User login

Progressive discoloration over the right shoulder

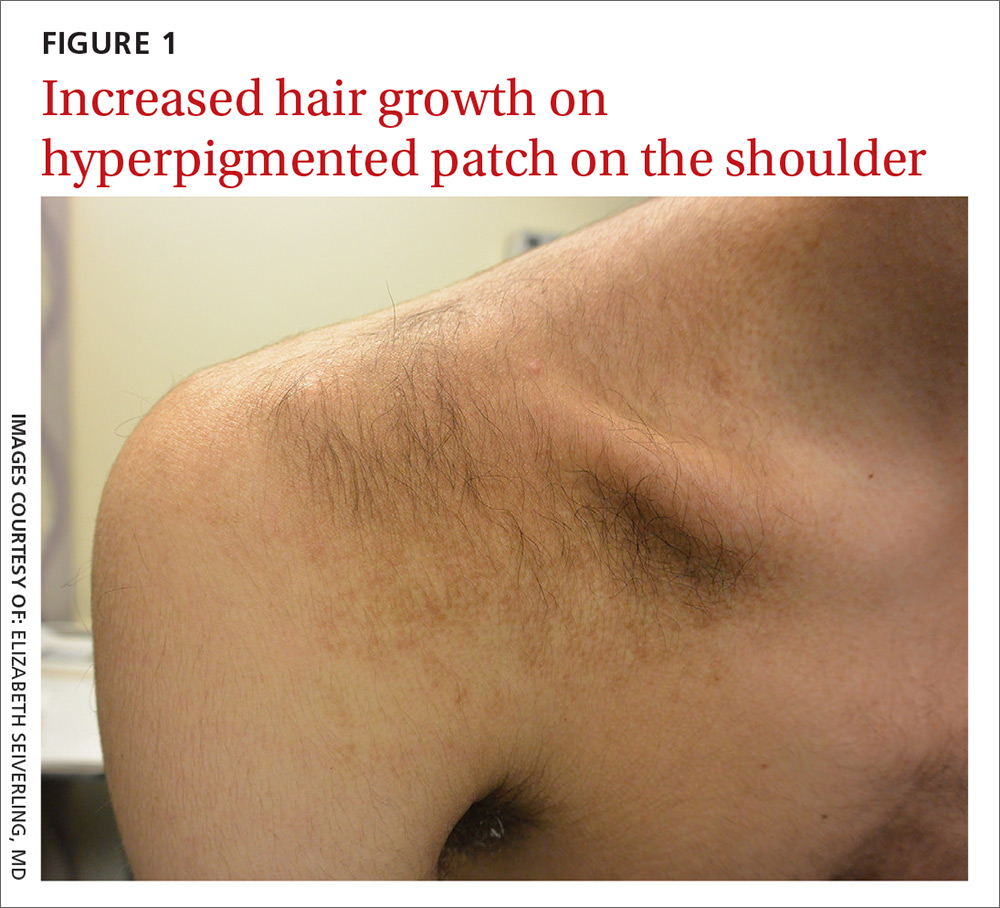

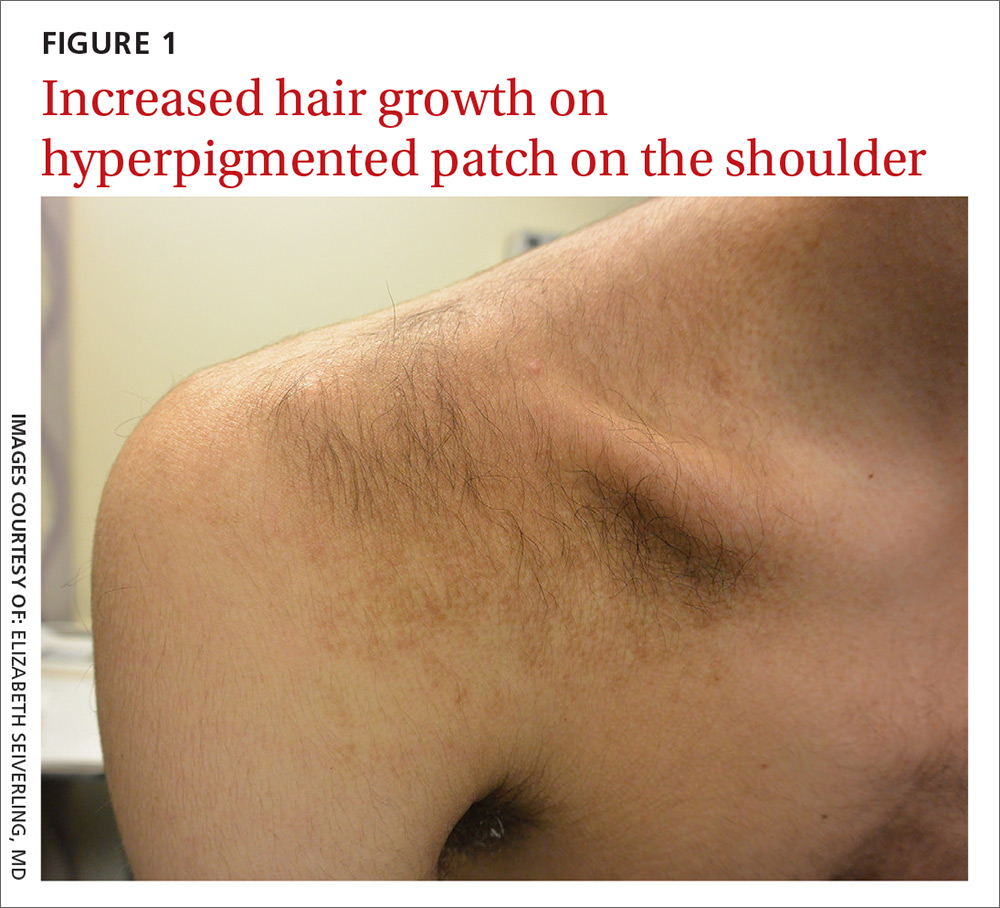

A 15-year-old Caucasian boy presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic brown patch on his right shoulder. While the patient’s mother first noticed the patch when he was 5 years old, the discolored area had recently been expanding in size and had developed hypertrichosis. The patient was otherwise healthy; he took no medications and denied any symptoms or history of trauma to the area. None of his siblings were similarly affected.

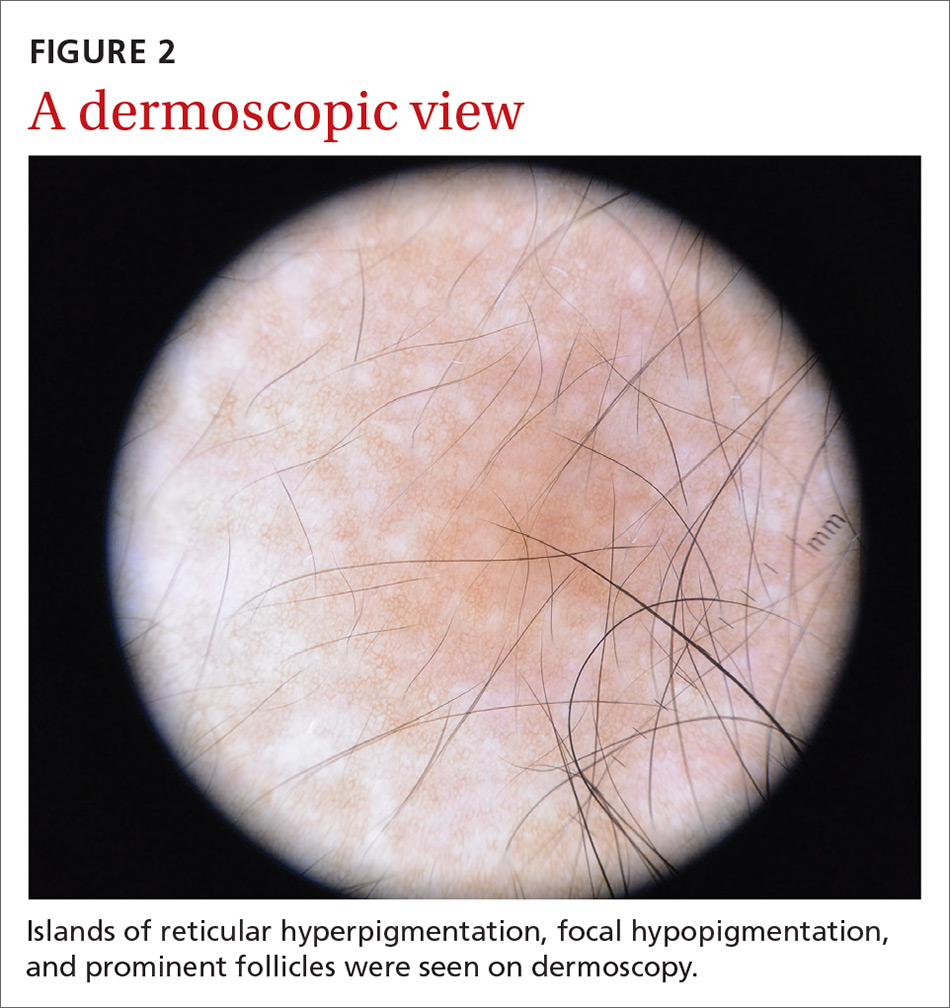

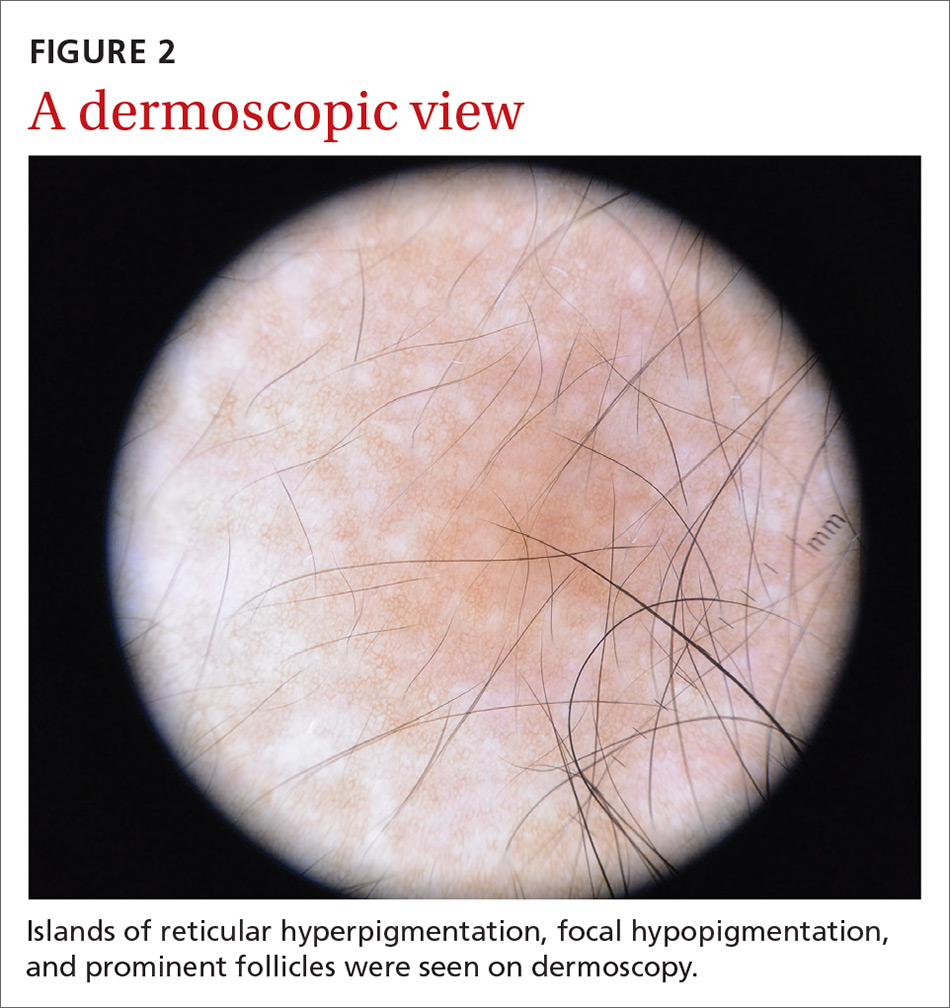

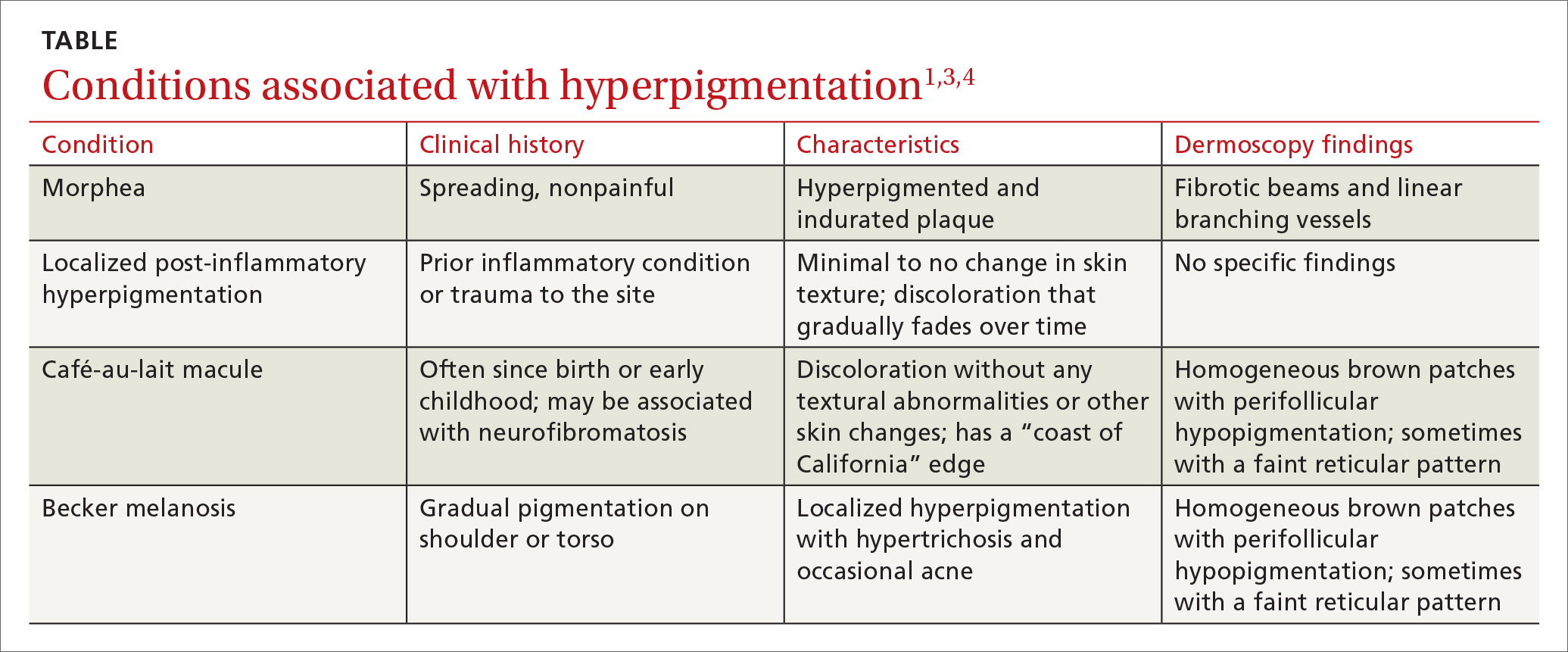

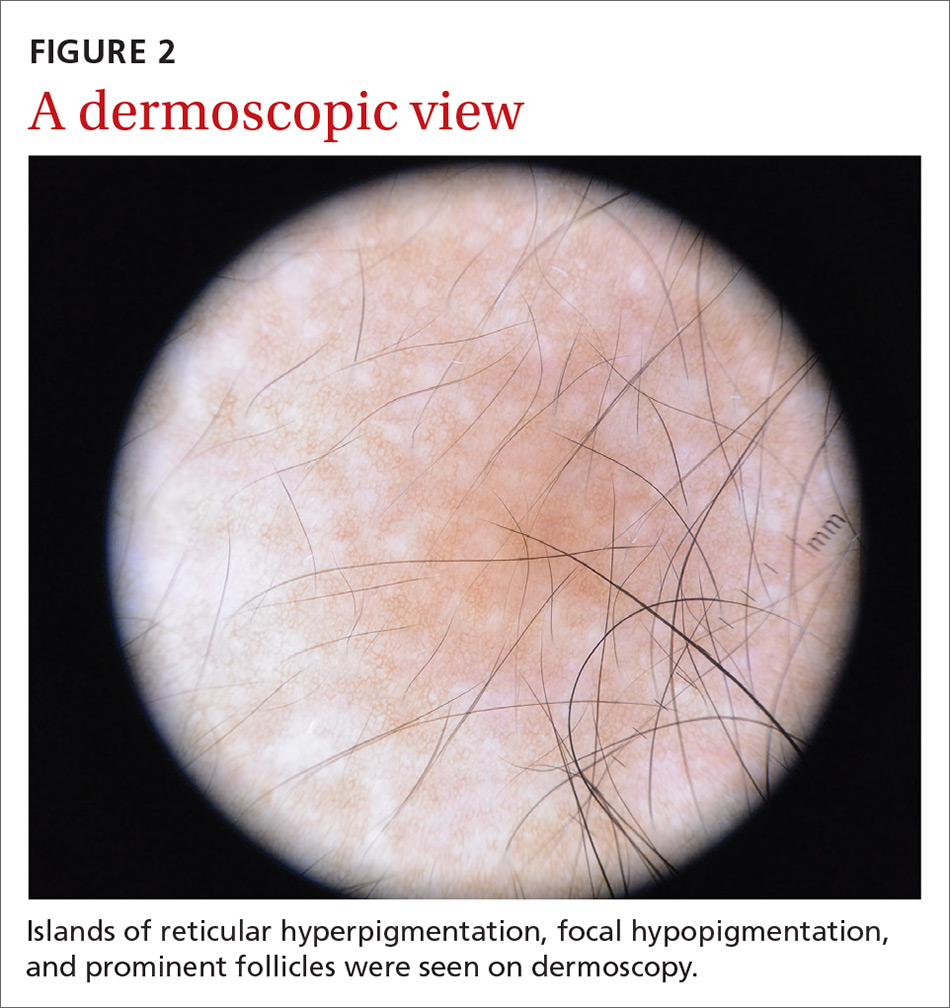

A physical examination revealed a well-demarcated hyperpigmented patch with an irregularly shaped border and an increased number of terminal hairs (FIGURE 1). The affected area was not indurated, and there were no muscular or skeletal abnormalities on inspection. Examination of the patch under a dermatoscope revealed islands of reticular (lattice-like) hyperpigmentation, focal hypopigmentation, and prominent follicles (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

DIAGNOSIS: Becker melanosis

Becker melanosis (also called Becker’s nevus or Becker’s pigmentary hamartoma) is an organoid hamartoma that is most common among males.1 This benign area of hyperpigmentation typically manifests as a circumscribed patch with an irregular border on the upper trunk, shoulders, or upper arms of young men. Becker melanosis is usually acquired and typically comes to medical attention around the time of puberty, although there may be a history of discoloration (as was true in this case).

A diagnosis that’s usually made clinically

Androgenic origin. Because of the male predominance and association with hypertrichosis (and for that matter, acne), androgens have been thought to play a role in the development of Becker melanosis.2 The condition affects about 1 in 200 young men.1 To date, no specific gene defect has been identified.

Underlying hypoplasia of the breast or musculoskeletal abnormalities are uncommonly associated with Becker melanosis. When these abnormalities are present, the condition is known as Becker’s nevus syndrome.3

Look for the pattern. Becker melanosis is associated with homogenous brown patches with perifollicular hypopigmentation, sometimes with a faint reticular pattern.4,5 The diagnosis can usually be made clinically, but a skin biopsy can be helpful to confirm questionable cases. Dermoscopy can also assist in diagnosis. In this case, our patient’s presentation was typical, and additional studies were not needed.

Other causes of hyperpigmentation

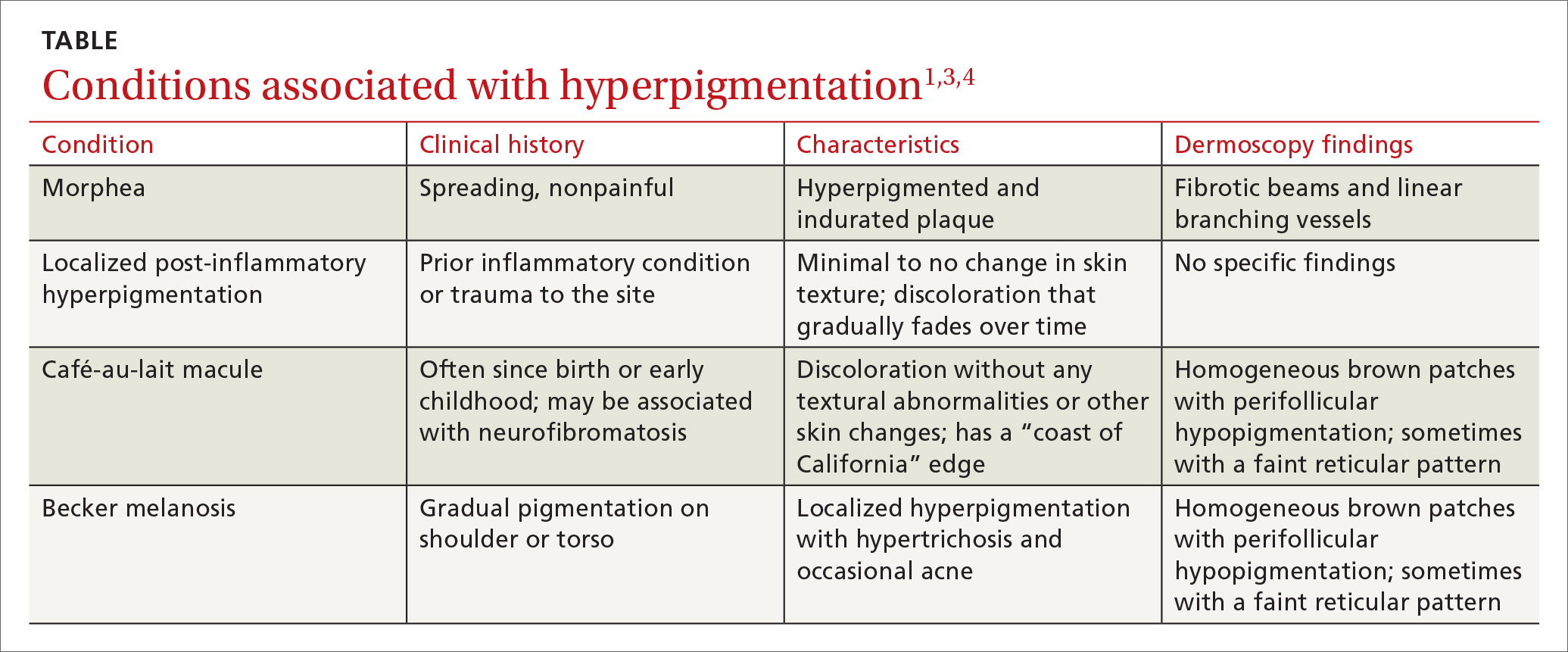

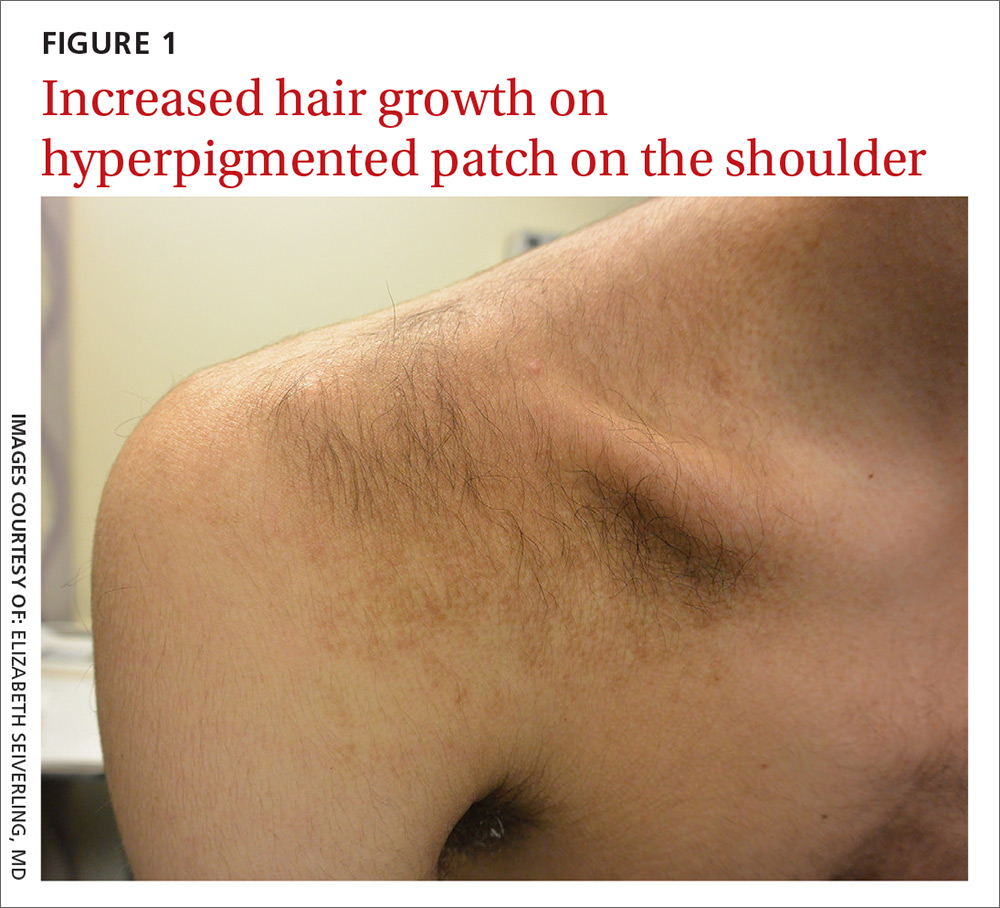

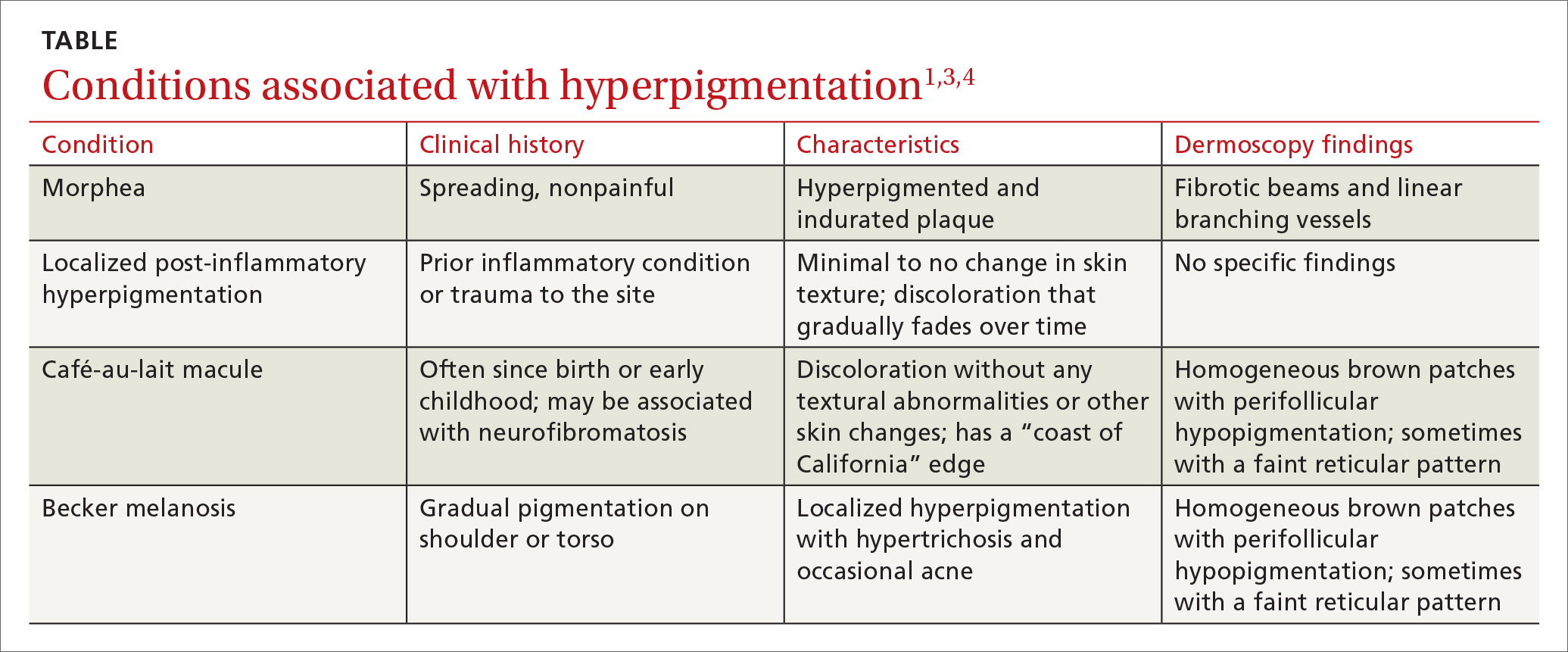

The differential diagnosis includes other localized disorders associated with hyperpigmentation (TABLE1,3,4).

Continue to: Morphea

Morphea represents a thickening of collagen bundles in the skin. Although morphea can affect the shoulder and trunk, as Becker melanosis does, lesions of morphea feel firm to the touch and are not associated with hypertrichosis.

Localized post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation occurs following a traumatic event, such as a burn, or a prior dermatosis, such as zoster. Careful history-taking can uncover an antecedent inflammatory condition. Post-inflammatory pigment changes do not typically result in hypertrichosis.

Café-au-lait macules can manifest as isolated areas of discoloration. These macules can be an important indicator of neurofibromatosis, a genetic disorder in which tumors grow in the nervous system. Melanocytic hamartomas of the iris (Lisch nodules), axillary freckling (Crowe’s sign), or multiple cutaneous neurofibromas serve as additional clues to neurofibromatosis. In ambiguous cases, a skin biopsy can help differentiate a café au lait macule from Becker melanosis.

To treat or not to treat?

No treatment other than reassurance is needed in most cases of Becker melanosis, as it is a benign condition. Protecting the area from sunlight can minimize darkening and contrast with the surrounding skin. Electrolysis and laser therapy can be used to treat the associated hypertrichosis; laser therapy can also reduce the hyperpigmentation. Nonablative fractional resurfacing accompanied by laser hair removal is also reported to be of value.6

Our patient was satisfied with reassurance of the benign nature of the condition and did not elect treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, 500 University Drive, Suite 4300, Department of Dermatology, HU14, UPC II, Hershey, PA 17033-2360; [email protected]

1. Rabinovitz HS, Barnhill RL. Benign melanocytic neoplasms. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2012;112:1853-1854.

2. Person JR, Longcope C. Becker’s nevus: an androgen-mediated hyperplasia with increased androgen receptors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:235-238.

3. Cosendey FE, Martinez NS, Bernhard GA, et al. Becker nevus syndrome. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:379-384.

4. Ingordo V, Iannazzone SS, Cusano F, et al. Dermoscopic features of congenital melanocytic nevus and Becker nevus in an adult male population: an analysis with 10-fold magnification. Dermatology. 2006;212:354-360.

5. Luk DC, Lam SY, Cheung PC, et al. Dermoscopy for common skin problems in Chinese children using a novel Hong Kong-made dermoscope. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20:495-503.

6. Balaraman B, Friedman PM. Hypertrichotic Becker’s nevi treated with combination 1,550nm non-ablative fractional photothermolysis and laser hair removal. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:350-353.

A 15-year-old Caucasian boy presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic brown patch on his right shoulder. While the patient’s mother first noticed the patch when he was 5 years old, the discolored area had recently been expanding in size and had developed hypertrichosis. The patient was otherwise healthy; he took no medications and denied any symptoms or history of trauma to the area. None of his siblings were similarly affected.

A physical examination revealed a well-demarcated hyperpigmented patch with an irregularly shaped border and an increased number of terminal hairs (FIGURE 1). The affected area was not indurated, and there were no muscular or skeletal abnormalities on inspection. Examination of the patch under a dermatoscope revealed islands of reticular (lattice-like) hyperpigmentation, focal hypopigmentation, and prominent follicles (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

DIAGNOSIS: Becker melanosis

Becker melanosis (also called Becker’s nevus or Becker’s pigmentary hamartoma) is an organoid hamartoma that is most common among males.1 This benign area of hyperpigmentation typically manifests as a circumscribed patch with an irregular border on the upper trunk, shoulders, or upper arms of young men. Becker melanosis is usually acquired and typically comes to medical attention around the time of puberty, although there may be a history of discoloration (as was true in this case).

A diagnosis that’s usually made clinically

Androgenic origin. Because of the male predominance and association with hypertrichosis (and for that matter, acne), androgens have been thought to play a role in the development of Becker melanosis.2 The condition affects about 1 in 200 young men.1 To date, no specific gene defect has been identified.

Underlying hypoplasia of the breast or musculoskeletal abnormalities are uncommonly associated with Becker melanosis. When these abnormalities are present, the condition is known as Becker’s nevus syndrome.3

Look for the pattern. Becker melanosis is associated with homogenous brown patches with perifollicular hypopigmentation, sometimes with a faint reticular pattern.4,5 The diagnosis can usually be made clinically, but a skin biopsy can be helpful to confirm questionable cases. Dermoscopy can also assist in diagnosis. In this case, our patient’s presentation was typical, and additional studies were not needed.

Other causes of hyperpigmentation

The differential diagnosis includes other localized disorders associated with hyperpigmentation (TABLE1,3,4).

Continue to: Morphea

Morphea represents a thickening of collagen bundles in the skin. Although morphea can affect the shoulder and trunk, as Becker melanosis does, lesions of morphea feel firm to the touch and are not associated with hypertrichosis.

Localized post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation occurs following a traumatic event, such as a burn, or a prior dermatosis, such as zoster. Careful history-taking can uncover an antecedent inflammatory condition. Post-inflammatory pigment changes do not typically result in hypertrichosis.

Café-au-lait macules can manifest as isolated areas of discoloration. These macules can be an important indicator of neurofibromatosis, a genetic disorder in which tumors grow in the nervous system. Melanocytic hamartomas of the iris (Lisch nodules), axillary freckling (Crowe’s sign), or multiple cutaneous neurofibromas serve as additional clues to neurofibromatosis. In ambiguous cases, a skin biopsy can help differentiate a café au lait macule from Becker melanosis.

To treat or not to treat?

No treatment other than reassurance is needed in most cases of Becker melanosis, as it is a benign condition. Protecting the area from sunlight can minimize darkening and contrast with the surrounding skin. Electrolysis and laser therapy can be used to treat the associated hypertrichosis; laser therapy can also reduce the hyperpigmentation. Nonablative fractional resurfacing accompanied by laser hair removal is also reported to be of value.6

Our patient was satisfied with reassurance of the benign nature of the condition and did not elect treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, 500 University Drive, Suite 4300, Department of Dermatology, HU14, UPC II, Hershey, PA 17033-2360; [email protected]

A 15-year-old Caucasian boy presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic brown patch on his right shoulder. While the patient’s mother first noticed the patch when he was 5 years old, the discolored area had recently been expanding in size and had developed hypertrichosis. The patient was otherwise healthy; he took no medications and denied any symptoms or history of trauma to the area. None of his siblings were similarly affected.

A physical examination revealed a well-demarcated hyperpigmented patch with an irregularly shaped border and an increased number of terminal hairs (FIGURE 1). The affected area was not indurated, and there were no muscular or skeletal abnormalities on inspection. Examination of the patch under a dermatoscope revealed islands of reticular (lattice-like) hyperpigmentation, focal hypopigmentation, and prominent follicles (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

DIAGNOSIS: Becker melanosis

Becker melanosis (also called Becker’s nevus or Becker’s pigmentary hamartoma) is an organoid hamartoma that is most common among males.1 This benign area of hyperpigmentation typically manifests as a circumscribed patch with an irregular border on the upper trunk, shoulders, or upper arms of young men. Becker melanosis is usually acquired and typically comes to medical attention around the time of puberty, although there may be a history of discoloration (as was true in this case).

A diagnosis that’s usually made clinically

Androgenic origin. Because of the male predominance and association with hypertrichosis (and for that matter, acne), androgens have been thought to play a role in the development of Becker melanosis.2 The condition affects about 1 in 200 young men.1 To date, no specific gene defect has been identified.

Underlying hypoplasia of the breast or musculoskeletal abnormalities are uncommonly associated with Becker melanosis. When these abnormalities are present, the condition is known as Becker’s nevus syndrome.3

Look for the pattern. Becker melanosis is associated with homogenous brown patches with perifollicular hypopigmentation, sometimes with a faint reticular pattern.4,5 The diagnosis can usually be made clinically, but a skin biopsy can be helpful to confirm questionable cases. Dermoscopy can also assist in diagnosis. In this case, our patient’s presentation was typical, and additional studies were not needed.

Other causes of hyperpigmentation

The differential diagnosis includes other localized disorders associated with hyperpigmentation (TABLE1,3,4).

Continue to: Morphea

Morphea represents a thickening of collagen bundles in the skin. Although morphea can affect the shoulder and trunk, as Becker melanosis does, lesions of morphea feel firm to the touch and are not associated with hypertrichosis.

Localized post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation occurs following a traumatic event, such as a burn, or a prior dermatosis, such as zoster. Careful history-taking can uncover an antecedent inflammatory condition. Post-inflammatory pigment changes do not typically result in hypertrichosis.

Café-au-lait macules can manifest as isolated areas of discoloration. These macules can be an important indicator of neurofibromatosis, a genetic disorder in which tumors grow in the nervous system. Melanocytic hamartomas of the iris (Lisch nodules), axillary freckling (Crowe’s sign), or multiple cutaneous neurofibromas serve as additional clues to neurofibromatosis. In ambiguous cases, a skin biopsy can help differentiate a café au lait macule from Becker melanosis.

To treat or not to treat?

No treatment other than reassurance is needed in most cases of Becker melanosis, as it is a benign condition. Protecting the area from sunlight can minimize darkening and contrast with the surrounding skin. Electrolysis and laser therapy can be used to treat the associated hypertrichosis; laser therapy can also reduce the hyperpigmentation. Nonablative fractional resurfacing accompanied by laser hair removal is also reported to be of value.6

Our patient was satisfied with reassurance of the benign nature of the condition and did not elect treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, 500 University Drive, Suite 4300, Department of Dermatology, HU14, UPC II, Hershey, PA 17033-2360; [email protected]

1. Rabinovitz HS, Barnhill RL. Benign melanocytic neoplasms. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2012;112:1853-1854.

2. Person JR, Longcope C. Becker’s nevus: an androgen-mediated hyperplasia with increased androgen receptors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:235-238.

3. Cosendey FE, Martinez NS, Bernhard GA, et al. Becker nevus syndrome. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:379-384.

4. Ingordo V, Iannazzone SS, Cusano F, et al. Dermoscopic features of congenital melanocytic nevus and Becker nevus in an adult male population: an analysis with 10-fold magnification. Dermatology. 2006;212:354-360.

5. Luk DC, Lam SY, Cheung PC, et al. Dermoscopy for common skin problems in Chinese children using a novel Hong Kong-made dermoscope. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20:495-503.

6. Balaraman B, Friedman PM. Hypertrichotic Becker’s nevi treated with combination 1,550nm non-ablative fractional photothermolysis and laser hair removal. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:350-353.

1. Rabinovitz HS, Barnhill RL. Benign melanocytic neoplasms. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2012;112:1853-1854.

2. Person JR, Longcope C. Becker’s nevus: an androgen-mediated hyperplasia with increased androgen receptors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:235-238.

3. Cosendey FE, Martinez NS, Bernhard GA, et al. Becker nevus syndrome. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:379-384.

4. Ingordo V, Iannazzone SS, Cusano F, et al. Dermoscopic features of congenital melanocytic nevus and Becker nevus in an adult male population: an analysis with 10-fold magnification. Dermatology. 2006;212:354-360.

5. Luk DC, Lam SY, Cheung PC, et al. Dermoscopy for common skin problems in Chinese children using a novel Hong Kong-made dermoscope. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20:495-503.

6. Balaraman B, Friedman PM. Hypertrichotic Becker’s nevi treated with combination 1,550nm non-ablative fractional photothermolysis and laser hair removal. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:350-353.

Sore on nose

The FP suspected a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or squamous cell carcinoma.

Informed consent was obtained, and the FP numbed the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine using a 30 gauge needle. The area was exquisitely tender, so a small needle was used and the anesthesia was injected slowly. (It is safe and recommended to use epinephrine for biopsy on or around the nose.) The physician performed a shave biopsy. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The biopsy results confirmed an infiltrative BCC. The physician recognized this as a more aggressive BCC and its location at the nasolabial fold suggested that the patient was at an increased risk for recurrence. He communicated these risk factors to the patient, and she accepted a referral for Mohs surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP suspected a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or squamous cell carcinoma.

Informed consent was obtained, and the FP numbed the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine using a 30 gauge needle. The area was exquisitely tender, so a small needle was used and the anesthesia was injected slowly. (It is safe and recommended to use epinephrine for biopsy on or around the nose.) The physician performed a shave biopsy. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The biopsy results confirmed an infiltrative BCC. The physician recognized this as a more aggressive BCC and its location at the nasolabial fold suggested that the patient was at an increased risk for recurrence. He communicated these risk factors to the patient, and she accepted a referral for Mohs surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP suspected a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or squamous cell carcinoma.

Informed consent was obtained, and the FP numbed the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine using a 30 gauge needle. The area was exquisitely tender, so a small needle was used and the anesthesia was injected slowly. (It is safe and recommended to use epinephrine for biopsy on or around the nose.) The physician performed a shave biopsy. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The biopsy results confirmed an infiltrative BCC. The physician recognized this as a more aggressive BCC and its location at the nasolabial fold suggested that the patient was at an increased risk for recurrence. He communicated these risk factors to the patient, and she accepted a referral for Mohs surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Growth on forehead

The FP was concerned about a possible melanoma due to the dark pigmentation and the positive “ABDCE criteria” of melanoma. The FP used his dermatoscope to determine whether this was a melanoma or a pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

The multiple leaf-like structures and blue-gray ovoid nests seen with dermoscopy suggested that this was a pigmented BCC. (The ulceration could be seen in either melanoma or BCC.) The FP told the patient that this was most certainly a skin cancer and she needed a biopsy that day. The patient consented and anesthesia was obtained with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine. The physician used a DermaBlade to perform a deep shave (saucerization) under the pigmentation. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The pathology confirmed pigmented BCC. The physician recommended an elliptical excision and scheduled it for the following week.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP was concerned about a possible melanoma due to the dark pigmentation and the positive “ABDCE criteria” of melanoma. The FP used his dermatoscope to determine whether this was a melanoma or a pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

The multiple leaf-like structures and blue-gray ovoid nests seen with dermoscopy suggested that this was a pigmented BCC. (The ulceration could be seen in either melanoma or BCC.) The FP told the patient that this was most certainly a skin cancer and she needed a biopsy that day. The patient consented and anesthesia was obtained with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine. The physician used a DermaBlade to perform a deep shave (saucerization) under the pigmentation. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The pathology confirmed pigmented BCC. The physician recommended an elliptical excision and scheduled it for the following week.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP was concerned about a possible melanoma due to the dark pigmentation and the positive “ABDCE criteria” of melanoma. The FP used his dermatoscope to determine whether this was a melanoma or a pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

The multiple leaf-like structures and blue-gray ovoid nests seen with dermoscopy suggested that this was a pigmented BCC. (The ulceration could be seen in either melanoma or BCC.) The FP told the patient that this was most certainly a skin cancer and she needed a biopsy that day. The patient consented and anesthesia was obtained with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine. The physician used a DermaBlade to perform a deep shave (saucerization) under the pigmentation. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The pathology confirmed pigmented BCC. The physician recommended an elliptical excision and scheduled it for the following week.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Rash on arm

The FP looked closely at the so-called rash and realized that while it could be nummular eczema it could also be a superficial basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

He explained the differential diagnosis to the patient and suggested that he perform a shave biopsy that day. The patient consented to the biopsy, and the physician numbed the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine. He used a DermaBlade and obtained hemostasis with aluminum chloride in water. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The biopsy result confirmed the FP’s suspicion: The lesion was a superficial BCC.

On the follow-up visit the FP explained the options for treatment, including electrodesiccation and curettage, cryosurgery, or an elliptical excision. He told the patient that the cure rates are about the same, regardless of which of these treatments were chosen. He also explained that either of the 2 destructive methods could be performed immediately, whereas the elliptical excision would require scheduling a longer appointment.

The patient chose the cryosurgery. (See the Watch & Learn video on cryosurgery.) After numbing the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine, the physician froze the lesion with a 3 mm halo for 30 seconds using liquid nitrogen spray. At follow-up 3 months later, there was some hypopigmentation, but no evidence of the BCC.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP looked closely at the so-called rash and realized that while it could be nummular eczema it could also be a superficial basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

He explained the differential diagnosis to the patient and suggested that he perform a shave biopsy that day. The patient consented to the biopsy, and the physician numbed the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine. He used a DermaBlade and obtained hemostasis with aluminum chloride in water. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The biopsy result confirmed the FP’s suspicion: The lesion was a superficial BCC.

On the follow-up visit the FP explained the options for treatment, including electrodesiccation and curettage, cryosurgery, or an elliptical excision. He told the patient that the cure rates are about the same, regardless of which of these treatments were chosen. He also explained that either of the 2 destructive methods could be performed immediately, whereas the elliptical excision would require scheduling a longer appointment.

The patient chose the cryosurgery. (See the Watch & Learn video on cryosurgery.) After numbing the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine, the physician froze the lesion with a 3 mm halo for 30 seconds using liquid nitrogen spray. At follow-up 3 months later, there was some hypopigmentation, but no evidence of the BCC.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP looked closely at the so-called rash and realized that while it could be nummular eczema it could also be a superficial basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

He explained the differential diagnosis to the patient and suggested that he perform a shave biopsy that day. The patient consented to the biopsy, and the physician numbed the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine. He used a DermaBlade and obtained hemostasis with aluminum chloride in water. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The biopsy result confirmed the FP’s suspicion: The lesion was a superficial BCC.

On the follow-up visit the FP explained the options for treatment, including electrodesiccation and curettage, cryosurgery, or an elliptical excision. He told the patient that the cure rates are about the same, regardless of which of these treatments were chosen. He also explained that either of the 2 destructive methods could be performed immediately, whereas the elliptical excision would require scheduling a longer appointment.

The patient chose the cryosurgery. (See the Watch & Learn video on cryosurgery.) After numbing the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine, the physician froze the lesion with a 3 mm halo for 30 seconds using liquid nitrogen spray. At follow-up 3 months later, there was some hypopigmentation, but no evidence of the BCC.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Growth on nose

The FP made the presumptive diagnosis of a nodular basal cell carcinoma.

He explained the importance of performing a biopsy and obtained informed consent. On the same day of the patient’s visit, he injected 1% lidocaine with epinephrine under the lesion with a single stick of a 30 gauge needle. He knew that it was safe to use epinephrine on the nose, and that it would prevent excessive bleeding during the biopsy. Contrary to the myth frequently taught in medical school, the nose is a very vascular area. The physician performed a shave biopsy that removed the top of the lesion flush with the skin around it. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The pathology report came back as a nodular basal cell carcinoma. On the following visit, the physician recommended Mohs surgery as a way to preserve the vital anatomy of the nasal ala and achieve the highest cure rate.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP made the presumptive diagnosis of a nodular basal cell carcinoma.

He explained the importance of performing a biopsy and obtained informed consent. On the same day of the patient’s visit, he injected 1% lidocaine with epinephrine under the lesion with a single stick of a 30 gauge needle. He knew that it was safe to use epinephrine on the nose, and that it would prevent excessive bleeding during the biopsy. Contrary to the myth frequently taught in medical school, the nose is a very vascular area. The physician performed a shave biopsy that removed the top of the lesion flush with the skin around it. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The pathology report came back as a nodular basal cell carcinoma. On the following visit, the physician recommended Mohs surgery as a way to preserve the vital anatomy of the nasal ala and achieve the highest cure rate.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP made the presumptive diagnosis of a nodular basal cell carcinoma.

He explained the importance of performing a biopsy and obtained informed consent. On the same day of the patient’s visit, he injected 1% lidocaine with epinephrine under the lesion with a single stick of a 30 gauge needle. He knew that it was safe to use epinephrine on the nose, and that it would prevent excessive bleeding during the biopsy. Contrary to the myth frequently taught in medical school, the nose is a very vascular area. The physician performed a shave biopsy that removed the top of the lesion flush with the skin around it. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The pathology report came back as a nodular basal cell carcinoma. On the following visit, the physician recommended Mohs surgery as a way to preserve the vital anatomy of the nasal ala and achieve the highest cure rate.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Chronic diarrhea in a 64-year-old woman

A 64-year-old woman with no significant medical history presented to the emergency department with worsening intermittent abdominal pain and chronic diarrhea, which had increased in frequency over the prior 3 months. She had taken loperamide, which yielded mild symptomatic relief. A complete metabolic panel revealed no significant abnormalities, with a normal inflammatory marker and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

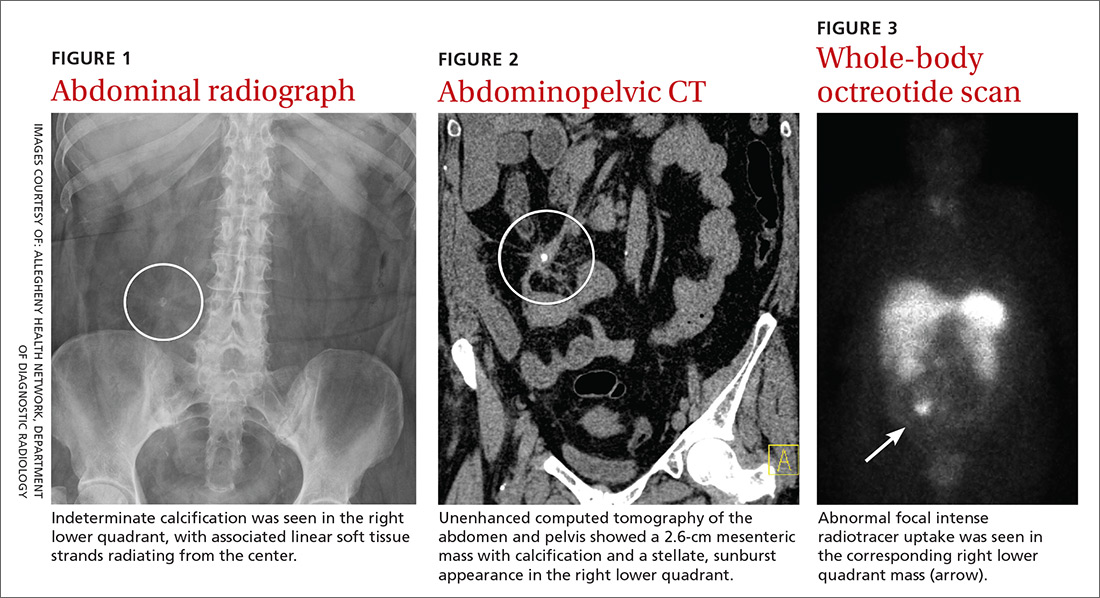

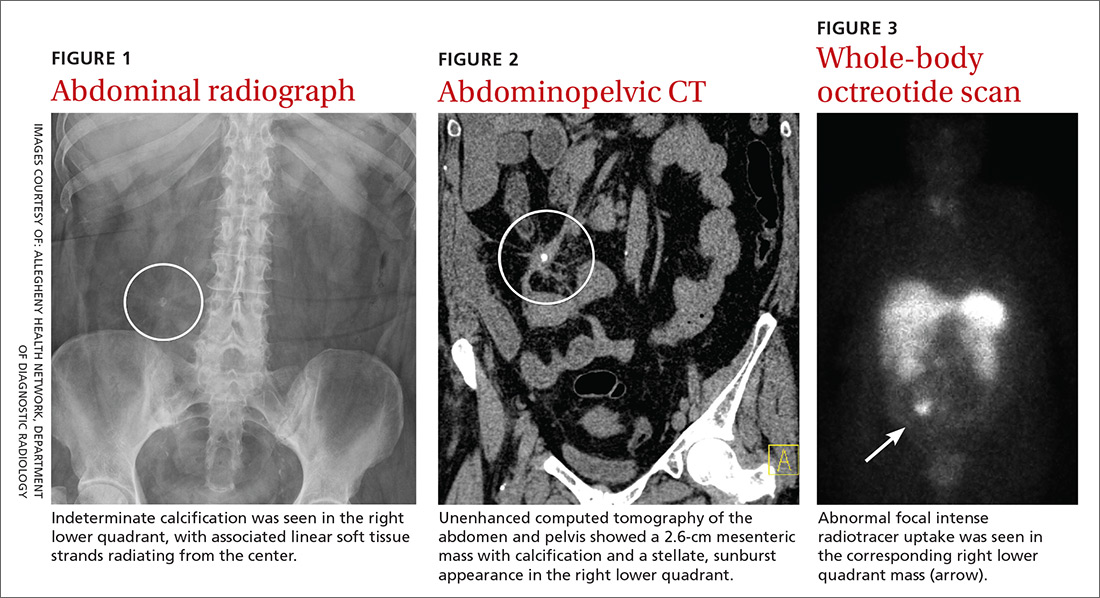

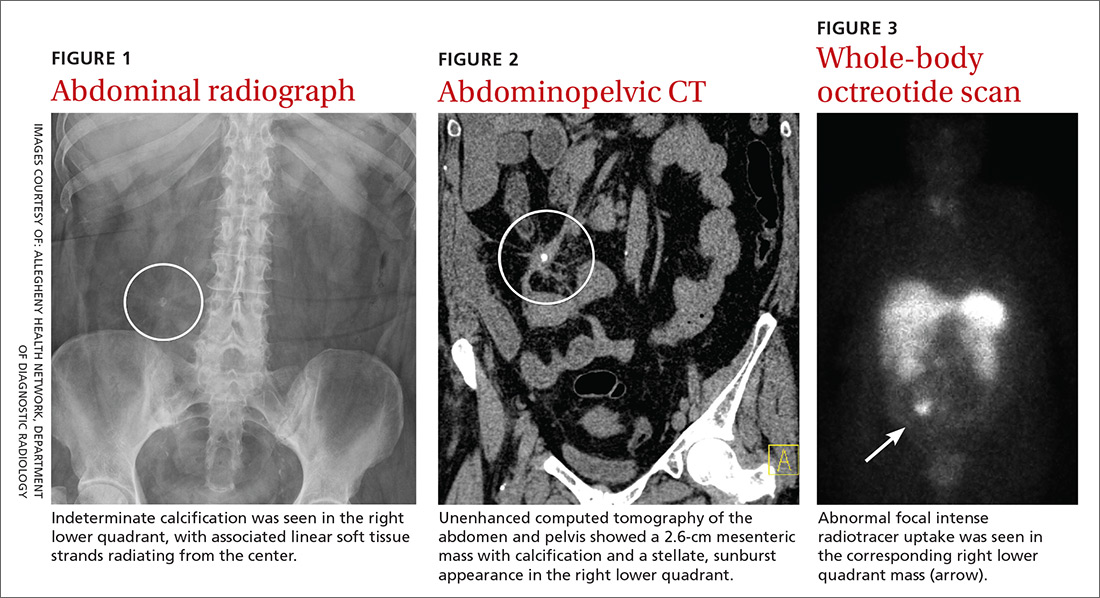

Physical examination revealed mild tenderness to palpation over the right hemiabdomen, but no rebound tenderness or guarding. An abdominal radiograph (FIGURE 1), computed tomography (CT) without contrast of the abdomen and pelvis (FIGURE 2), and a whole-body octreotide scan (FIGURE 3) were ordered.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Carcinoid tumor

Based on the patient’s symptoms and imaging studies, we suspected that she had a carcinoid tumor with mesenteric involvement. The CT showed a 2.6-cm mesenteric mass with a characteristic sunburst pattern and desmoplastic stranding, as well as numerous prominent retroperitoneal lymph nodes, suggestive of nodal involvement. The octreotide scan showed abnormal focal intense radiotracer uptake in the corresponding right lower quadrant mass, which confirmed our suspicion. There was no evidence of hepatic metastasis on the CT or octreotide scan.

Most common locations

Carcinoid tumors are the most common type of neuroendocrine tumors and are derived primarily from serotonin-producing enterochromaffin cells.1 These slow-growing, well-differentiated tumors usually originate in the gastrointestinal and bronchopulmonary tracts (67.5% and 25.3%, respectively), with uncommon primary sites involving the mesentery, ovaries, and kidneys.2 Generally, carcinoid tumors that arise in the mesentery are metastatic, often from an occult primary site. It has been reported that 40% to 80% of midgut carcinoid tumors spread to the mesentery.3

Carcinoid tumors are estimated to occur in 1.9 individuals per 100,000 annually.4 Traditionally, the appendix was cited as the most common location for these tumors. However, more recently, Modlin et al2 conducted a comprehensive analysis of epidemiologic data from the 13,715 carcinoid tumors registered in the National Cancer Institute database. Over the more than 25-year study period (1973-1999), Modlin and colleagues found a significant change in the distribution of gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors, with the incidence rates of small bowel (41.8%) and rectal carcinoids (27.4%) increasing, while appendiceal carcinoids decreased (24.1%).2

Gastrointestinal complications can arise from metastasis

Small bowel carcinoid tumors often manifest with intermittent abdominal pain, which can be caused by fibrosis of the mesentery, intestinal obstruction, or kinking of the bowel. Less common is the constellation of diarrhea, cutaneous flushing, and asthma seen with carcinoid syndrome. The prevalence of this syndrome is mediated by various humoral factors, the most notable of which is serotonin.

Continue to: Patients with carcinoid syndrome...

Patients with carcinoid syndrome often have metastasis to the liver, where serotonin is normally metabolized. This metastasis allows serotonin and other vasoactive substances to bypass hepatic metabolic degradation, resulting in the aforementioned symptoms. Carcinoid syndrome can also occur without hepatic metastasis in the setting of nodal involvement, which enables direct hormone release into the systemic circulation.5

Carcinoid syndrome affects fewer than 10% of patients with carcinoid tumors.6 Therefore, although carcinoid tumor should be suspected in patients with suggestive symptoms, other diagnoses must be considered.

Other disorders to consider on work-up

Chronic diarrhea and colicky abdominal pain are nonspecific features also associated with conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease and celiac disease, necessitating further work-up to elucidate the diagnosis.

Inflammatory bowel disease often involves elevated inflammatory markers, such as increased ESR and C-reactive protein.

Ulcerative colitis can show thickened and inflamed bowel walls on CT, with cross-sectional target appearance due to transmural involvement.

Continue to: Crohn's disease

Crohn’s disease usually affects the terminal ileum. CT is useful for identifying complications such as strictures/fistulas and abscesses.

Celiac disease involves elevated endomysial antibody and human tissue transglutaminase antibody. On CT, a characteristic jejunoileal fold pattern reversal can be seen.

A 24-hour urine test + imaging studies

The most useful diagnostic test for carcinoid tumor is the 24-hour urinary test for 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), the metabolic end-product of serotonin. The normal rate of 5-HIAA excretion ranges from 3 to 15 mg/d, whereas the rates of patients with carcinoid tumors may have elevated levels.7

What you’ll see. On CT scan, a carcinoid tumor affecting the mesentery appears as a soft tissue mass with calcification and desmoplastic stranding, which produces a “sunburst” appearance. Another diagnostic tool is the octreotide scan, which is considered the test of choice due to its high sensitivity for detection of the tumor and metastases.8 The increase in somatostatin receptors seen with carcinoid tumors allows not only imaging by octreotide scan but also therapy using octreotide with larger doses of therapeutic radioactive agents.

Continue to: If tumor is operable, surgery is curative

If tumor is operable, surgery is curative

Surgery is the only curative therapy and is the mainstay of treatment for carcinoid tumors. Local segmental resection is generally adequate for tumors <2 cm without nodal involvement. However, tumors >2 cm with regional mesentery metastasis and nodal involvement require wide excision of the bowel and mesentery with lymph node dissection because of the associated higher incidence of metastasis.9 If the tumor has metastasized to the liver and is considered inoperable, radiolabeled octreotide or 131I-metaiodobenzylguanidine are potential treatment options for arresting tumor growth and improving survival rates.10

Our patient underwent an uncomplicated surgical resection of the mesenteric carcinoid tumor and adjacent small bowel, as well as lymph node dissection. Intraoperatively, there was no evidence of tumor elsewhere in the abdomen or pelvis, including the liver, ovaries, and other solid organs, suggesting probable metastasis from an occult primary site. The patient had an unremarkable postoperative course and was reported to be asymptomatic on follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Don N. Nguyen, MD, MHA, Dept. of Diagnostic Radiology, 320 E. North Ave., Pittsburgh, PA 15212; [email protected]

1. Pinchot SN, Holen K, Sippel RS, et al. Carcinoid tumors. Oncologist. 2008;13:1255-1269.

2. Modlin M, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003; 97:934-959.

3. Park I-S, Kye B-H, Kim H-S, et al. Primary mesenteric carcinoid tumor. J Korean Surg Soc. 2013;84:114-117.

4. Crocetti E, Paci E. Malignant carcinoids in the USA, SEER 1992–1999: an epidemiological study with 6830 cases. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2003;12:191-194.

5. Sonnet S, Wiesner W. Flush symptoms caused by a mesenteric carcinoid without liver metastases. JBR-BTR. 2002;85:254-256.

6. Levy AD, Sobin L. Gastrointestinal carcinoids: imaging features with clinicopathologic comparison. RadioGraphics. 2007;27:237-257.

7. Maroun J, Kocha W, Kvols L, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of carcinoid tumours. Part 1: the gastrointestinal tract. A statement from a Canadian National Carcinoid Expert Group. Curr Oncol. 2006;13:67-76.

8. Woodside KJ, Townsend CM, Mark Evers B. Current management of gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:742-756.

9. de Vries H, Verschueren RC, Willemse PH, et al. Diagnostic, surgical and medical aspect of the midgut carcinoids. Cancer Treat Rev. 2002;28:11-25.

10. Akerstrom G, Hellman P, Hessman O, et al. Management of midgut carcinoids. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:161-169.

A 64-year-old woman with no significant medical history presented to the emergency department with worsening intermittent abdominal pain and chronic diarrhea, which had increased in frequency over the prior 3 months. She had taken loperamide, which yielded mild symptomatic relief. A complete metabolic panel revealed no significant abnormalities, with a normal inflammatory marker and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

Physical examination revealed mild tenderness to palpation over the right hemiabdomen, but no rebound tenderness or guarding. An abdominal radiograph (FIGURE 1), computed tomography (CT) without contrast of the abdomen and pelvis (FIGURE 2), and a whole-body octreotide scan (FIGURE 3) were ordered.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Carcinoid tumor

Based on the patient’s symptoms and imaging studies, we suspected that she had a carcinoid tumor with mesenteric involvement. The CT showed a 2.6-cm mesenteric mass with a characteristic sunburst pattern and desmoplastic stranding, as well as numerous prominent retroperitoneal lymph nodes, suggestive of nodal involvement. The octreotide scan showed abnormal focal intense radiotracer uptake in the corresponding right lower quadrant mass, which confirmed our suspicion. There was no evidence of hepatic metastasis on the CT or octreotide scan.

Most common locations

Carcinoid tumors are the most common type of neuroendocrine tumors and are derived primarily from serotonin-producing enterochromaffin cells.1 These slow-growing, well-differentiated tumors usually originate in the gastrointestinal and bronchopulmonary tracts (67.5% and 25.3%, respectively), with uncommon primary sites involving the mesentery, ovaries, and kidneys.2 Generally, carcinoid tumors that arise in the mesentery are metastatic, often from an occult primary site. It has been reported that 40% to 80% of midgut carcinoid tumors spread to the mesentery.3

Carcinoid tumors are estimated to occur in 1.9 individuals per 100,000 annually.4 Traditionally, the appendix was cited as the most common location for these tumors. However, more recently, Modlin et al2 conducted a comprehensive analysis of epidemiologic data from the 13,715 carcinoid tumors registered in the National Cancer Institute database. Over the more than 25-year study period (1973-1999), Modlin and colleagues found a significant change in the distribution of gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors, with the incidence rates of small bowel (41.8%) and rectal carcinoids (27.4%) increasing, while appendiceal carcinoids decreased (24.1%).2

Gastrointestinal complications can arise from metastasis

Small bowel carcinoid tumors often manifest with intermittent abdominal pain, which can be caused by fibrosis of the mesentery, intestinal obstruction, or kinking of the bowel. Less common is the constellation of diarrhea, cutaneous flushing, and asthma seen with carcinoid syndrome. The prevalence of this syndrome is mediated by various humoral factors, the most notable of which is serotonin.

Continue to: Patients with carcinoid syndrome...

Patients with carcinoid syndrome often have metastasis to the liver, where serotonin is normally metabolized. This metastasis allows serotonin and other vasoactive substances to bypass hepatic metabolic degradation, resulting in the aforementioned symptoms. Carcinoid syndrome can also occur without hepatic metastasis in the setting of nodal involvement, which enables direct hormone release into the systemic circulation.5

Carcinoid syndrome affects fewer than 10% of patients with carcinoid tumors.6 Therefore, although carcinoid tumor should be suspected in patients with suggestive symptoms, other diagnoses must be considered.

Other disorders to consider on work-up

Chronic diarrhea and colicky abdominal pain are nonspecific features also associated with conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease and celiac disease, necessitating further work-up to elucidate the diagnosis.

Inflammatory bowel disease often involves elevated inflammatory markers, such as increased ESR and C-reactive protein.

Ulcerative colitis can show thickened and inflamed bowel walls on CT, with cross-sectional target appearance due to transmural involvement.

Continue to: Crohn's disease

Crohn’s disease usually affects the terminal ileum. CT is useful for identifying complications such as strictures/fistulas and abscesses.

Celiac disease involves elevated endomysial antibody and human tissue transglutaminase antibody. On CT, a characteristic jejunoileal fold pattern reversal can be seen.

A 24-hour urine test + imaging studies

The most useful diagnostic test for carcinoid tumor is the 24-hour urinary test for 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), the metabolic end-product of serotonin. The normal rate of 5-HIAA excretion ranges from 3 to 15 mg/d, whereas the rates of patients with carcinoid tumors may have elevated levels.7

What you’ll see. On CT scan, a carcinoid tumor affecting the mesentery appears as a soft tissue mass with calcification and desmoplastic stranding, which produces a “sunburst” appearance. Another diagnostic tool is the octreotide scan, which is considered the test of choice due to its high sensitivity for detection of the tumor and metastases.8 The increase in somatostatin receptors seen with carcinoid tumors allows not only imaging by octreotide scan but also therapy using octreotide with larger doses of therapeutic radioactive agents.

Continue to: If tumor is operable, surgery is curative

If tumor is operable, surgery is curative

Surgery is the only curative therapy and is the mainstay of treatment for carcinoid tumors. Local segmental resection is generally adequate for tumors <2 cm without nodal involvement. However, tumors >2 cm with regional mesentery metastasis and nodal involvement require wide excision of the bowel and mesentery with lymph node dissection because of the associated higher incidence of metastasis.9 If the tumor has metastasized to the liver and is considered inoperable, radiolabeled octreotide or 131I-metaiodobenzylguanidine are potential treatment options for arresting tumor growth and improving survival rates.10

Our patient underwent an uncomplicated surgical resection of the mesenteric carcinoid tumor and adjacent small bowel, as well as lymph node dissection. Intraoperatively, there was no evidence of tumor elsewhere in the abdomen or pelvis, including the liver, ovaries, and other solid organs, suggesting probable metastasis from an occult primary site. The patient had an unremarkable postoperative course and was reported to be asymptomatic on follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Don N. Nguyen, MD, MHA, Dept. of Diagnostic Radiology, 320 E. North Ave., Pittsburgh, PA 15212; [email protected]

A 64-year-old woman with no significant medical history presented to the emergency department with worsening intermittent abdominal pain and chronic diarrhea, which had increased in frequency over the prior 3 months. She had taken loperamide, which yielded mild symptomatic relief. A complete metabolic panel revealed no significant abnormalities, with a normal inflammatory marker and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

Physical examination revealed mild tenderness to palpation over the right hemiabdomen, but no rebound tenderness or guarding. An abdominal radiograph (FIGURE 1), computed tomography (CT) without contrast of the abdomen and pelvis (FIGURE 2), and a whole-body octreotide scan (FIGURE 3) were ordered.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Carcinoid tumor

Based on the patient’s symptoms and imaging studies, we suspected that she had a carcinoid tumor with mesenteric involvement. The CT showed a 2.6-cm mesenteric mass with a characteristic sunburst pattern and desmoplastic stranding, as well as numerous prominent retroperitoneal lymph nodes, suggestive of nodal involvement. The octreotide scan showed abnormal focal intense radiotracer uptake in the corresponding right lower quadrant mass, which confirmed our suspicion. There was no evidence of hepatic metastasis on the CT or octreotide scan.

Most common locations

Carcinoid tumors are the most common type of neuroendocrine tumors and are derived primarily from serotonin-producing enterochromaffin cells.1 These slow-growing, well-differentiated tumors usually originate in the gastrointestinal and bronchopulmonary tracts (67.5% and 25.3%, respectively), with uncommon primary sites involving the mesentery, ovaries, and kidneys.2 Generally, carcinoid tumors that arise in the mesentery are metastatic, often from an occult primary site. It has been reported that 40% to 80% of midgut carcinoid tumors spread to the mesentery.3

Carcinoid tumors are estimated to occur in 1.9 individuals per 100,000 annually.4 Traditionally, the appendix was cited as the most common location for these tumors. However, more recently, Modlin et al2 conducted a comprehensive analysis of epidemiologic data from the 13,715 carcinoid tumors registered in the National Cancer Institute database. Over the more than 25-year study period (1973-1999), Modlin and colleagues found a significant change in the distribution of gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors, with the incidence rates of small bowel (41.8%) and rectal carcinoids (27.4%) increasing, while appendiceal carcinoids decreased (24.1%).2

Gastrointestinal complications can arise from metastasis

Small bowel carcinoid tumors often manifest with intermittent abdominal pain, which can be caused by fibrosis of the mesentery, intestinal obstruction, or kinking of the bowel. Less common is the constellation of diarrhea, cutaneous flushing, and asthma seen with carcinoid syndrome. The prevalence of this syndrome is mediated by various humoral factors, the most notable of which is serotonin.

Continue to: Patients with carcinoid syndrome...

Patients with carcinoid syndrome often have metastasis to the liver, where serotonin is normally metabolized. This metastasis allows serotonin and other vasoactive substances to bypass hepatic metabolic degradation, resulting in the aforementioned symptoms. Carcinoid syndrome can also occur without hepatic metastasis in the setting of nodal involvement, which enables direct hormone release into the systemic circulation.5

Carcinoid syndrome affects fewer than 10% of patients with carcinoid tumors.6 Therefore, although carcinoid tumor should be suspected in patients with suggestive symptoms, other diagnoses must be considered.

Other disorders to consider on work-up

Chronic diarrhea and colicky abdominal pain are nonspecific features also associated with conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease and celiac disease, necessitating further work-up to elucidate the diagnosis.

Inflammatory bowel disease often involves elevated inflammatory markers, such as increased ESR and C-reactive protein.

Ulcerative colitis can show thickened and inflamed bowel walls on CT, with cross-sectional target appearance due to transmural involvement.

Continue to: Crohn's disease

Crohn’s disease usually affects the terminal ileum. CT is useful for identifying complications such as strictures/fistulas and abscesses.

Celiac disease involves elevated endomysial antibody and human tissue transglutaminase antibody. On CT, a characteristic jejunoileal fold pattern reversal can be seen.

A 24-hour urine test + imaging studies

The most useful diagnostic test for carcinoid tumor is the 24-hour urinary test for 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), the metabolic end-product of serotonin. The normal rate of 5-HIAA excretion ranges from 3 to 15 mg/d, whereas the rates of patients with carcinoid tumors may have elevated levels.7

What you’ll see. On CT scan, a carcinoid tumor affecting the mesentery appears as a soft tissue mass with calcification and desmoplastic stranding, which produces a “sunburst” appearance. Another diagnostic tool is the octreotide scan, which is considered the test of choice due to its high sensitivity for detection of the tumor and metastases.8 The increase in somatostatin receptors seen with carcinoid tumors allows not only imaging by octreotide scan but also therapy using octreotide with larger doses of therapeutic radioactive agents.

Continue to: If tumor is operable, surgery is curative

If tumor is operable, surgery is curative

Surgery is the only curative therapy and is the mainstay of treatment for carcinoid tumors. Local segmental resection is generally adequate for tumors <2 cm without nodal involvement. However, tumors >2 cm with regional mesentery metastasis and nodal involvement require wide excision of the bowel and mesentery with lymph node dissection because of the associated higher incidence of metastasis.9 If the tumor has metastasized to the liver and is considered inoperable, radiolabeled octreotide or 131I-metaiodobenzylguanidine are potential treatment options for arresting tumor growth and improving survival rates.10

Our patient underwent an uncomplicated surgical resection of the mesenteric carcinoid tumor and adjacent small bowel, as well as lymph node dissection. Intraoperatively, there was no evidence of tumor elsewhere in the abdomen or pelvis, including the liver, ovaries, and other solid organs, suggesting probable metastasis from an occult primary site. The patient had an unremarkable postoperative course and was reported to be asymptomatic on follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Don N. Nguyen, MD, MHA, Dept. of Diagnostic Radiology, 320 E. North Ave., Pittsburgh, PA 15212; [email protected]

1. Pinchot SN, Holen K, Sippel RS, et al. Carcinoid tumors. Oncologist. 2008;13:1255-1269.

2. Modlin M, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003; 97:934-959.

3. Park I-S, Kye B-H, Kim H-S, et al. Primary mesenteric carcinoid tumor. J Korean Surg Soc. 2013;84:114-117.

4. Crocetti E, Paci E. Malignant carcinoids in the USA, SEER 1992–1999: an epidemiological study with 6830 cases. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2003;12:191-194.

5. Sonnet S, Wiesner W. Flush symptoms caused by a mesenteric carcinoid without liver metastases. JBR-BTR. 2002;85:254-256.

6. Levy AD, Sobin L. Gastrointestinal carcinoids: imaging features with clinicopathologic comparison. RadioGraphics. 2007;27:237-257.

7. Maroun J, Kocha W, Kvols L, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of carcinoid tumours. Part 1: the gastrointestinal tract. A statement from a Canadian National Carcinoid Expert Group. Curr Oncol. 2006;13:67-76.

8. Woodside KJ, Townsend CM, Mark Evers B. Current management of gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:742-756.

9. de Vries H, Verschueren RC, Willemse PH, et al. Diagnostic, surgical and medical aspect of the midgut carcinoids. Cancer Treat Rev. 2002;28:11-25.

10. Akerstrom G, Hellman P, Hessman O, et al. Management of midgut carcinoids. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:161-169.

1. Pinchot SN, Holen K, Sippel RS, et al. Carcinoid tumors. Oncologist. 2008;13:1255-1269.

2. Modlin M, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003; 97:934-959.

3. Park I-S, Kye B-H, Kim H-S, et al. Primary mesenteric carcinoid tumor. J Korean Surg Soc. 2013;84:114-117.

4. Crocetti E, Paci E. Malignant carcinoids in the USA, SEER 1992–1999: an epidemiological study with 6830 cases. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2003;12:191-194.

5. Sonnet S, Wiesner W. Flush symptoms caused by a mesenteric carcinoid without liver metastases. JBR-BTR. 2002;85:254-256.

6. Levy AD, Sobin L. Gastrointestinal carcinoids: imaging features with clinicopathologic comparison. RadioGraphics. 2007;27:237-257.

7. Maroun J, Kocha W, Kvols L, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of carcinoid tumours. Part 1: the gastrointestinal tract. A statement from a Canadian National Carcinoid Expert Group. Curr Oncol. 2006;13:67-76.

8. Woodside KJ, Townsend CM, Mark Evers B. Current management of gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:742-756.

9. de Vries H, Verschueren RC, Willemse PH, et al. Diagnostic, surgical and medical aspect of the midgut carcinoids. Cancer Treat Rev. 2002;28:11-25.

10. Akerstrom G, Hellman P, Hessman O, et al. Management of midgut carcinoids. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:161-169.

Growth lateral to right eye

The FP noted a horn-like growth on the patient's face with some scaling around it. He recommended a shave biopsy. His differential diagnosis included actinic keratosis and Bowen’s disease (also known as squamous cell carcinoma in situ).

A biopsy was performed with a DermaBlade using a shave technique deep enough to get the base of the horn and a good sampling of the abnormal-looking tissue. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathology report revealed a cutaneous horn in a squamous cell carcinoma in situ.

The patient was referred to Dermatology for further treatment. Options included treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil (over weeks to months), standard excision, or Mohs surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Cutaneous horn. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:985-988.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP noted a horn-like growth on the patient's face with some scaling around it. He recommended a shave biopsy. His differential diagnosis included actinic keratosis and Bowen’s disease (also known as squamous cell carcinoma in situ).

A biopsy was performed with a DermaBlade using a shave technique deep enough to get the base of the horn and a good sampling of the abnormal-looking tissue. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathology report revealed a cutaneous horn in a squamous cell carcinoma in situ.

The patient was referred to Dermatology for further treatment. Options included treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil (over weeks to months), standard excision, or Mohs surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Cutaneous horn. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:985-988.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP noted a horn-like growth on the patient's face with some scaling around it. He recommended a shave biopsy. His differential diagnosis included actinic keratosis and Bowen’s disease (also known as squamous cell carcinoma in situ).

A biopsy was performed with a DermaBlade using a shave technique deep enough to get the base of the horn and a good sampling of the abnormal-looking tissue. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathology report revealed a cutaneous horn in a squamous cell carcinoma in situ.

The patient was referred to Dermatology for further treatment. Options included treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil (over weeks to months), standard excision, or Mohs surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Cutaneous horn. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:985-988.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Brown spot on cheek

The FP noted that the patient had a dominant brown patch on her right cheek that was larger and darker than the other light brown spots found on her face. Fortunately, he had a dermatoscope and examined the spot closely, finding only features of a benign solar lentigo. There were no suspicious features for melanoma.

The FP gave the patient a choice between a broad shave biopsy that day, or having the lesion monitored (safe with a flat lesion) using photography and dermoscopy.

The patient didn’t want a biopsy on her face and was willing to have the area monitored. The clinical and dermoscopic photographs were taken and stored. The patient was given a follow-up appointment in 4 to 6 months and instructions to avoid the sun as much as possible. She was also told to use sunscreen and hats when out in the sun.

After 5 months, the previous photos were compared with the new photos on a computer screen and there were no changes. Everyone was reassured, and the patient indicated that she was being careful about her sun exposure.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine, R. Lentigo maligna. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:981-984.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP noted that the patient had a dominant brown patch on her right cheek that was larger and darker than the other light brown spots found on her face. Fortunately, he had a dermatoscope and examined the spot closely, finding only features of a benign solar lentigo. There were no suspicious features for melanoma.

The FP gave the patient a choice between a broad shave biopsy that day, or having the lesion monitored (safe with a flat lesion) using photography and dermoscopy.

The patient didn’t want a biopsy on her face and was willing to have the area monitored. The clinical and dermoscopic photographs were taken and stored. The patient was given a follow-up appointment in 4 to 6 months and instructions to avoid the sun as much as possible. She was also told to use sunscreen and hats when out in the sun.

After 5 months, the previous photos were compared with the new photos on a computer screen and there were no changes. Everyone was reassured, and the patient indicated that she was being careful about her sun exposure.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine, R. Lentigo maligna. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:981-984.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP noted that the patient had a dominant brown patch on her right cheek that was larger and darker than the other light brown spots found on her face. Fortunately, he had a dermatoscope and examined the spot closely, finding only features of a benign solar lentigo. There were no suspicious features for melanoma.

The FP gave the patient a choice between a broad shave biopsy that day, or having the lesion monitored (safe with a flat lesion) using photography and dermoscopy.

The patient didn’t want a biopsy on her face and was willing to have the area monitored. The clinical and dermoscopic photographs were taken and stored. The patient was given a follow-up appointment in 4 to 6 months and instructions to avoid the sun as much as possible. She was also told to use sunscreen and hats when out in the sun.

After 5 months, the previous photos were compared with the new photos on a computer screen and there were no changes. Everyone was reassured, and the patient indicated that she was being careful about her sun exposure.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine, R. Lentigo maligna. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:981-984.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.