gold WL. Necrotizing Pseudomonas chondritis after piercing of the upper ear. CMAJ. 2011;183:819-821.

5. Rowshan HH, Keith K, Baur D, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection of the auricular cartilage caused by “high ear piercing”: a case report and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:543-546.

6. Liu ZW, Chokkalingam P. Piercing associated perichondritis of the pinna: are we treating it correctly? J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127:505-508.

1. Sandhu A, Gross M, Wylie J, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa necrotizing chondritis complicating high helical ear piercing case report: clinical and public health perspectives. Can J Public Health. 2007;98:74-77.

2. Prasad HK, Sreedharan S, Prasad HS, et al. Perichondritis of the auricle and its management. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:530-534.

3. Fisher CG, Kacica MA, Bennett NM. Risk factors for cartilage infections of the ear. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:204-209.

4. Lee TC, Gold WL. Necrotizing Pseudomonas chondritis after piercing of the upper ear. CMAJ. 2011;183:819-821.

5. Rowshan HH, Keith K, Baur D, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection of the auricular cartilage caused by “high ear piercing”: a case report and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:543-546.

6. Liu ZW, Chokkalingam P. Piercing associated perichondritis of the pinna: are we treating it correctly? J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127:505-508.

Painful, slow-growing recurrent nodules

A 67-year-old woman presented with multiple painful nodules that had developed on her scalp, face, and neck over the course of 1 year. She also had a few nodules on her trunk and hip. There was no associated bleeding, ulceration, or drainage from the lesions. She had no systemic symptoms. The patient reported that she’d had a similar lesion on her frontal scalp about 15 years earlier, and it was excised completely. (She was not aware of the diagnosis.) She indicated that her mother and son had similar lesions in the past.

Her medical history was remarkable for diabetes and hypertension, which were well controlled on metformin and lisinopril, respectively. The patient had cancer of the left breast that was treated with mastectomy and chemotherapy 3 years prior.

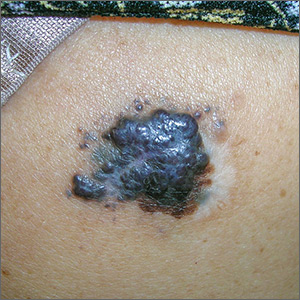

On physical examination, the patient had multiple firm, rubbery, tender nodules with tan or pink hue, measuring 1 to 1.5 cm. The nodules were located on the left side of her chin and right preauricular area (FIGURE 1), as well as the right sides of her neck and hip. Most of the nodules were solitary; the preauricular area had 2 clustered pink lesions. The largest nodule was located on the patient’s chin and had overlying telangiectasias.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Cylindroma

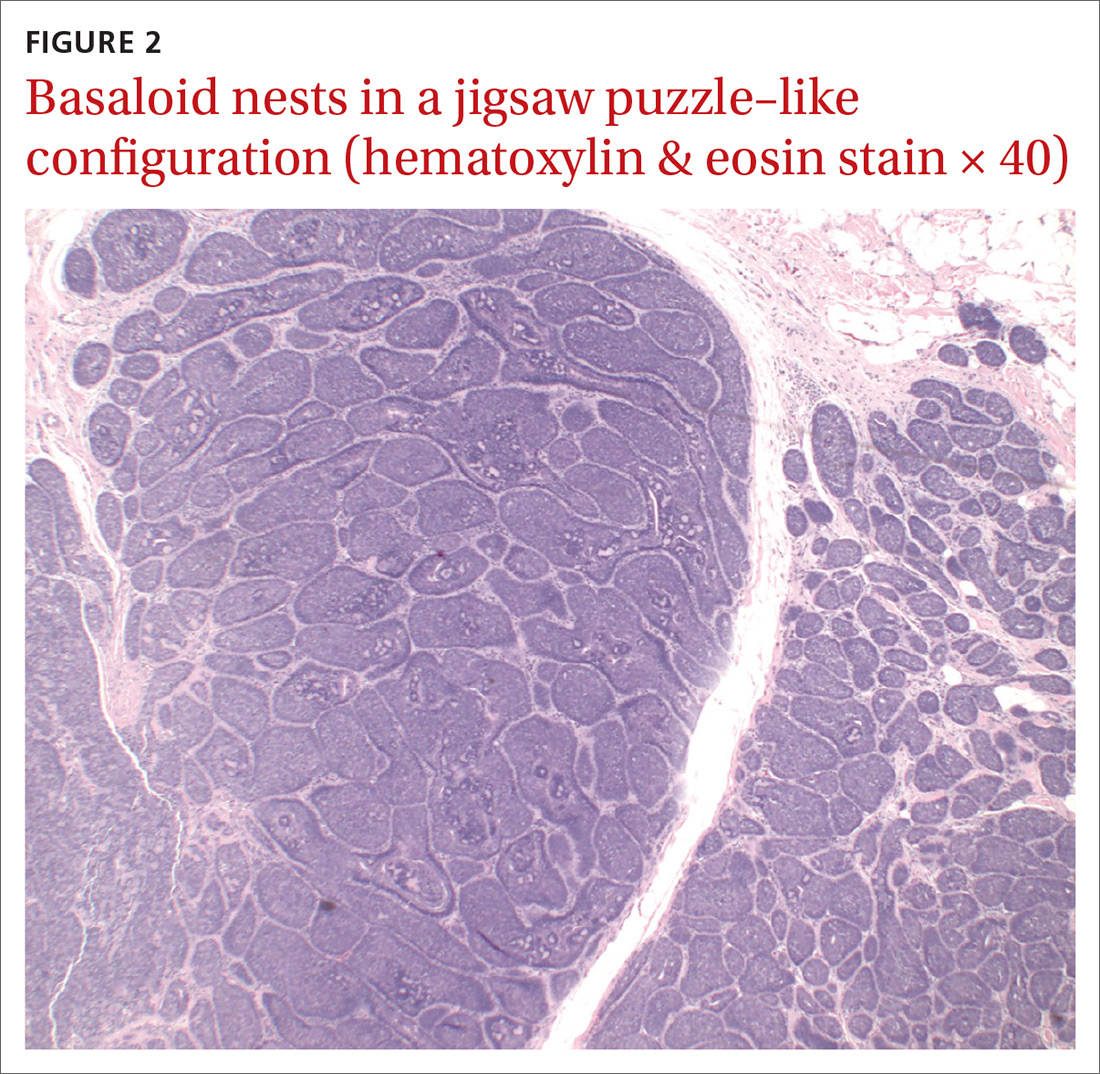

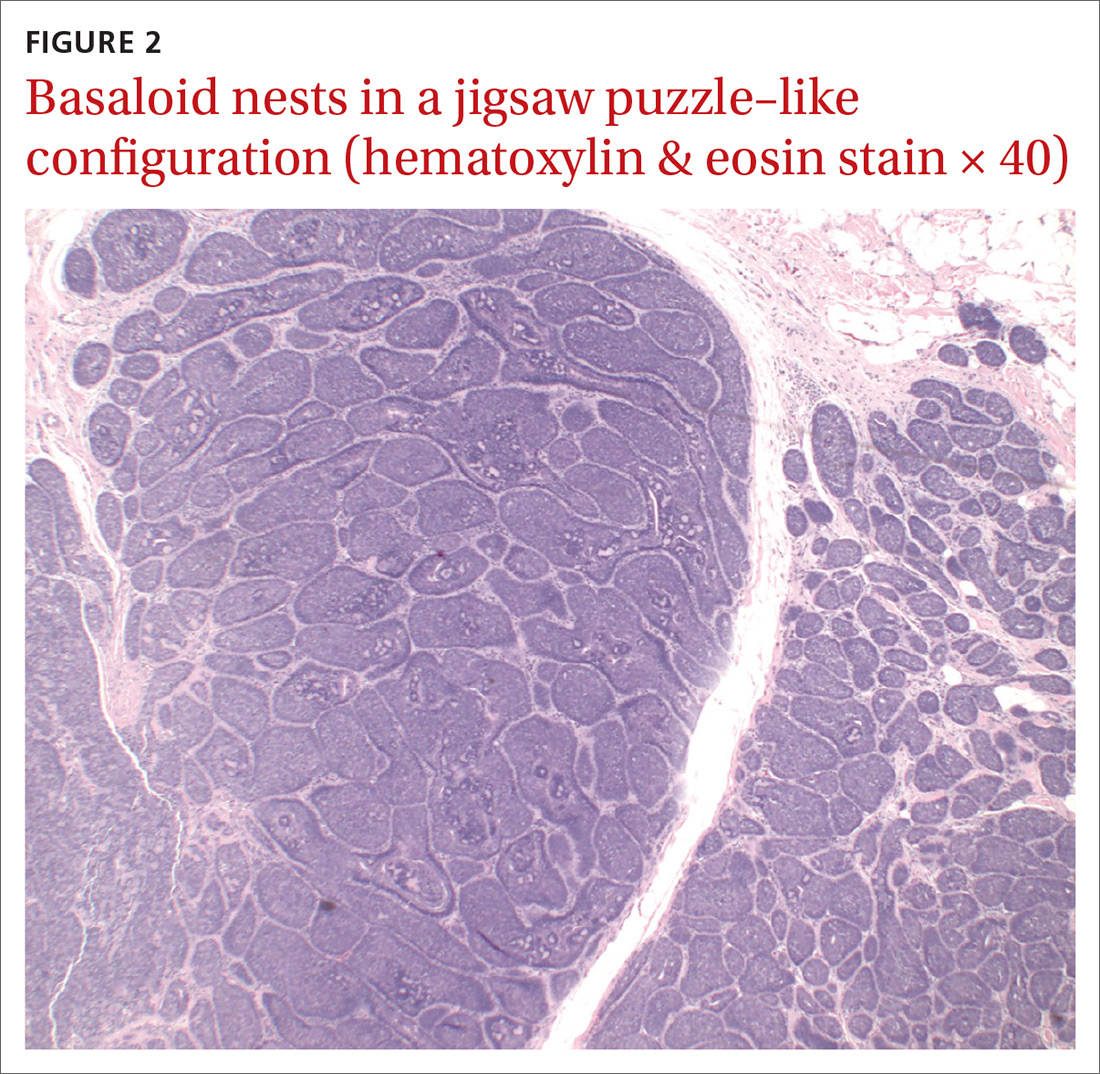

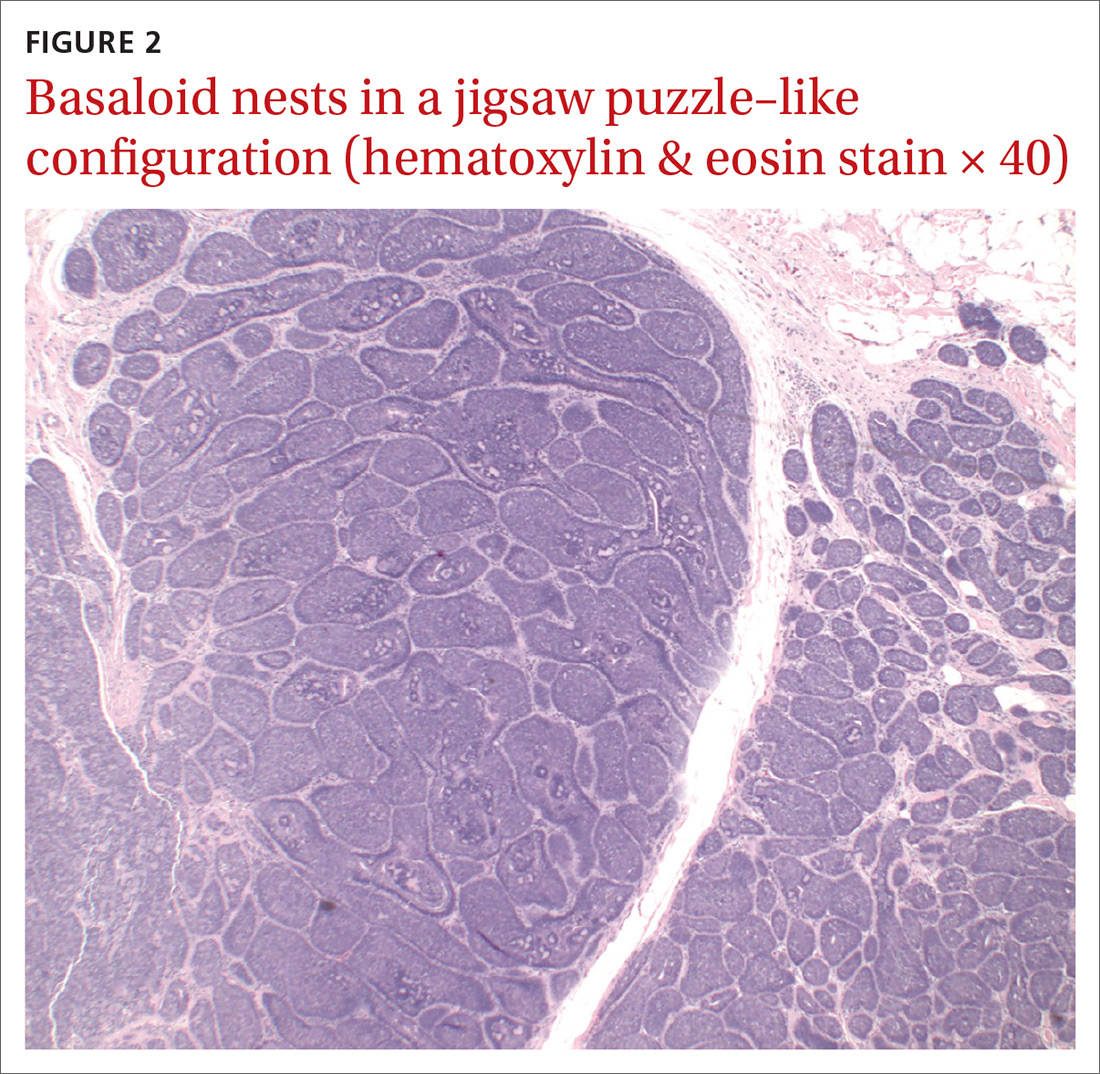

Definitive diagnosis was made by shave biopsy of the left hip lesion. Histopathology demonstrated various-sized discrete aggregates of basaloid cell nests in a jigsaw puzzle–like configuration (FIGURE 2), surrounded by rims of homogenous eosinophilic material. Histologic findings were consistent with cylindroma.1

Rare with a female predominance. Solitary cylindromas occur sporadically and usually affect middle-aged and elderly patients. Incidence is rare, but there is a female predominance of 6 to 9:1.2 Clinical appearance shows a slow-growing, firm mass that can range from a few millimeters to a few centimeters in diameter. The masses can have a pink or blue hue and usually are nontender unless there is nerve impingement.2

If multiple tumors are present or the patient has a family history of similar lesions, the disorder is likely inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern (with variable expression), which can be associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. This syndrome is related to a mutation of the cylindromatosis gene on chromosome 16. This is a tumor suppressor gene, inactivation of which can lead to uninhibited action of NF-

Rarely, cylindromas can undergo malignant transformation; signs include ulceration, bleeding, rapid growth, or color change.2 In these cases, appropriate imaging such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or positron emission tomography should be sought as there have been case reports of cylindroma extension to bone, as well as metastases to sites including the lymph nodes, thyroid, liver, lungs, bones, and meninges.4

Lipomas and pilar cysts comprise the differential

Lipomas are soft, painless, flesh-colored masses that typically appear on the trunk and arms but are uncommon on the face. Telangiectasias are not seen.

Continue to: Pilar cysts

Pilar cysts can mimic cylindromas in clinical presentation. Derived from the root sheath of hair follicles, they typically appear on the scalp but rarely on the face. Pilar cysts are slow growing, firm, and whitish in color5; several cysts can appear at a time.

Pilomatricomas are firm skin masses—usually < 3 cm in size—that can vary in color. There may be an extrusion of calcified material within the nodules, which does not occur in cylindromas.

Sebaceous adenomas are yellowish papules, usually < 1 cm in size, that appear on the head and neck area.6

Making the diagnosis. The clinical appearance of cylindromas and their location will point to the diagnosis, as will a family history of similar lesions. Ultimately, the diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy.

Treatment mainstay includes excision

Complete excision of all lesions is key due to the possibility of malignant transformation and metastasis. Options for removal include electrodesiccation, curettage, cryosurgery,3 high-dose radiation, and the use of a CO2 laser.2 For multiple large tumors, or ones in cosmetically sensitive areas, consider referral to Dermatology or Plastic Surgery. Further imaging should be sought to rule out extension to bone or metastasis. Patients with multiple cylindromas and Brooke-Spiegler syndrome need lifelong follow-up to monitor for recurrence and malignant transformation.3,7,8

Continue to: Our patient...

Our patient underwent complete excision of the left hip lesion. Other trunk lesions were excised serially. The patient was referred to a surgeon specializing in Mohs micrographic surgery for excision of the facial lesions. The patient and her family members were referred for genetic testing.

CORRESPONDENCE

Zeeshan Afzal, MD, McAllen Family Medicine Residency Program, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, 205 E Toronto Ave, McAllen, TX 78503; [email protected]

1. Elder D, Elenitsas R, Jaworsky CH, et al. Tumors of the epidermal appendages. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:775-777.

2. Singh DD, Naujoks C, Depprich R, et al. Cylindroma of head and neck: Review of the literature and report of two rare cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2013;41:516-521.

3. Sicinska J, Rakowska A, Czuwara-Ladykowska J, et al. Cylindroma transforming into basal cell carcinoma in a patient with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2007;1:4-9.

4. Jordão C, de Magalhães TC, Cuzzi T, et al. Cylindroma: an update. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:275-278.

5. Stone M. Cysts. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1920.

6. McCalmont T, Pincus L. Adnexal neoplasms. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1938-1942.

7. Gerretsen AL, Van der Putte SC, Deenstra W, et al. Cutaneous cylindroma with malignant transformation. Cancer. 1993;72:1618-1623.

8. Manicketh I, Singh R, Ghosh PK. Eccrine cylindroma of the face and scalp. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:203-205.

A 67-year-old woman presented with multiple painful nodules that had developed on her scalp, face, and neck over the course of 1 year. She also had a few nodules on her trunk and hip. There was no associated bleeding, ulceration, or drainage from the lesions. She had no systemic symptoms. The patient reported that she’d had a similar lesion on her frontal scalp about 15 years earlier, and it was excised completely. (She was not aware of the diagnosis.) She indicated that her mother and son had similar lesions in the past.

Her medical history was remarkable for diabetes and hypertension, which were well controlled on metformin and lisinopril, respectively. The patient had cancer of the left breast that was treated with mastectomy and chemotherapy 3 years prior.

On physical examination, the patient had multiple firm, rubbery, tender nodules with tan or pink hue, measuring 1 to 1.5 cm. The nodules were located on the left side of her chin and right preauricular area (FIGURE 1), as well as the right sides of her neck and hip. Most of the nodules were solitary; the preauricular area had 2 clustered pink lesions. The largest nodule was located on the patient’s chin and had overlying telangiectasias.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Cylindroma

Definitive diagnosis was made by shave biopsy of the left hip lesion. Histopathology demonstrated various-sized discrete aggregates of basaloid cell nests in a jigsaw puzzle–like configuration (FIGURE 2), surrounded by rims of homogenous eosinophilic material. Histologic findings were consistent with cylindroma.1

Rare with a female predominance. Solitary cylindromas occur sporadically and usually affect middle-aged and elderly patients. Incidence is rare, but there is a female predominance of 6 to 9:1.2 Clinical appearance shows a slow-growing, firm mass that can range from a few millimeters to a few centimeters in diameter. The masses can have a pink or blue hue and usually are nontender unless there is nerve impingement.2

If multiple tumors are present or the patient has a family history of similar lesions, the disorder is likely inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern (with variable expression), which can be associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. This syndrome is related to a mutation of the cylindromatosis gene on chromosome 16. This is a tumor suppressor gene, inactivation of which can lead to uninhibited action of NF-

Rarely, cylindromas can undergo malignant transformation; signs include ulceration, bleeding, rapid growth, or color change.2 In these cases, appropriate imaging such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or positron emission tomography should be sought as there have been case reports of cylindroma extension to bone, as well as metastases to sites including the lymph nodes, thyroid, liver, lungs, bones, and meninges.4

Lipomas and pilar cysts comprise the differential

Lipomas are soft, painless, flesh-colored masses that typically appear on the trunk and arms but are uncommon on the face. Telangiectasias are not seen.

Continue to: Pilar cysts

Pilar cysts can mimic cylindromas in clinical presentation. Derived from the root sheath of hair follicles, they typically appear on the scalp but rarely on the face. Pilar cysts are slow growing, firm, and whitish in color5; several cysts can appear at a time.

Pilomatricomas are firm skin masses—usually < 3 cm in size—that can vary in color. There may be an extrusion of calcified material within the nodules, which does not occur in cylindromas.

Sebaceous adenomas are yellowish papules, usually < 1 cm in size, that appear on the head and neck area.6

Making the diagnosis. The clinical appearance of cylindromas and their location will point to the diagnosis, as will a family history of similar lesions. Ultimately, the diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy.

Treatment mainstay includes excision

Complete excision of all lesions is key due to the possibility of malignant transformation and metastasis. Options for removal include electrodesiccation, curettage, cryosurgery,3 high-dose radiation, and the use of a CO2 laser.2 For multiple large tumors, or ones in cosmetically sensitive areas, consider referral to Dermatology or Plastic Surgery. Further imaging should be sought to rule out extension to bone or metastasis. Patients with multiple cylindromas and Brooke-Spiegler syndrome need lifelong follow-up to monitor for recurrence and malignant transformation.3,7,8

Continue to: Our patient...

Our patient underwent complete excision of the left hip lesion. Other trunk lesions were excised serially. The patient was referred to a surgeon specializing in Mohs micrographic surgery for excision of the facial lesions. The patient and her family members were referred for genetic testing.

CORRESPONDENCE

Zeeshan Afzal, MD, McAllen Family Medicine Residency Program, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, 205 E Toronto Ave, McAllen, TX 78503; [email protected]

A 67-year-old woman presented with multiple painful nodules that had developed on her scalp, face, and neck over the course of 1 year. She also had a few nodules on her trunk and hip. There was no associated bleeding, ulceration, or drainage from the lesions. She had no systemic symptoms. The patient reported that she’d had a similar lesion on her frontal scalp about 15 years earlier, and it was excised completely. (She was not aware of the diagnosis.) She indicated that her mother and son had similar lesions in the past.

Her medical history was remarkable for diabetes and hypertension, which were well controlled on metformin and lisinopril, respectively. The patient had cancer of the left breast that was treated with mastectomy and chemotherapy 3 years prior.

On physical examination, the patient had multiple firm, rubbery, tender nodules with tan or pink hue, measuring 1 to 1.5 cm. The nodules were located on the left side of her chin and right preauricular area (FIGURE 1), as well as the right sides of her neck and hip. Most of the nodules were solitary; the preauricular area had 2 clustered pink lesions. The largest nodule was located on the patient’s chin and had overlying telangiectasias.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Cylindroma

Definitive diagnosis was made by shave biopsy of the left hip lesion. Histopathology demonstrated various-sized discrete aggregates of basaloid cell nests in a jigsaw puzzle–like configuration (FIGURE 2), surrounded by rims of homogenous eosinophilic material. Histologic findings were consistent with cylindroma.1

Rare with a female predominance. Solitary cylindromas occur sporadically and usually affect middle-aged and elderly patients. Incidence is rare, but there is a female predominance of 6 to 9:1.2 Clinical appearance shows a slow-growing, firm mass that can range from a few millimeters to a few centimeters in diameter. The masses can have a pink or blue hue and usually are nontender unless there is nerve impingement.2

If multiple tumors are present or the patient has a family history of similar lesions, the disorder is likely inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern (with variable expression), which can be associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. This syndrome is related to a mutation of the cylindromatosis gene on chromosome 16. This is a tumor suppressor gene, inactivation of which can lead to uninhibited action of NF-

Rarely, cylindromas can undergo malignant transformation; signs include ulceration, bleeding, rapid growth, or color change.2 In these cases, appropriate imaging such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or positron emission tomography should be sought as there have been case reports of cylindroma extension to bone, as well as metastases to sites including the lymph nodes, thyroid, liver, lungs, bones, and meninges.4

Lipomas and pilar cysts comprise the differential

Lipomas are soft, painless, flesh-colored masses that typically appear on the trunk and arms but are uncommon on the face. Telangiectasias are not seen.

Continue to: Pilar cysts

Pilar cysts can mimic cylindromas in clinical presentation. Derived from the root sheath of hair follicles, they typically appear on the scalp but rarely on the face. Pilar cysts are slow growing, firm, and whitish in color5; several cysts can appear at a time.

Pilomatricomas are firm skin masses—usually < 3 cm in size—that can vary in color. There may be an extrusion of calcified material within the nodules, which does not occur in cylindromas.

Sebaceous adenomas are yellowish papules, usually < 1 cm in size, that appear on the head and neck area.6

Making the diagnosis. The clinical appearance of cylindromas and their location will point to the diagnosis, as will a family history of similar lesions. Ultimately, the diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy.

Treatment mainstay includes excision

Complete excision of all lesions is key due to the possibility of malignant transformation and metastasis. Options for removal include electrodesiccation, curettage, cryosurgery,3 high-dose radiation, and the use of a CO2 laser.2 For multiple large tumors, or ones in cosmetically sensitive areas, consider referral to Dermatology or Plastic Surgery. Further imaging should be sought to rule out extension to bone or metastasis. Patients with multiple cylindromas and Brooke-Spiegler syndrome need lifelong follow-up to monitor for recurrence and malignant transformation.3,7,8

Continue to: Our patient...

Our patient underwent complete excision of the left hip lesion. Other trunk lesions were excised serially. The patient was referred to a surgeon specializing in Mohs micrographic surgery for excision of the facial lesions. The patient and her family members were referred for genetic testing.

CORRESPONDENCE

Zeeshan Afzal, MD, McAllen Family Medicine Residency Program, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, 205 E Toronto Ave, McAllen, TX 78503; [email protected]

1. Elder D, Elenitsas R, Jaworsky CH, et al. Tumors of the epidermal appendages. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:775-777.

2. Singh DD, Naujoks C, Depprich R, et al. Cylindroma of head and neck: Review of the literature and report of two rare cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2013;41:516-521.

3. Sicinska J, Rakowska A, Czuwara-Ladykowska J, et al. Cylindroma transforming into basal cell carcinoma in a patient with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2007;1:4-9.

4. Jordão C, de Magalhães TC, Cuzzi T, et al. Cylindroma: an update. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:275-278.

5. Stone M. Cysts. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1920.

6. McCalmont T, Pincus L. Adnexal neoplasms. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1938-1942.

7. Gerretsen AL, Van der Putte SC, Deenstra W, et al. Cutaneous cylindroma with malignant transformation. Cancer. 1993;72:1618-1623.

8. Manicketh I, Singh R, Ghosh PK. Eccrine cylindroma of the face and scalp. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:203-205.

1. Elder D, Elenitsas R, Jaworsky CH, et al. Tumors of the epidermal appendages. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:775-777.

2. Singh DD, Naujoks C, Depprich R, et al. Cylindroma of head and neck: Review of the literature and report of two rare cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2013;41:516-521.

3. Sicinska J, Rakowska A, Czuwara-Ladykowska J, et al. Cylindroma transforming into basal cell carcinoma in a patient with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2007;1:4-9.

4. Jordão C, de Magalhães TC, Cuzzi T, et al. Cylindroma: an update. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:275-278.

5. Stone M. Cysts. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1920.

6. McCalmont T, Pincus L. Adnexal neoplasms. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1938-1942.

7. Gerretsen AL, Van der Putte SC, Deenstra W, et al. Cutaneous cylindroma with malignant transformation. Cancer. 1993;72:1618-1623.

8. Manicketh I, Singh R, Ghosh PK. Eccrine cylindroma of the face and scalp. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:203-205.

Erythema on abdomen

The FP was puzzled by the lack of response to treatment and decided to perform a 4-mm punch biopsy at the edge of the nonhealing ulcer. (Note that the correct location for a biopsy of an ulcer is on the edge, not in the middle). His differential diagnosis included pyoderma gangrenosum and a deep fungal infection. The pathologist called a week later FP with a surprising result: anaplastic large cell cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

Anaplastic large cell cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is a rare diagnosis—especially in a teenager—and it can’t be determined by appearance only. On follow-up, the FP explained the diagnosis to the patient and her mother. He called Hematology/Oncology to facilitate the referral.

The patient was treated by the specialist with weekly oral methotrexate and her skin cleared up completely. Although she would likely need treatment for years, the prognosis was good. This case is a reminder that when a treatment is not working for an expected diagnosis, it’s time to reconsider the diagnosis and do further testing to identify the correct diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chacon G, Nayar A, Usatine R, Smith M. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1124-1131.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP was puzzled by the lack of response to treatment and decided to perform a 4-mm punch biopsy at the edge of the nonhealing ulcer. (Note that the correct location for a biopsy of an ulcer is on the edge, not in the middle). His differential diagnosis included pyoderma gangrenosum and a deep fungal infection. The pathologist called a week later FP with a surprising result: anaplastic large cell cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

Anaplastic large cell cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is a rare diagnosis—especially in a teenager—and it can’t be determined by appearance only. On follow-up, the FP explained the diagnosis to the patient and her mother. He called Hematology/Oncology to facilitate the referral.

The patient was treated by the specialist with weekly oral methotrexate and her skin cleared up completely. Although she would likely need treatment for years, the prognosis was good. This case is a reminder that when a treatment is not working for an expected diagnosis, it’s time to reconsider the diagnosis and do further testing to identify the correct diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chacon G, Nayar A, Usatine R, Smith M. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1124-1131.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP was puzzled by the lack of response to treatment and decided to perform a 4-mm punch biopsy at the edge of the nonhealing ulcer. (Note that the correct location for a biopsy of an ulcer is on the edge, not in the middle). His differential diagnosis included pyoderma gangrenosum and a deep fungal infection. The pathologist called a week later FP with a surprising result: anaplastic large cell cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

Anaplastic large cell cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is a rare diagnosis—especially in a teenager—and it can’t be determined by appearance only. On follow-up, the FP explained the diagnosis to the patient and her mother. He called Hematology/Oncology to facilitate the referral.

The patient was treated by the specialist with weekly oral methotrexate and her skin cleared up completely. Although she would likely need treatment for years, the prognosis was good. This case is a reminder that when a treatment is not working for an expected diagnosis, it’s time to reconsider the diagnosis and do further testing to identify the correct diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chacon G, Nayar A, Usatine R, Smith M. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1124-1131.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Painful lump on back

The FP suspected that this could be a nodular melanoma that was mostly hypomelanotic (with minimal melanin visible, which explained why it was so pink). It looked like there was a flat nevus with brown coloration at one side of the base. The FP asked the patient whether she had a mole there in the past. The patient thought she did have a mole there since childhood, but had not thought about it. The light brown hyperpigmentation lateral to the lesion was likely secondary to scratching.

The differential diagnosis included melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma. Suspecting that it was most likely a nodular melanoma, the FP knew that a rapid diagnosis would be essential to an improved prognosis. Nodular melanomas are fast-growing melanomas that grow vertically, thereby making them one of the deadliest melanomas. A delay in the diagnosis of a nodular melanoma by even 3 to 6 months can change the prognosis from favorable to fatal.

The FP considered the options for biopsy but realized that cutting out the whole lesion would be time-consuming and require rescheduling for a different time. Getting a good sampling of the tumor with either a deep shave or a large punch biopsy would most likely provide the diagnosis. The FP presented the options to the patient, who indicated that the FP should do whatever he thought would be best. The FP performed a deep shave biopsy below the pigment on the edge and acquired a good-sized portion of the tumor. Aluminum chloride was initially used for hemostasis, but electrosurgery was ultimately required because of the vascular nature of the tumor. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The pathology report came back as a nodular melanoma with a depth of 4.1 mm. The patient was referred to Surgical Oncology for a wide local excision and a sentinel lymph node biopsy. The sentinel node biopsy was positive for metastasis. The patient was then sent to Medical Oncology to discuss further evaluation and treatment of her melanoma. The FP was saddened by the worrisome prognosis for this young mother.

He reflected that this nodular melanoma should have been diagnosed at least 6 to 12 months earlier when this patient was seeing an obstetrician regularly for health care. It was unfortunate that no one in the health care team during her pregnancy, labor, delivery, or postpartum care noted the melanoma and encouraged her to get evaluated. This supports the practice that we should not listen to lungs over the shirt. While every health care provider is not a dermatologist, the skin should not be ignored.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this could be a nodular melanoma that was mostly hypomelanotic (with minimal melanin visible, which explained why it was so pink). It looked like there was a flat nevus with brown coloration at one side of the base. The FP asked the patient whether she had a mole there in the past. The patient thought she did have a mole there since childhood, but had not thought about it. The light brown hyperpigmentation lateral to the lesion was likely secondary to scratching.

The differential diagnosis included melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma. Suspecting that it was most likely a nodular melanoma, the FP knew that a rapid diagnosis would be essential to an improved prognosis. Nodular melanomas are fast-growing melanomas that grow vertically, thereby making them one of the deadliest melanomas. A delay in the diagnosis of a nodular melanoma by even 3 to 6 months can change the prognosis from favorable to fatal.

The FP considered the options for biopsy but realized that cutting out the whole lesion would be time-consuming and require rescheduling for a different time. Getting a good sampling of the tumor with either a deep shave or a large punch biopsy would most likely provide the diagnosis. The FP presented the options to the patient, who indicated that the FP should do whatever he thought would be best. The FP performed a deep shave biopsy below the pigment on the edge and acquired a good-sized portion of the tumor. Aluminum chloride was initially used for hemostasis, but electrosurgery was ultimately required because of the vascular nature of the tumor. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The pathology report came back as a nodular melanoma with a depth of 4.1 mm. The patient was referred to Surgical Oncology for a wide local excision and a sentinel lymph node biopsy. The sentinel node biopsy was positive for metastasis. The patient was then sent to Medical Oncology to discuss further evaluation and treatment of her melanoma. The FP was saddened by the worrisome prognosis for this young mother.

He reflected that this nodular melanoma should have been diagnosed at least 6 to 12 months earlier when this patient was seeing an obstetrician regularly for health care. It was unfortunate that no one in the health care team during her pregnancy, labor, delivery, or postpartum care noted the melanoma and encouraged her to get evaluated. This supports the practice that we should not listen to lungs over the shirt. While every health care provider is not a dermatologist, the skin should not be ignored.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this could be a nodular melanoma that was mostly hypomelanotic (with minimal melanin visible, which explained why it was so pink). It looked like there was a flat nevus with brown coloration at one side of the base. The FP asked the patient whether she had a mole there in the past. The patient thought she did have a mole there since childhood, but had not thought about it. The light brown hyperpigmentation lateral to the lesion was likely secondary to scratching.

The differential diagnosis included melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma. Suspecting that it was most likely a nodular melanoma, the FP knew that a rapid diagnosis would be essential to an improved prognosis. Nodular melanomas are fast-growing melanomas that grow vertically, thereby making them one of the deadliest melanomas. A delay in the diagnosis of a nodular melanoma by even 3 to 6 months can change the prognosis from favorable to fatal.

The FP considered the options for biopsy but realized that cutting out the whole lesion would be time-consuming and require rescheduling for a different time. Getting a good sampling of the tumor with either a deep shave or a large punch biopsy would most likely provide the diagnosis. The FP presented the options to the patient, who indicated that the FP should do whatever he thought would be best. The FP performed a deep shave biopsy below the pigment on the edge and acquired a good-sized portion of the tumor. Aluminum chloride was initially used for hemostasis, but electrosurgery was ultimately required because of the vascular nature of the tumor. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The pathology report came back as a nodular melanoma with a depth of 4.1 mm. The patient was referred to Surgical Oncology for a wide local excision and a sentinel lymph node biopsy. The sentinel node biopsy was positive for metastasis. The patient was then sent to Medical Oncology to discuss further evaluation and treatment of her melanoma. The FP was saddened by the worrisome prognosis for this young mother.

He reflected that this nodular melanoma should have been diagnosed at least 6 to 12 months earlier when this patient was seeing an obstetrician regularly for health care. It was unfortunate that no one in the health care team during her pregnancy, labor, delivery, or postpartum care noted the melanoma and encouraged her to get evaluated. This supports the practice that we should not listen to lungs over the shirt. While every health care provider is not a dermatologist, the skin should not be ignored.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Dark spots in multiple locations

The FP considered whether this was a case of metastatic melanoma based on the appearance of the dark lesions, but thought that 22 years was a long time for a primary cancer to metastasize. After obtaining informed consent, the FP performed a 4-mm punch biopsy of one of the lesions on the patient’s trunk. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The FP sutured the area closed to minimize postoperative bleeding. The pathology report came back as metastatic melanoma. Unfortunately, melanoma can return even decades after the primary tumor is excised. The FP referred the patient to a medical oncologist who specialized in melanoma treatment. Unfortunately, the patient passed away within a year of the recurrent melanoma diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP considered whether this was a case of metastatic melanoma based on the appearance of the dark lesions, but thought that 22 years was a long time for a primary cancer to metastasize. After obtaining informed consent, the FP performed a 4-mm punch biopsy of one of the lesions on the patient’s trunk. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The FP sutured the area closed to minimize postoperative bleeding. The pathology report came back as metastatic melanoma. Unfortunately, melanoma can return even decades after the primary tumor is excised. The FP referred the patient to a medical oncologist who specialized in melanoma treatment. Unfortunately, the patient passed away within a year of the recurrent melanoma diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP considered whether this was a case of metastatic melanoma based on the appearance of the dark lesions, but thought that 22 years was a long time for a primary cancer to metastasize. After obtaining informed consent, the FP performed a 4-mm punch biopsy of one of the lesions on the patient’s trunk. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The FP sutured the area closed to minimize postoperative bleeding. The pathology report came back as metastatic melanoma. Unfortunately, melanoma can return even decades after the primary tumor is excised. The FP referred the patient to a medical oncologist who specialized in melanoma treatment. Unfortunately, the patient passed away within a year of the recurrent melanoma diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Rash with hair loss

The FP had never seen a condition like this before, so he used some online resources to come up with a differential diagnosis that included sarcoidosis, leprosy, drug eruption, and mycosis fungoides. Aside from an occasional drug eruption, the other conditions were ones that he had seen in textbooks only.

Based on that differential diagnosis, the FP decided to do a punch biopsy of the largest nodule, which was near the patient’s mouth. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The pathology report came back as folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. The FP researched the diagnosis and determined that this was a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that involved hair follicles and tended to occur on the head and neck. This explained the patient’s hair loss in his beard and right eyebrow. While the prognosis for mycosis fungoides is quite good, the same cannot be said for the folliculotropic variant.

The FP referred the patient to Dermatology for further evaluation and treatment. In consultation with Hematology, the patient was treated with a potent topical steroid, chemotherapy, and narrowband ultraviolet B light therapy. His condition improved, but ongoing treatment and surveillance were needed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chacon G, Nayar A. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1124-1131.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP had never seen a condition like this before, so he used some online resources to come up with a differential diagnosis that included sarcoidosis, leprosy, drug eruption, and mycosis fungoides. Aside from an occasional drug eruption, the other conditions were ones that he had seen in textbooks only.

Based on that differential diagnosis, the FP decided to do a punch biopsy of the largest nodule, which was near the patient’s mouth. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The pathology report came back as folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. The FP researched the diagnosis and determined that this was a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that involved hair follicles and tended to occur on the head and neck. This explained the patient’s hair loss in his beard and right eyebrow. While the prognosis for mycosis fungoides is quite good, the same cannot be said for the folliculotropic variant.

The FP referred the patient to Dermatology for further evaluation and treatment. In consultation with Hematology, the patient was treated with a potent topical steroid, chemotherapy, and narrowband ultraviolet B light therapy. His condition improved, but ongoing treatment and surveillance were needed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chacon G, Nayar A. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1124-1131.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP had never seen a condition like this before, so he used some online resources to come up with a differential diagnosis that included sarcoidosis, leprosy, drug eruption, and mycosis fungoides. Aside from an occasional drug eruption, the other conditions were ones that he had seen in textbooks only.

Based on that differential diagnosis, the FP decided to do a punch biopsy of the largest nodule, which was near the patient’s mouth. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The pathology report came back as folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. The FP researched the diagnosis and determined that this was a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that involved hair follicles and tended to occur on the head and neck. This explained the patient’s hair loss in his beard and right eyebrow. While the prognosis for mycosis fungoides is quite good, the same cannot be said for the folliculotropic variant.

The FP referred the patient to Dermatology for further evaluation and treatment. In consultation with Hematology, the patient was treated with a potent topical steroid, chemotherapy, and narrowband ultraviolet B light therapy. His condition improved, but ongoing treatment and surveillance were needed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chacon G, Nayar A. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1124-1131.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

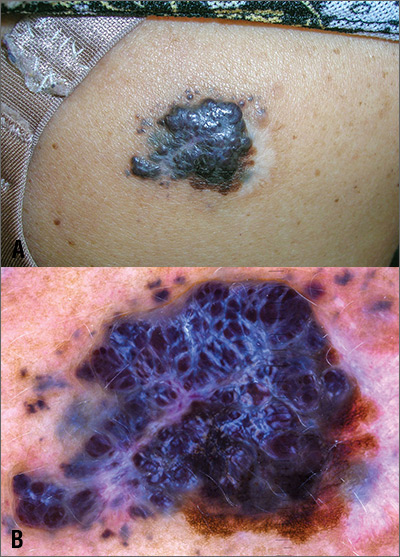

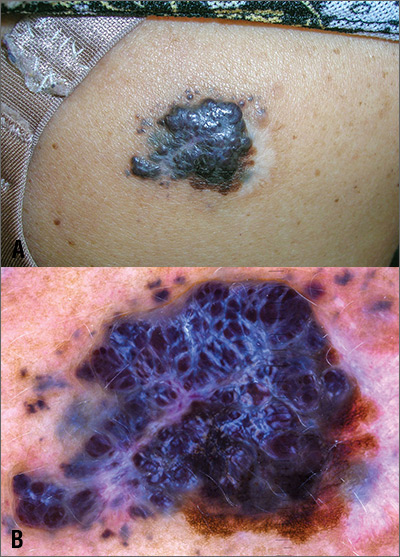

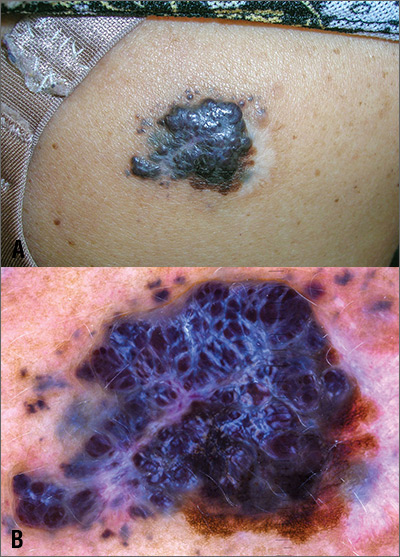

Large mass on shoulder

The FP was extremely concerned that this was a large melanoma due the lesion’s chaotic appearance, with multiple colors and an irregular border. Going through the ABCDE criteria, he noted that the lesion was Asymmetric, the Border was irregular, the Colors were varied, the Diameter was > 6 mm, and it was Enlarging by history.

With his dermatoscope attached to his smart phone, the FP looked at the lesion and took a photograph (Figure B). The image revealed a pigment network of the original nevus at 5:00 to 6:00 o’clock and extensions of the tumor due to in-transit metastases. Satellites were visible, especially in the top right and left corners. The FP noted the shiny white lines caused by collagen deposition found in growing tumors. (See “Dermoscopy in family medicine: A primer.”)

The FP knew that the mass needed to be biopsied, but because of its size, the best he could do would be to perform a partial biopsy. So on the day of presentation, the FP performed a 6-mm punch biopsy in the most raised area of the lesion to try and get sufficient depth and breadth for diagnosis and prognosis. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The pathology report indicated that the lesion was a nodular melanoma with a Breslow depth of 5.5 mm. This melanoma arose in a nevus, which occurs in about 30% of melanomas. Most melanomas arise de novo.

The FP referred the patient to a surgical oncologist for an excision with 2 cm margins and a sentinel lymph node biopsy. The sentinel node was in the right axilla and was remarkably negative despite the local in-transit metastases/satellites. One year after the original diagnosis was made, there was no evidence of metastatic disease and no new melanomas. The patient follows up with the dermatologist for skin and lymph node surveillance every 3 months.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP was extremely concerned that this was a large melanoma due the lesion’s chaotic appearance, with multiple colors and an irregular border. Going through the ABCDE criteria, he noted that the lesion was Asymmetric, the Border was irregular, the Colors were varied, the Diameter was > 6 mm, and it was Enlarging by history.

With his dermatoscope attached to his smart phone, the FP looked at the lesion and took a photograph (Figure B). The image revealed a pigment network of the original nevus at 5:00 to 6:00 o’clock and extensions of the tumor due to in-transit metastases. Satellites were visible, especially in the top right and left corners. The FP noted the shiny white lines caused by collagen deposition found in growing tumors. (See “Dermoscopy in family medicine: A primer.”)

The FP knew that the mass needed to be biopsied, but because of its size, the best he could do would be to perform a partial biopsy. So on the day of presentation, the FP performed a 6-mm punch biopsy in the most raised area of the lesion to try and get sufficient depth and breadth for diagnosis and prognosis. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The pathology report indicated that the lesion was a nodular melanoma with a Breslow depth of 5.5 mm. This melanoma arose in a nevus, which occurs in about 30% of melanomas. Most melanomas arise de novo.

The FP referred the patient to a surgical oncologist for an excision with 2 cm margins and a sentinel lymph node biopsy. The sentinel node was in the right axilla and was remarkably negative despite the local in-transit metastases/satellites. One year after the original diagnosis was made, there was no evidence of metastatic disease and no new melanomas. The patient follows up with the dermatologist for skin and lymph node surveillance every 3 months.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP was extremely concerned that this was a large melanoma due the lesion’s chaotic appearance, with multiple colors and an irregular border. Going through the ABCDE criteria, he noted that the lesion was Asymmetric, the Border was irregular, the Colors were varied, the Diameter was > 6 mm, and it was Enlarging by history.

With his dermatoscope attached to his smart phone, the FP looked at the lesion and took a photograph (Figure B). The image revealed a pigment network of the original nevus at 5:00 to 6:00 o’clock and extensions of the tumor due to in-transit metastases. Satellites were visible, especially in the top right and left corners. The FP noted the shiny white lines caused by collagen deposition found in growing tumors. (See “Dermoscopy in family medicine: A primer.”)

The FP knew that the mass needed to be biopsied, but because of its size, the best he could do would be to perform a partial biopsy. So on the day of presentation, the FP performed a 6-mm punch biopsy in the most raised area of the lesion to try and get sufficient depth and breadth for diagnosis and prognosis. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The pathology report indicated that the lesion was a nodular melanoma with a Breslow depth of 5.5 mm. This melanoma arose in a nevus, which occurs in about 30% of melanomas. Most melanomas arise de novo.

The FP referred the patient to a surgical oncologist for an excision with 2 cm margins and a sentinel lymph node biopsy. The sentinel node was in the right axilla and was remarkably negative despite the local in-transit metastases/satellites. One year after the original diagnosis was made, there was no evidence of metastatic disease and no new melanomas. The patient follows up with the dermatologist for skin and lymph node surveillance every 3 months.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Newborn with desquamating rash

A 9-day-old boy was brought to the emergency department by his mother. The infant had been doing well until his most recent diaper change when his mother noticed a rash around the umbilicus (FIGURE), genitalia, and anus.

The infant was born at term via spontaneous vaginal delivery. The pregnancy was uncomplicated; the infant’s mother was group B strep negative. Following a routine postpartum course, the infant underwent an elective circumcision before hospital discharge on his second day of life. There were no interval reports of irritability, poor feeding, fevers, vomiting, or changes in urine or stool output.

The mother denied any recent unusual exposures, sick contacts, or travel. However, upon further questioning, the mother noted that she herself had several small open wounds on the torso that she attributed to untreated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

On physical examination, the infant was overall well-appearing and was breastfeeding vigorously without respiratory distress or cyanosis. He was afebrile with normal vital signs. The majority of the physical examination was normal; however, there was erythematous desquamation around the umbilical stump and genitalia with no vesicles noted. The umbilical stump had a small amount of purulent drainage and necrosis centrally. The infant had a 1-cm round, peeling lesion on the left temple (FIGURE) with a small amount of dried serosanguinous drainage and similar superficial peeling lesions at the left preauricular area and anterior chest. There was no underlying fluctuance and only minimal surrounding erythema.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Based on the age of the patient, clinical presentation, and suspected maternal MRSA infection (with possible transmission to the infant), we diagnosed staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) in this patient. SSSS is rare, with annual incidence of 45 cases per million US infants under the age of 2.1 Newborns with a generalized form of SSSS commonly present with fever, poor feeding, irritability, and lethargy. This is followed by a generalized erythematous rash that initially may appear on the head and neck and spread to the rest of the body. Large, fragile blisters subsequently appear. These blisters rupture on gentle pressure, which is known as a positive Nikolsky sign. Ultimately, large sheets of skin easily slough off, leaving raw, denuded skin.2

S aureus is not part of normal skin flora, yet it is found on the skin and mucous membranes of 19% to 55% of healthy adults and children.3S aureus can cause a wide range of infections ranging from abscesses to cellulitis; SSSS is caused by hematogenous spread of S aureus exfoliative toxin. Newborns and immunocompromised patients are particularly susceptible.

Neonatal patients with SSSS most commonly present at 3 to 16 days of age.2 The lack of antitoxin antibody in neonates allows the toxin to reach the epidermis where it acts locally to produce the characteristic fragile skin lesions that often rupture prior to clinical presentation.2,4 During progression of the disease, flaky skin desquamation will occur as the lesions heal.

A retrospective review of 39 cases of SSSS identified pneumonia as the most frequent complication, occurring in 74.4% of the cases.5 The mortality rate of SSSS is up to 5%, and is associated with sepsis, superinfection, electrolyte imbalances, and extensive skin involvement.2,6

If SSSS is suspected, obtain cultures from the blood, urine, eyes, nose, throat, and skin lesions to identify the primary focus of infection.7 However, the retrospective review of 39 cases (noted above) found a positive rate of S aureus isolation of only 23.5%.5 Physicians will often have to make a diagnosis based on clinical presentation and empirically initiate broad-spectrum antibiotics while considering alternative diagnoses.

Continue to: A clinical diagnosis with a large differential

A clinical diagnosis with a large differential

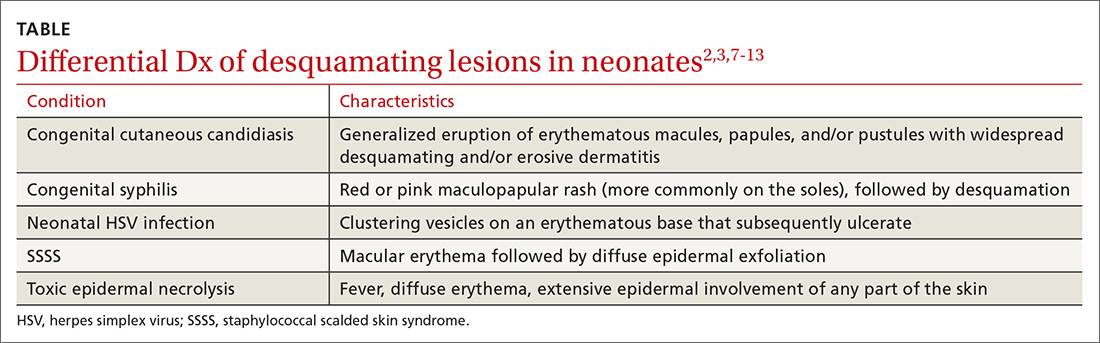

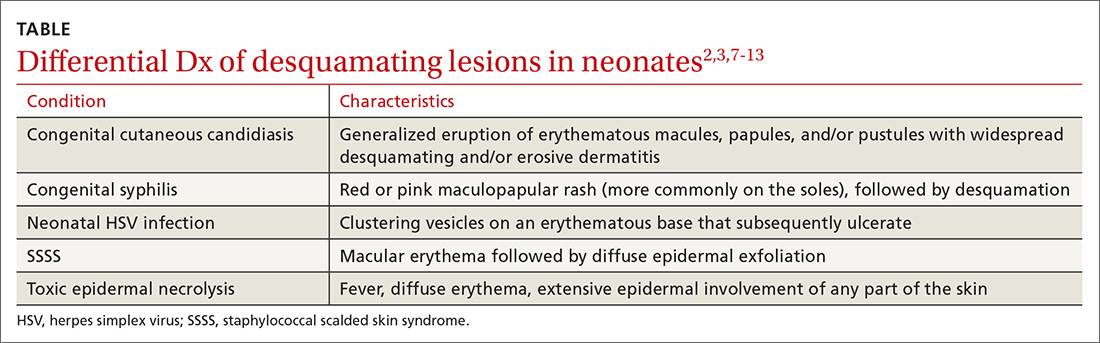

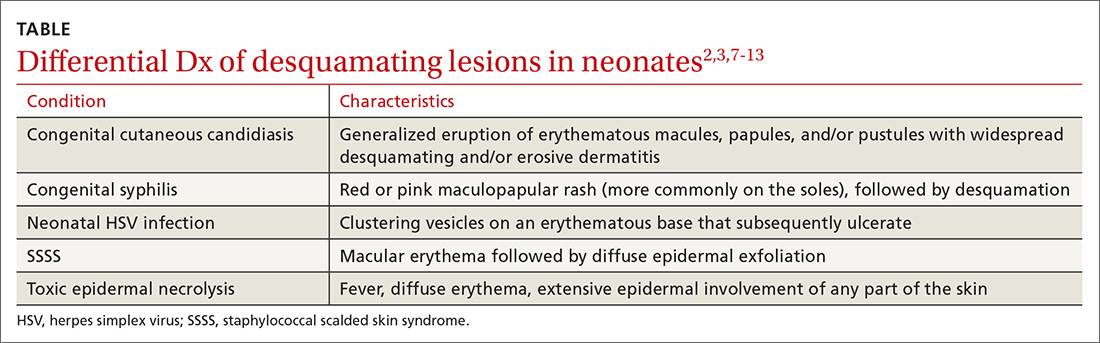

While biopsy rarely is required, it may be helpful to distinguish SSSS from other entities in the differential diagnosis (TABLE2,3,7-13).

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is a rare and life-threatening desquamating disease nearly always caused by a reaction to medications, including antibiotics. TEN can occur at any age. Fever, diffuse erythema, and extensive epidermal involvement (>30% of skin) differentiate TEN from Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), which affects less than 10% of the epidermis. It is worth mentioning that TEN and SJS are now considered to be a spectrum of one disease, and an overlap syndrome has been described with 10% to 30% of skin affected.8 Diagnosis is made clinically, although skin biopsy routinely is performed.7,9

Congenital syphilis features a red or pink maculopapular rash followed by desquamation. Lesions are more common on the soles.10 Desquamation or ulcerative skin lesions should be examined for spirochetes.11 A quantitative, nontreponemal test such as the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) or the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) will be positive in most infants if exposed through the placenta, but antibodies will disappear in uninfected infants by 6 months of age.8

Congenital cutaneous candidiasis presents with a generalized eruption of erythematous macules, papules, and/or pustules with widespread desquamating and/or erosive dermatitis. Premature neonates with extremely low birth weight are at higher risk.13 Diagnosis is confirmed on microscopy by the presence of Candida albicans spores in skin scrapings.13

Neonatal herpes simplex virus (HSV) symptoms typically appear between 1 and 3 weeks of life, with 60% to 70% of cases presenting with classic clustering vesicles on an erythematous base.14 Diagnosis is made with HSV viral culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Continue to: SSSS should be considered a pediatrics emergency

SSSS should be considered a pediatric emergency

SSSS should be considered a pediatric emergency due to potential complications. Core measures of SSSS treatment include immediate administration of intravenous (IV) antibiotics. US population studies suggest clindamycin and penicillinase-resistant penicillin as empiric therapy.15 However, local strains and resistance patterns, including the prevalence of MRSA, as well as age, comorbidities, and severity of illness should influence antibiotic selection.

IV nafcillin or oxacillin may be used with pediatric dosing of 150 mg/kg daily divided every 6 hours for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). For suspected MRSA, IV vancomycin should be considered, with an infant dose of 40 to 60 mg/kg daily divided every 6 hours.16 Fluid, electrolyte, and nutritional management should be addressed immediately. Ongoing fluid losses due to exfoliated skin must be replaced, and skin care to desquamated areas also should be addressed urgently.

Our patient. Phone consultation with an infectious disease specialist at a local children’s hospital resulted in a recommendation to treat for sepsis empirically with IV vancomycin, cefotaxime, and acyclovir. Acyclovir was discontinued once the HSV PCR came back negative. The antibiotic coverage was narrowed to IV ampicillin 50 mg/kg every 8 hours when cerebrospinal fluid and blood cultures returned negative at 48 hours, wound culture sensitivity grew MSSA, and the patient’s clinical condition stabilized. Our patient received 10 days of IV antibiotics and was discharged on oral amoxicillin 50 mg/kg divided twice daily for a total of 14 days of treatment per recommendations by the infectious disease specialist. Our patient fully recovered without any residual skin findings after completion of the antibiotic course.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jennifer J. Walker, MD, MPH, Hawaii Island Family Health Center at Hilo Medical Center, 1190 Waianuenue Ave, Hilo, HI 96720; [email protected]

1. Staiman A, Hsu D, Silverberg JI. Epidemiology of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in US children. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:704-708.

2. Ladhani S, Joannou CL, Lochrie DP, et al. Clinical, microbial, and biochemical aspects of the exfoliative toxins causing staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:224-242.

3. Kluytmans J, van Belkum A, Verbrugh H. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology, underlying mechanisms, and associated risks. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:505-520.

4. Ladhani S. Understanding the mechanism of action of the exfoliative toxins of Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;39:181-189.

5. Li MY, Hua Y, Wei GH, et al. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in neonates: an 8-year retrospective study in a single institution. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:43-47.

6. Berk DR, Bayliss SJ. MRSA, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and other cutaneous bacterial emergencies. Pediatr Ann. 2010;39:627-633.

7. Ely JW, Seabury Stone M. The generalized rash: part I. differential diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:726-734.

8. Bastuji-Garin SB, Stern RS, Shear NH, et al. Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:92.

9. Elias PM, Fritsch P, Epstein EH. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. clinical features, pathogenesis, and recent microbiological and biochemical developments. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:207-219.

10. O’Connor NR, McLaughlin M, Ham P. Newborn skin: part I: common rashes. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:47-52.

11. Larsen SA, Steiner BM, Rudolph AH. Laboratory diagnosis and interpretation of tests for syphilis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:1-21.

12. Arnold SR, Ford-Jones EL. Congenital syphilis: a guide to diagnosis and management. Paediatr Child Health. 2000;5:463-469.

13. Darmstadt GL, Dinulos JG, Miller Z. Congenital cutaneous candidiasis: clinical presentation, pathogenesis, and management guidelines. Pediatrics. 2000;105:438-444.

14. Kimberlin DW. Neonatal herpes simplex infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:1-13.

15. Braunstein I, Wanat KA, Abuabara K, et al. Antibiotic sensitivity and resistance patterns in pediatric staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:305-308.

16. Gilbert DN, Chambers HF, Eliopoulos GM, et al. The Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy. 48th ed. Sperryville, VA: Antimicrobial Therapy, Inc; 2014:56.

A 9-day-old boy was brought to the emergency department by his mother. The infant had been doing well until his most recent diaper change when his mother noticed a rash around the umbilicus (FIGURE), genitalia, and anus.

The infant was born at term via spontaneous vaginal delivery. The pregnancy was uncomplicated; the infant’s mother was group B strep negative. Following a routine postpartum course, the infant underwent an elective circumcision before hospital discharge on his second day of life. There were no interval reports of irritability, poor feeding, fevers, vomiting, or changes in urine or stool output.

The mother denied any recent unusual exposures, sick contacts, or travel. However, upon further questioning, the mother noted that she herself had several small open wounds on the torso that she attributed to untreated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

On physical examination, the infant was overall well-appearing and was breastfeeding vigorously without respiratory distress or cyanosis. He was afebrile with normal vital signs. The majority of the physical examination was normal; however, there was erythematous desquamation around the umbilical stump and genitalia with no vesicles noted. The umbilical stump had a small amount of purulent drainage and necrosis centrally. The infant had a 1-cm round, peeling lesion on the left temple (FIGURE) with a small amount of dried serosanguinous drainage and similar superficial peeling lesions at the left preauricular area and anterior chest. There was no underlying fluctuance and only minimal surrounding erythema.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Based on the age of the patient, clinical presentation, and suspected maternal MRSA infection (with possible transmission to the infant), we diagnosed staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) in this patient. SSSS is rare, with annual incidence of 45 cases per million US infants under the age of 2.1 Newborns with a generalized form of SSSS commonly present with fever, poor feeding, irritability, and lethargy. This is followed by a generalized erythematous rash that initially may appear on the head and neck and spread to the rest of the body. Large, fragile blisters subsequently appear. These blisters rupture on gentle pressure, which is known as a positive Nikolsky sign. Ultimately, large sheets of skin easily slough off, leaving raw, denuded skin.2

S aureus is not part of normal skin flora, yet it is found on the skin and mucous membranes of 19% to 55% of healthy adults and children.3S aureus can cause a wide range of infections ranging from abscesses to cellulitis; SSSS is caused by hematogenous spread of S aureus exfoliative toxin. Newborns and immunocompromised patients are particularly susceptible.