User login

Growing lesion on lip

The FP recognized the lesion as a probable squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) due to its appearance and location on the lower lip. He was also aware that immunosuppressive medications increase a patient's risk for SCC.

The FP performed a shave biopsy of a portion of the lesion and the result confirmed SCC. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) A careful head and neck exam did not reveal palpable lymph nodes. Given the location of the lesion and the risk for metastases, the FP referred the patient for Mohs surgery and provided counseling about sun avoidance, the consistent use of a hat outdoors, and the use of sunscreens when exposed to the sun.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

The new third edition will be available in January 2019: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/.

You can also get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized the lesion as a probable squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) due to its appearance and location on the lower lip. He was also aware that immunosuppressive medications increase a patient's risk for SCC.

The FP performed a shave biopsy of a portion of the lesion and the result confirmed SCC. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) A careful head and neck exam did not reveal palpable lymph nodes. Given the location of the lesion and the risk for metastases, the FP referred the patient for Mohs surgery and provided counseling about sun avoidance, the consistent use of a hat outdoors, and the use of sunscreens when exposed to the sun.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

The new third edition will be available in January 2019: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/.

You can also get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized the lesion as a probable squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) due to its appearance and location on the lower lip. He was also aware that immunosuppressive medications increase a patient's risk for SCC.

The FP performed a shave biopsy of a portion of the lesion and the result confirmed SCC. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) A careful head and neck exam did not reveal palpable lymph nodes. Given the location of the lesion and the risk for metastases, the FP referred the patient for Mohs surgery and provided counseling about sun avoidance, the consistent use of a hat outdoors, and the use of sunscreens when exposed to the sun.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

The new third edition will be available in January 2019: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/.

You can also get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Growths on scalp

The FP recognized the severely sun damaged scalp as a major risk factor for skin cancers. He looked closely at the lesions and realized that the ulcerated areas were at particularly high risk for squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

He performed broad shave biopsies with sufficient depth to obtain the needed diagnosis. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathology demonstrated that 2 of the 3 biopsy sites were positive for SCC (E and G were SCC, while F was read as actinic keratosis). Cutaneous SCC is a malignant tumor of keratinocytes. Most cutaneous SCCs arise from precursor lesions, often actinic keratoses. SCC usually spreads by local extension, but it is also capable of regional lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis.

Unsure of the margins of the tumors and aware that surgery of the scalp can be challenging, the FP referred the patient for Mohs surgery. The FP also provided counseling about sun avoidance, the consistent use of a hat outdoors, and the use of sunscreens when exposed to the sun.

The Mohs surgeon recommended field treatment with 5% fluorouracil cream twice daily for 4 weeks before surgery to minimize the amount of cutting that would be needed to clear the SCC from this diffusely sun-damaged scalp. After the 5% fluorouracil cream treatment, the surgeon waited 1 month to allow the scalp to heal before performing surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

The new third edition will be available in January 2019: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/.

You can also get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized the severely sun damaged scalp as a major risk factor for skin cancers. He looked closely at the lesions and realized that the ulcerated areas were at particularly high risk for squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

He performed broad shave biopsies with sufficient depth to obtain the needed diagnosis. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathology demonstrated that 2 of the 3 biopsy sites were positive for SCC (E and G were SCC, while F was read as actinic keratosis). Cutaneous SCC is a malignant tumor of keratinocytes. Most cutaneous SCCs arise from precursor lesions, often actinic keratoses. SCC usually spreads by local extension, but it is also capable of regional lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis.

Unsure of the margins of the tumors and aware that surgery of the scalp can be challenging, the FP referred the patient for Mohs surgery. The FP also provided counseling about sun avoidance, the consistent use of a hat outdoors, and the use of sunscreens when exposed to the sun.

The Mohs surgeon recommended field treatment with 5% fluorouracil cream twice daily for 4 weeks before surgery to minimize the amount of cutting that would be needed to clear the SCC from this diffusely sun-damaged scalp. After the 5% fluorouracil cream treatment, the surgeon waited 1 month to allow the scalp to heal before performing surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

The new third edition will be available in January 2019: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/.

You can also get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized the severely sun damaged scalp as a major risk factor for skin cancers. He looked closely at the lesions and realized that the ulcerated areas were at particularly high risk for squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

He performed broad shave biopsies with sufficient depth to obtain the needed diagnosis. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathology demonstrated that 2 of the 3 biopsy sites were positive for SCC (E and G were SCC, while F was read as actinic keratosis). Cutaneous SCC is a malignant tumor of keratinocytes. Most cutaneous SCCs arise from precursor lesions, often actinic keratoses. SCC usually spreads by local extension, but it is also capable of regional lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis.

Unsure of the margins of the tumors and aware that surgery of the scalp can be challenging, the FP referred the patient for Mohs surgery. The FP also provided counseling about sun avoidance, the consistent use of a hat outdoors, and the use of sunscreens when exposed to the sun.

The Mohs surgeon recommended field treatment with 5% fluorouracil cream twice daily for 4 weeks before surgery to minimize the amount of cutting that would be needed to clear the SCC from this diffusely sun-damaged scalp. After the 5% fluorouracil cream treatment, the surgeon waited 1 month to allow the scalp to heal before performing surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:999-1007.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

The new third edition will be available in January 2019: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/.

You can also get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Diffuse facial rash in a former collegiate wrestler

A 22-year-old Caucasian man with a history of atopic dermatitis (AD) was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a diffuse facial rash that had been present for the previous 7 days. The rash initially presented as erythema on the right malar cheek that rapidly spread to the entire face. Initially diagnosed as impetigo, empiric treatment with sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (800 mg/160 mg PO BID for 7 days), dicloxacillin (500 mg PO BID for 6 days), cephalexin (500 mg TID for 5 days), and mupirocin (2% topical cream applied TID for 6 days) failed to improve the patient’s symptoms. He reported mild pain associated with facial movements.

The patient had a history of similar (but more limited) rashes, which he described as “recurrent impetigo,” that began during his career as a high school and collegiate wrestler. These rashes were different from the rashes he described as his history of AD, which consisted of pruritic and erythematous skin in his antecubital and popliteal fossae. He denied any history of herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection.

A physical examination revealed numerous monomorphic, 1- to 3-mm, punched-out erosions and ulcers with overlying yellow-brown crust encompassing the patient’s entire face and portions of his anterior neck. Several clustered vesicles on erythematous bases also were noted (FIGUREs 1A and 1B). We used a Dermablade to unroof some of the vesicles and sent the scrapings to the lab for Tzanck, direct fluorescent antibody assay (DFA), and HSV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Eczema herpeticum secondary to herpes gladiatorum

The patient’s laboratory results came back and the Tzanck preparation was positive for multinucleated giant cells, and both the DFA and HSV PCR were positive for HSV infection. This, paired with the widely disseminated rash observed on examination and the patient’s history of AD, was consistent with a diagnosis of eczema herpeticum (EH).

Rather than primary impetigo, the patient’s self-described history of recurrent rashes was felt to represent a history of HSV outbreaks. Given his denial of prior oral or genital HSV infection, as well as the coincident onset of these outbreaks during his career as a competitive wrestler, the most likely primary infection source was direct contact with another HSV-infected wrestler.

Herpes gladiatorum refers to a primary cutaneous HSV infection contracted by an athlete through direct skin-to-skin contact with another athlete.1 It is common in contact sports, such as rugby and wrestling, and particularly common at organized wrestling camps, where mass outbreaks are a frequent occurrence.2 Herpes gladiatorum is so common at these camps that many recommend prophylactic valacyclovir treatment for all participants to mitigate the risk of contracting HSV. In a 2016 review, Anderson et al concluded that prophylactic valacyclovir treatment at a 28-day high school wrestling camp effectively reduced outbreak incidence by 89.5%.2

The lesions of herpes gladiatorum are classically limited in distribution and reflective of the areas of direct contact with infected skin, most commonly the face, neck, and arms. Our patient’s history of more limited outbreaks on his face was consistent with this typical presentation. His current outbreak, however, had become much more widely disseminated, which led to the diagnosis of EH secondary to herpes gladiatorum.

Eczema herpeticum: Pathogenesis and diagnosis

Also known as Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption, EH is a rapid, widespread cutaneous dissemination of HSV infection in areas of dermatitis or skin barrier disruption, most commonly caused by HSV-1 infection.3 It is classically associated with AD, but also can occur in patients with impaired epidermal barrier function due to other conditions, such as burns, pemphigus vulgaris, mycosis fungoides, and Darier disease.4 It occurs in <3% of patients with AD and is more commonly observed in infants and children with AD than adults.5

Continue to: Clinically, the most common manifestations are discrete..

Clinically, the most common manifestations are discrete, monomorphic, 2- to 3-mm, punched-out erosions with hemorrhagic crusts; intact vesicles are less commonly observed.4 Involved skin is typically painful and may be pruritic. Clinical diagnosis should be confirmed by laboratory evaluation, typically Tzanck preparation, DFA, and/or HSV PCR.

Complications and the importance of rapid treatment

The most common complication of EH is bacterial superinfection (impetigo), usually by Staphylococcus aureus or group A streptococci. Signs of bacterial superinfection include weeping lesions, pustules, honey-colored/golden crusting, worsening of existing dermatitis, and failure to respond to antiviral treatment. Topical mupirocin 2% cream is generally effective for controlling limited infection. However, systemic antibiotics (cephalosporins or penicillinase-resistant penicillins) may be necessary to control widespread disease.4 Clinical improvement should be observed within a single course of an appropriate antibiotic.

In contrast to impetigo, less common but more serious complications of EH can be life threatening. Systemic dissemination of disease is of particular importance in vulnerable populations such as pediatric and immunocompromised patients. Meningoencephalitis, secondary bacteremia, and herpes keratitis can all develop secondary to EH and incur significant morbidity and mortality.1

Fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, or eye pain should prompt immediate consideration of inpatient evaluation and treatment for these potentially deadly or debilitating complications. All patients with EH distributed near the eyes should be referred to ophthalmology to rule out ocular involvement.

Immediately treat with antivirals

Due to the potential complications discussed above, a diagnosis of EH necessitates immediate treatment with oral or intravenous antiviral medication. Acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir may be used, with typical treatment courses ranging from 10 to 14 days or until all mucocutaneous lesions are healed.4 Although typically reserved for patients with recurrent genital herpes resulting in 6 or more outbreaks annually, chronic suppressive therapy also may be considered for patients with EH who suffer from frequent or severe recurrent outbreaks.

Continue to: Our patient

Our patient. Given his otherwise excellent health and the absence of symptoms of potentially serious complications, our patient was treated as an outpatient with a 10-day course of valacyclovir 1000 mg PO BID. He was additionally prescribed a 7-day course of cephalexin 500 mg PO TID for coverage of bacterial superinfection. He responded well to treatment.

Ten days after his initial presentation to our clinic, his erosions and vesicles had completely cleared, and the associated erythema had significantly improved (FIGURE 2). Given the severity of his presentation and his history of 2 to 3 outbreaks annually, he opted to continue prophylactic valacyclovir (500 mg/d) for long-term suppression.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Madden, MD, 221 3rd Street West, JBSA-Randolph, TX 78150, [email protected]

1. Shenoy R, Mostow E, Cain G. Eczema herpeticum in a wrestler. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;25:e18-e19.

2. Anderson BJ, McGuire DP, Reed M, et al. Prophylactic valacyclovir to prevent outbreaks of primary herpes gladiatorum at a 28-day wrestling camp: a 10-year review. Clin J Sport Med. 2016;26:272-278.

3. Olson J, Robles DT, Kirby P, et al. Kaposi varicelliform eruption (eczema herpeticum). Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:18.

4. Downing C, Mendoza N, Tyring S. Human herpesviruses. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1400-1424.

5. Leung DY. Why is eczema herpeticum unexpectedly rare? Antiviral Res. 2013;98:153-157.

A 22-year-old Caucasian man with a history of atopic dermatitis (AD) was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a diffuse facial rash that had been present for the previous 7 days. The rash initially presented as erythema on the right malar cheek that rapidly spread to the entire face. Initially diagnosed as impetigo, empiric treatment with sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (800 mg/160 mg PO BID for 7 days), dicloxacillin (500 mg PO BID for 6 days), cephalexin (500 mg TID for 5 days), and mupirocin (2% topical cream applied TID for 6 days) failed to improve the patient’s symptoms. He reported mild pain associated with facial movements.

The patient had a history of similar (but more limited) rashes, which he described as “recurrent impetigo,” that began during his career as a high school and collegiate wrestler. These rashes were different from the rashes he described as his history of AD, which consisted of pruritic and erythematous skin in his antecubital and popliteal fossae. He denied any history of herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection.

A physical examination revealed numerous monomorphic, 1- to 3-mm, punched-out erosions and ulcers with overlying yellow-brown crust encompassing the patient’s entire face and portions of his anterior neck. Several clustered vesicles on erythematous bases also were noted (FIGUREs 1A and 1B). We used a Dermablade to unroof some of the vesicles and sent the scrapings to the lab for Tzanck, direct fluorescent antibody assay (DFA), and HSV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Eczema herpeticum secondary to herpes gladiatorum

The patient’s laboratory results came back and the Tzanck preparation was positive for multinucleated giant cells, and both the DFA and HSV PCR were positive for HSV infection. This, paired with the widely disseminated rash observed on examination and the patient’s history of AD, was consistent with a diagnosis of eczema herpeticum (EH).

Rather than primary impetigo, the patient’s self-described history of recurrent rashes was felt to represent a history of HSV outbreaks. Given his denial of prior oral or genital HSV infection, as well as the coincident onset of these outbreaks during his career as a competitive wrestler, the most likely primary infection source was direct contact with another HSV-infected wrestler.

Herpes gladiatorum refers to a primary cutaneous HSV infection contracted by an athlete through direct skin-to-skin contact with another athlete.1 It is common in contact sports, such as rugby and wrestling, and particularly common at organized wrestling camps, where mass outbreaks are a frequent occurrence.2 Herpes gladiatorum is so common at these camps that many recommend prophylactic valacyclovir treatment for all participants to mitigate the risk of contracting HSV. In a 2016 review, Anderson et al concluded that prophylactic valacyclovir treatment at a 28-day high school wrestling camp effectively reduced outbreak incidence by 89.5%.2

The lesions of herpes gladiatorum are classically limited in distribution and reflective of the areas of direct contact with infected skin, most commonly the face, neck, and arms. Our patient’s history of more limited outbreaks on his face was consistent with this typical presentation. His current outbreak, however, had become much more widely disseminated, which led to the diagnosis of EH secondary to herpes gladiatorum.

Eczema herpeticum: Pathogenesis and diagnosis

Also known as Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption, EH is a rapid, widespread cutaneous dissemination of HSV infection in areas of dermatitis or skin barrier disruption, most commonly caused by HSV-1 infection.3 It is classically associated with AD, but also can occur in patients with impaired epidermal barrier function due to other conditions, such as burns, pemphigus vulgaris, mycosis fungoides, and Darier disease.4 It occurs in <3% of patients with AD and is more commonly observed in infants and children with AD than adults.5

Continue to: Clinically, the most common manifestations are discrete..

Clinically, the most common manifestations are discrete, monomorphic, 2- to 3-mm, punched-out erosions with hemorrhagic crusts; intact vesicles are less commonly observed.4 Involved skin is typically painful and may be pruritic. Clinical diagnosis should be confirmed by laboratory evaluation, typically Tzanck preparation, DFA, and/or HSV PCR.

Complications and the importance of rapid treatment

The most common complication of EH is bacterial superinfection (impetigo), usually by Staphylococcus aureus or group A streptococci. Signs of bacterial superinfection include weeping lesions, pustules, honey-colored/golden crusting, worsening of existing dermatitis, and failure to respond to antiviral treatment. Topical mupirocin 2% cream is generally effective for controlling limited infection. However, systemic antibiotics (cephalosporins or penicillinase-resistant penicillins) may be necessary to control widespread disease.4 Clinical improvement should be observed within a single course of an appropriate antibiotic.

In contrast to impetigo, less common but more serious complications of EH can be life threatening. Systemic dissemination of disease is of particular importance in vulnerable populations such as pediatric and immunocompromised patients. Meningoencephalitis, secondary bacteremia, and herpes keratitis can all develop secondary to EH and incur significant morbidity and mortality.1

Fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, or eye pain should prompt immediate consideration of inpatient evaluation and treatment for these potentially deadly or debilitating complications. All patients with EH distributed near the eyes should be referred to ophthalmology to rule out ocular involvement.

Immediately treat with antivirals

Due to the potential complications discussed above, a diagnosis of EH necessitates immediate treatment with oral or intravenous antiviral medication. Acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir may be used, with typical treatment courses ranging from 10 to 14 days or until all mucocutaneous lesions are healed.4 Although typically reserved for patients with recurrent genital herpes resulting in 6 or more outbreaks annually, chronic suppressive therapy also may be considered for patients with EH who suffer from frequent or severe recurrent outbreaks.

Continue to: Our patient

Our patient. Given his otherwise excellent health and the absence of symptoms of potentially serious complications, our patient was treated as an outpatient with a 10-day course of valacyclovir 1000 mg PO BID. He was additionally prescribed a 7-day course of cephalexin 500 mg PO TID for coverage of bacterial superinfection. He responded well to treatment.

Ten days after his initial presentation to our clinic, his erosions and vesicles had completely cleared, and the associated erythema had significantly improved (FIGURE 2). Given the severity of his presentation and his history of 2 to 3 outbreaks annually, he opted to continue prophylactic valacyclovir (500 mg/d) for long-term suppression.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Madden, MD, 221 3rd Street West, JBSA-Randolph, TX 78150, [email protected]

A 22-year-old Caucasian man with a history of atopic dermatitis (AD) was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a diffuse facial rash that had been present for the previous 7 days. The rash initially presented as erythema on the right malar cheek that rapidly spread to the entire face. Initially diagnosed as impetigo, empiric treatment with sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (800 mg/160 mg PO BID for 7 days), dicloxacillin (500 mg PO BID for 6 days), cephalexin (500 mg TID for 5 days), and mupirocin (2% topical cream applied TID for 6 days) failed to improve the patient’s symptoms. He reported mild pain associated with facial movements.

The patient had a history of similar (but more limited) rashes, which he described as “recurrent impetigo,” that began during his career as a high school and collegiate wrestler. These rashes were different from the rashes he described as his history of AD, which consisted of pruritic and erythematous skin in his antecubital and popliteal fossae. He denied any history of herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection.

A physical examination revealed numerous monomorphic, 1- to 3-mm, punched-out erosions and ulcers with overlying yellow-brown crust encompassing the patient’s entire face and portions of his anterior neck. Several clustered vesicles on erythematous bases also were noted (FIGUREs 1A and 1B). We used a Dermablade to unroof some of the vesicles and sent the scrapings to the lab for Tzanck, direct fluorescent antibody assay (DFA), and HSV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Eczema herpeticum secondary to herpes gladiatorum

The patient’s laboratory results came back and the Tzanck preparation was positive for multinucleated giant cells, and both the DFA and HSV PCR were positive for HSV infection. This, paired with the widely disseminated rash observed on examination and the patient’s history of AD, was consistent with a diagnosis of eczema herpeticum (EH).

Rather than primary impetigo, the patient’s self-described history of recurrent rashes was felt to represent a history of HSV outbreaks. Given his denial of prior oral or genital HSV infection, as well as the coincident onset of these outbreaks during his career as a competitive wrestler, the most likely primary infection source was direct contact with another HSV-infected wrestler.

Herpes gladiatorum refers to a primary cutaneous HSV infection contracted by an athlete through direct skin-to-skin contact with another athlete.1 It is common in contact sports, such as rugby and wrestling, and particularly common at organized wrestling camps, where mass outbreaks are a frequent occurrence.2 Herpes gladiatorum is so common at these camps that many recommend prophylactic valacyclovir treatment for all participants to mitigate the risk of contracting HSV. In a 2016 review, Anderson et al concluded that prophylactic valacyclovir treatment at a 28-day high school wrestling camp effectively reduced outbreak incidence by 89.5%.2

The lesions of herpes gladiatorum are classically limited in distribution and reflective of the areas of direct contact with infected skin, most commonly the face, neck, and arms. Our patient’s history of more limited outbreaks on his face was consistent with this typical presentation. His current outbreak, however, had become much more widely disseminated, which led to the diagnosis of EH secondary to herpes gladiatorum.

Eczema herpeticum: Pathogenesis and diagnosis

Also known as Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption, EH is a rapid, widespread cutaneous dissemination of HSV infection in areas of dermatitis or skin barrier disruption, most commonly caused by HSV-1 infection.3 It is classically associated with AD, but also can occur in patients with impaired epidermal barrier function due to other conditions, such as burns, pemphigus vulgaris, mycosis fungoides, and Darier disease.4 It occurs in <3% of patients with AD and is more commonly observed in infants and children with AD than adults.5

Continue to: Clinically, the most common manifestations are discrete..

Clinically, the most common manifestations are discrete, monomorphic, 2- to 3-mm, punched-out erosions with hemorrhagic crusts; intact vesicles are less commonly observed.4 Involved skin is typically painful and may be pruritic. Clinical diagnosis should be confirmed by laboratory evaluation, typically Tzanck preparation, DFA, and/or HSV PCR.

Complications and the importance of rapid treatment

The most common complication of EH is bacterial superinfection (impetigo), usually by Staphylococcus aureus or group A streptococci. Signs of bacterial superinfection include weeping lesions, pustules, honey-colored/golden crusting, worsening of existing dermatitis, and failure to respond to antiviral treatment. Topical mupirocin 2% cream is generally effective for controlling limited infection. However, systemic antibiotics (cephalosporins or penicillinase-resistant penicillins) may be necessary to control widespread disease.4 Clinical improvement should be observed within a single course of an appropriate antibiotic.

In contrast to impetigo, less common but more serious complications of EH can be life threatening. Systemic dissemination of disease is of particular importance in vulnerable populations such as pediatric and immunocompromised patients. Meningoencephalitis, secondary bacteremia, and herpes keratitis can all develop secondary to EH and incur significant morbidity and mortality.1

Fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, or eye pain should prompt immediate consideration of inpatient evaluation and treatment for these potentially deadly or debilitating complications. All patients with EH distributed near the eyes should be referred to ophthalmology to rule out ocular involvement.

Immediately treat with antivirals

Due to the potential complications discussed above, a diagnosis of EH necessitates immediate treatment with oral or intravenous antiviral medication. Acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir may be used, with typical treatment courses ranging from 10 to 14 days or until all mucocutaneous lesions are healed.4 Although typically reserved for patients with recurrent genital herpes resulting in 6 or more outbreaks annually, chronic suppressive therapy also may be considered for patients with EH who suffer from frequent or severe recurrent outbreaks.

Continue to: Our patient

Our patient. Given his otherwise excellent health and the absence of symptoms of potentially serious complications, our patient was treated as an outpatient with a 10-day course of valacyclovir 1000 mg PO BID. He was additionally prescribed a 7-day course of cephalexin 500 mg PO TID for coverage of bacterial superinfection. He responded well to treatment.

Ten days after his initial presentation to our clinic, his erosions and vesicles had completely cleared, and the associated erythema had significantly improved (FIGURE 2). Given the severity of his presentation and his history of 2 to 3 outbreaks annually, he opted to continue prophylactic valacyclovir (500 mg/d) for long-term suppression.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Madden, MD, 221 3rd Street West, JBSA-Randolph, TX 78150, [email protected]

1. Shenoy R, Mostow E, Cain G. Eczema herpeticum in a wrestler. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;25:e18-e19.

2. Anderson BJ, McGuire DP, Reed M, et al. Prophylactic valacyclovir to prevent outbreaks of primary herpes gladiatorum at a 28-day wrestling camp: a 10-year review. Clin J Sport Med. 2016;26:272-278.

3. Olson J, Robles DT, Kirby P, et al. Kaposi varicelliform eruption (eczema herpeticum). Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:18.

4. Downing C, Mendoza N, Tyring S. Human herpesviruses. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1400-1424.

5. Leung DY. Why is eczema herpeticum unexpectedly rare? Antiviral Res. 2013;98:153-157.

1. Shenoy R, Mostow E, Cain G. Eczema herpeticum in a wrestler. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;25:e18-e19.

2. Anderson BJ, McGuire DP, Reed M, et al. Prophylactic valacyclovir to prevent outbreaks of primary herpes gladiatorum at a 28-day wrestling camp: a 10-year review. Clin J Sport Med. 2016;26:272-278.

3. Olson J, Robles DT, Kirby P, et al. Kaposi varicelliform eruption (eczema herpeticum). Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:18.

4. Downing C, Mendoza N, Tyring S. Human herpesviruses. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1400-1424.

5. Leung DY. Why is eczema herpeticum unexpectedly rare? Antiviral Res. 2013;98:153-157.

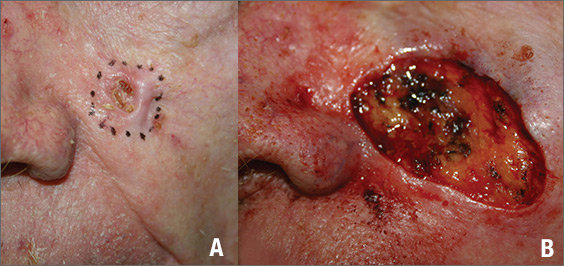

Mole near nose

The differential diagnosis for this lesion included a benign intradermal nevus and a basal cell carcinoma. So the FP recommended a shave biopsy to be sure that it was not cancer. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

After obtaining patient consent, he injected the 1% lidocaine with epinephrine and waited 5 minutes for the epinephrine to begin to work. He performed the shave with a Dermablade, and used a cotton-tipped applicator to apply aluminum chloride to the site. He used a twisting motion and pressure to achieve hemostasis. He dressed the lesion with petrolatum and some gauze.

Dermatopathology showed that this mole was a benign intradermal nevus. The FP reassured the patient and recommended that she be careful to avoid sun exposure.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The differential diagnosis for this lesion included a benign intradermal nevus and a basal cell carcinoma. So the FP recommended a shave biopsy to be sure that it was not cancer. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

After obtaining patient consent, he injected the 1% lidocaine with epinephrine and waited 5 minutes for the epinephrine to begin to work. He performed the shave with a Dermablade, and used a cotton-tipped applicator to apply aluminum chloride to the site. He used a twisting motion and pressure to achieve hemostasis. He dressed the lesion with petrolatum and some gauze.

Dermatopathology showed that this mole was a benign intradermal nevus. The FP reassured the patient and recommended that she be careful to avoid sun exposure.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The differential diagnosis for this lesion included a benign intradermal nevus and a basal cell carcinoma. So the FP recommended a shave biopsy to be sure that it was not cancer. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

After obtaining patient consent, he injected the 1% lidocaine with epinephrine and waited 5 minutes for the epinephrine to begin to work. He performed the shave with a Dermablade, and used a cotton-tipped applicator to apply aluminum chloride to the site. He used a twisting motion and pressure to achieve hemostasis. He dressed the lesion with petrolatum and some gauze.

Dermatopathology showed that this mole was a benign intradermal nevus. The FP reassured the patient and recommended that she be careful to avoid sun exposure.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

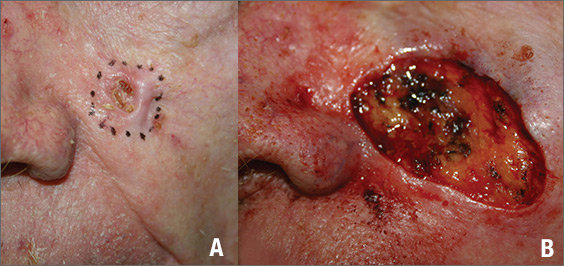

Multiple growths on face

Figure 1

While the differential diagnosis for these lesions (FIGURE 1A) included basal cell carcinoma, the FP had reason to suspect that these papules were actually sebaceous hyperplasia.

The FP saw a pattern of crown-like vessels and popcorn-like structures (FIGURE 1B) when he examined the patient with his dermatoscope. None of the vessels crossed the midline, and the popcorn-like structures were hyperplastic sebaceous glands. The FP photographed the largest lesion with a dermatoscope attached to his smart phone and showed the reassuring pattern to the anxious patient. He explained to her why this was not skin cancer and how hyperplasia of sebaceous glands is often normal for aging facial skin. He also offered her treatment if she thought that the lesions were cosmetically unappealing.

The patient said that she would be grateful to have the largest lesion treated because it did bother her when she looked in the mirror. The FP treated this lesion using electrosurgery with a blunt tipped electrode, on a setting of 2.1, without anesthesia. He warned the patient before he applied the activated electrode to the skin, and the patient tolerated the procedure well. The sebaceous glands melted easily with the current. The result appeared gray and was expected to heal with minimal to no scarring. At a future visit, the patient said that she was happy with the result and asked if additional lesions could be treated with the same electrosurgical approach.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Figure 1

While the differential diagnosis for these lesions (FIGURE 1A) included basal cell carcinoma, the FP had reason to suspect that these papules were actually sebaceous hyperplasia.

The FP saw a pattern of crown-like vessels and popcorn-like structures (FIGURE 1B) when he examined the patient with his dermatoscope. None of the vessels crossed the midline, and the popcorn-like structures were hyperplastic sebaceous glands. The FP photographed the largest lesion with a dermatoscope attached to his smart phone and showed the reassuring pattern to the anxious patient. He explained to her why this was not skin cancer and how hyperplasia of sebaceous glands is often normal for aging facial skin. He also offered her treatment if she thought that the lesions were cosmetically unappealing.

The patient said that she would be grateful to have the largest lesion treated because it did bother her when she looked in the mirror. The FP treated this lesion using electrosurgery with a blunt tipped electrode, on a setting of 2.1, without anesthesia. He warned the patient before he applied the activated electrode to the skin, and the patient tolerated the procedure well. The sebaceous glands melted easily with the current. The result appeared gray and was expected to heal with minimal to no scarring. At a future visit, the patient said that she was happy with the result and asked if additional lesions could be treated with the same electrosurgical approach.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Figure 1

While the differential diagnosis for these lesions (FIGURE 1A) included basal cell carcinoma, the FP had reason to suspect that these papules were actually sebaceous hyperplasia.

The FP saw a pattern of crown-like vessels and popcorn-like structures (FIGURE 1B) when he examined the patient with his dermatoscope. None of the vessels crossed the midline, and the popcorn-like structures were hyperplastic sebaceous glands. The FP photographed the largest lesion with a dermatoscope attached to his smart phone and showed the reassuring pattern to the anxious patient. He explained to her why this was not skin cancer and how hyperplasia of sebaceous glands is often normal for aging facial skin. He also offered her treatment if she thought that the lesions were cosmetically unappealing.

The patient said that she would be grateful to have the largest lesion treated because it did bother her when she looked in the mirror. The FP treated this lesion using electrosurgery with a blunt tipped electrode, on a setting of 2.1, without anesthesia. He warned the patient before he applied the activated electrode to the skin, and the patient tolerated the procedure well. The sebaceous glands melted easily with the current. The result appeared gray and was expected to heal with minimal to no scarring. At a future visit, the patient said that she was happy with the result and asked if additional lesions could be treated with the same electrosurgical approach.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

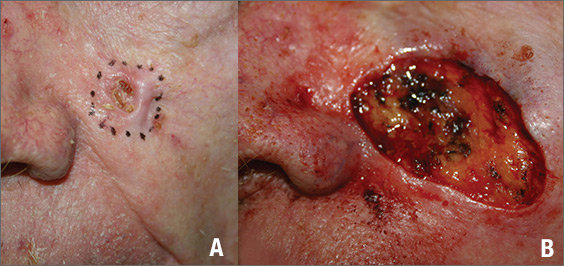

Growing lesion on cheek

Figure 1

The FP suspected that this was a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or squamous cell carcinoma. He leaned toward a BCC because of the pearly border on the edge, but knew that a biopsy diagnosis was needed before planning definitive treatment.

The FP recommended performing a shave biopsy that day. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) After obtaining patient consent, he injected 1% lidocaine with epinephrine and waited for the epinephrine to work. He performed the shave biopsy with a Dermablade, and used a cotton-tipped applicator to vigorously apply aluminum chloride to the site. He used a twisting motion and pressure to achieve hemostasis. The bleeding stopped, and the FP dressed the lesion with petrolatum and some gauze. Dermatopathology revealed a sclerosing BCC.

The FP realized this was an aggressive tumor and referred the patient for Mohs surgery. The surgery required 4 excisions to get clean margins (FIGURE 1B). The usual 4- to 5-mm margins with an elliptical excision would not have removed the full tumor.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Figure 1

The FP suspected that this was a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or squamous cell carcinoma. He leaned toward a BCC because of the pearly border on the edge, but knew that a biopsy diagnosis was needed before planning definitive treatment.

The FP recommended performing a shave biopsy that day. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) After obtaining patient consent, he injected 1% lidocaine with epinephrine and waited for the epinephrine to work. He performed the shave biopsy with a Dermablade, and used a cotton-tipped applicator to vigorously apply aluminum chloride to the site. He used a twisting motion and pressure to achieve hemostasis. The bleeding stopped, and the FP dressed the lesion with petrolatum and some gauze. Dermatopathology revealed a sclerosing BCC.

The FP realized this was an aggressive tumor and referred the patient for Mohs surgery. The surgery required 4 excisions to get clean margins (FIGURE 1B). The usual 4- to 5-mm margins with an elliptical excision would not have removed the full tumor.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Figure 1

The FP suspected that this was a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or squamous cell carcinoma. He leaned toward a BCC because of the pearly border on the edge, but knew that a biopsy diagnosis was needed before planning definitive treatment.

The FP recommended performing a shave biopsy that day. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) After obtaining patient consent, he injected 1% lidocaine with epinephrine and waited for the epinephrine to work. He performed the shave biopsy with a Dermablade, and used a cotton-tipped applicator to vigorously apply aluminum chloride to the site. He used a twisting motion and pressure to achieve hemostasis. The bleeding stopped, and the FP dressed the lesion with petrolatum and some gauze. Dermatopathology revealed a sclerosing BCC.

The FP realized this was an aggressive tumor and referred the patient for Mohs surgery. The surgery required 4 excisions to get clean margins (FIGURE 1B). The usual 4- to 5-mm margins with an elliptical excision would not have removed the full tumor.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

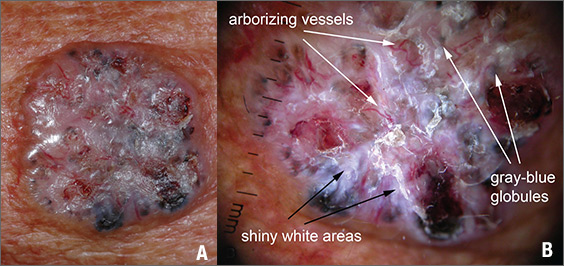

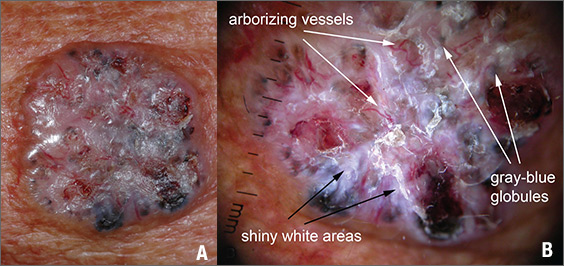

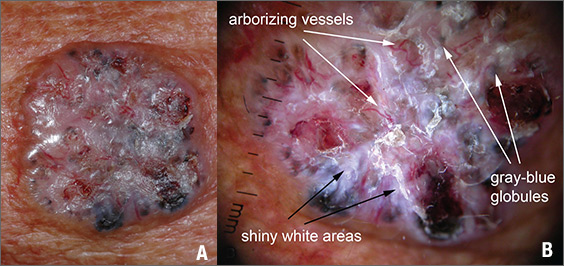

Growth on right cheek

Figure 1

The FP suspected that this was a nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with pigmentation. The physical exam was suspicious because of the pearly appearance, superficial ulcerations, and presence of telangiectasias with a loss of the normal pore pattern. Dermoscopy gave further evidence for a nodular BCC by revealing arborizing “tree-like” telangiectasias, ulcerations, shiny white areas, and gray-blue globules. Skin cancers often produce their own vascular supply and also ulcerate. The shiny white areas (which are the result of collagen deposition and occur in many skin cancers) are best seen with polarized dermoscopy.

The FP recommended a shave biopsy and performed one immediately after obtaining patient consent. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) Knowing that the BCC would be vascular, the FP injected 1% lidocaine with epinephrine and waited 15 minutes for the epinephrine to work.

After seeing another patient, he performed the shave biopsy with a Dermablade, and used a cotton-tipped applicator to vigorously apply the aluminum chloride to the site. He used a twisting motion and pressure to stop most of the bleeding and then used his electrosurgical instrument—with a sharp tipped electrode—to stop recalcitrant bleeders.

The patient was given a diagnosis of BCC on the follow-up visit. The FP referred the patient for Mohs surgery because of the large size and location of the tumor.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Figure 1

The FP suspected that this was a nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with pigmentation. The physical exam was suspicious because of the pearly appearance, superficial ulcerations, and presence of telangiectasias with a loss of the normal pore pattern. Dermoscopy gave further evidence for a nodular BCC by revealing arborizing “tree-like” telangiectasias, ulcerations, shiny white areas, and gray-blue globules. Skin cancers often produce their own vascular supply and also ulcerate. The shiny white areas (which are the result of collagen deposition and occur in many skin cancers) are best seen with polarized dermoscopy.

The FP recommended a shave biopsy and performed one immediately after obtaining patient consent. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) Knowing that the BCC would be vascular, the FP injected 1% lidocaine with epinephrine and waited 15 minutes for the epinephrine to work.

After seeing another patient, he performed the shave biopsy with a Dermablade, and used a cotton-tipped applicator to vigorously apply the aluminum chloride to the site. He used a twisting motion and pressure to stop most of the bleeding and then used his electrosurgical instrument—with a sharp tipped electrode—to stop recalcitrant bleeders.

The patient was given a diagnosis of BCC on the follow-up visit. The FP referred the patient for Mohs surgery because of the large size and location of the tumor.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Figure 1

The FP suspected that this was a nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with pigmentation. The physical exam was suspicious because of the pearly appearance, superficial ulcerations, and presence of telangiectasias with a loss of the normal pore pattern. Dermoscopy gave further evidence for a nodular BCC by revealing arborizing “tree-like” telangiectasias, ulcerations, shiny white areas, and gray-blue globules. Skin cancers often produce their own vascular supply and also ulcerate. The shiny white areas (which are the result of collagen deposition and occur in many skin cancers) are best seen with polarized dermoscopy.

The FP recommended a shave biopsy and performed one immediately after obtaining patient consent. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) Knowing that the BCC would be vascular, the FP injected 1% lidocaine with epinephrine and waited 15 minutes for the epinephrine to work.

After seeing another patient, he performed the shave biopsy with a Dermablade, and used a cotton-tipped applicator to vigorously apply the aluminum chloride to the site. He used a twisting motion and pressure to stop most of the bleeding and then used his electrosurgical instrument—with a sharp tipped electrode—to stop recalcitrant bleeders.

The patient was given a diagnosis of BCC on the follow-up visit. The FP referred the patient for Mohs surgery because of the large size and location of the tumor.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Persistent erythematous papulonodular rash

An 80-year-old white woman presented to our dermatology clinic with a rash across her abdomen that had been there for more than a year. While not itchy or painful, the rash was slowly expanding. The patient had tried treatments including topical antifungals and topical corticosteroids, but none had helped.

Her medical history was significant for dementia and stage III triple-negative breast cancer in the left breast (diagnosed 8 years prior), which was treated with a simple left mastectomy, chemotherapy, and radiation. She reported no history of skin cancer. She was not taking any medications and had no known drug allergies. A physical examination revealed an erythematous, papulonodular rash with diffuse induration in a band-like pattern across her entire upper abdomen and left flank (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Cutaneous metastasis of primary breast cancer

Based on our patient’s history, we gave a presumptive diagnosis of cutaneous breast cancer metastasis. A punch biopsy was performed. The pathology report showed nests of neoplastic cells within the dermis, which was consistent with this diagnosis. Immunohistochemical stains and fluorescence in-situ hybridization confirmed triple-negative breast markers for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2.

An uncommon phenomenonseen mostly with breast cancer

Cutaneous metastatic carcinoma is relatively uncommon; one meta-analysis reported the overall incidence to be 5.3%.1 While it is unusual, any internal malignancy can metastasize to the skin. In women, the most common malignancy to do so is breast cancer. One study found breast cancer to be associated with 26.5% of cutaneous metastatic cases.2 These metastases often occur well after the patient has been treated for the primary malignancy.

Identifying features. Most cutaneous metastases occur near the site of the primary tumor, initially in the form of a firm, mobile, nonpainful nodule.3 This nodule is typically skin-colored or red, but in the case of cutaneous metastases of melanomas, it can appear blue or black. In the case of breast cancer, the lesions most often arise on the chest and abdomen.4 Occasionally, metastases can ulcerate through the skin.

Some forms of cutaneous metastasis, such as carcinoma erysipeloides, can appear in specific patterns. Carcinoma erysipeloides has a similar appearance to cellulitis; it manifests as a sharply demarcated, red, inflammatory patch in the skin adjacent to the primary tumor.

Consider the clinical picture

Cutaneous metastatic lesions have a wide range of differential diagnoses due to their varied appearances. It is important to view the overall clinical picture when distinguishing such lesions. Although cutaneous metastasis is uncommon, it should always be considered when asymptomatic skin lesions resist treatment—even in someone without a known history of malignancy.

Perform a biopsy. The diagnosis can be confirmed with a skin biopsy. A punch biopsy is preferable, as visualization of the dermis is crucial, and histology often reveals nests of pleomorphic cells. Further cellular cytology can elicit the primary malignancy of origin.

Making our diagnosis

We ruled out several possibilities before arriving at our diagnosis. An infectious etiology (eg, cutaneous candidiasis) was considered, as was a cutaneous change due to radiation therapy. We also considered shingles, the early stages of which would have been similar in appearance to our patient’s lesions, and urticaria, which can manifest as erythematous papules and wheals across various parts of the body. A lack of specific symptoms (eg, pruritis, pain, fever) made these alternative diagnoses less likely. The fact that our patient’s lesions persisted for more than a year without any response to treatment—and that they continued to grow—alerted us of a more sinister etiology.

Continue to: Treating the tumor is often not possible

Treating the tumor is often not possible

Treatment first involves treating the underlying tumor. For cases in which cutaneous lesions are the first manifestation of an internal malignancy, investigation as to the source should be performed. The lesions can then be treated with a combination of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery.5,6

Unfortunately, in most cases of cutaneous metastases, the primary malignancy is already widespread and possibly untreatable. In such instances, palliative care is offered. Lesions are managed symptomatically, and prevention of skin irritation becomes the primary focus. Keeping the skin clean and dry helps to prevent ulceration and secondary infection.

In cases where the lesions ulcerate or crust, debridement can help. Excision of lesions, as well as pairing laser therapy with electrochemotherapy, may be helpful to improve the patient’s quality of life when lesions cause discomfort.

The prognosis for cutaneous metastasis due to breast cancer is often hard to predict because it is determined by other factors, such as the presence of internal metastases, which indicates a worse prognosis (on the scale of months). Some case reports have demonstrated that patients with metastases limited to the skin may have prolonged survival (on the scale of years).7

Our patient was offered an initial trial of radiation therapy, but she refused all treatment because the lesions did not cause discomfort, and she preferred to not go through further aggressive cancer treatment that could potentially cause complications and pain. We respected the patient’s wishes and counseled her on follow-up if the lesions became symptomatic or she decided she wanted to try treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Araya Zaesim, 1550 College St, Macon, GA, 31207; [email protected]

1. Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a meta-analysis of data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

2. Brownstein MH, Helwig EB. Patterns of cutaneous metastasis. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:862-868.

3. De Giorgi V, Grazzini M, Alfaioli B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of breast carcinoma. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:581-589.

4. Wong CYB, Helm MA, Kalb RE, et al. The presentation, pathology, and current management strategies of cutaneous metastasis. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:499-504.

5. Moore S. Cutaneous metastatic breast cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2002;6:255-260.

6. Ahmed M. Cutaneous metastases from breast carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011: bcr0620114398.

7. Cho J, Park Y, Lee JC, et al. Case series of different onset of skin metastasis according to the breast cancer subtypes. Cancer Res Treat. 2014;46:194-199.

An 80-year-old white woman presented to our dermatology clinic with a rash across her abdomen that had been there for more than a year. While not itchy or painful, the rash was slowly expanding. The patient had tried treatments including topical antifungals and topical corticosteroids, but none had helped.

Her medical history was significant for dementia and stage III triple-negative breast cancer in the left breast (diagnosed 8 years prior), which was treated with a simple left mastectomy, chemotherapy, and radiation. She reported no history of skin cancer. She was not taking any medications and had no known drug allergies. A physical examination revealed an erythematous, papulonodular rash with diffuse induration in a band-like pattern across her entire upper abdomen and left flank (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Cutaneous metastasis of primary breast cancer

Based on our patient’s history, we gave a presumptive diagnosis of cutaneous breast cancer metastasis. A punch biopsy was performed. The pathology report showed nests of neoplastic cells within the dermis, which was consistent with this diagnosis. Immunohistochemical stains and fluorescence in-situ hybridization confirmed triple-negative breast markers for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2.

An uncommon phenomenonseen mostly with breast cancer

Cutaneous metastatic carcinoma is relatively uncommon; one meta-analysis reported the overall incidence to be 5.3%.1 While it is unusual, any internal malignancy can metastasize to the skin. In women, the most common malignancy to do so is breast cancer. One study found breast cancer to be associated with 26.5% of cutaneous metastatic cases.2 These metastases often occur well after the patient has been treated for the primary malignancy.

Identifying features. Most cutaneous metastases occur near the site of the primary tumor, initially in the form of a firm, mobile, nonpainful nodule.3 This nodule is typically skin-colored or red, but in the case of cutaneous metastases of melanomas, it can appear blue or black. In the case of breast cancer, the lesions most often arise on the chest and abdomen.4 Occasionally, metastases can ulcerate through the skin.

Some forms of cutaneous metastasis, such as carcinoma erysipeloides, can appear in specific patterns. Carcinoma erysipeloides has a similar appearance to cellulitis; it manifests as a sharply demarcated, red, inflammatory patch in the skin adjacent to the primary tumor.

Consider the clinical picture

Cutaneous metastatic lesions have a wide range of differential diagnoses due to their varied appearances. It is important to view the overall clinical picture when distinguishing such lesions. Although cutaneous metastasis is uncommon, it should always be considered when asymptomatic skin lesions resist treatment—even in someone without a known history of malignancy.

Perform a biopsy. The diagnosis can be confirmed with a skin biopsy. A punch biopsy is preferable, as visualization of the dermis is crucial, and histology often reveals nests of pleomorphic cells. Further cellular cytology can elicit the primary malignancy of origin.

Making our diagnosis

We ruled out several possibilities before arriving at our diagnosis. An infectious etiology (eg, cutaneous candidiasis) was considered, as was a cutaneous change due to radiation therapy. We also considered shingles, the early stages of which would have been similar in appearance to our patient’s lesions, and urticaria, which can manifest as erythematous papules and wheals across various parts of the body. A lack of specific symptoms (eg, pruritis, pain, fever) made these alternative diagnoses less likely. The fact that our patient’s lesions persisted for more than a year without any response to treatment—and that they continued to grow—alerted us of a more sinister etiology.

Continue to: Treating the tumor is often not possible

Treating the tumor is often not possible

Treatment first involves treating the underlying tumor. For cases in which cutaneous lesions are the first manifestation of an internal malignancy, investigation as to the source should be performed. The lesions can then be treated with a combination of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery.5,6

Unfortunately, in most cases of cutaneous metastases, the primary malignancy is already widespread and possibly untreatable. In such instances, palliative care is offered. Lesions are managed symptomatically, and prevention of skin irritation becomes the primary focus. Keeping the skin clean and dry helps to prevent ulceration and secondary infection.

In cases where the lesions ulcerate or crust, debridement can help. Excision of lesions, as well as pairing laser therapy with electrochemotherapy, may be helpful to improve the patient’s quality of life when lesions cause discomfort.

The prognosis for cutaneous metastasis due to breast cancer is often hard to predict because it is determined by other factors, such as the presence of internal metastases, which indicates a worse prognosis (on the scale of months). Some case reports have demonstrated that patients with metastases limited to the skin may have prolonged survival (on the scale of years).7

Our patient was offered an initial trial of radiation therapy, but she refused all treatment because the lesions did not cause discomfort, and she preferred to not go through further aggressive cancer treatment that could potentially cause complications and pain. We respected the patient’s wishes and counseled her on follow-up if the lesions became symptomatic or she decided she wanted to try treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Araya Zaesim, 1550 College St, Macon, GA, 31207; [email protected]

An 80-year-old white woman presented to our dermatology clinic with a rash across her abdomen that had been there for more than a year. While not itchy or painful, the rash was slowly expanding. The patient had tried treatments including topical antifungals and topical corticosteroids, but none had helped.

Her medical history was significant for dementia and stage III triple-negative breast cancer in the left breast (diagnosed 8 years prior), which was treated with a simple left mastectomy, chemotherapy, and radiation. She reported no history of skin cancer. She was not taking any medications and had no known drug allergies. A physical examination revealed an erythematous, papulonodular rash with diffuse induration in a band-like pattern across her entire upper abdomen and left flank (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Cutaneous metastasis of primary breast cancer

Based on our patient’s history, we gave a presumptive diagnosis of cutaneous breast cancer metastasis. A punch biopsy was performed. The pathology report showed nests of neoplastic cells within the dermis, which was consistent with this diagnosis. Immunohistochemical stains and fluorescence in-situ hybridization confirmed triple-negative breast markers for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2.

An uncommon phenomenonseen mostly with breast cancer

Cutaneous metastatic carcinoma is relatively uncommon; one meta-analysis reported the overall incidence to be 5.3%.1 While it is unusual, any internal malignancy can metastasize to the skin. In women, the most common malignancy to do so is breast cancer. One study found breast cancer to be associated with 26.5% of cutaneous metastatic cases.2 These metastases often occur well after the patient has been treated for the primary malignancy.

Identifying features. Most cutaneous metastases occur near the site of the primary tumor, initially in the form of a firm, mobile, nonpainful nodule.3 This nodule is typically skin-colored or red, but in the case of cutaneous metastases of melanomas, it can appear blue or black. In the case of breast cancer, the lesions most often arise on the chest and abdomen.4 Occasionally, metastases can ulcerate through the skin.

Some forms of cutaneous metastasis, such as carcinoma erysipeloides, can appear in specific patterns. Carcinoma erysipeloides has a similar appearance to cellulitis; it manifests as a sharply demarcated, red, inflammatory patch in the skin adjacent to the primary tumor.

Consider the clinical picture

Cutaneous metastatic lesions have a wide range of differential diagnoses due to their varied appearances. It is important to view the overall clinical picture when distinguishing such lesions. Although cutaneous metastasis is uncommon, it should always be considered when asymptomatic skin lesions resist treatment—even in someone without a known history of malignancy.

Perform a biopsy. The diagnosis can be confirmed with a skin biopsy. A punch biopsy is preferable, as visualization of the dermis is crucial, and histology often reveals nests of pleomorphic cells. Further cellular cytology can elicit the primary malignancy of origin.

Making our diagnosis

We ruled out several possibilities before arriving at our diagnosis. An infectious etiology (eg, cutaneous candidiasis) was considered, as was a cutaneous change due to radiation therapy. We also considered shingles, the early stages of which would have been similar in appearance to our patient’s lesions, and urticaria, which can manifest as erythematous papules and wheals across various parts of the body. A lack of specific symptoms (eg, pruritis, pain, fever) made these alternative diagnoses less likely. The fact that our patient’s lesions persisted for more than a year without any response to treatment—and that they continued to grow—alerted us of a more sinister etiology.

Continue to: Treating the tumor is often not possible

Treating the tumor is often not possible

Treatment first involves treating the underlying tumor. For cases in which cutaneous lesions are the first manifestation of an internal malignancy, investigation as to the source should be performed. The lesions can then be treated with a combination of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery.5,6

Unfortunately, in most cases of cutaneous metastases, the primary malignancy is already widespread and possibly untreatable. In such instances, palliative care is offered. Lesions are managed symptomatically, and prevention of skin irritation becomes the primary focus. Keeping the skin clean and dry helps to prevent ulceration and secondary infection.

In cases where the lesions ulcerate or crust, debridement can help. Excision of lesions, as well as pairing laser therapy with electrochemotherapy, may be helpful to improve the patient’s quality of life when lesions cause discomfort.

The prognosis for cutaneous metastasis due to breast cancer is often hard to predict because it is determined by other factors, such as the presence of internal metastases, which indicates a worse prognosis (on the scale of months). Some case reports have demonstrated that patients with metastases limited to the skin may have prolonged survival (on the scale of years).7

Our patient was offered an initial trial of radiation therapy, but she refused all treatment because the lesions did not cause discomfort, and she preferred to not go through further aggressive cancer treatment that could potentially cause complications and pain. We respected the patient’s wishes and counseled her on follow-up if the lesions became symptomatic or she decided she wanted to try treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Araya Zaesim, 1550 College St, Macon, GA, 31207; [email protected]

1. Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a meta-analysis of data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

2. Brownstein MH, Helwig EB. Patterns of cutaneous metastasis. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:862-868.

3. De Giorgi V, Grazzini M, Alfaioli B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of breast carcinoma. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:581-589.

4. Wong CYB, Helm MA, Kalb RE, et al. The presentation, pathology, and current management strategies of cutaneous metastasis. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:499-504.

5. Moore S. Cutaneous metastatic breast cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2002;6:255-260.

6. Ahmed M. Cutaneous metastases from breast carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011: bcr0620114398.

7. Cho J, Park Y, Lee JC, et al. Case series of different onset of skin metastasis according to the breast cancer subtypes. Cancer Res Treat. 2014;46:194-199.

1. Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a meta-analysis of data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

2. Brownstein MH, Helwig EB. Patterns of cutaneous metastasis. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:862-868.

3. De Giorgi V, Grazzini M, Alfaioli B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of breast carcinoma. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:581-589.

4. Wong CYB, Helm MA, Kalb RE, et al. The presentation, pathology, and current management strategies of cutaneous metastasis. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:499-504.

5. Moore S. Cutaneous metastatic breast cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2002;6:255-260.

6. Ahmed M. Cutaneous metastases from breast carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011: bcr0620114398.

7. Cho J, Park Y, Lee JC, et al. Case series of different onset of skin metastasis according to the breast cancer subtypes. Cancer Res Treat. 2014;46:194-199.